Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 15/55/03. The contractual start date was in February 2017. The final report began editorial review in May 2018 and was accepted for publication in March 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Higginbottom et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Equality is a key aim for the NHS in the UK. 1 Over one in four births (28.2%) in the UK is to a foreign-born woman (rising yearly). 2 Fifty-six per cent of births in London in 2013 were to foreign-born women, creating superdiversity among maternity care clients. 3 Of concern is the fact that immigrant women appear disproportionately in confidential inquiries into maternal and perinatal mortality, indicating possible deficits in the care pathways. 4,5 Rapid demographic change and the need to maximise health potential in our diverse, multicultural UK society6 provides an urgent imperative in respect of drawing knowledge together in a systematic fashion. A synthesis of knowledge related to maternity care access and interventions is urgently required to inform policy and practice to appropriately configure interventions as per the NHS Midwifery 2020 vision, to guide the professional development of health-care professionals (HCPs) and to reshape care to ensure culturally congruent maternity care. The UK is in a period of superdiversity, defined as ‘distinguished by a dynamic interplay of variables among an increased number of new, small and scattered, multiple origin, transnationally connected, socio-economically differentiated and legally stratified immigrants7 largely arriving in the UK post 1990’. Consequentially, enhancements to maternity care for immigrant women will not only benefit these women but will also improve the health of future generations in the UK. 5,6,8 Insights into and understanding of the ethnocultural orientation of immigrant women in maternity is critical because it contributes not only to successful integration and social cohesion, but also to social justice in health care. 9–11 Moreover, the socioeconomic marginalisation and vulnerability of immigrant women may be exacerbated by pregnancy, making maternity a critical focus of attention for the health-care system. 10,12,13

Why now?

A knowledge synthesis is required to build a coherent evidence base that elicits an understanding of the factors behind disparities in accessibility, acceptability and outcomes during maternity care that can be used to improve and reconfigure this care. Substantial diversity exists within immigrant women populations; however, examples of commonalities may be found (e.g. late bookings for antenatal care,4,14 higher maternal and perinatal mortality,4,5 poor care and discrimination,9 obesity,15 postpartum depression,10,16 low birth weights and poor birth outcome,17,18 and higher rates of gestational diabetes15). These problems create an economic burden for the NHS. 19

Costs to the NHS

The effective and efficient use of precious NHS resources is vital to the UK, but the higher prevalence of poorer birth outcomes among immigrant populations increases costs for the NHS. Unfortunately, economic modelling of these costs is lacking, so definitive data cannot be provided.

An urgent imperative due to demographic change

This period of superdiversity in the UK means that many new and diverse groups now reside in this country. 20 Historically, the UK has hosted communities within whom a relationship existed via colonisation and the establishment of the commonwealth. However, in particular, increasing migration from Eastern Europe and non-Commonwealth countries is rapidly changing the demography of the UK. If the nation is to realise the full health potential of these future citizens, the NHS urgently needs a synthesis of the knowledge related to immigrant experiences of access and interventions in maternity care. Moreover, addressing health inequalities is a major goal of current NHS directives. The directives entitled Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS21 and Midwifery 2020: Delivering Expectations22 demanded enhancements to patient experiences. Developing interventions to militate against inequalities can make major contributions towards redressing inequalities. At present, NHS maternity services are so pressed for resources that they may not be accessible and acceptable to immigrant women. To improve outcomes for these women, effective recommendations for future policies may well sit outside the NHS.

Theoretical framework

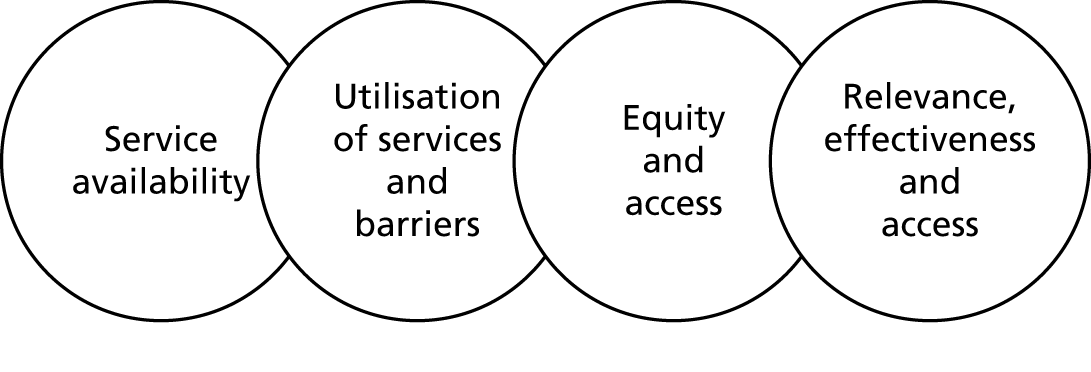

A theory of access to services developed by Gulliford et al. 23 maps out four dimensions (Figure 1):

-

service availability

-

utilisation of services and barriers to access (which includes personal, financial and organisational barriers)

-

relevance, effectiveness and access

-

equity and access.

FIGURE 1.

Gulliford theory of access. 23 Reproduced from Higginbottom et al. 24 © Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2019. Re-use permitted under CC BY. Published by BMJ. This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

We used this theoretical model in our systematic review, which was based on a synthesis project funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). Unlike most access models in the USA, this framework reflects the philosophy of the NHS in that its key principles are to provide horizontal access (ensuring equality of access in the population) and vertical access (meeting the needs of particular groups in the population, such as minority ethnic groups). The application of these principles is influenced by availability, accessibility and acceptability. The Gulliford et al. 23 model has been widely used in empirical research, with the main paper having been cited at least 386 times. With its emphasis on accessibility, acceptability, relevance and effectiveness, this model is entirely appropriate for assessing the provision of maternity services to minority ethnic groups. In this study, the theory of access was used in the configuration of the review findings. 23

This approach correlates with the research recommendations of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) on access and models of service provision. 25 Using a comprehensive theoretical framework was crucial, because previous reviews lacked comprehensiveness by addressing only women’s skilled use of maternity services,26 the early initiation of antenatal care by socially disadvantaged women,27 or the early initiation of antenatal care by black and minority ethnic (BME) women. 27 Moreover, in these reviews it was unclear whether or not the women in the studies were immigrants. Our review addresses these deficits.

Policy relevance

Evidence-based health care demands synthesised evidence to ensure that the highest-quality evidence is used to appropriately configure maternity services. 22 Synthesised evidence is also needed to realise the goals of the NHS National Maternity Review,6 which directly informs the NHS Five Year Forward View,1 the professional development of HCPs and organisational change.

Significance and wider context

Some UK locations have historically been destinations of choice for immigrants, but other rural and urban locations are increasing in diversity. These changes are resulting in challenges to the provision of maternity care. Ultimately, enhancements to maternity care for immigrant women benefit not only the women using the service, but also the health of future British generations. Listening and responding to the perspectives of these service users (via the research studies included in our review) will be essential for configuring services in ways that are culturally congruent and culturally safe. 28 Understanding the ethnocultural orientations of immigrant women in maternity is crucial; it contributes to successful integration and social cohesion, and ultimately to social justice in health care. 29,30 Women’s needs and rights are often marginalised within families, communities and legislation. Socioeconomic marginalisation and the subsequent vulnerability of immigrant women can be further exacerbated by pregnancy and childbirth, making these factors an important focus of attention for those concerned with enhancing maternal health. 12,31–34 Critically important is the strategic commitment in the UK to improve maternity services for all service users. 22 In this context, it is imperative to implement service models that are effective for the disadvantaged and to ensure that these services are appropriately personalised.

The UK is in a period of superdiversity,20 with a wide range of populations accessing UK maternity care. Facilitating the provision of appropriate health care for immigrant populations in the UK will be crucial for maximising their well-being and their health potential. Without the delivery of culturally appropriate and culturally safe maternal care, negative event trajectories may occur, ranging from simple miscommunications to life-threatening incidents,35 risking increased maternal and perinatal mortality. Indeed, immigrant women are over-represented in mortality statistics. 11,36,37 Although recent reviews have focused on specific aspects of maternity care,26,27,38 they have not considered a comprehensive conceptualisation of access23 or the current superdiversity. 20 Reconfiguration and redesign of NHS maternal services to meet the needs of immigrant women requires integration of all these aspects.

Globally, a considerable commonality exists among developed nations in the maternity care experiences of immigrant women: studies in the USA,17,39 Canada,13,40–43 Australia,44,45 Sweden46 and Germany10 all provided evidence of this in earlier international reviews led by Higginbottom et al. ,10,12 Small et al. ,8 and Gagnon et al. 41 However, the international comparative reviews by Small et al. 8 and Gagnon et al. 41 focused on South Asian and Somali women in the UK, thereby reflecting more established groups of immigrants and not the more recent superdiversity and current immigration patterns. In addition, two of the national surveys included in the Small et al. 8 and Gagnon et al. 41 reviews did not specify the number of immigrant women, limiting the overall usefulness of those reviews. We have addressed this deficit in our current review.

Our experienced information scientist-assisted search strategy (see Appendix 1) established that a systematic review of immigrant-receiving countries in Europe found substantial disadvantages for immigrant women in all of their maternal outcomes. The risk of low birth weight was 43% higher, the risk of preterm delivery was 24% higher, the risk of perinatal mortality was 50% higher and the risk of congenital malformations was 61% higher. 18 Providing appropriate maternity care successfully to immigrant women requires the legitimisation and incorporation of their pervasive traditional beliefs and practices to which they often adhere despite their new milieu. 47 Their beliefs and practices related to maternity care may differ considerably from Western biomedical perspectives,9,48 and the women may also be affected by migration issues and language barriers. 9,31,33–35,48,49 Maternity care interventions may mitigate many of these issues, thereby enhancing the health of the mothers and their children.

Providing culturally safe and relevant maternity care in an era of superdiversity

The provision of culturally safe50,51 and relevant maternity care is contingent on the recognition and comprehension of key theoretical concepts. In the following paragraphs we explore these key concepts in the context of superdiversity.

Cultural competence

Meeting the maternity care needs of diverse populations demands consideration of the issues of cultural safety and cultural competence. Leininger,52 a seminal theorist, described ‘culturally competent care as care that is sensitive and meaningful to the patients, that intersects well with their cultural beliefs, norms and values’. This type of care may consist of actions that identify, respect and promote the cultural uniqueness of each individual. 53 These important behaviours may be enhanced by continuing education for nurses and other health-care providers. 54 Although Leininger made an important contribution in this field in the last century, her work has been critiqued extensively,55 largely for its assumption that care and services will be improved by knowledge of different cultures without recognition of ‘the very complex ways in which race, socioeconomic status, gender and age may intersect’. 56 The approach tends to promote culture negatively, potentially contributing to stereotypical attitudes and propagating power imbalances. 57 Serrant-Green58 stressed that the diversity within all ethnic communities needs to be addressed.

The term cultural competence means different things to different people; it can be said to represent a diverse set of skills, knowledge, attitudes and behaviours. Cultural competence can operate at the level of the individual practitioner, within a service setting, and at the broader levels of the health-care organisation and in the wider health-care system.

Key dimensions of cultural competence are the following:

-

knowledge about diversity in beliefs, practices, values and world views, both within and between groups and communities, and recognition of similarities and differences across individuals and groups, as well as the dynamic and complex nature of social identities (sometimes called cultural knowledge)

-

acceptance of the legitimacy of cultural, social and religious differences, and valuing and celebrating diversity (sometimes called cultural awareness)

-

awareness of one’s own identity, beliefs, values, social position, life experiences and so on, and their implications for the provision of care (sometimes called cultural awareness or reflexivity)

-

understanding of power differentials and the need to empower service users (sometimes considered part of cultural awareness)

-

the ability to empathise, show respect and engender trust in service users (sometimes called cultural sensitivity)

-

recognition of social, economic and political inequalities and discrimination, and how these shape health-care experiences and outcomes for minority groups; and a commitment to address such inequities

-

effective communication strategies, including resources for cross-lingual and cross-cultural communication

-

resourcefulness and creativity to resolve issues arising during the provision of care across differences. 59

Organisational cultural competence

Organisational cultural competence refers to the structures, processes and strategies that operate within health-care organisations, to ensure the delivery of high-quality care and equitable outcomes to all clients, regardless of their ethnic, cultural or religious identities. This type of competence usually encompasses critical reflection on the inner workings of the organisation, including the underlying ways of operating that serve the interests of the dominant group within society. Cultural competence at an organisational level involves the commitment of adequate resources to support appropriate responses at the service delivery level.

Cultural safety

Culture is one of the most difficult terms or concepts to define, but is usually taken to be the beliefs, values, practices and symbols that are recognised by individuals who belong to a particular ethnic group. Although our focus here is on cultural safety,51 the issue of intersectionality must be acknowledged, because in reality a number of axes of inequality exist. For example, social class, ‘race’, ethnicity and gender intersect with culture and may increase the vulnerability60 of women in accessing maternity care services. Focusing on a narrow definition of culture when providing health care may lead to the stereotyping of clients and potentially to an inability of the practitioner to deal with diversity. Cultural safety aims to address these deficits by considering the historical and social processes that impact power relationships within and beyond health care. 50,51 Cultural safety is achieved when programmes, instruments, procedures, methods and actions are implemented in ways that do not harm any members of the culture or ethnocultural group who are the recipients of care. 61,62 Those within the culture are best placed to know what is or is not safe for their culture, which suggests the need for increased dialogue with immigrant women and a need for collaborative partnership approaches. 63,64

Cultural safety was first conceptualised in New Zealand by Dr Irihapeti Ramsden, a Maori nurse, in response to a need to acknowledge the impact of colonisation on the Maori population and its lasting effects in the provision of health care. 63 Ramsden conceptualised cultural safety as a product of nursing and midwifery education that facilitates culturally safe care as defined by the recipients. 50 Cultural safety has been endorsed by the Nursing Council of New Zealand64 and has been a key component of international nursing and midwifery education since the early 1990s. The concept is less commonly used in the UK context, although it seems to be eminently transferable and has a strong empirical basis which other models do not have. Hence, it has been adopted as the cultural safety model by statutory bodies in both New Zealand and Canada. 62

In the current period of superdiversity3,20 in the UK, responding to diverse needs of immigrant women in maternity care is an urgent imperative. 8,37 It would seem necessary to draw on the concepts of cultural safety51 and cultural competence65 in order to provide optimal care, the fundamental axioms and precepts being that the values and norms of the host community determine the service configuration and in fact NHS employees are the bearers of these cultural norms via professional practice. Other nation states, notably Canada,62 Australia and New Zealand,50,63 have integrated the key dimensions of cultural safety (e.g. into professional education for HCPs). Intersecting the primacy of host community values is the idea within the notion of cultural safety, that power dimensions exist between the dominant cultural groups and new ethnocultural groups, resulting in unequal power dimensions in the health-care interaction. These unequal power dimensions often have historical antecedents; an exemplar of this is the notion that Commonwealth immigrants arriving in the UK, and in sociological terms, may be regarded as ‘the other’. Culturally competent and safe care demands not just a focus on individual professional practice, but an embedding of the principles of culturally safe and competent maternity care at the organisational level via policies, procedures, guidelines, education and training of health professionals.

How is an immigrant defined: international and UK perspectives

Defining the term immigrant is complex and lacks consensus. Internationally, the term ‘immigrant’ is defined in various ways. For example, according to the Canadian Council for Refugees, an immigrant is an individual who relocates to permanently reside in Canada. 66 The Canadian Council for Refugees further explains that a person is a permanent resident if the right to live permanently in Canada is granted by the government to that person. The entry of the person into Canada may be as an immigrant or as a refugee. This definition indicates that in Canada an immigrant is defined on the basis of their legal residence status.

In Australia, the United Nations (UN) definition of international migration67 is used to define an immigrant. Accordingly, a person is an immigrant if they are born outside Australia and have been (or are expected to be) living in Australia for a period of ≥ 12 months. 68

In the USA, the Department of Homeland Security is responsible for collecting data on immigrants. According to the Department of Homeland Security, immigrants are foreign-born individuals and they are required to obtain legal permanent residence in the USA. 69 Here, the foreign-born individuals are the individuals who are not US citizens at the time of their birth. This definition includes naturalised US citizens, legal permanent residents (immigrants), temporary migrants (foreign students), humanitarian migrants (refugees and asylum seekers) and persons residing illegally in the USA. 69 This definition indicates that the USA defines immigrants according to different categories (e.g. permanent and short-term residence).

In the UK, there is inconsistency in defining the term ‘immigrant’ in different data sources and data sets relating to migration. 70 The terms immigrant and migrant are often used interchangeably to confer the same meaning. For example, the Annual Population Survey of Workers and Labour Force Survey71 uses country of birth as a basis for defining a ‘migrant’. According to these data sources, a person born outside the UK is classified as a ‘migrant’. However, many workers born outside the UK may become British citizens over a period of time.

A second source of data on migrants is applications made for obtaining a National Insurance number. This data source defines a migrant on the basis of nationality. Accordingly, applicants that hold nationality other than the UK are migrants. However, similar to the above, the nationality of a person is also subject to change over a period of time and, in some instances, individuals may acquire dual citizenship of a different nation state.

A third and important source of data on migrants is the Office for National Statistics (ONS). The ONS classifies migrants’ data in two data sets (i.e. short-term international migrant and long-term international migrant). Here ‘long term’ means holding the intention of staying > 1 year, whereas ‘short term’ is the intention of staying < 1 year. This suggests that the ONS considers the length of stay of a person in the UK important in determining migrant status. The classification of migrants into short and long term is recommended by the UN. The ONS uses the UN definition of long-term international migrant and estimates migrants both inside and outside the UK. Accordingly, a migrant is a person who relocates and changes his or her country of residence for a minimum of 12 months; therefore, the country of destination in essence becomes the country of usual residence. 72 In long-term international migration data, students and asylum seekers are also included, which is not the case in the USA.

Immigrants and the UK NHS

In service provision, the NHS follows rules set by the central government that determine an immigrant’s entitlement to free NHS care. These rules relate to the kind of services and the immigration status of the user. 73 This approach suggests that an asylum-seeker woman may not be entitled to full maternity care because of immigration status. 74 Furthermore, the collection of data on ‘immigrants’ in the health-care setting is not well established and the NHS usually collects data on ethnicity and nationality and not on the migration-related variables such as length of stay and country of origin.

Researchers in the University of Oxford’s Centre on Migration, Policy and Society have defined immigrants in health-care research based on ‘country of birth’, with recent immigrants being foreign-born individuals who have been living in the UK for ≤ 5 years. 75 Similarly, in another briefing paper on the health of migrants in the UK,74 researchers from the Centre on Migration, Policy and Society defined migrants as all those born outside the UK. The authors acknowledged that currently it is challenging to achieve a comprehensive understanding of migrants’ health due to the lack of evidence on migration-related variables (e.g. country of birth, length of stay in the UK, immigration status).

The statement of NICE, which provides clinical guidelines for health-care practice in the UK, is worth noting here. NICE,25 in its guidelines Pregnancy and Complex Social Factors: A Model for Service Provision for Pregnant Women with Complex Social Factors, identified recent migrant women having complex social needs. NICE defined a recent migrant as a woman who moved to the UK within the previous 12 months. In the guidelines, migrant women are conflated with asylum seekers, refugees and those lacking English-language proficiency. This suggests that there is implicit acceptance of the term migrant women in health care in respect of being born outside the UK, being in the purview of immigration control and having deficits in English-language proficiency.

Defining immigrants in health-care research

There is no consensus on the operational definition of ‘immigrants’ in the health-care research literature. For example, Urquia and Gagnon76 conducted a review of the literature (2000–9) to explore how the term ‘immigrants’ is defined in health-care research. The authors noted heterogeneity and ambiguity in the terminologies used in the field. The authors documented the following definition for international migrants:

A change of residence involving the spatial movement of persons across country borders. The change of residence may result in a new permanent residence (if the person is allowed to reside indefinitely within a country) or a temporary residence, as in . . . of international students and contract labour migrant workers . . .

Urquia and Gagnon76

The above definition is based on ‘length of stay’ and includes asylum seekers and refugees; however, in this definition the terms ‘permanent’ and ‘temporary’ are not further defined and specified. In fact, the authors are based in Canada, and therefore their definition may be mediated by Canadian perspectives on migration, which are somewhat different from those in the UK.

There are studies in which an immigrant is classified on the basis of country of birth. For example, Small et al. 8 published a systematic and comparative review of studies on women’s health in five developed countries, including the UK. For the purposes of their review, the authors defined ‘immigrant women as those women not themselves born in the country in which they are giving birth’. 8 In another study on maternity care,77 the author used similar terms (i.e. Somali-born women in the Finland context). This suggests that being born outside the country in which a women gives birth is the main defining factor. Salt78 has consistently used a definition of immigrant ‘as a person born outside the UK’ in his work. This is similar to a case in the US context, in which a systematic review on the health of immigrant women79 defined immigrant as ‘foreign born’.

In some other studies, the researchers have used broader terms to define immigrants. For example, an integrative review of the literature examining the potential influence of HCPs’ attitudes and behaviours on health-care disparities80 used a ‘broad definition’ and included all groups that, owing to ethnicity, place of birth, citizenship, residence status or the related variables, have minority status in the country in which they reside. The same approach is taken by a meta-synthesis81 undertaken on refugee and immigrant women’s experience of postpartum depression in three major European countries with high levels of immigration (Germany, Italy and the UK). The authors of this aforementioned meta-synthesis noted that there is inconsistency in the use of the term immigrant and thus ‘extended the inclusion criteria to all articles, where research had been undertaken on “ethnic minorities”, “migrants”, “refugees” and “asylum seekers” in the given country‘. 81

It is observed that ‘nationality’ is also used in maternity care-related research to classify immigrant women. For example, acknowledging the challenge of categorising immigrant and ethnic minority women, Jentsch et al. 82 used ‘overseas nationals’ in their study. In another review, Collins et al. 83 excluded papers that looked at second-generation immigrant women and those whose samples were selected only on the basis of ethnicity rather than immigration. In the UK, the terms ‘old’ and ‘new’ migrants are also used when talking about the demographic diversity and challenges of delivering public services, including health care. 7

Immigrant women in our proposal for the National Institute for Health Research

Our proposal submitted to NIHR noted various features of immigrant women in the UK that are related to the aforementioned discussion. The proposal acknowledged heterogeneity and diversity in the immigration pattern of immigrant women in the UK. The proposal highlights a variety of reasons for migration, diversity in country of birth and length of stay in the UK:

Our review is focused on immigrant women. This is heterogeneous group with migratory pattern that might be related to economic migration, the transgression of human rights and war, or have origins in the UK’s colonial history . . . The UK is in a period of superdiversity that is new and more diverse migrant groups (this includes both recent migrants and those who have been settled in the UK for many years) are resident in the UK, creating challenges for the National Health Service [NHS]. Increasing migration from Eastern Europe and non-commonwealth countries means that the synthesis of knowledge related to immigrant experiences of maternity care interventions and access is an urgent imperative because of rapidly changing demography and the potential to realise health potential of future citizens.

Higginbottom et al. 84 © Article author(s) (or their employer(s) unless otherwise stated in the text of the article) 2017. All rights reserved. No commercial use is permitted unless otherwise expressly granted. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The operational definition of an immigrant women used in this review

The preceding paragraphs suggests that the term ‘immigrant’ is defined in various ways in different countries and by different authors. However, two features are frequently referred to in these definitions (i.e. country of birth and length of stay). These factors are also noted in NICE guidelines on the provision of maternity care25 and are important in the entitlement, access and ability to use health care in the UK. For example, if you are born outside the UK, it is likely that you are knowledgeable about the UK health-care provision.

We adopted the following definition of an immigrant woman for our review and to inform our inclusion and exclusion criteria. A woman is an immigrant if she:

-

is born outside the UK

-

has lived in the UK for > 12 months or had the intention to live in the UK for ≥ 12 months (or more) when she first entered.

Therefore, we included studies on immigrant women in which the population studied fulfilled these two criteria. According to this definition, studies on population groups of foreign students, asylum seekers, recent legal refugees and immigrants, and illegal immigrants will also be eligible for inclusion. In many cases the study populations/sample may not be accurately and fully described. We therefore used linguistic ability (e.g. the need for an interpreter) as a proxy for immigrant status. Notwithstanding all of these perspectives, we acknowledge that the term ‘immigrant women’ is generic and refers to a highly heterogeneous group of individuals, with a complex and vast array of ethnocultural orientation, linguistic skills abilities, motivations for migration and socioeconomic status. However, there may be a commonality of experience in respect of the use of and familiarity with maternity care services in the UK. What is profoundly critical is the over-representation of immigrant women in maternal and perinatal mortality statistics.

Chapter 2 Aims and objectives

Our aim was to undertake a narrative synthesis (NS) of a wide range of empirical literature, including grey literature, to provide stakeholders with perspectives on maternity care access and interventions (NHS and non-NHS) directed at immigrant women in the UK. The topic is of great significance to the NHS because of the strategic commitment to address inequalities and the changing patterns of migration to the UK. Because established immigrant communities feature disproportionately in maternal and perinatal mortality, and because 26.5% of all UK births in 2013 were to foreign-born women,2 the topic is highly relevant.

We planned to identify the most effective and appropriate methods of services delivery by identifying the acceptability of relevant processes at the individual, community and organisational levels. These factors are recognised to be critical determinants of the effectiveness of services and of patient and client outcomes. We also planned to identify specific critical points in care delivery, which will enable the provision of tailored solutions for policy and practice changes. In addition, we aimed to explore the factors affecting the implementation of particular interventions that are designed to enhance access, equity, and clinical and psychosocial outcomes for immigrant women. To reach this aim, we used a Project Advisory Group (PAG) that included not only patient and public involvement, but also clinicians [an obstetrician, a general practitioner (GP) and midwives], commissioners and a policy-maker. This group was initiated during the establishment of our research questions and our early plans for dissemination, and its involvement continued for the entire duration of the project. We wanted to meet the following objectives:

-

to identify, appraise and synthesise empirical studies on the topic that used qualitative, quantitative or mixed methods of research

-

to identify, appraise and synthesise grey literature and non-empirical reports

-

to identify additional knowledge users and mechanisms of knowledge transfer

-

to share our findings through strategic end-of-grant knowledge transfer (ultimately, we wanted to establish the current knowledge base and generate important recommendations for future policy, practice and programming, thus mapping out pathways to health equity).

Methodology

Protocol and PROSPERO registration

Our study is registered with PROSPERO as CRD42015023605 (URL: www.crd.york.ac.uk/PROSPERO/display_record.asp?ID=CRD42015023605; accessed 5 June 2019) and the protocol has been published. 84

Narrative synthesis methods

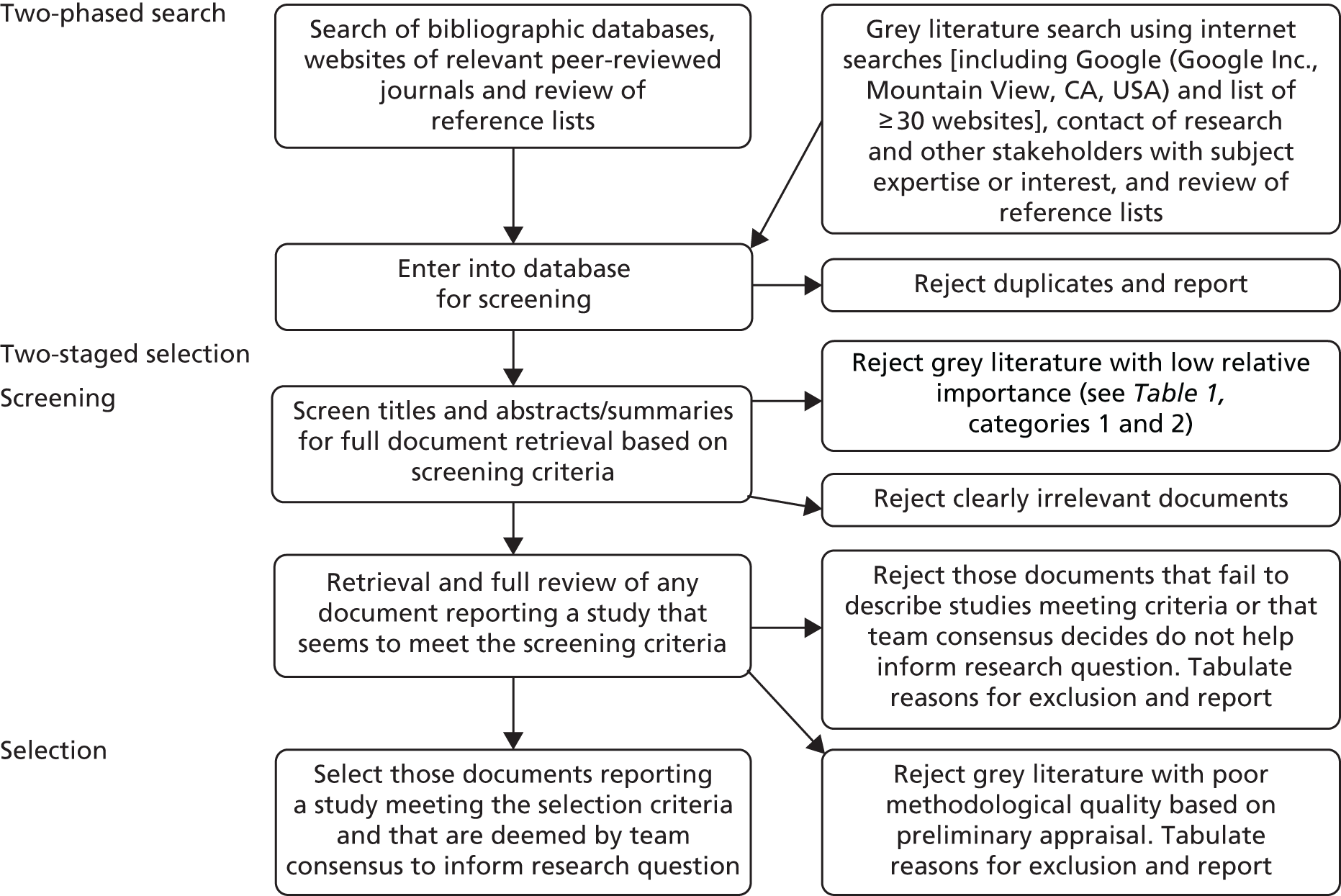

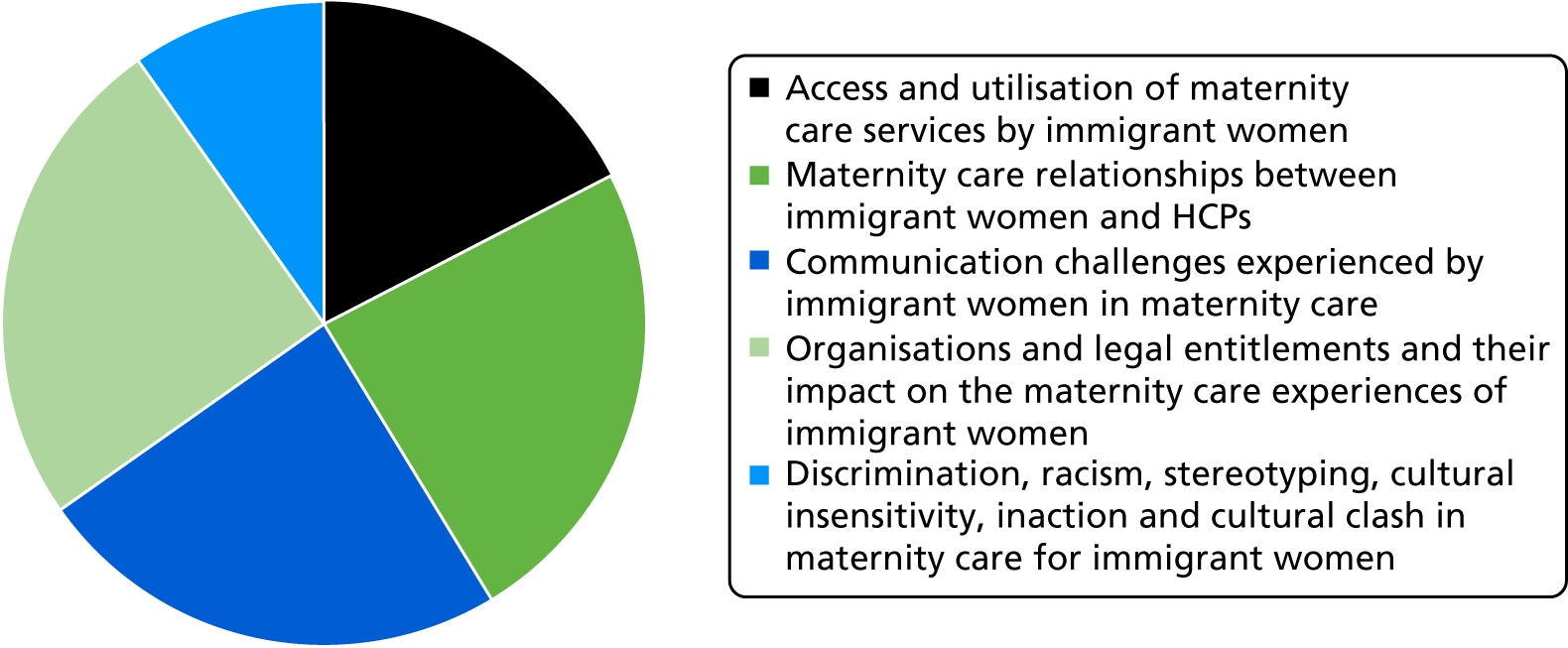

A NS review comprises four main elements (Box 1 and Figure 2).

Element 1: developing a theory of why and for whom.

Element 2: developing a preliminary synthesis of the findings of the included studies, following implementation of the search strategy.

Element 3: exploring relationships in the data.

Element 4: assessing the robustness of the synthesis.

FIGURE 2.

The four elements of a NS review. Reproduced from Higginbottom et al. 24 © Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2019. Re-use permitted under CC BY. Published by BMJ. This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Although a wide range of approaches exist on the spectrum of systematic reviews, ranging from aggregative to interpretive approaches,85 the purpose of selecting a NS approach (see Figure 2) was to produce highly relevant policy and practice evidence. Some systematic reviews are highly theoretical in nature; however, in considering our initial scoping review, it was established that much of our evidence was likely to be descriptive in nature and suitable for a thematic analysis which is associated with NS. A focus on narrative findings and the production of a thematic analysis is not merely the collation of key perspectives; importantly, the theming achieves a level of abstraction that produces new and potentially innovative insights. We conducted the review taking account of the original conceptualisation of the NS approach86 and of the new and emerging insights and guidance.

Element 1: developing a theory

This review had no predefined hypotheses. Our review focus on immigrant women’s access to and interventions in maternity care was developed and refined by mapping the available knowledge, and also ensuring the relevance of the knowledge synthesis (to policy-makers, other potential knowledge users and immigrant communities). The literature spanned a range of specific maternity care services, including antenatal, labour and postnatal care; maternal risk factors; health promotion; access to and availability and competency of maternity services; the role of culture and tradition; maternity outcomes in relation to perceived maternal risk factors; and responses to care interventions. We engaged in additional consultation with our PAG to further refine the review questions to increase their relevancy. We utilised Gulliford et al. ’s23 theory of access to inform our thematic outcomes (Box 2 gives an example of the scoping search strategy and Appendix 1 gives an exemplar of a final search strategy).

-

exp Maternal Health Services/or exp Postnatal Care/or exp Preconception Care/or exp Prenatal Care/or exp Perinatal Care/or exp Infant Care/or exp Midwifery/or exp Obstetrics/or exp Obstetric Nursing/

-

exp maternal welfare/or exp maternal care/or exp maternal child health care/or exp newborn care/or exp prepregnancy care/

-

exp General Practitioners/or exp Primary Health Care/or exp Family Health/or exp Community Health Nursing/

-

(((maternal or child* or baby or babies or fetus* or fetal* or embryo* or obstetric*) adj3 (health* or nurs* or care or service*)) or (midwif* or midwiv*)).ti,ab.

-

((birth* or matern* or mother* or pregnan* or childbearing or child-bearing or prenatal or pre-natal or postnatal or post-natal or perinatal or peri-natal or preconception or pre-conception or antenatal or ante-natal or postpartum or puerperium) adj3 (health* or nurs* or care or service*)).ti,ab.

-

exp Health Services Accessibility/or exp Healthcare Disparities/or exp Health Services/

-

(3 or 6) and (matern* or child* or baby or babies or fetus* or fetal* or embryo* or obstetric* or birth* or mother* or pregnan* or childbearing or child-bearing or prenatal or pre-natal or postnatal or post-natal or perinatal or peri-natal or preconception or pre-conception or antenatal or ante-natal or postpartum or puerperium).ti,ab.

-

1 or 2 or 4 or 5 or 7

-

(‘use’ or access* or utili* or consum* or block* or hurdl* or barrier* or hindr* or hinder* or obstacle* or exclu* or discrimin* or disparit* or disproportion* or inequal* or unequal* or inadequat* or insuffic* or stratif* or limit* or lack* or unreliab* or poor* or poverty* or depriv* or disadvantag* or insecur* or insensit* or status* or entitl* or uninform* or ill-inform* or benefit* or interven* or deliver* or effective* or cost effective*).ti,ab.

-

(3 or 6) and 9

-

‘Emigrants and Immigrants’/or Refugees/or ‘Transients and Migrants’/or ‘Emigration and Immigration’/

-

(((established or long-term or ‘first generation*’ or new* or recent* or current*) adj3 (migrant* or migrat* or immigrant* or immigrat* or emigrant* or emigrat* or emigre* or expat* or (ex adj pat*) or transient* or alien*)) or newcomer* or (new adj comer*) or incomer* or (in adj comer*) or ((international or overseas or foreign) adj2 (student* or employee* or worker*))).ti,ab.

-

(refugee* or (asylum adj seek*) or asylee* or (refused adj3 (asylum* or refugee*)) or (displaced adj person*) or exile* or (new adj arrival) or (country adj2 (birth or origin)) or transnational*).ti,ab.

-

(foreigner* or (foreign adj (born or citizen* or national* or origin*)) or (non adj (citizen* or native*)) or ((adoptive or naturali#ed) adj (citizen* or resident*)) or overstay* or trafficked or ‘spousal migrant*’).ti,ab.

-

(‘non-UK-born’ or ‘born outside the UK’ or ‘length of residence in the UK’ or ((‘not lawful*’ or ‘not legal*’ or unlawful* or illegal* or unauthori#ed* or ‘not authori#ed’ or uncertain or insecure or illegal or legal or legitimate* or permit* or visa* or irregular* or refused or undocumented) adj3 (residen* or student* or worker* or employee* or unemployed* or immigrant* or imigrat* or migrant* or migrat*))).ti,ab.

-

exp Ethnic Groups/or (ethnic* or ethno* or race or racial*).ti,ab.

-

exp african continental ancestry group/or exp asian continental ancestry group/

-

exp Vulnerable Populations/or ((vulnerab* or disadvantag* or minorit*) adj3 (individ* or person* or people* or population* or communit* or group*)).ti,ab.

-

(‘Black and Minority Ethnic’ or ‘Black and Minority ethnic’ or BME or BAME or african caribbean* or afro caribbean* or black african* or (west adj (indies or indian*))).ti,ab.

-

(south asia* or afghan* or bangladesh* or bengal* or bhutan

Chapter 3 Search strategy refinement and implementation

The comprehensive search strategy generated high rates of retrieval of records relevant to the research question of this project.

The search strategy used key terms used in consistently formulated text-based queries and search statements. These terms were based on subject headings, thesaurus terms, or related indexing and categorisation terms, appropriate for each literature database. An example of a detailed final search strategy is given in Appendix 1.

The strategies were also adapted to searching other data sources, such as existing systematic reviews, theses and clinical studies, to ensure the maximum possible retrieval of relevant records. Less-structured search queries were used to search various types of grey literature.

Refinements to the search strategy

In developing the search strategy across a number of the different databases, it became evident that terminologies used for maternal health-care services and immigrant status differ significantly, not only across the original journal articles but also in the different literature resources, in their standardisations of terms for subject headings, thesauri and other indexing and categorisation systems.

For example, across three major databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE and PsycINFO), parallel but differing terminologies were found. Moreover, medical subject headings (MeSH) (originally developed for MEDLINE) are searchable across all three databases, but they do not retrieve comparable answer sets and may need to be replaced or enhanced to do so (i.e. by using Emtree in EMBASE and enhanced MeSH terms in PsycINFO) (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

These concerns required iterative modifications to the original search strategies in each database to ensure that the observed variations in terminology were adequately reflected in both the index terms and the text-based queries that were developed for all of the databases.

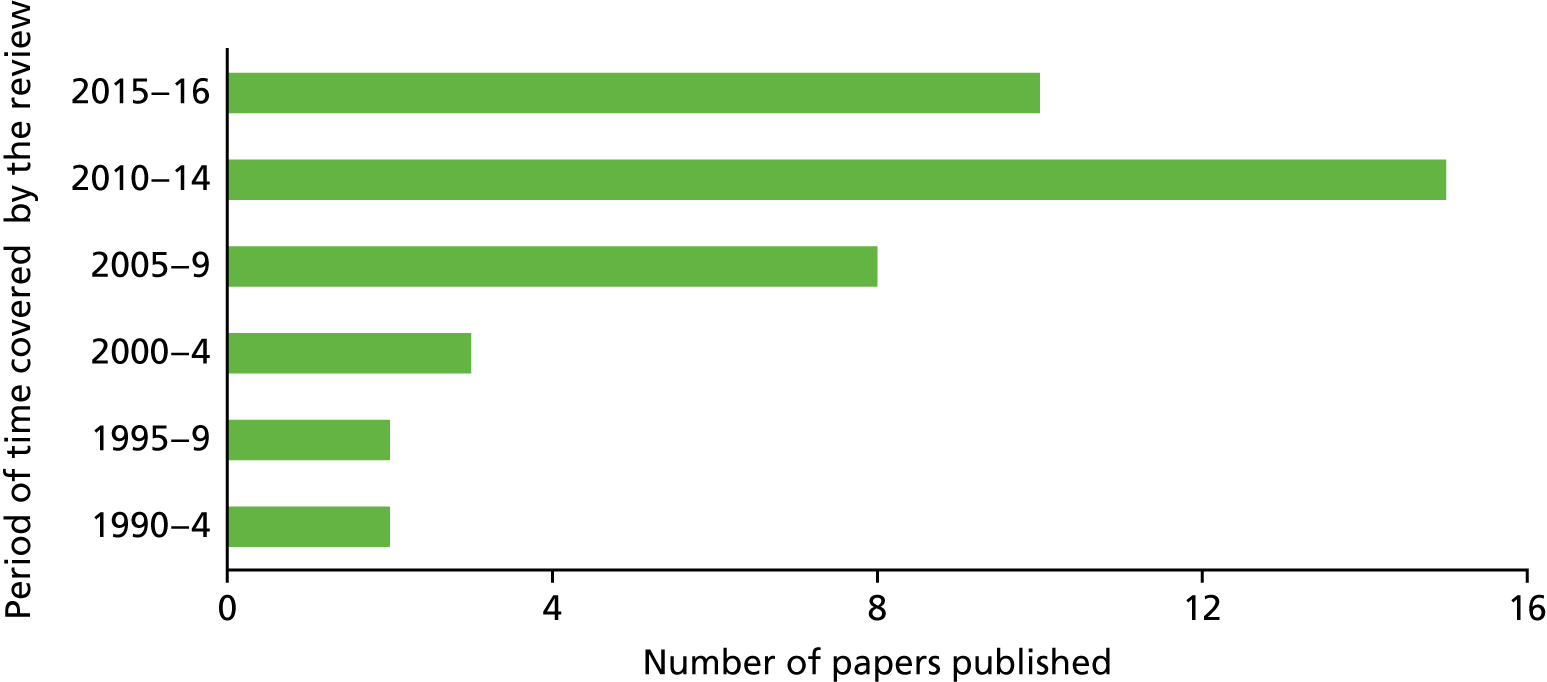

Search strategy and study selection

We included all empirically based studies that used a variety of methodologies (see Appendix 2) and focused on immigrant women, maternity care experiences, experiences and interventions, published between January 1990 and January 2018. Studies were published in English and included study locations in the UK (Table 1). We found several studies arising from Scotland and one from Wales; the remaining studies were based in England (see Appendix 3 for the table of excluded studies).

| Citation | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Criteria for selection: | Yes | No | Cannot say |

| 1. Publication date of January 2000 to January 2018 | |||

| 2. English | |||

| 3. Empirical research and findings | |||

| 4. Study participants live in the UK | |||

| 5. Study participants are immigrant women (if the study includes both immigrant and non-immigrant women, it must have findings specific to immigrant women) | |||

| 6. Related to maternity care access, interventions or experiences of maternity | |||

The NS approach relies primarily on the use of words and text to summarise and explain the findings of the synthesis, which are informed by a synthesis of the narrative findings of included papers. 86 Gina Higginbottom and Myfanway Morgan have successfully employed this review genre previously and have vast expertise in its usage. 87 Narrative synthesis is suitable for both quantitative and qualitative studies, as the emphasis is on an interpretive synthesis of the narrative findings of research, rather than on a meta-data analysis. 86 After applying rigorous systematic procedures for searching, screening and selecting literature for inclusion in the review, the articles were appraised for quality and the NS of the findings progressed.

We included studies that focused on immigrant women and adopted the following definition of an immigrant woman for the purposes of our review. A woman is an immigrant if she:

-

is born outside the UK

-

has lived in the UK for > 12 months or had the intention to live in the UK for ≥ 12 months when she first entered the UK.

Therefore, we included studies on immigrant women in which the population studied fulfilled these characteristics. Based on this, studies that focused on the following population groups were also eligible for inclusion: foreign students, asylum seekers, illegal immigrants and recent legal refugees and immigrants. In many cases the study populations/sample was not accurately and fully described. We therefore used linguistic ability (e.g. the need for an interpreter as a proxy for immigrant status). Our focus was on first-generation immigrant women regardless of their phenotype. Meaning that women of all ethnic groups are including women of white ethnicities, although we encountered few studies that focused on the latter and our review was constrained by the lack of various studies in the scientific literature. For example, we did not identify any studies meeting our criteria that focused on solely white immigrant women, such as Eastern European women.

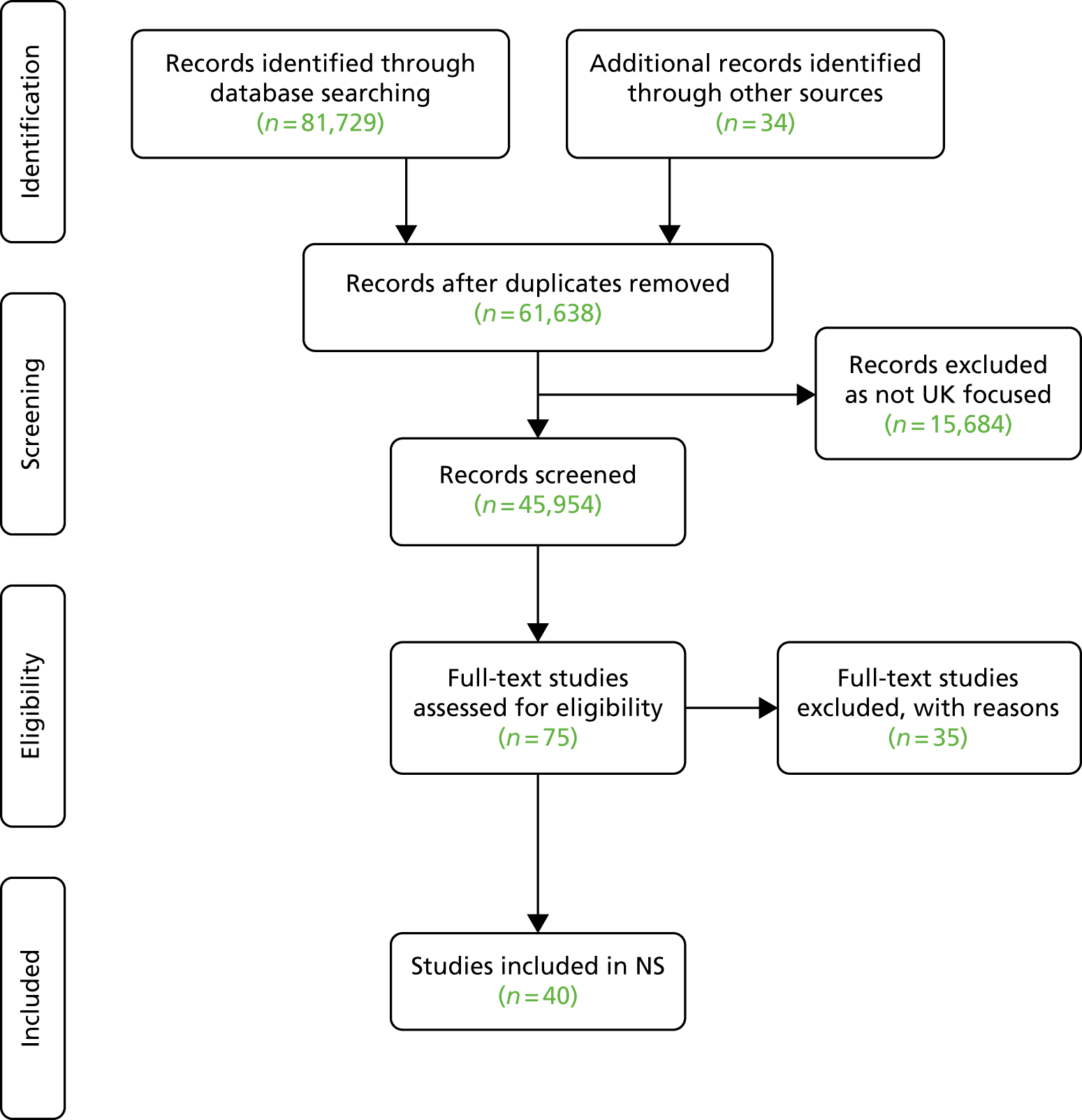

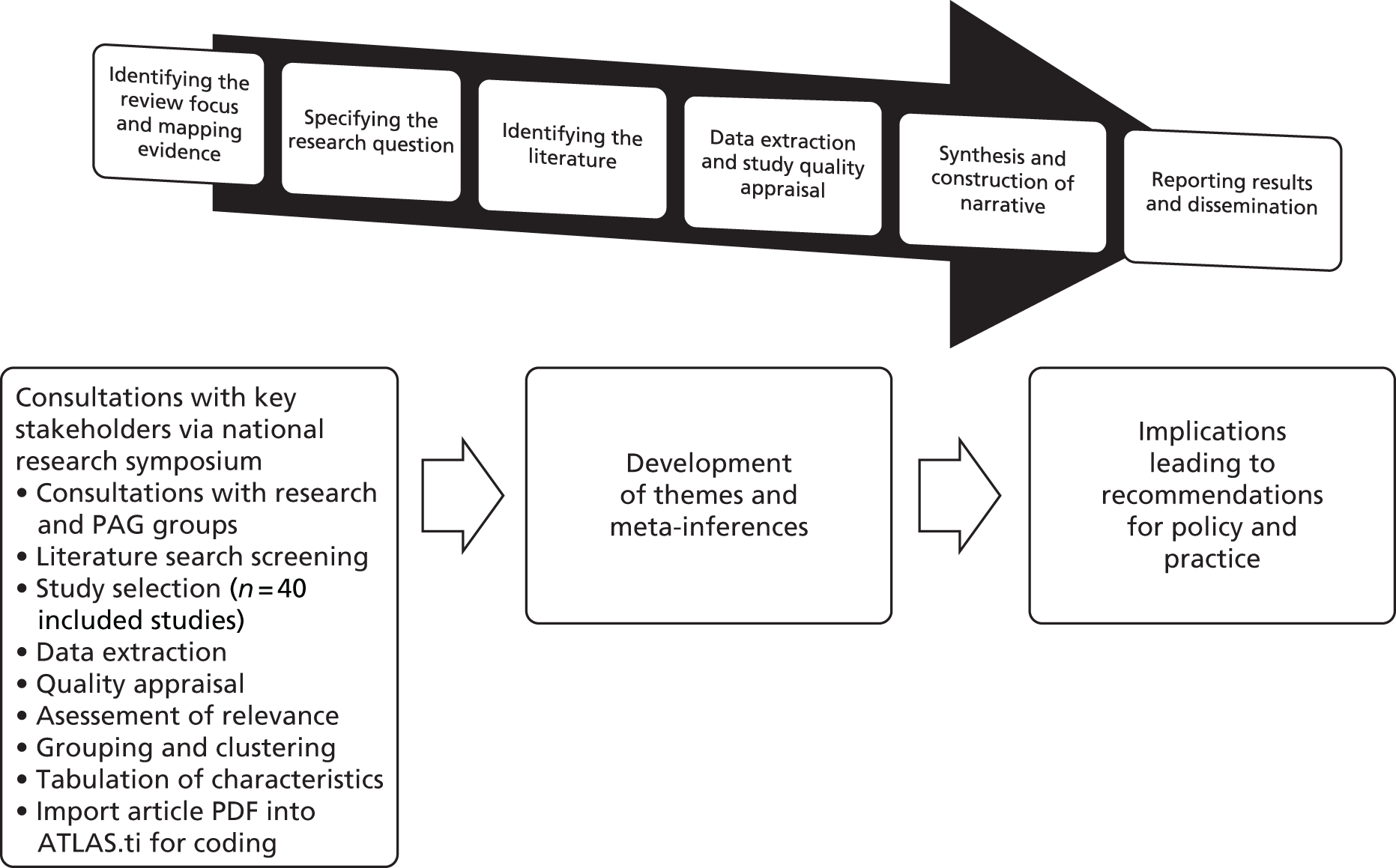

The search and selection strategies drew on established systematic review methods88 and incorporated recent guidelines for the selection and appraisal of grey literature. 89 Two search and selection phases were conducted. The first consisted of searching electronic databases and websites of relevant journals to identify empirical papers published in peer-reviewed journals. We considered empirical papers to be primary research publications that investigated working hypotheses or research questions and tested them by means of observations or experimentation, qualitative investigation or mixed-methods designs. The second phase targeted grey literature and included searches of selected databases, internet-based searches (see Report Supplementary Material 1), reviews of reference lists, and e-mail or telephone contacts with researchers and other stakeholders that had expertise or interest in the target topic. The processes we used to conduct the search and selection process are summarised in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Summary of the search and selection methodology. Reproduced from Higginbottom et al. 24 © Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2019. Re-use permitted under CC BY. Published by BMJ. This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Our focus was on access and interventions designed to promote or enhance maternity care for immigrant women, as articulated in the original review question. We chose the definition of intervention to be an integration of program facets or strategies designed to create behaviour changes or enhance health status amongst individuals or an entire population’. 90 In fact, in practice we identified few interventions that have been rigorously and scientifically appraised (that is not to suggest that these interventions do not exist, merely that they have not been evaluated).

We adopted the population, intervention, control and outcome of interest (PICO) approach to implement the search strategy as follows:

-

population – immigrant women

-

interest – maternity care

-

control – non-immigrant women (implicit comparator emerging in the results)

-

outcome of interest – experience of care.

Therefore, our search strategy development was based on:

-

search concept 1 – pregnancy, childbirth (implicitly females requiring maternity care), explicit terms covering women/females requiring all types of maternity care (antenatal, perinatal, postnatal, etc.)

-

search concept 2 – immigrant populations (which would not fully distinguish between ‘new’ and ‘second-generation’ immigrants, this would be done at the selection stage)

-

search concept 3 – terms used to identify access to, use of, deficiencies in, etc., service provision (to help identify groups with poorer health outcomes or vulnerabilities)

-

our final answer set of citations included concepts 1, 2 and 3.

Data search strategy and implementation

Development of literature database search strategies and search implementation

Team member Jeanette Eldridge is an experienced information scientist with whom we developed the scoping search strategy (see Box 2). An exemplar of final search strategies (see Appendix 1) incorporated revisions, as per the knowledge base of the academic team members (GH, MM, KB and CE) and included internet and literature database searches. Jeanette Eldridge constructed the detailed search strategies for each literature database and conducted the searches after review of these strategies by the entire team, including the PAG. The search focus was on studies that described access and compared interventions to improve maternity care experiences for immigrant women in the UK (Box 3).

Population: immigrant women from any country other than England, Scotland, Northern Ireland or Wales.

Phenomena of interest: maternity care.

Context setting: UK.

Study designs: qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods studies.

Language: English.

Date limitations: January 1990 to January 2018.

Exclusion criteriaContext studies: located in any country other than England, Scotland, Northern Ireland or Wales.

Participants: BME women born in the UK.

Study design: non-empirical research, opinion pieces or editorial.

Search implementation included independent double-screening and team review of ambiguous studies. Our search strategy was adapted for each of these databases so that relevant controlled vocabulary, searching techniques and keywords were used consistently. The reference lists of the included studies were reviewed for relevant citations. Additional hand-searches were undertaken of major relevant journals (e.g. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health, Journal of Health Services Research & Policy and Canadian Journal of Public Health) and in reviews published by topical research groups (e.g. Reproductive Outcomes and Migration, an international research collaboration). 41

We used a screening tool (see Table 1) to select studies congruent with our review questions (Box 4) and to ensure robustness of the NS. 86 A Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)91 flow chart illustrates the selection process that we implemented (Figure 4).

What interventions exist that are focused specifically on improving maternity care for immigrant women in the UK?

-

How do these interventions address inequality?

-

How do accessibility and acceptability manifest as important dimensions of access to maternity care services, as perceived and experienced by immigrant women?

FIGURE 4.

The PRISMA flow chart of the final selection process. Reproduced from Higginbottom et al. 24 © Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2019. Re-use permitted under CC BY. Published by BMJ. This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

We included studies that focused on immigrant women; therefore, we included studies on immigrant women in which the population studied fulfilled the characteristics previously mentioned (see Search strategy and study selection).

A relevancy appraisal of each record was undertaken by first reviewing the title and abstract (GH, CE, MM, JE, KB and BH). Records were shared with team members via the EndNote, Version 7, collaborative function (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA). We retrieved potentially relevant articles for further assessment against our inclusion criteria, with the entire team making the final decision. We used a PRISMA flow chart (see Figure 4) to document the steps used in the search and selection process. 91

Management of non-empirical reports and grey literature

Grey literature is a field in library and information science that deals with the production, distribution and access to multiple document types produced at all levels of government, academia, industry and other organisations. It can be in electronic and print formats, and it may not necessarily be controlled by commercial publishing (i.e. in cases in which publishing is not the primary activity of the producing body). 89,92 It is not published commercially or indexed by major databases, although can have an impact on research, teaching and learning. 89,92 Some examples include theses and dissertations, conference proceedings and abstracts, newsletters, research reports (completed and uncompleted), technical specifications, standards and annual reports.

We utilised the approach of McGrath et al. 93 to systematically review high-quality international grey literature (and non-empirical reports identified in the database searches). We also followed the principles expounded by the US National Library of Medicine. 89 The process consisted of (1) identifying the grey literature (including constructing a list of websites); (2) selecting documents via screening, preliminary selection, final selection and data extraction; (3) organising and tabulating data into categories; and (4) undertaking a narrative review of data. Our previous database searches had identified some grey literature, but further identification of grey literature required searches of the following databases: Web of Knowledge Science Citation Index, Web of Knowledge ISI Proceedings, ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Database and the Cochrane Methodology Register. We also searched using Google and Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA). In addition, we hand-searched the reference lists of all synthesised materials and approached relevant organisations, especially through the contacts of the PAG. We also corresponded with information specialists and other experts within this field. The PAG assisted with the identification and final selection of grey literature and the interpretation of findings.

Outcomes and management of identified records

The retrieved data sets (Box 5) were downloaded into an EndNote library. Duplicate records were identified and retained in a separate group within the EndNote library. The downloaded records normally included the title and abstract. Keyword terms and other bibliographic information were also included when available.

-

Ovid MEDLINE: 1948 to the present.

-

MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations: to daily update.

-

Ovid EMBASE: 1980 to Week 11 2017.

-

Ovid PsycINFO: 1972 to March Week 3 2017.

-

CINAHL Plus with full text/EBSCOhost: January 1990 to January 2017.

-

MIDIRS on Ovid: 1971 to April 2017.

-

Thomson Reuters Web of Science:a 1900 to 2017.

-

ASSIA on ProQuest: 1987 to the present.

-

HMIC on Ovid: 1979 to January 2017.

-

POPLINE (via www.popline.org/): 1970 to the present.

ASSIA, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts; CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature; HMIC, Health Management Information Consortium; MIDIRS, Midwives Information & Resource Service.

Thomson Reuters Web of Science includes the following: Science Citation Index Expanded:1900 to 2017; Social Sciences Citation Index: 1956 to 2017; Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science: 1990 to 2017; Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Social Science and Humanities: 1990 to 2017; Book Citation Index – Science: 2008 to 2017; Book Citation Index – Social Science and Humanities: 2008 to 2017; and Emerging Sources Citation Index: 2015 to 2017.

When individual full-text documents were required, they were obtained through a number of routes, including the EndNote ‘Find Full Text’ option, subscriptions to electronic journals and access to other physical or electronic resources available through the University of Nottingham, interlibrary loans of articles or books and direct contact with the authors or the originating institutions.

When records could not be definitively selected or excluded, they were assigned to a separate group and further reviewed by two members of the team. The full library was then annotated to show the final decision.

The bibliographic databases that were searched are listed in Box 5.

Data extraction

We conducted the following foundational activities in order to extract data:

-

Textual description: a systematic textual narrative was written for each study. We used headings adapted from Popay et al. :86 setting, participants, aim, sampling and recruitment, method, analysis and results (see Appendix 4).

-

Tabulation and summarisation of all studies to be included: these tables described the attributes of the studies and the results. Information was extracted from the textual description using the same headings as above and additional headings as necessary. Papers in the portable document format (PDF) were imported into ATLAS.ti qualitative data analysis software (Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany) using the ‘Attributes’ option to allow the tabulation of relevant data.

Element 2: developing a preliminary synthesis

Our analysis process began with the selection of included papers by the research team, with the final selected papers being reviewed by one researcher and the data of each paper extracted into a one-page textual summary (see Appendix 5). A second team member confirmed the study selection; furthermore, the entire team confirmed the selection at the reflective team meeting. We shared advance information with team members prior to meetings so that views could be elicited in an efficient fashion, with careful recording of views and decision-making processes in meeting minutes. Meetings included incisive debate regarding contentious papers. Team members Myfanwy Morgan, Catrin Evans and Gina Higginbottom are experienced systematic reviewers (evidenced in previous publications94), so we harnessed this expertise for the benefit of this review; pertinent practice perspectives by CM and Janette Eldridge provided technical systematic knowledge.

We engaged in careful reading and re-reading of papers to ensure familiarisation with the content. Once the final selection for inclusion was established, we undertook a tabulation of key variables of all included studies and an exemplar can be found in Appendix 5. Tabulation and extraction of key findings was facilitated by the production of the one-page textual summaries, as this format facilitated comparison and contrast of study findings in a systematic and coherent fashion.

The project principal investigator (GH) also undertook a detailed analysis of the narrative findings of each study using ATLAS.ti computer-assisted qualitative data analysis software, engaging in a line-by-line analysis of the narrative findings of each included study. The analysis created over 250 codes. The two perspectives were then merged to create a cohesive interpretation. The aforementioned processes are human resource intensive, iterative and demanded reconsideration several times. However, differences in interpretation between the researchers may still exist, although these differences are likely to be marginal and will not have an impact on the critical conclusions and implications for practice. Inevitably, the perspectives and foci of the research studies included limit our conclusions.

In element 2 (Table 2), we also applied the critical appraisals tools, made an appraisal and included this in the one-page textual summary we created (see Appendix 5).

| Element | Task | Explanation |

|---|---|---|

| Element 2: developing a preliminary synthesis | Textual description of the studies | A descriptive narrative was produced with the headings of setting, participants, aim, sampling and recruitment, method, analysis and results |

| The data extracted for the textual description allowed papers to be grouped and thus enabled patterns between and within studies to be identified. This grouping was informed by the research questions. Data were grouped by a particular feature; for example, the method, the country of origin of the sample studied, the maternity care setting, or the main findings | ||

| Translating data: thematic analysis | Main or recurrent themes in the findings were identified | |

| Element 3: exploring relationships within and between studies | Moderator variables and subgroup analysis | Study characteristics that vary between studies or sample (subgroup) characteristics that might help explain differences in findings were identified |

| Ideas webbing and concept mapping | ‘Ideas webbing’ conceptualises and explores connections between the findings reported in the review studies and often takes the form of a spider diagram. ‘Concept mapping’ links multiple pieces of information from individual studies, using diagrams and flow charts to construct a model with relevant key themes | |

| Qualitative case descriptions | Outliers or exemplars of why particular results were found in the outcome studies were described | |

| Element 4: assessing the robustness of the synthesis | Critical reflection | A summary discussion was developed that covered the following: (1) the synthesis methodology used (focusing on the limitations and their possible effects on the results); (2) evidence used (quality, reliability, validity and generalisability); (3) assumptions made; (4) discrepancies and uncertainties identified and how discrepancies were handled; (5) areas in which the evidence was weak or non-existent; (6) possible areas for future research; and (7) a discussion of the evidence, considering the ‘thick’ and ‘thin’ evidence and commenting on similarities and/or differences between the various sources of evidence |

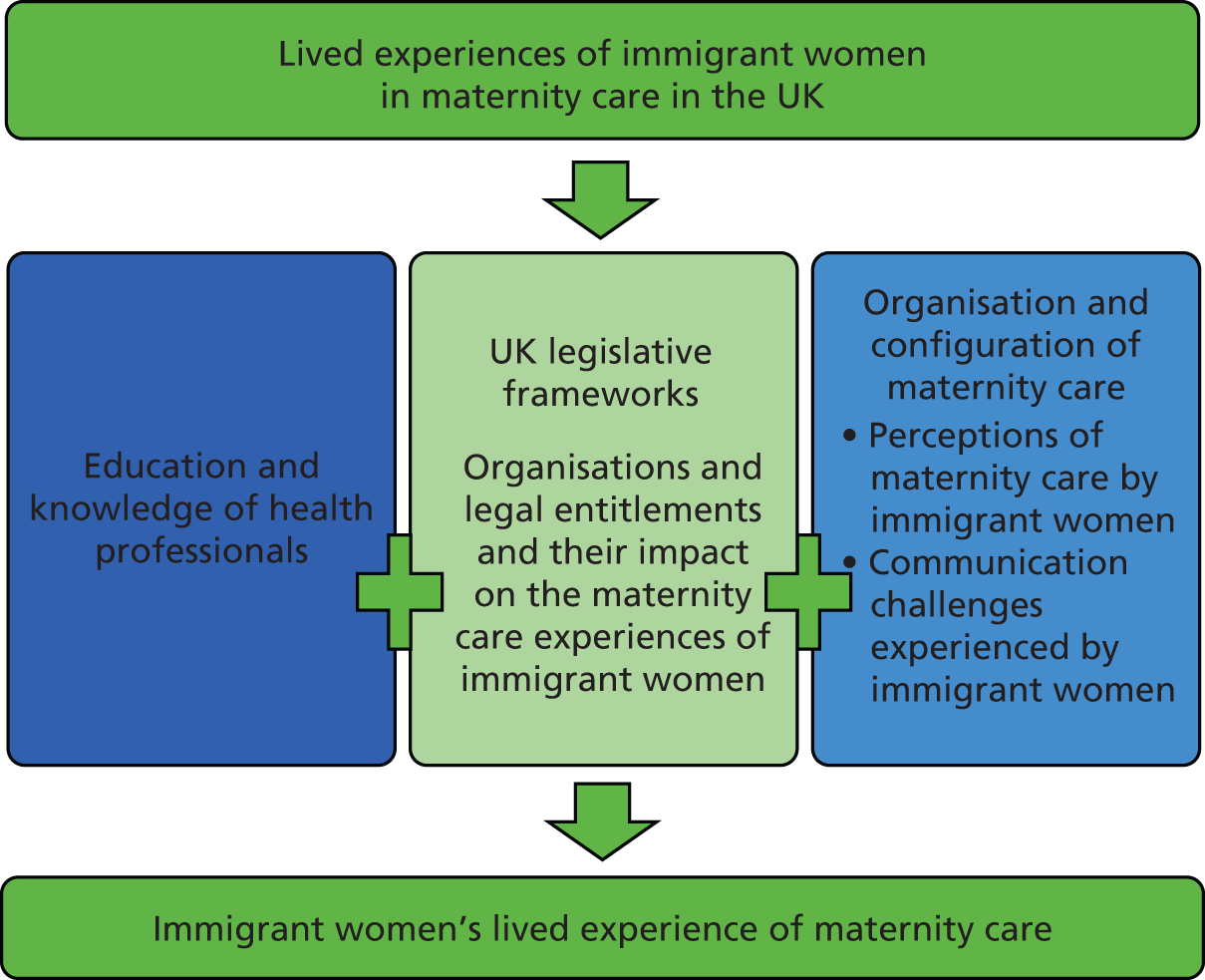

We proceeded to group and cluster the studies in respect of the data extracted for the textual description. This enabled identification of patterns between and within studies. During this grouping process, the research questions remained salient in our cognition. A particular feature grouped data, for example the method, the country of origin of the sample studied, the maternity care setting, or the main findings. We identified major themes in the narrative findings (see tables in Report Supplementary Material 1).

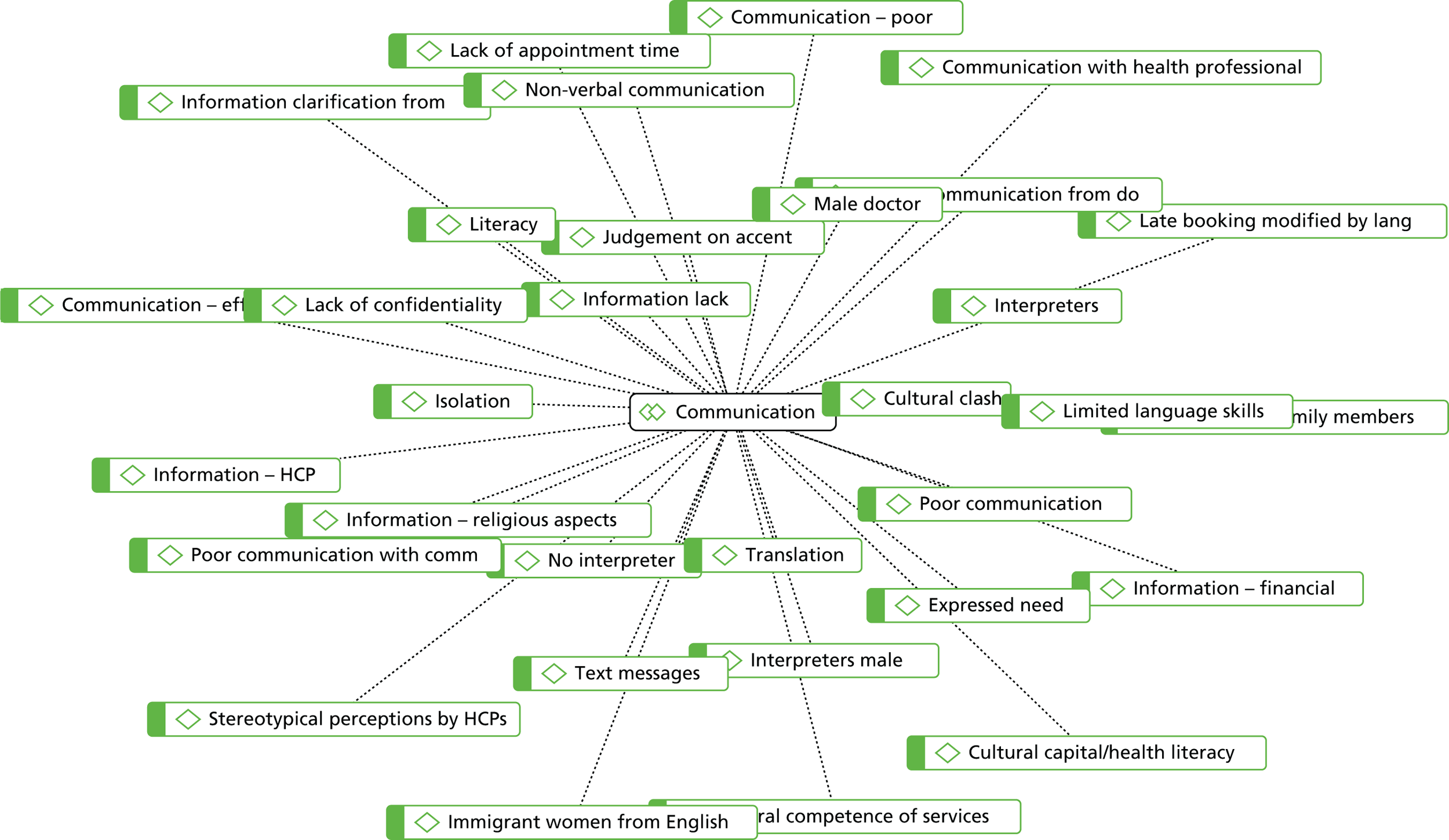

Following construction of the preliminary themes, we produced code/narrative theme tables to demonstrate how the basic meaning units related to the theme, utilising the codes produced in ATLAS.ti and aligning these to the manually extracted key findings. We defined codes individually in ATLAS.ti, enabling the essential meaning of key phenomena to be captured, facilitating cross-comparison and variations in phenomena to be established and observed. Codes are defined by Miles and Huberman95 as:

. . . tags or labels for assigning meaning to the descriptive of inferential information compiled during a study. Codes usually are attached to ‘chunks’ of varying size words, phrases, sentences or who paragraphs, connected or unconnected to a specific setting. They can take the form of a straightforward category label of a more complex one (e.g. a metaphor).

Miles and Huberman, p. 5695

‘Code families’ can be produced in ATLAS.ti and imported into the graphic ‘network builder’ in ATLAS.ti, resulting in topical or hierarchical graphic outputs. We assigned the codes to code families as illustrated in Figure 5, which shows all the codes associated with code family entitled ‘communication’. This code family is a constituent of theme 3 and serves as an exemplar of the extensive analytical work undertaken. ATLAS.ti facilitated a more sophisticated and nuanced analysis than via manual extraction. These data contributed to the production of a descriptive narrative in respect of each theme. Moreover, we created a tabular matrix illustrating how the themes that occurred are distributed over the individual studies (see Appendix 6). This distribution, to some extent, illustrates the weight of evidence in each theme.

FIGURE 5.

Graphic representation of communication theme using ATLAS.ti. HCP, health-care professional. Reproduced from Higginbottom et al. 24 © Author(s) (or their employer(s)) 2019. Re-use permitted under CC BY. Published by BMJ. This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

During the analytical processes we interrogated the data identifying using the following concept suggested by Roper and Shapira:96

-

setting – the environment or context

-

activities – patterns of behaviour that occur often

-

events – rare and infrequent activities

-

relationships and social structures – kinship, friendship, bonds, enemies, hierarchical

-

general perspectives – the group’s shared understandings

-

specific perspectives on the research topic(s) – how people understand the phenomena

-

strategies – ways of achieving goals

-

process – flow of events how things change over time

-

meaning – significance and understanding of behaviour

-

repeated phases – depictions of thought processes.

We presented these analytical processes and products at our reflective team meetings to ensure the rigour and robustness of our analytical steps. Through reflection and debate, team members were able to challenge initial interpretations, identify outliers and confirm the coherence of emerging interpretations. Team members independently produced interpretations of the possible meanings of these preliminary themes in order to achieve abstraction, prior to formulation of the higher-level final themes.

Our thematic findings are evolved via a systematic, comprehensive and thorough collaborative team process of comparing and contrasting the emergent themes to establish the ways in which these themes revealed and provided insights into the concepts embedded within the review questions. This iterative process, similar to qualitative research, involved deconstructing the narrative findings into meaning units and social processes as they manifested in the maternity care experiences of immigrant women. As mentioned, individual team members engaged in independent theming of tabular and coded data. We subsequently merged these individual perspectives to form the final harmonised themes, representing a ‘meta-inference’ in respect of the narrative findings of the included studies. Meta-inference is a term used in mixed-methods research to describe the merging of findings from the positivistic and the interpretative paradigms, as is the case in this NS. Tashakorri and Teddlie97 describe meta-inference as ‘an overall conclusion, explanation of understanding developed from the integration of inferences obtained from the qualitative and quantitative strands’.

We have constructed the themes in an indicative fashion (i.e. containing implicit indications) to provide tangible guidance for policy and practice that might be developed into transformational policy- and practice-relevant strategies that will benefit immigrant women and the NHS.

Element 3: exploring relationships within and between studies

Patterns emerging from cross-literary comparisons were subjected to further rigorous evaluation to identify factors that may explain differences, including variance in women’s experiences, in the effects of maternity interventions and in the implementation of maternity services (entire team involvement). This evaluation contributed to our understanding of barriers and enablers that shape maternity services for immigrant women. We also evaluated not only the relationships between the study characteristics and the reported findings, but also the ways in which these relationships may correspond with those reported in other types of literature, including non-empirical and grey literature (which was evaluated separately). Careful attention was paid to the heterogeneity of research methods, methodologies and population characteristics encompassed in the literature through the application of narrative methods. 98 Such methods are particularly suited to synthesising such findings. 86 Narrative methods99 help us to understand and acknowledge the broader influences of theoretical and contextual variables, such as race, gender, socioeconomic status and geographical location. These methods also enable researchers to understand the shaping of differences between reported outcomes for various study designs, in this case those related to childbearing populations, and the development and implementation of maternity services and health interventions across diverse settings.

Data synthesis and establishing relationships

Grouping and clustering

The data extracted in the tabulation allowed papers to be grouped and thus enabled patterns between and within studies to be identified. Groupings were organised by a particular feature (e.g. location, method, ethnic groups, form of analysis, or main findings) (GH, CE, BH and the PAG).

Thematic analysis

Systematically recurrent or salient themes or concepts across studies were identified. ATLAS.ti was used to manage the data and relevant themes were identified on an inductive basis. We generated over 250 codes in ATLAS.ti and these were mapped against the tabular thematic analysis (see Figure 5).

Ideas webbing and concept mapping

‘Ideas webbing’ conceptualises and explores connections among the findings reported in the review studies and it often takes the form of a spider diagram. ‘Concept mapping’ links multiple pieces of information from individual studies using diagrams and flow charts to construct a model with relevant key themes (all team members were involved).

Critical reflection

Popay et al. 86 recommended that a summary discussion of the synthesis should be provided, which includes the following: (1) methodology of the synthesis, focusing on the limitations and their possible impacts on the results; (2) evidence used in terms of quality, reliability, validity and generalisability (for quantitative papers), and possible sources of bias (for qualitative papers); we applied the principles of Lincoln and Guba100 (confirmability, transferability, credibility and dependability); (3) assumptions made; (4) discrepancies and uncertainties identified, and how discrepancies were handled; (5) areas in which evidence is weak or non-existent as possible areas for future research; and (6) whether the evidence is ‘thick’ or ‘thin’ and the similarities and differences in the evidence (entire team).

Methodological quality of included studies and quality appraisal

Key to ensuring the robustness of the synthesis is the methodological quality of key literature, the quality and quantity of the evidence base and the analytical methods used to develop the NS. We critically appraised research studies and weighted each accordingly (GH, MM, CE, and BH). Studies that lacked technical quality or were of questionable methodological integrity101 were critiqued and/or noted for key flaws in the synthesis. Although we identified a number of studies rated as weak, we did not reject any studies on the basis of quality. Despite debates existing regarding the availability of well-established methods for evaluating the reliability and trustworthiness of qualitative and mixed-methods studies, the methodological analysis and synthesis were conducted in a relational and systematic manner.

Appraisal of included studies was assessed using tools from the Center for Evidence-Based Management (CEBMa). 102 We used Good Reporting of A Mixed Methods Study (GRAMMS) for the mixed-methods studies. 103

We used high, medium and low as appraisal categories. 94 This approach is congruent with recent publications from the Cochrane Qualitative Research Group’s Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative Research (CERQual) publications, as they use this type of evaluation104 and it was previously used by Higginbottom et al. in published studies. 87 Studies are classified in three domains, high, medium and low, to enable a ‘macro’ evaluation:

-

High was assigned to studies that used a rigorous and robust scientific approach that largely met all CEBMa benchmarks, perhaps equal to or exceeding 7 out of 10 for qualitative studies, 9 out of 12 for cross-sectional surveys, or 5 out of 6 for mixed-methods research.

-

Medium was assigned if a study had some flaws but these did not seriously undermine the quality and scientific value of the research conducted, perhaps scoring 5 or 6 out of 10 for qualitative studies, 6–8 out of 12 for cross-sectional surveys, or 4 out of 6 for mixed-methods research.

-

Low was assigned to studies that had serious or fatal flaws and poor scientific value, and scored below the numbers of benchmarks listed above for medium-level appraisals in each type of research.

The past decade has witnessed a growth in the development of new approaches to systematic reviews, especially in the domain of qualitative evidence synthesis. Concurrently, innovative approaches to assessing quality have evolved. Popay et al. 86 suggest that we do evaluate the ‘richness’ of studies. Furthermore, this research team have utilised this approach in previous funded studies and publications. 86 Popay et al. 86 defined richness as ‘the extent to which study findings provide in-depth explanatory insights that are transferable to other settings’ (Table 3). We used established criterion in previous studies87 and appraised all the studies in this review using this evaluative tool (Table 4).

| Assessment | Conceptual definition |

|---|---|

| Thick papers |

Studies that offer greater insights into the outcomes of interest Provide a clear account of processes, including sample, its selection, and limitations and biases noted Clear description of analytical processes Present a developed and plausible explanation |

| Thin papers |

Offer only limited insights Lack a clear account of processes by which the findings are produced Present an underdeveloped and weak interpretation of findings produced Present a weak and underdeveloped interpretation of the analysis based on the data presented |

| Manual reference number | Quality as per the CEBMa tool | Relevance | Thick/thin |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Low | High | Thin |

| 2 | Low | High | Thin |