Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/157/44. The contractual start date was in January 2016. The final report began editorial review in August 2018 and was accepted for publication in November 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Glenn Robert reports that he was a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme researcher-led panel from 2013 to 2017. Jill Maben reports that she was a member of the NIHR HSDR programme researcher-led panel from 2013 to 2016.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Sarre et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Context

The broad context for this research study is the rapid and widespread adoption from 2008 onwards, both nationally in England and internationally, of a (still) largely unproven quality improvement (QI) intervention called the ‘Productive Ward: Releasing Time to Care’TM programme (Productive Ward; PW). PW sought to improve efficiency and productivity (and performance) at ward level in acute hospitals. PW was a major programme within the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement (NHSI) portfolio, which went on to be adopted and implemented in several countries, including Ireland, Denmark, the Netherlands, Belgium, Canada, the USA, Australia and New Zealand. It is still widely used in Australia in particular.

Our study is a retrospective evaluation of the lasting impact of a specific intervention over a 10-year period. However, we also had the opportunity to address recognised gaps in the QI literature relating to the ‘sustainability’ of interventions and the nature of their impact(s) over time. Reviews of studies of sustained change in health-care organisations suggest that the evidence base to help guide both national and local strategies is insufficient. 1 Most studies lack rigour and are not designed to test, empirically, hypotheses about the process of achieving sustained change. 2

Our first chapter briefly describes the origins, structure and aims of PW. We then outline the findings from two studies conducted by members of the research team that explored the early adoption and implementation of PW in English acute NHS Trusts in the period 2008–11. 3–5 Next, we summarise the wider evidence base as it relates to the effectiveness of PW in terms of its three stated aims. Finally, we review how the sustainability of innovations in the organisation and delivery of health services has been conceptualised and studied to date, highlighting the opportunity afforded by this study to supplement what is already known.

The ‘Productive Ward: Releasing Time to Care’™ programme

From 2005, the NHSI, whose role was to support the transformation of the NHS through innovation, improvement and the adoption of best practice, worked to develop PW as a QI intervention to empower ward teams by giving staff the information, skills and time they needed to regain control of their ward and the care they provided.

We have previously described the detailed and sophisticated (certainly in QI intervention terms) process of designing, testing and developing the PW. 5 In brief, PW was based on the Lean principles used by industries to improve processes, safety and reliability by ensuring that all work adds value by reducing waste and improving flow. The NHS worked with industry partners to apply Lean thinking to the NHS. PW was further developed through a planned design process that included drawing on social movement theory to work with four NHS sites that tested a prototype PW package in 2006, where staff were able to dedicate time to testing PW. As a result of this test phase, NHSI developed 10 modules, including one on leadership. From 2007, these modules were further refined through piloting at 10 ‘learning partner’ sites [one from each of the Strategic Health Authorities (SHAs) in England at the time] and two ‘whole-hospital’ test sites.

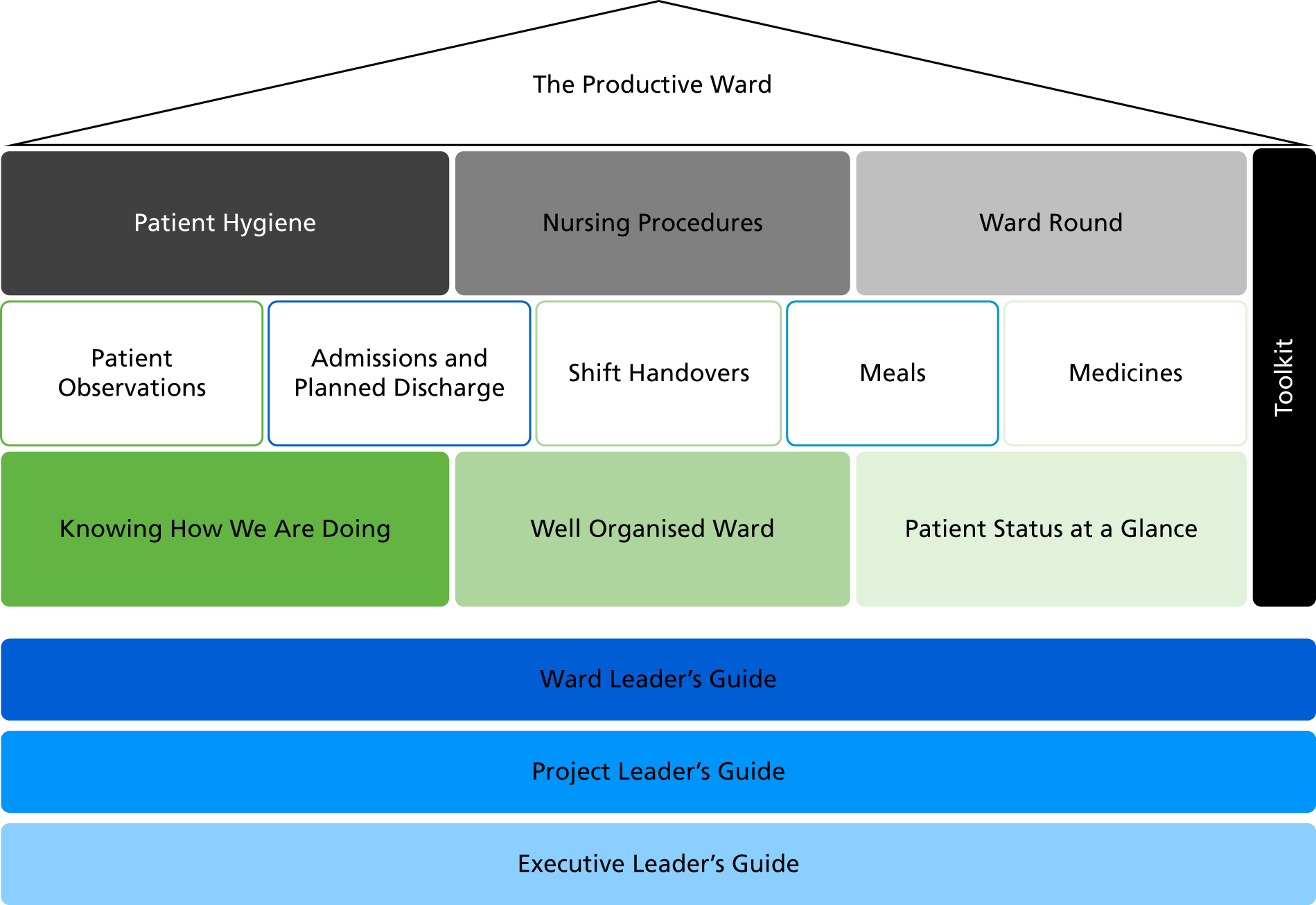

At the official launch in January 2008, PW consisted of three ‘foundation’ modules:

-

Well Organised Ward (WOW), which aimed to make the workplace more productive by having materials easily accessible

-

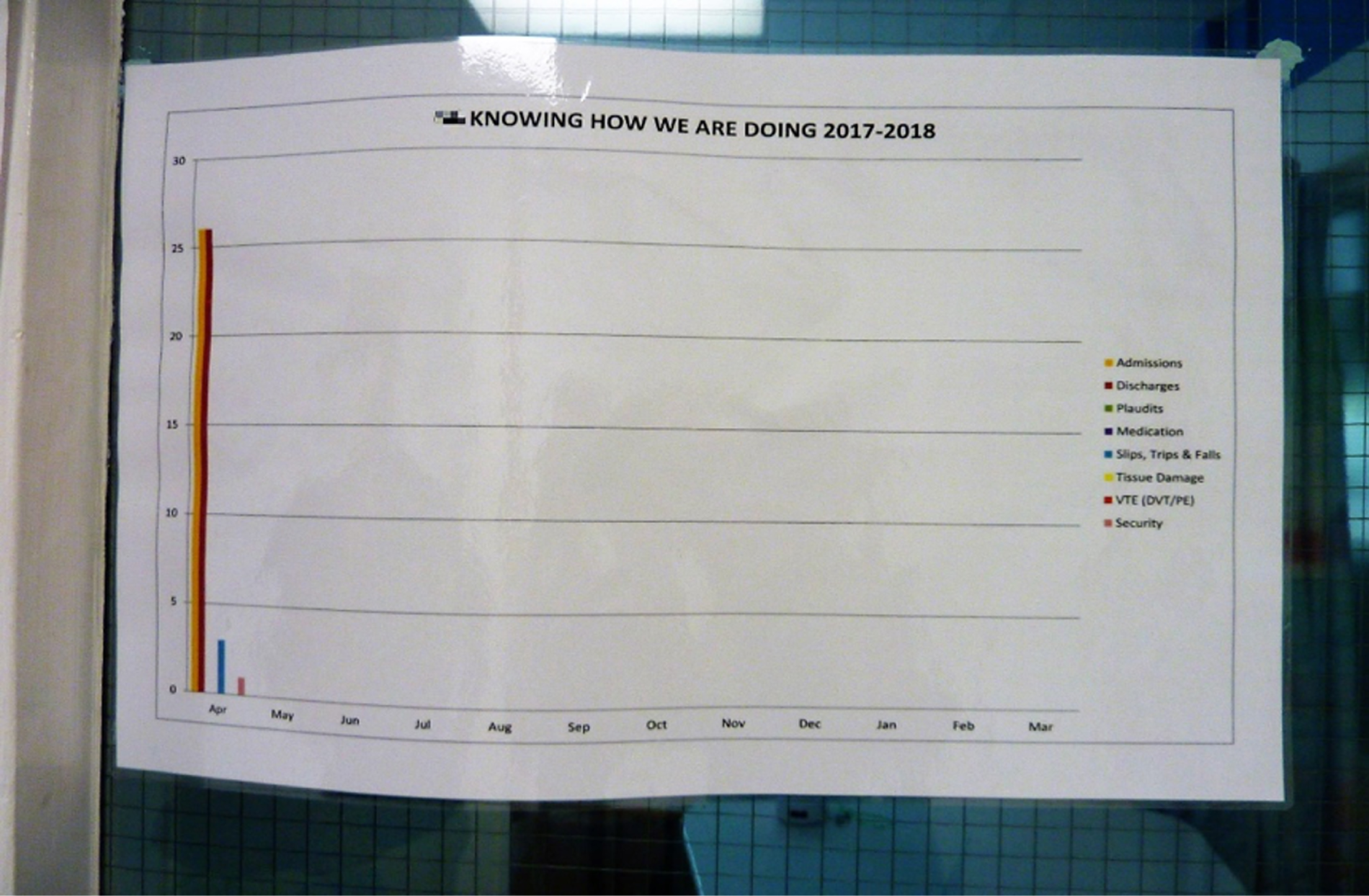

Knowing How We Are Doing (KHWD), which concerned the collection, display and use of ward-level metrics on patient safety and patient and staff experience

-

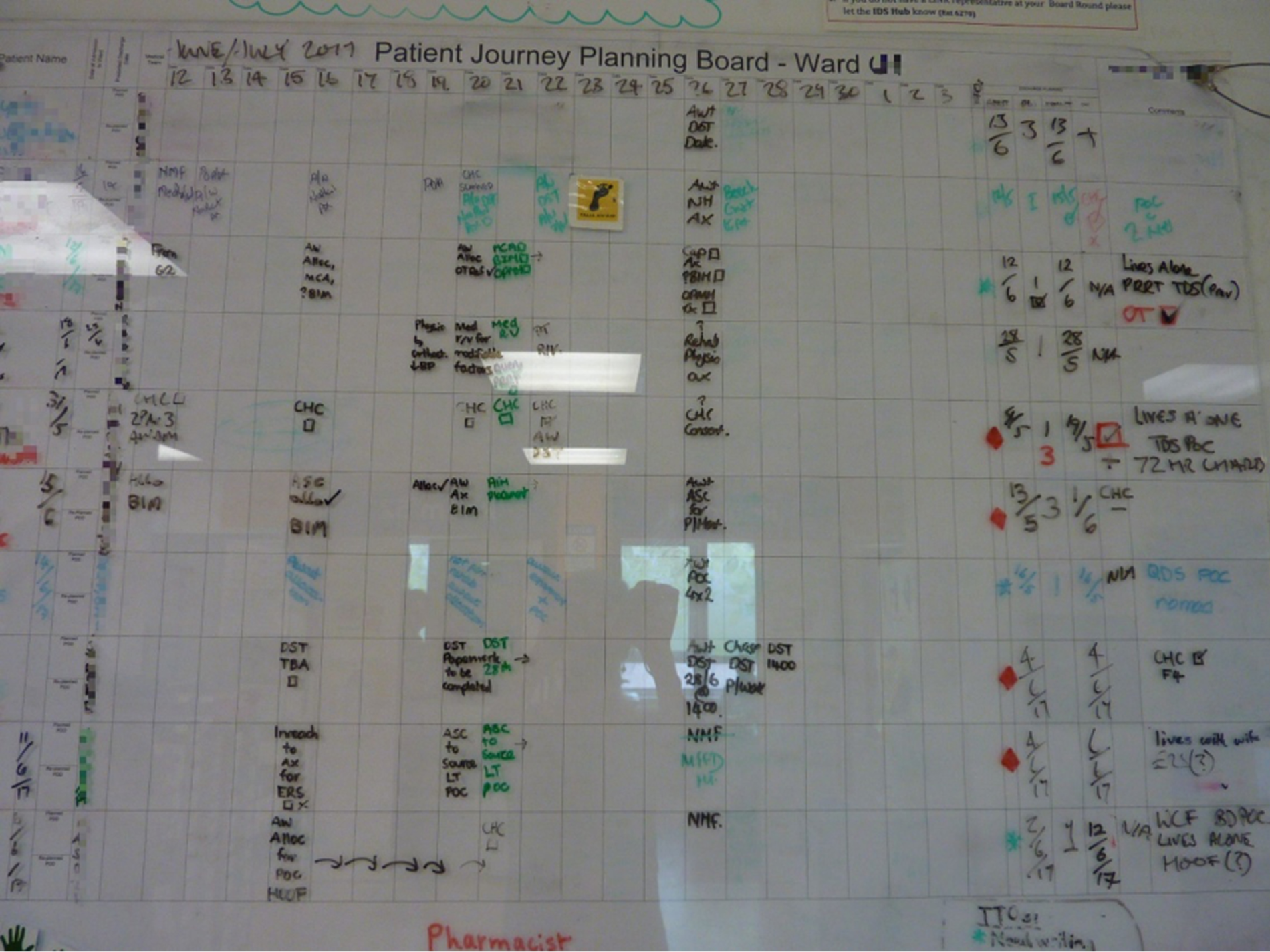

Patient Status at a Glance (PSAG), which used visual management of patient information so that it could be used most effectively.

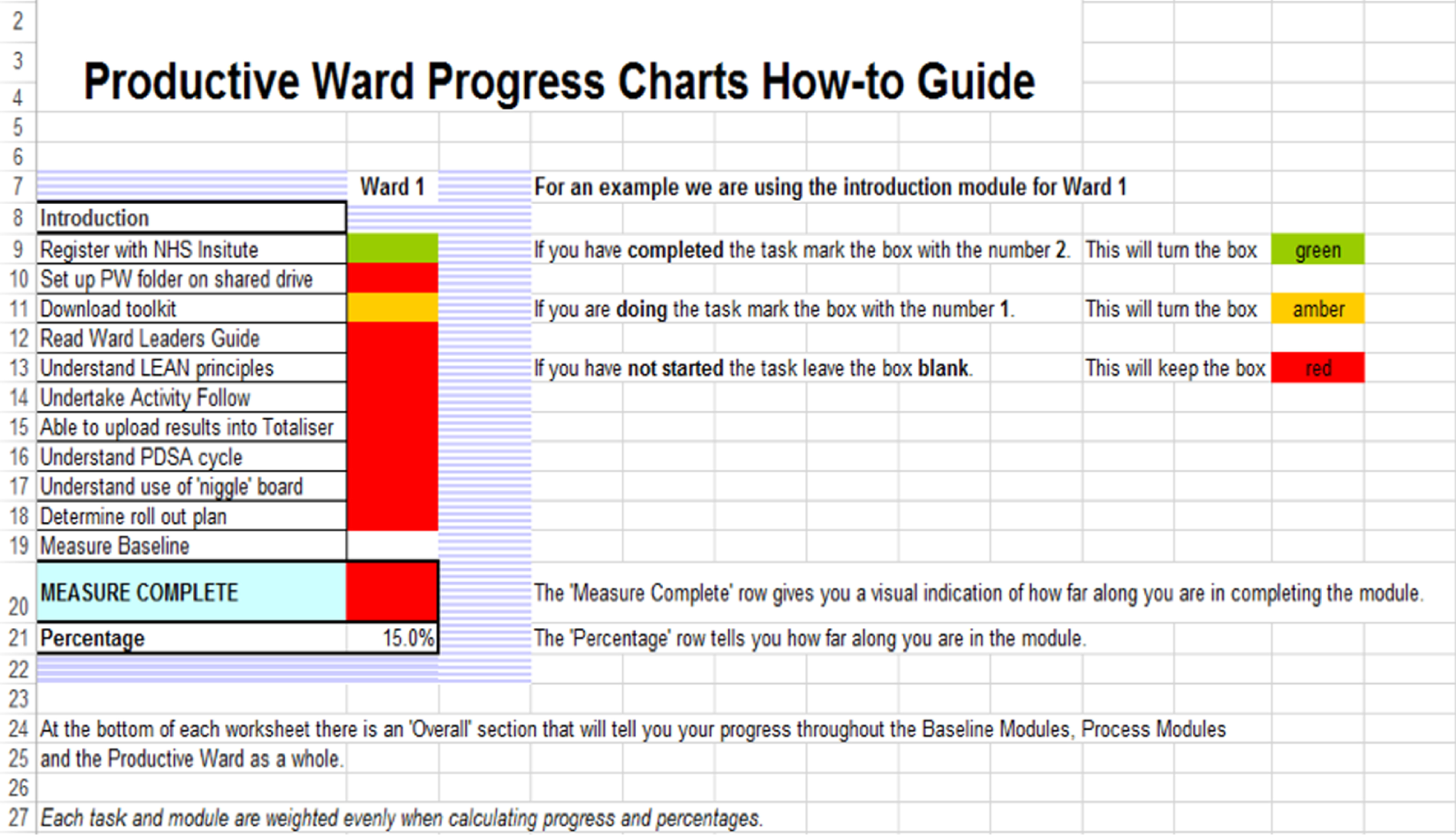

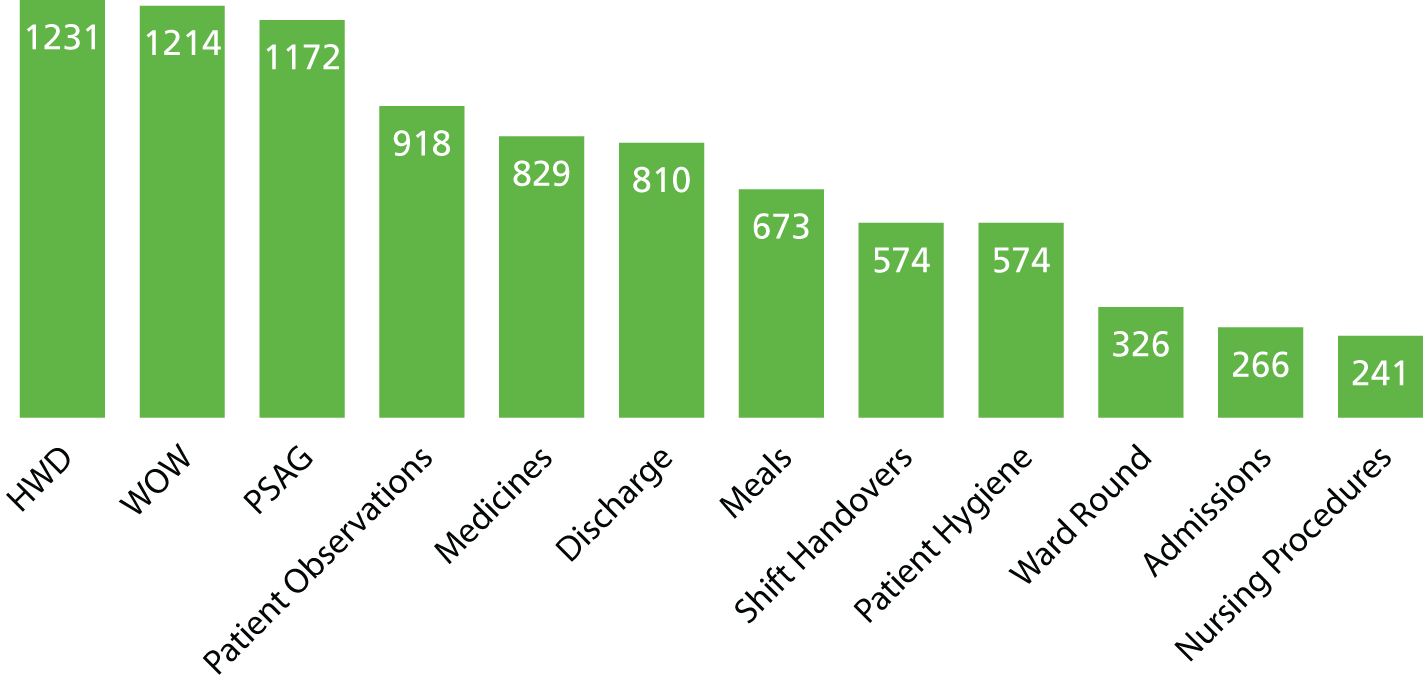

In addition, there were eight ‘process’ modules: Patient Hygiene, Nursing Procedures, Ward Round, Patient Observations, Admissions and Planned Discharge, Shift Handovers, Meals and Medicines. Local implementation was supported by ward, project and executive leader guides and an extensive ‘toolkit’ (Figure 1). The modules, guides and toolkit are summarised in Appendix 1.

FIGURE 1.

The structure of the Productive Ward: Releasing Time to Care™ programme. © NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement 2007–8. Reproduced with kind permission from NHS England Sustainable Improvement team.

The modules and toolkits to guide implementation were made freely available via the NHSI website and trusts could also purchase ‘standard’ or ‘accelerated’ support packages. The standard package (costing £8000) comprised three staff places at module implementation training, web access, online WebEx clinics and five places at the ‘The Productive Ward’ conference. The accelerated package (£25,000) comprised 10 staff places at module implementation training, two staff places at project support training, three on-site support visits from a NHSI facilitator over approximately a 6- to 12-month period, executive briefing, web access and online WebEx clinics, plus five places at the conference.

In May 2008, the government invested £50M to support the dissemination and implementation of the PW in England. This investment was provided on the basis of evidence from early test sites (2006–8), widespread commitment from nursing leaders and the promise of what PW might help to achieve across the NHS, namely doubling the amount of time nurses spend on direct care, reducing handover time by one-third and medicine round time by 63%, and cutting meal wastage rates from 7% to 1%. 6

Table 1 summarises the three aims of the PW and provides examples of the modules that might be expected to have contributed to each.

| PW aim | Examples of PW modules likely to have influenced this |

|---|---|

| Increase the proportion of time nurses spend in direct patient care | Core modules (WOW, KHWD, PSAG), Medicines, Patient Hygiene, Meals, Nursing Procedures |

| Improve experience for staff and patients | All modules |

| Make structural changes to the use of ward spaces to improve efficiency in terms of time, effort and money | Core modules (WOW, KHWD, PSAG), Shift Handovers, Admissions and Planned Discharge, Nursing Procedures |

The gathering (and, for some items, the display) of data on the metrics listed in Table 2 was central to PW. Nursing staff were encouraged to use data to inform QI locally through such activities as audit and ‘prepare, assess, diagnose, plan, treat, evaluate’ cycles.

| Core objective | Key measures | Definitions |

|---|---|---|

| Improve patient safety and reliability of care | Patient observations | Percentage of on-time, fully completed and correct patient observations |

Plus at least one of:

|

The gap in days between cases | |

| Improve patient experience | Patient satisfaction | Mean weekly scores based on standardised patient satisfaction questions |

| Improve efficiency of care | Direct care time | Percentage of time spent on direct care |

| Percentage of patients going home on agreed date (EDD) | Weekly percentage of EDD | |

| Length of staya | Mean length of stay on ward from ward admission to discharge | |

| Ward cost per patient spella | Mean monthly pay and non-pay costs per patient spell | |

| Improve staff well-being | Unplanned absence rate | Mean monthly absence hours (excluding absence episodes of > 3 days) |

The PW toolkit also included detailed guidance on how to implement PW,8 and comprised:

-

step-by-step advice on how to create strategic goals and alignment, ‘prep & plan’ and create showcase ward(s) through an application process, and how to select and sequence later wards

-

description of what the project leader ‘role is . . . is not’ (the guidance makes clear that the project leader should not micromanage wards or take responsibility for an individual ward’s implementation)

-

description of what the improvement facilitator ‘role is . . . is not’ (the guidance makes clear that the improvement facilitator should not ‘set objectives and tasks not agreed by ward leader’ or undermine the ward leader by ‘leading change on the ward’)

-

specific examples of weekly anticipated inputs, tasks and outputs from the three core modules

-

recommendations for the use of a ‘sustainability model and guide’ developed by the NHSI to ‘test the readiness of the ward to start and sustain any improvements they make’ and to ‘maximise your/a ward’s potential to sustain the Productive Ward’

-

outline of a proposed ‘Monthly Visit Pyramid’ of intervals at which the chief executive, medical director, nursing director, matron, ward manager and sister should visit the ward and hear about progress

-

a ‘10 Point Healthcheck’ for assessing whether or not each module had been effectively implemented.

Regarding the last item in this list, the guidance recommended that:

By looking at all of the Productive Ward 10 Point Healthcheck checklists from the modules the ward is implementing, a decision can be made about whether the ward can cope with a reduced facilitation support lead or whether the ward has fully adopted Productive Ward methods and principles.

NHSI, p. 71. 8

The NHSI developed several other interventions that became part of the ‘Productive Series’: the Productive Community Hospital, Productive Mental Health Ward, the Productive Leader, The Productive Operating Theatre, Productive Community Services, Productive Maternity Ward, Productive General Practice and Productive Endoscopy.

The NHSI was replaced in April 2013 by NHS Improving Quality, which took on the responsibility for PW. It continued to maintain and update the website until 2017. A fee-based ‘virtual college’ e-resource with accreditation was set up in 2011 and still operates for PW and other, later additions to the Productive series. A handful of ‘delivery partners’ operating under a licence currently offer a fee-based support package to trusts wanting to implement PW.

Earlier research into the adoption and implementation of Productive Ward in the period 2009–12

In collaboration with the NHSI, authors of this report (JM, PG and GR) and colleagues undertook research in the period 2009–10 exploring the development, early adoption and implementation of PW in England. 3,5,9,10 This earlier research established that 36% (140) of all NHS trusts (acute and non-acute) had adopted PW [i.e. they had purchased either an accelerated (n = 109) or a standard (n = 31) support package] by March 2009, with large variation between geographical regions (Table 3). The number of wards within adopting trusts at that time was highly variable, but was estimated by the NHSI to be 35% on average. 9 By May 2012, the NHSI reported that 70% of wards in the UK were implementing PW. 11

| SHA | Total number of NHS trusts | Purchased package: accelerated/standard (number of trusts) | Purchased either accelerated/standard package (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| East Midlands | 23 | 2/0 | 9 |

| South Central | 23 | 19/2 | 91 |

| South West | 39 | 13/13 | 67 |

| West Midlands | 38 | 2/3 | 13 |

| South East Coast | 28 | 19/0 | 68 |

| East of England | 40 | 27/0 | 68 |

| Yorkshire and the Humber | 37 | 2/10 | 32 |

| North West | 63 | 8/3 | 17 |

| London | 75 | 17/0 | 23 |

| North East | 23 | 0/0 | 0 |

| Total | 389 | 109/31 | 36 |

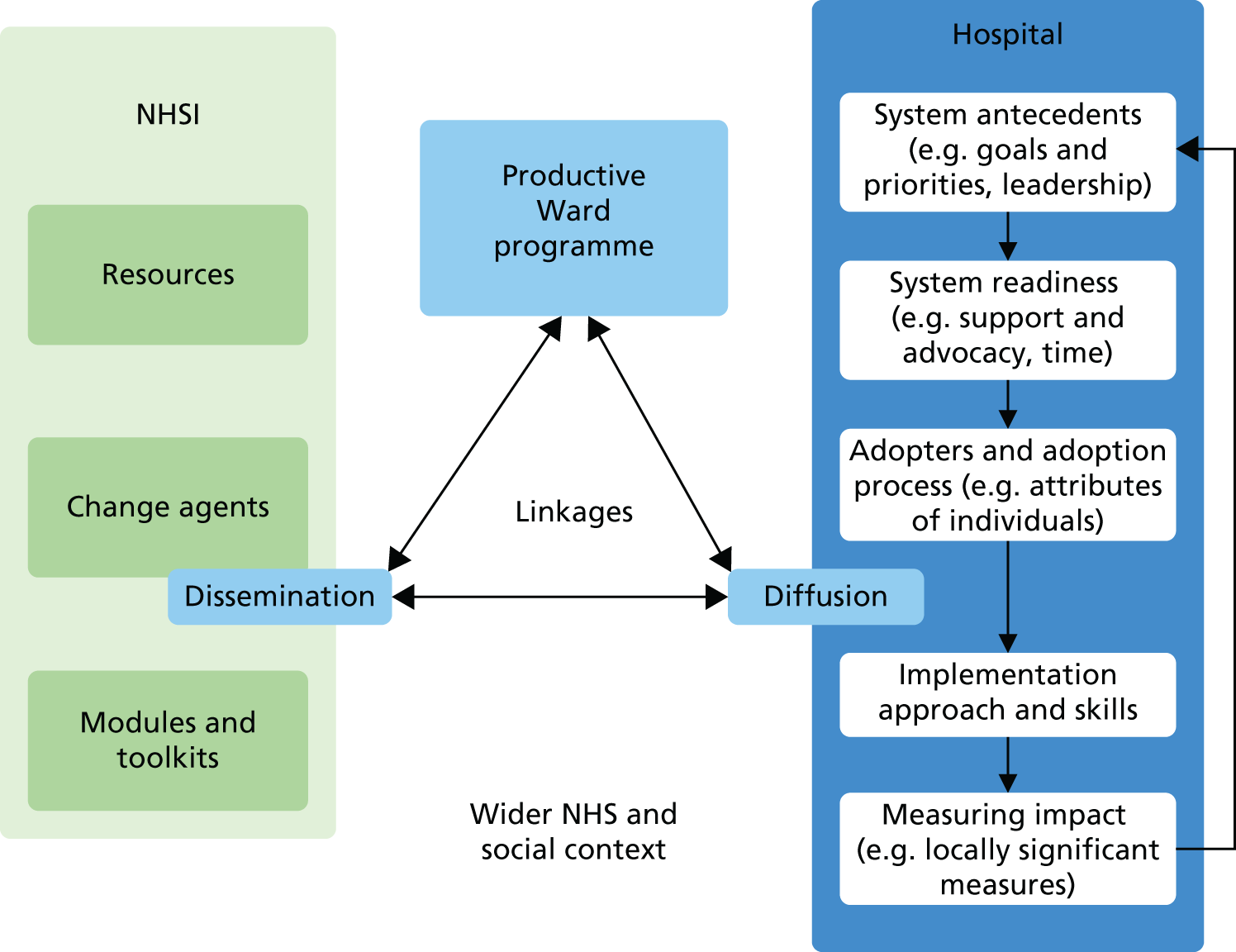

In this earlier national study we also explored the local components and key interactions that helped to explain the rapid rate and scale of the adoption, implementation and assimilation of PW into routine nursing practice in NHS trusts in England. The principal investigator of this current proposal (GR) had also contributed to a National Institute for Health Research-funded systematic review of the extensive literature on the diffusion of service innovations that had produced a model for understanding the complexities of the adoption, implementation and assimilation of innovations into day-to-day health-care services. 2 In our earlier study of the adoption of the PW, we adapted the original Greenhalgh et al. model, as shown in Figure 2.

We found that interactions between several factors had contributed to the rapid adoption of the PW in England:

-

The innovation itself was adaptable and well framed for different groups of staff.

-

The linkages between the external change agency and potential adopters were generally strong.

-

The readiness for change was heightened by the priority accorded to local QI agendas and the pre-existence of service improvement teams and expertise.

-

The wider NHS/societal context emphasised the need for efficiency and for meeting national targets, building leadership capacity and demonstrating commitment to QI.

We also reported that the key organisational factors that were perceived to have influenced the successful local implementation of the programme were:

-

staff having a ‘felt need’ for change and seeing PW as a simple, practical solution to real problems

-

engaging with the NHSI and drawing on the PW modules and resources

-

selecting initial wards on the basis of their desire to work on PW

-

emphasising local ownership of the programme and empowerment of ward staff, rather than using a directive approach

-

providing sufficient resources and support, in particular budgets allocated for backfill of staff time.

However, working in overstretched and busy clinical environments has been reported as presenting a significant challenge to ward teams’ active engagement with implementing PW. 12 This makes the provision of sufficient resources and support particularly crucial, and our earlier survey showed that the most frequently reported facilitating factor for local PW implementation was having dedicated project leadership. Having a realistic and flexible plan, support from a steering group, clinical facilitation and communication about PW helped to maintain the momentum of the work itself.

We also conducted a follow-up study in 2010 that sought to (1) inform efforts to maintain the momentum of PW, (2) support NHS staff going forward, and (3) discuss the mechanisms and arguments for continued commitment and investment. 4 Through fieldwork in eight case study trusts, we found that the programme had been successfully framed and communicated in a way that connected with front-line NHS staff’s need and will for change, and that it thrived where local leadership and ownership were strong. Our report forwarded 16 key lessons from the programme to that date that would assist hospitals with local implementation in the future.

A secondary analysis of our data from across our two earlier studies further explored the role of leadership in implementing PW, concluding that more research was needed to understand the interactions that lead to a sense of empowerment, and the impact that has on outcomes, as well as boundary-spanning communication and its effect on sustainability. 13

Despite widespread perception of significant benefits, it should be noted that front-line nursing staff in our initial study thought that more needed to be done to ensure that impact could be demonstrated in quantifiable terms. Our overall conclusion was that the PW programme had been rapidly adopted by NHS trusts in England (albeit with significant regional variation) but that a variety of implementation approaches were being employed that were likely to have implications for the successful assimilation of the programme into routine nursing practice and, therefore, for the impact of the programme as a whole.

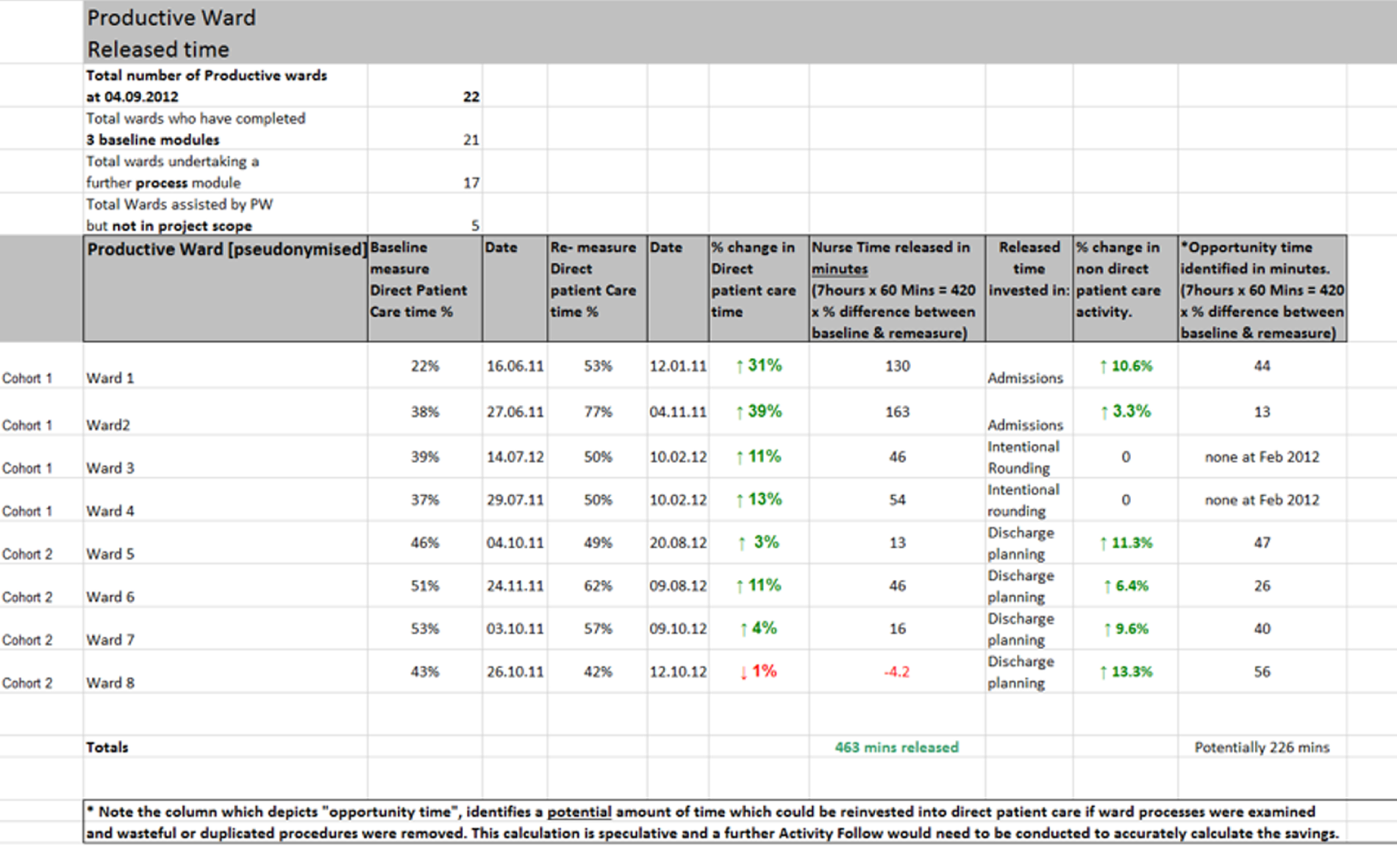

The evidence base

In our earlier research, we also assessed locally available data in five case study sites. 3 Issues about frequency and consistency of reporting made it difficult to analyse findings and assess impacts across whole organisations. (Recent Irish14 and Canadian15 evaluations of PW found similar limitations, echoing the findings of a systematic review16 we describe below.) We did identify routine clinical or administrative measures as potentially available across all trusts but found that these were not deployed to support the implementation of PW.

An impact assessment by the NHSI in 2011, based on interviews and nationally collected data from nine English trusts, suggested that, for every £1 spent implementing the programme, £8.07 would be returned. 17 A particularly striking assessment was that, by March 2014, a £270M benefit would be achieved from implementing PW across acute trusts in England, with trusts seeing an average return on investment of £1,321,676. The authors calculated that:

Most of this benefit will come from improvements to productivity and efficiency by improving length of stay and staff absence through quality improvements. A smaller proportion of the benefit will be attributable to stock reduction.

NHSI, p. 4. 17

However, the authors of this report noted the following limitations: the sample of nine trusts included in the study was not statistically significant; the interviews were with managers involved in implementing PW, and did not necessarily represent the view of trust boards; and figures may change over time.

Other limitations were that the sample was representative only of trusts that had implemented PW in more than half of their wards, and was restricted to medical divisions, which yielded the greatest benefits. In the context of the current study, it should also be noted that these figures were based on assumptions that changes would be sustained. In this vein, a systematic review16 of PW suggested that, although ‘organisations were keen to report the significant improvements experienced following the initial implementation . . . it is unclear whether or for how long these changes were sustained’. 16

This review reported that the evidence base largely comprises single site, descriptive studies, characterised by poor outcomes data and a distinct positive bias. 16

Two of the members of the advisory group of the current research study (Dr Mark White and Professor John Wells) later examined the literature relating to PW through a bibliometric analysis. 18 They found 64 grey literature publications, 13 evaluations and reports, and 21 peer-reviewed papers during the period 2006–13. However, only seven of the peer-reviewed papers presented the results of original research or outlined any methodology. White et al. 18 concluded that the literature ‘provides no empirical offering to the paucity of evidence required to gauge success and impact’.

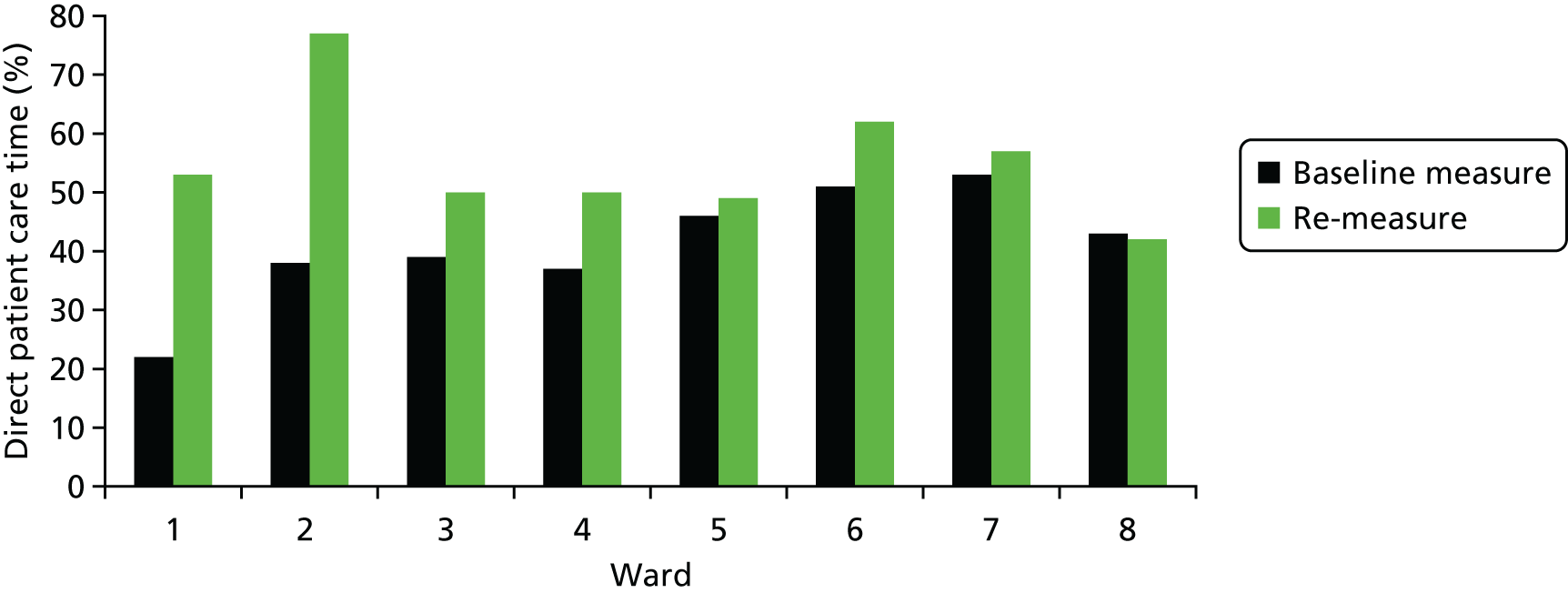

An informal scoping review that we carried out in 2017 on published outcome data on the key PW measures found that there had been few relevant publications since Wright and McSherry’s review; those that existed were small in scale and lacking in clarity and robustness. One possible exception was the evaluation of PW, along with others in the Productive series, by the Department of Health in Victoria, Australia,19 in 14 health service organisations (although this relied on self-report data submitted by the organisations themselves). The study found that PW was associated with the following outcomes from baseline to the end of the initial implementation period (12 months):

-

an average 11% increase in direct care time (from 37% to 48%)

-

a reduction in falls of 9% per 1000 bed-days

-

a 2.7% reduction in length of stay

-

a 33% increase in pressure sores in wards (attributed to more accurate reporting)

-

an unspecified increase in patient satisfaction

-

a reduction of 18.4% in staff unplanned leave

-

for each dollar invested, AU$15.68 of gross value released.

A study14 of the effects of PW over time on the ‘work engagement’ of ward-based teams in Ireland in 2013–14 used a standardised measure to collect data from a second national cohort (nine wards) at two time points and compared it with matched control sites. This study found that ward staff implementing PW had higher work engagement at both time points than the control group but that, of the three dimensions measured (vigour, dedication and absorption), only ‘vigour’ was significantly sustained. The authors note that one explanatory factor may be that early, self-selecting cohorts of wards implementing PW (the study’s intervention group) may have already had higher than average levels of work engagement.

A Canadian evaluation15 used the ‘Organising for Quality’ framework20 to examine the existing (pre-PW) QI capacity on eight wards and the impact of PW on this capacity. Focusing on two wards, one with high and one with low pre-existing QI capacity, the authors found that PW improved this capacity in both wards, but that the impact was stronger where the existing QI environment was already conducive to QI. One important factor was the ward’s motivation to implement PW. Early cohort wards either volunteered or were selected on the basis of their keenness to implement, whereas later wards felt obliged to implement; this affected ward staff’s ownership of PW. Other possible explanatory factors were the ward manager’s attitude to QI, leadership skills and style, and the delegation of responsibility to ward teams. Wards with greater pre-existing QI capacity recognised PW as a continuing QI programme and, after valuable initial support, decreased their reliance on a PW facilitator.

Theoretical perspectives have rarely been applied to PW. A recent longitudinal case study of the adoption and implementation of the PW in a Dutch hospital is an exception, in this case using an institutional logics perspective to explore the different ways in which the PW has been framed for both the nursing profession and health-care managers. 21 Other studies have explored the adaptation of Lean techniques (on which PW tools and modules are based to a large extent) in health-care organisations. 22–24 Despite significant claims by advocates, there is little empirical evidence of the sustained benefits of adopting such approaches. More broadly, a systematic review of reviews of Lean thinking in trusts concluded that the:

. . . immaturity of the research field makes it hard to find substantial evidence for effective Lean interventions in healthcare.

Andersen et al. 25

Finally, we are aware of a currently unpublished trial – using robust methods – of an augmented version of PW that has been the subject of conference presentations. 26 The intervention, ‘RTC+’, was implemented in one regional health authority in Scotland. The augmented version was created to fill an identified gap in the logic of PW, namely the assumption that nurses will use the time gained to increase direct care time, and that this will result in improved caring behaviours and attitudes of staff and, thus, improve patients’ experiences. RTC+ included three elements additional to PW:

-

a systematic, qualitative observation by facilitators of the caring practice of nurses (‘caring observations’)

-

asking patients to rate their experiences of care using the Valuing Patients as Individuals Scale

-

asking team members to report, via a survey, the quality of teamwork and staff relationships.

The study aimed to give clear operational definitions of all interventions tested using a logic model; assess the impact of these interventions using a quasi-stepped wedge trial; and indicate the extent to which any effectiveness may depend on context, based on a realist evaluation. The primary outcome measures used were not key PW metrics (see earlier) but, rather, standardised measures of patients’ evaluation of nurse communication, staff shared philosophy of care, and staff emotional burnout. The researchers have reported that they found that RTC+ was associated with statistically significant improvements in the first two primary measures and in patients’ overall rating of ward quality and nurses’ positive affect, as well as several items related to nursing team climate.

To sum up, to date there remains no robust, independent, peer-reviewed, published evaluation to support or challenge the claims frequently made for the impact of PW (which often rely on both the scaling up of the innovation and sustained impacts). A decade after the initial development of PW, there remains little robust evidence of the sustained impact of PW on the efficiency and productivity at ward level, despite its widespread and continuing adoption (both in the NHS and internationally).

Studying the sustainability of innovations in the organisation and delivery of health-care service

Our current study seeks to explore whether or not implementing PW has led to sustained impacts in English acute NHS trusts over the period 2008–18. However, as well as seeking to describe the sustained impact and wider legacies of PW, we aim to add to the theoretical knowledge relating to the assimilation of QI interventions into routine day-to-day practice and their sustained impact.

Our theoretical interest in this study focuses on the relationship between the timing of adoption, approaches to local implementation, forms of assimilation and sustainability within differing organisational contexts. Although our focus is mainly on the last three of these processes (i.e. implementation, assimilation and sustainability), timing of adoption is important in terms of how it may have an impact on longer-term sustainability given that it is likely to shape, for example, the availability of funding, the opportunity to learn from other organisations and the availability of supported networks. A particular contribution we hope to make is in response to Wiltsey Stirman et al. ’s27 observation from their review of the empirical literature, that:

Few studies that investigated sustainability outcomes employed rigorous methods of evaluation (e.g. objective evaluation, judgement of implementation quality or fidelity) . . . Very little research has examined the extent, nature or impact of adaptations to the interventions or the programs once implemented.

Wiltsey Stirman et al. 27

Similarly, Martin et al. 28 point to a gap in knowledge:

. . . around the nature of the challenges faced in trying to sustain and embed clinically led organisational innovations beyond initial implementation, the way in which these vary by context, and the strategies that might help overcome them. The literature is also relatively silent on the unintended consequences of sustainability.

Martin et al. 28

In designing our study (see Chapter 3, Methods), we have taken into account Wiltsey Stirman et al. ’s27 argument that ‘research that is guided by the conceptual literature on sustainability is critical to the development of the research in the area’ and that it is necessary to define sustainability, define outcomes or desired benefit, choose an appropriate time frame, and study fidelity and adaptation. In the following paragraph we provide an example of a recent contribution addressing similar interests in the health-care context before describing, in more detail, contemporary frameworks that we have used in our own study to help understand processes of implementation, assimilation and sustainability, respectively.

Martin et al. ’s28 study of the sustainability of a (meso-level) genetics services in the UK has some interesting insights for our own work. For example, they concluded that:

. . . evidence – in the narrow sense of robust information on clinical and cost-effectiveness – does not seem essential to sustaining meso-level change.

Martin et al. 28

As outlined in The evidence base, the lack of a robust evidence base for PW has done little to slow its adoption (both nationally and internationally), with advocates relying on similarly anecdotal and questionable evidence.

Another aspect that resonates highly with what we know of PW from earlier studies (see The evidence base) is what Martin et al. 28 highlight as the:

. . . organisational influence of service leads . . . [the] roles and positions of the service leads . . . impacted notably on their ability to make the case for the ‘value’, broadly defined, of their services.

Martin et al. 28

Frameworks for understanding local approaches to Productive Ward implementation

Implementation science is the scientific study of methods to promote the uptake of research findings into routine health care in clinical, organisational or policy contexts. One such commonly applied framework in the health-care context is the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research,29 which outlines four activities within an implementation process: planning, engaging, executing and reflecting, and evaluating.

Informing comprehensive frameworks such as the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research are specific lessons from the broader implementation/improvement science literature. Several of these merit particular consideration in the context of our study as they relate to important features of the recommended approach for implementing PW (see Earlier research into the adoption and implementation of PW in the period 2009–12). First, Dixon-Woods et al. 30 and Powell and Davies31 highlight how securing the support of one professional group – nurses, in the case of PW – can lead to the alienation of others (as cited in Kislov et al. 32). Second, Lozeau et al. 33 raise the possible ‘contradiction between rhetoric of empowerment and the command-and-control procedures for auditing the performance data representing the managerial agenda’ (as cited in Kislov et al. 32). This was certainly one potential scenario in relation to PW, given the heavy emphasis on data collection and audit in the programme combined with the tension between the rationales of productivity and ‘releasing time to care’. Third, Kislov et al. 32 themselves suggest that ‘formidable contextual influences can significantly distort improvement approaches, activities and techniques’ over time, something that, given the duration of the period we studied, was likely to be highly relevant in acute trusts.

Fourth, Kislov et al. 32 argue that:

. . . interest in quality improvement significantly varies between different organisations (Krein et al. 201034), with ‘early adopters’ being more likely to be recruited in the initial phases of new improvement projects (Walshe 200935).

Kislov et al. 32

In doing so, they garner the most resources and support to implement an initiative. Finally, it is a common critique of Lean-based approaches that, at least in implementation, they fail to take due account of the customer (the patient in the health-care context). 36 This was an issue that we took an interest in during our fieldwork.

A recent classification of implementation strategies has been developed by Powell et al. 37 and Waltz et al. 38 Powell et al. ’s37 study used a three-round modified Delphi process to generate expert consensus on a common nomenclature for implementation strategy terms, definitions and categories. A panel of stakeholders with expertise in implementation science and clinical practice reached consensus on a final compilation of 73 discrete strategies; Waltz et al. 38 later organised the 73 strategies into nine categories. We have used this categorisation to explore the similarities and differences between the implementation approaches used in our case study sites (see Chapter 3).

The next section outlines a framework for considering what happened to PW after the initial implementation phase, namely how it was, or was not, assimilated into routine practice.

Frameworks for understanding assimilation processes

Here we are concerned with what happens after the adoption and implementation of a service innovation such as PW. Wiltsey Stirman et al. ’s27 review of empirical studies found that ‘many of the innovations that are initially successful fail to become part of the habits and routines of the host organisations and communities’. As Greenhalgh et al. 39 note, empirical evidence strongly suggests:

. . . an organic and often rather messy model of assimilation in which the organisation moved back and forth between initiation, development, and implementation, variously punctuated by shocks, setbacks, and surprises.

Greenhalgh et al. 39

Certainly, over time, adaptation and/or abandonment40 were both potential outcomes of implementing PW.

Scheirer and Dearing41 outline how one detailed line of research defines sustainability as the institutionalisation or routinisation of programs into ongoing organisational systems. With this perspective, the maintenance of programme activities without special external funding, which was time-limited (usually up to 2 years) in the case of PW, is most likely to occur if the programme components become embedded into organisational processes. While this was the intention of designing and implementing PW, if this happens, researchers may no longer be able to identify a specific ‘programme’, as the activities have become a part of the organisation’s core services. These concepts are well developed in Yin’s42 concept of routinisation and are summarised by Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone,43 who explain that:

. . . a process of mutual adjustment occurs such that both the innovation and the organisation change to adjust to each other. The innovation eventually loses its separate identity and becomes part of the organisation’s regular activities, a process that has been referred to as ‘routinizing’ or ‘routinization’.

Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone43

Building on the work of Lozeau et al. ,33 Kislov et al. 32 argue that a potential ‘compatibility gap’ between a set of assumptions underlying the design of a managerial intervention (such as PW) and the actual cultural, structural and political characteristics of an adopting organisation can result in one of the following, each of which we view as a different form of assimilation or routinisation:

-

customisation, which involves both adapting the managerial technique and adjusting unit processes (i.e. the mutual adjustment described in quotation above) and recognising that adaptation, reinvention and ongoing development are part of continuous improvement

-

loose-coupling, whereby the technique is adopted only superficially, in a ritualistic way, with the functioning of the unit remaining largely unaffected

-

co-optation or corruption, whereby the technique becomes captured and distorted to reinforce existing roles and power structures

-

transformation, whereby the adopting unit modifies its functioning to fit the assumptions behind the managerial technique and the actual use of an innovation does not significantly differ from its intended use.

While Lozeau et al. 33 originally presented the different forms of assimilation outlined above as distinct scenarios, Kislov et al. 32 suggest that these could be viewed as ‘temporal stages of a broader evolutionary process’ (i.e. they are stages of the same process rather than distinct independent categories). Kislov et al. ’s32 own longitudinal case study of ‘facilitation’ as a managerial technique (in the context of health-care QI) found that the technique moved through transformation, customisation and loose-coupling, to corruption (where it was co-opted for producing outcomes prioritised by the most powerful stakeholders). We have applied Kislov et al. ’s typology to PW in a similar way.

Frameworks for understanding the sustainability of service innovations

In their systematic review of the diffusion of innovations in service organisations, Greenhalgh et al. 39 defined sustainability as ‘making an innovation routine until it reaches obsolescence’ (while noting an ambiguity in the notion of sustainability, namely that the longer an innovation is sustained, the less likely an organisation will be open to additional innovations). Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone43 similarly argue that if a programme (such as PW) has been sustained as originally planned, then the system will have stopped evolving and adapting. In their review of empirical studies of sustainability, Wiltsey Stirman et al. 27 found that partial sustainability was more common than continuation of the entire programme or intervention, even when full implementation was initially achieved, and that, in studies that employed independent fidelity ratings to assess the sustainability at the provider level, fewer than half of the providers sampled continued the practice or intervention at high levels of fidelity.

The term ‘sustainability’ is rarely used in the mainstream literature to relate to the diffusion of innovations, and is a contested theme in discourses on innovation in organisations. 39 Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone state:

Little consensus exists in the literature on the conceptual and operational definitions of sustainability. Several terms have been in use to refer to the phenomenon of program continuation. Among these are: program ‘maintenance’, ‘sustainability’, ‘institutionalization’, ‘incorporation’, ‘integration’, ‘routinization’, local or community ‘ownership’ and ‘capacity building’.

Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone43

However, ‘sustainability’ is widely and commonly applied in discussions of the ‘success’ (or otherwise) of QI interventions in health-care organisations. Historically in this context, the Modernisation Agency, the precursor to the NHSI in the NHS, defined sustainability as ‘when new ways of working and improved outcomes becomes the norm’ (cited in Greenhalgh et al. 39).

A (simplistic) starting point for how we are conceptualising sustainability in our study is that the term ‘refers to the process of changing organisational goals and procedures that are maintained beyond the initial introductory period’. 44 Alternatively, Martin et al. 28 defined ‘sustainability’ heuristically and inclusively as ‘continuation of a service beyond its initial pilot funding’, making no judgements about fidelity to original intent nor categorising the specific nature of what was intended to be sustained. Wiltsey Stirman et al. ’s27 review found that the most frequently cited definition of sustainability was Scheirer’s,41 which was, in turn, based on a framework set forth by Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone. 43 This framework identified (1) continued benefits, (2) continued activities and (3) continued capacity as three elements of sustainability. We find Shediac-Rizkallah and Bone’s43 definition – in the context of public health interventions – most pertinent to PW, namely that (1) it is a multidimensional concept of the continuation process encompassing a diversity of forms (i.e. an entire programme may be continued under its original or an alternative organisational structure; or parts of the programme may become institutionalised); and (2) continuation may occur at a number of levels (individual, network or organisational).

We have therefore adopted this definition as the starting point for how we conceptualise sustainability in our study.

The important point in the context of our study, as also alluded to in Martin et al. ’s28 conceptualisation, is that rigid definitions of sustainability (i.e. maintaining the original goals of the programme) should be rejected in favour of a more organic notion of continuing, ongoing (adaptive) change in a positive direction. Our goal in reconstructing the story of the PW was to recognise that, as some aspects of any programme must be abandoned with time while others must expand and adapt, in evaluating the sustainability of PW we will be required to make complex judgements about an evolving programme-in-context.

Chapter 2 Research aim and objectives

Our overall research aim is to establish whether or not PW has had a sustained impact in English NHS acute trusts since its introduction in 2007. Our study therefore seeks to identify and evaluate any sustained impacts and wider legacies of PW in trusts in England that have adopted it.

Our five related objectives are to:

-

identify non-adopters and cohorts of adopters; and explore the timing, scale, nature and perceived impact of PW adoption, implementation and assimilation into routine nursing practice

-

explore how local implementation and assimilation processes relating to the PW, including patient engagement, have shaped sustained impact and any wider legacies (including, for example, QI capabilities and nursing leadership development) of PW

-

investigate any wider legacies in terms of professional development

-

draw conclusions about the nature and extent of the sustained impact of PW on clinical microsystems in English trusts over a 10-year period and make recommendations to managers and clinicians as to how to maximise and sustain the benefits from QI interventions

-

add to the theoretical knowledge relating to the assimilation of QI interventions into routine day-to-day practice and their sustained impact.

Chapter 3 Methods

Our research design used a multiple methods approach. We addressed our overall aim and five related objectives by collecting data from three sources:

-

national surveys of (1) directors of nursing (DoNs) and (2) PW leads in NHS acute trusts in England

-

organisational case studies in six purposively selected NHS acute trusts that adopted PW at different times

-

telephone interviews with staff previously known to have led the implementation of PW in acute trusts.

The adapted Greenhalgh et al. 2 diffusion of innovations model, which we applied previously in our study of the early adoption and implementation of PW5 (see Chapter 1, Earlier research into the adoption and implementation of PW in the period 2009–12), provided the preliminary conceptual framework for our surveys and organisational case studies. We previously used this model to help analyse the local components, and key interactions, that helped to explain the rapid rate and scale of the early adoption and implementation of the PW in routine nursing practice in NHS hospitals in England. 5 In our current study, we drew on the model to initially inform our study of the later stages of the diffusion of innovations process, namely how PW has been assimilated into routine nursing practice and sustained (or not), and how its impact has been measured. Therefore, key contextual factors identified by the model as influential in these later stages of the process were included in our surveys and/or our organisational case studies.

Data sources

As outlined above, our three data sources were (1) a national survey of DoNs and PW leads in NHS acute trusts in England, (2) organisational case studies in six purposively selected NHS acute trusts that adopted PW at different times, and (3) telephone interviews with staff previously known to have led the implementation of PW in acute trusts. We describe each in in turn below.

National surveys

We carried out online surveys of DoNs and PW leads in English acute trusts. The objectives of the two surveys were to:

-

identify cohorts of non-adopting and adopting acute trusts of PW in England from 2006 onwards

-

explore how PW has been adopted, implemented and assimilated in English acute trusts and how this may have changed over time

-

collate perceptions of the nature and scale of any impacts that PW may have had.

All acute NHS trusts in England were eligible to participate in both surveys, with the DoN (or someone to whom the DoN delegated responsibility) and the current or most recent PW lead being eligible to complete the DoN and the PW lead survey, respectively.

The survey was designed as a two-step process. In the first step, DoNs at each acute trust in England were identified and invited to complete a short online survey. That survey included a request to provide contact information for the PW lead at the trust. In the second step, PW leads were contacted and invited to take part in a longer online survey. Both surveys were set up and distributed via SurveyMonkey® (Palo Alto, CA, USA; www.surveymonkey.co.uk). For each survey, two reminder e-mails were sent at fortnightly intervals to non-responders, with final follow-up telephone calls when necessary.

In formulating the survey, we received feedback on the wording of the DoN survey from three former DoNs and on the PW lead survey from three former PW leads, all of whom had agreed to act as critical friends. Revised versions were then circulated to the Project Advisory Group (PAG), and we received further feedback from five PAG members. After further refinement, colleagues carried out tests of the surveys to check that technical aspects were functioning. Finally, two DoN critical friends, one PW lead critical friend and a member of the study team, who was a former PW lead herself (RC), piloted and timed their completion of the online version to ensure that it did not take too long. As a result, the length of the DoN survey was found to be acceptable, but some questions were removed from the PW lead survey.

The final DoN survey (see Report Supplementary Material 1) consisted of up to 16 questions covering implementation, current use, perceived impact, reporting, influence on QI strategy, and future plans. The more detailed final PW lead survey (see Report Supplementary Material 2) had up to 40 items, covering implementation; feedback on modules and tools; staff, patient and carer engagement; use over time; costs and resourcing; learning and dissemination networks; data collection and reporting; perceived impact; personal and professional impact; and legacy. The surveys used a combination of open- and closed-response questions, including questions and statements with Likert scales. The surveys used skip logic to route respondents as appropriate. The only mandatory questions were the routing questions.

Different recruitment strategies were used for the two surveys, and each evolved over time. For the DoN survey an invitation to participate was sent to DoNs listed as in post as at April 2016 in NHS acute trusts in England according to a publicly available database. DoNs in all eligible trusts were e-mailed an invitation to participate, which included study details and a link to the online survey (see Report Supplementary Material 1). DoNs new in post during the lifetime of the survey were also identified through refreshed databases from the provider in July and November 2016 and through professional networks. In those cases where a new appointee was identified for a non-responding trust, an invitation was sent to the new appointee. Following an initially low response rate to the DoN survey, items publicising the survey, inviting DoNs to contact the researchers, were published in two online newsletters. Where Clinical Research Networks and/or R&D departments of eligible trusts offered to facilitate recruitment, or where DoNs asked us to resend the invitation to participate, we e-mailed a Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) version of the covering e-mail, containing a generic link to the DoNs survey. In all of these cases, the respondents were asked to enter the trust name in the survey so that we could identify them.

Given that not all DoNs provided us with contact details for a current or most recent PW lead, we applied for, and received, a substantial ethics amendment to diversify recruitment paths for the PW lead survey. Once this was received, we published an article in Nursing Times, drawing on preliminary analysis of the DoN survey, which invited PW leads to contact the researcher if they were interested in taking part in the study. PAG members who had worked in the NHSI also e-mailed former PW lead contacts to publicise the survey, and others passed on contact information to help us identify PW leads. A general publicity flier with contact details was circulated at relevant events and the survey was also publicised using Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; www.twitter.com). The researcher also contacted trust QI teams (or equivalent), where possible, in an attempt to identify PW leads.

The DoN survey was conducted between June and December 2016 and the PW lead survey was conducted between September 2016 and January 2017.

Organisational case studies

Based on Rogers’45 theory on the diffusion of innovation, we planned to categorise all survey responses as being from one of five types of trust:

-

‘early adopters’ (Rogers’ ‘innovators’, ‘early adopters’ or ‘early majority’) that:

-

implemented PW on all their wards (through either whole-hospital implementation or planned roll-out)

-

implemented PW on some of their wards

-

-

‘late adopters’ (Rogers’ ‘late majority’ or ‘laggards’) that:

-

implemented PW on all their wards (through either whole-hospital implementation or planned roll-out)

-

implemented PW on some of their wards

-

-

‘non-adopters’ that had never implemented PW on any wards.

We then planned to conduct organisational case studies46 in six adopting trusts. In sampling for our six case study sites, our strategy was to sample using the following criteria in order of priority: time of adoption (prioritising as ‘early’ sites the trusts that participated in our earlier study), implementation strategy and other characteristics. These criteria are described in more detail in the next paragraph. A list of eligible sites was drawn up, along with information on the sampling criteria, and a ‘top six’ was decided in discussion between team members; it should be noted that the process of recruiting the six sites then took 11 months. A significant time-lag often occurred between inviting trusts to participate as case studies, receiving agreement in principle from the DoN, receiving local R&D approvals and receiving the information we required to start data collection. This meant that, in practice, we had to readjust our ‘top six′ sample as we went along, each time applying the selection criteria in their order of importance in the light of existing participating sites.

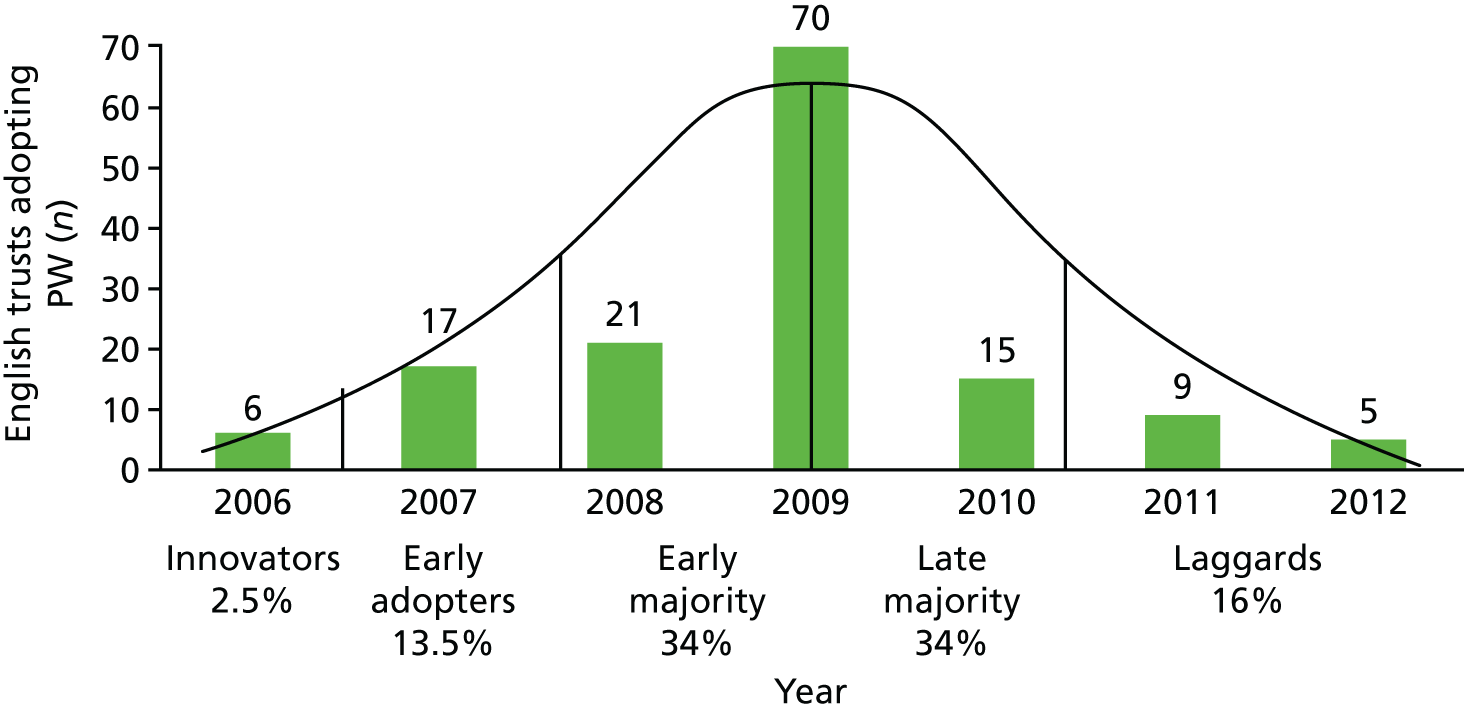

Our primary criterion was initially to sample trusts as distributed across Rogers’ adoption categories from the survey results alone. We encountered several difficulties with this. First, our sample was not large enough for us to assume that it represented the national picture on time of adoption. Second, year of adoption data proved unreliable, with DoNs and PW leads from the same trust often giving conflicting reports. We therefore drew on four sources of data – (1) public data for early pilot sites, (2) the date (if any) provided by the PW lead, (3) the date provided by the DoN and (4) the earliest date that the trust had purchased a PW box set from the NHSI – to reach our ‘best guess’ on adoption year for 141 English acute trusts identified by any or all of these means as having adopted PW. We ranked these sources in the order given above according to perceived reliability. The data provided by DoNs were considered less reliable than those given by PW leads because many DoNs would not have been in post at the time of adoption. The box set purchase data (provided with permission of a PAG member who had worked in the NHSI) were the least reliable because the purchase may not have been followed by implementation. We used the derived ‘best guess’ dates for all adopting English acute trusts (Figure 3) to try to sample case sites estimated to have adopted PW in different years, with the aim of attaining maximum variation.

In selecting the three ‘early’ adopting trusts, we ideally hoped to recruit three of the five trusts in which we have previously conducted in-depth case studies; this would have enabled us to draw on both the national picture of early adopters from our earlier survey study in 2008 and an existing qualitative data set (comprising 58 transcribed qualitative interviews and documentary materials from 2009 to 2010). These existing data sources would have provided significant contemporaneous insights into the local approaches to early implementation of the PW in these five trusts. However, we were able to recruit only one of the sites that had participated in the earlier study; two of the others had not taken part in the survey and the other two declined our invitation.

As a secondary consideration in sampling our sites, we also hoped to recruit two sites that implemented PW on a whole-hospital basis (the ‘big bang’ approach); two that implemented PW in selected wards only, with no plans for whole-hospital roll-out; and two that had planned for a whole-hospital roll-out from the start. This would have enabled us to compare and contrast what we assumed were likely to be significantly different local approaches to implementation. This was not possible because only two trusts responding to our survey reported implementing PW in some wards only (without a view to further roll-out); they did not agree to be contacted with a view to participating as a case study site. Two trusts reported implementing PW in all wards at once, although, as they were both early adopters, they were not approached, as trusts that had participated in the earlier study were prioritised.

Third, we also considered the following selection characteristics: geographical (e.g. urban/rural), size of trust/number of wards, Care Quality Commission (CQC) rating and age of hospital estate. Within a relatively small sample frame, we sampled for diversity with respect to region and type/size of trust as far as possible, but did not consider other characteristics. Our final set of organisational case studies with sampling characteristics is shown in Table 15.

Within each of the case study sites we randomly selected two wards in which to carry out interviews and observations. The rationale behind random selection was to be able to explore the story of PW in wards that were not suggested or selected on the basis of ‘successful’ implementation, or atypical legacy. Eligible wards were those that had implemented the three PW foundation modules and at least one process module. Additionally, we knew from our earlier research3 that > 59% of implementing wards were medical (24%), surgical (21%) or care of older people (14%). We therefore planned to sample three medical, two surgical and one care of older people wards from the three ‘early’ adopting trusts, with a similar sample in the three ‘late’ adopting trusts. The fact that we recruited sites over a protracted period, and were, therefore, unable to create a single sample frame with precise details of eligible wards, meant that it was impossible to recruit such precise numbers of each ward specialty without restricting choices unreasonably in sites recruited later. Therefore, we randomly selected eligible wards at each site as we went, from a trust-specific sampling frame consisting of eligible wards within these specialties, and ensured that the second ward selected was of a different specialty from the first ward.

Within each randomly selected ward, we purposively sampled a range of staff who would give a range of perspectives on PW implementation and legacy. We interviewed ward managers and other ward staff, focusing, where possible, on those who had been in post at the trust at the time of implementation. We were guided by the ward manager and other ward staff in identifying these longer-serving staff members. When possible, we approached staff directly to ensure that consent to participate was given without obligation; some ward managers preferred to pass on our request.

All interviewees at the sites were given (by e-mail or face to face) a participant information sheet, and at the start of the interview they were asked to sign a consent form. Interviews were recorded (with express permission) and transcribed verbatim. Interviews lasted between 7 and 78 minutes, with a mean length of 33 minutes. The organisational case studies were undertaken partly to allow the findings from the surveys (see National surveys) to be explored within a local context, essentially retracing the ‘story’ of the PW in each case study site. We conducted the following in each of our six case study trusts:

-

Semistructured face-to-face or telephone interviews with key staff or PPI representatives identified through purposive sampling47 to give us a range of perspectives on the implementation, assimilation and legacy of PW from board to ward, and within wards, from ward manager to health-care assistants and auxiliary staff (see Report Supplementary Material 3 and 4).

-

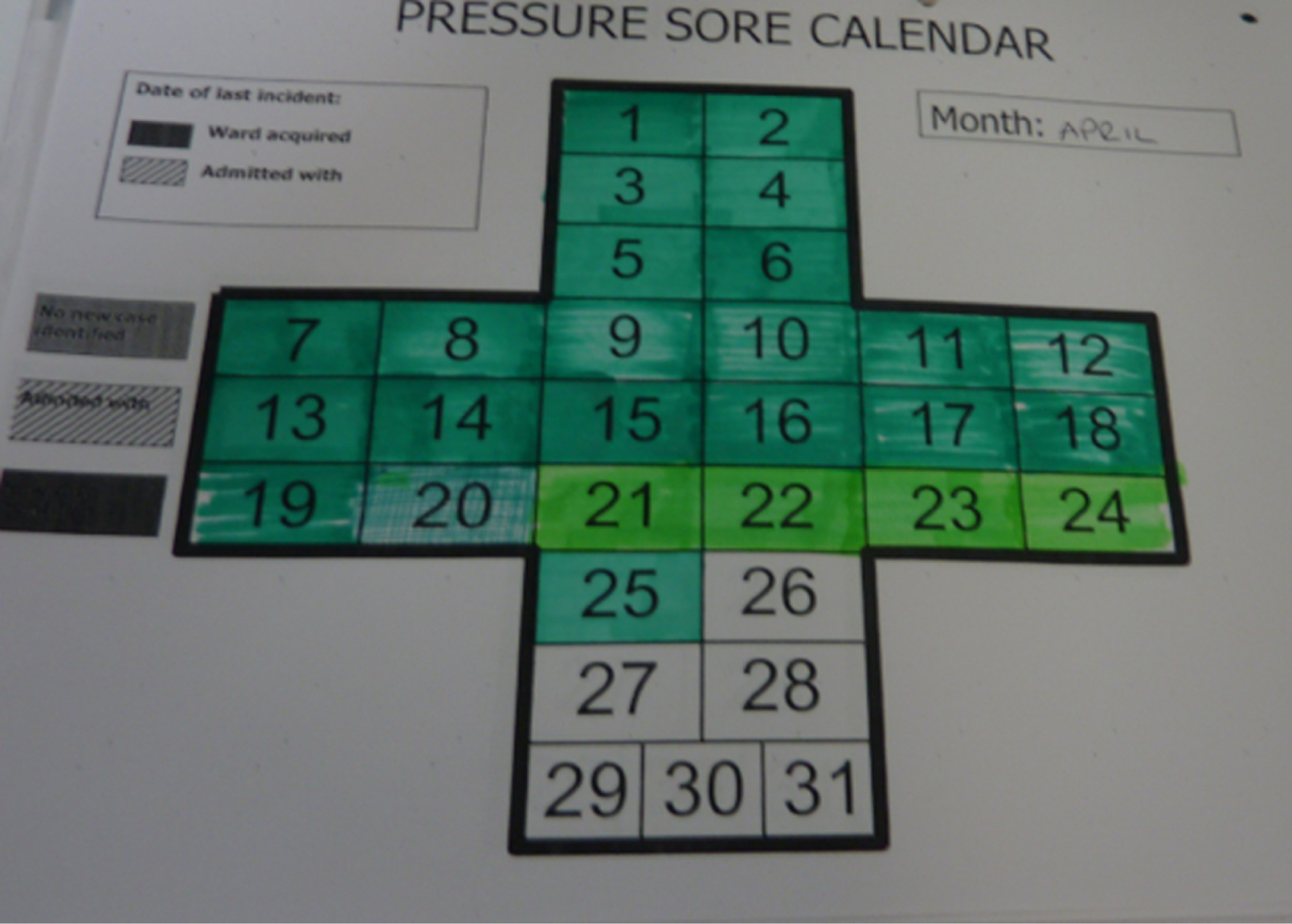

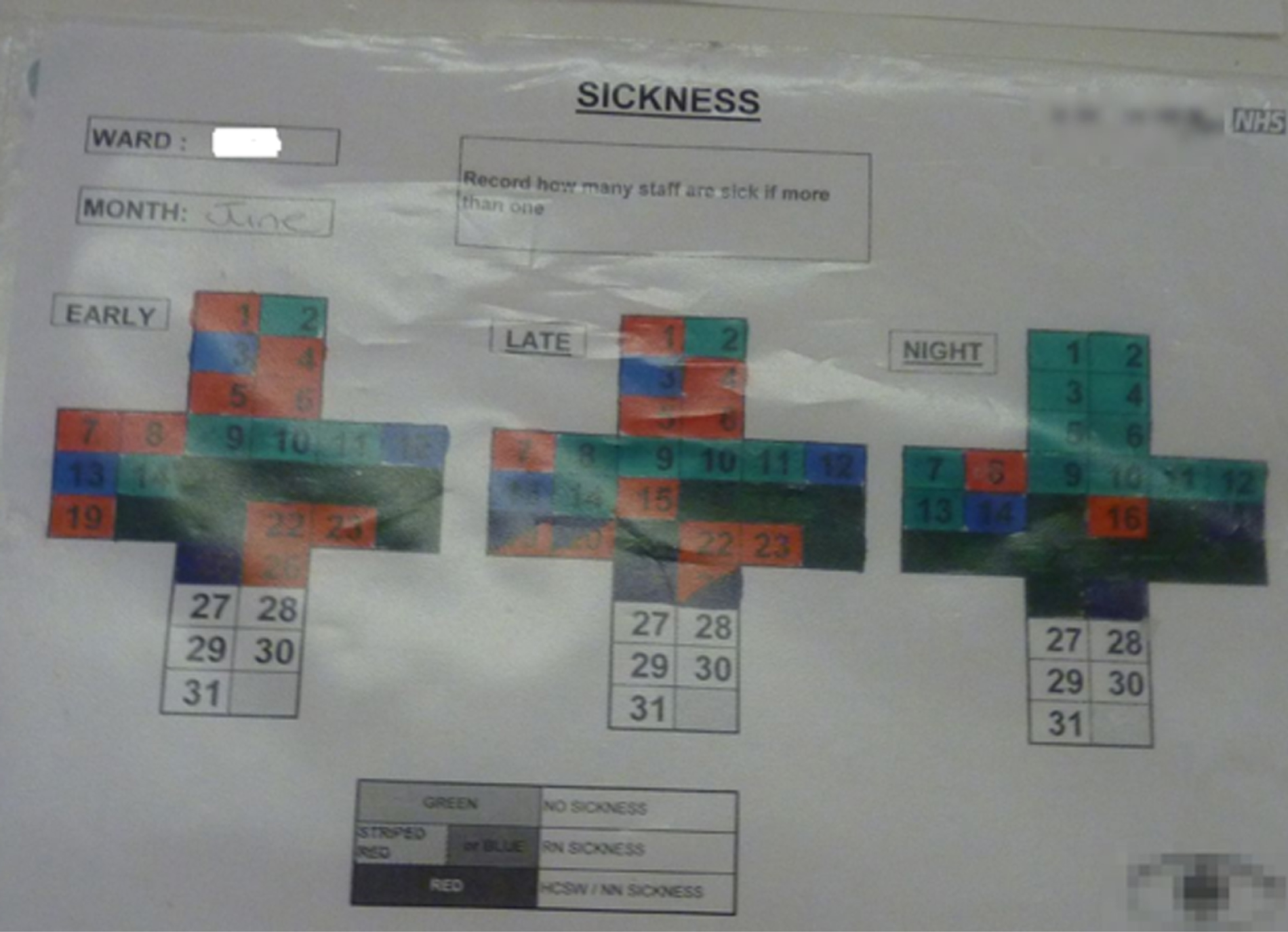

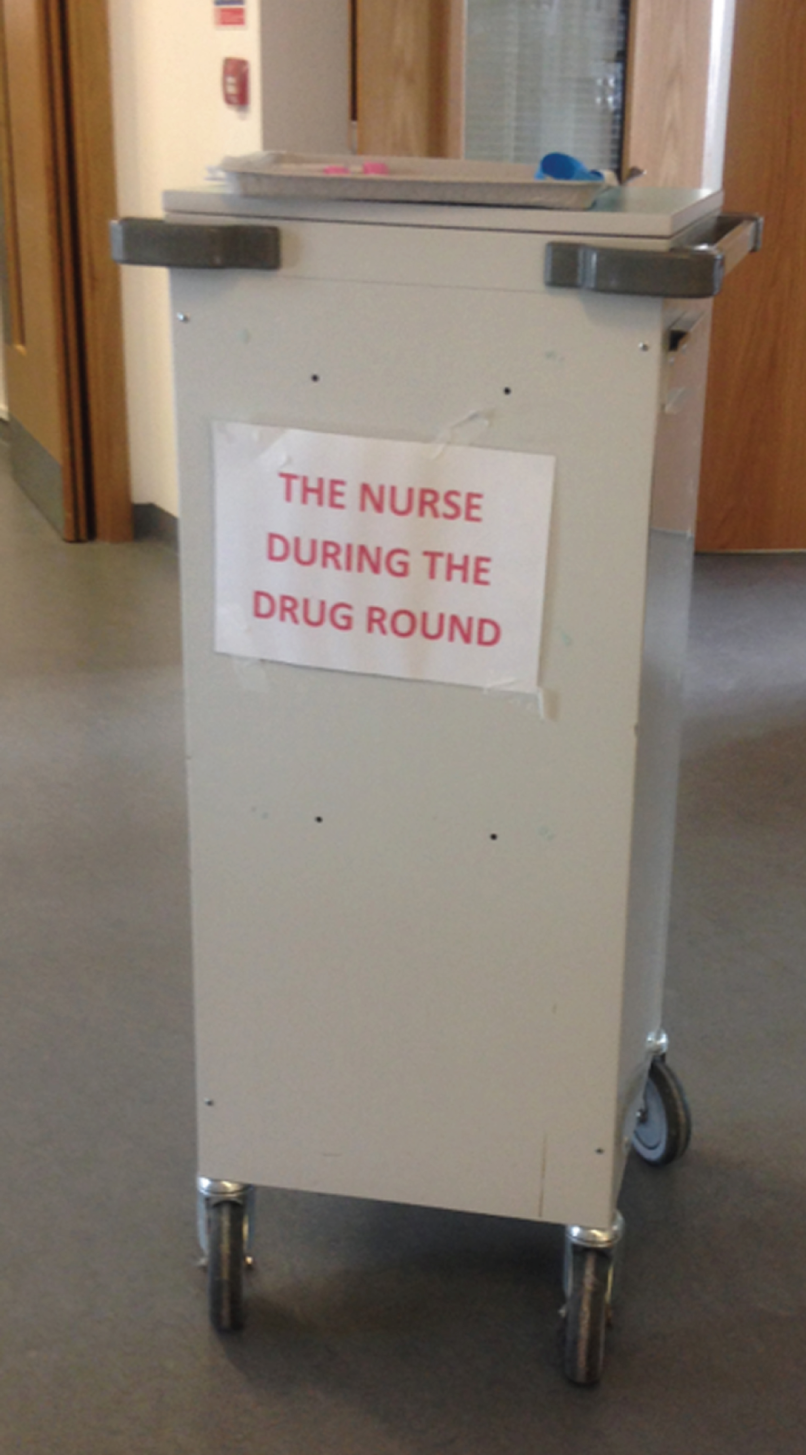

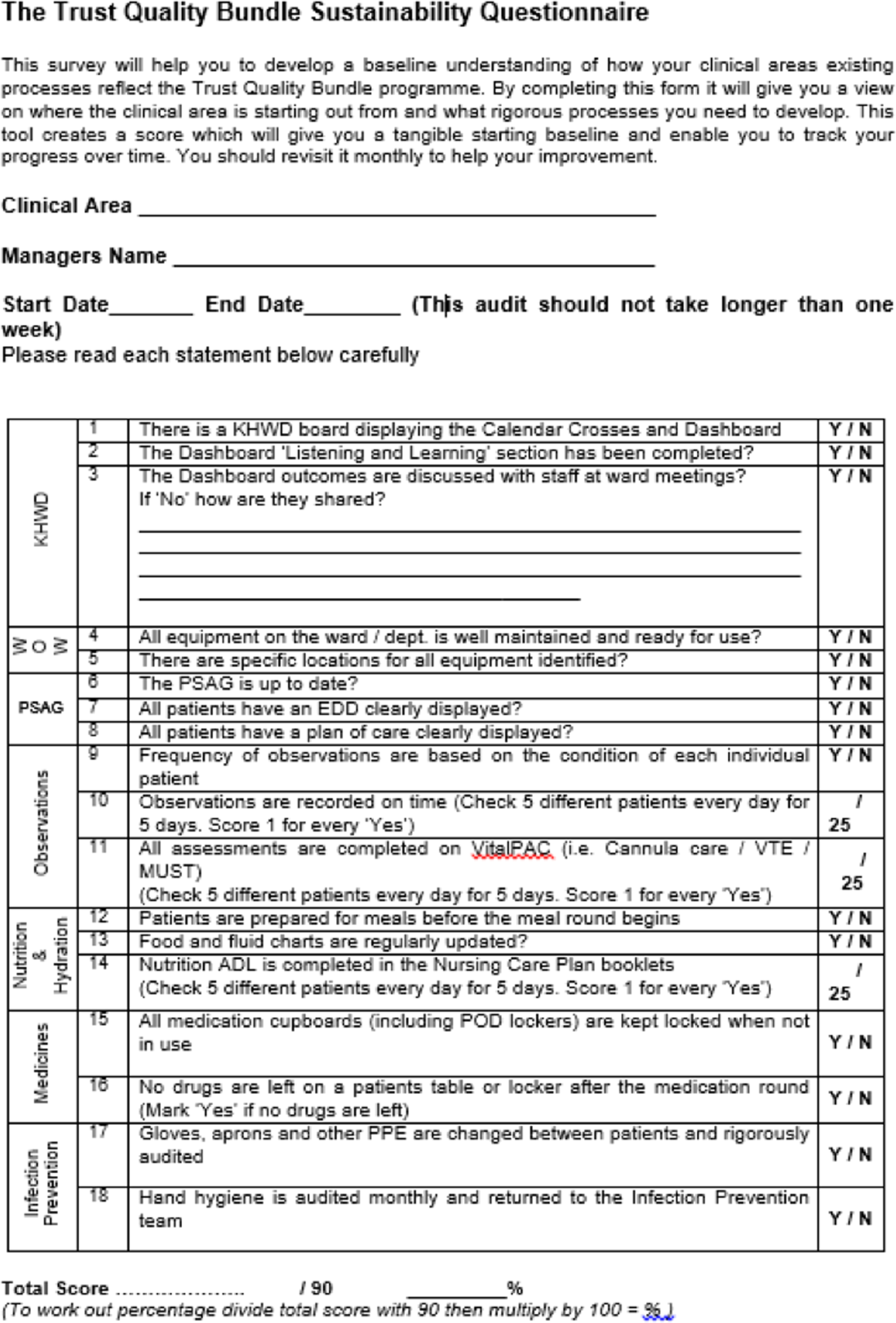

Structured observations of the ward environment using an observation guide (see Appendix 2) along with informal conversations with ward staff to note legacy on processes that were observable without intrusion (mealtimes, medicines round, patient observations) and evidence of material legacies of the PW (PSAG noticeboards, Safety Crosses notices, medicine trolleys, etc.) and (with permission) to photograph these. The observation template was derived from the ’10-point checklists’ at the end of the PW modules, which encapsulated their goals.

-

Short questionnaires to ward managers derived from the ’10-point checklists’ at the end of the PW modules, covering modules and aspects not suited to observation (see Report Supplementary Material 5).

-

Collation of local contextual data, including documentary (including electronic) materials relating to PW implementation, and monitoring of impact.

-

Completion of a brief pro forma questionnaire (see Appendix 3) to identify the use of ward-level metrics to monitor the impact of PW, followed by a focused assessment of available data.

Fieldwork was carried out between March 2017 and February 2018.

Telephone interviews with early Productive Ward leads

Some of the impacts of PW are likely to inhere in individuals involved in it. To capture these, we carried out telephone interviews with people who led PW at an early stage. Early PW leads were identified from an existing national database of contacts compiled as part of earlier studies of PW at NHS acute trusts carried out by members of the current research team;3,4 snowballing; personal contacts; and Twitter posts. Topics covered with these early PW leads (see Report Supplementary Material 6) included their past involvement with PW, their views on the programme, their experiences of implementation and sustainability, and any impacts that their involvement had on them personally or professionally.

We e-mailed an invitation to participate, along with a participant information sheet, to all contacts. One follow-up e-mail was sent to non-responders. Consent forms were sent ahead of time to all those agreeing in principle, and potential participants were invited to ask any questions beforehand, or at the start of the telephone call, before consenting. Signed consent forms were returned or, if preferred, verbal consent to each item on the consent form was audio-recorded.

Appointments for interviews were made at participants’ convenience. Interviews were carried out by telephone and were audio-recorded. Interviews lasted between 15 and 42 minutes, and on average 25 minutes. Audio files were transcribed verbatim by a third party and then checked for accuracy. Data were collected between February and December 2017.

Modes of analysis/interpretation

National surveys

For each survey the following method of analysis was used. The SurveyMonkey data were exported as a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet, which was prepared for analysis by removing blank surveys and by adding identification numbers and descriptive data (region, trust type, bed numbers) to identifiable trusts.

The analysis of the closed questions used descriptive statistics from the summary report generated by SurveyMonkey, and ranges and means were calculated for quantitative questions.

Open-comment fields were coded thematically. Initial broad themes were those that had formed the themes of the survey questions, both open and closed (i.e. implementation type and process; use over time of PW modules and toolkits; patient and carer involvement; perceived impact, etc.) Subthemes, such as difficulties in attributing impact, or inconsistency of impact, were identified through inductive analysis of open responses. This analysis was carried out by Sophie Sarre. A comprehensive report, based on all relevant data under these themes, was reviewed by the research team to allow agreement or refining of themes and to generate any additional questions we might explore.

Organisational case studies

To analyse the interview data, we used the Framework method. 48 Initial themes for the framework were developed from the theoretical literature, the topic guide (itself reflecting theoretical and empirical literature), familiarity with interviews, and the coding of four transcripts by Sophie Sarre. With regard to the theoretical literature, as an integral component of the coding framework, we used three existing frameworks to explore the (1) implementation,38 (2) assimilation32 and (3) sustainability41 of PW in the six case study sites. Each of these frameworks has been described in Chapter 1.

Data from each transcript were summarised under each theme, with the related line number from the transcripts given. Quotations were also included, along with initial interpretive comments. This process meant that data analysis was a combination of deduction (theory-driven exploration) and induction (data-driven generalisation). It also allowed us to examine similarities and differences of views within and between sites and participants.

The initial framework was refined through the following process. The framework was represented in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet that included a key with definitions of the themes and subthemes. Each of the other four members of the study team (JM, RC, PG and GR) coded a different transcript, drawn from two study sites. Any inconsistencies were discussed to refine definitions, and any additional codes required to capture the full range of data were identified and added. Following this process, Sophie Sarre analysed 12 transcripts from one site using the revised coding frame, and this analysis was presented to the PAG for comment. In addition, a further transcript, from a third site, was coded by three of the four team members (JM, RC and GR). The results were then re-examined for consistency. Any inconsistencies were discussed between Sophie Sarre and Glenn Robert until consensus was reached and the description of that theme was refined. An additional subtheme was added (‘training’). A final, third version of the coding framework was then developed, and tested on one further transcript by two members of the research team. This version was found to be robust and comprehensive enough for use in analysis, and the remaining transcripts were analysed end entered into this coding framework.

The completed coding framework was used to write up descriptive working papers of each of the sites. At this stage, documentary, observation and ward manager questionnaire data were included in the thematic narrative. Analysis occurred through this writing process. Summaries of findings were sent to PW leads at the case study sites for member checking, and any corrections were made to the working papers. At this stage, we also mapped each of the nine Waltz et al. 38 categories (encompassing 73 strategies) for each of the six sites. The longer working papers and our implementation map were used as the basis for the cross-case analysis.

In each of the case study sites, we also reviewed how metrics have been used locally to determine the impact of PW. These reviews were based on our secondary analysis of documentary sources and our earlier review (see Chapter 1, Earlier research into the adoption and implementation of PW in the period 2009–12), and our analysis included collating all local PW-related data in each case study site, judging the rigour and robustness of these data for (1) QI and (2) evaluation purposes, and assessing whether or not they showed improvements over time on the relevant PW modules (and related measures). Our assessment was partly informed by our earlier work, which included empirically-based recommendations relating to the measurement of impact of PW. 3,5 Based on our findings, we present revised recommendations for future data collection in Chapter 9.

We asked each site to complete a short questionnaire about the availability and use of data at a ward level to measure the impact of PW (see Appendix 3). We focused on asking about outcomes, measures or indicators that were either specified or alluded to in PW materials, with additional items specified based on items mentioned in reports, survey responses or common measures of nurse-sensitive indicators (Box 1).

-

Patient observations.

-

Patient falls.

-

Pressure ulcers.

-

MRSA infection rate.

-

C. difficile infection rate.

-

Patient satisfaction.

-

Direct care time.

-

% patients going home on EDD.

-

Length of stay.

-

Ward cost per patient spell.

-

Unplanned staff absence rate.

-

Financial (e.g. ward staffing costs).

-

Patient experience.

-

Drug administration errors.

-

VTE prevention.

-

Other (specify).

EDD, expected discharge date; MRSA, meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus; VTE, venous thromboembolism.

For each of the metrics we asked a series of questions to determine the data that might be available at ward level that had the potential for analysis that moves beyond the simple ‘before and after’ comparisons that are prevalent in the literature on the topic:

-

Has the trust collected these data at ward level?

-

Has the trust analysed these data specifically to monitor the impact of PW?

-

Are there data at more than one time point before implementation?

-

Are there data at more than one time point after implementation?

-

Has ward-level analysis been reported, within or beyond the trust?

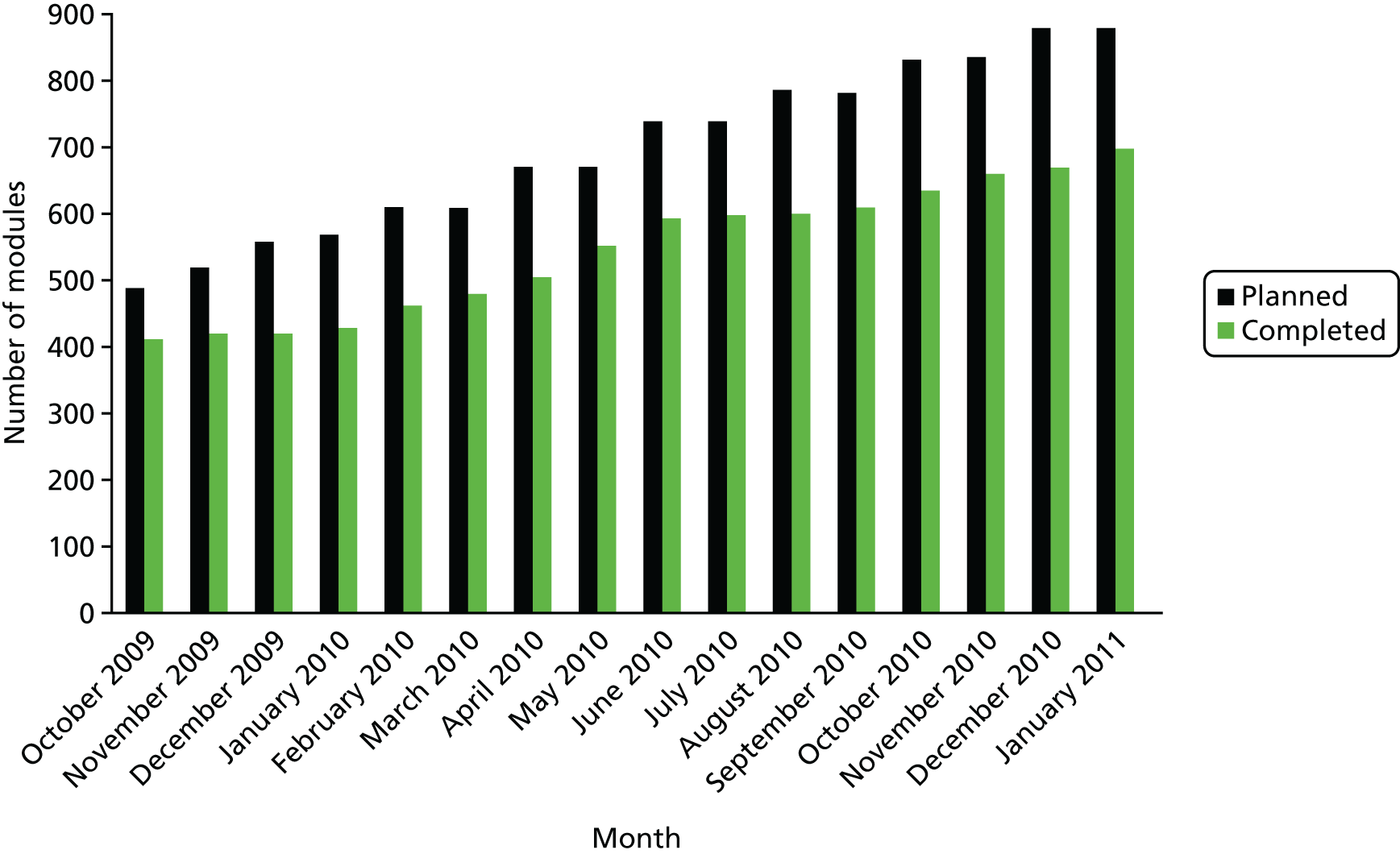

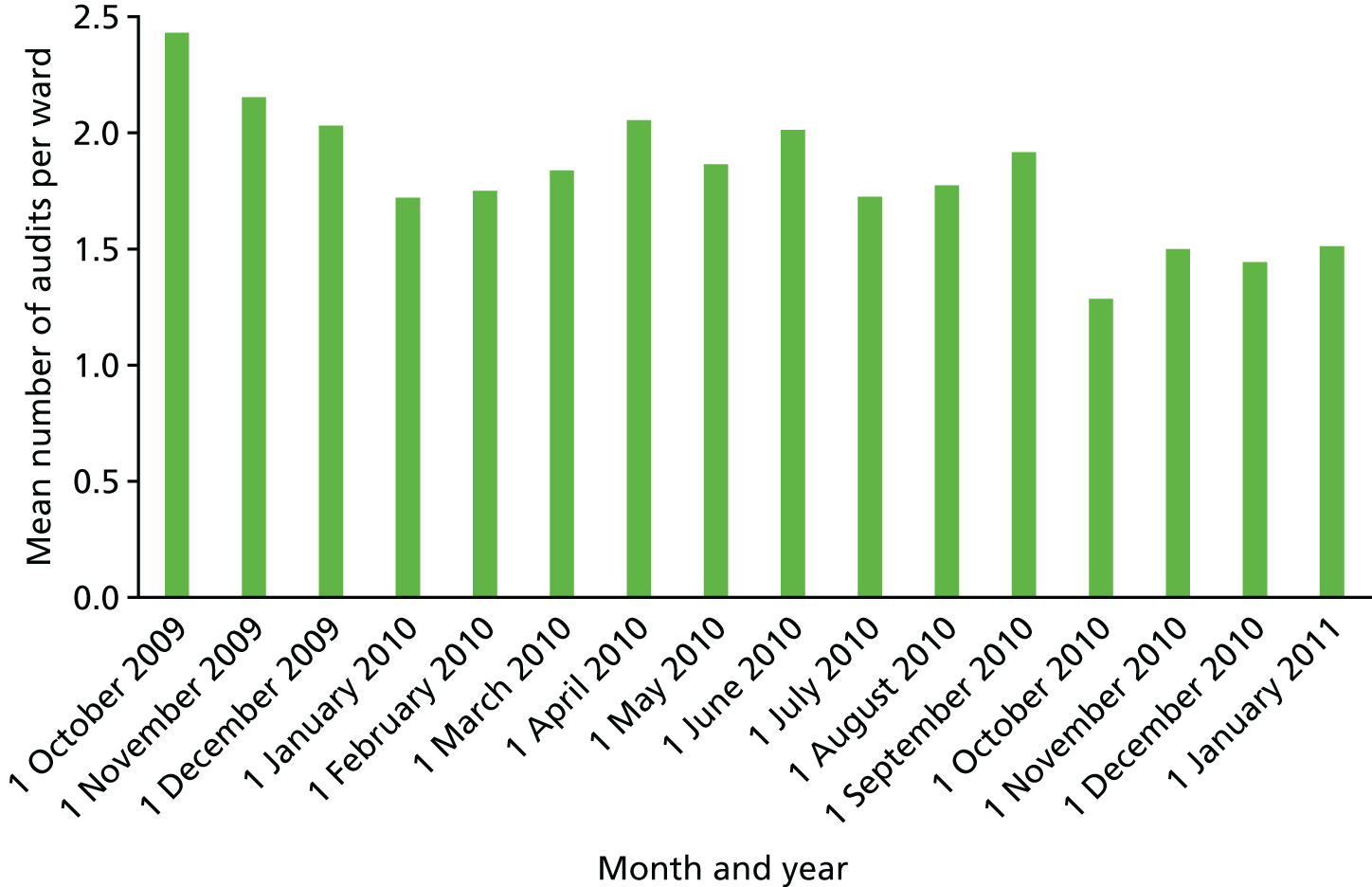

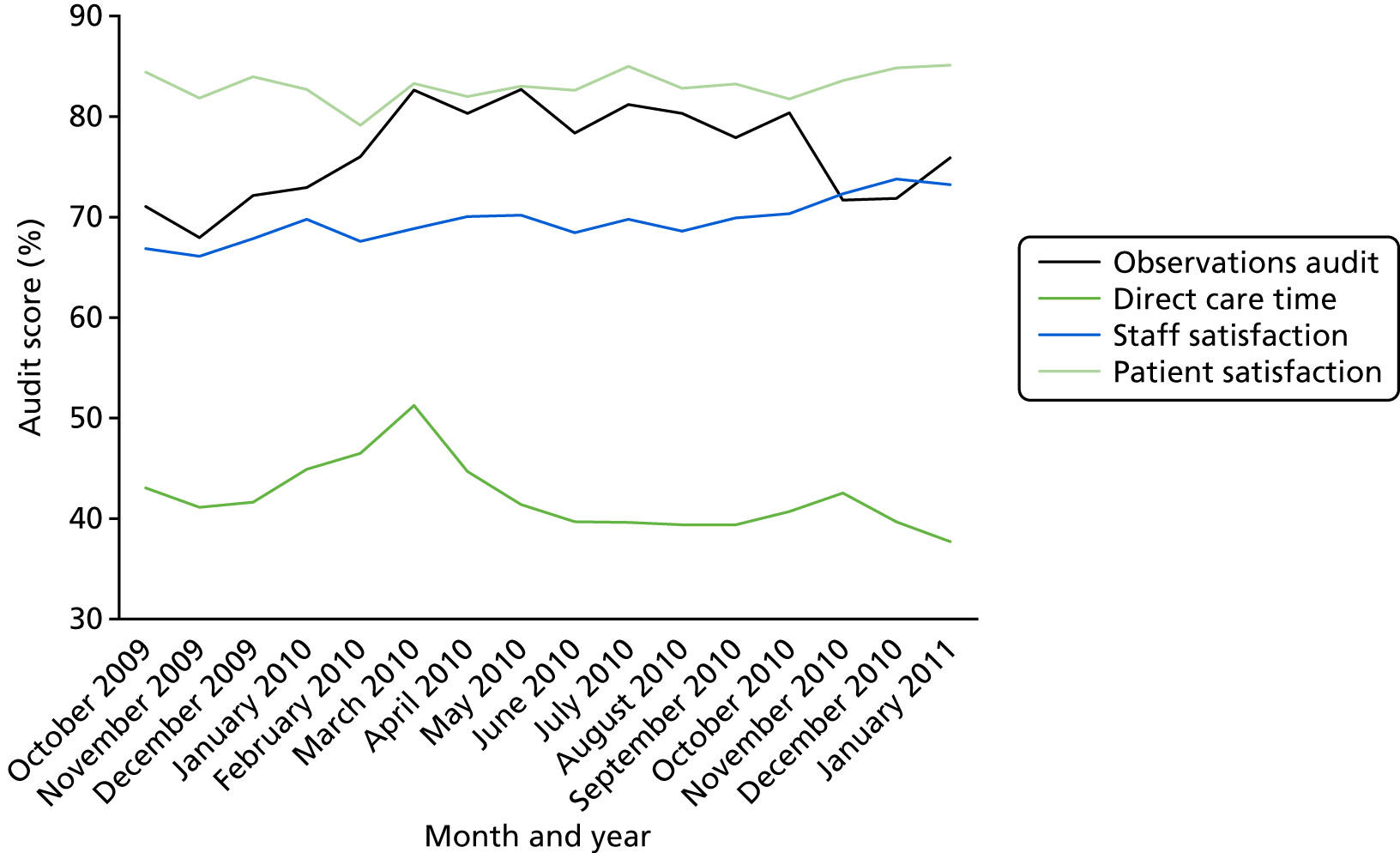

Where trusts indicated that data might be available that would permit a secondary analysis beyond before-and-after comparisons, we enquired further and requested/inspected samples of data. We ultimately determined that additional analysis was possible with data from one trust in which monthly records of module completion and audits were recorded over an 18-month period. These data, and our subsequent analysis, which was exploratory rather than planned, are described in detail in Chapter 6.

Telephone surveys with early Productive Ward leads

An initial coding framework was based on the topic guide and early familiarisation with interviews. A sample of three transcripts were then analysed by a researcher and a member of the research team to check for fit. Any discrepancies in coding were discussed until agreement was reached. At this stage, coding descriptions were clarified and an additional subtheme was added. Coding was then carried out in Microsoft Excel using a Framework approach. 48

Triangulating and combining data

We triangulated data at the points of data collection and analysis. When collecting data, we used case study interviews to explore survey responses for each trust and some of the issues raised across the piece. In the one case study site for which we had existing data, we also re-familiarised ourselves with the earlier analysis and with key transcripts from the previous study, and used interviews with the PW team to follow up on what had happened with respect to work and plans reported in earlier interviews. In case study interviews and telephone interviews, we used our emerging findings in probes and prompts as we went along.

When analysing data, we looked for similarities and differences (1) between the DoN and the PW lead survey responses; (2) between survey findings, case study findings and telephone interview findings; and (3) between case studies. The first two of these are noted in the discussion (see Chapter 8). The cross-case analysis is the subject of Chapter 5.

Study governance

All parts of the study were approved by the Health Research Authority London – Stanmore Research Ethics Committee (reference 16/LO/0918). We made three amendments: a non-substantial amendment to add one trust previously missing from our database of NHS acute trusts; a substantial amendment to widen recruitment routes to the online survey; and a substantial amendment to add observations and the use of photographs in our case study sites. Local R&D approval was not required for the survey or for telephone interviews. It was sought and given in the case study sites.

The PAG was chaired by an independent chairperson and included two PPI representatives, who also gave feedback on the wording of the online surveys, the participant information sheet and the consent form for patients. The PAG convened four times during the study. The research team met approximately every 6 weeks to review progress, agree on plans and contribute to analysis. All members of the research team contributed to ongoing discussions and provided input into the drafting of this report.

Chapter 4 Results of national surveys

This is our first findings chapter, which presents the results of the two national online surveys we conducted with DoNs (see Directors of nursing in English acute NHS trusts) and PW leads (see Productive Ward leads in English acute NHS trusts). At the end of the chapter, we combine the findings from these two surveys to (1) provide an overall picture of how PW has been adopted, implemented and assimilated in English acute trusts over time, and (2) collate perceptions of the nature and scale of any impact that PW is felt to have had (see Combined results of the director of nursing and Productive Ward lead surveys).

Directors of nursing in English acute NHS trusts

Introduction

Our findings are based on descriptive analysis of responses to closed items in the DoN survey, and thematic analysis of qualitative data from the open-response fields (see Chapter 3) and are organised around five phases of the ‘story’ of the PW:

-

adoption

-

implementation

-

assimilation

-

sustained impact

-

sustainability.

The survey response rate was 37% (56/153). This includes DoNs from four trusts that responded to our survey asked were not identifiable. Because the survey used question routing, not all of the 16 questions were put to all respondents, and not all questions presented achieved a full response rate. We received responses from each of the 13 commissioning areas in England. The representativeness of the sample in terms of the four commissioning regions is shown in Table 4, which also shows the proportion of respondents in terms of trust type.

| Acute trusts in England,a n (%) | Responding trusts,b n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Commissioning region | ||

| North of England | 49 (32) | 17 (33.7) |

| Midlands and East of England | 45 (29) | 12 (23) |

| South of England | 36 (24) | 12 (23) |

| London | 23 (15) | 11 (21) |

| Type of acute trust | ||

| Large | 36 (24) | 12 (22) |

| Medium | 33 (22) | 12 (20) |

| Small | 34 (22) | 12 (30) |

| Multiservice | 3 (2) | 0 (0) |

| Specialist | 17 (11) | 5 (7) |

| Teaching | 30 (20) | 11 (22) |

| Total | 153 (100) | 52 (100) |

| Of which, foundation statusc | 99 (65) | 38 (73) |

Adoption

We invited responses from trusts irrespective of whether or not they had ever used PW. We received only two responses from trusts that had never used PW, and from one trust where the DoN did not know whether or not it had been used. The two trusts that did not adopt PW attributed this to using other approaches and having other priorities. Given these other priorities, one elaborated that the project management required for PW was a deciding factor in choosing not to adopt. No trust reported beginning its involvement with PW later than 2012 (Table 5).

| Year of first involvement | Number | Per cent |

|---|---|---|

| 2006 | 4 | 8 |

| 2007 | 4 | 8 |

| 2008 | 12 | 26 |

| 2009 | 15 | 32 |

| 2010 | 8 | 17 |

| 2011 | 2 | 4 |

| 2012 | 2 | 4 |

| Total | 47 | 99 |

Implementation

Thirty-eight (81%) trusts had initially implemented PW in selected wards within a site, and nine (19%) had implemented PW in all wards across a whole hospital or trust (Table 6); the remaining 10 trusts did not respond to this question.

| Hospital typea | Commissioning regiona |

|---|---|

| Large | London |

| Large | North of England |

| Medium | North of England |

| Medium | South of England |

| Medium | London |

| Small | North of England |

| Specialist | North of England |

| Teaching | North of England |

| Unknown | – |

Among the trusts that reported originally implementing PW in ‘some’ wards, the majority (33/35, 94%) said that this was with a view to further roll-out (three trusts did not answer the question on roll-out, and two trusts recorded ‘don’t know’); in 26 of these trusts (79%), this roll-out was reported as having happened (with five reporting that it had not happened and one recording ‘don’t know’).

The criteria on which initial wards were selected were overwhelmingly based on positive ward attributes, predominantly wards where ward managers were keen to use it, wards that were thought able to rise to a challenge, and wards embracing innovation (in one case already using another Lean approach). Few trusts (n = 5) included one or more negative attributes in their selection criteria (wards not doing well in terms of staff well-being, patient outcomes and/or patient experience). No responding trusts relied solely on negative criteria for selecting initial wards.

Just over one-quarter of responding trusts (n = 11, 26%) said that impact measures had regularly been reported to the trust board.

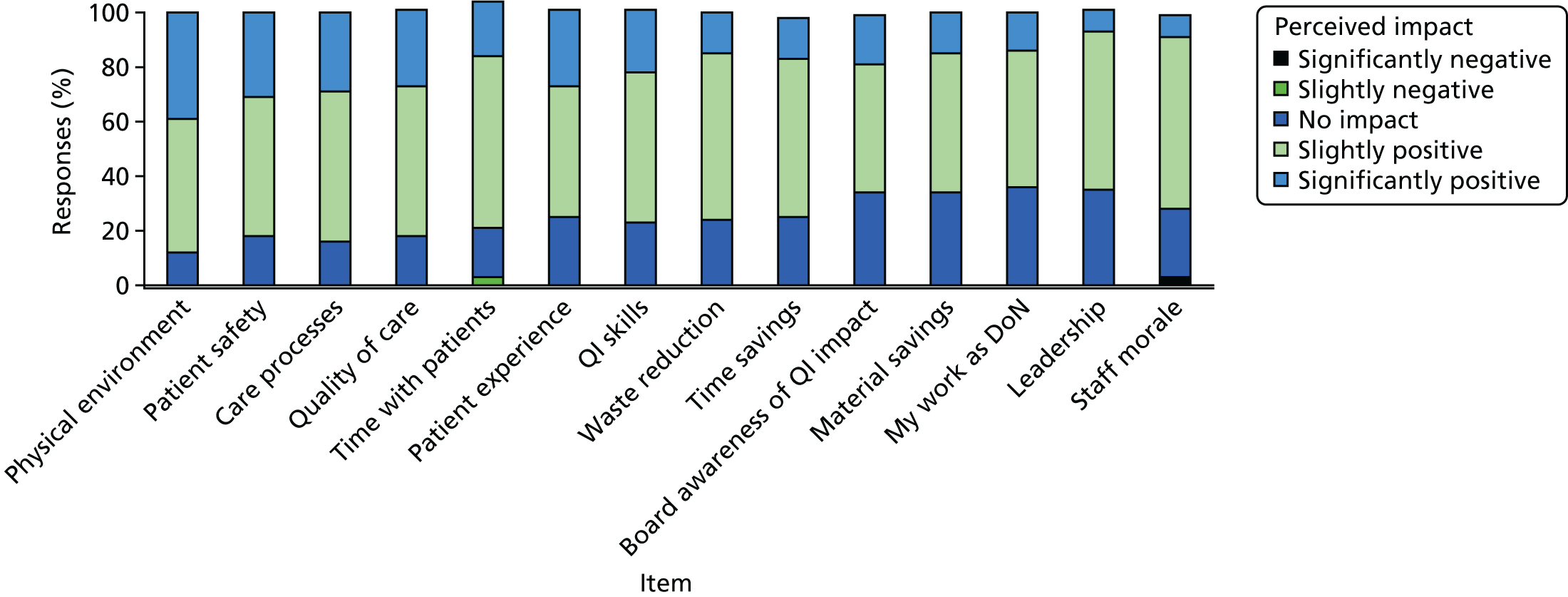

Perceived impact on patients and staff

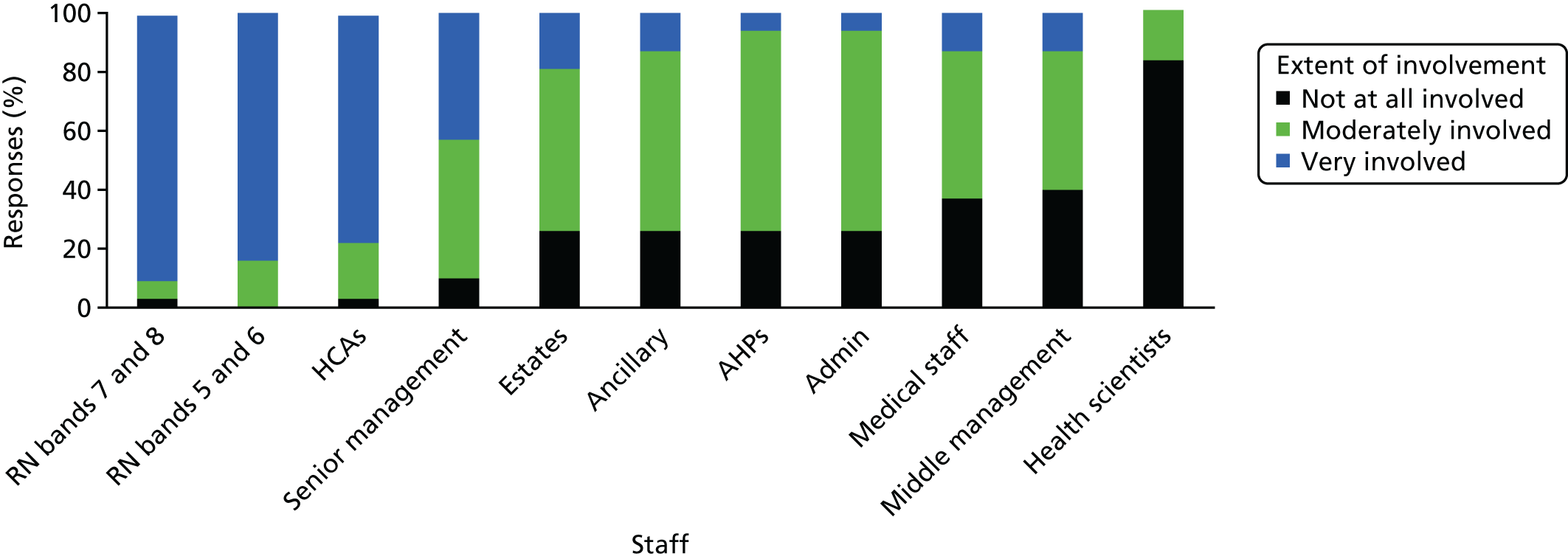

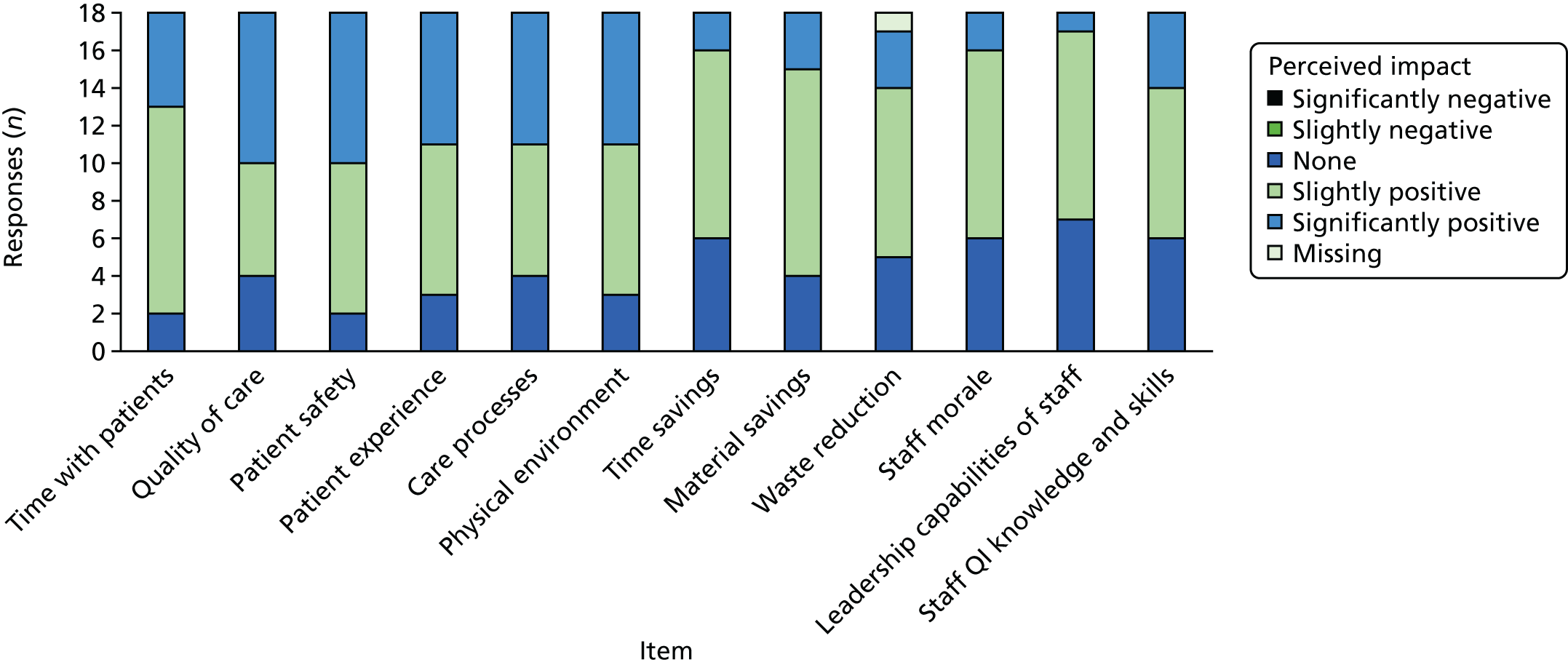

We asked respondents to indicate the scale of impact of PW (on a five-point scale from ‘a significant negative impact’, through ‘no impact’ to ‘a significant positive impact’) on a number of items. Some items were related to the four core objectives of the PW: patient safety and reliability of care, patient experience, efficiency of care and staff well-being. We also included items related to the wider legacy of PW in terms of staff leadership skills; and increased QI awareness, knowledge and skills. Responses are shown in Table 7 and Figure 4.

| Item | Perceived impact, n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Significant negative | Sligthly negative | No impact | Slightly positive | Significant positive | Total responses | |

| Physical environment | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 5 (12) | 20 (49) | 16 (39) | 41 |

| Patient safety | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7 (18) | 20 (51) | 12 (31) | 39 |

| Care processes | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 6 (16) | 21 (55) | 11 (29) | 38 |

| Quality of care | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7 (18) | 22 (55) | 11 (28) | 40 |

| Patient experience | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 (25) | 19 (48) | 11 (28) | 40 |

| Staff QI skills | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 9 (23) | 22 (55) | 9 (23) | 40 |

| Time with patients | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 7 (18) | 25 (63) | 8 (20) | 40 |

| Board awareness of QI impact | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 13 (34) | 18 (47) | 7 (18) | 38 |

| Waste reduction | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 10 (24) | 25 (61) | 6 (15) | 41 |

| Time savings | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 10 (25) | 23 (58) | 6 (15) | 40 |

| Material savings | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 14 (34) | 21 (51) | 6 (15) | 41 |

| My work as DoN | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 13 (36) | 18 (50) | 5 (14) | 36 |

| Leadership capabilities of staff | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 14 (35) | 23 (58) | 3 (8) | 40 |

| Staff morale | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 10 (25) | 25 (63) | 3 (8) | 40 |

FIGURE 4.

Directors of nursing: perceived impact of PW.

Overall, PW was reported as having a positive impact, although for each item a relatively high proportion (between 12% and 36%) of respondents noted no impact arising from PW. Twenty-one of the 41 DoNs reported at least one area in which PW had had a significantly positive impact. A negative impact was noted by three respondents (in three different trusts), and these related to time savings and staff morale. Conversely, one respondent remarked that the PW processes were ‘meaningful to staff at the front line’ (D039). The following open-ended response similarly suggests a sense of purpose engendered by PW as well as the encouragement it provided for networking and sharing between trusts: