Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 16/53/12. The contractual start date was in November 2017. The final report began editorial review in May 2019 and was accepted for publication in September 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Mark Pearson is a member of Health Services and Delivery Research Funding Committee (2019–present). Geoff Wong is Joint Deputy Chairperson of the National Institute for Health Research Health Technology Assessment Prioritisation Committee: Integrated Community Health and Social Care (A) (2015–present).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Carrieri et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Parts of this report have been reproduced from Carrieri et al. 1 © The Author(s). 2020 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

To restore balance and achieve physician well-being, we must first acknowledge that no one person or institution is to blame for the physician burnout epidemic. It is the unintended net result of multiple, highly disruptive changes in society at large; the medical profession; and the healthcare system.

Rothernberger2

The growing incidence of mental ill-health in health professionals, including doctors, across specialties and throughout careers3 is a major issue in many countries. 4–9 We use ‘mental ill-health’ as a broad term to encompass a variety of conditions, including psychological distress, stress, burnout, depression, addiction and suicide (see also Chapter 3, Terminology). A study conducted by American Medical Association and Mayo Clinic researchers in 2014 reported that 54% of physicians in the USA are experiencing professional burnout. 10 Suicide rates among doctors are also higher than in the general population. A review in the Journal of the American Medical Association of four decades of studies on physician suicide estimated that the chances of dying by suicide are 70% higher for male physicians and 250–400% higher for female physicians. 11 In the UK, the mental health of the NHS workforce, including that of doctors, is of great concern. 12–16 In 2015, the Head of Thought Leadership at The King’s Fund declared that stress levels among NHS staff are ‘astonishingly high’ and need to be treated as ‘public health problem’. 17 In the 2018 NHS staff survey, 39.8% of respondents indicated that they had been unwell in the previous 12 months because of work-related stress. This appears to be the worst result in 5 years. 18,19 In the UK, the key outcomes associated with mental ill-health in doctors include presenteeism (doctors working despite being unwell),20–22 absenteeism (doctors taking sickness leave frequently, which could result in gaps in the service)23 and workforce retention issues (doctors leaving the NHS either temporarily or permanently). 24–27 There is growing interest among different organisations and journals in understanding and addressing the issue of mental ill-health in doctors. This spans from the British Medical Journal collection on doctors’ well-being28 to the Health Education England’s NHS Staff and Learner’s Mental Wellbeing Commission. 29 Such initiatives mirror calls for internationally co-ordinated research efforts to develop evidence-based strategies to tackle the high incidence of mental ill-health among health-care professionals at a global level. 30,31

Current interventions and initiatives to tackle doctors’ mental ill-health seem to have limited effect. 18 One of the main reasons we have undertaken this research project is to better understand what is more likely to work and why (i.e. to develop evidence-based recommendations on how ‘the physician mental ill-health epidemic’2 can be addressed). The well-being of the health workforce, including doctors, not only is an important value in itself, but can significantly impact workforce planning, cost, health-care quality and patient outcomes. 32–34 Although mental ill-health is prevalent among all groups of health-care professionals working in the NHS, our research focuses on doctors across specialties and career stages. This focus reflects the current recruitment and workforce retention issues (e.g. doctors in training, general practice and emergency medicine), the significant potential for sick doctors to inadvertently cause harm to patients and the financial implications of doctors’ mental ill-health. 5,15

Why are doctors at risk of mental ill-health?

A considerable number of individual, occupational and broader sociocultural causative risk factors lead to mental ill-health. 2,24,35 Peer-reviewed and grey literature suggests that these factors include the emotionally demanding nature of the profession;23,36 the increasing workload resulting from attempting to provide more, and higher-quality, care on shrinking budgets;37 systems of clinical governance that lead to loss of autonomy and erosion of professional values;38 rigid organisational structures and inflexible working hours;39 and highly bureaucratic professional regulatory systems (e.g. appraisals, revalidation, Care Quality Commission visits). 40 Doctors are also at higher risk than the general population of developing addiction and substance misuse because of their knowledge of and access to drugs and potential for them to self-medicate. 12 Moreover, all of these factors may be aggravated by doctors’ tendency to avoid seeking help and support when unwell or under pressure41,42 and by a perceived stigma among doctors about mental illness. 7,43

The factors associated with mental ill-health and decisions to leave the medical profession include heavy workload, long working hours, high levels of regulation and scrutiny, perceived reduced autonomy, and fear of complaints and negligence claims. 24,25 Doctors’ presenteeism may be underpinned by collective norms to be present, fear of career repercussions, fear of letting down colleagues and patients, difficulties arranging cover, difficulties prioritising their own health needs and recognising their own vulnerability to illness, and work-related stress. 16,44

Current interventions and gaps

There is a large body of literature on interventions that offer support, advice and/or treatment to doctors experiencing mental health difficulties, and that address the associated impacts, such as presenteeism, absenteeism and workforce retention. 2,26 This literature tends to be restricted to specific disciplines and to be undertaken in silos. It also tends to focus on workplace interventions aimed at increasing doctors’ ‘productivity’ and ‘resilience’, placing responsibility for good mental health with doctors themselves. We found evidence of this from both systematic reviews and commentaries. 15,45–47 Our awareness of this tendency to focus on the individual, which also mirrors broader sociopolitical strategies and discourses,48,49 compounded by the realisation of its limitations, was one of the reasons that led us to undertake this study [see also a graphic report of the initial Care Under Pressure (CUP) symposium in 201550]. An important limit of this tendency is the lack of consideration of the organisational and structural contexts that may have a detrimental effect on doctors’ well-being. There are, however, commentators who have criticised this narrow view of resilience, for example arguing that interventions should also focus on organisational support and systemic factors contributing to mental ill-health, rather than on individual doctors,8,16,51 and advocating for a shift from ‘individual’ to ‘organisational resilience’. 46

The culture of the medical profession can also play an important role. As the ‘culture of medicine’ starts early in undergraduate medical programmes, doctors in training are affected both directly (e.g. by becoming ill themselves) and indirectly (e.g. through their colleagues being ill) by mental ill-health. Therefore, systemic strategies need also to start early in a doctor’s career, with medical training emphasising pathways to help and increasing awareness – and destigmatisation – of mental illness in doctors. 52 Interventions and initiatives that offer support, advice and/or treatment to doctors experiencing mental ill-health have not been synthesised in a way that takes into account the heterogeneity of these interventions and the many dimensions (e.g. individual, organisational, cultural, social) of the problem. Currently, it is not clear which components within these interventions matter more (or less) than others, for whom they matter and in what contexts. 53 For example, a given intervention might work well for some doctors and not others (which might be influenced by personal factors such as age, gender, seniority), and in some contexts and not others (as it might be influenced by organisational factors, such as the degree of organisational change, or societal factors, such as recent media portrayal). Therefore, there is a need for research approaches that are sensitive to the complexities of the problem of mental ill-health in doctors.

Methods

Project aim

This research aims to improve understanding of how, why and in what contexts mental health services and support interventions can be designed to minimise the incidence of doctors’ mental ill-health.

Project objectives

-

To conduct a realist review of interventions to tackle doctors’ mental ill-health and its impact on the clinical workforce and patient care, drawing on diverse literature sources and engaging iteratively with diverse stakeholder perspectives to produce actionable theory.

-

To produce recommendations that support the tailoring, implementation, monitoring and evaluation of contextually sensitive strategies to tackle mental ill-health and its impacts.

Review questions

-

What are the processes by which mental ill-health in doctors develop and lead to its negative impacts, and where are the gaps that interventions do not address currently?

-

What are the mechanisms, acting at individual, group, profession and organisational levels, by which interventions to reduce doctors’ mental ill-health at the different stages are believed to result in their intended outcomes?

-

What are the important contexts which determine whether or not the different mechanisms produce the intended outcomes?

-

What changes are needed to existing and/or future interventions to make them more effective?

Chapter 2 Review methods

Research plan

We followed a similar methodology to that used in a previous National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research programme project54 that was conducted by many of the same research team members. 54,55 Any evidence synthesis that seeks to make sense of interventions aiming to improve doctors’ mental ill-health must take into account the contexts in which these interventions are situated. This generates an in-depth understanding of which components within these interventions matter more (or less) than others, for whom they matter and in what ways. A realist review can synthesise relevant data found within qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods research. By following an interpretive, theory-driven approach to analysing data from such diverse literature sources, realist reviews move beyond description, to provide findings that coherently and transferably explain how and why contexts can influence outcomes. This is particularly relevant to complex programmes characterised by significant levels of heterogeneity. The plan of investigation followed a detailed protocol based on Pawson et al. ’s56 five iterative stages for realist reviews: (1) locating existing theories, (2) searching for evidence, (3) selecting articles, (4) extracting and organising data and (5) synthesising the evidence and drawing conclusions. The reporting is consistent with the Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) quality and publication standards for realist reviews. 57 The project ran for 18 months from November 2017 to April 2019. Regular project team meetings and stakeholder meetings throughout the lifecycle of the project ensured that multiple perspectives and interpretations were brought to bear on the research.

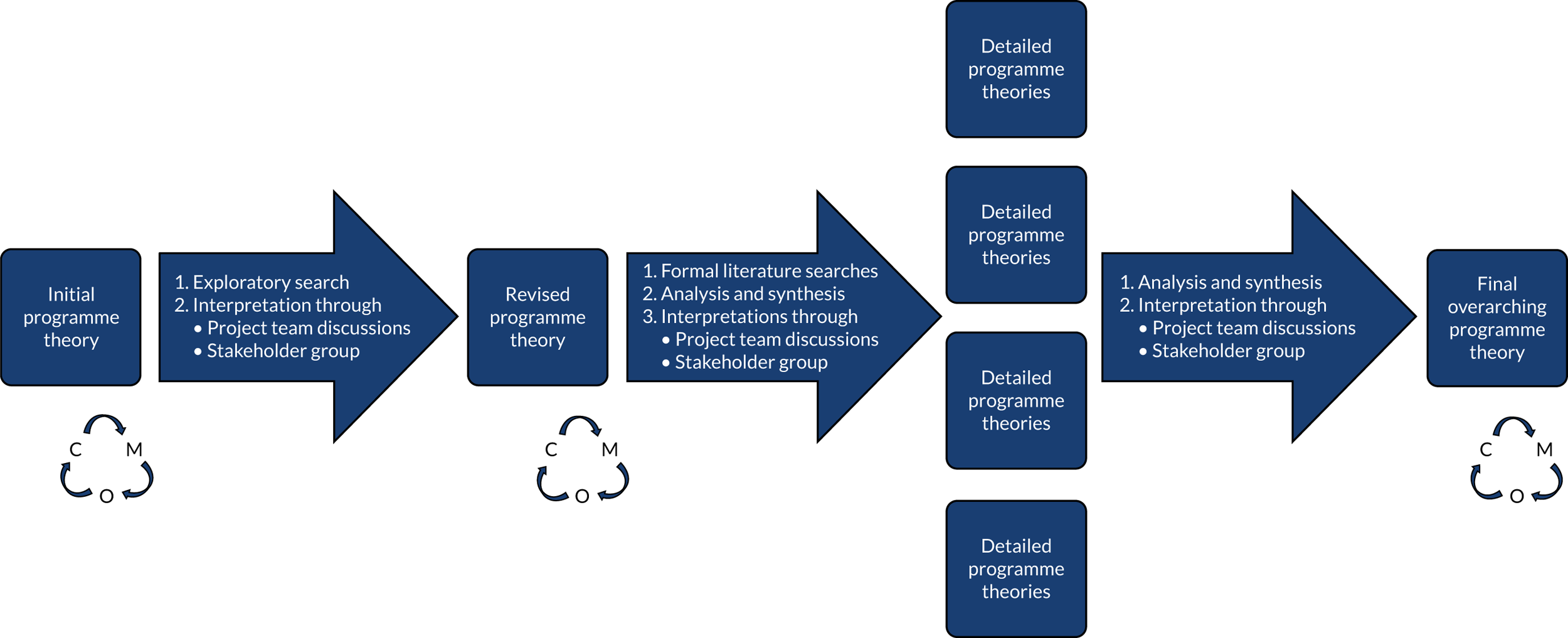

The protocol has been published in BMJ Open58 and the review has been registered with PROSPERO (CRD42017069870). The review design and methodology is explained in more detail in the sections below and illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of the project. Note that dashed arrows indicate iteration where necessary. Reproduced from Wong et al. 54 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Stakeholder group

A stakeholder group was recruited for the CUP review to provide content expertise, feedback on and refinement of our programme theory and to coproduce non-academic outputs. The stakeholder group did not provide us with data, but feedback and advice based on their expertise and experience. A total of 22 people were involved in the stakeholder group during the review, including patient representatives, clinicians, doctors in training, medical educators and academics. Consultations with stakeholder group members took place as part of 2-hour meetings at regular intervals throughout the project and e-mail exchange. Additional ‘satellite’ face-to-face meetings were also arranged with some stakeholders who could not attend the main meetings, as well as Skype™ (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and telephone conversations. Table 1 provides a list of the face-to-face meetings, including the number of participants and key topics discussed.

| Date | Stakeholder group members | Key topics discussed | Examples of stakeholders’ contribution |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 January 2018 | Four patient representatives, four clinicians and three academics | Discussed inconsistencies in current support for doctors in the NHS and the complexity of embedding intervention, particularly in the current overworked context of doctors |

|

| 21 February 2018 (satellite meeting) | Two medical educators, one of whom was a clinician, and one trainee | Discussed the support available to medical students across the UK and the impact of medical school on doctoring culture |

|

| 13 March 2018 | Three patient representatives, four clinicians and one academic | Discussed initial findings from the literature review and explored how these reflected stakeholders’ experiences |

|

| 21 May 2018 | Three clinicians and academics | Discussed initial findings for the literature review and explored how these reflected stakeholder’s experiences |

|

| 11 September 2018 | Three patient representatives, two academics, one representative from relevant medical organisation and two clinicians | Continued the discussion of emerging findings from the review. Assessed stakeholder’s views on who is responsible for doctors’ well-being at work, and if and how they would like to be involved with the production and dissemination of the project findings |

|

| 8 October 2018 (satellite meeting) | One medical educator and clinician, and one clinician and comics artist | Discussed initial findings from the literature review, explored how these reflected stakeholders’ experiences and discussed their willingness to be involved in co-production of dissemination output |

|

| 27 February 2019 | One clinician, one clinician and academic, one medical educator and three academics | Discussed the findings, how to convey them in an accessible way and the non-academic outputs |

|

| 12 March 2019 | Two medical educators and clinicians, one medical educator, one clinician, two patient representatives and one researcher | Discussed the findings, the dissemination strategy for the non-academic outputs and the stakeholders’ willingness to continue to collaborate in the production of these outputs |

|

Stakeholder group meetings took place at the University of Exeter or in London. To leave more time for discussion, we circulated any relevant preparatory material [e.g. summaries of previous meeting(s)], ahead of meetings when necessary. The meetings usually started with a brief slide presentation by our project team to introduce stakeholders to the topic under discussion and realist methods, and to provide a quick update on progress with the review. We presented high-level programme theory to the group in the form of statements and visual prompts to obtain their feedback. Discussions were designed to be more open ended in the early stages of the review, but focused on particular aspects of the programme theory as the project progressed. Later stakeholder groups focused on actionable findings and dissemination of the study. We used a framework called the evidence integration triangle (EIT)59 to ensure that discussions focused on the real-world impact of our study. The three components of the EIT (practical evidence-based interventions; pragmatic, longitudinal measures of progress; and participatory implementation processes) were used to structure discussions at the stakeholder group meetings and the workshop with policy-makers at the end of the project. Of the three components, the pragmatic longitudinal measures of progress proved by far the most challenging (see Chapter 5, Strengths and limitations of this review). Facilitation of the meetings ensured that everyone was able to contribute and voice their opinion, whether in agreement or disagreement. Notes from these meetings were used to set direction for the review and to refine programme theory, rather than as primary data for analysis, and the report does not include any verbatim data excerpts from these meetings.

Discussions with stakeholders helped ground the review in the practical reality experienced by participants and the challenges they faced in their respective roles. The sharing of these experiences re-enforced our decisions at times (e.g. to critically question the focus on ‘resilience’ in doctors) and prompted us to pay close attention to aspects that we had missed at others (e.g. the taboo around doctors expressing vulnerability). Stakeholders’ questions and contributions also prompted us to look more broadly in the literature for substantive explanatory theory, for example leading us to identify social cure theory and an emerging body of work on vulnerability that we drew on to shape our thinking and interpretation (for more information about the substantive theories used see Chapter 3, Summary of the 19 CMOcs in four main groupings). Our engagement with the stakeholder group and policy-makers also ensured that data were ‘translated’ and interpreted in ways relevant to the UK context.

In running the stakeholder group we took care to express realist review terms in everyday language so as to avoid methodological jargon, while still adequately conveying the nuances of the review findings. Stakeholder involvement also contributed significantly to the development of actionable findings in a form that would be usable and engaging. More details on actionable findings emerging from the review are presented in the Discussion.

The stakeholder group included strong patient and public involvement throughout the project. DC led the patient and public involvement component of the review following MP’s guidance. DC organised a briefing session with the patient representatives (n = 4 in total) before the first stakeholder meeting, to set the ground rules and to discuss the terms of their involvement and any key issues that needed to be addressed to facilitate meaningful participation. 60 In the stakeholder meetings, patients and members of the public provided significant input to programme theory development, often highlighting aspects and questioning assumptions that the rest of the group were taking for granted (e.g. the relational, financial, psychosocial complexity of the sickness absence pathway in the NHS, the importance of safe spaces in the workplace for doctors, and the complexities of making patients and the public aware that doctors are human and can become ill).

Steering Group

We set up a separate Steering Group to oversee the governance of the project and to provide high-level advice on dissemination strategies and conceptual aspects of the project. The group comprised one academic and clinician, one local NHS transformation manager and one patient representative. The range of expertise of the group included mental health services; nursing and complex intervention research methods; occupational stress in banking; stress involved in ‘fast-moving’ decision-making contexts, such as weather forecasting; and workforce management and resilience at both individual- and system-wide levels in the NHS.

Step 1: locating existing theories

In this first step of the review we identified theories that helped to understand (1) the processes leading to mental ill-health in doctors; and (2) how interventions aiming to support doctors experiencing mental ill-health are supposed to work (and for whom), when they work, when they do not, why they are not effective and why they are not being used. The rationale for this step is that interventions are ‘theories incarnate’ (i.e. interventions are underpinned by assumptions about why certain components are required). Such assumptions usually include a mix of scientific and experiential knowledge, including tacit assumptions that do not always become articulated (e.g. tacit knowledge). 61 Interventions are designed in a certain way based on assumptions about what is needed to achieve desired outcome(s). 62

To locate these assumptions, we iteratively drew on (1) discussions between DC and the clinical team of therapists working at the NHS Practitioner Health Programme; (2) informal discussions, advice and feedback from key content experts, representing multidisciplinary perspectives in our Stakeholder Group; and (3) an exploratory search of relevant literature.

Building the initial programme theory required iterative discussions (either at our regular face-to-face project team meetings or by e-mail) within the project team to make sense of and synthesise the different theories.

Step 2: searching for evidence

Main search

We developed a search strategy to identify examples of relevant programme theory in the published literature using MEDLINE via Ovid. Searching was designed, piloted and conducted by an information specialist (SB) in consultation with the review team. Search terms were derived from the titles, abstracts and indexing terms of relevant studies already known to the review team from background reading and consultation with stakeholders. These ‘empirically derived’ search terms were supplemented with relevant synonyms selected in consultation with the review team. Several versions of the search strategy were tested in MEDLINE via Ovid by checking that the relevant pre-identified studies were returned and by refining the search terms to optimise the sensitivity and specificity of the search (i.e. maximising the retrieval of known relevant studies while minimising the retrieval of irrelevant studies). In the process of testing and refining the search, we identified additional relevant studies which we also made sure were retrieved in subsequent iterations of the search.

The final search strategy consisted of the three components of the PICo (population, phenomenon of interest, context) question formulation tool:63

-

doctors and medical trainees (the population)

-

effects of mental ill-health in the workplace, such as presenteeism, absenteeism or burn out (the phenomenon of interest)

-

mental ill-health and workplace causes of mental ill-health, such as patient demand or work pressure (the context).

Each of the three components (population, phenomenon of interest, context) comprised relevant search terms combined using the OR Boolean operator. The three components were combined together using the AND Boolean operator. We found that this approach was the most effective way to retrieve our pre-identified set of papers and additional papers identified during the development of the search. Search terms included free-text terms (i.e. terms in the title and abstracts of bibliographic records) and indexing terms (e.g. medical subject headings in MEDLINE). We did not limit the search results by study type, date or language.

In December 2017 the final search strategy was translated and run in a selection of medical and psychology bibliographic databases, including MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process and Other Non-indexed Citations and PsycINFO (all via Ovid); and Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA) (via ProQuest). The MEDLINE search strategy is reproduced in Appendix 1. Search results were exported to EndNote (X8, Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and de-duplicated using the automated deduplication feature and manual checking.

As our review was particularly focused on the UK context, we supplemented the bibliographic database searches described above (which were conducted in databases that index international literature) with searches that aimed to retrieve UK-based studies. We did this by conducting author, forwards and backwards citation searching on UK-based studies and first authors of studies identified by the bibliographic database searches. UK-based source studies and authors were identified by searching the EndNote library of bibliographic database results for terms such as UK, England, Wales, Ireland and Scotland, in the title and abstract fields. Forwards and author citation searches were conducted on relevant studies thus identified using Scopus and Web of Science. (We first searched for the source study or author and associated citations in Web of Science and if Web of Science did not index the item of interest we repeated the process in Scopus.) Backwards citation searching was conducted manually by inspecting the reference lists of UK-based studies. We also hand-searched journals with a UK focus via the relevant journal websites, including the British Medical Journal and BMC Medicine.

Step 3: selecting articles

The review was limited to English-language literature. We applied the following inclusion criteria:

-

Mental ill-health and its impacts (e.g. presenteeism, absenteeism and workforce retention) – all studies that focused on one or more of these aspects. Note that generic occupational health services targeting whole populations of doctors, rather than doctors experiencing mental ill-health, were not included. Studies about improving clinical practice (and the indirect effect this may have on doctors’ well-being) were labelled as not included/minor relevance.

-

Study design – all study designs.

-

Types of settings – all health-care settings.

-

Types of participants – all studies that included medical doctors.

-

Types of intervention – interventions or resources that focus on improving mental ill-health and minimising its impact.

-

Outcome measures – all mental health outcomes and measures relevant to its impacts (e.g. absenteeism, presenteeism and workforce retention).

Using EndNote, DC screened the titles and abstracts of all articles resulting from the main and supplementary searches (forward citation tracking and author citation tracking). A random 10% sample of the three sets of results were also screened independently for consistency of application of the inclusion criteria by CP (the second reviewer). Small inconsistencies were identified that were resolved through discussion. DC then screened the full texts of the papers resulting from the first round of screening and classified them in categories based on their potential to contribute to programme theory.

We had initially planned to sort included studies into those which could make ‘major’ or ‘minor’ contributions to our programme theory. 62 By doing this we intended to prioritise studies from the UK, but also to include studies from other countries that provided useful insights for the UK. Our criteria for classifying studies as ‘major’ or ‘minor’ were as follows (see also Carrieri et al. 58).

Major

-

Studies that contributed to the research questions and were conducted in an NHS context.

-

Studies that contributed to the research questions and were conducted in contexts (e.g. publicly and universal-funded health-care systems) with similarities to the NHS.

-

Studies that contributed to the research questions and could clearly help to identify mechanisms which could plausibly operate in the context of the NHS.

Minor

-

Studies conducted in health-care systems that were markedly different from the NHS (e.g. fee for service and private insurance scheme systems), but where the mechanisms could plausibly operate in the context of doctors working in the NHS.

However, as the analysis progressed, we noted that even those documents that we had assumed would make a minor contribution still contained important and relevant data for our study, and hence we extracted and analysed data from all included documents.

The full text of a 10% sample of documents from the main search and a separate 10% sample of full texts from the supplementary searches were assessed and discussed between DC and CP to ensure that decisions for final inclusion and classification into categories have been made consistently. Small inconsistencies were identified that were resolved through discussion.

Step 4: extracting and organising data

Once article selection was finalised, DC analysed the full text of the included studies, using NVivo 12 Pro (QSR International, Warrington, UK) to manage the data. Initial coding followed both an inductive mode (codes emerging from the analysis of the literature) and a deductive mode (codes created in advance informed by the initial programme theory, stakeholder group discussions and exploratory literature searching). The coding framework resulting from the analysis of the richest papers (mostly UK policy documents, systematic reviews and qualitative research) was applied to the rest of the studies and refined as the analysis progressed. To ensure consistency in conceptual coding, CP assessed a random 10% sample of coded articles.

The analysis was driven by a realist logic. We sought to interpret and explain mechanisms causing mental ill-health in doctors and medical students (with a particular focus on presenteeism, absenteeism and workforce retention), and to identify relevant contexts or circumstances when these mechanisms were likely to be ‘triggered’. These contexts and mechanisms became our ‘causative factors’ codes. Examples of preliminary ‘causative codes’ included organisation and training levels, doctors’ profession and identity. We simultaneously sought to identify ‘guiding principles’ and features underpinning the interventions and recommendations discussed mostly in policy document, reviews and commentaries. The juxtaposition of these ‘guiding principles’ (underpinning interventions and recommendations) with the ‘causative factors’, allowed us to identify particular configurations of mechanisms and contexts that were more likely to reduce or prevent mental ill-health in doctors, as well as important limits and barriers to the access and effectiveness of such interventions. An obvious example was the link between the ‘coherence’ guiding principle code and the ‘lack of trust towards employer and loss of control’ causative factors code. This link highlighted the importance for doctors to have confidence in an intervention, whereas included studies reported instances in which there was lack of coherence between an intervention and the context in which it was implemented (e.g. the employer or leadership level failing to properly communicate such intervention and/or to making it accessible to the workforce).

We compared and contrasted these configurations of context-mechanism-outcome configurations (CMOcs) with the evolving programme theory, so as to understand the place of and relationships between each CMOc within the programme theory. As the review progressed we iteratively refined the programme theory driven by interpretations of the data included in the literature, and by feedback received by our stakeholders (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Programme theory development process. Reproduced from Papoutsi et al. 55 Contains information licensed under the Non-Commercial Government Licence v2.0.

We also coded articles for more descriptive categories, such as relevant background information, study characteristics and recommendations provided. The characteristics of the documents were summarised in Table 2 (see Appendices 2–4).

| Authors | Year | Country | Publication type | Method | Intervention level | Prevention | Screening | Therapy | Target | Career stage |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Allen et al.64 | 2017 | Australia | A | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | ✗ | Obstetrics, gynaecology | C, T | |

| Bakker et al.65 | 2000 | The Netherlands | B | Quantitative | Mixed | ✗ | GPs | C, T | ||

| Barbosa et al.66 | 2013 | USA | A | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | Medical students | U | ||

| Bar-Sela et al.67 | 2012 | Israel | A | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | Oncologists | T, C | ||

| Beckman68 | 2015 | USA | Com | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | Primary care | T, C, U | ||

| Benson and Magraith69 | 2005 | Australia | Com | Mixed | ✗ | GP | C | |||

| Bitonte and DeSanto70 | 2014 | USA | Com | Mixed | ✗ | Medical students | U | |||

| Blais et al.71 | 2010 | Canada | B | Quantitative | Mixed | ✗ | Physicians | T, C | ||

| Boorman72 | 2009 | UK | D | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | NHS workforce | C, T | |

| Bragard et al.73 | 2006 | Belgium | Com | Mixed | ✗ | Oncologists | T, C | |||

| Brazeau74 | 2010 | USA | Com | Structural | ✗ | Medical students | U | |||

| Bugaj et al.75 | 2016 | Germany | A | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | Medical students | U | ||

| Bugaj et al.76 | 2016 | Germany | B | Review | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | Medical students | U | |

| Bughi et al.77 | 2017 | USA | A | Quantitative | Individual | ✗ | First-year medical students | U | ||

| Peile and Carter et al.78 | 2005 | UK | Com | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | Medical students | U | ||

| Carvour et al.79 | 2016 | USA | B | Review | Structural | ✗ | Medical trainees | T | ||

| Chambers et al.80 | 2017 | New Zealand | B | Mixed | Structural | ✗ | Doctors and dentists | C | ||

| Chang et al.81 | 2013 | USA | B | Quantitative | Individual | ✗ | Medical students | U | ||

| Chaukos et al.82 | 2018 | USA | B | Quantitative | Mixed | ✗ | Residents | T, C | ||

| Clarke et al.83 | 2014 | UK | B | Qualitative | Mixed | Doctors | C, T | |||

| Clough et al.84 | 2017 | Australia | B | Systematic review | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | Doctors | C, T | |

| Cockerell85,86 | 2016 Part I; 2017 Part II | USA | Com | Individual | ✗ | ✗ | Physicians | T, C | ||

| Cornelius et al.87 | 2017 | USA | A | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | Emergency medicine residents | T, C | ||

| Cornwell and Fitzsimons88 | 2017 | UK | D | Mixed | NHS staff | C, T | ||||

| Davies et al.89 | 2016 | UK | A | Quantitative | Individual | ✗ | Doctors | C, T | ||

| de Vibe et al.90 | 2013 | Norway | A | RCT | Individual | ✗ | Medical and psychology students | U | ||

| Deng et al.91 | 2016 | China | B | Quantitative | Individual | ✗ | Oncology doctors and nurses | C, T | ||

| Department of Health and Social Care40 | 2008 | UK | D | Review | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | NHS doctors | C, T, U |

| Department of Health and Social Care92 | 2009 | UK | D | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | NHS workforce | C, T | |

| Devi93 | 2011 | USA | B | Review | Mixed | ✗ | Doctors and medical students | C, T, U | ||

| Dobkin and Hutchinson94 | 2013 | Canada | B | Literature review | Mixed | ✗ | Medical students | U | ||

| Doran et al.24 | 2016 | UK | B | Mixed | Structural | ✗ | GP | C | ||

| Downs et al.95 | 2014 | USA | B | Quantitative | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Medical students | U |

| Dunn et al.96 | 2007 | USA | A | Quantitative | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Physicians | C, T |

| Dyer97 | 2018 | UK | Com | Structural | ✗ | Doctors | T | |||

| Dyrbye et al.98 | 2016 | USA | A | RCT | Individual | ✗ | Physicians | T, C | ||

| Dyrbye et al.99 | 2017 | USA | B | Quantitative | Individual | ✗ | Medical students | U | ||

| Dyrbye et al.100 | 2017 | USA | B | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | First-year medical students | U | ||

| Eisenstein101 | 2018 | USA | Com | Mixed | ✗ | Doctors | C, T, U | |||

| Epstein and Krasner102 | 2013 | USA | Com | Mixed | Physicians – other HCPs | T, C | ||||

| Ey et al.103 | 2013 | USA | B | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | ✗ | Residents | T | |

| Ey et al.104 | 2016 | USA | A | Quantitative | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Medical trainees and faculty | U, T, C |

| Feld and Heyse-Moore105 | 2006 | UK | A | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | ✗ | Palliative care | T, C | |

| Firth-Cozens106 | 2007 | UK | B | Review | Mixed | ✗ | Psychiatrists (and doctors) | C, T | ||

| Flowers107 | 2005 | USA/UK | B | Review | Mixed | ✗ | Medical students | U | ||

| Foster et al.108 | 2012 | USA | A | Quantitative | Mixed | ✗ | Residents | T, C | ||

| Fothergill et al.109 | 2004 | UK | B | Systematic review | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | Physiatrists | T, C | |

| Gardiner et al.110 | 2015 | USA | B | Quantitative | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Family medicine residents | T, C |

| Gardiner et al.111 | 2013 | Australia | A | Quasi-experimental | Mixed | ✗ | GPs | C | ||

| Garelick et al.112 | 2007 | UK | B | Quantitative | Individual | ✗ | Doctors | T, C | ||

| Garside113 | 1993 | Canada | B | Review | Structural | ✗ | ✗ | Physicians (mostly primary health care) | T, C | |

| Gazelle et al.114 | 2015 | USA | Com | Individual | ✗ | ✗ | Physicians | T, C | ||

| Geller et al.115 | 2008 | USA | A | Mixed | Individual | ✗ | Clinical genetics | T, C | ||

| George et al.116 | 2012 | USA | A | Qualitative | Structural | ✗ | Year 1 medical students | U | ||

| Gerada117 | 2018 | UK | Com | Mixed | ✗ | Doctors | C, T | |||

| Goldhagen et al.118 | 2015 | USA | A | Quantitative | Individual | ✗ | Resident physicians | T, C | ||

| Goodman and Schorling119 | 2012 | USA | A | Quantitative | Mixed | ✗ | Physicians | T, C | ||

| Graham et al.120 | 2000 | UK | B | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | Doctors | C | ||

| Gregory and Menser121 | 2015 | USA | A | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | ✗ | Primary care | T, C | |

| Gulen et al.122 | 2016 | Turkey | B | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | Emergency medicine residents | T, C | ||

| Gunasingam et al.123 | 2015 | Australia | A | RCT | Structural | ✗ | ✗ | Junior doctors | T, C | |

| Haizlip et al.124 | 2012 | USA | Com | Mixed | ✗ | Physicians and trainees | T, C | |||

| Hamader and Noehammer125 | 2013 | Austria | B | Qualitative | Mixed | ✗ | Medical students, occupational health and psychology | U, T, C | ||

| Haramati et al.4 | 2017 | USA | Com | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Doctors and medical students | T, C, U | |

| Harrison et al.126 | 2014 | UK | B | Qualitative | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | Doctors | C | |

| Haward et al.127 | 2003 | UK | B | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | Cancer teams | C, T | ||

| Hegenbarth128 | 2011 | Switzerland | Com | Structural | ✗ | Doctors | T, C, U | |||

| Hill et al.129 | 2016 | UK | B | Systematic review | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | Palliative care staff | T, C | |

| Hill and Smith130 | 2009 | USA | B | Quantitative | Mixed | ✗ | Residents in academic otolaryngology | T, C | ||

| Hlubocky et al.131 | 2016 | USA | Com | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Oncology | C | |

| Hochberg et al.132 | 2013 | USA | A | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | ✗ | Resident surgeons | T, C | |

| Holoshitz and Wann133 | 2017 | USA | Com | Individual | ✗ | ✗ | Physicians | C | ||

| Horsfall134 | 2014 | UK | D | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | Doctors under investigation | C, T | ||

| Hotchkiss135 | 2008 | USA | B | Quantitative | Mixed | ✗ | Physicians | T, C | ||

| Howlett et al.136 | 2015 | Canada | A | Quantitative | Mixed | ✗ | Emergency medicine staff | |||

| Ireland et al.137 | 2017 | Australia | A | RCT | Individual | ✗ | ✗ | Doctors | T, C | |

| Isaksson Rø et al.138 | 2010 | Norway | B | Quantitative | Individual | ✗ | Physicians | T, C | ||

| Isaksson Rø et al.139 | 2012 | Norway | B | Quantitative | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | Doctors | T, C | |

| Kemper and Khirallah140 | 2015 | USA | A | Quantitative | Individual | ✗ | Doctors and other health workers | C, T | ||

| Kjeldmand and Holmström141 | 2008 | Sweden | B | Qualitative | Structural | ✗ | GPs | C | ||

| Kötter et al.142 | 2015 | Germany | B | Qualitative | Structural | ✗ | ✗ | Medical students | U | |

| Krasner et al.143 | 2009 | USA | A | Quantitative | Individual | ✗ | Primary care | C | ||

| Kumar144 | 2011 | New Zealand | C | Structural | ✗ | Psychiatrists | CT | |||

| Kushnir et al.145 | 1994 | Israel | A | Quantitative | Individual | ✗ | Occupational health | C, T | ||

| Lapa et al.146 | 2016 | Portugal | B | Quantitative | Mixed | ✗ | Anaesthesia | T, C | ||

| Lederer et al.147 | 2008 | Austria | B | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | Intensive care physicians/nurses | C, T | ||

| Lee et al.148 | 2016 | Taiwan | B | Quantitative | Mixed | ✗ | Hospital staff | C | ||

| Lefebvre149 | 2012 | Canada | Com | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Residents/physicians | T, C | |

| Leff et al.150 | 2017 | USA | Com | Structural | ✗ | ✗ | End-of-life care physicians and social workers | T, C | ||

| Lim and Pinto151 | 2009 | New Zealand | B | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | Radiologists | C, T | ||

| Linzer et al.152 | 2015 | USA | A | RCT | Structural | ✗ | ✗ | Primary care physicians | C | |

| Linzer et al.153 | 2001 | USA and the Netherlands | B | Quantitative | Mixed | ✗ | Physicians | T, C | ||

| Luthar et al.154 | 2017 | USA | A | RCT | Structural | ✗ | ✗ | Physicians | C, T | |

| Lyons and Dolezal155 | 2017 | UK and Ireland | Com | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | C, T, U | |||

| Mache et al.156 | 2017 | Germany | A | Quasi-experimental | Mixed | ✗ | Oncology | C, T | ||

| Maslach and Leiter157 | 2017 | USA | B | Review | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | C, T, U | ||

| McCartney158 | 2018 | UK | Com | Structural | ✗ | C, T | ||||

| McClafferty and Brown159 | 2014 | USA | B | Review | Mixed | Physicians/paediatricians | T, C | |||

| McCray et al.160 | 2008 | USA | B | Review | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Students-doctors, HCPs | U, T, C |

| McCue and Sachs161 | 1991 | USA | A | Quantitative | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | Paediatrics residents | T, C | |

| McKenna et al.162 | 2016 | USA | Com | Structural | ✗ | Medical students | U | |||

| McKevitt and Morgan163 | 1997 | UK | B | Qualitative | Structural | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Doctors | C, T, U |

| McKinley et al.164 | 2017 | USA | B | Review | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Paediatric residency | T |

| McManus et al.165 | 2011 | UK | B | Quantitative | Individual | ✗ | Doctors | T, C | ||

| McNeill et al.166 | 2014 | Australia | B | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | Medical students | U | ||

| Mechaber et al.167 | 2008 | USA | B | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | ✗ | Generalist physicians | C | |

| Merteen et al.168 | 2014 | UK | B | Quantitative | Individual | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Doctors | T, C |

| Mehta et al.169 | 2016 | USA | A | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | Palliative care team | T, C | ||

| Milstein et al.170 | 2009 | USA | A | Mixed | Individual | ✗ | ✗ | Paediatric house officers | T | |

| Montgomery et al.171 | 2011 | Greece/UK | B | Review | Mixed | ✗ | Hospital staff | T, C | ||

| Moutier et al.172 | 2012 | USA | B | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | ✗ | Medical students, residents, faculty | U, T, C | |

| Murdoch and Eagles173 | 2007 | UK | A | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | ✗ | Psychiatrists | C | |

| Myszkowski et al.174 | 2017 | France | B | Quantitative | Individual | ✗ | Internal medicine | T, C | ||

| NHS England175 | 2016 | UK | D | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | NHS workforce | ||

| Nielsen and Tulinius176 | 2009 | Denmark | B | Qualitative | Structural | ✗ | Nine GPs | T, C | ||

| Nomura et al.177 | 2016 | Japan | B | Mixed | Structural | ✗ | Paediatric residents | T, C | ||

| Oczkowski178 | 2015 | Canada | Com | Mixed | ✗ | Medical students/physicians | U, T, C | |||

| Oman et al.179 | 2006 | USA | A | RCT | Individual | ✗ | ✗ | Doctros/HCPs | C, T | |

| Paice et al.180 | 2004 | UK | B | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | Doctors in training | T | ||

| Paice et al.181 | 2002 | UK | B | Quantitative | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Doctors | C |

| Panagioti et al.47 | 2017 | UK | B | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | Physicians | C, T | |

| Penfold182 | 2018 | UK | Com | Structural | ✗ | Trainees | T | |||

| Pereira et al.183 | 2015 | Brazil | B | Qualitative | Individual | ✗ | Medical students | U | ||

| Prins et al.184 | 2007 | The Netherlands | B | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | ✗ | Residents | T, C | |

| Rabin et al.185 | 2005 | Israel | Com | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Doctors, mostly GP | T, C | |

| Raj186 | 2016 | USA | B | Systematic review | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Physicians/residents | T, C |

| Ramirez et al.187 | 1996 | UK | B | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | Gastroenterologists, surgeons, radiologists oncologists | C, T | ||

| Isaksson Rø et al.188 | 2016 | Norway | B | Qualitative | Structural | ✗ | Peer counsellors | C, T | ||

| Regehr et al.189 | 2014 | Canada | B | Review | Individual | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Physicians | T, C |

| Riley et al.190 | 2018a | UK | B | Qualitative | Mixed | ✗ | Mostly GPs | T, C | ||

| Riley et al.191 | 2018b | UK | B | Qualitative | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | Mostly GPs | T, C | |

| Ringrose et al.192 | 2009 | The Netherlands | A | Mixed | Structural | ✗ | ✗ | Medical residents | T | |

| Ripp et al.193 | 2016 | USA | A | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | ✗ | Residents | T, C | |

| Ripp et al.194 | 2017 | USA | C | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Medical students | U | |

| Ripp et al.195 | 2015 | USA | B | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | Internal medicine residents | T, C | ||

| Rippstein-Leuenberger et al.196 | 2017 | Switzerland | B | Quantitative | Individual | ✗ | Intensive care unit HCPs | C, T | ||

| Isaksson Rø et al.197 | 2008 | Norway | A | Quantitative | Mixed | ✗ | Doctors | C | ||

| Roberts et al.198 | 2002 | UK | C | Structural | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Psychiatrists | C, T, U | |

| Robertson and Cooper199 | 2010 | UK | D | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | NHS workforce | ||

| Rohland et al.200 | 2004 | USA | A | Quantitative | Individual | ✗ | Physicians | T, C | ||

| Rothenberger2 | 2017 | USA | B | Systematic review | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | Physicians, medical students, trainees | C, T, U | |

| Runyan et al.201 | 2016 | USA | B | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | Family medicine residents | T | ||

| Sallon et al.202 | 2017 | Israel | A | Quantitative | Mixed (mostly individual) | ✗ | ✗ | Hospital staff | C, T | |

| Sanchez et al.203 | 2016 | USA | B | Mixed | Structural | ✗ | Physicians | T, C | ||

| Schapira et al.204 | 2017 | Australia | Com | Mixed | ✗ | Oncology | T, C | |||

| Schattner205 | 2017 | Israel | Com | Structural | ✗ | Physicians | T, C | |||

| Schmitz et al.206 | 2012 | USA | Com | Structural | ✗ | Emergency medicine residents | T, C | |||

| Schneider et al.207 | 2014 | USA | B | Qualitative | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | Physicians | T, C | |

| Scholz et al.208 | 2016 | Germany | A | Quantitative | Individual | ✗ | Medical students | U | ||

| Seoane et al.209 | 2016 | USA | B | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | Medical students | U | ||

| Shanafelt et al.210 | 2012 | USA | B | Quantitative | Individual | ✗ | Surgeons | C | ||

| Shanafelt et al.211 | 2014 | USA | A | Quantitative | Individual | ✗ | ✗ | Surgeons | C | |

| Shapiro et al.212 | 2011 | USA | B | Review | Individual | ✗ | Physicians | C | ||

| Shapiro and Galowitz213 | 2016 | USA | Com | Structural | ✗ | ✗ | Doctors | T, C | ||

| Sharifi214 | 2012 | USA | B | Individual | ✗ | ✗ | Mental health care providers | C | ||

| Shiralkar et al.215 | 2013 | USA | B | Systematic review | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | Medical students | U | |

| Siedsma and Emlet216 | 2015 | USA | A | RCT | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Physicians | T, C |

| Sigsbee and Bernat217 | 2014 | USA | B | Review | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | Physicians | T, C | |

| Slavin and Chibnall218 | 2016 | USA | Com | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Medical students, residents, physicians | U, T, C | |

| Slavin et al.219 | 2011 | USA | Com | Mixed | ✗ | Medical students/practising physicians | U, T | |||

| Smith220 | 2016 | USA | A | Action research | Structural | ✗ | ✗ | Medical students | U | |

| Squiers et al.221 | 2017 | USA | B | Review | Mixed | Physicians | T, C | |||

| Talisman et al.222 | 2015 | USA | B | Mixed | Individual | ✗ | Physicians, health-care faculty | T, C | ||

| Tucker et al.223 | 2017 | Canada | A | Quantitative | Mixed | ✗ | Third year medical trainees | U, T | ||

| van Vliet et al.224 | 2017 | The Netherlands | A | Quantitative | Mixed | ✗ | Medical and nursing students | U | ||

| Verweij et al.225 | 2016 | The Netherlands | A | Mixed | Individual | ✗ | ✗ | GPs | C | |

| Waddimba et al.226 | 2016 | USA | B | Quantitative | Individual | ✗ | Physicians | T, C | ||

| Wald et al.227 | 2016 | USA/Israel | A | Mixed | Mixed | ✗ | Medical, nursing faculty and medical students | U, T | ||

| Warde et al.228 | 2014 | USA | B | Quantitative | Mixed | ✗ | Medical students | U | ||

| West et al.53 | 2014 | USA | A | RCT | Structural | ✗ | ✗ | Physicians | T, C | |

| West et al.229 | 2016 | USA | B | Systematic review and meta-analysis | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Physicians | T, C |

| Wild et al.230 | 2014 | Germany | B | Quantitative | Mixed | ✗ | Medical and psychology students | U | ||

| Wilkie and Raffaelli231 | 2005 | UK | Com | Structural | ✗ | ✗ | C, T | |||

| Williams et al.232 | 1998 | UK | D | Systematic literature review and interviews | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | C, T | |

| Winefield et al.233 | 1998 | Australia | A | Quantitative | Individual | ✗ | GPs | T, C | ||

| Wolf234 | 1994 | USA | B | Review | ✗ | Medical students | U | |||

| Zhang et al.235 | 2017 | Canada | A | Quantitative | Structural | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | Trainee surgeons | C, T |

| Zwack and Schweitzer236 | 2013 | Germany | B | Qualitative | Mixed | ✗ | ✗ | Physicians | C, T |

The aim of the analysis was to reach theoretical saturation, in that sufficient information has been captured to portray and explain the processes leading to mental ill-health and the mechanisms that can remedy this situation. Excerpts coded under specific concepts in NVivo were then exported into a Microsoft Word document (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Drawing on the analysis of the literature done in NVivo, Word documents were used as coding reports, to provide a more flexible space to test the viability of different CMOcs and build the narrative of the synthesis. This included adding explanatory text through abductive and retroductive analysis (see Step 5: synthesising the evidence and drawing conclusions).

Step 5: synthesising the evidence and drawing conclusions

We used a realist logic of analysis to analyse and synthesise the data. We used the coding of the included studies conducted on NVivo to draw relationships between contexts, mechanisms and outcomes, and to develop our initial programme theory. To develop and refine the CMOcs, and the programme theory, we made judgements about the relevance and rigour of content within included articles following a series of questions that are commonly used in realist reviews (see also Papoutsi et al. 54).

Relevance

-

Are the contents of a section of text within an included document referring to data that might be relevant to programme theory development?

Judgements about trustworthiness and rigour

-

Are the data sufficiently trustworthy to warrant making changes (if needed) to the programme theory?

Interpretation of meaning

-

If the section of text is relevant and trustworthy enough, do its contents provide data that may be interpreted as functioning as context, mechanism or outcome?

Interpretations and judgements about CMOcs

-

What is the CMOc (partial or complete) for the data?

-

Are there data to inform CMOcs contained within this document or other included documents? If so, which other documents?

-

How does this CMOc relate to CMOcs that have already been developed?

Interpretations and judgements about programme theory

-

How does this (full or partial) CMOc relate to the programme theory?

-

Within this same document are there data which inform how the CMOc relates to the programme theory? If not, are there data in other documents? Which ones?

-

In light of this CMOc and any supporting data, does the programme theory need to be changed?

We used abductive and/or retroductive reasoning (see Glossary), particularly to infer and elaborate on mechanisms (which often remained hidden or were not articulated adequately). This means that we followed a process of constantly moving from data to theory, in order to refine explanations about why certain behaviours are occurring, and tried to frame these explanations at a level of abstraction that could cover a range of phenomena or patterns of behaviour.

We sought relationships between contexts, mechanisms and outcomes both within the same included study and across different sources (e.g. mechanisms inferred from one study could help explain how contexts influenced outcomes in a different study). Therefore, we often synthesised data from different sources to compile CMOcs, as not all parts of the CMOcs were always articulated in the same source.

In summary, the process of evidence synthesis was achieved by the following analytic processes. 237

-

Juxtaposition of data sources: comparing and contrasting between data presented in different articles. For example, when data about mental ill-health in doctors in an in-depth qualitative source enabled insights into how outcomes are achieved, as described in a quantitative study.

-

Reconciling ‘contradictory’ or disconfirming data: when outcomes differ in apparently similar circumstances, further investigation is necessary to find explanations for why these different results occurred. This involved a closer consideration of context and what counts as context for different types of ‘problems’, in order to understand how the mechanisms triggered can explain differences in outcomes.

-

Consolidation of sources of evidence: when there are similarities between findings presented in different sources, a judgement needs to be made about whether these similarities are adequate to form patterns in the development of CMOcs and programme theory, or whether there are nuances that need to be highlighted, and to what end.

Chapter 3 Results

Results of the review

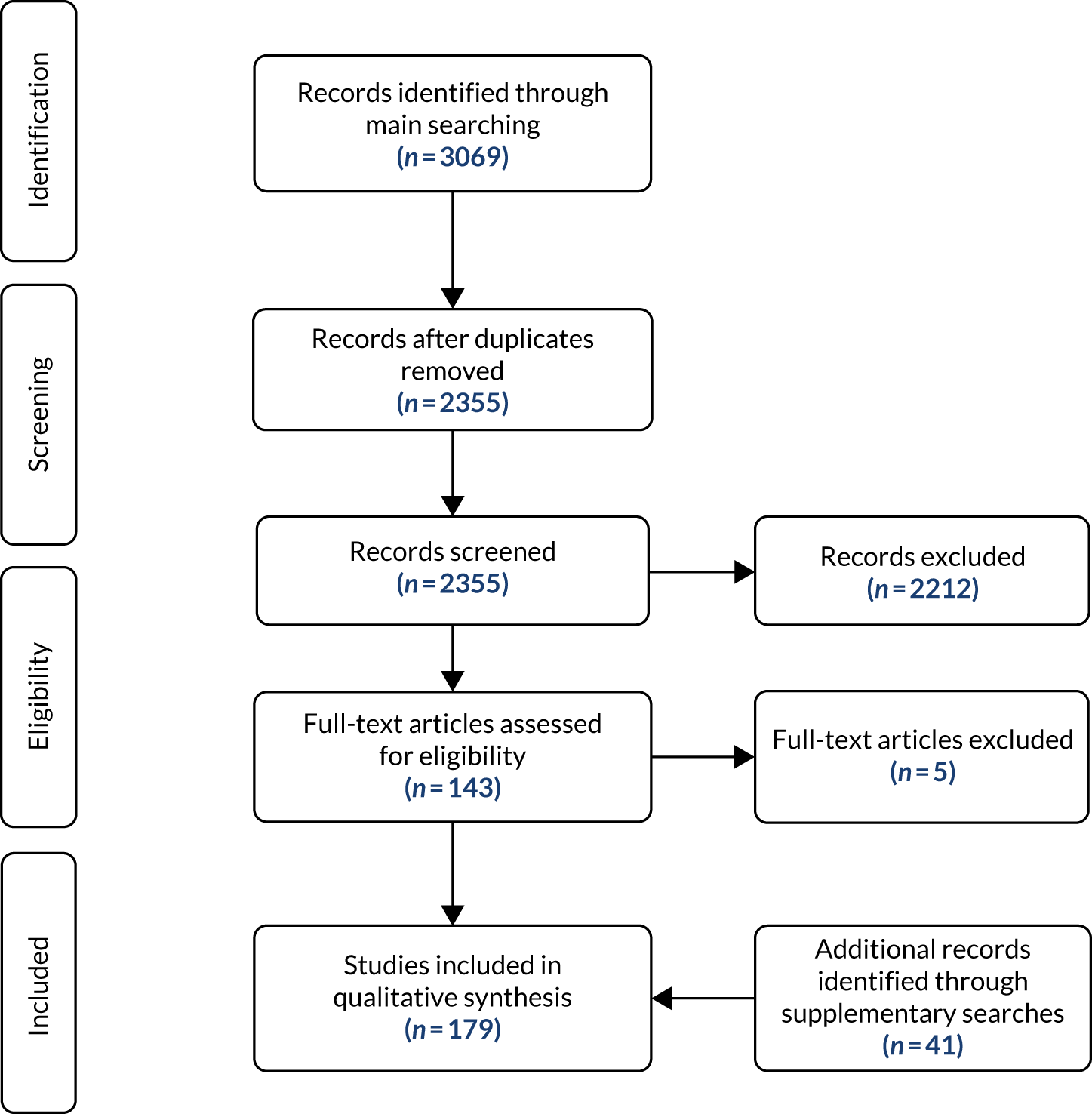

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Figure 3) reports the number of studies identified, included and excluded. Table 2 provides a description of the included studies. Of the 3069 records identified by the main searches, 179 articles met the inclusion criteria and were included in the study.

FIGURE 3.

The PRISMA flow diagram.

Characteristics of included studies

The country most represented in the included studies is the USA (45% of the included studies are published by authors working in the USA; 22.3% are from the UK). The majority of the included studies (74%) have been published in the 2010s. The most common study type is empirical research (which were not specific interventions, but included reviews, qualitative and quantitative studies that explored the issue of doctor’s mental ill-heath) (48%), followed by intervention studies (any empirical study based on an intervention) (27%), commentaries (20%) and policy documents (5%). In Realist synthesis findings, we use the term ‘grey literature’ to refer to both commentaries and policy documents. The most common level of intervention discussed in the included studies is mixed (46%), followed by structural (33%) and individual (21%). The majority of the interventions discussed are preventative, followed by treatment and screening. Most studies refer to doctors or physicians in general, rather than to specific specialties or career stages. Table 2 provides an overview of the studies included.

For a more in-depth description of these studies, see Appendices 2–4.

Cost information within included papers

As stated in the review protocol, our expectation was that the reporting of cost information in economic evaluations or other sources would make it unlikely to be able to link cost data directly to the context–mechanism–outcome configurations identified in the review. This expectation was proven to be founded, so consistent with the protocol we identified any source that made a reference to costs, including general estimates of financial losses due to mental ill-health and related problems, and the specific costs of interventions. This is presented in Appendices 2–4 in the last column of the tables with the heading ‘£’. When economic considerations were found in an included study, they were categorised into quantitative information (when figures are provided) or qualitative information (when no figures are provided). An example of quantitative information would be:

Together these factors have a serious impact on healthcare, contributing to an overall fall in provision of services with costs for absenteeism and high turnover for nurses alone estimated at $91,000–$98,000.17.

Sallon et al. 202

An example of qualitative information would be:

Thirty minutes allotted at least three times per week, built into students’ schedules, is more cost effective than eventual counseling, and more pragmatic as it attempts to prevent mental health issues.

Bitonte and DeSanto70

The majority of sources in which reference was made to costs contained unquantified claims of cost saving as a result of interventions (e.g. Bitonte and DeSanto70 and Ireland et al. 137), unquantified claims of increased direct and indirect costs as a result of burnout,2,84,194 or unquantified references to the ‘low costs’ of interventions. 123,154,172

One source quantified the direct costs of providing a ‘National Support Service’ for doctors134 and other sources contained summary statements of approximate costs of training that are ‘lost’ when health professionals leave their profession. 24,72,175 Two sources72,84 identified one or more studies in which the costs of an intervention were quantified. Inclusion of these cited sources was outside the scope of our review, but we note the observation in Clough et al. ’s 2017 systematic review84 that, even when cost information was reported, there was a lack of detail.

Less than one-quarter of included sources provided cost information [35/179 (19%)]. Of these, costs in five (3%) sources were quantified, 24 (13%) sources contained unquantified narrative claims and six (3%) sources contained a mix of quantified costs and unquantified narrative claims.

A minority of included sources quantified costs and there was a lack of methodological detail about how estimates of direct or indirect costs had been calculated. There was a paucity of detail about direct, indirect, or total costs that we could meaningfully extract. No included sources reported a health economic analysis (either cost–consequence modelling or prospective comparative evaluation), but it should be noted that our search strategy was not explicitly designed to locate such studies.

Realist synthesis findings

The presentation of the main findings from the analysis and synthesis of the literature reviewed is structured in five sections. Processes leading to mental ill-health in doctors focuses primarily on the processes leading to mental ill-health in doctors; Reducing mental ill-health: groups, belonging and relationality and Reducing mental ill-health: balance and timeliness focus on the factors which can reduce mental ill-health in doctors; whereas Implementation methods: engendering trust explores implementation methods (i.e. ideas on how to improve current interventions or the implementation of new ones). In Summary of the 19 CMOcs in four main groupings we provide an indication on how we have drawn on substantive theory.

These first four sections are organised as follows:

-

‘Overall narrative’ to introduce each CMOc or relevant group of CMOcs.

-

‘Realist analysis’: exposition of CMOcs.

-

‘Relevant extracts from papers included in the review’: illustrative quotations from the included literature that we have used to make our interpretations and inferences for each CMOc. Each of these quotation is contextualised, that is we provide a brief description of the type of source, country of origin, target population, career stage and year of publication. Some of these data consist of quotations presented in relevant included studies, other data come from interpretations drawn by the authors of these studies (e.g. in the discussion section). The full list of quotations extracted from the literature is available from the author on request.

The CMOcs collectively have been developed drawing on all sources included in this review: empirical studies and grey literature. After each specific CMOc, we provide an indication of the specific subset of resources which support it, for example to highlight that the supporting literature comes from a particular country or publication type.

Overview of all CMOcs

Box 1 provides an overview of all CMOs.

CMOc 1: underdeveloped workforce planning.

CMOc 2: normalisation of high workload.

CMOc 3: loss of autonomy.

CMOc 4: stigma towards vulnerability.

CMOc 5: hiding vulnerability.

CMOc 6: isolation.

Reducing mental ill-health: groups, belonging and relationalityCMOc 7: positive and meaningful workplace relations.

CMOc 8: functional working groups.

CMOc 9: balancing quality and quantity of time at work.

CMOc 10: limits of groups.

CMOc 11: ‘organic’ spaces to connect.

Reducing mental ill-health: balance and timelinessCMOc 12: recognising both positive and negative performance.

CMOc 13: balancing prevention of mental ill-health with promotion of well-being.

CMOc 14: acknowledging the positive and negative aspects of the profession.

CMOc 15: timely support.

Implementation methods: engendering trustCMOc 16: endorsement.

CMOc 17: expertise.

CMOc 18: engagement.

CMOc 19: evaluation.

Terminology

When it comes to stress, burnout and mental health in general, there is a plethora of different labels, mainstreamed and contested diagnoses, and unclear definitions – and their number continues to grow. 238 We have adopted the term ‘mental ill-health’ as an umbrella term to try to encompass this large variety of conditions and changeable labels. However, drawing on our analysis, we became aware that the term mental ill-health risks clouding important aspects of the issue we are investigating. Therefore, we have also adopted the term ‘vulnerability’ as a key term, which came up in the conceptual analysis. Vulnerability is a less clinical term and its meaning extends beyond mental ill-health, as it also allows us to focus on doctors’ suffering in general and on relevant contextual causative factors which may lead to a mental ill-health diagnosis. For example, vulnerability allows us to reflect on feelings of shame or fear that doctors who are facing psychological and emotional difficulties may experience due to external or internalised stigma (e.g. see CMOcs 4 and 5). Vulnerability lends itself to consider individual, organisational and wider sociocultural dimensions of the problem we are investigating. We discuss this idea further in How does existing substantive theory link with our findings?. For an in-depth recent reflection on the importance of the idea of vulnerability in medical education and clinical practice, we refer the reader to Piemonte. 239

Processes leading to mental ill-health in doctors

The studies included depict a complex picture of the different processes leading to mental ill-health in doctors, which mirrors the dimensions (individual biographical, organisational, professional and sociocultural) described in Chapter 1. However, the realist approach allowed us to uncover significant links between, or aspects of, these dimensions.

Alongside resources and workload, our analysis shows that there are other intertwined key organisational aspects that need to be considered to better understand and address the problem of mental ill-health in doctors: work structure, workforce planning and governance (see in particular Underdeveloped workforce planning and normalisation of high workload and Loss of autonomy).

Another important causative factor mentioned in the included studies is the medical culture and identity, and in particular the ideas of invulnerability, perfectionism, and the stigma around mental ill-health within the medical profession (see Stigma towards vulnerability).

Considerations of biographical aspects (i.e. related to individual doctors’ psychological predisposition to mental ill-health, personal contexts and/or traumatic events outside work) were often strongly intertwined with the dimensions described above. Therefore, we do not dedicate a specific CMOc to biographical factors alone.

Underdeveloped workforce planning and normalisation of high workload

A significant part of the included literature47,121 recognises that organisational aspects are associated with mental ill-health and can also represent a barrier to the access of interventions (if such interventions are available and accessible). Many studies suggest that both the individual doctors and the organisation have a role to play to address the issue of mental ill-health. 2,4,121,240 This argument is made also in relation to the organisation of medical schools. 142 We provide here two examples from a commentary and a research study respectively:

We are unlikely to ‘resilience our way out’ of this [the Mental Health of Medical Students, Residents, and Physicians] problem. Instead, multipronged interventions are needed that not only help individuals but also reduce the toxicity of the educational and clinical environments.

Slavin and Chibnall, commentary, USA, medical students, trainees, consultants, 2016218

. . . there is a general tendency to blame the person, rather than the job, for burnout. This [ . . . ] prevents a more realistic ‘both-and’ approach, which recognizes that both the person and the organization have a role to play in improving the workplace and people’s performance within it.

Maslach and Leiter, research, USA, doctors, consultants, trainees, medical students, 2017157

Among the organisational causes of mental ill-health in doctors, the included studies highlight the risks of ineffective workforce planning, alongside the lack of support for doctors experiencing work-related pressure. The studies which support this CMOc comprise research, commentaries and policy documents. Examples of underdeveloped work planning include demanding and rigid rotas, weak or absent ‘well-being’ services and weak or absent treatment support services. Examples of intervention include organisational measures to support workforce planning and well-being, and both the organisation and doctors recognising a shared responsibility for doctors’ well-being and patient outcomes.

CMOc 1: underdeveloped workforce planning

In a workplace in which basic support structures to enable doctors to do their job are not in place (context), doctors may feel that they must make up for the deficiencies of the organisation for patients and colleagues (mechanism). This may contribute to a toxic working culture in which overwork and its negative consequences are normalised (outcome).

Relevant extracts from papers included in the review

There were inconsistencies in the range of services offered by different NHS Trusts, and many services suffered from staff shortages and inadequate resourcing, with funding often historically based rather than related to current needs.

Boorman, policy document UK, NHS workforce, 2009. © Crown copyright72

Trainees [ . . . ] reported [ . . . ] seniors in a working culture ‘institutionally opposed’ to hearing complaints; doctors [ . . . ] emotionally blackmailed or bullied into reporting only timetabled hours, [ . . . ] individuals made to feel that working excessive hours was a personal failure of time management rather than the consequence of a systemic mismatch of workload.

Clarke et al. , research, UK, doctors, trainee, consultant, 201483

Physicians, it seems, have become quite skilled at sacrificing personal and family time in service to patients and the increasing demands of practice.

Beckman, commentary, USA, primary care, trainees, consultants, medical students, 201568

If burnout is a problem of whole health care systems, it is less likely to be effectively minimized by solely intervening at the individual level. It requires an organization-embedded approach. 47

Panagioti et al. , research, UK, physicians, consultants, trainees, 201747

The analysis also shows a link between inadequate workforce planning and support at the organisational level (which, as described by CMOc 1, can result in a toxic culture of normalisation of overwork) and doctors’ presenteeism, and/or their decision to leave the profession. This link is made explicit by CMOc 2. The studies which support CMOc 2 comprise research, commentaries and policy documents. As some quotations show, we did find some suggestions in the literature that women and trainees may feel extra pressure to work when ill. However, we do not have sufficient data to further stratify this CMOc.

Normalisation of high workload

CMOc 2: normalisation of high workload

When high workload and its negative consequences (e.g. distress, burnout) are normalised (context), overworked or sick doctors may feel they are letting down their colleagues and patients (mechanism). This can contribute to presenteeism (outcome) and associated negative consequences on mental health (outcome 1) and workforce retention (outcome 2).

Relevant extracts from papers included in the review

Importantly, presenteeism is unlikely to decrease if individuals are operating in environments where working through illness is viewed as ‘normal’ or, at worst, ‘necessary’ behaviour.

Chambers et al. , research, New Zealand, doctors and dentists, consultant, 201780

All doctors referred to the ‘burden’ which their absence placed on colleagues, who would be expected to assume their duties.

McKevitt and Morgan, research, UK, doctors, trainees, consultants, medical students, 1997163

Loss of autonomy

Another significant organisational factor that emerged strongly from the analysis of the included studies is the paradox that doctors increasingly have more responsibilities and tasks, but less control over their work. Doctors are trained to deal with complex issues and to be able to make difficult decisions. This requires a certain degree of work autonomy and control. However, the practice of medicine is increasingly subjected to stringent regulations and external control, and is becoming more clerical, leaving less space for clinical judgement and less time for working clinically with colleagues and patient-facing work (see also The relational nature of health, well-being and health care). The analysis shows that this loss of control can be linked to doctors perceiving a tension between their expectations and the reality of what their job entails. This CMOc is linked to the previous two CMOcs, as the increasing bureaucratisation of clinical work can also be perceived as signalling lack of appreciation of doctors and their job at an organisational level. Some studies also mention that technological innovation (e.g. electronic medical records may also play a role in the increasing bureaucratisation of clinical work72). The issue of electronic medical records is mostly present in US literature and is linked to billing practices. 221 However, lack of control and autonomy are also described in UK literature. 182 Crucially, the feeling of lack of autonomy and control is a potential cause of stress in itself, irrespective of other variables such as workload.

CMOc 3: loss of autonomy

When doctors experience lack of autonomy over their work (context 1) and when they feel that some aspects of their work are less meaningful (context 2), they may feel dissatisfied with their job (e.g. because they are unable to do the job they were trained for) (mechanism). This can make doctors more vulnerable to stress and mental ill-health, irrespective of workload (outcome).

Examples of contexts in which doctors feel more control include meaningful working relationship with colleagues and a sense of connectedness to the workplace and profession. These are discussed in Reducing mental ill-health: groups, belonging and relationality.

Relevant extracts from papers included in the review

Although most efforts at preventing physician burnout are focused on improving individual physician resilience, health care organizations are failing to change the system that is increasingly asking doctors to perform tasks, largely administrative in nature, for which they have no passion.

Squiers et al. , research, USA, physicians, trainees, consultants, 2017221

You spent more time ticking boxes than you did talking to the patients sometimes [ . . . ] that put more stress on me and I felt it affected my rapport with the patients.

Doran et al. , research, UK, general practitioners, consultants, 201624

This study confirms that autonomy and feeling well managed and resourced make a substantial contribution to overall job satisfaction. [ . . . ], the transfer of various responsibilities from clinicians to managers may undermine professional morale, as may the practice of establishing standards against which doctors’ performance is judged, without their involvement.

Ramirez et al. , research, UK, gastroenterologists, surgeons, radiologists oncologists, consultants, trainees, 1996187

Stigma towards vulnerability

The analysis identified a central taboo within the medical culture: the difficulty of managing the status of being a doctor, more specifically a too rigid demarcation between ‘being a doctor’ and ‘being a patient’. This demarcation appears to be endemic in the medical profession, but it can also be influenced by wider societal factors, including the fact that some patients may expect doctors to never be ill, or may find it counterintuitive and uncanny for a doctor to occupy simultaneously the role of doctor and of patient, and members of the medical profession may assume that patients have such expectations. Drawing on the analysis of the included studies, it is plausible to argue that most of the ideas of invulnerability of doctors and the stigma towards mental ill-health stem from a clear-cut distinction and separation between the role of doctors and that of patients. This distinction is coupled by an unrealistic expectation that doctors cannot/should not be patients (or that, if they become patients, their status of doctor is seriously under threat). Vulnerability, including emotional and psychological aspects of self-care for doctors, tends to be considered by other doctors as unprofessional. Although the focus of our research is mental health, it is important to highlight that, overall in the included studies, the culture of invincibility can refer to both physical and mental conditions.