Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/130/47. The contractual start date was in April 2014. The final report began editorial review in February 2019 and was accepted for publication in September 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Irene J Higginson was a member of the Health Technology Assessment Efficient Study Board (2015–16) and the Health Technology Assessment End of Life Care and Add-on Studies Board (2015–16). Wei Gao was member of the Health Technology Assessment End of Life Care and Add-on Studies Board (2015–16) and the Health Services and Delivery Research Commissioning Board (2009–15).

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Hepgul et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Long-term neurological conditions

Long-term neurological conditions (LTNCs) are a diverse set of conditions resulting from injury or disease of the nervous system that affect individuals for the rest of their lives. This includes long-term progressive conditions, such as idiopathic Parkinson’s disease (IPD), motor neurone disease (MND), multiple sclerosis (MS), progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) and multiple system atrophy (MSA). Affecting > 200,000 individuals in the UK, these progressive conditions lead to substantial deterioration in quality of life and result in the patient needing lifelong support from health and social care services. 1 Many patients have inadequate symptom control and inadequate psychological and social support, and there is a high burden for family caregivers. 2–5 There are also significant financial burdens to the individual, their families and the NHS, with increasing costs associated with disease progression. 6–8 Despite the progressive nature of these conditions, the scope for improving services to enhance quality of life of affected individuals through the provision of palliative care may be substantial.

Current treatment and service provision

In 2005, the Department of Health and Social Care published the National Service Framework, which set 11 quality requirements to transform the way health and social care services support people with LTNCs and their caregivers. 9 It highlighted the need for integrated care and joined-up services, and made recommendations for the provision of specialist neurology, rehabilitation and palliative care services to support people throughout and to the end of their lives.

However, a National Audit Office report concluded that implementation of the framework has been poor and that although access to neurology services improved, other important indicators of the quality of care for people with neurological conditions worsened. 10 The report highlighted that information and advice to patients and caregivers is inadequate, and ongoing care is fragmented and poorly co-ordinated. Indeed, in the UK and in many other health systems, there is often division among general practitioners, staff working in the community and hospital-based specialists. 11,12 It is increasingly recognised that a hard separation of these functions does not meet the needs of those with long-term conditions; therefore, much of the burden of illness often falls on the community and on lay caregivers. 2,5,13,14 This results in greater negative effects for both patient and caregiver well-being, as well as increased financial burden. 8,15 Attempts have been made to better co-ordinate care through integrative processes, such as joint budgets, governance, information systems, flows of data or case management. 16,17 These may be brought together more formally through different kinds of vertical integration, in which agencies involved at different stages of the care pathway form part of a single organisation or function, as well as horizontal integration of community-based services in examples such as health and social care teams for the frail elderly. 18 Another issue is that multimorbidity is the norm for people with LTNCs. Equally, their spouses or family caregivers may have health conditions that affect their ability to care, and the burden of caring may affect the health of caregivers. 2,13 Palliative care is person rather than disease focused and may have the potential to address these unmet needs.

Palliative care for long-term neurological conditions

Palliative care focuses on improving quality of life through a multidisciplinary approach and has been recognised as a valuable component of care for patients with chronic, life-limiting illnesses. 19–21 The place for palliative care in rapidly fatal neurological conditions is increasingly recognised; however, the evidence is scarce. 22 Indeed, a recent consensus review concluded that there is limited evidence to support any recommendations for the provision of palliative care for progressive neurological disease and that further research is urgently needed. 23 There are three Phase II trials of palliative care for patients with neurological conditions. 24–26 The results of our own Phase II trial of short-term integrated palliative care (SIPC) among 52 patients severely affected by MS found an improvement in pain and a significant reduction in informal caregiver burden at a lower cost and with no harmful effect, compared with standard care. 24 Similarly, in 78 MS patients and their caregivers, a 6-month home-based palliative care service was found to reduce symptom burden compared with usual care. 26 Furthermore, a new 4-month home-based specialist palliative care service for 50 patients with advanced neurodegenerative disorders (MND, MS, IPD, MSA and PSP) found a significant improvement in quality of life and physical symptoms (pain, breathlessness, sleep disturbance and bowel symptoms) across the conditions, although no effect was seen on caregiver burden. 25 We have also previously reported findings from a longitudinal observational study of IPD, MSA and PSP patients demonstrating the profound and complex mix of non-motor and motor symptoms in late stages of disease. 27 Symptoms were highly prevalent in all three conditions and were often unresolved, with half of patients deteriorating over 1 year. Furthermore, palliative problems were predictive of future symptoms, suggesting that an early palliative assessment might help screen for those in need of earlier intervention. 27 However, to the best of our knowledge, there are currently no Phase III trials.

Conceptual framework

People severely affected by LTNCs have many problems and concerns similar to those affected by advanced cancer, including symptoms, psychological needs, and family and caregiver concern. 28 Specialist multiprofessional palliative care teams (MPCTs) successfully improve these problems for cancer patients and are now available widely across the globe. 29,30 The Cochrane handbook outlines31 that, if there is empirical evidence that similar or identical interventions have an impact on other populations, these are quite likely to be effective. Thus, as a starting point, it is reasonable to hypothesise that input from specialist palliative care will help people with LTNCs. Our modelling work demonstrated that people severely affected by MS, Parkinson’s disease-related disorders and MND had many similar symptoms to those affected by advanced cancer,32 with additional problems of loss of care co-ordination. 33–35 These needs are within the remit of specialist palliative care, which offers a holistic approach attending to symptoms, psychological needs and better co-ordination of care. 36 People severely affected by LTNCs often have a longer trajectory of illness than those with advanced cancer and so our modelling found that staff, patient and caregiver groups favoured the idea of specialist palliative care input for a short term, working in a way that was well integrated with existing neurology and rehabilitation services.

Short-term integrated palliative care is modelled on our work to date, following the Medical Research Council guidance for the development and evaluation of complex interventions. 37 This included literature reviews38 and qualitative studies33,34 to determine need and to develop the theoretical underpinning of the service, appraisal of trial methods,32,39 service modelling and a successful Phase II trial randomising 52 patients. 24,29,40

Short-term integrated palliative care is a complex intervention41 in that it:

-

contains several components (assessment, symptom management, future care planning, follow-up visits)

-

aims to change behaviours by those staff delivering the intervention, those providing usual care to this patient group, and, to some extent, patients and families

-

targets patients, families and staff in primary, hospital and voluntary care, thus including different groups and organisational levels

-

has several complex outcomes, including change in symptom management and hospital admissions

-

is tailored to individual patient need and circumstances by those delivering SIPC

-

operates in a context in which there may be some variability between patient groups and settings in the usual care provided to patients with LTNCs; usual care is offered to patients in the intervention and control arms of the trial.

Short-term integrated palliative care could be developed with only small adaptions to existing health-care services. It is much more likely to be possible than other proposed alternatives, such as developing long-term palliative care models. The latter would be difficult to achieve without considerably expanding the number of palliative care specialists, beds and services. In contrast, SIPC builds on and integrates with existing services across the UK and seeks to empower patients, improve symptom control and integrate with existing services, improving their expertise. If found to be effective, the new SIPC service has the potential to be beneficial for a wider range of conditions and in more diverse care settings for patients and their families. This could result in better symptom control and improved quality of life for patients, as well as improved co-ordination of care, more efficient and appropriate use of services, and a reduction in the number of unnecessary emergency admissions at the end of life. This is also in line with other NHS initiatives seeking to move palliative care and discussions about preferences and priorities further upstream and encouraging patients to think about care preferences earlier in their disease trajectory. 42 Understanding whether or not SIPC is clinically effective and cost-effective, and its potential mechanism of action, will help to develop studies in these initiatives. Equally, if the SIPC is not cost-effective in more conditions and in wider settings, the findings will prompt development of customised improvement and modifications in specific LTNCs. 8,43–45

Importance of economic analysis

Health-care costs in the last year of life are high (18–30% of health-care spending), with resource use increasing in the last months of life. 43–45 Despite this, it is known that this expenditure offers poor value, as symptoms often remain uncontrolled. 46 In long-term conditions, including neurological conditions, costs rise with increased disability and as the disease advances. 8 These costs can be unpredictable and can affect caregivers and patients, as well as health and social services. 8 Hospitalisation is a main cost driver of health care and a major public health problem. Indeed, NHS England reports that £750M is spent on urgent and emergency care for patients with neurological conditions, including admissions to hospital, with nearly 4% growth in emergency admissions year on year. 47 Compared with age-matched controls, people with LTNCs, such as MS and Parkinson’s disease, are experiencing higher rates of hospitalisation. 48–50

However, maintaining patients in the community can also be costly to health and social care services. It can also place an increased burden on families and carers. Therefore, it is imperative to evaluate proposed service models in patients with advanced disease to see whether or not they affect health and social care costs. SIPC seeks to alleviate symptoms, prevent symptom escalation, improve care, and help patients and caregivers plan the future care they need, all of which may potentially avoid inappropriate hospitalisation. A full understanding of the cost-effectiveness of SIPC for the NHS is central to decision-making. Despite this need, health economic evaluations of interventions in advanced illness remain rare, especially cost-effectiveness studies. Most studies consider only costs, randomised trials are rare and many studies fail to account for confounding. 51,52

Evaluating a new service model for LTNCs, as well as addressing the concerns for people severely affected by these diseases, develops a potential model of service provision for other long-term diseases in advanced stages. With the ageing population, the predicted rise in the annual number of deaths, the increasing prevalence of long-term conditions and the likely increase in need for palliative care,53,54 it is both highly relevant and timely to robustly test new service models to improve care for this group. This project answers this need and tests an intervention that could be implemented by the current workforce and services.

Research group

This project was led by the Cicely Saunders Institute of Palliative Care, Policy and Rehabilitation at King’s College London, with the following collaborating institutions: The University of Nottingham; Nottingham University Hospitals NHS Trust; Cardiff and Vale University Health Board; University of Sussex; Brighton and Sussex Medical School; The Walton Centre NHS Foundation Trust; Sussex Community NHS Foundation Trust; Ashford and St. Peter’s Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust; Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust and King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust.

Chapter 2 Aim and objectives

Aim

The OPTCARE Neuro trial aimed to determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of SIPC services in improving symptoms, improving selected patient- and caregiver-reported outcomes and reducing hospital utilisation for people severely affected by LTNCs.

Primary objective

To determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of SIPC for people severely affected by LTNCs compared with standard care, according to the primary outcome of reduction in key symptoms at 12 weeks.

Secondary objectives

-

To map current practice and document the services available (and common care pathways) for patients with LTNCs and their caregivers and families in the areas of the study, to better understand variations in normal practice experienced by the control group.

-

To test the feasibility of offering SIPC and the trial methods across five centres, for people severely affected by LTNCs, and to modify the intervention and trial methods accordingly.

-

To determine the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of SIPC for people severely affected by LTNCs compared with standard care in the secondary outcomes: palliative care needs and other symptoms, patient psychological well-being and quality of life, caregiver burden/positivity and quality of life, improvement in patients’ and caregivers’ satisfaction and communication.

-

To determine the effects of SIPC for people severely affected by LTNCs on hospital admissions, length of hospital stay, emergency attendance and other service use over the trial period.

-

To determine the cost-effectiveness of SIPC for people severely affected by LTNCs.

-

To understand how the change process may work and to identify components of the SIPC that are most valued by patients, their families and caregivers, and other health-care professionals.

-

To determine how the effects change over time, whether or not earlier referral to palliative care affects the subsequent response to palliative care and when assessment or re-referral might be beneficial.

Chapter 3 Design and methods

Study design

This is a mixed-methods study comprising a Phase III, randomised controlled, multicentre, fast-track trial, including assessment of cost-effectiveness and an embedded qualitative component. It is a multicentre evaluation of a complex intervention, following the Medical Research Council guidance for the development and evaluation of complex interventions. 37 This study incorporates:

-

a set-up and feasibility phase to refine recruitment and methods

-

mapping usual care for patients with LTNCs across the different centres (by prior work collecting information about the services, and during the study recording services received at baseline and in the standard care group) to understand the context and baseline variations in practice and resources

-

a randomised controlled trial of SIPC offered from a MPCT, compared with best usual care in terms of outcomes and cost-effectiveness

-

an embedded qualitative component, to explore the ways in which the SIPC affects patients and caregivers, how the change process may work, how SIPC may be improved and to interpret quantitative results

-

a survey of health professionals to understand the impact of SIPC on local practice

-

economic modelling to estimate the NHS and societal resources required for and longer-term impacts of SIPC.

Mapping methods

Parts of the text have been reproduced from van Vliet et al. 55 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

The mapping exercise was conducted in eight centres with neurology and palliative care services in the UK. The centres were purposively selected to include our main recruitment centres and other larger centres. The eight centres included different geographical areas and represented both rural and urban areas. Data were provided by the respective neurology and specialist palliative care teams. Questions focused on catchment and population served, service provision and staffing, and integration and relationships. Data were transferred into tables to facilitate comparison between centres.

Survey methods

Parts of the text have been reproduced from Hepgul et al. 56 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Research teams from six trial centres (London, Nottingham, Liverpool, Cardiff, Brighton and Ashford) identified local neurology and palliative care professionals who were then approached via e-mail by the central trial team. Professionals were informed that, by completing the survey, they provided informed consent for use of their anonymised data. The surveys consisted of multiple-choice or open-comment questions, 13 questions for neurology or 10 questions for palliative care, with responses collected using online forms. The survey was launched in July 2015 and closed in April 2016. Data were transferred into tables to facilitate comparison of professional groups and data were explored descriptively.

Randomised trial methods

This was a randomised controlled, multicentre, fast-track, single-blinded trial of SIPC, provided in addition to existing services, compared with standard care. It was conducted and reported in accordance with Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT)57 and Methods of Researching End of Life Care (MORECare) statements. 58 The economic components were conducted and reported in accordance with the Consolidated Health Economic Evaluation Reporting Standards (CHEERS) statement. 59

Settings

The trial recruited patients and caregivers from seven centres in the UK (South London, Nottingham, Liverpool, Cardiff, Brighton, Ashford and Sheffield), all with MPCTs and neurology services. In all the centres, neurology services are consultant led with clinical nurse specialists for the relevant conditions. The majority of patient contacts are hospital based, with variable community outreach work. The centres’ respective local areas have networks of palliative care services, including inpatient hospices, community services and hospital support teams. The centres encompass urban, suburban and rural areas, with varying levels of deprivation and ethnic diversity.

Inclusion criteria

Eligible patients were:

-

adults (aged ≥ 18 years) severely affected by advanced or progressive stages of either:

-

MS – patients with either aggressive relapsing disease with rapid development of fixed disability or with advanced primary or secondary progressive disease, often with limitations, such as gait and upper limb function (we did not define referral based on disability, but expected most patients to have an Expanded Disability Status Scale60 of at least 7.5)

-

Parkinsonism and related disorders:

-

MND all stages

-

-

deemed (by referring/usual care clinicians) to have:

-

an unresolved symptom (e.g. pain, breathlessness) that has not responded to usual care

-

at least one of the following: another unresolved other symptom; cognitive problems; complex psychological (depression, anxiety, family concerns) needs; complex social needs; communication/information needs

-

-

able to give informed consent, or their capacity can be enhanced (e.g. with information) so that they can give informed consent, or a personal consultee can be identified and approached to give an opinion on whether or not the patient would have wished to participate

-

living in the catchment area of the SIPC service.

Eligible caregivers were:

-

adults (aged ≥ 18 years) identified by the patient as the person closest to them, usually a family member, close friend, informal caregiver or neighbour

-

able to give informed consent and to complete the questionnaires.

Eligible professionals were:

-

professionals involved in the care of patients with LTNCs

-

professionals (of neurology or palliative care services) who are part of a team involved in the delivery of the OPTCARE Neuro intervention.

Exclusion criteria

Patients who met the inclusion criteria, but:

-

were already receiving specialist palliative care or had done so in the last 6 months

-

lacked capacity and had no family member, friend or informal caregiver willing and available to complete questionnaires about their own and the patient’s symptoms and circumstances.

Recruitment procedure

Potential participants were identified through neurology teams (consultants and clinical nurse specialists) at outpatient clinics. Research nurses liaised directly with these teams, attending clinics when possible to ensure the accuracy of eligibility assessment. Awareness of the trial was raised by:

-

conducting local workshop sessions (e.g. lunchtime seminars) at recruiting centres to explain why the trial is being conducted; equipoise; how to identify and refer patients; and general information on palliative care needs

-

developing posters and flyers detailing the trial, the local research personnel and lead clinicians, to be displayed in appropriate places

-

working with our patient and public involvement (PPI) group, as well as other patient societies and charities.

Identifying clinicians discussed the trial with potential participants and provided written information when possible. If patients were interested and agreed to it, clinicians completed a standard referral form to check that the inclusion criteria were met and this was then sent to the local research teams. The research teams contacted patients by telephone to explain the trial, sent out written information if not already received and subsequently arranged a first visit (after a minimum of 24 hours unless the potential participant wished to waive this period). We also aimed to gather the views of informal caregivers and, when appropriate, asked patients to identify the person nearest to them (such as a family member or informal caregiver) who could also be approached to participate in the trial. If the caregiver was interested and met the inclusion criteria, they were also presented with written information regarding the trial. At the initial visit, researchers provided potential participants (patients and caregivers) the opportunity to further discuss the trial and ask any questions. Following this, written informed consent was obtained and baseline questionnaires administered with patients and their caregivers. As part of the consenting process, researchers discussed the need for the patients to nominate a consultee in case their capacity fluctuated during the course of the trial (see Mental Capacity Act).

If a patient met the inclusion criteria but the clinical team or researcher deemed them (using clinical judgement, in line with local policy guidance) to have reduced capacity, inclusion was discussed with informal caregivers, family members or close friends (in conjunction with the patient if appropriate) to determine the most appropriate person to act as the personal consultee. The research teams contacted the nominated personal consultee to explain the study, provide written information and subsequently arrange a first visit (after a minimum of 24 hours, unless the personal consultee wished to waive this period). At this initial visit, the patient was reassessed and if capacity was confirmed to be insufficient, the consultee was asked to confirm whether or not they believed the patient would like to be included in the trial and provided assent on their behalf. When caregivers provided assent for a patient lacking capacity, they were also asked to provide proxy information about the patient.

Mental Capacity Act

The commonality of cognitive impairment in advanced LTNCs required the inclusion of people with impaired mental capacity in the trial. The Mental Capacity Act62 informed the process of consent for patients lacking capacity. All participants were considered to have capacity unless established otherwise and all practicable steps were taken to enable individuals to decide for themselves if they wished to participate. Capacity was established using the Mental Capacity Act four-step process:

-

The individual is able to understand the information about the study.

-

The individual is able to retain the information (even for a short time).

-

The individual is able to use or weigh up that information.

-

The individual is able to communicate their decision. 62

A process of consent and assent tailored to an individual’s level of capacity and incorporating varying levels of capacity was used. Incorporating different processes of consent and assent has been successfully used in previous studies on end-of-life care. 63–65 For adults lacking capacity, a personal consultee was sought to give an opinion on whether or not the patient would have wanted to participate in the study had they had capacity to indicate this, and whether or not that participation would cause undue distress. 62,65 For adults with impaired capacity who were able to understand, retain and weigh-up information in the moment, a process of consent in the moment was used, with ongoing consent whereby informed consent to participate was reaffirmed prior to each data collection point. 66 If a participant’s capacity declined so that they were no longer able to give informed consent in the moment, researchers followed the procedure for adults lacking capacity as detailed above.

Advance consent was incorporated in the consent process for all patients in anticipation that some may lose capacity over the course of the trial and no longer have capacity to indicate their right to withdraw. The process of advance consent was informed by previous studies with older people65 and on end-of-life care. 67 Participants were asked to indicate if, should they lose capacity in the future, they wished to continue to be involved in the trial and, if yes, asked to nominate a personal consultee. The personal consultee was approached if the participant lost capacity to such an extent that they were no longer able to indicate their right to withdraw or to complete patient-reported outcome measures, requiring instead a proxy informant (e.g. informal or formal caregiver). The procedure of assent for adults lacking capacity was followed to ascertain the personal consultee’s opinion on the individual’s continued participation.

Data collection

Face-to-face visits were undertaken with patients at their location of choice (usually their home). Trained research nurses and researchers assisted, as required, in self-completion of patient and caregiver questionnaires, in accordance with the standardised schedule. Data were collected at baseline and then at 6, 12, 18 and 24 weeks post randomisation. Usually, caregivers self-completed their questionnaires during the patient interview but in some instances questionnaires were returned by post to the local project teams. For adults lacking capacity, baseline and outcome measures were obtained from the informal caregiver interviewer, as above. The use of a proxy informant is common in research on palliative care associated with patients’ advancing illness and deteriorating condition, and on the importance of capturing data at points of deterioration when a patient may most benefit from palliative care, notably the last days of life. In addition, informal caregivers provided the baseline information about the patient’s demographic circumstances and clinical history (e.g. age, educational level, diagnosis, time since diagnosis), as would normally be collected in the patient interview. Outcome assessors were blind to treatment allocation and accommodated separately from the intervention teams.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the combined score of eight key symptoms (pain, shortness of breath, nausea, vomiting, constipation, spasms, difficulty sleeping and mouth problems), as measured by the Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale for Neurological conditions 8 symptom subscale (IPOS Neuro-S8) at 12 weeks. The IPOS Neuro-S8 has been validated among people with LTNCs and found to be responsive to change. 68 The choice of primary outcome was based on the results of our Phase II trial and our modelling work: patients consider these important symptoms in neurological conditions; the SIPC aims to improve several complex symptoms that interact; and these symptoms are often overlooked by existing services but impact on quality of life. Secondary outcomes (all also measured at baseline and 12 weeks) included the following.

Patient outcomes

-

Patients’ palliative needs and symptoms, as measured by the IPOS Neuro, composed of 42 items, for which higher scores indicate more palliative care needs.

-

Patients’ physical symptoms as measured by the Integrated Palliative care Outcome Scale for Neurological conditions 24 symptom subscale (IPOS Neuro-S24) subscale,69 composed of 24 items, for which higher scores indicate more symptom burden.

-

Patients’ psychological and spiritual well-being, information needs and practical issues, as measured by the IPOS Neuro-8 non-physical subscale, composed of eights items, for which higher scores indicate more palliative care needs.

-

Patients’ psychological distress, as measured by the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS),70 composed of two separate subscales for anxiety and depression, each with seven items, for which higher scores indicate more distress.

-

Patients’ satisfaction of care, as measured by the modified FAMCARE-P16,71 composed of 16 items, for which higher scores indicate more satisfaction with care.

-

Patients’ self-efficacy, as measured by the Self-Efficacy for Managing Chronic Disease (SEMCD) Scale,72 composed of six items, for which higher scores indicate more self-efficacy.

-

Safety, adverse events and survival (days from consent to death).

Health economic outcomes and service use

-

Patients’ health-related quality of life and well-being as measured by the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L),73 composed of five dimensions plus a visual analogue scale, for which higher scores indicate better quality of life.

-

Hospital admissions, emergency attendances and other health and social care service use, including inpatient, outpatient, home-based services, and tests and diagnostics, as measured by the adapted version of the Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI). 74

Caregiver outcomes

-

Caregiver burden as measured by the Zarit Burden Inventory 12 items (ZBI-12),75 composed of 12 items, for which higher scores indicate more burden.

-

Caregiver positivity as measured by the ZBI-12 and positivity,75 composed of eight items, for which higher scores indicate more positivity related to caregiving.

-

Caregiver satisfaction as measured by the modified FAMCARE 2,71,76 composed of 17 items, for which higher scores indicate more carer satisfaction with patient care.

-

Caregiver assessment of patients’ problems and services, as measured by the IPOS Neuro and the CSRI.

Intervention

The SIPC focused on personalised care planning, case management and supporting existing care providers. 17 The SIPC was delivered by existing MPCTs, linked with local neurology and rehabilitation services. MPCTs comprised individuals specifically trained in palliative care from backgrounds in medicine, nursing or social work, together with other allied health professionals. All staff involved in the delivery of the intervention were provided with a standard manual and face-to-face training in advance of the trial commencing. For the purposes of the trial, MPCTs operated a key worker process, in which a specialist team member took initial responsibility for a referred patient.

Frequency and duration of intervention

The length of the intervention was 6–8 weeks from referral. This is broken downs as follows:

-

2 days for first telephone call (from receiving the patient referral).

-

Up to 5 days for first visit (i.e. end of week 1).

-

2–3 weeks for second visit (i.e. end of week 3–4).

-

3–4 weeks for third visit (i.e. end of week 6–8).

Following referral, a key worker (usually a specialist palliative care nurse) contacted the patient within 2 working days to arrange a visit within the next 5 working days to undertake a comprehensive palliative care assessment. As would be standard palliative care practice, at this initial visit a comprehensive palliative care assessment was undertaken, considering both patient and caregiver/family needs. The SIPC manual and training specified the following components to be covered in this assessment:

-

history to include illness understanding

-

completion of IPOS Neuro to aid identification of patient symptoms and needs

-

symptom control and management

-

continuity and co-ordination of care, access to services

-

psychosocial needs

-

information/communication needs

-

practical needs at home

-

decision-making and advance care planning

-

assessment of caregiver and family needs

-

medication review

-

referrals/appointments with other care providers

-

provide information about what is provided through SIPC, along with contact details.

Following this initial assessment, a problem list was generated and prioritised, and a proposed treatment plan agreed with the patient and their family. This may have involved a change in symptom management (e.g. medicine change), contact with other services and/or psychosocial support or counselling. Medicine change recommendations were in liaison with the patient’s general practitioner and/or neurologist, as appropriate, and followed regional and national best practice guidance (e.g. the Palliative Care Formulary77). The treatment plan for each patient was discussed and reviewed at a multiprofessional team meeting, to optimise the management of the patient and caregiver. A summary and action plan were then sent to the patient and all relevant health professionals.

The second contact (face to face or telephone) normally occurred within 2 weeks of the first visit, in order to review and evaluate the proposed plan of care. When appropriate, this included liaison with relevant health professionals for exchange of information, advice and co-ordination of care. The personalised problem list and plan were reviewed and updated, with a copy sent to the patient and all relevant health professionals. The final contact involved a review of outcomes from actions already taken and then discharge to local services, as appropriate. Specialist palliative care is always an individualised service responding to patients’ needs, and SIPC was intended to be the same; therefore, there was some flexibility to adjust to patients’ and families’ individual needs and requirements, and some patients needed prompt support after the first or second visit.

Patients and caregivers in both arms continued to receive usual care throughout the duration of the trial, regardless of trial arm allocation. This included support from specialist nurses, neurology services (outpatient and inpatient), rehabilitation services, community services, general practitioners, district nurses and social services.

Standardisation and compliance

To understand the delivery of the intervention, all MPCTs completed standardised documentation for each patient, recording the main activities and services provided. Each team was advised to use their own existing paper-based or electronic clinical records, in order not to duplicate work for busy clinical teams; however, they were asked to review their usual documentation to ensure that, as a minimum, they record and report:

-

mode of contact and duration for each contact

-

clinical details and severity of main problems

-

activities performed during contact, plan of care and referrals to other services

-

phase of illness (stable, unstable, etc.)

-

performance status using the Australia-modified Karnofsky Performance Scale (AKPS)

-

level of compliance was using the following classifications: complier (received full intervention as planned), partial complier/erratic user (received some but not all of the intervention, or recommendations not followed), overuser (in frequent contact with the service) and dropout.

Randomisation, blinding and allocation concealment

Following consent and baseline data collection, local research nurses entered the patients’ data and registered each patient on the online database [InferMed MACRO-4 (London, UK)]. The registration process allocated each patient a unique participant identification number, which was used to identify them throughout the course of the trial. Once the patient was registered and the baseline data were verified, the trial manager performed all randomisations centrally using an online randomisation system managed by the King’s College London Clinical Trials Unit (CTU).

Randomisation was performed in a 1 : 1 ratio, at the patient level, with minimisation for centre, primary diagnosis (MS vs. IPD vs. PSP, MSA and MND) and cognitive impairment (capacity vs. impaired or lacking capacity). The trial manager was notified of the trial arm allocation and arranged referrals to the palliative care teams for the intervention accordingly (i.e. immediately or after completion of the 12-week data collection visit). As the randomisation used a dynamic method via a system managed by the CTU, it was not possible for the investigators or the trial manager to know the allocation sequence in advance.

The research nurses conducting the data collection interviews and the trial statistician were blinded to the allocation, but received blinded randomisation confirmation e-mails. The trial manager telephoned patients and/or caregivers to inform them of their trial arm allocation and when they would be contacted by the palliative care team. During this telephone call, they were asked not to reveal their allocation to the research nurses at subsequent visits. This information was also sent to all participants in writing, worded as ‘It is important that you do not tell the researchers which group you have been assigned to. This is important for the information we collect from you’. After the primary end point of 12 weeks, in a small number of cases, research nurses were unblinded in order to conduct the qualitative interviews with patients and caregivers who had received the intervention.

Statistical methods

Sample size

Based on the data from our Phase II MS trial,40 the total required sample size required for five centres was 356 patients. In view of the advanced illness in this patient group, this included allowing for 17% attrition to the primary outcome at 12 weeks, giving 296 patients, or 148 in each arm, with data at both baseline and 12 weeks. The correlation between baseline and the outcome at 12 weeks in the pilot study was 0.55. Using a generalised linear model to adjust for the baseline score, with two-sided alpha = 0.05 and correlation of 0.40, the study will have 80% power for a medium effect size of 0.30. To allow for heterogeneity across conditions and centres, we used conservative figures (e.g. correlation 0.4 rather than 0.55; 17% attrition) to estimate the sample size.

Descriptive analysis

Continuous variables were summarised with descriptive statistics [n, mean, standard deviation (SD), median, minimum and maximum]. Frequency counts and percentage of subjects within each category were provided for categorical data. No significance testing was carried out. Summary tables (descriptive statistics and/or frequency tables) by trial arm were provided for all baseline variables, including demographic and clinical characteristics, cognitive impairment and functional performance status. Summary tables were also provided by those with and without valid primary outcome data (IPOS Neuro-S8 score at 12 weeks) (see Appendix 2).

Missing data

Attrition was summarised in accordance with the MORECare classification as attrition due to death, attrition due to illness or attrition at random. 58 For baseline and outcome data, the number with complete data at both time points is reported. The mechanism of missingness was assumed as missing at random, as bivariate analyses indicated that missingness was associated with patient capacity, age, performance status and ethnicity. Multiple imputation using chained equations was used to impute missing observations. Imputation models included the outcome variable of interest, a binary measure of patient capacity, patient age, patient performance status (as measured by the categorical AKPS measure) and a binary measure of patient ethnicity (white vs. other ethnicities). Twenty imputed values were generated for each variable with missing data, which were then combined as per Rubin’s rule. 78

Effectiveness analysis

Data were analysed on an intention-to-treat basis. The mean scores, mean change scores from baseline to 12 weeks post randomisation and their 95% (for primary outcome – IPOS Neuro-S8) or 99.55% confidence intervals (CIs) (for secondary outcomes) were reported. To account for clustering effects, a generalised linear mixed model (GLMM), with centre as a random effect, adjusting for baseline score of IPOS Neuro-S8 was used. For each of the primary and secondary outcomes, the change score was regressed on to the binary measure of trial arm. The statistical significance value (0.05/11 = 0.0045) for secondary outcomes was adjusted using Bonferroni correction to control for multiple testing.

Sensitivity analysis of effectiveness

Six sensitivity analyses followed for the primary and secondary outcomes. In the first, the analyses were adjusted for ethnicity (as between-arm differences were observed in additional exploratory analysis), using fully imputed data (n = 350). In the second, the two participants who were deemed ineligible for the study post randomisation were excluded; thus, the complete data set totalled 348 patients. The third and fourth sensitivity analyses assessed differences in change scores between trial arms in complete patient and caregiver data, respectively. The fifth sensitivity analysis used complete patient data, if available at both baseline and 12 weeks, and imputed proxy carer data if not. Caregiver data were used only when complete and available, at both baseline and 12 weeks, ensuring that scores were acquired from the same source (patient or caregiver) at both time points. The sixth sensitivity analysis included only patients with MS. For each of the sensitivity analyses, differences between change scores for each trial arm were tested using GLMM, adjusting for baseline scores.

Health economic methods

An economic component was included to assess the cost-effectiveness of SIPC compared with standard care. Cost-effectiveness was assessed by linking data on formal cost differences and outcome measurements differences.

Service use

Participants provided details of services used during the 12 weeks prior to baseline and then for the past 12 weeks post randomisation, using a version of the CSRI. 74 Services included hospital inpatient and outpatient care, primary health care (home care and community care), tests and diagnostics, social care, the provision of aids and home adaptations, and informal care provided by family members and/or friends. The number of contacts with services and, when relevant, the mean length of contacts were documented. The number of hours that family and friends spent providing personal care and help inside and outside the home and in other tasks per week was collected. To better understand the utilisation and associated costs, service items were grouped into health and social care (outpatient, day or community, home, palliative, rehabilitation, primary, social care, and tests and diagnostics) and informal care.

Missing data

For those participants who completed the CSRI, a blank return in the questionnaire on whether or not a participant used a specific service was assumed to indicate no use of that particular service. This followed the structure of CSRI questions. CSRI asks respondents to describe what services or care they have received, to tick when services are received, and then say how often and how much of these they received. It offers a long list of potential options and an open space to describe others. It does not ask ‘yes or no’ for each service in the long list, and the space can be left blank when services are not used. When a service was used, but either the number of contacts or duration of contacts was unknown, the median value from all other valid cases across the whole sample at that time point was used.

Missing data for the outcome variables [IPOS Neuro-S8 and EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) index score] were imputed using multiple imputation with chained equations after examining the associations between missingness and variables of interest such as patient capacity, age, performance status and ethnicity. For those participants who provided outcome data but no CSRI data, total care (health and social care and informal care) costs were also imputed, as described above.

Costs

Costs were calculated, in Great British pounds, by combining resource use data with unit costs obtained from standard sources, such as the NHS Reference Costs 2015 to 201679 or the Unit Costs of Health and Social Care 2016,80 where applicable. The unit costs of a home care worker or a nurse aid were used as a proxy for informal care. We assumed that the CSRI recorded all services provided for the participants, regardless of randomisation, and did not separate the services of the intervention from the rest. The horizon of the analysis is restricted to the trial period and no discounting was considered.

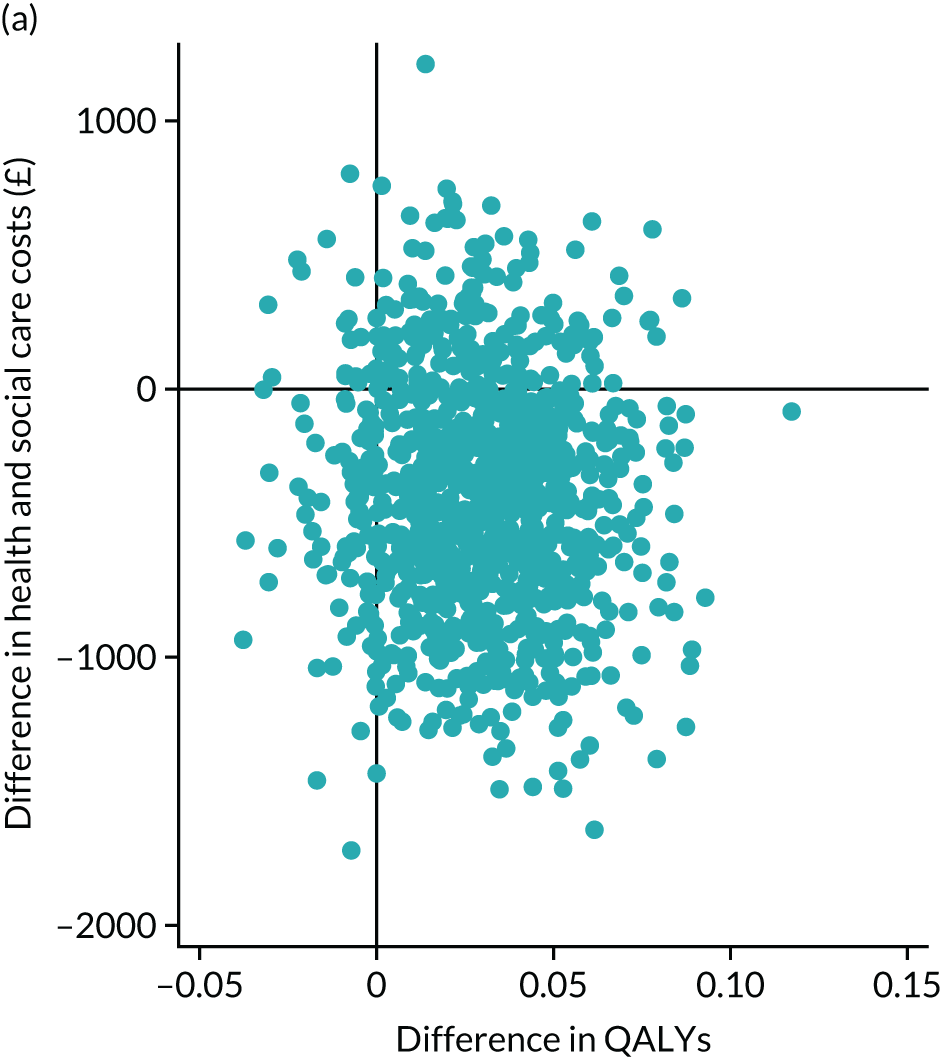

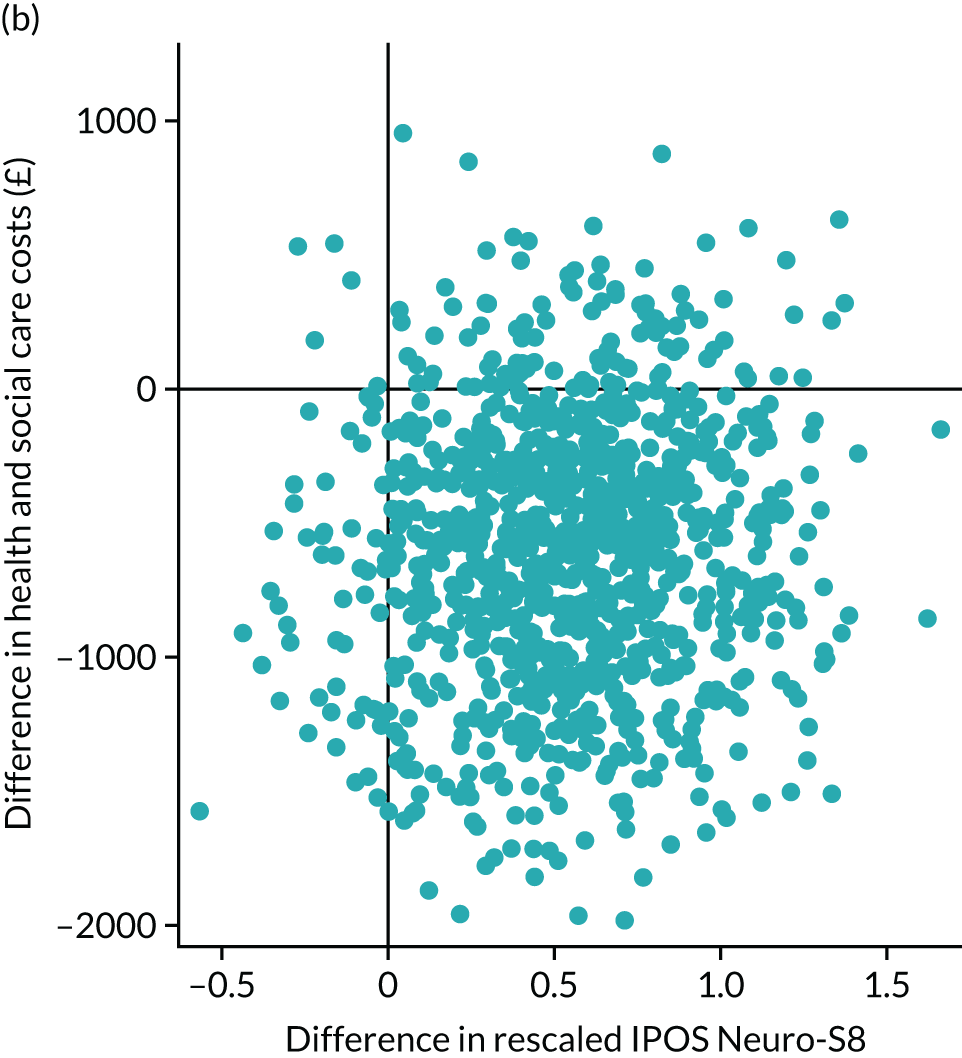

Cost-effectiveness analysis

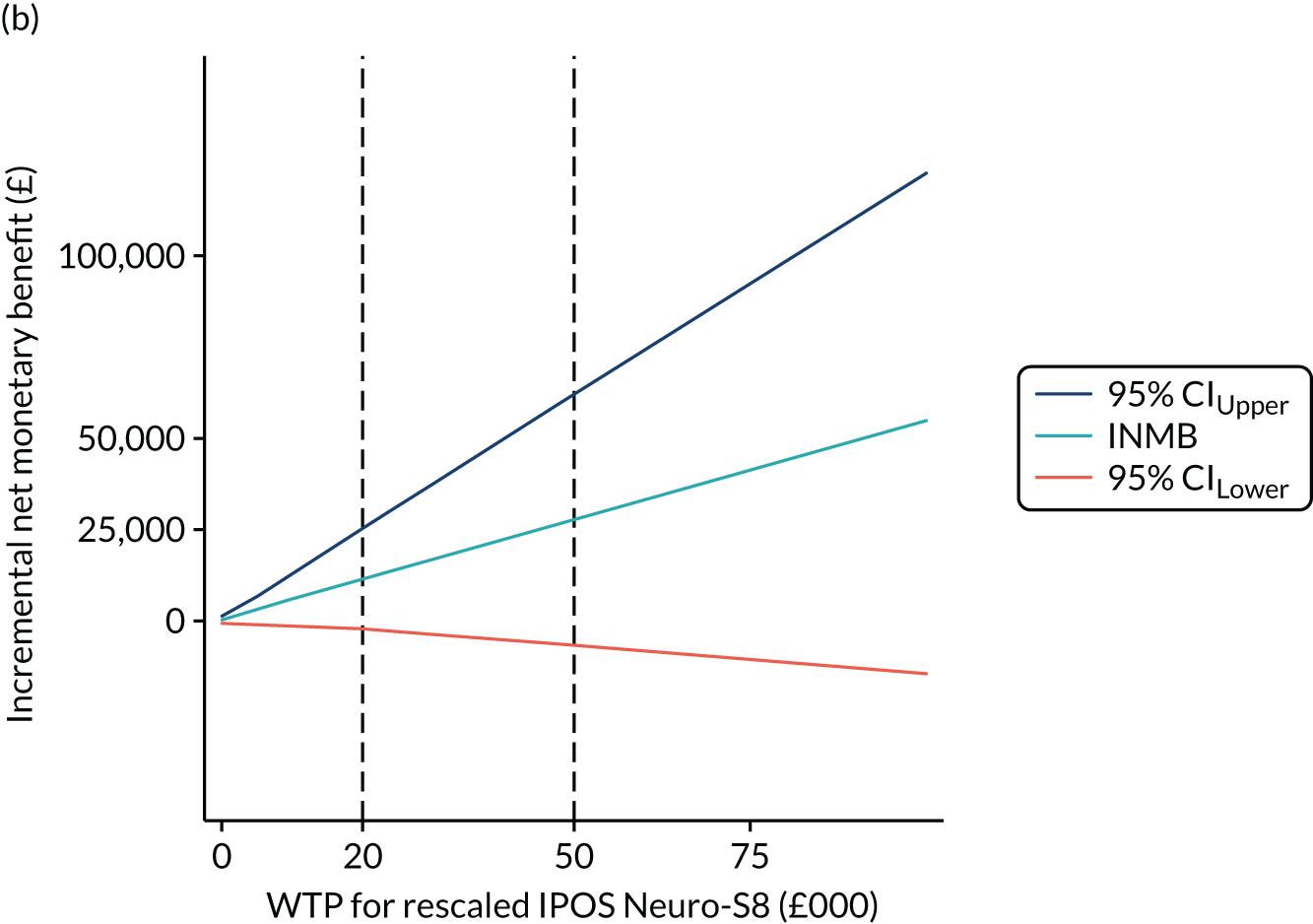

Cost-effectiveness, from an NHS perspective, was assessed by linking data on health and social care service cost differences and two outcome measurements differences: the primary outcome IPOS Neuro-S8 and EQ-5D index score [quality-adjusted life-year (QALY)]. IPOS Neuro-S8 total score was generated as the sum of eight items, ranging from 0 to 32. For cost-effectiveness analysis, this was rescaled by subtracting from 32 to make higher scores reflect better outcomes. EQ-5D-5L contains five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression), each of which has five levels (no problems, slight problems, moderate problems, severe problems and extreme problems). These levels are valued 1–5, respectively; however, as these numerals have no arithmetic properties and should not be used as a cardinal score, we calculated an index value using UK value sets for EQ-5D obtained by a crosswalk approach. 81

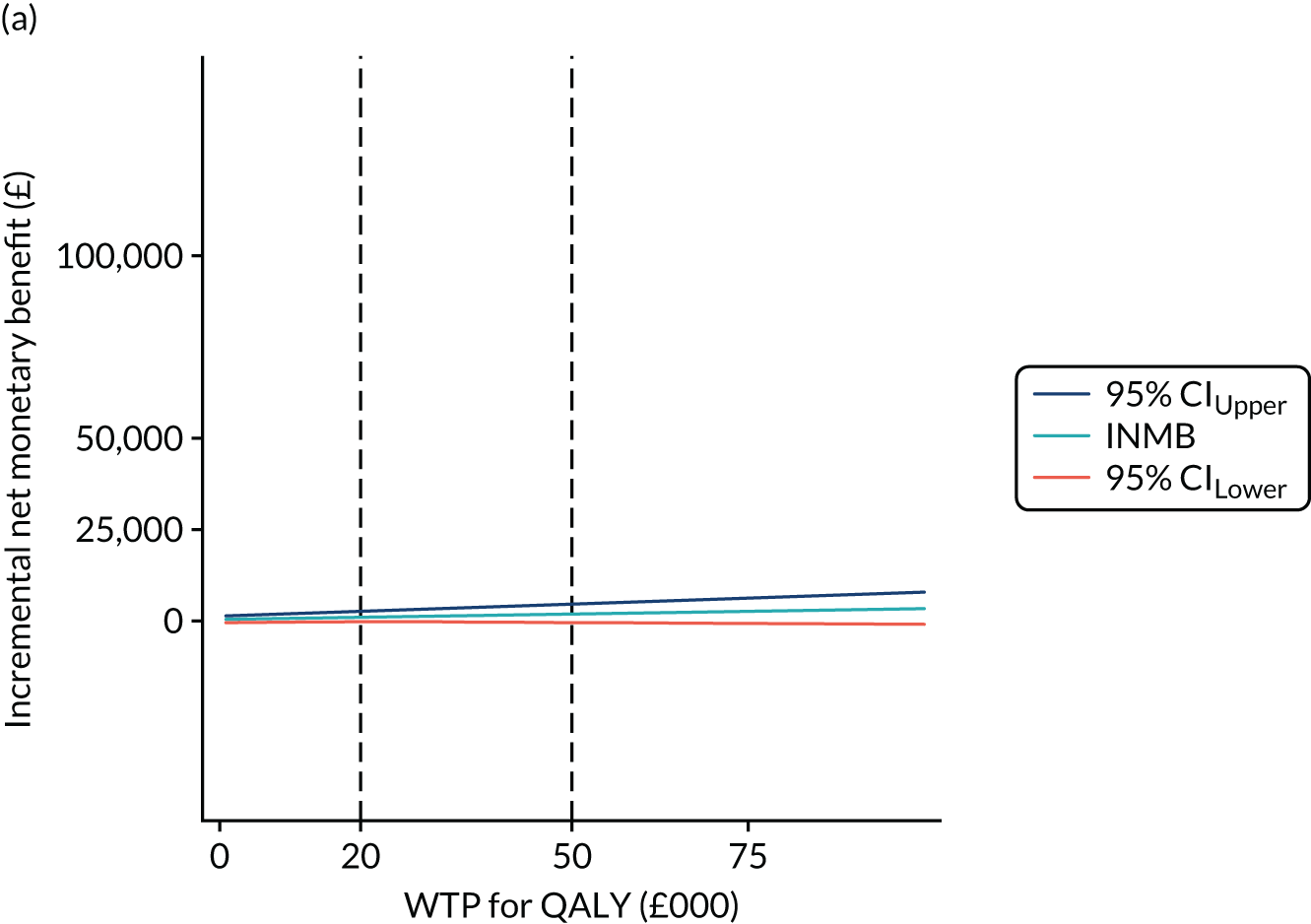

The mean and SD were examined for formal care costs and the two outcome measurements. Cost-effectiveness of SIPC was assessed by calculating incremental cost-effectiveness ratios (ICERs), using mean changes in formal care costs and outcome measurements, as shown in Equation 1. ICERs smaller than the willingness-to-pay (WTP) threshold (λ = e.g. £20,000, as the threshold used by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence) indicates that the cost-effectiveness of SIPC. The primary decision criterion for cost-effectiveness of SIPC was whether ICERs were larger or smaller than λ:

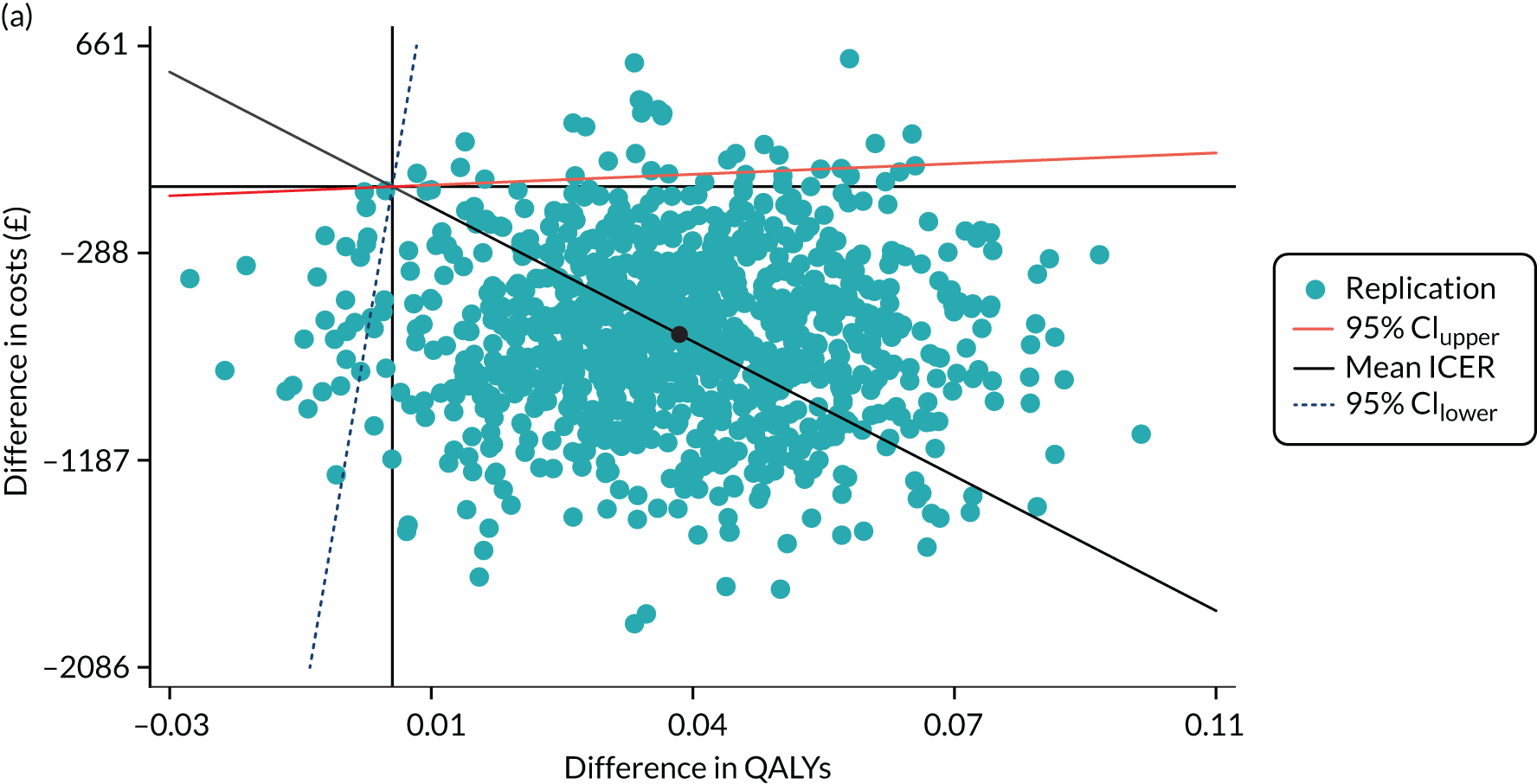

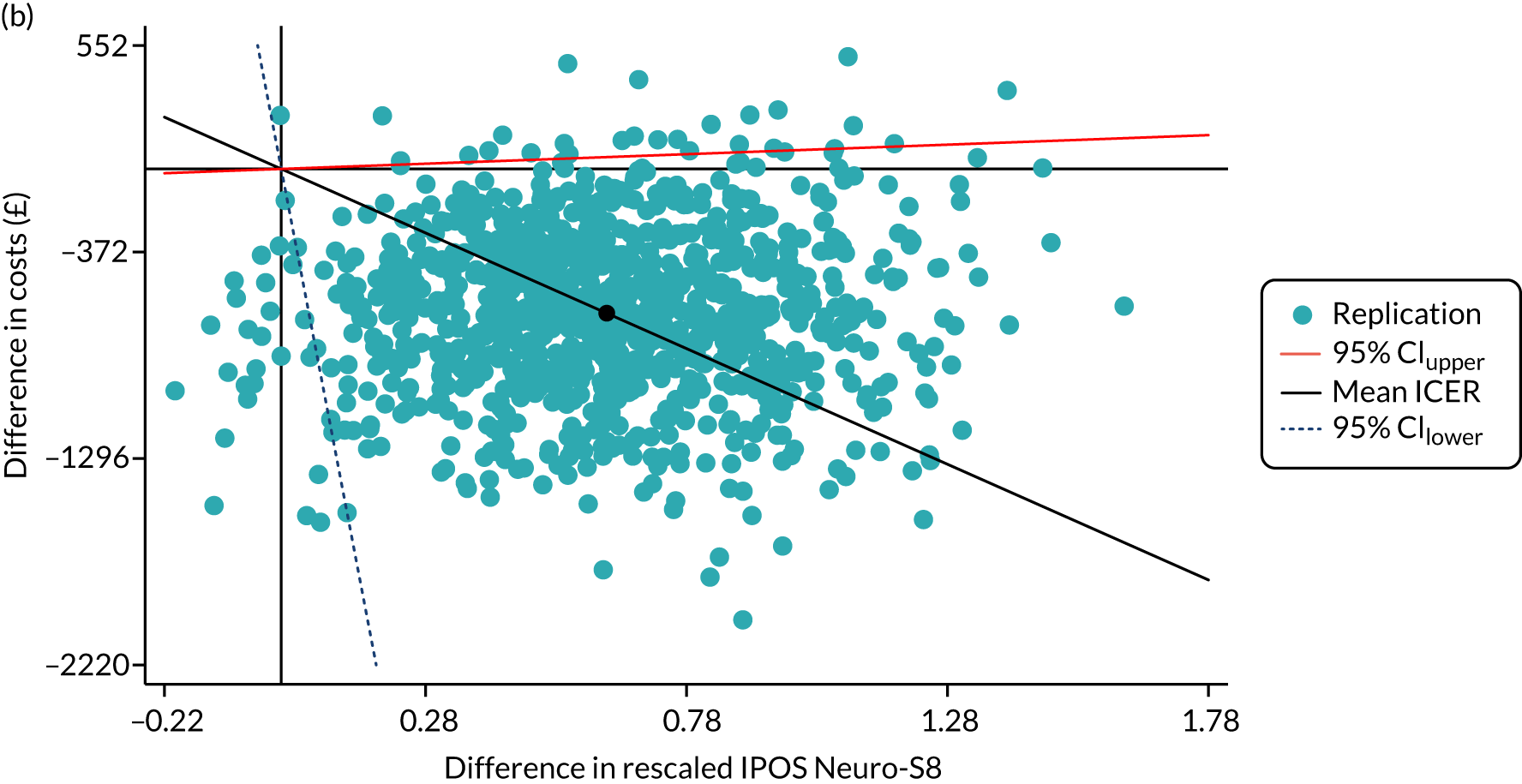

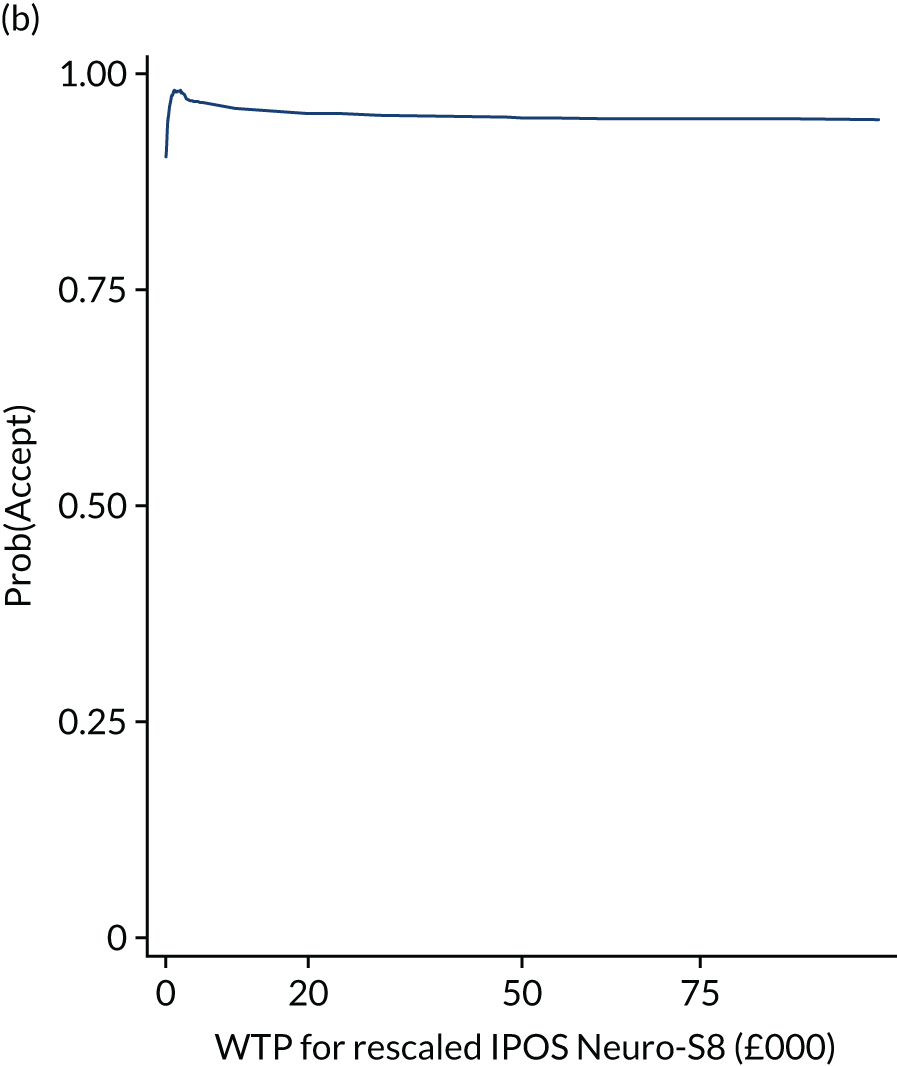

To understand the uncertainty around the ICERs, we produced the estimated differences in formal care cost and outcomes by bootstrapping with 1000 replications. Regression approach was used to predict the difference in costs and outcomes: the generalised linear model with a log-link function and the Poisson distribution for cost due to the skewed distribution, and ordinary least squares regressions for EQ-5D index score and IPOS Neuro-S8, after examining the distributions and model specifications. In each regression, baseline values were controlled for. Bootstrapping was conducted using complete cases only. These replications were plotted in cost-effectiveness planes. These planes have four quadrants and combine changes in costs and changes in outcomes: (1) north-east (SIPC is more effective and more costly); (2) north-west (SIPC is less effective and more costly); (3) south-west (SIPC is less effective and less costly); and (4) south-west (SIPC is less costly and more effective). 82 We examined the distribution of 1000 replications on the planes by four quadrants.

Finally, to account for the joint uncertainty of costs and outcomes, we conducted further analysis of the probability of SIPC being cost-effective with a set of WTP thresholds, as well as calculating the incremental net monetary benefit (INMB) of SIPC compared with standard care (details in Appendix 3).

Qualitative methods

Embedded within the trial was a qualitative component conducted concurrently,83 to explore which aspects of SIPC were most valued or had most impact on patients’ and caregivers’ experiences of care, how the change process of SIPC may be working and how the intervention is delivered in practice. The intention was to form a theoretical model of SIPC to inform implementation requirements and processes, and intended outcomes. The embedded qualitative study involved patients, caregivers and health-care staff.

Patient and caregivers

Individual interviews were conducted with participants who received SIPC (at 12 weeks for the intervention group and 24 weeks for the standard care group). We estimated a sample size in each study site of seven patients/caregivers, totalling 35 patients/caregivers. We sought to conduct maximum variation sampling to encompass the conditions eligible for inclusion in the trial. However, given that the trial sample largely comprised MS and IPD patients, this was not practical, and purposive sampling was used. Only participants who had indicated their consent to participate in these qualitative interviews at the initial trial consenting stage were contacted regarding these interviews. Interviews were conducted in participants’ own homes with patients, and caregivers when available, or with caregivers when patients lacked capacity to participate. The interviews were conducted by researchers and research nurses trained in and supervised during qualitative interviews. When possible, a researcher who was not involved in the main trial data collection conducted the interview to minimise the risk of unblinding.

Health-care staff

Focus groups were conducted with health-care staff from the respective centres to explore perceptions of SIPC, processes of SIPC delivery and the local context of service delivery models for patients with neurological conditions. We estimated a sample size of six service providers from each site, totalling 30 providers. Participants were identified by the local research teams for the central King’s College London team, who e-mailed invitations to participate. Eligible participants comprised health professionals involved in delivering the intervention in the respective study site (e.g. specialist nurses, neurologists, allied health professionals). Each group comprised representatives from the respective centres and disciplines involved in the care provision. When individual attendance at a focus group was not possible (e.g. clinical commitments), individual interviews were conducted (either face to face or by telephone) to ensure representation from all centres. The groups were facilitated by a researcher experienced in qualitative research methods and an observer to document, for example, group processes and interactions. All participants provided written informed consent.

Data analysis

Interviews and focus groups were digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim and anonymised prior to analysis. Data analysis drew on Coffey and Atkinson’s84 iterative approach of coding and describing the data, generating categories, through to forming hypotheses and generating theory. We explored the impact of SIPC at three main levels (people and context, processes and tasks, and underpinning theory)85 and sought to identify ways to enhance SIPC and the processes for wider implementation. The analysis approach emphasised theory generation by asking questions about the data and developing emergent lines of thinking to form and question emergent hypotheses. NVivo 11 software (QSR International, Warrington, UK) for qualitative analysis was used for data storage, coding, searching and retrieving, and recording analytical thinking. Quality appraisal sought to ensure systematic and rigorous attention to analysis and reporting by, for example, holding supervisory review meetings to consider the data analysis and emerging findings (held by CE and NH), attention to divergent cases and use of qualitative research software to assist comprehensive reporting, auditability and transparency of the findings.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement has been an integral part of all our research processes. An independent PPI group was set up specifically for OPTCARE Neuro, comprising both patients and caregivers with lived experience of MS, IPD, MSA and MND. The group advised on the application for ethics approval and the development of all participant materials, as well as the delivery of the trial and the interpretation of the findings. We engaged with our PPI members on multiple levels but predominantly through 3-monthly face-to-face meetings at which we benefited from the expert views of our members to help us prioritise the research questions and ensure that the study was undertaken in a way that was meaningful and relevant to both patients and caregivers. A member of our PPI group was a co-applicant on the funding application and an active member of the Study Steering Committee. We had PPI representation in the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee, which had oversight and responsibility for the conduct of the trial. We actively involved our PPI members in the interpretation of data, particularly the qualitative components of the study. This provided the study team with valuable insight to understand the data and their relevance for addressing the needs of this patient population.

Engagement

Engagement took place throughout the study. First, charities and patient societies supported and publicised the trial in order to improve recruitment and dissemination. Specifically, the PSP Association, the MS Society and Parkinson’s UK, which all featured details of the trial on their research web pages. The trial was also featured in an issue of the Multiple Sclerosis Trust’s Way Ahead magazine for MS health professionals, and in the PSP Association’s PSP Matters magazine, with two trial participants contributing to the article. In May 2016, the study team hosted a 2-day workshop and conference on palliative care in neurology. The first of these days was a closed meeting for OPTCARE Neuro teams, with representation from principal investigators, research nurses, clinicians and PPI members from all trial centres. A representative from each site gave a brief overview of local progress, and our PPI group also presented on their involvement. It was extremely productive to have all the teams together to exchange ideas and learn from each other. The second day was a conference that focused on clinical components of palliative care for patients with LTNCs, and some interim data from the mapping exercise and survey for professionals were presented. The conference had > 100 registrations and was attended by a mixture of clinicians, researchers, students, PPI members and representatives from charitable organisations and patient societies. The great turnout for the conference and the interest from the audience members highlighted the importance of the OPTCARE Neuro work. Last, throughout the course of the study, we have circulated 6-monthly newsletters to our study contacts, which included palliative care and neurology clinicians, academics, researchers and charities.

Ethics approval and research governance

The trial was conducted in compliance with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki (2013)86 and the principles of Good Clinical Practice and in accordance with all applicable regulatory requirements, including, but not limited to, the Research Governance Framework and the Mental Capacity Act 2005. 62 The protocol and related documents were submitted for review and approved by the London South East Research Ethics Committee (14/LO/1765).

Chapter 4 Results

Mapping results

Parts of the text have been reproduced from van Vliet et al. 55 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Centres varied in size of catchment areas (39–5840 square miles) and population served (142,000–3,500,000). Neurology and specialist palliative care were often not co-terminous. Service provision for neurology and specialist palliative care also varied; for example, neurology services varied in the number and type of clinics provided, and palliative care services varied in the settings in which they worked. The integration between neurology and palliative care teams varied between centres, but more clearly between diseases. For MS, the integration was limited, with most centres having no formal links. Only two centres broke this trend; one held an 8-weekly multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting, in which both MS and palliative care teams participated, and the other held a 3-monthly complex problem clinic with palliative care attendance. For MND, a different picture emerged of stronger integration. Most centres either held joint clinics or had a palliative care presence at MDT meetings. At one site, all MND patients were invited to clinics at the local hospice; whereas at another, all patients received a palliative care assessment. Good informal links were reported in one site where the MND and palliative care nurses shared an office, but there were with no joint visits. The least integrated site had no joint clinics and referrals were based on needs. Last, in Parkinson’s disease-related disorders the integration was very mixed. Approximately half of the centres had no joint clinics or formal relationships. Others had 2- to 3-monthly clinics or MDT meetings, with one site having a palliative care presence at weekly clinics. There was a difference between the subsets of diseases, with greater integration for MSA and PSP. The number of neurology patients per annum receiving specialist palliative care reflected these differences in integration (a range of 9–88 patients with MND, a range of 3–5 patients with Parkinson’s disease-related disorders and a range of 0–5 patients with MS).

Survey results

Parts of the text have been reproduced from Hepgul et al. 56 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

The survey received responses from 33 neurology and 26 palliative care professionals (20% response rate). Two-thirds of respondents in both groups had > 10 years of experience in their respective fields. Current levels of collaboration between the two specialties were reported to be ‘good/excellent’ by 36% of neurology professionals and by 58% of palliative care professionals. However, nearly half (45%) of neurology compared with only 12% of palliative care professionals rated current levels of collaboration ‘poor/none’. When asked if there were any particular disease areas for which links were better, both groups reported stronger links for MND. In addition, both professional groups felt that the new SIPC service being trialled would influence future collaborations for the better (65–70% in both groups). Participants were also asked what they thought would be the main barriers for the new SIPC service. The most common barriers identified by neurologists were resources, clinician awareness of services offered, continuing collaborations, and communication between teams beyond the trial and geographical limitations. Similarly, palliative care professionals also identified resources and clinician awareness of services offered (and importantly the appropriateness of referrals they may receive) as barriers. However, the key barrier they identified was that there may be a possible need for longer-term care beyond that offered by the SIPC service. They also drew attention to patients’ perceptions of palliative care as a potential barrier.

Randomised trial results

Participant flow

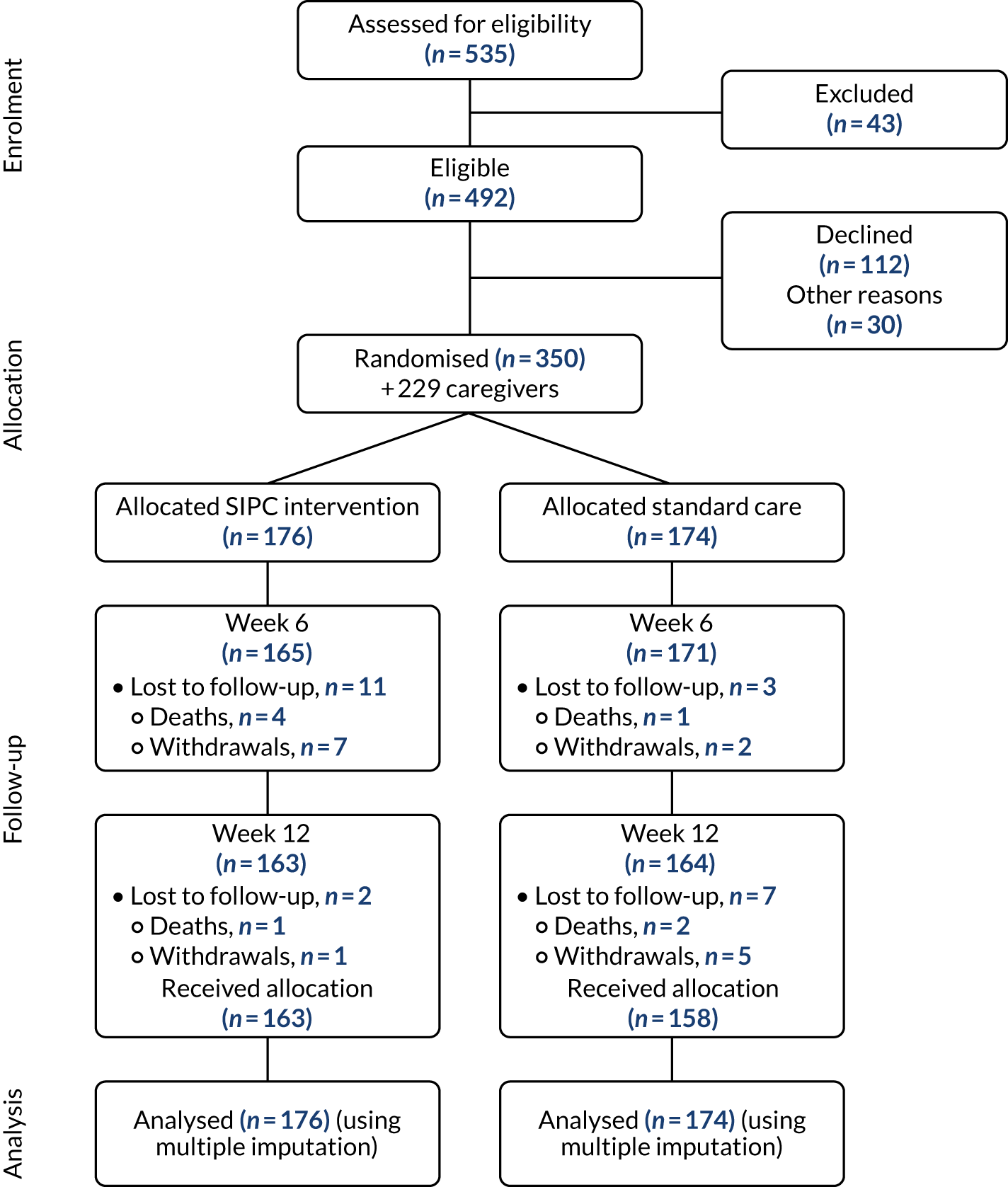

Recruitment began in three centres in April 2015. Two centres opened in July 2015 and November 2015, with an additional two centres opening in February 2016 and September 2016. The total recruitment period was 31 months, ending in November 2017, with all follow-up visits completed in May 2018. One centre, Sheffield, was opened but failed to sustain recruitment and therefore was closed. Other centres’ recruited numbers were broadly reflective of their catchment areas and local populations. Monthly recruitment rates over the course of the recruitment period are presented in Appendix 1. The trial recruited 350 patients living with a LTNC, plus 229 caregivers, with 176 patients in the immediate SIPC intervention arm and 174 in the standard care waiting list control arm. Table 1 details the screening and enrolment by each site and Figure 1 outlines the participant flow up to the primary end point of 12 weeks post randomisation.

| Screening and enrolment | Site | Total | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| London | Liverpool | Nottingham | Cardiff | Brighton | Ashford | Sheffield | ||

| Site opened | April 2015 | April 2015 | April 2015 | July 2015 | November 2015 | February 2016 | September 2016 | |

| Referred | 158 | 69 | 100 | 67 | 71 | 64 | 6 | 535 |

| Not in catchment area | 8 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 5 | 0 | 0 | 16 |

| Already receiving palliative care | 11 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 | 0 | 21 |

| Lacks capacity and no caregiver | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Not meeting diagnostic criteria | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Declined | 25 | 16 | 19 | 22 | 15 | 12 | 3 | 112 |

| Other | 11 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 30 |

| Enrolled patients (caregivers) | 100 (79) | 48 (37) | 76 (32) | 36 (23) | 50 (31) | 37 (26) | 3 (1) | 350 (229) |

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram showing the flow of participants. Reproduced with permission from Gao et al. 87 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Participant characteristics by trial arm

The baseline characteristics of the sample are presented in Tables 2 and 3 by trial arm. The groups are comparable, except for patient ethnicity, with more patients of ethnicity other than white in the SIPC group (13%) than in the standard care group (5%).

| Variable | Value | All | SIPC | Standard care |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 350 | 176 | 174 | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 66.8 (11.8) | 67.3 (10.9) | 66.4 (12.6) | |

| Gender, n (%) | Man | 179 (51.1) | 86 (48.9) | 93 (53.5) |

| Woman | 171 (48.9) | 90 (51.1) | 81 (46.6) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | Single | 35 (10.0) | 16 (9.1) | 19 (10.9) |

| Widowed | 38 (10.9) | 19 (10.8) | 19 (10.9) | |

| Married/civil partner | 231 (66.0) | 114 (64.8) | 117 (67.2) | |

| Divorced/separated | 44 (12.6) | 26 (14.8) | 18 (10.3) | |

| Not done/unknown | 2 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | |

| Living status, n (%) | Alone | 65 (18.6) | 35 (19.9) | 30 (17.2) |

| With spouse/partner and/or children | 244 (69.7) | 125 (71.0) | 119 (68.4) | |

| With friend(s)/with others | 41 (11.7) | 16 (9.1) | 25 (14.4) | |

| Education, n (%) | No formal education up to lower secondary school | 139 (39.7) | 67 (38.1) | 72 (41.4) |

| Upper secondary to post-secondary vocational qualification | 116 (33.1) | 53 (30.1) | 63 (36.2) | |

| Tertiary education | 91 (26.0) | 55 (31.3) | 36 (20.7) | |

| Not done/missing | 4 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) | 3 (1.7) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | White | 316 (90.3) | 166 (94.3) | 150 (86.2) |

| Other ethnic group | 32 (9.1) | 9 (5.1) | 23 (13.2) | |

| Employment, n (%) | No | 340 (97.1) | 173 (98.3) | 167 (96.0) |

| Yes | 10 (2.9) | 3 (1.7) | 7 (4.0) | |

| Feelings towards income, n (%) | Living comfortably on present income | 118 (33.7) | 58 (33.0) | 60 (34.5) |

| Coping on present income | 162 (46.3) | 85 (48.3) | 77 (44.3) | |

| Difficult on present income | 24 (6.9) | 12 (6.8) | 12 (6.9) | |

| Very difficult on present income | 14 (4.0) | 7 (4.0) | 7 (4.0) | |

| Not done/unknown | 32 (9.1) | 14 (8.0) | 18 (10.3) | |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | MS | 148 (42.3) | 74 (42.1) | 74 (42.5) |

| IPD | 140 (40.0) | 71 (40.3) | 69 (39.7) | |

| MSA | 12 (3.4) | 7 (4.0) | 5 (2.9) | |

| PSPa | 27 (7.7) | 13 (7.4) | 14 (8.1) | |

| MND | 23 (6.6) | 11 (6.3) | 12 (6.9) | |

| Years since diagnosis | ||||

| Mean (SD) | 12.3 (10.6) | 12.3 (10.8) | 12.4 (10.4) | |

| Range | 0–56 | 0–56 | 0–46 | |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | No | 99 (28.3) | 42 (23.9) | 57 (32.8) |

| Yes | 251 (71.7) | 134 (76.1) | 117 (67.2) | |

| Patient capacity, n (%) | Consent | 311 (88.9) | 157 (89.2) | 154 (88.5) |

| Personal consultee assent | 39 (11.1) | 19 (10.8) | 20 (11.5) | |

| AKPS, n (%) | Totally bedfast | 7 (2.0) | 3 (1.7) | 4 (2.3) |

| Almost completely bedfast | 10 (2.9) | 5 (2.8) | 5 (2.9) | |

| In bed > 50% of the time | 21 (6.0) | 10 (5.7) | 11 (6.3) | |

| Requires considerable assistance | 170 (48.6) | 77 (43.8) | 93 (53.5) | |

| Requires occasional assistance | 98 (28.0) | 54 (30.7) | 44 (25.3) | |

| Cares for self | 33 (9.4) | 19 (10.8) | 14 (8.1) | |

| Normal activity with effort | 9 (2.6) | 7 (4.0) | 2 (1.2) | |

| Not available/applicable | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.6) | 0 | |

| Not done | 1 (0.3) | 0 | 1 (0.6) | |

| Variable | Value | All | SIPC | Standard care |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | 229 | 121 | 108 | |

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 64.2 (13.3) | 63.3 (13.3) | 65.3 (13.4) | |

| Gender, n (%) | Man | 81 (35.4) | 41 (33.9) | 40 (37.0) |

| Woman | 148 (64.6) | 80 (66.1) | 68 (63.0) | |

| Marital status, n (%) | Single | 14 (6.1) | 7 (5.8) | 7 (6.5) |

| Widowed | 10 (4.4) | 4 (3.3) | 6 (5.6) | |

| Married/civil partner | 200 (87.3) | 109 (90.1) | 91 (84.3) | |

| Divorced/separated | 5 (2.2) | 1 (0.8) | 4 (3.7) | |

| Living status, n (%) | Alone | 9 (3.9) | 4 (3.3) | 5 (4.6) |

| With spouse/partner and/or children | 200 (87.3) | 109 (90.1) | 91 (84.3) | |

| With friends/with others | 20 (8.7) | 8 (6.6) | 12 (11.1) | |

| Relationship to patient, n (%) | Spouse/partner | 177 (77.3) | 97 (80.2) | 80 (74.1) |

| Son/daughter | 29 (12.7) | 17 (14.1) | 12 (11.1) | |

| Other | 23 (10.0) | 0 | 4 (3.7) | |

| Education, n (%) | No formal education up to lower secondary school | 96 (41.9) | 51 (42.2) | 45 (41.7) |

| Upper secondary school to post-secondary vocational qualification | 66 (28.8) | 37 (30.6) | 29 (26.9) | |

| Tertiary education | 62 (27.1) | 30 (24.8) | 32 (29.6) | |

| Not done/missing | 5 (2.2) | 3 (2.5) | 2 (1.9) | |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | White | 211 (92.1) | 113 (93.4) | 98 (90.7) |

| Other ethnic group | 18 (7.9) | 8 (6.6) | 10 (9.3) | |

| Employment, n (%) | No | 162 (70.7) | 86 (71.1) | 76 (70.4) |

| Yes | 67 (29.3) | 35 (28.9) | 32 (29.6) | |

| Illness, n (%) | No | 77 (33.6) | 41 (33.9) | 36 (33.3) |

| Yes | 140 (61.1) | 70 (57.9) | 70 (64.8) | |

Primary analysis of effectiveness

Point estimates and adjusted analyses, using multiply imputed data for the entire sample (n = 350), are presented in Table 4. There were no statistically significant differences between the trial arms for either the primary outcome or any of the secondary outcomes. The primary outcome (IPOS Neuro-S8) fell in both groups between baseline and 12 weeks, with a greater fall (i.e. improvement) in the SIPC group than in the standard care group (–0.78 vs. –0.28). This pattern was consistent for most secondary outcomes. Of note, for some secondary outcomes (indicated with table footnote c), lower scores indicate poorer outcomes. The missing data for the primary outcome due to withdrawal or unknown reasons were 4% at 12 weeks.

| Measure | Time point | All (n = 350) | SIPC (n = 176) | Standard care(n = 174) | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||||

| IPOS Neuro-S8, x¯ (CI) | Baseline | 6.93 (6.48 to 7.37) | 6.89 (6.24 to 7.54) | 6.96 (6.34 to 7.58) | |

| 12 weeks | 6.40 (5.93 to 6.86) | 6.11 (5.46 to 6.77) | 6.68 (6.02 to 7.34) | ||

| Change score | –0.53 (–0.90 to –0.16) | –0.78 (–1.29 to –0.26) | –0.28 (–0.82 to 0.26) | 0.14 | |

| Secondary patient outcomesb | |||||

| IPOS Neuro-S24, x¯ (CI) | Baseline | 26.92 (25.14 to 28.71) | 26.69 (24.23 to 29.15) | 27.16 (24.57 to 29.75) | |

| 12 weeks | 25.50 (23.60 to 27.40) | 24.74 (22.10 to 27.37) | 26.27 (23.58 to 28.96) | ||

| Change score | –1.42 (–3.20 to 0.35) | –1.95 (–4.38 to 0.48) | –0.89 (–3.15 to 1.36) | 0.22 | |

| IPOS Neuro-8, x¯ (CI) | Baseline | 11.51 (10.49 to 12.53) | 11.43 (10.07 to 12.79) | 11.58 (10.09 to 13.08) | |

| 12 weeks | 11.19 (10.13 to 12.24) | 10.59 (9.09 to 12.09) | 11.80 (10.34 to 13.26) | ||

| Change score | –0.32 (–1.32 to 0.69) | –0.84 (–2.09 to 0.40) | 0.21 (–1.25 to 1.68) | 0.06 | |

| IPOS Neuro, x¯ (CI) | Baseline | 47.04 (42.49 to 51.59) | 47.36 (41.94 to 52.78) | 46.72 (40.93 to 52.51) | |

| 12 weeks | 43.68 (37.74 to 49.61) | 43.14 (35.28 to 51.00) | 44.22 (37.55 to 50.89) | ||

| Change score | –3.36 (–8.41 to 1.68) | –4.22 (–10.87 to 2.43) | –2.50 (–8.37 to 3.37) | 0.53 | |

| HADS anxiety, x¯ (CI) | Baseline | 7.64 (6.95 to 8.34) | 7.78 (6.78 to 8.77) | 7.51 (6.52 to 8.50) | |

| 12 weeks | 7.51 (6.70 to 8.32) | 7.43 (6.28 to 8.58) | 7.59 (6.53 to 8.66) | ||

| Change score | –0.13 (–0.68 to 0.42) | –0.35 (–1.12 to 0.43) | 0.08 (–0.65 to 0.81) | 0.27 | |

| HADS depression, x¯ (CI) | Baseline | 8.22 (7.61 to 8.84) | 8.13 (7.29 to 8.97) | 8.31 (7.47 to 9.16) | |

| 12 weeks | 8.09 (7.44 to 8.74) | 7.96 (7.03 to 8.88) | 8.22 (7.35 to 9.09) | ||

| Change score | –0.13 (–0.58 to 0.32) | –0.17 (–0.79 to 0.45) | –0.09 (–0.78 to 0.59) | 0.69 | |

| EQ-5D VAS,c x¯ (CI) | Baseline | 52.49 (48.91 to 56.07) | 52.72 (47.91 to 57.53) | 52.25 (47.01 to 57.49) | |

| 12 weeks | 52.23 (48.29 to 56.16) | 53.69 (48.03 to 59.34) | 50.75 (45.36 to 56.14) | ||

| Change score | –0.26 (–4.87 to 4.35) | 0.97 (–5.01 to 6.94) | –1.50 (–8.05 to 5.05) | 0.27 | |

| SEMCD Scale,c x¯ (CI) | Baseline | 5.26 (4.90 to 5.62) | 5.39 (4.89 to 5.89) | 5.13 (4.63 to 5.64) | |

| 12 weeks | 5.11 (4.74 to 5.48) | 5.28 (4.75 to 5.82) | 4.94 (4.41 to 5.47) | ||

| Change score | –0.15 (–0.52 to 0.22) | –0.10 (–0.60 to 0.40) | –0.19 (–0.70 to 0.31) | 0.37 | |

| FAMCARE-P16,c x¯ (CI) | Baseline | 50.32 (47.92 to 52.72) | 50.33 (46.66 to 54.00) | 50.30 (47.08 to 53.53) | |

| 12 weeks | 47.75 (44.81 to 50.69) | 48.08 (43.75 to 52.41) | 47.41 (43.52 to 51.31) | ||

| Change score | –2.57 (–5.12 to –0.03) | –2.26 (–6.05 to 1.53) | –2.89 (–6.23 to 0.45) | 0.70 | |

| Secondary caregiver outcomesb | |||||

| ZBI-12,c x¯ (CI) | Baseline | 18.46 (16.57 to 20.35) | 18.25 (15.59 to 20.90) | 18.68 (16.28 to 21.08) | |

| 12 weeks | 18.76 (16.81 to 20.71) | 18.60 (15.93 to 21.27) | 18.92 (16.28 to 21.55) | ||

| Change score | 0.30 (–0.68 to 1.27) | 0.35 (–0.98 to 1.68) | 0.24 (–1.15 to 1.64) | 0.90 | |

| ZBI positivity,c x¯ (CI) | Baseline | 18.85 (17.66 to 20.03) | 18.97 (17.36 to 20.59) | 18.72 (17.05 to 20.38) | |

| 12 weeks | 18.50 (17.11 to 19.88) | 18.87 (17.08 to 20.67) | 18.12 (16.15 to 20.10) | ||

| Change score | –0.35 (–1.29 to 0.59) | –0.10 (–1.43 to 1.23) | –0.59 (–1.98 to 0.79) | 0.40 | |

| FAMCARE 2,c x¯ (CI) | Baseline | 53.89 (50.79 to 56.99) | 53.81 (49.64 to 57.97) | 53.98 (49.93 to 58.02) | |

| 12 weeks | 53.61 (49.78 to 57.44) | 53.99 (48.92 to 59.07) | 53.23 (48.38 to 58.07) | ||

| Change score | –0.28 (–3.47 to 2.91) | 0.19 (–4.86 to 5.23) | –0.75 (–4.64 to 3.14) | 0.67 | |

Sensitivity analysis 1

Imputed data for the entire sample adjusted for ethnicity are presented in Table 5. These estimates are consistent with those from the primary analyses, in favour of the SIPC arm, although not statistically significant.

| Measure | Time point | All (n = 350) | SIPC (n = 176) | Standard care (n = 174) | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome | |||||

| IPOS Neuro-S8, x¯ (CI) | Baseline | 6.93 (6.48 to 7.37) | 6.89 (6.24 to 7.54) | 6.96 (6.34 to 7.58) | |

| 12 weeks | 6.40 (5.93 to 6.86) | 6.11 (5.46 to 6.77) | 6.68 (6.02 to 7.34) | ||

| Change score | –0.53 (–0.90 to –0.16) | –0.78 (–1.29 to –0.26) | –0.28 (–0.82 to 0.26) | 0.13 | |

| Secondary patient outcomesb | |||||

| IPOS Neuro-S24, x¯ (CI) | Baseline | 26.92 (25.69 to 28.15) | 26.69 (24.99 to 28.38) | 27.16 (25.38 to 28.94) | |

| 12 weeks | 25.50 (24.19 to 26.80) | 24.74 (22.92 to 26.55) | 26.27 (24.42 to 28.12) | ||

| Change score | –1.42 (–2.64 to –0.21) | –1.95 (–3.60 to –0.30) | –0.89 (–2.45 to 0.66) | 0.25 | |