Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 16/116/46. The contractual start date was in August 2018. The final report began editorial review in October 2020 and was accepted for publication in February 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2021 Gulliford et al. This work was produced by Gulliford et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Gulliford et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

The problem of antimicrobial drug resistance

The threat of antimicrobial drug resistance is attracting the concern of national governments and international organisations. 1 Antibiotic-resistant infections are now increasing in frequency and are more often being identified when cultures are performed. In England, in 2018, nearly one-third of urinary tract infections (UTIs) caused by Escherichia coli were resistant to trimethoprim2 and 43% of E. coli bacteraemia isolates were resistant to co-amoxiclav. 2 The emergence of antimicrobial resistance requires action from a range of sectors, including the pharmaceutical industry, as well as agriculture and food production, as outlined in the O’Neill review. 3 However, antimicrobial resistance has the most immediate relevance in the health-care sector, in which antibiotics are prescribed and in which patients with resistant infections are seen. 3 The UK Government has developed a 5-year antimicrobial resistance strategy that identifies optimising antibiotic prescribing practices as a key element of antimicrobial stewardship. 4

Antibiotic prescribing in primary care

In the UK, primary care accounts for nearly three-quarters of all antibiotic prescribing. Respiratory tract infections (RTIs) represent the largest single group of indications for antibiotic treatment. 2 General practitioners (GPs) prescribe antibiotics, on average, at 52% of consultations for ‘self-limiting’ RTIs, including common colds, acute cough and bronchitis, sore throat, otitis media and rhinosinusitis,5 with little change over the last two decades (Figure 1). 6,7

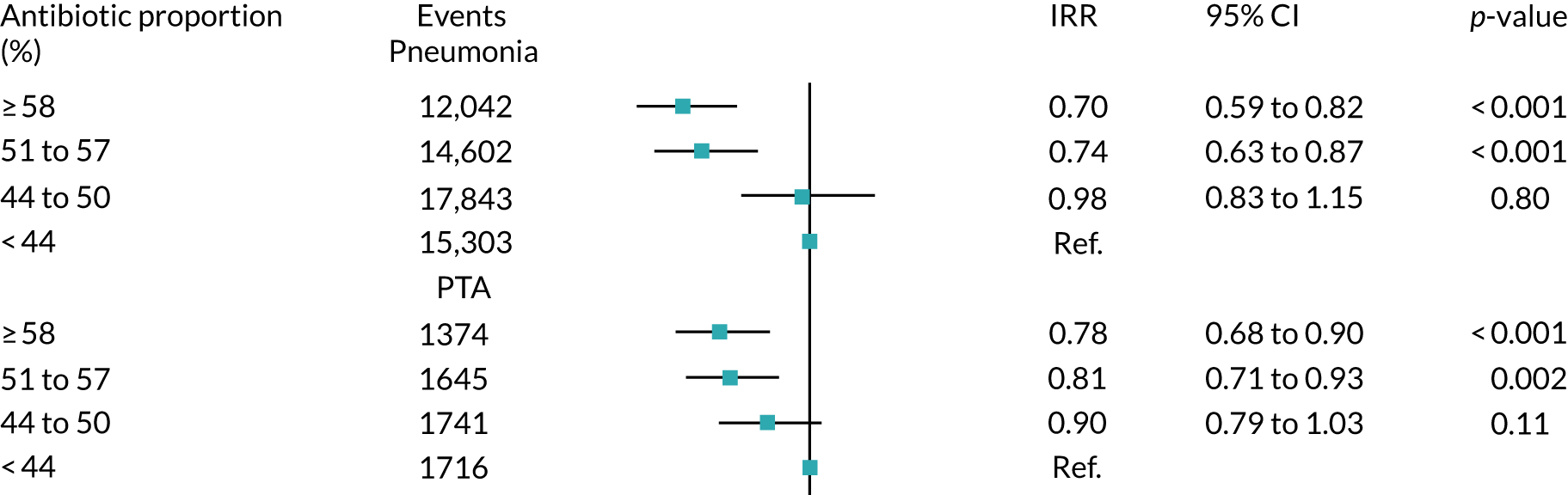

FIGURE 1.

Distribution of the proportion of the RTI consultations with antibiotics prescribed at 568 UK general practices. 6 Reproduced from Gulliford et al. 5 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

The other main indications for antibiotic prescription include UTIs and skin infections, for which there may be less discretion concerning whether or not to use antibiotics, with greater emphasis given to appropriate antibiotic selection. 8,9 Since the inception of this research project, analysis of electronic health records has shown that between one-third and half of all antibiotic prescriptions in primary care in the UK may not be associated with specific diagnostic codes, possibly because GPs have recorded free-text information or recorded non-specific codes (such as ‘had a chat with the patient’). 8,10 This poor recording of consultations for common infections in primary care makes it difficult to evaluate the appropriateness of existing prescribing patterns. Consequently, Hay11 recommended that strategies should be adopted to ensure that all antibiotic prescriptions and all infection consultations should be documented through the recording of appropriate medical diagnostic codes.

Evidence to support no-prescribing strategies

Evidence from systematic reviews of randomised controlled trials shows that antibiotic treatment for self-limiting RTIs generally has little, if any, effect on the severity or duration of symptoms and is commonly associated with unwanted symptomatic side effects, including rashes and diarrhoea. 12,13 These side effects may not always be reported, but may lead to non-adherence. Prescribing antibiotics also has the effect of medicalising conditions that are generally self-limiting and should be amenable to self-care. Patients given antibiotics for sore throat are 69% more likely to consult again for the same condition. 14 Consequently, UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines recommend that a no antibiotic prescribing, or delayed antibiotic, strategy should be agreed with most patients presenting with self-limiting RTIs. 15 Respiratory conditions represent one of the most important opportunities to reduce antibiotic use. In 2018, NICE developed and disseminated guidance for managing a comprehensive range of common infections in primary care, which summarised the indications for prescribing antibiotics and appropriate drug selection. 16

Evidence that prescribing may be reduced

Several approaches are now being developed and tested to promote more effective antibiotic stewardship in primary care. Deferred or delayed prescribing, in which a prescription is given but used only if needed, gives patients more control and is sometimes advocated; however, this strategy may be less effective at reducing antibiotic use while offering similar patient satisfaction to a ‘no-prescribing’ strategy. 17 Algorithms are being developed to identify patients who may need antibiotics. 18,19 Near patient testing for biomarkers of bacterial infection is being developed to enable targeted prescribing of antibiotics, but this is not yet fully proven and may be difficult to integrate into usual clinical practice. 20 Behaviour change approaches are being tested. In one study in England, high-prescribing GPs were sent an individualised letter signed by England’s Chief Medical Officer, which resulted in a 3% reduction in antibiotic utilisation. 21 Finally, a contractual financial incentive, known as a ‘Quality Premium’, has been introduced into the English NHS for meeting indicative targets for year-on-year reductions in antibiotic utilisation. 22

Recently, attention has focused on evidence to support reducing antibiotic utilisation in primary care. Smieszek et al. 23 analysed electronic health record data for general practices in England and compared observed antibiotic prescribing practice with recommendations from guidelines and expert opinion. The study found that at different general practices between 6% and 44% of antibiotic prescriptions might be inappropriate, with the highest proportions of inappropriate prescription being for sore throat, cough, sinusitis and otitis media. 23 Across Europe, the number of antibiotic prescriptions (defined daily doses) per 1000 population per day ranges from 10 (in the Netherlands) to 36 (in Greece), with a value of 20 in the UK. 24 Based on these international comparisons, with both low25 and high26 antibiotic prescribing being observed across Europe without risks to patient safety, it appears that a substantial reduction of antibiotic prescribing in primary care might be reasonable.

Giving antibiotic treatment when needed

Strategies to reduce inappropriate use of antibiotics must ensure that antibiotics can be used when they are needed. 27 Reducing antibiotic use might potentially compromise patient safety by increasing the risk of serious bacterial infections following minor infections that are expected to be self-limiting. 28 This is recognised in the NHS, where reducing bloodstream infections is a key antimicrobial stewardship metric, alongside reducing inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions. 22 Bacterial infections, such as sepsis, are still of public health importance. 29 Early recognition and treatment of sepsis is being promoted. Most general practice systems are now incorporating alerts that flag at-risk consultations. 30

The safety of reduced antibiotic prescribing is a major concern for clinicians. One GP respondent commented:

It’s the fear of litigation or things going wrong, and if you have arbitrary targets like this . . . and I don’t want to prescribe, but if it’s needed, then pressure of some sort of appraisal and maybe being told off is not really needed.

Gulliford et al. 31

Parents are also concerned about safety issues, which are an important motivation for seeking active treatment for children. 32 Advice given by clinicians concerning ‘safety-netting’ may appear vague and unhelpful if patients are advised to re-consult ‘if they are worried’ or ‘if [the patient] doesn’t get better’. 32 Patients may be concerned that a repeat consultation may be difficult to obtain. A systematic review of qualitative studies found that clinicians commonly prescribe an antibiotic ‘just in case’ it might be needed. 33 There is a lack of research providing quantitative estimates of risk that might allow clinicians to provide more evidence-informed advice.

Trends in bacterial infections

Serious bacterial infections represent a growing concern for health systems. In the UK, sepsis is estimated to account for 36,900 deaths and 123,000 hospital admissions annually. 34 The Global Burden of Disease Study estimated that there were nearly 50 million incident cases of sepsis worldwide in 2017, with 11 million deaths, representing 19.7% of global deaths. 35 Sepsis is defined as a syndrome resulting from the interaction between an acute infection and the host response, leading to new organ dysfunction. 36 Sepsis is an intermediate state that links an infection or an infection-causing condition to adverse health outcomes. The term sepsis is now more commonly used than the term ‘septicaemia’, which refers to bloodstream infection. In the health-care systems of high-income countries, records of ‘sepsis’ have been increasing in both hospital and primary care settings. 37–39

There is also evidence that certain localised infections have been increasing in frequency in the UK (Table 1). Thornhill et al. 46 observed that the incidence of infective endocarditis was stable in England between 1998 and 2010, but between 2010 and 2019 there was an 86% increase in the frequency of the condition. This was contemporaneous with changes to the recommendations for antibiotic prophylaxis at dental procedures. Empyema is an infrequent complication of lung infections. A study from New Zealand44 found that the incidence of empyema increased from 1 per 100,000 children aged 0–14 years in 1998 to 13 per 100,000 in 2009. This increase has also been observed in Australia,52 the UK43 and Europe. 45 Some studies suggest that the introduction of a polyvalent pneumococcal vaccine may have been associated with an increase in infections with non-vaccine strains of pneumococci that may be associated with increased risk of empyema,45 despite that the introduction of the pneumococcal vaccine has been associated with a substantial reduction in pneumonia in children overall. 53 Other authors suggest that lower early initiation of antibiotic therapy for more serious respiratory infections might also be a contributory factor. 44 There is also more limited evidence for increasing trends in the occurrence of osteomyelitis and septic arthritis. 48–50

| Condition | Trend |

|---|---|

| Sepsis | Increasing diagnosis and recording40 |

| PTA | Unchanged or decreasing incidence28,41 |

| Mastoiditis | Stable incidence42 |

| Empyema | Increasing incidence43–45 |

| Infective endocarditis | Increasing incidence46,47 |

| Osteomyelitis | Increasing incidence48 |

| Septic arthritis | Increasing incidence49,50 |

| Kidney infections | Increasing trend in UTI hospital admissions51 |

The reasons for these apparent increases in serious bacterial infection are complex. There have been changes to case definitions, diagnostic criteria and disease labelling. This is particularly relevant for diagnoses of sepsis. A study from the Massachusetts General Hospital (Boston, MA, USA)54 found that recording of severe sepsis or septic shock increased by 706% in the decade between 2003 and 2012, whereas objective markers of severe infection, including positive blood cultures, remained stable or decreased. Alongside increasing use of the term sepsis, case definitions have expanded to include patients with evidence of both acute infection and acute organ dysfunction as having ‘implicit sepsis’, even when sepsis was not explicitly diagnosed. 35,55 Changes in disease labelling might be less relevant for localised bacterial infections. Thornhill et al. 46 and Quan et al. 47 concluded that the increased incidence of endocarditis might be accounted for by wider demographic, social and medical changes that increase susceptibility and risk. These include the effects of population ageing, the increase in obesity, possibly the more widespread use of intravenous drugs, the increasing prevalence of comorbidities (including diabetes mellitus), the more widespread use of invasive medical procedures and the increasing numbers of patients with immunosuppressive disorders or receiving immunosuppressive treatments. Nevertheless, more restrictive use of antibiotics for common infections cannot be excluded as a contributory cause of these increasing trends in serious bacterial infections. Recent research, therefore, has begun to investigate the safety of reduced antibiotic prescribing in primary care.

Previous studies of safety outcomes of antibiotic prescribing

Only a few existing research studies directly address the safety outcomes of reduced antibiotic prescribing. Petersen et al. 56 reported a cohort study in 162 General Practice Research Database general practices from 1991 to 2001, showing increased odds of pneumonia after ‘chest infection’, peritonsillar abscess (PTA) after sore throat and mastoiditis after otitis media. The absolute risks for these complications were generally low, with > 4000 antibiotic prescriptions being required to prevent one case. However, in people aged > 65 years, one case of pneumonia might be prevented for every 38 ‘chest infections’ treated with antibiotic.

Little et al. 57 reported on a clinical cohort of 14,610 patients presenting with sore throat. Fewer than 1% had complications (including PTA, otitis media, sinusitis, impetigo or cellulitis). It was generally difficult to predict when these complications might arise based on clinical features of the initial presentation. 58 In a cohort study of patients with acute lower RTI, Little et al. 59 found that hospital admissions and mortality were rare complications and that these did not appear to be prevented by initial prescription of antibiotics.

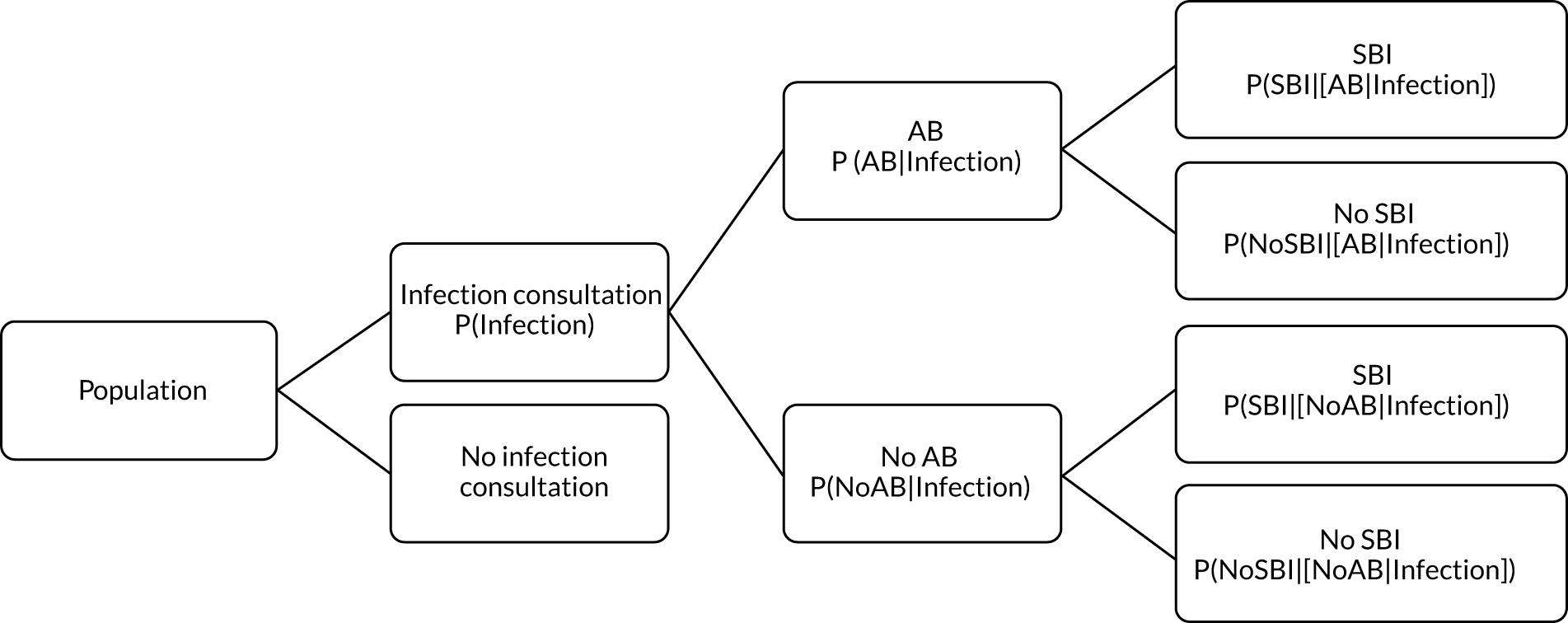

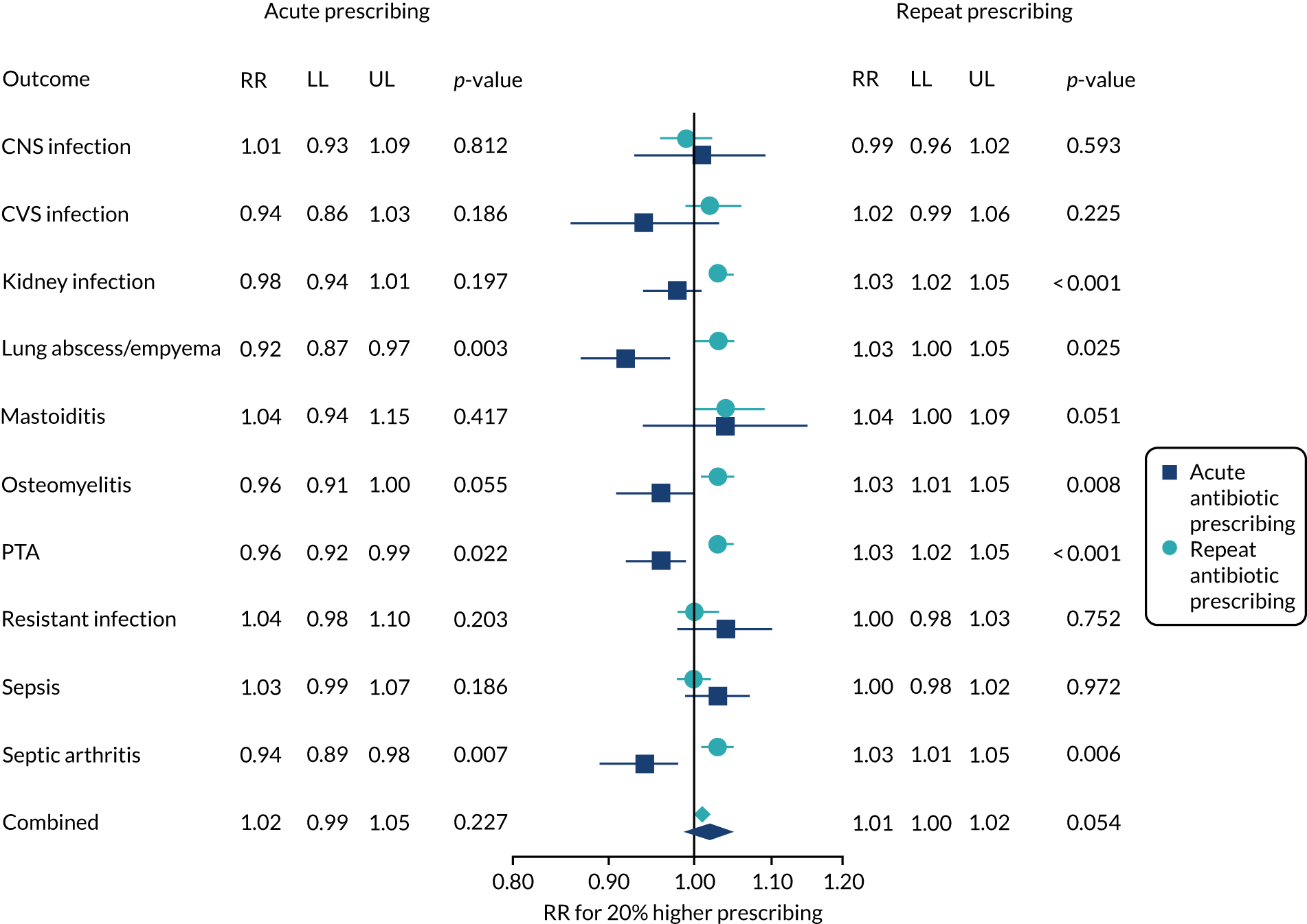

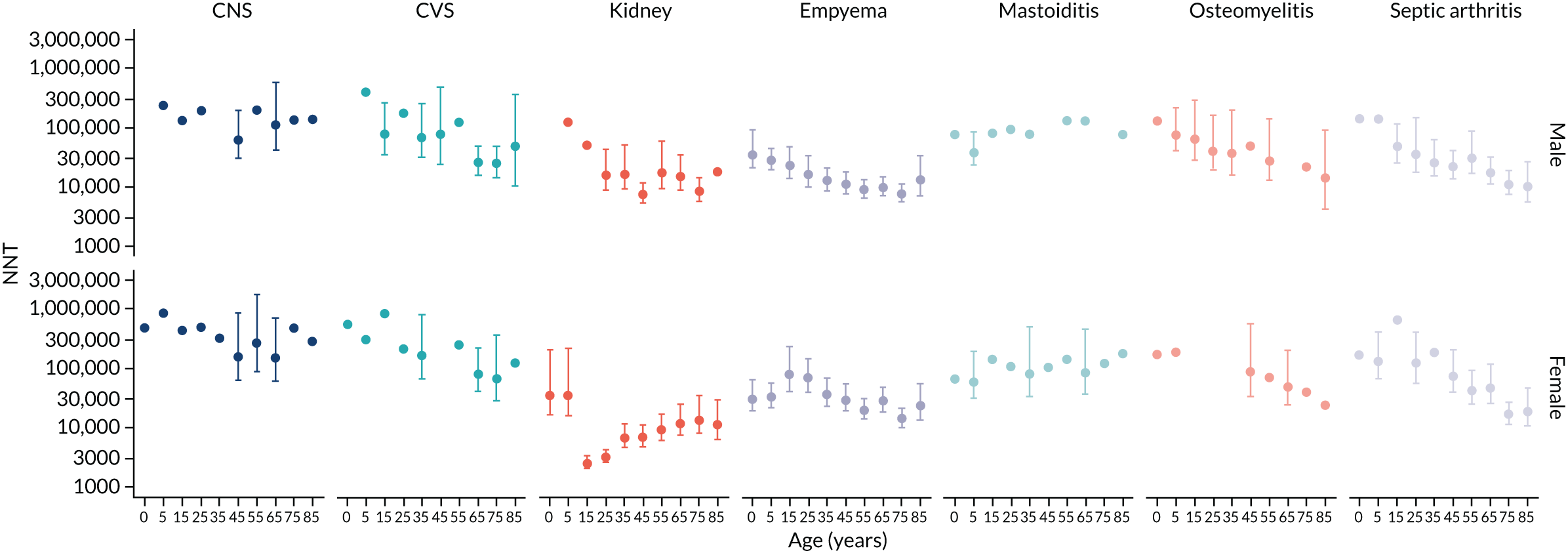

Our group reported a study using data for more than 600 Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD) general practices from 2005 to 2015. 28 Of the seven outcomes studied, we found that pneumonia and PTA were more frequent at general practices that prescribed antibiotics less frequently at consultations for self-limiting RTI (Figure 2). Absolute risks were small, with an average general practice experiencing one more case of pneumonia per year and one more case of PTA per decade for a 10% reduction in antibiotic prescribing. We found no association of practice-level antibiotic prescribing for RTI with incidence of empyema, mastoiditis, intracranial abscess, bacterial meningitis or Lemierre’s syndrome (i.e. infective thrombophlebitis of the internal jugular vein). However, these were rare outcomes and even in this large data set it was not possible to exclude the possibility of small increases in risk. 28

FIGURE 2.

Association of the incidence of pneumonia and PTA with the quartile of antibiotic prescribing proportion. Antibiotic proportion is the proportion of RTI consultations with antibiotic prescribed at that general practice. 28 CI, confidence interval; IRR, incidence rate ratio. Reproduced from Gulliford et al. 28 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Since the present research project was initiated, several other groups have reported analyses of electronic health records to evaluate potential safety outcomes of reduced antibiotic prescribing. Cushen and Francis60 used data from the CPRD to evaluate the occurrence of brain abscess and mastoiditis after otitis media, and brain abscess and orbital cellulitis after acute sinusitis. Their analysis found that antibiotic prescription was associated with lower risk of acute mastoiditis following otitis media [odds ratio 0.54, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.37 to 0.79] and of brain abscess following acute sinusitis (odds ratio 0.12, 95% CI 0.02 to 0.70). However, because of the low incidence of these conditions, the number of antibiotic prescriptions required to prevent one complication was > 2000 for otitis media and nearly 20,000 for acute sinusitis. 60

Gharbi et al. 61 conducted a cohort study, also using the CPRD, to evaluate the risk of bloodstream infection, hospital admission or mortality following UTI in adults aged ≥ 65 years. Their analysis suggested that patients with evidence of delayed initiation of antibiotics might have greater risk of these adverse outcomes. However, it is also possible that data-recording issues might have introduced bias (e.g. if more seriously ill patients are initially seen in urgent or out-of-hours settings and antibiotic prescriptions are not recorded into general practice records).

Mistry et al. 62 analysed CPRD data to develop a prediction model for infection-related hospital admission after a general practice consultation for RTIs and UTIs. The most important predictors were found to be age, Charlson Comorbidity Index and previous hospital admission in the last year. In this observational analysis, whether or not antibiotics were prescribed was not associated with hospital admission for infection-related complications.

The need for further research

The question of whether or not reducing antibiotic prescribing carries risks to patient safety is clearly important, but the evidence base is currently extremely limited. Previous research raises several questions about the safety of reducing antibiotic prescribing and requires more systematic and thorough study. Previous studies considered antibiotics prescribed for specific indications56 or for self-limiting RTIs,28 but antibiotic use for all indications should be evaluated. Previous studies relied on primary care records, but additional validation from hospital episode data is desirable because differential code selection might occur in primary care to justify an antibiotic prescription. 63 Different age groups require evaluation because these may have differing susceptibility to complications. With the rapid increase in numbers of older people, the effects of frailty64,65 and comorbidity on susceptibility to complications in the most vulnerable require evaluation. Universal compared with risk-stratified approaches to reduce antibiotic prescribing require evaluation.

The present use of targets for global reductions in antibiotic utilisation in the Quality Premium raises questions concerning the quality of the evidence available to inform target setting. Is a single target across all prescribing indications the optimal approach? Reducing antibiotic utilisation may be more readily achieved in some groups of patients and for some prescribing indications than others. This research aimed to provide the NHS with a more systematic understanding of potential safety outcomes of reducing antibiotic prescribing, therefore enabling the identification of safer strategies for reducing antibiotic utilisation. We aimed to quantify the risks of a comprehensive and systematically identified list of safety outcomes and distinguish population subgroups that may be at increased risk.

Chapter 2 Aims and objectives

This research asked whether or not it is safe to reduce antibiotic prescribing in primary care. Is there a risk that bacterial infections might be more frequent if antibiotics are prescribed less often? If so, what is the safest way for the NHS to promote reduction of antibiotic prescribing in primary care? The research specifically aimed to provide evidence concerning different prescribing indications and for different population groups based on risk stratification. The research aimed to develop new indicators of safe and appropriate antibiotic prescribing and to implement these into general practices.

The specific objectives were as follows:

-

Conduct an epidemiological analysis of electronic health records to estimate the relative and absolute risks of each outcome in association with lower antibiotic prescribing, based on both community- and individual patient-level associations.

-

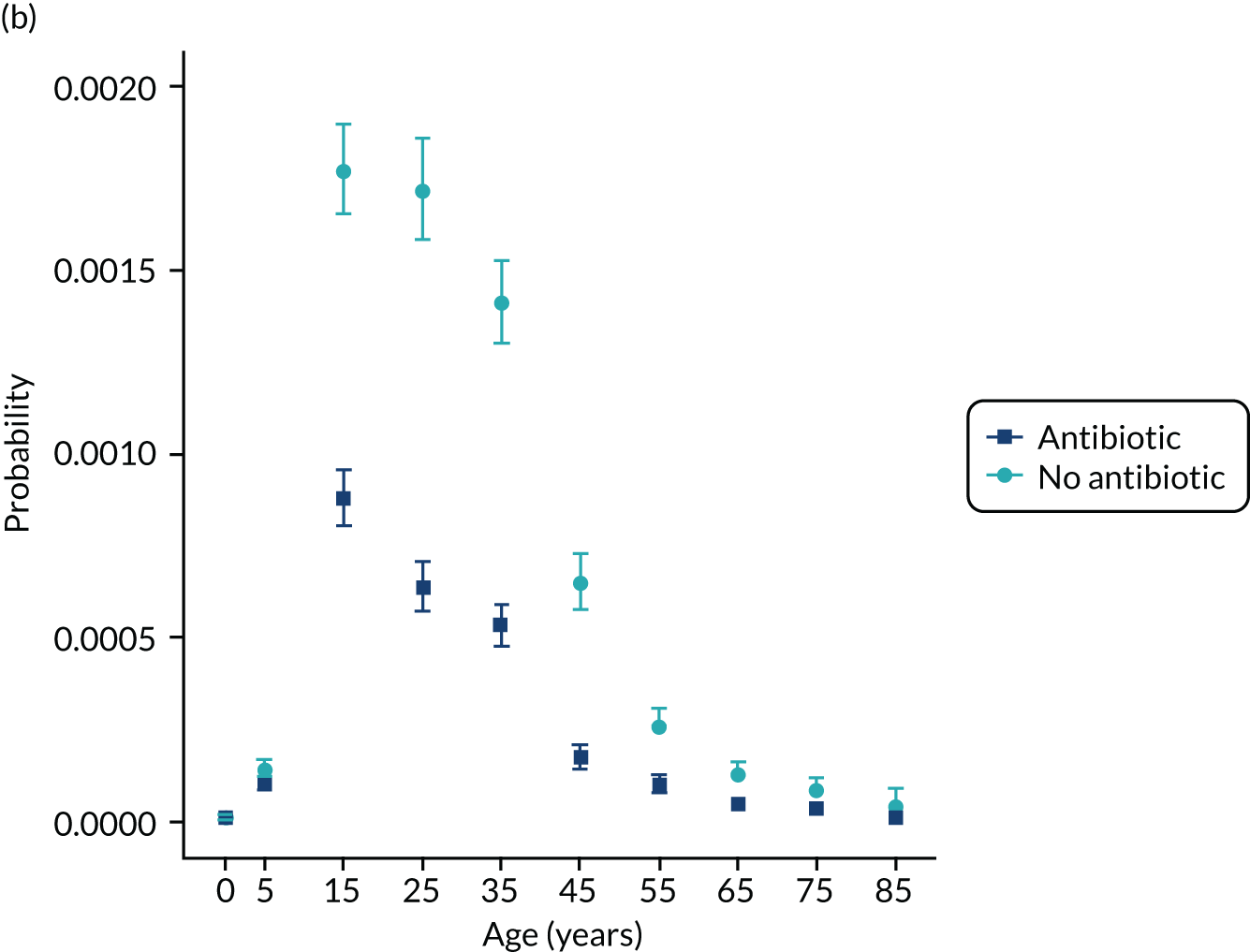

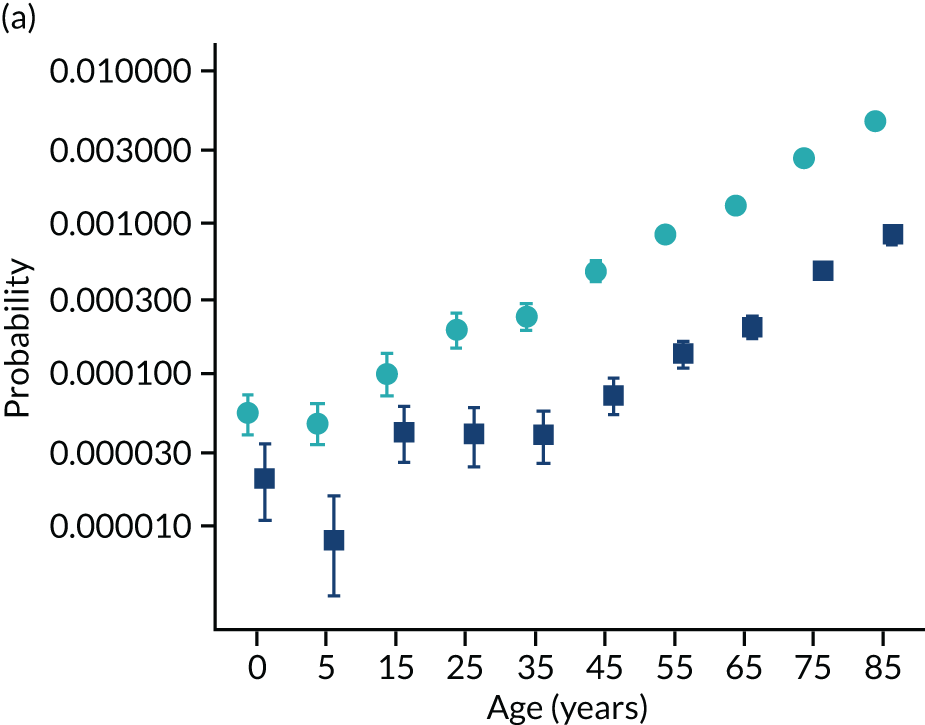

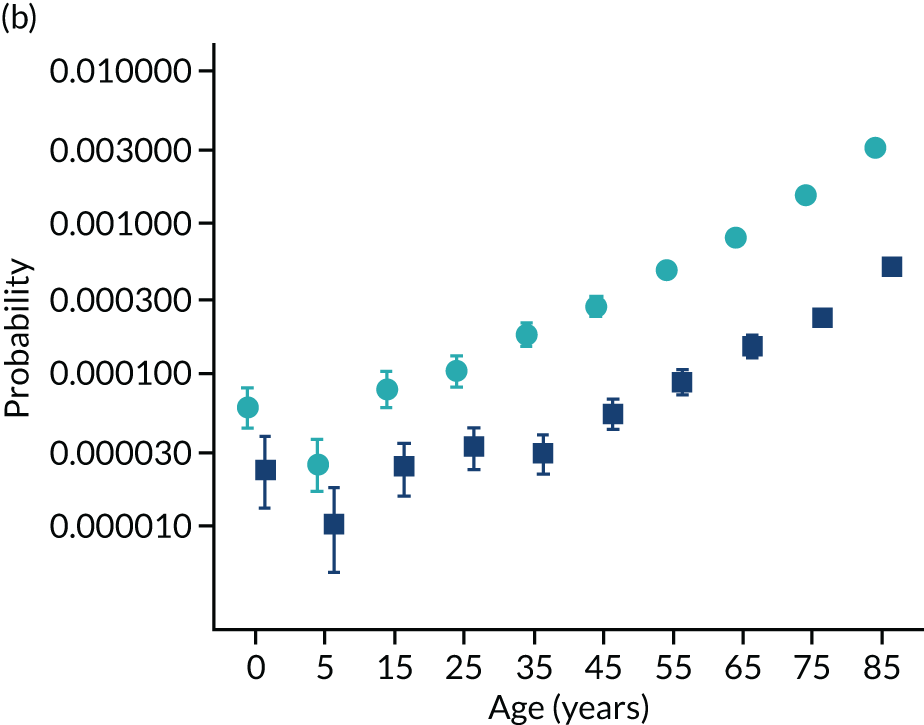

Construct a decision-analysis model to identify, for each safety outcome, risk groups in whom the incidence of the outcome may be highest (and lowest) and to estimate absolute risks of antibiotic prescribing or non-prescribing in these groups.

-

Engage with members of the public, patients and clinicians to understand their views and values in developing candidate indicators of safe antibiotic prescribing reduction and implement these indicators into general practices.

Chapter 3 Methods

Summary

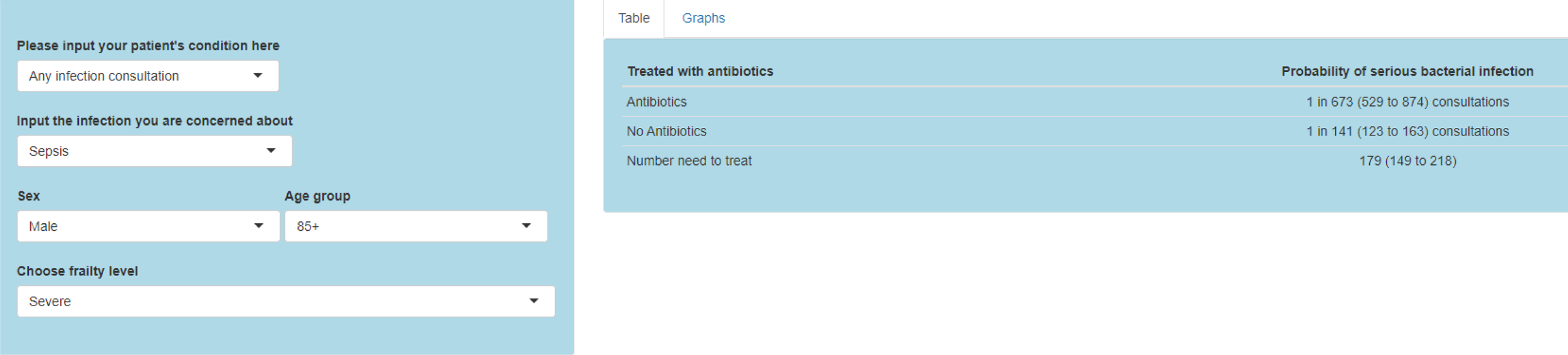

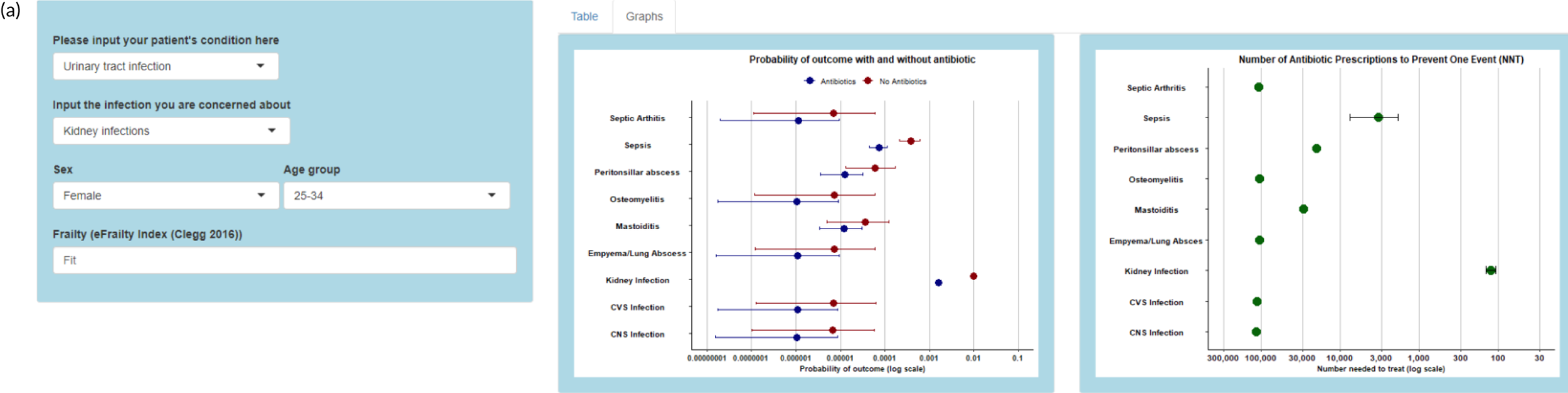

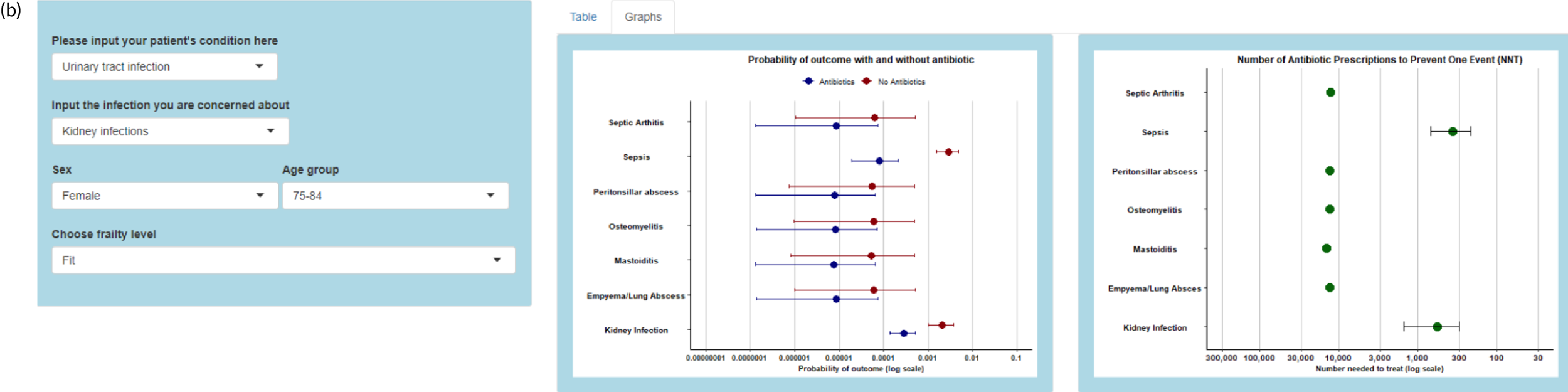

We conducted qualitative interview studies that included 31 patients who had recently consulted with infections in primary care and 30 primary care prescribers, and these informed the research of the perceptions and priorities of these groups. We conducted an epidemiological study, including data from CPRD GOLD (Vision® data) and CPRD Aurum (EMIS® data) to estimate secular trends and between-practice variation in antibiotic use. We also estimated whether or not overall antibiotic utilisation at general practices was associated with the incidence of 11 different serious bacterial infections. Drawing on epidemiological estimates, we developed a decision-analytic model that enabled us to estimate the probability of a serious bacterial infection following an infection consultation in primary care if antibiotics were prescribed or not. We initially developed and tested the mode using PTA as an outcome; we then evaluated the risk of sepsis and we finally evaluated a range of localised serious bacterial infections. We incorporated these modelling estimates into a Shiny application (app) (RStudio, Boston, MA, USA) so that they could be presented to primary care practitioners. We conducted qualitative interviews with practitioners to test the app and evaluate practitioners’ understanding of the estimates presented.

Qualitative research

Ethics statement

The proposal for the qualitative research study was reviewed and approved by the London – Hampstead NHS Research Ethics Committee (reference 18/LO/1874).

Study design

Semistructured interviews were conducted with patients and primary care prescribers, including GPs, nurses and pharmacists, in two English regions (one urban metropolitan area and one shire town with a high demand for primary care services). Metropolitan practices were invited to the study by the local Clinical Research Network that generated the expression of interest. A shire town practice was recruited through informal Clinical Research Network contact, which also helped to liase with potential respondents.

Patient interview study

Semistructured interviews were conducted with patients who consulted their general practice for an infection. Participants were invited to be interviewed if they had recently consulted and been diagnosed by a GP as having a bacterial infection. The bacterial infections were identified using Read codes for the relevant conditions, including RTIs, UTIs and skin infections as the major indications for antibiotic prescribing. An interview guide was developed to reflect expectational structures associated with antibiotics, as well as the experiences of illness and consultations. The items were informed by a review of the literature and included past and current experience of being prescribed antibiotics; knowledge, beliefs and attitudes towards taking antibiotics; and interactions with medical practitioners. The questions were discussed among the research team and piloted with a small number of patients before refining. The items in the topic guide were organised under six main headings (Box 1). All interviews were conducted by an experienced qualitative researcher (OB) to ensure consistent quality. The interviewer had a Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) in medical sociology and was an experienced qualitative researcher. Interviews were conducted in the period February–December 2019. Interviews lasted between 13 and 42 minutes.

To begin with, could you tell me about your recent experience of consulting the GP for infection?

What was the health issue and how it was dealt with? Did you have any expectations of specific treatment? Were you able to discuss them in the consultation? Was the risk associated with different treatment choices communicated and how? How was the issue resolved? Has seeing the doctor helped in infection management?

2. Knowledge of antibioticsOverall, what is your knowledge about different types of infections and associated treatment? Could you share with me what is your understanding of antibiotic treatment? How do the antibiotics work? What types of antibiotics are there? When should antibiotics be prescribed? What are the risks associated with non-prescribing of antibiotics? What are the potential complications and unwanted consequences of antibiotic treatment? Who should be making decision on antibiotic treatment? What was your previous experience of antibiotic treatment, if any? To what extent has your experience shaped your perception of antibiotics at present? Were there any changes in how you consider infections and their treatment? What has driven these changes?

3. Concerns about treatmentWould you say that you felt confident in managing the infection with/without treatment? Were you able to raise your concerns and have all your questions answered during the consultation? Have you experienced any difficulties in complying with the treatment plan?

4. Optimism regarding outcomesAre you hopeful for the antibiotic treatment to be the best possible course of action? If there was an uncertainty and anxiety around the treatment plan, how did you handle it? Have you been able to seize the impact of antibiotic treatment following the recent or previous consultations for infections?

5. Decision-making processesWhat would be your priorities in infection management? In consultations for infections, if a doctor’s advice differed from your interpretation, would you or have you challenged the decision? What would be/what were your actions following unresolved or repeated infection?

6. Social and environmental influencesSpeaking about the appropriate treatment for infections, what are the sources of information that are likely to influence your understanding? In your experience, are doctors consistent in their consultations for infections? What does your friends, family members and close networks believe with respect to antibiotic treatment and how does it compare with your beliefs? What are your perceptions of antimicrobial resistance?

What other information might be useful in making decisions on antibiotics treatment?

Recruitment of participants and data collection

The research invitations to participate generated expressions of interest from the general practices that agreed to purposively select patients who visited a primary care professional for infection in the last 6 months. Patient lists were approved by a GP acting as research gatekeeper in each practice and, initially, 927 patients were sent invitations to the study via the Docmail® postal system (Radstock, UK). The invitations contained a letter from the practice, inviting patients to participate, and an information sheet. Patients who agreed to take part either returned reply slips or contacted the researcher using the contact details provided. The researcher then communicated via e-mail or text message to establish the contact, followed by sending the consent form and confirmation of the interview meeting.

The sample size was determined using the pragmatic concept of ‘information power’,66 which proposes that the size of a sample with sufficient information power depends on the aim of the study, sample specificity, use of established theory, quality of dialogue and analysis strategy. Although our aim was broad, specificity was biased towards one group (almost half of the interviewees were older female patients consulted for UTI); therefore, we followed a theoretical model to explain the findings and the quality of the interviews was relatively high. As we aimed for a cross-case analysis, we decided to continue recruitment until the sample size reached 31 eligible patients.

Analysis

The interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed verbatim by a professional transcriber, imported to an NVivo 12 project (QSR International, Warrington, UK) and coded through an iterative six-phase process described in thematic analysis. 67 Data analysis occurred iteratively and involved familiarisation, coding, theme searching, theme reviewing, theme defining and naming, and producing the report. Repeated patterns in the data formed the basis for the codes, which were identified by the lead analyst (OB), and one single code for every different concept/idea was generated. To ensure that codes were applied consistently, a co-author (CB) independently coded a random sample of four interview transcripts. Coding was refined after discussion. Data identified by the same code were collated and all different codes were sorted into potential subthemes and themes using NVivo options of tree building. The potential themes were reassessed and reorganised to reflect major narratives and themes in the coded data. Finally, the analysts refined and named the five main themes and subthemes. Participants’ feedback on the transcripts or the summarised final findings was not sought because this was not feasible. However, the main themes were discussed at a patient and public involvement (PPI) meeting, as noted in Patient and public involvement.

Practitioner interview study

Interviews

The practitioner study investigated how primary care prescribers perceive risk and safety concerns associated with reduced antibiotic prescribing. Items for the interview were guided by the theoretical domains framework (TDF), which uses theories of behaviour change to understand factors influencing health-care practice. 68,69 The TDF comprises 14 domains, covering the main theoretical determinants of behaviour, and the interview was designed to reflect these domains (Box 2). 68 The interview was piloted with three GPs to ensure that the questions were appropriate, readily understood and covered relevant prescribing behaviours. All interviews were conducted by Olga Boiko to ensure consistent quality. All interviews except one telephone interview were conducted face to face on general practice (n = 26) and university (n = 4) premises in the period January–July 2019. The interviews lasted between 24 and 46 minutes. The participants were offered £60 to acknowledge their contribution.

What are the indications for antibiotic treatment?

To what extent do NICE (or local) guidelines influence your antibiotic prescribing?

What are the risks of antibiotic prescribing and non-prescribing?

How do you differentiate between infections and patients?

What are the common myths or stereotypes about antibiotics?

Can you give me an example that illustrates the inaccurate understanding of their purpose, mechanisms of action, risks and consequences?

In your view, is there the best way to elicit and manage patient expectations regarding antibiotics?

How would you communicate the risks associated with both prescribing and non-prescribing antibiotics?

How confident are you in decision-making around antibiotic prescribing?

Would you assess your approach to antibiotic prescribing as always adequate and, if so, what makes you think that?

Could you describe consequences of inappropriate treatment for infections?

What would be/what were your actions following unresolved or repeated infections?

What is your understanding of antimicrobial resistance?

What are your goals and priorities in infection management?

Are there any social norms or group pressures that affect your professional practice with regard to antibiotic prescribing and how?

Has your prescribing practice for antibiotics changed over the recent years?

Do you think patient expectations of antibiotic treatment have changed over the recent years?

Are you aware of the prescribing practice of other health-care professionals (your colleagues) in relation to antibiotics? Have you ever had to challenge their prescribing decisions?

Has anyone challenged your own decisions?

How hopeful are you usually that the antibiotic treatment is the best course of action?

Is it possible to assess both the short- and long-term impact of antibiotic treatment on the patients?

What is your decision-making strategy?

How anxious do you feel about the uncertainty around prescribing?

Which resources do you use to support your decisions on antibiotic prescribing?

Recruitment of participants

Contact details of primary care practitioners were obtained through the help of the local research facilitators and practice managers. Potential participants were then approached either directly by e-mail using the study information pack or indirectly via the practice manager or lead GP. The information pack included the invitation letter and study information sheet. A reminder was sent out 2 weeks after the initial approach to those who had not responded. A purposive sampling approach was followed. Forty-nine primary care providers from 10 general practices were invited and 30 agreed to take part. This number of participants was deemed sufficient, using the pragmatic concept of ‘information power’. 66 The uptake varied between practices (in five practices only a single primary care practitioner was interviewed). Interviews took place between January 2019 and July 2019.

Analysis

The interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed by a professional transcriber, imported to an NVivo 12 project and coded through an iterative six-phase process, as outlined above. 67 Repeated patterns in the data formed the basis for the codes, identified by the first author (OB), and one single code for every different concept/idea was generated. To ensure that codes were applied consistently, a co-author (CB) independently coded a random sample of four interview transcripts. Coding was refined after discussion. Data identified by the same code were collated and all different codes were sorted into potential subthemes and themes using NVivo options of tree building. Next, the potential themes were reassessed and reorganised to reflect major narratives and themes in the coded data. Finally, the themes and subthemes were refined and named (by OB, CB and MCG). The themes and subthemes were then mapped to the relevant domains of the TDF to assess the relative importance and salience of individual domains.

Epidemiological study

Ethics statement

The protocol for the epidemiological study was approved by the CPRD Independent Scientific Advisory Committee (protocols 18-041R and 19_110R). The CPRD holds overarching Multicentre Research Ethics Committee approval for the database and conduct of studies using fully anonymised data.

Data source

We carried out population-based cohort studies in the UK CPRD GOLD database, employing data for 2002–17. CPRD GOLD draws on general practices that use the Vision general practice software system. The Vision system has suffered from a declining market share in recent years. Consequently, CPRD has established the CPRD Aurum database, which draws data from general practices that use the EMIS general practice system.

The CPRD GOLD database collects data from the four countries of the UK, with about 30% of contributing practices located in England at the time of this study. The CPRD GOLD database has been well described70 and the high quality of the data collected has been documented in many studies. 71 CPRD records include details of consultations by general practice staff, as well as coded records of referrals to hospital or discharge letters from hospitals. The CPRD GOLD is a ‘live’ database, which is updated monthly. The October 2019 database release included data on 17.6 million patients, of whom 2.6 million were currently active. There were 320 general practices currently contributing to CPRD GOLD: 30% in England, 3% in Northern Ireland, 37% in Scotland and 30% in Wales. Data linkage in CPRD GOLD is restricted to volunteer general practices in England only. The CPRD Aurum database was more recently established and, at the time of this study (June 2019 release), was restricted to data collected from general practices in England. 72 The CPRD Aurum database included data on 883 general practices, from which patients were sampled, with 23.1 million patients, including 2.5 million currently active patients. This study was designed using the CPRD GOLD database. However, we conducted a substudy to compare antibiotic prescribing metrics between CPRD GOLD and CPRD Aurum.

The research aimed to evaluate safety outcomes of reduced antibiotic prescribing, including conditions such as sepsis, PTA and infective endocarditis. These are infrequent or rare events. Consequently, it was necessary to evaluate outcomes over a long period of time in the whole CPRD database to obtain sufficiently precise estimates of incidence rates. The period from 2002 to 2017 was selected for study. However, our licence agreement with CPRD places limits on the number of records that can be extracted for analysis. We were able to extract full CPRD data for the numerator, but for the denominator we were restricted to data included in the CPRD GOLD denominator file, which comprised age (year of birth), gender and study year. To address this, we employed sample data for the study denominator, as outlined below.

The research was further complicated by possible changes over time in the definition and recognition of outcomes. For example, definitions of sepsis have changed over time, and there have been substantial changes in professional and public awareness of sepsis as a complication of infection. There have also been changes in approach to antibiotic prescribing and antimicrobial stewardship during the period of study. This required analytical approaches that accounted for changes over time in key exposures or the incidence of outcomes.

As noted above, the CPRD GOLD is a ‘live’ database that is updated each month. The ‘last collection date’ for each general practice is updated for each release, as are the dates of death and the end of registration for each participant. In addition, the ‘up-to-standard’ date at which the general practice is judged to have been contributing research-quality data may be updated, even for historical data, based on an algorithm employed by CPRD. Patients have the possibility of ‘opting out’ of CPRD and the small number of opting-out patients may change over time. The present research was conducted over several years in the form of a series of related studies. The research is, therefore, based on data from several different releases of CPRD GOLD. In addition, we made ongoing revisions and updates to our medical code lists to enable updating consistent with our evolving understanding of conditions relevant for study. Consequently, the number of outcome events and person-years at risk may vary slightly when different analyses are compared, although relevant findings are expected to be consistent across different releases.

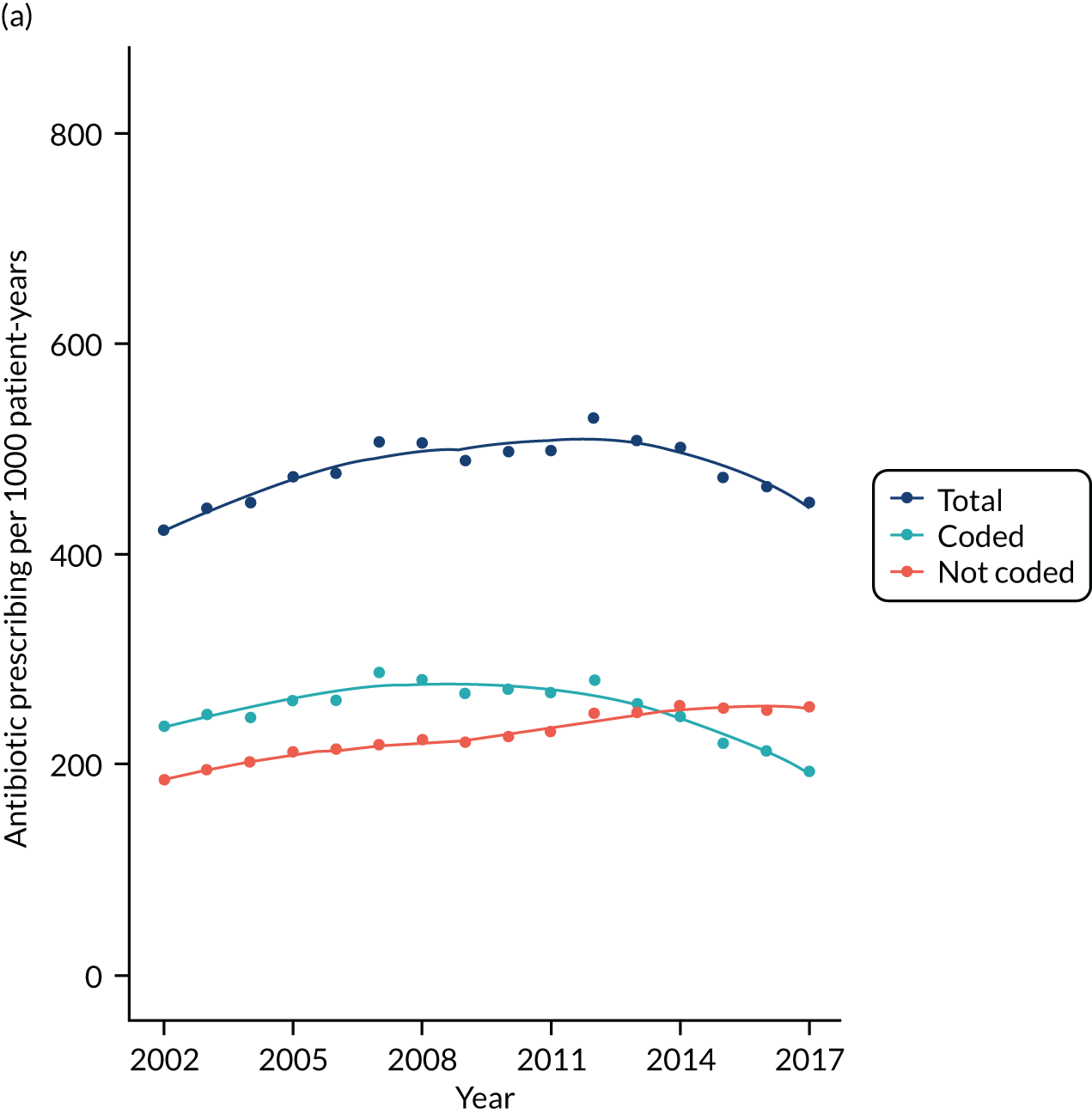

Antibiotic prescribing study

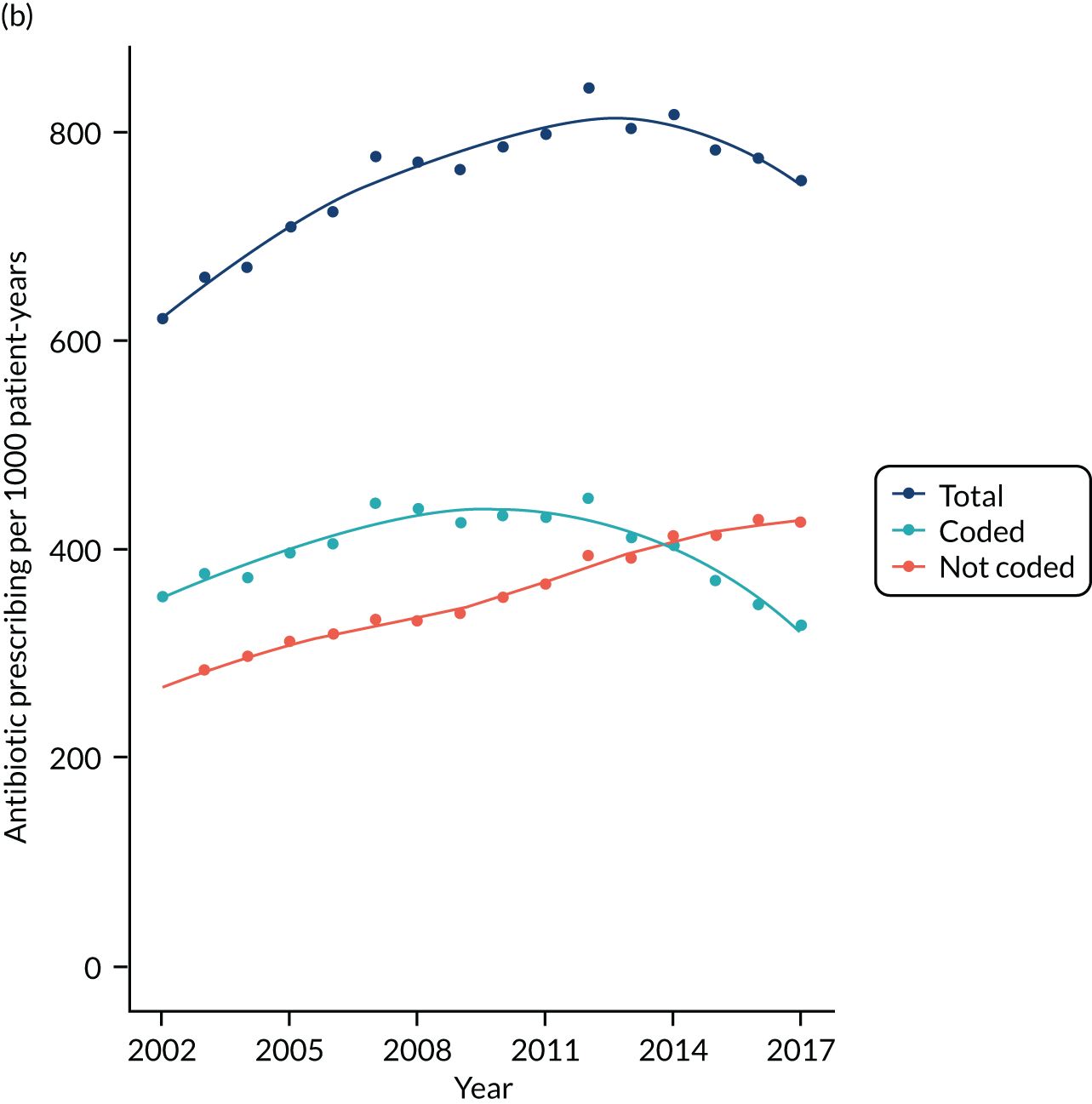

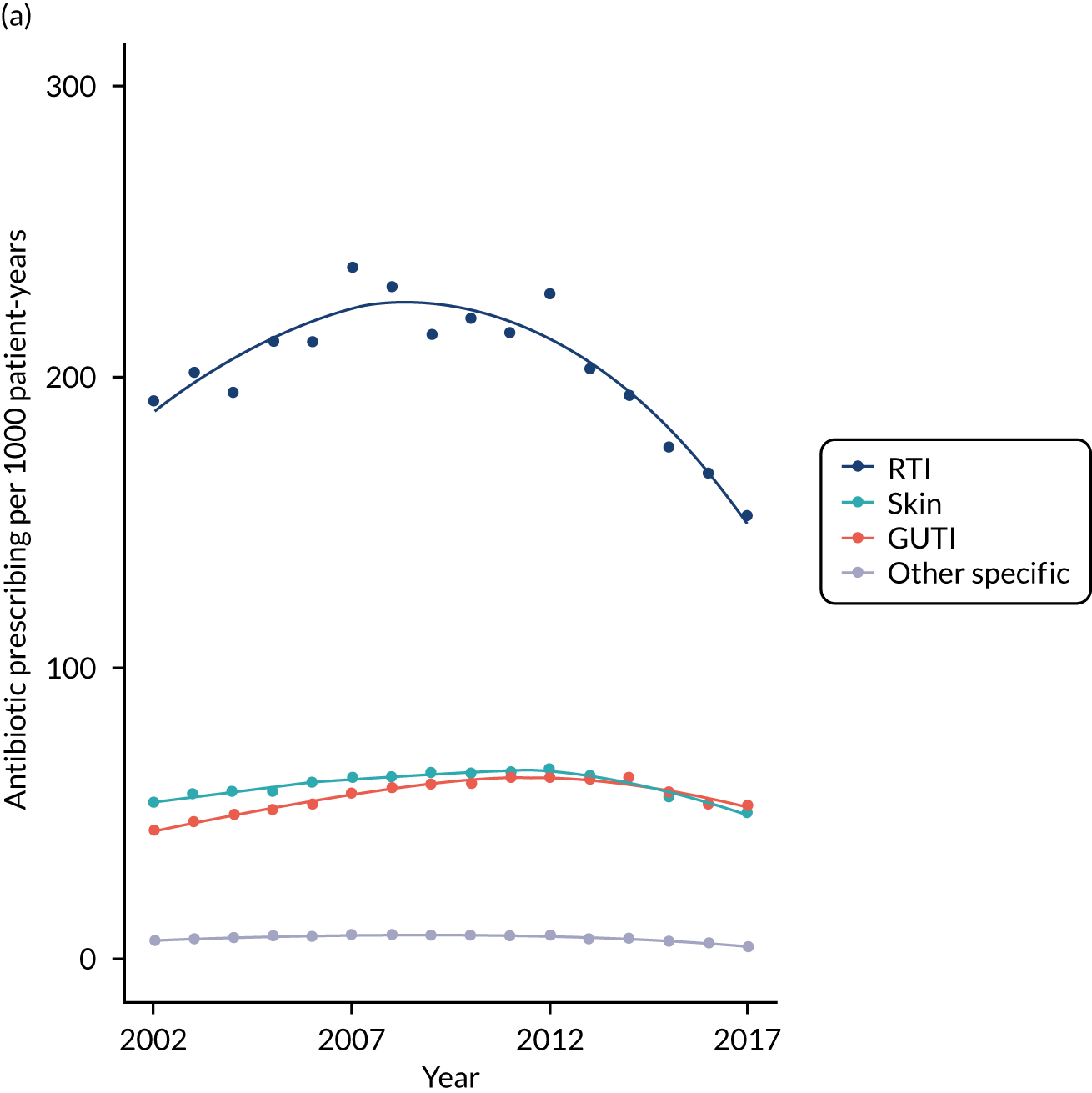

We evaluated rates for antibiotic prescription and infection consultations in the CPRD GOLD database between 2002 and 2017.

Selection of sample for antibiotic prescribing analysis

We estimated the infection consultation rates and the proportion of consultations with antibiotics prescribed from a sample of patients registered with CPRD GOLD. This was because it is not feasible to download and analyse data for the millions of records represented by all infection consultations and antibiotic prescriptions over 16 years. 39 A random sample of patients was drawn from the list of all registered patients from the November 2018 release of CPRD GOLD and was stratified by year between 2002 and 2017 and by general practice. The ‘sample’ command in the R program (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) was employed to provide a computer-generated random sequence. In each year of study, a sample of 10 patients was taken for each gender and age group, using 5-year age groups up to a maximum of 104 years. Each sampled patient contributed data for multiple years of follow-up. There was a total sample of 671,830 individual patients registered at 706 general practices who contributed person-time between 2002 and 2017. The sampling design enabled estimation of all age-specific rates with similar precision, while age standardisation provided weightings across age groups.

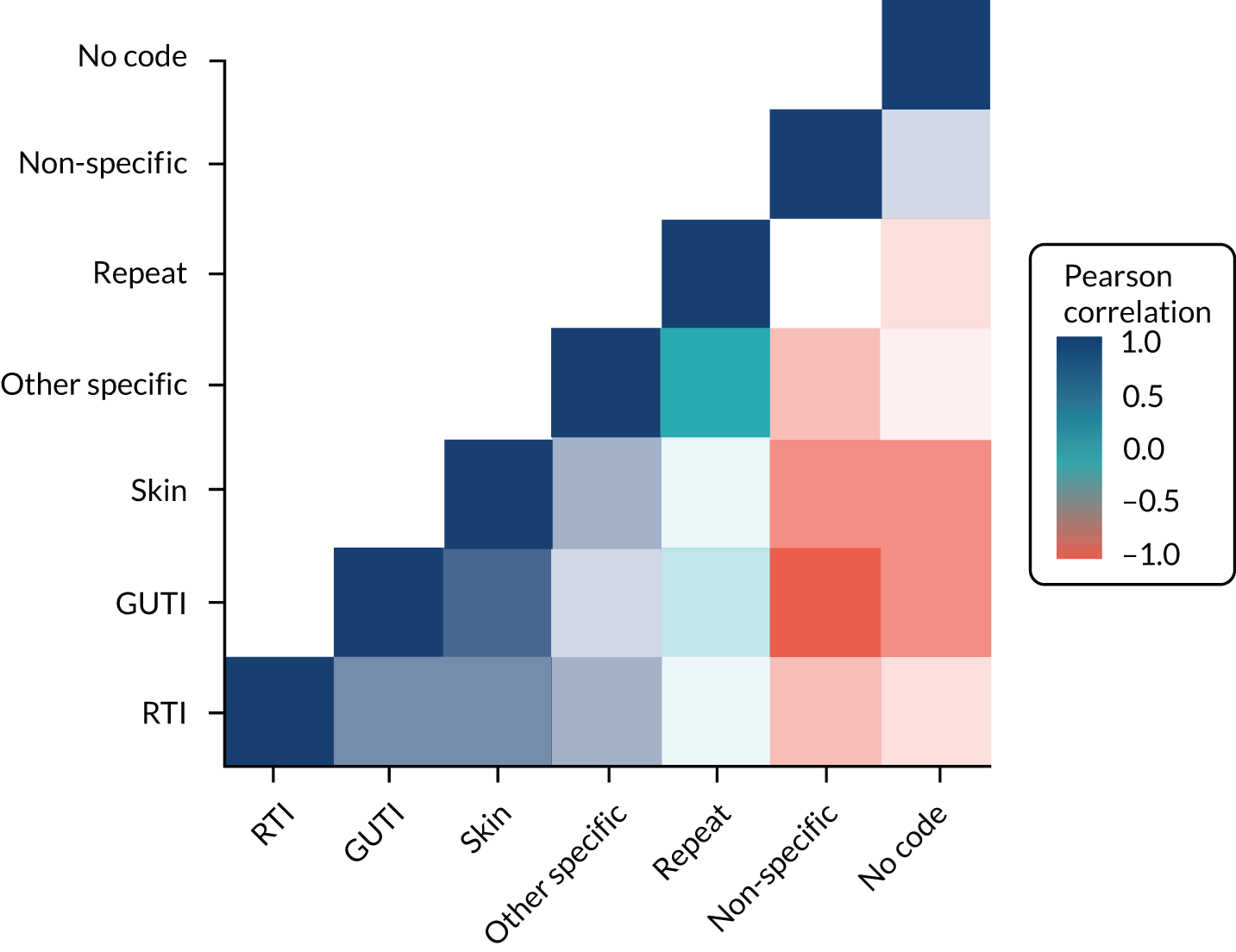

Main measures for antibiotic prescribing

Antibiotic prescriptions were evaluated using product codes for antibiotics that are listed in section 5.1 of the British National Formulary (BNF),73 excluding methenamine and drugs for tuberculosis and leprosy (see Report Supplementary Material 1 and 2). Different antibiotic classes and antibiotic doses were not considered further in this analysis. Multiple antibiotic prescription records on the same day were considered as a single antibiotic prescription. Medical codes recorded on the same date as the antibiotic prescription were used to classify the indication for prescription using categories of ‘respiratory’, ‘genitourinary’, ‘skin’ and ‘other specific’ indications (see Report Supplementary Material 1 and 2). All other codes were classified as ‘non-specific’ codes. A prescription was classified as ‘acute’ if it was the first prescription in a sequence or ‘repeat’ prescription otherwise, as reported previously. 10 Antibiotic prescriptions that were not associated with medical codes and were not repeat prescriptions were classified as ‘no codes recorded’.

For each participant in the antibiotic prescribing sample, we calculated the person-time at risk between the start and the end of the patient’s record. Person-time was grouped by gender, age group and comorbidity. Age groups were from 0 to 4 years, 5 to 9 years and 10 to 14 years, and then 10-year age groups up to ≥ 85 years. Comorbidity was evaluated as either present or absent in each person-year using the ‘seasonal flu at-risk codes’, which are used to identify individuals at higher risk of infection who may benefit from an influenza vaccination,74 as reported previously. 10 Seasonal flu at-risk Read codes include medical diagnostic codes for overweight and obesity, coronary heart disease, chronic kidney disease, chronic liver disease, chronic neurological disease, chronic respiratory disease, diabetes mellitus and disorders of the immune system, as well as drug product codes for asthma therapy, corticosteroid drugs and immunosuppressive drugs. Conditions were coded as present if they were ever diagnosed up to the end of the study year. Collectively, these provide a summary measure of potential susceptibility to infection complications.

Statistical analysis

In this stage of the analysis, we estimated general practice-specific estimates for antibiotic prescribing. We analysed antibiotic prescribing in primary care between 2002 and 2017. A hierarchical Poisson model was fitted using the ‘hglm’ package in the R program, with counts of antibiotic prescriptions as the outcome and the log of person-time as the offset (Equation 1):

Estimates were adjusted for the fixed effects of gender, age group, fifth of deprivation at the general practice level, comorbidity and region in the UK. Calendar year was included as a continuous predictor, together with quadratic and cubic terms to allow for non-linear trends. Random intercepts were estimated for each general practice and each estimate represented the adjusted log relative rate for antibiotic prescribing at that practice compared with the overall mean. The proportion of antibiotic prescriptions that were associated with specific medical codes was analysed in a similar framework, with coded prescriptions as the outcome and the log of antibiotic prescriptions as the offset. General practice-specific estimates for antibiotic prescription and infection consultation coding were, therefore, adjusted for calendar year, age group, gender, comorbidity, deprivation and region.

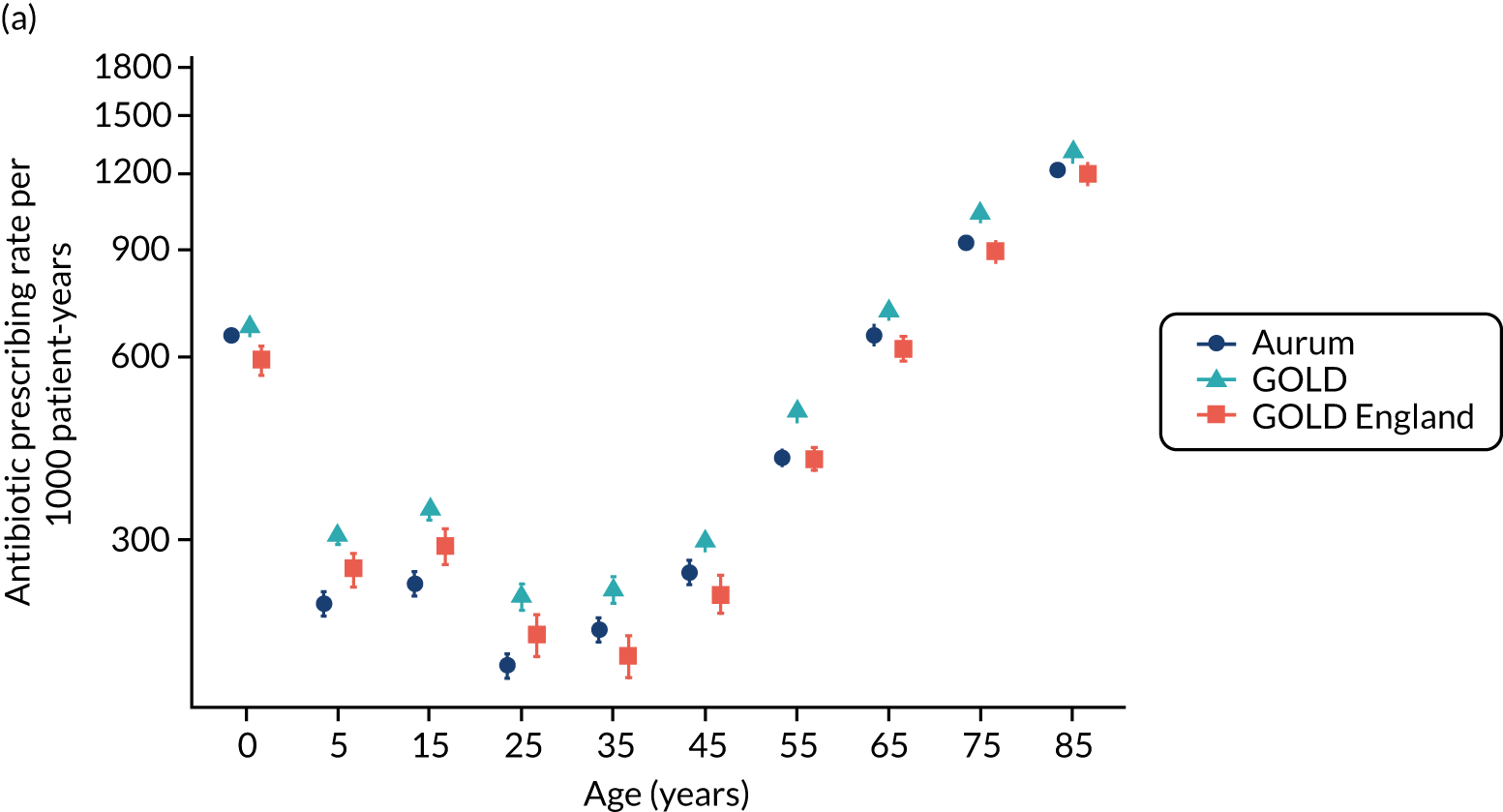

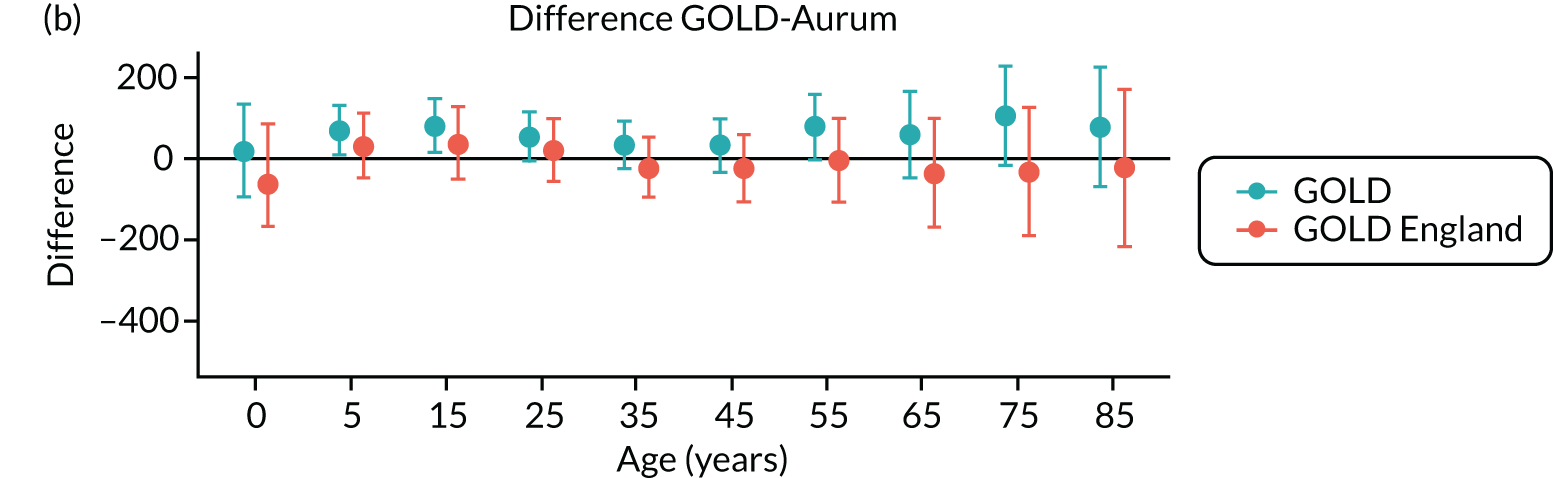

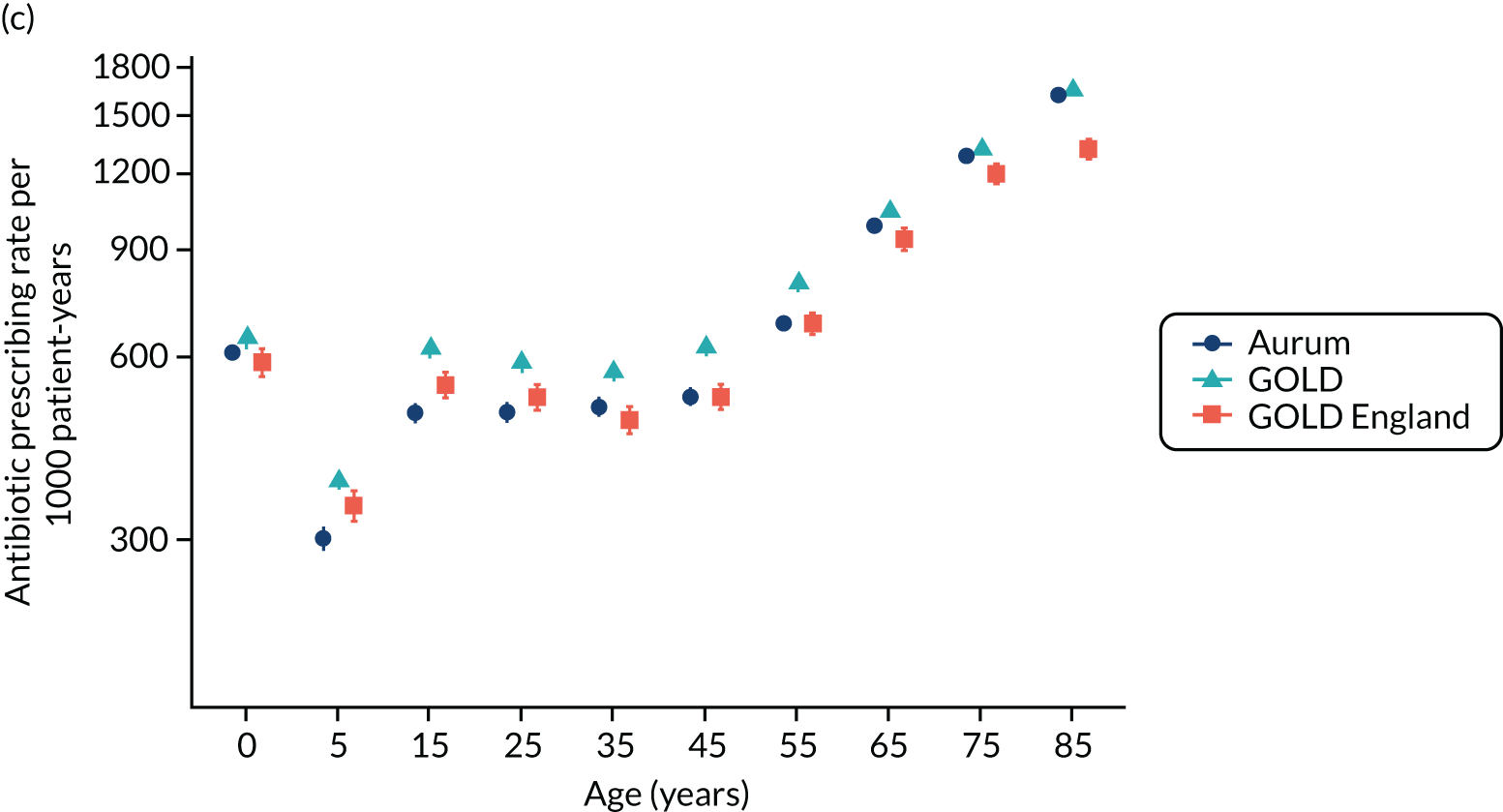

Comparison of antibiotic prescribing in Clinical Practice Research Datalink GOLD and Clinical Practice Research Datalink Aurum

To evaluate the transferability of our findings with respect to antibiotic prescribing between general practices using the Vision and EMIS practice systems, we conducted a substudy to compare estimates using sample data from the CPRD GOLD and CPRD Aurum databases. We evaluated antibiotic prescribing for the year 2017, as this was the most recent complete year for our study. 39

Data and participants

A sample of patients was drawn from the population of all patients registered in the CPRD Aurum database (June 2019 release) throughout 2017 by randomly selecting ‘n’ patients from each stratum of general practice, gender and age group. The value of n = 9 was selected to provide a total sample size of 158,305 patients. This sampling approach ensured that each general practice was equally represented in the analysis and that age-specific rates would be estimated with equal precision. Age was calculated as the difference between year of birth and 2017. Age groups were categorised as 0–4, 5–14, 15–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, 55–64, 65–74, 75–84 and ≥ 85 years. A comparison cohort of patients was extracted from the October 2019 release of CPRD GOLD using the online interface. In this release, there were 290 general practices contributing data to CPRD GOLD throughout 2017, including 112 in England. A sample of 160,394 patients was taken by randomly selecting 30 patients from each stratum of general practice, gender and age group. Patients were required to have at least 12 months of follow-up in the database, estimated as the difference between the latest of their registration start date and 1 January 2017, and the earliest of registration end, practice last collection date, CPRD derived death date and 31 December 2017. General practices that migrated from Vision to EMIS practice systems during 2017 were excluded.

Measures

We identified all antibiotic prescriptions issued in 2017, including all drugs from section 5.1 of the BNF,73 except antituberculous agents, antilepromatous agents and methenamine. The BNF includes the following categories of antibiotics: penicillins, cephalosporins (including carbapenems), tetracyclines, aminoglycosides, macrolides, clindamycin, sulfonamides (including combinations with trimethoprim), metronidazole and tinidazole, quinolones, drugs for UTI (nitrofurantoin) and other antibiotics. For CPRD GOLD, we employed a list of 2627 antibiotic drugs that were identified from searches of the CPRD GOLD product dictionary browser. Searches were made on the drug substance name, product name, BNF chapter and BNF codes. To identify the corresponding products in CPRD Aurum, dm+d codes (i.e. the prescribing codes from the NHS dictionary of medicines and devices75) associated with individual product codes in the CPRD GOLD dictionary browser were mapped to the corresponding dm+d codes in the CPRD Aurum product dictionary browser. A more complete search of the CPRD Aurum product dictionary browser was additionally undertaken on term, product name and drug substance. We also conducted searches using approximate string matching (‘fuzzy matching’) to match the CPRD Aurum product name to the CPRD GOLD product name or drug substance name from the CPRD GOLD antibiotic code list. The ‘agrep’ command was used in the R program, using the Levenshtein edit distance as a measure of approximateness. The resulting code list was edited manually, resulting in 896 CPRD Aurum product codes. CPRD Aurum product codes are up to 17 characters in length and the ‘bit64’ package in R was employed for data formatting and management. Although more product codes were identified for the CPRD GOLD database, only 195 CPRD GOLD product codes for antibiotics and 167 CPRD Aurum product codes were recorded in 2017.

We analysed medical codes recorded on the same date as antibiotic prescriptions. Medical diagnoses were identified by searching the CPRD GOLD medical dictionary browser for Read terms and inspecting the associated Read chapter hierarchy. As previously reported, all medical codes were subsequently classified as respiratory infections, genitourinary infections, skin infections, eye infections and ‘other codes’. 10 The CPRD Aurum medical dictionary includes Read terms, Read codes and SNOMED codes. To utilise the same codes, lists developed for CPRD GOLD were subsequently mapped to CPRD Aurum by matching Read codes. Evidence of infections was searched in the patient clinical and referral records in CPRD GOLD and in the observation tables in CPRD Aurum. We evaluated whether or not any medical code was recorded on the same date as an antibiotic prescription. We then classified medical codes into ‘respiratory infections’, ‘skin infections’, ‘genitourinary infections’ and ‘other codes’.

Analysis

Age-specific rates were estimated with 95% CIs from the Poisson distribution. Age- and sex-standardised rates, and associated 95% CIs, were calculated per 1000 person-years using the 2013 European Standard Population as reference. Estimates and 95% CIs were estimated to judge whether or not differences between the databases were of clinical or epidemiological importance. Potential differences between databases were evaluated using Bland–Altman plots and 95% CIs. 76 CPRD GOLD general practices in England were analysed as a subgroup.

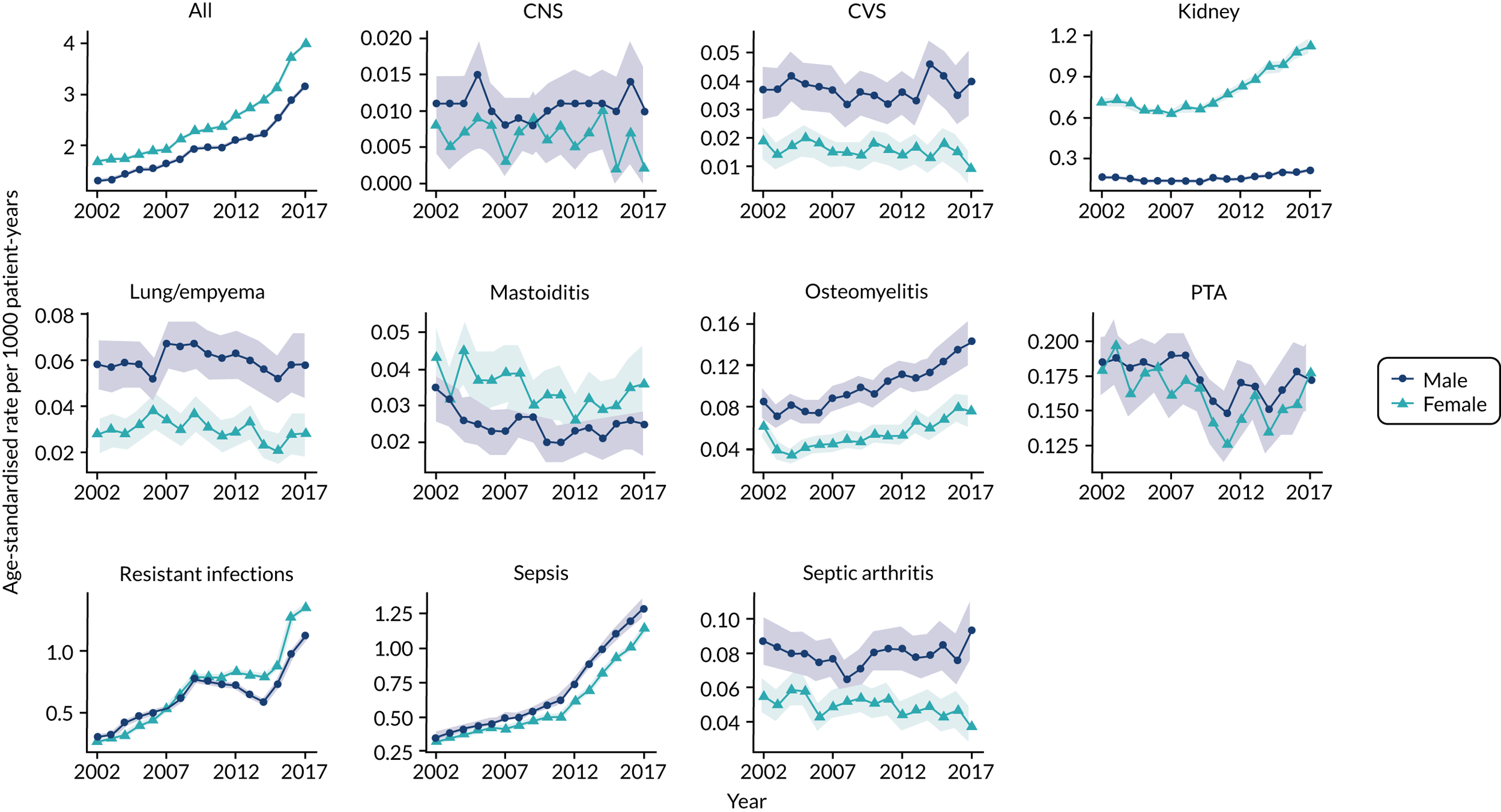

General practice-level analysis of serious bacterial infections

Incident cases of serious bacterial infection were evaluated in the January 2019 release of CPRD for the years 2002–17, with the CPRD denominator providing the person-time at risk. The mean duration of follow-up was 6.9 years. Serious bacterial infections were selected for study from review of the International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision (ICD-10),77 from the Read code classification78 and through discussion with the research team. The final list of conditions is summarised in Table 2 and includes bacterial infections of the central nervous system (CNS), bacterial infections of the cardiovascular system (CVS), kidney infections, lung abscess and empyema, mastoiditis, osteomyelitis, PTA, resistant infections and Clostridium difficile (C. difficile), sepsis and septic arthritis. Further details of case definitions are provided in Report Supplementary Material 1 and 2. Incident events were the first record for each type of serious bacterial infection in a patient > 12 months after the start of the patient record. However, a single patient might have first episodes of more than one type of bacterial infection. Possible recurrent events in the same patient were not evaluated further because, in electronic health records, it may not be possible to distinguish new occurrences from reference to ongoing or previous problems.

| Group | Number of codes | Number of first events | Five most frequent conditions (number of first events 2002–17) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CNS infection | 30 | 576 | Epidural abscess (117), cerebral abscess (112), brain abscess (79), intraspinal abscess (49) and drainage of abscess of subdural space (44) |

| CVS infection | 24 | 1697 | Acute and subacute endocarditis (594), bacterial endocarditis (276), subacute bacterial endocarditis (270), acute endocarditis NOS (166) and acute bacterial endocarditis (114) |

| Kidney infection | 22 | 30,827 | Acute pyelonephritis (19,284), pyelonephritis unspecified (7115), infections of the kidney (1670), acute pyelitis (1008) and pyelitis unspecified (745) |

| Lung abscess/empyema | 24 | 2932 | Empyema (2314), abscess of lung (149), abscess of lung and mediastinum (139), thorax abscess NOS (68) and pleural empyema (56) |

| Mastoiditis | 10 | 1970 | Mastoiditis and related conditions (1293), mastoiditis NOS (487), acute mastoiditis (146), acute mastoiditis NOS (31) and abscess of mastoid (27) |

| Osteomyelitis | 65 | 4921 | Acute osteomyelitis (3297), unspecified osteomyelitis (678), unspecified osteomyelitis of unspecified site (284), osteomyelitis jaw (78) and unspecified osteomyelitis NOS (75) |

| PTA | 6 | 11,338 | Quinsy (8611), PTA – quinsy (1748), O/E quinsy present (654), drainage of PTA (232) and drainage of quinsy (226) |

| Resistant infections and C. difficile | 31 | 42,185 | C. difficile toxin detection (20,175), meticillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus positive (9914), C. difficile infection (6397), meticillin-resistant S. aureus (4303) and meticillin-resistant S. aureus carrier (1017) |

| Sepsis | 100 | 39,059 | Sepsis (23,149), septicaemia (6204), urosepsis (4646), biliary sepsis (1233) and Clostridium infection (576) |

| Septic arthritis | 41 | 4254 | Septic arthritis (3649), pyogenic arthritis (184), arthropathy associated with infections (172), knee pyogenic arthritis (52) and staphylococcal arthritis and polyarthritis (39) |

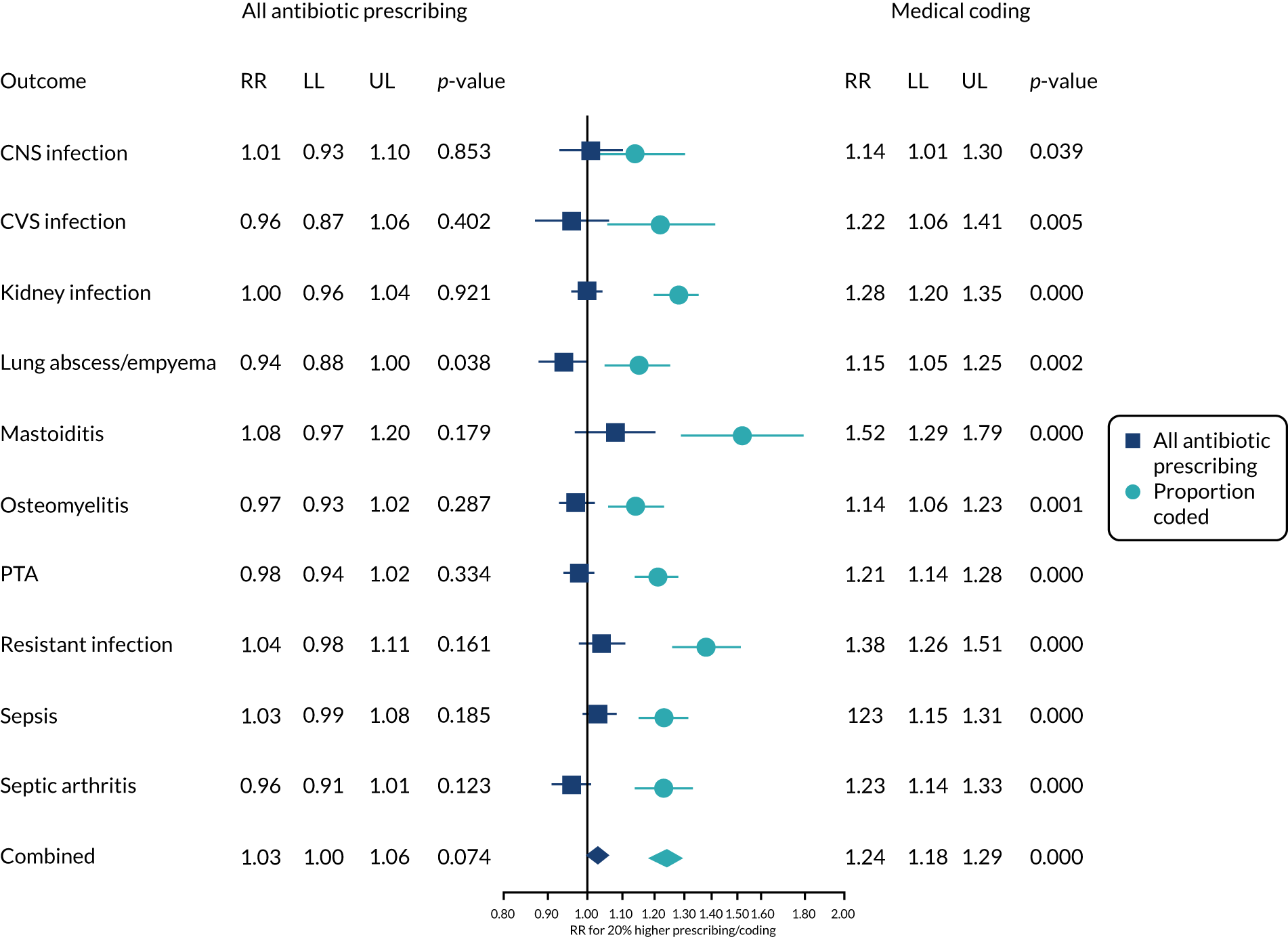

Serious bacterial infections were analysed as the outcome (Equation 2):

The antibiotic prescribing level for each general practice was included as a predictor using the general practice-specific estimates from Equation 1. These estimates initially had a mean of zero and a standard deviation of 0.19, which is consistent with an adjusted relative rate of antibiotic prescribing of 1.21 for a general practice prescribing 1 standard deviation above the mean. Estimates were, therefore, standardised to give the change in serious bacterial infection for a 20% relative increase in antibiotic prescribing rate at a practice, as this represents a change of approximately 1 standard deviation. A 20% change generally represents a substantial change in antibiotic prescribing. We also estimated the change in serious bacterial infection for a 20% relative increase in the proportion of antibiotic prescriptions, with specific medical codes recorded at a general practice. Models were adjusted for age group, gender, region, deprivation fifth and calendar year (including quadratic and cubic terms for calendar year), with the log of person-time as offset (see Equation 2). The results were visualised using forest plots.

Sample size considerations

At the design stage, we envisaged that there might be 68 million person-years of follow-up divided into four quartiles. The incidence of outcomes might be < 1 per 100,000 per year for intracranial abscess. 23 Comparing the lowest with the highest quartiles, there would be 80% power to detect relative risks of 0.71 for the rare outcome of intracranial abscess, with higher relative risks detectable for more frequent outcomes.

Modelling study

Decision tree

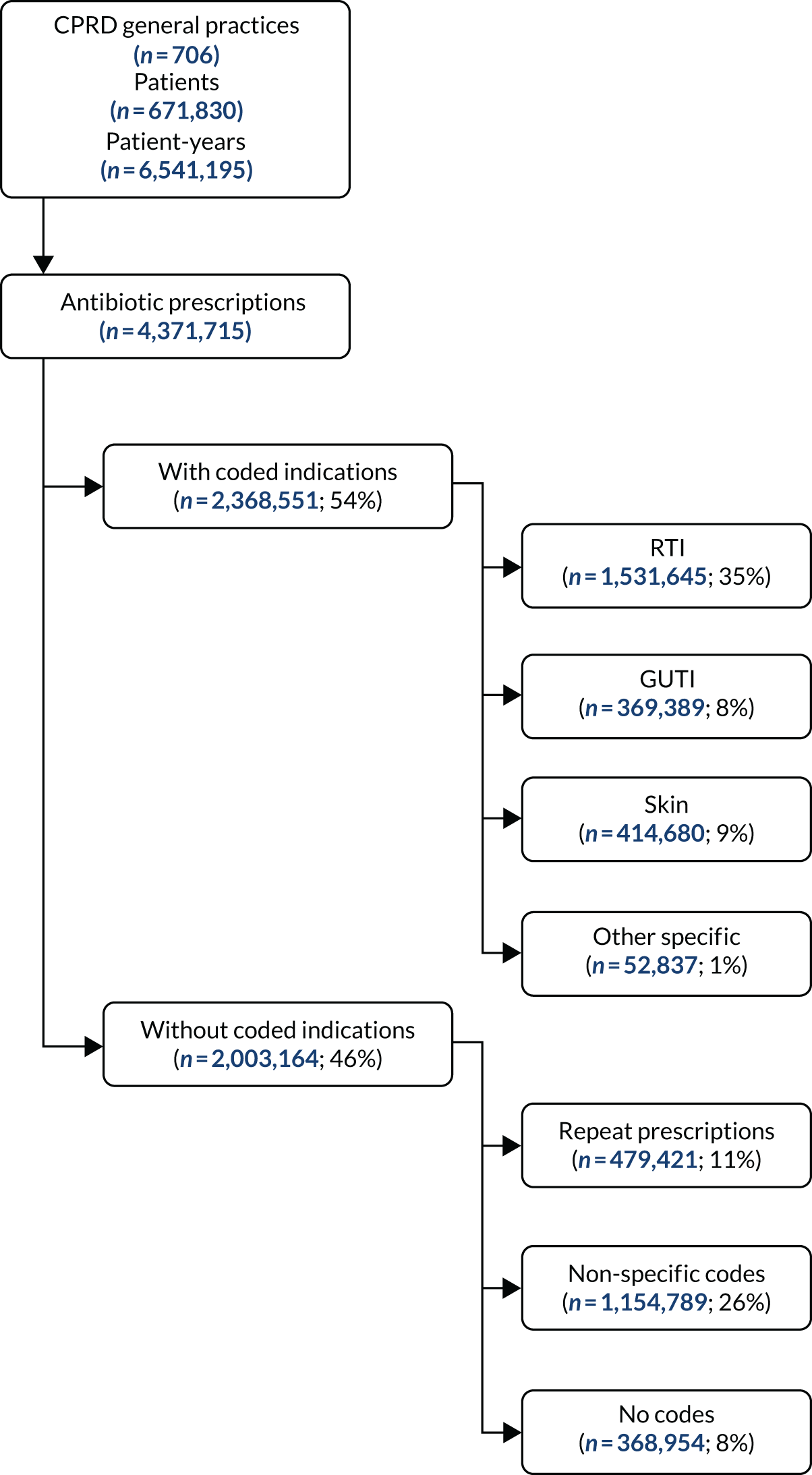

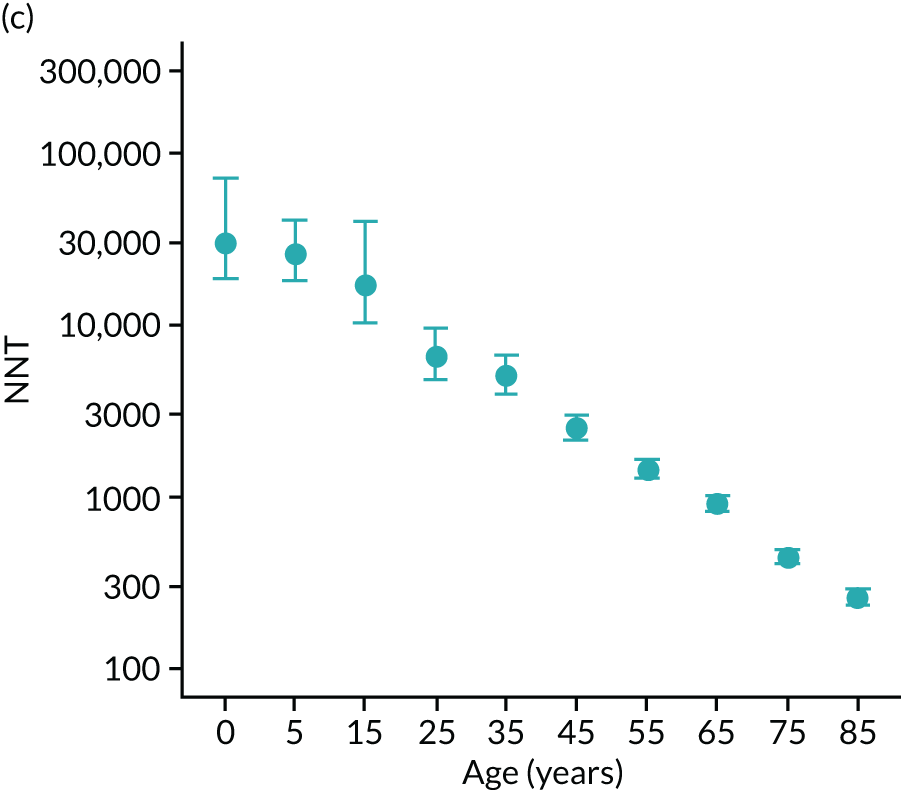

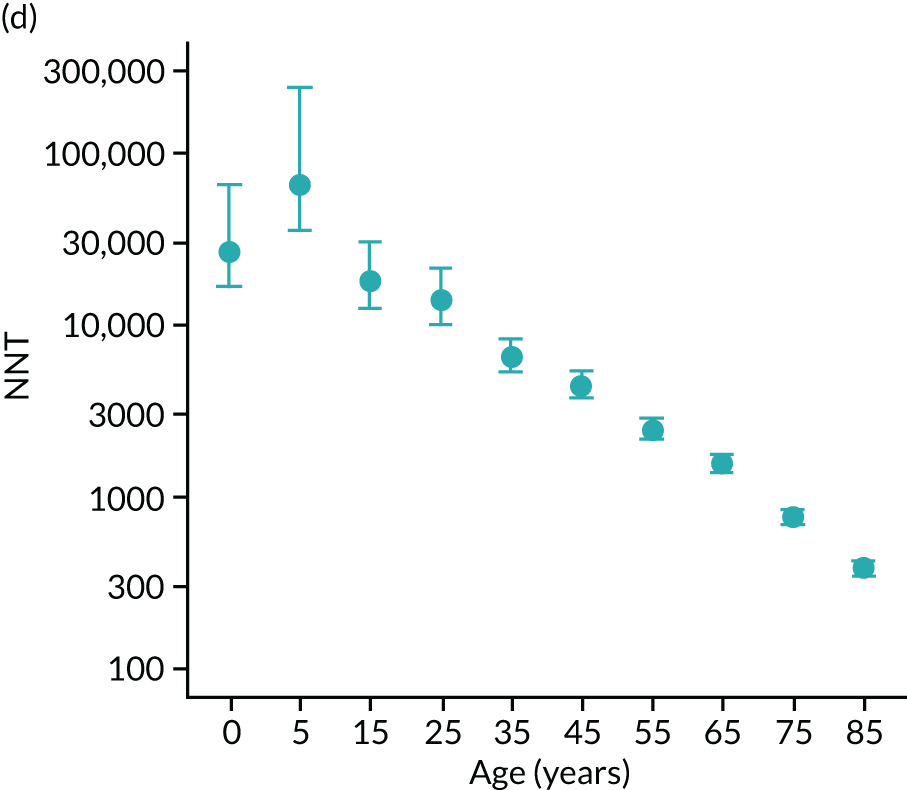

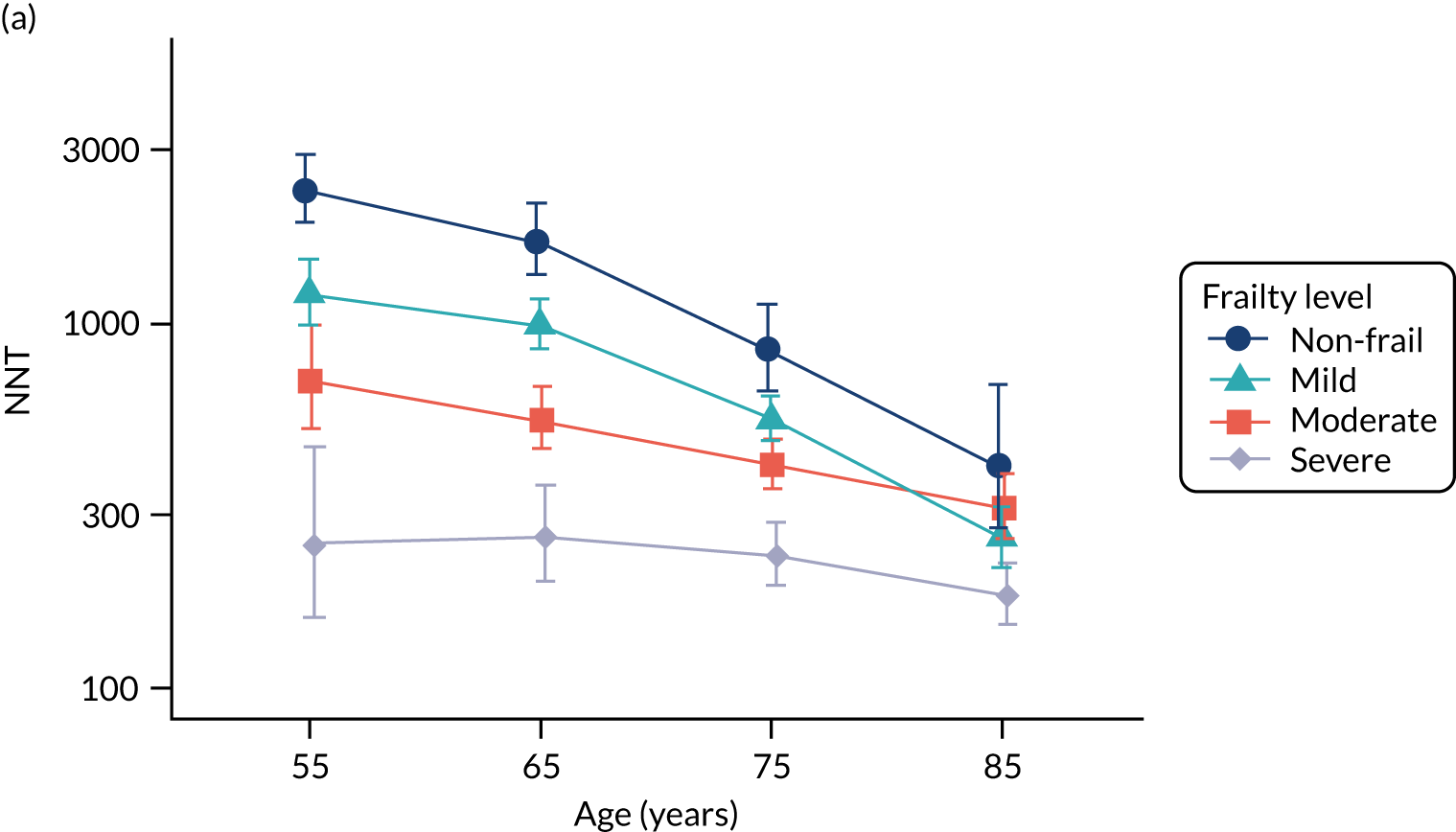

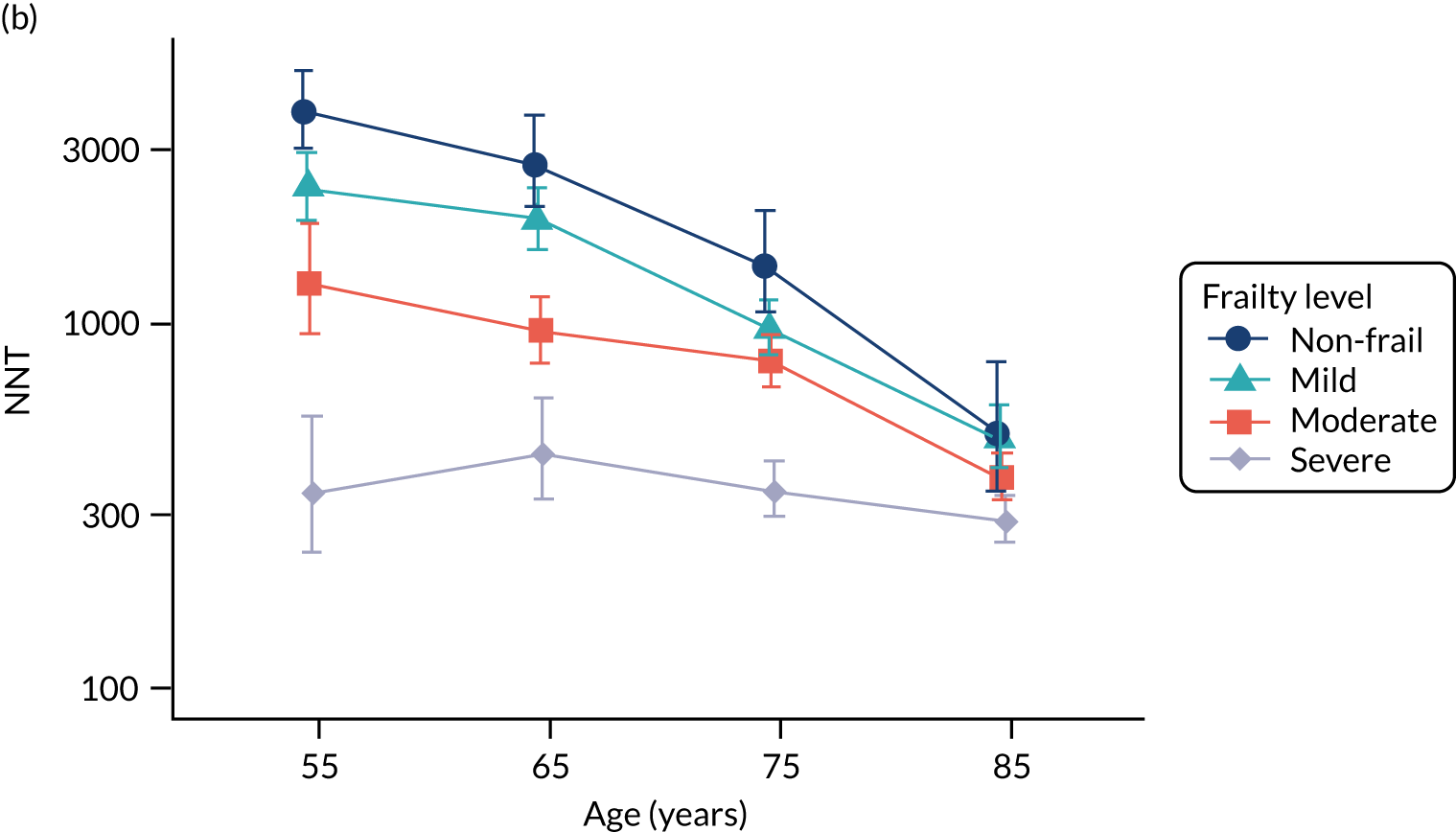

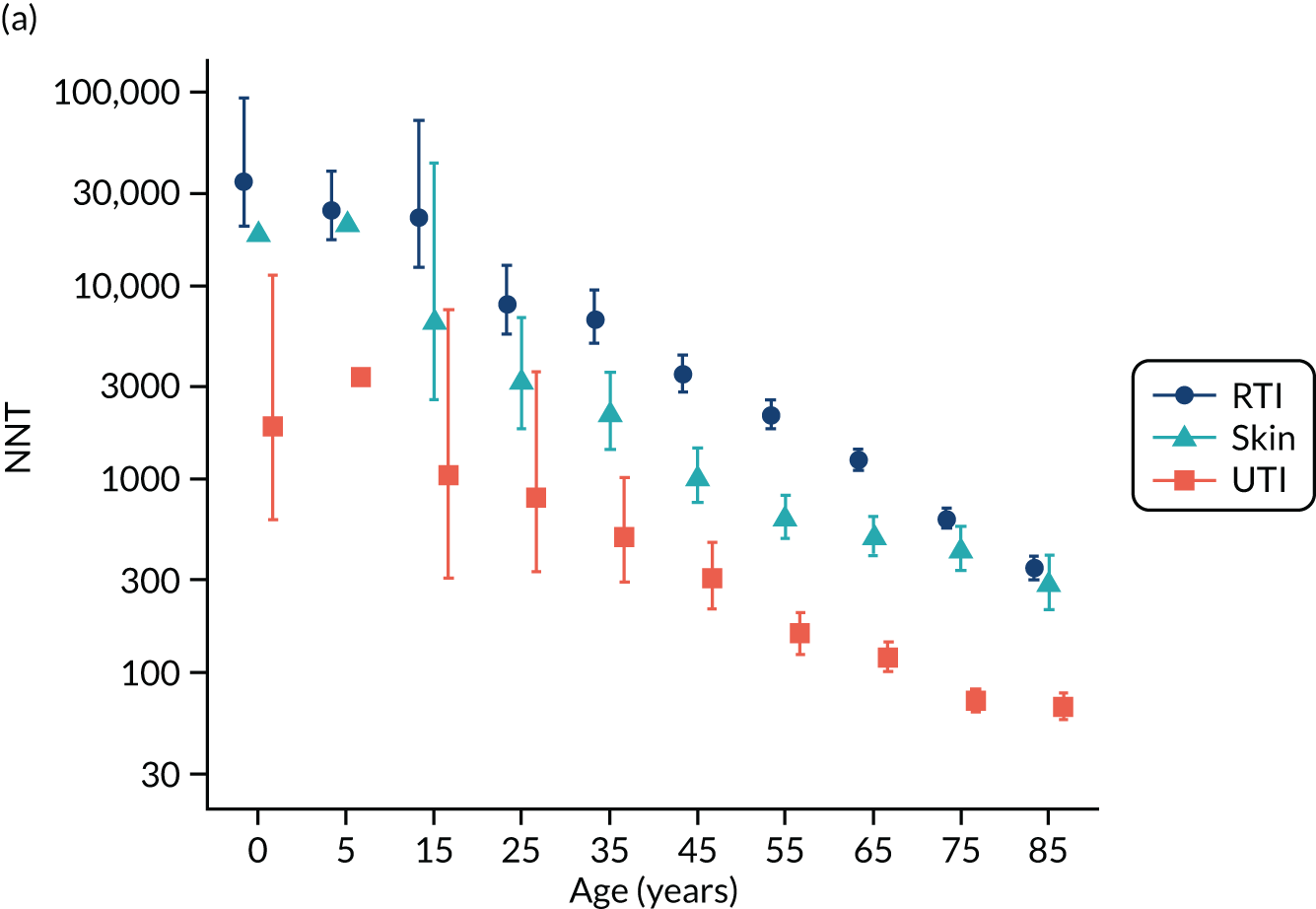

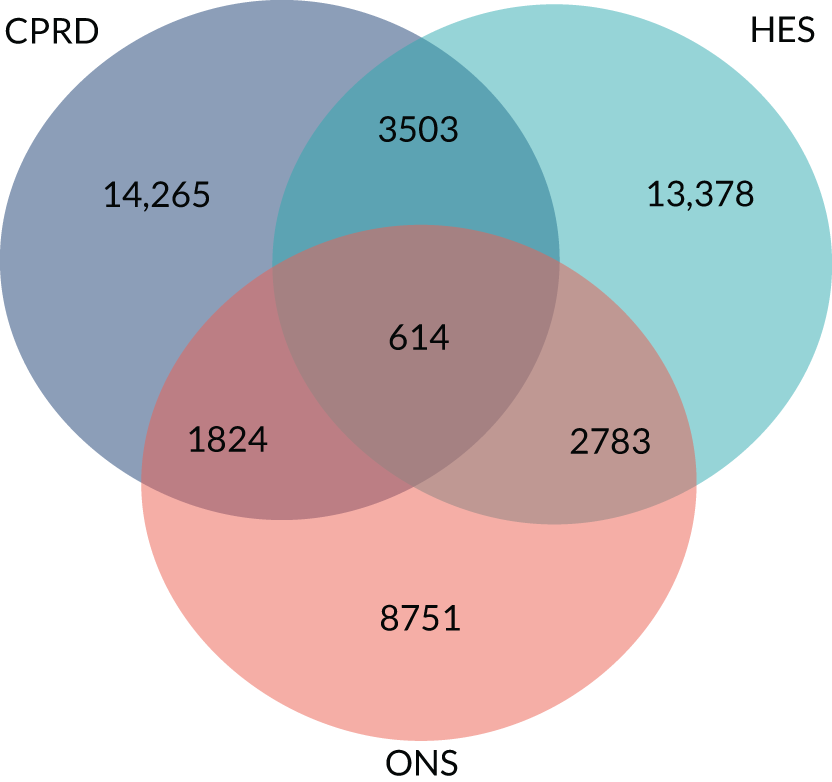

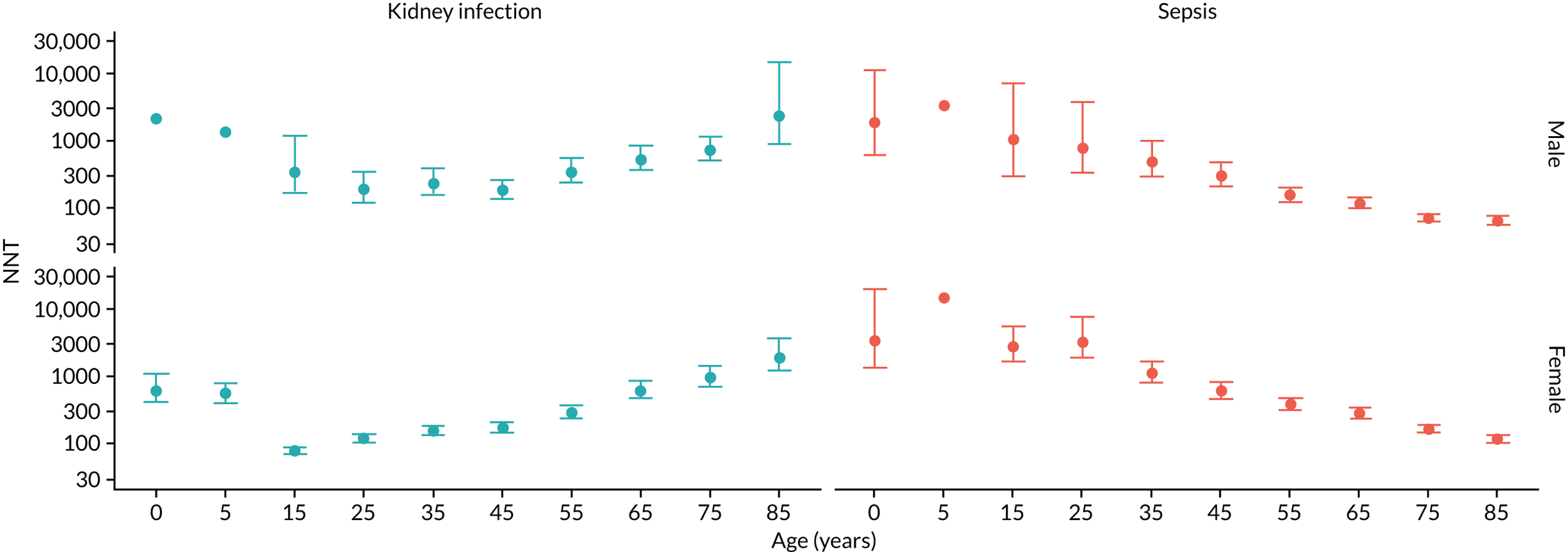

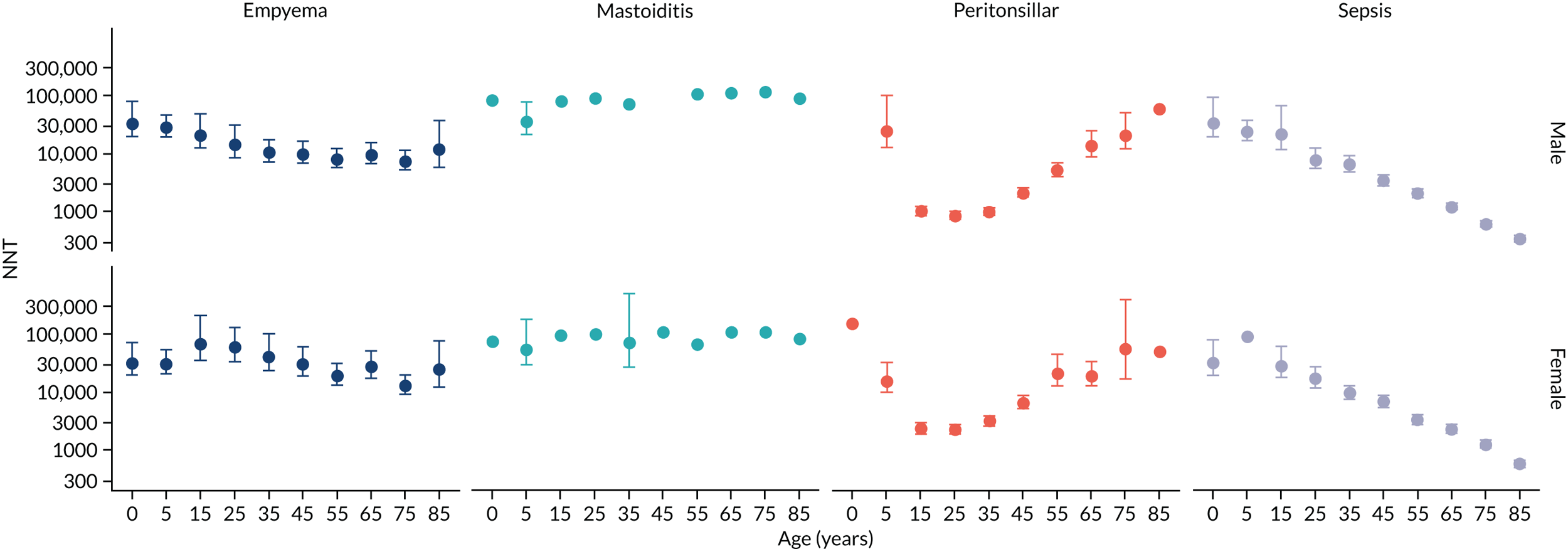

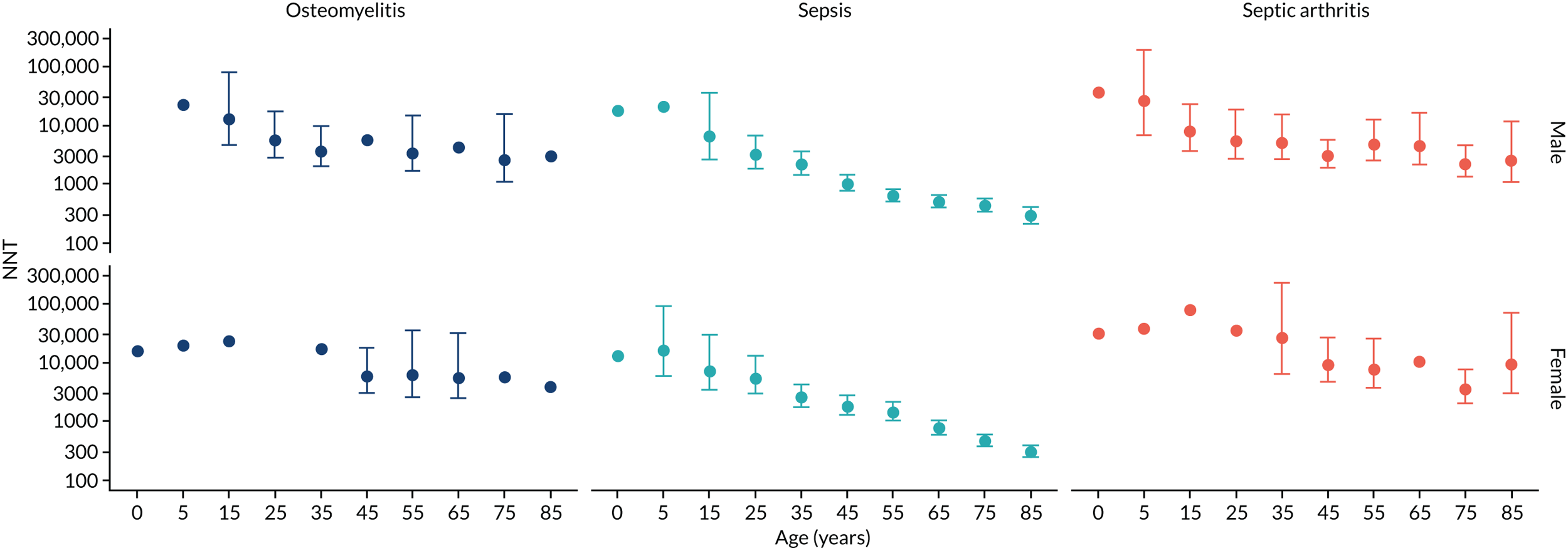

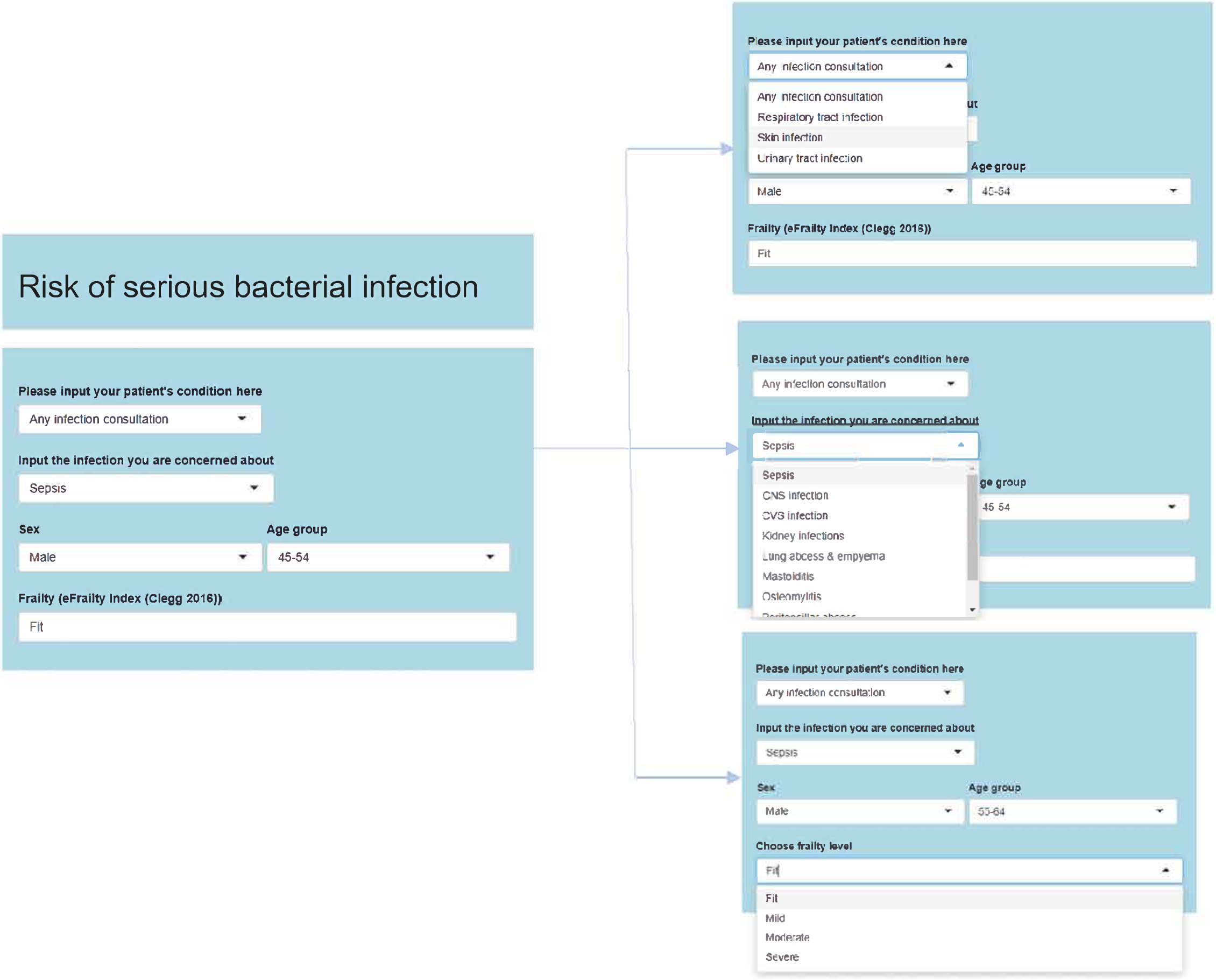

To evaluate the probability of a serious bacterial infection following an infection consultation in primary care we constructed a decision tree (Figure 3). 79 An individual developing an infection may decide to consult their general practice or not. If they consult, they then may be prescribed antibiotics and subsequently they may develop a serious bacterial infection. We used estimates from CPRD data analysis to populate the decision tree with empirical estimates for probabilities, as outlined in Table 3. We used Bayes’ theorem to estimate the probability of a serious bacterial infection following an infection consultation if antibiotics were prescribed or if antibiotics were not prescribed. We estimated the number needed to treat (NNT) (i.e. the number of antibiotic prescriptions required to prevent one serious bacterial infection) as the reciprocal of the difference in probability of sepsis with and without antibiotics. We obtained central estimates and 95% uncertainty intervals (UIs) from 10,000 random draws from the beta distribution. 80 All estimates were stratified by gender and 10-year age group. For the population aged ≥ 55 years, we also stratified by frailty category. In addition, we evaluated subgroups of common infections, including RTIs, skin infections and UTIs.

FIGURE 3.

Decision tree showing the probability of a patient consulting for an infection, being prescribed an antibiotic at that consultation and developing serious bacterial infection (see Table 3 for explanation of abbreviations). AB, antibiotic; SBI, serious bacterial infection.

| Term | Explanation | Data source |

|---|---|---|

| P(Infection) | Probability of a person consulting with infection in a 30-day period | From infection consultation rate per 30 days in sampled data set from CPRD |

| P(AB|Infection) | Probability of receiving an AB prescription on the same date as an infection consultation | From proportion of infection consultations with ABs prescribed in sampled data set from CPRD |

| P(SBI) | Probability of SBI per 30 days | From incidence of SBI from entire registered CPRD population |

| P(Infection|SBI) | Probability of patients with SBI, having consulted for an infection in 30 days preceding their sepsis diagnosis | Proportion of SBI cases with previous infection consultation, calculated from entire registered CPRD population |

| P(SBI|Infection) | Probability of SBI in the 30 days following an infection consultation | P(Infection|SBI)P(SBI)P(Infection) |

| P(SBI|[AB|Infection]) | Probability of SBI, having consulted for an infection and received an AB prescription | P([AB|Infection]|SBI)P([SBI|Infection])P(AB|Infection) |

| P(SBI|[NoAB|Infection]) | Probability of SBI, having consulted for an infection and not received an AB prescription | P([NoAB|Infection]|SBI)P([SBI|Infection])P(NoAB|Infection) |

| NNT | The number of additional AB prescriptions required to prevent one SBI | 1P(SBI|[AB|Infection])−P(SBI|[NoAB|Infection]) |

Data sources for decision model

Case definitions

We employed the same case definitions as outlined above. However, we refined our definition of sepsis to include only those conditions considered relevant as complications of infection consultations in primary care. This led to the omission of 23 Read codes, with 77 Read codes remaining to define sepsis (as outlined in Report Supplementary Material 1 and 2). In individual patient analyses, we also adopted a less inclusive approach to the definition of infection consultations, including ‘UTIs’ rather than ‘genitourinary tract infections’ (GUTIs), with further details provided in Report Supplementary Material 1 and 2. For the estimation of person-time, the current registration date was advanced by 12 months because only incident events 12 months after the patient’s start date were included in analyses.

Evaluation of frailty

We used Clegg et al. ’s65 electronic frailty index (eFI) to evaluate frailty level. The eFI includes 36 deficits that are evaluated as present or absent based on Read-coded electronic health records. Patients were classified as being ‘non-frail’ or having ‘mild’, ‘moderate’ or ‘severe’ frailty based on the number of deficits recorded. We evaluated frailty for each patient in each calendar year of the study81 to provide a frailty estimate for the index year of each sepsis episode. We also estimated consultation rates and antibiotic prescribing proportions by frailty category for the antibiotic prescribing sample. Given that full electronic health record data were not available for the entire CPRD GOLD denominator, we allocated person-time to frailty categories, using the proportion in each frailty category that we observed in the antibiotic prescribing sample. Although the concept of frailty may be applied at any age, frailty was evaluated from only age ≥ 55 years because most patients under the age of 55 years were classed as ‘non-frail’ or as having only ‘mild’ frailty (see Report Supplementary Material 3, Supplementary Table 2).

Outcome events

We ascertained serious bacterial infection events from the entire registered population of CPRD GOLD because these are generally rare events. Incident cases of sepsis were obtained from CPRD GOLD for the years 2002–17, with person-time at risk providing the denominator. The start of the patient record was the latest of 1 year after the patient’s current registration date, the date that the general practice began contributing up-to-standard data to CPRD GOLD or 1 January 2002. The end of the patient’s record was defined as the earliest of the end of registration, the patient’s death date or 31 December 2017. The mean duration of follow-up was 6.9 years. Serious bacterial infection events were evaluated using Read codes recorded in patients’ clinical and referral records. 39 There were 77 Read codes for sepsis and septicaemia but the four most frequent codes accounted for 92% of events, including ‘sepsis’ (two codes), ‘septicaemia’ and ‘urosepsis’ (see Report Supplementary Material 1 and 2). We included the incident first events in further analyses. Recurrent events in the same patient were not evaluated further because it may not always be possible to distinguish in electronic health records new occurrences from reference to ongoing or previous problems.

For each serious bacterial infection, we evaluated whether or not a consultation for a common infection was recorded within the preceding 30 days. We employed a 30-day time window with the intention of capturing data for acute infections and their short-term outcomes. We identified consultations for RTIs (including upper and lower RTIs), skin infections and UTIs (including ‘cystitis’ and uncomplicated ‘UTIs’ only) because these are the most important groups of conditions for which antibiotics are prescribed in primary care (see Report Supplementary Material 1 and 2). 10 We evaluated Read codes in patients’ clinical and referral records to identify consultations associated with common infections. We also evaluated whether or not an antibiotic prescription was issued during the 30 days preceding a sepsis event, either on the same date as an infection consultation or on a different date (see Report Supplementary Material 1 and 2). 10,39

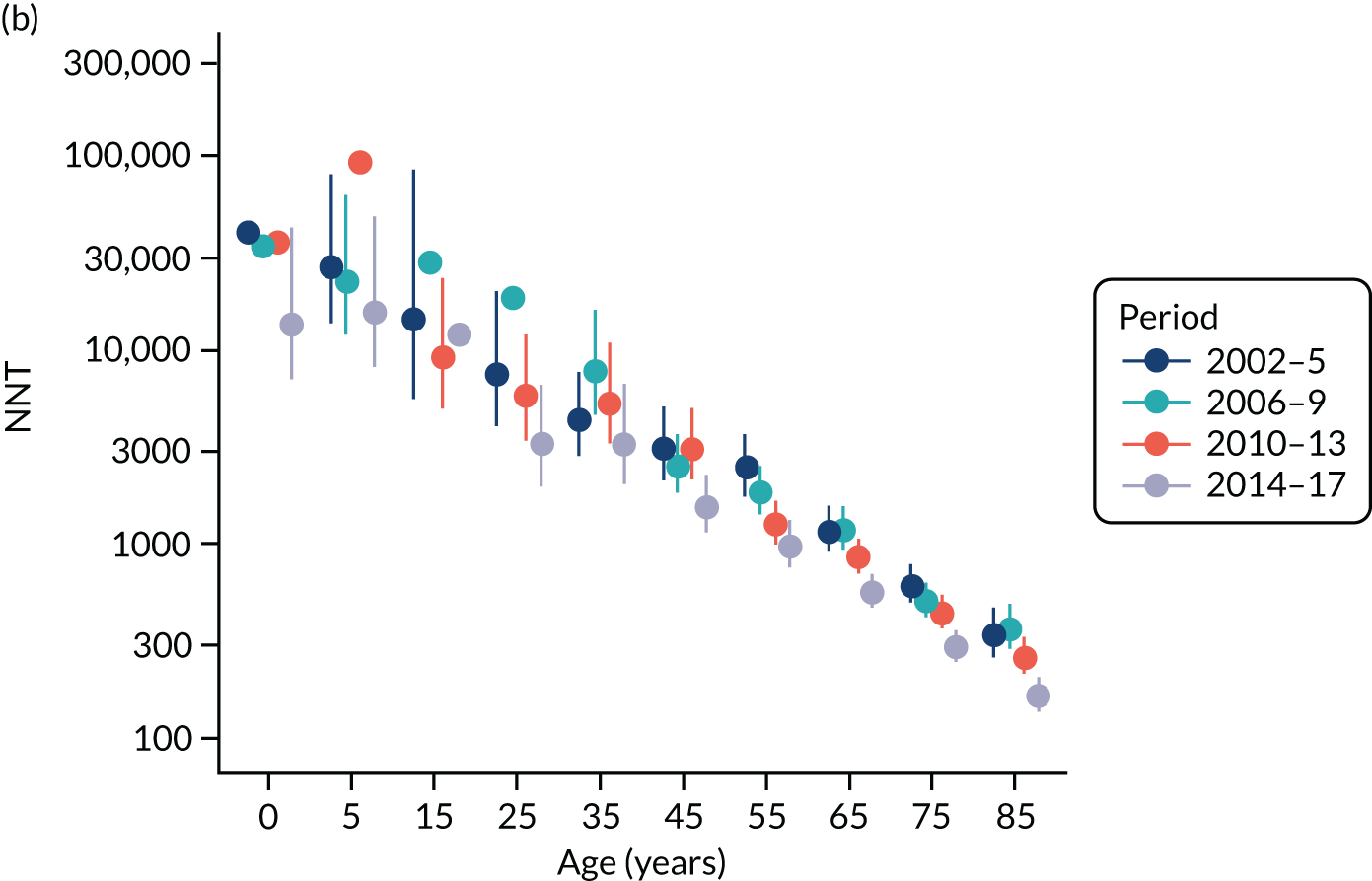

Sensitivity analyses

In sensitivity analyses for the outcome of sepsis, we evaluated whether or not use of a 60-day time window gave different results from a 30-day time window. The primary analysis reported data for a 16-year period, but the incidence of sepsis has been increasing. 24 We repeated the analysis using only data for 4-year periods from 2002–5 to 2014–17, to evaluate whether or not estimates differed from the whole period from 2002 to 2017. We also investigated whether estimates differed if sepsis diagnoses recorded in Hospital Episode Statistics (HES) or as causes of death on mortality certificates. The sample for linkage was obtained from CPRD (Linkage Set 16). The linked sample included data for 378 English general practices, with 5,524,983 patients providing primary care electronic record data linked to HES and mortality statistics. We searched for ICD-10 codes for sepsis and septicaemia. We included primary diagnoses from HES admitted patient care records and all mentions of sepsis in mortality statistics data. We repeated analyses using primary care electronic health records alone, primary care electronic health records with linked HES data or primary care electronic health records with linked HES and mortality data.

Data linkage

Study population and data sources

The study employed the UK CPRD GOLD database. The CPRD GOLD is a primary care database of anonymised electronic health records for general practices in the UK. The high quality of CPRD GOLD data is well established. 71 CPRD GOLD has a coverage of some 11.3 million patients, including approximately 7% of the UK population, of which it is broadly representative in terms of age and sex. 70 Consenting practices in England participate in a data linkage scheme. 82 Approximately 74% of all CPRD GOLD practices in England are eligible for linkage. Linkages are available for the HES and mortality registration data from the Office for National Statistics (ONS). HES admitted patient care data include admission and discharge dates and diagnostic data coded using the ICD-10. Mortality registration data include information on the date and causes of death coded using ICD-10. ONS identifies one underlying cause of death and secondary causes of death, including up to 15 additional causes of death. Linked area-based measures of deprivation include the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) and are based on a weighted profile of indicators. 83 We employed deprivation for the general practice postcode for this study because of the low proportion of missing values. The protocol was approved by the CPRD Independent Scientific Advisory Committee (protocol 18-041R).

Main measures

We included patient records between 1 January 2002 and 31 December 2017. The start of the patient record was the later of the patient registration date or the date that the general practice joined CPRD. The end of the patient record was the earliest of the last data collection date, the end of registration or the date of death. We evaluated the first records of sepsis > 12 months after the start of registration in primary care electronic health records as a primary diagnosis in HES or sepsis as any mentioned cause of death in mortality records. In UK primary care records, diagnoses recorded at consultations or referrals to or from hospitals were coded, at the time of this study, using Read codes. We identified sepsis records using a list of 77 eligible Read codes. Incident episodes of sepsis in CPRD were recorded using 55 Read codes, with four codes accounting for 92% of events, including ‘sepsis’ (two codes) (64%), ‘septicaemia’ (18%) and ‘urosepsis’ (10%). In HES and death registry records, sepsis diagnoses and sepsis deaths were defined using 23 ICD-10 codes for sepsis. In HES records, we evaluated the primary diagnosis, which accounts for the majority of the length of stay of the episode, with other diagnoses being referred to as comorbidities. 84 Incident diagnoses of sepsis in HES were coded with 20 ICD-10 codes, with three codes accounting for 89% of events, including ‘sepsis, unspecified’ (72%), ‘sepsis due to other Gram-negative organisms’ (13%) and ‘sepsis due to Staphylococcus aureus’ (5%). In mortality data, we included all mentioned causes of death because sepsis may be part of a sequence of morbid events and not always be an underlying cause of death. 24 ‘Sepsis, unspecified’ accounted for 93% of causes of death among those in the ONS death registry with sepsis as any mentioned cause of death.

Analysis

Incident sepsis events were identified for each data source. We calculated person-time at risk from the start to the end of the patient record. Person-time was grouped by gender and age group from 0 to 4 years, 5 to 9 years and 10 to 14 years, and then 10-year age groups up to ≥ 85 years. Incidence and mortality rates were age standardised using the European Standard Population for reference. We searched for concurrent events across data sources using a 30-day time window. We calculated age-specific incidence rates using primary care electronic health records and then adding HES records, mortality records or both. We fitted a logistic regression model to evaluate associations of gender, age group, fifth of deprivation and period of diagnosis with concurrent sepsis recording. All data were analysed in R.

Sensitivity analyses

To consider recurrent sepsis events, we conducted a sensitivity analysis using CPRD and HES where incident events were first sepsis records during each calendar year during the study period. We also evaluated the effect of extending the time window for concurrent events from 30 to 90 days.

Development and testing of the Shiny app

Design of study

The study used a qualitative design involving both semistructured and ‘think-aloud’ interviews with six GPs. The study was designed and conducted by LM in consultation with the study team. Face-to-face interviews were conducted online using Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, Inc., San Jose, CA, USA). Interviews lasted approximately 40 minutes. All interviews were recorded using Zoom and fully transcribed. The evaluation was constrained by the circumstances of the research during the COVID-19 pandemic and it was possible to conduct a preliminary study only.

Participants

Participants for early user testing were six GPs from practices across London, Southampton and Oxfordshire. Participants included GPs who were also academic researchers and GPs who worked in a practice setting only. Participants were recruited initially from members of the study team who were also practising GPs. In addition, two GPs who were colleagues of study members also agreed to take part following an invitation from the study team. This part of the research was conducted during January–July 2020 and its scope was limited by the circumstances of the research.

Procedure

General practitioners were first shown the web pages using the screen share function on Zoom. Think-aloud interviews (Box 3) were conducted at this point to study the reactions to the various features of the web pages. GPs were encouraged to discuss their views, thoughts and perceptions of each section as it was demonstrated by the interviewer. This technique allowed GPs to explore the various drop-down menu options and openly discuss the tool as they wished, but also ensured that opinions were obtained for all sections of the pages. Following this, a semistructured interview (Box 4) was conducted, drawing on our previous experience of developing electronic interventions. 31,85 The interview was designed to identify factors likely to influence successful implementation of the tool and discover likely responses to the proposed sections to further inform development and aid refinement of the web pages. GPs were asked questions regarding their views, expectations, acceptability and feasibility of pages. The semistructured interviews were used to explore and discover issues that may be related to the web page content and usage.

(Web pages presented on screen.)

Each section is displayed and explained.

Tell the participant that they can go back to view or explore any feature again.

Ask the participant to say aloud what they are thinking and feeling about each feature (content and functions).

To ask during interview-

Question why certain choices or comments are being made if a full description is not given.

-

Ask for comments on any features that were not discussed.

-

How would you feel about using this tool in practice?

-

How do you think these any of features could be improved?

(Prompts: title, list of problems, order of conditions, clear to use and order of presentation.)

Graphs-

How would you feel about using these graphs during a consultation?

-

How would you improve the presentation of these graphs?

(Prompts: clear to see how to access these/design.)

Design features-

Overall, how do you feel about the design of these pages?

-

How would you improve the design of these pages?

(Prompts: colour, areas, titles, font and functions clear.)

-

What would be the best way to access these pages during a consultation?

-

Would you be happy to share these with pages with patients? (Which parts?)

-

Do you feel that information presented is easy to interpret? (If not, which parts?)

-

Do you think that the information would be easy for other GPs to interpret?

-

Do you think that these pages could be useful in practice (could they be used during a consultation?)

-

Do you think that the pages could help to inform decision-making?

-

Do you have any further comments on the pages?

Analysis

Inductive thematic analysis was conducted on all transcripts to determine likely responses to the web pages and identify factors involved in the decision to use the tool. Analysis began after the first interview had been conducted and continued throughout data collection for all interviews conducted. Interviews were read in detail and re-read, and then following this immersion in the transcripts commonly occurring patterns and prominent themes were identified in the data and labelled with codes. Each code label referred to the operationalisation of the theme content. A coding manual was developed containing the label, a definition of each theme, positive examples from the interview transcripts and possible exclusions for each code. The coding manual was refined as more data became available and transcripts were re-read. The continuing process involved themes being linked, grouped, moved, re-labelled, added and removed to produce a set of themes and coding manual that adequately fit and thoroughly explained the data.

Public and patient involvement

The purpose of PPI in the project was to inform all stages of the research of patient and service user perspectives and concerns. A PPI group was formed that included patients and service users recruited from the NIHR Biomedical Research Centre at Guy’s and St Thomas’ Hospitals and from general practices in South London. The group included seven PPI members: five women and two men of diverse ages and ethnic origins. Most PPI members had experience of consulting with infections and some also had experience of antibiotic-resistant infections. Meetings were held at intervals during the project. Preliminary findings from the research were presented, and members were invited to discuss emerging findings and themes and comment on their relevance. The following chapters report discussion and reflection on the feedback received at the PPI group meetings.

Chapter 4 Patient expectations and experiences of antibiotics in the context of antimicrobial resistance

Adapted with permission from Boiko et al. 86 This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Summary

This part of the research investigated contemporary patient expectations and experiences of antibiotic prescribing through semistructured interviews with patients who recently consulted for infections in two English regions. The patient accounts reflected improved public knowledge. Although antibiotics were perceived to be much-needed medicines that should be prescribed when appropriate, patient experiences were nuanced and detailed with knowledge of antimicrobial resistance and the side effects of antibiotics. The research found that patients are seeking care and antibiotic treatment in reflexive, informed ways, with dependency between patient and practitioner expectations. Ensuring that present and future patients are informed about potential benefits and harms of antibiotic use will contribute to future antimicrobial stewardship.

Background

Public awareness of antibiotic resistance and the need for more judicious use of antibiotics is increasing, but inappropriate use of antibiotics remains widespread. 5,23 Older studies have ascribed a prominent role of patient influences on antibiotic prescribing, with many studies stressing the view that prescribers may be responsive to patient expectations for antibiotic treatment. 87 This ‘patient influence’ factor has been identified in most systematic reviews. 87 Estimates from patient surveys suggest that patients’ positive expectations for antibiotics are substantial, but have varied between studies. 88–94 Family physicians may assume that patients consulting for infections want antibiotics,95 but primary care clinicians can overestimate the extent to which patients are seeking and expecting antibiotic prescriptions,95,96 especially for parents of young children. 32 There is consistent evidence that GPs are more likely to prescribe antibiotics when their patients are perceived to be expecting them. 92,97–99 A systematic review found a generally positive association between physician perceptions of patient expectation and antibiotic prescription,100 but some studies find evidence of a negative association between expectation and prescription,88 with evidence of inconsistency between physicians’ perceptions and patients’ desire for antibiotics. It is also well established that prescribing antibiotics increases the likelihood that patients will consult in future illness episodes,14 raising the possibility that expectations are a consequence and not a cause of antibiotic prescribing.