Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 16/01/79. The contractual start date was in October 2017. The final report began editorial review in March 2020 and was accepted for publication in November 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. This report has been published following a shortened production process and, therefore, did not undergo the usual number of proof stages and opportunities for correction. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Brocklehurst et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background to role substitution in dentistry

Role substitution in NHS dentistry in the UK

Workforce planning is an important policy objective in the NHS to ensure that ‘the right number of people with the right skills are in the right place at the right time to provide the right services to the right people’. 1 ‘Skill mix’ is a term that is used to describe a model of care in which the whole of the clinical team is utilised in delivering service activity. 2 It can be further subdivided into role substitution and role supplementation. In dentistry, the former means that different members of the dental team undertake clinical tasks instead of a general dental practitioner (GDP), while the latter means that team members augment the activity of a GDP. 3 The use of role substitution in NHS dentistry has been advocated for some time, but its implementation appears to have lagged behind that seen in medical specialties owing to a number of factors, including professional regulation, NHS regulations and financial incentives. 2 These, along with the current evidence from the literature, will be explored in this chapter.

Professional regulation of role substitution in NHS dentistry

In 1921, the Dentists Act4 created the Dental Board of the United Kingdom, which became the professional body for dentistry and oversaw its practice. In 1956, following amendments made to the Act, the Dental Board was superseded by the General Dental Council (GDC). 5 This reflected the recommendations in the Teviot Report,6 which argued that the dental profession had become sufficiently mature to self-govern. The Act also facilitated the training of ‘dental auxiliaries’ for the first time [referred to as dental care professionals (DCPs) in the remainder of this report]. The newly formed GDC subsequently developed the regulated titles of dental hygienist (DH) and dental therapist (DT). The duties of the former related to the provision of preventative and periodontal treatment, and the latter was permitted to provide a range of direct restorative procedures and extract deciduous teeth. In 1983, UK dental schools began to offer ‘dual’ integrated training over a period of 2 years. The new ‘hygiene–therapist’ qualification was able to offer the full range of clinical activities that both DHs and DTs could legally undertake, although only an individual title of DH or DT was registerable with the GDC. 7 In 2002, the Dentists Act was again amended and allowed DTs to practise in NHS dental practices. 8 Before this time, the DT’s role had been limited to the provision of care in NHS Community Dental Service settings only; the provision of care in NHS Community Dental Service settings had formerly been restricted to GDPs since 1948.

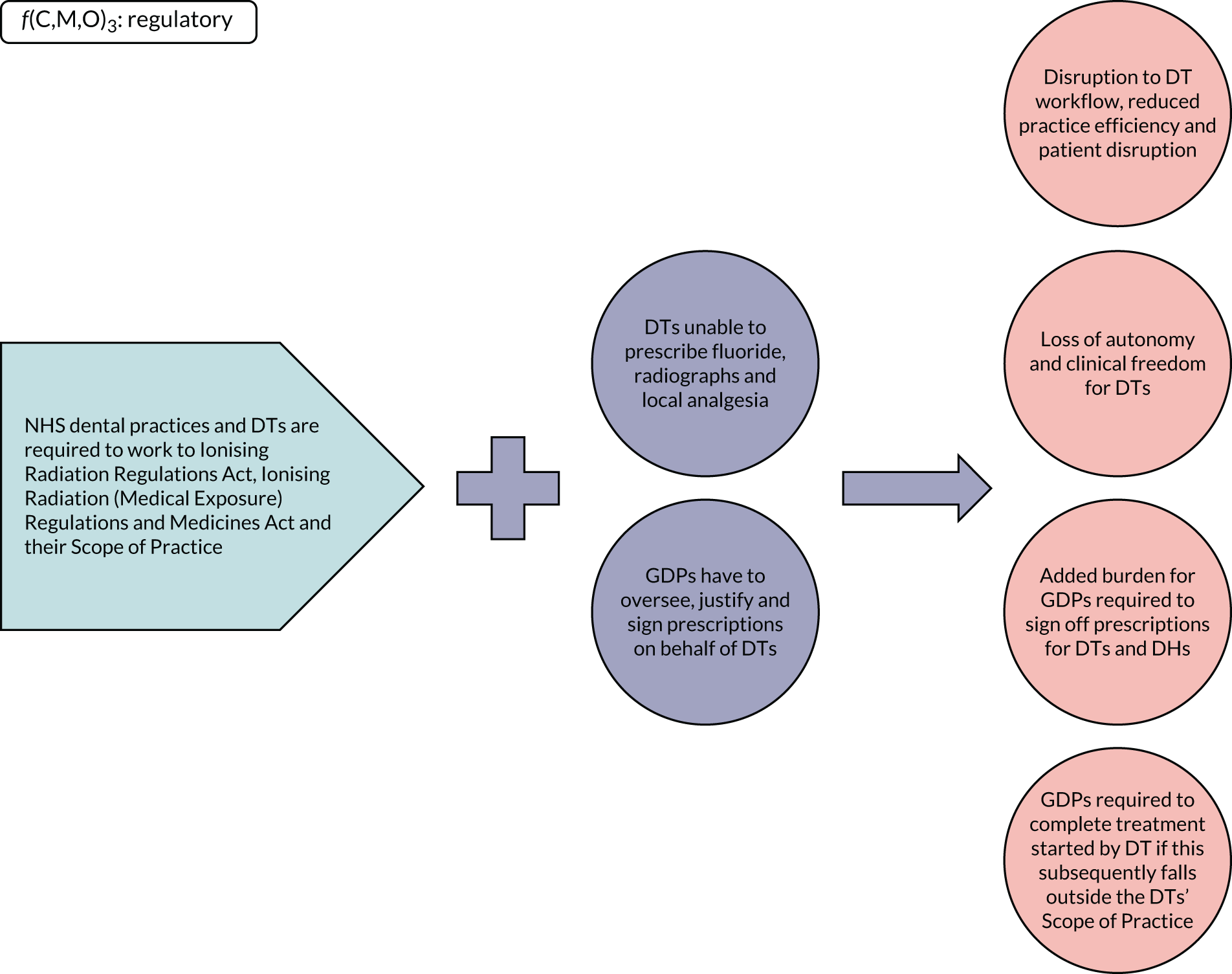

Despite this change, DCPs were not allowed to practice as ‘front-line’ clinicians in the NHS or in private practice. Instead, patients were required to see a GDP for an examination and treatment plan before being referred to DCPs for their NHS care (a condition in both the Dentists Act and the NHS regulations9). NHS regulations9 also prevented DCP services from being procured directly, with the ‘knock-on’ effect of DCPs not being able to receive a NHS pension (unlike their GDP counterparts). However, after a review of the available literature, a landmark decision by the GDC in 2013 allowed patients to have ‘direct access’ to dental care by DCPs without a referral from a GDP. 10 This was accompanied by an expansion of the DCPs’ Scope of Practice to incorporate undertaking examinations and developing treatments plans within their level of competence. 7 However, DCPs remained unable to contract directly with the NHS under NHS regulations9 and were also unable to prescribe dental radiographs or fluoride or administer local analgesia (owing to restrictions in the Ionising Radiations Regulations11 and the Medicines Act,12 respectively).

Policy recommendations on role substitution in NHS dentistry in the UK

Policy-makers have been interested in the potential of role substitution in NHS dentistry for some time. In 1993, the Nuffield report inquiry13 redefined the concept of the dental team through which dental care could be delivered and argued that the role of DCPs could be expanded. Subsequently, increasing attention has been paid to how role substitution can deliver the level of care in the NHS that is required to meet the population health need. This is now explicitly recognised in a number of policy documents that underpin NHS care. For example, both the Prudent Healthcare policy agenda in Wales14 and the NHS Long Term Plan15 call for greater use of role substitution.

In the UK, population oral health needs are changing. In the most recent epidemiological survey, 90% of young adults are expected to have > 21 teeth in 10 years’ time, and the levels of dental caries and periodontal disease have fallen dramatically. 16 By contrast, levels of dental caries in young children have remained relatively intransigent, despite the fact that dental caries, as a non-communicable disease, are entirely preventable. 17 As highlighted in the Child Dental Health Survey in 2013, ‘nearly a third (31%) of five-year olds and nearly a half (46%) of eight-year olds had obvious decay experience in their primary teeth. Untreated decay into dentine in primary teeth was found in 28% of five-year olds and 39% of 8 year olds’ (information from NHS Digital, licenced under the current version of the Open Government Licence). 17 This pattern of disease also follows a social gradient: ‘a fifth (21 per cent) of the five-year olds who were eligible for free school meals had severe or extensive tooth decay, compared to 11% of five-year olds who were not eligible for free school meals’ (information from NHS Digital, licenced under the current version of the Open Government Licence). 17

Equally, the increasing number of partially dentate older people with varying degrees of independence are giving rise to new health-care challenges. The oral health of care-home residents is much worse than their community-living peers (e.g. caries prevalence is 73% vs. 40%, respectively) and about half of all care-home residents now retain some of their natural teeth. 18,19 Poor oral health may also exacerbate a range of medical conditions, including pneumonia and delirium, which increases health-care costs and leads to poorer outcomes. 20 Despite this high level of need, dental service provision in residential care is poor, with little emphasis on prevention. 21,22 Access to domiciliary services is difficult and unscheduled care for dental problems (including hospital admissions) is common, complex to deliver and expensive. 20,23 The World Health Organization (WHO) argues that the design of long-term care systems that are fit for ageing populations should take priority,24 and the Royal College of Surgeons of England (RCS),25 Public Health England (PHE) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)26 have all called for more high-quality research. The Care Quality Commission (CQC) also highlighted the paucity of dental care in care homes in its report of June 2019. 27

Along with these pressing and emerging population health needs, there is evidence that many who attend dental practices have good oral health. In the Adult Dental Health Survey,28 71% of all dentate adults reported that they attended their GDP at least once per year. A total of 6% reported that they attended once every 2 years and a further 10% attended less often than every 2 years. The remaining 13% of dentate adults reported that they attended only when they were having trouble with their teeth. Data from the Business Services Authority (the organisation responsible for paying GDPs in England and Wales) suggest that many of those who do attend do not require any further treatment. 29 In 2018/19, out of the 39.7 million courses of treatment delivered in 1 year in England, 23.3 million (58.7%) related to patients having check-ups with no further treatment. The figures for 2017/18 and 2016/17 were 58.0% and 57.0%, respectively. That many who attend do not need further treatment is further supported by data from the Assessment of Clinical Oral Risk and Needs (ACORN) in Wales, where GDPs collect ‘risk’ and ‘need’ data as part of the Welsh Dental Contract Reform programme. A total of 60.4% and 47.8% of adults in 2019 were classified as ‘green’, that is as having no active dental caries or periodontal disease, respectively, and many of these patients appear to return to their dental practice within a 9-month period (Colette Bridgman, Chief Dental Officer for Wales, 2020, personal communication). This suggests that a substantive level of the resource being invested into primary dental care in the NHS relates to managing low-risk dental patients. As a result, there are increasing calls for the development of a NHS dental workforce to meet these emerging population oral health needs, and the procurement of relevant NHS service provision, while freeing up resources to increase the capacity to provide care and reduce social inequalities in oral health. 3

Role substitution in NHS dentistry

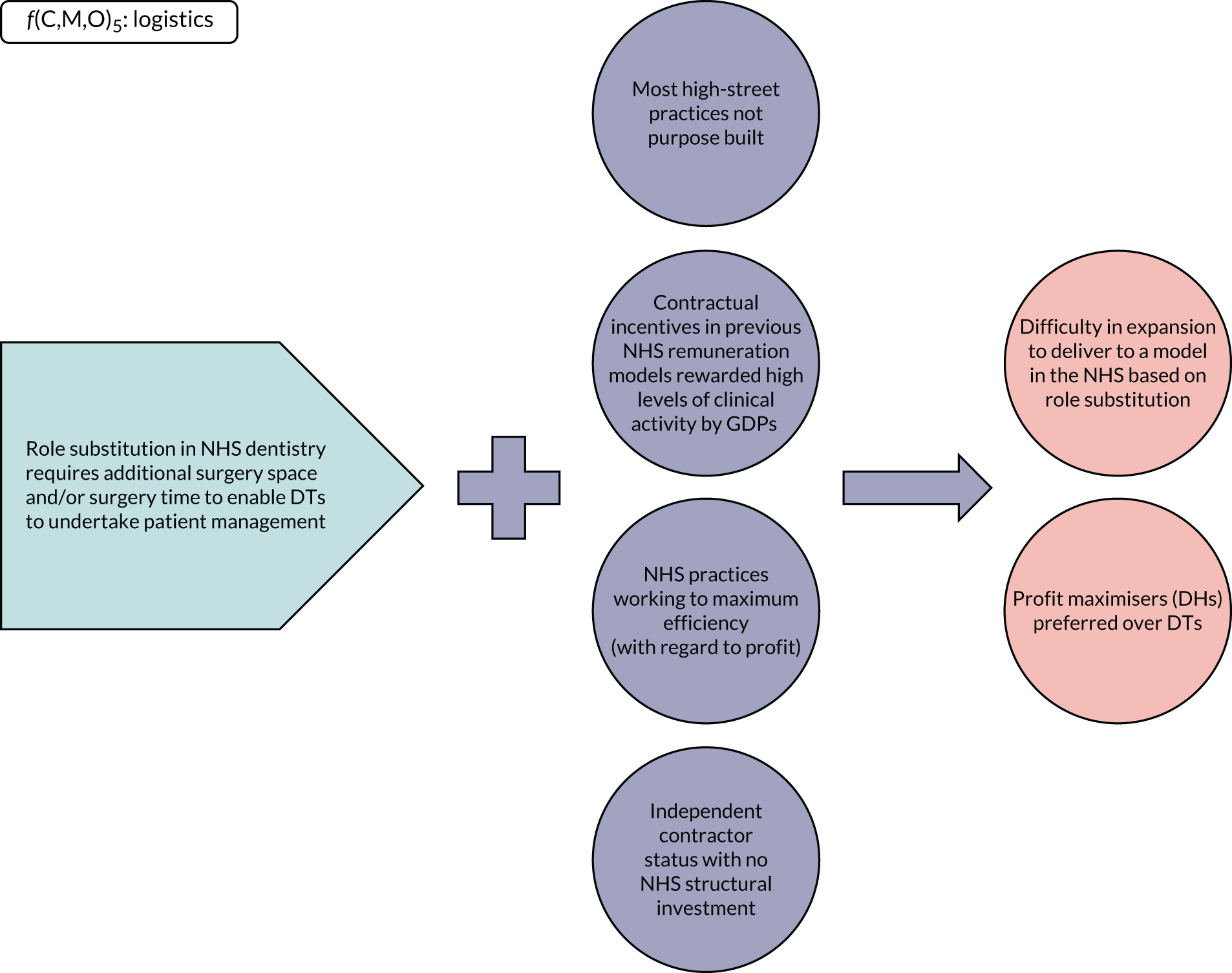

Dental care professional utilisation by NHS dental practices appears to be heavily influenced by the financial incentives inherent in the NHS contract. 30 NHS GDPs run their practices as businesses to offset the cost of the capital risk of the premises and the equipment that they own while ensuring liquidity to cover their overheads. 31 In medicine, transaction costs can be offset by economies of scale, which enable a broader range of services to be made available. 32 This is more difficult in NHS dentistry because, historically, many practices have not been ‘purpose built’ and some remain ‘single handed’. 33 This limits the extent of role substitution and supplementation undertaken in the NHS.

Although DHs appear to be well-accepted members of the dental team in the UK,30,34 financial considerations appear to play a significant part in the decision to use a DT in the NHS. 35,36 In one of the few studies that examined the profitability of using role substitution,37 patient charges generated did not cover the cost associated with their use in the current remuneration system. As a result, many DTs have been employed in the NHS as DHs in England rather than being utilised across their full range of skills. 35 In addition, some patients expect to pay less for treatment provided by a DCP than by a GDP. 38

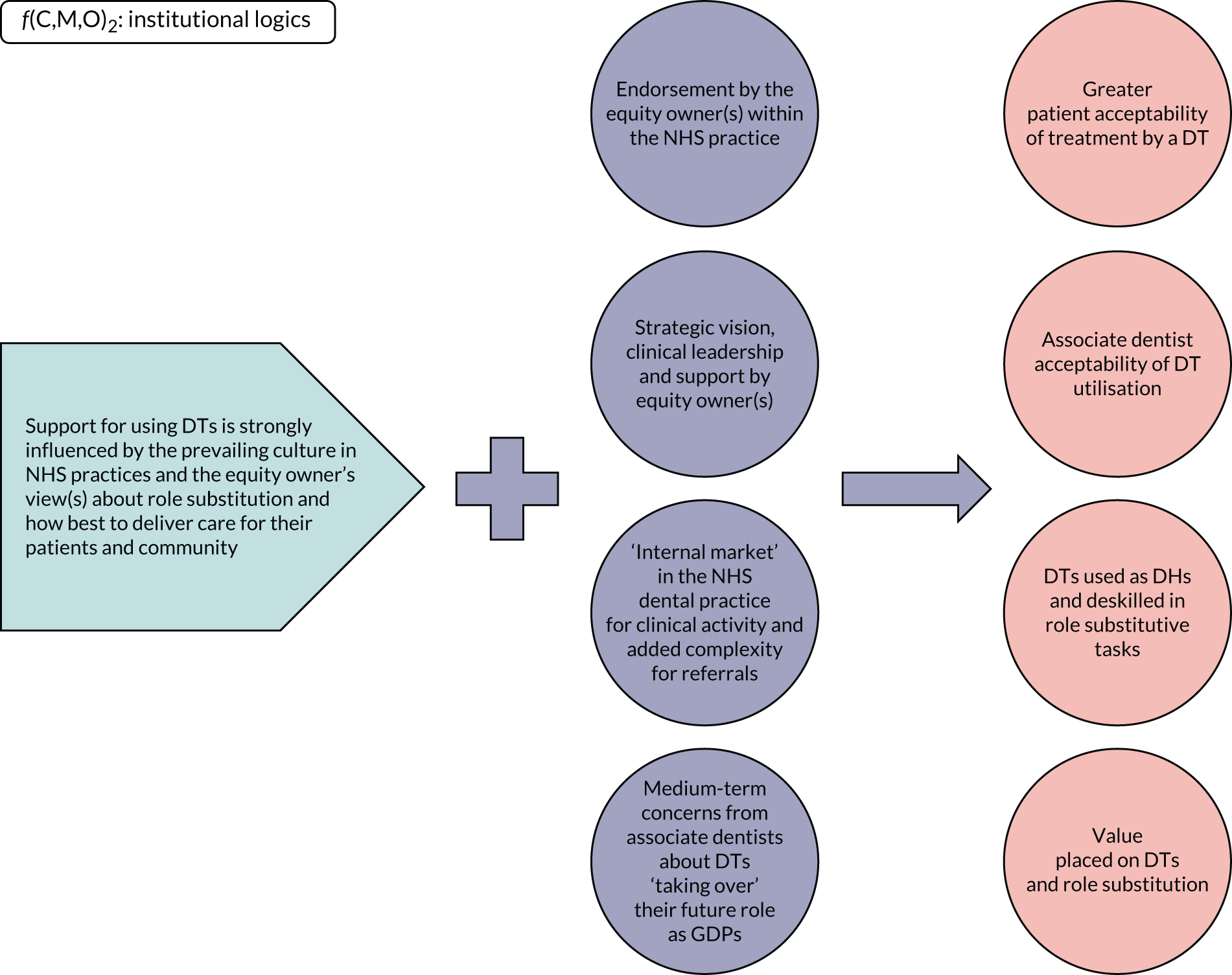

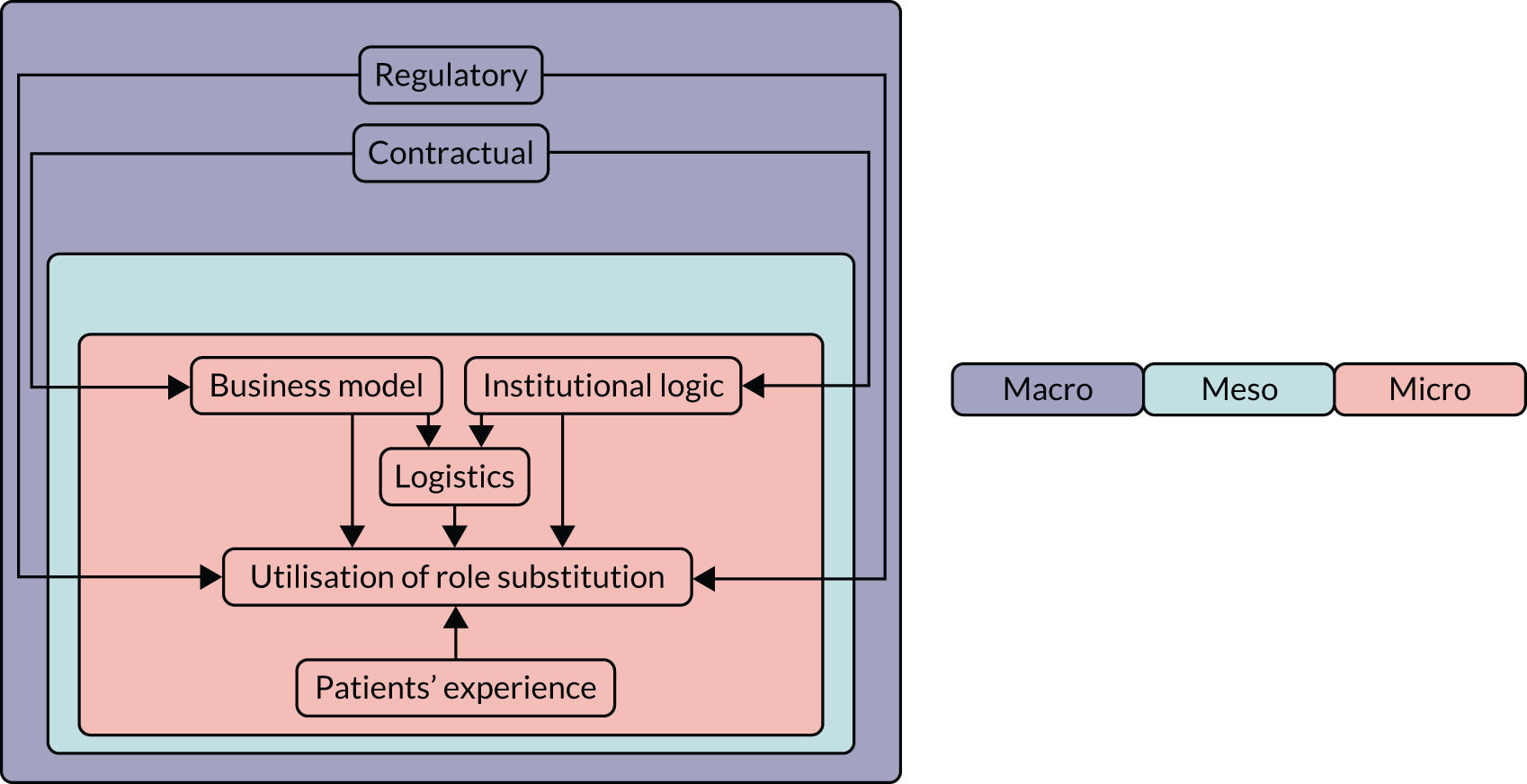

Dental practices operating in the NHS are acutely sensitive to the incentives in any given remuneration system. 39,40 This can influence the institutional logic of the dental practice (the culture in an organisation that shapes the collective behaviour and actions of those who work there) and whether or not role substitution is supported. 30,41,42 Retrospective payment systems, such as fee-for-service (FFS) (where a GDP submits a claim for every single item of completed treatment), have been shown to lead to overtreatment to maximise profit. 43,44 In these systems, the incentive for practices is to increase the amount of clinical activity delivered, which may not always suit the greater utilisation of role substitution. 30 In contrast, per-capita remuneration systems pay practices a fixed level of funding based on the number of registered patients. This breaks the link between treatment activity and practice income, giving practices greater autonomy on what to focus on. 45 This may lead some practices to place greater emphasis on prevention, which would favour role substitution and supplementation (to reduce staff costs and draw on the strengths of DCPs to deliver prevention). 30 However, per-capita systems can also lead to undertreatment and patient selection, that is, a preference for low-risk patients who require little treatment, given that funding for these practices is capped and unrelated to clinical activity. 46,47

Goodwin et al. 48 argue that institutional logics at any given NHS practice include not only dentistry as a business but also professional ethics and contextual factors based on where the practice is embedded. As highlighted by Watt et al. ,49 the most important factors influencing change in dentistry include concerns about financial risk, progressive practice environment, supportive organisational structure, supportive professional networks and opportunity for training. Therefore, the drive to maintain (and maximise) the viability of a NHS practice can also be tempered by a practice owner’s sense of duty to their patients and their ideas about how best to deliver care for their patients and community. 50 In our earlier study,30 the views of practice principles on the benefit of role substitution was found to be one of the most important factors, which could ameliorate concerns about the impact of using DCPs, in relation to the underlying NHS contract. Management of change is also a potential problem with role substitution because professionals seek to protect their clinical roles and maintain traditional clinical boundaries. 51,52 Managing a transition to role substitution takes time and good human resource skills. 53 McDonald et al. 54 found that the key factors that determined the acceptability of changes to role boundaries included the clarity around roles and responsibilities as well as personal relationships with colleagues, which raise issues of mutual trust and respect. Nevertheless, the influence of the underlying NHS contract remains substantive and warrants an understanding of the historical development of NHS funding and contractual reform across the UK.

The evolution of NHS dental contract in the UK

At the turn of the new millennium, Modernising NHS Dentistry55 set the agenda in England and subsequently gave primary care trusts (the organisations responsible for procuring NHS service provision at the time) powerful new commissioning tools to improve access to NHS dentistry and increase the provision of preventative services across England. This was further emphasised in Options for Change in 2002. 56

Prior to 2006, GDPs were paid on a FFS basis. This meant that GDPs claimed for every item of clinical activity that they undertook. As described in Role substitution in NHS dentistry, this payment mechanism can have a tendency to incentivise overtreatment because GDPs’ income is directly linked to the level of clinical activity undertaken on each patient. 43,45 It also had a negative impact on practices because many of the individual items of treatment were of a relatively low value and led to GDP complaints about being on a ‘treadmill’ (a high level of clinical activity on low-value items) to maintain the viability of their practices. 31 This was particularly relevant after 1990 because the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) had attempted to correct an overspend on the national dental budget and had placed a downwards pressure on the annual review process that controlled how individual items of treatment were costed. 57 In 2006, a new general dental services (GDS) NHS contract was introduced in England and Wales. 58 This contract collated NHS dental activity items into three broad bands in an attempt to lessen the number of individual items of treatment that GDPs would claim for on each patient:

-

band 1 – examination, radiographs and a simple scale and polish

-

band 2 – restorations, extractions and root canal treatments

-

band 3 – crowns, bridges and dentures.

These bands of treatment attracted 1, 3 and 12 units of dental activity (UDAs), respectively. The value of a UDA varied across NHS dental practices and was based on clinical activity and payments in a ‘reference year’ that were ‘earned’ under the previous FFS NHS dental contract in 2005. As a result, GDPs who had been undertaking significant levels of clinical activity in the reference year were rewarded with high UDA values, resulting in considerable heterogeneity and inequity across practices in England. For example, an examination (generating 1 UDA) in one practice could generate £18 whereas in another practice it could generate £30. Likewise, one or multiple fillings completed in a ‘course of treatment’ (generating 3 UDAs) would attract £54 or £90, respectively, for GDPs on the same NHS dental contract.

NHS dental contracts were raised with equity-owning GDPs in England and Wales (known as ‘providers’). They then subcontracted these contracts to non-equity-owning GDPs at their practices (known as ‘performers’). DCPs were provided with an income based on the proportion of clinical activity that they undertook, or were paid a salary. The former method of remuneration for DCPs led to a potential conflict of interest between performers (also known as ‘associate GDPs’) and DCPs, because both were funded based on the number of UDAs that they delivered. 30 Another important element of the 2006 contract was cost containment, which capped providers’ annual activity to an agreed number of UDAs per year, known as an annual contract value (ACV). 30 NHS GDPs were then paid one-twelfth of their ACV on a monthly basis. As a result, NHS GDPs’ outputs under the new contract in England were constrained and they were penalised if they underperformed (< 96% of their ACV) or overperformed (> 102% of their ACV).

The effect of this change to the NHS dental contract was significant changes in the types of treatments that were offered. For example, as providers and subcontracted performers were paid the same number of UDAs for endodontic treatment and extractions (which are often the two alternative treatment options for many teeth with advanced decay), the number of the former reduced in favour of the latter, given that the latter could be undertaken in one-quarter of the time in most cases. 39,40 Equally, one or multiple fillings completed within a course of treatment would generate the same level of revenue for a practice (3 UDAs). As a result, there was downwards pressure on the number of fillings undertaken in any one course of treatment, leading to multiple courses of treatment submitted for patients who required more than one restoration. 39,40 GDPs were also incentivised to make upper and lower partial or full dentures separately to claim two sets of band 3 payments. Preventative care was not remunerated separately and any preventative activity was expected to be undertaken in an existing course of treatment. 39,40

In addition to these unintended consequences at a regional and national level, the 2006 NHS dental contract proved unpopular with GDPs. 31 This was largely because of the loss of clinical autonomy and the need for practices to be accountable to local dental commissioners (DCs), who closely scrutinised providers’ ability to deliver to their ACV targets. GDPs argued that one form of treadmill had simply been replaced by another. As a result of this criticism, an independent review was undertaken in 2008/9 in England, which recommended the greater use of preventative care and a standardised approach to patient assessment, leading to patient care pathways. 59

This led to the development of a pilot programme in England in 2010, which was predominantly based on capitation. 60 It also required GDPs to undertake an oral health assessment that categorised patients into different risk categories (red, amber or green). However, the pilots in England were beset with a number of informatic problems, and based on concerns about the capitation payment system were relaunched in 2015 as ‘prototypes’. 61 Prototype practices were paid on the basis of a blended-funded system, drawing on features of the 2006 contract (a retrospective payment mechanism based on clinical activity) with capitation. This blended together the financial incentives to ‘care’ and prevent disease (associated with capitation payment mechanisms) with the incentives to undertake clinical activity (associated with FFS mechanisms). In similarity to the earlier pilots in England, the prototypes were based on establishing risk and then referring the patient to the appropriate patient care pathway.

An evaluation of the first year of prototyping was published in 2018. 62 Attendance marginally increased over the course of the evaluation period (3–6%). A total of 62% of prototype practices reported delivery of preventative care to adults according to evidence-based guidelines compared with 56% in the 2006 contract, with little change to the level of prevention offered to children (60% and 58%, respectively). The evaluation concluded:

. . . progress has been made in the first year of prototyping on the key issues of improving oral health, providing appropriate care and quality, and maintaining or increasing access to merit continuation of the programme.

The evolution of contractual reform followed a similar pattern in Wales, although the process was different under their devolved government. In 2011, eight dental practices took part in a pilot trial. 63 This process required these practices to deliver weighted ‘key performance indicators’ and a capitation target based on the number of unique patients treated in the practice within a defined time period. In 2012, the Quality and Outcome Pilot64 for adults was introduced, with the introduction of a dental care assessment and a risk-based preventative care plan. By 2016, all but two practices had reverted back to the 2006 UDA contract. The remaining practices continued as prototype practices to test new models of care and formed a ‘learning network’. An early evaluation of the Welsh pilots found a reduction in the number of patients attending NHS practices (7–10%) compared with baseline.

In 2017, the Welsh Government published Taking Oral Health Improvement and Dental Services Forward in Wales,65 which placed greater emphasis on incentivising needs-led care, role substitution/supplementation and prevention. This led to the development of a needs and risk assessment tool. In 2018 the Welsh Government increased the number of ‘contract reform’ practices to 23, and by late 2019 > 100 NHS practices had entered phase 1 of the process. This reduced ACV targets by 10% and raised all providers’ UDA values to a minimum of £25 to ensure greater parity across the nation. For this 10% reduction in their ACV, practices were required to undertake an ACORN at least once per year under the mantra ‘do it once, do it well’ (Colette Bridgman, personal communication). Phase 2 of the contract reform process saw further reductions in ACV targets (reduction to 70–80% of pre-reform levels) in exchange for greater emphasis on the provision of prevention, increasing the quality of care provided and greater utilisation of role substitution/supplementation. These policy objectives were further emphasised in The Oral Health and Dental Services Response to a Healthier Wales,66 published in 2018, and are being underpinned by a formal evaluation process undertaken by researchers at Bangor University. As of spring 2020, over one-quarter of the total NHS practice population was using ACORN and involved in the Dental Contract Reform programme in Wales.

In Northern Ireland, the predominant financial mechanism used to pay GDPs still resembles the pre-2006 contract in England and Wales, that is, the majority of funding draws on FFS and items of service as part of a retrospective payment system. An Oral Health Strategy for Northern Ireland67 was published in 2007 and reiterated the main themes identified by the Northern Ireland Primary Dental Care Strategy in 2006, namely a shift away from treatment in favour of prevention of disease while maintaining access to services. In 2014, the Northern Ireland Health and Social Care Board initiated a pilot NHS dental contract across the province, which involved > 30 GDPs. Similar to the English pilots, the chosen remuneration mechanism was prospective in nature, so reduced the incentive for GDPs to engage in unnecessary treatment. The underpinning policy intention was that practitioners would receive the equivalent gross income during the pilot period that they would have received under the GDS had they maintained their activity and list as per the baseline period. As highlighted in our evaluation of the pilot NHS contract led by Bangor University, we found ‘rapid changes in the patterns of care provided by GDPs to patients (compared with the control practices) when they moved from a FFS system to a capitation-based remuneration system’ and ‘there were statistically significant reductions in the volume of all treatments in the intervention practices during the capitation period’ (contains information licensed under the Non-Commercial Government Licence v2.0). 57 This highlighted the sensitivity that GDPs have to underlying incentives in the NHS dental contract.

In Scotland, the prevailing dental contract funding mechanism was similar to Northern Ireland’s model. After a consultation exercise in 2016, the Scottish Government published its Oral Health Improvement Plan68 in 2018 with a 41-point plan that focused on prevention, an oral health risk assessment and a personalised care plan. As highlighted by Brocklehurst et al. :57

. . . in contrast to the other three home nations, there were no plans for scrapping the item-of-service system of remuneration; instead there was an intention to ‘streamline’ items of service payments, which would be progressively introduced.

The proposed remuneration mechanism was based on a ‘mixed economy of item of service, capitation and continuing care payments’57 (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0).

Evidence base for the use of role substitution in dentistry

Proponents of role substitution argue that it has the potential to free resources, increase the capacity to care for high-need populations, improve access and reduce oral health inequalities. 69–71 In an international review, Nash et al. 72 concluded that ‘access to basic dental care will not be available without the utilization of dental therapists in the workforce’, and Johnson73 argued for a paradigm shift ‘from treatment to prevention, wellness and self care’.

Role substitution by DCPs has been established for some time in a number of European countries. 70,71 Sweden and the Netherlands legalised the independent use of DCPs in 1964 and 1978, respectively. 74 Finland, Denmark and Norway have allowed independent practice since 1994, 1996 and 2001, respectively. Similar practices are found in Switzerland, which started in 1997, and in Italy, where DHs have been able to work as independent practitioners since 1999. 74 In the USA and Canada, DH is a growing profession, and DHs can practice with varying degrees of independence in a number of US states, including California, Colorado, Montana, Nebraska, New Mexico, Oregon and Washington, and Canadian provinces, including British Columbia, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba, although some restrictions remain in terms of settings. 75 Tasmania has a liberal regulatory model in which DHs and DTs practice independently and can own their own practices. 74 DTs are also considered to be independent in New Zealand, although they are not able to treat adults. 74 In Samoa and Singapore, DTs must work under the supervision of a GDP. Fiji has allowed DTs to assume independent responsibility for managing clinics since 1985, and DTs have been allowed to practice independently in South Africa since 1994. 74

The research evidence for the greater use of DCPs is emerging. Despite suggestions from some elements of the dental professional that role substitution is unsafe, this is not borne out by the limited literature that is available. Two studies by Calache and Hopcraft,76,77 undertaken in Australia, found no evidence to question patient safety when adult patients were managed by DTs. No differences were found between DTs and graduating GDPs in infection control, local analgesia, cavity preparation, placement of restoration, occlusion and patient communication. 77 Knowledge and clinical skills were rated as good to high, and 80% of DTs were considered safe to treat adult patients. The potential of DCPs not to identify oral cancer is another frequently cited concern in terms of patient safety. However, in an in vitro study, Brocklehurst et al. 78 found that the diagnostic test accuracies of GDPs and DTs were similar when they were presented with a judgement task that required them to distinguish between malignant and benign diseases of the oral mucosa. Values of sensitivity and specificity were 81% and 73% for GDPs, compared with 77% and 69% for DTs, respectively. DTs also missed fewer frank carcinomas in the judgement task.

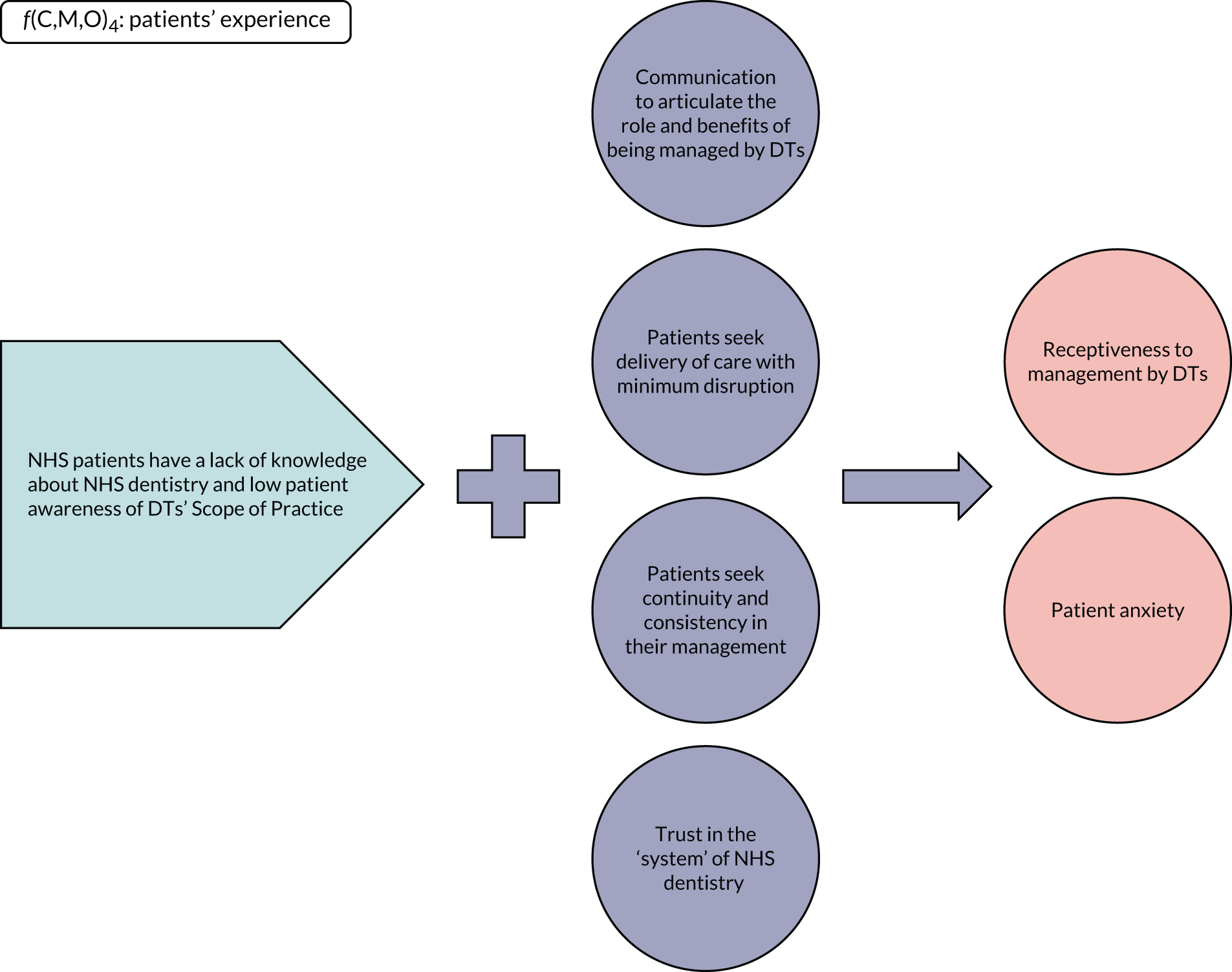

Although the social acceptability of DTs appears to be positive, public awareness of DTs as a professional group is not widespread. 38,79,80 In the UK, our earlier study found that the attitudes of practice owners were critical in the process of patients accepting treatment from DTs. 30 Despite this, it does appear that adults are willing to receive treatment from DCPs under the NHS and there is evidence of increased patient satisfaction. 80 In one of the Calache and Hopcraft studies,77 patients were very satisfied with the dental treatment that was provided. In another study conducted by the same team,81 356 direct coronal restorations were placed with high patient satisfaction. In Canada, 65.8% of respondents stated that they would visit an independent DH to maintain their oral health. In the USA, 98.0% of respondents strongly agreed or agreed that their care by DCPs was satisfactory (based on RAND criteria; RAND Europe UK, Cambridge, UK). 82 Perry et al. 83 reported 98.0% patient satisfaction. For DTs, the majority of adults and children’s caregivers receiving care in Alaska had a positive patient experience. 84 In the Netherlands, one-quarter of those surveyed (n = 1500) agreed that ‘simple dental treatments’ could be performed by a DH rather than by a GDP, and 15% agreed that a DH could undertake a check-up. 85,86 In another study, 85.0% of patients who received a simple restoration for the treatment of dental caries provided by a DCP claimed to be satisfied with the treatment provided. 87

In terms of efficacy, Wang and Riordan88 evaluated a population oral health programme undertaken in Norway that allowed DHs to undertake a check-up over a 3-year period. The quality of care provided was judged not to deteriorate over this time frame. 88,89 This is supported by Kwan et al. ,90 who compared the performance of DCPs with GDPs in an epidemiological programme. Sensitivity values for GDPs ranged from 0.54 to 1.00, and those for the DCPs from 0.80 to 0.94. The direction of effect in these studies has also been replicated by Patel et al. ,91 Kwan and Prendergast92 and Hopcraft et al. 93 In terms of restorative management by DCPs, Bader et al. 94 found that 74 out of the 84 direct amalgam restorations placed by DTs were considered to be completed to an adequate standard, compared with 32 out of 41 restorations provided by GDPs. This was not dissimilar to Wetterhall et al. ’s study,84 which found that 88.0% and 78.0% of amalgam restorations were rated as ‘satisfactory’ for DTs and GDPs, respectively. Calache et al. 81 evaluated 356 restorations placed by DTs in 115 patients. After 6 months, 95.0% were judged to be successful by blinded evaluators. This concurs with studies by Battrell et al. 95 and Freed et al. 82 Dyer et al. ’s Cochrane review96 identified four randomised controlled trials and one non-randomised controlled trial. Three found no evidence of a difference in retention rates of fissure sealants placed by DCPs compared with GDPs, and the study comparing the comparative effectiveness of ‘atraumatic restorative technique’ restorations found no difference in survival rates after 12 months. 96

These results concur with the findings of a number of studies97,98 led by our team that were undertaken with NHS clinicians. In 2012, we showed that both DTs and GDPs had comparable sensitivity and specificity in the recognition of occlusal caries in vitro. 97 In 2015, we tested the diagnostic test accuracy of DTs in vivo. 98 A total of 1899 adult NHS patients were screened by both a DT (index test) and a GDP (reference standard) prior to their routine NHS check-ups in 10 busy NHS practices. Both sets of clinicians made an assessment on the presence of dental caries and periodontal disease. The sensitivity and specificity values of DTs were 0.81 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.74 to 0.87] and 0.87 (95% CI 0.78 to 0.92) for dental caries and 0.89 (95% CI 0.86 to 0.92) and 0.75 (95% CI 0.66 to 0.82) for periodontal disease, respectively. This suggests that DTs could recognise the two most common oral diseases. Brocklehurst et al. 78 found that the diagnostic test accuracies of GDPs and DTs were similar when they were presented with a judgement task that required them to distinguish between malignant and benign diseases of the oral mucosa. Values of sensitivity and specificity were 81% and 73% for GDPs, compared with 77% and 69% for DTs, respectively. DTs also missed fewer frank carcinomas in the judgement task.

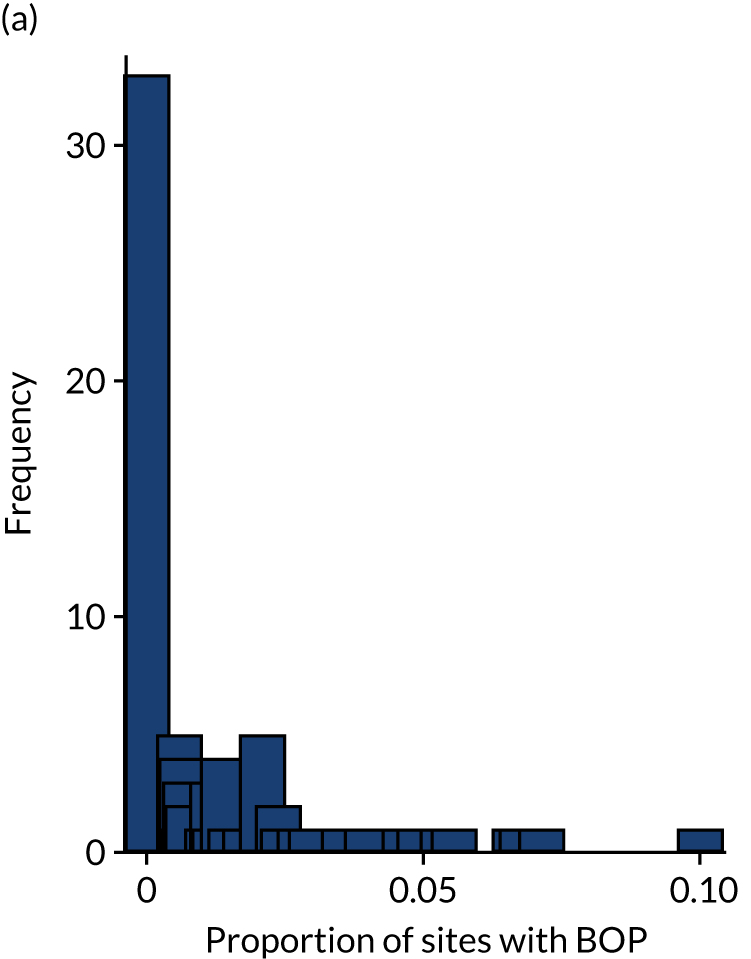

Although diagnostic test accuracy is important as a measure of efficacy, a more important consideration is an assessment of the effect on health of using DTs in front-line roles. Given that precise estimates of effect, recruitment, retention and fidelity were unknown, we undertook a study to test whether or not a definitive trial could be feasible in the NHS. 99 Over a 15-month period, adult NHS patients were randomised into one of three arms in two NHS dental practices: patients who saw only a DT (arm 1), those who saw both a DT and a GDP (arm 2) and, finally, those who saw only a GDP (arm 3). The initial recruitment rate for the study was 33.7%. This figure increased to > 82.1% when telephone calls or face-to-face recruitment were utilised. The retention rates were 60% for the DT and DT/GDP arms and 70% for the GDP arm. The proportion of sites with bleeding on probing (BOP), a measure of gum inflammation, at the end of the 15-month period was 46.7%, 14.5% and 32.1% in arms 1, 2 and 3, respectively (44.6%, 17.2% and 26.5% at baseline, respectively). Similarly, plaque levels were found in 68.2%, 43.7% and 60.9% of patients, respectively (60.5%, 44.9% and 56.3% at baseline, respectively). Because these values did not differ significantly from baseline values, it suggested that oral health can be maintained by role substitution.

The majority of the studies examining the efficiency of DCP utilisation are from the UK. 100,101 Harris and Sun102 concluded that role substitution in the UK ‘may be limited to particular situations where conditions are conducive’. Patients with high levels of disease (many restorations) were thought less suitable for referral because GDPs would undertake care in fewer visits and there was a risk of complications necessitating referral back to a GDP. 99 In our earlier study30 we found that the extent of role substitution in NHS dental practices appears to be relatively limited and largely restricted to the use of DHs for routine periodontal treatment. This appears to be directly related to the incentives and disincentives in the NHS dental contract. This meant that ‘NHS dental practices that utilised fewer non-dentist team members were associated with higher levels of technical efficiency, that is as role substitution in NHS practices increased, their relative efficiency dropped’. 30 As highlighted in the report, ‘when UDAs were used as the output measure in England, NHS dental practices operated at a mean level of efficiency of 64.0%. This changed very little when the outputs were measured in terms of number of patients seen, or the number of treatment plans generated. NHS dental practices that did not use any form of role substitution had a higher mean level of efficiency (68.0%; n = 39)’ (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). 30 Any use of DCPs was found to be associated with statistically significantly lower efficiency scores (14.0% lower for UDAs and 11.0% lower for treatment plans or patients seen) than no use of role substitution.

Discussion

As highlighted in this chapter, the potential use of role substitution in NHS dentistry is becoming increasingly recognised by policy-makers. Changes made by the GDC now make this more possible, but there remain regulatory barriers at this point in time: NHS general dental services regulations, the Medicines Act12 and the Ionising Radiations Regulations. 11 Financial incentives in NHS dental contracts also play a key role but can be mitigated by the institutional logics in a dental practice.

All dental contract reform programmes undertaken across the UK have placed an emphasis on increasing patient access and prevention while maintaining and improving the quality of service being delivered. In many cases, this is facilitated by the development of care pathways based on the risk status of the patient. In Wales, the use of role substitution is an explicit objective in the second stage of the contract reform process, and it is implicit in many other national programmes.

This means that it is timely to draw on the existing evidence base for the greater use of DCPs. However, the quality of the literature is relatively poor and, as Dyer et al. ’s Cochrane review96 highlighted, the number of trials empirically testing role substitution is limited. Although there have been a number of diagnostic test accuracy studies to demonstrate efficacy, no trials have examined the effectiveness of using DTs, instead of the GDP, to undertake the check-up. As highlighted by our feasibility study,99 there was some reservation about recruitment and retention rates in busy NHS dental practices. There were also specific design questions that remained unanswered. For example, what is the estimated size of effect of such an intervention and should the design be based on superiority or on the basis of non-inferiority (i.e. are DTs better than or no worse than a GDP in undertaking the check-up and any subsequent treatment that is required)? The latter question is a fundamental one and significantly influences the design of a definitive trial.

As a result, we proposed undertaking an individually randomised pilot study in the North West of England over a 15-month period based on the following population, intervention, control, outcome (PICO) format:

-

population – adult, asymptomatic, low-risk, routine dentate or partially dentate NHS patients

-

intervention – check-up and any subsequent treatment undertaken by a DT

-

control – check-up and subsequent treatment by a GDP (‘treatment as usual’)

-

outcome – proportion of sites that BOP (measured at six sites per tooth).

To facilitate the design of the definitive study, a realist-informed process evaluation was undertaken alongside the pilot study to explore the acceptability of using DTs as front-line clinicians, patient crossovers (from one arm to the other) and treatment fidelity. We also captured the contextual factors that shaped the intervention in NHS practices, mechanisms that sustained or potentiated effects, unexpected pathways and consequences and the contextual factors that shaped implementation. 103 This was framed from a realist perspective to understand ‘what is it about a programme that works for whom, in what circumstances, in what respects, over which duration’. 104 Realist methodology is becoming increasingly used in health services research because it recognises the complex and contingent nature that underpins the settings for new interventions and service delivery. This approach to process evaluation ‘supposes that regularities in the patterning of social activities are brought about by the underlying mechanism constituted by people’s reasoning and the resources they are able to summon in a particular context’. 105

Finally, we undertook a third workstream (WS) to develop and test the health economic data collection tool and rehearse the health economic analysis of the intervention compared with the current practice. We adopted the viewpoint of both the NHS and the patient, and collected resource use data that included the costs of dental consultation by GDPs and DTs, the use of primary and secondary NHS dental services, and participants’ out-of-pocket expenses relating to any dental problems during the pilot’s follow-up period.

Aims and objectives

The aim of this study was to inform the design for a definitive trial by undertaking a pilot study to determine whether or not DTs can maintain the oral health of low-risk routine NHS patients, who form the predominant proportion of the regularly attending practice population. The objectives of the research were to:

-

determine the most appropriate design of a definitive trial

-

determine whether or not BOP is the most appropriate primary outcome measure (POM) (and if not, determine the most appropriate measure)

-

confirm the appropriateness of the non-inferiority margin of the chosen outcome measure for the definitive trial (i.e. whether or not the effect estimate lies within an appropriate margin of non-inferiority)

-

further investigate recruitment, retention and fidelity rates

-

confirm willingness to be randomised among study participants

-

determine the potential for patient crossovers between arms (e.g. where the patient’s condition is considered too complex to be managed by the DT)

-

undertake a process evaluation underpinned by a realist framework to understand what works, for whom, why and in what circumstances

-

rehearse the health economic analysis and assess the health economic data collection tool, to inform the definitive trial design

-

explore patients’ preferences in a focus group setting, to inform a preference elicitation exercise [e.g. discrete choice experiment (DCE)] in the definitive trial.

Structure of the report

This report is arranged in chapters, as follows. Chapter 1 provides a review of the literature and describes the historical context of role substitution in dentistry. Chapter 2 describes the methods and results of the pilot study. Chapter 3 describes the realist-informed process evaluation and Chapter 4 details the health economic element of the study. Chapters 5 and 6 present the discussion and conclusions of the study.

Chapter 2 Pilot randomised controlled trial

Introduction

In 2013, the GDC expanded the Scope of Practice for both DHs and DTs following a review of the scientific evidence. 10 This allowed both DHs and DTs to see patients for the first time as the front-line health-care worker. This meant that they could now see patients directly without a referral from a GDP, undertake an examination, formulate a treatment plan and provide clinical treatment within their competence. For DHs, this amounted to the provision of preventative and periodontal care and for DTs this also included the provision of temporary and permanent restorations.

These changes formed the basis of this study and an opportunity to test an alternative care pathway using DTs to undertake the check-up on low-risk routine patients in the NHS. Two earlier NIHR grants investigated the efficacy and efficiency of using DTs in NHS practices [NIHR/CS/010/004 and Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) 11/1025/04]. The former demonstrated the diagnostic test accuracy and feasibility of using these groups to undertake check-ups and the latter found that dental practices using DTs in the NHS could be better organised. Pilot studies determine ‘whether something can be done, should we proceed with it, and if so, how’. 106 In WS1, we undertook such an approach to inform the design of a definitive trial.

Aims and objectives

The aim of this WS was to inform the design for a definitive trial by undertaking a pilot study over 15 months to determine whether or not DTs could maintain the oral health of low-risk routine NHS patients, who form a significant proportion of those who regularly attend NHS practices. The objectives of the research were to:

-

determine the most appropriate design of a definitive trial

-

determine whether or not BOP is the most appropriate POM (and, if not, determine the most appropriate measure)

-

confirm the appropriateness of the non-inferiority margin of the chosen outcome measure for the definitive trial (i.e. whether or not the effect estimate lies within an appropriate margin of non-inferiority)

-

further investigate recruitment, retention and fidelity rates

-

confirm willingness to be randomised among study participants

-

determine the potential for patient crossovers between arms (e.g. where the patient’s condition is considered too complex to be managed by the DT).

Methods

Workstream 1 was an individually randomised pilot study undertaken across the North West of England over a 15-month period:

-

population – adult, asymptomatic, low-risk, routine dentate or partially dentate NHS patients attending high-street dental practices

-

intervention – check-up and any subsequent treatment undertaken by a DT

-

control – check-up and subsequent treatment undertaken by a GDP (treatment as usual)

-

outcome – proportion of sites that had BOP.

Changes to design after pilot study commencement

The East Midlands (Nottingham 1) Research Ethics Committee provided a favourable ethics opinion on 9 November 2017 (Research Ethics Committee reference number 17/EM/0365). Subsequent to this approval, two substantial changes were made to the original protocol and these were approved by the East Midlands (Nottingham 1) Research Ethics Committee.

Amendment 1 (2 March 2018)

In the original protocol we stated in the participant inclusion criteria that the patient should not have presented with any active dental decay or required any dental fillings owing to caries within the previous 2 years. However, during the pre-trial training, consultation with the lead clinicians at participating practices suggested that this criterion was too strict. Therefore, this criterion was amended to read that the patient should present with no more than one active lesion in the last year or required no more than one dental filling owing to dental caries within the previous year.

Amendment 2 (16 March 2018)

In the original protocol we stated that we would recruit participants from up to six practices. However, early in the trial it became apparent that it would be difficult to fully recruit the number of participants that we required within the limited recruitment window. The decision was made to extend the number of practices to allow the study team to meet the recruitment target.

Amendments 1 and 2 mitigated any recruitment risks within the specified 5-month recruitment window and were also approved by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR).

Eligibility criteria

High-street NHS dental practices were recruited across the North West of England. Initially, contact was made with the NHS practices through the NHS Local Area Teams in Greater Manchester and Cheshire and Merseyside (the latter including the Local Dental Network). Paul Brocklehurst ran a workshop to present the study to interested practices on 30 May 2017 and sent follow-up e-mails in June 2017 to confirm practice interest. NHS practices were provided with an overview of the pilot and the associated remuneration that was available to them to undertake the pilot trial:

-

£530 payment to each recruited NHS practice for attending the pre-trial training event to cover the loss of earnings.

-

£50 payment to each recruited NHS practice per participant recruited into the trial, split into £25 at the beginning and £25 at the end of the pilot trial.

-

£25 and £7 payment per patient in the intervention arm for band 1 courses of treatment and £75 and £26 for band 2 courses of treatment (for exempt and non-exempt patients, respectively). This was to cover the loss of NHS payments to the practice caused by the participant being treated by the DT rather than their GDP.

The eligibility criteria for the practices were as follows:

-

The practice should employ at least one DT with at least 2 years’ clinical experience.

-

The majority (> 50%) of adult service provision should be in the NHS.

-

The patient should be treated under the NHS.

-

The practice should have the support of a practice manager.

The following were the eligibility criteria for the individual participants:

-

Adult (aged > 18 years) NHS patient on the recall list of the participating NHS practice

-

no more than one active lesion in the last year or required no more than one dental filling owing to dental caries in the previous year

-

highest basic periodontal examination (BPE) score of ≤ 2

-

asymptomatic at time of the NHS check-up

-

no predisposing medical history elevating oral health risk status

-

seen for routine NHS check-up at least 6 months ago

-

dentate or partially dentate.

New patients, adult patients presenting in pain, patients requiring root fillings or extractions and patients who were edentate or receiving ongoing periodontal treatment were excluded. Patients with sites that had a BPE code of ≥ 3 were excluded (on the recommendation of the Local Dental Network).

Pilot study setting

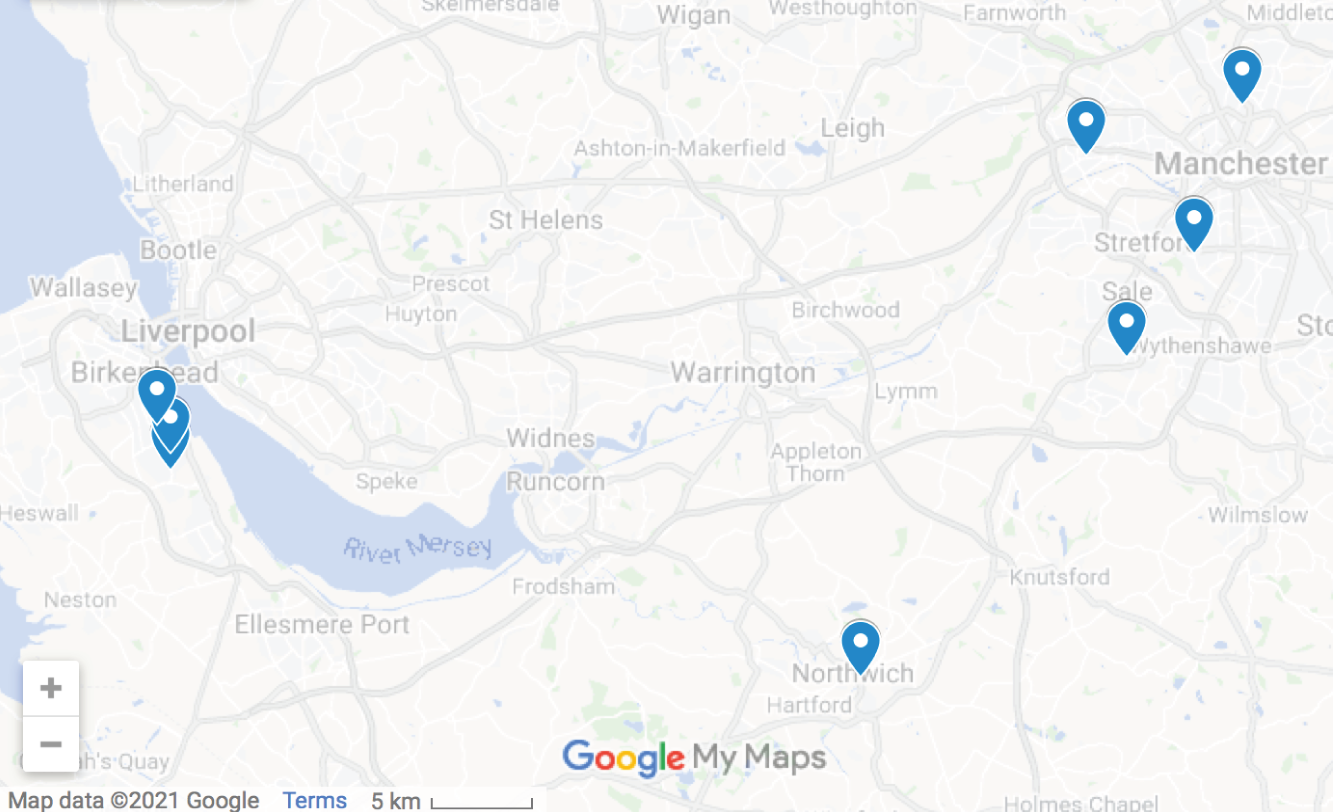

Eight high-street NHS dental practices were recruited across the North West of England. The geographic distribution of the practices is highlighted in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Geographic distribution of participating practices.

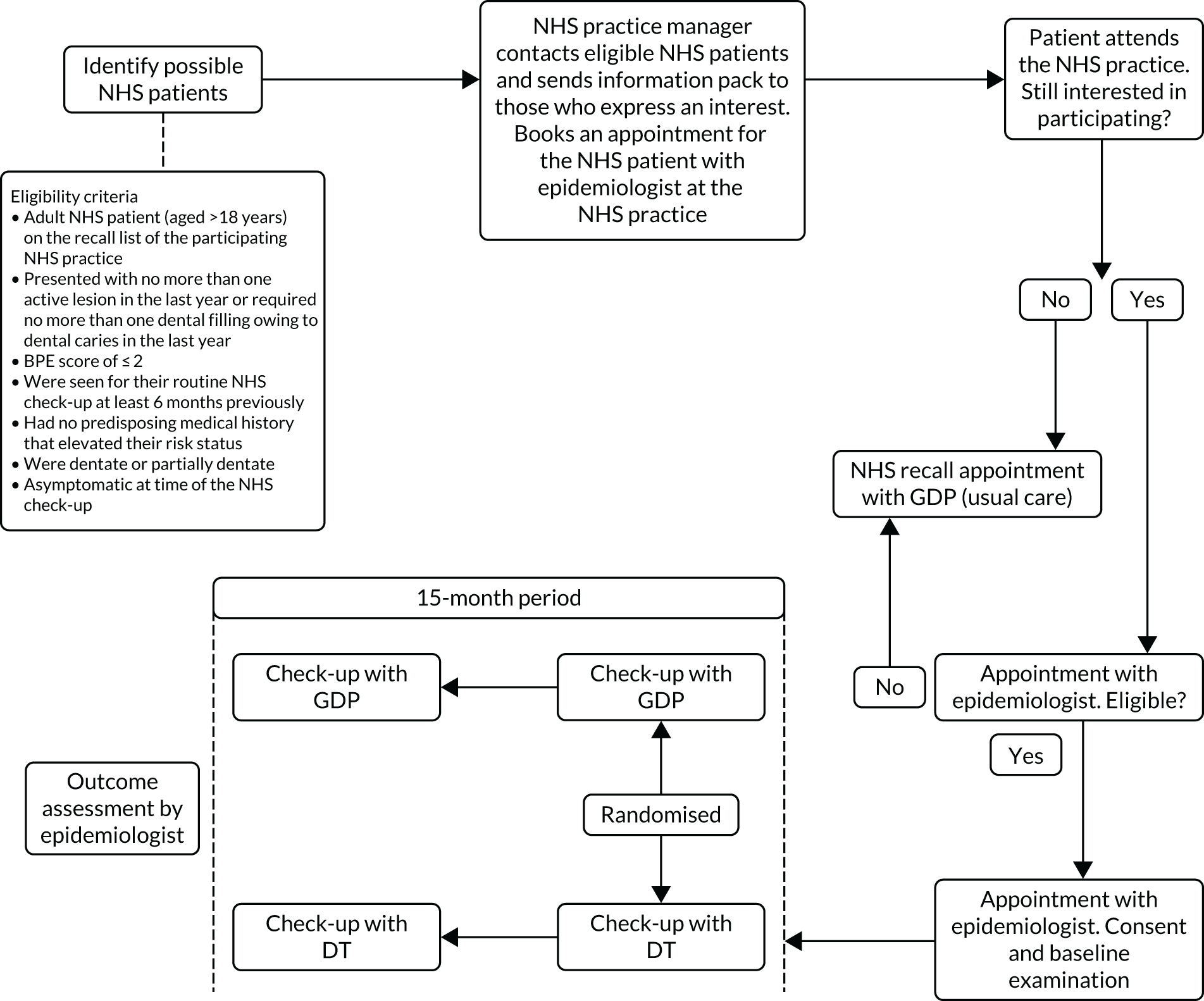

Patient pathway

The patient pathway for the pilot study is provided in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Participant pathway through the NHS practice.

On arrival for their check-up, identified patients were asked by a member of the research team if they had any questions about the study and if they wished to participate. If they agreed, the participant was then asked to sign the consent form and a unique patient identifier was provided to ensure anonymity. A unique patient identifier reference sheet was kept throughout the study, which enabled the participants to be tracked, when necessary. The participants were examined by a trained epidemiologist, who first checked if the patient was eligible for the study and then undertook the baseline measurements for the case report form (CRF) (see Appendix 1). The baseline CRF recorded details that included:

-

age and gender

-

exemption status and employment type

-

ethnicity

-

number of teeth remaining and number of sites (six per tooth)

-

number of sites with BOP (to enable proportion to be calculated)

-

number of sites with visible plaque present

-

Oral Health Impact Profile-14 items (OHIP-14)107 score

-

reported levels of dental anxiety.

The participant was randomised, using the North Wales Organisation for Randomised Trials in Health (NWORTH) Clinical Trials Unit sequential dynamic adaptive randomisation algorithm, to see a DT (intervention arm) or their GDP (control arm). 108 After randomisation, each participant received a check-up in accordance with the arm that they were allocated.

Intervention arm

Under the National Health Service (GDS) Regulations 2005,109 the current care pathway for regular attenders is for NHS patients to see their GDP for their check-up. This reflects the regulatory environment at the time, where DTs could not see patients directly or undertake an examination or treatment plan (i.e. GDPs were the only clinician type entitled to see patients directly under the NHS regulations).

In the latest epidemiological survey (conducted every decade) (n = 11,380), half of all dentate adults reported that they attended their GDP at least once every 6 months and a further 21% indicated that they attended at least once per year. 28 This meant that approximately three-quarters of all the participants in the pilot study were likely to be seen twice in the 15-month period. This concurred with our experience in the feasibility study, where patients were seen for three check-ups during the study period. 99

The patient pathway in the pilot was based on the procedure detailed in the published feasibility study. 99 Given that half of the adult population does not require any further treatment after a check-up (based on national Business Services Authority data), the pilot study focused on low-risk patients. 28 High-risk, complex or symptomatic patients were excluded.

In the intervention arm, participants underwent a check-up by a DT and any subsequent treatment within the DT’s Scope of Practice. The GDC allows DTs to undertake all of the routine direct restorative treatment that GDPs can, except for root fillings. Subsequent visits and treatment were recorded in a separate CRF that recorded the following details:

-

clinical activity/advice provided

-

need for any additional input from the GDP

-

agreement on the subsequent treatment (DT’s plan took precedence)

-

need for the patient to be seen by the GDP (i.e. treatment required was beyond the DT’s Scope of Practice)

-

detail of the treatment undertaken by GDP (if required).

At the end of the study, the same measures that were undertaken at baseline were collected by the trained and blinded epidemiologist, in addition to the following information:

-

dental pain/problems over the study period (including detail)

-

number of new decayed and filled teeth

-

proportion of sites where the BPE exceeded a score of 2.

If participants in the intervention arm experienced pain or presented with problems during the study, they were initially seen by the DT and then offered appropriate treatment, depending on the presenting problem. All treatment information was entered onto the CRF (see Appendix 1), which recorded the type of treatment undertaken and the clinician type involved. After the check-up and/or the completion of any opened treatment plans, the patient was placed back on the recall list according to the recommendations of the DT.

In the feasibility study, no patient crossovers were seen among the 60 patients recruited. 99 Patients were willing to be randomised and recruitment and retention rates were 82% and 78%, respectively. To assess patient crossover, records were kept of those participants who started off in the DT arm but crossed over to the control arm because they were considered to be too complex for a DT to manage their care (this was not seen in the feasibility study). 99

Control arm

When participants were allocated to the control arm, they saw their usual GDP and had their check-up and any subsequent treatment. After the check-up and/or the completion of any treatment, the patient was placed back on the recall list according to the recommendations of the GDP. In similarity with the intervention arm, baseline and outcome assessments were recorded on the CRF by a trained and blinded epidemiologist. The GDPs also entered all check-ups and treatment data on the appropriate CRF.

Randomisation

Randomisation was at the individual level (patient) and performed by the NWORTH Clinical Trials Unit. Treatment allocation was on a 1 : 1 basis using a sequential dynamic randomised adaptive algorithm. 108 This meant that each participant’s allocation was recalculated and was based on the overall allocation level, within stratification variables and within stratum level. This enabled the research team to maintain adequate allocation ratios while maintaining the required balance across the two arms.

A number of potential prognostic factors were considered as stratification factors:

-

deprivation

-

previous history of disease

-

number of teeth remaining.

It was decided by the study team that the most appropriate strata to choose was a proxy measure for material deprivation (exemption status). This was recorded on the CRF.

Primary outcome measures for the pilot

In alignment with the aims of a pilot study, the following were assessed:

-

willingness to be randomised among study participants

-

appropriateness of BOP as the POM

-

appropriateness of the non-inferiority margin (i.e. whether or not the effect estimate lay within an appropriate margin of non-inferiority)

-

recruitment, retention and fidelity rates

-

numbers of participant crossovers between arms (e.g. where the patient’s condition is considered too complex to be managed by the DT).

Proposed primary outcome for the definitive trial

The proposed clinical POM for a future definitive trial was the proportion of sites with BOP. BOP is relevant to both clinicians and patients. It was considered by the research team as stable, measurable and had potential to change over the timescale of the project. This view was reinforced by the fact that BOP was used as the primary outcome in a number of recent NIHR Health Technology Assessment trials conducted in a primary dental care setting. 110,111 Other measures of periodontal health (e.g. pocket depths) were considered to be more sensitive to measurement bias, would take a long time to express and were likely to exhibit a smaller effect. 112

Bleeding on probing is routinely assessed in clinical practice to measure the degree of gingival and periodontal inflammation. Whereas the presence of BOP at isolated sites is not a particularly good indicator of risk for future disease progression, absence or minimal levels of BOP are a very good indicator of periodontal health and tissue stability. 113–115 It is also highly relevant to patients, who often complain of bleeding gums as a first sign of gingival and periodontal problems. This pragmatic end point was relevant to both patients and clinicians and has high generalisability to everyday clinical practice. Furthermore, in the context of the pilot, BOP was considered to be the most sensitive measure for detecting signs of developing gingival inflammation.

Secondary outcome measures collected were based on simple adaptations of indices that are used commonly in clinical practice:

-

proportion of sites that have visible plaque present (measure of oral cleanliness)

-

number of new decayed and filled teeth

-

unplanned visits between check-ups

-

oral health-related quality of life (OHIP-14 score)

-

patient-centred outcomes to explore dental anxiety.

Dental caries was chosen as a secondary rather than a potential POM because it has a relatively low prevalence and longer time to expression in routine low-risk NHS adult patients. This view was further supported by our feasibility study. 99

Sample size

A key issue for a definitive trial to evaluate role substitution is whether or not the design of the definitive study should be a non-inferiority or a superiority design, that is, whether DTs are equally good as GDPs at maintaining the oral health of low-risk routine NHS dental patients (but cheaper) or whether DTs provide superior/inferior care to GDPs. High-quality evidence from the literature is limited in terms of the direction of effect for detecting oral disease and undertaking direct restorations (see Chapter 1).

We decided to base our design on non-inferiority, because this aligned with our policy question about whether or not DTs were as good as GDPs. We also thought that it would provide a more robust estimate of the expected CIs should the results show that a superiority design is warranted. Had the research team undertaken a pilot study based on a superiority design, this would have led to broader estimates of the CIs for the definitive trial if no effect was found (given the smaller number of participants required for a superiority design).

As a result, we estimated that 216 (arm ratio of 108 : 108) low-risk routine dental patients should be recruited across eight NHS dental practices in the North West of England. This accounted for an attrition rate of 30% over the 15-month period, which was similar to the attrition rate seen in our feasibility study and other dental practice-based trials. 99,116 This was based on the CI approach described by Cocks and Torgerson,117 which considers the likelihood of the main study finding a relevant effect size (using the logic that if the observed difference between the arms in the pilot trial was zero, then the upper CI would exclude the estimate that is considered clinically significant in a future trial). Based on an 80% CI, this equated to 9% of the sample determined for the definitive trial. Assuming that BOP would be the POM in the definitive trial, taking a non-inferiority margin of 5% would require a sample of ≈ 1618; 9% of 1619 is ≈ 150 (which becomes 216 when attrition is accounted for).

Exploratory data analysis of clinical outcomes

From the perspective of potential effectiveness, the analysis was focused on the difference in means in relation to the width of the non-inferiority margin for the proposed POM, BOP, and the differences in means and proportions for the potential secondary outcome measures. The effect estimate was based on the difference in means between the two arms and was evaluated with respect to clinical significance over the 15-month period. The remaining clinical and patient-reported outcomes were analysed similarly and interpreted. Three different analysis models were employed. For outcome measures with a baseline measurement, mixed-effects analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) models were employed with the dental practice as a random effect and the following factors as fixed effects: exemption from dental charges (yes/no), number of teeth and the baseline measurement. For outcome measures without a baseline measurement, mixed-effects analysis of variance (ANOVA) models were employed with the dental practice as a random effect and exemption from dental charges and number of teeth as fixed effects. For the behavioural change outcome measures using a dichotomous response scale (yes/no), mixed-effects logistic regression models were employed. Analyses were made on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis and a per-protocol basis, because per-protocol assessment is considered more conservative for non-inferiority designs. All statistical analyses were fully detailed in a statistical analysis plan that was developed and agreed before completion of data collection.

Ethics issues

Patient safety was paramount during the pilot study. Previous research undertaken by Brocklehurst et al. 78 has shown that DTs are safe as front-line health-care workers (in terms of detecting oral cancer and its precursors). Two large NIHR grants (led again by PB) have also shown that DTs are as good as GDPs in the detection of dental caries and periodontal disease. 97,98

Patient acceptability was another potential concern, but results from earlier studies suggest that this is positive (including a published feasibility study99 and a separate large NIHR project29). The purpose of the study was fully explained in the participant information sheet and patients had the opportunity to ask any questions to the dental team at the practice prior to being consented.

Patient confidentiality was also a key priority and CRFs from the study were anonymised. All forms and files were kept securely on a password-protected personal computer and any paper records kept in a locked drawer.

The protocol specified that all serious adverse events (SAEs) would be described and that we would compare SAEs between the intervention and the control arms. This was recorded on the SAE CRF and included the following details:

-

patient identification (ID)

-

details of SAE

-

severity of SAE (mild/moderate/severe)

-

date of SAE

-

location of SAE

-

consideration of whether or not the SAE was linked to trial participation.

Information on SAEs throughout the study was a standing item on the Trial Management Group, the Trial Steering Committee and the Data Monitoring Committee.

Study management

The study was managed in accordance with Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and overseen by NWORTH Clinical Trials Unit using a dedicated trial manager. The chief investigator is the director of the NWORTH Clinical Trials Unit, which is registered with the UK Clinical Research Collaboration (UKCRC) (#23) and has detailed standard operating procedures (SOPs). As a result, the pilot study adhered to NWORTH Clinical Trials Unit’s SOPs for all trial and data management and statistical and regulatory matters. GCP was employed throughout to ensure that the project was managed to the highest possible standard. Appropriate supervision and training of project-specific staff and training in GCP was ensured. Trial-specific training was provided to all practices at the start of the pilot and reviewed and reinforced throughout the study period. NWORTH Clinical Trials Unit’s quality assurance officer co-ordinated the oversight of monitoring, documentation and all aspects of quality management and regulatory issues. NWORTH Clinical Trials Unit’s senior trials manager provided advice to the management team on all aspects of the study.

The research was sponsored by Bangor University. The Trial Steering Committee consisted of an independent chairperson, independent members and PPI representatives. The group oversaw the running of the trial on behalf of the sponsor (Bangor) and funder (the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research programme) and had overall responsibility for the continuation or termination of the trial. It ensured that the trial was conducted in accordance with the principles of GCP and the relevant regulations and provided advice on all aspects of the study.

Results

The outcome of the pilot trial and suitability of a definitive trial design were assessed using the following:

-

willingness to be randomised – quantified by considering the numbers approached and who subsequently consented (or refused based on not wanting to be randomised) (see Recruitment and retention)

-

recruitment, retention and fidelity rates – quantified throughout following the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow chart process (see Recruitment and retention)

-

numbers of participant crossovers between arms (e.g. where the patient’s condition is considered too complex to be managed by the DT) – quantified from the logs kept by each dental practice (see Protocol deviations)

-

appropriateness of BOP as the POM – quantified by considering the potential effect size indicated by preliminary exploratory analysis (see Baseline measurements and Missing data)

-

appropriateness of the non-inferiority margin (i.e. whether or not the effect estimate lay within an appropriate margin of non-inferiority) – quantified by considering the outcome of the preliminary exploratory analysis (see Exploratory analysis of the primary outcome measure).

Recruitment and retention

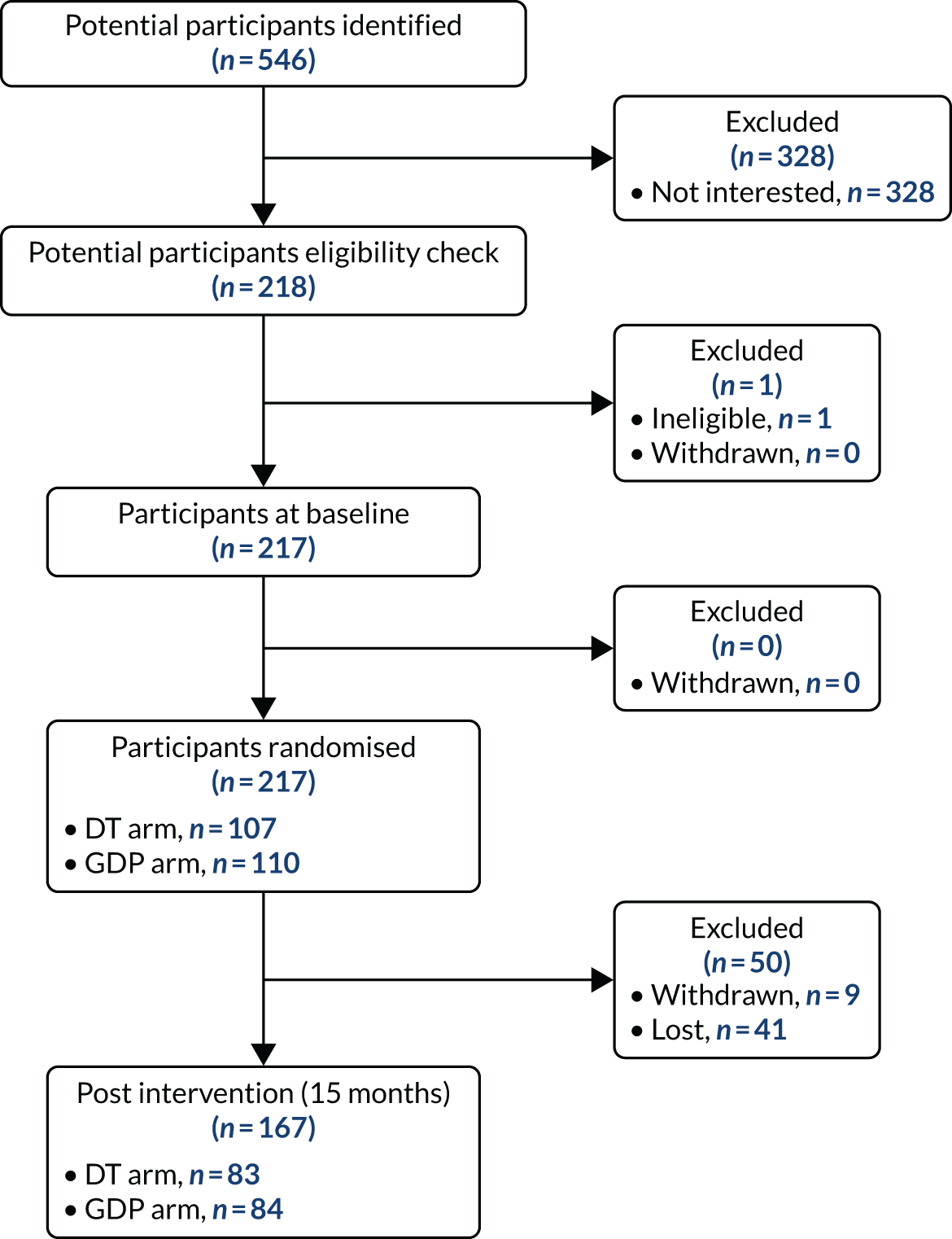

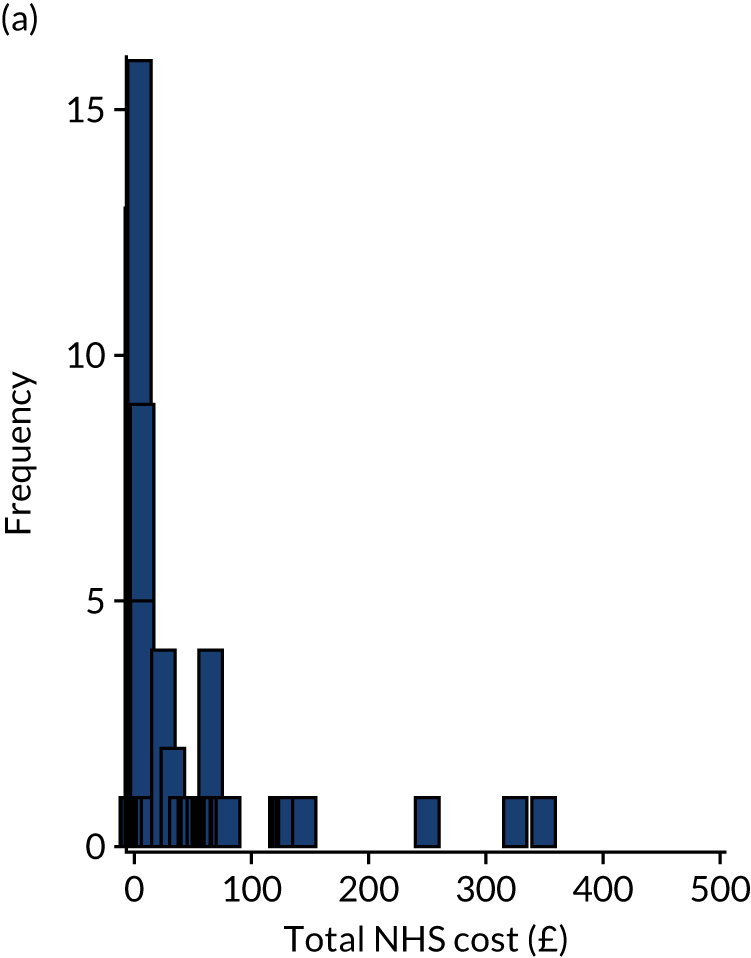

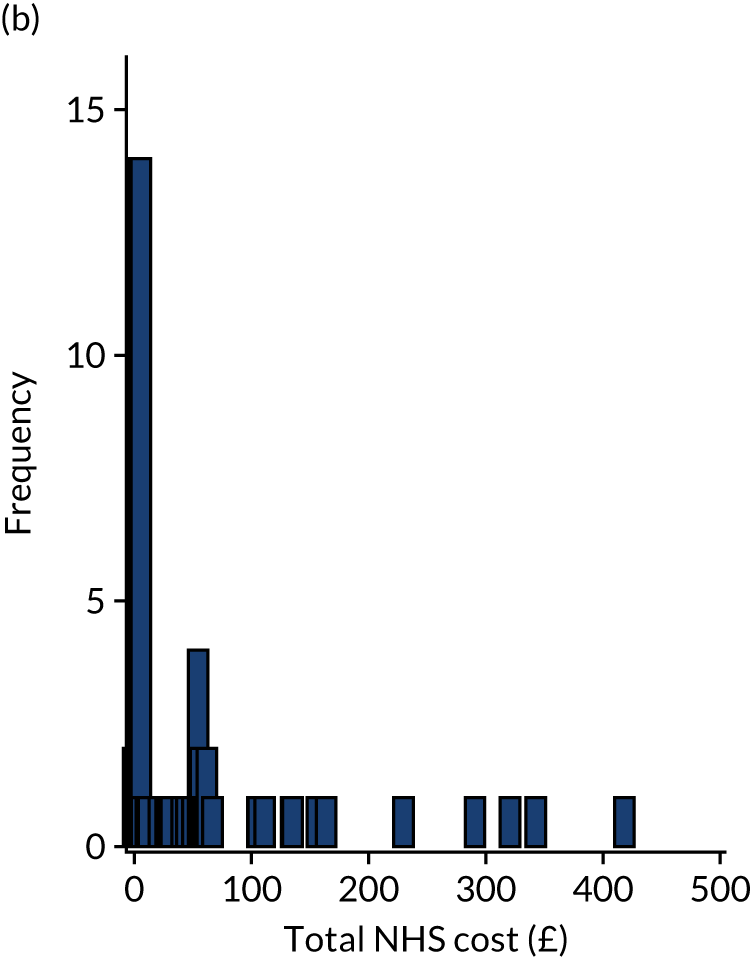

A total of 546 NHS patients were invited to participate in the pilot trial. A total of 217 patients agreed to participate over a 5-month period (March 2018 to July 2018) and 328 stated that they were not interested in participating. This equated to a recruitment rate of 39.7% and a mean recruitment rate of 43.4 participants per month. The mean number of participants recruited per site was 27.1, across eight NHS dental practices over the 5-month recruitment period (Table 1). Out of the 217 patients who were randomised, 107 were randomised to the DT arm and 110 were randomised to the GDP arm. The arms appeared well balanced on stratification variables (see Table 1).

| Dental practice | Date first participant recruited | Date last participant recruited | DT arm (n) | GDP arm (n) | Overall, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5 April 2018 | 3 May 2018 | 16 | 21 | 37 (17.1) |

| 2 | 17 July 2018 | 24 July 2018 | 9 | 9 | 18 (8.3) |

| 3 | 24 April 2018 | 29 May 2018 | 16 | 17 | 33 (15.2) |

| 4 | 2 May 2018 | 5 June 2018 | 18 | 18 | 36 (16.6) |

| 5 | 13 April 2018 | 9 July 2018 | 12 | 9 | 21 (9.7) |

| 6 | 15 March 2018 | 26 April 2018 | 6 | 4 | 10 (4.6) |

| 7 | 11 May 2018 | 22 June 2018 | 14 | 13 | 27 (12.4) |

| 8 | 12 March 2018 | 11 July 2018 | 16 | 9 | 35 (16.1) |

| Exempt | – | – | 10 | 13 | 23 |

| Non-exempt | – | – | 97 | 97 | 194 |

A total of 50 participants did not complete the follow-up assessment at 15 months. Among these 50 participants (23.0% of the total sample), nine participants withdrew from the trial and 41 were lost to follow-up. These 41 participants were lost because of the logistical difficulties of organising a follow-up appointment with an epidemiologist at the practice that the participant was attending. In some cases, participants could not be contacted (by mail, e-mail, telephone or text message), and other participants were unable to attend the practice on designated days owing to work or other commitments. The attrition rate was lower than the attrition rates obtained in previous dental-practice based trials. 99,115 This is represented in the CONSORT flow diagram (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

The CONSORT flow diagram for the pilot trial.

The attrition rates for the DT arm and the GDP arm were comparable (n = 24, 22.4%, vs. n = 26, 23.6%, respectively) over the 15-month period. There was no statistically significant difference in attrition across the randomisation stratification variables (arm, p = 0.873; dental practice, p = 0.676; number of teeth, p = 0.421; exempt from patient’s charge, p = 0.432).

Protocol deviations

There were 14 protocol deviations, all of which occurred in the DT arm. A total of 13 out of the 14 protocol deviations occurred because a participant was allocated to the DT arm but was seen once by the GDP in error, initially. The remaining protocol deviation occurred because a participant was allocated to an arm before being randomised. These 14 participants continued in the arm that they were allocated to but were excluded from the per-protocol analyses.

No participants permanently crossed over from the DT arm to the GDP arm, or vice versa. Therefore, there were no participants who were considered too complex to be managed by the DT. However, 20 participants from the DT arm were seen/treated by the GDP at interim visits, although two of these participants were seen by the GDP because the DT was unavailable. The treatment carried out by the GDPs during these visits included root canal treatment, extraction, crown fitting and restorations.

No adverse events were reported during the study.

Baseline measurements

Participants in the pilot trial were predominantly female (72.4%), non-smokers (92.2%) and white (93.1%) and were not exempt from patient charges (89.4%). The mean age of the participants was 46 years, with a standard deviation (SD) of 15.8 years and a range of 18–87 years. The participants’ occupations are summarised in Table 2.

| Occupation type | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Clerical and sales (e.g. administration, salesperson) | 12.0 |

| Professional and managerial (e.g. teacher, doctor, manager) | 35.5 |

| Semi-skilled and unskilled (e.g. factory worker, labourer) | 2.8 |

| Skilled blue collar (e.g. electrician, plumber, craftsperson) | 7.8 |

| Other | 40.6 |

| Prefer not to say | 1.4 |

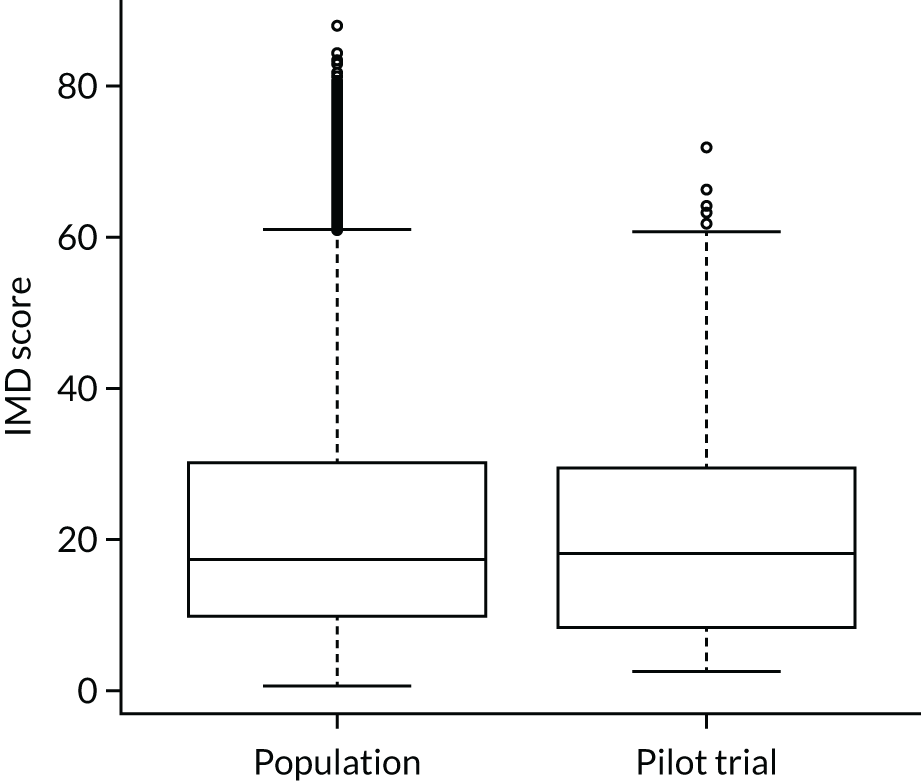

The mean participant Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) score was 22.49, with a SD of 17.02, and was comparable with the mean IMD score of the population (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Distribution of IMD scores.

Descriptive statistics of the dental-related measures at baseline are provided in Tables 3–5.

| Measure | n | Mean | SD | 95% CI | Median | IQR | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of teeth | 217 | 25.51 | 2.89 | 25.12 to 25.90 | 26 | 24–28 | 11–28 |

| Number of sites | 217 | 153.04 | 17.32 | 150.72 to 155.36 | 156 | 144–168 | 66–168 |

| Number sites with BOP | 217 | 5.08 | 5.97 | 4.28 to 5.88 | 3 | 1–8 | 0–36 |

| Number sites with dental plaque | 217 | 3.30 | 4.95 | 2.64 to 3.96 | 2 | 0–5 | 0–30 |

| Number of dental caries lesions | 217 | 0.01 | 0.10 | 0.00 to 0.02 | 0 | 0–0 | 0–1 |

| Percentage of sites with BOP | 217 | 3.39 | 3.98 | 2.86 to 3.92 | 2 | 0.60–5.13 | 0–23 |

| Percentage of sites with dental plaque | 217 | 2.25 | 3.32 | 1.81 to 2.69 | 1.19 | 0.00–3.03 | 0–19 |

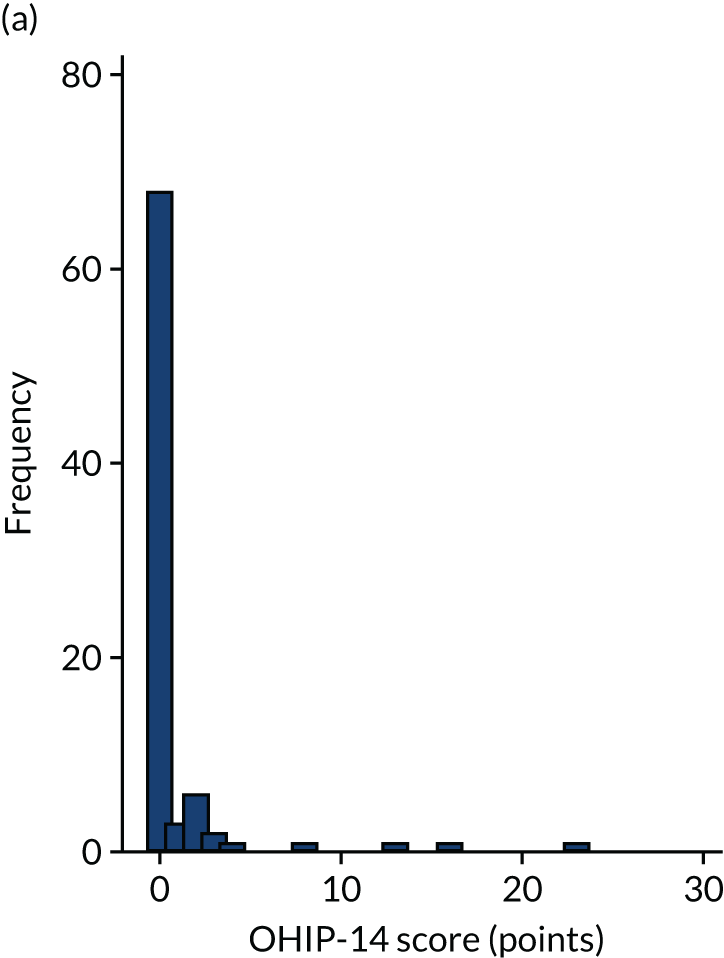

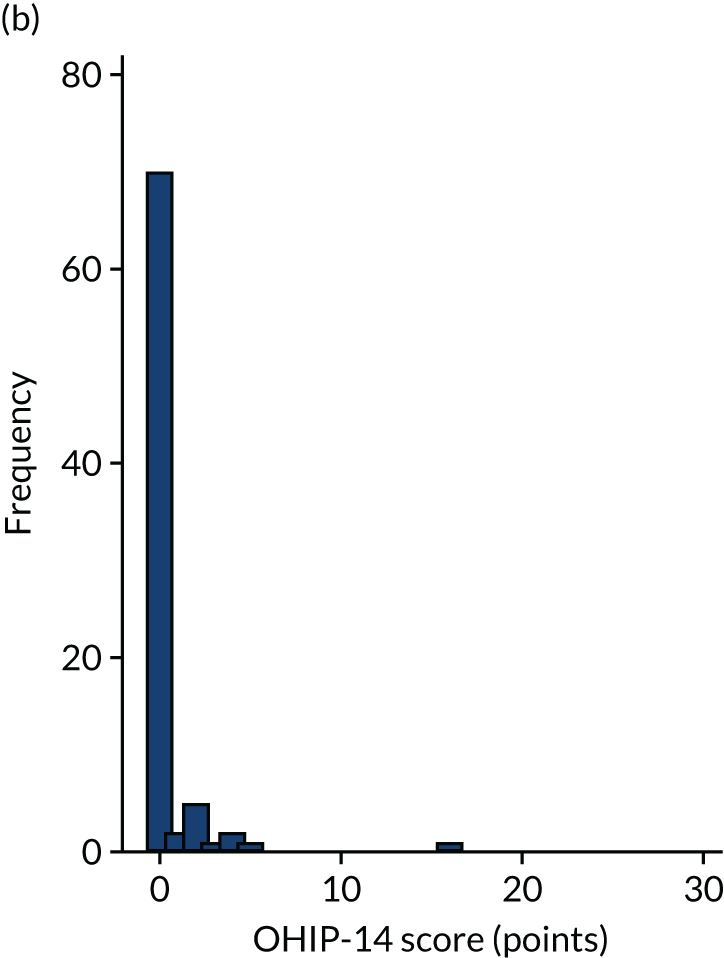

| OHIP-14 score (0–56 points) | 216 | 0.85 | 2.03 | 0.58 to 1.12 | 0 | 0–1 | 0–19 |

| Anxiety of GDP rating (1–10 points) | 217 | 2.10 | 1.77 | 1.86 to 2.34 | 1 | 1–3 | 1–10 |

| Anxiety of using DT rating (1–10 points) | 217 | 2.12 | 1.72 | 1.89 to 2.35 | 1 | 1–3 | 1–10 |

| Measure | n | Mean | SD | 95% CI | Median | IQR | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of teeth | 107 | 25.48 | 3.02 | 24.9 to 26.06 | 26 | 24–28 | 11–28 |

| Number of sites | 107 | 152.86 | 18.12 | 149.39 to 156.33 | 156 | 144–168 | 66–168 |

| Number sites with BOP | 107 | 5.60 | 6.20 | 4.41 to 6.79 | 3 | 1–9 | 0–28 |

| Number sites with dental plaque | 107 | 3.43 | 5.28 | 2.42 to 4.44 | 2 | 0–4 | 0–30 |

| Number of dental caries lesions | 107 | 0.02 | 0.14 | 0.01 to 0.05 | 0 | 0–0 | 0–1 |

| Percentage of sites with BOP | 107 | 3.79 | 4.24 | 2.98 to 4.60 | 2.08 | 0.60–5.95 | 0–17.95 |

| Percentage of sites with dental plaque | 107 | 2.36 | 3.61 | 1.67 to 3.05 | 1.19 | 0–2.88 | 0–19.33 |

| OHIP-14 score (0–56 points) | 107 | 1.07 | 2.43 | 0.60 to 1.54 | 0 | 0–2 | 0–19 |

| Anxiety of GDP rating (1–10 points) | 107 | 1.95 | 1.73 | 1.62 to 2.28 | 1 | 1–2 | 1–10 |

| Anxiety of using DT rating (1–10 points) | 107 | 1.98 | 1.7 | 1.65 to 2.31 | 1 | 1–2 | 1–10 |

| Measure | n | Mean | SD | 95% CI | Median | IQR | Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of teeth | 110 | 25.54 | 2.77 | 25.02 to 26.06 | 26 | 24–28 | 14–28 |

| Number of sites | 110 | 153.22 | 16.59 | 150.08 to 156.36 | 156 | 144–168 | 84–168 |

| Number sites with BOP | 110 | 4.58 | 5.73 | 3.50 to 5.66 | 2.5 | 1–6 | 0–36 |

| Number sites with dental plaque | 110 | 3.17 | 4.63 | 2.30 to 4.04 | 1.5 | 0–5 | 0–25 |

| Number of dental caries lesions | 110 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 to 0.00 | 0 | 0–0 | 0–0 |

| Percentage of sites with BOP | 110 | 3.00 | 3.70 | 2.30 to 3.70 | 1.76 | 0.60–4.28 | 0–23 |

| Percentage of sites with dental plaque | 110 | 2.13 | 3.02 | 1.56 to 2.70 | 0.94 | 0–3.07 | 0–19 |

| OHIP-14 score (0–56 points) | 109 | 0.64 | 1.52 | 0.35 to 0.93 | 0 | 0–1 | 0–11 |

| Anxiety of GDP rating (1–10 points) | 110 | 2.24 | 1.80 | 1.90 to 2.58 | 1 | 1–3 | 1–8 |

| Anxiety of using DT rating (1–10 points) | 110 | 2.26 | 1.74 | 1.93 to 2.59 | 1.5 | 1–3 | 1–8 |

Missing data

There was an exceedingly low level of missing data in the pilot trial in participants attending baseline and follow-up appointments. There were < 1% missing data for the different primary and secondary outcome measures that were collected across the two time points (baseline and follow-up). The majority of the data points were able to be analysed (76.9%). A summary of the missing data is presented in Table 6.

| Measure | Missing data | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow-up | |||

| n | % | n | % | |

| Number of sites with BOP | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Number of sites with dental plaque | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Number of teeth with dental caries | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| OHIP-14 score (0–56 points) | 1 | 0.5 | 1 | 0.6 |

| Anxiety of GDP rating (1–10 points) | 0 | 0 | N/A | N/A |

| Anxiety of using DT rating (1–10 points) | 0 | 0 | N/A | N/A |

| Anxiety during pilot trial rating (1–10 points) | N/A | N/A | 0 | 0 |

| Total number of unplanned visits | N/A | N/A | 0 | 0 |

| Total time with GDP or DT (minutes) | N/A | N/A | 1 | 0.6 |

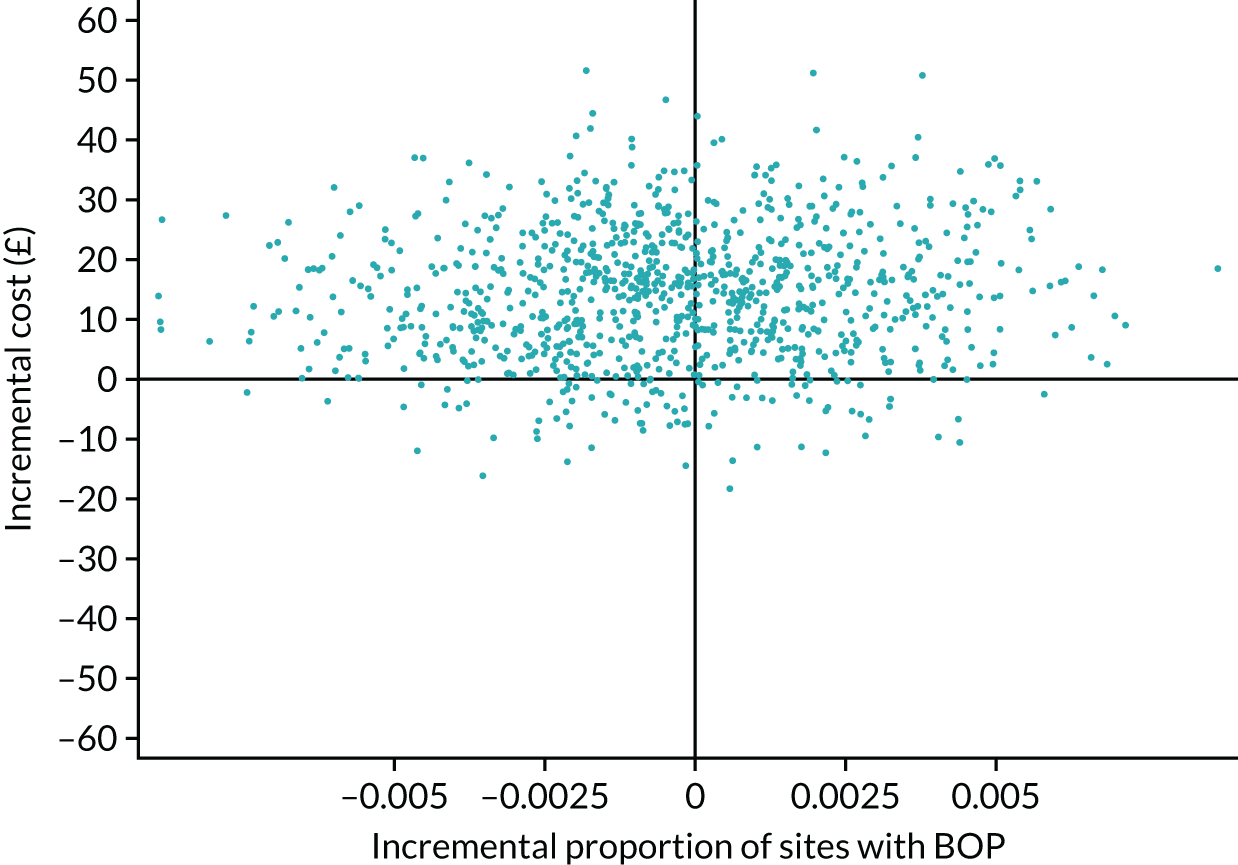

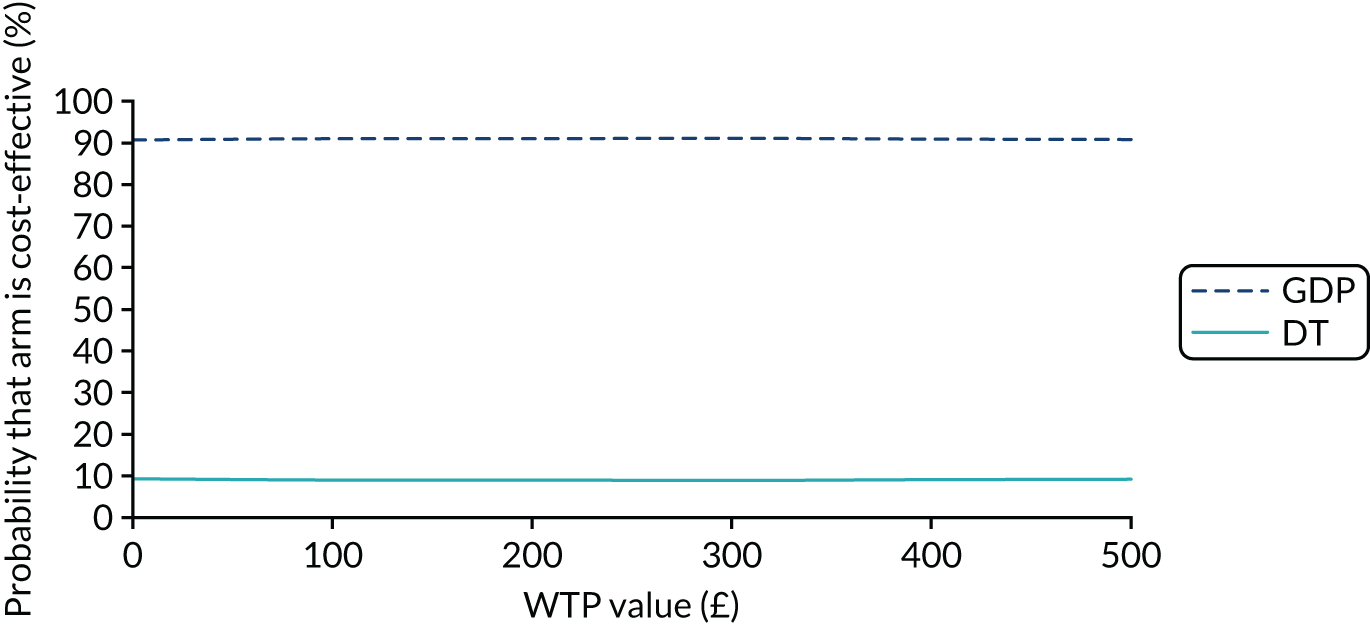

Exploratory analysis of the primary outcome measure

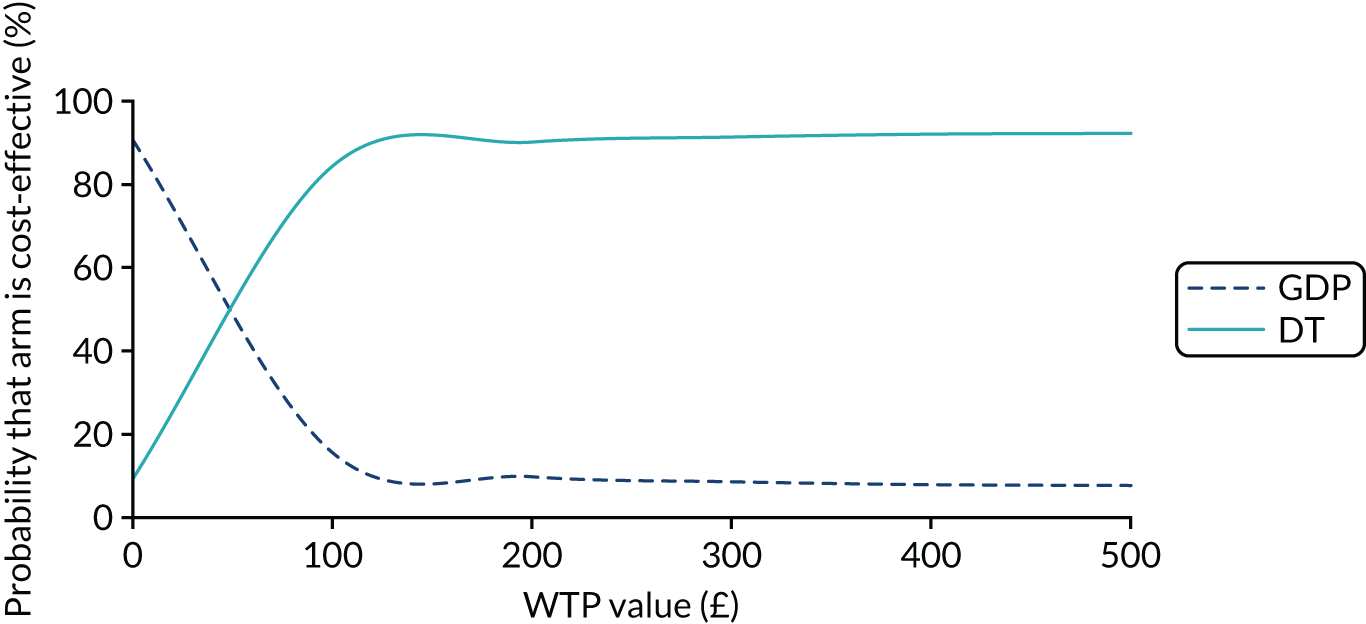

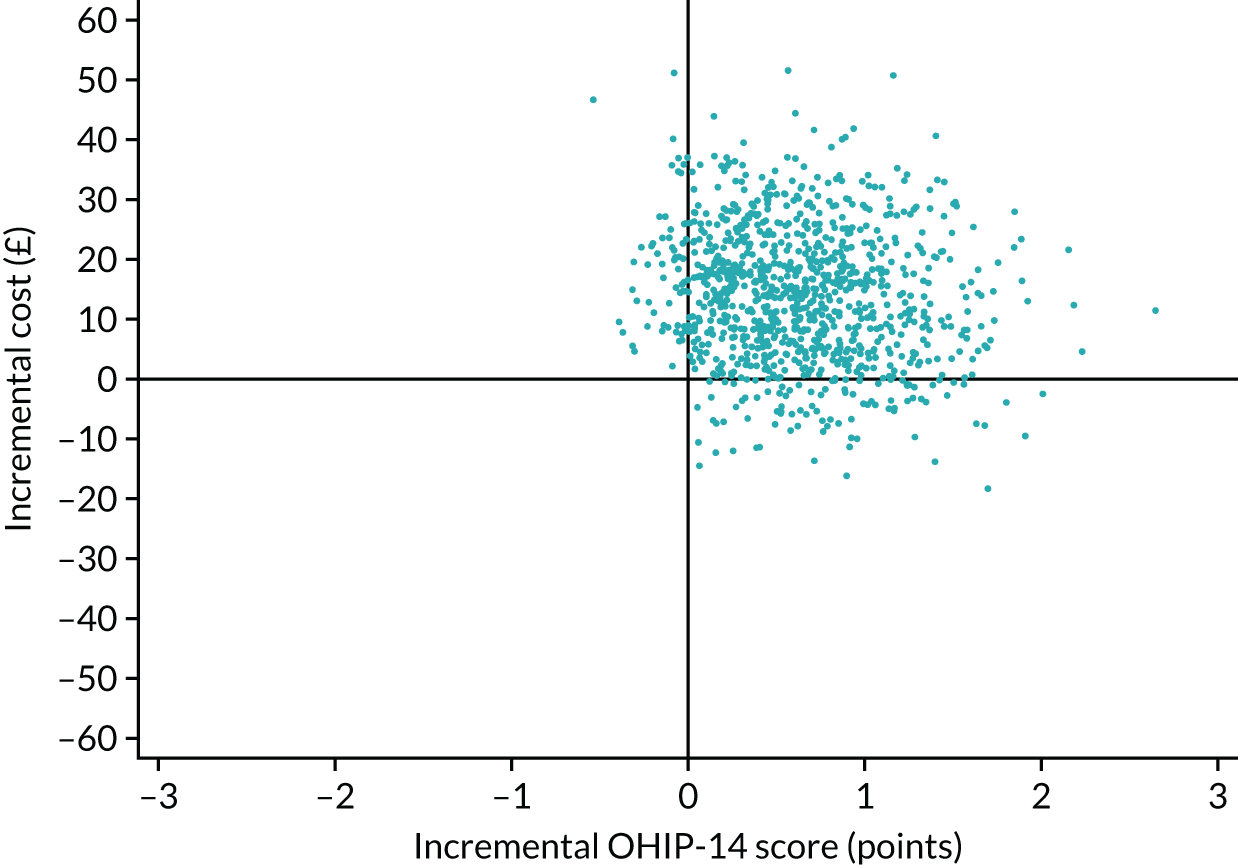

The difference between the percentage of sites with BOP in the DT arm and the GDP arm, based on a mixed-effect ANCOVA model, was 0.07% (95% CI –0.49% to 0.63%) over the 15-month period. This estimate is based on a mixed-effects ANCOVA model with the dental practice as a random effect and the following factors as fixed effects: exemption from dental charges (yes/no), number of teeth (≤ 26 teeth or > 26 teeth) and the proportion of sites with BOP measured at baseline.