Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/209/27. The contractual start date was in July 2014. The final report began editorial review in April 2018 and was accepted for publication in September 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Bryony Dean Franklin, Ann Blandford and Dominic Furniss report a joint grant from Cerner (North Kansas City, MO, USA). Bryony Dean Franklin reports a grant from the National Institute for Health Research outside the submitted work. Dominic Furniss reports personal fees from Becton, Dickinson and Company/CareFusion (Wokingham, UK) during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Blandford et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

This chapter includes material reproduced or adapted from Blandford et al. 1 and Fahmy et al. 2 These articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Infusion devices have been identified as an important source of errors, potentially compromising patient safety. 3 Smart pumps, in which the infusion device is integrated with information systems and drug libraries to set safe limits on medication administration,4 have been advocated as a key technology to block critical medication administration errors. Although such pumps have been widely implemented in the USA, take-up in England has been patchy and, even where smart pumps have been introduced, drug libraries may be only partially implemented. 5

There have been few studies of the role of infusion devices in ensuring safe medication administration practices, and most previous studies have taken place in the USA. 6,7 The overall aim of the study, referred to as ECLIPSE (Exploring the Current Landscape of Intravenous Infusion Practices and Errors), was to better understand current intravenous (IV) infusion practices in England and the possible role of smart pumps in managing patient safety.

Background

We open the background section by summarising what is already known about how infusion pumps are used across health care, the safety of IV medication administration and the role of smart pumps. We then briefly review the background to the analytical perspectives that we used (see Chapter 4). This is followed by an overview of broader perspectives that informed our data gathering and later analyses (namely human factors approaches, different perspectives on safety, and complexity science).

In this report, we use the terms ‘infusion devices’ and ‘pumps’ interchangeably to refer to both volumetric pumps (in which a bag of IV medication is hung on a drip stand and the rate of flow is controlled by the pump) and syringe drivers (in which the medication is prepared in a syringe, and the plunger is depressed at a controlled rate by the syringe driver to deliver the medication).

Intravenous medication practices

Infusion pumps are safety-critical devices in widespread use across many clinical areas: for pain management, delivery of antibiotics and chemotherapy, anaesthesia and fluid management. They are used in many clinical areas, from paediatrics to elderly care, in intensive care, in operating theatres and on general wards. Studies have found that infusion practices vary significantly both between and within hospitals. For example, in a series of observational studies, nurses in an oncology day-care unit were found to follow fairly basic procedures in setting up planned infusions,8 whereas nurses in an intensive care unit (ICU) routinely used advanced functionality, frequently setting up several pumps in parallel to deliver different medications. 9 There is an increasing drive towards standardising devices within organisations, intended to reduce the potential risks associated with staff using a range of different devices or devices configured in different ways, or being required to operate devices that they are not familiar with or have not been trained to use. However, not all clinical areas require the same functionality; for example, Carayon et al. 10 studied how nurses used infusion devices in different areas of the hospital. They compared the tasks actually carried out with the tasks as defined by ward protocol, identifying divergences in practice and highlighting ways in which those divergences increased overall system vulnerability.

Safety of intravenous medication administration

Intravenous medication is essential for many hospital inpatients. However, providing IV therapy is complex, and data suggest that errors are common. 11–13 In a systematic review of UK studies using structured observation of medication administration, errors were found to be five times more likely in IV than non-IV doses. 14 Internationally, published error rates vary from 18% to 173% of IV doses given, in studies using structured observation of medication administration. 15 An international systematic review estimated the probability of making at least one error in the preparation and administration of a dose of IV medication to be 0.73, with most errors occurring at the reconstitution and administration steps. 16 Although many of these errors do not result in patient harm, all can cause anxiety for patients and staff and can reduce patients’ confidence in their care. As a result, the administration of IV medication has been identified as a significant topic of concern by regulators, manufacturers and health-care providers. 3

The potential role of smart infusion pumps

To reduce errors associated with IV infusions, ‘smart pumps’ incorporating dose-error reduction software (DERS) have been widely advocated. 4,17,18 This software checks programmed infusion rates against pre-set limits for each drug and clinical location, using customisable ‘drug libraries’, to reduce the risk of infusion rates that are too high or too low. Limits may be ‘soft’ (in which case they can be over-ridden following confirmation by the clinician) or ‘hard’ (in which case they cannot). Smart pumps may be standalone or integrated with electronic prescribing and/or barcode administration systems, and usually allow administrative data, such as number and types of over-rides, to be downloaded for analysis. Although smart pumps were in use in 68% of US hospitals in 2011,19 a figure now likely to be much higher, their use is not yet as widespread in the UK. 5 Such technology can potentially identify and prevent some kinds of medication errors, but cannot prevent all possible errors. Smart pump use also comes at a cost, both financially and in terms of the changes needed to make their use effective. For instance, Husch et al. 6 carried out a hospital-wide point-prevalence study of errors in IV infusions using standard infusion pumps, and identified infusion rate errors in 37 cases (8% of all infusions) and wrong medication in 14 cases (3%). However, they estimated that only one of these errors would have been prevented using standalone smart pumps. More were judged to be potentially preventable if the pumps were integrated with other hospital systems, such as computerised prescriber order entry (CPOE) and barcode medication administration (BCMA). In a survey study involving 29 hospitals across Canada that either had implemented smart pumps or were in the process of doing so, Trbovich et al. 20 found that respondents did not take the steps necessary to realise the potential safety benefits of pumps; for example, they did not standardise drug concentrations, develop drug libraries, set dosing limits or monitor how pumps were used.

A recent systematic review identified 21 quantitative studies of smart pumps,21 the majority of which studied the over-rides recorded in the smart pump logs and/or used unreliable methods of identifying medication errors and adverse drug events, such as incident reports. The authors concluded that smart pumps can reduce but not eliminate error, and that the picture was far from conclusive. Furthermore, most studies were conducted in the USA; none was from the UK, where systems for prescribing and administering medication differ significantly from those in the USA. 22 For example, nurses play a more active role in preparing IV medication in the UK, and verbal orders are much less common. We therefore know little about the effect on patient safety of using smart pumps in general and nothing about their likely impact in the UK.

Assessing the severity of errors

As well as studying the prevalence of medication errors, their clinical importance must be taken into account when comparing drug distribution systems or assessing the effects of interventions. 23,24 Medication errors range from those with very serious consequences to those that have little or no effect on the patient. Assessing the clinical importance of errors therefore increases the clinical relevance of studies’ findings compared with studies based on prevalence alone. In many studies, actual error outcomes are not known, either because there is no longitudinal patient follow-up or because researchers intervene to prevent errors from causing patient harm. Methods of measuring the potential severity, or clinical importance, of medication errors are therefore needed to evaluate the effectiveness of interventions designed to reduce them.

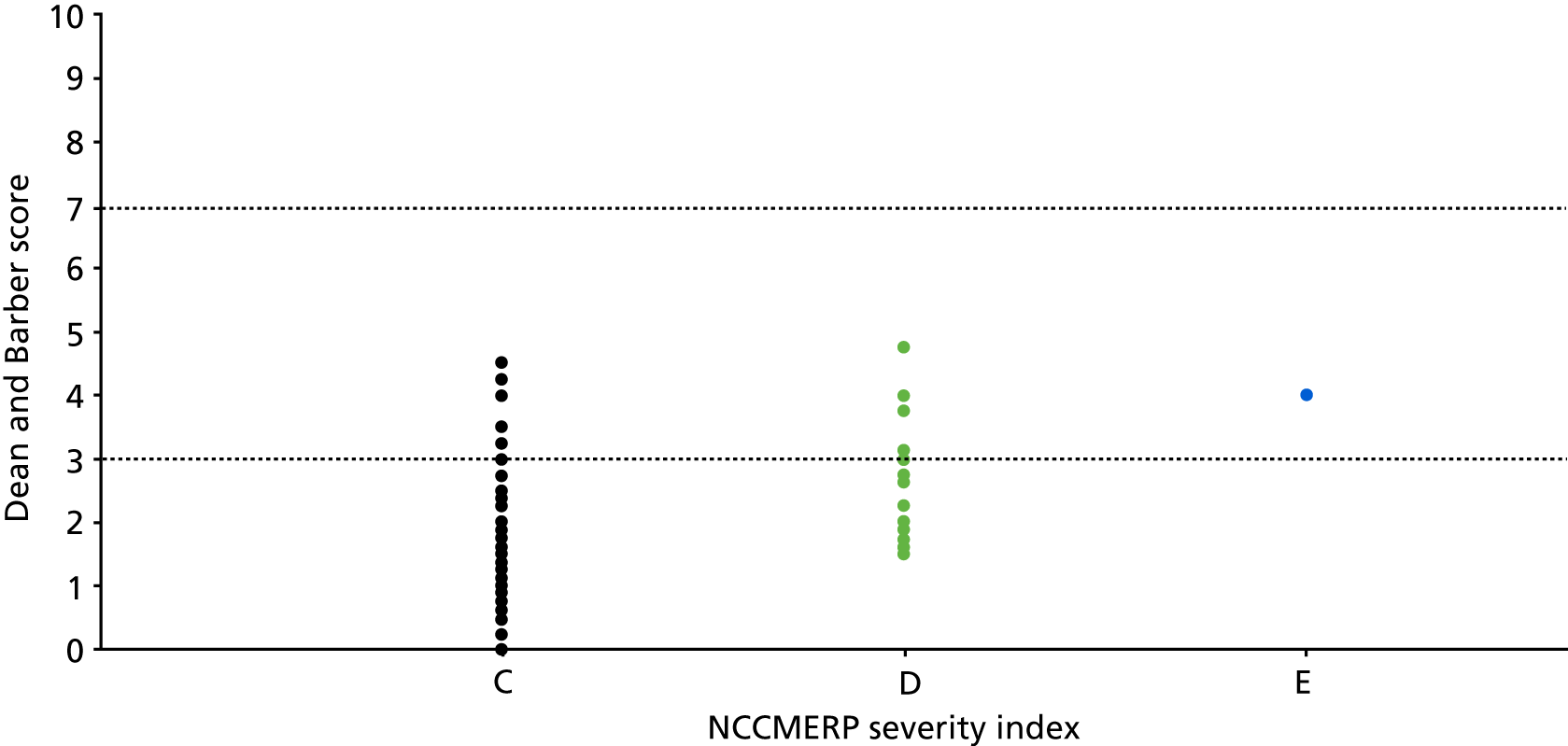

A systematic review of methods for measuring the clinical importance of prescribing errors identified a wide range of available methods but no comparative studies. 25 No comprehensive review has focused on methods to assess clinical importance of medication administration errors. However, in studies included in a systematic review of the prevalence and nature of medication administration errors, Keers et al. 26 noted that the two most commonly cited severity assessment methods were the US National Coordinating Council for Medication Error Reporting and Prevention (NCCMERP) severity index,27 and Dean and Barber’s method. 28 The former is an ordinal scale designed to be used by local staff who would usually have knowledge of actual outcomes and other contextual information, and the latter is an interval scale used by experts using descriptions of the errors without knowledge of their outcomes. In Chapter 3, we describe a comparison of these two methods of assessment to shed further light on the strengths and weaknesses of each.

Systems of practice: intravenous medication administration documentation

Numerous policies and procedures have been put in place at every participating hospital with the aim of reducing the risk of harm during IV infusion administration, and our first analysis presented in Chapter 4 focuses on variations in policy and practice around IV infusion administration.

A 2007 Patient Safety Alert for England and Wales29 made recommendations to reduce errors in injectable medicines, including risk-assessing procedures and products, reviewing protocols, providing technical information and competency-based training, and conducting an annual medicines management audit. It highlighted how procedures should be:

Clearly documented, reflect local circumstances and describe safe practice that all practitioners can reasonably be expected to achieve.

p. 3. 29

Before the ECLIPSE study, to our knowledge, no study had investigated whether or how health-care organisations had responded to this advice or how well these procedures are adhered to in practice.

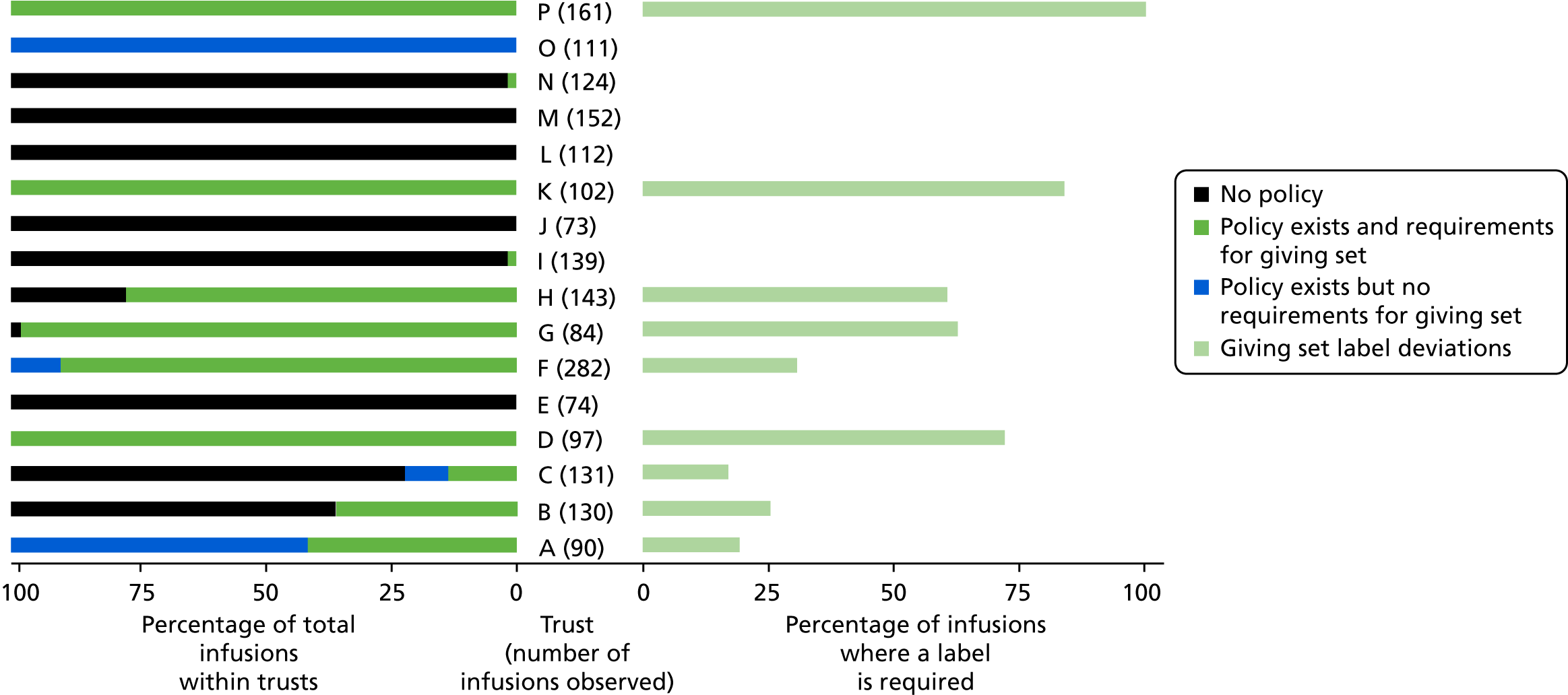

There has been limited research into procedural and documentation deviations of IV infusion administration. Husch et al. 6 included procedural and documentation errors in their study of 426 IV infusions in a US hospital; this study found two of the most prevalent error types to be no rate on the additive label, affecting 46% of infusions, and patient identification (ID) issues, affecting 13% of infusions. Schnock et al. 7 used a similar method across 10 US hospitals to examine 1164 IV infusions and reported 60% of infusions with an additive label that deviated from policy, 35% of infusions where giving sets were not labelled according to policy, and 0.2% of infusions where the patient had no ID wristband. No previous study has investigated procedural and documentation deviations in the UK and none has explored the surrounding context or possible reasons for the discrepancies identified.

Systems of practice: nursing

Parts of this section are based on Vos et al. 30 © 2019 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CCBY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

The second analysis presented in Chapter 4 focuses on the role of nurses as a source of system resilience. Nurses undergo training, education and lifelong learning in order to provide safe and high-quality care. 31–33 In nursing education, problem-solving is emphasised and is often presented as a systematic process in which one moves from assessment to eventually evaluating the effectiveness of an intervention. 33,34 However, daily nursing practice is often more complex than this linear picture suggests. The planning and implementation of nursing interventions, such as administering IV therapy, requires clinical judgement, and thus an interpretation of the situation by the nurse. 33,34 As a result, actions demand standard approaches to be modified or new approaches to be improvised according to the patient’s response. 34 This flexibility and variability in clinical work can result in a gap between ‘work-as-imagined’ (policy) and ‘work-as-done’ (practice),35–37 but can be paramount to achieving safer practice. 38

In the context of IV therapy, non-compliance with policy is a deviation. However, not all deviations from policy lead to negative consequences for patient care. 39 Larcos et al. 39 have proposed looking at ‘resilience’ in health-care practice to recognise flexibilities that might contradict policy. Examining the safety of IV therapy requires a broader view that also includes focusing on what goes right. The safety of IV therapy might also be influenced by clinical judgement, professionalism and knowledge.

Nurses are a key player in the delivery of high-quality IV therapy to patients. 40 Their decisions and actions contribute to the safety of IV therapy. However, it is unclear how this is accounted for in practice when measuring deviations from policy. One of our analyses (presented in Chapter 4) investigated those situations in IV therapy in which nurses are a source of system resilience in relation to quality and safety of IV practice through their actions and clinical judgement.

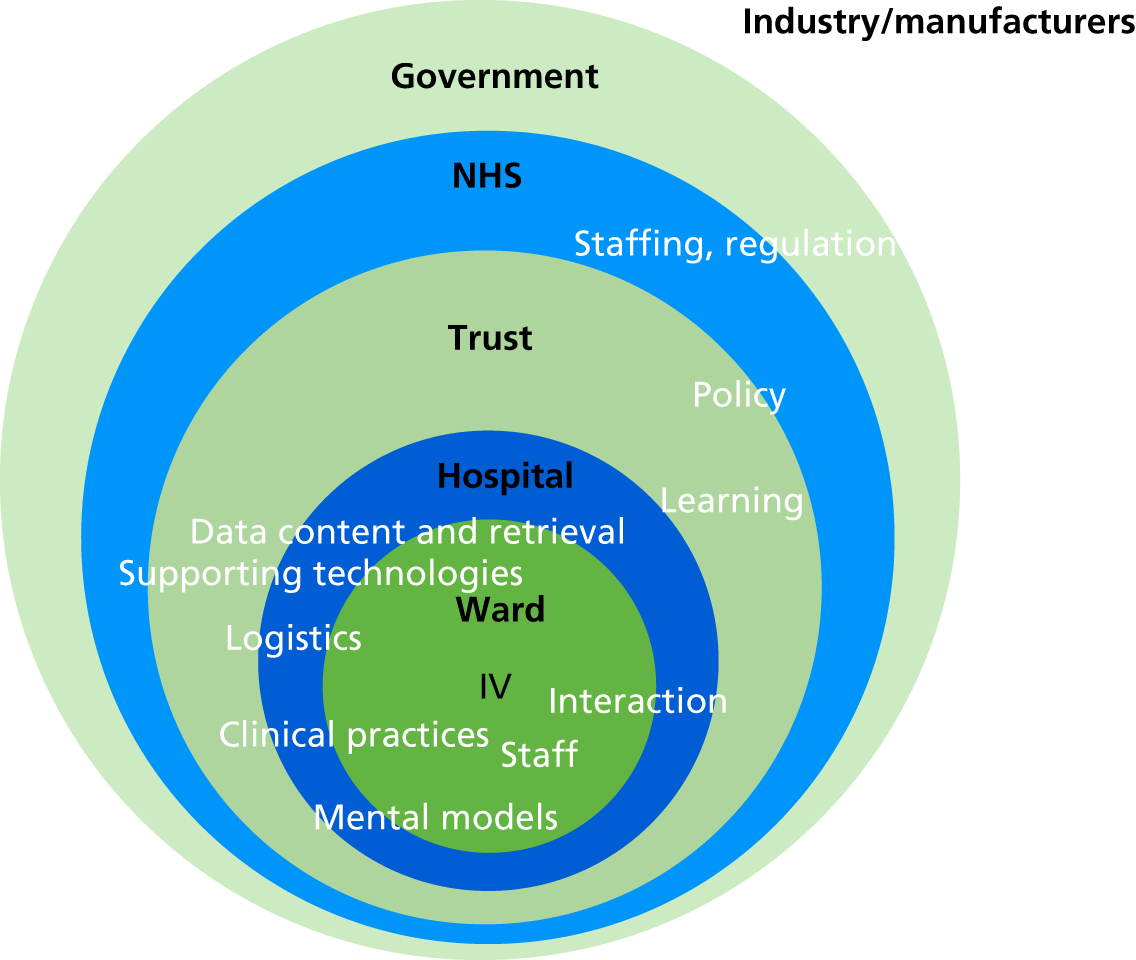

Systems of practice: layers of influence

The final analysis presented in Chapter 4 focuses on system adaptability. 41 It draws inspiration from the work of Brand,42 who argues that what makes an artefact adaptable is a design that differentiates between constructional categories according to their likelihood of change, coupling together elements that have the same rate of change into layers that are loosely coupled to other layers that have different change rates. This allows fast-changing layers to ‘slip past’ more stable layers, minimising the scale of impact of change, which makes the artefact easier and less costly to change to accommodate needs. This view is relevant to many designed artefacts that require adaptation and change during their useful lifespan to accommodate new or changing use requirements. This style of thinking can be adapted to view and assess the relative impact of an intervention in one layer on the functioning and performance of the entire artefact or system. The lower (more stable) layers are harder to modify than layers that are higher up in the hierarchy. Changes at the lower layers are also likely to have a greater impact than those at higher ones. The analysis reported in Chapter 4 identifies the layers for IV infusion administration.

Human factors and human error

Building on prior work on human error and IV medication administration, the ECLIPSE study was strongly informed by a human factors perspective. This approach is based on:

-

understanding the factors that contribute to errors occurring

-

focusing on what really happens in practice, which is often different from what is believed to happen

-

taking a ‘systems’ view that puts the person at the centre.

There is an extensive literature on human error, much of it summarised by Reason. 43,44 In brief, Reason identifies two main types of error. The first is mistakes, which occur when people do not have all the information needed to choose an appropriate action, or fail to plan or solve a problem correctly; mistakes can often be reduced by improved training. The second type is slips and lapses, which occur when people intend to do the correct thing, but inadvertently do something else as a result of distraction, fatigue or similar; slips and lapses cannot be eliminated through training, but can often be reduced through the design of tools or systems. Reason points out that the obvious causes of errors often appear at the ‘sharp end’ in the localised actions of an individual (e.g. a nurse programming an infusion pump), but that there are typically many latent failures behind these active failures (e.g. shortage of staff, working practices, local culture). He also distinguishes between errors and violations, with the latter classified into three groups: routine violations (cutting corners), optimising violations (doing something for personal gain) and situational violations (necessary to get the task done – often called workarounds). He argues that different causes of errors and violations require different counter-measures to prevent them or mitigate their effects. Reason focuses on major incidents about which there is general agreement that something went wrong. However, this is not always the case; for example, Furniss et al. 8 document ‘unremarkable errors’: when things did not go entirely according to plan and yet there was no untoward outcome.

Karsh et al. 45 contrast various paradigms for improving patient safety, arguing that, historically, most approaches (such as that presented by Reason44) have focused on minimising harm (by imposing barriers to prevent errors or injuries), and that an alternative human factors perspective is needed. They frame this in terms of designing systems to improve performance, including minimising hazards, and argue that both perspectives (imposing barriers to minimise the chances of bad things happening while also engineering systems to optimise performance) are necessary to improve safety.

There is a growing recognition that formalised descriptions of practices focus on ‘work as imagined’ and often miss the nuances and factors that most influence safety in practice. Blandford et al. 35 discuss this in terms of ‘work as imagined’ (as defined in training or in policies) and ‘work as done’ (as observed in practice). Heeks46 described this as the ‘design–reality gap’, pointing out that systems that do not match their users’ needs provoke workarounds, inefficiencies and sometimes rejection.

Workarounds have been studied extensively in various areas of health care. For example, Koppel et al. 47 provide an account of workarounds in BCMA, identifying 15 categories of workarounds and 31 categories of reasons for people employing workarounds; although workarounds are typically used to get work done in a timely way, they risk compromising patient safety and highlight issues in the broader system of care (in this case, the way in which BCMA has been implemented). Similarly, Debono et al. 48 present a systematic review of workarounds reported in 58 studies relating to nurses’ workarounds in acute-care settings; they highlight the paradox that workarounds can often simultaneously enable and compromise patient care.

Looking beyond the individual interacting with a device or other technology, a human factors systems approach places the person (the user of technology), the equipment and the task within the physical environment and the organisational setting, and accounts for behaviours within that context. This is exemplified in the work of Carayon et al. ,49 who adopt these concepts as foundational for the Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety (SEIPS) model for reasoning about patient safety. They argue that:

Human Factors Engineering interventions that do not consider issues across the whole system, including organisational factors, are unlikely to have significant, sustainable impact on patient safety and quality of care.

Carayon et al. 49

Carayon et al. present SEIPS as an approach for analysing a work context in terms of patient safety. We adopt this approach in one of the analyses reported in Chapter 7.

A complementary perspective that has also been widely applied for understanding health-care systems and health technology is that of distributed cognition. 50 One methodology for applying the theory of distributed cognition, Distributed Cognition for Teams (DiCoT),51 involves analysing a system in terms of physical structure, information flow, how artefacts support cognition, social structures and how a system has evolved over time. DiCoT has been applied to understanding infusion pump use in various settings including intensive care9 and an operating theatre. 52 This perspective informed our data collection in phase 2.

Safety I and Safety II

Traditionally, the literature on safety has focused on barriers to bad things happening (‘Safety I’). As summarised above, it has now been recognised that safety cannot be achieved only by creating barriers, but that performance must also be improved (‘Safety II’). Vincent and Amalberti53 propose a continuum of ways to keep a system safe, or optimising performance. At one end of the continuum they place ultra-adaptive performance, which embraces risk and relies on the skill of an individual; at the other end they place ultra-safe practice, which relies on standardised practices, checklists and policy, based on an expected standard of performance for each role, and limiting scope for individual excellence. Between these extremes they place high-reliability systems that invest trust in the team and manage risks by focusing on team performance and learning. Ultra-safe practices embody a Safety I culture, and high-reliability systems embody a Safety II culture. Although ultra-adaptive systems have a place in health care overall, they rarely play a substantial role in IV medication administration.

We aimed to incorporate a Safety II approach in interpreting our findings. This approach moves away from the traditional focus of classifying all deviations as errors, eliminating error and blaming the human for unreliable processing. Instead, it encourages one to think about deviations in terms of performance variability, how to understand and manage this variability, and that the human component can make positive contributions to safety. 38,53 Safety II maintains that mechanistic performance is inadequate because complex systems are open to surprises, often run in degraded states, and have competing goals and conflicting pressures. So, not all deviations are errors, humans can be a source of success and failure, and errors and discrepancies might point to system issues.

Safety II played an important role in the planning and conduct of our research: (1) it helped us understand that we were sampling everyday work and its consequences; (2) it encouraged us to take a more nuanced approach to any deviations from the medication ordered, classifying some as discrepancies rather than all being errors, as in previous research; (3) it has made us mindful of system resilience, such as where some deviations added to safety; and (4) it encouraged us to engage with local rationality and challenging trade-offs. Safety II advises that one should attend to where the system goes right as well as where it goes wrong. After all, often when safety is working well, it can appear that nothing is happening: there is the absence of incident. However, Safety II defines safety as the presence of something, something that is constantly created, so it makes sense to also look at practices that can potentially contribute to safety that might otherwise be overlooked.

Safety II recommends looking at ‘positive deviations’ in the system. However, ‘positive deviance’ is an established approach in health care that investigates excellence in performance. 54 This involves measuring performance and sampling those practices that are the highest performing. We did not take this approach. Instead, we learnt in earlier phases of our research that clearly defining and measuring IV infusion administration performance is challenging. Data from phases 1 and 2 pointed to something that was more variable and multilevelled than we had previously expected, with multiple contextual dependencies. Following this, therefore, we reviewed the literature on complex adaptive systems (CAS) to better understand how to interpret our findings in terms of complicated and complex systems.

Complexity science and complex adaptable systems

With hindsight, it is now evident that, in framing the ECLIPSE study, the perspective taken was of IV infusion administration as a relatively simple system, centred around the infusion pump. From that perspective, it made sense to ask simple questions around whether ‘smart pumps’ were safer than traditional pumps or gravity feed, and what best practice is in this area. However, our findings cannot readily be distilled into such simple questions or their answers. In the final months of the project, we therefore turned to richer theories that illuminate, and enable new interpretation of, our findings. In particular, prior research on complexity science and CAS provides promising avenues for future research and for interpretation of our existing data.

Complexity science is the science of systems that are difficult to define in simple or structured terms. 55 For example, Holland56 describes CAS as comprising a large number of agents that are diverse in both form (e.g. people and computer systems) and capability (e.g. multidisciplinary teams).

Plsek and Greenhalgh57 argue that behaviour emerges from such systems without being designed ‘top down’ through the local actions and interactions of agents within the system and that it is not generally possible to address problems in such systems by reducing them into a set of simple problems that can be addressed independently. Plsek and Greenhalgh57 propose trying multiple approaches and gradually evolving improved systems over time using techniques such as the plan-do-study-act (PDSA) cycle of quality improvement. 58 Plsek59 also argues that it is not possible to design CAS in detail, but that what needs to be set up are the conditions under which desired outcomes are more likely.

Complex systems are commonly contrasted with simple or complicated systems. A simple system is well understood, it is possible to apply evidence-based best practice, incoming information can be categorised, and an appropriate response can be generated; team members may need to co-ordinate activity, but there are no tight interdependencies. In complicated systems, cause–effect relationships are understood, but may be at-a-distance (in time or space); longitudinal studies may be needed to establish relationships; and team members need to co-operate to achieve desired outcomes. By contrast, in complex systems, cause–effect relationships are non-linear and there are many agents with different roles and relationships, making a conventional style of analysis that decomposes a system into independent subsystems impossible. A complex system includes both simple and complicated problems, but is not reducible to them. Glouberman and Zimmerman60 note that health-care systems are often managed and analysed as if they are complicated when in fact they are complex, and that managers address problems with approaches that are based on rational planning; these do not work as expected because they fail to take account of the complexity of the system.

The same point is made by Braithwaite et al. ,61 who argue that, to make ideas ‘stick’ in health care, it is essential to exploit people’s natural enthusiasms and networks, and that clinicians will ‘become more involved in promoting safer and better care if invited rather than compelled’. Braithwaite et al. 62 argue that, for CAS:

Despite the potential for unpredictability, non-linearity, and even messiness and chaos, there are patterns, behaviours, structures and routines which together define the system, and guide behaviour within it.

Braithwaite et al. ,62 p. 13

The examples they share are largely drawn from large-scale complex systems such as hospitals, and their focus is on the roles of people (particularly networks of people) and the diffusion of practices, with little attention paid to the design of tools or protocols.

Van Beurden et al. 63 summarise the Cynefin framework, which has four principal domains: simple, complicated, complex and chaotic. A fifth domain (disorder) applies when a problem is not well enough understood for it to be classified as one of the first four. They argue that, to effect positive change, it is necessary to develop ‘probes’ so as to ‘sense’ what configurations are most likely to succeed, and then ‘respond’ in ways that amplify effects. The Cynefin framework can be used to describe transitions between different domains as people find out more about what they are dealing with, either in discovering previously unknown information that increases complicatedness and complexity, or by discovering relationships and patterns that can simplify how one perceives the system. 64

Sittig and Singh65 introduce an eight-dimensional model to support reasoning about the design, deployment and evaluation of health information technology (IT) systems based on the perspective of health care as comprising CAS. The eight dimensions are hardware and software infrastructure; clinical content; the user interface; people such as end-users and developers; workflow and communication; internal organisational features such as policies and cultures; external factors such as regulation; and measurement and monitoring (which implicitly includes learning). These eight dimensions serve as a checklist, or set of probes, to ensure appropriate coverage of considerations in analysing the performance of technology in a complex adaptive health-care system.

These ideas of simple, complicated and complex systems, with their different properties and modes of problem-solving, have been applied in various areas of health care and health technology. For example, Greenhalgh et al. 66 have developed a framework to account for the (non-)adoption and spread of digital health interventions based on two orthogonal scales: the simplicity/complexity of the problem and domains of health concern (e.g. the health condition, the technology, the users, the organisational context). Glouberman and Zimmerman60 analyse the Canadian Medicare system as a complex system. Begun et al. 67 take a similar approach to analysing innovations in care delivery in the USA. Sittig and Singh65 focus specifically on health IT systems (e.g. electronic health records). No previous research has explicitly studied DERS or IV infusion administration as a complex system.

Aims and objectives

The aims of the ECLIPSE study were to describe the rates, types, clinical importance and causes of errors involving the infusion of IV medication in English hospitals, and to make recommendations for interventions with greatest potential for reducing harm from these errors.

The more specific objectives were:

-

to describe how IV infusions are administered in a sample of 16 English hospitals, including a specialist cancer hospital and two specialist paediatric hospitals, focusing on differences in terms of nursing practice, equipment, policies and processes, both within and between hospitals

-

to describe the rates, types and clinical importance of errors associated with the following modes of infusion delivery, in critical care, general surgery, general medicine, paediatrics and oncology:

-

gravity administration

-

standard infusion pumps and syringe drivers

-

smart infusion pumps and syringe drivers (with both hard and soft limits).

-

-

to explore variance in the rates, types and clinical importance of errors in relation to:

-

mode of infusion delivery

-

clinical area.

-

-

to explore the causes of the errors that occur and the extent to which innovations in technology or practice, such as the introduction of smart pump technology, electronic prescribing or bar code readers, could have prevented such errors

-

to identify best practices in safe and effective IV medication administration across different hospital contexts, including issues that are important to patients as well as staff

-

to establish how the findings differ from those of an ongoing US study, led by Bates,7 and to explore the reasons for any differences identified

-

to propose recommendations to prevent IV medication errors across different hospital settings in England.

In practice, as discussed below, it was found that the observations on IV medication practices could not be accounted for by considering IV medication administration as a simple or complicated system, but they could be accounted for by viewing it as a CAS. Consequently, research objective 4 was subsequently reframed in those terms, and research objective 7 has been addressed in a more nuanced way (see Chapters 7 and 8) than originally envisaged.

Structure of this report

In Chapter 2, we present the methods applied in the studies reported here; these are organised into two main phases. Phase 1 was a mixed-methods study involving point-prevalence observations supplemented by debrief interviews with the observers and focus groups with key staff members within the participating hospital. Phase 2 comprised in-depth observational study (using qualitative methods) of five of the participating hospitals. Phase 3 of the study involved engagement with stakeholder groups including patients, the public, health professionals, policy-makers and industry, and was conducted in parallel with phases 1 and 2.

The results of the quantitative observational study (phase 1), including further analyses of the quantitative data, are presented in Chapter 3. These results address the main overall aim of the ECLIPSE study, in describing the rates, types and clinical importance of errors involving infusion of IV medication in English hospitals. The analyses presented address objectives 2, 3 and 6 above.

Accounts in terms of systems of practice, based on the qualitative data from debriefs and focus groups in phase 1, are presented in Chapter 4. In this chapter, we present three complementary analyses of the data that focus on emergent themes, namely an analysis of the variations in policy and practice across hospitals (focusing particularly on IV medication procedures and documentation); an analysis of nursing practices, and how expert practices contribute to system resilience; and an analysis of perceived layers of influence. Collectively, these analyses address objective 1.

In Chapter 5, we present further analyses that aimed to explicitly address research objective 4, including further analysis of the phase 1 data and also an analysis of National Reporting and Learning System (NRLS) data to better understand the potential impact of smart pumps in the English NHS. These studies were not in the original protocol, but were added to provide an alternative perspective on the question about the value of smart pumps, at no additional cost to the project.

In Chapter 6, we present findings from the in-depth observational studies (phase 2), focusing on patient perspectives, contributing to objective 5.

In Chapter 7, we present the main findings from the in-depth observational studies (phase 2); in particular, we relate findings to views of IV medication administration as a work system and as a CAS. Findings reported in this chapter contribute to objectives 3, 4 and 5.

In the discussion (see Chapter 8), we draw together key themes from the study around the nature of the challenge, roles for technology, and the novel perspective on IV infusion administration offered by the theory of CAS; we also discuss strengths and limitations of the study, and highlight challenges experienced in conducting it.

In the concluding chapter (see Chapter 9), we highlight the value of informative variability for enhancing patient safety and experience of IV infusion administration, review implications for health care and make recommendations for future research based on our findings in order to address objective 7.

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter includes material reproduced or adapted from Blandford et al. 1 and Lyons et al. 68 These articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

This chapter is divided into four sections. The first describes the phase 1 mixed-methods study, including the point-prevalence study, debriefs and focus groups, and three supplementary studies. The second section describes the phase 2 methods, comprising deeper ethnographic observations on some wards as well as staff and patient interviews. The third section describes how we engaged with stakeholders during the project, which includes patients and the public, health-care professionals and industry. The final section highlights ethical issues considered in relation to data collection.

Phase 1: mixed-methods study across 16 hospitals

Study design

The study employed a mixed-methods approach bringing together complementary quantitative and qualitative methods. A quantitative point-prevalence study, using observational methods, was used to document the prevalence, types and clinical importance of errors associated with the infusion of IV medication, that is, ‘what’ and ‘how many’ deviations occurred in practice. Qualitative debriefs and focus groups with relevant hospital staff helped explain the findings, in other words ‘why’ the deviations occurred in practice. The design of the point-prevalence study was based closely on that used in a similar US multicentre study that studied general medical, general surgical, medical intensive care and surgical ICUs. 7 This approach, originally developed by Husch et al. ,6 involves trained staff systematically comparing details of each IV infusion in progress at the time of observation with the medication prescribed, to identify any discrepancies. Within the ECLIPSE study, once a preliminary analysis of quantitative data had been conducted, debriefs and focus groups were held with key staff to reflect on the point-prevalence results and relate these to details of hospital IV practices.

Study setting, recruitment and sample selection

The study took place within acute hospitals across England. Expressions of interest were sought from English NHS hospital trusts through the National Institute for Health Research Clinical Research Network, NAMDET and contacts from a previous study. 5 Interested parties were then invited to complete an online survey to provide an overview of their hospital, capacity to take part, infusion pump types and practices. Eighteen NHS trusts responded to the survey, providing information about 26 potential hospital sites. We aimed to include a mix of hospitals that used smart pumps with DERS and those that did not. Few hospital trusts that made use of smart pump technology across all clinical areas responded to the survey, so they were approached separately to maximise the number of observations involving smart pump technology. Hospitals were chosen purposively, with the aim of representing maximum variation in terms of type, size, geographic location, potential indicators of patient safety such as being a Bruce Keogh Trust,69 hospital mortality indexes70 and media reports, and their self-reported use of infusion devices and smart pump technology. Thirteen acute hospitals, two specialist children’s hospitals and one specialist cancer hospital took part in the first phase of the ECLIPSE study. Appendices 1 and 2 summarise the recruitment process and characteristics of each participating trust.

We conducted observations in three clinical areas (general medicine, general surgery and critical care) in 13 hospitals; in eight of these we also conducted observations in paediatrics and oncology day care. Two specialist children’s hospitals collected paediatric data only. One further trust collected oncology day-care data at three hospital sites.

Medication infusions included any medication, fluids, blood products and nutrition administered via an IV infusion, including patient-controlled analgesia (PCA). This slightly extends the focus of previous studies,6,7 which focused on medication and fluids (which are also legally classed as medications), to include other IV administrations. We aimed to include observation of 2100 infusions in total across all study sites to give a confidence interval around a 10% overall error rate across hospitals and clinical areas of 8.7% to 11.3%. 6,17

The debriefs were attended by the two observers and staff who helped to organise the research at the site, such as the local co-ordinator and the local principal investigator. A focus group was held at each site; these were attended by different hospital staff (including ward managers, senior nursing staff, patient safety specialists, medical electronics personnel, trainers, those with responsibility for procurement, and senior managers), so they varied in type and number of attendees. A member of the research team facilitated the debrief and focus group sessions.

Data collection

Point-prevalence study

Data were collected between April 2015 and December 2016. At each trust, two observers (usually a nurse and a pharmacist) employed in the organisation were given half a day of training by the research team to collect data. This training included highlighting the types of deviations to look for, conducting observations in the presence of the research team where possible, and using sample cases to facilitate discussion about classification of deviations identified (including assessing their severity). Observers were also requested to identify and familiarise themselves with relevant local policies and guidelines prior to data collection. Observers then spent one weekday or equivalent collecting data in each clinical area. Although the ward manager was consulted about suitable dates for observation, ward staff were not informed of specific observation dates. However, observation was not covert.

One clinical area could comprise one or more wards. Observers aimed to collect data on all IV infusions being administered at the time of data collection, including drugs, fluids, blood products and nutrition. Bolus doses were excluded, except where a prescribed bolus was given as an infusion, or vice versa. Completed infusions were excluded even if still attached to the patient. Patients were not observed if they were in isolation (because of infection risks), if they were receiving care that would have required interruption, or if they were off the ward.

Observers compared each medication being administered against the prescription and local policies and other guidance, and consulted clinical staff if needed to understand any deviations. Data were recorded using a standardised paper form (see Appendix 3) and subsequently uploaded to a secure web-based tool. 71,72 No patient identifiable data were recorded. Suspected errors were raised with clinical staff so they could be corrected if needed; local reporting practices were then followed.

Debriefs and focus groups

Following observational data collection at each trust, a report was drafted summarising that trust’s data (see Report Supplementary Material 1). This was presented at a debrief meeting with the observers, providing an opportunity to clarify aspects of the policies, practices and deviations observed. These clarifications sometimes led to updates to the data. For example, one site realised that giving set labels in its critical care unit were not compliant with its policy because they did not include the date the infusion was set up; another site initially included some infusions that were completed but were still connected to the patient, so these were subsequently excluded. Focus groups were then conducted with other local stakeholders to contextualise the findings, explore details of policies and practices and reasons for deviations, and discuss implications of the findings. Debriefs and focus groups were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim. Guides for debrief and focus group sessions can be found in Document A on the project web page (www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/1220927/#/; accessed 1 March 2019).

Identifying and assessing deviations

The observers at each site recorded any deviations from a prescriber’s written or electronic medication order, the hospital’s IV policy and guidelines, or the manufacturer’s instructions. This included administration of medication to which the patient had a documented allergy or sensitivity, but did not assess other aspects of the clinical appropriateness of the medication order. We also collected data on policy violations and procedural or documentation deviations that may increase the likelihood of medication administration errors occurring. We specified four types of procedural and documentation deviations a priori: (1) giving sets not labelled appropriately; (2) documentation of administration inaccurate or incomplete; (3) infusion additive labels missing, incomplete or incorrect; and (4) patient ID wristbands missing or with incorrect, illegible or missing information. We identified two further types of deviation where policies varied among trusts during the debriefs and focus groups: (5) prescription and administration of IV flushes, and (6) procedures for the double-checking of medication. Finally, we encouraged observers to record any other irregularities, anomalies or workarounds related to the administration. Some of these were grouped together for analysis and formed new categories. Table 1 presents definitions of deviation types.

| Types of deviation | Definition |

|---|---|

| Medication administration deviations (errors and discrepancies) | |

| Unauthorised medication/fluids (no documented order) | Fluids/medications are being administered but no medication order is present. This includes failure to document a verbal order if these are permitted as per hospital policy |

| Wrong medication or fluid | A different fluid/medication/diluent as documented on the IV bag (or bottle/syringe/other container) is being infused from that specified on the medication order or in local guidance |

| Concentration deviation | An amount of a medication in a unit of solution that is different from that prescribed |

| Dose deviation | The same medication but the total dose is different from that prescribed |

| Rate deviation | A different rate is being delivered from that prescribed. Also refers to weight-based rates calculated incorrectly including using a different patient weight from that recorded on the patient’s chart |

| Delay of dose or medication/fluid change | An order to change the medication or rate not carried out within 4 hours of the written medication order, or as per local policy |

| Omitted medication or IV fluids | The medication prescribed was not administered |

| Allergy oversight | Medication is prescribed/administered despite the patient having a documented allergy or sensitivity to the drug concerned |

| Expired drug | The expiry date/time on either the manufacturer’s or the additive label has been exceeded |

| Roller clamp deviation | The roller clamp is not positioned appropriately/correctly |

| Incomplete infusion or delayed completiona | |

| Procedural and documentation deviations (errors and discrepancies) | |

| Patient ID | Either patient has no ID band on wrist or information on their ID band is incorrect |

| Wrong or missing information on additive label | Any incorrect or missing information on the additive label, as required by hospital policy |

| Giving set not tagged according to policy | Tagging or labelling of giving set is different (either missing or incorrect) from that required by hospital policy |

| Documentation of the medication administration | Medication/fluids administered but not documented correctly on chart (e.g. missing signature, start time) |

| Documentation of the medication ordera | Medication/fluids administered based on an incomplete, poorly documented or ambiguous medication order, for example missing signatures or dates, the absence of a specific time to be administered where required, or the absence of clear instructions that a medication should be titrated to clinical need or within certain parameters |

Rating of deviations

Local observers rated each deviation using an adaptation of the NCCMERP severity index. 27 They were also provided with a guidance document that included examples of how to rate errors [see example in Document B on the project web page (www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/1220927/#/; accessed 1 March 2019); this is the version used at the final training site as the document evolved during the study as new issues came to light].

Ratings were based on the likelihood of the deviation resulting in patient harm had it not been intercepted, and were used to classify the deviations as discrepancies (rated A1 or A2) or errors (rated from C to I) (Table 2). Throughout, we used the original and adapted NCCMERP severity index as the basis of our thinking. The original NCCMERP index defines category A as ‘circumstances or events that have the capacity to cause error’, while category C is ‘an error occurred that reached the patient but did not cause patient harm’. As noted above, we had to adapt the NCCMERP index to consider whether or not observed deviations had the capacity to cause harm, rather than whether or not they had already done so.

| Harm | Category | Description |

|---|---|---|

| No error | A1 | Discrepancy but no error |

| A2 | Capacity to cause error | |

| Error, no harm | C | An error occurred but is unlikely to cause harm despite reaching the patient |

| D | An error occurred that would be likely to have required increased monitoring and/or intervention to preclude harm | |

| Error, harm | E | An error occurred that would be likely to have caused temporary harm |

| F | An error occurred that would be likely to have caused temporary harm and prolonged hospitalisation | |

| G | An error occurred that would be likely to have contributed to or resulted in permanent harm | |

| H | An error occurred that would be likely to have required intervention to sustain life | |

| Error, death | I | An error occurred that would be likely to have contributed to or resulted in the patient’s death |

On the basis that category A events have the ‘capacity to cause error’, rather than being errors in their own right, we referred to these as ‘discrepancies’ so as to explore nuances in definitions of and reporting of errors. We split this category into two, ‘discrepancy but no error’ and ‘capacity to cause error’, because our pilot sites identified situations in which there were discrepancies that it was agreed would be unlikely to cause an error (see Table 8).

No deviations were rated as B because the study method meant that all deviations reached the patient. There might be an argument that some of the workarounds that were observed were responses to errors that had happened elsewhere in the system, but as we did not conduct observations across the broader system (e.g. actions in prescribing or stock management in pharmacy), we focused our analysis on what was observable at the bedside.

Based on the ratings (see Table 2), we developed and clarified our classifications, recognising that deviations could be either errors or discrepancies, and could occur either in medication administration or in the associated procedural and documentation requirements.

Observers at each trust documented brief descriptions of any deviations identified and provided further qualitative insights during semistructured debriefs once data collection was complete.

Data management and analysis: point-prevalence study

Data cleaning and classification was a highly iterative process as data collectors and the team worked through the many ambiguities and contextual factors that shaped practice.

Data on all deviations were adjusted in response to the debriefs and focus groups held at each trust. Researchers within the research team then collated and analysed these data together. This multisite analysis led to further adjustments in the quantitative data to ensure that they were as consistent as possible between trusts, so that similar deviations that had been rated differently were made consistent. To help with this process, clinicians within the research team reviewed deviations that local observers found difficult to categorise, similar deviations of similar type coded differently by observers and all deviations rated as category D or above. Minor changes were made to classifications of type and severity as needed. Examples of some of the classification heuristics developed within the team and discussions around particular observations are included in Appendix 4.

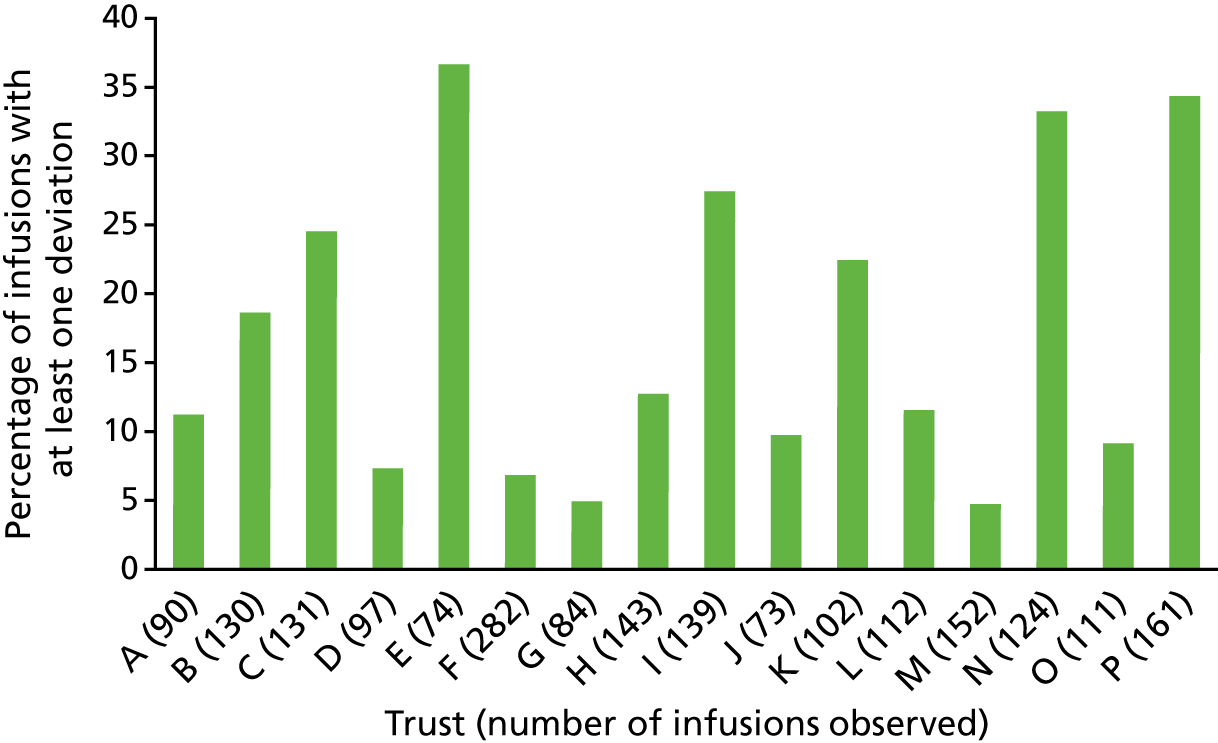

Error and discrepancy rates were calculated as the proportion of infusions with at least one error or discrepancy, using total opportunities for error (total number of doses administered, plus any omitted doses) as the denominator. Results were presented according to overall error and discrepancy rates, and individual types of errors and discrepancies, grouped into medication administration deviations and procedural/documentation deviations. Variations in deviation rates between clinical areas, delivery modes and infusion types were explored descriptively with their 95% confidence intervals, and chi-squared tests where appropriate. Qualitative data were analysed inductively.

Supplementary analyses

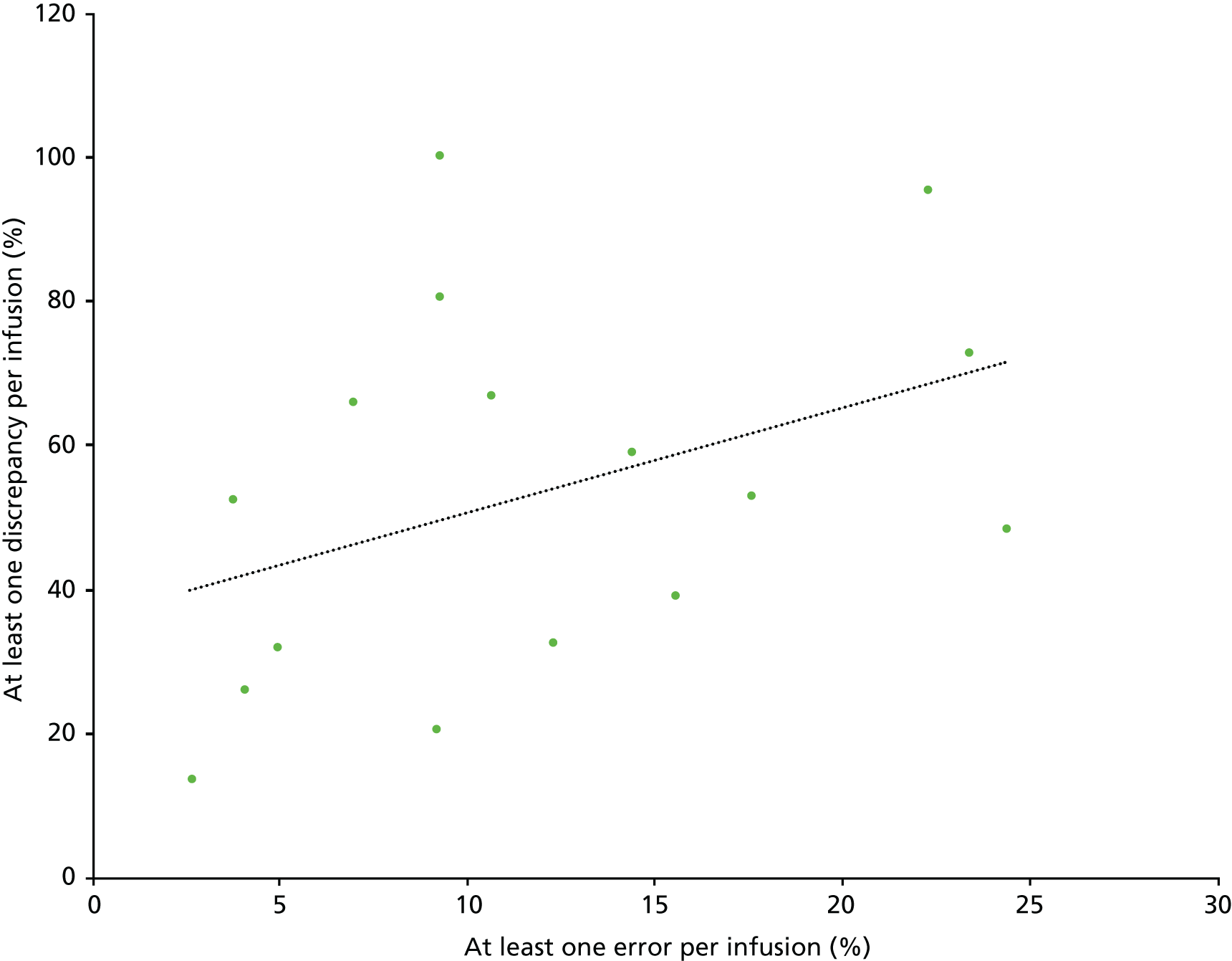

Two supplementary analyses of the data were conducted, comparing the NCCMERP method of assessing severity with an alternative approach, and comparing the findings from England against broadly equivalent data gathered in the preceding US study. 7

Comparison of two methods for assessing the severity of errors

A second method was used to assess the clinical importance of identified errors to explore any differences that may be found. The first method, using the adapted NCCMERP severity index, has been explained above. The second was the Dean and Barber28 method for assessing the severity of medication administration errors, developed and validated in the UK. This involves four experienced health-care professionals assessing each error on a scale of 0–10, where zero represents an error with no potential consequences to the patient and 10 represents an error which would result in death. The mean score across the four judges is then used as an index of severity, which has been shown to be both reliable and valid. Scores of < 3 are considered ‘minor’, those between 3 and 7 are considered ‘moderate’ and those of > 7 are considered ‘severe’. We recruited two experienced clinical pharmacists and two experienced nurses as the four judges. Judges were given a description of each error, blinded to the NCCMERP severity index scores previously allocated, and asked to rate each on the 0–10 scale. If identical errors occurred several times, only one was assessed. Scores from both methods were entered into SPSS (version 21; IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) for descriptive analysis. A scatterplot was produced to allow visual comparison between the two sets of scores, and the correlation between them was assessed using Spearman’s rank-order correlation.

Comparing findings from the USA and the UK

A comparative analysis was conducted on the findings from phase 1 of this project and a recent similar study from the USA. 7 We developed our protocol from that of this US study, and so the protocols broadly matched. There were differences in the number and type of hospitals that participated in each study; the US hospitals all used smart pumps, whereas these were used for only a proportion of infusions in the UK study; there were slight differences in the clinical areas and type of IV products included; and the US team classified all deviations as errors rather than separating these into discrepancies and errors. Once the separate studies had been completed, key members of both study teams convened to identify themes for comparison and contrast across the two studies. Initially, the well-sorted tool (www.well-sorted.org/) was used to enable all authors to individually identify themes and then collectively agree on key themes; then, through rounds of discussion and writing, themes were honed. Various analyses of the data from both studies were conducted to better understand what factors might be related to differences across countries, what might be due to levels of technological maturity, and what might be a result of other factors.

Developing accounts in terms of systems of practice

Three complementary analyses, drawing on the phase 1 qualitative data, were conducted to better understand the causes underpinning the quantitative data.

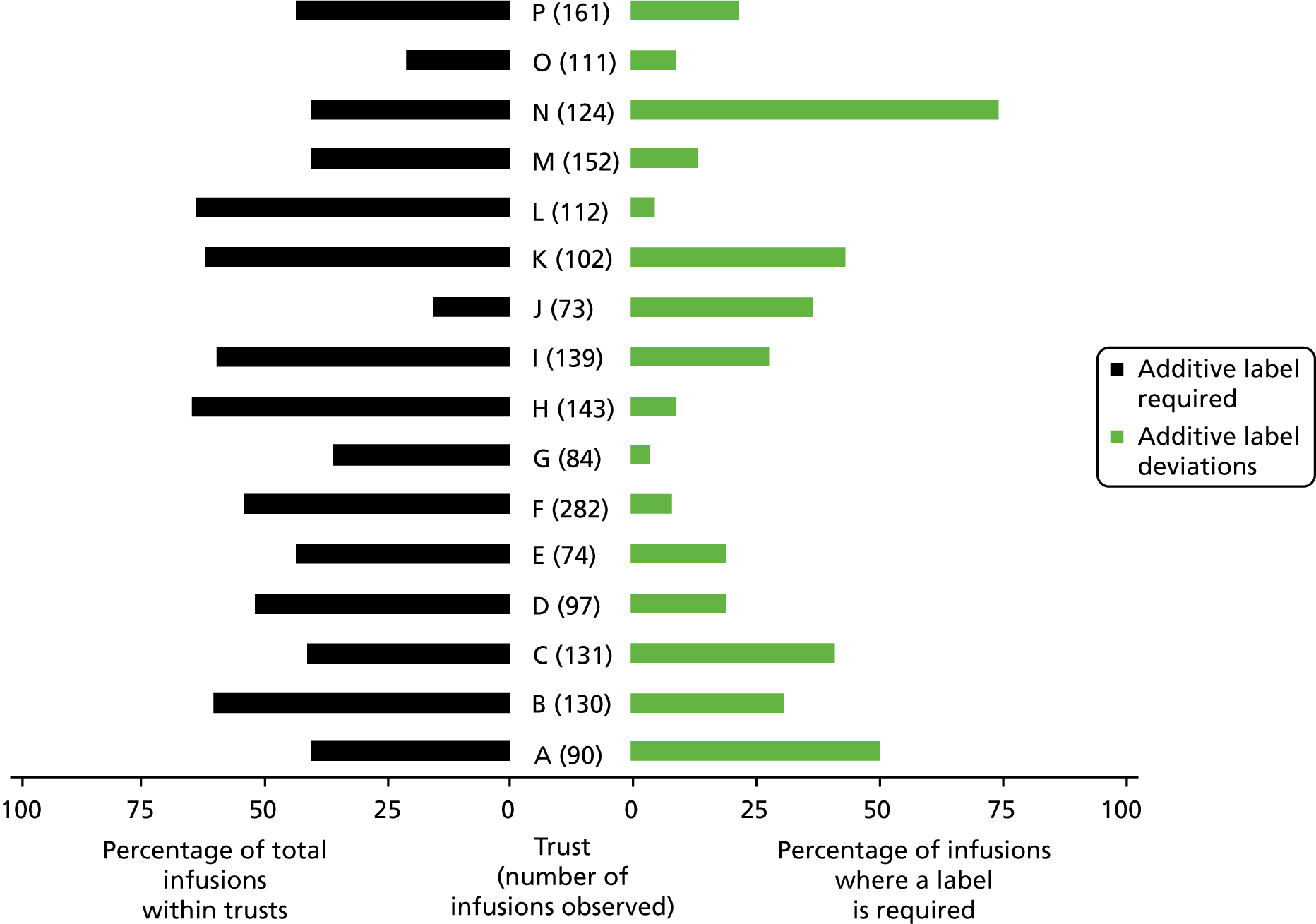

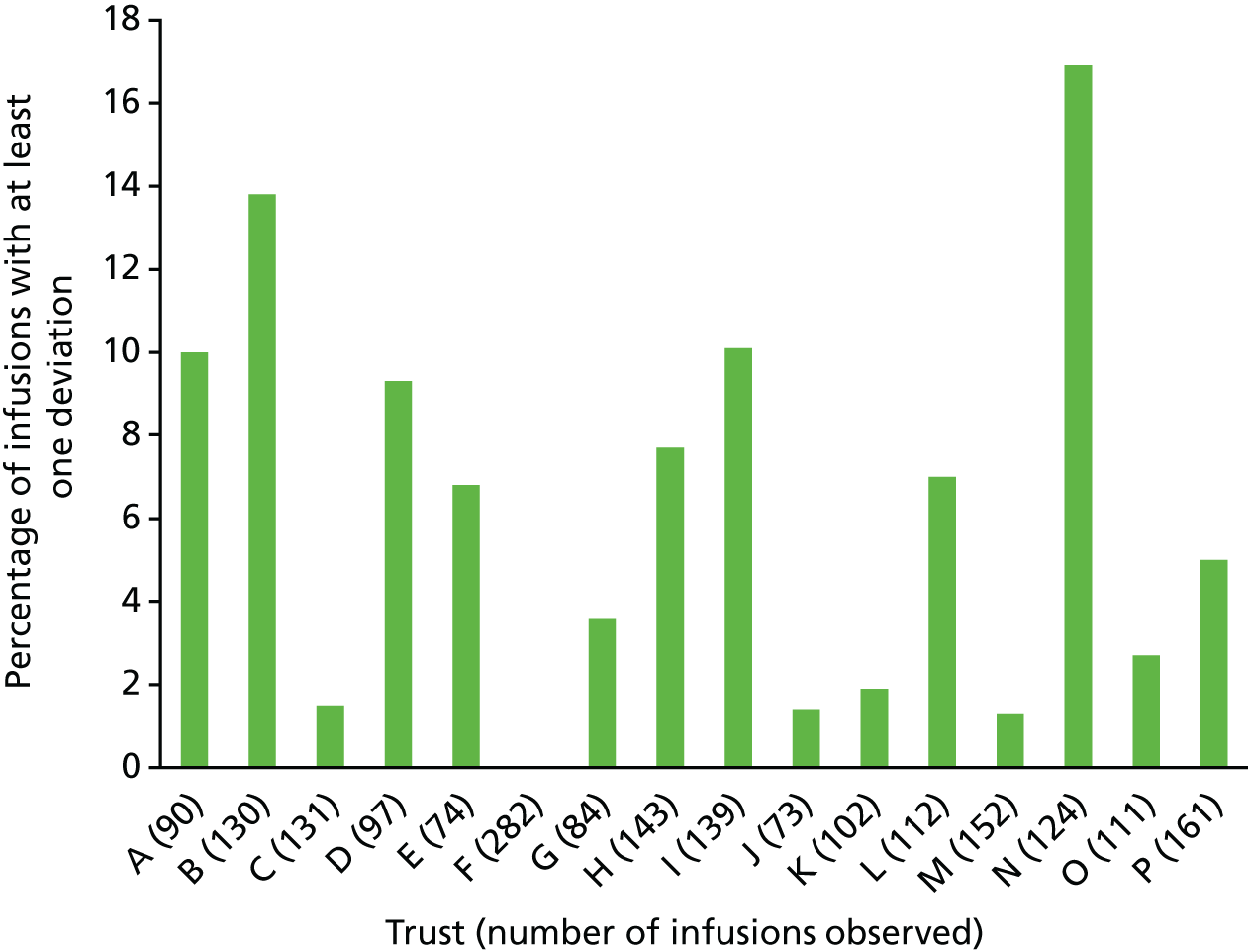

Procedural and documentation variations in intravenous infusion administration

The variance in procedural and documentation deviation type and frequency was explored alongside the variance of local policy. Policy requirements were found to be very different in some areas, and so split charts were used to present both the variability of local policy requirements and the rates of deviation against these. Deviation rates were calculated as infusions with at least one deviation against local requirements as the numerator, and the total number of doses administered as the denominator. Debrief and focus group data were analysed inductively, and used to contextualise the quantitative data and provide explanatory detail about issues within and across trusts.

Nurses as a source of system resilience

Nursing behaviour that contributed to system resilience in IV therapy was explored in the debrief and focus group data. The initial inductive analysis involved annotating the transcripts and line-by-line coding. A list of categories and themes was created from the emerging codes. In the final stage, a thorough analysis was conducted of those themes and categories relating to nurses’ behaviour and illustrating system resilience in IV therapy.

Identifying perceived layers of influence

A broad view of influences on IV medication deviations was also explored based on the debrief and focus group data. The analytical steps taken involved:

-

reading to highlight all the interesting elements in the data that relate in some way to IV medication administration (‘generating initial codes’ in thematic analysis73)

-

relating all such codes and constantly comparing them to each other to eliminate redundancies and identify themes (or categories) and establish category/subcategory relationships; this helps compress and summarise the data

-

refining the list of concepts into a more consolidated list

-

relating the concepts to each other and arranging them into related, but ordered, ‘layers’.

Supplementary studies

Two further analyses (not included in the original protocol) were conducted to further explore the role of smart pumps in contributing to patient safety. The first focused on the data from the point prevalence study, the second on data from the NRLS. Findings from these analyses are reported in Chapter 5.

Analysis of the errors identified in phase 1 to explore the role of smart pumps

The quantitative data set from phase 1 provides the opportunity to explore the potential role of smart pumps in preventing or contributing to errors. We therefore conducted a supplementary analysis of these data to identify:

-

the different types of errors identified in infusions given via smart pumps and those given using other types of pump

-

for errors identified in infusions that were not given via a smart pump, the extent to which these errors would have been likely to have been prevented using a smart pump

-

for errors in infusions that were given via a smart pump, the extent to which the use of a smart pump may have contributed to the error.

Each error of NCCMERP severity index category C or above was reviewed by two clinical members of the ECLIPSE study research team (a pharmacist and a nurse) to make a judgement as to whether the error would have been expected to have been prevented using a smart pump or whether a smart pump contributed to the error. Each error was reviewed and classified in discussion between the two researchers.

The following assumptions were made:

-

If using a smart pump, it was assumed that a suitable drug library entry was available and that staff would select and use the correct entry, and that any alerts arising as a result of soft limits would not be over-ridden if they were alerting to an error.

-

The following errors would not be prevented using any kind of smart pump:

-

omission errors, including those due to unavailability of pumps or giving sets, pumps not functioning or staff not knowing how to use the equipment

-

errors concerning patient ID

-

errors involving the administration of expired medication

-

labelling errors

-

delay in starting or completing the infusion.

-

-

The following errors would not be prevented using a standalone smart pump but may be preventable if smart pumps are integrated with electronic prescribing administration systems:

-

giving medication without a corresponding medication order

-

wrong rate errors where the rate was incorrect in relation to what was prescribed for that particular patient, but where the rate administered was within the usual range for the drug concerned

-

wrong rate errors concerning much lower (rather than higher) rates than those prescribed, in drugs for which very low rates are sometimes used in clinical practice.

-

-

For errors involving infusions of drugs or other fluids given via gravity feed where the rate was incorrect because the clamp was set incorrectly, it was assumed that these would be prevented by any pump (not necessarily a smart pump).

For the remaining errors (other wrong rate errors, dose/volume errors, wrong medication, concentration errors, and any other errors), each was reviewed individually with a judgement made on a case-by-case basis. Errors were classified using one of two sets of categories depending on whether or not a smart pump had been in use at the time of the error, as shown in Table 3.

| Smart pump device used? | Categories |

|---|---|

| No or not applicable |

|

| Yes |

|

To increase the rigour of this analysis, members of an expert panel were then invited to assess the preventability of a 25% random sample of the errors detected, stratified by smart pump use, traditional pump use or gravity administration. The panel members were a self-nominated group of 13 drug library experts who either had implemented or were in the process of implementing smart infusion devices in their organisation; they had previously been identified through the medication safety officer network for England to form a National Drug Library Expert Group.

All 13 experts were invited to participate by e-mail. Those who agreed (seven experts) were sent an anonymised sample of the data (listing whether a smart infusion pump, a traditional pump or gravity administration had been used and a description of the error) and requested to complete their assessment of preventability using the same predetermined categories (see Table 3). Participants were also requested to provide any comments or narrative about the errors listed, as well as comments on the assumptions made and the process of assigning categories. Agreement among the panel and between the panel and the research team was assessed descriptively.

Analysis of incidents reported to the National Reporting and Learning System

Having explored the potential role of smart pumps in preventing or contributing to administration errors within the ECLIPSE study point-prevalence data, most of which related to relatively minor errors, we took the opportunity to gain a complementary perspective through analysing data reported to the NRLS. All health-care organisations within England and Wales should report patient safety incidents to the NRLS. Although there is known to be considerable under-reporting in all incident-reporting systems, it is generally believed that serious errors are more likely to be reported. Although it was not part of our original protocol, we decided to conduct this supplementary analysis to complement the ECLIPSE study point-prevalence data. Our objectives were to identify more serious errors involving IV infusions and then to comment on the extent to which these may have been prevented by use of a smart pump or, for those that were given by a smart pump, the extent to which the smart pump may have contributed.

We requested data from the NRLS relating to incidents involving infusion pumps. Following approval by the NRLS and signing of a confidentiality agreement, we obtained anonymised reports for all incidents reported to have occurred between 1 January 2005 and 31 December 2015 that contained search terms relating to infusions or infusion pumps in any of the following fields: ‘description of what happened’ (field IN07), ‘action preventing reoccurrence’ (IN10), ‘apparent causes’ (IN11) and ‘device name’ (DE03). A full list of the search terms used is provided in Appendix 5.

From the data obtained, we selected those incidents rated as being of ‘moderate’ severity or above (moderate, severe or resulting in death; Table 4 provides definitions) that occurred in hospital inpatient settings, excluding operating theatres. We then removed all those relating to subcutaneous or other non-IV infusions; those where an IV infusion pump was mentioned in the report but the patient safety incident was unrelated; those that related to different types of pump, such as intra-aortic balloon pumps; and any others judged to be irrelevant.

| Harm category (relating to the actual harm experienced) | Definitions used within the NRLS |

|---|---|

| Low | Any unexpected or unintended incident that required extra observation or minor treatment and caused minimal harm to one or more persons |

| Moderate | Any unexpected or unintended incident that resulted in further treatment, possible surgical intervention, cancelling of treatment or transfer to another area, and which caused short-term harm to one or more persons |

| Severe | Any unexpected or unintended incident that caused permanent or long-term harm to one or more persons |

| Death | Any unexpected or unintended event that caused the death of one or more persons |

All reports were reviewed by two clinical members of the ECLIPSE study research team plus a third expert medication safety officer with experience of setting up drug libraries. The team discussed each case and made a judgement as to whether the error would have been expected to have been prevented using a smart pump or, for those that were given by a smart pump, the extent to which the smart pump may have contributed.

The same assumptions were made as in the section above, and the remaining errors (other wrong rate errors, dose/volume errors, wrong medication, concentration errors and any other errors) reviewed individually, with a judgement made on a case-by-case basis.

A separate subanalysis was conducted for those errors involving the wrong rate, dose or volume, using the same approach, as these are arguably those most likely to be preventable with a smart pump. To put these data into context, we then estimated the number of infusions given each year in the English NHS. This was done by identifying several sources of relevant data [National Patient Safety Agency (NPSA; now incorporated with NHS improvement) Safer Practice Notice 01: Improving Infusion Device Safety,74 electronic prescribing data from one study site, and IV giving set purchasing data from a second site] and estimating the average number of IV infusion administrations per bed per annum from each of these sources, and then multiplying by the number of beds in English hospitals. 75

Phase 2: in-depth observations and interviews in five hospitals

This phase of the project explored interesting contexts and practices from phase 1 more deeply in order to describe how practices differ and identify what aspects of the sociotechnical system have positive and negative effects on error types and rates. Phase 2 therefore aimed to develop a rich understanding of the factors that influence performance around IV medication administration.

Study design

Phase 2 was a qualitative study based on observations and interviews in five hospitals. Observations included staff administering IV medication and setting up pumps, supplemented by interviews with staff to further understand why certain errors occur within each context. Data gathering and analysis were driven from a human factors and sociotechnical system perspective. As described above, this emphasises how the safety and performance of a system is an emergent property of the ways the people, policy, practices, artefacts and equipment combine within it. The analysis focused on the causes of error, the need for any workarounds in practice, and identifying best practices in safe IV medication administration.

The patient’s role is often neglected in medical care;76 we addressed this by interviewing patients about their IV infusion experiences. These patient-centric findings have the potential to inform practice through better consideration of people’s requirements and preferences.

Study setting, recruitment and sample selection

The phase 1 results were used to identify hospitals and clinical areas for more detailed study in phase 2. These were selected on the basis of the most practically and theoretically interesting, for example where different kinds of errors or practices had been found. We also wanted to maintain a geographic spread and a mix of different smart and non-smart pump use from different manufacturers. Five different hospitals, from five different trusts, were included in phase 2, each with two different clinical areas:

-

site D – adult critical care and oncology day care

-

site G – general medicine and general surgery

-

site H – general medicine and oncology day care

-

site I – paediatric critical care and paediatric general surgery

-

site K – general surgery and paediatric general surgery.

Data gathering took place between October 2016 and December 2017.

In terms of sampling, there were three main strands of data collection at each phase 2 site:

-

Ten days on the wards work shadowing staff, conversations and observations of IV infusion preparation and administration. It was expected that about 40 IV infusions would be observed at each hospital site, which could include bolus doses.

-

Ten interviews with patients to get their perspective on the quality and safety of IV administration. Ethics approval to interview paediatric patients and/or their parents was not sought, which left a total of 35 interviews with adult patients.

-

Ten interviews with staff to discuss IV administration practices, discrepancies, errors, etc. These were stakeholders with some managerial responsibility for IV infusions at the trust, for example the local principal investigator, medical device safety officer, medication safety officer, medical device trainer, someone involved in the procurement of IV pumps, relevant senior nursing staff, relevant ward managers, relevant medical electronics personnel and relevant patient safety specialists.

Data collection

Data collection focused on:

-

establishing how IV infusion preparation and administration worked on the ward, including what triggered this process, what process was followed, what equipment was used, how it worked within the physical space and what issues there were

-

social interactions around technology, including whether patients were involved in the set-up of IV administrations (e.g. what they were told about their medications and how alarms were responded to)

-

what trade-offs and workarounds staff employed to achieve their goals

-

how different technologies such as pumps, barcode readers, CPOE and vital signs monitoring devices were used together, and how each contributed towards patient safety.

Different modes of data collection were used to collect these data, as follows.

-

Mode 1: scheduled interviews with clinical staff. This involved semistructured interviews with clinical staff addressing issues and activities to do with the administration of IV infusions. Interviews were audio-recorded. Document C on the project web page (www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/1220927/#/; accessed 1 March 2019) presents the topic guide used.

-

Mode 2: informal conversation with staff between tasks and during quieter periods (recorded as field notes). This involved talking to staff when there were naturally occurring breaks and lower quantities of work. This focused on clarifying observations the researcher had made.

-

Mode 3: interviewing patients at the bedside. This involved semistructured interviews with patients around issues and activities to do with the administration of IV infusions. Written consent was obtained. The interview was audio-recorded where possible (n = 24); otherwise, notes were taken (n = 11). All data were anonymised for analysis and subsequent reports. Document D on the project web page (www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/1220927/#/; accessed 1 March 2019) presents the topic guide used.

-

Mode 4: photographs of medical devices and their situations of use were taken. These facilitated discussion in the phase 2 workshop with representatives from participating sites, but were not a direct focus of analysis.

-

Mode 5: observing ‘everyday’ practice at the wards. This involved observing staff and patients, their workflow and their use of medical devices. The focus was on IV infusions, but in a wider context.

-

Mode 6: shadowing individual members of clinical staff. This involved observing the working practices of clinical staff, particularly focusing on tasks to do with administering IV infusions. This included calculating infusion rates, setting up devices, changing device settings, and performing the closing stages once a device had been finished with.

Extensive field notes were kept from the observational work. Photographs focused on physical spaces and the arrangement of equipment. Audio-recordings were transcribed and anonymised.

Data management and analysis

Consistent with common forms of qualitative data analysis (e.g. grounded theory77 and thematic analysis73), inductive methods were used to explore themes and patterns that emerged from the observational and interview data. Where applicable, we employed relevant theory to gain further insight and give theoretical weight to our analysis.

Data from patient interviews were analysed using a thematic analysis approach. The analysis consisted of a combination of deductive and inductive approaches, guided initially by the framework of the interview topic guide, but also allowing for the emergence of new themes.

The staff-related data were analysed using two complementary perspectives: SEIPS and CAS.

A Systems Engineering Initiative for Patient Safety analysis of the phase 2 observational and interview data

According to Carayon et al. ,49 the process for analysing a work system in terms of the SEIPS model involves five steps:

-