Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/156/06. The contractual start date was in November 2015. The final report began editorial review in May 2018 and was accepted for publication in November 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Louise Locock declares personal fees from The Point of Care Foundation (London, UK) outside the submitted work, and membership of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) Funding Board. Jennifer Bostock declares membership of the NIHR HSDR Funding Board. Chris Graham declares a conflict of interest in financial activities outside the submitted work (he is employed by the Picker Institute). Neil Churchill declares a conflict of interest in financial activities outside the submitted work (he is employed by NHS England). John Powell is chairperson of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) and Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation (EME) Editorial Board and Editor-in-Chief of HTA and EME journals. He is the principal investigator on another NIHR HSDR programme-funded project that was funded under the same call [HSDR 14/04/48: Improving NHS Quality Using Internet Ratings and Experiences (INQUIRE)]. Sue Ziebland declares a conflict of interest in financial activities outside the submitted work (Programme Director of NIHR Research for Patient Benefit). She is the co-investigator on another NIHR HSDR programme-funded project that was funded under the same call (HSDR 14/04/48: INQUIRE).

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Locock et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background and rationale

The importance of patient experience

Patient experience, alongside patient safety and clinical effectiveness, is widely acknowledged as a key component of quality of care. 1 Improving patient experience is a priority for the NHS, which has led the way in developing measures of patient experience, such as the NHS Adult Inpatient Survey. 2 Patients have a right to expect care that is compassionate, respectful and convenient, as well as safe and effective. Collecting data about patient experience, although important, is not enough: the data need to be used for improvement, and it is arguably unethical to ask patients to comment on their experience if these comments are not responded to and acted on. 3

Recent evidence suggests positive associations between patient experience, patient safety and clinical effectiveness for a wide range of disease areas, and between patient experience and self-reported and objectively measured health outcomes. 4–6 At a time of global recession, there is a risk that better-quality patient experience may be seen as a luxury rather than a top priority. However, the apparent conflict between maintaining tight financial control and providing good patient experience may not be as clear as is sometimes supposed.

First, we know that many of the things that matter most to patients are relational, for example paying attention to dignity, courtesy and kindness. These may not be resource-intensive in themselves (although they may involve emotional labour for staff, and may be easier to attend to if there is less pressure on staffing levels). Second, there is growing evidence linking person-centred care with decreased mortality and lower hospital-acquired infection rates, as well as a range of other organisational goals, such as reduced malpractice claims, lower operating costs, increased market share and better staff retention and morale. Hospital organisations in which care is person-centred are reported to have shorter lengths of stay and fewer medication errors and adverse events. 7–14 There is increasing evidence that good staff experience is a predictor of good patient experience. 13,15,16

Yet despite these compelling reasons for paying close attention to experience data, the quality of patient experience remains a concern, and continued media reports and inquiries have suggested that there is a long way to go in ensuring the provision of genuinely and consistently person-centred care at all levels of the organisation.

Current patient experience in the NHS

The NHS Adult Inpatient Survey in England is one of the most well-established patient-reported experience measures (PREMs); it has been providing national and trust-level data since 2002. However, the pace of change has remained slow on some of the most important questions for person-centred care. 17 The results of the 2016 NHS Adult Inpatient Survey indicate that there have been small, but statistically significant, improvements in a number of areas of care, compared with results dating back to the 2006, 2011 and 2015 surveys. 18 This includes patients’ perceptions of:

-

the quality of communication between medical professionals (doctors and nurses) and patients

-

the standards of hospital cleanliness

-

the quality of food.

However, in some areas a decline in reported experience has been noted, which goes against a trend since 2006 of largely stable or improving scores. This includes patients’ perceptions of:

-

their involvement in decisions about their care and treatment

-

the information shared with them when they leave hospital

-

waiting times

-

the support they receive after leaving hospital.

Only 56% of patients reported feeling as involved as they wanted to be in decisions about their treatment, which is down from 59% in 2015, and the proportion feeling that doctors and nurses ‘definitely’ gave their families all the information they needed when leaving hospital was down from 66% in 2015 to 64%. Only 55% of patients felt ‘definitely’ as involved as they wanted to be in decisions about discharge, down one percentage point on 2015; and 17% of patients reported waiting longer than 5 minutes for a call bell to be answered, up from 14% in 2006.

Since 2006, the proportion of patients who say that they have been asked to give their views on the quality of their care has increased substantially, rising from 6% in 2006 to 20% in 2015, but with a decrease of one percentage point to 19% in 2016. In other words, 81% of respondents said that they were not asked to give their views on the quality of their care, which indicates a substantial missed opportunity to learn from patients.

Existing evidence on using patient feedback and patient experience data for improvement

There is already good evidence of what matters most to many patients and how they experience services;19 the gap is in how trusts can respond to the available local and national data and use them to improve care. 3,17,20,21 It should, of course, be noted that the process of gathering and analysing data on patient experiences at local level can itself be part of building momentum for the use of these data in improvement. In narrative-based approaches such as experience-based co-design (EBCD), collecting experiences (narratives) and using them for improvement are closely linked as part of the same process of cultural change. 22 Nonetheless, there has been a lack of evidence about how organisations can move beyond collecting patient experience data to using them for improvement, and how best to use different types of quantitative and qualitative data from different national and local sources.

As Gleeson et al. 23 note, this is a relatively new field that does not have a large body of published evidence, a key factor behind the decision of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) to commission several new studies in this field, of which this report is one.

Dr Foster Intelligent Board research20 from 2010 into how trust boards use patient experience data found substantial variation in what data were collected and also, more importantly, in the degree to which the data were effectively analysed and used to improve services. Strikingly, the research found that, over 95% of the time, hospital boards’ minuted response to patient experience reports was to note the report but take no further action. Examples of when patient experience data were used to spark debate and action were rare, as were examples of non-executive directors challenging performance based on patient experience measures.

Since the Dr Foster research, studies have continued to show that interest in using experience data at senior level is not always matched by action or the skills to work with these data. Lee et al. 24 studied how two hospital boards of directors used patient feedback. They found that although the boards used both quantitative survey feedback data and in-depth qualitative data to help them develop quality strategies and design quality improvement (QI) work, they made less use of patient feedback to help monitor their strategies and assure quality. Even though the data contributed to the development of strategy and QI, in one of the sites this ‘did not result in formal board commitment to these initiatives’. The authors suggest that there is a need for further research to investigate how boards of directors can make better use of patient feedback, from a range of sources, and combine it with wider pressures and priorities to effect change.

Martin et al. 25 explored senior leaders’ use of ‘soft intelligence’ for QI, that is, informal, localised, often narrative or observational data of a kind not easily captured in standard quantitative metrics. They noted that senior leaders were highly aware of the value of such intelligence, gleaned perhaps from conversations with staff or just from walking on to the ward, and of ‘the idiosyncratic, uncalibrated views of patients or their carers’, but that they were unsure how to turn this potentially valuable material into a useful guide to action. In leaders’ efforts to make this material useful, they often sought to apply quantitative approaches, such as aggregating multiple comments or observations, or looking for triangulation with other sources. Seeking triangulation may be misguided, given the observed mismatch between what patients say about their experience in response to survey questionnaires and what they say in interviews,26 or between survey scores and free text. 27 Formal systemisation, Martin et al. 25 argue, risks losing the spontaneous ‘untamed richness’ of insights from soft intelligence. The alternative approach, they observed, was to downgrade soft intelligence from the status of evidence to that of illustration and motivation, for example using quotations to bring dry numerical data to life, but not focusing directly on its content as a guide to improvement.

Understanding how to use qualitative evidence, including narrative and observational data, alongside numerical evidence can indeed be challenging,20,28,29 and this is undoubtedly one of the key areas in which trusts need support and training. The status of complaints in this landscape of patient experience data is contested; as unsolicited and challenging examples of patient experience, they may be actively resisted. In their analysis of how health-care professionals make sense of complaints, Adams et al. 30 note that participants tended to characterise complainants as ‘inexpert, distressed or advantage-seeking’; they rationalised their motives for complaining ‘in ways that marginalised the content of their concerns’, and rarely used the content for improving care.

Meanwhile, the NHS also faces an explosion of other unsolicited sources of patient experience data online and through social media [e.g. NHS Choices, Care Connect, Care Opinion, blogs and Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA)], with little guidance on how to use them. As Dudwhala et al. 31 argue, unstructured data that have not been actively sought or sanctioned by health-care organisations are unlikely to have the impact of other, more formal, data sources. Similarly, in their study of how staff raise safety concerns, Martin et al. 32 note that organisational leaders tended to prefer such concerns to be routed through formal systems in order to provide evidence for action. However, as a result, some concerns were never voiced, because of staff anxiety about using these channels and becoming drawn into bureaucratic procedures. Thus, both staff and patient experiences that come through informal routes may gain little traction.

Although there is a growing number of studies about how patient experience data are (or are not) used at board or whole-organisation level, we still know remarkably little about how front-line staff make sense of, or contest, patient experience data, what supports or hinders them in making person-centred improvements and what motivates staff – and patients and families – to get involved in improvement work.

Quality improvement programmes and techniques abound, but few are strongly evidence based and few take seriously the need to involve patients and families throughout the process. A few studies have provided some evidence of promising front-line experience-based approaches. For example, facilitated feedback of survey findings at ward team level has been shown to have the potential to improve patient experience scores. 33 Studies of EBCD have shown how locally collected narrative and observational data can lead to both specific improvements in care and changes in attitude and behaviour. 34–38 Locock et al. 39,40 reported positive findings on the use of nationally collected narrative data alongside local observational data in EBCD to generate improvements, and a randomised controlled trial of EBCD is under way in Australia. 41 A UK evaluation of the patient- and family-centred care (PFCC) approach is also in progress. 42,43 However, there remains insufficient evidence to say which types of data or QI approaches are more or less likely to be useful to front-line teams in making care more person-centred in different contexts and settings, and how well these are received.

Gleeson et al. ’s23 systematic review of approaches to using patient experience data for QI has helped consolidate the evidence base. The authors state that their focus is on PREMs, but their review includes three studies reportedly using EBCD (interviews and observations) and one using PFCC (observations), alongside seven using questionnaire survey data. This reflects a broad interpretation of the word ‘measure’ to incorporate ethnographic approaches to understanding patient experience.

The systematic review results have several points of significance for this report:

-

Patient experience data were most commonly collected through quantitative PREM surveys (despite many authors acknowledging that clinical and ward staff generally find qualitative comments more insightful).

-

Qualitative data were acknowledged to be more difficult to use in terms of time and expertise.

-

Data were used to identify small incremental service changes that did not require a change in clinician behaviour.

-

Recording of the changes that were made or the impact that they had was poor.

-

None of the studies reported using ‘formal QI methods of data collection’. 23 [Arguably, EBCD and PFCC are themselves formal QI methods, but the review authors do not include EBCD and PFCC in their list of examples (total quality management, continuous quality improvement, business process reengineering, Lean and Six Sigma). As noted earlier, the process of data collection and the process of improvement are not always easily demarcated.]

-

Most studies used qualitative rather than quantitative methods to measure the impact of PREMs on QI.

-

Two studies which measured post-intervention PREM questionnaire results found no statistical improvement in experience.

-

EBCD appeared to generate more improvement efforts than questionnaire-based data, but ‘effects of the QI interventions were not measured or reported on’. 23

-

In many cases, staff reported using data not to only to identify areas for improvement but to support or provide a rationale for existing improvement projects.

Some studies have identified a mismatch between managerial expectations and how engaged and supported clinicians and other front-line team members feel to make improvements. For example, in a survey of hospital clinicians, 90.4% of respondents believed that improving patient satisfaction with their experience of hospitalisation was achievable, but only 9.2% thought that their department had a structured plan to do this. 44 Friedberg et al. 45 found that physicians’ use of patient experience reports was variable and, importantly, that little training in communication skills was provided, even though improving communication with patients was thought to be fundamental to the provision of person-centred care. These findings suggest that not enough is being done to make patient experience data available in a useful, accessible and credible way to clinical staff, and to empower them – with positive organisational support – to see improving patient experience as a priority that they can lead on.

Flott et al. 46 outline a familiar set of challenges in using feedback (in particular national survey data) at clinical level. These include:

-

scepticism about the quality of the data

-

lack of training in social research methods

-

statistical complexity and lack of technical guidance

-

aggregation of data at trust level that does not inspire local clinical ownership

-

isolated data that are not linked to other relevant data sources

-

contradictory results from different sources depending on how data are collected

-

disparities in external support to providers to help analyse feedback and how to drive improvement

Much of the research into using patient feedback for service improvement has focused on surveys of inpatient hospital care, but Burt et al. ’s47 study of improving patient experience in primary care confirms many of the same themes. They note that general practitioners (GPs) are positive about the concept of patient feedback, but struggle to engage with it and make changes under current approaches to measurement. Within practices, and in out-of-hours settings:

staff neither believed nor trusted patient surveys. Concerns were expressed about their validity and reliability and of the likely representativeness of respondents. Staff expressed a preference for free-text comments as they provided more tangible, actionable data.

Burt et al. 47

The authors conclude that supporting primary care staff to enable them to act on patient feedback remains a key challenge, and that surveys are necessary but not sufficient to generate meaningful data for improvement.

A recent study by Sheard et al. 48 has proposed a conceptual ‘patient feedback response framework’ to understand why front-line staff may find it difficult to respond to feedback. This has three components:

-

normative legitimacy (i.e. staff members express a personal belief in the importance of responding to patient feedback and a desire to act)

-

structural legitimacy (i.e. staff perceive that they have sufficient ownership, autonomy and resource available to establish a coherent plan of action in response to patient feedback)

-

organisational readiness (i.e. the capacity for interdepartmental working and collaboration at meso level, and senior hospital management/organisational support for staff to work on improvement).

The authors found that, although normative legitimacy was present in most (but not all) of their 17 case study wards, structural legitimacy and organisational readiness were more problematic. Even where staff expressed strong belief in the importance of listening to patient feedback, they did not always have confidence in their ability or freedom to enact change. A lack of organisational readiness and support could block change even when staff expressed high levels of structural legitimacy.

The original ‘theory of change’ underlying this study [Understanding how Front-line Staff use Patient Experience Data for Service Improvement (US-PEx)] was that high-level organisational support is necessary but not sufficient for person-centred service improvement; that many experiences that matter most to patients happen in front-line encounters; and that bottom-up engagement in person-centred improvement (as opposed to top-down, managerially driven initiatives) can be motivating for front-line staff,13 consistent with evidence that patient experience seems to be better in wards with motivated staff. 39 Sheard et al. ’s48 patient feedback response framework has provided us with an additional theoretical lens through which to view our findings.

Our study was focused on patient experience within a ward setting. However, shortfalls in patient experience often happen at the boundaries between services, for example between mental and physical health, child and adult services, adult and older people’s services, and primary and acute care. A major focus of integrated care systems is to improve care at these boundaries and even eliminate them altogether. In addition to a bottom-up/top-down perspective, therefore, we may need to add a third, lateral perspective of local but external clinical challenge. Multidisciplinary clinical teams working to improve integration of care, for example in areas such as frailty, may mutually challenge each other’s practice, culture and organisation.

Wider literature on quality improvement theory, methods and skills

There is, of course, an extensive broader literature on change in health care and what enables or frustrates change at both individual clinician and organisational levels, which in turn has fed into a more specific but still substantial literature on QI and ‘improvement science’. 49

Approaches such as normalisation process theory50 and the theoretical domains framework51 have drawn on sociological and psychological theory to develop explanations of how individuals within organisations change behaviour and adopt innovations, what motivates and deters them, what skills they require, who they listen to, and how they act collaboratively to make sense of52 and embed new practices. From the organisational change literature in health care, we know that certain common themes recur, particularly around the importance of a receptive context and an understanding of organisational history, of having both senior management and distributed leadership, of the engagement of opinion leaders and clinicians, of ‘fit’ with existing organisational goals and strategies, and of organisational support and resources. 53–56

From a human factors perspective, a daunting list of 760 challenges to the delivery of effective, high-quality and safe health care has been identified by Hignett et al. 57 The authors group these under eight headings, which, again, are remarkably consistent with other organisational studies:

-

organisational culture (26.4%)

-

staff numbers and competency (20.5%)

-

pressure at work (19.4%)

-

risk management culture (10.8%)

-

communication (10.5%)

-

resources (6.4%)

-

finance/budget (3.6%)

-

patient complexity (2.4%).

It is beyond the scope of this report to rehearse all of this wider organisational change literature, but it is clear that QI generally and patient experience improvement projects specifically are in most respects no different from other change initiatives, and that they need to pay attention to senior leadership; clinical and front-line engagement and motivation; dedicated project management support and skills; the role and attitudes of local opinion leaders/advocates for change; and the receptiveness of the context and organisational readiness to change. In a useful recent reflection on the state of the organisational change literature in health care, Fitzgerald and McDermott58 conclude that there is remarkably little evidence to support top-down, large-scale, transformational ‘big bang’ change of the kind exemplified by business process re-engineering, and that it remains ‘unproven rhetoric’. Strategies of incremental, accumulative change are, they argue, more likely to have long term impact.

Jones et al. 59 have recently constructed a measure of ‘QI governance maturity’ from working with 15 hospital boards. Consistent with wider organisational literature, they conclude that boards with higher levels of QI maturity had the following characteristics, which were particularly enabled by board-level clinical leaders:

-

explicitly prioritising QI

-

balancing short-term external priorities with long-term internal investment in QI

-

using data for QI, not just for quality assurance

-

engaging staff and patients in QI

-

encouraging a culture of continuous improvement.

It is commonly argued that QI is often ineffective when isolated in organisations and that it needs to be part of wider systemic efforts. Personal and organisational membership of formal and informal networks has been cited as a factor in effective QI in a Health Foundation60 study. The mechanism(s) through which this is achieved are difficult to identify precisely, although non-hierarchical and multidisciplinary exchange of ideas may be part of the answer.

‘Improvement science’ is a contested term. Walshe61 points to the dangers of ‘pseudoinnovation’:

. . . the repeated presentation of an essentially similar set of QI ideas and methods under different names and terminologies.

Walshe61

Improving health-care services can all too easily become equated with the use of certain ‘in vogue’ tools for improving quality. Advocates for different approaches will argue strongly that their way is the best (or even the only) way. Staff may feel overwhelmed by the array of methods promising a sure recipe for success, and concerned they cannot live up to the examples set by leading organisations in the field. As Walshe61 argues, QI needs sustained investment and support, but the rapid switching from one fashionable method to another has probably damaged the chances that any of these methods will be effective.

A recent King’s Fund report62 suggests that it is important for hospitals to adopt an established method for QI, one that is ‘modern and scientifically grounded’, and to ensure that all leaders and staff are trained in it. While using one consistent method may have advantages, the evidence behind most QI approaches remains fairly weak. Cribb63 argues that it is easier to identify a gap or shortfall in current practice than to identify, with any certainty, what specific approaches are likely to improve the situation.

In a systematic narrative review for Healthcare Improvement Scotland, Powell et al. 64 argue that:

Importantly, there is no one right method or approach that emerges above the others as the most effective.

Powell et al. ,64 p. 7

Consistent with the ‘contingency theory’ of management, which suggests that there is no one best or universal way to manage businesses or hospitals,65 the authors conclude that:

The specific approach (or combination of approaches) may be less important than the thoughtful consideration of the match and ‘best fit’ (however imperfect) for the particular circumstances in the local organisations using it.

Powell et al. ,64 p. 63

Most approaches have something to offer and will work some of the time in some settings, but are also likely to fail if good conditions are not in place. Powell et al. 64 identify the following as ‘necessary but not sufficient conditions’, regardless of the approach adopted:

-

provision of the practical and human resources to enable QI

-

the active engagement of health professionals, especially doctors

-

sustained managerial focus and attention; the use of multifaceted interventions

-

co-ordinated action at all levels of the health-care system

-

substantial investment in training and development

-

the availability of robust and timely data through supported information technology (IT) systems.

Lucas and Nacer66 also caution against becoming too focused on tools and techniques, arguing that:

Education for improvement practices can all too easily be reduced to, for example, ‘how to use a driver diagram’ or ‘how to lead an improvement project’.

Lucas and Nacer,66 p. 12

While Lucas and Nacer66 agree that learning such techniques is helpful, they continue that:

Without a clearer picture of what improvement really looks and feels like, the ‘packaging’ of improvement can end up becoming its lived reality.

Lucas and Nacer,66 p. 12

By contrast, ‘improvers are constantly curious, wondering if there is a better way of doing something’ (p. 12). They use a kind of ‘smart common sense’66 to keep reflecting (quotations reproduced with permission from The Health Foundation66).

Finally, we note Cribb’s63 argument for greater dialogue between what might be traditionally regarded as QI research, with its instrumental and applied focus on problem-solving, and wider social science in health care, which might not be intentionally focused on improvement but might, nonetheless, bring useful insights.

Conclusion

In summary, the literature on using patient experience data for improvement is incomplete. The focus to date has been primarily on quantitative survey data and their use at board level; much less is known about the use of other types of formal and informal data, and about their use at the front line. Surveys are important as measures, but their ability to provide a nuanced guide to understanding why patient experience is as it is, and how it could be improved, is limited. Yet other forms of data and ‘soft’ intelligence may be difficult for staff to analyse and use effectively. There is little reliable evidence from the wider QI and ‘improvement science’ literature to suggest that one approach is definitively better than the others. A thoughtful, eclectic approach that is sensitive to context and engages front-line and clinical staff at the same time as offering strong senior leadership may be more important than a particular technique.

This study set out to add to this evidence by exploring how front-line hospital ward teams engage with patient experience data when encouraged to do so, what challenges they face and how they can be better supported to work on patient-centred QI.

Chapter 2 Study methods

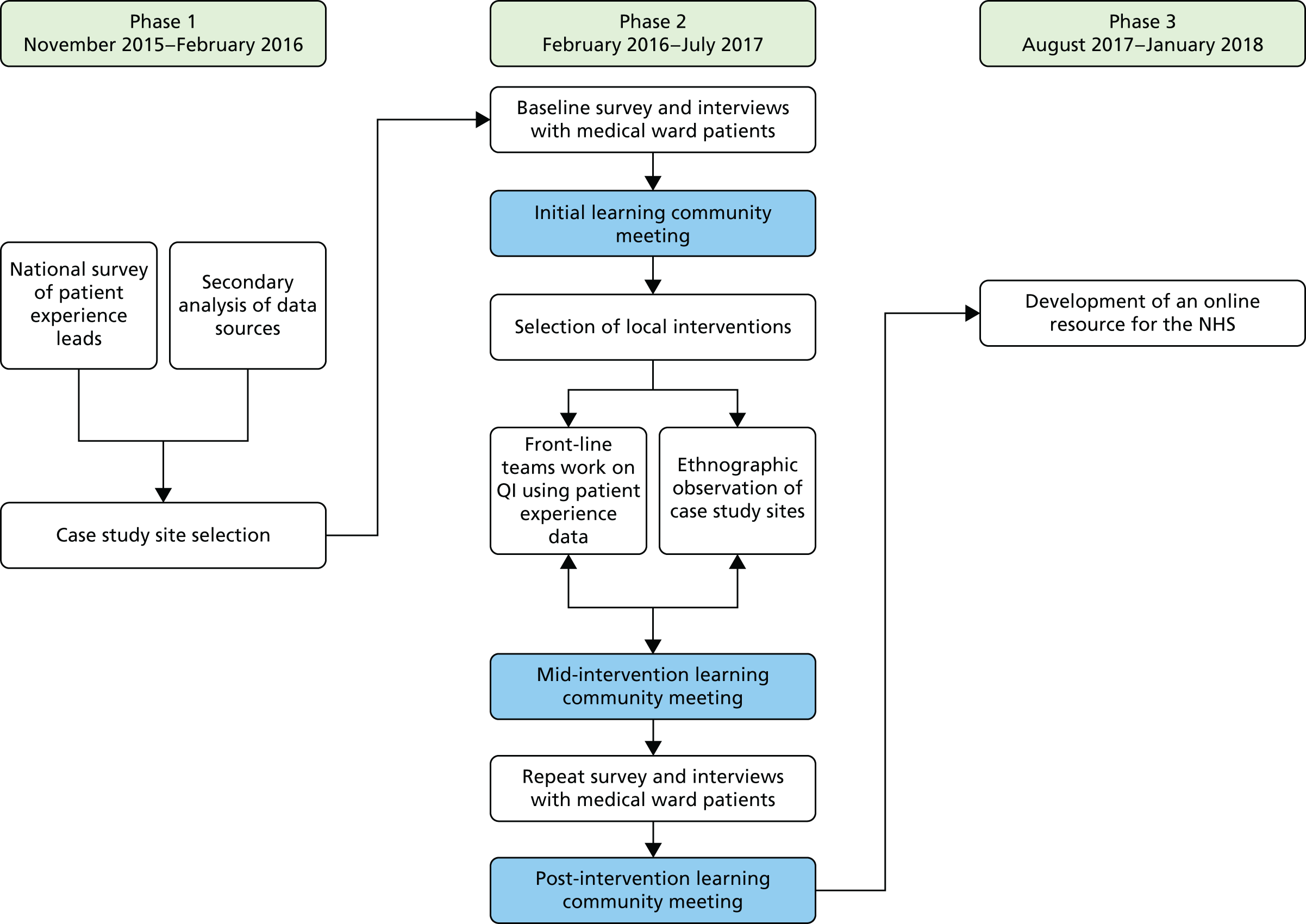

The study comprised three phases (Figure 1):

-

secondary analysis of existing survey data and new survey of trust patient experience leads

-

case studies in six medical wards

-

preparation of a toolkit or guide for NHS staff.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of US-PEx study.

The study was overseen by a study steering committee (for details of membership, see the project web page: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/1415606/#/; accessed 17 April 2019), which met approximately every 6 months. The full research team (see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/1415606/#/; accessed 17 April 2019) also met every 6 months, with a smaller core team (including the lay co-investigator) meeting quarterly. The lay panel met every 6 months, and stayed in contact by e-mail between meetings (see Chapter 3, Patient and public panel methods and reflections, for a detailed account of patient and public involvement).

The research team comprised a diverse range of people, including academics, a lay co-investigator, colleagues from the NHS at both front-line practice and senior policy levels, and third-sector co-investigators from the Picker Institute. Research team members brought both quantitative and qualitative expertise in patient experience research, and included people with disciplinary backgrounds in sociology, psychology, organisational behaviour, health services research, ethics, clinical primary care, mental health and public health, nursing, digital health and statistics. This range of perspectives has been a particular strength in analysing the findings through several different lenses.

Phase 1: secondary analysis of existing survey data and new survey of trust patient experience leads

In this section, we describe a secondary analysis of existing national patient and staff experience data, and a new survey of patient experience leads. The aim of this phase of the study was to select the six case study sites (acute trusts) to take part in this research.

Secondary analysis of existing national patient and staff experience data

Secondary analysis sources were the National Results from the 2014 Inpatient Surgery,2 the National Results from the 2014 NHS Staff Survey,67 NHS Friends and Family Test (FFT) 2015 response rates,68 and Care Opinion web metrics (James Munro, Care Opinion, 2016, personal communication).

NHS Adult Inpatient Survey 2014

The NHS Adult Inpatient Survey 20142 contains 70 questions about patients’ most recent experiences of being an inpatient in hospital, as well as eight demographic questions. Thirty-one questions relating to four domains were identified as most relevant to this analysis. The four domains were:

-

referral

-

inpatient care

-

discharge

-

self-management.

The responses to these questions were analysed to create an average score for each trust in order to identify the top, middle and bottom thirds of the distribution with regard to patient experience. An overall average score was calculated as the mean of the four domain scores, and trusts were then ranked on this overall score.

The list of questions and details of the analytic approach are available in Report Supplementary Material 1.

NHS Staff Survey 2014

Nine questions were analysed from the NHS Staff Survey 201467 relating to the following three domains of care, which were the most relevant to our research questions:

-

training and development

-

standards of care

-

patient/service user feedback

Analysis of the staff survey results differed slightly from the approach used with the inpatient survey. The list of questions and details of the analytic approach are available in Report Supplementary Material 1.

An inspection of the results led to the decision to remove one question that did not contribute to internal consistency.

Trust-level scores on the remaining questions were standardised, and the mean of the standardised items was calculated as the overall score for the trust. Trusts were then ranked on this overall score.

NHS Friends and Family Test response rates, August–October 2015

Trust-level response rates to the NHS FFT68 carried out on inpatient wards were reviewed. This provided useful contextual data for selecting case study sites by giving an indication of the importance that organisations place on collecting patient feedback when viewed alongside other measures. There are limitations to the use of these data for this purpose. In particular, the FFT can be administered via a range of methods, and the choice of methods can reasonably be expected to influence response rates. Nevertheless, we considered that the overall response rates would provide contextual evidence of the relative priority given to obtaining people’s feedback.

Data from August–October 2015 were downloaded from the NHS England FFT website. 68 For each trust, the average response rate to the FFT across the 3 months was calculated.

To inform case study site selection, trusts were sorted by average FFT response rate to identify the top, middle and bottom thirds of the distribution.

Care Opinion web metrics, January 2014–November 2015

Data from Care Opinion (James Munro, personal communication) were reviewed to provide contextual information on trusts’ use of and engagement with patient experience. Care Opinion extracted the following web metrics for each acute NHS trust from January 2014 to November 2015:

-

number of stories posted

-

number/percentage of stories read by the trust

-

number/percentage of stories responded to by the trust

-

number/percentage of stories that led to a change being planned

-

number/percentage of stories that led to a change reported as made if the trust had subscribed to Care Opinion

-

number of staff registered to use Care Opinion.

This information was incorporated into a spreadsheet alongside inpatient and staff survey scores and FFT average response rate.

Survey of patient experience leads

The aim of this survey was to provide national contextual information on the collection, use and impact of patient experience data on service provision. It also provided additional information for selecting case study sites.

A questionnaire, to be completed online by patient experience leads at acute NHS trusts, was developed. Eleven questions were included from an online staff survey in another NIHR-funded study examining real-time patient reported experiences of relational care at six NHS trusts in England (reference 13/07/39). 69 Additional questions were adapted from those included in the Beryl Institute patient experience benchmarking study. 70

The draft questionnaire was reviewed by the project team. At the request of the Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) board, we collaborated with researchers from King’s College London who were conducting a separate NIHR-funded study (reference 14/156/08) that was to include a national patient experience leads survey. 71 These researchers also reviewed the draft questionnaire. A few further adaptations were made to ensure that the researchers gathered the information they needed.

The final questionnaire (see Report Supplementary Material 2) had 33 questions, covering:

-

types, methods and frequency of patient experience data collections

-

reporting and use of patient experience data

-

facilitators of and barriers to using patient experience data.

Sites were given the opportunity to leave their contact details if they were interested in taking part in the wider study.

All acute trusts, including specialist children’s trusts, were invited to take part in the survey (n = 153). The survey was administered using the Snap WebHost survey platform (www.snapsurveys.com).

The lead contact for the most recent (2015) national adult inpatient survey at each trust was sent a pre-approach e-mail in November 2015 with information about the survey and a link to the participant information sheet. This e-mail gave trusts the option to opt out from receiving the survey invitation and to notify the research team if they wanted the invitation e-mail to be sent to a colleague. Two days later, trust contacts were sent an e-mail containing the link to the online survey, with a reminder e-mail 1 week later. The fieldwork was kept open for 6 weeks.

Ethics approval

Approval for the online staff survey was granted from the Central University Research Ethics Committee in October 2015 (reference MS-IDREC-C1-2015-203). The Health Research Authority approved the process for all acute trusts centrally in October 2015, thereby removing the need for local research and development (R&D) approval, unless a site opted out within 35 days (Integrated Research Application System project ID 192500). One site opted out of receiving an e-mail invitation to take part in the survey.

Case study site selection

The core research team reviewed the secondary analysis and patient experience leads survey results and then met to discuss potential case study sites.

The team shortlisted 14 trusts based on four main factors:

-

identifying a spread of trusts in the top, middle and bottom third based on the secondary analysis matrix

-

having a diverse geographical spread

-

having some trusts that scored more highly on the inpatient survey than the staff survey and vice versa (i.e. mixed)

-

willingness of trusts to take part (through either the patient experience leads survey or previous correspondence).

Trusts currently in special measures were excluded.

From this longlist, six trusts were identified as the first choice sites. The six trusts ranged in their inpatient and staff survey ranks, in addition to the extent to which they appeared to approach and respond to issues relating to patient experience, and fell into the following cells in the matrix (Table 1).

| Inpatient survey rank | Staff survey rank | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Top | Middle | Bottom | |

| Top | 2 | ||

| Middle | 1 | 1 | 1 |

| Bottom | 1 | ||

In February 2016, an invitation e-mail was sent to the six trusts inviting them to participate in the study. Five of the original six sites contacted agreed to take part. One trust did not have the capacity to become involved. The team therefore approached another trust with a similar profile from the secondary analysis, and this trust agreed to participate. Table 2 shows how the final six trusts fell into the inpatient/staff survey rank matrix.

| Inpatient survey rank | Staff survey rank | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Top | Middle | Bottom | |

| Top | 2 | ||

| Middle | 1 | 1 | |

| Bottom | 1 | 1 | |

Trusts were invited to nominate a ward. They were asked to propose a general medical ward whose staff were willing to take part. We did not specify criteria beyond this, leaving it to local contextualised knowledge. Although our initial aim was to carry out the research on general medical wards, through discussions with sites it became clear that there was an appetite for specialist and medical assessment units to be given the opportunity to participate. The research team considered the benefits and potential issues to each ward selection in turn, in consultation with the lay co-investigator (see Chapter 3), and in all cases decided that these wards should not be excluded. Indeed, the research team agreed that the different settings and populations might reveal different challenges to the use of patient experience data. The mix of reasons why specific wards were put forward forms part of our findings in Chapter 5.

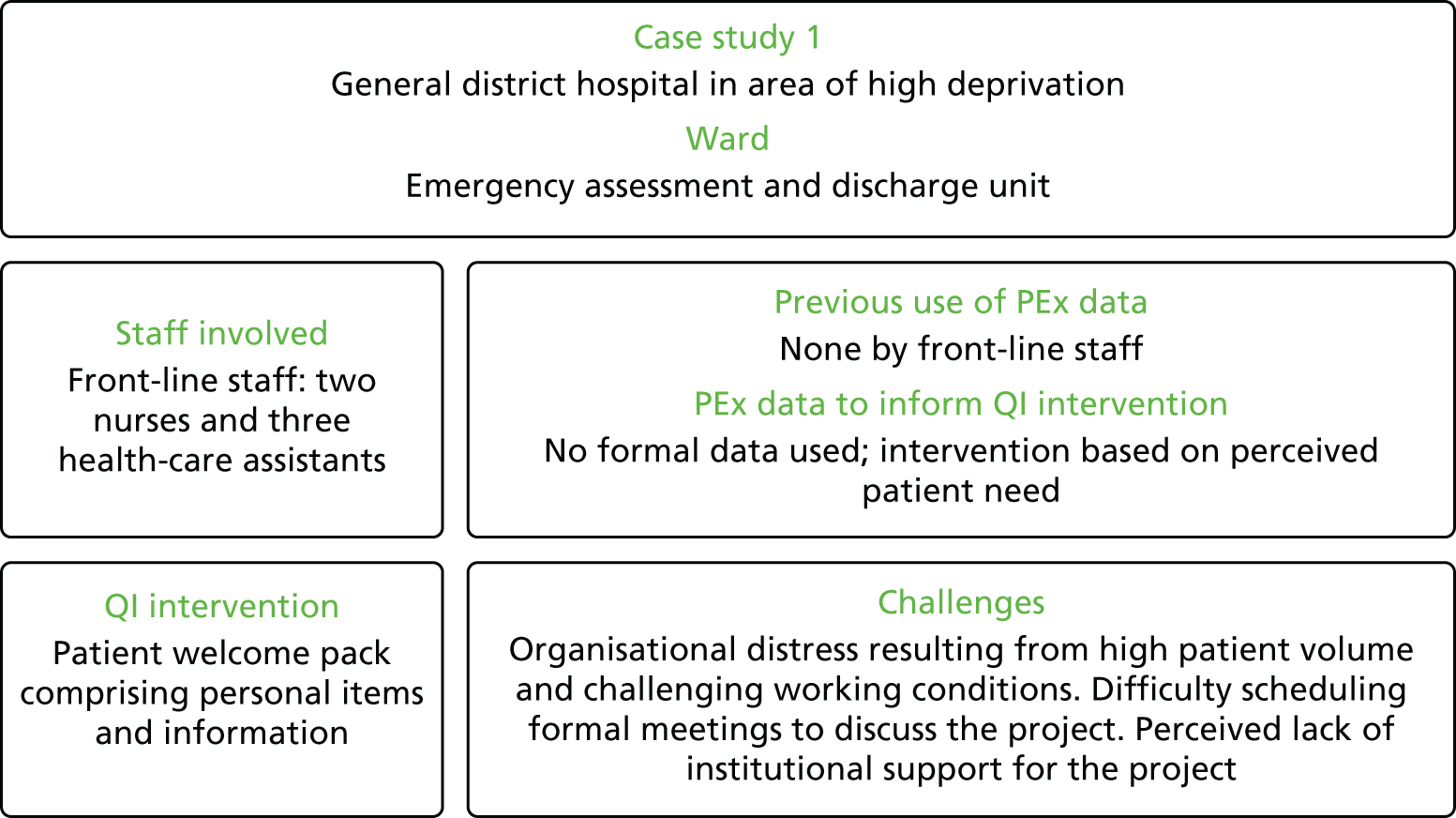

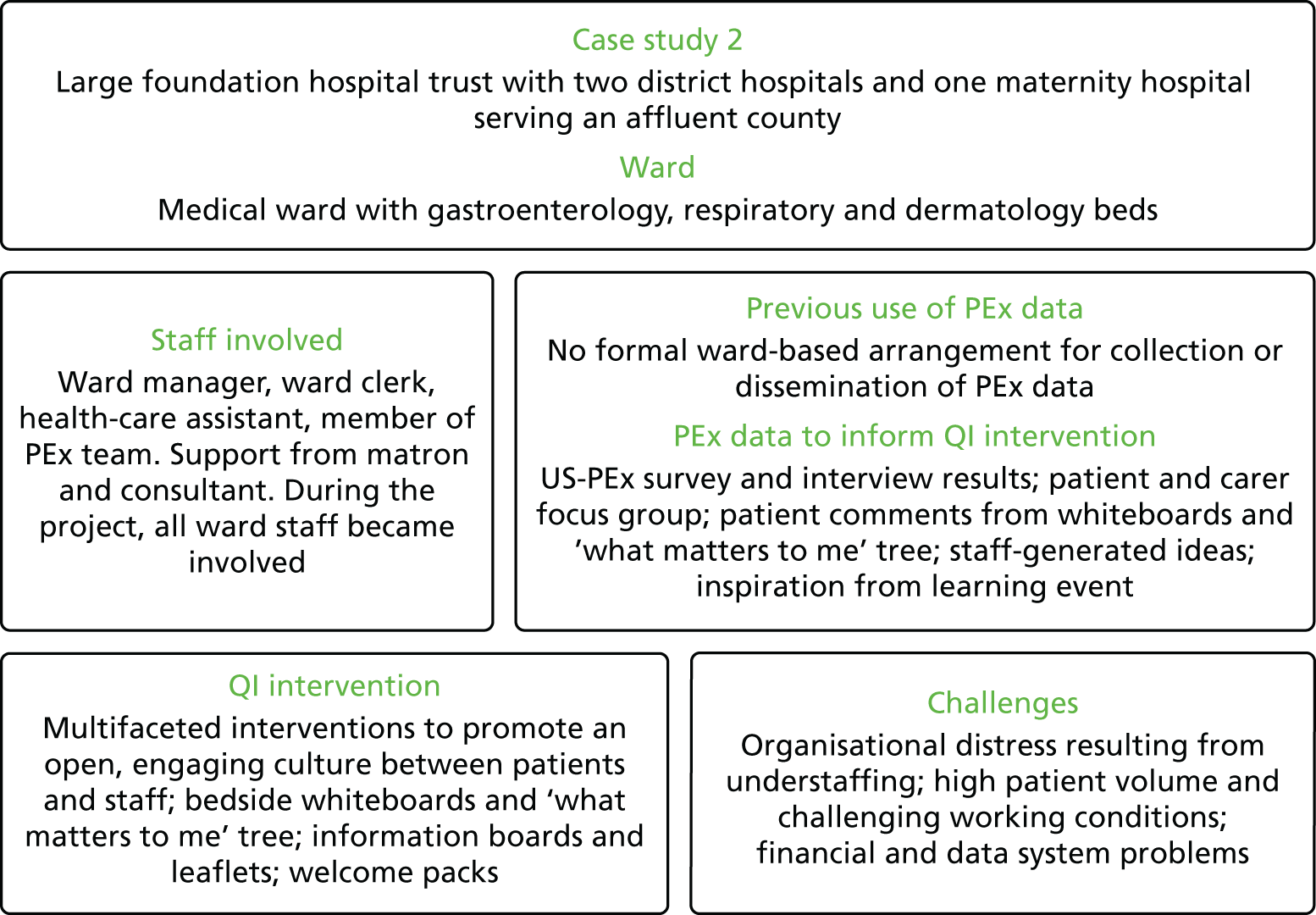

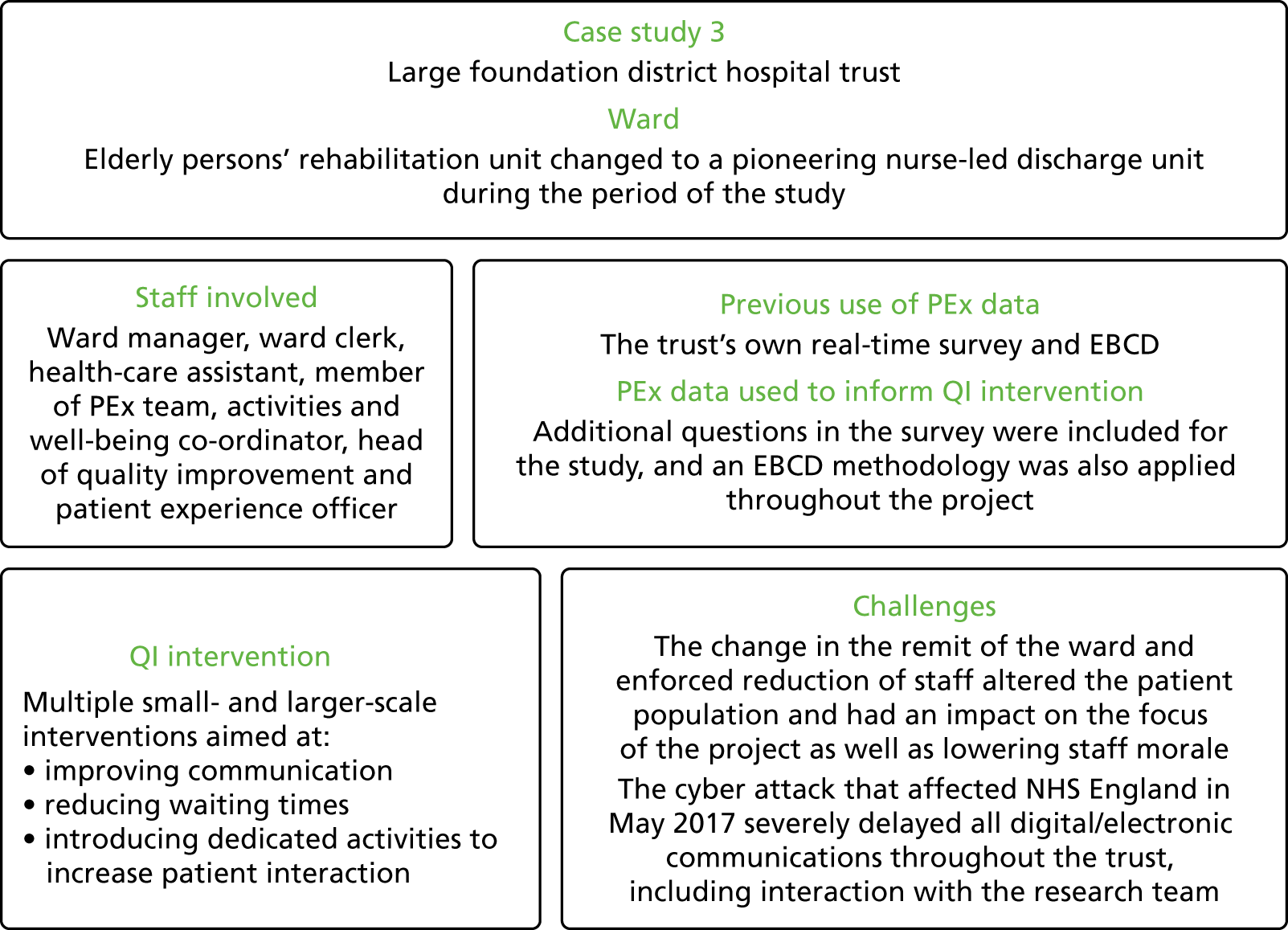

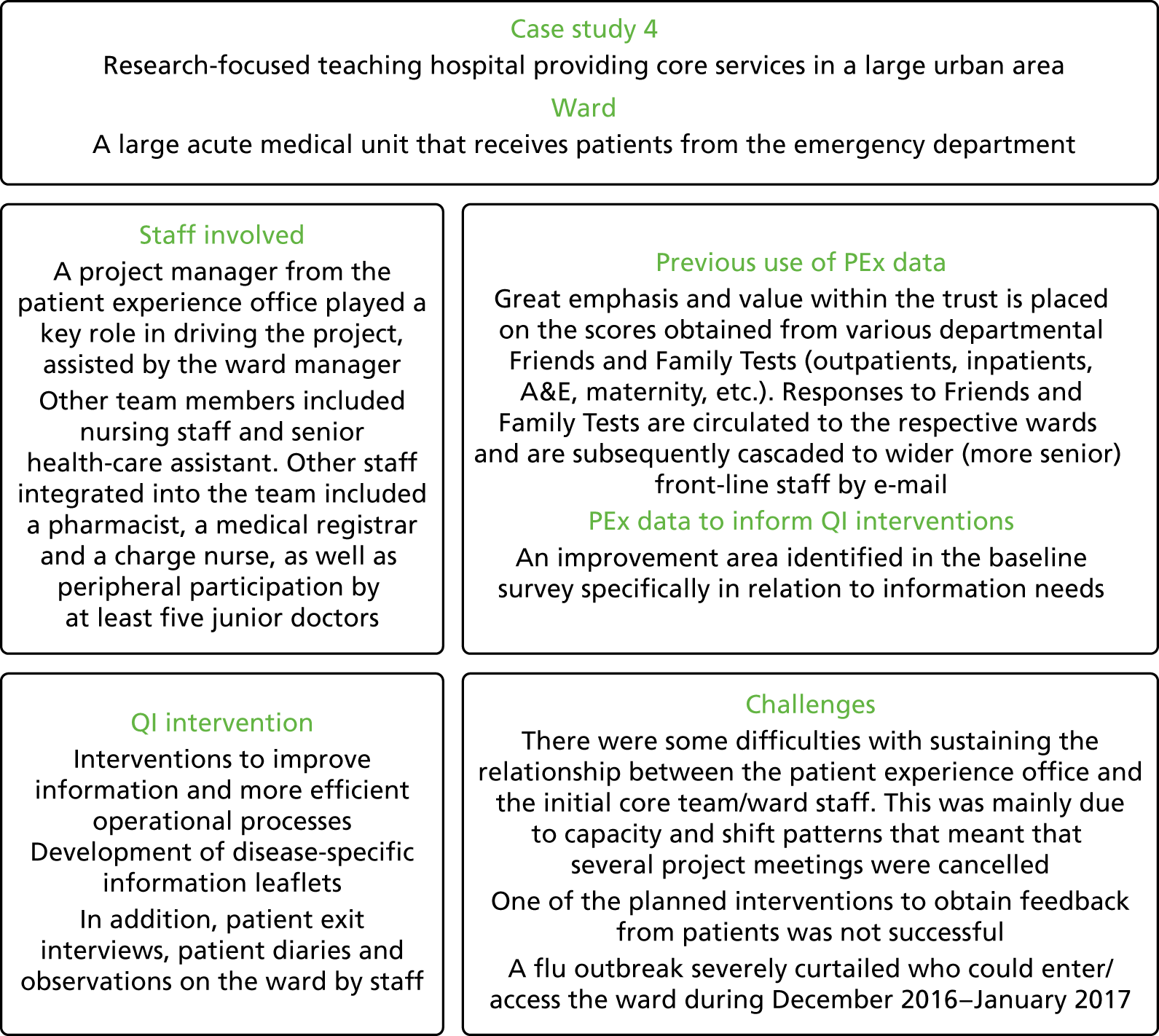

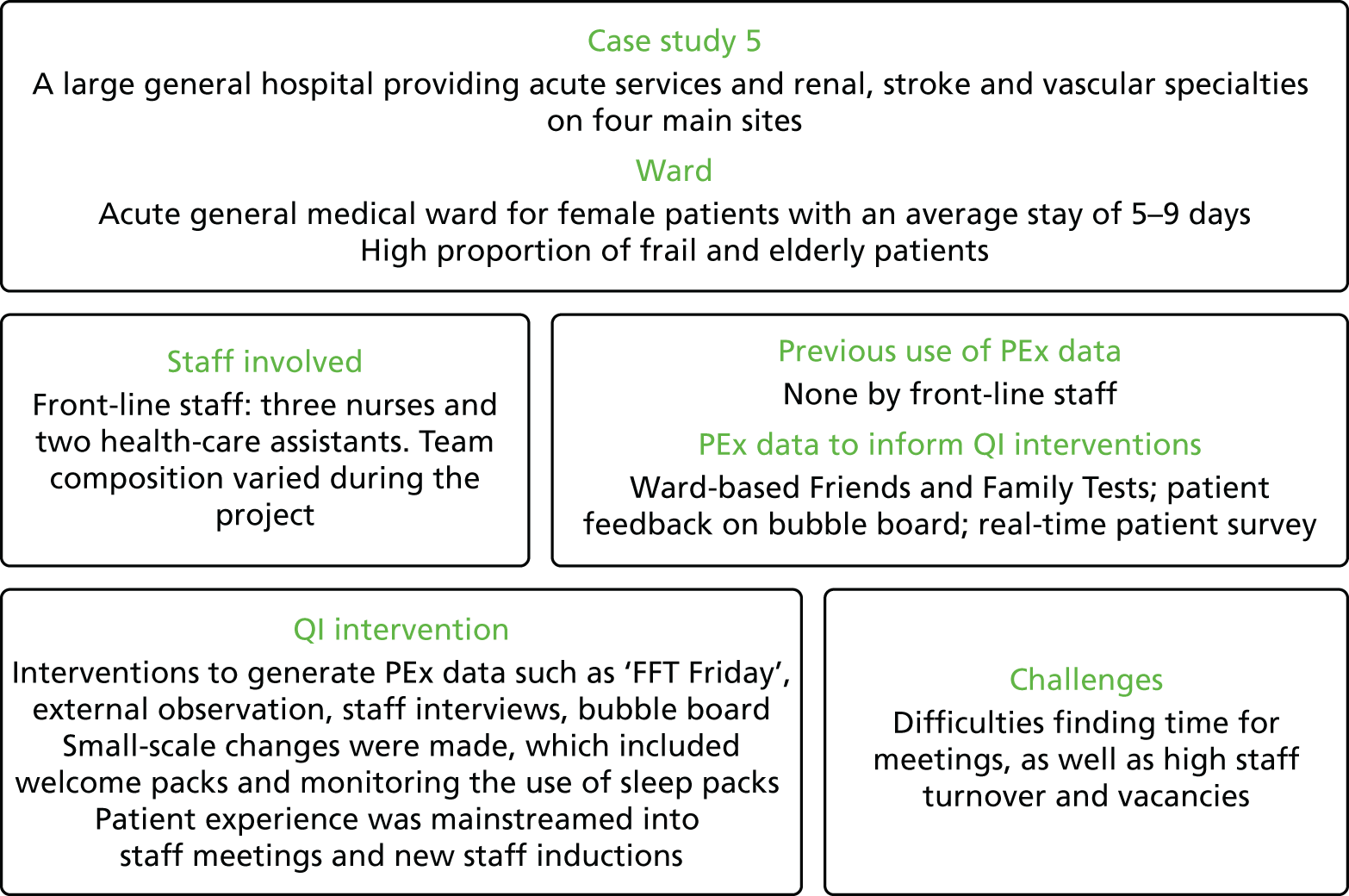

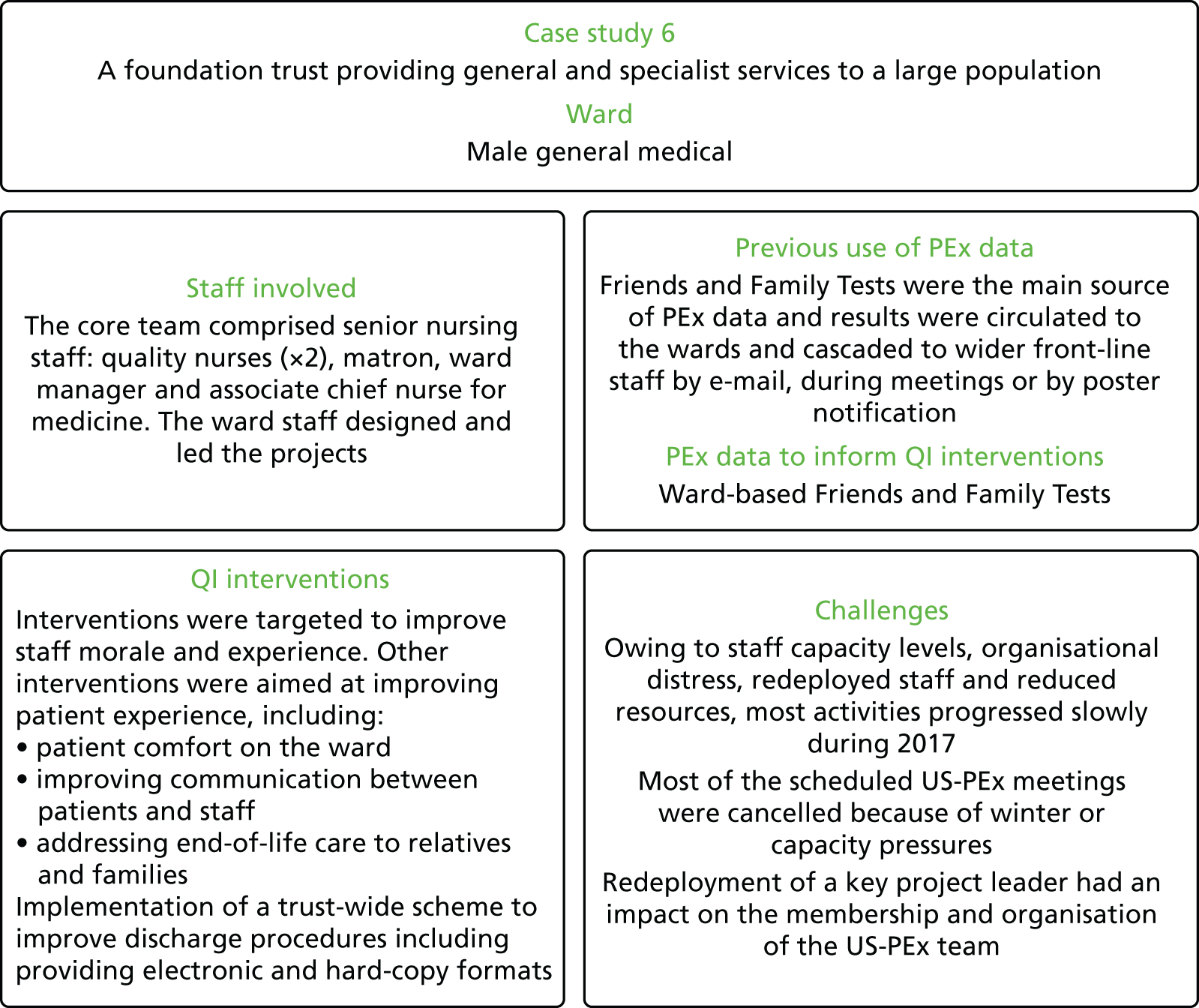

An anonymised summary description of each site and its improvement work is appended (see Appendix 1).

Phase 2: case studies in six medical wards

Once six front-line medical wards had been selected and R&D approval had been obtained, the study moved to phase 2, a mixed-methods case study approach. This had several steps:

-

a baseline patient experience survey and interviews in each site

-

preparation of resources and formation of a learning community to support front-line teams to plan patient-centred QI work

-

qualitative ethnographic observation of the front-line teams’ QI work

-

follow-up patient experience survey and interviews.

We describe each of these steps below and, where appropriate, reflect on how our methods evolved and adapted in real-world NHS settings.

Funding of £6000 was given to each NHS trust to allow staff to take part in research-related activities (such as attending the learning community and being interviewed). The cost of time spent on QI work was expected to be borne by the trust as part of routine commitment to improving patient experience.

Ethics and research and development approval

Ethics and R&D permissions were obtained through the new Health Research Authority combined approvals process (REC reference 16/NE/0071). This is intended to eliminate the need for site-specific approval processes by individual trusts. However, as the system was new, some trusts continued to require separate, additional information after central approval had been granted. This delayed the administration of the baseline survey, and in one case trust agreement came through only a matter of days before the front-line teams were due to take part in the first learning community (see Resource book and learning community).

Research Passports were obtained by the three study ethnographers. The ethnographers then applied individually for letters of access from each trust where they would be working on site. Trust requirements were varied; some required re-presentation in person of all the original documentation already verified by the trust issuing the Research Passport, whereas others did not. Again, this slowed the process of gaining site access for fieldwork. All necessary site access documents were obtained by August 2016, a period of approximately 5 months from first applying for Research Passports.

Patient Experience Survey and interviews

Case studies began with a baseline postal survey of patients discharged from the participating wards over a 4-month period (January–April 2016). This was supplemented by a small number of telephone interviews with patients.

A post-intervention survey and interviews were carried out with patients discharged during March–May 2017. The main aim of the pre- and post-intervention surveys was to see if any measurable changes in patient experience were found following the teams’ QI work, and to provide quantification of people’s experiences on the wards to accompany the mainly qualitative findings from other elements of the research. As well as using the results as part of our assessment of change, we chose to present the findings from both the pre- and post-intervention surveys to staff at each of the case study sites. This was originally intended to help them understand their current position and the impact of their work. It was not directly intended to provide them with information that might contribute to directing improvement, although in fact several teams found it helpful in this regard.

Development of the questionnaire

The questionnaire used for the baseline and post-intervention surveys focused on the experience of four areas of care:

-

referral to service

-

inpatient care

-

discharge

-

support for self-management.

A database of questions was compiled and mapped against the four areas. Candidate questions were selected from extensively tested, reputable sources such as the NHS Adult Inpatient Survey, the GP Patient Survey, the National Cancer Patient Experience Survey, and previously developed questions about self-management and demographic indicators. A longlist of 130 questions was reduced to 44 by three researchers independently assessing and then discussing their suitability for inclusion. Face validity of the draft instrument was assessed, with input from lay and staff co-investigators (JB and MG), which led to a small number of content changes.

Further detail on this process can be found in Appendix 2. See Appendix 3 for the survey and Appendix 4 for further methodological reflection.

Covering letters to accompany the questionnaire (for each of the three mailings) were also designed (see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/1415606/#/; accessed 17 April 2019).

Survey sampling

Ward teams drew a census of all patients discharged in a given period to whom the questionnaire was sent. Activity data from two of the sites showed that the actual number of discharges was much greater than anticipated and so a sample of patients was drawn, rather than a census. The sampling months for the baseline survey were January–March 2016 (one site also included patients discharged during April 2016 due to a smaller sample size). For the post-intervention survey, the sampling months were March–May 2017.

Survey fieldwork

The survey was sent to each site by post (Table 3). Fieldwork lasted for 12 weeks, during which two reminder mailings were sent to non-responders. Before each mailing, sites were asked to carry out a DBS (Demographic Batch Service) check for any patient deaths. An opt-out approach was used, stating that participation in the survey was completely voluntary. The low response numbers and rates in site 3 in particular are attributable partly to the fact that a high proportion of patients on the ward were living with dementia.

| Site | Pre-intervention survey | Post-intervention survey | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of surveys mailed to patients | Number of respondents | Adjusted response ratea (%) | Number of surveys mailed to patients | Number of respondents | Adjusted response ratea (%) | |

| 1 | 250 | 101 | 41 | 250 | 112 | 47 |

| 2 | 223 | 88 | 42 | 227 | 86 | 38 |

| 3 | 110 | 19 | 27 | 250 | 46 | 19 |

| 4 | 250 | 75 | 31 | 250 | 82 | 34 |

| 5 | 120 | 36 | 30 | 171 | 55 | 34 |

| 6 | 181 | 63 | 37 | 170 | 49 | 29 |

| Total | 1134 | 382 | 35 | 1318 | 430 | 34 |

Patient interviews

The survey was accompanied by in-depth interviews with patients and/or family or carers to gather more detailed information on their experiences. This was not intended to be representative of the overall patient population, but rather to add richer descriptive information alongside the quantitative data set (Table 4).

| Site | Pre intervention | Post intervention |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7 | 6 |

| 2 | 6 | 8 |

| 3 | 3 | 1 |

| 4 | 8 | 8 |

| 5 | 5 | 6 |

| 6 | 8 | 8 |

| Total | 37 | 37 |

The aim was to carry out eight telephone/face-to-face interviews per ward. A question was included in the survey allowing participants to indicate if they would be happy to be contacted to take part in a follow-up interview. Where possible, the researcher aimed to get a mix of interview participants in terms of their demographic characteristics. In one site, where cognitive impairment and ability to consent were an issue, numbers were still smaller than anticipated.

The topic guide used for the interviews followed the domains presented in the patient experience questionnaire, with probes focusing on referral, inpatient care, discharge and self-management (see Appendix 5).

The interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, and analysed using qualitative coding software (NVivo 10, QSR International, Warrington, UK). Framework analysis was used to identify, analyse and report themes and patterns within the responses from each ward. The findings from these interviews are summarised in the case descriptions (see Appendix 1).

Analysis and reporting to sites

Raw data from the survey were entered into Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and then transferred to SPSS version 23 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) for cleaning (including the correction of any wrong response codes and the application of any question routing rules) and analysis. The results for each ward team were analysed separately, with each team receiving a report of findings from the baseline survey and interviews, which included the following:

-

Response rate. An ‘adjusted base’ was used to calculate the response rate. The base excluded those questionnaires that were returned undelivered, deceased patients and patients who were ineligible to complete the survey.

-

Demographic profile of respondents. This included respondent profile, age and sex distribution of respondents and the ethnicity of respondents.

-

Infographic showing key results in a simplified pictorial format.

-

Frequency tables. Tables of frequency counts and percentages were created for each question.

-

Report of interview findings.

A similar report was produced following the post-intervention survey and interviews. This report, in addition to the content noted above, included a comparison between the baseline and post-intervention survey results. Z-tests were used to determine whether or not there had been any statistically significant changes between the two surveys at a confidence level of 0.95. Each z-test is equivalent to a chi-squared test on a subset of the whole data; using this test allowed the comparison of individual pairs of proportions.

A change in the profile of respondents in the post-intervention survey compared with the baseline survey may have affected the results, as we know that people tend to answer questions in different ways depending on certain characteristics. Our analysis of the survey data (across the six sites) showed that the sex of a respondent affected the results, with women reporting less positive experiences than men. If the post-intervention respondent sample had more male inpatients than the baseline survey did, then this could potentially lead to a trust’s results appearing better than if they had a higher proportion of female patients. To account for this, results were standardised by the sex of respondents to enable a more accurate comparison of results between the baseline and post-intervention surveys.

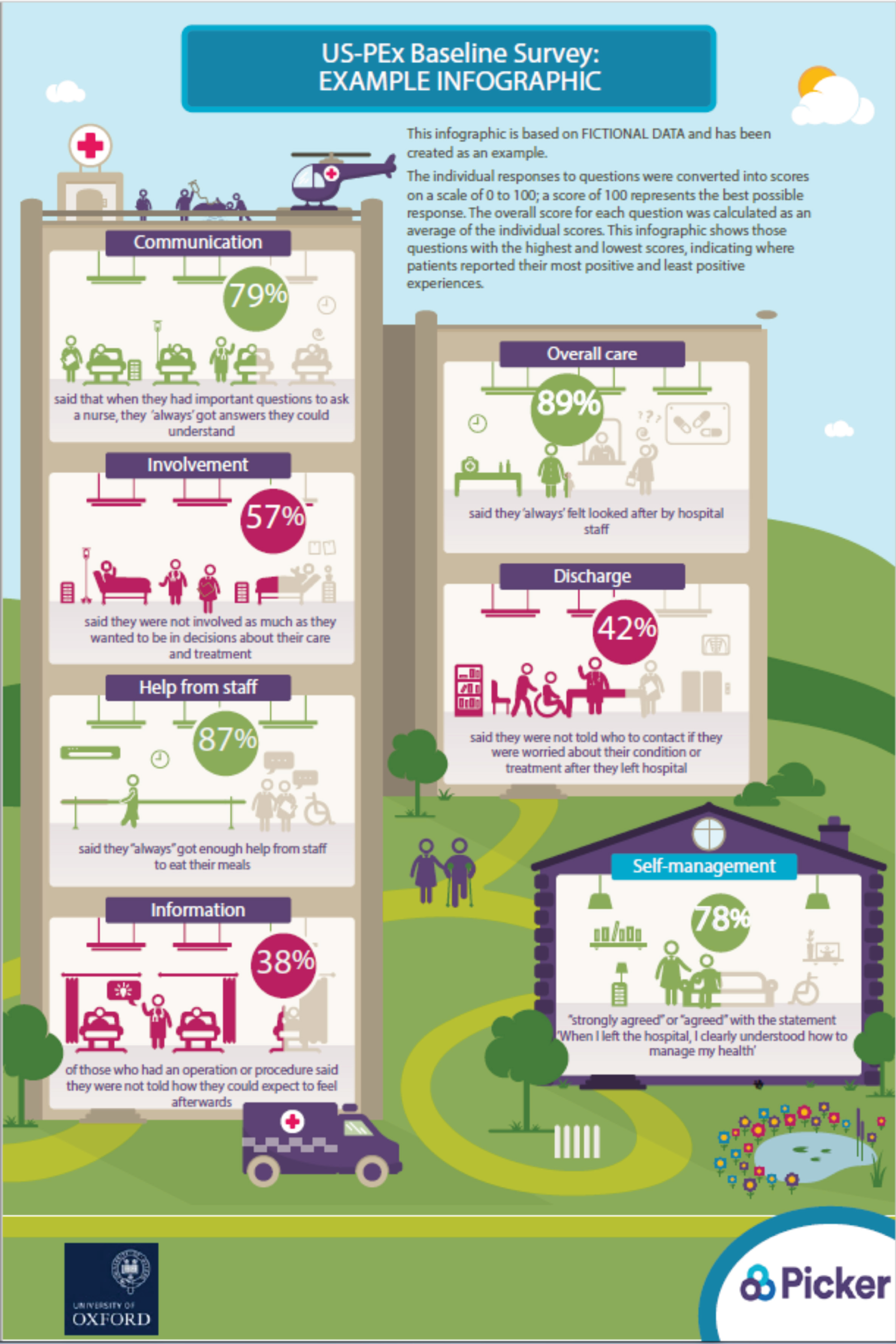

Alongside the mainly numeric data from the surveys, we produced accessible infographics to communicate key findings to staff with less experience of quantitative data. To select results to include in the infographic, the questions were scored to identify areas about which patients reported their most positive and least positive experiences.

The infographic showed the percentage figures for those questions with the highest scores (green), indicating where the ward was doing well, and for those with lower scores (red), where the ward had the most room for improvement (see Chapter 6, Making sense of patient experience ‘data’: where do ideas for change come from?, for an illustration of the infographic template).

Resource book and learning community

A ‘resource book’ was prepared for distribution to each team. This brought together short, accessible descriptions of different types of patient experience data and how they might be used, as well as brief summaries of key QI approaches. The resource book was developed by the principal investigator, initially using desk research to assemble information about different types of data, QI approaches and available evidence to support these for use in improving patient experience. Drafts were shared with members of the co-investigator team, as well as with the director of Care Opinion, and improvement advisers from The Point of Care Foundation and the NHS England Patient Experience Team, who commented on the accessibility of content and provided additional material. The content of the resource book has now evolved into an online guide hosted by The Point of Care Foundation (www.pointofcarefoundation.org.uk/resource/using-patient-experience-for-improvement/; accessed 8 May 2019) (see Phase 3: producing guidance for the NHS).

This material also formed the basis for the first ‘learning community’ event in July 2016. This was a 2-day residential workshop, facilitated by Professors Andrée Le May (chairperson of the NIHR Journals Library Editorial Group) and John Gabbay, to help prepare and support the front-line teams in planning their QI ideas. This was also attended by the lay panel, staff from NHS England, and speakers from Care Opinion and The Point of Care Foundation.

The original plan was to give all teams the results from the baseline survey from their ward by the time of the first learning community. Unfortunately, delays in obtaining site R&D approval meant that this was not possible for every site; in one case, site approval came through only a few days before the learning community took place.

The exact size and composition of teams was determined by each site, but attendance at learning community meetings was limited to up to five people from both clinical and non-clinical backgrounds. Sites were encouraged to focus primarily on front-line members of ward staff, and to bring a patient team member if possible. How teams were actually constituted forms part of our findings (see Chapter 5, Overview of phase 2 findings, and Chapter 8, The effect of team-based capital on quality improvement projects in NHS settings).

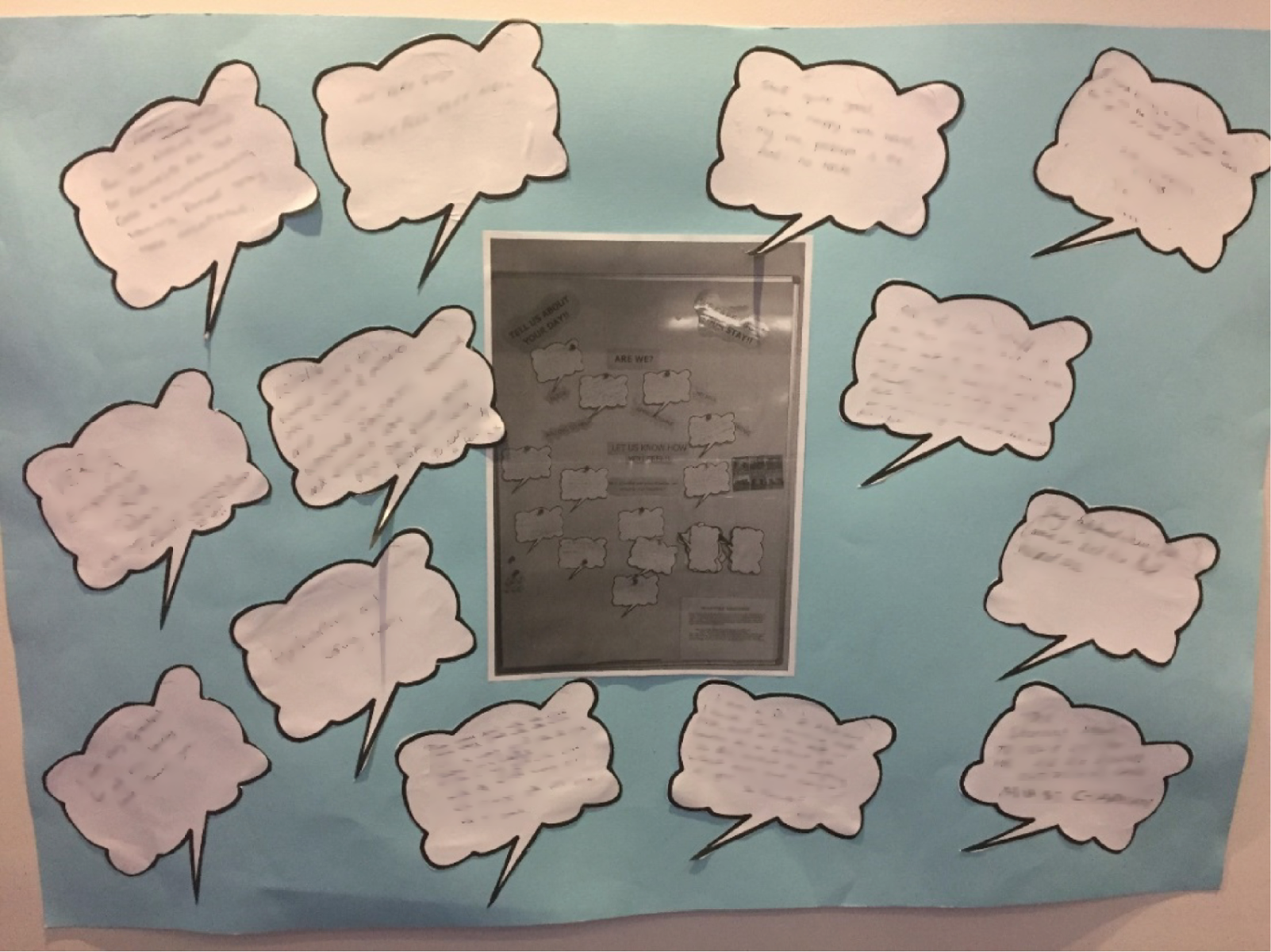

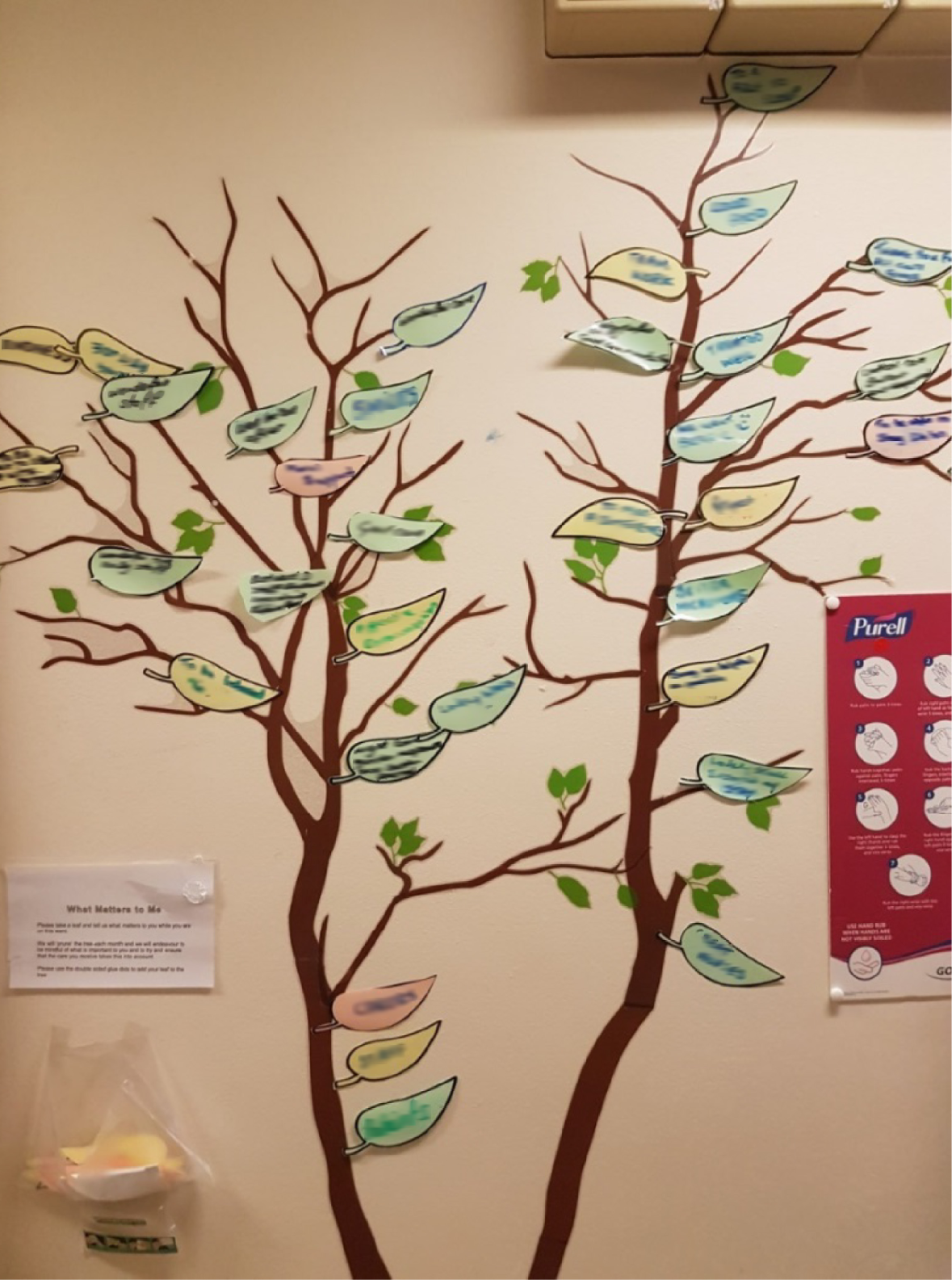

The first of the two days introduced the importance of understanding patient experience and concentrated on types of data and how to use them. Lay panel members gave a presentation on themes identified from their collective experiences, which had also been used to prepare a trigger film available for use in the sites if they wished. Members of the research team organised a ‘marketplace’, with stalls on survey data, narratives and interviews, observation, and online feedback/complaints. Lay panel members were involved in each stall. Front-line staff moved around stalls, as they chose, to learn about different options available to them and the strengths and limitations of both quantitative and qualitative data. The second day focused on QI techniques, particularly patient-centred approaches such as EBCD and PFCC. An overview of what is known about achieving organisational change and the importance of stakeholder mapping was also given. Before departing, teams had time in their own groups to plan their next steps.

Front-line quality improvement work and ongoing support

Teams then went back to their wards to decide what patient experience data to use, to design and implement their own QI projects, and to decide who else they needed to involve.

Two further learning community events were held: one at the mid-point of the fieldwork period in December 2016 and one at the end in July 2017. The purpose of the mid-point event was to enable teams to share progress and problems and to discuss their next steps. The intention was to offer supportive, formative input, with feedback from other teams and members of the research team. Emerging findings from the ethnographic study were also shared (see Focused team ethnography).

The third and final learning community meeting gave teams a chance to report on final outcomes, reflect on learning and help the research team shape the form and content of the guidance to be disseminated across the NHS. Senior managers from each trust were invited to hear presentations from the ward teams in the afternoon as a means of both celebration and dissemination; at least one senior manager from each trust attended, although uptake was not as high as had been hoped.

Teams were offered ongoing improvement advice and support during the fieldwork period by a senior adviser from the NHS England Patient Experience Team. It had also been planned to offer a monthly webinar with improvement advice and for the exchange of ideas between teams. However, a combination of difficulty finding time and technical resources to enable team members to join the webinar and the growing pressures of winter 2016–17 meant that the webinar was abandoned after two sessions. Other means of keeping in touch, such as a Facebook page (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA), were tried but did not prove useful to the front-line teams.

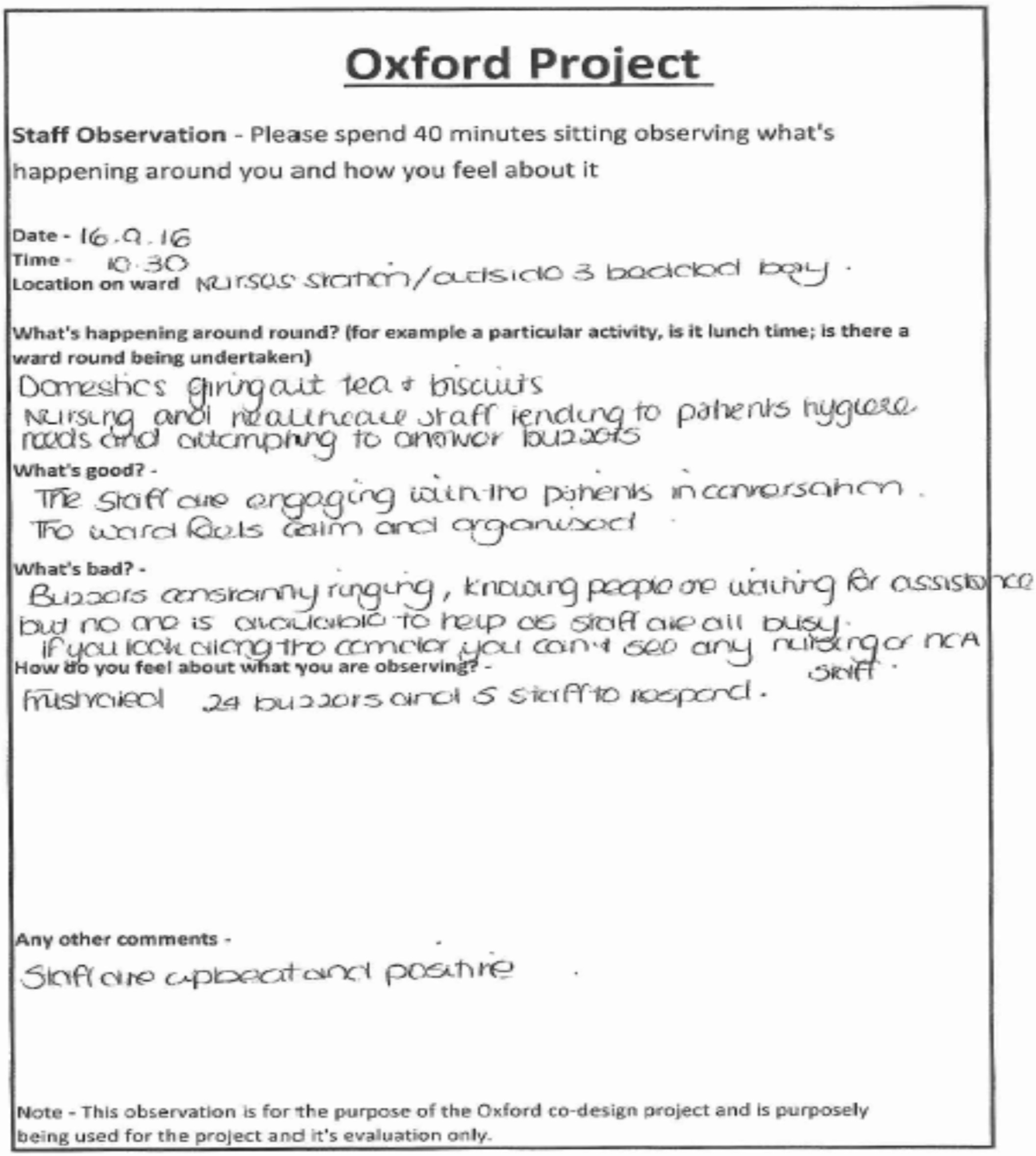

Focused team ethnography

In this section we describe in detail the qualitative component of the case study fieldwork. The QI work of the front-line teams was studied by a team of three researchers using ethnographic methods. Data collection included observational field notes, notes of informal conversation, semistructured interviews and continued documentary analysis. Primary responsibility for fieldwork in each site was allocated to one of the three ethnographers: one full-time (responsible for three sites) and two part-time (covering one and two sites, respectively).

‘Team’ and ‘focused’ ethnography

Team ethnography has its origins in late nineteenth-century expeditions to non-western locations. 72 Embedded within multidisciplinary academic teams (including psychologists, physiologists, mathematicians and geographers) were social anthropologists whose role was to obtain an ‘ethnographic’ perspective of the cultures encountered. Ethnography has been increasingly used for the applied study of contemporary organisations; it is not uncommon for one or several ethnographers to be embedded within the field of inquiry as part of wider interdisciplinary research. Jarzabkowski et al. ,73 for example, describe a team of five ethnographers conducting simultaneous fieldwork in 25 global reinsurance organisations across 15 countries. Thus, ‘team ethnography’ can refer both to the presence of an ethnographer in an interdisciplinary team, and to a team of ethnographers researching different case studies within one project.

In the US-PEx study, the full co-investigator team included a range of academic researchers, clinicians and non-academic partners (see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/1415606/#/; accessed 17 April 2019). Their role did not include fieldwork at any of the sites, but they provided discussion and reflection whenever ‘tales of the field’74 were summarised and discussed at research team meetings. Thus, the study consisted of a team ethnography that contained within it a core team of field-focused ethnographers. The ethnographers held regular meetings together and with the principal investigator to discuss fieldwork practicalities, review emerging findings, plan analysis and debate interpretations.

Team ethnography, in this second sense of a team of ethnographers working simultaneously, undoubtedly has challenges, given that no single ethnographer has detailed familiarity with all the sites. In this case, the original plan to recruit two full-time ethnographers was adapted to one full-time and two part-time team members, so the number of allocated sites differed. Thus, while one ethnographer drew on comparisons across three cases, another worked on one site in detail, but also conducted some fieldwork and analysis for another site. Such disparity is not unknown; for example, in the Atherton et al. 75 study, two ethnographers studied three sites each, while a third studied two sites. In the study by Jarzabkowski et al. ,73 small amounts of ethnographic fieldwork were undertaken by the principal investigator and co-investigator, alongside the main ethnographer. However, it does require deliberate strategies to overcome the limitations and ensure that, as far as possible, the analysis is shared and synthesised, rather than being the production of six disconnected ethnographies. This involves a shift in how individual ethnographers may have worked in previous settings. Strategies adopted in US-PEx included frequent, repeated meetings to tell each other the emerging story in different sites; standardising data collection tools (such as interview guides and observation pro formas); and agreeing a shared coding framework for analysis. We also worked regularly with our lay panel to sense-check our emerging interpretations, and used the second and third learning community events similarly with the ward teams to check that we were reflecting their experiences. Despite this, observation in the field remains a uniquely individual act. Data from ethnographic field notes and coding notes, included in Chapters 6–8, inevitably represent one person’s interpretation of a given observation.

At the same time, team ethnography brings advantages. It can bring multiple lenses and professional experience of different settings to bear; in this case, the three ethnographers came from different disciplinary traditions (sociology, anthropology and psychology). It also provides a forum for academic collaboration, in which observations may be shared and interpretations challenged and/or confronted. 73 Such team-based reflexivity establishes a collective sense-making process that differs from those normally associated with so-called ‘lone-ranger’ ethnographers. Schlesinger et al. 76 describe this as a positive model ‘because it sets up a deliberative process that involves testing the work as it is being done’. They add that:

. . . a collaborative approach to analysis leads to a deeper shared knowledge of the field and a more fluid and less temporally segmented process of knowledge production.

Schlesinger et al. 76

The wider research team, which included experts in different types of data and methods, also regularly reflected on emerging interpretations with the core ethnography team, and directed the gaze of future ethnographic fieldwork. For example, at a full team meeting 3 months into the fieldwork period (September 2016), the ethnographers raised observations that at two sites the teams appeared to be using the project as a way to bring about desired changes that they had identified before they had been involved in the project, based both on experience accumulated through their professional lives and on knowledge of the workings of their particular wards. Discussion among the full team identified the importance of keeping an open mind about what was meant by ‘using patient experience data’.

At another full team meeting, in November 2016, observations on the extent to which the ward teams did or did not involve input from patient experience officers, and the level of seniority of these staff, was discussed. It was agreed that, although the emphasis remained on empowering front-line staff, teams should be actively encouraged to seek help from their organisation. The ethnographers subsequently communicated this to the teams as part of formative feedback and were attuned to this in their work going forwards. At the same meeting, there was further evolving conversation on what constitutes ‘patient experience data’ and where they come from, including both direct and indirect sources (such as comments from the US-PEx lay panel and ideas from other case study sites). This became an important focus for the ethnographers.

Schlesinger et al. 76 also note that a team-based approach can enable a greater range, volume and complexity of work to be undertaken, which may be crucial within the limited timespan of available funding. This relates also to the nature of ‘focused ethnography’. Focused ethnography provides a rapid and condensed alternative to the time-consuming long-term engagements in conventional ethnography. 77–79 It aims to offer outputs within relatively short time frames to inform the immediate applied needs of organisations. 75 Table 5 summarises the key differences between conventional and focused ethnography.

| Conventional ethnography | Focused ethnography |

|---|---|

| Long-term field visits | Short-term field visits |

| Experientially intensive | Data/analysis intensity |

| Time extensity | Time intensity |

| Writing | Recording |

| Solitary data collection and analysis | Data session groups |

| Open | Focused |

| Participant role | Field-observer role |

| Insider knowledge | Background knowledge |

In addition to within-project discussion, the principal investigator and ethnographers took part in a learning set with investigators from other studies funded under the same call using ethnographic and qualitative methods. The research team also overlaps with that of the INQUIRE (Improving NHS Quality Using Internet Ratings and Experience) project (14/04/08), of which John Powell is the principal investigator and Louise Locock and Sue Ziebland are co-investigators. This cross-fertilisation of ideas has further strengthened the analysis.

Whereas in some medical studies ‘observational research’ may refer to a study design that that is not experimental (such as cohort studies), here we use observation to mean a set of techniques used by anthropologists and sociologists to study the everyday life of a group of people. Ethnographic observation entails the researcher being present with those under study to observe, record and understand the social structure and local culture that they inhabit. Ethnographic observation is distinguished by being a holistic approach to research that also involves interviews and the interpretation of material culture.

Pre-fieldwork case descriptions

Before commencing fieldwork, the ethnographers conducted desk-based research on the respective cases allocated to them. This aimed to provide preliminary ‘case descriptions’ of the six case study sites, and included reviews of relevant grey literature [such as Care Quality Commission (CQC) reports], relevant online feedback from sites such as Care Opinion and NHS Choices, and any articles/news items relevant to each trust and ward involved in the study. The process of gathering this information was maintained throughout fieldwork and beyond its completion.

Data collection

During the fieldwork period from July 2016 to September 2017 the team of ethnographers interviewed core front-line team members, wider team members from the ward (including any patients involved) and senior managers (including directors of patient experience and directors of nursing and/or quality) in each site. Front-line team members were interviewed at several time points to capture their reflections and experiences: at the beginning of the project, during their QI work, and at the end. Senior managers were interviewed towards the end of the study to capture their reflections on the progress of the front-line teams and whether or not, and how, this had had an impact on the wider trust (Table 6). Interview guides were developed for different groups (see Appendix 5 for sample guides).

| Site | Interviews | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Core team 1 | Core team 2 | Core team 3 | Senior level | Other | Total | |

| 1 | 4 | 0 | 4 | 8 | 2 | 18 |

| 2 | 6 | 2 | 5 | 5 | 0 | 18 |

| 3 | 7 | 5 | 3 | 3 | 0 | 18 |

| 4 | 5 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 11 |

| 5 | 5 | 0 | 3 | 5 | 0 | 13 |

| 6 | 5 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 17 |

Non-participant observations were carried out of QI meetings, conversations and workshops wherever possible. The exact nature and amount of observation varied by site, depending on its programme of work (see Table 7). Observations were guided by an agreed pro forma (see Appendix 6). As well as written field notes and individual notes, data collected included photographs (e.g. of comments boards or information displays prepared by front-line teams as part of their work).

| Site | Number of visits | Total hours of observation |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 7 | 45 |

| 2 | 8 | 48 |

| 3 | 8 | 54 |

| 4 | 12 | 58 |

| 5 | 8 | 48 |

| 6 | 8 | 46 |

| Total | 51 | 299 |

Front-line teams also provided information on changes made in each site and (when possible) data on staffing levels, staff sickness and vacancy rates, as part of describing the context in the winter of 2016–17. However, as noted in the findings, there were significant challenges in obtaining this information.

All participants were given an information sheet and gave written consent (see Appendix 7 for examples).

Analysis

Knoblauch80 describes the use of ‘data sessions’ conducted within groups as a further defining feature of focused ethnography, in which data are viewed, discussed and interpreted by multiple actors rather than by an individual working alone. Knoblauch describes the benefit of such collective sessions as a procedure that:

. . . opens data socially to other perspectives. In order to support this opening, data session groups are helpful, the more they are socially and culturally mixed.

Knoblauch. 80 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

As noted above, the ethnographers met regularly as a group and with the principal investigator to interrogate each other’s data and to identify the similarities and challenges raised in each other’s observations. Emerging findings were also shared iteratively with the wider research team, the lay panel and the Study Steering Committee, and at the second and third learning communities. Each of these forums became an integral part of the ongoing analysis, as ethnographic ‘tales from the field’ were shared collaboratively and opened to intersubjective interpretation by several socially and culturally mixed audiences.

In the final phase of all fieldwork, a series of ethnographer data sessions focused on the production of a coding framework (using NVivo 10) to co-ordinate the way in which data were analysed within the team. These data included all semistructured interview transcripts, field-based observations and individual field notes. Thirteen domains were identified by the three ethnographers as key areas, including, for example, ‘context’, ‘organisational culture and practices’ and ‘quality improvement’. Thematic analysis then established a wider framework that consisted of 58 separate codes across all 13 domains. Data were then coded and analysed using this framework (see Appendix 8).

Alongside this thematic analysis, one ethnographer (SP) devised a visual mapping method to help record and make sense of events in the three sites in which he was undertaking fieldwork. These ethnographic process maps used colour coding and symbols along a timeline to capture both the various workstreams undertaken by front-line teams and the key influences and events (both positive and negative). This provided an at-a-glance way of visualising the findings in each site, complementing the case descriptions and coded data and contributing to data analysis sessions. The approach was developed and refined by the team in the data sessions and a dedicated ‘mapping’ meeting. All three ethnographers produced versions of the maps for their sites (see Appendix 8 for a more detailed account of the evolution of this visual mapping technique and Appendix 9 for examples).

Realist informed evaluation

This study was not designed as a pure realist evaluation, but rather it aimed to be realist-informed. Alongside the holistic case study ethnography work and ‘thick’ case descriptions, therefore, the team considered realist explanations and candidate context–mechanism–outcome configurations emerging from the findings. Analysis workshops on case study analysis and realist evaluation were held with input from the Saïd Business School, University of Oxford, and the RAMESES II (Realist and Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses – Evolving Standards) project (a HSDR programme-funded study to develop methodological standards for realist evaluation). 81

The chief output of this is a consideration of ‘team capital’ as an explanatory mechanism, discussed in Chapter 8, The effect of team-based capital on quality improvement projects in NHS settings. Chapter 7, on staff experience, also explores possible mechanisms through which staff experience may affect patient experience.

Phase 3: producing guidance for the NHS

Phase 3 was the preparation of an online toolkit for NHS staff on understanding and using patient experience data for QI. During the lifetime of the study, research into stakeholder perspectives on toolkits from health-care research was being undertaken as part of a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) project at the University of Manchester,82 and early findings informed the methods adopted for phase 3. In particular, it was recommended that toolkits were more likely to have impact if they were produced and branded by a recognised source. As a result, the decision was taken not to produce the toolkit in-house, but to commission The Point of Care Foundation to produce and host it, alongside their existing and widely used toolkits on EBCD and PFCC. The core of the toolkit was the content of the resource book already produced for sites in phase 2. This was revised and edited to include findings from the US-PEx study, and illustrative films from staff at some of the participating sites. Those interviewed for the toolkit gave separate consent.

Chapter 3 Patient and public panel methods and reflections

I believe that the best patient experience comes from combining the skills and knowledge of clinical professionals with the lived experience of patients and carers. The US-PEx study was looking at that approach.

Lay panel member

The study was advised throughout by a lay panel, chaired by the lay co-investigator. This chapter describes the composition and activities of the panel, reflects on its role and reports some of the panel’s reactions to key findings.

Who were the lay panel and how were they recruited?

We advertised for lay members through a range of avenues to include as diverse a mix as possible in terms of age, ethnicity, geography, health condition and type of experience of inpatient care. We particularly encouraged people who had been involved in previous service improvement work to apply, as well as those with no improvement experience. As with many patient and public involvement (PPI) groups, the panel was lacking in those aged under 30 years; however, given the subject of study, we felt that this was not of particular concern as older people tend to have more hospital experience.

The lay panel comprised 10 lay advisors (see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/1415606/#/; accessed 17 April 2019), all of whom had experience of NHS inpatient care (including surgical) either as a patient or as a carer. It was expected that the motivation to become part of the panel would be from having had negative experiences; however, this was not universally the case. One panel member said of his time in hospital:

My experience was a very positive one, but I was motivated to get more involved in measures aimed at improving health care and, in particular, the patient experience.