Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 17/06/06. The contractual start date was in May 2018. The final report began editorial review in September 2019 and was accepted for publication in April 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Cotterill et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from our review protocol. 1,2 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Health workers routinely carry out behaviours that affect patient diagnoses, care, treatment and recovery. Many of these behaviours have clear guidelines for best practice. Examples include appropriate ordering of diagnostic tests,3,4 appropriate prescription of antibiotics,5,6 regular recall of patients with long-term conditions,7 hand-washing8 and choice of wound dressings. 9 Health workers face many challenges when following evidence-based professional practice, such as lack of time, competing demands and requests from patients. The issue of implementing best practice findings from clinical research to practice is termed the second translational gap,10 and can have significant impacts on patient and population health. Although there are no reliable published estimates, to our knowledge, of how well health professionals follow best clinical practices overall, we can draw on a couple of illustrative examples. In England, the USA and Canada it is estimated that 37%, 27% and 66% of patients with high blood pressure have their condition controlled, respectively, and health professionals can support improvement through prescribing medication, regular review of patients and lifestyle advice. 11 In England alone, 700 quality-adjusted life-years could be saved annually through just a 15% increase in this figure. 11 One out of 20 hospital admissions are caused by adverse drug events,12 and approximately half of these globally are believed to be preventable, owing to lapses in best practice in terms of prescribing or monitoring behaviours by clinicians. 13 There is evidence that social influences are important in clinical practice. 14,15

Social norms interventions

One proposed solution has been to implement behaviour change interventions based on social or peer norms. 16 Social norms are the implicit or explicit rules that a group uses to determine values, beliefs, attitudes and behaviours. A social norms intervention seeks to change the clinical behaviour of a target health worker by exposing them to the values, beliefs, attitudes or behaviours of a reference group or person. These social norms interventions can form part of an audit and feedback (A&F) initiative,17–19 or may be developed as another behaviour change intervention. 20 These are often interventions with reach: they can be implemented across multiple health workers and settings at low cost, so there is the potential for large absolute gain. We use the term target to refer to a health worker at whom a social norms intervention is aimed, with a view to changing their clinical behaviour. We use the term reference group or reference person to mean a person or group of people whose values, beliefs or behaviours are exposed to the target.

The ability of social norms to affect behaviour has been considered within several behaviour change theories and theoretical frameworks. For example, ‘subjective norm’ is a construct within the theory of planned behaviour,21 which describes subjective norm as an individual’s perceptions of whether valued others think one should perform a behaviour, combined with a motivation to comply with others’ beliefs. The theory of normative social behaviour22 proposes that behaviour can be changed through normative mechanisms, and has made distinctions between descriptive norms (beliefs concerning the prevalence of a behaviour) and injunctive norms (beliefs concerning what one feels they ought to do based on others’ expectations, linked to social approval). A descriptive norms message provides the target with information about the behaviour of others in the reference group. Examples of descriptive norms interventions include giving the target information about the behaviour of a reference person or group, or comparison of the target’s behaviour with the behaviours of a reference person or group. An injunctive norms message provides the target with information about the values, beliefs or attitudes of the reference group, conveying social approval or disapproval. Examples of injunctive norms interventions include providing the target with information about whether or not the behaviour has the approval/disapproval of the reference group or person; exposure (actual or promised) of the target’s behaviour to a reference group; and praise, commendation, applause or thanks (actual or promised) from a reference group or person.

The theoretical domains framework23 (which has drawn its domains and their content from multiple theories of behaviour change) includes a ‘social influences’ domain, which includes several normative constructs: social norms, social comparisons, group norms, descriptive norms and injunctive norms. The social influences domain goes beyond social norms to include a broader range of social concepts, such as emotional and practical support, demonstrating a behaviour and changing the social environment. The idea of using social norms as a behavioural intervention is present across disciplines (politics, economics, psychology and health) and there is variation between disciplines in how social norms are described.

Behaviour change techniques

The behaviour change technique (BCT) taxonomy v1 (the current version) is a list of 93 distinct BCTs that are used in behaviour change interventions. 24 A BCT is ‘a technique . . . proposed to be an active ingredient’24 of a behavioural intervention that contributes to behaviour change. We have chosen to identify and classify social norms intervention components in terms of the BCT taxonomy v1 because, based on international consensus, the taxonomy defines and labels all active ingredients of interventions. It incorporates previous behaviour change taxonomies and has involved significant effort from leaders in the field, and considerable investment from the Medical Research Council and the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) in developing the taxonomy. We believe that this is the most reliable tool currently available that can define BCTs. The names of BCTs that are included in the taxonomy have been italicised whenever they are used in this report.

The BCT taxonomy groups BCTs into categories, and none of the categories directly relate to social norms. This is perhaps surprising, given that the concept of social norms occurs in so many theories of behaviour change, including the Theoretical Domain Framework, but extensive work by a panel of experts resulted in the hierarchy of the taxonomy, and clearly it needs to meet the needs of a large and diverse community of researchers. An earlier version of the taxonomy had a ‘social influence’ category,23 which does not appear in the current version. 24 The BCT taxonomy v124 includes five BCTs that we believe involve social norms: social comparison (6.2), information about others’ approval (6.3), credible source (9.1), social reward (10.4) and social incentive (10.5). 24 The numbers in brackets follow the labelling of the BCTs in the BCT taxonomy v1. We have discussed this selection of social norms BCTs carefully, both within the research team and with our independent Study Steering Committee (SSC) of international experts.

Social comparison

‘Draw attention to others’ performance to allow comparison with the person’s own performance. Note: being in a group setting does not necessarily mean that social comparison is actually taking place.’24

‘Example: Show the doctor the proportion of patients who were prescribed antibiotics for a common cold by other doctors and compare with their own data.’24

Information about others’ approval

‘Provide information about what other people think about the behaviour. The information clarifies whether others will like, approve or disapprove of what the person is doing or will do.’24

‘Example: Tell the staff at the hospital ward that staff at all other wards approve of washing their hands according to the guidelines.’24

Credible source

‘Present verbal or visual communication from a credible source in favour of or against the behaviour. Note: code this BCT if source generally agreed on as credible e.g. health professionals, celebrities or words used to indicate expertise or leader in field and if the communication has the aim of persuading.’24

‘Example: Present a speech given by a high status professional to emphasise the importance of not exposing patients to unnecessary radiation by ordering x-rays for back pain.’24

The following two social norm BCTs have been amended slightly to ensure that the definition is sufficiently tight to allow us to identify and delineate interventions. Further details of the reasons for change are available in the protocol. 2

Social reward

The original definition of social reward was ‘Arrange verbal or non-verbal reward if and only if there has been effort and/or progress in performing the behaviour (includes ‘Positive reinforcement’). Examples: Congratulate the person for each day they eat a reduced fat diet’. 24

Our new tighter definition is as follows: arrange praise, commendation, applause or thanks if and only if there has been effort and/or progress in performing the behaviour (includes ‘positive reinforcement’). Example: arrange for a family doctor to be sent a thank you note for each week that they reduce their level of antibiotic prescribing.

Social incentive

The original definition for social incentive was ‘Inform that a verbal or non-verbal reward will be delivered if and only if there has been effort and/or progress in performing the behaviour (includes ‘positive reinforcement’). Examples: Inform that they will be congratulated for each day that they eat a reduced fat diet.’24

Our new tighter definition is as follows: inform that praise, commendation, applause or thanks will be delivered if and only if there has been effort and/or progress in performing the behaviour (includes ‘positive reinforcement’). Example: promise a family doctor in advance that they will be sent a thank you note for each week that they reduce their level of antibiotic prescribing.

Why it is important to undertake this research

There are health service contexts in which modification of the behaviour of health workers may have a beneficial effect on patient diagnosis, care and treatment, and on the costs of health care. These contexts include situations in which health workers are expected to follow evidence-based professional practice, such as prescribing, ordering tests, choosing treatments and adhering to guidelines. There are challenges in implementing recommended practice findings from clinical research into practice, referred to as the second translational gap. 10 Providing social norms interventions to health workers may help overcome these barriers to implementing recommended practice through a number of ways, including persuading them that they should change their individual behaviour, working collaboratively with their peers to develop action plans and change the organisation of care, observing good practice from other organisations and gaining support from senior managers. 16 This systematic review will summarise evidence on the use of social norms interventions to influence clinicians to implement recommended clinical behaviours. In advance of starting this review, our pilot work indicated that there were > 90 trials investigating the use of social norms interventions. A systematic review of the evidence was required to establish whether or not these interventions are effective, and what factors influence their effectiveness.

Health workers frequently receive A&F, which involves ‘providing a recipient with a summary of their performance over a specified period of time’. 17 Social norms interventions are sometimes included as one component of A&F, such as when the health worker is shown information about their own performance and also a comparison with their peers. 18,19 A&F has already been shown to be effective in changing health worker behaviour, but with large variation in outcomes depending on the context and the intervention design. 25 There is a need to understand the components for successful A&F. 17,26 The effects or mechanisms of the ‘social influence’ constituents of A&F have been identified in a systematic review as topics for further research. 17 As noted earlier, interventions based on social influence include social norms interventions; however, social influence is a broader concept that covers emotional and practical social support, changes to the social environment and modelling of behaviour. 23 Our review may contribute to this important research agenda by systematically examining the evidence for using social norms interventions with health workers.

Prior to starting the review and during its implementation we spoke to members of the public about this proposal and asked which aspects of the research were important and relevant to them. They told us that the research might contribute to cost savings to the NHS by reducing waste (e.g. waste of prescriptions or tests) without reducing patients’ quality of care, and provide opportunities for standardisation (e.g. use of social norms interventions to encourage nurses to use standard wound dressings when appropriate rather than ordering multiple types), which would affect costs. They identified the potential for social norms methods to be used in the curriculum for training health professionals. Patient safety is very important: patients suffer if antibiotics are wrongly prescribed and there is broader concern about antibiotic resistance. Social norms approaches could be applied to other health worker behaviours and could lead to changes in ways of thinking. Changes in health worker behaviour may lead to changes in patient behaviour too, for example patients may copy the health worker’s example of hand-washing. Patients told us that it would be interesting to extend this research in the future to how patients perceive staff behaviour and how health workers are influenced by social norms of patients, for example asking for/not wanting antidepressants or making comments about hand-washing. ‘Maybe the review will lead to broader research including patients in the social comparison equation. That seems important to me’ (PPI group member). Patients felt that they could have a role in social norms interventions, for example by reminding health workers to wash their hands or telling the general practitioner (GP) that they do not expect to be prescribed antibiotics for a cold; however, they were cynical about whether or not doctors would listen to patients when they present best practice (example was given of a relative who had better care in Australia, but the doctor in the UK did not want to hear about it). In response to this observation, we made sure to record any studies in the review that considered the role of patients in social norms interventions.

Scoping review

Prior to starting the systematic review, we conducted a scoping review. The purpose of the scoping review was to test out the search and screening procedures for the planned systematic review and provide information to help estimate the number of eligible studies and the amount of work involved. A systematic literature search on social influences (carried out on 9 November 2016) revealed a total of 3644 potentially eligible abstracts for our systematic review, after removing duplicates. Screening of these titles/abstracts generated 264 titles that met our initial screening criteria regarding study type, population and intervention. Reading the full text of 100 out of the 264 screened abstracts resulted in 42 being excluded, 51 being included and seven requiring further information. Among the 51 included papers, there were 35 unique trials. From this we estimated that there would be at least 135 articles and 93 unique trials in our review.

Before the scoping review we discussed our plans widely, including with the members of the SSC. This led us to revise the search strategy from the earlier work, aligning the search and coding framework more closely to social norms BCTs in the BCT taxonomy v1. 24 We also made a decision very early in the project to use the term ‘social norms interventions’ rather than ‘social influences’. This was because ‘social norm’ is a more specific term for the interventions we are interested in, whereas ‘social influence’ is used elsewhere in the literature as a broader term encompassing a wide array of behaviour change strategies, such as emotional or practical social support from others, restructuring the social environment and modelling or demonstrating behaviour. 23,27

Aim and research questions

The overall aim was to conduct a systematic review to assess, among health workers, the impact of social norms BCTs compared with controls (alternative interventions, no intervention or comparison of one social norms BCT with one or more other social norms BCTs) with compliance to evidence-based professional practice. The review addressed two research questions:

-

What is the effect of social norms interventions on the clinical behaviour of health workers, and resulting patient outcomes?

-

Which contexts, modes of delivery and behaviour change techniques are associated with the effectiveness of social norms interventions on health worker clinical behaviour change?

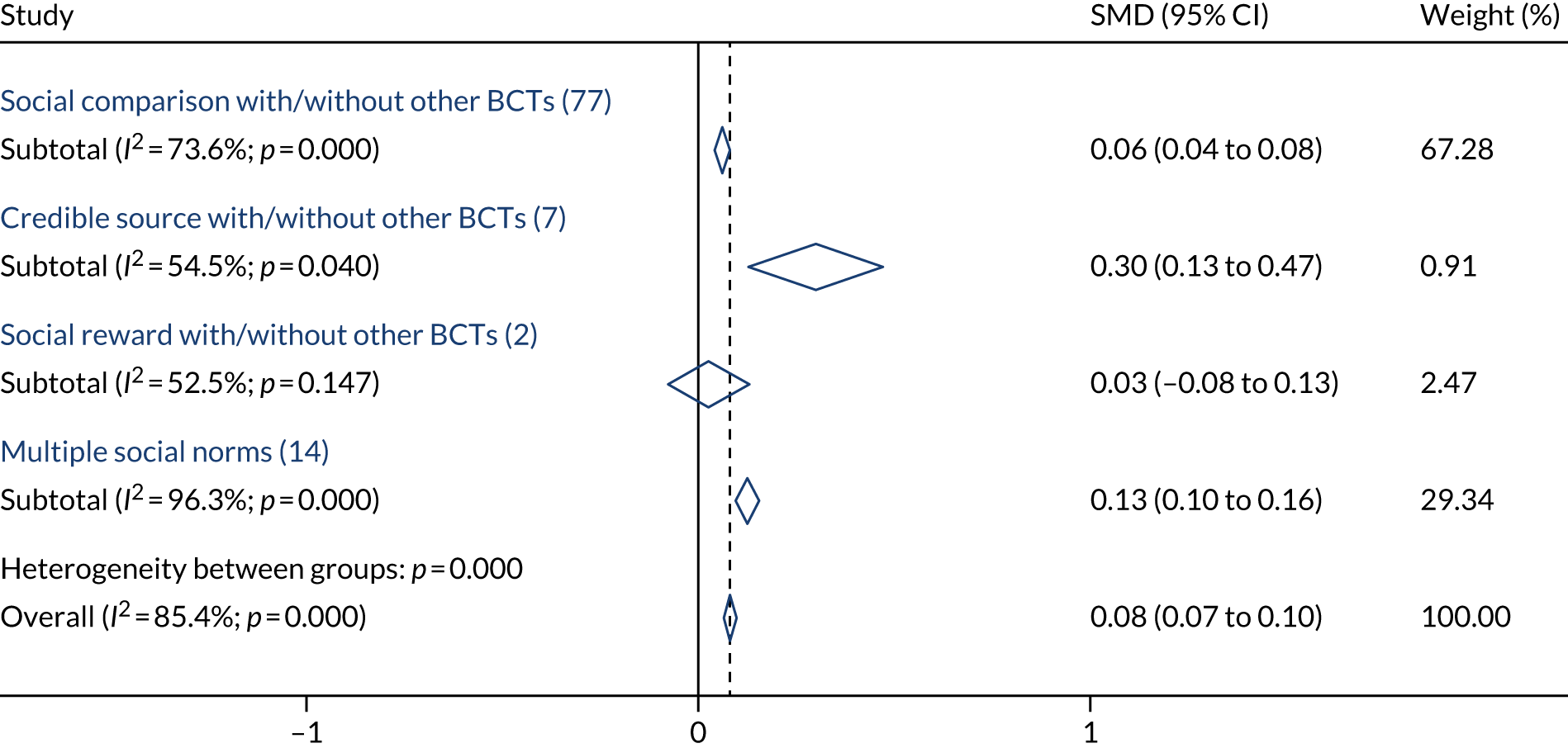

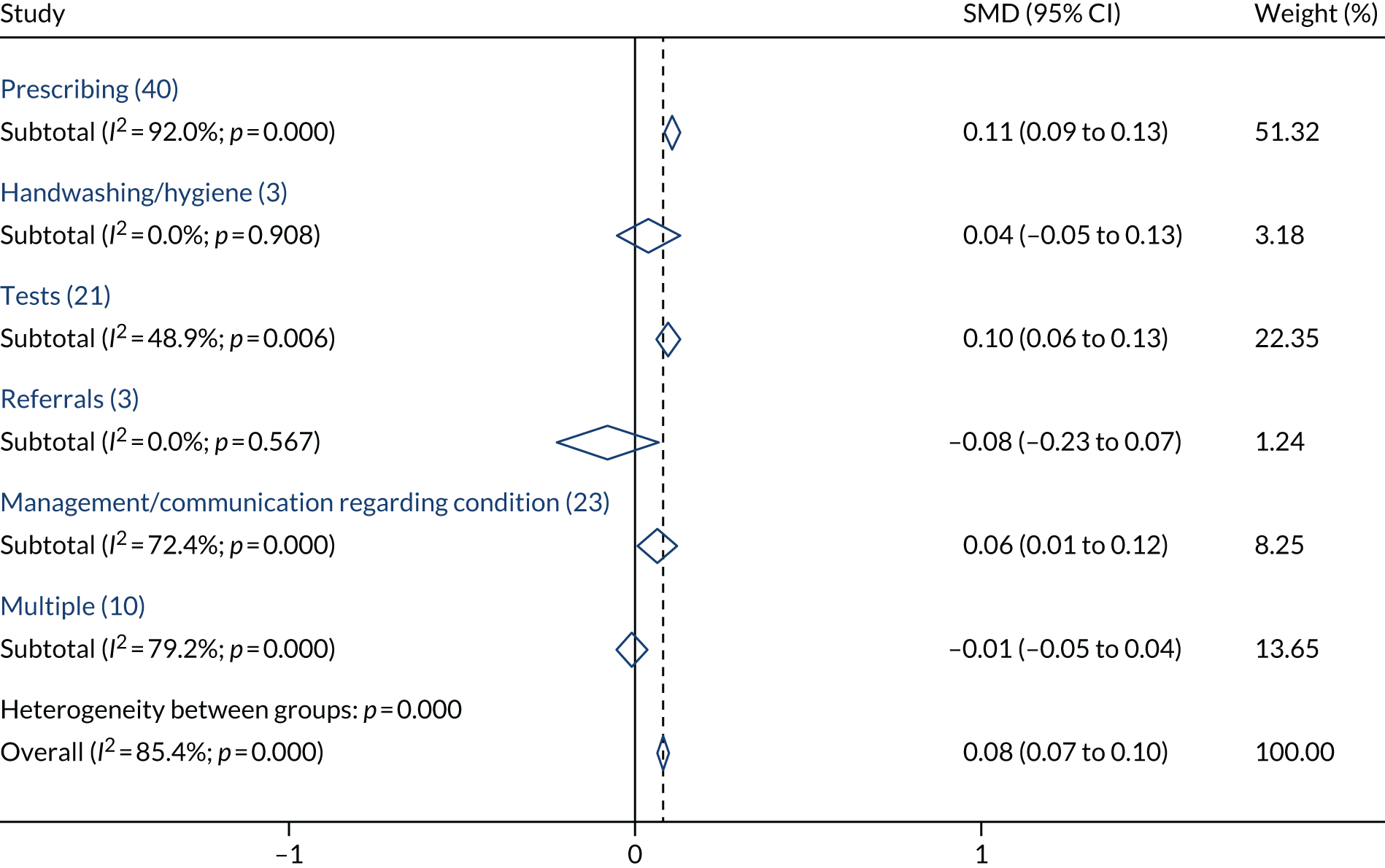

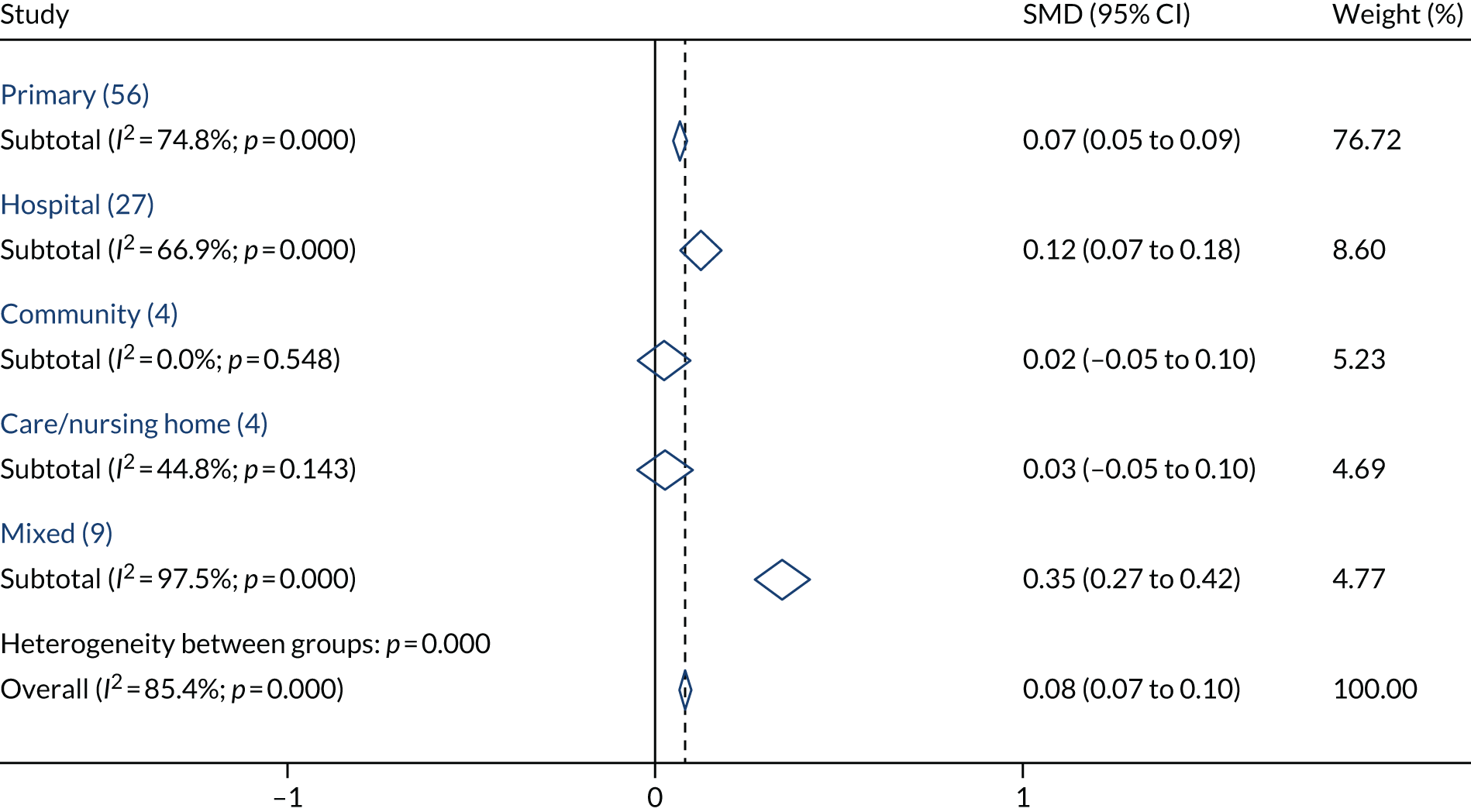

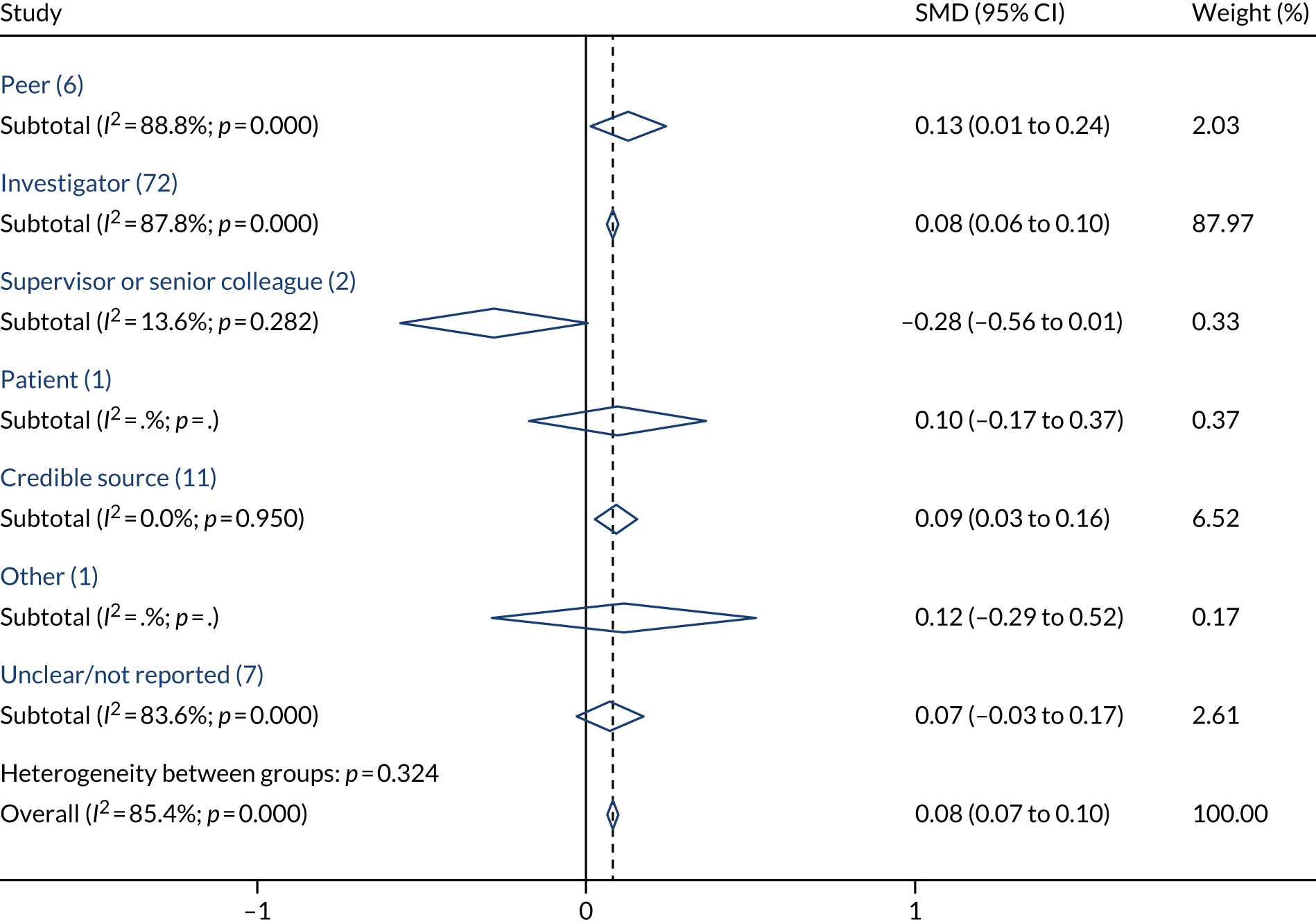

These questions were explored using forest plots and metaregression; network meta-analysis was undertaken to rank the effectiveness of the social norms interventions.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced from our review protocol. 1,2 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Changes to the protocol

The published protocol differs from the funding proposal in the ways listed below, and these changes were approved by NIHR during the early months of the project:

-

Change in terminology – ‘social norms’ replaces ‘social influence’. The justification for this was twofold. First, the term ‘social influence’ is a domain within the Theoretical Domains Framework23 and encompasses a broad range of social concepts, such as emotional and practical support, demonstrating a behaviour and changing the social environment, as well as social norms; it is not specific enough for the purpose of this review. Second, ‘social norms’ better captures the core mechanism by which we expected the interventions to have an effect.

-

We added to our inclusion criteria a requirement that included studies must state a behaviour that is being targeted for change. This was not a fundamental change from the earlier version, but was stated more clearly than previously.

-

Change from ‘health professional’ to ‘health worker’. This is a clarification rather than a change to the original inclusion criteria. It was always our intention to include all staff providing health care, and this change of terminology makes clear that not all health workers have professional qualifications.

Inclusion criteria

The inclusion criteria for the review were based on the population, types of intervention and study designs, as follows.

Population

The population of interest was health workers (including managers) responsible for patient care in a health-care setting. Health workers in training were included, but only if they were in a health-care setting (i.e. not in campus or laboratory environments). Any health-care setting was eligible, including primary care, secondary care, care homes, nursing homes and patients’ own homes. Interventions taking place in simulated environments were not eligible for inclusion.

Interventions

A social norms intervention seeks to change the clinical behaviour of a target health worker by exposing them to the values, beliefs, attitudes or behaviours of a reference person or group. We looked for the five BCTs that we considered to have a social norms element to them: 6.2. social comparison, 6.3. information about others’ approval, 9.1. credible source, 10.4. social reward and 10.5. social incentive. However, we were open to including studies that met all other inclusion criteria and had a social norms element, even if they did not include any of these five BCTs.

Included studies must have stated a clinical behaviour of health workers that was targeted for change through the use of social norms. If the behaviour was not specified, it was not possible to determine which aspects of an intervention were relevant to the anticipated behaviour change. Indeed, the BCT taxonomy v1 coding guidance states that the target behaviour needs to be specified and BCTs must target that behaviour for BCTs to be coded. 28 Clinical behaviour here is defined as any behaviour that is performed within a (non-simulated) environment that affects patient diagnosis, care, treatment or recovery. We have reported the number of studies identified by our search that met all other inclusion criteria but did not mention a target behaviour.

Comparators

All comparators were eligible for inclusion, including alternative interventions, no intervention or comparison of one social norms BCT with one or more other social norms BCTs.

Study designs

Only randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were included in the review. All designs of RCTs (cluster, factorial, parallel, cross over and stepped wedge) were eligible for inclusion. The justification for restricting the review to RCTs was that the review is concerned with the effectiveness of social norms, and RCTs are the best method for assessing the effectiveness of an intervention.

We included both published and unpublished research. Studies had to be reported in English because the research team had no resource for translation from other languages.

Search strategy

The search strategy was developed using an extensive iterative scoping process, involving the whole team including an information specialist (Jane Roberts). Lists of possible search terms were suggested by team members; these were developed into search strategies by Jane Roberts, who then ran preliminary searches. A sample of the titles and abstracts were reviewed closely by Sarah Cotterill and Mei Yee Tang and discussed by the wider team. This review involved consideration of whether searches were too inclusive or too restrictive, and examination of resulting abstracts to look for potential additional search terms.

The searches were based on three groups of terms: population, interventions and study design.

Population

A list of population terms was developed by looking at Cochrane reviews25,29 that included a similar population of health workers, augmented by job roles included in the UK national workforce data set produced by NHS Digital. 30

Interventions

Social norms interventions are not described consistently in the literature, and different terms are used in various academic disciplines. This presented us with the challenge of finding appropriate search terms to make sure that we would discover the full range of literature on this topic. We were aware that many studies involving A&F contain a social comparison element;25 therefore, we looked at the search terms that were used in a previous systematic review of A&F. 25 We omitted anything relating solely to ‘audit’, as this was not relevant for this review.

During the scoping phase, various feedback terms were tried out. The use of ‘feedback’ alone produced many irrelevant papers, such as those relating to educational feedback and electronic feedback. The final search, following extensive trial and error in the piloting phase, included ‘feedback’ when used alongside other relevant terms (audit, monitoring, peer, performance, data, individualised, web, personalised, comparative, team, practitioner, practice and clinical or social). We also included ‘benchmark’. We included some overall terms that are used in the literature on social norms: ‘norm’ used close to ‘social’, ‘descriptive’, ‘peer’ or ‘subjective’; ‘social influence’; ‘benchmarking’; ‘social or peer comparison’; and ‘social competition’. Terms that appeared in behavioural economics literature were included: ‘social proof’, ‘image motivation’ and ‘warm glow’.

Additional search terms were developed for each of the five social norms BCTs by looking at the text used to describe them in the BCT taxonomy v1,24,31 extensive discussion in the team and examining relevant articles. Additional terms for information about others’ approval and credible source included ‘positive reinforcement’, ‘congratulate’, ‘praise’ and ‘commendation’. Terms for social reward and social incentive included ‘social’, ‘verbal’ and ‘non-verbal’ alongside ‘incentive’ or ‘reward’. Finally, the search included terms to describe theories that are used to explain interventions based on social norms: the Theory of Planned Behaviour,32 the Theory of Reasoned Action,33 the Theoretical Domains Framework,34 Social Cognitive Theory,35 and the Theory of Normative Social Behaviour. 22

Study design

The search for RCTs was taken directly from the Cochrane RCT search described in the Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. 36 This was translated into other relevant databases.

The search was developed in MEDLINE and then adapted for other databases. Terms relating to the same concept (e.g. different types of health workers) were combined using the Boolean operator ‘OR’ and different concepts (e.g. health workers and social norms) were combined using ‘AND’. The search strategy was tailored for the different electronic databases using medical subject headings (MeSH) where appropriate, wildcard symbols and truncations (see Appendix 1). Backward- and forward-citation searching was not conducted owing to time and resource constraints.

Published literature was systematically searched on 24 July 2018 in electronic databases relevant to health and social care: Ovid MEDLINE, Ovid EMBASE, Healthcare Databases Advanced Search (HDAS) – Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), HDAS British Nursing Index (BNI), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Ovid PsycINFO and Web of Science (see Appendix 1 for search strategies and Appendix 1, Table 15, for the results).

Data collection

Study selection

The process for identifying studies for review followed the stages of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement. 37

All references generated from the search were managed in Covidence (Melbourne, VIC, Australia): an online screening and data extraction tool for systematic reviews. All reviewers were provided with instructions for both the title and the abstract, and full-text screening stages (see Appendix 2). At the title and abstract screening stage there was an initial learning phase (305 studies), during which the coders worked steadily through the task, applying the inclusion criteria to the papers and stopping after small batches to discuss any discrepancies as they went along. Disagreements and uncertainties were discussed with the wider research team. This process enabled the main coder to build up a high level of consistency. For the remaining studies, one reviewer (MYT) independently screened all of the titles and abstracts against the inclusion criteria, and another researcher (SC, SR or JW) screened a sample of 20% of the records. These were randomly selected using a random integer generator (www.random.org; accessed 1 September 2020). By the time that 20% of the records (493 studies) had been screened, there was very little difference between the decisions of the two coders, and we were confident that the main coder could make the exclusion decisions with reliability. Inter-rater reliability on these 493 studies was good38 (kappa = 0.68). Where there was any hesitation on her part about whether to include or exclude, she erred on the side of inclusion and continued to discuss any uncertainties with the wider team.

All of the studies at the full-text stage were independently screened by two researchers from the screening team (MYT, SC or SR). The two reviewers screened the papers concurrently using Covidence, and were not aware of the other person’s recommendation until after they had entered their own. The screening involved reading the full-text paper and deciding whether or not the paper met the eligibility criteria (a population of health workers in a health-care setting, a social norms intervention targeted at clinical behaviour change and a RCT). If the study was excluded, the reviewer entered a reason for exclusion. Any disagreements over the recommendation to exclude or the reason for exclusion were flagged up by Covidence and the two reviewers met to discuss. If they were unable to come to a consensus, there was moderation by a third researcher or discussion at a team meeting.

Data extraction and management

For efficiency, data extraction was conducted in three stages: stage 1 involved extraction of all data apart from the details of the intervention, stage 2 was the BCT coding (carried out by a different team concurrently with stage 1) and stage 3 was carried out later, because it relied on data collected during the BCT coding (e.g. we needed to identify which aspects of the intervention were based on social norms to assess the frequency or format of the social norms intervention). Data from included studies were extracted using data extraction forms derived from the Cochrane Effective Practice and Organisation of Care data collection form. 39

Stage 1 data extraction

See extraction form in Appendix 3, Tables 16 and 17.

Data were independently extracted by two researchers from the data extraction team (MYT, LH, SR and SC). Any disagreements were referred to a third researcher for consideration or discussed at a research team meeting.

Data extracted were:

-

setting of the trial (e.g. primary)

-

country in which trial was conducted

-

design of trial

-

aim of the trial

-

unit of allocation

-

primary outcome

-

secondary outcomes

-

time points

-

statistical analysis

-

inclusion/exclusion criteria (and whether or not the inclusion criteria targeted participants based on low target performance)

-

methods of recruitment

-

number of randomised clusters, if randomised RCT

-

subgroups measured (both health workers and patients)

-

target behaviour

-

total number of patients and health workers randomised

-

type of health worker targeted by the intervention

-

withdrawals and exclusions (after randomisation)

-

number of participants (both patients and health workers) randomised to group

-

number of clusters randomised to group, if cluster RCT

-

type of control

-

outcomes

-

quality assessment (risk of bias).

Stage 2 data extraction: coding of behaviour change techniques

See the BCT extraction form in Appendix 5, Table 19.

Specific BCTs were independently double coded using the BCT taxonomy v124 by at least two researchers. A BCT extraction form was produced to guide the process. Each study’s intervention descriptions from all of the relevant papers (e.g. protocol, process evaluation and main findings) were collated by Mei Yee Tang and transposed to the BCT extraction form so that the second coder (RP, SC or JR) could have the information required for BCT coding available in the one document for each study. All coders had access to the full papers on Covidence, so that they were able to find further relevant information that could help them with the coding task. Following coding, for each study Mei Yee Tang transferred the BCT codes and information extracted by both coders onto a single final BCT extraction form. As part of this process, any discrepancies were highlighted by Mei Yee Tang and the disagreements were resolved through discussion or by the moderation of another coder.

For each study, BCTs were separately coded for all arms (i.e. the control arm and all intervention arms). Mei Yee Tang coded BCTs for all studies, which were then independently double coded by another trained coder within the research team (SC, RP or JR). BCT coders also recorded the target population, target behaviour, whether or not guidelines were provided as part of the intervention and the direction of change in the behaviour that was desired.

Training

All coders completed online training on the coding of BCTs (www.bct-taxonomy.com/; accessed 1 September 2020) and attended a workshop facilitated by co-applicant Rachael Powell and study steering committee member Marie Johnson prior to starting the coding process. To ensure that all coders were familiar with the BCT coding process and coded consistently, a random sample (using www.random.org; accessed 1 September 2020) of three studies was selected for coding by all coders (MYT, RP, SC and JR). All coders coded the three intervention descriptions independently before meeting to discuss any issues that arose. This practice exercise with all BCT coders was repeated again on another four randomly selected studies. The two practice sessions helped to refine the coding process and revise the BCT extraction form (see Appendix 5, Table 19). A decision log was kept throughout the BCT coding process to record any decisions that were made to ensure the consistency of coding. Details are provided in Appendix 6.

Behaviour change techniques inter-rater reliability

Inter-rater reliability for each of the BCTs that were present at least once across all intervention arms was assessed using the prevalence-adjusted and bias-adjusted kappa (PABAK) statistic (see Appendix 7, Table 20), which adjusts for both the prevalence and the occurrence of BCTs. 40 In circumstances in which prevalence is low, the widely used chance-corrected kappa statistic is likely to underestimate reliability as it is highly dependent on prevalence. 41 To calculate the PABAK, the kappaetc module in Stata® I/C 14.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) was used to produce the Brennan–Prediger statistic. 42,43

Stage 3 data extraction: trial and intervention characteristics

See the stage 3 data extraction form in Appendix 4, Table 18.

Information relating to trial and intervention characteristics [focused on the social norms element(s) only] was extracted during stage three of data extraction using Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) by Sarah Cotterill and Mei Yee Tang:

-

Did the inclusion criteria target participants based on low target performance?

-

Frequency and intensity of intervention.

-

Format of intervention.

-

Source of the intervention (i.e. the person delivering the intervention).

-

Was this person delivering the intervention internal or external to the target person’s organisation?

-

Reference group/person used as the comparison/source of approval.

-

Type of comparison.

The processes of the third stage of data extraction, along with the accompanied instructions, were refined through piloting (see Appendix 4 for the final version). Six studies were independently extracted by Sarah Cotterill and Mei Yee Tang. The instructions were refined during this pilot phase and some categories were added to ensure that extraction was as consistent as possible. The piloting process was repeated until a high level of agreement was reached between the two coders.

In the protocol, we had envisaged that we would contact authors for additional information if the data needed to calculate effect sizes were not adequately reported in the paper. We were not able to do this owing to time constraints, but we made efforts to search for additional papers, including process evaluations and protocols. Once all of the data were extracted, they were transferred to Stata for analysis.

Assessment of risk of bias

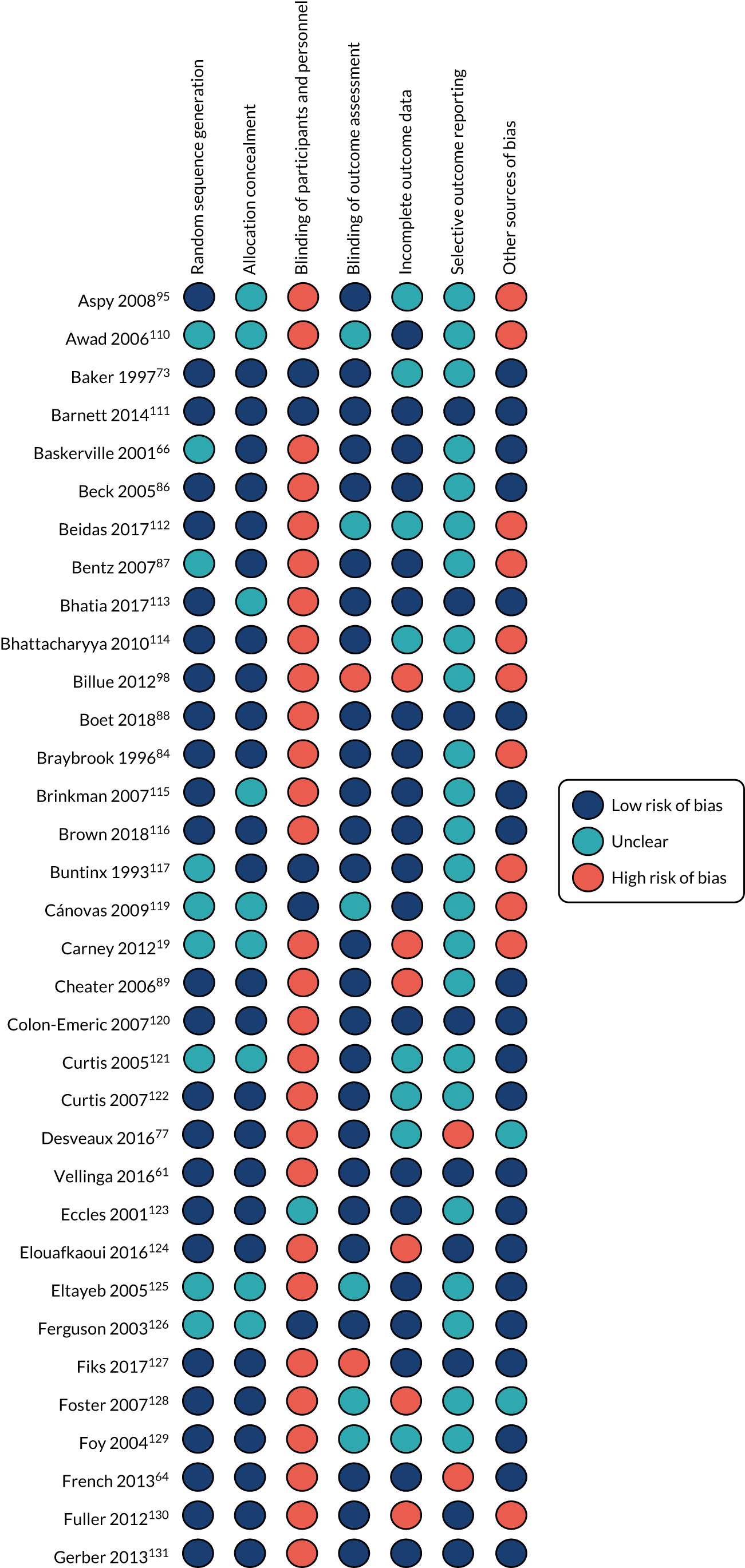

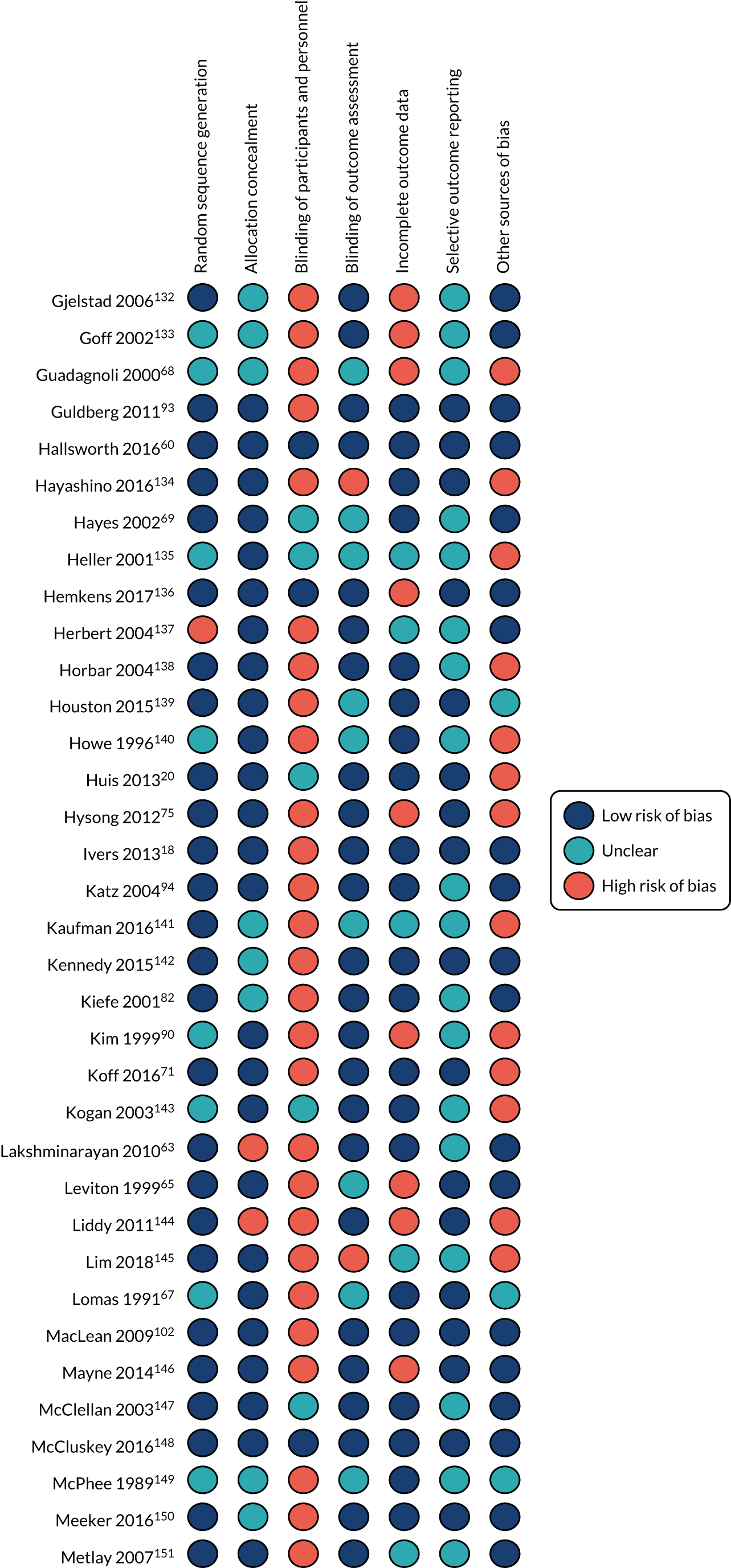

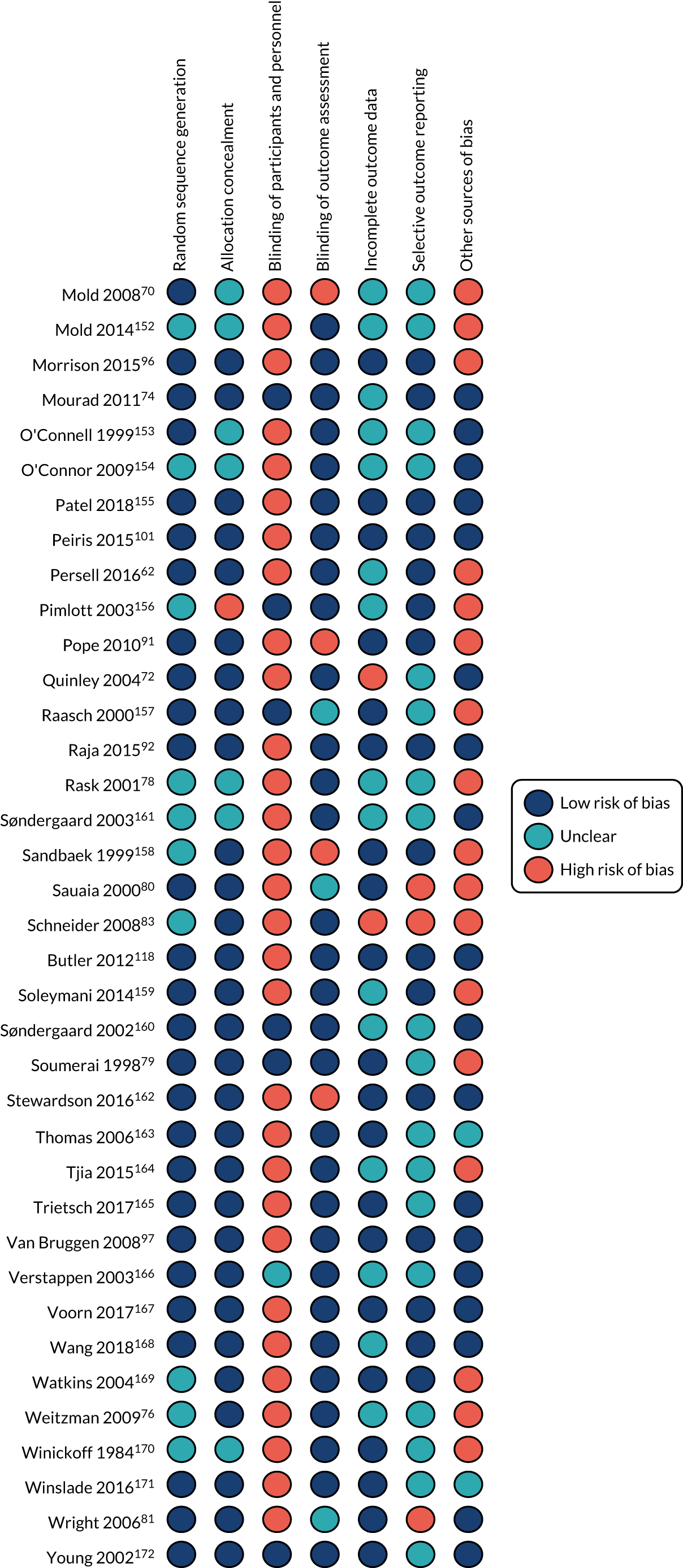

As part of the first stage of data extraction, risk of bias for each included study was independently assessed by the data extractors (LH, MYT, SC and SR) using The Cochrane Collaboration tool for assessing risk of bias36 across a range of criteria: selection bias, performance bias, detection bias, attrition bias, reporting bias, selective outcome reporting and other biases. Included studies were classified as having a high, low or unclear risk of bias for each criterion. All risk-of-bias criteria were added as part of the data extraction form in Covidence. Where disagreements occurred, a discussion between the two extractors took place to resolve the disagreement or a third data extractor would be brought in when an agreement could not be reached. Percentages of high/low/unclear judgements for each risk-of-bias criterion across included studies were calculated and reported as a bar chart to provide a summary of the risk of bias across criteria domains (see Figure 2). Text summaries across each criteria of bias were produced in line with The Cochrane Collaboration’s guidance for large reviews. 36 Judgements for each risk-of-bias criterion for all included studies were reported (see Appendix 15, Figure 20).

Data analysis

Outcomes and prioritisation

The primary outcome for the review was compliance of the health worker with the desired behaviour at the time point closest to 6 months post intervention. We expected studies to report different behaviours (e.g. prescribing, hand-washing and test ordering) and we expected studies to measure those behaviours in different ways. We converted any observed measure of health worker behaviour into a standardised mean difference (SMD) between groups in terms of compliance with the desired behaviour. Common examples included the mean number of times a behaviour was performed per health worker or the mean rate of behaviour (e.g. percentage of the population for whom antibiotic items were dispensed). At times, compliance was reported as a binary outcome, such as compliance versus non-compliance on a single occasion, and was expressed either in a binary format or using an odds ratio.

We used the methods of Chinn44 to convert binary outcomes to a SMD with associated standard errors (see Appendix 8 for the formula).

If several measures of compliance were reported in sufficient detail to enable the analysis of a trial, we used the following criteria to select the outcome for the primary analysis, in decreasing order of importance: (1) observed measure rather than self-report, (2) appropriate adjustment for clustering, (3) continuous measure, (4) final score rather than percentage change or change from baseline, (5) described as the primary outcome, (6) used to calculate the sample size and (7) reported first.

The secondary outcome for the review was patient health-related outcomes that were likely to result from targeting the health worker behaviour. These were converted to a SMD using a similar approach.

Some trials incorporated baseline measurements into their analyses. This was carried out either by adjusting for baseline values of the outcome measure or of other prognostic variables in an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA), or by reporting outcomes as changes from baseline. We have prioritised ANCOVA-adjusted estimates of the treatment effect where relevant or those from logistic regression, given that these are generally more precise. Change scores cannot be pooled through conversion to SMDs.

Missing data

Our preferred approach to dealing with missing data was to take steps to try to obtain them. We searched for companion papers by author searching and citation searching. Contacting trial authors was not possible owing to limited resources and the large number of studies. We imputed estimates of standard deviations where necessary by using any available information, such as p-values, confidence intervals (CIs), ranges or standard errors of baseline data, by pooling standard deviations from other similar studies that use the same type of outcome or by searching for trials that used the same outcome. Where necessary, for cluster randomised trials we imputed a value of the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) by pooling across similar studies.

Unit of analysis issues

Where any of the studies in the review were cluster randomised trials, we extracted both raw summary measures (e.g. means and numbers having had the event) and adjusted standard errors from appropriately analysed trials. Where it was not possible to obtain the adjusted SMD and its standard error directly, the methods that were used to calculate the SMD and standard error are shown in Appendix 9, Table 21.

Several studies had more than two relevant arms (e.g. two different social norms interventions and a control group). In each case, we extracted data on any comparison that was relevant to our primary research question, while avoiding double counting where possible. Where relevant, we combined study arms that contained identical BCTs. In cases with two different social norms interventions and a single control arm, where possible we divided the number of health-care workers in the control arm approximately evenly between the comparisons to avoid double counting, while retaining the correct intervention effect. In studies with more than one candidate control arm, we chose the comparison that provided the more pure test of social norms (e.g. social norms intervention + X vs. X is a more pure test of social norms than social norms intervention + X vs. usual care).

Where a study was a factorial trial analysed appropriately using linear or logistic regression, we extracted the covariate and standard error that best assessed the effect of social norms BCTs, for example a covariate comparing all arms containing a social norms BCT with all arms without.

Analysis of skewed data

If the primary outcome data were heavily skewed, meta-analyses based on SMDs of the untransformed data would be expected to produce biased estimates. In some cases, compliance was reported as ‘mean per cent compliance’ or similar, and there is a likelihood that this outcome is skewed when close to 0% or 100% owing to it being bounded. We removed data likely to be skewed (where mean compliance was close to 0% or 100%) in a sensitivity analysis.

Utilising the behaviour change technique coding in the analysis

The approach we took to utilising the BCTs in the meta-analysis was to create an Excel file of all the trials, listing the intervention and control BCTs on separate rows. We subtracted the control arm BCTs from the intervention arm BCTs to identify the BCTs that would be expected to be responsible for the differences between the two arms.

Using the five types of comparison (extracted during the BCT coding process), listed in Box 1, allowed us to separate out three different tests of social norms:

-

‘Pure’ test of social norms intervention alone (comparisons 1 and 2, see Box 1).

This involved trials with social norms BCT(s) in the intervention arm and no BCTs in the control arm (comparison 1). These trials were the purest test of social norms interventions: the BCTs being tested were those found in the intervention arm. For trials in which an intervention arm including a social norms BCT combined with other BCTs was tested against a control arm containing the same other BCTs (comparison type 2), the control arm BCTs were subtracted from the intervention arm to reveal the BCTs that would be expected to account for differences in outcome. For example, if the study tested social comparison and instructions on how to perform the behaviour (intervention arm) against instructions on how to perform the behaviour (control arm), the comparison type would be ‘social comparison’.

-

‘Complex’ test of a social norms intervention alongside one or more other BCTs (comparison 3, see Box 1)

This involved trials in which an intervention arm including a social norms BCT combined with other BCTs was tested against a control arm containing none of the same BCTs (comparison 3). The control arm was deducted from the intervention arm to reveal the test involved in the comparison. For example, if the study tested a complex intervention such as credible source, feedback on behaviour, social support unspecified and behavioural practice/rehearsal (intervention arm) against social support unspecified and behavioural practice/rehearsal (control group), the comparison would be ‘credible source’ and ‘feedback on behaviour’ versus control.

-

Social norms intervention occurring in both arms (comparisons 4 and 5; see Box 1)

In some studies, two different social norms interventions were compared (comparison 4) or the same social norms intervention appeared in both arms (comparison 5). Where social norms interventions occurred in both arms of a trial, the study did not provide useful information for the meta-analysis, because these trials do not test the effect of social norms interventions, but they were potentially useful to the review as follows:

-

Any study that directly compared one social norms BCT against another (e.g. social comparison vs. credible source) could potentially be included in the network meta-analysis.

-

Any study that compared the same social norms BCT in both arms, with the addition of other BCTs (e.g. with the addition of social support in one of the arms) or comparing differing modes of delivery (e.g. social comparison delivered in person or by e-mail) could potentially be included in the metaregression.

-

Any study where social norms BCT(s) were delivered in both arms as a control intervention, for the purpose of testing a separate intervention, in which the social norm was a minor part were not included in any analysis.

-

Comparison 1: social norms BCT vs. any control.

Comparison 2: social norms BCT + X vs. X.

Comparison 3: social norms BCT + X vs. any control.

Comparison 4: social norms BCT type A vs. social norms BCT type B.

Comparison 5: social norms BCT + X vs. social norms BCT + Y.

In summary, the information extracted for the analysis describes the BCTs that were tested in the study rather than all of the BCTs that make up the intervention. In some cases (comparison 1) the content of the comparison is the same as the content of the intervention arm, but in most cases (comparison 2 and 3) the content of the comparison is what is left of the intervention when the control arm is taken away. We regard this as the part of the intervention that was actively tested in the trial. A limitation of this approach is that we may have missed some interaction effects.

Feedback on behaviour

Early on in our coding, we observed that the BCT ‘feedback on behaviour’ was often found to be presented alongside a social norms BCT. The implementation of three social norms BCTs (social comparison, social incentive and social reward) would seem to be greatly facilitated by combination with ‘feedback on behaviour’. Social comparison, defined as ‘draw attention to others’ performance to allow comparison with the person’s own performance’,24 does not by definition require feedback on the target’s own behaviour to be provided, but providing such feedback (e.g. performance data) would be expected to facilitate comparison. Social reward, ‘arrange verbal or non-verbal reward if and only if there has been effort and/or progress in performing the behaviour’,24 and social incentive, ‘inform that a verbal or non-verbal reward will be delivered if and only if there has been effort and/or progress in performing the behaviour’,24 similarly do not require feedback on the target’s behaviour to be provided (e.g. the behaviour could be monitored by others without feedback to make the reward/incentive process clear to a target), but feedback on the behaviour fits very well with these social norms BCTs and might be expected to facilitate the action of these BCTs.

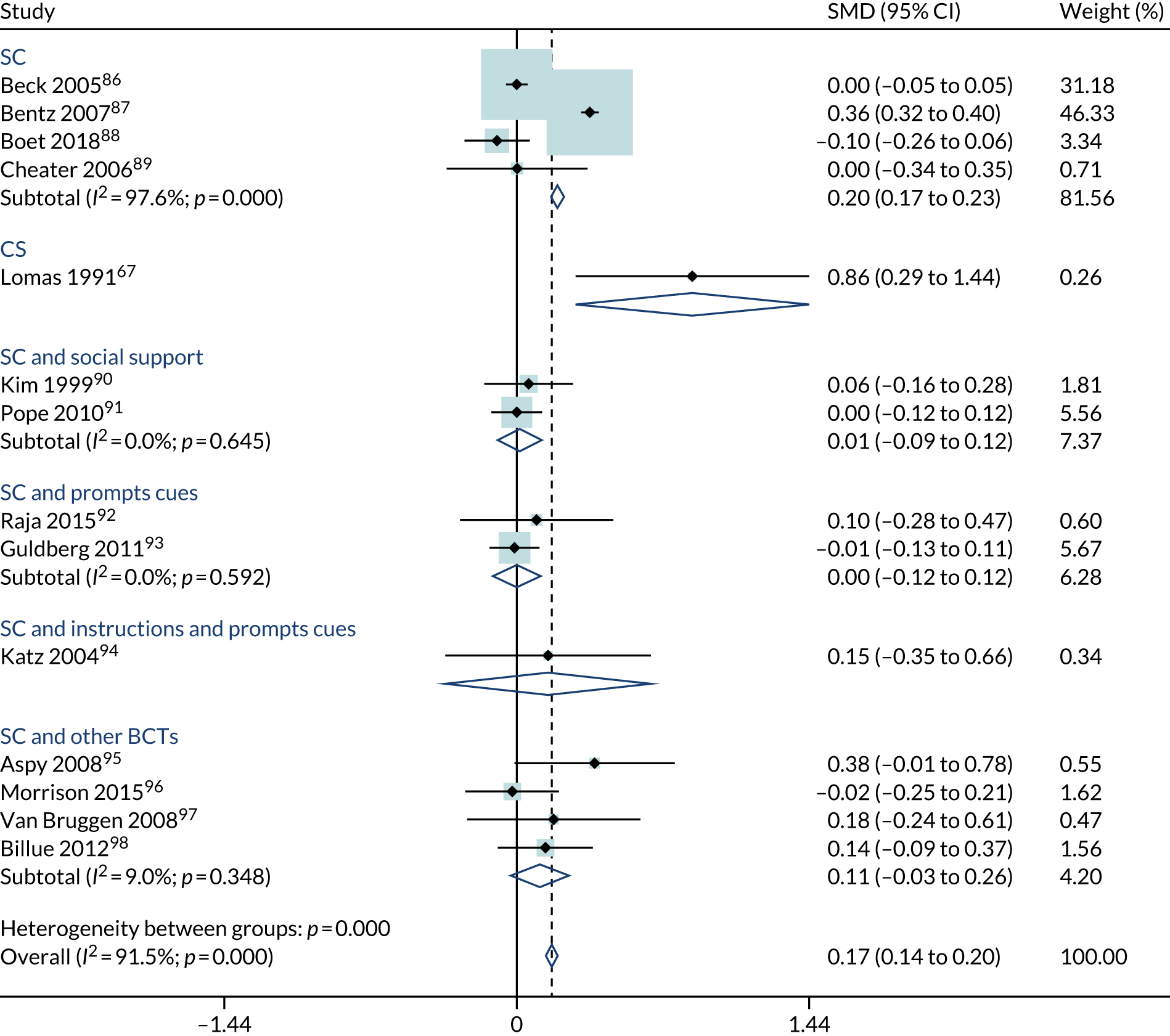

Because of the high prevalence of feedback on behaviour (present in 88/100 comparisons), we combined ‘feedback on behaviour’ with the social norms BCT with which it appeared for the purpose of primary analyses: in the forest plots we have listed each social norm with or without feedback. However, it was important to unpick the separate effects of feedback on behaviour: this was examined as part of the metaregression. As a sensitivity analysis, we examined the overall effects of social norms interventions with and without feedback on behaviour.

Data synthesis

Criteria for study data to be meta-analysed

We included in a meta-analysis those studies that report a primary outcome measure (clinical behaviour of a health worker) or secondary outcome (patient outcome) that can be converted into a SMD.

Planned approach for meta-analysis

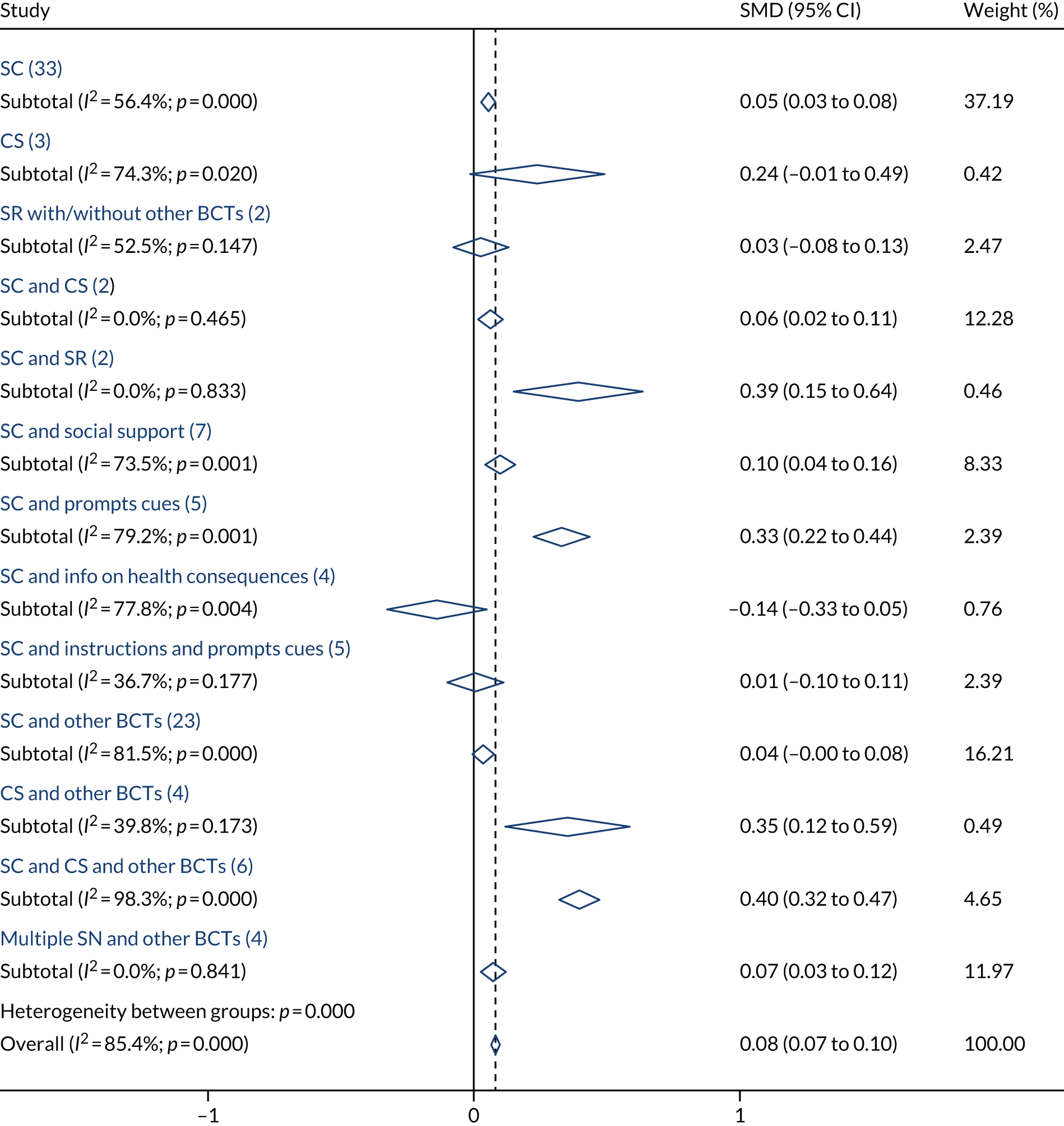

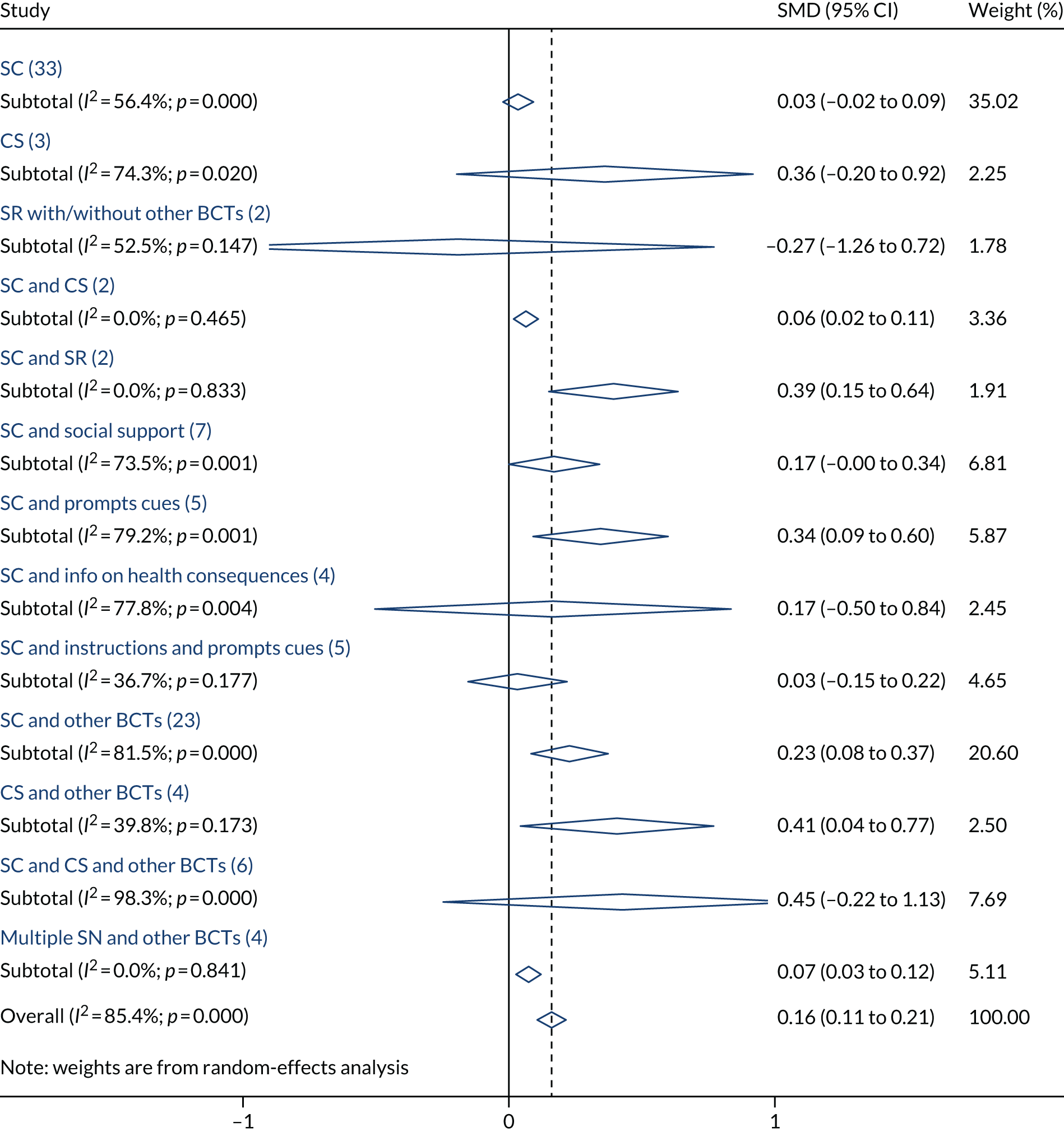

Research question (RQ) 1: what is the effect of social norms interventions on the clinical behaviour of health workers, and the resulting patient outcomes?

The comparisons used in the analysis to answer RQ1 are shown in Appendix 10, Table 22. We stratified the studies in the forest plot according to the type of comparison (see Utilising the behaviour change technique coding in the analysis) and the type of target behaviour, and pooled estimates across strata. The aim of this was to provide some initial insight into whether or not, and how, treatment effects vary systematically in trials using different social norms techniques, while remaining aware of the likely confounding by other trial characteristics. We considered I2 and tau when interpreting heterogeneity, but did not use it as the basis for analytic decisions. We preferred a fixed-effects approach rather than a random-effects approach to meta-analysis, which we consider to yield a summary of the evidence in these trials (i.e. the average effect), rather than an estimate of a common underlying treatment effect. However, we also reported a random-effects analysis.

Research question 2: which contexts, modes of delivery and BCTs are associated with health worker clinical behaviour change? To address this research question, we followed steps 1 to 3.

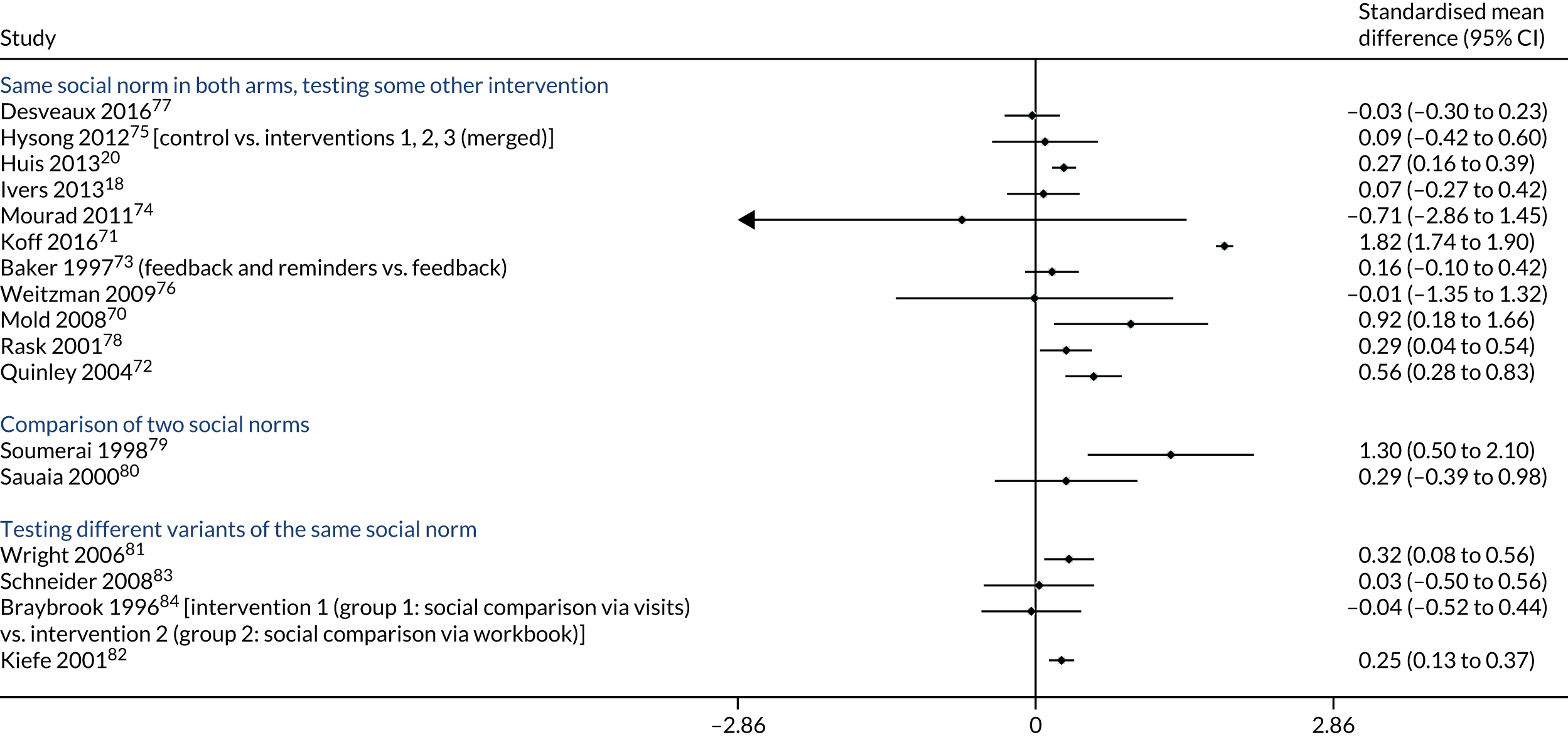

Step 1 – we explored sources of variation using forest plots and narrative description. In addition to those comparisons used in RQ1, we included the following types of comparison in a narrative description: (1) social norms intervention A versus social norms intervention B and (2) social norms intervention + X versus social norms intervention + Y, where X and Y are any BCT or combination of BCTs, and A and B are either two different types of social norms BCT or the same social norms BCT delivered by two different methods.

Step 2 – we undertook an exploratory analysis using multivariable metaregression to investigate sources of heterogeneity and explain variation in the results. Metaregression is an appropriate regression method in which weights are assigned to studies/subgroups based on the standard error of the treatment effect. Appendix 11, Table 23, shows the predictor variables together with anticipated parameterisations that we included in the metaregression analyses. Although controlling for multiple predictors at once is desirable, in practice this was governed by the number of trials and the observed distributions of the variables. We allowed for trials from the different comparisons to enter into a single metaregression given that we anticipated we would be able to control for comparators and co-interventions in the regression. We had intended to categorise the control conditions, but were unable to do this robustly.

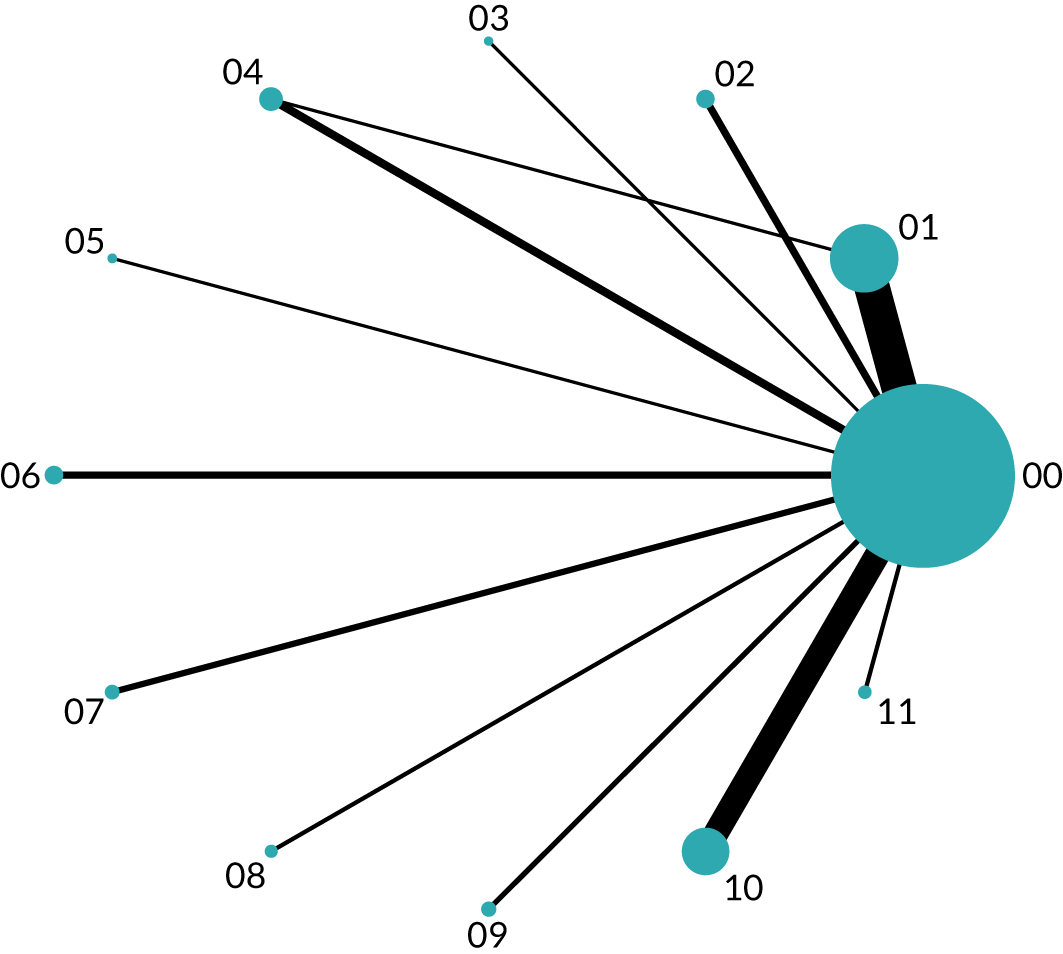

Step 3 – we used network meta-analysis to explore which social norms BCT, combination of social norms BCTs or combination of social norms BCT with other BCTs, if any, appears most effective. We considered two broad approaches for network meta-analysis, and made the decision to employ type (a) after consultation with our SSC.

-

Network meta-analysis

We examined data from all trials to look at the most commonly occurring combinations of social norms BCTs, either alone or alongside other BCTs. We built and examined a network diagram including social norms BCTs and commonly occurring combinations of social norms BCTs with other BCTs, plus control. Decisions about whether or not to ‘lump together’ BCTs or combinations of BCTs into categories were made after careful discussion by the project team. The justifications were recorded. The geometry of the network diagram was evaluated and no revisions were required to achieve a connected network. Fixed-effects and random-effects network meta-analyses were fitted in Stata.

-

Multi-components-based network meta-analysis. 45

Each intervention in the review would have been considered as a combination of BCT components. We would include all social norms BCTs along with other commonly found BCTs in a components-based network plot. This type of analysis ideally requires all available trials that test the BCT components of interest; our search strategy was not appropriate for this as we were focusing on the social norms components only. We therefore decided not to pursue this approach.

The results from direct and indirect evidence were compared to check for consistency. Trials grouped by comparison were examined to assess transitivity. Metaregression did not identify any clear potential effect modifiers; therefore, although we planned in the protocol to include these in the model, this did not happen.

Additional analyses

We carried out the following sensitivity analyses for the primary outcome:

-

include only studies with a low risk of bias (for the key domains of allocation concealment, sequence generation, attrition, selective outcome reporting and other sources of bias)

-

exclude continuous outcomes reported as ‘mean percentage’ that were < 20% or > 80%, as these are unlikely to come from a normal distribution

-

include only studies in which the standard deviation was not imputed

-

using alternative values of imputed ICC

-

studies with and without feedback on behaviour.

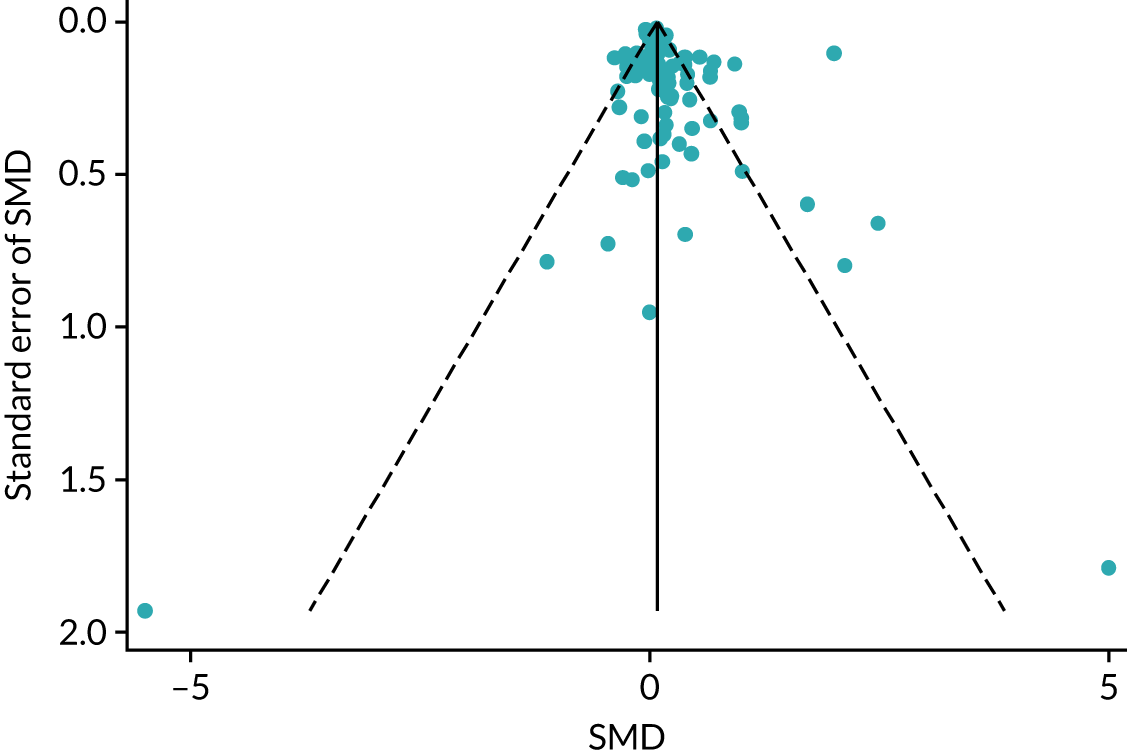

Publication bias

We aimed to minimise the impact of reporting biases by performing a comprehensive search for eligible studies. We investigated the impact of publication bias in the reported studies using a funnel plot.

Patient and public involvement

We recruited members of the public from two sources: (1) PRIMER (Primary Care Research in Manchester Engagement Resource: https://sites.manchester.ac.uk/primer/about-primer/; accessed 1 September 2020), a public involvement group in the Centre for Primary Care, University of Manchester, and (2) an advertisement on Citizen Scientist, which is based at Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust and promotes research and patient and public involvement (PPI) opportunities for members of the public. We advertised for anyone aged > 18 years who had used any type of NHS service: we were not looking for people with any particular condition or experiences.

Mr Manoj Mistry has been involved in the review from the start. He has a wealth of past experience of involvement in research and was an invaluable part of the review. He had input into the proposal before we submitted the funding bid and he was a member of the SSC, bringing a patient and carer perspective to the meetings. He attended all three SSCs and played a full and active role in the committee’s discussions.

Two PPI events were planned for this study. The first event took place in August 2018 at the University of Manchester. The aim of the first event was to discuss how the review would be relevant to members of the public, and to get feedback on the overall design of the review. Six members of the public (two female, four male), including Mr Manoj Mistry, participated in the workshop, and they discussed with us the relevance of the review for patients and carers. They felt that patients can have a role in changing health worker behaviour, for example by reminding health workers to wash their hands or telling the GP that they do not expect to be prescribed antibiotics for a cold, although they were cynical about whether or not doctors would listen to patients when they present potential best practice (example given of a relative who had better care in Australia, but the doctor in the UK did not want to hear about it). In response to this observation, we made sure to record whether or not any studies in the review considered patients’ role in social norms interventions (e.g. use of the information about others’ approval BCT, where the approval came from patients) (see Appendix 12, Table 24, for a short report of the meeting).

We had feedback from four public contributors on the Plain English summary, and Mr Manoj Mistry has reviewed this description and account of our PPI activity.

A second PPI workshop took place in October 2019 at the University of Manchester to discuss how best to disseminate the findings to a wider audience. Four of the original group members (including Mr Manoj Mistry) attended. We presented the preliminary findings from the SOCIAL study and asked the group what they considered to be the most important messages from a public perspective. We also asked the group to suggest suitable language for presenting the findings to a lay audience. They suggested that the main messages should be that the study provides evidence that social norms interventions can encourage the medical community to change behaviour, leading to better outcomes for patients.

One or two things make social norms interventions even more effective:

-

right message (i.e. the use of different social norms BCTs)

-

right place (i.e. context)

-

right method (i.e. mode of delivery).

Authority of the message sender is crucial.

Messages from all sources are important, including those from patients.

We plan to follow this approach when we write summary materials for a lay audience. There was concern (from some) about the term ‘behaviour change’. Alternatives were ‘influence’ or ‘improve’, but they did not all agree. The group wanted us to avoid being preachy or patronising or using a telling-off approach to health workers: they talked about health workers being ‘encouraged’ by social norms interventions, rather than ‘directed’. The group felt that social norms messages would also be useful with people who teach and mentor students and young professionals. The lack of effect for face-to-face delivery of social norms interventions was viewed as surprising.

Chapter 3 Results

Identification of included studies

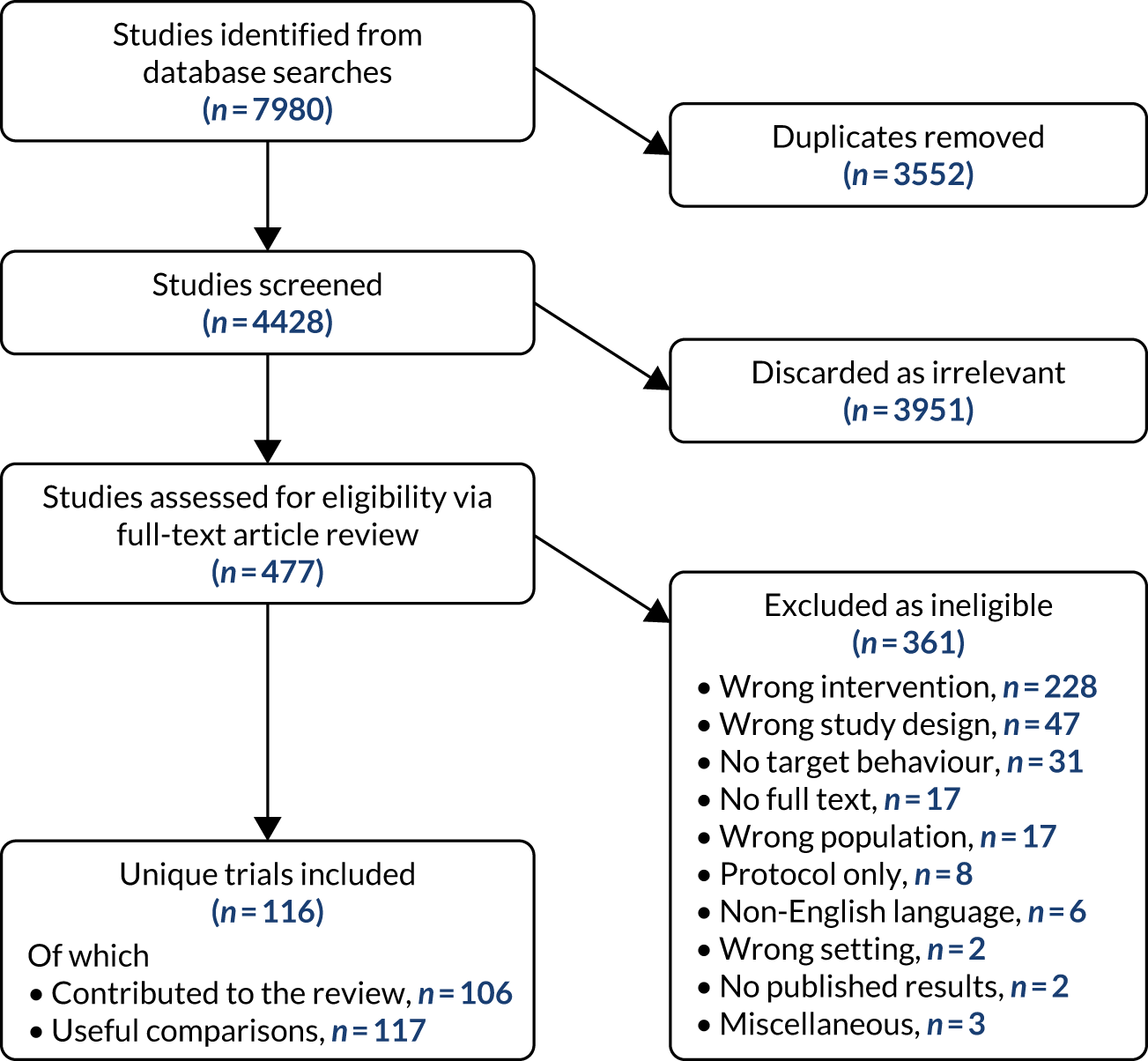

Of the 7980 studies identified using database searches, 3552 were identified as duplicates leaving 4428 separate studies to be screened. Of these, 3951 were discarded as irrelevant to the research questions under consideration, leaving 477 to be assessed for eligibility by full-text review of publications. Of these, 361 were excluded as ineligible for various reasons, as described in Figure 1. There were 116 studies that met the inclusion criteria, and 106 of these contributed findings to the review. Some of the 106 studies had more than one trial arm, and there were a total of 117 comparisons that tested the effect of social norms on the clinical behaviour of health workers. The remaining 10 studies met all of the inclusion criteria but did not provide usable outcome data: two reported the overall effect but did not compare the results between groups,46,47 six reported results unclearly or incompletely,48–53 one trial was discontinued before completion54 and one did not report results on our primary or secondary outcomes. 55 Searches for companion papers were unsuccessful and authors were not contacted owing to limited time. A brief description of the studies is provided in Appendix 13, Table 25.

FIGURE 1.

The PRISMA flow chart of the SOCIAL review.

Characteristics of included studies

Study characteristics

A detailed summary of study characteristics is shown in Table 1. Over half of the included trials were conducted in North America (Canada: n = 15, 14.2%; USA: n = 45, 42.5%) and the most common settings were primary care (n = 57, 53.8%) and hospitals (including both inpatient and outpatient: n = 31, 29.3%). GPs were the most frequently targeted type of health worker (n = 45, 42.5%), with many studies also targeting a mixture of health workers (n = 35, 33.0%). In terms of target behaviour, 40 studies (37.7%) aimed to change prescribing behaviours (including vaccinations), with 25 (23.6%) concerned with the overall management of conditions/communications (e.g. being friendly during consultations) and 21 (19.8%) focusing on arranging, conducting or administering tests/assessments (e.g. performing HbA1c testing). Of the 106 trials that contributed findings to the review, the majority (n = 70, 66%) were cluster RCTs, with 31 RCTs (29.2%), four stepped-wedge designs (3.8%) and one two-arm matched-cluster RCT. The majority of trials (n = 103, 97.2%) did not explicitly target participants with a low target performance. This is surprising, because the literature on social norms strongly suggests that social comparison is more likely to be successful if it is addressed to low performers: telling a high performer that they are already doing more than their peers does not motivate them to improve. 56,57 It is possible that some of the trials took place in contexts where the performance of all the health professionals was generally low at baseline, so they did not need to specifically seek out low performers to target, but no information was provided to support such an assumption. A complete list of all trials and their characteristics is included in Appendix 14, Table 26.

| Study characteristic (n = 106) | Frequency | % |

|---|---|---|

| Country | ||

| Australia | 8 | 7.5 |

| Canada | 15 | 14.2 |

| Denmark | 4 | 3.8 |

| UK | 13 | 12.3 |

| Netherlands | 6 | 5.7 |

| USA | 45 | 42.5 |

| Other/multiple | 15 | 14.2 |

| Setting | ||

| Primary (GP/general practice nurses) | 57 | 53.8 |

| Hospital (inpatient and outpatient) | 31 | 29.3 |

| Community | 4 | 3.8 |

| Care/nursing home | 4 | 3.8 |

| Mixed | 7 | 6.6 |

| Other | 3 | 2.8 |

| Type of health worker | ||

| Doctor (primary care) | 45 | 42.5 |

| Doctor (secondary care) | 19 | 17.9 |

| Other (nurse/dentist/AHP/pharmacist) | 7 | 6.6 |

| Mixture/whole team | 35 | 33.0 |

| Target behaviour | ||

| Prescribing (including vaccinations) | 40 | 37.7 |

| Hand-washing/hygiene | 4 | 3.8 |

| Tests/assessments | 21 | 19.8 |

| Referrals | 3 | 2.8 |

| Management communications | 25 | 23.6 |

| Other | 2 | 1.9 |

| Multiple behaviours | 11 | 10.4 |

| Type of trial | ||

| Cluster RCT | 69 | 65.1 |

| Factorial | 4 | 3.8 |

| RCT | 28 | 26.4 |

| Stepped wedge | 4 | 3.8 |

| Matched pairs, cluster RCT | 1 | 0.9 |

| Targeted at low baseline performance?a | ||

| No | 103 | 97.2 |

| Yes | 2 | 1.9 |

| Unclear | 1 | 0.9 |

| Intervention characteristic (n = 117) | Frequency | % |

| Source | ||

| Peer | 6 | 5.1 |

| Investigators | 83 | 70.9 |

| Supervisor/senior colleague | 2 | 1.7 |

| Patient | 1 | 0.9 |

| Respected source | 15 | 12.8 |

| Other | 1 | 0.9 |

| Not reported | 9 | 7.7 |

| Internal/external deliveryb | ||

| Internal | 17 | 14.5 |

| External | 81 | 69.2 |

| Unclear/not reported | 19 | 16.2 |

| Reference group | ||

| Peer | 97 | 82.9 |

| Professional body | 1 | 0.9 |

| Senior person | 9 | 7.7 |

| Patient(s) | 1 | 0.9 |

| Multiple | 4 | 3.4 |

| Unclear/not reported | 5 | 4.3 |

| Direction of change | ||

| Increase | 85 | 72.6 |

| Decrease | 30 | 25.6 |

| Maintenance | 0 | 0.0 |

| Unclear | 2 | 1.7 |

| Format | ||

| Face-to-face meeting | 16 | 13.7 |

| 10 | 8.5 | |

| Written (paper) | 29 | 24.8 |

| Separate computerised | 10 | 8.5 |

| Mixed | 18 | 15.4 |

| Unclear/not reported | 34 | 29.1 |

| Frequency | ||

| Only once | 35 | 29.9 |

| Twice | 10 | 8.5 |

| More than twice | 45 | 38.5 |

| Unclear/not reported | 27 | 23.1 |

Intervention characteristics

Details of intervention characteristics are shown in Table 1. Of the 117 comparisons, many were delivered using a written (paper) format (n = 29, 24.8%) or utilised a mixed format (e.g. face to face and written) (n = 18, 15.4%). Participants in 45 (38.5%) interventions received the intervention more than twice, whereas 10 comparisons delivered the intervention twice (8.5%) and 35 (29.9%) delivered the intervention only once. In the majority of comparisons, the investigators were the source of the intervention (k = 83, 70.9%) and the intervention was delivered by someone external to the target health worker’s organisation (k = 81, 69.2%). In 97 (82.9%) of the comparisons, the reference group/person was the target health worker’s peer. In terms of the desired direction of change, 85 (72.6%) studies aimed to increase the behaviour. There was a lack of clarity in reporting across many intervention characteristics within the included studies. For example, in 34 (29.1%) interventions, the format was unclear or not reported and the frequency of the intervention was unclear or not reported in 27 (23.1%) comparisons.

Description of the behaviour change techniques

The frequency of specific social norms BCTs occurring within the 100 comparisons that tested social norms interventions against a control are shown in Table 2. We found tests of social comparison (n = 79), credible source (n = 7) and social reward (n = 2) against control. Some studies tested more than one social norms BCT together: social comparison and credible source (n = 6), social comparison and social reward (n = 2) and multiple social norms BCTs (more than two) together (n = 4). The social norms interventions often occurred alongside other BCTs, and 22 different techniques were identified (see Table 2).

| Behaviour change technique | n |

|---|---|

| Social norms BCTs | |

| 6.2 Social comparison | 90 |

| 9.1 Credible source | 18 |

| 10.4 Social reward | 5 |

| 6.3 Information about others’ approval | 4 |

| 10.5 Social incentive | 1 |

| Other BCTs | |

| 2.2 Feedback on behaviour | 88 |

| 3.1 Social support (unspecified) | 25 |

| 4.1 Instruction on how to perform the behaviour | 20 |

| 7.1 Prompts/cues | 19 |

| 5.1 Information about health consequences | 18 |

| 1.2 Problem-solving | 12 |

| 1.1 Goal-setting (behaviour) | 9 |

| 8.1 Behavioural practice/rehearsal | 5 |

| 1.4 Action planning | 4 |

| 6.1 Demonstration of the behaviour | 4 |

| 1.3 Goal-setting (outcome) | 3 |

| 2.3 Self-monitoring of behaviour | 2 |

| 2.7 Feedback on outcome(s) of behaviour | 2 |

| 12.5 Adding objects to the environment | 2 |

| 1.7 Review outcome goals | 1 |

| 2.1 Monitoring of behaviour by others without feedback | 1 |

| 5.3 Information about social and environmental consequences | 1 |

| 8.2 Behaviour substitution | 1 |

| 9.2 Pros and cons, final | 1 |

| 10.3 Non-specific reward, final | 1 |

| 12.1 Restructuring the physical environment | 1 |

| 10.1 Material incentive (behaviour) | 1 |

The 117 comparisons belonged to the three comparison categories as follows (Table 3):

-

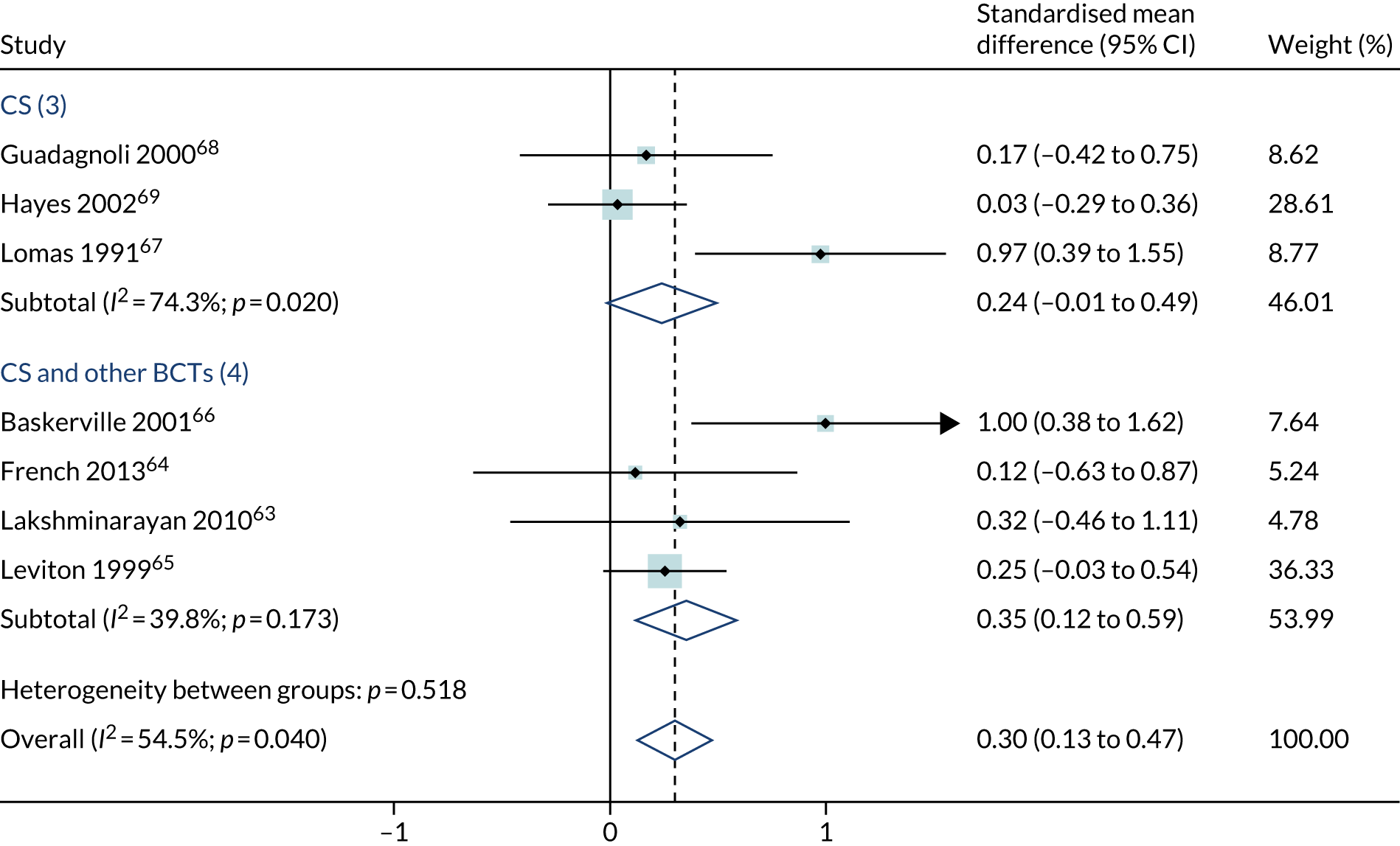

Pure comparisons. There were 36 comparisons that offered a ‘pure’ test of social norms interventions. Most of these tested social comparison (33 comparisons). There were far fewer comparisons testing credible source (n = 3), social reward (n = 1), social comparison and credible source together (n = 2), or social comparison and social reward together (n = 2).

-

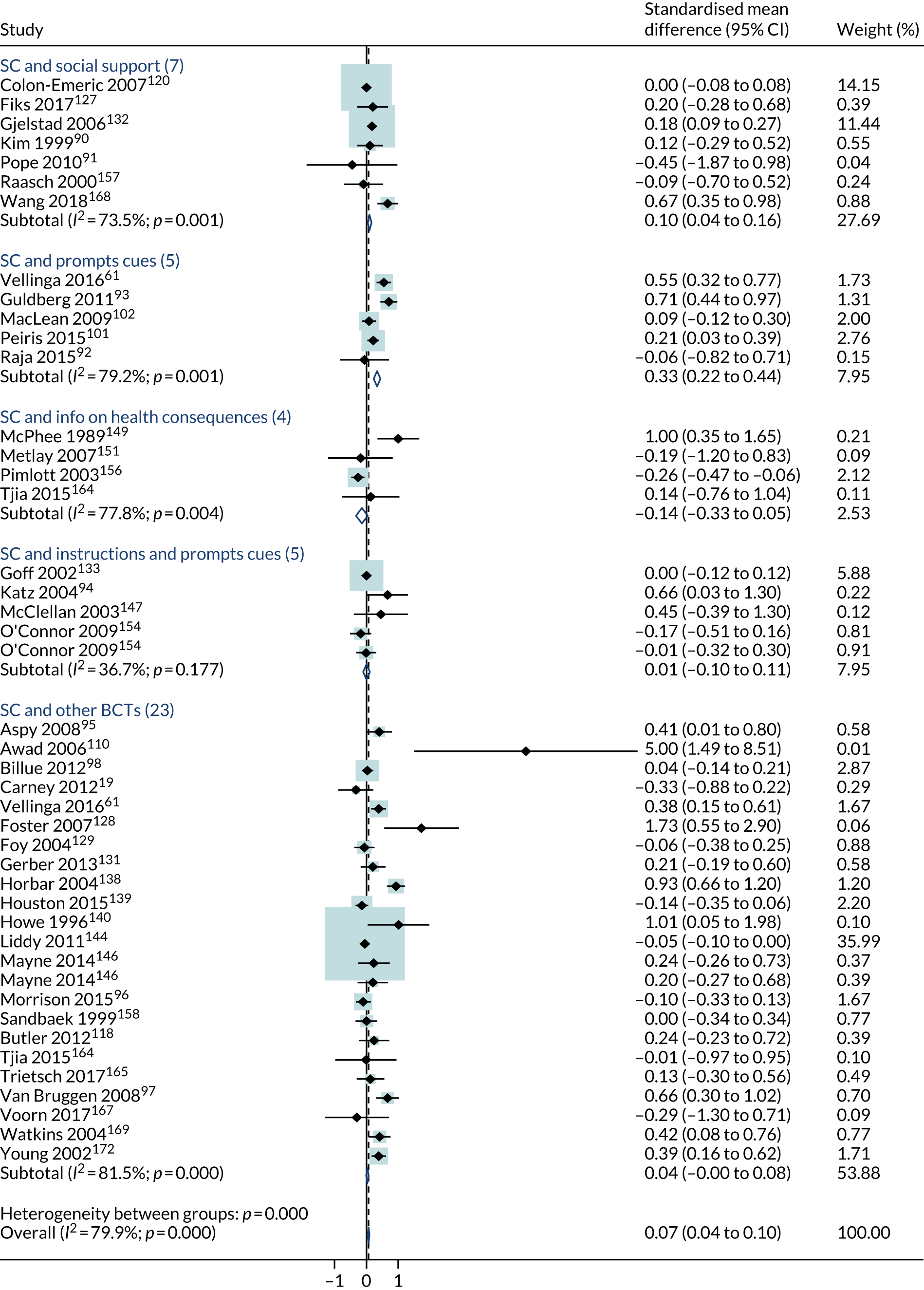

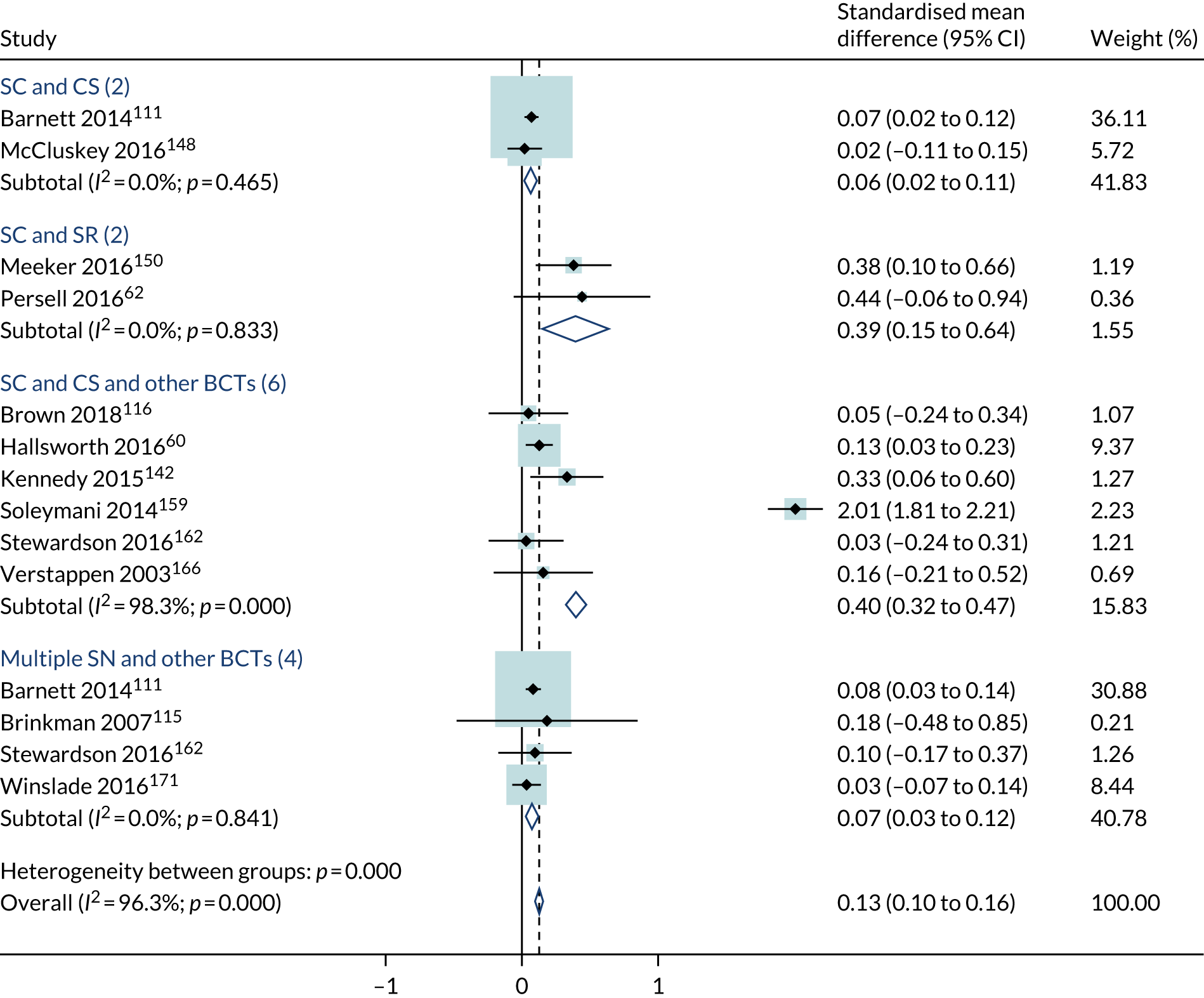

Comparisons involving other BCTs. Social comparison was combined with social support (unspecified) (n = 7), prompts and cues (n = 5), information about health consequences (n = 4) and instruction on how to perform the behaviour and prompts/cues (combined) (n = 5). Combined interventions involving social comparison with more than two other BCTs or where the combination occurred only once in the study were combined into one group: social comparison and other BCTs (n = 25). Credible source did not occur more than once with any one particular BCT, so there is one category of credible source with other BCTs (n = 4) and another of social comparison and credible source with other BCTs (n = 4). There was one example of social reward with other BCTs (n = 1). Where more than two social norms BCTs occurred together, they were combined in a category (n = 4).

-

Social norms BCTs in both arms. There were 17 comparisons in which both arms involved social norms interventions (Table 4).

| Social norms interventions comparison types | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Pure comparisons | |

| Social comparison | 33 (28) |

| Credible source | 3 (3) |

| Social reward | 1 (1) |

| Social comparison and credible source | 2 (2) |

| Social comparison and social reward | 2 (2) |

| Comparisons involving other BCTs | |

| Social comparison and social support (unspecified) | 7 (6) |

| Social comparison and prompts/cues | 5 (4) |

| Social comparison and information about on health consequences | 4 (3) |

| Social comparison and instruction on how to perform the behaviour & prompts/cues | 5 (4) |

| Social comparison and other BCTs | 23 (21) |

| Credible source and other BCTs | 4 (3) |

| Social comparison and credible source and other BCTs | 6 (3) |

| Social reward and other BCTs | 1 (1) |

| Multiple social norms BCTs and other BCTs | 4 (3) |

| Social norms BCTs in both arms | |

| Social norms BCTs both arms | 17 (15) |

| Total (n) | 117 |

| Comparison type | Frequency |

|---|---|

| Same social norms intervention in both arms, testing some other intervention (n = 11) | |

| Credible source and feedback on behaviour vs. credible source and feedback on behaviour with other BCTs | 1 |

| Social comparison vs. social comparison and goal-setting | 1 |

| Social comparison and feedback vs. social comparison and feedback plus information about others’ approval and other BCTs | 1 |

| Social comparison and feedback vs. social comparison and feedback with other BCTs | 7 |

| Social comparison and feedback vs. social comparison and feedback with a patient-level intervention | 1 |

| Comparison of two social norms interventions (n = 2) | |

| Credible source and social comparison and feedback on behaviour and other BCTs vs. social comparison and feedback on behaviour | 1 |

| Social comparison and credible source and feedback on behaviour vs. credible source | 1 |

| Testing different variants of the same social norms intervention (n = 4) | |

| Social comparison vs. social comparison, no other BCTs | 2 |

| Credible source vs. credible source | 1 |

| Social comparison and feedback and social support (unspecified) vs. social comparison and Feedback plus social support (unspecified) | 1 |

| Total | 17 |

Variation in trial characteristics by type of social norms intervention

Table 5 shows the key trial characteristics by the type of comparison. In total, 33 different comparisons were a pure test of ‘social comparison’ and these were quite varied in terms of type of target behaviour, type of health-care worker and type of setting; similarly, those trials that tested social comparison alongside other BCTs were also quite varied. There were 13 comparisons that tested ‘credible source’ alone or with other BCTs and four that included social reward, and again these were spread over a range of behaviours, contexts and settings. Reassuringly, there is no clear pattern to suggest that the use of BCTs was restricted to particular behaviours, contexts or settings, and this is consistent with the regression results, which suggested that the results were consistent after adjustment.

| Trial characteristic | Social norm comparison category, n (%) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Social comparison | Credible source | Social reward | Social comparison and credible source | Social comparison and social reward | Social comparison and social support (unspecified) | Social comparison and prompts and cues | Social comparison and information on health consequences | Social comparison and instructions and prompts/cues | Social comparison and others BCTs | Credible source and other BCTs | Social comparison and credible source and other BCTs | Social reward and other BCTs | Multiple social norms and other BCTs | |

| Comparisons with primary outcome data (n) | 33 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 7 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 25 | 4 | 4 | 1 | 4 |

| Target behaviour | ||||||||||||||

| Prescribing | 15 (45) | 1 (100) | 1 (50) | 2 (100) | 2 (29) | 1 (20) | 3 (75) | 1 (20) | 11 (44) | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | ||

| Hand/hygiene | 1 (25) | 1 (100) | 1 (25) | |||||||||||

| Tests | 7 (21) | 1 (14) | 3 (60) | 1 (25) | 3 (60) | 4 (16) | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | ||||||

| Referrals | 2 (8) | 1 (25) | ||||||||||||

| Manage conditions | 5 (15) | 3 (100) | 1 (50) | 2 (29) | 1 (20) | 5 (20) | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | ||||||

| Other | 12 (14) | 1 (4) | ||||||||||||

| Multiple | 6 (18) | 1 (14) | 1 (20) | 2 (8) | ||||||||||

| Type of HCP | ||||||||||||||

| Doctor: GP | 16 (48) | 1 (50) | 2 (100) | 4 (57) | 2 (40) | 1 (25) | 4 (80) | 11 (44) | 2 (50) | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | |||

| Doctor: secondary | 4 (12) | 3 (100) | 1 (14) | 1 (20) | 1 (20) | 2 (12) | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | |||||

| Other HCP | 4 (12) | 1 (100) | 1 (4) | 0 (0) | 1 (25) | |||||||||

| Mixed/team | 9 (27) | 1 (50) | 2 (29) | 2 (40) | 2 (40) | 1 (20) | 10 (40) | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | 1 (100) | 1 (25) | |||

| Setting | ||||||||||||||

| Primary | 18 (55) | 1 (50) | 2 (100) | 4 (57) | 4 (80) | 1 (25) | 5 (100) | 17 (68) | 2 (50) | 1 (25) | 1 (25) | |||

| Hospital | 6 (18) | 3 (100) | 2 (29) | 1 (20) | 2 (50) | 6 (24) | 2 (50) | 2 (50) | 1 (100) | 2 (50) | ||||

| Community | 1 (3) | 1 (100) | 1 (50) | 1 (25) | ||||||||||

| Care/nursing | 0 (0) | 1 (14) | 1 (25) | 1 (4) | 1 (25) | |||||||||

| Mixed | 7 (21) | |||||||||||||

| Other | 1 (3) | |||||||||||||

Outcome measures

Using the criteria described in Chapter 2, Outcomes and prioritisation, we selected a single primary outcome measure of compliance with desired behaviour for each relevant comparison. Of the 117 comparisons used in the review, 32 (27%) provided an odds ratio, 42 (35%) provided raw binary data and 43 (37%) provided mean with standard deviation (standard deviations were imputed where necessary).

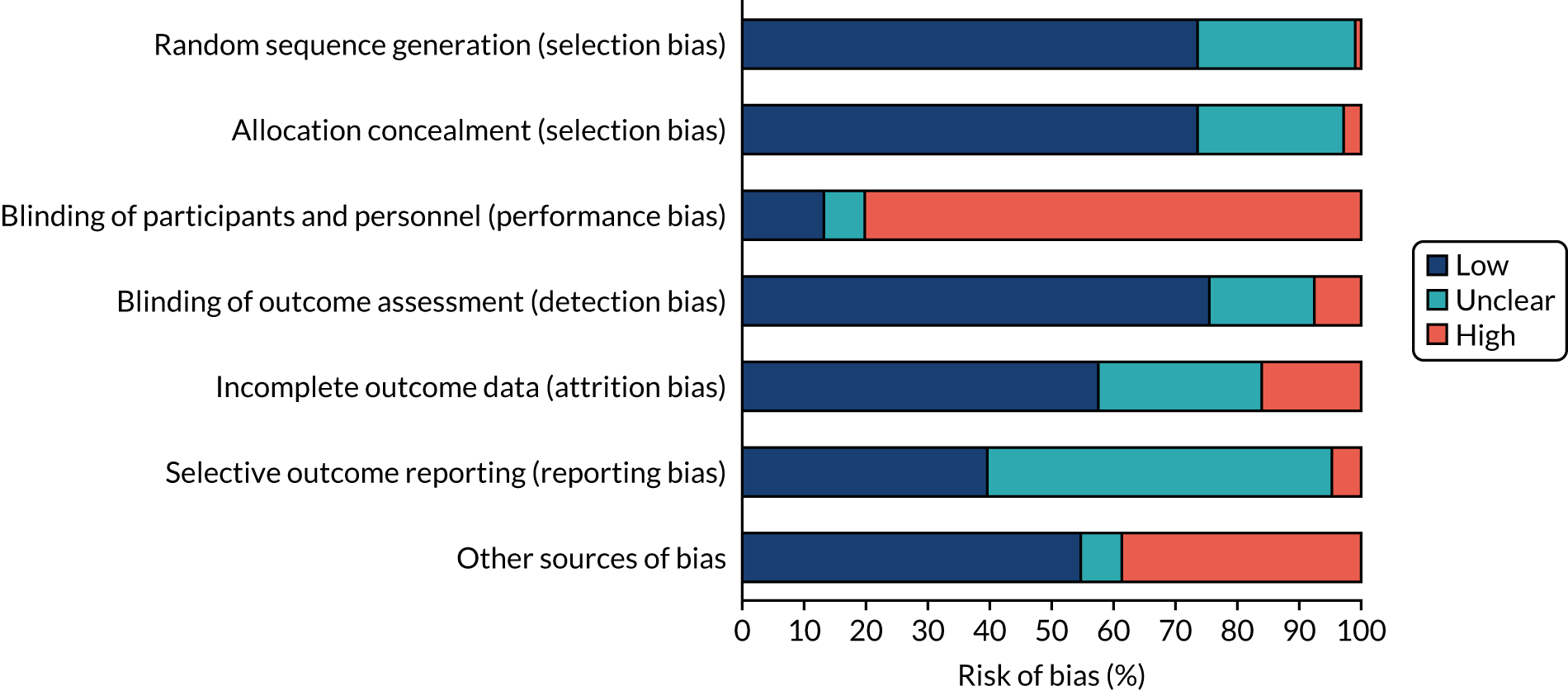

Risk of bias

A summary of each risk-of-bias item across the included studies (n = 106) is shown in Figure 2. Individual risk-of-bias assessments for all of the included studies can be found in Appendix 15, Figure 20.

FIGURE 2.

Review authors’ judgements about each risk-of-bias item presented as percentages across all included studies (n = 106).

Allocation

In terms of random sequence generation, methods were deemed sufficient to produce comparable groups for the majority of studies (n = 78, 73.6%) and were, therefore, considered to be at low risk of bias. Only one study was rated to be at high risk of bias, and this was because of the original randomisation being rejected because of a perceived lack of balance between groups. All other studies (n = 27) were rated as unclear because of insufficient information to permit a judgement. The majority of studies were also rated to be at low risk of bias for allocation concealment (n = 78, 73.6%), primarily because of recruitment and consent being conducted before randomisation took place. Three studies were rated to be at high risk of bias because randomisation took place before recruitment and/or obtaining consent. The remaining studies (n = 25) were considered unclear because there was insufficient information available, or because recruitment/consent had occurred post randomisation and it was unclear whether or not participants were aware of their allocation at the time of enrolment/consent.

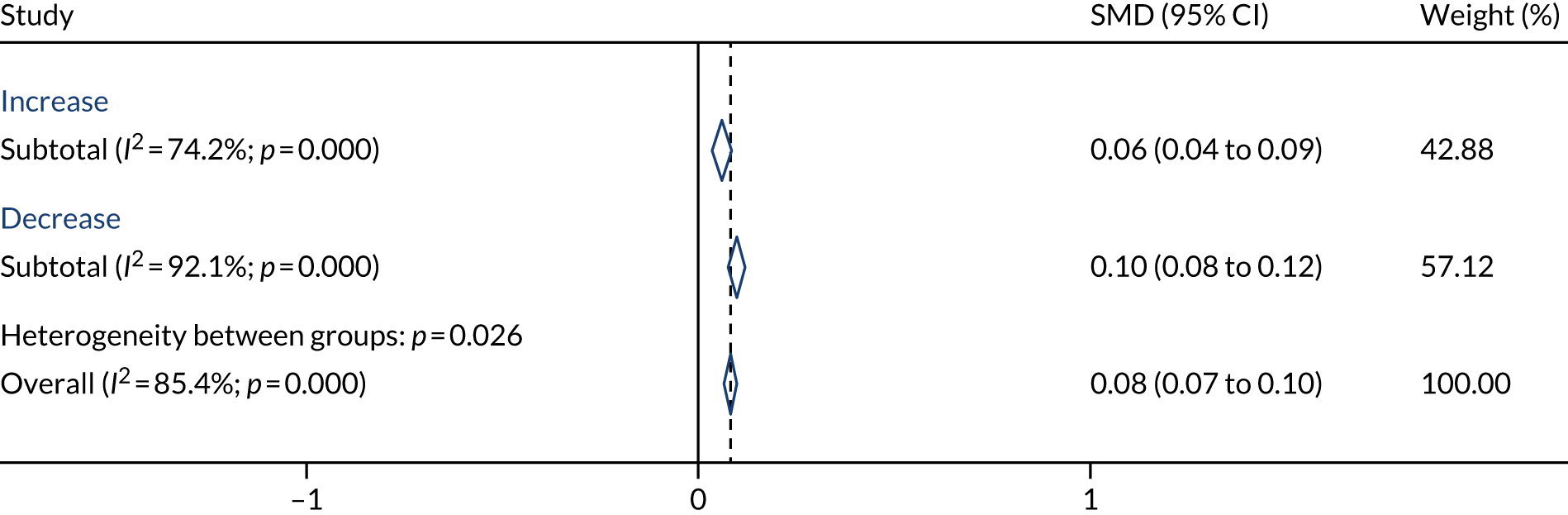

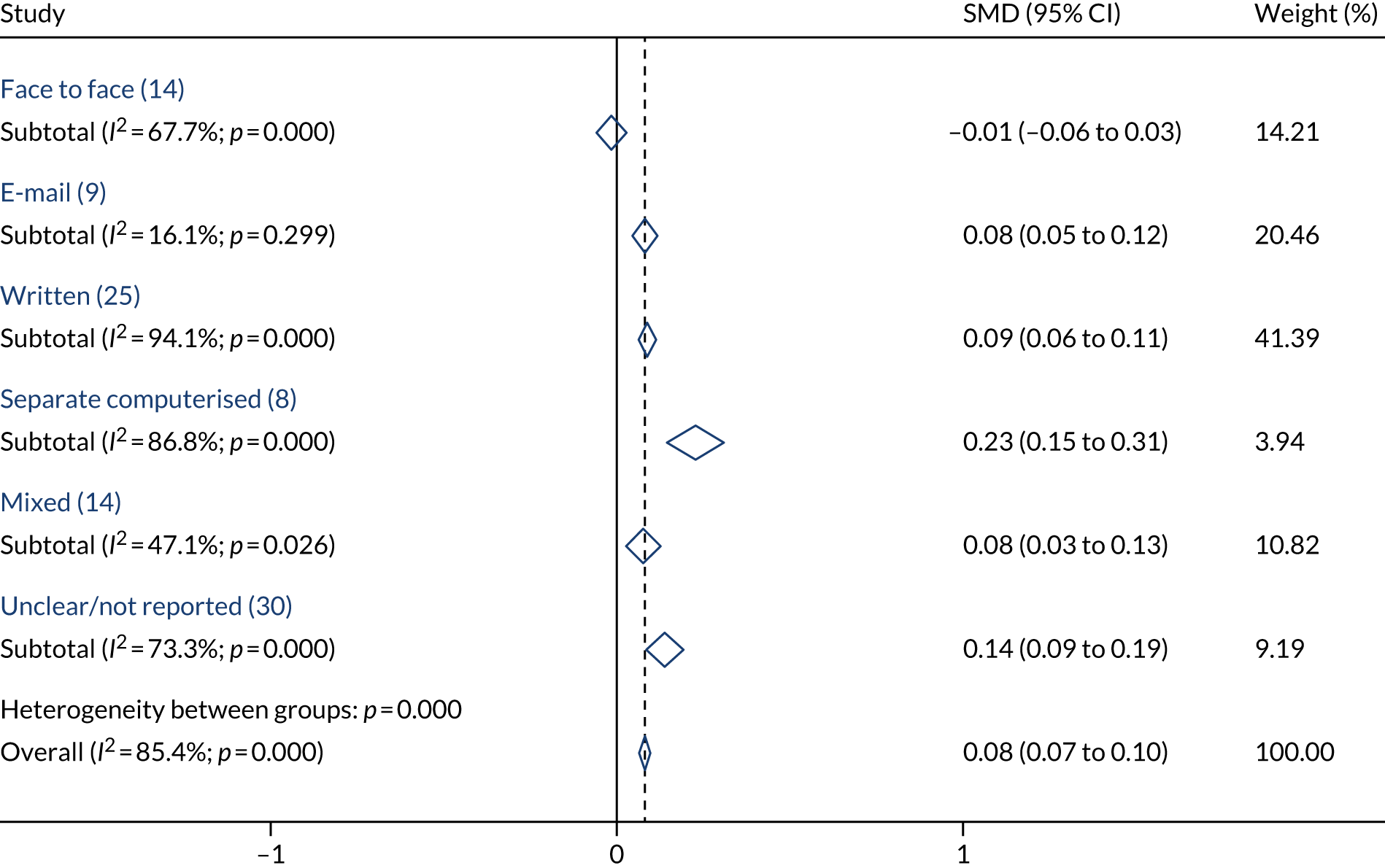

Blinding