Notes

Article history

The research reported here is the product of an HS&DR Evidence Synthesis Centre, contracted to provide rapid evidence syntheses on issues of relevance to the health service, and to inform future HS&DR calls for new research around identified gaps in evidence. Other reviews by the Evidence Synthesis Centres are also available in the HS&DR journal.

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 16/47/17. The contractual start date was in April 2018. The final report began editorial review in December 2018 and was accepted for publication in June 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Andrew Booth is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Complex Reviews Support Unit Funding Board (2015 to present) and the Health Services and Delivery Research Funding Committee (2019 to present).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Cantrell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background to the topic

In 2015 it was estimated that 2.16% of the adult population living in England had intellectual disabilities (ID). 1 People with ID face considerable, persistent and, to a degree, avoidable health inequalities. 2,3 These arise from disparities in the presence of disease,4 inequalities in access to and use of health-care services,5,6 and increased risk of exposure to common social determinants of ill health,7 for example poverty and social discrimination. 8 The life expectancy of people with ID remains significantly lower than that of the general population. 9 In the past 10 years, several inquiries into the deaths of people with ID have concluded that inadequate health care was a contributory factor and that these deaths were avoidable. 10–12

A number of inquiries into the early deaths of people with ID have reported shortcomings across a range of health services. 12–14 These point to factors, such as poor communication, that may be common across the full range of health services. Although our review covers initial access to primary care services rather than quality of ongoing health care provided, there are important lessons from these inquiries that are relevant to initial access to primary care.

UK government policy is for people with ID to have their health needs met in mainstream services, although there is considerable evidence that some people with ID may not be able to respond to and benefit from uniformly delivered services. 15 The statutory position is that mainstream services have a legal duty to make reasonable adjustments to enable those with protected characteristics to access these services; however, there is little guidance about what constitutes a reasonable adjustment.

People with ID are less likely to be able to access uniformly delivered health interventions. Public bodies have a legal duty to make ‘reasonable adjustments’ to policies and practices to provide fair access and treatment for people with learning disabilities (LDs). 16 However, more needs to be done in primary care, where services are often inaccessible to people with LDs because effective adjustments have not been put in place. 17

Similarly, some of the problems of access to primary health care sit outside health service responsibilities, for example the ability of paid support staff to recognise when an adult with intellectual disabilities might need primary care. Although the focus of this report focuses on access to primary care, the barriers to access and interventions shown by social care providers and disability organisations to be successful in improving access among this population have an important role to play in enabling access to these services.

Evidence suggests that people with ID use primary care services at rates less than or equal to the general population despite having greater health needs18 and their use of primary care is lower than expected in comparison with groups with other long-term conditions. 19 This suggests that people with ID do not access primary care services proportionately to their level of health need. Primary care services are particularly important because they provide an entry point to screening, treatment and secondary care. Difficulty and delay in accessing primary care may lead to serious negative health outcomes and disengagement with future health-care services, with concomitant cost to the individuals and to the UK NHS.

This work complements UK government policy, which emphasises the requirement to support people with ID to lead fully inclusive lives and this means meeting their health needs within mainstream services. 17 Public bodies have a legal duty to make ‘reasonable adjustments’ to policies and practices to provide fair access and treatment for people with LDs16 and health and social care services have a legal duty to reduce health inequalities under the Health and Social Care Act 2012. 20

Definitions

Intellectual disability has been defined as a significantly reduced ability to understand new or complex information and to learn new skills, along with a reduced ability to cope independently where this disability starts before adulthood, with a lasting effect on development. However, in practice, studies may recruit participants on the basis that they are known to statutory service providers. People with severe ID are likely to be known to service providers, however, some people with mild ID may live independently without service intervention, either from choice or because they do not meet eligibility criteria for ID services and, therefore, are not able to access support. This review will use the term ID throughout in recognition of the increasing use of this term in research.

In a review for the NHS Service Delivery and Organisation (SDO) programme, Alborz et al. 21 used Gulliford’s model of access; this distinguishes between having access, where services are notionally available; gaining access, where the user gains entry to and use of an appropriate service; and maintaining access, that is having continued use of a service. 22 We plan to focus on gaining access and use because the review focuses on first contact with services such as primary/community care. In addition, Alborz et al. 21 distinguished between access and effectiveness and focused on the ability to use a service rather than whether or not the service was provided to a high standard. In this review, we focus on access to a service as the primary outcome rather than the quality of the service received. However, we consider that patient engagement is crucial to the success of most health-care interactions; therefore, we will consider the extent to which health-care services are set up or adjusted to facilitate the engagement of people with ID during health appointments. We will also examine evidence for the effectiveness of any measures or interventions designed to improve access to relevant services.

Chapter 2 The mapping review methods

A systematic mapping review was undertaken to map the literature in the topic area and to help decide on the final scope for the targeted systematic review.

The mapping review aimed to examine the volume and characteristics of the available evidence about quality of access to primary health-care services for people with ID. The protocol for the mapping review is provided in Report Supplementary Material 1.

The mapping review includes the following types of health service:

-

NHS primary care

-

first-point community-based services [general practitioners (GPs), pharmacists, dentists and optometrists]

-

sexual health

-

health screening delivered in the context of primary and community care

-

palliative and end-of-life care delivered in the context of primary care.

Research questions

-

What are the gaps in evidence about access to primary and community health care for people with ID?

-

What are the barriers to accessing primary and community health-care services for people with ID and their carers?

-

What actions, interventions or models of service provision improve access to health services for people with ID and their carers?

Methods

The systematic mapping review was conducted in accordance with published methods. 23 The mapping review followed the scope of a previous review,21,24 with the exception that it focused on only primary and community care services.

We chose to build on the existing review for four compelling reasons:

-

We could follow (and hopefully enhance) the methods of the original review.

-

The time that had elapsed since the original work (approximately 15 years) provided a manageable quantity of literature for logistic purposes.

-

The conceptual framework produced by the original team could be used as a template for data extraction if appropriate.

-

Our updated review would follow seamlessly from the original work.

Areas of research activity and research gaps identified in the mapping review helped inform and finalise the scope for the targeted systematic review.

Literature search for the mapping review

The literature search was informed by methods of identifying the literature described by McNally and Alborz. 25

We searched the following databases (seven of the 14 bibliographic databases in the Alborz et al. review21):

-

MEDLINE (via Ovid, 1946 to 2018)

-

Science Citation Index Expanded; Social Sciences Citation Index (via Web of Science, 1900 to 2018)

-

The Cochrane Library

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (1996 to 2018)

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effect (1995 to 2015)

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (1898 to 2018)

-

Health Technology Assessment Database (1995 to 2016)

-

NHS Economic Evaluations Database (1995 to 2015)

-

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (via EBSCOhost 1974 to 2018)

-

Applied Social Science Index (via ProQuest, 1987 to 2018)

-

PsycINFO (via Ovid, 1806 to 2018)

-

Educational Resources Index (via ProQuest, 1966 to 2018).

The database search strategy was adapted from methods described in the existing review for identifying the literature. 25 The search strategy comprised key terms for ID and access. Additional terminology was added to include the primary care setting (e.g. GPs, dentists, optometrists) and recent or current legislation or guidance terms, such as the Disability Discrimination Act and ‘reasonable adjustments’. The existing review was conducted between 1980 and 2002 so this search was limited from 1 January 2002 onwards, thereby ensuring continuity of the evidence base. The search was also restricted to English-language and human studies. The search strategy is provided in Appendix 1.

Supplementary searching included grey literature searching of the websites of key UK charities and associations to identify reports about initiatives to improve access to services for people with ID. Snowballing by citation searching key studies was also performed in Google Scholar™ (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) and reference lists of included papers were scrutinised.

Screening

Study screening and selection was undertaken in EPPI-Reviewer 4 (Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre, University of London, London, UK). A team of three reviewers screened the identified references. An initial 100 references were screened by all three reviewers to check for consistency. Any queries were resolved through discussion with the other two reviewers.

Study selection was undertaken according to the inclusion criteria outlined in Table 1.

| Criterion | Eligibility |

|---|---|

| Population |

|

| Setting |

Evidence from any of the following settings: the UK, Canada, Australia, New Zealand or Europe The above settings have been selected because of their similar health-care systems. Papers from the USA will be excluded because US private service provision is not comparable with the UK primary care setting. However, the mapping review will investigate the impact of including qualitative research papers from the USA depending on their relevance |

| Outcomes |

Access to a service Alborz et al. 21 distinguished between access and effectiveness and focused on the ability to use a service rather than whether or not the service was provided to a high standard. We will also review studies reporting the effectiveness of any measures or interventions designed to improve access to the relevant services |

| Comparator | The general population may offer a comparator in some study types |

| Study design |

|

| Other limitations |

English language only Evidence published since 2002; the Alborz et al. 21 review searched up to 2002 |

Following screening at the title and abstract stage, the references that potentially met the inclusion criteria were considered further, and data were extracted for inclusion in the review. Citations not meeting the inclusion criteria were excluded.

Data extraction

Data extraction based on abstracts was undertaken in EPPI-Reviewer 4 using a template designed for the mapping review (see Appendix 2). Mapping at the abstract level is a typical component of systematic mapping review methodology, given that the primary purpose is to plan a subsequent review. The extraction form comprised the following items: paper identifying code, author, date, study design, setting – country, health-care professional (HCP), specialist topic, study population, sample size, needs assessment, study outcomes, tools used to measure outcomes, study result, and barriers and facilitators. For mapping purposes, references were categorised into sets according to HCP or specialist topic, and ‘needs assessment’ papers were also considered as a separate categorisation. Data extraction was completed using data included in each abstract. If the abstract was unavailable, brief details were extracted from the title for the mapping review on the understanding that the full text would be obtained if included in the targeted systematic review. An example of a completed data extraction table is in Appendix 3.

Patient and public involvement

During the mapping review, we consulted people with ID, family carers and formal paid carers so that the review of access to health care for people with ID could be informed by the views and experiences of stakeholders. The aim of this consultation was to:

-

illuminate the model of access to health care for people with ID

-

inform and refine our search strategies by identifying barriers to accessing health care and any solutions developed

-

identify gaps in the literature.

We contacted the clinical director and senior commissioning manager for services for people with ID in a Clinical Commissioning Group and asked them to identify relevant community groups for people with ID and their carers. We sent information about the review to these groups and asked to visit to discuss their experiences of accessing health care.

We met a group of people with ID (n = 8, plus one personal assistant) and a group of family carers (n = 5). Snowball sampling was used to identify formal carers and we spoke to staff who manage support services (n = 2). These were convenience samples depending on who attended the group or meeting on the day we visited.

Discussions were loosely guided by a topic guide covering how people identify a health need, what actions they take, the issues influencing their decision to take a particular course of action and the barriers to and facilitators of their access and use of the chosen service. 21 Notes were taken during each meeting and these were written up afterwards using bullet points to document the barriers and facilitators. These were organised under the headings ‘identifying and communicating symptoms of ill health’, ‘arranging and attending health appointments’ and ‘continuing access to services’. A brief summary is provided in Table 2.

| Barriers | Facilitators |

|---|---|

| Identifying and communicating symptoms of ill health | |

|

|

| Arranging and attending health appointments | |

|

|

| Continuing access to services | |

|

|

The barriers and facilitators were used to identify relevant search terms and for future comparison with the barriers and facilitators identified in the qualitative literature.

Detailed notes from the patient and public involvement (PPI) meetings are provided in Appendix 4.

We plan to present our findings following completion of the targeted review with the pre-existing groups of people with ID, and their paid and unpaid carers. Comments on the Plain English summary were received from the facilitator of the pre-existing group of people with ID.

We have continued to involve patients and members of the public through the Sheffield Evidence Synthesis Centre PPI group. Members of this group were asked to comment on the scope of the targeted systematic review.

Chapter 3 Mapping review findings

Literature search

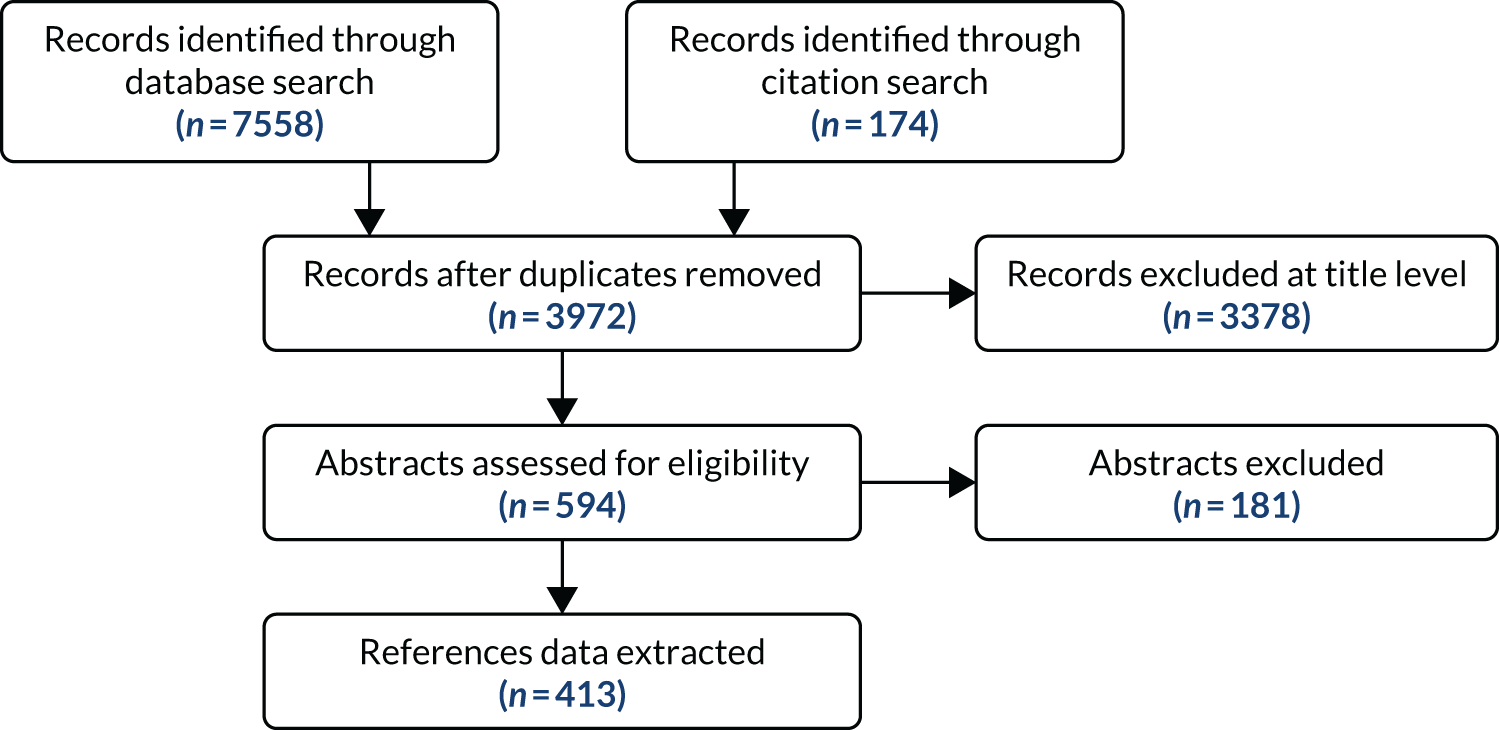

The database search retrieved 7558 records. Following deduplication, a total of 3972 records remained for screening. A total of 594 references were identified as ‘potentially include’. After further scrutiny, 181 of these were excluded. Common reasons for exclusion were that the study setting was secondary rather than primary care, the study was about a different population, the study was not about access to health care and the study was not a research study. A total of 413 papers met the criteria for inclusion in the mapping review (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Modified PRISMA flow diagram for mapping review.

Results

The mapping review comprised 413 studies.

Study design

All included abstracts were coded with one of the following study designs: quantitative, qualitative, mixed methods, review or unclear. Figure 2 shows the number of papers coded with each study design.

FIGURE 2.

Chart detailing study designs.

The chart shows an almost equal distribution of quantitative and qualitative studies. The large number of papers coded as having an unclear study design was a result of the limited information available in abstracts.

Geographical distribution of studies

Table 3 details the country of origin of included studies. The mapping review extracted data from abstracts only, meaning that country information was not available for a large proportion (n = 136) of the studies. The largest proportion of research studies investigated populations in the UK, followed by the USA, Australia and Canada.

| Country | Count |

|---|---|

| UK | 142 |

| USA | 33 |

| Australia | 27 |

| Canada | 20 |

| Ireland | 12 |

| The Netherlands | 11 |

| France | 3 |

| Norway | 2 |

| Spain | 2 |

| China | 1 |

| Germany | 1 |

| Greece | 1 |

| Hong Kong | 1 |

| India | 1 |

| Malaysia | 1 |

| Poland, Romania, Slovenia | 1 |

| Saudi Arabia | 1 |

| Taiwan | 1 |

| International (i.e. multiple countries) | 16 |

| Not stated | 136 |

Health-care professional

Table 4 shows the number of studies in the mapping review in which the role of a specific HCP was researched. A number of the studies were undertaken with multiple HCP participants.

| Code: HCP | Count |

|---|---|

| GP | 127 |

| Dentist | 41 |

| Optometrist | 11 |

| Pharmacist | 7 |

| Other community staff | 101 |

| Total | 287 |

General practitioner

One hundred and twenty-seven of the studies specifically investigated the GP role. The papers investigated a broad range of topics, including quality of primary health care, health checks, education or training for GPs, communication skills of GPs, out-of-hours primary care services and how to identify patients with an intellectual disability.

Dentist

Forty-one papers researched the role of dentists in treating people with ID. These studies investigated a variety of topics, including factors affecting access to dental service, oral care needs of people with ID, experiences of dental services from the viewpoint of people with ID and their carers, training of dentists and ethical issues to consider when treating patients with ID.

Optometrist

The role of the optometrist was researched in 11 of the included studies. These studies investigated the visual health needs of adults and children with ID, diabetic eye screening, inequalities in access to eye care and screening and how optometrists can provide eye care services to this population.

Pharmacist

Seven of the included studies related to the role of pharmacists. Topics researched included knowledge that people with ID have about their medicine, information that they want about their medications, medication-related interventions from pharmacists and whether or not pharmacists could play a role in blood pressure screening for hypertension in this population.

Other community staff

The ‘other community staff’ category covered a diverse range of staff, including practice nurses, health visitors, occupational therapists, community nurses and intellectual disability care staff. Within this large category, issues investigated included the needs of the population, the experiences of professionals and people with ID, health information exchange, the attitudes of professionals towards this population, training of staff, rural health care and the needs of specific groups within this population, including women and children.

Specialist topic

Table 5 shows the number of studies in the mapping review that related to services for specific conditions.

| Code: specialist topic | Count |

|---|---|

| Mental health | 30 |

| Palliative care | 25 |

| Sexual health | 21 |

| Other | 105 |

| Total | 176 |

Sexual health

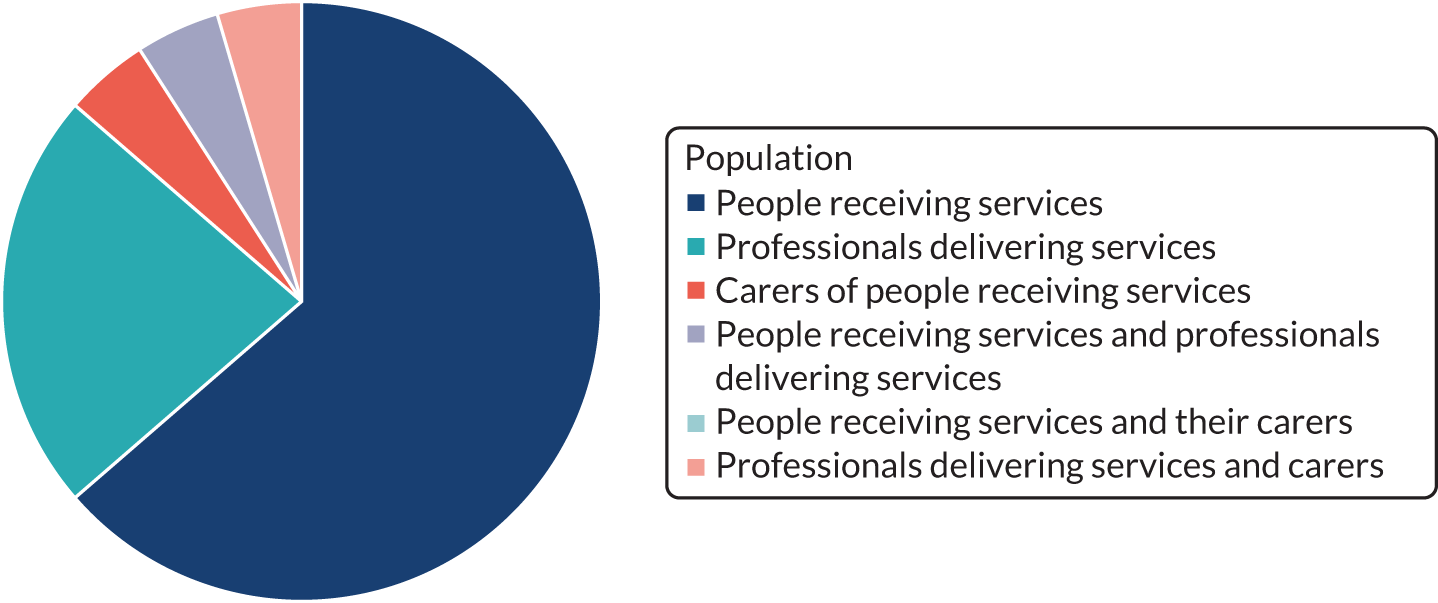

The delivery of sexual health services was researched in 21 of the included studies. The populations investigated in these studies can be subdivided into people receiving services (14 studies), professionals delivering services (five studies) and carers of people receiving services (one study). In addition, there was one study researching family carers, support workers and professional staff, as shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Pie chart of broad populations researched in sexual health studies.

The studies investigated sexual health services for people with ID. Topics of research included services available, self-advocacy, experiences, barriers, contraception, cervical smear testing, capacity to consent to sexual relations, service provision for gay men, and breast screening.

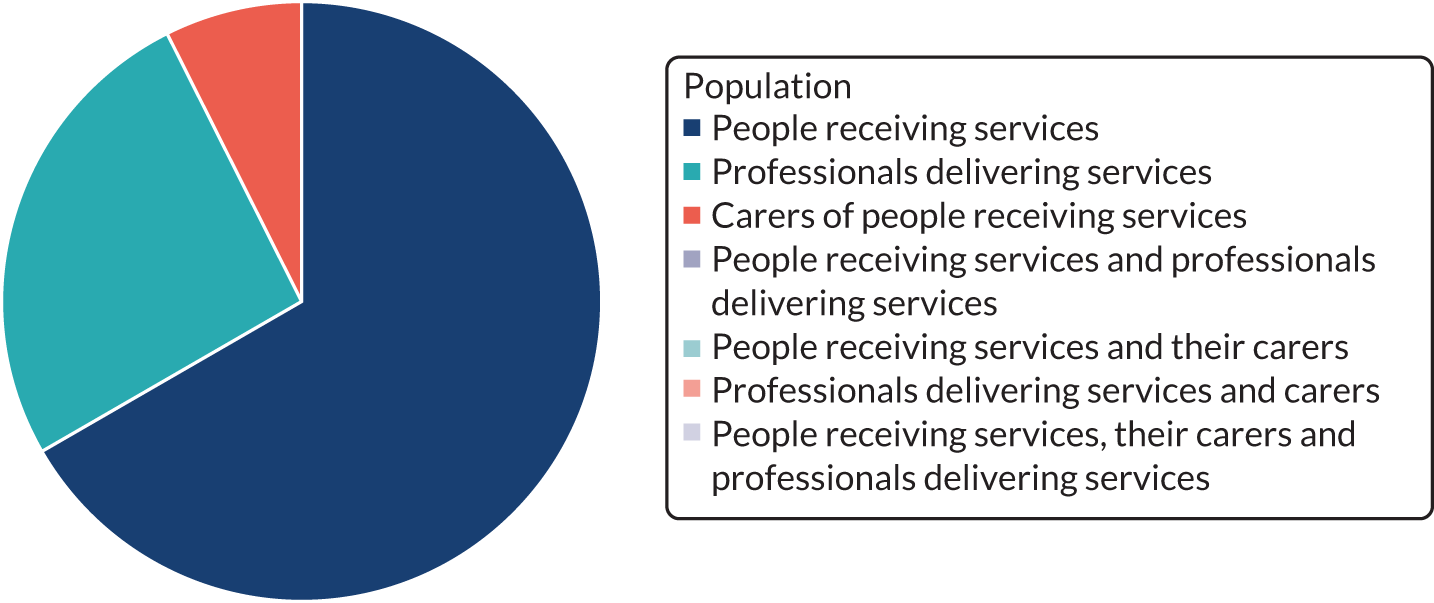

Palliative care

The delivery of palliative care services to people with ID was researched in 25 of the studies. The populations investigated in these studies can be subdivided into people receiving services (11 studies) and professionals delivering services (12 studies); one study researched a person with ID and the professionals involved in his care, and another study considered people with ID and their carers (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Pie chart of broad populations researched in palliative care studies.

The included studies researched challenges in providing palliative care to this population, identification of needs by HCPs, communication about illness, death and dying, and the role of carers in end-of-life care.

Mental health

Thirty of the studies in the mapping review researched the delivery of mental health services to people with ID. The populations investigated in these studies can be subdivided into people receiving services (18 studies) and professionals delivering services (seven studies); three studies researched people receiving the service, their carers and the professionals delivering the service, and two studies considered people with ID and their carers. The breakdown is shown in Figure 5. These studies investigated services available for people with ID and mental health problems, access to these services, experiences of these services and the needs of people with ID who develop dementia.

FIGURE 5.

Pie chart of broad populations researched in mental health studies.

Other

The ‘other’ category covered a broad range of specialist topics; more detail of the different areas of service provision is provided in Table 6.

| Specialist topic | Count |

|---|---|

| Access to health care | 3 |

| Accessible information | 1 |

| Autism | 1 |

| Blood test | 3 |

| Cancer care, not necessarily palliative | 2 |

| Cancer information | 1 |

| Cancer screening (includes breast and cervical) | 17 |

| Children and young people | 4 |

| Communication skills | 3 |

| Dementia | 4 |

| Diabetes services | 4 |

| Epilepsy | 1 |

| General practice | 1 |

| Gynaecological/reproductive health | 1 |

| Health checks/assessments | 13 |

| Health inequalities | 1 |

| Health information exchange | 1 |

| Health promotion | 5 |

| Health status, care utilisation and medical outcomes (review) | 1 |

| Health visiting | 1 |

| Hearing | 2 |

| Mainstream health services | 1 |

| Maternity services | 3 |

| Older people | 4 |

| Oral health care | 3 |

| Out-of-hours care | 2 |

| Pain | 2 |

| Polypharmacy and medication review | 1 |

| Primary care | 3 |

| Range of needs | 1 |

| Research | 1 |

| Satisfaction with care | 1 |

| Social prescribing | 1 |

| Substance use | 1 |

| Preventative health care | 3 |

| Rural health | 1 |

| Training | 1 |

| Transition paediatric to adult health care | 1 |

| Unmet need | 1 |

The ‘other’ category covers a variety of topics. Papers about cancer screening were the most common, followed by papers about health checks/assessments.

Needs assessment

Twenty of the 413 included references were coded as relating to needs assessment. Table 7 provides details of the different populations investigated.

| Population | Number of references |

|---|---|

| Older people | 5 |

| Children and young people | 4 |

| Staff working with people with ID | 2 |

| Palliative care needs of people with ID | 2 |

| Adults with ID | 1 |

| Mental health needs of people with ID | 1 |

| Adults with cerebral palsy and ID | 1 |

| Men with HIV with or without ID | 1 |

| People with ID and dementia | 1 |

| Evaluation of a needs assessment tool | 1 |

| Not given | 1 |

Reasonable adjustments

Several articles specifically considered changes or reasonable adjustments introduced to make services more accessible; examples are a specialist multiprofessional visual assessment clinic at a day centre to provide appropriate eye care to people with ID, techniques to engage people with ID in physical health assessment measures and the implementation of health checks.

Grey literature

A total of 16 UK-based sources (mainly comprising charitable associations) were searched for relevant grey literature (see Appendix 1). Of these, seven provided no further information relevant to the review. The remaining nine sources linked to between one and six documents that appeared relevant from the title, with a total of 28 documents potentially meeting our inclusion criteria.

Twenty-three of the documents were excluded on the grounds that they included no data (these were mainly guidance documents). Of the remaining five reports, one was a short review of the literature, thus providing a source for further identification of includable studies, three contained practice examples and case studies (without reporting outcome data) and one was a qualitative research study (Table 8).

| Author(s) and date | Title | Relevant data | Section(s) and page(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Faculty of Dental Surgery 201226 | Clinical Guidelines and Integrated Care Pathways for the Oral Health Care of People with Learning Disabilities | Guidelines with a short review of barriers to oral health care | Barriers to oral health care, pp. 7–10 |

| Public Health England 201527 | Health Checks for People with Learning Disabilities: Including Young People Aged 14 and Over, and Producing Health Action Plans | Suggestions for improving uptake of health checks (no outcome data) | Practice examples and case studies, pp. 11–14 |

| Public Health England 201628 | Making Reasonable Adjustments to Cancer Screening | Background: screening programmes, short review of research, short case studies of reasonable adjustments (no outcome data) | Resources and case studies, pp. 14–44 |

| Public Health England 201629 | People with Learning Disabilities in England: Main Report 2015 | Initiation and uptake of health check for people with ID | Health services, pp. 22–23 |

| The Disability Partnership 201630 | Evaluation Report of the 2015–16 Mencap-led Pharmacy Project | Results from surveys, interviews and focus groups about access to pharmacy services | All (methods and results are included) |

Two reports considered the implementation and uptake of health checks; one focused on reasonable adjustments to encourage uptake of screening for cervical, breast and bowel cancer; one identified barriers to accessing oral health care; and a final, Mencap-led, research study explored access to pharmacy services.

Data in the mapping review related to barriers and facilitators

Data relating to potential barriers to and facilitators of access for people with ID were extracted from results sections, where available. Of the included citations, 87 abstracts mentioned barriers to and 47 mentioned facilitators of access to primary health care. From the information available in the abstracts, we categorised the barriers and facilitators (some abstracts included more than one) in Tables 9 (barriers) and 10 (facilitators).

| Barrier | Number of citations |

|---|---|

| Wider determinants | |

| Independent living | 1 |

| Undefined roles for carers | 1 |

| Lack of knowledge of services | 1 |

| People with ID having difficulties attending (e.g. distance, finances, physical difficulties) | 3 |

| People with ID not understanding information/health literacy | 2 |

| ID factors (general) | 1 |

| People with ID communication skills | 1 |

| Identification of need | |

| Lack of perceived need/lack of willingness/fear of intervention | 4 |

| Organisation of health care | |

| Organisational/primary care characteristics | 5 |

| Facilities | 1 |

| Partnership working | 1 |

| Lack of services (including out of hours) and funding | 2 |

| Waiting times | 1 |

| Time/length of appointment times | 2 |

| Late referrals | 1 |

| HCPs | |

| Lack of guidelines/support for staff | 2 |

| Staff training/education | 3 |

| Staff knowledge/skill/confidence level | 6 |

| Staff awareness | 2 |

| Staff experience with people with ID | 2 |

| Identification of people with ID | 1 |

| Access to first-contact health care | |

| Interpersonal skills/welcoming | 2 |

| Staff communication skills | 11 |

| Staff attitudes and behaviour/lack of understanding/not supporting autonomy/lack of cultural sensitivity | 7 |

| Opportunities to engage in discussion about care | 1 |

| Consent | 2 |

| Comorbidities | 1 |

| Continuing health care | |

| Continuity of care | 1 |

| Monitoring health problems | 1 |

| Facilitator | Number of citations |

|---|---|

| Wider determinants | |

| Social cohesion/community connectedness | 2 |

| Residence (in relation to services) | 2 |

| Family characteristics/support/advocacy for people with ID | 3 |

| Liaison between family and carers | 1 |

| Education (HCP/peers) | 1 |

| Caregiver support/interventions | 3 |

| Identification of need | |

| Health check programmes/regular health checks | 2 |

| Organisation of health care | |

| Financial incentive for health checks (practice) | 1 |

| Walk-in clinics | 1 |

| Co-ordinated care | 1 |

| Adapted resources/methods | 4 |

| Lead practitioner or GP with a special interest | 1 |

| Data-sharing resources | 1 |

| Telephone accessibility | 1 |

| HCPs | |

| Teamwork/interprofessional working | 5 |

| Joined-up approach across agencies | 2 |

| Adopting and encouraging best practice | 2 |

| Staff training/shared learning | 6 |

| Staff skills/competence | 2 |

| Access to first-contact health care | |

| Timeliness and frequency of appointments | 1 |

| Familiar environment | 1 |

| Personal greeting in waiting room | 1 |

| Begin consultation at once | 1 |

| Communication aid | 1 |

| Advance planning/preparation before consultation | 6 |

| Written care plans | 1 |

| Knowledge of the person and their routines | 3 |

| Respectful HCP–service user relationship/personal connection/patience/taking time/patient centred/empowering | 8 |

| Helping people with ID understand/learn skills/recognising and minimising treatment effects | 3 |

| Counselling (screening) | 1 |

| Education/information | 5 |

| Reassure/evaluate anxiety/pain | 1 |

| Continuing health care | |

| Signposting and appropriate referral | 1 |

| Continuity/communicate with people with ID/carer outside consultation | 3 |

Identified barriers were often accompanied by facilitators that were suggested or implemented to minimise the impact of the barriers; for example, an identified lack of communication skills in HCPs could be modified by training staff or by people with ID using communication aids.

Professional communication, knowledge, skills and attitudes appeared to be commonly reported barriers to people with ID seeking primary health care. This is mirrored by facilitators relating to the professional, including service user relationship, staff training, and planning before a consultation. Our adding up of the numbers of citations within these categories needs to be considered with caution; potentially it might not reflect the literature as a whole, as abstracts provide only partial information. It was intended that the information derived from characterising the literature in this way during the mapping review would assist us in prioritising the focus of the systematic review and considering where and how the research in this area had developed since the original review by Alborz et al. 21

Chapter 4 Mapping review discussion

The mapping review identified a large number of studies on access to health-care services for people with ID. The evidence available for barriers to identification of need and continuing care appeared, from this review, to be less than for other domains of the Alborz et al. 21 model. Many barriers and facilitators identified in abstracts resonated with themes generated from the PPI discussions, particularly in arranging and attending health appointments, although less so at this point in identifying and communicating symptoms of ill health, and continuing access to services was also reported less often.

The Alborz et al. 21 review found that the evidence base on general practice was larger than those on many other areas of interest, and this mapping review found that studies specifying a role for the GP constituted the most common single HCP category. The 2003 review21 found only one study on access to optometry services, and we similarly found only a small number considering the specific role of optometrists in screening and eye care, and some on the unmet eye care need of this population. A small number of studies were found on the organisation of dental services in the Alborz et al. 21 review, but no studies were found about entry point access. By contrast, we found a reasonably sized body of literature related to dentists, dental services and oral care.

Limitations of mapping review

Although mapping reviews use systematic methods to identify, screen and code studies, a mapping review is not a systematic review. Mapping reviews generally omit some standard features of systematic reviews, for example study quality assessment, and do not attempt to assess the effects of interventions. The role of mapping reviews is to provide a descriptive account of the published literature and this should be taken into account when assessing the findings of this part of the overall evidence synthesis. The strength of the mapping review is in identifying areas where opportunities for further research or review are either present or not present and not to support actionable practice. For this reason, quality assessment is usually reserved for detailed follow-up analysis using the full text of included studies.

Mapping reviews can be based either on the full text of a limited number of identified studies or, more typically, on the abstracts of a wider literature base. In this specific case, informed by the previous Alborz et al. 21 review and preliminary scoping, we decided that mapping on the basis of abstracts only was the preferred option for logistical reasons. This was particularly appropriate given that revisiting key studies would be necessary for the subsequent systematic review. We recognised that abstracts are of variable quality and may be either informative (e.g. containing a list of key barriers and facilitators) or indicative (e.g. stating that a list of barriers and facilitators is present in the full text of the study). In addition, there is some evidence that the contents of abstracts may not fully reflect the detail of the papers, as authors may omit to revise abstracts when the main body of the text undergoes manuscript revision.

Chapter 5 Targeted systematic review methods

Aims and research questions

This targeted systematic review focused on evidence from the UK, building on the findings of the mapping review. The revised protocol for the targeted systematic review is provided in Report Supplementary Material 2.

The key elements of the targeted systematic review were:

-

development of the research questions based on the findings of the mapping review and information from PPI meetings

-

a focused systematic database search following inspection of the mapping review findings

-

a full data extraction of relevant studies

-

a quality assessment of included full peer-reviewed papers, and no formal quality assessment of conference abstracts or grey literature.

Research questions

-

What are the gaps in evidence about direct access to primary and community health-care services for people with ID?

-

What are the barriers to directly accessing primary and community health-care services for people with ID and their carers?

-

What actions, interventions or models of service provision improve access to primary and community health-care services for people with ID and their carers?

Search strategy

The findings from the mapping review helped develop the search strategy for the targeted systematic review. Searches covered the period 2002–18. We searched MEDLINE, The Cochrane Library, Web of Science, CINAHL (Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature), ASSIA (Applied Social Science Index), PsycINFO and ERIC (Educational Resources Index) for studies published from 1 January 2002 (the end date of the previous SDO review) to September 2018. A validated filter31 was used to identify UK studies. Further details of the database search, including a sample search strategy, can be found in Appendix 5. Further evidence was sought by contacting topic experts, people with ID and their carers. Broad searches for grey literature on ID (irrespective of setting) that were conducted during the mapping review provided the grey literature for the targeted review.

Selection of articles

Search results were uploaded to EPPI-Reviewer 4 for title and abstract screening. Screening was performed by a team of three reviewers, with a random sample of 10% of records from each reviewer double screened by one of the reviewers. Full papers were obtained for records that appeared potentially to meet the inclusion criteria (Table 11) and these were also uploaded to EPPI-Reviewer 4. Screening on full text followed a similar process to title and abstract screening. Any queries were resolved by discussion. The list of papers excluded at full-text review is available in Appendix 6.

| Criteria | Eligibility |

|---|---|

| Population |

|

| Setting |

|

| Outcomes |

Access to a service We will also review studies reporting the effectiveness of any measures or interventions designed to improve access to the relevant services |

| Comparator | The general population may offer a comparator in some study types |

| Study design |

|

| Other limitations |

English language only Evidence published since 2002. The Alborz et al. 21 review searched up to 2002 |

Data extraction

Data extraction was completed in EPPI-Reviewer 4 using a mix of tick-box and open questions (see Appendix 7). We focused on extracting data relating to the barriers to and facilitators of service access, service acceptability and effectiveness of the implementation of reasonable adjustments to primary care services for people with ID. An example data extraction for one of the included studies is in Appendix 8 and the data extraction table for the grey literature is in Appendix 9.

Quality assessment

Risk of bias was assessed using validated checklists published by the US National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute [URL: www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools (accessed 19 November 2018)] for quantitative study designs [controlled (randomised and non-randomised) intervention studies, observational cohort and cross-sectional studies, case–control studies and before-and-after studies with no control group]. Qualitative studies were assessed with the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) checklist for qualitative studies [URL: https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists/ (accessed 19 November 2018)]. Mixed-method studies were assessed using the appropriate checklist for the predominant methodology of the study.

Analysing and synthesising data

We performed a narrative synthesis of the evidence. The structure of the synthesis was determined by the themes that emerged from the included studies. We drew on a pathway of care model to explore evidence relating to the patient journey of care, including examination of the barriers and facilitators or influencing factors at each point in the pathway.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement in the development and conduct of the review is reported in Chapter 2. Further to this, we discussed the findings and recommendations from the review with a family carer representing the group of family carers (n = 1) and with a group of people with LDs (n = 10) plus a member of staff supporting the group (n = 1). These discussions covered the main findings and recommendations from the review. Prompts were used when needed to ensure that the discussions covered whether or not these findings were an accurate reflection of their experiences, whether or not there was anything missing and whether or not there was anything they would like to add to the findings or recommendations.

Chapter 6 Targeted systematic review results

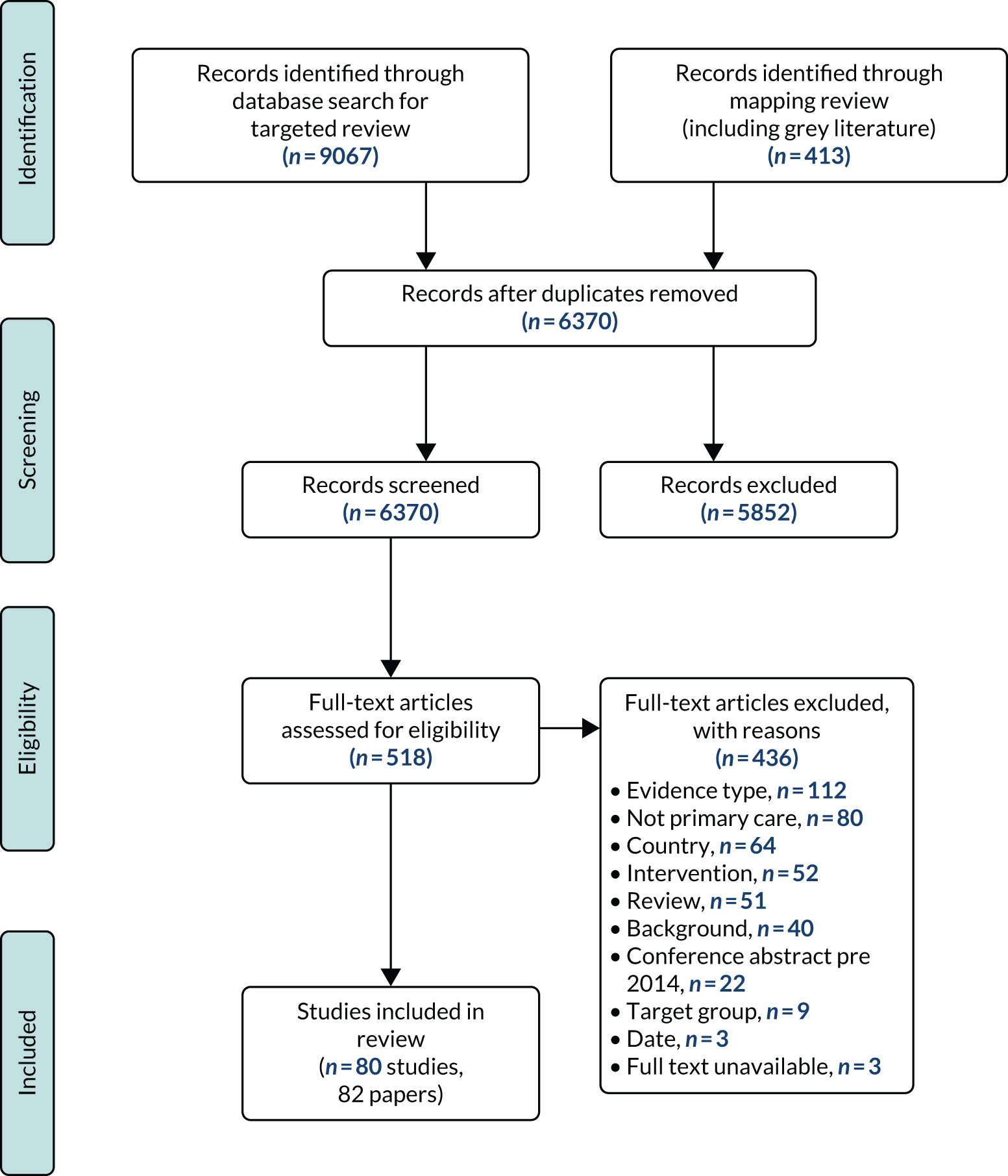

Results of literature search

The 413 potentially relevant references from the mapping review were rescreened against the new inclusion criteria while the additional literature searches for the targeted review were being completed. The database search for the targeted review retrieved 9067 references. After de-duplication of the search results, 5957 additional unique records were available for screening (Figure 6), giving a total of 6370 to be screened.

FIGURE 6.

The PRISMA flow diagram for the targeted systematic review.

Screening

The screening process was divided between three reviewers. A calculation of inter-rater agreement was made. A kappa coefficient was calculated that demonstrated excellent agreement between the reviewers (κ = 0.933, 95% CI 0.904 to 0.962). A total of 518 references were screened as ‘include’ based on a preliminary title and abstract screen. On further scrutiny of the full text, 436 of these were excluded. Common reasons for exclusion were that the study’s setting was secondary not primary care, the study was about a different population, the study was not about access to health care and the study was not a research study. Eighty-two publications reporting 80 studies were included in the targeted systematic review.

Study characteristics

The review synthesised the evidence from 80 studies reported in 82 publications; an alphabetical list of the included studies is in Appendix 10. All of the included studies were conducted in the UK and investigated adults with ID and their carers (paid or family carers or primary care health professionals working with individuals with ID).

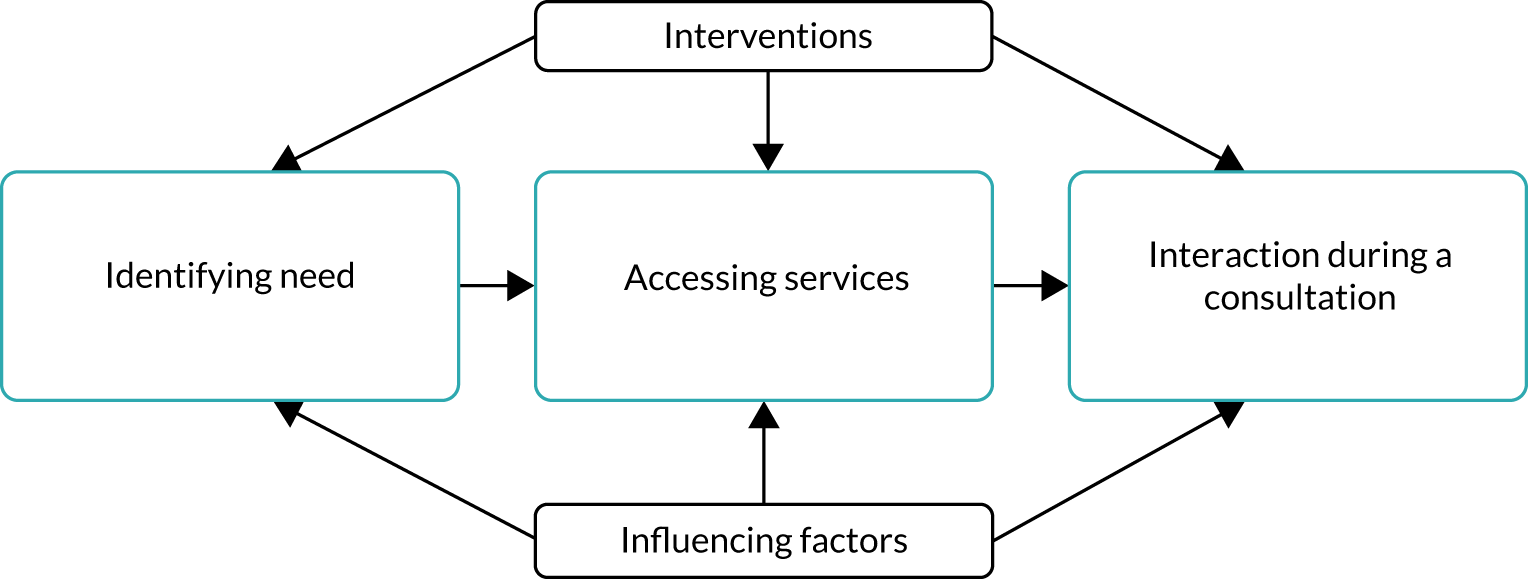

The synthesis was based around a pathway of care encompassing identifying need, accessing services and interaction during a consultation. The pathway model (Figure 7) was not prespecified but emerged from the examination of included study characteristics and was agreed by consensus among the review team. Included studies were grouped into the three clusters corresponding to the stages of the patient pathway. In addition, some studies evaluated innovations/interventions that aimed to improve access, which had an impact at different steps in the pathway model, and these formed a fourth cluster.

FIGURE 7.

Pathway model.

Influencing factors (barriers and facilitators) of access at each stage were also identified within the data. A common group of influencing factors that appeared to act at all stages was used to structure the narrative synthesis for each cluster of studies.

The evidence will thus be outlined within the following four clusters: identifying needs (14 studies), accessing services (24 studies), interaction during a consultation (19 studies) and interventions to improve access (23 studies).

Identifying need

Fourteen studies reported in 16 publications, published from 2003 to 2017, were included in this group (Table 12). Of these, three dealt with general practice,44,45,48 three dealt with a range of primary care services,36,37,49 three dealt with carers working at residential or supported living homes33–35,43 and two dealt with formal and informal carers of people with ID in residential or family homes. 38,39 The other three studies dealt with audiology services,42 cervical and cancer screening40 and sexual health. 41 The majority of the studies included in this cluster had a qualitative design.

| First author and year of study | Type of service | Type of study |

|---|---|---|

| Beacroft 2010/1133,34 | Residential and supported living homes in Surrey |

Cross-sectional33 Qualitative34 |

| Bland 200335 | Nursing homes | Cross-sectional |

| Bollard 201736 | All services | Qualitative |

| Donovan 200237 | All services | Qualitative |

| Findlay 2014/15 (same study)38,39 | Formal and informal carers | Qualitative |

| Hanna 201140 | Cervical screening and other cancer screening | Cross-sectional |

| McCarthy 200941 | Sexual health | Qualitative |

| McShea 201642 | Audiology | Qualitative |

| Northway 201743 | Supported living accommodation for people with ID in Wales | Qualitative |

| Turk 201244 | GP | Cross-sectional |

| Walker 201645 | GP | Very few data; mix of literature review; many relevant data linked to hospitals |

| Willis 201546 | Carers | Qualitative |

| Wilson 201047 | All services | Qualitative |

| Young 201248 | GP | Qualitative |

Accessing services

Twenty-four studies, published between 2003 and 2017, were included in this group (Table 13). Of these, six dealt with a range of primary care services,50,55,58,62,66,67 six dealt with with general practice,51–53,57,60,70 five dealt with cancer screening,59,63,68,69,72 two dealt with dental services,56,64 two dealt with mental health services,54,61 one dealt with diabetic retinopathy screening65 and one dealt with sexual health. 71 The majority of included studies used a cross-sectional (e.g. survey or audit) or qualitative (e.g. interviews or focus groups using qualitative methods for data analysis) design. Only two studies used a cohort or case–control design63,69 and two were classed as mixed methods. 54,71

| First author and year of study | Type of service | Type of study |

|---|---|---|

| Ali 201350 | All services | Qualitative |

| Allgar 200851 | GP | Cross-sectional |

| Black 200452 | GP | Qualitative |

| Carey 201653 | GP | Cross-sectional |

| Chinn 201654 | IAPT | Mixed methods |

| Cooper 201155 | All services | Cross-sectional |

| Doshi 200956 | Dentist | Cross-sectional |

| Jones 200857 | GP | Qualitative |

| Lennox 200358 | All services | Cross-sectional |

| Lloyd 201459 | Cervical screening | Qualitative |

| Lodge 201160 | GP | Cross-sectional |

| McNally 201561 | Community mental health | Qualitative |

| Nicholson 201162 | All services | Cross-sectional |

| Osborn 201263 | Cancer screening | Cohort |

| Owens 201164 | Dentist | Qualitative |

| Pilling 201565 | Diabetic retinopathy screening | Cross-sectional |

| Raghavan 200766 | All services | Cross-sectional |

| Redley 201267 | All services | Qualitative |

| Rees 201168 | Cancer screening | Cross-sectional |

| Reynolds 200869 | Cervical screening | Case–control |

| Russell 201770 | GP | Cross-sectional |

| Starling 20066 | Eye care | Cross-sectional |

| Williams 201471 | Sexual health | Mixed methods |

| Wood 200772 | Cervical screening | Qualitative |

Interaction during a consultation

Nineteen articles, published between 2004 and 2017, were included in this group (Table 14). Six of these studies dealt with GP services,75,79,82,83,91 four dealt with a range of primary services,74,77,78,84 three dealt with palliative or end-of-life care service,86,88,90 two dealt with sexual health services,81,85 two dealt with diabetes services,73,89 one dealt with dental services80 and one study dealt with non-specific cancers in this population. 87 The majority of these studies had a qualitative design,73–77,80,82,83,85,87,89,90 a few had a cross-sectional study design78,79,81,84,85,88,91 and one was a case study. 86

| First author and year of study | Type of service | Type of study |

|---|---|---|

| Brown 201773 | Diabetes | Qualitative |

| Gates 201174 | All services | Qualitative |

| Goldsmith 201375 | GP | Qualitative |

| Hames 200676 | GP | Qualitative |

| Hebblethwaite 200777 | All services | Qualitative |

| Heyman 200478 | All services | Cross-sectional |

| Jones 200779 | GP | Cross-sectional |

| Lees 201780 | Dental | Qualitative |

| McCarthy 201181 | Sexual health | Cross-sectional |

| Murphy 200682 | GP | Qualitative |

| Perry 201483 | GP | Qualitative |

| Powrie 200384 | All services | Cross-sectional |

| Thompson 200885 | Sexual health | Cross-sectional and qualitative |

| Tuffrey-Wijne 200286 | Palliative and end-of-life care | Case study |

| Tuffrey-Wijne 200987 | Cancer | Qualitative |

| Tuffrey-Wijne 200588 | Palliative and end-of-life care | Cross-sectional |

| Turner 201489 | Diabetes | Qualitative |

| Watchman 200590 | Palliative and end-of-life care | Qualitative |

| Williamson 200491 | GP | Cross-sectional |

Innovations to improve access (including health checks)

Twenty-three studies evaluated innovations to improve access (Table 15). The majority of the studies investigated innovations within GP services. 19,93–101,103–105,107–109,111–113 The remaining studies reported innovations in eye health,92 in Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT), in cardiovascular disease106 and for staff in care homes. 110 One of the included studies was a cluster randomised controlled trial,100 but most had a cross-sectional design.

| First author and year of study | Type of service | Type of study |

|---|---|---|

| Adler 200592 | Eye health | Cross-sectional |

| Baxter 200693 | GP | Cross-sectional |

| Biswas 200594 | GP | Cross-sectional |

| Buszewicz 201495 | GP | Cohort |

| Cassidy 200296 | GP | Case control and qualitative |

| Chauhan 201097 | GP | Cohort |

| Chauhan 201298 | GP | Cohort and qualitative |

| Codling 200799 | GP | Cross-sectional |

| Cooper 2014100 | GP | Cluster randomised controlled trial |

| Cooper 2006101 | GP | Case–control |

| Dagnan 2018102 | IAPT | Before and after |

| Felce 200819 | GP | Retrospective cohort (medical records scrutiny) |

| Ford 2015103 | GP | Cross-sectional |

| Glover 2013104 | GP | Retrospective cohort (routine data trends) |

| Harrison 2005105 | GP | Before–after |

| Holly 2014106 | Cardiovascular | Cross-sectional |

| Martin 2004107 | GP | Cross-sectional |

| McConkey 2015108 | GP | Cross-sectional |

| Romeo 2009109 | GP | Case–control |

| Taylor 2014110 | Care homes | Cross-sectional |

| Walmsley 2011111 | GP | Qualitative |

| Webb 2009112 | GP | Mixed methods |

| Webb 2009113 | GP | Mixed methods |

Study quality

The results of the quality assessment for all included studies, classified by study design, are presented in Appendix 11, Tables 27–32. One case study86 was included in the review but not assessed for quality. The methodological limitations of the included studies are discussed in this section. Overall, the studies in the review were rated as being at relatively high risk of bias. Only two were controlled intervention studies92,100 and only one of these was randomised (by clusters). 100 The randomised trial appeared to be rated as being at low risk of bias, although blinding of outcome assessment was incomplete and the study did not meet the criteria for high adherence to the intervention (see Appendix 11, Table 27). The non-randomised study92 had a number of weaknesses, including differences between groups at baseline, differences in background treatments (other than the intervention being evaluated) and lack of a sample size/power calculation (see Appendix 11, Table 28).

For quantitative (cohort and cross-sectional) observational studies, the main limitations identified were lack of a power calculation or justification of sample size, absence of blinded outcome assessment and not considering possible confounding factors in the analysis (see Appendix 11, Table 29). In the accessing services cluster, only two studies compared a sample of people with ID with a general population control group. 63,69 Studies involving people with ID and carers often had small samples recruited from specialist settings and hence were not necessarily representative. Other studies provided the perspectives of health professionals only, with little or no representation of people with ID. Only a few included studies were classed as case–control or uncontrolled before-and-after studies (see Appendix 11, Tables 30 and 31).

The included qualitative studies met most of the criteria on the CASP checklist for qualitative studies (see Appendix 11, Table 32). Some studies did not consider the relationship between researchers and participants, which is a major limitation in studies involving people with ID. Other studies reported few details of data analysis, so it was unclear whether or not the analysis was sufficiently rigorous.

Identifying need

There were 16 papers reporting 14 different studies in this cluster. Among these studies, health needs were identified by the person with ID,34,36,38,41,44 family carers,49,114 paid carers33,35,39,40,42,48,73,114,115 and health professionals. 37,45,48

Identifying health need depends on some knowledge of potential risks to health. Ten papers reporting eight studies looked at carers’ awareness and knowledge of risks and potential health needs relating to cardiovascular disease,48 hearing,42 cancer,40 men’s health,36 older people35 and pain. 33,34,37–39 Table 16 provides the key findings of the studies in the identifying needs cluster.

| First author and year of study | Type of service | Key findings |

|---|---|---|

| Beacroft 2010/201133,34 | Residential and supported living homes in Surrey | Poor recognition and management of pain |

| Bland 200335 | Nursing homes | Screening rare; generally good access to GPs |

| Bollard 201736 | All services | Useful for GPs and other HCPs to actively promote the health of men with ID, who, with minimal nudging, are prepared to take on health promotion advice |

| Donovan 200237 | All services | Nurses find it hard to explore pain symptoms with people with ID. Ability to interpret non-verbal pain signals was crucial |

| Findlay 2014/2015 (same study)38,39 | Formal and informal carers | Under-reporting of pain by people with ID |

| Hanna 201140 | Cervical screening and other cancer screening | Lack of professional carer knowledge about cancer and screening |

| McCarthy 200941 | Sexual health | Women’s limited knowledge of contraception |

| McShea 201642 | Audiology | Lack of knowledge among support workers about hearing loss |

| Northway 201743 | Supported living accommodation for people with ID in Wales | Role of residential care staff in supporting older people with ID |

| Turk 201244 | GP | People with ID and carers under-report pain/problems |

| Walker 201645 | GP | Mostly descriptive, mentions QOF116 coding |

| Willis 201546 | Carers | Carer role undefined in terms of health care |

| Wilson 201047 | All services | Majority of carers report good access to GPs and dentists but difficulties accessing allied health professionals |

| Young 201248 | GP | Move to engaging with services; suggests ways to improve self-management |

Influencing factors

Influencing factors in the framework were identified in the included studies as summarised in Table 17. The most commonly reported factors were uptake and relationships with staff. Individual factors are briefly discussed in the following sections.

| First author and year of study | Staff knowledge/skills | Joint working with LD services | Service delivery model | Uptake | Appointment making | Carer/support role | Relationships with staff | Time | Accessible information | Communication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beacroft 2010/201133,34 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Bland 200335 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Bollard 201736 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Donovan 200237 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Findlay 2014/2015 (same study)38,39 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Hanna 201140 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| McCarthy 200941 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| McShea 201642 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Northway 201743 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Turk 201244 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Walker 201645 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Willis 201546 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Wilson 201047 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Young 201248 | ✓ |

Carer knowledge/skills

Many people with ID rely on those supporting them to recognise that they have a health need and that services are available to meet that need. Recognising unmet health need is an important step towards accessing appropriate care. Carers needed an in-depth knowledge of the client to be able to recognise and interpret health-related changes in behaviour, whether acute or long term; recognising when someone is unwell or in pain is an important first step towards accessing primary care services. Five papers33,34,37–39 reporting three studies explored pain recognition and management. One study was an audit exploring residential staff members’ beliefs about pain, strategies for recognising and managing pain33 and experiences of when people with ID had experienced pain. 34 Two qualitative studies explored the experience of pain for people with ID from the perspectives of people with ID and caregivers38,39 and ID nurses. 37 They found that people with ID did not necessarily tell someone when they were in pain, although they relied on others to deal with their pain. 34,38 People with ID demonstrated pain through changes in verbal and non-verbal behaviour;33,37 however, caregivers and residential staff did not always recognise that these were signs of pain. 33,39 Worryingly, some staff still believed that people with ID have a higher pain threshold than the general population, and those with more experience and qualifications were more likely to think that was the case, suggesting that training does not address pain recognition and management. 33 Pain recognition and communication tools were not widely used. 33,34,38 A further study carried out a secondary analysis of health information provided by people with mild to moderate ID and their carers to see how well the two sources corresponded. This study found some evidence that carers did not always recognise all health problems that were significant to the client, and clients reported a high frequency of unreported and untreated pain. Worryingly, some people with ID said that they did not have anyone to talk to about their health. 44

Companion/carer/support worker role

Three studies43,48,114 reported that tensions between services and uncertainty about roles and boundaries affected identification of and response to health needs.

One study used semistructured interviews with managers of supported living accommodation to explore how residential social care staff support older people with ID to meet their health needs. 43 This study found that residential social care staff often felt that their role in recognising, monitoring and meeting clients’ health needs was not always understood by health professionals and that this had an impact on their ability to meet these needs.

One study carried out interviews with paid carers and unpaid family carers to explore views about their role in monitoring the health of people with ID. 114 This study found that there was uncertainty about who among residential care staff, day care services staff, welfare guardians and family members was responsible for recognising and managing health concerns. Relationships, and particularly communication between the different personnel and organisations, could be poor, and this lack of joined-up working contributed to delays and difficulties in identifying and addressing health needs.

These findings were echoed in the third study48 that used qualitative interviews with people with ID, carers and health professionals to look at perceptions of self-management of cardiovascular disease. This study found that paid carers played a pivotal role in supporting health management because they were present regularly in the home and likely to have a trusting relationship with the person with ID. However, the authors raised concerns about poor knowledge about healthy lifestyle choices among social care staff, which could have an impact on their ability to recognise a health need.

Service delivery model

Access to services depends on someone identifying a need and being aware that services are available to address that need. A number of studies35,40–42,117 explored knowledge of health risk and awareness of services to mitigate the risk.

A survey of residential staff carers found gaps in the knowledge of carers about the signs and symptoms of and risks and protective factors for cancer and, therefore, carers did not promote cervical screening or weight management services for cancer prevention. 40 This study also found that staff did not know about risk factors specific to the individual, for example their family history of diseases such as cancer or any previous screening or testing.

A health needs assessment undertaken by the Lincolnshire Learning disabilities Health Needs Assessment steering group also found that the uptake of cervical screening was low among women with ID (28%) compared with women in the general population (71%). It also found that 48% of women with ID declined cervical screening or were ‘exemption reported’, compared with 12% of other women. Women who were exemption reported did not routinely receive future invitations for screening. This highlights the importance of care staff educating and supporting women to undergo screening. The authors speculate that as the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) allows practices to omit exemption reported patients from the data on which their achievement scores are based, there might be a financial incentive to exemption report women who are more difficult to treat, such as women with ID. 45

A survey of care staff working in accommodation for people with ID about health problems in those aged > 65 years and their perceptions about access to support found that many were unaware of the screening tests available and whether or not clients had undergone screening. The authors highlighted the need for staff training to raise awareness of health screening and the age at which screening is appropriate. This includes screening for hearing loss; the patient may be symptom free and it is therefore easy to miss. 35

One study interviewed 20 residential and day care workers, focusing on their knowledge of hearing loss and use of hearing aids. 42 Care workers were aware that it was their responsibility to detect health problems in those unable to do so, but they lacked the skills to detect hearing problems and had reservations about the extent to which audiology services could verify and treat hearing loss in someone with ID. Carers also had negative perceptions about the use of hearing aids, the most common management option for hearing loss, and lacked the necessary skills to support their use in someone with ID.

One study interviewed 23 women with mild to moderate ID living in community-based settings about contraception use. 41 The study found that only 5 of the 23 women used family planning services, with the others preferring to consult their family doctor. Reasons for this may include lack of knowledge about family planning services among women and their carers and a preference for consulting someone familiar and trusted. The study concluded that family planning staff may have more time for consultations but may lack experience of working with women with ID.

Communication

One study49 used semistructured questionnaires and two focus groups with informal family carers of children and adults with ID ranging from mild to severe to explore their perceptions of access to health and social care services. It found that family carers felt that they had to fight to get services and perceived that those that shouted loudest and fought most had better access to services.

Similarly, a study that interviewed men who had mild to moderate ID to explore the factors affecting their health and their capacity to act on health promotion messages found that a good relationship with a GP was important to ensure ongoing access to GP services and that people particularly valued the GP talking to them directly and then talking to the carer if there was a need to clarify information. 36

Monitoring and record-keeping

It is important to record information to maintain an accurate medical history when clients are unable to do this for themselves. Bollard118 found that men with ID in their study used health passports but not all health professionals filled them in on each visit. Residential care managers interviewed by Northway43 raised concerns that some carers may not have the literacy and numeracy skills to maintain health records accurately.

Summary

All of the factors included in the framework were identified as having some influence on identifying need. The studies were mostly weak in design and some of the older studies are unlikely to represent current practice. The most commonly reported factors were uptake and relationships with staff.

Access to services

The access to services cluster comprised 24 studies; the types of services researched and the key findings of each study are provided in Table 18.

| First author and year of study | Type of service | Key findings |

|---|---|---|

| Ali 201350 | All services | Further improvement required in reasonable adjustments |

| Allgar 200851 | GP | Template useful for identifying people with ID in general practice |

| Black 200452 | GP | Many internal and external barriers to equal access |

| Carey 201653 | GP | Continuity of care and longer appointments are key improvements |

| Chinn 201654 | IAPT | Access involves negotiation between patients/carers and service, barriers and facilitators at many levels |

| Cooper 201155 | All services | Deprivation is not associated with worse access to services |

| Doshi 200956 | Dentist | Young Bangladeshi adults with ID have complex and unmet oral health needs |

| Jones 200857 | GP | Access issues identified by patients, social care staff or both |

| Lennox 200358 | All services | Many patients not accessing more specialised primary care (e.g. optician) |

| Lloyd 201459 | Cervical screening | Attendance at cervical screening facilitated by joint working between LD nurses and primary care |

| Lodge 201160 | GP | Relying on Read code searches to identify patients with ID may lead to underdetection |

| McNally 201561 | Community mental health | Mental health and LD specialists identified barriers to people with ID accessing mainstream mental health services |

| Nicholson 201162 | All services | Adults with ID living in rural areas were not disadvantaged compared with those in urban areas |

| Osborn 201263 | Cancer screening | People with ID less likely to be screened for cancer and situation not improving |

| Owens 201164 | Dentist | Improved model of access to dental care needed |

| Pilling 201565 | Diabetic retinopathy screening | National standards for access to screening are not currently being met. Reasonable adjustments (e.g. alternative screening method) could improve matters |

| Raghavan 200766 | All services | Participants accessed primary care services through their GPs. Barriers included lack of awareness, language difficulties and lack of culturally sensitive services |

| Redley 201267 | All services | Access depends on support from family and health professionals |

| Rees 201168 | Cancer screening | Limited awareness among health professionals of some screening programmes and recommended age limits for screening |

| Reynolds 200869 | Cervical screening | Need to improve training for staff taking smears and to improve communication between LD teams and GPs so that patients and carers can receive better support |

| Russell 201770 | GP | Advanced Read code search did not identify large numbers of new patients for register, suggesting other methods needed |

| Starling 20066 | Eye care | Need to monitor people with ID to ensure access to appropriate eye care |

| Williams 201471 | Sexual health | Most younger adults with ID wanted to attend mainstream sexual health services |

| Wood 200772 | Cervical screening | Many practices lacked robust methods to identify women with ID; most felt that there was a need for training and support to deliver cervical screening for women with ID |

Influencing factors

Influencing factors in the framework were identified in the included studies as summarised in Table 19. The most commonly reported factors were uptake and relationships with staff. Individual factors are briefly discussed in the following sections.

| First author and year of study | Staff knowledge/skills | Joint working with LD services | Service delivery model | Uptake | Appointment making | Carer/support role | Relationships with staff | Time | Accessible information | Communication |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ali 201350 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||

| Allgar 200851 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Black 200452 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Carey 201653 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Chinn 201654 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Cooper 201155 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Doshi 200956 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Jones 200857 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Lennox 200358 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Lloyd 201459 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||

| Lodge 201160 | ✓ | |||||||||

| McNally 201561 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Nicholson 201162 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Osborn 201263 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Owens 201164 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Pilling 201565 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Raghavan 200766 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||

| Redley 201267 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Rees 201168 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Reynolds 200869 | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||

| Russell 201770 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Starling 20066 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Williams 201471 | ✓ | |||||||||

| Wood 200772 | ✓ | ✓ |

Staff knowledge/skills

The importance of health professionals’ knowledge and skills in relation to access was highlighted in several studies. In most cases, staff in mainstream services lacked confidence in their skills to deliver services to people with ID or at least expressed a need for further training. This was true for cervical screening72 and mental health services. 61 In a study of sexual health services, young adults with ID in Scotland expressed a preference for accessing mainstream services and felt that staff in these services should be able to meet their needs. 71 In relation to cancer screening generally, Rees et al. 68 reported that community staff working with people with ID had low awareness of some national screening programmes and were unsure of age limits and recommended intervals for screening. Lloyd et al. 59 emphasised the importance of primary care staff skills and knowledge for conducting cervical screening, including investment of time in preparing women to be screened.

Joint working with learning disability services

Community learning disability (LD) teams offer specialist support and services to people with ID. Access to services is facilitated when community teams co-operate effectively with general practice, but the included studies revealed a mixed picture. In an early study,52 many GP staff were unaware of the community team and what it could offer their patients. However, when there is awareness, there may still be confusion over the roles of different services and how they can best work together. Chinn et al. 54 identified this as a problem in the context of mental health and the respective roles of IAPT and specialist LD services.

Included studies identified a particular role for joint working between general practice and community services in promoting screening (e.g. for diabetic retinopathy in people with ID and diabetes65 and supporting women with ID to attend cervical screening59).

Service delivery model

This topic overlaps Joint working with learning disability services and should be read in conjunction with it. The included studies identified a number of barriers to access associated with service delivery models. McNally et al. 61 reported that lack of resources limits access by people with ID to mainstream mental health services and it is important that services do not offer ‘false hopes’ about what they can provide. In another study, dental services were reported to not be available at suitable times, again limiting access. 64

Service delivery by general practice is supported by practice registers of patients with ID; however, inaccuracies in registration constitute a barrier to accessing some services (e.g. screening). Three studies examined aspects of searching practice records using Read codes to identify people with ID. The findings were mixed; one study found a simple template useful51 but two others suggested that searches based on Read codes may not identify all patients with ID and need to be supplemented with other methods. 60,70

Pilling65 found that ID was not always recorded for people with diabetes who were eligible for retinopathy screening, while cervical screening history was inadequately documented in another study. 69 Wood and Douglas72 also reported that many general practices lacked robust methods to identify women with ID, which would have a bearing on service provision for cervical screening for this group. These cervical screening studies are more than 10 years old so it may be that they do not reflect current practice. As noted previously, a more recent study59 highlighted the role of joint working across services in promoting cervical screening.

Uptake