Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 15/70/73. The contractual start date was in November 2016. The final report began editorial review in April 2019 and was accepted for publication in November 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of the authors

Karen Newbigging was a trustee of the Healthy Minds Board from 2012 to 2017 and a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) associate board member from 2016 to 2019. Doreen Joseph reports receiving personal fees during her time as a HSDR Researcher-Led Panel member (2018–20) during the conduct of the study. Benjamin Costello is a director and trustee of Bromsgrove and Redditch Network (BARN), a local council for voluntary services, which is also a volunteer centre; he is also a director and trustee of Redditch Nightstop.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Newbigging et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction and context

This chapter establishes the context for our study, which deployed a range of methods to provide a comprehensive and detailed description of the contribution of the voluntary sector (VS) in supporting people in a mental health (MH) crisis. The experience of a MH crisis can have a profound impact on the individual concerned, as well as on their family, friends and wider social network. If not managed well, a MH crisis can have adverse consequences and may influence a person’s willingness to seek help in the future. Consequently, the provision of effective MH crisis support across England is a cause for concern. However, many people in crisis are unable to access the help they need when they need it, and are dissatisfied with the help if they receive it. 1–4 The VS, which comprises not-for-profit organisations and informal groups, and is also known as the third sector, provides a range of services to support people experiencing a MH crisis. However, although this contribution is not well understood and has not been widely researched, the value of the VS is increasingly recognised and promoted within MH policy, possibly more so than in other areas of service development and delivery.

Defining a mental health crisis

Defining a MH crisis is by no means easy and, as Rapoport5 observed over half a century ago, ‘the term “crisis” is generally used in a rather loose and indeterminate way, covering a variety of meanings and a wide range of experiences’. Common themes in the way the term is used are as follows: (1) a crisis is a time of heightened vulnerability, (2) a crisis is commonly conceptualised as an event, which poses a threat and leads to a sense of disequilibrium, (3) a crisis can be a negative or positive experience, such that a crisis is viewed as a ‘turning point’,6 with both risks and a constructive potential for change and personal transformation, and (4) the resources available to an individual, both their personal coping strategies and the availability and effectiveness of support, will influence their response to a crisis.

Two aspects of a crisis that are commonly identified are the temporal dimension (i.e. an intense, and sometimes sudden, experience with the urgency of the situation emphasised) and the severity of the crisis. For example, Boscarato et al. 7 state that:

Crises can occur when a person encounters an overwhelmingly stressful situation that might exceed their capacity to cope, resulting in feelings of helplessness and tension. Disorganization and confusion might be subsequently experienced, leading to a ‘breaking point’, characterized by psychological decompensation and disturbed or destructive behaviour.

Boscarato et al. 7

Paton et al. 8 distinguish the current definitions of a crisis in a MH context. These are a pragmatic service-oriented approach (i.e. a person coming to the attention of crisis services because of a relapse of an existing MH condition), self-definitions of crisis (i.e. the person defines their own experience and recovery), a risk-focused definition (i.e. the person is at risk of harming themselves or others) and negotiated definitions (i.e. negotiated collaboratively between service users, carers and staff). 8 Traditional descriptions of a crisis emphasise the behavioural and symptomatic elements of a crisis, reflecting a biomedical framing based on clinical assessments of health and risk. 9,10 These are widely contested for neglecting or negating the experiential aspects of a MH crisis11 and they potentially dismiss the agency of the individual and their family or carers in crisis management. This study, therefore, explores crisis experiences and their conceptualisation, as these will have influenced policy, system development and consequently the role of the VS. We began with an inclusive and relatively neutral conception of a crisis as a ‘turning point’, such that a MH crisis is personally disruptive but can provide opportunities to strengthen personal and social resources, and to anticipate and manage MH problems. This definition was subsequently critiqued by the Study Reference Group (SRG) as overly positive, as discussed in Chapter 4.

The policy and practice context for mental health crisis care

Mental health policy

The provision of effective support for people experiencing a MH crisis has been a focus for policy and service development for over 25 years (see Report Supplementary Material 1). The recurrent theme has been ensuring that people experiencing a MH crisis have rapid access to effective support. The policy focus until recently was largely restricted to NHS services. The National Service Framework for Mental Health12 specified the form and function of crisis resolution home treatment teams (CRHTs) for people with a diagnosis of ‘severe mental illness’. The exclusion criteria13 included people with a diagnosis of personality disorder. In 2009, the Department of Health and Social Care14 drew attention to the role of the VS in providing alternatives to inpatient admission and to short-term sanctuary and support.

The inadequacy of a restricted policy focus for MH crisis care has attracted much attention over the last decade. The fragmentation of the crisis care system was identified by the National Audit Office,15 which recommended that specialist crisis provision by CRHTs should be integrated with other MH services, including acute inpatient care. A 2015 report by the Care Quality Commission (CQC)4 on crisis care and a 2016 report published by the Commission on Acute Adult Psychiatric Care16 similarly highlighted the fragmented nature of the MH system, underlining the inconsistency and inadequacy of MH crisis care provision. The CQC found that only 14% of the people surveyed felt that they had been provided with the right response. Those who had contact with different crisis services evaluated VS services much more positively for their warmth, compassion and capacity to listen and for taking people seriously than NHS services, particularly accident and emergency (A&E), CRHTs and community mental health teams (CMHTs). 4 This reinforced the findings from Mind’s1 survey of service users’ experiences of acute crisis, which emphasised the need for humanity, compassion, a less medically dominated response and greater choice and control,17 highlighting the value of user-led crisis services.

The NHS Mandate for 2014–1518 established specific objectives for the NHS to improve MH crisis care and introduced the Crisis Care Concordat (CCC),3 which identified four key stages of the crisis care pathway:

-

access to support before a crisis through the provision of information, preventative activities and supporting self-directed care

-

urgent and emergency access to crisis care

-

the quality of care during a crisis, including alternatives to inpatient admission

-

recovery and relapse prevention, enabling people to stay well.

This was supported by a series of statements, developed in consultation with service users and carers, describing what people could expect when they experienced a crisis across these different domains (as set out in Box 1). We adopted this description of the crisis care pathway as a reference point for understanding individual experience and system organisation.

When I need urgent help to avert a crisis, I, and people close to me, know who to contact at any time, 24 hours a day, 7 days a week.

People take me seriously and trust my judgement when I say I am close to crisis, and I get fast access to people who help me get better.

2. Urgent and emergency access to crisis careIf I need emergency help for my MH, this is treated with as much urgency and respect as if it were a physical health emergency.

If the problems cannot be resolved where I am, I am supported to travel safely, in suitable transport, to where the right help is available.

I am seen by a MH professional quickly. If I have to wait, it is in a place where I feel safe. I then get the right service for my needs, quickly and easily.

Every effort is made to understand and communicate with me.

Staff check any relevant information that services have about me and, as far as possible, they follow my wishes and any plan that I have voluntarily agreed to.

I feel safe and am treated kindly, with respect and in accordance with my legal rights.

If I have to be held physically (restrained), this is done safely, supportively and lawfully, by people who understand I am ill and know what they are doing.

Those closest to me are informed about my whereabouts and the people who need to know are told that I am ill. I am able to see or talk to friends, family or other people who are important to me if I so wish.

I am confident that timely arrangements are made to look after any people or animals that depend on me.

3. Quality of treatment and care when in crisisI am treated with respect and care at all times.

I get support and treatment from people who have the right skills and who focus on my recovery, in a setting that suits me and my needs.

I see the same staff members as far as possible and, if I need another service, this is arranged without unnecessary assessments. If I need longer-term support, this is arranged.

I have support to speak for myself and make decisions about my treatment and care. My rights are clearly explained to me and I am able to have an advocate or support from family and friends if I so wish.

If I do not have the capacity to make decisions about my treatment and care, any wishes or preferences I express will be respected and any advance statements or decisions that I have made are checked and respected.

4. Recovery and staying well/preventing future crisesI am given information about, and referrals to, services that will support my process of recovery and help me to stay well.

I, and people close to me, have an opportunity to reflect on the crisis and to find better ways to manage my MH in the future.

I am supported to develop a plan for how I wish to be treated if I experience a crisis in the future and there is an agreed strategy for how this will be carried out.

I am offered an opportunity to feed back to services my views on my crisis experience.

Reproduced from the Department of Health and Social Care. 3 Contains public sector information licensed under the terms of the Open Government Licence v3.0. See: www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/.

Through its focus on securing local agreements to improve the crisis care pathway, the CCC stimulated the development of a range of VS initiatives, including places of safety, crisis houses that can provide an alternative to inpatient care and crisis cafes or safe spaces that have the potential to divert people from A&E. This has been facilitated by additional resources being made available by NHS England, the Department of Health and Social Care19,20 and local commissioners. The evaluation of the CCC confirms that the VS is playing an important role in the local delivery of crisis services. 21

The Five Year Forward View for Mental Health2 emphasised that people with a mental illness have the right to the same high quality of care as people with physical health problems. This means that ‘people facing a crisis should have access to MH care 7 days a week and 24 hours a day in the same way that they are able to get access to urgent physical health care’2 (p. 12, emphasis added; contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). In outlining the required transformation of MH services, the Five Year Forward View for Mental Health2 asserted that the VS plays an invaluable role and that new models must be developed in partnership with experts by experience, community organisations and VS organisations (VSOs).

Proposals to improve the provision of MH crisis care were announced in NHS England’s Long Term Plan (LTP). 22 The LTP commits to ring-fencing and increasing investment in MH to accelerate the growth of community and crisis services for children, as well as for young people and adults. It proposes that community crisis services be expanded, so that they can be accessed via NHS 111, with additional resourcing to be supplied to provide a 24/7 community-based MH crisis response offering intensive home treatment as an alternative to acute inpatient admission. 22 The LTP also outlines an ‘improved NHS offer of urgent community response and recovery support’22 (p. 14; contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0), with waiting time targets for a MH crisis response to be introduced in 2020. The LTP expresses a commitment to increasing (1) alternative forms of provision, referring to safe havens and crisis cafes as more suitable than A&E, and (2) the role of crisis houses as preventing admission. Both of these commitments necessarily require the NHS to work in partnership with the VS in order to better meet people’s needs. These policy developments formally recognise that VSOs, and their particular ways of working, offer a specialist ‘niche’ within a wider ecosystem of MH crisis support.

The wider context for MH crisis care includes (1) increasing rates of use of the 1983 Mental Health Act (MHA), which are now at a record high;23 (2) the disproportionately high rates of detention of people from black, Asian and minority ethnic (BAME) communities, which continue unabated;23,24 (3) inequalities in access for other BAME groups; and (4) emerging evidence that an inadequate response or rejection can lead to increasingly desperate behaviour resulting in increased need for the use of section 136 under the MHA. 25 The MHA review identified the positive contribution of the VS in crisis care. 26 In recommending the provision of alternatives to detention and interventions to prevent crisis or the escalation of crisis, the report comments ‘[T]here should be a varied offer and funding of this provision, which will require a considerable change in culture and what services receive funding’24 (p. 86; contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). The government has also set an ambition for zero suicides,27 and the contribution of the VS to prevention and access to appropriate support is included in relevant guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 28 Finally, austerity and the wider welfare benefit reform have been implicated in the increased risk of a MH crisis29 and, together with perceived isolation, are associated with an increased risk of suicide. 29 This association between inequalities and poor MH is recognised by Public Health England’s initiative entitled the ‘Prevention Concordat for Better Mental Health’, which identifies the VS and community sector as contributors to its implementation. 30 All of this raises fundamental questions about the VS’s role in the provision of effective crisis care.

Although an analysis of wider health and social care policy is outside the scope of this study, it is worth noting that the policy context is conducive to the development of the VS. There are a number of specific policy themes that support the role of the VS: (1) an emphasis on prevention and tackling the social determinants of health, (2) a reframing of integrating health and social care by focusing on place-based approaches, which necessarily recognise the role of voluntary and community organisations,31 and (3) the promotion of asset-based community development approaches. The LTP suggests that integrated care systems be created across England by 2021 to organise commissioners and providers and motivate them to prioritise and make decisions about local provision to meet the needs of their population. These integrated care systems will be overseen by a performance and accountability framework, which will include an indicator of how well local systems are working together. The reforms also propose the introduction of integrated care trusts that will bring together primary and community services. Although the VS is identified as a player in this ambitious reform agenda, how this will play out in practice and the impact on the VS are, as yet, unclear.

The voluntary sector

The VS has been conceptualised as a third ‘terrain’ of organisations between the state and market, comprising charities and community groups, underpinned by a sector ethos that typically values accessibility, self-organisation, service-user-defined outcomes, informality and relational-based approaches. 32,33 The VS makes a wide-ranging contribution to MH, including user-led organisations (ULOs), national specialist MH VSOs, VSOs concerned with a specific social issue (e.g. domestic violence or homelessness) or with a client group (e.g. ex-service personnel), and small community organisations, which are ‘under the radar’ by virtue of their size or informality. 34 Across this diverse range of organisations, there is a wide range of approaches and activity, from intensive support, including supported housing and support in a hospital setting, to advocacy, support groups and peer-led networks (e.g. the Hearing Voices Network), peer support, social and leisure activities, and befriending.

In exploring the roles of non-profit organisations in MH, Karlsson and Markström35 identified two broad (and overlapping) groups. One group is organisations providing services, seen as complementary to or alternatives to public sector services. They seek collaboration, are often dependent on state grants and become more like public or private sector organisations through the process of collaboration, but typically retain strong priorities of self-help and peer support. The second group is characterised as voice-giving rather than service-orientated. This group values experiential knowledge and work to bring about change through services and campaigning.

The VS is described as having a ‘comparative advantage’ and Dayson and Wells36 suggest that this comparative advantage derives from three elements, namely how VSOs do their work, who they do it with and the role they play in their community. 36 In particular, VSOs have a distinctive approach to governance, which is characterised by ‘stakeholder ambiguity’. 37 Stakeholder ambiguity occurs because stakeholders are likely to have hybrid and overlapping roles (e.g. managers may be the same as, or relatively equal to, those in ‘volunteer’ and ‘service user’ roles within the organisation). Such relatively ‘flat’ hierarchies are often associated with an ethos of non-judgementalism, encouraging nurture/care and a high degree of ‘relational skill’. 32

These characteristics mean that the VS may be particularly well placed to provide MH crisis support, offering alternative approaches to public sector provision for populations that are ‘seldom heard’ or find themselves excluded by various mechanisms,38 for example women who have offended or are at risk of offending,39 homeless people40 or older people experiencing anxiety and depression. 41 Thus, the VS plays a particular role in advancing equality by facilitating access to support for people from disadvantaged groups who may be reluctant to access public sector services.

Voluntary and public sector relationships

Since 1997, there has been a significant rise in the involvement of the third sector and civil society in delivering public services. 42 VSOs are now firmly embedded in the delivery of public services including health and MH services. This process has happened in an evolving political context including periods of significant government investment under New Labour, as well as periods characterised by austerity and short-lived agendas, such as the ‘Big Society’ agenda, under the coalition government from 2010 and subsequent Conservative governments from 2015. 32 Alongside this, the increasing marketisation of public services has opened up new opportunities for VSOs by way of competition for health contracts, both between VSOs and with public and private sector organisations. 43 Widespread concerns about this involvement in delivering public services have been expressed, potentially compromising some of the VS’s cherished attributes, especially its perceived trustworthiness, political independence and ability to act as an alternative or challenge to the state. 43 For many commentators, the VS’s enhanced role in the delivery of public sector services has come at the price of a drive towards ‘professionalisation’ and more competitive, even unethical, behaviour. 44 Regardless of the rights and wrongs – and there is no clear consensus across what is a very diverse VS – there is a trade-off between (1) aligning more closely with the values and approach of the public (or private) sector while remaining a challenge and providing an ‘alternative’ to them and (2) particularly in the case of MH, genuinely involving service users. This is often expressed in terms of threats to VSOs’ ‘independence’ from the state and market. 45

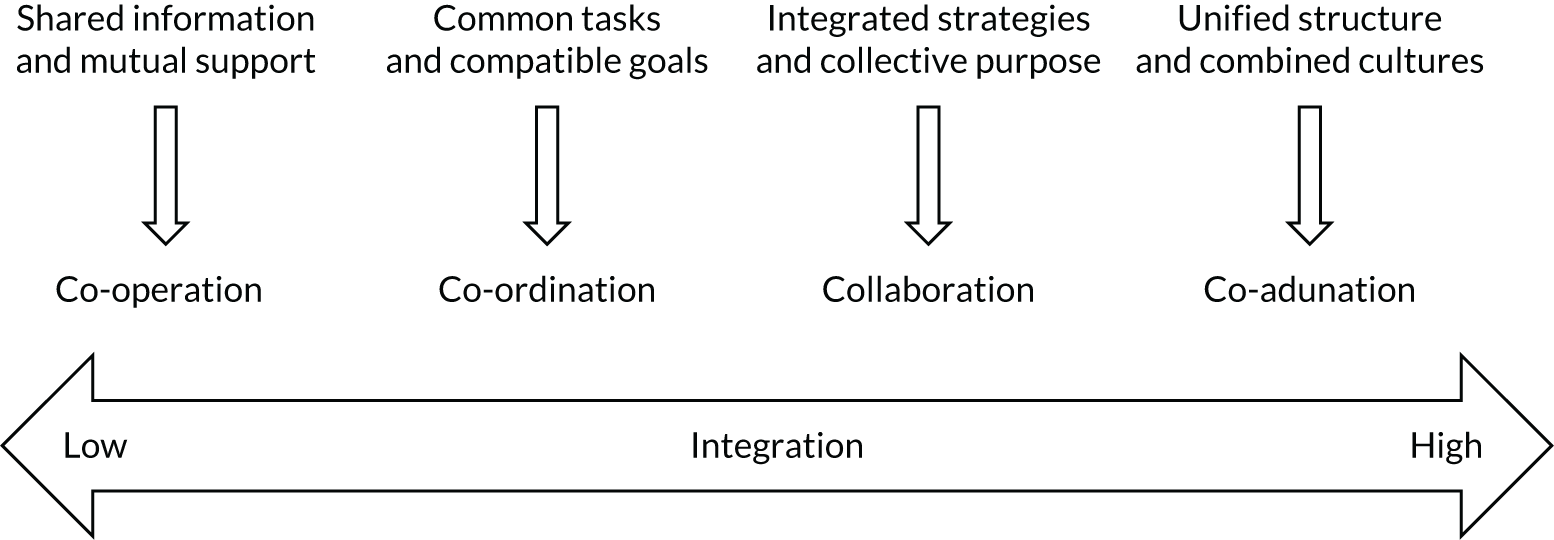

When VSOs work most closely in ‘partnership’ with the public sector, the relationship has been theorised as a collaborative or mutually dependent one arising from the inherent limitations of the two sectors in providing collective services – or, more formally, a system of services45 – suggesting there is some scope for synergy rather than a zero-sum game. This resonates with the CCC’s articulation of the crisis care pathway3 and Crisp et al. ’s16 reiteration of the importance of viewing the MH system as a whole, with synergy between the various elements necessary to provide a timely and effective response. Collaboration and synergistic relationships can have different meanings for the various stakeholders. We draw on the conceptualisation of collaboration by Gray46 as ‘a mechanism by which a new negotiated order emerges among a set of stakeholders’. Therefore, one hypothesis is that a more effective and efficient response to people experiencing a MH crisis will be achieved through effective collaboration between VSOs and public (and in some cases private) sector services. Our understanding of collaboration also draws on the work of Morrissey et al. 47 on MH service system change in a US context, which differentiates between collaboration at the service system level and at the individual client level. This underpins our research design in seeking to understand how different elements of the crisis service system are working together both as a system and for individual service users.

Commissioning the voluntary sector

An increasingly important factor in shaping the relationship between the VS and the public sector has been the rise of commissioning as the foremost mechanism for ‘purchasing’ services from the VS. Public sector commissioners [e.g. within local authorities and Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs)] are now required to shape and provide stewardship of local provider ‘markets’. 43 Commissioning was intended to enable a needs-based whole-cycle approach to purchasing services, thereby alleviating issues around fragmentation and allowing VSOs to have a greater influence on defining public services. However, commissioning remains ‘fragmented in policy and practice, between different localities and scales of government’. 48 Commissioning arrangements between the public sector and VSOs sit on a spectrum ranging from narrowly constituted ‘commissioning on price’, which resembles traditional procurement and tendering processes, to ‘intelligent/collaborative’ at the other end. 48 The integrity of commissioning – and the role and standing of commissioners – has also arguably been undermined by austerity and the widespread perception that it is one mechanism for enforcing ‘cuts’ to public services. Miller and Rees49 examined whether or not commissioning has created opportunities to improve the whole system of MH provision, finding that in reality commissioners felt they were ‘subjects’ rather than ‘masters’ of change. Apart from a few promising examples of individual service change, new commissioning arrangements were thought to be unable to bring about systemic change in MH services. This was attributed to a lack of personal expertise and knowledge of local services, limited influence on the whole system, poor communication, fragmented or inconsistent relationships between local authorities, VSOs and NHS services, and competitive tendering processes and contracts, which many VSOs felt limited their creativity or compromised the goals of their service provision. Some commentators have called for much more radical change to commissioning arrangements, including wholesale reform. 50,51 Therefore, linked to an examination of collaboration, understanding the extent to which current commissioning arrangements recognise and support the sustainability and contribution of VSOs to MH crisis care was also an important focus of this study.

This report

This report provides the context, aims, methodology and detailed findings of our study. This chapter has outlined the background for our study, covering the policy and practice context for the VS’s role in MH crisis care. Chapter 2 provides a literature review of relevant research to enable us to map the key concepts and develop the research tools. Chapter 3 describes the aims and methodology for undertaking our study, which involved four work packages (WPs), from outlining the landscape for the VS in MH crisis care to investigating the role at a system and individual level in four (anonymised) case study sites (sites A, B, C and D).

To address the research objectives, we have chosen to present the findings thematically, with each chapter synthesising the data from the different WPs. The Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Studies (COREQ)52,53 and the Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public (GRIPP2)54 checklists have been used as guides to ensure comprehensiveness and rigour in reporting our findings. We start with individual experience and foregrounding needs in a MH crisis (see Chapter 4) to establish the reference point for crisis care provision. Chapter 5 describes the different types of VSOs and how they are relevant to meeting these needs. We present a typology of the different types of VSOs and the role they play in MH crisis care. Illustrative descriptions of these different types of organisations are available in the Report Supplementary Material 2. We then present the findings on how people have accessed support from the VS, the nature of the support provided, its quality and adequacy and the difference it has made to people’s lives, both service users and their families/carers (see Chapter 6). We use individual case studies to illustrate people’s experience of accessing help and the VS response. We then examine the relationship between the VS and public sector services, mainly those provided by the NHS, and how well these two sectors are working as elements of a system of MH crisis support to ensure an effective pathway for people needing support in a MH crisis (see Chapter 7).

Finally, we present the findings on the role of commissioning in shaping the contribution of the VS to MH crisis care (see Chapter 8). This includes the sources of funding for VS activity and the relationship with commissioning, including the contracting arrangements, monitoring and the quality of these relationships. We identify the implications for the sustainability of the VS in this area and the recommendations that participants made to strengthen the commissioning of the VS. Chapter 9 provides a synthesis of our findings on the contribution of the VS to MH crisis, the limitations our research and our contribution to addressing the identified knowledge gap. Chapter 10 summarises the implications for policy, practice and further research in this area.

Quotations and illustrative crisis journeys

We have selected quotations to illustrate specific themes, and codes are used to refer to individuals and to maintain anonymity. The codes, which are used in combination, are provided in Table 1. Assigned numbers are sequential for each type of respondent. For example, the first service user to be interviewed in study site A is referred to as ASU1 and a participant in a carers’ focus group in study site B is referred to as BCaFG.

| Code | Participant reference |

|---|---|

| A, B, C and D | Study site |

| Ca | Carer |

| CCG | Clinical Commissioning Group |

| FG | Focus group |

| G | Group |

| LA | Local authority |

| MHP | Mental health professional |

| Po | Police |

| RS1 and RS2 | Regional stakeholders (in regions 1 or 2) |

| S | National stakeholder |

| SU | Service user |

| ULO | User-led organisation |

| VS | Voluntary sector |

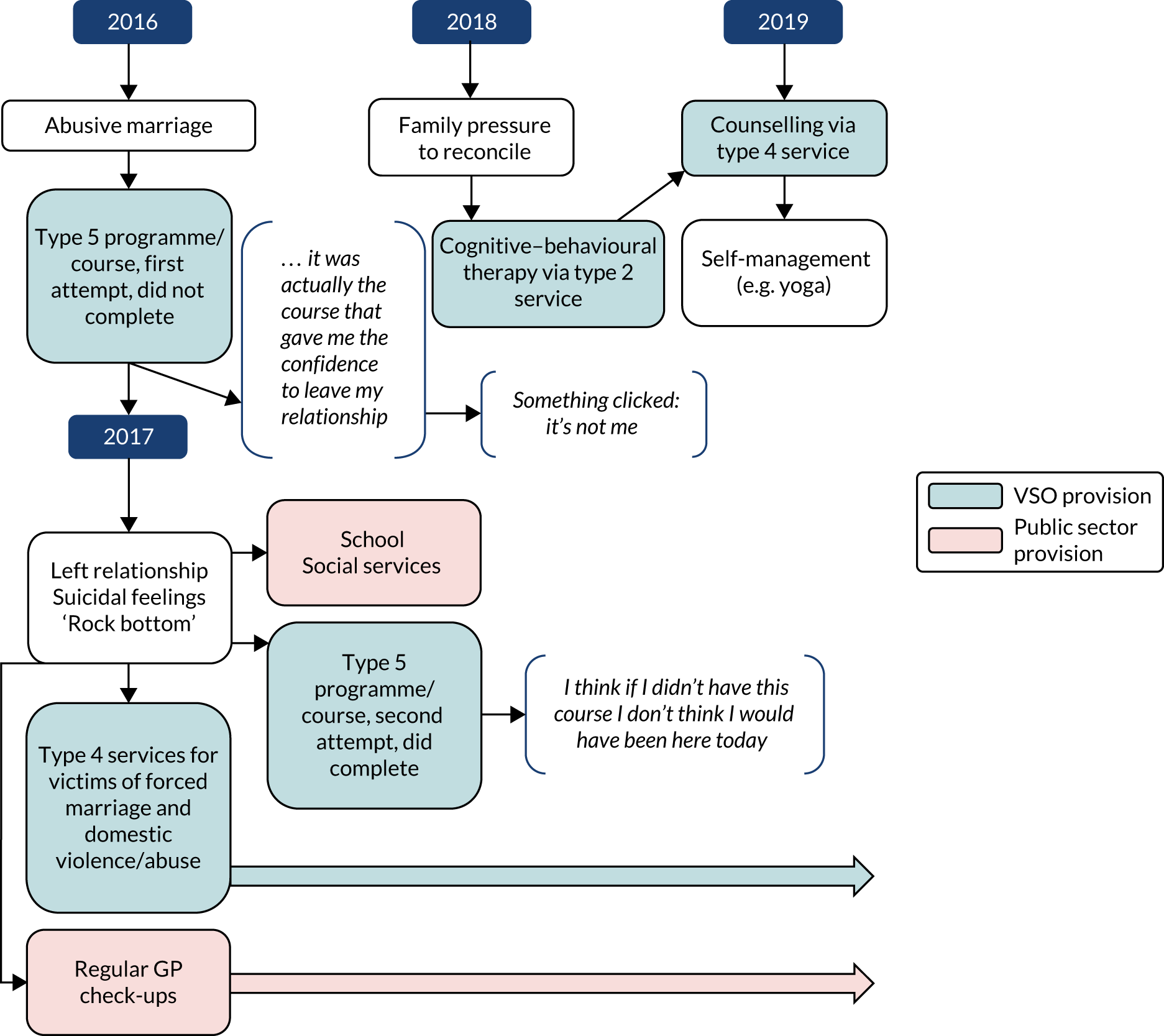

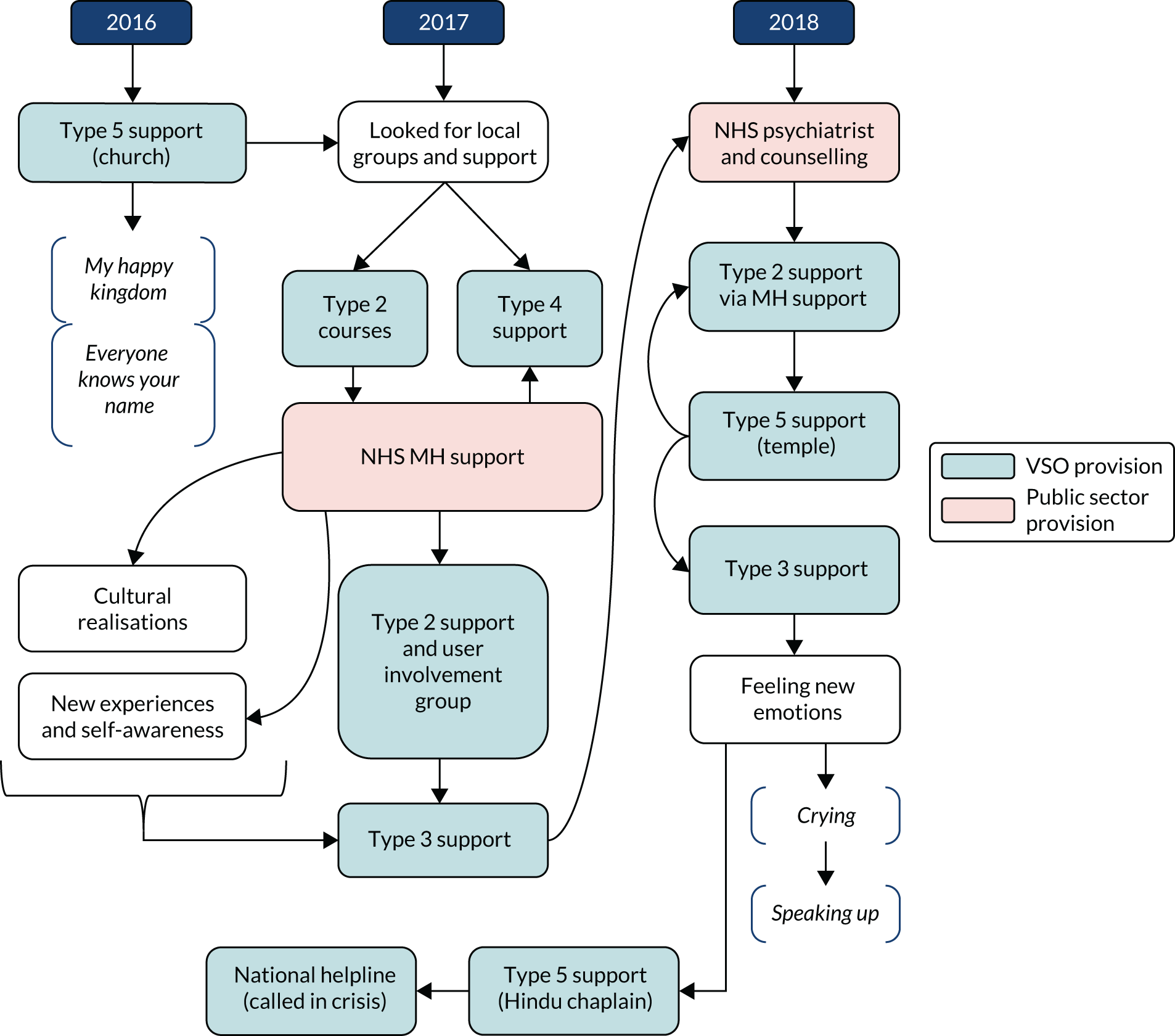

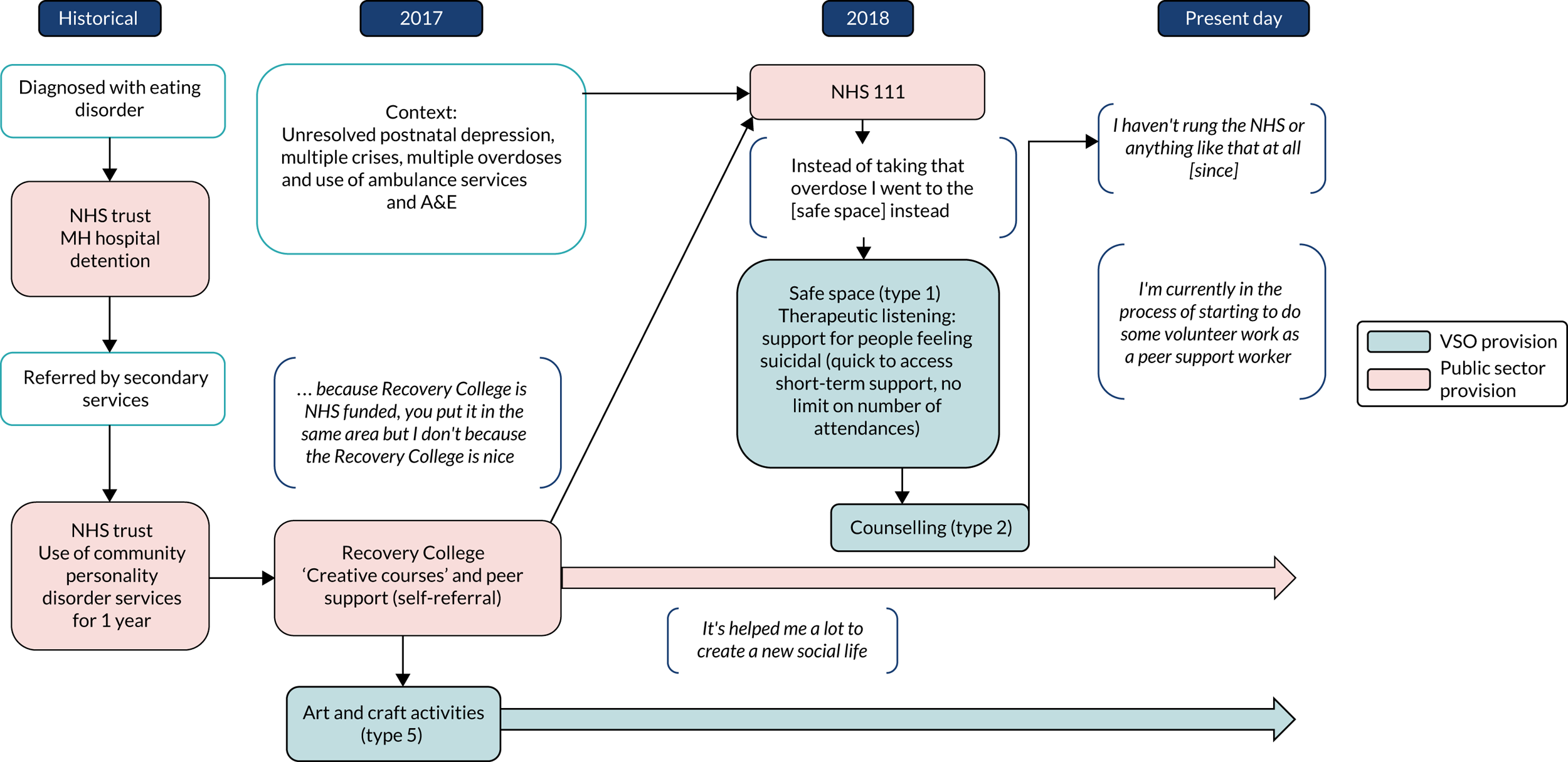

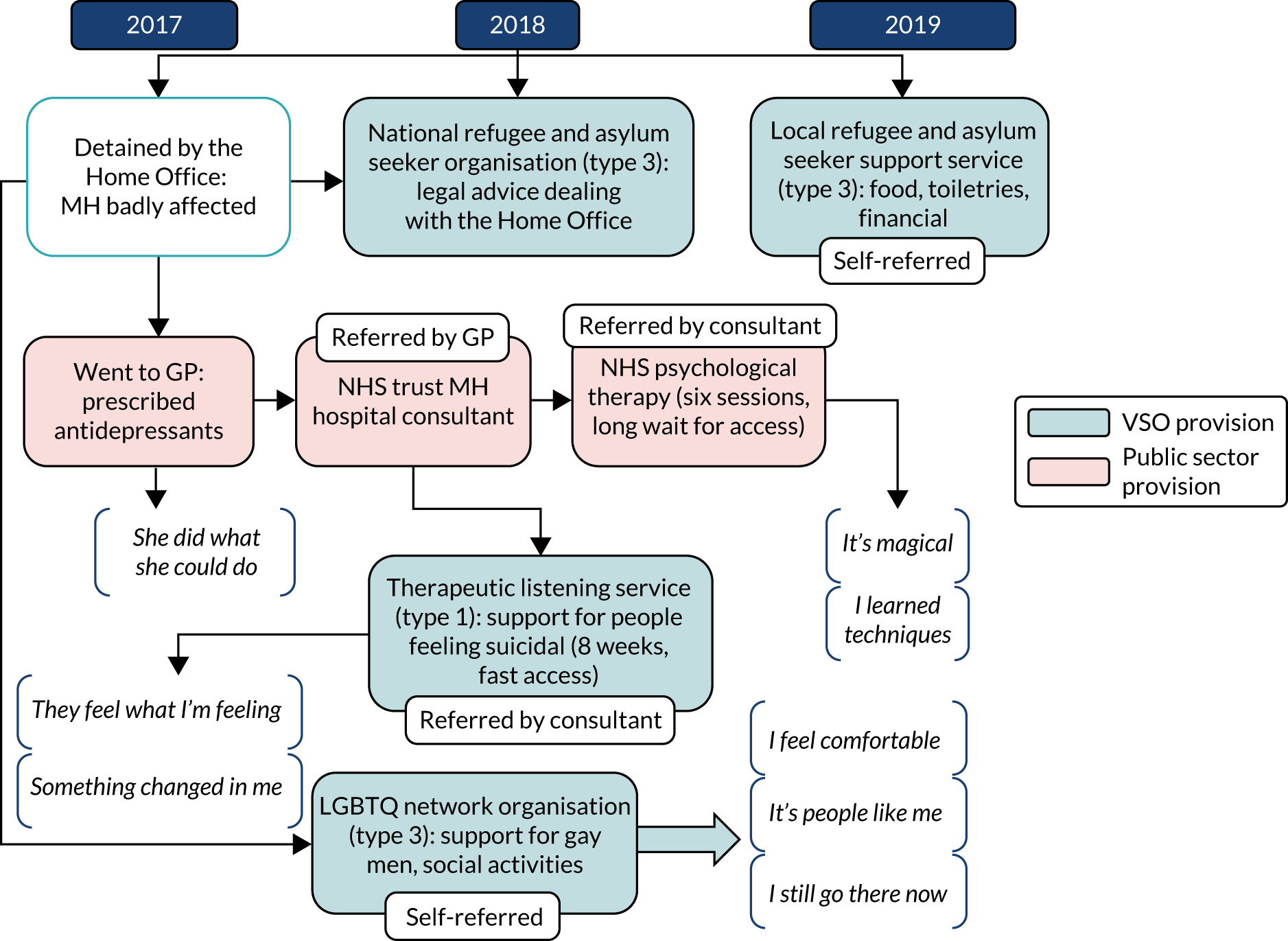

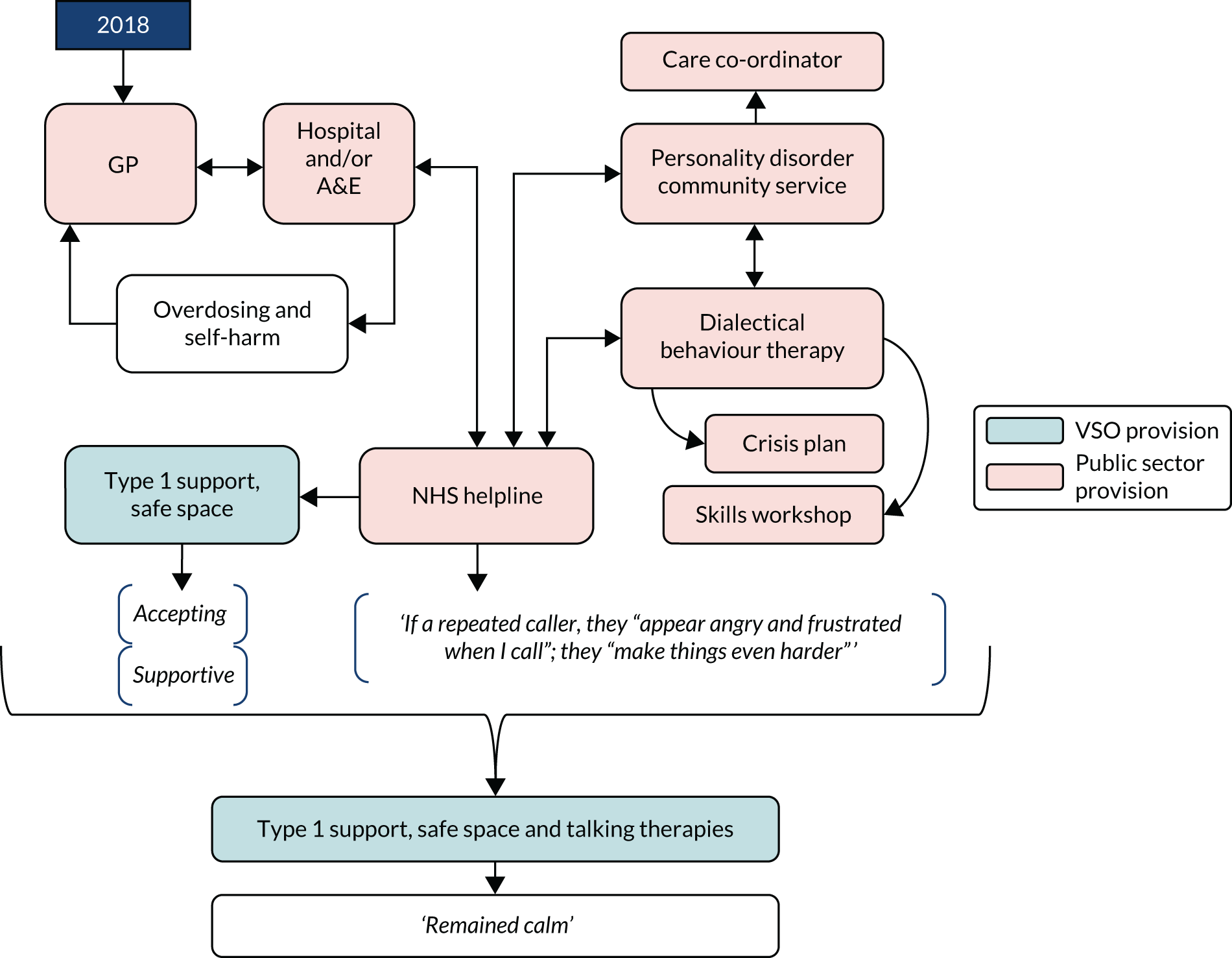

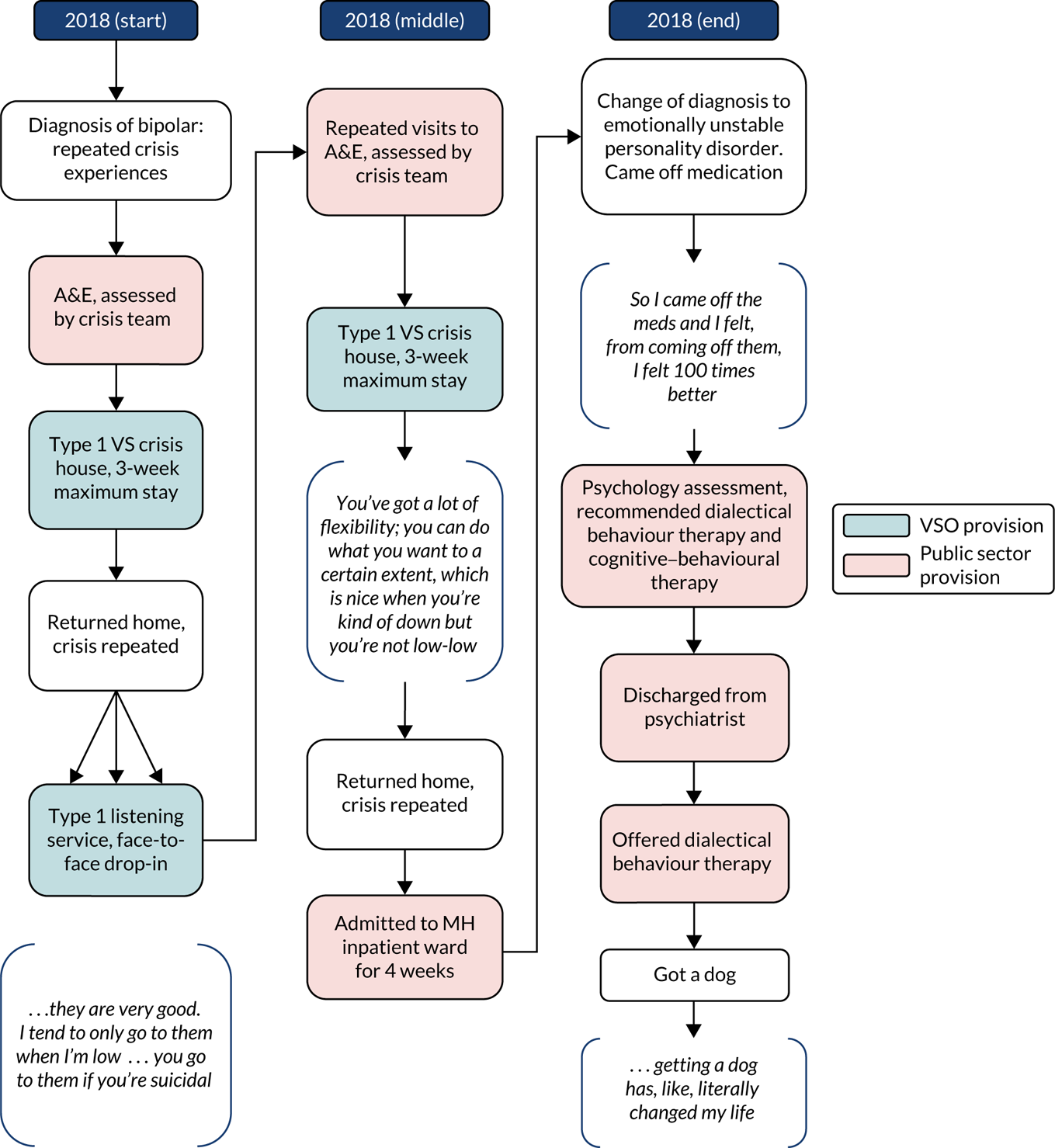

We have drawn on data from repeat interviews with service users to illustrate individual crisis journeys (see Figures 5, 6, 9, 10, 12 and 13). These illustrative crisis journeys show how the VS contributes to a patchwork of different types of support at different points in people’s individual journeys. They exemplify how the various types of VSOs reported in Chapter 5 contribute to supporting people with different aspects of their crisis, as well as using public sector services.

Language and choice of terms

Some of the language used in this report will be contested, as it was during our study. We use the term ‘mental health problems’ to describe the wide range of emotional difficulties that people experience, and we have used the term ‘mental illness’ and diagnostic labels as they were used by participants. The term ‘service user’ is used to refer to people who are using or have accessed MH support; we are aware that, because the experience of engagement with MH services is often distressing, disempowering and unwanted, some people prefer the term ‘survivor’. We have used the term ‘black, Asian and minority ethnic’ to refer to people from a wide range of communities serving black or Asian, or people from other racialised, minorities. Finally, we have used the term ‘voluntary sector organisations’ to refer to charities, voluntary organisations and community groups.

Chapter 2 Previous research on the role of the voluntary sector in mental health crisis care

In developing the proposal for this research, it rapidly became clear that the evidence for the contribution of the VS to MH crisis care was scant. We therefore undertook a rapid literature review to identify the knowledge base for the contribution of VSOs to MH crisis care, to map the key concepts and to inform the development of the research tools. Although a systematic review was beyond the scope of this study, our literature review was as comprehensive as possible and followed systematic review principles (see Appendix 1 for details on the method). This chapter provides a summary of the main themes.

Overview of the literature

Thirty papers relevant to the current study were identified (see Appendix 2 for a summary). These included papers from the UK, Canada, the USA, Norway and Australia. The papers fell into five main groups: experiences of a MH crisis and preferences for support (n = 9); evaluation and description of service models, including helplines and peer support (n = 9); alternatives to public sector provision, including comparisons of outcomes and cost-effectiveness, with the majority relating to alternatives to inpatient admission (n = 8); evaluation of new service models, including the VS (i.e. vanguards; n = 2); and the relationship between MH VS providers and MH public sector services (n = 2). The review identified significant gaps in the literature. The majority of the studies were qualitative studies, with five studies considering outcomes using rating scales55–59 and other studies analysing routinely collected data. 20,55,60–64

Conceptualising a mental health crisis

Many papers use the term ‘crisis’, often relying on traditional notions of a crisis. Several papers, however, identify different types of crises or describe important characteristics. The temporal dimensions of a crisis emerge as central, with a crisis as a process or condition and an emergency identified. 9,65 Bonynge et al. ,9 for example, distinguish between moderate (non-acute) crises, in which people are in need of urgent care, and severe crises, which are considered a MH emergency. The latter type of crisis was characterised by observing three or more of the following characteristics: (1) danger to self, (2) danger to others, (3) significant confusion, (4) significant depression and (5) significant functional decline. Sells et al. 66 explored the contexts and conditions for crisis and identified a recursive dynamic between a crisis and its consequences. For example, a chronic illness can lead to a loss of income, role disruption, and challenges to identity and routine, thus contributing to further crises. This suggests that a crisis is not necessarily sudden but can also be triggered by circumstances or life events. 1 Similarly, Gudde et al. 67 and Albert and Simpson68 describe the crisis experience as a process of ‘problem escalation’, with the lack of effective support creating an ‘emergency’, resulting in police intervention, or a cyclical process of short periods of hospitalisation then discharge until another crisis occurs.

Ball et al. 65 argue that there are significant differences between how crises should be understood for people who are living with a serious MH issue. 65 They propose that conceptualising crises in terms of ‘underlying vulnerability’ – traumatic life experiences, troublesome symptoms and ongoing circumstances – instead of a precipitating event leads to a better understanding of how broader conditions for crises are created. Reflecting the situated nature of a MH crisis, Thomas and Longden11 argue for a moral, emotional and contextual approach to understanding crises.

Exploring these dimensions of crises may enable an understanding to be gained of the function and nature of VSO interventions and support, in terms of which point of the crisis process these organisations intervene and what they are aiming to address (preventing readmission or breaking the cycle). It also raises the question of whether or not different services, organisations and individuals have a shared understanding of the crisis process.

Subjective experiences of crisis

Subjective accounts reveal the multifaceted nature of a MH crisis, situated in the context of people’s lives. Despite the inherently personal nature of crises, some common themes are evident: the feeling of ‘emotional darkness’, loneliness and a desire for togetherness, feeling scared and a sense of loss of control. 1,65,69 Hopelessness and seeing no end to the situation may lead to a suicide attempt. A service-user-led study of the experience of CRHTs frames a MH crisis as a journey. 70 Similarly, Gullslett et al. 69 describe MH crises as a ‘continuity of struggles in complex situations’. They identify two dimensions – existential/personal and contextual/social – and, depending on the individual and the situation, one of these might be more dominant. These themes were also identified by the Mind inquiry1 and Ball’s65 situation-specific theory. Other themes included the intervention of others, loss of identity and purpose, alienation, not coping or functioning, hopelessness, despair, self-blame and guilt. These themes were inter-related in complex ways and sometimes conflicting feelings were evident, for instance an awareness of the need for help and a desire to reach out to others, but limited emotional resources or capacity to do so.

Using a phenomenological approach in a study focused on carers’ experiences, Albert and Simpson68 identified that a MH crisis can also be a stressful time for carers. They suggest that they can experience a ‘double deprivation’, often unsupported by staff owing to different understandings of what constitutes a crisis, and not accessing support from their social network, preferring to limit the impact of the MH crisis. This highlights the wider impacts of a crisis and the importance of recognising carers’ knowledge and understanding.

These different experiences and understandings of a crisis indicated that it was important for our research to consider how the crisis experience is conceptualised.

Preferences and crisis responses

Given the intensely personal nature of a MH crisis and the conceptualisation of a MH crisis as a ‘turning point’,6 there is an opportunity for learning and building resilience if effectively supported. 71 Mind’s inquiry into crisis care1 identified four main themes for what people wanted from a crisis support service:

-

to feel cared for, not abandoned

-

choice and control, not coercion

-

a personal caring response rather than a medical one and

-

appreciating that one model does not fit all.

They recommended that there should be a greater range of options to meet different needs, including self-referral options, crisis houses, host families and services provided by peers. Similarly, a consultation exercise by Healthwatch Norfolk72 identified that the help and support provided by community organisations and VSOs, including telephone helplines, drop-ins, cafes, support groups, counselling and therapies, were highly valued and it recommended that their contribution to MH crisis care not be overlooked.

The personal response to a crisis varies from actively seeking help, to managing alone, to others stepping in to seek help. 65 Gudde et al. 67 explored the experiences of people with major mental disorders in a Norwegian context and identified a high threshold for contacting services as a result of previous negative experiences or inappropriate provision. Similar to other studies,1,67 service users wanted easy access to services to enable early intervention and to break a cycle of repeated hospitalisation. 67 Boscarato et al. 7 found that service users did not want a police intervention, with the majority preferring a more informal response. Hutchinson et al. 58 identified that men using a VS MH service were significantly more likely to be unemployed, have forensic histories, have less contact with other health services and have more unmet needs than those attending a service at a MH hospital in the same catchment area. Those attending the VS service cited wanting to escape ‘the system’, with the levels of dissatisfaction with public sector MH services particularly high among African Caribbean groups. These findings suggest that VSOs play an important role in enabling access for people from marginalised groups.

McGrath and Reavy73 underline the different needs of people in a crisis, to counter simplistic assumptions. They identified that people experiencing a MH crisis use space differently to maintain their sense of agency. Those experiencing a psychotic episode preferred outside space, as it ‘appears to open up new zones of fluid possibility, which potentially enables service users to de-centre, stretch out, and disperse some of the burgeoning intensity of experience’. 73 Other people preferred the privacy and the sense of safety afforded by being in an indoor safe space, which helped them restore feelings of agency and strength.

A key question, therefore, is the extent to which service users’ preferences and choices are heard, and the extent of their involvement in planning and defining their own support and recovery. Gudde et al. 67 concluded that service users identified active involvement, with dialogue-based care that placed equal value on their own coping mechanisms (acknowledging that these were not always ‘optimal’), as helpful. This included being understood as a ‘normal’ person, dealing with crises in an everyday context, and respectful, caring relationships.

Voluntary sector mental health crisis services

Crisis houses

One of the most frequently mentioned contributions that VSOs make to the provision of MH crisis support was the provision of alternatives to acute inpatient admission. 74 These are typically crisis houses to be used for up to a few days, or during the day-time or for slightly longer short-term stays of up to 2 weeks. Johnson et al. ’s74 study identified 131 alternatives to hospital admission across England and, although crisis houses are not uniquely provided by the VS, a significant proportion were VSO led.

Some of the perceived advantages of crisis houses over hospital wards, from the perspectives of service users and staff, are that (1) they are more homely (often located in converted residential buildings), less stigmatising and less clinical owing to the fact that they are led by nurses, counsellors, peer supporters and volunteers as opposed to clinicians (e.g. psychiatrists); and (2) pathways to admission can be less fraught, with less coercion and loss of liberty. 59,75 Morant et al. 76 identified the specific benefits of non-clinical crisis houses as providing a more holistic style of care; offering greater autonomy, choice and responsibility to clients; developing strong therapeutic and peer relationships; and enabling people to maintain their connections to ‘normal life’ and the community. This is echoed by Sweeney et al. 59 who found that service user satisfaction and therapeutic alliances were stronger and more positive in crisis houses than in inpatient wards. They attributed this to the homely environment, informal peer support and fewer negative experiences with staff in crisis houses. Thomas and Longden11 commend the Soteria77 and the Sanctuary78 models for their moral imagination, placing empathy at the core of caring.

As well as providing an alternative to admission, crisis houses or other interventions may aim to prevent readmission and promote recovery. 79 Griffiths et al. 80 described a transition intervention service after a stay in a VS crisis house, in response to evidence that 20% of people discharged from inpatient care were being readmitted within 90 days. 81 The intervention was designed to help with living skills, resilience and self-management, and the evaluation found significant improvements in social networks and self-management, although less improvement in the area of work. This highlights the role that VSOs can play in supporting recovery, a highly individualised process to realise people’s strengths and personal aspirations/goals.

Other papers focus on evaluating the value of crisis houses in terms of clinical and/or service outcomes. The evaluation by Larsen and Griffiths55 of the impact of a stay in a non-clinical VS crisis house showed significant increases in all recovery star domains (i.e. managing MH, identity and self-esteem, trust and hope, and self-care) and significant increases in personal goal-scoring data. The service was gate kept by the local MH team as an alternative to acute inpatient hospital admission or providing an intermediate step before returning to the community. Larsen and Griffiths55 highlight the open-door policy, which helped residents maintain independence and connections with the community, and staff training on reflective, compassionate practice, operating on the principle that the recovery process starts as soon as people enter the crisis house. The evaluation by Butt et al. 56 looked at a partnership between a VS crisis house in London and the local home treatment team as an alternative to admission and reported positive improvements in MH and safety, as assessed by service users and clinicians. Croft and İsfan61 also found that short periods of stay in peer respite care reduced inpatient and emergency admissions by up to 9–10 days for each day of stay in peer respite.

A number of factors facilitating the best use of non-clinical crisis houses were identified, including being locally valued, with public sector teams having knowledge of available services and a willingness to promote them, and being designed in collaboration with local MH services in response to local needs so that roles are clearly defined. 55,76 However, public sector staff sometimes found it a challenge to refer to crisis houses appropriately as a result of their small size and limited organisational capacity. 76

There is conflicting evidence on who accesses VS crisis houses, which may reflect the different organisational arrangements, including referral routes and relationships with MH services. Many of the studies tend to position crisis houses as a ‘softer’ alternative that are less appropriate for people with more serious MH issues (i.e. for people who do not require intensive supervision or have specific clinical needs) and, therefore, as less appropriate for compulsorily detained or highly disturbed patients. Crisis houses also seem to offer less comprehensive treatment packages, especially concerning physical health issues. 74,76 There is, therefore, the general suggestion that VSO-led non-clinical crisis houses may be of particular relevance for people who have not yet had contact with secondary MH services. However, Sweeney et al. 59 found that those attending a crisis house were more likely to be known to services and may, therefore, be more likely to seek help. Greenfield et al. ,57 in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) comparing a consumer-managed crisis residential programme (CRP) with four beds to a locked inpatient ward with 80 beds, found a greater severity of ‘illness’ and lower functioning scores for people in the CRP. Although life enrichment and functioning improvements were not significantly greater, self-esteem, social networking and satisfaction all improved for those in the CRP.

Service user involvement and peer support

Peer support is not limited to the VS, but peer support and championing service user involvement have been identified as particular strengths of the VS. Peers act as positive role models of hope and recovery,79 sharing their experiences and learning, and reducing the feeling of stigma and inequality. Gillard et al. 82 identified change mechanisms from peer support for people with MH issues provided by the VS and public sector as building trusting relationships based on shared experience, role modelling living well and recovery, and engaging service users with services and community. Peer support is also a potential benefit for the supporter as well as for the service user, providing a sense of value, a new role and a purpose. 66

User-led organisations are a unique feature of the VS, ranging from those representing a minority ethnic group, to those offering specific services (e.g. art or research), to those operating in particular geographical contexts (e.g. rural or metropolitan). 83 The review identified two evaluations of a survivor-led crisis house for individuals who repeatedly self-harm, Dial House in Leeds,60,84 which found that service users valued their informality, kindness, non-intrusive approach and peer support, and identified benefits in terms of both outcomes and cost-effectiveness.

Cost-effectiveness

A small number of studies have identified that VS provision is cost-effective or have argued that the reduction in the use of statutory MH services has led to potential savings. 64,85 For example, Croft and İsvan’s evaluation of a peer respite programme led to a reduction in the use of inpatient or emergency services, although these decreases were predicted to be time-limited. 61 Fenton et al. 62 identified that a residential crisis programme provided similar outcomes as inpatient care for a significantly reduced cost. Bagley60 identified a £5.17 benefit per £1 invested in Dial House (a ULO) and estimated the total added social value generated over 1 year as £1,757,843.73. Overall, the evidence for the cost-effectiveness of VS provision is scant and this is clearly an area for further inquiry, given the findings that service users prefer residential alternatives to hospital, including those provided by the NHS. 75

Systems, partnerships and processes

The importance of a whole-system approach to effective delivery of crisis care raises questions about how VSOs and the public sector, including the NHS, local authorities and the police, can best work together to ensure an effective and co-ordinated response. Bonynge et al. ,9 for example, scoped out the range of services offered by a US non-profit provider of a MH crisis care system in a rural setting, identifying a mixture of system components: urgent appointments, a crisis hotline, professional on-call services and five crisis beds (with a maximum stay of 72 hours). In examining how the system worked as a whole, they identified that distance was a challenge for mobile crisis services in rural settings, but that the combination of crisis services offered together reduced inpatient admissions by 11% and that many clients achieved stabilisation in the short period of time they used the crisis service. However, although people may use different services, the pathways to help are not always clear, with Healthwatch Norfolk72 identifying that approximately 50% of its respondents did not know who to contact if they needed help urgently.

A number of studies have considered the relationship between the VS and public sector services. The study by Johnson et al. 74 of alternatives to standard inpatient care found high levels of collaboration with NHS staff for non-clinical community-based alternatives, predominantly provided by the VS. Belling et al. 86 investigated the factors influencing the continuity of care by CMHTs through 113 semistructured interviews with MH staff, general practitioners (GPs), social workers and two VSOs. Alongside democratic and empowering leadership styles and decision-making, face-to-face communication facilitated cross-boundary working, including with the VS. Some poor communication between public sector and VS staff was noted, and was attributed to the high mobility of some people with MH issues resulting in highly complex networks of care and multiple interfaces at which communication breakdowns can happen. Information technology (IT) systems and information sharing between organisations was also cited as a significant problem.

Conclusion

The majority of papers identified in this literature review were concerned either with crisis houses or with the emotional or practical experiences of a MH crisis. Although the grey literature identified the particular role of the VS in MH in terms of longer-term, more holistic support, there are few academic studies that explore this. The dominant narrative in academic studies is focused on the VS and crisis houses and reducing admission to inpatient beds. Consequently, there is a gap in understanding the ‘whole system’ of crisis support, across the crisis journey described in the CCC. This includes sparse evidence on (1) a wide range of outcomes, (2) the collaboration between the VS and the public sector at the system and individual levels and (3) cost-effectiveness.

Chapter 3 Research design and methods

This chapter outlines the aims of our research, the research design and the methods adopted to address these aims. Additional details, including interview topic guides and questionnaires, are available in Appendices 3–15.

Aims and objectives

The primary aim of this research was to identify the contribution of the VS to MH crisis care and to identify the implications for policy and practice to strengthen the crisis care response. The specific objectives were to:

-

identify the different types of VS support being commissioned and/or provided to respond to the needs of people experiencing a MH crisis

-

develop a taxonomy of the different organisational types and forms of VS support available, service models (including characterising their relationships with public sector provision) and populations served

-

explore the configuration and the experience of a MH crisis system, including the factors and processes that facilitate the successful contribution of the VS to effective crisis care pathways

-

understand the crisis journey for individuals and their families and individual service user needs in a crisis, and how VSOs contribute to meeting their needs.

The scope of the study was MH crisis care in England. Assessments of clinical outcomes or cost-effectiveness, as well as comparisons with different types of service provision, were beyond the scope of this study.

Research design and methods

The design involved the use of multiple methods, both quantitative and qualitative, to provide a comprehensive and detailed analysis of the contribution of the VS to MH crisis care. The quantitative and qualitative methods complemented one another, with the quantitative methods providing an ‘extensive’ approach,87 to describe the landscape of VS provision, whereas the qualitative methods enabled an ‘intensive’87 investigation of meaning, experiences, relationships and processes. The study design ensured that the qualitative work was capable of being related to the wider picture through locating the qualitative data in a typology of VSOs derived from the quantitative data. To address the research objectives, the study was organised around four distinct but interconnecting WPs (Table 2).

| Objective (WP) | Research question(s) | Subquestions | Research method | Data collection and analysis | Outputs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) To identify the different types of VS MH crisis support (WP1 and WP2) | What is the contribution of the VS to MH crisis support? |

|

National scoping |

|

|

| (2) To develop a taxonomy of the different forms of VSO support available (WP1 and WP2) |

|

|

Mapping of VS support in two contrasting regions of England |

|

|

| (3) To explore the configuration and the experience of a MH crisis system (WP3) | How does the VS fit within the crisis system? |

|

Comparative case study of crisis systems in four CCC areas |

|

|

| (4) To understand the crisis journey for individuals and their families (WP4) | How does the VS support people experiencing a MH crisis? |

|

Comparative case study of crisis systems in four CCC areas |

|

|

The heart of the study was the comparative case study, at the system level (WP3) and at the level of individual service users and their families (WP4). The decision to use a case study design was threefold: (1) case study designs are particularly useful for enabling a real-time exploration of phenomena that are complex and dynamic;88 (2) it enabled an intensive examination of the VS contribution, contextualising both individual experience; and the VSOs within a system, to explore the relationships between VSOs and different system elements, and (3) the intensive examination had the potential to generate theoretical insights that could be applied in other contexts and provide the basis for subsequent evaluative work in relation to outcomes. The following section describes the four WPs, followed by data analysis and synthesis, methods adopted to ensure rigour, the research team composition, patient and public involvement (PPI) and ethics approval.

Work package 1: national scoping exercise

The focus for this WP was to identify the range of support that VSOs are providing to people experiencing a MH crisis. It involved reviewing the evidence and building a national picture of the contribution of the range of VS providers of MH crisis care in England. It comprised four elements: (1) a literature review (see Chapter 2), (2) assembling a database of candidate VSOs providing MH crisis care in England, (3) a national survey of VSOs to identify the type of crisis support being commissioned/provided and to whom, the type of organisation providing the support and the main methods of working, and (4) a purposive sample of interviews with national stakeholders (e.g. policy-makers, professional organisations and service user organisations) and national VSOs to provide further details on the different forms of VSOs, the type of crisis support they provide and how this contributes to the MH crisis care pathway.

Developing the database of candidate voluntary sector organisations

To develop the database for the survey, we identified the relatively small numbers of organisations that are active in the field of MH provision from a number of large databases. Appendix 3 describes the sources used, the process for selecting the candidate organisations for the survey and the decisions we made. We used the International Classification of Nonprofit Organizations (ICNPO) to help identify organisations of interest to this study. The result was a core list of 1982 charities, distributed across subsets of the ICNPO as follows:

-

MH and crisis intervention (n = 682)

-

other health (n = 215)

-

hospitals and rehabilitation (n = 51)

-

housing (n = 337)

-

civic and advocacy organisations (n = 85)

-

social services (n = 612).

We corroborated this against national surveys of third sector organisations in England,89,90 which have found that approximately 1% of charities and social enterprises (about 1800 organisations out of a total of 180,000) consider MH to be one of their three main areas of activity. This suggests that our number of charities (1982) is of the right order of magnitude and this list of VSOs was used as the basis for our survey.

National survey of providers

The purpose of the survey was to identify the range and types of services provided by VSOs to support people experiencing a MH crisis. A structured survey instrument was developed to capture information about the VSO and its scope (local, regional or national), income, and organisation and activity in relation to MH crisis care. This was piloted via relevant networks of the Study Steering Group members (SSG) (see Report Supplementary Material 3) and their comments were used to prepare the final version. The survey combined tick boxes and opportunities to provide free-text responses for the domains summarised in Box 2 (see also Appendix 4). The resulting Bristol Online Survey was sent to the 1982 VSOs identified and was promoted on the research web page and via social media.

-

Organisational form.

-

Whether or not organisations consider that they are involved in the provision of crisis support, and the form it takes.

-

How crisis services are organised and delivered.

-

Target populations and reach.

-

Aims and intended outcomes of provision.

-

Operational model and details.

-

Challenges and key determinants of success in providing MH crisis care.

-

Potential examples of positive practice.

Response rates were monitored and the survey was kept open for the duration of the data collection period from May 2017 to August 2018 to maximise responses. Two e-mail reminders were sent and a small number of telephone calls were made to non-respondents in those regions in which the response rate was lower (approximately 30 selected on a random basis) to encourage responses. Follow-up calls with a small number of VSOs generated illustrative examples of the different types of VS contribution (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

Survey respondents

Of the 1982 candidate charities, we established that:

-

a number declined to participate (n = 22)

-

a number of organisations had ceased to exist (n = 39) and

-

in some cases, the e-mail could not be delivered and/or it was impossible to locate accurate details (n = 105).

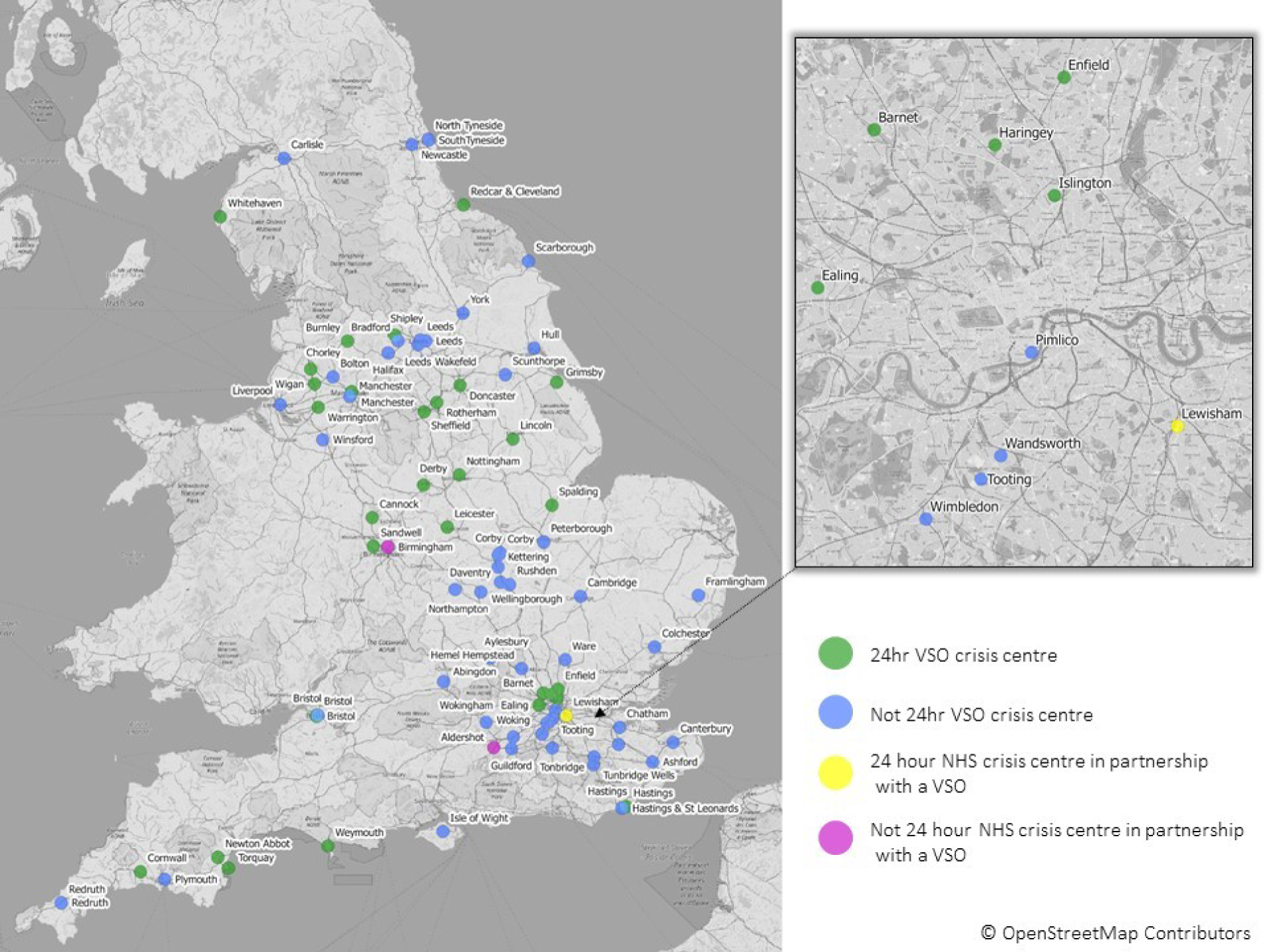

A further examination of the charitable objects identified that 204 of the remaining non-respondents were not providing direct services (i.e. grant-giving bodies, national offices or cases in which MH was very peripheral to the main aim of the charity). This left 1612 organisations. We received 220 responses, of which 171 were usable responses, making an overall response rate of 13.7% and a usable response rate of 10.6%. As the main function of the survey was to understand the breadth of VS provision, the responses were considered sufficient to develop an idea of classifications, which were then built on through the interviews at the national and regional levels, which in turn provided more detailed accounts of what some of those different types of VSOs were offering. The survey data were supplemented by interrogating information from the CCC, information from the positive practice website,91 information provided by participants and internet searching, to provide a list of crisis-specific VSOs across England. This information was inputted into a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet and then imported into geographic information software (GIS)92 to provide a map of the location of these VSOs (see Figure 10).

National stakeholder interviews

Interviews were undertaken with a purposive sample of national stakeholders representing policy-makers (e.g. the Department of Health and Social Care), professional bodies (e.g. the Royal College of Psychiatrists, the Royal College of Nursing and the College of Social Work), regulators (e.g. the CQC), national VS providers (e.g. Mind, Turning Point and Rethink) and national service user and carer organisations [e.g. the National Survivor User Network (NSUN)]. Twenty-seven participants were recruited, mainly via these representative organisations, with a small number recruited through snowball sampling (Table 3).

| Participant type | Number of completed interviews |

|---|---|

| Policy and arms-length body representatives | 4 |

| Service user organisations | 3 |

| Professional organisations | 3 |

| VS | 12 |

| Research | 3 |

| Other | 2 |

| Total | 27 |

| Declined | 10: no response or the invitee considered that they were not sufficiently knowledgeable about the VS |

The interviews covered the following aspects (see also Appendix 5):

-

the nature of the contribution that VSOs can make to MH crisis care

-

effective ways of integrating the VS contribution with that of with public sector services

-

challenges and key determinants of VS success in providing MH crisis care

-

potential examples of positive practice and

-

the future for MH crisis care.

Work package 2: regional mapping

Identifying regions and Clinical Commissioning Group areas

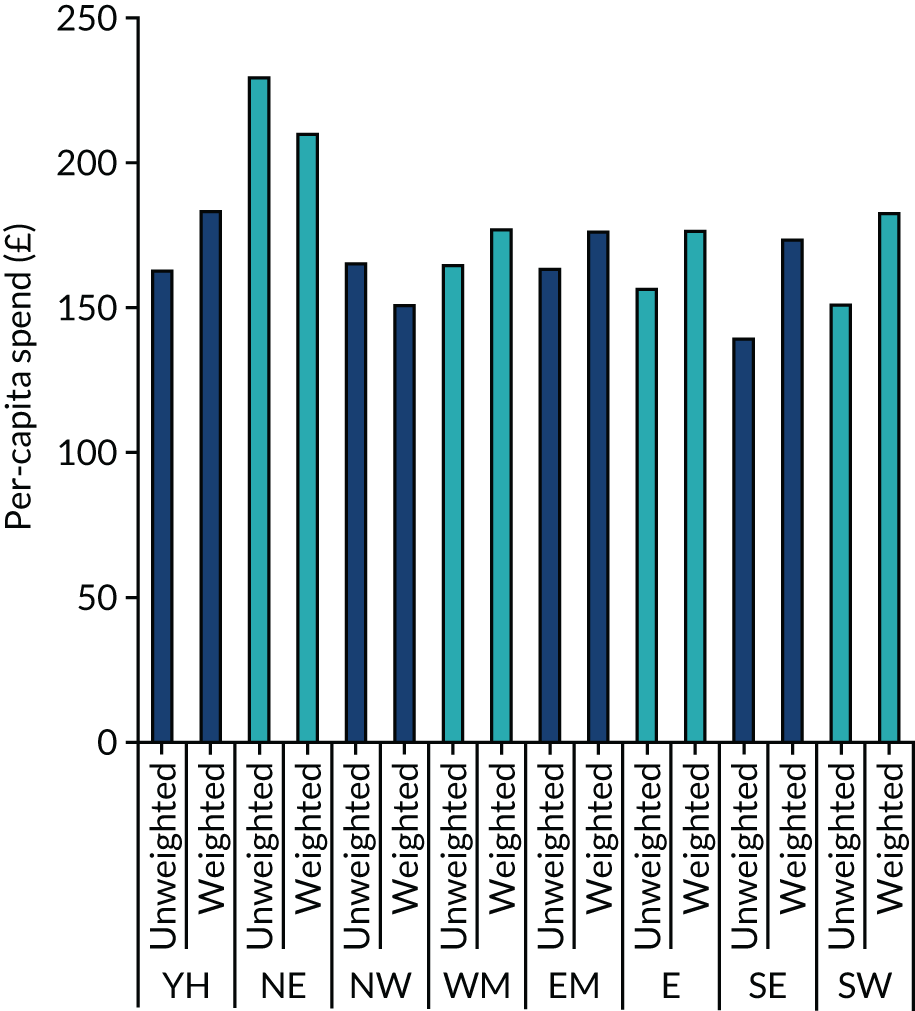

This WP contributed to identifying the different types of VSOs and developing the typology by gathering further detail at the regional level. We identified the region and CCG in which our identified VSOs were located by linking the postcode to digital boundary data using GIS. 92 This enabled us to identify areas with relatively high or low levels of VS presence. We identified regions using the definition of the regions on the ADASS website93 on the basis of contrasting expenditure (high and low) on MH services using data on per-capita CCG spending on MH (fifths or quintiles) for 2015/16. 94 The per-capita spend alongside the mean number of VSOs in each region (quintiles) were combined to give an overall indication of investment in the VS (as detailed in Appendix 6). From this, two regions were identified, the highest (RN1) and the lowest (RN2) on this combined measure. This measure does not definitively indicate the level of public investment in VSOs but did provide a basis for comparison. The number of VSOs does say something about the kind of VS activity in the region because these are based on postcodes and, therefore, the higher numbers of VSOs are actually registered in those regions and so are potentially locally rooted and active. The regions identified covered a large enough area to enable variations in the distribution and access to VS crisis support to be investigated. Because of the differences in the number of CCGs in the two regions (11 vs. 33), we took the pragmatic decision to focus on a subregion of RN2.

Within these regions there were two data collection methods: (1) targeted interviews with commissioners, VSOs and MH providers (n = 14) to identify additional activity that had not been picked up through the national scoping exercise and to explore the regional context for MH crisis care, the interface between VSOs and public sector services, and what factors facilitate effective crisis care pathways (see Appendix 7), and (2) further promoting the survey (used in WP1) to organisations identified from the interviews. Participants were identified through initial contacts with the relevant CCC and/or CCG leads, as well as additional snowball sampling. The main focus for the analysis was to identify variation within and between the two regions, the factors that have shaped this and the potential impact on MH crisis care delivery at the local level. This included variations in provision, capacity and crisis support. The analysis supported the development of the initial taxonomy developed in WP1, and the qualitative data were imported into NVivo (QSR International, Warrington, UK) and analysed alongside the data from the national stakeholder interviews undertaken in WP1, the stakeholder interviews in WP3 and the narrative interviews in WP4.

Work packages 3 and 4: comparative case studies of the voluntary sector contribution

The heart of the study was the comparative case studies, which enabled a detailed investigation of the VSOs’ contribution to MH crisis care. It focused on investigating how the VS elements of the MH crisis care system work together with public sector provision, and identified the challenges and determinants of success from the perspective of commissioners, VS and public sector providers, volunteers, service users and carers. We investigated the contribution of VSOs to the MH crisis care system (WP3) and at an individual level for service users, their families and carers (WP4). Each site had an academic lead and three co-researchers, with all team members being involved in data collection in at least two sites.

Selection of the case study sites

In selecting our case study sites, we adopted a realist approach to sampling,69 recognising that case study research moves back and forth between ‘ideas’ and ‘evidence’. Our original proposal was to identify case studies on the basis of sustainability and transformation partnerships (STPs), but variation, in terms of prioritising MH crisis care and the relationship with the VS, became evident in WP2. In adopting a realist approach, we necessarily surfaced our theoretical proposition that underpinned our sampling strategy (i.e. people experiencing a MH crisis have a wide range of needs and the VS forms one element of a wider MH crisis system able to respond). As the purpose of the CCCs was to bring together system partners, the CCC areas were, therefore, judged to be more fruitful than STPs in providing a context and connections for our research aims. We sought to identify sites that were information-rich (i.e. where there was VS provision of MH crisis support) but we made a deliberate choice not to restrict our sample to CCC areas that were being promoted as positive practice. Therefore, the selection criteria for selecting specific sites were refined as data emerged to enable us to select contrasting sites. The sampling criteria for CCC areas were:

-

Geography: case study sites were selected to include VS provision in rural, urban and coastal settings, and to ensure a geographic spread across England.

-

Population: sites were selected to (1) reflect variations in population density, which we anticipated would have an impact on access, and (2) include significant populations from BAME communities, specifically South Asian communities and African and Caribbean communities, because of the over-representation of African and Caribbean people detained under the MHA and the known barriers to accessing services for these populations.

-

Types of VS provision: cases were selected to provide contrast in terms of the types of type 1 VS provision identified from the earlier phases of work (e.g. a site with a crisis house and one without).

The four sites selected were located in East England, London, North-East England and the West Midlands. Table 4 provides a summary of the key features of the sites. Each site had a range of the different types of VSOs (see Chapter 6, Table 13). For formal crisis VSOs, two sites had crisis beds, provided by a housing association (site B) or a national MH VSO (site D), and two sites had a face-to-face appointment system, which was accessed either through self-referral (site C) or via the NHS (site A). All sites had a helpline provided by a national organisation, and two sites also had local helplines (sites A and C) and a range of other elements of VS provision including user-led services (sites A and C).

| Site | Description | Population (% BAME) | Population density (per km2, 2018) | Socioeconomic deprivation score (Index of Multiple Deprivation rank out of 326, 2015) | Public sector homeless per 1000 (2017–18) | Hospital admissions for MH per 100,000 (2017–2018 for CCG data) | Detentions under the MHA per 100,000 (2017–18) | Suicide rate (all persons) per 100,000 (2016–18) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Large rural areas, with two main centres of population: a university and a town with a relatively large migrant population | 852,523 (10% BAME) | 252 | 4.5% in the most deprived areas and 15% in the least deprived areas nationally | 1.1 | 234 | 21 | 10.45 |

| B | Satellite town, high BAME population, largest migrant group is South Asian. Many economically deprived wards | 327,378 (50% BAME; 20% of total population are South Asian) | 3725 | 20% of LSOAs in the most deprived areas and 55% in the bottom 20% nationally | 0.5 | 335 | 67 | 8.9 |

| C | Inner city, high BAME population, highly mobile population | 314,200 (48% BAME; 27% of total population identifies as black) | 11,000 | 35% of LSOAs in the most deprived areas nationally | 2.7 | 299 | 46 | 6.8 |

| D | Mix of urban, rural and coastal areas with ex-industrial towns. Some very deprived areas, mainly white population | 471,992 (6.5% BAME; largest group is South Asian) | 1361 | 25% of LSOAs in the most deprived areas nationally | Not available | 253 | CCG1: 31 CCG2: 85 | 11.9 |

Work package 3: the voluntary sector contribution within the crisis care system

To understand how the MH crisis care system was operating in each site, data were gathered to identify how different organisations providing MH crisis care worked together, the contribution of the VS to the MH crisis system, and what factors facilitated effective collaboration so that service users and their carers/families could access appropriate support. In each site, two data collection methods were used, as outlined in the following sections.

Semistructured interviews with key stakeholders

The key stakeholders interviewed included service user and carer organisations; local authority and NHS commissioners of MH crisis services and services for specific groups (i.e. learning disability and substance abuse services); NHS staff from a variety of crisis-related services (i.e. CRHTs, psychiatric liaison in A&E and first response services) and professional roles including team managers, GPs, psychiatrists, MH nurses, psychologists and community development workers; the police; councils for voluntary services; and Healthwatch. Participants were identified from initial interviews and web-based searches of the particular site. There were 13–27 stakeholders interviewed in each site (Table 5). The variation in the sample size for each site reflects the geography, organisational arrangements and availability of VSOs.

| Site | Participant type (n) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Commissioners | NHS staff | VSOs | Service user/carer groups | Other | Total | |

| A | 5 (3 CCGs, 2 local authorities) | 6 | 14 | 2 | 0 | 27 |

| B | 1 CCG | 4 | 6 | 1 | 1 | 13 |

| C | 3 (1 CCG, 2 local authorities) | 6 | 11 | 0 | 1 | 21 |

| D | 2 CCGs | 4 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 17 |

| Total | 11 (7 CCGs, 4 local authorities) | 20 | 42 | 3 | 2 | 78 |

The lines of inquiry for these interviews covered the following areas (see Appendix 8):

-

the crisis needs being met by different elements of the crisis care system

-

how well the system responds to the diversity of the needs of the whole population

-

how these different elements work together to provide an integrated MH crisis care pathway

-

the quality of current arrangements

-

the key challenges faced and how these are being addressed and

-

the current and likely future pressures on services.

Two members of the research team (usually a pairing of an academic researcher and a co-researcher) undertook the interviews, and how the interview would be conducted was agreed beforehand.

Two focus groups

Two focus groups, one for service users and one for carers, were held. These aimed to understand their experiences of VS provision and how this fits within the MH crisis care system. They provided an opportunity for a ‘collective conversation’96 and provided an important reference point for how their needs were met by the response of VSOs and the wider system. Focus group participants were recruited via the VSOs, service user and carer organisations, local authorities and NHS MH trusts in each case study site. Steps were taken to ensure diversity in the sample in terms of demographic characteristics, a range of MH problems and a range of crisis experiences. The criteria for inclusion were:

-

having experience of using VS MH crisis care in the past 2 years

-

being aged ≥ 16 years

-

having the capacity to consent to be involved in a research interview.

The focus groups were attended by 30 service users and 22 carers (Table 6), with it proving easier to recruit in some of the case study sites than others. Recruitment was particularly challenging in site A, in part reflecting the large rural nature of this site.

| Case study site | Service user focus group | Carer focus group |

|---|---|---|

| A | 3 (2 women, 1 man) | 2 (1 woman, 1 man) |

| B | 9 (6 women, 3 men) | 7 (5 women, 2 men) |

| C | 12 (8 women, 4 men) | 6 (4 women, 2 men) |

| D | 6 (3 women, 3 men) | 7 (5 women, 2 men) |

| Total | 30 (19 women, 11 men) | 22 (15 women, 7 men) |

Most participants were successfully recruited via VSOs and, consequently, limited demographic details were available. The focus groups in site B were predominantly made up of people of African Caribbean heritage. There were nearly twice as many women as men in both types of focus groups, and many participants had experience of using public sector services as well as VSOs.

All participants spoke English, although there was the option to use interpreters where necessary. The focus groups were co-facilitated by a co-researcher with relevant experience. The purpose of the focus groups was to understand the MH crisis system and, therefore, the topic guide covered experiences and needs in a MH crisis, experiences of the services used, how participants chose which services to access, how the different services they had used compared with each other and the pathway between these services, and recommendations for improving MH crisis support (see Appendix 9).

Work package 4: the voluntary sector contribution at an individual level

This element of the case studies aimed to develop a granular picture of individual crisis journeys to illuminate the VS contribution for individuals experiencing a MH crisis and to understand the operalisation of the interface between the VSO and different services.

Service user recruitment for narrative interviews

Different recruitment methods to identify service users were used across the sites, reflecting different arrangements for MH crisis care provision (Table 7). As VSOs did not always keep sufficient information on people using their services to enable recruitment, NHS organisations also facilitated recruitment. Potential participants were provided with information about the study (i.e. the participant information sheet) and could either complete a slip or send an e-mail indicating they were willing to take part and provide their contact details or give permission for the VSO or NHS to pass on details. The criteria for inclusion were:

-