Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/04/16. The contractual start date was in March 2016. The final report began editorial review in December 2018 and was accepted for publication in June 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Fiona Lobban and Vanessa Pinfold were the originators of the Relatives’ Education And Coping Toolkit (REACT) and, therefore, are not independent researchers. Jo Rycroft-Malone is Programme Director of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme, which funded this research, and is chairperson of the funding committe, and, at the time that the project was funded, was the deputy chairperson of the commissioned workstream of the NIHR HSDR programme.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Lobban et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background and rationale

In this chapter, we outline the potential benefits of digital health interventions (DHIs) to support self-management of long-term health conditions and describe the implementation challenges in reducing the gap between the potential that DHIs can deliver and what is currently available to service users and carers. We then consider the specific example of long-term mental health problems, and make the case for the need to better support relatives who care for people with psychosis or bipolar disorder. Finally, we describe the design and development of the Relatives’ Education And Coping Toolkit (REACT) and its use in this study to explore the factors affecting its implementation within early intervention for psychosis (EIP) teams in NHS trusts across England.

Digital health interventions in the NHS

Recent decades have seen a significant increase in the development and use of DHIs to support health-care delivery. DHIs can be defined as programmes that provide support and treatment for physical and/or mental health problems via a digital platform or device, for example a website or an app (an application, typically downloaded by a user to a mobile device). The support provided can be emotional, decisional and/or behavioural. 1,2 Many are available directly to users through the internet or app stores, whereas others are designed to be offered as part of broader health-care packages.

In this study, we were interested specifically in the use of DHIs in supporting patients and relatives to self-manage long-term mental health conditions, although much of the rationale and learning are potentially generalisable to long-term physical health conditions. The prevalence of long-term health problems has increased as the population ages, and costs to public health services are substantial. 3 By supporting people to understand their condition better, identify factors influencing the severity of symptoms, spot early signs of relapse, adopt strategies to manage these early signs and learn when and where to seek help most effectively, it is argued that we can improve the quality of life of individuals and their families, and save public money. 4

The attraction of DHIs to support long-term conditions is easy to see. They offer the potential for widespread dissemination of high-quality, standardised care, accessible at the user’s convenience. Hence, they are particularly suited to rural areas and developing countries, where face-to-face service delivery can be very challenging but access to mobile technology is developing at pace. 5

Self-management interventions are designed to empower users, and digital delivery offers the added potential of uniting people online to share their experiences and harness the power of peer support. Although DHI development costs can be substantial, ongoing delivery is likely to be more cost-effective than face-to-face support.

Research evidence to support the feasibility, acceptability and effectiveness of DHIs in mental health is mounting. Data exist to support the short-term benefits of web-based psychological treatments for depression and anxiety disorders, compared with waiting list controls. 6,7 Online interventions are being rapidly developed for psychosis and bipolar disorder, where data support their feasibility and acceptability. 8–11 For these reasons, there has been a strong policy push to develop the UK’s digital health provision. 12

The implementation challenge

The successful implementation of DHIs in routine health-care services is far more limited than in research. Despite substantial investment in development, many DHIs are not adopted by their intended users, are abandoned, fail to scale up locally or spread to other settings, or are not sustained over time. The challenges can be systemic (i.e. difficulties in embedding an intervention in existing health services) or at the individual level, with low uptake levels among service users, although the two issues can be connected, for example if users feel that the intervention is not well supported by their health-care professionals.

Attempts to offer an online cognitive–behavioural therapy programme, Beating the Blues, at scale in UK mental health services13 and as part of routine care in the USA14 highlighted great difficulties in getting patients to use the programme or staff to integrate it into practice. In many ways, this is unsurprising; this is a relatively new field of enquiry and the process of change will inevitably take time. However, given the substantial implementation gap that still exists for non-digital health interventions,15 it is crucial that we do not assume that the transition from evidence to impact is inevitable. We urgently need to understand the main factors inhibiting the implementation of DHIs and use this understanding to better inform their design, evaluation, commissioning and delivery, and maximise their potential benefits.

This understanding should also mitigate the potential harm of inadequately tested DHIs, such as the increased risk of serious of breaches of confidentiality for personal and sensitive data;16 expensive information technology (IT) failures;17–19 potential increases in health inequalities;20 and lack of evidence-based commissioning, resulting in ineffective or harmful interventions being offered in clinical practice.

Psychosis and bipolar disorder

Psychosis is an umbrella term that covers many conditions, the common feature of which is a loss of touch with reality. The lifetime prevalence of a psychotic episode ranges from 5% to 7%, with the majority having only one episode. 21 Approximately 0.48% of the population develop more enduring mental health problems such as schizophrenia,22 which is estimated to cost the economy of England over £5B annually. 23

The most common manifestations of psychosis are believing things that are generally accepted to be untrue by other people (delusions); being unable to think clearly and so sounding muddled and confused (thought disorder); and experiencing things that are not really happening, for example hearing or seeing things that other people cannot (hallucinations).

Bipolar disorder is the third most common mental health cause of disability globally,24 affecting 1–4.5% of adults25 and costing the English economy £5.2B annually, largely due to inadequate treatment. 23 Bipolar disorder is characterised by episodes of extreme low mood (depression) and extreme high or irritable mood (mania or hypomania in its milder form). Self-harm and suicidal behaviour, excessive spending, sexual disinhibition and heightened irritability can all escalate during mood episodes, and psychotic symptoms are also more likely to occur. Between episodes, functioning may return to normal levels, but many people will continue to report problematic subsyndrome levels of depression that affect their functioning and relationships. 26

The need to support relatives

Relatives of people with severe mental health problems (primarily psychosis and bipolar disorder) provide the vast majority of care. This saves the NHS an estimated £1.24B per year in the UK,27 but is associated with high levels of distress in relatives;28,29 significant practical, financial and emotional burdens;30 stigma; worry; shame and guilt;31 trauma;32 and loss. 33,34

Factors that increase the negative impact of psychosis on carers include being a female carer;35 living with the person with psychosis; young patient age and awareness of the patient’s suicidal ideation;36 reduced social support and family resources;36,37 use of emotion-focused coping strategies;38,39 and the beliefs that relatives hold about psychosis, particularly about its cause and control. 40–42

The frequency of suicide attempts within the bipolar disorder population is higher than for many other populations affected by mental health issues, and this is a distressing situation for carers to manage. 43 During periods of mania, extravagant spending, irritability and inappropriate and disproportionate behaviour become more frequent and extreme. 44–46 The challenge of learning to cope with manic and depressive episodes can not only negatively affect the service user but also diminish the carer’s and their family’s quality of life, with carers expressing feelings of helplessness, anger and anxiety. 47,48

It is important to note that some relatives also report positive aspects of caring for someone with a severe mental health problem, including identifying personal strengths, feeling a sense of love, caring and compassion, developing new insights about their lives and living, and greater intimacy with others as a result of their journey of coping with mental illness. 49,50

Relatives of people with psychosis or bipolar disorder face many common needs. These include how best to support someone in their recovery journey; how to deal with a mental health crisis; how to manage difficult situations; how to manage stress; and how to understand and navigate mental health services and the treatments they offer.

Furthermore, mental health services are often structured such that people with a psychosis or bipolar disorder diagnosis are managed within the same teams (e.g. community mental health teams or EIP teams). Therefore, interventions to support relatives that work across these conditions make practical sense.

The Relatives’ Education And Coping Toolkit intervention

To examine in depth the major factors affecting the implementation of an online self-management toolkit for relatives of people with psychosis or bipolar disorder in UK mental health services, this study employed a multiple case study design and used the understanding gained to develop an implementation plan to support uptake and use. Through strategic use of theory to guide our data collection, analysis and interpretation, we aimed to ensure that the key factors identified, and the strategies needed to maximise successful implementation, would be generalisable to other DHIs offered within clinical teams.

The programme that formed the basis for this study was REACT, a supported self-management toolkit offered by EIP teams, providing easily accessible evidence-based information and support for relatives of people with psychosis or bipolar disorder as recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines. 51,52 It has been shown to be effective in reducing distress and improving perceived support and ability to cope in relatives of people with psychosis in EIP services. 53

A comprehensive recovery-focused toolkit, REACT was originally offered in paper form to relatives of people with psychosis, with telephone and e-mail support from ‘REACT supporters’ from the clinical team. It was subsequently made available online, and broadened to cover relatives of people with bipolar disorder,54 with online support from members of the clinical team via confidential direct messaging, and from other relatives through a restricted-access forum moderated by the REACT supporters.

REACT was designed to be offered by a non-professional support worker (or equivalent) currently working in an EIP team, as it does not require highly trained health professionals, but does require experience in supporting psychosocial interventions, availability and flexibility. Importantly, support workers are relatively inexpensive, reducing cost barriers to further implementation.

In the REACT trial, one NHS trust employed and trained relatives with lived experience of supporting someone with psychosis or bipolar disorder as REACT supporters for relatives across the UK. However, for this study, serving EIP staff within each individual trust were given this role, identifying the most appropriate supporters (professional or non-professional), based on available staff resources and structure.

REACT supporters were trained for the role using standardised training materials provided online by the research team as part of our initial implementation plan. REACT contained 12 key modules, each consisting of high-quality standardised written information, videos of clinical experts or experts by experience sharing their knowledge and experiences to illustrate key points, and self-reflection tasks to ensure that content was personalised to the user. All videos of relatives telling their own stories were retold by actors to preserve anonymity. The modules included What is Psychosis?, What is Bipolar Disorder?, Managing Positive Symptoms, Managing Negative Symptoms, Managing Mood Swings, Dealing With Difficult Situations, Managing Stress (Doing Things Differently), Managing Stress (Thinking Differently), Understanding Mental Health Services, Treatment Options, Dealing With Crises and The Future.

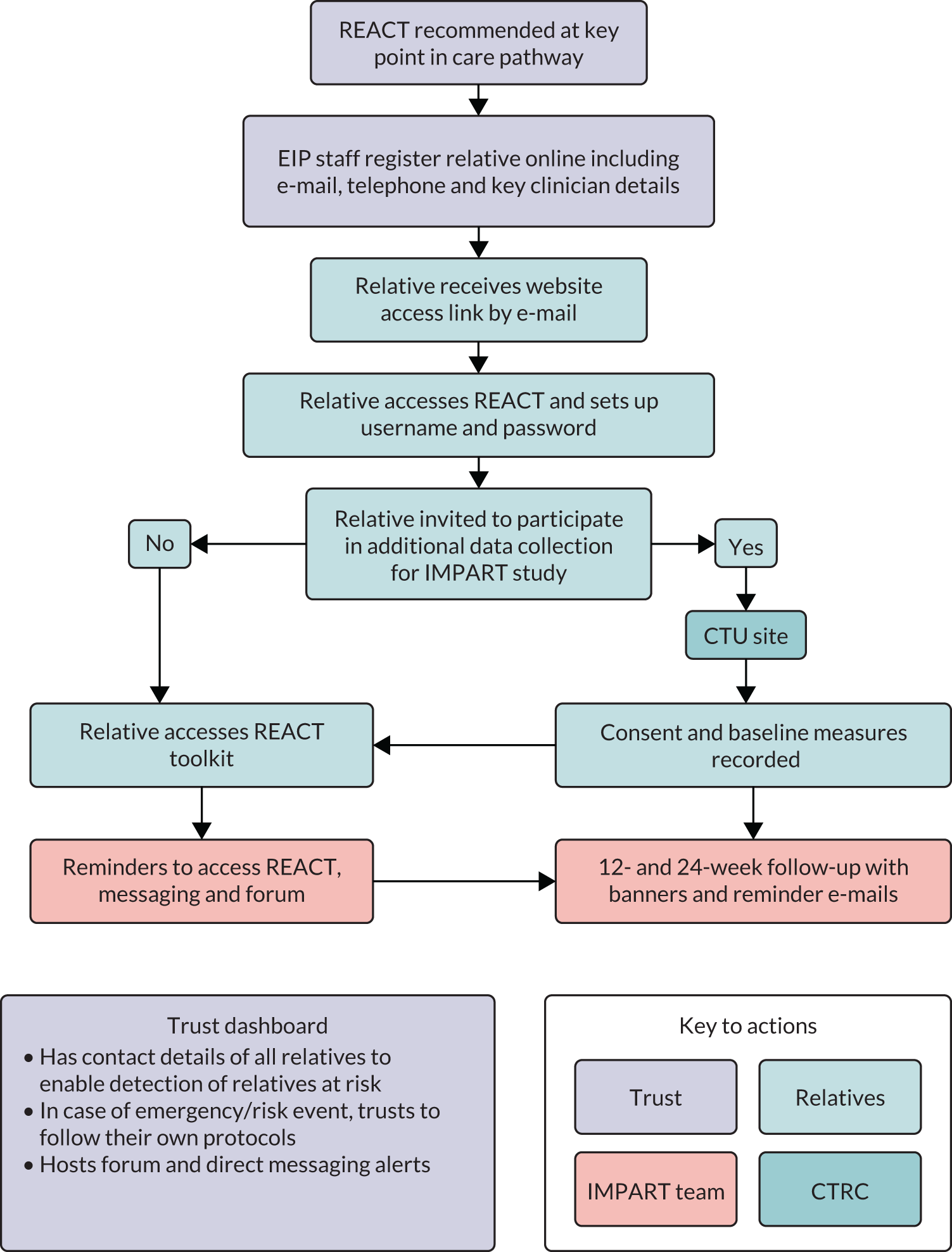

Figure 1 is a screenshot of the home page, which outlines the modules. A full description of each is given elsewhere. 55 REACT also includes a resource directory that signposts users to a wide range of relevant national and local resources. A ‘meet the team’ page ensures that relatives are fully informed about who is delivering the content of the website. Logos for the relevant NHS trust, Lancaster University, Lancashire Care NHS Trust, University College London (UCL), Liverpool Clinical Trials Research Centre (CTRC) and the McPin Foundation are prominently displayed on the log-in page. ‘Mytoolbox’ offers users a confidential space to save links to any information sources they may want to access easily in future, including specific content within the toolkit, their self-reflection tasks and external web links. A blog page offers a flexible space for additional communication with website users, which can be edited by REACT supporters. Each of the participating trusts could edit some elements of the toolkit to allow limited tailoring to their location or to a particular organisation (Table 1).

FIGURE 1.

Screenshot of the REACT toolkit homepage, showing modules and features. Reproduced with permission from Lobban et al. 56 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original.

| Editable function | Description |

|---|---|

| Logo | |

| Meet the team | Introduces the trust staff including the IMPART lead and REACT supporters |

| Emergency contact information | REACT is not a crisis intervention and so directs relatives to appropriate crisis support |

| Availability and contact e-mail addresses for REACT supporters | Hours available and how often the forum and direct messages are checked to manage expectation |

| Resources directory | Staff can edit the content to ensure that local knowledge is captured and shared |

| Forum welcome message, rules of use and suggested topic areas for discussion | This is an opportunity to introduce the forums and mention any particular rules, monitoring times or anything else appropriate |

Context: early intervention for psychosis teams

This study investigated the implementation of REACT within EIP teams in NHS mental health trusts: REACT was offered online and supported by a member of the EIP team.

Early intervention for psychosis teams are part of public sector clinical services in England, providing localised early intervention (EI) support to people with early signs of psychosis and/or other severe mental health problems (including bipolar disorder). Depending on the size of the NHS trust, there may be also be further embedded units, delivering care to distinct geographically defined areas.

Early intervention for psychosis teams were established to deliver care in line with NICE guidelines51 to people during the ‘critical period’ of the first 3 years following the onset of psychosis, and to reduce the duration of untreated psychosis, which has been shown to predict long-term outcomes. 57 Most teams work with people who have developed symptoms of psychotic illness for the first time for up to 3 years following their first contact with services (specific criteria vary between services). In the UK, EIP teams generally consist of a mix of psychiatrists, psychologists, care co-ordinators (social workers, community psychiatric nurses, occupational therapists) and support workers.

Although EIP services have not been immune to the funding challenges faced by all mental health services in the UK,58 they have received additional funding to facilitate the implementation of NICE guidelines and to meet the access and waiting time (AWT) standards for mental health services59,60 published in 2015 and mandated from April 2016. These standards required EIP teams to deliver eight standards, two of which were:

Where patients are in contact with their families, family members to be offered family intervention (FI).

Carers to receive focused education and support.

However, a national audit of EIP teams in England in 2016 showed poor implementation. 61 Of most relevance to this study, only 50% of relatives received a carer-focused education and support programme, and only 31% were offered structured family intervention, with only 12% receiving it. 61 Offering REACT was expected to help services to be compliant with the NICE Quality Standards for both psychosis (NICE Quality Standard 8062) and bipolar disorder (NICE Quality Standard 9563) by offering carers access to an education and support programme. Specifically, the guidelines recommend that carers are given written and verbal information in an accessible format about the diagnosis and management of psychosis and schizophrenia, positive outcomes and recovery, types of support for carers, role of teams and services, and getting help in a crisis.

When providing information, carers should be offered support if necessary. Importantly, REACT was not designed to replace structured face-to-face family interventions.

Relevant previous and parallel research

REACT was itself developed as part of a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Research for Patient Benefit-funded study to design and test the feasibility and acceptability of a self-management toolkit to support relatives of people with psychosis. 64 This involved a systematic review of the literature to identify the key components of interventions that were effective in improving outcomes for carers;65 focus groups with relatives to understand their experiences and what they want from a support intervention;66,67 and a feasibility trial to determine the acceptability of the intervention, preference for type of support, rates of recruitment and retention, and an estimate of the likely effect size on a range of outcomes for relatives. 53

Initially, REACT was offered as a series of paper booklets, supported by a support worker in an EIP team by e-mail or telephone. To increase accessibility, it was developed into an online intervention, and a clinical and cost-effectiveness trial was funded by NIHR under its Health Technology Assessment efficient design call for randomised controlled trials (RCTs) that tested efficient trial designs that could help address the problem of growing costs of large-scale definitive trials. 68

This funding offered the opportunity to test the online REACT intervention in an entirely online trial. REACT was offered nationally online, with REACT supporters drawn from trained relatives with lived experience of supporting someone with psychosis or bipolar disorder. The aim was to test the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of REACT. Funding was awarded for 36 months with a start date of October 2015. The results of the trial have not yet been published.

In parallel, we secured funding for this study through the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research funding stream. 69 The aim was to identify the factors affecting the successful delivery of an online intervention within EIP services. In this study, REACT was offered online within a series of NHS trusts, supported by staff in the trusts’ EIP teams. Although the IMPlementation of A Relatives’ Toolkit (IMPART) study included baseline and follow-up measures of outcomes for relatives, it was not designed to test clinical effectiveness, as there was no control group that was not receiving the intervention. The focus of this study was on understanding the process of implementation. This study was funded for 30 months from March 2016.

The two studies were complementary and used the same measures and follow-up period, giving the potential to compare both the reach and the outcomes achieved by providing REACT in these very different ways. This allows us to answer questions about which is likely to be the most effective service provision model, and to compare the effectiveness of peer- and clinician-supported approaches.

Research team

Our team included UK-based relatives, clinicians [clinical psychologists, psychiatrists, general practitioners (GPs)], academics, statisticians and health economists, with a common interest in developing and evaluating new ways to support people with mental health problems and their relatives. The team in its entirety came together specifically for this project. Although team members varied in background, training, epistemological and ontological stance, some important factors underpinned their successful collaboration:

-

a commitment to improving the lives of people with mental health problems and their relatives in non-stigmatising, empowering and recovery-focused ways

-

a recognition of the invaluable role that relatives play in supporting people with mental health problems, and the current lack of adequate support available to them

-

an interest in ensuring that evidence-based health care is delivered to service users and carers appropriately and in a timely fashion

-

an interest in the challenges of implementation of complex interventions into complex organisational systems

-

a commitment to identify efficient ways to carry out publicly funded research to provide value for money to the UK taxpayer.

The research was made possible by the involvement of our six participating NHS trusts. To ensure openness and transparency during data collection, we agreed to keep data confidential and to anonymise the trusts and individual participants. The six trusts were therefore allocated common bird habitats as pseudonyms, and the teams within them were named after birds likely to live within this habitat (thank you to Professor William Sellwood for this ornithological expertise).

Liverpool CTRC was extremely helpful in supporting this study. Although not funded directly, the centre supported the consent and data collection processes. It had built an online data collection infrastructure as part of the Health Technology Assessment-funded REACT trial, and adapted this for the purpose of this study.

Study management and oversight

Project Management Group

The initial Project Management Group (PMG) consisted of the grant holders who were responsible for developing the study ideas and delivering the project. This group included a relative who had spend many years supporting a family member with a diagnosis of schizophrenia (SF); two clinical academic psychologists (FL and SHJ) based in Lancaster; a clinical academic psychiatrist with a lead role nationally in EIP services (SJ) and a clinical academic GP who is director of an eHealth centre at UCL (EM); a trial statistician (CJS); a consultant clinical psychologist with a lead role in development and roll-out of EIP services (JS); the director of the McPin Foundation, which promotes service user involvement in research (VP); an internationally acclaimed expert in implementation theory and practice (JR-M); and a clinical lead for EIP teams in a local NHS trust (RS). The group met monthly via teleconference.

Additional members of the operational team based mainly in Lancaster evolved to include a lecturer in mental health with a special interest in implementation (and who joined the PMG) (NRF); two carer researchers; an IT developer (AW); five research associates over the lifetime of the project (VA, BG, EL, CM and PO); an individual who provided administrative support (BM); and two trainee clinical academics in psychiatry (GA-A) and clinical psychology (JB). They all met weekly in relation to specific tasks throughout the project and attended the PMG as required. Research associates based at the London site joined this operational meeting via teleconference.

Study Steering Group

A Study Steering Group (SSG) was appointed to oversee the project on behalf of the project sponsor (Lancaster University) and project funder (NIHR) and to ensure that the project was conducted to the rigorous standards set out in the Department of Health and Social Care’s Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care70 and the Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice.

The group was chaired by a clinical academic and expert in the delivery of mental health interventions in the NHS (Professor David Kingdon) and included a service user or relative (this role was occupied by three people throughout the course of the study), a senior clinical academic with relevant methodological expertise in health service research, a senior NHS manager in EIP services and a representative of Lancaster University as sponsoring organisation. The SSG met before the start of the study, at the end of the pilot phase and then annually until the end of the study. All meetings took place via teleconference.

Patient and public involvement strategy

The project was designed to involve relatives at every stage and level of decision-making. The funding bid was developed with a carer who had been involved in the original REACT toolkit evaluation and who was a co-applicant on this grant. Roles were designed and costed on the independent SSG for two patient and public involvement (PPI) experts. A co-ordinating agency (the McPin Foundation) was appointed to lead on the PPI programme, drawing on experience from other studies and their involvement in the development of the original REACT toolkit. We anticipated that involving relatives would improve the delivery of the project and the experience of relatives in the research process, and ensure that findings were more effectively disseminated. PPI involvement and a reflection of the challenges around PPI are given in Appendix 1.

Chapter 2 Aims, design and theoretical frameworks

This chapter sets out the overarching aims and objectives of the study. It describes the overall design and theoretical frameworks on which the study builds. The study is set out in three phases, the detailed methods and results of which are outlined in Chapters 3–7.

A full protocol56 for the study was published early in the study process following the guidance provided by the Standards for Reporting Implementation Studies (StaRI) statement. 71

Overall study aims and objectives

The overall aims of the study were to identify critical factors affecting the implementation of an online-supported self-management intervention for relatives of people with recent-onset psychosis or bipolar disorder into routine clinical care, and to use this information to inform an implementation plan to facilitate widespread use and inform wider implementation of DHIs.

The objectives were to:

-

measure the uptake and use of REACT by NHS EIP teams and relatives

-

identify critical factors affecting implementation of REACT

-

identify resources required (and cost implications) for successful implementation of REACT in EIP teams

-

investigate the impact of REACT delivered by EIP teams on relatives’ self-reported outcomes

-

develop a user-friendly REACT implementation plan and related resources to facilitate widespread use and dissemination

-

use the findings from this study to further develop theories of implementation of digital interventions in real-world practice.

Study design

This study used a theory-driven multiple case study design,72 taking a mixed-methods approach that integrated quantitative assessments of outcome (delivery, use and impact of REACT) and qualitative assessments of the mechanisms of implementation through observation, document analysis and in-depth interviews. The study was theoretically informed by normalisation process theory (NPT)73 and the non-adoption, abandonment, scale-up, spread and sustainability (NASSS) framework. 74

Our cases were six NHS trusts in England. Case studies can be particularly useful when trying to understand the implementation of a complex intervention in a real-world setting in which the process or context cannot be controlled. REACT was a ‘complex intervention’75 because it depended on the actions of individuals across different contexts and individuals adapting their behaviour over time. The intervention also produced multiple outcomes that needed to be understood. Implementation was made more complex by the dynamic context in which the intervention was situated, with competing demands on the system. A mixed-methods approach bringing together quantitative and qualitative assessments was therefore required to understand this complexity.

We also designed the study to have extensive input from stakeholder groups at each trust to ensure that the implementation plans were collaboratively designed and refined.

Theoretical frameworks

The IMPART study was theory driven while remaining strongly embedded in practice. Theory helped to guide our data collection and to frame our analysis, ensuring that we were drawing on previous learning about what was likely to be important, but also contributing our findings to a body of knowledge that could inform other studies.

However, we were careful to use theory only where appropriate, and actively seek data that did not fit our theoretical frameworks. There were many models, frameworks and theories that we could have used to guide our work and ensure that our findings could be interpreted within a theoretical framework that supported their potential to be generalised. 76 Our aim was to choose those frameworks that were most appropriate for each of our aims and the context in which this work took place.

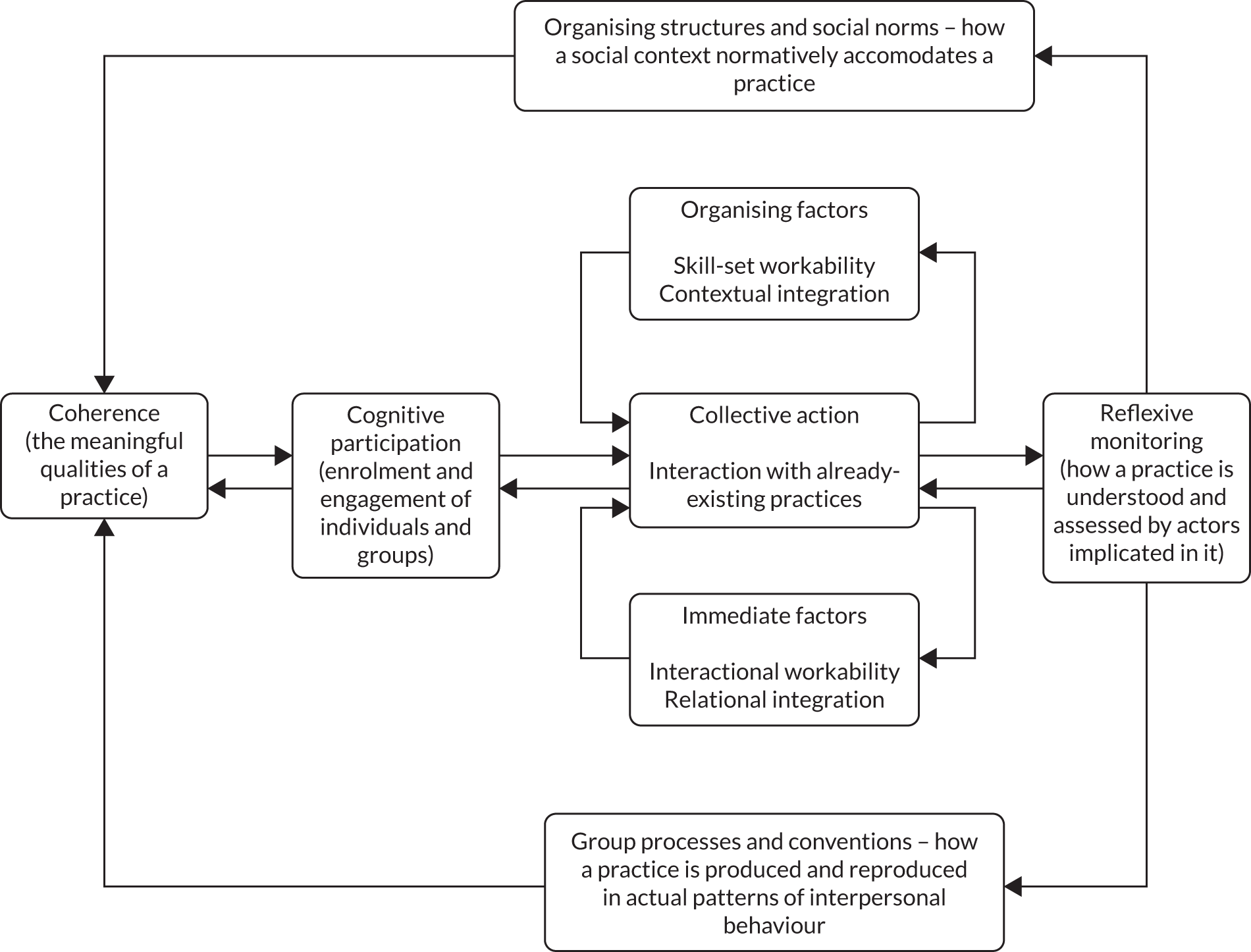

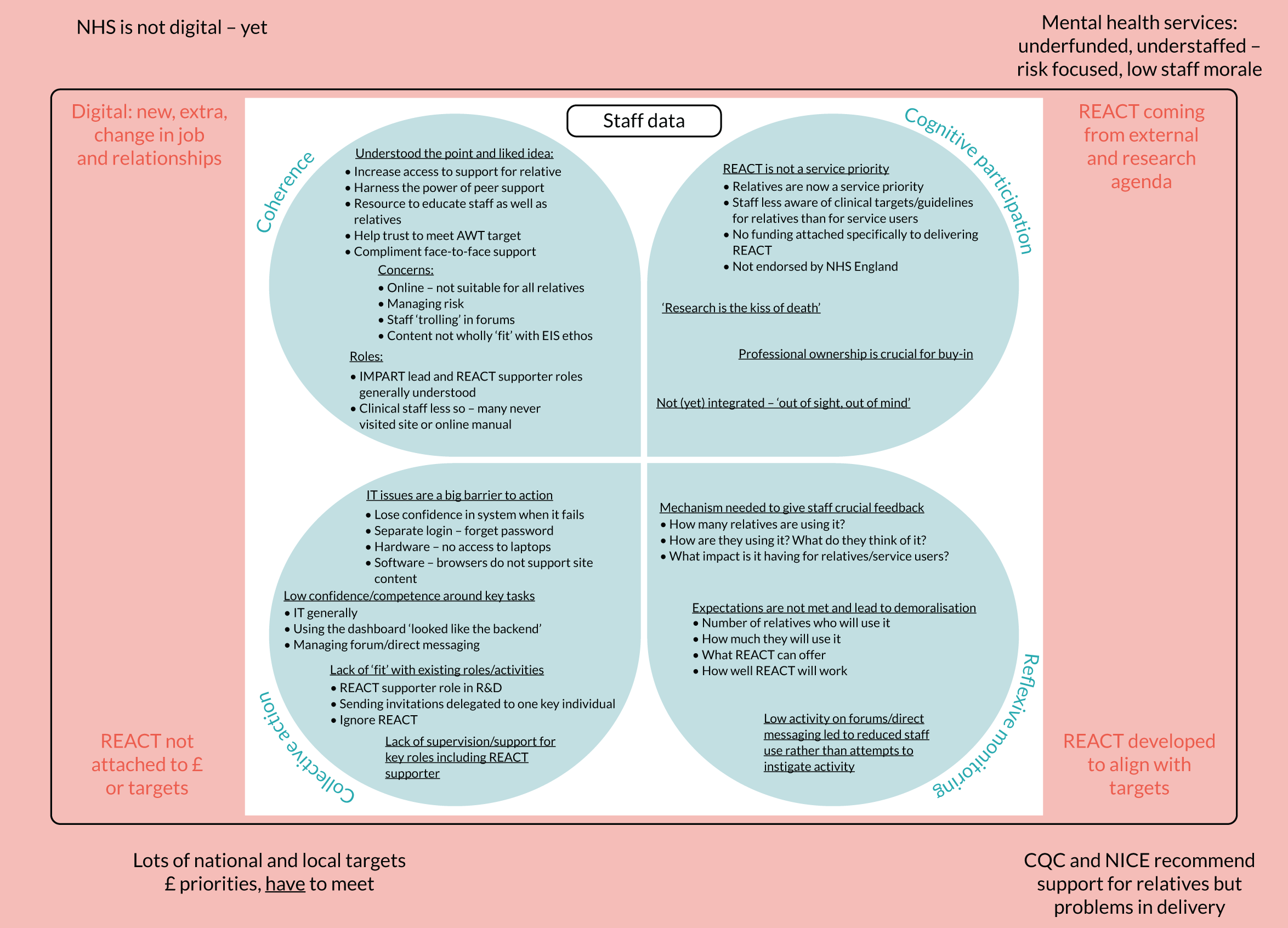

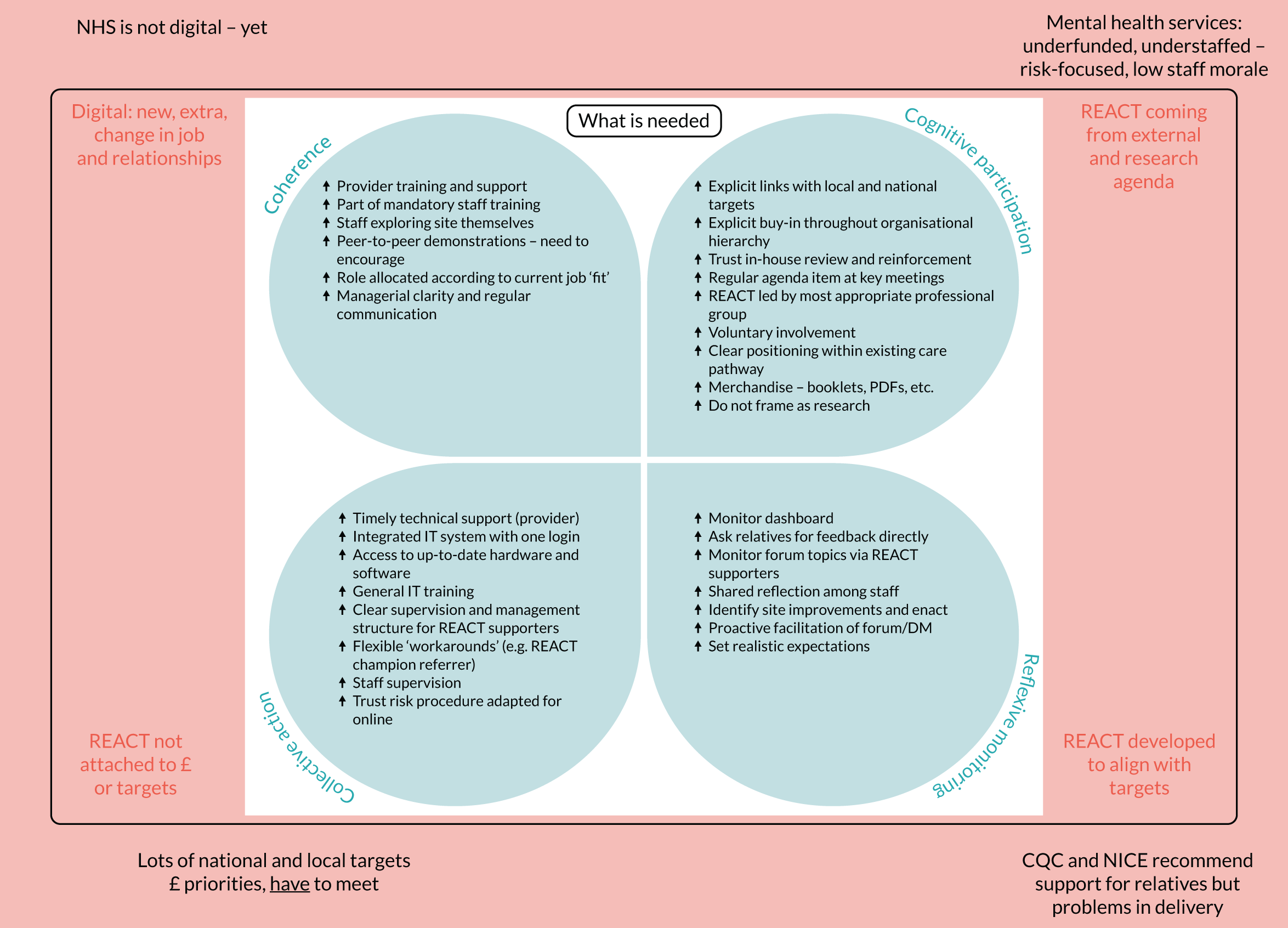

Normalisation process theory is a theory of action that focuses on a person’s actions rather than individual attitudes and beliefs (www.normalizationprocess.org; accessed 6 December 2019). NPT began as a model (normalisation process model) of the factors that promote or inhibit the routine work of embedding a new health technology into practice. The key constructs identified were interactional workability, relational integration, skill-set workability and contextual integration. The model has since been developed into a theory that includes the normalisation process model as constituting ‘collective action’ and adds concepts of ‘coherence’ (how actors make sense of a set of practices), ‘cognitive participation’ (the means by which they participate in them) and ‘reflexive monitoring’ (how these practices are then appraised). 77 Each construct represents a generative mechanism of social action. That is, each construct represents the different kinds of work that people do as they work around a set of practices, whether these are a new technology or the trial of a complex intervention (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Model of the components of NPT. Reproduced from May C, Finch T. Implementing, embedding, and integrating practices: an outline of normalisation process theory. Sociology 43(3), pp. 535–54. 73 Copyright © 2009 by BSA Publications Ltd. Reprinted by permission of SAGE Publications, Ltd.

Normalisation process theory is concerned with three core problems:

-

Implementation – the social organisation of bringing a practice or practices into action. This is defined as a pattern of organised, dynamic and contingent interactions in which individuals and groups work with a complex intervention, within a specific context or health system, over time.

-

Embedding – the processes through which a practice or practices become (or do not become) the routine everyday work of individuals and groups.

-

Integration – the processes by which a practice or practices are re-enacted and sustained among the social matrices of an organisation.

Normalisation process theory was chosen for use in the IMPART study for several reasons. First, NPT focuses specifically on the work carried out by staff to understand the process by which a complex health-care intervention is implemented, embedded and integrated (or not), and as we anticipated that more of our data would come from talking to staff, this matched our focus of concern. Second, NPT is a formal theory and, as such, facilitated the development of testable hypotheses in phase 1 of the study to help focus the collection and analysis of data in phase 2. Third, NPT has clear implementation constructs and a website with clear guidelines on understanding and guiding the implementation process. This allowed all members of the multidisciplinary team to learn about the theory independently (as well as within the group) and ensured a clear reference point for those working with the data and the coding framework. Finally, NPT has also been extensively applied in eHealth settings,78–80 allowing us to more easily compare our findings with previous studies.

Normalisation process theory proved a very useful model for guiding our collection and analysis of data from staff working in EIP teams. However, it was not easily adapted to help understand the experiences being offered by REACT or the wider context in which staff were operating. Both of these were essential to building an explanation of the implementation of REACT. To integrate our findings across all elements of the study, we therefore drew on the NASSS framework,74 which aims to help predict and evaluate the success of a technology-supported health or social care programme.

The NASSS framework was developed from an extensive systematic review of previous technology implementation frameworks, and a series of six empirical case studies, each testing a different type of technology-supported programme (e.g. video consultations, pendant alarm systems, care organising software) in different health-care settings. The framework outlines seven key domains that are important to consider in determining the success of implementation: the condition or illness, the technology, the value proposition, the adopter system (staff and patients/relatives), the organisation, the wider social context and the evolution (interaction and mutual adaptation) of these domains over time.

The NASSS framework was published after the study protocol was funded and, therefore, did not inform the study at the outset. However, while conducting data analysis and interpretation, we found that it provided a useful framework for explaining the findings as a whole. Therefore, the domains from the NASSS framework were used to structure and present our findings in Chapter 8. A diagram of the framework is presented in Chapter 8 (see Figure 19).

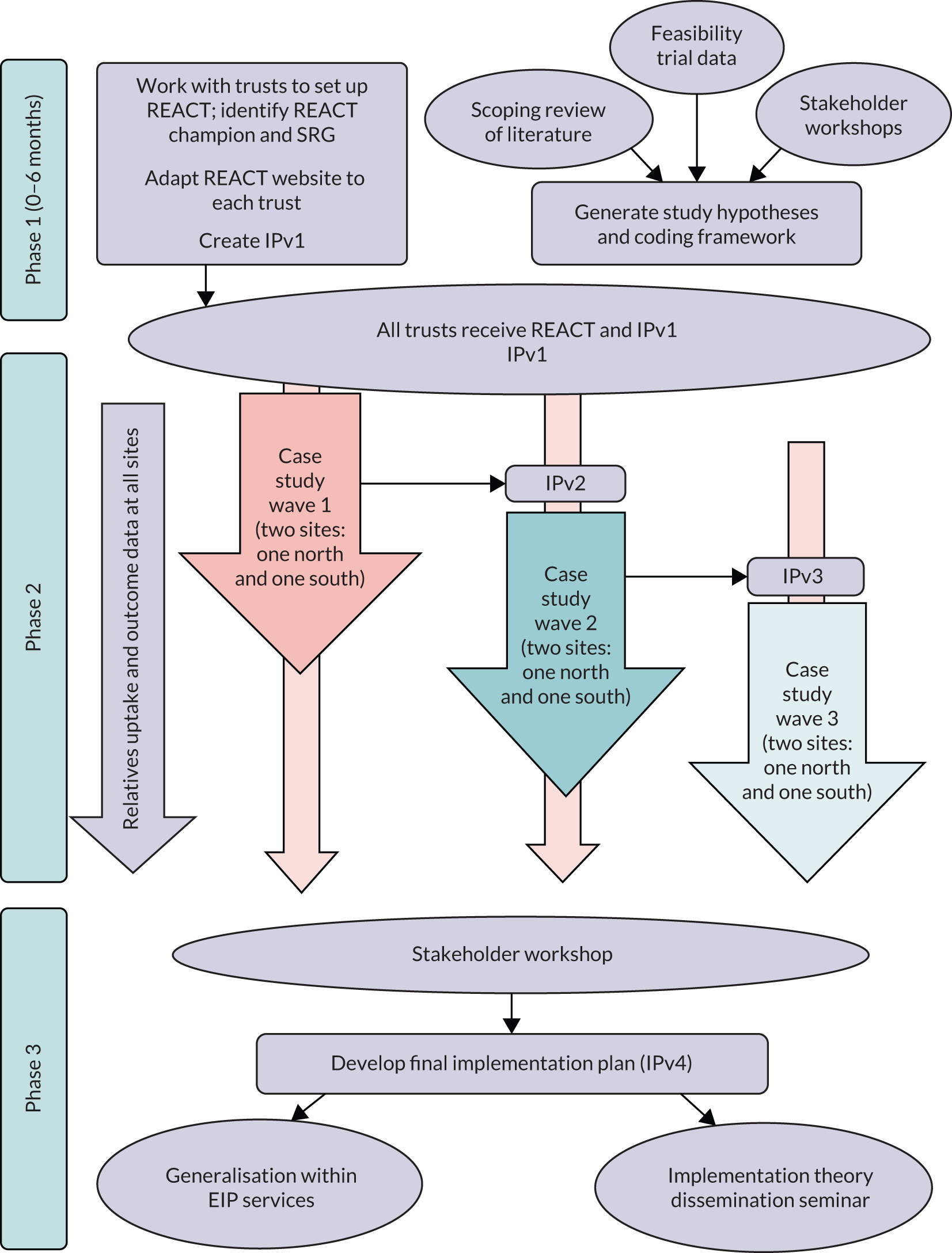

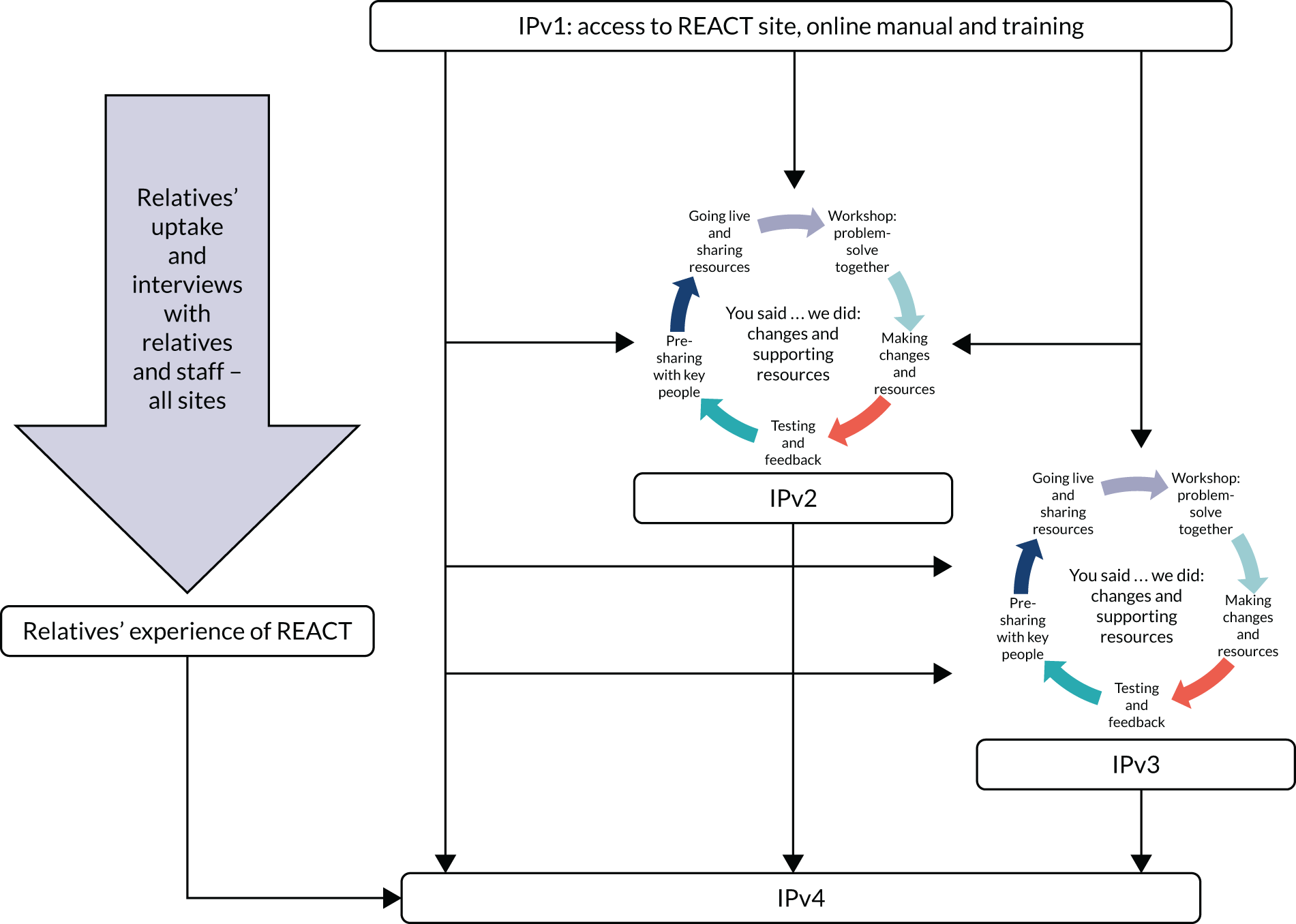

Three phases of the IMPART study

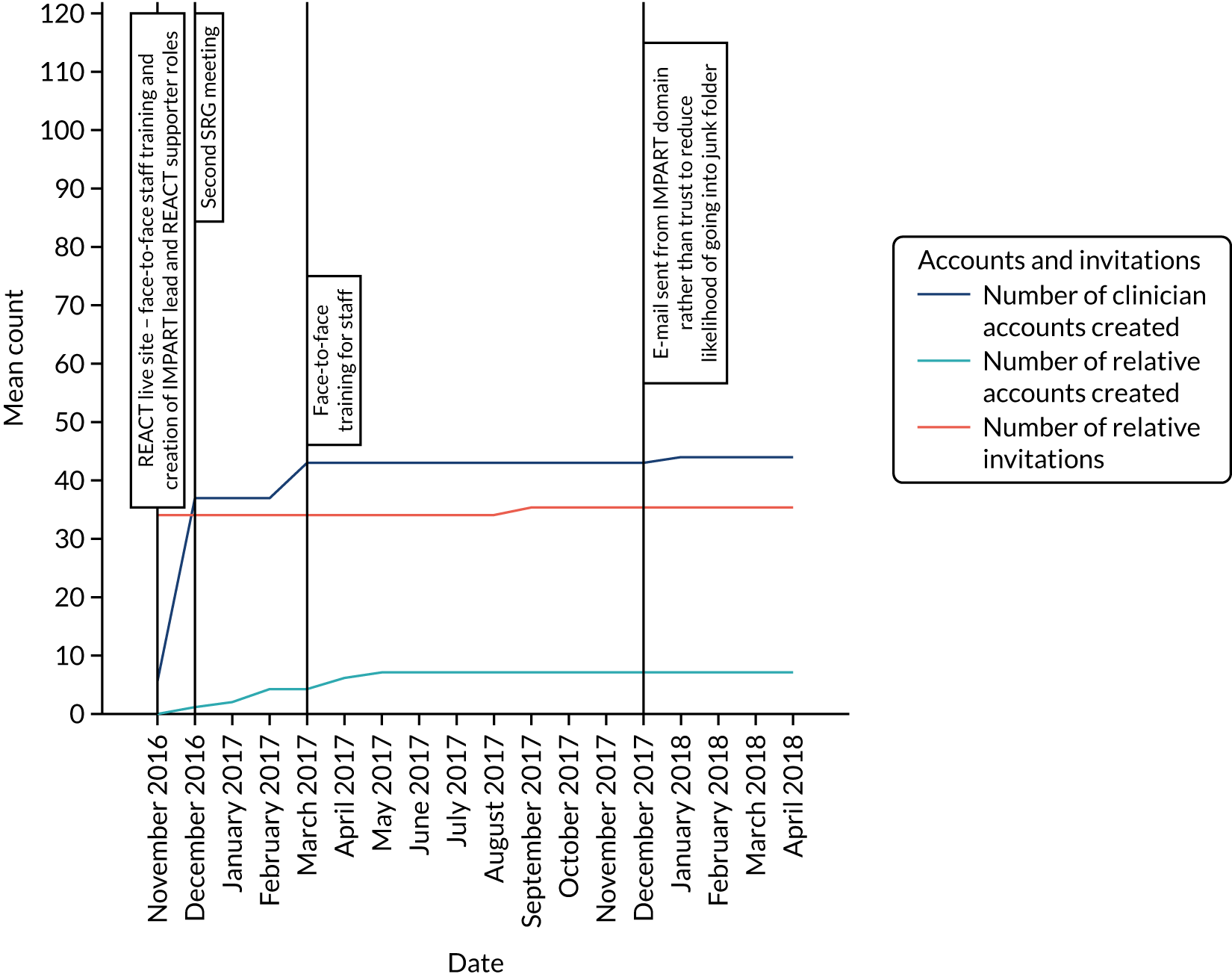

We used our iterative case study design flexibly, adapting our approach in response to activity on the ground. While maintaining a focus on specific trusts at each time point, we maintained good links with all trusts and listened to what was happening at each. The study was divided into three phases. The design is shown in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Flow chart showing the design of the IMPART study. IPv, implementation plan version; SRG, stakeholder reference group. Reproduced with permission from Lobban et al. 56 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original.

Phase 1: hypothesis generation

In phase 1, we outlined an implementation theory identifying the factors that we hypothesised would influence successful implementation of REACT and how they would lead to successful outcomes. Our study theory was informed by NPT, with specific hypotheses further informed by:

-

a systematic review of relevant implementation studies of DHIs for people with psychosis or bipolar disorder and/or their relatives to identify factors affecting implementation81

-

qualitative analysis of data relevant to implementation from the REACT feasibility trial,53 including interviews with EIP staff who have worked as REACT supporters and relatives who used REACT

-

stakeholder workshops including staff and relatives at each participating trust

-

synthesis of these data informed by our clinical and theoretical expertise in this area.

Phase 2: hypothesis testing

In phase 2, we used a case study design to test our hypotheses about which factors would influence the implementation of REACT. We developed an implementation plan to address these factors, and made it available in successively more developed forms across three waves.

Phase 2 was conducted across two geographical regions (North of England and South of England), with three NHS trusts participating in each. All six trusts were given the REACT toolkit and initial implementation plan [implementation plan version (IPv) 1] at the start of phase 2. The implementation plan included an online manual of detailed instructions outlining roles and responsibilities for key staff implementing REACT and face-to-face training sessions within each trust. Guidance for relatives on using REACT is embedded within the toolkit.

We collected detailed case study data in two of our participating trusts (one in each region) as wave 1. Key factors affecting implementation were identified and then discussed with stakeholders in the two trusts in wave 2. The research team worked collaboratively with these stakeholders to design IPv2 in these trusts. Further data were collected to test the impact of this and to identify additional factors affecting implementation. A third iteration (IPv3) was then developed with staff in the final two wave 3 trusts. Data from this wave, combined with ongoing longitudinal data from the four trusts in waves 1 and 2, informed the final version (IPv4).

Phase 2 required a mixed-methods approach, in which we collected quantitative data to describe the levels of implementation and outcomes within each trust, and qualitative data to identify the key factors that could explain these patterns of implementation. Consistent with the case series design, our data were first analysed within each trust before we attempted to analyse and explain similarities and differences between trusts.

The methods are described in detail in Chapter 4, and the design and objectives are summarised in Table 2.

| Objective | Data collected |

|---|---|

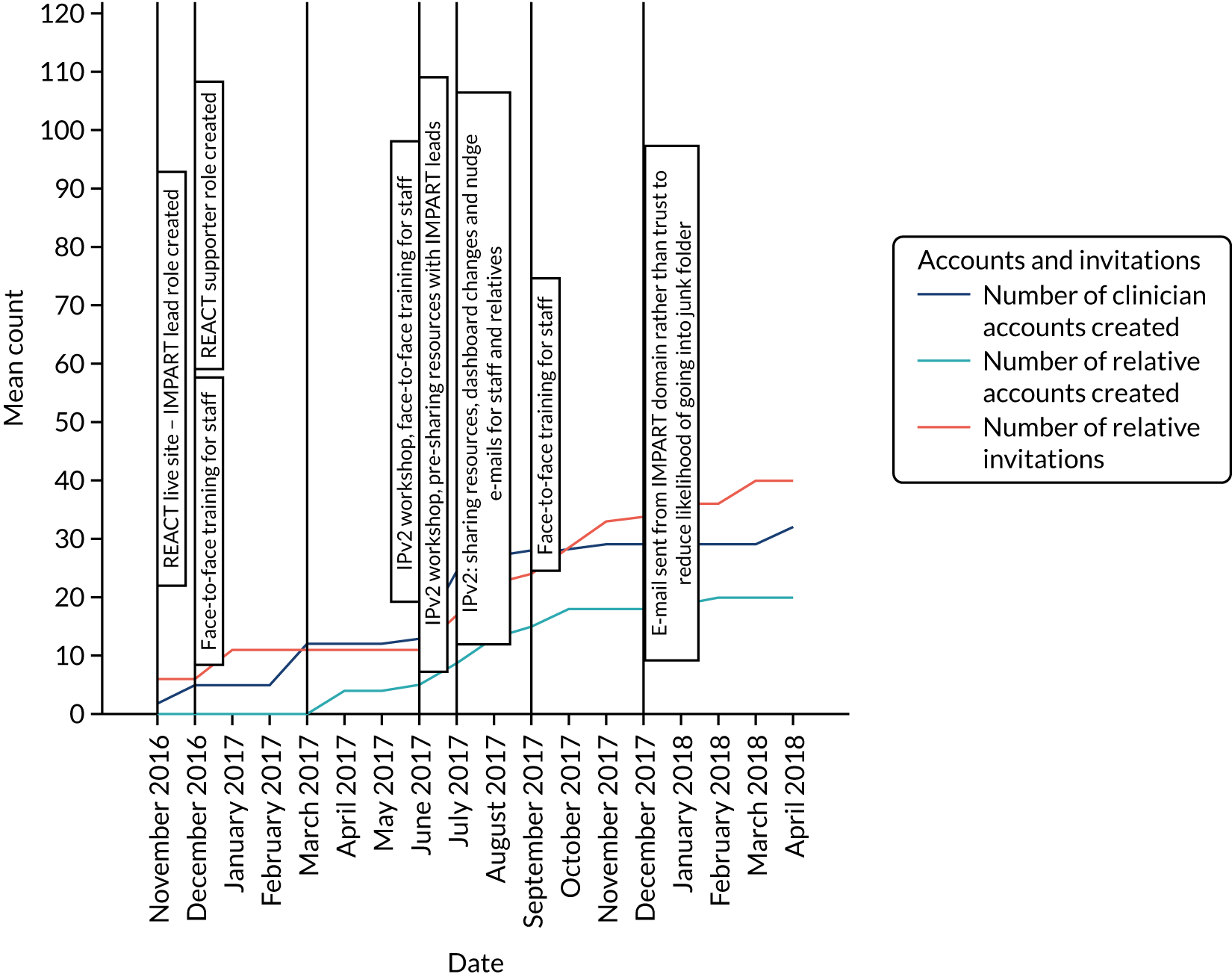

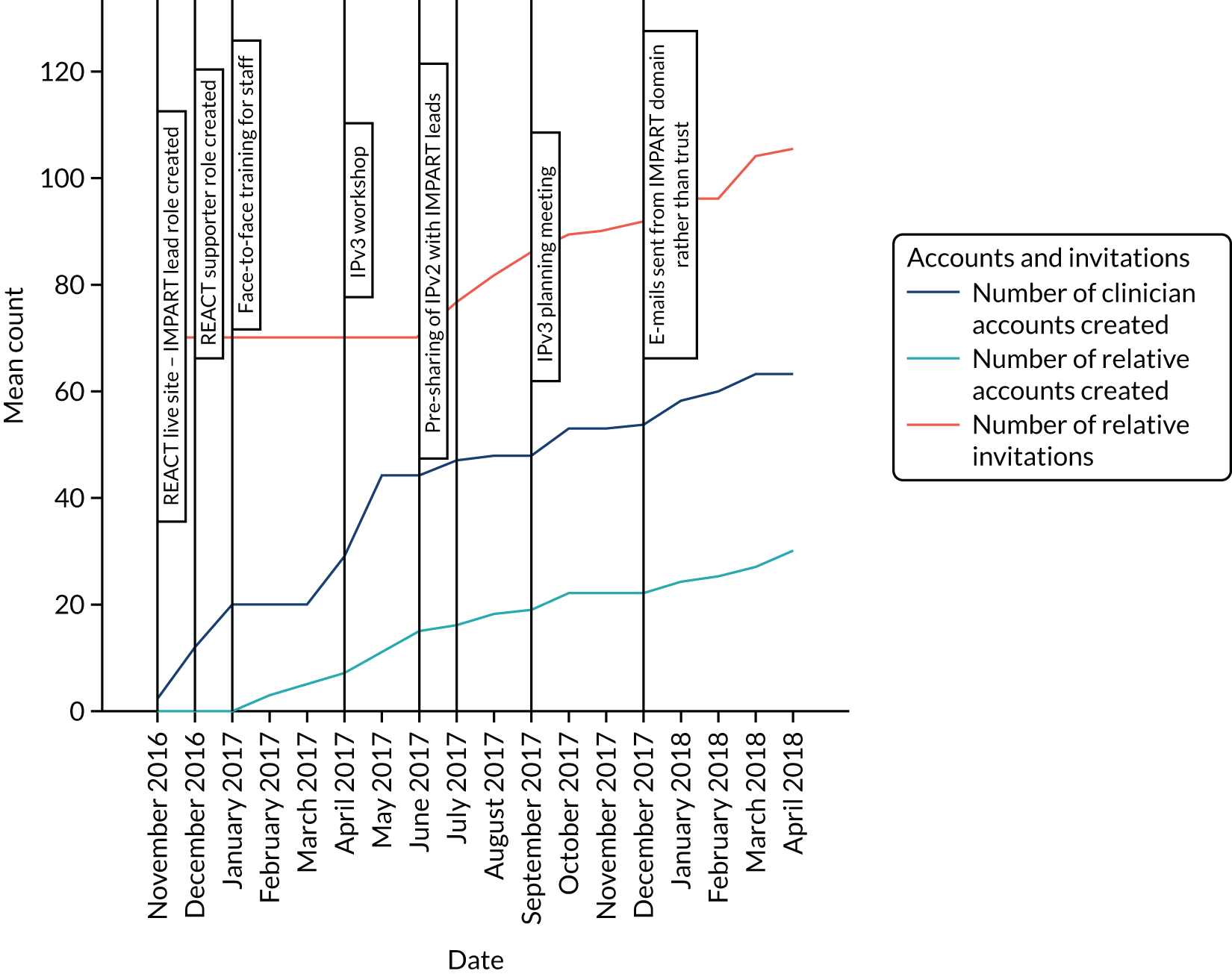

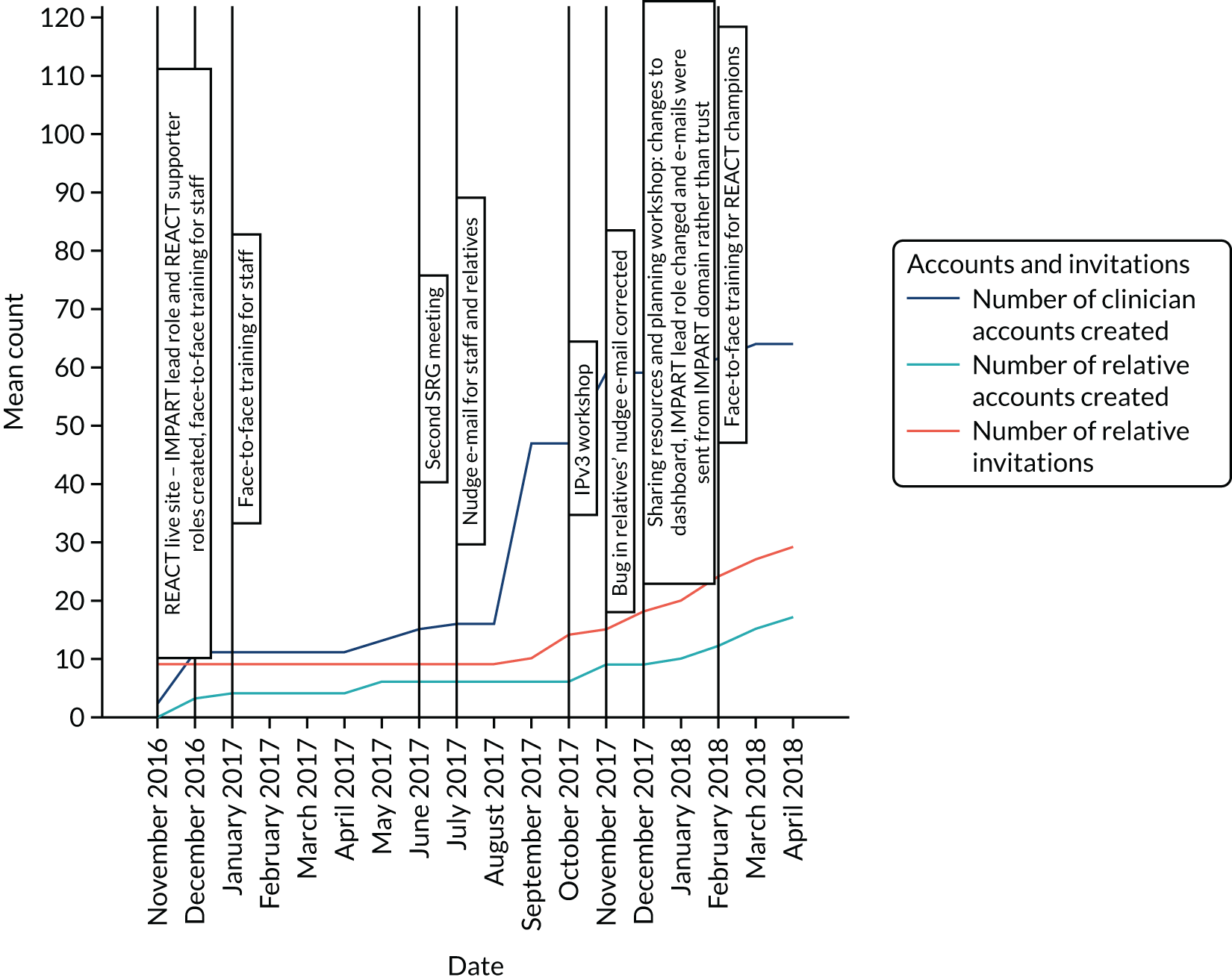

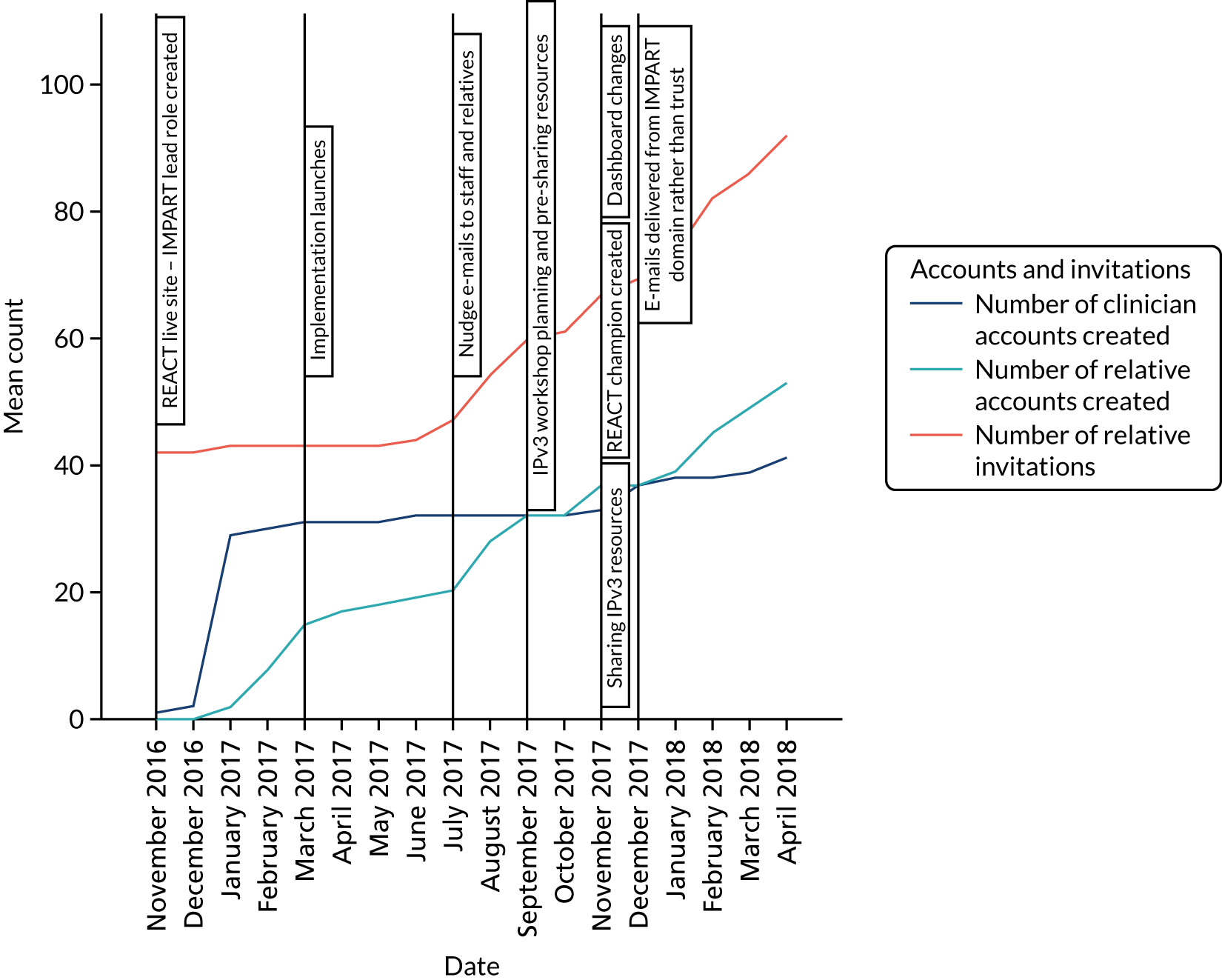

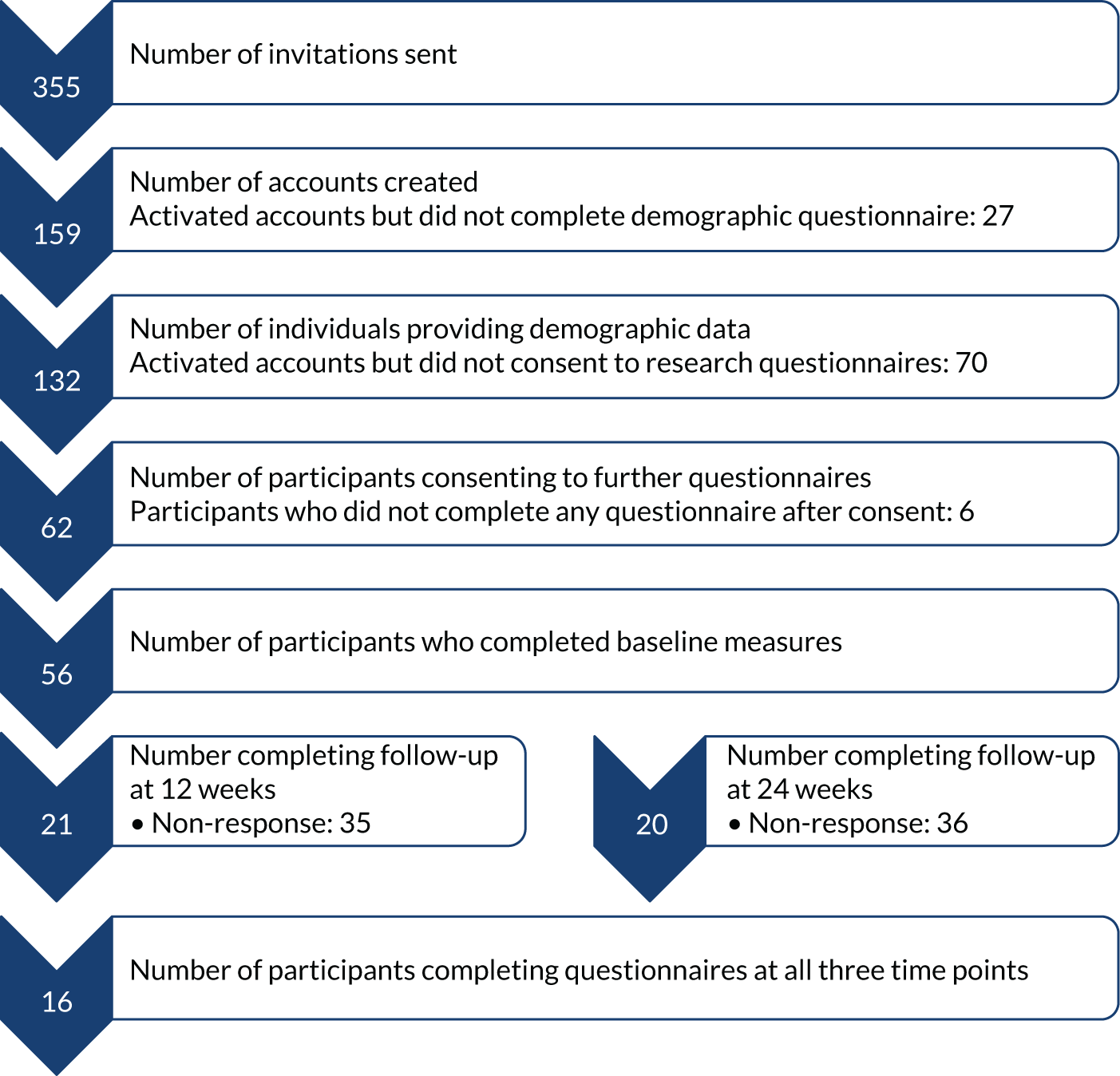

| Measure uptake and use of REACT by NHS EIP teams and relatives |

Number of clinician accounts created (quantitative) Number of relatives invited to use REACT (quantitative) Number of relative accounts active (quantitative) Levels of use of REACT by relatives (quantitative) |

| Identify resources required (and cost implications) for successful implementation of REACT in EIP teams | Online resources survey completed by staff at end of phase 2 (quantitative) |

| Investigate the impact of REACT delivered by EIP teams on relatives’ self-reported outcomes | Questionnaires assessing distress, well-being, quality of life and eHealth literacy, completed by relatives online at first use of REACT and at 12 and 24 weeks’ follow-up (quantitative) |

| Identify critical factors affecting implementation of REACT |

Stakeholder reference groups (qualitative) Interviews with key stakeholders including staff and relatives (qualitative) Document analysis (qualitative) Meeting observations (qualitative) |

Developing the implementation plans

In this study, we have used the term ‘implementation plan’ (or sometimes ‘implementation strategy’ or ‘implementation intervention’) according to the definition by Proctor et al. 82 to refer to a wide range of ‘methods or techniques used to enhance the adoption, implementation, and sustainability’ of an intervention (in this case, REACT). Implementation strategies have been widely reported in the literature across a wide range of contexts, interventions, and user groups, but identifying what is likely to work for whom, in what context and in relation to a specific intervention remains a challenge. Attempts have begun to meet this challenge, with the development of taxonomies to define and classify the array of strategies to facilitate further testing (e.g. Powell et al. 83 and Leeman et al. 84). Although offering helpful suggestions, this work did not yet help us to identify the best strategies to implement REACT. Therefore, we relied on a pragmatic analysis of our data from phase 2, and the NPT framework, to guide our successive versions of the implementation plan.

To develop successive implementation plan iterations in a time frame to suit the project and the needs of trusts, we needed the agility to make sense of the ‘bigger picture’ and then develop, implement and evaluate each new iteration. As far as possible, this was linked to specific data sources (interviews, workshops, documents and meeting observations) but did not rely on a full thematic analysis or coding of transcribed data, which would have been unfeasible in the time available. Regular multidisciplinary research team meetings and stakeholder reference group (SRG) meetings within the trusts ensured that this analysis remained grounded in the data. This was referred to as ‘level 1 analysis’, and is distinguished from level 2 analysis, which was much more detailed and involved coding of interview, document and meeting data using a framework analysis85 informed by NPT and our study hypotheses generated in phase 1.

We did not use NPT to guide our data collection or analysis with relatives, although we did consider this. Although the NPT framework could be usefully adapted to accommodate the very important role of the service user in delivering complex health-care interventions, we felt that this was beyond the scope of the study. We therefore approached our data more inductively and used an open thematic analysis to identify emerging themes.

Consistent with the accelerated creation-to-sustainment (ACTS) model described by Mohr et al. ,86 our approach to developing the implementation plans recognised that the success and sustainability of any DHI depended on understanding people’s experiences and the health service setting in which the DHI was intended to be used. Asking health professionals to engage with something new when resources (e.g. time and staffing) are scarce requires us to develop flexible and low-effort ways to facilitate this. New practices, particularly digital ones such as REACT, are often introduced with the promise of time and cost saving or enabling services to meet targets that are not currently being met. However, in the short term (and before these benefits materialise), staff are asked to invest time to learn new skills, become familiar enough with a new technology to be able to use or recommend it, and often to interact with service users in a different way.

The implementation of a DHI may also be one of a range of research activities that a trust or service is currently involved in. Therefore, our implementation plans were developed using collaborative iterative cycles developed through face-to-face workshops, and drawing on appreciative inquiry approaches,87 to recognise and enhance aspects that were working well while providing a safe context to identify what needed to be changed.

Phase 3: finalising the implementation plan

The aim of phase 3 was to synthesise all of the data across all six trusts to identify the key factors affecting implementation and develop a national implementation plan for REACT IPv4 (objective 4), but also to draw out the generalisable learning for the delivery of DHIs into NHS services (objective 5). We used local ‘data analysis days’ to engage staff in the analysis of trust-level data; key staff involved in REACT roles across all trusts in integration of findings across trusts; and the whole project team including carer relatives in a final 2-day ‘explanatory synthesis event’ in which we produced the final explanatory synthesis outlined in Chapter 8. We also presented the iterative development of the implementation plans and drew on all of the study data to agree a final version of IPv4.

Ethics

Ethics approval for the IMPART study was granted by the Health Research Authority and the East of England – Cambridge South Research Ethics Committee (reference 16/EE/0022). All EIP staff in each of the participating trusts were made aware of the study, and organisational research and development (R&D) approval was given for the research team to monitor the use of REACT and be present in the trust. All participants (staff and relatives) who provided additional individualised data (interviews, workshops, relatives’ questionnaires) provided informed written consent prior to participating in the study.

Chapter 3 Phase 1: hypothesis generation

The aim of phase 1 was to develop a study-specific logic model identifying the factors that we hypothesised would influence successful implementation of REACT. This model was informed by implementation theory and later served as a guide to data collection and analysis, making explicit our underlying assumptions and ensuring that analytic generalisations based on our findings could inform the growing field of implementation science. 72

We operationalised our model as a series of propositions in the form of:

X will happen, if Y.

For this study, this became:

The implementation of REACT is more likely to be successful, if . . . [list of key factors].

Most implementation theories are ‘mid-range theories’, defined as useful frameworks to guide practitioners in a general sense. 88 They may tell us the kind of factors likely to be important, but do not identify specific factors in any one context. For this, we need to generate a programme-specific logic model that integrates mid-range formal theories with informal theories (i.e. ideas and learning based on the previous evidence and experience of key stakeholders).

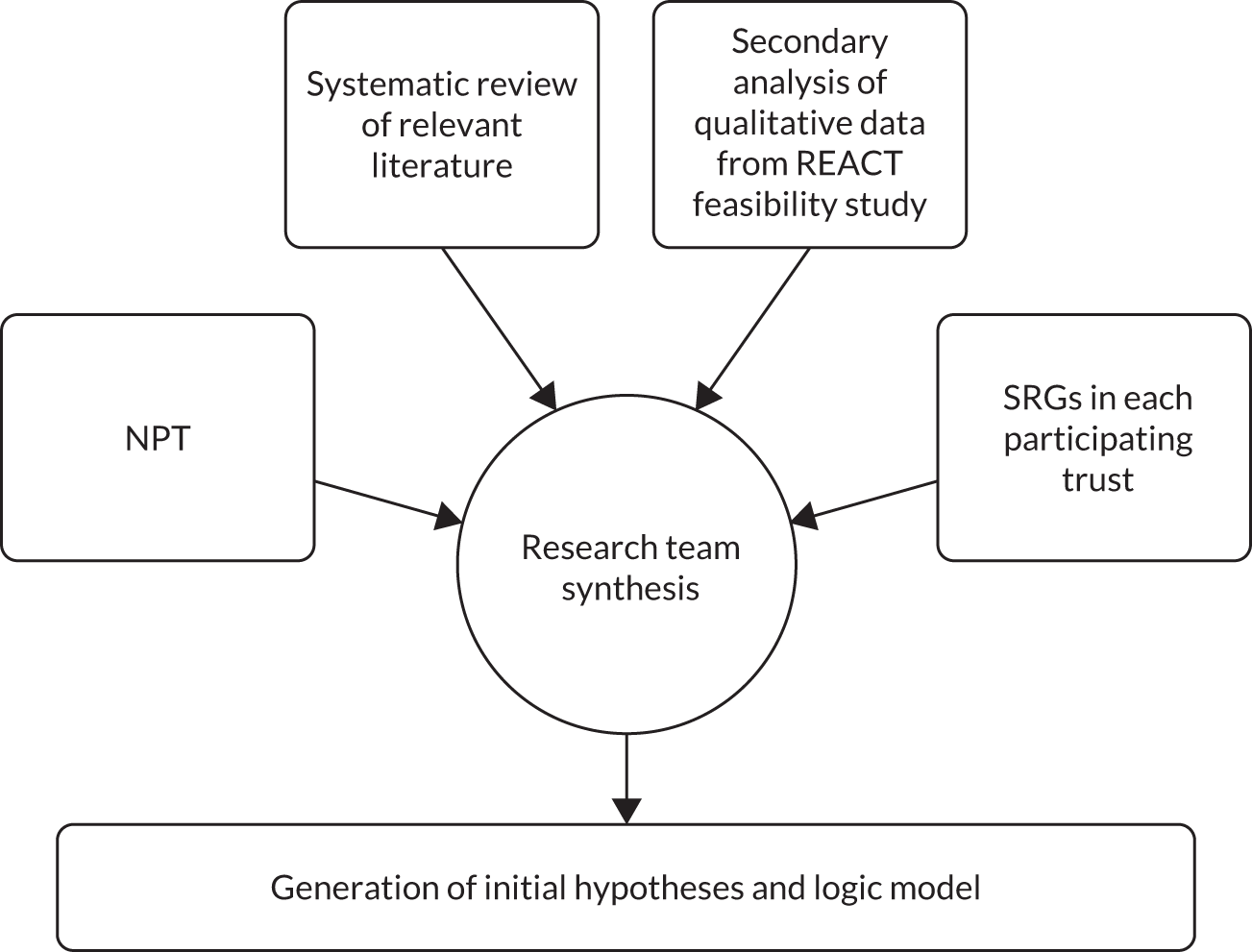

Developing the IMPART study logic model

Our logic model was informed by four key elements:

-

NPT73

-

a systematic review of relevant implementation studies of DHIs for people with psychosis or bipolar disorder and/or their relatives81

-

qualitative analysis of data from the REACT feasibility trial,53 including interviews with EIP staff and relatives

-

SRGs, including staff and relatives at each participating trust.

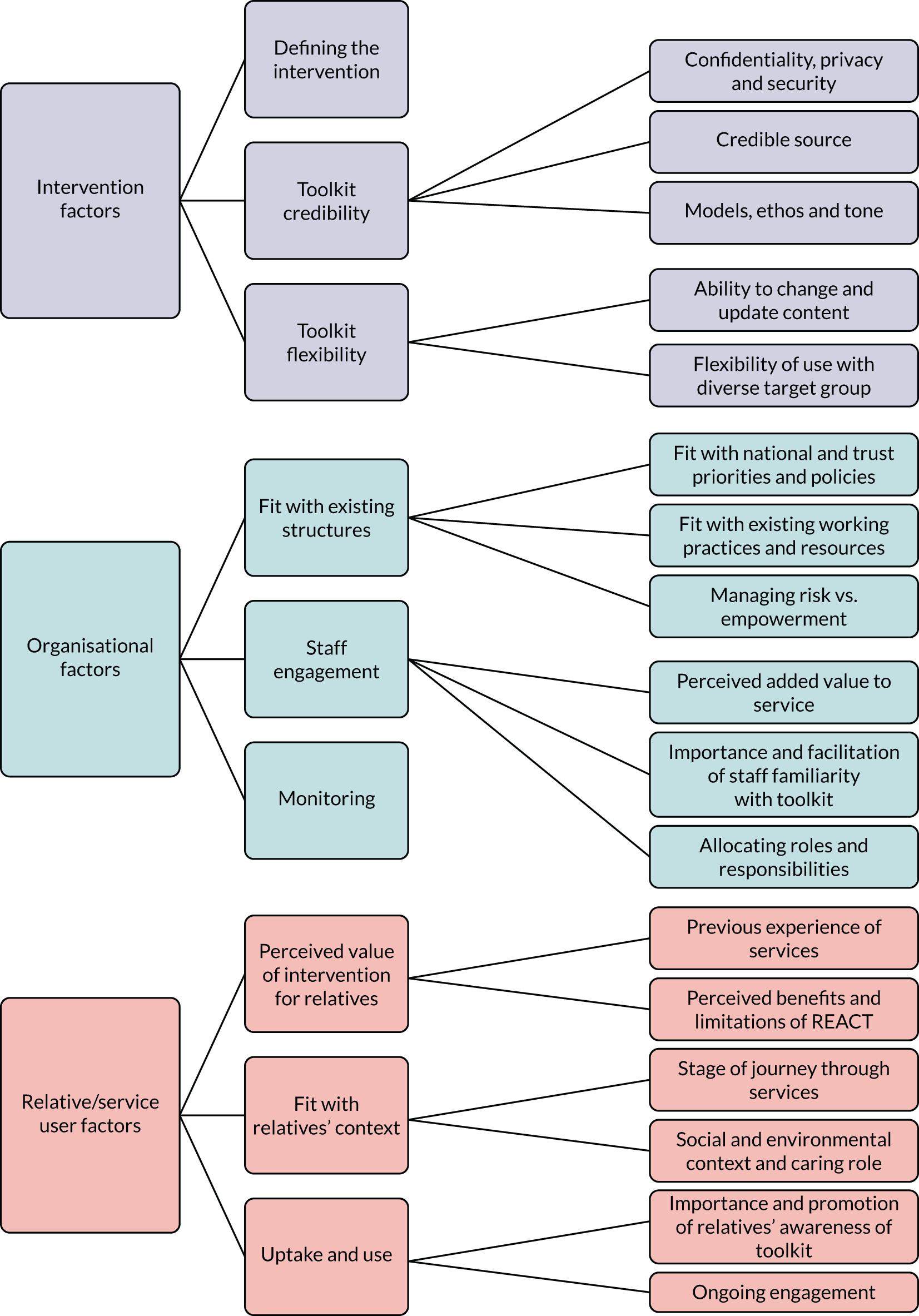

Synthesis of the findings from each element was informed by the clinical and theoretical expertise of our research team. The process is shown in Figure 4.

FIGURE 4.

Generation of study-specific hypotheses and study logic model.

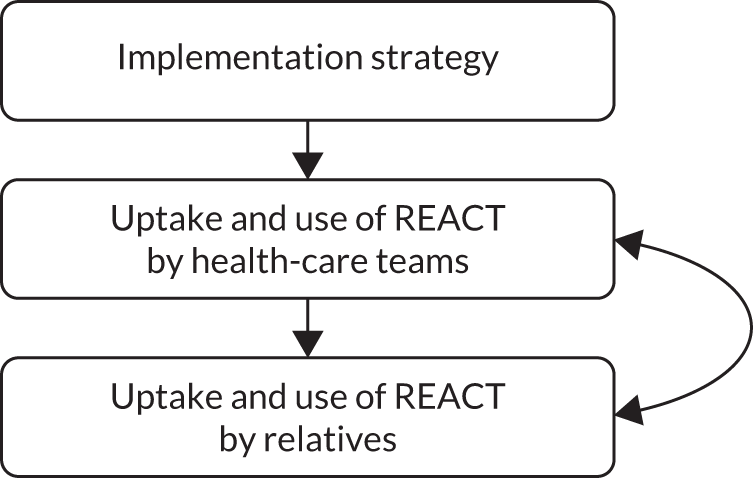

Our preliminary work, prior to the grant, had led us to hypothesise that uptake and use of REACT by relatives would be best encouraged by embedding REACT into routine health care, thus ensuring that relatives were introduced to the intervention by a trusted professional, who would subsequently promote its ongoing use. NPT suggested that this embedding into routine health care would be itself facilitated by positive feedback from relatives (reflexive monitoring, Figure 5). Thus, although our primary outcomes related to uptake and use by health-care professionals, we were also interested in uptake and use by relatives.

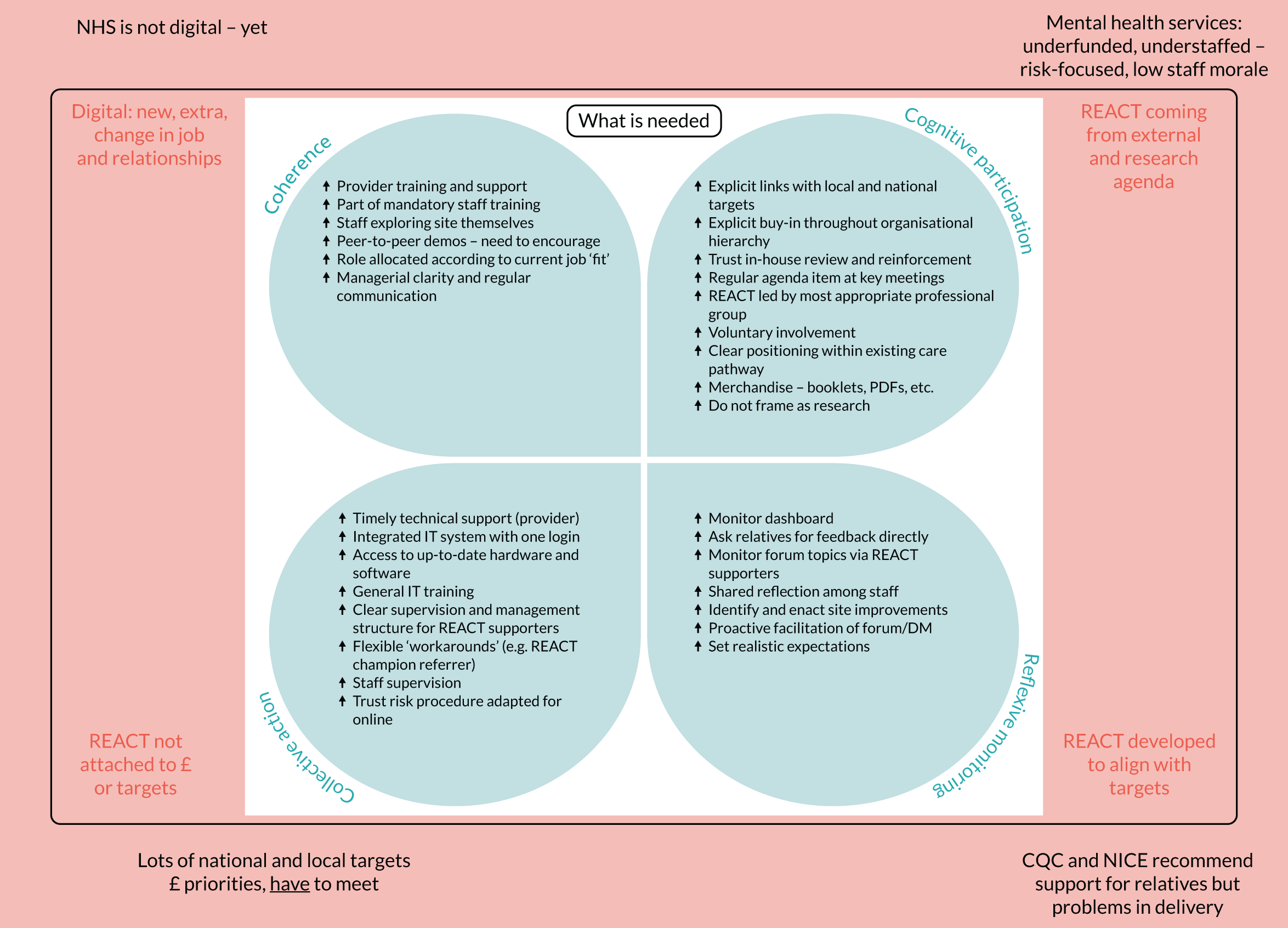

FIGURE 5.

Preliminary logic model at the time when the grant was submitted.

Developing the IMPART study-specific hypotheses

The methods and findings for each of the four pieces of work in phase 1 that informed the study-specific hypotheses are published in full elsewhere (NPT73 and the literature review81) or as appendices to this report (see Appendix 2 for the secondary analysis and Appendix 3 for the SRG report). In this chapter, we focus on the key findings from each and explain how these were synthesised to form the IMPART study-specific hypotheses. Appendix 4 shows how the key findings from each element in phase 1 informed the final study-specific hypotheses and evaluates these hypotheses in the light of the study’s findings.

Normalisation process theory

Normalisation process theory was used to inform the structure of the framework into which our hypotheses were organised, and which then guided our data collection and analysis. The framework was used flexibly and, in phase 2, evolved to include additional constructs. However, in phase 1, we used the 16 core components, organised within the four core constructs of NPT as outlined on the NPT toolkit:89

-

coherence – the sense-making work people do individually and collectively when faced with operationalising a set of practices

-

cognitive participation – the relational work that people do to build and sustain a community of practice around a new technology or intervention

-

collective action – the operational work people do to enact a set of practices

-

reflexive monitoring – the appraisal work people do to assess and understand how the new intervention affects them and others.

We used the online toolkit to train the whole team to ensure that everyone had a good understanding of the theory. Although our team included internationally recognised experts in the field of implementation science (notably JR-M and EM), it was important that all team members, including carer researchers, and other methodological and clinical experts also had a thorough working knowledge of the theory so that everyone could contribute to the data analysis.

We then used this shared understanding to map the findings from our literature review, secondary analysis of REACT feasibility study data and SRG meetings into the framework. This helped to develop the generic mid-range NPT components into study-specific hypotheses for the IMPART study. The process for this is presented in Appendix 4, Tables 27–31.

As an example, the NPT component ‘relational integration’ in the construct ‘collective action’ hypothesises that an intervention is more likely to succeed if staff maintain their trust in each other’s work and expertise throughout the intervention. Data from all three studies in phase 1 contributed to making this a study-specific hypothesis in REACT:

REACT is more likely to be successfully implemented (more relatives are invited to use it) if REACT is offered as part of an integrated package of care for relatives, and not a stand-alone intervention; access is restricted to relatives already supported within the team; staff can see and are confident that the forum is well managed; staff can see and are confident that direct messages are being responded to; REACT supporters and IMPART leads are clear and confident about managing risk identified in REACT.

Systematic literature review

We conducted a systematic review of studies published between January 1995 and October 2017 that identified factors affecting implementation of DHIs for people with psychosis or bipolar disorder, or their relatives. 81 In this chapter, we focus on the key factors relevant to understanding the work undertaken by staff to implement DHIs, and the uptake and use by service users or relatives. The review identified 26 eligible papers describing DHIs for service users, but none aimed at supporting relatives. This further highlighted the need for the IMPART study.

The majority of factors for effective implementation of DHIs were focused on the characteristics of staff supporting the DHIs, or the design of the intervention. The first key finding was that users were more likely to engage with a DHI if it was facilitated by a staff member or peer supporter, and had been proposed by a staff member who could understand and clearly articulate its benefits. Enthusiastic staff can serve as champions for DHIs, reinforcing engagement among service users and providing practical guidance. They can also mitigate the experience of DHIs as generic and impersonal. The importance of human support in successful implementation was a strong theme across several studies, and is consistent with the findings of other systematic reviews. 90

Engagement among service users was facilitated by the DHIs’ accessibility (independently, in their own time and in their own home) and the ability to share information with friends and family. Some felt that the DHIs made communication with staff members easier on issues such as drug and alcohol use, which they would have found difficult to broach face to face, or relieved the boredom of time spent in inpatient facilities.

Key barriers to engagement for both staff and service users were concerns about cybersecurity, complexity and poor interoperability. Concerns about data privacy or security were associated with disengagement. DHIs that were difficult to use or time-consuming did not succeed, and DHIs that did not integrate with existing IT systems were found to be frustrating, either because they required additional logins or because important information was not being shared between platforms. DHIs that were considered either too complex for users or too simplistic were also less likely to be sustained by staff or service users.

Some service users expressed concerns about the potentially negative impact of a DHI on their mental health, with reports of increases in paranoia or other exacerbations of symptoms. Symptom severity, particularly episodes of acute ill health, and negative symptoms of schizophrenia were barriers to engagement. These factors highlighted the importance of user-centred design in all aspects, and including all users.

Finally, cost was a consistent factor in the review. Although digital interventions are promoted as offering potential long-term savings, insufficient funding in the short term was linked to inadequate staff time, training, space and necessary equipment, all of which negatively affected implementation.

These factors were mapped onto the relevant NPT framework constructs.

Secondary analysis of REACT feasibility study data

The aim of this secondary analysis was to identify factors affecting implementation of REACT (in its paper version) during the REACT feasibility trial (2008–12). 53 This was a stratified RCT in which 103 relatives were allocated to receive either treatment as usual (TAU) or TAU plus the paper-based REACT toolkit intervention, in a ratio of 1 : 1. Compared with TAU only, those receiving the intervention showed reduced distress and perceived increased support and ability to cope at 6-month follow-up.

Participants were relatives, partners or close friends of people experiencing psychosis who were supported by EIP services in three participating trusts. Each participant was offered an initial face-to-face session introducing the toolkit and agreeing arrangements for support, which was offered by e-mail or telephone (relatives’ preference) for up to 1 hour per week over 6 months, with a minimum of monthly contact.

Six REACT supporters working across the EIP teams were trained and offered monthly group supervision for the duration of the project. The first 14 relatives to complete the 6-month follow-up were invited to take part in a qualitative interview about their experiences of REACT. Twelve consented but one data file was corrupted and could not be analysed. Interviews were also conducted with the four supporters still involved in the study at the end.

Our secondary analysis of these data sought to identify specific factors affecting implementation of REACT. Despite the toolkit being mainly offered in paper form during the trial [an online Portable Document Format (PDF) was also available], we still felt that the data had important insights to offer into the process of implementing this self-management toolkit for relatives as part of an existing care pathway. See Appendix 2 for a detailed description of the methods, participants and findings. Appendix 2, Table 25, provides a summary of the main findings.

The key themes to emerge from our analysis were the importance of timing (when REACT is offered); the perceived benefits for the relative; that structure and delivery of the support; and the balancing of the REACT supporter role with other job demands.

Timing

Both relatives and supporters identified the need for REACT to be offered to relatives as early as possible to ensure that it was available as they were making sense of the challenges they faced and developing ways of coping. It should therefore be clearly identified as an early step in the care pathway. However, an early offer should be regularly followed up with prompts to explore the use of REACT and highlight its potential value to relatives:

Everybody I met loved it, there was not criticism for the toolkit, except for ‘I’ve already figured this information out for myself, but had this been [there] a year ago . . . [it] would have been a godsend’.

REACT supporter

[My supporter] used to ring me and I would say, oh, something trivial was bothering me; he said, well why don’t you look at section this, section that, and I shouldn’t have to be prompted but, he would and then I would start reading it again then you know, . . . I was really yes, into it then.

Relative

Perceived benefits for relatives

REACT supporters were motivated to offer the intervention to relatives when they saw it as being directly relevant to the diverse range of relatives they worked with, easily accessible, engaging and up to date. Their work was driven by wanting to see specific benefits for relatives, including feeling valued in their role and developing greater knowledge about mental health and services, which would lead to greater confidence to engage with services and indirectly improve their relationship with service users:

It does really benefit if people understand what they are dealing with – I think that’s half the battle . . . [otherwise] they are just fighting against the unknown really all the time.

REACT supporter

Relatives highlighted the use of case studies as particularly engaging as they realised that they were not alone in the problems they faced. Even those who felt that they would have benefited from earlier access to REACT valued the reassurance of information that was consistent with the understanding they had already developed:

It confirmed what you had worked out for yourself, that you were actually on the right line.

Relative

Structure and delivery of support

Relatives and REACT supporters were in agreement that REACT would not work as a stand-alone intervention, and that support was crucial. REACT supporters saw their key role as listening to relatives and directing them back to relevant parts of the toolkit at an appropriate pace. Relatives valued support for giving prompts to visit particular modules, elaborating on topics in REACT with additional resources, talking through ways to manage specific scenarios and offering reassurance when appropriate. Although e-mail and other online written communication offered convenience and an opportunity to compose the content, both parties felt that face-to-face (ideally) and/or telephone support was necessary for engagement:

You need at least an initial contact face to face so then you know who you are talking to.

Relative

And it did help to – much more so than I think you could do on the phone – it did help to build that rapport and therapeutic relationship with the participant.

REACT supporter

REACT supporter role

REACT supporters found adding this role to their existing work a challenge, particularly finding the time to carry out the associated tasks and attending supervision. Some also felt that keeping boundaries between the role and other aspects of their job was not always easy. One supporter struggled with how best to manage negative feedback from a relative about another member of the clinical team. This highlights the importance of allocating REACT supporter roles to staff who have time and appropriate skills, and to ensure that they receive regular support and supervision.

These factors were mapped onto the relevant NPT framework constructs.

Stakeholder reference groups

Stakeholder reference groups met in each participating trust during phase 1 of the IMPART study. The aims were to:

-

establish good working relationships with key stakeholders in each trust

-

finalise delivery of REACT and IPv1

-

explore the views of EIP staff, service users and relatives on factors they thought likely to affect the implementation of REACT in their trust.

Each trust identified an IMPART lead to provide ‘on the ground’ insights into the workings of a particular site and to help researchers to access key data sources. Leads were asked to identify potential SRG members – ideally senior trust board members or EIP service leads, EIP team managers or clinicians, two EIP support workers, two EIP relatives and two EIP service users – and to help set up and co-chair the SRG meeting, held on NHS premises.

All SRG meetings were attended by at least two members of the IMPART research team: a research associate and the North of England or South of England site lead or PPI lead. See Appendix 3 for a detailed report of the methods and results forms including key themes arising from these meetings (see also Appendix 3, Figure 20).

The SRGs were well attended and provided invaluable predictions about factors that would be likely to affect implementation within each trust. However, staff were generally at a clinical and managerial level, with no involvement of senior trust representatives. In some trusts, the IMPART lead chose to hold separate staff and service user/relative meetings owing to fears that meetings would be used to air dissatisfaction with services.

There was a high level of consistency between trusts in terms of the factors considered likely to affect implementation of REACT. These factors included the promotion of its potential to meet the needs of relatives, saving staff time, helping trusts to meet their clinical targets, the flexibility of trusts to adapt REACT to their specific needs, staff confidence in the content and in their role in offering REACT, and the commitment of resources at an organisational level:

We need to make some decisions about the level of support we can give to it and whether or not we can afford to support the instant messaging and the forum, so I guess [we need] to have a clearer idea of what you think the time resource will be.

Staff member

Stakeholders felt that a key strength of REACT was its availability to relatives without requiring service user consent, as this targeted a currently unmet need.

Initial engagement from staff was anticipated to depend on engendering a sense of ownership of REACT within each team, which would be facilitated by ensuring that staff had easy access to the website and training, and by allocating key people to REACT roles. Ongoing use of the intervention by staff would be facilitated by the ability to monitor relatives’ levels of use, and to change and update the content in response to their feedback:

Will you be using any of the things that get spoken about in the forum to kind of tailor the toolkit? So if there are lots of discussions about sleep or diet will you then use that maybe to add to the toolkit for the future?

Staff member

Important barriers that stakeholders felt would need to be addressed before staff and relatives would engage were primarily linked to the REACT group (the online forum) and included confidentiality, security and privacy of data (mainly a concern of relatives); the challenge of managing disclosed risk of harm; and the website being used to air negative feedback (mainly a concern of staff).

The latter was particularly evident in one trust and was clearly linked to experience of an earlier online intervention in which some members of staff had been ‘trolled’. Most stakeholders felt that such risks could be managed by restricting access to the forum to invited relatives, and by having clear ground rules and regular moderation by a REACT supporter.

Despite the credibility of the intervention being clearly enhanced by multidisciplinary input to its development, including from service users/carers and health-care professionals, some concerns were expressed about lack of fit between the content of the toolkit and the ethos of the service. In one trust in particular, REACT was perceived as too medicalising by defining diagnostic terms such as schizophrenia. Staff in this trust wanted more content that focused on well-being and recovery than they felt was currently included:

It just seems to me that a lot of the discussion’s been around lifestyle stuff and families wanting to have more information about well-being in general – I just wonder if this is a very medical model and it’s coming from a very kind of, you know, medical perspective, and actually it needs to open up a little bit more to those kind of life.

Staff member

Challenges were also identified in using REACT to meet the diversity of relatives in terms of language, age, confidence with IT and reading skills. Generally, stakeholders felt that REACT was not suitable for those whose first language was not English, who were older, who were less IT confident or who had a lower reading ability:

[In] my family I’m the only one who speaks English for example, and how would they access this?

Service user

Relatives and staff in all trusts were clear that although they would value the information and peer support offered by REACT, particularly if offered early in their journey, it should be offered as part of an integrated package of care and should not replace face-to-face support:

It’s going to tick the ‘information for relatives and carers’ box, but I don’t want it to be instead of actually getting face-to-face contact and support with care co-ordinators and things like that.

Staff member

Key factors identified by the SRGs as likely to affect implementation of REACT were mapped onto the relevant NPT framework constructs.

Synthesis and generation of study-specific hypotheses

Guided by the online toolkit (www.normalizationprocess.org; accessed 6 December 2019), we began by developing our team-wide understanding of NPT’s four core constructs, then its 16 construct components, and then took the related questions from the interactive toolkit to generate a list of propositions relating to the general processes that NPT predicts are likely to lead to successful implementation of an intervention.

Once the analyses of the systematic review, REACT feasibility trial and SRG data were complete, we used another ‘data day’ to map the key findings from each of these data sets onto the NPT construct components. By using the structure of the NPT toolkit questions, we were then able to synthesise these data sources to generate our propositions specific to the IMPART study (see Appendix 4, Tables 27–30, column 5).

The propositions that resulted from this process under each of the four core NPT constructs are described in the following sections.

Coherence

REACT is more likely to be successfully implemented (i.e. more relatives will be invited to use it) if:

-

all staff have easy and independent access to the toolkit in their own time, with clear guidance on what it is, who it is for and what it offers

-

staff are given an opportunity to discuss whether or not, and how, to use REACT within their service; decisions from this are visibly endorsed at senior management level

-

staff can access training that clearly outlines their roles and responsibilities in delivering REACT

-

staff are able to view the content of the REACT toolkit and can see clear benefits for staff and/or relatives, such as –

-

accessibility

-

relevance

-

credibility

-

reassuring

-

non-stigmatising

-

fits with EIP service ethos

-

clear user involvement

-

inclusive

-

safe to use.

-

Cognitive participation

REACT is more likely to be successfully implemented (i.e. more relatives will be invited to use it) if:

-

there is a clear lead (‘champion’) who drives REACT forward within the trust

-

staff make explicit links between REACT and existing key trust targets and priorities

-

key roles are appropriately allocated

-

training is provided for tasks that may require new skills (e.g. forum moderation)

-

staff have a sense of ownership and take responsibility for promoting REACT within the service and offering REACT to relatives (and do not see this as the role of the researchers)

-

delivery of REACT is included as a regular agenda item at relevant operational meetings within clinical teams.

Collective action

REACT is more likely to be successfully implemented (i.e. more relatives will be invited to use it) if:

-

staff carry out their roles and responsibilities as outlined in the ‘how-to’ manual and have the resources to allow them to do this. Key tasks include –

-

IMPART lead creating REACT supporter and clinician accounts

-

all staff inviting relatives (requires access to computer and relatives’ details)

-

REACT supporters regularly moderating the forum (requires regular access to the online forum)

-

REACT supporters providing timely responses to direct messages

-

regularly updating blogs and local resources

-

-

REACT is offered as part of an integrated package of care for relatives, and not a stand-alone intervention

-

access is restricted to relatives already being supported within the team

-

staff can see and are confident that the forum is being well managed

-

staff can see and are confident that direct messages are being responded to

-

REACT supporters and IMPART leads are clear and confident about managing risk identified on REACT

-

IMPART lead and REACT supporter roles are allocated to people with the time, skills, organisational role and support to carry them out

-

REACT is clearly visible within the relevant clinical care pathway trust policy documents

-

REACT is customised with accurate trust details

-

staff are allocated time for training, supervision and carrying out their tasks specifically related to REACT

-

staff have easy access to computers or tablets and IT support to enable their online tasks related to REACT

-

staff can work easily between REACT and existing electronic health-care record/IT systems.

Reflexive monitoring

REACT is more likely to be successfully implemented (i.e. more relatives will be invited to use it) if:

-

staff can access regular data that show that relatives are using REACT

-

feedback from relatives is reviewed and shared as part of an operational meeting and can inform ongoing work

-

staff are able to gather direct feedback from relatives they have invited to use the website (if positive, this facilitates implementation)

-

staff are able to request or enact improvements to REACT as they see fit.

Discussion

The aim of this chapter was to explain the development of our study-specific model for the IMPART study. We created a list of hypotheses in the form of propositions about factors likely to affect the successful implementation of REACT, drawing on a mid-range theory (NPT), relevant data from a review of existing literature, our previous feasibility study and SRGs in each participating trust.

The process of developing these propositions helped our team to better understand NPT as a theory, and specifically its relevance to the IMPART study, and to operationalise each of the NPT constructs. They have guided our data collection by telling us the kind of data we are likely to need to test each one, and have informed the development of topic guides for staff interviews.

Integrating the three data sets into a NPT framework was not without challenges. NPT’s focus is the work undertaken by staff to deliver the intervention rather than the work undertaken by the user to then engage, although it does indirectly acknowledge the importance of user engagement in the reflexive monitoring of staff. In contrast, a substantial number of our data focused on the engagement of the end user with the DHIs, and so highlighted factors associated with characteristics of the DHIs or of the user. Although it would be possible to adapt NPT to explore the work undertaken by the relatives to engage with REACT, this was beyond the scope of this project. Therefore, data relevant to this engagement is not included in the NPT framework, but is used in Chapter 8 to help interpret the data collected from relatives set out in Chapter 7.

The hypotheses derived from phase 1 are revisited in Chapter 8, and tested in the light of the data collected in phase 2 (see also Appendix 4).

Chapter 4 Phase 2: methods

This chapter details the methods used for phase 2 of the IMPART study. The primary aims of phase 2 were to:

-

test our hypotheses about which key factors would influence the implementation of REACT across our six participating NHS trusts

-

develop an implementation plan.

An additional aim was to assess the effectiveness of REACT. We follow StaRI71 where appropriate.

Design

As described in Chapter 2, the design was a theory-driven multiple case study design72 using a mixed-methods approach integrating quantitative assessments of outcome (delivery, use and impact of REACT) and qualitative assessments of mechanisms including observation, document analysis and in-depth interviews with staff and relatives.

Context

The study took place across six NHS trusts in England. This context is described in detail in Chapter 1.

Sites

Preserving the anonymity of participating trusts and teams was of particular importance in this study owing to the sensitive nature of the data collected from carers and staff. A multilayered taxonomy of birds and habitats was used to identify trusts and teams within each trust.

Trusts were selected to be geographically and ethnically diverse to maximise the generalisability of findings. A summary is given in Table 3, drawing on the Royal College of Psychiatrists College Centre for Quality Improvement (CCQI) audit in 2014;92 specific figures are not provided so that trusts are not easily identifiable.

| Trust | Location | Wave | Population served | Summary data estimated from CCQI 2014 audit92 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Woods | South of England | 1 | Approximately 0.5 million people; large ethnic diversity; approximately half identify as white British; urban setting | Approximately 47% of service users and their families were offered family intervention; half of carers were offered education and support |

| Moor | North of England | 1 | Approximately 0.5 million people; predominantly white British; over half living in a rural setting | Approximately 3% of service users and families were offered family intervention; 6% of carers were offered education and support |

| Ocean | North of England | 2 | Over 2.5 million people in large urban area; vast majority identify as white British | Approximately 32% of service users and families were offered family intervention; 87% of carers were offered education and support |