Notes

Article history

This issue of the Health Services and Delivery Research journal series contains a project commissioned/managed by the Methodology research programme (MRP). The Medical Research Council (MRC) is working with NIHR to deliver the single joint health strategy and the MRP was launched in 2008 as part of the delivery model. MRC is lead funding partner for MRP and part of this programme is the joint MRC–NIHR funding panel ‘The Methodology Research Programme Panel’.

To strengthen the evidence base for health research, the MRP oversees and implements the evolving strategy for high-quality methodological research. In addition to the MRC and NIHR funding partners, the MRP takes into account the needs of other stakeholders including the devolved administrations, industry R&D, and regulatory/advisory agencies and other public bodies. The MRP funds investigator-led and needs-led research proposals from across the UK. In addition to the standard MRC and RCUK terms and conditions, projects commissioned/managed by the MRP are expected to provide a detailed report on the research findings and may publish the findings in the HS&DR journal, if supported by NIHR funds.

The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Michie et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 General introduction

Improving health by changing behaviour

Addressing many of the huge challenges facing the world today will require changes in behaviour at all levels, from governments to individual citizens. Whether it be climate change and environmental degradation, war and other conflicts, epidemic and pandemic diseases, or poverty and inequalities, the solution often lies in changing deeply ingrained patterns of behaviour. Many of the world’s leading causes of mortality result from diseases, such as cardiovascular disease, lung cancer, stroke and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), where behaviour contributes significantly to exposure to risk – smoking, poor diet, excessive alcohol consumption, physical inactivity and unprotected sex being cases in point. 1,2 In Western societies, such behaviour-related diseases contribute to approximately half of premature deaths. 3–6 Population health can also suffer significantly from a lack of certain behaviours (e.g. people not accessing health care when needed, not engaging with screening or vaccination programmes and not adhering to medication or other treatments and advice). The behaviour of health-care providers is also critical to population health, which can be significantly impaired if health professionals do not implement evidence-based practice, such as ensuring that the prescription and use of antibiotics is necessary and appropriate,6–9 or fail to follow infection prevention and control guidelines. 10

As well as reducing premature mortality and disability, behaviour change interventions have the potential to reduce health-care expenditure. 11,12 The latest analysis of the global burden of disease concluded that investing in preventing and controlling these diseases offers a high return for countries at all income levels and contributes to economic growth. 13 Interventions that target health-related patterns of behaviours have the potential to transform the health of populations, often at low cost,12–14 and there is good evidence that interventions have a positive impact on both health and equity across a number of areas. 15,16 Despite this, the effects of these interventions tend to be small, there is wide variation in effectiveness across contexts and the effects are often not maintained long term. 17,18 The effects are also usually not at the scale required to bring about a population-level impact (see Cochrane database for examples19–21).

Changing health-related patterns of behaviour across diverse populations and settings is not easy; it requires complex interventions (i.e. interventions that contain several interacting componets22) that target multiple levels within systems (e.g. communities or organisations) and can sustain their impact over time. 16 This in turn requires sophisticated methods for developing and evaluating interventions, including how to draw on theory and how to report interventions to maximise replicability and potential for faithful implementation. At present, authors do not reliably provide explicit reporting on the theoretical propositions underpinning interventions, their development and their evaluation. 15,22,23 Where theory-based interventions are reported, there is often little detail about how the theory was applied in the development or evaluation phase. 24–26 This is partly due to the paucity of methods to support this process. Methods are needed to support intervention reporting to move beyond describing them simply as being theory informed27 towards reporting how and why theoretical principles are tested. 28–31 One of the areas in which progress could be made is in the methods for intervention development and for accumulating knowledge across intervention evaluations. Progress has been made in improving, harmonising and standardising the reporting of interventions aimed at changing behaviour32–36 and their theoretical underpinnings. 37–40 This includes specifying interventions in enough detail to allow replication and to do this using consistent and shared terminology. 15,17,41,42

Behaviour change techniques: essential components of behaviour change interventions

Behavioural interventions are often delivered as part of complex systems that include a number of behaviour change techniques (BCTs). BCTs are conceptualised as fine-grained intervention components that on their own have the potential, in the right circumstances, to bring about behaviour change. 17,32,43,44 The Behaviour Change Technique Taxonomy version 1 (BCTTv1) is a formal, standardised system used to characterise behaviour change interventions, developed with input from 400 experts across 12 countries. 17,42 It consists of 93 BCTs organised into 16 groupings and provides labels and definitions of intervention techniques. This extensive shared vocabulary enables researchers and others to specify and describe the components of behavioural interventions, allowing better reporting and facilitating accurate replication and implementation of interventions. The BCTTv1 incorporates a number of cross-behaviour BCT taxonomies33,34 and some behaviour-specific taxonomies for physical activity,36 alcohol use,35 smoking45 and condom use. 39 The BCTTv1 has been used to specify the potentially ‘active ingredients’ in many types of intervention, for example those aiming to change physical activity and dietary behaviours,40,46 oral hygiene behaviours,47 hazardous and harmful drinking,48 sexual health behaviours,49–51 blood pressure control/management behaviours,52 antibiotic prescribing53,54 and type 2 diabetes preventative behaviours. 55

As well as being widely used for intervention reporting, the BCTTv1 is used to support intervention design and development and to synthesise information across intervention evaluations. Systematic reviewers have used it to identify BCTs in published reports of intervention evaluations and to generate evidence of the effectiveness of not only the intervention as a whole, but also the component techniques, either individually or as theoretical combinations that work synergistically. 25,26,56–59 This approach is recommended by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) in its guidance that research should investigate which BCTs are effective in promoting the initiation and maintenance of behaviour change. 15 Studies of published interventions have found that interventions using BCT combinations were more effective than those that used only one BCT. 60–62 For example, interventions that combine self-monitoring with BCTs that support self-regulation of behaviour, such as goal-setting or action-planning, have been found to be associated with improved effectiveness. 60 More than 350 articles reporting interventions coded by BCTTv1 are available for researchers and others to use in a searchable database, which is updated as researchers add to it (see www.bct-taxonomy.com/interventions; accessed 1 March 2020).

Specifying intervention content by BCTs has transformed methods for reporting the content of behaviour change interventions, which facilitates greater precision and consistency in research. 42,63 However, identifying which specific BCTs or BCT combinations are likely to be effective for a particular behaviour in its context is challenging. A review of 135 studies examined methods used to do this and found that, although a range of methods existed, they all have limitations. 64 The methods were (1) experimental manipulation of BCTs (where it is important to specify BCTs in the interventions, both in the experimental and in the control groups22,37,65–67), (2) observational studies comparing outcomes in the presence or absence of BCTs, (3) meta-analyses of BCT comparisons, (4) meta-regressions evaluating effect sizes with and without specific BCTs, (5) reviews of BCTs found in effective interventions and (6) meta-classification and regression trees (CART).

From the review findings, Michie et al. 68,69 concluded that there are limitations to all of these methods for drawing conclusions about BCT efficacy and that research in this area would be strengthened by triangulation of methods. Similarly, policy-makers and practitioners, when making decisions about what combination of BCTs to use in an intervention, should draw on findings across different methods. Another approach that would provide a fuller understanding of the impact that an intervention has on behaviour and health, and strengthen work in this area, is to link BCTs to other intervention features in an ontology of behaviour change interventions. 68,69 Research is currently under way to develop a Behaviour Change Intervention Ontology to support this approach (see www.humanbehaviourchange.org; accessed 1 March 2020).

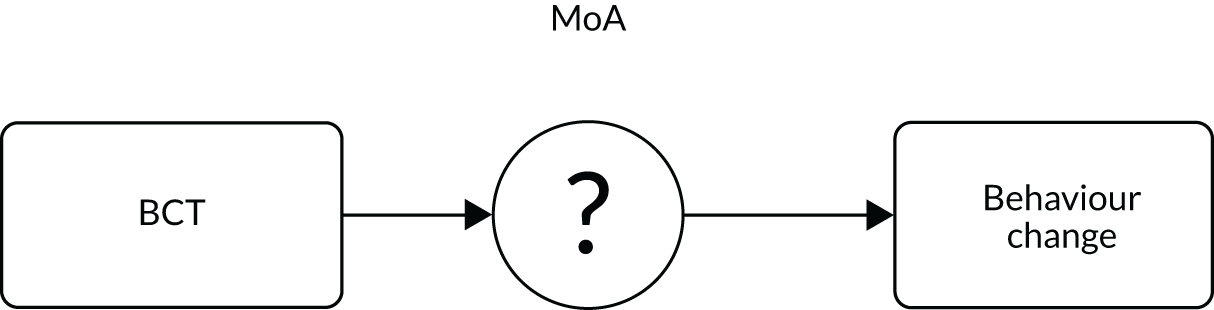

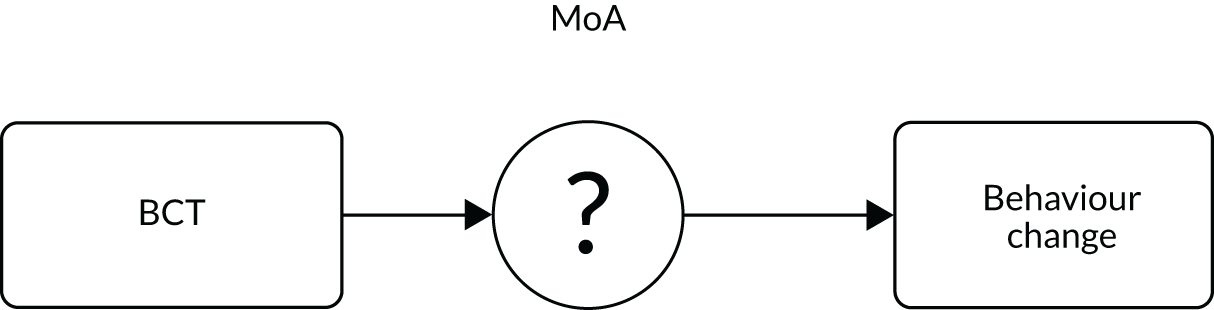

An important aim of this work is to increase our knowledge of the mechanisms of action (MoAs) through which the BCTs have their effect. The need for this has been recognised beyond behavioural science, for example, by the Cochrane Collaboration’s Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) Group70 and by NICE. 71,72 By linking BCTs to their hypothesised MoAs as described in behavioural theory, researchers and intervention designers may target MoAs more deliberatively, leading to interventions that are more likely to be effective. In addition, knowledge of these links makes it easier for investigators to design studies that can evaluate the processes underlying effective interventions and thus test and advance theory. Furthermore, it enables a theoretical understanding of interventions that have not been, or at least have not been reported as being, based on theory.

Behaviour change theory: specifying the mechanisms of action of behaviour change

Theories of behaviour change summarise accumulated knowledge about how behaviour change occurs, as well as explaining variation across behaviours, settings and populations. They have the potential to be useful tools in designing interventions to change behaviour, if applied systematically and appropriately. 28,29,37,73,74 This is reflected, for example, in the UK Medical Research Council’s framework for designing and evaluating complex interventions22 and the Intervention Mapping framework75 for planning health promotion programmes.

Theories of behaviour change attempt to explain and predict when, why and how behaviours do or do not occur and change. This involves proposing MoAs, defined as ‘the processes through which a behaviour change technique affects behaviour’, and moderators of change along various causal pathways. MoAs are theoretical constructs from theories of behaviour and behaviour change, such as ‘self-efficacy’ or ‘knowledge’, that mediate the effect of a BCT on a behaviour. By contrast, moderators are variables such as the population or the setting that may modify the effect of a BCT on a behaviour. As part of a multidisciplinary consensus exercise, theory was defined as:

A set of concepts and/or statements with specification of how phenomena relate to each other [providing] an organising description of a system that accounts for what is known, and explains and predicts phenomena.

There are numerous formal theories, which are more or less generalisable across behaviours, settings and populations. They vary in complexity and range of application, and many overlap. A multidisciplinary literature review led by psychologists, sociologists, anthropologists and economists identified 83 theories of behaviour and behaviour change, containing > 1700 theoretical constructs. 30,76 Because the review had strict inclusion criteria, there are likely to be many other relevant theories not included. Despite the abundance of theories, there is a paucity of guidance for researchers and intervention designers as to how they should decide about which theory or theories to draw on and how they should apply them to intervention design or evaluation. The result is that a relatively small number of theories dominate the field, and often they are poorly applied or their application is poorly reported. 26,77

Efforts to help in this process include the theoretical domains framework (TDF), which is an integrative framework of theoretical constructs relevant to understanding and changing behaviour. The framework was developed to make theories more usable and accessible to an interdisciplinary audience. 38,78,79 The TDF specifies 14 theoretical domains, each of which includes several theoretical constructs that are similar in definition but derive from different theories. The TDF has been used in intervention development and design,31,80,81 as well as in systematic reviews. 82–84 Although there are integrative frameworks, such as the TDF, and general intervention development frameworks, such as intervention mapping,22,75,85,86 a consensus is needed about how the individual MoAs specified in these theories can be linked with particular BCTs. 30,37 This would allow interventions to be developed in a way that was more precisely informed by theory than is generally current practice and would enable the theoretical understanding of interventions that were found to be effective but were not explicitly developed based on theory. However, we do not yet have an agreed method for systematically linking BCTs to individual hypothesised MoAs.

Linking behaviour change techniques with theoretical mechanisms of action

Although the BCTTv1 provides a shared language with which to describe intervention content, it does not directly specify which MoAs these BCTs target in the intervention. For interventions to have a good chance of being effective, their active components (i.e. BCTs) should target relevant MoAs.

There are a large number of BCTs and theories and models of behaviour and behaviour change. However, research investigating links between BCTs and MoAs has been sparse, despite a range of frameworks for developing behaviour change interventions [e.g. intervention mapping,87 precede–proceed model,88 the behaviour change wheel (BCW)89]. The importance of understanding the processes through which behaviour change may occur (a theory of change) has been recognised internationally, for example by the Cochrane Collaboration’s EPOC Group,70 NICE’s Public Health guidelines in the UK71,72 and the Science of Behavior Change programme of research in the USA. The Science of Behavior Change programme of research is building evidence about a discrete set of interventions by experimentally testing methods for changing specified MoAs (see https://commonfund.nih.gov/behaviorchange/index; accessed 1 June 2019). There is a need for many programmes of research to accumulate evidence about the processes by which the full range of BCTs have their effects; this will maximise our potential to develop effective interventions.

Preliminary work identifying links between BCTs and MoAs has been conducted in both primary research and evidence syntheses. 15,34,68,75,88,90 For example, a set of 35 BCTs has been mapped to theoretically derived domains in the TDF. 34 This approach has been used in developing behaviour change interventions31,34 and to identify theoretical mediators of change within process evaluations. 91–93 Associations between BCTs and theory have also been investigated in evidence syntheses such as systematic literature reviews and meta-analyses,26,94 and in primary research in relation to changing particular mechanisms of action, such as self-efficacy95–98 and behavioural intention. 99 Guidance about selecting BCTs to target processes of change have been developed in the form of intervention development frameworks (e.g. the BCW,85 Intervention Mapping75 and the TDF78,79). However, these are at a general level and do not include guidance or evidence about links between specific BCTs and MoAs.

This work shows the interest in and need for developing links between BCTs and their MoAs. However, there is no transparent, agreed method for identifying these links. This is needed to provide the tools for those (1) developing ‘theory-based’ interventions and (2) attempting to make theoretical sense of interventions that specify the BCTs used in interventions but without referring to theory and/or that specify MoAs but without identifying specific BCTs in interventions. Achieving this would enable evidence accumulation to continue to advance more systematically and efficiently.

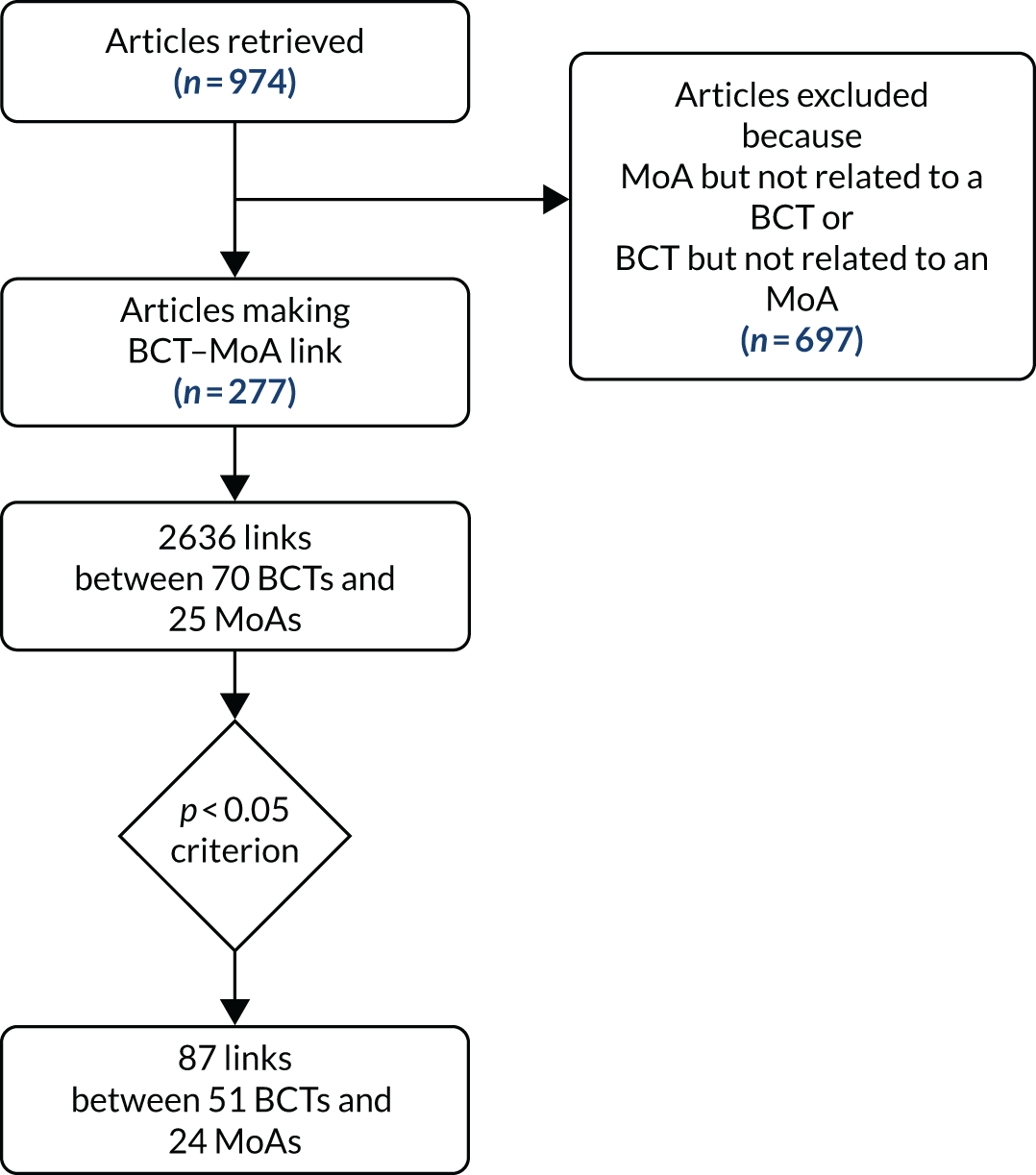

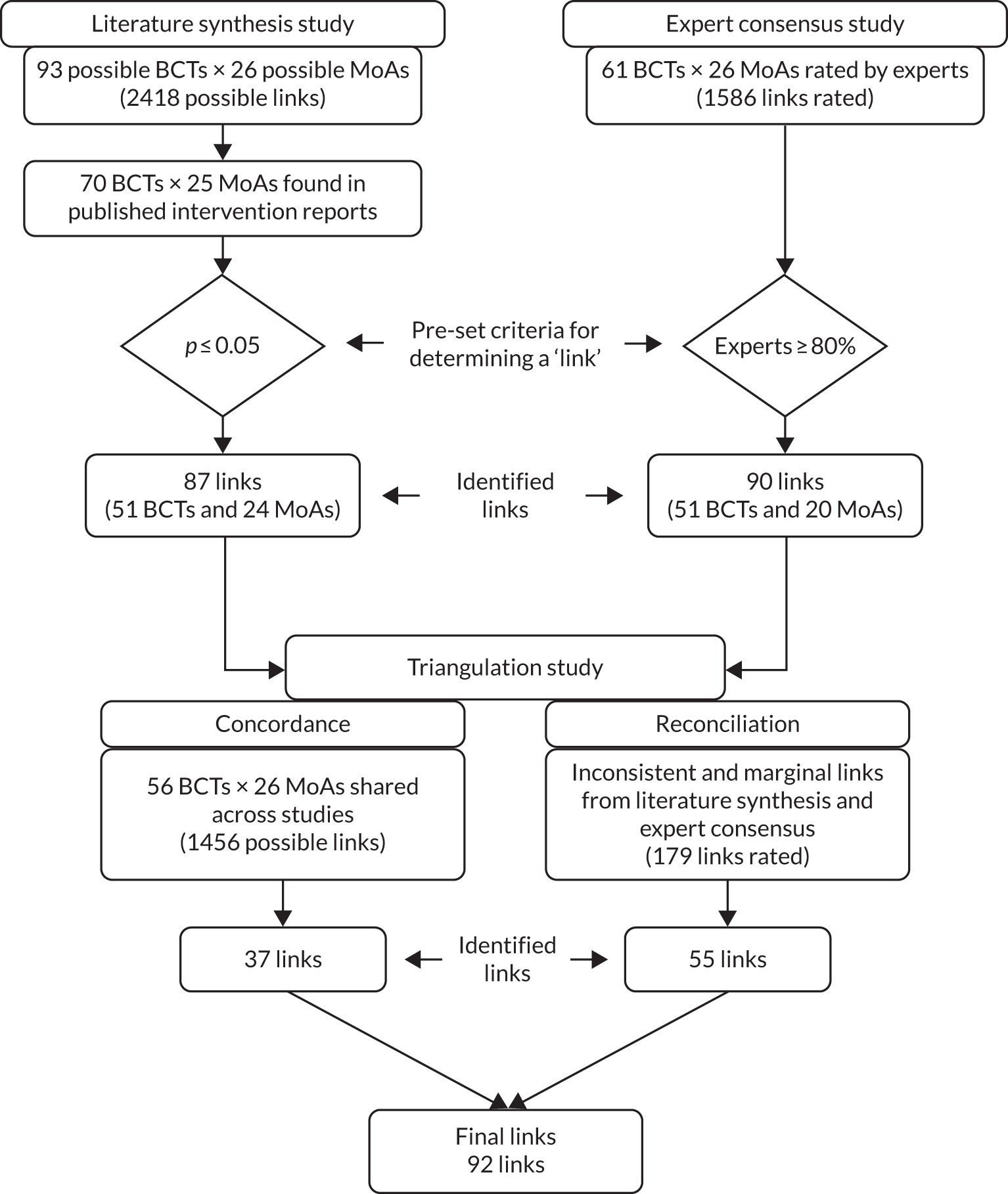

In this report, we present a programme of research using a range of methods to identify and operationalise links between behaviour change techniques and (1) specific mechanisms of action and (2) behavioural theories. 100 These are links as reported by behaviour change researchers in developing and/or evaluating behaviour change interventions, and as judged by experts in a consensus exercise. These links are therefore hypothesised rather than necessarily tested and shown to be robustly supported by evidence. It thus provides a valuable resource for researchers as to which links are most and least likely to be effective in changing behaviour through changing a particular MoA. The links are presented in the form of matrices and interactive heatmaps that allow data from three studies to be easily extracted for each link and additional data or comments to be added by users (https://theoryandtechniquetool.humanbehaviourchange.org/tool). The data come from two complementary sources. In study 1, the data are derived from a synthesis of published literature, which encapsulates thinking in past peer-reviewed work. Study 2 is of expert consensus, which encapsulates current thinking. Study 3 triangulates the data from the previous two studies, providing a reconciliation of findings about the hypothesised links between behaviour change techniques and their MoAs. Study 4 examines links between groups of BCTs and theories as a whole. The sequence of studies in this research programme is shown in the flow diagram in Figure 1. The matrices of links resulting from these studies will provide a methodological online resource available to behaviour change scientists and intervention designers, providing a more efficient and systematic way to identify and evaluate the theoretical processes hypothesised to underlie BCTs.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram outlining the sequence of studies.

Aims

-

To identify and integrate hypothesised links between (1) BCTs and MoAs and (2) BCTs and behavioural theories.

-

To generate a freely available, searchable online resource to support theory-based intervention development and evaluation.

Objectives

-

Intervention development and evaluation:

-

To triangulate literature analysis and expert consensus to identify links between BCTs and both MoAs and behaviour change theories.

-

To graphically represent the strength of BCT and MoA links through searchable matrices of the findings from literature synthesis, expert consensus and triangulation.

-

-

Efficient evidence accumulation:

-

To create an accessible and freely available online resource that allows researchers to share data, publications and conference reports relevant to individual links.

-

To seek engagement and collaborations with international scientific and intervention development communities.

-

The objectives of each study are listed below.

Study 1: identifying the links between behaviour change techniques and mechanisms of action described by authors of published intervention articles101

Objectives

-

Determine the number of times BCT–MoA links are described in studies.

-

Determine which specific BCTs are most frequently described as targeting specific MoAs.

-

Determine which specific MoAs are most frequently described as being affected by specific BCTs.

-

Determine whether or not specific BCT–MoA links demonstrate greater frequency than anticipated based on the average number of times the BCT–MoA link is described.

Study 2: an expert consensus approach to linking behaviour change techniques and mechanisms of action102

Objectives

-

Develop consensus on the MoAs through which BCTs may affect behaviour (i.e. links).

-

Develop consensus on the MoAs through which BCTs may not affect behaviour (i.e. non-links).

-

Develop consensus on the specificity of BCT–MoA links, specifically whether BCTs affect behaviour through one specific, or multiple, MoAs.

The study additionally sought to:

-

Determine for which BCT–MoA links experts did not reach consensus.

-

Determine whether or not all BCTs may be linked with at least one MoA.

-

Determine whether or not all MoAs may be linked with at least one BCT.

Study 3: triangulating evidence of links between behaviour change techniques and mechanisms of action from literature synthesis and expert consensus103

Objectives

-

Investigate the agreement between the studies in study 1101 and study 2102 by developing BCT–MoA link matrices to:

-

Determine the extent of agreement between the two studies for individual and overall MoAs.

-

Determine BCT–MoA links that for both studies were greater than the pre-set criteria as being either linked (i.e. met criteria for a link in both expert consensus and literature synthesis) or not linked (i.e. met criteria for a non-link in the expert consensus and the literature synthesis).

-

Determine BCT–MoA links for which agreement was not reached.

-

Utilise ‘reconciliation experts’ to resolve BCT–MoA links for which agreement was not reached.

-

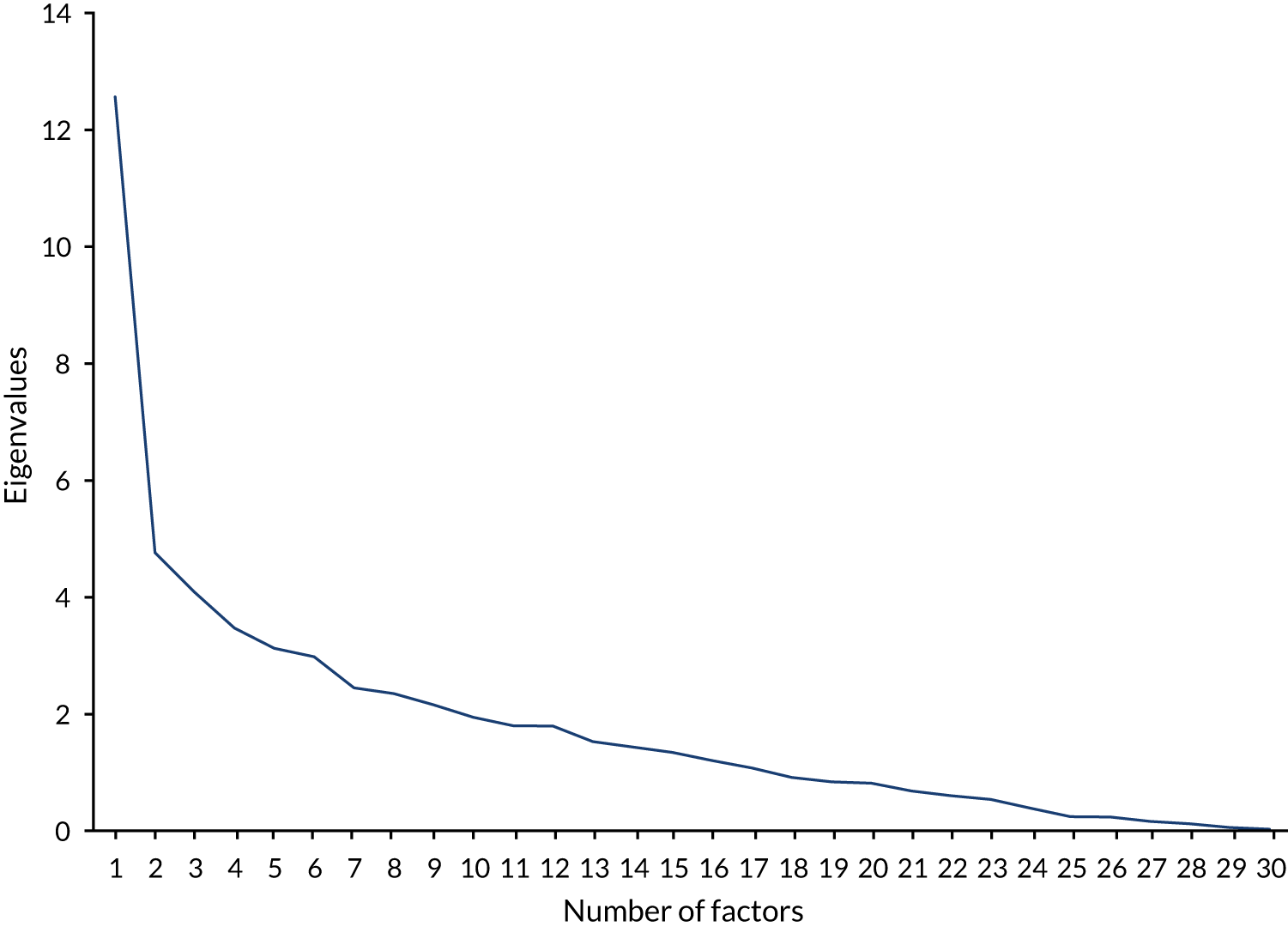

Study 4: do combinations of behaviour change techniques that occur frequently in interventions reflect underlying theory?104

Objectives

-

Determine the extent to which BCTs are frequently used together.

-

Determine how experts link groups of BCTs to specific theories.

-

Determine whether or not the theories that experts most frequently linked to specific BCT groups found across interventions are comparable to the theories that authors explicitly reported within interventions using similar groups of BCTs.

Chapter 2 Identifying the links between behaviour change techniques and mechanisms of action described by authors of published intervention articles

Abstract

Objective

To identify the links between BCTs and MoAs, as described in published intervention articles.

Methods

Two coders extracted links between BCTs and MoAs from 277 behaviour change intervention articles. The relative frequency of these was examined through a series of one-tailed binomial tests.

Results

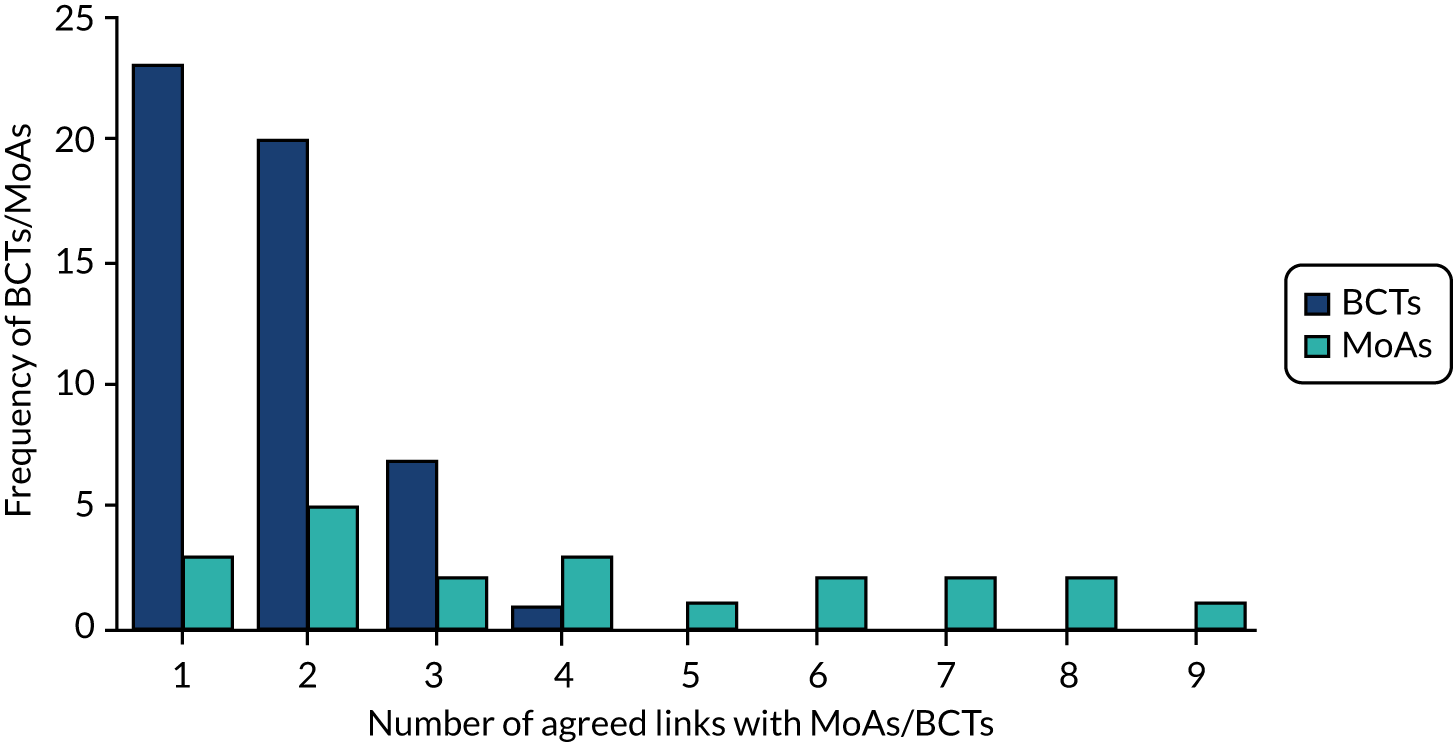

Seventy-seven BCTs were coded. Seventy BCTs were linked to at least one MoA, with links present for 25 of 26 possible MoAs. In total, 2636 BCT–MoA links were extracted from the intervention articles, with up to five MoAs linked to each BCT (mean = 1.71, range 1–5) and up to eight BCTs linked to each MoA (mean = 3.63, range 1–8).

Conclusions

The database of BCT–MoA links identified in this study provides a resource that can be used for intervention development (e.g. to identify BCTs that can be used to target relevant MoAs) and evaluation (e.g. to advance our understanding of theory by elucidating the processes of change underlying effective interventions).

Introduction

Cumulative progress in behavioural science could be improved by advancing our understanding of the processes through which behaviour change interventions have their effects. As outlined in Chapter 1, behaviour change interventions consist of BCTs that are the smallest, irreducible components, or the potentially ‘active ingredients’ that can bring about change in behaviour. The theoretical constructs that represent the processes by which these BCTs change behaviour are termed MoAs. Identifying links between individual BCTs and MoAs could aid intervention design (e.g. by enabling us to identify relevant intervention strategies that influence a particular MoA) and evaluation (e.g. by allowing us to better understand the processes of change in successful interventions).

A number of sources of evidence can inform our understanding of these links. One valuable source of evidence is the published intervention literature. By examining this literature, we can examine links described or hypothesised by intervention authors and/or links that have been empirically tested (e.g. through experimental studies and meta-analyses). Although the available evidence for the latter (i.e. that resulting from empirical tests of individual links) appears to be limited,26 extracting and examining researchers’ descriptions of links may provide a useful data set. For example, where published interventions describe the rationale behind BCT selection, including the MoA(s) a specific BCT is believed to target (e.g. based on a theoretical model, previous research, clinical guidelines), this can shed light on researchers’ thinking and inform our understanding of BCT–MoA links.

Any one intervention may include a number of BCT–MoA links, as behavioural interventions tend to be delivered as part of a complex system, and can involve a number of co-occurring BCTs. BCTs can enable behaviour change by augmenting factors that facilitate change, or by mitigating factors that inhibit change. For example, in a smoking cessation intervention, researchers may hypothesise that providing an individual with emotional social support will change behaviour by increasing motivation. Similarly, persuading someone about their capabilities may be hypothesised to change behaviour by decreasing negative emotions such as shame or worry.

In the above example, motivation and negative emotions can be conceptualised as MoAs. In this context, MoAs are constructs from theories of behaviour and behaviour change that can be viewed as ‘mediating’ the effects of interventions. They may be constructs that relate to the individual (i.e. psychological processes, e.g. self or identity) or to the social or physical environment (e.g. social influences from peers).

The rationale underlying the selection of BCTs is not clearly described in every intervention article and there is also not always a clear, linear pathway for how BCT X changes behaviour by changing MoA Y. However, given the increasingly available array of tools for intervention development and reporting,17,18,41 many of which offer some form of guidance regarding which BCTs can target which MoAs, it is reasonable to assume that there is a corpus of literature from which BCT–MoA links can be identified.

This study aimed to identify the hypothesised links between BCTs and MoAs to inform (1) how researchers can target MoAs of interest (i.e. informing an understanding about which BCTs to select) and (2) explanations of intervention effects (i.e. informing an understanding of the MoAs through which BCTs are having their effects). We also aimed to understand whether or not any BCT–MoA links were described with a relatively high level of frequency in the included corpus of intervention articles. Therefore, based on the published intervention literature, this study sought to determine:

-

the number of times BCT–MoA links are described by authors within studies

-

which specific BCTs are most frequently described as targeting specific MoAs

-

which specific MoAs are most frequently described as being influenced by specific BCTs

-

whether or not specific BCT–MoA links are seen with greater frequency than anticipated based on the average number of times the BCT–MoA link is described.

Method

Overview of search methods

We set out to collate published behaviour change intervention articles that reported the development and/or evaluation of an intervention, where there was at least one explicit link between a BCT and a MoA.

To do this efficiently (given time and resource constraints), our search strategy prioritised intervention articles where (1) intervention authors described BCTs using a taxonomy within the article, or systematic reviewers had retrospectively identified BCTs and (2) researchers had used a theoretical framework to identify/describe MoAs. Although we did not set out to conduct a systematic review, we developed a search strategy that we considered broad enough to capture a range of articles, covering a variety of behavioural domains, years and countries. A systematic review was not conducted as the main aim of the study was to locate a corpus of literature in which BCT–MoA links were most likely to be identifiable, and not to address a research question (e.g. to test how frequently or infrequently such links can be found in a representative body of literature), which would require a systematic review methodology. Additionally, it was considered infeasible given time and resource constraints. Our search strategy thus included (1) electronic (database) searches, (2) e-mails to behavioural science experts and (3) reviews of the reference lists of relevant systematic reviews. More detail on each of these is provided below. Note that the search was not explicitly restricted to health behaviour change interventions. However, because of the nature of our search strategy, all of the included papers were health related.

Searching electronic databases

We searched for intervention articles that had cited any of five published BCT taxonomies,17,33,35,36,45 the Theory Coding Scheme77 or the TDF. 38,78 This was done to identify articles that were likely to have explicitly described BCTs and/or MoAs. These ‘forward-searches’ were conducted in Web of Science and Google Scholar.

E-mailing behavioural science experts

The project’s International Advisory Board (IAB) (see Appendix 1), which included 42 members from 10 countries, was contacted and asked to send relevant intervention articles. We also e-mailed several national and international professional and scientific societies including the US Society for Behavioral Medicine, the European Health Psychology Society, UK Society for Behavioural Medicine and the British Psychological Society’s Division of Health Psychology. Researchers who received the request were also asked to relay the e-mail to relevant colleagues in their networks.

Reviewing interventions included in systematic reviews

Where the above search methods led to the identification of a relevant systematic review (i.e. one in which BCTs and/or theory had been coded), we reviewed the associated reference lists of included intervention articles. This included the review by NICE published as part of its guidance on behaviour change. 15 We downloaded and screened all relevant intervention articles identified through these reviews.

Inclusion criteria

Articles were included if they described a behaviour change intervention and if they included at least one identifiable link between a BCT and a MoA. Such links could be described in the text or in a table or figure provided that the MoA was clearly described as the process through which the authors hypothesised that the BCT would change behaviour. For example, an article would be included in which the intervention asked participants to reflect on their identity as a ‘smoker’ and hypothesised that this technique would change behaviour by changing participants’ self-image. We did not have any criteria relating to year of publication, target behaviour, journal, study quality or article type.

Intervention articles were excluded if descriptions were not detailed enough to allow us to identify a link. In some cases, the intervention was described in detail and a number of theoretical constructs were discussed. However, it was not clear whether or not the authors were proposing that the constructs were MoAs through which specific BCTs would change behaviour. In other cases, authors included lists of BCTs described as linked to a list of MoAs. It was not always clear, however, whether the authors were hypothesising that all of the listed BCTs were linked to all of the listed MoAs, or that there were more specific links. Thus, these articles were also excluded, because of uncertainty about specific individual links. We also excluded unpublished theses, articles and reports that were not peer-reviewed, and articles that did not report a behavioural outcome.

Screening procedure

The full texts of all intervention articles retrieved through the search methods above were reviewed by two researchers. Guidelines for screening were developed and updated iteratively, and discrepancies were resolved through discussion. All articles were first screened by the two researchers independently, until inter-rater reliability was at an acceptable level (κ = 0.9). Articles were subsequently screened by one reviewer; a summary of inter-rater reliability across all stages of screening and coding is shown in Appendix 2.

Overview of data extraction

Data were extracted in several stages. General data about the study were extracted into a ‘source’ table that was connected to another ‘links’ table using a unique identifying number. General data included author(s), year, study type (e.g. randomised controlled trial), target behaviour and whether or not the authors identified a theoretical model as underpinning the development of the intervention. BCTs were identified and extracted, irrespective of whether or not they were linked to a MoA. MoAs (if any) were then identified for each BCT. More detail on the coding of BCTs – and BCT–MoA links – is provided in Identifying links between behaviour change techniques and mechanisms of action.

Identifying behaviour change techniques

Behaviour change techniques were identified using the BCTTv117,33 by two researchers who were trained in BCT coding. Each article was initially coded by the two researchers independently, until inter-rater reliability was acceptable [prevalence and bias adjusted kappa (PABAK) = 0.9; see Appendix 2]. Subsequently, articles were coded by one researcher and checked by another researcher. PABAK105 was used to calculate inter-rater reliability because of its ability to account for high prevalence of negative agreement. 105 Coding guidelines were developed (see Report Supplementary Material 1 for BCT coding guidelines) based on those used for the BCTTv1 online training (www.bct-taxonomy.com). Examples of guidelines were that (1) BCTs should be coded only if they targeted one or more of the target behaviours or key preparatory behaviours of the intervention (2) the whole intervention description should be read before beginning to code BCTs, (3) where BCTs were previously coded in the intervention articles using BCTTv1, the authors’ original coding was maintained and (4) where an earlier taxonomy had been used (e.g. that used by Abraham and Michie33), coding was updated in line with BCTTv1 guidelines.

Identifying links between behaviour change techniques and mechanisms of action

For each of the BCTs identified, researchers examined whether the authors had described a link to one or more MoAs. MoAs were identified when they were described as a theoretical construct through which behaviour change was hypothesised to occur, and were clearly linked to one or more BCTs. Data regarding each link between a BCT and a MoA were extracted by two researchers independently. Percentage agreement was used to calculate reliability between coders. This was because coding was not conducted using a ‘finite’ list of MoAs during data extraction.

Coding guidelines were developed and updated iteratively where necessary and discrepancies were resolved through discussion. Examples of coding guidelines were that (1) each BCT–MoA link should be extracted only once in any intervention article, regardless of how many times it was described in the article and (2) the most specific links possible should be coded. For example, if BCT X was linked to the MoA ‘perceived efficacy’ and perceived efficacy was said to be made up of self-efficacy and response-efficacy, BCT X was linked to self-efficacy and response-efficacy.

The following data were extracted for each link:

-

BCT label and number (from the BCTTv1 taxonomy)

-

MoA label and definition [as specified by the author(s)]

-

explicitness of the link (some inference needed vs. no inference needed)

-

whether or not the links included groups of BCTs or MoAs (one BCT linked to one MoA vs. one or more BCTs linked to one MoA/one or more MoAs linked to one BCT)

-

whether or not the link was tested empirically in the article (MoA not measured and BCT–MoA link not tested vs. MoA measured but BCT–MoA link not tested vs. BCT–MoA link tested).

Categorising mechanisms of action

Following data extraction, to allow for more efficient data synthesis, we categorised all extracted MoAs into a set of 26 general MoAs (see Appendix 3). These were the 14 domains from the TDF38 and the 12 additional most frequent MoA constructs from a set of 83 theories of behaviour change identified by a multidisciplinary literature review led by psychologists, sociologists, anthropologists and economists. 30 Two coders categorised MoAs until intercoder reliability was > 90% (see Appendix 4 for guidelines). Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and MoAs that could not be categorised into any of the 26 were categorised as ‘other’.

Data analysis

Research questions 1–3

Descriptive analyses were used to examine the frequency of links between BCTs and MoAs, reflecting the number of articles in which a particular link was described. This was used to address the first three research questions:

-

How frequently is each possible BCT–MoA link described?

-

Which BCTs are frequently described as targeting a specific MoA?

-

Which MoAs are frequently described as influenced by a specific BCT?

Research question 4

The fourth research question concerned the relative frequency of each link. To address this, the observed frequency of occurrence was compared with the expected frequency of occurrence for each link using a series of one-tailed exact binomial tests using R (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). 106 A one-tailed test was used because the objective was to identify the ‘presence’ of links rather than their absence. These analyses were performed on the links for which MoAs could be categorised only (i.e. excluding the MoAs categorised as ‘other’).

As we did not have an a priori expected frequency of links that could be used for comparison, we calculated an expected frequency that represented an approximation of the frequency one may observe if the links between BCTs and MoAs are random. This value was calculated as the probability that a specific BCT was coded (calculated by dividing the frequency with which the BCT was linked with any MoA by the total number of BCT–MoA links) multiplied by the probability that a specific MoA was coded (calculated by dividing the frequency with which the MoA was linked with any BCT by the total number of BCT–MoA links).

The p-values from the binomial tests provide an indication of the likelihood of a particular link being identified. These values enable us to examine the frequency of a specific link (e.g. BCT X linked to MoA Y), by comparing this with the frequency with which BCT X and MoA Y were identified in any intervention. The binomial tests therefore provide indications of relative frequency such as links that are high in frequency relative to other links identified in the intervention articles. It is worth noting that this means that if a specific BCT or MoA was not identified often across the intervention articles, a link containing that BCT or MoA may emerge as relatively frequent – regardless of the absolute frequency of that link. By contrast, if a specific BCT or MoA was identified very frequently and linked to a range of BCTs or MoAs across the articles, links containing this BCT or MoA would be lower in relative frequency.

The links that we list as ‘relatively frequent’, based on these analyses, are those that emerged with a p-value of < 0.05. This was selected as an arbitrary minimum criterion for a particular link, and we present these data to serve as one indication of relative frequency only. No statistical inferences about the links that fall above or below this value are made. We welcome others applying more or less stringent criteria as they see appropriate.

We present the data resulting from these analyses (i.e. including those links that did not reach this threshold) in ‘heat maps’, generated using R. In these heat maps, individual values (in this case, the p-values) are given a colour that represents their relative frequency. We present the data in this way to provide the full data set ‘at a glance’ to aid readers in interpreting the findings.

Results

Characteristics of intervention articles

A total of 974 intervention articles were identified through our search methods. Of those, 697 (72%) were excluded after screening the full text based on our coding guidelines (e.g. the paper was not reporting on an intervention, the intervention description was not detailed/clear enough to code BCTs, or there was an underpinning theory described but individual links between specific BCTs and MoAs were not clear). The most common reasons for exclusion were that papers did not provide a ‘codable’ description of a link between at least one BCT and a MoA and/or they did not clearly identify MoAs.

In total, 277 intervention articles described at least one BCT–MoA link, covering > 10 target behaviours. These included physical activity (40%), dietary behaviours (18%), alcohol intake (10%) and smoking (cessation) (6%). The years of publication ranged from 1982 to 2016, with almost half (49%) published in or after 2010. Over three-quarters (78%) of articles reported on the outcome(s) of a behavioural intervention, rather than describing their design or development. No theoretical basis was specified for the intervention in 14% of the articles. In addition, 13% mentioned theory but did not specify how theory was applied to developing or evaluating interventions. The analyses and discussions described in this chapter are based on the 277 included articles. A full summary of study characteristics are in the study information and materials on Open Science Framework (https://osf.io/7qjvn/; (accessed 1 January 2020). Figure 2 is a flow diagram of the search strategy and the selection process of the articles.

FIGURE 2.

Flow diagram of search strategy.

Characteristics of extracted links

From the 277 articles, we extracted 2636 BCT–MoA links. Some inference was required to identify 33% of these links. In some cases, for example, a theoretical construct was identified as a MoA in the introduction of the paper (e.g. where authors were describing the underpinning theory of the intervention) and the intervention description then described an intervention component as aiming to target this construct. Because we needed the additional statement in the introduction identifying this construct as a MoA to code the link, we would code this as a link needing some inference. This is in contrast with where authors provided an explicit hypothesis [e.g. ‘we are including this intervention component (BCT X) as we hypothesise that it will change this mechanism (MoA Y), which in turn will change behaviour’].

Across the included articles, we identified 77 BCTs, of which 70 had at least one link to a MoA. The BCTs that were most frequently linked to a MoA were ‘4.1 instruction on how to perform the behaviour’ (182 times) and ‘1.2 problem-solving’ (177 times). The MoA that was most frequently linked to a BCT was ‘beliefs about capabilities’ (733 times), followed by ‘intention’ (318 times). From our set of 26 MoAs, ‘norms’ was the only MoA not identified. There was an empirical test of only 9% of the links within the intervention articles.

Frequency of extracted links (research questions 1–3)

We extracted approximately 10 links per study [mean = 9.56, standard deviation (SD) = 13.80]. Of the extracted links, 12% involved a single BCT and a single MoA, whereas 88% involved more than one BCT or MoA (e.g. one BCT linked to a list of three MoAs). The maximum number of BCTs identified as linked to a single MoA was eight (mean = 3.63, range 1–8). The maximum number of MoAs linked to a single BCT was five (mean = 1.71, range 1–5). A full list of the 2636 BCT–MoA links is available on the Open Science Framework study site (https://osf.io/7qjvn/).

Do any specific behaviour change technique—mechanism of action links occur more frequently than might be expected given the average frequency of behaviour change technique—mechanism of action links? (Research question 4)

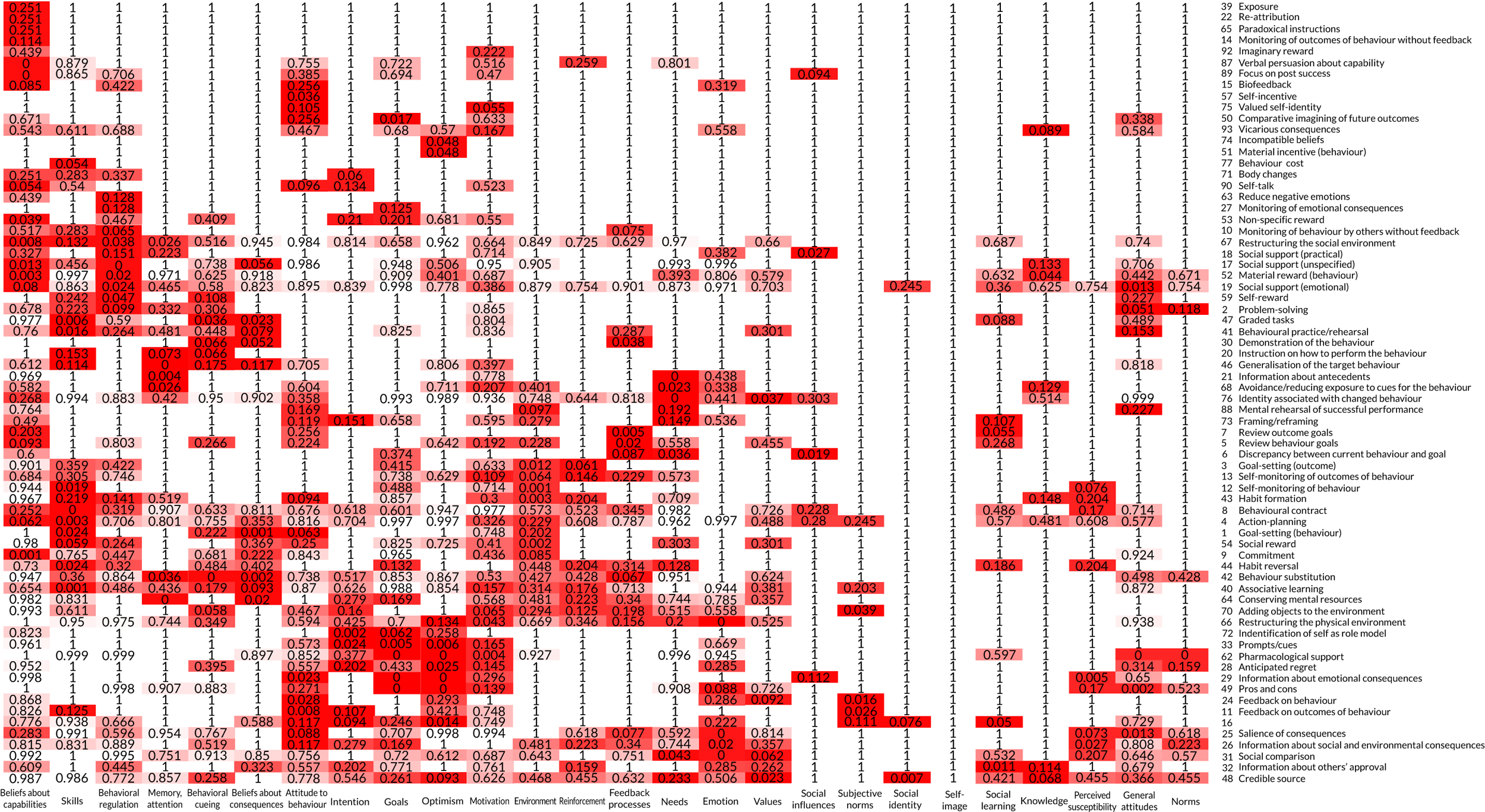

There were 87 links that occurred with a relatively high level of frequency, based on the p < 0.05 criterion. This included 51 out of 93 (55%) BCTs and 24 out of 26 (92%) MoAs. Of the MoAs that were linked to a BCT at least once (i.e. all except ‘norms’), only ‘optimism’ was not linked to any BCT at the p < 0.05 threshold. This MoA was derived from the TDF. 38 Several BCTs were coded frequently but did not meet the p < 0.05 threshold for being linked to a MoA. For example, the BCT ‘1.5 review behaviour goals’ was coded 36 times and ‘3.3 social support (emotional)’ was coded 14 times. However, the relative frequency with which these were linked to a MoA did not meet the threshold.

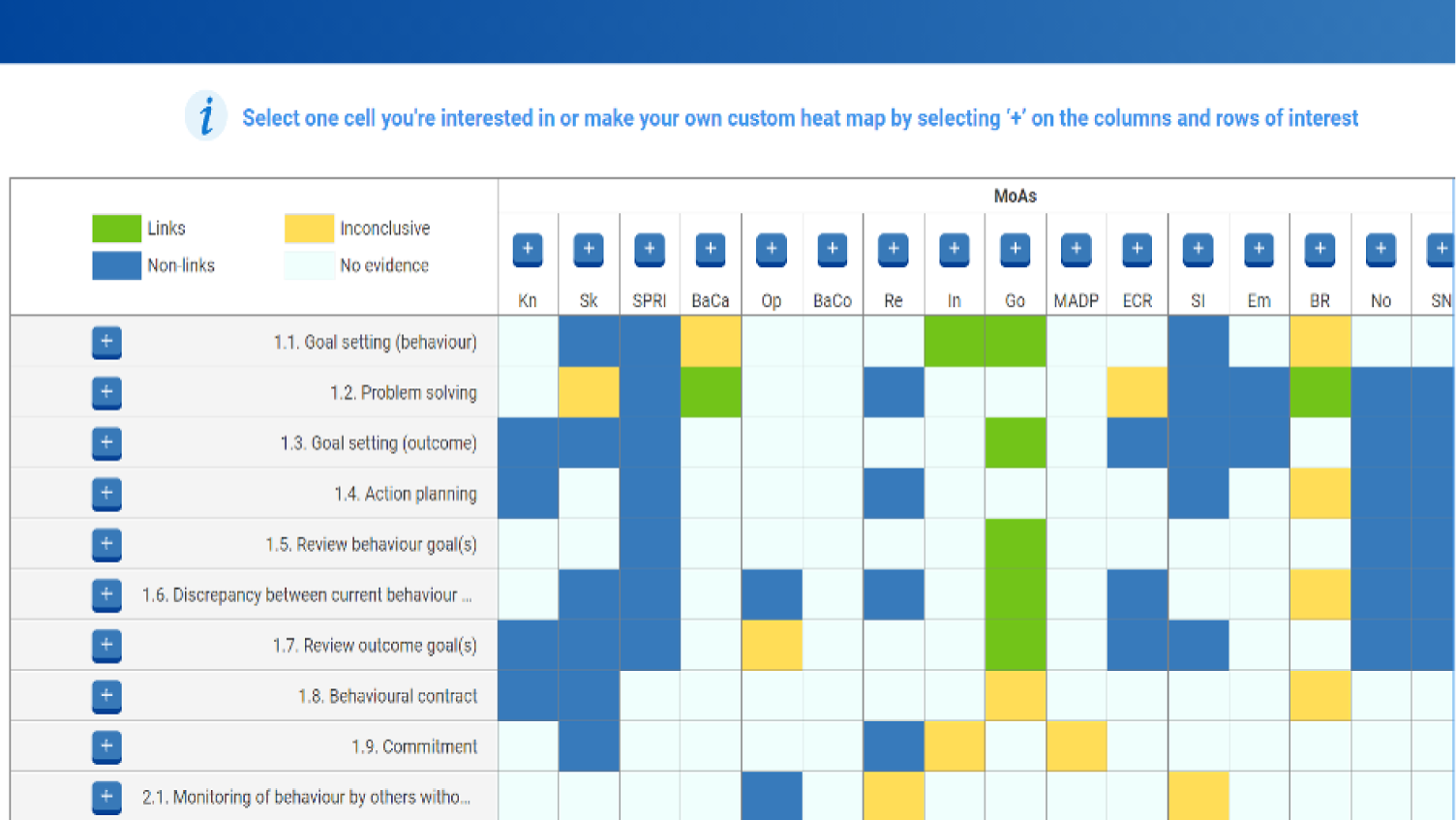

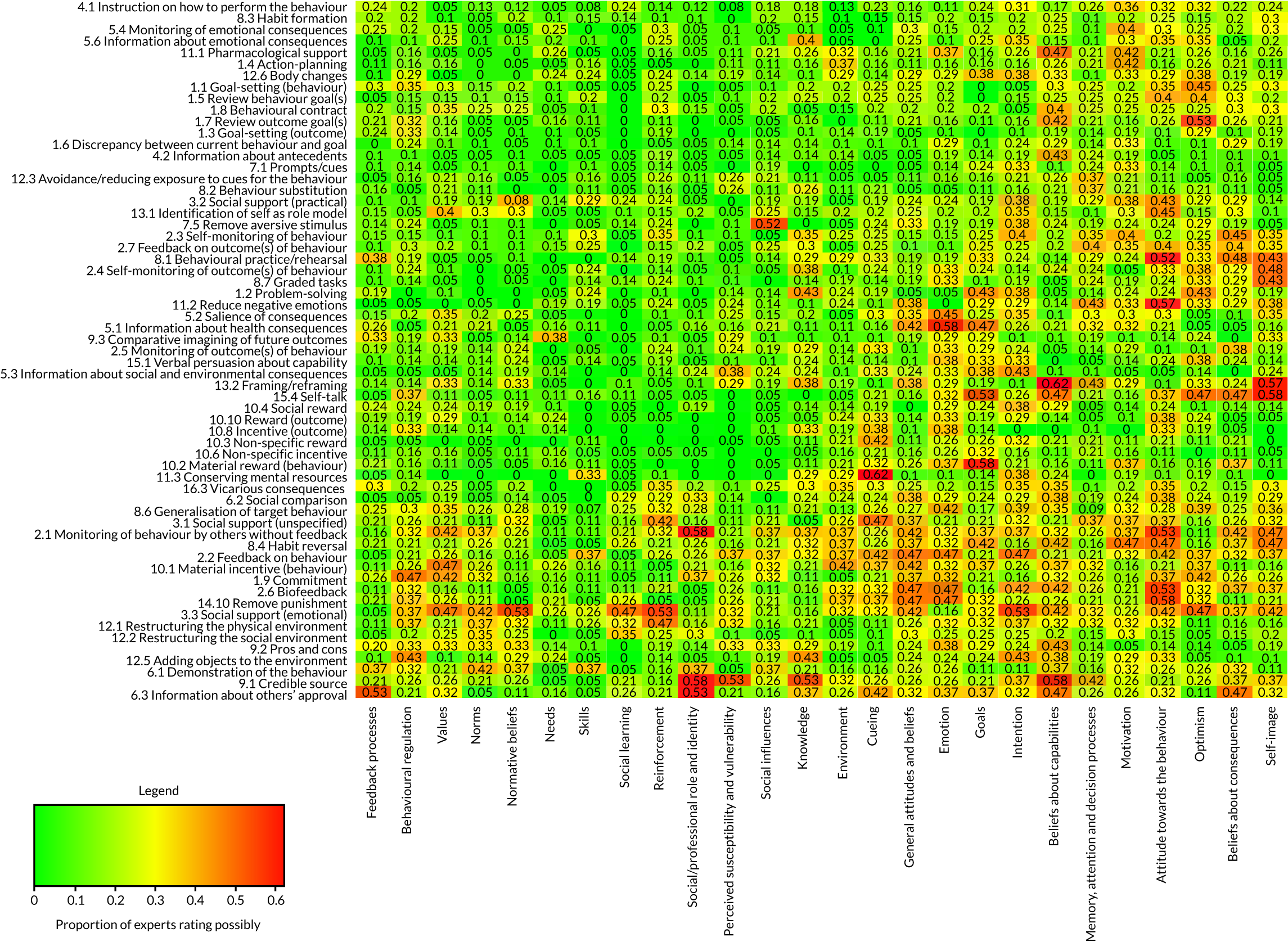

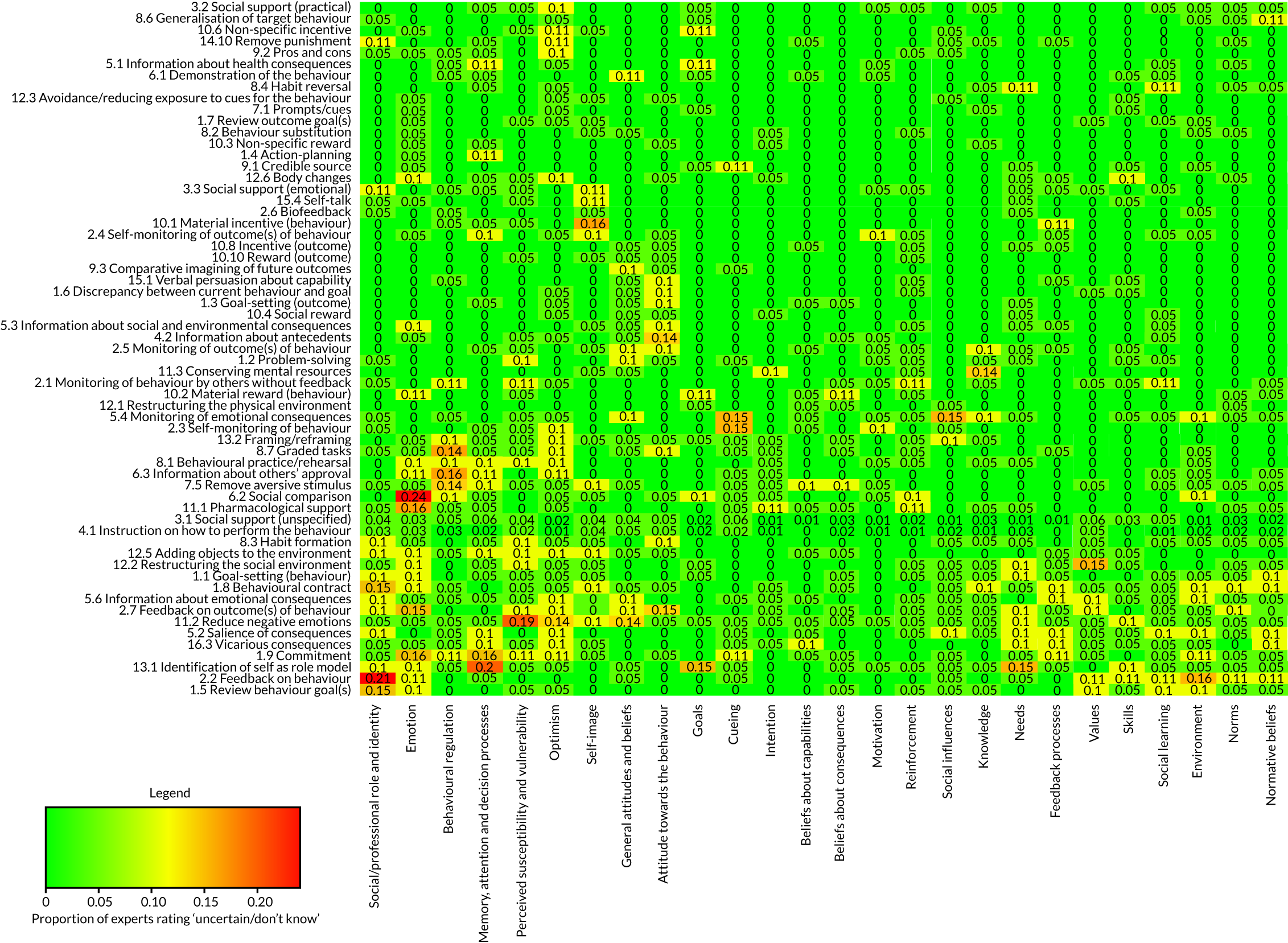

A heat map that displays a visual representation of link frequency, where darker colours represent p-values closer to zero, can be seen in Figure 3 and are also available online as part of an interactive online tool (https://theoryandtechniquetool.humanbehaviourchange.org/tool; see Discussion for more details).

FIGURE 3.

Heat map representing the relative frequency of BCT–MoA links.

Each cell contains a numerical value (i.e. p-value) and is coloured to reflect the relative ‘heat’ of that value (in this case, the relative frequency of a particular link). Rows and columns (i.e. BCTs and MoAs, respectively) are clustered by similarity, such that BCTs linked to similar MoAs are clustered together and MoAs linked to similar numbers of BCTs are clustered together.

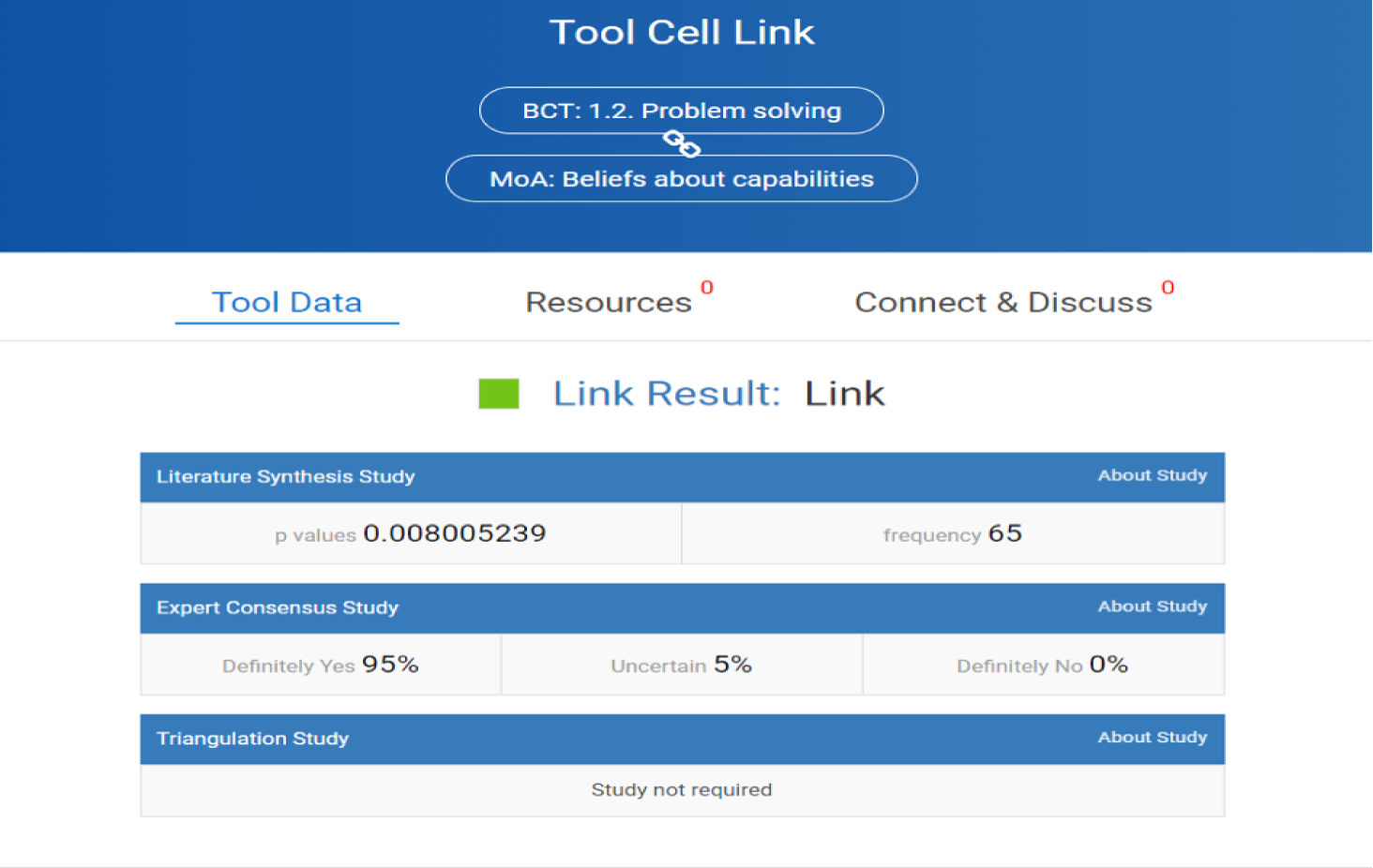

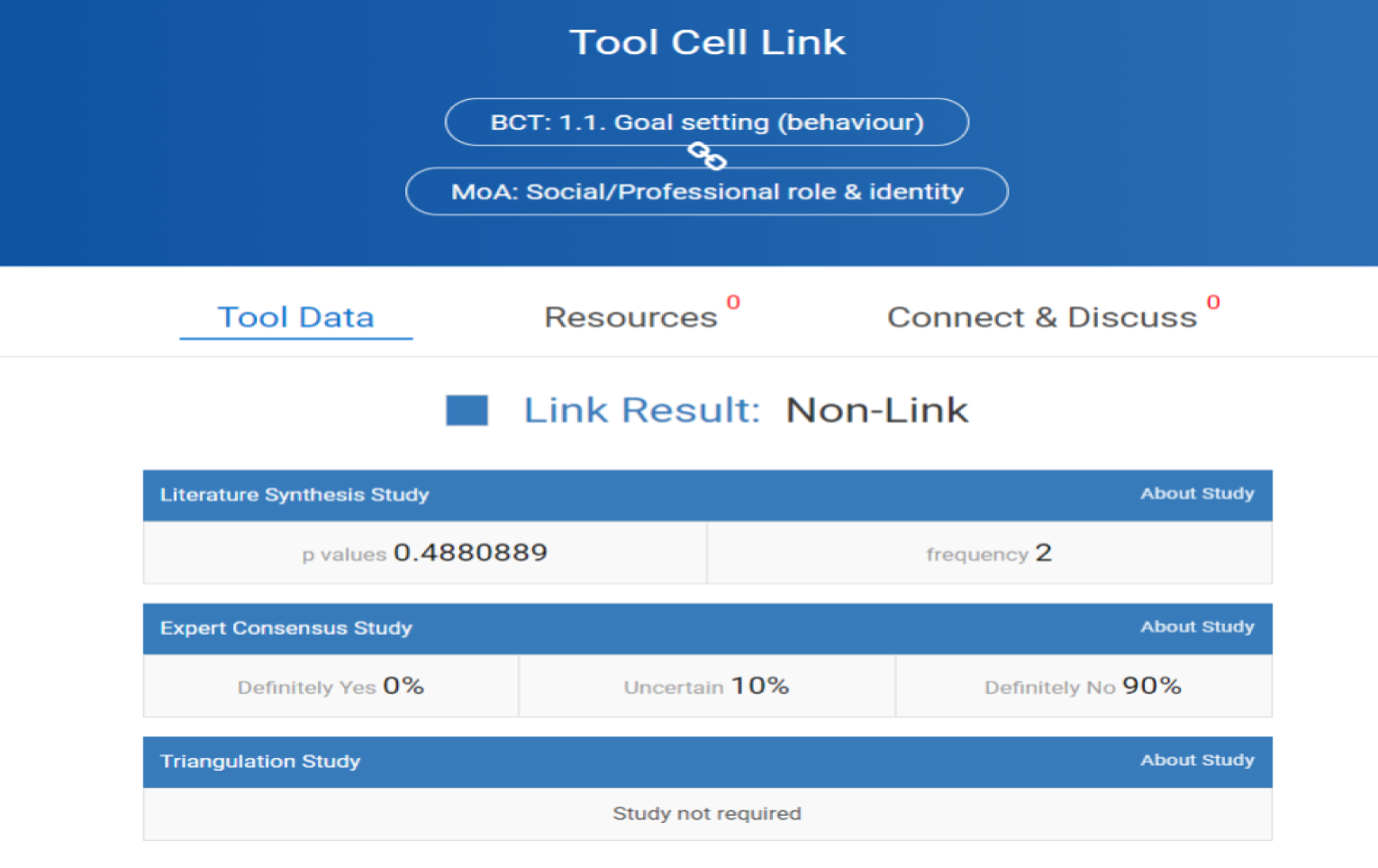

The 51 BCTs and the MoAs that were most frequently linked are shown in Table 1. These summarise the descriptions provided by authors of this set of interventions regarding how these 51 BCTs change behaviour. For some BCTs, there is one MoA for which there appears to be agreement. For example, the BCT ‘8.7 graded tasks’ that was frequently coded across interventions, was linked to only one MoA (‘beliefs about capabilities’) with a relatively high level of frequency (p = < 0.001). For other BCTs, there are links to multiple MoAs. In some of these cases, there is one seemingly ‘dominant’ MoA. For example, although the BCT ‘1.2 problem-solving’ was frequently linked to three MoAs, the link to ‘beliefs about capabilities’ (p = 0.008; occurring 65 times) occurred substantially more frequently than the next highest two: ‘environmental context and resources’ (p = 0.026; occurring nine times) and ‘skills’ (p = 0.038; occurring 18 times).

| BCT | MoA | Frequency | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Instruction on how to perform the behaviour (4.1) | Knowledge | 17 | 0.013 |

| Skills | 20 | 0.024 | |

| Goal-setting (behaviour) (1.1) | Behavioural regulation | 15 | 0.003 |

| Problem-solving (1.2) | Beliefs about capabilities | 65 | 0.008 |

| Environmental context and resources | 9 | 0.026 | |

| Skills | 18 | 0.038 | |

| Social support (unspecified) (3.1) | Social influences | 34 | < 0.001 |

| Social/professional role and identity | 5 | 0.037 | |

| Demonstration of the behaviour (6.1) | Beliefs about capabilities | 60 | 0.003 |

| Skills | 17 | 0.020 | |

| Social learning/imitation | 3 | 0.044 | |

| Action-planning (1.4) | Behavioural regulation | 14 | 0.001 |

| Feedback on behaviour (2.2) | Subjective norms | 19 | < 0.001 |

| Knowledge | 13 | 0.013 | |

| Information about health consequences (5.1) | Knowledge | 18 | < 0.001 |

| Beliefs about consequences | 26 | < 0.001 | |

| Attitude towards the behaviour | 19 | < 0.001 | |

| Perceived susceptibility/vulnerability | 10 | < 0.001 | |

| Intention | 28 | 0.004 | |

| Behavioural practice/rehearsal (8.1) | Skills | 24 | < 0.001 |

| Beliefs about capabilities | 47 | 0.013 | |

| Social comparison (6.2) | Subjective norms | 31 | < 0.001 |

| Social influences | 9 | 0.043 | |

| Information about social and environmental consequences (5.3) | Beliefs about consequences | 20 | < 0.001 |

| Attitude towards the behaviour | 16 | < 0.001 | |

| Knowledge | 13 | 0.002 | |

| Self-monitoring of behaviour (2.3) | Behavioural regulation | 18 | < 0.001 |

| Credible source (9.1) | General attitudes/beliefs | 2 | 0.007 |

| Social/professional role and identity | 4 | 0.023 | |

| Adding objects to the environment (12.5) | Environmental context/resources | 8 | < 0.001 |

| Prompts/cues (7.1) | Memory, attention and decision processes | 8 | < 0.001 |

| Behavioural cueing | 6 | 0.002 | |

| Environmental context/resources | 5 | 0.036 | |

| Graded tasks (8.7) | Beliefs about capabilities | 28 | < 0.001 |

| Pros and cons (9.2) | Beliefs about consequences | 12 | < 0.001 |

| Attitude towards the behaviour | 9 | < 0.001 | |

| Feedback processes | 3 | 0.005 | |

| Motivation | 5 | 0.023 | |

| Framing/reframing (13.2) | Self-image | 2 | < 0.050 |

| Attitude towards the behaviour | 7 | 0.014 | |

| Behaviour substitution (8.2) | Behavioural regulation | 5 | 0.016 |

| Social reward (10.4) | Reinforcement | 3 | 0.020 |

| Focus on past success (15.3) | Beliefs about capabilities | 23 | < 0.001 |

| Restructuring the physical environment (12.1) | Environmental context/resources | 9 | < 0.001 |

| Behavioural cueing | 3 | 0.020 | |

| Behavioural contract (1.8) | Goals | 4 | 0.002 |

| Information about others’ approval (6.3) | Subjective norms | 13 | < 0.001 |

| Intention | 12 | 0.043 | |

| Verbal persuasion about capability (15.1) | Beliefs about capabilities | 27 | < 0.001 |

| Feedback on outcomes of behaviour (2.7) | Subjective norms | 5 | 0.020 |

| Feedback processes | 2 | 0.027 | |

| Reduce negative emotions (11.2) | Beliefs about capabilities | 12 | 0.039 |

| Salience of consequences (5.2) | Attitude towards the behaviour | 4 | 0.025 |

| Commitment (1.9) | Values | 1 | 0.039 |

| Self-monitoring of outcomes of behaviour (2.4) | Behavioural regulation | 5 | 0.024 |

| Information about emotional consequences (5.6) | Beliefs about consequences | 6 | 0.005 |

| Attitude towards the behaviour | 5 | 0.006 | |

| Emotion | 2 | 0.024 | |

| Goal-setting (outcome) (1.3) | Goals | 4 | 0.003 |

| Social support (practical) (3.2) | Social influences | 4 | 0.023 |

| Environmental context and resources | 3 | 0.026 | |

| Discrepancy between current behaviour and goal (1.6) | Goals | 3 | 0.001 |

| Behavioural regulation | 3 | 0.019 | |

| Avoidance/reducing exposure to cues for the behaviour (12.3) | Needs | 1 | 0.027 |

| Identification of self as role model (13.1) | Self-image | 2 | 0.011 |

| Restructuring the social environment (12.2) | Environmental context/resources | 3 | 0.004 |

| Social influences | 6 | < 0.001 | |

| Non-specific reward (10.3) | Reinforcement | 2 | 0.005 |

| Habit formation (8.3) | Behavioural cueing | 3 | 0.001 |

| Behavioural regulation | 3 | 0.024 | |

| Review outcome goals (1.7) | Goals | 2 | 0.012 |

| Mental rehearsal of successful performance (15.2) | Motivation | 3 | 0.008 |

| Values | 1 | 0.026 | |

| Material incentive (behaviour) (10.1) | Attitude towards the behaviour | 1 | 0.048 |

| Monitoring of behaviour by others without feedback (2.1) | Needs | 1 | 0.019 |

| Social influences | 2 | 0.036 | |

| Generalisation of target behaviour (8.6) | Skills | 2 | 0.047 |

| Comparative imagining of future outcomes (9.3) | Beliefs about consequences | 3 | 0.017 |

| Identity associated with changed behaviour (13.5) | Values | 1 | 0.016 |

| Motivation | 2 | 0.028 | |

| Anticipated regret (5.5) | Emotion | 2 | 0.002 |

| Habit reversal (8.4) | Behavioural regulation | 4 | 0.006 |

| Behavioural cueing | 2 | 0.023 | |

| Memory, attention and decision processes | 2 | 0.036 | |

| Associative learning (7.8) | Reinforcement | 1 | 0.038 |

| Self-incentive (10.7) | Motivation | 1 | 0.036 |

| Incompatible beliefs (13.3) | Attitude towards the behaviour | 1 | 0.048 |

For those BCTs for which there are multiple MoAs linked, the data suggest that the authors may be hypothesising specific causal pathways (e.g. attitude → intention → behaviour). For instance, the BCT ‘5.1 information about health consequences’ was linked to the MoAs ‘beliefs about consequences’ (p < 0.001), ‘knowledge’ (p < 0.001), ‘perceived susceptibility/vulnerability’ (p < 0.001), ‘attitude towards the behaviour’ (p < 0.001) and ‘intention’ (p = 0.004).

Table 2 shows the 24 MoAs and the BCTs that were most frequently linked. It can be interpreted as a summary of the BCTs that the authors believe are suitable to target these 24 MoAs. In some cases, there is one clear BCT for a given MoA. For example, the MoA ‘perceived susceptibility/vulnerability’ was linked only to the BCT ‘5.1 information about health consequences’ (p < 0.001) and the MoA ‘social learning/imitation’ was linked only to the BCT ‘6.1 demonstration of the behaviour’ (p = 0.044).

| MoA | BCT | Frequency | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Attitude towards the behaviour | Information about health consequences (5.1) | 19 | < 0.001 |

| Information about social and environmental consequences (5.3) | 16 | < 0.001 | |

| Pros and cons (9.2) | 9 | < 0.001 | |

| Information about emotional consequences (5.6) | 5 | 0.006 | |

| Framing/reframing (13.2) | 7 | 0.014 | |

| Salience of consequences (5.2) | 4 | 0.025 | |

| Material incentive (behaviour) (10.1) | 1 | 0.048 | |

| Incompatible beliefs (13.3) | 1 | 0.048 | |

| Behavioural cueing | Habit formation (8.3) | 3 | 0.001 |

| Prompts/cues (7.1) | 6 | 0.002 | |

| Restructuring the physical environment (12.1) | 3 | 0.020 | |

| Habit reversal (8.4) | 2 | 0.023 | |

| Behavioural regulation | Self-monitoring of behaviour (2.3) | 18 | < 0.001 |

| Action-planning (1.4) | 14 | 0.001 | |

| Goal-setting (behaviour) (1.1) | 15 | 0.003 | |

| Habit reversal (8.4) | 4 | 0.006 | |

| Behaviour substitution (8.2) | 5 | 0.016 | |

| Discrepancy between current behaviour and goal (1.6) | 3 | 0.019 | |

| Self-monitoring of outcomes of behaviour (2.4) | 5 | 0.024 | |

| Habit formation (8.3) | 3 | 0.024 | |

| Beliefs about capabilities | Graded tasks (8.7) | 28 | < 0.001 |

| Verbal persuasion about capability (15.1) | 27 | < 0.001 | |

| Focus on past success (15.3) | 23 | < 0.001 | |

| Demonstration of the behaviour (6.1) | 60 | 0.003 | |

| Problem-solving (1.2) | 65 | 0.008 | |

| Behavioural practice/rehearsal (8.1) | 47 | 0.013 | |

| Reduce negative emotions (11.2) | 12 | 0.039 | |

| Beliefs about consequences | Information about health consequences (5.1) | 26 | < 0.001 |

| Information about social and environmental consequences (5.3) | 20 | < 0.001 | |

| Pros and cons (9.2) | 12 | < 0.001 | |

| Information about emotional consequences (5.6) | 6 | 0.005 | |

| Comparative imagining of future outcomes (9.3) | 3 | 0.017 | |

| Environmental context and resources | Restructuring the physical environment (12.1) | 9 | < 0.001 |

| Adding objects to the environment (12.5) | 8 | < 0.001 | |

| Restructuring the social environment (12.2) | 3 | 0.004 | |

| Problem-solving (1.2) | 9 | 0.026 | |

| Social support (practical) (3.2) | 3 | 0.026 | |

| Prompts and cues (7.1) | 5 | 0.036 | |

| Emotion | Anticipated regret (5.5) | 2 | 0.002 |

| Information about emotional consequences (5.6) | 2 | 0.024 | |

| Feedback processes | Pros and cons (9.2) | 3 | 0.005 |

| Feedback on outcomes of behaviour (2.7) | 2 | 0.027 | |

| General attitudes/beliefs | Credible source (9.1) | 2 | 0.007 |

| Goals | Discrepancy between current behaviour and goal (1.6) | 3 | 0.001 |

| Behavioural contract (1.8) | 4 | 0.002 | |

| Goal-setting (outcome) (1.3) | 4 | 0.003 | |

| Review outcome goals (1.7) | 2 | 0.012 | |

| Intention | Information about health consequences (5.1) | 28 | 0.004 |

| Information about others’ approval (6.3) | 12 | 0.043 | |

| Knowledge | Information about health consequences (5.1) | 18 | < 0.001 |

| Information about social and environmental consequences (5.3) | 13 | 0.002 | |

| Instruction on how to perform the behaviour (4.1) | 17 | 0.013 | |

| Feedback on behaviour (2.2) | 13 | 0.013 | |

| Memory, attention and decision processes | Prompts/cues (7.1) | 8 | < 0.001 |

| Habit reversal (8.4) | 2 | 0.036 | |

| Motivation | Mental rehearsal of successful performance (15.2) | 3 | 0.008 |

| Pros and cons (9.2) | 5 | 0.023 | |

| Identity associated with changed behaviour (13.5) | 2 | 0.028 | |

| Self-incentive (10.7) | 1 | 0.036 | |

| Perceived susceptibility/vulnerability | Information about health consequences (5.1) | 10 | < 0.001 |

| Needs | Monitoring of behaviour by others without feedback (2.1) | 1 | 0.019 |

| Avoidance/reducing exposure to cues for the behaviour (12.3) | 1 | 0.027 | |

| Reinforcement | Non-specific reward (10.3) | 2 | 0.005 |

| Social reward (10.4) | 3 | 0.020 | |

| Associative learning (7.8) | 1 | 0.038 | |

| Self-image | Framing/reframing (13.2) | 2 | < 0.050 |

| Identification of self as role model (13.1) | 2 | 0.011 | |

| Skills | Behavioural practice/rehearsal (8.1) | 24 | < 0.001 |

| Demonstration of the behaviour (6.1) | 17 | 0.020 | |

| Instruction on how to perform the behaviour (4.1) | 20 | 0.024 | |

| Problem-solving (1.2) | 18 | 0.038 | |

| Generalisation of target behaviour (8.6) | 2 | 0.047 | |

| Social influences | Social support (unspecified) (3.1) | 34 | < 0.001 |

| Restructuring the social environment (12.2) | 6 | < 0.001 | |

| Social support (practical) (3.2) | 4 | 0.023 | |

| Monitoring of behaviour by others without feedback (2.1) | 2 | 0.036 | |

| Social comparison (6.2) | 9 | 0.043 | |

| Subjective norms | Feedback on behaviour (2.2) | 19 | < 0.001 |

| Social comparison (6.2) | 31 | < 0.001 | |

| Information about others’ approval (6.3) | 13 | < 0.001 | |

| Feedback on outcomes of behaviour (2.7) | 5 | 0.020 | |

| Social learning/imitation | Demonstration of the behaviour (6.1) | 3 | 0.044 |

| Social/professional role and identity | Credible source (9.1) | 4 | 0.023 |

| Social support (unspecified) (3.1) | 5 | 0.037 | |

| Values | Identity associated with changed behaviour (13.5) | 1 | 0.016 |

| Mental rehearsal of successful performance (15.2) | 1 | 0.026 | |

| Commitment (1.9) | 1 | 0.039 |

In other cases, clusters of theoretically linked BCTs were linked to one MoA. An example is the MoA ‘emotion’ being linked to the BCT ‘5.5 anticipated regret’ (p = 0.002) and ‘5.3 information about emotional consequences’ (p = 0.024).

Discussion

This study provides the first data set summarising links between BCTs and MoAs, as described by authors of published intervention articles. There were 2636 links identified in this study, including 70 BCTs and 25 MoAs. Eighty-seven links were identified with a relatively high level of frequency (i.e. meeting the criterion of p-value of < 0.05). The findings of this study provide a summary of links that are described frequently (e.g. providing information about the health consequences of a behaviour is frequently hypothesised to increase knowledge), as well as those links that appear to be absent. Advancing the science of behaviour change at a theoretical and methodological level, through this and similar initiatives (see www.scienceofbehaviourchange.org), helps to provide a grounding from which researchers and practitioners can build innovative new interventions by combining BCTs, knowing where important gaps are and providing a basis for new hypotheses.

The findings indicate that, in some cases, there is one clear BCT for a given MoA and one clear MoA for a given BCT. In other cases, there are BCTs linked to more than one MoA and MoAs linked to more than one BCT. Some of the links that can be seen in our data set map closely to the theoretical literature. For example, in Bandura’s theory of self-efficacy,107 a number of intervention strategies that can be used to increase self-efficacy are described, including mastery experience, vicarious experience and verbal persuasion. These intervention strategies are comparable to the BCTs ‘8.1 behavioural practice/rehearsal’, ‘6.1 demonstration of the behaviour’ and ‘15.1 verbal persuasion about capability’, respectively, all of which were linked to the MoA ‘beliefs about capabilities’, a construct that is conceptually identical to self-efficacy in this study.

Although we identified at least one link for 91% of the coded BCTs and 92% of the MoAs, in a number of cases no clear links were identified. Two of the MoAs in our set of 26 were not linked to BCTs enough to meet the criterion of a p-value of < 0.05. These were ‘optimism’ and ‘norms’, both of which are found to be frequently occurring in behavioural theories. 30 This may reflect a lack of clarity or agreement in the behavioural intervention literature regarding the types of BCTs that should be employed to target these MoAs.

How can the findings be used?

The heat map (see Figure 3 and Tables 1 and 2), can be used both to identify BCTs that have the potential to target relevant MoAs (e.g. for intervention design and development) as well as to understand the MoA(s) through which BCTs are having their effects (e.g. for intervention evaluation and/or to advance our theoretical knowledge). For example, to include BCTs that will most likely have an effect on relevant MoAs (i.e. an ‘optimal’ BCT–MoA link), one can refer to Tables 1 and 2, which list the links that met the criterion of a p-value of < 0.05. By drawing on these findings, researchers may identify creative ways to target MoAs of interest (e.g. by including less commonly used BCTs).

Given the scope of this work, we cannot draw inferences about the extent to which these BCT–MoA links have been empirically tested. However, our data set can be used to develop a framework for designing and conducting empirical tests. This would help to inform the cumulative development of evidence that can provide clarity and reduce ambiguity about these links. This would also help researchers to examine those BCT–MoA links that currently appear to be underused. Thus, the database of BCT–MoA links resulting from this study can be used to identify links that have been (1) frequently described in the literature and that require empirical study and (2) infrequently reported and appear to be understudied.

There are several additional points to note. It is clear that, despite the importance of a rigorously applied theoretical basis15,22 to optimise effectiveness and enhance our understanding of intervention effects,23 a large number of intervention articles lack clarity in their description of the theoretical underpinning of the study. In this study, 72% of the articles identified through the search methods did not explicitly describe links between BCTs and MoAs. These findings are consistent with previous meta-analytic findings, which indicated that, although 50% of the interventions reviewed reported a theoretical basis, 90% did not report links between all BCTs and individual theoretical constructs. 26 Without clear descriptions of the hypothesised links between BCTs and MoAs, it can be difficult to draw generalisable theoretical conclusions.

Furthermore, it seems clear from this study that conceptualisations of what authors may refer to as a ‘theory-based’ intervention are highly variable. A large number of interventions that are reported to be based on theory in fact draw on implicit or partially applied theories. 24–26 Intervention descriptions often lack clarity about exactly how theory has been applied. This is particularly the case in the selection of BCTs and the links to, and measurement of, relevant theoretical constructs. We can only systematically advance our theoretical understanding of how interventions work if authors explicitly report how and why theoretical principles were tested28–31 rather than simply describing the intervention as being informed by theory. 27 A reliance on the latter, and a tendency to rely on implicit theoretical assumptions, has hampered intervention research.

It is worth noting that most of the links between BCTs and MoAs were not extracted as individual links, but as groups. This may indicate that authors considered there to be synergistic relationships among BCTs and/or MoAs (e.g. BCTs A, B and C and/or MoAs X, Y and Z work together in the behaviour change process). Another explanation is a lack of specificity in the selection of BCTs, targeting of MoAs and/or lack of detail in reporting interventions.

Limitations

There are a number of limitations to the current work. We did not undertake a full systematic review; the intervention articles were purposively selected to maximise the likelihood of being able to identify BCT–MoA links. This was because the aim of the study was to identify the links that were described in intervention articles, rather than to set out to examine the clarity with which they tended to be described. Although we attempted to collate articles from the international research community (e.g. by contacting the Society of Behavioral Medicine in the USA and the European Health Psychology Society), there is a wide range of published intervention evaluations that our data set of articles may not represent.

The extracted BCT–MoA links were based on authors’ descriptions and hypotheses. Very few had been tested empirically in the articles. Therefore, we were unable to synthesise the results of empirical tests of these links. This indicates that there is a need for empirical research that systematically tests the links that have been frequently described. With this aim in mind, work is ongoing in the USA to identify, measure and manipulate MoAs using experimental methods (see www.scienceofbehaviourchange.org).

We cannot use the findings of this study to draw conclusions about the links that did not appear in the included intervention articles. The links that appeared to be absent may reflect a belief among authors that they do not exist, or that they may be links that do not tend to be considered by intervention designers (despite being potentially useful). These links may also include MoAs that authors find difficult to operationalise, or those that authors tend to use implicitly and are therefore less likely to explicitly describe in detail.

Next steps

This was the first of three related studies that aim to examine the links between BCTs and (1) MoAs and (2) behavioural theories. 100 In the next stage, links between BCTs and MoAs were identified through an expert consensus study.

Chapter 3 An expert consensus approach to linking behaviour change techniques and mechanisms of action

Abstract

Objective

To build a shared knowledge of the links between BCTs and MoAs through expert consensus.

Methods

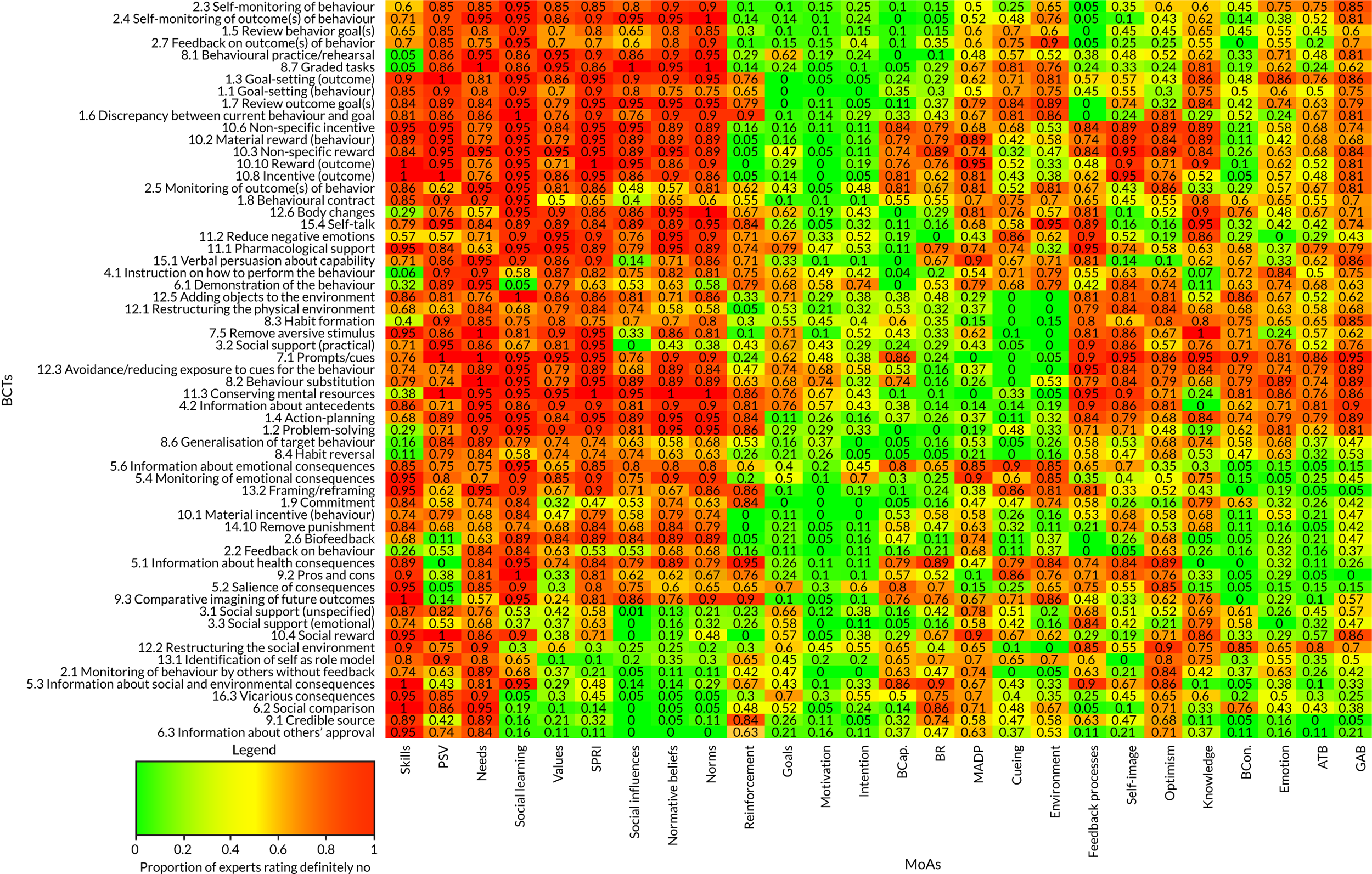

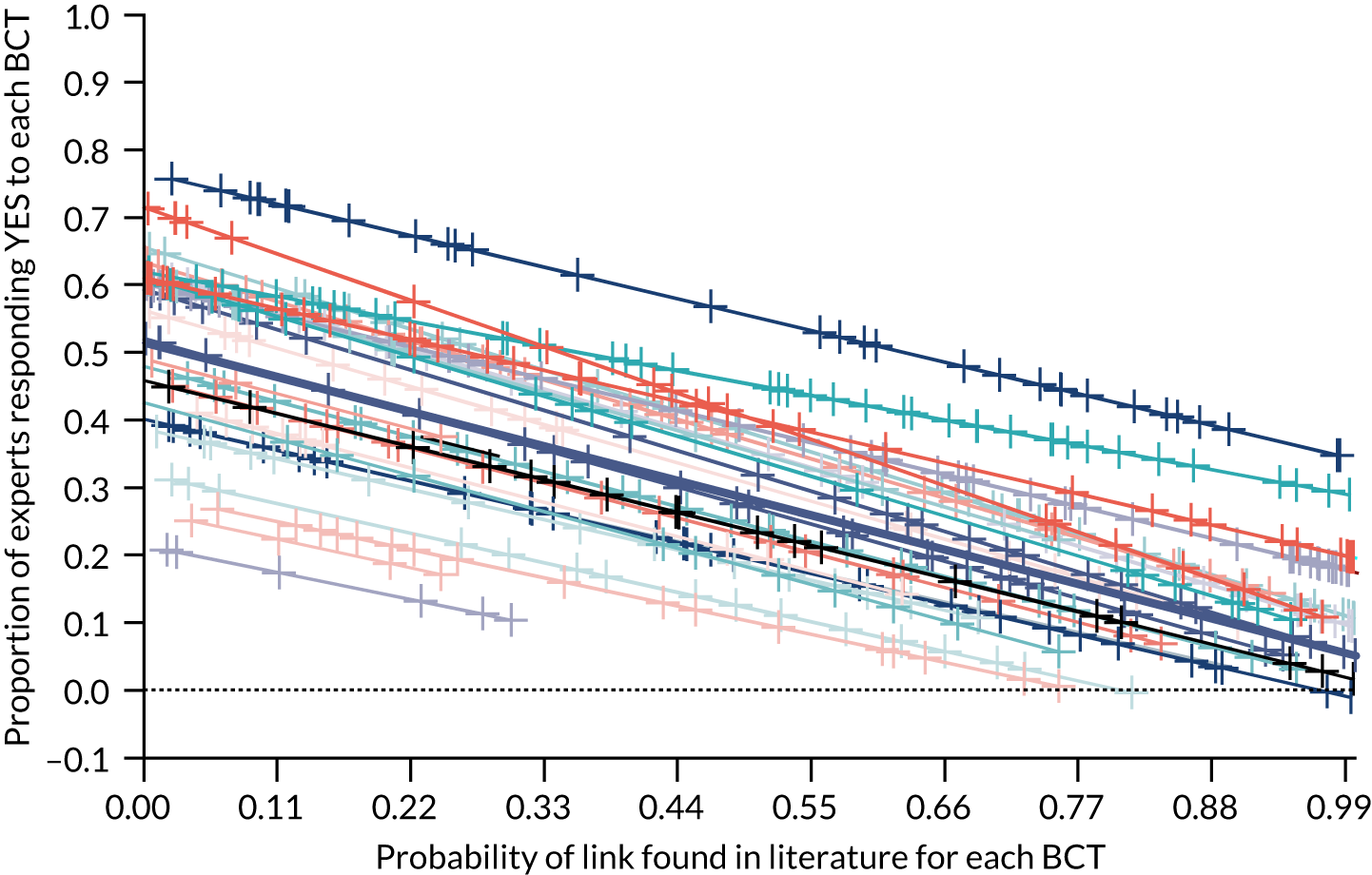

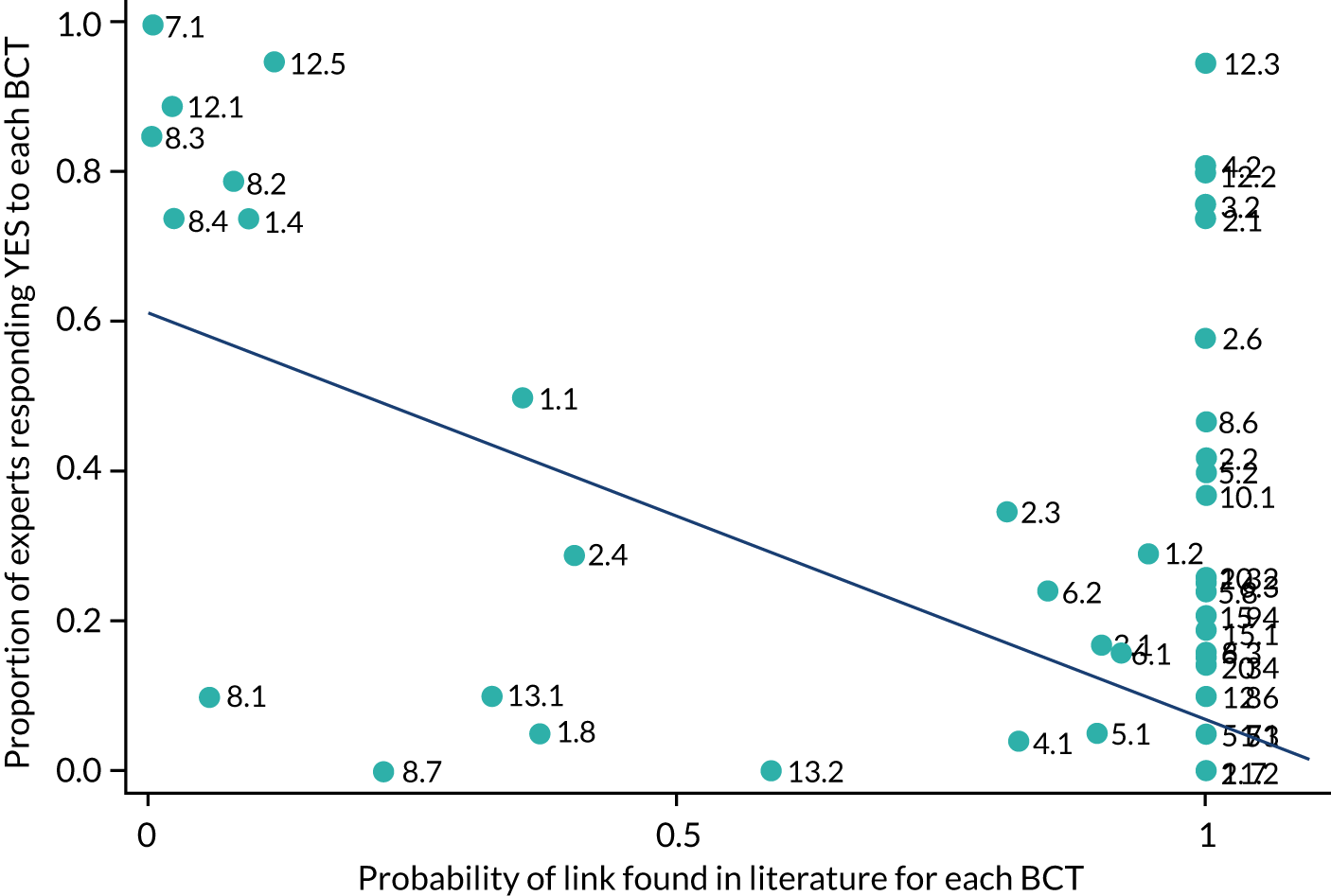

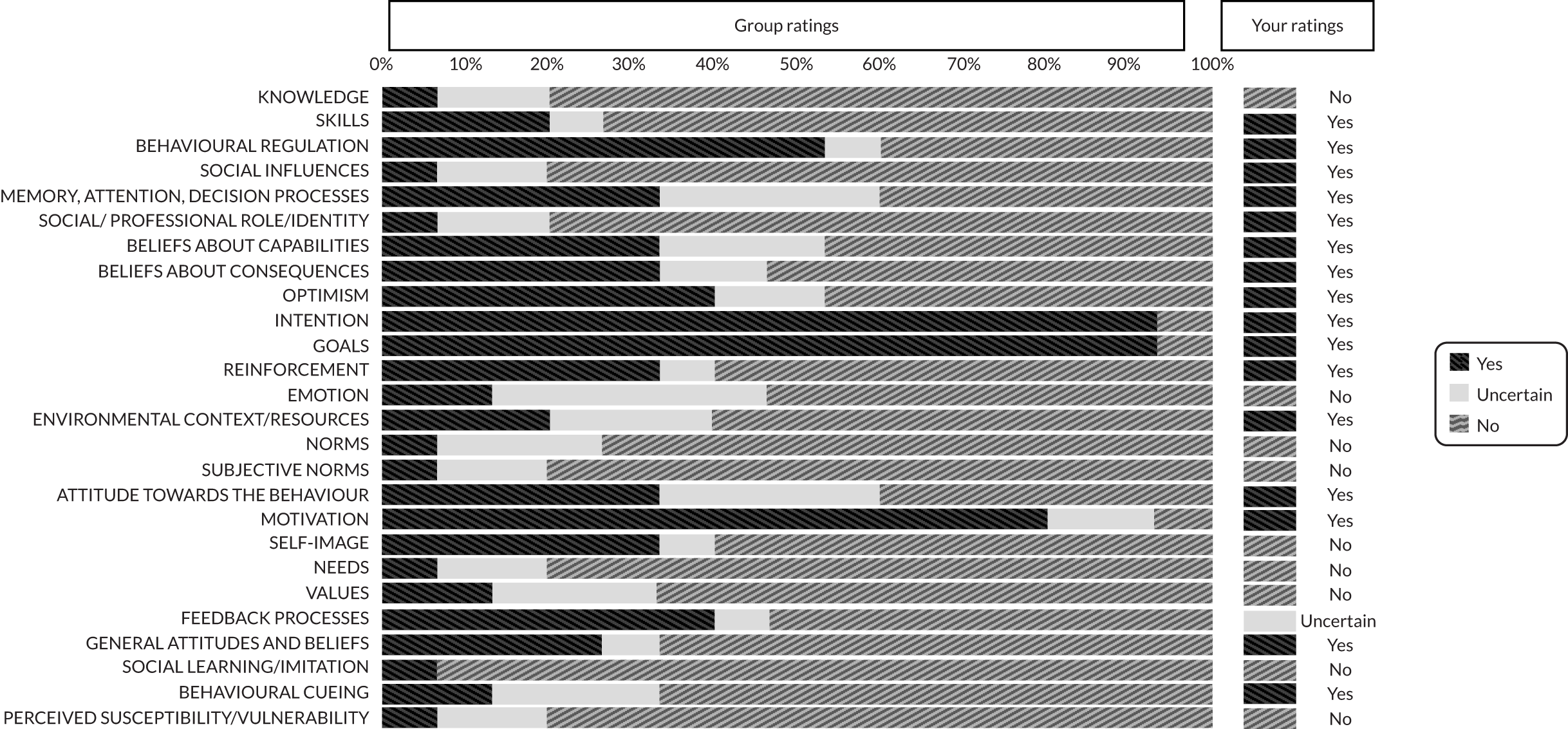

International behaviour change experts (n = 105) participated in a modified nominal group technique to examine links between 61 frequently used BCTs and 26 MoAs. Experts participated in three rounds to rate, discuss and re-rate links between BCTs and MoAs. Consensus was reached if at least 80% of experts agreed about a link.

Results

Of 1586 possible BCT–MoA link combinations (61 BCTs × 26 MoAs), 83.6% (51/61) of BCTs were definitely linked to at least one MoA [mean (SD) 1.44 (0.96), range 1–4], 76.9%. Twenty out of 26 MoAs were definitely linked to at least one BCT [mean (SD) 3.27 (2.91), range 9]. A total of 90 links were considered ‘definite’ (5.7%) and 464 (29.2%) were considered ‘definitely not’ links. Finally, 1032 (65.1%) were considered ‘possible’ or ‘unsure’ links. There were 10 BCTs (e.g. ‘action-planning’ and ‘behavioural substitution’) and six MoAs (e.g. ‘needs’ and ‘optimism’) with no identified links.

Conclusions

The identified agreed links between BCTs and MoAs provide a framework for specifying empirical tests of links in future studies and for researchers interested in developing and/or synthesising behavioural interventions.

Introduction

Identifying specific links between BCTs and MoAs is important for both developing interventions and understanding the processes through which interventions affect behaviour change. One method for generating evidence on the links between BCTs and MoAs would be to conduct experimental studies of BCT–MoA links by manipulating BCTs and measuring MoAs and subsequently conducting meta-analyses of their findings. 108 However, the sheer number of potential BCTs and MoAs and, consequently, BCT–MoA links render these methods relatively infeasible.

Indirect approaches, such as the examination of hypothesised links between BCTs and MoAs in published intervention literature (see Chapter 2), provide a valuable alternative source of evidence. However, the published intervention literature is limited by various publication biases. These include the selection of research projects (at least in part) being driven by funding requirements, reporting of projects by researchers and the selection of which findings to present for publication. Examining the current thinking of international experts in behaviour change provides a complementary source of evidence, capable of generating useful information on a large set of BCT–MoA links. Using an expert consensus approach permits a synthesis of the current hypotheses of experts in the field, limits the impact that publication or funding-related biases have and is informed by existing theory and evidence.

Expert consensus methods can be used to facilitate the development of research questions, solutions to existing problems and priorities for action. 109 Through expert consensus methodologies, differing ideas can be discussed, reported and organised to establish areas of consensus and priorities for further investigation. Furthermore, these methods cultivate the experts’ ownership of the resulting research, thereby increasing the likelihood that future research and practice will be influenced by the outcomes of the study. 110

This chapter reports the second in a series of four studies to develop and test a methodology for generating links between BCTs and MoAs. This study aimed to build consensus around the mechanisms through which BCTs may alter behaviour. The primary research questions were:

-

Which BCTs do experts agree influence behaviour through specific MoAs?

-

Which BCTs do experts agree do not influence behaviour through specific MoAs?

-

Do experts agree that BCTs influence behaviour through one or multiple MoAs?

The secondary research questions were:

-

Which links between BCTs and MoAs do experts disagree on?

-

Do experts agree on at least one link with a MoA for all BCTs?

-

Do experts agree on at least one link with a BCT for all MoAs?

Methods

Design

A formal consensus method drawing on nominal group technique (NGT)111 was used to examine the links between BCTs and MoAs across three rounds: (1) initial rating, (2) discussion and (3) final rating.

Participants

Experts with experience in behaviour change intervention design, evaluation and/or evidence synthesis were selected to represent a range of academic disciplines, professional backgrounds and geographical regions.

Recruitment

Participants were recruited via e-mail. E-mails were sent to (1) experts who had participated in in-person BCT training, online BCT training (www.bct-taxonomy.com/) and/or the BCTTv1 project42 (see www.ucl.ac.uk/health-psychology/bcttaxonomy), (2) members of the IAB for the research programme and (3) contact lists from professional societies and centres (University College London’s Centre for Behaviour Change, the Special Interest Group of the US Society of Behavioral Medicine, European Health Psychology Society, UK Society for Behavioural Medicine and Division of Health Psychology of the British Psychological Society). Recruited participants were also asked to recommend other participants, creating a ‘snowballing’ recruitment process.

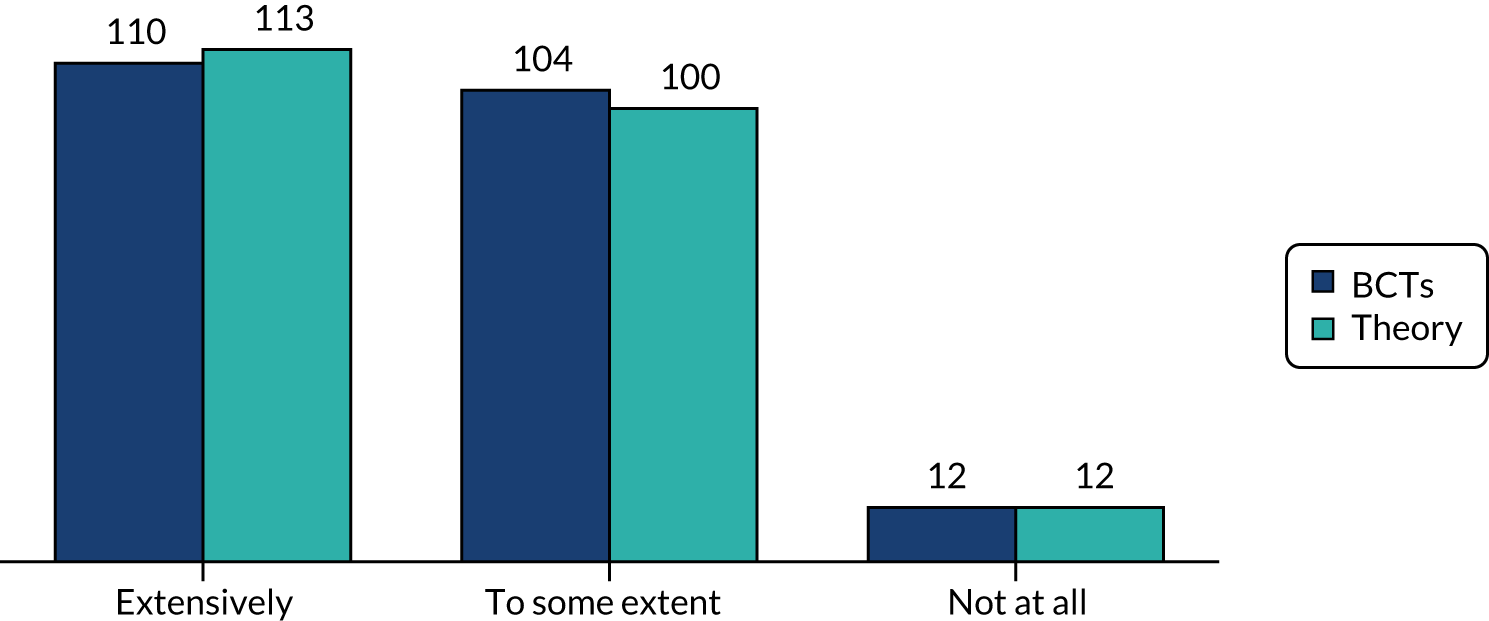

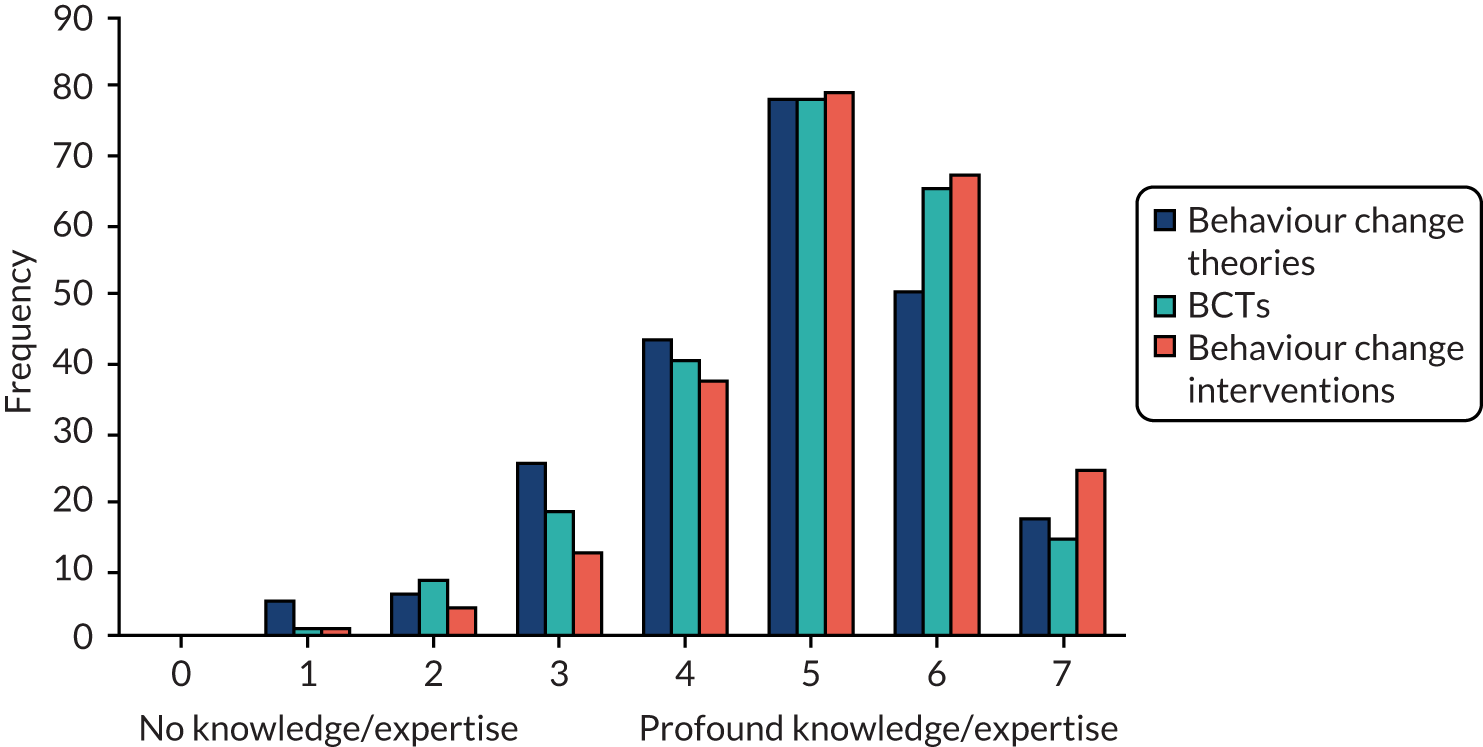

Participants interested in becoming an expert judge (n = 227) completed a self-reported survey (see Appendix 5) to evaluate their experience and expertise in behaviour change interventions. Eligibility criteria included (1) above-average self-rated expertise in BCTs, behaviour change theories and behaviour change interventions, (≥ 4 using a 7-point scale ranging from ‘0 – no expertise’ to ‘7 – profound expertise’) and (2) some experience with behaviour change intervention(s) that ‘used specific BCTs’ and ‘was specifically grounded in behaviour change theory/theories’. Just over half (54.2%) of interested participants were eligible. Eligible experts were sent a second questionnaire to collect demographic information to ensure that the selected panel contained experts reflecting a range of countries, professional backgrounds and academic disciplines (see Appendix 5).

Reviews of previous expert consensus studies found that panels with approximately 20 participants demonstrate stability of consensus. 112 Therefore, the final sample of experts (n = 105) was sufficient to establish consensus. Furthermore, dividing the experts into subgroups of 20 or more experts would also be sufficient. Approximately half of the experts were from the UK, 20% were from other European countries, 20% were from North America and 10% were from Africa, Australia or New Zealand. The majority of experts worked in an academic setting (75%) and in the field of psychology (60%).

Procedure

The expert ratings in rounds 1 and 3 were administered via the web-based survey software Qualtrics (Provo, UT, USA; www.qualtrics.com). The expert discussion in round 2 was managed via the online forum ‘Loomio’ (version 1.0, Loomio, Wellington, New Zealand). In rounds 1 and 3, experts rated links between a discrete set of BCTs and MoAs. To reduce participant burden, we limited the number of BCTs and MoAs included in the study. A subset of the 93 BCTs was identified by establishing those that were commonly used in the literature. In this instance, BCTs identified more than twice (n = 61) across a set of 40 systematically identified and coded intervention descriptions covering a range of different behaviours were used to determine the subset of BCTs. 42 We also restricted the set of MoAs included to the 14 theoretical domains described in the TDF38 and the 12 most frequently occurring MoAs (that did not overlap with the TDF domains) identified in a systematic review of 83 behaviour change theories. 30 A total of 61 BCTs and 26 MoAs were included in the final study; a full list of MoAs and their definitions provided in Table 3.

| Mechanism label | Mechanism definition |

|---|---|

| Knowledge | An awareness of the existence of something |

| Skills | An ability or proficiency acquired through practice |

| Social/professional role and identity | A coherent set of behaviours and displayed personal qualities of an individual in a social or work setting |

| Beliefs about capabilities | Beliefs about one’s ability to successfully carry out a behaviour |

| Optimism | Confidence that things will happen for the best or that desired goals will be attained |