Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/70/153. The contractual start date was in January 2016. The final report began editorial review in July 2019 and was accepted for publication in January 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Murray et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and rationale

This project considered children and young people who have little or no intelligible speech and need to use symbol communication aids to communicate. The children who benefit from such aids constitute a heterogeneous group, and they often have several co-occurring impairments that may include motor deficits (ranging from no control over any limb to minor impairment of one or more limbs), sensory and perceptual deficits (specifically hearing and vision) and, in some instances, cognitive deficits. When successfully prescribed, communication aids can have significant positive impacts on health and quality of life, reducing the risk of social isolation and mental health issues. 1–3

In an earlier study,4 0.5% of the population were estimated to require augmentative and alternative communication (AAC). This equates to 529 people per 100,000 population. Since 2014, NHS England has commissioned communication aid services as specialised services, delivering services to 1 in 2000 people, including, potentially, 8627 children and young people aged under 25 years. 5 Services were previously fragmented, and so this relatively new care pathway has limited decision-making resources to support the delivery or to assist in the monitoring of quality of provision.

The need for the current research was reflected in the second priority selected by the James Lind Alliance Childhood Disability Research Priority Setting Partnership, which asked ‘what is the best way to select the most appropriate communication strategies?’6,7 The proposed work reflected the need identified by the National Institute for Health Research’s (NIHR’s) call for research into the evaluation of health services to enhance the management of long-term conditions in children and young people.

Why focus on decision-making?

We know that communication aids, when successfully provided, can have a positive impact on the health and quality of life of children through to adulthood. 4 Unfortunately, symbol communication aids for children are reportedly prescribed without reference to evidence or best practice. 8,9 This may contribute to levels of aid abandonment, which in turn have an impact on the educational, employment and quality-of-life outcomes for aid users, and potentially result in higher costs to the NHS. 10,11 The process of communication aid decision-making has not been comprehensively documented or evaluated, and research evidence remains limited. 12–15 Currently, there are inadequate decision-making tools available to support the robust and effective identification and provision of communication aids. 16–19

In a 3-year government initiative, the financial cost to the NHS of inappropriate or non-provision of a communication aid was estimated to be £500,000 per individual over their lifetime. 10 The social and economic consequences of an inappropriate aid are reinforced by research that suggests that communication aid abandonment figures are between 30% and 50%. 3,11,20,21

Symbol communication aid decision-making is multifaceted, involving consideration of the child, the aid and the context of use. Symbol communication aids comprise three interconnected components: (1) the mode of communication (the aid), (2) the means of access and (3) the language representation system (e.g. the symbol).

The mode is the method by which the message is transmitted to the communication partner. This may range from noting the direction of the child’s gaze to indicate a choice, to the use of a computer-based speech output device. This project focused on computer-based devices because of the changes in specialised service provision in the UK. Service changes affected the resources that were available to pay for electronic symbol communication systems. However, the research focus does not imply that paper-based symbol communication systems have less merit in the development of communication skills. Indeed, as will become apparent in later chapters, they figured in many discussions during the current research.

Children with severe physical involvement cannot access the communication mode directly. In such instances, they need to be taught to use an indirect approach, for example using a scanning system involving switch operation. Means of access was not an intended focus of the proposed research, as we were interested in the language assessment and language representation considerations during the recommendation process. As will become apparent, it was a considerable focus for many participants and so was given greater consideration than originally anticipated.

The language representation system on a symbol communication aid may include different types of symbol set to substitute for spoken words, for example photographs, line drawings or a formalised set of symbols such as Picture Communication Symbols® (Tobbii Dynavox LLC, Pittsburgh, PA, USA). 22 The clinical decision-making debate concerning choice of language representation system was a particular focus of this research.

What do we already know about augmentative and alternative communication decision-making?

The challenge of making appropriate clinical decisions about communication aids for children with significant communication disability has long been debated in the field of practice, and the existing research highlights multiple issues.

Communication aids are a key intervention for children who cannot speak. The positive effects of using these systems include well-being, sense of belonging and educational attainment. 16,17,23–25

Expert professionals make variable decisions about appropriate technologies based on their knowledge of available systems, the medical and physical characteristics of the child, and the immediate rather than long-term use of communication aids. 14,26,27

Limited research evidence is available to determine the characteristics and features of communication aids and how these relate to successful use by a child. 2,12,28–30

Patient and family involvement in the decision-making process is often minimal, although it is recognised as key to the effective adoption of communication aids. 19,20,31–33

Little is known about the impact of acquiring language through aided communication on the educational and social experiences of these children. 18,34

Although there is literature on typical language and communication development, there is little research on symbolic-aided language learning trajectories or on how clinical decision-making tools may support recommendations. 28,34–45

Why decision-making episodes as the contexts for studying augmentative and alternative communication recommendation processes?

Currently there is a lack of understanding about the most valuable aspects of clinical expertise and a poor understanding about patient values in the clinical decision process. 45 Without research evidence to reinforce clinical expertise there is no means of determining the actual quality of provision. 26,27 Professionals make decisions between different communication aids based on clinical judgement, without the benefit of guidelines based on research evidence or patient values. 14,19,31,46,47

Aims and objectives

The overall aim was to contribute to improved long-term outcomes for children and young people with little or no intelligible speech who need symbol communication aids to communicate.

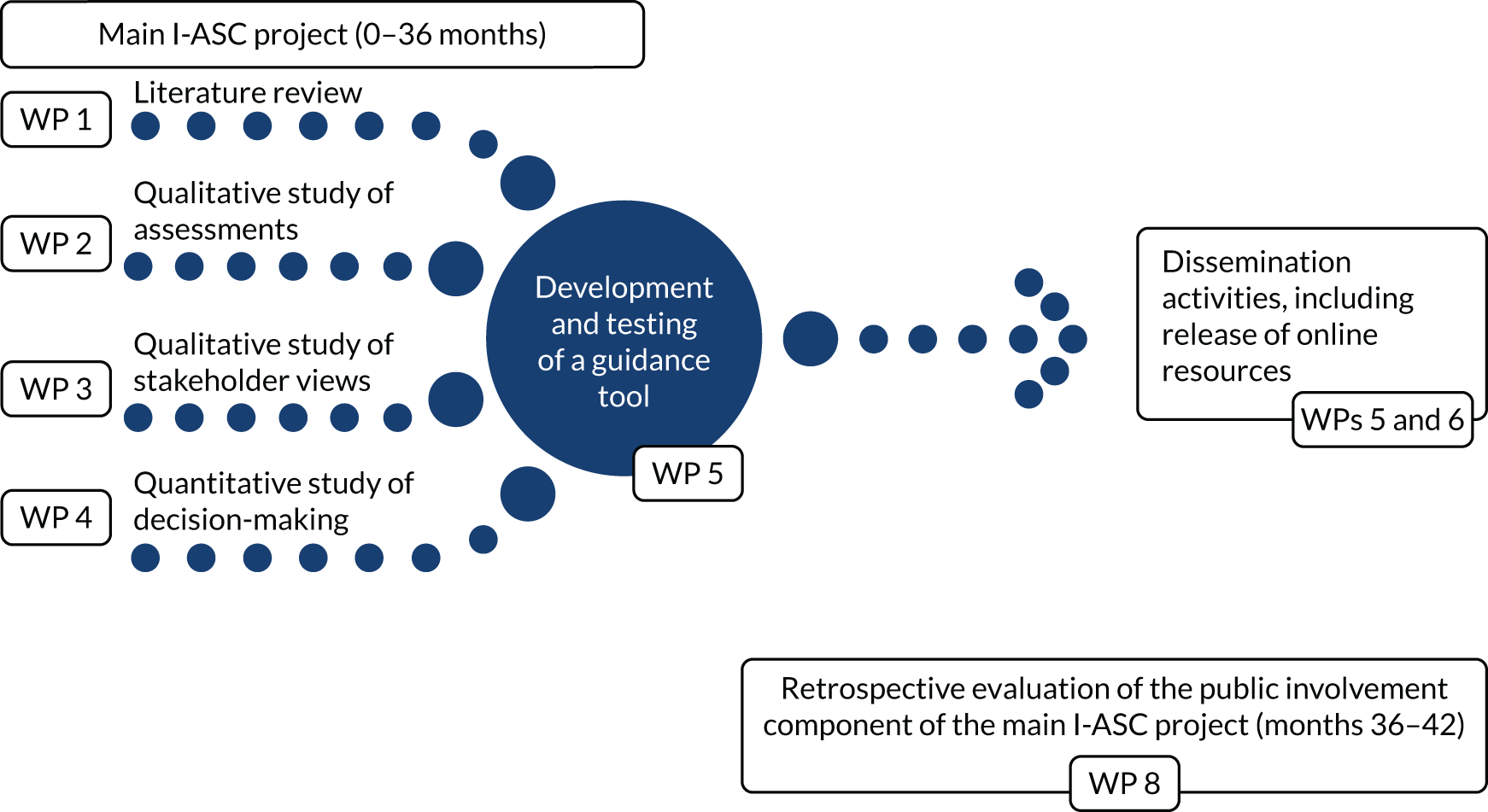

The specific aim was to influence current practice and enhance the consistency and quality of clinical decision-making in the provision of symbol communication aids. The research was delivered through specific work packages (WPs). WP 1 comprised three systematic literature reviews; WPs 2 and 3 were qualitative and included focus groups and individual interviews with different stakeholder groups; WP 4 was quantitative and delivered two surveys to professionals involved in communication aid recommendations; WP 5 focused on the development of resources to inform decision-making; WP 6 focused on disseminating the research findings; and WP 7 concerned project management. In 2018, a further work package was agreed (WP 8) and this sat separately from the preceding WPs, focusing on a retrospective evaluation of the public involvement aspects of the research. This WP is addressed separately throughout this report (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Schematic representation of the main I-ASC project WPs and retrospective public involvement work package.

Research objectives

-

To understand what is perceived as important in terms of symbol communication aid provision; how decisions are made; and what barriers and facilitators have an impact on these decisions (WPs 1–4).

-

To understand and agree the range of attributes that should be considered when making these decisions, related to the child, the family and the communication aid (WPs 1–4).

-

To establish how professionals currently make decisions (by exploring their stated preferences) and how they consider attributes (WPs 2–4). (Throughout, the term ‘professional’ is taken to mean any health professional or educationalist with a specific remit to determine the best symbol communication system for a child with little or no intelligible speech. The majority of these professionals are based in the NHS, but some were in independent practice.)

-

To explore how this process takes account of the perspectives of all involved, specifically how children and adults reflect on their experiences and how parents and professionals perceive the effectiveness of existing or historic recommendations (WPs 2–5).

Then, on the basis of the information gathered from WPs 1–4:

-

to develop decision guidance for professionals and all others involved to support their decision-making in matching symbol communication aids to children (WP 5)

-

to disseminate this guidance and the results of the project to influence practice and improve the quality and consistency of decisions (WPs 5 and 6).

Research questions

The study investigated four key research questions in order to meet the aims and objectives of the project:

-

What attributes related to the child and of generic communication aids do professionals consider important in making decisions about communication aid provision? (WPs 1–4)

-

What other factors influence or inform the final decision? (WPs 1–4)

-

What attributes are considered important by other participants (e.g. the child and family) and what impact do these have in the short, medium and long term? (WPs 1 and 3)

-

What decision support guidance and resources would enhance the quality, accountability and comparability of decision-making? (WPs 1–5)

Public involvement evaluation

In December 2018 a contract variation was awarded for a retrospective evaluation of public involvement activity in the I-ASC project to be completed. This is referred to elsewhere in the report as work package 8 (WP 8). As this WP was not an aspect of the original funding award, it was designed as a post hoc methodology to evaluate the public involvement contribution to the I-ASC project. Consequently, there were additional research objectives and questions.

Research objectives

-

To describe processes that support public involvement across all aspects of co-production in the research process.

-

To describe protocols that facilitate marginalised and vulnerable public involvement groups to make meaningful contributions to the research process.

-

To appraise the costs and benefits of extensive public involvement in research.

-

To develop guidance and practical tools to facilitate the co-production of research with public involvement co-researchers from hard-to-reach cohorts.

-

To disseminate this guidance in order to improve the quantity and quality of public involvement in the co-production of research.

Research questions

-

How and what can we learn from an evaluation of public involvement in a nationally funded project focusing on vulnerable and hard-to-reach patients?

-

How can public involvement research, implementing current guidance with vulnerable and hard-to-reach groups, be structured to avoid pitfalls and improve impact?

Work package 8 is described in the final chapter of this report (see Chapter 10), as it offers insights that transcend the research questions (1–4) related to decision-making.

Chapter 2 Methodology overview

Introduction

Design

The overarching research paradigm used was pragmatism. 48,49 Pragmatism accepts the existence of singular and multiple realities and focuses on finding solutions to practical problems. Within this paradigm, a mixed-methods approach is commonplace, and specifically supports an ethnographic frame of reference. This perspective was adopted specifically for WPs 2–4, with an exploratory approach to data modelling that would typically include focus groups, interviews and surveys. An ethnographic lens also supports mixed methods that take qualitative perspectives (WPs 2 and 3: observed and lived experiences) and apply them to quantitative interrogation (WP 4). This approach also defines the WP dedicated to an evaluation of public involvement (WP 8).

Method

In summary, for the main I-ASC research (WPs 1–4), our methodological investigation adopted a three-tier approach: first, three linked systematic reviews (WP 1); second, qualitative exploration of stakeholder perspectives through focus groups and interviews (WPs 2 and 3); and, third, quantitative investigation of professional perspectives using two surveys (WP 4). Chapters 4–7 provide the detailed methods used in these WPs.

The public involvement evaluation (WP 8) detailed in Chapter 10 adopted a mixed-methods approach.

Ethics approvals

Ethics approval was obtained from Manchester Metropolitan University (reference 1316, approved 18 November 2015) and the North West – Lancashire NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC reference 16/NW/0165, approved 13 April 2016). Ethics amendment 1 (public involvement contract variation) was approved by the North West – Preston NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC reference 16/NW/0165, approved 18 December 2018). The project’s Integrated Research Application System (IRAS) ID is 186234: ‘Symbol Communication Aids for Children who are Non-speaking: CDM’.

Data collection techniques

Primary data collection activities

Primary data collection activities were focus groups, individual semistructured interviews and surveys. All data collection was UK-wide.

Data management

Data were managed in accordance with the General Data Protection Regulation and Manchester Metropolitan University’s data protection policy.

Three linked systematic literature reviews: contextualising the evidence

The aim of the systematic literature reviews (WP 1) was to identify the current state of knowledge about AAC relevant to the overall project aims. The usual use of systematic reviews is to identify robust research in a focused area, either to inform interventions or to identify gaps that require further research. Owing to the dispersed nature of AAC research,50 a multifaceted search strategy was developed to navigate the literature. The review process followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. 51 Systematic reviews were completed exploring the following questions:

-

What are the language and communication characteristics of children and adults acquiring language through aided AAC systems?

-

What are the language and communication characteristics of communication aids considered in decision-making for AAC prescription?

-

What does the literature tell us about how professionals make decisions about communication aid recommendations for children?

The outputs from these systematic reviews supported the survey developments (WP 4) and informed the heuristic resources (WP 5).

Analysis procedures: qualitative and quantitative processes

With the exception of the systematic review process, this project adopted a sequential mixed-methods approach to data modelling. Two WPs had a qualitative focus (WPs 2 and 3), one WP was quantitative (WP 4) and one WP used mixed methods (WP 8). Justifications for the WP approaches are provided in the relevant chapters.

Qualitative data analysis: in summary

Coding scheme design

Two methods of data coding were adopted to support the analysis of focus group and interview data: thematic analysis52 and framework approach. 53 The former supported the inductive development of a network from open coding, and the latter enabled the deductive and inductive development of themes. With both approaches, analysis followed the stages of data interpretation, that is familiarisation with the data through to mapping and interpretation.

Intercoder reliability testing

Intercoder reliability testing was set up for all qualitative activity. This included lead researchers for the relevant WPs reading the transcripts to gain a sense of the data. Two researchers independently re-read and assigned initial codes to meaningful segments of the data, which was followed by discussion and some preliminary consensus on coding and then core research group members sharing and discussing coding. The key researchers led an iterative process of code refinement to develop the thematic network or map to the existing framework. Finally, the network and frameworks were illustrated using quotations from the data and presented to the wider research group for sense checking, credibility and transferability. Two researchers external to the core research group (critical friend group or additional co-investigator staff involved in the public involvement WP) provided independent coding reliability reviews to reduce the impact of researcher bias.

Quantitative data analysis

Two stated preference surveys investigated the decision-making of AAC practitioners. The first method, termed best–worst scaling (BWS) case 1, allowed the relative importance of factors in decision-making to be assessed. It quantified what AAC professionals regarded as the most important factors related to both children and their AAC systems. The second method, a discrete choice experiment (DCE), built on the findings from the BWS. Professionals completed this survey by making choices related to which of three hypothetical AAC systems they would choose for a stated hypothetical child.

Analysis was grounded in random utility theory and for BWS included estimates of the β parameters obtained from random parameters logit models. Analysis in the DCE included a one-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov test.

Public involvement (formerly patient and public involvement)

Two public involvement co-researchers, an adult who used a symbol communication aid and a parent of a communication aid user, were integral to the project development and the delivery of each WP. The public involvement co-researchers led the dissemination WP (WP 6). Their involvement throughout drew on their expertise in the areas of using a symbol communication aids, working for a company assessing and supplying communication aids, mentoring, personal knowledge of the impact of technology changes, project management, financial management, leading a UK charity, and marketing and publicity management, as well as first-hand experience of the current clinical decision-making process.

The project delivery also benefited from a critical friend group that comprised a young person who used AAC, support staff, parents of AAC users, professionals and researchers.

The public involvement in the I-ASC project resulted in an additional award to the project (contract variation) in December 2018 to evaluate the impact of public involvement across the project. As previously stated, this evaluation is detailed in Chapter 10.

Chapter 3 Overview of the data set

Introduction

The aim of the I-ASC project was to involve all stakeholder groups in contributing data to at least two WPs. This was achieved and is reflected in the numbers in Table 1. In this chapter, summary details of participant demographics are provided, with detailed participant characteristics included in the relevant WP chapters. The public involvement evaluation is not detailed here (see Chapter 10).

| Geographical location of event | WP (n) | Total (n) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 (focus groups) | 3 (interviews) | 4 (BWS) | 4 (DCE) | 5 (heuristic testing) | 6 (heuristic feedback an dissemination) | ||

| North West England | 4 | 14 | 16 | 7 | 5 | 131 | 177 |

| South East England | 13 | 14 | 7 | 34 | |||

| Yorkshire and The Humber | 17 | 9 | 12 | 22 | 3 | 185 | 248 |

| Wales | 9 | 8 | 17 | ||||

| West Midlands | 5 | 4 | 9 | 11 | 4 | 28 | 61 |

| Northern Ireland | 7 | 5 | 1 | 13 | |||

| East Midlands | 7 | 7 | 11 | 25 | |||

| South West England | 3 | 5 | 7 | 1 | 16 | ||

| East of England | 13 | 4 | 13 | 30 | |||

| London | 3 | 4 | 17 | 3 | 80 | 107 | |

| Scotland | 2 | 12 | 3 | 23 | 3 | 53 | 96 |

| North East England | 2 | 21 | 23 | ||||

| Non-UK | 1 | 3 | 5 | 70 | 79 | ||

| Total | 31 | 75 | 93 | 155 | 25 | 547 | 926 |

Data collection sites

Data collection sites were UK-wide and encompassed NHS and non-NHS (e.g. educational and charitable provisions) locations. Table 1 summarises the data collection locations by geographical area and contributors to each WP. Research participant numbers are provided for WPs 1–4. Contributions to heuristic development received during feedback trials and at dissemination events (WPs 5 and 6) are also provided. Please note that we have excluded the numbers of participants in the public involvement evaluation (WP 8) from this table as these are not relevant to the decision-making objectives of the main I-ASC study but are detailed in Chapter 10.

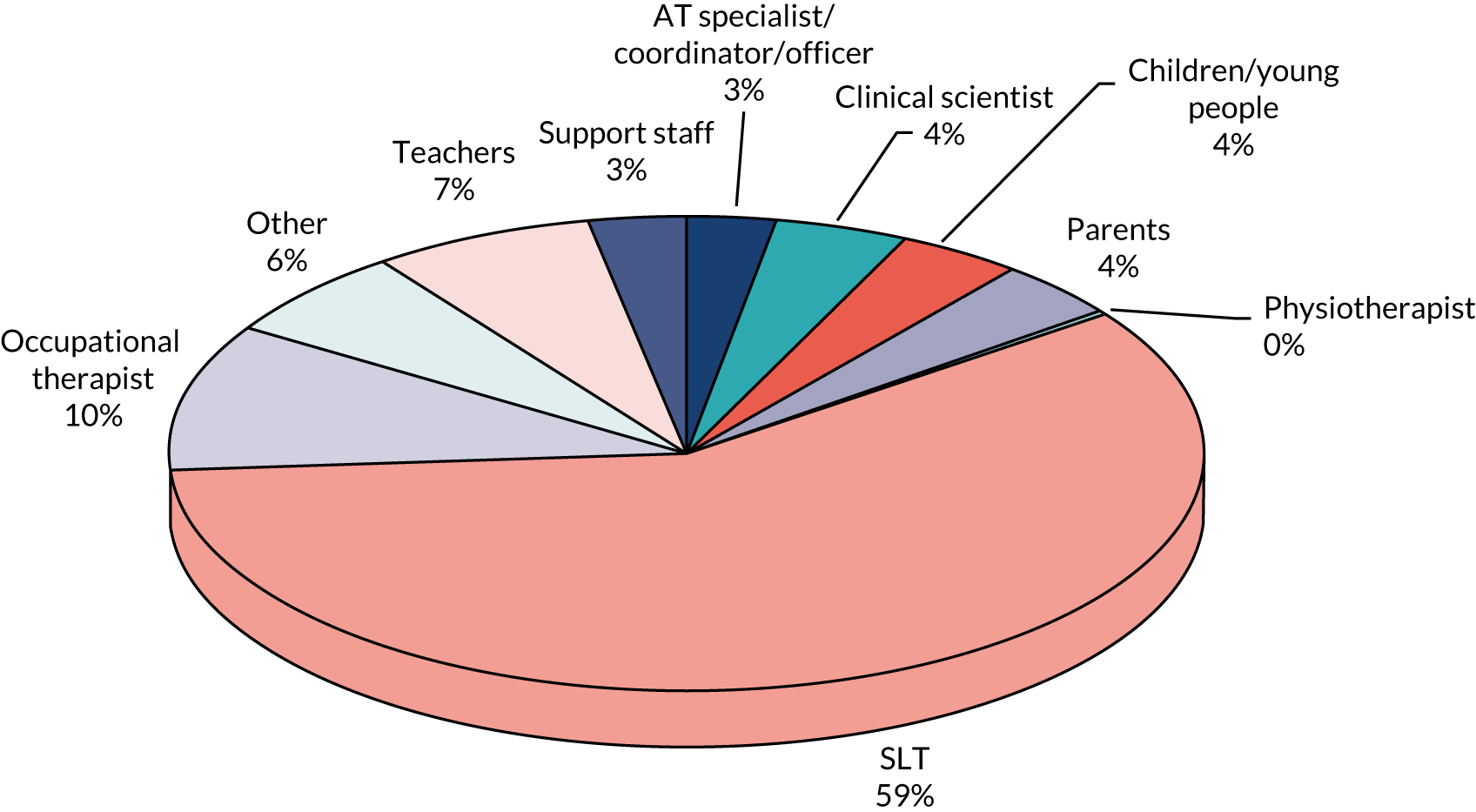

Participant demographics

Work packages 2—4 allow for participants to be described by perspective (e.g. parent, professional). These are given in Table 2. There is a predominance of speech and language therapists (SLTs) across the whole data set and this is presented visually in Figure 2. This is not surprising as SLTs are traditionally recognised as the key professionals involved in AAC decision-making.

| Participant type | WP (n) | Total (n) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 (focus groups) | 3 (interviews) | 4 (BWS) | 4 (DCE) | ||

| Child/young person/adult | 15 | 15 | |||

| Parent | 16 | 16 | |||

| Teacher | 7 | 4 | 11 | 22 | |

| Teaching assistant | 2 | 5 | 7 | ||

| Key worker | 1 | 1 | |||

| Support worker | 2 | 2 | |||

| Therapy assistant | 1 | 1 | |||

| Personal assistant | 1 | 1 | |||

| SLT | 15 | 20 | 66 | 117 | 218 |

| Assistive technology co-ordinator | 2 | 2 | |||

| AAC officer | 1 | 1 | |||

| Physiotherapist | 1 | 1 | |||

| Occupational therapist | 7 | 4 | 7 | 9 | 27 |

| Assistive technology specialist | 5 | 5 | 10 | ||

| Other | 7 | 8 | 15 | ||

| Clinical scientist | 5 | 1 | 4 | 5 | 15 |

| Total | 31 | 75 | 93 | 155 | 354 |

FIGURE 2.

Participant backgrounds across WPs 2–4. AT, assistive technology; PT, physiotherapist.

Recruitment figures across sites

It was not feasible to define accurately the recruitment figures related to specific sites owing to the anonymous survey completion component of our data set (WP 4). However, it is possible to indicate that we recruited the following across different components of the research programme:

-

six focus groups with specialised and local professionals (n = 31)

-

interviews with children, young people and adults with lived experience, their families and the professional teams who support them (n = 75)

-

two surveys of professionals (n = 248).

This indicates that a total of 354 participants contributed to the data collection components of the research project. This figure includes NHS and non-NHS participants.

An additional 25 volunteers supported heuristic resource development and a further 547 people attended dissemination events and provided feedback.

Conclusion

In the original project submission, we had anticipated such recruitment numbers for focus groups and interviews. We had hoped for enhanced survey completion figures and suspect that the actual numbers reflect an artefact of survey methodologies and, anecdotally, the content of the surveys and the time constraints on NHS employees.

Chapter 4 Setting the scene for the complexities of decision-making in augmentative and alternative communication: systematic literature reviews (work package 1)

Systematic reviews

Introduction

The broad aim of WP 1 was to identify the current state of knowledge about AAC relevant to the overall project aims. Systematic reviews are usually used to identify robust research in a focused area, either to inform interventions or to identify gaps that require further research. As Arksey and O’Malley54 identify, there are many forms of ‘review’, with many published reviews not meeting the robust standards and replicability required of a full systematic review. To ensure the highest standards of rigour and accountability, the study followed widely accepted, published protocols to guide the process, starting with the fundamental definition: ‘Systematic reviews aim to identify, evaluate, and summarize the findings of all relevant individual studies over a health-related issue, thereby making the available evidence more accessible to decision makers.’55

Rather than seeking to inform intervention or to identify the next steps in research, the aim of WP 1 was to identify the current state of knowledge in three areas needed to inform subsequent WPs. In particular, the quantitative component, WP 4 (BWS/DCE), required data on the characteristics of children who use AAC and the features of symbol communication aids to build the surveys and vignettes. Accordingly, reviews are framed as research questions, the answers to which would inform the BWS and DCE. The third area, which informed all subsequent aspects of the research project, was the current state of knowledge concerning decision-making regarding the provision or prescription of AAC. Because the reviews were not concerned with interventions, neither the usual PICO (patient problem, intervention, component and outcome) approach56 nor the AAC adaptation of PESICO (person, environments, stakeholders, intervention, comparison and outcome)57 was appropriate for structuring the research questions.

Generic point

Guidance sought from the NHS NW Research Design Service on the extent of double screening required indicated (Sarah A Rhodes, NIHR Research Design Service – North West, and University of Manchester, 8 October 2019, personal communication) that 100% double reviewing was not necessary as the reviews did not seek evidence of the effectiveness of interventions. The reviewers for systematic reviews 1 and 3 were very experienced and had several published systematic reviews, including Cochrane reviews. One of the reviewers for systematic review 2 had no previous experience of systematic reviewing; accordingly, it was decided that, for systematic review 2, 100% of the records would be double reviewed.

Systematic review 1: the language and communication characteristics of children and adults who use augmentative and alternative communication while language acquisition is under way

The research question was ‘What are the language and communication characteristics of children and adults acquiring language through aided AAC systems?’

Method

The review process followed PRISMA,51 was registered with PROSPERO (www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=36785) and commenced on 22 March 2016.

Search procedure

A multifaceted search strategy was developed to navigate the literature. Five electronic databases were selected, namely EMBASE™ (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), ProQuest® (ProQuest LLC, Ann Arbor, MI, USA), EBSCOhost (EBSCO Information Services, Ipswich, MA, USA), Scopus® (Elsevier) and Web of Science™ (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA). A hand-search of the Augmentative and Alternative Communication journal was completed and reference lists from a range of sources were also examined (Box 1 provides the search strategy).

(Symbol* OR (aided AND (communicat* OR language)) OR (Graphic AND Representation) OR ((Augmentative OR Alternative) AND Communication) OR Bliss OR Rebus OR Minspeak OR AAC OR (Assistive AND Technolog*) OR (Complex Communication Need*))

AND

Speech OR Language OR Communicat*

AND

Learn* OR Develop* OR Acqui*

Inclusion criteria

Participants

Studies were included if the participants were children, young people or adults whose speech was insufficient to meet everyday needs. Studies were excluded if the participants were typically developing or had an acquired condition. Where a study included both eligible and ineligible data, it was included only if the reported data could be disaggregated. As the focus of the review was language and communication, outcomes needed to include some indication of language or communication measures. Studies of people at pre-symbolic levels of communication were excluded.

Study types

Any primary, non-intervention research study of any design conducted from 1970 to 2018 was included. Searches were conducted in English, but records returned in any language were considered for the review.

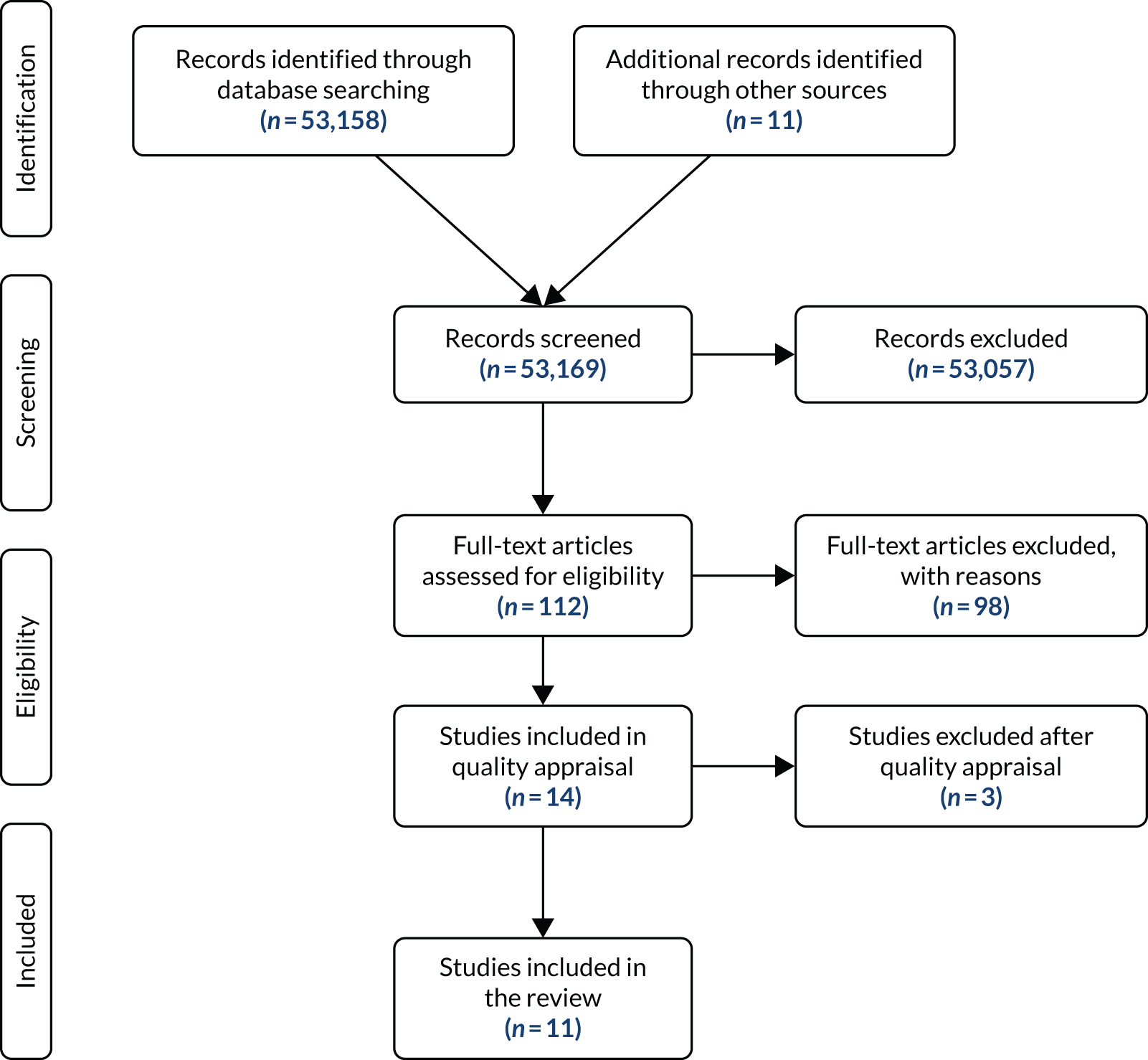

Screening process

The search process yielded 53,158 records, which were imported into EndNote™ [Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters), Philadelphia, PA, USA] for screening. One researcher conducted the title and abstract review and full-text review. An independent researcher completed inter-rater reliability checks. This researcher independently applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria to a sample of search records. The sample combined half of the included papers with a sample of the excluded papers as a reliability measure and the agreement rate was 100%.

Quality appraisal

The inclusion/exclusion criteria were used to screen all returned records, resulting in 112 studies being included in the full-text review. Following the full-text review, 14 papers were identified for quality appraisal (Figure 3). Two quality appraisal tools appropriate to the study designs were used: the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Checklist58 and the Evidence-Based Management Survey Checklist. 59 The 14 papers were appraised using relevant quality indicators and weight of evidence and relevance to the research question. 60 Two researchers independently completed this process before comparing the results. Eleven studies were agreed to meet the quality threshold. Three studies were excluded as they did not meet the agreed quality threshold: one from the USA,61 one from Ireland62 and one from Canada. 1

FIGURE 3.

Systematic review 1 PRISMA flow chart of language and communication characteristics of children.

Data extraction

Two researchers extracted relevant data from the studies. Information on study characteristics was extracted.

Results

The review comprised 11 research papers (Table 3), which represented 14 separate studies. Across all papers, 143 children and adult participants had used aided AAC. Most participants in the review papers had severe speech and physical impairments with no learning difficulties. The results, therefore, reflect children and adults with this profile, who are only one group of people who use AAC.

| Study (authors, country) | Description of study participants | AAC system(s) used | Aspect of language/communication studied | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blockberger and Johnston,30 USA and Canada |

20 children aged 5.8–17.1 years who could speak no more than 10 words and had no known hearing loss or second language issues Diagnoses: cerebral palsy, developmental delay, syndromes or no diagnosis Attained age-equivalent scores on the PPVT (receptive vocabulary assessment) of between 4 and 8:11 years. The children were compared with 20 children with typical development and 15 children with language delay |

Each of the children had their own individualised communication system, often combining unaided modes and light and high tech. Symbols used ranged from PCS, Minspeak® (Semantic Compaction Systems, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) and Dynasims to traditional orthography |

Understanding and expression of three grammatical morphemes: Possessive ‘s’ (e.g. Jack’s cars) Past tense ‘ed’ (e.g. ‘I walked to school’) Third person regular ‘s’ (e.g. ‘she walks’) |

The children using AAC had greater difficulty learning and using grammatical morphemes (both comprehension and expression) than children of the same age with typical development or younger children with language delays who had the same language learning level |

| Sutton,63 Canada |

Four adults with SSPI Two male and two female ranging in age from 18 to 29 years Receptive vocabulary (PPVT) age-equivalent abilities 8:4–11:10 years |

All had used Blissymbols for > 9 years with displays of 461–900 symbols One produced some intelligible spoken words Three produced vocalisations Participants were estimated to interact with 15–40 communication partners per week |

Social verbal competence |

Varying pattern of social verbal competence was observed across participants. Achievement scores did not reflect age, number of years using Blissymbols, number of symbols available or receptive vocabulary. However, number of communication partners per week and scores on the measure of social verbal competence seemed to correspond Participants had the most success with the informing function (three out of four scoring at a level of 13–14 years). Difficulty noted with the authority context (expressing in a formal register). Three out of four had most difficulty with the feelings function and one had most difficulty with the ritualising function Participants had the most success with speech acts that can be fulfilled with one word |

| Geytenbeek et al.,64 the Netherlands |

68 children out of 87 (19 did not pass screening) with severe cerebral palsy (GMFCSa levels 4 and 5). Anarthria (productive spoken vocabulary of fewer than five words). Able to match spoken words to objects. Children with severe hearing loss were excluded. Children without Dutch-speaking parents were excluded Also included 806 children with typical development |

Not specified | Language comprehension |

The children followed a typical developmental pathway but at a slower rate. The children using AAC were more delayed in learning ‘who’ questions and complex sentence types (significant difference in all sentence types) Children with dyskinetic cerebral palsy had better outcomes on complex syntactic analysis than children with spastic cerebral palsy |

| Lund and Light,16 USA | Seven young men with SSPI3 related to cerebral palsy. They ranged in age from 19 to 23 years and had a range of cognitive skills |

All had used AAC for at least 15 years. Systems used were communication boards (n = 2), computers (n = 3), Lightwriter (n = 1) and DynaVox (Tobii Technology, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) (n = 1) Five used indirect selection and two used direct selection |

Language comprehension | All participants scored below average on language comprehension |

| Redmond and Johnston,65 USA |

Four children with SSPI related to cerebral palsy or another neuromuscular condition Aged 11–15 years; had fewer than five spoken words and used AAC as their primary communication system; had normal hearing and normal corrected visual acuity; and were school-aged. Monolingual English; had no issues with an auditory detection probe Comparison groups: 11 children aged 4–6 years with typical development; 13 children aged 7–10 years with typical development; 21 adults |

Indirect access to black-and-white line drawings (no symbols) (n = 1) Direct access to a Liberator (PRC-Saltillo, Wooster, OH, USA) device with Minspeak (n = 1) Direct access to a DynaVox device with dynasyms (n = 1) Direct Lightwriter with traditional orthography (n = 1) The length of time the children had been using AAC was not specified |

Morphological competence: ability to recognise grammatical errors | Despite the wide variation in profile of the children with SSPI, a similar pattern of performance was observed across all four children. The children were able to identify when the past tense ending was missing from an irregular verb but they missed more errors than their peers who were typically developing but were matched as having the same vocabulary skills. Three out of four did better than vocabulary-matched peers in identifying when a regular past tense ending had been used where an irregular past tense ending should have been. The children with SSPI were more likely than vocabulary-matched peers to accept errors when a regular verb was missing the ending. Bare stem regular verbs were particularly challenging for children with SSPI and past tense irregular verbs were an area of strength |

| Soto and Hartmann66 and Soto et al.67 (two papers – results presented together), USA |

Four children aged 5–11 years with SSPI, average cognitive abilities and no hearing or vision difficulties Three girls and one boy Medical diagnoses: arthrogryposis and cleft palate (repaired) (n = 1), cerebral palsy (n = 2), muscular atrophy (n = 1) |

|

Narrative skills through five elicitation tasks |

Among the four children, narrative contribution ranged from very limited detail to appropriate levels of detail. Topic maintenance was a clear strength. Heavy reliance on co-construction with communication partner but could direct the conversation back to a previous point. However, lack of use of conversational control strategies, overuse of one-word utterance and the limitations of the AAC device often results in all children having to yield conversational control Appropriate event sequencing was observed in book-based activities but not in other activities. For the two youngest children, language production lacked structure and inclusion of basic story grammar elements There was a lack of action verbs and concrete supporting details in the narratives. Referencing was absent except for eye gaze use (could be considered ‘proto-referencing’) and occasional use of pronouns by some children Conjunctive cohesion: use of one-word utterances and short phrases meant that there were limited opportunities to use linking devices (such as ‘and’ or ‘because’). Pragmatic use of conjunctions was not evident and there was a lack of narrative coherence and fluency in narrative-telling |

| Soto and Toro-Zambrana,68 USA |

Three adults with SSPI related to cerebral palsy aged 25–32 years Two male and one female |

Blissymbol communication boards with 120 to 500 symbols | Morphosyntactic complexity of language output | The participants were able to convey a wide range of meanings with different language structures using their restricted vocabularies. They demonstrated use of a range of compensatory strategies to aid communication in the absence of the desired vocabulary being available |

| Sutton and Gallagher,69 Canada |

Two adults with SSPI related to cerebral palsy One male aged 25 years and one female aged 26 years |

Communication displays with 450 Blissymbols and alphabet access via numerical codes and yes/no responses | Ability to learn how to use encoding to mark regular and irregular past-tense endings | Suggests that individuals using AAC may have a reduced repertoire of language skills that may be related to modality restrictions (i.e. communicating through symbols has an impact on language learning) |

| Trudeau,70 Canada |

27 children with severe speech impairment aged 7:5–17:5 years whose first language was French Using AAC system for at least 3 months with at least 30 symbols Excluded if using an alphabet system or semantic compaction or if speech problem occurred after primary language development (2 years) |

15 had VOCAs with graphic symbols (range over 30–1000 with number of symbols unknown for four participants) Seven had symbol boards (with 60–700 symbols); 16 used direct selection; two used mixed methods; and two used scanning AAC experience ranged from 6 months to 41 years (unknown for six participants) |

Ability to construct and interpret symbol sequences |

The majority of participants showed consistent patterns in how they interpreted and constructed graphic symbol sequences, with a small number showing differences across interpretation and construction of sequences. As most were consistent, this suggests that learning to understand and learning to use graphic symbol sequences develop at the same time (rather than comprehension preceding expression) The majority used the spoken word order in the construction task unless they needed to change it to avoid ambiguity in the meaning Performance was not related to age or severity of the motor impairment or receptive vocabulary; however, performance was related to syntactic skills and cognitive abilities |

| van Balkom et al.,71 the Netherlands | Four adolescents with cerebral palsy |

All four participants used multimodal communication with communication boards; described as experienced graphic symbol users The participants’ communication boards had between 215 and 400 symbols One participant used single words; one used single words and PCS; two used rebus and single words |

Ability to describe pictures in children’s books |

Word order deviations from spoken language were observed Participants used an average of two graphic signs per message The majority of the graphic symbol messages were a succession of nouns with the use of nouns or noun combinations observed in the place of action verbs in some cases The participants demonstrated overt metalinguistic skills, such as the use of self-corrections, repetitions and other strategies, to overcome the restrictions of limited vocabularies to convey meanings |

Studies examined the language abilities of children and adults who were experienced aided communicators; the review results are detailed below.

Language understanding

Two studies16,64 reported on language understanding. In one study,16 68 children demonstrated their spoken sentence understanding. The results indicated that, although children followed a typical pattern of development, spoken sentence understanding was more typical of a child younger than their (chronological) age. In the second study,64 of seven young men who had been using AAC for ≥ 15 years, all participants scored below average (i.e. younger than their age) on language understanding. Participants did not have identified learning difficulties, so the results suggested that factors affecting language development included language learning opportunities and the influence of communicating with graphic symbols. Currently, we know too little; further research is needed to identify how AAC systems and language learning opportunities best support children to achieve their potential.

Expressive use of symbols

Three studies68,70,71 considered how participants generated graphic symbol output. There was variation across participants, with many using limited vocabularies successfully to communicate a range of messages and language structures. In one study, 72 adolescents used an average of two symbols per message to tell stories. It was clear that they used extra skills to communicate with fewer words, for example using strategies such as ‘it sounds like’. Some participants used different word orders from the spoken language in their environment. These word-order variations were used to make the intended message clearer. Word-order patterns did not appear to be related to age or motor impairment severity but did correspond to the child’s language-understanding abilities. In summary, there was wide variation in the language abilities of and graphic symbols used by children using aided AAC, and some children had developed highly creative skills to overcome the restriction of small expressive vocabularies. The limited data suggest that research is needed to understand how children develop these strategies and how to support the effective use of these.

Narrative skills

Two papers from one research project looked at the storytelling abilities of children who use AAC,66,67 which varied widely across participants. One study66 found that some children could give many details in their story, while others were unable to do this. All participants had some difficulty with independently telling stories and using different story elements. The results indicated that maintaining the topic of the story was an area of strength. Children overly relied on one-word messages and because of the limitations of their communication aids they often depended on their communication partner and allowed the partner to take control of the story. Specifically, children did not use many action words (e.g. ‘run’ or ‘jump’) or pronouns (e.g. ‘he’ and ‘she’) in their stories. Nor did they use joining words (e.g. ‘and’ or ‘because’). As a result, it was harder to follow their storylines. These findings suggested that children may need more opportunities to tell stories and may need AAC vocabularies that support storytelling.

Grammatical morphemes

Grammatical morphemes are small words or word parts of a language that can be used to change meaning. For example, adding the past-tense ending ‘–ed’ turns ‘I look’ into ‘I looked’ to show that the action happened in the past. Some studies looked at how children who use AAC understand and use grammatical morphemes. 30,65,69 The results suggest that children who use AAC find it harder to understand and use grammatical morphemes than children who are speaking. Children may leave out grammatical morphemes because they have limited opportunities to use them or because communicating with symbols may make it harder to learn grammatical morphemes. These results indicate that children may need more opportunities to learn grammar morphemes even if they are not expected to use them in everyday communication (e.g. drill and practice activities). It can be proposed that more thought needs to be given to AAC system design to support children learning to use grammatical morphemes.

Social competence

Using a test of social competence, one study63 looked at the ability of four young adults to adjust their communication abilities based on different social situations. Participants had most success with communicating messages that could be fulfilled with one word (e.g. ‘yes’) and with providing information (e.g. ‘That’s my coat’). Participants had difficulty expressing messages more formally (e.g. ‘Could I look at that?’) and expressing feelings (e.g. ‘I love it!’). The participants’ performance scores did not reflect their age, the number of symbols available on their AAC system or their language understanding. A further result was that participants who interacted with more people on a weekly basis achieved higher scores on the social competence test. This suggests that having more communication opportunities is important in supporting ongoing communication skill development.

Systematic review 2: the language and communication attributes of communication aids

The research question was ‘What are the language and communication characteristics of communication aids considered in decision-making for AAC prescription?’.

Method

Search procedure

A review protocol was drawn up using the PRISMA-P51 template and a search strategy was developed based on the research question. The search strategy is detailed in Box 2. The review commenced in March 2016.

(Symbol* OR (aided AND (communicat* OR language)) OR (Graphic AND Representation*) OR “Alternative Communication” OR “Augmentative Communication” OR “Augmentative and Alternative” OR “Alternative and Augmentative” OR AAC OR (Assistive AND Technolog*) OR (Complex Communication Need*))

AND

(attribute* OR feature* OR quality OR qualities OR characteristic* OR design* OR specification* OR (vocabulary AND (organisation OR organization))

This box has been reproduced from Judge et al. 72 with permission from Taylor & Francis Group (https://www.tandfonline.com/). The box includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original box.

Searches were carried out on the EBSCOhost, EMBASE, ProQuest, Scopus, Web of Science, the Cochrane Library and Augmentative and Alternative Communication journal electronic databases. When possible, searches were refined by excluding categories that could not be related to AAC (e.g. animal studies).

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Studies were included if their focus was the implementation of a graphic symbol AAC system. Papers were excluded if the focus was entirely on literacy. Any primary research study of any design conducted from 1970 to 2018 was included. Searches were conducted in English, but records returned in any language were considered for the review. Unfortunately, a translation of one paper from Korean could not be sourced within the available timeframe.

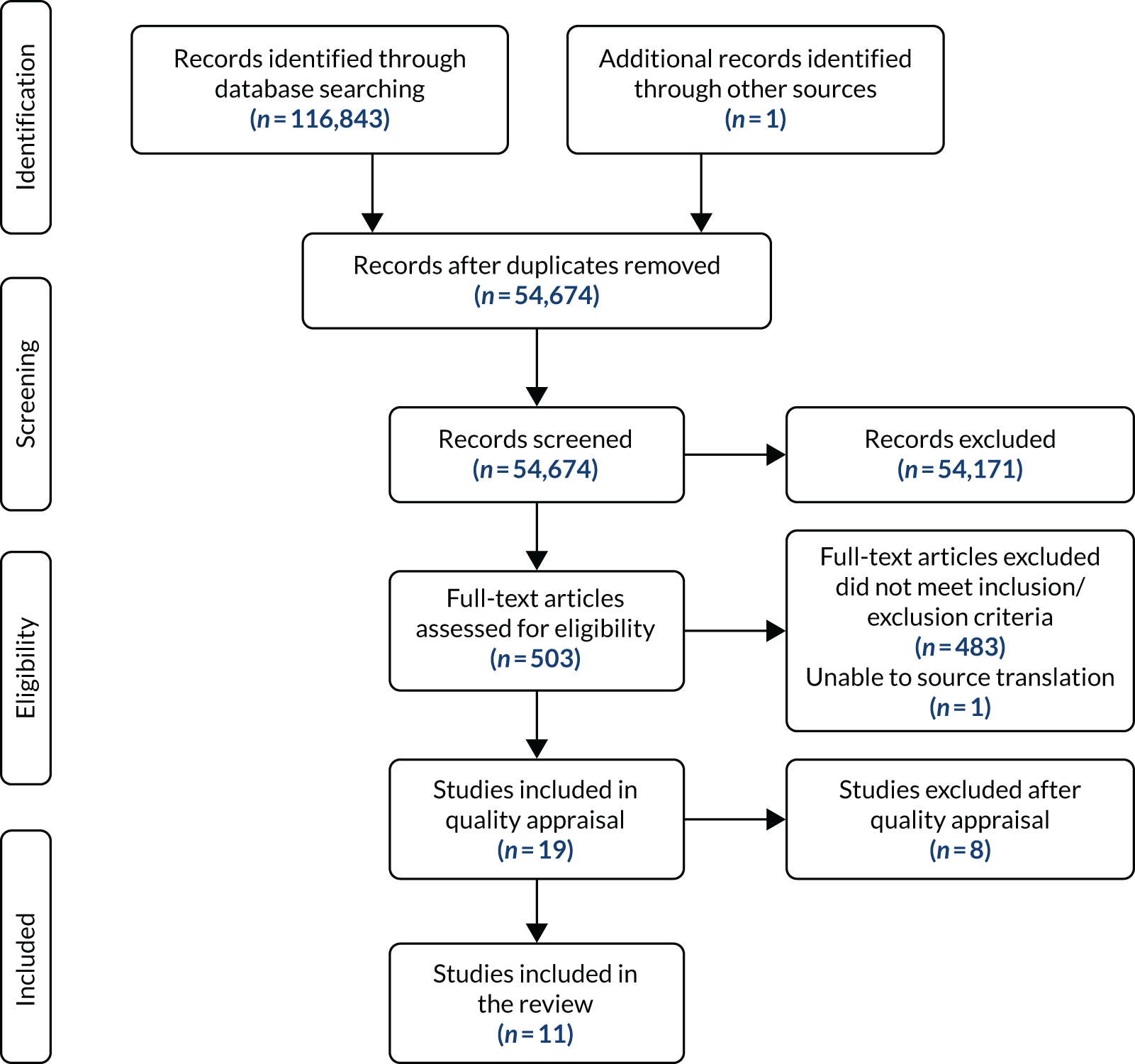

Screening process

The citations were downloaded to a local database and managed using the JabRef software tool (www.jabref.org). Owing to the number of papers, the initial review process was carried out in two stages. An initial title and abstract review stage excluded articles not related to AAC. Two researchers independently carried out a title and abstract review of the remaining literature to screen for relevance to the research question. Any paper marked by either researcher as meeting the inclusion criteria was retained for full-paper review. Both researchers reviewed the full text of the remaining papers independently. Papers included by both researchers were included in the review. Papers included by only one researcher were discussed until consensus was achieved, with a third researcher available if needed. Figure 4 details the review screening process.

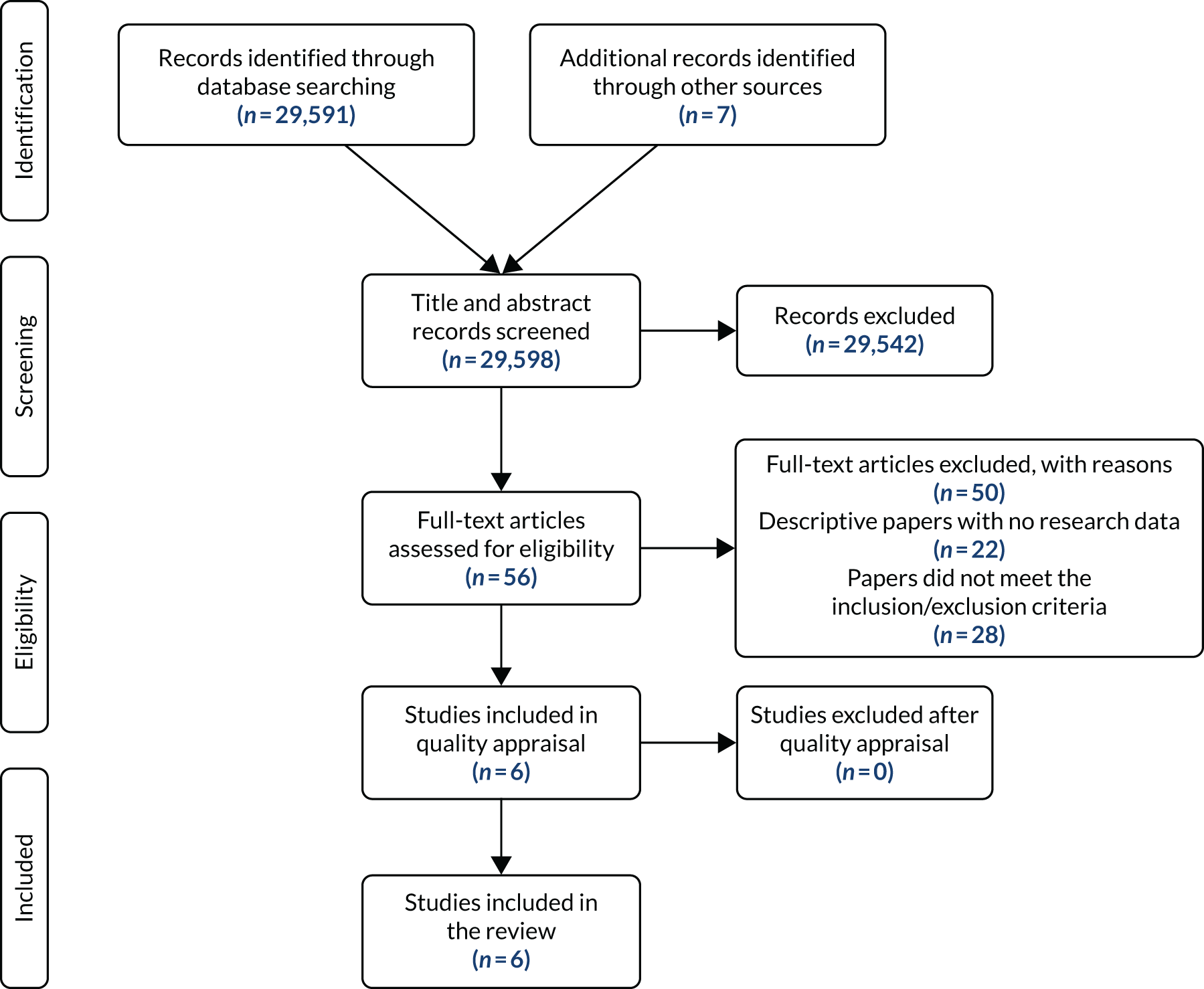

FIGURE 4.

Systematic review 2 PRISMA flow chart of language and communication characteristics of communication aids. This figure has been reproduced from Judge et al. 72 with permission from Taylor & Francis Group (https://www.tandfonline.com/). The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Quality appraisal

The Crowe Critical Appraisal Tool73 was used as the basis for quality appraisal as it supports the inclusion of a variety of study designs. It was chosen also because it allowed the outcome of the appraisal to be used as a criterion for acceptability. A score of < 40% on the tool was agreed to indicate that the paper was rated as weak. Quality appraisal was carried out by the two researchers independently. Papers rated as weak by both researchers were excluded from the review. 74–80

Data extraction

Two researchers worked jointly to extract relevant data from the studies. The following study characteristics were extracted: study design, participant sample size and characteristics, existing graphic symbol system(s) used by participants, language or communication attribute studied, intervention, measures and results.

Results

Data extraction was completed on 11 papers (Table 4). The included studies reported data from 66 relevant participants; 88% were reported as having cerebral palsy, 58% were reported to be children or young people and 58% were reported to be male. Eight of the studies, involving 73% of participants, took place in North America (USA, n = 6;81–86 Canada, n = 288,89) and the remaining three studies were carried out in the UK, Australia and South Africa. Five of the papers were published before 2000 and nine were published before 2005. Seven of the papers could be described as single-case (within-subject) experimental or quasi-experimental design, using the typology proposed by Tate;92 the remaining papers consisted of two surveys and two case studies.

| Study (authors, country) | Design | Sample size and characteristics | Existing graphic symbol system(s) used | Language or communication attribute studied |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hochstein et al.,81 USA (theme 1) |

Quasi-experimental 2 × 2 × 2 mixed factorial Only 2 × 2 relevant to this review |

Eight participants diagnosed with CP:

|

Not specifically detailedAll participants selected had to have a lack of familiarity with both of the two presentation systemsThe speech impaired children who had familiarity with AAC systems were only allowed to have familiarity with non-computerised systems or level static systems in which the levels had to be manually placed | Display levels and vocabulary abstractness

|

| Hochstein et al.,82 USA (theme 1) |

Quasi-experimental 2 × 2 × 2 mixed factorial Only 2 × 2 relevant to our review |

Two groups of eight (16 in total): CCN and speech skills (not relevant to review) CCN group: |

CCN group:

|

Presentation scheme: static or dynamic

|

| Reichle et al.,83 USA (theme 1) | Within subject, alternating treatment, repeated measures |

‘Sarah’: 16 years old, severe ‘mental retardation’, receptive language score in first percentile on formal assessment Approximately equal exposure to each display strategy prior to the study |

Macintosh PowerBook 540c (Apple, Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA) with Speaking Dynamically™ (Tobii Dynavox Llc, Pittsburgh, PA, USA) v1.2 software

|

Arrangement/layout of symbols:

|

| Hurlbut et al.,84 USA (theme 2) |

Quasi-experimental Authors describe as ‘within subject: multi-element baseline’ |

Three males with quadriplegic CP (range of type and severity)

|

|

|

| Light et al.,85 USA (theme 2) | Within subjects, repeated measures | Six physically disabled adults with functional literacy

|

Used communication aid for at least 1 year prior to study

|

|

| Light and Lindsay,86 USA (theme 2) | Within subjects, repeated measures | 12 adult participants with congenital disabilities

|

|

|

| Bornman and Bryden,87 South Africa (theme 3) | Descriptive survey | 12 South African adults with CCN who use AAC

|

|

|

| Yorkson et al.,88 Canada (theme 3) | Descriptive statistics |

Nine non-speaking adult users of AAC systems: two female, six male. Aged 20–36 years Eight CP, one CVA (not applicable to this review); moderate to severe physical handicap; range of spelling skills (< 2nd grade to 6th grade); intellectual ability broadly WNL |

Of participants with CP:

|

|

| Yorkson et al.,89 Canada (theme 3) | Case description including analysis of vocabulary list produced: percentage of structure words; and comparison with standard vocabulary lists | One participant, GT: 36 years, female; CP and spastic quadriparesis; not able to produce intelligible words; no formal education; recognised 5–10 sight words, no functional spelling; approximate age equivalence of 11 years 7 months in receptive language level skills; and motor limitations appeared to be greater obstacle to communication than language skills |

|

|

| Black et al.,90 UK (theme 4) | User-centred design and formative evaluation |

Three children with quadriplegic CP:1 and 3 – little functional speech 2 – functional speech, but sequencing/memory difficulties 1 – uses graphic symbols, ‘emerging literacy’, some whole-word reading 2 – literacy not clear ‘can copy type’ 3 – knows about 400 PCSs; can type simple sentences using on-screen keyboard |

|

|

| Stewart and Wilcock,91 Australia |

Single-case experimental design ABACA design across three cases: A, no prediction; B, regular prediction; and C, internal prediction |

Three participants:

|

|

|

Themes

Thematic analysis of the included papers resulted in three main themes of vocabulary organisation and design, symbol system and encoding, and vocabulary selection.

Vocabulary organisation and design

Three papers reported data from studies related to vocabulary organisation and design. These studies involved participants trialling communication aids with different combinations of static and dynamic organisational schemas. The primary aim of the first study81 was to investigate the nomothetic approach; however, the study had the secondary aim of examining the effect of display levels and vocabulary concreteness on the use of a communication aid. The study compared organisation schemas described as single level or dual level with a small number of symbols in a task where the participant was asked to match a symbol to a word spoken to them. The single-level display produced fewer errors, and concrete items were found to be easier to recall by participants than abstract ones. The second study82 was of similar design. In this study the static organisation promoted higher rates of vocabulary recognition during initial learning with the dynamic organisation scheme achieving higher rates after training (the seventh and eighth trials in the study). One study83 alternated organisational schemas between schemas they termed fixed, dynamic passive and dynamic active. The study involved a symbol-to-photograph matching task using a 30-symbol set with a single participant described as having ‘severe mental retardation’. For this participant there was no significant difference between dynamic active and fixed organisations tested in terms of speed or accuracy of symbol selection. The quality appraisal process identified two potential challenges to the validity of this result when considering it in the context of communicative use. First, it is not clear that the symbol-to-photograph matching task would transfer to unprompted use in communicative environments. Second, the method does not adequately explain the results for the ‘dynamic active’ condition. The method states that page changing occurred every time a symbol was pressed, with each screen displaying only half of the available symbols; this would suggest that for a randomly presented photograph the matched symbol would not be present on the communication screen for around half of all responses. The reported accuracy results are all > 60% (rising to > 90%) and so it appears that the experimenter chose the photograph to correspond to the current screen or that the method or condition was not fully described.

Symbol system and encoding

Three papers reported data from studies related to either the symbol system or the encoding methods used in symbol communication aids. One study84 had the aim of establishing which of two symbol systems was more easily acquired and maintained when an individual is trained in their use. Blissymbolics, a predominantly ideographic symbol system,93 was compared with line-drawn iconic pictures illustrated with the intention of showing a high degree of similarity to the object they represent. Twenty of each of the symbols were placed on a single-page communication board and provided to three males with cerebral palsy as part of a within-subjects study. Stimulus generalisation was evident in both symbol systems, but higher scores were reported with iconic pictures. Although students made spontaneous responses using both symbol types during daily activities, iconic pictures were used more frequently. A number of factors were identified in quality appraisal as limiting the interpretation of these results. Participants were all described as having ‘severe retardation’; however, the inclusion/exclusion criteria were not listed and it was reported that teachers felt that participants’ receptive language was above that reported in the test results. The test used to assess receptive and expressive language is not validated for this level of physical disability and it is not made clear if the assessment was carried out by the researchers or taken from records. The choice of items for the intervention was based on items that were readily visible in the environment, which limited the symbol vocabulary to nouns. Furthermore, in the spontaneous use task, both types of symbol were included on the communication board, which is unlikely to be representative of use in a naturalistic communication task. No description of the analysis or statistical methods is provided.

Two studies85,86 investigated the process of using short codes to create longer messages, termed ‘message encoding’. Both studies compared letter codes based on the first letters of salient words in the message (e.g. CE would expand to ‘can I have something to eat’), letter category codes based on the first letters of a category plus a specifier (e.g. RE would mean a ‘Requests to do with Eating’) and iconic codes derived from the icons and semantic associations proposed by Baker,94 that is, Minspeak® (e.g. the icon of an apple followed by a question mark would stand for food and requests). The first study found that the salient letter technique was associated with higher recall than the letter code or iconic technique. In both studies, concrete messages were also found to have significantly higher recall than abstract ones. There was no interaction effect between these two factors. The accuracy of code recall increased for all learning and testing sessions in both studies. The quality appraisal identified that the participant cohort in the first study was biased towards functionally literate individuals and those with cerebral palsy. The authors noted this and attempted to address it in the second study; however, in this study, all of the participants included were above the age of 6–7 years in reading ability and all but one had cerebral palsy.

Vocabulary selection

Three papers investigated the process of selecting the symbol vocabulary to use on a communication aid. One study87 aimed to investigate the social validity of a specific vocabulary set by determining the importance of identified vocabulary items to 12 adults who used AAC. The results suggested that participants concurred with most (80%) of the vocabulary selected by a variety of knowledgeable informants. The authors identified that the study had a low response rate, and participants were recruited as a purposive sample, which may have provided skewed data. There were also no test–retest or internal consistency reliability measures of the data collection tool. Two studies looked at vocabulary selection. The first study89 involved nine participants who contributed their vocabulary lists, which were compared with each other and then against standard vocabulary lists. The second study89 presented a case description of the process of vocabulary selection and a comparison of the selected vocabulary against standard vocabulary lists. Inspection of participants’ vocabulary lists highlighted that these were small vocabularies compared with estimates of common English words or standard vocabulary lists. Comparing against the standard lists showed that the larger vocabulary lists contained a greater proportion of users’ vocabularies, but no standard vocabulary list contained all words included in even relatively small user vocabularies.

Systematic review 3

The research question was ‘What does the literature tell us about how professionals make decisions in communication aid recommendations for children?’

Method

The review process followed the PRISMA guidelines. 51 The review was registered with PROSPERO (www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/; accessed 11 September 2018) and commenced on 14 July 2016.

Search procedure

Owing to the dispersed nature of AAC research,50 a multifaceted search strategy was developed to navigate the literature. Five electronic databases were selected, namely EMBASE, ProQuest, EBSCOhost, Scopus and Web of Science. A hand-search of the Augmentative and Alternative Communication journal was completed and reference lists from a range of sources were also examined. Box 3 summarises the search strategy.

(Symbol* OR (aided AND (communicat* OR language)) OR (Graphic AND Representation) OR “Augmentative Communication” OR “Alternative Communication” OR “Augmentative and Alternative” OR “Alternative and Augmentative” OR AAC OR (Assistive AND Technolog*) OR (Complex Communication Need*))

AND “Decision-making” OR “Decision-making” OR “Prescrib*” OR “Prescription” OR “Recommend*” OR Heuristic OR Framework

Inclusion criteria

Participants

Studies were included if the participants were professionals involved in decision-making about communication aid recommendations for children aged 0–18 years with developmental disabilities. Studies of professional decision-making about communication aid recommendation for adults with developmental disabilities were also included, as studies of adults who have grown up with communication aids have the potential to shed light on the outcomes of recommendations made in childhood. Studies of communication aid recommendation for adults with acquired disabilities, and for individuals at a pre-symbolic level of functioning, were excluded.

Communication aids

Studies of decision-making related to both light-tech aids and high-tech aids were included, as were studies in which the communication aids recommended used graphic symbol or traditional orthography representation. Studies related to manual sign or tangible symbols were excluded.

Study types

Any primary research study of any design conducted from 1970 to 2018 was included. Searches were conducted in English but records returned in any language were considered for the review.

Screening process

The search process yielded 29,591 records, which were imported into EndNote for screening. The lead researcher conducted the title and abstract review and full-text review. An independent researcher completed inter-rater reliability checks. This researcher independently applied the inclusion and exclusion criteria to a sample of search records. The independent researcher reviewed a sample of 403 records of included and excluded papers using agreed evaluation criteria. The agreement rate was 100%.

Quality appraisal

The inclusion/exclusion criteria were used to screen all returned records, resulting in 56 studies being included in the full-text review. Following the full-text review, six papers were identified for quality appraisal (Figure 5). Quality indicators were derived from two quality appraisal tools appropriate to study designs: the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) Qualitative Checklist58 and the Evidence-Based Management Survey Checklist. 59 The six papers were appraised using relevant quality indicators and weight of evidence and relevance to the research question. 60 Two researchers independently completed this process before comparing the results. Five studies were agreed to meet quality thresholds. One study was deemed acceptable following consensus discussion.

FIGURE 5.

Systematic review 3 PRISMA flow chart of clinical decision-making by professionals.

Data extraction

Two researchers worked jointly to extract relevant data from the studies. The following study characteristics were extracted: sample size and characteristics, data collection and analysis, team composition and service delivery model, experience level of team members, decision-making processes, child and parent involvement in decision-making, language representation and organisation considerations.

Terminology

Across the included studies, different terminology was used to describe the professionals involved. For ease of reading, the term speech and language therapist (SLT) has been applied to both speech and language therapists and speech–language pathologists (SLPs). The term specialist speech and language therapist describes a SLT with reported expertise in communication aid recommendation. The term generalist SLT describes a SLT who is involved in aid recommendation but is reported to have broad experience across clinical areas. The term professional describes any person involved in the aid recommendation processes in a paid capacity, including health and education professionals.

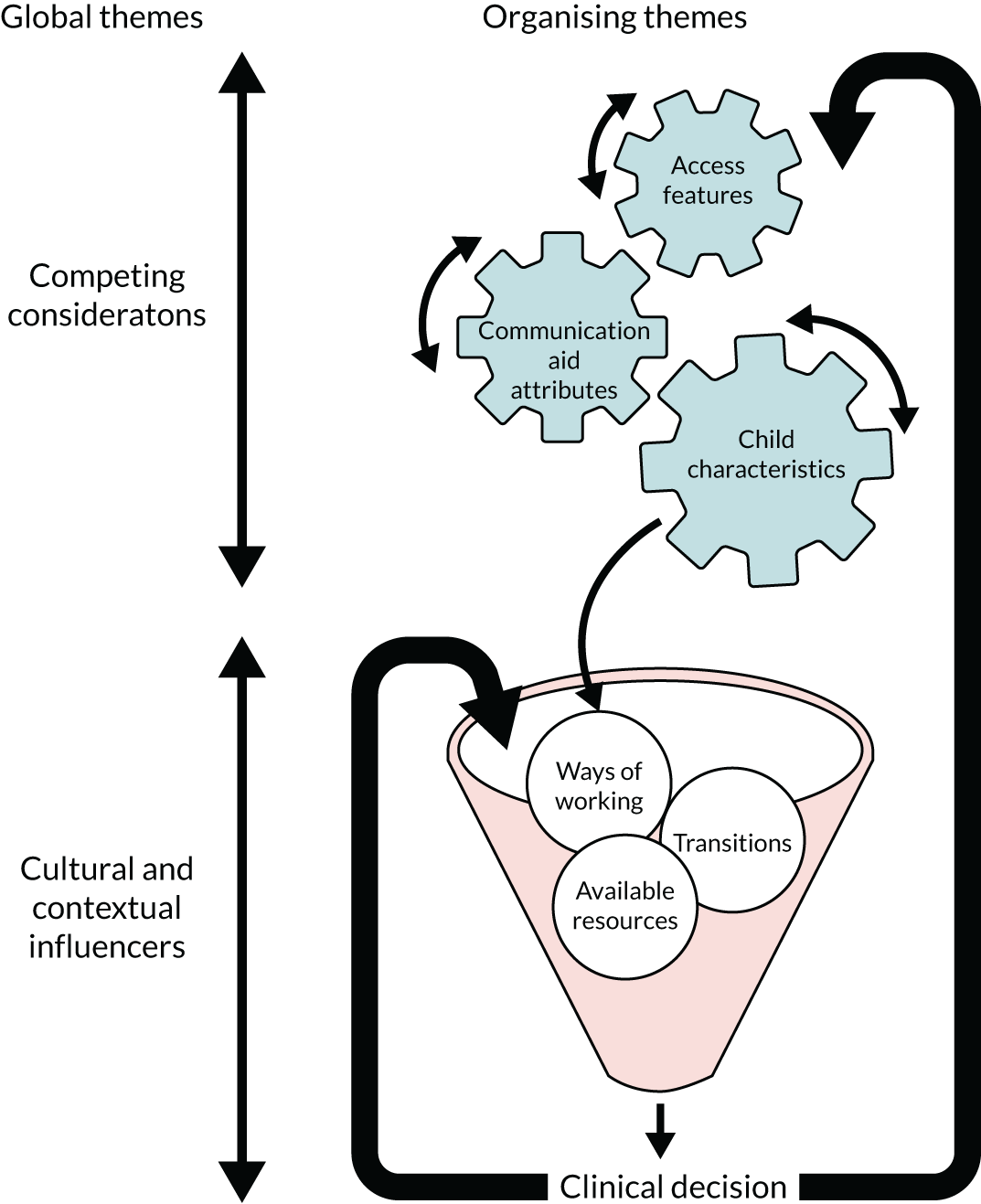

Results

Of the six included studies, three were from the USA27,95,96 two were from Canada9,26 and one was from South Africa;97 all were published in peer-reviewed journals from 1992 to 2017. In total, there were 405 participants (Table 5). The studies employed qualitative designs9,27,96 or survey designs. 26,95,97 Analysis generated either descriptive statistics and correlations or themes.

| Study (authors, country) | Sample size and characteristic | Data collection | Data analysis | Team composition and service delivery model | Professional experience level | Decision-making processes | Child and parent involvement | Language representation and organisation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Batorowicz and Shepherd,26 Canada | 92 professionals | Surveys | Descriptive statistics and estimation of degree of association among variables |

Size: professionals worked in teams of 5–33 people Composition: occupational therapists,a SLTs,b technology specialists, communication disorder assistants, educators and an audiologist Model: transdisciplinary prescription review |

6 months–25 years | A small team completes an assessment and provides a case presentation to a wider team. Discussion is used to share perspectives, innovation and creativity. The wider team is involved in the decision-making process | Parents were involved but not in the final decision | n/s |

| Dada et al.,97 South Africa | 77 SLTs with a minimum of 1 year’s AAC experience | Survey |

Descriptive statistics and estimation of degree of association among variables Thematic analysis |

85% of participants worked in a team Composition: teams included occupational therapists, teachers, physiotherapists, nurses, doctors, social workers, caregivers and psychologists |

9% had ≤ 2 years’ experience 45% had 3–5 years’ experience 9% had 6–10 years’ experience 36% had > 10 years’ experience 55% worked with children and 21% worked with children and adults (results for SLTs working with adults only and results pertaining to intervention only have been disaggregated) |

74% used a combination of standardised tests and functional and authentic assessments 21% used only functional assessments 5% used observation in natural settings Areas rated as important were communication of basic needs, choice-making and child preferences. Feature-matching was also used |

Child’s aid preference was rated important and respondents considered the child and family to be team members (89%). Participants rated having active family involvement higher than having families observe assessments |

Symbol iconicity and the system’s ability to support language developed were both rated as important 54% focused on a core vocabulary for the initial vocabulary selection and 45% indicated use of core and fringe for initial vocabularies 86% used category-based organisation, 7% based on parts of speech and 8% used a combination of both Language representation decisions were influenced by resource availability, ease of learning, previous clinical experience, child’s skills, family’s views, peer recommendation, published research, and access to social media |

| Dietz et al.,27 USA | 25 SLTs | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis |

Size: most worked in isolation or consulted other professionals as needed Team composition and model: not specified |

Three levels of experience Generalist SLTs: SLTs who provided a range of clinical services including AAC but did not specialise in AAC Specialist SLTs: SLTs who provided AAC services for at least 50% of their caseload and had skills in AAC assessment including supporting others Research/policy SLTs: SLTs who prepared future SLTs and who carried out AAC research |

Generalist SLTs: decisions based on standardised assessments, broader information-gathering and deficit focused Specialist SLTs: used functional communication tasks, focus on multimodality and the need for personalisation, multiple appointments to facilitate aid trialling |

Generalist SLTs: n/s Specialist SLTs: parents consulted to provide information and discuss results. Provided with feedback/reassurance – believe assessment should include an education role |

Generalist SLTs: gathered information on object and picture recognition skills but did not integrate this into decision-making Specialist SLTs: gathered information about language representation/organisation and vocabulary personalisation |

| Lindsay,9 Canada | 7 SLTs; 4 occupational therapists | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis |

Size: teams involving different professionals (including assistive technology consultants and communication disorder assistants) Model: transdisciplinary prescription review |

At least 1 year’s experience of AAC funding authorisation |

A small team assesses the child and makes a case presentation to a larger team. Discussion is used to make the recommendation decision Participants felt that device trials would support decision-making, but were precluded from trialling by the service model Child had to demonstrate proficiency with the aid to access funding |

Child’s level of prerequisite skill was more important than parental wishes. Parental preferences did influence recommendation | n/s |

| Locke and Mirenda,95 USA | 210 special education teachers | Survey | Descriptive and correlational measures |

Size: variable Composition: 16 types of professionals listed as team members (including hearing specialists and rehabilitation engineers) Model: multidisciplinary, 24%; interdisciplinary, 39%; and transdisciplinary, 32% |

78% had > 3 years’ experience teaching children with communication disorders | n/s | Parents were considered team members | n/s |

| Lund et al.,96 USA | 8 SLTs | Semistructured case study interviews | Thematic analysis | Composition: participants indicated they would work with different team members depending on the child’s diagnosis (e.g. occupational therapist for a child with cerebral palsy, psychologist for a child with autism) |

SLTs with expertise in AAC (participants and expertise definitions drawn from Dietz et al. 27) Specialist SLTs, n = 4 Research SLTs, n = 4 |

Major themes: Areas of assessment (what was assessed) Evaluation preparation Methods of assessment (how) Parent education The child’s medical diagnosis influenced the decision-making process |

Considering parental preference, information-sharing, parental education and managing expectations were discussed | Child’s receptive language and medical diagnosis influenced vocabulary size and organisation decisions |

Team composition and service delivery model

A range of professionals was identified as contributing to communication aid recommendation; both single professional and multiprofessional models were utilised in practice. Three types of team structure emerged:

-

Individual SLTs working in isolation with families. 27,97 Both generalist and specialist SLTs reported working alone without team support. 27

-

Team models used included multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary models. 95,97 Team composition varied, with up to 16 professional backgrounds contributing to individual teams, for example hearing specialists, occupational therapists and rehabilitation engineers. 95,97

-

The two Canadian studies9,26 reported the use of a prescription review model. In this structure, specialist team representatives conduct an assessment and then refer back to the whole specialist team for a case presentation and discussion. The case presentation is a critical feature in decision-making, with the larger team taking shared responsibility for the final recommendation. Team size in one of the studies ranged from 5 to 33 members. 26

Across the studies there were different perspectives on how team composition and structure influenced decision-making. Working in a team was reported in one study to be a moderate support for decision-making. 26 While the potential advantages of team working were recognised by SLTs working in isolation, some service structures were cited as preventing team working. 27 Other studies reported that teams formed on an ‘as needed basis’95 or professionals were consulted as needed,27 suggesting that teams were transient and not working together over a period of time to develop shared knowledge and skills. One study9 identified that the lack of time to work together as a team was a challenge to providing appropriate aid recommendations for children and another study97 reported that collaborating with other team members was challenging, with reasons unspecified.

Experience level of team members and decision-making processes