Notes

Article history

The research reported here is the product of an HS&DR Evidence Synthesis Centre, contracted to provide rapid evidence syntheses on issues of relevance to the health service, and to inform future HS&DR calls for new research around identified gaps in evidence. Other reviews by the Evidence Synthesis Centres are also available in the HS&DR journal.

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 17/06/04. The contractual start date was in April 2018. The final report began editorial review in January 2020 and was accepted for publication in July 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Price et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Parts of this report are reproduced or adapted with permission from Price et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

When encountering a [doctor] who is not thriving, it is often difficult to figure out what is wrong and how to help. And when confronted with a serious violation of professional ethics or a repeated threat to patient safety, it is equally unclear what to do . . . Unfortunately, problems often become worse, and if uncorrected, result in harm to patients, disruption of the healthcare team, and occasional dismissal . . .

Kalet et al. 2

Proficient and safe doctors, operating efficiently within teams, are an essential part of the provision of high-quality and safe care for patients. If the performance of a doctor is lacking, patients may be at risk. 3 Performance issues can be experienced by doctors at any stage in their careers for a variety of reasons, including health/well-being, personal reasons, the environment of the workplace, and not keeping up to date and participating in continuing medical education. Performance concerns are often complex and multifactorial, and can involve issues relating to knowledge, skills and professionalism. 4–6 To ensure patient safety, it is vital that if there are questions about the performance of a doctor they are identified quickly and, where appropriate, addressed through remediation. 7

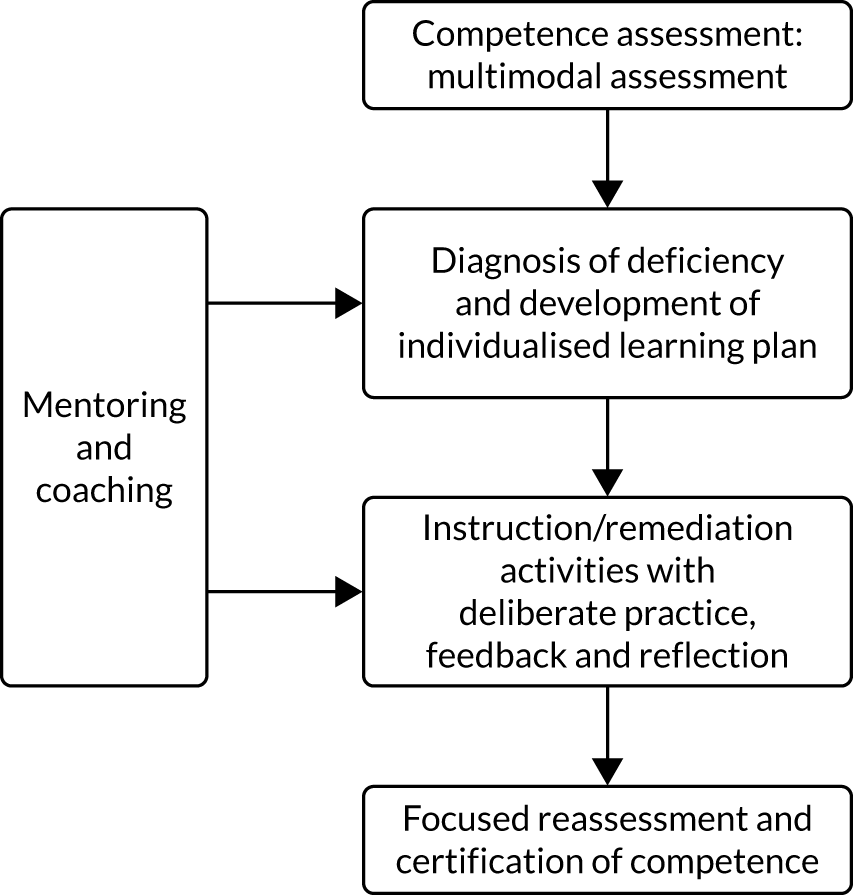

Remediation is the process by which a doctor’s poor performance is ‘remedied’ and the doctor returned to safe practice. 8 Remediation can be formally defined as ‘an intervention, or suite of interventions, required in response to assessment against threshold standards’. 9 Threshold standards are set by regulatory bodies [e.g. the General Medical Council (GMC)] to keep patients safe. What actually constitutes a remedial intervention ranges from informal arrangements to complete some reskilling, through to more formal programmes of remediation and rehabilitation. 10 It is generally agreed that there are three necessary components of remediation: (1) the identification of performance deficit, (2) remediation intervention and (3) reassessment of performance after intervention. 11

Remediation has been classified as a ‘wicked’ problem the medical profession has struggled with for decades. 12,13 One of the main difficulties relates to the fact that remediation has historically been conceptualised as a way of addressing a person’s lack of knowledge in a particular area. Although addressing knowledge is important, it is not enough to achieve behaviour change. 12,14,15 The performance of a doctor is shaped by a variety of different contextual factors, including the attributes and skills of colleagues, system resources and organisational culture. Viewing remediation as merely an educational exercise, ignoring the contextual factors influencing competence in individuals, is unlikely to be enough to address significant performance gaps. 12 In recent years, there has been an important shift in the conceptualisation of remediation towards being a behaviour change process (i.e. understanding what is necessary to produce lasting performance improvement for a particular doctor in a particular context). 7,12

Remediation interventions are widely used in health-care systems across the globe to address underperformance. When we use the term underperformance, we are referring to situations in which a doctor’s performance is below the standards required to ensure safe practice. It is estimated that approximately 6% of doctors (i.e. approximately 9400 doctors) in the hospital workforce in England may be underperforming at any time and that 2% (approximately 4100) of all practising doctors will be undergoing remediation. 10 These figures will have increased because of the process of revalidation, which is the UK’s relicensing system for practising doctors that is regulated by the GMC. 8 Medical revalidation was introduced in 2012 as a statutory requirement. It is the procedure by which all UK doctors evidence that they are up to date and fit to practise. This is achieved by collating supporting information as part of an annual appraisal. Then, usually every 5 years, a senior doctor called the ‘responsible officer’ within an associated organisation (known as the ‘designated body’) recommends a revalidation outcome decision to the GMC. If underperformance is identified through the revalidation process (or through any other route), the responsible officer has a statutory responsibility to ensure that the designated body offers ‘training or retraining’. 16 Specific guidelines for responding to a concern about a doctor’s practice have recently been published to support this process. 17 Data from research evaluating medical revalidation suggest that revalidation is helping to identify such poor performance. 18

It is difficult to quantify the real human cost of an underperforming doctor; however, approximately 12,000 patients die in England each year as a result of preventable medical errors. 19 There is also the corresponding financial cost of these errors to consider. The NHS paid out > £2227.5M in medical negligence claims in 2017/18 alone. 19 However, the true societal costs when things go wrong are unknown. The relatively few incompetent doctors need to be stopped from practising; however, there is a more widespread and difficult problem to solve that would improve the health of the public and patients in the NHS, and that is doctors who underperform. Remedying underperformance, where possible, is both a practical and a financial imperative, as doctors are in short supply and are expensive to train. 20 There are shortages of doctors in particular specialties and geographical areas. 21 The NHS in England, Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales has been under extreme pressure to cut spending in recent years. 22 On average, it costs £485,390 to train a general practitioner (GP) and £726,551 to train a consultant. 23 Therefore, offering remediation to retain expensively trained but underperforming doctors is a logical financial solution.

Although offering remediation to underperforming doctors makes sense on a practical and financial level, there is another important reason related to the ‘duty of care to doctors’. 24 Rather than ‘striking off’ or ‘firing’ a doctor who is underperforming, providing the necessary support and remediation, and the opportunity to improve, is imperative in a caring workplace. The GMC states that its aim is to ‘protect patients and the reputation of the profession’ (Reproduced with permission from General Medical Council. 24 © 2015 General Medical Council). Once this has been achieved, the GMC says that it also has a parallel duty of care to the doctors to encourage and enable remediation in suitable circumstances. 24 Remediation is therefore important for a doctor’s personal and professional development, as well as their patients’ safety and well-being.

Despite the importance of remediation in the regulation of doctors and in ensuring patient safety, research on remediation is lacking. 12,25 Three systematic reviews and one thematic review have been conducted on remediation across the continuum of medical education. 11,25–27 All four reviews on the topic of remediating doctors identify a lack of research that would provide a firm theoretical base to guide remediation interventions. The reviews were also unable to identify why particular interventions work for some doctors and not for others (i.e. detailed analyses on important contexts were missing):

. . . we cannot delineate precisely what works, and why, in remedial interventions for medical students and doctors.

Cleland et al. 25

This issue was also highlighted by research recently commissioned by the GMC, which investigated the impact on doctors of undertakings (i.e. remediation measures agreed with the doctors), conditions (i.e. remediation imposed on the doctors) and official warnings. 24 The study had a small sample size; however, the outcomes suggested that stipulating remediation in some cases engendered more reflective and safer practice, but in other cases it engendered more defensive or unchanged practice. 24 In other words, the same interventions were producing different outcomes in different contexts and for different doctors. An important issue that has limited our deeper understanding of remediation interventions for doctors has been the way in which systematic reviews have been carried out. In particular, the previous systematic reviews on remediation use inclusion criteria that were too restrictive (e.g. by study design, intervention type) and, hence, were only able to draw on a narrow body of literature. In summary, ‘rigorous approaches to developing and evaluating remediation interventions are required’. 25

To design high-quality remediation interventions, it is fundamental to understand the theory of how remediation of doctors is supposed to work, for whom and the contexts that lead to different outcomes. Our review will make an empirical contribution to the existing body of knowledge by developing a programme theory of how remediation of doctors is supposed to work, for whom and in what contexts. The review will enable us to develop recommendations for the tailoring, design and implementation of remediation interventions for underperforming doctors. Finally, this research will produce new knowledge about a poorly understood area of health-care delivery that has a direct impact on the standard of care received by patients.

Review questions

Aim

The REalist SynThesis of dOctor REmediation (RESTORE) review aimed to identify why, how, in what contexts, for whom and to what extent remediation interventions work for practising doctors to restore patient safety. The review was structured around the following objectives and review questions.

Objectives

-

To conduct a realist review of the literature to ascertain why, how, in what contexts, for whom and to what extent remediation programmes for practising doctors work to restore patient safety.

-

To provide recommendations on tailoring, implementation and design strategies to improve remediation interventions for doctors.

Review questions

-

What are the mechanisms by which remediation interventions work to change the behaviour of practising doctors to produce their intended outcomes?

-

What are the contexts that determine whether or not remediation interventions produce their intended or unintended outcomes?

-

In what circumstances are these remediation interventions likely to be effective?

The next chapter provides a detailed description of the methods utilised in the review. Chapter 3 presents the results, followed by the discussion in Chapter 4. Finally, the conclusions and recommendations are presented in Chapter 5.

Chapter 2 Review methods

We followed a realist approach to evidence synthesis to understand the contexts in which remediation interventions are most effective. Realist review is a practical, methodological approach designed to inform policy and practice. The realist review approach is distinct from other types of literature reviews, as it is based on an interpretive and theory-driven approach, synthesising evidence from qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods research. 28 The unique contribution of this approach is that it yields transferable findings that explain how and why context can affect outcomes. 28 It does so by developing programme theories that explain how, why, in what contexts, for whom and to what extent interventions ‘work’. 29,30

Realist review methods are particularly suited to research on the remediation of doctors, as they focus on the contextual factors that determine the outcomes of an intervention. 31 Like other interventions that seek to promote behavioural change, remediation is highly context dependent (i.e. the same intervention will vary in its success depending on, for example, who delivers it and how it is delivered, the characteristics of the learners, the circumstances surrounding it, and the tools and techniques used). Research designs that seek to ‘strip away’ this context limit an understanding of ‘how, when and for whom’ the intervention will be effective. 31 A realist review takes context as central to any explanation by exploring how an intervention manipulates context to trigger mechanisms that cause behavioural change.

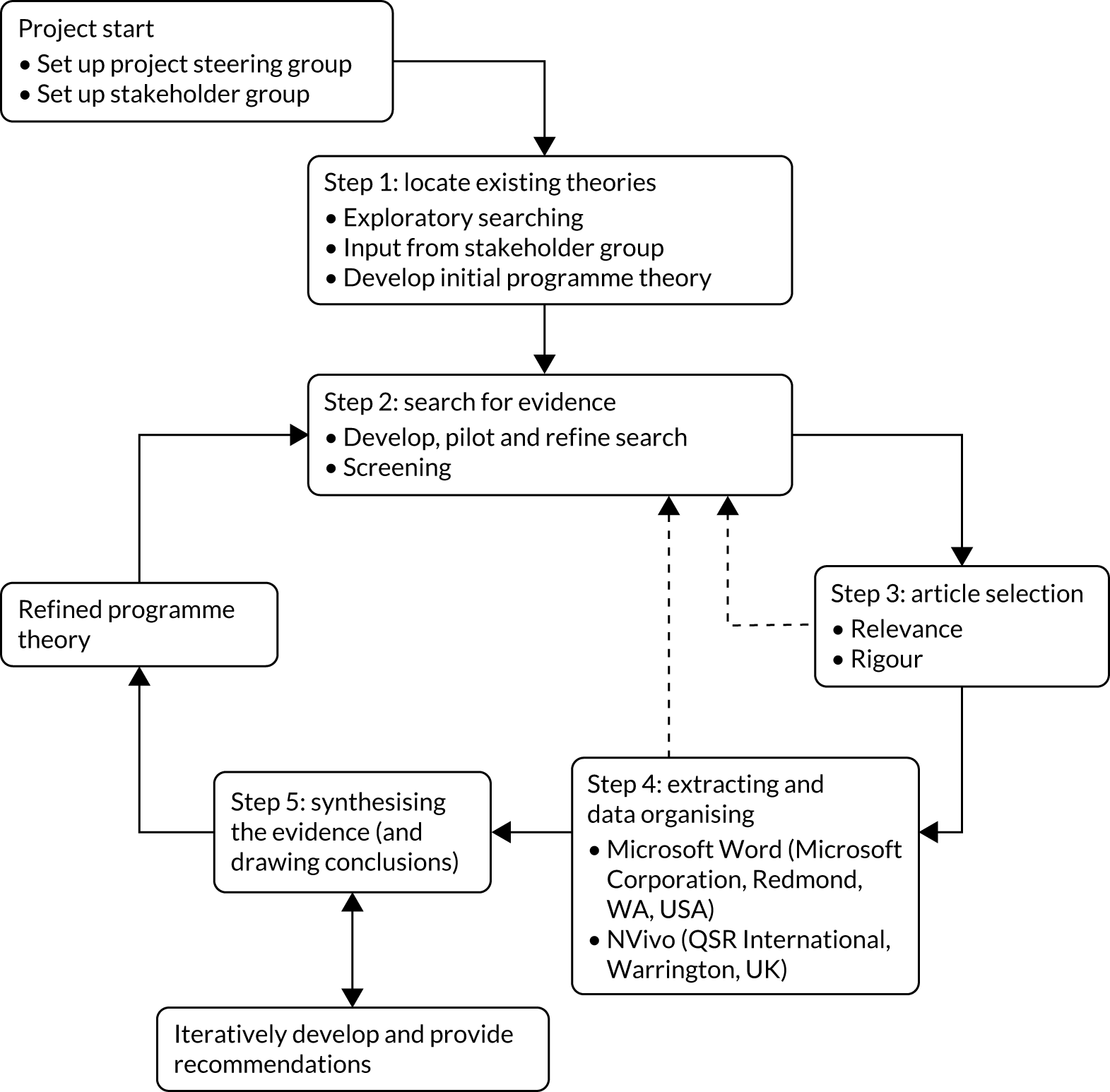

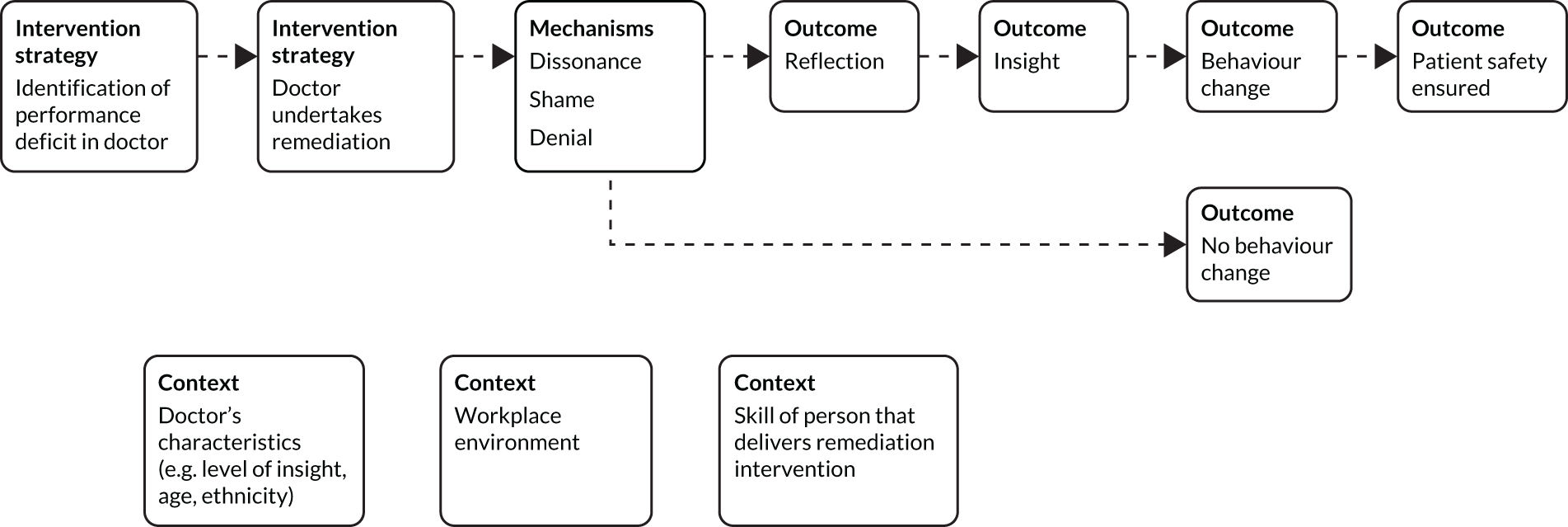

The research design is illustrated in Figure 1. 32 The plan of investigation followed a detailed protocol based on Pawson’s33 five iterative stages for realist reviews: (1) locating existing theories, (2) searching for evidence, (3) selecting articles, (4) extracting and organising data and (5) synthesising the evidence and drawing conclusions. The review ran for a 22-month period from April 2018 to January 2020. The review was registered with PROSPERO (CRD42018088779) and the protocol was published in BMJ Open. 34 The review was informed by the quality and publication standards and training materials for realist reviews that were developed by one of the core research team members (GW). 35 We were granted ethics clearance by the University of Plymouth, Faculty of Health and Human Sciences and Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry Research Ethics and Integrity Committee.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of the project. Dashed arrows to indicate iteration where necessary. Reproduced with permission from Wong et al. 32 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Stakeholder group

A diverse stakeholder group was recruited for the RESTORE review to provide subject knowledge for programme theory refinement, to optimise dissemination plans and to aid the generation of feasible and practical recommendations. A total of 12 people were consulted throughout the review, including doctors who have undergone a remediation programme, personnel who identify underperforming doctors and initiate involvement in remediation programmes, personnel involved in the delivery of remediation programmes, responsible officers, remediation coaches, remediation researchers, patient and public representatives, and members of relevant medical bodies. Two-hour meetings with stakeholder group members took place at regular intervals throughout the project. Individual telephone calls were also held if stakeholders were not able to attend meetings (n = 4) and e-mail exchange was also used. A list of the meetings that took place is presented in Table 1. The table includes the number of participants who attended each meeting and the topics discussed. The review team members also attended stakeholder meetings.

| Date | Stakeholder group members | Key topics discussed |

|---|---|---|

| 26 June 2018 | Seven participants:

|

Explored definitions and conceptualisations of remediation, when remediation works and why, and definitions of a ‘practising doctor’ |

| 12 October 2018 | Eight participants:

|

Discussed aspects of the emerging programme theory, including the identification of underperforming doctors, intervention activities, processes engendering behaviour change and the concepts that might be important to CMOcs, and how these reflected stakeholders’ experiences of remediation |

| 16 May 2019 | Five participants:

|

Continued to discuss findings of the review, including remediating insight, autonomy and professional identity, goal-setting, triggers and consequences, and facilitating change |

| 13 November 2019 | Six participants:

|

Discussed and refined the recommendations of the review and the dissemination strategy |

In the early stages of the study, the review team struggled to recruit to the stakeholder group any doctor who had undergone remediation. Members of the review team and stakeholder group used existing contacts to try to recruit remediated doctors. The professional support unit at Health Education England South West (Bristol, UK) was also approached by NB and they e-mailed all of their trainees undergoing professional support to ask if they were interested in being involved in the stakeholder group. As undergoing remediation is a sensitive issue, we offered the remediating doctor the option of feeding into the stakeholder group via individual telephone calls. Finally, we recruited a remediated doctor to the group in January 2019. TP had two meetings with this stakeholder who provided valuable insight into the remediation process.

We organised stakeholder meetings to take place at the University of Exeter Medical School (Exeter, UK). At each meeting, a brief slide presentation was given by the review team at the start of the meeting to introduce stakeholders to the topic under discussion. The programme theory was presented to the group in the form of diagrams and statements in order to obtain stakeholders’ feedback. The final stakeholder group meeting focused on the dissemination of the findings. The meetings were facilitated in an inclusive way, providing everyone the opportunity to contribute and voice their opinion, whether or not they were in agreement.

All stakeholder meetings were audio-recorded. The recordings were not used as a form of data, but were used to enable the project team to focus on the meeting, as opposed to being distracted by note-taking. Stakeholders were informed of the purpose of the recording and verbal consent to audio-recording was gained at the start of each meeting. Detailed summaries of the meeting were produced by TP and shared with all members of the stakeholder group, regardless of whether or not they had attended the meeting. The meeting notes were used to orientate the review and to inform programme theory development, and were not used as primary data for analysis. The report does not include any direct quotations from these meetings.

The input of stakeholders in the review provided a reality check based on their ‘on the ground’ experiences of remediation. The use of realist review terms was kept to a minimum in the meetings to avoid discussions focusing too much on methodological concepts. Stakeholder involvement also contributed significantly to refinement of recommendations and dissemination of findings in accessible formats.

Patient and public involvement

The RESTORE review included strong patient and public involvement (PPI) throughout the project. LW, our PPI representative, was a co-applicant and a member of the review team and attended all of the team meetings, meaning that she had direct input into the management of the study from start to finish. As well as LW, we also had further PPI input in the stakeholder meetings from a representative from an existing PPI forum that we had established for two other studies on revalidation, funded by the GMC and the Department of Health and Social Care. In the stakeholder meetings, patients and members of the public provided significant input to programme theory development, often highlighting unique aspects of the remediation process.

Steering group

A steering group was set up for the project and comprised the review team plus representatives from the finance department and research and innovation department at the University of Plymouth. The steering group met four times throughout the study (June and October 2018, and May and November 2019). During these meetings, the steering group was updated about the progress of the study, provided scientific and budget oversight, and made sure that the project was delivered as proposed in the protocol. The steering group ratified all changes that were made during the study (e.g. the change of principal investigator and other staff changes).

Step 1: locate existing theories

The purpose of this step was to locate existing theories that explain why, how, in what contexts, for whom and to what extent remediation programmes for practising doctors work. This involved identifying the theories that explain how remediation interventions are supposed to work to bring about behavioural change in clinical settings. Having already established from previous systematic reviews on the topic25–27 that there is limited theory underlying existing remediation interventions, the realist review approach allowed for the literature net to be cast wider to include literature from other fields and other professions, where potentially similar mechanisms may be in operation.

An initial programme theory was devised by TP and NB during the funding application phase of the project (see Appendix 1). This initial programme theory included some early thoughts on the mechanisms that may interact with important contexts to produce certain outcomes. The elements incorporated in this programme theory were identified through literature included in the personal libraries of TP, NB and JA, which had been carefully and purposefully collected on the topic area. This initial programme theory was then shared with the review team and the stakeholder group for further refinement. The informal searches carried out in step 1 were different from the more formal searching that was carried out in step 2 (see Step 2: search strategy), as their purpose was to quickly identify the kinds of theory that may be relevant. Therefore, exploratory and informal search methods, including citation tracking and ‘snowballing’, were used. 36 We carried out these informal searches during April and May 2018. We used terms such as ‘remediation’ and ‘underperformance’ in Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) and MEDLINE databases. Once the theories had been identified, we built an initial programme theory to test in the review.

Step 2: search strategy

Formal search

In step 2, the goal was to find a body of relevant literature to further develop and refine the initial programme theory developed in step 1. The searches were designed, piloted and carried out by AW, an experienced information specialist with expertise in carrying out searches for realist reviews. AW used MEDLINE (via Ovid) to develop the search strategy. An iterative process was adopted, whereby search terms were added, removed and refined to achieve a balance of sensitivity and specificity in the results. The overall aim was to capture a broad range of relevant literature while minimising irrelevant literature.

As the search developed, sample sets of results were screened by TP and NB. This facilitated the selection of relevant search terms. In addition, highly relevant studies that had already been identified by the review team through their own personal libraries were used to test the search strategy (i.e. if these papers were returned in a particular search it confirmed the effectiveness of the search). The final search strategy used a range of search terms for the concepts ‘remediation’, ‘performance’ and ‘doctors’, which were combined using the AND Boolean operator (see Appendix 1).

The following databases were searched on 4 June 2018: MEDLINE (via Ovid), EMBASE (via Ovid), PsycINFO (via Ovid), Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) (via Ovid), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (via EBSCOhost), Education Resources Information Center (ERIC) (via EBSCOhost), Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA) (via ProQuest) and Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) (via the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination). The search syntax and indexing terms were amended where needed from the original MEDLINE for use in these databases.

The search results were exported to EndNote X7 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and deduplicated using the ‘find duplicates’ function. The search strategies for the main database search are reproduced in full in Appendix 1.

Inclusion criteria

The following inclusion criteria were applied.

-

Aspect of remediation, including all documents that focus on the remediation of practising doctors. We defined remediation as ‘an intervention, or suite of interventions, required in response to assessment against threshold standards’. 37

-

Study design, including all study designs.

-

Types of setting, including all documents about primary or secondary care settings.

-

Types of participant, including all practising doctors. A practising doctor can be defined as a licensed doctor who has graduated from medical school and is practising medicine. Studies about only medical students were excluded.

-

Outcome measures, including all remediation-related outcome measures.

-

Language, including studies published in the English language.

-

Publication date, including all studies published up until June 2018.

Additional searches

Although we conducted a grey literature search in the main search using HMIC, following a discussion with our third stakeholder group, where some of the stakeholders highlighted the relevance of some key grey literature, we decided to do a subsequent search specifically to identify grey literature. Searches for grey literature were conducted on 25 June 2019. The following databases/websites were searched: Google Scholar, OpenGrey, NHS England, North Grey Literature Collection, National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Evidence, Electronic Theses Online Service, Health Systems Evidence and Turning Research into Practice. The databases were searched with free-text keywords and controlled vocabulary where appropriate, using terms such as remedi*, reskilling, and retraining, combined with the concept of doctors.

Citation searching was undertaken, including searches of the reference list of all included documents and ‘cited by’ searches of certain papers that were particularly rich in terms of building the programme theory. The ‘cited by’ searches were undertaken using Google Scholar. Stakeholders were also asked to identify any literature they thought relevant. Any literature identified through grey literature searching, citation searching and via stakeholders that satisfied the inclusion criteria were included in the review.

The supplementary searches were purposive and undertaken on an ad hoc basis, as and when more data were needed on specific theories regarding different aspects of our programme theory of how remediation is supposed to work (e.g. insight, dissonance, psychological safety, feedback and behaviour change). Google Scholar was searched using topic keywords. Once relevant references were found, backwards and forwards citation searching techniques were used to identify further relevant papers.

Step 3: article selection

Documents were selected based on relevance (i.e. whether or not data can contribute to theory development and refinement). 38 We did not assess the rigour of the included studies, as we had already established from previous systematic reviews on remediation that existing literature was of poor quality. An initial random sample of 10% was assessed and discussed by TP and NB to ensure that selection decisions were made consistently. TP then screened all the remaining titles and abstracts to ensure that they matched the inclusion and exclusion criteria. A 10% random sample was reviewed independently by NB to ensure consistency around the application of the inclusion criteria. Very few inconsistencies were identified, and these were resolved through discussion. All of the screening was carried out in Rayyan. Rayyan is a free web application designed to help reviewers manage the screening process. If TP was uncertain over the relevance of an article, then it was initially discussed with NB. If it was still unresolved after discussion with NB, then it was discussed with the review team. The full texts of included articles were screened again using the inclusion and exclusion criteria. Again, a 10% random subsample was reviewed independently by NB to ensure consistency around the application of the inclusion criteria. No inconsistencies were identified. The results were screened in alphabetical order. TP read all of the included papers and ultimately included all documents or studies that contributed to the development of some part of the programme theory.

Grey literature searches were exported into a Microsoft Word document (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and screened in Word by TP. NB carried out a 10% check to ensure consistency in article selection.

Step 4: extracting and organising data

Once article selection was complete, TP uploaded the electronic versions of the included articles into NVivo 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) for further analysis. Articles were coded in alphabetical order. The coding concentrated on the conceptual level of the data, categorising content into analytical categories to enable these to be refined further. Therefore, we did not code the data in terms of context, mechanisms and outcomes at this stage, but approached coding with an open mind to understand what themes were emerging from the data. Initial coding categories included barriers to and facilitators of remediation, strategies employed by remediation programmes and processes engendering change. Coding was both inductive (i.e. the codes were identified from analysing the literature) and deductive (i.e. the codes generated were informed by the initial programme theory, stakeholder group discussions and exploratory literature searches). For example, insight was identified as an important theme in the first stakeholder meeting and was present in some of the literature. However, the way that insight was described by the stakeholder group covered a wider range of subthemes than used specifically in the literature under the term ‘insight’. We therefore went back to the literature to look for data on processes related to the way in which our stakeholder group had described the concept of insight.

When conceptual coding was complete, we began to consider whether or not the categories (or subcategories within them) contained data that could be identified as contexts, mechanisms and outcomes. In other words, we applied a realist logic of analysis to make sense of the data (see Step 5: synthesising evidence and drawing conclusions). Initially, we focused on the returned literature that was richest in terms of theoretical depth. This allowed us to build context–mechanism–outcome configurations (CMOcs) that could be tested with the data from the wider literature.

To develop and test (i.e. confirm, refute or refine) the CMOcs, TP presented the CMOcs in narrative form on a Word document, along with extracted data to support the CMOcs plus a descriptive explanation of each CMOc. These CMOcs were examined by the review team and further refined. CMOc development was conducted using a realist logic of analysis, whereby we first considered the outcomes (intermediate and/or final desired) that had been identified in the literature and by our stakeholder group, and then worked backwards (using retroduction where needed) to infer the mechanisms that might generate the outcome, and the contexts created by the remedial intervention that might trigger the mechanism. In most cases, although the mechanisms were sometimes alluded to, they were not directly referred to in the literature itself. In these cases, the review team would suggest mechanisms that offered a potential ‘fit’ with the data. At this point, we conducted further supplementary searches to examine the literature relating to these mechanisms and to test whether or not they offered a viable explanation in the CMOc. In some cases, mechanisms were derived from substantive theory (the role of which is described in Use of substantive theory).

Throughout this process of CMOc development, we compared the CMOcs with the evolving programme theory. The programme theory was updated periodically by TP, presented in diagrammatic form with accompanying narrative explanation and discussed at review team meetings. It was important to consider the relationship between the CMOcs and the programme theory. Although, for the main part, the CMOcs would inform the shape of the programme theory, its overall shape enabled us to consider other potentially important outcomes that required further investigation. It also enabled us to consider the linkage between CMOcs and the sequence of intermediate outcomes.

Throughout the review, the programme theory was iteratively refined based on our interpretations of the data included in the literature. The characteristics of the documents were extracted into a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet separately for the results of the main search and the supplementary searches (see Appendices 2 and 3).

Step 5: synthesising evidence and drawing conclusions

A realist logic of analysis was used to interrogate the data and develop and test the initial programme theory, which we used to explain what it is about remediation of doctors that works and for whom, in what circumstances and respect, and why. To develop, refine and test the programme theory, we moved between the data (as extracted and coded in NVivo and Word documents) and the analysis, advice and feedback offered by the review team and the stakeholder group. To operationalise a realist logic of analysis, we asked these questions of our data (Box 1).

Are the contents of a section of text within an included article referring to data that might be relevant to programme theory development?

Judgements about trustworthiness and rigourAre these data sufficiently trustworthy to warrant making changes to the programme theory?

Interpretation of meaningIf the section of text is relevant and trustworthy enough, does its contents provide data that may be interpreted as being context, mechanism or outcome?

Interpretations and judgements about CMOcsWhat is the CMOc (partial or complete) for the data?

Are there data to inform CMOcs contained within this article or another included article? If so, which other article?

How does this CMOc relate to CMOcs that have already been developed?

Interpretations and judgements about programme theoryHow does this (full or partial) CMOc relate to the programme theory?

Within this same article, are there data that inform how the CMOc relates to the programme theory? If not, are there data in other articles? Which ones?

In the light of this CMOc and any supporting data, does the programme theory need to be changed?

Reproduced with permission from Papoutsi et al. 39 Contains information licensed under the Non-Commercial Government Licence v2.0.

Throughout the review, we moved iteratively between the analysis of examples, refinement of programme theory and further iterative searching for data to test specific parts of the programme theory. The final realist programme theory is presented in a diagram and through a narrative description of CMOcs.

As mechanisms were often hidden or not articulated very well, we used retroductive reasoning (see Glossary) to infer and elaborate on the mechanisms. Retroductive analyses are analytical processes that seek to identify the hidden causal processes that lie beneath identified patterns or changes in those patterns. 39 Therefore, our approach involved repeatedly going from data to theory, to refine explanations about the occurrence of certain behaviours. We tried to construct these explanations at a level of abstraction that would encompass a range of phenomena or patterns of behaviour.

We tried to identify relationships between contexts, mechanisms and outcomes within individual studies, but also across different sources (i.e. inferred mechanisms from one study could help explain the way contexts influenced outcomes in another study). The synthesis of data from different sources was often required to compile CMOcs, as not all parts of the configurations were always present in the same source.

In summary, the process of evidence synthesis was achieved by the following analytical processes:

-

juxtaposition of sources of evidence (i.e. where evidence about behaviour change in one source allows insights into evidence about outcomes in another source)

-

reconciling of sources of evidence (e.g. when results differ in similar situations, these are further examined to find explanations for these differences)

-

consolidation of sources of evidence (i.e. where different outcomes occur in similar contexts, reasons can be developed as to how and why these outcomes happen differently).

Use of substantive theory

In realist reviews, a substantive theory is an existing and established theory within a particular subject area that describes patterns of behaviours at a greater level of abstraction from the intervention than is the aim of a realist review. 35 A substantive theory can help to make sense of emerging CMOc patterns and, therefore, aid in their development and/or may be used to provide an analogy (i.e. situate the causal explanation provided by the CMOcs with what is already known from existing research).

In some cases, substantive theories, particularly related to behaviour change, were cited or alluded to in the returned papers. However, much of the literature was not very theoretically rich. In these instances, substantive theory drawn from outside the returned literature became an important component in CMOc development. Some of the theories that informed the development of the programme theory related to the way in which remediation was conceptualised. Early in the review, through discussions among the review team and the stakeholder group, we began to conceptualise remediation as practice change, rather than an educational process. This drew us to theories of behaviour change to help make sense of the intermediate outcomes in the remediation process. In other cases, substantive theory would be drawn from previous realist research that considered interventions with similar contexts.

Chapter 3 Results

Results of the review

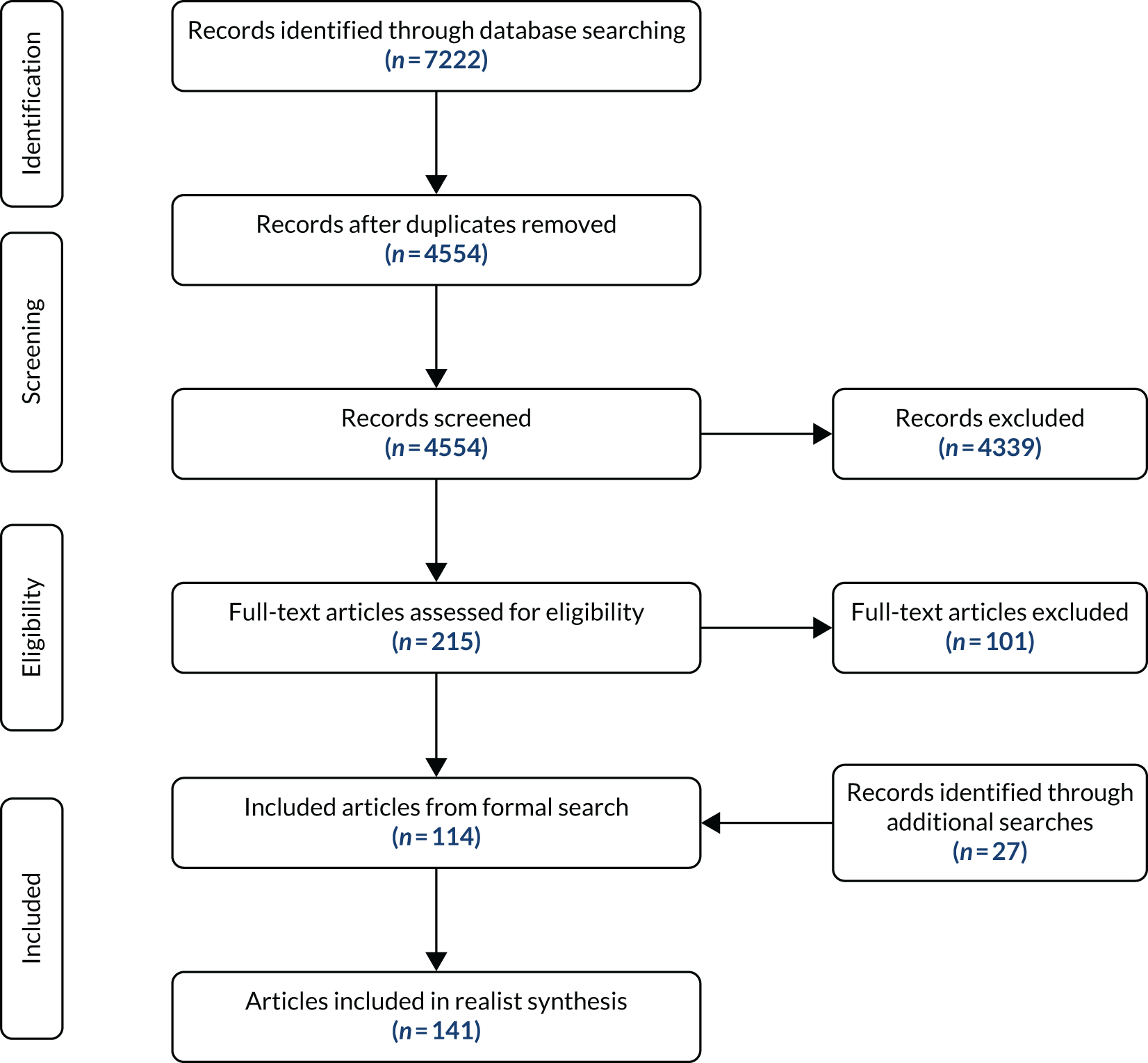

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram (Figure 2) reports the number of studies identified, included and excluded. A description of the characteristics of the included studies is available in Appendices 3–7. The main search returned 4554 articles. Of these articles, 114 were included in the review. A further 27 articles were returned from the additional searches (i.e. citation searches, grey literature searches, requests to stakeholders and supplementary searches).

FIGURE 2.

The PRISMA flow diagram. Reproduced with permission from Price et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Study characteristics

Of the 141 studies included in the review, 64% related to North America, with 14% coming from the UK. The majority of studies were published between 2008 and 2018 (72%). Forty per cent of the articles were commentaries, 37% were research papers and 31% were case studies. Of the research papers, 64% were quantitative, 19% were literature reviews and 14% were qualitative. Forty per cent of the articles were about junior doctors/residents and 31% were about practising physicians, whereas 17% were a mixture of both (with some including medical students). Forty per cent of studies focused on remediating all areas of clinical practice, including medical knowledge, clinical skills and professionalism. Twenty-seven per cent of studies focused on only professionalism and 19% focused on knowledge and/or clinical skills. Thirty-two per cent of studies described a remediation intervention, 16% outlined strategies for designing remediation programmes and 11% outlined remediation models. Appendices 3–7 provide a more in-depth overview of the characteristics of the included studies.

Conceptualisation of remediation and implication for the review

The purpose of this review is to gain a better understanding of what is working in remediation programmes to produce their effects. There is already an extensive literature on how doctors or trainees learn at different stages of their career, but remediation is a particular type of intervention, describing the process by which doctors are returned to safe levels of practice after having fallen below accepted standards. We decided in the early review meetings that the most useful approach to focus our review was to start to identify what was unique about remediation compared with, for example, medical education or, indeed, education more generally.

Remediation is, by definition, concerned with rectifying underperformance or poor behaviour. In the case of medicine, a remedial intervention is linked to a judgement on an individual’s fitness to practise medicine safely (i.e. relating to threshold standards of competence). This link between performance standards and patient safety associates remediation with failure, because the safe practice of medicine is the sine qua non of the medical profession. 8,40,41 However, at the same time, implicit in the term ‘remediation’ itself and the process it describes is the potential for remedy. 8 Therefore, remediation is conceptually nebulous. A study of stakeholders involved in remediation in Canada revealed that they held a dual conceptualisation of remediation (i.e. remediation was understood as both an educational and a regulatory intervention). 13 This latter conceptualisation directly links to the inherent association between remediation and the minimum standards required for practice. Remediation may be seen as a direct threat to professional practice, which is a particular challenge as it discourages doctors from self-identifying as needing help and engaging with remediation processes at an early stage.

In this sense, these interventions ‘work’ when they can create the opportunities and resources to overcome the barriers that are unique to remediation. Some of the more theoretically rich literature, combined with early discussions with stakeholders, led us to conceptualise remediation not so much as an educational intervention, but a change in practice and behaviours that would influence the learning experience. Reference to behaviour change theory early in the review, combined with stakeholder and review team discussions, enabled us to tease out the various outcomes that were relevant to CMOc building.

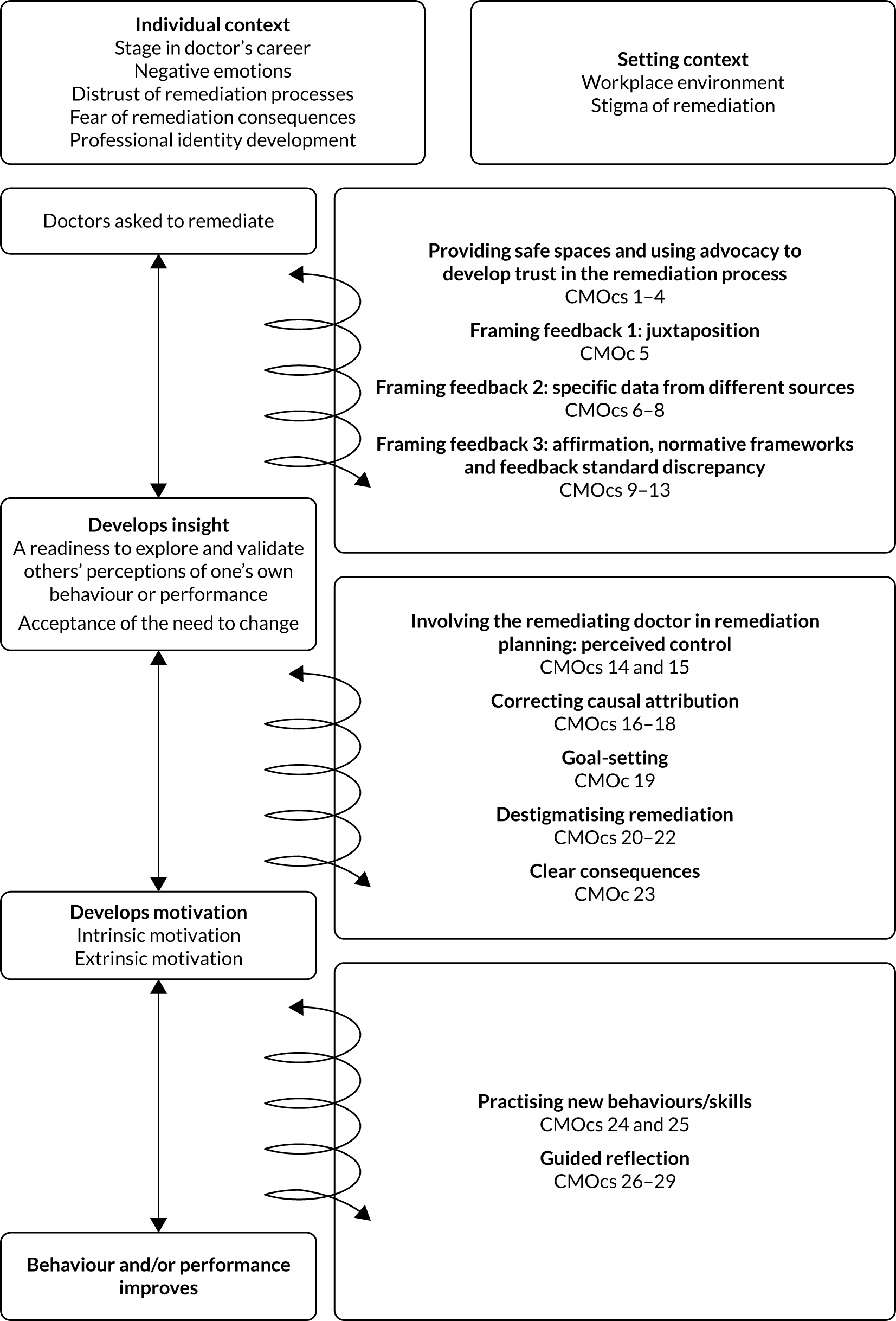

This conceptualisation has informed the development of the programme theory and, therefore, the structure of the way in which the results are reported here. Although remediation is by no means a linear process, there is a logical sequence whereby certain outcomes would precede others. Accordingly, the results are grouped into three categories, based around the kinds of outcome that occur at these stages in a remediation process: (1) insight, (2) motivation and (3) practice change. Within these three broad categories, the results are organised around the intervention strategies that are used to facilitate these outcomes.

Despite the logical sequence of the outcomes, it is important to emphasise that, early on, we identified remediation as a non-linear and an iterative process. For example, although a degree of insight into the nature of a problem may be an important outcome that precedes a remediating doctor from being motivated to change, insight can further develop all the way through a remediation programme.

The results are presented here in such a way as to ensure that they are both accessible and academically robust. Each section begins with a narrative explanation of how the different parts of the remediation process work to produce a particular outcome. This is then followed by a realist explanation in the form of a series of CMOcs, alongside a comprehensive explanation of the evidence base underpinning the CMOcs. The realist explanations for the CMOcs will include reference to substantive theory, where necessary. The purpose of structuring the findings in this way is so that the findings can be read and understood without having to read the realist explanations. The realist explanations of how we arrived at those findings are important for transparency. To provide a full and coherent explanation of our findings, there are elements of discussion in this chapter.

Summary of CMOcs

Table 2 provides a summary of the 29 CMOcs identified through our research in their three main clusters. This constitutes our final programme theory. The programme theory is also presented graphically in Figure 3.

| Cluster/CMOc | Summary |

|---|---|

| Insight | |

| Providing safe spaces and using advocacy to develop trust in the remediation process | |

| CMOc 1 | When a remediating doctor fears the consequences of remediation or does not trust the remediation process (C), an environment of trust will not develop (O) because they do not feel psychologically safe (M). An intervention strategy that can be used to change this context is the provision of a safe space where issues can be discussed in confidence |

| CMOc 2 | When a remediating doctor feels that their discussions are confidential and is able to express any negative emotions they feel (C), they will be more likely to feel psychologically safe (M), leading to an environment of trust (O) and a readiness to explore perceptions of their performance (O) |

| CMOc 3 | When a remediating doctor experiences empathy and positive regard (C), psychological safety is invoked (M), leading to a trusting relationship (O) and a readiness to explore perceptions of their performance (O). Advocacy may be used as an intervention strategy to provide opportunities for the remediating doctor to experience empathy and positive regard |

| CMOc 4 | If a remediating doctor has their motivations validated (C) then this may invoke psychological safety (M), leading to an environment of trust (O) and a readiness to explore others’ perceptions of their performance (O). An intervention strategy that may be used to provide validation is advocacy, where the advocate can acknowledge the motivations of the remediating doctor and their dedication. The role of an advocate may be most effective when the advocate has no role in the summative judgements about the remediating doctor |

| Framing feedback 1: juxtaposition | |

| CMOc 5 | When a remediating doctor’s perceptions of good practice/behaviour are juxtaposed against data on their actual practice/behaviour (C) then this may lead to an uncomfortable professional dissonance (M), which, in turn, invokes an acceptance of the need to change (O) |

| Framing feedback 2: specific data from different sources | |

| CMOc 6 | When feedback contains specific performance data and/or clear examples of reported behaviours, and is derived from a number of different sources (C), it is more likely to be validated by the remediating doctor (M), leading to an awareness of the discrepancy between perceived and actual performance or behaviours (O) |

| CMOc 7 | When a remediating doctor accepts that their perceptions of their performance or behaviours are not the same as their actual performance or behaviour (C), dissonance (M) leads to an acceptance of the need to change (O) |

| CMOc 8 | When feedback is perceived as a generalised judgement about an individual doctor, the remediating doctor is more likely to be defensive (C) and, therefore, go into denial (M), leading to rejection of the feedback (O) and/or rejection of the standards to which that feedback pertains (O) |

| Framing feedback 3: affirmation, normative frameworks and feedback standard discrepancy | |

| CMOc 9 | When a remediating doctor perceives remediation to be a threat to their career or their professional identity (C) then they may deny either the veracity of the feedback itself or the standard to which they are being held (M), leading to non-engagement in the programme (O) or superficial engagement (O) |

| CMOc 10 | If a coach or mentor is able to affirm a remediating doctor’s strengths and offer perspective (C) then the doctor is more likely to accept negative feedback (O) because they have received professional affirmation (M) |

| CMOc 11 | If feedback data are presented in a way that makes the problem seem manageable (C) then dissonance (M) may lead to the doctor accepting the need to change performance or behaviours (O). Intervention strategies that make issues seem manageable include affirming prior achievements, breaking up issues into manageable chunks and setting realistic goals |

| CMOc 12 | If feedback is framed in terms of a remediating doctor’s professional values (C) then a mechanism of normative enticement (M) may lead to accepting the need to change (O) |

| CMOc 13 | In the context of a remediating doctor who accepts that there is a performance issue but does not receive validation of their professional motives/unconditional positive regard/affirmation of their professional identity (C) then identity dissonance (M) may lead to rejection of medical professional identity (O) |

| Motivation | |

| Involving the remediating doctor in remediation planning | |

| CMOc 14 | If the remediating doctor has a role in planning aspects of the remediation process (C) then they may perceive that they have some control over the process (perceived agency) (M) and be intrinsically motivated to change (O) |

| CMOc 15 | When a remediating doctor rejects their professional identity (C) then they lack the motivation to change (O) because of normative rejection (M). Intervention strategies that can mitigate against a loss of professional identity include maintaining a degree of autonomy for the remediating doctor in the remediation programme |

| Correcting causal attribution | |

| CMOc 16 | When the remediating doctor is able to identify those aspects of their performance or behaviour that have caused problems that they can change (C) then they have more perceived control over the process (M), leading to greater motivation to engage (O) |

| CMOc 17 | When a remediating doctor is given specific strategies for learning or behaving (C) then, because of improved self-efficacy (M), they have greater motivation (O) |

| CMOc 18 | When a remediating doctor explores their own emotional triggers (C) then they are less likely to react to these triggers (O) because they are self-aware (M) |

| Goal-setting | |

| CMOc 19 | When the remediating doctor has a clear goal and a realistic sense that a goal is achievable (C) then they may have greater belief in their own ability to achieve these goals (self-efficacy) (M), which may lead to more motivation to change (O). Interventions that may create this context include SMART goal-setting strategies |

| Destigmatising remediation | |

| CMOc 20 | When the process of remediation is reframed in a more positive light (C) then the remediating doctor feels more psychologically safe (M), leading to greater motivation to engage in the programme (O) |

| CMOc 21 | When remediation is framed as punishment (C) and/or when a community of practice stigmatises those who have to be remediated (C) then the remediating doctor may feel alienated from their peers (M), leading to a sense of isolation (O) |

| CMOc 22 | When a doctor feels isolated from their peers (C) then normative rejection (M) may lead to a lack of motivation to change (O). Remediating in groups and/or networking with peers undergoing remediation may lessen the sense of isolation |

| Clarity of consequence | |

| CMOc 23 | When a remediating doctor understands the consequences of not changing their behaviour or improving performance (C) then they may be able to evaluate the costs and benefits of change (M), and may be motivated to engage with remediation (O) or change their goal (O) |

| Facilitating practice change | |

| Practising new behaviours/skills | |

| CMOc 24 | With repeated performance of correct behaviours or skills (C), performance or behaviour improves (O) because of repetition (i.e. practice) (M). This practice can be in situ if appropriate, but can be simulated if needed |

| CMOc 25 | When repeated performance is accompanied by appropriate feedback and guided reflection (C) then positive improvements are more likely (O) because the remediating doctor is able to integrate new knowledge and experiences into their learning (M) |

| Guided reflection | |

| CMOc 26 | When a remediating doctor has been guided through what the feedback means (C) then they are more likely to engage with the feedback (O) because it makes sense to them (M). Intervention strategies that may help to bring this about include regular face-to-face meetings and open reflective questioning from a trained coach |

| CMOc 27 | When feedback makes sense to a remediating doctor (C), dissonance is more likely to be invoked (M), leading to the remediating doctor gaining further insight into their performance or behaviours (O) |

| CMOc 28 | When the process of reflection is guided by someone from outside the remediating doctor’s employing organisation (C) then the feedback will be perceived as less threatening (M), leading to more meaningful reflection (O) |

| CMOc 29 | When a remediating doctor is allowed to develop and keep a reflective log that is meaningful to them (C), they have the opportunity to integrate their new learning and experiences (M), leading to insight into their own progress (O) and sustained changes in performance or behaviour (O). This may work best when the reflective logs are not assessed, but when their completion is nonetheless verified |

Facilitating remediation: developing insight

Based on our analysis and interpretation of the data, a remediating doctor must have insight for remediation to be successful. If they do not have insight going into remediation, then the remediation programme must work to help them develop insight. Insight is mentioned in a number of the returned papers,7,40,42–50 but two papers,42,43 in particular, have been useful in conceptualising insight in the context of remediation. Hays et al. 43 note that the term insight has been poorly defined in the setting of medical education, and that, in this setting, insight may be a combination of awareness of one’s own and others’ performance and the capacity to reflect. Brown et al. 42 discuss insight as a readiness to explore, intellectually and emotionally, our own and others’ thoughts and behaviours. Taken together, and considering the unique circumstances surrounding remediation, insight can be understood as comprising two different aspects, which we have used to help delineate some of the outcomes of the remediation processes in this review:

-

a readiness to explore others’ perceptions of one’s own behaviour or performance, and to validate those perceptions

-

acceptance that one’s own performance or behaviour is divergent from accepted standards.

Providing safe spaces and using advocacy to develop trust in the remediation process

As remediation is a threat to a doctor’s professional identity, and may also be perceived as a threat to their career, feelings such as anger and mistrust may prevent a doctor from even engaging with negative feedback on their performance or behaviour. 51 A recurring theme in the literature is that a remediating doctor is more likely to be ready to explore and to validate others’ perceptions of their behaviour or performance if they have trust in the people involved in remediation and trust in the process of remediation itself.

The actual word ‘trust’, although used on occasion,52,53 does not appear frequently in the returned literature. However, the idea of developing trusting relationships is implicit in a number of papers. 49,50,52,54–62 Trust also emerged as an important theme in the stakeholder meetings. To develop this relationship, the literature points to features of remediation programmes that might bring about trust. In particular, the literature noted the importance of developing safe spaces and using advocacy to engender trusting relationships.

The literature describes the need to create a ‘safe space’ in which a confidential discussion can take place, without fear of sanction or judgement. 49,52,54,55,57–62 A safe space is important because remediating doctors usually fear the consequences of being identified as needing remediation. One aspect of creating a safe space is to provide assurance of confidentiality. The literature refers to conversations in a remediation process that are not only confidential, but allow the remediating doctor the opportunity to express negative emotions, such as anger and shame, that might be invoked by being identified as needing remediation. 44,54 Our stakeholders suggested that this provision of confidentiality may also facilitate the remediating doctor to express any mental health issues that may not have come to light.

Trust can also be developed through building personal relationships during the process of remediation. Sometimes, such a relationship is described in the context of a coaching model53–56,59,60,63–66 and elsewhere in terms of a mentoring programme. 44,48,49,55,63,67–75 Regardless of the term used, a key focus in the literature is that someone in the remediation programme takes on the role of being an advocate for the remediating doctor.

Advocacy is described as offering ‘unconditional positive regard’76 in the context of a one-to-one relationship in a remediation programme. Empathy and validation are key to this role,75 which has been described as a ‘therapeutic relationship’. 77 In practice, this may mean empathising on specific issues, such as working conditions being very challenging, and acknowledging that others have similar struggles,55 or that behavioural norms have changed since the remediating doctor did their training. 76 Shapiro et al. 53 point to the importance of validating a doctor’s good motivations, even if the ultimate goal is to reach a point where the remediating doctor understands that they were not acting in a way that was compatible with this motive. 53

The person performing this advocacy role may be a senior doctor76 or a peer55,71 in a role labelled as either coach, mentor or other. A key point noted in a number of papers is that advocacy is deemed to be most effective when the individual fulfilling this function has no role in the summative evaluation of the remediating doctor or the final outcome of the process. 54,56,76 The advocate does not necessarily have to be intimately involved with the delivery of the remediation programme, but should be familiar with the case. 78 Our stakeholders suggested that this individual should be someone who is chosen by the doctor. Having this supportive relationship and non-judgemental encouragement allows for trust to develop, which, in turn, means that the remediating doctor is more likely to engage in the process and be ready to explore concerns about their performance or behaviour.

Realist analysis of providing safe spaces and using advocacy to develop trust in the remediation process

Extract 1 (Box 2) is typical of the way in which insight is addressed in the literature (i.e. a lack of insight is a barrier to remediation, but is potentially remediable). The emphasis on the importance of insight was mirrored in the stakeholder group discussions, in which a lack of insight was unequivocally associated with failure in remediation. The link between establishing safe spaces because of the reactions and vulnerability of the remediating doctor is drawn from data such as those in extracts 2–6 (see Box 2) and was verified explicitly in the stakeholder group discussions. The stakeholder group, both within meetings and in later e-mail exchanges, also emphasised the importance of trust as an important outcome when someone feels psychologically safe.

1. Paice:46

The question of insight is one that tends to come up whenever underperformance is discussed . . . studies on this phenomenon have shown that when offered extra training in the activity concerned the poor performers improve . . . This research suggests that lack of insight . . . [is] not an unsurmountable obstacle to remediation.

2. Egener:76

Confidentiality is critical to the physician/client’s honest disclosure of events and his or her personal reactions to those events.

3. Kalet et al. :54

It [coaching relationships] allows a safe space for a learner to express vulnerable emotions such as anger, shame, sadness, or to explain cultural issues that may have arisen. These issues generally must be recognized and validated before the majority of remediation can occur.

4. Kimatian and Lloyd:44

A compassionate and empathetic approach to the remediation process should include an opportunity for the resident to have a frank, honest, and private discussion with a trusted mentor, advisor, or objective coach or counselor.

5. Samenow et al. :79

The priority of the program’s first day is to create a safe environment conducive to transformative learning. Ground rules, including confidentiality, are established.

6. Shapiro et al. :53

In developing a system for reporting, evaluating, and responding to professionalism lapses, we created a process that is confidential, centralized, clear, and respectful.

7. Shapiro et al. :41

Denial is often based on a profound fear of the external and internal consequences of accepting the judgement of others. Thus it is important to create an environment that is as psychologically safe for the resident as possible.

8. Whiteman and Jamieson:49

We start by discussing their situation and exploring their narrative account, trying to harness the work done in their last GP appraisal – often viewed in a positive light as a piece of work done by a non-judgemental peer.

9. Papadakis et al. :58

The core message of this [first] meeting is: ‘We have important feedback that you need to hear . . . We value you, and we want to support you in your efforts to change’.

10. Paglia and Frishman:80

For a concerned programme director, denial that there is even a problem is often the major barrier to assisting a resident in the process of remediation. One way to circumvent denial is to provide a safe environment.

11. Egener:76

While the process is framed as education, in truth it is a therapeutic relationship, not unlike the patient–physician relationship. Empathy, genuineness, and unconditional positive regard are the most transformative elements of such relationships.

12. Mar et al. :71

The events leading to the decision for the need of and the conduct of a remediation plan are likely to involve some element of controversy. The resultant stress may be mitigated by the presence of an advocate at any meetings with the resident, by ensuring a fair process.

13. Smith et al. :78

The resident is under stress during this process and benefits from general encouragement in efforts to improve from the cheerleaders.

14. Sargeant et al. :55

To his surprise, as he talks with the facilitator and shares his dismay at these results and his frustration about not being able to do anything, he finds that the facilitator understands his perspectives and confirms that he is not alone – others feel this way, too.

15. Egener:76

The physician/consultant [person acting as coach or mentor] validated his sense of unfairness at having to change behavior that had previously been tolerated.

16. Kalet et al. :54

It is worth the effort to identify a ‘neutral party’ to conduct at least some of the remediation so that program leaders are freer to make difficult decisions if need be . . . it ensures that the learner can develop in a safe environment without threat of high stakes reprisal.

17. Warburton and Mahan:56

We advocate use of the term coaching to signify a process by which a struggling trainee receives individualized mentorship and guidance from an individual who is committed to his/her success and is not directly involved in his/her reassessment.

18. Egener:76

The consultant assumes the roles of coach, mentor, or teacher, but for several reasons the referring source must remain the sole evaluator of success.

19. Shearer et al. :47

Most institutions implemented some form of mentorship program for residents in remediation. It was commonly specified that a mentor . . . must be someone who would not play an evaluative role with the resident.

Therefore, CMOc 1 establishes the context that remediation is feared by those who engage in the process and that they will not engage if they do not feel psychologically safe (Table 3). CMOcs 2–4 refer to the role of psychological safety as a generative mechanism that leads to outcomes of trust and, because there is trust, a readiness to explore performance or behavioural concerns. Only one paper41 that was returned in the remediation literature search explicitly mentions psychological safety (see Box 2, extract 7). Psychological safety was examined as a concept at the suggestion of a member of the review team. We subsequently conducted a supplementary literature search to examine whether or not the concept was appropriate to help understand the causal mechanisms at work in building trusting relationships.

| CMOc | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | When a remediating doctor fears the consequences of remediation or does not trust the remediation process (C), an environment of trust will not develop (O) because they do not feel psychologically safe (M). An intervention strategy that can be used to change this context is the provision of a safe space where issues can be discussed in confidence |

| 2 | When a remediating doctor feels that their discussions are confidential and is able to express any negative emotions they feel (C), they will be more likely to feel psychologically safe (M), leading to an environment of trust (O) and a readiness to explore perceptions of their performance (O) |

| 3 | When a remediating doctor experiences empathy and positive regard (C), psychological safety is invoked (M), leading to a trusting relationship (O) and a readiness to explore perceptions of their performance (O). Advocacy may be used as an intervention strategy to provide opportunities for the remediating doctor to experience empathy and positive regard |

| 4 | If a remediating doctor has their motivations validated (C) then this may invoke psychological safety (M), leading to an environment of trust (O) and a readiness to explore others’ perceptions of their performance (O). An intervention strategy that may be used to provide validation is advocacy, where the advocate can acknowledge the motivations of the remediating doctor and their dedication. The role of an advocate may be most effective when the advocate has no role in the summative judgements about the remediating doctor |

The literature returned in the supplementary search showed that psychological safety was specifically concerned with developing trust within the contexts where perceptions of risk and fear are prevalent. Extract 3 (Box 3), from the most recent study83 we could find on psychological safety in medical education, also discusses its importance in relation to building relationships of trust. This focus on overcoming perceptions of risk and threat is well suited to the environment of remediation and provides a credible explanation of how intervention strategies can create the contexts that lead to trusting relationships in a remediation programme, in turn leading to a readiness to explore a problem. As a mechanism, psychological safety describes a process in which the opportunities and resources provided by the programme (i.e. the provision of a safe space and the advocacy role) alter the reasoning of individuals, enabling them to take the psychological risk of exploring their performance or behaviour.

1. Newman et al. :81

[Psychological safety is] the degree to which people view the environment as conducive to interpersonally risky behaviours.

2. Edmondson et al. :82

Psychological safety today is seen as especially important for enabling learning and change in contexts characterized by high stakes, complexity, and essential human interactions, such as hospital operating rooms . . . psychological safety plays a vital role in helping people overcome barriers to learning and change in interpersonally challenging work environments.

3. Tsuei et al.:83

PS [psychological safety] appeared to free them to focus on learning in the present moment without considering the consequences for their image in the eyes of others. Feeling safe also seemed to facilitate relationship building with the mentors.

These CMOcs identify the different contexts that can facilitate psychological safety, including a confidential and safe space for discussion and support provided by advocacy. Some papers note that part of this advocacy role may be acknowledging a doctor’s intentions and professional motives. Extracts 8–15 (see Box 2) imply that a more psychologically safe environment can be created with such validation, and this has informed the contexts noted in CMOc 2.

For CMOcs 3 and 4, we assert that the advocacy role may be most effective when this individual has no role in summative judgements about the performance of the doctor, and this point is explicitly noted in the literature (see Box 2, extracts 16–19). Although not developed in the literature, the notion of trust here offers a reasonable explanation (i.e. if someone is feeling judged then it is likely to be more difficult for them to build a trusting relationship and feel that they are being validated). This was also noted in stakeholder group discussions.

If a remediating doctor is ready to explore a potential behavioural or performance concern, and there is enough trust to validate others’ perceptions and judgements, a further aspect of developing insight is to accept the need to improve performance or change behaviour. 84 The acceptance comes when a remediating doctor realises that their behaviours or performance do not meet the standards that they consider to be important to the practice of medicine. However, as noted above, the fear and anger that accompany remediation may mean that, rather than accept these standards, a remediating doctor may just reject them or reject the feedback itself. Therefore, the important question is how can feedback be delivered in such a way that a remediating doctor accepts that they must improve their performance or change their behaviour?

Framing feedback 1: juxtaposition

One strategy is to use the remediation process to elicit the remediating doctor’s own ideas about what makes a good doctor, and then compare their own behaviours to these standards. One ethics remediation programme in the USA starts by asking all participants on the first day of the programme to describe the ‘ideal healer’. On the second day of the programme the participants describe their own actions and are presented with their previous ideals. 85,86 The authors expressly stated that the purpose of these programmes is to create a ‘professional dissonance’ or ‘ethical discomfort’85 that can be reconciled through an acceptance that the remediating doctor’s behaviour does not conform to the expectations of either the profession or the remediating doctor’s idea of what constitutes a good doctor. As these values come from the remediating doctor, rather than an external source, they may be perceived as being more authentic and less challengeable.

Acceptance may also occur when a remediating doctor’s own perceptions of their performance or behaviours are juxtaposed with the perceptions of trusted colleagues. Samenow et al. 79 describe a university hospital’s professional behaviours remediation programme. The first part of the programme for a referred doctor involves collecting feedback on behaviour from different members of staff. Similar to the aforementioned ethics remediation programme, the express purpose is to create a ‘disorientating dilemma’ where the remediating doctor contrasts their own perceptions of their behaviour with that of their colleagues. Another version of the juxtaposition strategy is to use video simulations in which actors act out unprofessional behaviours. The remediating doctor views a number of simulations, the last of which (unbeknown to them) has been specifically devised to show behaviours similar to their own behaviours. 65 Again, the purpose here seems to be contrasting their views on professional behaviours with their own behaviours.

Realist analysis of framing feedback using juxtaposition

Dissonance as a mechanism appears quite explicitly in the literature. In Box 4, extracts 2 and 3 discuss this in almost realist terms. In describing the disorientating dilemma or ethics discomfort that is induced through the strategy of juxtaposition, the authors offer a causal explanation of the way in which change can occur. This is based on the premise that the remediating doctor must accept the need to change performance or behaviour, which is noted or implied throughout much of the literature. This was also a continuing theme in stakeholder group discussions. Similarly, in extract 4, a process of guided reflection is used to enable the remediating doctor to compare their own actions with how they were perceived by others.

1. Caldicott and d’Oronzio:85

If the goal of the Program is to revitalize a commitment to the profession and reinforce its ethical values . . . the first two modules provide the experiential basis, ethical discomfort, and emotional energy for the undertaking. The task of the remaining five modules is to . . . create professional dissonance.

2. d’Oronzio:86

The contrast between knowing the idealized virtues and behaving in ways judged to be unprofessional creates a dramatic, dynamic tension.

3. Samenow et al. :79

The survey serves two purposes: to give objective feedback to physicians on how they are perceived, which they can then compare with their self-perceptions, and to monitor progress post intervention for as long as necessary.

4. Rumack et al. :87

We have found that some residents recognize such [unprofessional] behaviors only when they are videotaped and given directed feedback.

Context–mechanism–outcome configuration 5 (Table 4) describes the process whereby strategies that create this juxtaposition invoke change through dissonance. The outcome created here is the acceptance of the discrepancy between their own and acceptable behaviours.

| CMOc | Description |

|---|---|

| 5 | When a remediating doctor’s perceptions of good practice/behaviour are juxtaposed against data on their actual practice/behaviour (C) then this may lead to an uncomfortable professional dissonance (M), which, in turn, invokes an acceptance of the need to change (O) |

Framing feedback 2: specific data from different sources

Gaining insight from accepting feedback is important at all stages of remediation. Initial presentation of feedback may be part of what Papadakis et al. 58 have termed the ‘feedback conversation’. 58 As remediation progresses, feedback and reflection on new skills and progress will create more insight and more progress. Trust may then link into feedback, in that the remediating doctor may react more readily to the feedback received if they have a trusting relationship.