Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 15/137/01. The contractual start date was in May 2017. The final report began editorial review in February 2019 and was accepted for publication in November 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Ian D Maidment was a member of the West Midlands National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Research for Patient Benefit Committee (January 2014 to December 2018). Geoff Wong is Joint Deputy Chair of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment Programme Prioritisation Committee A. Andrew Booth holds several NIHR committee memberships: NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) Funding Committee (2018 to present), Systematic Reviews Programme Advisory Group (2018 to present) and the Complex Reviews Advisory Group (2015 to 2018). He is also co-director of the NIHR HSDR Evidence Synthesis Centre and a newly awarded NIHR Public Health Research Evidence Synthesis Centre. Sylvia Bailey is a member of Pharmacy Research UK Scientific Advisory Panel.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Maidment et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

I didn’t take all [these medications] at once. It’s gradually built up. You wonder where it’s all going to end.

OP29 – older person

I just feel overwhelmed sometimes about making that decision. It just feels too much sometimes.

C32 – informal carer

You’ve attempted to address your responsibility as a clinician with a responsibility of a budget. And you know, the population side of it. But you’ve also done what you think is best for the individual in front of you. That’s the challenge.

P53 – general practitioner

Overview

The number and proportion of older people in the UK population is increasing. 1,2 In terms of their health, many older people are living with more than one long-term condition. 1,3,4 There are challenges in living with multimorbidity, such as reduced quality of life and increasing amounts of time spent engaging with health and care services. 5–9

Older people are taking increasing numbers of medications to treat multimorbidity. 10 There are burdens11–15 and risks8,16 from medication taking and medication management that fall disproportionately on older people. Medication-related adverse events include both medication errors and side effects. 17–20 These events have been estimated to be responsible for 5700 deaths and cost the UK £750M annually. 21 More recently, definitely avoidable adverse drug reactions have been estimated to cost the NHS £98.5M every year and have contributed to 1708 deaths. 22

Burdens and risks also have an impact on informal carers1,2,23–26 and practitioners involved in supporting older people’s health and care. 3,4,6,8,27–29

These circumstances raise significant challenges for older people, informal carers, and health and care practitioners and services.

In light of these challenges, the MEdication Management in Older people: Realist Approaches Based on Literature and Evaluation (MEMORABLE) study seeks to understand how medication management works and to propose interventions that will contribute to making improvements. 30,31

Older people

In the UK in 2010, more than 10 million people were aged > 65 years. 32 According to the Office for National Statistics:2

The UK population is ageing – around 18.2% of the UK population were aged 65 years or over at mid-2017, compared with 15.9% in 2007; this is projected to grow to 20.7% by 2027.

In 2017, one in five people in the UK population was over the age of 65 years and this is expected to increase to one in four by 2037. Longevity is linked to lifestyle improvements as well as advances in technology and health care. 2

Older people’s health: multimorbidity

As they age, some older people are living with multimorbidities that affect their lives. These are conditions that cannot be cured but can be managed with medication and other treatments. 3 In 2011, just over half of those aged > 65 years resident in the community reported having long-term conditions affecting what they do, day to day. 1 Many older people aged ≥ 75 years are living with two or more long-term conditions. 4

There are challenges for older people who are living with multimorbidity and for their families, practitioners and services. These challenges arise from a reduction in quality of life, increasing difficulties with day-to-day activities and more time spent engaging with and being supported by the health and care system. 5–8

These challenges are exacerbated when they are also associated with increasing cognitive impairment or a diagnosis of dementia. 19,33–36

Medication taking among older people: polypharmacy

As a result of more people living with multimorbidity, older people’s medication use including prescribed and over-the-counter treatments has ‘increased dramatically’ over the last 20 years:10

The number of [older] people taking five or more items quadrupled from 12 to 49%, while the proportion of people who did not take any medication has decreased from around 1 in 5 to 1 in 13.

Gao et al. 10

There can be clinical indications for polypharmacy such as in diabetes mellitus or hypertension for example, or among older people with multimorbidity. 3,37 However, there are also risks, including adverse drug reactions involving side effects and drug interactions6 as well as side effects associated and unique to each different medication. 17–19 For a health service that developed around curing acute, single conditions and treatments, multimorbidity and polypharmacy are emerging as areas of concern, with implications for policy and practice. 27,29,38–44

Burdens and risks

Older people experience burden as a result of their experience of ageing, multimorbidity and polypharmacy. 11–15,42 Polypharmacy, intended to assist with the management of symptoms and conditions, also has risks associated with it, such as drug–drug and drug–disease interactions, inappropriate prescribing, risks of non-adherence to complex drug regimens and medication errors. 7,16–19 Patients should be protected from avoidable harm. 45 Nonetheless, harms continue,20,46,47 leading to significant costs. 21

Informal carers and practitioners

Informally, many older people rely on family carers to manage their medications. 48 The number of informal carers is growing and the demands on them are increasing, according to the Office for National Statistics’ report in 2013:1

In 2011, 14 per cent (1.3 million) of the household population aged 65 and over provided unpaid care (this includes: looking after a partner, older parent, or adult child); this included 6.9 per cent who provided 1-19 hours unpaid care a week, 1.8 per cent who provided 20-49 hours of unpaid care a week, and 5.6 per cent who provided 50 hours or more unpaid care a week.

Formally, within health and care, a range of practitioners provide services to support older people along complex care pathways. 4,6,8 They too face a number of challenges; for example, the evidence base for practitioners can be based on evidence for a single diagnosis41 and services can appear fragmented and communication between them difficult. 3,5,6,9,28

The MEMORABLE study

The MEMORABLE study has been designed and carried out in response to the background outlined above. It uses realist methodology49–51 to understand how, why, for whom and in what circumstances medication management works. With that understanding, MEMORABLE then proposes interventions that will contribute to improvements. To achieve these purposes, its aims and objectives are set out below (taken from the protocol for this study). 30

Aim

To use realist synthesis including primary data collection to develop a framework for a novel multidisciplinary, multiagency intervention(s) to improve medication management in older people who have complex medication regimens and are resident in the community.

Objectives

Underpinning the overall aim were three linked objectives. The second and third objectives, in particular, were closely related. Objective 2 was focused on the key principles and underlying mechanisms, whereas objective 3 was more focused on developing an applied intervention based on the findings from earlier objectives:

-

to understand how and why any potentially relevant interventions to optimise medication management work (or do not work) for particular groups of older people in certain circumstances

-

to synthesise the findings from objective 1 into a realist programme theory of an intervention(s) to support older people living in the community to manage their medication

-

to use realist programme theory developed from objective 2 to inform the development of an intervention(s) to assist older people living in the community to manage their medication.

Chapter 2 sets out the methods by which this research has been carried out, from which the findings are reported in Chapter 3.

Chapter 2 Methods

This chapter sets out the way MEMORABLE was carried out. It describes the research groups that contributed to MEMORABLE, provides an overview of the realist research methodology and sets out the work packages and steps followed in this realist research process. Additional MEMORABLE documents are available at www2.aston.ac.uk/lhs/research/memorable (accessed March 2020), including information on those involved in the project and recording how it progressed (e.g. minutes, newsletters).

Research groups/patient and public involvement

The MEMORABLE study was supported by a number of working groups that provided its governance, management and delivery structure. These are listed below in the order in which they were established, along with details of their membership, activities, outputs and contributions to the study as a whole. These groups enhanced the capacity of the staff employed on MEMORABLE, Dr Ian Maidment (the Chief Investigator) and Dr Sally Lawson (the Research Associate) and enriched the range of experience and expertise available from the start to the end of the study.

Co-applicant Group

This was an informal group of five individuals who were invited by the chief investigator to collaborate on the development of the initial research proposal. Support and advice about the need for the research also came from a patient and public involvement (PPI) event in November 2015 run by Dr Maidment and the research’s PPI lead, Mrs S Bailey. The event involved eight older people and their informal carers.

The Co-applicant Group brought together topic, practice, research, information and public participation interests in medication management. Members collaborated on the development and submission of the MEMORABLE proposal to the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). They generated the initial Protocol31 and MEMORABLE’s first published paper: Developing a framework for a novel multi-disciplinary, multi-agency intervention(s), to improve medication management in community-dwelling older people on complex medication regimens (MEMORABLE) – a realist synthesis. 30 The Co-applicant Group evolved into the Project Group.

Project Group

With an established membership of nine, this group was the monthly reference point for work on MEMORABLE, responsible for overseeing the project and disseminating the research. Members provided expertise in medication management, medicine, nursing, pharmacy, research and information methodology, and PPI. This group was key to maintaining momentum in the research and assuring delivery of the protocol.

Stakeholder Group

This group had a more fluid membership than the Project Group, including experts by experience, practitioners, managers and researchers. It had an independent lead from within the Project Group, who co-chaired it with the Chief Investigator. It met on five occasions to review key outputs from the research. Each meeting lasted for about 1.5 hours. Meetings were scheduled to fit with the evolution of the research and the need to gain diverse input from multiple perspectives. The group provided advice and feedback to the Project Group on the veracity of the emerging evidence, programme theories and proposed interventions, as well as the dissemination strategy. It had an important role in making sure that recommendations from the research were appropriate, practicable and likely to make a difference for older people, informal carers and practitioners.

Research Team

This small team of five included the chief investigator and the research associate. It was one of the key sources of topic, practice, research and information expertise for MEMORABLE. It met five times to consider discussion papers prepared by the research associate. Meetings were usually face to face and lasted for half a day, with follow-up contact by telephone and e-mail, if needed. It was the forum to engage in extended discussion and debate, and to resolve topic and research issues. The team significantly augmented the expertise available to the chief investigator and research associate, and provided detailed support to and scrutiny of the research, its content and outputs.

Patient and public involvement

While this study was being carried out, the Project Group regularly checked what was being done. The group had a PPI lead who was a co-applicant for the study and who contributed to all meetings, and is a co-author of this report. The PPI lead also provided advice on the way MEMORABLE was engaging with older people and informal carers, including advice on the types and the content of information, as well as facilitating links with potential participants in the research. In addition, the Stakeholder Group provided advice on findings and recommendations as these emerged from the study. This group had several older people and informal carers on it, along with people working in health, care and research. Both groups contributed to the dissemination strategy for MEMORABLE. The researchers valued and benefited from people’s expert, experiential input to the many discussions and debates. However, they also acknowledge the difficulties of ensuring that there is PPI ‘representation’ and the need to consider the workload (volume and time scale) that such a complex study can create for a single PPI lead.

Realist methodology

This section sets out some of the principles of realist methodology49,51–54 with a short account of the way that they were applied in MEMORABLE. Work packages and steps in the research process has the more detailed account of how these principles were followed in practice.

Realist approach

This theory-driven approach helps explain the way complex interventions work in real-world situations. It supports the identification of what works, for whom, why and in which circumstances: the methodology’s four ‘W’s. 49–53,55,56 Thus, it enables researchers to address complexity53 by unpacking the context-sensitive mechanisms that are the generative causal processes found within an intervention. 49,51,57 Realist approaches are interested in the behaviours of those involved, from individuals to groups and organisations; the influential factors that bring about, prevent or modify those behaviours; and the outcomes that result, intended and unintended. One of the purposes of this approach is ‘to improve the thinking that goes into service building’. (Reproduced from Pawson et al. 50 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 3.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/.)

As medication management can be understood as a complex intervention,58,59 the characteristics and purpose of realist methodology are particularly well aligned to meeting MEMORABLE’s aims and objectives.

Realist review and realist evaluation

Realist methodology has two arms. The first, realist review, explores data from secondary sources such as published studies and reports60 and the second, realist evaluation, engages with primary data. 61 MEMORABLE was set up as a realist synthesis, combining realist review with realist evaluation. In this approach, knowledge from the literature was analysed with the first-hand experiences of those engaged in medication management, augmenting the potential contribution of both data sets to theorising about how this complex intervention works.

Theory in realist methodology

Two levels of theory are associated with the realist approach: programme theory and substantive theory.

Programme theory is generated within a study to explain what the intervention has been set up to do and how that intervention might work. 51,60 Initial or candidate programme theories developed at the start of a realist research project are then confirmed, refined or refuted through iterations of data synthesis. 50,51,53 Finalised, evidence-based programme theories can inform the development of recommendations or specific proposals. These might involve modifying an existing intervention, or perhaps suggesting a new intervention to try to achieve the outcomes that matter, typically by addressing contextual influences.

In addition to the iterative way programme theories evolve, they have another characteristic which is that they are finally formulated at a ‘middle-range’ level of abstraction. 51 This means that the programme theory is specified in a way that permits empirical testing. Both realist reviews and realist evaluations aim to produce middle-range realist programme theories. Being realist in nature contributes to the transferability of theories to other settings in which that same intervention may be delivered, or even to other interventions. This transferability is based on the assumption that in other settings or interventions the same mechanisms may be in operation. This is the way that realist methodology contributes to the accumulation of knowledge. 55,62 Candidate or initial programme theories for MEMORABLE were drafted at the beginning of the research: see Step 4: Candidate programme theories and substantive theory. Final programme theory for a key stage in medication management is contained in Figure 5.

Underpinning the analytical work on programme theories are the context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configurations. 51,53,56 Generated from the data, they have explanatory potential in their configured format. It is, therefore, important that they are set out and reported in their entirety rather than disaggregated into lists of single components. 63 CMO configurations contain:

-

Contexts – influential factors that activate people’s responses, enabling or inhibiting their decisions and actions. In MEMORABLE, contexts can include older people’s diagnoses or medication, the interpersonal relationships they have with health and care practitioners as well as system factors such as access to services or information.

-

Mechanisms – the vital but often hidden operational ‘cogs’ that turn in response to the influence of contexts. Mechanisms can include the way people feel, think or act in relation to the resources in an intervention. They are activated by, and sensitive to, contexts. It is the interaction between contexts and mechanisms that leads to outcomes. 51,52,57 In MEMORABLE, mechanisms included older people’s, practitioners’ and informal carers’ diverse responses to what was happening in medication management such as confidence, control, experience and expertise, and mutual trust.

-

Outcomes – the pattern of impacts and effects resulting from the way that contexts and mechanisms interact. In MEMORABLE, these included older people’s and informal carers’ coping experiences, achieving appropriate or inappropriate treatment, following adherent or non-adherent behaviours, quality of life as well as health and care relationships and resource use.

The CMO configurations are generated from, and stay close to, the data and are used to explain causation and therefore why certain outcomes happen under certain contexts within the scope of a programme theory.

Substantive theory is pre-existing, higher-level theory about how phenomena are supposed to work, perhaps domain-specific such as theories of behaviour, learning or change. 64 Identifying and applying substantive theory brings a particular lens to the research, helping with the development of initial programme theories, supporting data analysis and providing analogy. In MEMORABLE, normalisation process theory (NPT)65,66 was chosen as the relevant substantive theory. See Chapter 3, Medication management as implementation, for details of NPT and its application in the research.

Having provided an overview of the research methodology, the next section sets out a more detailed account of the way the methodology was followed in the work packages and the steps by which MEMORABLE was delivered.

Work packages and steps in the research process

This section begins by describing the work packages that were initially set out in the protocol. 31 It then continues with an account of the iterative and flexible way that they were followed in practice, responding to the data and emergent concepts generated within the research.

Work packages

The protocol31 identifies three work packages to be carried out within MEMORABLE, following on from Project Start Up led by the Co-applicant Group, described in Co-applicant Group above. These packages conform with a realist research process,49,51,55 based on the recommended phases for this type of study:50 defining the scope of the review, searching for and appraising the evidence, extracting and synthesising findings, and drawing conclusions and making recommendations. The protocol details each package as follows:

-

Work package 1: realist synthesis (understanding context and mechanism) – this package focuses on the realist review and involves developing the search strategy; selecting and screening articles for their relevance/rigour; analysing data; and developing the candidate or initial programme theories.

-

Work package 2: realist evaluation (exploring mechanism) – this package is about gathering and analysing experiential, narrative data through realist-informed interviews (29 older people and informal carers, and 21 practitioners from health and care, including formal carers).

-

Work package 3: developing framework for intervention(s) and dissemination – this final package involves refining the programme theories; undertaking any additional interviews or searching as required; identifying key mechanisms and related contexts; identifying and developing intervention strategies needed to change contexts and trigger mechanisms; presenting the intervention framework for feedback and further refinement; and dissemination.

Steps associated with work packages in the research process

The MEMORABLE study progressed through seven sequential and partly iterative steps (Figure 1). This figure highlights the non-linear way that the research advanced, with overlaps and iterations, particularly around steps 3, 4 and 5. Such overlaps and iterations are expected in researching a complex intervention such as medication management. 58,59,68

FIGURE 1.

Research process summary: work packages and steps. Reproduced with permission from Maidment et al. 67 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Describing this figure, below, steps are grouped by work packages (work package 1: realist synthesis – steps 1–4; work package 2: realist evaluation – step 5; work packages 1 and 2: iterations – steps 3a and b, 4a and 5a and b; and work package 3: developing framework for interventions and dissemination – steps 6–7). The results from this process are presented in Chapter 3.

Work package 1: realist synthesis (understanding context and mechanism)

Step 1: scope of the research

Medication management was scoped during Project Start Up through two strands of work. First, the Co-applicant Group drafted the MEMORABLE protocol,31 setting out the background to the research, highlighting:

-

increases in the number of older people and comorbidity in the population1,2

-

safety concerns and consequences of susceptibility to poor medication management in terms of harm and hospital admission20,21,27,28

-

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance identifying the need for a collaborative approach to supporting older people with long-term conditions in managing their medication. 71

Second, just prior to the start of research, a formative Project Group held a day’s facilitated workshop to share knowledge on the principles and practice of realist methodology and to discuss the practicalities of applying them to MEMORABLE. This enabled the group to establish ownership of the planned research and build the team. It also mapped out a simple, tentative medication management process, drawing on the experience and expertise of those present. This mapping process began to theorise about the dynamics and complexity of the intervention and informed subsequent work on the stages of medication management. Although this early informal theorising does not follow the formal progression of the research process set out in Figure 1, it was nonetheless a valuable early contribution to scoping how medication management might work that was gradually refined as data were accumulated; a candidate programme theory in all but name (see Table 5).

Step 2: initial literature search and review

This step involved searching for and reviewing abstracts to broaden the understanding of medication management within MEMORABLE’s aim and objectives. Within a realist review, the aim of the search and synthesis noted by Pawson53 is to identify a body of literature to support ‘explanation building . . . to articulate underlying programme theories’ so that these can be interrogated using the evidence. In MEMORABLE, evidence would be enriched by combining data from the literature and interviews. Accordingly, the literature search was not intended to maximise the number and range of articles on medication management but to be more purposeful in identifying articles with rich data that would best support the generation and exploration of programme theories about what works, for whom, why and in which circumstances. This followed Pawson’s guidance on abstracting policy and theory building, described in detail by Booth et al. 55

The Research Team, which included a qualified information professional, conducted a pilot search to sensitise the team to the literature and to help in determining the scope of the protocol and subsequent review. 52 Details of this pilot search are given in Appendix 1. Once this initial set of literature had been reviewed closely, categorised and coded, the team finalised a search strategy for the initial literature search that would contribute to the review itself.

The initial literature search used terms set out in Table 1, accessing MEDLINE (724 references), CINAHL (Cumulative Index of Nursing and Allied Health Literature) (152 references) and EMBASE (139 references). It included published articles from 1 January 2009 to 31 July 2018. The initial cut-off was chosen because 2009 was the year in which NICE published its clinical guideline on medication adherence. 72 The Research Team had anticipated that systematic reviews published from 2009 onwards would access earlier studies, sufficient to cover the scope of the MEMORABLE realist review.

| Topic | Search terms |

|---|---|

| Medication management |

Medication adherence – polypharmacy – medication management – medicines optimisation – concordance – compliance – adherence – regimen Health services misuse/inappropriate prescribing – drug prescriptions/practice patterns – physicians/inappropriate prescribing – drug utilisation/medication errors – de-prescribing |

| Older people | Age/aged |

| Long-term conditions | Chronic disease |

| Other limitations | English language |

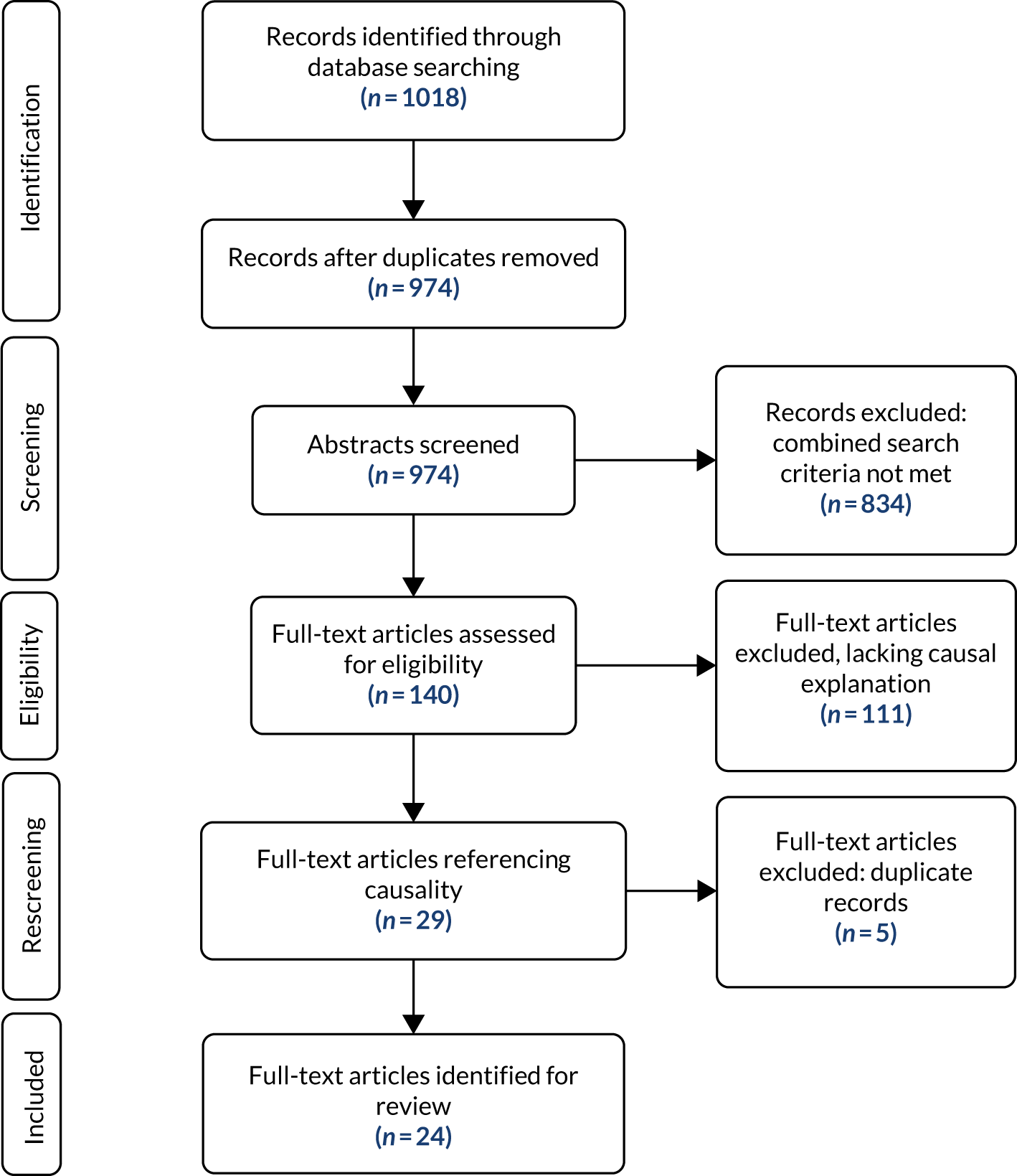

A total of 1018 abstracts were identified, reducing to 974 once duplicates, for example, were removed (Figure 2). 73 Abstracts were then reviewed for inclusion, referral or exclusion by the Research Associate using agreed criteria: population (≥ 60 years, living at home in the community), setting (UK, relevant high-income country), condition (multimorbidity) and interest (medication management). A 10% sample was also reviewed by two members of the Research Team to ensure consistency. A total of 140 articles were agreed for full-text review. The review was piloted by mapping abstracted data using a logic model format74 to identify descriptive accounts of medication management. This contributed to a better understanding of medication management, amplifying and updating the background information in the protocol.

FIGURE 2.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram: medication management. Reproduced with permission from Maidment et al. 67 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

On reviewing the initial data set, the researchers concluded that the breadth and volume of the data explored a range of diverse issues that extended beyond the scope of the immediate needs of the research. More importantly, as a data set, the 140 articles generally lacked explanatory accounts to support the analysis of programme theories. As the research priority was to understand more clearly how medication management might work, it was agreed to focus more closely on a subset of articles containing causal accounts of this intervention. This approach was endorsed by the Project Group.

Step 3: further literature searches and review

Following this decision, the 140 articles were then searched for those containing the terms ‘concept, framework, model or theory’ to identify those articles that might include a logic model, programme theory or a theory of action or change. 74 A total of 29 articles were identified for full-text review and 24 were reviewed following the exclusion of duplicate articles that contained two of the search terms, such as concept and theory.

Articles were analysed and the data were coded into NVivo Pro 11 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). Two approaches were followed. The first used a predetermined coding framework based on the five factors and associated characteristics listed in a World Health Organization (WHO)12 report on adherence to long-term therapies. These factors and characteristics were frequently cited in the literature. The data were structured and reported using the five factors as headings with 27 associated subheadings, listed below to highlight their relevance to MEMORABLE:

-

patient factors – relevant to older people and informal carers: demographics (age, diagnoses-multimorbidity, education, gender, living situation, nationality-culture), independence-dependence-functional ability (dexterity, hearing and sight, mobility, self-care, self-management), knowledge-beliefs-attitudes (about health, about medication, health burden, health literacy), mental health (anxiety, depression, cognitive capacity), physical health

-

medication factors – aligned with polypharmacy: adverse events (including consequences of taking or missing doses, drug–disease interactions, drug–drug interactions, drug–food interactions), medication changes, medication information and instructions, medication name and type, medication number and regimen, packaging, storing, time horizon to benefit

-

health-care provider factors – addressing practitioner and practice issues: challenges, communication and shared decision-making, co-ordination and consistency of care, person-centred care, practitioner roles, trust and confidence

-

health-care system factors – covering health and care organisations: access to dispensers of medication, access to information, access to prescribers, access to review

-

socioeconomic factors – the infrastructural underpinning of health and care organisations: evidence, finance, policy, technology.

However, this initial framework proved unwieldy because coding was constrained to fit with the list of existing factors and terminology, rather than more accurately reflecting the accounts in each text and the causal links between factors identified within and between texts. A different approach was needed. A second analysis coded data directly from the articles. Individual nodes and the eventual node structure emerged, emphasising the meaning and links attributed in each text and across multiple texts. The node summary is set out in Appendix 2. Nodes were then grouped under headings such as diagnoses, medication, health and care relationships, and an analysis framework established (Table 2). This framework combines the headings or factors and the levels at which they operated to ensure that coding was causally structured. In the table, factors are set out as potential contexts, mechanisms or outcomes, by levels, and a working definition formulated for the research. This work made an important contribution to sense-making at this stage and to later analysis.

| Factor in analysis framework | Working definitions in MEMORABLE | |

|---|---|---|

| Potential contexts | ||

| Individual level | Diagnoses: multimorbidity | Two or more long-term conditions |

| Medication: polypharmacy and treatment regimen | Five or more medications or, if fewer, a complex regimen that is proving difficult to manage | |

| Identity and day-to-day life | Older people aged ≥ 60 years, encompassing the individuality of older people and the unique bundle of personal influences on their decisions and actions | |

| Interpersonal level | Health and care relationships and communication | Formal relationships and communication with practitioners |

| Family and social relationships and communication | Informal relationships and communication with significant people in older people’s lives, including informal carers | |

| Institutional/infrastructural level | Health and care system | The provision of services by organisations |

| Support systems and information | Access to support and information services including via third sector or online, and published resources (e.g. patient information leaflet) | |

| Potential mechanisms | ||

| Individual level | Workload | Can be ‘high or increasing’ (e.g. ‘high’: a large number of medications and a complex regimen, or ‘increasing’: the addition of a new medication) or ‘low or decreasing’ (e.g. ‘low’: a few medications with a simple, stable regimen, or ‘decreasing’: further simplification of the regimen) |

| Capacity | Can be ‘high or increasing’ (e.g. ‘high’: knowledge and motivation about medication management or ‘increasing’: gaining knowledge and confidence by experience) or ‘low or decreasing’ (e.g. ‘low’: unable or unwilling to make sense of their medication and how it should be taken, or ‘decreasing’ as a result of an acute exacerbation or loss of informal support) | |

| Burden | The combination of workload and capacity as it impacts on people’s health and well-being. Burden can come from people’s diagnoses, their medication at the individual level, health and care relationships at the interpersonal and the heath and care system at the institutional or infrastructural level | |

| Potential outcomes | ||

| Individual level | Coping experience | The way people are able to manage the burden of medication management in their day-to-day lives |

| Health literacy | People’s knowledge of their health, diagnoses and medication | |

| Appropriate/inappropriate treatment | Whether or not medication is prescribed to meet people’s treatment needs, optimising safety, benefit and cost | |

| Adherence/non-adherence | The degree to which people take their medications as recommended by and agreed with the prescriber | |

| Performance/clinical outcomes | The impact of the medication in terms of the diagnosis or symptoms for which it was prescribed | |

| Quality of life | The impact of taking medication on the older person that accords with their values, goals and preferences | |

| Interpersonal level | Health and care relationships | The interaction between older people or informal carers and practitioners |

| Family and social relationships | The interaction between older people and informal carers as well as a wider network of family and friends | |

| Institutional/infrastructural level | Resources | The operational and strategic goods, services and other outputs provided by organisations |

This analysis was summarised in a discussion paper for a Research Team meeting to inform their work on drafting initial programme theories and reported to the Project Group.

Step 4: candidate programme theories and substantive theory

In this step, the Research Team continued to refine the tentative medication management process developed in step 1 as a theory of action or process. In addition, they drafted three candidate programme theories about medication management; one from the perspective of older people, one from the perspective of informal carers and one from the perspective of practitioners. These three candidate theories were developed from the literature searches and preliminary review, and drew on the Research Team’s own wider expertise and experience. It appeared that the ‘dissonance’ of agendas between different participants might have some traction:

-

Older people – if an older person, living in the community with multiple diagnoses and complex medication regimens, feels that there is a dissonance/difference between their own priorities and those of the practitioners dealing with their medication management, then positive outcomes will not be achieved for and with them.

-

Informal carers – if an informal carer who is providing help with medication management for an older person living in the community with multiple diagnoses and complex medication regimens feels that there is a dissonance/difference between the priorities of the person they care for, themselves or the practitioner dealing with their medication management, then positive outcomes will not be achieved for and with the older person.

-

Practitioners – if a practitioner feels that they have to focus on structural/practice outcomes, then they are not able to accommodate other agendas/priorities, leading to a lack of influence on the knowledge, attitudes, behaviours and outcomes of older people who are living with multiple diagnoses and complex medication regimens in the community.

These theories extended the Research Team’s attempts to explain what works in medication management, for whom, why and in which circumstances to achieve the outcomes that mattered to those involved in the process.

Informed by the data, the simple medication management process that was mapped out informally in step 1 was also revised at this time. In its original format, it appeared to suggest that medication management was a linear process. However, it became increasingly clear that the process model needed to accommodate more of the complexity of potential loops and iterations that people might experience in their day-to-day lives (see Tables 5 and 6). These concepts were then available to discuss with interview participants in work package 2.

Several substantive theories of interest were considered at this stage but none were sufficiently well evidenced from the literature, pending clarification from the interview data.

Work package 2: realist evaluation (exploring mechanisms)

Step 5: interviews and analysis

In order to enrich the data through which the candidate programme theories were being evaluated and to construct CMO configurations by which they might be explored, interviews were carried out with older people (n = 13), health and care practitioners (n = 21) and informal carers (n = 16) (total N = 50). A summary of interviewee profiles are set out in Appendix 3. This work was subject to approval by the sponsor (Aston University), by a regional Research Ethics Committee by proportionate review and by the Health Research Authority (approval issued 26 September 2017: REC reference: 17/EE/3057).

Invitations to participate in the research were issued directly through recruitment sites, such as NHS secondary and primary care organisations, and Join Dementia Research; by purposefully sampling individuals known to the researchers through professional and work contacts; and indirectly through publicity for the launch of the research and an item about MEMORABLE aired on BBC Breakfast that generated interest in taking part [see URL: www.youtube.com/watch?v=rz5UZ3mWx3o&feature=youtu.be (accessed March 2020)].

All recruits received a participant information sheet and consent form to complete before taking part in an interview that generally lasted about 1 hour. Interview schedules for each group followed a realist approach49,75 (see Appendix 4 for annotated details of the common contents). Older people and informal carers were usually interviewed face to face and practitioners most often by telephone. Interviews were audio-taped. The tapes were anonymised and transcribed, the transcripts then being checked for accuracy by the Research Associate. The transcripts were kept on password-protected computers for analysis.

Interviews were designed to enable a purposeful conversation to evolve in which the participant could describe how and why medication management worked for them as a process and to achieve the outcomes that mattered to them. The Research Associate followed the interview schedule using a conversational interviewing style, enabling participants to provide causal accounts of medication management in their day-to-day lives. The approach was nuanced to participants’ experiences and expertise: how older people fitted a complex regimen into their daily routines; how practitioners were directly involved in administering, prescribing or reviewing medication, or indirectly involved by managing staff that undertook those activities; and how informal carers supported increasingly dependent relatives.

Interview data were abstracted for a small number of randomly sampled participants in each group, whether older people, informal carers or practitioners, to trial the analysis framework. This involved the identification of explanatory statements for the factors that they identified as significant from their own experience. When possible, links between factors were identified from the transcripts. These were reviewed, while the recording was listened to, to check accuracy and aid interpretation. Hearing the nuances in the original narrative was found to be valuable, such as the pauses and emphases by which ‘structures and plots’76 could be better understood. Data were initially mapped into an Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet to test the framing of the analysis and the way it might help identify causal patterns. Once verified, this enabled the larger data set to be coded using NVivo.

At this point, data from the literature and an increasing number of interviews were being analysed separately, driven by the way the work packages were being progressed in series. The researchers were discussing and reflecting on both data sets in order to refine the process, respond to emerging themes and obtain a better understanding of this complex topic. The Research Associate worked iteratively, carrying out further cycles of purposeful searches and more integrated data analysis to engage more fully with the increasing volume and richness of data being generated.

Work packages 1 and 2: iterations

Steps 3a/5a: further literature searches and review, interviews and evaluation (iteration) – to identify key concepts and processes

Based on access to increasingly extensive data sets, the Research Team identified shared decision-making as an important aspect of the work transacted in the medication management relationships. From this, they were able to develop the understanding of the stages in the medication management process further. They distinguished those stages that were carried out individually by the older person and in which individual decision-making would feature, from those in which the older person interacts with a health or care practitioner through shared decision-making.

Informed by the richness of the data becoming available, discussion and debate in the team resulted in ‘dissonance of agendas’ being discounted as a candidate theory for intervention development. Based on emergent themes, the team acknowledged the increasingly complex work involved in medication management day to day and decreasing capacity from factors such as ageing, disease progression and frailty affecting older people; informal carers’ lack of knowledge and support, or competing demands from work roles; and practitioner time constraints. Informed by their own experiences, discussions with the wider Stakeholder Group supported by data from simple searches on workload capacity, burden emerged as the key potential mechanism of interest, experienced individually and transacted interpersonally.

To inform the way burden might be located in MEMORABLE, a limited search for articles that linked burden to multimorbidity, chronic disease and polypharmacy was conducted. 14,77,78 As part of the analysis, a further nine articles were sourced from those studies, largely kinship and sibling studies. 79–81 In line with MEMORABLE’s primary focus on the experience of older people living with comorbidities and polypharmacy, burden was disaggregated into burden associated with older people’s diagnoses and ‘the lifetime burden of chronic illness’39 as well as ‘treatment-generated disruptions’. 13 The scope of burden was also extended to older people’s interactions with health and care practitioners and systems15,39 to include ‘the workload of healthcare and its impact on patient functioning and wellbeing’. 82 The significance of informal carer and practitioner burden was also acknowledged although these concepts were pursued through narrative data rather than the literature.

Step 4a: theorising (iteration) – substantive theory

Informed by the analysis of selected data and having distinguished the way that older people engage in medication management through their decisions, individual and shared, and actions or behaviours at different but linked stages, the researchers identified NPT65,66 as a substantive theory to guide further analysis of the data. Adopting this theory corresponded with highlighting implementation as a key characteristic of medication management in terms of the work in introducing new medication management practices, and making those practices routine in the day-to-day activities of older people and informal carers.

Steps 3b/5b: further literature searches and review, interviews and evaluation (iteration) – to focus on causality from integrated data sets

Here, the combined data were reviewed and evaluated for causal accounts to prepare for drafting CMO configurations. Starting with the re-review of literature, configurations were set out in NVivo. Each configuration was allocated to a node (n = 59) with associated child nodes, one for each context, mechanism and outcome. Data were then abstracted from the interviews and mapped into the same configurations, some of which were modified in the process and new configurations generated.

Progress on this configuring process highlighted the complexity of medication management. In light of the breadth, volume and quality of data being generated, particularly from the interviews, the researchers agreed to balance the need to understand the breadth of medication management with a more detailed causal analysis focused on the reviewing/reconciling medications (Stage 5) [see Chapter 3, Reviewing/reconciling medication (Stage 5)]. This decision was based on the potential significance of this stage to the overall process for several reasons, including recognition of this stage’s importance in terms of interpersonal decisions and actions, and relevance to Stage 2 in which the other interpersonal work occurred when getting a diagnosis and/or medications. In addition, the researchers could establish links between Stage 5 and Stage 3 in which changes would start to be implemented and Stage 4 in which older people would continue to take their medications over time, and in which, in both stages, non-adherence may emerge as an issue of concern. Finally, the researchers were aware of published policy and guidance on the topic that could clarify standards of practice and their intended impact, causally explained or not.

A key feature of realist approaches to literature searching is the enhancement of the original search with core terms that had not been initially identified as important but whose centrality has emerged during the preliminary literature analysis. 52 Table 3 describes the supplementary searches on medication review (2000–18). Consequently, the discussion paper was informed by a purposive literature search for substantive literature relating to medication review, targeted at the MEDLINE database. A total of 244 review articles were identified and reviewed in relation to different configurations of medication review, published between January 2000 and December 2018. A larger set of non-review articles (3234 references) published over the same period was retrieved as a data set to support exploration of specific issues identified from the initial review subset.

| Search terms | Articles |

|---|---|

| (Search 16) Search “medication review*” OR “medicines use review*” OR “medicines review*” OR (medicine utilization review*) OR (medicine utilisation review*) OR (medicines utilization review*) OR (medicines utilisation review*) Filters: Review; Publication date from 2000/01/01 to 2018/12/31; English | 244 |

| (Search 15) Search “medication review*” OR “medicines use review*” OR “medicines review*” OR (medicine utilization review*) OR (medicine utilisation review*) OR (medicines utilization review*) OR (medicines utilisation review*) Filters: Publication date from 2000/01/01 to 2018/12/31; English | 3234 |

The Research Team chose not to add additional qualifiers beyond the concept of ‘medication review’ for two reasons. First, the population seemed to be self-defining from the terminology (i.e. the large majority of retrieved items referenced an aged population anyway). Second, the list of potentially qualifying terms, such as polypharmacy, would be quite extensive and would be difficult to make sufficiently exhaustive compared with the relative advantage of undertaking this sensitive search.

Informing this step, the Research Team considered a discussion paper written by the Research Associate that listed the full set of CMO configurations. It also included subsets of configurations for reviewing and reconciling medications (Stage 5) and two areas of interest around risk identification and individualised information that had emerged from the data and appeared to have the potential to generate proposed interventions.

In addition to the involvement of the Research Team in these decisions, the Project Group also approved this work, including the focus on reviewing/reconciling medications (Stage 5). The opinions of the Stakeholder Group were also sought on emerging themes: medication management is not ‘one thing’; older people’s goal about what they want from their medication and how, is very important to them; family carers’ awareness of the responsibility and challenges when they support older relatives with their medication; more and more practitioners, in different roles, from different organisations and with different ways of working are involved in medication management. The Stakeholder Group discussions enhanced the way that researchers understood these themes, supporting the analysis.

Work package 3: developing framework for intervention(s) and dissemination

Step 6: final programme theories

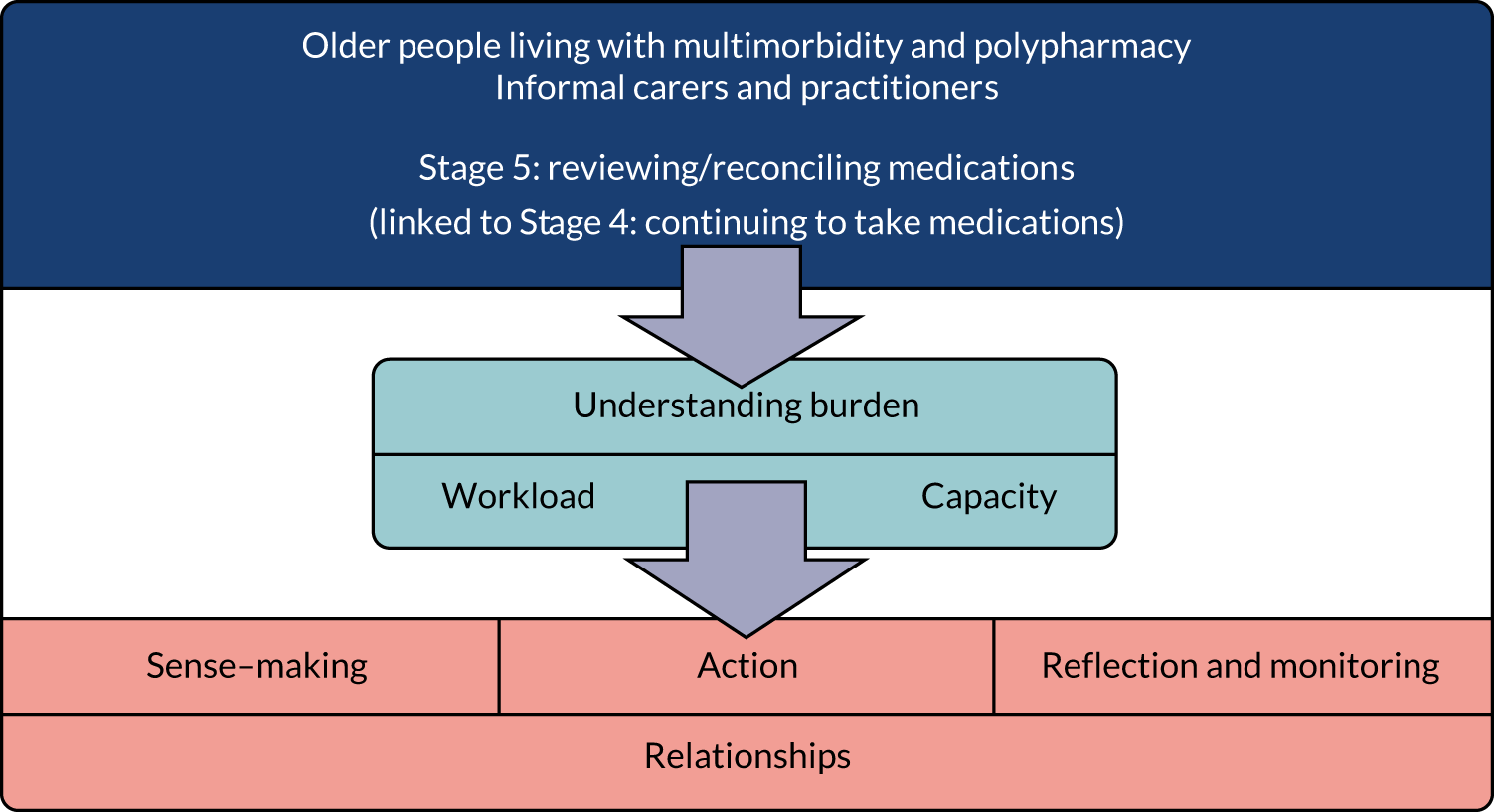

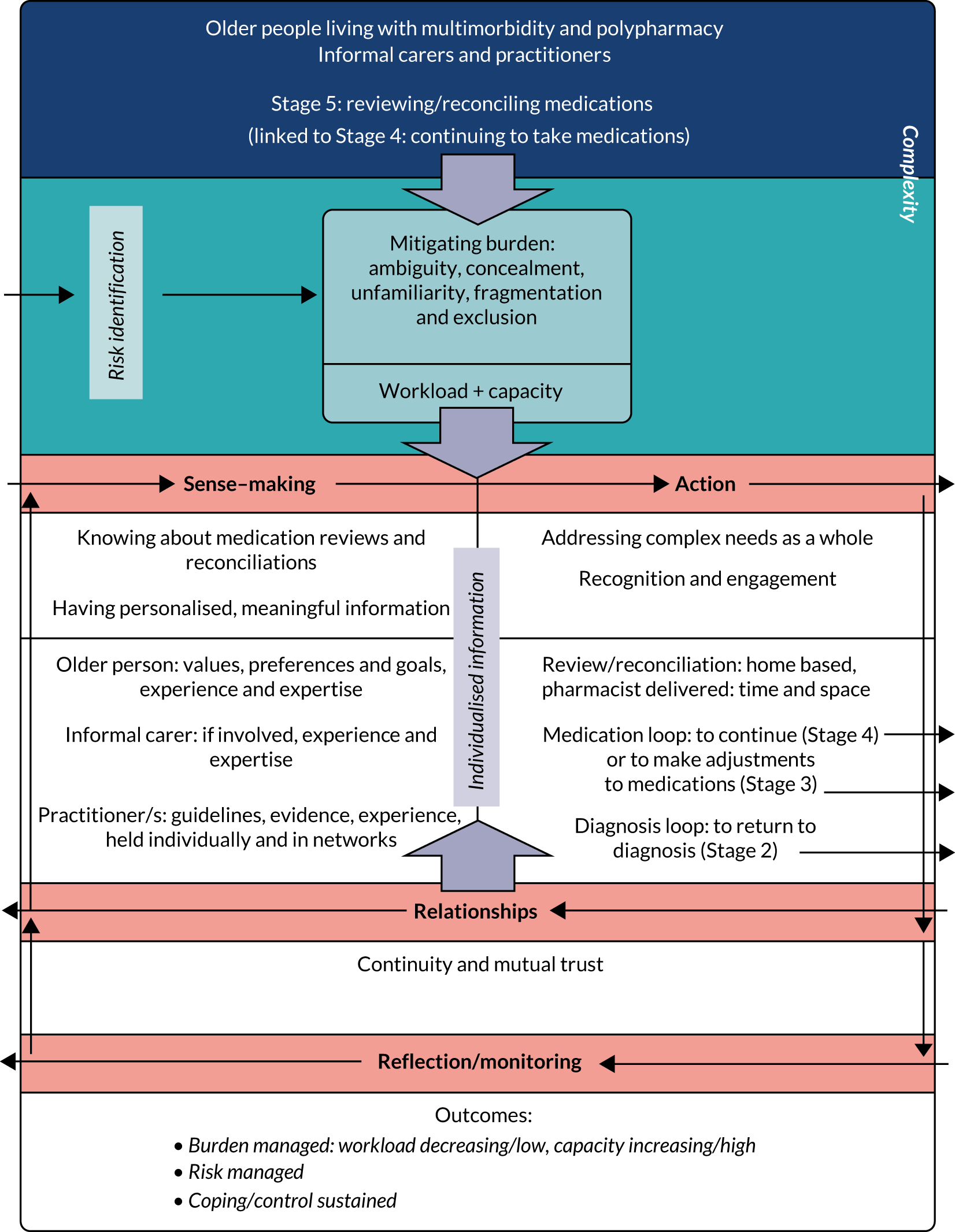

Final programme theory for a key stage in medication management is contained in Figure 5, based on both evidence and experiential data.

Step 7: intervention proposals

The intervention proposals emerged from the data, with an evidence and experience base. The Research Team identified the interventions most likely to improve medication management through discussion and debate of the data analysis, themes and concepts. This took place at a face-to-face meeting. Proposed interventions were prioritised as being most likely to bring about improvements in medication management, directly relevant to the expressed needs of older people and informal carers (individualised information) and improving practice (risk identification). They are reported in Chapter 3 and are considered in Chapter 4.

Having completed the account of the method underpinning MEMORABLE, the next chapter sets out the results.

Chapter 3 Findings

Using a realist approach and following the work packages and steps described in Chapter 2, this chapter sets out the findings from the literature and interviews in three sections.

-

Medication management: this section sets out how the data have been analysed and interpreted to develop a series of subprogramme theories about aspects of medication management. These subprogramme theories explain medication management in five ways: as a good practice, as a complex intervention, as implementation, as burden and as experience. The breadth of this work provided an explanatory structure of the complexity of medication management, necessary for the identification and more detailed analysis of Stage 5 as a key and critical stage.

-

Reviewing/reconciling medication: this section is about Stage 5 of medication management in which older people and practitioners are engaged, with or without the support of informal carers, achieving personally meaningful outcomes while enabling medication adherence and medication optimisation. This more in-depth work supported the generation of an explanatory theoretical framework, conceptualised around burden.

-

Proposed interventions: selected for their potential to contribute to the improvement of medication management.

-

Risk identification of older people and informal carers who are not coping with the burden of managing their medications. These are the people who might benefit from an additional, needs-generated intervention such as a review.

-

Individualised information about older people and their unique experiences of complex diagnoses and treatments, developed collaboratively by them, their informal carers if they are actively involved, and practitioners. This would be in an agreed format that encompasses their health, multimorbidities and polypharmacy, situated in their day-to-day lives and reflecting their values, goals and preferences. It would contribute to improved coping and self-management.

-

Reporting MEMORABLE’s findings begins with medication management.

Medication management

I think practice has improved. I think we are, we do more stuff than we used to. I think we sort of follow guidelines a lot better than we used to . . . But you’re sort of, you’re juggling all these things of what the textbook is telling me I should do, what is best for this 90-year-old person who’s on 1001 tablets already, what is the benefit? Actually, is it going to help this individual?

P53 – general practitioner

Medication management is introduced from the perspective of good practice. It is then considered as a complex intervention, as implementation, as burden and as experience. Understanding medication management through the combined analysis of literature and narrative data are pivotal to the research.

Medication management as good practice

Good practice recommendations from medication management policy and guidelines informs practitioners’ work, and the management and commissioning of the services in which they operate. Policy and guidelines are generally aligned with preferred outcomes: adherence,12,72 in which the older person’s actions matches the prescriber’s recommendations, informed by their involvement in and agreement with decisions about their treatment, and optimisation33 that aims to ensure that older people get the best possible outcome from any treatment. Reports from two organisations are noted below, framing medication management practice.

First, a formative WHO12 report endorses a behavioural approach to medication adherence, expressed in an information–motivation–behavioural skills model. Behaviours are characterised by type, frequency, consistency, intensity and/or accuracy. A broad level explanation of behavioural change and adherence is contained in Annex 1 in the WHO report. Good practice is delivered through the practitioner’s clinical and communication competencies, such as providing emotional support (empathy, validation, relationship building); giving information (empowering, tailoring, supporting health literacy); asking adherence-specific questions (monitoring, feedback) and; discussing therapeutic options, negotiation of regimen and discussion of adherence (collaboration, shared decision-making). By pursuing this approach, the practitioner secures the preferred change in the individual. Adherence is however subject to the caveat:

. . . almost everyone has difficulty adhering to medical recommendation, especially when the advice entails self-administered care.

Second, turning to the evolving policy framework for medication management in the UK, 2009–2018, NICE has published relevant guidance on adherence, optimisation and multimorbidity. 33,41,72 It has also issued several linked documents including a guideline and pathway for older people with social care needs,71,83 a flow chart for optimisation,84 and a key therapeutic topic document on multimorbidity and polypharmacy. 29

The NICE guidance on multimorbidity and polypharmacy29,41 acknowledges the complexity of managing future morbidity and mortality. NICE highlight two associated risks: first, in relation to multimorbidity, for which multiple treatments may be recommended although the evidence base is specific to the treatment of single conditions and, second, in relation to polypharmacy, for which benefits decrease and the risk of harm increases with the addition of each medication. NICE also underscore the responsibility of health-care professionals to make decisions appropriate to the circumstances of the individual patient, in consultation with the patient. Good practice interventions accordingly include the need for:

-

an individualised approach to accommodate needs, treatment preferences, lifestyle and concerns through individualised and planned care, assessment and treatment;

-

partnership with shared decision-making to ensure that there are informed discussions and decisions in which the patient experience is understood; and

-

outcomes that include not only clinical aspects of medication safety and effectiveness but also the outcomes that matter to the individual, including improving quality of life and reducing treatment burden.

Despite an extensive, supporting evidence base, the NICE documents do not explain how these good practice interventions might work to enable practitioners to adapt them to local or individual circumstances. 85 Such an approach may appear to support the view that the act of ‘doing’ good practice might suffice. In such circumstances, practitioners could struggle to make informed, individualised decisions and assure good practice within the evidence available, noted by Hughes et al. 86

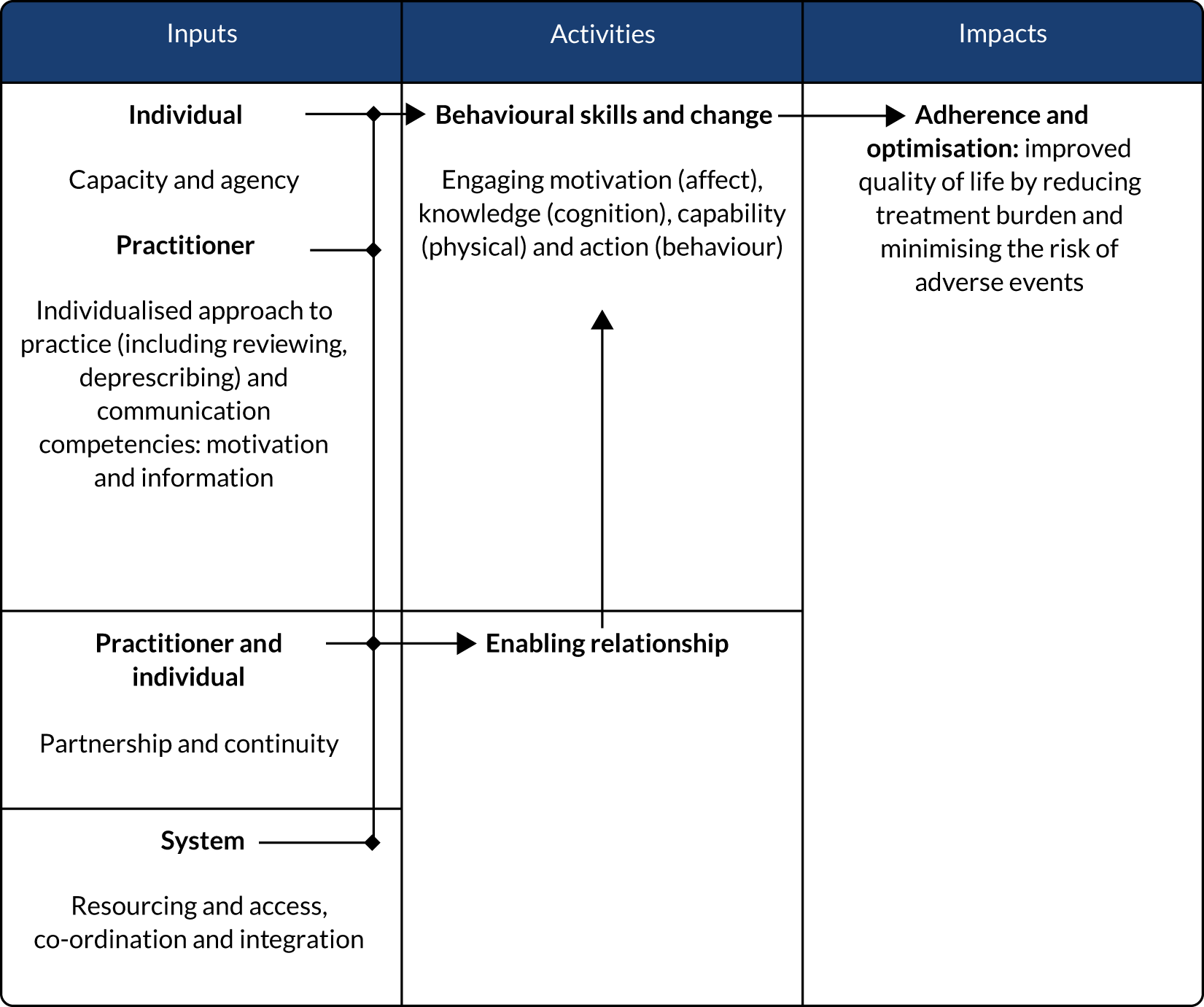

To summarise, key elements of good practice from these strategic reports on medication management have been mapped out in Figure 3, as a logic model: individual, interpersonal and system-level inputs, individual and interpersonal activities, and expected impacts.

Medication management as a complex intervention

Complexity and causality

A total of 24 articles containing rich conceptual data on medication management were identified through screening the initial search results, prioritised because they appeared to have a causal account of how medication management might work (Table 4). They were identified through the presence of the screening terms ‘concept, framework, model or theory’ that might indicate a logic model, programme theory, or a theory of action or change within them. 74 Articles that included more than one of these screening terms were categorised by the Research Team based on their primary focus.

| Authors | Title | Year | Country | Topic | Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Concept (n = 4) | |||||

| Cheraghi-Sohi et al.87 | The influence of personal communities on the self-management of medication taking: a wider exploration of medication work | 2015 | UK | Personal communities involved in medication work | Semistructured interviews and the construction of network diagrams |

| Fried et al.88 | A Delphi process to address medication appropriateness for older persons with multiple chronic conditions | 2016 | USA | Translating framework concepts into specific strategies to identify and remediate inappropriate regimens, focusing on deprescribing to reduce medication burden | Modified Delphi process: three rounds of anonymised web-based surveys |

| Naik et al.89 | Patient autonomy for the management of chronic conditions: a two-component re-conceptualization | 2009 | USA | Autonomy: decisional (about treatment) and executive (carry treatment plan out) in the context of multiple conditions | Concept development |

| Upadhyay and Joshi90 | Observation of drug utilization pattern and prevalence of diseases in elderly patients through home medication review | 2011 | India | Medication review by pharmacists | Community-based survey |

| Framework (n = 5) | |||||

| aBartlett Ellis and Welch91 | Medication-taking behaviours in chronic kidney disease with multiple chronic conditions: a meta-ethnographic synthesis of qualitative studies | 2016 | Australia, England and the USA | Medication taking and medication adherence behaviours | Qualitative study review |

| Boskovic et al.92 | Pharmacist competencies and impact of pharmacist intervention on medication adherence: an observational study | 2016 | Croatia | Results of pharmacists intervention on adherence in the community | Observational study |

| Coleman93 | Medication adherence of elderly citizens in retirement homes through a mobile phone adherence monitoring framework (Mpamf) for developing countries: a case study in South Africa | 2014 | South Africa | Intervention development: technology | Case study with qualitative interviews |

| Schuling et al.94 | Deprescribing medication in very elderly patients with multi-morbidity: the view of Dutch general practitioners. A qualitative study | 2012 | Netherlands | Exploring experienced general practitioners’ views on deprescribing and involving older people in these decisions | Qualitative study |

| Yap et al.95 | Medication adherence in the elderly | 2016 | Singapore | Systematic review of the barriers to adherence in the elderly | Case study |

| Model (n = 9) | |||||

| aDoucette et al.96 | Initial development of the Systems Approach to Home Medication Management (SAHMM) model | 2017 | USA | Systems approach to safe and effective home medication management | Model development |

| Hennessey and Suter97 | The Community-Based Transitions Model: one agency’s experience | 2011 | USA | The acquisition and use of health coaching competencies in home care clinicians at health transitions | Model development |

| Jonikas and Mandl98 | Surveillance of medication use: early identification of poor adherence | 2012 | USA | Identification of population level adherence and risk of poor adherence | Model development |

| Khabala et al.99 | Medication Adherence Clubs: a potential solution to managing large numbers of stable patients with multiple chronic diseases in informal settlements | 2015 | Kenya | Assessment of the people’s care through nurse-facilitated Medication Adherence Clubs | Retrospective descriptive study |

| aKucukarslan et al.100 | Exploring patient experiences with prescription medicines to identify unmet patient needs: implications for research and practice | 2012 | Canada and USA | Identification and characterisation of patients’ unmet needs when taking prescribed medication | Grounded theory approach to interview content analysis |

| aMcHorney et al.101 | Structural equation modeling of the proximal-distal continuum of adherence drivers | 2012 | USA | Identification of adherence drivers | Model development |

| Lau et al.102 | Multidimensional factors affecting medication adherence among community-dwelling older adults: a structural-equation-modelling approach | 2017 | China | Multidimensional factors affecting medication adherence: measuring medication adherence, professional-help relationship and self-care abilities | Exploratory cross-sectional approach using interviews and modelling |

| Milani and Lavie103 | Health care 2020: reengineering health care delivery to combat chronic disease | 2015 | USA | Modifying the health-care delivery model to include team-based care in concert with patient-centred technologies | Review |

| Shepherd et al.104 | Health services use and prescription access among uninsured patients managing chronic diseases | 2014 | USA | Identification of relationships between population characteristics, health behaviour and outcomes | Longitudinal quasi-experimental design with convenience sample for assessment and notes review |

| Theory (n = 6) | |||||

| Geryk et al.105 | Medication-related self-management behaviours among arthritis patients: does attentional coping style matter? | 2016 | USA | Coping styles | Internet-based survey |

| Haslbeck and Schaeffer106 | Routines in medication management: the perspective of people with chronic conditions | 2009 | Germany | Routines in medication management along chronic illness trajectory | Semistructured interviews: initial and follow-up |

| Laba et al.107 | Understanding if, how and why non-adherent decisions are made in an Australian community sample: a key to sustaining medication adherence in chronic disease? | 2015 | Australia | Intentional non-adherent decisions and behaviours | Semistructured interviews and theory-informed iterative thematic framework analysis |

| Marks108 | Self-efficacy and arthritis disability: an updated synthesis of the evidence base and its relevance to optimal patient care | 2014 | n/a | Self-efficacy, pain and disability, adherence to therapeutic strategies and outcomes, applicable to assessment and treatment | Review and synthesis |

| Jorge de Sousa Oliveira et al.109 | Interventions to improve medication adherence in aged people with chronic disease – systemic review | 2017 | USA, China, Portugal and Italy | Nursing interventions to improve medication adherence in older people with chronic disease | Systematic review |

| Skolasky et al.110 | Psychometric properties of the patient activation measure among multimorbid older adults | 2011 | USA | Patient activation measure (Hibbard): psychometric properties and model evaluation | Interviews + completion of measure. Cross-sectional and latent class analysis |

Informed by the causal attributions in these articles, relevant factors and combinations of factors were identified and coded into NVivo. The codes are listed in Appendix 2.

This analysis confirms that medication management aligns with the description of complex interventions and their evaluation set out by the Medical Research Council:58,59 several interacting components, the number and difficulties of behaviours among those involved, the number of groups or organisational levels targeted by the intervention, and the number and variability of outcomes.

The following issues emerged from the analysis, associated with the two main groups: older people and practitioners. Some additional articles have been added to the references in Table 4 where these have augmented the understanding of particular factors:

-

Older people: the way they manage the workload13–15 associated with their medications is influenced by their diagnoses, including multimorbidities, symptoms and illness trajectories that overlay ageing processes;11,12,78 the medications they take, including high-risk drugs, doses and complex regimens;89,91,111 and the relationship and interaction with the prescriber. 112–114 Together, these affect behavioural responses such as control, self-efficacy and coping styles87,89,91 through the adoption of routines106,115 that lead to the outcomes that matter to them. Cheraghi-Sohi et al. 87 describe older people’s individuality in the way that they manage their medication: ‘Medication-taking appears to be a personalised, contingent and contextually situated type of work with participants developing highly individualised routines and strategies’.

-

Practitioners in health and care: doctors in particular87,89,103 as well as pharmacists92,94,96 and nurses87,91 are identified as significant in medication management, following a patient-focused care model100,102,103 as part of a health and care system in which there is co-ordination and continuity. 100,103 The immediacy of their work, face to face with older people, is highlighted in prescribing,88,90,91 deprescribing88,94 and information-giving. 91,94,97,100 Establishing a trusted therapeutic relationship89,91,100 enables practitioners to extend their influence over older people’s medication management decisions and actions when they are at home. Lau et al. 102 highlight the importance of practitioners engaging with older people as individuals to enable them to improve the way that they manage their medications: ‘Adherence interventions should be tailored to the needs of a patient to enhance self-management capacity regarding medication use’.

These findings are supported by the interview data reported later in this chapter; see Medication management as experience.

Structuring complexity

Medication management is often described in the literature as a single intervention. However, its real-world complexity has been addressed in MEMORABLE by disaggregating it into stages differentiated by activities and participants (Table 5):

-

Activities – each stage has a distinct group of purposeful activities or work associated with it, such as Stage 1: identifying a problem and Stage 4: continuing to take medications. However, stages are linked and generative so that what happens in one stage informs another. For example, having received a diagnosis and medications in Stage 2, an older person starts to take their new medications in Stage 3 and continues to take them in Stage 4, making them part of their day-to-day routine.

-

Participants – Stages 1, 3 and 4 are where an older person is managing their medications on their own. This is indicated in Table 5 with a ‘(1)’ next to ‘older person’. However, the older person may have the support of an informal carer depending on their particular needs, shown as (1 + 1). Stages 2 and 5 are interpersonal stages where the older person and the practitioner work together, shown as (1 : 1), next to ‘older person and practitioner’. Although informal carers were only identified in association with ‘informal carer burden’ in the screened literature, they have been included in the table to reflect their involvement, as described in the interviews.

| Stage | Stage 1: identifying problem | Stage 2: getting diagnosis and/or medications | Stage 3: starting, changing or stopping medications | Stage 4: continuing to take medications | Stage 5: reviewing/reconciling medications |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Who | Older person (1) | Older person and practitioner (1:1) | Older person (1) | Older person (1) | Older person and practitioner (1 : 1) |

| Older person may be supported by an informal carer (1 + 1) | Older person may be supported by an informal carer (1 + 1) | Older person may be supported by an informal carer (1 + 1) | Older person may be supported by an informal carer (1 + 1) | Older person may be supported by an informal carer (1 + 1) | |

| Doing what | Older person identifies something is wrong | Older person and practitioner agree what is wrong, how to treat it. A prescription is issued and filled | Older person adjusts daily medication routine to include new medication or adjust or omits current medication | Older person fits new routine into day-to-day life |

Practitioner confirms medication safety and efficacy Older person and practitioner agree appropriateness, adherence and fit with day-to-day life |

Stages 2 and 5 are where good practice, discussed previously, is situated. Adherence on the other hand can now be located in Stage 3, as an aspect of a single event when the older person is starting, changing or stopping medications, or when continuing to take them in Stage 4, requiring repetition and consistency. However, Volpp and Mohta116 indicate that the factors that initiate behavioural change are different from those that sustain it although ‘human interaction and social support’ are noted as significant to both.

Developing the stage structure further, Table 6 adds more detail to what is happening in each stage and across stages, locating and linking decision-making and behaviours. The table confirms that the older person (1) is self-managing in Stages 1, 3 and 4, although they may also be benefiting from support with medication management through the involvement of an informal carer (1 + 1). These stages are where the older person engages in individual decision-making to exert control or agency: in Stage 1, when identifying that something is different and potentially problematic, and Stages 3 and 4, when setting up and following routines. However, the emergence of a problem in Stages 3 or 4 may result in a ‘disruption’ loop where the older person reverts to Stage 1 to address a concern.

Interview data confirm that a strong sense of control or striving for control supports adherence and optimisation to get the best from medications that make a tangible difference in older people’s lives. On the other hand, a strong sense of autonomy and weak external influence, such as ambiguity in the advice from the prescriber about the importance of certain medications, could in some instances be linked with an increased likelihood of intentional non-adherence. Media coverage about problems or risks with certain medications, or trusted friends’ stories of their own bad experiences of particular treatments, can compound the weakness of prescriber advice. As a result, older people’s decisions may not always appear consistent as they try to fit medication management with the many other choices and opportunities that they are exposed to on a daily basis. However, non-intentional non-adherence appears to be linked more with occasional forgetfulness or cognitive decline. This suggests that an effective approach to medication management may involve discussing how the older person fits this complex staged work into their day-to-day lives, and copes with it, rather than focusing on more abstract concepts such as adherence.

Turning to the interpersonal stages identified in Table 6, these are where decision-making is shared. The first of these is Stage 2, where practitioners provide a diagnosis and medications. This stage is important for what the practitioner does and communicates in an often time-limited event. Of equal importance is the way these activities draw on older people’s needs and concerns to explain the problem as they perceive it (Stage 1), together with experiences of coping with their medication routines day to day (Stage 4). Adding to the understanding of the way stages link and are generative, work in this stage also feeds forward to influence what an older person does when they are back at home (Stages 3 and 4). This is where older people, sometimes with the support of informal carers, may need to make changes to what they are already doing to fit new medications into their routines and day-to-day lives.