Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/156/23. The contractual start date was in October 2016. The final report began editorial review in October 2019 and was accepted for publication in April 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Gavin D Perkins reports that he is a National Institute for Health Research senior investigator (2015 to present).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Bion et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and context

High-profile failures in health care,1–3 the paradigm for which were the events at the Mid-Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust,4 demonstrate the important contribution that staff attitudes and behaviours make to the experience of health care and to patient outcomes. They also show how easy it is for good intentions to be subverted, and how entire organisational cultures can become dysfunctional through the actions or inactions of individuals. Despite a near-universally expressed desire to provide the best possible care to their patients, staff may find themselves hampered by ‘inner context’ factors, such as power differentials, inadequate leadership, burdensome bureaucracy and overlapping and competing priorities, or conflicting organisational and personal values and beliefs that are aggravated by ‘outer context’ factors, such as health service pressures or attitudinal changes within wider society. 5,6 These factors may give rise to individual behaviours that at the micro level degrade patient experience of care from ‘excellent’ to ‘good’ or from ‘good’ to ‘poor’, and in the aggregate contribute to failure of whole organisations.

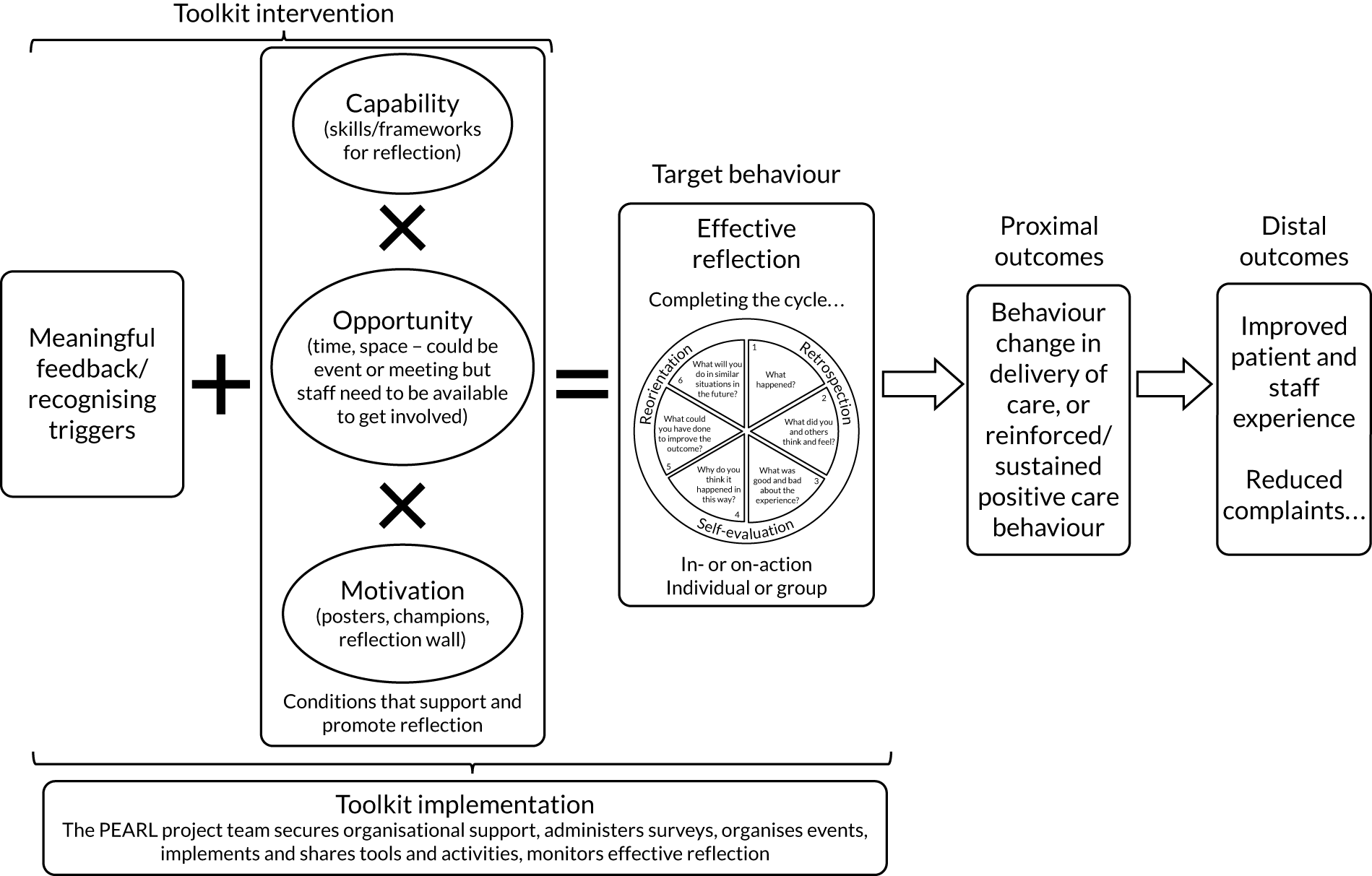

Our hypothesis is that dysfunctional behaviours that are harmful to both patients and staff can be mitigated by promoting insight and empathy through effective reflective learning at the level of the individual and of the organisation. We developed a preliminary logic model that links theories of behaviour change with those of learning to create a reflective learning framework (RLF). The tangible expression of this framework is a toolkit that links meaningful feedback from patients and staff to stimulate effective reflection ‘on-action’ and ‘in-action’ to promote optimal care.

Patient and staff experiences offer important insights into health-care quality

Patient and staff experiences offer important insights into the quality of health care, which complement organisational-level data on processes and outcomes. 7–9 Patient experience is an explicit outcome measure in the UK NHS10,11 and in the regulation of care quality. 12 All NHS trusts are required to collect patient experience data through surveys13,14 and additional insights are available through patient complaints. 15 In the USA, patients are surveyed through the Hospital Consumer Assessment of Healthcare Providers and Systems,16 whereas in Australia health organisations are required to involve consumers in accreditation processes. 17 Staff experience also provides insights into care quality: earlier action on staff concerns could have mitigated failings in care. 4 The NHS staff survey18 has been conducted annually since 2003. Patients and staff appear to share complementary insights into care quality: patient satisfaction is higher in hospitals in which nurses also reported better care quality. 19,20 Patient and staff perceptions appear to offer both overlapping and unique insights into safety in hospital. 21

Patient and staff experience is strongly influenced by staff attitudes and behaviours

The NHS National Inpatient Survey13 asks respondents to rate their overall experience on a scale of 0 (‘very poor’) to 10 (‘very good’). In 2017, 50% of respondents rated their experience as ≥ 9. 13 This indicates that there are substantial opportunities within the health system for ‘learning from excellence’. 22 However, ‘good’ ratings by patients (as opposed to ‘very good’) may also disguise important opportunities for improvement. 23 A survey by Healthwatch England (London, UK) reported that half of those experiencing substandard care do not report it. 24 Patients who respond to surveys with perfect ratings but with negative free text frequently describe lapses in staff behaviours and attitudes,25 such as communication, empathy, courtesy, consideration, compassion and patient focus. A study of patient-reported safety incidents26 found that 22% were related to communication failures alone, whereas a systematic review of patient complaints27 judged that one-third of complaints were related to staff–patient relationships. This may well be an underestimate given that staff behaviours are mentioned in up to two-thirds of all complaints (Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham local data on file). Attitudes and behaviours of other members of staff are also important determinants of staff (dis)satisfaction, as demonstrated by the 487,727 respondents to the NHS staff survey18 in 2018. Taken together, patient and staff experience, both positive and negative, provide an important opportunity for improvement through behaviour modification.

Patient and staff experience data are not used optimally to change behaviours

Despite this investment in data acquisition, health systems have difficulty using patient and staff experience data to improve care, particularly the non-technical skills related to attitudes, behaviours and culture. 28–30 Reflective learning underpins approaches to improving non-technical skills, but the processes by which experiences are translated into reflection, and reflection into behavioural change, are not well understood. Using patient experience to improve care is not a trivial task. 31 Lapses in care are usually multifactorial, the product of interactions between the individual and the ‘system’; however, from the perspective of the patient, quality is largely about trust-based relationships with specific individuals,32 not ‘systems’. Trust boards and quality governance committees must contend with the competing priorities of hundreds of quality indicators each month and may prioritise avoiding falling below a quality threshold rather than achieving higher values of a performance standard once met. A review in 201233 that examined how hospitals had used research from the UK National Inpatient Survey concluded that ‘simply providing hospitals with patient feedback does not automatically have a positive effect on quality standards’. Even trusts with a tradition of collecting and using patient survey data may struggle to convert these data into tangible improvements. 34 In a study of 50 clinical and managerial staff in three English hospitals, Sheard et al. 35 found that ward staff had difficulty using patient feedback, and the collection of patient experience feedback was a ‘self-perpetuating industry’ conducted ‘at the expense of pan-organizational learning or improvements’. 35 They concluded that ‘macro and micro prohibiting factors come together in a perfect storm which [prevents] improvements being made’. 35 In a systematic review, Gleeson et al. 36 reported that ‘patient experience data were most commonly . . . used to identify small areas of incremental change to services that do not require a change to clinician behaviour’. 36 Institutional commitment to using patient feedback may not be reflected at the front line, where single individuals can adversely influence other members of staff. 37 Conversely, front-line staff can struggle to get their voices heard at senior levels; one of the recommendations of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust inquiry4 was to establish ‘Freedom to Speak Up Guardians’ in all NHS trusts to ensure that staff concerns are heard and acted on. 38 These findings indicate that changing behaviours requires a change in underlying attitudes at individual, group and organisational levels. How is this best achieved?

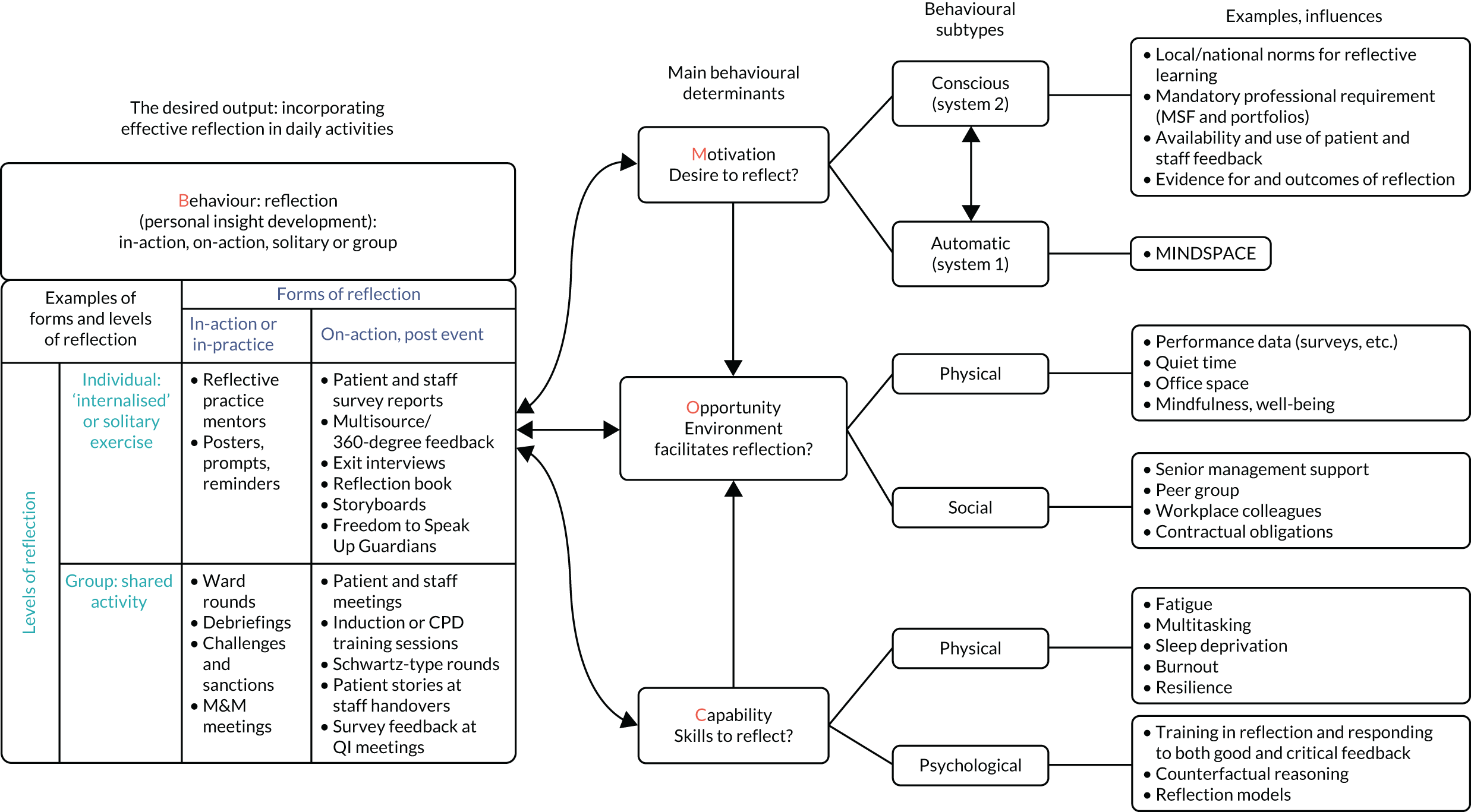

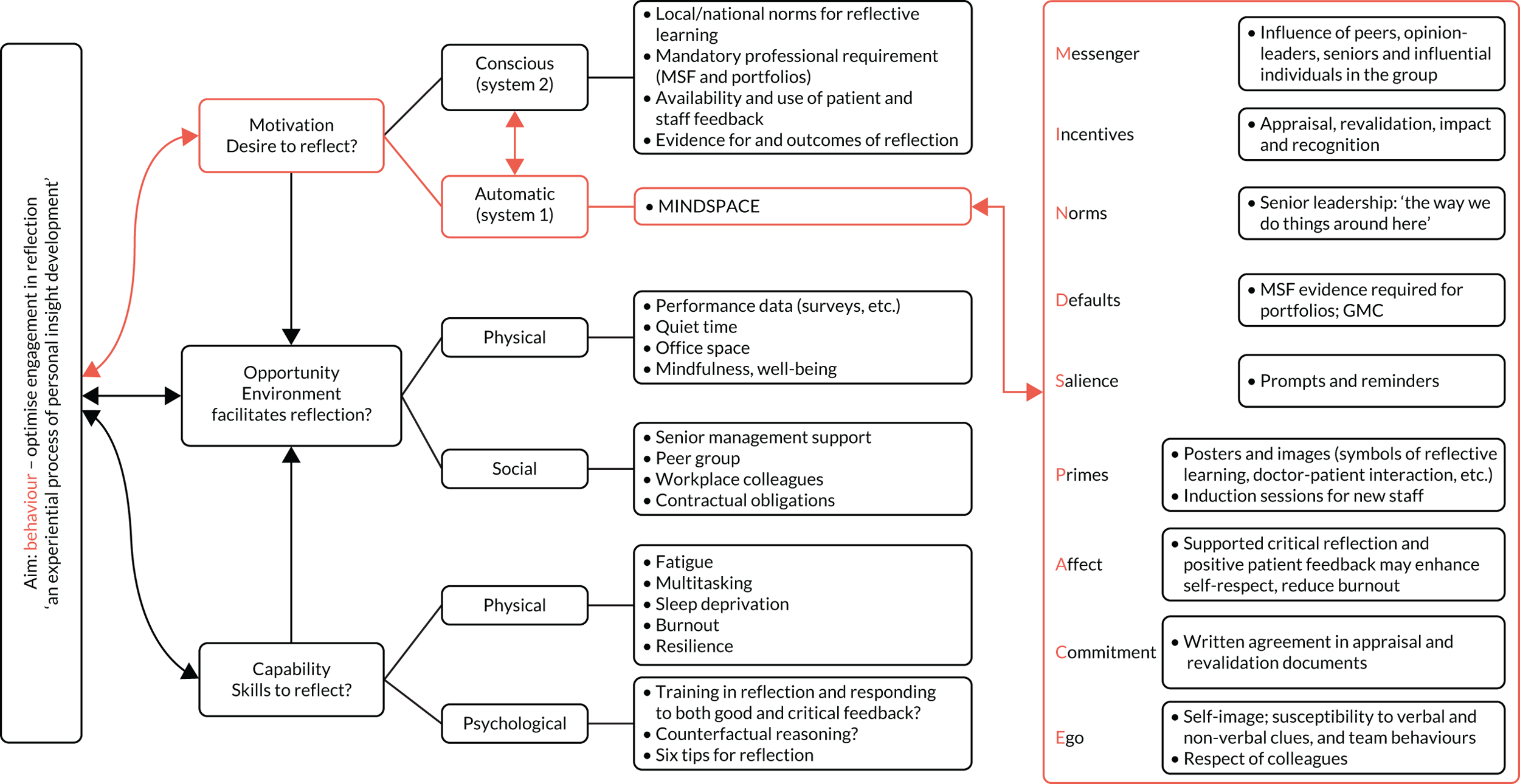

Reflection as behaviour

Behavioural modification is a universal preoccupation, and behavioural sciences now inform government policy. 39 A large number of techniques exist and a proposed behaviour change taxonomy has so far identified 93 different interventions. 40,41 However, evidence supporting the primacy of one technique over another is not strong. 42,43 Many interventions involve personal insight development through reflection, but few behaviour change theories express this explicitly. One which does is the Capability, Opportunity, Motivation – Behaviour (COM-B) framework,44 which assimilates 19 behaviour change theories into a single framework in which the behaviour of interest has three determinants, each with two subtypes: capability (physical and psychological), opportunity (physical and social) and motivation (reflective and automatic). The automatic subtype for motivation relies on heuristics, is engaged in conditions of complexity and stress, and maps to Daniel Kahneman’s ‘System 1’ thinking. 45 The reflective component of motivation is slower, more effortful and analytical (Kahneman’s ‘System 2’ thinking). These two subtypes of motivation map to the ‘peripheral’ and ‘central’ routes described in the elaboration likelihood model of persuasion. 46,47 Factors influencing motivation (particularly the automatic subtype) are summarised by the acronym MINDSPACE (messenger, incentives, norms, defaults, salience, priming, affect, commitment and ego). 48 As the behaviour of interest here is reflection itself, we need to consider both the automatic factors that influence the desire to reflect and the more effortful elements of ‘reflecting on the need for reflection’.

We next consider how theories of reflection as a behaviour link to theories of reflective learning as a tool for personal insight development.

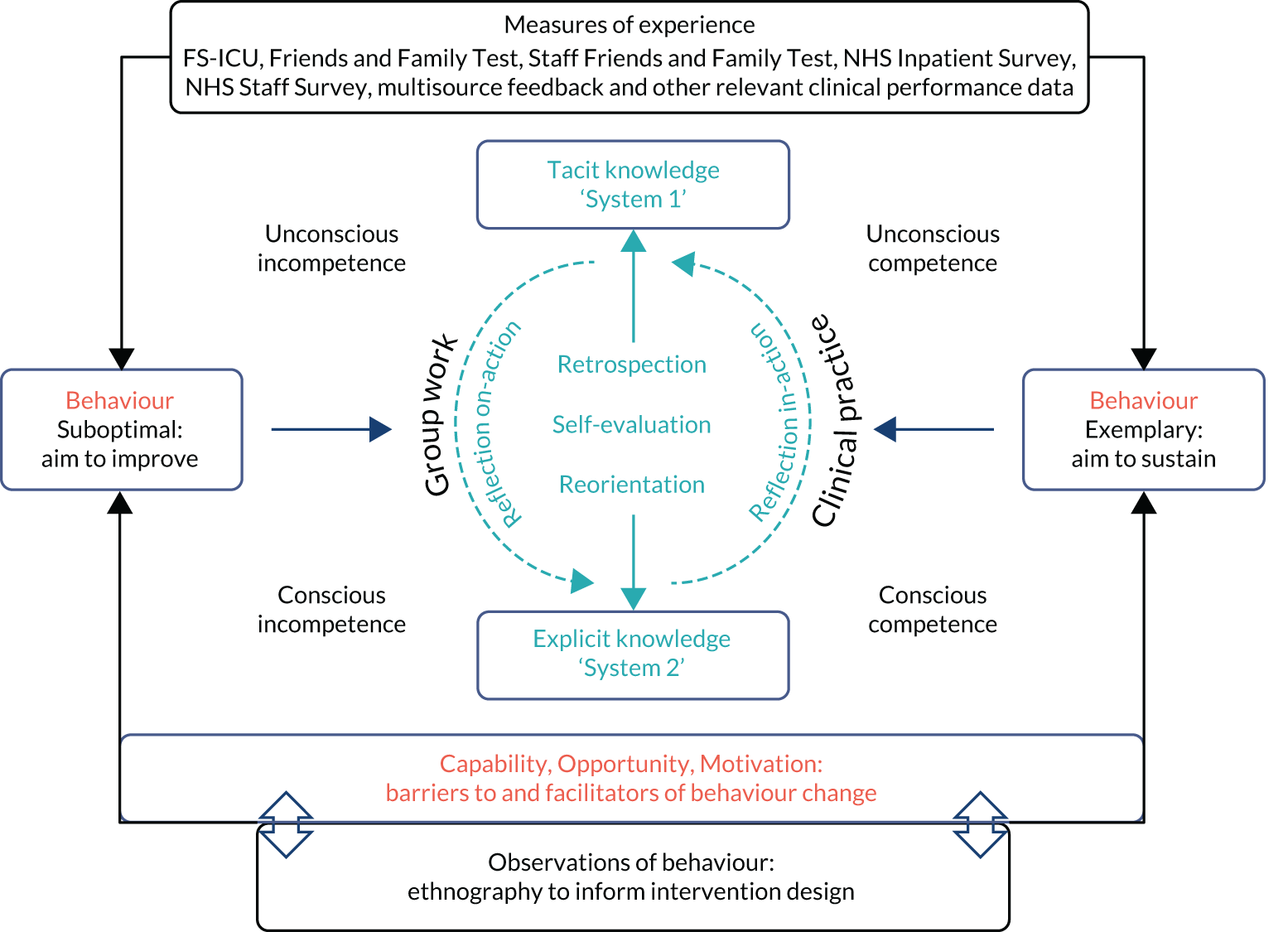

How does reflection stimulate learning?

Kolb and Fry49 presented reflection as a four-stage model: experience, observation, analysis and recalibration. Schön50 described reflection ‘in-action’ and ‘on-action’. Others emphasise the importance of an emotional component to reflective learning,51 including the ‘disorientating dilemma’:52 the realisation that there is a gap between desired and actual behaviours. Sandars53 describes reflection as a metacognitive process that creates a greater understanding of self and situation to inform future actions: looking back to look forward. This involves a transition from tacit to explicit knowledge54 in which socially acquired norms of behaviour55 are modified either through individual reflection or, more powerfully, through group activities. 56 The process shares similarities with Broadwell’s57 four stages of competence: unconscious incompetence (unaware of problem), conscious incompetence (data received, now being processed), conscious competence (using data to improve or disseminate excellence) and unconscious competence (effortless excellence). Effective reflection appears to involve making this transition while recalibrating and reinterpreting experience in-action and on-action.

Reflective learning could be deployed more effectively to improve care quality

First described by Dewey in 1933,58 reflective learning is now a mandatory tool in the education, appraisal and revalidation of health-care professionals. In the UK, the General Medical Council (GMC) and others define reflective practice as:

The process whereby an individual thinks analytically about anything relating to their professional practice with the intention of gaining insight and using the lessons learned to maintain good practice or make improvements where possible.

General Medical Council. 59

They state that:

. . . reflecting on . . . experiences is vital to personal wellbeing and development, and to improving the quality of patient care.

General Medical Council. 59

Reflection is incorporated in all UK health-care postgraduate training programmes and is evidenced in professional portfolios, which, for doctors, must include multisource feedback from patients and colleagues. The Nursing & Midwifery Council require five written reflections over 3 years by nurses for revalidation. 60

However, despite the widespread promotion of reflection as a tool for self-improvement, evidence that it actually improves performance is weak,61–63 as is the evidence that feedback from patient experience surveys promotes effective reflection. 64 We are biased towards favourable events and judgements65,66 and tend to reject adverse patient feedback,67 thereby missing the opportunity to learn from either through critical analysis. Poor performers additionally lack insight into their abilities. 68 It takes emotional strength and resilience to take a critical view of one’s own skills, particularly those relating to attitudes and behaviours given that these touch us personally; undesirable information is processed as a threat with physiological correlates that can actually impede learning. 69 In the UK, doctors are concerned that honest reflections documented in personal portfolios might incriminate them in a court of law. 66 Guidance on reflective practice for doctors70 proposes that solely negative events and errors should be used for reflection, rather than permitting a mix of both negative and positive events. The GMC also mandates reflecting on ‘significant events’, which are defined as ‘any unintended or unexpected event, which could or did lead to harm of one or more patients’59 (Reproduced with permission from the General Medical Council. 59 © 2020 General Medical Council. All rights reserved), in guidance on supporting information for appraisal and revalidation. 71 The emphasis on negative events could be viewed as diminishing the value of learning from positive experiences and role models. 22 The current emphasis on reflection for appraisal has had the effect of diminishing its potential for translation into lifelong reflective practice. 72 If reflective learning is to be effective, it must involve more than just completing a form and ticking boxes.

Could communication skills training substitute for training specifically in reflection? A review of 243 studies73 of teaching communication skills to medical undergraduates identified only 16 interventional studies, and of these only two reported behavioural outcomes, making it difficult to determine whether or not ‘communication skills’ are sufficient or even if such courses are effective at all. At postgraduate level, the effects of communication skills training appear to be weak or evanescent. 74–79 In one randomised controlled trial (RCT) of staff training in end-of-life care,80 communication skills were associated with worse depression among patients in the intervention group.

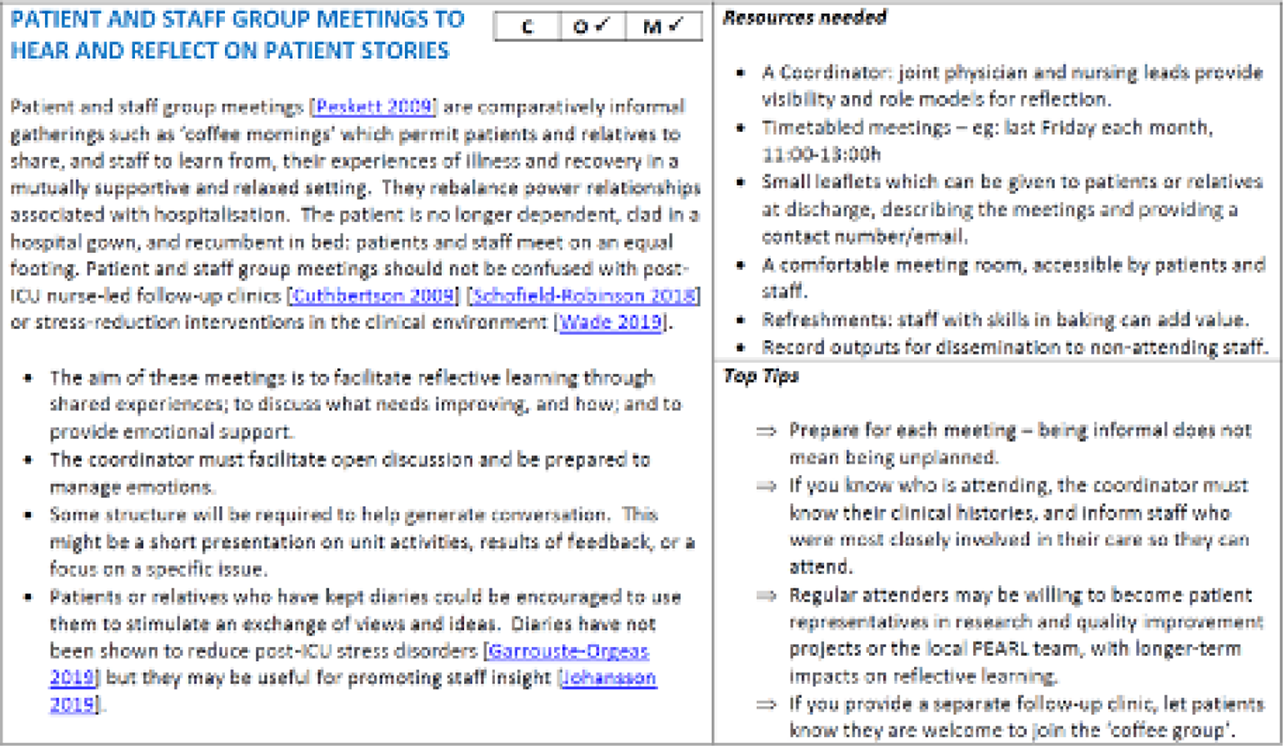

By contrast, interventions that focus on engaging staff in workplace-based activities, which improve teamworking,81 insight, patient-centred care and empathy, may be more effective and more durable. 82–93 The Cleveland Clinic offers short videos on empathy,94 and similar internet-based resources demonstrate how emotion may be engaged to stimulate reflection and promote mutual understanding. 95,96 For reflective learning to improve patient and staff experience, it probably needs to influence hearts as well as minds. Techniques for reflection need to be based on insights from behavioural sciences and evaluated using relevant process and outcome measures. In summary, the work of reflection must become a social enterprise rooted in a community of learning. This is the ethos of the Patient Experience And Reflective Learning (PEARL) project.

Aims and objectives

The aims of the PEARL project were to develop methods for acquiring patient and staff experiences; to use those experiences to promote effective reflection, insight and empathy; and to develop tools that would help staff apply effective reflection in clinical practice to improve care. In the longer term, our aim is to evaluate the impact of the toolkit through a RCT.

Specific objectives were:

-

establishing surveys for recording patient and staff experience

-

determining attitudes to and uses of patient and staff experience data

-

determining attitudes to, techniques for, barriers to and opportunities for reflective learning

-

developing a RLF – a programme theory or logic model – linking experiential feedback to reflective learning and change

-

mapping factors that influence reflective learning to the COM-B framework of behaviour change

-

developing and piloting methods in the form of a toolkit to incorporate effective reflection in routine practice.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from the PEARL protocol by Brookes et al. ,97 previously published in BMJ Open. This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Workstream 1: introduction and overview of workstreams

The PEARL project was conducted over a 3-year period at the following NHS trusts: University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust (Queen Elizabeth Hospital), Heart of England NHS Foundation Trust (these two have since merged) and Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust (Royal Victoria Infirmary and Freeman Hospital). This was a mixed-methods project combining both qualitative and quantitative data with patient and staff co-design techniques. The project consisted of four interlinking workstreams (WSs):

-

Workstream 1 (WS1) included setting up the project and establishing and supporting the local project teams to form the collaboration (see Appendix 1).

-

Workstream 2 (WS2) involved developing, disseminating, collating and reporting the patient and relative survey and the staff survey.

-

Workstream 3 (WS3) involved the ethnographic work, which was conducted in two phases.

-

Workstream 4 (WS4) was the co-design of the RLF and the toolkit.

We describe these in detail below.

Location

The project was located in the acute medical units (AMUs) and intensive care units (ICUs) of the four participating hospitals.

Acute medical units are generally the first point of emergency admission to hospital for patients, usually from the emergency department (ED) or following direct referral by general practitioners in the community. Of those admitted, around 40% of patients may be discharged home from the AMU within 48 hours and 60% transferred to general or specialist wards for continuing care. Specialist acute physicians will generally work 12-hour daytime shifts in the AMU, providing twice-daily ward rounds; weekend cover may be provided by acute physicians or by a general physician on duty. Nurse-to-patient ratios may be in the region of 1 : 6. The clinical team has to cope with large numbers of patients, a rapid turnover and making quick and accurate diagnostic and therapeutic decisions in conditions of uncertainty.

Intensive care units care for the most severely ill patients in the hospital using highly trained staff and complex equipment. Nurse-to-patient ratios are usually 1 : 1 or 1 : 2, providing care to one of the most vulnerable populations in health care, requiring burdensome technical support for multiple failing organ systems and experiencing a mortality rate of around 30%. 98 Intensive care consultants usually conduct two ward rounds per day, 7 days per week, and provide continuous care for periods of several days, or whole weeks, as well as undertaking regular night duties to maximise continuity of care. Providing reliable care in this complex environment requires both high-level technical and non-technical skills. Non-technical skills include effective teamworking, situational awareness and leadership, and the ability to integrate information across locations and over time to co-ordinate communication and actions, and to provide care with compassion.

Participants

Each participating unit established a local project team consisting of clinical, managerial and administrative staff as well as patient and relative representatives with experience of the AMU or ICU. Teams held bimonthly local project team meetings that were chaired by a non-executive director (executive director at one trust).

Staff on the units participated in interviews and observations (carried out as part of WS3) as well as the co-design work to develop interventions to enhance reflection (WS4).

Participants in the experiential data collection workstream (WS2) were patients and relatives who had spent time in the AMU or ICU. Their experiences were collected through the PEARL project patient and relative experience survey. Staff experience data were collected from staff whose primary working area was the AMU or ICU at the participating trusts, using the PEARL project staff experience survey.

Project set-up

Local project leads for each participating unit were appointed. The leads then established a local project team, which consisted of medical, nursing, allied health professional (AHP), administrative and managerial colleagues from their units. The teams were also encouraged to invite patient and relative representatives. Once established, the team agreed local arrangements for project delivery following confirmation of capacity and capability for their site. Existing opportunities for feedback and reflection were identified. With direction from the central project team, local teams held meetings once every 2 months to review project outputs, encourage team reflection (e.g. through existing meetings, team briefs and formal reports) and consider methods for incorporating feedback in routine practice.

In addition, we held four plenary workshops (three of which were co-design activities), nine facilitated local co-design meetings (three in each centre) and one further local co-design meeting without central facilitation. Our ethnographers observed all of these activities and provided feedback on each.

Workstream 2: the PEARL project patient and relative survey and staff survey

General aspects of survey development

The aim of the PEARL project surveys was to acquire experiential data from patients, relatives and staff that could be fed back to the local teams as evidence of the need for reflection, and as a motivating stimulus. We were sensitive to the need to avoid duplicating existing survey work and to minimise the burden on recipients of the surveys and the administrative load for local teams. We describe first the generic considerations for both surveys, followed by the specific development of each survey.

A survey subgroup was established, which consisted of project management committee members (including patient representatives) and the local project leads. A scoping review was undertaken of English-language surveys that had been used in the UK and focused on the experience of care of patients or relatives, or the experience of providing care by health-care staff.

Data acquisition varied between these surveys: some employed questions and others used statements with strength of agreement ratings. The working group, therefore, prioritised a standard approach for the patient and staff surveys, expressing a preference for the use of statements with strength of agreement ratings using a 5-point Likert scale. A limited number of direct questions were also included in the patient and relative survey.

Survey statements were selected or excluded through iterative discussion. The focus of attention was to identify those aspects of health-care behaviours that were within the competence and capability of individuals to address. We aimed as far as possible to preserve the original wording of the source surveys to retain questionnaire validity; where questions had been used, these were edited to statements. For the staff survey, we also conducted a modified Delphi process to prioritise the final set of questions (see Staff experience survey).

For the format of the surveys, we considered at an early stage whether these should be paper based or web based. A study from the Netherlands comparing both formats in colorectal registry cancer patients found a preference for paper surveys among respondents aged > 70 years, which was offset by a trend for web-based responses among those aged < 70 years. 99 A study from Denmark100 found lower response rates, higher completion rates and much lower administrative costs for an e-mailed web-based survey than the postal paper-based format; however, they did not factor in the costs of developing or hosting the web-based survey. Patients may not possess, and medical record departments do not universally record, e-mail addresses or mobile telephone numbers (for social media applications) for sending out invitations to complete the survey, and fewer young people now use e-mail as a primary mode of communication. The local project teams and the patient representatives were of the view that paper-based surveys were preferable at this stage, but recognised that these would in the future be supplanted by web-based approaches.

Participant information sheets accompanied each survey, explaining their purpose and that completion was optional, not mandatory. Questionnaires were anonymous; no person-identifiable information was collected.

The research ethics committee approved implied consent for those respondents who returned the completed questionnaires using the free-post return envelopes.

Analysis was undertaken by the central project team. Each completed survey was reviewed, focusing particularly on the free text to ensure that if serious concerns had been raised the relevant local project lead could be informed for subsequent investigation.

Responses were allocated subject numbers and reported to the Clinical Research Network using the National Institute for Health Research’s (NIHR’s) Central Portfolio Management System for uploading research accruals. Dissemination logs outlining the numbers of surveys disseminated were kept locally, with figures reported to the central team to allow calculation of response rates for each unit.

Surveys were scanned using Formic software (Formic Solutions, Uxbridge, UK) and the data uploaded to a spreadsheet for analysis. Data were presented to the units as standardised reports that showed the proportion of respondents selecting each level of strength of agreement with each statement. The data management team checked a random sample of 10% of the responses to ensure that there were no problems with the scanning. When issues were identified the data management team would undertake further action: either check all data or request a new scan of surveys. Free-text responses were transcribed manually and listed verbatim in the reports. They also underwent thematic analysis using NVivo software (QSR International, Warrington, UK).

Patient and relative experience survey

Questions from the following existing UK-validated questionnaires were reviewed for inclusion by the survey subgroup:

-

NHS National Inpatient Survey13

-

Jenkinson et al. ’s Picker Patient Experience Questionnaire101

-

Sullivan et al. ’s Reduced NHS National Inpatient Survey AMU questionnaire102

-

Family Satisfaction in ICU survey103

-

NHS Friends and Family Test. 14

From these surveys, we extracted those questions that were most relevant to attitudes and behaviours and were applicable to any acute care area in the hospital. We excluded questions that related to logistics (e.g. waiting list delays), related to technical aspects of care (e.g. complications of treatment) or were location specific (e.g. outpatient clinic attendance). This allowed us to use the same survey for the AMUs and the ICUs. We focused on questions relating to non-technical aspects of care (e.g. care delivery and communication), which could be influenced by individual members of staff.

The survey that best met our criteria was the Family Satisfaction in ICU survey,103 which provided the majority of the questions in the final set and obviated the need to undertake a prioritisation exercise for question selection. An additional question was from the Friends and Family Test. 14 Two free-text options were included to ask which aspects of care could be improved and what went well. Limited demographic information was requested. Respondents were given the option of providing their contact details if they wanted a response from the local project lead.

We chose not to offer the survey in languages other than English, partly on grounds of cost–benefit (the process of translation, reverse translation and validation for multiple languages would have added considerable complexity) but mainly because the aim of the survey was to obtain sufficient information to provide material for staff reflection, not to provide a comprehensive assessment of the clinical service, which was the responsibility of the trust.

The final survey that was developed was reviewed and piloted by the whole collaboration prior to implementation.

Eligibility

The PEARL project patient and relative experience survey was offered on alternate days to patients who had been in the AMU for ≥ 24 hours and to patients who had been in the ICU for ≥ 48 hours, to take into account the numbers of patients and the median length of stay for each type of unit. Family members were invited to complete the survey if the patient did not have full capacity to do so. Units liaised with their informatics departments to create automated lists of eligible patients on a weekly basis. A letter accompanied each survey, which contained information on the purpose of the enquiry. If patients had died during their hospital stay, a different letter was sent to the next of kin, expressing condolences and asking if they would mind completing the survey from their perspective. Surveys were accompanied by a pre-paid return addressed envelope.

Dissemination

The PEARL project patient and relative survey was distributed for a continuous 2-year period from June 2017 to May 2019. Participating units were given three different options for disseminating the PEARL project patient and relative experience surveys to eligible participants:

-

option 1 – offer the questionnaire on unit discharge (implied consent from the return of the questionnaire)

-

option 2 – take consent and provide questionnaire on unit discharge

-

option 3 – clinical team post out the questionnaire following hospital discharge (implied consent from the return of the questionnaire).

During piloting, hospital teams used the method most suitable for their unit (unit size and capacity varied widely). The teams found that personally handing out the questionnaires to patients on the unit was very time-consuming and, therefore, all units moved to posting out the questionnaires following discharge from hospital.

Surveys were sent with the appropriate cover letter, participant information sheet and pre-paid return envelope. Completed surveys were sent back to the central project team for processing and analysis.

Surveying bereaved families

Previous studies have shown that satisfaction with care is often higher in bereaved families; therefore, we did not want to exclude these families from the PEARL project. Each local team was encouraged to liaise with the bereavement services in their trust for support with any interactions project staff may have with the families at a sensitive time. An appropriately adapted cover letter for families of the bereaved accompanied the PEARL project questionnaire, clearly providing the contact details of the local project lead at each site for the relatives to make contact with if they felt upset and wanted to speak or meet with someone from the research team. Counselling was available for families, which was provided through the bereavement departments at trusts, if they felt that they would benefit from this.

Processing and analysis

Once the completed questionnaires arrived to the central team they were initially reviewed, and any serious concerns were flagged to the appropriate local project leads for investigation.

Responses were allocated subject numbers and logged as a research accrual with NIHR’s Central Portfolio Management System. Each centre recorded the number of surveys distributed and reported these data to the central team to allow calculation of response rates for each unit.

Surveys were developed and prepared for digital scanning. The responses were digitised, analysed and reported to each local project team on a quarterly basis. Once the surveys were scanned, the data management team would take a random sample of > 10% of the data and check that there were no issues with the scanning. When issues were identified, the data management team would undertake further action: either check all data or request a new scan of surveys.

Data were presented to the units as standardised reports that showed the proportion of respondents selecting each level of strength of agreement with each statement. Performance–importance plots (PIPs) were also provided to illustrate the relationship between the level of satisfaction with each item in the questionnaire and how that particular item influenced overall satisfaction. Free-text responses were transcribed and underwent thematic analysis using NVivo software. Using sentiment analysis, the first node divided free text into positive or negative responses; those containing both were allocated to both categories. Within each of these categories, secondary coding employed emergent themes as these were identified by the researchers reviewing the data.

The reports that were returned to the centres were a graphical representation of the survey data returned in the previous quarter, even if they were from an earlier quarter. Data from the NHS Friends and Family Test for the corresponding time period were obtained for the corresponding hospital sites or trusts and an estimate for the national AMU and ICUs. Not all organisations use the Friends and Family Test in ICUs and each trust has different naming conventions for their ICUs/AMUs, so we may not have captured the results of the Friends and Family Test for all AMUs/ICUs.

In addition to the stacked bar charts and pie charts, a domain score was calculated for experience of communication and experience of care, and PIPs were also generated. The domains are a weighted score of all relevant indicators in which a strong positive statement is given a score of 100, a positive statement a score of 80, a neutral statement a score of 50, a negative statement a score of 20 and a strong negative statement a score of 0.

Performance–importance plots were generated for each unit and for the combined ICU/AMU. The PIPs report the correlation between each question and the overall satisfaction score and how many respondents chose the ‘best’ answer for this question. From the median values for each axis, four quadrants are identified: areas performing well, areas in higher need of improvement, areas potentially overperforming and areas that may need improvement but are a lower priority.

Staff experience survey

Development of the survey: Delphi method for prioritisation and selection of survey items

The aim of the PEARL project staff survey was to gain insights into individual, contextual and organisational influences on staff behaviour that might affect patient experience. This included attitudes towards reflection and to the use of patient experience data.

As with the patient and relative survey, it was felt that there was no single existing survey that met our requirements for the project. Therefore, we assembled material from four existing UK-validated surveys that focused on staff experience and patient safety: the NHS Staff Survey18 from 2016, Hospital Survey on Patient Safety Culture,104 Teamwork and Safety Climate Survey105 and the GMC Trainee Survey. 106 To these we added questions derived from the PEARL project ethnography topic guides. These were based on the COM-B44 framework and the theoretical domains framework. 107 Where the original surveys employed questions, we converted these to statements using a 5-point strength of agreement Likert scale, retaining as much of the original phrasing as possible (as with the patient and relative experience survey).

We used a prioritisation method (Delphi) for statement selection because of the diversity and range of options available. The statements were circulated by e-mail to the collaboration and the respondents were asked to rate each statement using a four-point scale: ‘definitely include’, ‘probably include’, ‘probably exclude’ and ‘definitely exclude’. Each e-mail ‘round’ carried forward the outputs from the preceding round.

Responses were categorised as follows:

-

Statements that achieved ≥ 75% agreement to definitely include did not go into the next round, but were extracted and reserved for the final survey.

-

Statements that achieved ≥ 50% agreement to either definitely or probably exclude were removed.

-

Statements that achieved < 100% but ≥ 50% agreement to either definitely or probably include were retained for the next round.

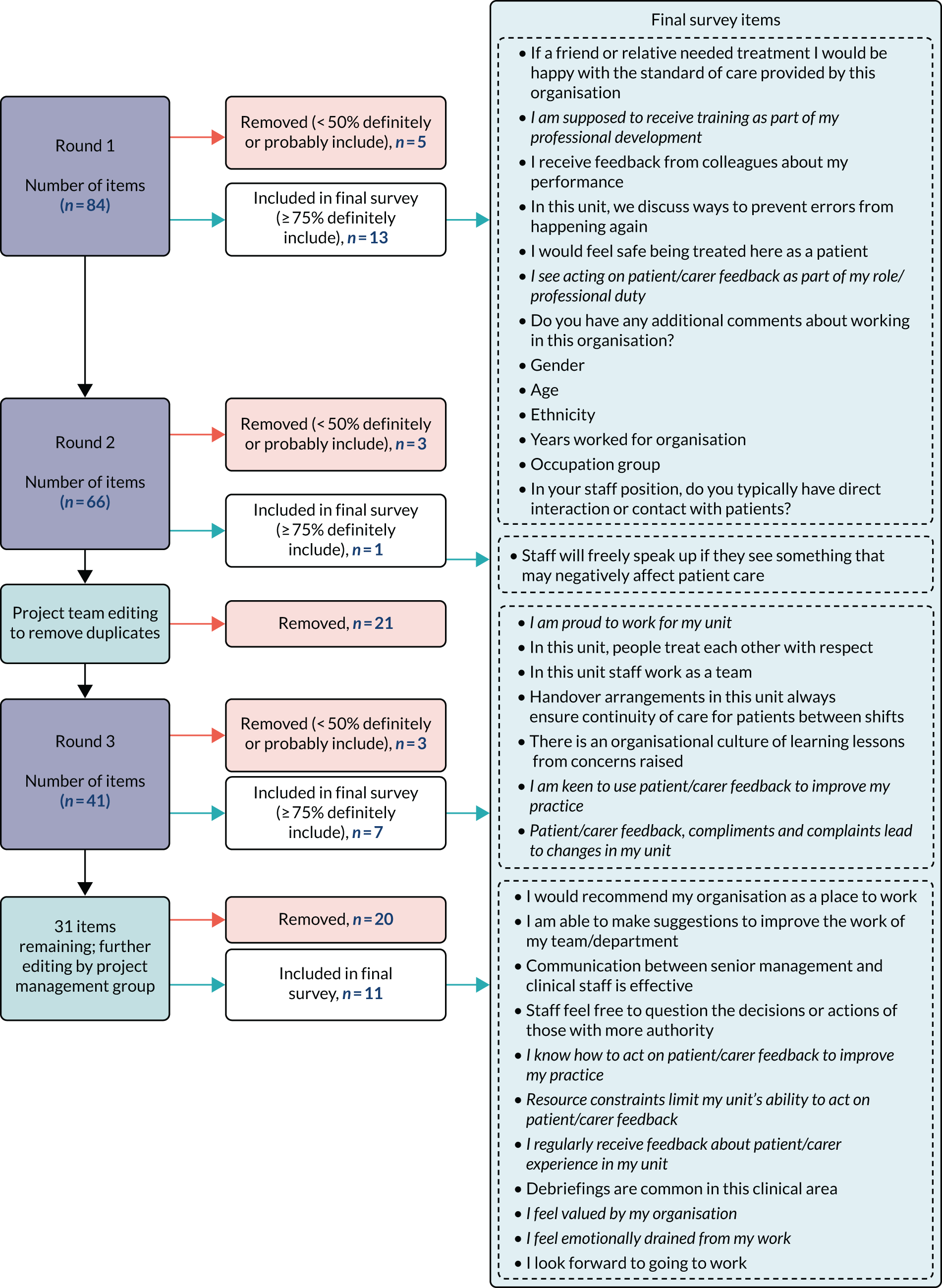

Following three rounds of Delphi prioritisation, a final set of survey questions emerged to form the final PEARL project staff survey. The Delphi process and outputs are presented in Figure 1. Basic demographic questions were included along with one free-text question asking ‘Do you have any additional comments about working in this organisation?’.

FIGURE 1.

The PEARL project staff survey Delphi methodology flow chart. Italic text indicates an item developed from PEARL ethnography topic guides.

Eligibility

The PEARL project staff survey was offered to all clinical, administrative and managerial staff whose primary working area was the AMU or ICU at the participating hospitals. This included doctors (consultants to foundation grade), nurses (bands 5 to 8), administrative and clerical staff (including operational managers), health-care assistants, maintenance and ancillary staff, AHPs and pharmacists. Dissemination logs were maintained locally, with figures reported to the central team to allow calculation of response rates for each unit.

Sampling and consent

The staff survey was distributed twice for a 2-month period during the PEARL project (January to February 2018 and January to February 2019). As with the patient survey, implied consent applied and the surveys were anonymous.

Dissemination

Local units were advised to use the method of dissemination most appropriate for them. Options included via staff pigeon holes, attachment to monthly payslips, at weekly/monthly staff meetings, in staff/locker rooms or posting out. Questionnaires were disseminated with a pre-paid return envelope for completed responses to be sent back to the central project team for processing and analysis.

Processing and analysis

As with the patient and relative survey, once the completed staff surveys were received by the central team a random sample of 10% was reviewed by the data management team and any issues identified were resolved before further processing. All free text was transcribed and classified using NVivo; any serious concerns were flagged to the appropriate local project leads for investigation.

The responses were digitised, analysed and reported to each local project team as standardised reports that showed the proportion of respondents selecting each level of strength of agreement with each statement. In addition to the stacked bar charts and pie charts, an overall domain score was calculated for staff experience. The domain score was calculated using the responses to statements relating to perceptions of care quality and the working environment and excluded those statements relating to personal reflection: a strong positive statement was weighted with a score of 100, a positive statement with a score of 80, a neutral statement with a score of 50, a negative statement with a score of 20 and a strong negative statement with a score of 0. Data from the NHS staff Friends and Family Test for the corresponding time period were obtained for the corresponding hospital sites or trusts. National comparative data for AMUs and ICUs were estimates because different naming conventions for these units between trusts meant that some may have been omitted. For the second survey, comparisons were made with the results of the first survey.

Survey validity and reliability

Before disseminating the first survey, we decided to exclude any question with any of the following response characteristics:

-

a non-response rate of > 10%

-

a lack of discrimination (defined as > 70% of all respondents ‘strongly agreeing’ or ‘strongly disagreeing’ with the statement)

-

redundant (defined as questions with an item-scale Cronbach’s α of < 0.7).

Based on the initial analyses of the first survey, no question met any of the above criteria; therefore, all questions were retained for the second round. Following the second round the analyses were repeated and again no question met any of the above criteria for removal.

Workstream 3: ethnography – phase 1 and phase 2 methods

Workstream 3 took place in two phases.

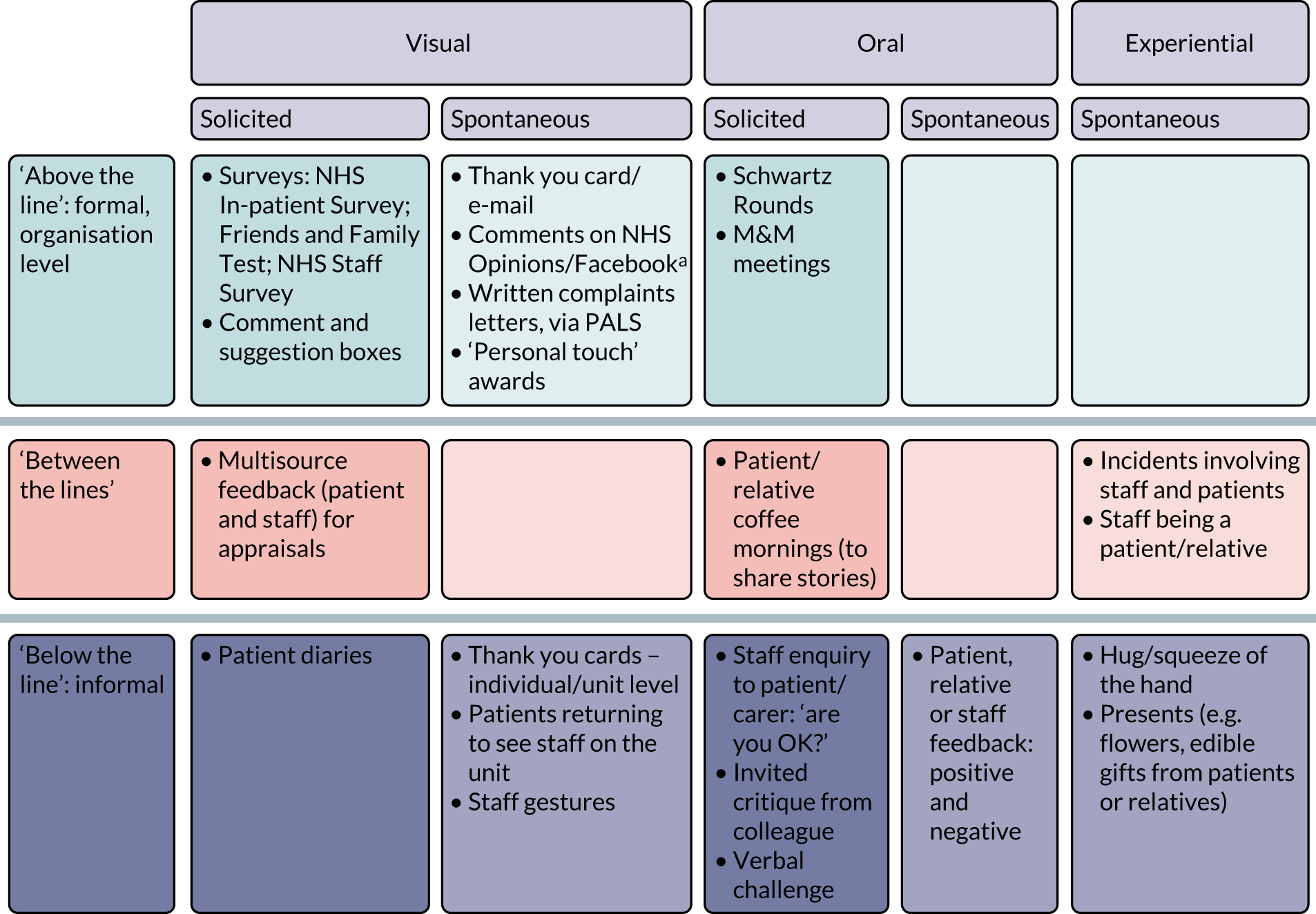

Phase 1 aimed to investigate current use of patient experience data, to explore options for the feedback of data as part of the reflective learning process and to investigate experiences of, barriers to and opportunities for workplace-based reflective learning.

Phase 2 focused on observations of local co-design meetings and of the implementation and piloting of components of the toolkit in practice. Findings from both phases were used to inform the development of the RLF and toolkit in WS4.

Phase 1

Ethnographic research that was conducted in phase 1 focused on gaining insight into attitudes and practice relating to feedback and reflection on patient experience, through observing day-to-day practice and interviewing a purposive sample of staff across the sites. Topic guides were developed to ensure consistency between ethnographers for phases 1 and 2.

Our key aims for phase 1 were to:

-

systematically describe the approaches used to feedback experiential and quality and performance metrics in ICUs and AMUs

-

obtain staff views about credibility, utility and impact of different approaches to feed back patient experience data

-

explore staff engagement with reflective learning based on patient experience data and identify how individual and group reflection can be promoted in practice

-

identify the factors that affect the extent to which reflection is translated into action at the front line of practice

-

inform the co-design of the RLF and toolkit.

We conducted observations and interviews in eight acute care units (three AMU-type and five ICUs) in the three NHS trusts participating in the PEARL project, between May and December 2017. Characteristics of the sites were as follows:

-

Site P1 had an ICU and a high-dependency unit (HDU), referred to jointly as ‘critical care’, as well as a separate large AMU.

-

Site P2 had an ICU and a separate clinical decisions unit (CDU) (equivalent to an AMU) with an acute medical clinic attached to it.

-

Site P3 was split over two sites: one site had two ICU wards with attached HDUs and an AMU (referred to as the ‘assessment suite’) and the other site had one ICU with an attached HDU.

We conducted > 140 hours of observations in ICUs and AMUs, including 81 informal documented conversations with a wide range of staff. We collected relevant documents, such as newsletters and photos of patient experience displays, in the units. Observations were recorded as written field notes and audio-recorded debriefs. We undertook 45 formal, semistructured interviews with a purposive sample of staff members, including administrative, nursing and medical staff, sampled to include diversity in their role and level of involvement in trust activity around patient experience data. Interviews and observational visits were conducted in two rounds (May to June 2017, prior to the introduction of the PEARL project patient experience questionnaire, and November to December 2017, after data collection had started). We conducted 36 interviews in round 1, which were focused on the collection and use of patient experience data and engagement in reflection, and nine interviews in round 2, which focused in more detail on reflection in practice. Interviews lasted between 10 and 90 minutes (mean 38 minutes). Informed consent was obtained for interviews. Breakdown by site is shown in Table 1.

| Interview characteristic | P1 | P2 | P3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Approximate observation time (hours) | 43 | 49 | 55 |

| Interviews (n) | |||

| Formal | 15 | 14 | 16 |

| Informal | 17 | 23 | 41 |

| Staff (n) | |||

| Medical | 5 | 6 | 6 |

| Nursing | 6 | 7 | 7 |

| Administrative | 4 | 1 | 3 |

Phase 2

Phase 2 involved observations and interviews. The main aim of phase 2 was to gain insight into staff experiences of using tools to select and design interventions to promote reflection in practice in order to inform the development and implementation of the reflective learning toolkit.

We conducted observations of the local project team meetings in which sites piloted components of the draft toolkit that had been designed to support the selection of reflective practice interventions, and planned for implementation (April to May 2019). We conducted interviews with members of staff at each site who had attended these meetings in order to gain feedback on the approach taken in the meetings and how well the draft toolkit components had worked as well as to capture their experiences of developing and trialling their selected interventions (June 2019). We observed four meetings in total (site P1, two meetings; sites P2 and P3, one meeting each). The first meeting at site P1 lasted approximately 1 hour and the second meeting was approximately 2.5 hours long; the meetings at sites P2 and P3 lasted around 2 hours. Observations were recorded as written field notes and audio-recorded debriefs. We conducted 15 interviews (June to July 2019) with a range of staff (five per site) about their experience of choosing interventions during the meeting and the progress in implementing any chosen interventions on the ICU or AMU wards. Informed consent was obtained for all interviews. Interviews lasted between 26 and 85 minutes (mean 49 minutes). Breakdown by site is outlined in Table 2.

| Interview characteristic | P1 | P2 | P3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Approximate meeting observation time (hours) | 3.5 | 2 | 2 |

| Number of interviews (n) | 5 | 5 | 5 |

| Staff (n) | |||

| Medical | 1 | 4 | 3 |

| Nursing | 4 | 1 | 2 |

Analysis of phases 1 and 2

Interviews and observation debriefs were recorded and professionally transcribed verbatim; anonymisation took place during transcription. We conducted regular team debriefs during the data collection period to reflect on emerging findings and guide ongoing data collection, and we discussed findings with the wider team. Analysis of data from phases 1 and 2 was conducted separately.

For phase 2 we conducted an analysis to characterise the features of meaningful patient experience feedback and to explore the barriers to and facilitators of effective reflection on patient experience in practice. A thematic analysis approach was taken to analyse the transcripts of the interviews and observational data. 108 A subset of interviews was read in close detail and open-coded to create a code frame and initial thematic categories; these were discussed with the wider study team. The coding frame was then applied to the remaining interviews and observational data transcripts. As new themes arose, there was flexibility to extend the coding frame to capture these. We used case studies, narrative reports and visual data displays as ways of facilitating comparison across sites and synthesising findings. Findings from the analysis of phase 1 data were used throughout the co-design process to inform the development of reflective practice interventions and the toolkit as a whole. Phase 2 data were subject to a separate thematic analysis closely linked to the aims of identifying lessons for development of the toolkit. NVivo 11 software was used to support the management, coding and querying of the data.

Workstream 4: co-design of the reflective learning framework and development and piloting of the toolkit

Introduction

Co-design refers to a set of practices that can be used to allow diverse stakeholders to come together to address a shared issue. The ‘co’ prefix refers to the participatory nature of the activity and ‘design’ refers to both the technical skills and practices of design and the unique approach to problem-solving approach used by designers.

Co-design has previously been used in health care. The most widely published approach is experience-based co-design, which accesses the experiences of patients and relatives and staff from videoed interviews109 or directly in interactive group discussions. The PEARL project co-design approach was supported by the Translating Knowledge into Action (TK2A) theme110 of the NIHR Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care Yorkshire and Humber. The TK2A theme is a multidisciplinary team of health service researchers who have developed over the last 10 years111 methods drawn from design practice, with a focus on the use of creative practice to support the successful sharing and synthesising of knowledge. 112

The reflective learning framework

The RLF is the programme theory or logic model for the PEARL project. It is the health services equivalent of a systems specification in computing or a drug’s mechanism of action. It describes how reflective learning might ‘work’. We developed the RLF iteratively throughout the project, making modifications to the theory as we gained insights from the ethnographic work and from our observations of the co-design process for the toolkit. We based our approach on that recommended by Davidoff et al. 113

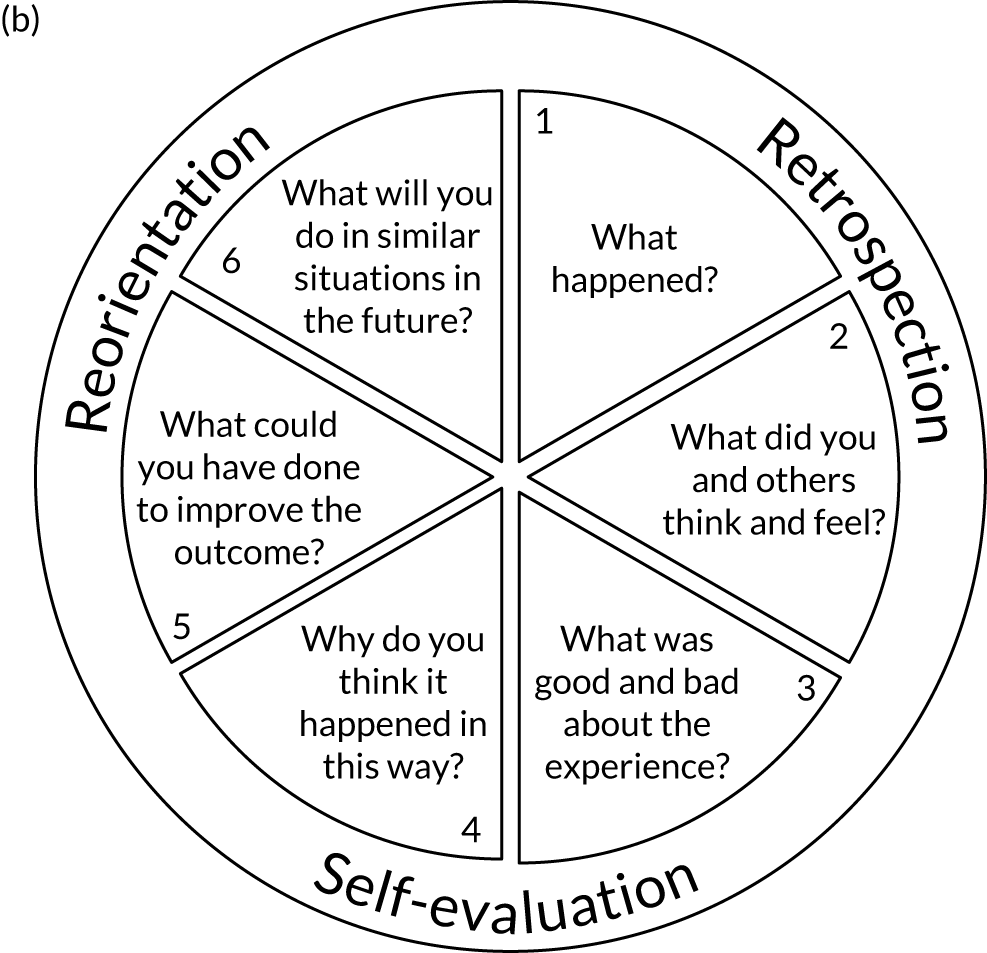

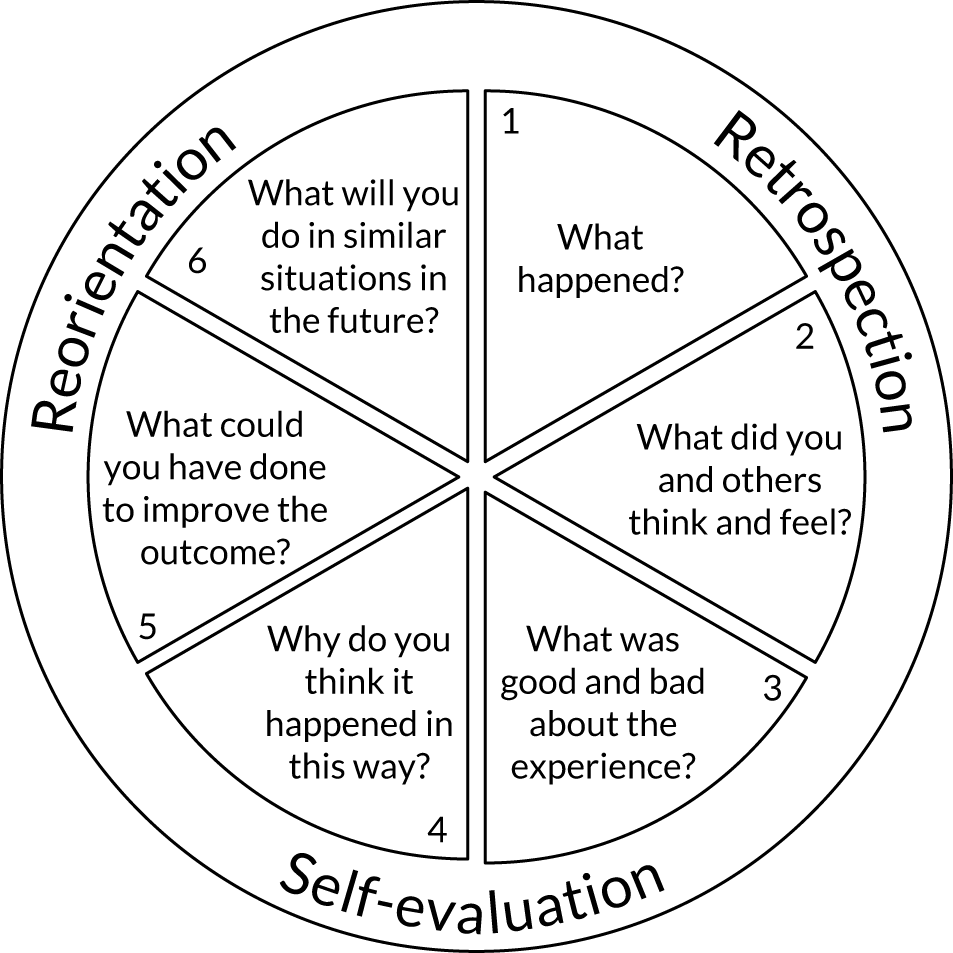

We defined reflective learning as an experiential process of personal insight development in which one’s own and others’ experiences are used to produce a change in attitudes and behaviours. We characterised the features of effective reflective learning based on Dewey’s58 three phases of reflection (retrospection, self-evaluation and reorientation), to which we subsequently added Gibbs’ six-step cycle114 and Schön’s50 categorisation of reflection occurring in-action or on-action.

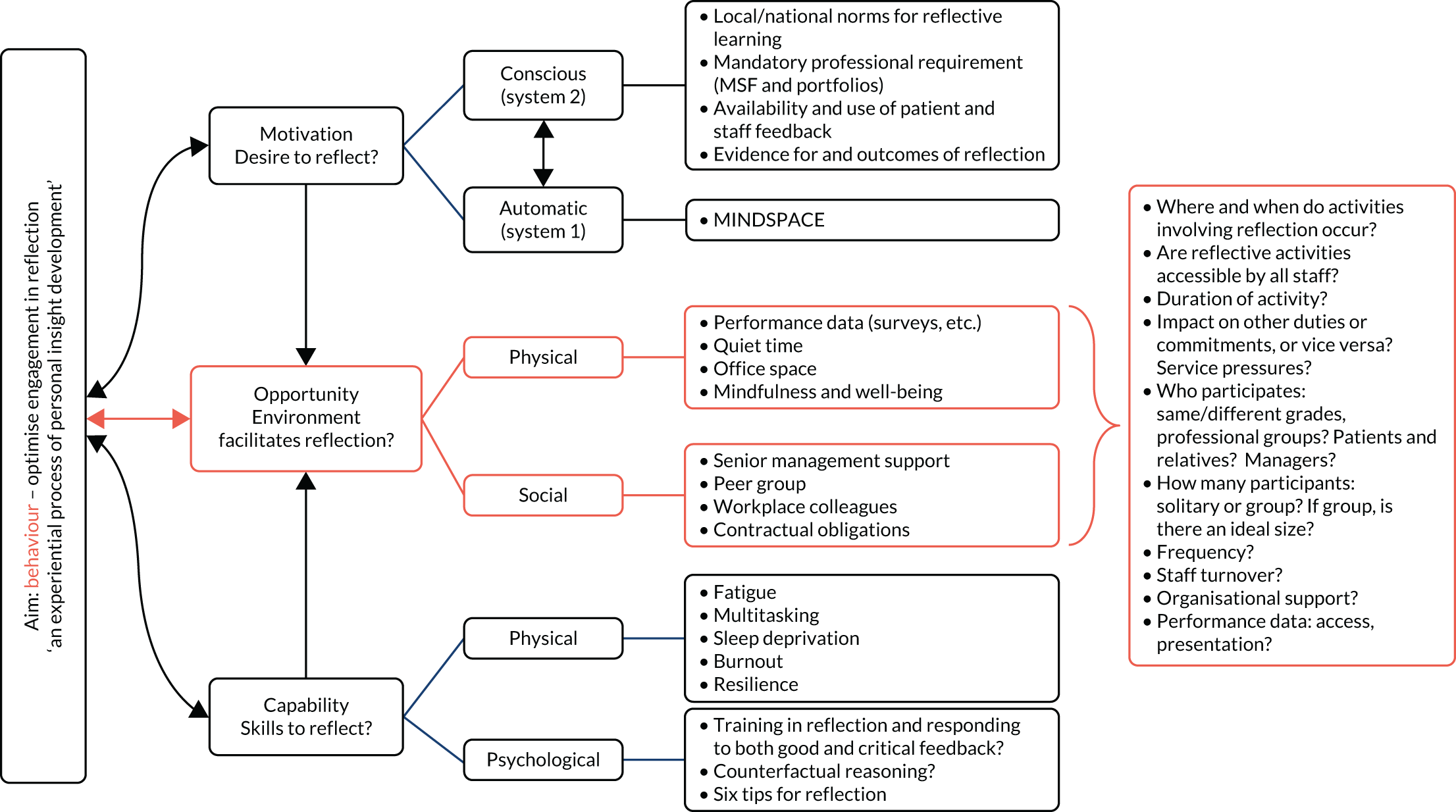

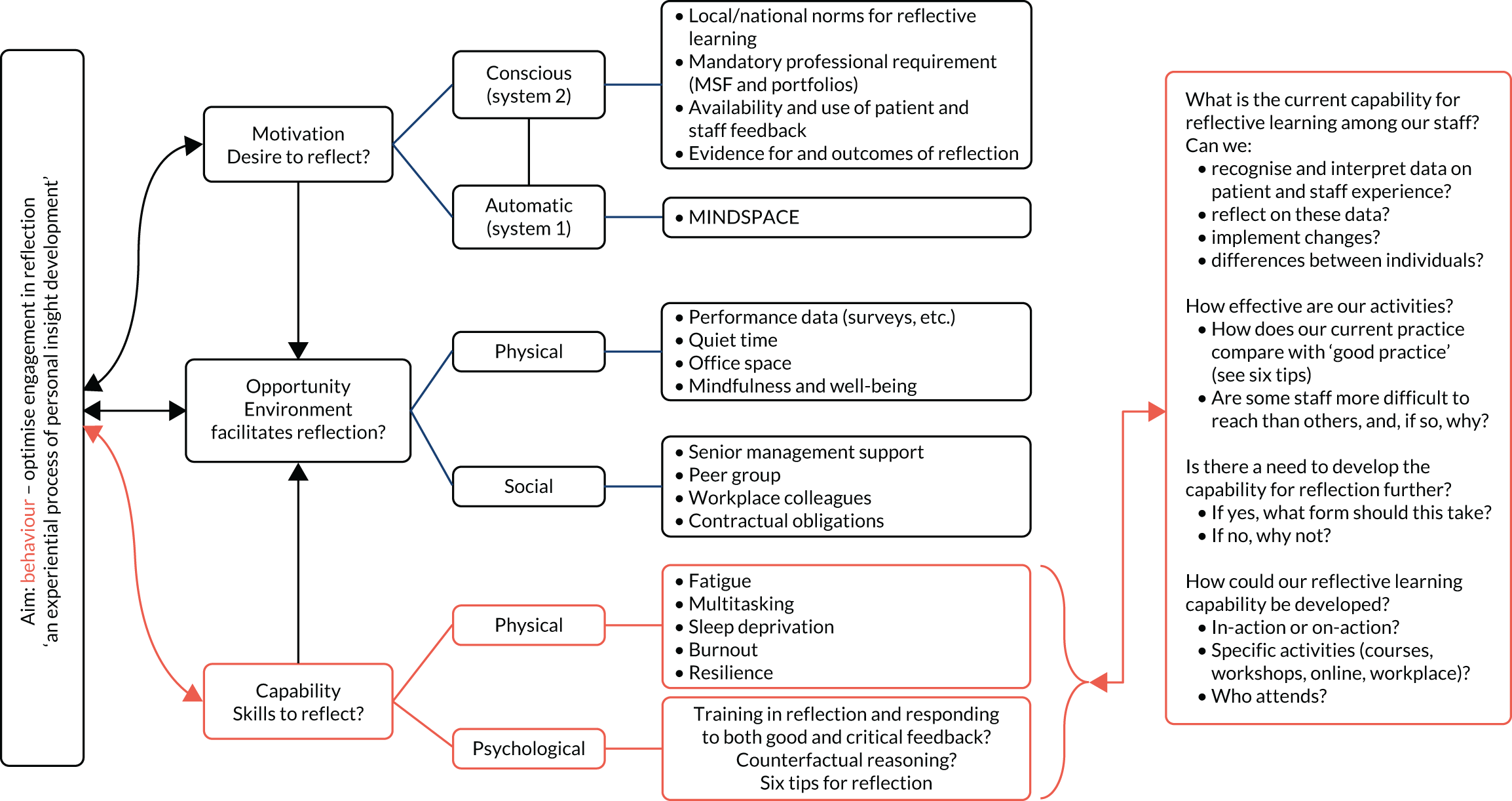

In mapping out the factors affecting engagement in effective reflective learning, we drew on the COM-B framework. 44 With effective reflective learning as the behaviour of interest, the COM-B framework identifies three domains of determinants, each with two subtypes: capability (physical and psychological), opportunity (physical and social) and motivation (reflective and automatic). As the COM-B framework was both parsimonious and evidence based, we decided to incorporate it in our preliminary version of the RLF. An important element of our conceptualisation is that the ‘B’ in COM-B signifies engagement in effective reflective learning: completing the cycle of insight development, attitude change and resulting change in interpersonal behaviour and practice.

This framework incorporates the dynamic in which an input (e.g. experiential information from the surveys) would, depending on the ‘COM’, result in the behaviour of effective reflective learning (primary output). This would generate measurable changes in attitudes and practices, and enhanced care delivery and teamworking (proximal and distal outcomes).

Iterative versions of the RLF were developed by the core project team and presented for critique at the co-design workshops. Participants at the co-design workshops reviewed the RLF for both understandability and scientific credibility and provided feedback that was used in the next iteration. The COM-B framework was used to classify interventions to drive engagement in effective reflective learning as these emerged from the co-design process. We show the evolution of the RLF in Chapter 3.

Toolkit co-design

The co-design meetings

Three facilitated and supported local meetings were held at each of the three sites (nine meetings in total) plus three plenary workshops for all participants. A fourth local meeting was then conducted by each team working without an external facilitator or project team support.

There were three main aims of the co-design meetings:

-

to identify ‘touchpoints’ – key moments in the experience of health care – that provide insights into how we use reflection to understand ourselves and others

-

to understand how different individuals may experience reflection

-

to create or adapt interventions to promote reflective learning in the workplace.

Participants

The co-design meeting participants included a broad range of patients and staff, not just members of the PEARL project team. There were between 10 and 20 attendees, which resulted in manageable and productive meetings. Patients and relatives were equal contributors; they received prior explanation about the purpose of the meetings and the facilitators ensured that they had time and space to develop their own ideas and voice. Mutual understanding emerged from this process. For example, a mother and son gave important insights into communication behaviours, such as staff directing questions and information to the mother when it was quite possible to communicate directly with her son (the patient). Conversely, at the end of one co-design session, an erstwhile patient said that he had not realised how emotional the experience of delivering acute care was for the staff. These and many other insights provided useful examples for linking the COM-B theory to practical reflection tools.

Planning

Each co-design meeting was planned in advance by the PEARL project management committee and facilitator. Recognising that taking time out of the working day is often difficult, local teams were asked to obtain approval from managers and colleagues, and allowances were made for last-minute variations in the number of participants, consequent on the demands of the clinical services. A meeting room was booked, with refreshments and lunch, for a minimum of 4 hours.

Facilitation

Facilitation of the nine co-design local meetings and the three workshops was provided by the Art and Design Research Centre, Sheffield Hallam University (Sheffield, UK). Skilled and sensitive facilitation was essential to promote the flow of conversation, manage emotions, permit periods of silence, allow humour to release tension and ensure that everyone had an opportunity to express their ideas and opinions, regardless of status, seniority or specialty. The facilitation team comprised three members of the TK2A team. The theme lead and clinical researcher are a nurse and physiotherapist, respectively, both having worked on creative co-design projects across a broad range of topic areas for the last 10 years. The third member of the TK2A team is a designer who has worked in health-care contexts and co-design since completing their doctorate. The team were able to function as experts in the co-design process but could claim independence from the team, unit and hospital. A scribe recorded key points, conclusions and actions, and how these were derived. Each meeting was observed by two ethnographers for subsequent distillation and analysis.

The tools and techniques used for co-design were based in part on the NIHR’s Better Services by Design website. 115 The process was underpinned by the ‘double diamond’ approach (‘discover, define, develop, deliver’) in which the first workshop focuses on the key issue, the second expands the discussion to consider the wider context, the third refocuses on developing specific interventions and the final workshop allows participants to report their piloting of the interventions.

Each session started with a brief summary of the purpose of the project and a recap of the preceding activities. The facilitator then invited everyone to introduce themselves, followed by an ‘ice-breaker’ exercise to promote the conditions required for co-design to take place, after which the group undertook the activities described below. Each small working group (between two and four for each meeting, dependent on numbers) was supported by the facilitators and team. Plenary sessions allowed sharing of discussions and outputs. A summary was constructed at the end from all of the participants.

Co-design 1: reflectable moments

The aim of this first workshop was to allow the group to explore the meaning of reflection and how it ‘works’. Participants were invited to describe ‘reflectable moments’: events or activities that stimulated reflection in themselves or others, what feelings were aroused, how these feelings were used to gain insight into oneself or others and how those insights could stimulate generalisable learning. This process aroused emotions that the facilitator channelled into creative energy.

Participants modelled reflectable moments using cut-out figures (Figure 2) to recreate the characters and situations that they had encountered. This allowed the participants to tell their story with both realism and a degree of detachment, recognising the benefits of making the intangible tangible through creative practices. 116

FIGURE 2.

Co-design meeting 1 resources. (a) Cut-out figures; and (b) reflection wheel.

Analysis of the thought processes used by the participants allowed us to combine the three-stage Dewey model58 and six-step Gibbs cycle114 into a single ‘reflection wheel’. It was also clear that individuals varied in their approaches to reflection: in-action, on-action, solitary and group.

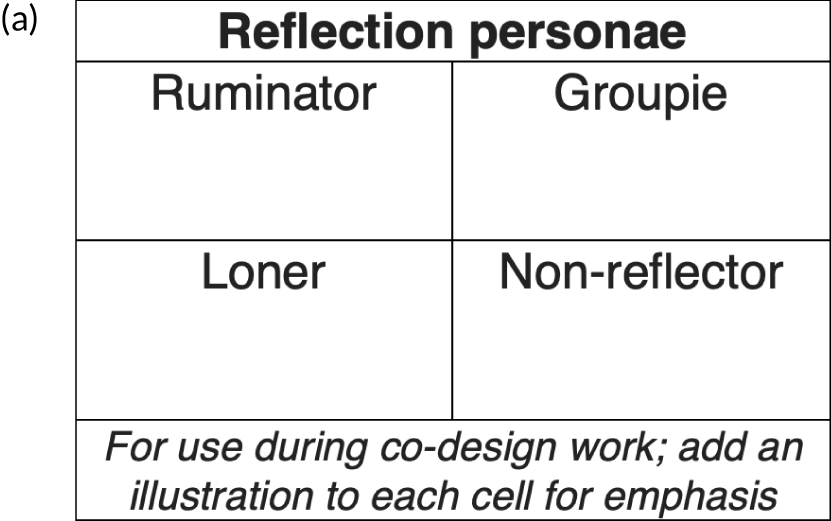

Co-design 2: reflection personae

The second workshop gathered participants’ opinions and experiences of reflective behaviours as demonstrated by others, by creating reflective character types or personae. Individuals may accommodate more than one reflection stereotype, but isolating these in caricatures permits participants to focus on specific issues and promotes examination of one’s own attitudes to reflective learning.

The participants were invited to form four groups to consider one each of the following types: the ‘groupie’, the ‘ruminator’, the ‘loner’ and the ‘non-reflector’ (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Co-design meeting 2 resources. (a) Reflection personae; and (b) reflective learning activities table.

For each of these personae:

-

Small group session 1 – participants created a fictitious but believable character based on that reflection type using the template (20 minutes).

-

Plenary session 1 – participants described that character to the other groups (5 minutes for each group).

-

Small group session 2 – participants discussed how each character would respond to a good feedback scenario and a negative feedback scenario (20 minutes).

-

Plenary session 2 – participants considered what actions or interventions might promote effective use of feedback by each character (5 minutes for each group).

The scribe classified outputs from plenary session 2, which were subsequently transcribed using the 2 × 2 table to categorise actions and interventions according to whether they were predominantly in-action or on-action interventions and for use by groups or individuals.

Co-design 3: designing interventions to incorporate reflection in everyday activities

The third meeting was conducted twice: the first time it was facilitated and supported by the PEARL project management committee and the second time it was conducted independently by the local teams using additional tools. We describe here the second of these two meetings.

Participants were asked to examine the list of prioritised reflection tools and activities (see Table 9).

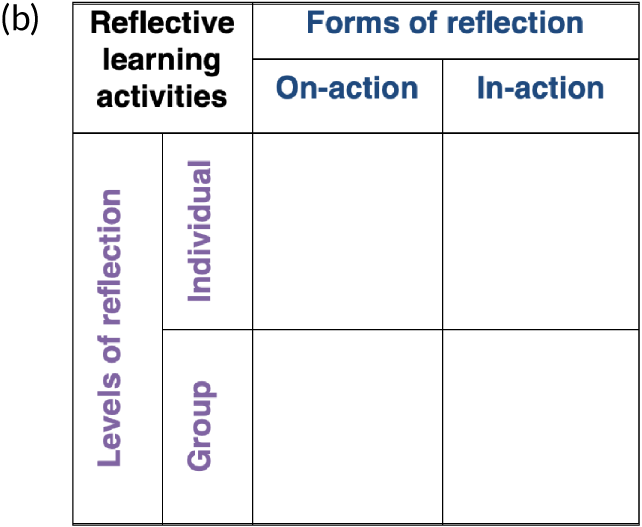

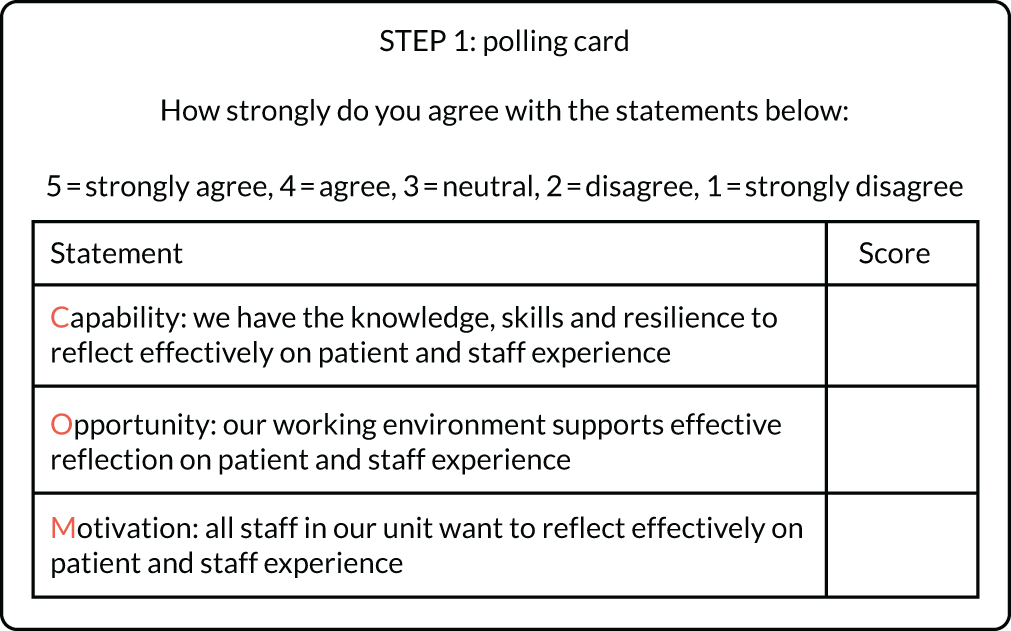

In step 1, participants were given polling cards to give their private views on the extent to which the unit staff had the capability, opportunity and motivation to reflect on patient and staff experience (Figure 4). The anonymous responses were collected, the scores for each element (capability, opportunity and motivation) were summed and the percentage agreement for each proposition was determined by dividing the sum of the scores for each element by the number of respondents and multiplying by 100.

FIGURE 4.

Co-design meeting 3 resources.

In step 2, the difference between the actual percentage agreement and the maximum percentage agreement (100%) provided an indication of the perceived gap between the current position and the ideal position for each element of the framework. Participants were asked to discuss the possible reasons for each gap, for example by asking ‘What would be needed for you to give this element a top rating of 5?’.

In step 3, based on the gap analysis, from the list of prioritised interventions (see Table 9) and working in small groups the participants developed a maximum of three using the reflection specification template (Table 3). Participants were asked to focus on actions or activities that promote reflection, not on those that ‘fix the problem (identified using the feedback collected)’. For example, when considering how to enhance reflection during handovers or ward rounds, using a checklist is unlikely to promote reflection (although it will be highly beneficial for many other reasons), whereas starting the handover or round with some feedback from one of the surveys, encouraging input on the round from the relatives or ending the round with a quick debrief, could stimulate reflection by giving everyone a voice.

In step 4, in plenary session, participants presented their activity to the whole group. A task management and delivery plan was completed for each activity.

In step 5, teams were asked to pilot the intervention using rapid cycle approaches (test, evaluate, retest and spread) and provide feedback to the final plenary workshop.

| Reflection intervention | |

| Describe briefly here the nature of the intervention (e.g. ward round, handover, debriefing, posters, coffee mornings, induction training) and then complete the right-hand column below: | |

| What will you do? | • |

| Why will this activity help staff be reflective? | • |

| Who can participate in this activity? | • |

| When will it occur? In-action (‘hot’), near action (‘warm’), or on-action (‘cold’)? | • |

| Where will the reflection take place/be located? | • |

| How can the reflection be structured or supported? | • |

| Barriers: what might limit the effectiveness of this reflection? | • |

| Enablers: what factors might make the reflection more effective? | • |

| Outputs: what impact will this particular act of reflection have? | • |

Prioritisation of the reflection activities and tools

We identified potential candidate tools and interventions for inclusion in the toolkit in several ways. During the co-design meetings and workshops, staff identified numerous methods for promoting reflective learning. Some of these activities were already in routine use, others were aspirational and some were unconstrained by practical considerations. The ethnographers also identified and described approaches for reflection in practice from their observations and interviews.

We combined the outputs of these nine workshops with the findings from the observational and interview work undertaken by the ethnographers to assemble a list of tools and activities that had the potential to enhance reflective learning. This list was then circulated to the local project teams as a questionnaire, with the request that each member rated each of the tools or activities for effectiveness and feasibility using a 5-point Likert scale (5 = strongly agree, 4 = agree, 3 = neutral, 2 = disagree and 1 = strongly disagree). Effectiveness was defined as ‘the likely impact of the activity if it were to be introduced to your unit’. Feasibility was defined as ‘the likelihood that it could be introduced and would be acceptable to most staff’.

Responses were aggregated and median ratings were determined. The following cut-off points were used to determine inclusion, exclusion or further consideration:

-

inclusion – effectiveness median of 4 or 5

-

exclusion – effectiveness median of 1 or 2, or effectiveness median of 3 and feasibility median of 1, 2 or 3

-

further consideration – effectiveness median of 3 and feasibility median of 4 or 5.

The outputs from this process are described in Chapter 3.

Patient and public involvement

The PEARL project has put patients and relatives at the centre of the research because they were involved in the inception in the initial design, contributing as full collaborators. There was patient and public involvement (PPI) representation on all of our project teams and committees. The central project team had two PPI representatives, the Project Steering Committee had one PPI representative and the local project teams had eight PPI representatives.

Patient and public involvement representation in the local project teams were as follows: site 1 benefited from two PPI representatives, one of whom was disabled, and sites 2 and 3 each had three PPI representatives. A benefit of the PPI members attending was the opportunity for local leads to consult with them about the running of the project locally (such as raising awareness of the patient and relative experience survey). Patients and relatives also offered their thoughts on the feedback received in the reports from the project surveys, and contributed to actions that were taken as a result of the feedback.

The PEARL project is a developmental project using co-design to develop the RLF. To develop the framework, the PPI representatives in the local project teams were equal partners in the co-design meetings and the facilitated plenary workshops (described above). They have informed decisions about the extent to which PPI representatives can contribute to this type of co-design process. An example of PPI engagement is that they developed the cue cards that were used in group work for stimulating effective reflection.

All PPI representatives who have been involved in the project are full members of the PEARL project collaboration and are acknowledged as co-authors in all publications and project outputs. They will also participate in dissemination activities.

Chapter 3 Results

Given the inter-related nature of the four workstreams, we present the project outputs by theme rather than by workstream.

Overview

There was excellent engagement by the three trusts, with the AMUs and ICUs working together to form a unitary local project team at each centre. This was a comparatively novel collaboration for the staff because acute medicine and intensive care medicine are distinct specialties working in separate locations. Each local project team included patient representatives, with the initial contact being made through existing unit-based patient groups, Patient Advice and Liaison Service (PALS) or personal interaction after a period of clinical care. The fast-paced throughput of the AMUs made it more difficult for the staff to establish longer-term relationships with patients, unless the acute physicians also undertook follow-up clinics. The patient representatives supported the co-design meetings and workshops, with a median of two members from each centre attending each session.

Each local project team was chaired by a non-executive director (two centres) or an executive director (one centre). The choice of the executive director was made by the chief executive of that trust. The chairpersons tended to provide support locally rather than engage in the plenary workshops.

The PEARL project patient and relative experience survey

Respondents and response rates

The PEARL project patient and relative survey was distributed continuously for 2 years from June 2017 to May 2019. A total of 18,616 surveys were disseminated and 4747 responses were received (overall response rate 25.5%). Response rates were higher in ICUs (35.4%) than in AMUs (20.1%) (Table 4).

| Trust | AMU/ICU | Number of eligible patients | Number of questionnaires administered | Number of questionnaires returned | Per cent of eligible patients receiving questionnaire | Response rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1 | AMU 1 | 8508 | 6131 | 1212 | 72.1 | 19.8 |

| ICU 1 | 5574 | 3177 | 1112 | 57.0 | 35.0 | |

| Site 2 | AMU 2 | 5173 | 3276 | 593 | 63.3 | 18.1 |

| ICU 2 | 784 | 426 | 114 | 54.3 | 26.8 | |

| Site 3 | AMU 3 | 4125 | 2642 | 620 | 64.0 | 23.5 |

| ICU 3 | 1357 | 1051 | 342 | 77.5 | 32.5 | |

| ICU 4 | 1206 | 937 | 380 | 77.7 | 40.6 | |

| ICU 5 | 1413 | 976 | 374 | 69.1 | 38.3 | |

| All AMUs | 17,806 | 12,049 | 2425 | 67.7 | 20.1 | |

| All ICUs | 10,334 | 6567 | 2322 | 63.5 | 35.4 | |

| Overall | 28,140 | 18,616 | 4747 | 66.2 | 25.5 | |

Approximately 60% of surveys were completed by the patient, 20.5% by family members and the remainder by both the patient and the relative. Given the difference in the severity of illness, it was expected that more ICU than AMU responses would have been completed by the relative; however, this was not the case: the distribution of respondents in the categories was similar for both AMUs and ICUs (Table 5).

| Trust | AMU/ICU | Patients, n (%) | Relatives, n (%) | Patients supported by a relative, n (%) | Unknown, n (%) | Total, n |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1 | AMU 1 | 705 (58.2) | 275 (22.7) | 220 (18.2) | 12 (1.0) | 1212 |

| ICU 1 | 702 (63.1) | 220 (19.8) | 180 (16.2) | 10 (0.9) | 1112 | |

| Site 2 | AMU 2 | 381 (64.2) | 108 (18.2) | 101 (17.0) | 3 (0.5) | 593 |

| ICU 2 | 46 (40.4) | 37 (32.5) | 30 (26.3) | 1 (0.9) | 114 | |

| Site 3 | AMU 3 | 446 (71.9) | 86 (13.9) | 83 (13.4) | 5 (0.8) | 620 |

| ICU 3 | 167 (48.8) | 117 (34.2) | 56 (16.4) | 2 (0.6) | 342 | |

| ICU 4 | 258 (67.9) | 66 (17.4) | 54 (14.2) | 2 (0.5) | 380 | |

| ICU 5 | 255 (68.2) | 65 (17.4) | 53 (14.2) | 1 (0.3) | 374 | |

| All AMUs | 1532 (63.2) | 469 (19.3) | 404 (16.7) | 20 (0.8) | 2425 | |

| All ICUs | 1428 (61.5) | 505 (21.7) | 373 (16.1) | 16 (0.7) | 2322 | |

| Overall | 2960 (62.4) | 974 (20.5) | 777 (16.4) | 36 (0.8) | 4747 | |

The self-identified ethnicity of the respondents was predominantly white British (88.8%) (Table 6).

| Trust | AMU/ICU | White, n (%) | Non-white, n (%) | Unknown, n (%) | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1 | AMU 1 | 1055 (87.0) | 131 (10.8) | 26 (2.1) | 1212 |

| ICU 1 | 966 (86.9) | 125 (11.2) | 21 (1.9) | 1112 | |

| Site 2 | AMU 2 | 468 (78.9) | 111 (18.7) | 14 (2.4) | 593 |

| ICU 2 | 93 (81.6) | 18 (15.8) | 3 (2.6) | 114 | |

| Site 3 | AMU 3 | 590 (95.2) | 20 (3.2) | 10 (1.6) | 620 |

| ICU 3 | 321 (93.9) | 12 (3.5) | 9 (2.6) | 342 | |

| ICU 4 | 362 (95.3) | 13 (3.4) | 5 (1.3) | 380 | |

| ICU 5 | 361 (96.5) | 7 (1.9) | 6 (1.6) | 374 | |

| All AMUs | 2113 (87.1) | 262 (10.8) | 50 (2.1) | 2425 | |

| All ICUs | 2103 (90.6) | 175 (7.5) | 44 (1.9) | 2322 | |

| Overall | 4216 (88.8) | 437 (9.2) | 94 (2.0) | 4747 | |

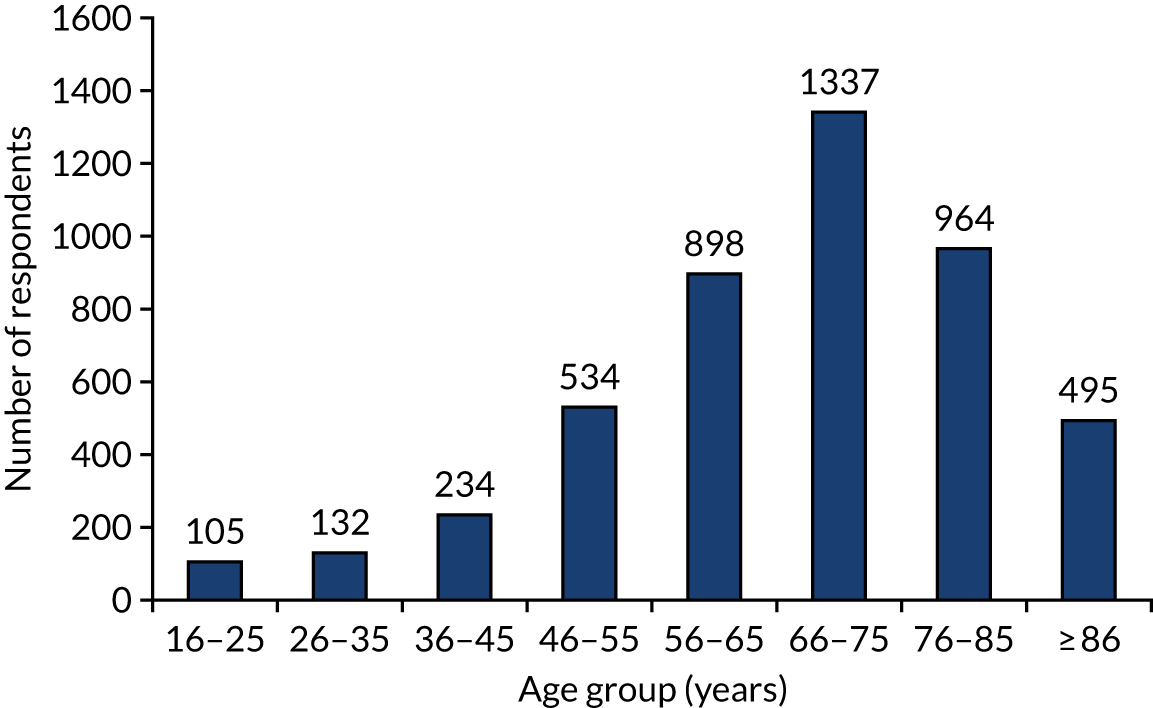

Age characteristics of the respondents are shown in Figure 5. In total, 59.8% (n = 2796) of respondents were aged ≥ 66 years.

FIGURE 5.

The PEARL project patient and relative survey: respondents by age.

Quantitative analysis of survey responses

Respondent ratings from ICU patients and relatives were more positive for all questions than for AMUs. In response to the NHS Friends and Family Test question ‘How likely are you to recommend our unit to friends and family if they needed similar care or treatment?’, 93.5% of ICU patients and relatives selected ‘extremely likely’ or ‘likely’, compared with only 74.3% of AMU respondents (p < 0.0001). This difference was also evident in response to the question ‘How would you rate the overall quality of care you/your relative received in the unit?’: 93.1% of ICU respondents selected ‘excellent’ or ‘good’, compared with 72.0% of AMU respondents (p < 0.0001). There was concordance between patients and relatives in the ICU in their responses: 93.9% of ICU patients selected ‘extremely likely’ or ‘likely’, compared with 92.0% of ICU relatives in response to the Friends and Family Test; 93.4% of patients rated care as ‘excellent’ or ‘good’, compared with 92.3% of relatives. In AMUs, however, patients rated care more positively than relatives: 76.2% of patients compared with 66.7% of relatives selected ‘extremely likely’ or ‘likely’ to the Friends and Family Test question, and 74.4% of patients but only 62.6% of relatives rated AMU care as ‘excellent’ or ‘good’ (p < 0.0001).

All other questions in the PEARL project patient and relative experience survey (excluding question 5, ‘were you ever in pain?’) were phrased as statements with a 5-point Likert scale of agreement for responses (strongly agree to strongly disagree). Notable differences were seen between ICU and AMU respondents, with higher ratings for perceptions of being treated with dignity and respect in ICU respondents (97.0%) than in AMU respondents (88.9%) (p < 0.0001). No other differences were evident between responses from patients and responses from relatives. Confidence in staff was high for both the ICU and the AMU, but again differences were apparent: ICU respondents were more likely to express confidence in doctors (97.7%) and nurses (96.5%) than AMU respondents (88.8% and 88.3%, respectively).

All respondents stated that they were more likely to get answers that they could understand from both doctors (89.2%) and nurses (92.7%) in the ICU than in the AMU [77.6% (p < 0.0001) and 80.2% (p < 0.0001), respectively]. Relatives stated that they were more likely to understand the responses they received from nurses than responses they received from doctors (ICU 93.2% vs. 86.9%, p < 0.0001; AMU 78.6% vs. 72.7%, p < 0.0001).

Significant differences were seen in response to the statement ‘I was able to speak to a doctor when I wanted to do so’: 75.4% of ICU respondents agreed or strongly agreed with this statement, compared with 53.7% of AMU respondents (p < 0.0001). No difference in response was seen between ICU patients and ICU relatives; however, there was a notable difference between AMU patients and AMU relatives: 57.1% of patients agreed or strongly agreed with the statement, compared with 45.8% of relatives (p < 0.0001).

Analysis using performance–importance plots

To illustrate the relationship between the level of satisfaction with each item in the questionnaire and how that particular item influenced overall satisfaction, PIPs were generated. As described in Chapter 2, the PIP compares the percentage of ‘best response’ ratings for each survey item with the correlation coefficient of each item and the overall weighted satisfaction score. Figures 6 and 7 include guidance on interpreting such plots.

FIGURE 6.

Performance–importance plot: aggregated ICU patient survey responses (n = 2322).

FIGURE 7.

Performance–importance plot: aggregated AMU patient survey responses (n = 2425).

The results for ICU respondents are shown in Figure 6 and for AMU respondents in Figure 7. Each survey statement is identified by a number. The survey statement responses relating to communication are coded dark blue and those relating to clinical care are coded light blue. The two questions relating to overall satisfaction are coded orange.

Three conclusions can be drawn from inspection of these plots. The first is that all of the responses relating to communication are clustered in or near the left-upper quadrant, indicating that perceptions of the adequacy of communication strongly determine overall satisfaction. The second is that ICU respondents have a higher median best satisfaction rating (54%) overall than AMU respondents (31%). The third is that, despite this difference between AMUs and ICUs, the pattern is retained: patient and relative experience of communication with staff remains the main driver of (dis)satisfaction.

There are several plausible explanations for these differences between AMUs and ICUs. Compared with ICUs, AMUs have much lower nursing and medical staffing intensities, a higher patient throughput, shorter lengths of stay and, therefore, less time for staff to establish fiduciary relationships with patients and families. It is also likely that, given the high throughput and short length of stay, the AMU data are ‘contaminated’ by patient and relative experiences acquired before AMU admission (e.g. in the ED or a ‘holding area’ awaiting admission) and after transfer out of the AMU to other wards in the hospital with even lower staffing levels.