Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/1023/17. The contractual start date was in June 2013. The final report began editorial review in February 2018 and was accepted for publication in August 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Tamsin Ford is chairperson of the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Surveillance Service that was used to run part of the study, which is an unpaid position (other than travel expenses). Kandarp Joshi reports grants from Sunovion Pharmaceuticals, Inc., outside the submitted work. He was principal investigator for the Aberdeen site for a Sunovion-sponsored multisite trial on the efficacy and safety of lurasidone in paediatric schizophrenia. Jonathan Kelly reports that Beat has contracts with some NHS trusts and clinical commissioning groups that provide and commission, respectively, community eating disorders services for children and young people. In these contracts, Beat works with the local services to deliver awareness-raising training for professionals and, in some cases, to offer peer coaching for carers. The funding Beat receives in return for its role in this project is not ‘on my behalf’. Beat is a co-applicant on another research project called ‘TRIANGLE’ (short title), which is also funded by the National Institute for Health Research. The funding Beat receives in return for its role in this project is not ‘on my behalf’. Beat is a co-applicant on another research project called ‘Mind the Gap’ (short title), which is funded by the Welsh Assembly Government and is investigating referral pathways from identification to specialist treatment for people with eating disorders (of all ages) in Wales.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Byford et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Anorexia nervosa is a serious and enduring eating disorder and mental health problem, with high morbidity and the highest mortality among psychiatric disorders. 1,2 The annual incidence in the most vulnerable group (adolescent girls aged 15–19 years) is between 110 and 135 per 100,000. 3,4 Anorexia nervosa is commonly associated with severe physical, psychological and social impairments, and a significant cost burden. 5,6 Although the majority of adolescents with anorexia nervosa eventually recover, the illness is often protracted, with a mean duration of 5–6 years. 7 Because of the life-threatening nature of this condition, a significant proportion of young people with anorexia nervosa are treated as inpatients in hospital. In England, the number of hospital admissions for anorexia nervosa rose consistently by 37% between 2011–12 and 2015–16. 8,9 Although some admissions (mainly on paediatric wards) are brief, many are as long as 6–12 months, and some are even longer. Hospital stay is disruptive to school, family and social life, and relapse rates for inpatient treatment are high (25–30% after first admission and 50–75% after subsequent admission),7,10 with evidence that clinical outcomes may be worse even when severity is accounted for. 11 By contrast, among those who respond well to outpatient family therapy, relapse rates are as low as 5–10%. 12–14

In the UK, at the time the Cost-effectiveness of models of care for young people with Eating Disorders (CostED) study began, there were several possible referral routes for young people with anorexia nervosa. One was from primary care to a generic child and adolescent mental health service (CAMHS) with varying levels of expertise in eating disorders and a variable mix of individual or family-based treatments. In some cases, this may include a specific eating disorders ‘mini team’. Another referral route was from primary care directly to a specialist community eating disorders service for children and young people. These are dedicated tertiary-level multidisciplinary services that cover a larger geographical area than single CAMHS and have been reported to reduce rates of admission to hospital by as much as 60–80%. 15 Other routes into specialist community care include referrals from accident and emergency, social care and education. Finally, patients may be so unwell that they are admitted immediately to paediatric care or to an inpatient facility, thus bypassing community services.

To date, few studies have compared the relative benefits of different care pathways for young people with anorexia nervosa. The available evidence, although limited, supports a case for specialist outpatient treatment having a higher probability than CAMHS and inpatient treatment of being the most effective strategy. 16,17 Other indicators found to favour a community eating disorders service for children and young people over a generic CAMHS include case identification, rates of hospital admission and continuity of care. Evidence suggests that case identification of adolescent anorexia nervosa in specialist areas is 50% higher than in non-specialist areas; hospital admission rates are significantly lower among patients whose treatment started in a specialist service (16%) than among those whose treatment started in a generic CAMHS (40%), and continuity of care is notably better for young people whose treatment began in a specialist outpatient service than for those whose initial assessment took place in generic CAMHS. 17

Economic evidence also supports the case for specialist outpatient treatment for young people with anorexia nervosa, suggesting that specialist outpatient treatment is cost-effective compared with both inpatient treatment and generic outpatient treatment. 18 However, the data for this study were collected between 2000 and 2003, so service configurations may now be very different. A recent systematic review19 of economic evaluations of prevention and treatment for eating disorders identified only 13 such studies in total; only three of these focused on anorexia nervosa, and only one focused specifically on young people, which was the study already identified. 18

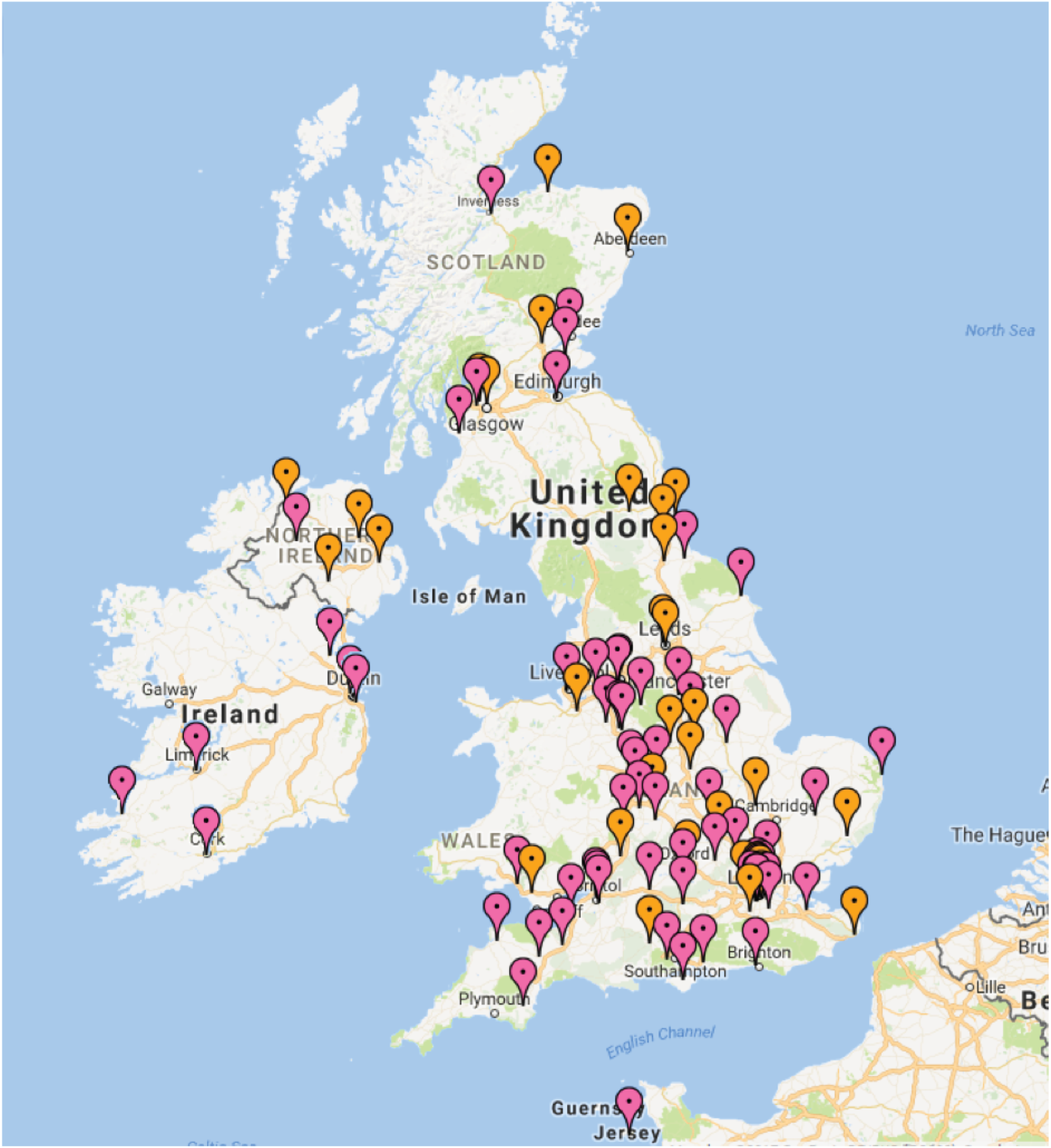

Despite these findings, many parts of the UK and the Republic of Ireland (RoI) had little or no specialist eating disorders provision for young people, although this has started to change in England following the publication of guidance for commissioning standards and requirements for the provision of community-based eating disorders services for children and young people in June 2015. 20 The available evidence suggests that, if the above findings are generalised, investing in the development of such services could have significant implications for the NHS, with the potential to improve health outcomes through reductions in relapse rates, to reduce costs through reductions in hospital admissions and to improve the quality of life of young people and their families. The CostED study aimed to provide evidence of the potential savings to be made from investment in specialist eating disorders services, alongside evidence that patient and family outcomes will be enhanced or at least be no worse than the situation at the time that the CostED study was undertaken.

Aims and objectives

The primary aims of the CostED study were to evaluate the cost and cost-effectiveness of alternative community-based models of service provision for child and adolescent anorexia nervosa and to model the impact of potential changes to the provision of specialist NHS services using decision-analytic modelling techniques. The data collected for this purpose were also used to generate up-to-date estimates of the incidence of anorexia nervosa in secondary care services for young people in the UK and the RoI, and to map specialist and generic services for eating disorders across the UK and the RoI.

The specific objectives of the study were to:

-

identify all new community-based incident cases of anorexia nervosa in young people aged between 8 years and 17 years and 11 months in the UK and the RoI over an 8-month period using a psychiatric surveillance system

-

classify the model of community-based care provided for each case identified at baseline as either specialist or generic, using information from reporting clinicians on service characteristics and applying consensus criteria obtained using a Delphi survey

-

calculate the relative cost of all notified incident cases of child and adolescent anorexia nervosa in the UK and the RoI and determine the cost-effectiveness of different models of care provision at 6- and 12-month follow-ups through questionnaires to reporting clinicians

-

model the impact on cost and cost-effectiveness of potential changes to the provision of specialist services in the UK and the RoI using decision-analytic modelling techniques.

The hypotheses of the study were that:

-

assessment and treatment by highly specialist or tertiary specialist community-based eating disorders services for child and adolescent anorexia nervosa in the UK and the RoI would be less costly to health services over a period of 12 months than assessment and treatment by, or referral via, generic (non-specialist) CAMHS

-

assessment and treatment by highly specialist or tertiary specialist community-based eating disorders services for child and adolescent anorexia nervosa in the UK and the RoI would be more cost-effective from the health service perspective over a period of 12 months than assessment and treatment by, or referral via, generic (non-specialist) CAMHS

-

increasing the availability of highly specialist or tertiary specialist community-based eating disorders services for child and adolescent anorexia nervosa in the UK and the RoI would be cost saving to health services over the medium to long term.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from Petkova et al. 21 © Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2019. Re-use permitted under CC BY. Published by BMJ. This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Study design

An observational surveillance study was undertaken using the Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Surveillance System (CAPSS), a system designed to ascertain cases of rare childhood mental health conditions in the UK and the RoI through monthly reporting by clinicians. 22

This method of case identification aimed to identify all new community-based incident cases of anorexia nervosa in young people aged between 8 years and 17 years and 11 months in the UK and the RoI over an 8-month period (objective 1). Data were collected directly from clinicians who notified cases to CAPSS and included information on service characteristics to enable each notifying service to be classified as either specialist or generic (objective 2), use of health services to support the calculation of the cost of all notified cases (objective 3), and clinical characteristics and outcome measures, which were used alongside the cost data to assess the cost-effectiveness of different models of care provision (objective 3) and to model the impact on cost and cost-effectiveness of potential changes to the provision of specialist services in the UK and the RoI using decision-analytic modelling techniques (objective 4).

Objective 2, to classify the model of community-based care provided for each case identified as either specialist or generic, additionally required information on criteria considered to be important to support the classification of a service as a specialist eating disorder service. These criteria were identified using a Delphi survey to achieve consensus.

Sampling

The study comprised young people aged between 8 years and 17 years and 11 months in contact with child and adolescent mental health services for a first episode of anorexia nervosa in accordance with Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fifth Edition (DSM-5), diagnostic criteria. 23 New cases of anorexia nervosa were notified by clinicians via CAPSS on a monthly basis for a period of 8 months, from 1 February 2015 to 30 September 2015. The CAPSS methodology, which, in order to maximise the accuracy of incident data, does not require patient consent, has been operating successfully since 2009 and is based on the well-established British Paediatric Surveillance Unit system (www.rcpch.ac.uk/work-we-do/bpsu; accessed 8 February 2019). CAPSS aims to facilitate epidemiological surveillance and research into uncommon child and adolescent mental health conditions, to increase awareness within the medical profession and public alike and to allow psychiatrists to participate in surveillance of uncommon child and adolescent mental health conditions. 22

At the time of the CostED study, CAPSS used a report card, known as the yellow card, which contains a list of the conditions currently being surveyed at any one point in time. More recently, CAPSS introduced an e-mail system, but that was not available at the time of the CostED study. The yellow cards (or e-mail notifications), along with reporting instructions and protocols for new studies, are sent every month to all hospital, university and community child and adolescent consultant psychiatrists across the UK and the RoI. The reporting clinicians are sent the yellow cards (or e-mail notifications) from the CAPSS office and asked to tick boxes against any of the reportable conditions they have seen in the preceding month, or to tick a ‘nil return’ box if none has been seen, and return the card to the CAPSS office. A tear-off slip is provided with the card to enable psychiatrists to keep a record of patients reported. ‘Positive’ returns are identified by the CAPSS administrator, allocated a unique CAPSS ID (identifier) number and notified to the appropriate research investigator, who then contacts the reporting clinician directly to request completion of a brief data collection form using the CAPSS ID.

For the CostED study, the report card contained a tick box for anorexia nervosa and was sent to reporting clinicians along with a study-specific protocol card detailing the case notification definition for anorexia nervosa (Box 1). Yellow cards or e-mails were sent monthly for the 8-month period of surveillance. The case notification definition, which was approved by the CAPSS Executive Committee, was based on DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for anorexia nervosa and was intended to aid clinicians in their decision of whether to tick ‘yes’ or ‘no’ on the yellow card, and therefore notify a case. It was not intended to identify whether or not a case met study inclusion criteria, which was determined by the CostED research group after receipt of all relevant data.

Please report any child/young person aged 8 to 17 years and 11 months inclusive, who meets the case notification definition criteria below for the first time in the last month. One bullet point criterion from each group below should be fulfilled.

Group A-

Restriction of food, low body weight, or

-

Weight less than expected for age.

-

Fear of gaining weight, or

-

Fear of becoming fat, or

-

Behaviour that interferes with weight gain, for example excessive exercising, self-induced vomiting, use of laxatives and diuretics.

-

Body image disturbance, or

-

Persistent lack of recognition of the seriousness of the current low body weight.

-

Patients who are not underweight.

-

Patients with bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder, avoidant restrictive food intake disorder or other failure to thrive presentations.

Setting

Cases were notified by clinicians in community-based or hospital-based secondary or tertiary NHS CAMHS in the UK or the RoI.

Procedures

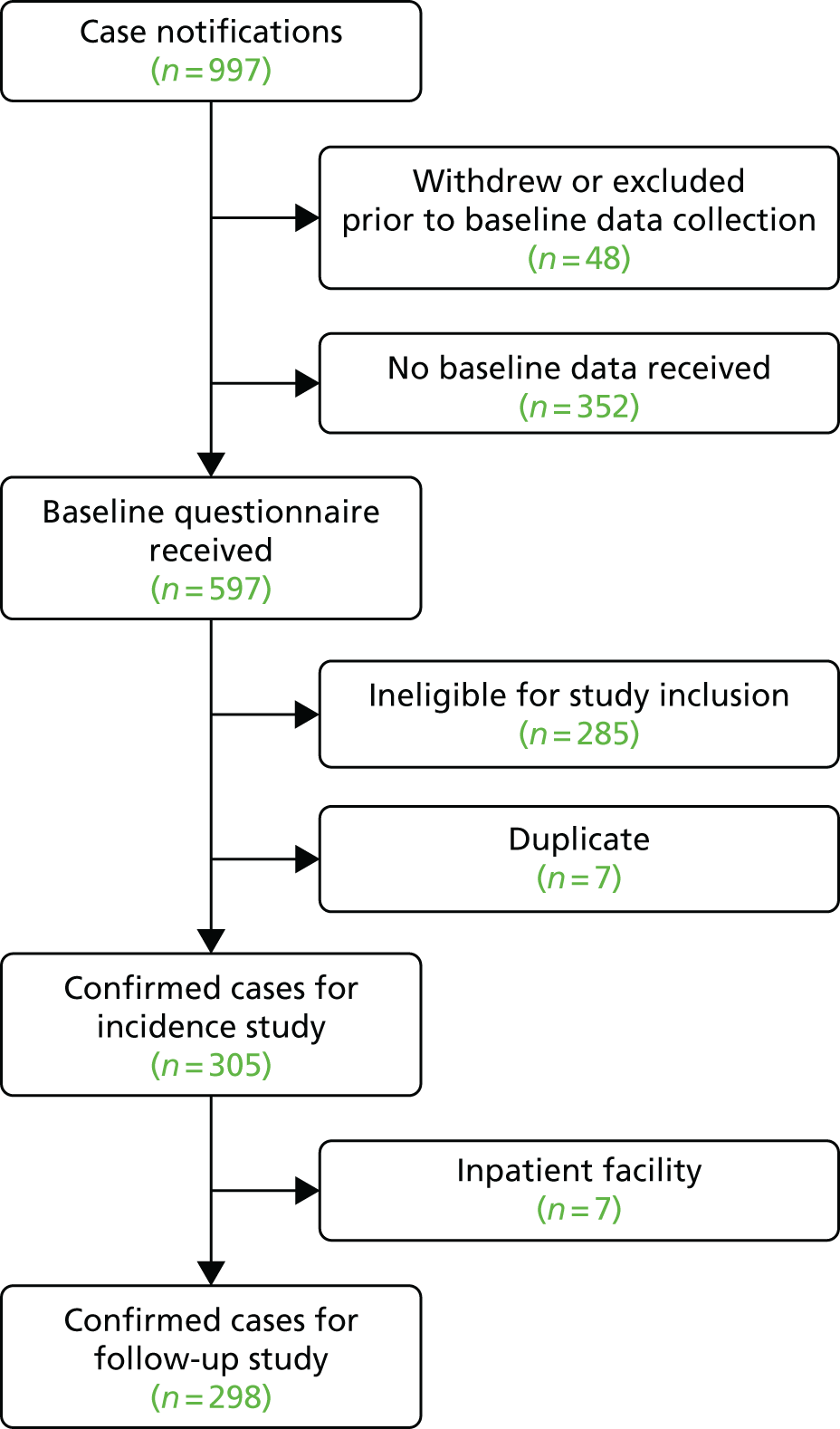

On receipt by the CAPSS system of a new notification of a case of child and adolescent anorexia nervosa, reporting clinicians were sent a baseline questionnaire for each case that they reported (identified via the unique CAPSS ID number). The questionnaire covered characteristics of the notifying service (to enable classification of services as specialist or generic), clinical characteristics of the notified case (to assess case eligibility for follow-up and for inclusion in the incidence study and to provide baseline assessments of outcome) and referral pathway information for the notified case (to ensure that assessment and diagnosis had not happened prior to the study surveillance period). Data collected via the baseline questionnaires are detailed in full below (see Data).

In line with CAPSS procedures and ethics requirements, the baseline questionnaire also contained a limited set of standard patient identifiers. The patient identifiers included a NHS or a Community Health Index number (unique patient identifiers used in the regions of interest), a hospital number, the first half of the postcode or the town of residence for the RoI, sex, date of birth and ethnicity (white, mixed, Asian, black, Chinese, other or unknown). In Northern Ireland, identifiers were further limited to age in years and months (instead of date of birth) and hospital identifier (instead of hospital number) to further reduce the risk of patient identification, given the relatively small geographical area. In keeping with the requirements of the Northern Ireland Privacy Advisory Committee, all patient-identifiable data from Northern Ireland were retained by the local research team, deduplicated, anonymised and subsequently sent for analysis to the central research team at King’s College London.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

For the incidence study (objective 1), cases were assessed as eligible for inclusion if the young person (1) was between 8 years and 17 years and 11 months of age, (2) had no previous episode of anorexia nervosa that came to the attention of services, (3) had received a clinical assessment in the reporting service during the study surveillance period (1 February 2015 to 30 September 2015), (4) had not been referred from another secondary health service (to ensure that assessment and diagnosis had not happened prior to the study surveillance period) and (5) had the following clinical symptoms: ‘restriction of energy intake relative to requirements’ and ‘persistent behaviour that interferes with weight gain, despite low weight’. For all other study objectives (objectives 2–4), cases additionally had to be notified by a community-based service, thus excluding notifications from inpatient services. However, cases excluded because they were notified by an inpatient service were eligible for inclusion if they were subsequently notified by a community-based service after discharge from the inpatient service.

The two symptoms noted above were initially used to assess eligibility, but these were later checked using a tighter analytical definition based on the DSM-5 criteria. The purpose of this two-stage approach was to be overinclusive and maximise the likelihood of the sample reflecting the actual population of young people accepted for treatment by CAMHS. The tighter analytical definition included the following symptoms:

-

‘restriction of energy intake relative to requirements’

-

‘intense fear of gaining weight or of becoming fat’ or ‘persistent behaviour that interferes with weight gain, despite low weight’

-

‘perception that body shape/size is larger than it is’ or ‘preoccupation with body weight and shape’ or ‘lack of recognition of the seriousness of the current low body weight’.

Only one case that met the broad criteria failed to meet the tighter criteria, thus confirming the validity of the broad criteria applied.

Cases were excluded if the clinician-reported data were insufficient to assess eligibility. Duplicates were identified by comparing NHS/Community Health Index numbers, hospital numbers/hospital identifiers and date of birth/age in years and months, as appropriate. The management of duplicates was dependent on the outcome for the original notification for which a duplicate had been identified. Four scenarios were considered, and each was assessed in different ways, as follows:

-

If the first notification met the study inclusion criteria, the duplicate notification was excluded and the original notification retained.

-

If the first notification resulted in exclusion on grounds of age (patient too young) or clinical ineligibility, the duplicate notification was assessed as a new case to determine if the case now met eligibility criteria.

-

If the first notification had been excluded because of a previous episode of anorexia nervosa, an assessment and diagnosis date prior to the study recruitment period, or referral from another secondary care service, the duplicate notification was also excluded.

-

If the first notification contained insufficient information to judge eligibility for study inclusion (e.g. missing date of birth), the duplicate notification was checked to see if it contained the missing information and, if it did, the first notification was reassessed for eligibility and the duplicate was excluded.

Data

On notification from CAPSS, clinicians reporting cases of anorexia nervosa were sent a baseline questionnaire, and, if the case was found to be eligible for study inclusion, follow-up questionnaires were sent 6 months and 12 months after the date of initial assessment and diagnosis (as reported by clinicians in the baseline questionnaires). Clinicians completed questionnaires from clinical records. Although 12 months is a relatively short period in the treatment of anorexia nervosa, this had to be balanced against the burden on clinicians, NHS interest in the results and the impact on the total duration of the study.

Items missing from baseline or follow-up questionnaires were pursued directly with reporting clinicians by e-mail and telephone. Unreturned or incomplete forms were also chased by e-mail and post. If any of the symptoms required for case definition was absent despite chasing, cases were individually assessed for eligibility by a consultant child and adolescent psychiatrist co-investigator (MS). If there were too many missing data to assess the case, the case was excluded.

In addition to the patient identifiers described in Procedures, the baseline questionnaires contained sections on characteristics of the service, clinical characteristics, outcomes and care pathway of the case notified. In addition, the baseline questionnaire asked whether or not the patient had experienced a previous episode of anorexia nervosa for which they received treatment and whether or not the service was an inpatient service, as the study inclusion criteria focus on community-based new, incident cases of anorexia nervosa. The 6- and 12-month follow-up questionnaires contained identical sections but excluded the question on previous episodes of anorexia nervosa, and in addition included a section on health service use to provide data for costing purposes.

Service characteristics

Service characteristics included in the baseline and both follow-up questionnaires were initially identified using UK definitions of specialist eating disorders services that were available at the time the CostED study started (2013). 24 The criteria were then refined through discussions with clinical members of the CostED study research group to minimise the burden on reporting clinicians while retaining the criteria considered most critical to the classification of services in the CostED study as specialist or generic. The following questions were included:

-

How many cases of eating disorders does the service see per year?

-

Does the service offer specialist outpatient treatment for eating disorders?

-

Does the service hold weekly multidisciplinary meetings dedicated to eating disorders?

-

Does the service provide multidisciplinary specialist outpatient clinics dedicated to eating disorders?

-

How long has the service existed: < 1 year, between 1 and 2 years, between 3 and 5 years or > 6 years?

Clinical characteristics

Clinical characteristics for each notified young person were included in the baseline and follow-up questionnaires to enable assessment of case eligibility by the CostED research team at baseline and to assess outcomes for the young people at follow-up. Clinical characteristics included weight and height and the following clinical features, which required a response of yes, no, not known or not applicable: restriction of energy intake relative to requirements, intense fear of gaining weight or of becoming fat, persistent behaviour that interferes with weight gain despite low weight, perception that body shape/size is larger than it is, preoccupation with body weight and shape, lack of recognition of the seriousness of the current low body weight, excessive exercise, self-induced vomiting (plus estimate of frequency if yes), laxative or diuretic abuse and binge eating (plus estimate of frequency if yes). In addition, clinicians were asked if females had reached menarche and, if they had, whether or not they exhibited secondary amenorrhoea. Note that although amenorrhoea is no longer included in the diagnostic criteria, it is an indicator of significant weight loss and would support the diagnosis of anorexia nervosa.

Weight and height were used to calculate percentage of median expected body mass index (BMI) for age and sex (%mBMI), which involves dividing the young person’s BMI by the median (i.e. 50th centile) BMI for the same height, age and sex taken from appropriate growth charts such as those of the Child Growth Foundation. 25,26

Outcomes

Clinicians were asked to report scores for two generic outcome measures at baseline and both follow-ups: the Children’s Global Assessment Scale (CGAS)27 and the Health of the Nation Outcome Scales for Children and Adolescents (HoNOSCA). 28 The CGAS is completed by clinicians and is used to rate the emotional and behavioural functioning of children and adolescents in the family, school and social context. Clinicians score the young person on a scale from 1 to 100 using a classification that includes 10 categories ranging from ‘extremely impaired’ (score 1–10) to ‘doing very well’ (score 91–100). The questionnaires contained a copy of the CGAS classification system, describing each of the 10 categories, to support scoring by clinicians. 27 The HoNOSCA is a routine outcome measurement tool rating 13 clinical features on a 5-point severity scale. It assesses behaviours, impairments, symptoms and social functioning of children and adolescents with mental health problems, producing a total score on a scale from 0 to 52, with a higher score indicating a poorer outcome. More specific emotional and behavioural routinely used outcome measures, such as the Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire,29 are poor at capturing eating disorders, and, although there are eating disorders-specific outcome measures in use, such as the Eating Disorders Examination Questionnaire,30 these are less likely to be used in non-specialist services.

In addition, all cases were classified as ‘no remission’, ‘partial remission’ or ‘full remission’ at the 6-month follow-up and as ‘no remission’, ‘partial remission’, ‘full remission’ or ‘relapse’ at 12 months. These categories were defined by clinical members of the research group as follows.

Full remission at 6 months

Menstruating at 6 months if amenorrhoea at baseline and above minimally healthy weight (%mBMI of > 85%) and no compensatory behaviours or bingeing (i.e. ‘no’ to all of the following five symptoms: restricted eating, excessive exercise, self-induced vomiting, laxative abuse and binge eating) and minimal impact on function (CGAS score of > 70).

Partial remission at 6 months

Do not meet criteria for full remission and above minimally healthy weight (%mBMI > 85%) and limited impact on function (CGAS score of > 60).

No remission at 6 months

Do not meet criteria for full remission or partial remission.

Relapse criteria at 12 months (if in partial or full remission at 6 months)

Admission to hospital between 6 and 12 months or ‘yes’ to symptoms of vomiting and/or binge eating or weight loss of > 5% of %mBMI combined with ‘yes’ to any one of the following symptoms: restricted eating, excessive exercise, self-induced vomiting, laxative abuse or binge eating.

Full remission at 12 months (if no remission or partial remission at 6 months)

Menstruating at 12 months if amenorrhoea at 6 months and above minimally healthy weight (%mBMI > 85%) and no compensatory behaviours or bingeing (‘no’ to all of the following five symptoms: restricted eating, excessive exercise, self-induced vomiting, laxative abuse and binge eating) and minimal impact on function (CGAS score of > 70).

Partial remission at 12 months (if no remission at 6 months)

Do not meet criteria for full remission and above minimally healthy weight (%mBMI > 85%) and limited impact on function (CGAS score of > 60).

No change at 12 months (if no remission, partial remission or full remission at 6 months)

If a participant is in no remission at 6 months and does not meet the criteria for either partial remission or full remission at 12 months, then the participant remains in no remission. If a participant is in partial remission at 6 months and does not meet criteria for relapse or full remission at 12 months, then the participant remains in partial remission. If a participant is in full remission at 6 months and does not meet criteria for relapse at 12 months, then the participant remains in full remission.

Referral pathway

Referral pathway information was included in the baseline questionnaire to ensure that assessment and diagnosis had not happened prior to the study surveillance period and clinicians were asked to report whether or not the case had been referred from another secondary health service. If yes, the clinician was asked to report the type of service (inpatient psychiatry, paediatrics, specialist CAMHS, specialist eating disorders service or other – please specify). To enable us to follow up those who had moved to another CAMHS, clinicians were asked in the baseline and follow-up questionnaires if the patient had been referred to another service and, if so, to which service.

Health service use

As data were to be collected from clinical records, the perspective of the economic evaluation was limited to secondary/tertiary health services for which data were likely to be available to all reporting clinicians. The 6- and 12-month follow-up questionnaires contained a section on the use of these health services, which included hospital inpatient admissions (including the following ward types: paediatric, general child/adolescent psychiatry, general adult psychiatry, child/adolescent eating disorders unit, adult eating disorders unit or other), outpatient attendances [including paediatrics, specialist eating disorders service (CAMHS or adult) and other psychiatric service (CAMHS or adult)] and day-patient attendances [including paediatrics, specialist eating disorders service (CAMHS or adult) and other psychiatric service (CAMHS or adult)]. For inpatient admissions, respondents were additionally asked to report whether or not the facility was in the independent sector.

In a previous study [the Treatment Outcome for Child and Adolescent Anorexia Nervosa (TOuCAN) study], which took a societal perspective, 2-year total costs were found to be heavily dominated by hospital costs and CAMHS community outpatient costs. 18 Together, these accounted for > 90% of the total 2-year costs. 31 Similarly, a more recent study found that service costs in a population of adolescents with eating disorders were driven by hospital admissions. 32 Thus, although our approach was narrower than that usually adopted for an economic evaluation (i.e. excluding broader health and social care services), it was considered appropriate to minimise respondent burden while still providing evidence of the key costs in this population.

Sample size

The calculation of a sample size (which allows inferences to be made about the population as a whole) was not appropriate for the CostED study, because the aim of the study was to collect population-level data. However, some estimate of expected numbers was considered beneficial to support the estimation of study resources. The following provides estimates for expected baseline and follow-up rates, based on evidence available for the UK.

Primary care incidence of anorexia nervosa estimates

Based on data from primary care in the UK, between 1994 and 2000, the incidence rate of anorexia nervosa among children and adolescents (aged between 10 and 19 years) was 34.6 per 100,000 for females and 2.3 per 100,000 for males. 33 Among children aged 0–9 years, the incidence rate was zero. More recent UK estimates using data from 2000 to 2009 for young people aged 10–19 years indicate a small increase in incidence rates to 37.1 per 100,000 for females and 3.2 per 100,000 for males. 34 We applied these more recent estimates, broken down by age and sex when possible, to population data for the UK and the RoI35,36 for young people aged between 10 and 18 years. Estimates for younger children were available only from the earlier study. 33 The results are reported in Table 1. These incidence rates suggested an estimated number of new cases of anorexia nervosa in those < 18 years old in primary care in the UK and the RoI over an 8-month period of 886 (approximately 810 females and 76 males).

| Age (years) and sex | Incidence | Population by age | Number of cases | Source | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK | RoI | UK | RoI | Total | |||

| 8–9 | |||||||

| Both | 0.00 | 1,333,900 | 126,416 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Currin et al.33 |

| 10–14 | |||||||

| Female | 24.00 | 1,741,600 | 147,415 | 418 | 35 | 453 | Micali et al.34 |

| Male | 2.50 | 1,825,400 | 155,076 | 46 | 4 | 50 | Micali et al.34 |

| 15–18 | |||||||

| Female | 47.50 | 1,494,000 | 110,237 | 710 | 52 | 762 | Micali et al.34 |

| Male | 3.80 | 1,581,800 | 115,700 | 60 | 4 | 65a | Micali et al.34 |

| Total 12 months | 1329 | ||||||

| Total 8 months | 886 | ||||||

Secondary care incidence of anorexia nervosa estimates

Data from secondary care studies were more limited. Data from a London care pathways study17 suggested an incidence rate of 54.6 per 100,000 for young women aged between 13 and 18 years, including anorexia nervosa and eating disorders not otherwise specified – anorexia nervosa sub-type (EDNOS-AN), a proportion of whom would now be diagnosed with anorexia nervosa using DSM-5 criteria. Data for young men were not reported as the numbers were so small. For the younger ages, data were available from a British national surveillance study carried out in 2005/6 using the CAPSS system. 37 Application of these rates to UK and the RoI population data35,36 is reported in Table 2, broken down by age and sex when data allowed. For males aged 13–18 years, primary care rates were used because of the lack of secondary care data for this group. 34 These incidence rates suggested an estimated number of new cases of anorexia nervosa in the UK and the RoI of 957 over an 8-month period, which is slightly higher than the primary care estimate above. However, given that the majority of these cases were estimated using London data (females aged 13–18 years),17 we adjusted the London data downwards to take into account the fact that incidence rates in London may be higher than the UK and the RoI more broadly as a result of higher incidence of eating disorders in urban versus rural areas,38 as well as a higher concentration of specialist eating disorders services. We reduced London incidence rates by 10% and by 20%, as shown in Table 2.

| Age (years) | Sex | Incidence | Population by age | Number of cases | Source | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UK | RoI | UK | RoI | Total | ||||

| 8 | Total | 0.00 | 666,300 | 63,581 | 0 | 0 | 0 | Nicholls et al.37 |

| 9 | Total | 0.72 | 667,600 | 62,386 | 5 | 0 | 5 | Nicholls et al.37 |

| 10 | Total | 1.42 | 683,300 | 61,181 | 10 | 1 | 11 | Nicholls et al.37 |

| 11 | Total | 1.69 | 703,100 | 60,587 | 12 | 1 | 13 | Nicholls et al.37 |

| 12 | Total | 3.63 | 715,500 | 60,926 | 26 | 2 | 28 | Nicholls et al.37 |

| 13–18 | Female | 54.60 | 2,208,700 | 168,213 | 1206 | 92 | 1298 | House et al.17 |

| 13–14 | Male | 2.50 | 750,300 | 61,018 | 19 | 2 | 20a | Currin et al.33 |

| 15–18 | Male | 3.80 | 1,581,800 | 115,700 | 60 | 4 | 65a | Currin et al.33 |

| Total 12 months | 1440 | |||||||

| Total 8 months | 960 | |||||||

| London incidence rate at 8 months, reduced by 10% | 864 | |||||||

| London incidence rate at 8 months, reduced by 20% | 768 | |||||||

Estimated incidence of anorexia nervosa

The estimates presented in Primary care incidence of anorexia nervosa estimates and Secondary care incidence of anorexia nervosa rates suggest a total population of new cases of anorexia nervosa of between 800 and 900 over the 8-month surveillance period. Using data from the previous British national surveillance study,37 Table 3 reports expected rates of case notification at baseline and response rates at 6- and 12-month follow-up, dependent on whether the number of new cases is the higher (n = 900) or the lower (n = 800) of these estimates. The estimates in Table 3 suggest that approximately 590–660 notifications should be received at baseline and follow-up data should be available for between 300 and 330 cases at 6 months and between 220 and 250 cases at 12 months.

| Expected rates of notification and follow-up | Lower estimate | Higher estimate |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline notifications | ||

| Expected new cases in UK and the RoI | 800 | 900 |

| 75% referred by psychiatrists (excludes paediatricians) | 600 | 675 |

| 85% of all psychiatrists expected to report | 510 | 574 |

| Plus 15% expected duplicatesa = total baseline notifications | 587 | 660 |

| Follow-up rates | ||

| Expected new cases excluding duplicates | 510 | 574 |

| 85% with sufficient data to assess eligibilityb | 434 | 488 |

| 80% with no reporting errorsc | 347 | 390 |

| 85% response rate at first follow-up = 6-month estimate | 295 | 332 |

| 75% response rate at second follow-up = 12-month estimate | 221 | 249 |

Incidence of child and adolescent anorexia nervosa

Accurate epidemiological estimates of the number of new cases of anorexia nervosa per year are helpful for service planning. In the UK, the most recent incidence data available are from 2000 to 2009. 34 To date, the majority of incidence estimates have come from primary care records,33,34 which may fail to accurately record all cases of eating disorders. 39,40 This may be particularly true in the UK context, given guidelines41 requiring assessment and diagnosis of anorexia nervosa to be carried out by child and adolescent psychiatrists in secondary or tertiary care settings. As a result, secondary care records are a more reliable source of data on anorexia nervosa incidence than are primary care records.

Aim

The incidence component of the CostED study (objective 1) aimed to estimate the incidence of anorexia nervosa in secondary care services among all young people, male and female, between the age of 8 years and 17 years and 11 months in the UK and the RoI, using cases notified to the CostED study.

Analysis: incidence study

All data analyses were carried out in the software packages Stata® IC version 14.2 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) and Microsoft Excel® 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA).

Observed incidence rates (IRs) (IR0), defined as the number of new cases occurring during a specified period of time in a population at risk of developing the disease, were calculated as follows: the number of confirmed new cases of anorexia nervosa in the study’s 8-month surveillance period converted to 12 months [(number of cases over 8 months/8) × 12], then divided by the population at risk and multiplied by 100,000 to give the observed incidence rate per 100,000 young people:

The population at risk, used as the denominator, was calculated as the total number of children of each sex and each year of age between 8 and 17 in the UK and the RoI, minus the number of prevalent cases of patients who, once diagnosed, are no longer part of the ‘at-risk’ population. Population data for young women and young men aged 8 to 17 years in 2015 were obtained from the Office for National Statistics for the UK35 and from the Central Statistics Office for the RoI. 42 To estimate the number of prevalent cases each year, incident cases in the previous age band were used as a proxy. For example, incident cases of patients aged 8 years were used as a proxy for prevalent cases in the estimation of the ‘at-risk’ population aged 9 years, and so on.

To consider incidence among unobserved missing cases, adjustments were needed to take into account unreturned notification cards to CAPSS and unreturned questionnaires for positive case notifications.

Just over half of all CAPSS notification cards sent out were returned (50.16%). To account for incidence among the 49.84% of unreturned cards, two assumptions were made about the unreturned cards, and a correction applied to the observed incidence rate as appropriate.

-

Assumption 1: to take into consideration the possibility that unreturned cards are more likely to be negative (i.e. ‘nil’ returns), it was assumed that half of the unreturned cards (24.92%) were ‘negative’ and the other half followed the same proportion of ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ as the returned cards. This assumption translates to a correction coefficient of 1.50, derived from (24.92 + 50.16)/50.16.

-

Assumption 2: assuming no bias in the likelihood of unreturned cards being either negative or positive returns, it was assumed that all unreturned notification cards followed the same proportion of ‘negative’ and ‘positive’ as the returned cards. This assumption translates to a correction coefficient of 1.99 derived from (49.84 + 50.16)/50.16.

These assumptions provide a range of incidence rates from a minimum (observed incidence rates) to a maximum (assumption 2), within which the actual rate is likely to fall. It is hypothesised that assumption 1 provides the most realistic estimate because it assumes that there is a bias in the response rates with greater likelihood that unreturned cards are negative (i.e. clinicians are less likely to return ‘nil’ returns than ‘positive’ returns) but does not assume that all unreturned cards are ‘nil’ returns.

Approximately two-thirds of the questionnaires that were sent to clinicians reporting positive cases of anorexia nervosa were returned (63%), leaving one-third (37%) unreturned. As all these questionnaires relate to a ‘positive’ notification, we applied a correction coefficient of 1.59, derived from (37 + 63)/63, which assumes that the incidence rate for the unreturned questionnaires is the same as the incidence rate identified in the returned questionnaires for each year of age.

As well as reporting the observed incidence rates (IR0), we combined the correction coefficients described above to generate two adjusted incidence rates.

Adjusted incidence rate 1

Confirmed new cases of anorexia nervosa converted to 12 months, multiplied by the correction for unreturned CAPSS notification cards under assumption 1, multiplied by the correction for unreturned questionnaires, then divided by the population at risk and multiplied by 100,000. This estimate applies the proportion of observed positive and negative cases to half of the cases unobserved as a result of unreturned CAPSS notification cards (the other half assumed ‘nil’ returns) and to all data unobserved because of unreturned questionnaires:

Adjusted incidence rate 2

Confirmed new cases of anorexia nervosa over 12 months, multiplied by the correction for unreturned CAPSS notification cards under assumption 2, multiplied by the correction for unreturned questionnaires and then divided by the population at risk and multiplied by 100,000. This estimate applies the proportion of observed positive and negative cases to all data unobserved as a result of unreturned CAPSS notification cards and to all data unobserved as a result of unreturned questionnaires:(3)IR2=(confirmed new cases of anorexia nervosa converted to 12 months×1. 99×1. 59)/the population at risk×100,000

For each incidence rate, IR0, IR1 and IR2, total, age-specific and sex-specific annual incidence rates for anorexia nervosa for the year 2015 and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated based on the Poisson distribution43 using the Stata version 14.2 command ‘ci means [N new anorexia nervosa cases 12m], Poisson [exposure(total population)]’ for positive integers/whole incidence numbers (Stata interprets any non-integer decimal point number between 0 and 1 as the fraction of events and converts it to an integer number) and an online CI calculator for rational/fraction numbers (www.openepi.com/PersonTime1/PersonTime1.htm; accessed 13 February 2017). Annual incidence rates were stratified by discrete age (8–17 years) and sex.

Classification of child and adolescent mental health services as specialist or generic

Specialist eating disorders services are not clearly defined, with definitions changing over time20,24 and little indication of how these criteria have been determined. The absence of a clear consensus on what constitutes a specialist eating disorders service hampers attempts to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of such services, and thus to assess the value of future investment to expand provision to a greater proportion of the population.

Aim

The aim of the service classification component of the CostED study was to obtain consensus on the key features of a specialist child and adolescent eating disorders service from a range of stakeholders in order to support the classification of notifying services as either specialist or generic (objective 2).

Study design

The Delphi survey method was used to collect opinions from a wide range of stakeholders in eating disorders, and to reach consensus on the key criteria for a community-based CAMHS to be classified as a specialist eating disorders service. The Delphi approach is a technique designed to combine individual opinions into group consensus, iteratively, through a series of rounds of structured questionnaires. Responses from each round are analysed, summarised and fed back to the participants, who are given an opportunity to respond again to the emerging data. 44–50 The availability of online survey platforms enabled this study to use the Delphi technique to involve geographically distant respondents in larger numbers than are traditionally used in studies employing face-to-face discussion.

Respondents

A range of stakeholders, including service users and their families, child and adolescent psychiatrists, paediatricians, other eating disorders professionals and service commissioners, were invited to take part in the Delphi survey using two different methods: direct e-mail contact and an open web link invitation. Direct e-mails were sent to 687 named child and adolescent psychiatrists using the CAPSS database and to five service commissioners known by the research group to be working in child and adolescent mental health. The open web link invitation was circulated by a range of networks including the eating disorders faculty of the Royal College of Psychiatrists, a group of approximately 1500 child and adolescent and adult psychiatrists, and the Child and Adolescent Feeding and Eating Disorders Network (Café-Net). Café-Net is a multidisciplinary network of approximately 300 child and adolescent feeding and eating disorders professionals working in eating disorders services, whose members include child and adolescent psychiatrists, paediatricians, psychologists, psychotherapists, family therapists, dietitians and nurses. Service users and their families were invited to take part via a survey web link advertised by Beat, the UK national eating disorders charity, via its e-newsletter (approximately 21,500 e-mail addresses) and its research e-newsletter (approximately 456 e-mail addresses of people who signed up to receive updates about opportunities to take part in research).

Criteria for specialist eating disorders services

Criteria relevant to the classification of specialist eating disorders were identified as described in Service characteristics. The included criteria are summarised in Table 4, alongside the UK guideline criteria available at the time24 and, for comparison, guideline criteria for England that became available after the CostED study began. 20

| Criterion | Guidelines available at the start of the CostED study24 | Associated questions included in questionnaire to clinicians | Comment | Guidelines that became available after the CostED study began20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interventions | Patients are offered individual interventions, including CBT and family-based interventions | ‘Does the service offer specialist outpatient treatment for eating disorders?’ | The clinical group advised that a wide range of interventions are available and that focusing only on CBT and family-based interventions would be too narrow | Use up-to-date evidence-based interventions to treat the most common types of coexisting mental health problems (e.g. depression and anxiety disorders) alongside the eating disorder |

| Staff | The service will have a multidisciplinary staff team, including at least one consultant psychiatrist, one nurse and one therapist | ‘Does the service hold weekly multidisciplinary meetings dedicated to eating disorders?’ and ‘Does the service provide multidisciplinary specialist outpatient clinics dedicated to eating disorders?’ | Given the CAPSS requirement to keep the CostED questionnaire brief to minimise reporting burden, it was not possible to request data on all staff in reporting services so the focus was placed on the multidisciplinary nature of the eating disorders provision | Include medical and non-medical staff with significant eating disorders experience |

| Activity | There will be ≥ 25 new referrals per annum | ‘How many cases of eating disorders does the service see per year?’ | Included | The service should receive ≥ 50 new eating disorders referrals per year, which are likely to include anorexia nervosa, bulimia nervosa, binge eating disorder and related diagnoses |

| Population | Not stated | ‘Approximate population of catchment area covered by the service?’ | Included on the advice of clinical research team members on the assumption that specialist services are more likely to be made available to a wider catchment area | Cover a minimum general population of 500,000 (all ages) |

| Age of service | Criteria not included | ‘How long has the service existed for?’ | Included on the advice of clinical research team members on the assumption that more established services will have had longer to become ‘specialist’ | Criteria not included |

| Intensity | Outpatient and inpatient treatment are provided | Criteria not included | Excluded as the focus of the CostED study was on community-based services | Criteria not included |

| Referral pathway | Criteria not included | Criteria not included | Criteria outlined as part of guidelines published after the CostED study began | Enable direct access to community eating disorders treatment through self-referral and from primary care services (e.g. GPs, schools, colleges and voluntary sector services) |

These criteria were included in the Delphi survey and respondents were asked to rate the importance of each criterion in considering whether or not a community-based eating disorders service can be classified as a specialist service. Responses were rated on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 = not important to 5 = extremely important. Full details of the criteria, associated questions and responses are contained in Table 5. Some questions were associated with follow-up subquestions that were asked only of those who rated the main criterion as important (2 = slightly important, 3 = moderately important, 4 = very important or 5 = extremely important).

| Question | Criterion | Question | Response |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Offering specialist (evidence-based) outpatient treatment for eating disorders | How important is this in considering whether or not a community-based eating disorders service can be classified as a specialist service? | 1 = not important, 2 = slightly important, 3 = moderately important, 4 = very important, 5 = extremely important |

| 2 | Holding weekly multidisciplinary meetings dedicated to eating disorders | How important is this in considering whether or not a community-based eating disorders service can be classified as a specialist service? | 1 = not important, 2 = slightly important, 3 = moderately important, 4 = very important, 5 = extremely important |

| 3 | Providing multidisciplinary specialist outpatient clinics dedicated to eating disorders | How important is this in considering whether or not a community-based eating disorders service can be classified as a specialist service? | 1 = not important, 2 = slightly important, 3 = moderately important, 4 = very important, 5 = extremely important |

| 4 | Number of cases of eating disorders a service sees per year | How important is this in considering whether or not a community-based eating disorders service can be classified as a specialist service? | 1 = not important, 2 = slightly important, 3 = moderately important, 4 = very important, 5 = extremely important |

| Sub 5 | Number of cases of eating disorders a service sees per year | If important, what is the minimum number of cases of eating disorders that a community-based eating disorders service should see per year before it can be classified as a specialist service? | 1 = ≥ 10, 2 = ≥ 25, 3 = ≥ 50, 4 = ≥ 75, 5 = ≥ 100 |

| 6 | Population size of the catchment area covered by the service | How important is this in considering whether or not a community-based eating disorders service can be classified as a specialist service? | 1 = not important, 2 = slightly important, 3 = moderately important, 4 = very important, 5 = extremely important |

| Sub 7 | Population size of the catchment area covered by the service | If important, what is the minimum approximate population of the catchment area that a community-based eating disorders service should cover before it can be classified as a specialist service? | 1 = ≥ 25,000, 2 = ≥ 50,000, 3 = ≥ 100,000, 4 = ≥ 250,000, 5 = ≥ 500,000, 6 = ≥ 750,000, 7 = ≥ 1,000,000, 8 = national coverage |

| 8 | Length of time a service has existed | How important is this in considering whether or not a community-based eating disorders service can be classified as a specialist service? | 1 = not important, 2 = slightly important, 3 = moderately important, 4 = very important, 5 = extremely important |

| Sub 9 | Length of time a service has existed | How long should a community-based eating disorders service have existed for before it can be classified as a specialist service? | 1 = < 1 year, 2 = 1–2 years, 3 = 3–5 years, 4 = ≥ 6 years |

Procedure

The Delphi survey involved two rounds. Round 1 took place between 29 January 2016 and 6 May 2016 and included all six main questions and three subquestions listed in Table 5. Round 2 took place between 20 July 2016 and 20 September 2016 and included only the main questions (and their associated subquestions, if relevant) when consensus had not been reached in round 1. For each question and subquestion included in round 2, data from round 1 were reported to allow respondents to consider their response in relation to the group average from round 1. If consensus was not reached in round 2, the item was excluded from the final criteria checklist for analysis purposes but included in a sensitivity analysis. For brevity and to encourage maximum participation, no other information was collected as part of the survey, apart from e-mail addresses, which were included in round 1 in order to be able to recontact round 1 participants to complete the round 2 survey.

Consensus

Consensus decision rules for the main criteria in this study were finalised prior to data analysis and focused on the percentage of respondents rating each criterion as either 4 (very important) or 5 (extremely important). The literature to date does not provide a clear definition of what percentage agreement is required before consensus is reached in Delphi panels. Values vary from 51% to 100%,44–50 with 75% being the median threshold to define consensus. 44 We conservatively chose 80% as our threshold to conclude that consensus had been reached that a criterion was essential when categorising a service as a specialist eating disorders service. The threshold below which we considered consensus to have been reached to exclude a criterion was set at < 50%, again relatively conservatively compared with previous literature. 49 Percentage responses between 50% and 79% were considered ‘consensus not reached’, and criteria falling into this range in round 1 were included in round 2 of the Delphi survey. The decision rules are summarised in Table 6.

| Percentage of respondents rating criterion as 4 or 5 (%) | Decision rule |

|---|---|

| 80–100 | Consensus reached and item included in checklist |

| 50–79 | Consensus not reached |

| 0–49 | Consensus reached and item excluded from checklist |

Analysis: classification study

Responses to the Delphi survey were collected using the online survey platform SurveyMonkey® (Palo Alto, CA, USA). Following survey completion, responses were imported in Microsoft Excel 2010 and converted to a Stata IC version 14.2 data set when analysis was conducted. Responses were summarised using descriptive statistics, including the number and percentage of responses in each category and the median and mode measures of central tendencies for ordinal data. The predetermined consensus decision rules described above were applied to all responses.

Using data from the CostED study, consensus criteria were applied at both the service level and the patient level to provide estimates of the proportion of notifying services classified as specialist or generic, and the proportion of CostED participants being assessed in specialist versus generic community-based services. In the main analysis, services were classified using only those criteria for which consensus had been reached in the Delphi survey. Classification was repeated in a sensitivity analysis that additionally included criteria that remained uncertain after both Delphi survey rounds. Data from subquestions are reported only when associated with a main question for which consensus was reached to include the criterion or when consensus was uncertain and thus the criterion was included in the sensitivity analysis.

Cost, effectiveness and cost-effectiveness analysis

Cost of health service contacts

Data on inpatient, outpatient and day-patient health service contacts, described in Health service use, were used to calculate the 6- and 12-month costs of all cases eligible for follow-up and to assess the relative cost of alternative community-based models of service provision (objective 3). All resource use data related to the period February 2015 to September 2016 (8 months of surveillance and 12-month follow-up) and costs, in Great British pounds, were for the 2015/16 financial year. Discounting was not necessary as the follow-up length was not more than 12 months. Costs for NHS hospital admissions and outpatient and day-patient contacts, which included CAMHS contacts, were taken from NHS Reference Costs 2014–15. 51 The cost of independent sector hospital admissions and contacts were provided by a range of independent sector organisations and NHS trusts via personal communications and the average cost used when more than one figure was provided. Unit costs are summarised in Table 7.

| Service | Unit cost (£) | Source |

|---|---|---|

| NHS inpatient cost per night | ||

| Eating disorders unit: child/adolescent | 510.14 | NHS Reference Costs 2014–15 51 |

| Eating disorders unit: adult | 455.02 | NHS Reference Costs 2014–15 51 |

| General psychiatry: child/adolescent | 633.07 | NHS Reference Costs 2014–15 51 |

| General psychiatry: adult | 197.29 | NHS Reference Costs 2014–15 51 |

| Paediatric if stay is 1 night | 426.99 | NHS Reference Costs 2014–15 51 |

| Paediatric if stay is > 1 night | 592.27 | NHS Reference Costs 2014–15 51 |

| Other NHS | 389.10 | NHS Reference Costs 2014–15 51 |

| Independent sector inpatient cost per night | ||

| Eating disorders unit: child/adolescent | 695.00 | Personal communication |

| General psychiatry: child/adolescent | 668.00 | Personal communication |

| Outpatient cost per contact | ||

| Eating disorders service | 262.12 | NHS Reference Costs 2014–15 51 |

| Other psychiatry | 298.57 | NHS Reference Costs 2014–15 51 |

| Paediatric | 194.36 | NHS Reference Costs 2014–15 51 |

| Day-patient cost per contact | ||

| Eating disorders service | 274.21 | NHS Reference Costs 2014–15 51 |

| Other psychiatry | 326.16 | NHS Reference Costs 2014–15 51 |

| Paediatric | 446.60 | NHS Reference Costs 2014–15 51 |

Analysis: costs and outcomes

All analyses compared participants initially assessed and diagnosed in specialist eating disorders services with those initially assessed and diagnosed in generic CAMHS, with services classified using the results of the Delphi analysis already described (see Classification of children and adolescent mental health services as specialist or generic). All analyses were adjusted for prespecified baseline covariates including baseline CGAS score, baseline %mBMI, age, sex and region (England, Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland or the RoI).

Total costs per participant in each group over the 6- and 12-month follow-up periods were compared using standard parametric t-tests. Although cost data are commonly skewed, the advantage of this approach, as opposed to logarithmic transformation or non-parametric tests, is the ability to make inferences about the arithmetic mean, which is more meaningful from a budgetary perspective. 52 The robustness of this approach was confirmed using bootstrapping. 53 Outcomes tested for differences at the 6- and 12-month follow-up points included the CGAS score, HoNOSCA and %mBMI. All were tested using standard t-tests.

We had originally proposed additionally exploring differences between children (between 8 and 12 years old) and adolescents (between 13 and 17 years old) and between young people living in rural or urban areas. However, neither proved possible. For the comparison of children and adolescents, the sample of children proved too small, with only 35 (12%) of the follow-up sample being between 8 and 12 years of age. Furthermore, full 12-month cost data were available for only 18 cases and outcome data were available for a maximum of 23 cases (%mBMI) and a minimum of three cases (HoNOSCA) at 6-month follow-up and for a maximum of 13 cases (%mBMI) and a minimum of three cases (HoNOSCA) at 12-month follow-up. For the purpose of comparing rural and urban areas, the first half of a postcode proved inadequate to enable locations to be accurately classified, with a large proportion of the first halves of postcodes covering a mixture of rural and urban areas. Without full postcodes, this analysis could not be undertaken.

All analyses used complete-case data. Missing items in questionnaires were chased up directly with reporting clinicians via both e-mail and telephone. Missing follow-up questionnaires (or cases that could not be included as a result of key missing items) were assumed to be missing at random, and sensitivity analysis examined the effect of these missing cases on total costs (over the periods 0–6 months, 6–12 months and 0–12 months) and outcomes (%mBMI, CGAS score and HoNOSCA at 6 and 12 months) using multiple imputations to test the robustness of the complete-case analyses. 54

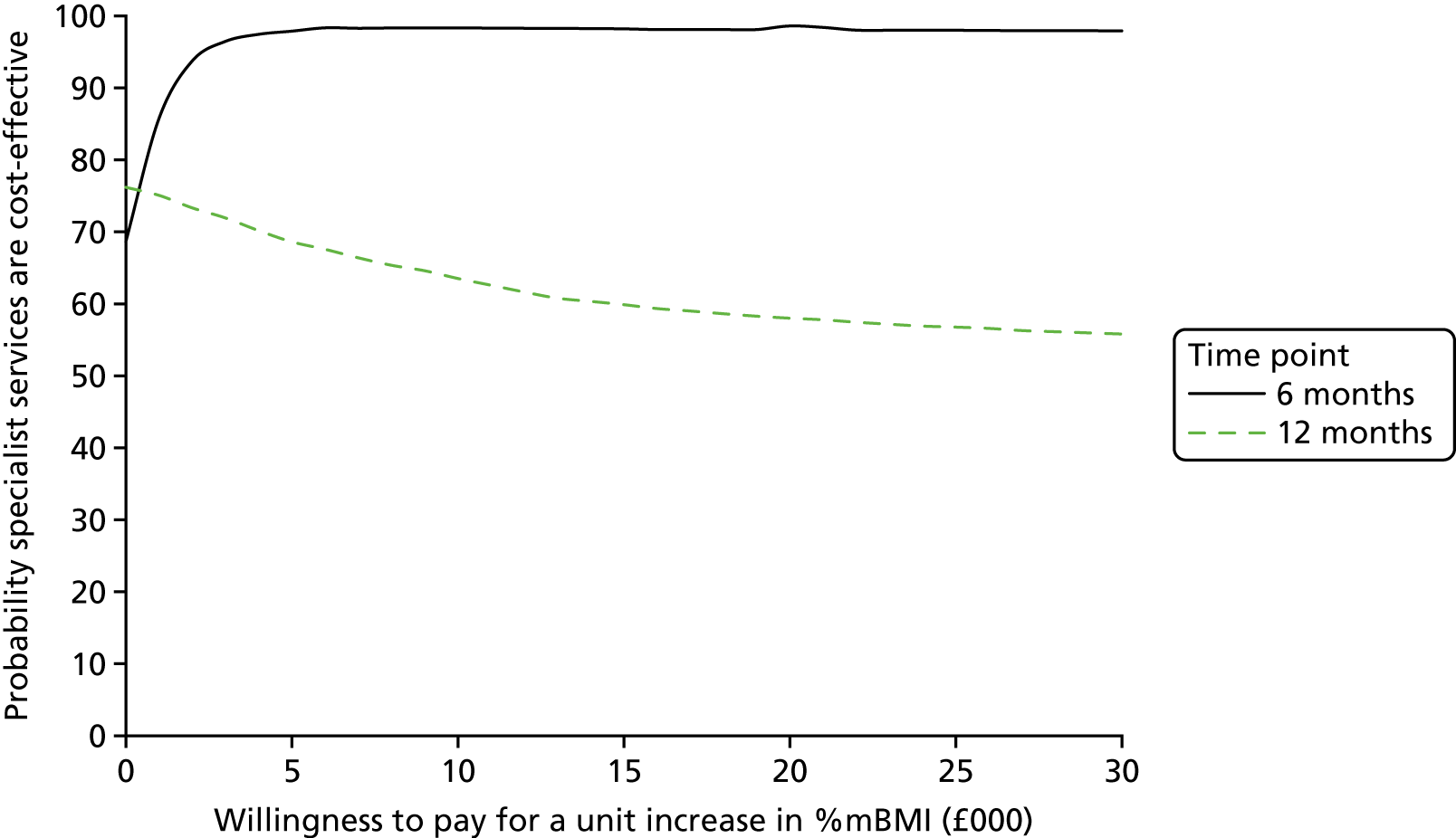

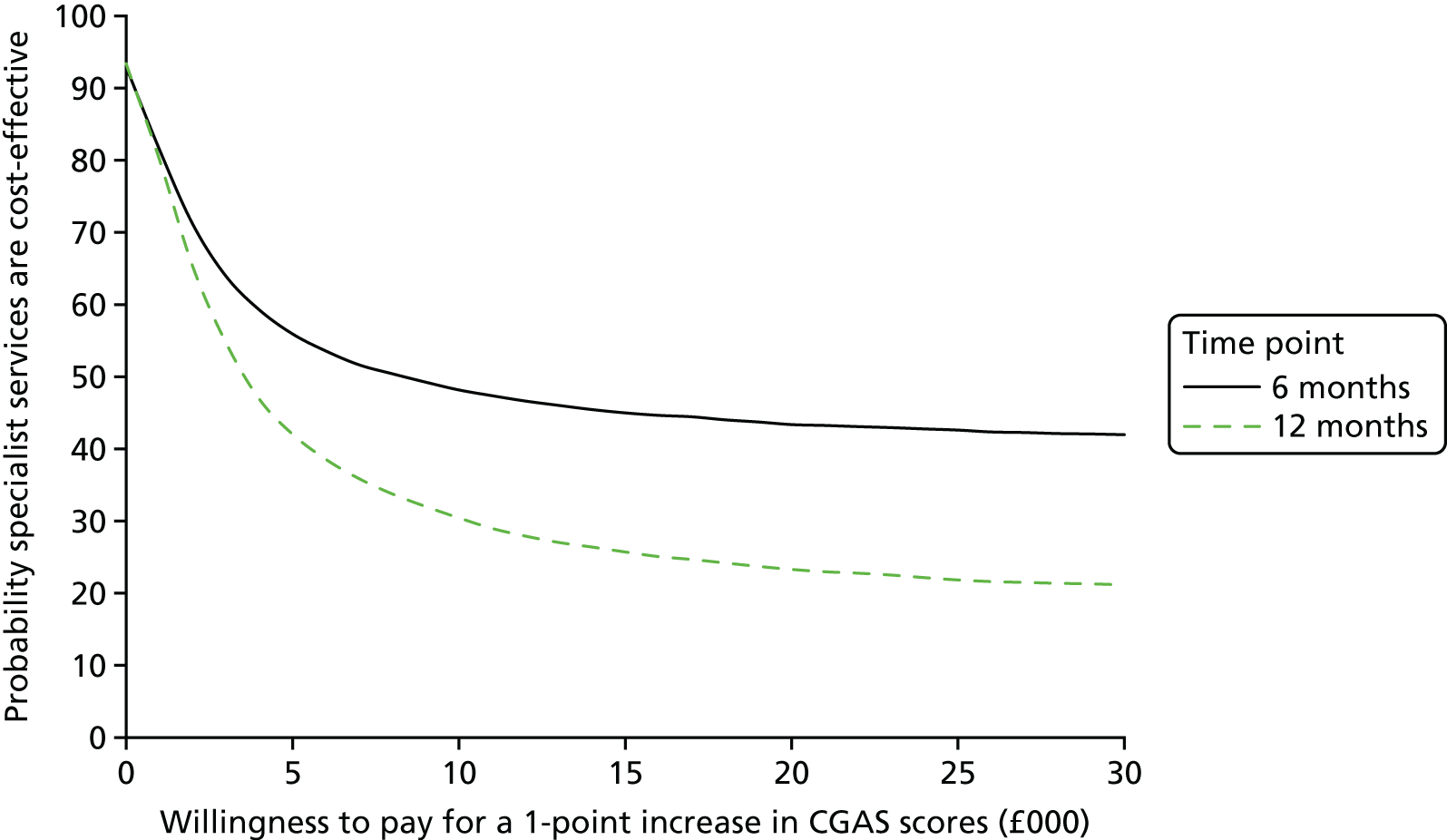

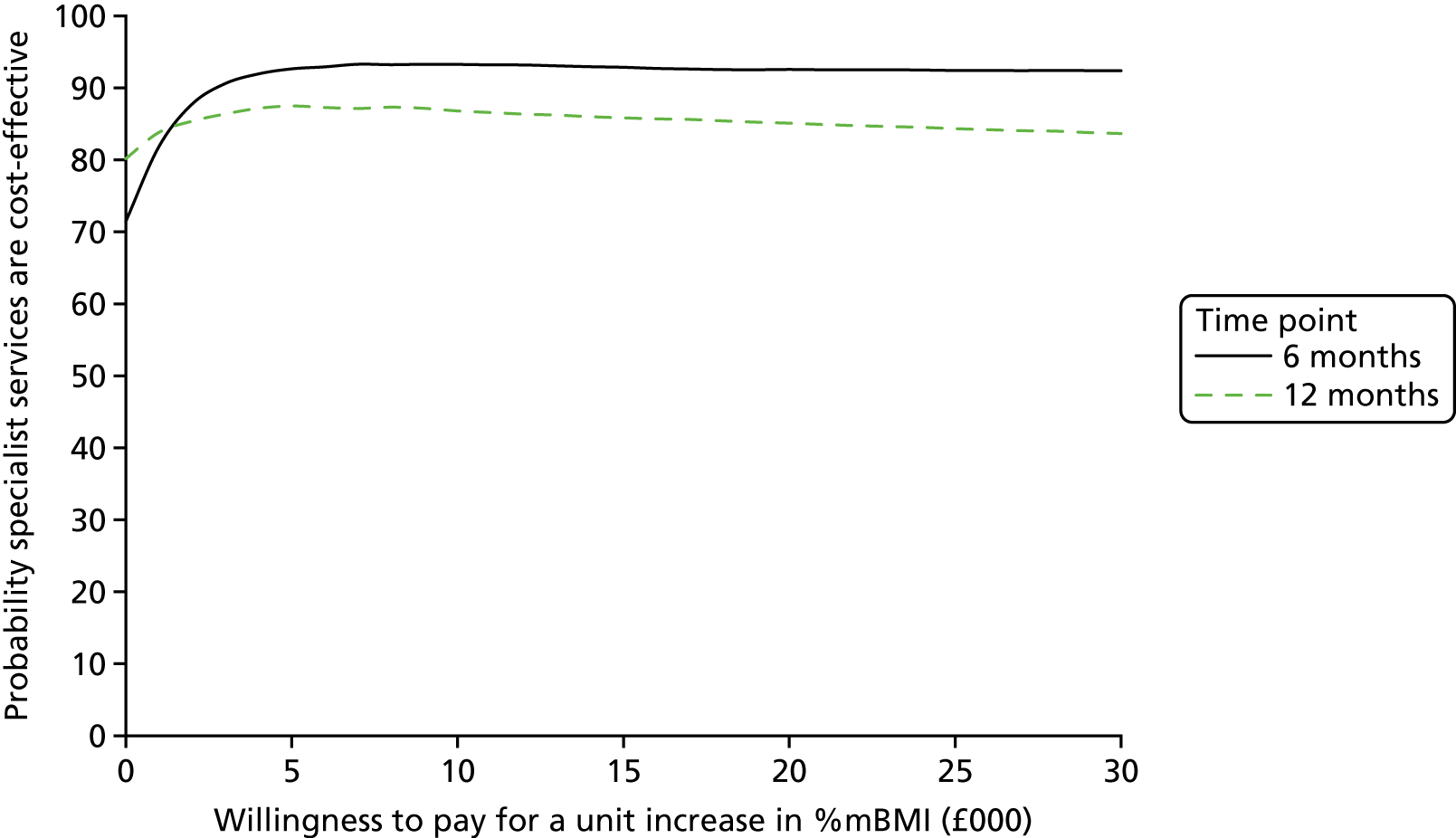

Analysis: cost-effectiveness analysis

Individual-level cost and outcome data were used to calculate the relative cost-effectiveness of initial assessment and diagnosis of anorexia nervosa in a community-based specialist eating disorders service compared with initial assessment and diagnosis in a community-based generic CAMHS at the 6- and 12-month follow-up points. Although the 12-month follow-up point was considered the primary end point given the chronic and long-term nature of anorexia nervosa, missing data were expected to be higher at the 12-month point, so assessment of cost-effectiveness at the 6-month follow-up point was also considered important.

The prespecified primary measure of effectiveness for the cost-effectiveness analysis, as outlined in the proposal and the original protocol, was the HoNOSCA. The %mBMI was specified as a secondary cost-effectiveness analysis because, although more narrowly focused on weight, data on weight and height were expected to be available for a greater proportion of the population than data on clinical outcomes. The preference in economic evaluation is to measure outcomes using broad, preference-based, generic measures of quality of life capable of generating quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs). 55 However, the CostED study was limited to measures of outcome likely to be available from clinical records and, although weight-related outcomes are key to anorexia measures, the HoNOSCA was chosen as the primary measure because it is a broader measure of outcome than %mBMI.

It became clear from the baseline questionnaires, however, that the number of missing HoNOSCA data was substantial (79% missing at baseline), suggesting that this measure was not being routinely used in many outpatient services. For this reason, the protocol was amended, replacing the HoNOSCA with the CGAS, for which a greater proportion of data were available (8% missing at baseline). As expected, the number of missing data was smallest for %mBMI (1% missing at baseline), and, therefore, %mBMI was retained as the measure of effectiveness in a secondary cost-effectiveness analysis.

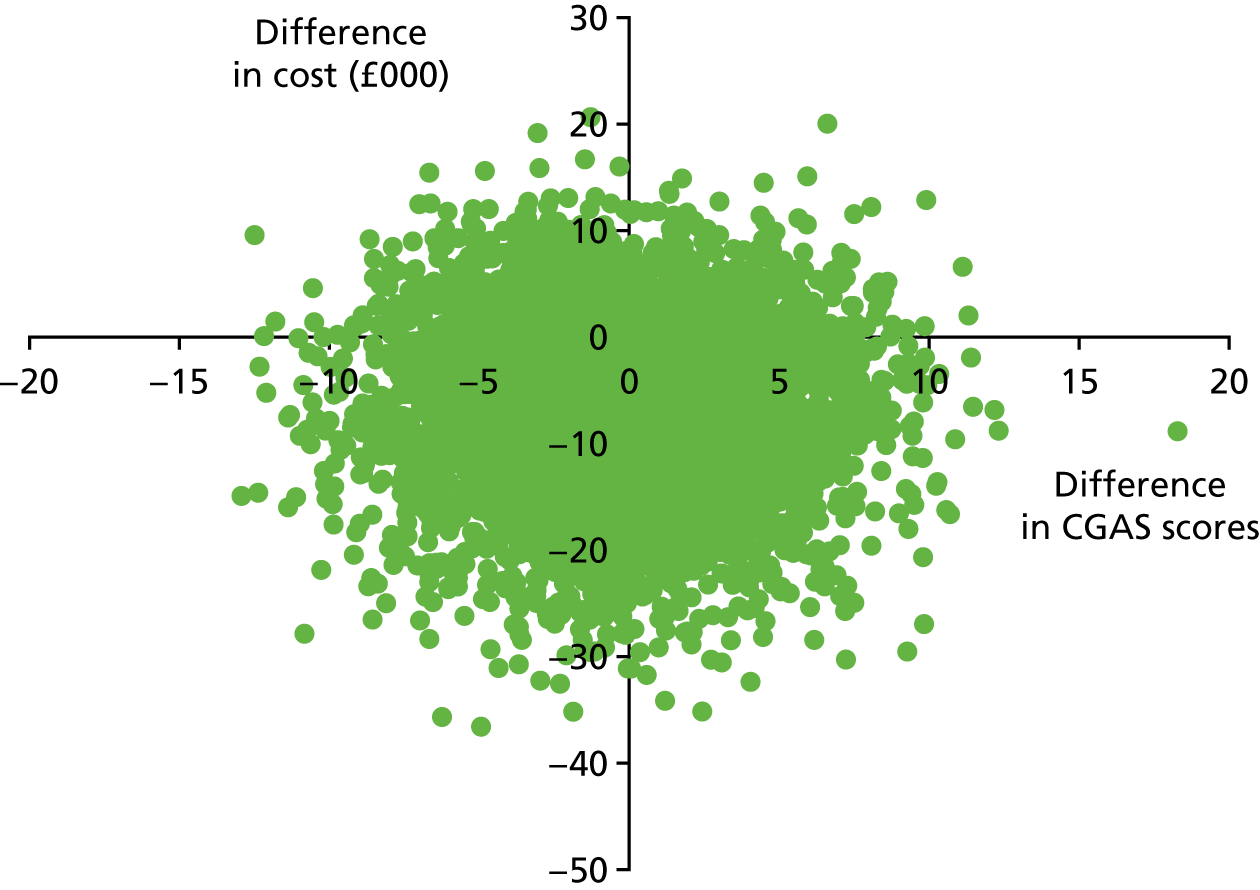

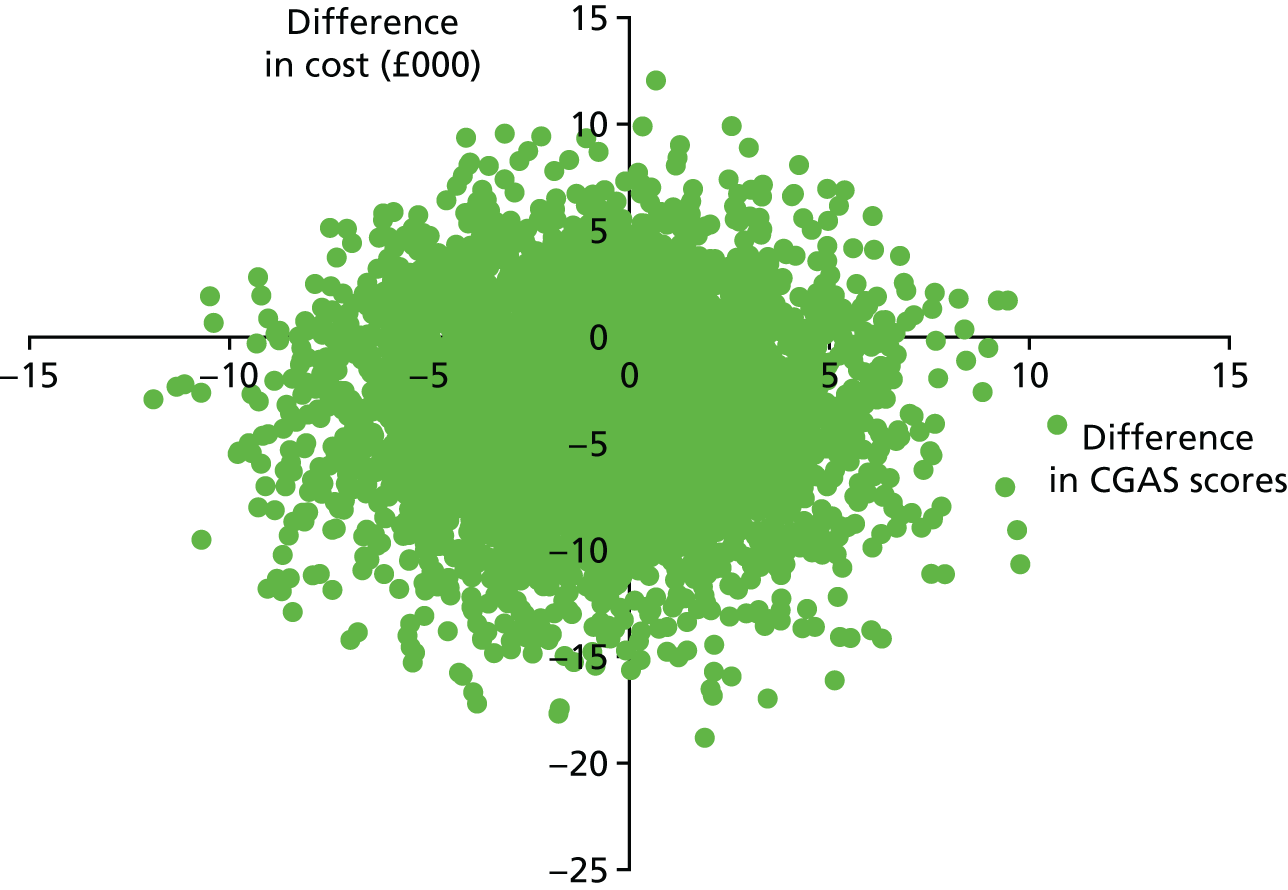

The cost-effectiveness of specialist versus generic services was explored in a decision-making context, with a focus on the probability of one service model being cost-effective compared with the other given the data available, rather than a focus on statistical significance. This is the recommended approach for economic evaluation in the UK context. 56 Cost-effectiveness analysis is concerned with the combined difference in costs and effects between interventions and was assessed by taking the recommended net benefit approach. 57 One treatment can be defined as cost-effective relative to a comparator if (1) it is less costly and more effective and is thus dominant; (2) it is more costly and more effective, but the additional cost per extra unit of effectiveness is considered worth paying by decision-makers; or (3) it is less costly and less effective and the additional cost per extra unit of effectiveness generated by the alternative is not considered worth paying. In scenario (1), in which one intervention is dominant, cost-effectiveness is confirmed. In scenarios involving a trade-off, such as (2) and (3), incremental cost-effectiveness ratios are calculated as the difference in mean costs between one intervention and another (in this case specialist minus generic services) divided by the difference in mean effect between the two groups.

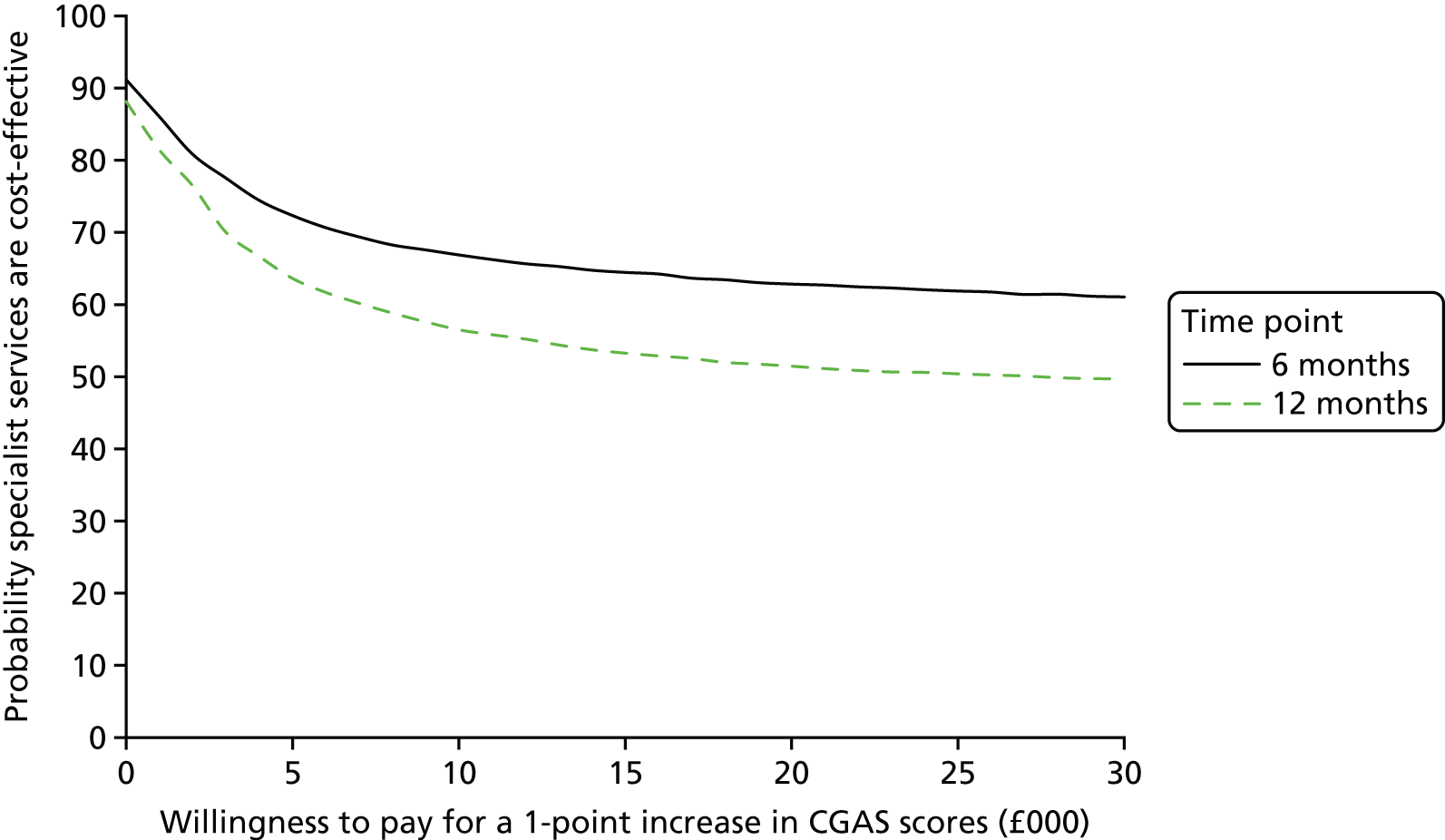

A joint distribution of incremental mean costs and effects for the two groups was generated using non-parametric bootstrapping53 to explore the probability that each treatment is the optimal choice, subject to a range of possible maximum values (ceiling ratio) that a decision-maker might be willing to pay for an additional unit of outcome gained. Willingness to pay was varied from £0 to £30,000. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves were then generated by plotting these probabilities for a range of possible values of the ceiling ratio. 58,59 These curves are the recommended decision-making approach to dealing with the uncertainty that exists around the estimates of mean costs and effects as a result of sampling variation and uncertainty regarding the maximum cost-effectiveness ratio that a decision-maker would consider acceptable. 56,59

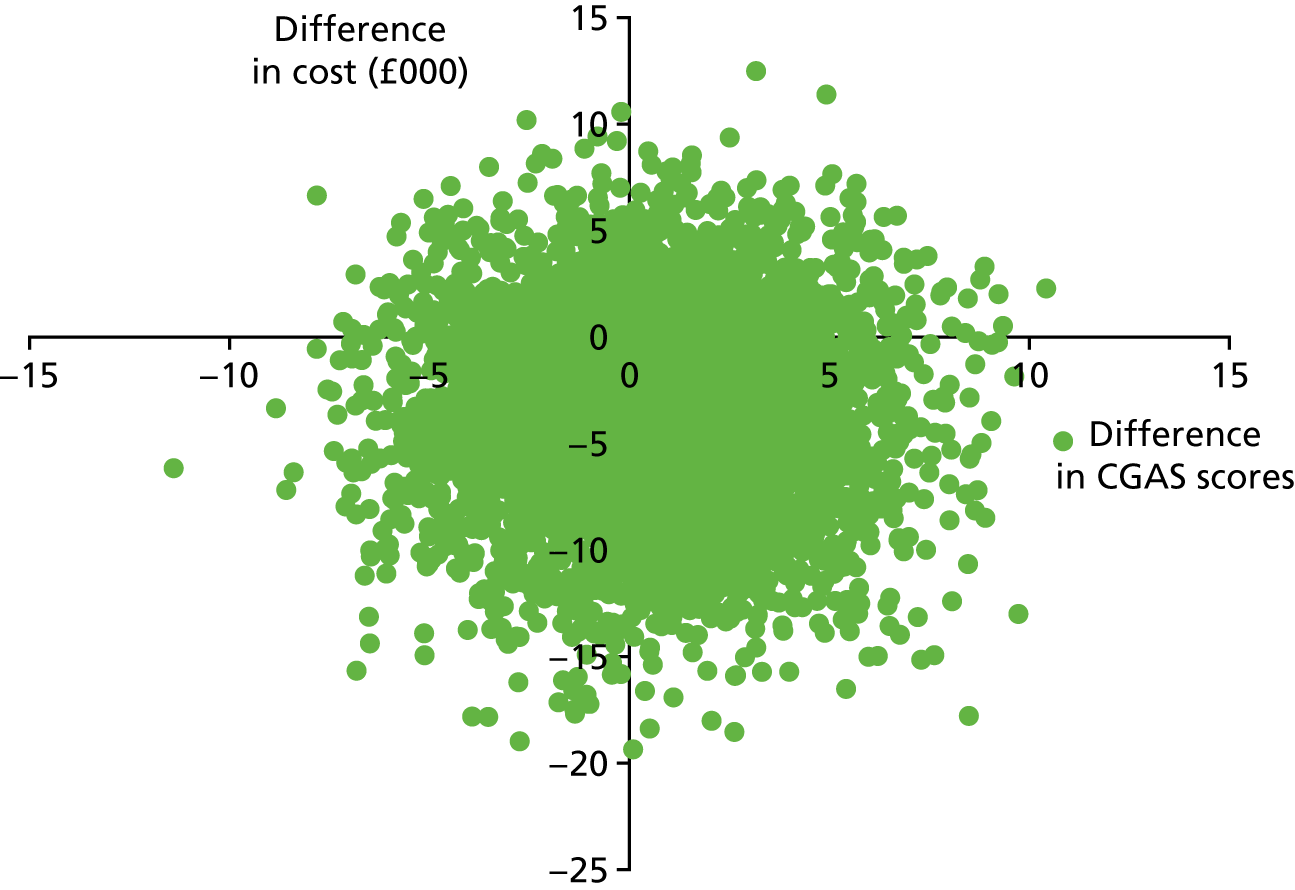

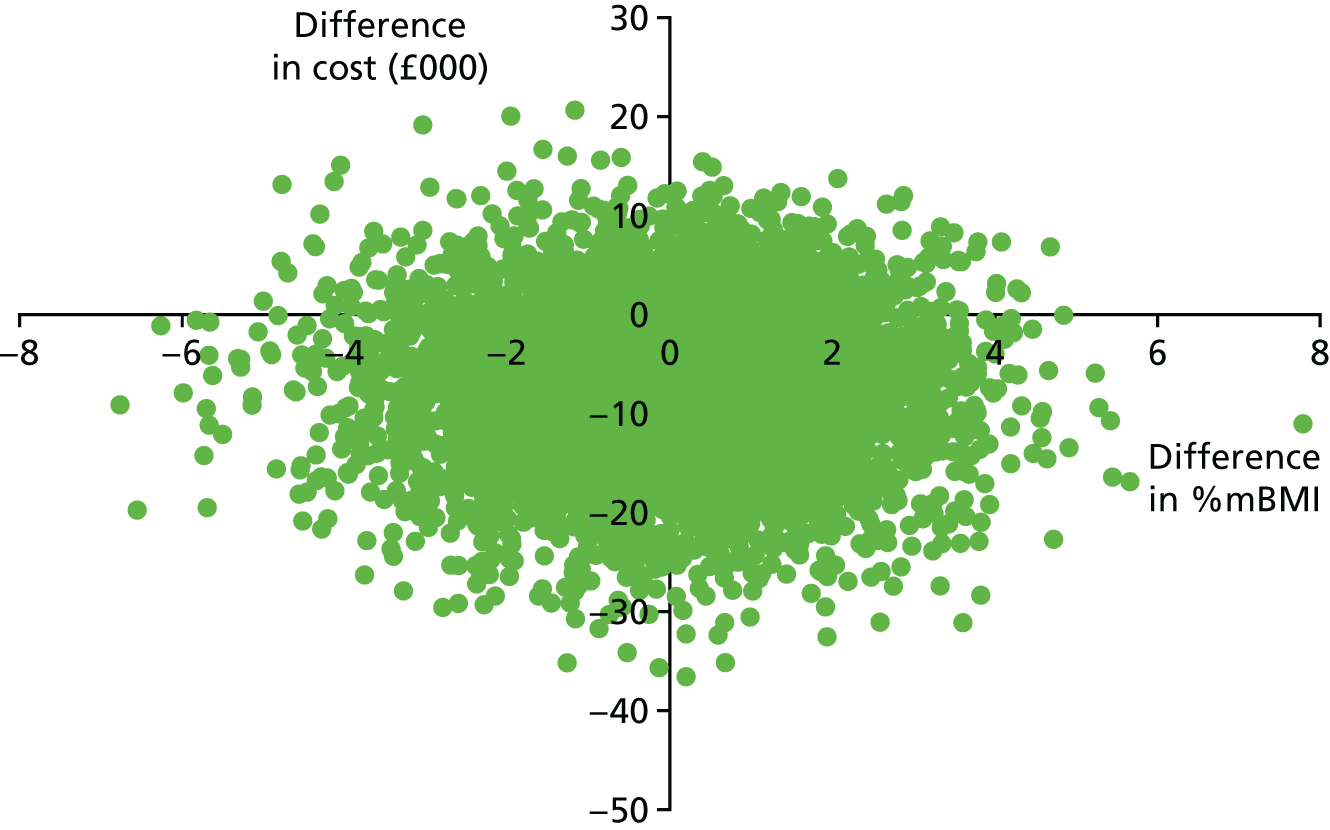

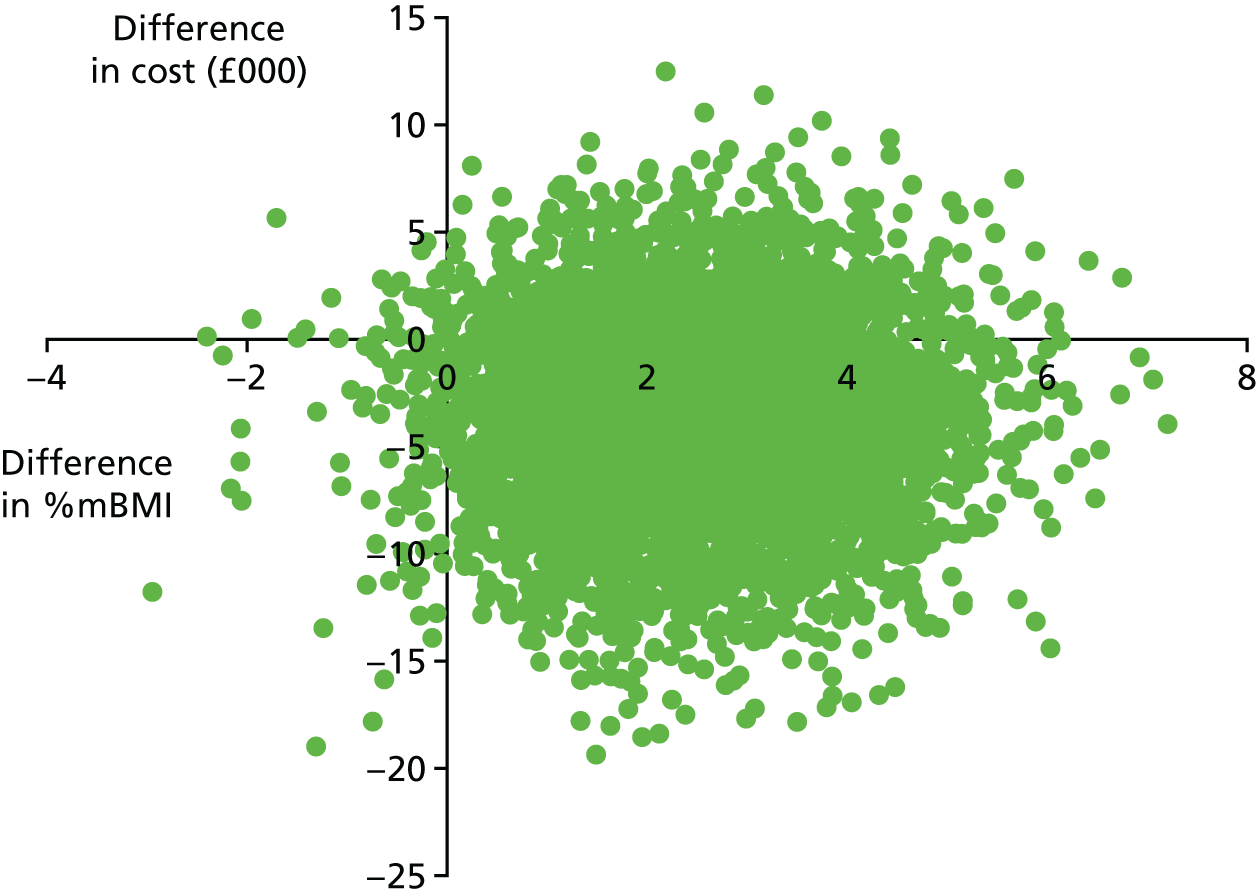

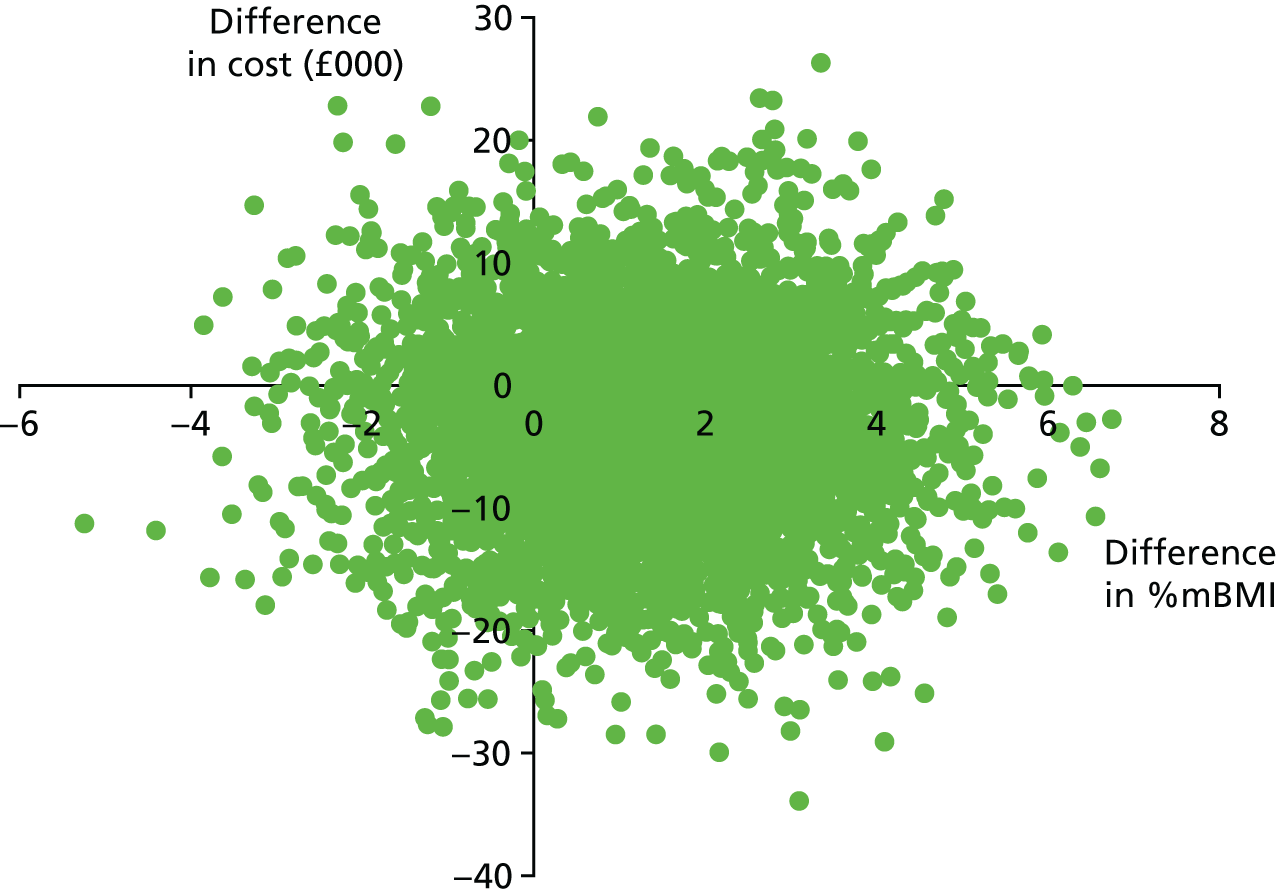

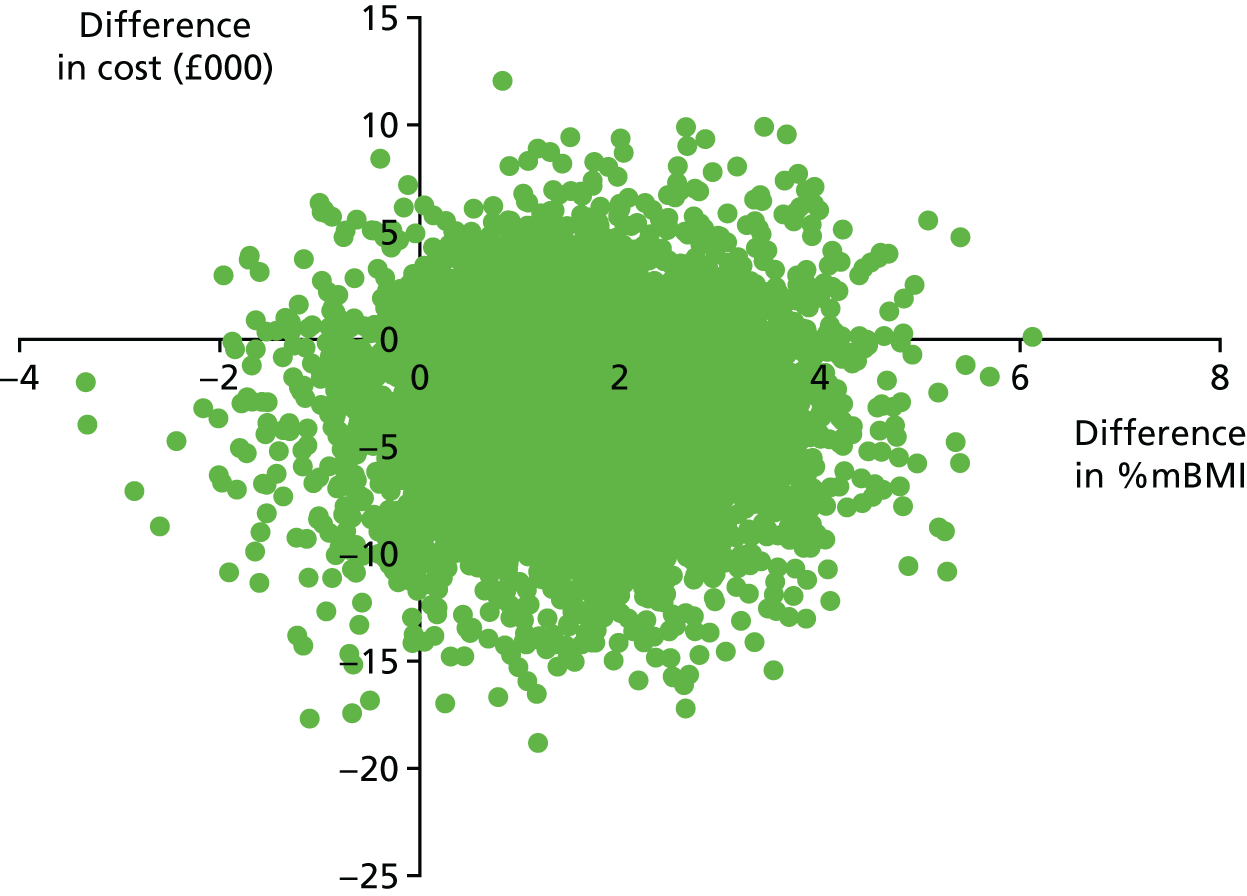

Cost-effectiveness planes are also presented to illustrate the spread of scatter points across the four quadrants of the plane, whose four quadrants can be described as follows:

-

North-west quadrant – the costs of the intervention group are higher than the costs of the control group (above the x-axis) and the outcomes are worse (to the left of the y-axis); thus, the control dominates.

-

North-east quadrant – the costs of the intervention group are higher than the costs of the control group (above the x-axis) and the outcomes are better (to the right of the y-axis); thus, there is a trade-off between the two groups.

-

South-west quadrant – the costs of the intervention group are lower than the costs of the control group (below the x-axis) and the outcomes are worse (to the left of the y-axis); thus, there is a trade-off between the two groups.

-

South-east quadrant – the costs of the intervention group are lower than the costs of the control group (below the x-axis) and outcomes are better (to the right of the y-axis); thus, the intervention dominates.

Decision-analytic modelling

Aim

The aim of the decision modelling component of the CostED study was to explore the economic impact of changes to the configuration of specialist eating disorders services for children and adolescents, specifically the impact of increasing the availability of specialist services. The decision model was therefore designed to enable us to vary the proportion of a hypothetical cohort of young people who received specialist eating disorders services or generic CAMHS. As a result, model results are presented for the full hypothetical cohort, rather than separately for specialist eating disorders services versus generic CAMHS. Thus, these results are not attempting to explore the relative cost-effectiveness of specialist versus generic services but are instead focused on the overall impact for the cohort, as the proportion of young people being assessed by specialist or generic services is varied.

Design

Decision analysis is a structured way of thinking about the likely impact of a decision or policy change. It involves the construction of a logical model to represent the relationship between inputs (costs) and outputs (outcomes) in order to inform resource allocation decisions under conditions of uncertainty. 60 Decision models use mathematical relationships to define possible consequences that flow from a set of alternative options being evaluated. 61 Each pathway in a decision model is associated with a probability, an outcome and a cost, with the cost being the sum of the costs of each of the events an individual experiences in that pathway. Decision modelling commonly uses existing data on costs, outcomes and probabilities from a range of possible sources including from completed studies, from the literature or from expert opinion.

Once constructed, the assumptions and the data used in a model can be varied, for example as new data become available. In addition, models can be used to explore ‘what if?’ scenarios to provide decision-makers with information on the likely impact of changes to services, such as changes in treatment length, personnel or capacity. This is the approach taken in the CostED study, with data being taken from the CostED surveillance study but alternative scenarios being explored.

Model structure

The structure of the model was based on knowledge and understanding of the course of anorexia nervosa over time and was developed in close collaboration with the clinicians and service managers in the research group. The model was developed to determine the economic impact of changes to the configuration of specialist eating disorders services for children and adolescents, specifically the impact of increasing the availability of specialist services. To do this, the model needed to summarise the possible pathways that a young person could take following a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa in a generic CAMHS or in a specialist eating disorders service, and the relative treatment effect afforded by each treatment option, in order to then be able to alter the mix or number of patients taking each pathway. Changes to the data passing through the pathways would then support the exploration of changes to the provision of specialist services in the UK and the RoI.

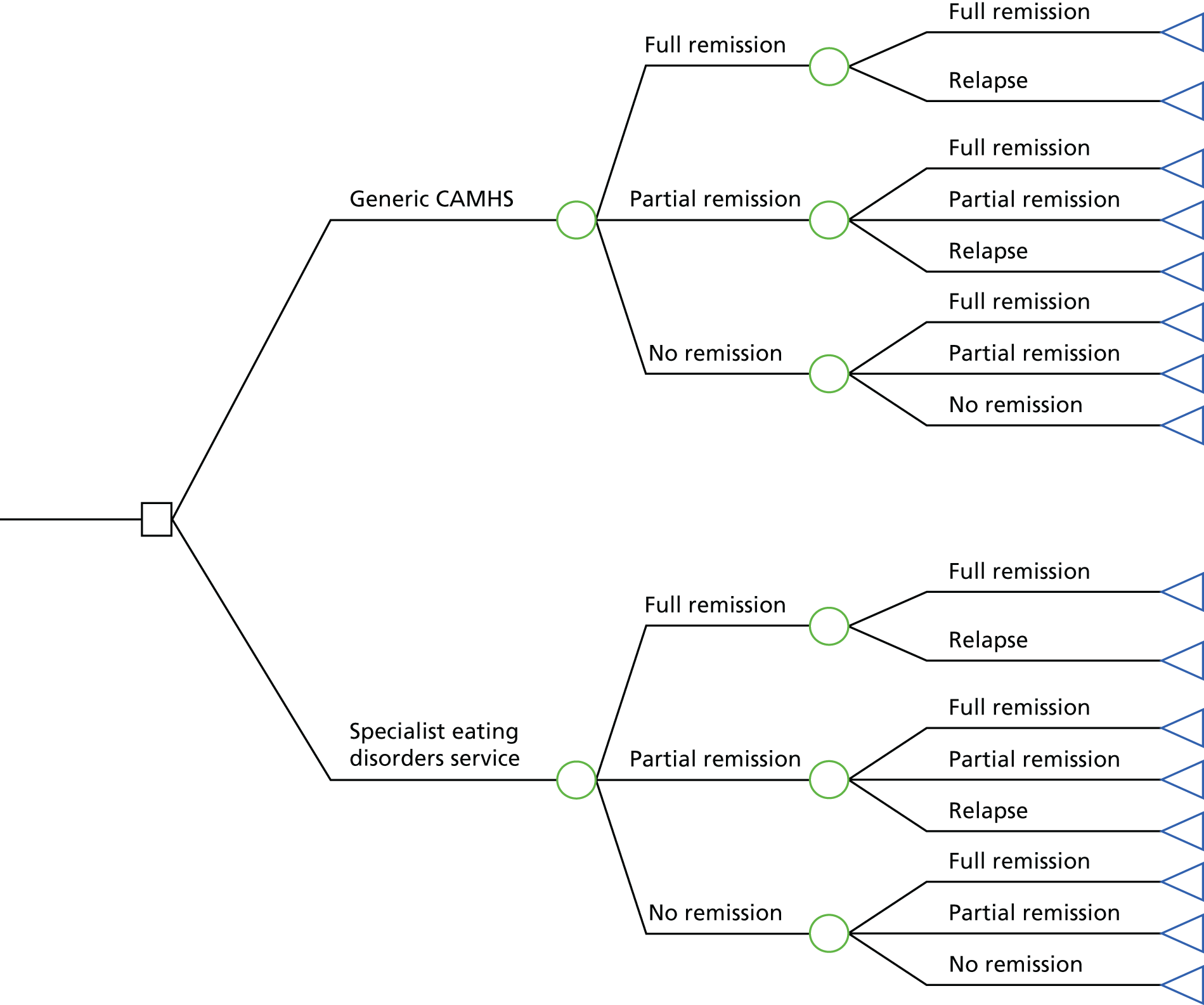

The basic decision model structure is shown in Figure 1. The pathway starts on the far left, where a young person is assessed and diagnosed with anorexia nervosa in either a generic CAMHS or a specialist eating disorders service. As outlined earlier (see Outcomes), young people are then assessed at 6 months and at 12 months for their remission or relapse status. At 6 months, the young person is in full remission, partial remission or no remission. At 12 months, young people who had been in full remission at 6 months can either remain in full remission or relapse at 12 months, young people who had been in partial remission at 6 months can relapse, remain in partial remission or enter full remission at 12 months, and young people who had been in no remission at 6 months can remain in no remission or enter partial or full remission at 12 months.

FIGURE 1.

Decision-analytic model.

A second model, to be run over 5 years, was originally planned using data from the TOuCAN study (see Health service use), which included a 5-year follow-up in addition to the original 2-year follow-up. 62 The TOuCAN study included both cost and HoNOSCA data over the full 5-year period, and thus would have been of value had the HoNOSCA remained the primary outcome measure of the CostED study. However, the substantial number of missing HoNOSCA data meant that it was not possible to use the HoNOSCA in the CostED study in any meaningful way and the primary outcome measure had to be changed to the CGAS (see Analysis: cost-effectiveness analysis), which was not included as an outcome measure in the TOuCAN study. No other sources of long-term cost and CGAS data for young people with anorexia nervosa were identified.

Model inputs

The model used data collected in the CostED study and followed the same timeline (12 months). Each remission and relapse state has cost, effect and outcome variables associated with it, as well as a probability of being in each state.

Model probabilities

Probabilities were calculated based on the number of people in each remission or relapse state in each arm (generic CAMHS or specialist eating disorders service) at the two time points (i.e. the 6- and 12-month follow-ups). All participants start with diagnosed anorexia nervosa and baseline CGAS scores equal to the mean CGAS score among all young people in the relevant study arm (generic CAMHS or specialist eating disorders service). No historical treatment data are factored into their treatment as all are incident (new) cases of anorexia nervosa.

Model costs

Costs were estimated directly from the study data as the total cost of all participants in the relevant remission or relapse state, in each arm and for each time period (baseline to 6 months and 6 months to 12 months), divided by the number of people in that state, to get the average cost per person in each state.

Model effects

The size of the treatment effect of an intervention is the power of that intervention to achieve a chosen outcome. To build a flexible model that can be used to test scenarios, a relative treatment effect needs to be developed. In this case, change in CGAS score was chosen as the treatment effect, with the change score selected on the basis that this study is not a randomised controlled trial (RCT) and thus there is no reason to assume that CGAS scores will be similar at baseline. This was calculated by combining two variables: the number of people in each remission or relapse state at each time period, and the average change in CGAS scores in each state. A weighted average of CGAS scores by each remission and relapse state in each arm was estimated to give the total treatment effect of each group.