Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/97/12. The contractual start date was in April 2016. The final report began editorial review in May 2018 and was accepted for publication in November 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Carmel Hughes is a member of the Health Services and Delivery Research Commissioned Panel. Mark Loeb has worked for the World Health Organization as a consultant to develop antibiotics for an essential list of medicines and algorithms for appropriate antibiotic use. Martin Underwood is a member of National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Journals Library Editors Group. He was chairperson of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence accreditation advisory committee from 2013 until March 2017, for which he received a fee. He is chief investigator or co-investigator on multiple previous and current research grants from NIHR and Arthritis Research UK and is a co-investigator on grants funded by Arthritis Australia, Australian National Health and the Medical Research Council. He has received travel expenses for speaking at conferences from the professional organisations hosting the conferences. He is a director and shareholder of Clinvivo Ltd (Tenterden, UK), which provides electronic data collection for health services research. He is part of an academic partnership with Serco Ltd (Hook, UK) related to return-to-work initiatives. He is an editor of the NIHR journal series, for which he receives a fee. He has accepted an honorarium for advice on Research Excellence Framework submission from Queen Mary University of London. He is co-investigator on an Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation grant, receiving support in kind from Orthospace Ltd (Caesarea, Israel).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Hughes et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Introduction

Care homes (with or without nursing) provide care for older people who can no longer live independently. The most frequent acute health-care intervention that care home residents receive is the prescribing of medications. 1 There are serious concerns about the quality of prescribing for care home residents generally, and in particular the prescribing of antimicrobials (antibiotics, antifungals and antivirals). 1 Care homes have been identified as important ‘reservoirs’ of antimicrobial resistance (AMR). 2,3 This has important implications for individual residents, and has broader public health implications due to the development of widespread AMR. A number of prescribing decisions (not just antimicrobials) for care home residents may be made over the telephone,4 and this can lead to medicines-management problems, with erratic medication reviews and prescribing errors.

We have previously shown that Northern Ireland (NI) nursing homes have the highest levels of, and greatest variation in, antimicrobial prescribing among facilities in 20 other European countries/jurisdictions. 5 England was ranked fourth in terms of overall prescribing. 5 Similar findings were reported for residential homes (those facilities that are not required to have qualified nursing staff). 6 Indeed, antimicrobial prescribing in care homes is seen as a global problem, contributing to increasing resistance. 1 There are several policy-level reports that have highlighted this issue, such as Infections and the Rise of Antimicrobial Resistance from the Chief Medical Officer (CMO) in England. 7 The ageing population and increasing requirements for high-quality long-term care are important considerations for the NHS8 and were recognised in the CMO’s report on AMR. 7 This report highlighted ‘the older adult’, with an acknowledgement of this population’s greater vulnerability to infection, which can be exacerbated by living with other older people with risk factors for infection in care homes. The report stated that infections could be managed better, with the appropriate prescribing of antimicrobials being highlighted as an aspect of health care that needed to be tackled in the context of AMR. This theme was echoed in the UK Five Year Antimicrobial Strategy 2013–20189 and in the earlier NI Strategy for Tackling Antimicrobial Resistance (STAR) 2012–2017. 10 These reports emphasised the importance of better stewardship of antimicrobials, which encompasses optimising therapy for individual patients, prevention of overuse, misuse and abuse of antimicrobials and the subsequent minimisation of resistance at both patient and community levels. Education of the health-care workforce was seen as an essential element to draw attention to AMR and appropriate antimicrobial stewardship. 7,9,10

The CMO’s report7 indicated that ‘there is a need to take an international view of this problem [AMR] and work with other nations’ to tackle it. Indeed, there have been a number of international commentaries and studies focusing on antimicrobial prescribing in the care home setting, particularly from North America. Morrill et al. 11 described AMR as a national security threat to the USA and issued a ‘call to action’ to address antimicrobial stewardship in care homes. Thompson et al. 12 noted a high prevalence of antimicrobial prescribing in care homes with nursing in four states in the USA and that there was little documentation to support such prescribing. Scales et al. 13 reported that nurse leaders within care homes and associated medical staff could act as champions for antibiotic stewardship, and Kistler et al. 14 noted that health-care providers may need more support to guide the decision-making process to reduce the excessive use of antimicrobials. Crnich et al. 15 reported that structured assessment, communication between care home staff and prescribers and education about AMR were important facets of interventions that may be effective in supporting antimicrobial stewardship.

Therefore, a more ‘whole-systems’ approach, involving education, diagnosis, treatment and feedback, may help improve practice more broadly. One such study that incorporated a number of these components was conducted by Loeb et al. 16 and focused on prescribing for urinary tract infections (UTIs). In this study, 12 nursing homes in Ontario (Canada) and Idaho (USA) were randomised to receive a multifaceted intervention (based on education and the use of a structured approach to the management of infections) and 12 care homes were allocated to usual care. The intervention consisted of the application of diagnostic (signs and symptoms) and treatment algorithms for UTIs at nursing home level, supported by small group educational interactive sessions for staff, videotapes, written material, outreach visits and face-to-face sessions with physicians. Findings indicated that fewer courses of antimicrobials were prescribed for suspected UTIs in the intervention care homes than in the usual care care homes. No significant differences were found between the intervention and control sites in terms of the total numbers of antimicrobials, admissions to hospitals and mortality.

Rationale for the research

We ran a short feasibility study, based on the original Canadian study,16 in two nursing homes in NI, using some of the same intervention components,17 such as interactive sessions, written material, outreach visits to care homes and educational sessions with general practitioners (GPs), along with the use of algorithms. The intervention was well received by staff and GPs and provided confidence that we could extend this approach on a greater scale. However, this feasibility work was conducted in only two care homes in one region of the UK and focused on one infection (i.e. UTIs), and therefore the relevance of our findings was extremely limited. To extend this research, we considered that it was important to undertake a more comprehensive piece of work that would adapt the intervention that was originally developed for the Canadian care home setting for use in two UK geographic regions in a non-randomised feasibility study, extending the focus to infections common in care homes (including respiratory and skin infections). Importantly, it was also considered essential to address aspects of intervention adaptation, implementation and acceptability by undertaking a process evaluation, which would overarch the conduct of the feasibility study.

At the time of writing this report, a search of trial registries revealed no ongoing intervention studies of this specific topic, although we are aware of one US-based study that is currently recruiting to a trial that will seek to reduce antimicrobial use in nursing home residents with Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias and that will focus on UTIs and lower respiratory tract infections. 18 This study is quite specific in terms of the target population and target infections. The study described in this report is broader in its scope and context (i.e. including care homes with and without nursing care) and is more relevant to the UK setting.

Aims and objectives

Our aim was to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of a multifaceted intervention on rational prescribing for infections in a non-randomised feasibility study in care homes. The intervention consisted of an educational and management approach, supported by discussion of residents cases. The objectives of the study were as follows:

-

to recruit six care homes – three in NI and three in the West Midlands, England

-

to adapt and develop an intervention (a decision-making algorithm and small group interactive training) originally developed and implemented in Canadian care homes

-

to deliver training in respect of the intervention in the care homes and associated general practices

-

to implement the intervention in the six feasibility care homes

-

to undertake a process evaluation of the non-randomised feasibility phase and test data-collection procedures.

The outcomes that we were interested in for this feasibility study were primarily related to the process evaluation; these included the acceptability of the intervention in terms of recruitment and delivery of training, the feasibility of data collection from a variety of sources, the feasibility of measuring appropriateness of prescribing and a comprehensive overview of the implementation of the intervention. Patient and public involvement (PPI) was embedded in all aspects of the study through our care home representative on the research team and the role of participating care home staff and family members (see Patient and public involvement).

Structure of the report

-

Chapter 1 describes the background to and rationale for the study.

-

Chapter 2 gives an overview of the research approach and methods, providing detail about the study design, data collection and analysis.

-

Chapter 3 focuses on the recruitment of care homes.

-

Chapter 4 describes the adaptation of the intervention, covering the adaptation of the decision-making algorithm and of the small group interactive training materials.

-

Chapter 5 focuses on the implementation of the intervention and the collection and analysis of the associated data.

-

Chapter 6 details the process evaluation that was conducted over the course of the study.

-

Chapter 7 focuses on a survey that was posted to care homes in NI and the West Midlands to assess interest in participating in a larger study.

-

Chapter 8 discusses the key findings from the study, its strengths and limitations, proposals for future research and final conclusions.

Study organisation and oversight

Sponsor

Queen’s University Belfast acted as sponsor and subcontracts were drawn up with the University of Warwick and the Northern Ireland Clinical Trials Unit (NICTU). Indemnity cover was outlined in the letter from the sponsor. The study was led by Carmel Hughes (chief investigator) and a multidisciplinary team of investigators from Queen’s University Belfast, University of Warwick, McMaster University and the NICTU, all of whom had the necessary expertise and experience to undertake the work. The day-to-day running of the 2-year study was undertaken by research fellows based at Queen’s University Belfast (AC) and Warwick (RP), and an intervention developer based at Queen’s University Belfast (CS) oversaw the production of all intervention material.

The funder [the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)] agreed that we did not require a Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee. Although the proposed research is a feasibility investigation, it has been registered with the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) registry (reference 10441831).

Feasibility Study Management Group

The management of the study was overseen by the Feasibility Study Management Group, which consisted of all authors listed on this report, in addition to the manager of the NICTU and other staff from the NICTU as and when required. The Feasibility Study Management Group met on a monthly basis over the course of the study, using teleconference facilities, and all meetings were chaired by the chief investigator at Queen’s University Belfast (CH) or the principal investigator at the University of Warwick (DE). An agenda was prepared in advance of each meeting and circulated to all members; minutes of each meeting were compiled and circulated prior to the next meeting. All agendas and minutes are available to the funder for scrutiny. The Feasibility Study Management Group also met face to face on two occasions (in May 2016 and February 2018). Other ad hoc meetings were held between the chief investigator and other members of the research team to address particular issues. Close attention was paid to progress as assessed against the study timetable and the achievement of key milestones and deliverables. As requested by the funding body, we submitted 6-monthly reports outlining progress and provided other information/data as required. The key milestones for the project were recruitment of care homes; completion of the adaptation of the Canadian intervention model; training in care homes and associated practices; completion of the implementation phase and process evaluation; and analysis and write-up of the study.

Study Steering Committee

An independent Study Steering Committee (SSC) was established and met on two occasions (face to face) over the course of the study (in November 2016 and December 2017). An agenda was prepared in advance of each meeting and circulated to all members; file notes of each meeting were compiled and circulated after the meeting. All agendas and file notes are available for scrutiny by the funder. The role of the SSC was to provide independent oversight of the study as outlined in the study charter, with a particular focus on participant safety, adherence to the protocol, consideration of new information and progress of the study. Professor Catherine Sackley (King’s College London) agreed to act as the independent chairperson. Professor Sackley has experience of care home research and cluster trials. Professor Stephanie Taylor (Queen Mary University of London), Dr Kieran Hand (University of Southampton) and Mr Gordon Kennedy (Research Volunteer, Alzheimer’s Society) also sat on the SSC as independent members. Two members of the research team (CH and DE) attended the two meetings to provide advice and context for the study. SSC members each signed a copy of the charter, and highlighted any conflicts of interest where relevant.

Patient and public involvement

For this feasibility study, we convened an Advisory Group to provide PPI perspectives as well as to contribute to the study design and development. This group was convened with the assistance of the Independent Health & Care Providers, a member organisation that consists of those providing care to vulnerable and older adults. The group was composed of staff and resident family members and it contributed to the drafting of information sheets and related documentation prior to the start of the study. As part of our research team, we had Mr Robert (Bob) Stafford, who is Head of Care and Compliance at Orchard Care Homes. Mr Stafford has responsibility for care compliance across the organisation, which consists of over 100 care homes across the UK. As someone who has direct experience of managing and overseeing care homes, his perspective has been invaluable. He actively participated in all Feasibility Study Management Group meetings and advised on implementation and troubleshooting as and when required. In addition, care home staff contributed to aspects of study conduct, particularly in respect of refinement of data-collection forms, insight into the research process and how the study affected workload.

Ethics considerations and approval

We considered the potential ethics issues for this study very carefully and took advice from a number of organisations. We were advised that the data required for the proposed primary outcome (drug dispensing data) could be obtained without requiring individual resident consent as the data would be available at care home level from community pharmacies and we would not be able to link this back to individual residents. We also needed to collect data from care homes in respect of the resident population and hospitalisations and mortality. In this case, data were extracted, anonymised and/or aggregated by the direct care team (care home staff). We consulted with the Health Research Authority, the Office of Research Ethics Committees Northern Ireland and the Privacy Advisory Committee in NI, which advised that our general approach was acceptable.

The research team have considerable experience of carrying out research within care homes. The team is very aware that a care home is the ‘home’ for each and every resident within it and that care homes are also complex workplaces for the staff. The team liaised closely with the care homes’ managers to ensure minimum disruption to the day-to-day running of the care homes. When possible, researcher visits to the care homes were pre-arranged and the researchers had appropriate training and approvals. Researcher visits were an important part of this study, during which the researcher acted as an ‘observer’. In a setting such as this, non-participant observation is almost impossible as residents and staff may want to interact. The researchers were respectful of residents’ wishes and space and remained in public areas of the care home.

The interviews undertaken with the various stakeholders were held at a time and place to suit participants. In this study, all interviews and focus groups with care home staff took place in the care homes and all interviews with GPs took place in GP surgeries.

The REACH (REduce Antimicrobial prescribing in Care Homes) study was reviewed by Office of Research Ethics Committees Northern Ireland Health and Social Care Research Ethics Committee B and given a favourable opinion (reference 16/NI/0003).

Summary

Care homes for older people are viewed as reservoirs of AMR. Previous research has shown high levels of antimicrobial prescribing in care homes in NI and England. Several national policies have advocated for better antimicrobial stewardship and looking to international examples of how best to manage this issue. A more ‘whole-systems’ approach, involving education, diagnosis, treatment and feedback, may help improve practice more broadly. This informed the conduct of the feasibility study that is described in this report, and which was based on Canadian research that demonstrated that the use of a decision-making algorithm and training sessions with staff led to fewer courses of antimicrobials being prescribed for suspected UTIs. Our study was set up to develop and adapt the Canadian approach to encompass respiratory and soft tissue infections, and addressed aspects of implementation and acceptability in a mixed-methods process evaluation. The study was managed by members of the research team, it had external oversight through a SSC, it had PPI input and all necessary approvals were in place prior to the start of the research.

Chapter 2 Research approach and methods

Introduction

This chapter provides an overview of the research approach and methods, describing the study design, theoretical underpinning, and data collection, management and analysis.

Overview of methods

The REACH study is a non-randomised feasibility study that employed a mixed-methods design. A feasibility study is a piece of research that assesses whether a future main study can be carried out. 19 As a feasibility study, our focus was on the facilitators of or obstacles to implementation of our intervention and to test and adapt our processes to inform a possible larger study. Therefore, our methods and theories were chosen to reflect the focus on our ability to implement the intervention. This study was grounded within the Medical Research Council’s framework for the development of complex interventions. 20

In this section, we present an overview of the methods used within this study and the theoretical frameworks that underpin these. The study consisted of a recruitment phase, adaptation phase, implementation phase and process evaluation, as outlined in Figure 1. PPI was embedded throughout the study via the contributions of Mr Bob Stafford, who was a member of our research team.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of the REACH study.

Recruitment of care homes

We recruited a purposive sample of six care homes meeting specific inclusion criteria; this stage is detailed in Chapter 3.

Adaptation of intervention

We adapted and developed an intervention (a decision-making algorithm and small group interactive training) originally developed and implemented in Canadian care homes. 16 The methods used to adapt the decision-making algorithm included a literature review, a consensus meeting, pre-implementation focus groups with care home staff and relatives of residents, interviews with GPs and ongoing internal review by the study team. The training programme was based on the programme that was delivered in Canada and updated with respect to current practice of related training programmes provided by professional organisations, alongside internal review by the Feasibility Study Management Group. We planned to seek National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) accreditation for the processes used to develop the intervention material. However, NICE disbanded its Accreditation Advisory Committee in the summer of 2016, so it was no longer possible to seek accreditation. The adaptation of the intervention is fully reported in Chapter 4.

Implementation

We implemented the intervention in the six participating care homes over a 6-month period. This included delivering the training and implementation of the decision-making algorithm. We aimed to collect data on dispensed antimicrobial medicines, use of hospital services, contacts with health and social care professionals, use of the decision-making algorithm, adverse events, hospital episode statistics [from the Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) database] and health economics. We report the implementation of the intervention in Chapter 5.

Process evaluation

We undertook a process evaluation of the feasibility study and explored data-collection procedures. We adopted a mixed-methods approach, using quantitative data from the implementation phase and qualitative data, which included (1) pre-implementation focus groups with care home staff and relatives of residents, and interviews with GPs, (2) observational data during implementation and (3) post-implementation focus groups with care home staff and interviews with REACH Champions (staff who promoted the use of the intervention and provided additional training if required; see Chapter 3, Methods), managers and GPs. We report the process evaluation in Chapter 6.

In order to assess interest in a future larger study, a survey of care homes in NI and the West Midlands was planned, the results of which are reported in Chapter 7.

Normalization process theory

The underpinning theory for this research was normalization process theory. 21,22 This is a sociological theory that aims to explain the social processes that can lead to the routine embedding, or normalization, of a new health organisational practice, focusing on the work that individuals and groups do to enable an intervention to become normalised. Normalization process theory has previously been used to explore the implementation of complex interventions, such as electronic records in maternity units,23 medical revalidation24 and a cardiovascular disease prevention programme in primary care. 25 There are four main constructs to normalization process theory, each of which has four components:26

-

Coherence (individually and collectively the ‘sense-making work’ people do when operationalising new practices):

-

Internalisation – understanding the importance of the problem the new practice addresses.

-

Differentiation – understanding the difference between usual and new practice.

-

Individual specification – understanding the individual tasks and responsibilities around the new practice.

-

Communal specification – building a shared understanding of the collective tasks around the new practice.

-

-

Cognitive participation (the relational work or engagement that people do to build and sustain a community of practice around new practices):

-

Initiation – who is responsible for driving and engaging others in the new practice?

-

Enrolment/buy-in – which stakeholders need to buy-in to it and how can this be done?

-

Legitimation – do participants believe that they can make a legitimate and valid contribution to it?

-

Activation – what actions and procedures are needed to sustain the new practice?

-

-

Collective action (the operational work done to enable the intervention to happen):

-

Interactional workability – what is the interactional work that people do with each other, with artefacts and with other elements of a practice when operationalising it in everyday settings?

-

Relational integration – what is the knowledge work that people do to build accountability and maintain confidence in a set of practices as they use them?

-

Skill set workability – who (with what skill set) is allocated the work as the new practice is operationalised?

-

Contextual integration – what resources or support are available or required to allow the new practice to be operationalised?

-

-

Reflexive monitoring (the formal and informal appraisal and understanding of the new practice or intervention, and how this affects participants and others):

-

Systemisation – how participants determine the usefulness of the new practice for themselves and others.

-

Communal appraisal – how participants work together with different types of information to determine whether or not the new practice works (e.g. formal data analysis meetings or casual collecting of anecdotes).

-

Individual appraisal – how participants individually appraise effects of an intervention on them and their settings (e.g. how the new practice affects an already demanding workload).

-

Reconfiguration – how participants seek to modify the new practice to make it workable in their setting.

-

The general theoretical argument of normalization process theory is that these constructs, and their components, represent a set of generative mechanisms that give structure to the different kinds of individual and collective actions that people do as they respond to a call to implement a new set of practices,26 as staff in care homes were asked to do in this study. These components are not linear, but are in dynamic relationships with each other and with the wider context of the intervention, such as organisational context, structures, social norms, group processes and conventions. 21,22 The elements of this theory are directly applicable to the approach that we have taken with the intervention in this study and provide ‘sensitising concepts’,27 or initial ideas for us to pursue, when reviewing the literature, producing our discussion guides and developing our analysis. In the context of this study, the social organisation of work refers to the decisions staff may take to contact a GP when they suspect that a resident may have an infection.

Data collection

Qualitative data collection

Our primary data collection throughout the study was qualitative. We conducted focus groups with care home staff and relatives of residents and semistructured interviews with GPs as part of the adaptation of the intervention (see Chapter 4). Observation field notes, focus groups (care home staff) and interviews with REACH Champions, care home managers and GPs post intervention were planned and carried out (see Chapter 6).

Quantitative data collection

We developed a protocol to inform pharmacies/dispensaries on the data requirements of the study. Pharmacies that supplied our recruited care homes were asked to provide two anonymised downloads of drugs dispensed to the care home: (1) for the year leading up to our implementation phase and (2) for the 6-month period of implementation. This is reported in Chapter 5.

Screening logs (see Chapter 3), training attendance registers and study case report forms (CRFs) (see Chapters 5 and 6) were developed to capture data associated with intervention implementation. Further data were collected from a care home survey to assess interest in a future larger study (see Chapter 7).

Data analysis

Qualitative data

All interviews and focus group recordings were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim by an organisation external to Queen’s University Belfast. The transcription process was subject to a non-disclosure agreement. The transcribed data were uploaded into NVivo® 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) (a qualitative data analysis software tool) and data analysis was based on the constant comparison method. 27 These methods are fully explained in Chapters 4 and 6.

Quantitative data

Analysis was primarily descriptive, providing an overview of the characteristics of participating care homes and residents. Data on antimicrobial prescribing extracted from community pharmacy computerised records at baseline and at the end of the implementation phase were summarised. We planned to undertake a sample size calculation, estimate the effect size and intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) from this non-randomised feasibility study, thus informing the parameters for a full study. Subject to the quality of data collected from community pharmacies, if feasible, we had planned to undertake an interrupted time series analysis to explore the trends in the prescription of antimicrobials before and after the intervention.

Data management

All data collected during the study were handled and stored according to relevant legislation and standard operating procedures utilised by Queen’s University Belfast, the University of Warwick and the NICTU. Data were stored on secure servers and access to these data was restricted to authorised personnel. Any data transfer was in accordance with standard operating procedures and required data-sharing agreements to be in place. Study-related documents were made available for internal monitoring and audit activities; this was highlighted in participant information sheets. Study documentation and data will be archived for at least 5 years after completion of the study in accordance with the standard operating procedures of Queen’s University Belfast and the NICTU.

All CRF data returned to the NICTU were dealt with in accordance with its standard operating procedures and accessed only by authorised personnel. A member of the research team checked the data that were entered into a study-specific database designed by the NICTU. After all data had been entered into the database, the original CRFs were securely stored in archiving facilities.

Safety and adverse event management

An adverse event is defined as any untoward medical occurrence in a participant that does not necessarily have a causal relationship with the research treatment/intervention. We did not expect any adverse events related to the intervention in this feasibility study. However, we did expect a large number of reports to be made by staff owing to the nature of this population, but did not attempt to monitor these in real time. Adverse event forms were reviewed when received. Any such events were dealt with in accordance with the NICTU standard operating procedures for safety reporting. We also collected data on hospitalisations and mortality as reported by the care homes through other methods of data collection and monitored these data very carefully. In the original Canadian trial on which this feasibility study is based,16 no differences in admissions to hospitals or mortality between the intervention and control arms were found.

Summary

We have provided a brief overview of the methodologies and theoretical underpinning related to this study. Specific methods for particular aspects of this study will be described in the following chapters.

Chapter 3 Recruitment of care homes

Introduction

In this chapter, we report on the recruitment of care homes. We gave careful consideration to the number and type of care homes required for this feasibility study. Residential care homes are staffed 24 hours a day and provide meals and help with personal care (activities such as washing, dressing and going to the toilet). Nursing homes also provide personal care, but in addition provide specialised nursing care for those who are sick, injured or require regular monitoring, and are required to employ at least one qualified nurse for 24 hours a day. Residential and nursing homes in the UK are collectively known as care homes. We planned to recruit both nursing and residential facilities to this study.

Aim and objectives

Our aim in this phase of the study was to recruit six care homes for participation in this study: three in NI and three in the West Midlands, England.

Methods

The sample size was informed by the research team’s previous experience in care home studies regarding what was considered acceptable for a feasibility study, regarding what would provide the type and quality of data required and to allow us to understand the process and implementation challenges. 4,28,29 We planned to recruit a purposive sample of six care homes: three in NI and three in the West Midlands, with two nursing homes and one residential home in each area. This was to reflect the broad breakdown of nursing home versus residential home numbers in the overall care home sector. The basic inclusion criteria were homes:

-

with/without nursing care, providing 24-hour care for residents aged ≥ 65 years

-

with a minimum of 20 (permanent) residents

-

associated with a small number of general practices (up to four per home providing care for a minimum of 80% of residents within a home)

-

with an exclusive arrangement with one pharmacy for dispensing medications (we also required that the pharmacy used specific dispensing software).

The recruitment process was conducted during April to June 2016. Our recruitment method differed slightly in NI and the West Midlands owing to particular contextual features of each research site. In NI, we compiled a list of care homes from the website of the Regulation and Quality Improvement Authority, the independent body responsible for monitoring and inspecting the availability and quality of health and social care services in NI. We then applied the following inclusion criteria to the Regulation and Quality Improvement Authority list to include care homes:

-

within a 20-mile radius of Belfast (to ensure proximity to Queen’s University Belfast)

-

with ≥ 20 permanent residents

-

providing care for residents aged ≥ 65 years regardless of disability

-

that were not dual registered (i.e. providing nursing and residential services)

-

not owned by health trusts

-

that were members of the Independent Health and Care Providers and any home identified as interested in research.

In the West Midlands, many care homes are part of the NIHR Clinical Research Network (CRN) Enabling Research In Care Homes (ENRICH) programme. 30 The ENRICH programme aims to bring together care home staff, residents and researchers in order to facilitate the design and delivery of research. We asked the CRN to distribute a flyer to these homes, which sought their interest in participating in the REACH study based on the inclusion criteria for the study.

This process identified refined samples of homes in NI and the West Midlands. The research fellows at Queen’s University Belfast and the University of Warwick then randomised their respective lists of nursing and residential homes and, beginning with number 1 on each randomised list, contacted the manager to confirm the initial inclusion criteria at each site. In NI, the survey also applied additional inclusion criteria to identify those homes with four or fewer general practices providing care for a minimum of 80% of residents and with an exclusive arrangement with one pharmacy for dispensing medications. For those homes in each area that met these initial inclusion criteria, we asked the home manager if they were interested in receiving information about how their home could participate in the REACH study.

For those homes that were willing and eligible to participate in the study, we asked the managers to provide contact details of the pharmacy that dispensed medications to their homes. We then contacted these pharmacies to ascertain the type of dispensing software used to ensure that the anonymised dispensing data we required for the study could be downloaded from these systems. We continued contacting care homes and pharmacies until we obtained the requisite number of homes that were fully eligible for the study.

We telephoned the managers of each care home that was eligible and willing to take part in our study, and made arrangements to visit on a mutually convenient date. At this visit, we verbally provided more detail about the study and answered any immediate queries that the managers had. We also provided written information, including an invitation letter, a participant information sheet and a consent form. The participant information sheet informed each home manager of the requirement to identify up to two members of staff (to account for different shifts within the homes) who could act as ‘REACH Champions’: individuals who would be responsible for delivering training to staff unable to attend the original REACH training session. Some managers agreed to take part in the study at this point and completed the consent form. Two homes in NI were part of a group of homes and so the managers of these homes advised that permission to take part in the study should be sought from the management group. The research fellow at Queen’s University Belfast contacted the management group and permission was obtained. The remaining homes were revisited within 1 week and written consent was obtained. The research fellows in each site maintained regular contact with the homes between taking consent and the start of the research processes.

Results

Following screening using the initial sampling criteria, 49 nursing homes and 16 residential homes in NI and seven nursing homes and eight residential homes in the West Midlands were identified (Table 1). This list of homes was randomised, from which the final sample for the feasibility study was recruited, is shown in Table 1.

| Sampling | Number of care homes | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NI | West Midlands | |||

| Nursing homes | Residential homes | Nursing homes | Residential homes | |

| Sampling frame | 261 | 197 | 31 | |

| Initial sampling criteria | ||||

| ≤ 20-mile radius | 127 | 94 | 7a | 8a |

| ≥ 20 residents | 121 | 53 | ||

| Aged ≥ 65 years regardless of disability | 119 | 53 | ||

| Care homes not dual registered as nursing and residential | 81 | 53 | 7b | 8b |

| Care homes not part of health trust | 81 | 37 | 7b | 8b |

| Care homes interested in researchc | 49 | 16 | 7 | 8 |

| Homes randomised for telephone contact | 49 | 16 | 7 | 8 |

| Additional sampling criteriad | ||||

| Homes contacted | 18 | 8 | 4 | 1 |

| More information needed from homes to verify eligibility | 8 | 4 | 0 | 0 |

| Homes not eligible | 7 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Homes eligible and not interested | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Homes eligible and interested | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

We recruited three homes (two nursing and one residential) in both NI and the West Midlands (Table 2).

| Site | Unique reference | Nursing/residential | Number of beds (resident occupancya) | Number of general practices serving ≥ 80% of residents | Part of chain? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| NI | A | Nursing | 62 (36) | 4 | Yes |

| B | Nursing | 32 (32) | 2 | No | |

| C | Residential | 36 (36) | 1 | Yes | |

| West Midlands | D | Nursing | 56 (42) | 1 | No |

| E | Nursing | 51 (51) | 1 | No | |

| F | Residential | 40 (37) | 1 | Yes |

The number of beds ranged from 32 to 62, with occupancy at almost 100% in all homes apart from home A. In NI, more general practices provided care to the homes, whereas in the English homes, each participating home was served by one practice. Homes varied in ownership, with three being part of a chain and the remaining three being owned by single proprietors. All homes were each associated with one pharmacy that supplied all medication.

Summary

We successfully recruited six homes that met the inclusion criteria for participation in the study. The approach taken in the two geographic sites was largely comparable, but also took into account some contextual differences, such as the role of ENRICH in England. We noted the key characteristics pertaining to homes, such as number of beds and number of general practices associated with the homes.

The six recruited homes then progressed to the adaptation phase of the study, which is described in Chapter 4.

Chapter 4 Adaptation of the intervention

Introduction

In this chapter, we report on the adaptation of the intervention to reduce antimicrobial prescribing. The Canadian study16 had provided ‘proof of concept’ that antimicrobial prescribing could be influenced by a multifaceted intervention consisting of a decision-making algorithm and small group interactive training. However, context in research is important;31 in this case, the difference is between the Canadian care home context and that of the UK. Transposing the intervention from Canada to the UK without any modification was unlikely to be successful. Furthermore, we anticipated that the evidence on management of infections in older people would have developed since the Canadian study was undertaken (the last follow-up was in 2003). 16

Aims and objectives

The aim of this phase of the research was to adapt and develop an intervention (a decision-making algorithm and small group interactive training) originally developed and implemented in Canadian care homes. The objectives were as follows:

-

to undertake a series of rapid reviews encompassing the most up-to-date literature on the management of the three target infections

-

to conduct a consensus meeting, using the nominal group technique, with health-care professionals, to adapt the decision-making algorithm

-

to undertake focus groups and interviews with key stakeholders, including care home staff, family members of residents and GPs, to adapt the decision-making algorithm

-

to develop a training programme outlining the use of the decision-making algorithm, communication techniques between health-care professionals and aspects of the study process

-

to produce an updated and refined decision-making algorithm, which, in conjunction with the training programme, would be used in the implementation phase of the study.

We report on the adaptation of the decision-making algorithm and follow this with a description of the adaptation of the small group interactive training programme.

Methods

Adaptation of the decision-making algorithm

The approaches developed by Loeb et al. in 200132 and 200516 were updated and adapted for UK use through a series of iterative steps: production of a rapid scoping literature review, focus groups with care home staff and family members of residents and semistructured interviews with GPs. As part of discussions with other members of the Feasibility Study Management Group, it was also agreed that a consensus group meeting with health-care professionals would provide further additional input into the development and adaptation of the intervention. The process was also informed by continual iterative internal review and analysis within the research team.

Production of rapid reviews

We undertook a rapid scoping review of the literature to obtain the most up-to-date evidence for the management and diagnosis of UTIs, respiratory tract infections (RTIs) and skin and soft tissue infections (SSTIs) in older people living in care homes. We considered systematic reviews, guidelines, reports, review articles and randomised controlled clinical trials published between 2000 and 2016.

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched the following electronic databases for primary studies: the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (via The Cochrane Library, 2016, issue 4), MEDLINE (via Ovid, 1946 to May week 1 2016), EMBASE (via Ovid, 1980 to week 41 2016), CINAHL plus EBSCOhost (1980 to May 2016), PubMed (1996 to May 2016) and SCOPUS (1983 to May 2016). We supplemented this with forward citation tracking. In addition, we contacted experts in the field of antimicrobial and geriatric medicine for advice on further potential studies. We conducted a ‘grey’ literature search of NICE, the European Centre for Disease Protection and Control, the Infectious Disease Society of America, the Society for Healthcare Epidemiology of America and NHS Evidence, using the appropriate terminology as applicable. This search focused on identifying guidelines relating to the management, stewardship, initiation, diagnosis and treatment of infections in the care home setting (see Appendix 1).

Screening and review of literature

We downloaded all titles and abstracts retrieved by electronic searching to the reference management database RefWorks (Pro Quest, LLC, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) and removed duplicates. Two review authors (AC and CS) independently examined the remaining references. A reference was included if it was:

-

relevant to the key question ‘what is the most up-to-date evidence for the management of urinary tract, respiratory tract and skin infections and the stewardship of antimicrobials?’

-

a review, guideline or report from a professional organisation or clinical trial

-

published between 2000 and 2016

-

related to the care home setting

-

written in English.

We excluded those articles that clearly did not address the management and diagnosis of the key infections in the care home setting and obtained copies of the full text of potentially relevant references. At least two review authors (CS and AC) independently assessed the eligibility of the full-text papers.

Data extraction and management

Three reviewers (AC, DE and CS) independently extracted data from relevant publications using a predefined extraction table containing the following elements: author and year, setting (i.e. nursing or residential care home), type of publication [i.e. review article, randomised controlled trial (RCT), NICE guideline], population (i.e. older people), infection (i.e. urinary, respiratory or skin/soft tissue infection), objectives, relevant data relating to the target infections from each article and comments (from the reviewers AC, DE and CS), such as whether or not the paper was particularly useful or if it cited the original algorithm by Loeb et al. 16 An article was thought to be particularly useful if it informed the reviewers about new evidence relating to urinary, respiratory or skin/soft tissue infection. This process took place during a 3-day face-to-face meeting between Anne Campbell, David Ellard and Catherine Shaw to discuss and agree discrepancies in their interpretation; those discrepancies that could not be agreed were resolved by an additional author (CH).

An additional meeting was held between Catherine Shaw, Carmel Hughes and Michael Tunney to further discuss the findings from the evidence tables. This involved individual examination of the extracted data alongside group discussion, with the aim of reaching a final conclusion as to which articles should be used to update the algorithm.

The data extracted during this process were used to update the algorithm for the consensus meeting (see the following section) and informed ongoing iterative discussions within the research team during the process of adaptation.

Consensus group meeting

Ethics approval was granted by the School of Pharmacy, Queen’s University Belfast Ethics Committee, to conduct a consensus group meeting using the nominal group technique (reference 022PMY2017). Potential participants were identified through personal networks of members of the research team in Belfast, and were approached by e-mail and given brief details about the consensus group meeting. Participation was voluntary and required written informed consent. All participants received an honorarium for their time, as noted in the relevant information sheet.

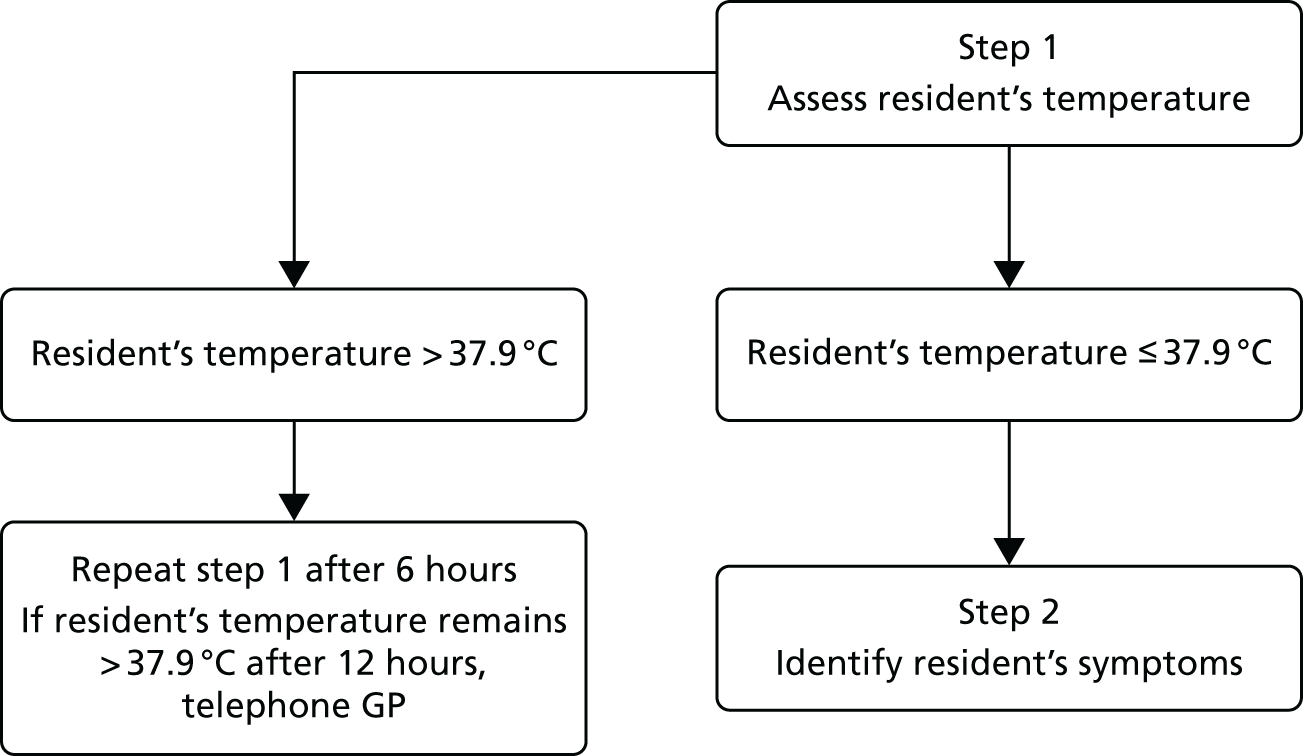

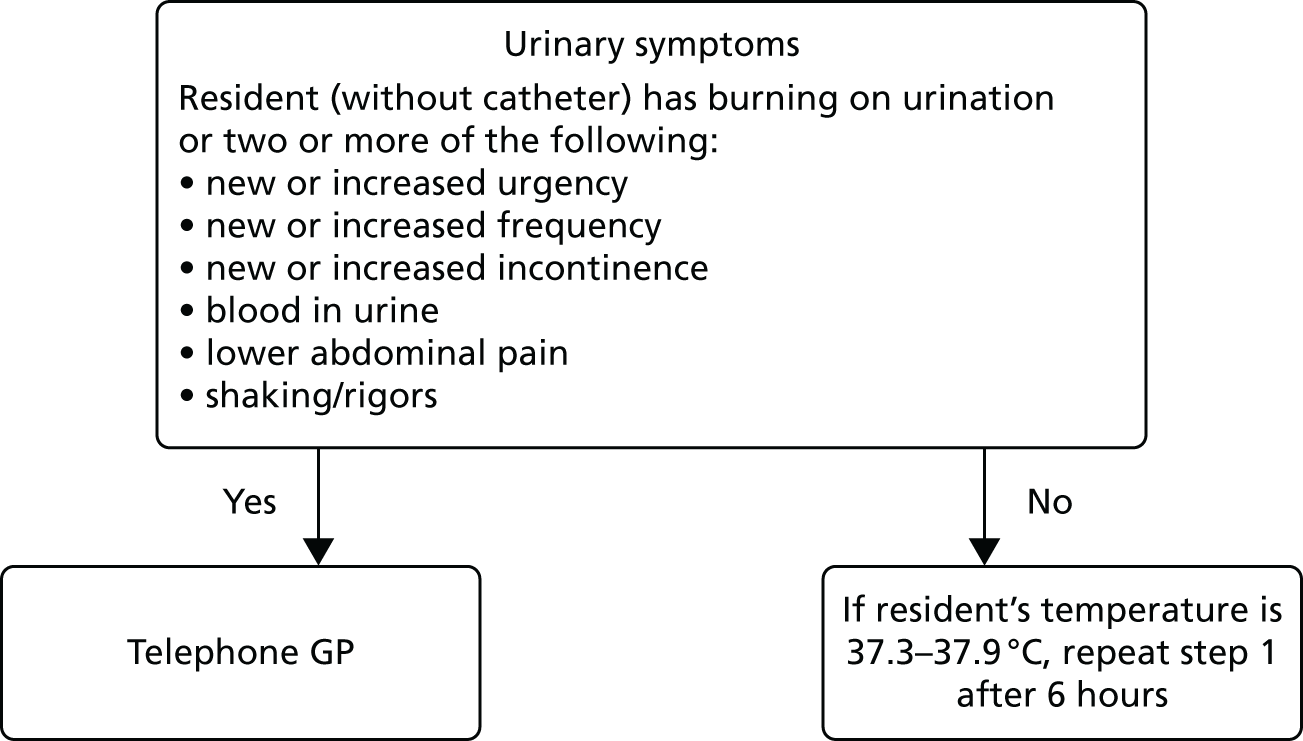

Prior to the meeting, each participant was provided with a draft version of the decision-making algorithm as shown in Figure 2, alongside supporting documents (comprising key papers that provided the research team with updated evidence in relation to urinary and respiratory infections in care homes that had been retrieved from the literature search) to allow them to familiarise themselves with the material. No new evidence was found relating to SSTIs (see Adaptation of the decision-making algorithm).

FIGURE 2.

Draft algorithm presented to the consensus group. b.p.m., breaths per minute; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease.

Nominal group technique

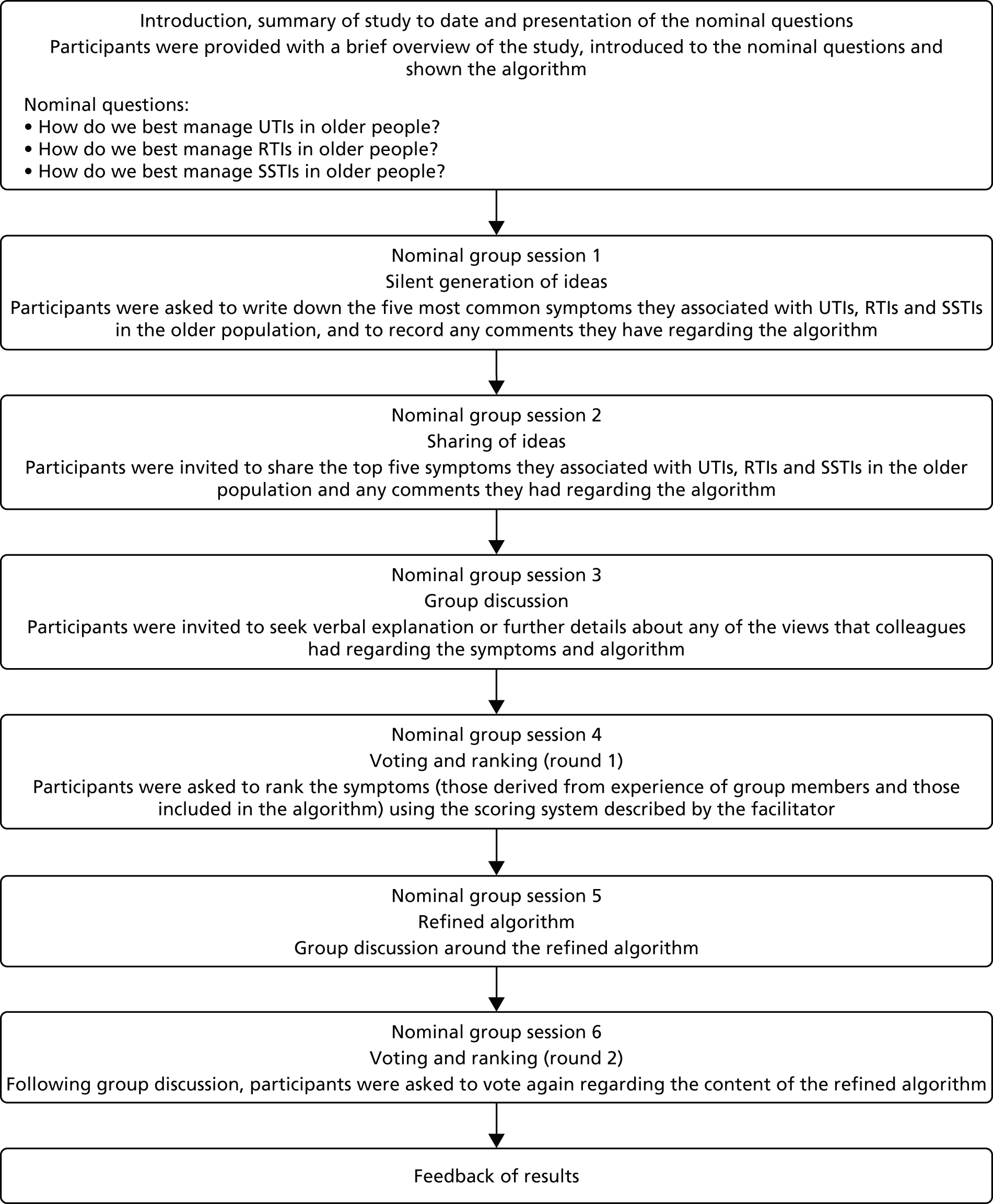

The consensus group meeting format was based around the nominal group technique. 33 Potential benefits of nominal group technique include significant idea generation that may happen through face-to-face discussion and debate, even though it may be in a limited and prestructured format. 34 The research team formulated three nominal questions: (1) how do we best manage UTIs in older people?, (2) how do we best manage RTIs in older people? and (3) how do we best manage SSTIs in older people? These questions were presented to the participants during the face-to-face meeting (Figure 3). Initially, each participant recorded his or her views regarding the nominal questions independently and privately.

FIGURE 3.

The REACH consensus group nominal group technique. Reproduced from Hughes et al. 35 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

The group members were asked to write down the five most common symptoms they associated with UTIs, RTIs and SSTIs in the older population, and to study the algorithm (see Figure 3, session 1) and supporting evidence. This allowed the participants to refamiliarise themselves with the material. They were then encouraged to share the five most common symptoms they associated with each infection with the rest of the group (see Figure 3, session 2). The facilitator noted these symptoms and any comments on a whiteboard for each member to see. The next step involved group discussion of the symptoms and comments made, and members of the group had the opportunity to seek further explanation from one another if required (see Figure 3, session 3). The symptoms included within the algorithm were discussed. Participants were then asked to rank the top five symptoms of each infection, derived from their personal experience (most common symptoms listed previously) and those included within the algorithm (from the literature), based on their clinical expertise. Participants were provided with a separate table for each infection to guide the ranking of the symptoms and were asked to complete the table by selecting a numerical rating for each one, with the most important receiving a rank of 5 and the least important receiving a rank of 1 (see Figure 3, session 4).

When each participant had ranked their top five symptoms of each infection, the data were entered onto a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet by the facilitator. The ratings for each symptom were summed and item totals were ranked. The facilitator compared the ranked symptoms with those included in the algorithm as presented. If there were any discrepancies between the top-ranked symptoms and those included within the algorithm, the algorithm was amended accordingly and presented back to the group. Further discussion ensued (see Figure 3, session 5) and this was followed by another round of voting and ranking of the symptoms to be included in the algorithm (see Figure 3, session 6), which was amended accordingly again.

Pre-implementation focus groups and interviews

Sampling and recruitment

We aimed to recruit care home staff as users of the intervention and family members of residents, given that family members may be influential in decision-making in relation to the prescribing of antimicrobials. 4 To recruit care home staff and family members of residents prior to the implementation of the intervention, the research fellows at Queen’s University Belfast and the University of Warwick asked the manager in each participating care home for assistance. They provided managers with individual participant information packs for care home staff and family members. Each participant information pack included the following documents: an invitation letter, a participant information sheet and a consent form. The research fellows asked the managers to distribute this information to senior and junior care home staff and family members. The research fellows were available in person, by telephone or by e-mail to provide further explanation. We aimed to recruit 4–12 participants for each focus group36 and to include senior and junior staff in the care home focus groups. The managers of the care homes were not invited to take part in the focus groups so as to prevent the management relationship directing or constraining the group discussion. 36 To recruit GPs, the research fellows approached the practice manager in each general practice associated with the participating care homes. They provided the practice manager with a verbal overview of the study and asked that an invitation letter, information sheet and consent form be sent to a named GP. A follow-up telephone call was made to the GP. All focus group and interview participants received an honorarium for their time, as noted in the relevant information sheet. Participation was voluntary and written consent was obtained from all participants.

Interview and focus group discussion guides

Even though this stage of the study focused on developing and adapting the intervention and did not involve its implementation, we considered the first three constructs of normalization process theory – coherence, cognitive participation and collective action – as these were useful in alerting us to factors that may have an impact on its implementation; hence these constructs were used in the development of topic guides. The fourth construct, reflective appraisal, was not considered useful at this stage given that the intervention was not yet implemented. We used these three constructs to create the following broad working definitions so that normalization process theory could be usefully applied within our study:23–25

-

Making sense (coherence) – how do participants understand the issue of AMR and what is their usual practice?

-

Engagement and commitment (cognitive participation) – what do participants see as necessary to engage staff in the new practice?

-

Facilitating the use of the intervention (collective action) – how do participants envisage the intervention working and what are the factors that may facilitate or inhibit its use?

These three constructs of normalization process theory were used to shape the questions within the discussion guides for focus groups (see Appendix 2 for care home staff and Appendix 3 for family members) and individual interviews (see Appendix 4) that were devised and agreed by members of the research team. For example, both guides included questions about usual practice when a resident was suspected to have an infection.

Conduct of the interviews and focus groups

At the beginning of a focus group or interview, the facilitator assured participants regarding confidentiality, gave a brief background to the study and offered participants an opportunity to ask any questions. We then used questions from the discussion guides, with appropriate prompts, to ask participants about their usual practice when a resident was suspected to have an infection. The participants in the care home staff and family member focus groups were also asked about their understanding of AMR. Next, participants were shown a version of the decision-making algorithm and, using the ‘think–pair–share’ approach,37 were asked to reflect on it for a few moments. We then asked the participants, using appropriate prompts, questions that included how easy the algorithm was to follow; what they perceived to be missing, not needed or confusing; and any concerns they had about the use of the algorithm. This process is described in Box 1.

We distributed the decision-making algorithm to participants and asked them to think briefly about it on their own (1–2 minutes). We then asked them to imagine that they had a resident with a suspected infection and to consider how well they thought the decision-making algorithm would actually work in practice.

Focus groupsWe asked participants to form groups of two or three people to discuss the algorithm (3–4 minutes) and to think about at least one question they would like to ask or one comment they would like to make about it. We then asked each small group of participants about their questions or comments.

Focus groups and interviewsWe proceeded to use the questions and appropriate prompts from the discussion guides to stimulate discussion (25 minutes).

Data analysis

All interviews and focus group recordings were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim by an external organisation. The transcripts were checked against the recording by the research fellow in each area to ensure accuracy and anonymisation. The transcribed data were uploaded into NVivo® and repeatedly read to increase familiarity with the data. Data analysis was based on the constant comparison method. 27 A selection of focus group and interview transcripts were first open coded inductively, with codes created from the patterns and themes emerging from the data, and an initial coding frame was developed. This thematic coding frame was then applied to subsequent transcripts and iteratively refined as new codes were defined (see Appendix 5 for care home staff and family member interviews and Appendix 6 for GP interviews). We used the framework matrix facility within NVivo® to assist the analytic process. These matrices enabled the research fellows to summarise the text associated with a theme in order to develop a narrative for each of them. These themes were then structured in accordance with key aspects of the decision-making algorithm. A COREQ (consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research) checklist was completed for this aspect of the study and can be found in Appendix 7.

Internal review by the Feasibility Study Management Group

In addition to the activities outlined in the previous section, the algorithm was also reviewed and refined by the research team through an iterative process. Via the monthly Feasibility Study Management Group meetings that involved all members of the research team, aspects of each draft of the algorithm were discussed and debated. Changes were made by the research team based on results from the literature review, consensus meeting, focus groups and interviews. The final algorithm was agreed on by all members of the research team.

Adaptation and development of training material

The training material was developed at Queen’s University Belfast by Catherine Shaw, with input from members of the research team, based on the learning and results from the adaptation of the decision-making algorithm (see Adaptation of the decision-making algorithm) and the approaches taken by Loeb et al. 16 in the original Canadian study.

We were aware of the different staff categories within care homes (Table 3) and how this would need to be considered in the planning and development of training. The most important differentiating feature was the presence of qualified nurses in care homes with nursing. Other care staff who were not qualified nurses were designated as senior or junior care staff (largely based on their experience), along with activity co-ordinators in English care homes. The role of an activity co-ordinator is to facilitate and support activities in a care home; these may include activities for individual residents, groups of residents or for the whole care home.

| Different categories of staff | Nursing homes | Residential homes |

|---|---|---|

| Nursing staff | ✓ | |

| Senior carers | ✓ | ✓ |

| Junior carers | ✓ | ✓ |

| Activity co-ordinators (English homes) | ✓ | ✓ |

As a result of discussions within the research team, it was decided that the main focus of the training would be those we perceived to be senior staff within the care home, for example nursing staff and senior carers in nursing homes and senior carers in residential homes. These were seen as the staff who would implement the decision-making algorithm. However, we realised that those we perceived to be junior staff (junior carers in each home) also have a role as they are often the carers who will have most contact with residents and will observe if there is a change in their health status. However, they do not have responsibility for contacting GPs. Therefore, we decided that there would be two levels of training, both of which would cover the principles of the project. However, for the junior staff, training would focus on raising awareness of the decision-making algorithm and its use during the study, rather than instructing them on how to use it. It was anticipated that this level of training would be sufficient to enable junior staff to alert more senior staff in the event of a resident with a suspected infection.

The key document that informed the development of the training was the REACH decision-making algorithm. Based on this, careful consideration was given as to what should be incorporated in the training and in what format. Content was informed by material related to AMR, the background to the study, use of the decision-making algorithm, communication skills and illustrative case studies.

Formats considered were:

-

manuals

-

Microsoft PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) presentations

-

online platforms

-

video

-

DVD.

Early in the development stage, it was decided that the preferred formats for the initial training were a manual (hereafter known as a study handbook) and a Microsoft PowerPoint presentation. We also recognised that it was not possible for all staff to attend the training session, as care-related activities needed to continue in the care home and night staff may be unable to attend a designated session. We were also aware that turnover of staff can be substantial in care homes (figures range from 19–42% annually). 38,39 Thus, we anticipated that further training would be needed over the course of the study for staff who were unable to attend a training session as well as newly employed staff. Therefore, we decided to also develop the training in DVD and online formats.

Catherine Shaw drew on her previous ethnographic research experience in the care home setting, the skills and knowledge from within Queen’s University Belfast and the research team that had developed similar training materials in the past. 17 It had also been recommended to the chief investigator that there should be a focus on communication skills, particularly between care home staff and GPs (Professor Kevin Brazil, Queen’s University Belfast, 2014, personal communication). The situation–background–assessment–recommendation (SBAR) tool was developed by the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement (now incorporated into NHS Improving Quality). This tool provides an easy way for health-care professionals to clarify what information needs to be communicated when making recommendations to other health-care professionals for immediate attention and action. 40

A software package that supports the production of infographics, presentations and flyers (Piktochart®; Bayan Baru, Malaysia) was used to make the training material visually appealing. A short video on AMR was also produced for inclusion in the training material. Each draft of the material was critiqued by Anne Campbell and Carmel Hughes, and a pilot version was delivered to a group of postgraduate students and staff within the School of Pharmacy at Queen’s University Belfast. Feedback from this exercise informed the final content and delivery of the training.

The development of each component is described in more detail in the following sections.

Study handbook and Microsoft PowerPoint presentation

The handbook was the main source of information for the participants; the Microsoft PowerPoint presentation contained all the information included within the study handbook, but in a condensed format that was visually appealing. The introduction in the study handbook and presentation was informed by reference to the literature in respect of AMR, the key signs and symptoms of the three target infections, non-specific indicators such as a change in behaviour and avoidance of an over-reliance on temperature as an indicator of infection in older people and those with dementia. Thereafter, the content of the study handbook and presentation focused on specific aspects of implementation. It was agreed within the research team that the training would also include reference to the key data-collection forms used over the course of the study.

Decision-making algorithm and step-by-step guide on its use

The development of the algorithm is described in this chapter (see Adaptation of the decision-making algorithm). A copy of the decision-making algorithm was provided within the study handbook as a point of reference for care home staff during the training sessions and while the study was ongoing. The step-by-step guide was developed to provide information on each component of the algorithm, including a rationale supporting why certain elements regarding management of infection were included or not included. For example, a common misconception is that change in smell/colour of urine is a valid indicator of UTI, but this was not confirmed/supported within the literature. Thus, an explanation of this was provided alongside the UTI signs and symptoms box. Another misunderstanding regarding infection is the differentiation between bacterial RTIs and viral RTIs; this was also explained in more detail within the guide. It was intended that staff would study this guide during the training session and refer to it throughout the duration of the study to gain clarity or reassurance.

Case scenarios

The research team also considered ways in which the use of the algorithm could be illustrated in a more practical way. This was achieved through the development of three case scenarios (one for each infection). These scenarios were designed to be reflective of everyday life within the care home setting and Catherine Shaw was able to draw on her previous ethnographic experience of studying care homes to produce these scenarios. Each case scenario was divided into two parts. The first part set the scene by providing information about the care home resident and the (mostly non-specific) symptoms with which they presented. This part of the scenario would be used to elicit a description of usual practice by staff during training. The second part of the scenario presented the same information but would then ask staff to apply the decision-making algorithm. The team also developed worked examples of using the decision-making algorithm for inclusion in the study handbook and presentation.

Communication using the situation–background–assessment–recommendation tool

The team referred to the original SBAR tool developed by the NHS Institute for Improvement and Innovation40 to consider how best to include it in the training material. SBAR consists of four standardised stages or ‘prompts’ that help staff to anticipate the information needed by colleagues and to formulate important communications with the right level of detail. This was considered important in the context of care home staff relaying information to GPs in an appropriate manner. As with the use of the decision-making algorithm, the research team developed scenarios that would provide the staff with the opportunity to become familiar with the tool and its use through role play. These scenarios would highlight the situation (identifying the staff member who was calling, from where, in relation to which resident and describing the issue), background (in this case, details about the resident), assessment (signs and symptoms of the suspected infection) and recommendation (what the staff member plans to do and requesting further support if necessary).

Mode of training delivery

The training was designed for face-to-face delivery with groups of staff members using both the presentation and the study handbook, with the latter to be provided to all participants. The format of the training material was designed to be interactive, with the presentation of more didactic information interspersed with a video on AMR and activities such as case studies and role play between participants. It was felt that these interactive activities would illustrate the ‘real-world’ use of the decision-making algorithm and SBAR tool and instil a degree of confidence in staff participating in the study.

Development of alternative modes of delivery

To help support the training (and indeed ongoing training) of care staff, a REACH training video was made by Catherine Shaw, again with support from the research team and colleagues at Queen’s University Belfast. This video was based on the handbook and included short film clips and information from the original Microsoft PowerPoint presentation. The aim of this video was to provide care homes with an alternative training vehicle for refresher training or training of new staff who had not been able to attend the original training sessions. The content was also transferred to a flash drive and online platform.

Results

Adaptation of the decision-making algorithm

Production of rapid reviews

Our searches retrieved 1905 articles. Just under 1500 articles (1487) remained after removal of duplicates, with the addition of another 24 records identified from other sources (hand-searching of other papers), of which 118 were carried through to the next stage. References were included if they met the pre-established criteria outlined in Introduction. The main reason for exclusion of articles at this point was that they did not relate to the older population or the care home setting. Following the 3-day meeting, 38 articles and two guidelines were included and data from these documents were extracted into evidence tables. The main reason for exclusion at this stage was that the article did not specifically relate to the management of urinary, respiratory or skin infection in care home residents. Following a further review of the evidence tables by members of the research team (CS, CH and MT), a further 34 articles were excluded because they did not provide any updated evidence in relation to UTI, RTI or SSTI.

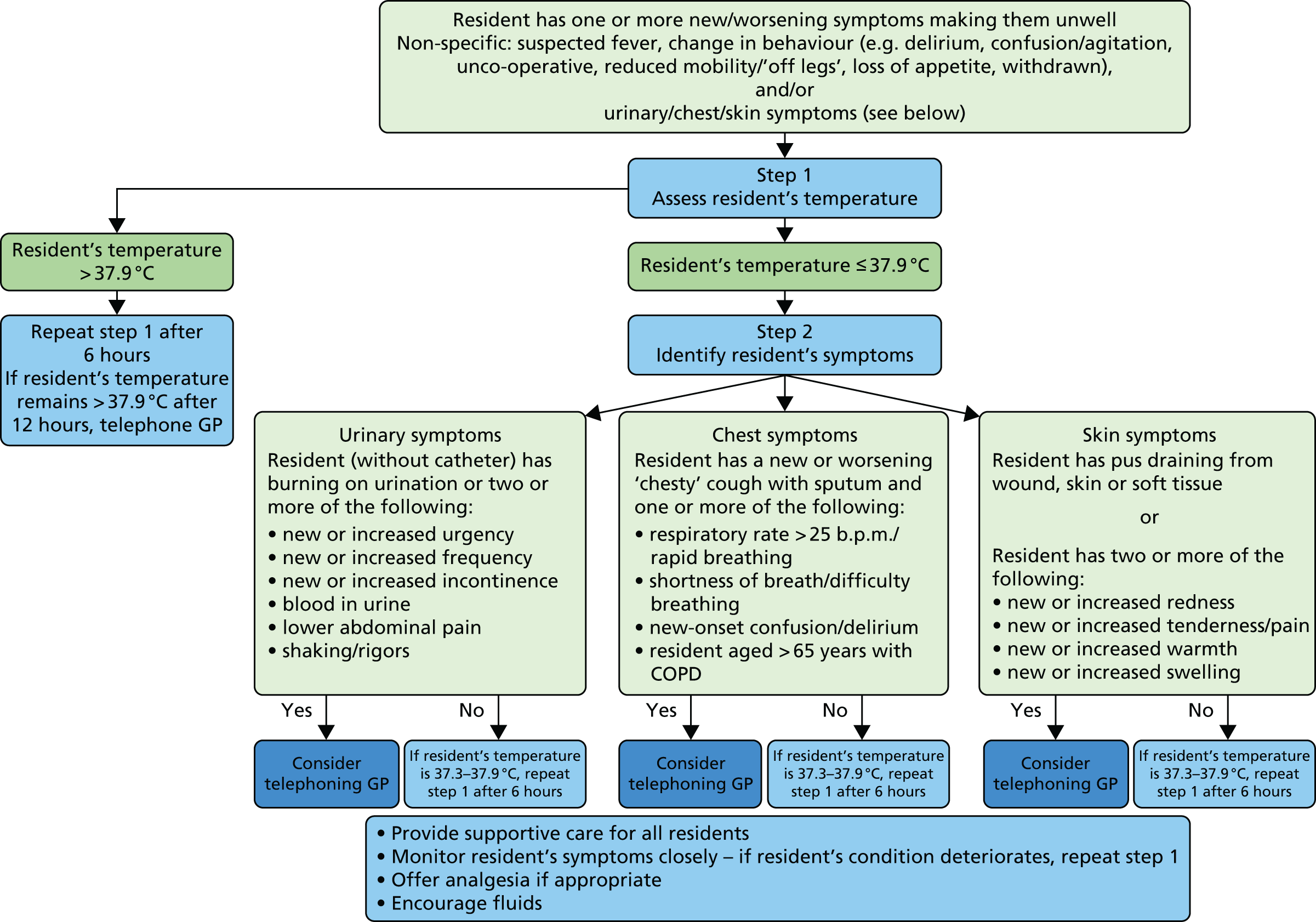

An overview of screening and assessment of all papers/resources is provided in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram outlining the review process for identification of new evidence. Reproduced from Hughes et al. 35 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

The extracted evidence from the remaining six papers is summarised in Table 4.

| Article | Setting | Design | Population and condition | Objective | Relevant information for updating/refining algorithm | Group agreement for updating algorithm |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Falcone et al.41 | Community and hospital (includes care home setting) | Review | Older people, pneumonia (community-acquired pneumonia, health-care-associated pneumonia and hospital-acquired pneumonia) | This review sought to produce a summary of therapeutic recommendations on the basis of the most up-to-date clinical and pharmacological data | Signs and symptoms most commonly associated with pneumonia: cough, fever, chills, pleuritic chest pain. Extrapulmonary symptoms such as nausea, vomiting, alternation to sensory stimuli or diarrhoea may also be present. It is important to remember that pneumonia in older patients tends to occur more often with extrapulmonary manifestations. For example, the appearance of a delirium or acute confusion is found in approximately 45% of elderly patients with pneumonia | Agreed to add in extrapulmonary symptoms |

| Juthani-Mehta et al.42 | Nursing home | Prospective observational cohort study | Older people, UTI | To identify, among non-catheterised nursing home residents with clinically suspected UTI, clinical features associated with bacteriuria plus pyuria | The most commonly reported clinical features for suspected UTI in this cohort were change in mental status (39%), change in behaviour (19%), change in character of the urine (i.e. gross haematuria and change in the colour or odour of urine, 15.5%), fever or chills (12.8%) and change in gait or a fall (8.8%). Dysuria, change in character of urine and change in mental status were significantly associated with the combined outcome of bacteriuria plus pyuria. Absence of these clinical features identified residents at low risk of having bacteriuria plus pyuria (25%), and presence of dysuria plus one or both of the other clinical features identified residents at high risk of having bacteriuria plus pyuria (63%) | Change in character of urine (i.e. gross haematuria and change in the colour or odour of urine) was considered but not supported by more recent guidelines |

| SIGN 8843 | All settings | Guideline | Older people, UTI | To provide guidance in the diagnosis and management of suspected UTI in older people |

|

Agreed to add supportive care advice to algorithm |

| Stone et al.44 – updated McGeer et al.45 | Long-term care | Position paper | Older people, infection (general) | To update the 1991 McGeer criteria (infection surveillance definitions for long-term care facilities) using an evidence-based structured review of the literature in addition to consensus opinions from industry leaders including infectious diseases physicians and epidemiologists, infection control specialists, geriatricians, and public health officials | Acute swelling of the testes, epididymis and prostate should be included in surveillance definitions for UTIs as these symptoms are a common complication of UTI in both catheterised and non-catheterised males | Agreed to add acute swelling of testes, epididymis and prostate |