Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 16/115/18. The contractual start date was in December 2017. The draft report began editorial review in September 2019 and was accepted for publication in May 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Burton et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

At both national and local levels, there is a general consensus that the NHS could get better at ensuring that the least effective interventions are not routinely performed, or only performed in more clearly defined circumstances.

Ellul et al. 1

The challenge

Across the globe, health and care systems are under pressure to demonstrate that actions to ensure efficient use of resources are prioritised, but do not compromise the quality of the care provided to patients and the public. Alongside this growing emphasis on more efficient use of resources for health and care services2 is the stark reality of overspending across health services. In the UK, for example, just 5% of NHS providers overspent their annual budgets in 2010/11. However, two-thirds of NHS trusts were in deficit by 2015/16. 3 In the USA, it has been estimated that 30% of medical spending is unnecessary. 4 The problem is further compounded when non-evidence-based decisions are known to have poor outcomes, can cause harm and/or are of low value, but nonetheless continue to be made.

Government policy in high-income economies highlights the importance of the delivery of health and care that is efficient, is prudent and makes best use of resources when these may be limited. In the UK, Realistic Medicine5 promotes treatment that is focused on the probability of benefit rather than the possibility of benefit. In her second report, the Chief Medical Officer for Scotland outlines how the intention of Realistic Medicine5 is to place the patient at the centre of decision-making, utilising a personalised approach to their care while concurrently reducing harm and waste. The challenges to these ambitions are certainly not underestimated, in particular when the desire to provide safe, personalised care at an individual level may be in tension with broader aims of Realistic Medicine, notably when ‘tackling unwarranted variation in care, managing clinical risk, and innovating to improve, are essential to a well-functioning and sustainable NHS’. 5

In Wales, the principles of prudent health care6 have been launched, primarily to discourage the tendency to intervene when a lesser intervention might suffice. The policy driver for prudent health is a ‘healthier’ Wales, the Welsh Government’s long-term plan for health and care, which informs much of today’s health agenda across Wales. Prudent health-care principles are applied by the Bevan Exemplars (i.e. health professionals who test out innovation at the heart of care provision) and Bevan Advocates (i.e. public representatives who work to support the principles by sharing experiences and developing person-centred approaches to support prudent health care). 7,8 What is apparent through scrutiny of these and other examples of similar policy drivers across the globe is the emphasis on the importance of using only clinical and other practices that are effective, valuable and reflect a high quality of care for patients. A foundation for both the Scottish and Welsh initiatives, together with the What Works Network in England, is the robustness of an evidence base on which to verify decisions. 9

Current policy drivers include the Choosing Wisely10 campaign in Canada and the USA. The Choosing Wisely mission is a proactive campaign to encourage conversations between clinicians and patients, thereby helping people to choose care that is safe, is evidence based and does not duplicate interventions the person may have already received. Additionally, the use of low-value practices is an area of growing interest for the patient and public agenda, which is too often faced with reports of poor practice, wastage and duplication of services. Although there is potential for the patient and the public agenda, as a significant channel, to drive improvements in this area (e.g. challenging expectations around antibiotic prescribing), the success of these approaches are often not captured by meaningful data.

There is often insufficient consideration about how best to stop or withdraw existing practices and services that have been identified as low value, non-evidence based or unsafe. This is the knowledge gap that has led to this review being undertaken. To provide managers, commissioners and service leaders with practical information on how to successfully change/replace practices, meaningful evidence is required to understand the challenges and complexities involved, and provide solutions to ultimately improve service efficiency and quality. Despite reflecting a renewed dedication to evidence-based health care,11 researchers have previously highlighted that stopping interventions, policies and practices lacks guidance for practitioners and managers. 12

De-implementation at practice level

Although still in its infancy, interest is developing across health and care in de-implementation. 11,13,14 De-implementation is often described, at practice level, as a process of disinvesting or abandoning practices or interventions that may be harmful or ineffective,11 or no longer necessary. 15 Although the term is associated with ‘stopping practices that are not evidence based’,4 or the discontinuation of interventions that should be stopped,15 to date, a comprehensive definition of de-implementation at practice and service level is largely absent. This review aims to address this gap.

Furthermore, although there may be an assumption that de-implementation is the reverse process of implementation, with some transferability of the mainstay implementation theory and frameworks between the two, McKay et al. 15 suggest that de-implementation should be considered separately from recognised stages of implementation, including adoption and sustainability. Although many similarities may be apparent in the literature,15 which cross-reference the work of others,4,16 the factors that shape the processes of implementation and de-implementation are likely to be different and, if similar, work in different ways. 11 In one example, Hahn et al. 14 found that the usual strategies for implementation success, such as improving awareness and knowledge, were unlikely to be effective for de-implementation.

Prasad and Ionnidis11 refer to de-implementation as the abandonment of practices (i.e. a process that is contingent on a multitude of factors, not only research evidence, but also financial and professional conflicts, and cultural and societal values). 17,18 The process of de-implementation as the abandonment of existing practice is also supported by Voorn et al.,19 who argue that theory and evidence about agents, barriers, facilitators and interventions is limited. There are reports from individual studies that have specifically paid attention to de-implementation. For example, van Bodegom-Vos et al. 4 explored the literature and analysed data about implementation and de-implementation from two studies among Dutch orthopaedic surgeons. The authors4 conclude that further research is required to understand the required leadership and champion characteristics that can accelerate the process of de-implementation. The authors4 also call for more research to establish the factors that influence the success (or not) of de-implementation and to provide better understanding of the range of de-implementation strategies.

De-implementation at system level

According to Robert et al. ,20 system-level approaches focus on ‘policies to remove interventions from across wider geographical areas and/or patient populations, and strategic reconfiguration of services leading to organisational downgrading or closure’. Therefore, closing acute and community services, stopping the particular use of a medical technology and removing drugs from a formulary would fall under this remit. 20 They found a stark contrast between expert and practice opinion about what should determine related decisions, underpinned by technical and political processes. For Robinson et al. ,21 priority-setting and rationing was seen as one of resource scarcity when referring to withdrawing or cutting services. Williams et al. 22 describe the replacement and removal of interventions and services as they become obsolete or are superseded by others.

A recognised priority for international health-care financing23 is de-implementation under the guise of disinvestment. This is an underdeveloped area, especially regarding the lack of overt disinvestment frameworks in use. 24 According to Harris et al. ,25 there is little evidence to guide health-care staff and systems to take a systematic approach towards disinvestment. Paprica et al. 26 agree that there is a lack of guidance and point to political and social factors that can hinder evidence-informed disinvestment strategies. This approach is not always related to a whole service, as there can be partial or selective disinvestment approaches. 26 Elshaug et al. 23 suggest an ever-present economic dimension in their definition of disinvestment, as ‘healthcare practices, procedures, technologies, or pharmaceuticals that are deemed to deliver little or no health gain for their cost, and thus do not represent efficient health resource allocation’. It is unclear whether or not disinvestment always includes the shifting of resources to other health services and technologies that have greater clinical effectiveness or cost-effectiveness, although this is assumed by Polisena et al. 27 and Rooshenas et al. 12 in their definitions. There appears to be better clarity about the concept of rationing, mainly that it is focused on the one core idea of limiting or denying a potentially beneficial treatment because of its scarcity. 28 Dickinson et al. 29 conceptualise rationing as ‘the withholding of resources to the cost of individual patients’, compared with priority setting, which applies to populations.

Previous reviews

The study of de-implementation has gained impetus in recent years. Norton et al. 30 sought evidence of de-implementation research grants funded in the UK and the USA. The authors included only 20 grant proposals focused on de-implementing across a range of health services and practices. We sought the evidence from previous reviews about de-implementation and found that Niven et al. ,13 which, to date and to our knowledge, is the sole evidence review of de-implementation. Niven et al. 13 set out to systematically review the literature on de-adoption and used scoping review methodology for the task. The authors found a large number of different terms relating to the process of de-adoption with no established taxonomy. Niven et al. 13 suggest that lack of clarity is having a negative impact on communication and ‘branding’. When terms such as knowledge translation and implementation science are well established, Niven et al. 13 suggest that de-adoption and de-implementation as ‘natural antonyms of adoption and implementation, ought to be used as terms that brand the process of reducing or removing low-value clinical practices’. 13 The review authors propose a model that providers and decision-makers can use to guide efforts to de-adopt ineffective and harmful practices. The complexity of de-adoption is highlighted in their review, as is the potential of employing an active change intervention for successful de-adoption. 13 Crucially, the review identifies a number of questions for further research ‘to determine an ideal strategy for identifying low-value practices, and facilitating and sustaining de-adoption’. 13

We conclude from this review and current discourse about de-implementation and de-adoption that further understanding of the dimensions of both is required to inform health and care stakeholders how best to move forward. For managers and clinicians this included the need to disentangle the practices that may be ineffective for one population group but effective for another, and better understand the factors that determine why practices should be de-implemented or de-adopted. There exists a clear gap in the evidence to enable managers and service leaders to understand how best to de-implement using different approaches when they may be operating in different circumstances. In Chapter 2 we explain the rationale for choosing a realist approach for the review in conjunction with the review aims and objectives articulated below.

Review questions

The main aim of this review was to produce useful programme theory and practical guidance for policy-makers, managers and clinicians to help them with de-implementation processes and procedures.

The objectives of the review were to:

-

generate a concept analysis of de-implementation

-

identify and map the range of different de-implementation approaches and/or strategies currently being utilised across health and care, paying attention to ways in which they are assumed to work

-

produce a typology of de-implementation types, processes and contexts

-

examine and understand the range of anticipated and unanticipated impacts of these approaches and/or strategies across different settings and stakeholders, paying attention to contextual conditions that influence these impacts

-

generate an evidence-based realist programme theory that explains the successful processes and impacts of de-implementation

-

explore, through stakeholder engagement in the review methods, decision-making processes associated with de-implementation

-

produce recommendations about ways in which different approaches and/or strategies can help managers and service leaders plan and prioritise de-implementation in a systematic and efficient manner

-

stimulate a wider debate about avoiding and stopping services that are considered wasteful, of low value and non-efficient for future provision.

Summary

In this first chapter we have sought to provide the important context for this subject across health and care today. What has emerged in this chapter is the lack of clarity about the concept of de-implementation and the levels at which de-implementation operates. These knowledge gaps, together with the suggestion that future research is focused on ‘similarities and differences between the study of de-implementation of health practices and programs and related areas of inquiry, such as health-care delivery, implementation science, improvement science, and others’,30 have led to this review. In the next chapter we report on the methods employed for the review.

Chapter 2 Review methods

Introduction

As articulated in Chapter 1, this review drew on realist principles to address the review aims and objectives, as well as significant research team experience. 31–33 In this chapter we present the review methods and follow published publication standards (i.e. points 5–13 from the list of items to be included when reporting a realist synthesis). 34 Further details of the review methods are presented in the published review protocol. 35

Changes in the review process

No changes were made to the published protocol.

Rationale for using realist synthesis

Realist synthesis was considered to be the most appropriate method to use for this review. In Chapter 1, reference to the fact that there is likely to be a complex array of approaches to de-implementation operating in a variety of contexts means that realist synthesis is a natural fit for this review. Realist synthesis is theory driven,36 whereby the focus is on understanding underlying elements or mechanisms of a programme that interact within contexts to result in success or failure. Using this approach is a recognition that programmes are implemented in different contexts and, hence, operate through different mechanisms to produce different patterns of outcomes. 37 Therefore, a realist synthesis can facilitate an evidence-based explanation of how complex programmes operate within different conditions.

A realist review begins with the construction of an initial programme theory, developed through the collection of evidence from the literature and relevant stakeholders (Phase 1). This initial theory is refined to create a final programme theory that provides plausible explanations of why certain interventions work (or do not work) in certain circumstances. This is an iterative rather than linear process, as the theory is repeatedly tested and refined with accumulating knowledge (Phases 2 and 3). The realist methodology is a theory driven, interpretive approach to uncover underlying mechanisms that account for why people change because of the intervention resource. The interpretive approach is driven by various forms of reasoning (e.g. deductive methods and inductive reasoning), but fundamental to the realist method of inquiry is abductive or retroductive reasoning. 38 Retroduction is a mode of inference in which events are explained by postulating (and identifying) mechanisms that are capable of producing outcomes. According to Wynn and Williams,39 retroduction is characterised by the use of causal mechanisms as the basis for explanation.

In realist synthesis, programme theory ‘describes how an intervention may work to change people’s behaviours’. 40 The intervention is not the theory but a ‘resource’ people choose to use to help behaviour change. 41 To construct programme theories, different sources of evidence are sought through a systematic process that includes stakeholder engagement, an overview of relevant extant theory40 and scrutiny of primary research of the topic under the lens. 42 In this case, the focus was on de-implementation of programmes or interventions.

In realist synthesis, programme theory is expressed as conjectured and then final context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configurations. Mechanisms describe ‘the pathway from resource to reasoning and response’,40 and resources can be described as those that are ‘material, cognitive, social or emotional’. 31 The reasoning and response may stem from the perspectives of the receivers, the organisers and/or those involved in the delivery of programmes/interventions.

Review strategy

Programme theory development and refinement involves a number of interconnected steps. As is usual, in this realist synthesis, stages were conducted in an iterative rather than linear fashion, in contrast to a traditional systematic review approach. 43 As agreed in our funded protocol, the realist synthesis was undertaken over four phases (see Appendix 1):

-

concept analysis and initial programme theory development

-

retrieval, review and synthesis of evidence

-

refining programme theory

-

programme theory evaluation.

The review process iterated between theory development, interrogation of evidence and theory refinement based on the team’s previous experiences. 32,33

Scoping the literature

The review was preceded by a scope of the evidence34 to outline the possible theoretical underpinnings of de-implementation and to clarify understanding. We determined a list of key words from our initial team conceptualisation of de-implementation and undertook a preliminary scope of evidence using a related published search strategy. 13 For this initial scoping search, we undertook a title-only search in Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and MEDLINE, limited to human and English language, using TI (disinvest* OR dis-invest* OR ‘decrease use’ OR discontinu* OR dis-continu* OR abandon* OR reassess* OR re-assess* OR obsole* OR ‘medical reversal’ OR contradict* OR withdraw* OR ‘health technology reassessment’ OR deimplement* OR de-implement*) N3 (healthcare or technolog* or device* or intervention* or health practi?e* or medical or medical practi?e* or procedur* or drug or drugs or biotechnology*) and found 100 results in CINAHL and 1123 results in MEDLINE. A percentage of these were screened for titles of interest to the review. We also carried out a search to identify relevant reviews and guidelines. We found 55 titles that appeared initially of interest to this element of the review.

Theoretical platform

The theoretical platform guided the literature scoping and consultation work with stakeholders. To initiate the process, we undertook a desktop exercise to consider the range of different theories and approaches that underpin the implementation research evidence base. Elements of these theories provided the platform for Phase 1 work and the following:

-

innovation and unlearning, for example the role of context and systems in challenging and renewing organisational memory (e.g. Cegarra-Navarro et al. 44)

-

organisational psychology (i.e. stages of renewal and decline) (e.g. Lester et al. 45)

-

habit formation and breaking habits, including how habits are formed (e.g. Lally et al. 46) and the role of habit in implementing research on clinical behaviour change (e.g. Nilsen et al. 47)

-

ecology and life cycle assessment (e.g. Atkins et al. 48)

-

health-care rationing (e.g. Rooshenas et al. 12) and the ethics of rationing (e.g. Scheunemann and White28)

-

technology adoption and the diffusion of innovations (e.g. Rogers49 and Greenhalgh et al. 50)

-

implementation and knowledge mobilisation (e.g. Rycroft-Malone et al. 51 and Ferlie et al. 52)

-

decision-making theories and strategic decision-making (i.e. rational and non-rational) (Oliveira53)

-

organisational management, complexity thinking, resource-based view (e.g. Plesk and Wilson,54 and Burton and Rycroft-Malone55)

-

leadership and theories of leadership (e.g. The King’s Fund,56–58 Tomlinson,59 West et al. 60 and Wong and Cummings61)

-

efficiency/prudent systems and processes (e.g. Aylward et al. 62 and The King’s Fund63)

-

nudge and behaviour change (Sunstein and Thaler,64 Marteau et al. ,65 Evans and Stanovich66 and Parkinson et al. 67)

-

human factors/cognitive task analysis (e.g. Catchpole68 and the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality69)

-

persuasion theories used as a stage in the diffusion process (e.g. Rogers70) and attitude change (e.g. Wood71)

-

organisational sociology, with focus on culture and power as contextual factors and receptive contexts (Pettigrew and Whipp72).

Phase 1: concept analysis

In Phase 1, a concept analysis of ‘de-implementation’ was undertaken. The rationale for undertaking this work at this stage was twofold:

-

There is an identified conceptual confusion surrounding the term ‘de-implementation’ and the desire for better clarity.

-

There is a requirement for better understanding to inform the development of the initial programme theory.

Background

‘De-implementation’ was the overarching concept for this review. However, as articulated in Chapter 1, the term is used inconsistently and interchangeably within the extant literature. 73 For example, de-implementation may describe explicit and directional functions (i.e. withdrawal or stopping interventions) or abandoning medical practices when evidence of efficacy is weak or absent, or when harm is demonstrated. 11 However, for this review, we consider that de-implementation may also be more implicit and, at best, inferred within theories that inform the implementation research evidence base.

Concept analysis

A concept analysis is defined as a formal, linguistic procedure used to determine the essential attributes of a concept. It focuses on the use of words to explain phenomena. 62 Concept analysis is a technique that requires critical approaches to uncover subtle elements of meaning embedded in concepts, where a concept is thought of ‘. . . as mental constructions; they are our attempts to order our environmental stimuli . . . that contain defined attributes’. 74

Process

Drawing on the results of the scoping search, we identified clustered attributes (i.e. antecedents, process and outcome) and specified model, related and contrary cases that place the concept in context. We aimed to identify empirical referents that could be used to evaluate the occurrence of the concept in practice, policy or research. Walker and Avant’s74 concept analysis procedure was followed. The procedure describes an iterative eight-step process:

-

Select a concept.

-

Determine the aims and purposes of analysis.

-

Identify all uses of the concept that are discovered.

-

Determine the defining attributes.

-

Identify a model case.

-

Identify borderline, related, contrary, invented and illegitimate cases.

-

Identify antecedents and consequences.

-

Define empirical referents.

Search strategy for the concept analysis

The search strategy for the concept analysis entailed a restricted scoping review of the literature,75 instigated by the 43 terms identified by Niven et al. 13 We undertook a title-only search in CINAHL and MEDLINE, limited to human and English language, using TI (disinvest* OR dis-invest* OR ‘decrease use’ OR discontinu* OR dis-continu* OR abandon* OR reassess* OR re-assess* OR obsole* OR ‘medical reversal’ OR contradict* OR withdraw* OR ‘health technology reassessment’ OR deimplement* OR de-implement*) N3 (healthcare or technolog* or device* or intervention* or health practi?e* or medical or medical practi?e* or procedur* or drug or drugs or biotechnology*). We also used snowballing techniques to identify clusters of relevant papers and checked references lists of relevant published reviews.

Results

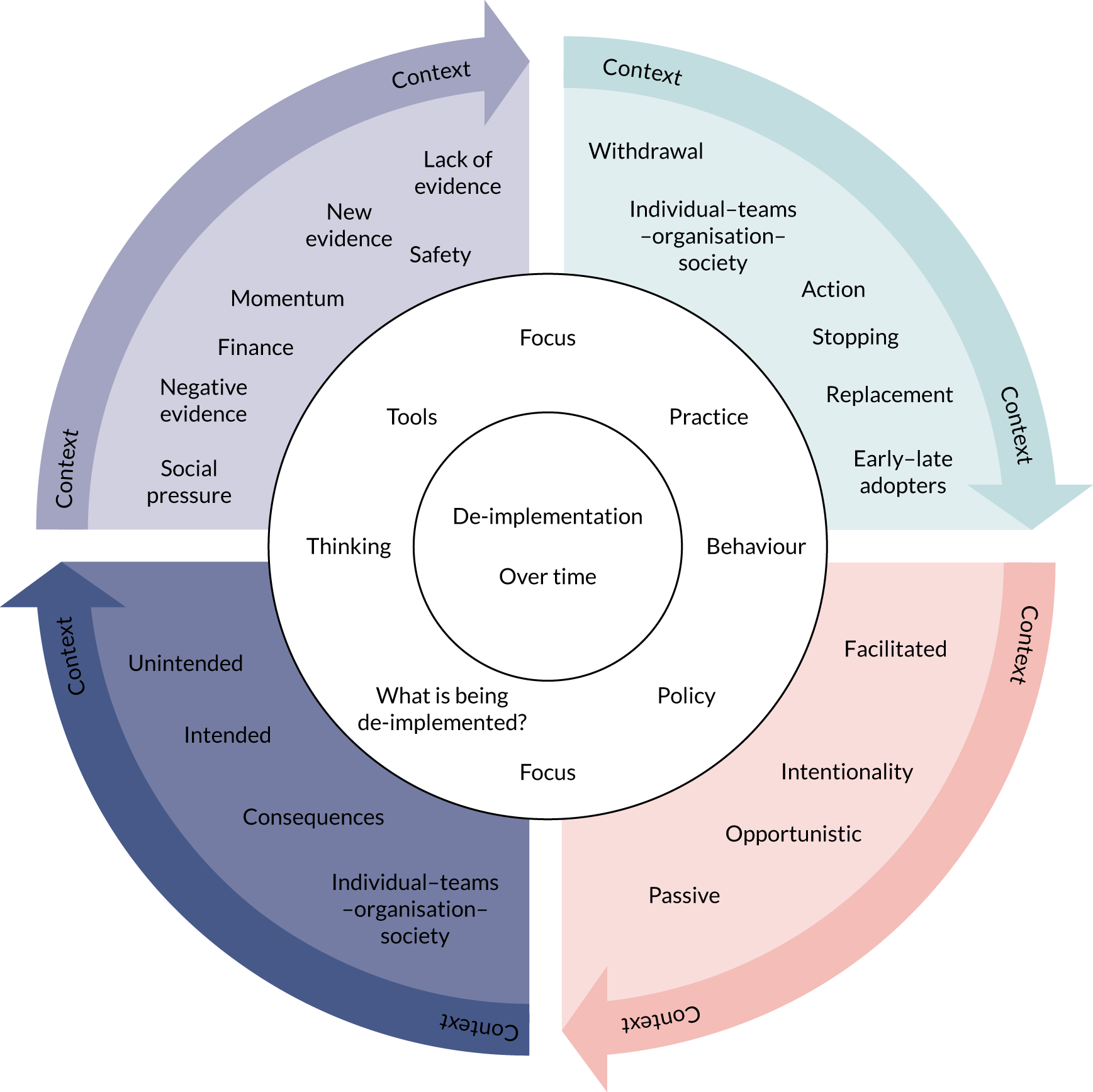

In total, the search returned 214 papers, representing 26 terms that referred to de-implementation (Table 1). PJ, CRB, LW, BH and JRM undertook desktop work to develop and agree an extraction template. We extracted data from a total of 38 papers selected on the basis of their descriptive depth across the range of terms identified in the papers or suggested by stakeholders. These were used to develop an initial framework of de-implementation attributes represented in Figure 1.

| Terms | Number of papers |

|---|---|

| Abandonment | 2 |

| Contradicted | 1 |

| De-adoption | 11 |

| De-commissioning | 5 |

| Decreased use | 2 |

| De-implementation | 31 |

| De-innovate | 1 |

| De-prescribing | 33 |

| Discontinuation | 7 |

| Disinvestment | 52 |

| Elimination | 1 |

| Evidence reversal | 1 |

| Exnovation | 3 |

| Health technology reassessment | 7 |

| Low value | 13 |

| Medical reversal | 12 |

| Mis-implementation | 2 |

| Obsolete/obsolescence | 3 |

| Overuse/overdiagnosis/overtreatment | 7 |

| Rationing | 7 |

| Reduce inappropriate testing | 2 |

| Substitution | 2 |

| Withdraw | 8 |

| De-escalation | 0 |

| Desist | 0 |

| Disincentivise | 0 |

| Retract | 0 |

FIGURE 1.

Concept analysis defining attributes and antecedents.

Uses of the concept

Van Bodegom-Vos et al. 4 differentiated between terms such as de-adoption and discontinuation as clinician initiated, whereas terms such as disinvestment and de-implementation required a strategy to be in place for abandonment to occur. According to van Bodegom-Vos et al. ,4 de-implementation is the preferred term to apply to the reduction of procedures with little evidence base, as it can incorporate a wider range of approaches than just the removal of financial incentives. Wang et al. 76 described four types of change related to de-implementation:

-

partial reduction

-

complete reversal

-

substitution with related replacement

-

substitution with unrelated replacement of existing practice.

Critical attributes

We identified five critical attributes for de-implementation. The attributes identified are described in Table 2.

| Critical attribute | Description |

|---|---|

| What is being de-implemented | This is the focus of change and relates to one or more context areas, such as clinician behaviour change or organisational policy |

| Push or driving force | Factors motivating the de-implementation process (e.g. lack of evidence of effectiveness, financial constraints or safety issues) |

| Nature of action | What is the continuum of the de-implementation process from complete termination to replacement with another innovation? |

| Degree of intentionality | To what extent is the de-implementation process intentional and planned or passive and opportunistic? |

| Consequences | Intended or unintended and at what level, in what context and over what time? |

What is being de-implemented?

This attribute is the focus for change, directed either at behaviours (e.g. clinicians or managers) or more broadly at policy level, with both contexts often being targeted simultaneously. 19

Push or driving force

There are several reasons why the de-implementation of a process or procedure becomes prominent at certain times. New evidence can emerge that shows a better way of proceeding, there may be concern about the safety of a procedure or there can be the removal of incentives.

Goal of the action

This attribute describes the goal of the de-implementation strategy. For procedures with safety issues, the objective may be to withdraw the drug or procedure entirely. However, in other contexts, the procedure may be of value to a particular defined group, but not for the majority, and so the de-implementation approach is to reduce the number of people who do not derive benefit. In many cases, the low-value procedure could be replaced by a more effective alternative (i.e. a case of medical reversal that can in certain contexts be an effective stratagem). 77

Degree of intentionality

This attribute highlights the purposefulness of the de-implementation process. The strategy adopted for the abandonment of a procedure may be passive as clinicians increasingly adopt a newer intervention, but this process is not actively initiated or led, leading to the eventual stopping of the procedure. Other strategies may be planned and facilitated, such as the closure of a facility.

Consequences

The results of the de-implementation process may not have been as intended (e.g. the strategy may have had the objective of stopping the procedure, but the strategy achieved only a diminution in practice).

Case studies

Walker and Avant’s74 concept analysis process proceeds through the development of several cases that represent all the attributes of the concept (i.e. a model case, a borderline case that has some attribute and a contrary case that clearly does not contain attributes of the concept). Walker and Avant74 stipulate that the cases can be taken from real-life examples, literature or cases constructed by authors. For all three case examples in our concept analysis, we have drawn on evidence from the literature on de-implementation, rather than construct our own cases. We found that having examples drawn from evidence is a useful starting point for further refinement of the concept.

Model case

A model case is an example that articulates the attributes within the concept. Walker and Avant74 recommend that the model case should be a ‘pure case’. A study by Schondelmeyer et al. 78 serves as a model exemplar.

What is being de-implemented

Clinician behaviour was the target of the intervention and stopping or reducing the use of continuous pulse oximetry (CPO) in children with wheezing, specifically preventing the overuse of CPO for children who were on room air with decreased need for bronchodilator medication. 78

Driving force

The need for the de-implementation of CPO related to safety issues for the patient (i.e. alarm fatigue) and evidence from national organisations, such as Choosing Wisely (Philadelphia, PA, USA), for the lack of evidence in its widespread use. 78

Nature of action

The objective of the de-implementation process was the reduction of CPO use, not its withdrawal, as in certain patient groups CPO is recommended. There was also an element of substitution, with intermittent pulse oximetry replacing CPO. 78

Degree of intentionality

De-implementation was planned using the Plan, Do, Study, Act quality improvement cycle. A period of staff engagement preceded the implementation of the project and included a consensus-based agreement that blood oxygen saturation of ≥ 90% on room air for 2 hours or the reduction of salbutamol treatment to over 2-hourly periods constituted withdrawal of CPO monitoring. The de-implementation intervention consisted of a local guideline that emphasised waste reduction and patient safety related to alarm fatigue. This information was distributed to all nurses and doctors during staff meetings and educational conferences. In addition, at nurse handovers, reminders of the guidelines were given with a three-question assessment tool that determined the need for CPO continuation. 78

Consequences

The primary outcome measure was the median time per week that children were on CPO. The pre de-implementation time was 10.7 hours and post intervention it was 3.1 hours. There were no significant differences in intensive care readmissions when compared with a control unit. 78

Borderline case

Borderline cases are examples where most, but not all, attributes are referenced. A study by Kost et al. 79 is outlined below.

What is being de-implemented

Again, it was clinician behaviour that was targeted in reducing low-value procedures identified by the Choosing Wisely campaign. Procedures were low-back pain X-rays, antibiotics for sinusitis, Papanicolaou tests for women aged < 21 years or women who have had a non-cancerous hysterectomy, annual electrocardiography screening for low-risk patients, and scanning of women with no risk factors who are aged < 65 years and men with no risk factors who are aged < 70 years for osteoporosis. 79

Driving force

As identified by Choosing Wisely, in the case of each of these procedures there is a lack of evidence as to their value without further risk indicators. There are financial incentives in de-implementing these five practices. 79

Nature of action

The aim was to stop, or at least substantially reduce the number of, these procedures in the identified populations. There was no indication of substitution with other procedures. 79

Intentionality

The de-implementation initiative was on the passive continuum, with a 1-hour in-person seminar or webinar reviewing the five Choosing Wisely recommendations. 79

Consequences

A chart review (of 1089 patients) was employed 6 months pre de-implementation and 6 months following de-implementation. Results showed some intended and unintended consequences, including reduction in sinusitis antibiotic prescribing (statistically significant) and osteoporosis scanning; however, there was no change in use of low-back pain imaging, Papanicolaou tests or annual electrocardiography procedures. The absence of de-implementation in these three procedures may be due to high rates of adherence to the guidelines before the de-implementation intervention was initiated. 79

This borderline case79 has most of the attributes, but critically lacks an adequate de-implementation strategy as in the model case. In addition, this study79 highlights the increasing difficulty of de-implementing low-value procedures that already have a high disinvestment outcome.

Contrary cases

Contrary cases show minimal attributes that signify the concept, and we denote this through a paper by Chamberlain et al. 80 The paper80 tracks National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines for the overuse of caesarean sections in women with hepatitis, endometrial biopsies to investigate infertility and varicocele operations to treat infertility in men.

What is being de-implemented

Clinician decision-making and behaviour are the targets of the NICE guideline recommendations for the three procedures. 80

Driving force

NICE recommendations indicated that there is a lack of evidence to support continuation of the procedures. The NICE reminder prompts had not been previously evaluated and the Chamberlain et al. 80 study assessed the impact of four reminders for each procedure over a 12-year period.

Nature of action

NICE recommended that these procedures are discontinued without substitution. 80

Degree of intentionality

The NICE guidelines’ recommendations are a passive method of communicating discontinuation of the procedures, and the study drew on opportunistic data collected through the national Hospital Episode Statistics 6 years before guidance and 6 years post guidance. 80

Consequences

The outcomes were unintended, in that the three procedures did not decrease in line with the NICE disinvestment advice. Indeed, there was an increase in procedural use of endometrial biopsies and caesarean sections in women with hepatitis. 80

Empirical referents of de-implementation

According to Walker and Avant74, empirical referents are ‘categories of actual phenomena that demonstrates the occurrence of the concept itself’. The focus of most de-implementation strategies is clinician decision-making behaviours, usually to reduce habitual practices. However, other areas for de-implementation would rest at the organisational and policy levels. The driving force of de-implementation is an essential attribute, as it initiates and provides a rationale for de-implementation. The drivers may be on a continuum from strong to weak, as the force of negative evidence or patient safety would push disinvestment quicker than weaker evidence. The action attribute is again on a referent continuum from stopping to a reduction in the procedure. Substitution with a more effective procedure may result in greater de-implementation of the low-value procedure and different strategies maybe required for early and late adopters. As described in the model case, if the de-implementation strategy is planned and facilitated, then there is a greater chance of a reduction in the process or procedure.

Summary

The process of concept analysis enabled the extraction of the defining attributes of de-implementation within health and social care. Five critical attributes were noted as essential to understanding de-implementation. These were (1) the focus of change, (2) the reasons or push to pursue de-implementation, (3) the extent of de-implementation that is achievable, (4) the degree of planning involved and (5) the intended or unintended consequences. The five critical attributes provided a basis for initial theory development. Case studies were helpful to explicate how de-implementation functions in different contexts.

Initial programme theory development

The concept analysis was part of the Phase 1 work to help the development of the initial programme theory; the construction of a practical framework to represent the ideal about de-implementation, what works, how and under which conditions; and seek evidence about de-implementation of programmes and interventions. This work drew on the initial searches completed to develop the concept analysis, and theory and evidence that we considered relevant, as articulated already in the scoping and theoretical platform sections.

Stakeholder engagement (Phase 1)

Phase 1 work to develop the initial programme theory additionally included consultation with stakeholders. Stakeholder engagement is essential to the success of a realist synthesis. For this review, stakeholder engagement was designed to help elaborate on the review context, refine the review questions, contribute to initial programme theory development, interpret the evidence and assist with dissemination. Here, we report on the stakeholder engagement programme of work to contribute to initial programme theory development.

Stakeholders were purposively sampled to ensure representation from relevant constituencies (i.e. health and care services managers, organisational leaders, patients and the public representation). We identified stakeholders from across different areas of the NHS in the UK. Included were service and clinical managers, senior clinicians, service commissioners and representatives from patient and public involvement groups.

Discussions with stakeholders throughout the study took place in individual telephone interviews (see Appendix 2) or in a workshop format (see Appendix 3). Discussions were designed to be more open ended in the early stages of the review to develop an understanding of the complexities of the contexts in which de-implementation efforts are situated. In total, 10 stakeholders consented to take part, comprising four patient representatives and six clinicians and/or service managers. Discussions became more focused on particular parts of the initial programme theory as the review progressed. Integration of data was guided through the principles of framework analysis. 81

Initial programme theory

The culmination of the work undertaken in Phase 1 was the development of a framework (see Figure 1) that provides an initial explanation of the complexity of de-implementation, and the contextual conditions that underpin the process. This was subsequently used to bound theoretical development. The conceptual components of de-implementation in health care are:

-

De-implementation = f (what is being de-implemented; push or driving force; nature of action; degree of intentionality), which results in intentional and unintentional consequences, over time, for different stakeholders.

Our initial perspective was that de-implementation is associated with five main variables that operate in time and context. The first variable is what is being de-implemented. This is the focus of change and can relate to one or more context areas, such as clinician behaviour change or organisational policy. The second variable is the driving force for de-implementation (e.g. lack of evidence of clinical effectiveness or cost-effectiveness, financial constraints or safety issues). The third variable of nature of the action is the continuum of the de-implementation process from complete termination to replacement with another innovation. The fourth variable is intentionality, that is, to what extent the de-implementation process is intentional and planned or passive and opportunistic. Finally, the outcomes of de-implementation can be both intentional and unintended. Through an iterative process of discussion among the project team and referencing back to the initial proposal literature, we developed elements of the initial programme theory. These were in the form of ‘if–then’ statements that linked different components of the initial programme theory. The development and prioritisation of these statements were regularly discussed with key stakeholders throughout Phase 1 via face-to-face meetings and telephone calls. The statements were then used to guide the search and synthesis of evidence from the literature.

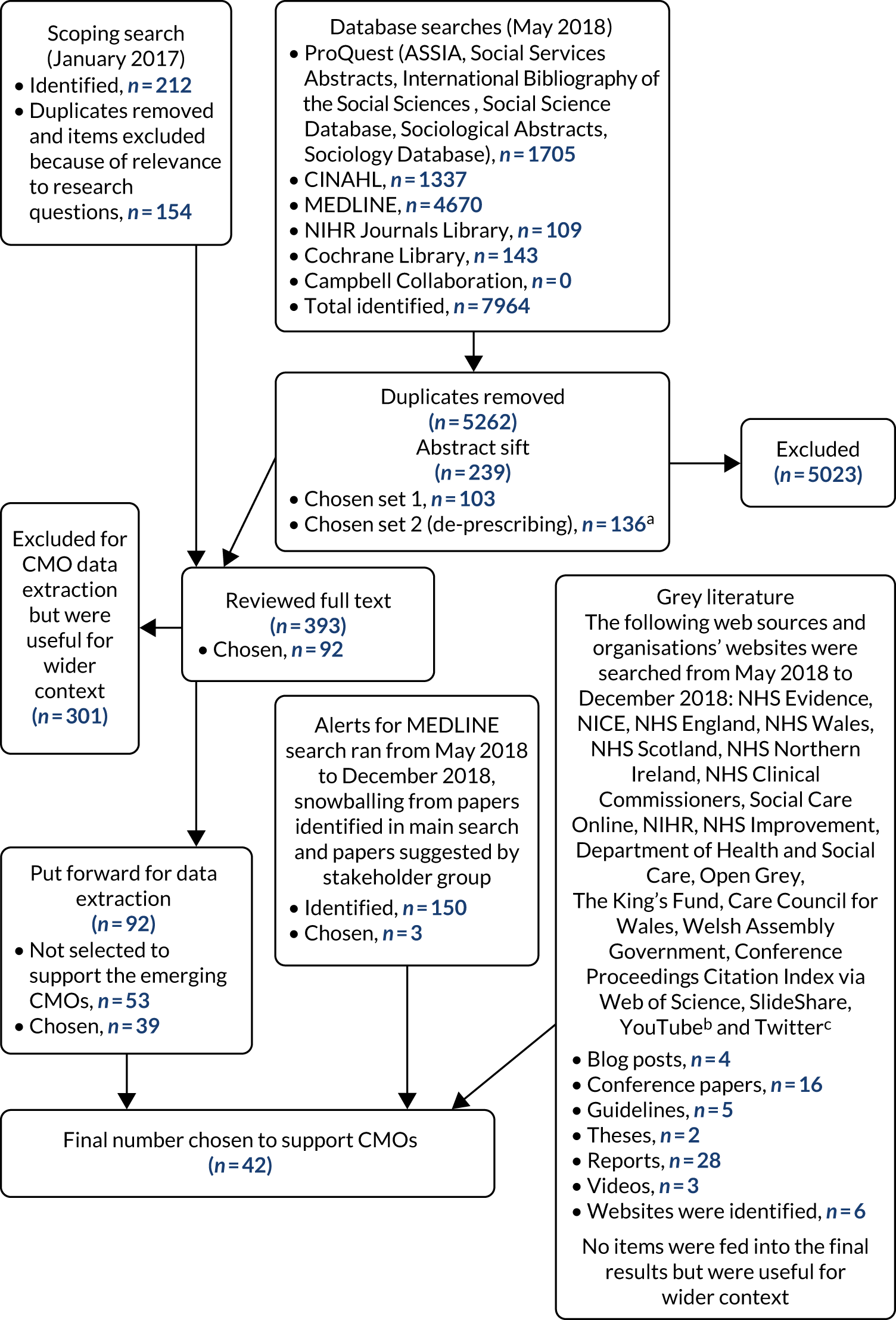

Phase 2: searching processes

Primary search of databases

The major health, social and welfare databases were searched using keywords identified through search development and database-specific ‘keywords’ associated with the initial programme theory, adapted for each information source. Key terms around the main concept were identified from key literature reviewed during the scoping phase and also taken from Niven et al. 13 It was noted that a single shared terminology, for example a medical subject heading term for de-implementation, is lacking. There were no date limits or material type restrictions on the search. Methodological filters were not used to avoid excluding any potentially relevant papers. Systematic searches were conducted in 11 databases subscribed to by Bangor University, Bangor, UK: MEDLINE and CINAHL via EBSCOhost, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts, Social Services Abstracts, International Bibliography of the Social Sciences, Social Science Database, Sociological Abstracts and the Sociology Database via ProQuest, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Journals library, the Cochrane Library and The Campbell Collaboration. See Appendix 4 for an example search strategy. Our search was not limited to health and social care and we sought evidence to capture the emergence of the ‘what matters is what works’ philosophy,82 and international policy campaigns to improve efficiency in health and social care services (e.g. the American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation). 83

Selection and appraisal of documents

The searches took place in April and May 2018. References were stored in Mendeley database software (Mendeley Desktop; Elsevier, London, UK). The systematic databases search yielded 7964 references. After removing duplicates, 5262 hits remained for title screening. Hits for each database are shown in Appendix 5. An abstract shift was completed on the 5262 remaining papers and this left 239 references that were deemed relevant to the research question.

Within the primary search of 5262 papers, a large proportion of articles were on the specific topic of de-prescribing. De-prescribing is a specific type of process for reducing low-value interventions, but represented the largest element within the literature on de-implementation. These papers were reviewed in a separate sift of the evidence. A total of 136 de-prescribing articles were chosen for full-text review. A key feature of a realist review is theory formulation, and literature is examined that best supports the development of the programme theory.

The original scoping review conducted for proposal submission included 212 references. After duplicates were removed, the remaining 154 papers along with the 239 papers identified in the database search provided a total of 393 papers for full-text review. Other members of the project team then subjected these 393 papers to an independent assessment, and this reduced the number of papers for extraction to 92. Exclusion of a large number of papers at this stage was because of the evidence base being largely descriptive.

Alerts were set up for the database searches and were scanned up to December 2018. Three additional papers were added through snowballing, from database alerts and from project group and stakeholders (see Appendix 5). Internet-based searches for grey literature were conducted for workforce development project reports, national inspection and regulation quality reports, and evaluative information about these initiatives (see Appendix 5 for a list of the organisations searched). Although none of this grey literature evidence was included in the final data analysis, it was useful to inform/contextualise the findings. The final number of papers for inclusion to support the programme theory was 42.

Data extraction

Screening for relevance to the initial programme theory involved a systematic approach, using a system developed in a previous funded realist study. 84 Evidence was excluded unless it related to one or more of the programme theory areas. In realist synthesis, the programme theories being ‘tested’ are made visible through bespoke data extraction forms. 31 In this review, a bespoke extraction template was developed around the initial programme theory (see Appendix 6). Evidence was included if we considered it to be ‘good and relevant enough’. 42 PJ, LW, CRB, JRM and BH undertook member checking in the reviewing and extracting processes, and any discrepancy in opinions about the relevance of evidence was resolved through discussion. PJ, CRB and LW undertook data extraction from the identified 92 papers. Following the data extraction process, 42 papers were deemed to be relevant for inclusion and analysis. These were primarily intervention studies. Thirty-seven papers related to de-prescribing across acute and community settings, seven papers reported on interventions, including reducing imaging for low-back pain, and diagnostic test ordering. One paper reported on a realist evaluation of an included intervention for reducing benzodiazepine use in older adults. The 42 papers (see Appendix 7 for list of final included papers) were then subjected to a realist critique to help identify mechanisms that underpinned the interventions, and the contextual conditions that were necessary to trigger them.

Analysis and synthesis processes

The realist synthesis is theory driven and uses abduction to understand CMO configurations. Synthesis is a process of triangulation, so that different sources of evidence are considered in a process of theory development, testing and refining. To provide structure, we organised the extracted information into data tables that represent the different bodies of evidence that inform the programme theory areas. We then undertook an abductive and retroductive approach85 to understand the best explanation of the cause in the evidence about de-implementation and look for recurring patterns in the data. We then linked the patterns to form a refined programme theory, consisting of CMOs (i.e. explanatory statements reflecting the complexity of de-implementation strategies and processes). This process was facilitated by the further development of a set of plausible hypotheses – again in the form of ‘if–then’ statements about what might work, for whom, how, why and in what circumstances – about de-implementation (see Appendix 8).

Phase 3

To test and refine the programme theory, in Phase 3 we provided a check of validity of the evidence in relation to ‘what works’, how and under which conditions in the current approaches to de-implementation of health and care practice and interventions. We conducted a further 21 telephone interviews using the sampling strategy identified in Phase 1, and analysed the data to test the synthesis findings and refine the programme theory. A semistructured interview schedule (see Appendix 9) ensured that the interviews were focused on ‘sense-checking’ from the participants’ perspectives (see Appendix 10 for an overview of participants’ roles). The interviews were conducted by telephone and lasted no longer than 30 minutes. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed.

Phase 4

The purpose of Phase 4 was to develop actionable recommendations for interventions that help the de-implementation of low-value treatments and services. This is discussed fully in Chapter 4.

Ethics process for the review

The study fell outside the scope of NHS and social care requirements for ethics review; however, we sought ethics approval from Bangor University’s Health and Medical Sciences Research Ethics Committee to conduct the interviews. Approvals were granted on 22 May 2018 (research proposal number 2017-16242).

As we were enrolling participants for telephone interviews and workshops who were NHS staff, we did require research governance approval from the NHS. Approvals were granted on 24 August 2018 (reference 18/HCRW/0001).

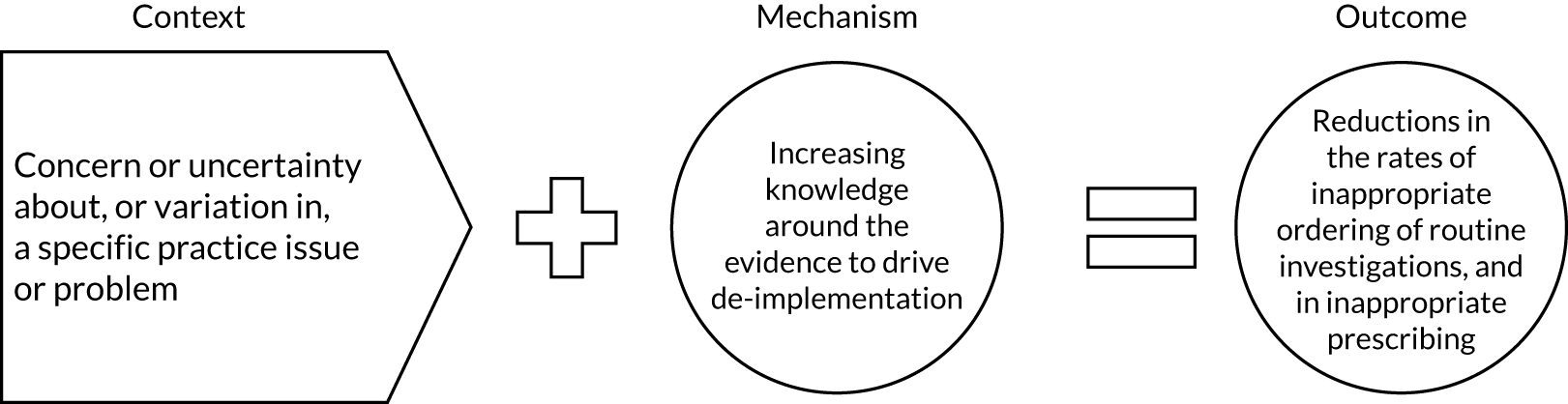

Chapter 3 Findings

The theory development, refinement and testing process, as described in Chapter 2, led to the elaboration of six CMO configurations. The total number of papers used in the analysis was 42, and these are described in Appendix 5. The nature of the interventions used in the included studies is discussed in Chapter 4. We now present each of the six CMOs. We suggest that the CMOs should not be seen as mutually exclusive, as how the different elements of each interact is important.

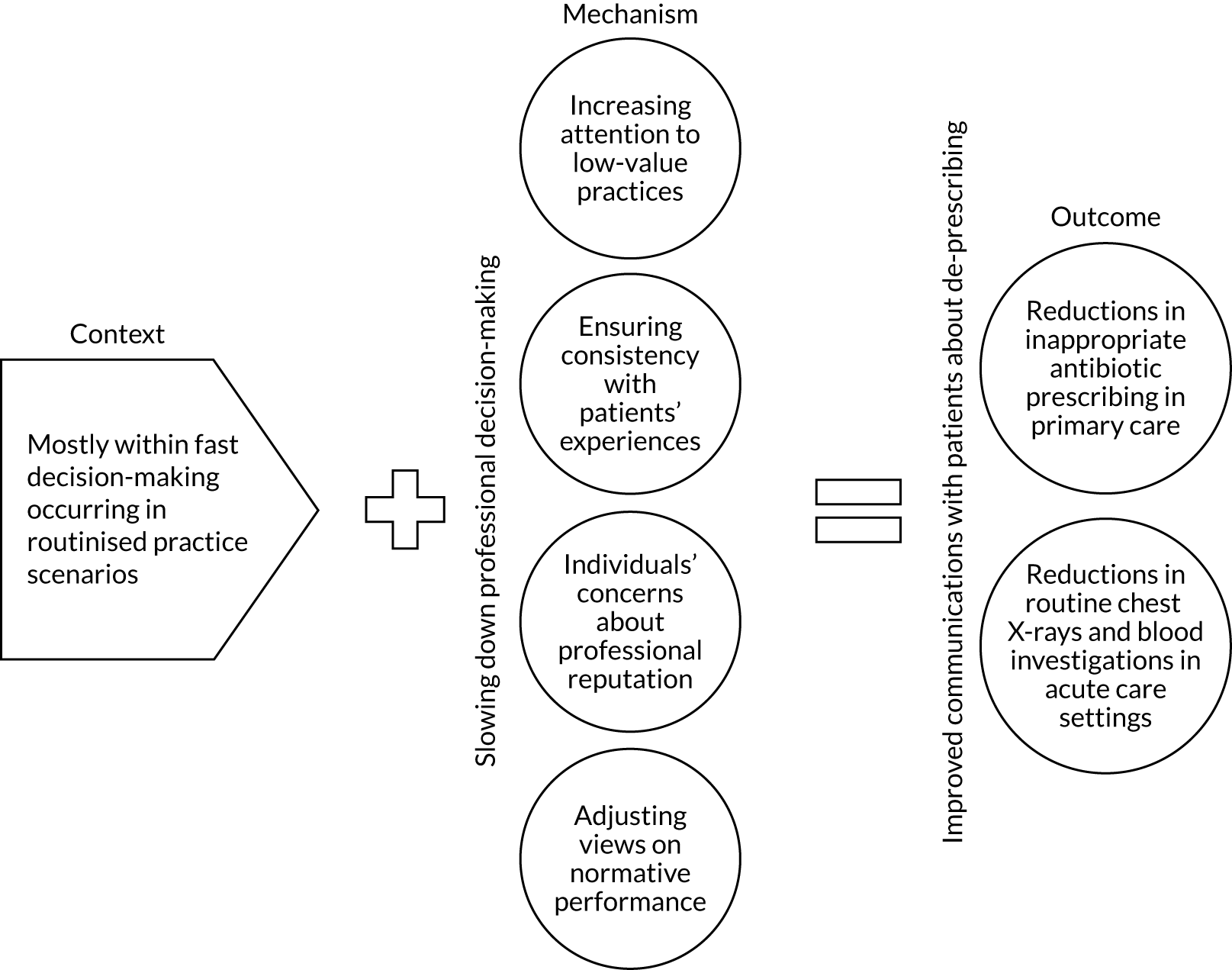

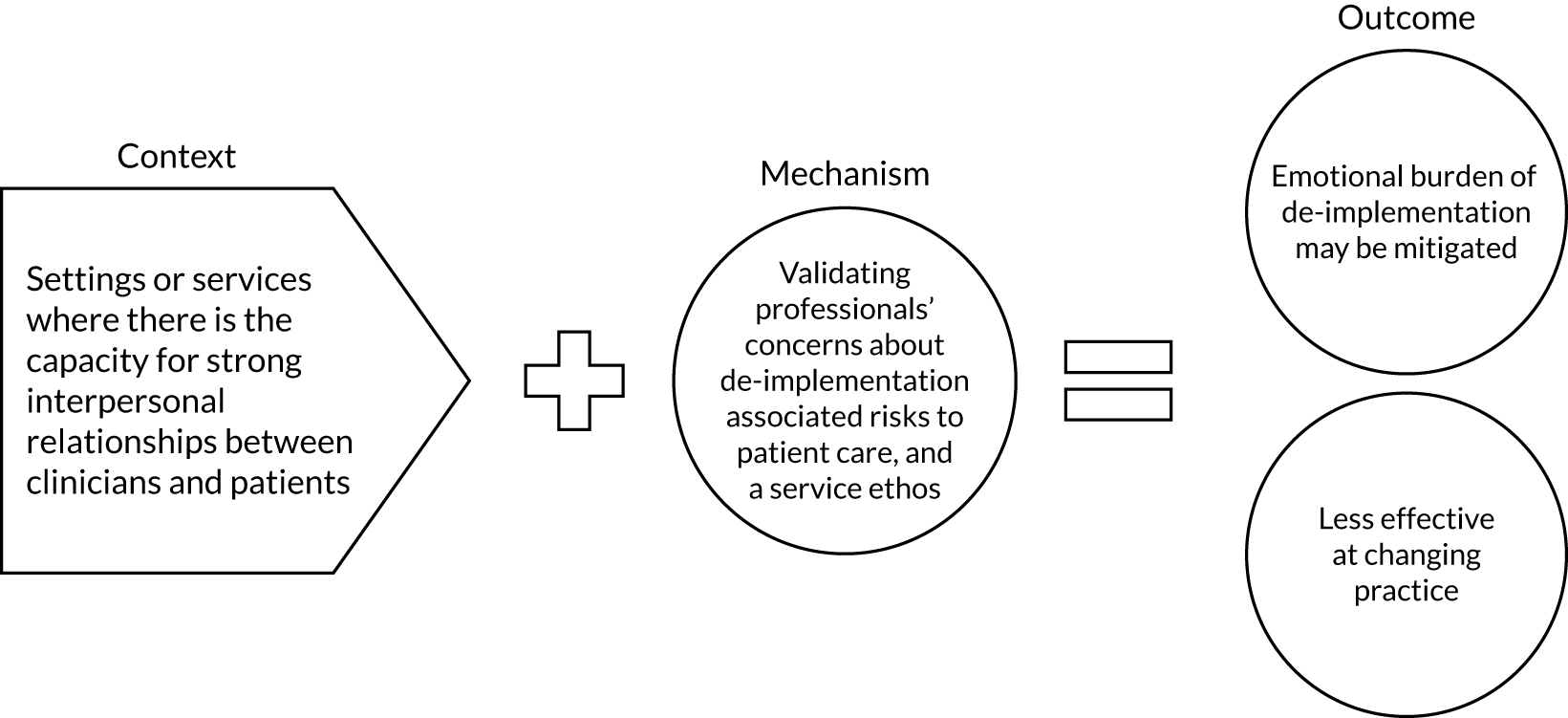

Context–mechanism–outcome 1: nudging professional practice

De-implementation interventions that attempt to change clinician behaviour in the context of fast or habitual decision-making (context) may be effective when they include aspects of precommitment, accountable justification and benchmarking performance against peers. Changes in practice may be prompted by slowing decision-making through increasing attention to the low-value practice behaviour (mechanism 1), ensuring that practice is consistent with an individual patient’s expectations (mechanism 2) and prompting professionals’ concerns about professional reputation (mechanism 3). Effectiveness was mixed across changes to professional behaviour, with impacts visible on communication with patients (outcome 1) and in some aspects of prescribing practice (outcome 2) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Context–mechanism–outcome 1.

Context

The included evidence indicates that interventions that were designed to disrupt the contexts in which clinicians’ decision-making processes were operating, and to make these processes more conscious and deliberate, show promise for de-implementation. A reliance on intuitive or ‘fast’ thinking86 to reduce cognitive load within the everyday demands of professional practice can interfere with the thinking necessary for the more deliberative and scientific approaches required to limit low-value care.

Within the studies included in this analysis, many of the service contexts are routine primary care clinical decision-making by physicians.

The Meeker et al. 87 study intervention explicitly included information to physicians that their prescribing rates would be monitored. To some degree, the very positive results from this simple public declaration of precommitment to de-implementation may be due to an awareness of practice surveillance.

The Kullgren et al. 88 and the Trumbo et al. 89 studies were aligned with the Choosing Wisely campaign, which may have influenced, in some way, clinicians’ decisions to precommit to de-implementation. However, the influence of a national campaign warrants further attention, as neither of these studies88,89 demonstrated significant instrumental changes to practice.

Increasing attention to low-value practice

Precommitment is a professional’s statement of intent in which they make visible to others that they will behave in certain ways. Precommitment was generated and communicated in different ways, including the use of invitations to professionals to precommit to de-implementation,87,88 point-of-care reminders for those who did precommit88 and/or general declarations of professional intention (e.g. a poster with a signed photograph of the professional made visible to the patient). 87

A simple public declaration of physicians’ intention to de-implement was tested within outpatient primary care clinics in the USA. It focused on the inappropriate use of antibiotics for acute respiratory infections. 87 These declarations comprised a poster with a signed photograph of the physician made visible to all patients, and committed the physician to the reduction in inappropriate antibiotic prescribing. The intention to de-implement was elicited after a presentation on the study in a standard clinic meeting. If physicians participated in the study, they were informed that this would involve randomisation to display a poster of precommitment within their own patient examination rooms and that, regardless of randomisation, all their antibiotic prescribing data would be monitored. The study intervention ran over a 12-week period, commencing mid-February to accommodate one flu cycle. Baseline data summarising 10 months’ antibiotic prescribing practice were extracted from the electronic health record.

The study was small. A total of 14 physicians completed the study, with data available for 954 patient care episodes. The adjusted baseline rate of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing was similar for the intervention and control practices, at 43.5% and 42.8%, respectively. Nevertheless, at the end of the 12-week trial, the inappropriate prescribing pattern decreased to 33.7% for the intervention clinicians and increased to 52.7% for the controls. The data did not demonstrate any ‘workaround’ by physicians by selecting antibiotic-appropriate diagnosis codes. There was an increase in the reduction of inappropriate prescribing rates for each additional month that the poster was displayed, although this failed to reach statistical significance.

Kullgren et al. 88 incorporated precommitment into a more comprehensive professional behavioural de-implementation intervention that was evaluated in a 12-month stepped-wedge cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) of 45 primary care physicians in six practices in the USA. The intervention was designed to reduce the incidence of orders of low-value interventions, and was designed to nudge decision-making away from the low-value practice by raising professionals’ awareness of evidence-based recommendations to de-implement very close to the decision point. The precommitment was in the form of an invitation to comply with recommendations for the management of three clinical problems: imaging in uncomplicated low back pain and headaches, and the prescription of antibiotics for acute sinusitis. Precommitment was obtained after a presentation about the de-implementation study. If clinicians did precommit, this was in the form of a signed statement after the initial study presentation. Medical administrative staff were provided with training to identify potential patients who fell into one of the three clinical problems and then applied a Post-it® note (3M Cynthiana, KY, USA) on the patient’s documentation that was immediately visible to the physician during consultation. Training was in the form of a brief (10-minute) individual session, reinforced with a one-page summary of their role. These staff-applied point-of-care prompts were introduced to physicians, reminding them of their signed precommitment statement. Paper-based prompts were used as these were thought to minimise the risk of computer fatigue and to increase visibility. Prompts were attached to a patient education handout to support physicians’ attempts to reduce low-value interventions. Weekly e-mails with links to resources to improve communication with patients about low-value services were also sent to participating physicians.

Electronic health record data were used to measure the primary effect of the intervention (i.e. any reduction in physicians’ ordering of targeted low-value clinical interventions). Any potential for physicians to order different interventions rather than simply to cease ordering was also evaluated. The collection of electronic ordering data was supplemented by a physician survey that included attitudinal items about intervention components. A sample of physicians was also invited to participate in a telephone interview that explored how their practice was influenced (or not) through their precommitment and associated reminders.

Primary outcome analysis demonstrated no reduction in the incidence of low-value orders other than a small but statistically significant reduction in back pain imaging orders [–1.2%, 95% confidence interval (CI) –2.0% to –0.5%; p = 0.001]. A sensitivity analysis that reviewed clinical encounters with relevant clinical codes, rather than those encounters solely identified by the trained medical administrative staff, showed reductions in inappropriate orders for all three clinical problems during the intervention period. However, these effects were not sustained over a 3-month follow-up period. Reductions in the ordering of imaging for uncomplicated low back pain were mirrored by an increase in the percentage of visits with a potential alternative order of minimal value (1.9%, 95% CI 0.5% to 3.3%; p = 0.007).

Survey data demonstrated that most physicians (63.6%) found patient education handouts helpful, and precommitment itself was thought to be helpful by nearly half (47.7%) of those physicians who completed the survey. Fewer physicians felt that the precommitment reminders (31.8%) and other resources to support communication (20.4%) were helpful. Interview data suggested that the patient education handouts were most helpful in facilitating communication during the clinical encounter, even for ‘the more difficult patients where I would have been tempted not to follow guidelines’. 88

Although the qualitative data indicate that the intervention materials helped in the communication process with patients, the overall results of this study of precommitment as a means of de-implementing low-value interventions were disappointing. The authors conclude that the limited effect of precommitting to reducing the use of low-value treatments without alternative management strategies may be due to the feeling physicians have ‘. . . to do something’. 88

Other strategies identified in the synthesis to increase professionals’ awareness of low-value practices include both the use of suggested alternatives and accountable justification. Both strategies, along with feedback on performance relative to peers, were evaluated in the context of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing in 47 US primary care practices. 90 The ‘suggested alternatives’ intervention comprised an alert on the electronic health record that highlighted to physicians that a prescription of antibiotics would not be generally indicated for the particular diagnosis, and an alternative course of action was suggested. In addition to increasing attention to a low-value practice, the assumption was that ‘prescribers may infer that a suggested alternative ought to be considered, thus reducing the likelihood that an antibiotic would be prescribed’. 90 Although the accountable justification intervention similarly drew attention to the low-value practice, physicians were required to complete an additional activity through the electronic health record to make an inappropriate prescription for antibiotics. This activity was completion of a free-text justification of the treatment decision. Physicians were also informed that this justification would be visible with the patient’s notes as an ‘antibiotic justification note’. A 2 × 2 × 2 factorial design was used to test different combinations of no intervention with these two interventions and a peer comparison intervention across the 47 primary care practices. Findings showed no statistically significant reduction in prescribing rates for the ‘suggested alternatives’ intervention. However, the absolute difference for accountable justification was –18.1% (difference in differences –7.0%, 95% CI –9.1% to –2.9%). Increasing the sense of professional accountability was anticipated to trigger reputational concerns and a desire to act in line with recommendations within clinical guidelines.

Individuals’ concerns about professional reputation

In the Meeker et al. 90 study, independent, statistically significant reductions in inappropriate antibiotic prescribing were seen for both ‘accountable justification’ and ‘peer comparison’ interventions. As above, the requirement to provide a justification for sustaining a low-value, unrecommended intervention may have worked through triggering professionals’ concerns about their reputations in different ways (i.e. reminding clinicians of the low-value nature of the prescribed intervention, forcing an additional level of critical scrutiny of the decision itself and raising concerns about professional reputation through the documentation of an unadvised course of action).

However, ‘peer comparison’ was also shown to be effective. This monthly e-mail-based intervention provided participating physicians with a ranking (i.e. highest to lowest inappropriate prescribing rate). Those in the lowest decile of prescribers were informed that they were ‘top performers’, whereas others were informed that they were ‘not a top performer’. The absolute difference for peer comparison was –16.3% (difference in differences –5.2%, 95% CI –6.9% to –1.6%), with the authors90 pointing to the positive reinforcement provided to those who managed to successfully reduce inappropriate prescribing. Three studies89,91,92 of performance feedback that included an element of social comparison were identified, although in only one study91 the feedback alone was the focus of investigation. Social comparison feedback is a technique that ‘. . . provides participants with information on their own performance compared to their peers to correct misperceptions about norms that may drive overuse of some tests’. 91 Trumbo et al. 89 included comparative performance feedback alongside education and other supportive interventions. However, in a study by Sacarny et al. ,92 feedback to physicians included the statement that performance was being placed under official administrative scrutiny. Although the previous two studies88,90 focused on physicians’ ordering of investigations within inpatient settings, this study focused on ‘off-label’ prescribing of antipsychotic medication for older and disabled adults. All of these studies were conducted in the USA.

The de-implementation intervention investigated by Sacarny et al. 92 attempted to manipulate concerns about professionals’ reputations. The investigation was conducted across a study population of 5055 primary care physicians who were the highest prescribers of an off-label antipsychotic medication enrolled in the Medicare programme. The evaluation design was a placebo-controlled parallel-group investigation of comparative performance in the form of three peer comparison letters to each of 2528 physicians randomised to the experimental intervention. These letters indicated that individuals’ prescribing of antipsychotic drugs was high relative to their peers and was under review by Medicare. The letters were clearly worded to draw attention to inappropriate levels of prescribing and were sent several months apart over the 9-month intervention period. The control group of physicians (n = 2527) received ‘placebo’ letters about medicine regulations. A baseline cohort of patients were identified from those receiving the study medication from any study provider up to 1 year prior to the study, and these patients were classified as being either ‘guideline concordant’ or as having ‘low-value prescribing’ against prespecified clinical criteria.

The intervention demonstrated a decrease of 11.1% (95% CI 9.2% to 13.1%; p < 0.001) in existing and new prescribing practices compared with the control group who received ‘placebo’ letters. The intervention also produced a decrease of 27.1% in the volume of new antipsychotic drug prescriptions over 9 months (95% CI 23.1% to 31.1%; p < 0.001), which persisted over a 2-year period. The authors conclude that letters providing comparative performance data and indication of external surveillance to the ‘highest prescribing physicians in the Medicare programme led to statistically significant, persistent decreases’ in antipsychotic prescribing. 92 The use of both the ‘carrot’ and ‘stick’ approach to providing performance feedback was also attested to in our stakeholder engagement, as in the quotation below from a clinical director of cardiology during a telephone interview:

. . . so I met with the individual [consultants] first and then with their teams, them and their teams and the individual meetings were basically ‘look here’s your data, you’re losing the organisation £1,000,000 a year, you’re keeping people in too long, and more people are dying than they should’. My approach was ‘how can I help you to improve this’ and you know what I also said was ‘obviously if these things can’t improve I’m going to have to look at whether you should be supervising other junior doctors, I’m going to have to look at what you can and can’t do’.

Academic_M5

Adjusting views on normative performance

Ryskina et al. 91 used a single-blinded RCT to evaluate a simple social comparison performance feedback intervention. Social comparison feedback is a technique that ‘. . . provides participants with information on their own performance compared to their peers to correct misperceptions about norms that may drive overuse of some tests’. 91 The clinical focus of the study was in-hospital laboratory routine test ordering, which is long considered to be an overused practice in the USA. In Ryskina et al. ’s91 study, 114 physicians were randomly allocated to one of two groups: a control group that received no feedback or an experimental group that received a personalised e-mail of their routine laboratory ordering (including blood count, metabolic panel, liver function and common coagulation tests) compared with the average of all clinicians from the previous week’s test ordering. These individuals also had access to a continuously updated and personalised dashboard that provided the context to these data, including patient-level details. No statistically significant reduction in the experimental group physicians, in terms of the count of routine laboratory orders placed by each physician per patient-day, was identified, regardless of individual physicians’ pre-intervention ordering rates relative to their peers. However, there was a general reduction in laboratory testing. Ryskina et al. 91 surmised that there may have been ‘cross-contamination’ between the groups, but also that the intervention group did not access their review e-mails and personalised dashboards regularly. This lack of engagement may be because of the clinicians having to physically access the e-mails themselves, presenting an added barrier. However, if the information was automatically accessible without needing to access the data then the difficulty for the physician would be reduced.

In addition to comparative performance feedback, Trumbo et al. 89 provided additional support to enable staff to reduce unnecessary ordering of chest X-ray investigations within two critical care settings [i.e. cardiovascular intensive care units (CVICUs) and medical intensive care units (MICUs)] in one US hospital over a 9-month period. The intervention provided information about Choosing Wisely’s evidence of the consequences of daily routine chest X-rays through a face-to-face session with staff members at each unit, giving feedback on current chest X-ray ordering rates and providing a rationale for reducing routine ordering. ‘Peer champions’ were recruited from each unit following this session. Two advanced nurse practitioners from the CVICU and three physicians (residents) from the MICU volunteered as peer champions. Their role was to co-ordinate data responses and encourage colleagues to adhere to the recommendations, as well as providing weekly feedback on X-ray ordering. Improvement science methods, including Plan, Do, Study, Act cycles, were used to facilitate de-implementation. There were no control settings on the evaluation design. The two critical care units were compared against their pre-intervention X-ray ordering data. The CVICU achieved a small but statistically significant fall in X-ray ordering from a pre-intervention rate of 1.16 (interquartile range 1.06–1.28) chest X-rays per patient per day to a post-intervention rate of 1.07 (interquartile range 0.94–1.21; p < 0.001) chest X-rays per patient per day. The MICU, which had a pre-intervention rate lower than the CVICU, showed no change over a 33-week period. Quantitative data were augmented by observation and semistructured interviews with stakeholders. Reasons for differences between the intensive care units were related to the turnover of staff and reduced quality improvement initiatives in the MICU that showed no significant decrease in X-ray ordering. Trumbo et al. 89 reported ‘messaging about reducing unnecessary tests went well when framed at the unit level but may be counterproductive if used to question individual ordering decisions’. 89 Although it is unclear from the presented data why this conclusion was drawn, two clinical incidents (unrelated to chest X-rays) that occurred during the study time frame may have posed additional de-implementation challenges.

The provision of comparative performance feedback has been linked to both prompt reputational concerns about being a professional outlier and correct views on normative performance. This mechanism is extended in studies that focused on more supportive forms of peer and collegial mentoring. Here, there was an explicit focus on using peer support as a means for de-implementation,93 albeit as part of a complex array of education, training, printed information and ongoing external facilitation. This comprehensive strategy was evaluated in a cluster randomised trial93 covering 765 patients from 72 units in 32 Norwegian nursing homes. The purpose of the trial93 was to limit the use of inappropriate prescribing of antihypertensive medication. The primary outcome was the number of antihypertensive medications prescribed (with description defined as fewer drugs at month 4 than at baseline), together with patients’ systolic blood pressure and pulse measurements.

Findings showed that the medications were significantly reduced in the intervention group (n = 43, 32%) compared with control (n = 11, 10%). Blood pressure increased for the intervention patients from 128 ± 19.5 mmHg to 143 ± 25.5 mmHg at 4 months, but at 9 months this fell back to the pre-intervention average of 134 mmHg, with no effect on pulse. Gulla et al. 93 concluded that in long-term hospital care the introduction of planned medication reviews with collegial mentoring can reduce antihypertensive drug prescribing and potential side effects without increasing patient blood pressure in the longer term. However, following the termination of the study, the difference between the intervention and control units became negligible, with the authors emphasising that continued collegial support and education are essential for achieving sustained de-implementation.

Outcomes

Three groups of de-implementation interventions, drawing on ideas from behavioural economics on behaviour change, were identified across the evidence: (1) seeking professionals’ precommitment to de-implement, (2) seeking accountable justification for sustaining low-value practices and (3) benchmarking professionals’ performance against peers. As complex interventions with multiple components, and depending on contextual conditions, each study intervention had the potential to trigger any or all of the four submechanisms that we have identified. Consequently, we are not able to identify outcomes associated with each of these submechanisms. Our summary indicates the observed outcomes of interventions that, broadly speaking, were designed to slow decision-making, and make this more thoughtful and deliberate. 88

There is mixed evidence on the impact of obtaining precommitment in delivering prescribing behaviour change away from low-value clinical interventions. Interventions that solely raise awareness of low-value practices appear to have little impact on de-implementation, even when these are delivered close to clinical decision points, although this has been tested in few clinical scenarios. Disrupting routine fast decisions through the use of precommitment that also raises patients’ expectations around de-implementation87 may be more effective. In addition, professionals’ concerns around delivering treatment that is consistent appear to be more effective in reducing inappropriate prescriptions of antibiotics. Precommitment appears to work in terms of changing dialogue with service users, but this may be dependent on the precommitment being made explicit to patients. As a result, the precommitment may be more associated with a desire to be congruent with expectations, rather than with the clinical issue per se.

The findings from Meeker et al. ’s87 study are encouraging. The study intervention was of minimal cost and was more effective than a more comprehensive approach to precommitment. 88 Although not translating into instrumental changes to prescribing practices, materials such as reminders, patient education materials and online resources to support communication with patients were found to be appreciated by physicians in this study.

Collegial or peer support approaches to reducing low-value treatments and tests appear to have some effect, but in a much wider package of de-implementation activity, or through invoking professional rivalry90 and concerns about individual performance with respect to peers. However, providing an additional threat associated with sustaining the low-value practice was also seen to be effective. 92 Peer evaluation of practice, in the context of pharmacist review of physician practice, did not appear to be effective in delivering change in prescribing of practice.

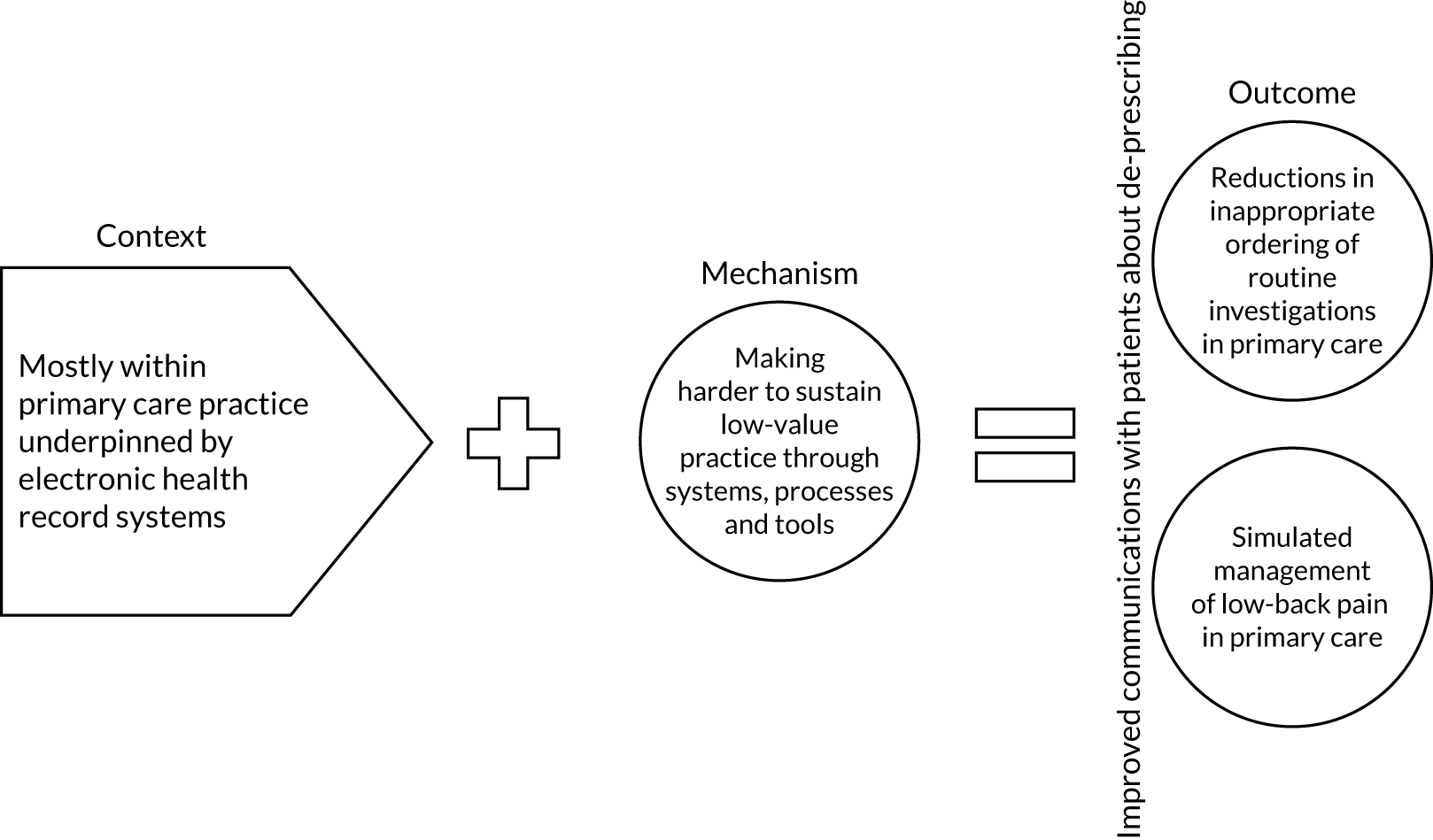

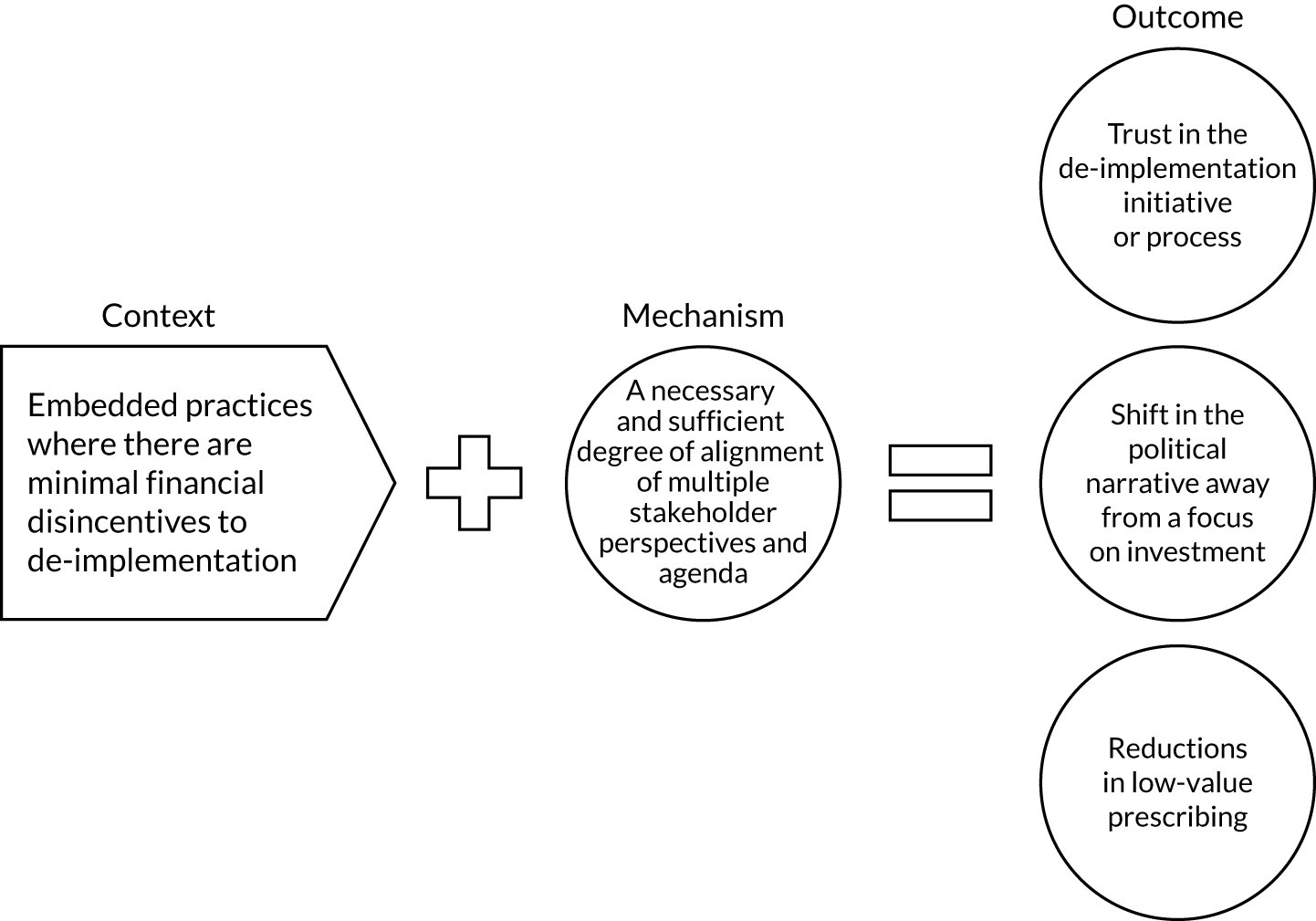

Context–mechanism–outcome 2: designing de-implementation through technology

In the context of clinical practice underpinned by electronic health records, de-implementation interventions that amend the design of these systems (context) may be successful when their design makes sustaining low-value practice harder (mechanism). Things may be made harder by changing information displays/choice options. Impacts were demonstrated in the reduction of orders for unnecessary diagnostic tests (outcome) (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Context–mechanism–outcome 2.

Context