Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/54/25. The contractual start date was in April 2015. The final report began editorial review in December 2019 and was accepted for publication in June 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Renedo et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Context

Transitions from paediatric to adult health services cause problems worldwide, particularly among young people living with a long-term condition affecting their health and future life. 1,2 Improvement of young people’s health and their health-care experiences during the period of transition to adult services has become an important priority area both in the UK3–5 and internationally. 6 Health transition is a gradual process that spans the period from early adolescence to adulthood and continues until the person adjusts and is fully established as an adult patient in adult care services. 7 It constitutes a significant developmental phase7,8 when multiple difficulties arise from the interaction between young people’s health condition and physical, psychological and social developmental changes,9,10 including transitions occurring in other areas of life. Transition to adult care is crucial for those with long-term conditions. This is a time of increased medical vulnerability. 11 Multiple demands emerge from the diverse social contexts of the young person beyond health care, including demands for increased competency and autonomy in self-management10 of their own condition and societal expectations about how the young person should develop into a responsible adult, including achieving particular educational and career goals. All these demands and parallel transitions in other aspects of a young person’s life occur against the background of changes in their health care as the young person is transferred to adult services. For young people, pursuing aspirations to live a ‘normal’ life while simultaneously self-managing their condition during transition can prove very taxing. 9

Young people’s experiences of care across the health-care system during the process of transition to adult care, including the clinical care they receive and any support they are given to prepare them for adult services (i.e. transitional care), can have a major impact on their health and future life. 1,2 Poor experiences of care during the transition period are likely to disengage young people from services, lead to poor health outcomes and shape their future adult patterns of engagement with services. 12

One long-term condition for which the period of transition to adult health-care services is a particularly challenging period13–16 and for which there is a need for better health care17,18 is sickle cell disorder (SCD). SCD is an inherited blood disorder characterised by an abnormal haemoglobin that results in sickle-shaped red blood cells that tend to fragment, leading to anaemia, jaundice, fatigue and extreme tiredness. During physical stresses the sickled red cells block small blood vessels, causing excruciating, severe painful episodes, splenic hypofunction with consequent increased susceptibility to severe infection, and chronic organ damage resulting in significant disability and reduction in life expectancy. 19 Episodic acute painful episodes are a constant threat for people with SCD and can become more frequent with age. 20 They are unpredictable, can be excruciating and sometimes emerge together with acute chest syndrome, stroke and infections. 21 They require timely medical treatment. Both acute painful episodes and chronic pain affect everyday life and can have important long-term health implications. Almost one-third of people with SCD report having pain nearly every day, and over half report pain for more than half of the time. 22 There is a high prevalence of other comorbidities among young people with SCD, including asthma, cardiac dysfunction, chronic lung disease, avascular necrosis of the long bones and organ damage. 15,23

Sickle cell disorder poses an important global public health challenge. 24 In the UK, between 12,500 and 15,000 people live with SCD,21 with London accounting for the majority of the national SCD cases and SCD-related hospital admissions. 25 The vast majority of patients live in London or larger urban conurbations in the UK. 26 Approximately 250 new cases are identified every year via newborn screening in England. 27 SCD is the most common genetically inherited significant health-threatening condition among newborns in England. It predominantly affects people of black African and African-Caribbean origin. 28

Sickle cell disorder provides an excellent case study for examining transition to adult health-care services. It is a complex condition that is rapidly becoming more common in the UK,29 and SCD patients aged 16–20 years report poorer experiences of care than those in other age groups, particularly during emergency attendances. 18 People with SCD who are aged 20–29 years are hospitalised more often than those in other age groups and have the highest rates of short-duration emergency admissions for SCD painful episodes. 25 This suggests that care needs to improve during transition into adult services so that young people are better equipped to avoid these emergency hospitalisations when they reach adulthood. Similar outcomes have been found among patients in the USA, where acute care utilisation and rehospitalisation rates among 18- to 30-year-old patients are higher than in any other age group,30 suggesting that young people reaching adulthood need extra support to avoid hospitalisations and poor health outcomes. 15 McLaughin and Ballas31 also showed that mortality among US children with SCD on chronic transfusions is very high if these children are not adequately followed up in adult clinic following transfer from paediatric services.

In the USA, overall childhood mortality rates have decreased significantly, but mortality has increased among young adults at the age corresponding to transition between paediatric and adult care. 13 In the USA, many young people move to adult services with poor preparation and support. 14

Despite evidence indicating that there are gaps in transitional care for young people with SCD in many different settings, we lack knowledge about what works to improve care during transition,32 about the type of support SCD patients need during this period and about the ways in which their social contexts mediate their experiences of transition and problems during this period. Poorly managed and poorly supported transitions can have major negative sequelae, not just for young people but also for their families and health services, including poor treatment compliance, health deterioration, disengagement with services and increased rates of emergency hospitalisations,5,32,33 sometimes with life-threatening consequences.

Transition is a period of vulnerability for young people with any long-term condition. 34 However, the unpredictability of SCD and the threat of painful episodes bring additional challenges. 35,36 There is also stigma associated with SCD because of poor understanding of the condition both socially and among health-care staff, which increases the burden on young people with the condition. 36–38 Patients can be stereotyped as drug-seekers39 (i.e. abusing pain relief and being addicted to opioid painkillers). 40

Sickle cell disorder can be ‘racialized’. 41–44 In England, black African and African-Caribbean communities are most affected by SCD,28 as well as by the negative health and social impacts of societal inequalities. 28,45,46 Health services for SCD are limited compared with those for patients living with ‘disorders such as cystic fibrosis, which primarily affects people of Northern European descent’. 43 Complicating this further is the stigma associated with the SCD diagnosis in some communities. 47

Quality transitional care to prepare young people to adjust to adult services is increasingly considered a central element of any youth-friendly health-care service. 48,49 Improvements in transitional care need to be grounded in comprehensive understanding of the holistic needs and experiences of patients during transition,4 including across the health-care system (i.e. beyond specialised care), and consider their wider social contexts (such as relationships, education, work and other life transitions). Limited research from the USA50–52 has explored the role of health-care service components in achieving successful transition for patients with SCD. We lack understanding, however, about how transitions between child and adult health-care services interact with wider social contexts. For other long-term conditions, although there is a considerable body of research on how transition is supported in specialist care, there is little research examining how experiences of clinical care across the health-care system (i.e. beyond specialised care) affect the transition process. 53 SCD transitional care needs to include consideration of developmental issues beyond health and should take into account the young person’s perspective on their own transition to adulthood and adult services. 15 However, young people’s voices are not usually included in health-care transition research to the extent needed54 and their experiences of transitions in care outside specialist services across the health-care system remains largely unexamined. Top-down approaches to health-care service planning55 that do not involve patients dominate current provision. 56 Self-management of SCD is demanding and requires close self-monitoring [e.g. keeping hydrated (drinking water), keeping warm, resting, avoiding arduous physical activity, and being attentive and responsive to signs of a possible painful episode]. 57,58 These self-management practices are inculcated in young people with SCD as a form of ‘self-regulatory governance’. 58

Listening to children’s and young people’s voices – and acting on what they say – is crucial to help develop better, more youth-friendly services7 and adolescent-responsive health systems59 and enabling educational and work contexts6 to help young people to stay healthy. Survey data and superficial accounts of young people’s experiences, which often treat young people as passive subjects, need to be supplemented with in-depth understandings of wider factors influencing health. 60 Understanding young people’s experiences across the health-care system and in their wider social context during the process of transition is crucial.

Our qualitative research study explored the experiences of young people with SCD as they transitioned from paediatric to adult NHS services, with a focus on how their clinical experiences were integrated into their whole lives. We examined the world beyond the clinical realm and investigated wider aspects of young people’s lives that affect their SCD transitions, such as education, relationships and work. 61 We adopted a ‘slow co-production’ approach56 and involved patients as research participants and also as team collaborators (see Chapter 3) in an in-depth qualitative exploration that aimed to produce ‘patient-centred knowledge’. 56,61 By engaging in this way, that is with young people’s own experiences and voiced needs, we aimed to inform service provision that meets the NHS goal of providing ‘patient-centred’ transitional care5,62 and to help inform global efforts to improve adolescent health.

Chapter 2 Research objectives

The objective of this study was to inform transitional care and support for young people. We used a sociological, person-centred approach, looking beyond the clinical context to other areas also affected during transitions to adulthood. Our specific aims are listed below:

-

to examine experiences of health-care transition from the patient perspective, taking into account social aspects of young people’s lives outside health-care services

-

to examine how young people with SCD move from using paediatric to adult health-care services

-

to examine how social context affects transition

-

to investigate young people’s experiences of living with SCD during transition to adulthood

-

to examine how health-care transition affects young people’s health-care-related behaviour and quality of life

-

-

to understand how current health care meets the holistic needs of young people with SCD during transition

-

to explore how young people experience care relationships and interactions with health-care providers during transition

-

to understand young people’s concerns during health-care transition

-

to explore how these relate to health-care professionals’ views

-

-

to understand the type of support young people with SCD require to improve their transition experiences and develop recommendations to improve NHS transitional care for this population

-

to use the findings to inform the development of resources to support the successful move of young people with SCD into adulthood and adult care successfully

-

to reflect on how lessons from SCD can be applied to health-care transitions more generally.

Chapter 3 Patient and public involvement

We worked closely with non-clinical, non-academic SCD experts (i.e. patient and carer representatives) throughout. Patient and carer experts Cherelle Augustine, Nordia Willis and Patrick Ojeer [hereafter referred to as CA, NW and PO and collectively as patient and public involvement (PPI) experts] were involved in the project from its inception, working on developing the research questions and funding proposal, advising on the project throughout data collection and being involved in parts of the substantive analytical work, as well as playing an important part in dissemination activities. 46 Their work has been vital to ensure that patient perspectives have been central during study design, data analysis and knowledge translation. 46,56

In our role as academic researchers we adopted a responsive approach to working with PPI experts in the project, as well as with other patients, carers and patient groups. Our previous experience suggested that this would help ensure that patients were involved in a meaningful and sustainable way. For instance, we soon discovered that large stakeholder and steering group meetings would be inappropriate and difficult to achieve. Instead, we worked with our PPI experts to ensure that we were holding smaller, more appropriate meetings (sometimes one to one). These smaller meetings meant that we were able to adapt to the needs and other commitments of those involved, as well as to reschedule meetings to accommodate other commitments or illness.

During the project, as well as regular meetings with PPI experts, we held discussions with SCD patient charities and with patient group representatives from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care Northwest London (CLAHRC NWL) SCD Early Years Steering Group. This group developed and validated a patient-reported experience measure for SCD. 18 The NIHR CLAHRC NWL was a programme funded by NIHR to facilitate collaborations between researchers, clinicians and patients to help ensure that research evidence was translated into health-care practice. 63 The NIHR CLAHRC NWL SCD Early Years Steering Group included clinicians and paediatricians (including one specialising in SCD) as well as others who work in different conditions affecting children and young people. Through these different fora we discussed the development of study materials, findings, the practical implications of the findings and how to move forward, including how best to translate our findings into outputs that would benefit patients.

Involvement during inception and initial stages of the project

The idea for the project originated from our interactions with patients and patient charities during our investigation into patient involvement in SCD health-care improvement in the NIHR CLAHRC NWL. 64–66 NW and CA [two young people with SCD and founders of Broken Silence (London, UK), a charity organisation for young people with SCD] and PO (father of a SCD patient) were involved from the start. We worked with them to identify research questions and to understand their transition experiences and obtain their views on the project’s aims and methods, all of which we incorporated into the final study.

PO emphasised that the aims should be to assess how transitional care enables patients to be treated in accordance with the NHS ethos ‘no decision about me without me’. 67 Our objectives were formulated accordingly.

Broken Silence highlighted the need to create tangible resources that would benefit patients, particularly to empower them. This influenced CM’s and AR’s original idea of using research findings to co-produce support resources with young adults with SCD to help patients achieve better self-care and be better able to navigate the health-care system. As we explain later, we used our findings to inform a programme for young people that supports this aim (see Chapter 9).

We consulted CA and other young people at various stages of the development and design of study materials (i.e. information sheet, consent form and topic guides). They advised us not to use the term ‘disease’ in our project title and tag line (i.e. ‘This Sickle Cell Life: voices and experiences of young people with sickle cell’) and gave input when we liaised with the graphic designer over the look and feel of the project materials.

Patient and public involvement experts have extensive networks,65 and for this project CA, NW and PO helped us broaden our reach to different stakeholders. We drew on their networks to launch the project and elicit comments and suggestions during later stages (e.g. during analysis and during the process of reflecting on how the findings might be translated into practice).

With the help of our PPI contacts and via their networks we arranged a launch event that was attended by many people with SCD, with some travelling considerable distances to do so. Participants also included service providers, researchers and postgraduate students. They were enthusiastic about the project. We presented study aims, answered questions about the project and invited comments and suggestions. Participants gave us insights and suggestions for data collection and analysis. We arranged the event so that participants would have time to network with one another over tea and biscuits. Participants reported finding the event enjoyable, meeting new people and following up with people they had met at our event (e.g. being able to invite new contacts to a SCD workshop for patients and carers).

Involvement during data collection

CA helped us recruit interviewees from outside health-care services, which was one of our planned ways to include those who might engage with services less often. After discussions with CA, and noting her deep knowledge and excellent ideas for the project, we arranged a contract and an amendment of ethics approval for her to conduct some of the interviews for the project. We provided training to prepare her to conduct interviews (on qualitative research interviewing and ethics). CA found patient recruitment outside services difficult (as did we; see Chapter 5) and was unable to recruit any further interviewees. We continued working with her on other aspects of the project, including data analysis, write-up and dissemination.

Involvement during analysis and knowledge translation

The PPI experts informed the analysis and interpretation of the data and helped us think about how to translate findings into useful resources to support transitions. They facilitated relationships with charities working with people with SCD and also assisted with work to help get the findings into practice. During our meetings, we also answered questions about the project and invited comments and suggestions for further analysis and interpretation. The PPI experts contributed with ideas for further analysis, helping put the data into context.

Patient and public involvement experts collaborated on analysing and disseminating findings. Their additional role as authors46 emerged from our discussions of the findings and analysis for which they provided substantive insights. We (academics) worked with the PPI experts to develop ways of writing together that were not unduly burdensome for them while also ensuring that they had appropriate authorial voice. We wished to balance the types of tasks that it was reasonable for non-academic authors to do while avoiding unethical ‘gift’ authorship. One article has been published at time of writing. 46 There has been considerable interest from others in our process of writing together and we hope to explore this further together, reflecting on what worked well and what worked less well during the co-authorship process. We hope to write about our reflections so that others can try out similar experiments and/or comment on the process.

The Sickle Cell Society (London, UK), a national patient charity representing the sickle cell community, NIHR CLAHRC NWL and CA were all involved in translating our findings into practice. We presented our analysis and discussed it with them in a reflective session on knowledge translation and implications for practice. They helped us decide how best to translate findings into useful resources to support transitions. This collaboration resulted in our findings feeding into the development of a programme delivered by the Sickle Cell Society to support transitions for young people with sickle cell and their families [see Chapter 2, objective (d)]. The programme’s second phase is greatly informed by our findings as well as issues prioritised by the Sickle Cell Society and its network of individuals and families affected by SCD. The work includes a public awareness campaign that aims to address the wider social context of transitions identified in our study (e.g. lack of awareness and knowledge about sickle cell in school contexts, among peers and at work). We include more information about the programme in Chapter 9.

During knowledge translation, CA arranged and joined us in a meeting with the patient charity Sickle Cell & Young Stroke Survivors (www.scyss.org). We discussed our findings and ways to put them into practice via useful resources to improve transitions for young people with SCD. The meeting helped us put the data into context as well as providing useful discussions about the development of resources.

Our discussions with PPI experts in the project, sickle cell disease specialists, SCD charities, PPI/co-production experts and health-care quality improvement professionals resulted in our changing our original plan, which was to co-produce project output resources via collaborative workshops. We originally proposed four workshops with young patients with SCD to discuss the findings and reflect on ways in which they could be translated into useful resources, including a digital story/film. As our study progressed, emerging findings and our engagement meetings with various stakeholders helped us realise the importance of:

-

Addressing the wider social context of young people (e.g. developing resources targeted not at young people with SCD themselves but at others who also have an impact on their life and health care). This also dovetails with our findings that highlight the importance of removing responsibility for improvement from young people with SCD to avoid perpetuating the idea that the locus of control for the condition rests solely in the young person.

-

Working with patient charities who were already working with young people with SCD and representing their voices (as detailed above) to translate the findings into resources. We were also alerted to the existence of SCD digital stories, including one about transition.

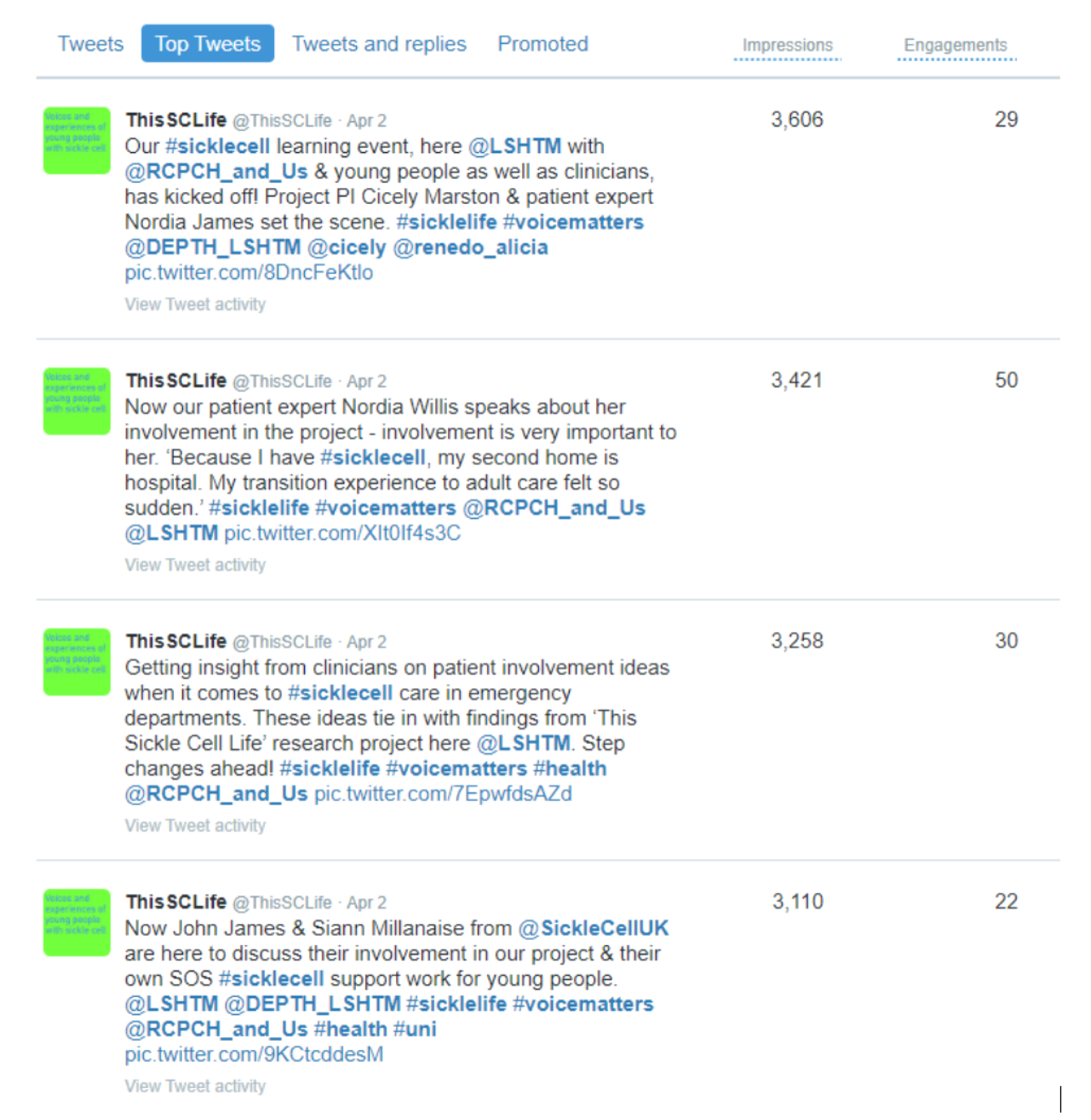

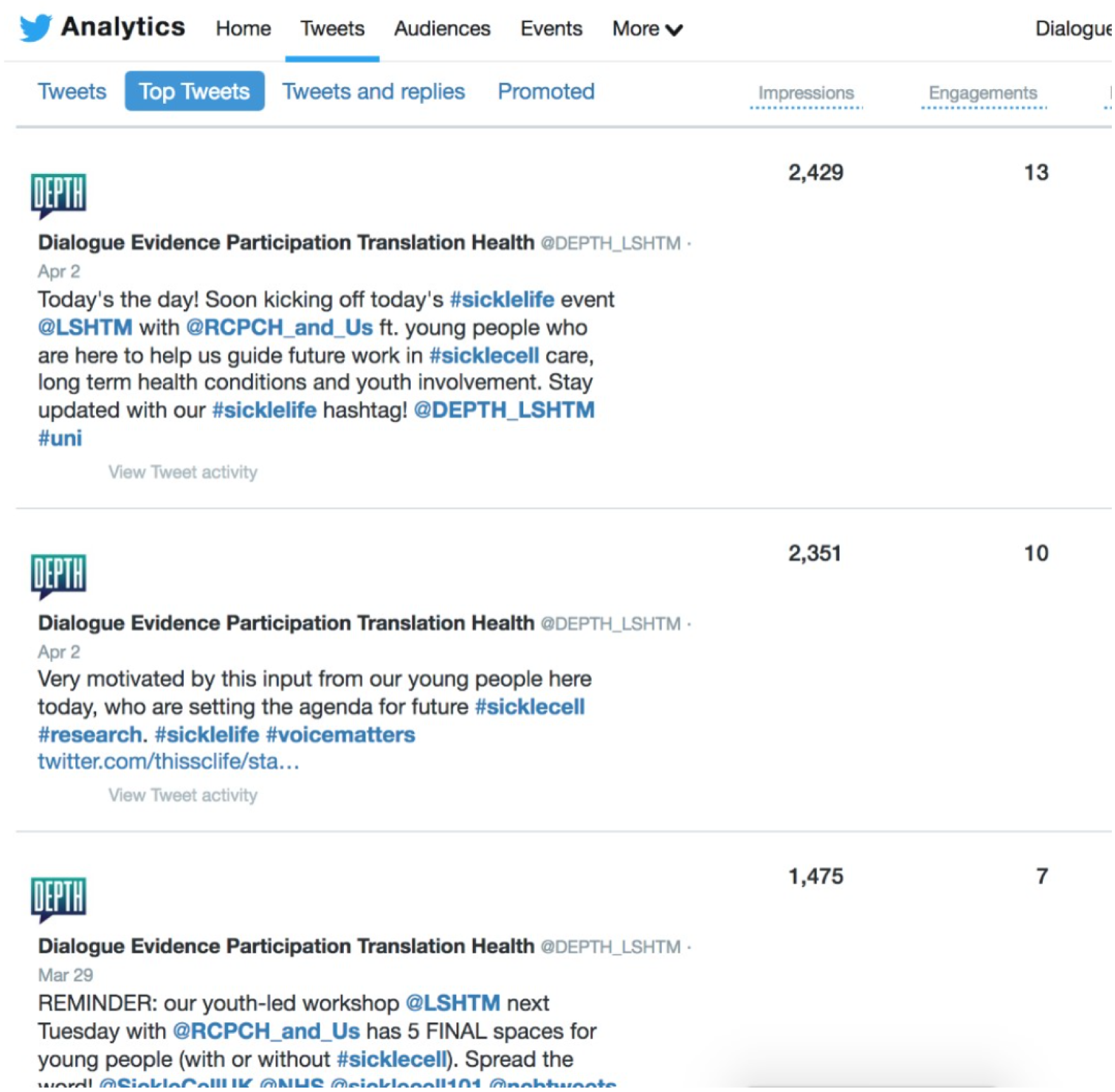

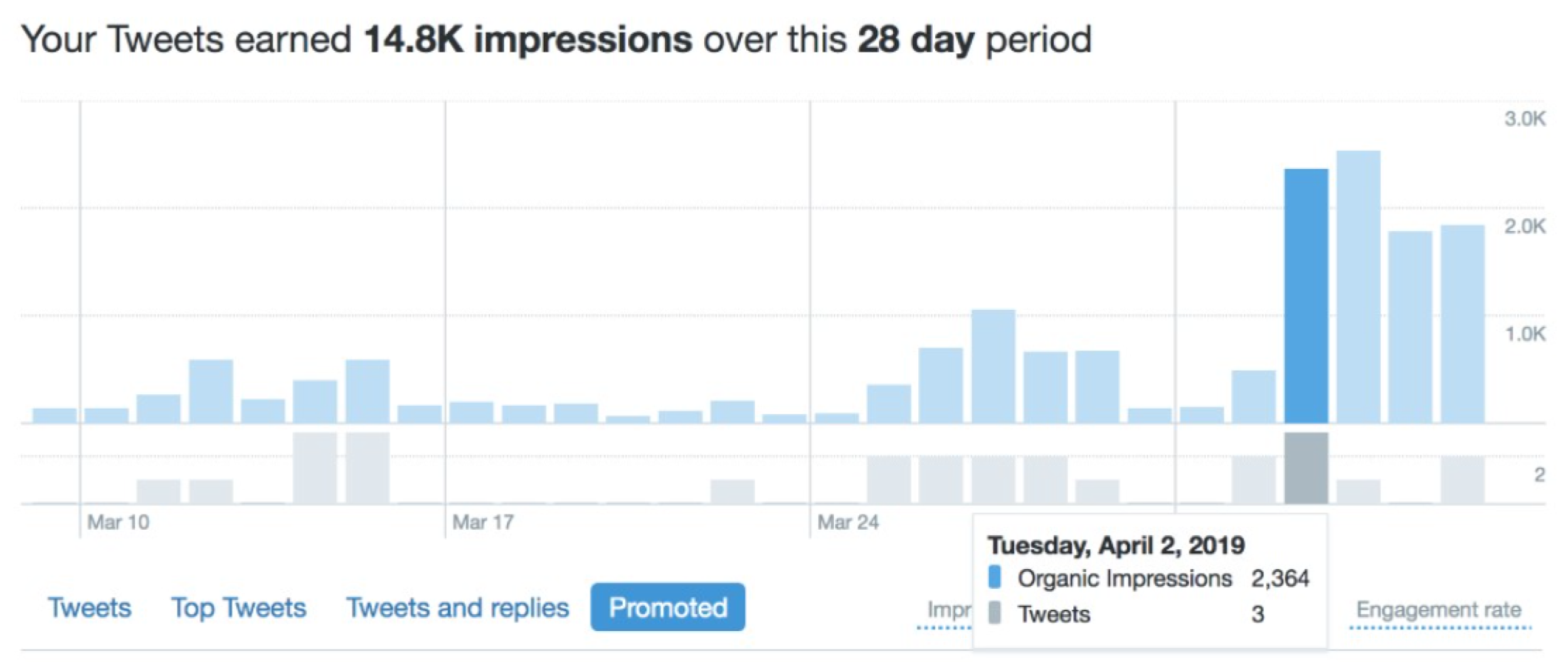

We changed our plan to accommodate our new knowledge of the situation and the preferences of the people we were working with. Instead of creating workshops and a film we worked with the engagement team &Us at the Royal College of Paediatrics and Child Health (RCPCH) to deliver a participatory event to collaboratively reflect on the findings, their implications and next steps (e.g. co-produce ideas for improving transition). &Us involved young people in the planning of the event, and we also engaged stakeholders via the NIHR CLAHRC NWL Early Years Steering Group, from whom numerous ideas emerged to shape and guide the event. We worked with the &Us project team to take advantage of their expertise in events run by, and for, young people. Young people with SCD and other long-term conditions participated in the event and the discussions it generated about outputs for the project.

The participatory event also involved other key stakeholders, including carers of people with SCD, representatives from NHS England and school staff. We were careful to ensure that we included accident and emergency (A&E) doctors and non-specialist health-care providers, both because our findings had indicated that they were particularly important stakeholders when it comes to improving transitions and also because they were identified by the PPI experts as key stakeholders (see Chapter 9). NW co-delivered part of the event and PO participated in it. We used participatory approaches throughout the plan for the event.

The event has generated meetings with various stakeholders and facilitated further discussions about the implications of our findings for practice and further issues identified by participants (including young people) at the event (see Chapter 9).

Reflections on patient and public involvement challenges and facilitators

It takes time and resources to build meaningful and sustainable PPI relationships. We had already developed relationships with PPI experts prior to grant development and funding application. Had we not had this relationship we would not have developed the project in the first place (i.e. the PPI experts had sensitised us to the importance of the issues and they were crucial in shaping the study with us).

Advantages of taking a co-productive, dialogical approach included a flexible and responsive approach to involvement that considered how non-academic partners wanted to participate and how they were able to participate, long-term engagement of PPI experts in the project (i.e. from inception to dissemination), PPI input iteratively shaping the research process and knowledge produced throughout, and the chance for PPI experts to see how their input was shaping different aspects of the project. Challenges included structural constraints to do with the grant writing and funding process, lack of time to support joint writing and lack of academic structures to support writing with non-academic partners.

We were subjected to funding deadlines that were not flexible enough to incorporate PPI at the late stages of the funding application. The turnaround time to respond to reviewer comments was far too short for us to ensure that PPI experts had an input. We had approximately 1 week between receiving comments and the deadline for our response.

We requested an extension; however, this was refused because the funding panel meeting date was fixed and the turnaround time limited accordingly. Not only were we unable to include the external PPI experts in the response to reviewers, but a key member of the academic team was also unavailable during that week. In the context of a chronic condition where individuals may need to rest this is particularly problematic because participants should not be expected to put their health at risk to respond to unexpected and tight deadlines. The tight turnaround time, without prior notice of the deadlines involved, would also disproportionately disadvantage those with caring responsibilities who may need to plan time to meet short deadlines. We fed these reflections back to NIHR at the time and so the specific procedures may now have changed. We note that NIHR has been highly supportive of our PPI involvement efforts throughout and has taken limitations of its processes seriously. In addition, NIHR supported us when we wished to implement better PPI strategies that deviated from our original plan.

Meaningful and sustainable PPI throughout the project has been assisted by having dedicated resources to ensure that PPI experts are paid for their time, commitment from all partners to collaborative working to meet the goal of improving the lives of young people with SCD and flexibility. 56

A flexible approach to respond to PPI expert needs and preferences was crucial. 65 We tried to ensure that the meeting formats encouraged dialogue and that times and locations were convenient. Our aim was to make the project’s ‘participatory spaces’65 as inclusive and collaborative as possible. For instance, our smaller meetings were often informal and included coffee shop meetings, workshops and ad hoc one-to-one teleconferences to discuss specific issues. These different formats enabled us to share ideas and critical reflections with one another in ways that encouraged dialogue.

The work was time-consuming for PPI experts. Having resources to pay them for their time on the project was important. As researchers we were paid for our time working on the project and we wanted the time and expertise of PPI experts to be recognised too. NIHR also recognised the importance of these payments and agreed to fund them.

We present quotations from PPI experts reflecting on their involvement in the project, with their permission:

Working with the LSHTM [London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine] team on the This Sickle Cell Life transition project has been an absolute pleasure. Not only has my point of view and experience as a person living with sickle cell disease been utilised and considered as professional expertise. I have been empowered and trained to partake in the project in a more hands-on role and been invited at every stage of the project to contribute and co-produce content based on the research outcomes.

Quotation 1, CA reflecting on her participation

What stood out about working in the project was that I was listened to fully and that it was truthful; researchers were not trying to steer me in a particular direction. You get involved in research projects and they often have a predicted hypothesis. Our presence [PPI experts] was always at the forefront, I was involved at every stage. This is true working together, what I define as working together as a team.

Quotation 2, NW reflecting on her participation

What I have appreciated is working in a co-productive way; the team’s receptiveness to suggestions and their open-minded attitudes. We have all worked on equal footing. I have felt acknowledged as an equal partner. I have always been recognized at the decision-making process and have been able to see my contribution. This was reflected at the participatory event with RCPCH where it really felt that it was our work, the work of the whole team. In other PPI projects there is not such feeling.

Quotation 3, PO reflecting on his participation

Chapter 4 Literature review

Health care for sickle cell disorder

In adult health services long-term clinical care for SCD is predominantly provided by haematologists, who are mostly based in large teaching hospitals that may not be close to patients’ homes. In paediatric services, care is often led by paediatric haematologists in collaboration with paediatricians with an interest in haemoglobinopathies at local centres. The differences in service delivery structure and access to expertise may affect young people’s experiences of care when they are transitioning from child to adult services. Acute painful episodes requiring medical attention are usually managed outside the specialist services in the nearest hospital, in A&E departments or on general (non-specialist) paediatric/medical wards. The disadvantage for people with SCD is that expertise in managing the condition may be severely limited or completely absent in non-specialist health services. 68 In recent years increased attention has been paid to meeting the need for better SCD care in the UK. 18 This has led to the creation of dedicated pain management day centres for SCD in many hospitals, tailored transition care clinics for young people moving between specialist paediatric and adult services, the establishment of an NHS Specialist Commissioning Group for SCD and thalassaemia, and development of National Institute for Health and Care Excellence guidance21 and Sickle Cell Society standards for care. 68

Hospital admissions rates among people with SCD as primary diagnosis in England rose between 2001/2 and 2009/10, from 21.2 per 100,000 population to 33.5 per 100,000 population. 25 Most of the admissions lasted < 24 hours, but hospital readmissions and in-hospital mortality among SCD patients were highest among those with comorbidities and from the most socioeconomically deprived areas. 25,69 Painful episodes are the most common reason both for attending emergency services and for hospitalisations among people with SCD. 70 They can be excruciatingly painful and require timely treatment not only to alleviate pain but also because they can be accompanied by other acute complications [e.g. stroke, liver or splenic sequestration, acute chest syndrome (a life-threatening complication of SCD) and infections]. 21 Treatment of painful episodes often requires strong analgesics and the reassessment of response to pain relief every 30 minutes until pain is improving and for at least 4 hours afterwards. 21 Careful monitoring for complications during treatment of painful episodes is also essential. Poor monitoring of respiration after administration of opioids can lead to death. 71

One US study showed that patients with SCD waited significantly longer for pain relief on acute presentation to the A&E department than patients presenting with pain from renal colic (chosen as a comparable condition). 72 The patient-reported experience measure developed and validated for children and young people in the UK by Chakravorty et al. 18 has substantiated this finding. There is a widespread problem of poor knowledge about SCD among non-specialist health-care providers and the general public, as well as an overall poorer experience of care in the emergency setting than in planned specialist care. Lack of timely provision of pain relief is of particular concern. 18 Failure to manage acute painful episodes adequately can lead to morbidity. 73 Management of painful episodes is an excellent example of an aspect of care for which it is not only desirable but essential that SCD patients and clinicians work together to achieve optimum health outcomes. Engaging with patients’ pain reports with an attitude of ‘empathy and acceptance’20 is crucial for developing trusting care relationships and should be part of physical/clinical management. 20,74 In the UK, national guidelines21 emphasise that health-care providers should treat patients who are experiencing a painful episode as experts in their own condition, and must take patients’ own views and preferences into account. However, patients with SCD experiencing painful episodes can be seen as ‘problem patients’. 75 Lack of legitimacy of SCD patient voices extends far beyond the clinic. Our paper on patient experiences of pain management18 was rejected from one journal based on a reviewer’s and editor’s claim that patient perspectives cannot be considered as a source of evidence on their own without further supportive evidence/data.

Living with sickle cell disorder

Sickle cell disorder research has been dominated by a biomedical model that ignores the social dimensions of the disease. 76–79 However, we know that people’s social context plays a key role in supporting or undermining how they cope with SCD. 78,79 The attitudes of others to the condition and their ‘disabling responses’, including lack of sensitivity to young people’s concerns, can make young people with SCD feel excluded and misunderstood. 79 Experiences of living with SCD while trying to live a ‘normal’ life are complex for young people. 79 The unpredictability of the condition makes the SCD experience uncertain, with periods of acute pain threatening the person’s sense of autonomy24 as well as affecting school attendance79,80 and employment. 81 Coping experiences need to be understood not only in relation to personal resources and capabilities but also in the broader context of how others respond to the condition and the life changes experienced during transitions to adulthood. 79 With some exceptions (see, for example, Dyson et al. 24,58,80 and Atkin and Ahmad79) there is little research on the experiences of young people living with SCD80 and, in particular, on how the social context in which they live shapes these experiences. We know, for example, that young people’s negative experiences of how others react to their condition and self-management practices (e.g. being denied drinking water or toilet breaks) at school mediate their experience of SCD, making their illness experiences worse80 and limiting their ability to cope. 79 Support at school is poor. 24 The stress created by teachers’ and peers’ responses can contribute to triggering painful episodes. 24 School policies (e.g. attendance and active participation in physical activities) and routines have also been found to be disabling of young people’s attempts to maintain health. These may completely contradict clinic recommendations for self-care. 58 Experiences of racism can also be part of the life of individuals with SCD and intensify the experiences of marginalisation that they already encounter because of their condition. 24,79 The invisibility of SCD symptoms contributes to others failing to appreciate the seriousness of the condition, including SCD pain experiences. This in turn affects how others react to young people’s SCD,58,79 often with insensitivity. 79

Pain is central to the experience of living with SCD and has a significant impact on quality of life. Communicating pain to others, including health-care providers, can be a challenge for individuals with SCD, who see their pain experiences as ineffable. 82,83 Research shows that people with SCD find that their pain reports are not always taken seriously and can be treated with scepticism. 79,82 Some children and young people with SCD may minimise the expression of pain to avoid worrying their parents or peers79,83 and can develop pain coping strategies (e.g. watching television, listening to music, socialising)82,84–86 that may not make their pain visible to observers. 82 These coping strategies may mean that others disbelieve pain reports. 83 The fact that the condition manifests in very different ways in different people can also contribute to others’ disbelief of young people’s reports of their illness experiences and self-management needs. 24

People living with SCD engage in ‘bracketing SCD’24 in their life, distancing themselves from the condition and not making it a central aspect of their identity. 79,87 Attending to social aspects of young people’s illness experiences and the role of others on the development of coping strategies and self-identity is crucial,78 particularly during transition to adulthood. Identities include ideas we form about ourselves and our bodies, as well as understandings of how we should behave, that can affect how we act in relation to health,88–90 and this in turn can affect our health. Our in-depth sociological approach and conceptual framework,61 which we present below, contributes to such understanding by locating health-care transitions in the broader social context of young people’s lives and their transitions to adulthood. In doing so, we respond to calls for social science approaches to SCD and move away from research that has located the problem within internal (physical or psychological) characteristics of the person. 24

Conceptual framework: transition and the importance of identity development

Health literature around transition between paediatric and adult health-care services often implies that transition to adulthood is a linear process at the end of which young people are independent,91 adopt healthy adult lifestyles and are economically productive. 6 Adolescence is framed as a vulnerable and problematic phase that needs to be addressed through transitional care support. 91 In this view, young people are potentially ‘at risk’92 (e.g. not adhering to treatment or disengaging from services)3 and in need of improvement. During transition, they must become autonomous, compliant and responsible adults who take control of their condition. 91 In line with this implied view, transitional care recommendations and guidelines in the UK and elsewhere focus on encouraging young people to develop into ‘patient experts’, with the necessary health literacy and skills to take individual responsibility for self-management of their condition. 3,6,93,94 There is also an implication that developing adult-like rationality will result in healthy behaviours. 91

However, there are multiple interconnecting factors beyond individual capabilities that influence young people’s understandings and responses to health issues. For this reason, it is essential to move beyond the linear conceptualisation of transition to take account of more complex features of the phenomenon. Here, we draw on sociological and anthropological literature that views transitions as messy and non-linear processes that involve identity development. 95–97

We conceptualise health-care transition as a lengthy, complex and dynamic process98,99 that continues after the transfer into adult services4,100 and interacts with other aspects of transitions to adulthood (e.g. starting sexual relationships or moving from education to work). Borrowing from biosocial and ecological approaches to transition,17 we take young people’s wider social contexts into account, including the micro-system (e.g. home, health services, school, friends) and the macro level of sociocultural norms and attitudes circulating in young people’s social groups (e.g. connected with adolescence, health and illness) and the interactions between these. This approach helps us move beyond the clinical realm and examine how health-care transition intersects with transitions to adulthood within the wider social context, including within education, work and social life. We contribute to this model by focusing on the role of identity development during transition. 61

Life-long health-related habits develop during transitions to adulthood. 101 Young people are urged to improve their self-management skills and health-related knowledge during this transition period. 5,6 However, transitions, including health transition, require not only skills development but also the development of new identities (i.e. a sense of who one is and how one should behave as an adult, for instance as an adult rather than a child patient). 61,102 Identity formation and the tensions around identity development are crucial during transitions and any effort to support young people during this period should take these developmental issues into account. 10 Identities shape individuals’ approach to health90,103 and health-related practices. 90,104 Understanding how identities develop during transitions can help in understanding why young people move into healthy adult life successfully or not, especially in relation to how they adapt to their health conditions. 105

We lack understanding of how health transition shapes young people’s identities or how these identities contribute to how they develop into adult patients.

Transitions can be conceptualised as complex and non-linear, involving intense identity work. 95,96 Identities function as ‘recipes for living’ or ‘interpretative frameworks’ through which health behaviours and health experiences are mediated. 88 Transitions involve multiple changes in young people’s lives that produce ‘ruptures’ in their existing habits, knowledge and self-definitions. 106 Ruptures during transitions require young people to redefine their identities and understandings so that new ways of acting can emerge. During this process, young people must reconstruct understandings of what constitutes an ‘adult’ and an ‘adult patient’ for themselves, as well as negotiate related values and ideas about these concepts circulating in their sociocultural environments. 107 These concepts and related social ideas are functional for the young person. They work as frames of reference for them to make sense of their new experiences and to develop identities that regulate their behaviours in new contexts and relationships. 107 The identities they develop during transition are the outcome of young people’s efforts to address changes in their lives and to respond to normative ideas and demands about how one should behave as an adult that circulate in their social contexts,107,108 including, for example, ideas around healthy lifestyles, self-management and demands from educational and health-care systems.

How identities develop during transition can help us understand whether or not young people develop images of themselves that help them adapt to their condition, engage in protective health practices and function effectively through the different life changes they experience. A focus on identity also offers a way to take into consideration the role of the social context in organising young people’s transition experiences and shaping their sense of self. Particularly important during transition is the process of working through the ambivalence and tension between different self-images and establishing an integrated adult identity to navigate the demands of adult life. 109 We hypothesised that living with a long-term condition may prolong this identity development process and make it more challenging. 61

Chapter 5 Methodology

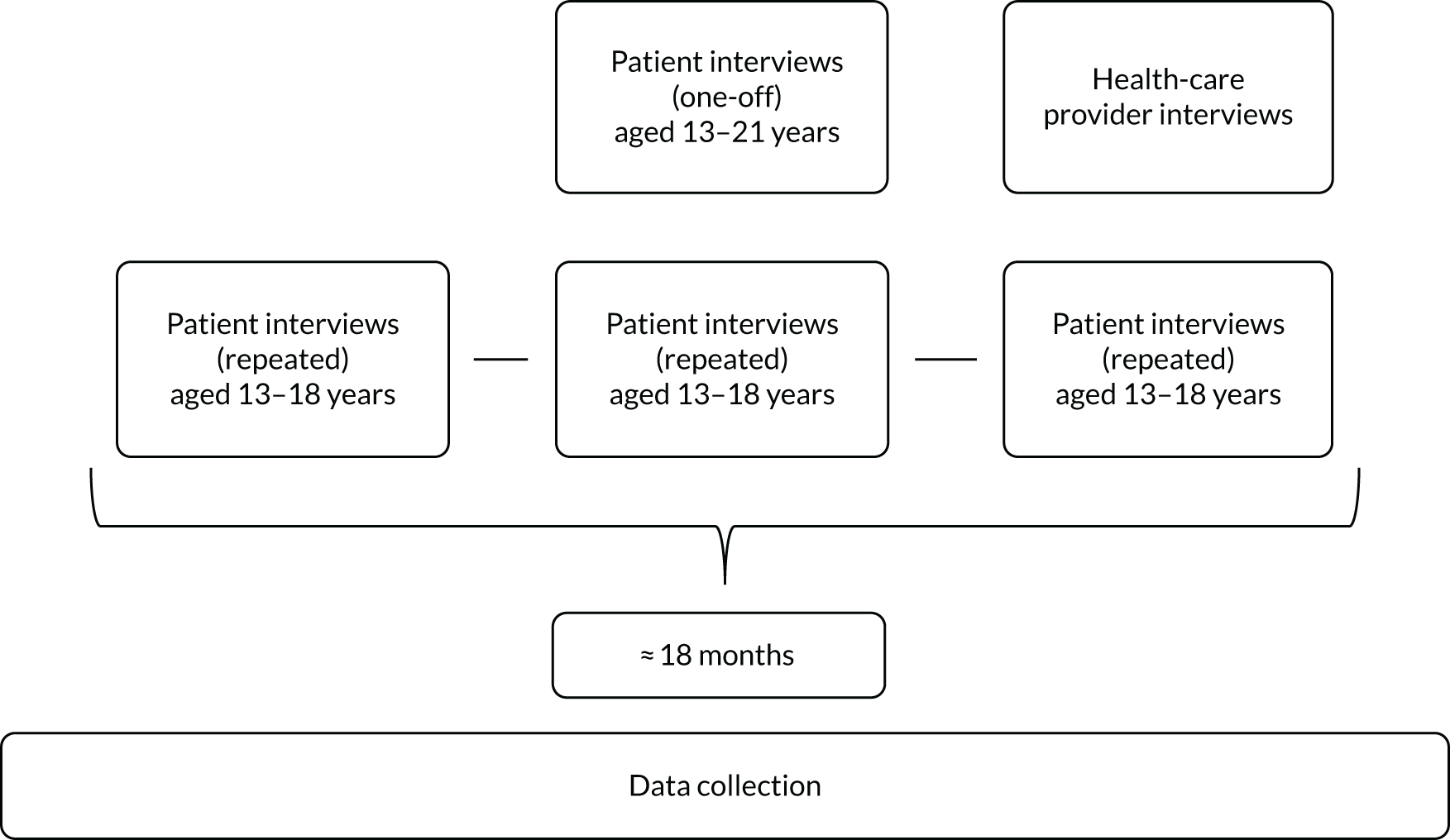

We explored the lived experiences of participants and their views on transition. We used a longitudinal, qualitative design (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Data collection.

We recruited participants from as wide a range of locations as possible in two cities (i.e. London and another large English city).

London is the UK city with most cases of SCD,25 and we added another UK city to provide a point of comparison. We do not name this city because outside London there are comparatively few people with SCD and we do not wish to compromise confidentiality.

Data collection comprised 80 interviews with 48 young people with SCD (30 women and 18 men aged 13–21 years). This included 27 one-off interviews (17 interviews with 19- to 21-year-olds and 10 interviews with 13- to 18-year-olds) and 53 repeated interviews with 21 13- to 18-year-olds, interviewing them two or three times over a period of approximately 18 months.

The longitudinal element of the study included repeated interviews with younger participants to capture their experiences during the process of transitioning, as well as any changes happening over time during this period. This approach was useful to capture the evolving experience of the unpredictable nature of SCD110 and developmental processes. 111

We conducted single interviews with older participants who had already been transferred to adult care. We included this wide range of ages because transition is a dynamic process and we wanted to cover ages when the concept of transition is introduced in health-care services through to the post-transfer period in adult services. It was also important to include younger participants (aged 13–15 years) because the concept of transition is generally first introduced at this age, making their concerns and experiences particularly relevant. Interviewing older participants who had already been transferred to adult services allowed us to capture both their retrospective accounts and their current experiences of adult services, which we approached as part of the ongoing transition process.

Interviews

Patient interviews

We recruited participants via sickle cell disease specialist health-care services and from communities via our network of contacts with patient advocates. For recruitment via health-care services, clinical staff from those services first approached potential participants and told them about the study, giving them the opportunity to be contacted by us if they were interested in participating. Among those potential participants, 16 whom we approached did not go on to participate (in most cases because they did not return our calls or were busy). We originally proposed to conduct approximately 105 interviews across different age groups. During the analysis we conducted alongside data collection we reached thematic saturation112 (i.e. when the key themes about transition and the experience of living with SCD were being addressed and new interviews added little extra information). At that point we closed recruitment to the project. In addition, recruitment was very challenging. Partly for this reason, we enlisted the help of PPI expert CA (who has SCD; see Chapter 3); however, CA was also unable to recruit any further participants and we judged that the difficulties of recruiting new participants and the resources that would have been required would most likely not be offset by extra information gained from new interviews.

Patient interview topic guides were shaped by discussions with PPI experts in the project56 and fully reflected our research questions to explore young people’s experiences of navigating health transitions beyond clinical settings to consider the wider context of young people’s lives. We explored their experiences of receiving health care as well as experiences of growing up and moving into adulthood, including changes they were experiencing in their life more generally, such as in education, relationships and life at home and work, and how these inter-related with their health experiences. Topic guides for follow-up interviews were informed by specific topics that emerged in first interviews on which we wanted to follow up. In repeated interviews we also captured their lived experiences and changes since the previous interview. Eliciting good-quality accounts from the youngest participants proved difficult using traditional interview techniques. Participants told us that SCD and life with SCD was not something that they were used to talking about. For example, they found it hard to articulate their pain experiences verbally. They said that others’ lack of experience of this type of pain made articulating it harder because others would not be able to understand their experiences. To help participants describe their experiences we gave them a pen and paper and asked them to draw their experiences of living with SCD (e.g. pain experiences and managing SCD in other spaces of their life outside hospital) and to talk while they drew to tell us about the representations they were producing (see Appendix 2). Once they finished the drawing we also asked them to explain the representation they had produced and used the conversation to introduce follow-up questions. The drawings helped them use imagery and metaphors to represent what they described as ineffable experiences. One participant told us that drawing provided an alternative mode of expression. The dynamics of the interview suggested that the act of drawing and doodling while talking also created a more relaxed space, where the focus was moved from the young person to the drawing and what the drawing represented.

AR conducted the interviews. As we explain in Chapter 3, we had hoped for CA (a PPI expert) to conduct some interviews through recruitment outside health-care services, but unfortunately she was unable to recruit and conduct interviews. AR is a white university researcher without SCD and her position may have influenced what participants did or did not want to report (see Chapter 7, Limitations of the study). AR was not an employee at any of the health service or recruitment sites.

Health-care provider interviews

AR conducted 10 interviews with health-care providers from specialist SCD teams.

The health-care provider interviews explored experiences of providing care for patients with SCD undergoing health-care transition (either preparing for transfer or having undergone transfer to adult services), as well as their views on best approaches to transitional care.

We adopted a flexible approach to conducting interviews to respond to participants’ needs and preferences. Participants chose interview locations and times. Interviews with young people were mostly conducted in homes, with some in hospitals. Provider interviews were conducted in the health-care settings where they work.

Interviews with patient participants lasted between 60 and 90 minutes and those with providers were 45–60 minutes long. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim by a transcription agency, with checks for accuracy by the research team. We took fieldnotes after interviews to record our experiences of conducting the interview, key topics discussed by participants, characteristics of interview locations and other reflections about how different aspects of the interview might have influenced the interview dynamics, including what young people told us.

Analysis

We used NVivo version 11 server software (QSR International, Warrington, UK) to organise the data. For the analysis of interviews we adopted an inductive, iterative approach following some of the steps of grounded theory,112 a particularly useful approach to studying lived experiences of chronic illness, and thematic analysis. 113 We developed the coding frame inductively from the interview data set. We started with open line-by-line coding to stay close to the data and moved in later stages to more focused coding to synthesise, categorise and compare the text data. 112 The coding frame was also in part based on our original interest in understanding young people’s experiences of transition in different arenas of their life, including their experiences of interacting with health-care services during this period. The coding frame and the emerging analytical themes were refined alongside repeated rounds of coding and ‘memo-writing’112 (about codes, about emerging analytical themes and about each case/participant) and via regular reflective dialogues with patient and carer PPI experts. The analysis focused not only on what participants were saying (i.e. the ‘whats’ of their experiences) but also on how their experiences and views were recounted in the interview situation. 114

We also attended to the types of social positions participants adopted at different points of the interview, which helped us identify the type of identities they were constructing through their narratives. 61,64,104 In the analysis we took into consideration the interactional and socially constructed nature of interview narratives,114 reflecting on the ways in which we as white academic researchers without SCD might have participated in the co-production of data (i.e. what participants reported) and how participants positioned themselves in the interview. We reflected on contextual issues, such as how the physical location of the interview (i.e. health-care services vs. home), might have shaped the relationship between interviewee and interviewer, rapport between them and the data generated. The interviewer, AR, introduced herself as a researcher who was independent of participants’ health-care services, with no connection with any type of service provision. We wanted to minimise possible participant concerns about being judged by us (e.g. about whether or not they were taking responsibility for their condition). The study information leaflets were designed to be youth friendly (we worked on these resources with young people; see Chapter 3) and clearly communicated researcher independence. In an attempt to be more approachable we also did not include our academic work titles (e.g. Dr) in study materials. Trying to conduct interviews on participants’ ‘home turf’ was also a deliberate attempt to facilitate rapport with participants.

Changes to the original protocol

We originally planned to collect diary data from 15 patient interviewees to supplement their interview accounts of their experiences during transition. We invited interview participants to volunteer to complete diaries in which we asked them to tell us about their everyday life with SCD. We gave them an open brief and an opportunity to talk (via audio-recorder) or write about or take photographs that related to their thoughts, feelings and experiences of living with SCD. Completion rate was low and diaries were very short (in most cases they contained one or two brief diary entries). We received only six diaries from the 24 participants who had volunteered to complete them. We had offered this activity to many participants because we had anticipated low levels of completion. We also adopted a flexible and open approach to the task, offering young people a choice of audio, photographic or written formats. We received one photographic diary (consisting of just one photograph accompanied by a sentence explaining why this had been chosen to explain the participant’s experiences), two written diaries and three audio-recorded diaries that were transcribed verbatim. We analysed the diaries using a thematic approach. These did not yield different/additional data, although they sometimes added detail or nuance as well as reiterated issues explored in the interviews. We had chosen diaries as a complementary data collection technique because they are thought to be non-intrusive ways of collecting longitudinal data about health-care and social experiences during transition. 115 Our participants, however, fed back to us that the diaries interfered with their daily responsibilities (e.g. homework) and with their desire not to think about their condition.

We originally planned 15 interviews with specialist health-care providers to compare young people’s concerns about and views on transition with those of specialist SCD health-care staff. Our emerging findings, however, indicated that the problems they experienced were not within specialist services and so we reduced the total number of interviews. The 10 interviews gave us a sense of the context of specialist care and helped contextualise patient accounts of specialist services.

We originally planned to analyse contemporaneous medical case notes for diary participants, with their consent, to compare the clinical records of their health status and treatment alongside their subjective diary and interview accounts of transition experiences (e.g. having many pain crises might have an important effect on transition experiences). We did not engage in this task because we had so few diaries and also because the interviews gave us detailed accounts of timings and experiences of painful episodes, acute hospitalisations or SCD-related complications.

In response to our findings, engagement with various stakeholders and discussions with PPI experts, we changed our original plan to conduct four workshops with young people with SCD to co-produce output resources. Instead, we conducted a participatory event (reported in Chapter 9). We explain the reasons behind these changes in Chapter 3.

Ethics approval

We received a favourable ethics opinion for the study from the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) (reference 10107) and approval from the NHS Research Ethics Committee (reference 15/LO/1135). Participants aged 16–21 years and parents/carers of 13- to 15-year-olds gave informed consent to participate. The 13- to 15-year-olds additionally provided their own informed assent. At the end of each interview we gave participants referral information about external agencies they could contact for support on issues raised. We gave patient participants gift vouchers to compensate them for their time. To protect anonymity we identify only participant age range in our reporting, not exact age.

Chapter 6 Results

During transitions, young people find it challenging to develop and practise patient expertise, including involvement in decisions about their own care [see Chapter 2, objectives (a) and (b)]. We report some of our findings elsewhere,46,61,83,116 and some of the interview quotations used in the other publications are reproduced in this report (in some cases the quotes have undergone minor edits for readability).

In the quotations presented in this report, we have used ‘[ . . . ]’ to indicate where we have cut text from the interview transcript. Short pauses are indicated with ‘( . )’, and ‘. . .’ indicates that the interviewee did not finish the sentence.

Young people struggle with health-care transitions. There are tensions between the expectations of them as adult patients (e.g. being independent and engaging in good self-care) and the realities of the disabling environments they have to navigate [see Chapter 2, objectives (a) and (b)]. On the one hand, adults in the health-care context (e.g. health-care providers) and parents/carers demand that the young person must learn more about their condition and body and act responsibly to stay healthy. On the other hand, when young people attempt to practise these new behaviours and use their patient expertise, for instance by making requests about the care they receive, they are often disregarded. This disregard typically manifests in non-specialist health-care settings during unplanned visits (e.g. in A&E and on general hospital wards if they are admitted as inpatients for unplanned care). 46,116 Disregard for their voice is also manifested in their social context via their schools and peers.

These findings form four key themes: (1) the push for young people to engage in self-care, (2) obstacles to achieving self-care, (3) young people’s mistrust of hospital care and (4) the problems young people encountered in their schools and social contexts. We present these in detail below and end the section by describing how young people navigate the obstacles they encounter.

The push for young people to engage in responsible self-management and develop patient expertise

Transition involves young people trying to discipline themselves in response to the push for responsible self-management and patient expertise that they experience from health-care services and carers while also often working hard in other areas of their life (e.g. education and work) to become the type of adult they are expected to be (e.g. self-actualising and productive) [see Chapter 2, objective (a)]. 61

Young people growing up with SCD develop personalised knowledge about how SCD affects them. 46,61 Participants presented themselves at the interview as being – and working on becoming – disciplined patients who take responsibility for self-monitoring and managing their condition, with expertise in their own body and knowledge of SCD. They described themselves as knowledgeable about their bodily limits, their pain experience and the therapeutic practices and medications that work for their individual bodies. Their personalised knowledge includes differentiating the types of pain episodes and their consequences. They talked about increasingly learning about the timing of pain events and how different types of pain involve different lengths of recovery. They spoke about knowing which pain relief medication to take (depending on the stage of their painful episode) and talked about regulating how much pain relief medication they take. They said that this is important to ensure that stronger pain relief would be effective when needed. They often talked about being aware of risks to their health and of practices that are good or bad for their condition, including which pain relief and medication would be ineffective or inappropriate for them. They asserted their patient expertise, explaining that they know their body and how it is affected by SCD better than anyone else, yet they still recognise that the transition between paediatric and adult services is a process that involves commitment to learning about themselves and how the condition affects them. Participants talked about always carrying water and pain relief medication with them. They articulated extensive awareness and monitoring of their own body. They talked about listening to their own body, monitoring it (e.g. temperature, types and levels of pain), drinking water, avoiding cold weather and regulating their social life to stay healthy:

I always have water and my medicine in my room [ . . . ] I don’t go out as often, I’ve realised that, um, I like to study more [ . . . ] I know how to keep myself warm with clothing and stuff before anything else [ . . . ] I arrange my sleeping patterns in a way, like I’m getting enough sleep and stuff. So right now I’m trying to prevent feeling really tired and having fatigue [ . . . ] since I was younger they’ve always told me like water is the main thing [ . . . ] So I’m keeping hydrated and stuff [ . . . ] I just try and do it [read up on SCD] as much as possible so I’m learning about it each time [ . . . ] so I understand.

Quotation 4, A6, 16- to 18-year-old woman.

For participants, transition to adulthood involves learning to regulate everyday life and behaviours temporally and spatially to avoid and manage pain episodes. For instance, participants choose to manage a pain episode at home when possible, because for them this facilitates rest and a quick recovery. They have learned about the importance of responding promptly to the first signs of a potential crisis to avoid the pain episode escalating and having to be admitted to hospital. Participants also talked about regulating their behaviour spatially to self-manage their condition:

I have to be aware, just in case I do get sick. ’Cause sometimes in the day it could also just hit me [ . . . ] So I have to be just, like, aware, to make sure that I don’t overdo myself, or I don’t walk too much [ . . . ] especially in, like, really hot weathers or really cold weathers, so I have to make sure to, like, not go out for too ( . ) for a really long period of time. And also to always drink water [ . . . ] to keep myself hydrated [ . . . ] I try to make sure that I’m not going out too ( . ) too often, or if I do go out with my friends I’d make sure to go around [the neighbourhood] and not too far away, and make sure that my mum knows exactly where I am in case I do fall ill, then she’d be able to pick me up.

Quotation 5, Z1, 16- to 18-year-old woman.

For instance, participants typically talked about staying at home and avoiding socialising to manage SCD-related fatigue. When planning social activities or choosing where (or whether or not) to go to university, participants expressed a desire to stay close to home and hospitals (see Quotation 5). They talked about planning carefully ahead of social outings. This includes thinking about travel arrangements and about where activities take place to ensure access to their hospital in the case of an emergency or access to a lift to avoid fatigue. Participants said that they had developed their own techniques to self-manage a pain crisis and know how to ration pain relief to ensure its effectiveness. They regulate their social and everyday life around their self-management needs.

When speaking during interview, participants (more typically younger ones) produced accounts in which they addressed themselves in their talk and asked themselves to improve their self-management behaviour and become more responsible patients (see Quotation 7). For instance, they referred to the need to listen to their own body and monitor their body temperature and energy levels to avoid pain episodes (see Quotations 9 and 10). Calls for self-improvement to become a disciplined patient (who cares for themself) were more common among younger participants and echoed the discourses about individual responsibility that were conveyed by doctors/nurses and family/carers. Older participants presented themselves as already having moved into this type of responsible patienthood. For instance, they reported on their competent self-management practices. Participant Z1 (aged 16–18 years) (see Quotations 5 and 8) presented herself as expert in her own body and actively addressing its needs. She positioned herself as knowledgeable about pain and about how to manage it and talked about how socialising is an aspect of her life that she needs to carefully regulate to ensure that she maintains health. Although more common among older participants, younger ones also positioned themselves as having autonomy in self-care and being knowledgeable about their condition:

I know what I have to do to keep myself well [ . . . ] everything they [doctors, nurses] tell me to do, like get sleep or do this, I just do them, because I know it’s crucial for me.

Quotation 6, U10, 13- to 15-year-old boy

You have to be on top of all your appointments, you have to be on top of your prescriptions for instance, you can’t run out of them, things like that. You just have to be aware of yourself and look after yourself [ . . . ] just have to ( . ) be more aware of my sickle cell and not get caught up in everything. I don’t really know how to explain that but ( . ) if I am doing my [university degree] here, I just have to remember if I’m in the library all night, to eat well, to drink well, to keep warm, not do anything that’s unnecessary like go out in the rain, if I don’t need to. I just think you have to be more aware of it and it’ll be fine.

Quotation 7, I7, 19- to 21-year-old woman

I can cope on my own [ . . . ] I know when to take my tablets, I know when I have to like take a like break [ . . . ]. I know that like if I do, like, overexert myself then I will get ill and I’d know, like, I just know when I need to stop.

Quotation 8, Z3, 19- to 21-year-old man

Participants talked about transitioning into healthy adulthood in individualising terms (as an issue dependent on their own actions and self-improvement into disciplined patienthood). When asked about what type of support and resources would help them in their transition, their responses framed transition as a matter of personal change (i.e. an issue to be managed by the individual). They did not generally refer to how others could help them, but instead located control of health and of moving into healthy adult life within a purposeful and independent self who takes responsibility for their own health. Participants framed successful health-care transition as an individual change: a process of developing health-related knowledge and learning how to actively monitor their own body while regulating behaviour and their own life to maintain their own health. For instance, when talking about how to achieve a healthy future, participant E4 (see Quotation 10) talked in individual terms, focusing on better self-management and healthy lifestyle choices:

I have to try and be, yeah, you have to try and like relax more and [ . . . ] like not use a lot of my energy and like keep drinking water and stay away from like heaters [ . . . ]

Quotation 9, I5, 13- to 15-year-old girl (emphasis added by authors).

The reasons like I’m ill [ . . . ] is ’cause I wasn’t really paying attention to the way I was feeling. [ . . . ] I could have prevented it [pain crisis] if I’d paid attention [ . . . ] I should pay attention to this. ’Cause, yeah, attentiveness, that’s the thing I need to work on [ . . . ] I think I’m slowly getting there [ . . . ] like trying to change it [ . . . ] I am paying more attention in everything, really.

Quotation 10, E4, 19- to 21-year-old woman (emphasis added by authors).

Transition as a process of becoming a self-disciplined patient is learned through relationships with health-care professionals and echoed in relationships with parents and carers (see Quotations 11, 15 and 16). Participants talked about older adults’ constant reminders to take responsibility for their health (e.g. to stay hydrated and wear warm clothes) and about the risks of not doing so (see Quotations 15 and 16). Although this could be annoying for the young person, these exhortations could act as a reminder ‘to help me to stay healthy’ (E4, 19- to 21-year-old woman). Participants’ interview accounts illustrate how reminders to take responsibility are internalised and work to encourage them to be disciplined patients. At interview they addressed themselves in talk, drawing on someone else’s voice (presumably adult carer or health-care professional) to remind themselves about the type of adult patient they ought to be and about the consequences of not taking individual responsibility (see Quotation 11). Here, they were echoing the self-management and involvement in own care discourses they heard from health-care professionals and carers. Participants E4 and I5 (see Quotations 9 and 10) asked themselves to improve self-management practices and learn how to listen to their own bodies to avoid pain crises. Participant O7 (see Quotation 11) draws on what we interpret as the nurse’s voice to remind himself about the risks of not taking responsibility:

I didn’t care that much, um, but then [ . . . ] as you get older you know that you really need to start doing it [taking medication, attending appointments] [ . . . ] sometimes you get tired and you like you don’t want to take any medication, and you don’t want to go into hospital, um but then when they [doctors/nurses] tell you what the consequences will be, you get to understand more [ . . . ] she [nurse] told me what will happen if I don’t take it and how [ . . . ] there’s a possibility I could die, and then she said I won’t be able to [practise favourite sport] and so when I heard that [ . . . ] I thought, OK, I have to start taking it then [ . . . ] I’ve just mostly learned about how to keep my ferritin levels down [ . . . ] they check it at hospital so they’ll know if I’ve had medication or not. And so it makes you think, oh they’re going to find out [that I am not taking medication] anyway, so [ . . . ] oh I should just grow up and do it [ . . . ] and just take my medication and just go to the hospital, because it’s only helping you.

Quotation 11, O7, 13- to 15-year-old boy (emphasis added by authors).

They’d [doctors and nurses] always be like, yeah, you should be taking antibiotics. We know more about your condition than you do, we’ve done all this research, this is this, is this, you know? [ . . . ] just kind of felt like every time I went there, they would tell me all the possibilities of my condition and all the bad things that could happen because I had sickle cell. And all the things that I had to be doing and how I had to be like, I had to be on medication for the rest of my life.

Quotation 12, I9, 19- to 21-year-old woman

It [going to routine clinic appointments with a specialist team] teaches me just to look after myself. [Interviewer: How?] It just, you just, you realise like you’ve gotta look after yourself.

Quotation 13, Y4, 19- to 21-year-old man

Although participants talked about parents’ reminders to engage in self-management practices as if they were annoying (see Quotation 16), the parent gaze nevertheless works as a reminder to take responsibility. One participant told us how, after a long hospital stay, she had made the decision to start taking responsibility to engage in desired self-management practices. Her parents’ comments about an unhealthy lifestyle might have helped foster a sense of individual responsibility for the consequences of her choices:

My [mum/dad] was just telling me, you probably didn’t drink water, you probably didn’t do your exercise. ’Cause I probably wasn’t drinking water ’cause, um, the only thing I would drink is like fizzy drinks [ . . . ] I tend to drink a lot of water now [ . . . ] that’s the key.

Quotation 14, I8, 13- to 15-year-old girl.

They [parents]’re kind of, you know, lecturing me, or just reminding me every hour to drink water and to keep warm and things.

Quotation 15, A5, 16- to 18-year-old woman

My mum, they either just come one like in the middle of the day and say, I know you haven’t been drinking enough. And the thing is, I probably have. I’m not going to show you every time I’m drinking water, oh look I’m drinking water. I feel like I’m old enough to be thinking that by myself. Maybe when I was a lot younger, but that has been something that’s constantly annoyed me for a while, is people telling me what they think that I should be doing, even though I’m probably doing it anyways.

Quotation 16, I7, 19- to 21-year-old woman

Obstacles to enacting patient expertise: being disregarded and feeling invisible

As we have shown above, young people growing up with SCD developed an in-depth sense of individual responsibility for their own condition and personalised knowledge about their body and how it is affected by SCD. However, participants talked about having their expertise questioned or disregarded both during health-care encounters in non-specialised unplanned hospital settings and in interactions with others in their social contexts [see Chapter 2, objectives (a) and (b)] [see Health-care context (non-specialist hospital unplanned care) and Social context].

Health-care context (non-specialist hospital unplanned care)