Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/04/28. The contractual start date was in December 2015. The final report began editorial review in May 2018 and was accepted for publication in April 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Miranda Scanlon reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) during the conduct of the study. Outside the submitted work, Miranda Scanlon reports personal fees from Which? (London, UK), the National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit (University of Oxford, Oxford, UK), Rod Gibson Associates Ltd (Wotton-under-Edge, UK) and the Midwifery Unit Network, and grants from NIHR. Jim Thornton is a member of the NIHR Health Technology and Assessment and Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Editorial Board (from 2012 to present).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Walsh et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Parts of this report are reproduced from Walsh et al. 1 © Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2020. Re-use permitted under CC BY. Published by BMJ. https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Introduction

Since 1993, maternity care policy in England has promoted women’s choice of place of birth. This became the national choice guarantee in Maternity Matters in 2007,2 with three options: (1) birth in a maternity hospital [obstetric-led unit (OU)]; (2) birth in two types of midwifery-led units (MUs), either alongside midwifery unit (AMU) or free-standing midwifery unit (FMU); or (3) birth at home. Department of Health and Social Care-commissioned research into the outcomes of childbirth in different settings3 reported that outcomes for low-risk pregnant women and their babies were better and costs reduced if birth occurred in MUs, both AMUs or FMUs, rather than OUs. Planning to have a baby in a MU reduced caesarean rates by two-thirds.

The most recent National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines on intrapartum care therefore recommend MUs for low-risk women (i.e. women without significant health risk factors who would be predicted to have a normal labour and birth). 4 Sandall et al. ’s5 research suggests that this could be around 45% of all birthing women. However, despite the advantages of MUs, a recent survey found that only 11% of women gave birth in MUs, with the vast majority continuing to give birth in OUs. 6 If 20% of births occurred in MUs, savings to the NHS maternity budget could be around £85M. This represents a 3% saving on the current budget of £2.6B for maternity care. 7

In addition, our survey showed that MUs were not equally distributed across the country. One-third of local maternity services had no MUs, whereas others achieved 20% of all births in these facilities (designated ‘high performing’), and the remainder had MUs but they were frequently underutilised, with < 10% of all births in MUs (designated ‘low performing’).

The explanation for the survey results is unclear. There may be a range of context-specific or more general barriers to establishing and operating MUs. Little is currently known about such barriers or what facilitates MU provision. However, the unequal provision may result in many women being unnecessarily exposed to the risk of caesarean and to a birth experience that is less satisfying, although this may also be explained by the selection of women likely to achieve better outcomes. In addition, local maternity services may not be realising the cost savings of MUs.

Rationale for the research

This study explored the reasons for organisational anomalies in the provision of maternity services by undertaking comparative case studies of NHS trusts with contrasting MU configurations in England. Specifically, we investigated higher-performing trusts (those with > 20% of their total births in MUs) and lower-performing trusts (those with < 10% of their total births in MUs). In addition, we undertook case studies in trusts without MUs. The study also sought to identify interventions to address barriers to and facilitators of the provision of MUs and developed service guidance to inform future maternity service commissioning and provision.

Home birth was excluded from our study because our focus was only on MUs.

Aims and objectives

The study set out to:

-

describe the configuration, organisation and operation of MUs, both AMUs and FMUs, in England

-

build an understanding of key issues and barriers to uptake by women that MUs face (including why some maternity units have closed MUs)

-

explore why some maternity services in England have no MUs

-

identify why some maternity services in England have ≥ 20% of all births in MUs

-

identify why some maternity services in England have MUs, but are running at substantial undercapacity (≤ 10% of all births)

-

convene a national maternity care stakeholders’ workshop to discuss appropriate interventions and service guidance to inform future maternity service commissioning and provision regarding improving the availability and utilisation of MUs.

Structure of the report

Chapter 1 describes the background and rationale for the study. Chapter 2 describes the research approach and methods, with details of the design and analysis. Chapter 3 reports the findings of the national mapping survey of MUs in England. Chapter 4 describes the findings from the case study sites. Chapter 5 describes the stakeholder workshop, which included individuals from a range of constituencies, designed to generate guidance for maternity care providers and commissioners. Chapter 6 discusses in more depth the integrated findings from stages 1–3. Chapter 7 is the conclusion, summing up the key findings, their implications for maternity services and recommendations for further research.

Updated literature review

The literature review, updated from the original research submission, identifies the existing, contemporary (from 2000 to 2017), English-language research of MUs (AMU and/or FMU). The search terms ‘birth cent*’, ‘midwife led unit’, ‘birthplace and midwife’, ‘place of birth’ and ‘midwife’ as title or keyword were used to search four databases: MEDLINE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), EMBASE and PubMed. A manual search of key journals and article references was also undertaken.

There was a range of study designs utilised in research evaluating MU clinical outcomes, including randomised controlled trials (RCTs) or quasi-RCTs, prospective cohort studies, retrospective cohort studies and mixed-methods case studies. Although one RCT8 and one cohort study9 have been undertaken in the context of the opening of a MU, with access to it being dependent on agreement to participate in the study, the RCT was confounded by the two arms receiving different models of care. 8,9 RCTs may not be appropriate or possible (acceptable to women) in a context in which women already have ready access to either birthplace type. 10 Although observational studies are subject to selection bias, which weakens the ability to draw causal inferences,11,12 this design can accommodate several outcomes within the same study. 13 Arguably, they are the best design for answering research questions regarding the identification of differences in clinical outcomes between the different birthplace types, given the complexity of both childbirth and birthplace. 14–16

The Cochrane review into alternative (MUs) compared with conventional settings (OUs) for birth included 10 trials, including a total of 11,795 women, relating to AMUs only, with six of them undertaken over 25 years ago. 3,17–21 There are also several observational studies into AMUs, with comparison OU outcomes. 19,22,23 The limited contemporary research into the comparative clinical outcomes for FMUs and OUs includes prospective studies,24–26 a retrospective study27 and population-based cohort studies. 19,28 There are also studies reporting only MU clinical outcomes, with no OU comparison outcomes from the same context. 29–32 All but a few of these studies report similar or improved neonatal outcomes for women planning a MU birth compared with women of similar risk planning an OU birth. The few discrepant studies reporting worse neonatal outcomes for FMU babies than those born in an OU are from the USA. 33–35 The lack of integration of MUs in the US maternity system arguably limits the applicability of this, and other research from the USA, in the UK context. Studies that are not relevant to the context or focus of the MU study are not for inclusion here, for example those combining all out-of-hospital births for comparison with OU births,36 those evaluating a model of care rather than birthplace type37 or those from remote rural38 or developing country contexts (e.g. Nepal).

The Birthplace in England study3 is the largest and most comprehensive comparative birthplace research to date. It included 64,538 women defined as ‘low risk’ (19,706 women planning a OU birth, 16,710 women planning an AMU birth, 11,282 women planning a FMU birth and 16,840 women planning a home birth). This study is relatively recent and set in the local context, making it the dominant reference in the birthplace literature and in the latest NICE intrapartum and birthplace guidelines. 39

Specifically, the caesarean rate varied from 11% (OUs) to 4% (MUs), the assisted vaginal birth rate (forceps and vacuum assisted) varied from 15% (OUs) to 7% (MUs) and the rate of normal birth varied from 73% (OUs) to 90% (MUs). In addition, in OUs and MUs the epidural rate was 30% and 12.5%, the intravenous oxytocin rate was 23% and 8.5% and the episiotomy rate was 19% and 10%, respectively. 3 These differences are critically important. Operative births and labour interventions put the mother at greater risk both physically and psychologically. The major complications of caesareans are severe haemorrhage, thromboembolism, infection and risks for subsequent pregnancies. 40 Emergency caesareans are also linked to post-traumatic stress. 41 Assisted vaginal birth is associated with perineal trauma, anal sphincter tear and urinary stress incontinence. 42 Epidurals increase the risk of assisted vaginal birth43 and intravenous oxytocin is more likely to be associated with fetal compromise. 44 Higher rates of episiotomy are linked with additional perineal trauma. 45

The reduction in all of these labour interventions and operative birth outcomes could be achieved if low-risk women birth in MUs. Critically, outcomes for babies when women birth in MUs are no different from those born in OUs. 3 The Birthplace in England study also found that having a baby in a MU was cheaper. The unadjusted mean costs were £1435, £1461 and £1631 for births in FMUs, AMUs and OUs, respectively. 46 MUs also improve continuity of care and one-to-one care in labour47 and increase women’s sense of control and their satisfaction with care,17 areas in which the Care Quality Commission say current maternity services need to improve. 48

In 2014, McCourt et al. 49 reported follow-up research to the Birthplace in England study3 on AMUs’ organisation, staffing and provision. They called for further research into the facilitators of and barriers to expansion of MU capacity.

In the past 2 years, research from New Zealand,50,51 Australia52 and the Netherlands53 on MU outcomes continues to show the consistent trend to fewer birth interventions. In addition, an English study found that FMUs were cost-effective. 54

This updated literature review provides additional background evidence and context for the rationale for this study, outlined at the beginning of this chapter (see Rationale for the research).

The next chapter details the research approach and methods.

Chapter 2 Research approach and methods

This chapter details the research design and rationale for the methods of the three stages of the research. It describes the individual components of each stage, including a discussion of the theoretical underpinning for the analyses of the case studies.

It also provides a brief overview of how the study was organised and managed, and the public involvement throughout all stages.

Study organisation and management

The study was overseen by the co-investigators, a Project Management Team (made up of the researchers and a subset of the research team, which met monthly) and an advisory group (which met twice a year). The overall role of the advisory group was to ensure that the study was conducted in line with the protocol, and that the design, execution and findings were valid and appropriate for all stakeholders in maternity care. The role was also to ensure linkages with any emerging intelligence related to the topic.

Public involvement in the research

Public involvement was integrated into the study throughout all phases, including project design, implementation, management and dissemination. Four service users were recruited through an established local service user maternity network [URL: www.nottsmaternity.ac.uk (accessed 8 July 2019)] that worked with the university maternity research group. Black, Asian and minority ethnic representatives were part of this group, but none volunteered for our project. This service user reference group reviewed the study design, all study documents and the research process, including data collection and feedback on emergent findings presented at the stakeholder workshop, and have continued with dissemination activities with their networks over the past 12 months.

User involvement in the study design

One of the co-investigators (MD) has had a long history with maternity care research in the UK as a service user representative. She contributed to the original idea for the research and to the subsequent protocol.

User involvement in the study implementation

A service user reference group was established once the funding had been secured and met twice per year over the lifetime of the project. Group members advised on approaches to achieve recruitment of women into focus groups. All members participated in data collection, specifically in facilitating women’s focus groups at the six case study sites across England. In preparation for this, they, together with other members of the research team, participated in a bespoke training workshop on focus group facilitation. At the stakeholder workshop, one member of the service user reference group co-presented the preliminary findings to stakeholders and two other members co-facilitated two of the small group discussions held throughout the day.

Research design and methods

The design was in three stages, utilising mixed methods. The mixed-methods approach is most aptly described as explanatory sequential. 55 Within this typology, quantitative data collection and analysis (stage 1) inform later stages of qualitative data collection and analysis (stages 2 and 3). This is then followed by a final interpretation phase (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Stages of the mixed-methods research.

The six objectives of the project overall are mapped as follows (and outlined in Chapter 1) to these three stages, commencing with stage 1.

Stage 1 (objectives 1 and 2)

Objective 1

To describe the configuration, organisation and operation of MUs (both AMUs and FMUs) in England.

Method

Telephone survey of all NHS trusts in England with maternity services.

Data collection

Our data collection was aided by information provided by BirthChoiceUK and the consumer organisation Which? Both of these companies provide web-based information about maternity service provision across the UK. BirthChoiceUK holds a database containing details of maternity unit configurations, which was supplied to Which? for the development of the Which? Birth Choice website. 56 Which? also audits MU provision and utilisation across the UK. We entered into a data agreement with Which? for it to share the details of maternity units and configurations along with information it had collected about birth numbers in MUs in England. We developed our own data collection pro forma after consulting both the Birthplace in England mapping data collection tool57 and pages on the Which? Birth Choice website relating to maternity units, and populated it from the Which? Birth Choice data. Heads of midwifery (HoMs) in the 134 trusts across England were then sent the survey. We then telephoned the HoMs, who confirmed, clarified or completed missing entries in the survey for their current maternity services. These telephone interviews, which lasted up to 30 minutes, took place over a 3-month period between March and May of 2016. Actual annual number of births was completed using the Which? Birth Choice data and updated in the telephone interviews, as required.

Ethics

This first stage of the research was classed as service evaluation and thus did not require Research Ethics Committee (REC) approval.

Sample

One hundred and thirty-four HoMs, representing all NHS trusts providing all publicly funded maternity care in England, were contacted by the research staff. Home birth was excluded from our data.

Analysis

Descriptive summary statistics and narrative description of configuration, organisation and operation of AMUs and FMUs was undertaken.

Objective 2

To build an understanding of key issues and barriers to uptake facing MUs (including why some maternity services have closed FMUs).

In trusts in which a FMU had been closed within the previous 8 years, the HoM was interviewed to gain their perceptions of the reasons for closure. An analysis of media (newspaper, radio, television) coverage of the closure of the relevant units was also undertaken.

Method

A systematic search of media reports, content and discourse analysis was carried out guided by framing theory. 58

Data collection

The LexisNexis database was searched systematically to identify all media reports directly relating to the 14 FMUs in England that had closed between 2008 and 2015. Multiple FMUs from the same NHS trust were considered as one site, as were two units from different but nearby trusts that had closed after recommendations from the same service review. After screening, two services (Mid Yorkshire Hospitals NHS Trust, Wakefield Birth Centre; and Wiltshire Primary Care Trust, St Peter’s Maternity Unit, Shepton Mallet) were found to have no relevant articles, leaving a remaining eight services. The number of articles about each site ranged from 2 to 65. A total of 190 articles were included in the analysis. These included local newspaper articles (n = 175), transcripts of local television news items (n = 5) (all from one site) and articles from national publications (industry publications and national newspapers) (n = 11).

Analysis

Data were extracted onto a bespoke template in Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), which provided a framework for analysis, working on two levels, to (1) identify and analyse the relevant content using a structured approach and (2) identify and analyse the discourse present in the media reporting in each case. The approach enabled us to capture the range of voices and to compare perspectives, identifying who the authors and speakers were in each report and relating this to extracted content and discourse. The aim of this was not to triangulate in terms of validation but to recognise that media analysis captures events not as ‘facts’ but as representations of them. The template was drafted in relation to the study objectives and discussed and revised within the research team. It was intended to be used flexibly, allowing for the amendment of categories when needed, and some categories on the template were combined in the light of the initial data extraction work. Two team members extracted data for each site independently of each other, using a separate sheet for each media report, and any areas of difference were discussed to reach consensus. Using a purpose-built macro, the data were then collated into a single spreadsheet for each site and a thematic approach was used to synthesise the findings within and then across all services.

Once the emergent themes had been identified, framing theory58,59 was used to guide the synthesis of themes in relation to discourse.

Stage 2 (objectives 3–5)

Objectives

To explore why some maternity services in England achieve ≥ 20% of all births in MUs.

To explore why some maternity services in England have opened MUs but are running under capacity (≤ 10%).

To explore why some maternity services in England have no MUs.

Method and justification

Case study methodology was the most appropriate approach for these aims, as it facilitates the exploration of large, complex organisations, such as maternity services. It does this by combining a range of data collection methods, including interviews and focus groups, with a variety of sampling techniques, to achieve data saturation and thus gain an in-depth understanding of the social processes and organisational culture within each study site. 60 Specifically, this project explored why organisational change, premised on a relatively strong evidence base, had not been achieved across England in relation to the provision and utilisation of MUs. Within each site, both individual interviews and focus groups were used to produce a detailed and rounded analysis of the case. A comparative case study approach enabled the identification of common and differentiating determinants of the successful implementation of MUs. 61 In-depth exploration of each study site was necessary to gain an understanding of the complex set of inter-related factors that played a role in the local uptake and implementation of MUs. The case studies provided sufficiently detailed descriptions of the local social processes and contextual factors to develop an understanding of the potential for individual findings to be sensitively generalised to other sites. 62

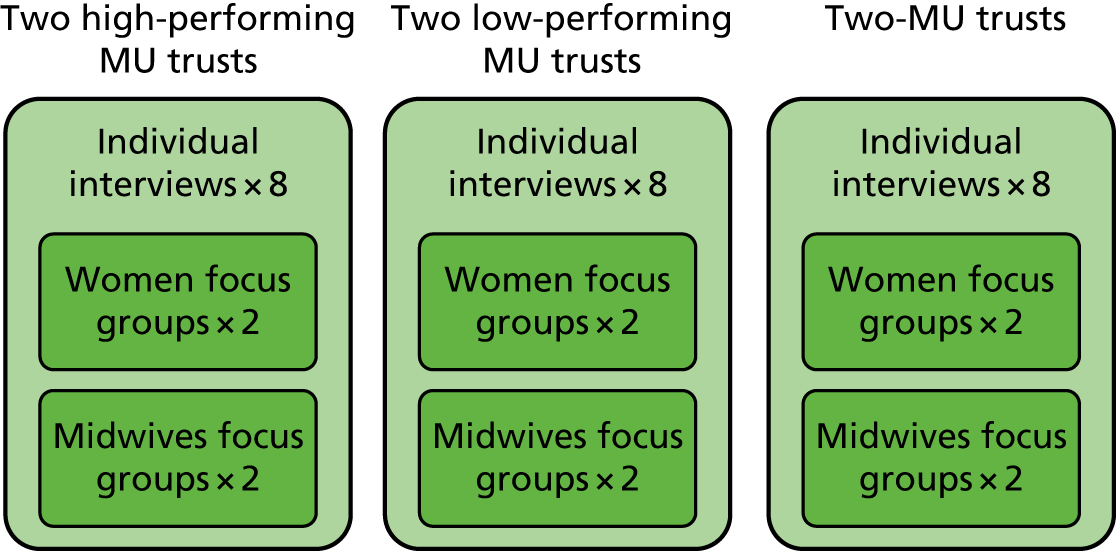

Using the data from stage 1, six case study sites were purposively sampled to identify:

-

two high-performing services with both an AMU and a FMU, achieving ≥ 20% of total births

-

two low-performing services with one or more MUs (AMU or FMU), achieving ≤ 10% of total births

-

two services with no MUs.

Within each of the three categories, study sites were chosen to represent both rural and urban settings to enhance diversity. Six sites (two from each category above) were chosen to obtain a cross-section of local maternity care services that might approximate typical adoption, integration and utilisation of MU services.

Theoretical/conceptual framework

The theoretical and conceptual frameworks underpinning the case study methodology are described below.

This research sought to identify and analyse factors that help to explain variations in MU provision, with a view to identifying routes to overcoming barriers to change. Findings of the potential economic efficiency of MUs over OUs46 suggest that financial drivers alone do not explain the inequitable provision of MUs across the country. In recent years, there has been a widespread focus on the gap between research evidence and practice. 63,64 Prior research supported by the National Institute for Health Research describes multifaceted barriers to and drivers of change in the NHS, including contextual conditions, the nature of innovations and the processes of implementation. 65,66 Considering this work, a wide range of factors may be thought to facilitate or create barriers to the establishment and utilisation of MUs. Previous research has identified a number of important institutional factors shaping maternity services and potentially hindering innovation, including issues of professional power and the midwifery–obstetrics relationship,67,68 resource constraints and workforce issues,69 the environment of litigation and risk management,70,71 as well as inaccurate media portrayals of birth. 72 Currently, however, the prevalence and impact of potential barriers to the creation and utilisation of MUs remains unclear. In addition, a large body of research on innovation diffusion and implementation has demonstrated that innovations, particularly those that involve complex organisational change, do not move directly from evidence into practice, but are adapted, and in some cases transformed, through the process of implementation. 67,73 To explicate this process, our study utilised Damschroder et al. ’s74 Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR), supplemented by theory that considers the wider institutional forces shaping health-care organisations and organisational change. 75,76

The CFIR provides useful insights for investigating why implementations fail, or are only partially successful, to guide future implementation efforts. 77 This was selected to provide a conceptual framework to analyse the contexts of MU implementation and systematically identify the factors influencing the extent to which MUs are adopted into practice and utilised. The CFIR was developed through meta-review of previous implementation literature and theories, and identifies 39 underlying constructs previously found to have an impact on the course and extent of implementation. The CFIR has now been used by a number of studies to identify factors affecting implementation, including the implementation of complex service initiatives,78–80 and has been found to be an effective tool to identify barriers to and facilitators of implementation. 81 Within the CFIR, constructs are divided between five major domains:

-

characteristics of the intervention itself, including the essential ‘core’ and adaptable ‘periphery’ elements, its design, complexity, cost and degree of flexibility

-

outer context of change, including pressure from patients, partners and other stakeholders

-

inner context of change, including the features of the local organisation, its culture, structure, practices and resources

-

individuals involved in change, their preferences, beliefs and identities

-

process of change itself, including details of planning, engaging and executing.

This framework is not intended to be applied wholesale, but rather offers a long list of constructs to consider for inclusion when investigating particular instances of implementation. We drew on CFIR to identify relevant constructs in early stages of the study to inform data collection and subsequent approaches to analysis, as outlined in the sections below. The current research sought to explore both the variation in initial engagement with MUs as well as subsequent implementation in sites that do engage. Therefore, the CFIR, geared towards understanding specific instances of implementation, was supplemented by theory geared towards consideration of the factors affecting MU adoption at a more general level. A large volume of recent work on health-care organisations has identified regulative, normative and cultural features of the health-care institutional environment75 that shape the potential for innovation and change. 76 Waring et al. 82 suggested the guiding categories of power, organisation, culture and knowledge, which have previously been adopted to make sense of the complex set of inter-related social factors known to affect processes and outcomes of health-care organisations. These categories guided the analysis of the more macro elements of the ‘outer context’ of change.

Data collection

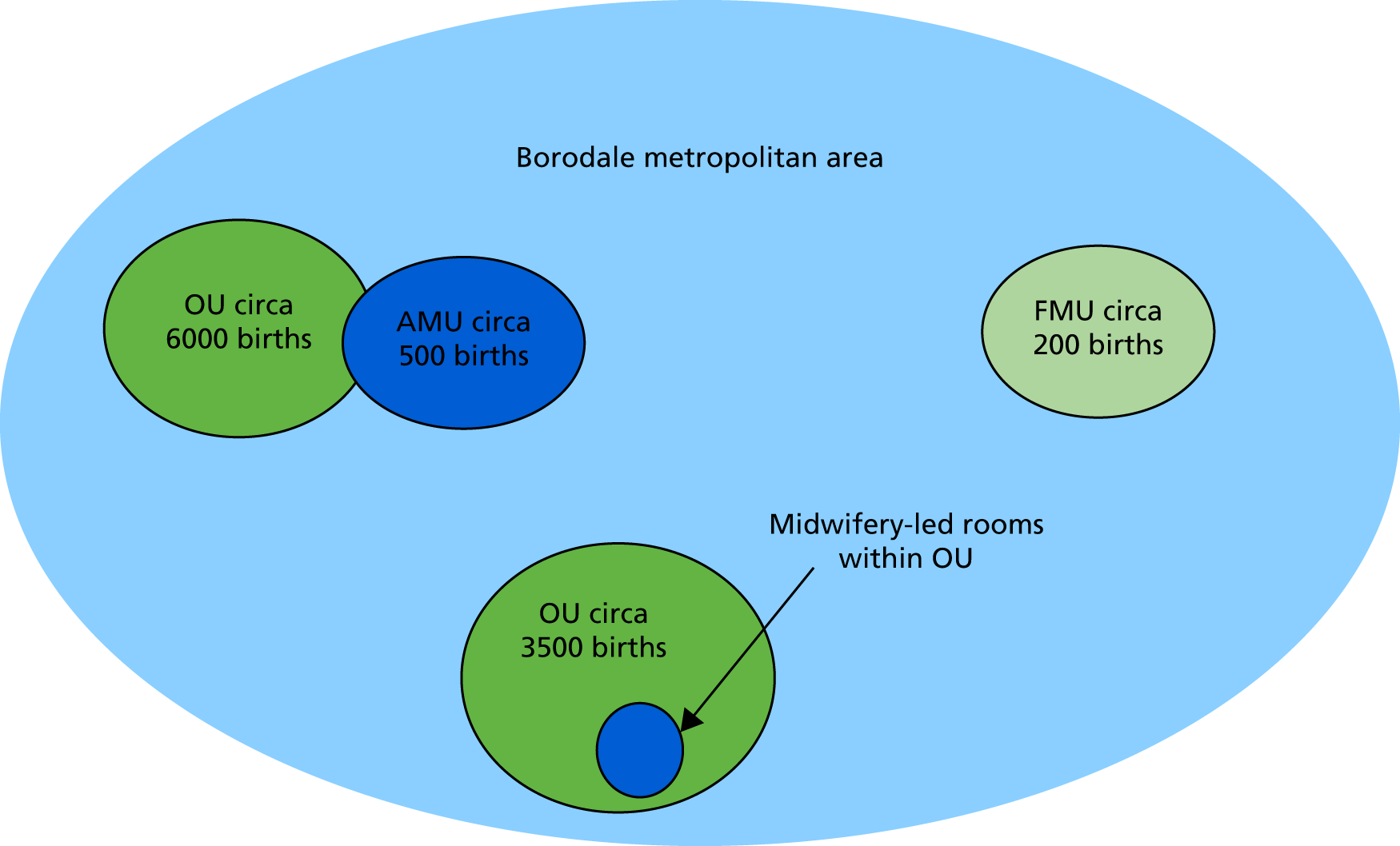

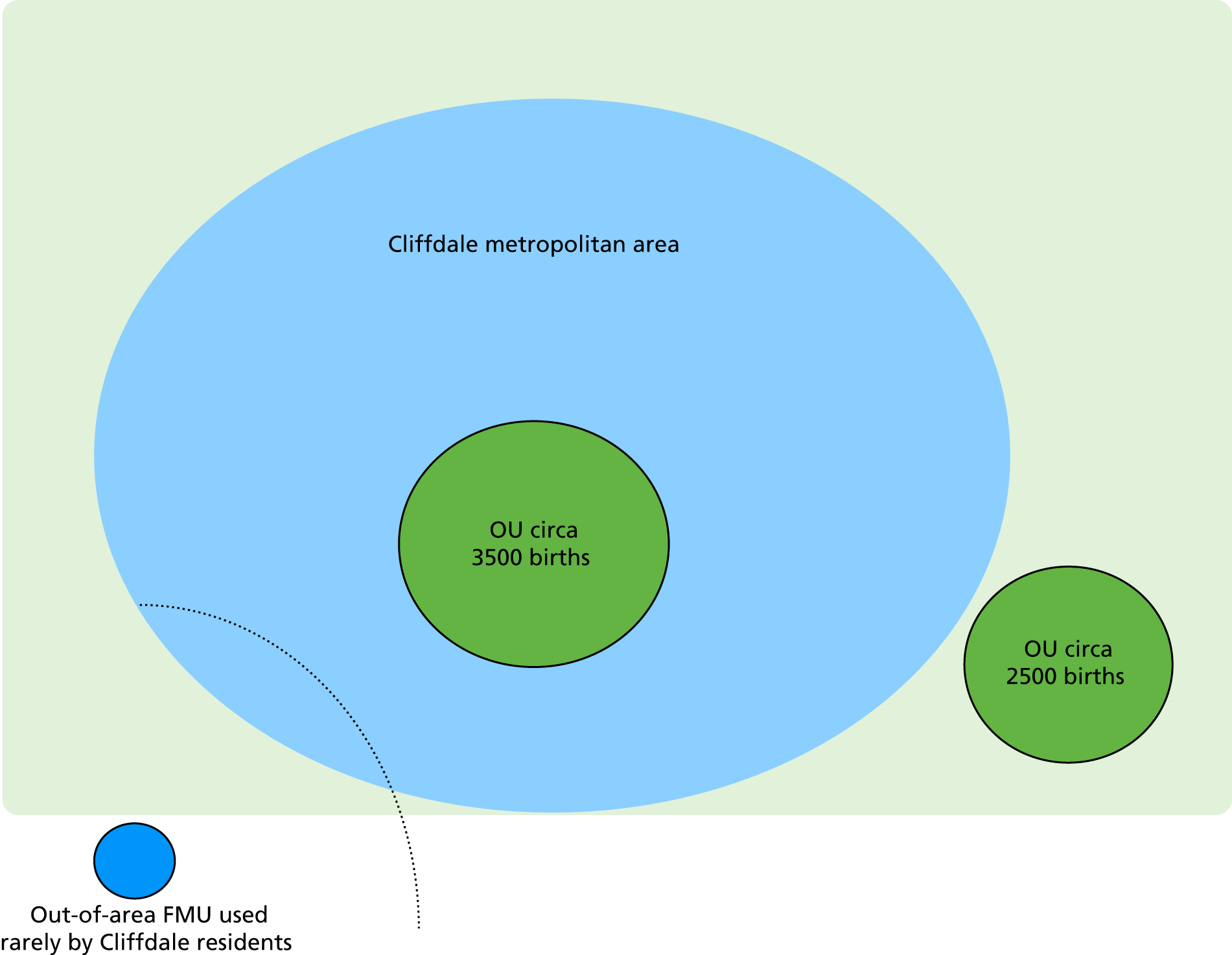

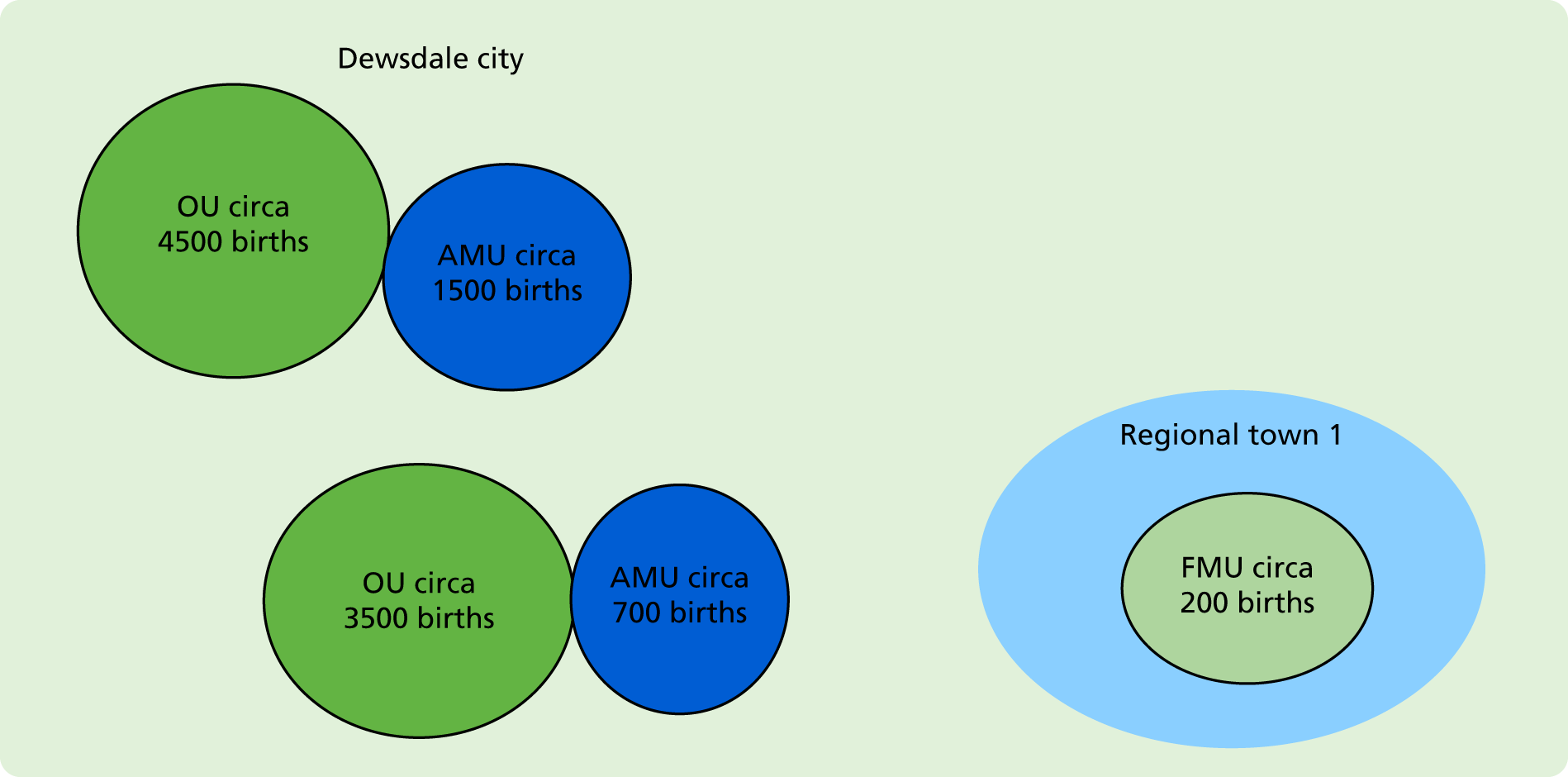

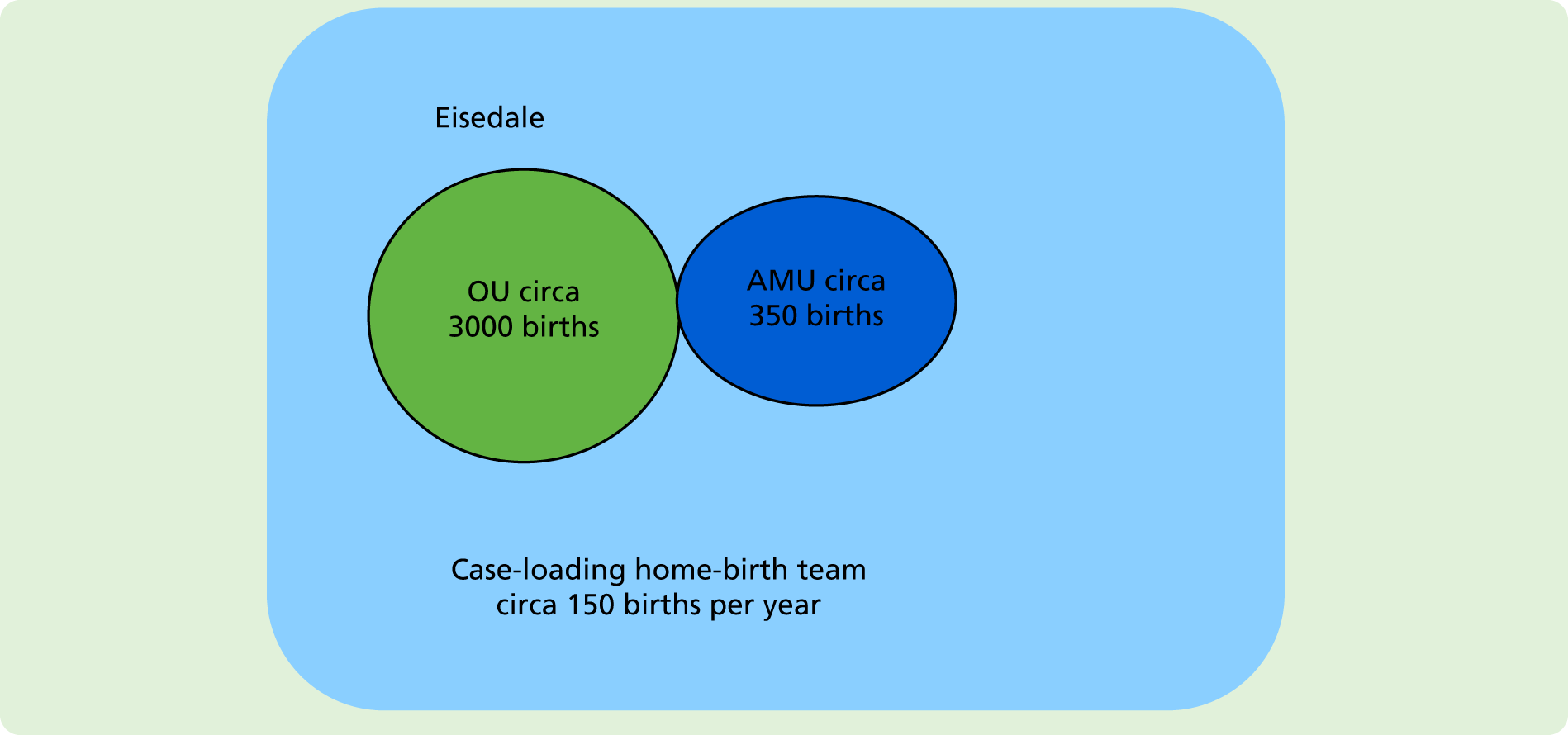

Data collection consisted of in-depth telephone interviews and focus groups of midwives and service users, held locally (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Case studies.

The interview schedule was developed by the research team, drawing on the findings from the first stage of the study, existing literature regarding the organisation of maternity services and literature on implementation and organisational change, and was reviewed by the service user reference group and the advisory group. Questions were focused on discussing the evolution of services in each of the sites.

Interviews

At each site, digitally recorded semistructured telephone interviews were undertaken with the chief executive of the NHS trust, HoM, senior obstetrician, community midwifery lead, business manager for maternity service, neonatologist, GP commissioner of local maternity services, Maternity Services Liaison Committee service user or user group representative and local maternity support/campaigning groups. These interviews lasted between 30 and 60 minutes and a minimum of eight interviews were carried out at each site. They were professionally transcribed verbatim.

Focus groups

Focus groups with service users and with clinical midwives were conducted at each site. The focus group guides were developed by the research team in collaboration with service users.

In each site, two focus groups were held with six to eight women who had given birth in the previous 12 months. These groups were held at venues in the local community of case study sites. The groups were co-facilitated by a service user from the Nottingham Maternity Research Network (service user reference group) and a member of the research team. They lasted on average 45 minutes and were digitally recorded and transcribed. Topics explored included interviewees’ perception of local service options around place of birth and the functioning of MUs. Within each site, we attempted to recruit as diverse a sample of participants as possible (e.g. different ethnic groups, different socioeconomic classes, different parity and age), but this was hampered by having to rely on local informants. In the end, we recruited women whom informants knew through Facebook (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA; www.facebook.com) contacts mainly. We achieved diversity in relation to age, parity and minority ethic Asian representation, but not very well in relation to social class.

In addition, we undertook two focus groups with six to eight midwives in each site, exploring how choice of place of birth was presented, how MUs were functioning where they existed and midwives’ perceptions of why they had not been developed in sites without them.

Ethics approval

The stage 2 case study was reviewed and given a favourable opinion by the West Midlands – Solihull REC on 1 April 2016 (REC reference number 16/WM/0136).

Analysis plan and revisions

The process for analysis of qualitative case study data was as follows.

Both DW and CG attempted to each code a women’s focus group discussion according to the CFIR, but it became clear from early on in this exercise that the transcript codes did not map across to the CFIR domains and constructs, except in very selected areas. This was because the women’s transcripts reflected their personal experience of care and not the broad sweep of a major service implementation project. Following a team discussion, it was decided that the women’s focus group discussion would be open-coded and analysed thematically, utilising the principles of thematic analysis as outlined by Braun and Clarke,83 supported by NVivo software (QSR International, Warrington, UK). This approach follows six distinct stages: (1) familiarisation with data, (2) generating initial codes, (3) searching for them, (4) reviewing themes, (5) defining and naming themes and (6) writing up findings.

All other interviews and the midwives focus groups (MFGs) were analysed using the CFIR. First, in the pilot analysis, five members of the research team (DW, DC, HS, CG and SB) coded the same three interviews to the constructs in the CFIR, which are grouped into six domains, mentioned above. This coding was placed within NVivo, with nodes and subnodes created to match the domains and constructs of the CFIR. These team members then met to compare coding and discuss how data related to each of the constructs. A second pilot round was then undertaken with the same team members coding an additional two transcripts. Once it had been agreed that a shared understanding of CFIR constructs had been achieved, case study sites were then divided between the project members involved in coding (DC two sites, DW two sites, SB one site and HS one site). The remaining interviews and MFGs were then coded according to the constructs within the CFIR. It was considered appropriate for an individual coder to complete analysis of a whole site in order to develop an in-depth understanding of the case. During this stage, ‘open’ codes were also added within CFIR constructs to further identify how the data related to the broader construct. For example, data relating to the construct ‘patient needs and resources’ were also coded by the nature of specific patient needs and resources referred to, such as ‘patient need for choice’ or ‘patient need for convenient locale’.

At this stage, a number of issues with coding data to the constructs in the CFIR were encountered. One issue that arose was that there were differences in the number of open codes created by each coder, with some coders adding a larger number of codes with greater specificity in relation to the data. In addition, data from the MFGs and the individual interviews often related to multiple constructs, and were therefore coded in several places, under the framework. One of the consequences of this was the production of many additional nodes within NVivo, which made handling the full data set cumbersome; it also meant that it was difficult to test inter-rater reliability following this coding stage.

To address this, following this coding, a wider team of co-investigators (DW, HS, SB, CMc and LC) who had previously undertaken case study analysis met to start the process of collapsing codes into themes. In addition, the research fellow who had not participated in the coding, but was very familiar with the data scrutinised, reorganised and reduced the codes within each construct to reflect the important themes of the data and relate this to the logic of the CFIR construct in which it was located, in a process akin to axial coding.

This process of reduction revealed six cross-cutting themes that were relevant under multiple CFIR constructs (see Table 22). We then had to make a decision on how to report the findings: whether to give priority to the cross-cutting themes or to the CFIR domains as the organising headings. If we chose the former, it rendered the theoretical underpinning of the CFIR redundant, superseded by these six primary themes. However, the CFIR, as well as being empirically validated in multiple organisational research projects,74 had provided us with a heuristic template via its five headline domains of (1) intervention characteristics, (2) outer setting, (3) inner setting, (4) individual characteristics and (5) process. We therefore decided to locate the cross-cutting themes within these domains.

In addition, narrative summaries and within-site comparisons of each case study site were produced to tell the ‘story’ from each site and to tease out areas of unanimity and dissonance between the respondents. These sections utilised and synthesised elements of the broad domains of the CFIR (inner setting, outer setting, characteristics of individuals, intervention characteristics and process) to shape each story. This facilitated more congruence in the reporting of the data collected in each site, which lost some of its distinctiveness and rootedness when coded as one data set into NVivo.

A ‘within-case’ analysis proceeded to ‘cross-case’ comparisons. Waring’s84 categories of power, organisation, culture and knowledge assisted in providing a macro-lens to inform this level of analysis. In this way, a comprehensive picture of both the ‘inner’ and ‘outer’ context for change assisted in distilling the key barriers to and facilitators of MUs developed (see Chapter 6).

The CFIR assisted analysis of interviews and MFGs were juxtaposed with the thematically analysed women’s focus group at the level of the cross-case analysis.

Stage 3 (objective 6)

Objective

Convene a national maternity care stakeholders’ workshop to discuss appropriate interventions and service guidance to inform future maternity service commissioning and provision, regarding improving the availability and utilisation of MUs.

The workshop aimed to engage participants in a dialogue to enhance the ontological, educative and catalytic authenticity of the research. 85 The team presented their findings from stages 1 and 2. Workshop participants collaborated in mixed interdisciplinary small groups, led by two facilitators from the project team, service user network and advisory group, in examining and suggesting potential interventions. This was done in the following way. The participants were asked first to discuss appropriate interventions in response to the findings, and then to categorise these as immediate/short term (up to 3 months), medium term (6–12 months) or long term (> 12 months). Underpinning this process, we impressed on delegates the importance of remaining cognisant of the feasibility and utility of each of the proposed interventions in relation to their own organisations or areas of work. Finally, we asked the groups to target their interventions according to different stakeholder groups: providers (managers, different professional groups), commissioners and service users. The workshop thus linked research knowledge with decision-making processes and potential interventions. 86

Data collection

Data were captured by field notes and on flip charts throughout the day, which were then transcribed. Through this process of debate and discussion, further service guidance was co-developed by stakeholders and the research team.

Sample

The workshop was attended by 56 people. Our objective was to include all groups representing those involved in the maternity services, including service users, maternity care professionals, NHS trust managers, maternity policy representatives, service providers, service commissioners and politicians, and academics with an interest in maternity care.

Stakeholder workshop attendees were:

-

four members of the service user reference panel

-

head of policy of the National Childbirth Trust

-

representative of the chief executive of the Royal College of Midwives (RCM)

-

midwifery representative from the Department of Health and Social Care

-

three co-investigators on the Birthplace in England study3

-

national clinical director for Maternity and Women’s Health in NHS England

-

director of nursing, Commissioning and Health Improvement

-

chairperson of NICE Intrapartum Guideline Group

-

knowledge mobilisation research fellow (maternity services)

-

two representatives of former local supervising authority midwifery officers

-

two consultant midwives

-

neonatologist

-

consultant obstetrician

-

three representatives of Maternity Transformation, NHS England

-

chief executive officer (CEO) of Birthrights

-

two doulas

-

midwifery clinical leads from an AMU and a FMU

-

two representatives of the Midwifery Unit Network

-

two representatives from two maternity and neonatal networks in England.

Ethics

This third stage of the research was classed as service evaluation and thus did not require REC approval.

Analysis

The workshop data were synthesised by HS and reviewed by DW and LC.

Changes to the protocol

The original protocol had included local media analysis regarding changes in MU provision at the case study sites. However, as a result of extensive delays with clinical governance approvals at most of the sites, there was insufficient time to undertake the local media analysis and undertake all of the focus group and individual interviews. Only site 1 had undergone recent, significant maternity service reconfiguration and this process was covered quite comprehensively in individual interviews. In addition, our media analysis of closed FMUs from stage 1 became more extensive than originally intended. We were confident that this aspect of the project illustrated the impact of local media commentary on service reconfigurations and therefore adequately compensated for the loss of media analysis from the case study sites.

Documentary analysis was also in our protocol and was to include minutes of strategic meetings about MU service changes and local policy and guidance about MU access, organisation and operation. However, when we asked case study sites for these records, they were either unable or unwilling to produce them, despite repeated requests. We made the pragmatic decision to not pursue this.

The next chapter details the results for stage 1 of the project: the mapping, organisation and operation of MUs and the findings about the closure of FMUs, both from the media analysis and the interviews with HoMs of MUs where FMUs had closed.

Chapter 3 Findings phase 1: mapping, organisation and operation of midwifery-led units

The aim of the initial phase was to report on the types, numbers and utilisation of MUs in England, 6 years on from the Birthplace in England study,3 and present the results from the first part of a larger funded study of the facilitators of and barriers to optimal use of MUs. It compares the results with the Birthplace Mapping Survey57 and comments on the changes that have occurred over that time. In addition, it discusses in more depth the potential utility of MUs to birth a greater proportion of low-risk women. This has already been published and is referenced in the Acknowledgements.

Definition of alongside midwifery units

To enable accurate mapping of service configuration it was first necessary to review how terms are operationalised. MUs are defined as a clinical location offering care to women with straightforward pregnancies during labour and birth, in which midwives take primary professional responsibility for care. Although the definition of a FMU is clear (MU that is a geographical distance from a host OU and therefore requires a vehicle transfer if complications occur in labour), an AMU is less clearly defined. The Birthplace in England study3 defined it as a MU in which diagnostic and therapeutic medical services, including obstetric, neonatal and anaesthetic care, are available, should they be needed, in the same building, or in a separate building on the same site. 57 Transfer will normally be by trolley, bed or wheelchair. Follow-on research projects from the Birthplace in England study3 add that AMUs should be able to accurately identify their admissions and births in their record systems. 87 However, these criteria allow for a number of hybrid arrangements, for example:

-

midwifery-led rooms within the physical space of a traditional labour ward

-

a midwifery-led area adjacent to a labour ward, but with no separate staffing or management

-

a midwifery-led area that allows for labour interventions, such as continuous fetal monitoring

-

a midwifery-led area that is regularly used for labour ward overflow

-

no separate data collections of processes or outcomes within the MU.

Within our team, we had extensive discussions before agreeing the following criteria for defining AMUs for the mapping stage of our study:

-

midwifery-led care setting

-

‘low-risk’ women, with case-by-case exceptions only

-

separate physical space from OU, with minimum demarcation being a line on the floor that excludes (e.g. having a AMU-style room within an obstetric labour ward)

-

only emergency secondary/tertiary-level care is permissible within the space; epidurals, continuous electronic fetal monitoring and medical induction/augmentation require transfer to the adjacent OU

-

does not provide care for labouring high-risk women when the OU is short of rooms (unless exceptional circumstances)

-

ability to measure number of births per year.

These criteria are slightly more restrictive than the Birthplace in England study3 and we estimate that they resulted in the exclusion of a very small number (possibly two or three) AMUs included in the previous research. Our data set therefore reflects this number.

Results

All 134 trusts participated in the survey (response rate 100%).

The results will be presented in four ways: (1) number and type of MUs as an indicator of place of birth choice, (2) changes since the Birthplace in England study,3 (3) the number of births per year in AMUs compared with FMUs and (4) MU births as a percentage of all births within each individual trust, excluding home birth. The last gives some indication of the utilisation of MUs as defined by percentage of women on a midwifery-led pathway that birth in them.

Number and type of midwifery-led units

The local configuration of maternity services (trusts) in England is constantly evolving. There has been a tendency for trusts to expand and merge so that there are now fewer trusts in England providing maternity services than at the time of the Birthplace Mapping Survey57 in 2010, reduced from 148 to 134. There has been a similar reduction in the overall number of OUs, from 177 to 159. Many of the existing small OUs operate in areas that are more rural. Most trusts have just one OU (n = 106), but 25 trusts now have two OUs and one trust has three.

One hundred and thirty-two trusts have at least one OU and, of these, 65% have at least one AMU. The majority of trusts (52.2%) have one OU and one AMU. Almost 27% of trusts have one OU and no AMU. Ten trusts with two OUs have no AMUs. The trust with three OUs has two OUs with an attached AMU and one OU without an AMU. This accounts for all 97 AMUs (Table 1).

| Number of OUs in the trust | Total | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Number of AMUs in the trust | ||||||||||

| 0 | 2a | 1.5 | 36 | 26.9 | 10 | 7.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 48 | 35.8 |

| 1 | 0 | 0.0 | 70 | 52.2 | 5 | 3.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 75 | 56.0 |

| 2 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 10 | 7.5 | 1 | 0.7 | 11 | 8.2 |

| Total n/% of trusts | 2 | 1.5 | 106 | 79.1 | 25 | 18.7 | 1 | 0.7 | 134 | 100.0 |

Twenty-nine per cent of all trusts (39 out of 134) have a FMU. Of these, six trusts have two FMUs, five trusts have three FMUs and two trusts have four FMUs, with the majority of trusts with FMUs having only one. Of these, there are two FMUs that are not part of a trust with an OU. Multiple FMUs were found to exist exclusively in rural areas. In total, there are 61 FMUs (Table 2).

| Number of OUs in the trust | Total | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |||||||

| n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | n | % | |

| Number of FMUs in the trust | ||||||||||

| 0 | 0 | 0.0 | 79 | 59.0 | 16 | 11.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 95 | 70.9 |

| 1 | 2 | 1.5 | 16 | 11.9 | 8 | 6.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 26 | 19.4 |

| 2 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 3.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 0.7 | 6 | 4.5 |

| 3 | 0 | 0.0 | 4 | 3.0 | 1 | 0.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 5 | 3.7 |

| 4 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.5 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 2 | 1.5 |

| Total n/% of trusts | 2 | 1.5 | 106 | 79.1 | 25 | 18.7 | 1 | 0.7 | 134 | 100.0 |

In summary, there are 23 trusts with an AMU attached to an OU and at least one FMU.

Within these 23 trusts there are:

-

three trusts with two AMUs and one FMU

-

eight trusts one AMU and two FMUs

-

three trusts with one AMU and three FMUs

-

one trust with one AMU and four FMUs.

The clusters of FMUs (e.g. three or more) attached to trusts (hub and spoke arrangement) tend to exist in counties that are more rural.

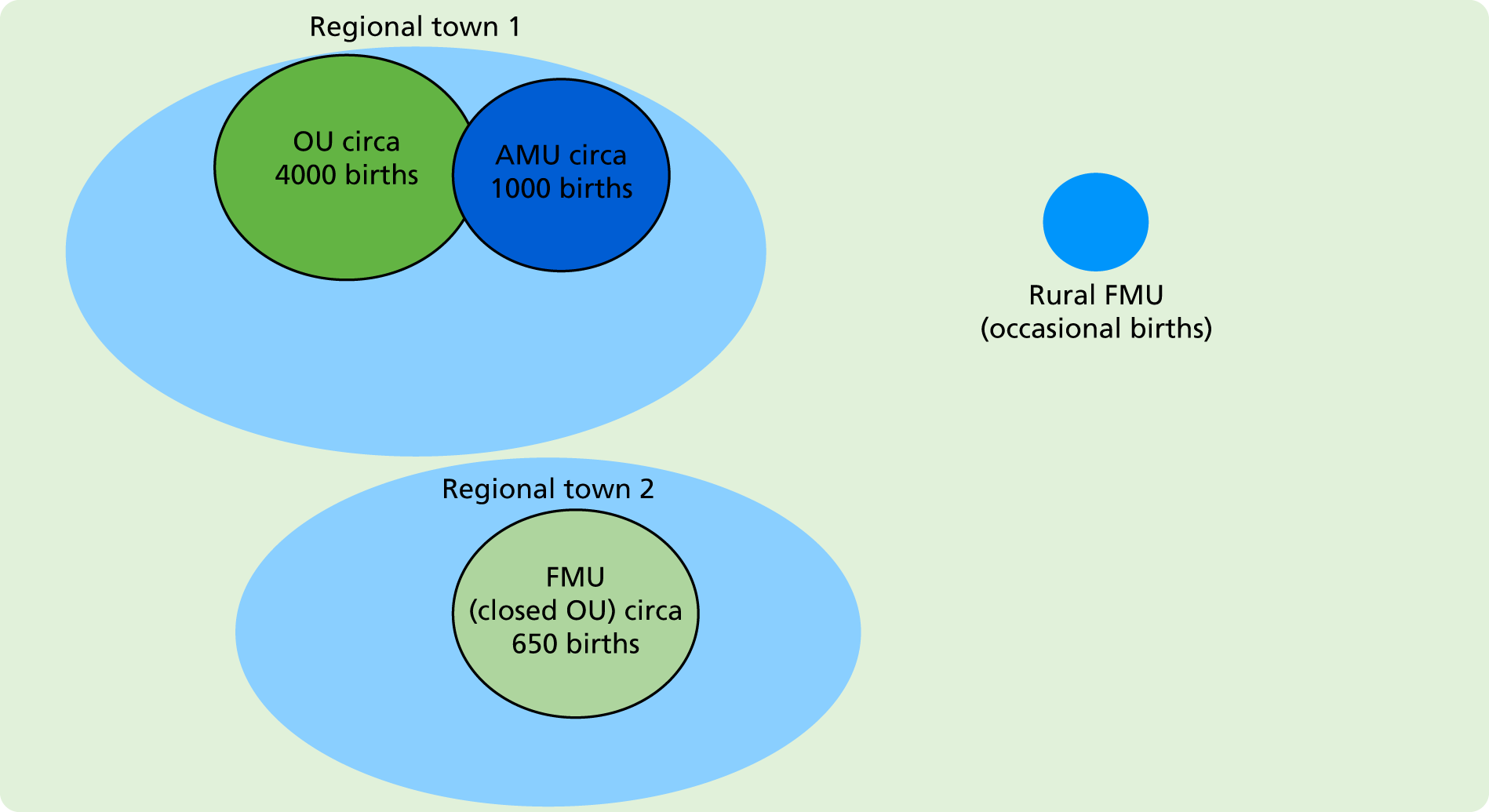

Figure 3 represents the current configuration.

FIGURE 3.

Flow chart of trusts, AMUs, FMUs and OUs.

Changes since the Birthplace in England study

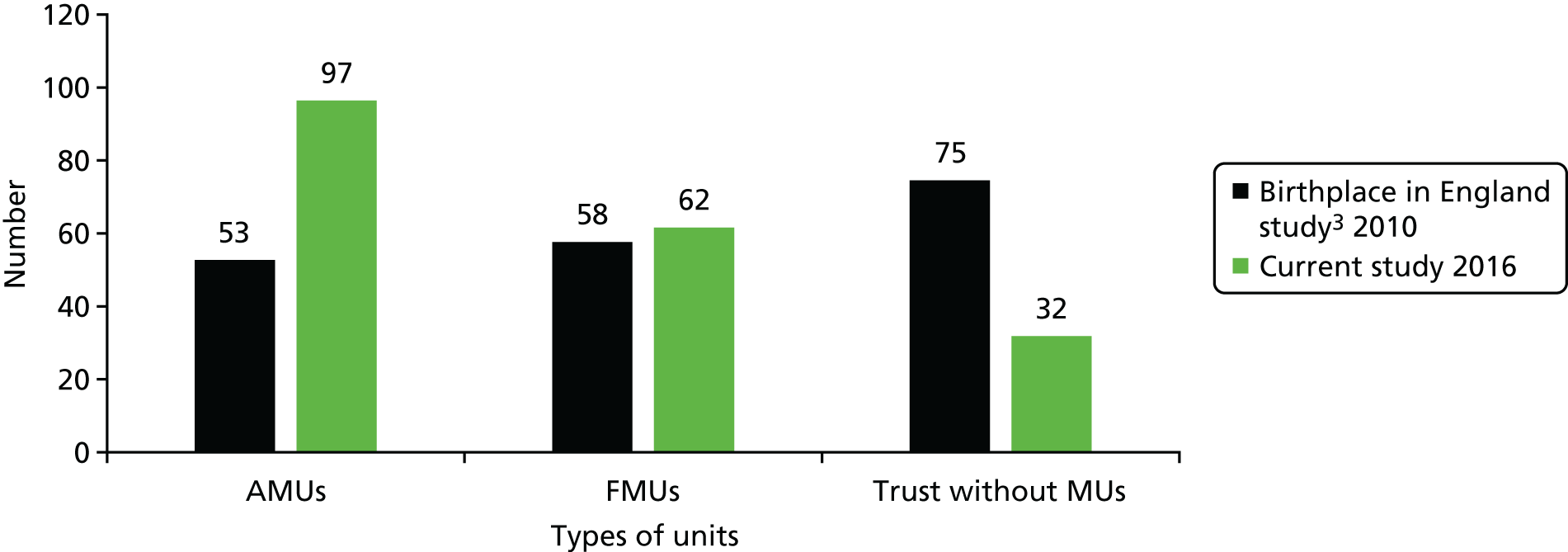

Over a 6-year period, there has been an increase of 44 AMUs and three FMUs since the Birthplace Mapping Survey was undertaken in 2010. 57 The number of trusts without a MU has fallen from 75 (50%) to 32 (24%), and, of these 32 trusts, 27 have one OU and five have two OUs (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Numbers of AMUs, FMUs and trusts without MUs in England: change since Birthplace in England study. 3

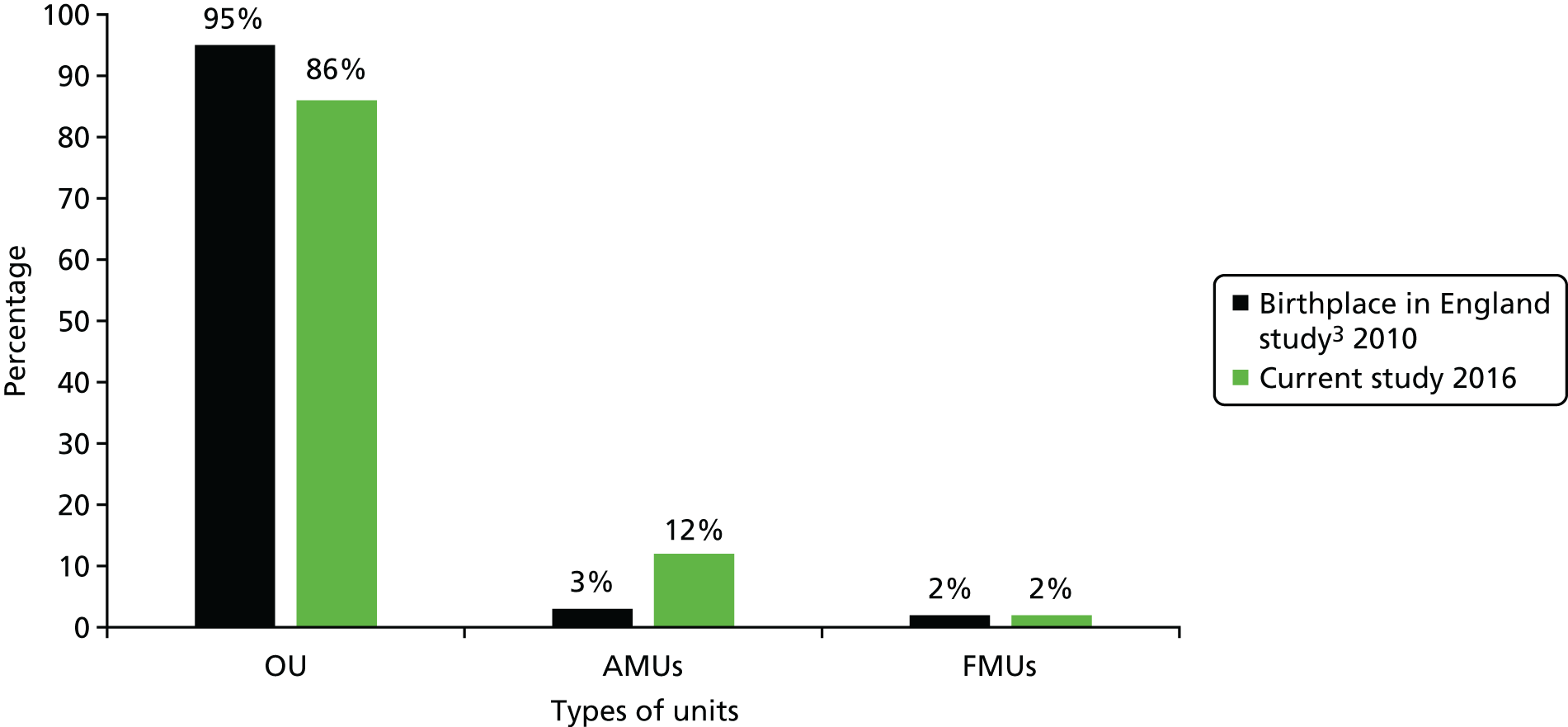

The increase in the number of MUs is reflected in a higher national percentage of all births occurring in such units. In comparison with findings from the Birthplace Mapping Survey,57 MU births across England increased from 5% to 14% of all births over the 6-year period, almost entirely related to the increase in AMU provision (Figure 5).

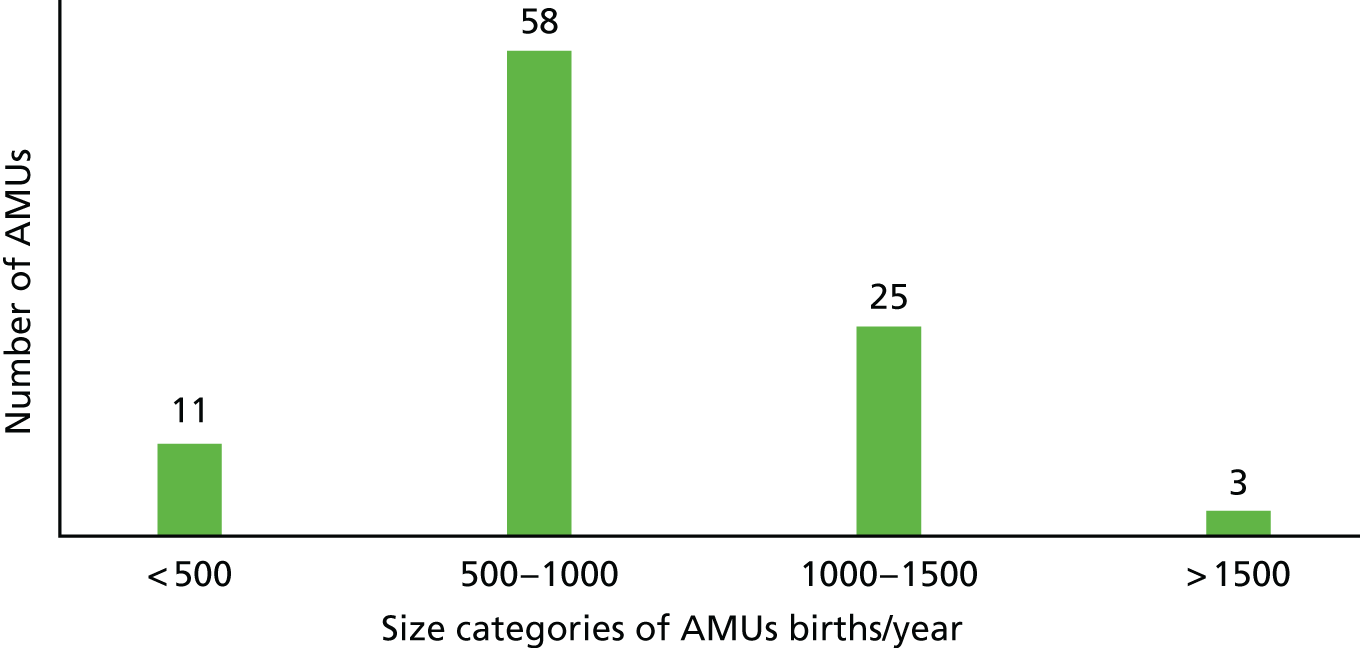

Number of births per year in midwifery-led units

The number of births in each AMU varies considerably, from 100 to 2000 births per year, but most range between 500 and 1000 births per year. Below we have categorised AMUs into bands based on their number of births per year (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Size of AMUs: numbers of births per year.

Size categories of alongside midwifery units birth per year

The differences in the number of births per year between AMUs is partly related to the number of births in their linked OU. For example, three of the five largest AMUs in England are linked to the three largest OUs. However, number of births is also dependent on the ability of each local maternity service to optimise access to its AMUs. A later section of the findings highlights this (see Chapter 4, Information and knowledge about midwifery-led units).

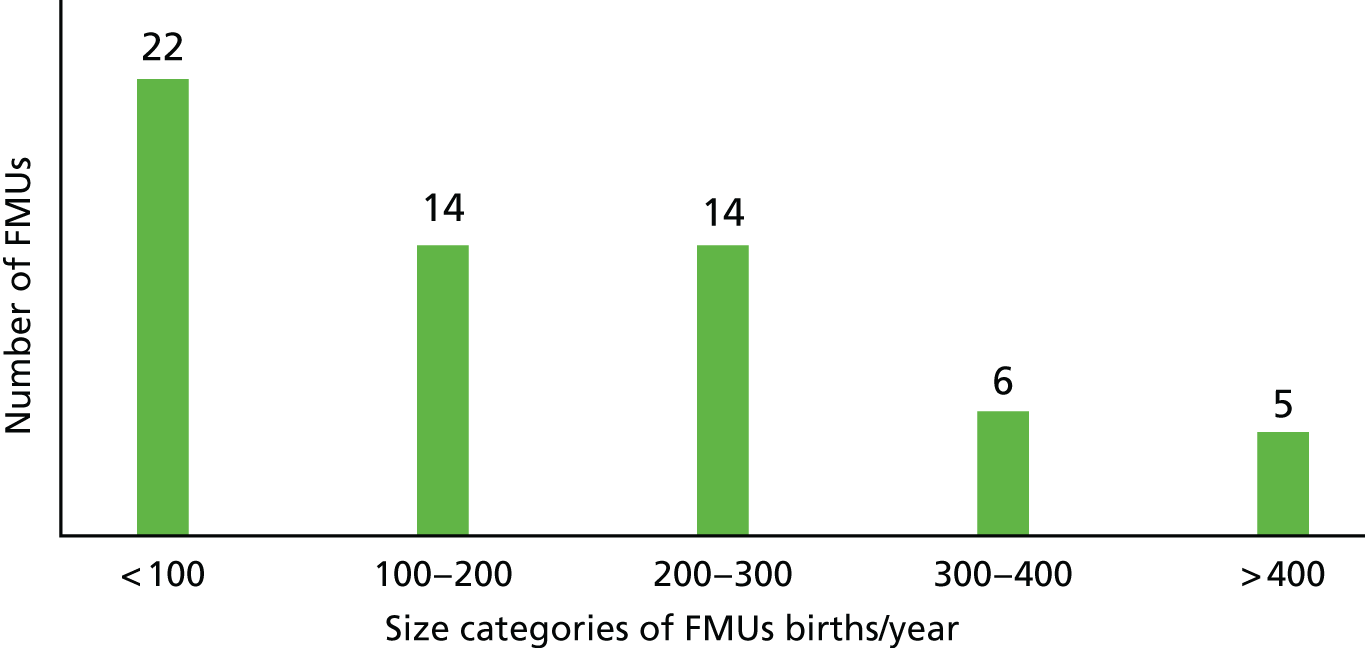

The number of births in FMUs is much smaller than in AMUs because they generally serve smaller population areas, typically more rural communities. 57 They appear to have more restrictive access criteria. 89 For example, women planning a vaginal birth after a previous caesarean are not encouraged to birth in FMUs, but it became clear in our survey that some local services allow this in AMUs, as we asked a question about access criteria for the two types of MU. The range was between 10 births per year to 650 births per year, with the majority between 10 and 200 births per year. As above, we categorised FMUs into bands based on their number of births per year (Figure 7).

FIGURE 7.

Size of FMUs: number of births per year.

Thirty-six of the 61 FMUs (59%) are supporting < 200 births per year. There has been a small but steady trend towards metropolitan FMUs opening in a town or city where an OU has closed in the past 15 years. 90 The three FMUs with the highest number of births in England were established in the last 5 years because of this change. Two other FMUs, supporting in excess of 400 births, opened in large cities where existing OUs were situated.

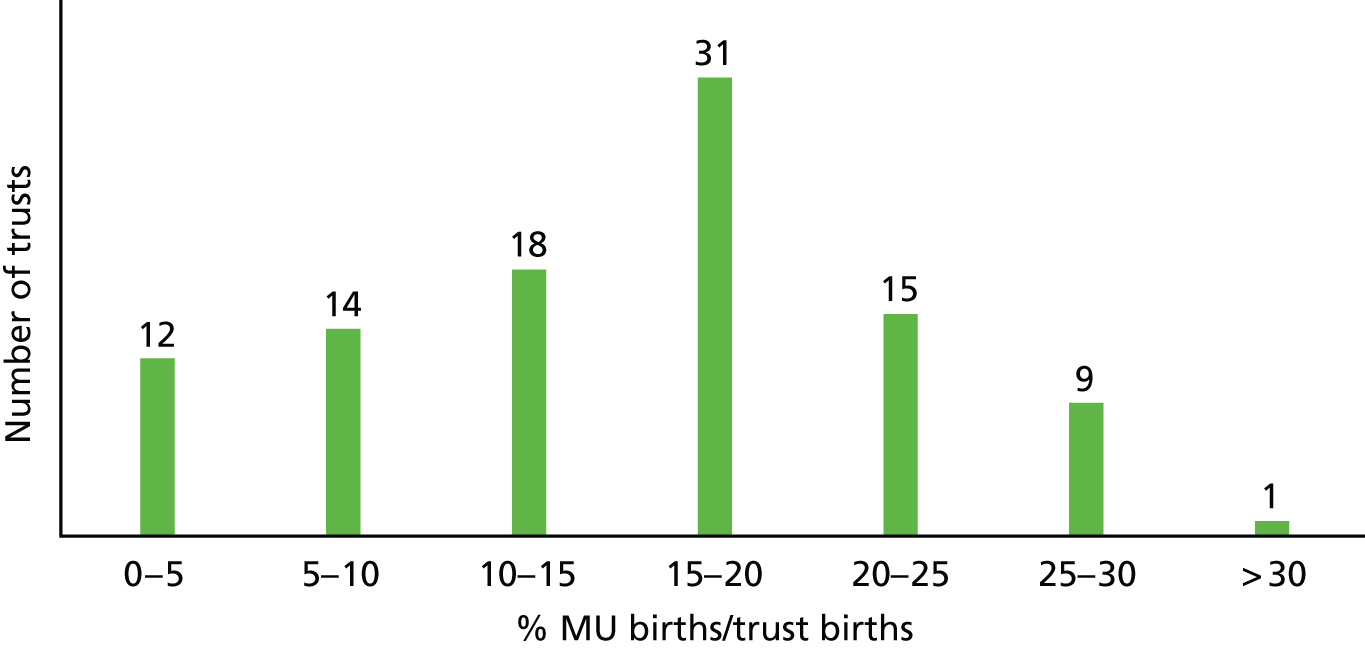

Midwifery-led unit percentage of all births per linked trust

After excluding home birth, the number of MU births as a percentage of all births per linked trust gives some indication of their optimum utilisation. This is based on the assumption that the best care for women on a midwifery-led pathway includes access to MUs for labour and birth. For the purpose of this study, we calculated the number of MU births as a percentage of all trust births, excluding home births (in trusts with both AMUs and FMUs, trusts with just AMUs and trusts with just FMUs), to reflect utilisation. We then counted the number of trusts that had MUs birthing women according to different percentage bands (0–5%, 5–10%, 10–15%, 15–20%, 20–15%, 25–30%, > 30%). This revealed wide variations (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8.

Utilisation of MUs: numbers of trusts by percentage bands of MU births/all trust births.

In the trust with the lowest percentage of all births in its MU(s) the figure was 4% and in the trust with the highest it was 31%. Seventy-two per cent (72%) of MUs were birthing < 20% of their total trust births, excluding home births, with only 11% achieving > 25%. AMU utilisation (number of AMU births as a percentage of all attached unit births) was similar (Figure 9).

FIGURE 9.

Utilisation of AMUs numbers of OUs by percentage bands of AMU births/all units births.

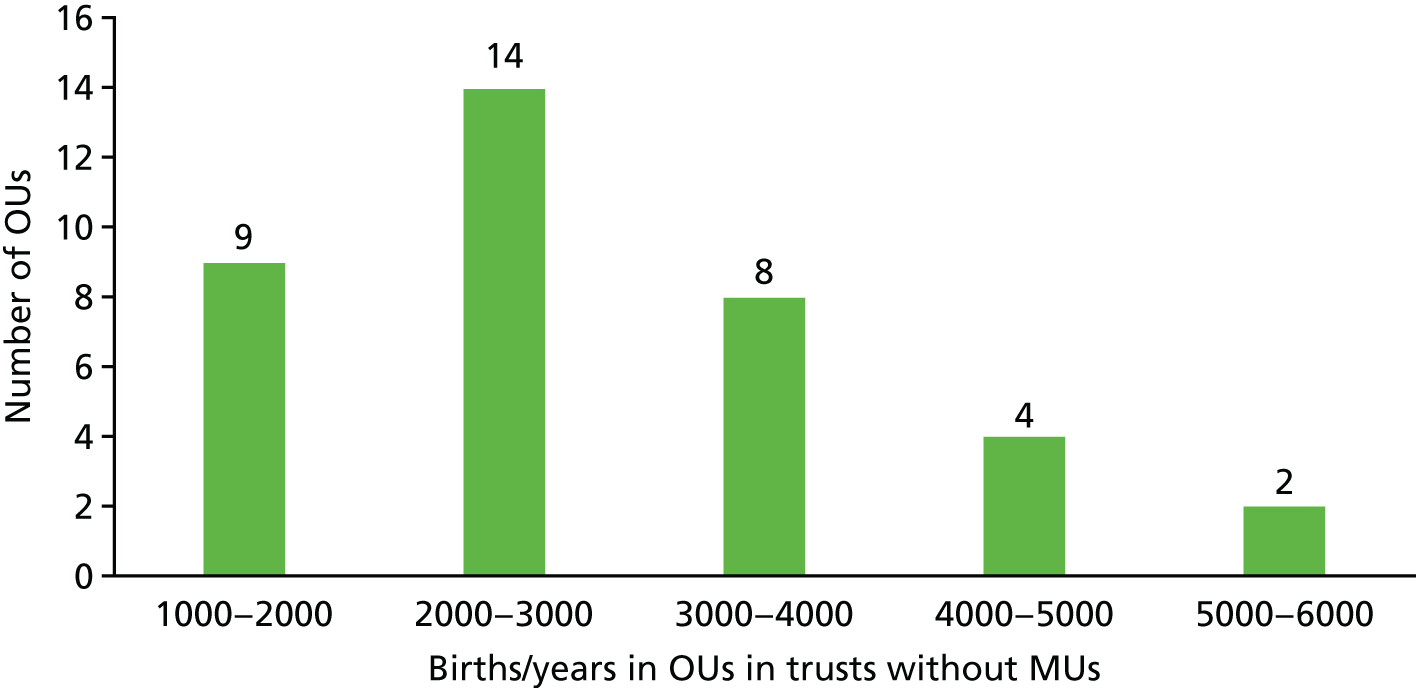

Trusts without any midwifery-led units

Of the 32 trusts without MUs, five have two OUs. Of these five trusts, four have their OUs in different towns or cities covered by the trust and the other has two OUs in one large city. The size of these OUs varies from 1300 births per year to 5700 births per year (Figure 10).

FIGURE 10.

Size of OUs without MUs: number of births per year.

Size of OUs does not appear to affect whether or not an AMU is established. Variations in choice of MUs are particularly striking in large metropolitan areas, where we found examples of a city having two AMUs for a population of 10,000 births, whereas a city in the same region with a similar number of births had no MUs.

Results of the organisation and operation of midwifery-led units

This second section reports the results from both AMUs and FMUs of how they are organised and operated.

Alongside midwifery units

Staffing

We recorded whether or not AMUs had core staff (i.e. designated midwives assigned to permanently staff the AMU, rather than midwives allocated from the OU for each shift or some other variant). We then compared trusts achieving > 20% of all trust births in their AMUs with those trusts achieving 10% to 20% and those under 10% (Table 3).

| AMUs | AMU core staff, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Missing | |

| Trusts with AMUs (N = 97) | 87 (89.7) | 10 (10.3) | 0 |

| Trusts > 20% (N = 26) | 23 (88.5) | 3 (11.5) | 0 |

| Trusts 10–20% (N = 53) | 47 (88.7) | 6 (11.3) | 0 |

| Trusts < 10% (N = 7) | 6 (85.7) | 1 (14.3) | 0 |

Eighty-six AMUs had core staff and there was no difference between higher-performing and lower-performing trusts.

The vast majority of AMUs have a designated midwife clinical lead, but lower-performing AMUs are less likely to (Table 4).

| AMUs | Midwife clinical lead for AMU(s), n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Missing | |

| Trusts with AMUs (N = 97) | 90 (92.8) | 6 (6.2) | 1 (1) |

| Trusts > 20% (N = 26) | 24 (92.3) | 1 (3.8) | 1 (3.8) |

| Trusts 10–20% (N = 53) | 50 (94.3) | 3 (5.7) | 0 |

| Trusts < 10% (N = 7) | 6 (85.7) | 1 (14.3) | 0 |

Community midwives staff approximately 60% of AMUs on a shift system (Table 5).

| AMUs | Community midwife scheduled shifts in AMU, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Missing | |

| Trusts with a community midwife in AMU (N = 58) | 34 (58.6) | 24 (41.4) | |

| Trusts > 20% (N = 17) | 10 (58.8) | 7 (41.2) | 0 |

| Trusts 10–20% (N = 36) | 21 (58.3) | 15 (41.7) | 0 |

| Trusts < 10% (N = 5) | 3 (60) | 1 (20) | 1 (20) |

Staff movement to obstetric-led unit

Nearly all (97%) AMU midwives are moved into OUs to work for part or all shifts regularly. This means that they may often be caring for low-risk women on OUs who are suitable for MUs (Table 6).

| AMUs | Staff moved from/to AMU(s) during shift, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Missing | |

| Trusts with AMU(s) (N = 86) | 83 (96.5) | 2 (2.3) | 1 (1.2) |

Closures

Related to the movement of staff out of AMUs was the finding that one-third of AMUs experience closures, with one-fifth closing frequently (more than once per month) (Tables 7 and 8). The closure lasts for the duration of a shift in most cases. Lower-performing AMUs close three times more often than higher-performing AMUs. Movement of staff out of AMUs to OUs and closure of AMUs were expedient and a response to shortage of midwives on OUs and/or workload on OUs. Movement was almost always asymmetrical, in the direction of OU.

| AMUs | AMU(s) closed at any time, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Missing | |

| Trusts with AMUs (N = 86) | 24 (27.9) | 59 (68.6) | 3 (3.5) |

| Trusts > 20% (N = 26) | 5 (19.2) | 21 (80.8) | 0 |

| Trusts 10–20% (N = 53) | 15 (28.3) | 35 (66) | 3 (5.7) |

| Trusts < 10% (N = 7) | 4 (57.1) | 3 (42.9) | 0 |

| AMUs | AMU closure frequency, n (%) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequently (≥ 1/month) | Infrequently (every 6 weeks) | Rarely (every 6 months) | Very rarely | Other | Missing | |

| Trusts in which AMU closed (N = 24) | 5 (20.8) | 3 (12.5) | 8 (33.3) | 4 (16.7) | 3 (12.5) | 1 (4.2) |

Capacity

Higher-performing AMUs had more birth rooms (five to eight), whereas lower-performing AMUs had fewer birth rooms (two to four). The latter had fewer births per room (< 200/year), although even the larger AMUs underutilised their room capacity. Thus, all AMUs could absorb more births per year.

Access and physical location

Data were collected on whether trusts had an opt-out or opt-in model for women accessing their AMU (Table 9). Opt-out implies that low-risk women wanting a hospital birth were sent to the AMU unless they specifically requested to labour in the OU (i.e. a standard midwife-led or low-risk pathway). Opt-in means that women are sent to the OU unless they ask for the AMU. In addition, a small number of services operate a hybrid model that, for example, leaves the decision to the admitting midwife.

| AMUs | AMU(s) opt-out or opt-in policy, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opt out | Opt in | No/other | Missing | |

| Trusts with AMUs (N = 86) | 49 (56.9) | 22 (25.6) | 14 (16.3) | 1 (1.2) |

| Trusts > 20% (N = 26) | 19 (73.1) | 2 (7.7) | 4 (15.4) | 1 (3.8) |

| Trusts 10–20% (N = 53) | 29 (54.7) | 15 (28.3) | 9 (17) | 0 |

| Trusts < 10% (N = 7) | 1 (14.3) | 5 (71.4) | 1 (14.3) | 0 |

Fifty-seven per cent of AMUs had an opt-out policy and this appeared to be associated with higher utilisation. Of the higher-performing AMUs, 73% had an opt-out policy, whereas only 14% of the lower-performing AMUs had an opt-out policy.

Eighty-one per cent of trusts used NICE recommendations91 to ascertain women’s eligibility for AMU care, though > 50% of trusts adapted or broadened these recommendations to allow other women access to their AMU (Table 10).

| AMUs | AMU eligibility criteria guidelines source, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NICE | NICE and adapteda | Other/own | Missing | |

| Trusts with AMUs (N = 86) | 30 (34.9) | 40 (46.5) | 9 (10.5) | 7 (8.1) |

| Trusts > 20% (N = 26) | 10 (38.5) | 12 (46.2) | 2 (7.7) | 2 (7.7) |

| Trusts 10–20% (N = 53) | 18 (33.9) | 24 (45.3) | 6 (11.3) | 5 (9.4) |

| Trusts < 10% (N = 7) | 2 (28.6) | 4 (57.1) | 1 (14.3) | 0 |

| All trusts with MU (N = 102) | 40 (39.2) | 45 (44.1) | 9 (8.8) | 8 (7.8) |

We also asked if women who did not meet the local eligibility criteria were sometimes allowed access to AMU (Table 11).

| AMUs | AMU access for ineligible women, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Other | Missing | |

| Trusts with AMUs (N = 86) | 72 (83.7) | 9 (10.5) | 4 (4.6) | 1 (1.2) |

| Trusts > 20% (N = 26) | 25 (96.2) | 1 (3.8) | 0 | 0 |

| Trusts 10–20% (N = 53) | 41 (77.4) | 7 (13.2) | 4 (7.5) | 1 (1.9) |

| Trusts < 10% (N = 7) | 6 (85.7) | 1 (17.3) | 0 | 0 |

High-performing trusts were more likely to allow this eligibility.

Alongside midwifery units were co-located in three ways: (1) 63% were on the same floor as the main labour ward, (2) 36% were on a different floor and (3) 1% were in a different building (Table 12).

| AMUs | AMU location, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Same floor | Different floor | Different building | |

| Trusts with AMUs (N = 97) | 61 (61.9) | 35 (36.1) | 1 (1) |

| Trusts > 20% (N = 27) | 15 (55.6) | 11 (40.7) | 1 (3.7) |

| Trusts 10–20% (N = 63) | 40 (63.5) | 23 (36.5) | 0 |

| Trusts < 10% (N = 7) | 6 (85.7) | 1 (14.3) | 0 |

There may be an association between smaller MU birth numbers and the location of the AMU on the same floor, but the numbers were too small to be conclusive.

Facilities

Number of rooms

The majority of AMUs had two to four rooms and very few had more than eight rooms.

Trusts with a small proportion of births in MUs were very likely to have small numbers of rooms in their AMU, and more than twice as likely to do so as trusts with > 20% of MU births. Nearly half of trusts with > 20% MU births had five to eight rooms in their AMUs (Table 13).

| AMUs | Number of rooms, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 2–4 | 5–8 | 9–12 | |

| Trusts with AMUs (N = 97) | 52 (53.6) | 39 (40.2) | 6 (6.2) |

| > 20% MU births AMUs (N = 27) | 10 (37.0) | 13 (48.1) | 4 (14.8) |

| 10–20% MU births AMUs (N = 63) | 36 (57.1) | 25 (39.7) | 2 (3.2) |

| < 10% MU births AMUs (N = 7) | 6 (85.7) | 1 (14.3) | 0 |

Birthing pools

Nearly all AMUs had at least one birthing pool (98%), but trusts with higher proportions of births in MUs did not appear to have a greater proportion of rooms with pools than trusts with lower proportions of births in MUs (Table 14).

| AMUs | Proportion of rooms with birth pools, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| < 25% | 25–75% | > 75% | |

| Trusts with AMUs with pools (N = 84) | 5 (6.0) | 60 (71.4) | 19 (22.6) |

| Trusts > 20% (N = 26) | 3 (11.5) | 18 (69.2) | 5 (19.2) |

| Trusts 10–20% (N = 51) | 2 (3.9) | 35 (68.6) | 14 (27.5) |

| Trusts < 10% (N = 7) | 0 | 7 (100) | 0 |

Free-standing midwifery units

Staffing

Approximately half of the trusts with FMUs had core midwifery staff in their FMUs (Table 15). The differences between the three groups (< 10%, 10–20% and > 20%) must be interpreted with caution, as the FMUs did not figure strongly in overall birth proportions, particularly in trusts with both AMUs and FMUs.

| FMUs | FMU core staff, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Other | Missing | |

| Trusts with FMUs (N = 39) | 21 (53.8) | 12 (30.8) | 5 (12.8) | 1 (2.6) |

| Trusts > 20% (N = 15) | 10 (48) | 3 (25) | 1 (6.7) | 1 (6.7) |

| Trusts 10–20% (N = 13) | 6 (29) | 5 (42) | 2 (15.4) | |

| Trusts < 10% (N = 11) | 5 (24) | 4 (33) | 2 (18.2) | |

For FMUs with no core staff, community midwives must staff them when they accompany women for birth.

Just over 50% of FMUs were staffed 24 hours per day, whereas the remainder were either open during daytime hours only (e.g. for clinics) or open when women booked there went into labour. Nearly all FMUs had a midwife clinical lead. Community midwives played a major role in staffing, mostly as the second midwife for births. Twelve trusts ran their FMU by a fully integrated model of core staff and community midwives.

Staff movement

Over half of FMU staff were moved within or between shifts, most often to the host OU (Table 16).

| FMUs | FMU staff moved (N = 22) (trusts with FMU N = 39), n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FMU to OU | FMU to AMU | Community to FMU | Unspecified or anywhere | Missing | |

| Trusts with FMU staff moved | 8 (36.4a) | 5 (22.7a) | 4 (18.2a) | 3 (13.6a) | 3 (13.6a) |

Closures

Nearly 40% of FMUs were closed more than once every 6 months (Table 17).

| FMUs | FMU(s) closed at any time, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Open for births only | Other | Missing | |

| Trusts with FMUs (N = 39) | 15 (38.5) | 15 (38.5) | 12 (30.8) | 6 (15.4) | 1 (2.6) |

Access

Unlike AMUs, only 5% of FMUs had an opt-out policy, whereas nearly 50% operated an opt-in policy (Table 18).

| FMUs | FMU policy, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Opt out | Opt in | Unclear | No | Missing | |

| Trusts with FMUs (N = 39) | 2 (5.1) | 18 (46.2) | 16 (41) | 1 (2.6) | 2 (5.1) |

Just over one-third of trusts had stricter eligibility criteria for their FMU than for their AMUs (Table 19).

| FMUs | FMU eligibility criteria guidelines stricter than AMU, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N/A, no AMU | Yes | No | Other | Missing | |

| Trusts with FMUs (N = 39) | 16 (41) | 14 (35.9) | 6 (15.4) | 2 (5.1) | 1 (2.6) |

Facilities (birthing pools)

Almost all FMUs (98%) had rooms with birthing pool facilities and most had more than one (Table 20).

| FMUs | FMU proportion of rooms with birth pools, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| < 25% | 25–75% | > 75% | |

| Trusts with FMUs with pools (N = 39) | 3 (7.7) | 20 (51.3) | 16 (41.0) |

Consultant midwives attached to midwifery-led units

Only 40% of trusts had a dedicated consultant midwife and these tended to be in higher-performing sites (43% vs. 29%) (Table 21).

| MUs | Consultant midwives attached to MU, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Missing | |

| Trusts with MU(s) (N = 102) | 38 (37.3) | 61 (59.8) | 3 (2.9) |

| Trusts > 20% (N = 28) | 12 (42.9) | 15 (53.6) | 1 (3.6) |

| Trusts 10–20% (N = 57) | 21 (36.8) | 35 (61.4) | 1 (1.8) |

| Trusts < 10% (N = 17) | 5 (29.4) | 11 (64.7) | 1 (5.9) |

Case-loading and midwifery-led units

Although 20% of trusts say they had some form of case-load model (care from a midwife or small group of midwives throughout all phases of care), the percentage of women who could avail themselves of it was only 1–2%. In fact, only two AMUs and two FMUs had case-load models for some of their women. Women planning a home birth are the most common group to have access to case load care, although one trust had case-load midwifery implemented for > 50% of its population.

Closure of free-standing midwifery units in England

As part of the mapping phase of this study, we identified 10 FMU services in England closed permanently in the 10 years prior to the analysis. This first section (see Media analysis) explores the representation of the closure of these units in print and television media to better understand the public rationale for closure decisions and the climate or public atmosphere in which such decisions take place.

A second section reports on the findings from interviews of HoMs where FMUs closed (see Head of midwifery interviews).

Media analysis

Despite persuasive evidence in favour of FMUs, maternity policies along with professional organisations such as the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists (RCOG) have supported AMUs over FMUs. 92 The opening and closing of FMUs has been tracked for a report to the RCM,90 which identified that in England in February 2013 there were 59 FMUs (compared with 53 in April 2001). During these 12 years, 30 new units opened and 21 units were permanently closed. A further three were temporarily closed, with the possibility that they will not reopen. Previous studies have documented the cyclical struggle for survival of FMUs in England, their small size and invisibility having rendered them vulnerable to closure by their larger host organisations. 93,94 This is of interest, given evidence from the Birthplace in England study3 that FMUs outperform AMUs regarding reductions in labour and birth interventions. 25 They are also more cost-effective than AMUs in relation to the primary outcome of neonatal adverse outcome and the secondary outcome of maternal morbidity, although this is reduced if only low-risk women without complications at the onset of labour are compared. 46 In addition, organisational research has found that midwifery satisfaction is very high in these settings95 and they are much less prone to problems of staff recruitment and retention, which are a contemporary challenge to the sustainability of the maternity workforce. 96

The aim of this part of the project was to explore what an analysis of media coverage of the closure of FMUs might tell us about the reasons given for the closures, how are these closures presented publicly and by whom, and whether media representations support or disrupt pervading cultural norms around place of birth in England.

The methods we utilised are described in Chapter 2.

Content analysis

The articles reported on planned or proposed changes to the existing maternity services in their areas. These plans all involved the closure of a local FMU, with some including the opening of a new AMU on a hospital site in a nearby town or city. A simple count showed that service users were quoted almost twice as often (46 times) as the next most frequently quoted stakeholders [local council politicians and commissioners (24 times)]. These were followed by senior trust staff (mostly directors of nursing and a few HoMs), at 22 times, health campaigners (18 times), CEOs (16 times) and members of parliament (14 times).

A preliminary analysis of the basic content of the articles revealed a number of trends. The newspaper coverage appeared to present a binary relationship between a medical model of care (in which birth close to medical back-up, such as in or close to an OU, was regarded as safer and more desirable) and a contrasting social model of care (in which birth was kept locally within the community).

A straightforward count of the reasons given for the closures revealed two predominant reasons: the perceived underuse of the units and the assumed high cost of running them.

Those in favour of closing units often argued that women were not choosing to use them, resulting in underuse of the facilities, which were then presented as unaffordable.

Commissioners and trust senior managers used the press releases on which many of the newspaper articles were based to justify their decisions to close units. Thus, closures were constructed as inevitable or unavoidable and largely outside their control. Often the underlying assumptions behind this discourse were not challenged within the articles.

When opposing voices were represented, those in favour of keeping the units open were more likely to be of the opinion that the units were desirable from the point of view of a social model of care, keeping birth within the local community, avoiding long journeys in labour, and that underuse was caused by lack of eligibility or provision of relevant information. Opposing voices were mainly those of service users, local politicians and community campaigners.

Voices supporting closures

Our content analysis revealed that very little of the media reporting focused on safety per se and made very little reference at all to clinical evidence. However, the assumption that being closer to obstetric care was safer, despite this being contrary to the evidence, was implicit in the arguments in support of the closure of FMUs in favour of AMUs:

We feel that a midwife-led unit close to the maternity department would provide the best of both worlds – the possibility of a natural birth without medical intervention, but the security of knowing an obstetrician is close by in case of emergencies.

Trust chief executive, Scarborough Evening News97

Free-standing midwifery units were often portrayed as undesirable or inferior places to give birth:

The vast majority [of women in Grantham] opt to give birth at other hospitals where they can get:

None of which they can currently get at the Midwifery Led Birthing Unit at Grantham Hospital.

Journalist, Grantham Journal. 98

Trust CEOs, commissioners and some journalists asserted that the problem was that there was a lack of demand for FMUs from women. Women were assumed to have a free and informed choice about where they plan their births and they were not choosing FMU care:

The midwives do a great job but women are clearly choosing to go elsewhere for their care.

Clinical Commissioning Group accountable officer, Grantham Journal. 98

Chief executive officers and commissioners also used the articles to explain how much money their FMU was costing their service, quoting the specific amount of money that they perceived was ‘lost’ each year. In some cases, the financial losses were attributed directly to women’s decisions on place of birth:

Only 274 out of 5440 new mothers from Brent gave birth there in 2006, along with 18 from Harrow, leading to a deficit of £300,000 a year.

First-time mother, Kentish Gazette99

In Brent, where the FMU had been opened on the site of a closed OU, the CEO presented his decision to close the unit as a moral one:

I have a responsibility to make the best use of taxpayers’ money and the Brent Birthing Centre is losing £300,000 a year. As an accountable officer, that is not something I can sustain.

CEO, Harrow Times100

Articles deployed a combination of managerialist and consumerist discourses whereby managers were depicted as sharing out limited resources for the greater good, whereas women exercised a ‘free, consumer choice’ not to birth in FMUs:

It’s important we provide the best care possible for every pound spent, for everyone in Derbyshire.

Medical director, Derby Evening Telegraph101

It’s about how you provide the best model of maternity service for the area. We can’t continue to run the whole service in this way and something has to change.

Hospital trust CEO, Hull Daily Mail102

Often the proposed changes involved the closure of the FMU and the opening of an AMU in another of the trust’s hospitals. This was at times framed as a ‘relocation’ of the FMU, rather than a closure, and in the case of the Brent Birth Centre the new AMU was given the same name as the closed FMU.

Closures were frequently framed as ‘gains’, for example the opening of a new MU or more money to invest in other services:

What do the proposals mean for women living in North Tyneside? When a woman becomes pregnant, no matter whether she is considered to be low or high risk she will be able to choose to deliver her baby at either Northumbria Specialist Emergency Care Hospital or Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle.

Commissioner, Chronicle Live103

I hope that most of the journal’s readers will be reassured to know that the changes that have been announced this week will bring about an expansion in the services on offer at Grantham Hospital and an improvement in the treatment and care given to local people.

Nick Boles, MP, Grantham Journal104

Voices opposing closure

Service users and campaigners privileged women’s right to birth locally, expecting that trusts had a duty to provide and support women’s opportunities to choose these places of birth.

In Kent, campaign messages emphasised the importance of women being able to birth locally to avoid long journeys in labour and to retain birth within the local community. Changes were questioned by service users using highly emotive language that drew on images of family, home and community:

The move would force Canterbury mothers-to-be into long journeys to hospital and mean Kent’s only city would disappear from birth certificates [our emphasis].

Kentish Gazette 105

Both of my children were born there as were their mother and me. I was therefore hoping to see a third generation eventually come into the world at Buckland.

Philip Moore, East Kent Mercury106

Service users and campaigners argued that the FMUs remained desirable places to give birth, but that many women were prevented from using FMUs through eligibility guidelines or a lack of information:

I think one of the fundamental issues is the lack of publicity the centre gets from GPs and midwives at booking in appointments. Two friends of the family who are expecting didn’t know the Jubilee Birth Centre existed until I told them!

Half the pregnant ladies were not given the chance to use it. They were told, you have to go to Lincoln.

Campaigner, Yorkshire and Lincolnshire Regional News and Weather107

For those opposing the closures, the arguments were more likely to be framed in terms of a ‘loss’. The loss of the unit or of local services and possible implications for the economic well-being of a local community, and other local services:

So North Tyneside General . . . will soon have no A&E [accident and emergency] and likely no maternity at all after already being degraded. What is to become of it? A cottage hospital where people go to die in old age? The demise of hospital services for residents . . . is disgraceful.

Claire Louise Keys, service user, Evening Chronicle108

However, campaigners supporting the Jubilee Birth Centre in Hull were reported as satisfied with the trust’s proposal to ‘relocate’ the FMU to the main hospital to become an AMU:

Jubilee Supporters' Group campaigner Sian Alexander, said: ‘While I am sad to see the Jubilee close permanently, I'm glad the trust at least acknowledges the importance of midwifery-led care and I hope the spirit of the Jubilee will be able to live on, albeit in another place’.

Hull Daily Mail 109

Head of midwifery interviews

Thematic analysis of the HoM interviews relating to 8 of the 10 FMU closures from the media analysis revealed common threads across most sites. These were:

-