Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 16/115/17. The contractual start date was in February 2018. The final report began editorial review in March 2020 and was accepted for publication in October 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Knighting et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background and rationale

This mixed-methods systematic review focuses on young adults with complex health-care needs due to life-limiting and life-threatening conditions (LLCs) or complex physical disability.

Young adults with life-limiting or complex physical disability needs

Young adults with LLCs or complex physical disabilities are often regarded as distinct populations, but they share experiences of health-care services and a lack of available respite care services to meet their needs. They are often described as having complex health-care needs because of a single diagnosis or multiple diagnoses (e.g. illness, congenital conditions or trauma), and many individuals live with multimorbidities. They commonly need continuous health care, with support from similar services across a range of conditions and disabilities, but survival to adulthood and the consequent transfer from children to adult services has increased the demand for appropriate services to meet their complex health-care needs. There is therefore a clear rationale for combining the population of young adults with LLCs and those with complex physical disabilities for the purpose of exploring service provision for young adults with complex health-care needs to inform future research and service development. This section describes and defines the patient population included in the review.

Definition of life-limiting conditions

The population of children with LLCs who survive to adulthood is rising annually in England. Owing to medical advances, the number of 16- to 19-year-olds with palliative care needs has increased by 45% over the past decade to 1 in 10 young people, with approximately 55,721 young adults (aged 18–40 years) with complex needs living in England in 2010. 1,2 Their needs are diverse, involving complex life-long symptom and medication management, and palliative care. 3 Many of these children and young people die in infancy and childhood, but those surviving into adulthood tend to have degenerative and progressive conditions lasting for many years. This results in complex health-care needs and high dependency on care that is mainly provided by family members, with support from paid carers and health and social care professionals. The duration and frequency of care for these young adults differs from those of adults with terminal illness, who predominantly require care during the last 12 months of life. In contrast, the care needs of young adults with LLCs are longer term and are associated with higher costs that escalate as their condition deteriorates. The increasing proportion of young people surviving to adulthood has consequently placed increasing demands on commissioners and service providers to meet their complex needs as they transition to adult services. 1,3

Over 300 diagnoses are encapsulated within the population of children and young adults with LLCs, which can be grouped into the following four broad categories:4

-

Life-limiting conditions where a cure is possible but may fail (e.g. cancer or irreversible organ failure).

-

Conditions that, although treated intensively over a period of time, inevitably lead to early death (e.g. cystic fibrosis).

-

Progressive conditions where treatment is exclusively palliative and often extends over many years (e.g. muscular dystrophy).

-

Irreversible but non-progressive conditions that give rise to severe disability and sometimes premature death (e.g. disabilities following brain or spinal cord insult or severe cerebral palsy).

Drawing on key terms from the literature and the definition from Together for Short Lives (TfSL),1–4 the UK charity for children, young people and young adults who are expected to have short lives, we have defined a young adult with LLCs as follows:

Young adults with a life-limiting or life-threatening condition, where there is no reasonable hope of cure and from which they are expected to die.

Definition of complex physical disability

Over the last 13 years, the prevalence of children and young people with severe disability and complex needs has risen because of increasing survival rates. 4,5 In 2007, there were an estimated 100,000 disabled children with complex care needs in England, with a projected increase of 50% over the following decade. 4,6 There is therefore an urgent need to gather evidence on the life experiences of this rising population to explore their needs and assess implications for future service demand. 4

There is wide variation in the definitions of disability and severity, particularly compared with definitions used in the adult population. 6 The Equality Act 2010 defines ‘disability’ as a physical or mental impairment that has a ‘substantial’ and ‘long-term’ negative effect on a person’s ability to engage in normal daily activities. 7 Complex physical disability can be grouped into the following three broad categories:8

-

sudden onset conditions (e.g. acquired brain injury, spinal cord conditions, peripheral nervous system conditions, multiple trauma)

-

progressive and intermittent conditions (e.g. neurological and neuromuscular conditions, severe musculoskeletal or multiorgan disease or physical illness/injury)

-

stable conditions with or without degenerative change (e.g. congenital conditions, post-polio syndrome or other previous neurological injury).

Complex physical disability is sometimes referred to as ‘severe’ or ‘profound’ disability and may overlap with other health conditions, creating a complex patient profile. These profiles often include learning disability or cognitive impairment; however, this review has focused on health-care needs and the population was therefore restricted to young adults with complex health-care needs due to complex physical disability. Given the variance in definitions of disability between children and adults, we also included complex physical disability arising from cancer diagnosed as a young adult.

For the purpose of this review, we defined a young adult with complex physical disability as follows:

Young adults with impairments and/or physical disabilities due to congenital or acquired physical disability, or major neurological trauma, which require a complex level of physical management and support.

Definition of complex health-care needs

Defining the concept of ‘complex’ is challenging, as it may vary according to setting and perspective. 9 The health-care needs of a young adult population with LLCs or complex disability may range from complex to highly complex. For example, young adults who are dependent on long-term ventilation or have complex drug regimens are often considered too complex for many respite care services, leading to ineligibility for universal respite care and therefore requiring specially commissioned services. The variation in terminology, the spectrum of complexity and inflexibility of adult assessment processes may result in inequality of care and loss of funding for services, including respite care. Therefore, adoption of a broad definition facilitated the capture of all relevant evidence. There is no consensus-based definition of complex health-care needs,3 but it typically refers to physical, mental and/or health needs that vary across the population in different and often multidimensional ways. It has been argued that the term ‘complex’ relates more to the complexity of service provision rather than individual needs, and that the term ‘multifaceted condition’ may better describe the interconnectedness of an individual’s varied health and social care needs. 10 However, complex health-care needs is a term commonly used in the literature and variation between definitions suggest that complex needs can be considered both in terms of breadth (i.e. the wide range of needs) and depth (i.e. the high level of needs). 11 We have therefore defined complex health-care needs as follows:

Complex health-care needs that are substantial and ongoing that typically involve multiple health concerns and require a co-ordinated response from more than one service.

Definition of young adult

There is no universal consensus on the definition of a young adult in the UK. For example, the Ministry of Justice uses the age band of 18–20 years, the National Health Survey for England uses 16–24 years and the Crime Survey for England & Wales uses 18–25 years. 12 UK services do not tend to define respite services by age group and therefore it is important to use a sufficiently broad age range to capture our target population. Services for children with complex health-care needs may be extended beyond 18 years of age, but the upper limit varies by specific service and geographical location. For example, the upper limit is 23 years at Claire House Children’s Hospice (Wirral, UK), 35 years at St Elizabeth Hospice (Ipswich, UK) and 40 years at The J’s Hospice (Essex, UK), with the lower limit for many adult NHS services set at 16 or 18 years. The Care Quality Commission and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommend initiation of transition planning when the child is aged 13 or 14 years, although this may vary according to individual preferences. 13,14 Drawing on key definitions from the literature,2,15 feedback from stakeholders, and the profile of known UK service provision and TfSL, we adopted the following definition:

Young adults are defined as people aged 18–40 years.

Respite care and short breaks for young adults with complex health-care needs

Respite care and short breaks are an essential component of ongoing support for children, young people and young adults with complex health-care needs. 16,17 They provide relief from the caring environment, with multidimensional benefits for all members of the family. 18,19 TfSL defines three main functions of short break care: ‘1) to provide the child or young person with an opportunity to enjoy social interaction and leisure facilities; 2) to support the family in the care of their child in the home or an alternative community environment such as a children’s hospice; and 3) to provide opportunities for siblings to have fun and receive support in their own right’ (reproduced with permission from Together for Short Lives). 19 Typically, such provision includes residential hospice care or a similar service, day care, host family respite and home-based support, including sitting services and holiday cover. Respite care and short breaks are provided by both formal and informal carers. Formal carers are typically defined as registered professionals or care staff who work privately, for provider organisations or who receive payment for their services. Informal carers are often family members or friends who provide the same type of care on an unpaid basis, although some informal carers may receive payments through personal care budgets managed by families. This section summarises current respite care and short breaks services that helped shape our definition of the intervention.

Current service provision

There are clear differences between child and adult services in the way that respite care is conceptualised, funded and provided. 20 Typically, the term ‘short breaks’ is used in children’s services to encompass all levels of care, whether residential or in the home, and is a key service provided by children’s hospices and some specialist children’s services. 21 Planned respite care in adult services focuses on the need to give the carer a break from caring rather than providing opportunities for the person receiving care, and is typically referred to as ‘respite’ or ‘replacement’ care. The respite care and short breaks provided by children’s services may be inappropriate for young adults and the upper age limit for eligible access varies between providers and commissioners. On the other hand, typical adult services predominantly serve the needs of older people, those with cancer or other terminal diagnosis, and people requiring end-of-life care, rather than fluctuating health conditions and may be inappropriate respite care for young people with complex health-care needs due to a LLC or complex physical disability. 16,22–25 With notable exceptions such as cystic fibrosis and long-term ventilation, adult sector staff in the UK generally have little experience of paediatric conditions or of supporting young adults with complex needs. 3,13,24,26 Limited respite care, particularly for those with highly complex health needs, is available for planned short breaks or emergency family situations once young adults with complex health-care needs have transitioned to adult services. 3,13,27

The definition of ‘residential short breaks’ for young people with disabilities varies considerably between social care authorities, ranging from residential schools, sitting services and day care in the home or other settings, to flexible packages tailored to suit individuals. 6 This is an element of the wider problem of service model variation across health and social care in terms of service definition, commissioning, funding and delivery, even within the same authority. 5 However, estimates from local authorities suggest that only 8 in 10,000 disabled children aged 0–17 years receiving social care services, and 18% of children receiving a service from disabled children’s teams, had received residential short breaks. 6

The nature and costs of respite care may vary considerably, depending on the provider and level of complex health needs to be supported, and estimating costs may therefore be a complex process. Referral, assessment models and procedures may also vary between services and the care required by young adults with complex health-care needs is highly individual. Decision-making and care planning may be further complicated by legal and policy changes associated with the transition to adult services, including the transfer of parental to personal responsibility (unless there are capacity issues), and many families are ill-prepared for these changes. The changes associated with transition may also have an impact on the wider family, for example where housing and welfare support assessments move away from the whole ‘family’ (such as using parental income and other dependents to assess need) to assessment of the young adult alone, with their family largely disregarded in the assessment process. Consequently, young adults may face significant barriers to accessing appropriate care and support as they make the transition to adult services. 28,29 Parents have described the transition process as ‘like falling off a cliff’ when the support from children’s services ends and appropriate adult services are not in place, adding to the complex burden of living with complex health-care needs for young adults and their families. 30

Benefits of respite care and short breaks

The limited evidence indicates that respite care and short breaks may have a broad range of benefits, such as increasing family-carer resilience,27 improving the psychological well-being of parents,16,31 reducing the risk of carer breakdown23,27 and avoiding costly unplanned hospital admissions, a longer length of stay and social care intervention. 32,33

However, most of the evidence on the use and impact of respite care and short breaks relates to children’s services, such as hospices, rather than services for young adults with LLCs, partly because, until relatively recently, so few children survived into adulthood. However, more people with LLCs are now surviving beyond childhood and their needs may increase as they grow older, for example with the desire for independence and the need for support outside the family as ageing parents develop their own health problems. With a rapidly growing population of young adults making the transition from child to adult services, there is growing evidence of poor continuity of care, including respite care provision, that leads to the needs of the young adult and their family being unmet. The consequences of poor continuity of care may include adversely affected social, educational, vocational and spiritual outcomes; inadequate management of complex comorbidities; deterioration in the young adult’s physical and mental health; family-carer burnout; and inappropriate, costly hospital admissions. 24,34,35 Most disturbingly, earlier death may result from poor transition and loss of services. 35

Definition of respite care and short breaks

A systematic review of respite care provision for older people with dementia identified eight models of respite care and short breaks, and characterised services according to duration, pattern of use, location, response (e.g. planned or emergency care) and the characteristics of service users and staff. 36 The types of respite care included day care, home day care, clubs, interests or activity groups, home-based support, host family respite, overnight respite in specialist facilities, overnight respite in non-specialist facilities and holidays. 36 Other types of care, such as emergency residential respite and emergency home-based respite, are also described in the literature. These reflect many of the known service types for young people with LLCs and complex physical disability, illustrating variations in service configuration. It is also likely that other types of care will evolve in response to growing demand.

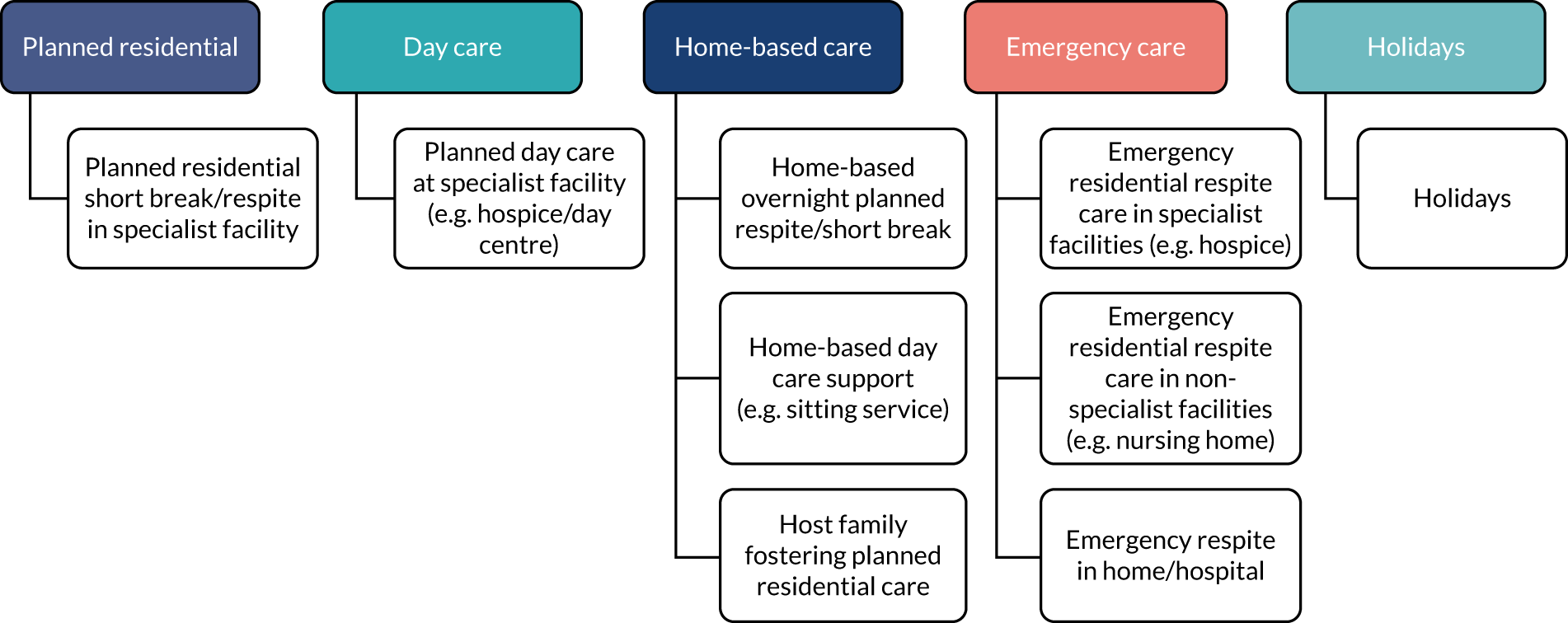

Following an initial scoping of evidence for the review protocol, we characterised nine service types (Figure 1), grouped into five overarching service categories. However, we note that some providers may offer more than one type of service.

FIGURE 1.

Preliminary types of respite care.

The definition of short breaks and respite care used by children and adult services differ by service type and intended outcomes. More information on the intended outcomes by service types can be found in the logic models that form the conceptual framework for the review in Appendices 8–20. This is partly attributable to the flexibility required to meet the needs of both service users and providers when developing services. Some of the factors that may influence service delivery include:33

-

location (e.g. in the person’s own home, at a carer’s home, residential or community setting)

-

duration (e.g. for a few hours, overnight, several days)

-

timing (e.g. weekdays, weekends, evenings)

-

provider (e.g. local authorities, health agencies, voluntary/independent agencies)

-

care funding (e.g. use of personal budget, care package, provider or charity funded).

Drawing on the literature and policy statements we used the following definition of respite care and short breaks:

Respite care and short breaks are the temporary provision of formal or informal physical, emotional, spiritual or social care for a dependent person.

Formal respite care is provided by organisations or individuals who receive financial payment, including family carers paid through management of personal care budgets.

Informal respite care does not involve financial payment.

Need for the review

Children, young people and young adults with complex health-care needs have multiple comorbidities and/or disabilities in addition to their primary diagnosis or condition. They are therefore at increased risk of other health-care problems. Care for these young people is an ongoing, complex process, with no simple care pathway and often multiple, unplanned episodes of illness. The Department of Education and Skills’ report Aiming High for Disabled Children: Supporting Families37 made a clear policy commitment to improving available data on disabled young people and their access to services, but further work is required to improve access to specialist services, such as short breaks/respite care. 38 Seven out of 10 families caring for someone with profound or multiple disabilities report having reached or come close to ‘breaking point’ because of a lack of short break services. 39

The Care Quality Commission found a significant shortfall between policy and practice during transition from child to adult services due to fragmentation of the system, which can be confusing and difficult to navigate for young adults with complex health-care needs, their families and staff caring for them. 13 This is supported by evidence showing that poor service provision following transition to adult services has a significant impact on both the life expectancy and quality of life for these young adults, including early death and increased psychosocial burden on families and carers. 20,24,34,35 Previously published research by the review team35,40 and a national survey of hospices and health-care professionals conducted by the team in 2015 identified significant gaps in the evidence base, challenges in providing respite care for young adults with complex health-care needs and the need for robust evidence to inform service development. 41

Commissioning of respite services is devolved in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. Commissioners and service providers in England and Wales have a statutory duty under the Children and Families Act 201442 and the Care Act 201443 to ensure seamless provision of responsive, appropriately funded and integrated services for young adults with complex health-care needs as they transition to adult services. 1,13,22 Despite the rising number of young people with complex health-care needs surviving into early adulthood, and the consequent escalation in care service demand for themselves and their families, the current scale, cost and types of available respite care have not been collated and evaluated at a national level. Comprehensive data collation is challenging because of the range of public and private providers, fragmented development of independent services and the variability in funding practices, including commissioned care (NHS or social care), local authority, charity funded and use of personal budgets.

Evidence on the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of respite care/short breaks and the views and experiences of service users is published in a variety of sources across the evidence spectrum. Given the uncertainties concerning types of available care and lack of clarity on the optimum types of service provision, it is essential to systematically review the plethora and diversity of sources, and to integrate these into a cohesive summary, highlighting gaps in evidence to inform future research.

Chapter 2 Aims and objectives

The aim of this mixed-methods review was to identify, appraise and synthesise evidence relating to the type and impact of respite care and short breaks provision for young adults (aged 18–40 years) with complex health-care needs. The review aimed to explore policy intentions, service intentions and service-user perspectives (i.e. factors that may inhibit or facilitate the delivery of such care) and cost-effectiveness to develop a conceptual framework for respite care, and to form the basis of recommendations for future service development and the need for new research.

To achieve the above aim, our objectives were as follows:

-

To explore current UK policy, not-for-profit organisation (NFPO) publications and guideline recommendations regarding respite care and short break provision for young adults (aged 18–40 years) with complex health-care needs due to a LLC or complex physical disability.

-

To identify and characterise the different types of formal and informal respite care and short break provision for young adults (aged 18–40 years) with complex health-care needs due to a LLC or complex physical disability.

-

To develop a series of logic models that embody the programme logic and programme theories of respite care and short break types for young adults (aged 18–40 years) with complex health-care needs due to a LLC or complex physical disability that will inform service planning and commissioning.

-

To determine the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different types of formal and informal respite care and short break provision for young adults (aged 18–40 years) with complex health-care needs due to a LLC or complex physical disability.

-

To better understand the impact, experiences and perceptions of respite care and short break provision from the perspectives of service users and providers.

-

To make recommendations for further empirical research to inform intervention development and evaluation.

Systematic review questions

For young adults (aged 18–40 years) with complex health-care needs due to a LLC or complex physical disability we considered the following:

-

What are the current UK policy and guidance recommendations for the provision of respite care and short breaks? (Objective 1.)

-

What types of respite care and short breaks are provided in the UK and similar global economies? (Objectives 2 and 3.)

-

What is the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different types of formal and informal respite care and short break provision? (Objective 4.)

-

What is the economic impact of respite care and short breaks? (Objective 4.)

-

What are service users’ and providers’ views of current respite care provision and the need for new services? (Objective 5.)

-

What are the facilitators of and barriers to providing, implementing, using and sustaining respite care and short breaks, taking into account the different perspectives of young adults, family members and providers? (Objectives 3–5.)

Chapter 3 Methods

This section describes in detail all aspects of the search strategy, screening and selection of evidence, data extraction and quality appraisal, methods of synthesis and the role of members of the Patient and Public Advisory Group (PAG) and Steering Group (SG). As anticipated, because of the complexity of the mixed-methods approach and the nature of the evidence, there were minor methodological departures from the published protocol. 44 A summary of the differences between the protocol and the review are described in Summary of deviations from the protocol.

Overview

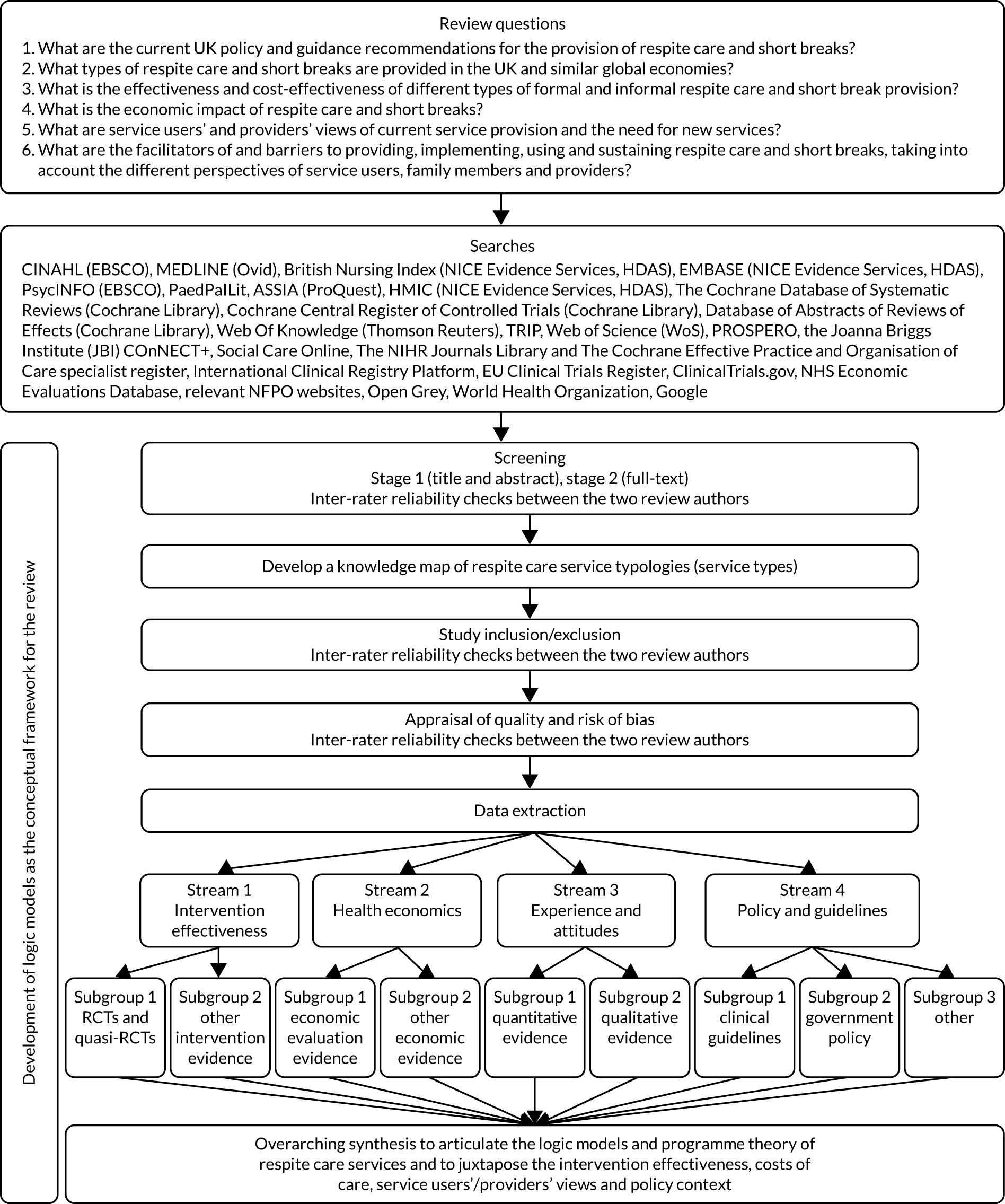

To achieve the review objectives set out in Chapter 2, we conducted a two-stage mixed-methods systematic review, adopting a similar approach to that used in other mixed-methods systematic reviews. 45,46 Figure 2 depicts the planned flow of work through the two stages, incorporating the development of logic models as the conceptual framework for the review.

FIGURE 2.

Mixed-method systematic review flow chart.

We conducted comprehensive literature searches of electronic databases and grey/unpublished literature. The results were independently assessed for inclusion through two screening stages and categorised as included in stage 1 and/or stage 2 as follows.

Stage 1: knowledge map of types of respite care services

We identified, catalogued and described different types of formal and informal respite care and short break services for young adults (aged 18–40 years) with complex health-care needs due to a LLC or complex physical disability. We developed an initial logic model for each type of service to illustrate the differences in context, service configuration, populations, implementation and intended outcomes for various stakeholders.

Stage 2: evidence review

We synthesised evidence in method-specific streams and grouped the evidence according to the types of service identified in stage 1, extracted key descriptive information from each source and evaluated methodological quality. Results and recommendations were extracted from each source and synthesised within each evidence stream. We also identified key policies and extracted the policy intent concerning respite care.

Further development and refining the logic models as a conceptual framework

Building on the knowledge map identified in stage 1 and the evidence synthesised in stage 2, we continued to further develop and refine a series of logic models that encapsulated the essential elements and intended outcomes of different types of respite care service provision, forming a conceptual framework for the review, which became a product of the review when fully developed(see Appendices 8–20).

Identifying the literature

Evidence selection criteria

We defined selection criteria using the SPICE (Setting, Perspective, Intervention/phenomenon of interest, Comparison, Evaluation) framework47 (Table 1).

| Criterion | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Setting | Services and providers of formal respite care and short breaks, including hospices, residential care homes, adult day services, individual providers and paid carers/family carers working within young adults’ home settings, and informal care from unpaid family members |

Services and providers of care other than respite care and short breaks Services specifically commissioned for young adults with a learning disability or mental health needs |

| Perspective | Young adults (aged 18–40 years) with complex health-care needs due to a LLC or complex physical disability receiving respite care and/or short breaks, and their parents, families, carers and/or those involved in the commissioning or delivery of their care |

Young people aged < 18 years or people aged > 40 years Young adults who do not require respite care/short breaks |

| Intervention/phenomenon of interest | Formal (paid) and informal (unpaid) respite care/short breaks in relation to intervention effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, stakeholder experience and attitudes, UK policy and guidance | Care other than respite care and short breaks |

| Comparison | Any type of formal and informal respite care/short break | Care other than respite care and short breaks |

| Evaluation |

Evidence from 1 January 2002 to 18 September 2019 from the 35 OECD countries will be included Intervention effectiveness: any quantitative service user, family, carer and service provider outcomes, such as quality of life, well-being, health impact, stress and coping, family cohesion or satisfaction with care Cost-effectiveness: information on the costs and economic impact of care, such as incremental cost per QALY, cost per admission avoided, staff costs, equipment and transport Experience and attitudes: qualitative, quantitative and mixed methods information, such as concepts and themes arising from recognised methods (e.g. grounded theory analysis, thematic analysis, framework analysis), surveys or reports that capture attitudes, beliefs, preferences and opinions on the provision of respite care Policy and guidelines: recommendations, directives, actions or anticipated outcomes identified in UK policy statements or guidelines |

Streams 1 and 2: outcomes unrelated to effectiveness, experience or economic evidence Stream 3 (experience and attitudes): unconfirmed reports and anecdotal opinion (e.g. newspapers, social media, online blogs) Stream 4: non-UK policy or guidelines |

Search strategy

The investigative team and SG, led by our information specialist (MM), developed the search strategy to identify relevant published and unpublished evidence (e.g. primary studies, evaluations, policy documents). The search strategy was informed by the complexity of the SPICE framework and the need to identify all data from a diverse range of sources. 47 To minimise missing evidence, our overall strategy was to maximise sensitivity of the searches.

We developed an exploratory search using the MEDLINE database. The investigative team and SG identified an initial set of keywords to inform the search strategy and discussed the search structure. The review team also identified a set of key relevant studies and the full text of these studies was analysed to identify additional relevant keywords. The information specialist mapped the keywords to relevant thesaurus terms in MEDLINE. Analysis of the MEDLINE records of key relevant studies identified additional relevant thesaurus terms.

We conducted a sensitivity analysis on the search strategy by comparing the retrieval of different search techniques (e.g. proximity operators, phrase searching and field searching) to develop a search strategy that ensured the retrieval of all key relevant studies. The final version of the exploratory search was adapted for other search sources (see Appendix 1).

We limited the search to evidence available from January 2002 onwards because of significant changes in service demand [including an increase by 45% over the past decade to 1 in 10,1 changes in the law (e.g. Children and Families Act 2014,42 Care Act 201443) and new policy/guidance documents published during the last 17 years]. As the review is specifically concerned with the provision of respite care or short breaks in the UK, we also limited the search to the 35 Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) countries considered comparable, except for evidence relating to stream 4 (policy and guidelines), which focused entirely on domestic policy.

We searched the following sources from 1 January 2002 to 26 September 2018: Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (EBSCOhost), MEDLINE (Ovid), British Nursing Index (NICE Evidence Services, Healthcare Databases Advanced Search), EMBASE (NICE Evidence Services, Healthcare Databases Advanced Search), PsycINFO (EBSCOhost), Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA) (ProQuest), Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) (NICE Evidence Services, Healthcare Databases Advanced Search), the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (The Cochrane Library), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (to 31 March 2015) (Archived by Centre for Reviews and Dissemination), Web Of Science (Thomson Reuters), Trip, PROSPERO, Joanna Briggs Institute Systematic Reviews and Implementation Reports (Wolters Kluwer), Social Care Online and the National Institute for Health Research Journals Library.

To further identify evidence for each specific stream, the strategy was adapted and applied to the following databases:

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (The Cochrane Library), International Clinical Trials Registry Platform (URL: http://apps.who.int/trialsearch/), EU Clinical Trials Register (URL: www.clinicaltrialsregister.eu/ctr-search/search) and ClinicalTrials.gov (URL: https://clinicaltrials.gov/).

-

NHS Economic Evaluations Database and Health Technology Assessments (Centre for Reviews and Dissemination).

Additional evidence was identified through internet searches (Google and Google Scholar, Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA), relevant NFPO websites, hand-searching and consultation with the SG and PAG.

We also searched the International Journal of Paediatric Palliative Care (URL: www.worldcat.org/title/paedpallit-the-international-journal-of-paediatric-palliative-care/) for relevant evidence. All searches were updated in February 2019 and September 2019. For the update run on 18 September 2019, we modified the full search strategy to improve specificity by eliminating redundant terms (see Appendix 2). Sensitivity and specificity of the modified strategy was validated by comparing the new and existing strategies for the update in MEDLINE. Results screened by two reviewers confirmed the same list of included items and the modified strategy was therefore implemented across all databases for the full update search.

Grey and unpublished literature

Results from scoping searches suggested that relevant information was likely to be found within the grey literature (e.g. central and local government evaluations and impact assessments, or unpublished data produced by third-sector organisations). We conducted a broad search for grey and unpublished literature via Open Grey (formerly System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe, URL: www.opengrey.eu/), Grey Literature Report (URL: www.greylit.org), the World Health Organization (URL: www.who.int/en/) and Google. In addition, we:

-

asked SG and PAG members to identify relevant known literature

-

asked SG and PAG members to identify topic experts, useful websites and organisations to contact (see Appendix 3)

-

scanned relevant websites for potentially relevant literature

-

targeted topic experts, stakeholders and service providers through a ‘call for evidence’, which was shared through networks, direct e-mails and social media.

In addition to examining the reference lists of included evidence identified through database searching, a purposive and iterative approach to searching the literature was undertaken. The CLUSTER (Citations, Lead authors, Unpublished materials, Scholar search, Theories, Early examples, Related projects)48 approach aims to identify additional relevant outputs that may include a ‘sibling’ paper (i.e. papers from the same study, for example qualitative studies, economic evaluations or process evaluations associated with a randomised controlled trial) or ‘kinship’ studies that inform relevant theoretical or contextual elements. Table 2 shows the key details of this approach, which emphasised the need to adopt multiple search techniques (e.g. citation searching, ‘key pearl’ searching, ancestral searching) to supplement and enhance the main search, and to ensure identification of relevant evidence and grey literature. It aims to identify additional material associated with a study of interest, rather than those simply using the same terminology, therefore overcoming the limitation of selected terminology common to most search strategies.

| Element | Search procedure | Source |

|---|---|---|

| Citations | Identify at least one ‘key pearl’ through consensus with review team | Preliminary searches of databases and grey literature |

| Lead authors | Check reference list of ‘key pearl’ and conduct lead author search | Full text of ‘key pearl’, search of reference management collection, Google (e.g. institutional repository, author publication web page) |

| Unpublished materials | Make contact with lead author | |

| Scholar searches | Citation searches on ‘key pearl’ and other relevant studies and conduct search of ‘project name’ | Web of Science/Google Scholar |

| Theories | Follow up ‘key pearl’ and other cluster documents for citations of theory. Recheck for mention of theory in titles/abstracts/keywords and conduct iterative searches for theory in combination with condition of interest | Full text of ‘key pearl’, search of reference management collection and databases |

| Early examples | Follow up ‘key pearl’ citation and other cluster documents for citations to project antecedents and related projects | Full text of ‘key pearl’ |

| Related projects | Conduct named project and citation searches for relevant projects identified from cluster documents, seek cross-case comparisons by combining project name/identifier for cluster with project name/identifiers for other relevant projects | Web of Science/Google Scholar, databases |

Where possible, we implemented search alerts in source databases to identify additional relevant studies as the review progressed. Results from the searches of multiple electronic databases and other sources were combined and de-duplicated using EndNote reference management software [Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA; URL: https://endnote.com (accessed 9 December 2020)] and then entered into Covidence, a web-based systematic review management platform [Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, VIC, Australia; URL: www.covidence.org (accessed 8 December 2020)]. The use of a single comprehensive search strategy enabled identification of all potential evidence for the knowledge map and review streams. Included sources were then filtered into the appropriate review stage and review stream.

Evidence selection

Multiple reviewers (MOB, LB, BJ, BR and JD) independently screened titles and abstracts for eligibility against review selection criteria for stage 1 (knowledge map) and/or stage 2 (evidence review). Additional reviewers (GP and KK) independently verified eligible evidence. The full texts of eligible records were retrieved and screened for inclusion in the review by multiple reviewers and independently verified as before. Reasons for exclusion of full-text records were recorded. Disagreements were resolved through discussion and consultation with separate reviewers (SS and JN), where necessary. We coded multiple publications from individual studies using a single core reference and source identifier. Owing to the high volume of search results and the need to streamline review processes, the selection of evidence for stages 1 and 2 of the review was undertaken concurrently (sequential stage 1 and 2 selection was planned in the review protocol).

Stage 1: knowledge map methods

One of the key review objectives was to identify and characterise the different types of formal and informal respite care and short break services provided for young adults (aged 18–40 years) with complex health-care needs due to a LLC or complex physical disability. The criteria for inclusion in the stage 1 knowledge map were less restrictive than selection criteria for inclusion in the evidence review because we were looking for examples of these services (Table 3). To enable inclusion of relevant respite services for our target population, evidence was included if it met the following three criteria: (1) it broadly met the perspective (population) element of the SPICE criteria; (2) it broadly met the intervention (respite care/short breaks) element of the SPICE criteria (see Table 1) and (3) it provided a sufficiently detailed specification of service provision to inform the stage 1 knowledge map. Evidence that did not provide a sufficiently detailed description of services to be included in stage 1 may nevertheless have met the following full SPICE criteria for stage 2.

| Criterion | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Perspective | Young adults (aged 18–40 years) with complex health-care needs due to a LLC or complex physical disability (including those where no upper age limit is stated) |

Young people aged < 18 years or people aged > 40 years Young adults who do not require respite care/short breaks |

| Intervention/phenomenon of interest | Any type of evidence about respite care/short breaks in any setting |

Care other than respite care and short breaks Services specifically commissioned for young adults with learning disability or mental health needs |

This process presented some challenges because of the complexity of commissioned services. Many respite services are commissioned for people with a range of different needs and the population mix therefore includes people with other needs as well as our target population. To maximise sensitivity of the stage 1 search and to avoid missing relevant services, we retained a very broad selection strategy at this stage. Mixed populations were included when young adults aged 18–40 years were clearly part of the wider population. Similarly, services provided for populations with a range of needs were also included, providing that young adults with complex health-care needs were part of the wider service population. However, the review focuses on the provision of respite care for young people with complex health-care needs and evidence about services for people with solely educational or social care needs were therefore excluded.

The following information from evidence included in the stage 1 knowledge map (where available) was extracted and logged:

-

evidence bibliographic details

-

location (setting)

-

description of the intervention guided by the TIDieR (Template for Intervention Description and Replication) checklist49

-

information on service delivery processes required for programme theory and logic models.

Using preliminary categories published in the protocol as a starting point, and considering the population, timing, location and level of care provision, the evidence was used to categorise distinct service types that were validated following consultation from our PAG and the review SG.

Development of logic models

The information extracted from each item of evidence was synthesised to create a profile of each service type. The profiles catalogue the service aims and objectives, eligibility criteria, delivery components, implementation resources, user expectations and intended outcomes for various stakeholders. Some aspects of service specification, such as implementation resources and user expectations, had to be inferred because of a lack of information and this is noted in footnotes of the logic models, where appropriate.

The logic models evolved throughout the stage 1 knowledge map, the stage 2 evidence synthesis and the overarching synthesis. We developed logic models for the different types of respite care using Cochrane guidance50 and examples of good practice. 51,52 The logic models illustrate the programme theory for each type of respite care/short breaks service. Each model encapsulates the intended service aims, how the service is intended to work and for whom, the potential resources needed to deliver the service, and the anticipated outcomes and outputs from the service (i.e. how the services are conceptually designed to work). The models were continually updated and the completed logic models for each type of respite service were independently validated by the PAG and SG (see Appendices 8–20).

Stage 2: evidence review methods

Evidence was included in the stage 2 evidence synthesis only if it met all of the SPICE study selection criteria (see Table 1). This necessarily meant that some evidence was included in only one of the stages. The evidence included at each stage is reported in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (see Figure 3). Sources included in stage 2 were categorised as one of the following four streams of evidence.

Evidence stream 1: intervention effectiveness (review question 3)

Quantitative evidence of the effectiveness of the intervention (i.e. respite care and short breaks), such as randomised, quasi-randomised controlled trials, before-and-after studies, observational cohort studies or other types of quantitative evidence of effectiveness.

Evidence stream 2: health economics (review questions 3 and 4)

Quantitative evidence relating to health economics, such as economic evaluations (e.g. cost–utility and cost-effectiveness analyses), reports of care costs and other economic evidence (e.g. cost of illness or burden of disease studies).

Evidence stream 3: experience and attitudes (review questions 2, 5 and 6)

Qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods evidence exploring experience and attitudes relating to the provision of respite care or short breaks. Studies using recognised methods of data collection and analysis, such as surveys, interviews, focus groups, observational techniques, case studies, process and realist evaluations, and studies that include independent or components of a mixed-methods design.

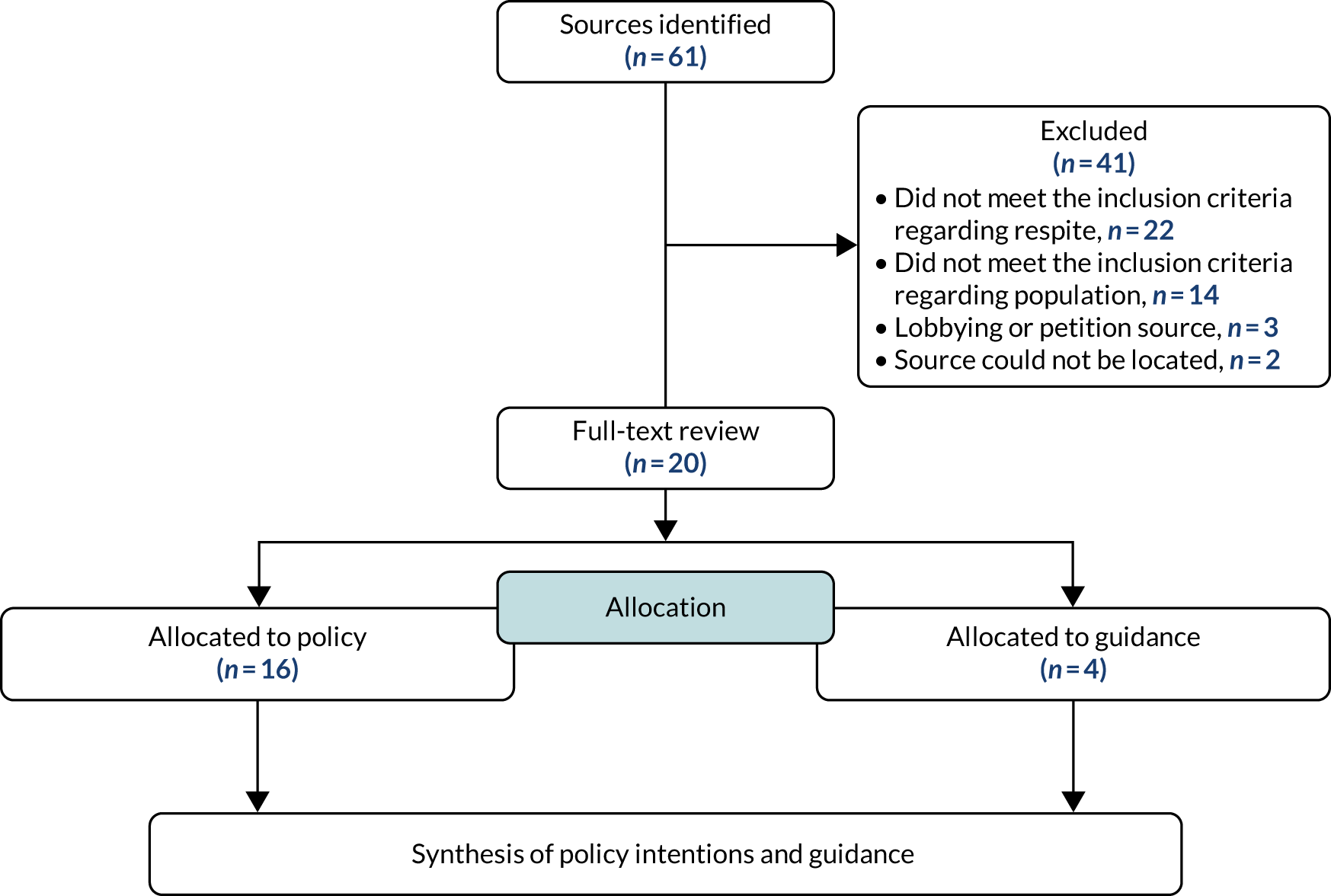

Evidence stream 4: UK policy and guidelines (review question 1)

All relevant current UK government policy, clinical guidelines and NFPO literature.

Data extraction

Bespoke extraction forms were developed for each evidence stream, tailored to the type of evidence and the underlying review question. Where it was available, we extracted the following information on study characteristics and their results:

-

publication characteristics [e.g. type (peer reviewed), year, country of data collection, dates of study data collection, publication language, source of study funding]

-

aims, objectives and target audience (policy)

-

methods (e.g. study design, recruitment/selection, data collection methods, methods of analysis)

-

participant characteristics [e.g. type of complex health-care needs and/or carers, study inclusion/exclusion criteria, age (mean, range), sex proportion, ethnicity, number in each study group, baseline characteristics]

-

intervention characteristics (e.g. type of service, setting, duration of care)

-

a description of all outcomes, measurement frequency, duration of follow-up and results reported in any format

-

the authors interpretations/conclusions

-

study limitations.

Data were extracted by one reviewer from the team assigned to each stream (GP, LB, MOB, BJ, JD, JN or BR) and accuracy was independently verified by a second reviewer (KK, GP or CM). Disagreements were resolved through consensus or by a third reviewer allocated to each stream by expertise (SS, BR, JN or CM). Data from sources with multiple publications were extracted and reported using the core reference as a source identifier.

Knowledge map: evidence matrix

We categorised each item of evidence by type of respite care or short break (identified in stage 1) and one of the four types of evidence stream to create an evidence matrix. The nature, quantity and quality of evidence was summarised and reported for each evidence stream and for each type of respite care/short breaks service (see Appendix 23). The matrix template was included in the review protocol. 44

Quality assessment strategy

The methodological limitations of included evidence were assessed by two reviewers (GP and KK) and disagreements resolved through consensus or by a third reviewer (JN or SS). No evidence was excluded on the basis of methodological strengths and limitations. However, design limitations were taken into account during synthesis and are included in the discussion.

No studies were identified for streams 1 or 2, but the intended quality assessment methods are described in the published protocol. 44

We used the CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme)53 appraisal tool to assess the methodological limitations of the qualitative studies included in stream 3. We did not use other appraisal tools described in the protocol, for example the Mixed Method Appraisal Tool for mixed-methods studies, as they were not applicable to any of the included evidence.

For stream 4, we intended to use the AGREE II (Appraisal of Guidelines, REsearch and Evaluation Version II) instrument to assess quality, but we did not identify any relevant practice guidelines. The quality of law and policy documents was not appraised.

Methods of data synthesis

Detailed methods are provided for streams 3 and 4, as no evidence was identified for inclusion in streams 1 and 2. Planned methods for all evidence streams are in the published protocol. 44 For reference, a detailed model of the review design and planned evidence syntheses are in Appendix 4.

Evidence stream 3: experience and attitudes

Framework synthesis was used to translate evidence from qualitative studies. Drawing on the planned review questions in the protocol and the logic models created in stage 1 of the review, we developed an iterative coding framework for the qualitative evidence (see Appendix 5). Each source was independently coded by two reviewers (LB, MOB, BJ or GP). Disagreements were resolved through consensus or by a third reviewer (KK). Evidence contributing to each code was collated and synthesised. The emergent themes are reported narratively and supported by tabulated summary of the evidence for each respite care type in the evidence matrix (see Appendix 23).

Evidence stream 4: UK policy and guidelines

We conducted content analysis of the evidence from UK policy using a documentary analysis informed approach54 to tabulate the evidence, based on an iterative coding framework (KK and GP). The content of each document was analysed using the eight-step process recommended for textual analysis. 55 This approach is an efficient and effective way of gathering, extracting and synthesising data from documents.

Overall synthesis

We planned to use the framework method for overall synthesis, advocated by the Evidence for Policy and Practice Information and Co-ordinating Centre. 56,57 The team planned to conduct within-service type and evidence stream integration of qualitative and quantitative data57 by juxtaposing evidence in an a priori framework, based on the review questions and policy intentions, and moving on to develop themes and subthemes to support further elicitation of the programme theory (i.e. types of service) and outcomes (i.e. benefits and harms), leading to further development and refinement of the logic models. Team members with expertise in quantitative and qualitative analysis and synthesis were assigned to each stream to ensure appropriate skills for synthesis of mixed-methods evidence. Arbitrators were also assigned to each evidence stream to mediate disagreements and uncertainties. However, as we did not identify any quantitative or mixed-methods evidence, the qualitative findings are reported according to each relevant review question [see Chapter 6, Experience and attitudes (evidence stream 3)]. This is supported by the evidence matrix described above (see Knowledge map: evidence matrix). Findings were then used to further develop the logical models as the overarching integration framework.

Overall assessment of the evidence

We used GRADE-CERQual (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation-Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research) to assess the overall confidence of the synthesised qualitative findings against four domains: (1) methodological limitations, (2) relevance of evidence to the review question, (3) coherence of the finding and (4) adequacy of data supporting the finding. 58 Two reviewers from the team (KK and JN) independently made an overall assessment using the aforementioned domains to assign a level of confidence for each synthesised qualitative finding:

-

high confidence (i.e. it is highly likely that the finding is a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest)

-

moderate confidence (i.e. it is likely that the finding is a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest)

-

low confidence (i.e. it is possible that the finding is a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest)

-

very low confidence (i.e. it is not clear whether the finding is a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest).

Table 4 provides a GRADE-CERQual qualitative evidence profile.

| Review finding | GRADE-CERQual assessment of confidence in the evidence | Explanation of GRADE-CERQual assessment | Studies contributing to the review finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| Respite services facilitated the development of independence and empowerment of young adults through opportunities to make choices and engage in a range of different activities, share their views to plan and develop services, and spend time away from parents | High confidence | No concerns, all perspectives included | Five sources59–63 |

| A significant benefit of respite services was the opportunity for young adults to socialise with peers and to interact with different staff to prevent isolation, create a sense of camaraderie with others who faced similar challenges and to allow engagement in activities they may not be able to access at home | High confidence | Minor concerns for methodological limitations. No concerns for relevance or adequacy. All perspectives included | Five sources59,62,64–66 |

| Respite care provided a sense of hope and lifted the spirits of young adults by fostering a sense of belonging where people did not feel defined by their disability or health condition | Low confidence | Only two sources. Moderate concerns for methodological limitations, coherence and relevance. No parent and service-provider perspective | Two sources62,65 |

| Respite care provided parents with time to themselves to rest, recuperate and engage in personal hobbies or interests while having a break from their 24/7 caring responsibilities, which reduced their physical and psychological strain | High confidence | Minor concerns for methodological limitations, coherence and adequacy. No concerns for relevance. No service-provider perspective | Nine sources59,61,62,65–70 |

| Respite care is a support mechanism for parents and the wider family, helping to re-establish family cohesion through time with partners and other children, which builds resilience for the family to continue with the demands of providing care | High confidence | Minor concerns for methodological limitations. No concerns for coherence, adequacy or relevance. No service-provider perspective | Five sources27,60,61,71,72 |

| Practical barriers to accessing respite care were identified, including volume and complexity of paperwork; delay between referral and service provision; the distance between home and the service; limited access to condition-specific services; lack of physical space for equipment in the available setting; lack of appropriately trained staff and limited inclusion of BAME populations | High confidence | Minor concerns for methodological limitations, coherence and adequacy. No concerns for relevance. No young adult perspective | Seven sources27,35,59,61,65,67,71 |

| Barriers to respite care from both the ‘anticipated’ loss of services during transition planning and ‘actual’ loss of services were identified because of the lack of age-appropriate and developmentally appropriate adult services, and the lack of a knowledgeable and experienced staff to provide safe care for young adults with complex health-care needs. Despite the anticipated increase in service demand as both young adult service users and their parents age, there is a lack of suitable alternatives for planned and emergency respite, which could result in a range of potential harms for young adults, parents and the wider family, and for service providers supporting young adults through transition | High confidence | Minor concerns for methodological limitations. No concerns for coherence, adequacy or relevance. All perspectives included | 12 sources22,27,35,59,61,63,64,67,73–76 |

| Trusted relationships between young adults, their parents and providers is an essential element of an acceptable respite service. This trust was underpinned by confidence in appropriately trained staff, providing safe care to the young adults and enabling young adults’ decision-making, which enriched their experience of the service. Lack of trust and confidence would result in poor uptake of services | High confidence | No concerns, all perspectives included | Nine sources27,59–64,69,73 |

| Respite care is viewed as acceptable by young adults, parents and providers when services offer a degree of flexibility and adaptability to the individual needs and wishes of the young adult and parents, including the types of respite accessed and the choice and control of activities engaged in. Parents also expressed a preference for flexibility in their dealings with the services rather than rigid timetables | Moderate confidence | Moderate concerns for methodological limitation. Minor concerns for coherence. No concerns for adequacy or relevance. All perspectives included | Six sources35,61,63,65,67,73 |

| The lack of appropriate respite care services for young adults was identified across the evidence. All stakeholders acknowledged that for services to be acceptable and improve outcomes for young adults, they should be designed and developed with young adults’ interests, life course stage and needs in mind. Young adults valued spending time with peers and wanted staff to be of a similar age and sex to themselves. Respite care in residential homes for the elderly or adult hospices where activities did not align with the young adult’s interests or preferences was viewed as unacceptable. Involving young adults and parents in the development or planning of services was encouraged to improve the acceptability of the service to its users | High confidence | Minor concerns for methodological limitations and coherence. No concerns for adequacy or relevance. All perspectives included | 10 sources27,35,61–65,67,73,76 |

| The need for appropriately trained and experienced staff is acknowledged as a vital resource for the implementation and delivery of safe respite care services for young adults, and for their care to be considered comparable to the standard of care at children’s hospices | High confidence | No concerns, all perspectives included | Four sources60,61,64,75 |

| Funding, commissioning and capacity issues were identified as the key barriers to the development and provision of appropriate respite services for young adults. Providers spoke of inequalities in the funding and commissioning of services across the life span due to inconsistencies between requirements to pay for respite care in children and adult hospices in the third sector, and lack of understanding of the commissioning process among some providers that required encouragement to meet their assessment duties. The challenges of commissioning and delivering services were perceived to be exacerbated by the low volume but high cost of care for this population. Children and adult hospices lack the funding and capacity to provide all the care needed, requiring partnership working and funding with statutory and NHS support to meet current and future need. Parents felt under pressure to agree to short breaks that cost much less than those provided by services for those with individual care packages and continuing health-care funding | High confidence | No concerns. No young adult perspectives | Six sources35,59,61,62,67,76 |

The role of the Steering Group

The SG comprised individuals with an in-depth knowledge of care for young adults with complex health-care needs or the provision of respite care/short breaks, for example those with professional roles in commissioning or delivering services, clinical experts, and parent and young adult representatives from the PAG. The SG was chaired by the review manager (KK) and a young adult from the PAG. The group contributed to the review process electronically and met on four occasions to advise the review team on all aspects of the systematic review, including the scope of the searches, interpretation of results and dissemination of the research findings. The group specifically contributed to the following:

-

Development of the protocol (i.e. clarification of concepts and definitions, particularly in relation to inclusion criteria).

-

Identification of unpublished evidence.

-

Identification of ongoing and arising issues relevant to the review (e.g. current service provision, changes to local or national policies or best practice).

-

Summary of implications of the review findings, particularly in terms of service delivery or policy.

-

Validation of the knowledge map.

-

Validation of the logic models as the conceptual framework.

-

Review of drafts of the final report.

-

Planning and dissemination of the review findings to relevant audiences.

The role of the Patient and Public Advisory Group

The PAG comprised individuals who represented young people with complex health-care needs, carers and parents/guardians. A young adult and a parent from the initial PAG for the funding application remained involved throughout the study. Other original members of the PAG withdrew because of changes in health or life circumstances. Recruitment of additional members of the PAG through social media and our networks initially proved challenging. Some potential participants commented that they were not attracted to systematic reviews, while others were interested but were not able to participate owing to competing demands on their time or deterioration in the health status of the young adult. We continued to recruit members during the study, including for the development of a film and other media outputs, which was more successful in attracting young adults. During the study, five young adults, two parents and four carers were involved in the PAG.

We adopted an inclusive and flexible approach to working with members of the PAG in an effort to overcome challenges in meeting at a mutually agreed time and location. This included working together via telephone, Skype™ (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) or e-mail to suit individual preferences and the needs of members for whom travel was challenging because of their complex health conditions. All PAG members received ongoing support and guidance throughout the study. A parent and young adult were members of the SG and attended meetings to enable representation and appropriate feedback between the two groups. There were between three and eight contacts with each member of the group, depending on their preferred level of involvement and length of time with the study. Some members engaged individually via telephone or Skype, some attended up to four meetings at the university and others took a combined approach, depending on the weather and their health. All members of the group said that they felt that their contribution to the study was meaningful and that they had enjoyed being part of the study.

The aim of the PAG was to ensure that the experiences of service users was included in the review processes. The PAG was invited to contribute to the following activities at appropriate points during the study:

-

finalising the protocol (e.g. clarifying concepts and definitions, co-writing the Plain English summary)

-

identifying unpublished evidence

-

identifying ongoing and arising issues relevant to the review (e.g. current service provision, changes to local or national policies or best practice)

-

interpreting the review findings

-

validating the knowledge map

-

validating the logic models as the conceptual framework

-

reviewing drafts of the final report

-

planning and developing materials to raise awareness of the review (e.g. audio clips, ‘talking head’ video clips, blogs, a short film).

Members of the PAG will continue to be involved in the dissemination of the review findings to relevant audiences, including ‘talking heads’ video clips and co-presenting at future conferences or regional events to share findings. A film workshop was held in December 2019 to plan the structure of the film and record ‘talking head’ videos of the young adults’ experience and why they feel respite care is important. A second workshop was planned to record ‘talking heads’ and plan an animation of the findings at the university; however, because of the coronavirus pandemic, this work was placed on hold and is now being arranged to take place remotely, when group members are available. The media outputs are planned for release in April 2021. All dissemination materials will be made available on the study website and social media, and will be included in any conference presentations.

Both the SG and PAG were vitally important in providing context from their lived experience of using and providing respite services during the study. This was particularly key when the knowledge map categories and types of respite care needed to be validated. It was reassuring that the types of respite care identified and the growth of certain types, such as the social activities, was reflected in the experience of our members. Their experience also supported and validated the themes identified in the qualitative evidence, particularly where there were areas of overlap or uncertainty about aspects of the provision. The views and experience of the SG and PAG members also enhanced the development of the recommendations for research, policy and practice to ensure that they are appropriate and will support the development of knowledge and the necessary service provision.

Summary of deviations from the protocol

We intended to conduct stages 1 and 2 sequentially but because of the volume of search results, and to improve efficiency, these stages were run concurrently.

We conducted two updates of the study searches, which used a modified version of the original search to improve sensitivity and specificity.

Owing to the nature of the evidence included in the review, some planned processes were not required. These instances are described in the relevant sections of the report.

Chapter 4 Search results

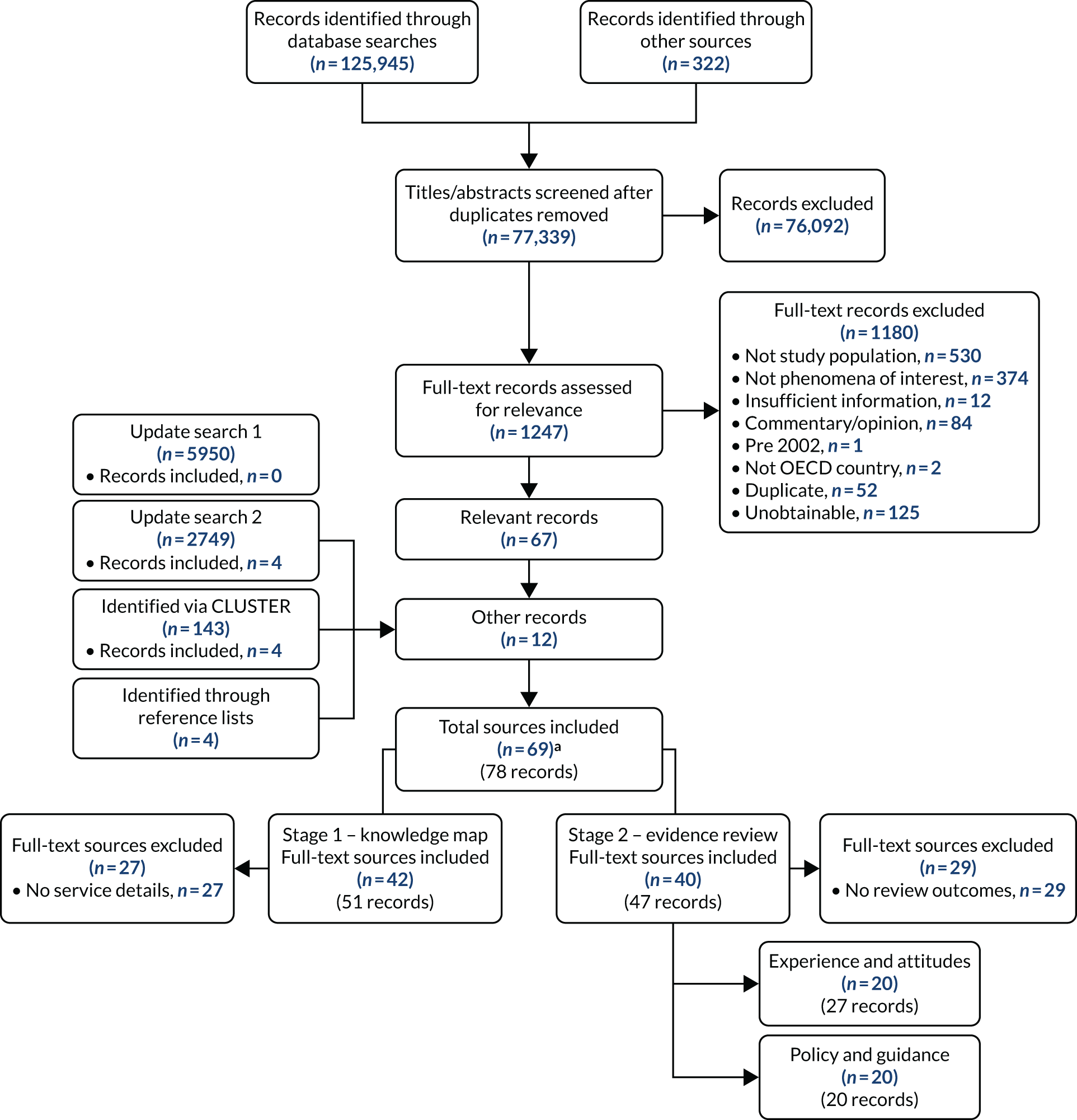

To support the transparent reporting of review methods, we have included an annotated PRISMA checklist. 77 A systematic search conducted in 2018 identified 126,267 records that, following de-duplication, resulted in 77,339 unique records that were entered into Covidence. Of these records, we considered 76,092 irrelevant following inspection of their titles and abstracts. The full texts for the remaining 1247 records were obtained and scrutinised for selection.

We formally excluded 1180 records, which are listed by exclusion category in Appendix 6. We excluded 530 records that did not include our review population, 374 records that did not relate to respite care or short breaks (i.e. the phenomena of interest), 12 records where there was insufficient information for selection, 84 unconfirmed reports or anecdotal opinions, two records not published in OECD countries, 52 duplicate records and 125 records for which the full text was unobtainable.

The remaining 67 records were selected for inclusion. We identified a further 8699 records following updated searches in February and September 2019 and four of these were selected for inclusion. A further eight records were included following CLUSTER searching (n = 4) and searches of reference lists (n = 4). A total of 78 unique records relating to 69 sources were selected for inclusion in the stage 1 knowledge map and/or the stage 2 evidence review. 22,26,27,30,35,41,59–76,78–131 The selection process is summarised in a flow diagram (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

A PRISMA flow diagram. a, Some sources are included in only the knowledge map or the evidence review and some are included in both.

It is important to note that some sources are included in the knowledge map only, some in the evidence review only and some records were included in both. Brief reasons for exclusion from stages 1 or 2 are listed in Figure 3. Details of the records contributing to stages 1 and 2 are listed in Table 5.

| Source | Title | Knowledge map (n = 51 records from 42 sources) | Experience and attitudes (n = 27 records from 20 sources) | Policy and guidance (n = 20 sources) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abbott and Carpenter73 | Becoming an Adult. Transition for Young Men with Muscular Dystrophy | No | Yes | No |

| Arnold and Godwin78 | The Shakespeare Hospice Transitional Care Service Innovation in Practice | Yes | No | No |

| The Asian Health Agency79 | Ashra Carers Project: Children & Young People with Special Needs | Yes | No | No |

| Barnet Country Council80 | Barnet Short Breaks Duty Statement 2017/2018 | Yes | No | No |

| Beresford et al.63 | My Life: Growing Up and Living with Ataxia-Telangiectasia: Young People’s and Young Adults’ Experiences | Yes | Yes | No |

| Bishop81 | Making The Most Of Life | Yes | No | No |

| Bona et al.82 | Massachusetts’ Pediatric Palliative Care Network: Successful Implementation of a Novel State-Funded Pediatric Palliative Care Program | Yes | No | No |

| Brighton and Hove City Council83 | Brighton & Hove City Council Short Breaks Statement 2017–18 | Yes | No | No |

| Brook84 | Jacksplace – A Hospice Dedicated to Teenagers and Young Adults in Hampshire | Yes | No | No |

| Care Quality Commission85 | Claire House Children’s Hospice Inspection Report | Yes | No | No |

| Care Quality Commission87 | Francis House Children’s Hospice Inspection Report | Yes | No | No |

| Claire House Children’s Hospice86 | Claire House Children’s Hospice Local Offer Statement | Yes | No | No |

| Dawson and Liddicoat62 | ‘Camp Gives Me Hope’: Exploring the Therapeutic Use of Community for Adults with Cerebral Palsy | Yes | Yes | No |

| Department of Education and Skills and DHSC89 | Commissioning Children and Young People’s Palliative Care Services: A Practical Guide for the NHS Commissioners | No | No | Yes |

| DHSC90 | Carers and Disabled Children Combined Policy Guidance Act 2000 and Carers (Equal Opportunities) Act 2004 | No | No | Yes |

| Department for Children, Schools and Families and DHSC91 | Aiming High for Disabled Children: Short Break Implementation Guidance | No | No | Yes |

| DHSC26 | Better Care, Better Lives. Improving Outcomes for Children Young People and Their Families Living with Life-Limiting and Life-Threatening Conditions | No | No | Yes |

| Department for Education92 | The Breaks for Carers of Disabled Children Regulations 2011 | No | No | Yes |

| Department for Education and DHSC88 | Special Educational Needs and Disability Code of Practice: 0 to 25 Years | No | No | Yes |

| DHSC93 | Care Act 2014 – Care and Support Statutory Guidance | No | No | Yes |

| East Anglia Children’s Palliative Care Managed Clinical Network94 | The East of England Children and Young People’s Palliative Care Service Directory | Yes | No | No |

| aGans et al.95 | Impact of a Pediatric Palliative Care Program on the Caregiver Experience | Yes | No | No |

| Gans et al.96 | Better Outcomes, Lower Costs: Palliative Care Program Reduces Stress, Costs of Care for Children with Life-Threatening Conditions | Yes | No | No |

| Grinyer et al.71 | Issues of Power, Control and Choice in Children’s Hospice Respite Care Services: A Qualitative Study | Yes | Yes | No |

| Hanrahan97 | A Host of Opportunities: Second NHSN Survey of Family Based Short Break Schemes for Children and Adults with Intellectual and Other Disabilities in the Republic of Ireland | Yes | No | No |

| Health Information and Quality Authority98 | Draft National Standards for Residential Centres for People with Disabilities (Consultation Document) | No | No | Yes |

| HM Treasury 200799 | Aiming High for Disabled Children: Better Support for Families | No | No | Yes |

| Hutcheson et al.59 | Evaluation of a Pilot Service to Help Young People with Life-Limiting Conditions Transition From Children’s Palliative Care Services | Yes | Yes | No |

| Institute of Public Care and National Commissioning Board Wales100 | Integrated Services for Children and Young People with a Disability in Conwy. A Case Study | Yes | No | No |

| Kerr et al.74 | A Cross-Sectional Survey of Services for Young Adults with Life-Limiting Conditions Making the Transition From Children’s to Adult Services in Ireland | No | Yes | No |

| Kirk and Fraser22 | Hospice Support and the Transition to Adult Services and Adulthood for Young People with Life-Limiting Conditions and Their Families: A Qualitative Study | No | Yes | No |

| Knighting et al.101 | An Evaluation of the Rachel House at Home Service for the Children’s Hospice Association Scotland (CHAS): Summary Public Report | Yes | No | No |

| aKnighting et al.67 | Meeting the Needs of Young Adults with Life-Limiting Conditions: A UK Survey of Current Provision and Future Challenges for Hospices | Yes | Yes | No |

| Knighting et al.41 | Children and adult Hospice Provision for Young Adults with Life-Limiting Conditions: A UK Survey (Poster at Hospice UK Conference) | Yes | Yes | No |

| Knighting et al.102 | Highlights From a UK Survey of Children and Adult Hospice Provision for Young Adults with life-Limiting Conditions | Yes | Yes | No |

| aKnighting et al.103 | Short Break Provision for Young Adults with Life-Limiting Conditions: A UK Survey with Young Adults and Parents | Yes | Yes | No |

| Knighting et al.75 | Family Respite Care Survey with Young Adults and Parents: Summary Findings Report | No | Yes | No |

| Knowsley Council104 | Knowsley Children and Family Services Short Breaks Statement | Yes | No | No |

| Leason105 | Let’s Face the Music and Dance | Yes | No | No |

| Luzinat et al.68 | The Experience of a Recreational Camp for Families with a Child or Young Person with Acquired Brain Injury | Yes | Yes | No |

| MacDonald and Greggans70 | ‘Cool Friends’: An Evaluation of a Community Befriending Programme for Young People with Cystic Fibrosis | Yes | Yes | No |

| Marsh et al.35 | Young People with Life-Limiting Conditions: Transition to Adulthood. ‘Small Numbers, Huge Needs, Cruel and Arbitrary Division of Services’. Executive Summary of Phase 1 Report for Marie Curie Cancer Care | No | Yes | No |

| Martin House Children’s Hospice60 | Supporting Children with Life-Limiting Conditions and Their Families – Research Examining Service Provision in Yorkshire and the Humber | Yes | Yes | No |

| Martin House Children’s Hospice106 | Professionals’ Booklet | Yes | No | No |

| aMitchell et al.27 | Short Break and Emergency Respite Care: What Options for Young People with Life-Limiting Conditions? | Yes | Yes | No |