Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/04/02. The contractual start date was in April 2016. The final report began editorial review in March 2019 and was accepted for publication in August 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Maxwell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction, background and aims

Introduction

Pelvic organ prolapse (POP) affects women of reproductive age and beyond; it is a condition seen in up to 50% of parous women and up to 75% of women attending outpatient gynaecology clinics. 1,2 Treatment options for prolapse include surgery and conservative management [with pessaries or pelvic floor muscle training (PFMT)]. A high proportion of women go on to have surgical intervention, which is often prone to failure, with the same prolapse recurring or another prolapse occurring in another location, which can lead to repeated operations. 3 Mesh-related complications are frequently reported, and have a removal rate of up to 35%. 4 In Scotland, in 2014, the use of synthetic mesh implants in the treatment of POP was suspended; this suspension was subsequently introduced in NHS England in 2018.

These highly publicised suspensions of synthetic mesh implants make the need for non-surgical options to treat this condition even more pressing. 5 Clear evidence of the clinical effectiveness and potential cost-effectiveness of PFMT in the management of prolapse is now available. This evidence concludes that PFMT should be recommended as a first-line treatment for POP. 6 The Pelvic Organ Prolapse PhysiotherapY (POPPY) trial was a multicentre randomised controlled trial of the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of individualised PFMT compared with a lifestyle-advice leaflet in women with newly diagnosed symptomatic stage I, II or III prolapse. 6 The POPPY trial constitutes the largest, most rigorous, pragmatic trial of PFMT for prolapse and, as such, provides the necessary evidence to inform future practice. Individualised PFMT provided by specialist women’s health physiotherapists (WHPs) was found to be effective in reducing women’s symptoms of prolapse and in improving prolapse-related quality of life. It also showed potential to be a cost-effective treatment. However, knowledge of efficacy and effectiveness is not enough to ensure implementation.

Background

In the UK, there is currently limited availability, and variation in the availability, of specialist WHPs to deliver PFMT to the large numbers of women who may benefit from it. 7,8 In the UK, there are approximately 800 specialist physiotherapists working in women’s health, as registered with the Pelvic, Obstetric and Gynaecological Physiotherapy (POGP) group. The number of women aged > 40 years in the UK (based on the 2011 census9) is approximately 15.9 million; taking a symptomatic estimate of 10% into account means that there are approximately 2600 symptomatic women for each specialist physiotherapist in the UK. It is unlikely that PFMT will be available to meet the demand unless it can be delivered in other formats, for example by other types of health-care professionals (HCPs).

Implementation science is an emerging field involving complex and multilevel processes. 10 It aims to advance knowledge of implementation by providing generalisable knowledge that will be useful for other settings and contexts. It can help to identify barriers to implementation, but should also extend this to how and why implementation processes are effective. 11 To do this, we need to study implementation strategies and the contexts and processes in which implementation strategies are delivered. Such research is a necessary step in the Medical Research Council’s evaluation of complex interventions framework. 12

Research to improve the implementation of evidence-based PFMT was required. Delivery methods that can enhance service capacity and increase the availability and choice for women are required, but these need to be tested to ensure that the outcomes achieved under trial conditions are maintained. We needed to know whether or not the NHS could deliver PFMT using different staff skill mixes and/or different numbers of sessions and still maintain the benefits observed under trial conditions. We also needed to know how PFMT is implemented in everyday practice and understand the barriers to and facilitators of successful uptake and delivery. It was anticipated that this knowledge would enhance the likelihood of PFMT being rolled out more widely if service models could be successfully tailored to suit different local circumstances and resources, thereby increasing the availability of such services for the many women who would benefit from this treatment.

In addition, trial follow-up rarely extends to more than 1 or 2 years post trial. An observed reduction in ‘further treatment’ following PFMT was initially established in the POPPY trial. A record linkage-based study of longer-term follow-up of the original POPPY trial participants would show whether surgery is prevented or delayed by the use of PFMT. These data would help inform NHS managers as to what long-term benefits they might expect if they implemented PFMT.

Aims

Overall aims

-

To maximise the delivery of effective PFMT for women with prolapse through the study of its implementation in three diverse settings. This would involve developing different service delivery models, such as using different staff skill mixes, with the format of delivery being determined locally.

-

To assess the impact of PFMT on longer-term treatment outcomes using linked health-care data for the majority of the original POPPY trial participants (i.e. those based in Scotland).

Specific aims

-

To understand the barriers to and facilitators of implementing PFMT across varying NHS locations from managerial, delivery staff and women’s perspectives and experiences, and to develop different models of delivery in response to these.

-

To explore the potential for different groups of staff skill mix to deliver PFMT without compromising the achievement of clinical outcomes.

-

To explore fidelity or variation to the PFMT protocol (e.g. number of sessions) and the impact of any variations.

-

To establish the levels of support required by non-specialist physiotherapists to deliver PFMT.

-

To explore the acceptability and outcomes for women of different delivery models.

-

To establish the costs and benefits associated with each model of delivery.

-

To contribute to knowledge of how and why implementation processes are successful (or not) through exploring what works, for whom and in what circumstances.

-

To establish whether or not the benefits observed among the POPPY trial participants are maintained at longer-term follow-up and across different NHS settings.

Chapter 2 Overview of methodology, study design, intervention description and patient and public involvement

Methodology

Theoretical frameworks

The study was informed by two theoretical frameworks from implementation science theory: the realist evaluation framework13 and the reach, effectiveness, adoption, implementation and maintenance (RE-AIM) framework. 14 The realist evaluation approach was used to understand how the intervention was implemented in different study sites, what contextual factors influenced its implementation and what ‘mechanisms of action’ lead to successful (or unsuccessful) delivery and outcomes. The RE-AIM framework was used to determine the overall public health effect of the intervention, using specific and standard ways of measuring the key indicators of potential impact and the widespread adoption and sustainability. The combination of both of these frameworks enabled us not only to evaluate the intervention’s internal and external validity, but also to take account of the context in which the intervention was delivered and identify the mechanisms that made it work (or not) to produce the observed outcomes. Realist evaluation is explained in more detail in Chapter 4, alongside its methods, and the realist evaluation findings are presented in Chapter 5.

The RE-AIM framework

The RE-AIM framework, developed by Glasgow et al. ,14 is designed to enhance the quality, speed and health impact of efforts to translate research into practice, and is based on five dimensions: reach, efficacy/effectiveness, adoption, implementation and maintenance. Its purpose is to expand the assessment of interventions beyond efficacy to multiple criteria that may better identify the translational quality and public health impact of health interventions, balancing the emphasis on internal and external validity. The RE-AIM framework helped to focus on important outcomes for implementation research at both the individual (recipient/use) and the organisation/system level (agents of delivery). The specific aspects of the RE-AIM framework are explained in the following paragraphs, along with the types of data gathered in this study for each of these aspects, which are presented across the findings chapters (see Chapters 4–6 and 9).

Reach

Reach refers to the absolute number, proportion and representativeness of the target population that is touched by the intervention. In this study, reach was assessed by exploring whether or not the increased service capacity resulted in or could lead to changes in the target population (e.g. reaching those with mild to moderate POP, the number of referrals from various sources and increased accessibility of PFMT in local areas). Reach was assessed using both qualitative and quantitative data.

Effectiveness

Effectiveness refers to the impact of an intervention on important outcomes. In the context of this study, effectiveness was explored both quantitatively (i.e. whether or not the different models of PFMT service delivery remained effective when compared with the outcomes from the original POPPY trial) and qualitatively (i.e. the experience of improvement reported by women and staff delivering PFMT and the experience of quality of care reported by women).

Adoption

Adoption refers to the willingness by the target settings, institutions and staff to implement, support and embed the intervention into their routine practice. In this study, adoption was assessed by the extent of uptake of PFMT by staff, the continued participation (or dropout) in the delivery of PFMT and the level of support provided by services and staff for the adoption of PFMT delivery.

Implementation

Implementation refers to the fidelity and consistency of intervention delivery as intended, and the cost of the intervention. In this study, implementation was monitored using the qualitative data on how the intervention was delivered locally and the extent to which it was implemented by the services as intended, as well as the quantitative data on the service delivery costs for different models of delivery.

Maintenance

Maintenance refers to the extent to which an intervention becomes institutionalised or part of the organisational practices/policies. At individual level, it refers to long-term outcomes of the intervention. In this study, the maintenance of intervention effects in individuals and settings over time was monitored via the outcomes data and the record linkage-based follow-up of the original POPPY trial participants, who were based in Scotland. It was also assessed through qualitative data on the future plans of study sites to continue the intervention and to train more staff in PFMT delivery.

Design

This study included the following components.

Realist evaluation

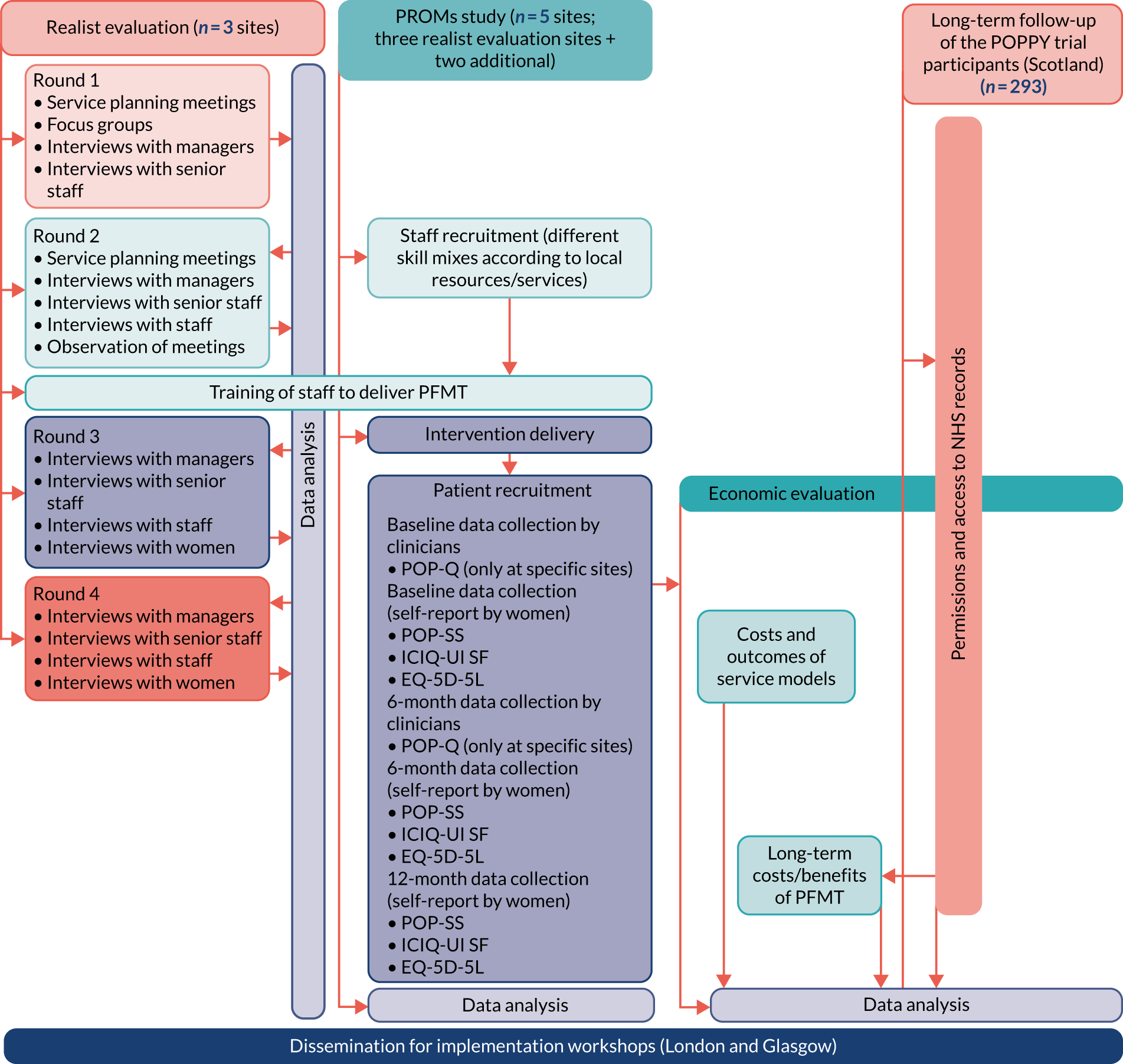

A realist evaluation was carried out that used case studies of implementation of PFMT delivery in three varying NHS settings (see Chapters 4 and 5). The realist evaluation allowed for substantial local stakeholder engagement and for local sites to make decisions on how to deliver PFMT [e.g. using different skill mixes such as specialist physiotherapists, women’s health nurses and junior (band 5) physiotherapists, as well as different numbers of sessions] (Figure 1). The realist evaluation would elicit local folk theories around how implementation was supposed to work [context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configurations], track how implementation was working (including fidelity to the PFMT protocol) and lead to an understanding of what influenced outcomes.

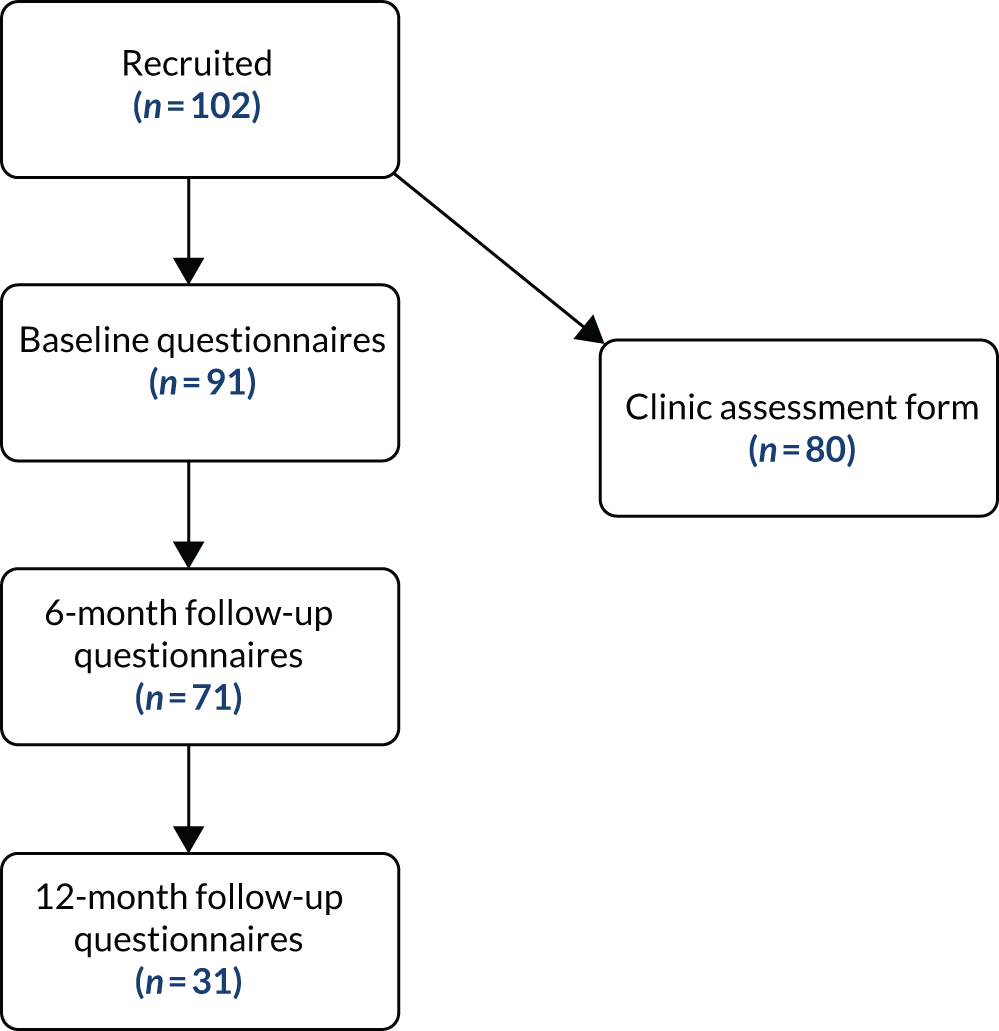

FIGURE 1.

The PROPEL intervention flow chart. EQ-5D-5L, EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version; ICIQ-UI SF, International Consultation on Incontinence Questionnaire – Urinary Incontinence Short Form; POP-Q, Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification; POP-SS, Pelvic Organ Prolapse Symptom Score; PROM, patient-reported outcome measure; PROPEL, PROlapse and Pelvic floor muscle training: implementing Evidence Locally. Reproduced from Maxwell et al. 15 This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. This figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Patient-reported outcome measures study

A robust patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) study, which used the same outcome measures as the original POPPY trial, was conducted in five NHS sites (three case study sites plus two additional sites, see Figure 1) to observe the outcomes for women receiving the different models of care (see Chapter 6). It was intended that, in the skill mix of staff across sites, there would be a mix of specialist physiotherapists, other physiotherapists and different types of nursing roles. It was also intended that the skill mix of staff would allow for a comparison of the specialist-delivered outcomes with the non-specialist-delivered outcomes. This would also allow comparison of the delivery of PFMT by specialist physiotherapists in the everyday world of the NHS with those observed in trial conditions.

Longer-term follow-up

Longer-term follow-up of up to 6 years of the original POPPY trial participants was carried out using record linkage of hospital and outpatient data [provided by Information Services Division Scotland via the NHS electronic Data Research and Innovation Service (eDRIS) (see Chapter 7).

Economic evaluation

An economic evaluation was carried out, which was concerned with the associated costs and outcomes of different service delivery models for delivering PFMT. In addition, an economic assessment of the long-term costs associated with accessing further pelvic prolapse treatment over time was conducted for the original POPPY trial participants, who were resident in Scotland (Chapter 8).

The applicability of study findings and outcomes

Finally, ‘dissemination and implementation workshops’ (in England and Scotland) were run to discuss the applicability of study findings and outcomes with service managers/women’s HCPs/general practitioner (GP)/patient and public representatives from across the country, with discussion of implications for planning of local services and identification of any further key barriers to or facilitators of change (see Chapter 9).

Intervention description

The PROlapse and Pelvic floor muscle training: implementing Evidence Locally (PROPEL) intervention that was being evaluated in this study is fully described using the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) checklist (see Appendix 1). 16 Participants attended an initial assessment and treatment visit with a PROPEL intervention clinician to determine their personalised PFMT protocol, and the patient was provided with any additional lifestyle information deemed necessary to assist with their treatment. Further appointments were scheduled at the patient’s and clinician’s discretion; the sessions progressed using the PFMT protocol until the clinician or patient decided that no further appointments were required, at which point the patient was discharged from the service. Alternatively, if it became apparent that the patient’s condition was more complex than initially thought, the clinician had the choice to refer the patient to specialist physiotherapy. During each appointment, clinicians completed a clinician assessment form to record all information.

Training to deliver pelvic floor muscle training

Staff who were identified in round 2 of the realist evaluation as potential staff to deliver the PROPEL intervention were approached by either specialist physiotherapists or a consultant within their trust. The staff who were to deliver the PROPEL intervention attended a 1-day training session held within their site. The training session was developed specifically for the PROPEL intervention and in conjunction with the POGP. It was delivered by two POGP-registered specialist physiotherapist trainers to a maximum of five new staff per site. In addition, a member of the research team was present at all training sessions to ensure that all questions regarding study specifics could be answered. Training manuals were produced and provided to the participants. Further details on the training are provided in Appendix 2.

Patient and public involvement

The Bladder and Bowel Foundation (BBF) (Kettering, UK) was an initial partner in this research and a co-applicant that contributed to the study design and provided expertise concerning the involvement in this study of women with prolapse. The BBF specifically provided input to the discussions on the delivery options women may receive, on the issues of recruitment of women and on the feasibility of patient data collection processes. They also provided members’ views of their experiences of health care and how they would value opportunities for PFMT, and the likelihood of its acceptability to women with POP.

However, the intention that the BBF would continue to be represented throughout the conduct of this study as a full partner and member of the project management team was not realised, because the BBF ceased to exist just at the point of the PROPEL intervention commencing. We then worked to identify another organisation that could step in to fulfil the role of the BBF. On the advice of our Study Steering Committee (SSC) we approached PromoCon (Worsley, UK), which later became Bladder and Bowel UK, as an organisation that represented people with bowel and bladder problems, and PromoCon agreed to become a part of the PROPEL intervention team. However, the process of understanding the organisational commitment and who would be able to take on the lead role within the PROPEL intervention from within PromoCon was confounded by the organisation’s own impending changes and its move to forming Bladder and Bowel UK. Therefore, it took some time within the PROPEL intervention to secure the support of another patient and public involvement (PPI) organisation; this had an impact on our ability to recruit individual women with experience of POP to sit on our project management group (PMG) and our SSC.

With the help of Bladder and Bowel UK, we finally recruited two PPI representatives: one became part of the PMG and the other joined the SSC. We continued to try and recruit further PPI representatives well into the 2 years after the study initially began, but without any further success. However, the two women recruited to the PMG and the SSC remained with the study to the end and contributed greatly to our meetings and how we communicated with both women and HCPs.

Although our PPI representatives were not actively involved in data collection or analysis tasks, they did provide input to project management, commenting on project documentation and reports to the funder, but, specifically, they were extremely valuable in discussing local site problems. There were difficulties in getting sites up and running and there were issues concerning staff attrition rates (mainly as a result of illness or retirement), which all affected the ability of sites to recruit sufficient numbers of women. Our PPI representatives were sympathetic to these issues, but also offered insight and sometimes solutions, such as contacting other local women’s groups to raise awareness of the study.

Our PPI representatives had always been intended to support dissemination of these findings to lay audiences and were included as key participants in our proposed dissemination and implementation workshops, which were intended, for example, for NHS managers, service leads, urogynaecologists, and physiotherapists with a remit for POP. One of our PPI partners attended two workshop events (London and Glasgow) and was a powerful voice not only in the telling of her own experiences, but also in encouraging managers and HCPs to take the PROPEL intervention findings on board and act on them. The feedback from the dissemination events overwhelmingly rated the contribution of the PPI representative as ‘excellent’.

We will continue to work with our PPI representatives in producing further outputs for lay audiences and will also disseminate these via Bladder and Bowel UK.

The experiences of our PPI representatives of working with the PROPEL intervention are described as follows:

I welcomed the opportunity, my first, to be involved as PPI representative in this project.

In my view anything that reduces the number of women having to undergo surgery can only be good for patients. Having increased numbers of skilled staff and reducing the costs involved in surgery would also be of benefit for NHS trusts.

I did find it difficult to offer any specific input to the project, particularly latterly when I was less able to attend meetings. I found the experience interesting and would certainly participate as PPI in the future.

PPI representative 1 (PMG)

I feel very privileged to have been a PPI on this study as the subject matter is very relevant to my patient experience within the NHS. I work within the NHS (in an unrelated field) so have (a little) understanding of the difficulties faced on a daily basis with staffing and funding issues. But more importantly I have years of patient experience and know how difficult I personally found it to access women’s health physiotherapy in my area. Hence, I appreciated being involved in a study that could not only improve patient outcome, but look at the implementation aspect of providing an NHS service.

Having never been involved in a research project before, I found the team supportive, friendly and above all willing to listen. It is sometimes difficult partake in discussions when you are not experienced or qualified in the field, but I felt that the patient voice was heard. I feel my experience with administrating an online support group for women with pelvic pain and prolapse helped with my ability to voice the patient point of view.

My highlight was speaking about my patient experience at the dissemination meetings. It was well received and I felt it emphasised why the research was undertaken and what a difference it could make to patient outcomes. It was fantastic to hear of the success of the project and that physiotherapy works in terms of patient improvement and cost savings. I look forward to being involved in the next study. Thanks to the PROPEL team for all their hard work.

PPI representative 2 (SSC)

Chapter 3 Description of case study sites and implementation of training

Introduction

The PROPEL intervention initially aimed to include three diverse sites across the UK in which to develop new models of PFMT service delivery. These three sites, A, B and C, had been identified during the funding application process and were keen to be involved in the study from this stage. It became apparent during the recruitment of women to the PROMs study and from the delays in sites to implement the new models that we would find it difficult to reach our recruitment target through these three original sites. Through one of our co-applicants who had previously been on the executive committee of the POGP, we sent out an invitation to around 20 women’s health services throughout Scotland and England. We had a number of positive responses, which resulted in the recruitment of two further ‘light-touch’ sites to the study. By this stage in the study, round 1 of data collection for the realist evaluation had been completed in sites A, B and C and the decision was made, with the agreement of the PMG, not to include these two new sites in the full realist evaluation, but to gain some reflection on their experiences of setting up and delivering PFMT in their regions. This decision was made to avoid further delays in recruiting women to the PROMs study and to maximise follow-up of women, while at the same time adding to our knowledge of ‘what works’ for implementation.

Overview of sites

Site A

This site had two components for delivering PFMT to women with prolapse in a secondary care setting:

-

community continence service

-

two hospital-based women’s physiotherapy services.

In both settings, the teams delivering PFMT were composed of band 7 [Agenda for Change (AfC)] and band 6 (AfC) specialist WHPs. Service planning meetings (SPMs) were held with the community and hospital teams separately, as they functioned under different management. Clinicians from these three teams had previously taken part in the POPPY trial.

Community

Initially, the community lead indicated that there was a need for an increase in capacity and was keen for continence nurses to be involved and be trained to deliver the PROPEL intervention. In addition, the community lead had indicated that they wanted to use group sessions for women with prolapse to educate them about PFMT before they were referred on for one-to-one treatment. After discussion with the team, it emerged that there was strong resistance to clinical groups other than physiotherapists being trained to deliver PFMT. In addition, not all of the physiotherapists in the team felt that they had the capacity to take part in the PROPEL intervention. Ultimately, two physiotherapists from the community agreed to participate.

Hospital

At the first SPM, the lead of the hospital service indicated that their preference was to not change their model of PFMT service delivery, citing staff shortages. After discussion among the core research team, the decision was made that we would use this as an opportunity. A total of nine specialist WHPs were recruited from the two hospital-based teams to deliver the PROPEL PFMT intervention to women with prolapse. This meant that they could continue with their normal service while the research team were able to collect data on the outcomes of PFMT, as delivered by specialist WHPs in a real NHS setting outside the constraints of a trial setting. It was agreed that they would continue to deliver the same specialist service to women recruited to the PROPEL intervention, including any adjunct therapies that they would prescribe normally. Nine specialist WHPs took part in the study, initially to recruit women to the focus groups in round 1 of the realist evaluation with a view to deliver PFMT through the PROPEL intervention in the two hospital teams. Six months into the project, the service lead approached the research team with fears that, because of further staff shortages, they were unsure if they would be able to continue to be involved in the PROPEL intervention. A number of meetings followed during which the research team provided the site with options that would enable them to continue their involvement in the PROPEL intervention, in a decreased capacity if necessary. This resulted in the loss of one of the hospital-based teams’ participation and a reduction in members of the team taking part in the remaining team.

At the end of the service planning process at this site, it was confirmed that five specialist WHPs from the hospital team and two from the community team would take part in the PROPEL intervention. The benefit of using this model of service delivery were twofold. First, we would be able to see if the outcomes obtained by specialist physiotherapists in the PROPEL intervention were comparable with those seen in the POPPY trial. Second, this specialist model provided us with a comparison group, similar to that in the POPPY trial, to use as a benchmark for the outcomes achieved by other clinician groups recruited and trained across the other four study sites.

Site B

Site B was a rural site with a large geographical area and an existing model of PFMT service delivery by a small number of specialist WHPs in hospital settings. Owing to the large area that this service was required to cover, they had concerns around the capacity of the existing service and the accessibility of this service to women. It was these issues that had led them to become involved in the PROPEL intervention at the outset.

From the outset, the central research team and the local principal investigator (PI) had difficulties engaging key managerial stakeholders in the service planning process. This was, in part, attributed to major changes taking place in the urogynaecology service locally in both a physical and organisational capacity. SPMs took the form of a more bottom-up approach to planning the new model of service delivery, with one specialist WHP leading the development process for the model that would be used in the PROPEL intervention. The local PI was very motivated and had previously been involved in providing additional training in this area with clinicians who had a special interest in this area of service delivery. Like site A, the service planning took longer than anticipated; consequently, there were delays in recruiting women to the realist evaluation and the PROMs study. There was significant discussion about which clinicians would be trained to deliver the PROPEL intervention. During discussion with the SSC about the groups of clinicians who were being trained to deliver the PROPEL intervention, we were advised that sites A–E set up a triage step within their referral process for potential PROPEL intervention participants. In site B, this meant that all women referred with POP received an initial assessment, which was carried out by a specialist WHP who identified if the woman met the inclusion criteria for the study. Only at that point were women approached about participating in the study.

This site had the most diverse clinical mix taking part in the study: district nurses, continence lead nurse specialists, musculoskeletal and general physiotherapists and urogynaecology nurses. The mix in the staff who were trained meant that the point of delivery of the new model of service was also a lot more diverse and was much more accessible for the women receiving this intervention. The large number of clinicians trained at this site and their diverse roles resulted in the point of delivery of PFMT services moving from a hospital to a community-based setting in many cases. It also meant that women who consented to take part in the PROPEL intervention could receive their treatment closer to home, as the clinicians trained for the PROPEL intervention were located across a variety of places in this site. Eight clinicians were trained to deliver the PROPEL intervention.

Site C

This urban site previously delivered limited PFMT services through a small number of specialist WHPs in a hospital setting. Similar to site B, this site was interested in moving these services to a community-based setting so that they were more accessible. At the initial SPM, which was the best-attended meeting at this site, it was highlighted that a community-based urinary continence team, which included physiotherapists and band 6 and 7 (AfC) nurses, was the preferred model of PROPEL PFMT intervention service delivery. The lead of this team indicated at this meeting that they would have to take this proposal to their management before this could be taken forward; however, they were keen to see this happen. One week following this meeting, the research team were informed by the site’s research and development department that the proposed community continence team were currently involved in another research project and would not have the capacity to take part in the PROPEL intervention alongside this existing project. It was agreed that further possible models of service delivery would be discussed at the next scheduled SPM.

The next SPM was poorly attended; despite this, further possible models of service delivery were discussed, which still focused on having a community-based element to the PROPEL PFMT intervention service delivery. SPM attendees identified community-based physiotherapists, who were not part of the continence team, as possible participants. They also discussed the possibility of training a number of urogynaecology nurses who were based in the hospital, to supplement the community physiotherapists. Following this meeting, the research team received interest directly from a number of these physiotherapists. Unfortunately, these physiotherapists did not have the support of their managers and were therefore unable to take this model of service delivery forward.

At this stage in the planning process, the research team flagged up the issues around the slow progress in setting up a new model of PFMT delivery to the independent SSC in this site. It was decided that this site would need to be given a deadline to have identified the clinicians who would be taking part in the PROPEL intervention, so that this site could be taken forward without causing catastrophic delays to the study. Finally, the decision was made locally that, despite wanting to set up a community service, this would not be possible at that time; instead, it was decided to follow up with a model using urogynaecology nurses based in the hospital to deliver the new service delivery model. Three nurses agreed to be trained to take part in the PROPEL intervention.

Sites D and E

Each of these were urban sites with a wide socioeconomic spread. As discussed previously, these sites were recruited as ‘light-touch’ sites to be involved in the women’s PROMs study only and not in the realist evaluation. The result of not having to go through the data collection process around the service planning for new models of service delivery was that these sites were set up more quickly and started recruiting only shortly after the original three sites. Site D implemented a model of service delivery that was made up of four band 6 and 7 (AfC) musculoskeletal physiotherapists. Site E implemented a model of service delivery that was made up of two band 5 (AfC) nurses and two physiotherapists: one band 5 and one band 6 (AfC).

Womens’ input into service planning for the PROPEL intervention

The women’s focus group data that were collected in round 1 of data collection for the realist evaluation were summarised and fed back at a SPM at each of the sites. The focus group study was designed so that each site had data on the issues that were important to women currently using these services; this included topics around awareness of women in the existing service, referral pathways and treatment received. These data were collected and fed back to sites so that the views of women could be considered in the process of designing a new model of delivering PFMT to women in the PROPEL intervention.

Overall, 26 clinicians were initially trained to deliver the PROPEL intervention (Table 1). In total, six of these withdrew from the study prior to treating any women using the PROPEL intervention protocol. They cited a number of reasons for this, including injury, lack of confidence, lack of capacity, organisational issues and moving away from their current post.

| Site | Service context | Service model adopted | Skill mix trained |

|---|---|---|---|

| A | Urban, POPPY site | No change. Existing primary and secondary care provision of specialist physiotherapy. Referrals triaged | Specialist physiotherapists (existing team):

|

| B | Rural | The PROPEL intervention PFMT training was provided to a variety of clinicians over a large geographical area. This included clinicians with special interest, district nurses, continence nurses and physiotherapists. The PROPEL intervention women were triaged by specialist physiotherapists prior to referral to the PROPEL intervention service. Community based and secondary care based |

Musculoskeletal physiotherapists, band 6 (n = 2) General physiotherapist, band 6 (n = 1) District nurses (n = 2) Lead nurse specialist in continence, band 6 (n = 1) Urogynaecology (n = 2) |

| C | Urban | New provision of PFMT delivery developed for the PROPEL intervention based in secondary care. Consultant triaged and referred to the PROPEL intervention service provided by urogynacology nurses | Urogynaecology nurses:

|

| D | Urban | Community health-care setting. Current PFMT service delivered by small number of specialist physiotherapists. Four clinicians to deliver the PROPEL intervention service in a community health-care setting | Musculoskeletal physiotherapist, 1 × band 5, 2 × band 6 and 1 × band 7 |

| E | Urban | Current PFMT service delivered by small number of specialist physiotherapists. Four trained clinicians to deliver the PROPEL intervention service in a community health-care setting |

Urogynaecology nurse (n = 2) Physiotherapists (band 5, n = 1 and band 6, n = 1) |

Training

Pelvic floor muscle training

Clinicians at sites B–E received the same standardised training as outlined in Appendix 2; assessors at these sessions completed a checklist to verify the completion of aspects of the training, using the checklist in Appendix 3. As the staff identified in site A were already fully trained specialist WHPs, they were not required to undertake this training. Instead, these clinicians undertook a training session with members of the PROPEL intervention research team, which focused on the paperwork that they would be required to complete during the treatment of women recruited locally to the study. These staff were also given copies of the self-report questionnaires that the women would be receiving, so that they were familiar with what women in the study would be asked to complete.

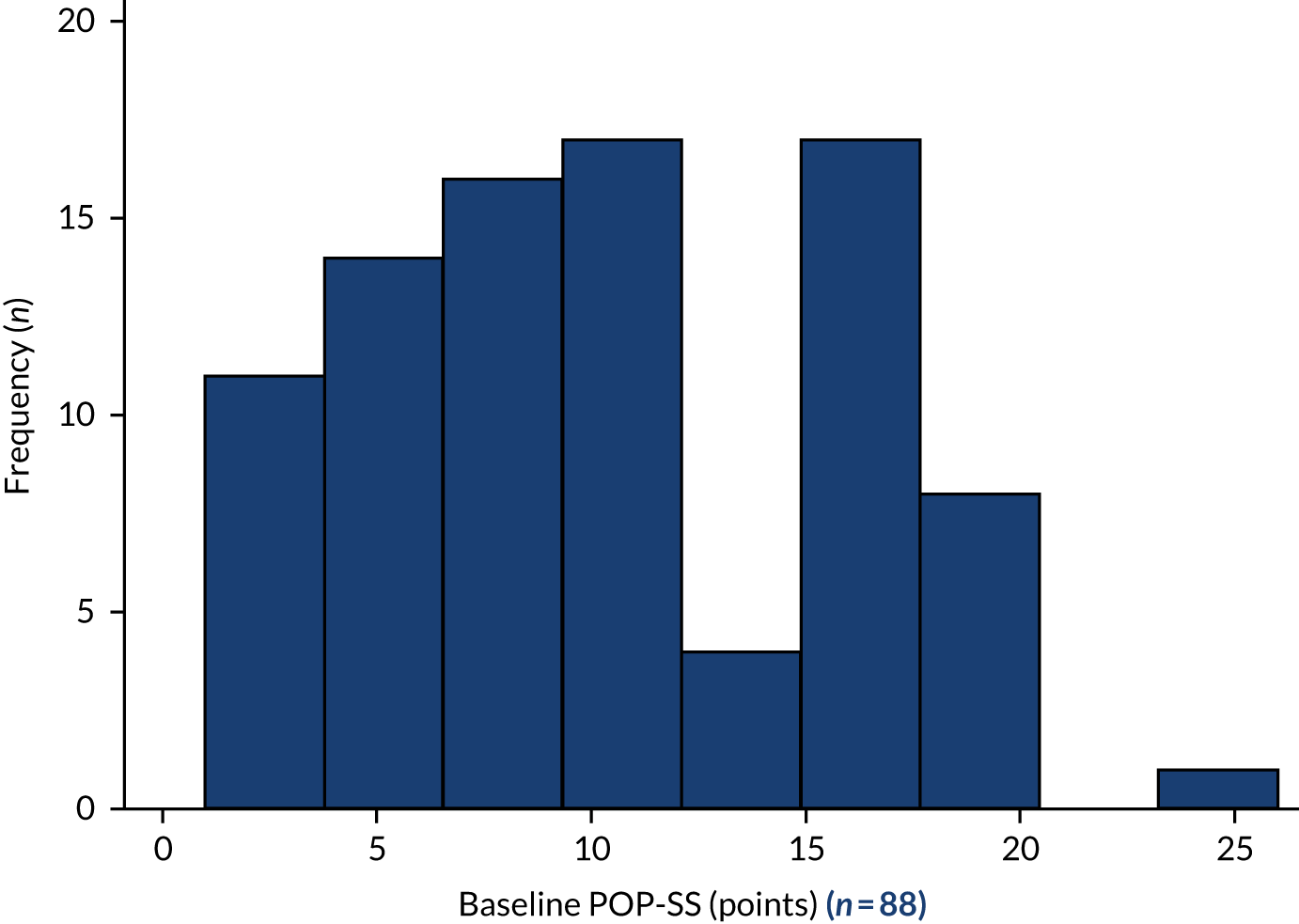

Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification System training

Although the Pelvic Organ Prolapse Quantification System (POP-Q) is a validated research tool for objectively measuring the stage of prolapse in women, it is not a measure that is commonly used in the clinical setting (see Appendix 4). 18,19 As seen in Chapter 2, Design, and Figure 1, it was planned to carry out the POP-Q assessment at baseline and at the 6-month follow-up for each woman recruited to the PROMs study. It quickly became apparent from meetings with the staff who would be delivering PFMT locally that the POP-Q assessment was not a commonly used clinical measure, even among the specialist WHPs.

In site A, the POP-Q training was delivered to the staff delivering the PROPEL intervention by a consultant urogynacologist who was working in this site. Each clinician taking part in the PROPEL intervention was given the option of completing a simplified POP-Q staging assessment or a full POP-Q assessment on women at baseline when they attended their first appointment, and again 6 months after a woman began her treatment (see Appendix 5).

The specialist WHPs in site B who were involved in triaging women for the PROPEL intervention were provided with similar training from a urogynaecologist working in another specialist women’s health centre. After this training had been completed, all POP-Q assessments at this site were carried out by a band 7 (AfC) specialist WHP at the time of a woman’s triage appointment. On completion of their PFMT treatment by the newly trained clinicians, women then attended an extra appointment with the band 7 specialist WHP, who completed their follow-up POP-Q assessment. Owing to the geographical area and the constraints that this imposed on the specialist physiotherapists, only a proportion of the women recruited to the PROPEL intervention at this site received these baseline and follow-up POP-Q assessments.

Similarly in site C, it was the consultant gynaecologist who undertook the baseline and follow-up POP-Q assessments with women, rather than the newly trained urogynaecology nurses. They were, therefore, well placed to complete the POP-Q baseline assessment at the triage stage. For their follow-up POP-Q assessment, women were invited to come back in for an additional appointment with the consultant after completion of their PFMT treatment.

The POP-Q was a secondary outcome measure. Owing to the difficulties and time delays the research team encountered in organising the POP-Q training for clinicians, in both sites A and B, the decision was made by the PMG [and ratified by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)] that we would not carry out the POP-Q assessments on the women recruited in the two light-touch sites. The delays between clinicians receiving the PFMT intervention training and the recruitment of women were 4, 2.5 and 4 months in sites A, B and C, respectively. These delays were incurred as a result of these three sites requiring training to carry out the POP-Q assessments.

Chapter 4 Realist evaluation methods

Parts of this chapter are adapted with permission from Abhyankar et al. 17 This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Realist evaluation approach

Realist evaluation belongs to the family of theory-based evaluation approaches. Theory-based evaluations aim to clarify the ‘intervention theory’, that is clarify how intervention activities are understood to cause or contribute to outcomes and impacts. Realist evaluation was used in this study to understand how the intervention was implemented in different study sites, what contextual factors influenced its implementation and what ‘mechanisms of action’ led to successful (or unsuccessful) delivery and outcomes.

Realist evaluation has emerged in response to the need for knowledge that extends beyond that obtained by the traditional outcome-focused evaluation approaches that ask the question – is the intervention effective? Realist evaluation is founded on the premise that interventions are complex and are introduced into social systems that are also complex. It maintains that no interventions are universally effective, but that some things work for some people in some contexts. Realist evaluation therefore asks what is it about the intervention that works, for whom, in what contexts and why. 20

Realist evaluation contends that it is not interventions that work; rather, it is the people involved in interventions who make them work. Interventions introduce opportunities, resources or ideas for change, but whether or not these actually lead to the intended outcomes depends on how people react to, interpret and act on these resources. It is people’s reasoning and capacity in response to the intervention elements that represent the real ‘mechanisms of action’ in any intervention. These mechanisms of action are, however, contingent on the social context in which people work. Certain contexts enable people to act, whereas others place limits on people’s behaviour. 21 Realist evaluation thus seeks to explain the complex relationship between the mechanisms activated by the intervention, the context that influences their workings and the intended and unintended outcomes they produce. The explanatory proposition of realist evaluation is that interventions work (have successful outcomes – O) only in so far as they introduce appropriate ideas and opportunities (mechanisms – M) to groups in the appropriate social and cultural conditions (contexts – C). The task of an evaluation is to identify the linked patterns of contexts, mechanisms and outcomes (CMO configurations) to explain how particular outcomes were brought about by certain mechanisms being triggered in certain contexts. 20

This study aimed to implement a complex intervention, the delivery of PFMT using different staff skill mixes, in complex NHS systems consisting of a number of actors, varying resources, diverse geographical locations and service configurations. The implementation also involved actions and decisions from people in multiple roles at different levels, for example from service managers and finance directors at organisational level to front-line staff delivering and supporting the PFMT intervention, as well as women receiving PFMT. Given the interplay of multiple factors operating in different personal or organisational contexts with different priorities and goals, realist evaluation provided an appropriate framework and methodology to explore and explain the implementation of PFMT.

Realist evaluation typically involves three broad phases. Phase 1 seeks to identify the ‘folk’ theories about how and why the intervention will bring about change. This involves eliciting ideas about how the intervention is expected to be implemented and work, what intended and unintended outcomes are likely, what may be their mechanisms of action and what contextual factors may enable or constrain these mechanisms. Data are gathered from those involved in the implementation of the intervention and its key stakeholders. These data are used to build hypotheses about the causal relationships between specific contexts, mechanisms and outcomes; these are known as the CMO configurations. Phase 2 involves testing these theories by gathering data on the actual implementation process; this unfolds the mechanisms and outcomes and impacting contexts. In the third and final phase, the intervention theories are refined through iterative data analyses and interpretation to provide middle-range theory statements about why and how the intervention worked, for whom and in what contexts.

Phases and methods of realist evaluation

The realist evaluation was conducted in three broad phases, using a longitudinal, multiple case study design. The five study sites described in Chapter 3 were considered as ‘cases’, although the full realist evaluation was conducted in three sites only. Cases were defined at the level of the NHS trust in England and NHS Health Board in Scotland, as these represent the units through which health services are organised, governed and delivered in local areas. Defining the ‘cases’ at the level of these broad units helped to ensure that the influence of contextual conditions at various levels (i.e. from financial, organisational and managerial level to clinician, practice and patient level) was encompassed in the evaluation.

Data collection

The three phases of the realist evaluation aimed to identify, test and refine a theory explaining how and why the PROPEL intervention worked (or not). It involved data collection at four time points over an 18-month implementation period. The methods used in each phase are outlined in the following sections. Table 2 presents the number and type of data sources collected in rounds 1 to 4.

| Round | SPMs | Managers/service leads | Senior clinicians | Staff delivering PFMT | Women |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Total, n = 12

|

Total, n = 5

|

Total, n = 2

|

No interviews in this round |

Total, n = 21 Focus groups, n = 17Interviews, n = 4 (all in site C) |

| 2 | Total, n = 26

|

Total = 6

|

Total = 3

|

Total = 11

|

No interviews in this round |

| 3 | N/A | Total, n = 10

|

Total, n = 4

|

Total, n = 10

|

Total, n = 18

|

| 4 | N/A | Total, n = 5

|

Total, n = 2

|

Total, n = 18

|

Total, n = 15

|

Phase 1: identifying folk theories of change

Phase 1 took place during the planning stages of the intervention through two rounds of data collection and aimed (1) to track local decisions on what to implement and how, rationales for service delivery decision-making and ideas about how implementation is supposed to work and (2) to elicit folk theories of change from the implementers and key stakeholders of the intervention about how the intervention was intended to be implemented and work in their areas, for example the likely outcomes of the intervention, possible mechanisms of action and potential contextual influences.

Rounds 1 and 2: development and operationalisation of the service delivery models

Focus groups with women who were receiving care for prolapse in each study site were conducted in round 1, to provide service user input to the local SPMs, where the models for PFMT service delivery were discussed and decided on. The focus groups explored women’s experiences of prolapse and treatments, their experiences of local services and care, their preferences for service delivery models, acceptability of PFMT and their visions for a responsive and woman-centred service. Women aged ≥ 18 years who were seeking and receiving care for prolapse through the local gynaecology/women’s health service in each site were eligible to take part. Women were identified and recruited by either the specialist pelvic floor dysfunction physiotherapists/WHPs or the consultant gynaecologists/urogynaecologists in local sites. The initial plan was to hold four focus groups across the three sites (one site would host two focus groups because of the large geographical size of the service area), with a minimum of four and a maximum of 10 participants per focus group. However, participant availability prevented a focus group being held in one location (site C), because of the geographical location and the inability of participants to travel. Instead, four individual telephone interviews were conducted with consenting participants in that area, using the same topic guide as for the three focus groups. The combined use of focus groups and individual interviews for pragmatic reasons may have lowered the homogeneity in the data collection process, with a potential threat to the trustworthiness of findings. 22 However, the absence of any observed differences in the type of data collected by each method and the convergence of key themes across the two methods suggests enhanced trustworthiness of findings. 23

Focus groups were conducted in private rooms at local hospitals and were facilitated by two researchers. The focus groups each lasted approximately 1 hour and involved four, five and nine participants. The telephone interviews lasted approximately 20–30 minutes. Focus groups and interviews were recorded digitally, transcribed verbatim and summarised by the research team. The summaries were presented at the SPMs to enable inclusion of service user voice into the decisions about service design.

The liaison specialist physiotherapist in each site identified and invited local service managers, clinical leads, consultants and other relevant staff groups to attend a series of SPMs. The first SPM was convened in round 1, and aimed to familiarise the attendees with the evidence base for PFMT and discuss its potential benefit for local management of POP. Members of the research team attended this meeting to explain and reinforce study aims. The planning team then discussed the current service provision and the local capacity issues, as well as how these might be addressed with the available or an extended staff pool. Initial options for service delivery models were discussed with ‘actions’ for any fact-finding, involvement of others or other actions necessary to help finalise decisions about service models.

A second SPM was convened in round 2 by study sites to finalise the service delivery model to be implemented, plan the operationalisation of the new model within current service structures and identify staff groups for training in PFMT delivery. The meeting involved the same attendees as the first meeting, plus any new members as deemed appropriate by the local service. Members of the research team attended this meeting to ensure that study aims and objectives were met and to observe the decision and planning process. Both meetings were audio-recorded to track the decisions being made as well as the folk theories around how implementation is supposed to work, what may be the likely outcomes and what contextual factors may impede or facilitate the implementation. The decisions were finalised over two planning meetings in sites A and B and three meetings in site C.

Two rounds of individual semistructured interviews were conducted with a number of stakeholders in each site to identify local theories of change. Service leads or managers and senior practitioners (urogynaecology consultants/senior nurses or allied health-care professionals/GPs) who were likely to be key decision-makers were identified from the SPM attendees and invited to take part in round 1 and 2 interviews. Further interviewees were identified using a snowballing technique. The interviews were conducted by a member of the research team, either face to face or via telephone, and were facilitated by topic guides developed specifically for the purpose of the interview round. Round 1 interviews explored the contextual detail about the site (e.g. how care is currently organised, gaps in the service and need for change, and proposals for changes in service delivery), anticipated barriers to and facilitators of implementation (e.g. resources, capacity issues, training, funding and buy-in from stakeholders), potential mechanisms (e.g. attitudes towards PFMT delivery by non-specialists and the challenges to implementation of different proposals) and anticipated outcomes. Round 2 interviews explored staff views about the operationalisation of the decisions about service delivery models, attitudes and reactions of various staff towards the new service model, how this will be translated to the staff groups identified for PFMT training and service delivery, the potential barriers to and facilitators of implementation of the new model, the involvement of and potential impact on other staff groups or services, and intended and unintended outcomes. The exception to this was site A, where the staff groups were interviewed only once, in round 2, as this site was not implementing any changes to its existing service models. The interviews in this site focused more on understanding how the current service was organised and working, what worked well and why and what areas needed improvement.

In round 2, additional interviews were also conducted, with the staff being asked about delivering PFMT under the new service model to explore their views on the new service model, their involvement in PFMT delivery, their expectations of training and the new role, their concerns and anticipated problems and how these might be overcome, and the anticipated impact on their professional role. In site A, which was not implementing any changes, these interviews focused on understanding how the service was delivered and working, what worked well and why, what needed improvement and what it was about their service and care that led to positive outcomes for women. Interviewees were identified from staff lists provided by local service leads. Interviews were conducted by members of the research team, either face to face or by telephone, and were facilitated by topic guides that were relevant to those staff groups.

Phase 2: testing the folk theories

The initial folk theories of change were tested by collecting data on contexts, mechanisms and outcomes at the operational level in each study site, to explore how the intervention was implemented and worked in different areas. This was carried out through two further rounds of data collection. Round 3 took place ‘during’ the implementation stages once staff had begun to deliver PFMT to women under the new service model, and focused on exploring how the new service model was operating and any problems that had arisen during implementation. Round 4 took place after the intervention period had ended, as dictated by the achievement of site-specific recruitment and treatment target, and focused on exploring whether or not the implementation was perceived to be successful, whether or not/how the intervention worked, what lessons were learnt from implementation and the plans for continuation of PFMT delivery locally. In this phase, data were also collected from staff in the light-touch sites D and E, to explore the implementation process, barriers, facilitators and outcomes in those areas.

Rounds 3 and 4: delivering and reviewing the models

Round 3 interviews with service leads/managers explored the process of referrals to newly trained staff, any anxieties or concerns around training and support, service delivery, local resources required for delivery and any perceived effect on women, staff and services. Round 4 interviews explored service leads’/managers’ perceptions of success of the models, the models’ sustainability, modifications that may be necessary, key drivers for success, areas and extent of perceived impact, and future plans for further expansion of services.

Round 3 interviews with consultants/senior nurses/allied HCPs/GPs explored their views on implementation and the perceived impact on other service areas. Round 4 interviews explored their views of the overall implementation and impact, key drivers for success and views on continuation or expansion of services.

Round 3 interviews with staff delivering PFMT explored their experiences and views of implementation, concerns regarding their role in its delivery, problems experienced in service delivery and perceived impact on factors such as women’s outcomes and their workload. Round 4 interviews explored their overall experience of delivering PFMT and the impact they felt that their role had for women and services, and key drivers of success.

Round 3 interviews with women receiving PFMT from the newly trained staff explored their expectations and experiences of PFMT treatment, experience of care, and perceived impact on symptoms and quality of life. Round 4 interviews explored their experience of the intervention, adherence to therapy appointments and the prescribed PFMT programme; perceptions of treatment, outcome and care; and intentions to continue with PFMT.

Interviews were conducted via telephone by a member of the research team and were guided by topic guides that were specific to the participant groups being interviewed.

Data analysis

Round 1 and 2 data analysis

Data from round 1 and 2 interviews and SPMs were transcribed verbatim and analysed using the thematic framework approach adapted for use in realist evaluations. 24,25 Data analysis proceeded in parallel with data collection. A coding frame was developed in round 1 using data from two transcripts (one from a service lead/manager and one from a senior practitioner), the summaries of the first SPM from sites B and C and the three core concepts from realist evaluation: CMO. Two members of the research team (PA and JW) read and reread the transcripts to familiarise themselves with the data. Data from the transcripts were sectioned into ‘meaningful units of analysis’, which were essentially segments of data containing discrete bits of information. Each unit was assigned a code that reflected the meaning of the data segment in relation to the main topics covered in the interviews, for example problems in service, current and potential enablers and barriers, and interim and long-term outcomes. The codes were initially assigned by two researchers independently, but were subsequently compared and refined until they accurately described the meaning contained.

Codes from the four transcripts and meeting summaries were then considered together to look for similarities, which were either merged into one or grouped together under higher-order themes. The codes were also classified as describing a context, a mechanism or an outcome. Codes describing any pre-existing factors outside the control of intervention designers, such as social or service structures, enabling or disabling conditions, resources, relationships, cultures, staff/service capacities and motivations, were categorised as contexts. Codes that suggested a change in people’s minds and actions (e.g. reasoning, feelings, behaviours, judgements, decisions and attitudes at individual, interpersonal, social and organisational levels) in response to the changes introduced by the implementation, as well as those described as interim outcomes of the intervention, were considered as mechanisms. Finally, codes that described the intended and unintended consequences of the intervention at the level of women, staff or services were classified as outcomes.

Following these classifications, an initial coding framework was developed that was then systematically applied by another researcher with experience in qualitative research to all of the transcripts from rounds 1 and 2. New codes were added as they emerged from subsequent data. Once all of the data had been coded, the content of the coding framework was revisited and refined. The coding framework was used to summarise the data for each study site to capture the site-specific processes of implementation and theories of change. Specifically, the coded data were used to identify linked patterns of CMOs and generate initial CMO configurations (i.e. hypotheses about what mechanisms would be triggered in each site, under what condition/contexts, to achieve what outcomes). Once the theories of change were identified for each site, these were compared across the sites to note similarities and differences. Although the sites differed in terms of macro-level contextual factors (e.g. geographic location, organisation of care and existing service models), a number of micro-level contextual factors were similar across the sites (e.g. staffing issues, support and buy-in from management and availability of resources). This meant that it was possible to look for patterns of CMOs that cut across the site boundaries. Cross-case comparisons were used to then identify an overall folk theory of how the intervention will work through different mechanisms being trigged in different contexts to generate diverse outcomes.

Round 3 and 4 data analysis

Data from rounds 3 and 4 were analysed using the thematic framework approach, similar to that described in phase 1. Briefly, a coding frame was developed using data from four round 3 transcripts (one from each participant group: service manager, senior practitioner, delivering staff and women, from across the three sites). Two researchers (PA and another researcher with experience in qualitative research) independently read and reread the transcripts and coded smaller segments of data. The codes were compared, discussed and refined until the meaning and content of each was agreed. The codes were then grouped into higher-order themes according to the similarities and relationships among them. They were also classified according to the concepts of CMOs, to explore how the different contexts influenced the implementation of the intervention, what mechanisms of actions were triggered and what outcomes were produced. Codes were classified as context if they described something that existed prior to the implementation or something that had developed/emerged/changed during the intervention, but was unrelated/not attributed to the intervention itself. Codes were classified as mechanisms if they described activities or actions taken by those implementing the intervention/touched by the intervention, including their thought processes, feelings, decisions and reactions. Codes were classified as outcomes if they described something that happened as a result of the intervention, whether intended or unintended and whether higher-level outcomes or indicators of higher-level outcomes. The initial coding frame was applied systematically to all data from rounds 3 and 4 (by TA), adding further codes or categories as they emerged from the data.

Once all of the data had been coded, the next step was to identify CMO patterns in the data. Initially, this process was carried out at the level of individual study sites to provide a ‘story of implementation’ by understanding the outcomes of implementation in each site, their underlying mechanisms of action and the contextual factors triggering those mechanisms. Data from each transcript were summarised and tabulated using a framework consisting of rows that indicated a data source and columns that indicated the CMOs. The data summaries were compared across the participants to develop overall CMO configurations for the site in the next phase of analysis.

The next phase of analysis focused on ‘testing’ the initial theories of change identified in phase 1 for their adequacy in explaining the observed CMO patterns. This involved explicitly comparing the observed CMO patterns (how and why the intervention actually worked or not) with the hypothesised CMO patterns (how and why it was expected to work). The analytical process was outcome led; that is, we began with the groups of outcomes that were anticipated in phase 1 folk theories to result from the intervention (e.g. women’s health outcomes, reach of intervention) and looked for evidence in the phase 2 data on how much or how well those outcomes were achieved in each site. An attempt was also made to map these outcomes to the elements of the RE-AIM framework to begin an assessment of the impact, adoption and sustainability of the intervention. We then sought to explain the observed outcomes in each site, by looking for the possible linked mechanisms and contextual factors that appeared to trigger those mechanisms. These constituted the site-specific CMO configurations.

Theory refinement

Phase 3: refining intervention theories

Once the site-specific CMOs were developed that explained when, why and for whom certain outcomes were achieved (or not), cross-case comparisons were performed to refine the CMOs and develop middle-range theories about the intervention. For each outcome, we compared and contrasted the CMO models emerging from all three sites, as well as the two light-touch sites. The analysis was carried out a higher level of abstraction, transcending the individual sites. The CMOs were refined by identifying the facilitating or impeding contextual factors that were common across the sites, and re-examining the linked mechanisms in relation to each outcome. This meant that a particular CMO was now able to explain the workings of the intervention in more than one site where the specific contextual factors were present.

Chapter 5 Findings of the realist evaluation

Parts of this chapter are adapted with permission from Abhyankar et al. 17 This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article's Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article's Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Phase 1: folk theories of change – how was the intervention expected to work?

In rounds 1 and 2, participants in each site described the wider context in which their service operated in, the current configuration of the service for prolapse care, the perceived gaps in service and the key drivers for change. This description was followed by an account of proposed service models and implementation plans, anticipated and unanticipated outcomes, explanations of how the intervention was expected to work and the existing and potential barriers and facilitators likely to affect implementation.

The PROPEL intervention introduced an opportunity to deliver PFMT using different staff skill mixes to a wider population of women with prolapse than that currently reached by specialist physiotherapy services. The PROPEL intervention provided an opportunity for sites to reconfigure local service and referral pathways, and supported provision of training in PFMT delivery to new staff skill mixes. The PROPEL intervention also provided some limited resources to support the new models of service delivery, such as specialist physiotherapist time to support those newly trained while they engaged in recruiting and delivering PFMT to the study population. Across the three sites, the intervention was expected to affect three key sets of outcomes: (1) have an impact on public health by way of widening the reach and accessibility of PFMT to the target group in local areas, (2) have an impact on women’s health by way of improvements in prolapse symptoms and quality of life and/or reduction in surgeries and (3) have an impact on services by way of shortened waiting lists for PFMT and a reduction in specialist workload, so that their resources can be focused on more complex cases.

The context and organisation of prolapse care varied significantly across the three sites. Several contextual factors were identified in round 1 and 2 data that seemed likely to influence the implementation of the intervention, which, in turn, would affect the achievement of anticipated outcomes. In the following section, we describe the context in each site before articulating the initial CMOs that emerged from data explaining how the intervention was likely to work and what factors were expected to facilitate or impede the implementation.

Context of care in study sites

Site A

Site A was a large urban area with primary and secondary provision of specialist physiotherapy services for women with prolapse. It was a previous participant in the POPPY trial, and several POPPY trial physiotherapists were providing input into prolapse care. The service had been well established for over a decade and offered PFMT to women with prolapse through specialist physiotherapists working in the acute and community settings. The staff expressed pride in the service, describing it as providing gold-standard care. The reasons for this were cited as:

-

all specialist physiotherapists being highly trained in PFMT for prolapse

-

having good working relationships and flow of communication with nurses, consultants, pain clinics and incontinence services

-

having a team approach to practice and respect for each other among different professionals

-

having adequate levels of staffing and resources to deliver the service.

Improvements were seen to be needed in raising awareness among GPs about prolapse and PFMT to enable direct referrals, in improving waiting times and referral pathways and in improving follow-up care. The team’s motivation for taking part in the study was to showcase their gold-standard service, rather than implement any changes.

Site B

Site B, in contrast to site A, had a large geographic spread in remote and rural areas with limited availability of specialist physiotherapy services. The incontinence service worked closely with the physiotherapy service, but was seen mainly as a ‘pad provision’ service that needed to become more holistic and proactive in assessing and treating urinary incontinence. Both services suffered from shortages of staff; specialist physiotherapists were few in number and the continence service lacked a clinical lead at the time of the study. The geographic spread of the area meant that the patients and staff had to travel long distances for care, which was compounded by shortages of staff. Despite the challenges, there were high levels of motivation among the staff; many had a special interest in women’s health and the service had a history of training musculoskeletal physiotherapists in delivering PFMT on a needs basis. Nurses and physiotherapists were enthusiastic about being trained in PFMT delivery and were supported and encouraged by their managers.

Site C

Site C was an urban area with limited specialist physiotherapy provision available for prolapse, where women were triaged by the urogynaecology consultants. There was said to be a lack of co-ordination between primary care and secondary care services with regards to incontinence and prolapse. There was enthusiasm about the PROPEL intervention among acute and community nurses, management and some consultants, and there was a perceived need for service redesign.

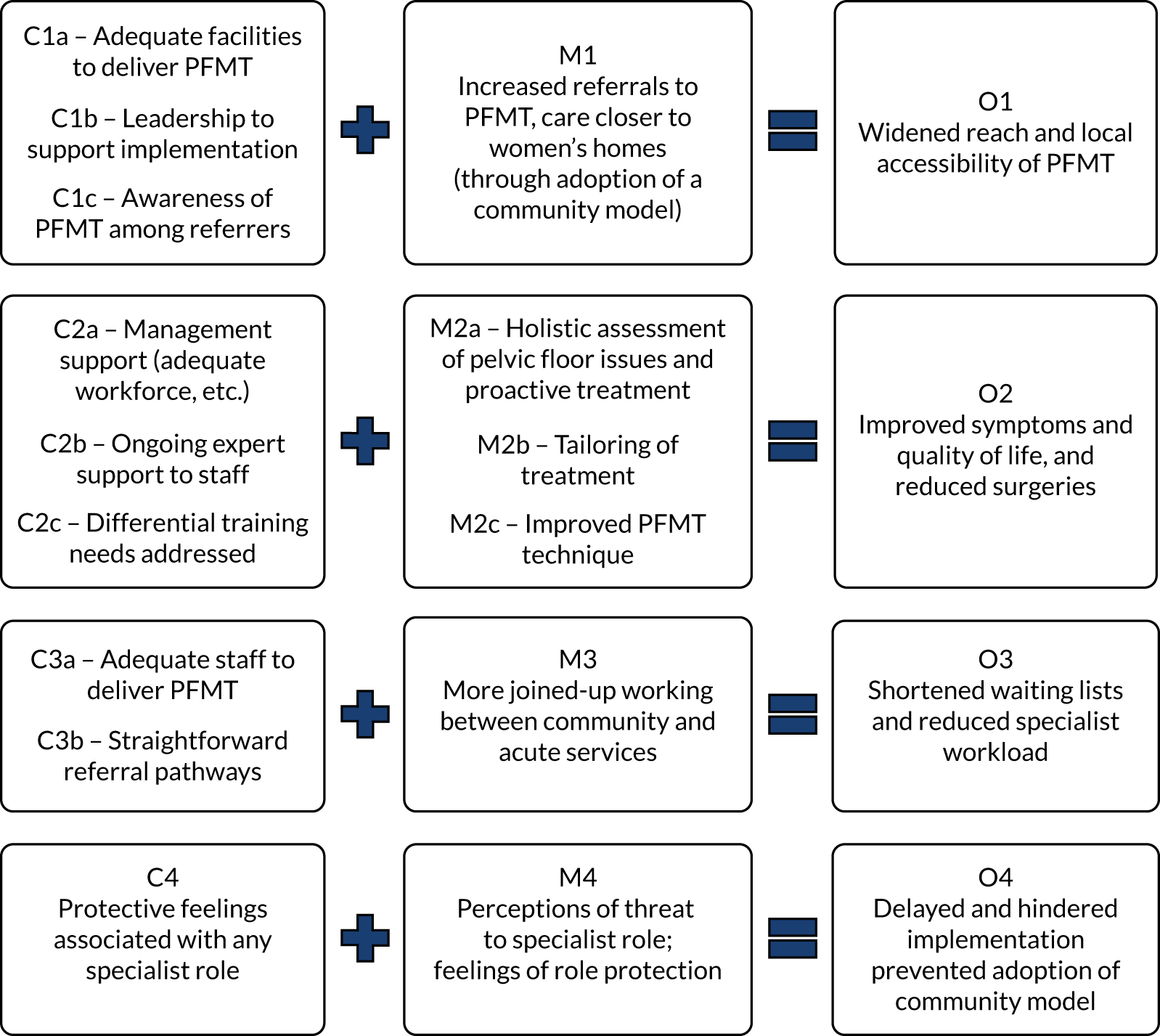

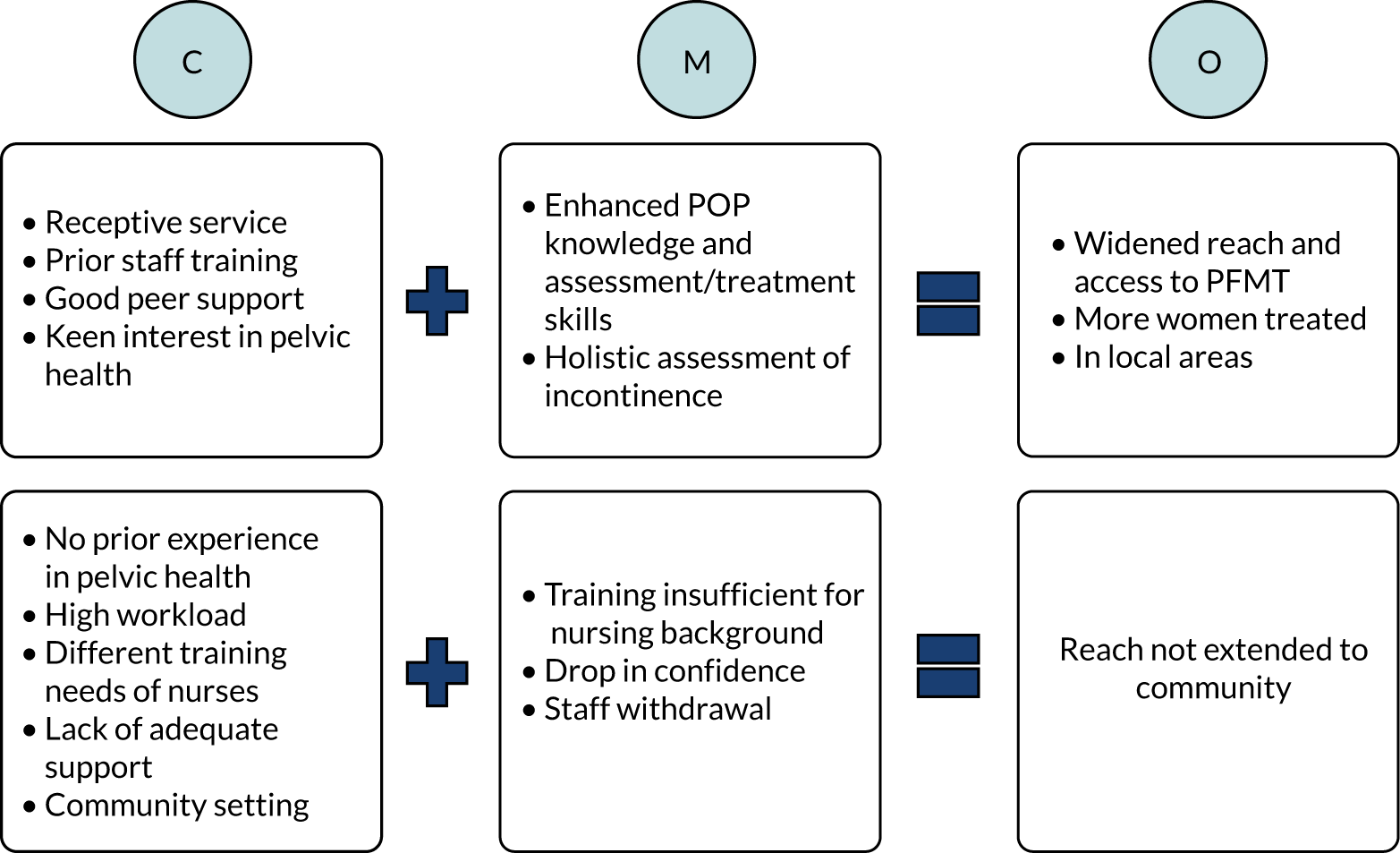

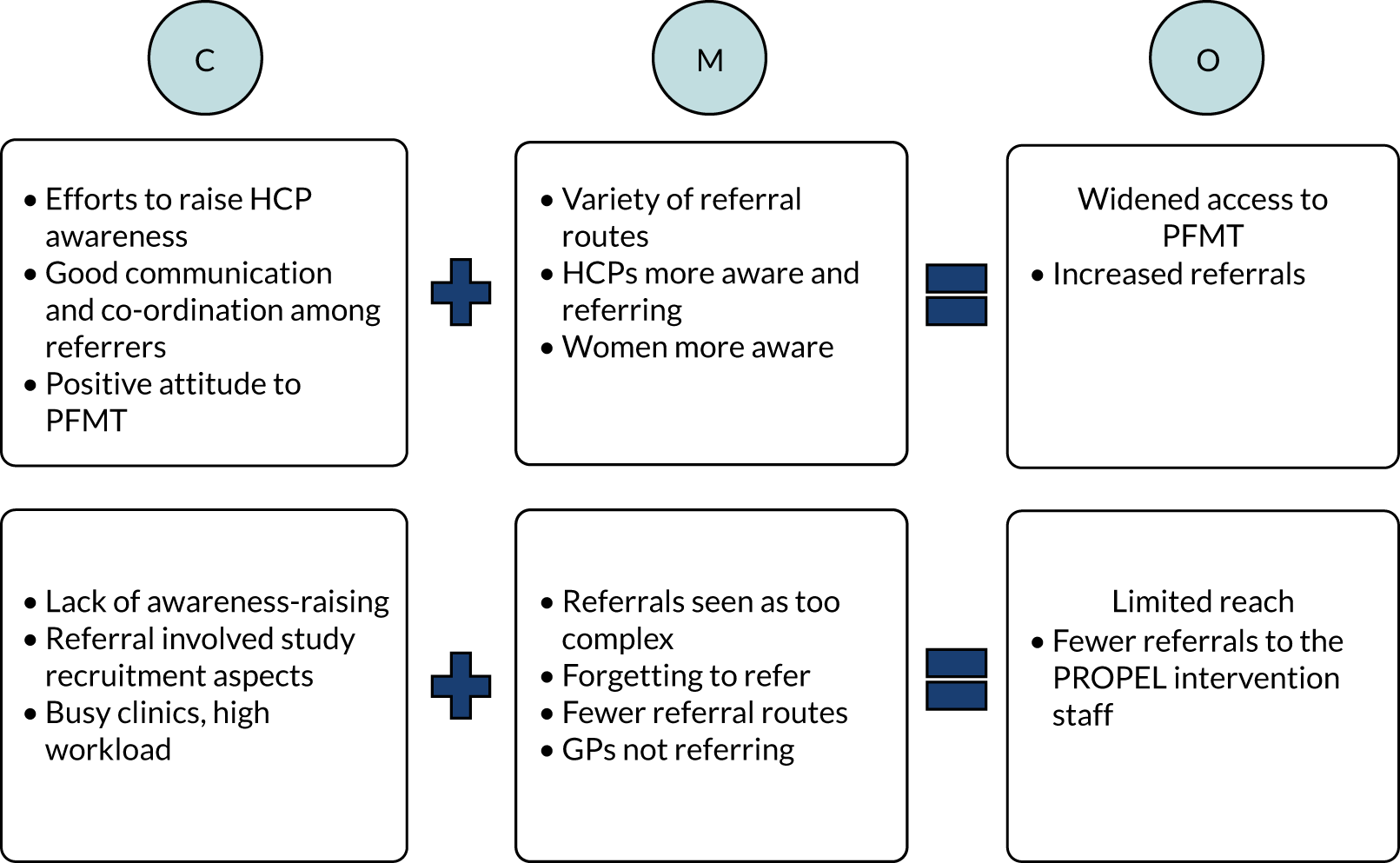

Theories about how the intervention would work, for whom and in what contexts

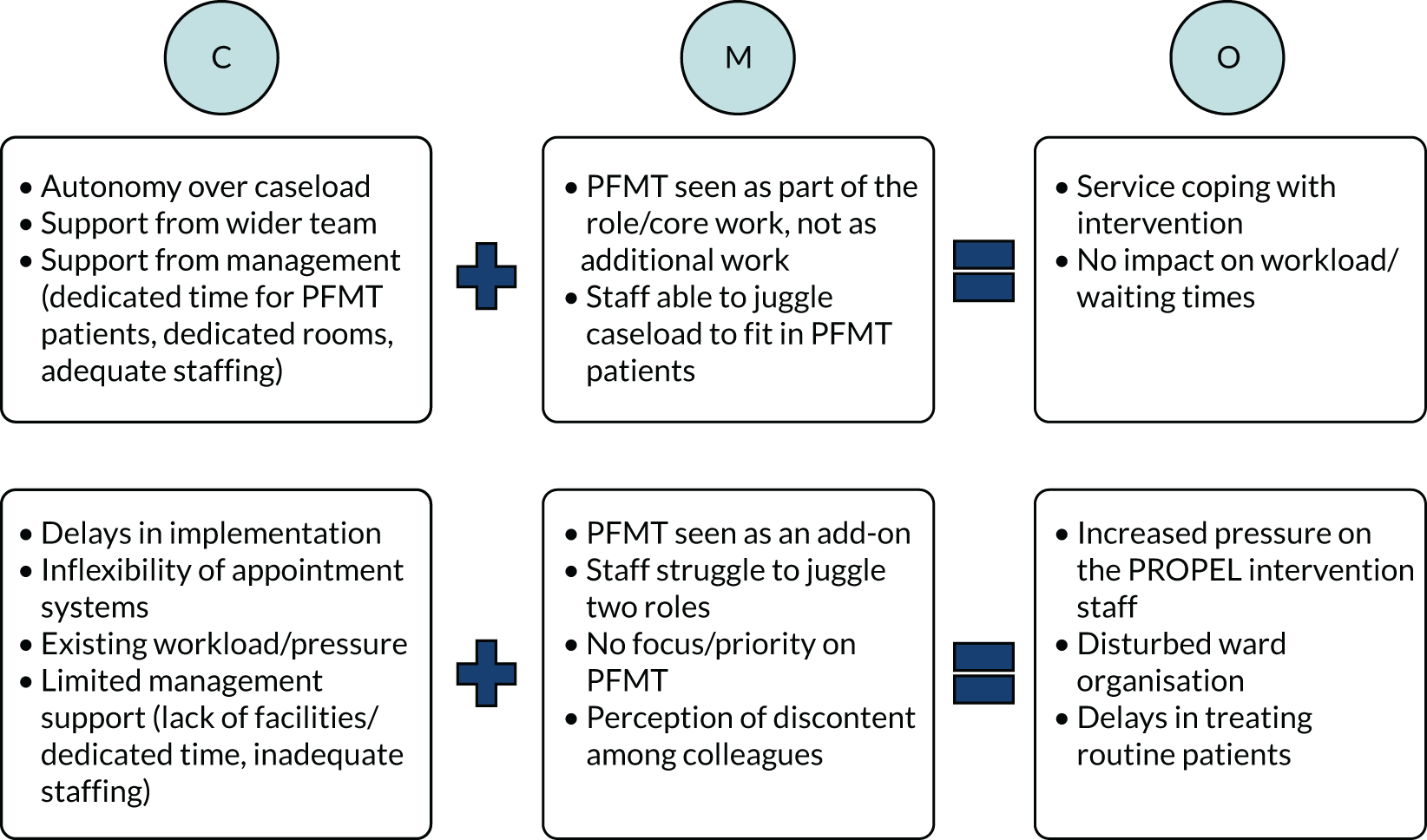

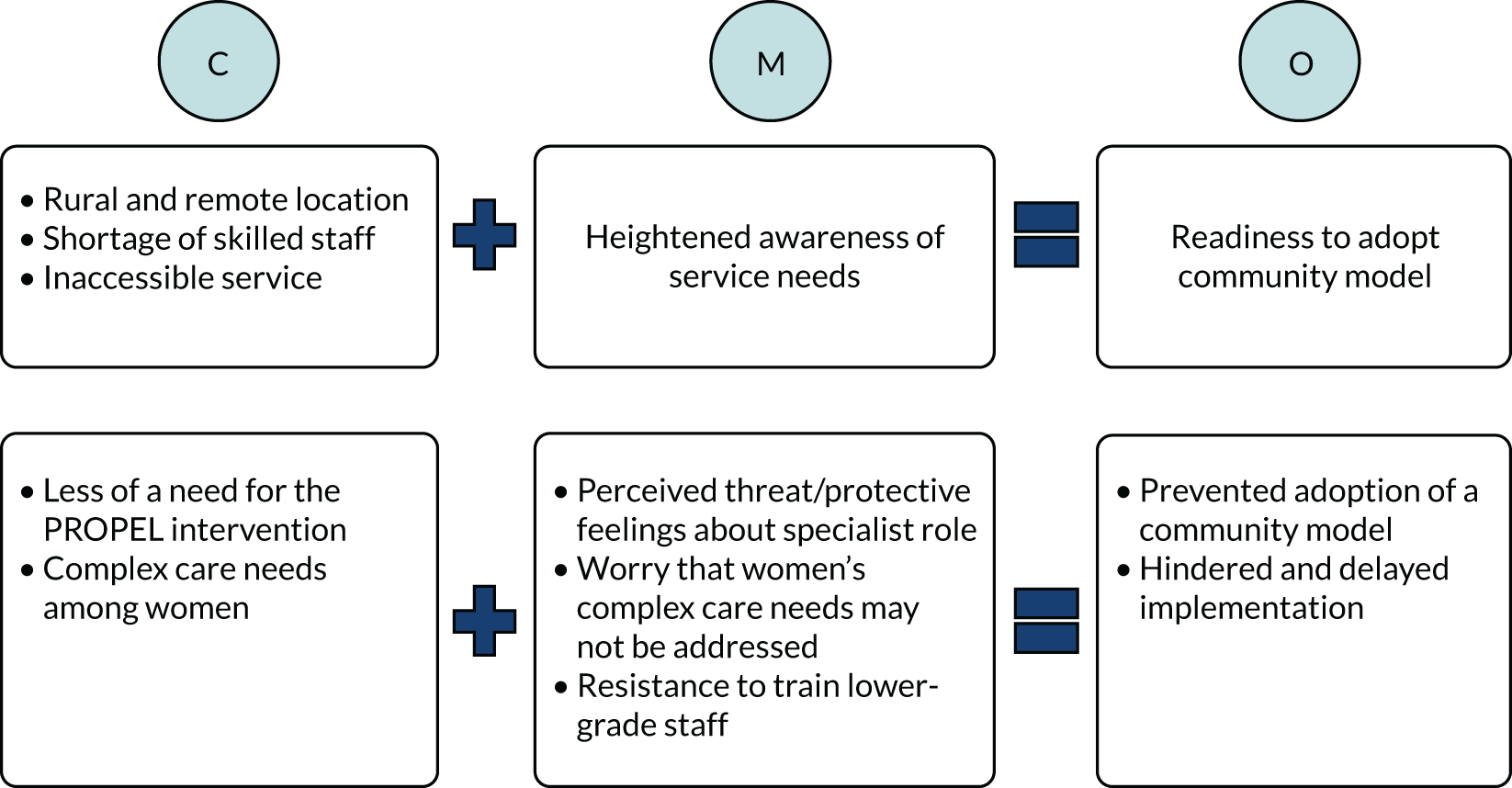

Four sets of CMO configurations were identified from the data, which contained folk theories around how each of the intended outcomes would be brought about and what may facilitate or impede these processes (Figure 2). The data also revealed an unintended outcome that was expected to affect implementation. Each CMO is described briefly and illustrated via a diagram.

FIGURE 2.

The CMO configurations 1–4. C, context; M, mechanism; O, outcome. Reproduced with permission from Abhyankar et al. 17 This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (http://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated in a credit line to the data. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Context–mechanism–outcome configuration 1: widening the reach of pelvic floor muscle training through increased local provision of care

It was anticipated that using different staff skill mixes to deliver PFMT would widen the reach and accessibility of PFMT in local areas because it would increase the number of referrals to PFMT and increase the provision of PFMT in the community, closer to women’s homes, through adoption of a community model of service delivery. This mechanism was dependent on whether or not adequate facilities (e.g. private rooms in clinics) were available to carry out internal assessments and deliver PFMT, whether or not there was strong leadership in services to support the work and whether or not GPs and other potential referrers were aware of PFMT and new referral options. In sites B and C, there were concerns that a lack of appropriate facilities may be a challenge to successful implementation.

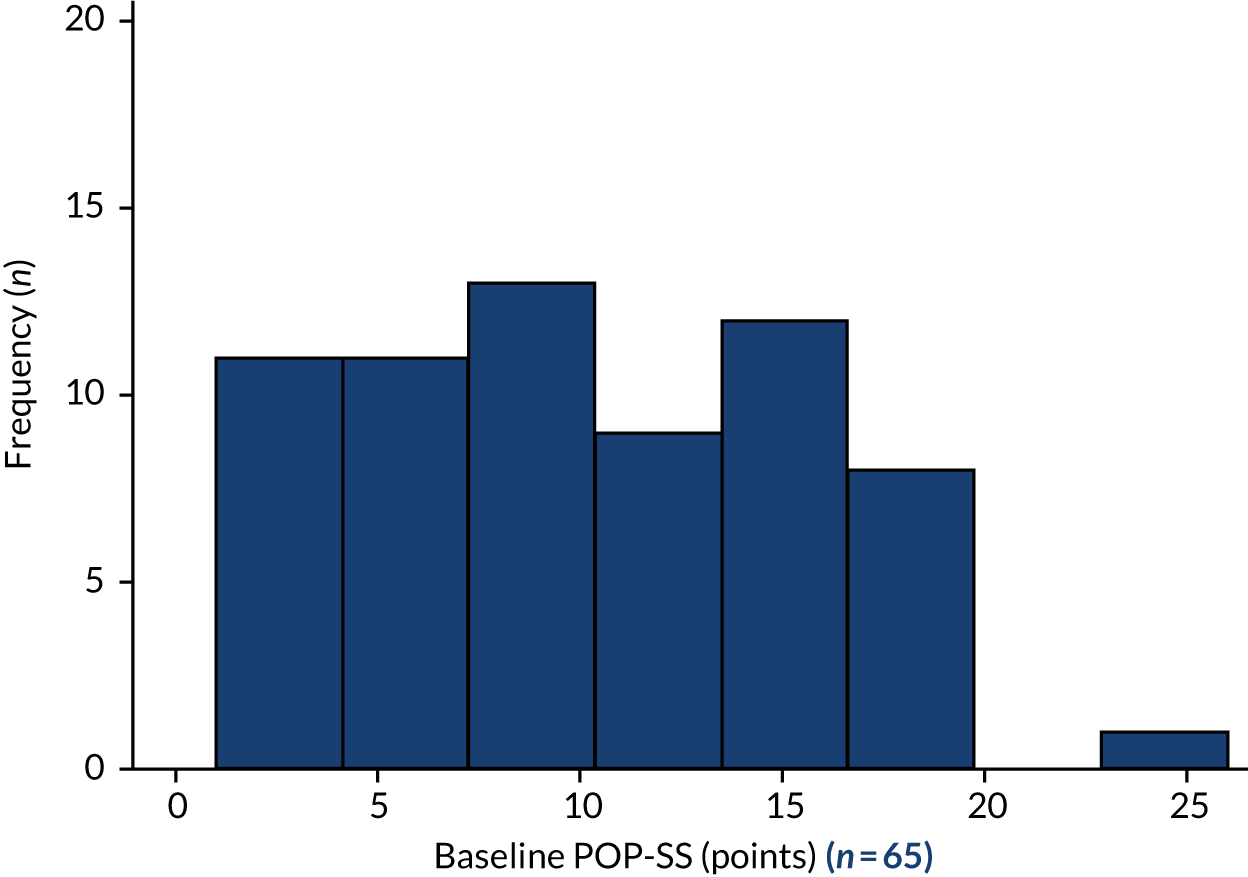

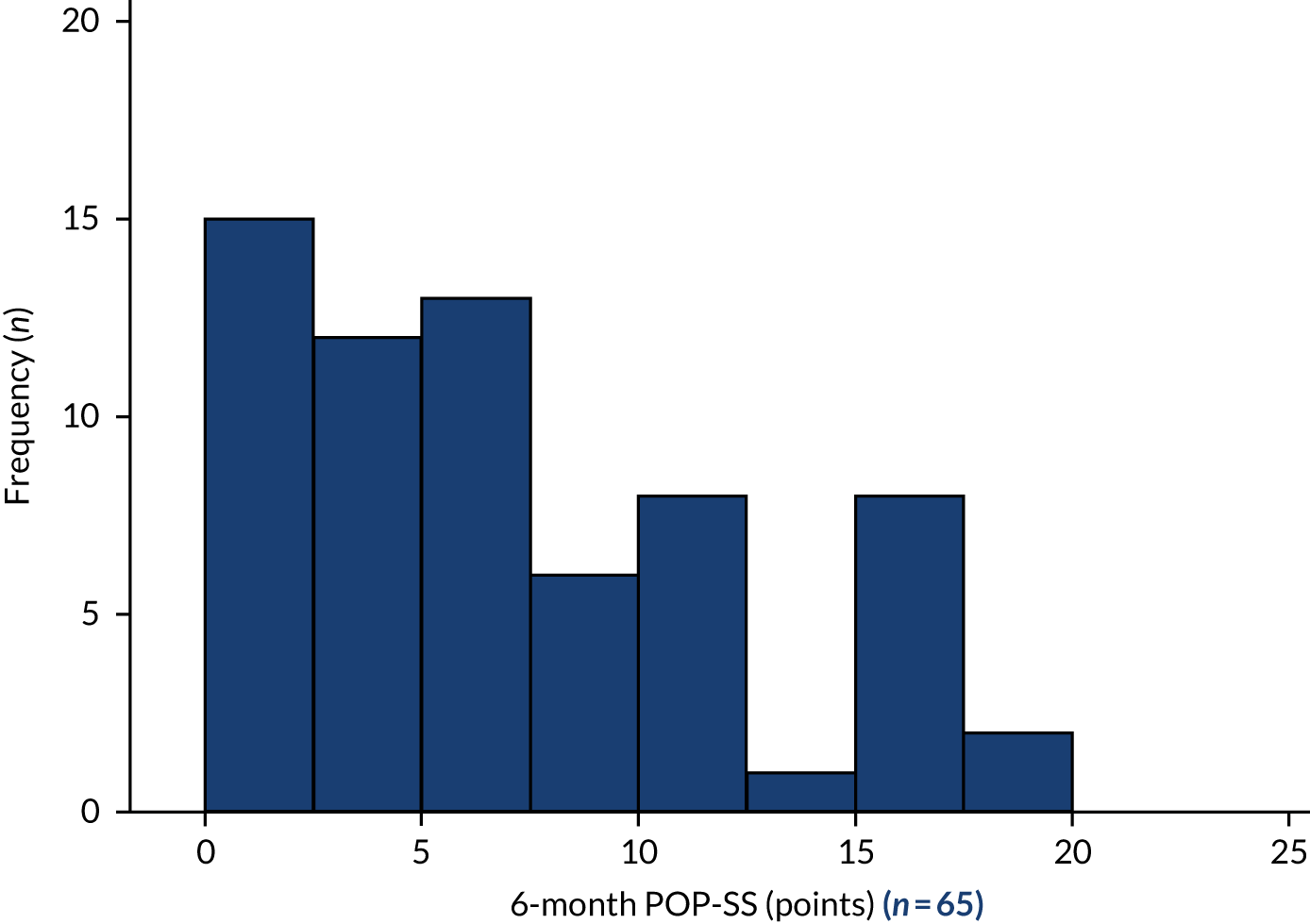

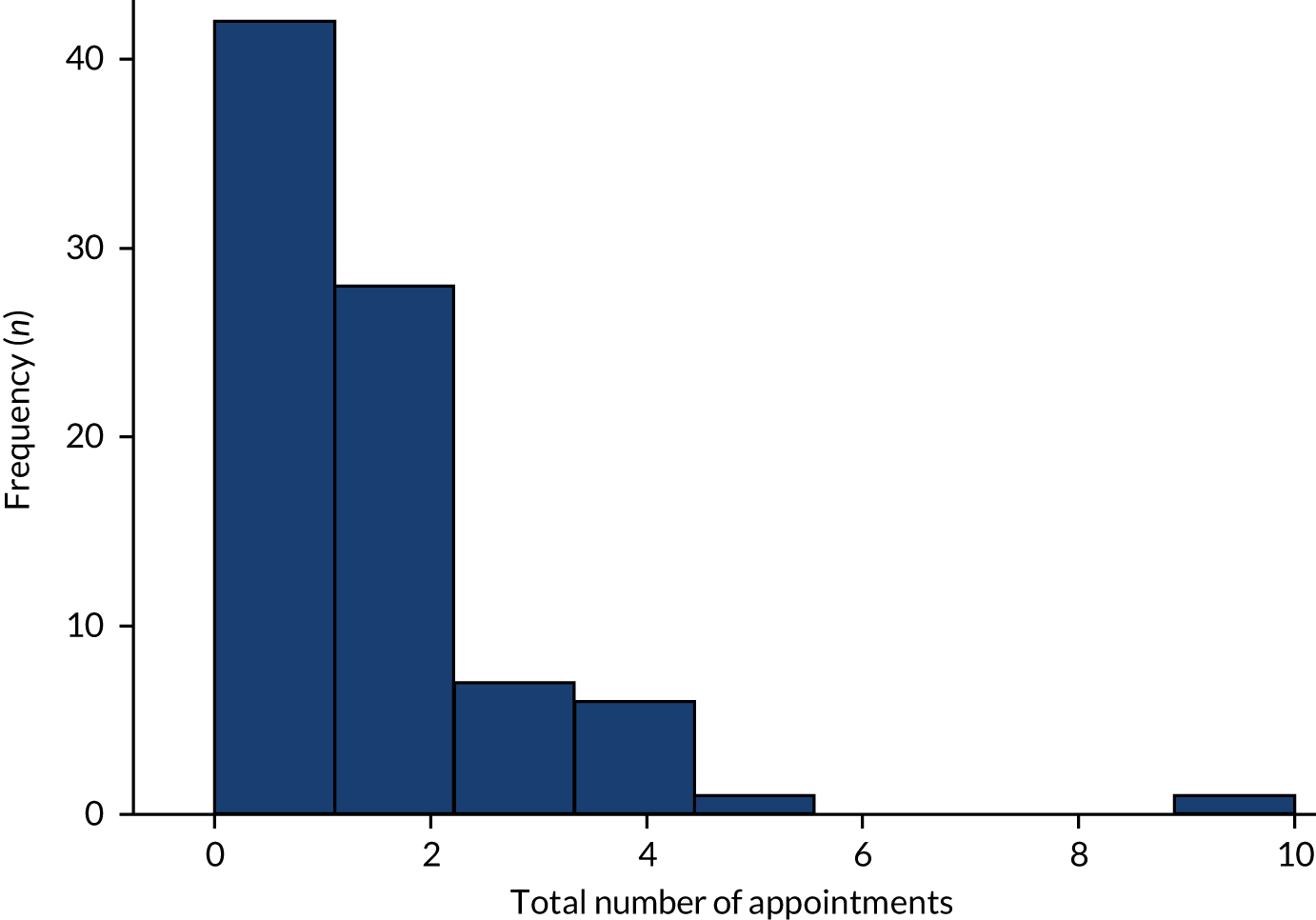

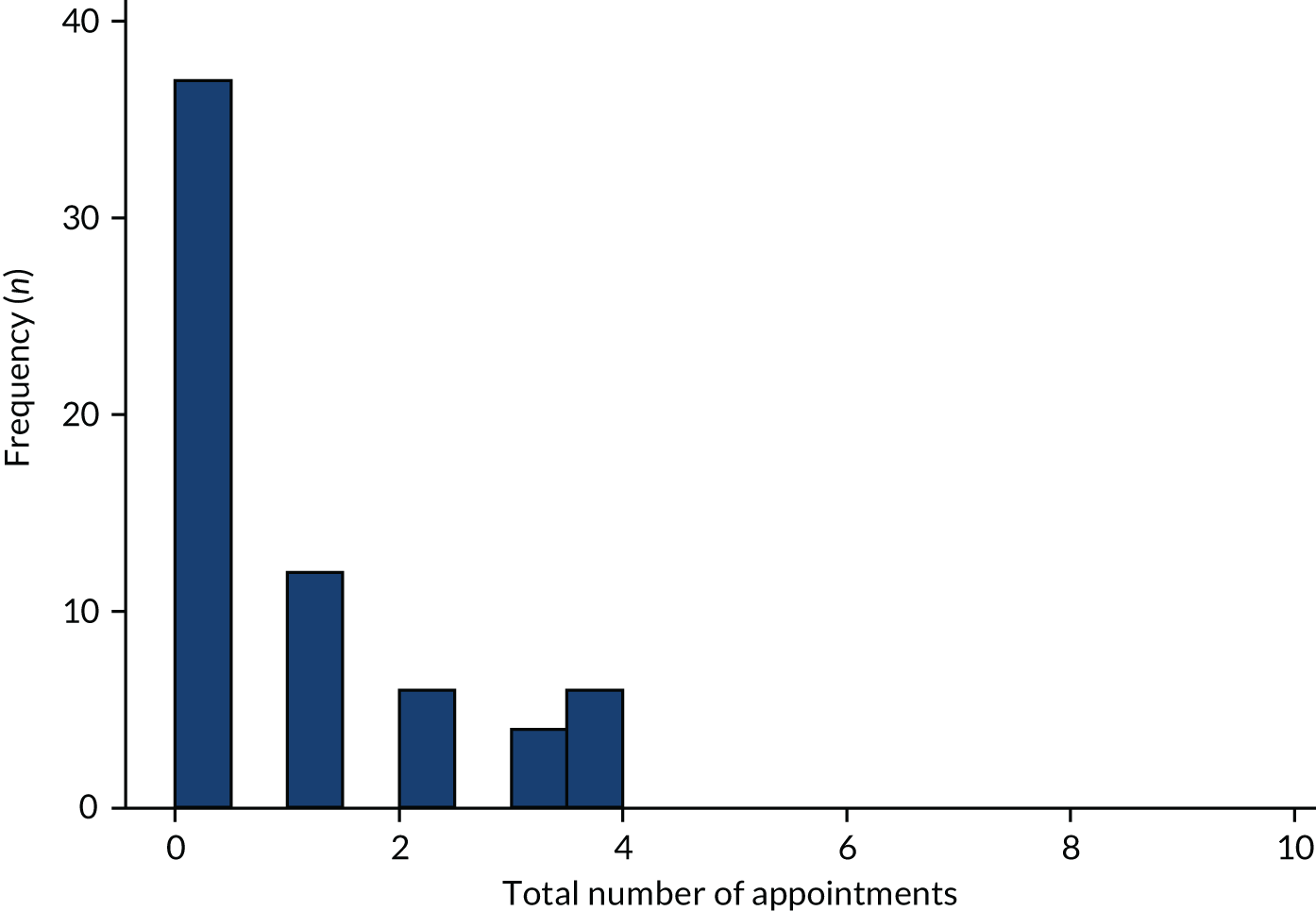

Context–mechanism–outcome configuration 2: improving women’s health outcomes through holistic and proactive care