Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 15/71/06. The contractual start date was in January 2017. The final report began editorial review in July 2019 and was accepted for publication in November 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Iestyn Williams was a member of the Health Services and Delivery Research Prioritisation Committee (Commissioned) (2015–19). Magdalena Skrybant and Richard J Lilford are also supported by the National Institute for Health Research Applied Research Collaboration West Midlands.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Ayorinde et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Publication and related bias

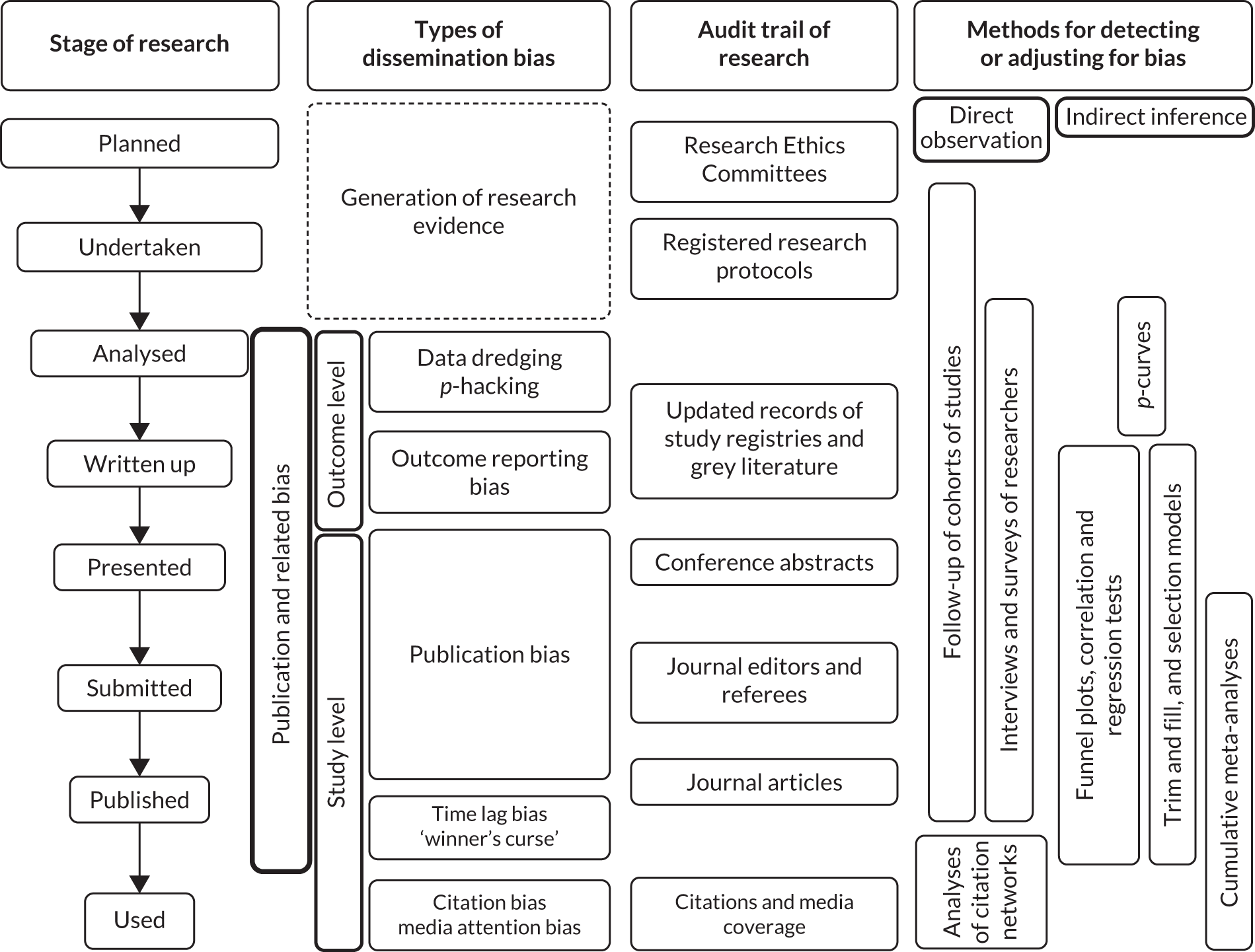

Publication bias refers to the phenomenon by which research findings that are statistically significant and/or are perceived to be interesting or favourable are more likely to be published than those that are not statistically significant or perceived to be interesting. Publication bias occurs at study level (i.e. when a study is not published at all owing to the nature of its findings). Similar bias may manifest at outcome level (i.e. a study may have evaluated several outcomes, but only the findings related to a subset of the outcomes that are statistically significant or judged to be worth noting are reported in its publication). This is termed ‘outcome reporting bias’. 1 Bias can also occur when researchers carry out analyses of data collected from research. For example, multiple analyses may be performed using different techniques or different subsets of the data until statistically significant results are obtained, which are then published. This is referred to as ‘data dredging’ or ‘p-hacking’. 2,3 These biases are a major threat to evidence-based decision-making, as they distort the full picture of the ‘true’ evidence gathered from research and may lead to misinformed decisions. Here we use the term ‘publication and related bias’ to refer to these biases collectively (Figure 1). Further bias may occur following the publication of research findings, such as citation bias and media attention bias, which alongside publication and related bias are collectively known as dissemination bias. 4 For the present study, we focus on publication and related bias that occurs up to the stage of publication (see Figure 1), as biases that occur following publication can largely be overcome through systematic literature search, which is becoming a standard practice when evidence is synthesised to support decision-making.

FIGURE 1.

Various forms of bias in the process of research publication. See Glossary for the definition of ‘winner’s curse’.

A large body of literature has demonstrated the existence of publication and related bias in clinical research. 1,4,5 In particular, several high-profile cases highlighting the non-publication and/or under-reporting of unfavourable results from clinical trials of new pharmaceuticals have raised ethical concerns over publication bias and have highlighted the potential harm it may cause to patients. 6–8 These concerns have led to mandatory clinical trial registration9,10 and, more recently, mandatory reporting of findings of registered trials. 11 By contrast, health services and delivery research (HSDR) has not been subject to similar levels of regulation and scrutiny, and the issue of publication bias appears to be largely ignored. Our preliminary scoping of the health services research literature found only a small number studies addressing this topic, which suggests the possible existence of publication bias. 12–15 The paucity of documented evidence was affirmed in our discussions with some leading experts in health services research.

The lack of published literature on publication and related bias in HSDR compared with clinical research is surprising, given that publication bias has also been documented in many other scientific disciplines, such as social science,16 management research17 and ecology. 18 As there is no obvious reason to believe that HSDR is immune to publication and related bias, and such bias could have substantial implications for health service decisions relying on HSDR, we set out to explore the existence and extent of publication and related bias in this field in order to inform best practice in the reporting and synthesis of evidence from HSDR.

Aims and objectives

The primary aims of this study were to gather prima facie evidence of the existence and potential impact of publication and related bias in HSDR, to examine current practice in systematic reviews of HSDR literature, and to explore common methods in relation to the detection and mitigation of the bias.

The above aims were to be achieved through five distinct but inter-related work packages (WPs), each with a specific objective:

-

WP 1 – a systematic review of empirical and methodological studies concerning the occurrence, potential impact and/or methodology related to publication bias in HSDR, to provide a summary of what is known from current literature.

-

WP 2 – an overview of systematic reviews of intervention and association studies in HSDR, to describe current practice and potential challenges in assessing publication bias during evidence synthesis.

-

WP 3 – in-depth case studies to evaluate the applicability of different methods for detecting and mitigating publication bias in HSDR and to provide guidance for future research and practice.

-

WP 4 – a retrospective study to follow up the publication status of cohorts of HSDR studies to directly observe publication bias in HSDR.

-

WP 5 – semistructured interviews with health services researchers and commissioners, journal editors and service managers, and a focus group discussion with patient representatives to explore their perception and experience related to publication bias.

These WPs complemented each other to provide a full picture of both empirical evidence and current practices related to publication bias in HSDR (Figure 2). Detailed methods for the WPs are described in the next chapter.

FIGURE 2.

Overview of the five complementary WPs included in this study. HSRProj, Health Services Research Projects in Progress; NIHR, National Institute for Health Research.

Structure of the report

The rest of this report is organised as follows: Chapter 2 details the scope and methods of each of the five WPs described above. Chapters 3–7 present the findings from each of the WPs. Chapter 8 includes discussions of specific issues related to methods and findings of individual WPs, and provides some discourse of findings across the WPs and wider issues related to use of evidence to inform decision-making in health services. The chapter concludes with issues worth considering by different stakeholders of HSDR in relation to publication and related bias, and recommendations for future research.

Chapter 2 Overview of methods

Scope

The subject area of HSDR is very broad. In order to draw a boundary that allowed a focused investigation, we used the definition adopted by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) and defined HSDR as ‘research that produces evidence on the quality, accessibility and organisation of health services’. In addition, we targeted two types of quantitative studies: (1) intervention studies, which were carried out to evaluate interventions to improve and optimise the effectiveness and/or efficiency of the delivery of health services; and (2) association studies, which were carried out to evaluate associations between different variables along the service delivery causal chain. 19 A large number of variables can be covered in association studies in HSDR. These include structure variables (e.g. characteristics of a hospital, nurse–patient ratio); generic processes (e.g. continuous professional development, institutional human resource policy); intervening variables (e.g. safety culture, staff knowledge and morale, etc., that could be influenced by structure and generic processes and then impact on many downstream processes);19 targeted processes (e.g. door-to-balloon time for treating myocardial infarction, adherence to guidelines for management of patients with diabetes); and health service utilisation, patient, carer or health care provider outcomes and context (e.g. weekdays vs. weekends, low- and middle-income countries vs. high-income countries). We recognised that intervention studies cannot be completely separated from association studies, as the former is a special case of the latter. Nevertheless, such classification reflected how research questions are often asked in HSDR (e.g. whether or not an intervention works vs. whether or not certain factors affect one another or influence outcomes in the health system). We hypothesised that association studies may be more vulnerable to selective publication and reporting than intervention studies, as a causal relationship is assumed between an intervention and outcomes, whereas relationships between different factors examined in association studies are exploratory and not necessarily causal. In addition, evaluation of interventions may be more likely to be specifically funded with a mandate from the funder to disseminate results, whereas association studies may be carried out without specific funding and related incentive for publication.

The criteria for selecting intervention and association studies were applied in conjunction with the definition of HSDR described in the previous paragraph. Eligible studies may focus on any aspects of health systems and health policy, health-care organisations, people who organise and deliver the health services, and users and carers of the services, as well as related processes, outcomes and contextual factors. Studies concerning clinical research and health technology assessment (i.e. those focusing on interventions applied directly to individual patients), disease epidemiology and genetic associations have previously been examined in detail4 and, therefore, were not included in this study. We were aware of potential grey areas in which the boundary between HSDR and non-HSDR studies may be vague. These were dealt with by consulting members of the Project Management Group and Study Steering Committee.

A wide variety of research designs, including quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods research, have been used in HSDR. 20,21 This study focused on quantitative research and mixed-methods research that incorporated an element of quantitative estimation of intervention effects or association, although we acknowledged that qualitative research can also be subject to publication bias. 22 As the mechanisms and manifestation of publication bias for qualitative research are likely to be different, and methods for evaluating its occurrence and impact are not well developed, we felt that issues related to qualitative research were beyond the scope of the study and warranted a separate investigation. 23

Methods for assessing publication and related bias

Many methods have been developed in order to detect publication and related bias and estimate and/or mitigate its potential impact. 4,24,25 Methods used to detect publication bias can be broadly classified as either making indirect inference or employing direct observation.

Several statistical methods, such as funnel plots and related regression tests, can suggest that publication and related bias may be present during the synthesis of evidence across many studies. 24,25 However, these widely used methods allow only indirect inference, as they rely on the identification of specific patterns in the findings across studies that are suggestive of publication bias, but cannot rule out alternative causes. 26 As a result, evidence on publication and related bias obtained using these methods is generally weak and could be misleading if assumptions underlying these methods do not hold.

Direct evidence on publication and related bias can be obtained in two ways:

-

Identifying a cohort of studies (usually through a registry) and then following these up over time to determine whether or not they are published; this is sometimes described as an inception cohort study and is often undertaken retrospectively given the length of time between the inception of a research and publication of its findings (if published).

-

Consulting stakeholders who are involved in generating and/or disseminating research evidence through surveys or interviews to find out their experience.

These methods of direct observation are labour intensive, but may provide the strongest evidence on the presence (or absence) of publication and related bias. A major challenge in HSDR lies with the difficulty in identifying study cohorts owing to the lack of registries.

Among the five WPs included in this study, WP 1 systematically reviewed previous studies that set out to investigate publication and related bias in any substantive areas of HSDR, using either direct or indirect methods. WP 2 examined a random sample of systematic reviews of HSDR topics with regard to their practice in assessing publication and related bias. WP 3 explored issues surrounding commonly used methods for detecting publication and related bias in more depth using case studies. WP 4 identified four cohorts of HSDR studies from various sources and followed them up to check their publication status and to explore if this was associated with the direction or strength of study findings. WP 5 gathered perceptions and experiences of HSDR stakeholders on this issue through interviews and a focus group discussion. The methods for each WP are described in detail below.

Work package 1: a systematic review of empirical evidence on publication bias in HSDR

Protocol registration

The protocol of this systematic review was registered with PROSPERO, registration number CRD42016052333.

Search strategy

The diverse research disciplines, subject areas and terminologies related to HSDR pose a challenge for searching relevant literature. 27 We used a combination of different information sources and search methods to ensure that our coverage of literature was as comprehensive as possible and was inclusive of disciplines closely related to HSDR. These included searches of general and HSDR-specific electronic databases, citation search of key papers (snowballing), search of the internet and contact with experts.

Electronic database searches

We searched general databases, including MEDLINE, EMBASE, Health Management Information Consortium, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and Web of Science™ (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) (which includes Social Science Citation Index), using indexed terms and text words related to HSDR (defined broadly) and publication and related bias. We also searched HSDR-specific databases, including Health Systems Evidence and systematic reviews published by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care review group. Searches were undertaken in March 2017 and were updated in July/August 2018. The search terms for MEDLINE and EMBASE can be found in Appendix 1.

Forward and backward citation search (commonly known as ‘snowballing’)

Reference lists of all studies that met the inclusion criteria for this review (see Inclusion criteria) were examined. Google Scholar was used to locate other potentially relevant studies by examining articles subsequently published that have cited the included studies.

Internet searches

The importance of grey literature in health services research has been highlighted in a report funded by the US National Library of Medicine. 28 In order to locate grey literature, we searched websites of key organisations linked to HSDR, such as The Health Foundation, The King’s Fund, the Institute for Health Improvement, the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the RAND Corporation. In addition, we searched the NIHR HSDR programme’s website and the US Health Services Research Projects in Progress (HSRProj)’s database for details of previously commissioned and ongoing studies.

Consultation with experts

We presented a draft study plan in a meeting associated with the Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care West Midlands, which was attended by international experts in HSDR. Members of the Study Steering Committees were consulted to identify any additional studies that may not have been captured by other means.

Study screening and selection

Records retrieved from electronic databases and subsequently obtained from other sources were imported into EndNote X9 (Clarivate Analytics) to facilitate identification and removal of duplicates. Titles and abstracts of de-duplicated records were screened to exclude clearly irrelevant records. Full-text publications were retrieved for the remaining records, and inclusion and exclusion decisions were made independently by two reviewers for each study based on the selection criteria described in the next paragraph. Screening of all records was conducted independently by two reviewers and any disagreements were resolved by discussion or through consultation with the wider research team.

Inclusion criteria

Studies of all designs that set out to examine any forms of publication and related bias in any fields of HSDR within the scope of this project were included. Specifically, a study needed to meet the following criteria:

-

have investigated data dredging/p-hacking, selective outcome reporting or publication bias, or evaluated methods for detecting these forms of bias

-

have provided empirical, quantitative or qualitative evidence (i.e. not just commentaries or opinions)

-

be concerned with HSDR-related topics.

Data extraction and risk-of-bias assessment

The following information were extracted from each included studies:

-

citation details

-

methods of selecting study sample and characteristics of the sample

-

methods for investigating publication bias

-

key findings, limitations and conclusions reported by the authors.

We were not aware of the availability of any suitable tools for assessing the risk of bias of the included studies, which adopted diverse methods. We therefore critically appraised individual studies based on epidemiological principles, such as representativeness of study sample, potential bias in the sampling and data collection processes, and issues related to confounding. Included studies were read by at least two authors. Key methodological weaknesses of each study were recorded and summarised. We expected that there will not be sufficiently large number of studies with comparable measures for conducting tests for small study effects and publication bias. However, we searched extensively for grey and unpublished literature.

Data synthesis and reporting

Study characteristics, methods and findings were tabulated and narrative summaries compiled. As anticipated at the beginning of the study, data were insufficient for quantitative synthesis.

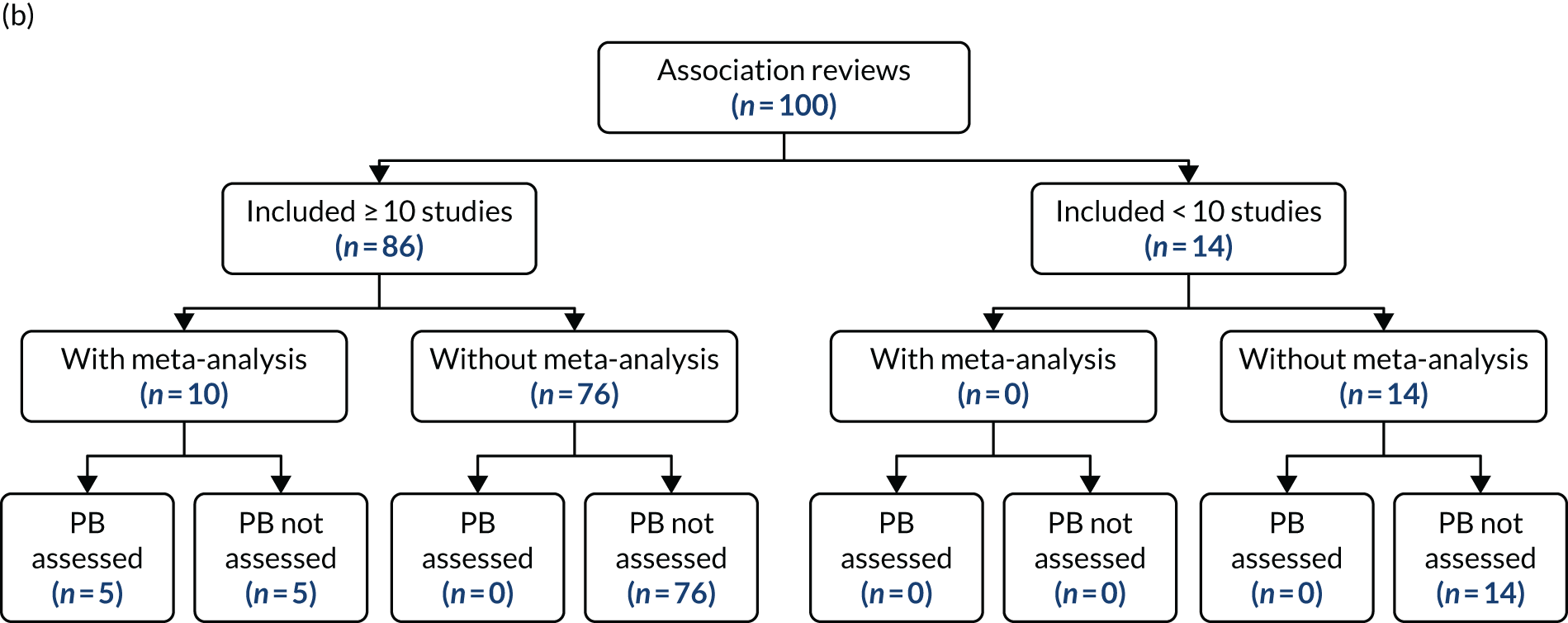

Work package 2: overview of current practice and findings associated with publication and related bias in systematic reviews of intervention and association studies in HSDR

Systematic reviews have emerged in various fields, including HSDR, as a key tool for summarising the rapidly expanding evidence base in a way that maximises the completeness, while minimising potential bias in their coverage of relevant evidence. Steps to identify and reduce various types of bias are built into the process of a systematic review. The following steps are particularly relevant for publication and related bias:

-

comprehensive search of literature, including attempts to locate unpublished studies

-

assessment of outcome reporting bias of included studies

-

assessment of potential publication bias using funnel plots, related regression methods or other techniques.

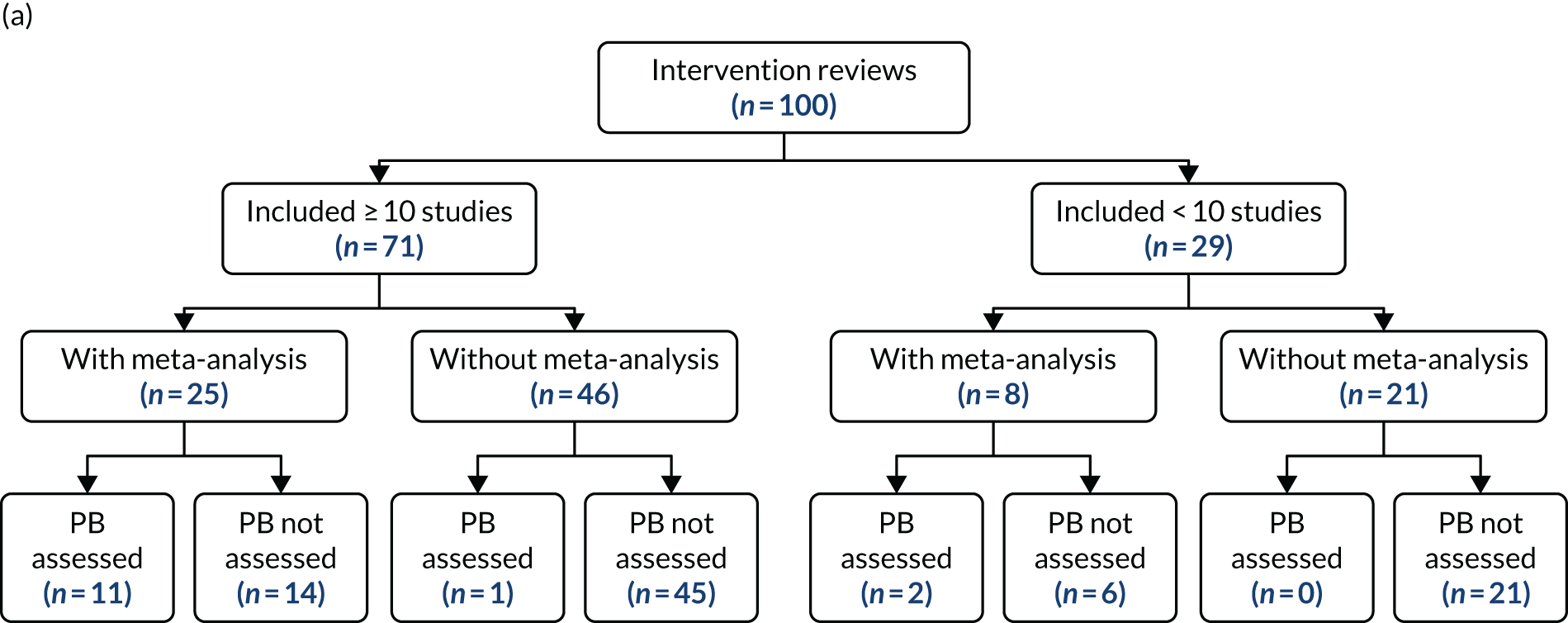

This WP examined a random sample of 200 HSDR systematic reviews and inspected each review with regard to whether or not the above measures for minimising and detecting publication and related bias were considered and/or performed. Data were also collected on the methods used and findings from the assessment of publication and related bias. We focused on systematic reviews covering two main types of quantitative study: intervention studies and association studies (see Scope). We explored whether or not the practice of assessing publication and related bias differed between these two types of studies, and whether or not this was associated with various characteristics of the review and the journal in which it was published.

Protocol registration

The protocol for this methodological overview of systematic reviews (meta-epidemiological study) was registered with PROSPERO (registration number CRD42016052366).

Search and sampling strategies

Health services and delivery research systematic reviews examined in this WP were obtained from Health Systems Evidence,29 a database that focuses on evidence related to health systems and services research, and has a comprehensive coverage of systematic reviews, economic evaluations and policy documents related to HSDR. The database is continuously updated and covers several bibliographic databases, including MEDLINE and the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, as its sources. 30 We downloaded (with permission from the database owner) records for all systematic reviews that were classified as ‘systematic reviews of effects’ (n = 4416) and ‘systematic reviews addressing other questions’ (n = 1505) in May 2017, and then assigned a random number to each record. We screened each record against our inclusion criteria, described in the next paragraph, in ascending order based on the assigned random number until the targeted number of reviews (100 each for intervention and association reviews) was reached. On the basis of a baseline rate of 32% for formally assessing or providing partial information with regard to publication bias reported in a previous meta-epidemiological study31 of systematic reviews published by the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care review group, the sample size has 80% power to detect a 20% difference in the characteristics and findings between the two types of reviews.

Inclusion/exclusion criteria

For this project, a systematic review was defined as a literature review with explicit statements with regard to research question(s), a strategy for literature search and criteria for study selection. Review articles that did not meet this definition were excluded.

A systematic review needed to fulfil the following requirements to be included:

-

It focused on a topic related to HSDR, as defined for this project.

-

It examined quantitative data concerning intervention effects or associations between different factors.

-

It reported at least one quantitative effect estimate or one result (p-value) of a statistical test. These could be obtained from studies included in the review and it was not necessary for a review to have carried out meta-analyses to be included.

Systematic reviews that investigated the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of clinical interventions (i.e. those traditionally falling under the provenance of health technology assessment) and those exploring the association between risk factors and disease conditions (i.e. those falling under the provenance of clinical and genetic epidemiology) were excluded.

The eligibility check was carried out by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer. Disagreements were resolved through discussions between the reviewers. The Project Management Group was also consulted when required.

Assessment of included systematic reviews

Included systematic reviews were examined with regard to the characteristics of the review, the methods used to assess potential publication and related bias, and findings and/or any issues raised concerning the assessment. The following data were extracted:

-

Key study question(s) for which quantitative estimates were sought (e.g. associations or intervention effects).

-

Databases searched and whether or not an attempt was made to search grey literature and unpublished reports, or reasons for not doing this.

-

Types of studies included, in terms of study design (whether or not the review included only controlled trials); whether or not a meta-analysis was carried out; and number of studies included in the review (≥ 10 vs. < 10, the minimum number recommended for the use of funnel plots and related methods for assessing publication bias). 26

-

Methods (if used at all) for detecting and/or mitigating potential publication bias (apart from comprehensive search), for example funnel plots and related regression methods, trim and fill.

-

Methods for assessing outcome reporting bias.

-

Findings of assessment of publication and outcome reporting biases, or reasons for not assessing these.

-

Whether or not the review authors reported adherence to systematic review guidelines, such as Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)32 and Meta analysis of Observational Studies in Epidemiology. 33 All Cochrane reviews were considered to have adhered to the Methodological Expectations of Cochrane Intervention Reviews standards,34 even if this was not explicitly stated.

-

Whether or not the review authors reported using Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) for assessing overall quality of evidence. 35

In addition, we obtained the impact factor for the journal in which each review was published from the ISI Web of Knowledge based on the records for year 2016, or from the journal’s website if the former was not available. Each journal’s website was also searched to ascertain whether or not it explicitly endorsed systematic review guidelines.

Data extraction was carried out by one reviewer and checked by another, with any discrepancies resolved by discussion or by contacting authors for further information and clarification.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics were compiled to summarise the characteristics of HSDR systematic reviews, the practice of assessing publication and related bias among the reviews, and their findings. Exploratory comparisons of review characteristics, practice and findings of assessing publication bias were made between intervention and association reviews, using both univariable and multivariable logistic regression.

Work package 3: case studies to explore the applicability of methods for detecting and dealing with publication and related bias

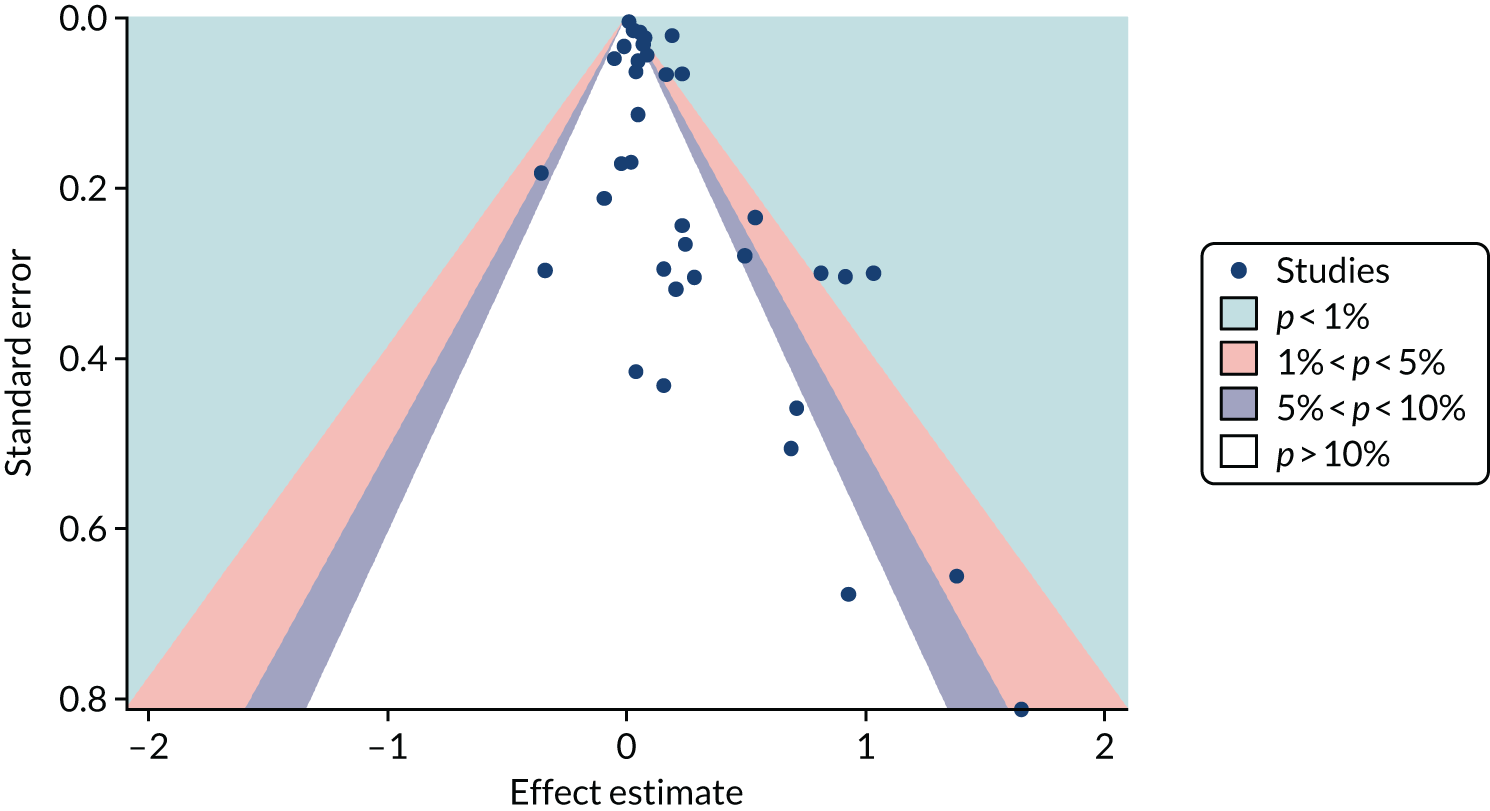

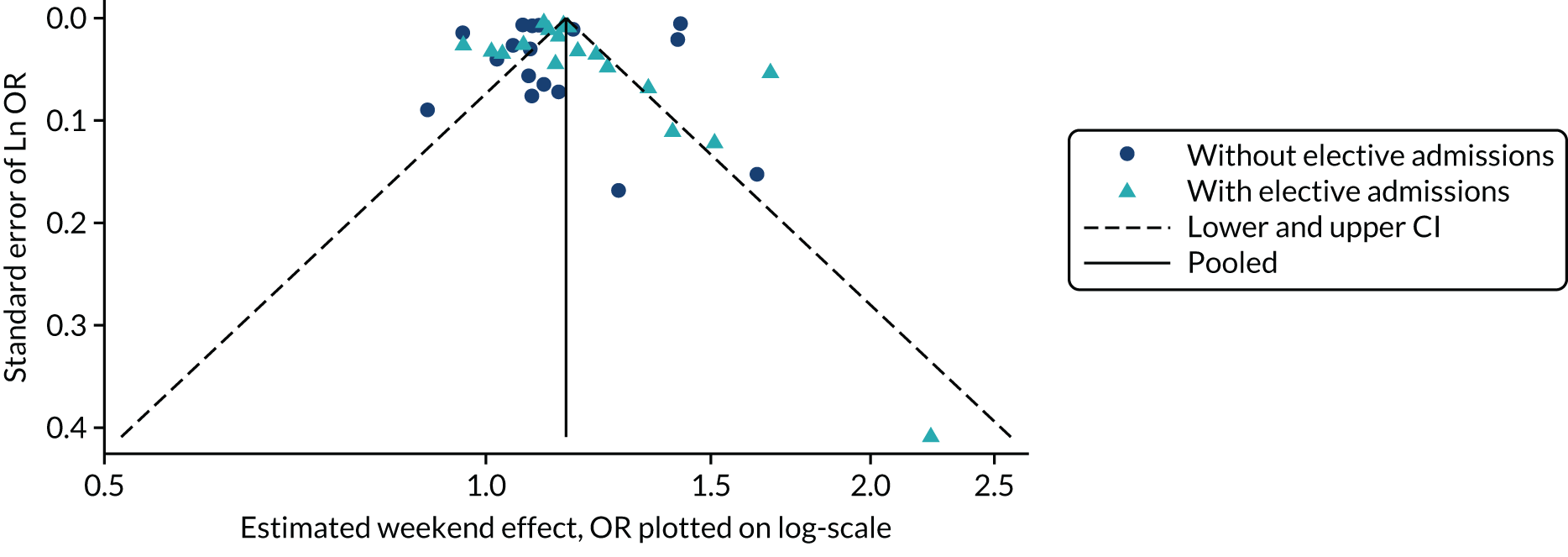

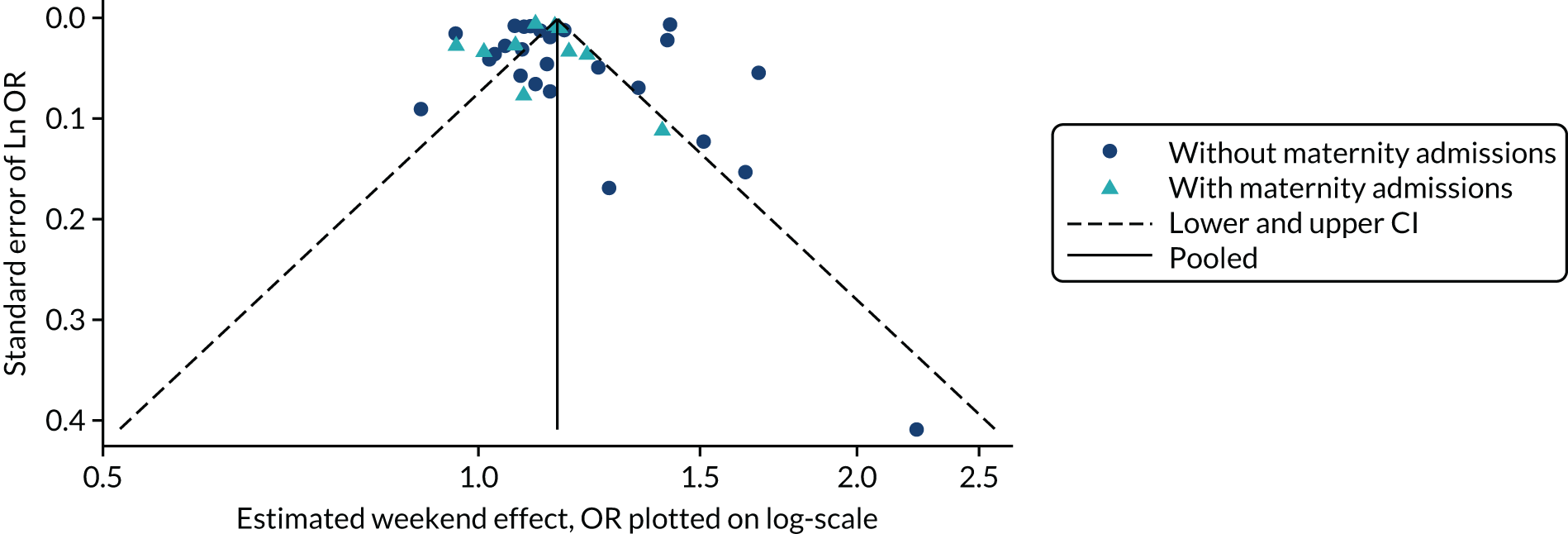

Several methods have been developed to facilitate the detection and potential adjustment of publication and related bias. Among these, funnel plots and related regression methods are the most widely used and have been adopted in many systematic reviews. The key assumption for these methods is that the precision of a study (mainly determined by its sample size) is not correlated with the actual size of the intervention effect or association being estimated and, hence, the results of smaller studies are scattered more widely due to random variation, forming an inverse funnel shape when plotted against precision. Asymmetry in a funnel plot would suggest possible publication bias. Figure 3 shows an example of an asymmetrical funnel plot compiled (by authors of this report) using data from a published systematic review of mortality risk associated with out-of-hours admissions in patients with myocardial infarction. 36

FIGURE 3.

An example of an asymmetrical funnel plot.

Although the assumption behind funnel plots and related regression methods holds for many clinical interventions, this is not necessarily true in many HSDR studies. For example, early evaluation of a quality improvement intervention in a small number of sites may observe a large intervention effect due to the expertise and dedication of the personnel and thoroughness of implementation, which may be difficult to maintain when the intervention is scaled up in a larger study. Alternatively, an intervention that appears to be highly effective in early small-scale studies may have an apparently diminished intervention effect by the time it is subject to a large-scale evaluation due to a system-wide improvement triggered by the same social pressure that prompted the intervention. 37 On the other hand, the availability of data from large databases covering nearly the whole population may render the influence of small studies negligible. These different types of heterogeneity arising from the complexity of HSDR interventions and associations, and the context in which they are deployed and observed, pose a potential threat for the validity of applying these conventional methods. In addition, funnel plots and related regression methods require a sufficiently large number of studies (e.g. ≥ 10), which may not be available for many topics in HSDR.

The WP 2 described above allowed us to obtain an overview of current practice of examining publication and related bias in systematic reviews of HSDR, including a description of if and what methods have been used. Nevertheless, when formal methods, such as funnel plots and related regression methods, have been used, there remain potential issues concerning the validity and applicability of these methods. 26,38 WP 3 aimed to address these issues through more detailed case studies. In addition, WP 3 offered an opportunity to explore novel methods, such as the p-curve for identifying p-hacking (see Investigation of p-hacking using p-curves), which could be very relevant for HSDR.

Selection of cases to be studied

Given that the purpose was to shed light on the applicability of existing methods to HSDR, we purposively sampled five systematic reviews to ensure reasonable coverage of this diverse field. The selection of cases was guided by the following considerations:

-

The review included a sufficiently large number of studies (≥ 10) to meet the minimal requirement for using funnel plots and regression methods.

-

Covering reviews of various sizes in terms of number of studies included.

-

Inclusion of both reviews that evaluate intervention effectiveness and those investigating associations.

-

Coverage of major issues and scenarios likely to be encountered during evidence synthesis of HSDR.

-

The topics were of general interest for health services researchers, practitioners and the general public.

We had to drop one of the sampled case studies due to practical considerations (see Deviations from the original protocol). The following four topics were subsequently chosen in consultation with the Study Steering Committee, taking into account the above criteria, possible saturation of issues and scenarios covered, and practicality within the project timeline:

-

case study 1– the association between weekend and weekday admissions and hospital mortality

-

case study 2 – the association between organisational culture and climate and nurses’ job satisfaction

-

case study 3 – the effectiveness of computerised physician order entry systems on medication errors and adverse events

-

case study 4 – the effectiveness of standardised hand-off protocols on information relay, patient, provider and organisational outcomes.

Three of the cases (case studies 2–4) were identified through WPs 1 and 2, and one case (case study 1) was built on a systematic review associated with another NIHR HSDR programme-funded project that we have been involved in.

Data collection and presentation

For each systematic review selected as a case study, we extracted information on the methods and findings related to publication bias from the original articles. The information was presented in a structured format, with commentary on the methods and findings related to publication bias provided, to highlight any issues particularly relevant to HSDR. In addition, we utilised detailed numerical data from a systematic review of association studies on the weekend effect available to the principal investigator of this project to carry out further analyses for case study 1, in which we explored commonly used methods for detecting publication bias, as described in the next paragraph.

A large number of tools have been developed to facilitate the assessment of risk and potential impact of publication and related biases. 25,39 We chose five of the techniques that are widely used and relatively easy to implement, and tested their applicability in case study 1: (1) funnel plots, (2) Egger’s regression test, (3) Begg and Mazumdar’s rank correlation test, (4) trim and fill and (5) meta-regression. 24 In addition, given the theoretical risk of p-hacking in analyses without predefined protocols, which may not be rare in HSDR, we also tried a relatively new technique of p-curves to explore its potential utility for detecting this practice. 2 Findings from the application of these statistical techniques were presented with detailed critiques, highlighting potential issues that could impact on the validity of these methods and the interpretation of their findings.

Funnel plots and related methods

We constructed a funnel plot for the primary meta-analysis of case study 1. Funnel plot asymmetry was assessed by Egger’s regression40 and the Begg and Mazumdar’s rank correlation test,41 and by visual inspection given the relatively low level of statistical power of the tests. In the Egger’s regression test, the effect size is regressed against its precision (inverse variance). In the absence of asymmetry, the regression line would pass through the origin (with an intercept equalling zero). A significant deviation of the intercept from zero signifies funnel plot asymmetry (p < 0.05 for the Egger’s regression test). In the Begg and Mazumdar’s test, a rank correlation test is conducted to explore the correlation between (standardised) effect sizes and their standard errors. A significant correlation (p < 0.05) for the Begg and Mazumdar’s rank correlation test suggests that effect sizes vary with standard errors (smaller studies tend to have larger standard errors), which indicates a small study effect and thus potential publication bias.

The ‘trim and fill’ method was used to estimate the potential impact of small study effects. 42 In this method, the asymmetry of a funnel plot is assumed to be caused by publication bias, and alternative estimates correcting for the bias are calculated first by trimming out smaller studies with more extreme effect size estimates causing the asymmetry, and then by reintroducing these studies along with their ‘missing’ counterparts. The method provides a way to estimate how sensitive the results of meta-analyses are to the small study effects. It is important to recognise that publication bias is just one potential cause of small study effects and to interpret findings with caution accordingly.

Evaluating the association between estimated effect sizes and other potential effect modifiers through meta-regression

The regression methods used alongside funnel plots essentially test the existence of an association between observed effect sizes and precision (or sample sizes) of studies. As described above, heterogeneity in the intervention components, study design, settings and context commonly seen in HSDR may confound this association. One approach to investigating this issue is to use multivariate meta-regression analyses, including both sample size and potential confounding factors (e.g. quality of study, or year of publication, as a proxy for changes in context) as covariates. If the association between observed effect sizes and sample sizes persists after adjusting for potential confounders, the likelihood of observed funnel plot asymmetry being caused by publication bias increases. In case study 1, we carried out meta-regression to explore whether any association found between effect sizes and sample sizes (or precision) could be attributed to other confounding factors.

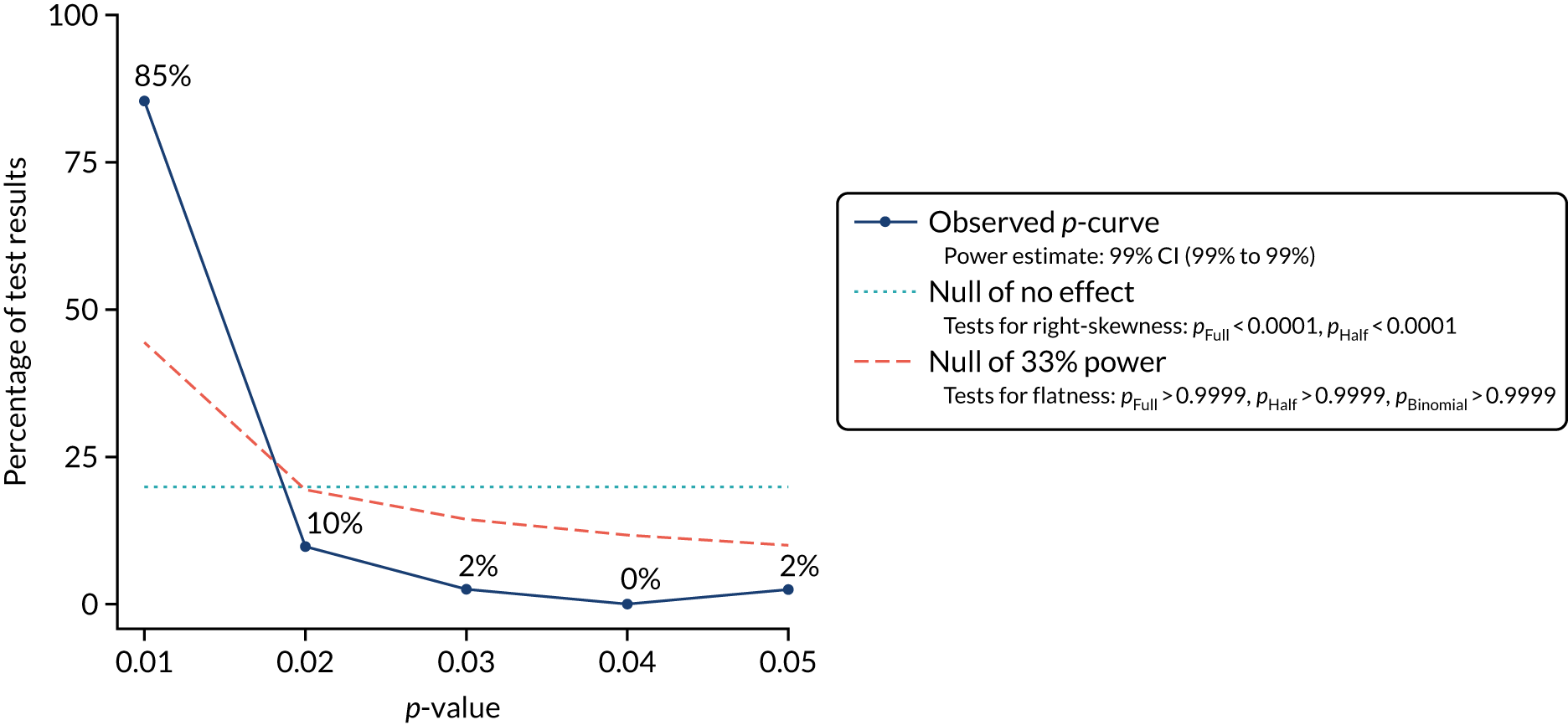

Investigation of p-hacking using p-curves

Repeating analyses using different analytical approaches and data sets until a statistically significant result is obtained – so called ‘p-hacking’ – introduces a bias closely related to publication bias. 3 Recently, a novel methodology, termed ‘p-curve’, that allows the detection of p-hacking from published literature has been developed. 2 The method is based on the fact that, when the null hypothesis is true, the distribution of p-values is uniform and, therefore, should take the shape of a straight line when a collection of p-values from studies that declare statistical significance are plotted. When p-hacking exists, however, the distribution of p-values will be distorted and a spike in the region just below p = 0.05 would be observed. 3 The method has been tested within psychology and biology literature and demonstrated apparent p-hacking in these fields. 2,3 Although we were not aware of the application of p-curve in health services research, p-hacking is a possible threat in HSDR, particularly in the increasing number of analyses of data sets from routine databases. We therefore proposed to use p-curves to explore the potential occurrence of p-hacking in HSDR in case study 1, for which we had more detailed data. We first calculated z-scores for each individual effect estimate included in the meta-analysis of this case study. These were then entered into the tool developed by Simonsohn et al. 43 to generate p-curves.

Work package 4: follow-up of publication status of cohorts of health services research studies

The previous three WPs drew on crucial evidence on issues concerning the extent of publication bias and methods of detecting it in HSDR from the literature. Nevertheless, most of the evidence gathered was indirect in nature, as observations made (such as asymmetry in funnel plots and significant tests) were indicative of the existence of such bias, rather than confirmatory. WP 4 consisted of a retrospective investigation of cohorts of HSDR studies, which were followed over time to ascertain whether their publication status was associated with the statistical significance, or perceived ‘positivity’ or interest of their findings. The main objective was to provide a direct observation of the presence or absence of publication bias in HSDR, as measured by the presence or absence of an association between the publication status of HSDR projects and the statistical significance and perceived ‘positivity’ (see Extraction of study information and classification of study findings) of their findings. In addition, if publication bias was observed, whether it was associated with study design, study type (intervention vs. association) and/or sample size would be explored.

Selection of study cohorts

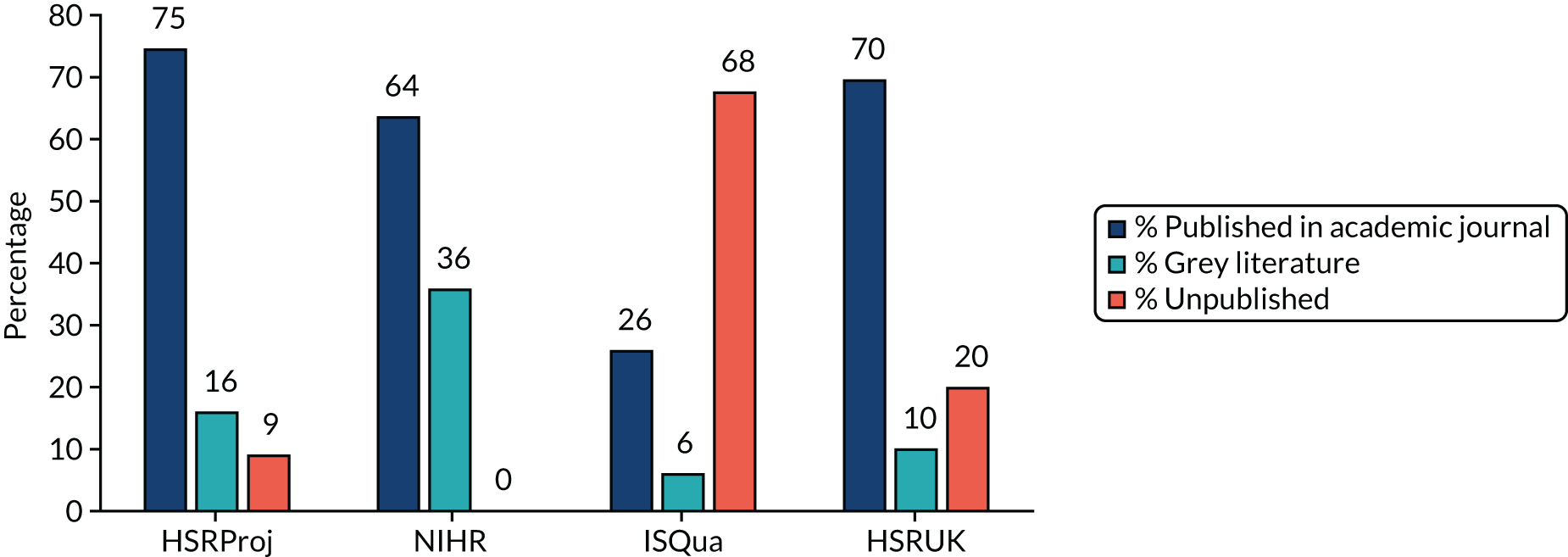

We initially planned to identify and follow two cohorts of 100 HSDR studies, which would provide confidence limits of under ± 10% for each cohort (assuming a publication rate of 60%) and an 88% power to detect a 20% difference between the two cohorts. To increase the diversity of HSDR covered in our sample, we subsequently added two cohorts of 50 studies, each from HSDR-related conferences. Further details are described in National Institute for Health Research cohort, HSRProj cohort, Health Services Research UK conference cohort and ISQua conference cohort.

Studies initially sampled for each of the cohorts were checked against the following criteria:

-

The research question fell within the scope of HSDR defined for this project.

-

The study included a quantitative component that was not one of the following: descriptive studies not making any comparisons or evaluating any associations; simulation and other studies that were mainly based on modelling or development of models; and methodological studies associated with development and validation of tools.

Studies that did not meet these inclusion criteria were discarded and replaced until the targeted sample size was achieved for each cohort.

National Institute for Health Research cohort

The only comprehensive database of UK HSDR studies that we were aware of is the project portfolio of the NIHR HSDR programme-funded projects, including those previously commissioned under the NIHR Service Delivery and Organisation (SDO) programme and the NIHR Health Services Research programme. These studies have gone through a highly competitive bidding and peer review selection process and are likely to be the most well-funded projects among HSDR studies. In addition, the NIHR has had a strong policy to mandate the publication of research findings and, indeed, the HSDR programme has been routinely publishing its funded studies submitted from July 2012 onwards in its Health Services and Delivery Research journal, which is published as part of the NIHR Journals Library. Studies included in the HSDR database are therefore ‘atypical’ and are least likely to be subject to publication bias. Nevertheless, given the prominence of this portfolio of studies, evaluating the presence or absence of publication bias and documenting the impact of the establishment of the HSDR journal series on the publication of these studies were both very important.

In July 2017 we requested records from the NIHR on projects that had been funded by the NIHR SDO, Health Services Research and HSDR programmes that had been completed by the end of 2014. A total of 338 projects were included in the records supplied. We initially screened all studies completed between 2009 and 2012 (n = 131), but the targeted sample size of 100 studies could not be achieved after excluding projects that were not a primary study including a quantitative component (e.g. evidence synthesis projects and those that adopted exclusively qualitative methods). Consequently, we extended the year range for project completion to between 2007 and 2014 for the final sample of 100 projects.

HSRProj cohort

In order to complement the cohort of studies funded by the NIHR, we identified another cohort of studies from the US-based HSRProj database [URL: wwwcf.nlm.nih.gov/hsr_project/home_proj.cfm (accessed 17 December 2019)]. The HSRProj is hosted within the US National Library of Medicine and is the largest (and the only one that we were aware of) publicly accessible prospective registry of health services and public health research that covers multiple institutions and funding bodies. As of 2017, the database held information on > 32,000 projects (including both ongoing and completed projects) undertaken by nearly 5000 organisations from > 50 countries (mainly from the USA). Although it is unlikely that projects registered with this database were representative of all HSDR, the coverage in terms of number of projects and types of studies made it one of the best alternative sources to assemble a cohort of HSDR studies.

The HSRProj database classifies its project records into three categories: ongoing, completed or archived. Records are archived 5 years after the project’s end date. We took a random sample of 100 studies from the 1531 studies recorded as being completed in 2012 (to allow sufficient time for publication). As the HSRProj had a broad scope (e.g. including public health projects and comparative effectiveness research), studies that were initially sampled but judged to be falling outside the scope of this project were excluded and replaced during the assembly of the study cohort.

Health Services Research UK conference cohort

We obtained all abstracts presented in the Health Services Research UK (HSRUK) conferences during 2012–14 from Universities UK. We aimed to sample a total of 50 studies, with equal numbers from oral and poster presentations. However, only 19 of available abstracts for poster presentations met the inclusion criteria and, therefore, we sampled 31 abstracts from oral presentations.

ISQua conference cohort

We randomly selected a total of 50 abstracts from the International Society for Quality in Health Care (ISQua) 2012 conference using the abstract books published by the conference, with equal number from poster and oral presentations (25 each).

Extraction of study information and classification of study findings

Information on title, authors, abstract and funding source and contact information for the lead investigator for the sampled studies were supplied by the NIHR, downloaded and imported from the website of HSRProj or obtained from conference abstracts. Each study was classified according to study type (intervention vs. association) and study design features [method of data collection (bespoke vs. routine data vs. mixed) and, for intervention studies, whether or not there was a concurrent control group].

We also classified each study according to statistical significance (with a p-value of ≤ 0.05 considered statistically significant). For studies focusing on one outcome or with one prespecified primary outcome, we coded statistical significance based on this outcome. When results were reported for more than one outcome or association and a main outcome could not be easily discerned, we classified the findings from each study as ‘all or mostly significant’, ‘mixed (one or more significant result, but for less than two-thirds of the outcomes/associations)’ or ‘all or mostly non-significant’.

Statistical significance may not be the main mechanism through which publication bias occurs. For example, the findings of a study may be regarded as positive or favourable if a cheaper way to deliver a service is as effective as a more costly option (i.e. no significant difference in outcomes between the options). We therefore adopted the method used by Song et al. 4 and classified the findings of each study as ‘positive’ or ‘non-positive’. Studies coded as positive included those that were considered (by the original study authors) as being ‘positive’, ‘favourable’, ‘significant’, ‘important’, ‘striking’, ‘showed effect’ and ‘confirmatory’. Non-positive result refers to other results labelled as being ‘negative’, ‘non-significant’, ‘less or not important’, ‘invalidating’, ‘inconclusive’, ‘questionable’, ‘null’ and ‘neutral’. The ‘positivity’ classification was used as a sensitivity analysis in place of ‘statistical significance’ given that the two measures are likely to be highly correlated.

Some of the larger HSDR projects had multiple components (e.g. quantitative and qualitative) and/or involved multiple stages (e.g. pilot study, process evaluation and effectiveness trial), and may have produced multiple publications. In such cases, we chose the quantitative component/publication that was considered to be closest to the stated primary aim(s) of the project, or chose the earliest publication for data collection and coding if the most relevant component or publication could not be determined. For a project encompassing multiple methods and stages, we focused on the publication or findings associated with the later stage (usually an effectiveness trial) of the project.

All data extraction and coding decisions were made by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer. Any discrepancies were resolved through discussions.

Verification of publication status

The publication status of each study was verified firstly by searching PubMed and Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA), using information on title and lead investigator/author. When no publication was identified, or when it was not clear if the identified publications were direct outputs from the selected project, we attempted to contact the investigators by e-mail to verify the status of publication and to request information on published articles or unpublished study results, and reasons for non-publication if this is the case. We sent up to two reminders when no response was received and other means (e.g. search of funding agency’s website) were pursued to enhance the completeness of follow-up. We classified publication status for each study as published (in academic journals), grey literature (available on the internet in a form other than an article published in academic journals, such as a technical report or working paper) or unpublished.

Data analysis

Descriptive statistics concerning study type, study design, findings and publication status were computed. Univariable and multivariable logistic regression were carried out to explore the association between publication status and statistical significance and positivity of study findings, controlling for potential confounders. Our prespecified variables were type of study (intervention vs. association), method of data collection (routine data, bespoke data collection or mixed), funding source [no specific funding, local funding, national funding (HSDR programme), national funding (others)], size of study (number of institutions or number of individuals) and, for intervention studies, studies with concurrent controls compared with before-and-after studies (including time series without a control group). We dropped two variables, funding source and study size, during data collection, as (1) the NIHR cohort has a single funding source by default and this information was not available for a large proportion of studies in the conference cohort; and (2) attributing a study size to a given study based on number of participating institutions, number of individual patients, number of observations or number of events could be arbitrary, and inclusion of study sizes based on different units could lead to difficulties in interpretation. In addtion, we collected information with regard to study design [randomised controlled trial (RCT) vs. non-RCT] among studies with concurrent controls, but did not include this in multivariable analyses, as all RCTs adopted bespoke data collection and had a concurrent control group by definition.

Work package 5: semistructured interviews and a focus group discussion with health services researchers, journal editors and other stakeholders

Work package 5 sought to complement direct evidence collected from the retrospective cohort study in WP 4 by exploring the perceptions and first-hand experiences of health services researchers and commissioners, journal editors, service managers and users, with regard to the occurrence and impact of publication and related bias. It contributes to the overall aim of obtaining (qualitative) evidence on the extent and existence of publication bias. It was also intended to contribute to the development of methods for the detection and mitigation of publication bias in HSDR. As well as generating important data on the perspectives of key actors in the HSDR process, this WP was designed to support analysis of results deriving from prior WPs.

Objectives

Interviews and the focus group were designed to:

-

enable qualitative exploration of quantitative findings derived from WPs 1–4, for example in relation to current rates and types of publication bias in HSDR

-

gauge the views of a sample of those currently commissioning, publishing or conducting HSDR as to the prevalence (or existence) and perceived impact of publication bias

-

identify and explore current and future strategies for prevention, detection and mitigation of any bias detected

-

explore the experiences and views of service managers and patient and user experts involved in HSDR.

Methods

Selection and recruitment of key informants

We undertook in-depth interviews with 24 key informants in the field of health services research to explore their perceptions, experience and preferred solutions to overcoming problems associated with publication bias in HSDR. We conducted a focus group with eight patient and service user representatives to explore these issues from a patient and service user perspective.

Potential interviewees were invited by the lead researcher for WP 5 (IW) via e-mail in the first instance. Invitation e-mails were tailored to the individual respondent (see Appendix 2) and included a short summary of the project, with further detail attached (i.e. participant information leaflet, see Appendix 3). Those agreeing to take part were requested to return a signed consent form (see Appendix 4), either by e-mail (scanned signed copy or provision of an electronic signature) or by post. Those not providing a consent form consented verbally to the audio-recording of the interview. Non-responders were sent a reminder e-mail within 2 weeks of the initial e-mail, and this was trailed in the initial invitation. Those declining to take part were asked to give reasons for declining. Of the 27 targeted respondents who did not take part, eight cited lack of available time, four indicated a lack of interest or expertise in the topic and 15 did not respond.

We sought to ensure that the sample included researchers from different epistemological traditions and at various stages in their careers. Researchers included in the sample were selected to include individuals:

-

with a track record of HSDR publication

-

at different stages of their careers (indicated by level of seniority)

-

specialising in aspects of HSDR, such as systematic review, improvement science, management, health sociology, health economics and operations research.

We did not require that those included had a specific research interest in publication bias, but instead designed our interview schedule to enable them to reflect on publication bias from their standpoints and experiences (see Appendix 5).

Editors and assistant editors of key UK health services journals were also included, along with journal editors from outside the UK. Three respondents were included primarily because of their roles at major funders of UK HSDR, and two interviewees were included as national and local decision-makers within the English NHS. Details of the final sample are presented in Table 1.

| Research participant | Primary identifier | Secondary identifier | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Senior researcher | 7 | 7 | 14 |

| Junior/mid-career researcher | 4 | 1 | 5 |

| Journal editor | 7 | 3 | 10 |

| Researcher funder/commissioner | 3 | 1 | 4 |

| Patient/service user representative | 8 | 0 | 8 |

| Manager | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Consultant evaluator | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Clinician | 0 | 5 | 5 |

| Total | 32 | 17 | 49 |

Our final sample therefore included 14 senior researchers (with seven of these interviewed primarily in this capacity and seven in a secondary capacity), five junior mid-career researchers (four in this capacity and one in a secondary capacity), 10 editors (seven in this capacity and three in a secondary capacity), four funders (three in this capacity and one in a secondary capacity), two managers, one private consultant and eight patient and service user representatives. Five of these respondents were also practising clinicians.

Topic guides for the interviews and focus group were informed by previous phases of the study and focused on the informants’ perceptions and past experience of publication bias in HSDR, and their opinions on possible approaches to its mitigation.

We obtained ethics approval from the University of Warwick Biomedical and Scientific Research Ethics Committee (REGO-2017-1918 AM01). Although assurances were given that, when possible, all steps would be taken to ensure anonymity, it was made clear that in a relatively small sample of high-profile interviewees full anonymity may be compromised. In acknowledgement of the sensitivity of the subject material we put safeguards and assurances in place so that respondents felt able to speak freely and candidly. For example, we assured interviewees that, as well as anonymising transcripts, steps would be taken to ensure that any identifying details are redacted in subsequent reports. Participants were offered the opportunity to comment on a draft report of this WP so that they could be assured that all identifying features had been removed.

Data collection and analysis

Interview and focus group data were collected during the period September 2017–August 2018, with interviews conducted by a single member of the research team and the focus group facilitated by two members. All interviewees opted for a telephone interview format. Interviews ranged from 20 to 45 minutes in length and the focus group lasted 1.5 hours. Example interview schedules can be found in Appendix 5. Permission to voice-record the interviews was obtained in all cases (including the focus group), and recorded interviews were fully transcribed for subsequent analysis.

Data were analysed inductively to gauge participants’ perspectives and experiences within the framework provided by the research aims, as well as issues identified in prior WPs. Findings from earlier interviews were used to inform subsequent interviews to facilitate the exploration of different perceptions, experiences and opinions among the interviewees. For internal validity, all interviews were fully transcribed and we used qualitative coding software (NVivo version 11; QSR International, Warrington, UK) to facilitate data storage and retrieval during analysis. 44 Two members of the research team contributed to the building of thematic coding frames from qualitative data and shared independent coding of a data subset in order to ensure consistency. Identified themes were regularly discussed at meetings of the core project team. External validity and transferability of analysis were addressed through detailed description and data triangulation between WPs. 45

Saturation checks conducted during the final three interviews suggested that, although additional themes of interest were still forthcoming, these did not relate to the core research aims. 46 These are put forward as areas for possible future investigation in Chapter 8 of this report. Results are presented in Chapter 7, using verbatim quotes to illustrate main themes. 47

Patient and public involvement

This project involved two public contributors from its inception. One of the public representatives (MS) was a member of the Project Management Group and co-author of the report, and helped with planning and facilitating the focus group discussion for WP 5. Another public representative sat on the Study Steering Committee. Both members of the public regularly participated in project meetings and discussions, received meeting minutes, provided advice on all issues related to patient and public involvement (PPI) and dissemination of findings. The project also benefited from input from NIHR Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care West Midlands PPI Supervisory Committee Advisors.

Deviations from the original protocol

This 2-year project tackled a complex area of HSDR, which is very broad in scope and diverse in methods. Several challenges needed to be overcome in order to deliver the proposed research within the time and resources available. As a consequence, some amendments of the methodological approaches were made during the conduct of the project, which deviated from the original protocol. These are described below with rationale behind the changes explicated.

Work package 1

The original protocol noted that the systematic review will cover HSDR and ‘cognate fields’. Given the multidisciplinary nature of HSDR, many different fields, such as management, economics and psychology, could be considered as cognate. Although our literature searches retrieved some studies investigating publication and related bias in these fields, it became clear that it was not feasible in the scope of our study to systematically review all of this diverse literature, taking into account other WPs. We do, however, provide a brief description and discussion of these studies in Chapter 8.

Work package 2

The initial plan was to identify the required sample of HSDR systematic reviews through searches of general databases, such as MEDLINE, by combining HSDR-related terms with systematic review filters. Retrieved records would then be screened to verify whether or not they were systematic reviews of a HSDR topic. However, owing to the lack of specificity of HSDR-related terms, this approach resulted in the retrieval of a very large number of systematic reviews, many of which would fall outside the scope of HSDR defined in this project. The process for undertaking this step of screening would be very time-consuming and could substantially delay the progress of the project. We therefore obtained our sample of HSDR systematic reviews directly from the Health Systems Evidence database, after consulting the Study Steering Committee (see Search and sampling strategies).

We planned to collect information concerning the number and type of variables (e.g. structure, process, outcome or context) investigated by each of the included systematic reviews. Nevertheless, it became clear during data extraction that many HSDR systematic reviews covered diverse interventions in different settings, and reported findings for a large number of outcomes and/or associations. The variables and associations explored were often not clearly stated in the methods section, but were scattered in tables and text throughout the articles. We therefore had to drop this item from our data collection.

We were to classify the type of journal in which the review was published into four categories: medical, health services research and health policy, management and social science, and other. However, initial examination of sampled systematic reviews showed that very few reviews were published in management and social science journals and other outlets, and the distinction between ‘medical’ and ‘health services research and health policy’ categories could be vague. Therefore, on the advice of the Study Steering Committee, we classified journals according to whether or not they endorsed systematic review guidelines instead, as this would be a feature that might be associated with assessment of publication and related bias in published systematic reviews.

Work package 3

The original plan was to select 5–10 systematic reviews for in-depth examination, and to utilise data reported in these reviews to carry out further analyses and test different methods for detecting publication and related bias. However, it became apparent that detailed quantitative data on outcomes and coding on study-level variables that are likely to be effect modifiers were often not adequately reported in published reviews, and it would not be practical for the project team to locate and extract data from individual studies included in the reviews. Consequently, on the advice of the Study Steering Committee, we selected four systematic reviews to be included as case studies (case studies 1–4) and focused on one of them (case study 1), for which we were able to access original data to conduct detailed further analyses. We provided critiques of the methods and findings for the remaining three case studies (case studies 2–4). In addition, we obtained data and worked on another systematic review as a potential further case study. It was based on a data set that included 272 RCTs, supplied by colleagues from the Cochrane Collaboration in relation to an ongoing, updated systematic review on the effectiveness of quality improvement strategies for the management of diabetes that has previously been published. 12,48,49 Unfortunately, due to the substantial time required for obtaining and organising the data and for carrying out imputation of unavailable data (e.g. standard errors of effect estimates), and considering that the owners of the data set are yet to analyse and to publish main findings from the data at the conclusion of this project, we are unable to include this further case study in this report. Nevertheless, we have completed preliminary analyses and it is our intention to continue this effort and to publish the completed case study in collaboration with colleagues from the Cochrane Collaboration.

Work package 4

We planned to obtain cohorts of HSDR studies to be followed up from the NIHR’s registry of funded projects and the HSRProj database. These were carried out as planned. During one of the Study Steering Committee meetings, members of the committee pointed out that these samples are likely to be the most well-funded projects and may cover only the upper end of the spectrum of existing HSDR. They therefore recommended that the project team identify further cohorts from other sources, such as HSDR-related conferences. As a result, two additional cohorts drawing from the HSRUK and the ISQua were included.

Work package 5

We intended to carry out semistructured interviews for various groups of HSDR stakeholders, including health services researchers, journal editors, HSDR funders, service managers and patient and public representatives. Interviews were undertaken as planned for most of the stakeholders. However, considering the experience from initial interviews and following discussions with the PPI advisors of the project, we decided to hold a focus group discussion instead of individual interviews for the patients and public stakeholder group. This was because they were unlikely to have much previous exposure to the concept and terminology associated with publication and related bias, and thus might have difficulties in forming a clear and considered opinion. It was felt that the dynamics of a focus group discussion would assist participants to clarify their thoughts on salient topics. This change was approved by the University of Warwick’s Biomedical and Scientific Research Ethics Committee, which issued initial approval for the project, and was agreed by the NIHR HSDR programme.

Chapter 3 Findings of systematic review of empirical evidence on publication and related bias in HSDR

This chapter presents findings from WP 1 of the project, in which we systematically searched and reviewed empirical studies that set out to investigate the occurrence of publication and related bias in HSDR.

Literature search and study selection

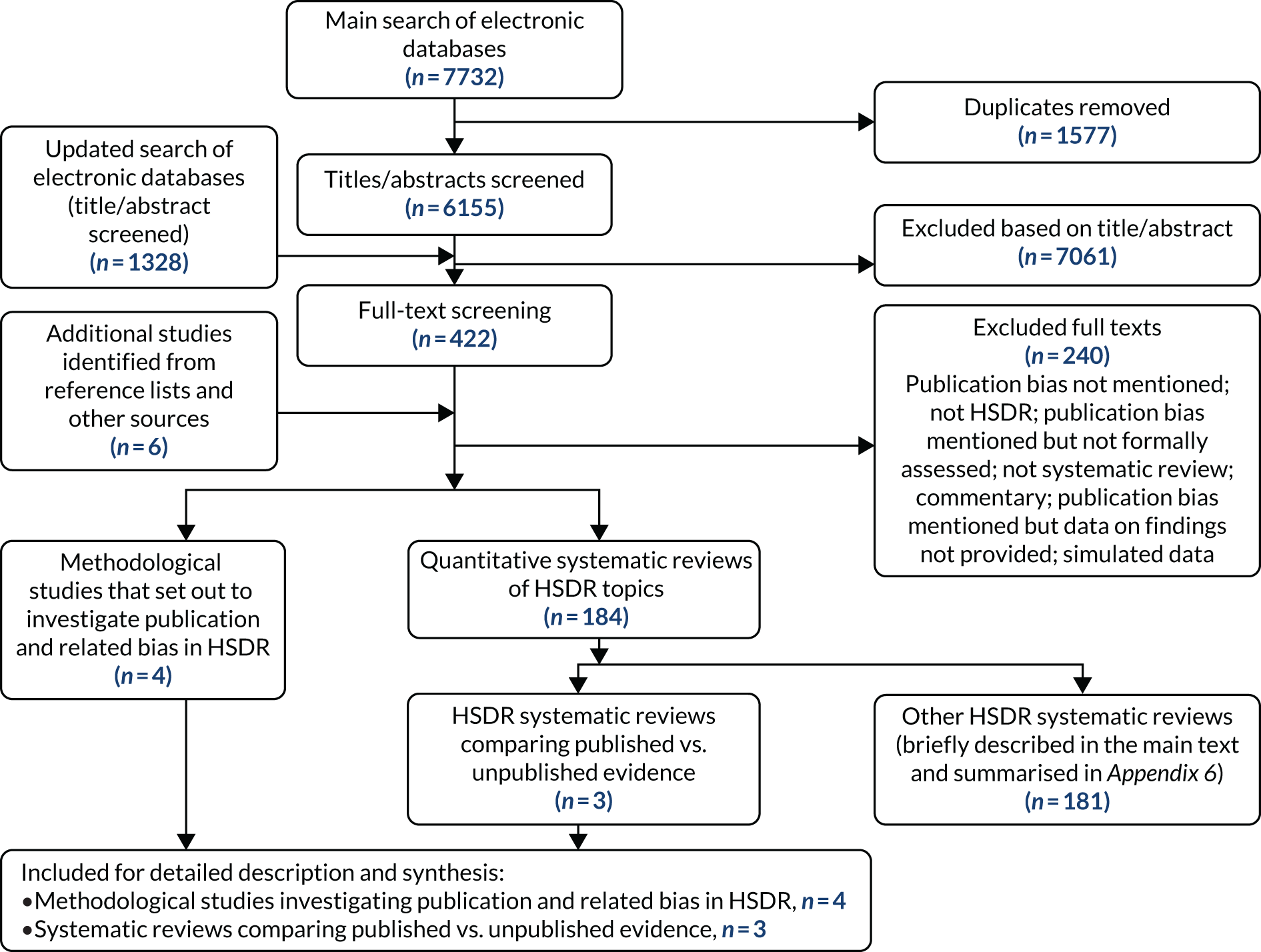

Initial searches of electronic databases in March 2017 retrieved 7732 records. After removing duplicates, the titles and abstracts of 6155 records were screened. Of these, 422 records were considered potentially relevant and their full-text articles were retrieved. Six additional full-text articles were identified and obtained from other sources.

Of the 428 full-text articles examined, 188 were retained. Of these, four were methodological studies that set out specifically to investigate publication and related bias in HSDR13–15,50 and three were systematic reviews of substantive HSDR topics, in which evidence from published literature was compared with grey literature and unpublished studies (and thus provided direct evidence on publication bias). 51–53 These seven studies were examined and are described in detail in this chapter. The remaining 181 studies were systematic reviews of substantive HSDR topics, in which publication and outcome reporting bias was assessed as part of the review process. As these reviews provided only indirect evidence on publication bias, they are briefly described in this chapter and are summarised in Appendix 6.

Two hundred and forty retrieved full-text articles did not meet the inclusion criteria and were excluded. The primary reasons for exclusion were not mentioning publication and related bias at all (we examined systematic reviews that might have examined publication and related bias, even if this was not explicitly stated in the titles and abstracts); mentioning these biases but without assessing them; and topics being outside the definition of HSDR adopted for this project. A flow diagram for the literature retrieval and study selection process is shown in Figure 4. We carried out an updated search in July/August 2018. This retrieved 1328 new records, but no relevant methodological studies were identified.

FIGURE 4.

Flow diagram for literature search and study selection process for the systematic review. This figure has been reproduced from Ayorinde et al. 54 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Methodological studies investigating publication and related bias in HSDR

Four studies specifically set out to investigate publication and related bias in a substantive topic area of HSDR. The objectives, methods, key findings and limitations of these studies are summarised in Table 2. Three studies investigated publication bias in health informatics research,14,15,50 and one study explored potential reporting bias or p-hacking arising from researchers competing for limited space of publication in high-impact journals in health economics and policy literature. 13

| Study (HSDR topic) | Objective(s) | Method(s) | Key finding(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Machan et al. 200650 (health informatics) | To determine (1) the percentage of evaluation studies describing positive, mixed or negative results; (2) the possibility of statistical assessment of publication bias in health informatics; and (3) the quality of reviews and meta-analysis in health informatics with regard to publication bias |

Descriptive analysis of random sample of 86 evaluation studies and planned to construct funnel plot Examined characteristics and quality of reviews and meta-analyses (n = 54) in medical informatics |

For the primary studies, 69.8% positive results, 14% negative and 16.3% unclassified For the reviews 36.6% had a positive conclusion, 61.5% were inconclusive and only one review came to a negative conclusion |

| Ammenwerth and de Keizer 200715 (health informatics) | To determine (1) the percentage of IT evaluation studies that are not published in international journals or proceedings; and (2) typical reasons for not publishing the results of an IT evaluation study | E-mail-based survey conducted in spring 2006. Participants were drawn from various working groups of the American Medical Informatics Association, the European Federation for Medical Informatics and the International Medical Informatics Association; and first authors of MEDLINE-indexed IT evaluation papers published between 2001 and 2006 (total n = 722) | Response rate 19% (136/722). 118 of the respondents reported completion of 217 evaluation studies. Of these studies, 47% (103/217) were published in peer-reviewed international journals, proceedings or books; 49% (107/217) were unpublished or published only locally. Common reasons for non-publication included ‘not of interest for others’, ‘no time for writing’, ‘limited scientific quality’, ‘political and legal reasons’ and ‘only meant for internal use’ |

| Vawdrey and Hripcsak 201314 (health informatics) | To measure the rate of non-publication and assess possible publication bias in clinical trials of electronic health records | Follow-up of health informatics trials registered in ClinicalTrials.gov (2000–8) | Trials with positive results were more likely to be published (35/38, 92%) than trials with null results (10/14, 71%; p = 0.052); the study authors reported p < 0.001 |

| Costa-Font et al. 201313 (health policy) | To examine the winner’s curse phenomenon (studies needing to have more extreme results to be published in high-impact journals) and publication selection bias, using quantitative findings on income and price elasticities, as reported in health economics research | Funnel plot and multivariate analysis to examine the association between estimated effect sizes (and their statistical significance) and the impact factors of the journals in which they were published | Meta-regression analysis demonstrated that both publication bias (reflected by positive correlation between effect size and standard error) and the winner’s curse (reflected by an independent association between effect size and journal impact factor) influence the estimated income/price elasticity |

Of the four studies,13–15,50 only one was an inception cohort study that tracked individual research projects from the start and thus provided direct evidence of publication bias. 14 Studies included in this cohort were clinical trials of electronic health records registered with ClinicalTrials.gov during 2000–8. Findings from 76% (47/62) of completed studies were published. Of these, 74% (35/47) reported predominantly positive findings, 21% (10/47) reported neutral results (no significant effects) and 4% (2/47) reported negative or harmful results. Of the 15 unpublished trials, three had positive findings and four had neutral results based on information supplied by the investigators. Findings for the remaining eight studies were unknown. The authors found that trials with positive findings were more likely to be published than those with neutral findings (see Table 2), but cautioned that the sample included in the cohort may be atypical of general studies in the field.

Another study15 in health informatics was an e-mail-based survey of people who were likely to be involved in the evaluation of health information systems. Participants were asked about (1) what information systems they had evaluated in the past 3 years; (2) where they published the results of the evaluation; and (3) the reasons for non-publication of the results, if this was the case. A response rate of 19% (136/722) was achieved, with 118 respondents reporting the completion of a total of 217 evaluation studies. Most of these respondents were from an academic background (92/118), with a small number from information technology management, industry and government institutions. Approximately half of the identified evaluation studies were published in peer-reviewed journals, proceedings or books, whereas the remaining half either were published only locally (e.g. internal reports) or were unpublished (see Table 2). Reasons cited for not publishing included: not of global interest (35%), publication in preparation (31%), no time for publication (22%), limited scientific quality (17%), political and legal reasons (14%) and for internal use only (13%).

A low response rate was the major limitation of this study. Nevertheless, the survey provided some insights concerning reasons behind non-publication. Like most surveys, the study findings could be influenced by sampling, response and recall bias. It is also worth noting that publication was still being considered or under way for about one-third of the unpublished studies at the time of the survey, and, therefore, the actual publication rate might be higher.

The third methodological study50 in health informatics utilised evaluation studies identified from a specialist health informatics database that covered literature published between 1982 to 2002, and adopted three different approaches to assessing publication bias: (1) statistical analyses of the small study effect; (2) examination of the percentage of evaluation studies with positive findings compared with percentage of studies with mixed or negative findings; and (3) examination of the percentage of systematic reviews reporting positive, neutral or negative results. The authors did not identify sufficient number of studies with the same outcome measures to carry out statistical analyses of the small study effect. Although the percentages of primary studies with negative findings and systematic reviews reporting negative results were low (see Table 2), these were not good indicators for the existence of publication bias, as there is no estimate of what the ‘unbiased’ proportion of negative findings should be for evaluation studies and reviews of health informatics interventions.

The fourth methodological study13 included in this review examined quantitative estimates of income elasticity of health care and price elasticity of prescription drugs reported in the published health economics literature. 13 The authors identified a positive correlation between effect sizes and the standard errors of income and price elasticity estimates using funnel plots and meta-regression, which suggested potential existence of publication bias. Having adjusted for this, they also found an independent association between effect size and journal impact factor. This suggested that studies reporting larger effect sizes (i.e. more striking findings) were more likely to be published in ‘high-impact’ journals. However, the finding still needs to be interpreted with caution, as other confounding factors could not be ruled out for these observed associations. In addition, the authors acknowledged that studies in the field concerned were often reported in grey literature, which was not examined in this study.

Systematic reviews of substantive HSDR topics providing evidence on publication and related bias