Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/19/12. The contractual start date was in July 2015. The final report began editorial review in September 2018 and was accepted for publication in April 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Paul Brocklehurst is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research Funding Committee, the NIHR Health Technology Assessment Prioritisation Committee and the NIHR Academy Doctoral Fellowship Panel.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Brocklehurst et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Context and overview of the report

Introduction

In 2013, our team published a Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Group review on the effects of different methods of remuneration on the behaviour of primary care general dental practitioners (GDPs). 1 The aim of this review was to evaluate the effects of different methods of remuneration on the level and mix of activities provided by GDPs and the impact this has on patient outcomes. It concluded that ‘financial incentives within remuneration systems may produce changes to clinical activity undertaken by primary care GDPs. However, the number of included studies is limited and the quality of the evidence from the two included studies was low/very low for all outcomes. Further experimental research in this area is highly recommended’. 1 In medicine, a review of reviews found that serious methodological limitations restricted the completeness and generalisability of the evidence for how changing remuneration systems affected patient care. 2 There was also insufficient evidence to determine the effect of financial incentives on the quality of health care provided. 3

Over the last decade, policy-makers across the UK have acknowledged the need to reform NHS dental contracts. In 2013, a change in the payment system for NHS dental contracts was considered by policy-makers in Northern Ireland, such that GDPs would be paid by a system based on the principles of capitation rather than the predominant fee-for-service (FFS) system. The main reasons behind this initiative were to contain costs, promote prevention rather than treatment of disease, secure access and improve the quality of care provided to NHS dental patients. The Department of Health, Social Services and Public Safety (DHSSPS) in Northern Ireland, in conjunction with the Northern Ireland Health and Social Care Board (NIHSCB), made a commitment to pilot a change in the remuneration system and work collaboratively with the academic team to undertake a rigorous evaluation of the impact of the pilot. This policy initiative provided an opportunity to build on the findings of the Health Services and Delivery Research report (11/1025/04) ‘Determining the optimal model for role substitution in NHS dental services in the UK: a mixed-methods study’4 to undertake a broader-based, economic study to investigate the impact of a change in the remuneration system in Northern Ireland on productivity and the quality of care provided.

Negotiations between the DHSSPS in Northern Ireland and the British Dental Association, the organisation representing the interests of GDPs in Northern Ireland, together with the budgetary constraints of the proposed pilots, had fixed the timetable for the evaluation and the number of practices that would be involved. These negotiations ensured that the payment package for GDPs working under the new financial arrangements (i.e. those in the new pilot) would be based on the total remuneration received under the previous year’s FFS contract.

Working in partnership with the academic team, this provided an opportunity to expand the evaluation and add academic rigour to the process that was originally envisaged by the DHSSPS and the NIHSCB. The outputs of the study would also add to and complement the information emerging from the NHS contract reform pilots in the other home countries. Importantly, this study provides detailed, longitudinal information at a patient level in test and control populations, which has not been possible in other NHS dental contract reform pilots. As the dental pilots in Northern Ireland were to switch from FFS remuneration to a capitation-based payment system and then back to FFS after 12 months, it also provided a unique opportunity to observe and document the scale of effect and issues around implementation and record any unintended consequences of the two changes in remuneration (FFS to capitation, capitation to FFS).

The evidence from the literature would suggest that practitioners respond very quickly to changes in the dental contract to ensure the viability of their practices;5–7 for example, changes to the NHS dental contract in England in 2006 saw an immediate drop in the types of clinical activity that reduced profit margins for practices and an increase in clinical activity in areas where profit margins could be improved. 5,6

Aim and objectives

The aim of the proposed research was to evaluate the impact of a change in the system of provider remuneration on the productivity, quality of care and health outcomes of NHS dental services in Northern Ireland.

The objectives of the research were to:

-

use a difference-in-difference (DiD) approach to measure changes in activity and costs over the different phases of the study in terms of –

-

productivity, as measured by the mean quantity of care delivered per provider

-

service mix, as measured by the proportions of key indicator treatments (these include examination plus scale and polish, radiographs, fillings, root canal treatment, crowns and bridgework)

-

GDPs’ time spent delivering patient care

-

change in cost of care, as measured by the volume of care weighted by the standard item treatment costs

-

co-payment income

-

-

assess GDPs’ and patients’ views about how, why and to what extent the changes in remuneration affect the delivery and quality of care

-

measure changes in patient-reported oral health knowledge, attitudes and behaviour

-

measure changes in patient-rated oral health outcomes and quality of care.

The research programme was co-produced including design and execution by a partnership between academics, policy-makers and senior NHS advisors and managers. The intention was to produce high-quality, stand-alone academic outputs that would contribute to the evidence base but concurrently provide valuable information for policy-makers and senior NHS decision-makers to inform the development of NHS dental services in Northern Ireland.

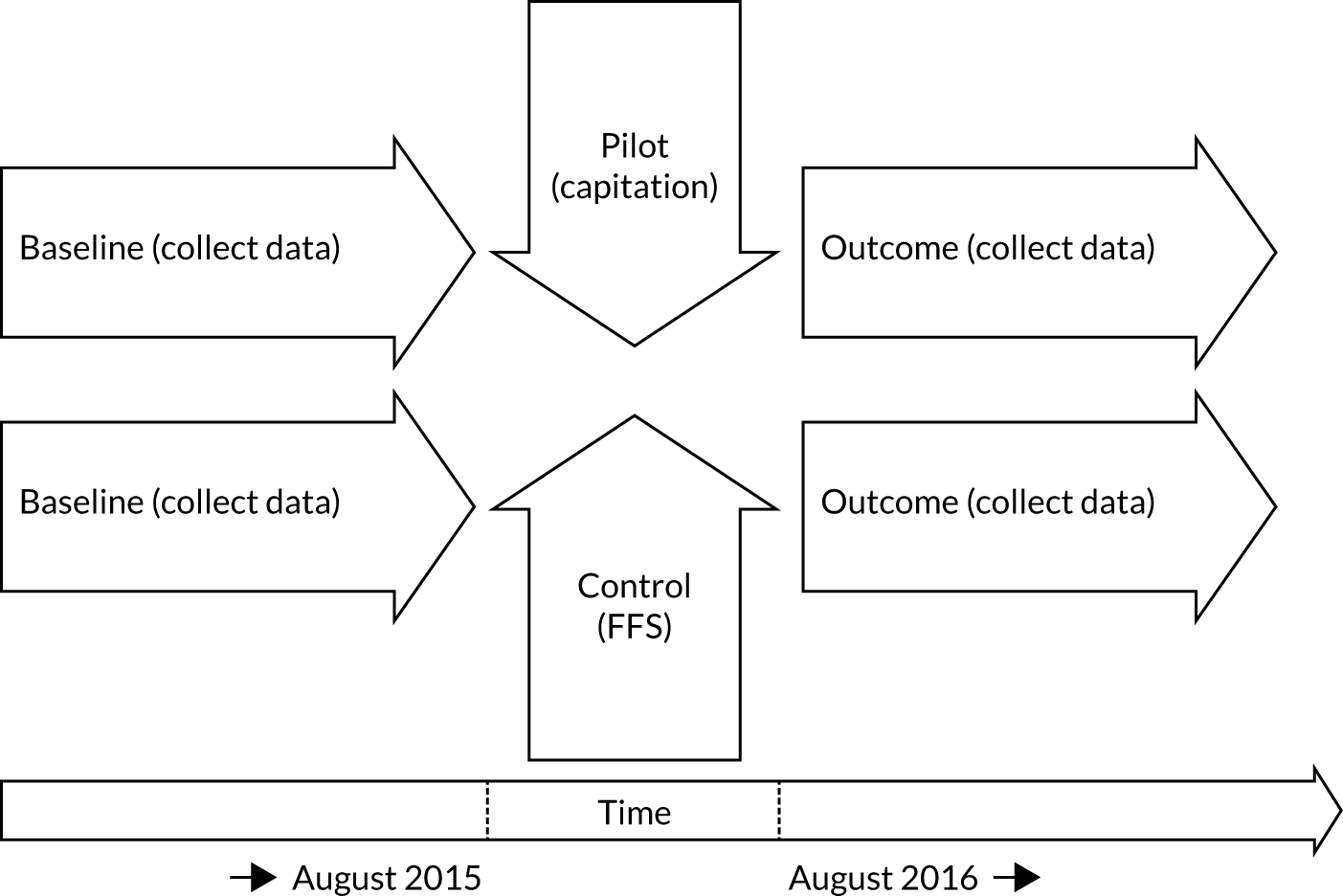

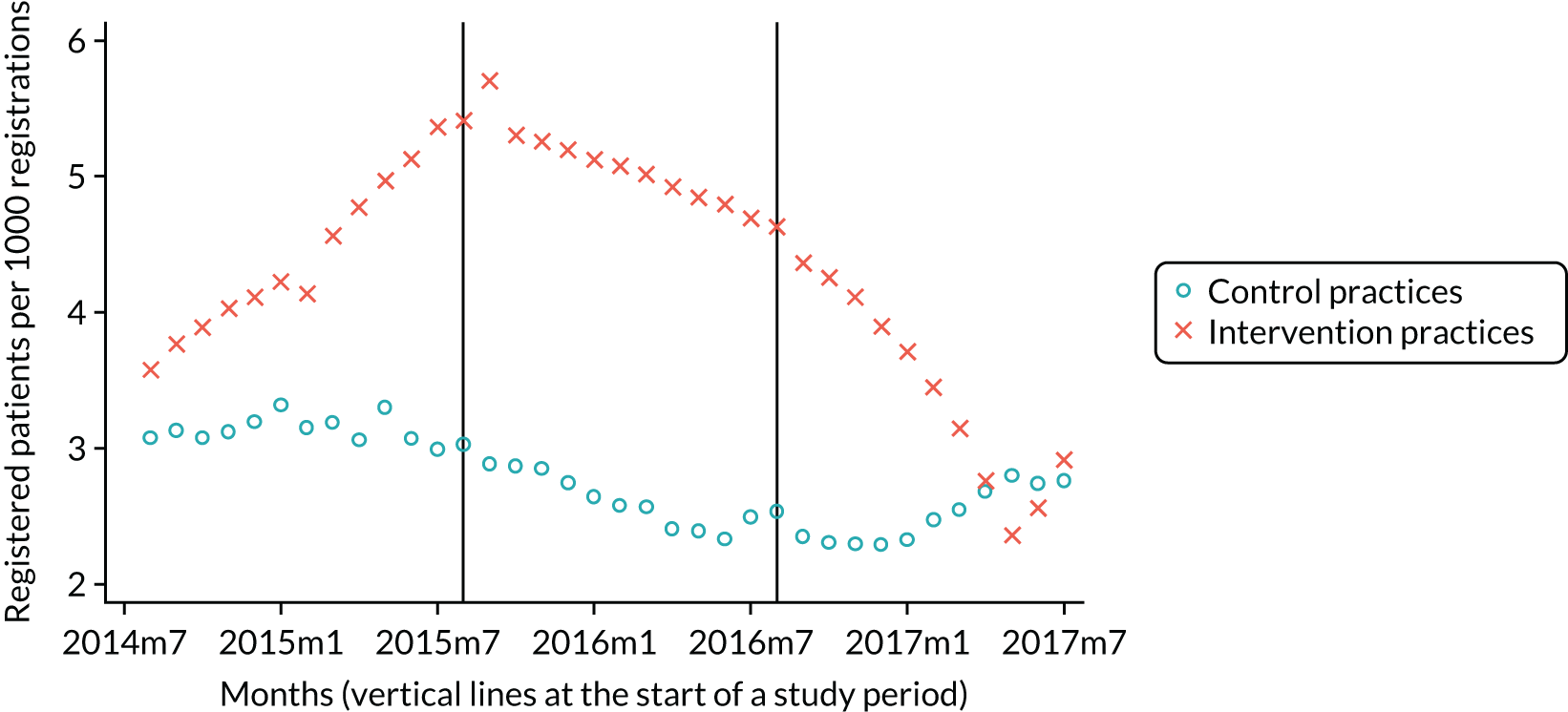

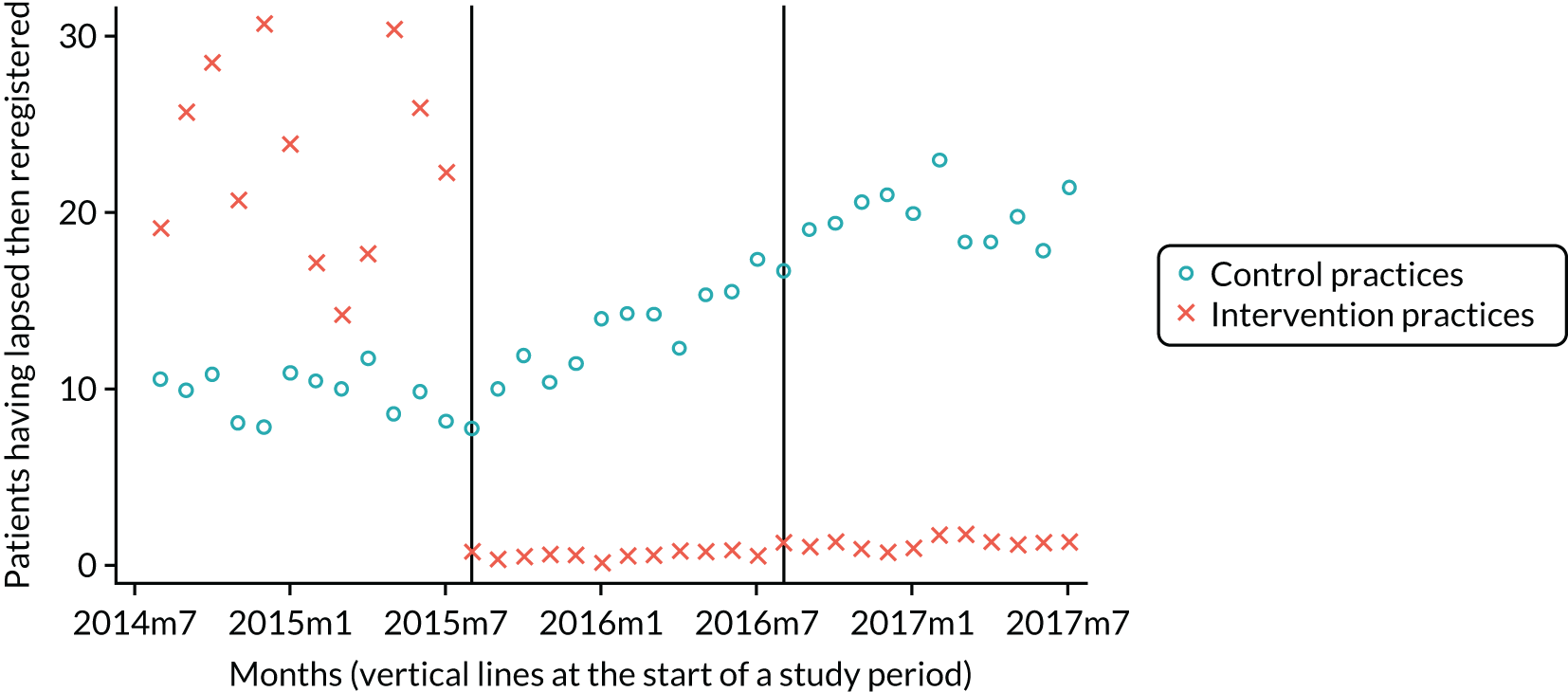

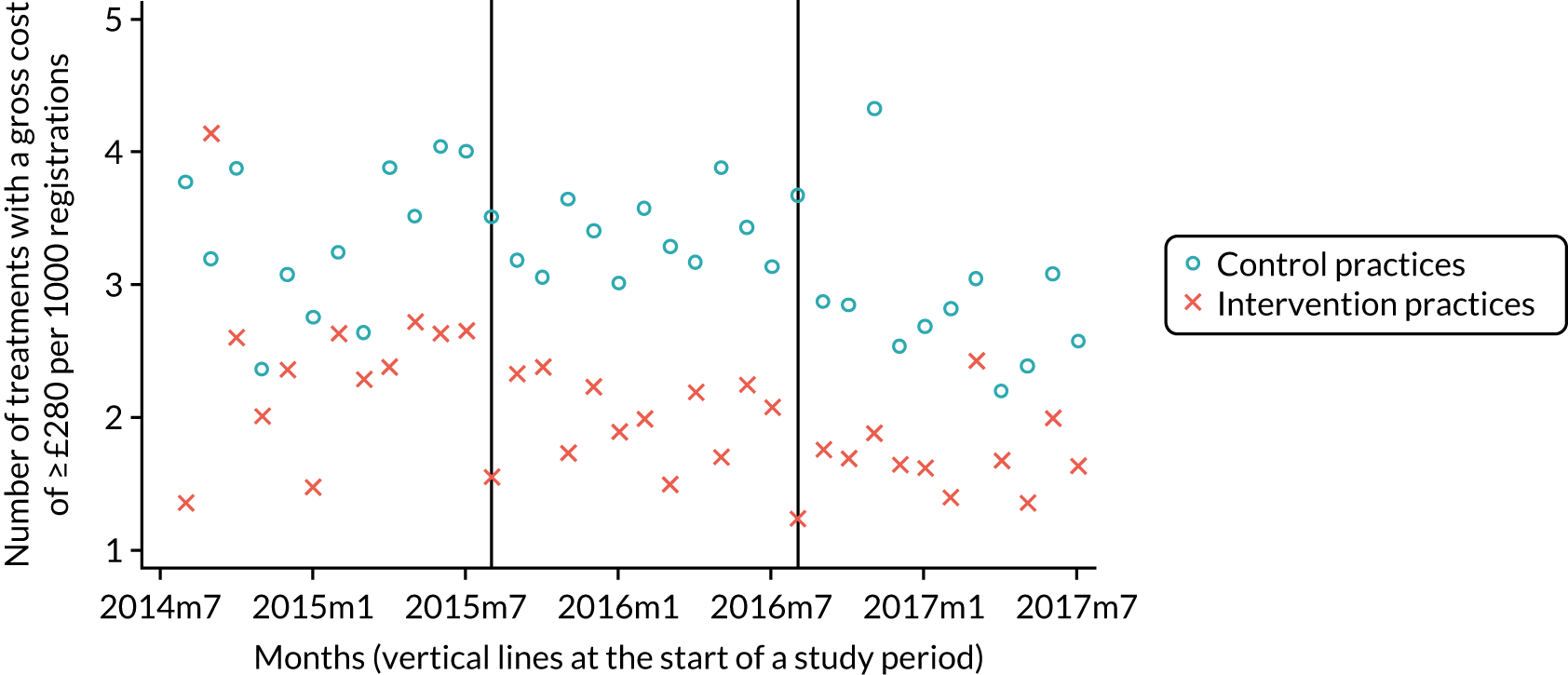

Research design and project overview

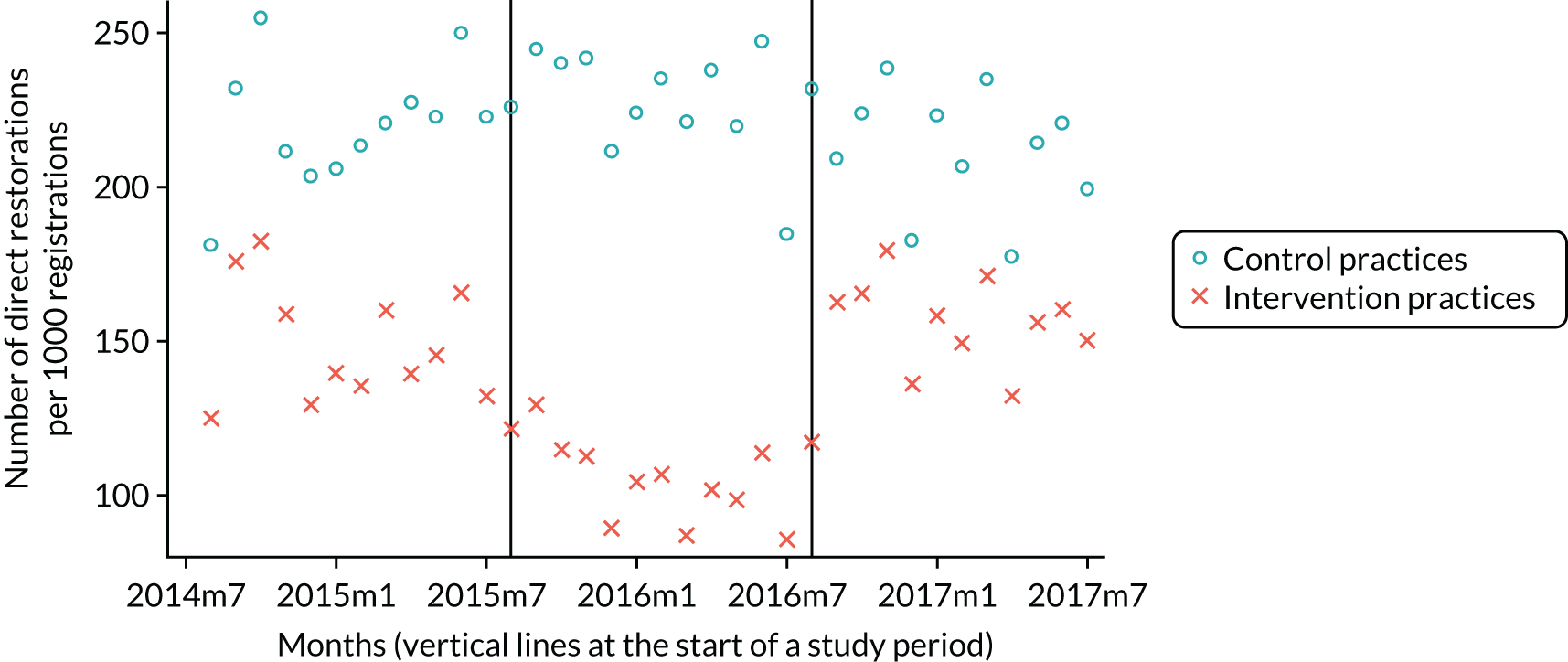

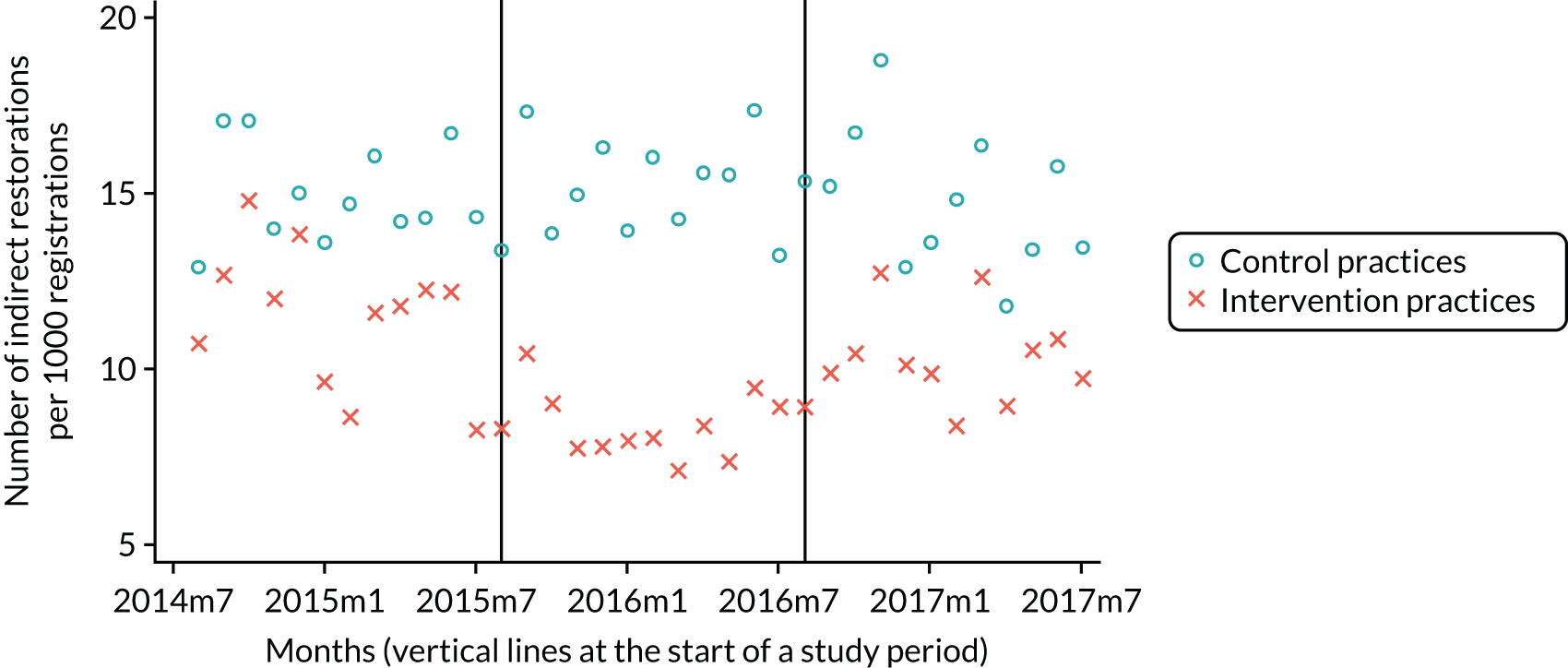

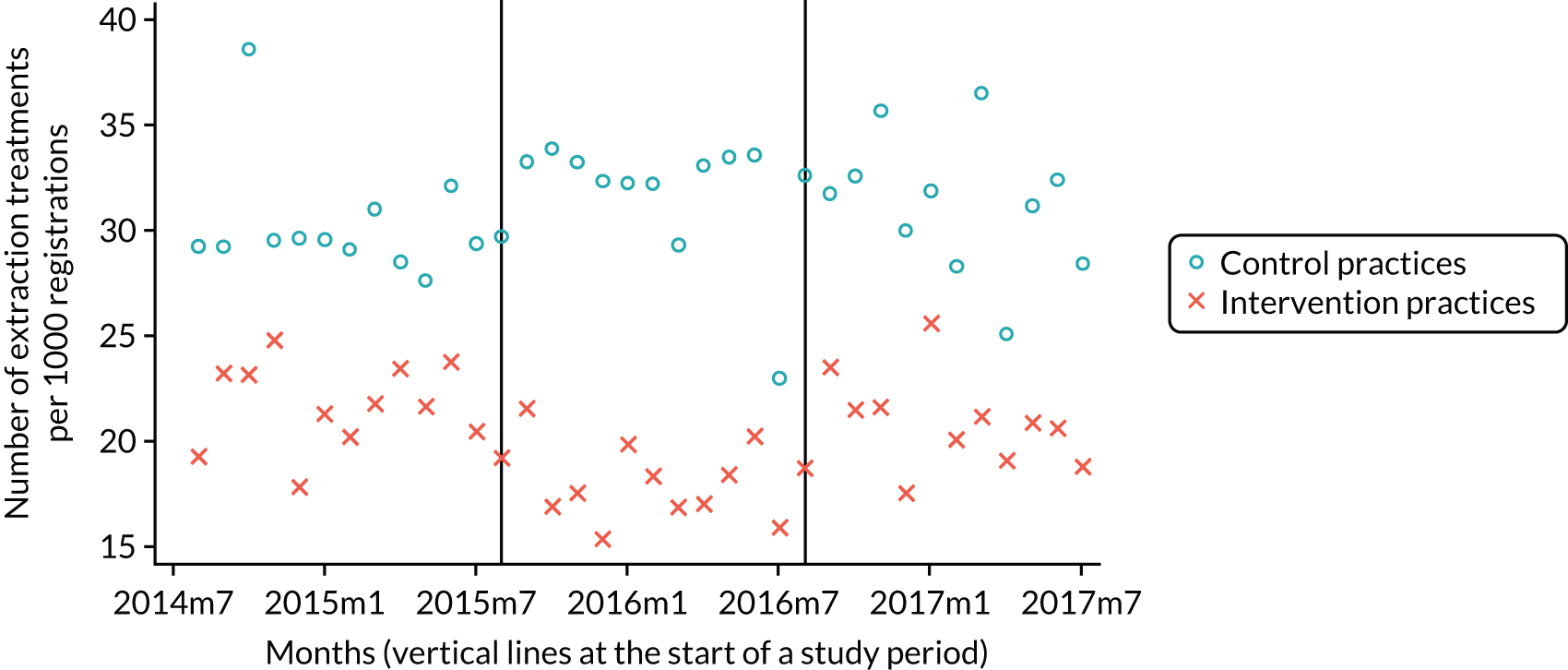

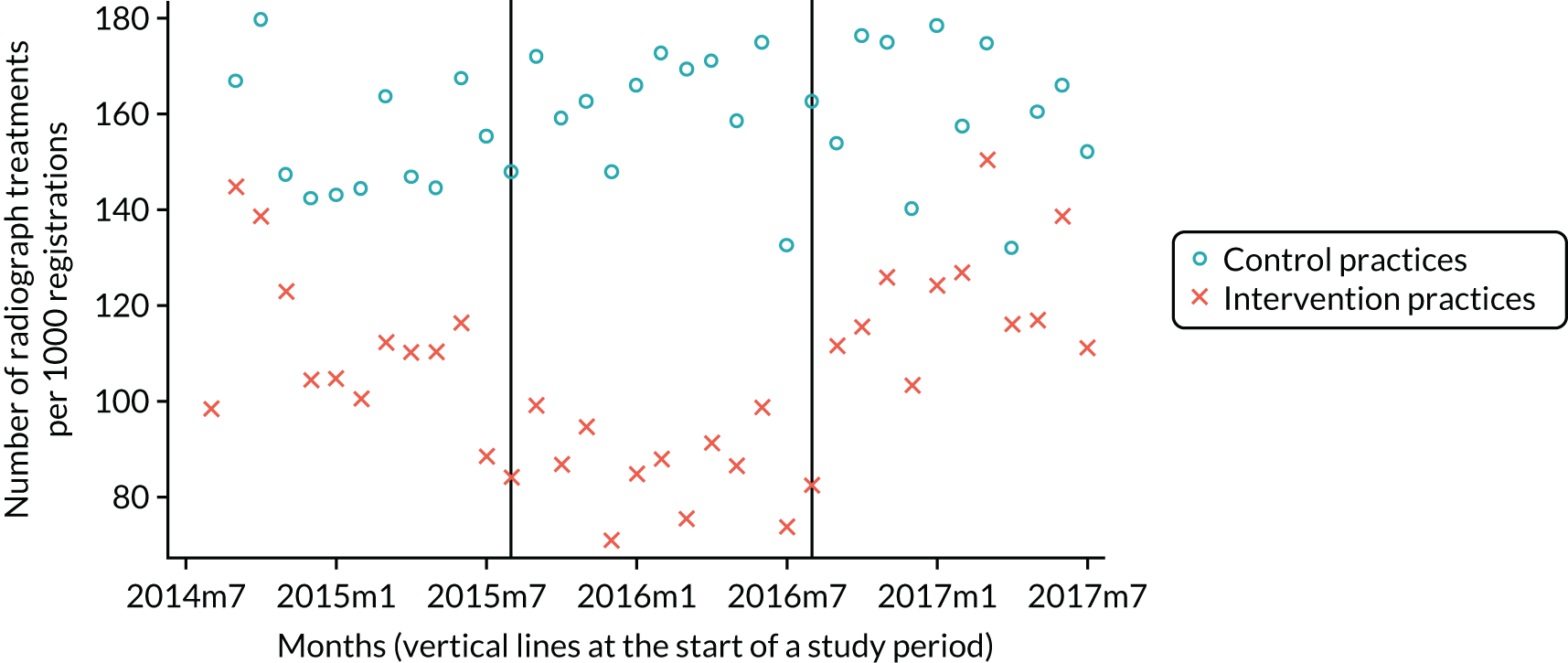

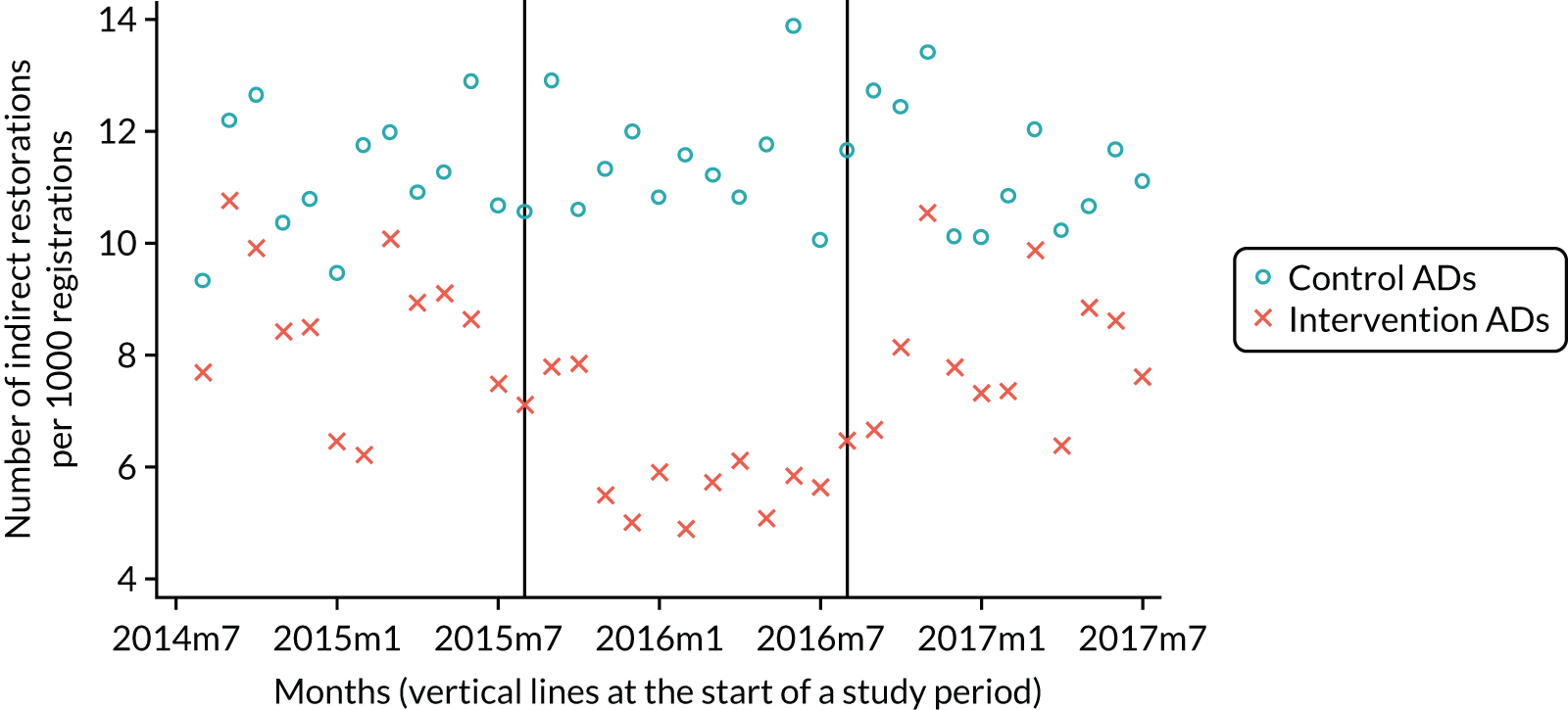

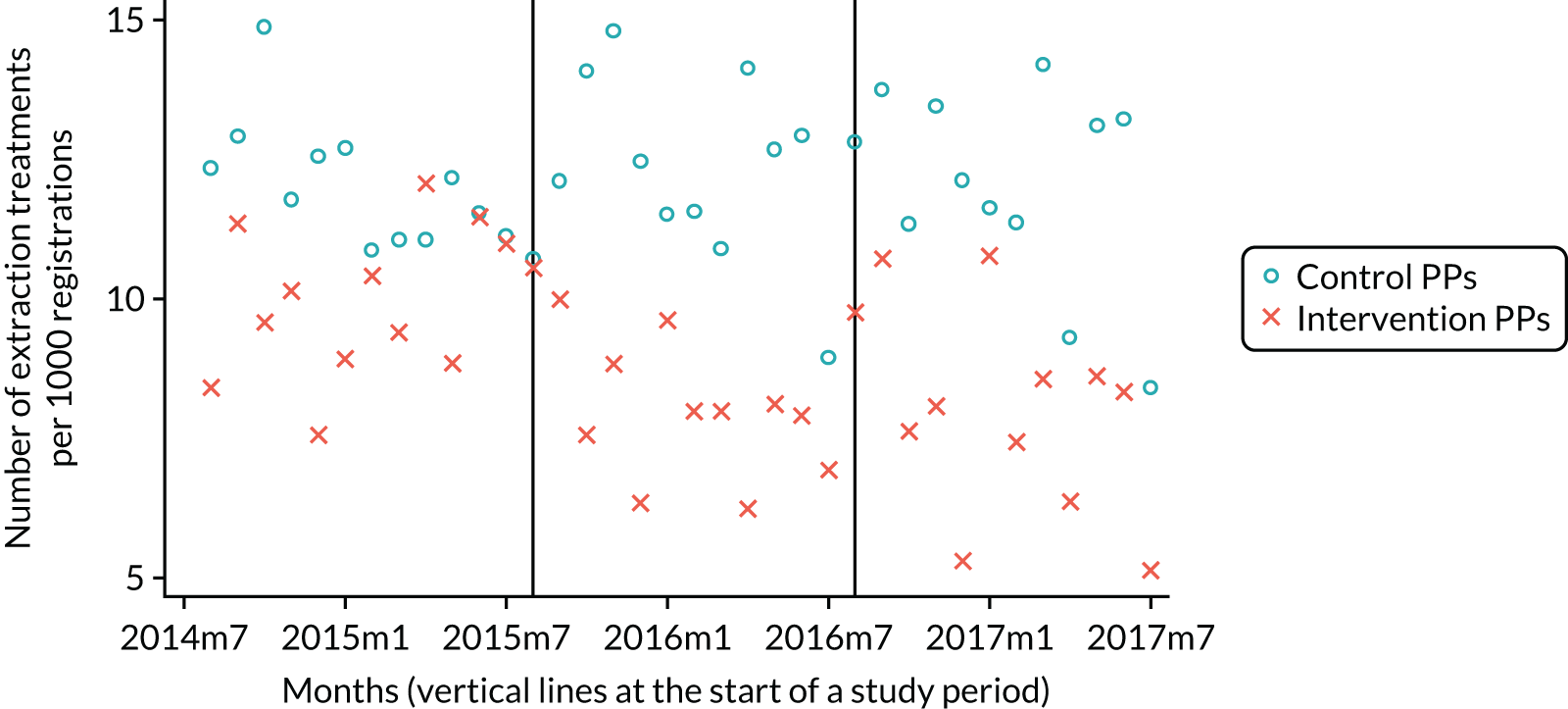

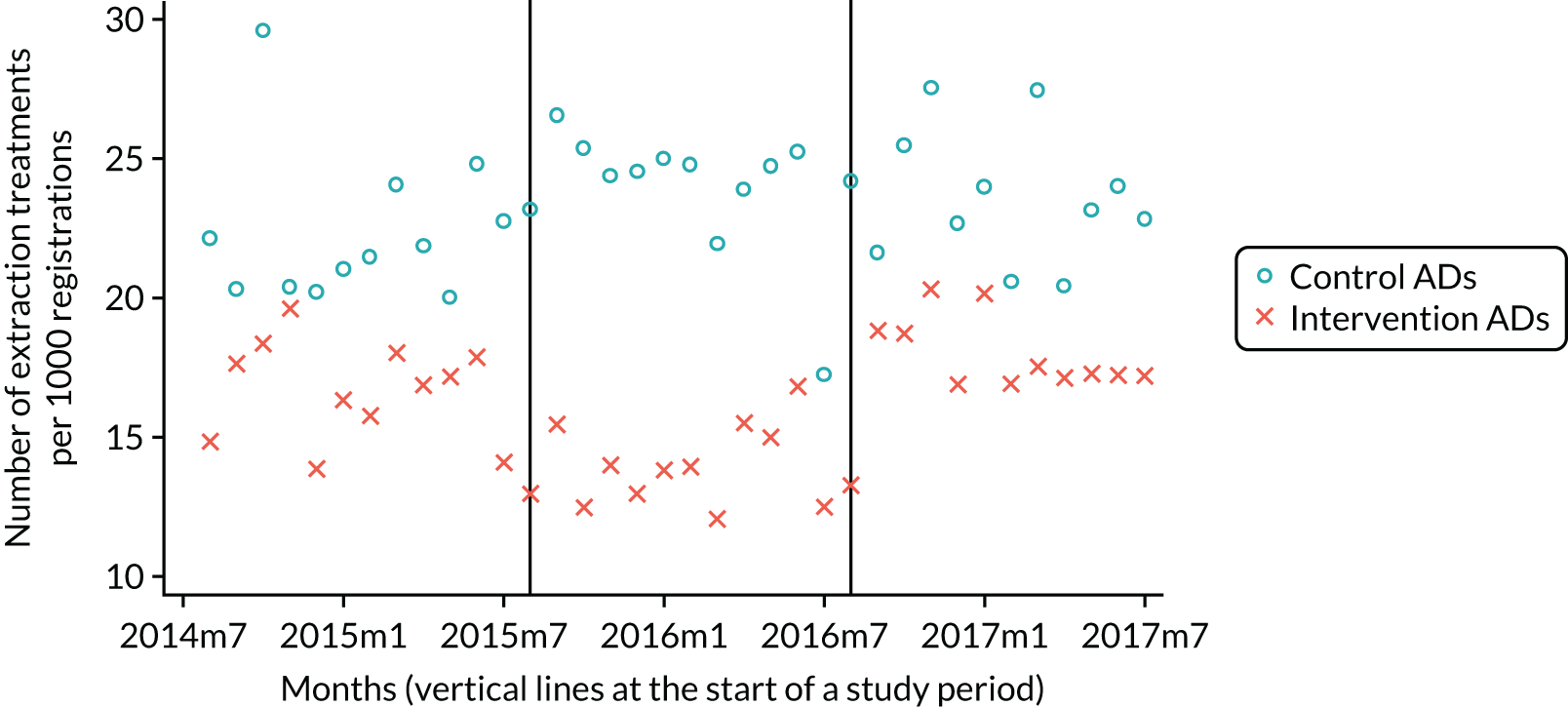

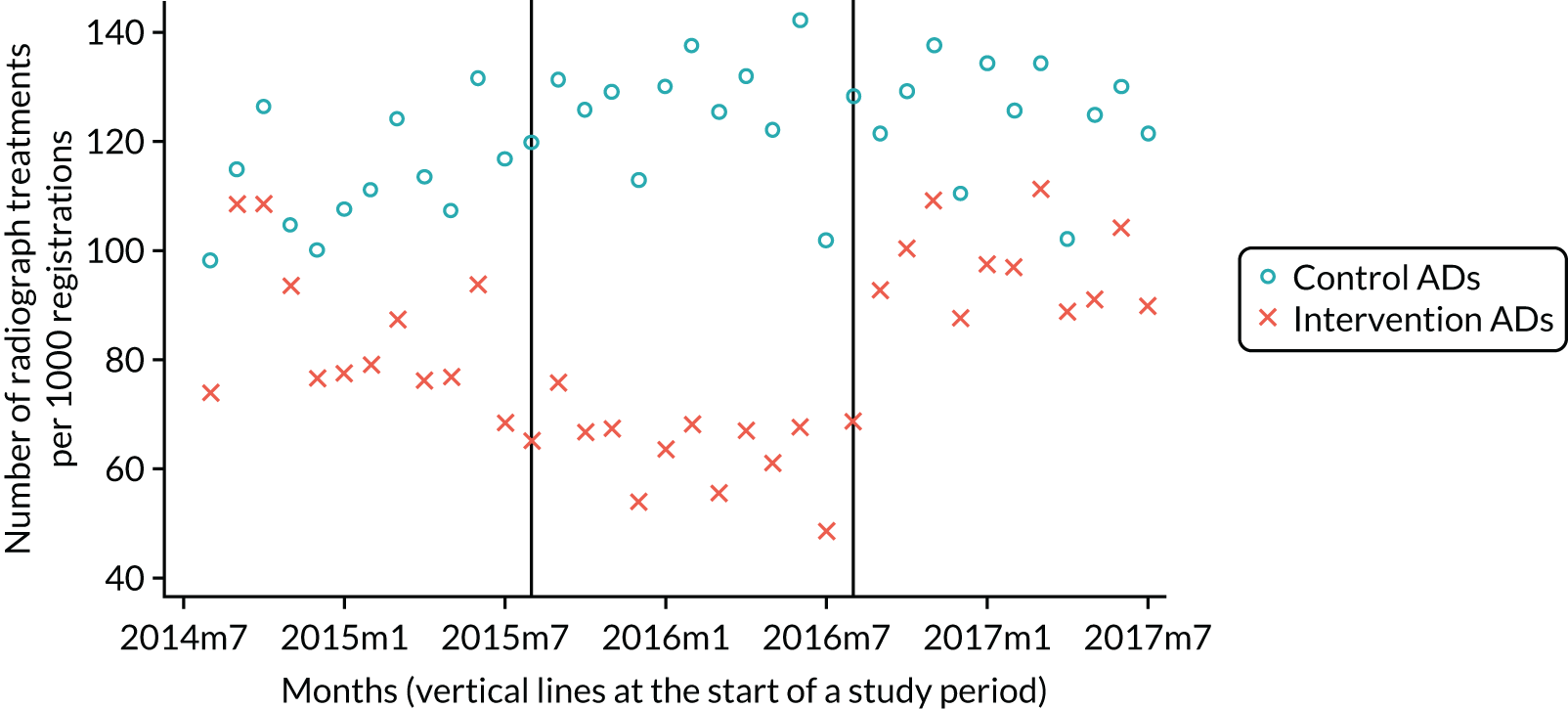

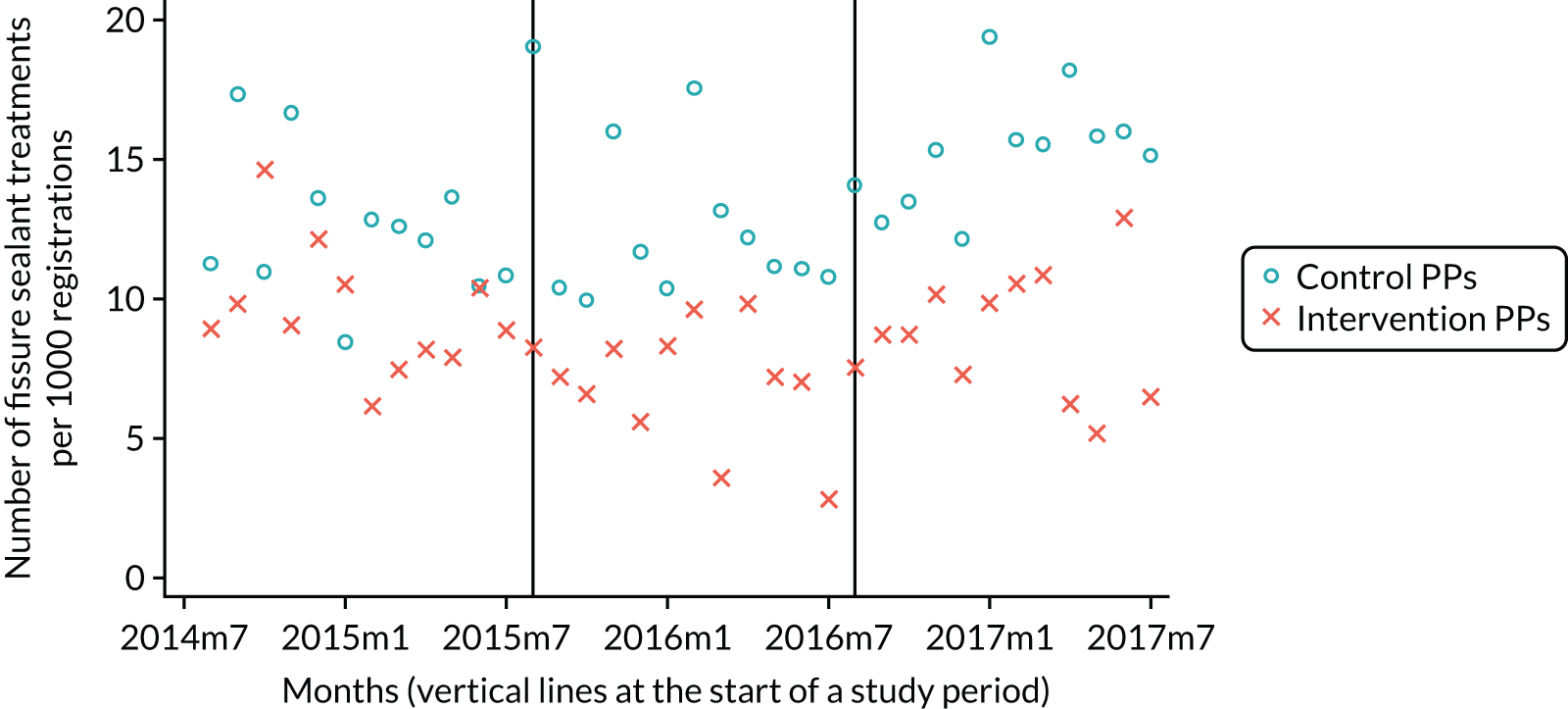

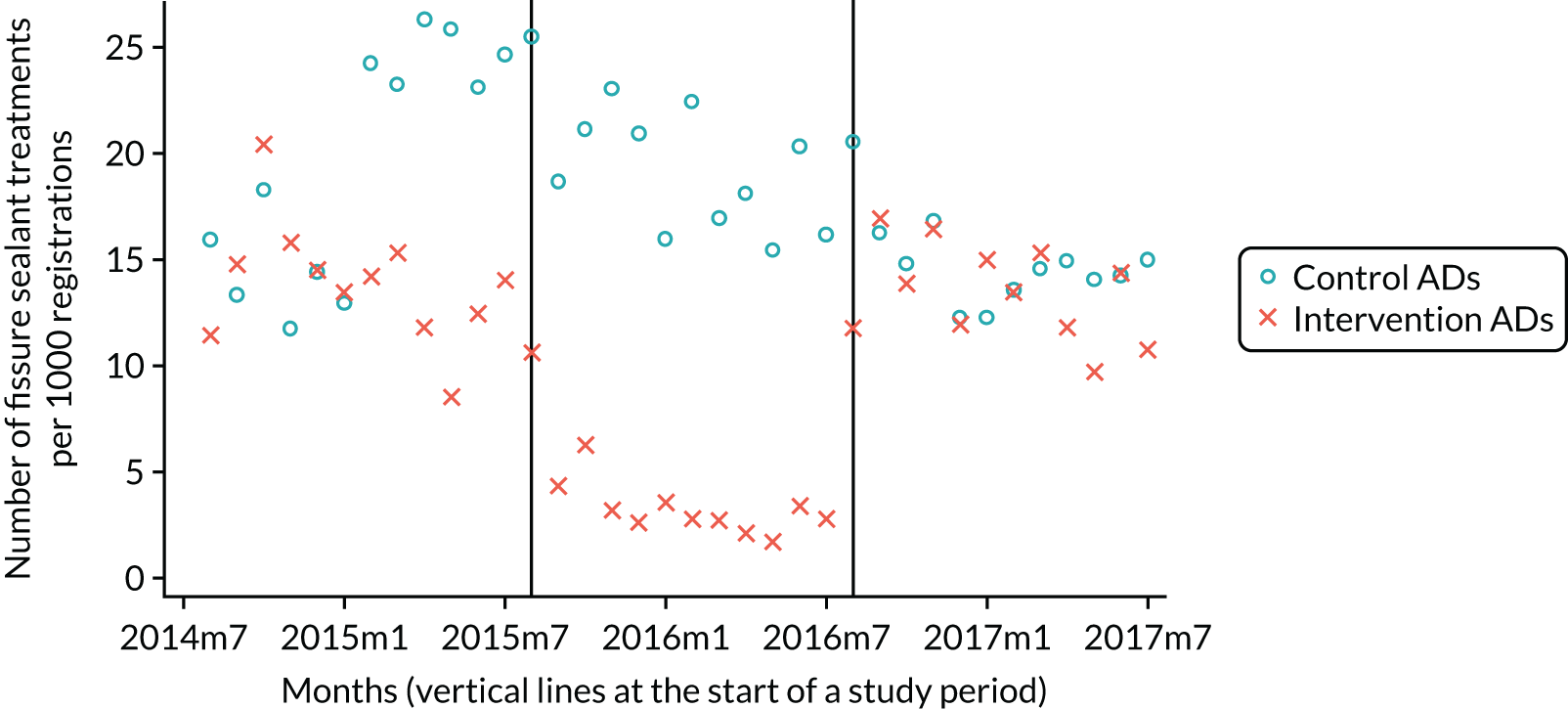

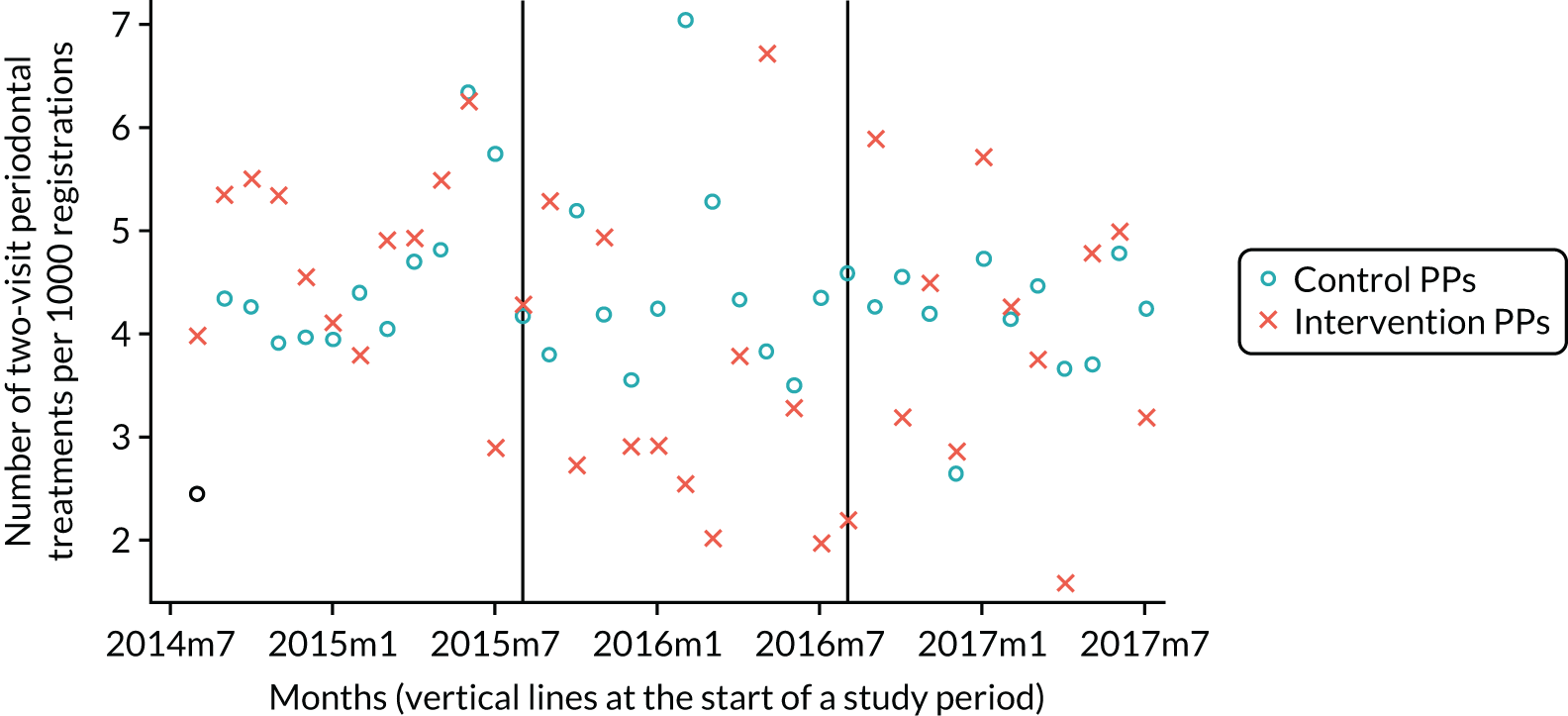

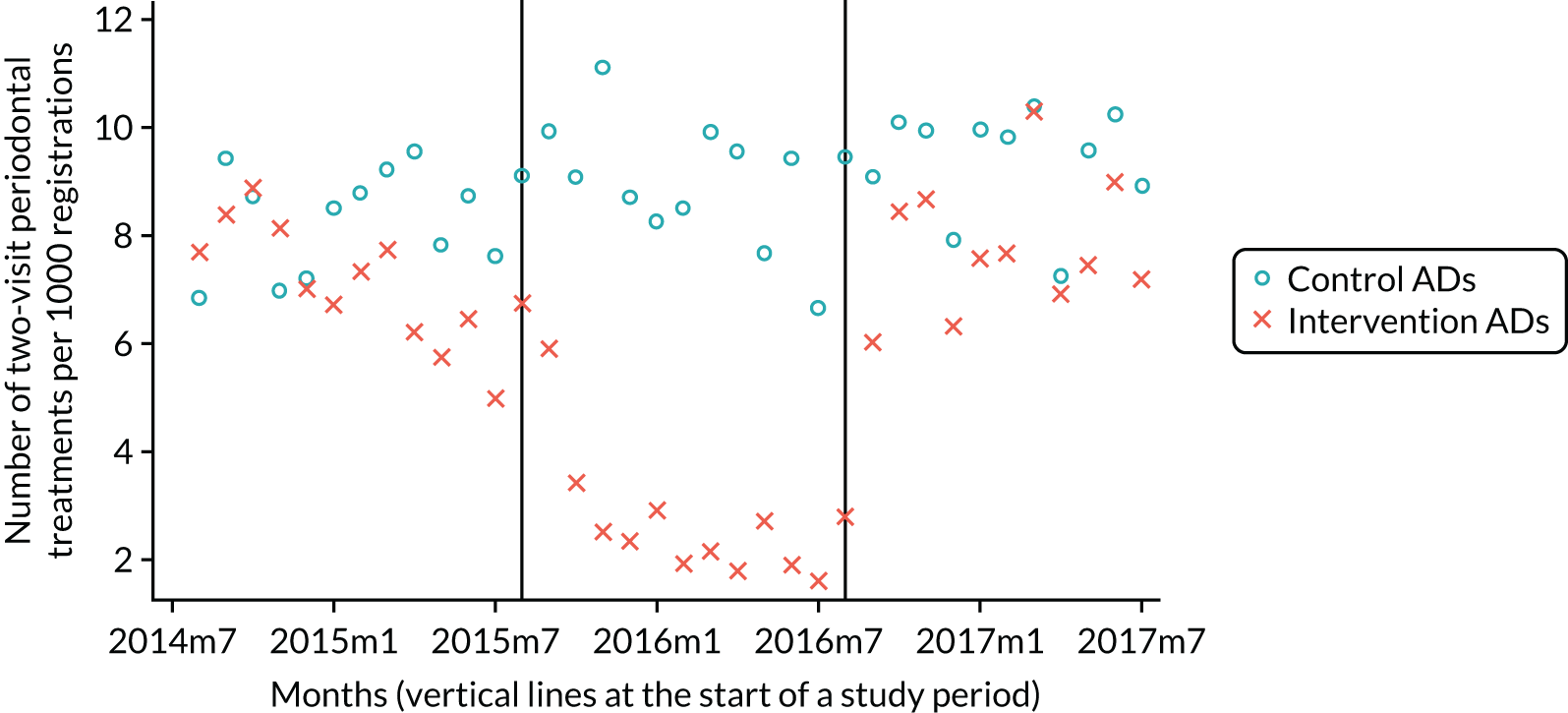

The research was undertaken across three workstreams, using a mixed-methods approach. The first workstream used a DiD design to quantitatively measure the change in service mix, productivity, GDP time spent delivering patient care, changes in the cost of care and changes in co-payment income. The DiD compared the change in outcomes before and after the change in contract model (using matched controls). Control practices were matched according to practice size, rurality and deprivation. For each outcome, an appropriate rate was determined (e.g. number of fillings per 1000 patients seen) and represented on a graph to demonstrate changes to activity levels over time (before and during the pilot). This approach had been adopted before. 6 The DiD analyses were supplemented with additional statistical analyses [interrupted time series (ITS)] on selected variables.

The second workstream used serial cross-sectional surveys of patients in pilot and matched control groups to collect data at each of the three distinct phases (baseline, capitation, reversion) of the programme. This recorded patient-rated and patient-reported measures of oral health status, oral health knowledge, attitudes and behaviour and the quality of care provided.

In the final workstream, qualitative interviews were undertaken with practices’ principals, practice associates, patients and policy-makers in Northern Ireland. The overarching philosophy underpinning the approach was informed by realist evaluation. 8 This approaches policies as ‘theories incarnate’ and seeks to understand ‘what works for whom and under what circumstances’. In other words, whenever a policy is implemented, it is testing a theory about change. Empirical approaches to evaluation seek to establish generative causation (i.e. ‘what’ happens). Realist evaluation also looks at ‘how’ and ‘why’ things happen (i.e. establish successive causation). It starts by making explicit the theories about how the policy might work, identifying the mechanisms through which specific outcomes are hypothesised to occur. This approach was informed by the DiD analyses to understand how and why changes occurred to provide generalisable findings. 9

Structure of the report

This report is arranged in chapters as follows. Chapter 2 provides a review of the literature and describes the historical context of NHS dentistry and the evolution of policy on dental services in Northern Ireland and the other three home countries. Chapter 3 describes the methods and results of the DiD and the additional statistical analyses. Chapter 4 describes the qualitative study of the Northern Ireland pilot and Chapter 5 details the findings from the serial cross-sectional surveys of patients. Chapter 6 integrates all the findings from the empirical work and provides an overview and assessment of the impact of changing provider remuneration on the activity and quality of care provided by NHS GDPs in Northern Ireland. Chapter 7 summarises our conclusions, identifies the limitations of the programme and discusses implications for policy, clinical practice and further research.

Appendices 1–6 provide detailed information on the methods for the matching of control practices, the DiD analyses, the patient questionnaire used in the serial cross-sectional surveys and the analysis for each question in the questionnaire. Appendix 5 also details the data envelopment analysis (DEA) and stochastic frontier modelling (SFM) technical efficiency methods and analyses we completed as per protocol. Appendix 1 also includes a reproduction of the HS45 form, which is used by GDPs in Northern Ireland to claim for the treatments provided during each course of treatment. The contents of these forms returned by GDPs and collated and checked by the Business Services Organisation (BSO) of NIHSCB provided the raw data for the DiD analyses.

Chapter 2 Literature review and policy analysis

Introduction

This chapter provides the context for the programme of research undertaken. It describes the organisation of NHS dentistry in Northern Ireland and the other home countries and the financial incentives present in NHS contracting systems.

Overview of remuneration in dentistry

The payment systems for GDPs working in a primary care environment (‘high-street’ dentistry) are varied, but fall into two broad categories:

-

a retrospective payment system that pays GDPs for every item of clinical activity that they undertake (known as FFS)

-

a prospective payment system that pays GDPs for the number of patients for whom they are providing care (known as per capita or capitation).

Fee for service has been the predominant model for adult service provision across all four nations of the UK, whereas per-capita payments is the predominant model for the provision of NHS care for children in Northern Ireland and Scotland.

Across the UK, non-exempt adult patients pay a substantive element of their cost of treatment (approaching 80%) and this is known as patient charge revenue (PCR). Although the remuneration systems across the UK differ, the process for PCR payments is relatively similar, with the GDP collecting the PCR directly from the patient. The remaining monies (approximately 20% for a completed course of treatment) are paid by the government. For exempt patients (as a result of low income, pregnancy, being nursing mothers or children/young adults up to 18 years of age), the cost of treatment is paid entirely by the government. In Northern Ireland, approaching half of all patients make a financial contribution to their NHS dental treatment.

The GDPs in the UK operate their practices as small businesses and differ from many other health-care professionals in that they take all of the financial risk for service provision. 6,10 They also receive little or no support for initial start-up costs or for the development of their capital infrastructure. As Harris et al. 11 explained, ‘dental practice premises and facilities are owned by the principal(s)/body corporate as capital assets’. The costs involved are then incorporated into the sum of practice overheads and reimbursed through the dental remuneration scheme. The financial risk concerned with falling levels of property value rests solely with the GDP. As a result, GDPs are particularly sensitive to financial incentives within NHS dental contracts. 1,5–7 Changes in the clinical activity of GDPs in the UK following the introduction of new methods of payment in the NHS have been documented. 5,6,12 In addition, unlike primary care physicians, whose predominant function is the management of symptomatic patients or those with chronic conditions, the majority of service delivery in the NHS, in terms of volume of activity, is based on the ‘check-up’ of largely asymptomatic patients. Again, as highlighted by Harris et al. ,11 ‘the independent contractor status of GDPs and GMPs [General Medical Practitioners] has meant both types of practitioners have developed commercial and entrepreneurial as well as professional identities’.

Financial incentives in NHS general dental services

NHS dental contract reform seeks to change the way GDPs are paid in order to influence their behaviour in such a way that it aligns with policy goals. NHS GDPs are part of an altruistic profession, yet much of their activity in primary care is driven by the ‘profit principle’ to maintain the viability of their practices. This is understandable, as dental practices operate as small businesses; with a mixed income of NHS and privately remunerated activity, and unlike general medical practitioners, the majority of a GDP’s NHS income comes from delivering services. As a result, NHS GDPs are sensitive to incentives within the remuneration system. 1,5–7 There are two main systems of remuneration, namely prospective capitation-based systems and retrospective payments for completed activity, or FFS systems. Capitation payments tend to secure effectiveness at the cost of patient selection (GDPs preferentially registering low-need patients and refusing access or even deregistering high-need patients) and undertreatment. 10,13,14 The inherent incentives can be described as ‘service broadening’, providing minimal treatment to as many patients as possible. This contrasts with ‘service deepening’, where inherent incentives can lead to profit maximisation and the delivery of large amounts of treatment to a limited number of patients. The FFS systems incentivise the provision of treatment quantity but often suffer from cost containment problems, supplier-induced demand and the possibility of overtreatment. 10,13,15 There is also a salaried approach to remuneration, which removes the link between income and the level and type of services delivered or the number of patients served. However, this often leads to high costs in patient care. 10

Oral health follows a social gradient, with the poorest experiencing the highest burden of dental disease. 16 However, access to services providing prevention and treatment of oral diseases is often determined by an individual’s ability to pay for services, unless they can be classified as exempt from patient charges. 17 As a result, access to services tends to be greatest in those groups with lowest treatment needs. 18,19 Public funding of health and social care should provide a means of overcoming the divergence between the ability to pay for care and need for care. It offers the opportunity for improving both efficiency (increasing health gains produced from available health-care resources) and equity (removing barriers to access services or the type of care provided that is associated with individuals’ income or wealth). However, reforming public sector-funded contracts of independent contractors to incentivise behaviour to realise the aims of policy-makers, such as increasing efficiency and addressing inequity, is fraught with difficulty. In an evaluation of the 2006 contract reform in England, Whittaker and Birch12 found that the dental reforms had a negative impact on access, with a fall in NHS dental service use among populations with previously good access to NHS care and a move to private practice. This study highlighted the perils of reforming public health-care systems producing unintended consequences, in this case in contrast to a key policy requirement of expanding NHS access; the 2006 dental reforms reduced NHS use among those who previously had good access to care.

Co-payments received via PCR have been a fundamental component of the NHS dental contract since the 1950s, making up a significant proportion of the dental budget. Patient charges are made in exchange for the provision of specific items of treatment. This means of collecting payments from patients, to supplement health-care budgets paid for from general taxation, is a readily understood transaction for patients and the administrative processes to collect PCR are well established in NHS dental practices. Changing the means of collecting PCR, such as monthly direct debits to secure access (as used by insurance schemes and third-party payers) or paying for prevention advice and services (which are perhaps not as tangible as receiving a filling), would be less readily understood by patients and would require significant changes to administrative systems and processes. Any changes to a remuneration system runs the risk of producing a fall in PCR, leading to a gap in the NHS dental budget that the state would have to fill. The level of patient charges can also affect patient behaviour. In the USA, Manning et al. 20 found that dental service use increased as co-payments decreased in a randomised trial of alternative insurance plans, and Parkin and Yule21 found a negative relationship between price and dental care use in Scotland. Little is known about the impact of remuneration system on the efficiency of NHS practices and how they might influence outputs such as access.

Organisation of NHS general dental services until 1990

Dental services were included in the NHS from its inception in 1948. The National Health Service Act 194622 had three key principles: (1) no one would ever have to fear not getting care they needed because they could not afford it, (2) it would be free at the point of delivery and (3) it would be based on clinical need. As a result, NHS dental services across the UK were provided free of charge to the entire population. GDPs were considered to be independent contractors under the National Health Service (General Dental Services Contracts) Regulations 200523 and so could establish their practice anywhere in the UK. GDPs’ general dental services (GDS) remuneration was paid on a FFS basis (i.e. the volume and type of work undertaken) and even though they were self-employed, GDPs were eligible to join the NHS Superannuation Scheme. By 1950, the government had become concerned about the affordability of the new service, given the volume of work being undertaken by NHS GDPs (mostly extractions and fillings) as a consequence of high unmet need and the availability of a new, free service. This resulted in the introduction of the Patient Charge Regulations (1952), which required patients to contribute to the bulk of the cost of treatment according to a Statement of Dental Remuneration (a list of available NHS treatments). 24

Other than minor changes to the Statement of Dental Remuneration, the shape of NHS GDS provision remained relatively static until the introduction of a new contract across the whole of the UK in 1990. For the first time, the NHS dental contract contained an element of prospective payment and patients were required to register with a GDP. The remuneration arrangements for adults and children were split, with adults still treated under FFS arrangements (plus relatively small additional continuing care payments), while the care of children was remunerated on a wholly capitation basis. As a result, approximately 20% of the income for NHS GDPs was based on the number of dental patients registered (on a per-capita basis), rather than simply being based on the volume of activity on a FFS basis. The policy intention of the 1990 contract was to encourage registration and promote prevention and continuity of care, moving service provision away from treating disease to maintaining oral health. 25 However, higher than expected expenditure in the following year led to the government making substantive cuts to NHS dental fees in 1991. The dental profession felt that they were unfairly penalised by this ‘clawback’ and this led many GDPs to feel unhappy with the new NHS system of payment. 26 This triggered a progressive shift towards the provision of privately funded dentistry within the profession, resulting in a growing reduction in the availability of NHS services.

Policy development post 1990

After 1990, influenced by the devolution of NHS health-care policy, the provision of GDS started to become more diverse across the home countries of the UK, with different policy objectives and contracts emerging. The following sections highlight these changes and provide a useful backdrop to the study.

The evolution of a new NHS dental contract in England

By the mid-1990s, difficulties in accessing dental services for NHS patients in England were becoming a political issue and it was increasingly recognised that reform of the NHS contract was necessary. As highlighted by the Bloomfield Report,26 the ‘system of remuneration for GDPs seems to have an inherent leaning towards instability which threatens to undermine the commitment of dental practitioners to the NHS’. In 1997, the NHS (Primary Care) Act enabled the voluntary establishment of personal dental services (PDS) pilot schemes to explore alternative ways of delivering NHS dental services. 27 A key feature of these new contracts was how they were tied to local issues around the need for and access to care through contracting arrangements with NHS primary care trusts (PCTs) in England. For NHS GDPs, the new PDS contracts offered greater flexibility for the provision of services and there was less emphasis on the volume of activity provided. Instead, NHS GDPs were paid on a per-capita basis and rewarded for improving access to care and maintaining oral health for those patients who were already registered. The net effect of paying the PDS schemes was a dramatic reduction in NHS service activity, a fall in the provision of complex treatments and a loss of PCR as a consequence of the fall in activity. 28 The latter development was particularly worrying for the government as patient charges made up a substantial proportion of the budget for NHS dentistry. However, many viewed the PDS pilots as a success, given the focus on addressing the needs of the local population. 28,29

At the turn of the new millennium, ‘Modernising NHS Dentistry’ was introduced in England. 30 Improving access was considered to be the most important policy objective for the government and the new proposals gave PCTs powerful new commissioning tools to improve access to NHS dentistry, to increase the provision of preventative services and to monitor the performance of GDPs. This was further emphasised in ‘Options for Change’ in 2002. 29 However, a tension remained for the government: how could they concomitantly improve access to care and increase the provision of prevention while maintaining PCR, which was reliant on ensuring that activity levels did not fall?

In 2006, a new NHS dental contract was introduced in England and Wales, organised around a local commissioning model. 31 This contract paid GDPs according to activity categorised into three broad bands, rather than the 400 individual treatment items in the Statement of Dental Remuneration, and a new contract currency, units of dental activity (UDAs), was introduced to set activity targets and pay GDPs according to the activity they provided. A band 1 course of treatment attracted 1 UDA and included an examination, radiographs and a simple scale and polish. Band 2 courses of treatment attracted 3 UDAs and included restorations, extractions and root canal treatments, whereas more complex crowns, bridges and dentures attracted 12 UDAs as a band 3 course of treatment. Patient charges were also simplified so that there were only three levels of payment tied to each band of treatment.

For the first time, contracts were raised with practices rather than with individual GDPs. Contracts were held by practice principals (PPs) (equity owing), now referred to in the NHS as providers, and non-equity-holding associate dentists (ADs) were labelled performers. Practice owners raised internal contracts with each of their associates based on a price per UDA delivered. To reflect variation in earnings and activity among NHS practices, the value of a UDA was calculated for each practice individually based on the practice earnings during a reference period, although, for most, this meant that 1 UDA was worth between £20 and £25. Annual activity targets were also set in the form of UDAs required per year, based on historical activity produced during the reference period. One feature of the 2006 NHS contract was that GDPs would receive 3 UDAs for a band 2 course of treatment (i.e. paid the same) if they provided one restoration in a single visit or multiple restorations over a number of visits. In a similar manner, NHS GDPs were also allocated 12 UDAs for one band 3 course of treatment irrespective of whether they provided one crown or multiple crowns within one course of treatment.

A key feature of the 2006 contract was cost containment [i.e. GDPs’ NHS annual activity and revenue were capped at an agreed number of UDAs per year for an agreed price, known as an annual contract value (ACV)]. The NHS GDPs were then paid one-twelfth of their ACV on a monthly basis. As a result, NHS GDPs’ outputs under the new contract in England were constrained and they were penalised if they underperformed (< 96% of their ACV) or overperformed (> 102% of their ACV). Patient registration in the 2006 contract also ceased to exist, along with the contractual responsibility for NHS GDPs to provide continuing care and emergency care for their patients. Instead, this latter responsibility was devolved to PCTs along with the planning and securing of NHS dental services for their locality.

The effect of the 2006 NHS contract change in England was investigated by an earlier National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research programme funded study (08/1618/158). Large and abrupt changes in the provision of a number of treatments coincided with the introduction of the 2006 contract. 6 The number of complex treatments provided (root canal treatments, crowns and bridges) fell dramatically whereas the number of extractions rose just as dramatically. This appeared to reflect an increase in those activities that were easier and less costly to perform at the expense of those treatments that were more time intensive or that incurred laboratory costs for making crowns and bridges. The authors concluded that ‘the change in treatment patterns suggests that significant numbers of GDPs [were] attempting to hit their UDA contract targets in the most efficient way possible, i.e. shifting towards treatments where rewards are high relative to costs, as opposed to selecting on the basis of clinical factors’. 6 In addition, McDonald et al. 5 remarked that ‘it is the interests of GDPs, as opposed to patients, which [were] being prioritized’.

In England, the 2006 contract was unpopular with GDPs from the start; a major underlying reason was a loss of autonomy and their accountability to local commissioners. Only 2 years after its introduction, the contract was criticised by the House of Commons Health Select Committee,32 which based its criticism on the four areas that the contract had sought to improve, namely:

-

Patient experience – the contract was criticised for not helping to address the access problem (GDPs could hit their UDA activity targets largely by confining care provision to their long-standing, regularly attending patients) and the simplified patient charging system was also criticised as being insensitive.

-

Clinical quality – the contract did not incentivise preventative care and there were concerns about a fall in the volume of complex treatments such as root canal treatments, crowns and bridges.

-

Local commissioning – there was concern that many PCTs lacked the capacity and expertise to effectively commission dental services.

-

Improving GDPs’ working lives – the UDA activity targets were particularly unpopular with GDPs.

As a result of this criticism, an independent review (the Steele report) was published in 2009. 33 The report emphasised the need for prevention to produce better health outcomes and a standardised approach to patient assessment and disease risk categorisation leading to evidence-based care pathways. To support this approach, a move to a blended contract was envisaged based on capitation, with incentives to provide appropriate levels of activity and to improve quality.

Following the Steele report, in December 2010, the Department of Health and Social Care published NHS Dental Contract: Proposals for Pilots. 34 Three types of pilot were identified to test different remuneration models:

-

Practices were paid on a simple 100% capitation basis.

-

Practices were remunerated based on the number of weighted capitated patients they had; the capitation weighting was calculated according to age, gender and the deprivation status.

-

As per type 2, but with a separately identified budget for higher-cost treatments.

Elements of a reformed contract were piloted in 70 NHS dental practices in England, recruited between July and September 2011, and the findings of the pilots were published in 2014. 34 This report was a service evaluation and a control population was not identified. The evaluation of the oral health assessment, which formed the cornerstone of the new approach to care, was limited to professional and social acceptability. The pilots sought to introduce a new care pathway based on managing disease risk [using a high-, medium- and low-risk scale, the so-called RAG (red, amber, green) rating of risk] through the provision of preventative care. The ability of the associated risk algorithms to correctly classify patients and predict future disease has not been tested. With the methodological limitations, the findings were mainly descriptive in nature. The report acknowledged its methodological limitations, saying that the findings were:

. . . difficult to demonstrate with absolute confidence away from a clinical trial (which the pilots explicitly are not) and we have little or no comparable data from GDS outside the pilot.

Initially, quality was to be measured and incentivised by including quality payments as a small percentage (≈10%) of the practices’ remuneration package. The newly derived, but unvalidated, Dental Quality Outcomes Framework (DQOF) was intended to be used to measure quality and form a ‘pay-for-performance’ element of the remuneration system. However, in the first 2 years of piloting, the DQOF remuneration adjustments were not applied:

. . . due to issues with the robustness of the clinical data on which the DQOF clinical indicators are based.

As there were no control practices, the evaluation was restricted to a simple before-and-after design using a mixed-methods approach. There were significant problems encountered in collecting clinical data from information technology (IT) systems to support the standardised clinical assessment used in the pilot. The evaluation was also hampered by the fact that the collection of data on individual items of treatment ceased with the 2006 contract. Data entry for the new IT systems in the pilot was slow and onerous for practices, resulting in missing data and concerns about data quality. Dental charting data for many patients were incomplete or absent, making it impossible to apply the DQOF financial adjustments. Quantitative data presented in the report were confined to assessing the impact on access and patient experience. 34 Across all of the practices, there was a fall in the total number of unique patients seen for the duration of the pilots, albeit with significant variation across the practices. There was little association between a patient’s recall interval and the assessment of their risk, the ‘6-month check-up’ seemed to be well established and moving to a recall interval dictated by the risk assessment proved difficult. The pilots were generally popular with GDPs and patient satisfaction rates were higher (95.8%) than the national mean for all NHS dental practices of 92.2%, but these universally high scores demonstrate the unresponsive nature of this metric. In addition, baseline satisfaction rates for the pilot practices were not collected.

In 2015, the Department of Health and Social Care introduced a ‘prototype’ remuneration model but without a formally described, a priori evaluation plan. 35 The prototype process was introduced with the stated intention to test whole versions of a possible new contract rather than key elements required to inform the design of a new system (as was the intention in the pilots). Two contract models were tested, both aiming to continue to test the patient pathway based on the standardised assessment and risk stratification model. The UDAs remained as the contract currency to measure and remunerate activity delivery. Two types of prototype were implemented:

-

blend A prototypes included –

-

capitation (band 1)

-

activity (bands 2 and 3).

-

-

blend B prototypes included –

-

capitation (bands 1 and 2)

-

activity (band 3).

-

The intention was for both prototype models to also include remuneration adjustments made according to performance against the DQOF. 36 The prototypes involved greater financial risk for practices than the pilots (in which practices were guaranteed an income matched to a historical reference period); all prototypes were to be able to overdeliver by 2%, but would also have 10% of their contract value at risk if there was underdelivery of patient numbers and UDA activity. The protocol agreement scheme commenced on 1 December 2017. The Department of Health and Social Care and NHS England aimed to recruit a further 20 practices with an anticipated start date of October 2018.

The Department of Health and Social Care published an evaluation of the first year of prototyping in May 2018. 37 The prototype contract models started in spring 2016 and in the evaluation report the prototype practices were described as wave 3 of a larger evaluation programme with pilot practices described as wave 1 (recruited in 2011) and wave 2 (recruited in 2013). The evaluation included practices from all three waves but was problematic in that 40% of the original pilot practices did not continue into the prototype phase. Practices were split into two groups (blends A and B). Although it was originally intended that 10% of the contract value would be based on DQOF performance, it was agreed that for 2016/17 there would be no financial incentives used to try to improve quality. A post hoc matched set of practices working under the 2006 remuneration system was identified to enable comparisons between the prototypes with behaviour under the 2006 system. No methodological details were provided about how the matching was undertaken, nor were any analyses provided that compared the prototype practices with controls. Comparisons were restricted by the limited data available from comparator practices (primarily UDA claims and payments).

Data for the evaluation were provided by the NHS Business Services Authority using the same activity data for the comparator 2006 contract practices. Pilot/prototype practices were also asked to complete a monthly survey; these data were supplemented by two specific surveys undertaken in December 2016–January 2017 and in July–August 2017 to support the evaluation. The report restated the objective of the English Dental Contract Reform Programme:

. . . to maintain or improve access, quality and appropriateness of care and improve oral health, within the current cost envelope, in a way that is financially sustainable for dental practices, patients and commissioners.

However, a hierarchy for these (often competing) requirements was not identified.

The evaluation concluded:

. . . progress has been made in the first year of prototyping on the key issues of improving oral health, providing appropriate care and quality, and maintaining or increasing access to merit continuation of the programme.

The indicators to measure oral health improvement included the number of teeth with dental decay (children and adults) and the basic periodontal examination scores and the number of sextant bleeding sites in adults. Trends in GDP-assessed caries and periodontal risk were also reported but these oral health indicators were reported for the pilot/prototype practices alone and were not compared with the 2006 contract practices.

Appropriateness was assessed by adherence to the care pathway advocated in the Steele review,33 more specifically by the proportions of adults and children in the pilot/prototype practices who had received an oral health assessment. In all prototypes, 87% of adults and 86% of children received an oral health assessment and 99% of prototypes met the DQOF standard for recording an up-to-date medical history. Appropriateness was also assessed by process indicators identifying adherence to the prevention guidelines Delivering Better Oral Health: An Evidence-based Toolkit for Prevention. 38 Prototypes were compared with 2006 contract practices using FP17 (the form used by NHS GDPs to claim for activity provided) data reporting practice-reported adherence to national guidance. 38 For adults, 62% of prototype practices reported delivery of prevention according to the guidelines compared with 56% in 2006 contract practices; for children, these percentages are 60% and 58%, respectively. However, in prototype practices, only 28% of courses of treatment in children reported that fluoride varnish was applied compared with 41% in the 2006 contract practices. This latter finding gave cause for concern and the report recommended that a patient survey should be carried out to determine the impact of prevention advice on patients’ oral health behaviour. It is difficult to see how a survey would add much to the evidence base for the relationship between providing prevention advice and eliciting a sustained change in behaviour. The issue of recall attendance intervals was also considered under appropriateness, and the report recommend that:

. . . a detailed piece of work is undertaken to understand the reasons and rationale from patient and professional perspectives for the approach to implementing the longest recall periods recommended by NICE.

However, there was no mention of the soon-to-be published National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)-funded INTERVAL trial (ISRCTN95933794), the results of which are likely to influence the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance on recall intervals. 39

Assessment of the impact of quality in dentistry is limited by the underdeveloped conceptual understanding of quality in dentistry and how to measure it. 40,41 The report identified high percentages of prototype practices meeting all of the DQOF outcome indicator thresholds. The evaluation reported that 97% of patients treated in the prototype system were ‘quite’ or ‘very satisfied’ with NHS dentistry, compared with 96% of patients treated in the 2006 contract system. These very high satisfaction levels may not mean that all NHS services provide a highly satisfactory service; it may reflect that this indicator lacks responsiveness or that patients do not have sufficient knowledge and information to make an informed judgement of the quality of care provided. The report recommended that the development of the DQOF and its application should be continued but without commenting on how research could contribute to this goal.

In the reporting the impact on access and accessibility, these concepts were not defined. Access was measured by the practice capitated patient lists (number of patients attending in a 24-month period), which increased in waves 1 and 2 practices (initial pilot practices), but remained below the expected capitated numbers set in the contracts. During the first year of prototyping in wave 1 practices, attendance in a 24-month period increased from 85% to 88% of the baseline and for wave 2 practices it increased from 89% to 95% of the baseline. During the same period in matched 2006 contracts, access increased from 101% to 103% for wave 1 and stayed constant at 103% for wave 2. The fall in access in the prototypes was attributed to the concentration on embedding and delivering the clinical pathway in the early stages of piloting. Accessibility for patients was measured through a standard patient survey question and 90% of patients who responded reported that ‘the time it took to get an appointment was as soon as necessary’ compared with 91% in the 2006 contract practices. However, this is a limited view of accessibility, applying to only current users of a service and not to individuals living within a practice catchment area who may wish to access the service. This points to the need for clear and agreed definitions of access and accessibility, which are necessary to develop appropriate and valid measures of these important concepts for policy. Value for money was not assessed and the report acknowledged the difficulty of measuring this complex concept and stated that at this early stage there are insufficient ‘steady state’ data to undertake meaningful analysis. There was no elaboration on the measures or possible study designs that could be employed to undertake a rigorous health economic evaluation of different remuneration systems. A significant omission in the report was a lack of analysis of the impact of the pilots on PCR, especially as the objectives of the English Dental Contract Reform Programme include maintaining or improving service and health within the current cost envelope:

. . . in a way that is financially sustainable for dental practices, patients and commissioners.

Sustainability of prototype practices was compared with 2006 system practices using percentage contract achievement and, using this blunt measure, practices in all three waves performed to a similar level as the control 2006 system practices. However, a much broader and deeper means of assessing practice sustainability is required, given the multiple levers practices have at their disposal to improve their productivity and profitability, such as adjusting NHS/private mix and employment of skill mix. 4

The report made two further conclusions. The first was that the clinical model advocated by Steele33 is well accepted by the profession (standardised assessment of risk signposting the following of defined care pathways) but the business model requires further development to improve the sustainability for practices. The second conclusion was that additional practices should be recruited to the programme and randomly allocated to the blends to improve the robustness of evaluation. However, there was no suggestion that evaluation could be commissioned from an external party or that academic expertise could be harnessed to improve ‘the robustness of evaluation’ (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). 37

It has been 10 years since the publication of the Steele report33 and a new English NHS dental contract is still to be implemented. This cautious, incremental approach seems to be reflected across all four of the home countries, which is not surprising given the complexity of the issues involved and the clinical, financial and political risk involved.

The evolution of a new NHS dental contract in Northern Ireland

The development of a new NHS contract in Northern Ireland can be plotted from a review of dental policy over the last 10 years traced through the content of a number of key documents.

In 2004, the DHSSPS produced a ‘Public Attitudes Survey on Oral Health’, which was undertaken to inform the development of an oral health strategy and primary dental care strategy for Northern Ireland (Donncha O’Carolan, NIHSCB, personal communication, 2019). Respondents were asked for their views on dental services, which could potentially form part of the Department’s planned Oral Health Strategy for Northern Ireland. 42 Respondents identified access to basic treatment, better access to emergency treatment and treatment for those with learning disabilities to be the most important aspects of the service that they wanted to see protected and enhanced.

The consultation document An Oral Health Strategy for Northern Ireland was subsequently launched in September 2004 and the final report, The Oral Health Strategy for Northern Ireland, was published in June 2007. 42 Although the main focus of the strategy was public health and community-based preventative interventions, it contained a section on dental services. The strategy reiterated one of the main themes of the Northern Ireland Primary Dental Care Strategy, launched in November 2006, which proposed a shift in the focus of a new GDS contract away from treatment of disease towards prevention. 43 The Oral Health Strategy stressed the need to maintain and improve access to dental services, especially for disadvantaged groups and for individuals with special care needs and implicitly acknowledged the policy aim of modernising dental services but warned about the need to maintain high levels of access and satisfaction in any reform of dental services.

The DHSSPS’s Primary Dental Care Strategy is a key document to help understand policy-makers’ thinking on the need for a new dental contract. 43 In the foreword, the Minister for Health said:

. . . there is widespread agreement that the way that dental services are currently delivered needs to change in order to better meet the needs of patients and GDPs and other oral healthcare professionals.

This sentiment was expanded on in the recommendations section of the strategy, in particular recommendation 10 (paragraph 6.19) stated:

. . . a new Northern Ireland wide GDS primary dental care contract framework will be developed and will provide the basis to commission services to meet local need.

Recommendation 17 (paragraph 8.4) stated that:

. . . any new arrangements should be piloted before rolling out across Northern Ireland.

Many of the recommendations echoed developments in England (see The evolution of a new NHS dental contract in England), which were implemented in the PDS pilots of 2004–6, prior to the introduction of the 2006 English contract. Some of the ideas developed in the early English PDS pilots were translated into the NHS dental contract implemented in England in 2006, in particular an emphasis on local commissioning to make services more responsive to population health needs, a need and desire to secure access to dental services for the whole population, a shift in emphasis from repairing the effects of dental disease to disease prevention and a greater role for skill mix. It was telling that recommendation 16 (paragraph 7.3) of the DHSSPS’s Primary Dental Care Strategy stated:

. . . the new patient charging arrangements in England should be monitored with a view to introducing a similar system in Northern Ireland.

This points to a history of health policy in Northern Ireland tracking developments in England and also an implicit acknowledgement that one of the main difficulties faced by policy-makers designing a new dental contract involves protecting that part of the budget derived from PCR. The 2006 English dental contract gave policy-makers certainty on annual spend for the service while buying a minimum level of access to NHS services (but not necessarily guaranteeing accessibility of NHS dental services particularly for those with greatest need).

Following publication of the DHSSPS’s Primary Dental Care Strategy, the evolution of policy thinking can be traced from the content of the DHSSPS’s Dental Branch Annual Reports from 2006/7 to 2010/11 (no further reports were produced after 2011). 44–48 The 2006/7 report contained a ministerial announcement for a new dental contract and commented on how new contractual arrangements in Northern Ireland would differ significantly from the 2006 contract introduced in England and Wales. 44 More specifically, at that time there was a view that providing a defined range of treatments and rewarding quality would be desirable in a new Northern Ireland contract and that the English UDAs contract currency was not favoured by the profession in Northern Ireland. The report stated:

. . . a commitment to piloting the new contract before rolling out across the region in order that any problems may be addressed and allow GDPs to be familiar with the operational aspects of the contract.

The 2007/8 report commented on a growing concern about access to dental services in Northern Ireland. 45 In response to these concerns, a package of financial support for health service GDPs to increase the registration of NHS patients and a tender for additional dental services were announced in the Northern Ireland Assembly. The report also references a joint communication issued from the DHSSPS and the British Dental Association in September 2007. The key points highlighted in the statement were:

-

The DHSSPS did not intend to introduce the (2006) English contract into Northern Ireland. The DHSSPS was aware of the problems experienced with the new contract in England and intended to learn from these.

-

The contract was to be a block contract but would not be measured in UDAs; alternative remuneration arrangements were to be made.

-

There was to be a strong emphasis on prevention.

-

The new arrangements were to be piloted before rolling out across Northern Ireland.

The report also referenced a commissioned report produced by Professor O’Neill from Queen’s University Belfast to advise on a remuneration model for a new contract. Professor O’Neill’s report advised a blended system of remuneration comprising payment through a block component along with a limited FFS component.

The 2008/9 Dental Branch Annual Report identified access to dental services as ‘very problematic’ and stated that the Minister for Health was prioritising resolution of this problem through ‘a successful outcome to the dental tender’ (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). 46 In May 2009, the Minister for Health awarded a contract to Oasis Dental Care [Oasis Dental Care (Central) Limited, Bupa Dental Care, Bristol, UK], which resulted in the opening of 14 new NHS dental practices, providing care for 57,000 patients, across Northern Ireland operating under pilot PDS contracts (analogous to the pre-2006, wholly capitation-based, English PDS pilots).

Although the access problem dominated policy, work on a new dental contract continued and more details were given about the anticipated remuneration system. A blended payment system was planned, consisting of regular care (capitation) payments along with supplementary item-of-service payments for a clearly defined range of essential services. The Northern Ireland Dental Branch Annual Report of 2008/9 acknowledged publication of the Steele review and noted that the recommendations were consistent with the framework of the proposed Northern Ireland contract. 45

The Northern Ireland Dental Branch Annual Report of 2009/10 provided an update on the initiative to tender for PDS contracts to improve access supported by the £17M injection of funding. 47 More information was again provided on the planned new contract, in particular details about a proposed weighted capitation formula for the proposed capitation element of the blended contract. The weighted capitation formula used to calculate the capitation fee was based on patient age, patient gender, patient socioeconomic position (based on small area measure of deprivation derived from the patient’s postcode) and practice list turnover (as measured by new registrations). It was also anticipated that block payments would be made to reward quality using indicators such as postgraduate qualifications, charter marks, outputs from practice inspections and clinical audit activities.

An update on the proposed pilots of the new contract was provided in the final Dental Branch Annual Report in 2010/11. 48 The NIHSCB began a consultation on the piloting of a new dental contract on 11 October 2010. The consultation ended on 31 January 2011 and was considered by the board of the NIHSCB on 31 March 2011, which supported the outcome of the consultation process, namely that pilot PDS legislation should be used to pilot the elements of the new dental contract.

In 2011, the Patient and Client Council (PCC) published Talking Teeth: Patient Views of General Dental Services in Northern Ireland. 49 The PCC commissioned the report to explore the experiences of patients as they access GDS services and the care that they receive in the NHS. The Chief Dental Officer provided a foreword to the report, which referenced the planned reforms of dental services including proposals to introduce a new dental contract. The report stressed that its findings should be considered within the context of that time and highlighted three key issues:

-

a £17M investment to ease problems of access

-

a planned new general dental contract

-

that economic recession had the potential to change (reduce) public demand for private dental care thereby freeing up capacity in the general dental system for NHS work and potentially helping to alleviate concerns about NHS dental access.

The final point was an interesting comment, as the acute access problem experienced in Northern Ireland was believed to have been caused primarily by GDPs expanding their care in the private sector prior to the financial crisis of 2007/8. The PCC report concluded that patients’ level of satisfaction with dental services was high but that there was confusion about whether or not treatment is provided via an NHS contract or privately. Dental treatment was viewed as expensive and people were worried about the lack of information regarding costs. Access and inequalities in access were concerns and there was support for the suggestion that NHS funding and services should concentrate on a smaller number of basic treatments. A key recommendation was that:

. . . access to basic dental treatments should be prioritised by Health and Social Care.

In June 2016, the NIHSCB produced the report Evaluation of the Oasis Pilot Personal Dental Services (pPDS) Scheme 2010–2015 (Michael Donaldson, NIHSCB personal communication, 2019). The contract started in April 2010 for an initial 3 years then extended for two additional 1-year periods, ending on 31 March 2015. The remuneration system used for these pilots was based on a simple capitation arrangement and co-payments were collected based on the existing item-of-service schedule operated by GDS practices. Capitation payments were based on the 38 GDPs in the programme, each managing a patient list of 1500 patients, resulting in a maximum of 57,000 patients being registered with Oasis Dental Care. Each registered patient attracted an annual fee of £97.74, which resulted in the contract value still being capped at £5.4M per year. A mid-term review of the pPDS was carried out in 2012 by the NIHSCB, approved by the DHSSPS and published in 2013. The mid-term review concluded that access to NHS dentistry had rapidly and significantly improved and that the service appeared to be at least equivalent to the service provided by other (GDS) dental providers in Northern Ireland in terms of the delivery of appropriate, efficient and cost-effective services.

The final report of 2016 concluded that access was not a problem for NHS dentistry in Northern Ireland and that the quality of care provided was comparable to that provided under the GDS. Following completion of the pilot, the 14 Oasis practices moved from pPDS into the GDS. The report commented on the learning, which had been acquired from the pPDS programme to inform the development of a new contract for Northern Ireland, in particular that consideration should be given to how new patients register with dental practices in a capitation-based contract.

The report expressed concerns that it may not be possible to monitor each individual GDP across the whole of Northern Ireland in the same way as the pPDS and that consideration should be given to how monitoring can be scaled up to ensure both quality of care and the level of service provision. There were also concerns that large number of patients who registered with Oasis during the pilot scheme received no treatment. In the pPDS and the GDS, patients aged > 18 years can register with a GDP without ever being examined. The report suggested that by enforcing an examination as part of the registration process more patients might become aware of their treatment needs and receive some preventative advice.

Our research group used data from the pPDS to independently evaluate the effect the newly introduced capitation payment system had on the delivery of primary oral health care and access to services in Northern Ireland. 4,50 This independent study was published in 2017 and treated the pPDS as a natural experiment comparing the NHS treatment claim forms submitted between April 2011 and October 2014 from the 14 Oasis practices with those of a group of matched, control GDS practices, remunerated using the GDS retrospective FFS system. This study could find no evidence of patient selection (excluding high-need patients) in the Oasis practices. However, patients were less likely to visit the GDP and received less treatment when they did attend, compared with those belonging to the control GDS practices. The extent of preventative activity offered did not differ significantly between the two practice groups. The most surprising finding was that there was no difference in PCR between the capitation-remunerated pilot practices and the FFS GDS controls.

In June 2014, the NIHSCB issued a call to all existing GDS practices across Northern Ireland for expressions of interest in participating in wave 1 of the new dental contract pilots and two practices were recruited. This was followed by a similar call in February 2015 for participation in wave 2 of the pilots and a further 11 practices were recruited. The pilot contracts were practice based, not with individual GDPs. The system of remuneration used was based on a form of capitation that was time limited: wave 1 practices would operate under the pilot contract for 18 months and wave 2 practices would operate for 12 months before reverting back to the FFS contract.

In terms of remuneration, the underpinning intention was that practitioners would receive the equivalent gross income during the pilot period that they would have received under the GDS had they maintained their activity and list as per the baseline period (Michael Donaldson and Donncha O’Carolan, NIHSCB, personal communication, 2019). The level and method of payment for patients’ contributions during the pilot would remain the same as for existing GDS patients. The PCR would continue to be collected by the practices and the monthly instalment payments from the BSO to pilot practices would be adjusted to account for the patient charges collected. The risk of any shortfall in patient contributions from the GDPs’ baseline gross income would be carried by the NIHSCB.

In the lead up to the pilots, the Chief Dental Officer posted a policy paper, Current Direction of the New Primary Care (General) Dental Contract, on the DHSSPS website on 6 April 2015, which provided a summary of policy development since 2006 and an update on the thinking of the DHSSPS on the design of the pilots. 51 This paper announced a shift in policy away from the earlier proposed model using a weighted capitation formula supplemented by FFS payments for defined treatments. Instead, the DHSSPS proposed that the latest model for the new dental contract would be calculated through a global sum formula with no routine item-of-service payments. Therefore, the model would be a predominantly simple capitation arrangement with additional payments making up a small proportion of the total remuneration system. It was envisaged that these payments would be determined by developing quality indicators; however, ‘further work on the development of the relevant indicators is necessary’. 51 This change in policy direction was attributed to feedback from GDPs, and was seen as a means of securing a stable budget by avoiding fluctuating costs of FFS claims and producing less complex data returns.

The evolution of a new NHS dental contract in Wales

In Wales, there had been similar dissatisfaction with the 2006 contract, which closely mirrors the current English contract. Dissatisfaction was largely for the same reasons as in England: the 2006 contract did not overtly incentivise prevention or quality and GDPs felt that they were still on a ‘treadmill’, not dissimilar to the treadmill of a FFS system, but with a cap on earnings. In Wales, the pilots for new remuneration systems involved eight dental practices starting in April 2011 and ending in March 2016. 52

Piloting activities could be divided into two phases. In the first phase, two pilots were involved:

-

In the Quality and Outcome Pilot, practices switched their entire GDS contract from the UDA system to a new contract based on a target number of weighted key performance indicators (KPIs), such as number of patients offered a Dental Care Assessment and a capitation target based on the number of unique patients treated in the practice within a defined time period.

-

The Preventive Dental Care for Children and Young People Pilot applied to only patients aged < 18 years. A proportion of each practice’s existing contract value, based on the proportion of children in the practice’s patient profile, was allocated to the pilot. The practices, again, were required to meet a certain number of weighted KPIs, including a capitation target for patients aged < 18 years.

In November 2012, the decision was taken to extend the Quality and Outcome Pilot for an extra year but to discontinue the Preventive Dental Care for Children and Young People Pilot at the end of March 2013, as originally intended. 53 There were some changes to the Quality and Outcome Pilot: a revised Dental Care Assessment was introduced with a disease risk assessment (high, medium or low – similar to England) and the requirement to produce a risk-based preventative care plan for each patient. From April 2015, four of the six pilot practices reverted to their former UDA contract. The remaining two practices were permitted by their health board to continue working under the pilot model into the next financial year, before returning to a UDA contract.

A mixed-methods design was used for the evaluation of the Welsh pilots in a similar approach to that used in England. 49 The main focus was on the qualitative component of the evaluation. Similar findings were reported to those of the evaluation report for the English pilots. The change in remuneration system was universally popular with the GDPs, and there was subjective reporting (by GDPs) of reductions in disease risk and improved oral health of their patients. Like the English pilots, there was a decrease in access: the number of patients seen across all pilot practices ranged between 7% and 10% less than in the year immediately preceding the pilot programme.

Consequently, there was a reduction in PCR: in the first year of the pilot, there was a drop in PCR of over one-third on the previous year under the 2006 arrangements. However, over the 4 years of the pilot, the level of PCR across the practices steadily increased and it was estimated that if the upwards trend in PCR continued at the same rate it would eventually have reached levels similar to the pre-pilot year. However, no time frame was given for when PCR would reach baseline levels. At the end of the pilot programme, the majority of the pilot practices reverted to the 2006 contract and most reported that this has been detrimental to teams and patients, but no specific information was provided on the nature of these detrimental effects. Two of the pilot practices continued as ‘prototype practices’; neither practice is monitored by UDAs but both continue to evolve the model developed in the pilot as part of ‘a learning network’ rather than a formal evaluation.

In August 2017, there was a change of tack in policy. The Welsh Government published Taking Oral Health Improvement and Dental Services Forward in Wales; this policy document outlined the key priorities for NHS dentistry, and contract reform was identified as one of the priorities. 54 The document criticised the current dental contract as being focused on treatment activity and not incentivising needs-led care and prevention. It also criticised the 2006 contract for not encouraging the use of skill mix. The document cited the learning from previous dental pilots in Wales and the ongoing experiences of the dental prototype practices to inform the design of the new programme. Part of this process included the development of a needs and risk assessment tool.

The document did not present a defined ‘new’ dental contract; instead, a more pragmatic approach was advocated to use the flexibility within the existing 2006 contract to produce reform without the need for wholesale change in contract regulations. The document was clear that this approach must be underpinned by robust need and outcome measurement. Examples were given of possible scenarios, such as substituting a proportion of UDAs within a given total contract value by other measures to encourage, for example, a change in care delivery to increase access for high-need groups. This pragmatic approach did not require additional investment and the flexible proportion of the contract could be changed (by negotiation with practices) according to changing population needs.

In February 2018, the Welsh Government announced that from January 2018 a further 23 prototype dental practices would be recruited to expand the flexible adaptation of existing contracts, in particular testing the use of the needs and risk assessment tool. 55 The new Contract Reform programme aims to increase value and quality, based on a needs-based approach to care. Key elements include adopting a needs-led preventive approach to care; extending the use of skill mix as part of prudent dental health care; the acceptance of and provision of care to new patients with higher needs; encouraging ‘well patients’ to attend at longer intervals; and delivering high-quality evidence-based care according to need. As of December 2019, over one-quarter of the dental practices in Wales were participating in the Contract Reform programme.

The evolution of a new NHS dental contract in Scotland

In Scotland, the NHS dental contract has not changed substantially since 1990 and the situation is similar to that in Northern Ireland. The GDPs providing care to children (aged < 18 years) are paid primarily on a capitation basis, receiving a basic monthly fee for the care and treatment of children covering examinations, X-rays, scale and polish, and preventative care. A smaller proportion of the remuneration package for children is made up from additional item-of-service fees for fillings and extractions. The majority of the care provided to adults is still paid on a fee-for-item basis with a small monthly fee payable for the provision of continuing care to registered patients.

In January 2018, the Scottish Government published its Oral Health Improvement Plan, following publication of a consultation exercise in September 2016. 56 The plan is ambitious, setting out 41 actions or commitments to be delivered within a non-specified time scale. Like the other three home countries, there is an aspiration to focus on prevention, highlighting the need for a shift from restorative to preventative dentistry, which was well supported during the consultation exercise.

An explicit action in the plan was to:

. . . change payments to GDPs and introduce a system of monitoring to ensure that all dental practices provide preventive treatment for children.

There was also an aspiration to introduce a preventative system of care for adults by phasing in an oral health risk assessment. This assessment would be more comprehensive than a risk assessment of dental disease alone and would include a comprehensive clinical examination and a discussion about lifestyle choices, including diet, alcohol use and smoking. The patient would receive a personalised care plan based on the outcomes of the assessment.

Interestingly, and in contrast to the other three home nations, there were no plans for scrapping the item-of-service system of remuneration; instead there was an intention to ‘streamline’ item-of-service payments, which would be progressively introduced. NHS health boards would in future take a more proactive approach to the listing of practices, exerting tighter controls on GDPs wishing to set up new practices in their locality. There were also plans to develop a new system to oversee external clinical quality monitoring under the direction of newly appointed directors of dentistry in each health board. The plan echoes the evolutionary approach taken in the prototypes in England and Wales in that:

. . . our intention is to proceed in a progressive manner in order for practices that provide GDS to have the opportunity to plan accordingly whilst maintaining their financial stability.

In terms of changes to remuneration, the plan recognised the current, mixed economy of item of service, capitation and continuing care payments as a strength and stated that the Scottish Government would:

. . . continue to retain a mix of payments going forward, but the balance of payments will change accordingly.

There were no explicit plans described in the document to evaluate the impact of implementing the ≈40 actions set out in the plan or for how the envisaged changes in remuneration would influence and incentivise the behaviours of GDPs.

Summary

As policy has developed in each of the home countries, there are some common threads emerging from the approaches taken. Primarily, there is a desire to focus on and pay for prevention rather than treatment and to approach this via a standardised assessment to identify and categorise a patient’s risk of oral disease and then formulate a personal prevention plan, which will guide the care provided to patients. This approach presupposes that we have validated tools to categorise a patient’s risk with an acceptable degree of precision and that preventative interventions delivered by GDPs in general practice can effectively mitigate this risk. Indeed, the recent findings of the Northern Ireland Caries Prevention in Practice (NIC-PIP) trial suggest that even with high levels of adherence to practice-delivered prevention regimes, caries prevention delivered in practices is very expensive and limited in its effectiveness. 57 The Improving the Quality of Dentistry (IQuaD) trial has recently evaluated the costs and effects of scale and polish, a long-standing treatment provided to maintain gingival and periodontal health, and could find no evidence that this intervention provides a health benefit to patients, but patients want this treatment provided by the NHS. 58 The NIHR-funded INTERVAL trial will report shortly on the effects of different recall (for dental check-ups) on oral health and will compare intervals decided according to the GDP’s judgement of disease risk with standardised recall periods. 39 The idea of GDPs providing prevention rather than treatment can be traced back to the capitation pilots that led to the 1990 contract; it has always received widespread support across the dental profession and chimes with wider NHS policy, but without hard evidence to demonstrate that the significant costs of this approach for the NHS produce a worthwhile return on investment. These pragmatic trials conducted in dental practices will provide strong evidence about prevention provided by GDPs and what is achievable and how affordable it is for the NHS.

In developing a new remuneration system, there is a tension between this desire to shift the emphasis away from treatment to prevention while maintaining co-payment income. Each country is mindful of the need to secure income from PCR, in Scotland through retaining the largely fee-for-item system and in England and Wales through retaining activity targets as part of a blended contract. In an ideal world, incentives in a blended contract would ensure that essential treatment needs of new and existing patients are provided for and that this activity would generate sufficient co-payment income. This supposition is dependent on GDPs’ assessments of the needs of their patients, which could be influenced in an unpredictable way by the details of a new contract, particularly if there are activity targets to hit as part of a blended arrangement. It also supposes that the future needs of the population will require the activity necessary to maintain co-payment revenue, which is a risky assumption particularly if needs assessment is based on historical activity delivered under existing contracts and incentive structures. The literature strongly suggests that a move from FFS to capitation produces a fall in activity and a consequential fall in co-payment revenues. The literature suggests that a change in remuneration produces a large immediate fall in activity before a gradual increase (bounce back) over time (NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research programme 08/1618/158). The evidence base for the level of activity and the way activity changes (profile of treatments) in response to remuneration changes is underdeveloped, particularly why GDPs change their behaviour and the drivers and restraining factors in relation to behaviour change are poorly understood.

Access to NHS care in each country remains a priority and improvement in quality is also an aspiration, albeit with different approaches to achieve these ends. There is a need to define what is meant by access and accessibility. Gaining access for patients who have regularly attended a practice does not seem to be a significant problem but provision for irregular attenders, with high need, often living in more disadvantaged areas seems to be more problematic, which should be a concern for an NHS service.

Concluding remarks

The preceding sections have highlighted a range of issues relating to the NHS dental contract in Northern Ireland. The evidence base is underdeveloped in terms of how and why GDPs’ behaviour changes as a result of changing remuneration systems and how this behaviour change (often in an unintended way) has an impact at the macro level of the volume and type of care provided for populations and has an impact at a micro level on the care provided for individual patients. The pilot contracts in Northern Ireland offered an opportunity for academics and decision-makers in the NHS to investigate these issues in a co-production partnership. Chapter 3 sets out the research questions prompted by the literature review and the circumstances leading up to the commissioning of the dental contract pilots in Northern Ireland.

Chapter 3 Difference in difference

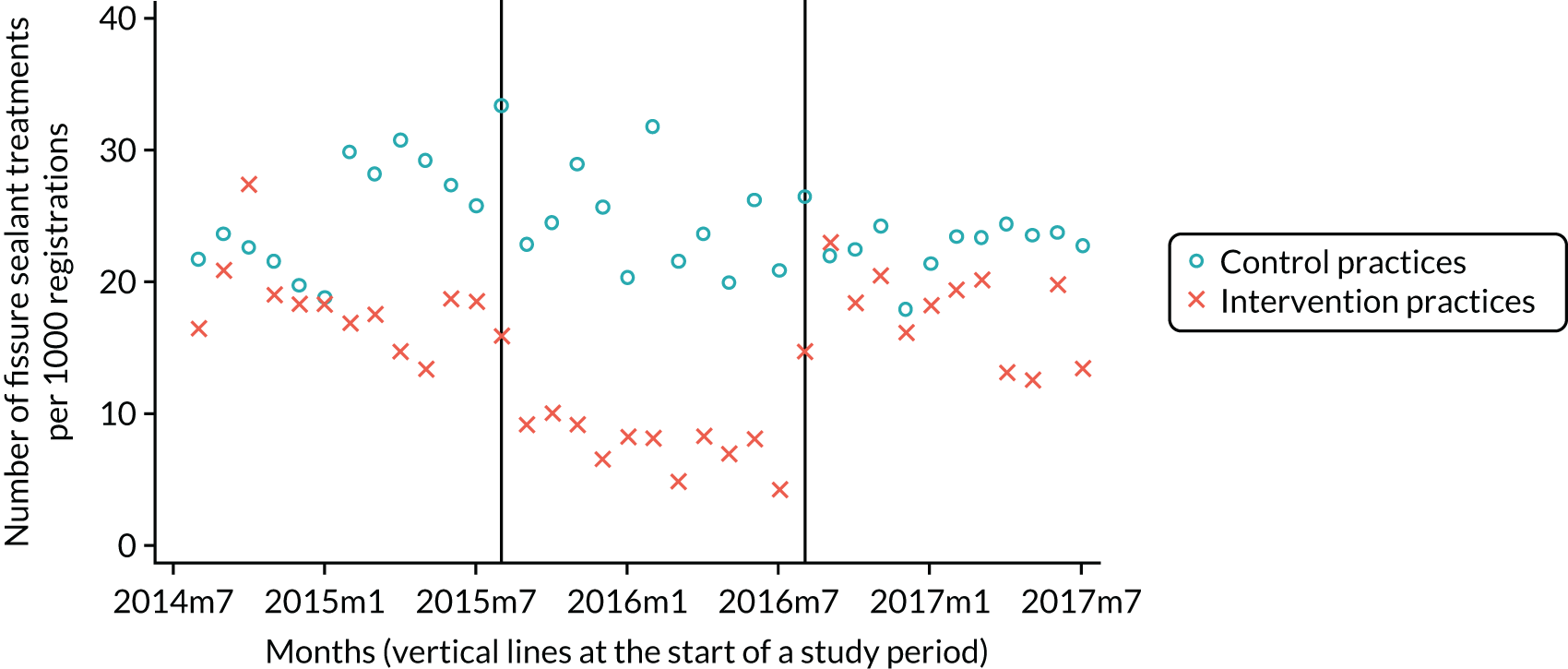

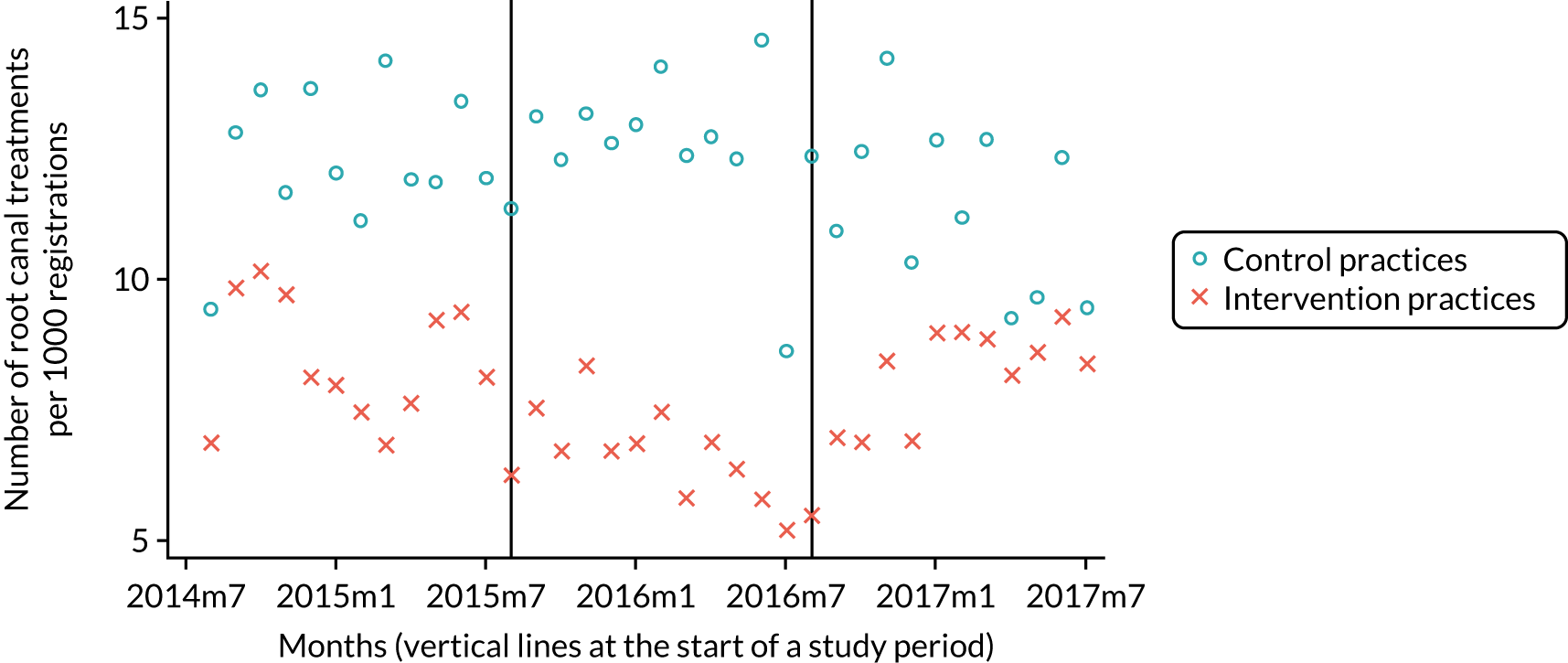

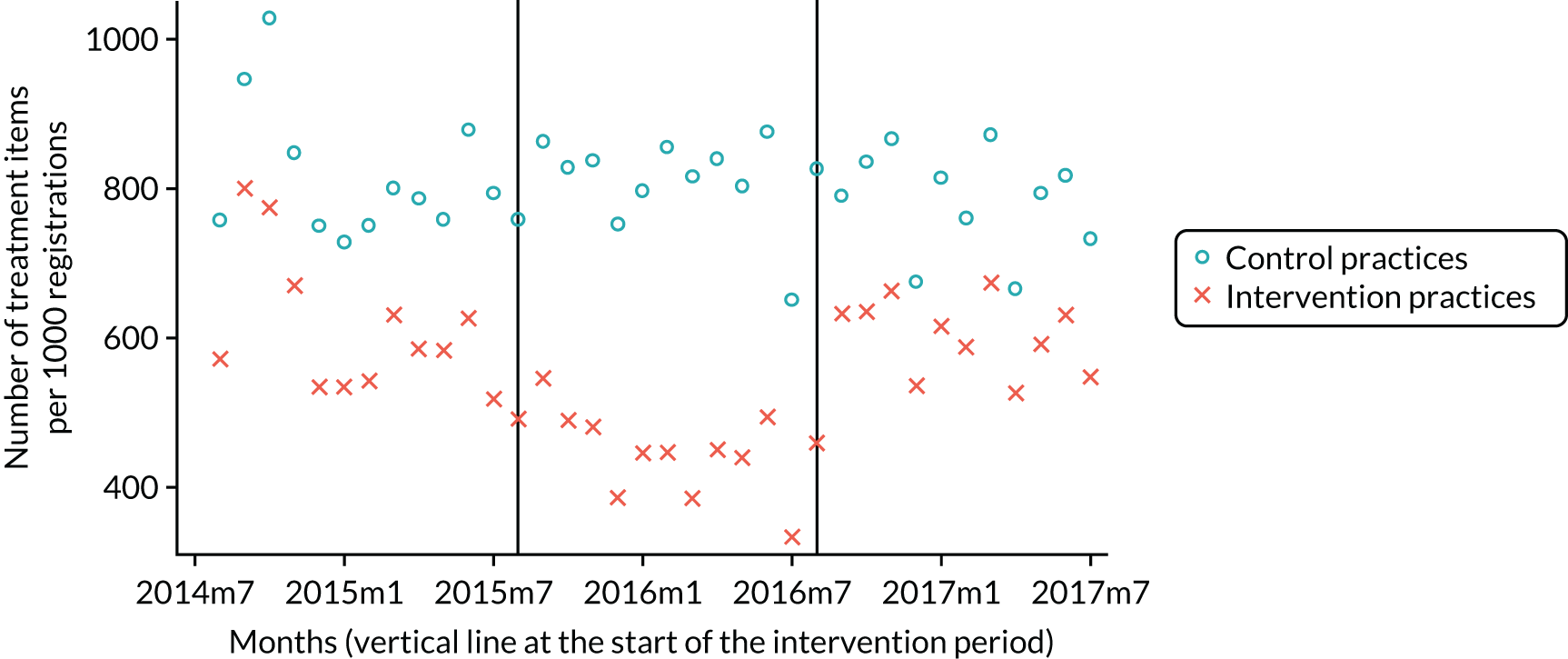

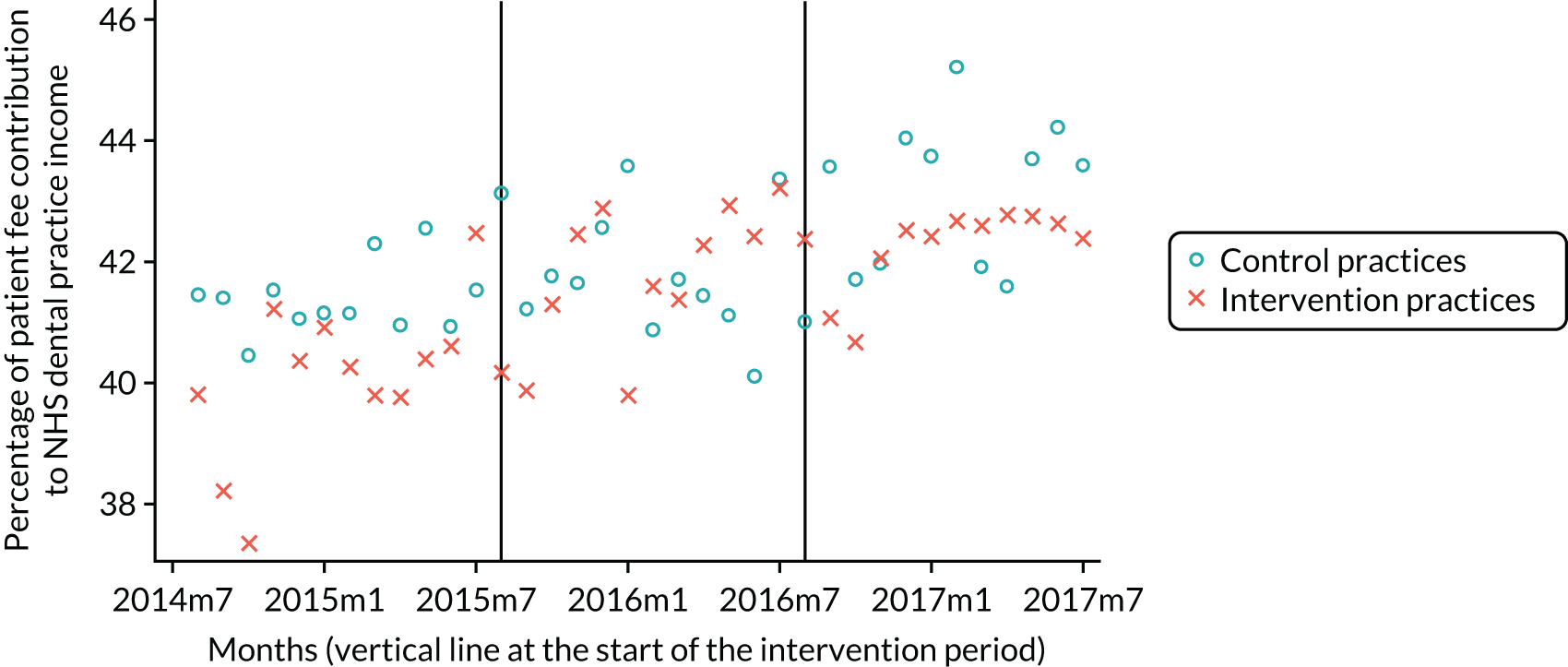

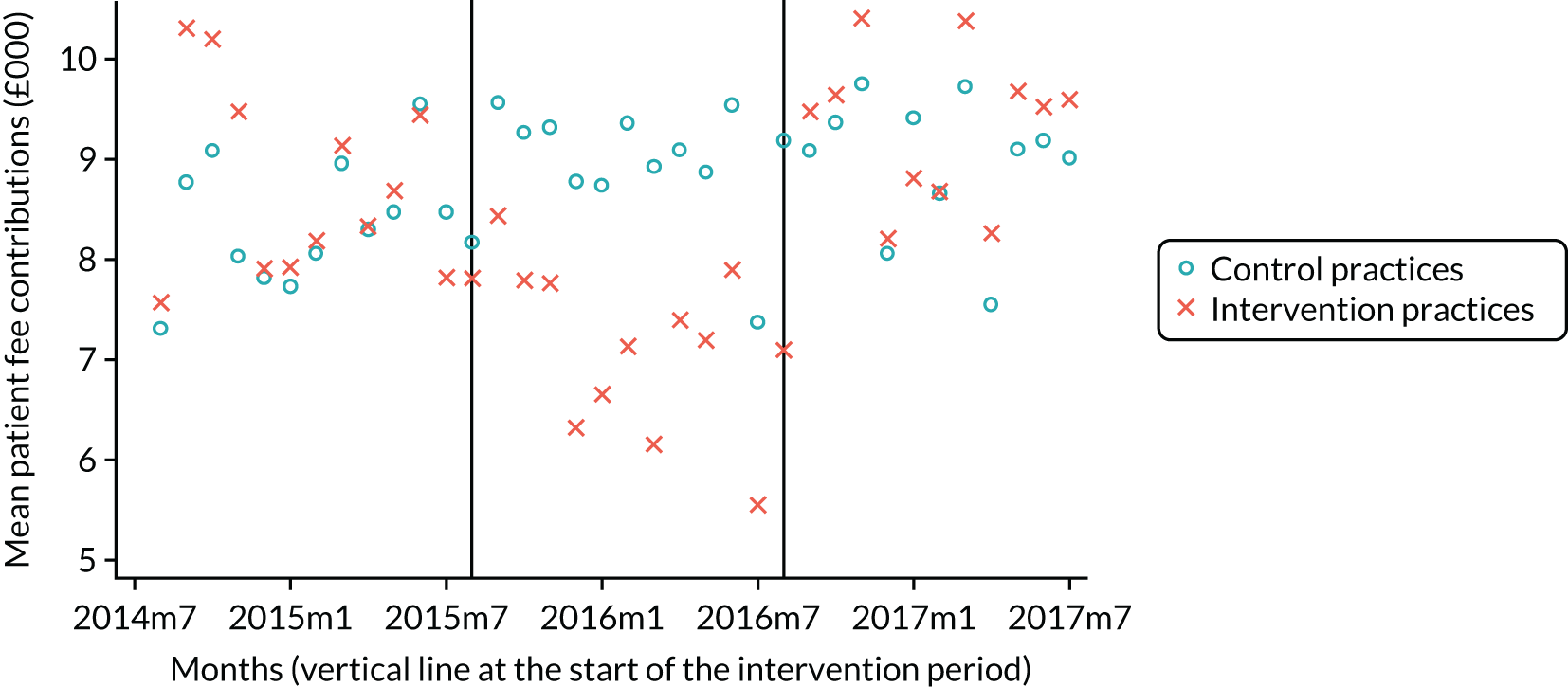

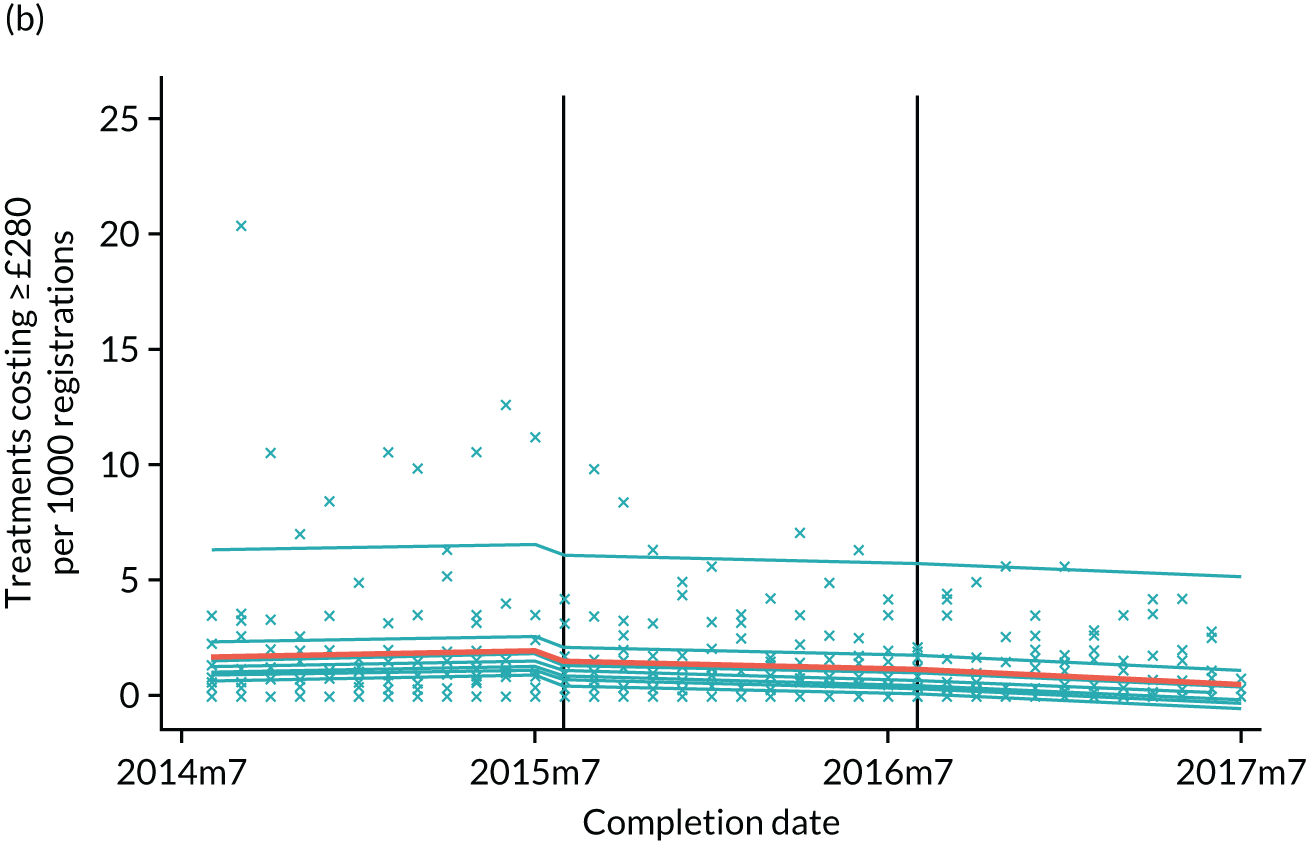

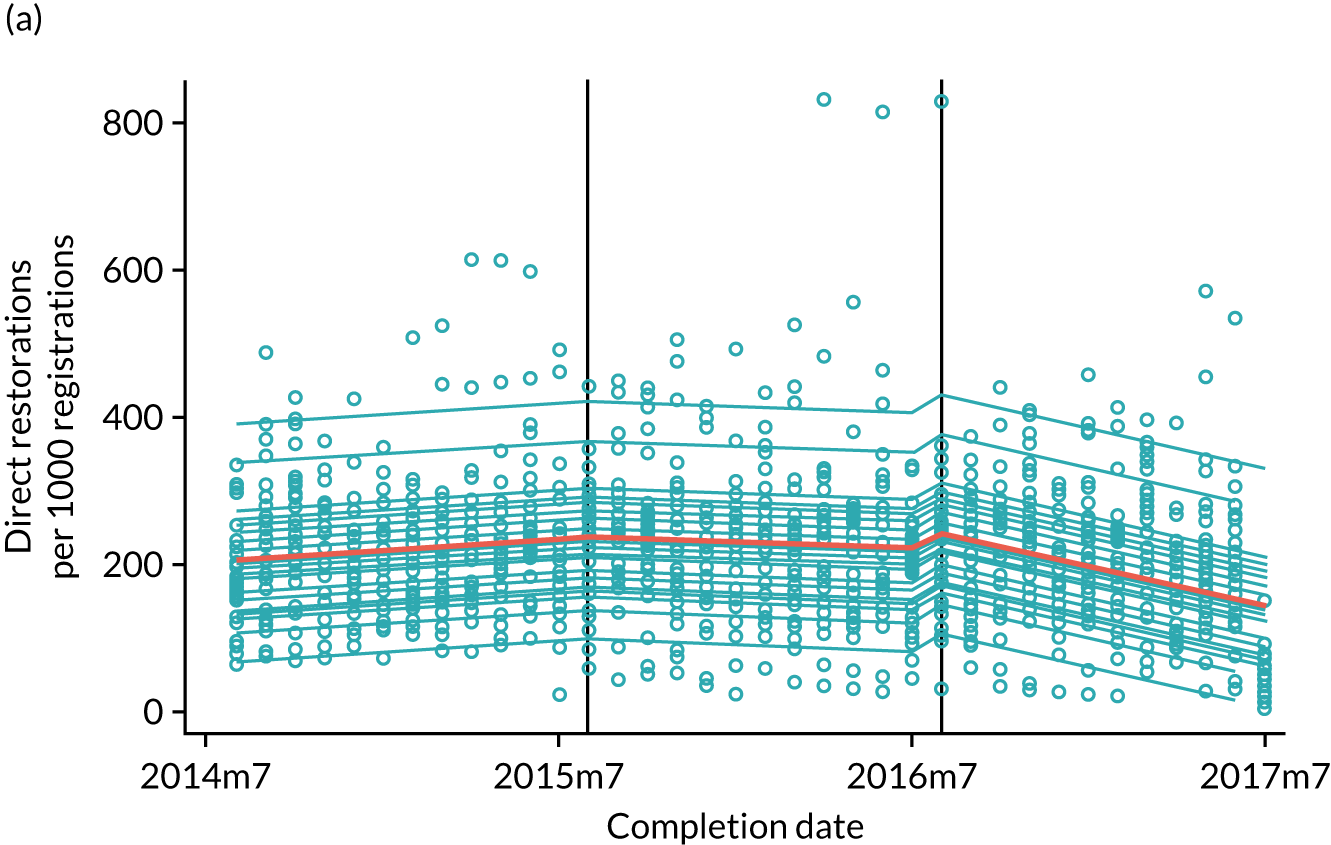

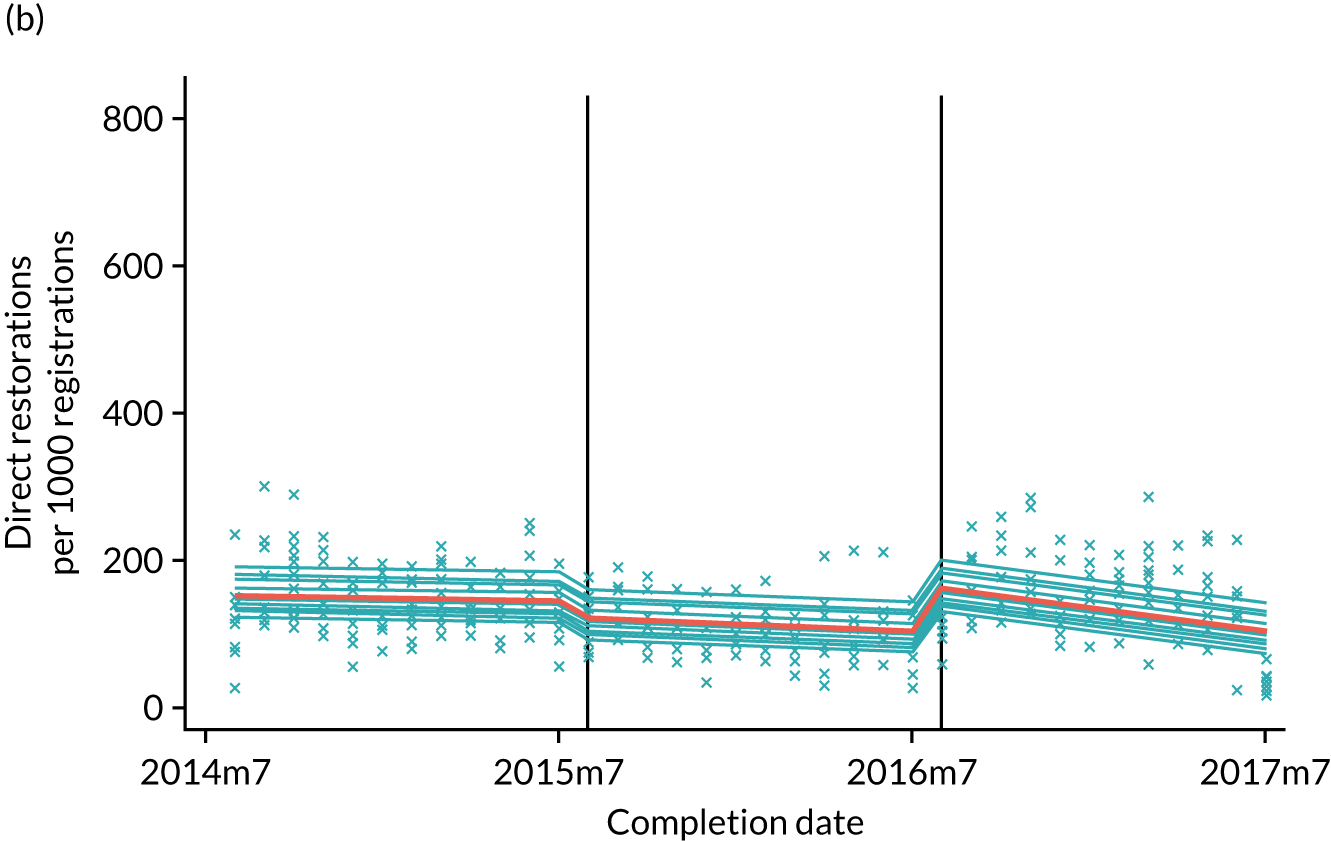

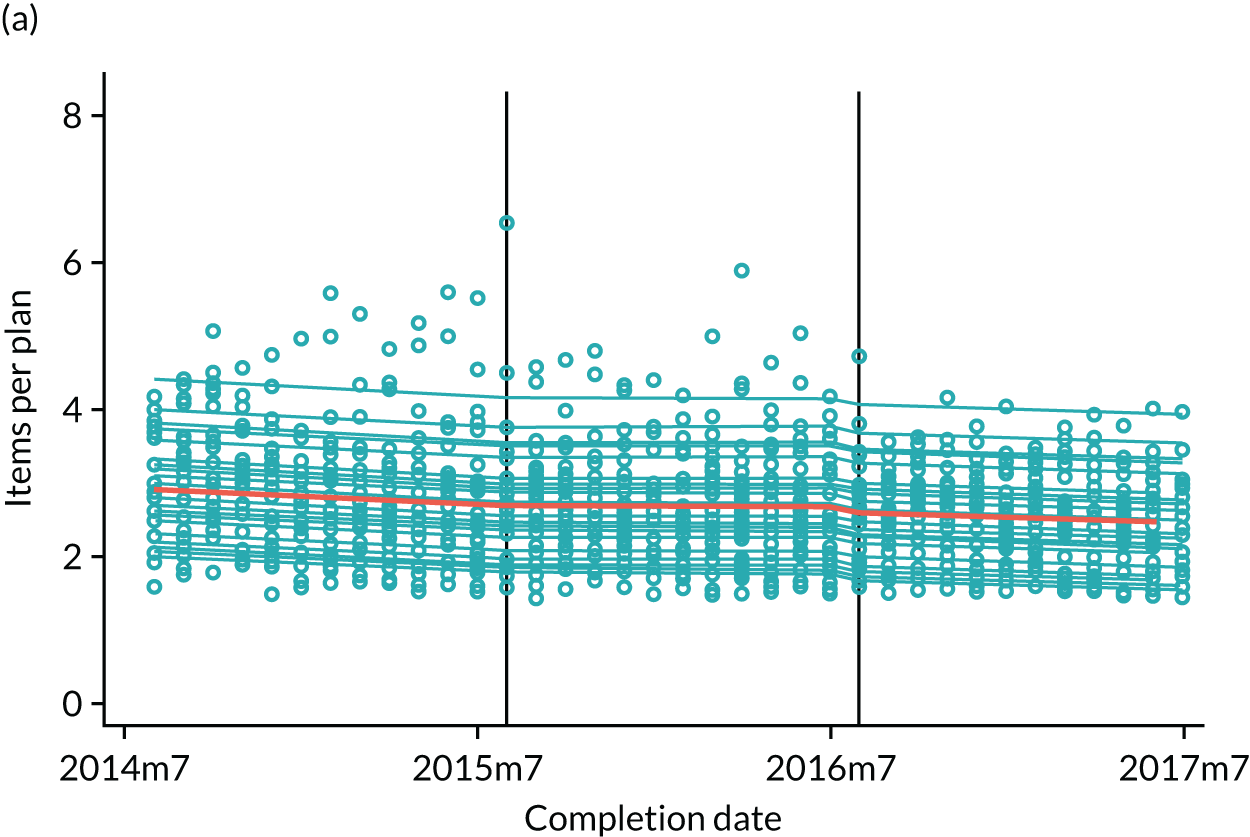

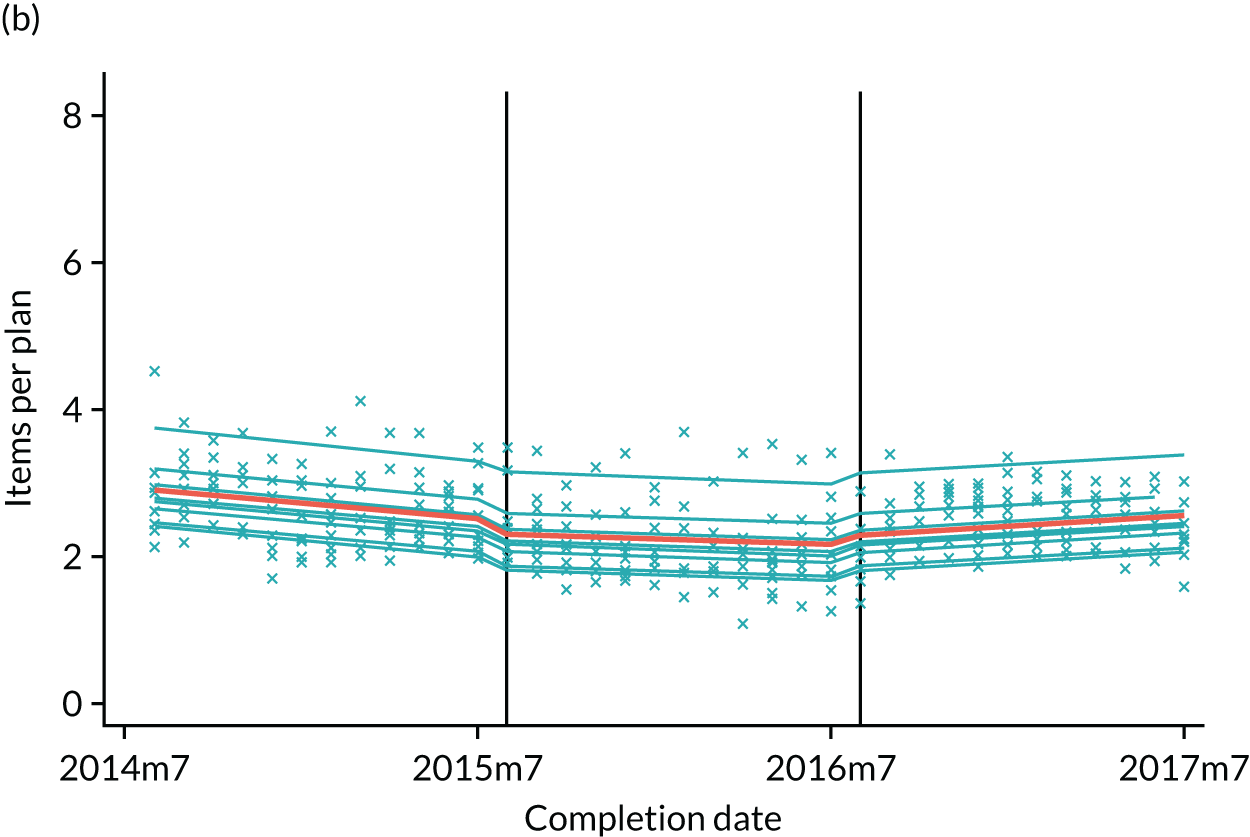

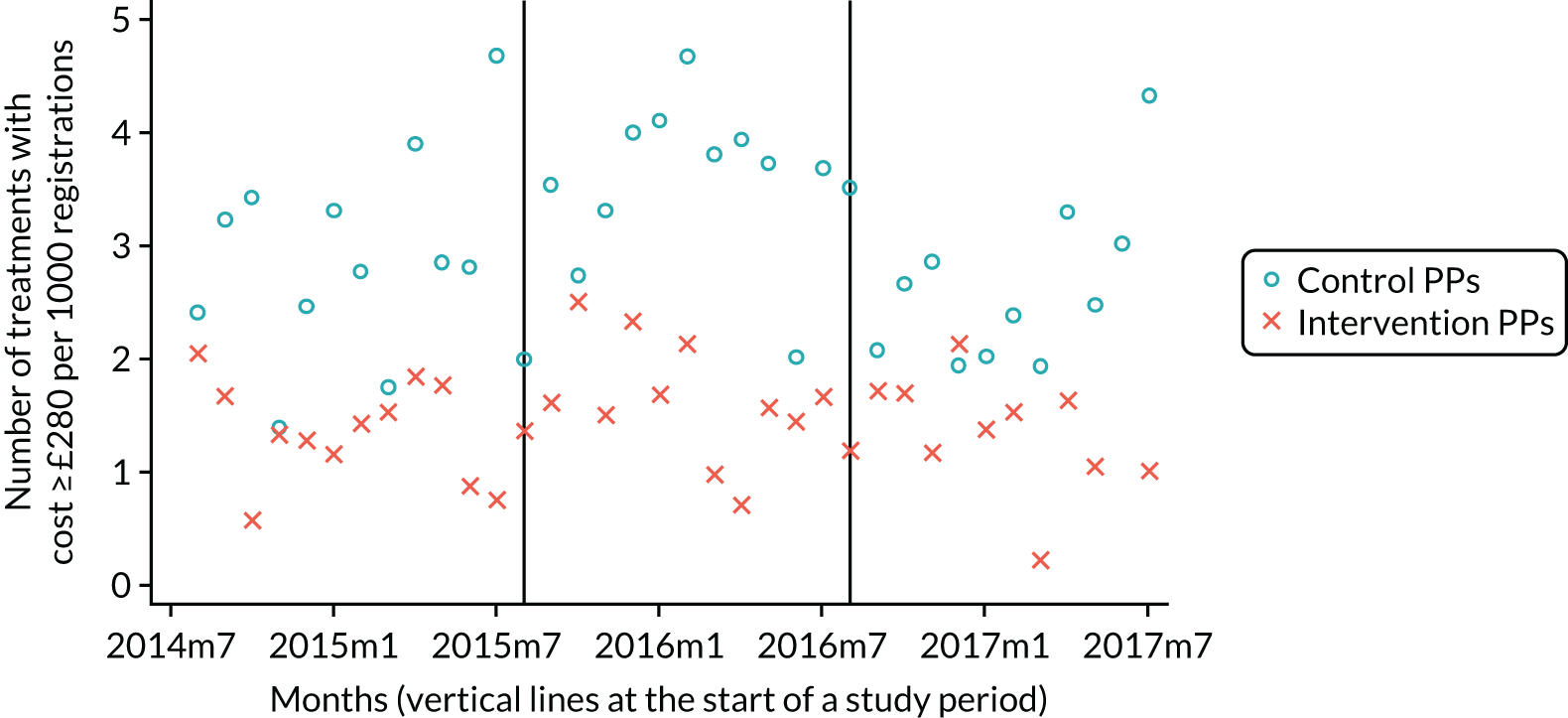

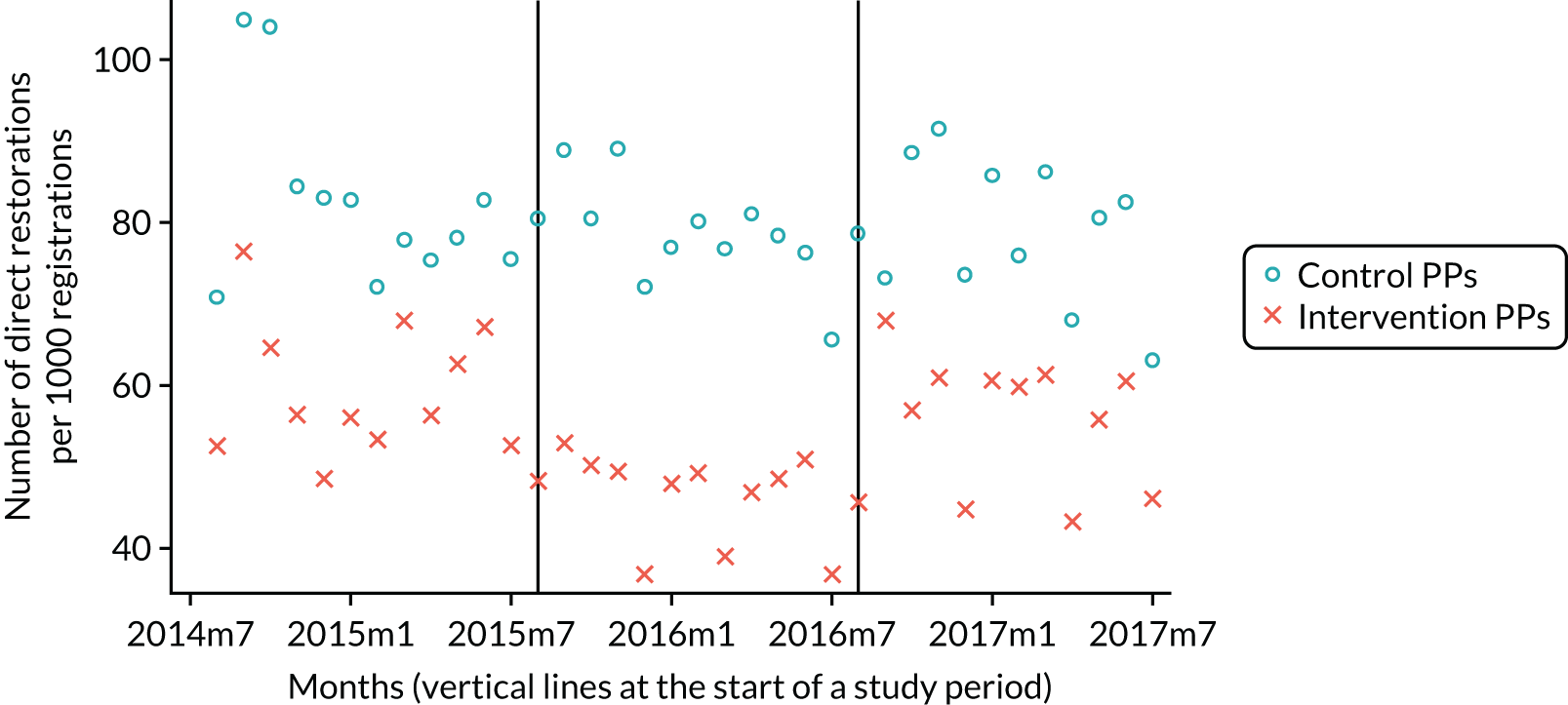

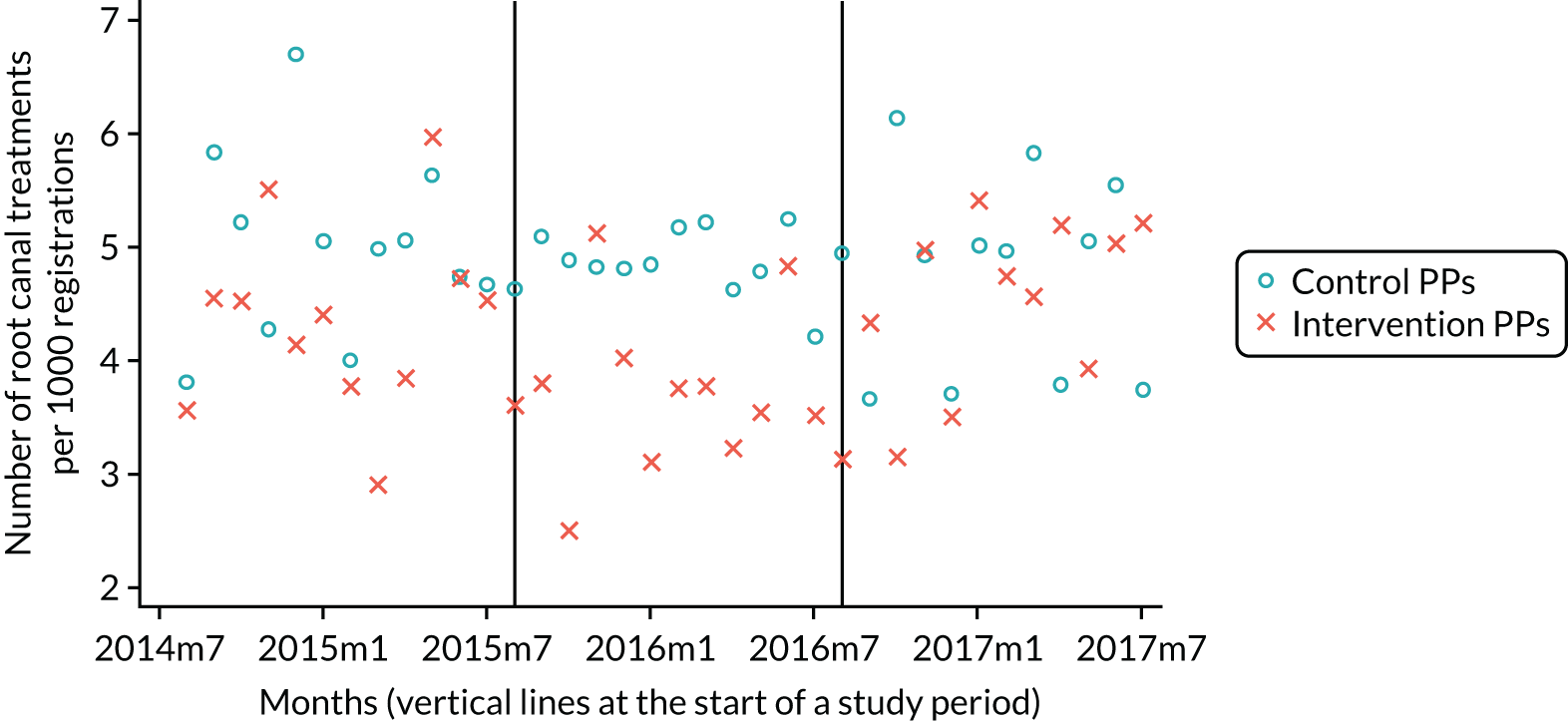

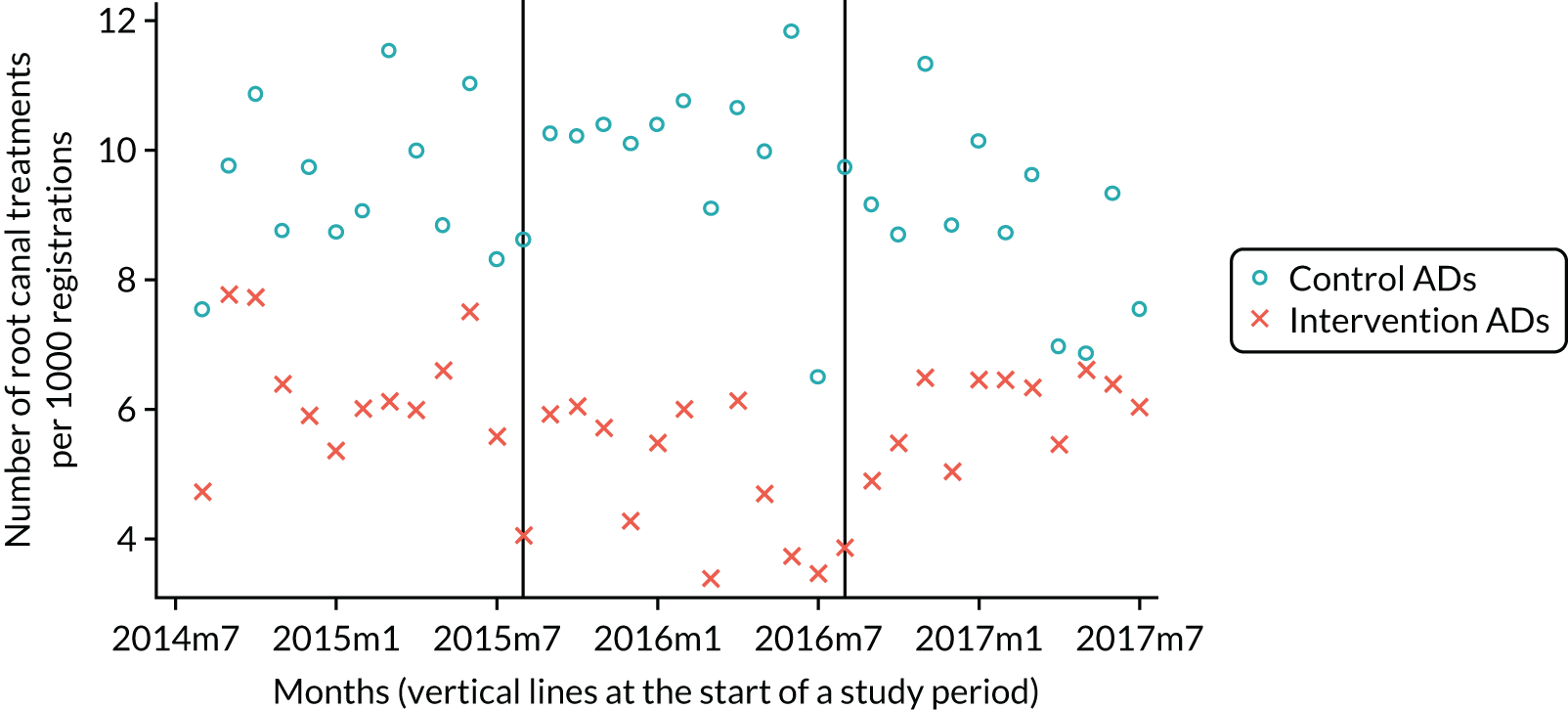

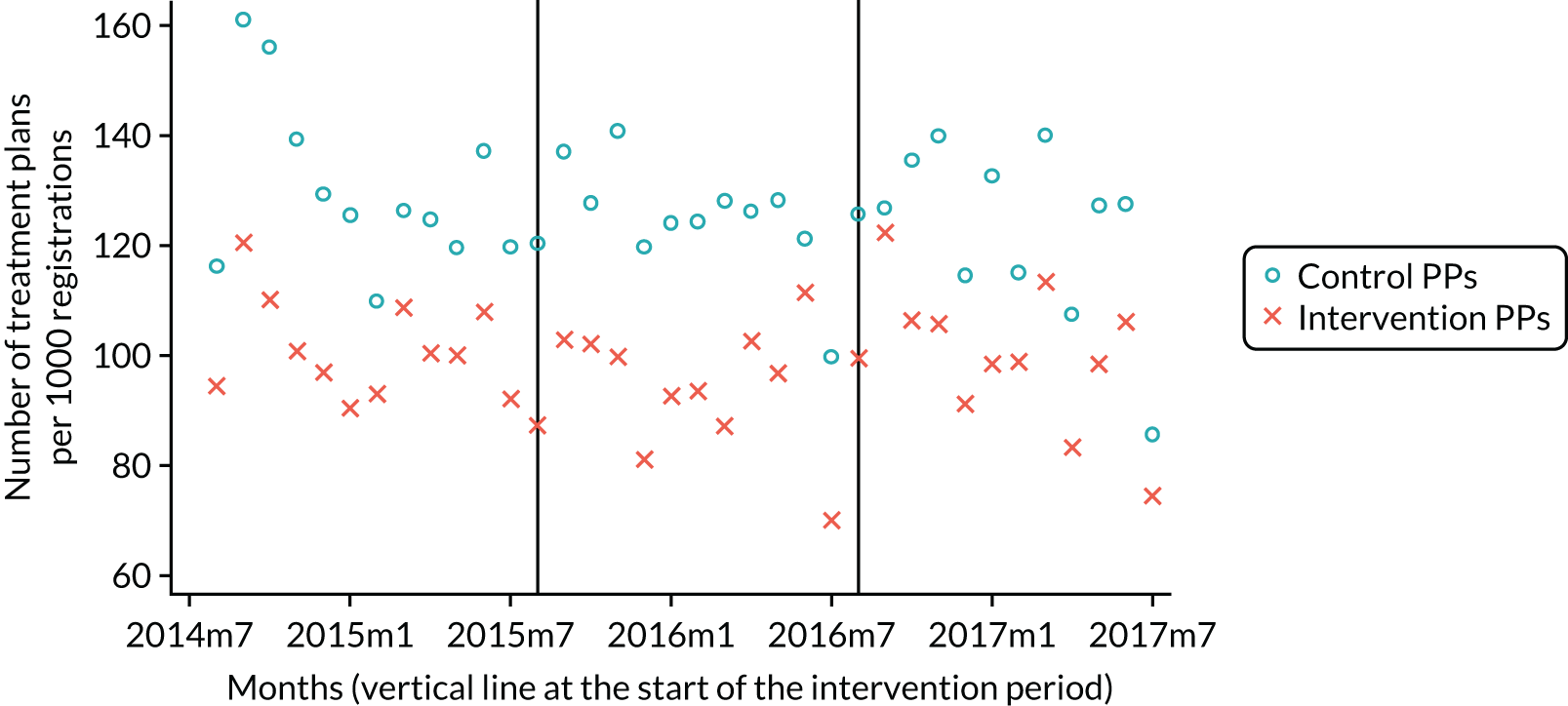

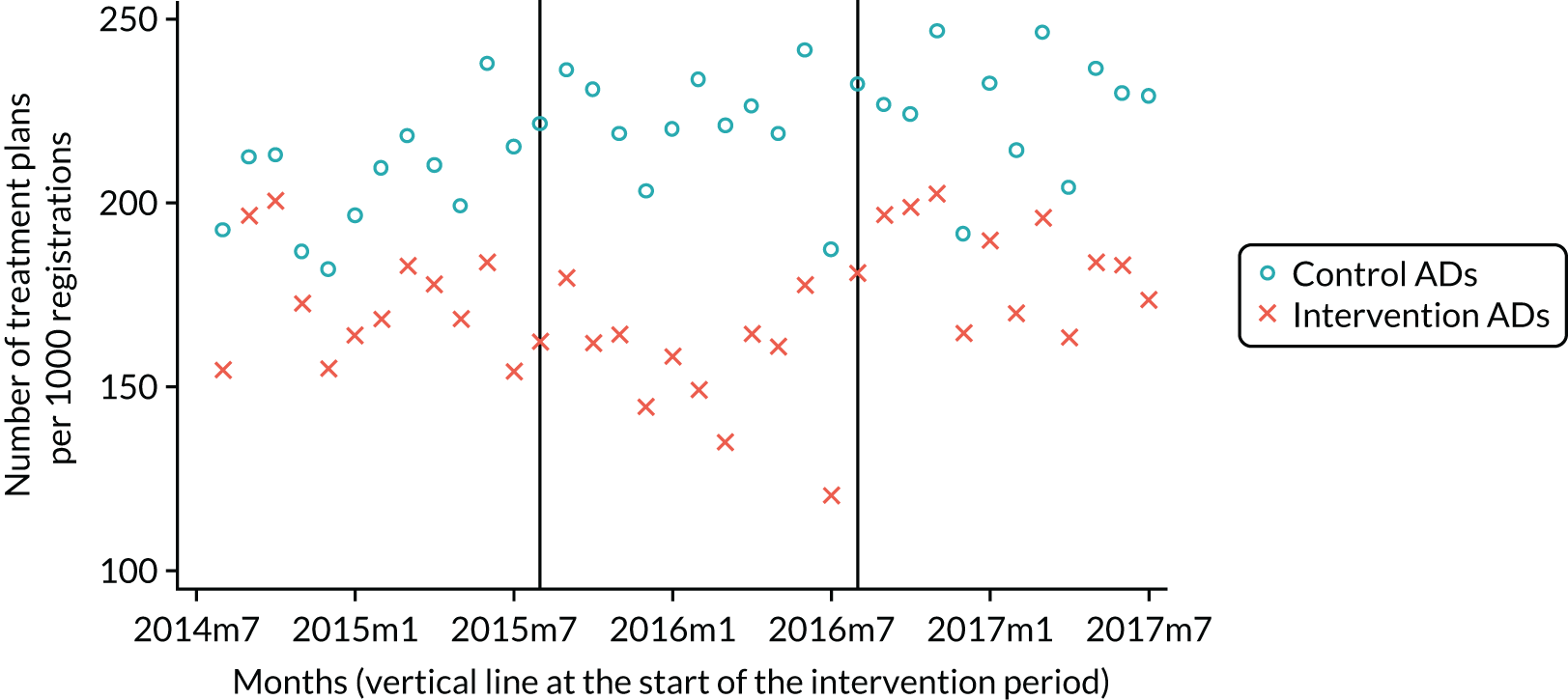

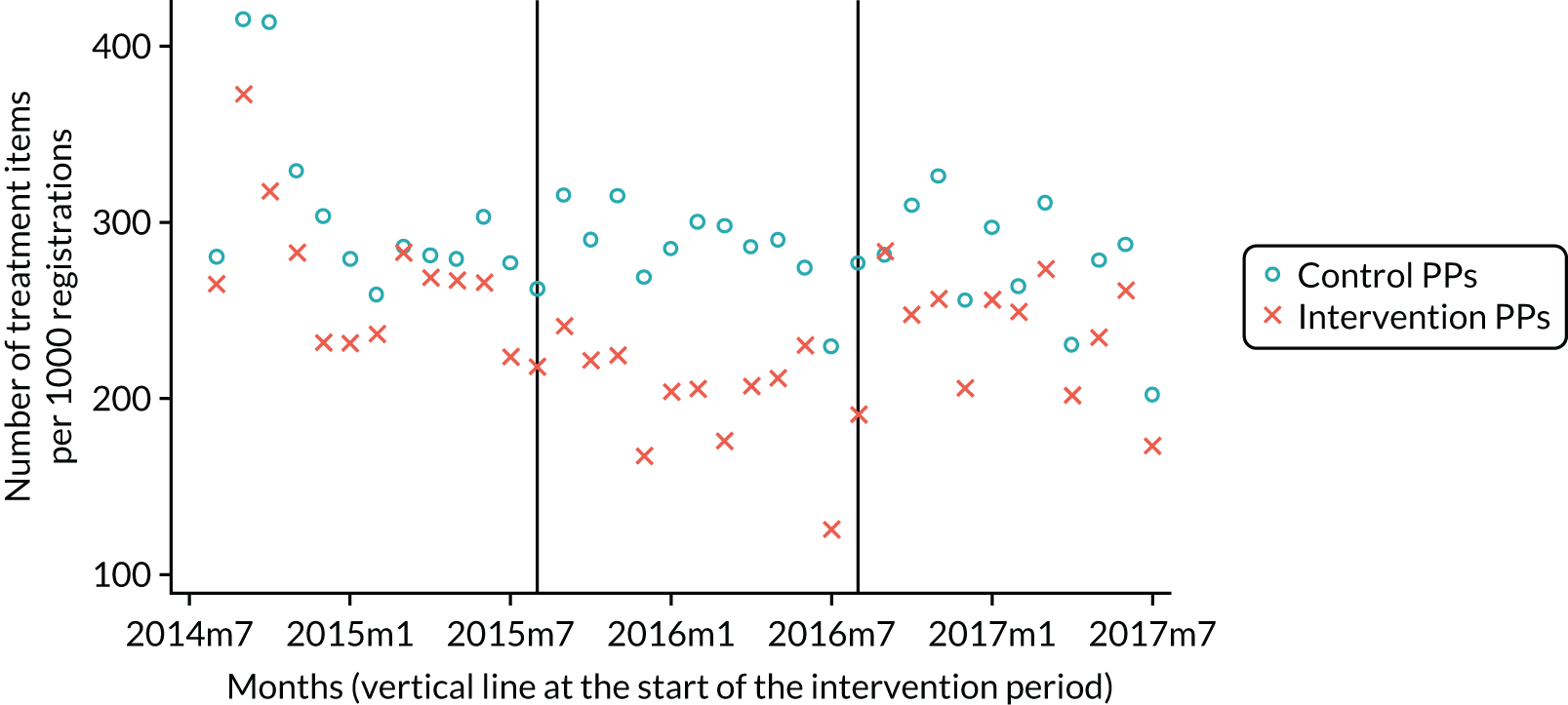

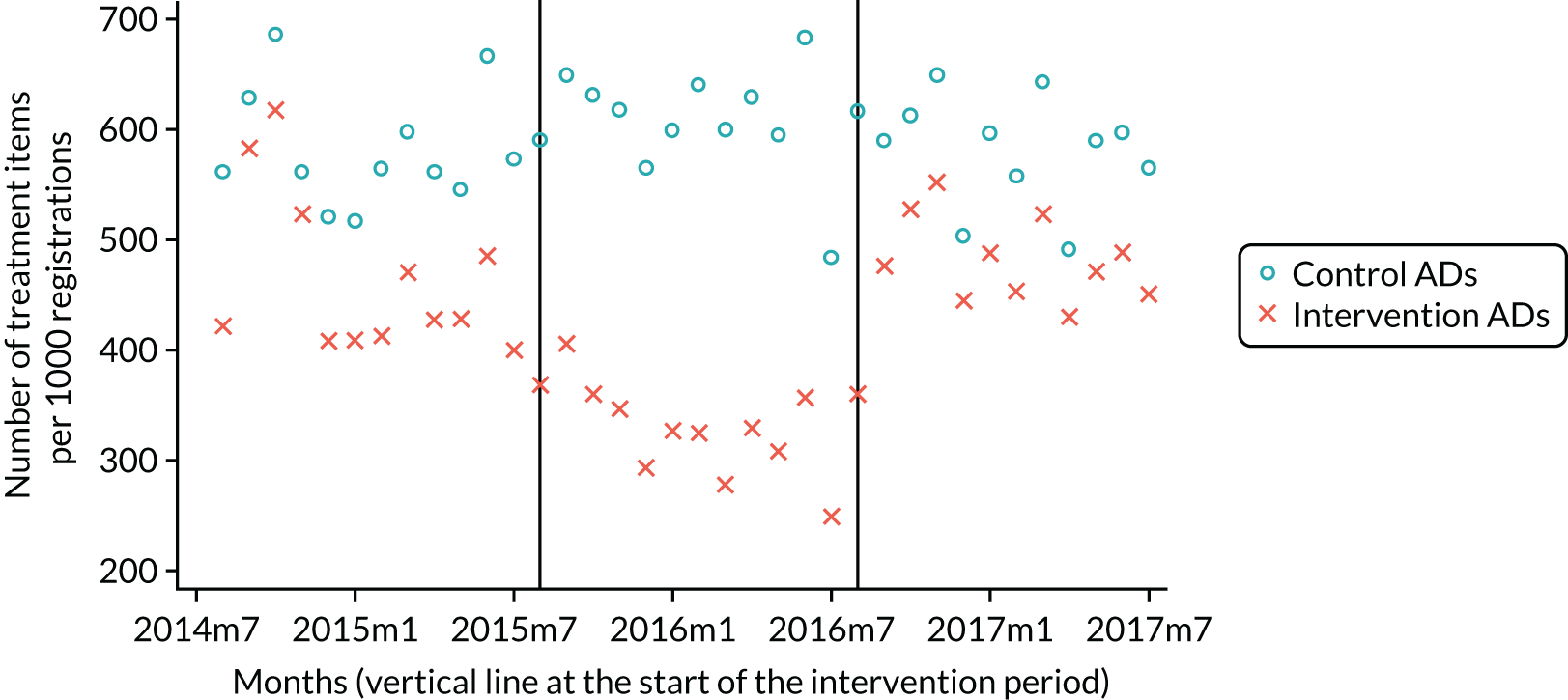

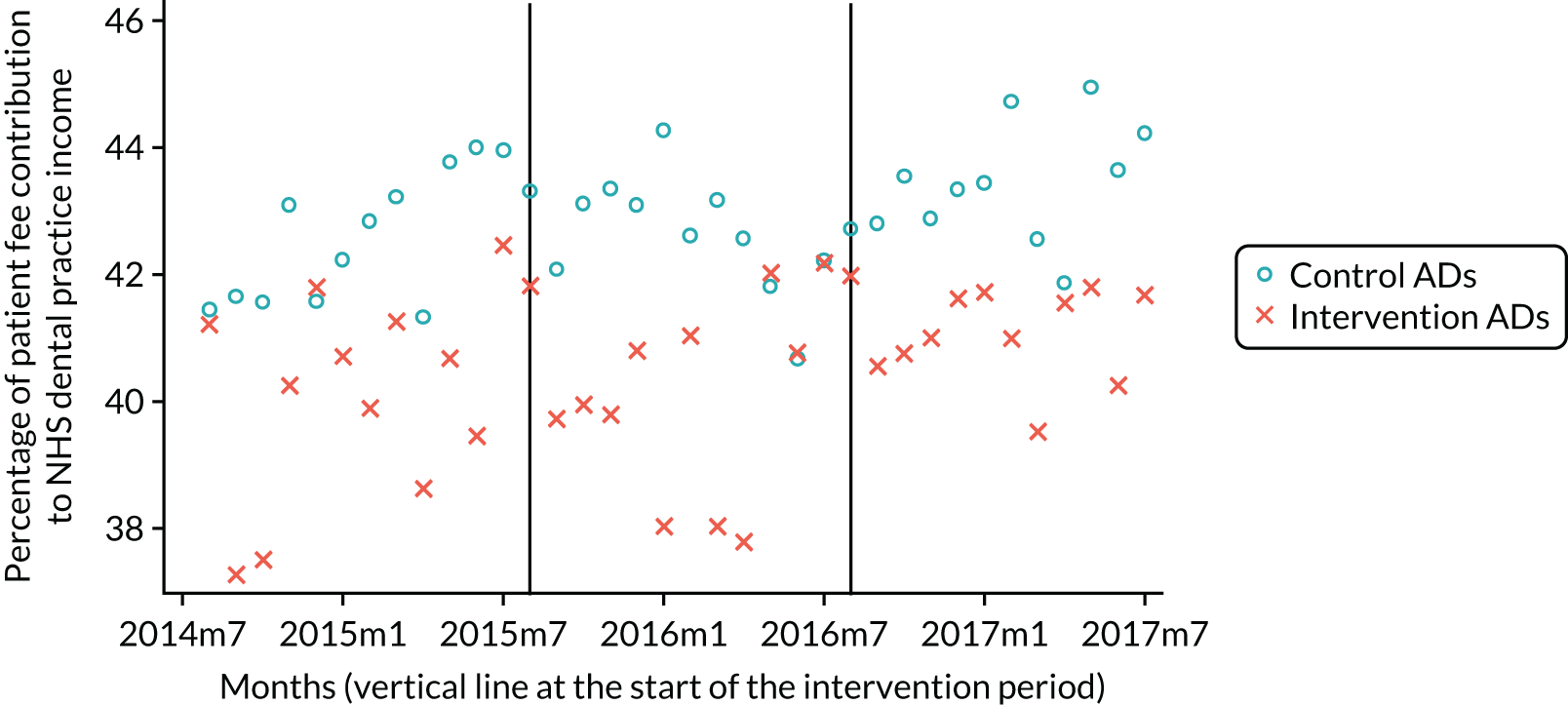

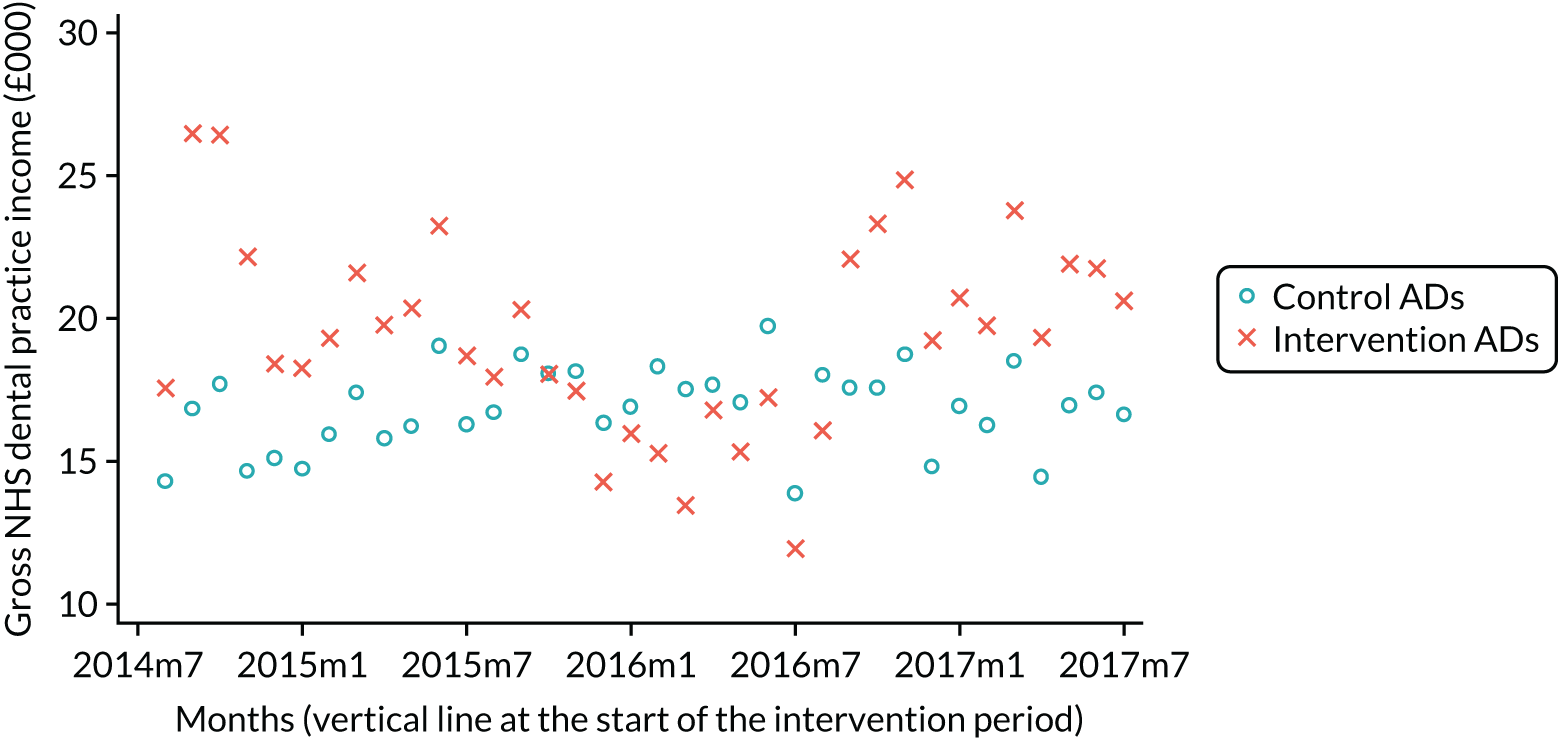

Introduction