Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/136/70. The contractual start date was in January 2014. The final report began editorial review in October 2018 and was accepted for publication in April 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

All authors report grants from the Department for Children, Schools and Families (now the Department for Education), grants from the Department of Health and Social Care, non-financial support from the Youth Justice Board for England and Wales, grants and non-financial support from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network, during the conduct of the study. David Cottrell reports being the chairperson of the NIHR Clinician Scientist Fellowship panel during the conduct of the study. Ian M Goodyer reports personal fees from Lundbeck (Copenhagen, Denmark), outside the submitted work, and was a member of Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation Prioritisation Group during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Fonagy et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Conduct disorder (CD) is the most common behavioural disorder in childhood and adolescence. 1 It is characterised by antisocial behaviour, or violation of acceptable social norms, such as aggression, destructive behaviour or habitual deception. 2 The prevalence of the disorder is approximately 8% of boys and 5% of girls aged 11–16 years. 1 However, among looked-after children aged 11–15 years, the prevalence of CD was found to be 40.5%. 3 As of 2014, there were a total of 1,240,000 known cases of CD in England. 1

The main risk factors for developing CD include poor or erratic parenting, impulsiveness, and growing up in a low-income household or a high-crime area. 4 The disorder is associated with increased risk of criminal behaviour, substance abuse, and poor academic achievement and employment going into adulthood. 5,6 These risks are associated with significant financial, societal and interpersonal costs. 7 The average potential savings from early intervention have been estimated at £9300 per child. 8 Without intervention, about 50% of adolescents with CD will develop antisocial personality disorder, and those who do not will still go on to have long-term psychological and behavioural problems. 9

Multisystemic therapy (MST) has previously been identified by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) as a promising intervention for reducing recidivism in delinquent young people and improving individual and family pathology. MST is an intensive, family-focused programme, combining aspects of cognitive–behavioural and family therapy. 10 In the USA, there has been some evidence that MST can reduce criminal activity11 and recidivism,12 and improve antisocial behaviour13 and family cohesion14 compared with management as usual (MAU). However, other studies, outside the USA, have found no differences between MST and MAU on measures of antisocial behaviour15 and criminal conviction. 16 This heterogeneity in results can be explained in a number of ways, including differences in fidelity of treatment implementation, variable quality of standard MAU services, differences in sentencing policies between national justice systems (specifically alternatives to incarceration), and the quality of integration of MST with other services.

The Systemic Therapy for At Risk Teens (START) trial is a national randomised evaluation of MST in the context of the UK, developed to inform policy-makers, service commissioners and professionals about the value of MST in the management of antisocial behaviour compared with standard management practices. Results from the first phase of the trial (from baseline to 18-months’ follow-up) have been reported in The Lancet Psychiatry. 17 A total of 684 families took part in the pragmatic, individually randomised, single-blind, controlled superiority trial conducted across nine community-based MST services in England. Young people aged 11–17 years were randomly allocated to receive either MST (n = 342) or MAU (n = 342). The primary outcome for the first phase of the trial was proportion of out-of-home placements. Secondary outcomes included offending data [collected via the Police National Computer (PNC), a centralised database], substance misuse, individual and family well-being, and a range of behavioural and cognitive outcomes. Data were collected at baseline, and at 6-month intervals until 18 months. An economic evaluation to assess the cost-effectiveness of MST compared with MAU was also conducted.

Overall, there were no significant differences between the groups in the proportion of out-of-home placements [odds ratio (OR) 1.25, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.77 to 2.05; p = 0.37] or time to first offence [hazard ratio (HR) 1.06, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.33; p = 0.64]. However, the total number of offences at 18 months was greater in the MST group (average 0.65 offences, 95% CI 0.28 to 1.02 offences; p = 0.00067). Improvements in CD diagnoses (> 40% reduction) were notable in both groups, but no group differences were found. Longitudinal models consistently supported short-term reductions in self-reported depression and parent-reported delinquency in the MST group compared with MAU, but these differences were not sustained in the long term. There was no evidence of MST’s superiority with regard to secondary outcomes, with the exception of parental well-being and self-reported callous and unemotional traits. The mean total service costs were not found to be significantly different (MST £28,687 vs. MAU £30,928; adjusted difference –£1623, 95% CI –£7684 to £4438; p = 0.60).

Overall, the results from the first phase of the trial suggest that, although MST followed by MAU led to behavioural and emotional improvements, there was no evidence to suggest its superiority to MAU alone among a population of adolescents with moderate to severe antisocial behaviour problems.

Objectives

The second phase of the START trial extended the follow-up period to 4 years for secondary outcomes and to 5 years for the primary outcome. The aim was to evaluate the medium- to long-term effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of MST compared with MAU in the UK. Extending the follow-up period enables stakeholders to make informed, evidence-based decisions about the role of MST in treating CD.

The primary objective was to compare MST with MAU in terms of the proportion of young people who had criminal convictions by 5 years post intervention. This was evaluated using data from the PNC, a centralised database of offending data across the UK. Secondary outcomes included measures of psychiatric problems and outcomes in areas where CD can result in poor outcomes: educational attainment, work adjustment, social relationships, pregnancy and physical health.

In addition, the cost-effectiveness of MST compared with MAU was explored at the 4-year follow-up in terms of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) and offending. Two qualitative substudies were also designed for a subsample of the families to better understand the subjective experiences of young people and their parents or carers and to better characterise the life circumstances and quality of young people’s lives post intervention. Qualitative Study 1 was carried out approximately 18 months post randomisation. Qualitative Study 2 took place around the 48-month follow-up visit.

Chapter 2 Methods

The first phase of the START trial involved a follow-up period of 18 months. The present report concerns the second phase, which followed families from 18 months to 4 years for self-report data and to 5 years for objective offending data. In this section we describe the trial as it was designed at the outset, including recruitment, randomisation, data collection procedures, and descriptions of the MST and MAU interventions. This is followed by methodology specific to the second phase of the trial, including the approaches to statistical and health economic analyses, and descriptions of the methodologies used for the two qualitative studies. The full description of the trial design and study methodology used in the first phase of the trial can be found in the protocol paper. 18

Trial design

The trial was a pragmatic, individually randomised, multicentre superiority study. Allocation was carried out by minimisation, controlling for the number of past convictions, gender and age at onset of criminal behaviour. Treatment centre was also included in the minimisation stratification to control for differences between centres.

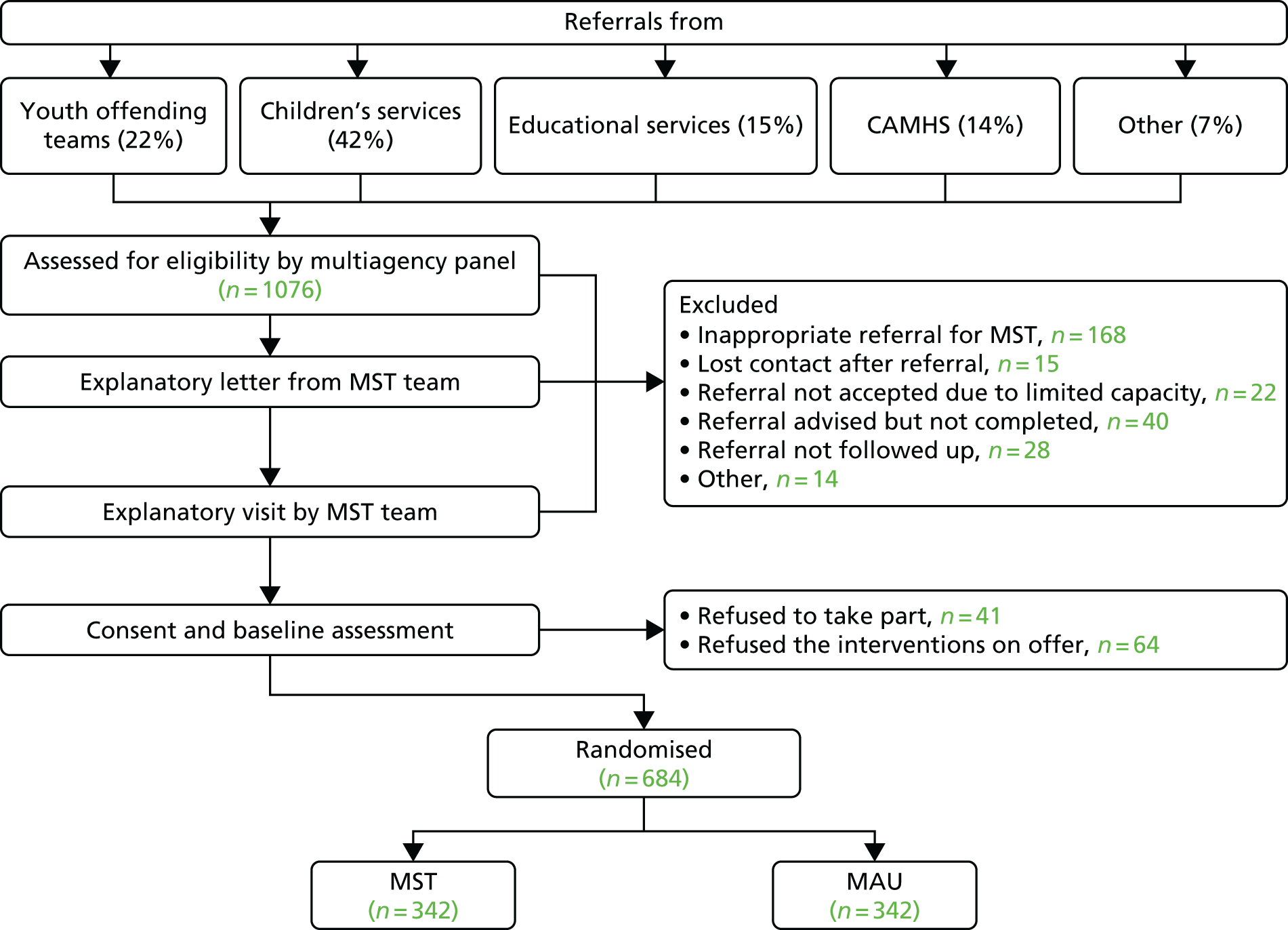

Figure 1 illustrates participant referral flow. Participants were referred to the trial by youth offending teams, children’s services, educational services, child and adolescent mental health services (CAMHS) and other referrers. Referred participants were screened for eligibility by a multiagency panel at each site. Those who met the inclusion criteria were considered eligible, and were sent a plain-English letter explaining the study and consent procedures and inviting them to take part. After a brief period (1–2 weeks), the families were contacted by a member of the MST team to arrange an explanatory meeting in person. This meeting was used to explain to the family what participation in the trial entailed and give them the opportunity to ask questions, but also to identify any potential exclusion criteria (e.g. risk of injury to worker, severe substance dependence). Unless the family decided at this stage to not take part, a member of the research team contacted them telephone, no longer than 3 days later, to arrange a second meeting. The second meeting entailed reviewing and completing consent forms, and completing pre-randomisation questionnaires and measures of the secondary outcomes in the study. Both information sheets and consent forms were written with input from families who had previously completed MST, and ensured to be appropriate and accessible in terms of language and age. Following the second meeting, if the family agreed to take part and no contraindications were identified, a member of the research team contacted the MST site to obtain allocation (1 : 1 ratio).

FIGURE 1.

Referral flow.

Assessments for secondary outcomes were conducted at baseline, and at 6, 12, 18, 24, 36 and 48 months post randomisation. Measures were typically completed in the family home. A member of the research team telephoned in advance to arrange the visit at a convenient time for the family. The questionnaire pack required approximately 2 hours to complete for both the young person and the parent or carer. After each visit, the family received £25 to thank them for their time.

Research assistants were carefully supervised on an ongoing daily basis by the trial co-ordinator, and had additional supervision meetings once every 2 weeks with the project co-ordinator, who had substantial experience in clinical and research activities with young people, including in MST.

The study protocol was approved by the London South-East Research Ethics Committee (reference number 09/H1102/55). The trial was overseen by the Trial Steering Committee and the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee. Both committees were independently chaired and reviewed trial progress throughout the study. Progress reports were submitted to the funder every 6 months. One serious adverse event was recorded: a participant in the MAU group had died. This participant had been seen by the research team at the 12-month follow-up, and news of their death was reported to the research team at 36 months. The sponsor and the ethics committee reviewed the case and agreed that the death was not related to the intervention or the trial.

Eligibility criteria for participants

The aim of the trial was to increase generalisability by using the minimum number of entry criteria. Young people were considered to be eligible for the trial if they met the following inclusion criteria:

-

were aged 11–17 years

-

had sufficient family involvement for MST to be applied, excluding adolescents already in local authority care or foster accommodation

-

had no existing agency involvement (e.g. the family were already engaged with a therapist) that would interfere with MST

-

met one of the following criteria indicating their suitability for MST:

-

– persistent (weekly) and enduring (≥ 6 months) violent and aggressive interpersonal behaviour OR

-

– a significant risk of harm to self or to others OR

-

– at least one conviction and three warnings, reprimands or convictions in the last 18 months OR

-

– current diagnosis of externalising disorder and a record of unsuccessful outpatient treatment OR

-

– permanent school exclusion.

-

Additional referral criteria were developed to reflect the different referral routes into the trial, including Youth Offending Services, Social Services, CAMHS and education services. As a result, eligible candidates could be referred if they met three of the following features indicative of ‘risk status’:

-

excluded or at significant risk of school exclusion

-

high levels of non-attendance at school

-

an offending history or at significant risk of offending

-

previous episodes on the Child Protection Register

-

previous episodes of being looked after

-

previous referral to family group conference to prevent young person from becoming looked after

-

history of siblings being looked after.

Exclusion criteria included:

-

history or current diagnosis of psychosis

-

generalised learning problems (clinical diagnosis) as indicated by intelligence quotient (IQ) below 65

-

risk of injury or harm to a worker

-

presenting issues for which MST has not been empirically validated, in particular substance abuse in the absence of criminal conduct or sex offending as the sole presenting issue. 18

Settings and locations in which the data were collected

Nine MST pilot sites across England participated in the trial: Peterborough, Leeds, Trafford, Barnsley, Sheffield, Reading, Hackney, Greenwich, and Merton and Kingston. Data were typically collected in the family home, or, in rare cases where this was not possible, at another safe, private and convenient location, such as a meeting room in a local authority building.

Chapter 3 Interventions

Key elements of the interventions are described below, but additional information can be found in Appendix 5. It should be noted that MST is a multifaceted programme and the MST intervention as described below is related specifically to MST implementation for young people with CD. Other MST adaptations exist for young people with substance misuse problems, problem sexual behaviour and psychiatric emergencies, and for family reunification for young people in care.

Multisystemic therapy

Multisystemic therapy is a manualised, licensed programme for young people exhibiting antisocial behaviour and their families. The programme uses a social-ecological approach with the aim of simultaneously affecting the multiple systems around the young person, including home life, school, peer relationships and the wider community. The techniques used in MST draw from cognitive–behavioural therapy, behavioural therapy, strategic family therapy and structural family therapy.

The MST therapist works intensively with the family, focusing primarily on the young person’s caregiver(s) to improve their parenting skills and the parent–child relationship, improve communication problems, foster support from social networks, encourage the young person’s participation in education and reduce any associations with delinquent peers. The intervention lasts between 3 and 5 months, depending on the family’s needs. Average treatment duration in this trial was 139 days. The therapists have a small caseload (four to six cases), meet with the family three times a week in the family home, and are available to be contacted 24 hours a day. The content of the programme is individualised to the specific needs of each family.

All nine trial sites were licensed by MST services to deliver the programme. Each MST team consists of at least three specially trained clinicians supervised by an accredited MST supervisor. Each team is offered weekly 1-hour conference calls for consultation with a staff member of MST services. Clinical teams additionally benefit from input and collaboration with local mental health-care professionals with postgraduate qualifications in the field of psychology, counselling or social work.

Treatment fidelity is maintained through (1) manualised weekly group supervision with a MST expert from MST services, (2) a well-developed quality assurance system and twice-yearly implementation reviews, and (3) the Therapist Adherence Measure – Revised (TAM-R). The TAM-R assessment is evaluated using a rating scale completed by a research assistant by speaking with the parents or carers. These assessments were carried out by an independent research group to maintain research separation and prevent possible researcher bias. Results from the first phase of the trial (baseline to 18 months) found good levels of treatment adherence, with an average TAM-R score of 0.698 (standard error 0.012, range 0.610–0.806) across all sites; the cut-off point for satisfactory adherence is 0.61.

After completing the MST programme, participants in the MST group received MAU.

Management as usual

Because this was a pragmatic trial involving several collaborating services across nine different sites, it was never possible to prespecify MAU content. As a result, MAU consisted of the standard care offered to young people and families who met eligibility criteria for the trial. There was a significant amount of variability in the MAU group in the type of care offered, the duration and intensity of care, and practitioners’ theoretical approaches. However, it was expected that all treatment approaches were designed in line with current community practice and treatment guidelines issued by the Social Care Institute for Excellence and NICE. Families in the MAU group were offered services specific to their particular needs (e.g. intervention for substance misuse or support for re-engaging with education). A range of professionals was involved in MAU care, including social workers, probation officers and specialist therapists.

Service use was monitored using a version of the Child and Adolescent Service Use Schedule (CA-SUS) designed specifically for the trial. The CA-SUS recorded contact with all health, social care and criminal justice sector services, including the number and duration of contacts. Results suggest that MAU programmes were multicomponent, no less resource-intensive than MST, and consistent with the complex needs and difficulties of this population. The use of MAU services in both the MST and the MAU groups, including mean number of contacts, total duration of all contacts and percentage of young people making use of each service, can be found in Table 1. At 12 months’ follow-up, the MST group had slightly briefer contacts with all services combined [t(484) = 2.03; p = 0.0429], but these differences were no longer observed at 18 months.

| Follow-up time point | Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MAU | MST | |||||

| Number (SD) of contacts | Duration (SD) of contacts (minutes) | Number (%) used | Number (SD) of contacts | Duration (SD) of contacts (minutes) | Number (%) used | |

| Baseline | ||||||

| CAMHS | 1.42 (3.9) | 75.61 (222.9) | 72 (25.3) | 2.47 (9.7) | 128.79 (495.1) | 72 (24.7) |

| Social care | 4.74 (10.7) | 252.33 (815.5) | 122 (42.9) | 5.45 (12.4) | 344.77 (949.7) | 123 (42.2) |

| YOT | 6.12 (14.2) | 290.6 (715.9) | 87 (30.6) | 5.17 (11.8) | 321.96 (1644.6) | 82 (28.1) |

| 6-month follow-up | ||||||

| CAMHS | 1.5 (6.0) | 94.41 (417.3) | 53 (19.9) | 2.13 (8.4) | 267.95 (2443.8) | 56 (22.3) |

| Social care | 5.82 (16.2) | 286.28 (711.2) | 102 (38.3) | 4.42 (11.5) | 250.05 (821.4) | 91 (36.2) |

| YOT | 4.47 (10.8) | 222.07 (613.2) | 67 (25.1) | 4.93 (11.3) | 240.7 (600.3) | 70 (27.8) |

| 12-month follow-up | ||||||

| CAMHS | 4.02 (19.1) | 547.04 (4050.1) | 50 (20.4) | 1.66 (7.3) | 77.03 (270.6) | 57 (23.8) |

| Social care | 5.44 (15.4) | 318.85 (1179) | 92 (37.5) | 4.52 (9.8) | 256.24 (679.3) | 91 (38) |

| YOT | 5.07 (13.7) | 228 (587) | 57 (23.2) | 4.59 (14.7) | 194.18 (554.9) | 55 (23) |

| 18-month follow-up | ||||||

| CAMHS | 6.84 (21.3) | 729.19 (4250) | 89 (40) | 6.27 (19.9) | 486.35 (3066.3) | 89 (42.5) |

| Social care | 13.93 (27) | 716.67 (1553.1) | 138 (62.1) | 12.43 (22.4) | 722.71 (1576.8) | 122 (58.3) |

| YOT | 14.21 (29.9) | 640.53 (1415.9) | 87 (39.1) | 12.92 (24) | 584.38 (1175.1) | 92 (44) |

Chapter 4 Outcomes

The primary outcome [i.e. the proportion of young people with criminal conviction(s) in the MST group compared with MAU at 5-year follow-up] was assessed using objective data from the PNC. The police database export includes offence date, offence type, offence outcome (e.g. conviction, caution) and disposal category (e.g. immediate custody, community service, caution). Offence outcomes are classified as violent, non-violent or breach for the purposes of the analysis.

Table 2 contains a summary of the secondary measures and time points at which data were collected. Appendix 1, Table 20, contains additional data on internal consistency of the measures used (where applicable).

| Measure name | Measure construct(s) | Collected at (time point) | Completed by | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 6 months | 12 months | 18 months | 24 months | 36 months | 48 months | Parent | Young person | Teacher | ||

| Family Information Form | Demographic information | ✗ | (If necessary) | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| SDQ20 | Antisocial behavioural problems and beliefs, and young people’s and parental well-being | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| ICUT21 | Callous and unemotional traits | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| SRD22 | Conduct problems | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| ABAS23 | Antisocial behaviour and attitudes | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Youth Materialism Scale24 | Materialistic values | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Conners Comprehensive Behavior Rating Scale (ADHD and Learning & Language subscales)25 | ADHD symptoms | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| APQ26 | Parenting controls, and skills for monitoring and supervision | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Loeber Caregiver Questionnaire27 | Family functioning (parental supervision and involvement) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| FACES-IV28 | Family functioning (family adaptability and cohesion) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| LEE29 | Family functioning (levels of expressed emotions) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| CTS230 | Degree of conflict in the parental relationship | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| SMF31 | Well-being and adjustment | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| GHQ32 | Screen for minor psychiatric disorders | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| DAWBA33 | Psychiatric disorders | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| WASI-II34 | Child IQ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||||

| Expectancies Questionnaire | Nature of delivery of interventions in MST and MAU groups | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| CPAS35 | Nature of delivery of interventions in MST and MAU groups | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| RTC | Nature of delivery of interventions in MST and MAU groups | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| CA-SUS | Data on use of all services and other resource use | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| EQ-5D-3L measure of health-related quality of life36 | QALYs | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |

| CLES-A37 | Significant life events | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| SF-3638 | Quality of life | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| ARQ39 | Psychological resilience | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| K-SADS40 | Screening for affective disorders and schizophrenia | ✗ | ✗a | ||||||||

| ASR41 | Behavioural and emotional problems | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| ABCL41 | Behavioural and emotional problems | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||||||

| Adult Materialism Scale42 | Materialistic values | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗a | ||||||

| SCID40 | Screening for personality disorders | ✗ | ✗a | ||||||||

| National Pupil Database | Educational participation (attendance and exclusions) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | |||||||

Changes to trial outcomes

Educational attainment (number of absences and exclusions) was initially intended to be collected from the National Pupil Database. However, it became apparent during the first phase of the trial that the data available from the database are collected over rigid time periods tied to school term dates. As a result, the data could not be reliably matched to the data collection points for the participants in the study, and therefore were not collected during the second phase. Data on whether participants were in full- or part-time education or employment were still collected as part of the Adult Self-Report measure and the Work and Relationships questionnaire.

The trial initially included an intention to carry out a characterisation of the MST and MAU services using the Children and Young People – Resources, Evaluation and Systems Schedule (CYPRESS) measure. This was unfortunately not possible during the second phase of the trial. Most of the MST sites had closed by 24-month follow-up and it was not possible to contact the practitioners associated with the MAU services delivered in the first phase of the trial, who had frequently left their posts or were no longer delivering the relevant service. As a result, a meaningful CYPRESS evaluation was not possible. However, we include a report on the CYPRESS evaluation carried out during the first phase of the trial in Appendix 6.

The Child Attachment Interview was trialled, but was determined to be not acceptable to the young people within the sample, and was therefore discontinued in favour of retaining the collaboration of the participants.

Sample size

Annual recruitment into MST was estimated at 140 families per year. Of these, approximately 30% were estimated to meet the criteria and agree to randomisation. By this calculation, each site was estimated to be able to recruit and treat about 70 families over 1.5 years, for a total of 700 participants (350 in each group). On the assumption that 30% of the MAU group would have out-of-home placements, this sample size would give 86% power to detect a 10% difference in out-of-home placements (a reduction from 30% to 20%).

Randomisation

Participants who met the criteria and screening procedures were randomised on a 1 : 1 basis by an assistant from University College London’s Trials Unit who was independent of the trial team.

Randomisation was initiated by the research assistant using a secure telephone randomisation service that ensured both allocation and concealment. A computer-generated algorithm incorporating a random element generated the allocation using the following stratification factors: treatment centre, gender, age (11–14, 15–17 years), age at onset of severe conduct problems (2–11, ≥ 11 years) and number of past convictions (≤ 2/≥ 3). These strata were selected because previous research has shown that younger age at onset and more previous convictions are associated with poorer prognosis. Minimisation ensured an even distribution of participants across both treatment groups.

Investigators and RAs were blind to treatment allocation. Allocation data were kept physically inaccessible to investigators and RAs to avoid leakage of the information. All coding, data entry and data cleaning were conducted by research team members blind to allocation. Treatment fidelity was assessed by a geographically separate research group who did not have access to outcomes.

Patient and public involvement

Each MST site had its own dedicated patient and public involvement group, which met regularly to advocate for patients and liaise with the clinical team. These groups were independent of the trial and provided an extra layer of oversight to service delivery. The trial itself had patient involvement at both the planning and the delivery stages. During study design, a meeting was organised by Music and Change UK, a mental health charity that advocates for young people. The purpose of the meeting was to receive feedback from young advisors on the study methodology and content. During the course of the study, a Trial Steering Committee met regularly to discuss the study progress and resolve arising issues. The committee included a patient-public liaison member: this was a parent of a young person with similar mental health and behavioural problems to those of the young people who took part in the study. The parent was able to advise the committee and the research team on conducting the research in a mindful way and keeping family perspectives in mind.

Chapter 5 Statistical methods

All analyses, except where specified, were prespecified in a statistical analysis plan agreed with the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee.

Missing data

All analyses were performed with statistical methods that handle missing outcome data that are missing at random. That is, the probability of an observation being missing depends only on observed variables that are accounted for in the model.

As an additional analysis, we used multiple imputation on a data set with all baseline and outcome variables. Twenty complete data sets were imputed using predictive mean matching. Pooled analyses were performed using Rubin’s rules. 43 This analysis should be treated as exploratory, as it will be using postbaseline data in the imputation, meaning that comparisons between groups cannot be treated as causal.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was analysed using a mixed-effects logistic regression model with a fixed effect for treatment group allocation. The model was adjusted for number of convictions prior to randomisation, gender, age at onset of criminal behaviour (early or late) as fixed effects, and site as a random effect. The model was fitted in R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) using the glmer function in the library lme4.

The primary analysis estimated the effect of group (i.e. the OR between MAU and MST) from the model, along with the CI and p-value, calculated from the Wald test, for whether or not the difference is significant.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes were analysed according to whether they were time-to-event, count data or continuous data.

The time-to-event outcome (time to first offence) was analysed using a Cox proportional hazards model adjusted for the same fixed effects as the primary outcome.

The count data outcomes (number of offences, and delinquency volume and variety outcomes) were analysed using Poisson mixed models adjusted for the same fixed and random effects as the primary outcome. An additional baseline effect was included for the delinquency outcomes representing the measurement at the baseline.

The continuous outcomes (all questionnaire outcomes) were analysed with a linear mixed-effects model adjusted for the same fixed effects as the primary outcome. In addition, a random intercept and slope for each individual were included.

For both the count and the continuous outcomes, separate treatment effects for each follow-up time were included. The estimated treatment effect for each time, together with the CI and p-value, was extracted directly from the model.

For young person outcomes that are measured only in participants aged ≥ 18 years, we treated observations not taken because of age as missing.

Subgroup analyses

The primary outcome and time to first offence outcome were tested for subgroup effects, with the following moderators considered:

-

gender

-

age

-

onset of CD (≤ 11 years vs. > 11 years old)

-

baseline Inventory of Callous-Unemotional Traits (ICUT) score*

-

baseline peer delinquency score*

-

baseline Antisocial Beliefs and Attitudes Scale score*

-

previous offence or no previous offence at baseline

-

diagnosis of CD or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder at baseline

-

diagnosis of CD, depression or anxiety at baseline

-

referral path.

Variables marked with * were treated as continuous variables, and the others were treated as binary.

For the primary analysis results, two-sided p-values < 0.05 were considered significant. For secondary outcomes, there was a considerable multiple testing burden. We applied a procedure called Benjamini–Hochberg44 to control the false-discovery rate at 5%. The false-discovery rate is the proportion of rejected null hypotheses that are in fact true (i.e. the proportion of positive findings that are in fact false positives). Thus, we do not control the probability of making any type I error, but control the proportion of significant results that are type I errors to be < 5%. This procedure was applied separately to the non-imputed and imputed analyses.

Chapter 6 Economic evaluation

Please note that in this chapter some material has been reproduced from the protocol paper (Fonagy et al. 18). This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

The economic evaluation took a wide-ranging perspective and included all health, social care and education-based services, plus costs falling on the criminal justice sector, costs resulting from crimes committed and out-of-pocket expenses for trial participants. 17 Although a NHS/Personal Social Services perspective is preferred for submissions to NICE,45 this perspective is likely to be too narrow to capture all of the relevant costs associated with this population.

The primary economic evaluation, a cost–utility analysis, was undertaken, using QALYs as the measure of effect. A secondary analysis explored cost-effectiveness in terms of the primary outcome, namely the proportion of the sample with criminal convictions over the follow-up period. Both analyses were carried out at the 48-month follow-up point.

Resource use and costs

Resource use was recorded in interviews with young people and their families using CA-SUS. 46,47 For this medium- to long-term follow-up of the original trial, the CA-SUS was completed at 30 months, for the period since the end of the trial (24 months), and at the 36-, 42- and 48-month follow-ups, covering service use for the period since the previous assessment of these data.

Resource use data were collected in the following domains:

-

delivery of the MST intervention

-

use of accommodation services – foster care, residential care, staffed accommodation

-

use of education services – mainstream school, specialist school, residential school, hospital school, pupil referral unit, home tuition, further education

-

use of NHS secondary care services – inpatient stays (mental health and all medical specialties), outpatient appointments (mental health and all medical specialties), accident and emergency attendances (including use of ambulance services)

-

use of community-based services – counsellor, family therapist, social worker, family support worker, education welfare officer, mentor, advice service

-

use of prescribed psychotropic medication – antidepressants, medication for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, benzodiazepines, medication for sleep disturbance, antipsychotics, antiepileptics

-

criminal justice system resource use – police custody, youth custody, probation officer, youth offending team, solicitor, court appearance. 17

Nationally applicable unit costs were applied to each item of service use reported in the CA-SUS to calculate the total costs for each trial participant. Unit costs for education services were taken from national statistics of school income and expenditure for local authority maintained schools in England for 2011–12 and 2012–13. 48 Unit costs for hospital services were taken from the national schedule of NHS Reference Costs 2012 to 2013. 49 Costs contained in the 2013 Unit Costs of Health and Social Care were used to calculate costs of accommodation and of community-based health, social and voluntary sector services. 50 The cost of medication was calculated based on averages listed in the British National Formulary51 for the generic drug and using daily dose information collected using the CA-SUS. Unit costs for the criminal justice sector were taken from the 2013 Unit Costs in Criminal Justice52 and reports from the Home Office on the cost of criminal justice. 53

The cost of the MST intervention was calculated using a standard microcosting approach54 and utilised data on salaries of therapists as well as employer on-costs (National Insurance and superannuation), and appropriate managerial, administrative and capital overheads and conditions of service. 50 Costs of MST training, provision of MST supervision and the MST licence were also incorporated into the total cost of the intervention. 17 A detailed costing schema of the MST intervention has been published previously. 17 All unit costs are reported in UK pounds sterling for the 2012–13 financial year and inflated where necessary. Costs and outcomes were discounted at a rate of 3.5% annually, as recommended by NICE. 45

Effectiveness

The primary outcome of the economic evaluation was QALYs, calculated from health states derived from the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L), measure of health-related quality-of-life instrument and using the area under the curve approach. 55 The EQ-5D-3L was completed at 30, 36, 42 and 48 months’ follow-ups.

Economic analysis

Service use was reported descriptively using means and standard deviations (SDs). No statistical comparisons were made in order to avoid problems with multiple significance testing.

Differences in costs and outcomes between trial groups were compared using random-effects linear regression. The total costs, as well as the costs per sector, over the 48-month follow-up period in each trial group were summarised using the mean and SD for two data sets: the observed data and the multiply imputed data. Analyses compared mean costs, despite the skewed nature of cost data, to enable inferences to be made about the arithmetic mean, which is the most meaningful summary statistic for cost. 56 The validity of the results was confirmed by examining CIs from bias-corrected accelerated non-parametric bootstrap. Differences in QALYs were compared using the mean and SD for three data sets: observed data, mean imputation of baseline data and multiply imputed data. Differences in proportion with criminal convictions were compared using the mean and SD for two data sets: observed data and multiply imputed data. In all cases, multiple imputation followed the approach described in Missing data.

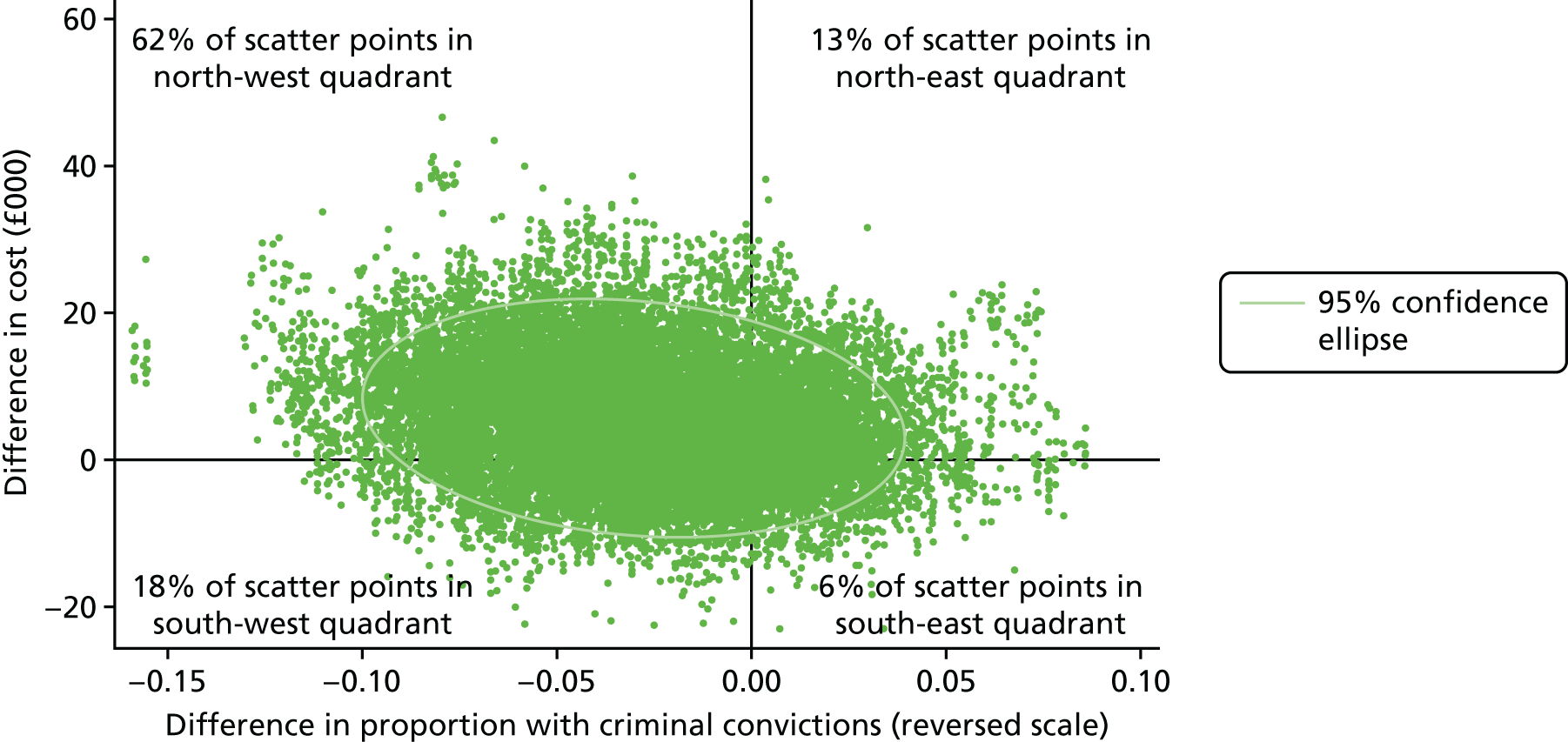

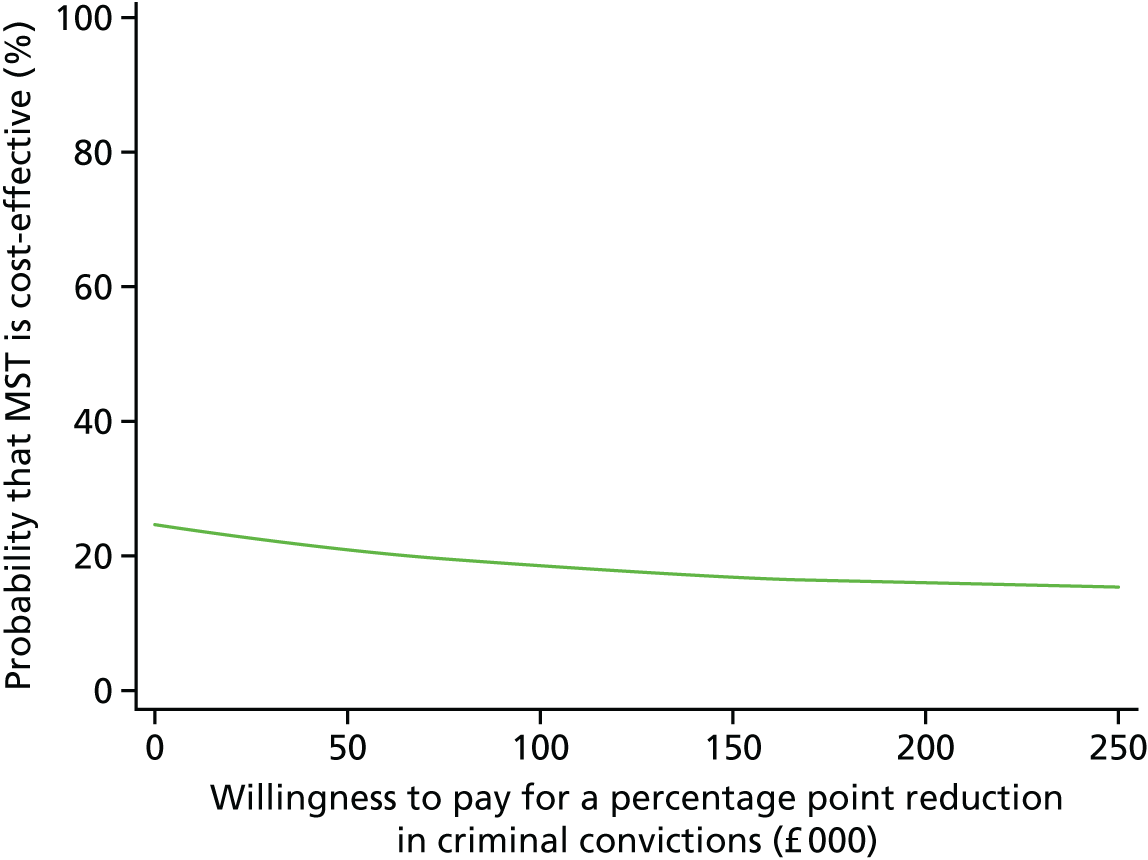

Cost-effectiveness of MST compared with MAU at 48 months’ follow-up was assessed by calculating incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs): the additional cost of one intervention compared with another divided by the additional effect. 17,57 ICERs are calculated from four sample means and are therefore subject to statistical uncertainty. Cost-effectiveness planes were generated using 1000 bootstrapped resamples from regression models of total cost and outcome by trial group. These were then used to calculate the probability that MST is the optimal choice for different values a decision-maker is willing to pay for a unit improvement in outcome (the ceiling ratio, λ). Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves are presented by plotting these probabilities for a range of possible values of λ to explore the uncertainty that exists around estimates of mean costs and effects, and to show the probability that MST is cost-effective compared with MAU. 17,58

In line with the clinical analyses, all economic analyses were controlled for treatment centre, number of previous convictions, gender and age at onset of criminal behaviour, plus the baseline measurement of the variables of interest.

As a result of an administrative error, the EQ-5D-5L was excluded from the outcome packs in the early stages of the original study, which resulted in extensive missing EQ-5D-3L data [68% (n = 462) at baseline, 49% (n = 336) at 6 months, 37% (n = 251) at 12 months, and 33% (n = 223) at 18 months], and economic analyses using QALYs were abandoned in the original economic evaluation. 17 Given that the data were missing completely at random, we have attempted to impute these missing values to generate a complete sample for economic analyses in the present study. The impact of missing data is explored in sensitivity analyses by employing different means of imputing these data, including multiple imputation, mean imputation and identification of an appropriate imputation value from the current literature.

Chapter 7 Qualitative study 1

Key aspects of the qualitative study design, methodology and outcomes are summarised in the main body of this report. Supplementary documents (interview schedules and coding frameworks) are available in Appendix 7, Tables 46–51.

Recruitment

Families taking part in the START trial were invited to take part in an optional qualitative interview about their experiences of MST following the completion of the 18-month follow-up period (i.e. approximately 1 year after finishing MST). Families who had completed their 18-month follow-up measures were approached to take part in the study. In total, 14 young people and 13 of their parents or carers agreed to be interviewed. Of the five families who did not take part, two initially agreed but an appointment could not be scheduled successfully, and three more did not respond to the letter and could not be reached by telephone.

Following the initial letter and information sheet inviting families to take part, families were contacted by telephone to arrange for the interview to take place. All interviews took place in the family home. Informed written consent procedures were completed immediately prior to the interview.

Participants

Of the young people who took part in the study, eight (57%) were male. The mean participant age at the time of interview was 16 years. Six were white British (43%), five were of mixed ethnicity (36%), two were black British (14%) and one participant was Asian (7%).

Procedure

Parents or carers and young people were interviewed separately using semistructured interview schedules. Questions were open-ended, with suggested prompts and follow-up questions. The interview schedules covered topics including participants’ experience of MST, changes (or lack thereof) during and after MST, and the ways in which participants believed MST helped (or did not help) them. The purpose of the interview and the interview schedule was to encourage participants to describe their experiences with MST from their own perspective and in their own words. Interviews were audio-recorded and lasted for an average of around 45 minutes for young people and 70 minutes for parents or carers.

Analysis

Audio-recordings of the qualitative interviews were transcribed verbatim. Transcripts were analysed using a framework analysis. 59 The method is a systematic analysis designed to facilitate analysis of large numbers of qualitative data. A thematic coding framework is developed first, which is then used to code occurrences of each thematic category within the entire data set. The process is dynamic, with both the coding framework and the coding patterns continuously revised throughout.

Chapter 8 Qualitative study 2

Similar to the first qualitative study, the main aspects of the methodology and results are summarised below, but supplementary material is available in Appendix 8.

Recruitment

The purpose of the second qualitative study was to evaluate the long-term impact of MST as young people began their transition into adulthood and how this affected their maturity levels, their relationships and their outlook on the future. Families who took part in the START trial were invited to take part in this study 4 years after baseline evaluation. In total, 32 young people agreed to take part in the study; 16 had been allocated to the MST group, and 16 had been allocated to the MAU group.

Participants

Participants were matched on the basis of age, gender and region where possible. Sixteen participants were male, with a mean age of 18.3 years (SD 1.25 years, range 17–21 years); the other 16 participants were female, with a mean age of 17.7 years (SD 1.01 years, range 16–19 years). Participants in the MST group were found to be significantly younger (mean age 17.4 years, SD 0.81 years) than those who received MAU [mean age 18.6 years, SD 1.21 years, t(30) 3.09; p < 0.01].

Procedure

Participants were approached following the completion of their 48-month follow-up measures. All interviews were conducted in the participants’ homes. The semistructured interviews lasted an average of 57 minutes (range 19−117 minutes). The interview schedule focused on recent events in the young person’s life (e.g. ‘how have things been going over the last month or so?’), on important life relationships (e.g. ‘how would you describe your relationship with your parents?’) and on the future (‘how do you feel about your future?’). MST-related questions began with a prompt (e.g. ‘do you remember working with [insert name] during [insert rough date]?’) and continued with a general question (‘what can you tell me about that?’).

Analysis

Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed verbatim and anonymised. Each transcript was analysed individually using interpretative phenomenological analysis. 60 A key organising construct emerged from this process: considering participant material in terms of how far it demonstrated a participant being forward-looking and hopeful in outlook (‘mature’) or static and frustrated (‘stuck’). Material illustrating this construct within each of four life domains (family relationships, peer relationships, child–adult transition and work-related experiences) was recorded in a table for each of the first 16 participants. Each entry in the tables was codified in terms of presence or lack of maturity and this coding system was then applied to the other 16 cases. The aim was to see whether or not there was a difference in the degree of maturity displayed between MST and MAU groups. The researcher ratings were then checked against an independent rater, blinded to condition.

Chapter 9 Results

This section will outline the baseline characteristics of the sample, including participant flow and attrition, demographic variables at baseline and diagnostic summary. We begin by focusing on the primary outcomes (offending), followed by the secondary; these are the results from self-report data pertaining to psychological and emotional well-being, social adjustment, family functioning, and behaviour, as reported by both the young person and their parent or carer. This is followed by the results of the economic analysis and the relative costs and cost-effectiveness of the interventions. The results of the qualitative studies presented here are not exhaustive; we aimed to emphasise the key findings and give some sense of the subjective lived experiences of the young people and their families who took part in the trial. However, we were conscious of not rendering the section inaccessible because of excessive length.

Participant flow

Although 684 participants were initially randomised, one participant asked to be entirely removed from the trial during the second phase (i.e. from the 24-month follow-up point onwards). As a result, the total number of participants in the second phase was 683.

Figure 2 illustrates participant flow at each follow-up point. Table 3 outlines the different reasons why data were not collected. Every effort was made to ensure that data were collected. The research team offered flexible appointments to the families in order to accommodate other commitments, in terms of both time and location. Communication was carried out by telephone calls, text messages, e-mails and letters, according to family preference or to minimise the loss of contact. Other professionals involved with the families also helped with engagement and sometimes facilitated data collection meetings. In Table 3, ‘dropped out’ refers to a participant who explicitly requested to no longer participate in the trial and to not be contacted. Data for each time point had a set time window within which they could be collected; if it was not possible to collect the data within that window, they were classed as ‘overdue’.

FIGURE 2.

Participant flow.

| Reason | Follow-up time point (n) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 24 months | 36 months | 48 months | |||||||

| MST | MAU | Both | MST | MAU | Both | MST | MAU | Both | |

| Data collected | 239 | 239 | 478 | 225 | 208 | 433 | 183 | 166 | 349 |

| Refused | 4 | 10 | 14 | 6 | 8 | 14 | 9 | 9 | 18 |

| Lost contact | 8 | 14 | 22 | 23 | 24 | 47 | 37 | 49 | 86 |

| Moved abroad | 3 | 1 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 3 | 8 |

| Failed attempts | 13 | 12 | 25 | 7 | 13 | 20 | 19 | 13 | 32 |

| Overdue | 11 | 17 | 28 | 10 | 25 | 35 | 11 | 24 | 35 |

| Unknown | 0 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Other | 6 | 4 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Dropped out | 58 | 40 | 98 | 68 | 60 | 128 | 76 | 76 | 152 |

| Total | 342 | 341 | 683 | 342 | 341 | 683 | 342 | 341 | 683 |

Follow-up measures took place between August 2011 (earliest 18-month follow-up point) and September 2016 (latest 48-month follow-up point). Offending data were additionally collected up to September 2017.

Baseline data

Tables 4 and 5 outline the demographic and diagnostic characteristics of the young people in the sample at baseline. Appendix 2, Table 21, contains data on the routine care received by young people in each group at baseline.

| Characteristic | Group | |

|---|---|---|

| MST (N = 342) | MAU (N = 342) | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 13.7 (1.4) | 13.9 (1.4) |

| Sex, n (%) | ||

| Female | 126 (37) | 124 (36) |

| Male | 216 (63) | 218 (64) |

| Socioeconomic status (range 1–6), mean (SD) | 3.0 (1.4) | 2.9 (1.3) |

| Proportion on state benefits or earning < £20,000 each year, n (%) | 258 (75) | 267 (78) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | ||

| White British/European | 261 (76) | 274 (80) |

| Black African/Afro-Caribbean | 38 (11) | 33 (10) |

| Asian | 6 (2) | 10 (3) |

| Mixed/other | 34 (10) | 17 (5) |

| Marital status of parent(s) or carer(s), n (%) | ||

| Single or widowed | 142 (42) | 131 (38) |

| Separated or divorced | 77 (23) | 59 (17) |

| Married or cohabiting | 123 (36) | 147 (43) |

| Average number of siblings,a mean (SD) | 2.5 (1.3) | 2.5 (1.4) |

| Number with siblings offending, n (%) | 118 (35) | 126 (37) |

| Offences in the year before referral | ||

| Non-offender on referral, n (%) | 124 (36) | 111 (32) |

| Total number of offences, mean (SD) | 1.1 (2.2) | 1.2 (2.5) |

| Violent offences, mean (SD) | 0.4 (1.0) | 0.4 (0.9) |

| Non-violent offences, mean (SD) | 0.5 (1.2) | 0.6 (1.3) |

| Number with custodial sentences, n (%) | 4 (1) | 6 (2) |

| Diagnosis | Group, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| MST (N = 342) | MAU (N = 342) | |

| CD | 262 (77) | 270 (79) |

| Oppositional defiant disorder | 14 (4) | 14 (4) |

| Any CD | 274 (80) | 280 (82) |

| Social phobia | 12 (4) | 9 (3) |

| Obsessive–compulsive disorder | 1 (< 1) | 2 (1) |

| Post-traumatic stress disorder | 25 (7) | 26 (8) |

| Separation anxiety disorder | 7 (2) | 15 (4) |

| Specific phobia | 6 (2) | 13 (4) |

| Generalised anxiety disorder | 6 (2) | 9 (3) |

| Panic disorder | 5 (1) | 3 (1) |

| ADHD combined | 113 (33) | 91 (27) |

| ADHD hyperactive-impulsive | 8 (2) | 3 (1) |

| ADHD inattentive | 13 (4) | 12 (4) |

| Pervasive developmental disorder or autism | 3 (1) | 4 (1) |

| Eating disorders | 2 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Tic disorder | 7 (2) | 4 (1) |

| Major depression | 30 (9) | 42 (12) |

| Any emotional disorder | 73 (22) | 90 (26) |

| Mixed anxiety and CD | 46 (13) | 56 (16) |

| Number without diagnosis | 50 (15) | 50 (15) |

| Number of Axis I diagnoses, mean (SD) | 1.5 (1.0) | 1.5 (1.1) |

| Onset of CD | 148 (43) | 149 (44) |

| ICUT score, mean (SD) | 33.5 (9.7) | 32.7 (9.6) |

| Peer delinquency score (SRDM), mean (SD) | 5.0 (4.7) | 4.9 (4.7) |

Outcomes and estimation

Primary outcome

There were no significant differences between the MST and MAU groups in the proportion of young people with a recorded criminal conviction at the 60-month follow-up. In the MST group, 55% (188 out of 342) had a criminal conviction at this end point, compared with 53% (180 out of 341) of those in the MAU group (OR 1.13, 95% CI 0.82 to 1.56; p = 0.44).

Interaction tests were carried out for prespecified subgroups. Of these, only baseline peer delinquency score was found to be significant (p = 0.015). The effects of gender, age, onset of CD, baseline ICUT score, baseline Antisocial Beliefs and Attitudes Scale score, offender status at baseline, diagnosis of CD or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder at baseline, and diagnosis of CD, depression or anxiety at baseline were not significant; all p-values can be found in Table 6.

| Variable | Interaction p-value |

|---|---|

| Sex | 0.077 |

| Age | 0.46 |

| Onset of CD | 0.81 |

| Baseline ICUT score | 0.46 |

| Baseline peer delinquency score | 0.015 |

| Baseline ABAS score | 0.21 |

| Offender status at baseline | 0.67 |

| Diagnosis of CD or ADHD at baseline | 0.82 |

| Diagnosis of CD, depression or anxiety at baseline | 0.87 |

| Referrer path | N/Aa |

Secondary offending outcomes

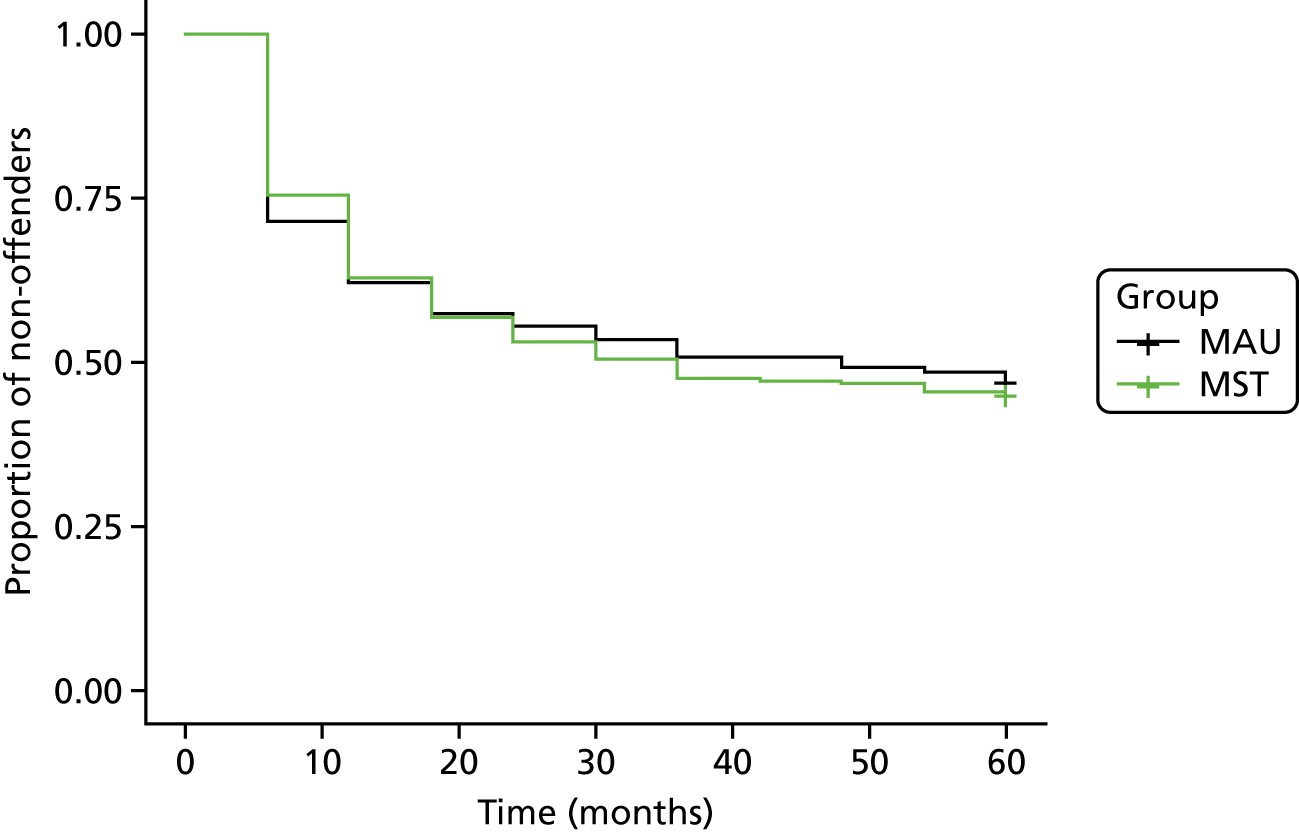

No group differences were found in median time to first offence; median value was 36 months post baseline for the MST group, and 48 months for the MAU group (HR 1.03, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.26; p = 0.78). There was a significant interaction of baseline peer delinquency scores (p = 0.015), but not of any of the other prespecified subgroups (p > 0.05). Figure 3 illustrates the proportion of non-offenders over the follow-up period.

FIGURE 3.

Kaplan–Meier plot of time to first offence. Reprinted from The Lancet Psychiatry, volume 7, Fonagy et al. , Multisystemic therapy versus management as usual in the treatment of adolescent antisocial behaviour (START): 5-year follow-up of a pragmatic, randomised controlled, superiority trial, pp. 420–30,19 copyright (2020), with permission from Elsevier.

There were significantly more overall offences in the MST group than in the MAU group at 24, 36 and 48 months’ follow-up. The mean number of offences in the MST group at 24 months was 0.75 compared with 0.41 in the MAU group (adjusted mean difference 0.37 offences, 95% CI 0.05 to 0.69 offences; p = 0.024). At 36 months, young people in the MST group had an average of 0.45 offences, compared with 0.37 in the MAU group (adjusted mean difference 0.38, 95% CI 0 to 0.69; p = 0.048). At 48 months, those in the MST group had an average of 0.39 offences compared with 0.38 in the MAU group (adjusted mean difference 0.38 offences, 95% CI 0.03 to 0.72 offences, p = 0.033). However, these differences were no longer present at the 60-month follow-up. There were also no significant group differences when the numbers of violent and non-violent offences were analysed separately. Tables 7–9 contain a summary of secondary offending outcomes.

| Follow-up time point | Group, mean number | Difference (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MST | MAU | |||

| 24 months | 0.75 | 0.41 | 0.35 (0.03 to 0.67) | 0.031 |

| 36 months | 0.45 | 0.37 | 0.33 (–0.02 to 0.67) | 0.063 |

| 48 months | 0.39 | 0.38 | 0.35 (0 to 0.69) | 0.049 |

| 60 months | 0.30 | 0.28 | –0.08 (–0.46 to 0.31) | 0.700 |

| Follow-up time point | Group, mean number | Difference (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MST | MAU | |||

| 24 months | 0.22 | 0.12 | 0.15 (–0.26 to 0.57) | 0.78 |

| 36 months | 0.12 | 0.11 | –0.01 (–0.49 to 0.47) | 0.96 |

| 48 months | 0.11 | 0.14 | 0.11 (–0.37 to 0.58) | 0.66 |

| 60 months | 0.08 | 0.08 | –0.29 (–0.85 to 0.28) | 0.32 |

| Follow-up time point | Group, mean number | Difference (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MST | MAU | |||

| 24 months | 0.32 | 0.18 | 0.34 (–0.03 to 0.71) | 0.075 |

| 36 months | 0.20 | 0.17 | 0.34 (–0.08 to 0.75) | 0.110 |

| 48 months | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.38 (–0.04 to 0.8) | 0.078 |

| 60 months | 0.10 | 0.11 | –0.15 (–0.67 to 0.37) | 0.560 |

Young person-rated secondary end points

After correcting for multiple testing, there were no significant group differences on any of the self-report measures completed by young people between the 24- and 48-month follow-ups.

The full results of the secondary outcomes completed by young people can be found in Appendix 3, Tables 22–35.

Analyses of employment and education did not yield significant group differences. At the 48-month follow-up, 70% of young people in the MST group were in education or employment, compared with 82% of those in the MAU group (OR 0.53, 95% CI 0.27 to 1.03; p = 0.062).

There were also no differences in pregnancy (becoming pregnant or fathering a pregnancy), with 17% of young people reporting a pregnancy over the course of the follow-up period in the MST group, compared with 22% in the MAU group (OR 0.72, 95% CI 0.46 to 1.13; p = 0.16).

Parent-rated secondary end points

Parents in the MAU group (mean 8.22) reported higher scores on the Inconsistent Discipline subscale of the Alabama Parenting Questionnaire than those in the MST group (mean 7.74) at the 24-month follow-up (95% CI –1.05 to –0.24; p = 0.0023). The differences were no longer significant at the 36- and 48-month follow-ups.

No other group differences were statistically significant after correcting for multiple testing. The full results of the parent-rated secondary outcomes can be found in Appendix 4, Tables 36–45.

Economic evaluation

Data completeness

Service-use data were available for 313 (92%) participants in the MST group and 298 (87%) participants in the MAU group. Three participants in the MST group and two in the MAU group were identified as influential outliers,61 that is, with total costs in the 99th percentile, and were removed from the analysis. As noted in Chapter 2, because of an administrative error, the EQ-5D-3L measure was excluded from the outcome pack at the beginning of the trial, so complete health-related quality of life data were available for only 95 (27%) participants in the MST group and 72 (21%) participants in the MAU group. The availability of EQ-5D-3L data at each time point is summarised in Table 10.

| Follow-up time point | Group, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| MST | MAU | |

| Baseline | 111 (32) | 110 (32) |

| 6 months | 190 (55) | 158 (46) |

| 12 months | 223 (65) | 210 (62) |

| 18 months | 244 (71) | 218 (64) |

| 24 months | 240 (70) | 217 (64) |

| 36 months | 213 (62) | 184 (54) |

| 48 months | 167 (49) | 141 (41) |

| Complete | 95 (27) | 72 (21) |

Resource use over follow-up

The use of services over the period from study entry to 48 months’ follow-up was broadly similar across the two groups and is detailed in Table 11. Accident and emergency was the most commonly used secondary health-care service in both groups (accessed by 53% of MST and 56% of MAU participants), whereas general practitioner (GP) contacts in a GP surgery were the most commonly used primary-care service (used by 70% in MST and 73% in MAU), and around 50% in both groups had contact with a social worker. Criminal justice system services were also commonly used across both groups, with a high proportion of participants reporting contacts with police (61% in MST and 64% in MAU) and stays in police custody (28% in MST and 30% in MAU). Time spent in foster and residential care was longer in the MST group (total 29 days on average in MST, 18 days in MAU), but use of staffed accommodation was higher in the MAU group (14 days MST, 18 days MAU). The majority of young people were registered in mainstream education at some point over the follow-up period (58% MST, 57% MAU), but a relatively large proportion were registered in specialist schools (26% in both groups) or pupil referral units (29% MST, 26% MAU).

| Service | Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MST (n = 310) | MAU (n = 296) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | Range | % using | Mean (SD) | Range | % using | |

| MST (hours of direct contact) | 35.65 (24.49) | 0–114 | 75 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Accommodation | ||||||

| Foster care (days) | 11.77 (64.03) | 0–746 | 7 | 7.64 (40.79) | 0–418 | 7 |

| Residential care (days) | 17.06 (79.28) | 0–556 | 6 | 10.36 (68.03) | 0–953 | 5 |

| Staffed accommodation (days) | 14.45 (56.34) | 0–365 | 11 | 18.26 (72.38) | 0–641 | 11 |

| Other (days) | 3.77 (21.90) | 0–207 | 5 | 5.26 (35.59) | 0–378 | 5 |

| Education | ||||||

| Mainstream school (hours) | 1124.56 (1453.50) | 0–6020 | 58 | 958.43 (1323.47) | 0–9360 | 57 |

| Specialist school (hours) | 293.78 (729.36) | 0–5629 | 26 | 301.94 (874.59) | 0–10,355 | 26 |

| Residential school (hours) | 21.46 (163.25) | 0–2063 | 3 | 26.38 (214.87) | 0–3120 | < 1 |

| Hospital school (hours) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3.70 (37.47) | 0–488 | < 1 |

| Pupil referral unit (hours) | 198.00 (423.63) | 0–2290 | 29 | 168.00 (370.49) | 0–2275 | 26 |

| Home tuition (hours) | 22.95 (135.40) | 0–1430 | 7 | 10.84 (64.31) | 0–780 | 6 |

| Further education (hours) | 421.61 (635.50) | 0–3120 | 50 | 422.47 (664.70) | 0–3868 | 50 |

| Secondary health care | ||||||

| Inpatient stay (nights) | 0.71 (3.23) | 0–44 | 15 | 3.48 (26.99) | 0–365 | 21 |

| Outpatient appointments (contacts) | 1.99 (5.20) | 0–40 | 35 | 2.37 (9.15) | 0–143 | 39 |

| Accident and emergency (contacts) | 1.40 (2.93) | 0–20 | 53 | 2.03 (4.83) | 0–62 | 56 |

| Community based | ||||||

| GP: home (contacts) | 0.21 (0.84) | 0–7 | 9 | 0.29 (1.87) | 0–28 | 8 |

| GP: surgery (contacts) | 5.64 (10.75) | 0–137 | 70 | 6.07 (9.38) | 0–76 | 73 |

| GP: telephone (contacts) | 0.45 (1.74) | 0–20 | 12 | 0.29 (1.83) | 0–28 | 8 |

| Practice nurse (contacts) | 0.82 (2.62) | 0–25 | 26 | 1.06 (4.97) | 0–76 | 26 |

| District nurse, health visitor, midwife or school/college nurse (contacts) | 2.16 (8.70) | 0–86 | 18 | 2.31 (8.92) | 0–100 | 22 |

| Community paediatrician (contacts) | 0.05 (0.28) | 0–3 | 4 | 0.07 (0.49) | 0–6 | 3 |

| Care co-ordinator, case manager, key worker (contacts) | 5.25 (28.37) | 0–312 | 12 | 4.88 (21.77) | 0–198 | 15 |

| Psychiatrist (contacts) | 0.66 (2.81) | 0–35 | 13 | 1.34 (5.76) | 0–55 | 15 |

| Clinical psychologist (contacts) | 0.56 (2.69) | 0–30 | 12 | 1.75 (9.02) | 0–83 | 14 |

| CAMHS worker (contacts) | 2.32 (8.39) | 0–89 | 25 | 3.61 (9.77) | 0–75 | 32 |

| Community psychiatric nurse (contacts) | 0.25 (1.97) | 0–27 | 4 | 0.48 (4.37) | 0–53 | 4 |

| Counsellor (contacts) | 1.71 (7.18) | 0–73 | 12 | 2.74 (10.25) | 0–104 | 17 |

| Family therapist (contacts) | 0.54 (4.19) | 0–50 | 4 | 0.93 (3.96) | 0–39 | 10 |

| Art/drama/music/occupational therapy (contacts) | 0.16 (1.57) | 0–26 | 3 | 0.31 (2.28) | 0–26 | 4 |

| Social worker (contacts) | 11.55 (24.12) | 0–214 | 47 | 11.73 (20.29) | 0–117 | 54 |

| Family support worker (contacts) | 4.97 (17.56) | 0–160 | 22 | 7.19 (22.12) | 0–176 | 26 |

| Social services youth worker (contacts) | 1.91 (11.12) | 0–156 | 8 | 1.98 (10.16) | 0–113 | 11 |

| Accommodation key worker (contacts) | 4.70 (24.26) | 0–232 | 12 | 1.52 (9.76) | 0–135 | 7 |

| Educational psychologist (contacts) | 0.53 (3.80) | 0–52 | 7 | 0.33 (2.26) | 0–28 | 6 |

| Education welfare officer (contacts) | 2.67 (11.71) | 0–113 | 17 | 0.61 (2.78) | 0–26 | 13 |

| Connexions worker (contacts) | 3.21 (9.84) | 0–100 | 37 | 4.44 (11.80) | 0–80 | 36 |

| Mentor (contacts) | 6.92 (27.53) | 0–228 | 18 | 5.86 (22.37) | 0–214 | 19 |

| Drug/alcohol support worker (contacts) | 2.42 (8.70) | 0–65 | 15 | 2.10 (8.27) | 0–77 | 15 |

| Advice service, e.g. Citizens Advice, housing association, careers advice (contacts) | 1.02 (4.70) | 0–52 | 13 | 0.84 (4.33) | 0–52 | 12 |

| Helpline (contacts) | 0.52 (8.52) | 0–150 | 3 | 0.03 (0.22) | 0–2 | 2 |

| Complementary therapist (contacts) | 0.07 (0.79) | 0–12 | 1 | 0.32 (5.23) | 0–90 | 1 |

| Criminal justice system | ||||||

| Police custody (days) | 3.93 (28.35) | 0–364 | 28 | 1.20 (4.08) | 0–44 | 30 |

| Youth custody (days) | 3.32 (20.53) | 0–180 | 5 | 5.08 (28.31) | 0–231 | 6 |

| Probation officer (contacts) | 2.27 (14.57) | 0–180 | 6 | 2.09 (10.60) | 0–120 | 9 |

| Youth offending team worker (contacts) | 16.64 (43.73) | 0–396 | 37 | 17.25 (38.48) | 0–264 | 39 |

| Police (contacts) | 11.49 (29.50) | 0–305 | 61 | 14.61 (58.70) | 0–675 | 64 |

| Solicitor (contacts) | 2.15 (6.04) | 0–63 | 36 | 1.96 (4.66) | 0–46 | 34 |

| Court appearance as victim (number) | 0.07 (0.48) | 0–5 | 4 | 0.04 (0.24) | 0–3 | 3 |

| Court appearance as defendant (number) | 1.31 (4.48) | 0–63 | 29 | 1.28 (4.23) | 0–46 | 29 |

The use of services over the long-term follow-up period only, between the 24-month and 48-month follow-up, is detailed in Table 12. Again, service use was broadly similar across the two groups during this period and the patterns of use differed little. Accident and emergency remained the most commonly used secondary health-care service in both groups (accessed by 36% in MST and 40% in MAU), and GP contacts in a GP surgery remained the most commonly used primary health-care service (accessed by 60% in MST and 62% in MAU). Police contacts were higher in the MST group (45% in MST vs. 36% in MAU), but there was little difference between the groups in terms of other criminal justice sector resources. In terms of education, as would be expected given the age of the population, a smaller proportion of young people were registered to attend mainstream school over the 24- to 48-month follow-up period, and a larger proportion were in further education.

| Service | Group | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MST (n = 300) | MAU (n = 286) | |||||

| Mean (SD) | Range | % using | Mean (SD) | Range | % using | |

| Accommodation | ||||||

| Foster care (days) | 9.27 (50.94) | 0–646 | 6 | 6.51 (38.69) | 0–358 | 4 |

| Residential care (days) | 16.75 (76.79) | 0–540 | 6 | 8.20 (54.64) | 0–720 | 4 |

| Staffed accommodation (days) | 14.83 (57.09) | 0–365 | 11 | 18.35 (73.14) | 0–641 | 10 |

| Other (days) | 3.06 (21.09) | 0–207 | 3 | 3.60 (31.29) | 0–360 | 3 |

| Education | ||||||

| Mainstream school (hours) | 339.70 (735.60) | 0–5577 | 28 | 257.06 (757.88) | 0–9360 | 25 |

| Specialist school (hours) | 126.81 (413.96) | 0–3120 | 15 | 149.42 (706.76) | 0–10,205 | 22 |

| Residential school (hours) | 17.71 (159.46) | 0–2062 | 2 | 23.45 (206.58) | 0–3120 | 4 |

| Hospital school (hours) | – | – | – | 1.71 (28.86) | 0–488 | < 1 |

| Pupil referral unit (hours) | 56.68 (221.74) | 0–1980 | 11 | 73.63 (246.04) | 0–2275 | 13 |

| Home tuition (hours) | 10.59 (100.80) | 0–1320 | 3 | 1.06 (8.86) | 0–102 | 2 |

| Further education (hours) | 316.51 (513.90) | 0–3120 | 45 | 309.91 (547.07) | 0–3560 | 44 |

| Secondary health care | ||||||

| Inpatient stay (nights) | 0.41 (1.89) | 0–16 | 9 | 2.87 (24.13) | 0–365 | 14 |

| Outpatient appointments (contacts) | 1.19 (3.94) | 0–40 | 24 | 1.70 (8.75) | 0–140 | 28 |

| Accident and emergency (contacts) | 0.70 (1.30) | 0–9 | 36 | 0.89 (1.67) | 0–11 | 40 |

| Community based | ||||||

| GP: home (contacts) | 0.13 (0.64) | 0–7 | 6 | 0.26 (1.88) | 0–28 | 6 |

| GP: surgery (contacts) | 3.75 (9.05) | 0–130 | 60 | 4.06 (7.49) | 0–53 | 62 |

| GP: telephone (contacts) | 0.31 (1.17) | 0–10 | 1 | 0.24 (1.76) | 0–28 | 8 |

| Practice nurse (contacts) | 0.70 (2.64) | 0–25 | 18 | 0.75 (3.39) | 0–46 | 18 |

| District nurse, health visitor, midwife or school/college nurse (contacts) | 1.73 (8.39) | 0–86 | 13 | 1.41 (5.54) | 0–53 | 15 |

| Community paediatrician (contacts) | 0.03 (0.24) | 0–3 | 2 | 0.02 (0.22) | 0–3 | 1 |

| Care co-ordinator, case manager, key worker (contacts) | 3.83 (20.49) | 0–217 | 11 | 2.67 (17.09) | 0–198 | 10 |

| Psychiatrist (contacts) | 0.44 (2.52) | 0–33 | 8 | 0.87 (4.69) | 0–52 | 9 |

| Clinical psychologist (contacts) | 0.32 (2.12) | 0–30 | 7 | 0.72 (4.88) | 0–52 | 7 |

| CAMHS worker (contacts) | 1.47 (6.21) | 0–59 | 15 | 1.86 (7.10) | 0–60 | 19 |

| Community psychiatric nurse (contacts) | 0.14 (1.26) | 0–16 | 2 | 0.34 (3.49) | 0–52 | 2 |

| Counsellor (contacts) | 0.86 (3.59) | 0–26 | 9 | 1.72 (8.98) | 0–104 | 9 |

| Family therapist (contacts) | 0.17 (2.34) | 0–40 | 2 | 0.30 (2.43) | 0–29 | 3 |

| Art/drama/music/occupational therapy (contacts) | 0.13 (1.54) | 0–26 | 2 | 0.15 (1.63) | 0–26 | 2 |

| Social worker (contacts) | 6.74 (15.79) | 0–116 | 36 | 6.34 (14.09) | 0–100 | 36 |

| Family support worker (contacts) | 3.14 (14.10) | 0–160 | 16 | 3.73 (16.43) | 0–169 | 15 |

| Social services youth worker (contacts) | 1.69 (11.11) | 0–156 | 6 | 1.26 (8.49) | 0–100 | 6 |

| Accommodation key worker (contacts) | 4.31 (23.06) | 0–232 | 10 | 1.26 (8.38) | 0–105 | 6 |

| Educational psychologist (contacts) | 0.25 (3.07) | 0–52 | 3 | 0.05 (0.28) | 0–2 | 3 |

| Education welfare officer (contacts) | 1.24 (7.54) | 0–100 | 8 | 0.21 (1.69) | 0–26 | 5 |

| Connexions worker (contacts) | 2.05 (7.98) | 0–100 | 27 | 2.54 (8.21) | 0–61 | 27 |

| Mentor (contacts) | 1.77 (7.64) | 0–65 | 8 | 1.97 (12.05) | 0–176 | 9 |

| Drug/alcohol support worker (contacts) | 1.40 (6.75) | 0–65 | 10 | 1.16 (5.58) | 0–49 | 9 |

| Advice service, e.g. Citizens Advice, housing association, careers advice (contacts) | 0.99 (4.75) | 0–52 | 12 | 0.85 (4.40) | 0–52 | 12 |

| Helpline (contacts) | 0.53 (8.66) | 0–150 | 2 | 0.03 (0.22) | 0–2 | 2 |

| Complementary therapist (contacts) | 0.07 (0.77) | 0–12 | 1 | 0.01 (0.18) | 0–3 | < 1 |

| Criminal justice system | ||||||

| Police custody (days) | 3.67 (28.68) | 0–363 | 19 | 0.58 (2.65) | 0–37 | 17 |

| Youth custody (days) | 1.40 (14.24) | 0–180 | 1 | 3.31 (23.40) | 0–210 | 2 |

| Probation officer (contacts) | 2.31 (14.78) | 0–180 | 5 | 1.32 (7.52) | 0–72 | 6 |

| Youth offending team worker (contacts) | 9.53 (38.53) | 0–396 | 22 | 8.14 (23.72) | 0–192 | 23 |

| Police (contacts) | 5.42 (20.07) | 0–200 | 45 | 6.52 (35.55) | 0–481 | 36 |

| Solicitor (contacts) | 1.40 (4.75) | 0–60 | 25 | 0.93 (2.51) | 0–20 | 24 |

| Court appearance as victim (number) | 0.04 (0.39) | 0–5 | 2 | 0.02 (0.21) | 0–3 | 2 |

| Court appearance as defendant (number) | 1.13 (4.41) | 0–62 | 24 | 1.01 (3.94) | 0–45 | 23 |

The use of prescribed psychotropic medication is summarised in Table 13. Antidepressants were most frequently prescribed in both groups (used by 12% of participants), and a slightly greater proportion in the MAU group used medication than in the MST group.

| Medication type | Group, % prescribed | |

|---|---|---|

| MST (n = 310) | MAU (n = 296) | |

| Antidepressants | 12 | 12 |

| ADHD | 11 | 11 |

| Benzodiazepines | 0 | < 1 |

| Sleep disturbance | 4 | 5 |

| Antipsychotics | 1 | 3 |

| Antiepileptics | < 1 | 2 |

Costs over follow-up

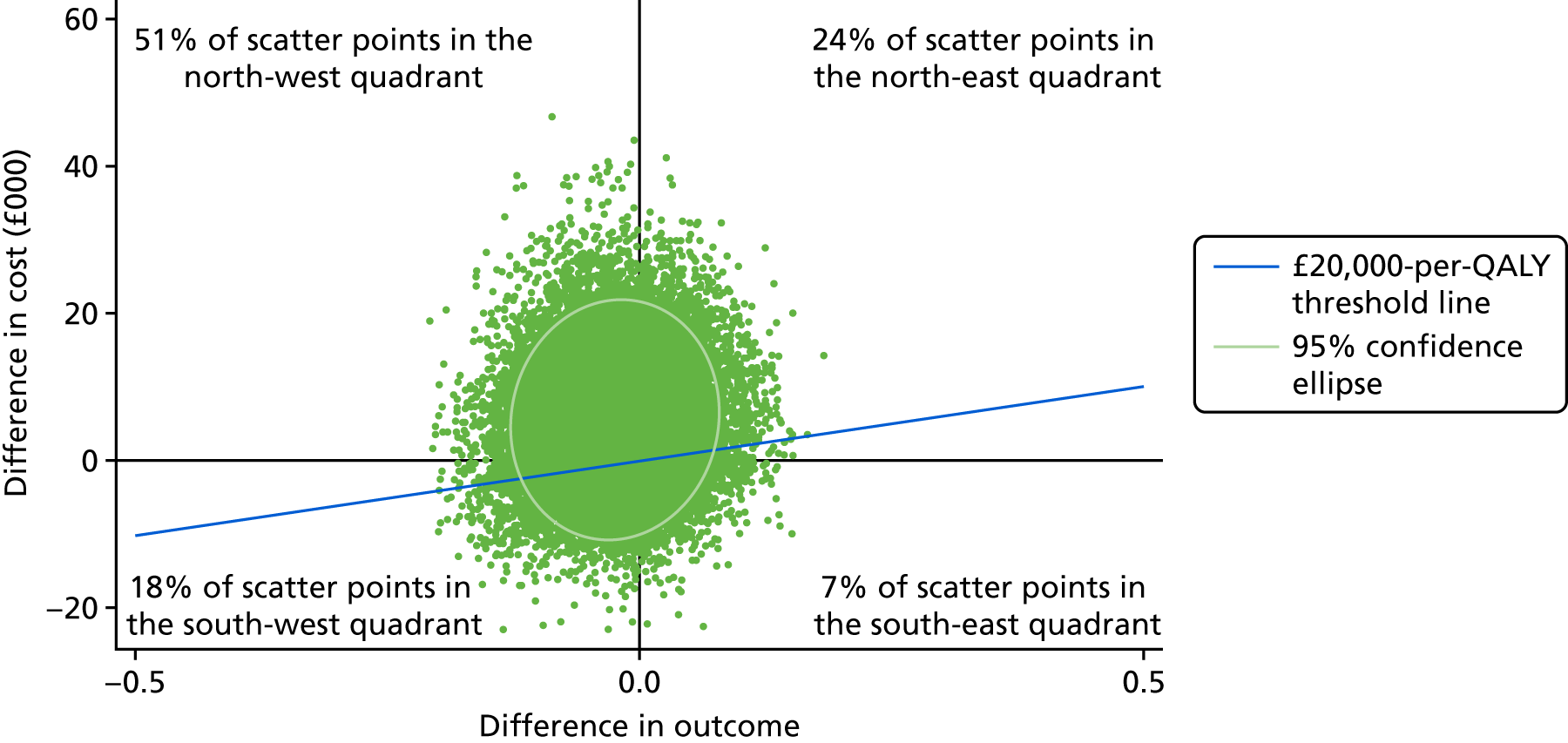

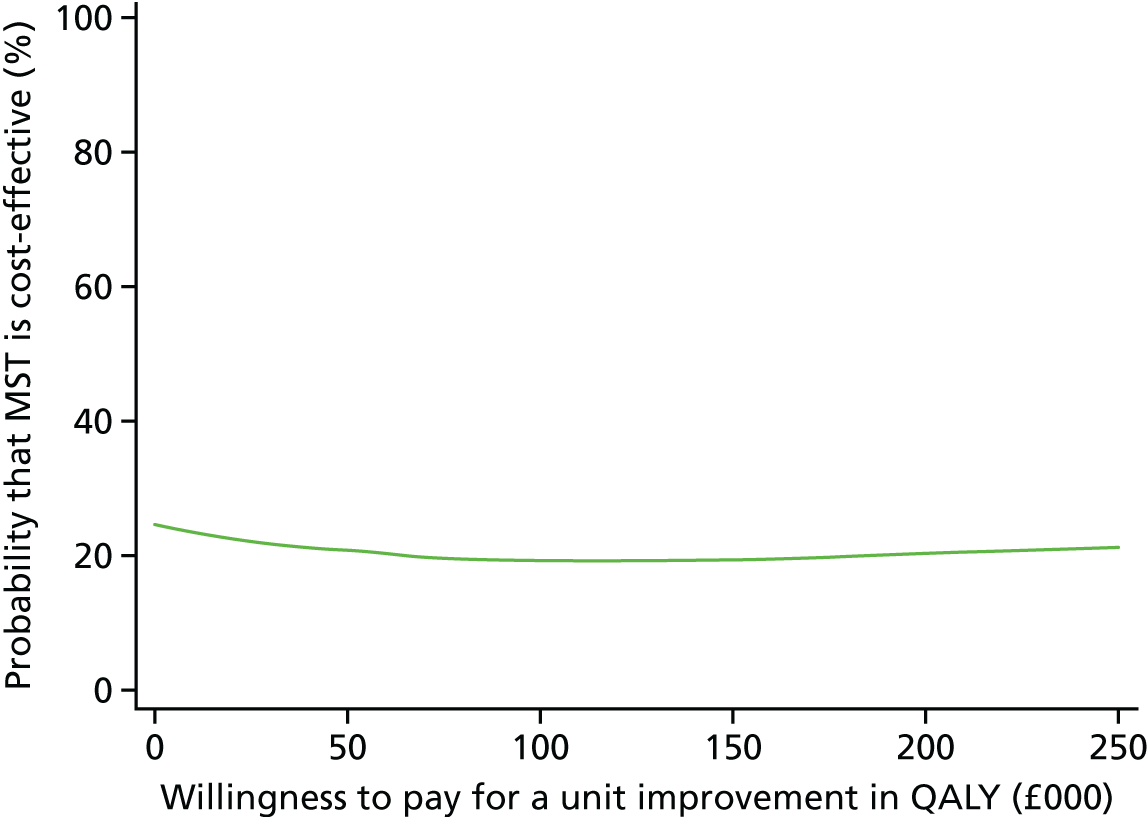

The total costs per participant over the 48-month follow-up period for observed and multiply imputed data are summarised in Table 14. For observed data, total mean costs of services used were slightly higher for the MST group (£52,846.46) than for the MAU group (£51,582.36). However, this difference was not statistically significant (adjusted mean difference £481.51, 95% CI –£10,374.50 to £11,337.51; p = 0.931). The total costs were also higher, by a greater magnitude, in the MST group than in the MAU group for multiply imputed data (£62,579.80 for MST and £55,983.17 for MAU). However, this difference was also not statistically significant (adjusted mean difference £5629.48, 95% CI –£11,163.70 to £22,422.67; p = 0.511). The majority of the total costs comprised criminal justice services costs and community services costs, both of which were higher in the MST group, but these differences were very small and not statistically significant (adjusted mean difference of £58.09 for community services and £200.92 for criminal justice services).

| Service | Group, mean (SD) | Difference | 95% CI | p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MST | MAU | Mean (MST – MAU) | Adjusted mean (MST – MAU) | |||

| Observed | (n = 310) | (n = 296) | ||||

| Intervention | 2132.57 (1810.46) | 2132.57 | 2128.86 | 1888.29 to 2369.42 | < 0.0001 | |

| Accommodation | 3972.15 (12,554.36) | 4133.77 (17,615.73) | –161.62 | –304.00 | –2745.36 to 2137.36 | 0.807 |

| Education | 9465.69 (15,968.87) | 8736.11 (18,457.71) | 729.58 | 1013.44 | –1645.85 to 3672.72 | 0.454 |

| Secondary health care | 805.74 (2064.53) | 2503.71 (15,617.96) | –1697.97 | –1650.53 | –3404.31 to 103.25 | 0.065 |

| Community services | 15,479.16 (34,953.72) | 15,369.85 (27,817.58) | 109.31 | 58.09 | –4980.52 to 5096.70 | 0.982 |

| Medication | 194.92 (1871.70) | 188.58 (1592.41) | 6.33 | 4.29 | –276.05 to 284.64 | 0.976 |

| Criminal justice | 21,353.46 (42,097.75) | 20,920.34 (38,634.21) | 433.12 | 200.92 | –6105.67 to 6507.51 | 0.950 |

| Total | 52,846.46 (69,254.61) | 51,852.36 (67,148.76) | 994.10 | 481.51 | –10,374.50 to 11,337.51 | 0.931 |

| Multiply imputed | (n = 342) | (n = 341) | ||||

| Total | 62,579.80 (6817.81) | 55,983.17 (5189.48) | 6596.63 | 5629.48 | –11,163.70 to 22,422.67 | 0.511 |

Outcomes over follow-up period

Table 15 summarises EQ-5D-3L utility scores over the follow-up period. Utility scores were higher in the MAU group than in the MST group at both baseline and 48 months’ follow-up. The mean utility scores decreased over the trial period in both groups (from 0.885 to 0.767 for MST and from 0.912 to 0.833 for MAU).

| Follow-up time point | Group | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MST | MAU | |||

| n | Mean score (SD) | n | Mean score (SD) | |

| Baseline | 100 | 0.885 (0.194) | 98 | 0.912 (0.139) |

| 6 months | 184 | 0.882 (0.188) | 151 | 0.906 (0.153) |

| 12 months | 216 | 0.889 (0.189) | 199 | 0.874 (0.205) |

| 18 months | 237 | 0.882 (0.196) | 214 | 0.885 (0.174) |

| 24 months | 236 | 0.885 (0.197) | 215 | 0.887 (0.182) |

| 36 months | 209 | 0.869 (0.225) | 183 | 0.862 (0.197) |

| 48 months | 163 | 0.767 (0.308) | 140 | 0.833 (0.243) |

Table 16 summarises QALYs over follow-up for three data sets: observed data, mean imputation of baseline data and multiply imputed data. In all cases, QALYs were slightly lower in the MST group than in the MAU group, but none of these differences was significant. In the observed data, mean QALYs were 3.219 in the MST group compared with 3.360 in the MAU group (adjusted mean difference –0.123 QALYs, 95% CI –0.289 to 0.042 QALYs; p = 0.142). Using mean imputation of missing baseline results, a recommended approach for dealing with missing baseline data,62 QALYs were 3.172 in the MST group compared with 3.300 in the MAU group (adjusted mean difference –0.091 QALYs, 95% CI –0.247 to 0.064 QALYs; p = 0.246). Multiple imputation of missing data resulted in much smaller differences (adjusted mean difference –0.025 QALYs, 95% CI –0.131 to 0.081 QALYs; p = 0.643). No suitable imputation value was identified from current literature, so this analysis was not undertaken.

| Data set | Group | Difference | 95% CI | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MST | MAU | |||||||

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | Mean (MST – MAU) | Adjusted mean (MST – MAU) | |||

| Observed data | 95 | 3.219 (0.611) | 72 | 3.360 (0.437) | –0.142 | –0.123 | –0.289 to 0.042 | 0.142 |

| Mean imputation of baseline data | 163 | 3.172 (0.613) | 140 | 3.300 (0.460) | –0.128 | –0.091 | –0.247 to 0.064 | 0.246 |