Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/04/40. The contractual start date was in January 2016. The final report began editorial review in August 2019 and was accepted for publication in March 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Diane Sellers reports grants and personal fees from Nutricia Advanced Medical Nutrition (Trowbridge, UK) and personal fees from Nutricia Global (Danone, Hoofddorp, the Netherlands) outside the submitted work.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Craig et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Context

Evidence reviews recommend that health and social care professionals attend to non-clinical factors and ensure that there is consistent and structured support for children with neurodisability and their caregivers in care pathways when a gastrostomy feeding tube (GFT) is recommended, ensuring that decision-making is informed. 1,2 The provision of psychosocial support (PSS) is an under-researched area and this study aimed to explore how these recommendations have been implemented in practice to identify exemplar models. In short, the study aimed to identify what PSS exists for parents of children with neurodisability with complex feeding needs and for children, how PSS is accomplished in different service models and local configurations of health and social care. It also aimed to identify any gaps in provision, with a view to delivering minimum standards of PSS and making recommendations for change.

Neurodevelopmental conditions, such as cerebral palsy, are the most common cause of disability, estimated to affect 3–4% of children in the UK. 3 This population of children are also the most frequent users of health services. 4 Research suggests that parents of disabled children (70% of mothers and 40% of fathers of severely disabled children) are vulnerable to stress as a result of the demands of care, which can, in turn, negatively affect children’s well-being and family functioning. 5 Indeed, there is research to suggest that chronic stress, associated with caring for children with multiple and complex needs, can negatively affect caregivers’ quality of sleep, physical health and immune function. 6,7

Children with cerebral palsy are at particular risk of oromotor problems affecting their ability to obtain an adequate nutritional intake by mouth, including difficulties chewing, swallowing and feeding, with implications for their nutrition, growth and overall health. 8 Dysphagia, although often under-recognised in this population of children, is common,9 with a reported prevalence ranging from about one-fifth of children with cerebral palsy of any degree10 to 99% in children with severe cerebral palsy and intellectual disability. 11 Pulmonary aspiration is also common (where food or fluid enters the airway), resulting in poor respiratory health, and is considered a significant cause of premature death in this group of children. 12 Caregivers report that mealtimes are prolonged and stressful. 13,14 A GFT, surgically placed in the child’s stomach, is usually recommended where a child’s swallow is considered unsafe and/or growth is compromised, and commercially prepared feeds obtained on prescription are administered through the GFT. Following gastrostomy, insertion stress may also increase in the short term for some families as a result of complications of the procedure, aftercare, the need to learn new nursing techniques and the grief associated with coming to terms with a medicalised way of feeding and other psychosocial sequelae. 15–18

Moreover, the recommendation of gastrostomy can generate parental opposition to the procedure,19 creating conflicts about the feeding management of children and the decision to have a GFT. A systematic review of 11 qualitative research studies conducted in the UK, Canada and Australia1 highlighted the decisional conflicts that parents experience when considering a GFT and the role of services in shaping parental experiences of care and ameliorating stress. Eight out of the 11 studies reported that health-care professionals (HCPs) did not provide enough support to families. Four studies reported that families felt pressured to accept a GFT and six studies reported that professionals failed to appreciate the difficulty of the decision-making process for parents and the impact of GFT feeding on child and family life. Lack of information, conflicting information and lack of opportunity to meet with other families, in addition to concerns about the operative procedure, were also reported.

Conflicts may also arise in schools and other institutional settings between parents and surrogate feeders. Parents may support oral feeding while surrogate feeders have concerns about the safety of feeding children orally owing to the risk of aspiration. 20 It is unclear how disagreements about children’s feeding and growth are managed by professionals, and the attitudes of professionals towards the use of safeguarding legislation where conflicts arise are unexplored. This is compounded by the lack of strong evidence on the effectiveness of a GFT,21 although the intervention is associated with improvements in children’s health, weight gain and maternal mental health. 22,23 We aimed to explore professionals’ experiences of managing conflict.

There is a growing parent-led movement in the use of blended diets (BDs) (i.e. blended food prepared at home and inserted into the GFT). It is estimated that 500 children start BDs each year;24 the continuing number is unknown. However, not all professionals support the practice because of concerns about the risk of gastrointestinal infection, undernutrition and GFT blockages (because many GFTS are not designed for BDs), although there is little robust evidence to support these concerns. 25 The British Dietetic Association (BDA) has developed a policy statement about the use of BDs to create a permissive culture of open discussion between parents and dietitians and offers recommendations in the absence of national guidance;26 where dietitians believe it is in the interests of the child, they can suggest a BD, providing that this is in keeping with their employer’s policy. This raises another potential area for conflict around children’s feeding management, and we aim to examine local practice in relation to BDs in our case study, although this will be discussed in depth in future publications.

This research builds on the doctoral study27 and subsequent work of the chief investigator, who was involved in conducting a prospective controlled trial on the benefits23 and costs28 of GFT interventions and an interview study on parental support needs. 29 This work suggested that clinicians prioritised children’s growth and nutrition and less attention was afforded to parental, particularly mothers’, anxieties about GFT feeding in everyday contexts. Mothers’ narratives were often underpinned by a sense of blame for having failed to establish, or maintain, oral feeding and, hence, children’s growth. The recommendation of a GFT challenged culturally available narratives on ‘good mothering’ and normative child development mediated through oral feeding and mealtimes invoked as sites of intimacy, pleasure, child participation, socialisation and inclusion. 30,31 The emotional side of the decision-making process was often neglected in clinical decision-making despite being a clearly emotive issue for both parents and clinicians. It is through this, and other bodies of work that have also investigated the social meanings that parents attach to GFT interventions, that a range of PSS needs have emerged. 14,18,32–34

In this study we aim to focus on how services provide PSS. As we progressed through the study, this term evolved to place greater emphasis on the emotional aspects; hence, the term psychosocial and emotional support (PSE) is a recommendation. We drew on a broad definition of PSS that includes the practical issues of having to learn new feeding regimes and nursing procedures in caring for a child with a GFT (which also have psychosocial effects, as our study illustrates), including replacing GFTs and what are, arguably, additional stressors when things go wrong [e.g. infection of the gastrostomy site (stoma), GFTs getting blocked], in addition to the actual decision-making process. In this study we aimed to use the term PSS as a means of emphasising the non-clinical aspects of decision-making and support. However, this was often difficult for professionals to disentangle and, therefore, presented a tension throughout the study because professionals understood support, including PSS, through the lens of their professional background, risk and clinical practice. This is discussed further in Chapter 6 and in relation to the analytical construct of ‘hidden work’, a finding of the research.

Aims and objectives

The overall aim of the study was to explore how different neurodisability services meet the PSS needs of children/young people with complex feeding needs and their families when making a decision to have a GFT and issues that arise following surgery.

We aimed to (1) identify different service support models nationally, (2) compare the implementation and operation of support and key resource differences and (3) provide an estimate of their costs.

Research objectives

-

Establish a national (UK) picture of models and practice via an online survey.

-

Compare the implementation and operation of four contrasting service models and practice using a collective case study research methodology.

-

Analyse how support is accomplished in different organisational structures, including health and social care sectors, and the role of schools in supporting children and families.

-

Provide rich description of contrasting supportive practices and the interface between services and other key agencies.

-

Identify different features of service configurations and supportive practices and analyse their costs, specifically to (1) assess the resources required for each of the models considered and how these costs impinge on health and social care services and (2) estimate the costs of providing psychosocial care.

-

Identify whether or not any models of support utilise service user involvement or third-sector organisations (i.e. families with experience of GFT feeding or voluntary organisations) and analyse how service users/family support organisations interface with the formal health and social care sectors and how they are resourced.

-

Analyse professionals’ understanding of support issues and how services provide support, the support needs of young people and their families and how these were met.

-

Derive best practice guidance on support issues from an explication of the service models identified in the study and service specifications and make recommendations for change to inform commissioning decisions and set standards of support for children and families.

-

Make recommendations for embedding support for a wider constituency of children with complex health needs and their families, including recommendations for training and skilling the wider children’s workforce, by deriving general principles of how services can provide support and where in the care pathways this should happen.

Structure of report

The report is formed of six chapters. Chapter 2 details the methodological approach and methods for the three-phase mixed-methods study, including the national survey, the collective case study, the study of resource utilisation and costs, and willingness to pay (WTP) for PSS. We outline our theoretical model used throughout the report and our public and patient involvement (PPI) work in the same chapter. There is also a discussion of data integrity. Chapter 3 presents the findings of the web-based survey (WBS). Chapter 4 describes each of the four cases in our case study in detail. Chapter 5 details the findings of the resource use, costings and WTP studies. Chapter 6 summarises the findings of the study in relation to our synthesis model.

Chapter 2 Research methodology

Research design

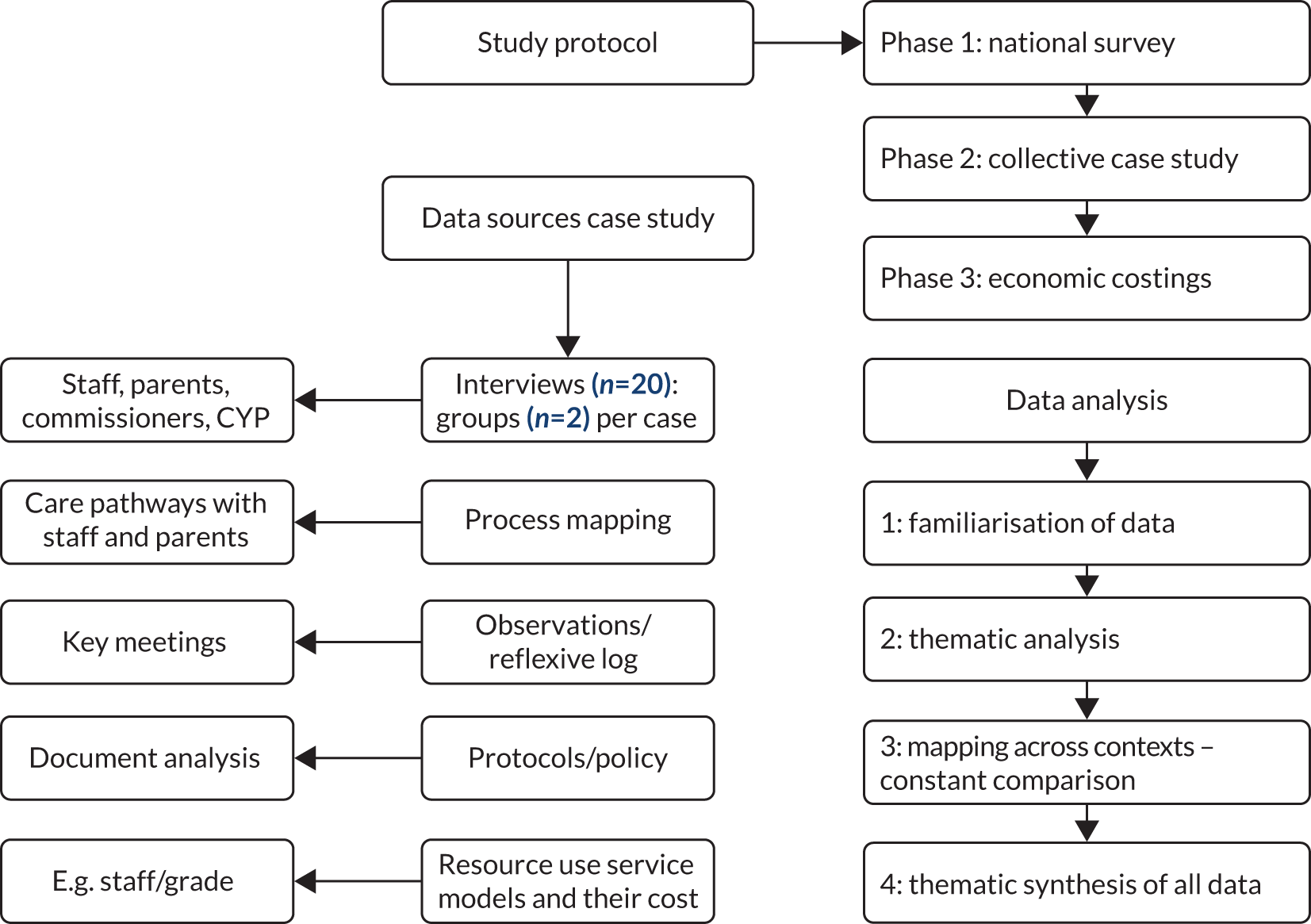

The research design was an explanatory, sequential mixed-methods approach with a qualitative, collective case study as the dominant or priority method. 35 The study entailed three phases: an exploration of service delivery support through a WBS to explore and scope best practice and identify case study sites for phase 2 (phase 1), a case study of four exemplar services (phase 2) and an estimate of the resources and costs of PSS (phase 3). The results of the WBS were used to inform the case study and data from phase 2 were used to inform the WTP study in phase 3. Data were kept ‘analytically distinct’35 across the three phases and are synthesised in a final chapter, although the findings of each phase fed into the next. Figure 1 illustrates the work scheme.

FIGURE 1.

Work scheme. CYP, children and young people.

Phase 1: web-based provider survey mapping practice

Phase 1 of the project addressed objective 1 and involved a web-based national survey of policy and practice distributed to all disability feeding teams in the UK using a professional database (round 1) hosted by the British Academy of Childhood Disability (BACD). The BACD is a multidisciplinary organisation and subgroup of the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health. The database was established for the purposes of research and to improve child health and service development initiatives. On our behalf, the BACD e-mailed all leads of disability services registered nationally with a link to our WBS.

The survey (see Appendix 1) aimed to provide a picture of established practice in relation to PSS. In addition, we aimed to identify further case study sites from the findings of the survey.

Fifty-four questions, including open-ended questions, were intended to gather data on the following themes: type of organisation, care pathways, how PSS was delivered and by whom, access, perceptions of best practice support (open-ended), areas for improvement and associated barriers (open-ended), parental peer involvement, and information about resolving conflict (including the use of safeguarding). Respondents were also asked if they would be willing to participate in phase 2, an in-depth qualitative case study of practice. The WBS was sent out to our PPI group for comment and was piloted informally, in-house, with members of the Project Advisory Group (PAG) and selected clinicians and academics.

Owing to an initial poor response rate (see Appendix 2 for the dissemination log), and on the advice of the BACD to expand our methods of dissemination, we e-mailed our survey link to research managers of the research and development (R&D) departments of all trusts using the National Directory of NHS Research Offices to cascade our survey link to the relevant staff/clinicians at child development centres (CDCs)/disability services (including their equivalent in Scotland) and feeding teams. This required permission for a non-substantial amendment from the Health Research Authority (HRA)/Camden and King’s Cross Research Ethics Committee (REC). In addition, we disseminated the link through various professional networks identified through the project co-investigators, including gastroenterology, speech and language therapy, and dietetics. In Scotland, we distributed the WBS through the National Managed Clinical Network for Children with Exceptional Healthcare Needs (NMCN CEN), NHS National Services Scotland. As R&D departments had to assess for capacity and capability, the deadline was extended.

Data were collected between July 2016 and May 2017; this period included a pause to obtain permission to disseminate the survey link through the R&Ds. The survey was designed, and data analysed, using Qualtrics XM (Provo, UT, USA) and exported into Microsoft Excel® 2016 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) for analysis. Open-ended questions were analysed thematically, drawing on approaches described by Braun and Clarke. 36 Text was organised into meaningful categories, compared across all responses and labelled using principles borrowed from constant comparative analysis. 37 Codes were stored in an Excel spreadsheet with illustrative quotations.

Phase 2: collective case study

We drew on Stake’s description of a ‘collective case study’38 for phase 2, that is, an instrumental case study that ‘provides insight into a phenomenon of interest’39 to gain an understanding of how support for children and parents was accomplished across complex care landscapes in four sites. ‘Collective case study’ describes a methodological approach whereby a number of individual cases are purposefully sampled because of their variety, range, contradictions or complexity. 40 Each case is investigated in depth but a common set of questions are asked of each to make comparisons. Robson describes a case study as ‘a strategy for doing research which involves an empirical investigation of a particular contemporary phenomenon within its real-life context using multiple sources of evidence’. 41 This is important when analysing complex health-care organisations and systems of care because it allows for both depth and breadth of analysis through multiple data sources and the differing perspectives of key players. 42,43

The cases are intended to provide exemplars of different service configurations and four cases were chosen to balance the need for a small sample to facilitate in-depth data collection and sufficient scope to explore variations in support in different local systems. In this study, a ‘case’ covers the local health and social care system rather than a single service so that these issues and linkages can be explored. Because these local configurations were sometimes complex, crossing health, education and social care boundaries, the cases often emerged through a mapping of the care landscape and was an iterative process. 44 Segar et al. 44 noted that, rather than having clear boundaries, ‘fuzziness and emergence are inherent to the case’.

Selection criteria case study sites: integration and support

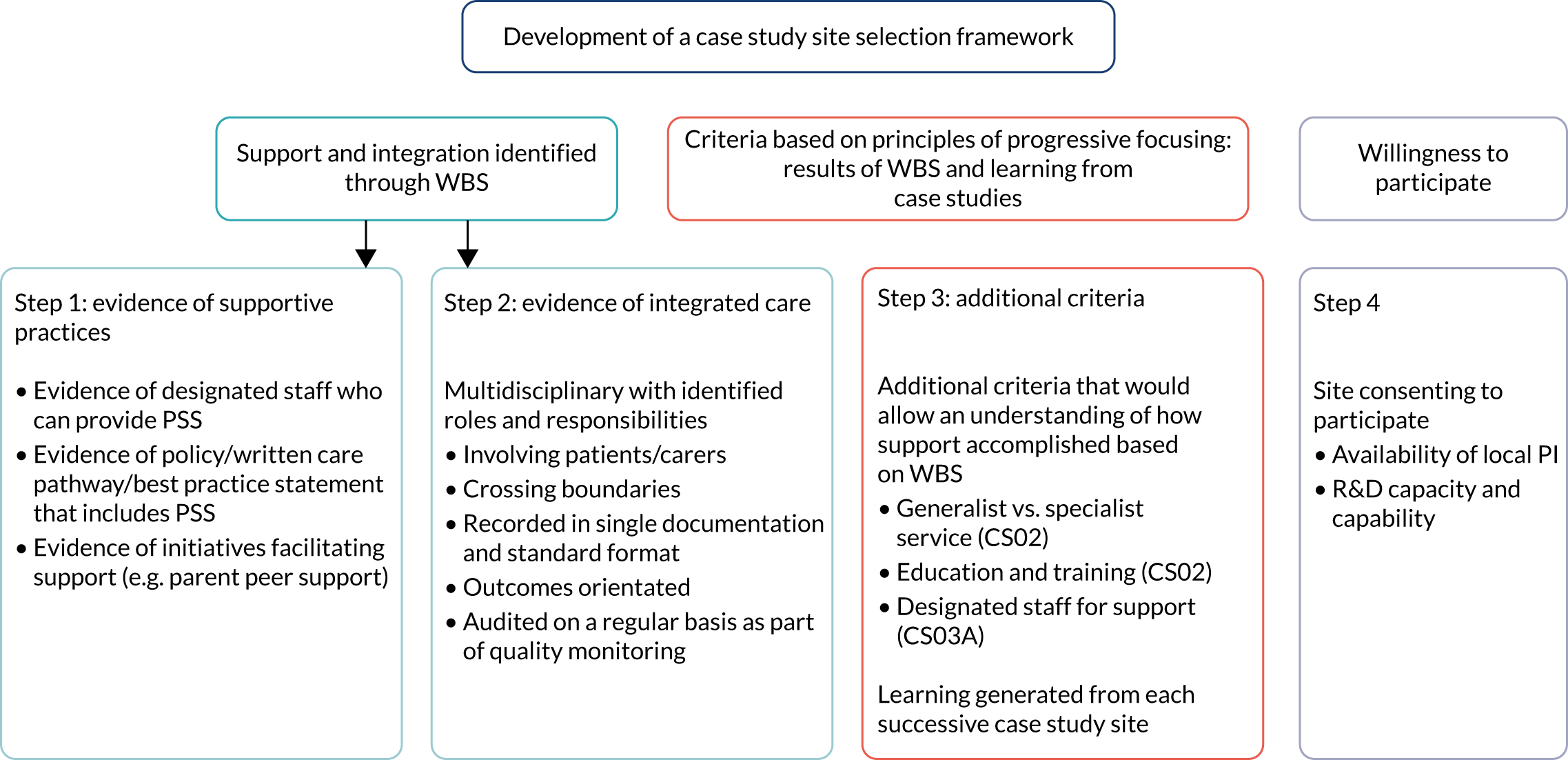

Previous research on organisational case studies has selected sites according to best practice or performance criteria; for example, the Birthplace study45 selected sites according to the findings of the 2007 Health Commission Services Review. However, there were no policy recommendations to inform the selection of neurodisability services. Given the lack of guidance on models of service delivery, and how services should provide support, we identified cases in terms of the integration of PSS as a proxy for the structured support recommended in evidence reviews and also aimed to look at variation. We developed a four-step approach to the selection of cases (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Development of a case study site selection framework. CSO2, case study site 2; CS03A, case study subsite 3A; PI, principal investigator.

Steps 1 and 2

We initially aimed to identify services from the WBS using the criteria of support (step 1) and integrated care pathways (step 2) (Figure 3). We operationalised ‘higher’ levels of support as involving designated staff offering PSS and written care pathways that included PSS. Our operational definition of integrated care, as a care pathway approach, was ‘structured multidisciplinary care plans which detail essential steps in the care of patients with a specific clinical problem’. 46 The standards of integrated care pathways are provided in step 2. We asked respondents in our WBS to indicate which of the criteria outlined in steps 1 and 2 applied to their service to guide our case study selection. 47

FIGURE 3.

Preliminary selection criteria integration vs. support.

Step 3

Step 3 involved using the learning garnered from our first case study and WBS and applying these findings to the selection of subsequent cases, drawing on ideas from Stake’s progressive focusing methodology,48 which allowed additional criteria to emerge in relation to our study aims. For example, as it became clear that some services had examples of best practice but no formal care pathway, and on the advice of members of the PAG, we adopted a more flexible approach to the selection of our cases using theoretical criteria. 48

Step 4

Willingness to participate was also an important criterion as an indication of staff or organisations’ willingness to learn or show case examples of best practice. Interest and ‘opportunity to learn’ were therefore privileged over ‘typicality’ of service. 39

It should be noted that, although the initial criteria of integration and support (see Figure 3) informed the selection of case study 1, the results of our WBS, and our PAG, suggested that not all services would have written care pathways and that support was often provided generically as part of the multidisciplinary team (MDT). Assumptions that care involving designated staff equated to a higher level of support was problematised through our findings. Indeed, the concepts of ‘high’ and ‘low’ integration and support are themselves discursive constructions and highly contested in the absence of evidence and guidance. Therefore, we chose additional sites according to theoretical sampling and what those services could tell us about PSS initiatives using theoretical sampling based on the learning and experience garnered from the field work.

Selection of case study sites

All case study site services, apart from the service at case study site 2 (CS02), which was described as a generic service, were specialist services in which MDTs delivered care to children with complex feeding needs. All sites referred to specialised tertiary centres for the placement of a GFT. Three of our cases were based in England and one in Scotland (we do not provide exact regional locations to preserve anonymity). Two of our case study sites were in the 20% most deprived authorities in England, with approximately one-fifth of children living in low-income families; one of our case study sites was in one of the least deprived authorities, with approximately 7% of children living in low-income families. 49 The cases and rationale for their selection were as follows:

-

Case study site 1 (CS01) was selected because it met our initial criteria of integration and support. We initially designated this site as high in integration, between health and education via a co-located special school, and support (defined as availability of designated staff). In addition, there was a strong parental network organised around the school.

-

Case study site 2 (CS02) was chosen because it was an example of a generalist, rather than a neurodisability, service, where children were cared for by a MDT and staff had generic responsibility for all children but specialised in caring for children with complex feeding needs. Staff were supported by the NMCN CEN, which serves as a forum for disseminating best practice across Scotland. The WBS identified that the NMCN CEN had developed a training module for staff specifically on the importance of providing emotional support to parents when making decisions about GFT feeding. This was also underpinned by policy, that is, a best practice statement and guideline based on research findings. 50 Education and training were identified as aspects of best practice in our WBS and as gaps by some staff in our first case study.

-

The services of a psychologist were available at case study subsite 3A (CS03A) but were not available at case study subsite 3B (CS03B), reflecting an inequality in access to resources, although both services were homed in the same NHS trust. Both sites referred children who needed a GFT to the same tertiary centre [case study tertiary site 3C (CS03C)], which had recently implemented a nurse assessment model. We selected CS03A to specifically examine (1) the experiences of parents of younger children and (2) the role and function of designated staff to offer support (e.g. a psychologist), a theme raised in the WBS. The comparison was felt to be useful in understanding commissioning, staffing arrangements and resources: themes identified in our WBS as barriers and levers in the provision of PSS.

-

Our final site, case study site 4 (CS04), could be described as a hospital-based, district service. There was no written care pathway. This site was a mini case study because the recruitment of parents was particularly difficult. Moreover, the tertiary referral centre did not have capacity to participate.

Data collection

Interviews with key stakeholders

We conducted semistructured interviews and focused group discussions in each case with a theoretical sample of service managers, staff (health care, social care, education) and parents and children (the children were included whenever possible). In addition to face-to face interviews we offered participants telephone or Skype™ (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) interviews. We used visual mapping of service configurations as an interview aid with professionals, where possible, to better understand referral pathways in local systems of care. 51 Interview schedules were semistructured and required a degree of flexibility depending on where families were in their feeding journey (see Report Supplementary Material 2 and 3). Flexible interviews were necessary for children to accommodate their communication preferences.

Observations and document review

This was not an ethnographic study so the role of observation and review of documents operated as follows: prior to the interviews we obtained key documents relevant to the case study (e.g. service documents, care plans, care pathways, mission statements, protocols on eating and drinking) to sensitise us to the context of service delivery and identify aspects that could be corroborated in interviews. We conducted observation of selected aspects of services at key junctures, including appointments and meetings with family groups. Non-participant observations aimed to provide a baseline understanding of the context of care and sensitise us to the influences of this on care delivery. Both observation and document review helped to highlight issues of relevance that could be explored in interviews and assist with triangulation of data.

Data management

Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed, de-identified and stored in NVivo version 11 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). Key documents and notes of observation were added to the NVivo database alongside interviews.

Analysis of data

The lack of research on how services provide support to children and families, coupled with diversity of provision due to a lack of guidance on how services should be organised, and the complex nature of family journeys (which often traversed multiple health-care organisations, education and social care), provided the rationale for a largely descriptive approach to the case study to provide sufficient contextual detail. 52 Our approach to analysis involved four levels:

-

description of services to highlight how support was accomplished across each service configuration and their contexts, building on the findings of the WBS

-

visual service mapping highlighting linkages in and between services to illustrate pathways and complexity derived from interviews and checked in feedback sessions

-

themes highlighted in the WBS

-

theoretical model of decisional conflict.

The original plan was to analyse the qualitative interviews using a framework analysis53 combined with a narrative approach to provide rich illustrations and storied accounts. However, the case study generated to some extent heterogeneous data in line with our progressive focusing methodology, which allowed us to focus on different strengths of services in each of our cases to illustrate how support was accomplished across a diverse array of organisations we have loosely termed ‘local service configurations’. Therefore, our cases cut across health care, social care and educational provision and across different sectors of provider. This provided a rationale for a prioritised focus on a thematic analysis,54 which we felt was more sensitive to the different perspectives and the dynamic nature of the project.

An analytical framework was developed in relation to the research questions, findings from the WBS and model of decisional conflict. 1,55 Care was taken to attend to similarities and differences in the data in and across case study sites using principles derived from constant comparative analysis where possible. 37 Data were organised in relation to our theoretical framework and are presented in a synthesis model in Chapter 6. It should be noted that not all key themes are presented in every case study site to the same degree of analysis; in some cases there were no data relating to that theme or there was less evidence of a particular phenomenon in that setting.

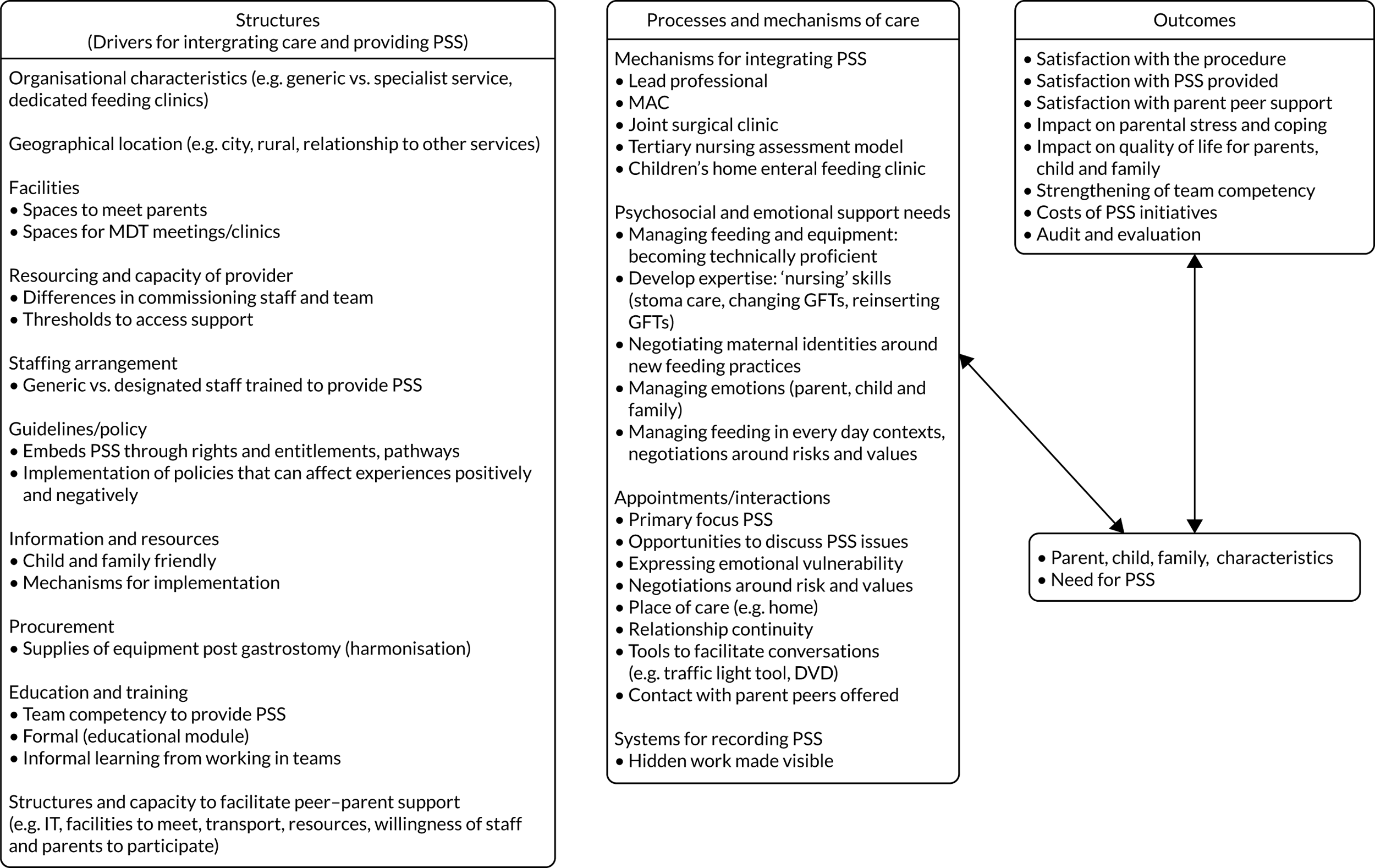

Theoretical model and data synthesis

We drew on Manhant et al.’s1,55 model of decisional conflict as a way of organising and categorising data specifically on decisions about feeding. Based on a systematic review of qualitative interview studies, the model outlined three sources of decisional conflict between HCPs and families arising from the recommendation of a GFT, including the values that parents attach to the meaning of feeding and GFTs; the child and family context, including unique family circumstances; and processes of care, which includes characteristics of organisations or care configurations, how these and HCPs interact with families to make decisions and the role of support and information. This theoretical framework informed the interview schedules as well as the analysis and synthesis of data.

Data synthesis

We collected and analysed the WBS (phase 1) and the case study data in two consecutive phases, with the qualitative case study being the primary component. Themes identified in the WBS were explored in greater depth in interviews in the case study and used to identify case study sites for phase 2. The phase 2 case study data were used to inform the scenarios in the WTP study in phase 3; otherwise, analysis in each phase remained distinct. We present findings in terms of a synthesis model that takes into account structures and outcomes in addition to processes of care and populate this model with our descriptive themes in Chapter 6. 56

Recruitment of staff and families

All staff and families were approached by the appointed principal investigator or research nurse at each case study site. The research team did not have direct contact with families initially. The research nurses contacted families by phone to advise them an information pack would be sent out, with their permission, inviting them to participate in the study. Packs were then sent out and followed up with a telephone reminder by the local staff 2 weeks later. Health-care staff received e-mail invitations advising them about the research, followed by the information packs and e-mail reminders. The local principal investigators and research nurses also sent out packs to school-based staff where the clinical teams delivered clinics. Consent forms were returned to the research team. Parents consented for their children to participate. Inclusion criteria are described in Appendix 3.

Phase 3: resource utilisation and cost implications of psychosocial support

We adopted a two-step approach to the study of costs of support, comprising an estimate of the resources involved (study 1) and WTP for support (study 2). Resource questionnaires were developed and disseminated to parents and staff across all case study sites via the local principal investigators or research nurses (study 1) and a survey was disseminated more widely through social media (study 2).

Study 1: estimation of resource use

Questionnaires on resource use concerning health service appointments were sent out to 103 parents and carers of children who had had a GFT or in whom placement of a GFT was being considered (see Report Supplementary Material 4). Information requested included demographic data concerning the child; details of HCP appointments related to the GFT in the previous 12 months; the length of each appointment, who was present and what issues were discussed; and whether or not emotional PSS was given and, if so, for how much time. Further questions asked if their problem was resolved and if they would have liked specific appointments to discuss emotional psychosocial issues. Questions were also asked about their satisfaction with each appointment and if they were offered the opportunity to talk to other parents or families and, if not, if they would have liked the opportunity to do so. The questionnaire also asked how satisfied parents were overall with their care on a scale from 1 to 5, and provided free-text comments on their child’s feeding and the PSS that they received or would like to have received. Questionnaires were also sent to HCP staff (see Report Supplementary Material 5). In Chapter 4, we report mainly on data from the parental questionnaire as well as reporting on the training and confidence in supporting families from the professional questionnaire.

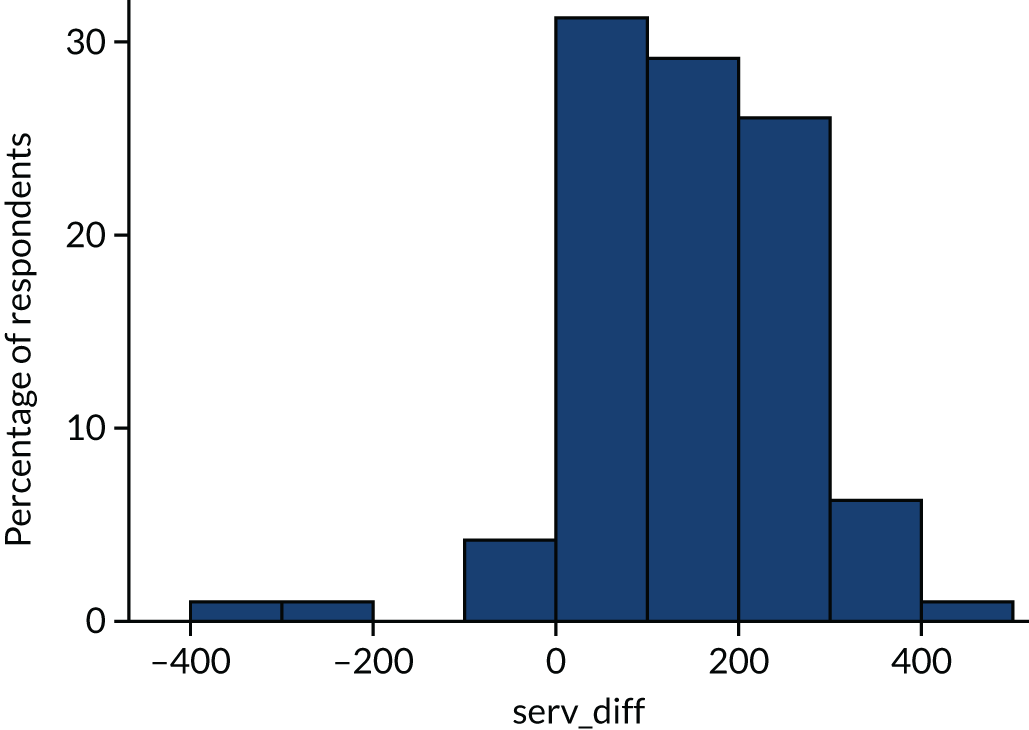

Study 2: willingness to pay

Parents and HCPs were asked to value two different services: a hypothetical model of care that reflected usual practice across all four case study sites (service A) and service B, which reflected an enhanced care package of support based on data gleaned from the interviews and organised around the principles of structured and consistent support. 1 They varied slightly in terms of professional support and the frequency and type of psychological support offered. The aim of such questioning was to determine what value parents would put on each service relative to the other and, therefore, which model of care (service A or B) they would prioritise and thereby express a strength of preference for, using a hypothetical ‘purchasing price’ as a measure of such value (see Report Supplementary Material 6 for descriptions of the two hypothetical service scenarios).

The questionnaire and scenarios were piloted with our PPI parent group for ease of completion and among members of the PAG. Owing to the amount of time it would have taken to gain permission to disseminate the questionnaire through our case study sites, we decided to seek ethics approval through the University of Hertfordshire and distribute our questionnaire through professional and parental networks and social media, including Facebook (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA; www.facebook.com) and Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; www.twitter.com). The questionnaire was distributed via Qualtrics from 3 April 2019 to 28 May 2019.

Patient and public involvement

Involving parents and young people in the process of research

A PPI reference group was formed comprising three parents and three young people and organised by Triangle (Brighton, UK) (co-applicant), an independent organisation that provides consultancy and advocacy services that enable children and young people to communicate about important matters. Triangle conducted the PPI on our behalf. The research team provided Triangle with a brief, or instrument, and asked for comment. Triangle liaised with parents and children on our behalf. In relation to children’s participation, a member of the research team usually observed the consultation. Our lay chairperson was involved in all aspects of the research study.

Input into data collection tools and project information sheets

Parents provided feedback on project information sheets. Parents also provided feedback on the form and content of the WBS; this task was not accessible to young people. We asked for feedback from parents on the scenarios used in the WTP questionnaire in terms of wording and ease of understanding.

The young people’s PPI group gave feedback on the content of the children’s interview schedule, which included social stories about children eating. The comments the young people made included concerns about the social stories that involved a child choking (used to illustrate that oral feeding was unsafe), which they felt could raise anxiety. This was removed. Their comments ‘we are all different’ and ‘only people who have been trained by my SLT [speech and language therapist] should help me with eating and drinking’ were, with their permission, used on the project website. Parents provided feedback on the interview schedule for professionals and parents by commenting on the wording of questions and the content of the interview schedule and made suggestions to simplify questions and ask additional questions.

Input into the website

The young people’s PPI group and parents’ group provided feedback on the project website hosted by the University of Hertfordshire. The feedback addressed the visual appeal, potential audience and content. One parent felt that the images of children implied that all children with gastrostomies were wheelchair users and advised us to change this, which we did. There was a comment that the characters portrayed needed to be more ethnically diverse. We made these changes. Use of the term PPI was also questioned: one parent felt that it had medical and insurance connotations. We changed the wording to ‘community engagement’.

It also became apparent that the website was not accessible to children through the university system: it took substantial time to locate the website using its augmentative and alternative communication (AAC) systems because of the length of the URL and the number of clicks involved. This was partly a result of the ways in which universities manage website pages, which researchers have little control over. Therefore, we purchased an independent URL to make the website more directly accessible. We also provided feedback to the PPI group on what changes we had made in response to its involvement, in line with best practice guidance. 57

Outputs

We fed back our results to parents and asked them to read our lay summary for ease of understanding. Parents and children commented on the minimum standards of support, which are included as supplementary information.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was obtained from the HRA National Research Ethics Service Committee Camden and King’s Cross (REC reference 16/LO/0214).

The WTP study was reviewed by the University of Hertfordshire’s Health, Science, Engineering & Technology Ethics Committee with Delegated Authority (reference UH03705) and received ethics approval.

Written consent from parents and staff to participate in interviews was obtained.

Box 1 indicates changes to the original protocol.

The survey was disseminated through R&D departments of trusts using the National Directory of NHS Research Offices and a range of professional networks, in addition to the BACD database. This required a non-substantial ethics committee amendment.

Phase 2: case studyWe amended the protocol to offer telephone or Skype interviews to staff and parents to maximise opportunities for participation.

We had initially planned to use framework analysis as an approach to the analysis of qualitative data supplemented by a storied approach to participants’ narratives. We adopted a thematic analysis to the qualitative data. We had planned to use Greenhalgh et al. ’s42 organisational theory of factors influencing diffusion of innovation and barriers to implementation in relation to our data. However, the data did not lend themselves to this approach, although we have described the barriers to implementation of PSS. We use Mahant et al. ’s1 model of decisional conflict as described in the protocol.

Phase 3: resource utilisation and costsIt was not possible to assess costs from children’s clinical records because it became apparent that PSS is generally not recorded in the clinical notes as a distinct activity. Rather, support was integrated into the clinical appointments and children and families were rarely referred to a psychologist or specialist where this would be recorded.

We changed the timing of the dissemination of the resources questionnaire to coincide with the initial invitation to participate, rather than later, owing to concerns about sample attrition and low response rates.

Owing to the small number of questionnaires returned by parents, the cost analysis draws on data across all four cases in the case study rather than four separate models. Similarly, in the WTP study, we aggregated data across parents and professionals, given that professionals were the largest participant grouping.

TimescaleThe project was paused for 12 months, from 2017 to 2018, owing to a change of sponsor while the project moved to the University of Hertfordshire.

Integrity of data

Generalisability

We aimed to use the case study to bring into relief approaches to embedding PSS in a variety of settings through interviews with a range of stakeholders, observations of care processes and a review of service documents. We concur with Sharpe et al. ,40 who argue that the different views of a range of participants across diverse contexts allows for some degree of generalisability, particularly when supported by additional data from other sources, in our case from phases 1 and 3 and the case study with data from across the four cases.

Interviews were coded by an independent researcher (JL) and checked by another researcher (EB). The chief investigator (GC) also reviewed 10% of transcripts for coding.

The case study has also been reported with regard to Rodgers et al. ’s58 consensus standard for the reporting of case studies in organisations (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

Member checking

Feedback sessions were conducted at two case study sites (CS01 and CS04), which involved face-to-face meetings with HCPs, and descriptive information about the case studies was sent to two sites (CS02 and CS03) for comment to validate the findings. The mapping of services was either sent to the principal investigators at each site for comment or discussed in feedback sessions.

Triangulation

Cohen et al. ’s59 definition of triangulation as an approach that maps out and explains the richness and complexity of a phenomenon by studying it from more than one standpoint reflects the way in which triangulation was handled in this study. To this end, a range of professionals and services were identified using theoretical sampling and we employed different methods to provide data (interviews, document review and observation). These different data sources provided a more balanced and holistic picture of services, which can often look, feel and be experienced as different from varying perspectives and across case study sites. Theoretical triangulation and synthesis was used by applying Mahant et al. ’s1 model of decisional conflict, and themes were compared across case study sites.

Chapter 3 Results of the web-based survey scoping best practice

The WBS was disseminated through two distinct routes. The first route was via the BACD database during July and October 2016. The WBS was opened 71 times; 30 respondents provided no information beyond the initial consent, leaving 41 respondents. After the removal of duplicates (n = 2) and the responses of a respondent who had indicated that there was no feeding team, this left 38 respondents. The second route was via the R&D departments of individual NHS trusts, which resulted in a time delay reflecting the need for additional permissions. Between December 2016 and May 2017, the WBS was opened 47 times; 21 respondents provided no information beyond consent, leaving 26 respondents. There were 64 WBSs returned with different degrees of completion, which explains variations in the denominator. We disseminated the WBS through professional networks during both periods. Owing to the multiple routes we used to disseminate the WBS, we do not have a denominator, and hence response rate, for the WBS.

Respondents

Table 1 illustrates the number of responses to the survey questions. Most respondents were based in services in England (83%). There were no responses from Northern Ireland, which may be the result of a different mechanism of dissemination (see Appendix 2). The WBS was completed by a range of professionals, although those with a dietetic background, and paediatric consultants, represented the highest number of respondents. We report on the main themes that we aimed to explore in phase 2 and that would help identify additional case study sites; namely the delivery of PSS, perceptions of good practice, areas for improvement and associated barriers and levers. Table 2 provides a thematised account of responses from the open-ended questions. In addition, we report on parental involvement and decisional conflict.

| Responses | n (% of completed responses) |

|---|---|

| In which nation is your service based? (N = 63) | |

| England | 52 (83) |

| Wales | 5 (8) |

| Scotland | 6 (9) |

| Northern Ireland | 0 (0) |

| Professional background of person completing survey (N = 49) | |

| Consultant paediatrician | 10 (20) |

| Dietetics | 14 (29) |

| Children’s community nursing | 7 (14) |

| Nurse specialist | 4 (8) |

| Other | 7 (14) |

| School nurse | 1 (2) |

| SLT | 3 (6) |

| Staff nurse | 2 (4) |

| Consultant gastroenterology | 1 (2) |

| About care pathways | |

| Does your service have any of the following?a (N = 35) | |

| Written care pathway | 13 (37) |

| Best practice statement guidance | 7 (20) |

| Multidisciplinary guidance | 9 (26) |

| Written dysphagia policy | 9 (26) |

| Other | 13 (37) |

| About the PSS offered | |

| Is PSS offered to the following groups? (N = 45) | |

| Children | 24 (53) |

| Young people | 22 (49) |

| Parent/carer | 31 (69) |

| No PSS offered | 20 (44) |

| Is PSS documented or formalised? (N = 43) | |

| Yes | 15 (35) |

| No | 28 (65) |

| Do you have a process/tool in place to measure outcome of PSS? (N = 38) | |

| Yes | 7 (18) |

| No | 31 (82) |

| Do children/families have to meet a threshold to receive PSS? (N = 25) | |

| Yes | 7 (28) |

| No | 18 (72) |

| How well do you feel your service supports children/families? (N = 44) | |

| Very well | 8 (18) |

| Room for improvement | 29 (66) |

| Not very well | 6 (14) |

| No support | 1 (2) |

| Is there something you would like to do differently to improve the PSS offered? (N = 43) | |

| Yes | 38 (88) |

| No | 5 (12) |

| Parental peer support | |

| Does your team offer referrals to other parents who have experience of gastrostomy? (N = 38) | |

| Yes | 23 (60.5) |

| No | 15 (39.5) |

| If yes, is the referral formalised in any way? (N = 23) | |

| Yes | 19 (82) |

| No | 4 (18) |

| Are there any established parent or voluntary groups that you work with as part of your service? (N = 35) | |

| Yes | 6 (17) |

| No | 29 (83) |

| Decisional conflict (N = 39) | |

| Does the service have written guidance or approaches to managing conflict when the parents/child disagree? | |

| Yes | 8 (21) |

| No | 31 (79) |

| In the last 12 months | |

| Has children’s weight/growth raised concern about safeguarding?b (N = 34) | |

| Yes | 30 (88) |

| No | 4 (12) |

| Have you or your team used safeguarding legislation in relation to children’s feeding/weight/growth? (N = 34) | |

| Yes | 16 (47) |

| No | 18 (53) |

| Do clinicians/therapists receive clinical supervision/guidance/support when working with children and families who disagree? (N = 41) | |

| Yes | 31 (76) |

| No | 10 (24) |

| Question | Themes |

|---|---|

| Please identify three key aspects of your service that you feel are examples of good practice in delivering PSS to children and families? |

|

|

|

| What changes would you like to make? |

|

| What would help you to make those changes? |

|

| What barriers, if any, would you need to overcome to make those changes? |

|

Psychosocial support

A total of 44% of respondents reported not offering PSS according to the definition provided, and approximately half of respondents reported offering some form of PSS to children and young people. Possibly owing to the severity of children’s disability or young age, PSS was mainly offered to parents. In approximately two-thirds of cases, PSS was not documented or formalised and most respondents had no method of measuring the outcome of a PSS intervention. In a small number of cases, children/families had to reach a threshold, or meet criteria, to receive support. For example, one service indicated that ‘a child must be less than 4 years of age and attending a local CDC to be eligible for clinical psychology input’ and that ‘this resource is not readily available to other branches of the feeding team’.

Perceptions of good practice

Respondents were asked to identify three key aspects of good practice in their service. Staffing arrangement such as dedicated feeding clinics, MDT working and specialist staff were mentioned:

The service is just dedicated to enterally fed patients, so the clinical expertise is very specific, and the advice provided is current and from experienced clinicians.

Very good multidisciplinary teamworking and communication between whole team across all sites.

Of interest was the support provided from a clinical psychologist to the rest of a team:

Opportunity for individual sessions with a clinical psychologist. [Their] presence increases all the team members’ awareness of issues, which we discuss at team workshops.

This specialist support contrasted with services where PSS was integrated within the appointment:

We address nutritional, physical and emotional aspects of feeding problems simultaneously.

Practice approaches included values-based, family-centred and holistic care that recognises that approaches other than traditional biomedical ones are important. Having access to up-to-date knowledge was also mentioned and the importance of high-quality clinical care. Linking families together was perceived as an aspect of good practice.

Areas of change needed in the provision of psychosocial support and perceived levers and barriers

Two-thirds of respondents felt that they could improve on how they delivered PSS, which might be an indication of practitioners who were more reflexive about service improvements. It may also be easier to respond in this way rather than endorse a more negative response. The majority (88%) of respondents felt that they would like to do things differently.

Perceived barriers to implementing changes were identified, including commissioning, workforce issues and the need for better communication across teams:

Different services being commissioned by different trusts. For example, in [name of area] speech therapy and community paediatrician is provided by [name of trust] while dietetics and children community nurse by [name of different trust].

Workforce issues were also raised, suggesting the need for support for staff in addition to parents:

High levels of stress experienced in looking after children with complex neurodisability and their families.

The need for improved communication between services and the tertiary centre, and within the service, were also mentioned so that HCPs had advanced notice of those children due to have surgery:

If medical staff bringing children in to insert a tube, more communication with wider team so they can give support.

Peer–parent support

A number of services indicated that they linked families considering a GFT for their child with those families who had experience, sometimes through signposting to national parent organisations, although this did not appear to be a formalised arrangement. There was an acknowledgement that families had opportunities to meet parents through schools:

Actually no [i.e. not formalised], but I wanted to say that it is by means of PINNT [Patients on Intravenous and Naso-gastric Nutrition Treatment (Christchurch, UK); a support and advocacy group for people receiving home artificial nutrition]. In addition, many of the families already know other families with a child with a gastrostomy from their shared special needs school. So, when they come to my nurse-led clinic, most have already seen a gastrostomy. This may increase or decrease their anxiety.

We have used Contact A Family [London, UK] in the past but do not routinely signpost families in this way.

Similarly, several services reported that they had relationships with established parent or voluntary groups, although this was not specifically feeding related:

[Name of city] parent-carers – mutual participation in meetings. Not specific to feeding.

[Name of national organisation], part of our NHS organisation, involving parents and young people in service design. Not specifically for feeding issues.

When asked in what way parents or groups were involved in supporting families considering a GFT, responses included ‘additional and independent support’. Resourcing parental involvement was also raised as an issue:

We did have a support group, we did run for families who tube feed but we haven’t had a meeting for a long while as it’s very time-consuming to arrange and we struggle with time in work to arrange but it is something that we are hoping to restart soon.

One service mentioned that a food and nutrition group involved two parent members in addition to school and HCPs.

Decisional conflict

Few services had written guidance or approaches to managing conflict when parents disagreed with the recommendation of a GFT and 88% reported that children’s feeding, weight or growth had raised safeguarding concerns. Just under half reported using safeguarding frameworks because of concerns, although it is possible that this was due to additional concerns. The majority of respondents reported that they had access to clinical supervision when dealing with disagreements.

Summary of survey findings

Evidence reviews have suggested that services should offer consistent and structured support in care pathways to ensure high-quality decision-making when families consider a GFT for children. The results of our WBS suggested that a range of practitioners delivered support. The majority of services did not appear to have a formalised way of documenting PSS or of measuring the outcomes of PSS initiatives, which we aimed to explore further in our case study because this has implications for services’ ability to monitor and evaluate PSS provision through audit and research, which may prove useful in justifying resources, given that lack of resources was mentioned as a barrier to developing PSS. Indeed, one barrier to the implementation of PSS initiatives mentioned was the lack of evidence of effectiveness.

Although difficult to determine different typologies of service from survey responses, reflecting a limitation of the method, respondents made the distinction between specialist (e.g. specialist enteral clinics) and generalist services. The availability of designated staff (e.g. a psychologist) to offer PSS was mentioned as an aspect of best practice and perceived as an opportunity to improve care. This contrasted with approaches in which PSS appeared to be integrated within clinical appointments. We aimed to explore these different staffing arrangements of specialist and generalist services, and designated PSS compared with integrated PSS offered by a MDT, in our case study. There was some evidence of children having to meet thresholds to receive PSS, perhaps from designated staff, and access to a psychologist was available in some branches of one service but not others. Inequality in the provision of PSS is a theme we therefore aimed to investigate further.

Not all services offered PSS to children, which may reflect a lack of expertise in communicating with children who, as often the case in this population, are non-verbal (between 42% and 60% of these children are estimated to have a communication impairment). 10,60 Although some services appeared to have involved local parent groups in general service developments, this was not feeding specific, but indicates the potential availability of resources in the locale for developing peer support initiatives. Professionals also signposted families to national organisations, but we do not know if this was followed through. Generally, peer-to-peer parent support was arranged informally and on an ad hoc basis. Concerns about time and resourcing to do this well were raised. There was some ambivalence about whether peer-to-peer parent support was beneficial or could raise anxiety. An example of how the parent voice could be embedded in practice was provided by parents sitting alongside HCPs and teachers on a food and nutrition group in one service. Parental peer support was explored in phase 2.

Children’s weight and growth raised safeguarding concerns for the majority of respondents, with little evidence of guidance to support staff. How clinicians manage conflict, risk and safeguarding was explored in our case study.

Perceived barriers to change were identified, including staffing arrangement, facilities, resources and commissioning. Resourcing and competing needs were dominant themes, reflecting an awareness of financial constraints as a barrier to providing PSS. These themes were explored in phase 2.

Limitations

It proved very difficult to disseminate a WBS nationally, despite extensive efforts, following a poor response rate using a professional database. Appendix 2 illustrates an extract from our dissemination log using the BACD database. This suggests that only 43 out of 225 recipients initially opened the e-mail containing the survey link sent to CDCs (our target audience) by the BACD on our behalf, with 11 out of 43 opening the survey link. Low response rates to surveys involving doctors are commonly reported, including rates of 29% in Canada61 and 30% in the UK. 62 Moreover, the research team had to rely on gatekeepers to disseminate the survey. Future efforts could second a member of the BACD to help with telephone reminders to improve response rates, and there is evidence that incentives increase participation;63 however, these approaches would have implications for resourcing.

Information request overload may have had some bearing. Anecdotal evidence from our networks suggest that clinicians receive many requests for information, including for research, commissioner requests and national professional body surveys. The length of the WBS may have been a factor affecting the differences in responses to questions, although evidence that length affects response fatigue is not conclusive;64 rather, WBS content, interest and motivation in the context of time pressures may be factors. However, responses to questions later in the survey did appear to wane. Given the lack of formalised and documented approaches to recording PSS, it is possible that respondents may have had to find the answers to the survey from different data sources and hence left the survey but then did not return to complete it.

As a result of the above, we are unable to claim that the results are representative, although we did identify topics worthy of further exploration in our case study. Methodologically, surveys are a crude tool for capturing data about complex services crossing boundaries. For example, there was some evidence to suggest that responses reflected PSS across services rather than individual services. Similarly, it proved difficult to classify services and models of psychosocial support from the responses provided in the WBS. There was a tendency of staff to respond with stock responses such a ‘MDT working’ as an aspect of best practice, which provided little insight into how teams functioned. This is a limitation of the method. There are also methodological issues regarding individual responses that ‘speak’ on behalf of whole teams and services, hence the need for a mixed-methods study that allowed us to explore the themes raised in this WBS.

Chapter 4 Findings of the collective case study

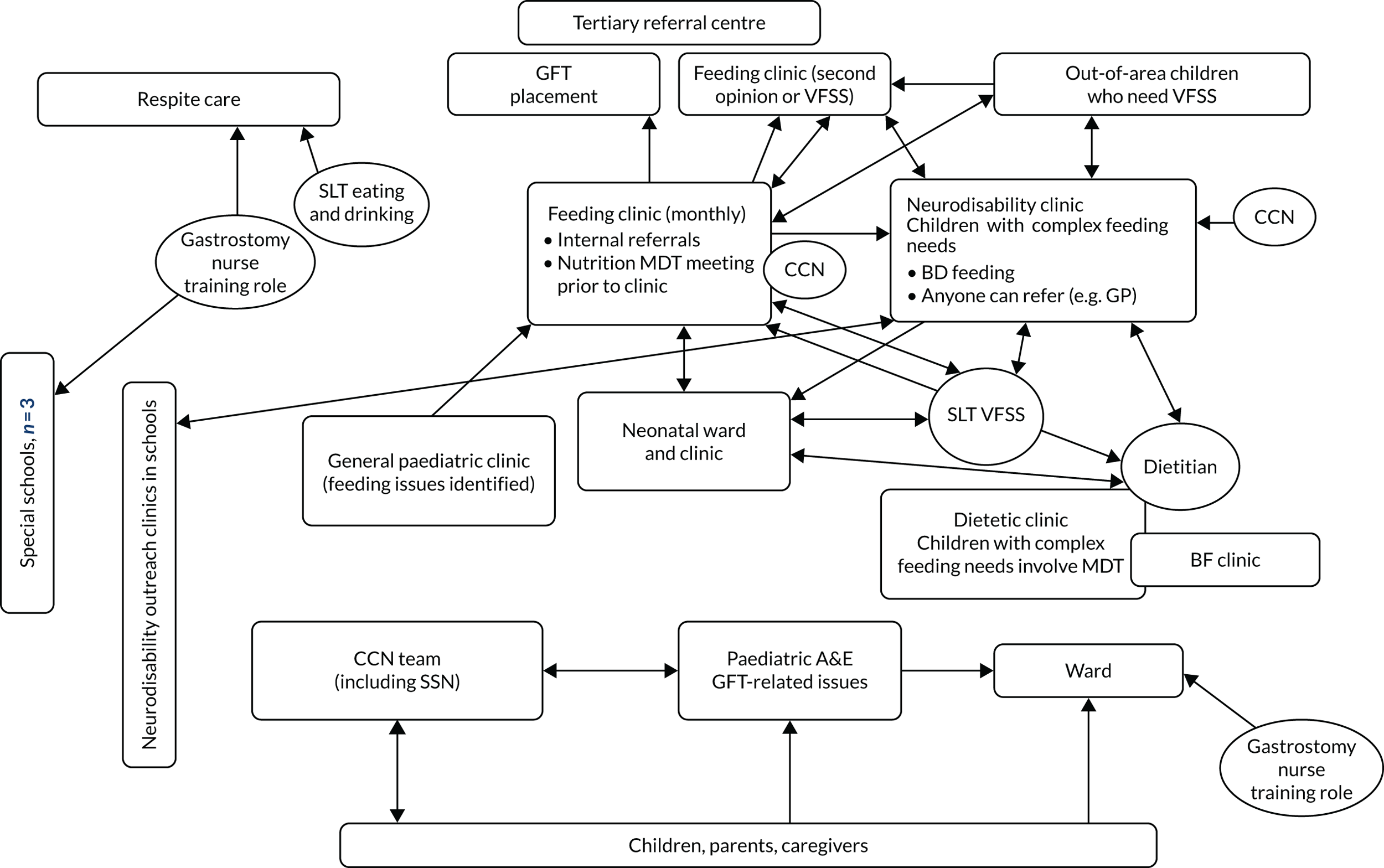

Structure of the results chapters of the case study

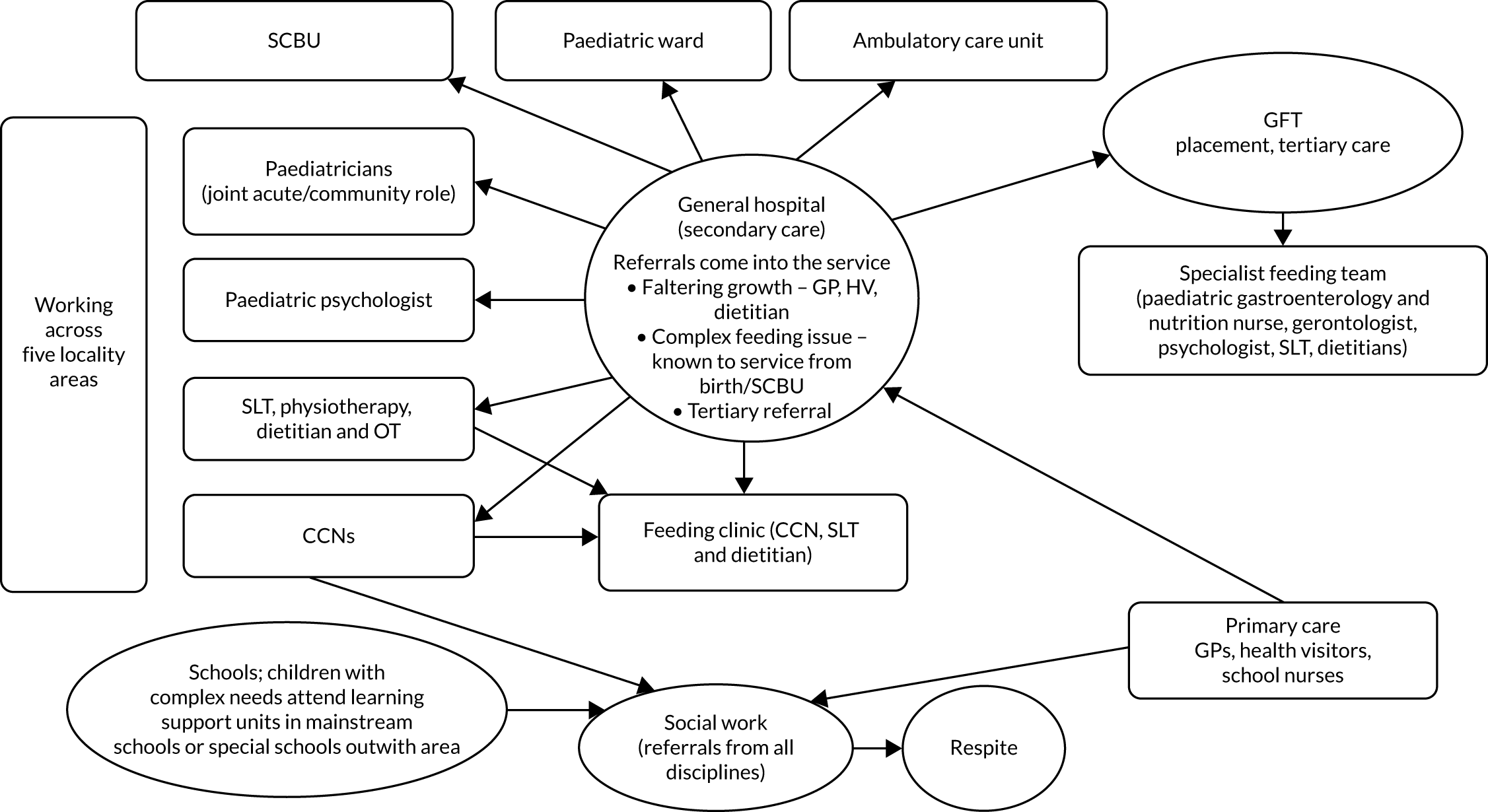

This chapter details each of the four case study sites. Each case begins with an overall description based on documents and interviews, and this is followed by an outline of how support is delivered in relation to our themes developed from an analysis of interviews, observations and review of service documents. Each case is accompanied by a service map detailing the relationship between key nodes in the service and ‘referral pathways’ where possible, although pathways were often informal and crossed different sectors of provision, including education. These maps were produced iteratively, with the aim of highlighting complexity, and served as a focus for reflection in feedback sessions with teams where possible.

Interview participants

Table 3 illustrates the number of participants interviewed (including joint interviews or group discussions). These were children (n = 3), parents (n = 26) and staff (n = 58) across the four case study sites. The small number of children interviewed reflected their young age, severity of cognitive impairment and parental gatekeeping (access and consent issues). However, there was a group of children involved in the PPI group; these children’s involvement is detailed in Chapter 2, Patient and public involvement. There were 40 hours of observation of care processes.

| Participant | CS01 | CS02 | CS03 | CS04 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Parent | 11 | 9 | 5 | 1 |

| Child | 2 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Staff | 20 | 15 | 15 | 8 |

To maintain confidentiality, professional and biographical information is presented in aggregate in Report Supplementary Material 7 rather than per case study.

Case study site 1

Overall description of the case

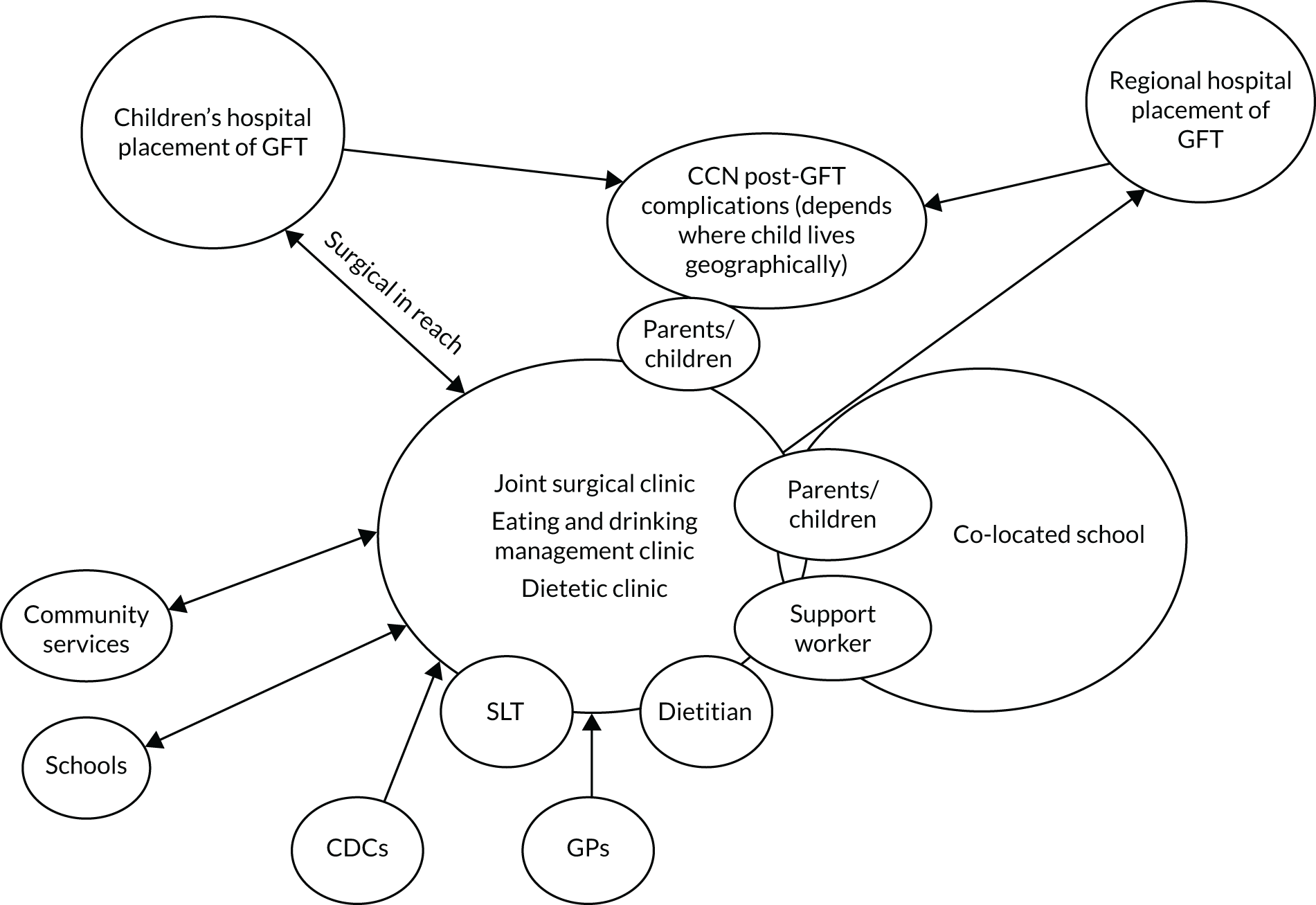

Case study site 1 is described as a specialist clinical service and a co-located, charitable-funded special school and associated services. The clinic saw children attending the co-located special school and children in the local catchment who may have attended other schools in the area. Figure 4 shows the configuration of care at CS01. There had been a recent move in this setting to pool budgets for health and education, and clinical services received payment from education and NHS Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), with agreed levels of funding for each child. However, for older children (aged 19–25 years), funding for health was described as ‘piecemeal’ (in an orientation interview) and dependent on NHS Continuing Healthcare assessment funding, reflecting inequities in service provision for young people.

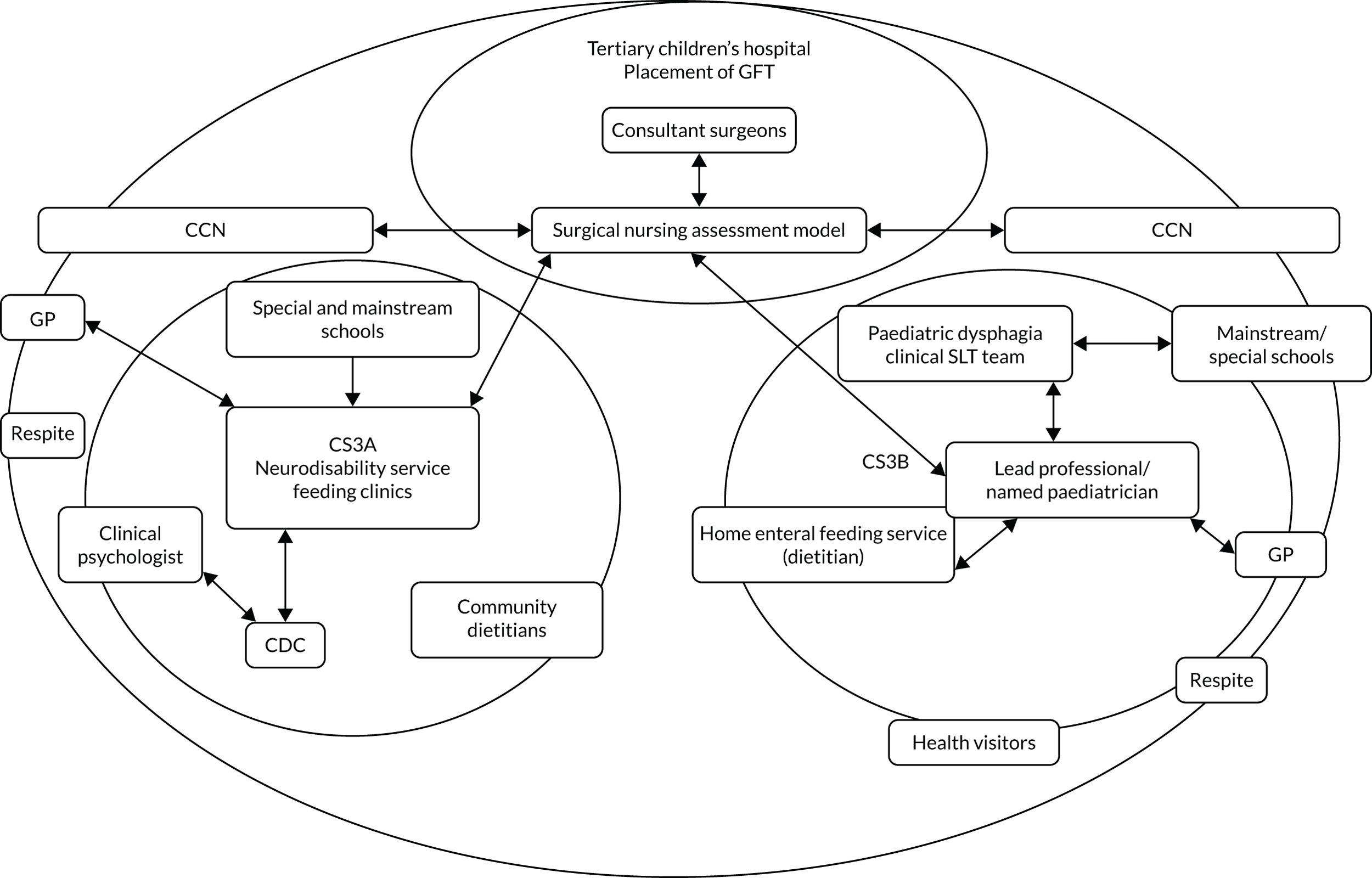

FIGURE 4.

Configuration of care: CS01. CCN, children’s community nurse; GP, general practitioner.

The CS01 clinical service provided a range of specialist health-care services for children and young people with neurodisability and complex feeding needs/GFT. Referrals to outpatient services could be made through any NHS HCP and were accepted without prior approval, provided that they could be accommodated by the outpatient clinic allowance set out in the contract financial schedule. The allowance for outpatient clinics was therefore used to provide outpatient access to non-pupils (as described in the service specification document for the CS01 clinical service; details omitted to preserve anonymity). Pupils attending the co-located special school had an assigned paediatrician who visited the school and was linked with the school therapists, nurses and teachers. This helped to simplify referrals to the clinical services and the joint assessment of children.

Staffing arrangement

The nutrition team, which was part of the nutrition service that provides clinical care to children and young people with complex neurodisability, included a paediatrician, dietitian, nutrition nurse specialist and SLT and offered a dietetic clinic. Team meetings, which were attended by clinical staff, parents and school representatives, aimed to address any issues around feeding. A paediatrician was linked to the nutrition clinic and therefore came in direct contact with pupils at the CS01 school. There were three main clinics where children and families could be seen: a dietetic clinic, a drinking and management clinic and a joint surgical clinic (discussed later as an aspect of integrating community and tertiary services).

The dietetic clinic was run by a senior paediatric dietitian, lead clinician and nutrition nurse specialist. The clinic was for children and young adults for whom there are dietary or nutritional concerns, and all individuals fed by a GFT or nasogastric (NG) feeding tube were reviewed in this clinic once per year to ensure that their intake was nutritionally adequate (sources: Dietetic Clinics leaflet developed by the CS01 clinical service; CS01 dietetic clinic observation notes).

The eating and drinking management clinic was run by the specialist SLT, who was the clinical lead for eating and drinking difficulties. The service was for children and young adults who have complex eating and drinking needs and who did not attend the co-located school. Referrals could be made to this service by the SLT, general practitioner (GP) or paediatrician. The clinics were held monthly throughout the year. Funding was covered through a service-level agreement or individually commissioned service (source: Eating and Drinking Management Clinic leaflet developed by the CS01 clinical service).

Integrating support

A named paediatrician co-ordinated the MDT for nutrition and took responsibility for ensuring that PSS was provided. A key worker scheme operated through the school to cater for social care needs and represent children at health meetings. In general, however, the health team viewed the paediatrician as the ‘key worker’, although this term was not used. The joint surgical clinic included a consultant paediatrician in neurodisability, visiting paediatric surgeon from the local children’s hospital (tertiary centre), paediatric dietitian, paediatric SLT and nutrition nurse. This clinic was for children aged < 19 years with feeding issues that required a surgical opinion about the need for a GFT. Investigations were organised from the clinic. Referrals could be made to this service by either a paediatrician or a GP. Clinics were held six times per year (source: Joint Surgical Clinic leaflet developed by the CS01 clinical service). Surgery for the insertion of a GFT was performed at the tertiary hospital, with the surgeon leading the process and community nurses supporting the parents before and after surgery (CS01, S10, FG).

Integrating support: health and education

This case study site provided a highly specialised and resource-intensive service characterised by a high level of integrated care between NHS therapy and health services and education, which enabled support around the decision-making phase of a GFT for school-aged children, post-gastrostomy care and feeding choices before and after surgery. Integrated care was enabled through a three-way partnership between the clinical services, co-located school and children/families. Integration was manifested in the way that health care was personalised to the needs of individual children, embedded in the school curriculum and co-produced by teachers and therapists working together (therapists were involved in teaching and teachers were involved in health care).

Parents interviewed at CS01 identified their main support as coming from the co-located school, where multidisciplinary working takes place, facilitated by the partnership between the school, parents and clinical services. They often compared their experiences with previous experiences of their child in other locations:

They’re very sensitive to the needs of the children here [in the school] and they group them accordingly . . . I can honestly say that [name of child], and all the children here, they’re in a very good place. And I think in order [to achieve] . . . what constitutes a good environment for children with needs, is having the clinical services, the experienced staff all the time and the school together.

CS01, parent (P)2, focus group (FG)

The benefits of integrated health care in minimising health-care burden (e.g. attending appointments, time out of school to attend appointments) were valued by parents:

All schools around the country for children with physical disabilities should be like [CS01 school]. When you come to [CS01] you can say that and I always say ‘give a child and a parent 6 months and you’ll see the difference in both of them’, because the child has the team behind them, and the parent gets their life back.

CS01, P1, joint interview (JI)

The views of parents were supported by members of the school and clinical staff, but for them the emphasis was less on the co-location aspect of the school and more on the place where the MDT came together. As one of the teachers said:

In terms of the way the school is joined up with clinical services, we are a multidisciplinary team, or that’s one way to describe it. We join up with the therapists, as well as the nursing and doctor team. We have a bleep system where we can call nurses . . . We had a doctor in the classroom yesterday and three nurses.

CS01, staff member (S6), individual interview (II)

It is important to bear in mind that the clinical services at CS01 were not only for those children in the special school. Other children could access the clinical service as an outpatient but could not access all services owing to the unique funding arrangements at CS01. However, we were not able to conduct interviews with families attending other schools.

Psychosocial support

Policy and guidelines

Children’s rights to psychosocial, emotional support (although not specifically about feeding) were enshrined in a charter that underpinned the work of the school and the clinical services. It was co-produced by children and young people in conjunction with care staff, allied HCPs and nursing and teaching staff. The charter stated that to be as healthy as possible, children can ‘[r]ely on an adult to have up-to-date information about their health needs and impairments, including psychosocial and emotional needs, as well as their health and medical needs’ (source: charter outlining children’s rights while in the care of services developed jointly between the clinical services, school and children and young people). The charter then stated that ‘these rights must be actively supported and embedded in practice at [CS01]’. The values and rights are reinforced through staff induction, ongoing training and integrated teamworking, and feature in job descriptions (local principal investigator, CS01, 2019, personal communication).

Staffing arrangement: psychosocial support

At CS01, support for feeding issues could be provided by any member of the MDT and was usually provided as part of the appointment. There was a psychologist, clinical psychologist and psychiatrist within the clinical services; the psychologist worked with children with behavioural difficulties in the school. Psychologists did not routinely participate in appointments with families but could be drawn on as the need arises and can support the team. A clinician reflected on how this works:

So, you need to go up a tier, and when I say up a tier, involve someone else if it’s not working well. So, here, for example, we have a behavioural therapist who works within this team; it isn’t part of our clinics, but if there was a concern, then I would involve them because they’re more rehearsed and have more skills. And then again, it’s that integrated working, working together to try and do it better.

CS01, S10, FG

Feeding practices: risks, values and emotions

Clinicians generally had a good appreciation of the values that parents attached to feeding a disabled child and the difficulty that some families experienced accepting a recommendation to have a GFT and, in some cases, to stop feeding children orally:

I think it’s a very mechanical way of feeding a child and I think if you’re a mum, sort of loving, nurturing and caring is really closely wrapped up in feeding, so I think if you’re having to do something that’s so clinical in terms of nurturing your child, you’re removing some of the closeness and bonding and relationship factors within that relationship. So, I think that’s really important that that’s managed carefully.

CS01, S3, II

The risks associated with oral feeding and association with poor respiratory health were seen as a particular stumbling block for parents:

And I think in some cases where there has been a real danger, a real worry about aspiration and [children] becoming repetitively unwell with chest infections . . . it’s sometimes quite hard for parents to believe it’s to do with their eating and drinking. . . . I think parents have had a lot of resistance to that idea, because I think probably, it’s almost parents feeling that it’s their own fault that their child has been ill.

CS01, S4, II

The emotional aspect of the consultation and parental need for support was acknowledged:

We do give emotional support because we explain to them exactly what we’re going to do, and what the benefits and the disadvantages are. We also listen to the parents and sometimes they say, ‘No, no way, I don’t want this’. [Murmurs of agreement.] Well, we don’t want to force them to have it, we understand that, but we do try to convince them it’s really in the interests of the child, and we will try to convince them, so it’s actually very emotional work you do, you can’t change that.

CS01, S1, JI

However, another professional in the same group felt that the support they provided to families was not always enough. The professional commented that the practice of documenting that the risks and benefits of the procedure had been explained to parents in the clinical notes might address the medicolegal aspects of a surgical intervention, but did not always guarantee that the emotional aspects of the procedure had been addressed to the satisfaction of parents. The consequences of not having adequately prepared families for the procedure were evident in an example recounted by the clinician, although it was stressed that this was not a typical case:

They [the family] didn’t feel supported . . . so, they just felt it just all happened so quickly, and they didn’t really know what was happening.

CS01, S2, II

In one observation of the joint surgical clinic involving the MDT [surgeon, consultant paediatrician, dietitian and SLT] prior to the clinic, a child’s case was discussed, including the medical history, current feeding issues and potential solutions, and recommendations were identified jointly. The parent (father) was then brought in. He engaged in conversation with the SLT and dietitian, who recommended that he made a one-to-one appointment within the next few weeks to make sure that fluid intake was under control. The observer noticed that, although care was taken in the meeting to check the father’s wishes, emotional issues were not raised or discussed (CS01 clinic observation notes).

Another member of staff felt that having additional appointments separate to routine clinical appointments would improve how the team communicated and delivered support. There was a feeling that a lot of communication was happening in e-mails that was not the optimal way to provide support:

I would like to identify set points where a conversation is had with the child outside of a clinic appointment, because I don’t think that that . . . I think it’s a bit ad hoc at the moment, and I’m sure that some people are getting missed in terms of that.

CS01, S8, JI

The nurses were perceived to have a key role in providing support to families because they were the ones working closely with children and were better able to address parental concerns about the lived experience of having a GFT, for example what it means to have a GFT, how parents would manage the GFT and how parents would feed their child. Dietitians were also seen as playing a key role.

The dilemmatic65 and emotional nature of feeding practices, particularly where a child is not able to communicate her own preference, is nicely summed up in a joint interview involving two mothers in which one mother is reflecting on feeding her child by mouth even though her child has a GFT. The second mother clearly recognises the importance of oral feeding to her friend’s maternal identity. This psychosocial aspect of feeding contrasts with the very factual approach to explaining the risks of the procedure and does, perhaps, speak to the complexities involved in supporting parents. Information about risk appeals to reason but not to the emotional investments in feeding a child food by mouth: