Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 15/137/04. The contractual start date was in March 2017. The final report began editorial review in July 2018 and was accepted for publication in January 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Evans et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Female genital mutilation/cutting

Female genital mutilation (or female genital cutting) – henceforth abbreviated to FGM/C (female genital mutilation/cutting) – refers to all procedures that involve the partial or total removal of the external female genitalia or other injury to the female genital organs for non-medical reasons. 1 FGM/C is categorised by the World Health Organization (WHO)1 into four types, with differing degrees of severity, as described in Box 1.

Often referred to as clitoridectomy, this is the partial or total removal of the clitoris (a small, sensitive and erectile part of the female genitals), and in very rare cases, only the prepuce (the fold of skin surrounding the clitoris).

Type 2Often referred to as excision, this is the partial or total removal of the clitoris and the labia minora (the inner folds of the vulva), with or without excision of the labia majora (the outer folds of skin of the vulva).

Type 3Often referred to as infibulation, this is the narrowing of the vaginal opening through the creation of a covering seal. The seal is formed by cutting and repositioning the labia minora, or labia majora, sometimes through stitching, with or without removal of the clitoris (clitoridectomy).

Type 4This includes all other harmful procedures in the female genitalia for non-medical purposes (e.g. pricking, piercing, incising, scraping and cauterising the genital area).

Female genital mutilation/cutting is practised in 30 countries across north and sub-Saharan Africa and in parts of the Middle East and Asia. 2 The UK is in a period of ‘super-diversity’, which is characterised by high rates of migration from countries all over the world (rather than mainly from former colonies as in previous decades). 3–6 As a consequence, the UK’s population is increasingly diverse and includes many groups from countries where FGM/C is practised. 5–7 Hence, the need to address FGM/C within the NHS is already significant and is expected to increase. 6,8–10

Evidence suggests that women and girls who have undergone FGM/C experience many barriers to accessing appropriate care in the UK. 11 Research also suggests that health professionals lack knowledge, experience and confidence in addressing FGM/C-related issues. 12 FGM/C-related services in England and Wales are reported to be fragmented and highly variable, lacking clear referral or care pathways, and difficult for women/girls to access. 13–15 FGM/C therefore presents a growing health issue for the NHS and there is a need to develop more and better services in this area. 13

This project seeks to inform the development of services for FGM/C-related health care through two syntheses of qualitative evidence regarding the views and experiences of service access, service provision and quality of care from the perspectives of (1) women/girls who have undergone FGM/C and (2) health professionals.

Size of the problem

Globally, it is estimated that over 200 million women and girls have experienced FGM/C. 2 In Europe, where many nations are ‘destination’ countries for migrants from FGM/C-practising areas, it is thought that over half a million women and girls are FGM/C survivors. 16 In England and Wales, a comprehensive report published in 2015 estimated FGM/C to be a significant problem, with over 137,000 women/girls directly affected, as follows:9

-

10,000 girls aged < 15 years

-

103,000 women and girls aged 15–49 years

-

24,000 women aged ≥ 50 years.

The same report estimates that women with FGM/C have made up approximately 1.5% (nearly 11,000) of all UK maternity episodes since 2008. 9 In the recording cycle April 2016 to March 2017, there were 9179 attendances reported in NHS trusts and general practices in England where FGM/C was identified or where a procedure for FGM/C was undertaken. Eighty-seven per cent of these attendances were in midwifery or obstetric services. 17 The 2017–18 figures for England show a slight reduction in numbers, to 6195 newly recorded attendances. 18 The figures show that all major urban areas in the UK have significant populations affected by FGM/C, with most areas of the country affected to some extent. 9,17

The current figures from England suggest that FGM/C attendances are primarily by women of childbearing age. For example, out of 6195 recorded attendances in 2017–18, only 2.9% were for women aged ≥ 45 years. 18

With respect to FGM/C-related needs among girls, It has been estimated that approximately 60,000 girls in the UK aged 0–14 years have been born to mothers who have undergone FGM/C and may themselves be at risk of the procedure. 9 However, current figures from England suggest that it is primarily adult women rather than girls/teenagers who are accessing NHS services. For example, in 2017–18, only 1.13% of all recorded attendances were for girls under the age of 18 years. 18

Health consequences of female genital mutilation/cutting

Female genital mutilation/cutting is associated with significant negative physical, psychological and sexual health sequelae. 19–21 In the short term, these include infection, urinary retention or injury to other tissues (e.g. vaginal fistulae). In the longer term, they include psychological problems, post-traumatic stress disorder, painful intercourse and other sexual problems, relationship problems, chronic pain, chronic infections, infertility and complications in childbirth. 22–25 Hence, it is essential that women and girls affected by FGM/C have access to services that can identify and meet these multiple complex health needs and that services include mental health-care as well as physical health-care provision. 13,20,21,26

Health problems may be particularly severe for women with type III FGM/C, also referred to as infibulation. This type of FGM/C is practised predominantly (but not exclusively) in countries in the Horn of Africa, such as Somalia, Sudan, Ethiopia, Eritrea and parts of Kenya. Women with type III FGM/C require a degree of deinfibulation in order to have sexual intercourse and to give birth.

Currently, deinfibulation is recommended for women and girls reporting medical or psychosexual symptoms related to type III FGM/C, or on request (i.e. personal choice). 1 In addition, national and global guidelines specifically recommend that deinfibulation is undertaken to prevent obstetric complications. 14,27–29 However, the optimal timing for deinfibulation is unclear. 30,31 The evidence base regarding outcomes of antepartum deinfibulation compared with intrapartum deinfibulation is weak. 28,32–34 Nonetheless, there are compelling clinical reasons for preferring antepartum deinfibulation. 35 These include the fact that it can be carried out under local anaesthetic in an outpatient setting, thus reducing costs and risks associated with any emergency procedures that may emerge during labour. In addition, given the lack of familiarity with type III FGM/C of many health professionals in destination countries (such as the UK), planned antepartum deinfibulation ensures that it is undertaken by trained and experienced professionals. 32

Costs of female genital mutilation/cutting

There is a lack of data on the economic burden of FGM/C in high-income countries such as the UK. 36 However, recent policy documentation cites a report commissioned by the Department of Health and Social Care estimating the annual cost of FGM/C to the NHS to be £100M if all needs were met/treated in a single year. This estimate comprises £34M associated with physical health needs and £66M associated with mental health needs. 15

Legal and policy context of female genital mutilation/cutting in the UK

Female genital mutilation/cutting has been illegal in the four countries of the UK since 1985 and is considered a form of abuse (FGM/C undertaken outside the UK on UK nationals or residents was criminalised through additional Acts in 2003 for England37 and 2005 for Scotland38). In 2014, the UK Government published a declaration to end FGM/C, and initiated a National FGM/C Prevention Programme. 39 A series of policy changes have been introduced as part of this programme in order to obtain more accurate information on the size and scale of the problem and to enhance safeguarding processes; these are (1) mandatory recording, (2) mandatory reporting and (3) use of a FGM/C Risk Indication System (RIS).

Acute NHS trusts in England have had to record all cases of FGM/C within a FGM/C prevalence database since April 2014. This database has now been re-named the FGM/C Enhanced Dataset (an Information Standard – SCCI2026). The Information Standard requires clinicians across all NHS health-care settings to record in clinical notes when patients with FGM/C are identified and what type of FGM/C has been identified (patient consent is not required). 15 In addition to mandatory recording, from October 2015 a new statutory duty has been introduced through the Serious Crime Act40 requiring all regulated health professionals to report cases of FGM/C in girls under the age of 18 years to the police (known as ‘mandatory reporting’). In addition, a new national health system, the FGM/C RIS, was introduced in 2015, aiming to support safeguarding of girls up to the age of 18 years. The system allows health professionals to add an indicator on a girl’s electronic summary care record to highlight that she may be at risk. This information can then be confidentially shared among health professionals. To set the indicator, professionals are required to seek parental consent.

These measures signal a new policy drive across the NHS to address FGM/C prevention (as well as care) and to significantly improve the identification of women and girls have who undergone FGM/C. 10,13,26 However, all of the above measures place an additional burden of work on health professionals and require additional training and support to understand the legal complexities, the logistics of how to use the systems and the sensitivities of discussing FGM/C with patients/communities and greater awareness of local safeguarding pathways. 15,41 The ways in which these changes will have an impact on the experience of health-care delivery from a patient’s or professional’s perspective are, as yet, unclear. However, systematically examining the existing evidence base on FGM/C may help to identify some of the potential implications of these new policies for practice and future research.

In some communities (particularly in Sudan) in which FGM/C type III is common, reinfibulation is practised after childbirth. However, in the UK and most high-income countries, it is illegal for professionals to undertake reinfibulation. 42,43

Female genital mutilation-/cutting-related service provision and development in the UK

Currently, there is limited evidence regarding the availability and accessibility of FGM/C-related care across the UK. However, there are strong indications that it is it poorly co-ordinated and sub-optimal. 13 To date, FGM/C-related care within the NHS has primarily been provided in the context of maternity services. Specialist clinics run by specialist midwives have been established in a number of maternity services, which provide medical interventions as well as access to counselling and other psychological services. However, the majority of maternity services do not offer this specialist provision, although most now have a designated lead for FGM/C. In these non-specialist settings, care tends to be focused primarily on medical management (e.g. deinfibulation), with limited attention to other health needs or to considering the FGM/C-prevention agenda [Project Advisory Group (PAG) opinion]. 13,44 Accurate information on the accessibility and quality of FGM/C-related care within maternity services is difficult to estimate as there are no up-to-date statistics available.

There is a lack of evidence on FGM/C management in non-maternity settings. However, the view of the expert PAG for this project is that communication about, or management of, FGM/C in non-maternity settings is currently poor, with a lack of clear referral or care pathways, and with health professionals lacking confidence and experience around FGM/C. Access to any non-maternity-focused specialist FGM/C services is, therefore, limited and highly variable across the UK.

As of 2017, there were 16 specialist FGM/C clinics across England (these numbers may now have changed as services are re-commissioned, but are not thought to be greatly increased). 45 Many of these specialist services are actually based within maternity services and referral pathways from other services are not well established. Moreover, the majority of these specialist clinics (n = 11) are located in London, with the remaining five based in other urban areas. 13,45 Therefore, many FGM/C-affected communities currently do not have access to specialist services, and this is an issue particularly for those living in rural areas and other low-prevalence areas. This situation potentially creates inequalities in access to care, as highlighted in recent reports. 8,46,47

In the current policy and legislative climate, health professionals across all sectors, especially primary and maternity care, are required to be knowledgeable about FGM/C and to have the requisite skills to deal with affected women/girls and communities in a sensitive and appropriate manner. 10,13 This is particularly important not only to ensure that health-care encounters are focused on supporting women/girls who are living with the consequences of FGM/C but also to address the sensitive issue of prevention. 13 To achieve this agenda, NHS England has recently published health professional training standards. 41 In addition, several professional and multi-agency guidelines have been published that call for greater levels of specialist and holistic service provision, clearly delineated FGM/C-related care pathways and clear referral pathways, backed up by enhanced training of health professionals. 10,13–15,26,27,29

Why this research is needed and why it is needed now

Currently, there are limited resources to inform FGM/C-related training and service development. Much of the existing body of research relates to understanding the practice of FGM/C,48 the prevention of FGM/C49–51 and the psychosocial and clinical consequences of FGM/C. 19,21,24,52,53 A recent expert commentary on FGM/C identified key gaps in the evidence on clinical management and on models of service delivery. 30 Furthermore, a recent series of systematic reviews undertaken by WHO to inform global guideline development found that evidence on the clinical effectiveness or cost-effectiveness of different models of care for FGM/C is lacking. 54,55

Given the complexity of service development and the sensitivity of FGM/C, it is imperative to take into account the views and experiences of all stakeholders. This project therefore proposed to undertake two systematic reviews focusing specifically on qualitative evidence: one related to women’s/girls’ experiences of health care in relation to their FGM/C and one related to health-care professionals’ views and experiences of service provision. Given the current focus in the UK on the development of care pathways for non-pregnant women as well as pregnant women,15 the reviews sought to understand relevant issues across all health-care settings and across the life course. In addition, in order to ensure that the equity agenda was addressed, the reviews sought to explore issues around access to care as well as experience of care.

A brief look at the existing evidence indicates further why these reviews are important and what kind of issues they will illuminate to be useful for service development.

Perspectives of women/girls who have undergone female genital mutilation/cutting

In the UK context, evidence suggests that several barriers to FGM/C-related care-seeking exist from the perspective of women/girls. Some of these relate to accessibility in terms of not knowing where to go or who to speak to and not being aware of any specialist provision. 11 Other barriers highlighted in existing research relate more directly to quality of care, such as feeling judged or misunderstood or feeling unable to communicate about FGM/C-related problems. 11,56–59

At the time of project development, rigorous searches were undertaken to identify any existing published reviews, protocols, registered reviews and registered review titles [including on PROSPERO, The Cochrane Library and the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI) Database of Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports databases]. At that time, there was no registered ongoing work in relation to women’s/girls’ views and experiences of FGM/C-related health care. This was a key gap. Since this project commenced, the above-mentioned WHO systematic review series was published54 and included three qualitative reviews. However, these were focused on evidence related only to specific clinical interventions rather than health-care experiences more generally. Hence, they identified a very limited number of studies. Nonetheless, they highlighted that women’s experiences were often negative and characterised by unmet needs for information and support. 60–62 Two additional reviews, by Hamid et al. 63 and Turkmani et al. ,64 have very recently been published, focusing specifically on the pregnancy and birth experiences of migrant women affected by FGM/C. Their findings are consistent and conclude that pain and anxiety around birth could be exacerbated by traumatic memories of FGM/C and by a perceived lack of provider competence in managing FGM/C. They also found that attitudes to FGM/C changed as women adjusted to life in a new country, but that this process could be difficult as women encountered negative reactions to FGM/C from health-care professionals from the West. 63,64

Health professional perspectives and service delivery issues

There are three existing systematic reviews on health professional perspectives around FGM/C. 12,65,66 These have identified a significant lack of knowledge, confidence and competence around FGM/C and have concluded that more and better training is required. These reviews provide useful evidence but still leave gaps in our understanding. In particular, the reviews have focused primarily on quantitative evidence, which, while highlighting trends, have been unable to provide a more nuanced picture of barriers to and facilitators of service provision. The need to consider wider factors in understanding health professionals’ practice is illustrated by a 2013 study of FGM/C management in a large London maternity unit. 67 This found that, in spite of the existence of protocols, guidelines and training, clinical care for women/girls with FGM/C was suboptimal. The maternity unit had access to a FGM/C specialist service, but 41% of women with FGM/C were not identified until they arrived in the labour ward. Hence, even though a specialist service existed, it was not being optimally used to benefit women with FGM/C, and a significant percentage of opportunities were missed to provide women with specialist care. Similar findings were reported from a study in a maternity unit in Switzerland where, in spite of staff training and the existence of clear guidelines, FGM/C was correctly identified and managed in only 34 (26.4%) of 129 cases reviewed. 68 Likewise, an audit in Lothian in Scotland (between 2010 and 2013) showed that of 487 women from FGM/C-practising countries, only 18% had any documentation relating to FGM/C, suggesting that opportunities for detection may have been missed. 69 The reasons for this lack of adherence to protocols are unclear; hence, we suggest that reviewing the related qualitative evidence may shed greater light on organisational and personal factors that may influence health professionals’ views and behaviour in this area. 70–80

Gaps in existing knowledge: what this project will add

With the exception of the reviews by Hamid et al. 63 and Turkmani et al. ,64 existing reviews on women’s and health professionals’ experiences have all taken a multicontext (or ‘lumping’) approach to the evidence81,82 and have included research from high- and low-income settings across the world. Many key themes from these reviews are therefore drawn from evidence from very different cultural and health system contexts and are not easily transferable to a UK or high-income setting. In order to address this shortcoming, the reviews in this project included evidence from high-income Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) contexts only.

The recent reviews by Hamid et al. 63 and Turkmani et al. 64 are similar to the review that we have undertaken with respect to women’s/girls’ experiences. However, those reviews focused only on English-language papers and looked only at the birth experience, whereas the reviews in this project have looked at all aspects of FGM/C-related health care, including factors influencing care-seeking and service access. In addition, in contrast to Hamid et al. 63 and Turkmani et al,64 the reviews in this project have looked at all clinical settings and at all stages of the life course, not just maternity. This wider perspective is particularly important in terms of illuminating decision-making on topics such as timing of deinfibulation and care for non-pregnant women who may be experiencing symptoms. In addition, in accordance with The Cochrane Library83 and JBI84 methods, our reviews have included grey literature and research published in languages other than English. Hence, our reviews provide a significantly more detailed, holistic and comprehensive picture. This is exemplified by the fact that the review on women’s experiences (review 1, see Chapter 3) identified 57 relevant papers, whereas the reviews by Hamid et al. 63 and Turkmani et al. ,64 identified only 14 and 16 papers, respectively.

Situating female genital mutilation/cutting within a wider migration-related health policy and service context

Although this project is concerned specifically with health care related to FGM/C, it is important to situate this within the wider UK health-care context of service provision for migrant populations in a context of super-diversity. 5–7,85,86 The vast majority of women with FGM/C in the UK are first-generation migrants and evidence shows that this group experiences a wide range of challenges around seeking and receiving health care. 87–89 Likewise, health providers report a range of challenges in delivering care to migrant populations. 90,91 These challenges are particularly acute within maternity settings, where many women with FGM/C are first identified, where migrant women are consistently shown to have poorer outcomes and where improvement of patient safety is a national policy imperative. 92–98 Likewise, the NHS is under pressure to develop service models that can address the needs of a super-diverse population. 3,7,99 In a time of stretched resources, more innovation and better evidence is needed to help guide this endeavour. Therefore, we hope that, although the reviews are specific to FGM/C, the reviews may also serve to illuminate key issues that may help this wider effort.

Research aims and purpose

The aim of this study was to undertake two separate systematic reviews of qualitative evidence to understand the experiences, needs, barriers and facilitators around seeking and providing FGM/C-related care from the perspectives of (1) women and girls who have undergone FGM/C and (2) health professionals. The two separate sets of review results will be integrated into a final synthesis and used to (1) formulate recommendations for NHS training, service development and improvement, (2) pinpoint key dimensions of quality of care that can be operationalised for use in future service improvement evaluations or patient-reported outcome measures and (3) identify areas where further research is required.

Aim and objectives of review 1

Aim

To explore the experiences of FGM/C-related health care across the life course for women and girls who have undergone FGM/C.

Objectives

From the perspective of women and girls who have undergone FGM/C:

-

illuminate factors that influence FGM/C-related health-care-seeking and access to health services across the life course

-

explore how quality of care is perceived and experienced in different health-care settings and with different groups of health-care professionals

-

characterise and explain elements of service provision considered important for the provision of acceptable and appropriate health care

-

describe factors perceived to influence open discussion and communication around FGM/C (including prevention) with health professionals.

Aim and objectives of review 2

Aim

To explore the views and experiences of health professionals of all cadres of providing care for women/girls who have undergone FGM/C.

Objectives

From the perspective of health professionals:

-

explore how quality of care for women/girls who have undergone FGM/C is perceived in different health-care settings and among different professional groups

-

characterise and explain elements of service provision considered important for the provision of high-quality care to women/girls who have undergone FGM/C

-

illuminate factors perceived to facilitate or hinder appropriate provision of care for women and girls who have undergone FGM/C

-

identify processes and practices perceived to influence open discussion and communication around FGM/C (including prevention) with women/girls from affected communities.

Research team and patient/public involvement

This project was conducted by a core research team that was advised by a PAG. The core team comprised (1) academics with expertise in ethnicity and health, gender-based violence, qualitative methodologies and systematic reviewing (CE, RT, GH and JM), (2) an information specialist (JE), (3) a FGM/C specialist midwife who has served as part of NHS England’s National FGM Prevention Programme (JA) and (4) a FGM/C and women’s rights activist who runs a community organisation promoting African women’s rights, runs many anti-FGM/C campaigns nationally and internationally and runs a local FGM/C support group (VN). The PAG also comprised individuals with expertise in a range of areas, including obstetrics, general practice, midwifery, the voluntary sector (focusing on FGM/C issues) and specialist commissioning. In terms of patient and public involvement, we took the approach of ensuring that our community expert was a co-applicant on the project from its inception. Indeed, the project itself was co-constructed out of conversations between Valentine Nkoyo and Catrin Evans. Hence, patient and public involvement has been built into every stage of this project and has been key to its execution.

Structure of the report

Chapter 2 of this report presents the methodology underpinning the two reviews and the methods used. It includes a detailed description of the literature search that was undertaken. The results of the search are also presented in Chapter 2. This is because a single literature search was undertaken for both reviews, hence it needs to be presented in depth only once. Chapters 3 and 4 provide detailed descriptions of the results of reviews 1 and 2, respectively. Chapter 5 presents an integrated synthesis of reviews 1 and 2 that illuminates the health-care challenges around FGM/C in a holistic manner to account for, and explain, both patient and professional viewpoints and experiences. Chapter 6 discusses the review findings in the context of the wider literature and sets out the implications and recommendations of the synthesis. Chapter 7 presents the project conclusions.

Chapter 2 Methodology and methods

Introduction

In this chapter, we describe the methodology and methods used in both reviews. The literature search was conducted for both reviews at the same time (i.e. as one step). However, the other stages were conducted sequentially (i.e. we undertook all of the stages of review 1 first, followed by those of review 2). Given that the methods followed were exactly the same, the methods used in each stage are described in this chapter only once.

The research aims and objectives were constructed to identify insights about lay/health professional experiences of FGM/C-related health care and perceived appropriateness and acceptability of services. These are questions best answered by qualitative research;100,101 indeed, it is increasingly recognised that qualitative evidence syntheses have an essential role to play in understanding barriers to and facilitators of service initiatives. 102,103 The overall design and synthesis methodology for each review was the same. Both have been reported as per Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) guidelines. 104

Methodology

There are many possible approaches to qualitative evidence synthesis, with most discussions in this area characterising the different types along a continuum between aggregation and interpretation. 105 If the purpose of a synthesis is to generate new theoretical insights, a highly interpretive approach such as meta-ethnography may be most suitable, informed by an idealist epistemological stance. However, if the purpose is to inform policy or practice, a more aggregative or thematic approach informed by a realist epistemology is often advocated. 106 The latter is also suggested in cases in which the existing evidence is likely to be descriptive (as in much health services research) rather than highly theoretical or conceptual. 107 An initial scoping of the literature suggested that this was the case for the proposed syntheses. A thematic synthesis approach involves using thematic analysis techniques to identify key themes from primary research studies. 108,109 Synthesis involves an iterative and inductive process of grouping themes into overarching categories and exploring the similarities, differences and relationships between them. Thematic synthesis explicitly aims to move beyond generating a list of descriptive themes (as would be the case in meta-aggregation110) in order to identify new, higher-order, analytical insights that can contribute to new understandings of a phenomenon. Review recommendations, however, are clearly formulated to inform policy and practice. As such, thematic synthesis was considered the most suitable approach for the two systematic reviews. 111 Both reviews were conducted following the guidance set out by the Cochrane Qualitative and Implementation Methods Group. 83,103,110–114

Protocol and PROSPERO registration

Both review proposals were registered separately with the PROSPERO database. 115,116 A combined protocol for both reviews has been published in BMJ Open. 117

Search strategy and study selection

An exhaustive and sensitive search strategy was developed by an experienced information scientist (JE). The search strategy was designed to identify papers for both reviews; thus, it is reported here as one search.

Search inclusion and exclusion criteria

The review inclusion and exclusion criteria are set out in Table 1.

| Criteria | Details |

|---|---|

| Inclusion criteria | |

| Population |

Review 1: women and girls who have undergone any form of FGM/C, as defined by the WHO1 Review 2: any cadre of health-care professionals or health-care students who are involved in the care of women/girls who have undergone FGM/C |

| Phenomenon of interest |

Review 1: experiences of FGM/C-related health care across the life course Review 2: views on, and experiences of, providing care for women/girls who have undergone FGM/C |

| Country/context/setting | The reviews were limited to studies that were undertaken in high-income OECD country settings. The OECD grouping118 includes the majority of countries with similar social and political value systems and levels of economic development, and, therefore, whose research findings could be transferable to the UK (see List of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries). In addition, in terms of migration, high-income OECD countries tend to be migrant ‘destination’ countries and share a need and a challenge to adapt their health services to the needs of communities that practise FGM/C. ‘High income’ was defined in accordance with the World Bank criteria.119 Both reviews included studies from any health-care setting, health sector or health context within a high-income OECD country |

| Study design | Any type of qualitative study and any type of mixed-methods study that reported qualitative findings |

| Language | Any language |

| Date | No date limit |

| Exclusion criteria | |

| Context | Studies relating to middle- and low-income countries or non-OECD high-income countries |

| Participants |

Review 1: studies not related to women’s or girls’ experiences of health care or health professionals Review 2: studies that did not include the views/experiences of health-care professionals or students |

| Study design | Quantitative study designs and papers that did not report empirical research (e.g. commentaries or opinion pieces) |

List of Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development countries

-

Australia.

-

Austria.

-

Belgium.

-

Canada.

-

Chile.

-

Czech Republic.

-

Denmark.

-

Estonia.

-

Finland.

-

France.

-

Germany.

-

Greece.

-

Hungary.

-

Iceland.

-

Ireland.

-

Israel.

-

Italy.

-

Japan.

-

Korea.

-

Latvia.

-

Luxembourg.

-

Mexico.

-

The Netherlands.

-

New Zealand.

-

Norway.

-

Poland.

-

Portugal.

-

Slovak Republic.

-

Slovenia.

-

Spain.

-

Sweden.

-

Switzerland.

-

Turkey.

-

UK.

-

USA.

Search strategy

The searching process was conducted in three phases.

The first phase consisted of searching 10 electronic literature resources [both individual databases and hosted multifile collections (see Table 2 for full details)] that covered the relevant disciplinary areas, so that empirical research published in peer-reviewed journals or book chapters could be identified. The searching used a combination of index terms and text-based queries. Several of the resources (e.g. MEDLINE® In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations) provide access to literature not yet assigned to a medical subject heading (MeSH) term or other indexing, so it was important to include text-based queries for comprehensive and current retrieval.

Key index terms included:

-

exp Circumcision, Female/ (MeSH and MEDLINE)

-

exp female genital mutilation/ (Emtree and EMBASE)

-

exp circumcision/ (Ovid PsycINFO).

The different terminologies reflect different indexing principles and practices in the individual literature databases, and were incorporated into the overall strategies for completeness. Following the initial searches, the same strategies were set up as monthly alerts for four main literature databases (see Table 3 for details) until 31 December 2017 (i.e. the searching was not completed as a one-off process). Example full strategies for Ovid MEDLINE and CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) on EBSCOhost are provided in Appendices 1 and 2.

The second phase comprised an extensive search for relevant grey literature, particularly to identify research reports or theses not formally published but still available in the public domain through institutional websites or thesis repositories. 120–122 This part of the searching process included five resources to help identify this type of grey literature (see Table 2). Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) and Google Scholar were also interrogated and key experts in the field were contacted to elicit additional suggestions of relevant documents. 123

The third phase of the search involved hand-searching the reference lists of related systematic reviews and of all the included studies.

Table 2 provides a list of the databases searched and the search dates. Box 2 provides a list of the grey literature sources.

| Electronic databases searched [date range] | Date of search |

|---|---|

| Ovid multifile search (MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO) [inception to 10 March 2017] | 10 March 2017 |

| POPline (via www.popline.org/) [1970 to present] | 10 March 2017 |

| ProQuest multifile searcha [inception to 10 April 2017] | 10 April 2017 |

| ASSIA on ProQuest [1987 to present] | 26 May 2017 |

| Ovid MEDLINE [1948 to present] and MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations [1948 to 26 July 2017] | 26 July 2017 with monthly alert thereafter (cut-off date for included results: 31 December 2017) |

| Ovid EMBASE [1980 to 2017 week 11] | 3 August 2017 with monthly alert thereafter (cut-off date for included results: 31 December 2017) |

| CINAHL Plus with Full Text/EBSCOhost [inception to 2017] | 11 August 2017 with monthly alert thereafter (cut-off date for included results: 31 December 2017) |

| Ovid PsycINFO [1972 to March week 3 2017] | 14 August 2017 with monthly alert thereafter (cut-off date for included results: 31 December 2017) |

| MIDIRS on Ovid [1971 to April 2017] | 18 August 2017 |

| HMIC on Ovid [1979 to present] | 18 August 2017 |

| Clarivate Analytics Web of Scienceb [1900–2017] | 18 August 2017 |

-

The British Library EThOS (ethos.bl.uk).

-

Networked Digital Library of Theses and Dissertations (www.ndltd.org).

-

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (www.nice.org.uk).

-

Trove – National Library of Australia (trove.nla.gov.au).

-

Open Grey (www.opengrey.eu/).

-

Google (www.google.com).

-

Google Scholar (https://scholar.google.co.uk).

-

Experts in the field.

Balancing sensitivity versus specificity within the search strategy

In developing the original search strategies for the reviews, search terms around FGM/C seemed to generate suspiciously small answer sets in the main literature databases (MEDLINE and EMBASE) despite the use of a large range of synonyms for FGM/C. To address this, the librarian devised additional search statements that brought in terms relating to the possible physical or psychological complications that are identified as health impacts of FGM/C, making use of the descriptors in a UK Department of Health and Social Care FGM/C guidance document. 124 This aimed to retrieve relevant documents, based on symptoms or impacts described, without necessarily mentioning FGM/C or other synonyms. These search statements can then be seen as a proxy for FGM/C in the strategy. In addition, we identified from hand-searching that some relevant studies were not indexed in the databases using FGM/C-related terminology. This appeared to be attributable to the study’s main focus being on a different issue, for example pregnancy experiences or care for a particular migrant group (e.g. Somali). Therefore, the search strategy was broadened by using additional ‘proxies’ for FGM/C (originating countries, e.g. “Somali*”) plus pregnancy terms OR physical/mental complications/disorders associated with FGM/C to draw in such papers, which did not overtly capture FGM/C in the title, abstract or MeSH/Emtree indexing. Because these proxy search statements are necessarily less specific, the high sensitivity was tempered by focusing the strategies to limit retrieval to studies relating to OECD countries and specifically excluding RCTs.

Management of identified records

All retrieved data sets were downloaded into group sets within an EndNote library (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA). Using the EndNote grouping functionality, individual group folders were created for each of the database search results sets. Each record was annotated to identify from which database search it had originated. The ‘Find Duplicates’ feature was used to identify duplicate articles from across the different database searches. The duplicates were then moved to a separate ‘Duplicates’ group, leaving one unique representative of each article in the ‘Search Results’ group, usually selecting the MEDLINE representative to be retained, if available.

Screening and selection

Two members of the project team independently screened all potential studies based on a review of titles and abstracts, grouping them into yes, no or unsure using the screening tool in Table 3. Areas of disagreement were resolved through discussion and by consultation with other team members at team meetings.

| Screening criteria | Y | N | U |

|---|---|---|---|

Does the study report findings related to………………

|

|||

| Is the study conducted in an OECD country? | |||

|

Is it a qualitative study? Or Does it report qualitative findings from a mixed-methods study? |

|||

Are the participants………………

|

Full texts of all studies with an initial assessment of yes or unsure were then obtained. These were retrieved via online searches and using the interlibrary loan scheme. If papers and reports could not be retrieved through these channels, authors were contacted by e-mail or via ResearchGate (www.researchgate.net) with full-text requests. All full-text papers were then independently assessed by two team members, alongside discussion with the wider team in cases of uncertainty. Reasons for exclusion were documented (see Appendix 3 for a table of all excluded studies with reasons).

Management of foreign-language papers

Non-English-language papers found to be relevant on the basis of their English-language abstract were sent for complete academic translation. This included a summary of the study purpose or aims and the complete methods and findings sections of the studies. A total of 13 papers were translated by outsourced translators who had experience and training in research. After translation, these texts were then assessed for inclusion and quality appraised and data were extracted if selected for inclusion.

Quality assessment

The role of critical appraisal in qualitative evidence synthesis is contested and there is a lack of agreement on (1) the appropriateness of excluding studies, (2) the potential impact (or not) of excluding eligible papers on review outcomes and (3) the criteria on which quality should be established. 126–129 For these reasons, the team adopted an inclusive approach to critical appraisal, using the appraisal process to enable an in-depth understanding of each paper and to facilitate a critical, questioning approach to the study findings. 130 Studies were not excluded on the basis of quality; rather, the quality assessment was used (1) to judge the relative contribution of each study to the overall synthesis and (2) to assess the methodological rigour of each study as part of a process of assessing confidence in the review findings. 131–135

Following the guidance of the Cochrane Qualitative Methods and Implementation Group136 and the JBI,84 reports and theses from the grey literature were appraised in the same way as papers that were published in peer-reviewed journal articles. 120,122,123

Study quality was assessed by two reviewers (RT and CE) using the Joanna Briggs Institute Qualitative Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI-QARI). 137,138 The domains examined in this tool have been found to be more coherent and more sensitive to assessment of validity than other commonly used tools (see Appendix 4). 128 Team meetings were used to achieve a shared and consistent approach in operationalising the domains in the tool. A third reviewer (GH or JM) was asked to comment on any papers for which there was uncertainty or disagreement and discussions were held until a final consensus on assessment for all the papers was achieved.

The JBI-QARI has 10 questions. These were applied to each individual paper and an aggregate score was calculated (Table 4). In addition, reviewers’ comments were recorded, providing an explanatory rationale for why questions had been answered in a particular way. There is some debate over the use of critical appraisal tools to ‘score’ papers, especially if arbitrary scores are used to exclude papers from a review. 110,135,140 However, as explained above, we did not use the score to exclude papers. Rather, we adopted this approach primarily to enable us to determine an overall, if somewhat crude, picture of the quality of the whole body of evidence within each review, and to assist with the assessment of methodological limitations as a key part of the process of establishing the level of confidence in each of the review findings (see Assessment of confidence in the review findings: CERQual). 112 A criticism of ‘scoring’ qualitative critical appraisals is that it can be hard to distinguish between the poor conduct of a study and poor reporting, especially where journal word limits constrain the level of detail that can be reported. 110 In addition, there is no consensus regarding the relative importance of any one domain within an assessment tool over another, and, hence, whether or not they should all be given an equal weight. In view of these concerns, we chose to adopt a ‘weighting system’ used in previous studies by Higginbottom et al. ,141,142 in which papers were grouped into one of three ‘bands’ (high, medium or low) to enable a broad-brush evaluation to be made of their relative quality, as shown in Table 4.

| Quality evaluation | JBI-QARI aggregate score | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| High | > 7 | A study with a rigorous and robust scientific approach that meets most JBI benchmarks (perhaps 7 or more ‘Yes’) |

| Medium | 5–7 | A study with some flaws but not seriously undermining the quality and scientific value of the research conducted (perhaps 5–7 ‘Yes’) |

| Low | < 5 | A study with flaws and poor scientific value (perhaps below 5 of the benchmarks met) |

As an additional strategy for overcoming the potential limitations of solely relying on a checklist to assess quality, we also chose to assess the ‘richness’ of the studies. This is an approach outlined by Popay et al. ,143 and subsequently operationalised further in Noyes and Popay144 and Higginbottom et al. 141,142 This approach defines study ‘richness’ as ‘the extent to which the study findings provide explanatory insights that are transferable to other settings’. 144 ‘Thick’ papers create or draw on theory to provide in-depth explanatory insights that can potentially be transferable to other contexts. By contrast, ‘thin’ papers provide limited or superficial description and offer little opportunity for generalising. Each paper was assessed by Ritah Tweheyo and Catrin Evans against the criteria, as set out by Higginbottom et al. 141 (Table 5), and categorised as either ‘thick’ or ‘thin’.

| Richness | Operational definition |

|---|---|

| Thick papers |

|

| Thin papers |

|

Extraction of study characteristics

Details of each of the included papers were extracted into a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) file using the domains from the JBI data extraction template (see Appendix 5). 137,146 Data extraction of study characteristics was primarily undertaken by one reviewer (RT); however, a second and third reviewer (CE and JM) double-checked the extractions of a subsample of papers for accuracy. In addition, the team had regular meetings to discuss any uncertainties, to ensure consistency of approach and to agree definitions.

Categorisation of study relevance

After data extraction, papers were categorised by Ritah Tweheyo and Catrin Evans in terms of their relevance to the respective review question. This assessment was made in order to gain a better understanding of the nature of the body of evidence, and also to facilitate the coding process, as described further in Thematic analysis and synthesis. Study relevance was defined as high, medium or low, as set out in Table 6.

| Study relevance | Definition |

|---|---|

| High (specific) | FGM/C-specific health care, for example the study is focused on a specific aspect of care related directly to FGM/C (e.g. deinfibulation, childbirth for women who have had FGM/C, psychological care) |

| Medium (direct) | Other health-care context (e.g. where the study focus is on the maternity care experience of a particular group more generally and where some of the findings relate to the experience of FGM/C) |

| Low (indirect) | Where the study focus is on general attitudes towards FGM/C and/or experiences and consequences of FGM/C, and where some FGM/C-related health-care issues are reported, but are not the main focus of the paper |

Extraction of study findings

PDF (Portable Document Format) files of all of the included papers were imported into NVivo 11 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) software and the ‘findings/results’ sections were coded and analysed. If ‘findings’ were located in other parts of the papers (e.g. the discussion sections), these were also coded. 147

Thematic analysis and synthesis

Analysis and synthesis of the study findings followed the principles of inductive thematic analysis,108,109 and comprised four stages, as suggested by Thomas and Harden. 107 This was followed by a final, fifth step in which the findings from both reviews were combined into an integrated synthesis from which implications for policy, practice, education and research were derived.

The first stage involved intensive and repeated reading of all of the included papers to gain an overall in-depth understanding of their context and key findings. This stage was returned to many times during the analysis and synthesis to ensure that emerging interpretations remained deeply contextualised.

The second stage involved line-by-line coding of the findings of the primary studies. We coded only findings that were directly relevant to the review question. Where there were multiple papers from the same study, we ensured that distinct findings were coded from each (i.e. we did not code duplicate findings). Owing to the large number of papers in each review, we decided to start the development of the coding framework by focusing on studies that were likely to yield the richest and most relevant findings. Hence, we started with the studies that had been categorised as both ‘thick’ and highly relevant. These generated a large number of free codes, assigned line by line to the text according to its meaning and content. Subsequent studies were coded using the initial framework of codes and adding to them as new codes were identified. Ritah Tweheyo and Catrin Evans both independently coded the initial set of studies, conferring until the initial coding framework was agreed. Subsequently, Ritah Tweheyo completed the rest of the coding, with Catrin Evans and Gina Higginbottom regularly reviewing and discussing the evolving framework.

The third stage involved analysing the codes to explore areas of similarity or difference, grouping them together based on shared meanings to create new codes, and then organising these into a set of descriptive themes that captured the meaning of their constituent codes. In NVivo, this was represented as a hierarchical tree structure with several layers. Each theme was formulated to describe a key phenomenon in such a way as to capture its core meanings but also to explain and account for possible differences or variations in the phenomenon. To ensure rigour of the analytical process, the team actively sought to identify and understand possible ‘disconfirming’ cases that might challenge emerging interpretations,148 and to explore possible subgroup or contextual differences. These processes were aided by the creation of a theme matrix (see Appendices 8 and 12), in which each theme was mapped to its constituent studies. This helped the team to clearly see how common the theme was among the studies and what kind of study contexts or samples the theme related to, and to explore why it may have been present in some studies but not in others. During the analysis, the team referred to a list of questions to help them to develop the descriptive themes, as set out in Box 3.

-

Define, explain and contextualise the core concept.

-

Explore key groups it may (or may not) apply to.

-

Explore key settings/circumstances it may manifest in or be affected by.

-

Explore causes, manifestations, variations and consequences in terms of perceived quality of care and potential clinical outcomes or clinical trajectories.

-

Identify ‘gaps’ within the theme.

-

Explore any key variations between the studies and the study contexts.

-

Explore implications of the date ranges of the included studies.

-

Explore and understand examples where the theme does not seem to apply.

Descriptive themes are derived from an interpretative process of constructing codes based on underlying meanings and considering how and in what ways these codes are related to each other. Thus, they represent a highly rigorous process that combines the findings of each study into a whole via a listing of themes. Nonetheless, Thomas and Harden107 argue that descriptive themes represent only the first step of synthesis, as, at this point, they generally do not yet ‘go beyond’ the findings of the primary studies to identify new concepts, understandings or hypotheses. This is achieved in the fourth stage, comprising the development of higher-order or ‘analytical’ themes, which constitute the key findings of the reviews.

For the fourth stage of synthesis, analytical themes were evolved through an in-depth process of comparing and contrasting the meanings of the descriptive themes, analysing these in relation to how they were, or were not, able to illuminate the review questions, and inferring broader phenomena, categories of meaning or social processes that they related to. This was a cyclical process that involved re-reading the papers, re-reading the codes and in-depth discussion among team members. Using this analytical process, the descriptive themes were organised into five analytical themes for review 1 and six analytical themes for review 2.

As far as possible, the descriptive and analytical themes were formulated as ‘directive’ findings indicating clear messages and/or suggesting clear lines of action for policy and practice. 137

The fifth and last stage of the synthesis involved bringing the findings from both reviews together to generate an overarching novel synthesis. This was done by creating short statements of findings for all of the themes (descriptive and analytical) in each review, listing them out, juxtaposing review 1 themes against review 2 themes and comparing and contrasting these. This process enabled the team to identify key phenomena that could explain and illuminate aspects of FGM/C-related health care through understanding both women’s and professionals’ views and experiences together. An overarching synthesis comprising four ‘synthesised findings’ was then drafted and extensively consulted and revised by the whole team until a final version was agreed.

Assessment of confidence in the review findings: CERQual

Assessment of confidence in the findings of each review was undertaken using the Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research (CERQual) approach. 110,112,131,136,149–153 Ritah Tweheyo and Catrin Evans led this process, working together and discussing the final assessments with the research team. CERQual is a relatively new, transparent method for assessing confidence in the findings in qualitative evidence syntheses; it is akin to the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, and Evaluation (GRADE) approach for establishing confidence in evidence of effectiveness for each outcome in a quantitative review. 154 The assessment of confidence in the evidence is made for each individual review finding and considers four elements: (1) methodological limitations (the extent to which there are problems in the design or conduct of primary studies that contributed to evidence of a review finding),136 (2) relevance (the extent to which the body of evidence from the primary studies supporting a review finding is applicable to the context specified in the review question),149 (3) coherence (whether or not the finding is well grounded in data from the primary studies and can provide a convincing explanation for patterns found in the data)152 and (4) adequacy of data (an overall determination of the degree of richness and number of data supporting a review finding). 151 Based on assessments made of any concerns across these four individual domains, each review finding is assigned one of four levels of confidence: high, moderate, low and very low.

In this project, the CERQual assessment was made for each of the descriptive review findings. Each descriptive review theme was summarised into a succinct ‘summary of a review finding’. These were then presented in a ‘summary of qualitative findings table’ containing several columns, including the summary of the review finding, the studies that contributed to the review finding, the assessments for each of the CERQual domains, the overall CERQual assessment of confidence in the evidence and an explanation of this assessment (see Appendices 9 and 13).

The CERQual assessment was made for each of the descriptive review findings (themes), rather than for the analytical themes or the themes in the overarching integrated synthesis, as the latter comprise an aggregation of descriptive themes as well as descriptions of patterns or explanations that are inferred as part of the interpretative process. There is, as yet, relatively little guidance for, or experience with, applying CERQual to higher-level analytical themes or theories. 150 The process of applying CERQual to our higher-order themes would, therefore, have required an extended period of methodological development and testing, which was beyond the scope of this project, and which is recognised as being part of the ongoing research agenda for CERQual development. 150

As of yet, unlike GRADE assessments, ‘dissemination bias’ within qualitative evidence synthesis is rarely discussed and needs further methodological consideration. 153 However, in this review, we sought to minimise possible dissemination bias by undertaking an exhaustive literature search that (1) was highly sensitive rather than specific, (2) included a range of grey literature (research reports, evaluations and theses) as well as published papers, (3) did not limit the date, (4) did not limit the language and, (5) included the original thesis or report in addition to the published paper when the former contained findings that were not reported in the latter. In addition, as noted above, we maintained an inclusive approach and did not exclude any studies on the basis of quality.

Reflexivity, rigour and quality of the synthesis

As with primary qualitative research, there are a number of strategies that can be adopted to enhance the rigour and trustworthiness of qualitative evidence synthesis. 148,155 We utilised a range of different approaches, as outlined in this section.

First, we were aware that our own theoretical, cultural and political positions might influence the ways in which we engaged with the texts and developed the interpretations. 156,157 The initial analysis and synthesis process was undertaken primarily by two reviewers (RT and CE), aided by the wider project team. Ritah Tweheyo is a black African public health researcher, originally from Uganda, and Catrin Evans is a white nurse and health services researcher from the UK. Neither has direct experience of FGM/C, and neither has worked clinically with women/girls who have experienced FGM/C. Both have had experiences of ‘being migrants’ and having to adjust to foreign health systems, but in different contexts. Both have experienced childbirth. Both consider themselves to be feminists and anti-racist (but again, these standpoints have emerged from different subjectivities). Both are anti-FGM/C but recognise the inherent political and epistemological tensions that exist when individuals located ‘outside’ cultures and communities try to explain a phenomenon that is deeply culturally and socially shaped. During the analysis, we continually challenged ourselves by asking if and how our emerging interpretations were being influenced by our own perspectives and repeatedly returned to the original papers to re-embed coded text within its wider study context and to check our interpretations. As an example, there were many accounts in the papers in review 1 in which women described extremely humiliating, distressing and stigmatising experiences in their health-care encounters, often linked to their race or ethnicity. Although we knew from prior reading that such experiences had previously been reported, reading so many accounts at first hand proved to be a shocking and distressing experience for us as reviewers. We had not expected this to be such a pervasive theme and we felt strongly that we wanted this aspect of women’s experience to be heard in the review. However, we occasionally wondered if we were perhaps giving too much prominence to women’s negative experiences and failing to give sufficient attention to instances where women had reported positive care experiences. This led us back to reading and, in some instances, re-coding the original papers, and this prompted us to develop a more nuanced approach to understanding women’s care experiences.

Second, the analysis process also explicitly drew on the expertise within, and challenge from, the project team. Team members were sent exemplar papers to read before meetings, so that our discussions were grounded in the papers and hence enabled challenge and conceptual development of the initial interpretations of Ritah Tweheyo and Catrin Evans. The same approach was used during consultations with the PAG. However, this consultative process was not always straightforward, as all involved had vast experience and strong views. At times, we had to step back and remind ourselves to base our interpretations on the data from the included papers and not on our own wider experiences.

Third, once the descriptive and analytical themes had been finalised by the project team, we organised a national research stakeholder engagement event in which the draft review findings were presented. Over 65 people attended this event, representing FGM/C survivors, FGM/C activists, community organisations with FGM/C as a remit, academics, researchers, midwives and general practitioners (GPs). Their inputs contributed to the report in four important ways: (1) to explore the credibility of the key findings, (2) to put these into the contemporary UK context, (3) to identify gaps in evidence/understanding and (4) to put forward key implications/recommendations for service development and future research.

The nature of stakeholder validation in the context of a review is controversial and poorly described. 158 Generally, non-author stakeholders have not necessarily read the included papers and thus are not directly familiar with the underlying research findings; they may or may not have direct experience of the issues to which they pertain, hence there is some debate over their ability to ‘validate’ the emergent themes. Therefore, as suggested by Booth et al. ,148 we used our stakeholder event to challenge our interpretations as well as to explore the credibility of our findings. After each of the review presentations, stakeholders were asked to comment on the questions in Box 4.

-

Based on your own experience and perspectives, do the themes seem to capture the main issues?

-

Were any review themes surprising for you? Why?

-

Were there any review themes that you do not agree with? Why?

-

Do you think that there are any issues missing from the review findings that you would have expected to see?

The feedback from the event was reassuring in that there was a very strong sense of validation of the findings. When participants indicated that they had found a theme surprising, we returned to that theme and re-examined it. For example, two of the descriptive themes in review 2 (around professionals’ experiences of deinfibulation and reinfibulation) were rewritten in a more nuanced manner as a result of this process. Participants had felt that further detail and country-specific exploration was required in these themes, as they felt that in the UK context, professionals would know the relevant laws and would not experience the ambivalence described. Likewise, participants noted a number of perceived omissions (e.g. nothing on the impact of mandatory reporting and little on mental health issues), which, again, prompted us to go back and check that these were actual omissions in the evidence and did not reflect errors in the review process. Some comments helped us to analyse the findings in more detail (e.g. one participant asked how the policy and legal context around FGM/C in different countries might have influenced the findings). The event was also used to elicit suggestions for the implications of the review (see Appendix 14 for a full description of the stakeholder event).

Finally, in order to capture feedback from medical practitioners (a group that had been largely absent from the national event), the review findings were then also presented to a group of 30 obstetric and gynaecology registrars during one of their training days. This group included doctors working in cities with a relatively high prevalence of FGM/C as well as some working in settings with a very low prevalence. The subsequent discussions of their own experiences showed a very high level of congruence with the findings of review 2 (at least within the English context), and further helped to shape the implications from a medical perspective (see Appendix 17 for detailed feedback from this group).

Summary of the review process

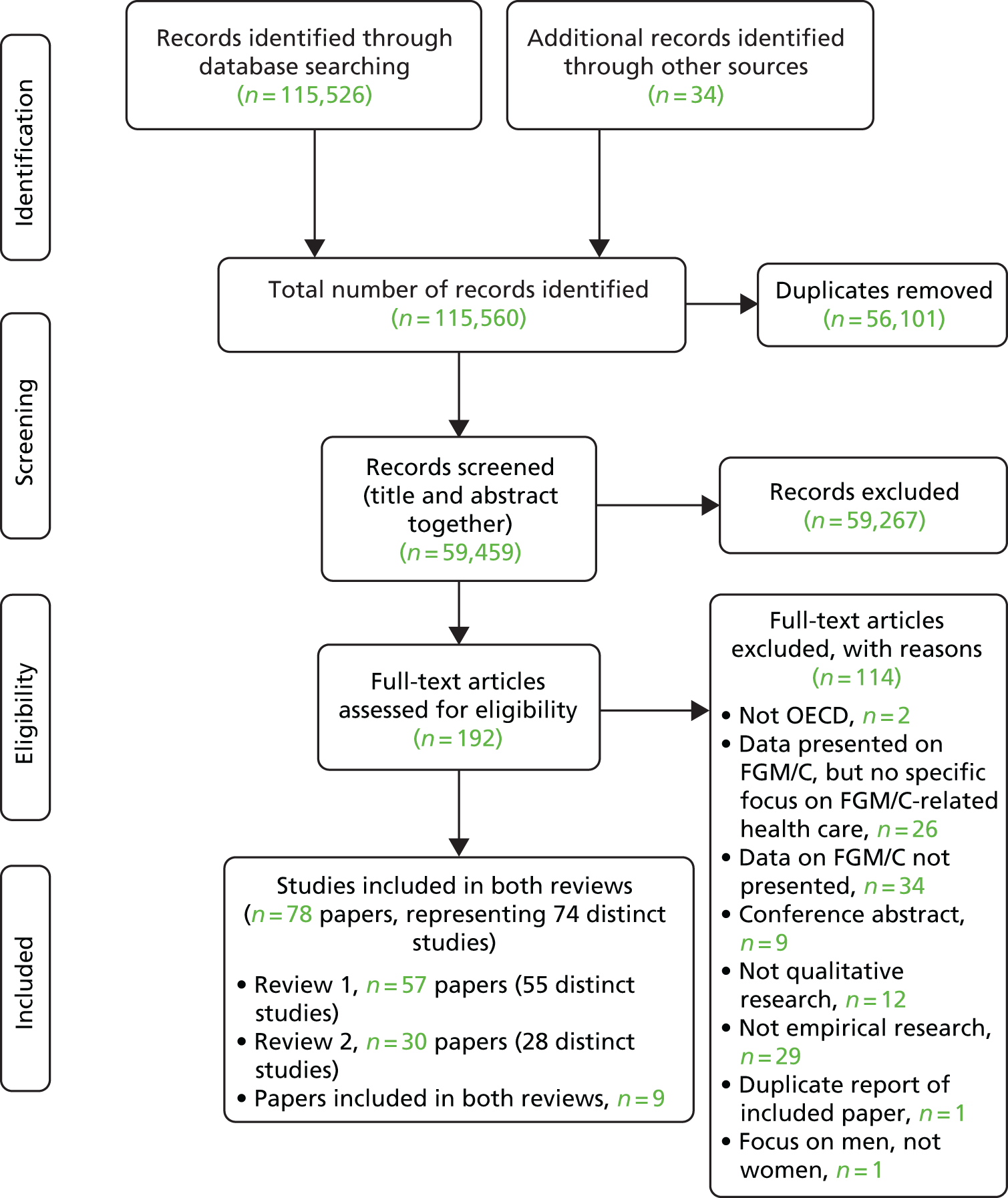

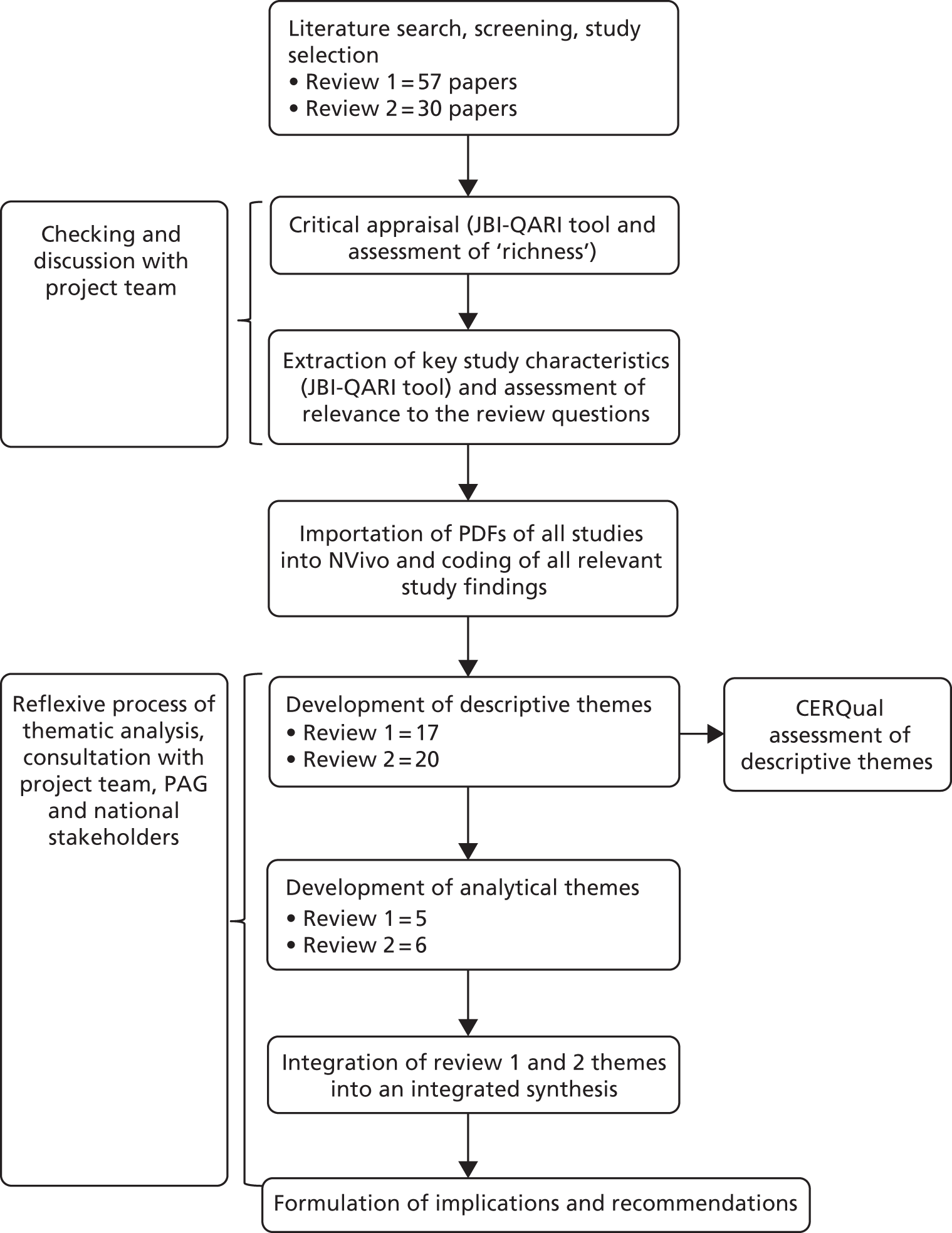

Figure 2 provides a clear depiction of all of the steps in the review process.

FIGURE 2.

Flow chart of the review process.

Chapter 3 Review 1 results

Characteristics of studies in review 1

As described in Chapter 2, 57 papers met the inclusion criteria for review 1. Two studies were reported in multiple publications,159–162 hence review 1 includes 55 distinct studies reported in 57 publications. Regarding these duplicate studies, in both cases these were a doctor of philosophy (PhD) thesis and an associated peer-reviewed journal article. The PhD theses were included in addition to the journal article, as they contained relevant findings that were not reported in the published paper.

Of the 55 distinct studies, 46 were unique to review 1 and nine were also included in review 2 (as their samples included health professionals as well as patients). 56,78,161,163–169 Fifty-three papers were in the English language; two were in German170,171 and two were in Spanish. 172,173

See Appendix 6 for a detailed summary of study characteristics.

Type of publications

Over half of the included papers were peer-reviewed journal articles. In total, the review included 13 master’s and PhD theses,78,159,161,165,170,171,173–179 10 unpublished research reports,47,57,58,164,168,169,180–183 one book chapter184 and 33 peer-reviewed journal articles. 56,59,160,162,163,166,167,172,185–209

Date range of studies

The studies represented a mixture of older and more-recent research, with publication dates ranging from 1985 to 2017. However, 29 papers had been published since 2011, hence half of the papers reflected a more contemporary context.

Geographical setting of studies

The studies represented a wide range of OECD countries, covering 14 different countries in Europe, North America and Australasia. Specifically, review 1 included studies from Australia,168,169,197,203 Austria,171 Canada,159,160,175,177,178,191 Finland,192 France,193 Germany,164,170 the Netherlands,206,208 New Zealand,165,197 Norway,167,199 Spain,172,173 Sweden,186,189,194,200,209 Switzerland,161,162 Scotland (UK),174,181,182 England (UK)47,56–59,163,179,180,183–185,196,202,204,205 and the USA. 78,166,176,187,188,190,195,198,201,207 Research undertaken in the UK (including Scotland and England) provided the most input to the review, contributing over one-third of the papers (n = 18), followed by research undertaken in the USA (n = 10).

Sample/population/type of female genital mutilation/cutting

The studies were primarily of adult women. Only one study included girls under the age of 18 years but did not report health-related experiences of this group. 186 There were no studies that focused specifically on health-care issues related to FGM/C in older (post-childbearing) women. Hence, although the aim of the review was to explore FGM/C across the life course, the studies all focused on generic issues relating to adult women and no further age-specific differentiation could be made.

The vast majority of studies were of women from FGM/C-practising countries in sub-Saharan Africa, and the majority of these included women specifically from countries in the Horn of Africa (Somalia, Sudan and Eritrea), where type III FGM/C is most commonly practised. Hence, the findings included in the review predominantly reflect issues affecting these population groups and issues that may be specific to having experienced type III FGM/C. Only three studies explicitly reported including women from Egypt/the Middle East but did not differentiate these women’s experience from the rest of the sample. 166,176,184 The sample compositions of the included studies were as follows: Somali women,56,59,78,159,160,163,167,175,177,178,184–188,190–192,194,195,198,201,202,206,207,209 Somali and Eritrean women,161,162,168,205 Eritrean women,170,200 Somali and Sudanese women,57,179,199 Senegalese and Nigerian women,172 and mixed samples including women from several different countries. 47,58,164–166,169,171,173,174,176,180–183,189,193,196,197,203,204,208 Almost half of the studies (n = 27) focused exclusively on women from Somalia.

Where there were mixed samples, none of the studies provided an in-depth differentiation of women’s experiences on the basis of the type of FGM/C they had experienced.

Focus, context and relevance of studies

The studies had varied research aims and foci; for example, some studies focused very directly on FGM/C-related health experiences (e.g. Moxey and Jones202), whereas others explored FGM/C as a general issue, not focusing only on health (e.g. O’Brien et al. 181). Other studies explored health issues in a general way (e.g. Abdullahi et al. 185), or focused on sexuality/identity (e.g. Abdi163) or on different aspects of life as a migrant (e.g. Guerin et al. 197), but all included some findings that concerned FGM/C-related health care.

The largest number of studies (n = 18) focused specifically on women’s birth/maternity care experiences. 56,59,78,165,167,174,187–189,191,193,194,198,200,202,203,209 Other study contexts were as follows: general views on health care,57,160,166,168–171,173,184,204,207 general attitudes towards FGM/C,47,58,159,163,164,178,181–183,186,201 experiences of sexual/reproductive health services,161,162,172,176,192,197 cervical screening,185,190,195,206 psychological issues,179,196,208 deinfibulation, 199,205 GP services,180 identity175 and pain/embodiment. 177

Notably, only three studies included psychological health-care needs/experiences as a specific issue. 179,196,208 There were no studies that examined women’s experiences of surgical reconstruction following FGM/C.

As described in Chapter 2, in order to assist development of the initial coding framework, we categorised each of the papers according to their overall relevance to the research aims. Sixteen papers were rated as being of high relevance,59,78,161,167–169,174,175,179,183,189,193,196,200,202,207 19 papers were rated as being of medium relevance56,162,165,172,178,180,185,187,188,190–192,195,199,203,206,208,209 and 22 papers were rated as being of low relevance. 47,57,58,159,160,163,164,170,171,173,176,177,181,182,184,186,194,197,198,201,204,205

Methodological quality of included studies

The papers were each appraised by two reviewers using the JBI-QARI138 (see Appendix 7 for full details of the quality appraisal of each paper).

As described in Chapter 2, a broad scoring range was used to provide a ‘rough’ sense of the overall quality of the body of evidence. In accordance with this categorisation, 30 papers were assessed as being of high quality,59,78,159,161,163,167–169,173,174,177–179,181–183,186,190,192,193,195,196,199–203,205,206,208 21 papers were assessed as being of medium quality47,56–58,162,164,165,170,172,175,176,185,187–189,191,194,198,204,207,209 and six papers were assessed as being of low quality. 160,166,171,180,184,197

A methodological weakness in many studies was a lack of apparent philosophical standpoint (question 1 of the JBI-QARI), making it difficult to assess the congruency of the chosen methodology. Likewise, many studies did not identify any clear methodology (simply stating that they adopted a generic ‘qualitative approach’), making it difficult to judge the congruence of the methodology with the research question and the methods (questions 2 and 3 on the JBI-QARI). Finally, a weakness across many studies was a lack of discussion of reflexivity (questions 6 and 7 on the JBI-QARI). Given the sensitive nature of FGM/C (and sexuality or migrant health care) as a topic, the failure to explore the researcher’s own theoretical position or their role, professional background, ethnicity, experience of FGM/C or relationship to the participants makes it hard to judge the dependability of the findings. 155 A related issue that could affect the transferability of the findings concerns the study samples and the methods of recruitment that were used. 155 The JBI-QARI does not assess in detail how recruitment was conducted; however, many studies had derived their samples from community organisations or used snowball sampling. The majority of studies did not discuss the potential implications of these recruitment strategies for influencing the results towards a particular standpoint (e.g. for or against FGM/C) or towards a particular view of health care or willingness to openly discuss FGM/C.

In addition to the JBI-QARI quality assessment, the papers were also categorised according to their ‘richness’ in terms of being ‘thick’ or ‘thin’ (i.e. their relative ability to provide explanatory insights and plausible interpretations based on a clear account of the research process). 141–143 Thirty-three papers were classified as ‘thin’47,56–58,159,160,162–164,166,170–173,176–178,180–182,184–188,191,192,194,197,201,205,208,209 and 24 papers were classified as ‘thick’. 59,78,161,165,167–169,174,175,179,183,189,190,193,195,196,198–200,202–204,206,207 The ‘thicker’ papers tended to be studies that were informed by an anthropological theoretical approach, that had followed a clear methodological stance or that had moved beyond mere description in their analysis towards a more interpretive and analytical account of the phenomenon of interest.

As noted previously, 23 papers were unpublished research reports or master’s and PhD theses (i.e. grey literature). 47,57,58,78,159,161,164,165,168–171,173–183 The lack of peer review in these included papers could be considered a potential threat to the quality of the review findings; however, our detailed quality appraisal did not indicate any clear correlation between being published and the quality rating. For example, four theses and three unpublished research reports were rated both ‘thick’ and of ‘high quality’ (30% of the grey literature). 78,161,168,169,174,179,183 However, out of 33 peer-reviewed journal articles, only 11 were rated as being both high quality and ‘thick’ (33% of the published journal articles – a very similar percentage). 59,167,190,193,195,196,199,200,202,203,206 Indeed, of the six papers rated as being low quality (all of which were also rated ‘thin’), half (n = 3) were peer-reviewed journal articles160,166,197 and one was a peer-reviewed book chapter. 184 Most of the papers were rated as being somewhere between high quality and low quality.

Review 1 themes