Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/46/02. The contractual start date was in December 2015. The final report began editorial review in December 2018 and was accepted for publication in August 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Andrew Judge reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme, during the conduct of the study; that he is a subpanel member of the NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research programme (1 September 2015 to present); that he has received personal fees from Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer (London, UK); and that he is a member of the Data Safety and Monitoring Board (which involved receipt of fees) from Anthera Pharmaceuticals (Hayward, CA, USA). Andrew Price reports personal fees from Zimmer Biomet (Warsaw, IN, USA), DePuy (Raynham, MA, USA) and Smith & Nephew (London, UK); and grants from NIHR and Versus Arthritis (Chesterfield, UK), outside the submitted work. Cyrus Cooper reports personal fees from Alliance for Better Bone Health [Proctor & Gamble Pharmaceuticals, Inc. (Cincinnati, OH, USA) and Sanofi S.A. (Paris, France)], Amgen Inc. (Thousand Oaks, CA, USA), Eli Lilly and Company (Indianapolis, IN, USA), GlaxoSmithKline (Brentford, UK), Medtronic plc (Dublin, Ireland), Merck Sharp & Dohme (Kenilworth, NJ, USA), Novartis International AG (Basel, Switzerland), Pfizer Inc. (New York, NY, USA), F. Hoffmann-La Roche AG (Basel, Switzerland), Servier Laboratories (Suresnes, France), Takeda Pharmaceutical Company (Tokyo, Japan) and UCB Biopharma (Brussels, Belgium). Daniel Prieto-Alhambra is a member of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment Clinical Trials Committee (1 March 2018 to present); he reports grants from Amgen Inc., UCB Biopharma and Servier Laboratories and other from Janssen (Beerse, Belgium), outside the submitted work. George Peat holds an honorary public health academic contract with Public Health England (London, UK). Nigel Arden reports grants from the NIHR HSDR programme during the conduct of the study; grants from Bioiberica (Barcelona, Spain) and Merck Sharp & Dohme; and personal fees from Flexion Therapeutics (Burlington, MA, USA), Regeneron Pharmaceuticals (Tarrytown, NY, USA), Freshfields Bruckhaus Deringer, Eli Lilly and Company and Pfizer Inc., outside the submitted work.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Judge et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Hospital Episode Statistics1 and patient-reported outcome measures2 data were made available by NHS Digital, and re-used with the permission of NHS Digital. All rights reserved.

Background

Osteoarthritis presents an important health burden as the population becomes older and increasingly obese. 3 Almost half of those aged > 75 years seek medical care for osteoarthritis, with a large impact on health-care costs and health-related quality of life. 4 It is a leading cause of worldwide disability, with an estimated annual loss of productivity cost of £3.2B in the UK,5 with pain being the primary symptom that causes people to seek out pharmacological (e.g. prescription analgesia) and non-pharmacological (e.g. exercise programmes supervised by physiotherapists) treatment and, in severe cases, joint replacement surgery. Over 200,000 people with severe hip or knee pain caused by osteoarthritis have joint replacement surgery each year in the NHS, and this number is expected to increase. 6

A 2010 White Paper7 outlined the future of the NHS, making it more accountable to patients through greater choice and information, with a strong focus on clinical outcomes. To shift decision-making as close as possible to individual patients, the government has devolved power and responsibility for commissioning services to general practitioners (GPs) and their practice teams working in consortia. The NHS Act 2006,8 as amended by the Health and Social Care Act 2012,9 places duties on the NHS Commissioning Board and Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) to have regard to the need to reduce variations in access to, and outcomes from, health-care services for patients, and to assess and report on how well they have fulfilled this duty.

There are well-known geographical variations in the uptake of common surgical procedures, including total hip replacement (THR) and total knee replacement (TKR),10,11 as publicised through The NHS Atlas of Variation in Healthcare. 12 A recent study found evidence of significant unexplained variation among hospitals in both health outcomes and resource use following THR or TKR,13 but little is known about factors that can explain why such variation exists. In the NHS, as part of the Patient Choice Agenda,14 patients can choose which hospital they want to have their surgery in. Information on the outcomes of surgery between different hospitals would help patients in making their decision. Geographical variation in outcomes of surgery may be explained by a hospital treating more complex, sick patients. However, differences in patient outcomes could also be explained by how hospitals organise their services,10 such as bed availability, numbers of operating theatres and specialist surgeons, using new surgical techniques, such as minimally invasive surgery,10 or centralising care into specialist high-volume hospitals. 15,16

Between April 2009 and March 2011, the Department of Health and Social Care established an Enhanced Recovery Partnership Programme17 to support the NHS to implement and realise the benefits of enhanced recovery in colorectal, musculoskeletal, gynaecological and urological major elective surgical pathways. Through this programme, a new ‘enhanced recovery’ patient pathway for THR and TKR has now been introduced across all NHS hospitals. 18 Enhanced recovery is a complex intervention19,20 that focuses on key areas of care across the pathway: preoperatively (for the patient to be in the best possible condition for surgery), perioperatively (the patient has the best possible management during and after their operation) and postoperatively (the patient experiences the best rehabilitation). It is hoped that this will benefit patients through patient education before and after surgery, which includes making changes around the home, doing exercises to strengthen the joint and changing diet to help reduce the risk of complications and speed up recovery. Patients for whom it is suitable will benefit further by being able to return home earlier to continue their recuperation at home with appropriate support. This in turn will benefit the hospital by freeing up space for other patients on the waiting list. A greater number of frail older people with complex comorbid conditions now receive THR or TKR. The new enhanced recovery pathway (ERP) could specifically benefit these patient groups. 21

There is limited evidence concerning the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of enhanced recovery programmes in TKR and THR. 22 There is a need for information on what the core active ingredients are and how they are exerting their effect. 20 This is important because, when implemented nationwide in diverse hospital settings, the intervention may be adapted to local circumstances that inhibit its effectiveness. 23 A recent synthesis of evidence about effectiveness and implementation of enhanced recovery programmes highlights ‘barriers’ to and ‘facilitators’ of implementation. 22 Barriers include resistance to change, inadequate funding, lack of support from management, high staff turnover, poor documentation and shortness of time. Facilitators include a dedicated enhanced recovery lead, the presence of multidisciplinary team working, and ongoing education for staff and patients. Studies of patients’ experiences of enhanced recovery following colorectal surgery have been carried out,24–26 but we know little about experiences for TKR and THR, or the elements of pathway-driven care that patients like most and least. Organisational processes and collaboration between professionals are crucial to the delivery of safe and satisfactory care,27 but the organisational contexts that can support or inhibit delivery of enhanced recovery have not been explored.

Aims

To determine the effect of hospital organisation, surgical factors and the ERP on patient outcomes and NHS costs of hip and knee replacement.

Objectives

-

Identification of hospital organisation, surgical factors and the ERP as determinants of geographical variation in patient outcomes and NHS costs.

-

Natural experiment to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the enhanced recovery treatment pathway.

-

Qualitative study (process evaluation) on implementation of ERPs in four hospital settings.

Design and methodology

The project comprises a patient forum and two main work packages. The project began with a patient forum to identify the outcomes that matter most to THR and TKR patients (patient-identified outcomes). Findings from the forum inform the primary and secondary outcomes of the study.

Work package 1

Work package 1 aims to explore geographical variation in patient outcomes of surgery. Using Hospital and Community Health Service (HCHS), KH03 and Supporting Facilities data sets linked to the National Joint Registry (NJR), Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) and patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), we explore how hospital organisational factors (e.g. staff, beds, operating theatres) and surgical factors (e.g. minimally invasive technique, surgeon volume, operative time, implant fixation, thromboprophylaxis) explain geographical variation in patient outcomes, adjusting for patient case mix. The results are displayed as maps, highlighting the level of variation in patient outcomes across CCGs.

Work package 2

Work package 2 focuses specifically on the enhanced recovery care pathway.

Process evaluation

Here we characterise the enhanced recovery intervention as used in practice in different hospital settings (tertiary care centre of excellence, teaching hospital, district general hospital, private hospital) and understand organisational processes that enable or impede implementation of the ERP. The qualitative work uses an ethnographic approach.

Natural experiment

We evaluate the impact that the ERP has had on NHS costs and patient outcomes [PROMs, length of stay (LOS), complications, revision]. We used interrupted time series analysis to examine changes in secular trends in outcomes and NHS costs before and after the introduction of the new treatment pathway.

Economic evaluation

This describes the hospital and non-hospital NHS costs for THR and TKR, and the cost-effectiveness of the ERP.

Chapter 2 Data sources

National Joint Registry

Starting in 2003, the NJR6 has collected information on all hip and knee replacements performed each year in both public and private hospitals in England, Wales and, since 2012, Northern Ireland. Data are entered into the NJR using forms completed by surgeons at the time of surgery and revision operations are linked using unique patient identifiers.

Hospital Episode Statistics

The HES database holds information on all patients admitted to NHS hospitals in England, including diagnostic International Classification of Diseases codes, providing information about a patient’s illness or condition, and Operating Procedure Codes Classification of Interventions and Procedures (OPCS-4) procedural codes for surgery. It covers a smaller geographical area than the NJR and does not include privately funded operations. Data for all-cause mortality are provided by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and linked to the HES database.

Patient-reported outcome measures

Since April 2009, PROM28 data have been collected on hip and knee replacements performed in public hospitals in England. Preoperative and 6-month quality-of-life questionnaires [the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)29] and joint-specific PROMs [the Oxford Hip Score (OHS)30 and Oxford Knee Score (OKS)31] are collected.

Clinical Practice Research Datalink

The Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD),32 formerly the General Practice Research Database, was established in 1987 and contains anonymised individual patient data from electronic primary health-care records from practices across the UK. Data cover clinical and referral events in primary and secondary care, and comprehensive demographic information, medication prescription data, clinical events, specialist referrals, hospital admissions and their major outcomes. As of June 2017, 693 general practices contributed data to the CPRD. In total, data from an estimated 14.2 million patients are available within the CPRD, of whom 2.8 million were active in 2017.

Hospital organisational characteristics

The NHS HCHS Workforce Statistics in England provide details on the workforce within NHS organisations, including numbers of consultants and specialties (e.g. trauma and orthopaedic, anaesthetists), registrars and other doctors in training. The NHS quarterly Bed Availability and Occupancy data set has data on the number of available beds and occupied beds, whereas the Supporting Facilities data set provides information on operating theatres and dedicated day-case theatres. The data are published quarterly and can be linked to HES data through the hospital provider code. 10

Data applications

National Joint Registry, Hospital Episode Statistics and patient-reported outcome measures

Approval for NJR data was received on 8 July 2016 (NJR internal reference RSC2016/11). Confidentiality Advisory Group section 251 approval was received on 20 September 2016 (Confidentiality Advisory Group reference 16/CAG/0111). A Data Access Request Service application was made to NHS Digital for HES and PROMs data to be linked to data from the NJR. This was approved, with the data-sharing agreement signed on 23 January 2016. Data from the NJR were received on 14 March 2017. HES and PROM data were made available to download on 7 April 2017.

Clinical Practice Research Datalink, Hospital Episode Statistics and patient-reported outcome measures

Independent Scientific Advisory Committee approval was received on 5 July 2016 (protocol number 11_050AMnA2R). The CPRD subsequently announced a new linkage to PROMs, so a further Independent Scientific Advisory Committee amendment was submitted and approval was obtained on 10 January 2017 (protocol number 11_050 AMnA2RA2). CPRD data linked to inpatient and outpatient HES were received on 9 May 2017 and linked PROMs data were received on 25 July 2017.

Data summary

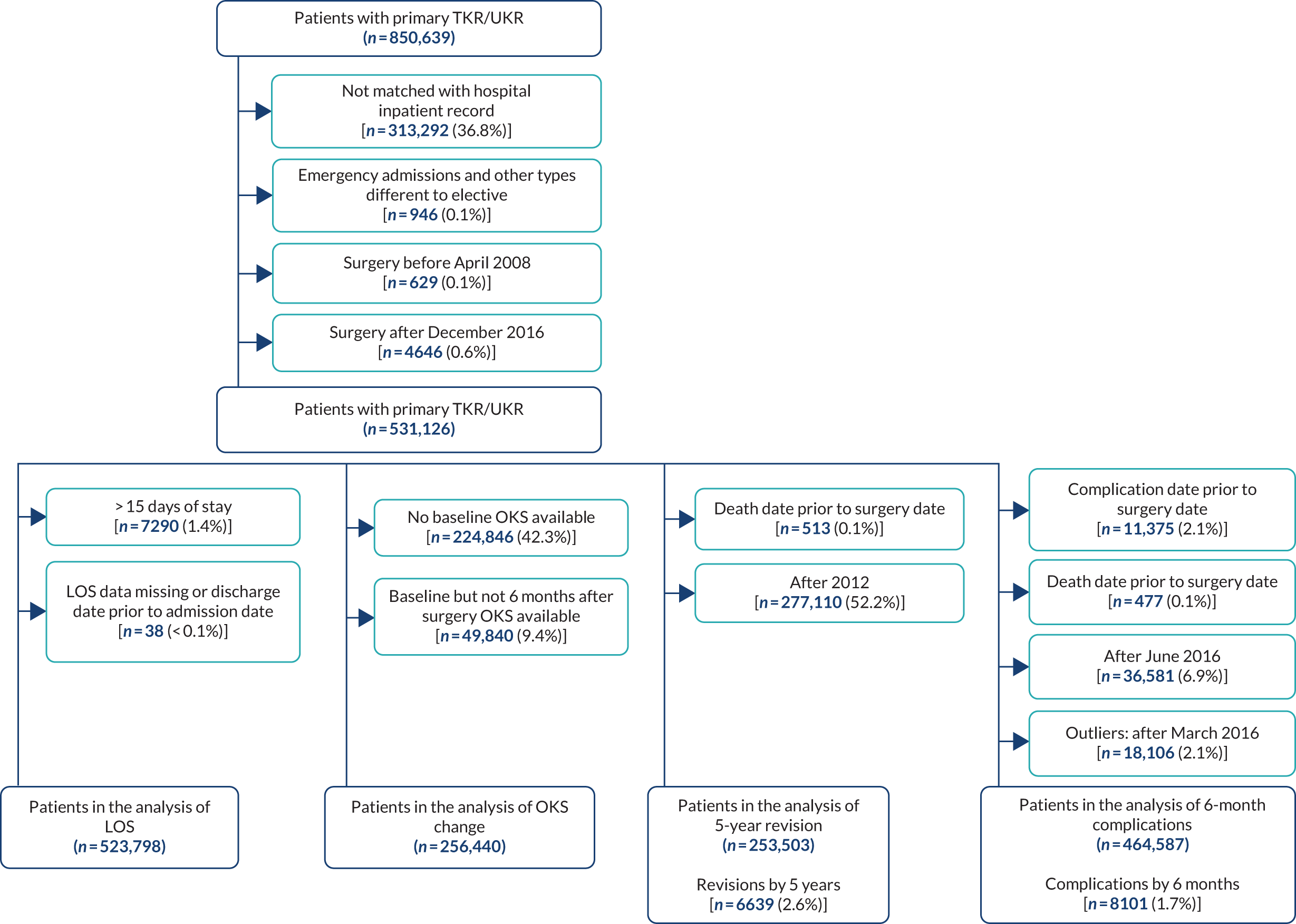

Data were available on 746,822 primary THRs from the NJR (2003–17). HES data were obtained for years 2008–17, of which 445,611 could be linked to NJR data. PROMs data (2009–16) were available for 229,025 patients with complete preoperative and 6-month postoperative OHSs (Figure 1). There were 841,139 primary TKRs and unicompartmental knee replacements (UKRs) in the NJR (2003–17), with HES data (2008–17) linked for 531,790 patients and PROM data (2009–17) linked for 258,297 patients, with preoperative and 6-month postoperative OKSs (Figure 2).

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram on selection of primary THR patients. Navy shows inclusion; light blue shows exclusion.

FIGURE 2.

Flow diagram on selection of primary TKR patients. Navy shows inclusion; light blue shows exclusion.

In the CPRD data, we have 72,339 primary THRs and 64,071 primary TKRs from 1995 to 2017. Linked HES data were available for 42,204 hips and 38,606 knees. PROM data from 2009 onwards were linked to 5184 hips and 5352 knees.

Descriptive summary statistics of the variables available for analysis from the NJR (Table 1), HES (Table 2), hospital organisational factor (Table 3) and PROMs (Table 4) linked data sets are described below.

| Category | Unilateral primary hip replacements | Unilateral primary knee replacements |

|---|---|---|

| Total (n) | 440,640 | 531,524 |

| Age (years) at operation | ||

| Mean (SD) | 69.1 (10.8) | 69.6 (9.5) |

| Range | 18–117 | 18–102 |

| Age categories (years), n (%) | ||

| < 50 | 21,045 (4.8) | 12,205 (2.3) |

| 50–59 | 57,333 (13.0) | 65,771 (12.4) |

| 60–69 | 131,691 (29.9) | 175,354 (33.0) |

| 70–79 | 158,015 (35.9) | 197,931 (37.2) |

| 80–84 | 48,300 (11.0) | 55,868 (10.5) |

| ≥ 85 | 24,256 (5.5) | 24,395 (4.6) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 263,961 (59.9) | 302,295 (56.9) |

| Male | 176,679 (40.1) | 229,229 (43.1) |

| Side, n (%) | ||

| Right | 196,585 (44.6) | 252,958 (47.6) |

| Left | 244,055 (55.4) | 278,566 (52.4) |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 28.9 (5.2) | 31.0 (5.4) |

| Range | 16–60 | 16–60 |

| Missing, n (%) | 124,706 (28.3) | 150,496 (28.3) |

| ASA grade, n (%) | ||

| P1 | 59,934 (13.6) | 52,158 (9.8) |

| P2 | 310,596 (70.5) | 391,903 (73.7) |

| P3 | 68,326 (15.5) | 85,949 (16.2) |

| P4 | 1769 (0.4) | 1494 (0.3) |

| P5 | 15 (0.0) | 20 (0.0) |

| Year of primary hip replacement, n (%) | ||

| 2007 | 1 (0.0) | |

| 2008 | 29,070 (6.6) | 34,130 (6.4) |

| 2009 | 39,279 (8.9) | 46,892 (8.8) |

| 2010 | 44,717 (10.2) | 53,130 (10.0) |

| 2011 | 47,312 (10.7) | 57,285 (10.8) |

| 2012 | 50,793 (11.5) | 60,679 (11.4) |

| 2013 | 52,836 (12.0) | 62,168 (11.7) |

| 2014 | 57,156 (13.0) | 69,600 (13.1) |

| 2015 | 57,536 (13.1) | 70,686 (13.3) |

| 2016 | 58,416 (13.3) | 72,350 (13.6) |

| 2017 | 3525 (0.8) | 4603 (0.9) |

| Type of surgeon, n (%) | ||

| Other | 84,646 (19.2) | 110,724 (20.8) |

| Consultant | 355,994 (80.8) | 420,800 (79.2) |

| Type of approach, n (%) | ||

| Other | 166,376 (37.8) | |

| Posterior | 274,264 (62.2) | |

| Lateral parapatellar | 4911 (0.9) | |

| Medial parapatellar | 495,866 (93.3) | |

| Mid-vastus | 16,015 (3.0) | |

| Subvastus | 6094 (1.2) | |

| Other | 8638 (1.6) | |

| Primary indication, n (%) | ||

| Osteoarthritis | 426,826 (96.9) | 525,652 (98.9) |

| Osteoarthritis and other | 13,814 (3.1) | 5872 (1.1) |

| Primary thromboprophylaxis, n (%) | ||

| None | 13,373 (3.0) | 18,967 (3.6) |

| Aspirin only | 21,716 (4.9) | 28,905 (5.4) |

| LMWH (± other) | 289,732 (65.8) | 384,276 (72.3) |

| Other (no LMWH) | 115,819 (26.3) | 99,376 (18.7) |

| Primary mechanical prophylaxis, n (%) | ||

| None | 26,306 (6.0) | 29,036 (5.5) |

| Any | 414,334 (94.0) | 502,488 (94.5) |

| Primary graft femur, n (%) | ||

| None | 437,943 (99.4) | 526,675 (99.1) |

| Any | 2697 (0.6) | 4849 (0.9) |

| Primary graft tibia, n (%) | ||

| None | 529,515 (99.6) | |

| Any | 2009 (0.4) | |

| Primary complication, n (%) | ||

| None | 433,428 (99.0) | 528,917 (99.5) |

| One or more | 4438 (1.0) | 2607 (0.5) |

| Missing | 2774 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Primary cup fixation, n (%) | ||

| Uncemented cup | 275,877 (63.3) | |

| Cemented cup | 160,131 (36.7) | |

| Missing | 4632 (1.1) | |

| Primary fixation, n (%) | ||

| Cementless | 22,865 (4.3) | |

| Cemented | 504,910 (95.1) | |

| Hybrid | 3359 (0.6) | |

| Missing | 390 (0.1) | |

| Type of primary implant, n (%) | ||

| MoM resurfacing | 7803 (1.8) | |

| THR (any bearing) | 423,499 (98.2) | |

| Missing | 9338 (2.1) | |

| Type of resurfacing stem fix, n (%) | ||

| Cemented HR stem | 7097 (91.0) | |

| Uncemented HR stem | 706 (9.1) | |

| THR or missing | 432,837 (98.2) | |

| Femoral fixation, n (%) | ||

| Cementless | 25,219 (4.8) | |

| Cemented | 499,559 (95.2) | |

| Missing | 6746 (1.3) | |

| Tibial fixation, n (%) | ||

| Cementless | 23,158 (4.4) | |

| Cemented | 498,538 (95.6) | |

| Missing | 9828 (1.8) | |

| Type of primary stem fixation, n (%) | ||

| Uncemented THR stem | 193,118 (45.4) | |

| Cemented THR stem | 232,520 (54.6) | |

| Resurfacing or missing | 15,002 (3.4) | |

| Type of primary bearing, n (%) | ||

| MoM | 16,175 (3.8) | |

| Non-MoM | 412,223 (96.2) | |

| Missing | 12,242 (2.8) | |

| Details of primary bearing, n (%) | ||

| MoM | 16,175 (3.8) | |

| MoP | 263,520 (61.5) | |

| CoC | 68,487 (16.0) | |

| CoP | 78,878 (18.4) | |

| CoM | 1245 (0.3) | |

| MoC | 93 (0.0) | |

| Missing | 12,242 (2.8) | |

| Primary implant type, n (%) | ||

| MoM THR | 8372 (2.0) | |

| HR | 7803 (1.8) | |

| Non-MoM THR | 412,223 (96.2) | |

| Unicondylar/hinged/linked/custom/preassembled | 40,471 (7.7) | |

| Bicondylar | 484,529 (92.3) | |

| Missing | 12,242 (2.8) | 6524 (1.2) |

| Primary head size (mm), n (%) | ||

| ≤ 28 | 172,885 (40.1) | |

| 32 | 145,693 (33.8) | |

| 36–42 | 101,341 (23.5) | |

| 44–48 | 5346 (1.2) | |

| 50–52 | 4510 (1.1) | |

| ≥ 54 | 1527 (0.4) | |

| Missing | 9338 (2.1) | |

| Minimally invasive, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 17,911 (4.1) | 27,999 (5.3) |

| No | 422,729 (95.9) | 503,525 (94.7) |

| Unit type, n (%) | ||

| Public hospital | 336,285 (76.3) | 403,302 (75.9) |

| Independent hospital | 82,109 (18.6) | 100,399 (18.9) |

| Independent treatment centre | 22,246 (5.1) | 27,823 (5.2) |

| Surgical volume per consultant | ||

| Mean (SD) | 98.0 (80.5) | 88.4 (60.4) |

| Range | 1–693 | 1–434 |

| Resurfacing volume per consultant | ||

| Mean (SD) | 2.3 (8.7) | |

| Range | 0–160 | |

| Missing, n (%) | 12,242 (2.8) | |

| THR volume per consultant | ||

| Mean (SD) | 94.7 (78.3) | |

| Range | 0–687 | |

| Missing, n (%) | 12,242 (2.8) | |

| TKR volume per consultant | ||

| Mean (SD) | 79.3 (54.3) | |

| Range | 0–409 | |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | |

| UKR volume per consultant | ||

| Mean (SD) | 8.0 (16.7) | |

| Range | 0–218 | |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | |

| PFJR volume per consultant | ||

| Mean (SD) | 1.1 (2.7) | |

| Range | 0–56 | |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Surgical volume per unit | ||

| Mean (SD) | 341.3 (253.0) | 383.5 (266.2) |

| Range | 1–1286 | 1–1633 |

| Resurfacing surgical volume per unit | ||

| Mean (SD) | 6.8 (17.9) | |

| Range | 0–192 | |

| Missing, n (%) | 12,242 (2.8) | |

| THR surgical volume per unit | ||

| Mean (SD) | 328.0 (243.9) | |

| Range | 0–1272 | |

| Missing, n (%) | 12,242 (2.8) | |

| TKR surgical volume per unit | ||

| Mean (SD) | 348.0 (243.0) | |

| Range | 0–1429 | |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | |

| UKR surgical volume per unit | ||

| Mean (SD) | 30.9 (43.8) | |

| Range | 0–384 | |

| Missing, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | |

| PFJR surgical volume per unit | ||

| Mean (SD) | 4.6 (6.1) | |

| Range | 0–67 | |

| Outcome, n (%) | ||

| Death | 33,473 (7.6) | 36,921 (7.0) |

| Revised | 7600 (1.7) | 10,293 (1.9) |

| Unrevised | 399,179 (90.7) | 484,308 (91.1) |

| Missing | 388 (0.1) | 2 (0.0) |

| Time to revision (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 2.2 (2.2) | 2.4 (1.7) |

| Range | 0–9 | 0–9 |

| Not revised or missing, n (%) | 433,040 (98.3) | 521,231 (98.1) |

| Time to death (years) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 3.6 (2.1) | 3.7 (2.1) |

| Range | 0–9 | 0–9 |

| Alive or missing, n (%) | 406,535 (92.3) | 494,603 (93.1) |

| Category | Unilateral primary hip replacements | Unilateral primary knee replacements |

|---|---|---|

| Total (n) | 440,640 | 531,524 |

| IMD quintiles at primary surgery, n (%) | ||

| Least deprived (20%) | 106,613 (24.2) | 115,670 (21.8) |

| Less deprived (20–40%) | 108,818 (24.7) | 122,769 (23.1) |

| Less deprived (40–60%) | 79,678 (18.1) | 101,703 (19.1) |

| More deprived (20–40%) | 74,417 (16.9) | 97,473 (18.3) |

| Most deprived (20%) | 71,114 (16.1) | 93,909 (17.7) |

| Rurality at primary surgery, n (%) | ||

| Urban ≥ 10,000 population | 315,071 (71.5) | 398,650 (75.0) |

| Town and fringe | 56,321 (12.8) | 62,623 (11.8) |

| Village/isolated | 69,248 (15.7) | 70,251 (13.2) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White | 386,149 (97.3) | 451,169 (93.4) |

| Non-white | 10,806 (2.7) | 32,103 (6.6) |

| Missing | 43,685 (9.9) | 48,252 (9.1) |

| Comorbidities at primary surgery, n (%) | ||

| None | 326,661 (74.1) | 374,092 (70.4) |

| Mild | 80,211 (18.2) | 113,913 (21.4) |

| Moderate | 22,785 (5.2) | 30,315 (5.7) |

| Severe | 10,983 (2.5) | 13,204 (2.5) |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index, n (%) | ||

| AIDS | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Metastatic solid tumour | 628 (0.1) | 323 (0.1) |

| Severe liver disease | 1072 (0.2) | 1135 (0.2) |

| Lymphoma | 389 (0.1) | 384 (0.1) |

| Leukaemia | 610 (0.1) | 666 (0.1) |

| Non-metastatic tumour | 4784 (1.1) | 4979 (0.9) |

| Diabetes mellitus with end organ damage | 1090 (0.3) | 1711 (0.3) |

| Moderate–severe renal disease | 18,249 (4.1) | 22,028 (4.1) |

| Hemiplegia | 505 (0.1) | 709 (0.1) |

| Dementia | 1380 (0.3) | 1224 (0.2) |

| Chronic pulmonary disease | 56,225 (12.8) | 74,930 (14.1) |

| Mild diabetes mellitus (without end organ damage – includes ketoacidosis and coma) | 40,035 (9.1) | 67,315 (12.7) |

| Mild liver disease | 525 (0.1) | 806 (0.2) |

| Peptic ulcer disease | 610 (0.1) | 872 (0.2) |

| Peripheral vascular disease | 4048 (0.9) | 4235 (0.8) |

| Stroke/cerebrovascular disease | 1623 (0.4) | 1926 (0.4) |

| Congestive heart failure | 1643 (0.4) | 1624 (0.3) |

| Myocardial infarction | 481 (0.1) | 375 (0.1) |

| Complication within 6 months, n (%) | ||

| Stroke | 839 (0.2) | 999 (0.2) |

| Respiratory infection | 2977 (0.7) | 3124 (0.6) |

| Acute myocardial infarction | 941 (0.2) | 1099 (0.2) |

| Pulmonary embolism/deep-vein thrombosis | 1865 (0.4) | 2193 (0.4) |

| Urinary tract infection | 3258 (0.7) | 3676 (0.7) |

| Wound disruption | 786 (0.2) | 1609 (0.3) |

| Surgical site infection | 2028 (0.5) | 3136 (0.6) |

| Fracture after implant | 455 (0.1) | 179 (0.0) |

| Complication of prosthesis | 4590 (1.0) | 4250 (0.8) |

| Neurovascular injury | 70 (0.0) | 128 (0.0) |

| Acute renal failure | 2031 (0.5) | 2537 (0.5) |

| Blood transfusion | 526 (0.1) | 414 (0.1) |

| Revision NJR + HES, n (%) | 8622 (2.0) | 13,626 (2.6) |

| Reoperations only, n (%) | 1616 (0.4) | 2722 (0.5) |

| LOS (days) | ||

| Mean (SD) | 4.8 (3.8) | 4.7 (3.6) |

| Range | 0–378 | 0–737 |

| Missing, n (%) | 35 (0.0) | 36 (0.0) |

| Readmission within 6 months, n (%) | 87,675 (19.9) | 120,034 (22.6) |

| Category | Unilateral primary hip replacements | Unilateral primary knee replacements |

|---|---|---|

| FTE (n) | 440,640 | 531,524 |

| Specialty group | ||

| Trauma and orthopaedic surgery | ||

| Median (IQR) | 41.1 (29.9–56.9) | 40.9 (29.9–56.6) |

| Range | 0.1–115.5 | 10.4–115.5 |

| Missing, n (%) | 167,434 (38.0) | 202,251 (38.1) |

| Rehabilitation medicine | ||

| Median (IQR) | 3.3 (1.5–6.7) | 3.0 (1.0–6.6) |

| Range | 0.2–21.0 | 0.2–21.0 |

| Missing, n (%) | 330,039 (74.9) | 401,909 (75.6) |

| Grade | ||

| Consultant | ||

| Median (IQR) | 34.5 (23.8–50.4) | 34.9 (24.0–51.3) |

| Range | 1.0–143.3 | 1.0–143.3 |

| Missing, n (%) | 167,916 (38.1) | 202,682 (38.1) |

| Middle-grade doctor | ||

| Median (IQR) | 20.8 (13.1–31.8) | 21.1 (13.3–32.5) |

| Range | 1.0–116.2 | 1.0–116.2 |

| Missing, n (%) | 173,421 (39.4) | 208,469 (39.2) |

| Trainee doctor | ||

| Median (IQR) | 9.0 (5.0–13.0) | 9.0 (6.0–14.0) |

| Range | 0.6–37.0 | 0.6–37.0 |

| Missing, n (%) | 200,001 (45.4) | 237,983 (44.8) |

| Beds: specialty group | ||

| Trauma and orthopaedic surgery (overnight) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 69.0 (50.5–91.9) | 68.2 (50.4–92.2) |

| Range | 0.0–167.2 | 0.0–167.2 |

| Missing, n (%) | 163,889 (37.2) | 197,443 (37.1) |

| Rehabilitation (overnight) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 0.0 (0.0–16.8) | 0.0 (0.0–16.7) |

| Range | 0.0–164.1 | 0.0–164.1 |

| Missing, n (%) | 163,889 (37.2) | 197,443 (37.1) |

| Anaesthetics (overnight) | ||

| Median (IQR) | 0.0 (0.0–16.8) | 0.0 (0.0–16.7) |

| Range | –0.1 to 40.1 | –0.1 to 40.1 |

| Missing, n (%) | 163,889 (37.2) | 197,443 (37.1) |

| Beds: total available | ||

| Overnight | ||

| Median (IQR) | 764.2 (541.8–1024.9) | 778.8 (557.6–1040.2) |

| Range | 0.0–2195.8 | 0.0–2195.8 |

| Missing, n (%) | 147,090 (33.4) | 177,083 (33.3) |

| Number of operating theatres | ||

| Median (IQR) | 20 (14–29) | 21 (14–30) |

| Range | 2–63 | 2–63 |

| Missing, n (%) | 93,737 (21.3) | 113,194 (21.3) |

| Number of dedicated day-case theatres | ||

| Median (IQR) | 4 (2–6) | 4 (2–6) |

| Range | 0–17 | 0–17 |

| Missing, n (%) | 93,737 (21.3) | 113,194 (21.3) |

| Category | Unilateral primary hip replacements | Unilateral primary knee replacements |

|---|---|---|

| Total (n) | 440,640 | 531,524 |

| OHS: follow-up at 6 months | ||

| Median (IQR) | 42 (34–46) | |

| Range | 0–48 | |

| Missing, n (%) | 214,080 (48.6) | |

| OHS: preoperative | ||

| Median (IQR) | 17 (11–23) | |

| Range | 0–48 | |

| Missing, n (%) | 173,399 (39.4) | |

| OKS: follow-up at 6 months | ||

| Median (IQR) | 36 (28–42) | |

| Range | 0–48 | |

| Missing, n (%) | 275,089 (51.8) | |

| OKS: preoperative | ||

| Median (IQR) | 18 (12–23) | |

| Range | 0–48 | |

| Missing, n (%) | 227,822 (42.9) | |

| EQ-5D: follow-up at 6 months | ||

| Median (IQR) | 0.80 (0.69–1.00) | 0.73 (0.62–0.88) |

| Range | –0.59 to 1.00 | –0.59 to 1.00 |

| Missing, n (%) | 214,787 (48.7) | 274,554 (51.7) |

| EQ-5D: preoperative | ||

| Median (IQR) | 0.26 (0.00–0.62) | 0.52 (0.06–0.69) |

| Range | –0.59 to 1.00 | –0.59 to 1.00 |

| Missing, n (%) | 176,497 (40.1) | 231,053 (43.5) |

| EQ-5D health scale change | ||

| Mean (SD) | 8.9 (22.8) | 3.4 (20.9) |

| Median (IQR) | 6 (–5 to 20) | 1 (–9 to 15) |

| Range | –100 to 100 | –100 to 100 |

| Missing, n (%) | 233,271 (52.9) | 296,581 (55.8) |

Chapter 3 Patient forum

Introduction

Among the priorities identified through the work of the James Lind Alliance Priority Setting Partnership for Hip/Knee Replacement was the need to involve patients to identify the outcomes that matter most to them (patient-identified outcomes). 33 We utilised the University of Bristol Musculoskeletal Research Unit’s patient involvement group: the Patient Experience Partnership in Research (PEP-R). 34 The PEP-R comprises 12 patients with musculoskeletal conditions, most of whom have had joint replacement and all of whom have experience of long-term pain.

Methodology

The session was organised and facilitated by Amanda Burston (patient and public involvement co-ordinator based at the University of Bristol’s Musculoskeletal Research Unit). At the forum session, patients were provided with a plain English description of the project and the outcome measures available in the data sets, sent out in advance, along with information on patient and public involvement in research. In the session, the patient and public involvement co-ordinator fostered discussion about the different outcome variables and, using consensus techniques, captured patients’ views about the outcomes that matter most to them. Views were linked to service users’ own individual experiences, which they were encouraged to share with others.

At the end of the meeting, the group’s views were collated and drafted into a brief report that was sent out to group members after the meeting. The meetings lasted around 2.5 hours, and included a comfort break, refreshments and opportunity for discussion. Patients were reimbursed for their time and expenses.

Results

Prior to the meeting, the group was given a list of eight outcomes for consideration and discussion: LOS, readmission, reoperation, revision surgery, complications, mortality, OHS and OKS on pain and function, and EQ-5D quality-of-life scores. The meeting began by refreshing the group on what the research project was about in relation to work package 1 (variation in patient outcomes of surgery) and work package 2 (ERP). The group was then asked to evaluate which patient outcomes are most important to them.

Top outcomes

Pain and function

It was suggested that when presenting geographic variation in outcomes of surgery, we should consider stratifying according to preoperative pain and function. The group agreed that stability and mobility are important.

Complications

Infection was the main issue. Everyone thought that infection was important. However, this was in the context of hospital-acquired infection, such as meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (S. aureus) (MRSA), rather than an infection in the hip or knee joint related to the operation itself. From earlier consultations with surgeon co-applicants, it was found that surgeons worry about different complications to patients. Surgeons are more worried about deep-vein thrombosis, rather than infection.

Mid-outcomes

Length of stay

It was agreed that the right LOS was not one size fits all, as there is no point in being sent home early if the support is not in place. The group agreed that LOS was an important outcome, but very dependent on the level of support at home.

Revision/reoperation/readmission

The group felt that revision, reoperation and readmission should be evaluated as one outcome. It was thought that if reoperation was 5 years later, rather than 10–20 years later, it would have a very different sentiment for the patient.

Mortality

Rate of mortality was ranked low by the group but it was thought that patients’ families may rank the outcome higher.

Other important outcomes and areas of discussion

-

Choice of pain relief.

-

Patient education on both pain relief and physiotherapy.

-

Continuity of care.

-

Length of time between discovery of problem and operation. This fed into the need to stratify according to preoperative pain and function when looking at patient outcomes, as the time taken to get to surgery can have an effect.

-

Managing expectations. A group member explained that a friend who had recently had a knee operation was disappointed with the results, as she expected to be able to go back to line dancing club two or three times a week without pain or difficulty with her knee.

-

The group agreed that patient satisfaction and overall outcomes are dependent on the patient’s overall outlook and positivity. It was also thought that, if there is a long time between diagnosis and surgery, then the patient becomes that much older, but the operation is not going to wind the clock back.

The group felt that the maps describing geographical variation in outcome need to be clear to patients about what hospitals include (e.g. some hospitals do not take more complex patients). Some group members explained that they chose certain hospitals because of reputation and ‘word of mouth’. One group member said that they found it difficult to find any information on outcomes when choosing a hospital, but that they made a final choice of hospital on infection rate. It was explained to the group that, for all outcomes, patient data will be adjusted for patient situation and comorbidities.

Chapter 4 Identification of hospital organisation and surgical factors as determinants of geographical variation in patient outcomes and NHS costs

Aims

Use the NJR, HES and PROMs linked data sets to identify patient, surgical and hospital organisational factors that can explain geographical variation in patient outcomes.

Methodology

Data source and sample size

Hospital organisational factors from the HCHS Workforce Statistics, the Bed Availability and Occupancy data set and the Supporting Facilities data set were linked to the NJR, HES and PROMs data via the hospital provider code. Details of the NJR, HES and PROMs linked data have been previously described in Chapter 2. For this analysis, we use the most recent 3 years of data, from 2014 to 2016.

Main outcome measures

The primary outcomes of interest are informed by the findings of the patient forum (as described in Chapter 3). As a measure of patient-reported pain and function, we used the absolute change in OHSs and OKSs. 30,31 Each question is scored between 0 (meaning worse symptoms) and 4 (denoting least symptoms). Scores from these 12 questions are added, getting a total score spanning from 0 (the worst possible score) to 48 (the best possible score). We calculated the difference between the total scores 6 months after the operation and at baseline to obtain a measure of change associated with the surgery.

Further outcomes included the proportion of complications at 6 months after surgery. For a list of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10),35 codes used to identify complications of surgery, see Report Supplementary Material 1. We defined complications as one or more from the following list: stroke (excluding transient ischaemic attack), respiratory infection, acute myocardial infarction, pulmonary embolism/deep-vein thrombosis, urinary tract infection, wound disruption, surgical site infection, fracture after implant, complication of prosthesis, neurovascular injury, acute renal failure and blood transfusion. For a list of the OPCS-4 codes used to identify blood transfusion complication, see Report Supplementary Material 2. LOS was calculated as the number of days between the hospital admission and discharge date. We estimated the inpatient cost relating to the index episode using NHS Reference Costs from 2015–16. 36 We estimated the mean cost per bed-day based on the health-care resource use [Healthcare Resource Group (HRG)] for each patient and their LOS. For methods to support the estimation of bed-day cost, see Report Supplementary Material 3.

Predictor variables

Patient-level characteristics (case mix)

Age, sex, body mass index (BMI), area deprivation, rurality, ethnicity, Charlson Comorbidity Index, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade, baseline OHS/OKS, baseline EQ-5D, calendar year of primary THR/TKR, primary indication.

Surgical factors

Whether or not a minimally invasive technique was used, annual surgeon volume/caseload, grade of operating surgeon, surgical approach, patient position, implant fixation, type of mechanical or chemical thromboprophylaxis, anaesthetic type, type of bone graft if used.

Hospital organisational factors

Unit type (public, private, independent-sector treatment centre). As a measure of centralisation of services, we calculated the annual volume of procedures performed in each hospital trust. From the quarterly hospital surveys, we have information on hospital staffing according to the full-time equivalent (FTE) of specialty groups (trauma and orthopaedic surgery, rehabilitation medicine) and staff grades (consultants, middle-grade doctors, trainee doctors). Data on bed availability within specialty groups (trauma and orthopaedics, rehabilitation). We further obtained data on numbers of available operating theatres, including the number of dedicated day-case theatres.

Exclusion criteria

We included only patients receiving planned surgery (Figure 3) between 2014 and 2016. We excluded patients without information for the 2001 census lower-layer super output area. Patients with missing data for LOS were also excluded. We excluded patients without information on baseline and/or 6-month follow-up OHS/OKS scores for the analysis of change in OHS and OKS.

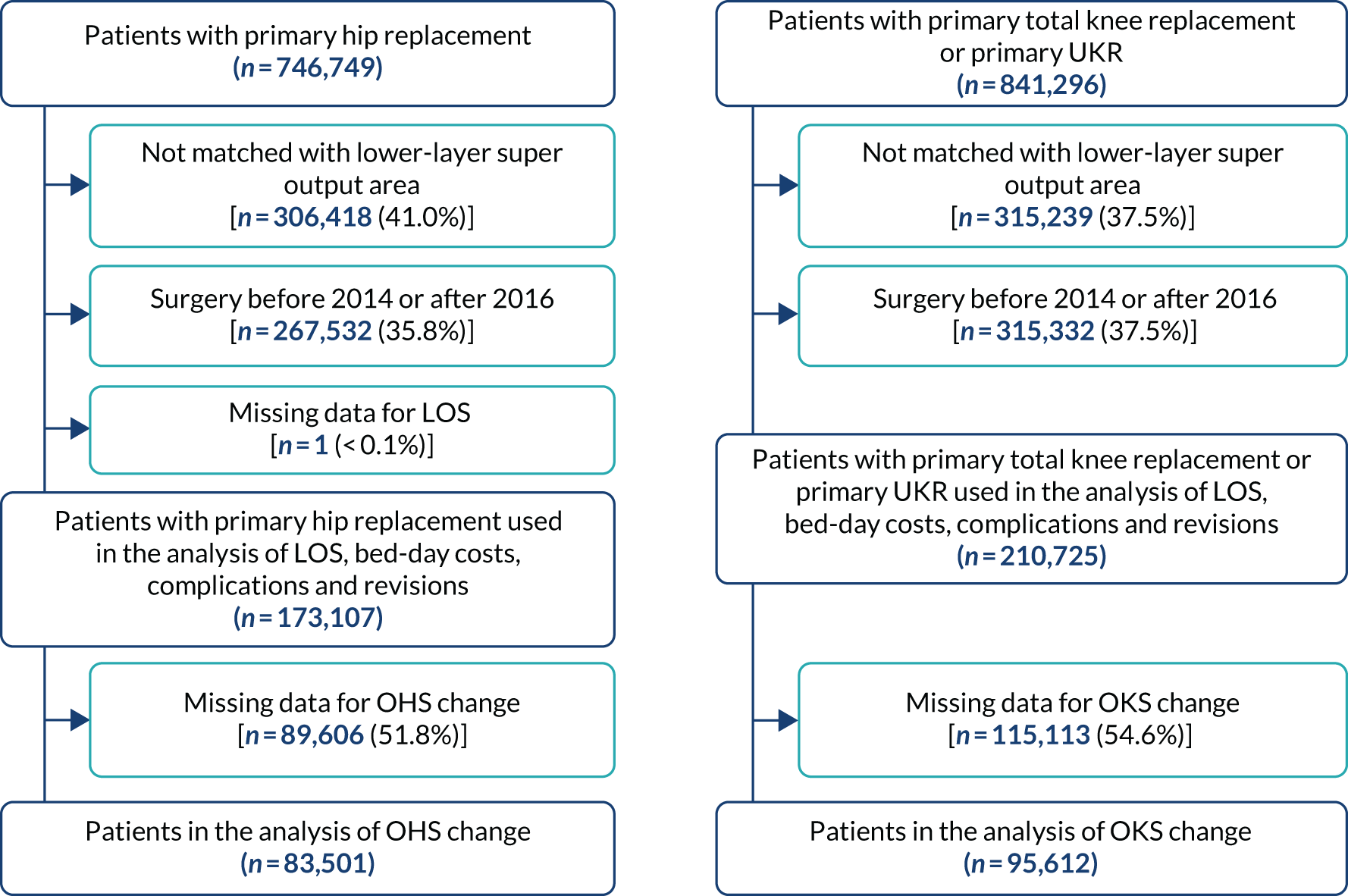

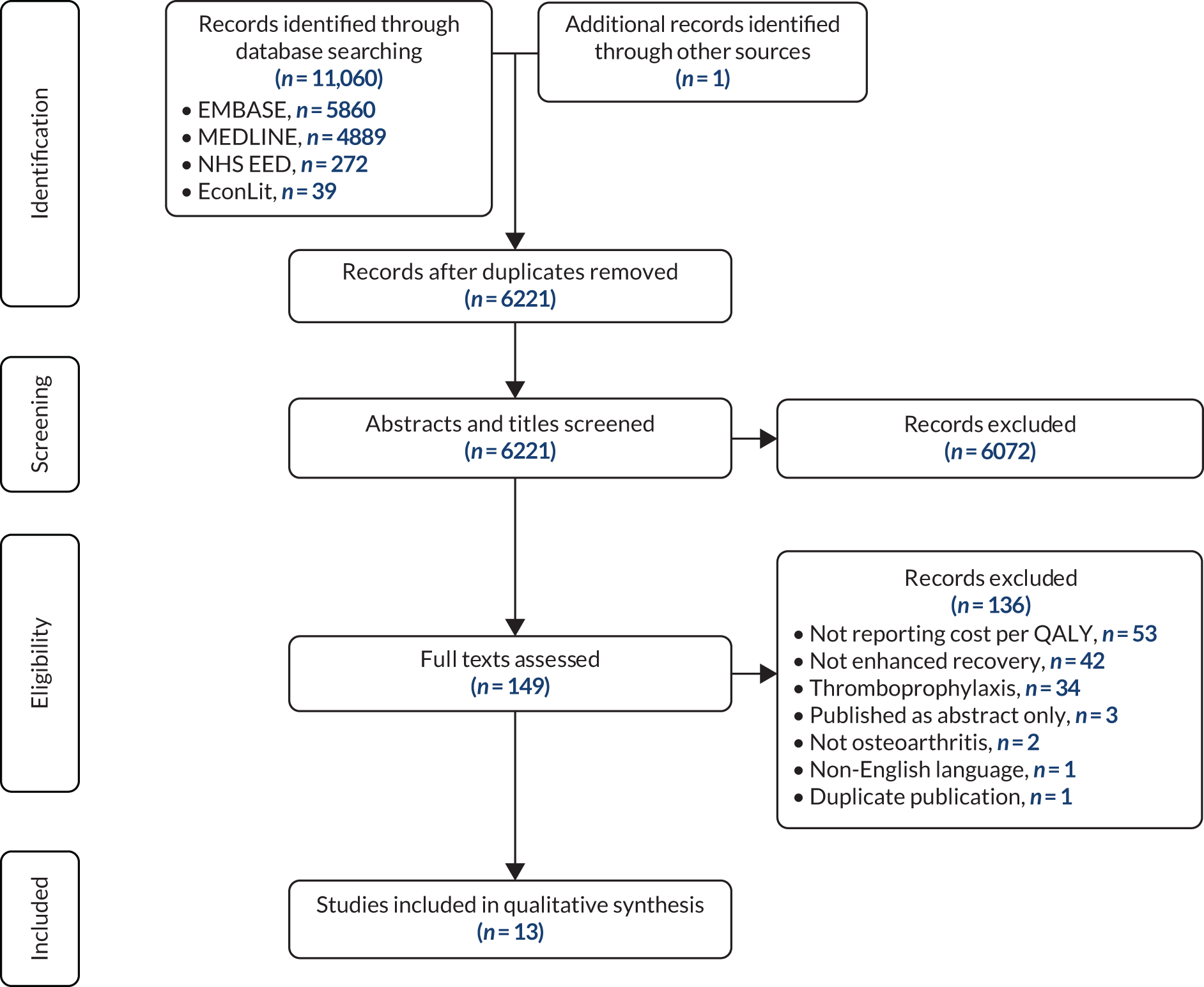

FIGURE 3.

Flow diagram showing selection of patients for inclusion in this study (navy shows inclusion and light blue shows exclusion). Reproduced from Garriga et al. 37 © 2019 Garriga C et al. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Sample size

To account for clustering within the data (patients nested within CCGs), we need to inflate the required sample size by the design effect [1 + (n – 1)p], where p is the intracluster correlation and n the mean cluster size. From our previous work, the intracluster correlation was 0.0135 for hip and 0.014 for knee replacement. 38 There are 207 CCGs in England and the CCG is the cluster. If we expect to have 100 patients from each CCG group, the design effect is (1 + 99 × 0.014) = 2.4.

For OHS and OKS outcomes, the minimally important difference between groups39,40 has been estimated to be 5, with a standard deviation (SD) of 10. Using a two-sided, two-sample t-test, with 90% power, at a 5% level of significance, to detect a difference in mean OHS and OKS of 5 requires a sample size of 85 in each exposure group. Assuming a 50% response rate to the 6-month follow-up OHS and OKS questionnaires inflates the sample size to 170 per exposure group. The required sample size per exposure group adjusted for clustering is 2.4 × 170 = 408. Several exposure variables will be considered in the model. Including up to 50 degrees of freedom would require a sample size of around 20,000 patients, assuming equal-sized exposure groups. Hence, this is more than adequately powered. We note that this does not account for multiple testing.

For the other binary outcomes, for complications of both THR and TKR, within 6 months of operation, rates of stroke and myocardial infarction were < 0.5%, and of anaemia, urinary tract infection, wound infection and pulmonary embolism/deep-vein thrombosis were < 3%. 41 The NJR annual report shows 90-day mortality of 0.5% and 1-year mortality of 1.5%. Rates of revision are around 5% at 10 years and rates of revision/reoperation are higher, at up to 20%. 42 For the rarest outcomes, to detect a difference in proportions of 0.5% compared with 1%, using a two-sided, two-sample chi-squared test, with 90% power at a 5% level of significance, requires 6650 patients per exposure group. As HES encompasses elective admissions to all English hospitals, we expect no loss to follow-up, as this information would be captured. For the design effect of 2.4 (for which we assume the same intracluster correlation as above), the sample size increases to 15,960 per degree of freedom. Hence, even for these rarest outcomes, with an actual sample size of > 350,000, we can still include over 20 degrees of freedom in the model.

Geographical variables

Within our HES data set, the smallest level of geography available to us is the lower-layer super output area (LLSOA) that a patient lives in. LLSOAs have a population between 1000 and 3000, and between 400 and 1200 households. There are 32,482 LLSOAs in England as of 2001. For the multilevel analysis, we use this as an intermediate level between the patient level and the CCG level. From the ONS Open Geography Portal, we obtained a polygon shapefile for the 2017 CCG areas in England. Maps were produced using these boundaries.

We start by looking at the structure of the geographical data (CCG areas) for a hospital that a patient is treated in. To do this, we use the ArcGIS 10.5 software (ESRI, Redlands, CA, USA) to do a point-in-polygon overlay, providing a spatial join of the hospital points with the CCG areas. This shows us that there are CCG areas that do not have any hospitals within them. For knee replacement, there are 173 CCGs that have a hospital contained within their boundary (175 CCGs for hips). Hence, out of the 207 CCG areas, there are 34 that do not have a hospital in their boundary for hips and 32 for knees. For this analysis, we want a ‘nested data set’; currently, if our data structure is to have patients within hospitals within CCGs, it does not work as there are CCG areas with no hospitals, which, therefore, would appear blank on a CCG map of England when displaying outcomes of surgery.

To have a nested data structure, we instead will base this on the CCG area for a LLSOA that a patient lives in. By doing a spatial join of the LLSOA points with the 2017 CCG polygon file, this provides us with a nested data set of patients (level 1) within LLSOA (level 2) within CCG (level 3) (Table 5).

| Classification number | Classification | Number of units | |

|---|---|---|---|

| TKR/UKR | THR | ||

| 3 | NHS CCGs | 207 | 207 |

| 2 | 2001 Census LLSOA code for England | 31,715 | 30,850 |

| 1 | Patients | 210,725 | 173,107 |

However, with this structure to the data, we now need to allocate a hospital organisational characteristic according to the LLSOA areas. This is done by using a spatial join based on the distance between two points (hospital and LLSOA). For each LLSOA, we can then identify the nearest hospital and attribute the hospital’s characteristics to that LLSOA area.

Statistical analysis

The hierarchical structure of the data consists of patients (level 1), nested within LLSOA (level 2), within CCGs (level 3). Multilevel regression models are used to describe the association of patient, hospital organisation and surgical factors and patient outcomes of surgery. This controls for evidence of clustering in the data, by allowing outcomes to vary across LLSOAs and CCGs. Failure to control for evidence of clustering can lead to estimates of standard errors that are spuriously precise and a potential source of bias. Analyses are conducted separately for THR and TKR.

The general form of the multilevel model is given as:

where Yijk is the outcome variable in patient i, in LLSOA j, in CCG k. CONS is the constant term, the vector of explanatory variables, Uj is the LLSOA residual error term distributed N(0,σj2), Vk is the CCG residual error term distributed N(0,σk2), and eijk is the individual-level residual error distributed N(0,σe2).

It is assumed that the set of random effects explains the clustering in the data, such that different observations in the same cluster are independent. We examine continuous outcomes (e.g. LOS, OHS, OKS) using linear regression, and binary outcomes (complications at 6 months) using logistic regression. Normal distributional assumptions are assumed for both linear and logistic multilevel regression models. We use normal probability plots that plot the ranked residuals against corresponding points on a normal distribution curve, to assess our assumption that level 2 and 3 residuals are normally distributed.

In order to generate the predicted outcomes across the 207 CCGs, we first estimate the linear predictor, which is the sum of the betas for each patient i in the data set. The overall predicted outcome in each CCG is then just the mean of the linear predictor for each CCG:

To incorporate evidence of clustering, the multilevel regression model has an estimate of the residual CCG variation. This is additional CCG-level variation in outcomes that is not explained by the variables in the regression model. So, for each of the 207 CCGs, k, we add the mean of the linear predictor to the CCG-level residual:

We fit the following models: (1) null model of the actual observed outcomes; (2) model that adjusts for patient case-mix variables; (3) model further adjusting for surgical variable; and (4) model adjusting for hospital organisational variables. Analyses were conducted using Stata version 15.1 statistical software (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Multilevel analyses were imported to Stata from MLwiN version 3.00 (MLwiN Centre for Multilevel Modelling, Bristol, UK), using the Stata command runmlwin.

Results

Between 2014 and 2016, there were 173,107 primary THRs and 210,275 TKRs (see Figure 3). Almost 60% of patients were women and the average age was ≈69 years. The mean BMI at primary surgery was in the obese range (≈30 kg/m2). The ASA grade of 83% of patients was ‘mild’ or ‘fit’. Additional patient, surgical and hospital organisation factors are summarised for hip replacement and TKRs/UKRs in Appendix 1, Table 25.

Predictive variables

Length of stay

Patients aged ≥ 80 years, in ASA grades 3 and 4, and with two or more comorbidities had longer LOS (see Appendix 1, Tables 26 and 27). Shorter LOS was seen in private hospitals or private treatment centres and with better quality-of-life scores (EQ-5D). Hospitals with ≥ 100 beds available overnight for trauma and orthopaedics had longer LOS for THR than hospitals with < 35 beds. Knee implants other than bicondylar (unicondylar, hinged, linked, custom or preassembled) were associated with shorter LOS for patients undergoing knee surgery.

Oxford Hip Score and Oxford Knee Score change

Greater absolute change in OHS and OKS was associated with better preoperative EQ-5D score (see Appendix 1, Tables 28 and 29). Greater change in OHS was associated with bigger femoral head size (≥ 44 mm) and less deprived areas. Patients aged ≥ 60 years had greater change in OKS. Smaller improvements were associated with worse condition for operation (ASA grades 3 and 4), and patients with comorbidities for both OHS and OKS outcomes.

Complications at 6 months

Older patients (aged 80–84 or ≥ 85 years) with comorbidities and worse ASA grades had higher probabilities of developing a complication in the following 6 months (see Appendix 1, Tables 30 and 31). Thromboprophylaxis based on aspirin and < 200 hip replacements per year in the hospital were also related to complications at 6 months. Fewer complications were associated with minimally invasive hip replacement surgery. For TKR, private treatment centres and unicondylar, hinged, linked, custom or preassembled implants had a lower percentage of complications at 6 months.

Variation in outcomes

Length of stay

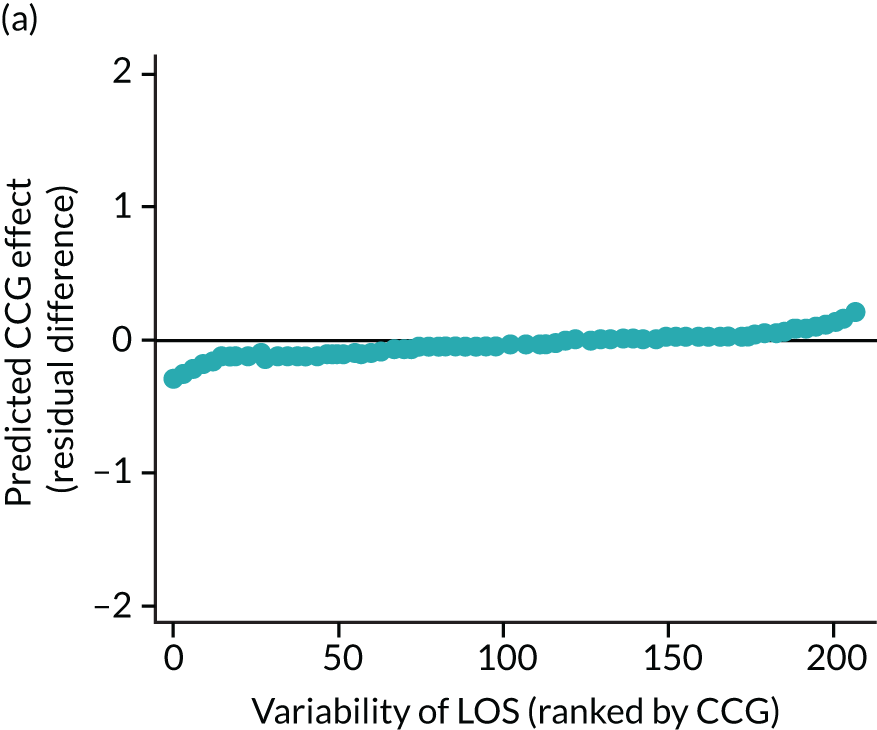

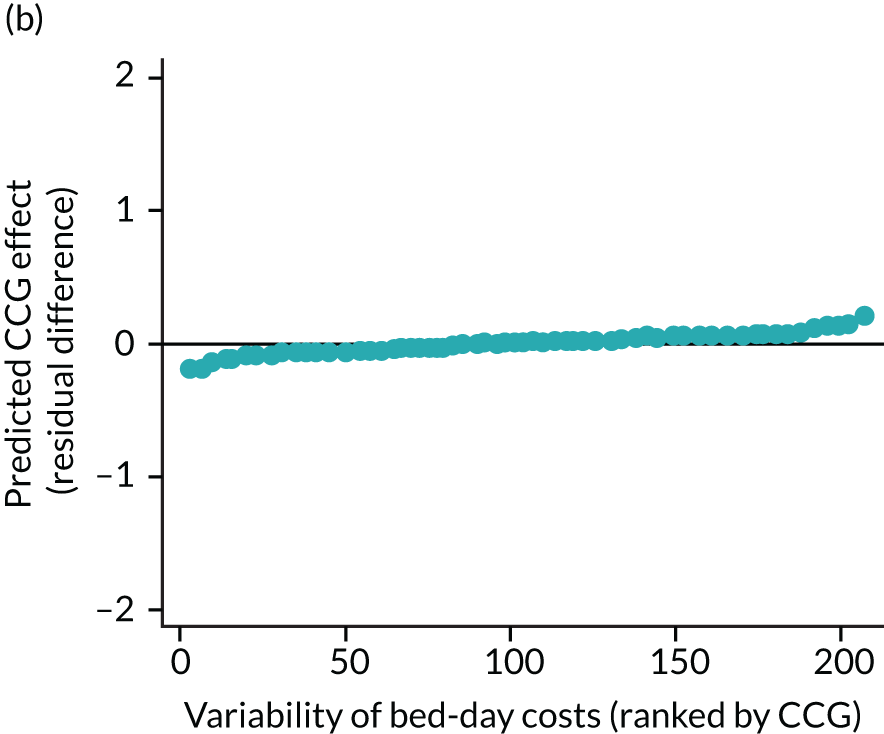

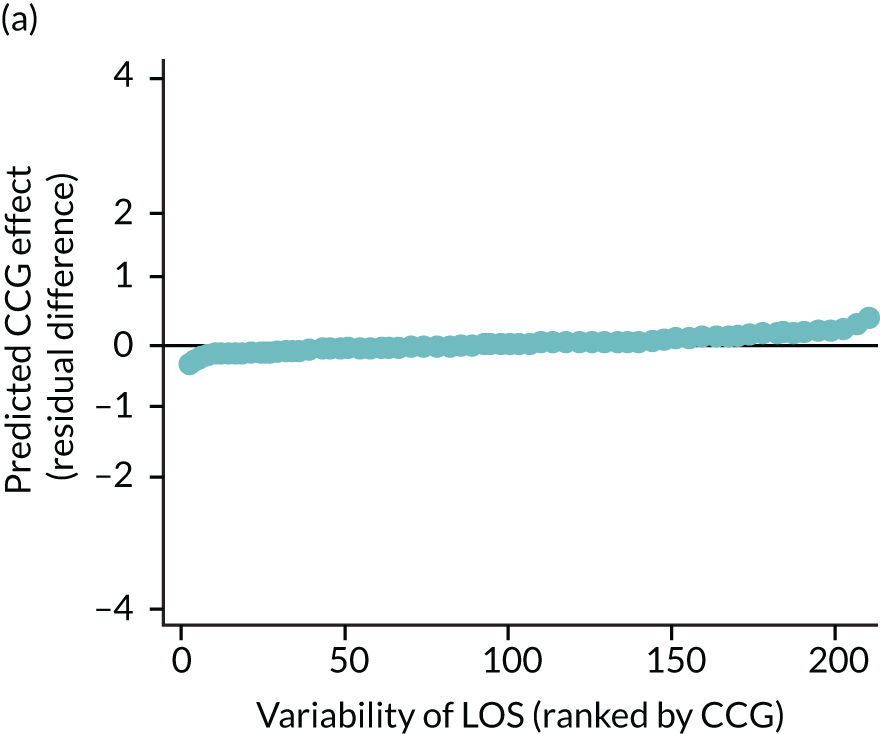

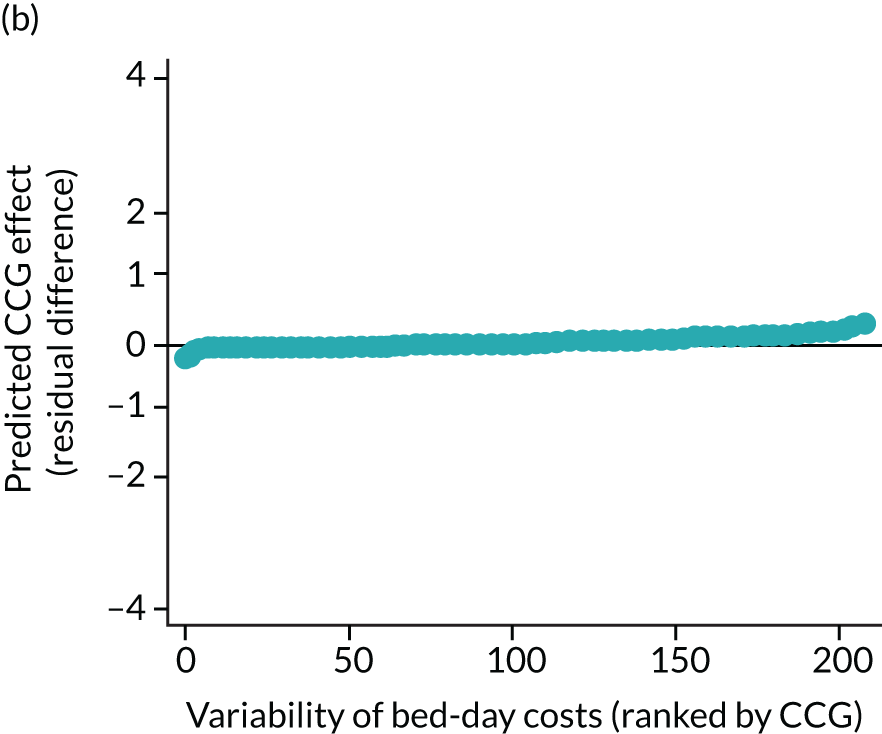

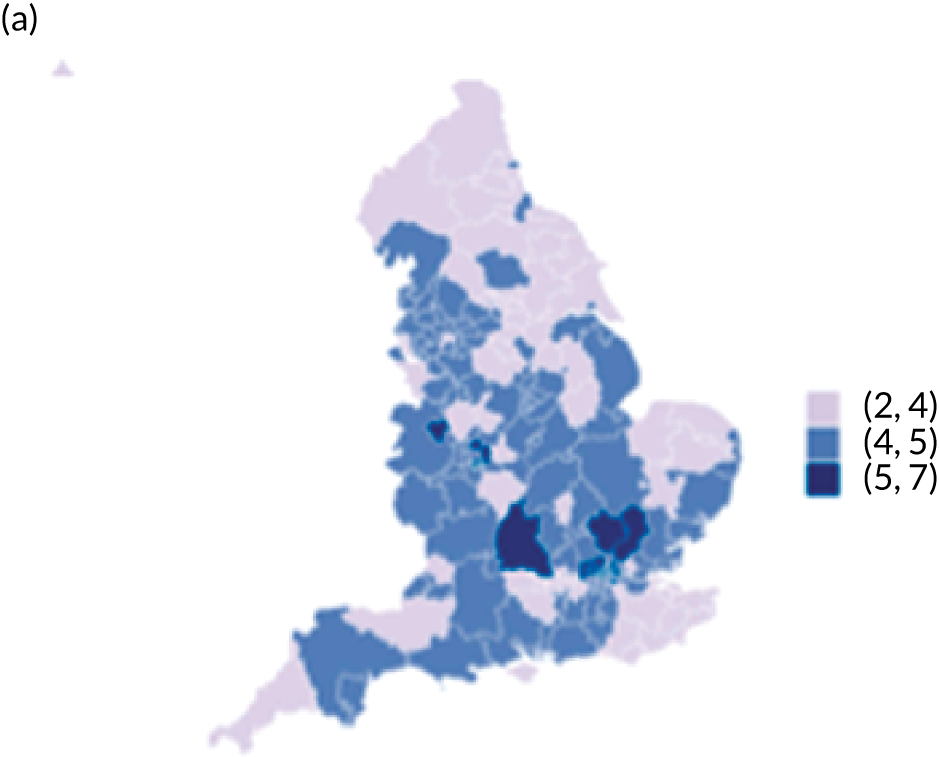

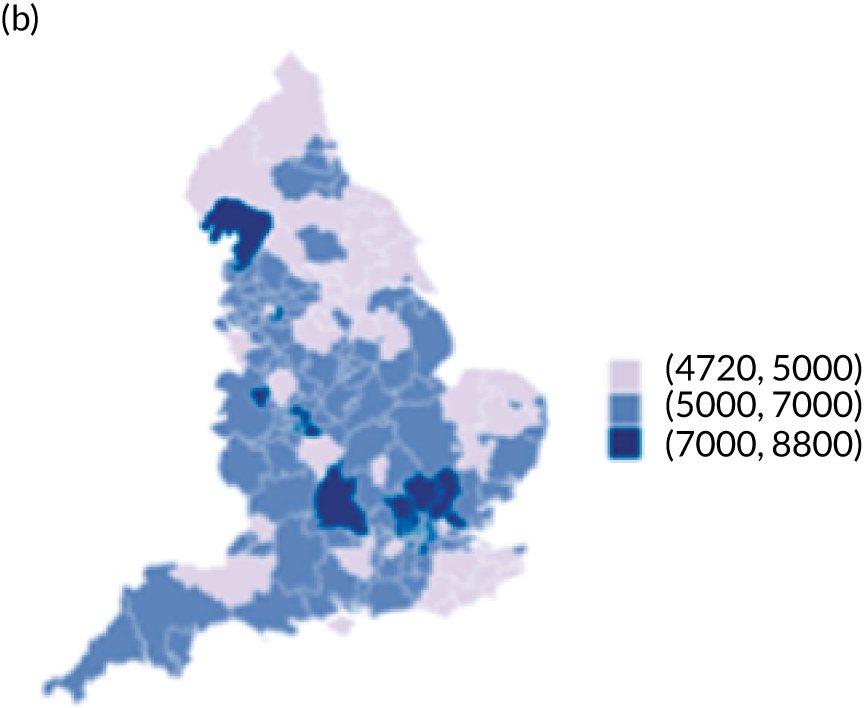

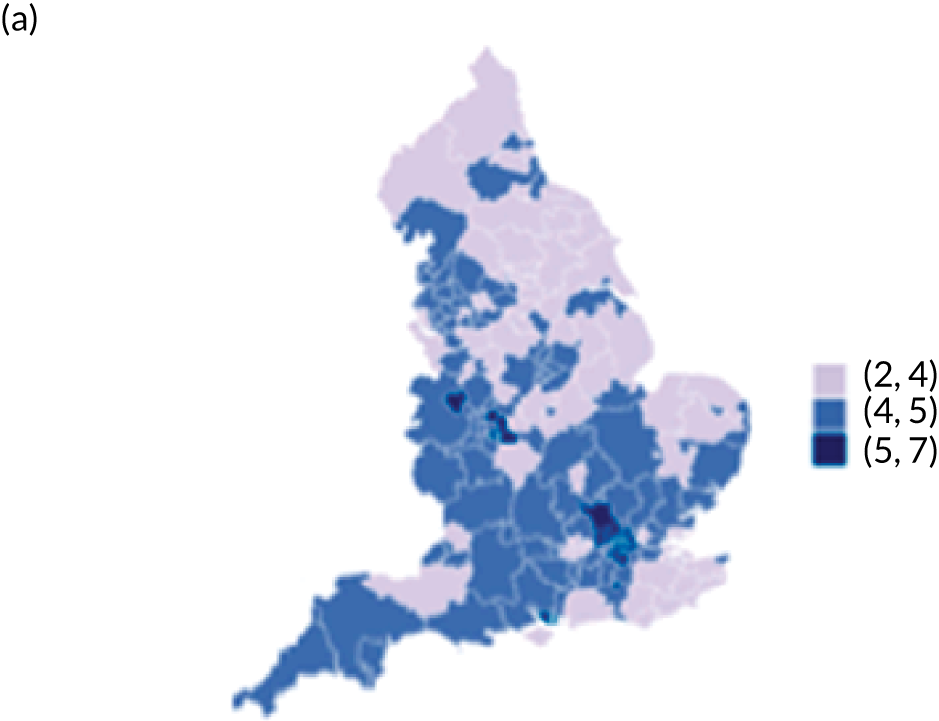

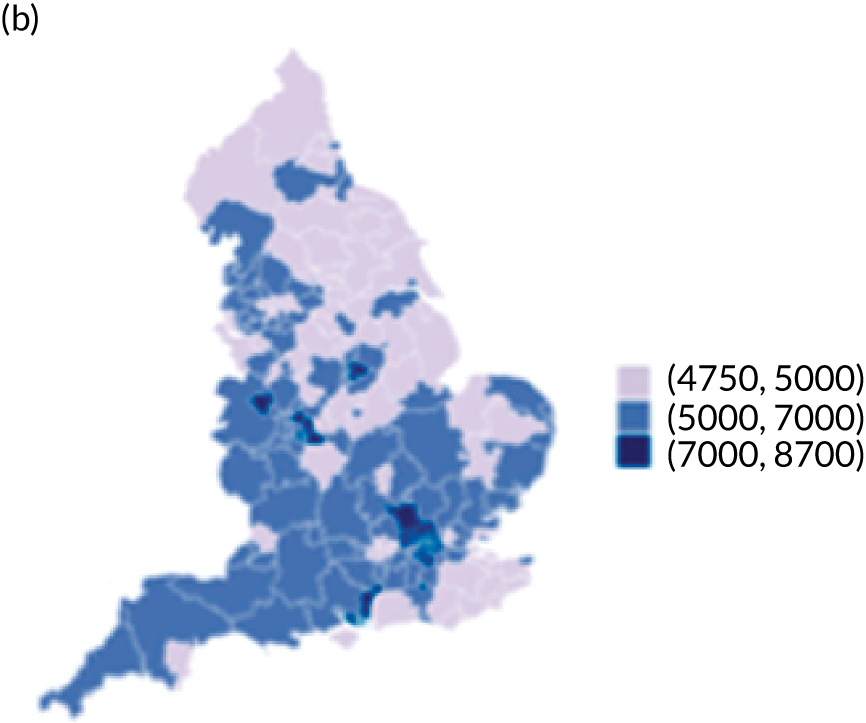

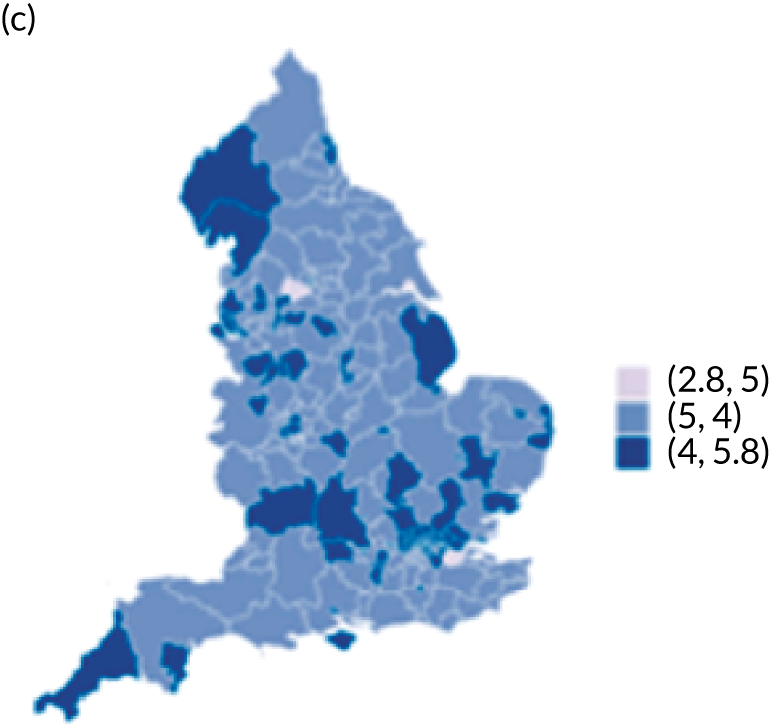

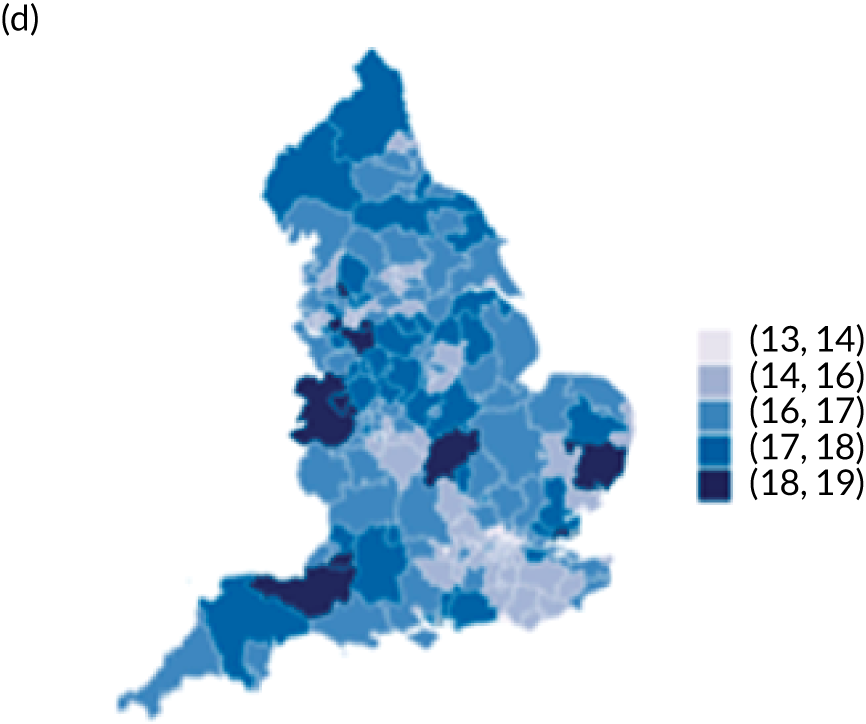

The observed mean LOS by CCG ranged between 2.5 and 6.2 days for THRs, and between 2.7 and 6.6 days for TKRs. Variability across CCGs was high, with 54 out of 207 CCGs having significantly shorter mean LOS and 58 CCGs having longer mean LOS for THR (Figure 4). Variability between CCGs was even more marked for patients undergoing TKR, with 72 CCGs with significantly shorter mean LOS and 62 CCGs with longer mean LOS (Figure 5). Table 6 shows the five CCGs with the lowest estimates of mean LOS (≈3 days) and the five CCGs with the highest mean estimates (≈6–7 days) for THR and TKR patients, respectively. Maps of England with CCG boundaries show that the London region had longer mean LOS, whereas North England and the East Coast have shorter mean LOS for both THR and TKR (Figures 6 and 7). The mean bed-day costs ranged between £4727 (SD £1026) in the NHS Scarborough and Ryedale CCG (within Yorkshire and the Humber region) and £8800 (SD £1572) in the NHS Hillingdon CCG (within London region) for THR. The mean bed-day costs for TKR oscillated between £4758 (SD £1096) in the NHS Scarborough and Ryedale CCG and £8692 (SD £1507) in the NHS Central London CCG.

FIGURE 4.

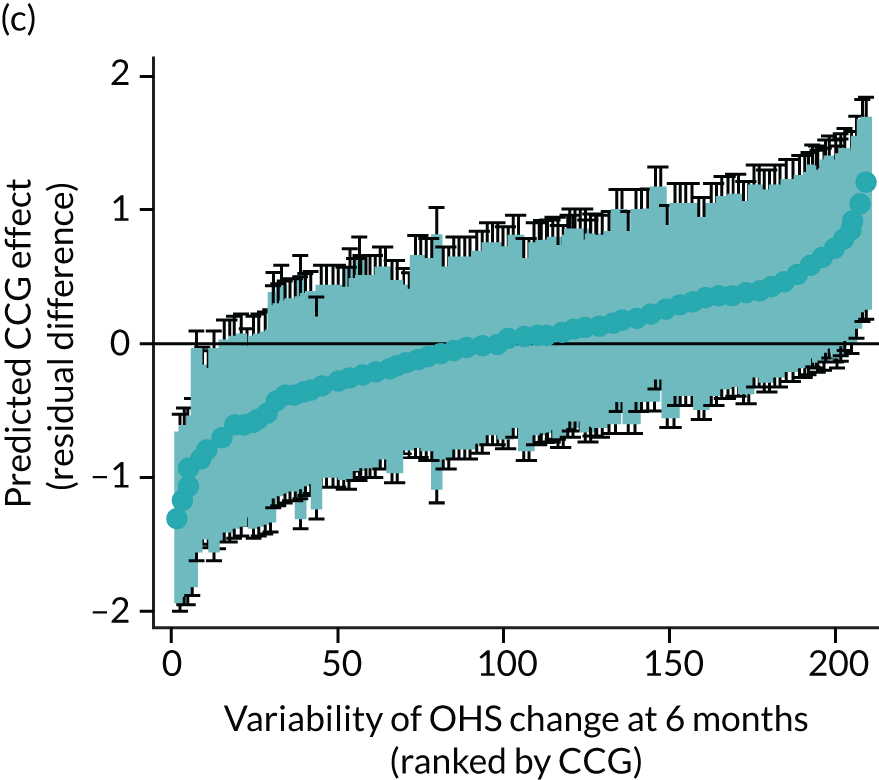

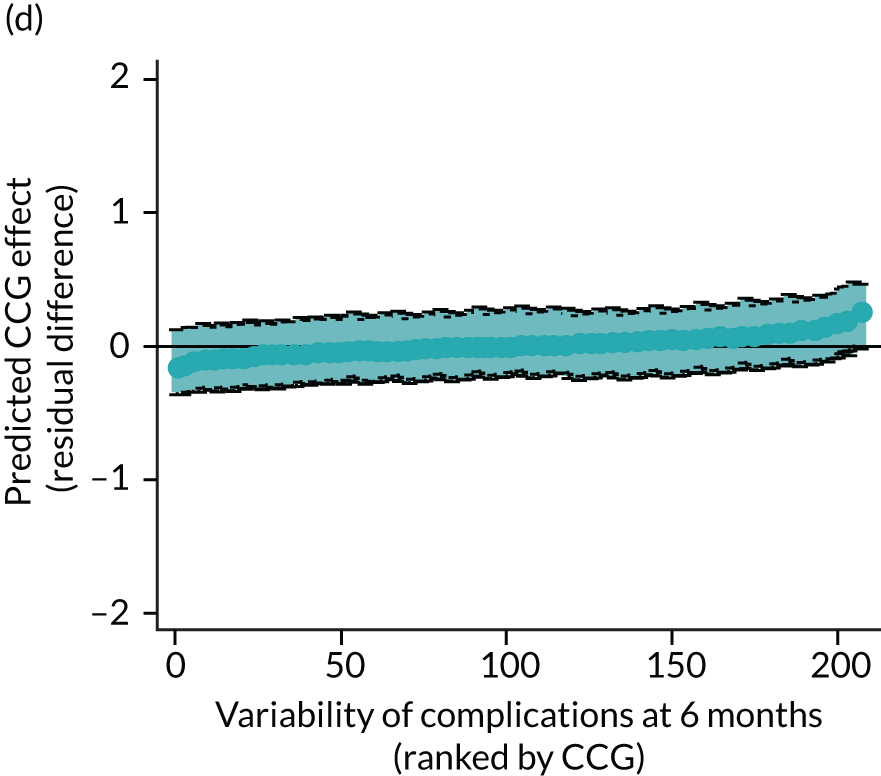

Caterpillar plots showing variation in outcomes across CCGs (THR). (a) LOS (54/207 CCGs have significantly shorter LOS than average, whereas 54 CCGs have longer LOS); (b) bed-day costs (56/207 CCGs have significantly lower costs than average, whereas 53 have higher costs); (c) OHS change at 6 months (13/207 CCGs have significantly less change at 6 months, whereas 11 have more change); and (d) complications at 6 months (4/207 CCGs have significantly higher percentages of complications at 6 months than average).

FIGURE 5.

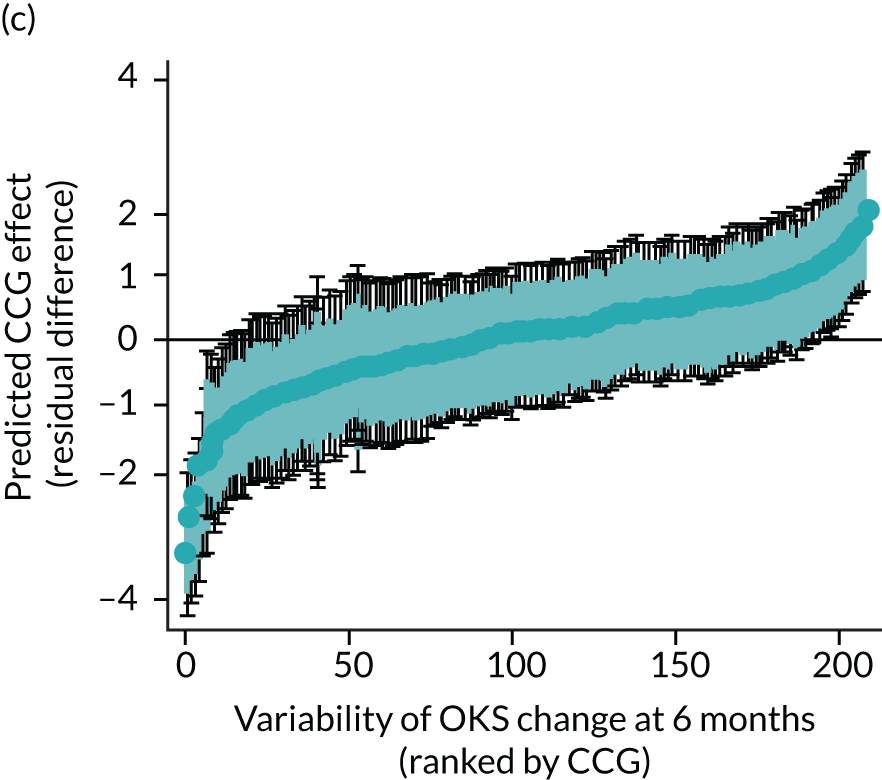

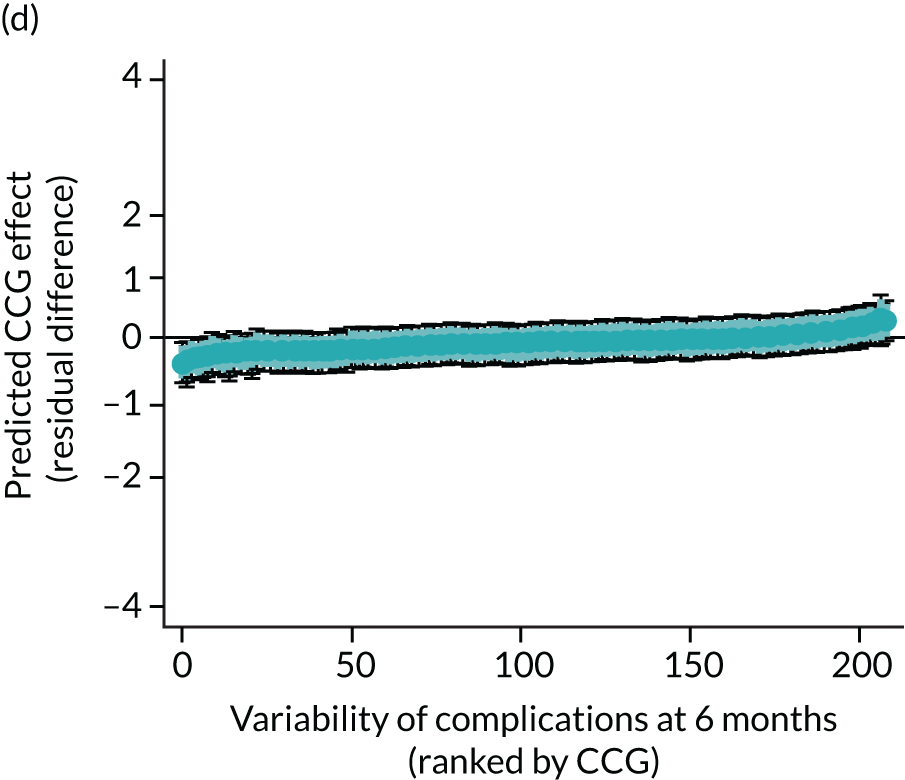

Caterpillar plots showing variation in outcomes across CCGs (TKR). (a) LOS (72/207 CCGs have significantly shorter LOS than average, whereas 62 have longer LOS); (b) bed-day costs (65/207 CCGs have significantly lower costs than average, whereas 56 have higher costs); (c) OKS change at 6 months (25/207 CCGs have significantly less change at 6 months, whereas 26 have more change); and (d) complications at 6 months (7/207 CCGs have significantly lower percentages of complications at 6 months than average, whereas eight have higher percentages).

| THRs | TKRs/UKRs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Five lowest | Five highest | Five lowest | Five highest | ||||

| CCG | Predicted (SD) | CCG | Predicted (SD) | CCG | Predicted (SD) | CCG | Predicted (SD) |

| Mean LOS (days) | |||||||

| Scarborough and Ryedale | 2.7 (1.0) | Hillingdon | 6.1 (1.8) | Scarborough and Ryedale | 2.9 (1.0) | West London | 6.6 (1.7) |

| Hastings and Rother | 2.9 (1.0) | Harrow | 6.1 (2.1) | Northumberland | 3.2 (0.7) | Hammersmith and Fulham | 6.6 (1.8) |

| Hambleton, Richmondshire and Whitby | 3.1 (0.8) | Camden | 6.1 (1.9) | Bassetlaw | 3.3 (1.4) | Camden | 6.5 (1.8) |

| Northumberland | 3.1 (0.9) | Barnet | 5.8 (2.0) | Hastings and Rother | 3.4 (1.0) | Central London (Westminster) | 6.1 (1.6) |

| High Weald Lewes Havens | 3.3 (1.4) | Central London (Westminster) | 5.7 (2.0) | Salford | 3.4 (1.0) | Barnet | 6.1 (1.6) |

| Mean bed-day cost (£) | |||||||

| Scarborough and Ryedale | 4727 (1026) | Hillingdon | 8800 (1572) | Scarborough and Ryedale | 4758 (1096) | Central London (Westminster) | 8692 (1507) |

| Hastings and Rother | 4880 (1051) | Harrow | 8647 (1881) | Northumberland | 4930 (720) | City and Hackney | 8686 (1247) |

| Northumberland | 4998 (867) | Camden | 8250 (1561) | Bassetlaw | 4960 (1329) | Lewisham | 8676 (1585) |

| Hambleton, Richmondshire and Whitby | 5187 (908) | Barnet | 8132 (1788) | Hastings and Rother | 5294 (1050) | West London | 8639 (1438) |

| High Weald Lewes Havens | 5219 (1305) | Waltham Forest | 8060 (1710) | Salford | 5344 (1008) | Camden | 8600 (1493) |

| Mean OHS change (points) | Mean OKS change (points) | ||||||

| Mid Essex | 24.6 (5.3) | Brent | 18.7 (6.2) | Ipswich and East Suffolk | 18.8 (4.2) | City and Hackney | 13.1 (4.3) |

| Ipswich and East Suffolk | 24.1 (4.9) | Islington | 19.1 (6.4) | Eastern Cheshire | 18.5 (4.2) | Newham | 13.4 (4.3) |

| Stoke on Trent | 24.1 (5.0) | Harrow | 19.2 (6.6) | Castle Point and Rochford | 18.5 (4.0) | Islington | 13.6 (5.4) |

| Scarborough and Ryedale | 23.7 (5.4) | Kingston | 19.4 (6.6) | Warrington | 18.5 (4.2) | Brighton and Hove | 13.7 (4.5) |

| Nene | 23.6 (5.3) | Croydon | 19.4 (5.9) | Nene | 18.5 (4.2) | Barnet | 13.8 (4.7) |

| Mean complications at 6 months (%) | |||||||

| High Weald Lewes Havens | 3.0 (2.4) | Tower Hamlets | 5.4 (4.1) | Hull | 2.9 (1.4) | Herts Valleys | 5.8 (2.7) |

| Leeds West | 3.1 (1.9) | Newham | 5.3 (3.2) | Dartford, Gravesham and Swanley | 2.9 (1.4) | South Devon and Torbay | 5.7 (3.1) |

| Solihull | 3.2 (2.0) | Camden | 5.2 (3.4) | Calderdale | 2.9 (1.5) | Tower Hamlets | 5.5 (2.4) |

| Herefordshire | 3.2 (2.0) | Enfield | 5.1 (3.0) | Hambleton, Richmondshire and Whitby | 3.1 (1.4) | Camden | 5.4 (2.8) |

| West Leicestershire | 3.2 (2.1) | Hillingdon | 5.0 (3.3) | Erewash | 3.1 (1.6) | Newham | 5.4 (2.7) |

FIGURE 6.

Map of patient outcomes across 2017 CCGs (THR). (a) LOS (days); (b) bed-day costs (£); (c) complications at 6 months (%); and (d) OHS change at 6 months (points). Ultrageneralised clipped boundaries in England V4. Reproduced with permission. 43 Source: Office for National Statistics licensed under the Open Government Licence v.3.0. Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2019.

FIGURE 7.

Map of patient outcomes across 2017 CCGs (TKR). (a) LOS (days); (b) bed-day costs (£); (c) complications at 6 months (%); and (d) OHS change at 6 months (points). Ultrageneralised clipped boundaries in England V4. Reproduced with permission. 43 Source: Office for National Statistics licensed under the Open Government Licence v.3.0. Contains OS data © Crown copyright and database right 2019.

Oxford Hip Score and Oxford Knee Score change

Observed mean OHS change by CCG ranged between 17.5 and 24.9 points, and mean OKS change ranged between 11.2 and 19.1 points. The estimated percentage of variation in OHS and OKS scores lying between CCGs was 1.0% and 1.3%, respectively. In turn, 4.0% and 5.7% of the variation in OHS and OKS scores, respectively, was attributed to differences at the level of LLSOAs. Caterpillar plots exploring the variability for OHS change (see Figure 4) and OKS change (see Figure 5) show little variability between CCGs. However, they presented wide confidence intervals (CIs), representing high variability within each CCG. The mean OHS improvement ranged between 24.6 points (SD 5.3 points) in the Mid Essex CCG (within East England) and 18.7 points (SD 6.2 points) in NHS Brent CCG (within London region). The mean OKS improvement oscillated between 18.8 points (SD 4.2 points) in NHS Ipswich and East Suffolk CCG (within East England) and 13.1 points (SD 4.3 points) in NHS City and Hackney CCG (within London region).

Complications at 6 months

Observed complications at 6 months by CCG ranged between 2.0% and 8.6% for THR, and between 1.5% to 8.4% for TKR. Complications at 6 months showed low variability between CCGs for patients undergoing THR (see Figure 4) and TKR (see Figure 5). Complications at 6 months ranged between 3% and 5–6% for patients with THR and patients with TKR. CCG maps show that the London region was associated with a higher percentage of complications.

Discussion

Main findings

There is substantial variation in patient outcomes of THR and TKR across CCG areas. This variation remained after adjusting for patient case mix and surgical factors. Hospital organisational factors had little to no influence on explaining this variation.

Strengths/limitations

Strengths of the study include use of the NJR data set, which, to the best of our knowledge, is the largest arthroplasty data set in the world, allowing us to generalise the results to the UK. The NJR has near complete coverage of all operations, particularly in the most recent years of data. Linkage to HES allowed us to examine a wide range of confounding factors and enabled us to link in hospital organisational factors; however, the limitation of this is that analysis was restricted to England only and private operations are not included in the HES data set. The large sample size has allowed us to explore geographical variation in rare complications. The main limitation of the study is missing data, which was particularly prevalent for the hospital organisation factors. To overcome this, we used multiple imputation methods, but only single imputation was possible given the complexity of the multilevel regression models fitted.

What is already known

A large number of studies within the literature have identified factors predictive of patient outcomes of THR and TKR. In respect of patient case-mix variables, it has been shown that baseline levels of pain and functional disease severity,44–51 age,46,49,52,53 sex,46,48,54 obesity,48,52,55 comorbidities46,48,51 and social deprivation50 are all related to patient-reported outcomes of pain and function. Less is known about predictors of complications of surgery, although we have previously shown that such complications are rare, with obesity associated with small but clinically insignificant effects. 41 Predictors of LOS are less commonly studied, with literature mostly relating to enhanced recovery interventions, although our work in Chapter 5 shows that age and comorbidity are associated with longer LOS. Much of this work on predictors of outcomes of THR and TKR is formally synthesised within large systematic reviews56 and in the published National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Programme Grants for Applied Research report [Clinical Outcomes in Arthroplasty study (COASt)57].

We have previously demonstrated evidence of geographical variation and inequity in access to THR and TKR for patients operated on in 2002 (between 12 and 14 years before the patients in our study were operated on). 10 However, in those patients who navigate through the care pathway and obtain access to joint replacement surgery, there has been little research exploring geographical variations in outcomes of surgery. A previous NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research study by Street et al. 13 used HES data to explore variation in PROMs for THR and TKR across hospitals in England. Using multilevel regression modelling, they looked at whether or not patient factors (age, sex, comorbidity, deprivation) and hospital factors (volume, teaching hospital) predicted (1) health outcomes (EQ-5D, OHS, OKS) or (2) resource use (LOS, hospital costs). The key findings were significant unexplained variation among hospitals in both health outcomes and resource use. This is consistent with the findings of our study; however, our research takes this forward by looking at variation in other relevant outcomes (complications, LOS) and looking at a broader range of patient, surgical and hospital organisational factors as predictors of geographical variation in outcomes. Our findings suggest that such factors do not explain this variation. Hence, there are probably other unmeasured historical organisational factors and processes specific to individual local hospitals that may explain why such variation exists. Specifically, we have shown that it cannot be explained by ‘our population is different’, as we have well accounted for patient case-mix factors.

Conclusions

We have identified potentially unwarranted variations in patient outcomes of THR and TKR. This variation cannot be explained by differences in patient case mix, surgical factors or hospital organisational factors. This information is informative to patients in deciding where to have their surgery and to commissioners in monitoring variations in outcomes of surgery.

Chapter 5 Natural experiment to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the enhanced recovery treatment pathway

Aims

To assess whether or not implementation of the UK Department of Health and Social Care national enhanced recovery after surgery (ERAS) programme in THR and TKR has had an impact on trends in LOS, bed-day costs, PROMs, complications and revision surgery.

Methodology

Data sources

The NJR, HES and PROMs linked data sets (see Chapter 2).

Outcomes

Length of stay, cost per bed-day, absolute change in OHS and OKS, and complications at 6 months after surgery (see Chapter 4 for details). The rate of revision up to 5 years after primary THR and TKR was also evaluated. This included revisions declared to the NJR by the surgeons and revisions reported to HES. We specified our analysis time in years, reporting the rate as number of revisions per 1000 implant-years. For a list of the OPCS-4 codes used to identify hip revision, see Report Supplementary Material 4; for knee revision, see Report Supplementary Material 5.

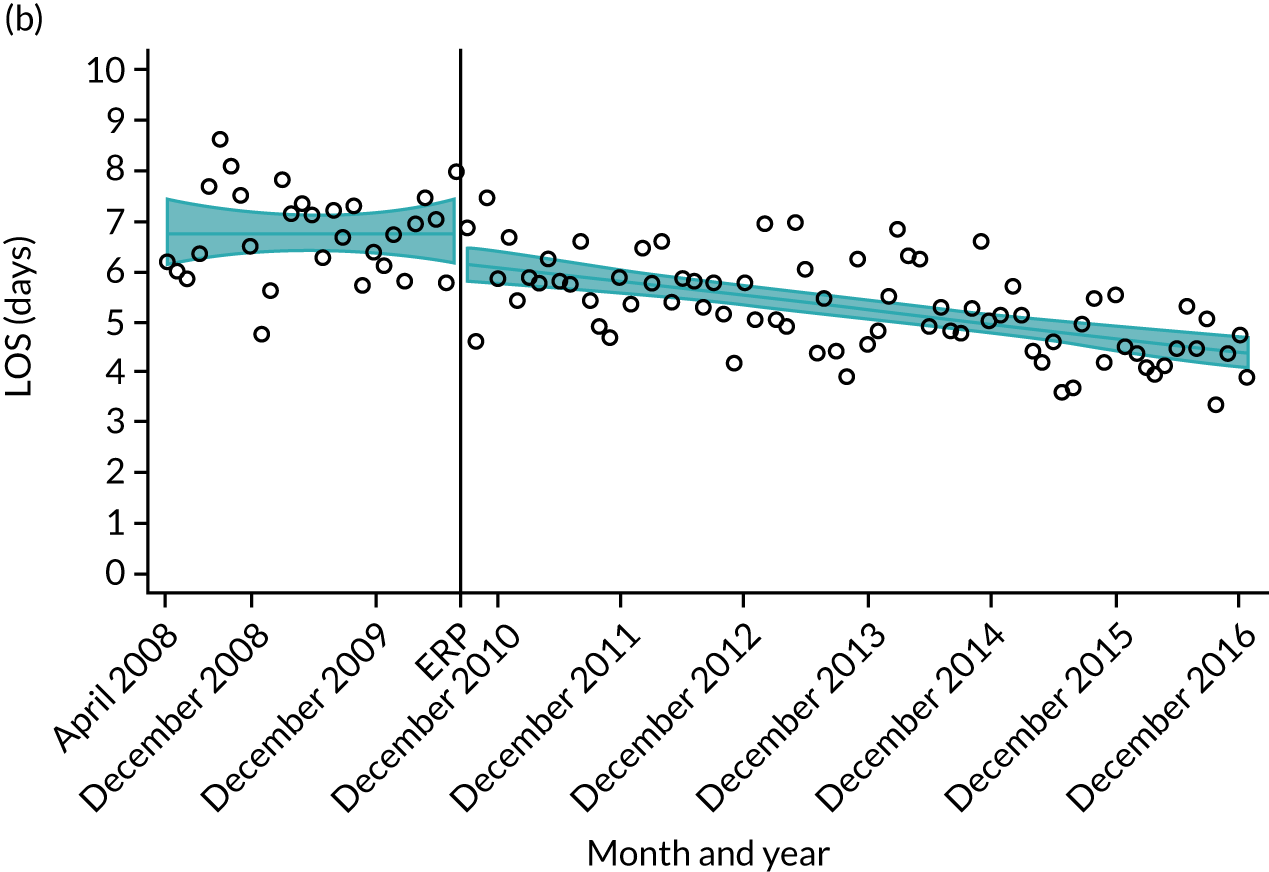

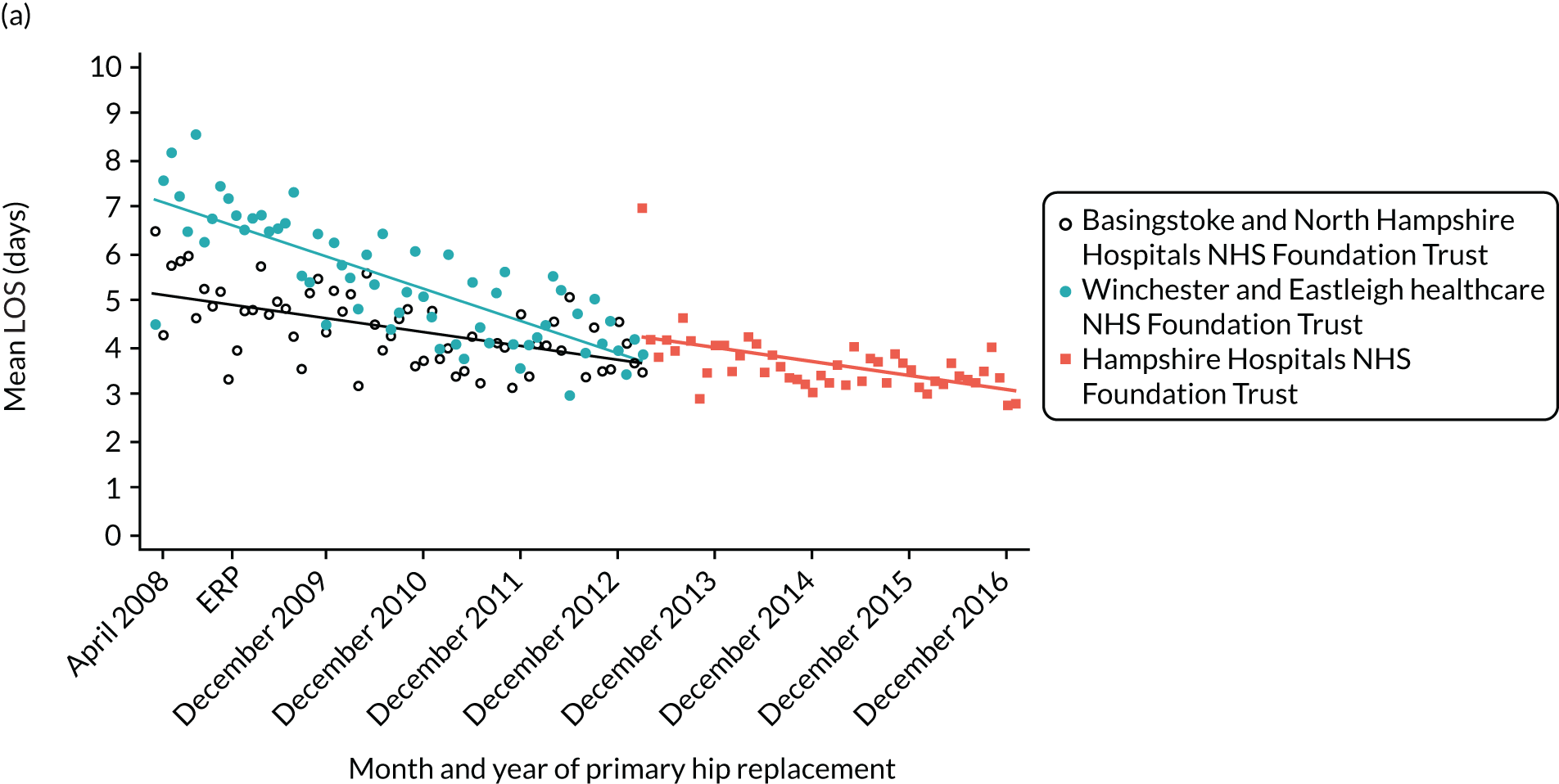

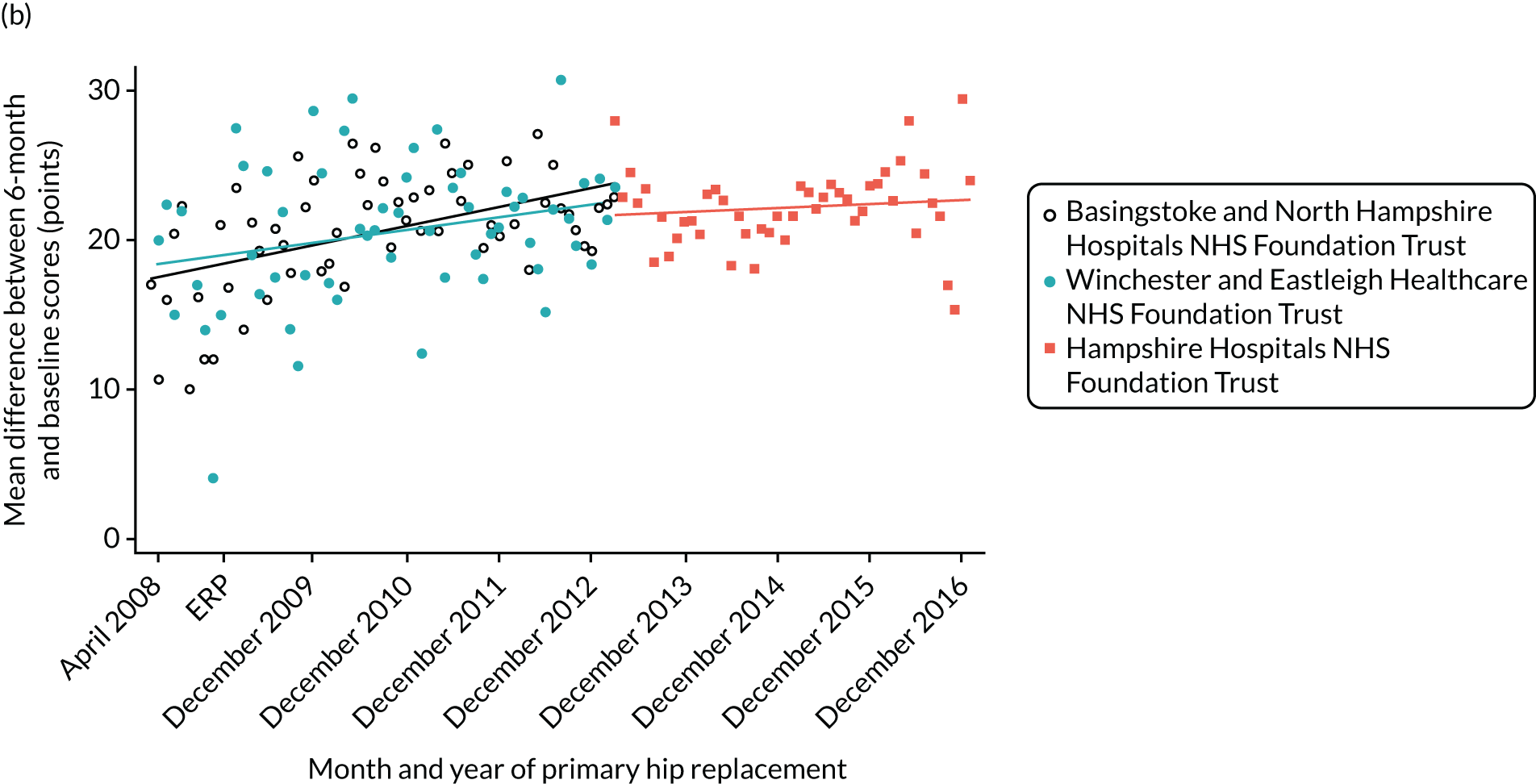

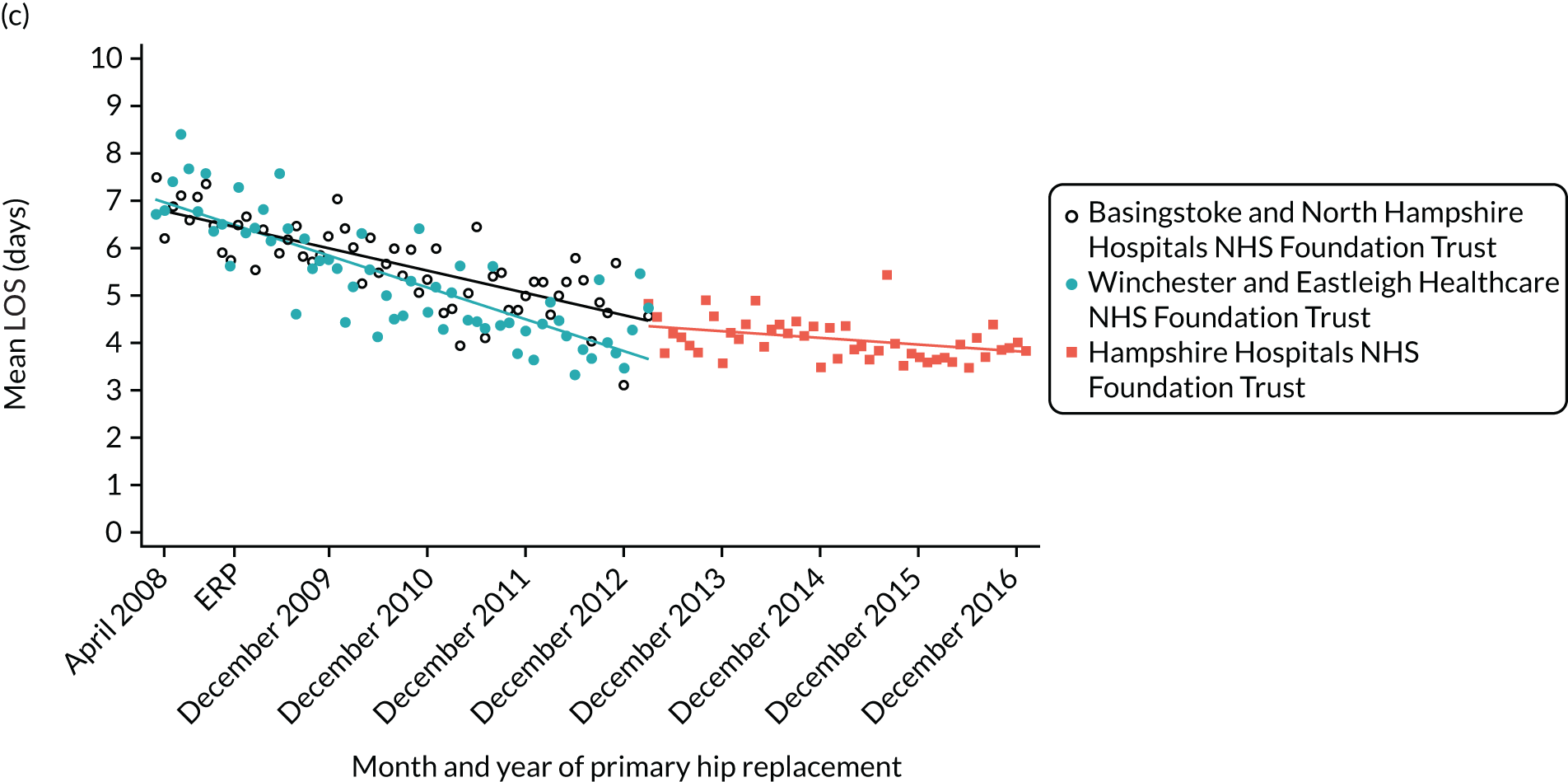

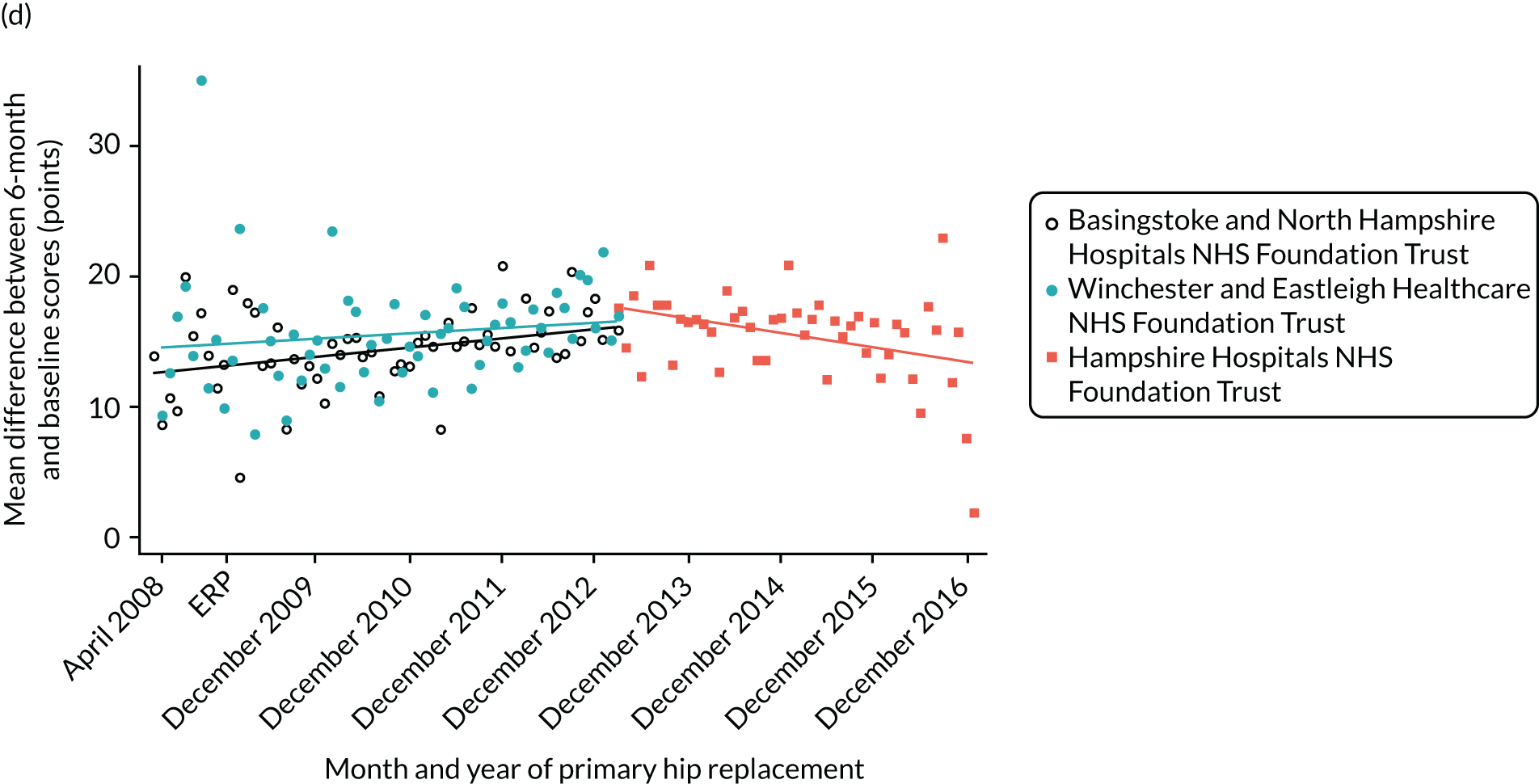

Intervention

The primary exposure (‘intervention’) is the period when the new ERP was introduced (between April 2009 and March 2011).

There is likely to be variation in the dates when individual hospitals introduced ERAS and variation in the type of ERAS service a hospital has adopted. Hence, in addition to looking at the national picture, we have looked at individual trusts in a region of England. In this region, adoption of enhanced recovery in orthopaedics was monitored by the Musculoskeletal Clinical Leaders Network when the pathway was being introduced to hospitals in 2009 and 2010. For this reason, information is available on the dates when individual hospitals in the region introduced their programmes. As outcomes of revision surgery and complications are rare, we focus just on outcomes of LOS and PROMs for the analysis of individual hospitals.

Potential modifiers

We evaluated whether or not trends in LOS and OHS and OKS over time differed by age (18–59, 60–69, 70–79, 80–84, ≥ 85 years) and evaluated the presence of comorbidities (yes/no). For a list of the ICD-1035 codes used to identify comorbidities, see Report Supplementary Material 6.

Statistical analysis

We used a natural experimental study design. 58 We evaluated the ERAS impact on trends before, during and after the implementation of the intervention. 59,60 The timing of implementation of ERP varied by trust and was assumed to span the 2 years of the implementation period (April 2009–March 2011). To do so, we described the trends by calculating monthly outcomes, being means (LOS, bed costs, OHS, OKS), proportions (complications) and rates (revision), together with their 95% CIs. We estimated a fractional polynomial over the study period and plotted the resulting curve along with the CI.

In interrupted times series studies, sample size calculations are related to the estimation of the number of observations or time points at which data will be collected. 61 According to the quality criteria of Ramsey et al. ,62 at least 10 pre and 10 post data points would be needed to reach at least 80% power to detect a change (if the autocorrelation is > 0.4). Our outcomes will be estimated at monthly intervals and, as autocorrelation is unknown, we will allow at least 2 years either side of the date of interest (24 pre and 24 post data points).

We used an interrupted time series approach to estimate changes in outcomes during and immediately following the intervention period, while controlling for baseline levels and trends. We modelled aggregated data points of each outcome of interest by month using segmented linear regression:59

The equation used on trusts in the South Central region excluded the intervention period because this was assumed to be a date point:

Here, Yt is the mean LOS, mean OHS/OKS change, mean proportion of 6-month complications and mean 5-year revision rate (taking place in month t). ‘Time’ is a continuous variable representing number of months from the start of observation period (i.e. April 2008) at time t. β0 estimates the baseline level of the outcome at the beginning of the time series (i.e. April 2008). β1 estimates the trend before ERAS implementation. β2 is the change in level immediately following the intervention. β3 estimates the change in the trend in the monthly mean after ERAS started (i.e. ERAS implementation trend). β4 is the change in level immediately following the end of the intervention. β5 estimates the change in the trend in the mean monthly number or rate (depending of outcome) after ERAS ended (i.e. ERAS post-implementation trend). We checked the autocorrelation with the previous month, 2 months, etc., until the previous 12 months, using Durbin’s alternative test. 63 Autocorrelation would invalidate the interpretation of the model. For this reason, we estimated the linear regression models with Newey–West standard errors. 64 Parsimonious models were generated using the variables selected through backward regression.

Separate models are fitted for THR and TKR. All analyses were conducted using Stata.

National results

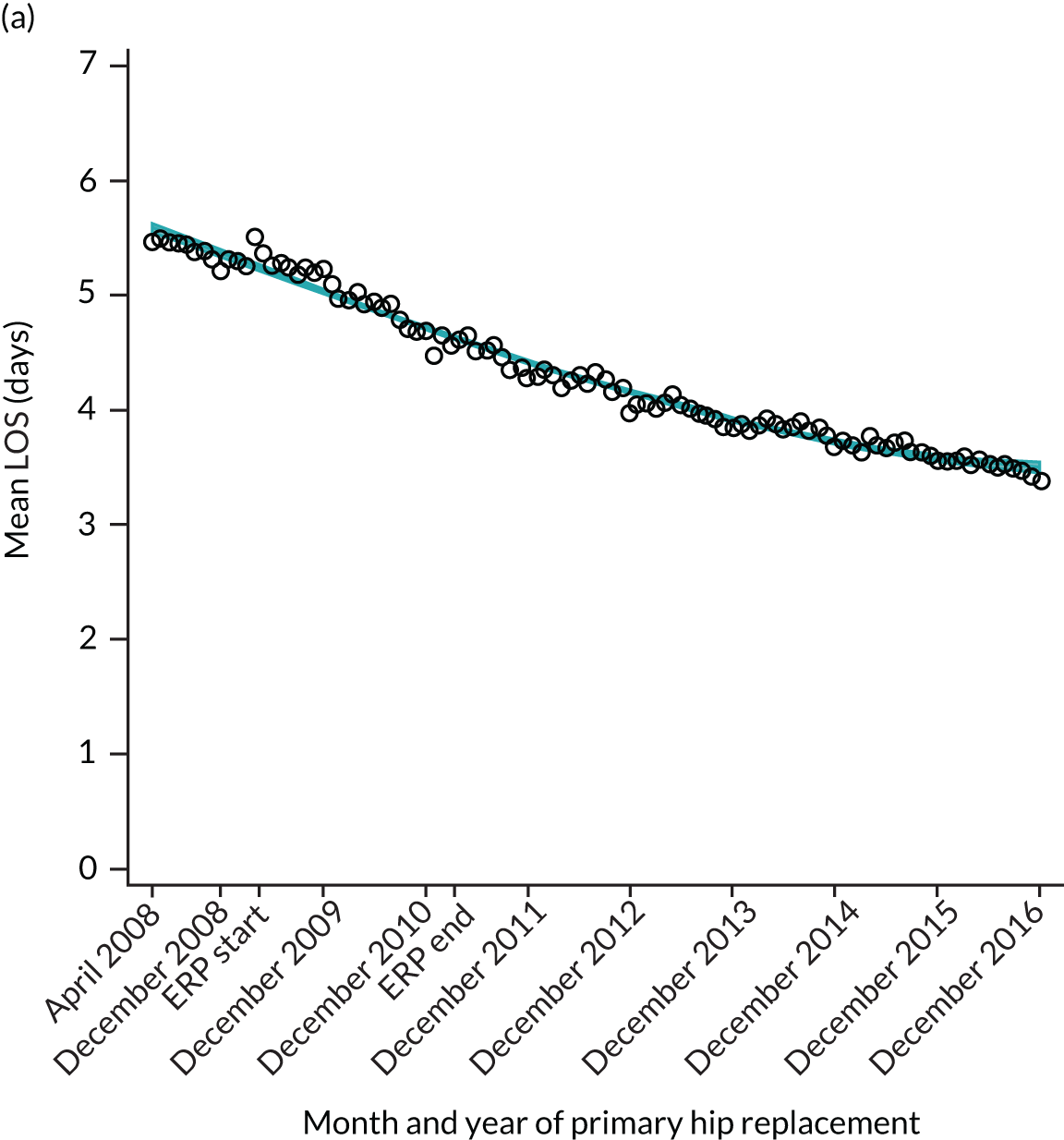

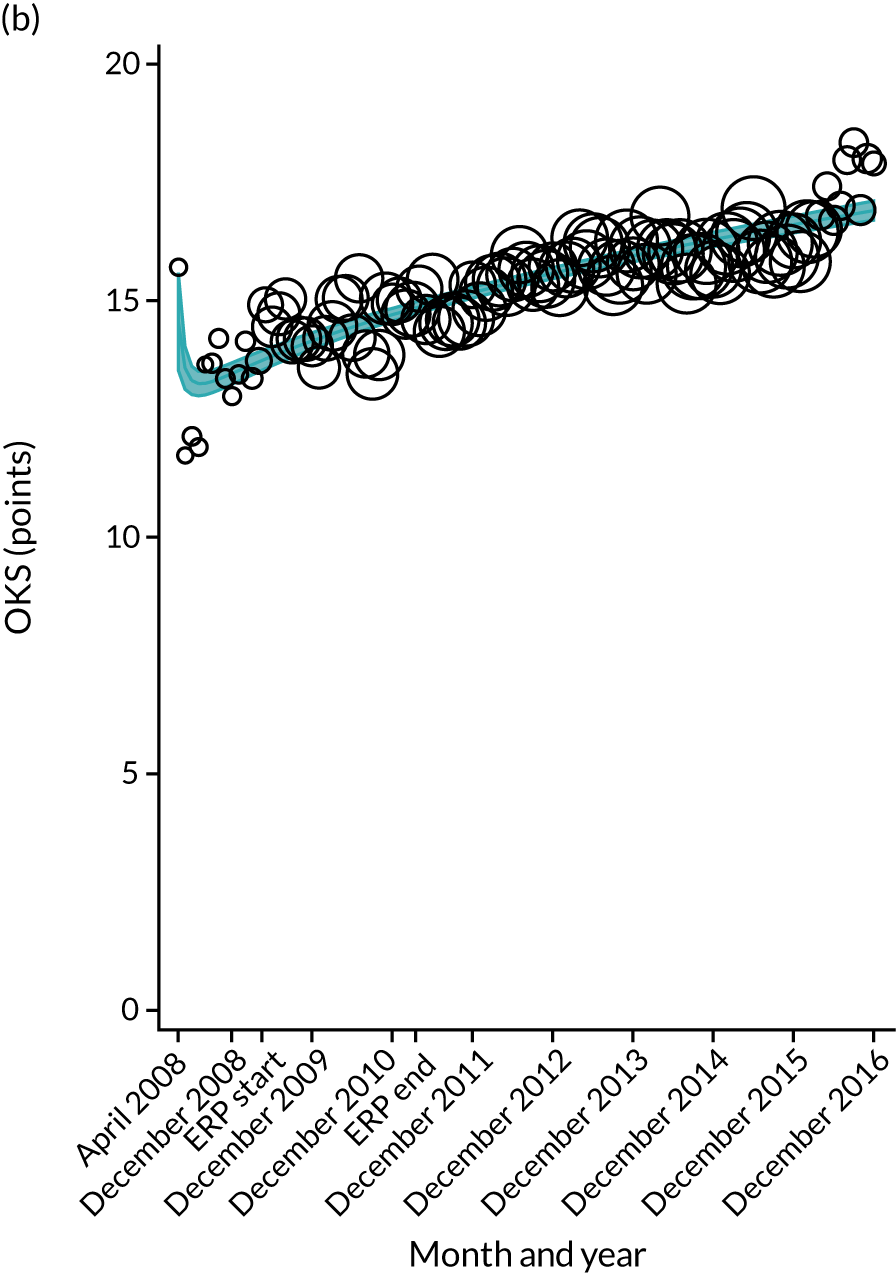

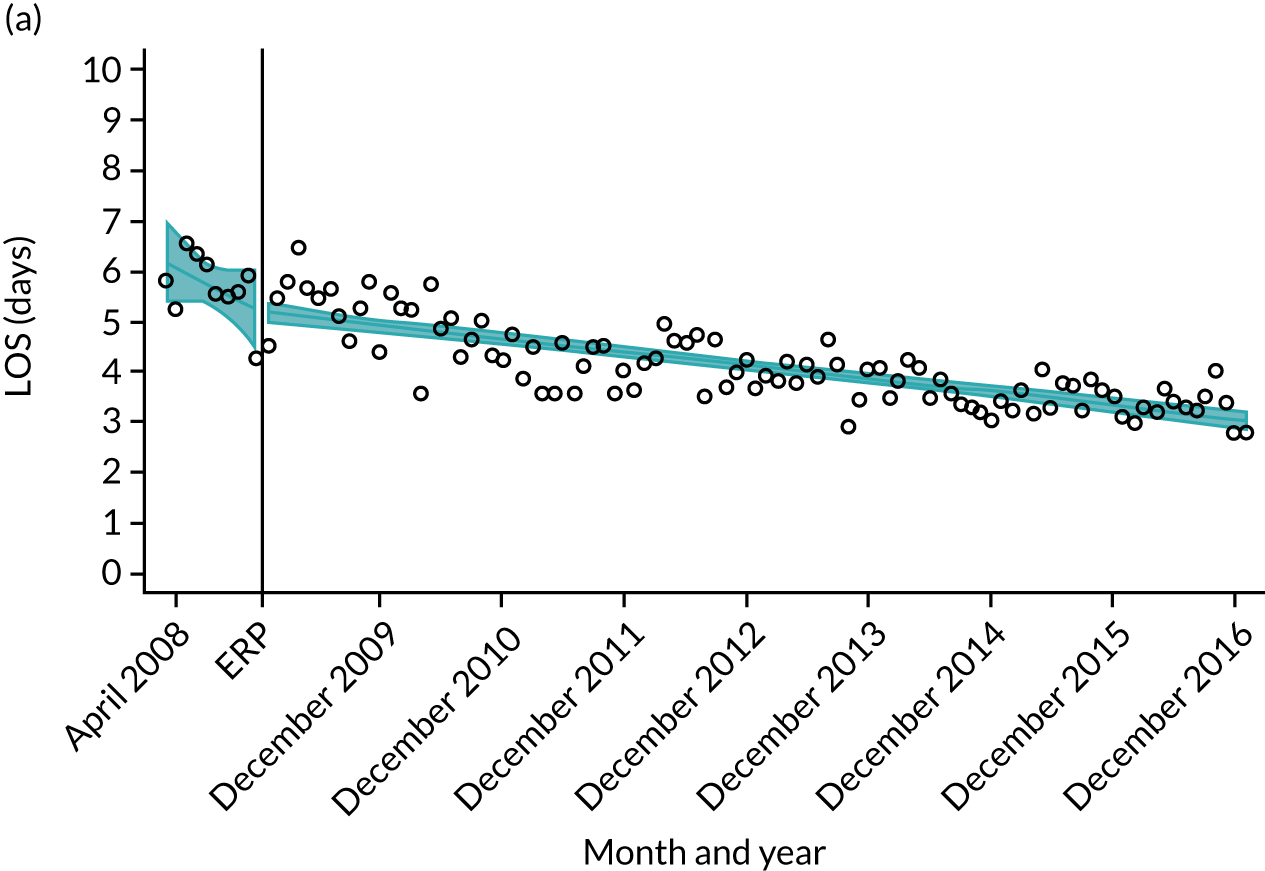

Length of stay

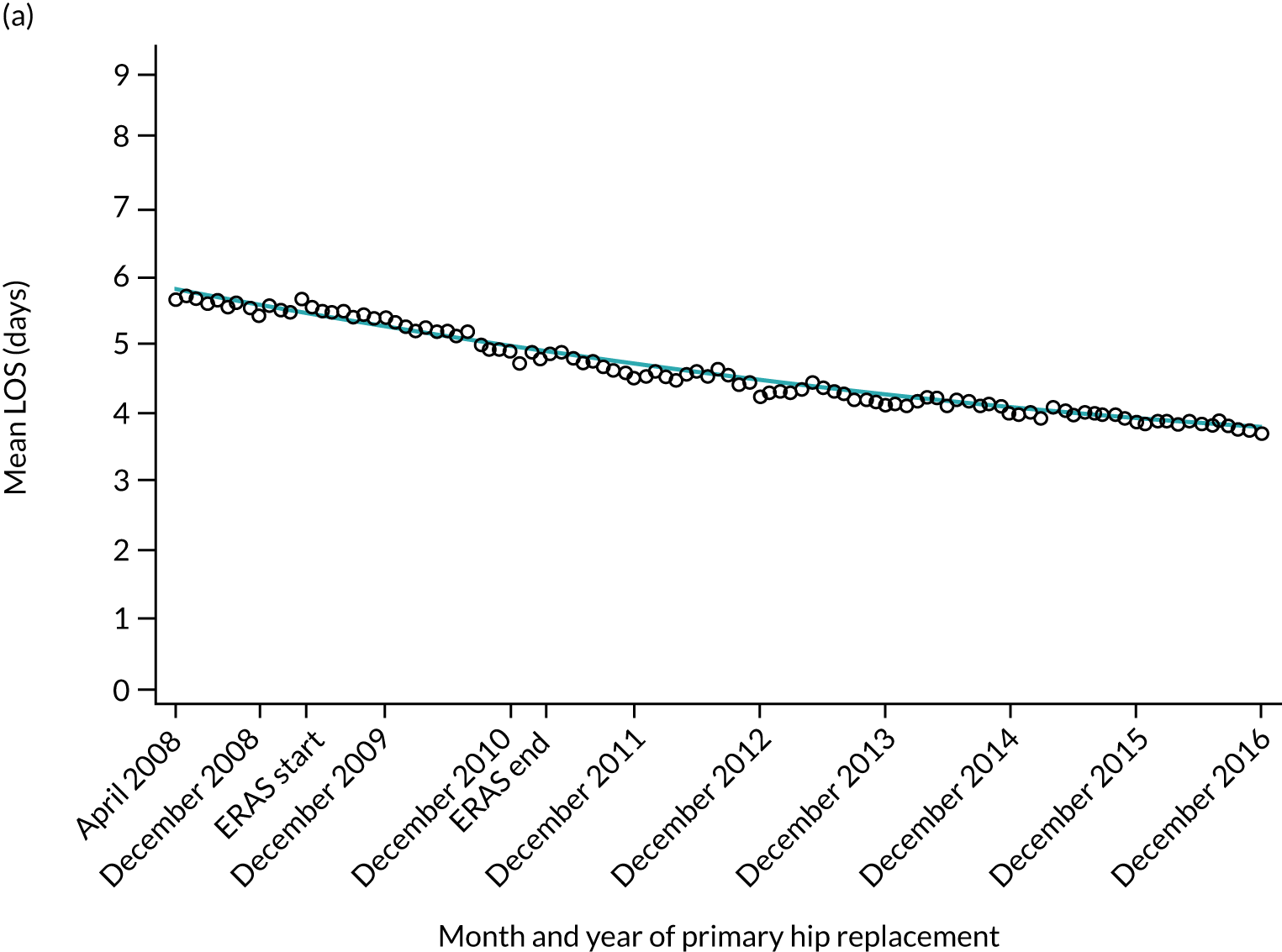

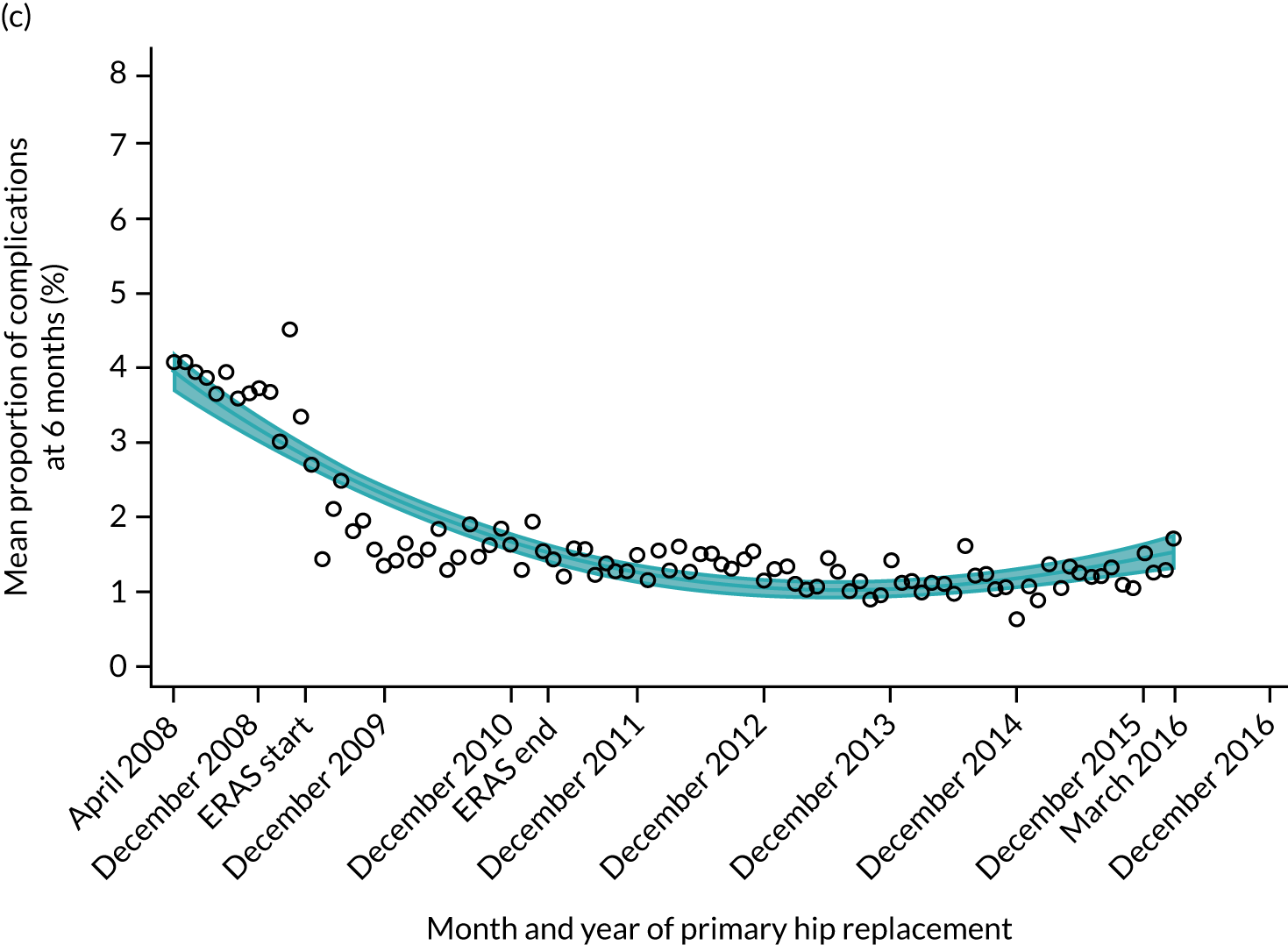

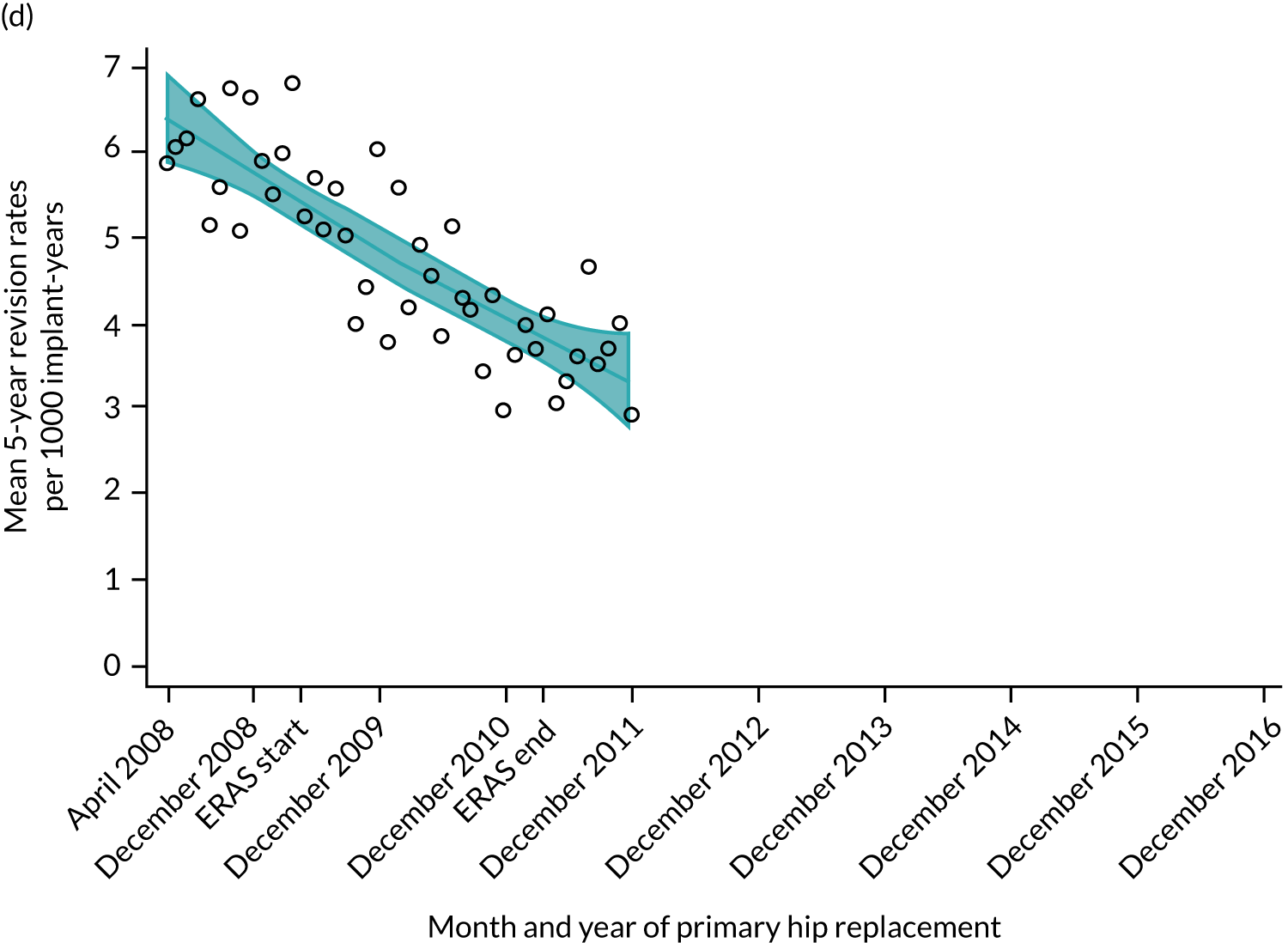

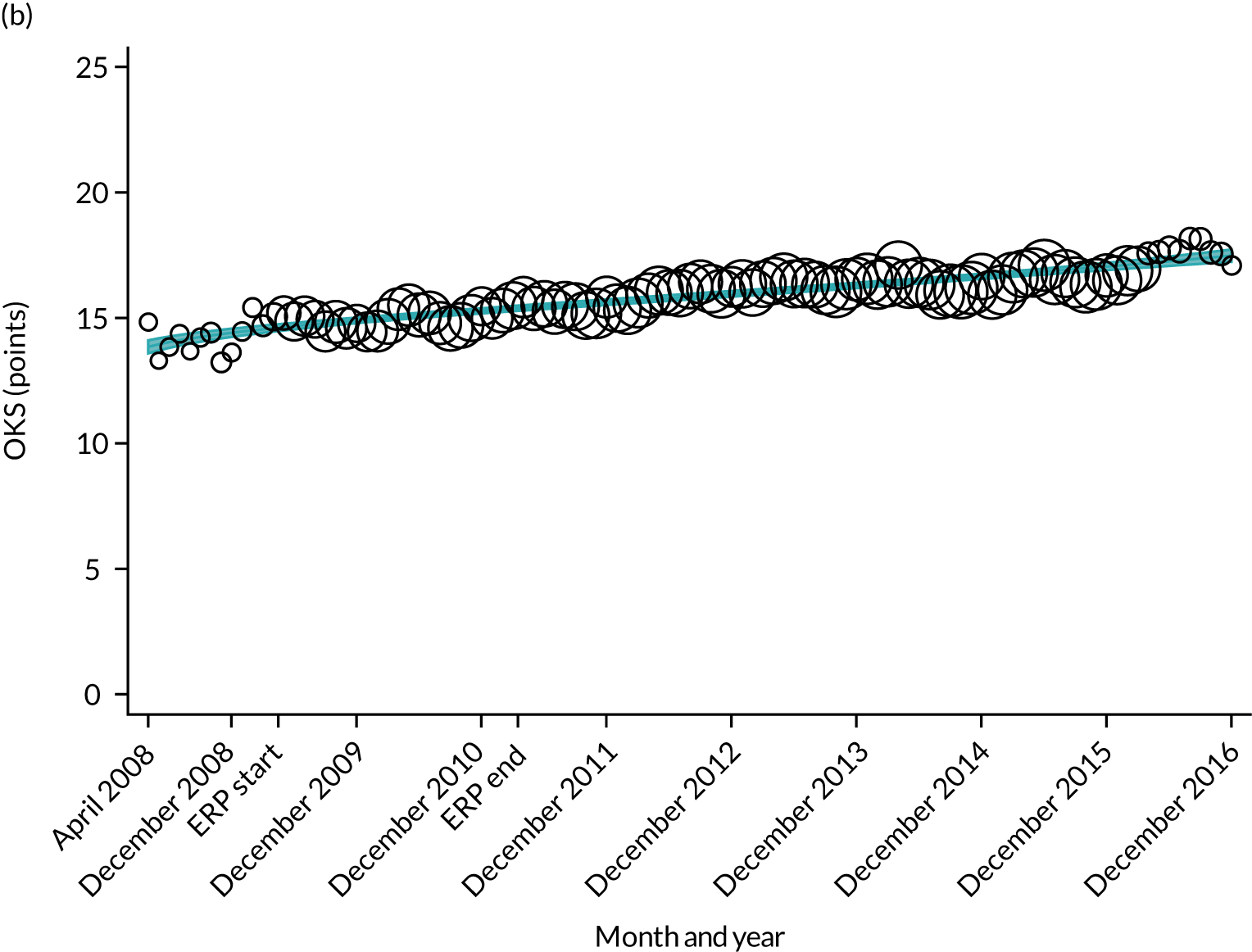

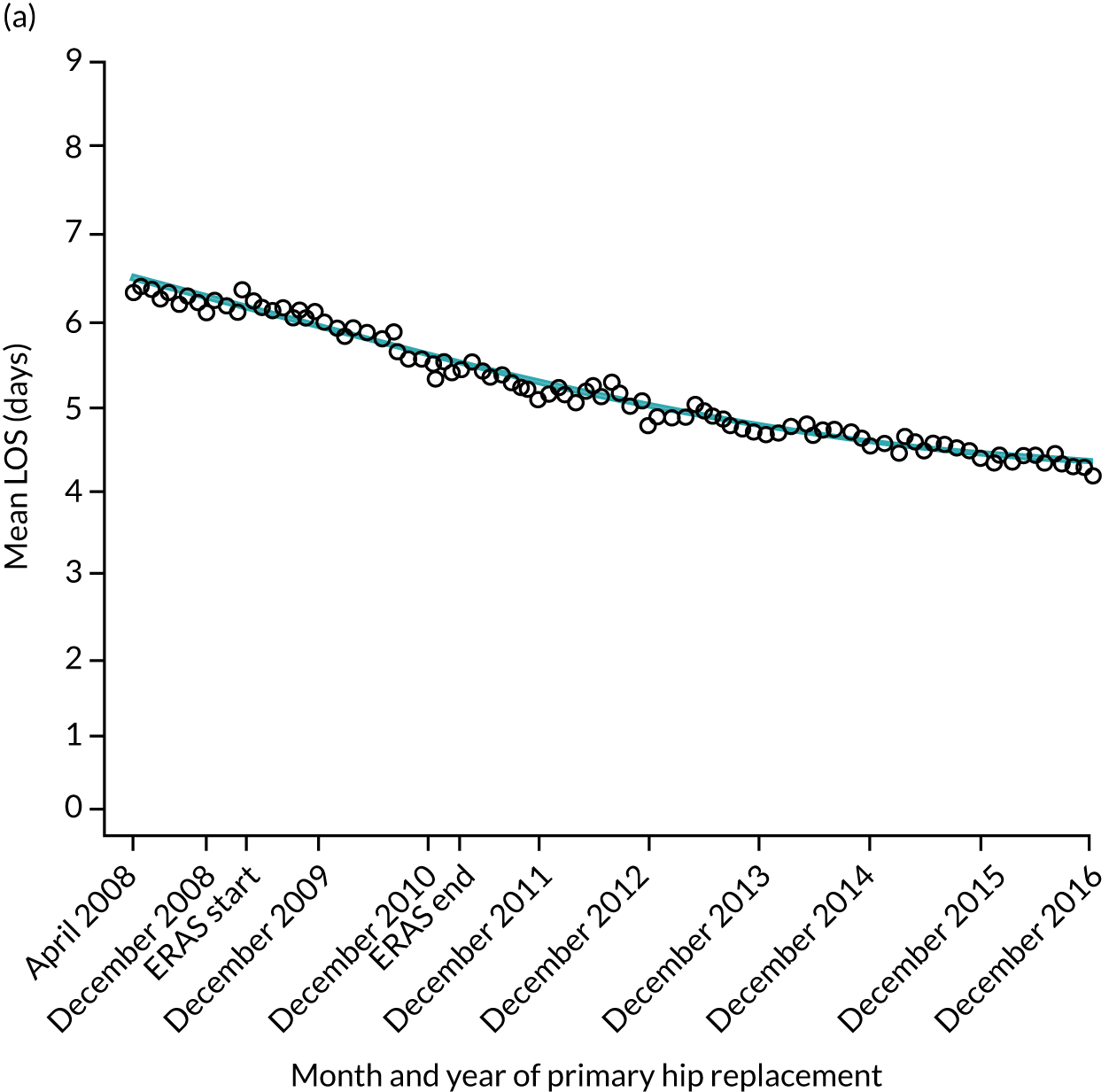

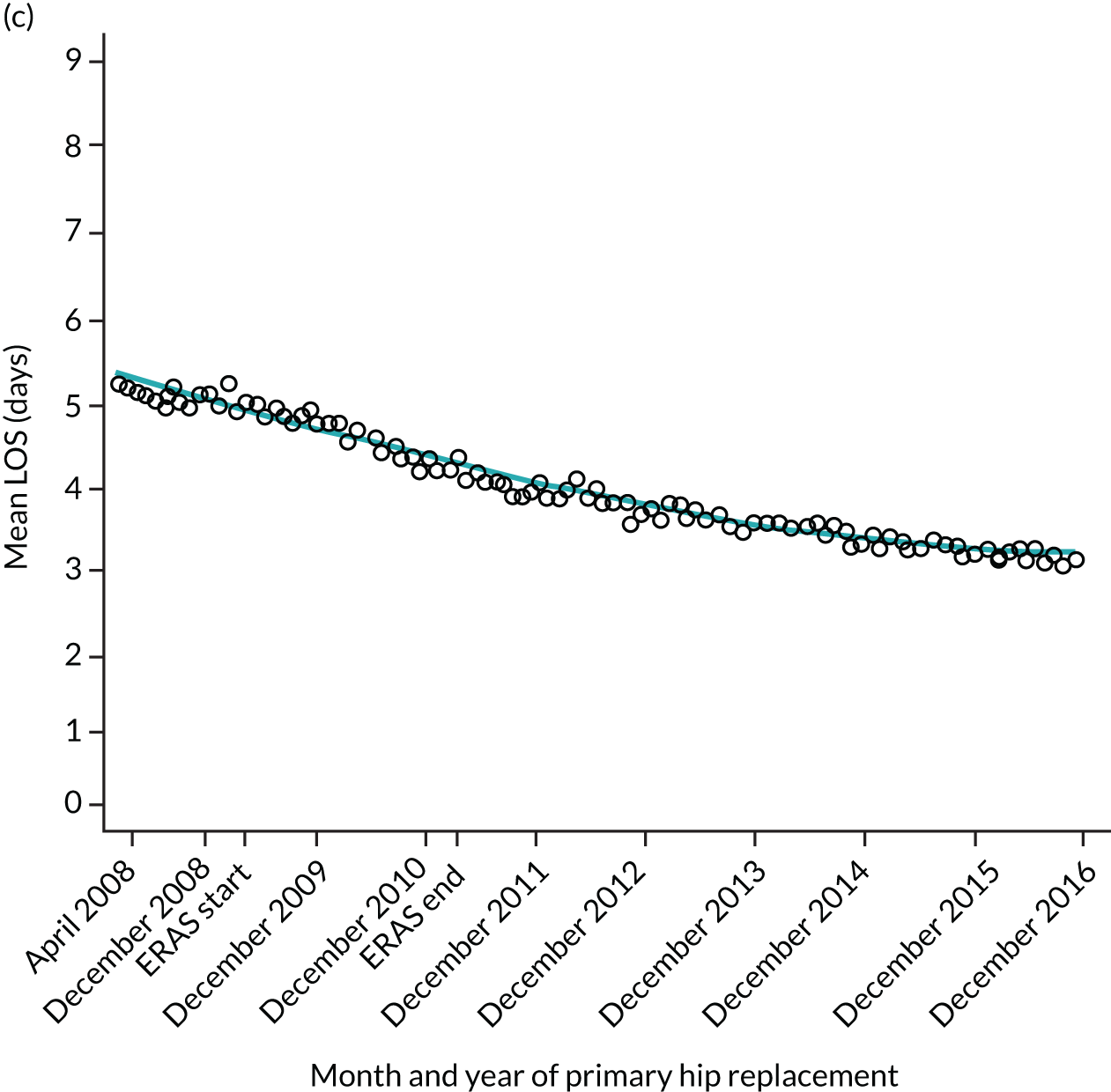

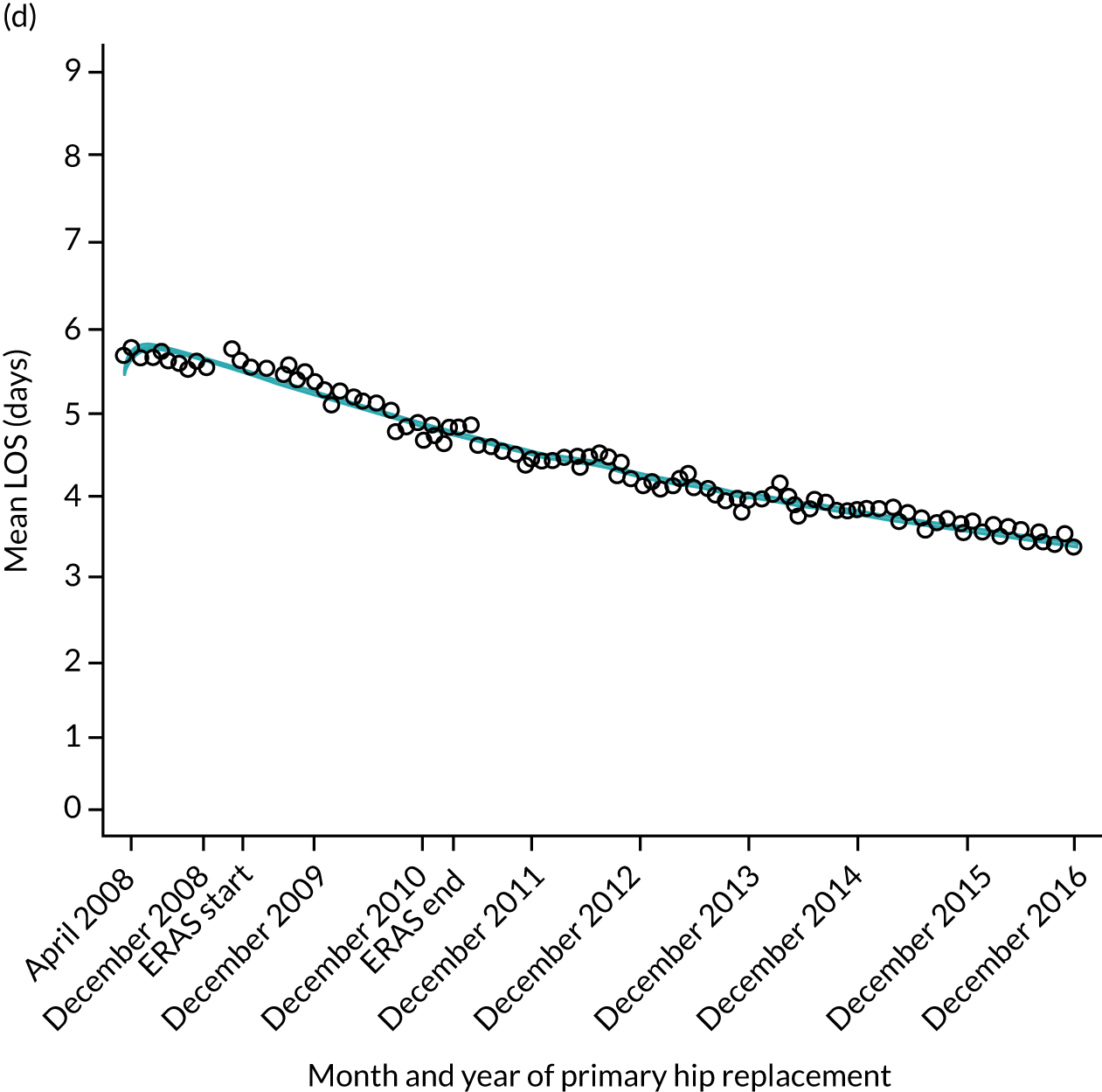

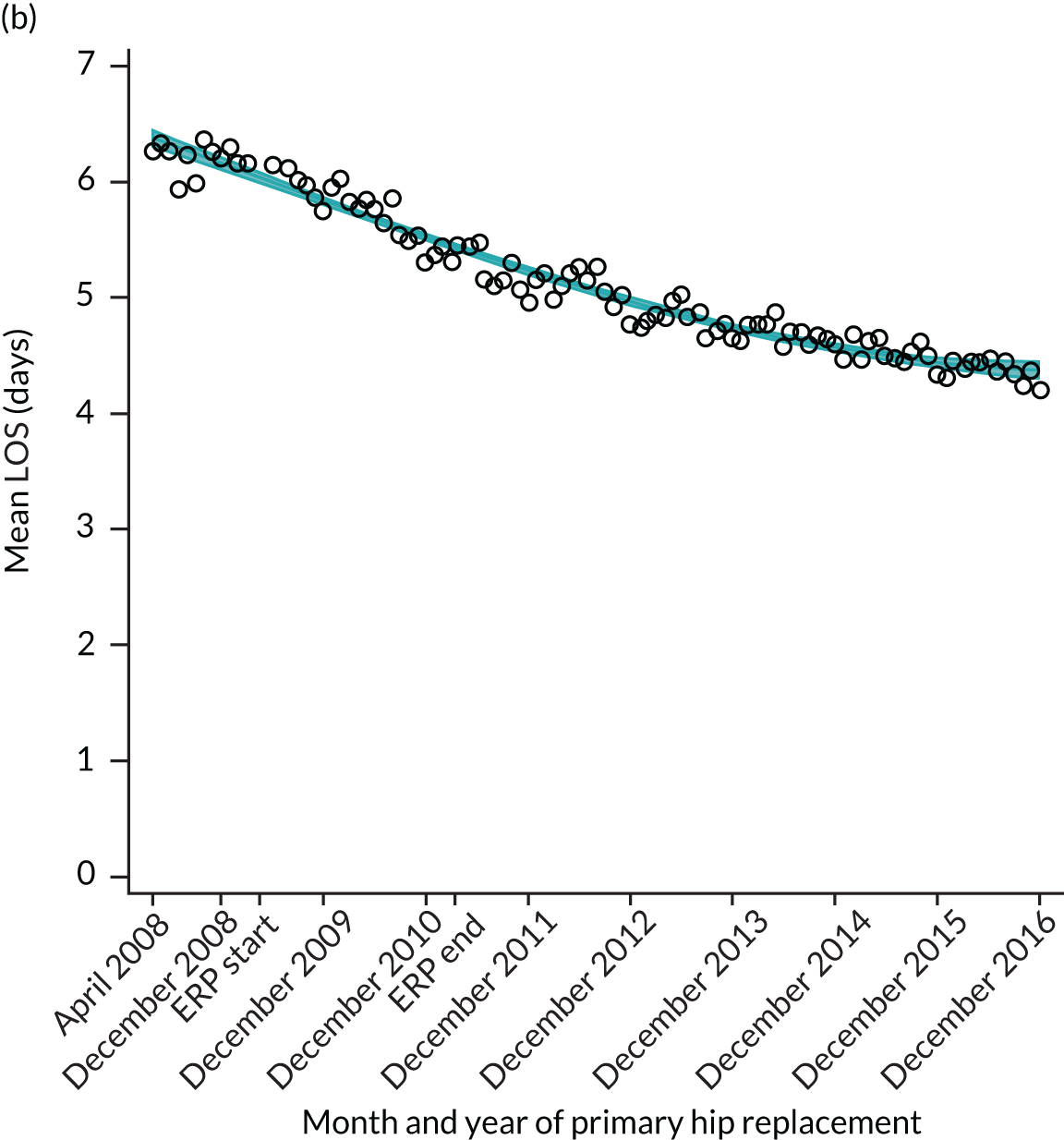

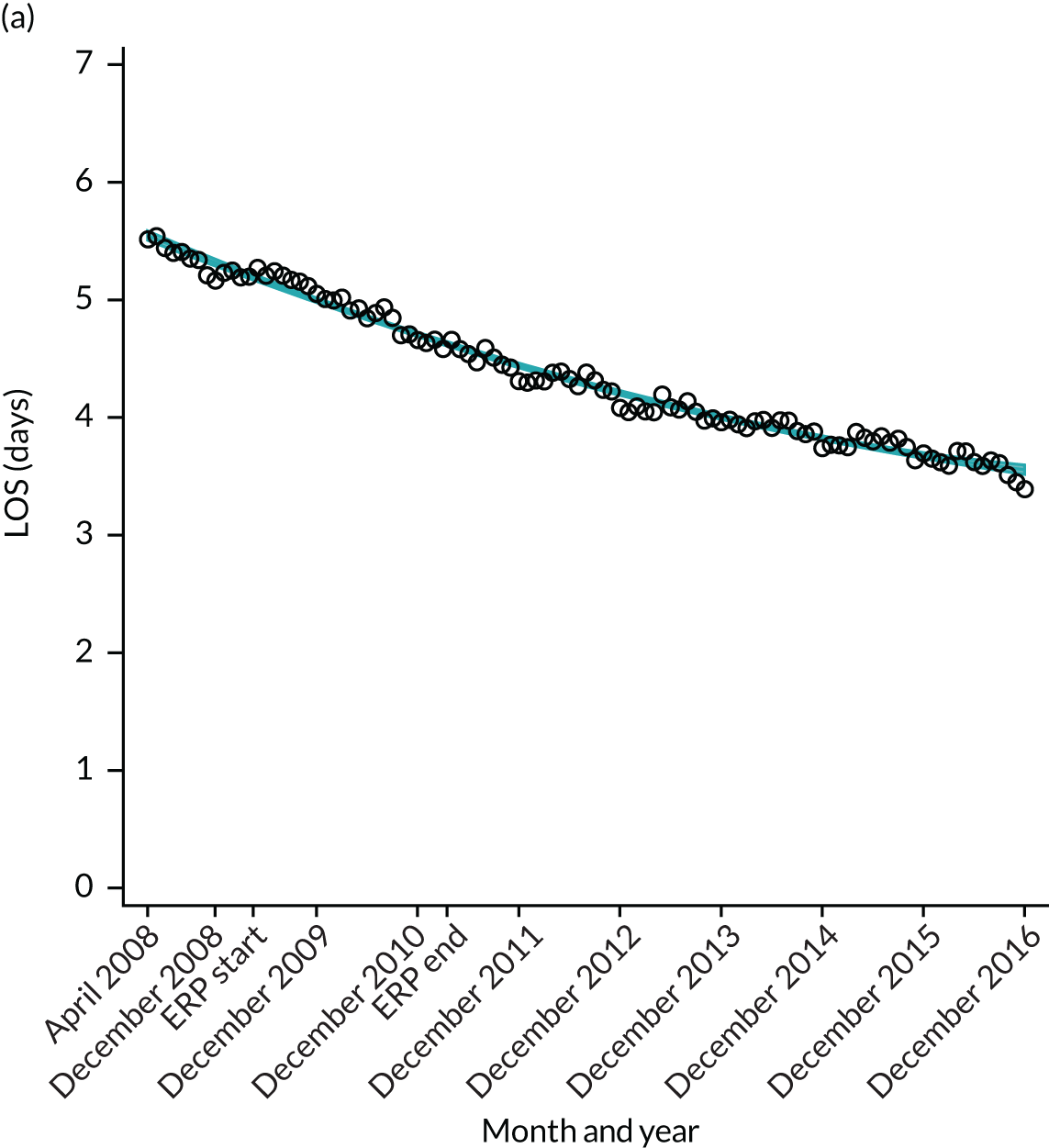

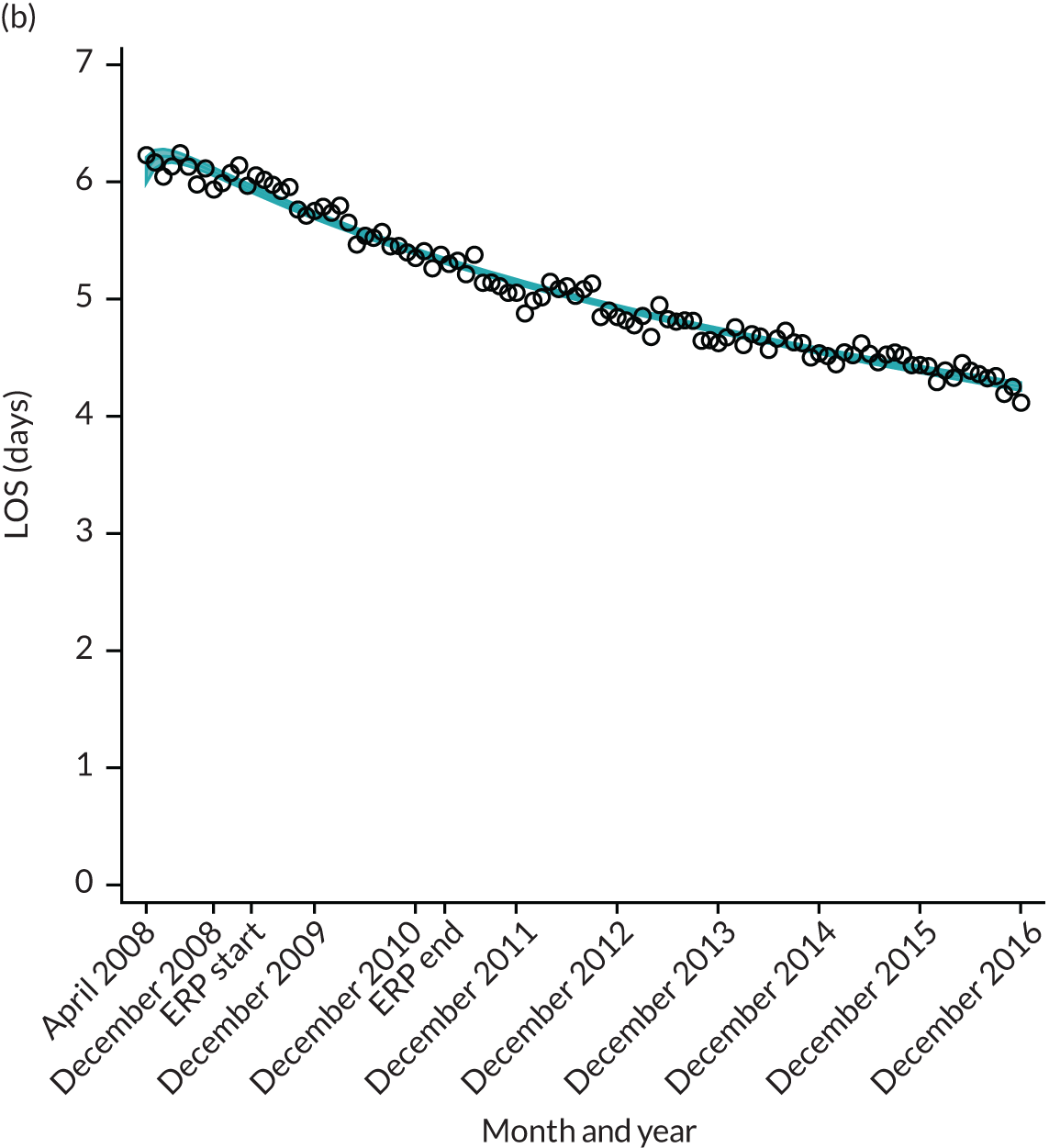

For THR, the mean LOS decreased from 5.6 days in April 2008 to 3.6 days in December 2016 (Figure 8), For TKR, the mean LOS decreased from 5.7 days in April 2008 to 3.6 days in December 2016 (Figure 9). Prior to ERAS, LOS was already decreasing significantly (Table 7). The rate of reduction in mean LOS was higher during the implementation period (April 2009–March 2011), and slowed afterwards (April 2011–December 2016).

FIGURE 8.

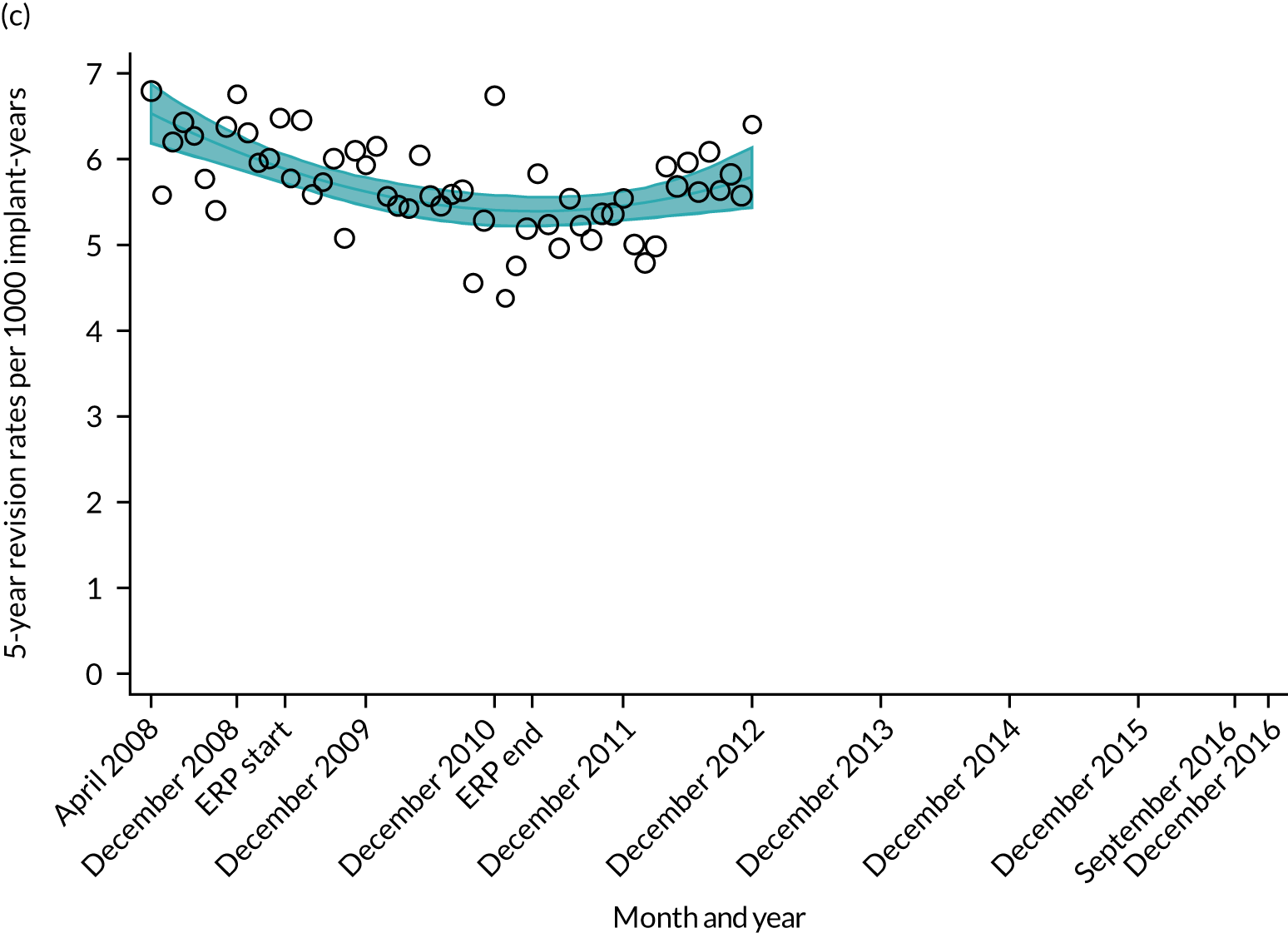

Trends in outcomes following primary hip replacement in England, 2008–16, by month. (a) LOS (days); (b) OHS 6 months – OHS baseline; (c) primary hip replacements with a complication in the following 6 months; and (d) primary hip replacements with a revision in the following 5 years. Reproduced from Garriga et al. 65 © Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2019. Re-use permitted under CC BY. Published by BMJ. This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Minor changes have been made to the formatting.

FIGURE 9.

Trends in outcomes following primary TKR/UKR in England, 2008–16, by month. (a) LOS (days); (b) OKS 6 months – OKS baseline; (c) primary knee surgeries with a revision in the following 5 years; and (d) primary TKR/UKR with a complication in the following 6 months. Reproduced from Garriga et al. 66 © The Author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license, which permits others to share this work, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

| Parameter | Coefficient | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| LOS | |||

| Intercept | 5.674 | 5.655 to 5.693 | < 0.001 |

| Monthly trend | –0.020 | –0.023 to –0.017 | < 0.001 |

| Level change ERAS0 | 0.176 | 0.120 to 0.232 | < 0.001 |

| Trend change after ERAS0 | –0.013 | –0.017 to –0.009 | < 0.001 |

| Level change ERASend | –0.102 | –0.203 to –0.001 | 0.049 |

| Trend change after ERASend | 0.019 | 0.015 to 0.022 | < 0.001 |

| OHS 6 months – OHS baseline | |||

| Intercept | 17.063 | 16.896 to 17.230 | < 0.001 |

| Monthly trend | 0.158 | 0.130 to 0.186 | < 0.001 |

| Level change ERAS0 | 0.772 | 0.538 to 1.006 | < 0.001 |

| Trend change after ERAS0 | –0.131 | –0.161 to –0.101 | < 0.001 |

| Level change ERASend | 0.564 | 0.208 to 0.920 | 0.002 |

| Trend change after ERASend | –0.013 | –0.025 to –0.001 | 0.039 |

| Complication by 6 months | |||

| Intercept | 4.044 | 3.465 to 4.624 | < 0.001 |

| Monthly trend | –0.078 | –0.096 to –0.061 | < 0.001 |

| Level change ERAS0 | – | – | – |

| Trend change after ERAS0 | – | – | – |

| Level change ERASend | – | – | – |

| Trend change after ERASend | 0.078 | 0.056 to 0.100 | < 0.001 |

| Revision rates by 5 years | |||

| Intercept | 5.940 | 5.820 to 6.060 | < 0.001 |

| Monthly trend | – | – | – |

| Level change ERAS0 | – | – | – |

| Trend change after ERAS0 | –0.098 | –0.105 to –0.090 | < 0.001 |

| Level change ERASend | – | – | – |

| Trend change after ERASend | 0.103 | 0.068 to 0.139 | < 0.001 |

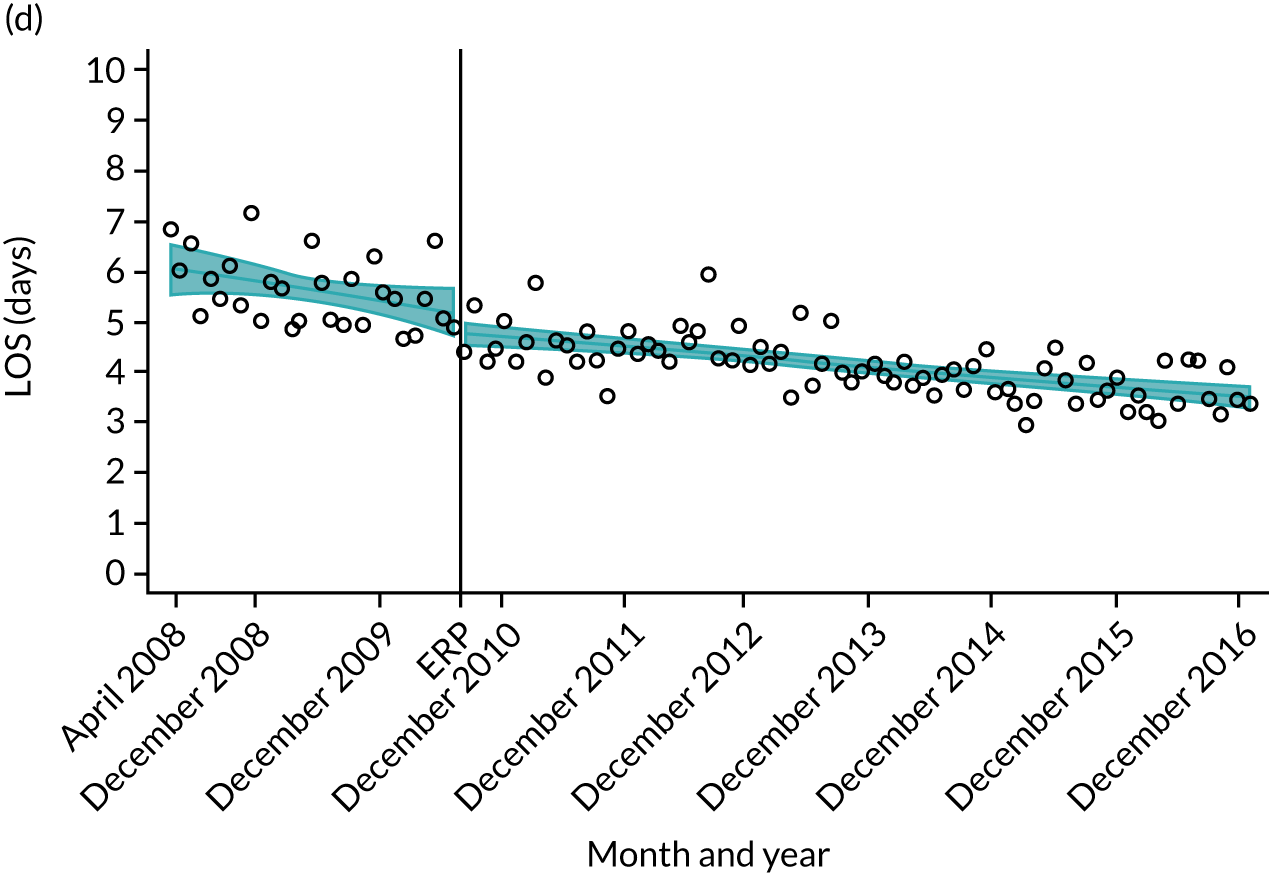

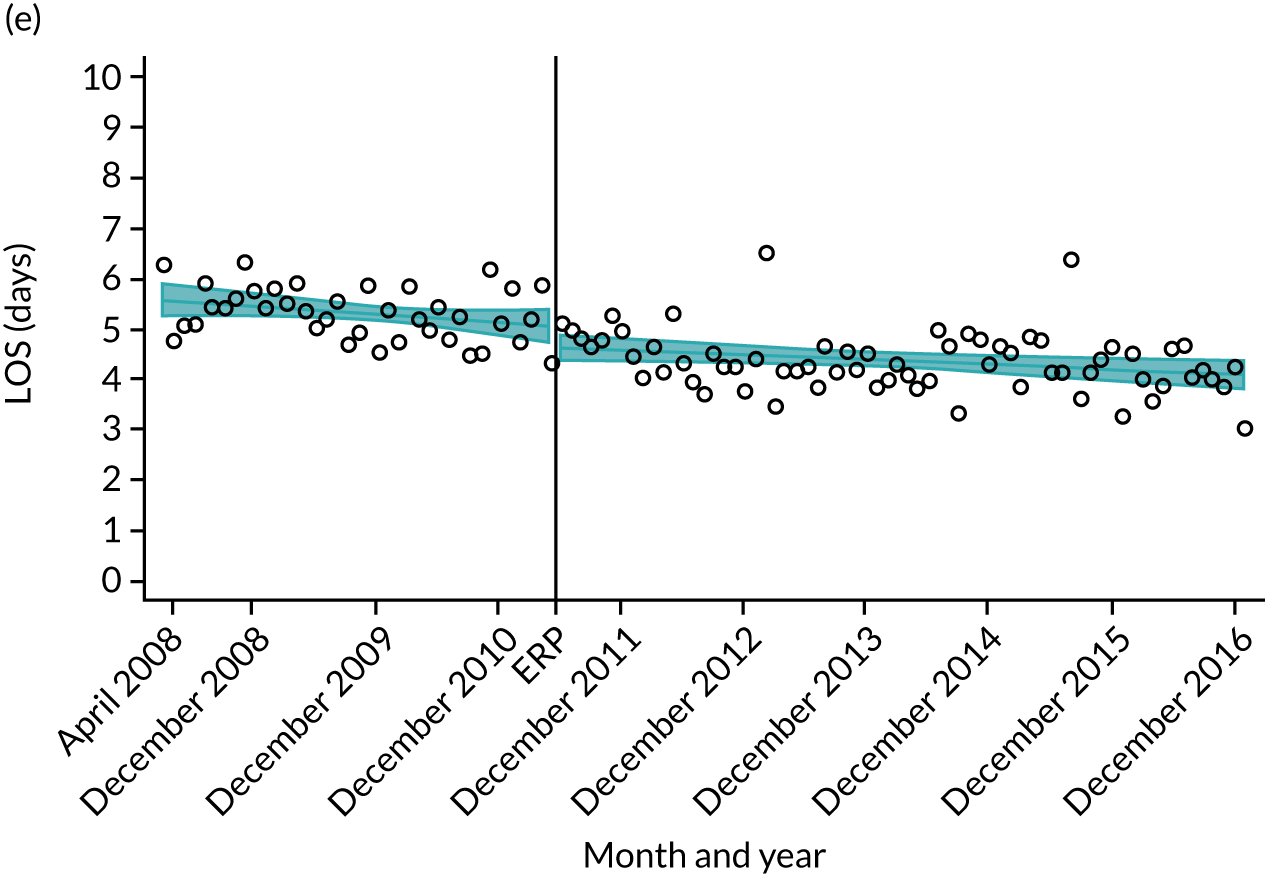

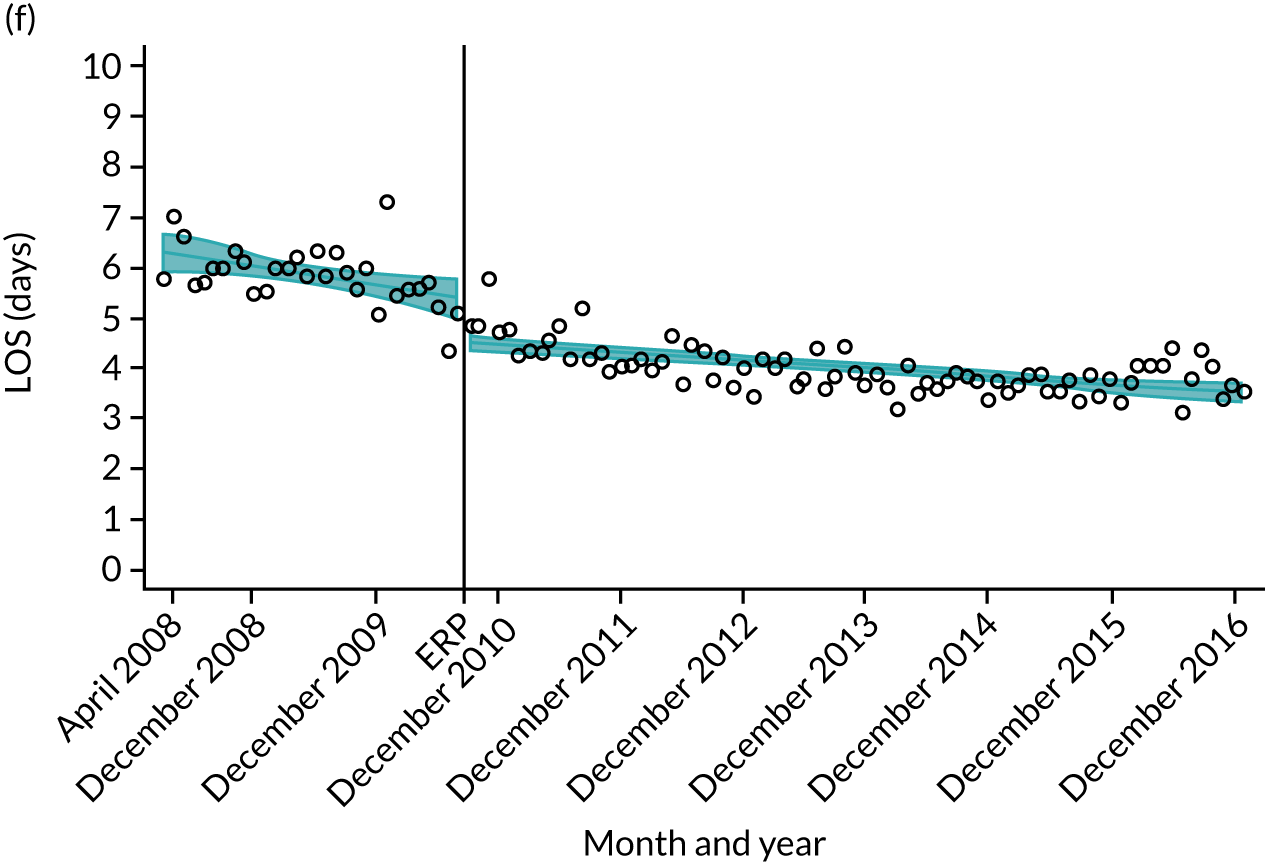

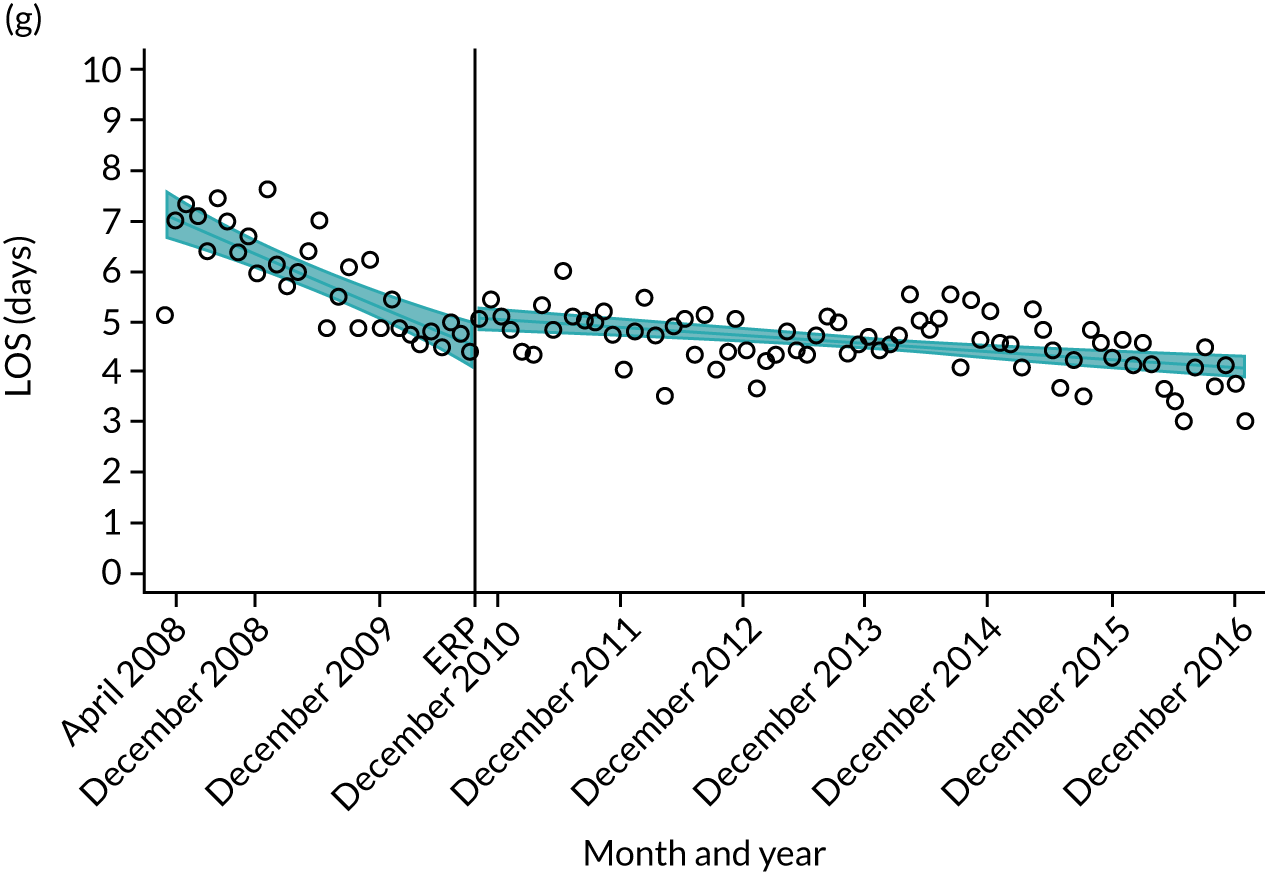

Although older patients had a longer LOS, the secular trends in decreasing LOS were observed across all age groups (e.g. for THR, 4.7 days to 3.0 days in those aged 18–59 years; and 8.1 days to 5.3 days in those aged ≥ 85) (Figures 10 and 11). Secular trends also decreased in patients with and without pre-existing comorbidity (Figures 12 and 13).

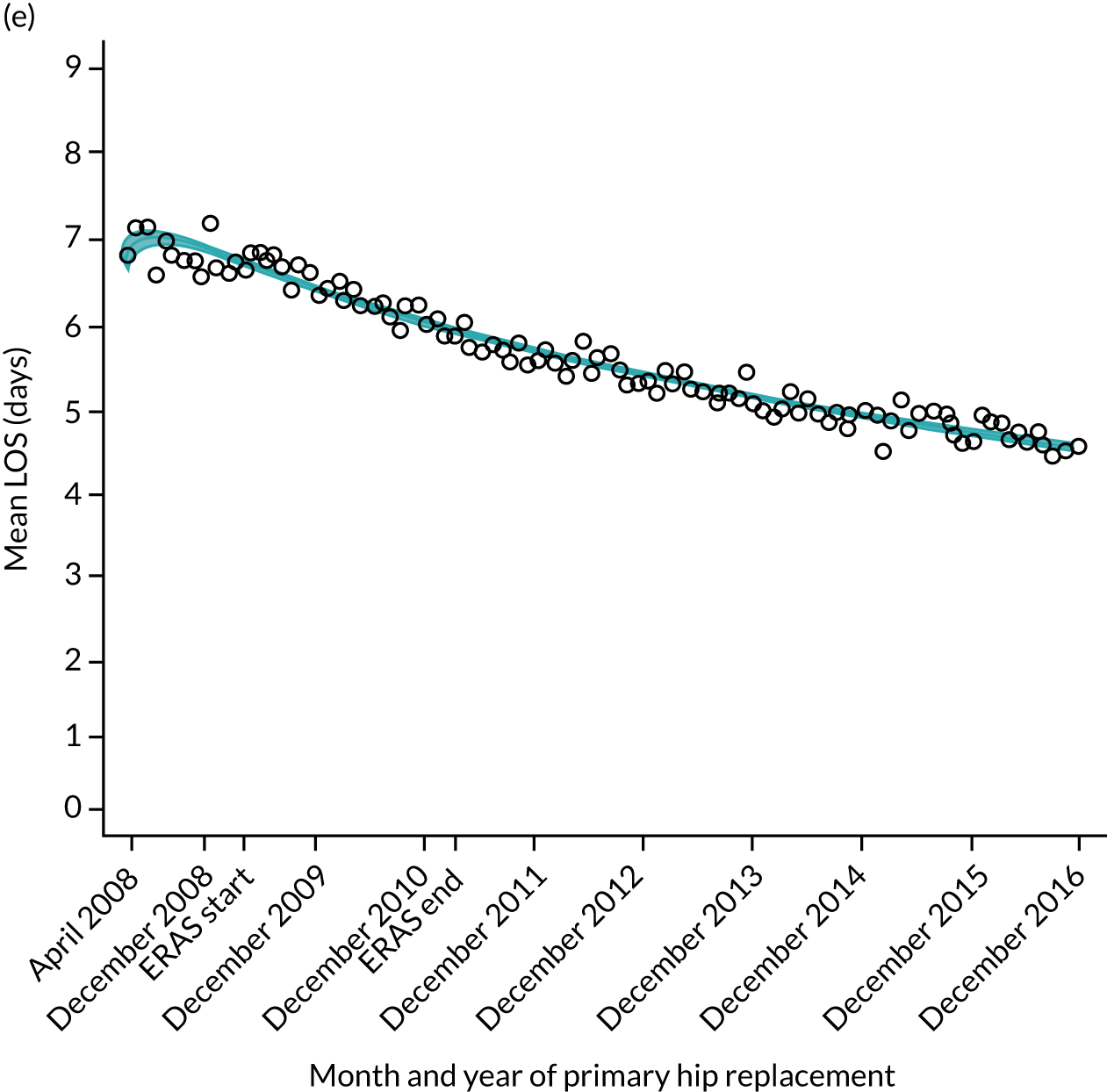

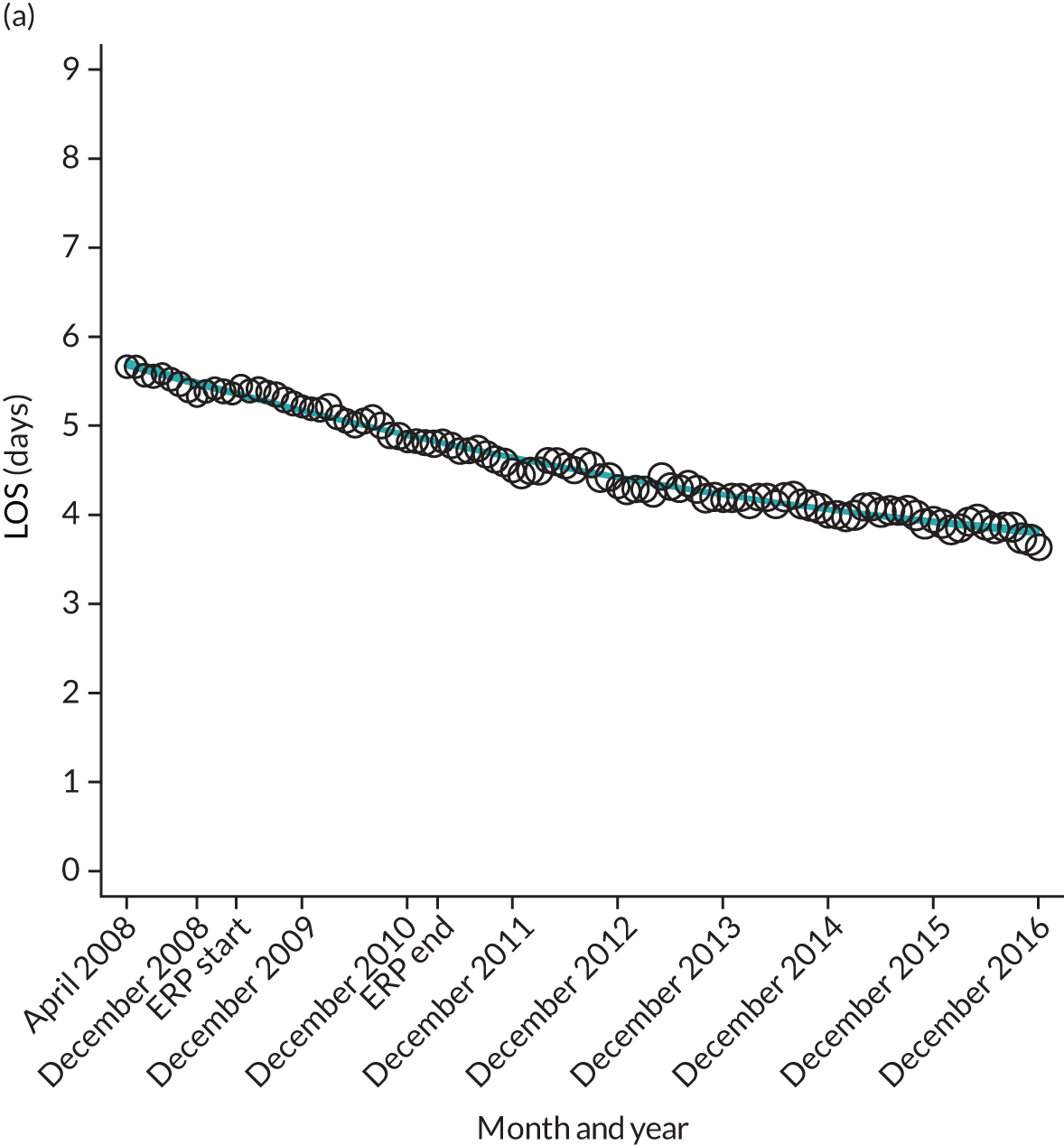

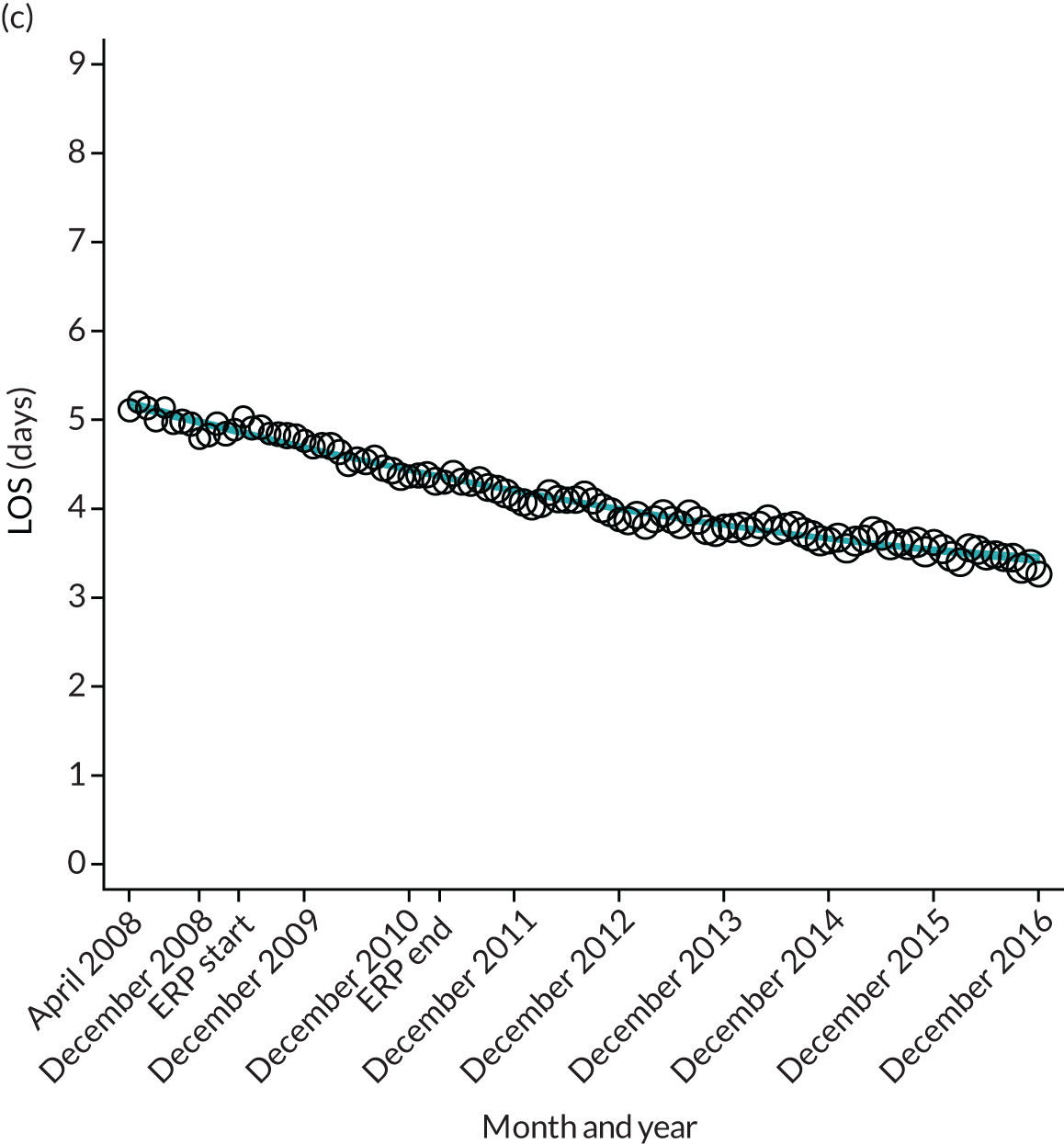

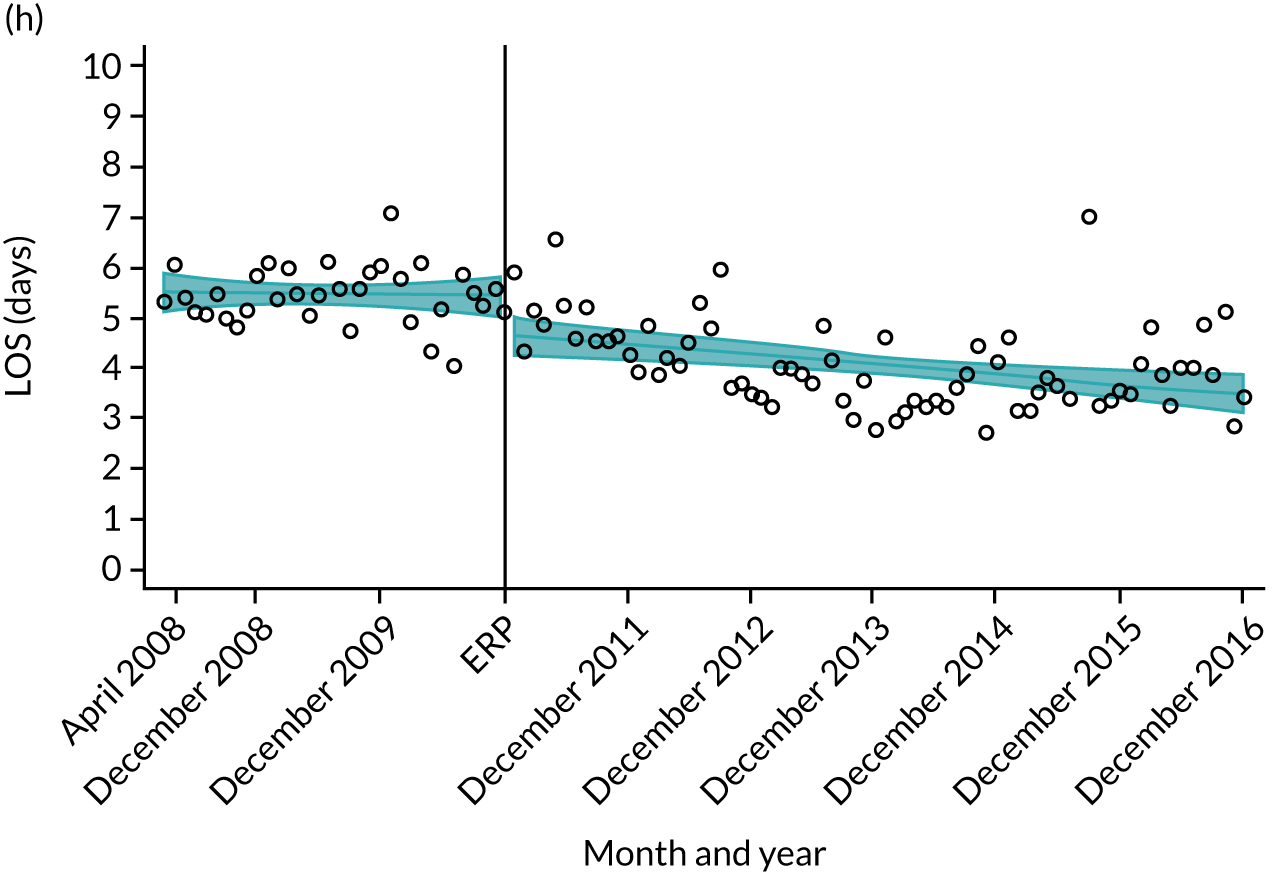

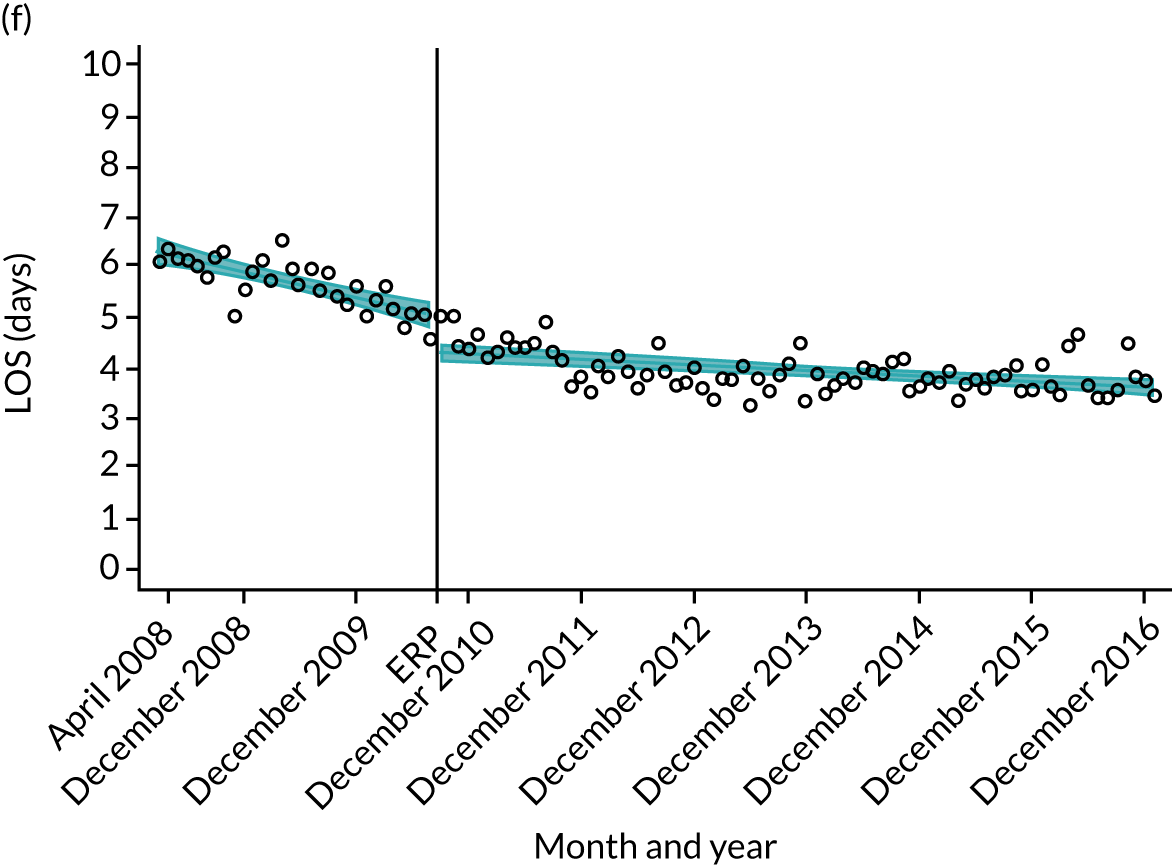

FIGURE 10.

Trends of LOS at hospital following primary hip replacement according to age categories in England, 2008–16, by month. (a) All ages; (b) 18–59 years; (c) 60–69 years; (d) 70–79 years; (e) 80–84 years; and (f) ≥ 85 years. ERP implemented in England from April 2009 to March 2011. Reproduced from Garriga et al. 65 © Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2019. Re-use permitted under CC BY. Published by BMJ. This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Minor changes have been made to the formatting.

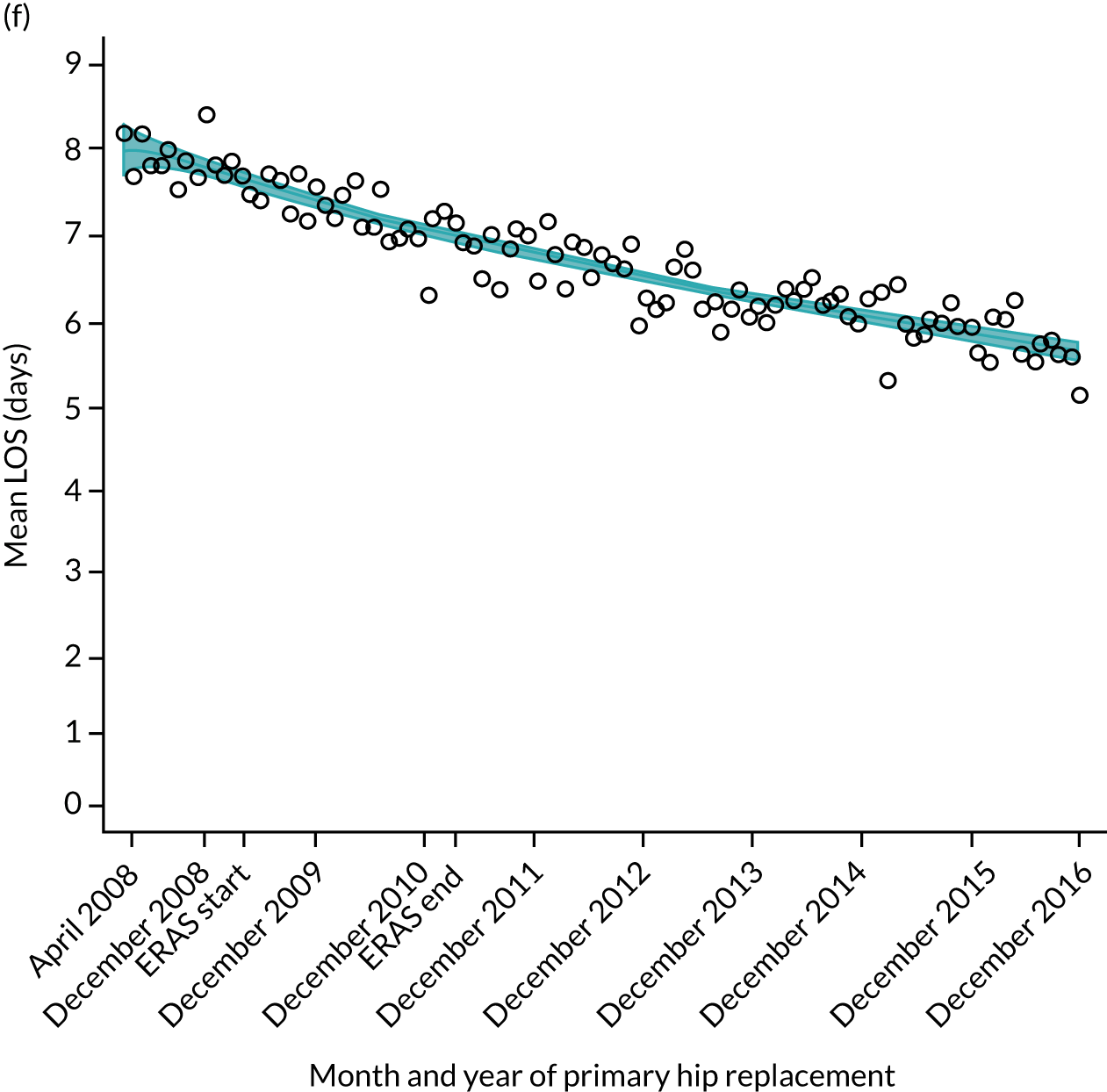

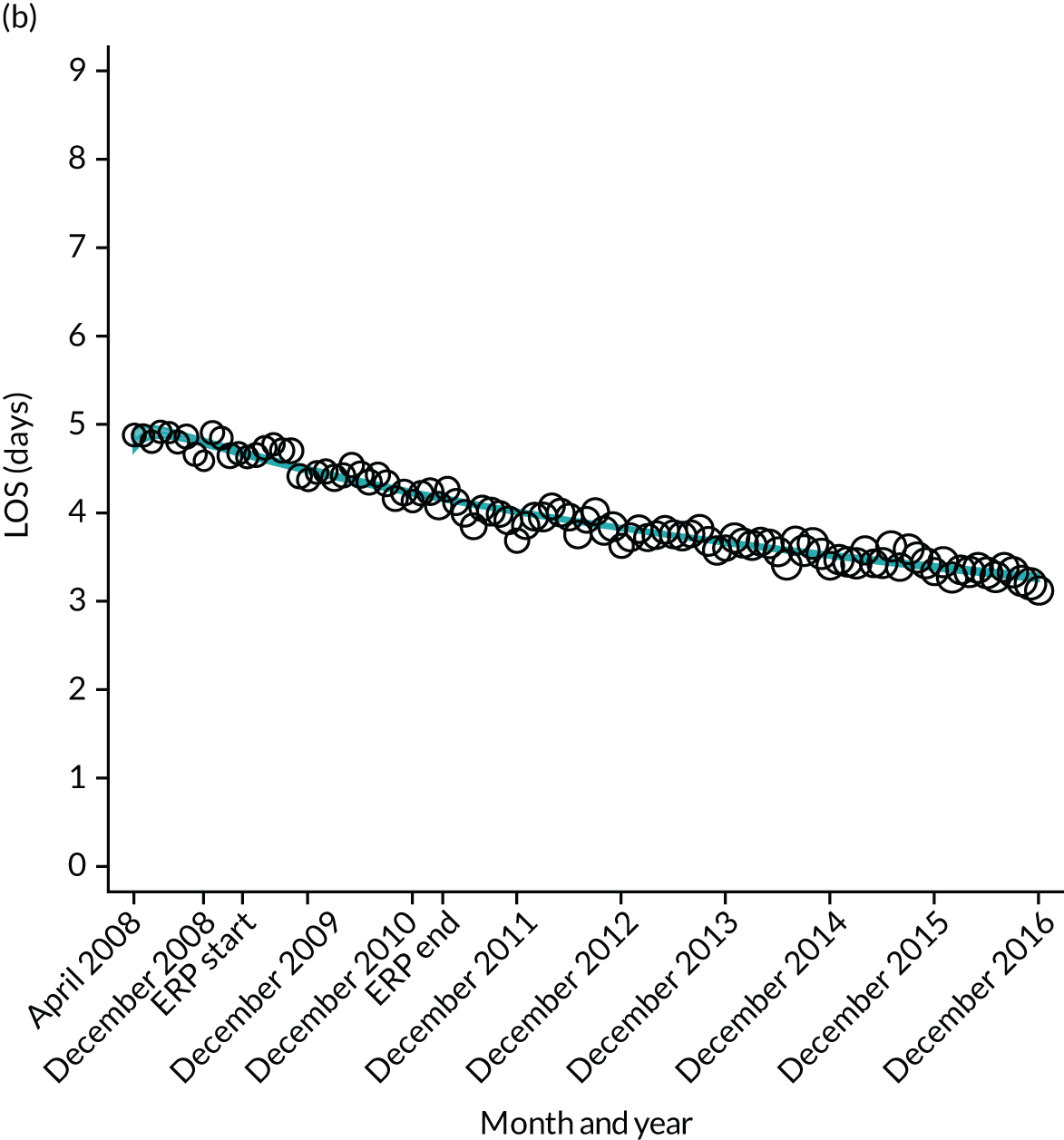

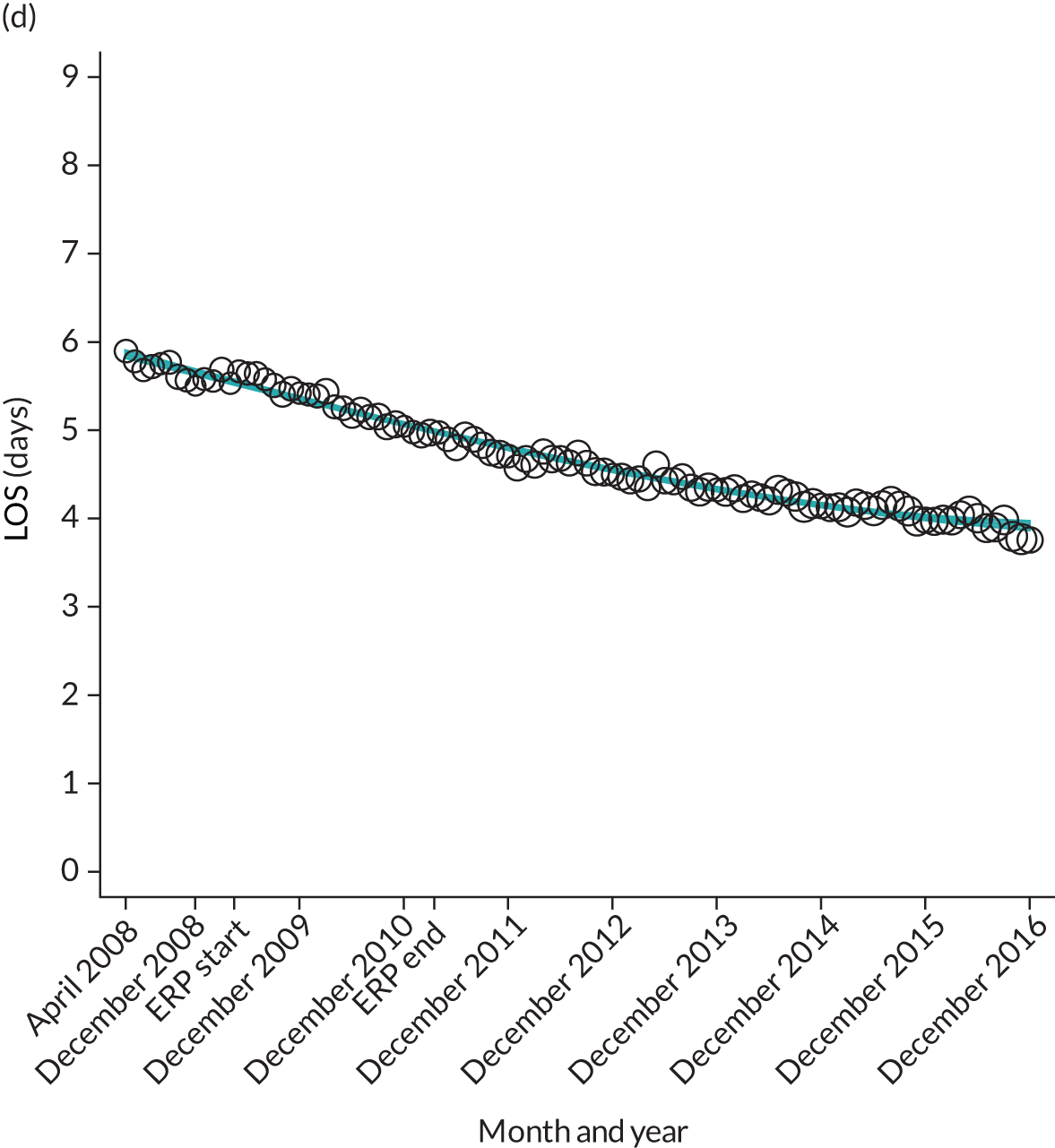

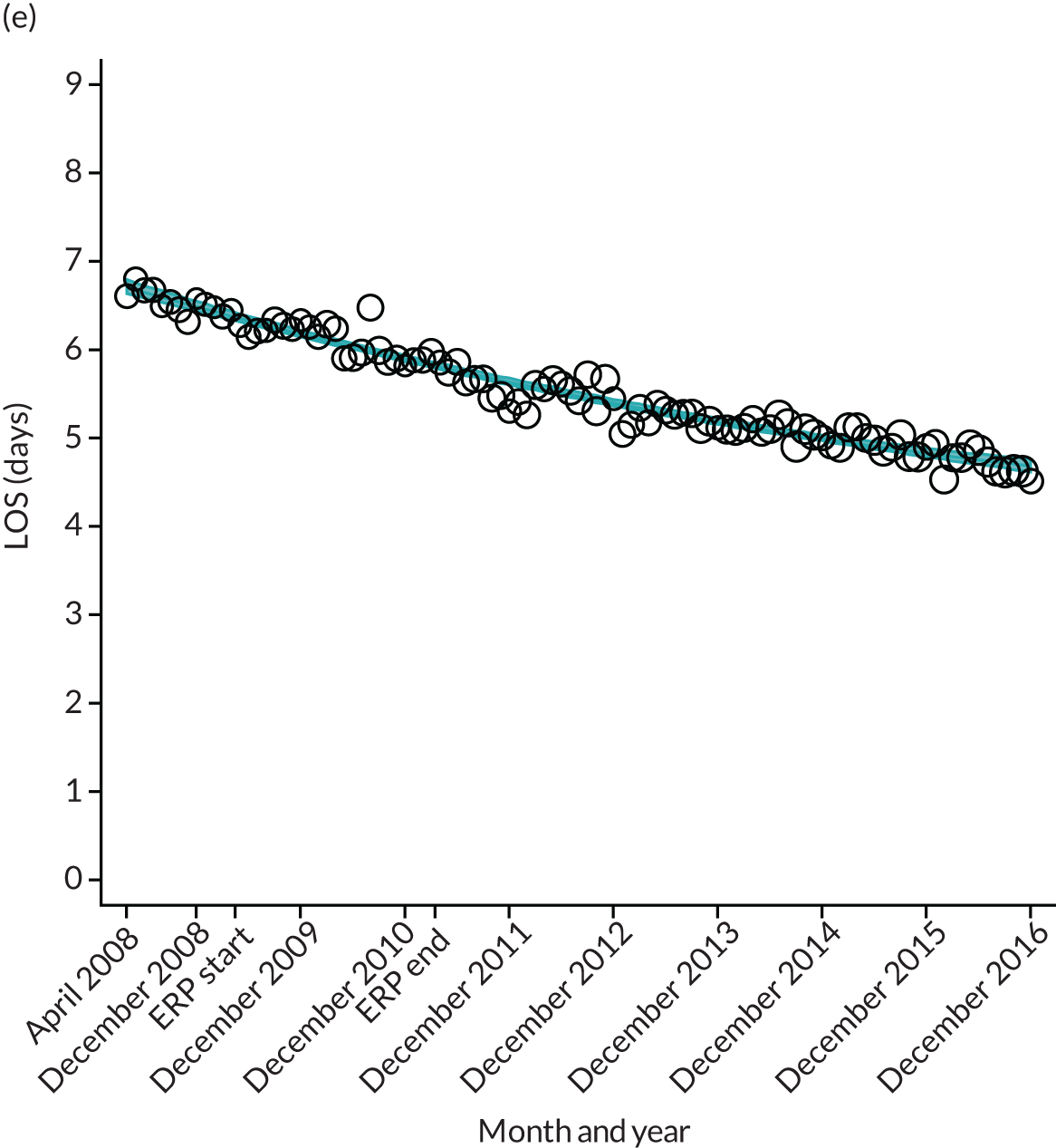

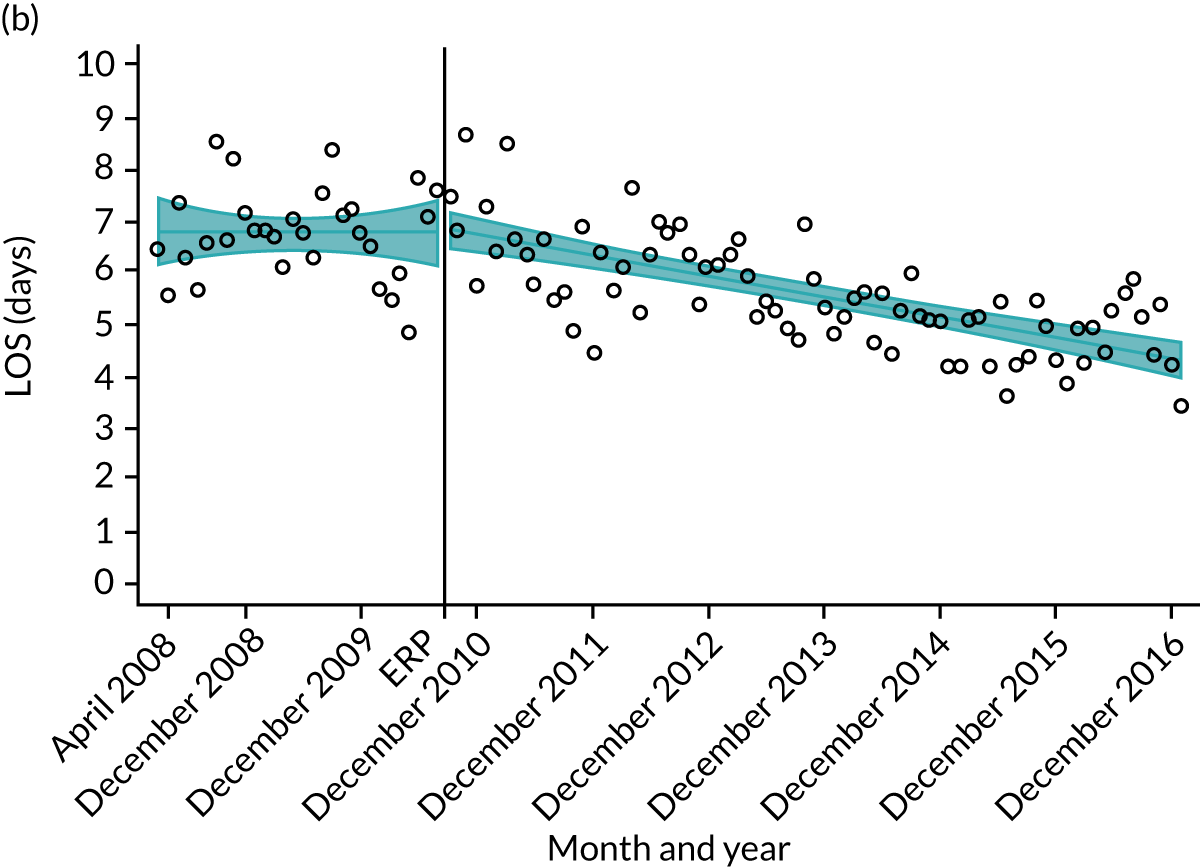

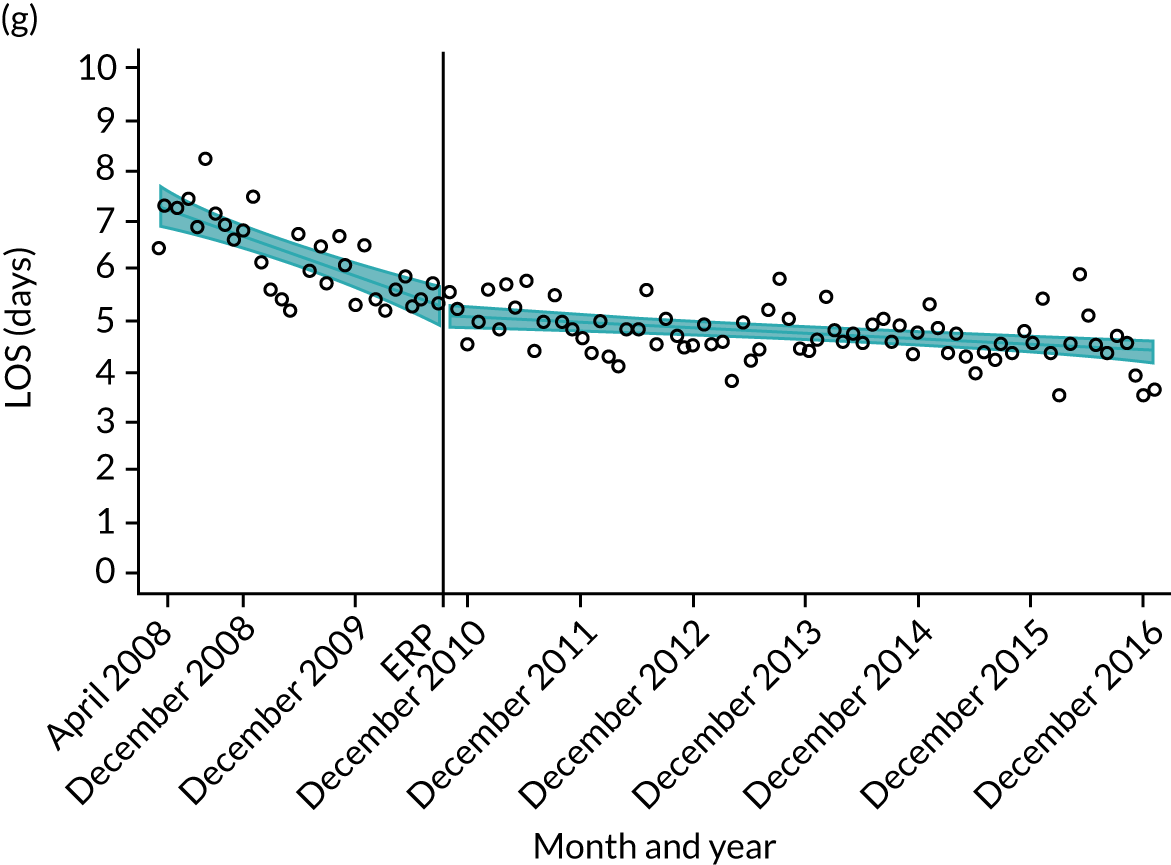

FIGURE 11.

Trends of LOS at hospital after primary TKR/UKR according to age categories in England, 2008–16. (a) All ages; (b) 18–59 years; (c) 60–69 years; (d) 70–79 years; (e) 80–84 years; and (f) ≥ 85 years. ERAS programme implemented in England from April 2009 to March 2011. Reproduced from Garriga et al. 66 © The Author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license, which permits others to share this work, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

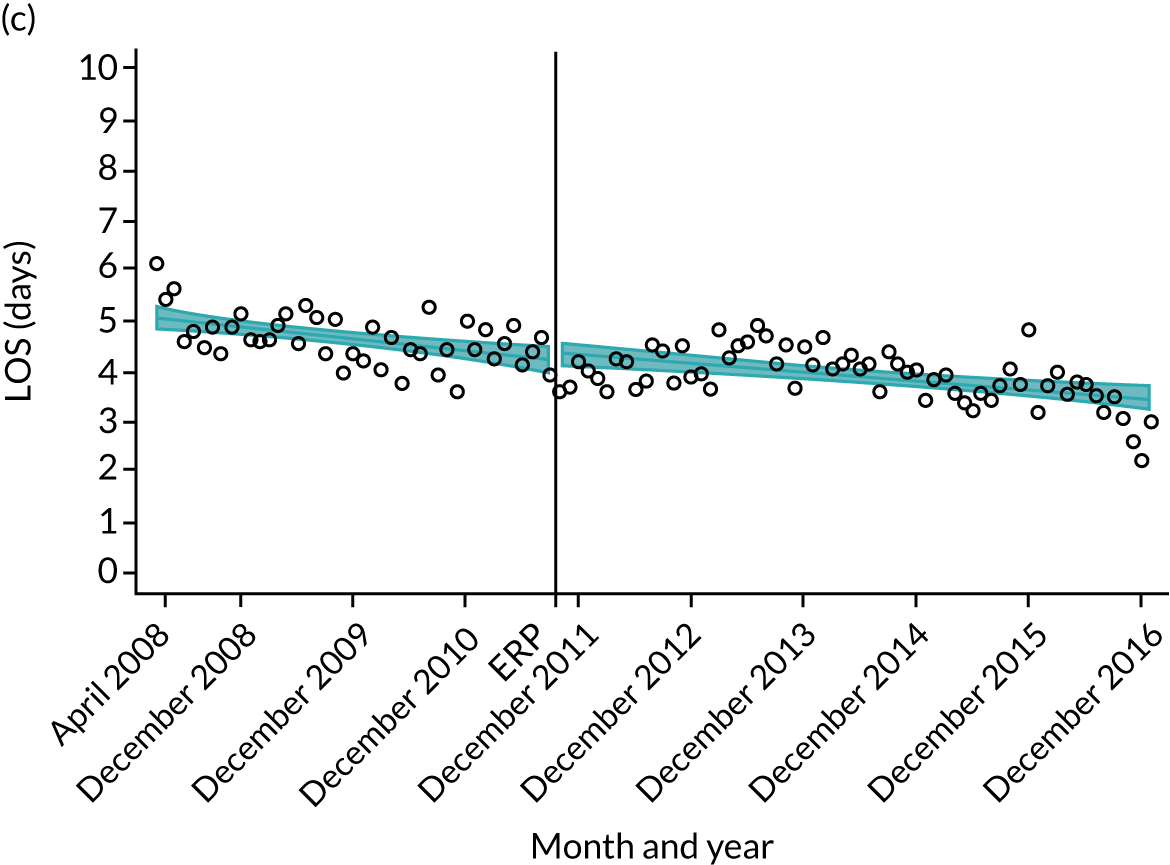

FIGURE 12.

Trends of LOS at hospital following primary hip replacement by patients with/without comorbidities in England, 2008–16, by month. (a) Without comorbidities; and (b) one or more comorbidities. ERP implemented in England from April 2009 to March 2011. Reproduced from Garriga et al. 65 © Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2019. Re-use permitted under CC BY. Published by BMJ. This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Minor changes have been made to the formatting.

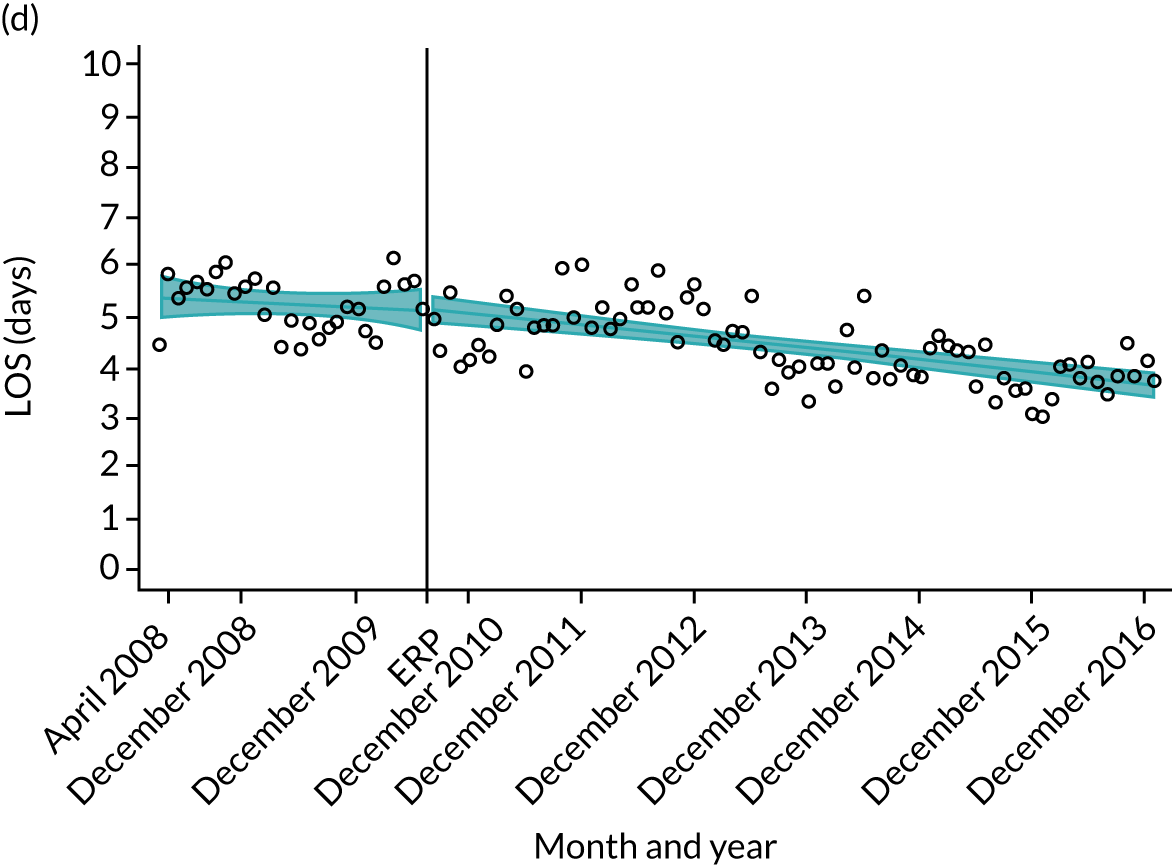

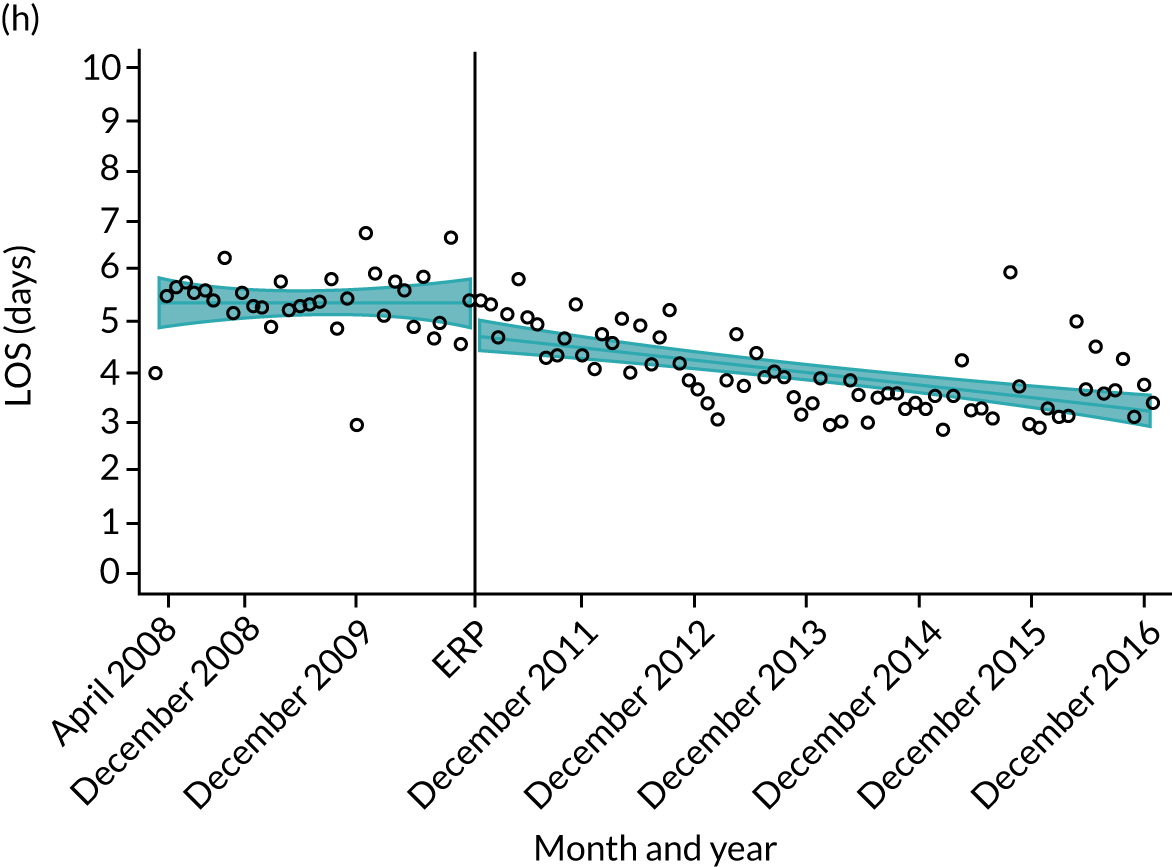

FIGURE 13.

Trends of LOS at hospital after primary TKR/UKR by patients with/without comorbidities in England, 2008–16. (a) Without comorbidities; and (b) one or more comorbidities. Reproduced from Garriga et al. 66 © The Author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license, which permits others to share this work, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

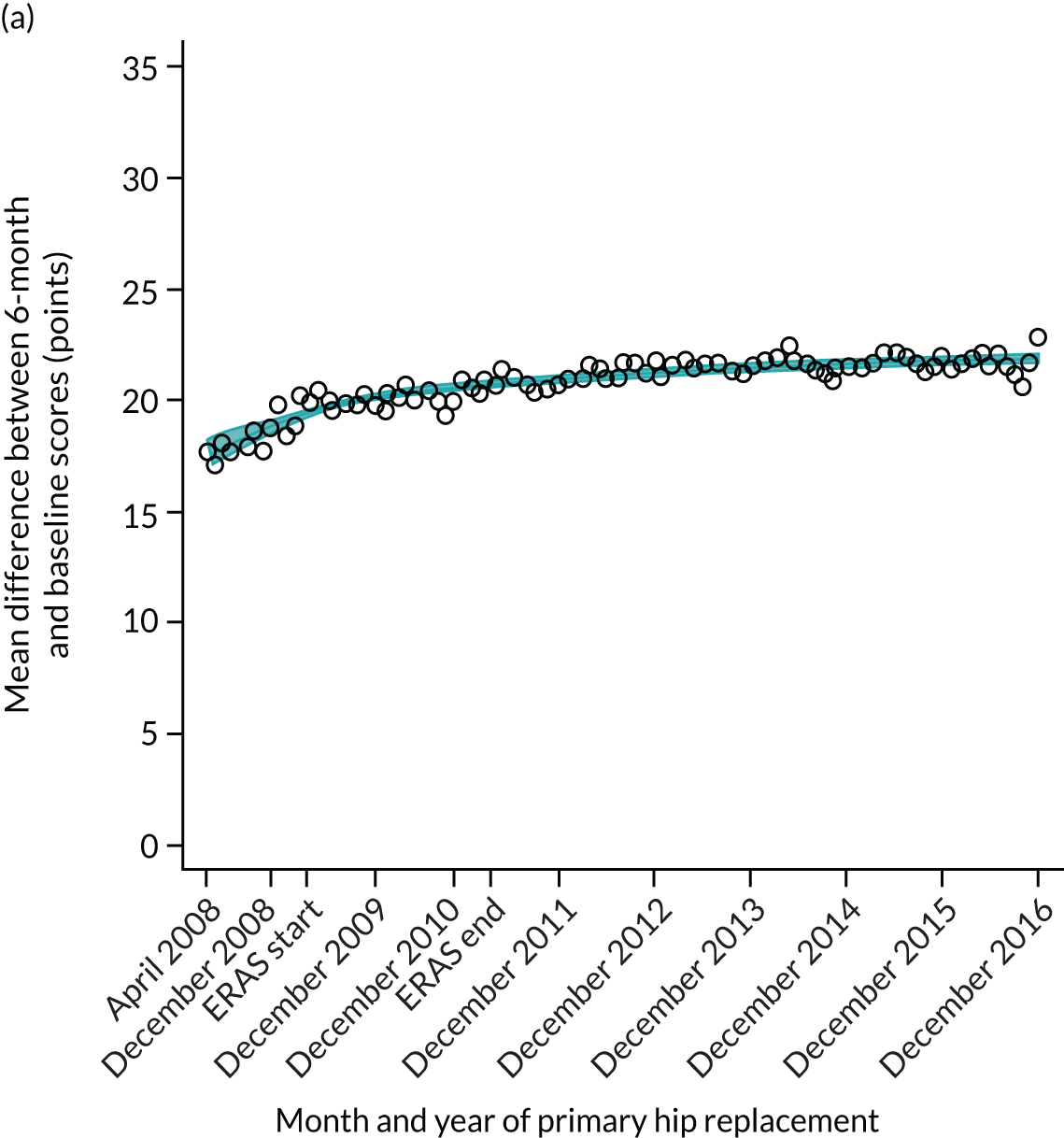

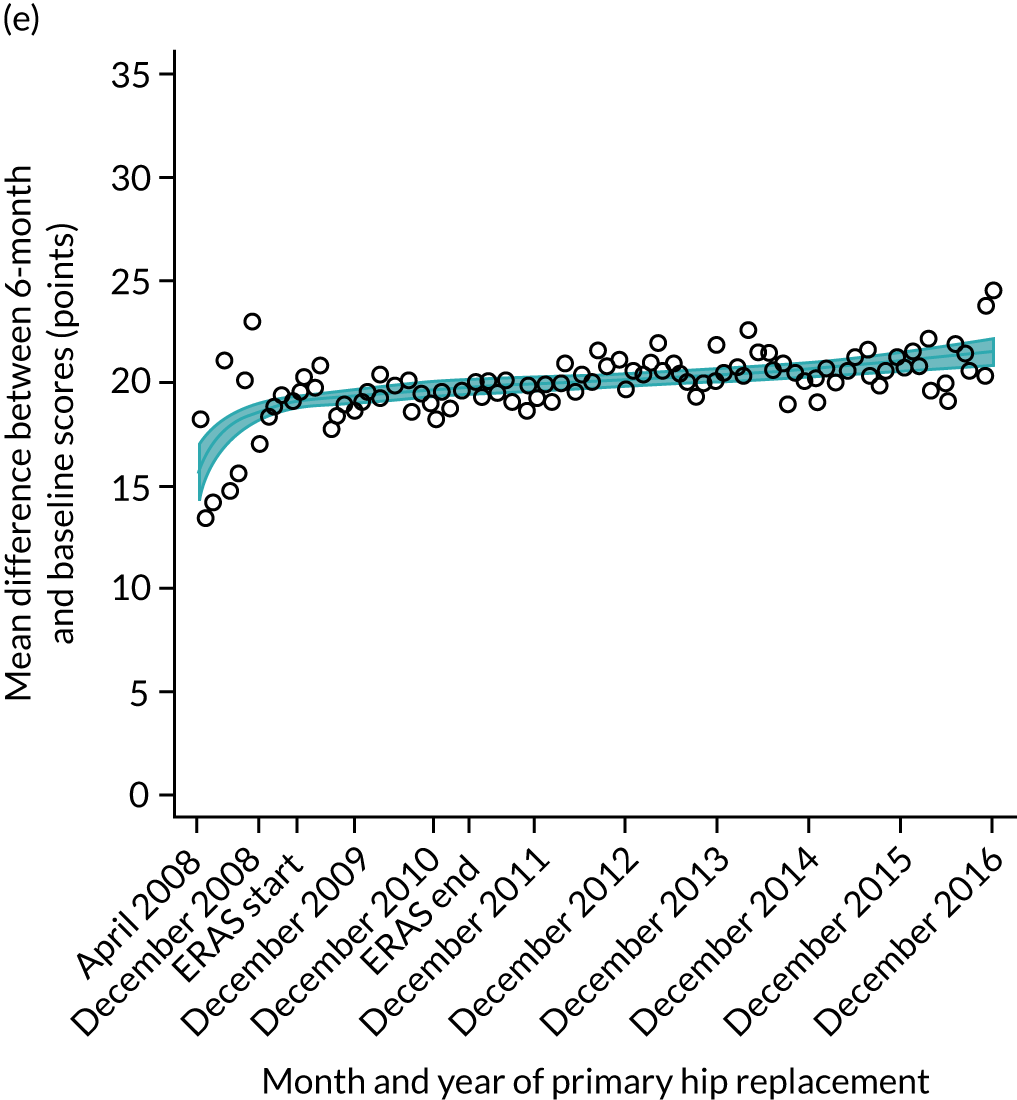

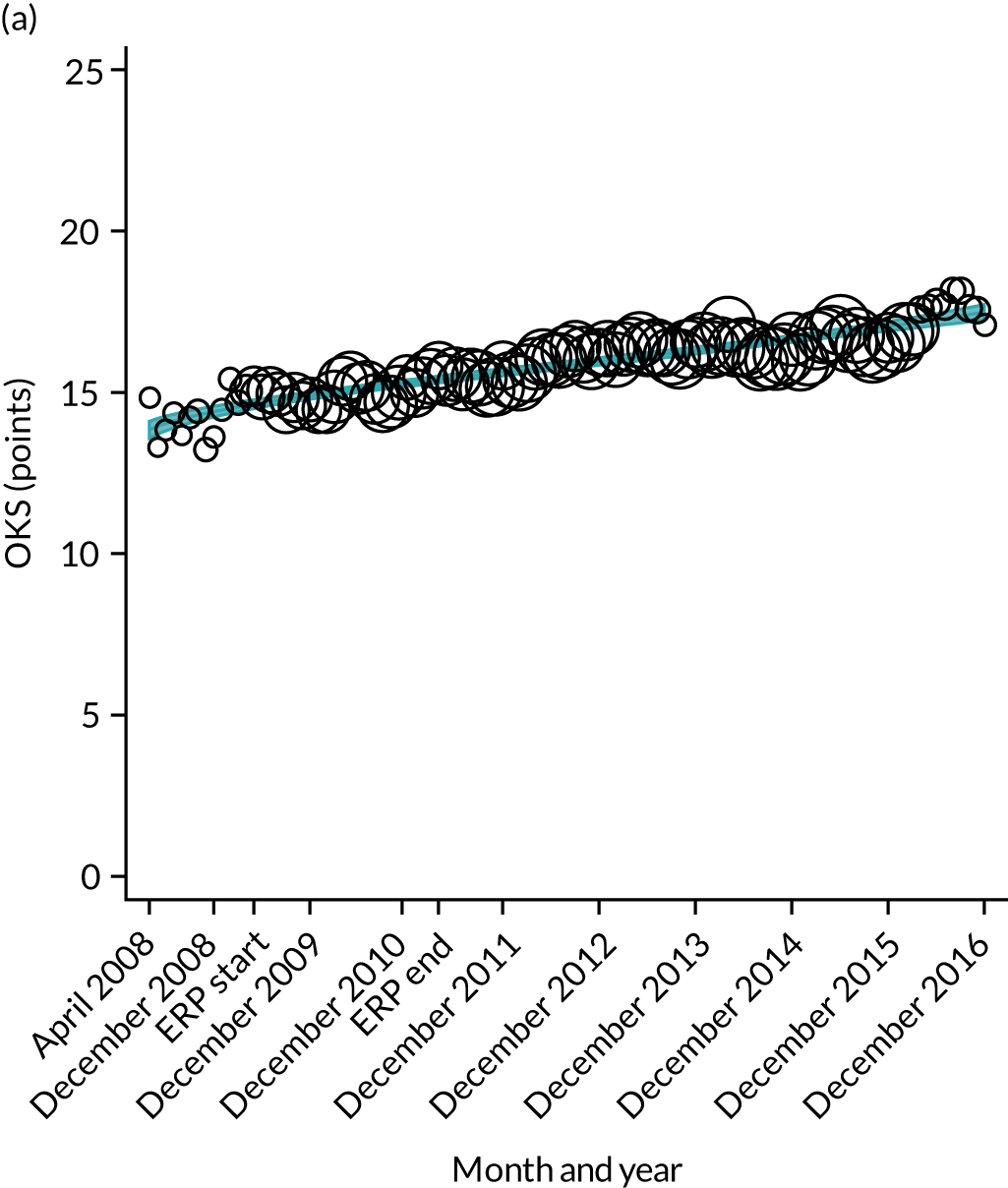

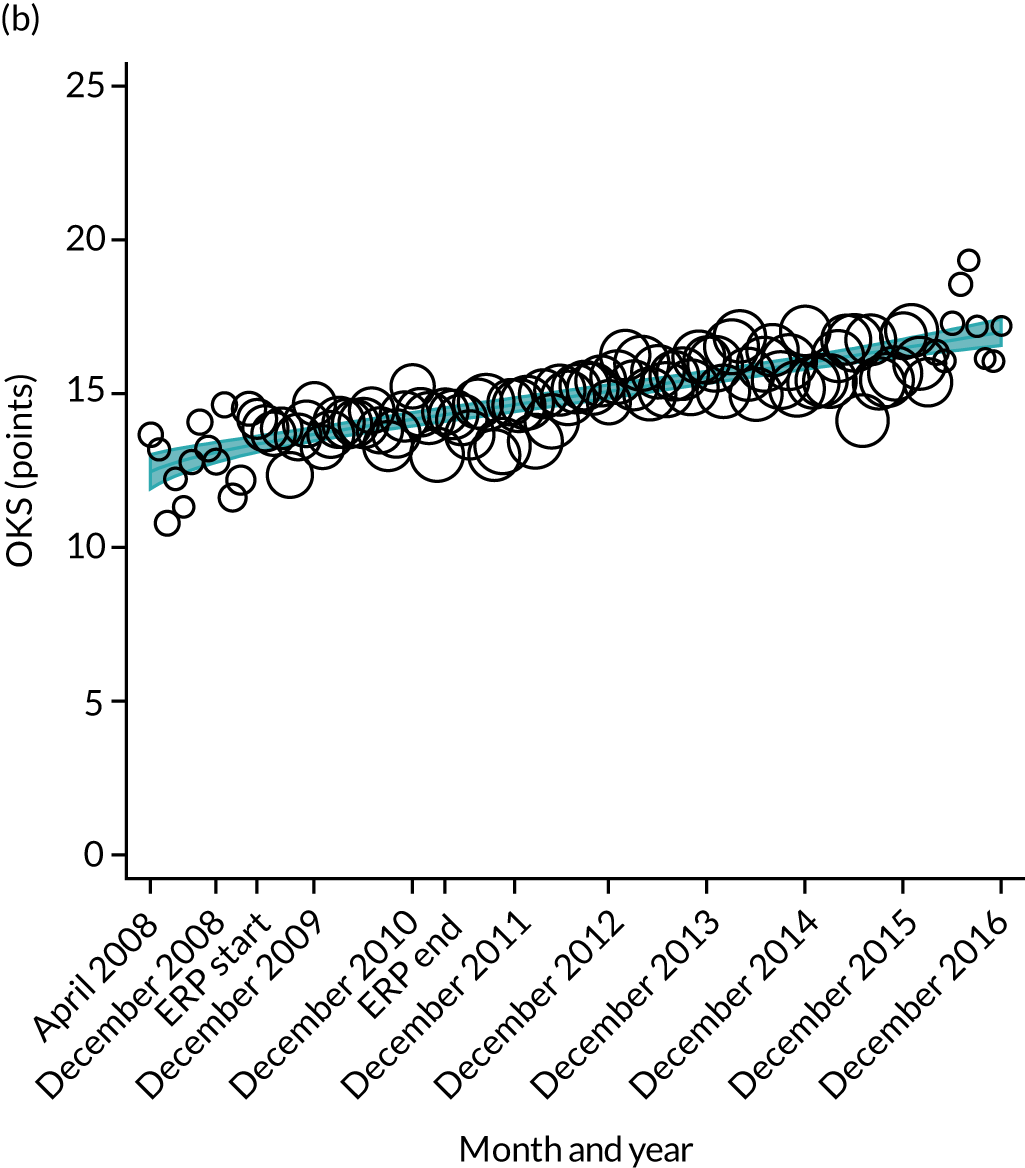

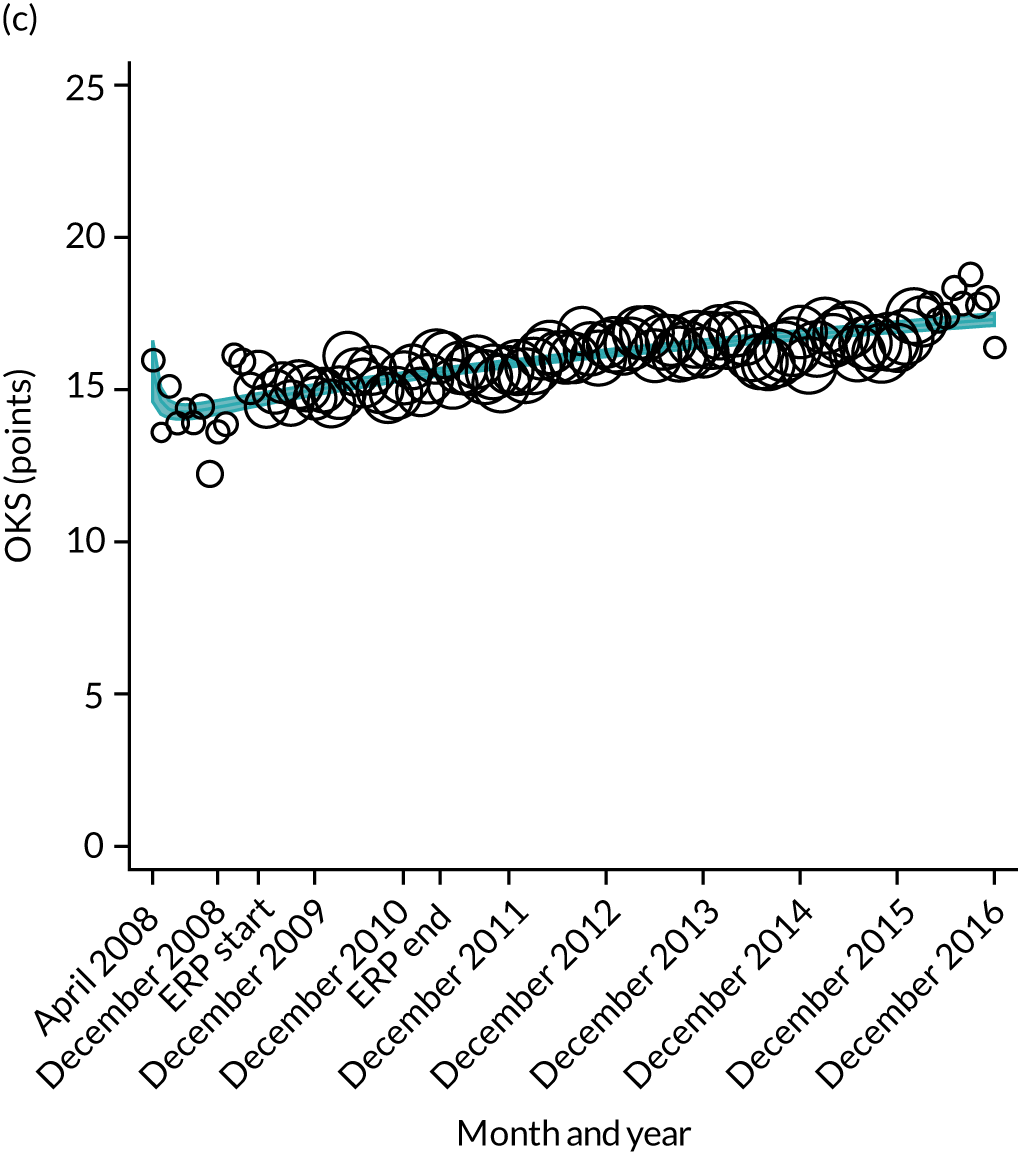

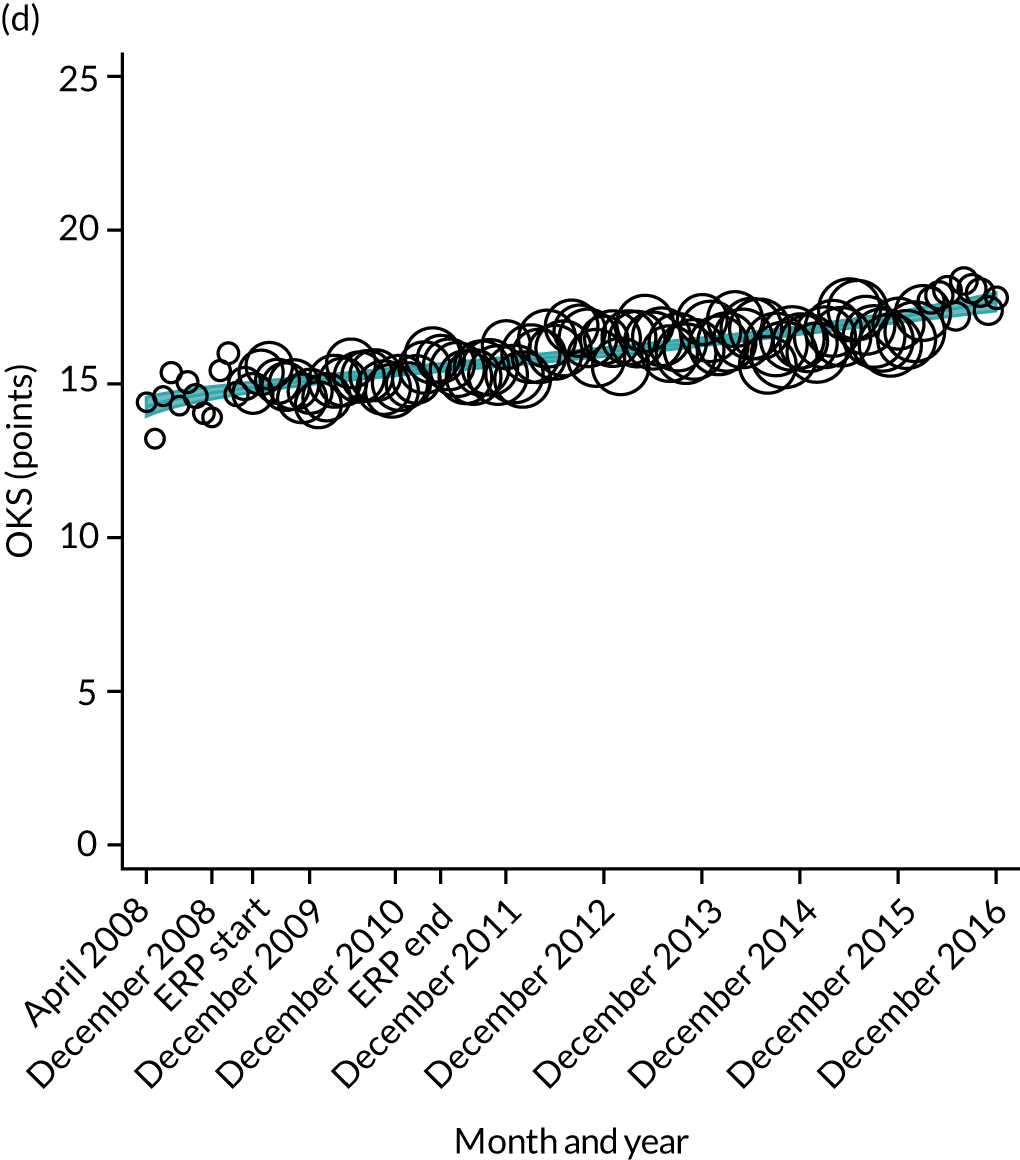

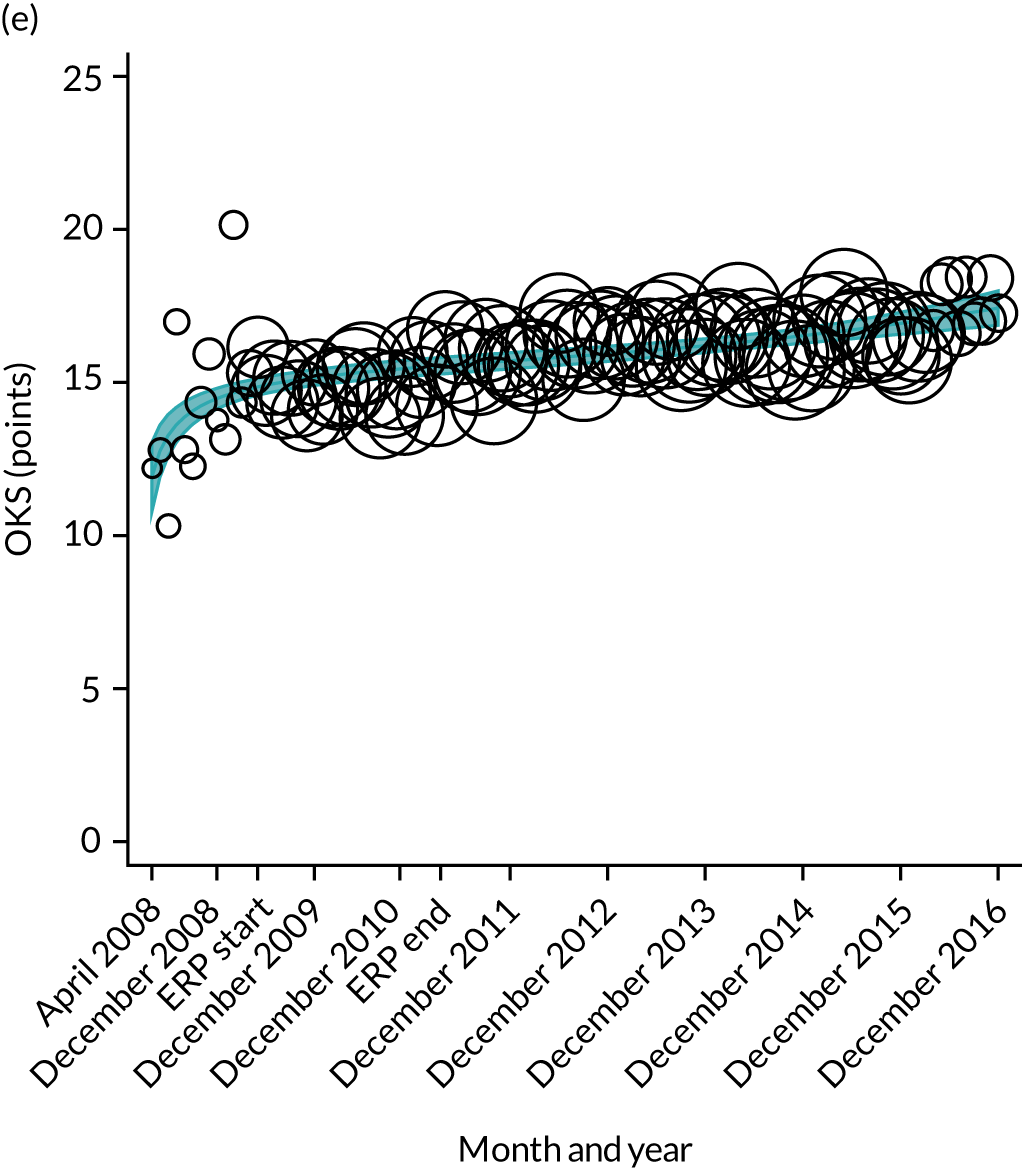

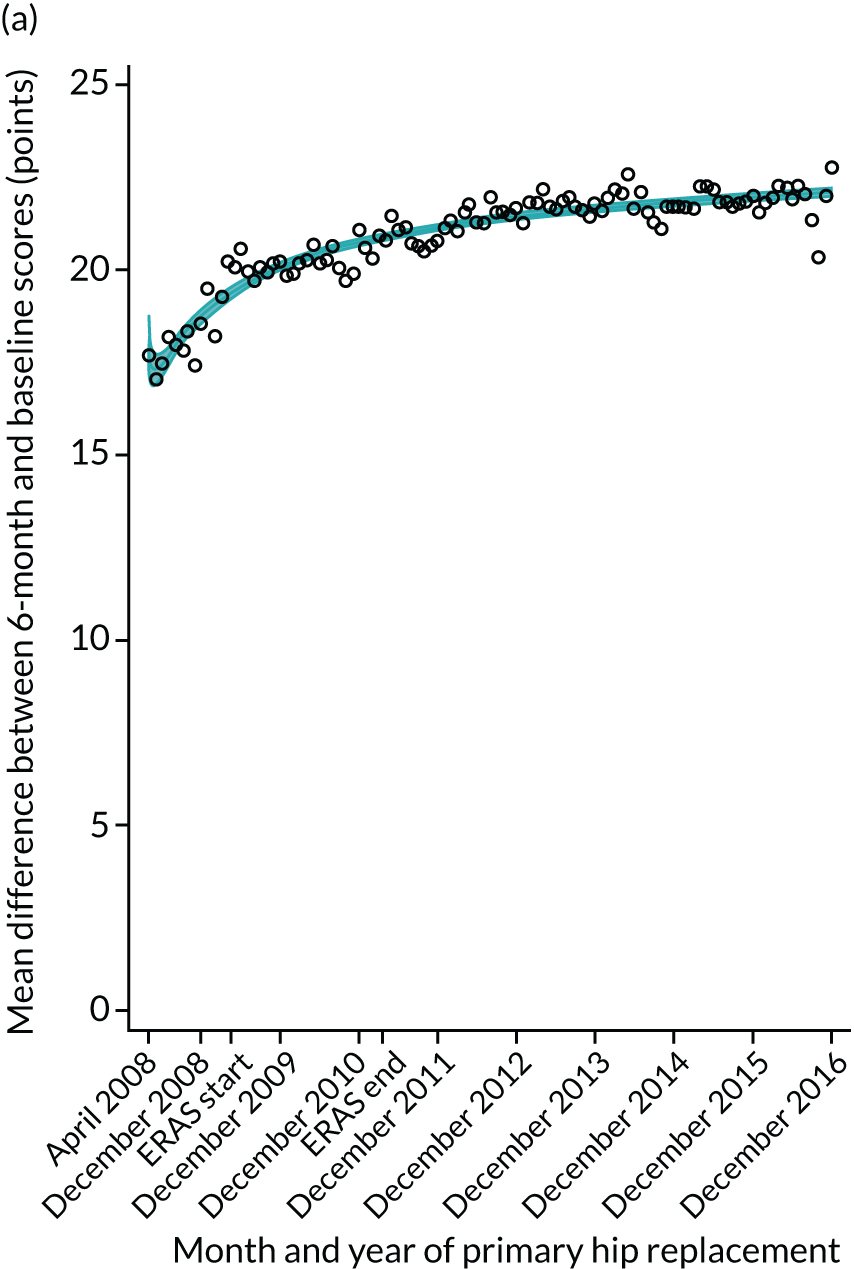

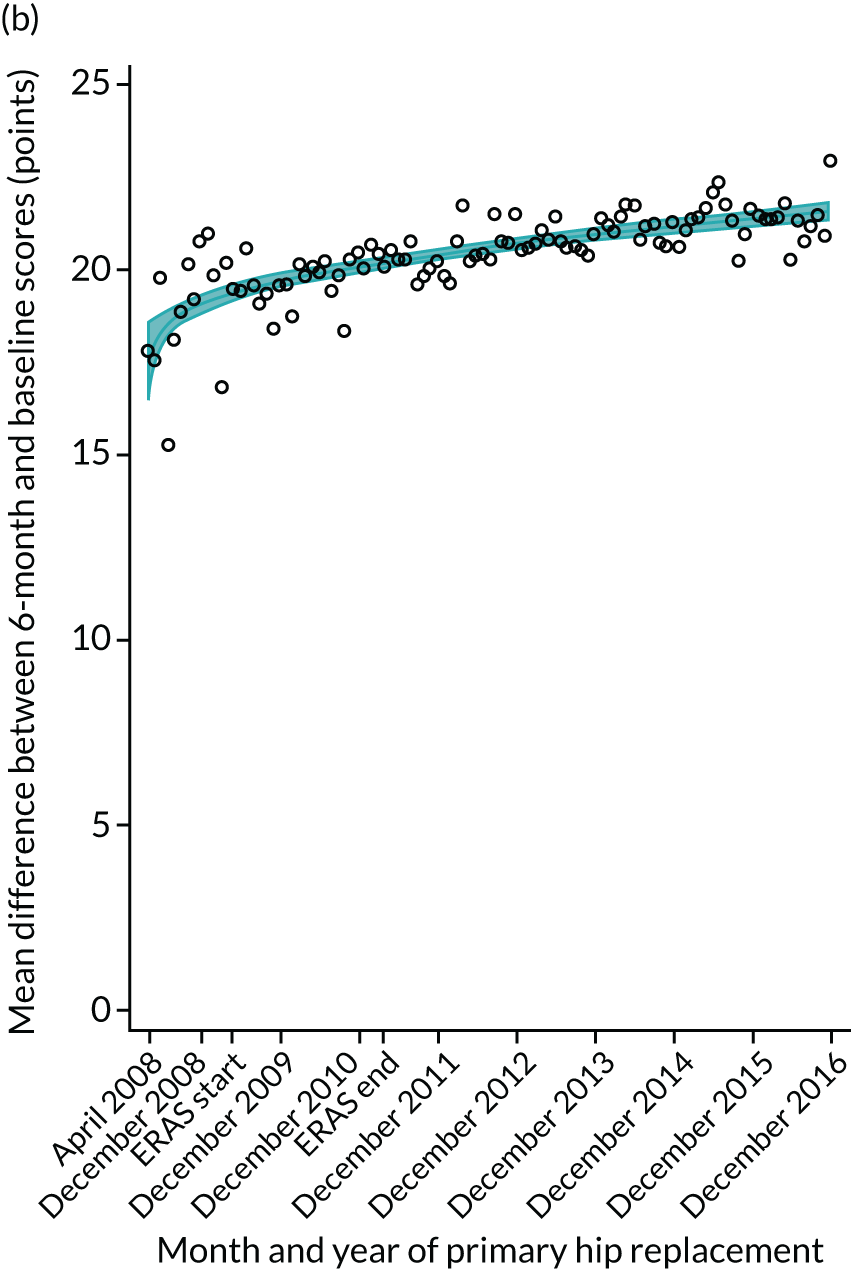

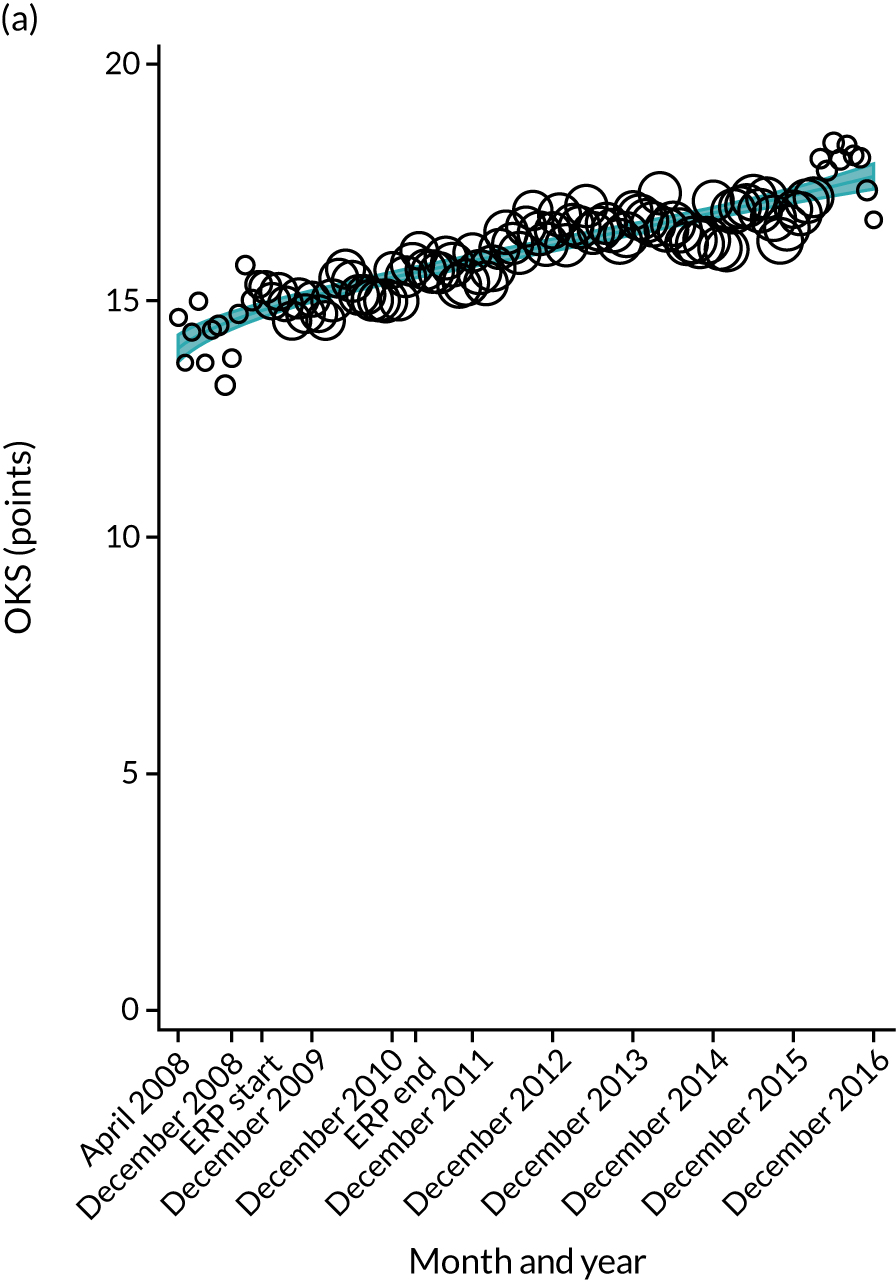

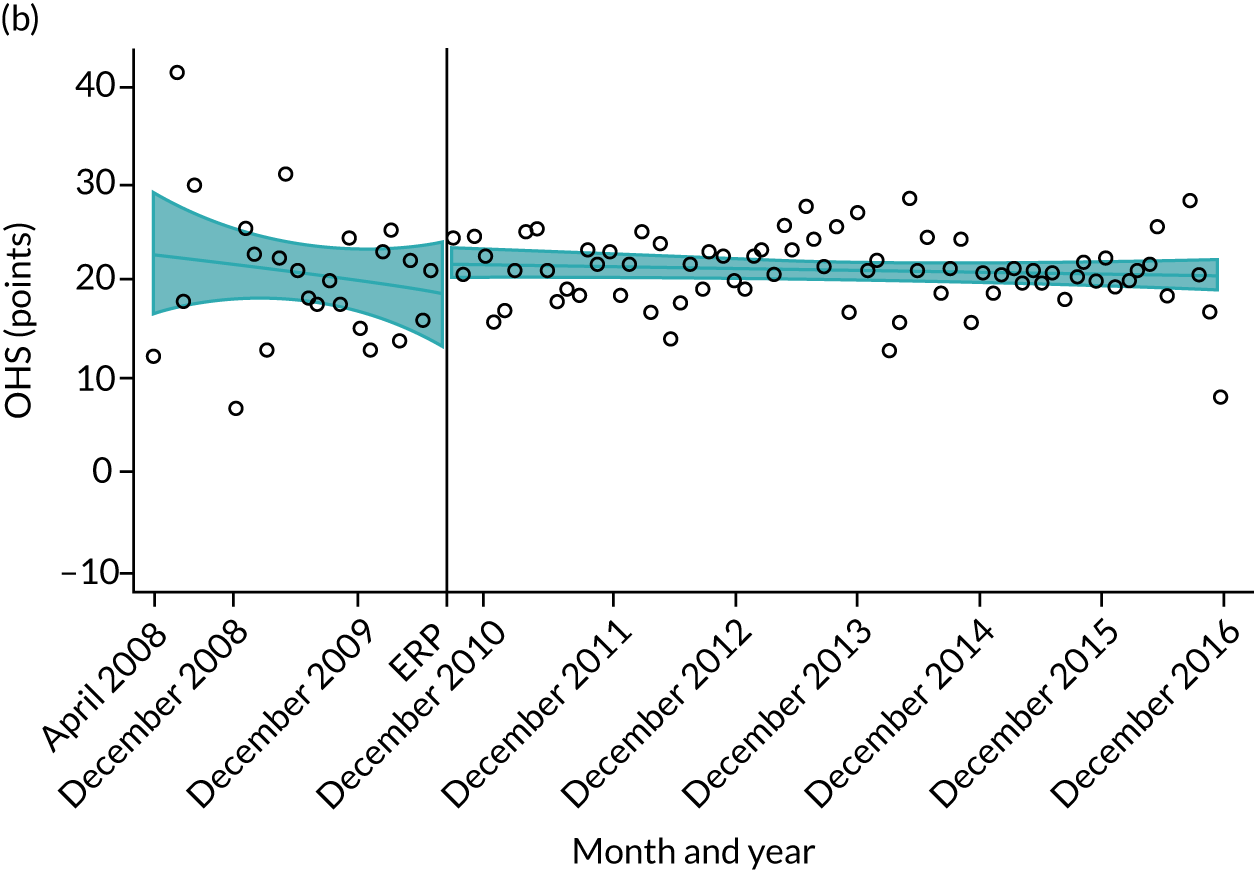

Oxford Hip Score and Oxford Knee Score change

Over the study period, there was an improvement in PROMs, with an increment in OHS 6 months after surgery of 17.7 points in April 2008 to 22.9 points in December 2016 for THR (see Figure 8). For TKR, there was an increment in OHS 6 months after surgery of 15.0 points in April 2008 to 17.1 points in December 2016 (see Figure 9). This secular trend was seen in patients with and without comorbidities, and in all age groups except in those aged ≥ 85 years, for whom the change in OHS and OKS was stable over the time period (Figures 14–17).

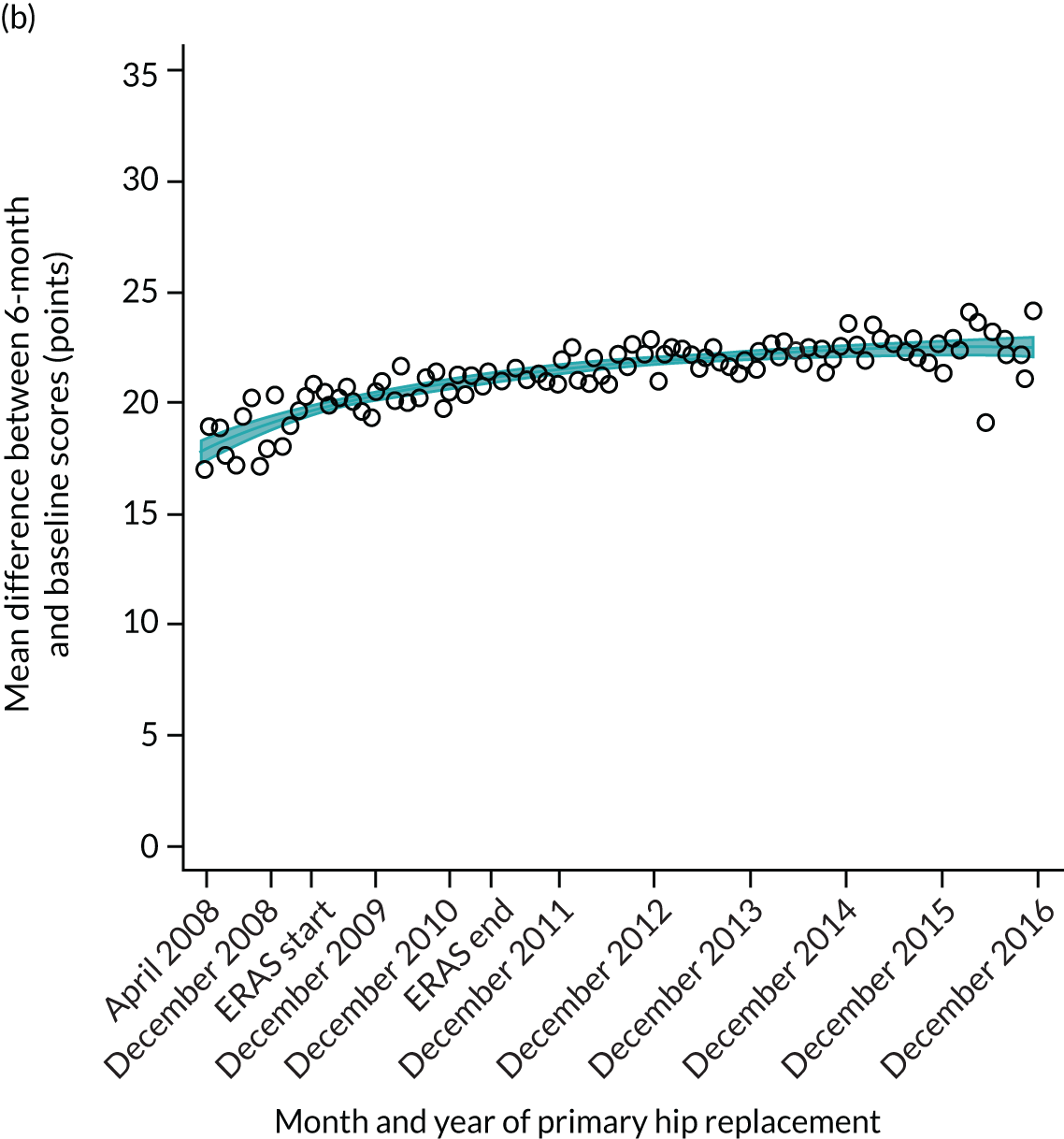

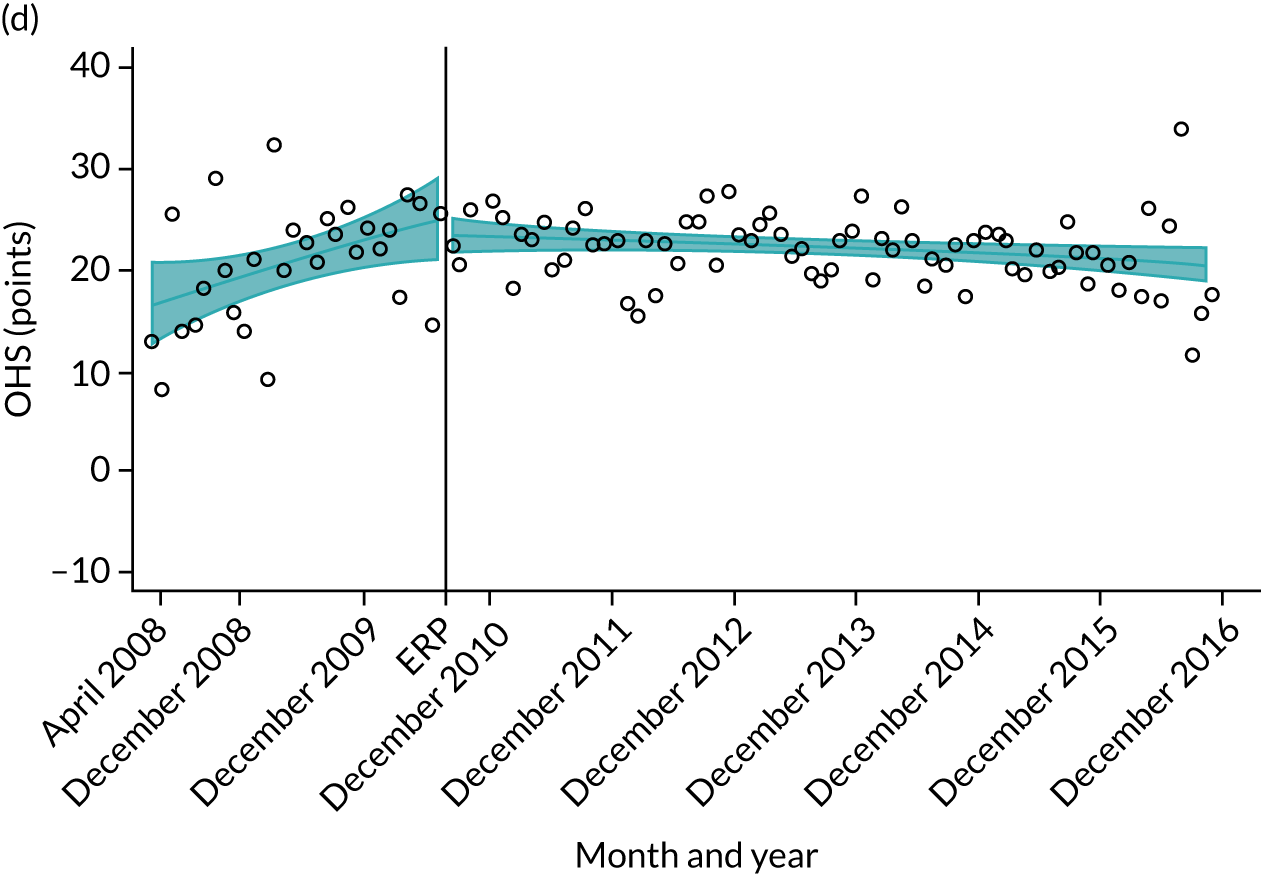

FIGURE 14.

Trends of OHS change following primary hip replacement according to age categories in England, 2008–16, by month. (a) All ages; (b) 18–59 years; (c) 60–69 years; (d) 70–79 years; (e) 80–84 years; and (f) ≥ 85 years. Reproduced from Garriga et al. 65 © Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2019. Re-use permitted under CC BY. Published by BMJ. This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Minor changes have been made to the formatting.

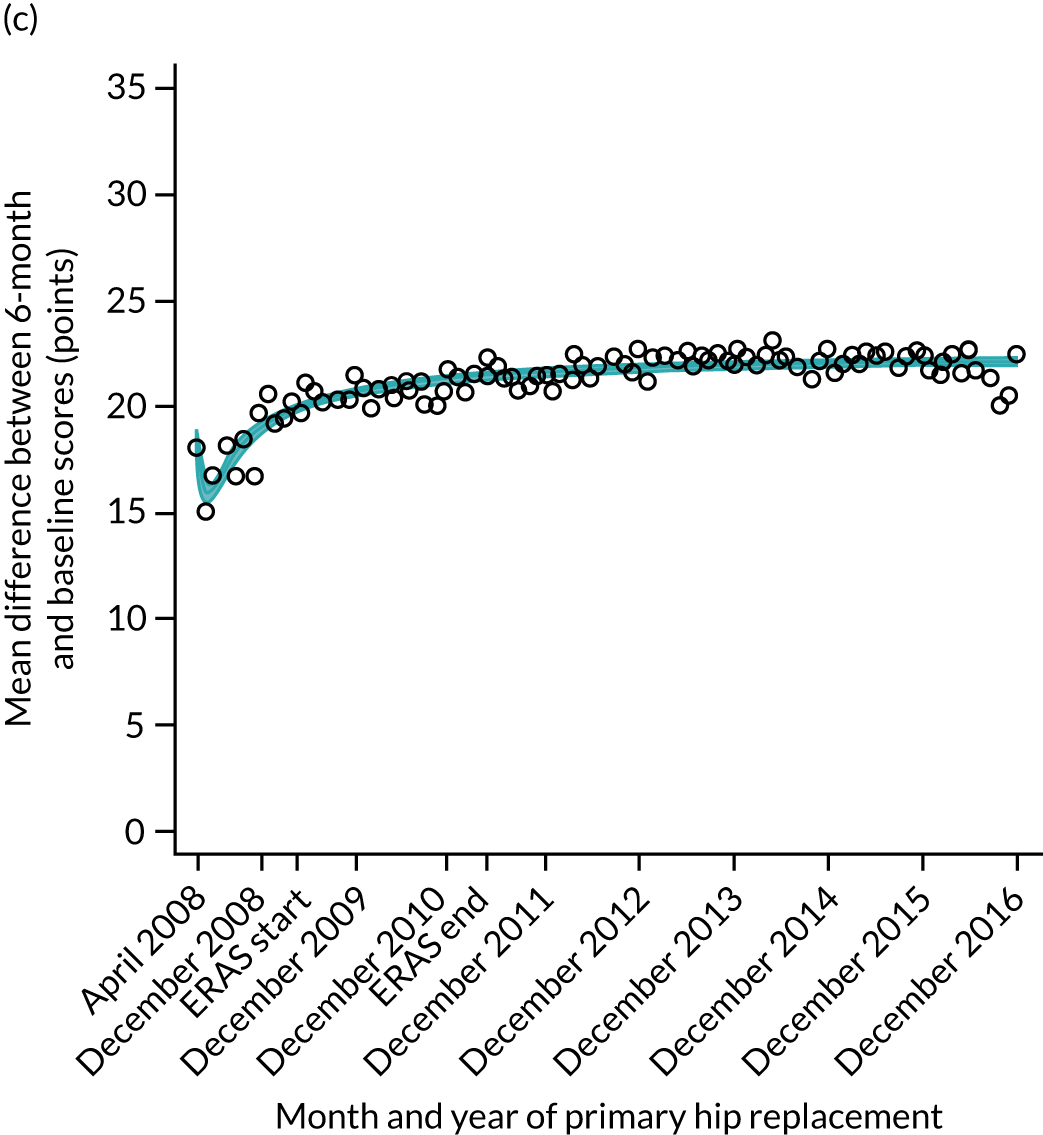

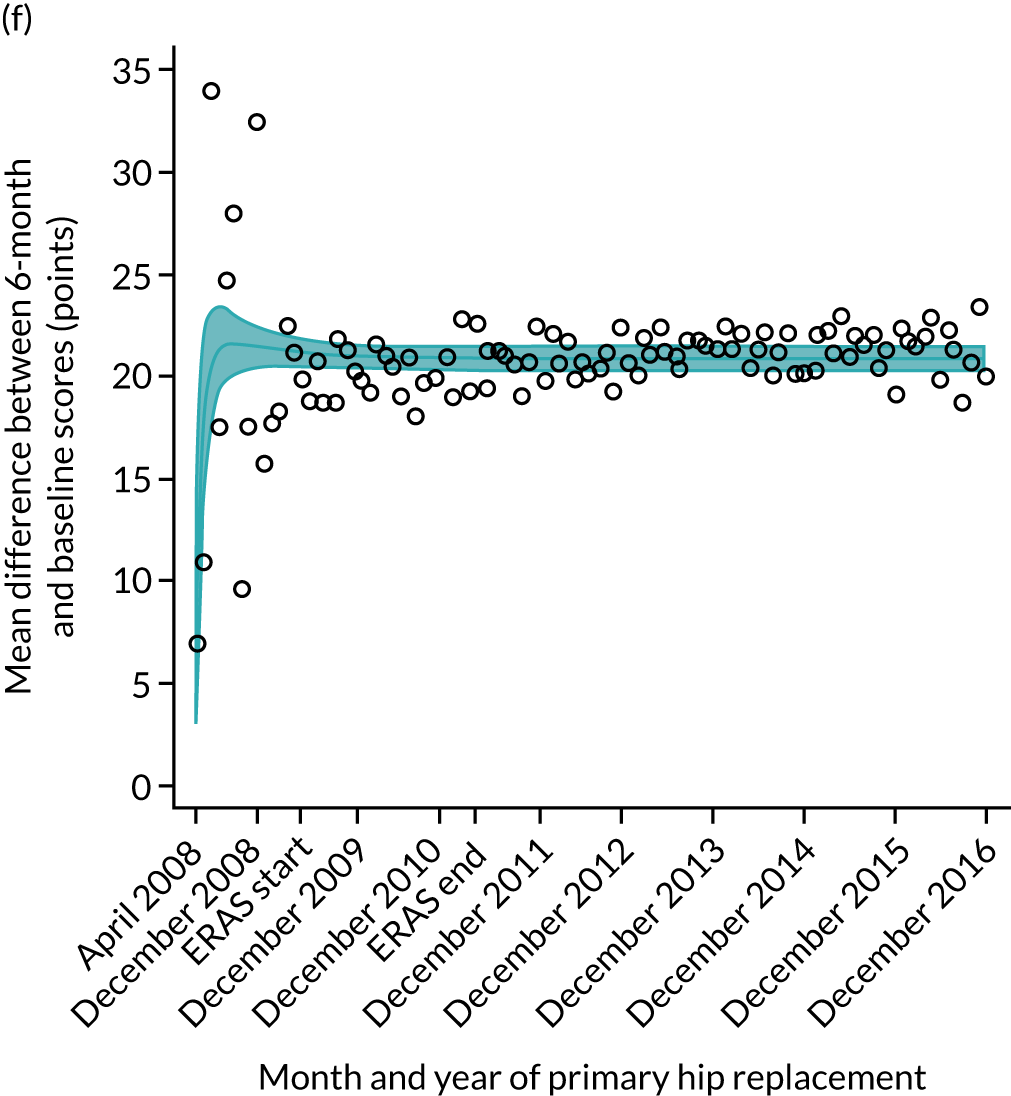

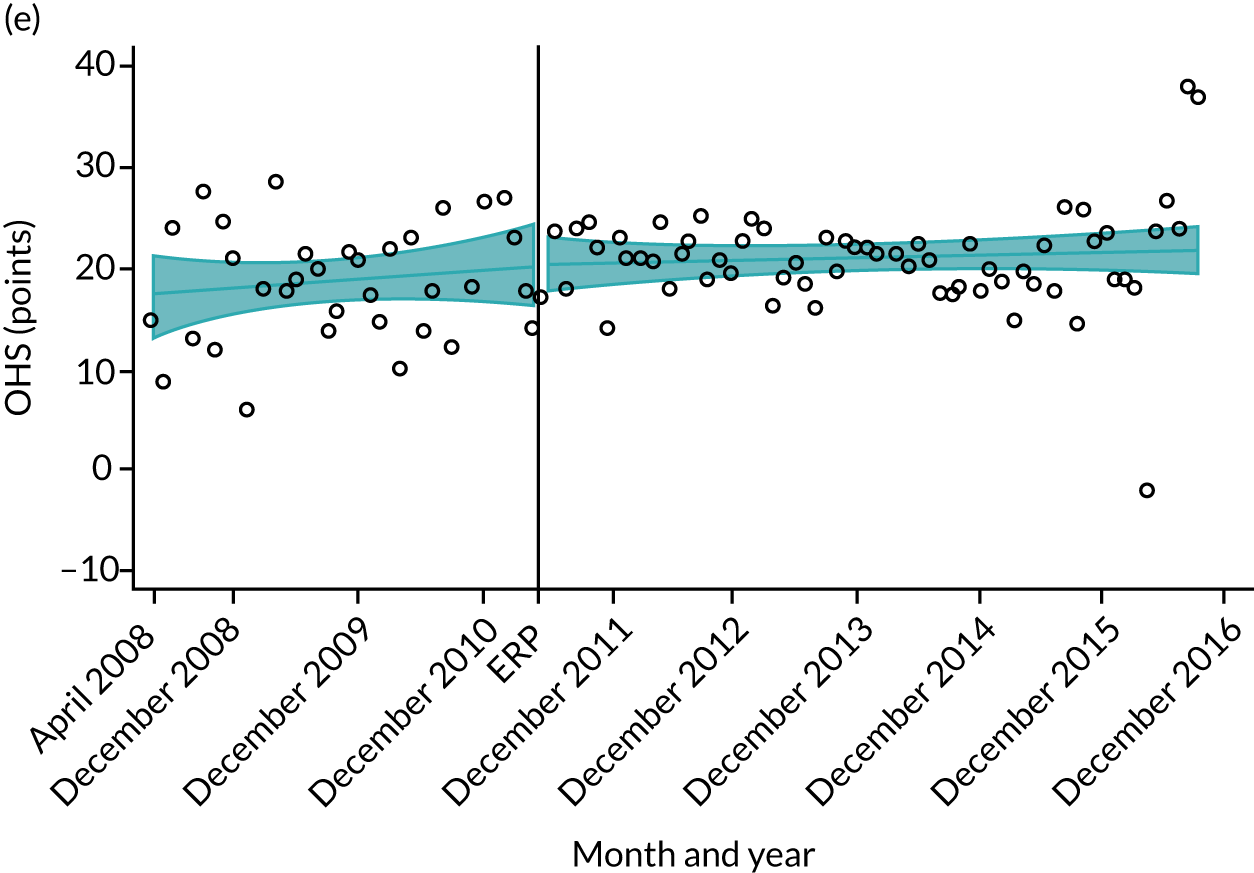

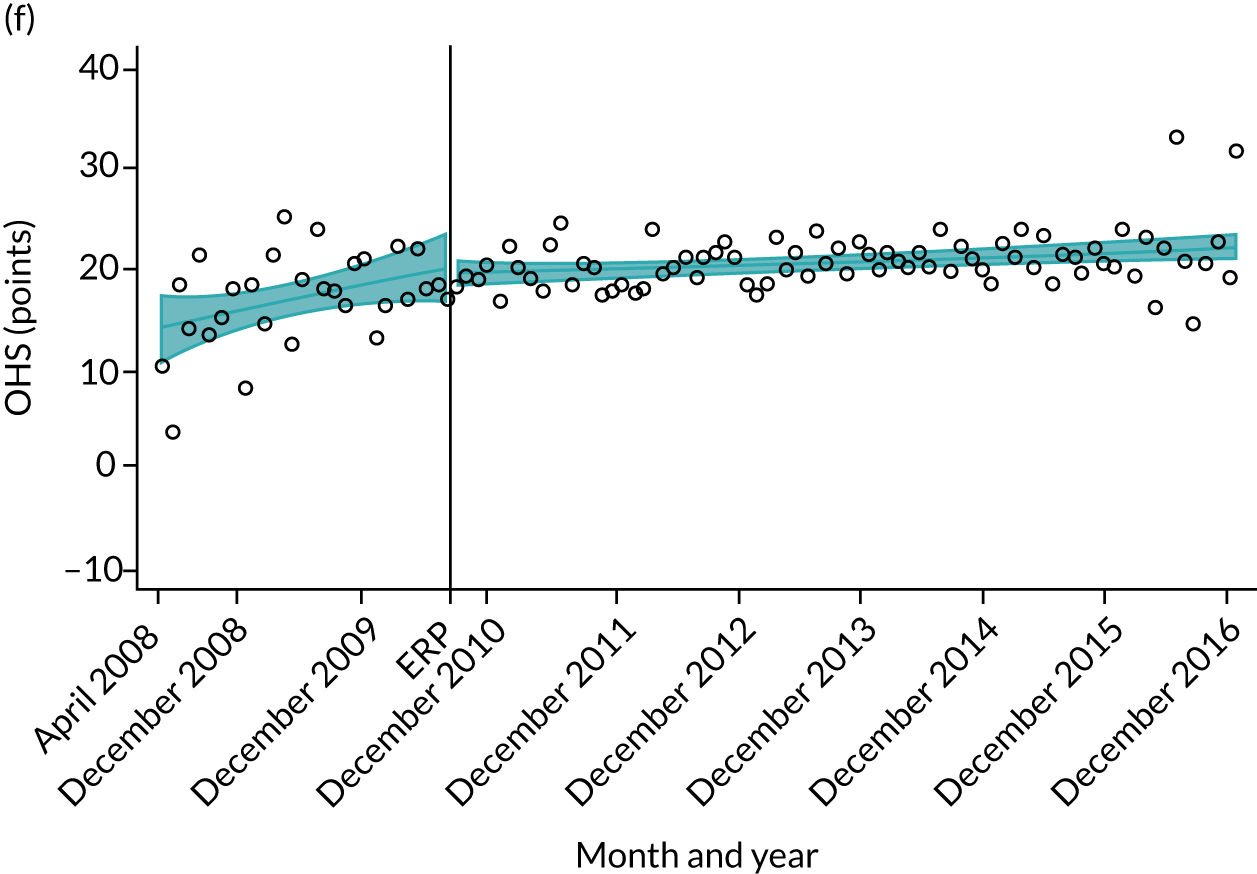

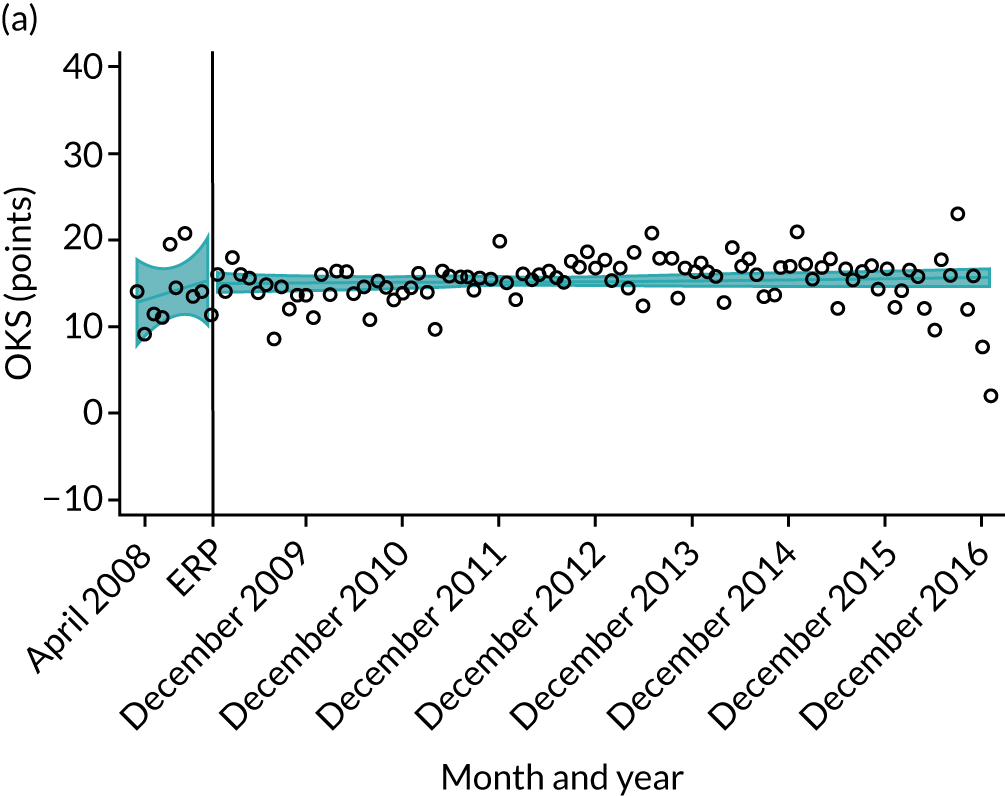

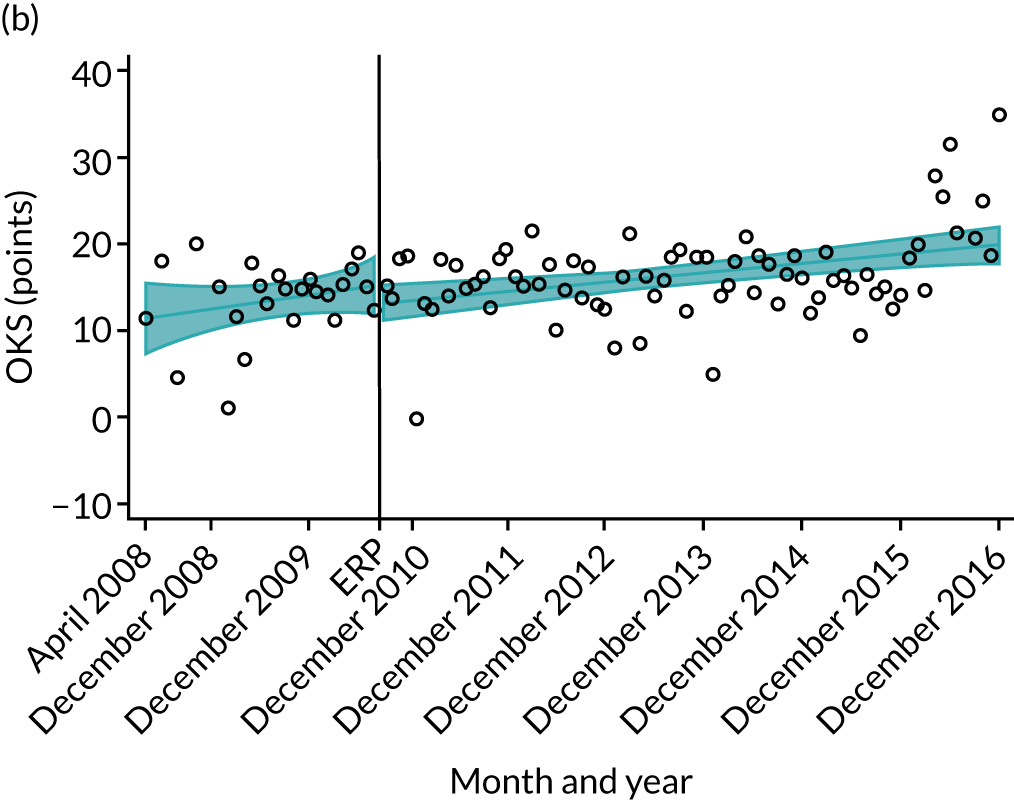

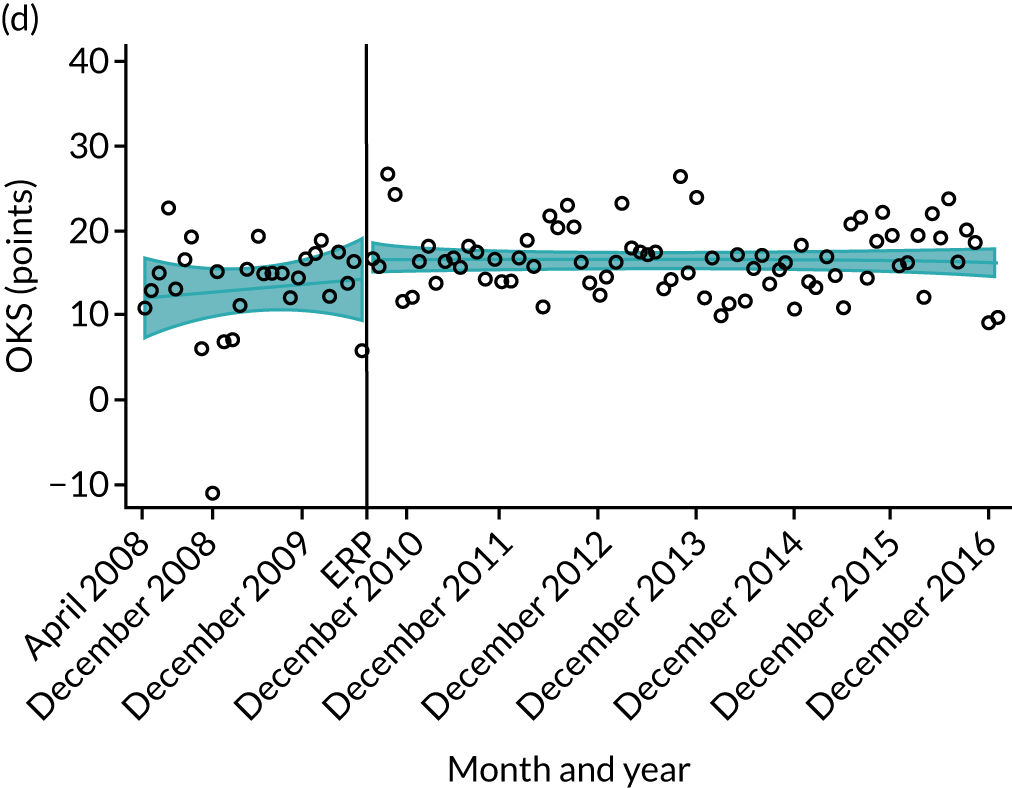

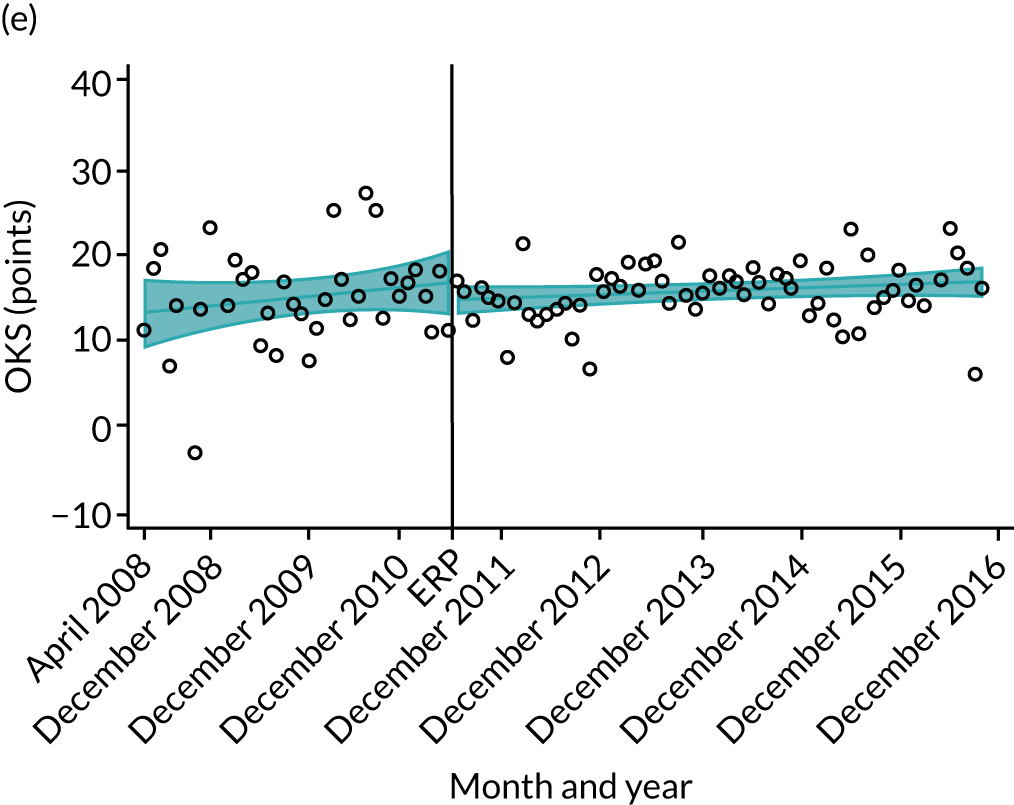

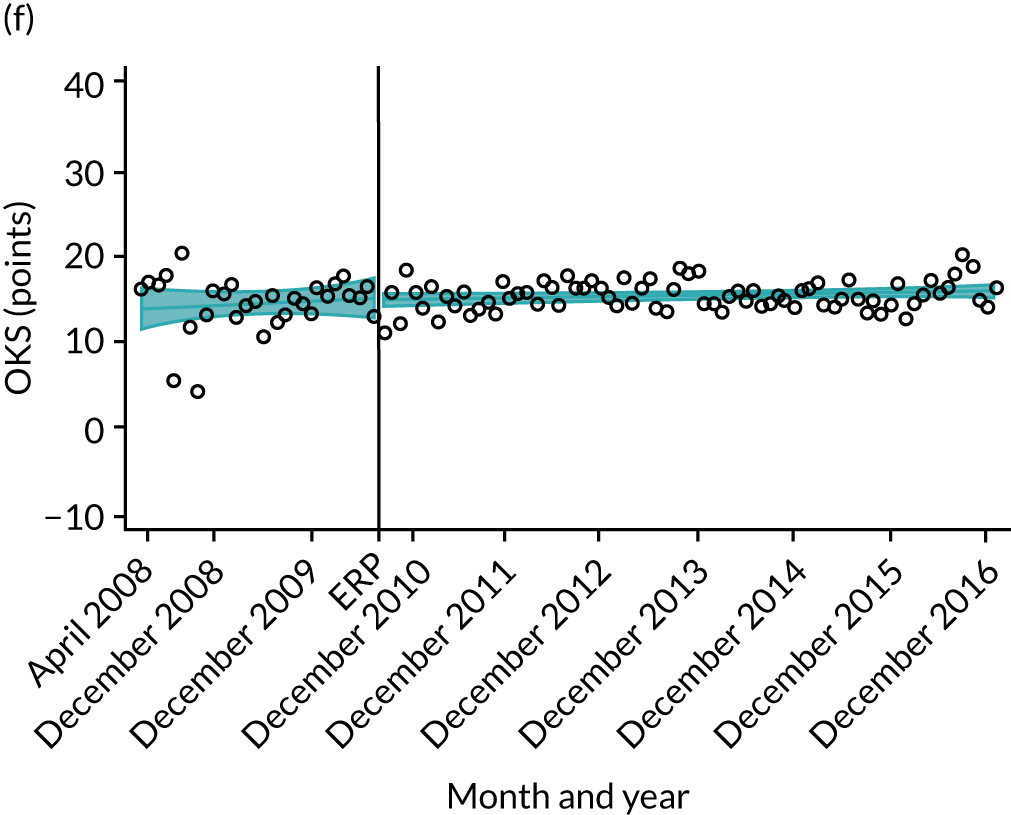

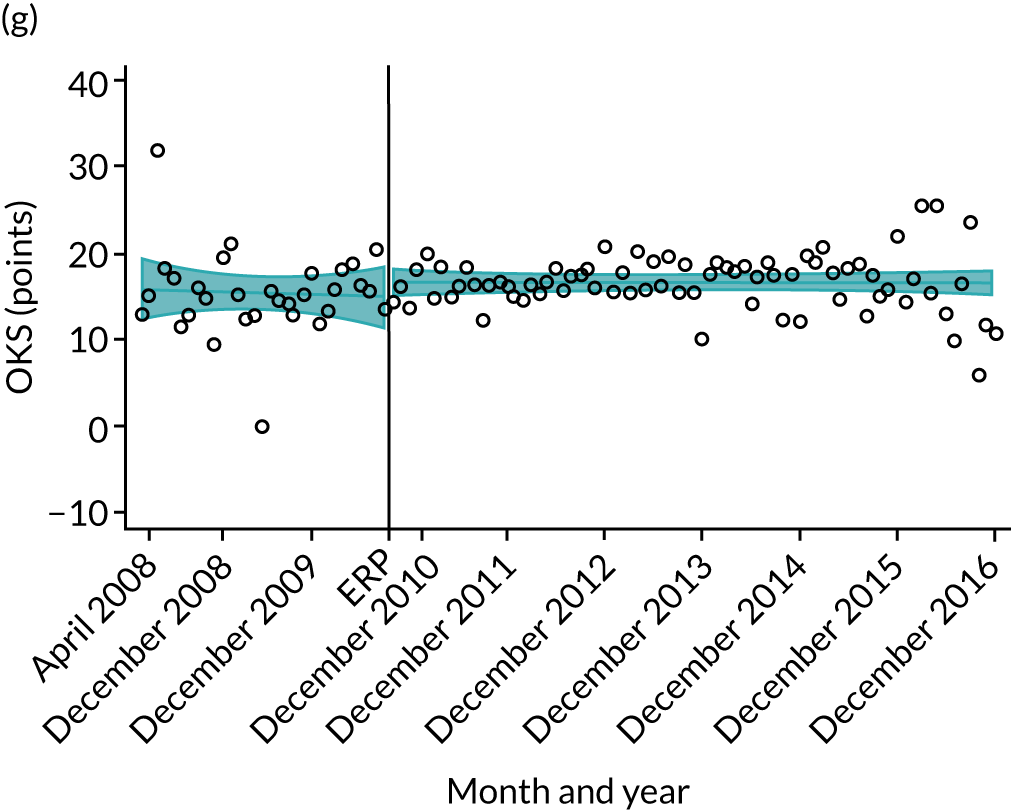

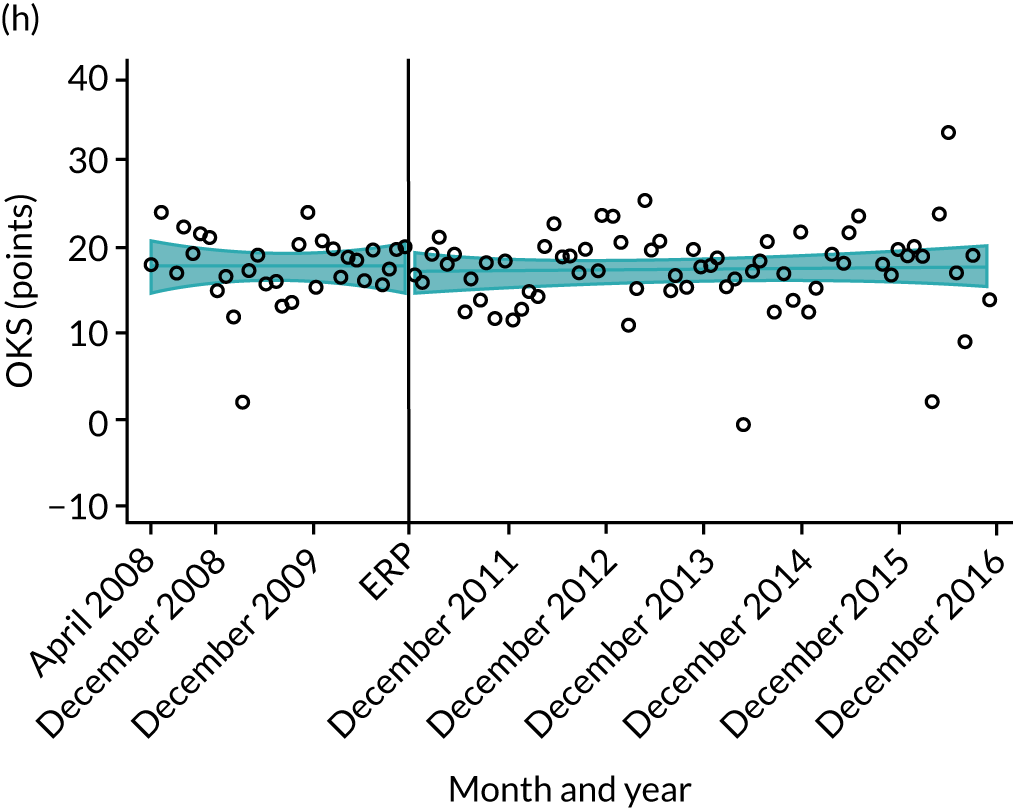

FIGURE 15.

Trends of OKS change (OKS 6 months – OKS baseline) after primary TKR/UKR according to age categories in England, 2008–16. (a) All ages; (b) 18–59 years; (c) 60–69 years; (d) 70–79 years; (e) 80–84 years; and (f) ≥ 85 years. Reproduced from Garriga et al. 66 © The Author(s). This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) license, which permits others to share this work, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

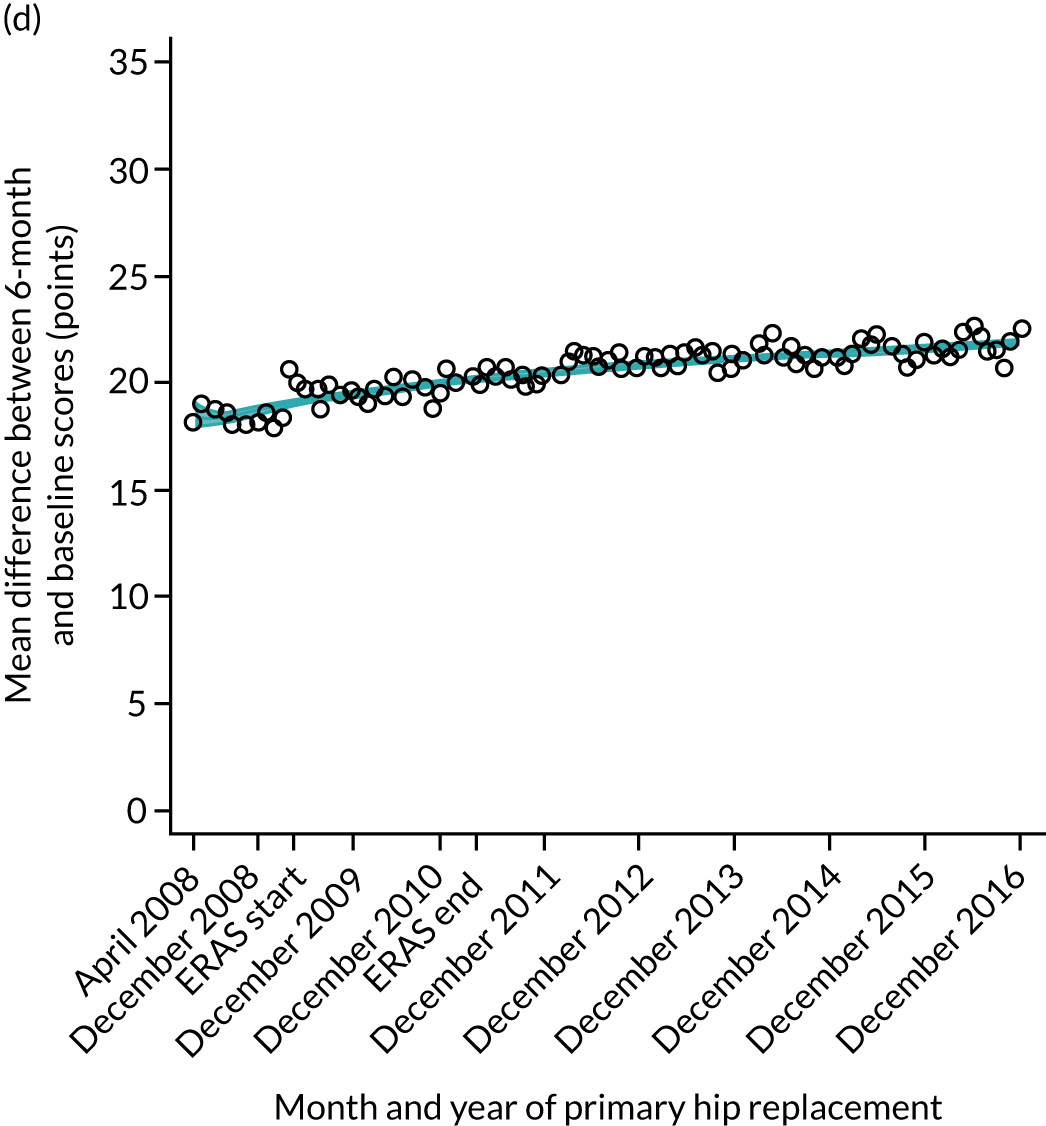

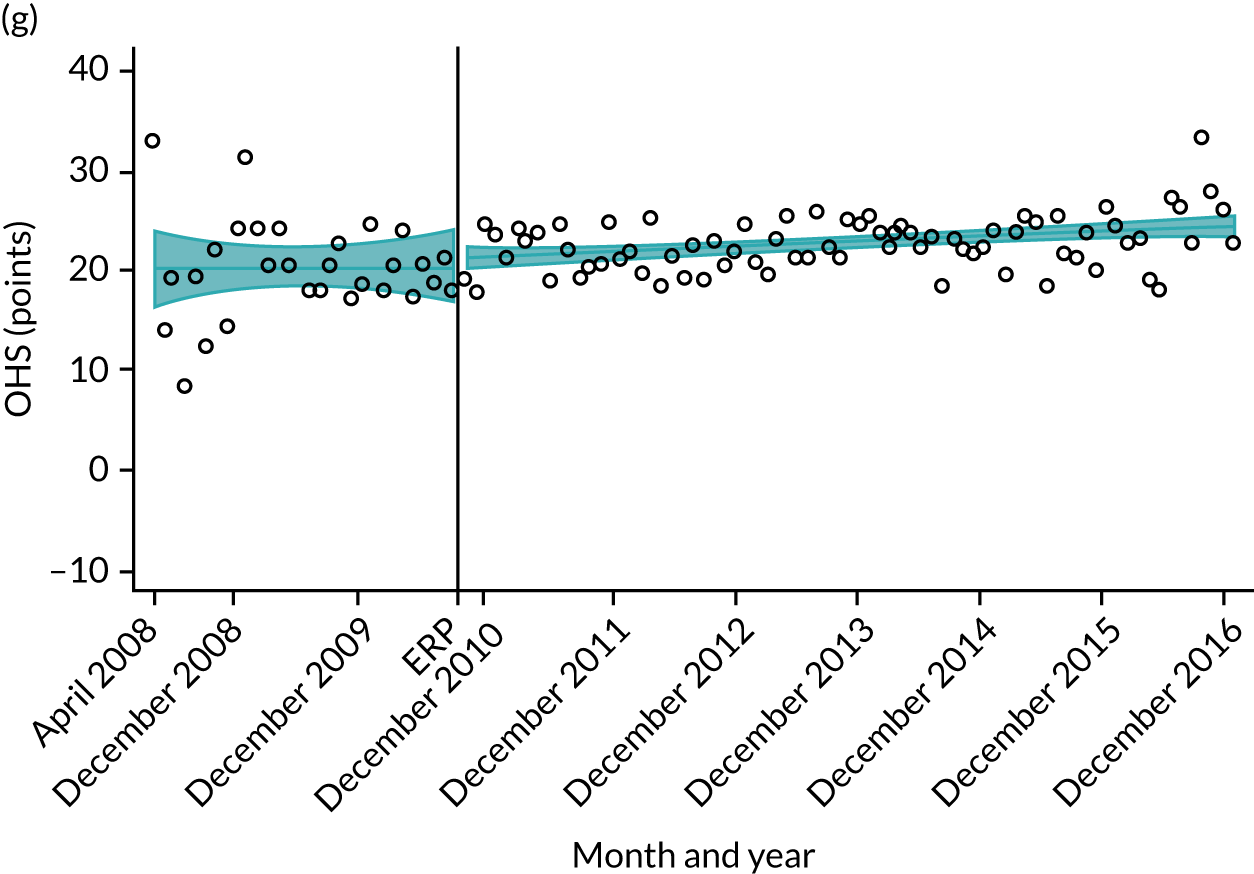

FIGURE 16.

Trends of OHS change following primary hip replacement by patients with/without comorbidities in England, 2008–16, by month. (a) Without comorbidities; and (b) one or more comorbidities. Reproduced from Garriga et al. 65 © Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2019. Re-use permitted under CC BY. Published by BMJ. This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. Minor changes have been made to the formatting.

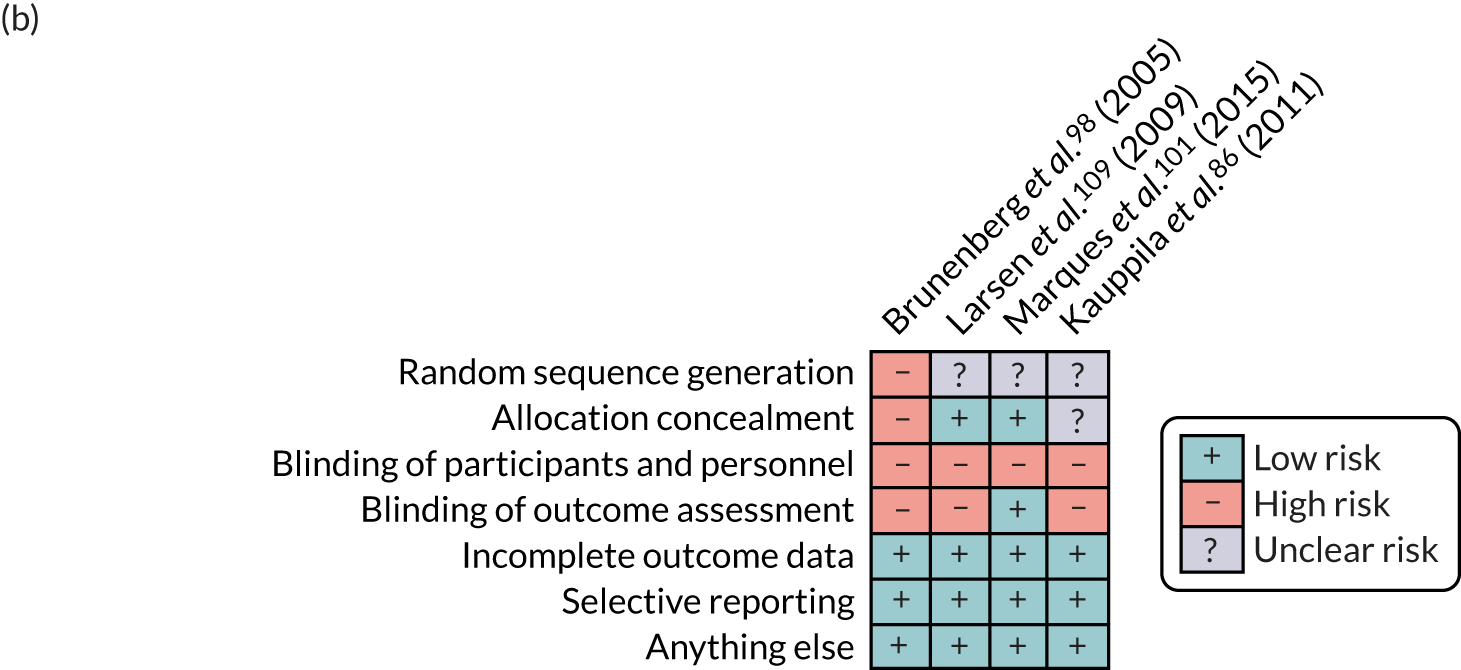

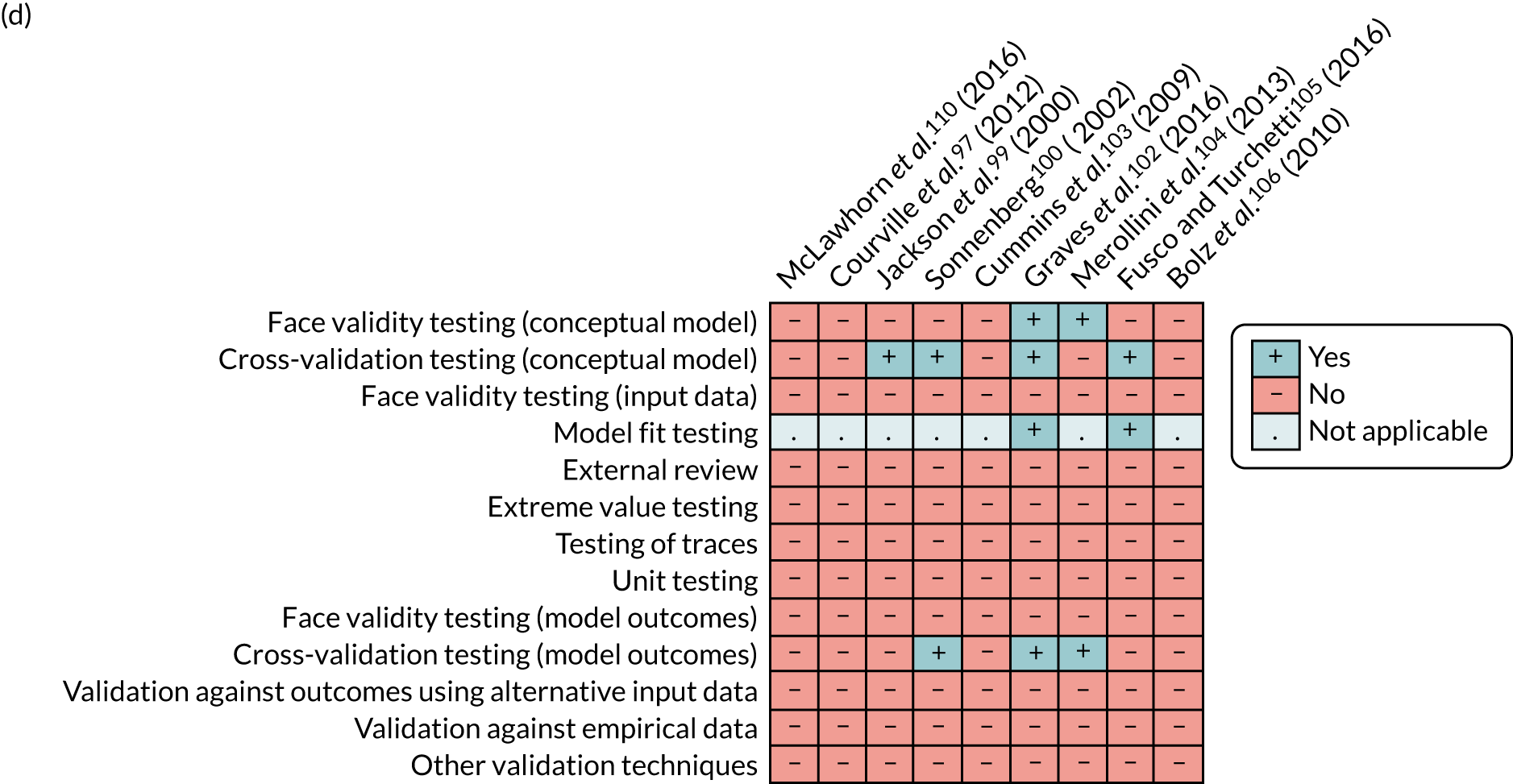

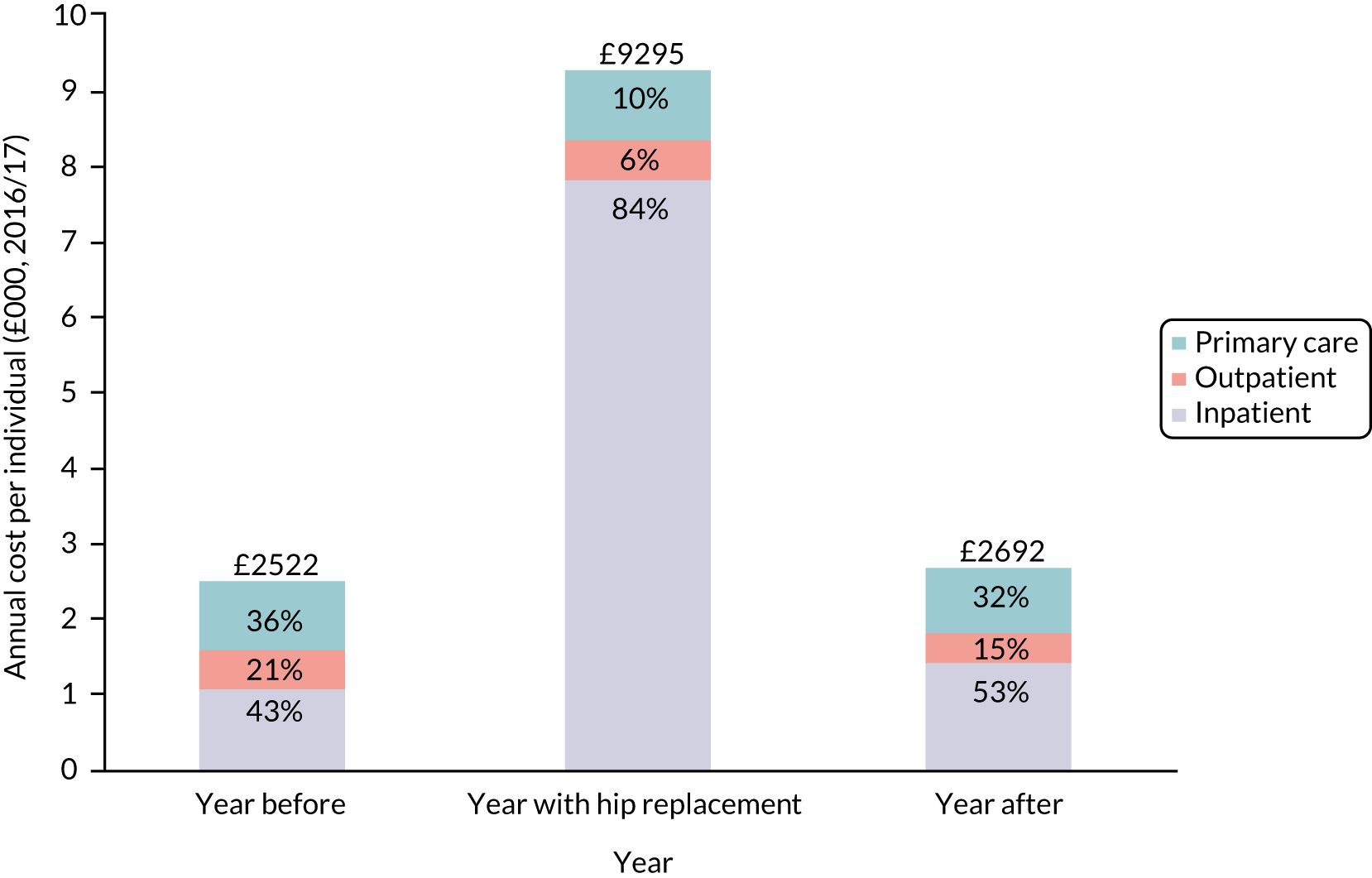

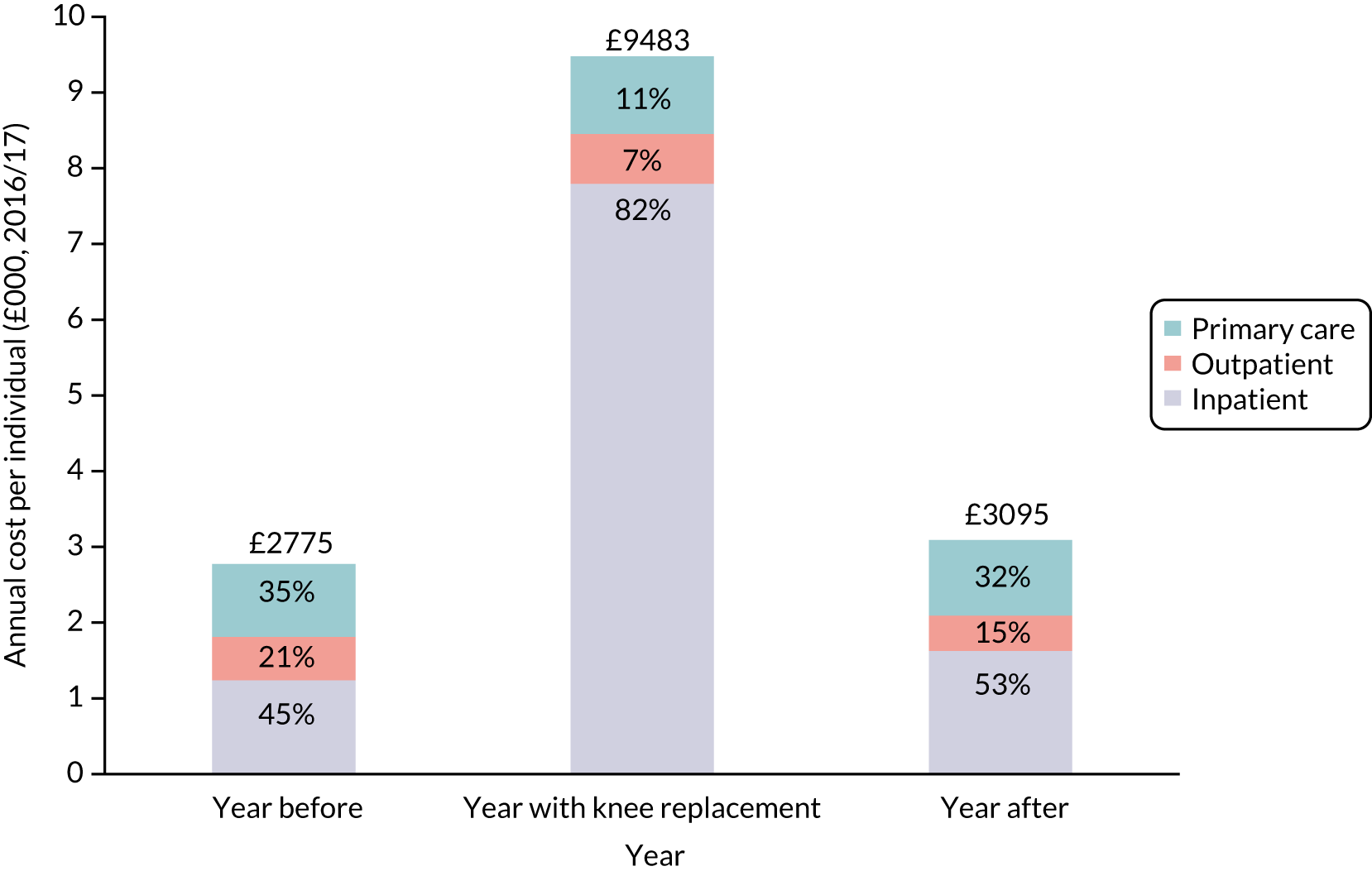

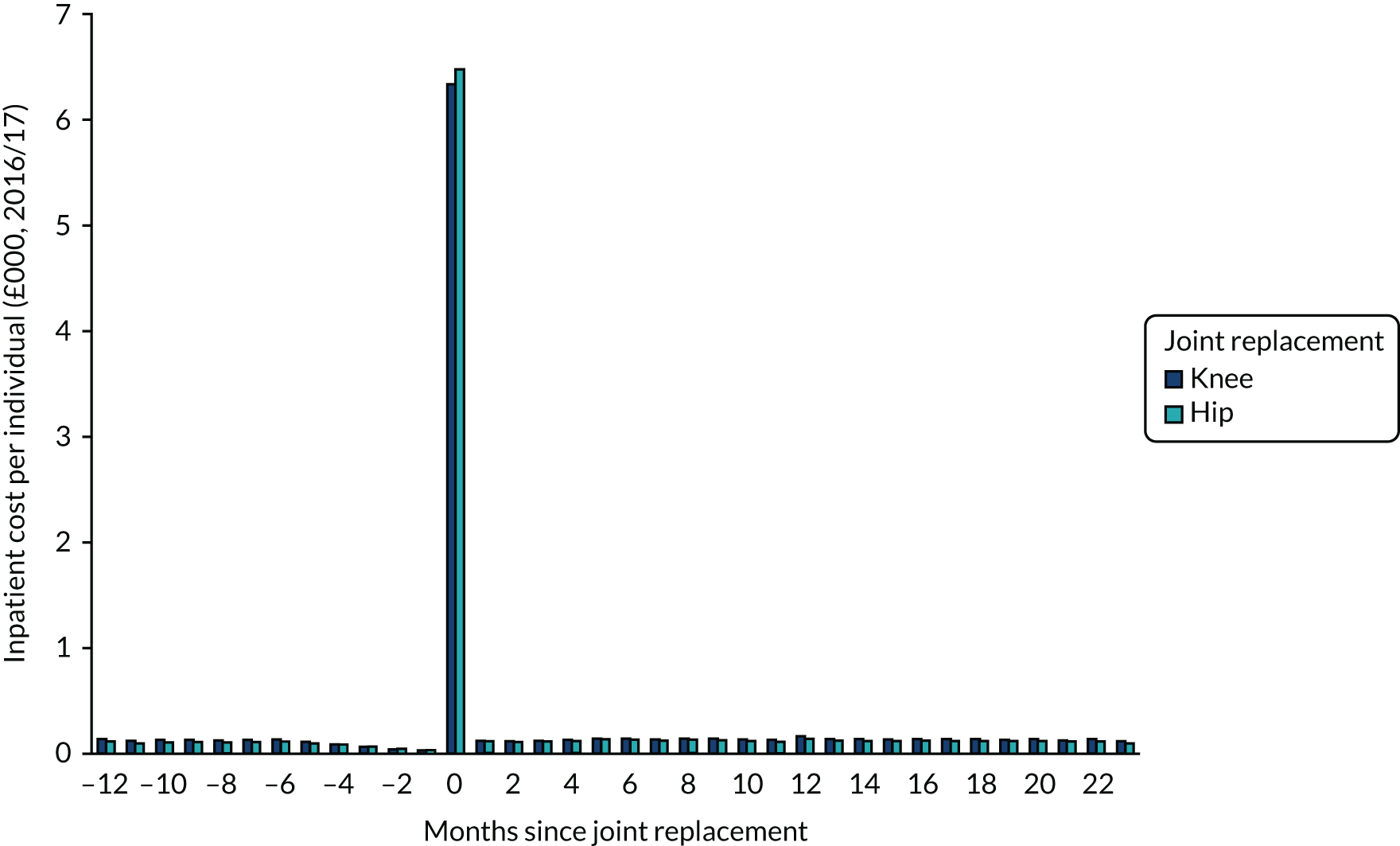

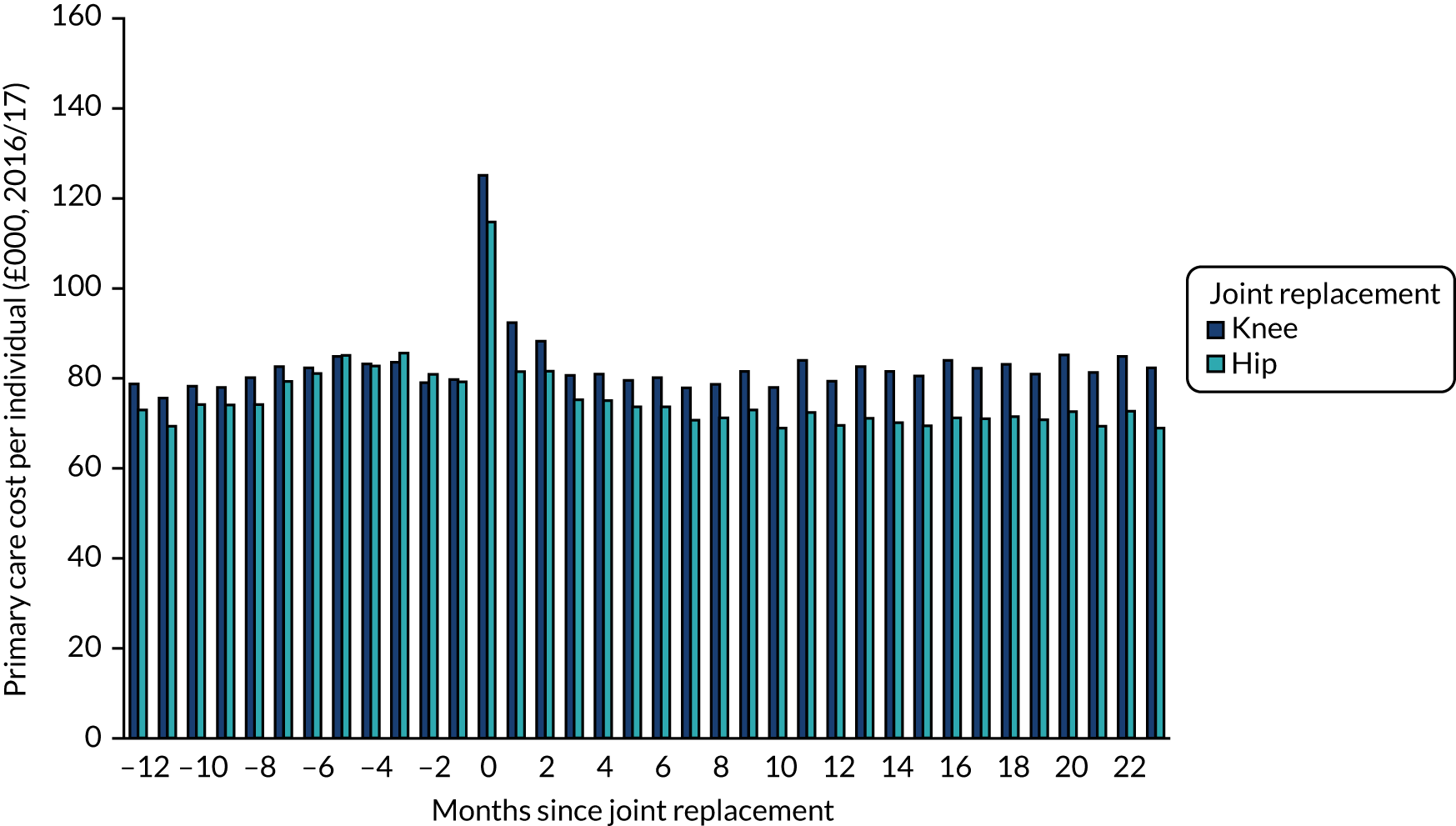

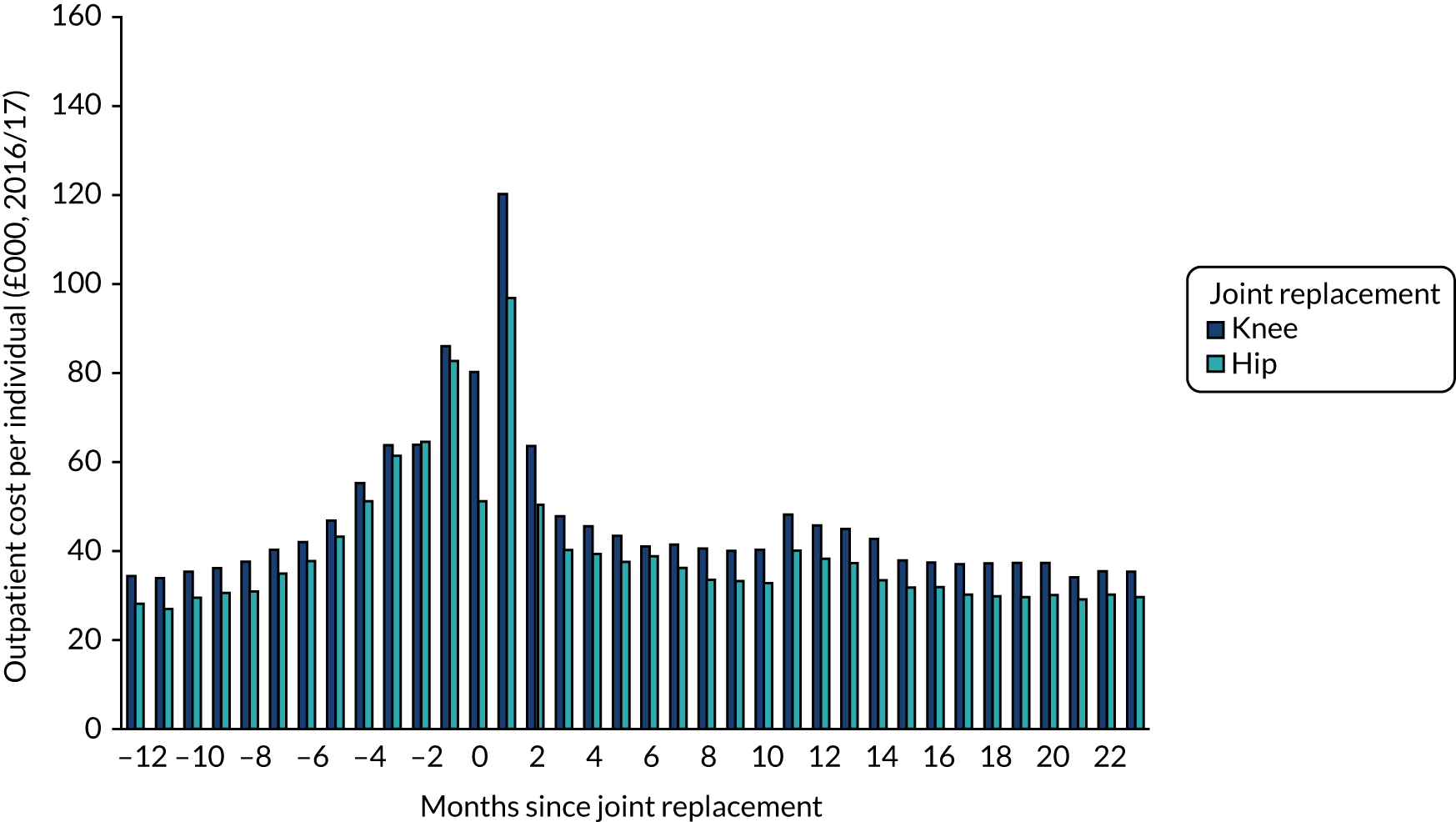

FIGURE 17.