Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/04/48. The contractual start date was in November 2015. The final report began editorial review in October 2018 and was accepted for publication in June 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

John Powell declares current membership of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Technology Assessment and Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Editorial Board (2005 to present), of which he is chairperson and editor-in-chief (since April 2019). In addition, John Powell is a co-investigator on another NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR)-funded project, which was funded under the same call [Understanding how frontline staff use patient experience data for service improvement: an exploratory case study evaluation and national survey (HSDR 14/156/06)]. Louise Locock declares personal fees from the Point of Care Foundation (London, UK) outside the submitted work. In addition, Louise Locock is principal investigator on another NIHR HSDR-funded project, which was funded under the same call [Understanding how frontline staff use patient experience data for service improvement: an exploratory case study evaluation and national survey (HSDR 14/156/06)]. Sue Ziebland declares her work as programme director of the NIHR Research for Patient Benefit programme (2017 to present). Sue Ziebland is also a co-investigator on another NIHR HSDR-funded project, which was funded under the same call [Understanding how frontline staff use patient experience data for service improvement: an exploratory case study evaluation and national survey (HSDR 14/156/06)]. Sue Ziebland is a NIHR Senior Investigator. We acknowledge support from the NIHR Oxford Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care at Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust for salary support to John Powell, Anne-Marie Boylan and Michelle van Velthoven.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Powell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background and rationale

Introduction

Digital health is fast becoming a new determinant of health. Access to and use of digital services will soon influence both the care options available to individuals and the outcomes they gain from them. 1 In this context, a new challenge for the NHS is to know how to interpret online patient feedback in relation to other sources of data on patient experience, and if and how to act on this content to improve services. Online feedback may have advantages, such as timeliness and transparency, but anecdotally it is sometimes seen as providing unrepresentative information from just a few users and, at the extreme ends of feedback, from overly negative and very positive experiences. The overarching aim of this study was therefore to provide the NHS with the evidence required to make best use of online patient feedback to improve health-care delivery in combination with other local qualitative and quantitative information on patients’ experiences.

Background

Person-centredness is a fundamental pillar of health-care quality,2,3 and patient experience is associated with patient safety and self-rated and objectively measured health outcomes for a wide range of disease and service areas. 4–6 Despite the importance placed on creating a patient-centred, responsive health system, a series of high-profile investigations, including those by Sir Robert Francis into the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust,7 Sir Bruce Keogh’s investigation into struggling trusts8 and Don Berwick’s national review of patient safety,9 noted a failure at both the team and organisational level within the NHS in recognising and responding to feedback from patients and their families and carers.

At the same time, as most ‘traditional’ feedback mechanisms, such as surveys and complaints systems, are struggling to elicit good response rates and be used to make a difference, health-care providers are receiving large amounts of (often unacknowledged) commentary from patients and carers via the internet. 10–17 Gathering, interpreting and responding to solicited and unsolicited online consumer feedback is now established practice and fundamental to success in industries, such as retail, travel and hospitality industries. 18,19 In 2015, the UK Competition and Markets Authority estimated that online reviews influence £23B of consumer spending each year. 20 The digital consumer has become accustomed to leaving such feedback on products and services, and these industries harness crowdsourced evaluations to drive consumer choice and to inform service improvements, albeit this has not been without challenges, including the potential gaming and manipulation of feedback.

The internet is having a major impact on people’s relationships within health care and people are already commentating on their health experiences online. 10,21–25 UK and US data show that online feedback on health care is increasing and likely to continue to grow fast. 26,27 This includes comments on structured patient rating sites [e.g. NHS Choices (URL: www.nhs.uk), iWantGreatCare (URL: www.iwantgreatcare.org) and Care Opinion (URL: www.careopinion.org.uk)], and also unstructured and unsolicited commentary about treatment, health services and illness in online settings, such as blogs, forums and social media. (Note: in this document we use terms such as feedback or comments to refer to all of this solicited and unsolicited content.)

When we started this project, NHS England had just committed to using internet feedback as part of its vision for a digital NHS founded on the concepts of participation, transparency and transaction. NHS managers and health-care practitioners will therefore need to understand how to interpret, respond to and harness online content from patients. Patients, carers and the public need to understand how they can provide useful feedback to the NHS and what influence this can have. Yet, there is no consensus or clear policy about how and who should use online feedback to deliver NHS and patient benefit, and there is a very limited evidence base. Little is known about the people who provide online content on their experience of care, why they do this, whether or not there are issues of inequality and what influence this feedback has on other patients, practitioners and organisations. We need to understand the strengths, weaknesses and uses of the data. There is some limited work on this from outside the UK14,28,29 (e.g. from surveys conducted by the Pew Research Center). 14 However, research exploring motivation to provide feedback is sparse and the focus is on administrative procedures for handling complaints, rather than patients themselves. 30 In the USA, 40% of a nationally representative sample reported that online ratings were ‘very important’ in choosing a physician. 13 In Germany, online raters were more likely to be younger, female and more educated. 14 A small UK study suggested that the views of certain groups may be disproportionately represented in ratings. 15

We need better data to provide a robust understanding of online feedback from a user’s perspective andthe role of online feedback in improving health-care services, and more information about the authors and receivers of feedback. We also need to understand individual, professional and organisational issues influencing the use of online feedback in health care. Many clinicians appear resistant to using online feedback, worrying about selection bias, vulnerability to gaming or malice, and have the concern that subjective patient experience and objective care quality may be only tangentially related. 31 To the best of our knowledge, before this study, there were no representative data on health professionals’ attitudes to and experiences of online feedback and no in-depth analysis of the organisational issues to guide its use in NHS organisations.

Objectives

We therefore had three research objectives, each of which addressed gaps in the current evidence base:

-

to identify the current practice and future challenges, for online patient feedback, and to determine the implications for the NHS

-

to understand what online feedback from patients represents and who is excluded, with what consequences

-

to understand the potential barriers to and facilitators of the use of online patient feedback by NHS staff and organisations, and the organisational capacity required to combine, interpret and act on patient experience data.

We also had a fourth ‘knowledge translation’ objective:

-

to use the study findings to develop a toolkit and training resources for NHS organisations, to encourage appropriate use of online feedback in combination with other patient experience data.

Methods

The study comprised five projects, listed here and aligned with our three research objectives:

-

stakeholder consultation and evidence synthesis (scoping review) regarding use of online feedback in health care (to address objective 1)

-

questionnaire survey of the public on the use of online comment on health services (to address objectives 1 and 2)

-

qualitative study of patients’ and carers’ experiences of creating and using online comment (to address objectives 1 and 2)

-

survey and focus groups of health-care professionals (to address objectives 1 and 3)

-

ethnographic organisational case studies with four NHS secondary care provider organisations (to address objectives 1 and 3).

There was one minor change to the protocol during the course of the study. Our questionnaire survey of the public was originally going to form one part of the Oxford Internet Surveys (OxIS) for 2015, but OxIS did not take place and so we used exactly the same method but as a standalone survey.

Research team and advisers

The research team had quantitative and qualitative expertise in the areas of digital health and patient experience research, and included people with disciplinary backgrounds in health services research (especially in primary care and public health), sociology, science and technology studies, psychology, epidemiology and nursing and statistics, as well as a lay co-investigator with experience as an expert patient and blogger. This range of perspectives has been a particular strength throughout the programme, enabling us to examine findings through several different lenses. We also participated in the learning set established to bring together the other projects funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme under its themed call for patient experience projects. Our project was not originally submitted to this call, but given the obvious synergy of our topic area, the funders subsequently included it with these other studies. The learning set meetings were very helpful in building a community of collaborative researchers interested in this area, and in sharing our emerging findings and receiving constructive feedback to inform our methods, analyses and discussion.

The study was overseen by a Study Steering Committee (SSC) (see Appendix 1 for membership), which met approximately every 6 months. The full research team also met every 6 months, with a smaller core team meeting monthly. Our public and patient involvement (PPI) activity was led by the lay co-investigator, who was a full member of the project team and we were advised by a Patients, Carers and Public Reference Group (PCPRG) chaired by an independent lay representative, which met as needed and which also provided feedback via e-mail (full details of our PPI activity is in Chapter 7).

Structure of monograph

Each of our five projects is described in a separate chapter (see Chapters 2–6), with full details of methods and findings. Chapter 7 describes our PPI activity, and an overarching synthesis of findings and their implications is provided in Chapter 8. Research ethics considerations are covered in each project chapter.

The next chapter describes the first of our projects: the stakeholder consultation and evidence synthesis work.

Chapter 2 A scoping review and stakeholder consultation charting the current landscape of the evidence on online patient feedback

Summary

As the initial project, this scoping review and stakeholder consultation aimed to identify and synthesise the current practice, state-of-the-art practice and future challenges in the field of online patient feedback. We searched electronic bibliographic databases and conducted hand-searches up to January 2018. We included primary studies of internet-based reviews and other online feedback (e.g. from social media and blogs), from patients, carers or the public, about health-care providers (individuals, services or organisations). Key findings were extracted and tabulated for further synthesis, guided by the themes arising from a consultation with 15 stakeholders with online feedback expertise from a range of backgrounds, including health-care policy, practice and research. We found that, as with much digital innovation, research is lagging behind practice. The current literature helped to clarify the frequency of online commentary and challenged the assumption that feedback is usually negative. The review identified gaps in the evidence base, which can guide future work, especially in understanding how organisations can use feedback to deliver health-care improvement.

Method

When we began this work, to the best of our knowledge, no synthesis of the existing body of literature on online patient feedback (reviews and/or ratings) had been conducted. Collating knowledge and developing an understanding of current research was an important precursor to further work in this area. Adopting a scoping review methodology allowed us to access and review existing evidence, summarise and disseminate research findings and identify gaps in the existing literature.

Scoping studies ‘aim to map rapidly the key concepts underpinning a research area and the main sources and types of evidence available’. 32 They are useful when reviewing literature on complex topics or areas that have not been reviewed before. The depth of the subsequent analysis of findings depends on the purpose of the review. 33 Unlike other types of reviews, such as quantitative systematic reviews, the scoping review does not appraise the quality of research evidence. However, it does consider the strengths and limitations of individual studies and critique the existing body of knowledge.

To identify relevant literature, a list of free-text and thesaurus terms likely to retrieve articles about online patient feedback was compiled using an iterative process of consultation between the research team and an information specialist.

Searches were run in May 2015 and updated in January 2018. Five databases were searched: MEDLINE (In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Ovid MEDLINE, 1948–present, accessed through OvidSP), EMBASE (1974–present, accessed through OvidSP), PsycINFO (1967–present, accessed through OvidSP), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (1981–present, accessed through EBSCOhost) and Social Science Citation Index (1956–present, accessed through Web of Knowledge). Titles and abstracts were subsequently screened for relevance using the following inclusion criteria.

-

Topic area: the main focus of the article had to be about online feedback (to include internet-based reviews, ratings and other online feedback, such as found in social media and blogs) from patients, carers and/or the public, about health-care providers (individuals or organisations).

-

Type of paper: original research.

-

Study design: all study designs.

-

Date: 2000 to present.

Titles and abstracts were screened independently by two authors (AMB and VW) using Covidence (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, VIC, Australia), a software package designed to aid the screening process. Disagreements were resolved in discussion with a third author (JP). Full texts were screened using the same criteria and process (again by two authors, with referral to a third in cases of disagreement). All included articles can be found in Report Supplementary Material 1. We have used a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram to illustrate this, although as this was a scoping review of diverse studies we do not follow PRISMA reporting more generally (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram demonstrating the final search and screening process.

Once full-text articles had been selected, they were randomly assigned to one of two authors for single data extraction. Data were extracted and tabulated using a standard pro forma (in a scoping review, it is not necessary to conduct double extraction). The following data were extracted: information on authors, date of publication, study aims, sample, methods and findings. Reference lists were checked for further articles to include.

The articles were thematically grouped by aim for further analysis in a process of data charting. A descriptive narrative synthesis of the findings was produced through individual analysis and discussion within the research team.

Stakeholder consultation

We conducted a stakeholder consultation with 15 representatives from a range of organisations, including policy-makers, senior clinicians working in patient experience, patient experience managers, regulators, representatives from patient feedback organisations and service users who have read or provided feedback. They had all collected or used online feedback. The aim of this exercise was to identify stakeholder priorities and questions to guide the literature review. In other words, we wanted to respond to the preoccupations of stakeholders and to see the extent to which the current evidence base could address the questions they had about online feedback. They were consulted about their perceptions and concerns about online feedback, including what they thought was important for the future. Consultations were conducted individually, in person or on the telephone, and notes were taken to capture the data, which were then analysed inductively. Ethics approval was not required.

In the stakeholder consultation, we identified six key issues to help navigate the online patient feedback landscape, which addressed evidence gaps identified by stakeholders:

-

Who provides and who uses reviews?

-

How do organisations currently use reviews?

-

What is the content of reviews?

-

Why is online feedback given?

-

What are staff and service user attitudes towards online feedback?

-

How reliable is online feedback?

Findings

Search results

The search yielded 29,039 papers. Twelve further papers were identified through hand-searching and citation checking. After duplicates (n = 14,221), animal studies, conference abstracts, non-English-language papers and those published before 2000 (n = 13,911) were excluded, 310 papers were accepted for full-text screening, after which 78 papers were included in the review.

Where, when and what kind of research has been conducted?

The majority of the 78 included papers described studies conducted in the USA (n = 4415,26,29,34–74). Others were from the UK (n = 1227,75–85), Germany (n = 811,28,86–91), the Netherlands (n = 349,92,93), China (n = 394–96), Austria (n = 197), Canada (n = 198) and Switzerland (n = 199). Five studies10,21,100–102 were conducted using patient feedback collected in more than one country.

As presented in Table 1, the majority of included studies used quantitative methods and were predominantly exploratory or descriptive cross-sectional studies, surveys or experiments, or employed machine learning. There were also qualitative and mixed-methods studies.

| Design | Studies |

|---|---|

| Quantitative | Bardach et al.;34 Bidmon et al.;86 Black et al.;35 Burkle and Keegan;36 Emmert et al.;103 Emmert et al.;28 Emmert and Meier;87 Emmert et al.;11 Emmert et al.;88 Frost and Mesfin;37 Gao et al.;26 Gao et al.;38 Galizzi et al.;75 Gilbert et al.;39 Glover et al.;40 Gray et al.;41 Greaves et al.;76 Greaves et al.;104 Hanauer et al.;42 Hao;94 Johnson;43 Kadry et al.;44 Kinast et al.;45 Lagu et al.;15 Lewis;105 McCaughey et al.;46 Merrell et al.;47 Riemer et al.;48 Samora et al.;49 Segal et al.;50 Sobin and Goyal;51 Terlutter et al.;89 Thackeray et al.;52 Timian et al.;74 Trehan et al.;53 and van Velthoven et al.77 |

| Experimental | Grabner-Kräuter and Waiguny;97 Hanauer et al.;54 Jans and Kranzbühler;92 Kanouse et al.;55 Li et al.;56 and Yaraghi et al.57 |

| Machine learning | Brody and Elhadad;58 Brooks and Baker;78 Greaves et al.;79 Hao;94 Hawkins et al.;59 Hopper and Uriyo;60 Paul et al.;61 Ranard et al.;62 Rastegar-Mojarad et al.;63 and Wallace et al.64 |

| Mixed methods | Ellimoottil et al.;65 Emmert et al.;90 Greaves et al.;80 Lagu et al.;100 Lagu et al.;66 MacDonald et al.;98 Reimann and Strech;101 Smith and Lipoff;67 and van de Belt et al.93 |

| Qualitative | Adams;10 Adams;21 Bardach et al.;68 Brown-Johnson et al.;102 Detz et al.;69 Kilaru et al.;70 Kleefstra;106 López et al.;29 Nakhasi et al.;71 Patel et al.;81 Patel et al.;82 Rothenfluh et al.;99 Shepherd et al.;83 Speed et al.;84 Sundstrom et al.;72 and Zhang et al.95 |

Who provides and who uses online reviews?

From the literature, it is apparent that public awareness of rating sites differs, that at present the numbers of people providing online reviews are still low, but people are starting to use these sites more frequently. A German survey28 showed that 32% of the public were aware of health rating sites (people were more commonly aware of rating sites for other products and services) and health rating sites were seen as less important sources of health information than other sources (e.g. recommendations of friends and family). 54

Posting (providing) a rating was a slightly more established activity in Germany than in other countries: a German survey87 (2013) showed that 11% of participants had posted online feedback. In studies in Austria (2014)54 and in the USA (2015),97 the prevalence was 6%. 54,97 The most recent UK figure, as identified in our own Improving NHS Quality Using Internet Ratings and Experiences (INQUIRE) survey (see Chapter 3), was 8%. 77 Other studies showed that women were more likely than men to post feedback. 89,90

People who provide online feedback are likely to be younger, have higher levels of education89 and have a long-term condition. 52,89 Likelihood to use online review sites may also be influenced by the doctor–patient relationship:75 perceiving the relationship to be friendly, feeling listened to and being the same sex as the general practitioner (GP) seem to predict use, and willingness to use was predicted by autonomy in health-care decisions. However, patients who felt that they had clear explanations from their GP were less likely to use online review sites. Men and those with less formal education were less likely to use these sites,52,89 as were people with higher incomes. 75

How are online reviews used by organisations?

From this scoping review, it was evident that this is a clear gap in the literature: no papers that considered the purpose of online patient feedback or uncovered the practices and processes governing its use in health-care organisations were found. However, evidence that some services have begun to incorporate online reviews into service improvement was uncovered: in Germany, a survey88 found that ophthalmology and gynaecology services were the most likely to implement change based on online patient feedback. Similarly, there was limited research on the value of online review in health-care inspection or monitoring agencies, although its potential was noted despite some concerns, for example by staff in a study of the Dutch Health Inspectorate. 49 This is particularly true of structured patient feedback websites, which were thought to contain more pertinent additional information than other social media platforms [e.g. Facebook (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA; www.facebook.com) and Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; www.twitter.com)]. 93 The structured websites were considered by patients to provide ‘on the ground’ or ‘bottom-up’ quality monitoring.

What is the content of reviews?

Characteristics of reviews

Strikingly, the included studies repeatedly showed that the majority of reviews were positive and that numeric ratings for health-care providers tended to be high. 51,90,91,100 Reviewers often recommended the health service to other patients. 85,100 Positive reviews were more likely to be posted by females, older adults and those with private health insurance. 91 Having a long-standing relationship with a health-care professional was also linked to providing a positive review. 69

Reviews tend to be short. A sentiment analysis of 33,654 reviews of 12,898 medical practitioners in the New York State area found that, on average, reviews were 4.17 sentences long and 15.5% contained only one line of text. 58 Lengthier commentaries were more likely to be negative. 90 When family members reviewed health services, they were more likely to comment on matters of patient safety. 68

In general, comments tended to concern services or providers, clinical and administrative staff, and the physical environment. They often related specifically to clinicians and focused on knowledge and competency,10,98 patient-centred communication,10,95,98 personal character traits,10,29 professional conduct,10 dignified care100 and co-ordination of care. 69 Waiting times and length of appointments often featured in the reviews29,45,95,100 and other themes focusing on the service or environment pertained to cleanliness,67,100 scheduling appointments,67 insurance,45 access,69 administrative staff45,69 and parking. 11 Again, these facets of patients’ experiences were more frequently commented on in positive (rather than negative) terms. 78

Who is reviewed?

Male staff were more likely to be the subject of reviews than female staff, who were more likely to receive positive feedback. 87,91 When comments and ratings were specifically aimed at professional staff, they included mainly generalists. 29 Two studies indicated that some specialties (e.g. radiology) were less frequently commented on and some subspecialties received a higher number of reviews (e.g. facial plastic surgery) than other services. 51 Two studies showed that surgeons were reviewed quite frequently on German and US websites and plastic surgeons in California had a large number of online ratings and reviews. 73

How and why do service users use these sites?

In general, the included studies report that these sites are used to post feedback, or to help choose a doctor or another health professional (e.g. dentist). 28,42,52,54,97 Twenty-eight per cent of respondents in a 2014 US survey54 had used reviews and ratings websites to find a doctor. A 2013 German survey28 showed that 25% of respondents had used the websites for this purpose. In the latter survey, 65.35% of the 1505 respondents had chosen a doctor based on the reviews and ratings, whereas 52.23% had used the online feedback to identify which doctors to avoid. In a nationally representative survey in the USA,42 35% of those who had used rating sites in the last year said that good ratings had a positive effect and 37% said that poor ratings had a negative effect on physician choice. Further evidence of the impact of the valence of reviews on physician choice was found in an experimental study, which confirmed that negative review content reduces the willingness to choose a doctor and that presenting negative reviews before positive ones has a greater (negative) effect than if the positive reviews are presented first. 56

Qualitative research exploring the motivations to post or read online reviews is limited. An English interview study82 with primary care patients who had never posted feedback found that they suggested they would do so only if they wanted to review an extremely positive or extremely negative experience at their general practice. They did not see the value in providing feedback on routine or ordinary experiences.

The number of negative reviews read, and the order in which they were read, was also found to have an impact. Reading negative reviews before positive reviews led to patients becoming less willing to consult a particular doctor. 56 Characteristics of the reviewers, including perceived trustworthiness, credibility and expertise, were also found to have an impact. When it came to content, fact-oriented reviews were reported as preferred over emotional-oriented reviews, or those containing slang or humour. 97 In addition, those who used a rating or review website to read comments were then more likely to rate a health-care experience in future. 89 Patients are more likely to spend more time on websites that contain comments (i.e. not just numeric ratings),55 which, the authors speculate, may increase the potential for ‘suboptimal choices’. 55

How do staff and service users feel about online feedback?

Based on the extant literature, health professionals hold a range of concerns about online feedback, but patients’ attitudes are more varied. Further to the research reported earlier about the perceptions of monitoring agency staff, three studies using interviews and surveys explored health professionals’ views. 43,70,81 In a qualitative interview study in England, GPs expressed their apprehension, particularly on the validity and representativeness of online feedback. 81 Twelve per cent of doctors responding to a survey deemed online rating websites useful and 39% agreed with the feedback they had received. 43 In another survey, 65% of US hand surgeons said that they were sceptical of feedback websites, with 82% reporting that it had no implications for their practice. 70

Patients have varied attitudes towards online feedback. A qualitative interview study82 about reviews and ratings in general practice in England found that participants questioned the need for online feedback and were unsure if GPs would use it. For some, the benefits of online feedback were that it could be posted remotely, could be shared with other patients and would be taken seriously by GPs. Others were concerned about privacy and security, and believed that online feedback could be ignored. In a qualitative study99 conducted in Switzerland, parents reported that review websites were more like a directory of services than a decision aid, asserting that there was not enough information to guide a choice. For them, the most effective way to evaluate a health professional was to do so in person.

How reliable are online ratings and reviews?

Comparisons have been made between traditional measures of experience and satisfaction, such as the NHS Inpatient Survey in England and the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems (HCAHPS) in the USA, and feedback on rating and review websites (e.g. Yelp or NHS Choices). These have shown similarities between online feedback and standardised measures of patient satisfaction and experience, although the online reviews tend to contain more information.

Online reviews and ratings of specific hospitals were correlated with survey responses in both England and the USA. 34,58,76,79 A strong correlation (r = 0.49; p < 0.001) was found in the USA between Yelp scores and overall scores on the HCAHPS. 34 In an English study,76 the number of patients willing to ‘recommend the hospital to a friend’ was correlated with a hospital’s overall rating on the national inpatient survey (Spearman’s ρ = 0.41; p < 0.001). Weak correlations were established between positive online recommendations and lower hospital mortality ratios (Spearman’s ρ = –0.20; p = 0.01), and better ratings of hospital cleanliness were weakly associated with lower rates of infections, particularly meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) (Spearman’s ρ = –0.30; p = 0.001) and Clostridium difficile (C. difficile) (Spearman’s ρ = –0.16; p = 0.04). 85

Analysis of online reviews in both England and the USA showed that their content was similar to the domains on patient surveys, suggesting that the surveys do cover items that matter to patients. Significant associations were found between scores on the NHS Inpatient Survey in England and online feedback on domains such as hospital cleanliness, dignified and respectful treatment, and involvement in decisions about care. 79 However, studies in the USA showed that more topics were raised in online feedback than on the HCAHPS,34,62 indicating the potential for it to supplement existing measures of patient experience. However, the additional topics may have been more salient to some services than others. 58

Discussion

As with many digital health innovations, the research of the field of online ratings and reviews lags behind the practice and the issues of interest to stakeholders. We know that there are many websites collecting online patient feedback and we know that people are using them; however, this scoping literature review has shown that the current evidence base is limited to a relatively small number of, often small-scale, studies from which it is hard to draw definitive conclusions. Our initial consultation with stakeholders about their priorities helped guide our questions, but it is clear from the literature that, as yet, current research does not address all areas of interest.

We can conclude that patients in several high-income countries are using online feedback sites to choose health professionals and to gauge public opinion about them, and that this use is increasing. These sites are also beginning to be used to monitor health services, especially in the Netherlands, demonstrating their potential for the care quality regulators.

Papers examining the content of online reviews reveal that patients commented on a range of factors about their health-care experience, including waiting times, environmental factors and staff. 100 Comments about staff predominantly related to medics themselves and centred on their perceived knowledge, skills, competence and communication ability. 10,42 Such findings illustrate that patients can, and do, comment on a range of aspects of their experience. Studies also consistently demonstrate that the majority of reviews are positive, and that negative reviews may be influential both in terms of their content106 and the order in which they are read. 56 Several studies found that negative reviews tend to be expressed with more words than positive comments. 63,90 This could mean that negative comments provide detail that could be used in locating and addressing the problem. Such findings also have implications for the design of online platforms for capturing feedback, which should allow the option of free-text comments, as well as check boxes and scales.

In general, online feedback has been shown to complement standardised patient surveys and can correlate with other measures of quality. Two US studies (Bardach and colleagues68 and Ranard and colleagues62) showed that more topics were raised online than in a patient survey. We can speculate that without the constraints of a structured survey, patients might be able to provide a more diverse range of data for use in quality and service improvement.

Few studies have focused on the attitudes and perceptions of health professionals in relation to online patient feedback. Patel and colleagues81 found that health professionals were concerned about its usability, validity and transparency. Our initial search uncovered numerous editorials and opinion pieces written by, and for, health professionals who were sceptical about online reviews.

Two other literature reviews have sought to examine the research in this field. Verhoef and colleagues107 followed Arksey and O’Malley’s33 protocol to conduct a scoping review of literature about the relationship between quality of care and social media and rating sites. Their 29 papers included opinion pieces and original research, and focused on the relationship between social media and care quality.

Emmert and colleagues‘28 systematic review aimed to answer eight questions about the percentage of physicians who were rated, the average number of ratings, the relationship of rating with physician characteristics, whether ratings were more likely to be positive or negative, the significance of patient narratives and the problems with rating sites and how they could be improved. The current review provides updated information on these questions; we have provided a synthesis of research on the content of patient comments, a more complete description of users of these sites, including patients who post reviews or are influenced by the reviews they read, and other use by inspectorate bodies.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

This was a broad scoping review of the literature that was guided by a stakeholder consultation. It included a large number of diverse peer-reviewed primary research studies. We employed rigorous, systematic and transparent processes throughout and were guided by a protocol that was reviewed by an information specialist. Reference management (EndNote X7.4; Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and Cochrane-recommended systematic review (Covidence) software were used to manage the review, ensuring that all papers were accounted for.

We conducted a broad search, ensuring that all relevant databases were included. However, as we did not search the grey literature, it is possible that we have failed to find some relevant non-peer-reviewed work. The search was conducted in English and, although it yielded some papers in other languages, these were excluded as we did not have capacity to assess them for inclusion. However, we did review German-language papers, as one team member is a native speaker, although none of these were subsequently included.

The majority of studies included in the review were quantitative, descriptive or small scale, although some included qualitative analyses and machine learning approaches. The included research was mainly conducted on US patient feedback sites so its application to the UK context is potentially limited. Health care in the USA is largely privatised and patients exercise more choice in seeking out a health-care provider, so it is perhaps unsurprising that much of the academic activity in this area of ‘reputation’ sites has been undertaken in the USA. All of the research was conducted in high-income countries.

We chose to conduct a scoping literature review rather than a systematic review because this is an emerging field and previous reviews on related topics indicated that there was limited but varied literature on the subject. We also felt that it was important to include a wide range of study designs. However, a limitation of the adopted method, acknowledged by its proponents Arksey and O’Malley,33 is that it does not present a clear process for synthesising data. Arksey and O’Malley33 also state that quality appraisal is not necessary in scoping reviews, so we did not explicitly aim to appraise the quality of the included studies.

Conclusion

By systematically searching for and presenting research evidence that addresses the preoccupations of the stakeholders we consulted, this scoping review charts the current landscape of online patient feedback research.

We have demonstrated that research in this area has emerged rapidly in recent years, but remains limited in both quantity and quality, given the spread of the phenomenon of online feedback. Many of the concerns of stakeholders remain unaddressed in the extant literature and therefore informed our own primary work in the INQUIRE project. For example, in the next few chapters we describe our findings about which patients provide and use reviews, and why do they do this; what the attitudes of professionals are towards online feedback; and how health-care organisations approach online feedback. The evidence gaps also inform our other recommendations for further research presented in the final chapter (see Chapter 8).

Chapter 3 A cross-sectional survey of the UK public to understand use of online ratings and reviews of health services

Summary

We conducted a face-to-face cross-sectional survey of a representative sample of the UK population to investigate the self-reported behaviour of the public in reading and writing online feedback in relation to health services. Descriptive and logistic regression analyses were used to describe and explore the use of online feedback. A total of 2036 participants were surveyed, and of the 1824 internet users (90% of the sample), 42% (n = 760) had read online health-care feedback in the last year and 8% (n = 147) had provided this feedback in the same period. People who were more likely to read feedback were younger, female, with a higher income, experiencing a health condition, urban-dwelling and more frequent internet users. For providing feedback, the only significant association was with more frequent internet use. The most frequent reasons for reading feedback were finding out about a drug, treatment or test, and informing a choice of treatment or provider. For writing feedback, the most frequent reasons were to inform other patients, praise a service or improve standards of services. Ninety-four per cent of internet users in the general population had never been asked to leave online feedback by their health-care provider. In conclusion, many people read online feedback from others and some write feedback, although few are encouraged to do so. This emerging phenomenon can support patient choice and quality improvement, but needs to be better harnessed.

This chapter is based on material reproduced from van Velthoven and colleagues. 77 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Introduction

Given the absence of any recent or robust data on use of online feedback of UK health services, despite huge interest in this area in the UK and elsewhere, to our knowledge, we undertook the first nationally representative UK survey on providing and using online feedback about health and health services among the general population. In this chapter, we describe the results of a survey measuring the frequency of use, user characteristics and self-reported behaviour of members of the public in reading and writing online feedback on health services, health professionals and medical treatments or tests. Previous work on the use of online feedback by patients has been relatively limited. 14,36,75,106 Surveys found that those who are more likely to use online feedback of health services include people who are younger,14,75 live in (sub)urban areas and have higher levels of education. 75 Prior to us starting this project, to the best of our knowledge, the last UK survey75 was published in 2012. The survey75 was conducted among a small non-representative sample of 200 people living in one borough in London and showed that just 29 people (15%) were aware of doctor-rating websites and only six people had used them. In a US survey conducted in 2012, 65% of 2137 participants were aware of online patient feedback websites and 23% had used them. 42 Of 854 respondents in another US survey in 2013, 16% said that they had previously visited a patient feedback website. 36 Although there are some caveats in the non-comparability of studies that have been conducted in different settings, using different questionnaires, it seems that the number of people using online feedback is rising rapidly from a very low baseline over time. Subsequent to undertaking this project, a separate study108 conducted in 2016 has been published examining the prevalence of knowledge and use of online feedback specifically in relation to UK general practice, showing a very low prevalence of usage in relation to feedback specifically about GPs (0.4% prevalence), in combination with a low awareness among the public of GP rating sites (15% awareness).

Methods

Study design

A cross-sectional face-to-face questionnaire-based household survey was conducted with members of the UK public about their use of online ratings and reviews (see Appendix 2). A market research agency, ICM Unlimited (London, UK), conducted the fieldwork. ICM Unlimited had previously conducted the OxIS on behalf of the Oxford Internet Institute, which uses similar methodology and which collaborated on this project, advising on design of the survey and choice of provider. 109 Similar to the OxIS, a two-stage design was used for sampling. First, a random sample of output areas stratified by region was selected. Second, within each selected output area a random selection of addresses was used. ICM Unlimited recruited and interviewed participants by sending interviewers to the homes of selected people in February 2017.

Ethics approval and consent

The survey received institutional ethics approval from the University of Oxford Central University Research Ethics Committee (reference SSH_OII_C1A_074).

Participants

We included adult members of the UK general public who were willing and able to give informed consent for participation in the study, lived in the UK, were able to speak and read English and were aged ≥ 16 years. To select participants, a random location sampling system was used in which we randomly selected output areas as the geographical sampling unit. Each output area consisted of around 150 households and all properties were available to the interviewer to achieve the target number of interviews (usually four or five per point). Demographics quotas were applied to ensure that the profile of achieved interviews in each sample point reflected the known population of the area. 109

Variables

We collected data on participant’s characteristics, including age, sex, ethnicity, annual household income, education level, living in an urban or rural area, health status and internet use (see Appendix 3). There were also 20 questions relating to online feedback (see Appendix 2, Table 15).

These questions were principally designed based on items from previous surveys14,75 and on policy documents and reports by online feedback organisations,110 and were informed by our concurrent survey of health-care professionals (see Chapter 4). We piloted the questionnaire with a patient and public reference group and tested it using two rounds of cognitive interviews (also with the public). Questions were asked about if, where and why participants read or wrote online ratings or reviews of health services, individuals, drugs, treatments or tests.

Data sources

All data were obtained through face-to-face interviews with participants. Surveys were completed on a tablet and transferred to the study team in a Microsoft Excel® spreadsheet (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). The names and any other identifying details of participants were not collected in any of the surveys.

The survey was a fully representative sample of the population of Great Britain aged ≥ 16 years. A sample size of 2000, with a margin of error percentage of 2, was chosen to maximise accuracy within reasonable resource constraints. 109 Data were weighted to the sociodemographic profile [census data that included sex, age, socioeconomic grade, region and ACORN (A Classification Of Residential Neighbourhoods) group of the target population (UK citizens aged ≥ 16 years)].

Quantitative variables and statistical methods

All analyses were conducted using the statistical software package IBM SPSS Statistics version 22 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). Descriptive analyses of participants’ characteristics and the prevalence of providing and of reading online feedback were conducted. Non-internet users were excluded from these analyses, as they would not be reading or writing online content.

We coded the outcome as binary: use of any type of feedback compared with no use. Logistic regression was used to explain the use of online feedback (as the dependent variable), with the following independent variables that were considered to be potentially relevant: age, sex, education, income, living in rural or urban area and frequency of internet use. These sociodemographic and internet use variables have been shown to influence the uptake of a wide range of online activities, including health. 111 Ethnicity was not included in the logistic regression analyses because of the small number of participants in the ethnicity subgroups. In the results, we present the model fit (%), chi-squared, p and R2 (Nagelkerke) values. We used binary logistic regression in SPSS and included all variables that were found to be statistically significant in univariate analysis in the model. Missing data were not imputed.

Results

This section has been reproduced from van Velthoven and colleagues. 77 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Our total sample comprised 2036 participants, of whom 1824 used the internet over the past year; it is this group of internet users in the general population who were included in further analyses (their characteristics are shown in Table 2, as well as the characteristics of those who read and provided feedback). Appendices 3 and 4 show characteristics of the 10% of our sample who were non-users of the internet (n = 212). Our main findings were that of the 1824 internet users, 42% (n = 760) had read feedback about health services, or about health professionals or about medical tests or treatments during the past year, whereas 8% (n = 147) had written such feedback in the same period.

| Total (N = 1824; 100%) | Readers (N = 760; 42%) | Writers (N = 147; 8%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % of total sample | n | % within demographic subgroup | n | % within demographic subgroup | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 16–34 | 616 | 34 | 290 | 47 | 58 | 9 |

| 35–54 | 639 | 35 | 253 | 40 | 49 | 8 |

| 55–64 | 256 | 14 | 110 | 43 | 20 | 8 |

| ≥ 65 | 313 | 17 | 107 | 34 | 20 | 6 |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 904 | 45 | 344 | 38 | 65 | 7 |

| Female | 920 | 50 | 416 | 45 | 82 | 9 |

| Educationa | ||||||

| No formal qualifications | 177 | 10 | 61 | 35 | 11 | 6 |

| GCSE/O level/CSE/vocational qualifications/A level or equivalent | 864 | 47 | 348 | 40 | 66 | 8 |

| Bachelor’s degree or equivalent/MSc/PhD or equivalent | 636 | 35 | 307 | 48 | 58 | 9 |

| Still studying | 14 | 1 | 7 | 47 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Other | 119 | 7 | 37 | 31 | 12 | 10 |

| Household income | ||||||

| ≤ £24,999 | 470 | 26 | 213 | 45 | 45 | 10 |

| £25,000–49,999 | 431 | 24 | 178 | 41 | 40 | 9 |

| £50,000–74,999 | 141 | 8 | 62 | 44 | 9 | 6 |

| £75,000–99,999 | 72 | 4 | 37 | 51 | 3 | 4 |

| ≥ £100,000a | 76 | 4 | 45 | 60 | 8 | 11 |

| Ethnic origina | ||||||

| White | 1563 | 86 | 635 | 41 | 120 | 8 |

| Other | 252 | 14 | 120 | 48 | 25 | 10 |

| Health status: long-term illness, health problem or disabilitya | ||||||

| Yes | 373 | 21 | 183 | 49 | 39 | 10 |

| No | 1449 | 80 | 576 | 40 | 108 | 8 |

| Area | ||||||

| Urban | 499 | 27 | 240 | 48 | 52 | 10 |

| Suburban | 1057 | 58 | 424 | 40 | 75 | 7 |

| Rural | 251 | 14 | 89 | 36 | 19 | 8 |

| Internet access frequencya | ||||||

| Several times a day | 1490 | 82 | 669 | 45 | 132 | 9 |

| Around once a day | 185 | 10 | 56 | 30 | 10 | 5 |

| Less than once a day | 148 | 8 | 35 | 24 | 5 | 3 |

Associations between people’s characteristics and use of online feedback

Age, sex and ethnicity

The highest proportions of feedback readers and writers were among those aged 16–34 years and the lowest proportions were among those aged ≥ 65 years (see Table 2). People aged 16–34 years were significantly more likely to read online feedback [odds ratio (OR) 1.695, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.278 to 2.246; p = 0.000] than those aged ≥ 65 years (Table 3). Of women, 45% (n = 416) read and 9% (n = 82) gave feedback, compared with 38% (n = 344) and 7% (n = 65) of men, respectively (see Table 2). Men were significantly less likely to read online feedback than women (OR 0.742, 95% CI 0.615 to 0.894; p = 0.002) (see Table 3). Among people with an ethnicity other than white, 48% (n = 120) read and 10% (n = 25) wrote reviews, compared with 41% (n = 635) and 8% (n = 120) of people with a white ethnicity, respectively (see Table 2).

| Predictor variable (individual data) | Readers (n = 760)a | Writers (n = 147) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | 95% CI | p-value | OR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Age (years) | ||||||

| 16–34 | 1.695 | 1.278 to 2.246 | 0.000 | 1.496 | 0.885 to 2.529 | 0.133 |

| 35–54 | 1.250 | 0.942 to 1.657 | 0.122 | 1.190 | 0.696 to 2.035 | 0.525 |

| 55–64 | 1.446 | 1.029 to 2.031 | < 0.005 | 1.204 | 0.633 to 2.291 | 0.571 |

| ≥ 65b | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Sex | ||||||

| Male | 0.742 | 0.615 to 0.894 | < 0.005 | 0.786 | 0.560 to 1.105 | 0.166 |

| Femaleb | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Education | ||||||

| No formal qualifications | 1.185 | 0.720 to 1.950 | 0.504 | 0.583 | 0.249 to 1.364 | 0.213 |

| GCSE/O level/CSE, vocational qualifications (= NVQ 1 + 2), A level or equivalent (= NVQ 3) | 1.519 | 1.006 to 2.296 | < 0.05 | 0.722 | 0.379 to 1.375 | 0.322 |

| Bachelor’s degree or equivalent (= NVQ 4), master’s degree/PhD or equivalent | 2.102 | 1.382 to 3.198 | 0.001 | 0.877 | 0.457 to 1.682 | 0.692 |

| Still studying | 1.933 | 0.641 to 5.834 | 0.242 | –c | –c | –c |

| Other | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Household income | ||||||

| ≥ £100,000b | 1.784 | 1.088 to 2.924 | < 0.05 | 1.113 | 0.503 to 2.463 | 0.792 |

| £75,000–99,999 | 1.237 | 0.754 to 2.029 | 0.400 | 0.424 | 0.131 to 1.372 | 0.152 |

| £50,000–74,999 | 0.955 | 0.654 to 1.395 | 0.812 | 0.644 | 0.307 to 1.351 | 0.244 |

| £25,000–49,999 | 0.846 | 0.650 to 1.102 | 0.216 | 0.957 | 0.612 to 1.498 | 0.848 |

| ≤ £24,999 | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Health status: long-term condition | ||||||

| Yes | 1.463 | 1.164 to 1.839 | 0.001 | 1.434 | 0.974 to 2.110 | 0.067 |

| Nob | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Area | ||||||

| Urban | 1.697 | 1.241 to 2.320 | 0.001 | 1.426 | 0.823 to 2.473 | 0.206 |

| Suburban | 1.226 | 0.920 to 1.633 | 0.164 | 0.934 | 0.552 to 1.578 | 0.798 |

| Ruralb | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

| Internet use | ||||||

| Several times a day | 2.680 | 1.808 to 3.974 | 0.000 | 3.206 | 1.216 to 8.449 | < 0.05 |

| Around once a day | 1.440 | 0.880 to 2.357 | 0.147 | 1.965 | 0.629 to 6.141 | 0.245 |

| Less than once a dayb | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR | NR |

Education and household income

The highest proportion of readers and writers were also among those with degree-level qualifications and above (see Table 2), and these people were significantly more likely to read online feedback than those with other qualifications (see Table 3). People in the highest income bracket of ≥ £100,000 were significantly more likely to read online feedback than those with the lowest income (≤ £24,999) (OR 1.784, 95% CI 1.088 to 2.924; p = 0.022).

Health status

Of people with a long-term condition, health problem or disability, 49% (n = 183) read and 10% (n = 39) wrote online feedback (see Table 2), and they were significantly more likely to read it than those without such a health condition (OR 1.463, 95% CI 1.164 to 1.839; p = 0.001) (see Table 3).

Area and internet use

Of people living in urban areas, 48% (n = 240) read and 10% (n = 52) wrote online feedback (see Table 2), and they were significantly more likely to read it than those living in rural areas (OR 1.697, 95% CI 1.241 to 2.320; p = 0.001) (see Table 3). People accessing the internet several times a day were significantly more likely to read (OR 2.680, 95% CI 1.808 to 3.974; p = 0.000) and write (OR 3.206, 95% CI 1.216 to 8.449; p = 0.018) online feedback than those who went online less than once a day (see Table 3).

Regression analysis

Our multivariate regression model for ‘reading feedback’ showed a model fit of 55%, which increased to 61% when the following significant variables were included: age, sex, education, income, health status, area and internet use (see Table 3). For writing reviews, the only significant variable was internet use, and no multivariate model is presented.

Frequency of reading and writing online feedback for different domains: health services, health professionals, and medical treatments and tests

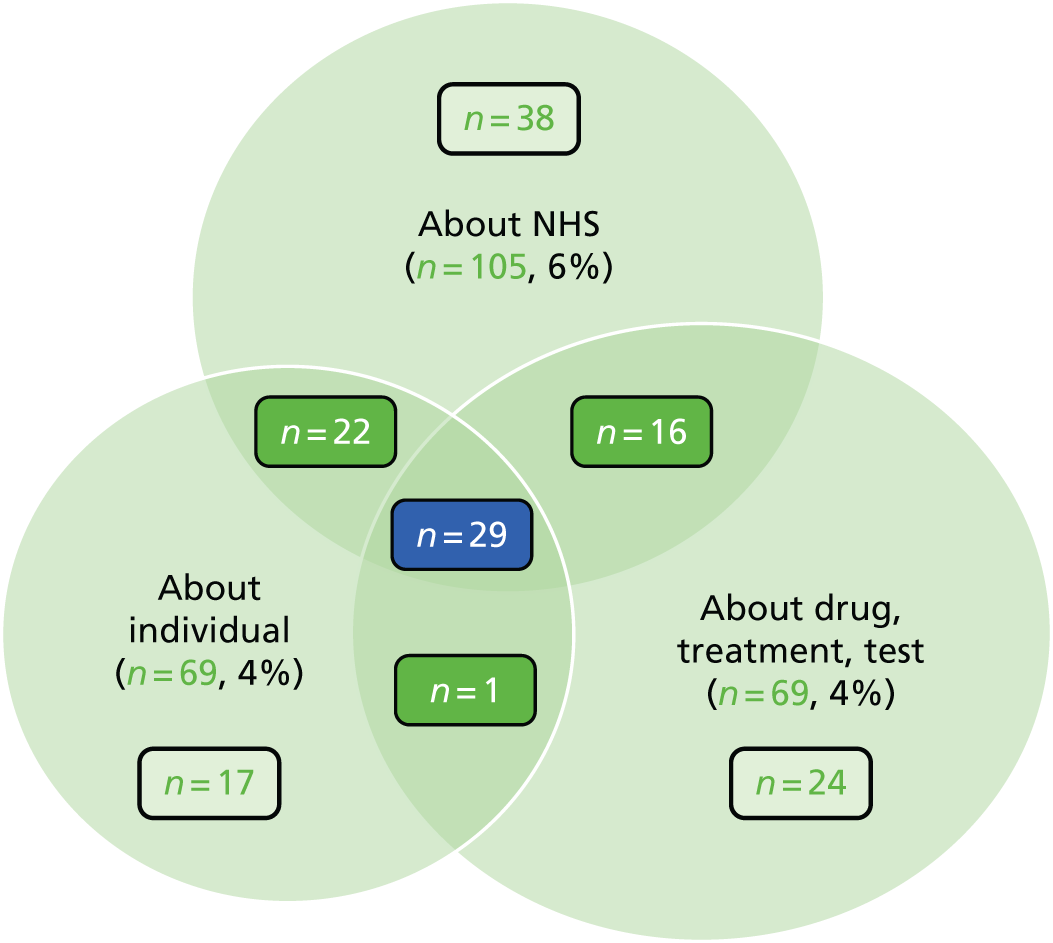

Of the 1824 internet users, 28% (n = 507) had read feedback about (NHS) health-care organisations, 18% (n = 331) had read feedback about health professionals and 32% (n = 579) had read feedback about drugs, treatments or tests (see Appendices 7 and 8). Far fewer participants had written reviews: 6% (n = 105) about health-care organisations, 4% (n = 69) about health professionals and 4% (n = 69) about drugs, treatments or tests (see Appendix 9). Most participants who read or wrote feedback had done this once or every few months/monthly over the past year (Table 4 and see Appendix 10).

| Frequency | Subject of feedback | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NHS organisations | Individuals | Drugs, treatments or tests | ||||||||||

| Read (N = 507) | Written (N = 105) | Read (N = 331) | Written (N = 69) | Read (N = 579) | Written (N = 69) | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Daily/every couple of days | 14 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 9 | 3 | 3 | 5 | 11 | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| Weekly/fortnightly | 44 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 42 | 13 | 6 | 9 | 49 | 9 | 6 | 9 |

| Monthly/every few months | 230 | 45 | 29 | 27 | 149 | 45 | 22 | 32 | 335 | 58 | 30 | 43 |

| Once in the last year | 220 | 43 | 66 | 63 | 131 | 40 | 37 | 54 | 183 | 32 | 32 | 46 |

Of the 760 participants who read feedback about a health-care organisation, a health professional or a treatment or test, 42% (n = 320) read feedback about one of these, 29% (n = 223) read feedback about two and 28.6% (n = 217) read feedback about three. Appendices 9 and 11 show that, of the 147 participants who wrote feedback about a health-care organisation, a health professional or a treatment or test, 53% (n = 79) wrote feedback about one of them, 26% (n = 39) about two and 20% (n = 29) about three. In comparing readers and non-readers with writers and non-writers, we first found that 7% of the whole sample of internet users (128/1824) had both read and written a review. Of the 760 participants who read feedback, 83% (n = 633) had not written a review. Of the 147 participants who wrote feedback, 13% reported not reading feedback. Fifty-seven per cent of the whole sample of internet users (1044/1824) had not read or written feedback over the past year.

Websites on which online feedback of health services was read and written

The most frequently used formal review website for both reading and writing feedback was NHS Choices (used by 49% of ‘readers’ and 35% of ‘writers’), followed by WebMD (15% and 5%, respectively) and Care Opinion, formerly Patient Opinion (6% and 9%, respectively) (see Appendix 12). The most frequently used social media outlets for reading and writing online feedback were Google Reviews (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) (31% and 14%, respectively) and Facebook (25% and 23%, respectively).

Reasons for using online feedback of health services

Table 5 shows the most frequent reasons among 760 ‘readers’ for reading reviews: finding out about a drug, treatment or test (41%); choosing where to have treatment (19%); or choosing a health-care professional (17%). The most common reasons for providing reviews were to inform other patients (39%), praise a service (36%) or improve standards of NHS services (16%). Of the total sample, only 112 (6%) participants had been asked to write a review. Of those people who were asked to write a review, only 28 (25%) had written a review. The eight people who said they had often been asked to write a review had not done so.

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Reasons for readinga (N = 760) | ||

| To find out about a particular drug, medical treatment or test | 313 | 41 |

| To choose where to have my treatment | 145 | 19 |

| To choose a health-care professional | 134 | 18 |

| Before booking an appointment, to find out about which NHS services were available | 84 | 11 |

| After an appointment, I wanted to compare my NHS experience with others | 67 | 9 |

| Example for writing my own online review | 22 | 3 |

| Was looking for general information/just browsing | 16 | 2 |

| Used it to research my medical condition/symptoms | 11 | 2 |

| Used it for professional reasons/work/study | 11 | 2 |

| Came across it accidentally/was not looking for it | 7 | 1 |

| Was looking for general feedback | 5 | 1 |

| Was looking for information for a friend/someone else | 3 | .4 |

| Other | 47 | 6 |

| Do not know | 60 | 8 |

| Reasons for writinga (N = 147) | ||

| To inform other patients | 57 | 39 |

| To praise the service received from my doctor or other health-care professional | 53 | 36 |

| To improve standards of care in the NHS | 23 | 15 |

| To complain about a NHS service | 9 | 6 |

| To complain about a treatment | 7 | 5 |

| Do not know | 6 | 4 |

| To complain about a health-care professional | 5 | 4 |

| Asked to by a medical professional | 3 | 2 |

| I was asked to (unspecified by who) | 3 | 2 |

| Other | 12 | 9 |

| Asked to write (N = 1824b) | ||

| No | 1711 | 94 |

| Yes | 112 | 6 |

| Asked to write and written a review (N = 28) | ||

| Asked once | 20 | 71 |

| Asked a few times | 8 | 29 |

| Often asked | 0 | 0 |

| Asked to write and not written a review (N = 84) | ||

| Asked once | 41 | 49 |

| Asked a few times | 35 | 42 |

| Often asked | 8 | 9 |

For 147 ‘writers’ (36%), writing a review to provide praise for a service was a far more common motivation than to complain about a service (6%), treatment (5%) or professional (4%).

Discussion

The striking findings from this work are that about 1 in 12 members (8%) of the general population who use the internet had provided online feedback about some aspect of health care in the last year, and two in five people (42%) had read such online feedback in the past year. To the best of our knowledge, this survey provides the first representative UK population data on the use of online feedback about health care. As such, it provides key baseline prevalence data for future engagement with online feedback by patients. Although the majority of the population had not used online feedback of health services over the past year, these figures show that this phenomenon can now be considered a mainstream activity for many people, and, although writing feedback remains unusual (but not rare), the frequency of reading feedback suggests that this user-generated content has the potential to have a wide influence. As might be expected, the least represented users of online feedback of health services were people aged ≥ 65 years, without formal qualifications, at lower social grades, accessing the internet less often than once a day and those living in rural areas.

The findings of this survey are representative of the general population of internet users in the UK. Not everyone in the general population uses health services in a 1-year period, so it is not surprising that reading feedback is not universal. Overall, people are still far less likely to read and write reviews of health services than they are to do so for non-health-related commercial services. 112 On average, 42% of internet users in our survey read online feedback on some aspect of health care in our study. This is higher than shown in previous studies. 36,42 For example, the previous work in the UK, from 2012, had shown very low awareness (15%) and usage (3%) of doctor rating sites in a convenience sample survey of 200 people in London. 75 More recently, a study by Patel and colleagues,82 conducted in 2016, looked only at the use of rating sites in relation to GPs and showed a low prevalence (0.4%) for this very specific form of online feedback. The higher figures found in our survey compared with previous work can be explained by our broader scope across the whole of health care, as well as by increasing use over time.

Our findings on age and sex are in line with those of a German study87 that examined the characteristics of patients using a national public reporting instrument to leave feedback on their health-care experiences. This study87 found that 60% of 107,148 patients rating physicians were female and 51% were aged 30–50 years. Only 14% of writers in our study left feedback to complain, which is in line with a survey in the USA,36 in which 9% of 854 patients provided an unfavourable review. Likewise, the German study87 found that only 3% of 127,192 ratings of 53,585 physicians were rated with an insufficient score and 5% with a deficient score in their overall performance, and in a UK study78 the NHS services received three times more positive (total 223,439) than negative (total 73,363) reviews.

About 1 in 10 people did not use the internet in our study, which is in line with Ofcom data112 and shows an increase in use of the internet compared with the OxIS conducted in the UK in 2013, in which about 2 in 10 people were non-internet users. 14 In line with previous research, people with a lower level of education, lower income or social grade, of older age or living in rural areas were less likely to be regular internet users. 111 We also found that these variables were associated with lower use of reading online feedback. It may be that people in urban areas use feedback more, as they have more genuine choice in terms of health-care provider in their locality.

Strengths and weaknesses of the study

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest representative general population survey conducted across the UK. It addressed an evidence gap in a fast-moving and under-researched area. This survey method relies on participant self-report to a face-to-face questionnaire; for this reason it may be influenced by recall bias, presentation bias and social desirability bias. Cognitive interviews with members of the public were conducted to optimise the design of questions, with the aim of minimising other response bias caused by question wording or item order. As a result, we had a relatively small number of ‘other’ and ‘do not know’ responses. Non-English speakers were excluded as the survey was conducted in English. Data from cross-sectional surveys can be used only to investigate associations between variables, not causation, and the nature of quantitative findings means that, although we can identify prevalence of use, in this study we cannot provide any deeper, qualitative understanding of the phenomenon of using online feedback of health services.

Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, we have provided the first UK-wide representative data on the use of online feedback, which show that although many people (> 40% of internet users) read online feedback about health care, fewer currently provide it and very few have been asked to provide it. Encouragingly, users are motivated to become more informed, to make choices, to provide praise and to improve standards of care.

Chapter 4 Cross-sectional surveys of doctors and nurses to identify UK health-care professionals’ attitudes to and experiences of online feedback

Summary

We conducted cross-sectional self-completed online questionnaires of 1001 registered doctors and 749 nurses or midwives involved in direct patient care in the UK, and a focus group with five allied health professionals (AHPs). A total of 27.7% of doctors and 21% of nurses were aware that patients or carers had provided online feedback about an episode of care in which they were involved, and 20.5% of doctors and 11.1% of nurses had experienced online feedback about them as an individual practitioner. Feedback on reviews or ratings sites was seen as more useful than social media feedback to help improve services. Both types were more likely to be seen as useful by nurses than doctors, and by hospital-based professionals than community-based professionals. Doctors were more likely than nurses to believe that online feedback is unrepresentative and generally negative in tone. The majority of respondents had never encouraged patients or carers to leave online feedback. The findings from the focus group and from free-text comments in the survey showed concerns about representativeness and a reported lack of communication from management about what feedback is for, if it is received, and how it should be used. Despite enthusiasm from policy-makers, many health-care professionals have little direct experience of online feedback, rarely encourage it, and often view it as unrepresentative and with limited value for improving quality of health services. Differences in opinion between doctors and nurses have the potential to disrupt use of online patient feedback.

This chapter is based on material reproduced from Atherton and colleagues. 110 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text. It is also based in part on material under review: Turk A, Fleming J, Powell J, Atherton H, University of Warwick and University of Oxford, 2019.

Introduction

In this chapter we address the question of how health-care professionals, who may be subject to both institutional- and personal-level feedback, regard and interact with online patient feedback. There is some evidence to suggest that medical professionals, including GPs, hospital doctors and surgeons, appear cautious about the value of online content, particularly in relation to validity of feedback and representativeness of the patient population and concerns about a lack of fundamental relationship between subjective patient experience and objective care quality. 31,70,81,88 Nurses’ or midwives’ attitudes towards online patient feedback have not previously been reported. Given that the attitudes held by health-care professionals are a major influence on the speed and success of adoption of new technological initiatives in health-care settings, there is a need to understand their viewpoints and establish current usage,113,114 and therefore to guide both practitioners and policy-makers in responding to this new form of feedback. Guidance to date has focused on patient experience data gathered using traditional methods, including surveys and focus groups. 115

We therefore conducted surveys of UK doctors, and of nurses and midwives, and a focus group with AHPs, with the aim of defining the characteristics, attitudes and self-reported behaviours and experiences of health-care professionals towards online patient feedback.

Our objectives were, in the case of doctors, nurses and midwives, to outline attitudes, behaviours and experiences and to determine whether or not these differed by clinician type, professional setting and according to demographic variables, including age and sex. For AHPs, we sought to explore their attitudes, behaviours and experiences in the context of their role working alongside other health-care professionals.

Methods

Ethics approval and consent

The survey of doctors was approved by the Central University Research Ethics Committee at the University of Oxford. The survey of nurses and midwives was approved by the Joint Research Compliance Office at Imperial College London and Imperial College Healthcare NHS Trust. The questionnaire started with a statement regarding consent, with an option to give consent or to decline. All responses were anonymous.

The focus groups were approved along with the other elements of project 5, the organisational case studies. Approval was by the Medical Sciences Interdivisional Research Ethics Committee (reference R32336/RE001) and the Health Research Authority. Participants provided written informed consent.

Study design

We conducted a cross-sectional self-completed online questionnaire design. The survey was administered to doctors and to nurses or midwives using different routes. We also conducted a focus group with AHPs.

Participants

Participants in the survey were registered UK doctors, nurses and midwives currently practising in the UK and involved in direct patient care. Participants in the focus group were AHPs working at one of the case study sites from the project 5 element of the INQUIRE study (see Chapter 6).

Survey variables

The survey was designed to identify who uses or has had experience of using online sources of patient feedback and their attitudes towards this type of commentary. We drew on previously conducted research49,81 and on policy documents and reports by online feedback organisations,116 to determine the key elements. The survey comprised eight questions on demographic and professional characteristics and six topic-based questions related to online feedback (see Appendix 13). For the doctors’ survey, there was an additional free-text question, ‘If you would like to leave a comment about online patient feedback please do so here’. It was not possible to add this question to the survey of nurses (see Recruitment and data collection).

Attitudinal questions used Likert scales. The survey questions were piloted in two ways: (1) the survey company commissioned to administer the survey (see Recruitment and data collection for details) to doctors provided guidance and feedback on the survey questions and possible response options based on its extensive experience of surveying doctors on a range of topics; and (2) individual local clinicians provided feedback on the wording and order of questions through various iterations of the survey. Our lay co-investigator provided feedback on the survey questions at each iteration.

Recruitment and data collection

The online survey of doctors was administered by Doctors.net.uk, a UK online portal and network for the medical profession with around 200,000 members. Doctors.net has been widely used in academic surveys of doctors. 117,118 The survey was administered online via this platform to a quota-sampled119 representative group of secondary care (across specialties) and primary care doctors. Doctors received a direct invitation via e-mail, based on information from their individual Doctors.net profile. Doctors were sent the invitation until 1000 participants were recruited. All study participants were entered into a prize draw.

There was no equivalent route available to survey nurses and midwives. Instead, the same survey questions were included in a wider survey about how nurses and midwives use digital technologies. The online survey link was distributed by the Royal College of Nursing (RCN) via targeted e-mails sent to RCN nursing forums for e-health, midwifery, district nursing and RCN children and young people. It was also distributed via RCN online bulletins and the RCN Twitter feed (@theRCN; Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA). In order to bolster the sample, the link to the survey was distributed to 10,000 people registered with the Nursing Times. The survey ran from 17 May to 29 September 2016.