Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 15/77/05. The contractual start date was in August 2016. The final report began editorial review in September 2017 and was accepted for publication in January 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Karen Spilsbury is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Hanratty et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

NHS England’s ‘vanguard programme’ has been leading on innovating and integrating services to meet the changing needs of local populations. Four categories of vanguard site were defined: integrated primary and acute care systems, multispecialty community providers, urgent and emergency care systems, and care for older people living in care homes. This evidence synthesis aims to provide empirical underpinning for the innovation that is already under way in the six vanguard care home sites. It will also contribute to the evolution and refinement of new care models as they are developed, evaluated and disseminated across the NHS and social care.

The mixed economy in the care home sector poses unique challenges to the integration of services. The funding of care homes, resident care and in-reach services is a mix of public and private. The majority of care homes are commercial bodies that must work across organisational and disciplinary boundaries, and liaise with state-funded health and social care services, independent professionals, social enterprises and charities. 1 Residents of care homes have increasingly complex health-care needs. Levels of multimorbidity, frailty and disability are rising as the care home population ages. 2 Across the care home sector, recruiting and retaining the nursing and support workforce and high staff turnover are ongoing challenges. Technology offers many potential benefits to care and communication, but the availability and uptake of this are variable. Over recent years, a consensus has emerged that services for care home residents need to improve in a range of ways. These include better access to co-ordinated and multidisciplinary care, partnership working,3 enhanced dignity and privacy, and staffing levels matched to the needs of residents. 3,4 The vanguard programme is part of the policy response to these identified needs. It aims to develop and evaluate new models of care, with a renewed emphasis on prevention, active rehabilitation and health promotion in care homes. This is expected to enhance well-being while also reducing resource use. 5

This report presents the findings from a rapid synthesis of the evidence on enhancing health in care homes through the organisation, delivery and quality of services to care home residents. The six vanguard care home sites are, and have been, developing locally appropriate services that have potential for national replicability, adaption and spread. To maximise the benefit to the wider NHS from the investment in this programme, it is important that innovation is followed by dissemination, and underpinned, when possible, by existing evidence. A review now is timely to ensure that any changes that are spread across the NHS are grounded in evidence-based good practice. Gaps in our knowledge also need to be identified for ongoing evaluation and research. Vanguard sites are being encouraged to learn from international experience. Our review will provide an objective, critical synthesis of relevant findings from other countries that aims to help vanguard sites and others to consider novel ways of working and radical change to enhance care.

Our work is focused around four inter-related issues: technology, communication and engagement, workforce and evaluation. These are key enablers of care home vanguard success, as identified in early guidance for vanguard sites. 6 They are also expected to be enduring issues with relevance to other settings. By considering some of the issues pertinent to developing and evaluating new models of care in and with the care home sector, this work aims to inform the ongoing work of the vanguard programme to meet the challenges of commissioning and delivering care across a range of providers.

The term ‘care home’ is used in this report to describe residential care for older adults in facilities with registered nurses (RNs) on site (nursing homes) and those without (residential care). Under this umbrella term, we have considered research on similar settings in high-income countries.

Chapter 2 Aims and objectives

The aim of this review was to identify and synthesise evidence underpinning new models of care to enhance health in care homes. The focus was in four key areas: technology, communication and engagement, workforce and evaluation.

Objectives

Our objectives were to:

-

identify the potential uses, benefits and challenges of technology in care homes and for enhancing communication between care homes and partner organisations (what is the impact of technology, who benefits and how?)

-

identify flexible uses of the nursing and support workforce, and innovative ways of working and retaining staff to benefit resident care

-

identify and critically describe the key characteristics and benefits of effective communication and engagement between care homes, communities and other health-related organisations, including barriers to and facilitators of the initiation and maintenance of successful relationships

-

summarise existing evidence on approaches to the evaluation of new models of care in care homes, including an assessment of the quality of care received by residents.

Specification of questions for rapid systematic reviews

We worked with the vanguard sites to ensure that we specified questions for review that were relevant to commissioners, providers and front-line staff. After completing the mapping reviews, we identified a range of potential questions for each of the four themes (technology, communication and engagement, workforce and evaluation) that could be answered by a focused evidence synthesis. An interactive workshop with representatives of the vanguard sites and NHS England was held to prioritise single questions for each theme. The potential questions are shown in Appendix 1. The selected questions are as follows:

-

Technology – which technologies have a positive impact on resident health and well-being?

-

Communication and engagement – how should care homes and the NHS communicate to enhance resident, family and staff outcomes and experiences?

-

Evaluation – which measurement tools have been validated for use in UK care homes?

-

Workforce – what is the evidence that staffing levels (i.e. ratio of RNs and support staff to residents or different levels of support staff) influence resident outcomes?

Chapter 3 Methods: overview

For each of the four themes, the evidence synthesis comprised two stages: (1) a broad mapping review of published material within the theme and (2) a systematic review that addressed a specific question. The general methods for each are described in this chapter, including details of the how the methods were tailored to each specific theme.

Literature searches

Two information scientists developed the search strategies. They combined relevant search terms with indexed keywords [such as medical subject headings (MeSH)] and text terms that appeared in the titles and/or abstracts of database records. The searches were applied to selected, specific databases for each topic, in addition to a common set of databases that included MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Science Citation Index, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) and the Index to Theses. Searches were restricted to studies published in English between 2000 and 2016 in high-income countries (see Appendix 2). Grey literature and unpublished studies were sought via GoogleTM (Mountain View, CA. USA) and websites of organisations relevant to each search.

Technology searches also included PsycINFO, the Association of Computing Machinery’s Digital Library and IEEE Xplore® Digital Library, alongside the following grey literature resources: ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, NHS Evidence, Health Management Information Consortium, The King’s Fund, Nuffield Trust, Health Foundation, Social Care Institute for Excellence, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, and Archiv.org.

Communication and engagement searches included PsycINFO, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Health Technology Assessment, NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) and Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA). Grey literature searches were not undertaken.

Workforce searches included Arts and Humanities Citation Index and ASSIA. In addition, grey literature sources included Google, GreyLit.org, Theses Canada, Open Grey, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses, Care Quality Commission, Age UK, Alzheimer’s Society, Nuffield Trust, Carers UK, Abbeyfield, The King’s Fund, National Institute for Health Research School for Social Care, Personal Social Services Research Unit, Royal College of Nursing, Vanguards and the Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Evaluation searches included Cochrane Database of Methods Studies, CENTRAL, Health Technology Assessment, NHS EED and PsycINFO. Grey literature sources included Google, Joseph Rowntree Foundation, Kellogg, The King’s Fund, Nuffield Trust, ProQuest, RAND Corporation, Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and Social Care Online.

References and abstracts of journal articles and grey literature were downloaded into an EndNote X7 (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA) library and deduplication was undertaken. Two researchers screened titles and abstracts for initial inclusion. Initial screening was undertaken in EndNote or Rayyan (Mourad Ouzzani, Hossam Hammady, Zbys Fedorowicz, and Ahmed Elmagarmid. Rayyan – a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews 2016;5:210); the latter is a web application for title and abstract screening for systematic reviews. 7 The criteria used across all four mapping reviews were inclusive. By allowing any study design or outcome, the review team were able to fully scope the available evidence base. Full papers were retrieved for all studies that met the broad criteria and were of potential relevance to the mapping review. All papers retrieved were further scrutinised to obtain a final set of papers for inclusion in the mapping review.

Mapping review: broad inclusion criteria

Technology

Any study concerning the use of novel digital technology to enhance health and well-being in care homes, encompassing novel technologies as well as established technologies that are new to the care home setting, which reported staff, resident or service outcomes and/or barriers and facilitators.

Communication and engagement

The focus of eligible studies was communication or engagement between more than one care home, or between care homes and communities or health-related organisations. Studies also needed to report one of the following outcomes:

-

a measure of communication or engagement external to the care home (i.e. studies of communication between patients and/or staff only within a care home were not included)

-

resident outcomes (e.g. quality of care, health and safety, clinical outcomes)

-

staff outcomes (e.g. well-being, safety, satisfaction).

Workforce

Studies that report on new staff roles (e.g. a NHS ‘in-reach’ role in a care home or an enhanced role for support workers in the home) or report on staffing levels in care homes. Studies were also required to report one or more of the following outcomes:

-

resident outcomes – health status, improvement or maintenance of functional ability, activities of daily living (ADL), falls, mortality, quality of life or well-being measures

-

staff outcomes – well-being, satisfaction or recruitment and retention

-

service use outcomes – on use of external NHS and social care, or other, services and care home organisation or profits/commercial success

-

impacts on relationships or integration between care homes and partner organisations.

Evaluation

Studies including tools for measuring quality of care, or aspects of patient health or quality of life, validated in a UK care home, that reported any of the following outcomes: (1) resident outcomes (health status, improvement or maintenance of functional ability, ADL, falls, mortality, quality of life or well-being measures) and (2) methods of care quality assessment.

Mapping review: data extraction

Information was extracted from each study into a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet. The data included citation, location (country) of study, study design, target population, name and brief details of the intervention. Mapping data extraction was conducted by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer.

Data extraction: technology mapping

Data were also extracted on the presence of an assessment of the costs of, barriers to, and facilitators of, the implementation and acceptability of the technologies. For each of the mapped studies, the interventions were listed, and descriptive categories were developed from this list: digital records, telehealth, surveillance and monitoring, robots, communication (excluding telemedicine or telehealth interventions), education and gaming. An eighth category (technologies) was used for the heterogeneous mix of studies that did not fall into any of the preceding seven categories.

Data extraction: communication and engagement mapping

Data were also extracted on target population (whether in the care home or communication partner) and setting of communication partner (e.g. another care home or a hospital emergency department), and outcomes were separated according to whether they related to communication or engagement, care home residents, staff or organisation.

Data extraction: workforce mapping

Outcomes were classified as relating to staff, residents or services.

Data extraction: evaluation mapping

Additional data extracted included sample size, sample characteristics, description of the intervention and control comparator conditions, outcomes and outcome measures used, and results.

Mapping review: synthesis

Mapping findings were tabulated in tables and narratively. These results were presented to the vanguard group and used to help formulate potential review questions for each theme. A range of potential questions for each of the four themes (technology, communication and engagement, workforce and evaluation) were derived that could be answered with a focused evidence synthesis. An interactive workshop with representatives of the vanguard sites and NHS England was held to prioritise single questions for each theme.

Systematic review questions

-

Technology: which technologies have a positive impact on resident health and well-being?

-

Communication and engagement: how should care homes and the NHS communicate to enhance resident, family and staff outcomes and experiences?

-

Evaluation: which measurement tools have been validated for use in UK care homes?

-

Workforce: what is the evidence that staffing levels (i.e. ratio of RNs and support staff to residents or different levels of support staff) influence resident outcomes?

The systematic reviews were conducted according to the principles outlined in Centre for Reviews and Dissemination’s guidance on the conduct of systematic reviews8 and reported following the guidance of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. 9 The protocols were written in accordance with the new PRISMA-P initiative10 and registered on PROSPERO, the international database of prospectively registered systematic reviews in health and social care (www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

After being mapped, papers were screened once more (independently by two reviewers) to identify those that met the criteria for inclusion for each systematic review. For three of the themes (communication and engagement, evaluation and workforce), additional focused searches were conducted to ensure that the material included in the review was comprehensive.

The inclusion criteria for each systematic review are now outlined.

Technology review

Types of participants

Studies had to be focused on care homes, nursing homes or residential aged care facilities.

Intervention

The intervention of interest was equipment or methods that incorporate digital technology (any electrical device that can store, generate and transfer data) to enhance health and well-being in care homes, encompassing novel technologies as well as established technologies that are new to the care home setting.

Outcomes

The relevant outcome was care home residents’ health, functional ability or well-being.

Study design

Relevant study designs included randomised controlled trials (RCTs) (including parallel-group trials, cluster randomised trials and crossover trials) and non-randomised controlled studies.

Communication and engagement review

Types of participants

Studies had to be focused on care homes, nursing homes or residential aged care facilities; the communication partner could be a hospital, another health-related organisation or a community health partner.

Intervention

The intervention of interest was some form of tool that improved communication or an explicit statement that that the study was focusing on communication between care homes and other health-related organisations. Studies were excluded if the focus of communication was not relevant to the UK (e.g. US Medicaid or Medicare processes).

Outcomes

Communication or engagement outcomes, for example staff views on communication, resident outcomes (health/well-being, safety and quality of care) and/or staff outcomes (well-being, safety and satisfaction).

Study design

Randomised controlled trials, cluster RCTs, quasi-experimental studies, interrupted time series and pre- and post-intervention studies.

Workforce review

Types of participants

The populations of interest were staff and residents from a care home setting. The term ‘staff’ included people paid a salary or wage (not volunteers) within any of the following categories: (1) people employed directly by care homes, (2) staff employed by the NHS, excluding pharmacist interventions, (3) staff of local authority social services and (4) staff of private providers. Relevant staff employed by care homes included (1) registered or licensed nurses; (2) personnel providing personal care and support with ADL and instrumental ADL who are not registered or licensed nurses – job titles may include care assistant, nursing assistant (NA), auxiliary and social care worker; (3) care home managers; and (4) personnel who provide and/or direct activities in the home.

Intervention

The intervention of interest was staffing levels, which was defined as the ratio of RNs and support staff to residents or different levels of support staff, and the role mix of staff within nursing homes.

Outcomes

Relevant resident outcomes were one or more of the following: health status, quality of life or well-being measures, improvement or maintenance of functional ability (e.g. ADL), adverse events (e.g. falls), health service utilisation and mortality. Relevant staff outcomes were measures of health, well-being, satisfaction or recruitment/retention/turnover.

Study design

Relevant study designs were systematic reviews, RCTs, non-randomised trials, primary and secondary cohort/panel studies and cross-sectional studies.

Evaluation review

Types of participants

The population of interest was residents, families, carers or staff from a care home setting.

Intervention

The intervention of interest included approaches to the evaluation of new models of care in care homes, and approaches to the assessment of the quality of care received by care home residents.

Outcomes

Relevant outcomes were (1) resident outcomes (health status, improvement or maintenance of functional ability, ADL, falls, mortality, quality of life or well-being measures) and (2) methods of care quality assessment.

Study design

All comparative studies were considered eligible.

Data extraction and quality assessment

For all reviews, data extraction was conducted by one researcher and checked by a second researcher for accuracy, with any discrepancies resolved by discussion or consultation with a third researcher when necessary. A standardised data extraction form for each review was developed, piloted on an initial sample of papers and refined as necessary. Data extracted included study citation, country of origin, design, sample size, sample characteristics, description of the intervention and control comparator conditions, outcomes and outcome measures used, and findings. All data extraction was undertaken in Microsoft Excel.

Quality assessment was undertaken alongside the data extraction. The quality of RCTs was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool, which focuses on the domains shown to have an impact on the trial results in particular (selection, performance and detection biases and attrition). 11 All and non-RCTs (observational studies) were assessed using the ROBINS-I (Risk of Bias In Non-Randomised Studies – of Interventions) tool, which also focuses on the bias domains likely to have an impact on results (selection, measurement, performance, attrition, detection and outcome). 12 Both tools focus on the internal validity of a study. Discrepancies between reviewers’ ratings were resolved through discussion. For some interventions considered, the blinding of participants would have been impractical and the blinding of assessors would have been challenging. For this reason, ratings of the measurement of outcome data were considered to be less important. Most of the studies were given a low quality score in this domain. To summarise the ratings from the ROBINS-I, each domain was judged to exhibit low, moderate, serious or critical risk of bias. Low risk of bias indicates that the study is comparable with a well-performed randomised trial in the domain being evaluated. Moderate risk of bias indicates that the study is sound for a non-randomised study but not comparable with a rigorous randomised trial. Serious risk of bias indicates the presence of important problems, and critical risk of bias indicates that the study is too problematic to provide any useful evidence on the effects of intervention. If insufficient information is provided to determine the risk of bias of a certain domain, the domain is marked as having no information.

Data synthesis

Data from the individual studies were tabulated and discussed in a narrative overview. Owing to the nature of the available evidence, a quantitative analysis of the results, including a meta-analysis, was not appropriate. There was extensive heterogeneity in study design, settings and outcome measures across the included studies.

Chapter 4 Mapping and rapid evidence syntheses

In the following sections, the findings are presented from four mapping reviews and four rapid, systematic evidence syntheses. The mapping reviews are broad-ranging and intended to provide a flexible and interactive resource. In this report, the data are tabulated for information. For dissemination purposes, they will be made available in a colourful, diagrammatic and interactive format.

Section 1: digital technology interventions and care home residents’ health, well-being and functional status

Background

Digital technology is expected to play an increasingly important role in enhancing the health, well-being and safety of care home residents. The list of potential applications of technology in this setting is long, and includes remote monitoring, communication between care homes and external agencies and families, medicines optimisation, assistive technologies and the promotion of physical and social activity. 13 Recent developments have focused in particular on the introduction of platforms that link electronic health and care data records,14,15 tools for remote consultation and diagnosis, sensor-based technologies that monitor movement and physical activity16,17 and social robots that act as companions or serve to support ADL. 18

Research in this field has accumulated rapidly over the last 10 years, but a clear message on the most acceptable, effective and cost-effective choices for care home residents, providers and commissioners has yet to emerge. Previous evidence syntheses have examined the effectiveness of individual technologies (e.g. robotic pets, sensors and telehealth), specific outcomes (e.g. wandering, falls)19–22 and the implementation of complex infrastructure information technology (IT) systems. Telemedicine in long-term care has been used to enable a range of medical specialists to provide advice in care homes. 21,23 Existing reviews of the evidence suggest that this is a feasible approach, but this work is dominated by qualitative and descriptive studies of service utilisation and staff satisfaction. Similarly, a review of the use of gaming technologies in long-term care settings points to positive effects on physical and social activity and a potential role in rehabilitation, but the six included studies were mainly descriptive or small. 24 Wearable or environmental sensors have multiple potential uses in residential care: they detect movement by pressure, position and infrared light, and can alert staff that a resident has risen from a chair or got out of bed and may be at risk of falling. A recent systematic review of the effectiveness of sensors in geriatric institutions described a high rate of false alarms and inconsistent findings, and only 1 of the 12 included studies was conducted in a care home. 20 Robots in older adult care have also attracted a great deal of attention from researchers and practitioners. They can be divided into two groups: rehabilitative robots that are designed to support physical assistive technology and are not interactive (e.g. smart wheelchairs and artificial limbs) and assistive robots that either support ADL or have a companion function. Research generally reports positive findings for the impact of robots on older people’s well-being. Kachouie’s review of social assistive robots25 also suggested that these may have potential to reduce nurses’ workload. However, this work identified limitations common to many existing studies, including a failure to consider cultural and linguistic sensitivities or to elicit participants’ expectations or perceptions, a gender bias among research participants (the majority are older women), little work with residents’ families, and methodological concerns about study design, conduct and reporting. 25

Previous research has provided useful insights, but important gaps remain in our understanding of the value, impact and best use of digital technology in care homes. Care home organisations are interested in the potential of technology to enhance quality of life, boost social interaction and enhance resident safety. Policy-makers and commissioners may also wish to advocate for the use of technology to increase efficiency and reduce demands on health services. All are faced with a disparate body of evidence from a wide range of sources, some of which is relevant to long-term care. Previous reviews of the evidence have synthesised research from across different care settings and have included qualitative, non-experimental and small-scale studies that provide useful information on the acceptability of and satisfaction with technological interventions, but are an uncertain basis for resource allocation decisions. Care homes and their residents are unique in many ways, and it cannot be assumed that an intervention that is suitable for the community can be readily transferred to a care home. To our knowledge, no review has focused exclusively on technological interventions in care homes.

The aim of this work was to (1) map the existing evidence on the use and outcomes of digital technology interventions in care homes, describe the body of work, and identify gaps in our understanding and areas where evidence is strong; and (2) conduct a focused systematic review on the impact of digital technology interventions on the health, well-being and functional status of care home residents.

Methods

See Chapter 3 for details of methods.

Findings of mapping review

Which technologies have a positive impact on resident health and well-being?

Number and characteristics of studies

After deduplication, 6240 studies were identified for title and abstract screening, and 338 were identified for full-text screening. In total, 281 articles were included in the mapping review, listed in Table 1. Basic data on all of the studies in this mapping review are presented in Report Supplementary Material 1,Table 1.

| First author | Year of publication | Review |

|---|---|---|

| Abdelrahman26 | 2015 | Technology |

| Age UK27 | 2013 | Technology |

| Age UK28 | 2010 | Technology |

| Age UK29 | 2012 | Technology |

| Alexander30 | 2009 | Technology |

| Alexander31 | 2015 | Technology |

| Alexander32 | 2016 | Technology |

| Aloulou33 | 2013 | Technology |

| Alzheimer’s Society34 | 2011 | Technology |

| Alzheimer’s Society35 | 2015 | Technology |

| Anonymous36 | 2009 | Technology |

| Anonymous37 | 2011 | Technology |

| Anonymous38 | 2010 | Technology |

| Anonymous39 | 2008 | Technology |

| Anonymous40 | 2009 | Technology |

| Anonymous41 | 2013 | Technology |

| Babalola42 | 2014 | Technology |

| Bäck43 | 2013 | Technology |

| Bäck44 | 2012 | Technology |

| Baker45 | 2015 | Technology |

| Bakerjian46 | 2009 | Technology |

| Banks47 | 2008 | Technology |

| Banks48 | 2013 | Technology |

| Barbour49 | 2016 | Technology |

| Baril50 | 2014 | Technology |

| Baril51 | 2014 | Technology |

| Barrett52 | 2009 | Technology |

| Bartle53 | 2017 | Technology |

| Beeckman54 | 2013 | Technology |

| Beedholm55 | 2016 | Technology |

| Bemelmans19 | 2012 | Technology |

| Bemelmans56 | 2015 | Technology |

| Bemelmans57 | 2016 | Technology |

| Bennett58 | 2015 | Technology |

| Bennett59 | 2016 | Technology |

| Bereznicki60 | 2014 | Technology |

| Bezboruah61 | 2014 | Technology |

| Biglan62 | 2011 | Technology |

| Biglan63 | 2009 | Technology |

| Blair Irvine64 | 2012 | Technology |

| Bobillier Chaumon65 | 2014 | Technology |

| Bollen66 | 2005 | Technology |

| Bond67 | 2000 | Technology |

| Bowen68 | 2013 | Technology |

| Brandt69 | 2011 | Technology |

| Brankline70 | 2009 | Technology |

| Bratan71 | 2004 | Technology |

| Braun72 | 2014 | Technology |

| Broadbent73 | 2016 | Technology |

| Broder74 | 2015 | Technology |

| Brown75 | 2000 | Technology |

| Bruun-Pedersen76 | 2015 | Technology |

| Burdea77 | 2015 | Technology |

| Burns78 | 2007 | Technology |

| Bygholm79 | 2014 | Technology |

| Campbell80 | 2011 | Technology |

| Campbell81 | 2017 | Technology |

| Castle82 | 2009 | Technology |

| Centre for Workforce Intelligence83 | 2013 | Technology |

| Chae84 | 2001 | Technology |

| Chan85 | 2000 | Technology |

| Chan86 | 2001 | Technology |

| Chang87 | 2013 | Technology |

| Chang88 | 2014 | Technology |

| Chang89 | 2015 | Technology |

| Chen90 | 2012 | Technology |

| Cherry91 | 2011 | Technology |

| Chesler92 | 2015 | Technology |

| Clark93 | 2009 | Technology |

| Cobb94 | 2007 | Technology |

| Courtney95 | 2006 | Technology |

| Centre for Policy on Ageing96 | 2014 | Technology |

| Curyto97 | 2002 | Technology |

| Daly98 | 2005 | Technology |

| Damant99 | 2015 | Technology |

| De Luca100 | 2016 | Technology |

| De Luca101 | 2016 | Technology |

| de Veer102 | 2011 | Technology |

| Degenholtz103 | 2008 | Technology |

| Degenholtz104 | 2010 | Technology |

| Degenholtz105 | 2011 | Technology |

| Degenholtz106 | 2016 | Technology |

| Demiris107 | 2008 | Technology |

| Demiris108 | 2013 | Technology |

| Dewsbury109 | 2012 | Technology |

| Dorsten110 | 2009 | Technology |

| Doshi-Velez111 | 2012 | Technology |

| Driessen112 | 2016 | Technology |

| Eccles113 | 2012 | Technology |

| Edirippulige23 | 2013 | Technology |

| Elliott114 | 2016 | Technology |

| Eyers115 | 2013 | Technology |

| Field116 | 2008 | Technology |

| Filipova117 | 2015 | Technology |

| Fossum118 | 2011 | Technology |

| Fossum119 | 2012 | Technology |

| Fournier120 | 2004 | Technology |

| Freedman121 | 2005 | Technology |

| Fu122 | 2015 | Technology |

| Gaver123 | 2011 | Technology |

| Gerling124 | 2012 | Technology |

| Gerling125 | 2015 | Technology |

| Ghorbel126 | 2013 | Technology |

| Gietzelt127 | 2014 | Technology |

| Grabowski128 | 2014 | Technology |

| Grant129 | 2014 | Technology |

| Guilfoyle130 | 2003 | Technology |

| Guilfoyle131 | 2002 | Technology |

| Hamada132 | 2008 | Technology |

| Handler133 | 2013 | Technology |

| Hardy134 | 2016 | Technology |

| Harrington135 | 2003 | Technology |

| Hensel136 | 2006 | Technology |

| Hensel137 | 2007 | Technology |

| Hensel138 | 2009 | Technology |

| Hex139 | 2015 | Technology |

| Hitt140 | 2016 | Technology |

| Hobday141 | 2010 | Technology |

| Hoey142 | 2010 | Technology |

| Hofmeyer143 | 2016 | Technology |

| Hori144 | 2004 | Technology |

| Hori145 | 2006 | Technology |

| Hoti146 | 2012 | Technology |

| Hsu147 | 2011 | Technology |

| Hui148 | 2001 | Technology |

| Hui149 | 2002 | Technology |

| Hung150 | 2007 | Technology |

| Hustey151 | 2009 | Technology |

| Hustey152 | 2010 | Technology |

| Hustey153 | 2012 | Technology |

| Iio154 | 2014 | Technology |

| Irvine155 | 2012 | Technology |

| Irvine156 | 2012 | Technology |

| Jiang157 | 2014 | Technology |

| Johansson-Pajala158 | 2016 | Technology |

| Johnston159 | 2001 | Technology |

| Jøranson160 | 2015 | Technology |

| Jøranson161 | 2015 | Technology |

| Jøranson162 | 2016 | Technology |

| Jung163 | 2009 | Technology |

| Kachouie25 | 2014 | Technology |

| Kanstrup164 | 2015 | Technology |

| Kapadia165 | 2015 | Technology |

| Keogh166 | 2014 | Technology |

| Khosla167 | 2012 | Technology |

| Khosla168 | 2013 | Technology |

| Kidd169 | 2006 | Technology |

| Kidd21 | 2010 | Technology |

| Knapp170 | 2015 | Technology |

| Kong171 | 2012 | Technology |

| Kosse20 | 2013 | Technology |

| Lai172 | 2015 | Technology |

| Lattanzio173 | 2014 | Technology |

| Lawrence174 | 2010 | Technology |

| Lesnoff-Caravaglia175 | 2005 | Technology |

| Libin176 | 2004 | Technology |

| Lin177 | 2014 | Technology |

| Little178 | 2016 | Technology |

| Loh179 | 2009 | Technology |

| Loveday16 | 2016 | Technology |

| Low180 | 2013 | Technology |

| Lyketsos181 | 2001 | Technology |

| MacDonald182 | 2005 | Technology |

| Maiden183 | 2013 | Technology |

| Mansdorf184 | 2009 | Technology |

| Mariño185 | 2016 | Technology |

| Marston24 | 2013 | Technology |

| Martin-Khan186 | 2012 | Technology |

| McDonald187 | 2012 | Technology |

| McGibbon188 | 2013 | Technology |

| McNeil189 | 2013 | Technology |

| Meador190 | 2009 | Technology |

| Meißner191 | 2014 | Technology |

| Michel-Verkerke192 | 2012 | Technology |

| Mickus193 | 2002 | Technology |

| Millington194 | 2015 | Technology |

| Miskelly195 | 2004 | Technology |

| Mitzner196 | 2014 | Technology |

| Morley197 | 2012 | Technology |

| Morley198 | 2016 | Technology |

| Morrissey199 | 2015 | Technology |

| Moyle200 | 2013 | Technology |

| Moyle201 | 2013 | Technology |

| Moyle202 | 2015 | Technology |

| Moyle203 | 2017 | Technology |

| Munyisia204 | 2012 | Technology |

| Munyisia205 | 2011 | Technology |

| Munyisia206 | 2013 | Technology |

| Murphy207 | 2005 | Technology |

| My Home Life208 | 2012 | Technology |

| Naganuma209 | 2015 | Technology |

| Nagayama210 | 2016 | Technology |

| Nakai211 | 2000 | Technology |

| Namazi212 | 2003 | Technology |

| Niemeijer213 | 2011 | Technology |

| Niemeijer214 | 2014 | Technology |

| Niemeijer215 | 2015 | Technology |

| Novek216 | 2000 | Technology |

| Oliver217 | 2006 | Technology |

| Oliver218 | 2010 | Technology |

| Pallawala219 | 2001 | Technology |

| Park220 | 2012 | Technology |

| Pillemer221 | 2009 | Technology |

| Pillemer222 | 2012 | Technology |

| Potts223 | 2011 | Technology |

| Qadri224 | 2009 | Technology |

| Qian225 | 2015 | Technology |

| Rabinowitz226 | 2010 | Technology |

| Rantz227 | 2010 | Technology |

| Rantz228 | 2013 | Technology |

| Rantz229 | 2015 | Technology |

| Rantz230 | 2017 | Technology |

| Ratliff231 | 2005 | Technology |

| Remington232 | 2015 | Technology |

| Richardson233 | 2014 | Technology |

| Robinson22 | 2006 | Technology |

| Robinson234 | 2007 | Technology |

| Robinson235 | 2013 | Technology |

| Robinson236 | 2013 | Technology |

| Robinson237 | 2015 | Technology |

| Robinson238 | 2016 | Technology |

| Rochon239 | 2006 | Technology |

| Rosen240 | 2002 | Technology |

| Rosen241 | 2003 | Technology |

| Rudston242 | 2013 | Technology |

| Russell243 | 2015 | Technology |

| Šabanović244 | 2013 | Technology |

| Sabelli245 | 2011 | Technology |

| Sanctuary Care246 | 2016 | Technology |

| Sävenstedt247 | 2003 | Technology |

| Sävenstedt248 | 2004 | Technology |

| Schneider249 | 2016 | Technology |

| Shibata250 | 2004 | Technology |

| Sicurella251 | 2016 | Technology |

| Silverman252 | 2006 | Technology |

| Smith253 | 2014 | Technology |

| South East Health Technologies Alliance254 | 2016 | Technology |

| Specht255 | 2001 | Technology |

| Spiro256 | 2005 | Technology |

| Stephens257 | 2015 | Technology |

| Sugihara258 | 2015 | Technology |

| Sung259 | 2015 | Technology |

| Tabar260 | 2015 | Technology |

| Tak261 | 2007 | Technology |

| Tak262 | 2008 | Technology |

| Tak263 | 2012 | Technology |

| Tak264 | 2013 | Technology |

| Tang265 | 2001 | Technology |

| Thorpe-Jamison266 | 2013 | Technology |

| Tinder Foundation267 | 2016 | Technology |

| Tiwari268 | 2011 | Technology |

| Toh269 | 2015 | Technology |

| Toh270 | 2015 | Technology |

| Torres-Padrosa271 | 2011 | Technology |

| Trinkle272 | 2003 | Technology |

| Tseng273 | 2013 | Technology |

| Van der Ploeg274 | 2016 | Technology |

| Vandenberg275 | 2015 | Technology |

| Vogelsmeier276 | 2007 | Technology |

| Vowden277 | 2013 | Technology |

| Wagner278 | 2004 | Technology |

| Wagner279 | 2001 | Technology |

| Wakefield280 | 2004 | Technology |

| Walker281 | 2006 | Technology |

| Walker282 | 2008 | Technology |

| Wang283 | 2011 | Technology |

| Webster284 | 2014 | Technology |

| Weiner285 | 2002 | Technology |

| Weiner286 | 2004 | Technology |

| Welsh287 | 2010 | Technology |

| Wigg288 | 2010 | Technology |

| Yu289 | 2006 | Technology |

| Yu290 | 2007 | Technology |

| Yu291 | 2013 | Technology |

| Zelickson292 | 2003 | Technology |

| Zhang293 | 2012 | Technology |

| Zhang294 | 2016 | Technology |

| Zhuang295 | 2013 | Technology |

| Zwijsen296 | 2010 | Technology |

| Zwijsen297 | 2012 | Technology |

Countries

The USA was the setting for around two-fifths of the work (114 studies). 26,30–32,36,42,46–49,64,67–70,74,75,77,82,87–89,91,93–95,97,98,103–108,110–112,117,120,121,128,129,133,134,136–138,140,141,143,151–153,155,156,159,172,175,176,178,181,184,189,190,192,196–198,212,217,218,221,222,224,226–233,239–241,243,244,250,252,255,257,260–264,266,272,276,278–282,285,286 A further 94 (33%) studies were from high-income countries outside the USA and Europe. 19,23–25,33,37–41,50–52,61,62,66,73,78,81,84–86,90,92,101,114,116,122,125,130–132,142,144–150,154,157,164–168,171,174,177,179,180,182,185–187,201–205,209–211,216,219,220,225,235–238,245,249,251,253,256,258,259,265,268–270,273–275,283,289–291,293,295 A minority of studies were conducted in Europe (n = 78, 28%), half of these in the UK. 16,20–22,27–29,34,35,43–45,53–60,63,65,71,72,76,79,80,83,96,99,100,102,109,113,115,118,119,123,124,126,127,134,139,158,160–162,164,170,173,183,188,191,192,194,195,199,200,206–208,213–215,223,234,242,246–248,254,267,271,277,284,296,297 Most of the work was recent, with a rapid increase in the annual publication rate post 2009: approximately three-quarters of the articles were published after that date.

All of the 38 UK studies were published after 2010. They comprised 14 reviews or reports relating to technology and care homes,21,22,27–29,35,83,96,99,170,208,234,254,267 three case studies,80,134,246 three qualitative studies,115,124,194 two observational studies,16,139 one pilot RCT,277 one protocol,45 12 descriptive studies58,59,71,109,113,123,188,195,207,223,242,284 and two opinion pieces. 34,53 Telehealth and surveillance technologies were both the subject of six articles,16,71,113,115,195,234 and single articles were identified on gaming,125 robots,80 digital records134 and communication technologies. 246 The remaining 21 studies comprised a mix of topics, including general overviews of technology in long-term care, digital exclusion and assistive technologies.

Methodologies

A range of research methods had been employed, but most studies fell into the lower categories of the established hierarchies of evidence. 298 The biggest single group of studies (n = 78, 28%) comprised those that were descriptive or non-experimental, including case studies and small feasibility studies. 36,38,40,42,44,48,50–52,58–61,63,68,71,74–77,79,80,88–90,93–95,97,98,109,111,113,114,120,123,126,134,137,142,144,145,150,167,169,173,174,178,180,182,183,185,188,190,193,195–197,200,207,209,211,218–220,223,226,228,242,243,246,249,250,255,258,265,267,271,284,285,288,290,294 A further 16 (6%) were opinion pieces34,46,53,189,198,217,232,239,251,256,260,278,279,286,287,292 and a small number were of narrative, non-systematic overviews of the current state of research. Qualitative methods have been extensively used to explore various aspects of technology in care homes; these were the main focus of 59 (21%) studies. 30,31,33,55,57,65,66,69,78,103,107,108,110,115,118,119,121,124,129,130,136–138,140,146,158,159,164,168,171,176,179,192,194,199,212–216,224,225,233,237,241,245,247,248,257,268,270,273,275,276,283,291,293,296,297

Table 2 shows the breakdown of research methods by intervention topic. Qualitative and descriptive studies form the largest groups for all topics. However, for robots, gaming and education, more than one-third of the studies are experimental or quasi-experimental.

| Study design | Topic, n (%) | Total, n | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Digital records | Telehealth | Communications | Robots | Surveillance | Gaming | Education | Technologies | ||

| Systematic review | 2 (5) | 2 (3) | 0 | 2 (5) | 2 (6) | 1 (7) | 0 | 2 (3) | 11 |

| Experimental and quasi-experimental | 5 (12) | 11 (18) | 3 (27) | 12 (31) | 2 (6) | 5 (36) | 8 (57) | 9 (16) | 55 |

| Observational | 3 (7) | 11 (18) | 0 | 5 (13) | 4 (13) | 2 (14) | 1 (7) | 3 (20) | 29 |

| Cross-sectional | 7 (16) | 2 (3) | 2 (18) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 3 (20) | 16 |

| Qualitative | 12 (28) | 9 (15) | 5 (45) | 7 (18) | 9 (42) | 2 (14) | 2 (14) | 13 (19) | 59 |

| Descriptive | 10 (23) | 19 (32) | 1 (9) | 11 (28) | 13 (33) | 4 (28) | 2 (14) | 23 (52) | 83 |

| Overview and reports | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 11 (16) | 11 |

| Other | 4 (9) | 6 (10) | 0 | 1 (3) | 0 | 0 | 1 (7) | 6 (25) | 18 |

| Total | 43 (100) | 60 (100) | 11 (100) | 39 (100) | 31 (100) | 14 (100) | 14 (100) | 70 (100) | 282 |

Qualitative research can provide invaluable insights into resident and staff experiences and perceptions of new uses of technology. Fifty-nine of the included articles described studies that used qualitative methods to investigate interventions in all categories. 30,31,33,55,57,65,66,69,78,103,107,108,110,115,118,119,121,124,129,130,136–138,140,146,158,159,164,168,171,176,179,192,194,199,212–216,224,225,233,237,241,245,247,248,257,268,270,273,275,276,283,291,293,296,297 Twelve explored technologies related to digital records, nine related to telehealth and surveillance technologies, seven related to robots, two related to communication technologies and two related to gaming. The remaining 18 studies covered a mix of topics.

One in 10 articles (n = 29, 10%) reported on observational (case control and cohort) studies, and just under one in five (n = 53, 19%) was an experimental or a quasi-experimental design, including before-and-after studies. Many of these were pilot studies and did not appear to be powered to detect significant differences between any intervention and control groups. Eleven systematic reviews of previous evidence were identified. Only two of these followed established guidance for producing systematic reviews. 19,22

Interventions or topics

The mapped studies described technologies directed at care processes, resident and staff experiences and outcomes of care. More than half of all articles (n = 145, 51%) related to the use of technologies that were likely to directly influence experiences and processes of care (communication, telehealth, digital health records, surveillance and monitoring). Thirty-nine articles (14%) related to the use of robots that may have companion or rehabilitative functions. 19,25,39,43,47,48,55–57,73,80,87–89,132,160–162,167–169,176,196,200–203,209,220,235–238,244,245,250,251,259,268 The use of technology for education or training with staff or residents’ families (e.g. online training in dementia care or injury prevention) was the subject of 14 (5%) articles. 45,64,134,141,155,156,171,182,184,240,241,243,281,282

Studies were concerned with the impact of technology on residents (n = 106, 38%), staff (n = 78, 28%) or a mix of residents and staff (n = 95, 34%). Only a small minority were concerned exclusively with residents’ families (n = 3, 1%).

When outcomes were measured or discussed, these related to residents in 107 (38%) articles and to staff in 70 (25%) articles. Thirty-three (12%) articles considered the impact of technology on the use of other services, and 30 (11%) presented or discussed costs or any form of economic assessment.

Barriers to, and facilitators of, technology use in care homes

Barriers to, and facilitators of, technology use were considered in just under half (n = 123, 43%) of the articles. One hundred and thirteen of these described interventions in telehealth, digital records or communication, topics of particular importance and current relevance to health care in care homes. The barriers and facilitators listed in these articles were examined more closely and grouped into 10 categories. Table 3 shows the number of articles mentioning barriers or facilitators, by category. Many of the identified barriers were also potential facilitators of the uptake and use of technology. The most frequently occurring issues were ease of use, staff attitudes and structural concerns. Cost and ease of use were most often discussed as barriers, whereas staff attitudes and work demands were more likely to be facilitators.

| Factor | Articles, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Communication technologies (N = 11) | Digital records (N = 43) | Telehealth (N = 60) | |

| Cost | |||

| Barrier | 2 (18) | 3 (7) | 10 (17) |

| Facilitator | 1 (9) | 2 (5) | 3 (5) |

| Structural issues | |||

| Barrier | 4 (36) | 10 (23) | 11 (18) |

| Facilitator | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Ease of use | |||

| Barrier | 4 (36) | 8 (19) | 4 (7) |

| Facilitator | 1 (9) | 10 (23) | 4 (7) |

| Staff attitudes/motivation | |||

| Barrier | 3 (27) | 8 (19) | 4 (7) |

| Facilitator | 2 (18) | 12 (28) | 8 (13) |

| Integration with existing systems | |||

| Barrier | 3 (27) | 2 (5) | 2 (3) |

| Facilitator | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Access to training | |||

| Barrier | 4 (36) | 2 (5) | 3 (5) |

| Facilitator | 1 (9) | 4 (10) | 2 (3) |

| Reliability of technology | |||

| Barrier | 1 (9) | 3 (7) | 5 (8) |

| Facilitator | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Legal/regulatory issues | |||

| Barrier | 1 (9) | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Facilitator | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Incentives | |||

| Barrier | 0 | 1 (2) | 0 |

| Facilitator | 0 | 1 (2) | 1 (2) |

| Work demands | |||

| Barrier | 0 | 5 (12) | 6 (10) |

| Facilitator | 1 (9) | 11 (26) | 4 (7) |

Table 3 shows the number of articles on communication technologies, digital records and telehealth that discuss barriers to, and facilitators of, the implementation or use of technology.

Findings of systematic evidence synthesis

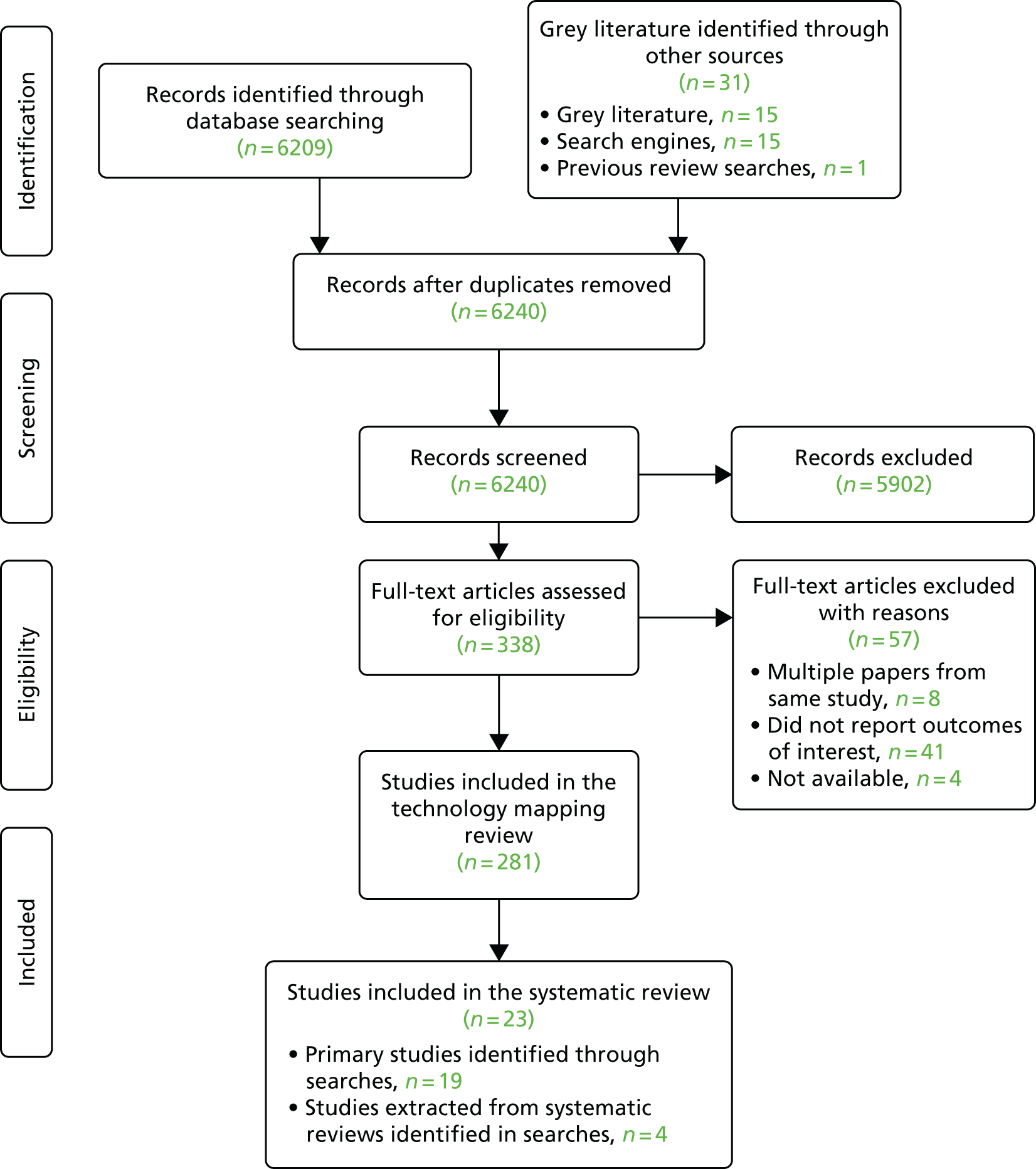

Twenty-three studies met the inclusion criteria for the systematic review. The PRISMA diagram for this study is shown in Figure 1. Ten studies were conducted in the USA,47,169,176,210,222,227,230,299–301 two in Australia,203,274 two in New Zealand166,236 and one in each of Belgium,54 Canada,147 Italy,101 Japan,250 Singapore,163 Norway,160 Taiwan,177 the Netherlands56 and the UK. 277 Thirteen randomised studies were included (six individually randomised parallel group trials, two individually randomised crossover trials and five cluster randomised trials),47,54,101,147,160,177,203,210,230,236,274,277,299 as were 11 non-randomised studies of interventions. 56,161,163,166,168,169,176,222,227,250,300,301 Details of the studies included in this systematic review are shown in Tables 4–7.

FIGURE 1.

Technology PRISMA flow diagram.

| Authors, year of publication, location | Design | Sample size (care home residents) | Sample characteristics | Interventions and comparators | Outcomes and measures | Overall risk of bias rating | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beeckman, 2013, Belgium54 | Cluster RCT | 11 wards in four nursing homes (464 residents and 118 professionals) | Mean resident age 84.5 years, 76% female, (intervention group); mean age 84.9 years, 82.8% female (control group) |

|

Prevalence of pressure ulcers, prevention measures, knowledge and attitudes among staff | High | Residents in the intervention group were significantly more likely to receive adequate pressure ulcer prevention, but there were no differences in pressure ulcer prevalence between the groups. Professionals’ knowledge was unchanged |

| Hsu et al., 2011, Canada147 | Crossover RCT | 34 residents | Mean age 80 years; 71% female (whole sample); participants were cognitively intact, with upper extremity dysfunction |

|

Scores on the following measures: a numeric rating scale of pain intensity, Physical Activity Enjoyment Scale and a six-item measure of functional capacity | High | Enjoyment of activity was significantly greater in the intervention group (p = 0.014); for all other outcomes similar improvements were shown in both groups |

| Jung et al., 2009, Singapore163 | Quasi-experimental study | 45 residents | Age range 56–92 years (whole sample) (gender balance not stated) |

|

Scores on the UCLA Loneliness and Rosenberg Self-Esteem scales; Bradburn Affect Balance Scale; Physical Activity Questionnaire for Elderly Japanese | Critical | Intervention group participants scored significantly higher on affect (p < 0.05), self-esteem and physical activity and significantly lower on loneliness (p < 0.01) than those in the control group |

| Keogh et al., 2014, New Zealand302 | Quasi-experimental study | 34 residents | Mean age 83 years; 88% female |

|

Functional ability (bicep curl and Four Square Step Test), physical activity (Rapid Assessment of Physical Activity) and quality of life World Health Organization Quality of Life Questionnaire – Brief Australian version) | Critical | Significantly greater increases in functional ability, physical activity and quality of life in the intervention group (p < 0.05) |

| Lin et al., 2014, Taiwan177 | Randomised study, parallel groups | 24 residents | Residents in long-term care facilities with chronic stroke. Mean age 74.6 years, 16.6% female (intervention group); mean age 75.6 years, 41.6% female (control group) |

|

Balance and satisfaction, measured using scores from the Berg Balance Scale and Barthel Index. Technology satisfaction was based on the technology acceptance model | Some concerns | Significant effect on Berg Balance Scale scores, total and self-care score of Barthel Index and basic daily activity were observed in both groups (p < 0.05). No significant changes in mobility were observed (p = 0.088), and measures of perceived usefulness and satisfaction were similar in both groups |

| Nagayama, 2016, USA210 | Pilot cluster RCT | 12 facilities (44 residents) | Mean age 82.1 years; 85.2% female (whole sample) |

|

Health status, measured using the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) and the Short Form Questionnaire-6 Dimensions (SF-6D) utility score; quality-adjusted life-years; scores on the Barthel Index of Daily functioning and total care cost | High | The intervention group had a significantly greater improvement in Barthel scores (p = 0.027). No other outcome was significantly different between groups. The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, calculated using the change in BI score, was US$63.10 |

| Authors, year of publication, location | Design | Sample size (care home residents) | Sample characteristics | Interventions and comparators | Outcomes and measures | Overall risk of bias rating | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bemelmans et al., 2015, the Netherlands56 | Quasi-experimental time series study (ABAB) within-subject comparison | 91 residents | Female 80.3%; residents with dementia and (1) undesirable psychological/psychosocial unrest or mood, and (2) care providers experienced difficulties in providing ADL-related care |

|

IPPA scores | Serious | IPPA scores and mood improved significantly following the therapeutic PARO intervention (p < 0.01). No effects were seen with the care support application |

| De Luca et al., 2016, Italy101 | Randomised study | 59 residents | Mean age 79 years; 67.8% female |

|

Measures of neurobehavioral symptoms and quality of life; blood pressure and heart rate; admissions to health-care services | High | Significant reductions in Geriatric Depression Scale (p < 0.01), Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (p < 0.05) scores, mean blood pressure, heart rate and admission to health-care services (p < 0.05) and improved quality of life (p < 0.05) between groups favouring the intervention |

| Jøranson et al., 2015, Norway160 | Cluster RCT | 10 care homes; 60 residents | Age range 62–95 years; 67% women; diagnosed with dementia or cognitive impairment (MMSE score of < 25/30) |

|

Regular medication prescribed, assessed using the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical Classification System; scores on the Brief Agitation Rating Scale and Norwegian versions of the Cornell Scale for Symptoms of Depression in Dementia and MMSE | High | The intervention group experienced significant reductions in agitation and depression at 3 months. Symptoms increased in the control group |

| Libin and Cohen-Mansfield, 2004, USA176 | Quasi-experimental | Nine nursing home residents | Mean age 90 years, all female; residents with dementia |

|

Agitated behaviour, measured using the Mapping Instrument (ABMI); affect, measured using Lawton’s Modified Behaviour Stream; residents’ engagement with the stimuli, assessed using various measures but not validated tools | Serious | The intervention group experienced significant increases in pleasure (p = 0.007) and interest (p = 0.028). Non-significant effects in relation to anger, anxiety and engagement were reported in both groups |

| Moyle et al., 2017, Australia203 | Parallel, three-group cluster RCT | 28 long-term care facilities (415 residents) | Mean age 84 years, 73% female (main intervention group); mean age 86 years, 81% female (second intervention group); mean age 85 years, 72% female (control group), documented diagnosis of dementia |

|

Changes in participants’ levels of engagement, mood states, and agitation, using the video coding protocol – incorporating observed emotion Scheme, and the CMAI-SF. Measurements were taken at baseline and at 1, 5, 10 and 15 weeks | Some concerns | Participants in the PARO group were more engaged verbally (3.61 points) and visually (13.06 points) than participants with the plush toy. Both PARO (3.09 points) and the plush toy (3.58 points) had significantly greater reductions in neutral affect than usual care. PARO was more effective than usual care in improving pleasure (1.12 points) and agitation (3.33 points). When measured using the CMAI-SF, there was no difference between the groups |

| Robinson et al., 2013, New Zealand236 | RCT with parallel groups | 40 residents in a residential care facility | Age range 55–100 years, 67.5% female |

|

Loneliness (UCLA loneliness scale), depression (Geriatric Depression Scale), and quality of life (Quality of Life for Alzheimer’s Disease scale) | High | Compared with the control group, residents who interacted with the robot had significant decreases in loneliness during the study period. Residents talked to and touched the robot significantly more than the real resident dog (p < 0.05). There were no other significant differences in change scores from baseline to follow-up between groups |

| Shibata et al., 2004, Japan250 | Quasi-experimental | 23 residents/attendees at health service facility that provides nursing home stays, rehabilitation and day care | Mean age 84.6 years, 66.6% female (intervention group); mean age 85.5 years, 81.8% female (control group) |

|

Participant mood, assessed using a face scale, Profile of Mood States and comments from the nursing staff | Moderate | Average face scale scores improved by an average of 2 points for the intervention group and by 0.7 in the control group; decreases in Profile of Mood States ‘depression-dejection’ ratings were by an average of 14 points in the intervention group and 7 points in the control group |

| Van der Ploeg et al., 2016, Australia274 | Pilot randomised, crossover, repeated measures study | Nine residents from five nursing homes in Melbourne | Mean age 86.7 years (range 83–93 years); 66% female |

|

Changes in Cohen-Mansfield Agitation scores | High | Skype conversations lasted longer than telephone calls (12 vs. 10.3 minutes). Mean agitation counts fell by 24.1 points during Skype calls and 12.9 points during landline calls. These differences were not statistically significant |

| Authors, year of publication, location | Design | Sample size (care home residents) | Sample characteristics | Interventions and comparators | Outcomes and measures | Overall risk of bias rating | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banks et al., 2008, USA47 | Cluster RCT | 38 residents in three long-term care facilities | Age and gender profile of the sample not stated |

|

Resident loneliness (UCLA scale) and attachment to pets (MLAPS) | Some concerns | Residents receiving a dog intervention (robotic or living) were significantly less lonely than those in the control group (p < 0.05), regardless of their attachment to pet score. There were no differences between the robotic or living dog group in reducing loneliness |

| Jung et al., 2009, Singapore163 | Quasi-experimental study | 45 residents | Age range 56–92 years (whole sample) (gender balance not stated) |

|

Scores on the UCLA Loneliness and Rosenberg Self-Esteem scales; Bradburn Affect Balance Scale; Physical Activity Questionnaire for Elderly Japanese | Critical | Intervention group participants scored significantly higher on affect (p < 0.05), self-esteem and physical activity and significantly lower on loneliness (p < 0.01) than the control group |

| Kidd et al., 2006, USA169 | Quasi-experimental | 23 residents | No data on age and gender of the participants |

|

Questions relating to social interaction and play with the robot designed specifically for this study | Critical | Participant responses to questions indicated higher levels of social interaction and play in the intervention condition |

| Robinson et al., 2013, New Zealand236 | RCT with parallel groups | 40 residents in a residential care facility | Age range 55–100 years; 67.5% female |

|

Loneliness (UCLA Loneliness Scale), depression (Geriatric Depression Scale), and Quality of Life (Quality of Life for Alzheimer’s Disease scale) | High | Compared with the control group, residents who interacted with the robot had significant decreases in loneliness over the study period. Residents talked to and touched the robot significantly more than the real dog (p < 0.05). There were no other significant differences in change scores from baseline to follow-up between the groups |

| Vowden and Vowden, 2013, UK277 | Cluster RCT (pilot study) | 16 nursing homes (39 patients) | Mean age 79.47 years, 58.8% female (intervention); mean age 82.67 years, 55.6% female (control) |

|

Cost savings and usefulness of the system, assessed using opinions and quotations provided by experts and care home staff | High | No statistical analysis because of small sample size; the study authors reported that the case studies included in their article illustrate the potential benefits of the system |

| Authors, year of publication, location | Design | Sample size (care home residents) | Sample characteristics | Interventions and comparators | Outcomes and measures | Overall risk of bias rating | Results |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Holmes et al., 2007, USA300 | Quasi-experimental design | Two units; 118 residents | Average age on both units was 87 years (±7.5 years); 78 residents (38 on the intervention unit and 40 on the comparison unit) |

|

Reduction of falls, accidents and injuries for residents; decrease in staff time spent on direct care and staff burden | Critical | No significant reduction in falls and injuries, but there was a significant improvement in affective disorder in the intervention group, relative to the comparison group |

| Kelly et al., 2002, USA301 | Crossover design | 47 patients | 66% (n = 31) were female; no data on age |

|

Fall rate per 100 patient-days | Critical | Significant reduction in fall rate of 91% (p = 0.02). Patients had 11 falls in the pre period (4.0 falls per 100 days), 1 fall in the during period (0.3 falls per 100 days) and 17 falls in the post period (3.4 falls per 100 days) |

| Lapane et al., 2011, USA299 | Cluster RCT (to determine the extent to which the use of a clinical informatics tool for monitoring plans reduces adverse outcomes) | 25 homes comprising 3480 residents | 50% aged ≥ 85 years, 33% aged 75–84 years, 18% aged 65–74 years; 73% female (intervention recipients) |

|

Incidence of delirium, falls, hospitalisations and mortality | High | Significant difference in the rate of potential delirium onset between groups (adjusted hazard ratio 0.42, 95% confidence interval 0.35 to 0.52) favouring the intervention. No other significant effects were observed |

| Pillemer et al., 2012, USA222 | Quasi-experimental study to investigate the impact of introducing a HIT system on resident outcomes | 761 residents | Mean age, 79.6 years, female 68.17% (intervention group); mean age 79.2 years, 63.55% female (control group) |

|

Resident satisfaction with care; average number of falls; ADL (Performance Activities of Daily Living scale); mood (Feeling Tone Questionnaire); Observed behaviour frequency of behavioural states based on rater observations | Critical | No statistically significant impact of the introduction of HIT system on residents for any outcomes, except a negative effect on behavioural symptoms |

| Rantz et al., 2010, USA227 | Quasi-experimental study to investigate the contribution of bedside EMRs and on-site clinical consultation by gerontological expert nurses on cost, staffing and quality of care in nursing homes | 18 facilities; 8166 residents | No data were provided on age or gender. Facilities were split into four groups, all willing to implement bedside EMR systems |

|

Cost reports (total costs per resident and nursing staff), staffing and retention, various quality indicators and measures for resident outcomes including ADL, motion, behavioural/depressive symptoms, pressure sores, urinary tract infection, delirium, physically restrained | Serious | Total costs increased in the intervention groups that implemented technology. Staffing and retention remained constant. Improvement trends were detected in resident outcomes for ADLs, range of motion, and pressure sores in intervention groups |

| Rantz et al., 2017, USA230 | Prospective, randomised controlled study to assess the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of using data from an environmentally embedded sensor system for early recognition of illness | 171 residents in 13 assisted living communities | Mean age 83.6 years, 74.4% female (intervention group); mean age 86 years, 72.9% female (control group) |

|

SF-12, GDS, MMSE, activities/instrumental ADL and IADL, gait speed and profile (GAITRite), hand grip, falls, emergency room visits, hospitalisations, nursing home stays, physician visits | Some concerns | Functional decline was significantly more rapid in the comparison group, suggesting that alerts from sensor data promote early detection and intervention. No differences were identified in SF-12, GDS, MMSE, ADL or IADL scales, or grip strength measures between groups. There were no difference in health-care costs between groups |

Study quality

Thirteen of the included studies were RCTs; the remaining 11 were non-randomised, observational studies. Full details of the validity assessment are presented in Appendix 3, Table 18. The quality of reporting was variable between studies and across criteria. Of the 13 RCTs, nine were considered overall at a high risk of bias, whereas the other four were rated overall as having some concern of bias. Risk of bias across the domains for each RCT was variable, but in general RCTs were either rated as being at high risk of bias because of the measurement of outcomes or flagged as having some concerns because of deviations from intended interventions. Although the lack of blinding of participants and/or assessors may be justifiable given the nature of the interventions, the deviations from the intended interventions support the overall risk-of-bias assessment of high or some concern. None of the RCTs was rating as being at a low overall risk of bias.

Of the 11 non-randomised studies, 10 were considered to be at serious or critical risk of bias, with one considered to be at moderate risk. The majority (n = 10) were considered as having serious or critical risk of bias owing to confounding and measurement outcomes. Confounding relates to when one or more prognostic factor that predicts the outcome also influences or predicts who receives the intervention. Although the lack of blinding may be justifiable given the nature of the interventions, because of issues with confounding all 10 studies remained at serious or critical risk of bias.

The quality of the studies for each of the individual interventions is summarised alongside the results. With only one non-randomised study rated as being at moderate risk of bias and four RCTs rated as having some concern of bias, the overall evidence base to support the effectiveness of individual technologies is weak.

Quality assessments are shown in Appendix 3, Tables 18 and 19.

Results of evidence synthesis

The findings from the 24 studies investigating associations between digital technology interventions and care home residents’ health, functional ability and well-being are synthesised in the following section, grouped by outcome.

Studies investigating the effects of interventions on physical health, physical activity and functional status

Six studies assessing the effects of interventions on physical health, physical activity and functional status were included. They were conducted in Singapore, Taiwan, New Zealand, Belgium, Canada and the USA. 54,147,163,177,210,302 The Belgian study involved 144 participants; the sample size of the other five studies ranged from 34 to 45 residents. 54 Two were quasi-experimental studies, two were randomised studies (one with parallel groups and one crossover) and two were cluster randomised studies. All except one were rated as being at high or critical risk of bias.

Research teams from three countries have evaluated the potential of Nintendo® (Windsor, UK) Wii technology to enhance physical functioning, in addition to reporting on outcomes such as health and quality of life. Playing specific Wii games appeared to have a greater impact on physical and psychological health than playing traditional board games when implemented over a 6-week period with 45 residents of a Singapore care home. 163 This quasi-experimental study was successful in its aim to increase physical activity; participants also reported increases in positive affect and self-esteem, and lower levels of loneliness, than those in the control group, suggesting that the intervention has the potential to have a broad impact on well-being. 163 A quasi-experimental mixed-methods study166 from New Zealand evaluated the impact of an 8-week programme of Nintendo Wii sports games. Significantly greater increases in functional ability, self-reported physical activity levels and quality of life were reported among the 13 members of an intervention group than among 13 residents who continued with their normal ADL. However, the Wii was less successful when used with residents in Canada who had existing impairments. A Nintendo Wii bowling game was added to standard care for 34 residents with upper limb dysfunction from two long-term care facilities. Wii bowling participants reported greater enjoyment of physical activity than residents receiving standard care, but changes in functional status, pain intensity and the extent to which pain disturbed the resident were similar in both groups after the intervention. 147

Other studies of digital technology interventions failed to demonstrate any improvement in functional status over and above usual care. In a pilot trial in Taiwan,177 the effectiveness of balance training via a telerehabilitation system was compared with conventional therapy for 24 care home residents with chronic stroke. During a 4-week period, balance and functional status improved, but there were no significant differences between the intervention and control groups. Mobility, including 50-yard walking and going up and down stairs, was unaffected. Another pilot cluster RCT,210 this time from the USA, evaluated an iPad (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA) application [the Aid for Decision-making in Occupation Choice (ADOC)]. This application was developed for use with occupational therapists, and displayed images of daily activities that could be selected by the clients in an attempt to promote shared decision-making and occupation-based goal-setting. The ADOC was found to be acceptable to therapists and clients, and able to maintain or improve ADL, compared with an impairment-based approach. The authors report that it also appeared to be a cost-effective intervention. No significant differences in health status or quality of life were detected between the intervention and control groups.

This combination of studies does not present strong evidence for a positive impact of technological interventions on the physical health and functional status of care home residents. However, the Nintendo Wii appears to be a promising intervention for increasing physical activity and enhancing mood and social functioning.

Studies investigating the effectiveness of interventions for improving mental health and well-being

Ten studies described digital interventions aimed at influencing mental health and well-being in care home residents. 56,101,132,160,163,169,176,236,250,274 A majority measured symptoms of depression and dementia. They also report on agitation, a set of behaviours associated with emotional distress that impair social functioning and ADL. Examples of agitation include excessive motor activity, such as pacing and/or verbal and physical aggression. Agitation is common in dementia and cognitive impairment, but it is important to note that it can have other causes. 303

Mood and agitation

The influence of robotic animals on mood and agitation among care home residents has been investigated in studies from five countries: the Netherlands,56 Norway,160 New Zealand,236 Japan250 and the USA. 176 In all but one of these studies,176 the intervention was with PARO, a robotic seal (www.PAROrobots.com). A sixth study, from Korea, discussed the need to explain and promote the PARO intervention with care home staff, but it presented no data on outcomes and is not included in this review. 132

PARO is the most commonly available robotic pet developed for use by people living with dementia. PARO is built to resemble a baby seal, and moves its head and legs and makes sounds when interacting with people. PARO contains sensors that detect touch, light, sound, temperature and position. This allows the PARO device to respond when it is being held or stroked, and move in the direction of sounds. PARO can be programmed to respond in a certain way to stimuli, and remember the users’ previous actions and behaviour patterns.

Two studies rated as being at high/serious risk of bias described the positive impact of PARO on mood and agitation. The short-term effects of intervening with PARO robotic seal were assessed in a quasi-experimental time series study (with within subject comparisons) in the Netherlands.

The effects of PARO on the psychological well-being and psychosocial functioning of residents with dementia were measured, along with its ability to facilitate daily care activities. Ninety-one residents completed this study. The authors described a strong positive effect of PARO on mood and on an individual goal attainment scale (Inventory of Positive Psychological Attitudes) when used in a therapeutic intervention. The potential of PARO to support delivery of care by enhancing resident co-operation was unproven. 56 PARO has also been used successfully in Norway in group interventions to tackle symptoms of agitation and depression among care home residents with dementia or cognitive impairment. A cluster RCT160 involving 60 residents described significant improvements in the intervention group, 3 months after the end of a 12-week intervention. Medication usage was unchanged. In a smaller study in Japan,250 PARO also appeared to have a positive impact on mood when deployed with 11 older people living in a long-stay facility. Twelve people in a second facility were given a less interactive version of PARO as a placebo, but the results between the groups were similar, which implies that PARO’s ability to move and interact may not be an essential component of the intervention.

Only one published study,236 a RCT from New Zealand rated as being at moderate risk of bias, failed to detect any positive effects on quality of life for PARO. The intervention was compared with a real dog who lived with residents in a care home. No differences were detected between the groups in quality of life or depression. 236 This study is discussed further in Social relationships (loneliness and isolation): the influence of robotic animals.