Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 15/70/101. The contractual start date was in March 2017. The final report began editorial review in April 2020 and was accepted for publication in February 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2021 Pollock et al. This work was produced by Pollock et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Pollock et al.

Chapter 1 Context and introduction

This report presents findings of a 30-month study that was funded by the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research programme [URL: www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr (accessed 16 March 2021)]. The study investigates how patients, their social networks and the health-care professionals (HCPs) who support them engage in the tasks of managing complex medication regimens and routines of care in the domestic setting for patients with severe and terminal illness who are approaching the end of life. In recent decades, there has been a shift of care from hospital or institutional settings to the home for increasingly complex and serious illness. 1–5 This transition has been made possible by advances in treatment and technologies of care that enable patients to remain at home despite experiencing serious and debilitating conditions, which would previously have required institutional care. 6–8 Home as a place of care and death is widely regarded as the best and preferred option for most patients. 9 However, a consequence has been that patients and their family and friend caregivers (FCGs) are required to take on the responsibility for increasingly demanding programmes of care, including managing complex medicines regimens. 6,10–14 Managing the demands of serious illness and the health-care system that provides treatment is hard work. 15,16 Family caregivers are critical in enabling seriously ill patients to be cared for and die at home. 17,18 To date, however, there has been little professional acknowledgement or understanding of the nature of the tasks undertaken or the burden of care assumed by families. 13,19 There has also been little research into how patients and family caregivers manage the challenges of home health care or what they feel about the responsibilities involved in the tasks of medicines management for terminally ill and dying patients. The Managing Medicines study used qualitative methods to investigate these issues from the multiple perspectives of patients, FCGs and HCPs from a wide range of roles in community and specialist care.

Increasing need for palliative and end-of-life care

Worldwide, it is predicted that the number of people dying in need of palliative care will double in the next four decades, with the most rapid increases being among those aged > 70 years and those with dementia. 20,21 Indeed, it has been proposed that expertise in palliative care should be promoted among all HCPs as ‘everybody’s business’. 22,23

In the UK, most people die in late old age and after prolonged and increasing comorbidity and/or frailty. 24 The UK population of those aged > 85 years has increased by almost one-third in the last decade. 25 Demand for health care continues to rise, not just from the ageing population but because of the increasing number of people living with complex, multiple and chronic conditions. 26 Alongside this increased demand, there has also been a reduction in social care provision and a promotion of policy drivers to encourage death at home, which is presumed to be the preference of the majority of people. 27–29 Regardless of the place of death, patients usually spend much of their last year of life being cared for at home, where they and their FCGs are often required to manage complex medication regimens, often involving powerful medicines that have a high risk of adverse side effects. 6,7

Informal care

The UK health-care system is heavily indebted to the contribution of informal carers. 30,31 The UK Census of 2011 estimated that 6.5 million people provide informal care for a friend or relative. More recently, Age UK (London, UK)32 puts the figure at 9 million people, with 18% of the population helping friends and family members with increasingly complex care needs. In 2015, unpaid care work was estimated to have an economic value of £132B per year. 30,31,33 The number of carers continues to increase, as does the intensity and duration of the support that they provide. 30,34,35 Many carers (especially spouses) are themselves old and in poor health. 36 Recent polls suggest that over > 2,000,000 carers are aged > 65 years. 34 Carers UK (London, UK) reports evidence of the detrimental effects that caring can have on carers’ physical, mental, social and financial health and well-being. 37,38 The critical role of FCGs in supporting patients to remain at home and be cared for at the end of life has not been widely recognised. 39 Questions have been raised about whether or not we are reaching the practical limits of informal carer capacity. 35,40 Support for medicines management to control distressing symptoms is a core area of home health care in which FCGs are heavily involved. 41 However, little is known about the complex realities of managing medicines from the point of view of patients or carers or how they respond to the challenges involved. 42,43

Managing medicines

Medicines management is a socially situated activity that is carried out mainly within the domestic setting. 6,44 Its work is embedded into daily routines and organised in terms of space, as medicines are located in different places within the house, and time, as medicine-taking is scheduled alongside the goals and activities involved in carrying on with life. 17 Therefore, different medicines may be laid out daily in different parts of the house to correspond with the movement of people through their daily routines (e.g. some by the bedside table, some on the kitchen sideboard and others in the sitting room beside the television). Some people may prefer to keep medicines concealed in cupboards rather than on display, given their signification of compromised health. 45 However, this may prove difficult, if not impossible, where space is restricted and the number of medicines and the amount of associated equipment and medical paraphernalia becomes extensive. Some medicines must be taken with and some without food and some must be taken at specified times before or after meals. Others may be taken on an as-needed basis. Medicine-taking must be managed around ongoing activities, such as work, leisure and social arrangements, and, when necessary, medicines may need to be taken outside the private space of the home. The complexity of the relationships between patients, prescribers and family caregivers, and the practical and lifestyle issues that medications may impose on patients, are substantial and infrequently acknowledged or understood by HCPs. 7,18,41,46–49

Many people are reported to express ambivalence towards medicine-taking. Medicines may be valued as a means to sustain an active life or be resisted as toxic substances, signifying loss of health and personal agency. 50–52 Low adherence has been a long-standing professional concern. It is often stated that up to 50% of patients do not take their medicine as prescribed. 19,53 However, accounts of how patients and FCGs undertake the work of medicines management suggest that non-adherence is often unintentional rather than deliberate and a common by-product of attempts to integrate complex regimens of medicine-taking into the demands of everyday lives. 17–19,52,53

The tasks of managing medicines are complex and various, and include organising timely access and supply of medicines; ordering prescriptions; acquiring information and understanding the purpose, use, dose and side effects; monitoring the benefits and harms; taking as prescribed; and liaising effectively with a range of different HCPs and services. 18,42,43 In addition to the practical work of medicines management, many patients contend with a subjective and emotional burden resulting from concerns about loss of health, personal autonomy and the adverse effects and potential toxicity of taking powerful medicines over the long term. 50,54

Managing medicines at the end of life

The burden of care, including medicines management, increases with illness severity and complexity, and as patients approach the end of life. 55 The palliative care population is identified as being at high risk for experiencing inappropriate prescribing and medicine side effects. 56,57 Twenty per cent of patients take eight or more medicines at the point of referral to palliative care, and the number of prescribed medicines increases as death approaches. Some reduction in long-term medicines tends to be offset by prescribing of new medicines to control symptoms (such as pain, nausea and agitation) as the end of life approaches. 22,58,59 As patients become more ill and severely debilitated, the tasks of medicines management are increasingly delegated, most often to family caregivers. Increasingly complex tasks can be involved, including giving injections, changing syringe driver cartridges and managing peritoneal dialysis, chest drains and percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG). 8,33,60

Our literature review of carers’ experience of managing medicines for patients dying at home identified that FCGs face increasing demands for care, but there was limited professional knowledge or understanding of the challenges that they face, how they cope with these challenges or how they can best be supported. 61 The literature reports widespread concerns among carers about managing end-of-life medication for the dying person in the home. 12,42,43,56,62–64 Patients and their FCGs report being inadequately informed and supported in medicines management. 42,43,62 They experience anxiety about administering powerful medicines, especially for pain relief. 65 Morphine carries a high symbolic load as being addictive, causing loss of consciousness and a signifier of impending death. 65,66 There are concerns about giving correct and timely doses and balancing the control of symptoms with the risk of overdosing or hastening death. Although FCGs can struggle to manage medications for someone who is seriously ill and dying at home, there is an expectation that they will take on these roles, and the performance of this is often judged by professional standards. 8,61 Conflict and disagreement between FCGs and professional staff have been widely reported. 12,42,43,62,63

Previous studies report a high incidence of pain and other distressing symptoms among dying patients. 62,66,67 The last days of life often involve aggravation of existing symptoms, including pain, or the sudden onset of nausea, vomiting, shortness of breath, agitation, confusion, retained respiratory secretions and weakness. 68 Patients may also become unable to swallow, requiring medicines to be administered in other forms, including patches, liquids, sublingually or subcutaneously. Pain is reported to be the greatest fear, and pain control is accorded a higher priority than place of death in public surveys. 69–72 However, evidence suggests that a high incidence of pain and distress is reported for patients dying at home62,66,67,72 and that pain is less well controlled in the home than in institutional settings. 29,73 In addition to the distress caused to patients and FCGs, failure to control symptoms at home leads to costly and unwanted use of health-care resources, including out-of-office hours (OOH) visits and unscheduled hospital admissions. 19,57,68

Burden of treatment theory

The work of managing medicines carried out by patients and FCGs, especially at the end of life, involves considerable burden and sometimes unwanted responsibility. 7,74 de Swaan’s75 characterisation of patients and carers as ‘proto-professionals’ is applicable in this context, where the home is annexed as an extension of the hospital and patients and FCGs are increasingly required to undertake the administration of complex regimens of care. These regimens also involve considerable effort, time and cost, which are required to attend appointments for routine tests and consultation with a wide range of different health professionals and services outside the home. The extent of work being carried out in the informal sector is not widely acknowledged by professionals, nor are the very considerable demands and associated burden placed on patients and FCGs confronting the considerable challenges and vulnerabilities of old age, serious illness, frailty and incapacity within a bewilderingly complex and bureaucratic system. 48,56

May et al. 7,74,76 have theorised burden of treatment relating to four main areas of work:

-

Coherence involves the unfolding process of making sense of illness and developing an understanding of treatment within a complex system of care.

-

Appraisal involves the work of assessing efficacy and quality of health care, and monitoring and adjusting treatments.

-

Relationship work refers to the effort required by patients and FCGs in negotiating support from others within informal and professional networks.

-

Enacting work is the effort put into operationalising treatment, including taking/administering medicines, monitoring supplies, ordering prescriptions, attending appointments and communicating with HCPs.

May et al. 7,74,76 propose that treatment burden should be a barometer of the quality of health care and that the goal should be to achieve ‘minimally disruptive medicine’. The question then becomes not how an overstretched health-care system can cope with the pressure of unrelenting demand from patients, but rather how do overburdened patients and FCGs cope with the pressure of the unrelenting demand imposed on them by a complex and bureaucratic system? The patient deficit model is rooted in a discourse of non-adherence, non-participation and a presumed lack of competence. By contrast, a professional deficit model can be proposed, which is rooted in poor communication and lack of organisational co-ordination.

Some patients have a more positive experience of health care than others. May et al. 7,74,76 highlight the extent to which individual responses are shaped by the opportunities afforded by their location within interconnected structures of socioeconomic advantage, environment, local infrastructures and health-care resources, and the resilience enabled by personal and professional networks of care through which information and material resources flow. 7 The acquisition and deployment of social capital is particularly difficult for people who are old, frail or lacking capacity or who have other challenges to contend with, such as belonging to a disadvantaged or underserved group. The burden of treatment theory proposes that care, and the capacity of patients to benefit from care, must take account of the wider context of social and structural constraints in which they are embedded. It highlights the extent to which personal agency is underpinned and enabled by the relationships that the individual has with others and how personal and professional networks may enable or disable access to key resources, including effective health care.

Diversity and disadvantage

Inequalities in access and provision persist in palliative care, particularly for patients affected by conditions other than cancer, from social and economic disadvantage and who come from ethnic minority groups. 77–81 Little research has been carried out into how terminally ill patients from socially and ethnically diverse backgrounds or patients who confront forms of social and personal disadvantage (e.g. homelessness, serious mental ill health, substance misuse or cognitive or sensory impairment or disability) manage medicines at home. 82,83 Ethnic and cultural differences can influence health-seeking behaviour, illness experiences and access and use of services and treatment. 84 The UK continues to be more ethnically diverse, with ethnic minority groups accounting for one-fifth of the population in England and Wales in 2018. 85 Ethnic minority populations are also ageing and increasingly experiencing life-limiting illnesses, which has considerable implications for the provision of palliative and end-of-life care. 86 Reduced access results, in part, from lack of information about the services that are available. Markham et al. ’s84 study to explore the reasons for low levels of hospice use among ethnic minority groups found that many had very limited or erroneous knowledge of palliative care services. A further barrier was that many key terms, such as ‘cancer’, ‘palliative care’ and ‘terminal care’, did not have direct translations into languages such as Hindi and Gujarati. Differing cultural approaches to death and dying meant that frameworks [e.g. advance care planning (ACP)] and decision-making could be problematic. 84 Little is known about how attitudes to medicines and medicines use, especially pain relief, are shaped by religious and cultural beliefs, or how HCPs respond to the consequences of these. 87–89

There has been very limited exploration of how people with disabilities manage medications, particularly at the end of life. In a study of the pharmacy needs of people with visual impairments in Scotland, Alhusein et al. 90,91 found that pharmacists had limited training and no policy to support them when dealing with patients with visual and hearing impairments. Patients reported that they did not always tell pharmacists about their impairment, but struggled to identify medications when the name, shape or colour of them changed. Patients also reported finding the layout of pharmacies to be challenging, not knowing if they had been seen or not hearing their name called when collecting medications. This led many to prefer to use the telephone or online ordering services, although these have communication challenges of their own. 90

Research is lacking into the needs of other underserved and marginalised groups, such as the homeless, asylum seekers, travellers and people affected by substance misuse and serious mental ill health. Symptom control and pain management can be a critical issue in end-of-life care for people with substance misuse. 92 Fractured relationships and family conflict can also make end-of-life care challenging. 81 Services for substance misuse often use a ‘recovery’-focused approach, which may not be useful as a patient shifts into palliative care because it restricts the dialogue that can be had around end-of-life care and ACP. 93

Optimising medicines management at the end of life

Good communication between patients and FCGs, between families and HCPs, and between HCPs, is fundamental to identifying and managing issues with medication in end-of-life care. 94,95 Timely access to medicines and support in understanding their purpose, dose and use are critical for patients and their FCGs in managing care at home. However, interprofessional communication and co-ordination of services is frequently reported to be poor, particularly in relation to securing patient and FCG access to medicines OOH. 12,42,62,96–98 Links between community and secondary care providers and between usual care and OOH providers are particularly unstable. 99,100

Community pharmacists

Although community pharmacists (CPs) evidently have relevant and specialist expertise in medicines management, historically they have predominantly occupied a medicine supply function in relation to community health-care teams. 57,101 Nevertheless, there is considerable scope for CPs to be involved in more direct and proactive advice giving to HCPs, patients and carers about the safe management, storage and disposal of medicines. Several initiatives have explored the extension of CP roles and clinical contact in community care, including Medicines Use Reviews, the New Medicine Service and non-medical prescribing. 57,101 However, it is not clear if, as a profession, pharmacists are keen to engage in greater involvement in supporting medicines management in palliative and end-of-life care or the logistical barriers that this would entail. 97 It is still rare for pharmacists (as well as other non-medical prescribers) to prescribe in palliative care. 102 A few schemes have indicated promise in developing greater involvement of CPs and greater integration of pharmacists within care pathways and integrated multidisciplinary teams (MDTs). 55,57,103–106 Lack of public and professional awareness of the existence or scope for such role development is one obstacle to greater CP involvement in medicines management. 107 However, CPs reportedly remain uncertain about their role in direct patient care and communication. 108 Indeed, Ziegler et al. 109 report that half of all qualified non-medical prescribers, including pharmacists, who work in palliative care do not prescribe. The current impact of non-medical prescribing in palliative care remains minimal.

Deprescribing

Polypharmacy is a major contributor to the burden of managing medicines for patients approaching the end of life, as well as increasing the risks of non-compliance and medicine incompatibility and side effects. 56,110 Evidence suggests that, far from reducing, the number of prescribed medications can increase, particularly for older patients. 110–113 Arevalo et al. 114 state the average number of medications taken in the last 7 days of life to be nine medications. Additional prescribing may often be required for the relief of symptoms, such as pain and nausea, occurring in the last days of life. However, in a Swedish cohort study of 58,415 decedents, Morin et al. 111,112 report that 32% of patients continued and 14% initiated at least one medicine of questionable clinical benefit in the last 3 months of life. Such ‘potentially inappropriate medications’ or ‘problematic polypharmacy’56 is common in palliative care. 59,115 Reasons for deprescribing not taking place include the reluctance of prescribers to broach difficult conversations about the significance of patients no longer needing to take medicines that were formerly prescribed to help keep them alive. 116,117 In addition, clinicians may want to avoid the additional workload of monitoring withdrawal or making changes to dosette boxes, as well as having concerns about creating conflict with the professional who originally prescribed the medication. 118,119 This example illustrates the continuing impact of professional hierarchy and deference, and the pitfalls that can occur when the professional network becomes overly complex. Different prescribers may become involved in individual patient cases without having a clear picture of the active care network or a sense that any one individual role should assume responsibility for undertaking an overview and rationalisation of what has been prescribed and is still needed. This is another area in which CPs could potentially play a greater role: in rationalising and simplifying the prescribed medicines with which patients and FCGs contend. Patient responses to deprescribing are unknown; however, given what is established about a widespread tendency to minimise medicines consumption, it is likely that many would be receptive. 50,54 Indeed, the tendency of many patients to undertake their own experiments to establish the efficacy and acceptability of particular medicines,120 often considered to be ‘non-compliance’ from a professional perspective, could alternatively be considered a form of patient-initiated ‘deprescribing’.

Anticipatory prescribing

The prescribing of anticipatory medicines (AMs) in end-of-life care has become widespread. 121,122 AMs presented in ‘just in case’ boxes comprise a small supply of injectable medicines and necessary equipment to treat the symptoms most likely to occur in the period shortly before death (e.g. pain, nausea, agitation, respiratory distress and excessive salivary secretions). 123 Most AMs continue to be prescribed by general practitioners (GPs), although other clinicians, including OOH doctors and non-medical nurses and CP prescribers, may also do so. The medicines are kept in the patient’s house in anticipation of future need. In most cases, the AMs are administered by community nurses (CNs), who undertake on-the-ground decisions about the appropriate time and dose of medicines to be used. 124 If regular or increased doses are required, a syringe driver is likely to be set up. In most cases, this would be prescribed by a GP but administered by CNs. Given the frequently reported problems of access to end-of-life care medicines,125 AMs have been widely welcomed as a means of ensuring that HCPs have a rapid and effective means of responding to an exacerbation of symptoms and distress in dying patients. However, the availability of AMs, especially in care homes, is also expected to reduce the demands and costs of OOH care and unscheduled patient hospital admissions. 68,121

Although AMs have become widely used and are recommended as good practice, they have been subject to little formal evaluation or research and their safety and efficacy have yet to be established. 121 Concerns have been raised about the increasingly early timing of prescribing AMs, the tendency for their use once prescribed and available in the home, and the potential risks keeping controlled drugs in patients’ homes for prolonged periods of time. 99 In addition, as most prescribed AMs are not actually used, there is a great deal of waste, with little supervision of their use or disposal. 121,126

Prescribers remain responsible for the use of AMs, but have little control over how and when they are administered. Lack of trust and communication between professionals and services can be a major obstacle to their timely and effective delivery. 12,62,99 There is evidence that CNs can struggle with administration, decision-making and ethics issues. 96 Appropriate use of AMs requires a reasonably accurate assessment of the likelihood of imminent death, which is notoriously hard to achieve. Wilson et al. 127 also found that district nurses (DNs) tend to err on the side of caution, adopting a conservative and parsimonious approach to the initiation and subsequent use of AMs, especially for pain relief.

In a situation of rising patient need and increased pressure on health-care resources, including a declining number of available professionals (e.g. CNs),128 questions have been raised about the scope for extending patient and FCG roles to directly administering medicines, including AMs, particularly to enable prompt relief of pain and other acute symptoms. The provision of such ‘emergency medication kits’ and the giving of subcutaneous injections for use by patients and relatives at home is well established in countries such as Australia129–131 and the USA. 132 Such practices remain uncommon in the UK, with only a small body of exploratory work and local policy having been developed to date. 133–136

The prescribing and subsequent use of AMs is a very significant moment in the patient’s dying trajectory. Little is known about what patients are told or understand about these or how they respond to such information, or about what FCGs would feel about taking a more active role in making decisions and using AMs directly. A few studies have reported that AMs are welcomed by families, who find their availability reassuring, especially when experiencing increasingly difficult circumstances of care at home,131 although these findings tend to be based on professional perceptions rather than patient and FCG testimony. 122,124 However, much more research needs to be undertaken to establish the understanding and acceptability of AMs for patients and FCGs, and the extent to which FCGs are willing to take a more proactive approach to managing medicines in end-of-life care.

Networks of care in a complex system

As health care has shifted from the institution to the home, domestic households are at the centre of complex networks of practice and health-care management that involve diverse health and social services and professionals, as well as wider informal networks of friends and family and technologies, including the internet and social media. 5,6,137 The consequences of colonising the private space of the home as a site of care for co-resident family members as well as patients have yet to be established. FCGs (co-resident or otherwise) are critical to enabling terminally ill patients to remain at home, increasingly often to the point of death. However, little is known about the experience of care, the nature of the tasks undertaken or how the labour of care, including medicines management, is distributed across the informal network. Cheraghi-Sohi et al. 17 found that chronically ill patients preferred to retain administrative and functional responsibility for medicines management and delegated relatively few tasks to family members. Medicine-taking was a moral practice and the capacity to self-manage care was bound up with patients’ sense of self and agency. However, patients confronting terminal illness often face extended periods of increasing dependency on others to support them with the tasks of care, including medicines management. We know little about the distribution of labour within the home, how FCGs feel about the practical and emotional responsibilities of managing complex regimens of care, or how their changing roles affect relationships within the home. Professional services and the relationships established between professionals and between professionals, patients and FCGs can be critical to the experience of end-of-life care and to enabling patients to remain at home. For patients approaching the end of life, the experience of great debility and vulnerability occurs in conjunction with increasing care needs from informal and professional networks and often an increase in the complexity of care. At a time of great physical effort and emotional distress, the family must adjust to increasing complexity of care and rapidly changing inputs from professional services. Effective medicines management is critical to the control of symptoms and to the experience of death and dying for patients and their FCGs.

In the Managing Medicines study, we wanted to explore the range of services and people involved in supporting patient care, particularly in relation to how the tasks of medicines management were distributed throughout the patient’s informal and professional networks. 17,138 Reflective accounts of bereaved family caregivers (BFCGs) provided insights into the entire trajectory of end-of-life care and the nature and impact of the experience of informal care provision. We also wanted to understand the experience of care of patients from disadvantaged and underserved groups, and how professional services identify and respond to the difficulties and concerns arising in medicines management for patients in these groups. 82,83

Aims and objectives

Aim

To explore how seriously ill patients, their FCGs and the HCPs who support them engage collaboratively in managing medicines prescribed for relief of symptoms towards the end of life, and to provide evidence from a detailed study of barriers to, facilitators of, and information about and training needs for the improved support at home of terminally ill people and their families.

Objectives

-

To explore how patients and FCGs, particularly from minority, underserved and hard-to-reach groups (e.g. ethnic minority groups, the economically disadvantaged, those affected by severe mental health problems or those affected by non-cancer disease) manage medicines prescribed for patients with serious and terminal illness being cared for and dying at home.

-

To compare and contrast the experience of symptom control and FCG involvement in medicines management for patients who have been referred to specialist palliative care (SPC) services and patients who have not been referred.

-

To establish what further support, information and training FCGs and HCPs need to feel confident in managing medicines, including those for end-of-life care, for patients being cared for and dying at home.

-

To explore lay and professional stakeholder perspectives (including those of GPs, CPs and nurses) about how CPs could be better integrated into the network of care and support for families and professionals in medicines management and end-of-life care.

-

To use the knowledge gained, from the perspective of all stakeholders, to make empirically founded recommendations for service development and effective commissioning in relation to medicines management to improve the care and experience of patients being cared for and dying at home and that of their FCGs.

Structure of the report

This chapter has provided a background to the study and considers the policy context in which it is set, alongside evidence available from previous studies. The next chapter outlines the design and methods of the study before five further chapters present a summary of patient and public involvement (PPI), participant demographics and the empirical findings from workstreams 1 and 2. Chapter 8 presents a summary of the stakeholder workshops that constitutes workstream 3 and the conclusions and recommendations resulting from these. Chapter 9 includes a discussion and critical appraisal of the findings in relation to the current literature and health-care policy. Finally, Chapter 10 provides a summary of the findings and their significance, and considers their implications for the development of policy and practice to optimise service development and professional support for patients and FCGs confronted by the challenges of managing medicines for serious and terminal illness within the home.

Chapter 2 Methodology

Study design

The Managing Medicines study explored how terminally ill people, their families and the HCPs who care for them engage in the tasks of managing complex medication regimens and routines of care at home.

A qualitative study design was employed to generate data in three workstreams:

-

HCP and BFCG interviews

-

family-centred case studies

-

stakeholder workshops.

Qualitative methods of data collection and analysis facilitate the in-depth exploration of participants’ experiences and their views. They are particularly suitable for use where little is known about the issue and in the study of sensitive and complex topics. Semistructured interviews allow participants and researchers to explore core topics, while simultaneously offering the flexibility to follow-up on new issues of interest and importance. 139–141 Case studies are eminently suited to the examination of complex real-world situations in which a variety of perspectives are at play. 142,143 The engagement of several participants within each case enables the comparison of different perspectives, and longitudinal follow-up allows for an exploration of processes and experiences developing over time, rather than the cross-sectional snapshot provided by one-off interviews. Interview data were supplemented by additional data sources, including observations, photographs and medical records. Each case was followed up, where possible, for a period of approximately 3 months.

Setting/context

The study was based in the East Midlands, UK, with participants recruited across the counties of Nottinghamshire and Leicestershire.

Ethics and governance approvals

NHS Research Ethics Committee approval was obtained in March 2017 (reference 17/EM/0091) and for two subsequent amendments to allow an increase the sample size for workstreams 1 and 2 and to include the option to seek consultee advice in relation to research involvement of patients lacking capacity. Permission was also sought, via the Health Research Authority, from the appropriate NHS trusts for their sites to act as patient identification centres in recruiting participants to the study.

Engaging severely ill patients and, recently, BFCGs in research projects presents challenges and requires flexibility and sensitivity throughout the process. Previous research has reported that participants find taking part in qualitative research to be a positive experience, even when they anticipate that this might involve discussion of distressing issues. Indeed, some people find the opportunity to reflect on their experience in the ‘neutral’ context of a research interview to be helpful and may value the opportunity to contribute to a research effort that may benefit others. 144,145 As a research team, we believe that not offering vulnerable people the opportunity to take part in research because of assumptions made about their experiences and preferences is discriminatory and exclusionary. 146,147 Prior to the decision take part, participants were asked to consider how they would feel about discussing their experience of illness and dying. They were assured that participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study at any time. Some participants did become emotional during the interviews, but all clearly indicated their preference to continue the discussion.

Eligibility

Workstream 1: health-care practitioner and bereaved family caregiver interviews

Health-care professional interviews

The purpose of the HCP interviews was to explore participants’ experience of supporting medicines management for seriously ill patients being cared for and dying at home. HCPs with experience of providing care or prescribing, dispensing or administering medicines for such patients were eligible to participate.

Bereaved family and friend caregiver interviews

Interviews with BFCGs explored participants’ experiences of professional and informal support for medicines management in relation to the last months of care of their deceased relative or friend. These included the extent to which participants had undertaken different types of tasks and responsibility for medicines management, the support that they had received from their professional and informal networks, and how well they felt that the health-care system had co-ordinated this aspect of care. BFCGs of patients who had been cared for at home during a substantial part of the last 6 months of life were eligible to take part.

Workstream 2: case studies

Patients who were identified by a member of their clinical team as likely to be in the last 6 months of life and to be experiencing issues with medicines management were eligible to participate in workstream 2. Where a patient did not wish or was not able to take part directly in the study (e.g. because of poor health), the key participant was a FCG who might be a family member or a friend. HCPs were also invited to take part after being nominated by the patient as someone closely involved in their care. Each case was developed on its own terms. There was no standard configuration. Some cases lacked a FCG or nominated HCP (e.g. where the patient lived alone). More than one FCG or HCP could be recruited for each case. Participants had to be ≥ 18 years of age and with capacity to consent.

Workstream 3: stakeholder workshops

The purpose of the stakeholder workshops was to disseminate the study findings, identify priorities for implementation in education and practice, and promote collaboration in the development of education and training resources and research. Members of lay and professional stakeholder groups who had experience and/or expertise of medicines’ management for patients being cared for at home at the end of life were eligible to take part in the workshops.

Recruitment

The data collection period for all three workstreams ran from June 2017 to June 2019.

Workstream 1: health-care practitioner and bereaved family caregiver interviews

Eligible HCPs were identified through service managers and professional networks, or following presentations about the study given by members of the research team to local services and practices. Each HCP was given or e-mailed the information about the study and was invited to contact the research team if they wished to take part.

Bereaved family and friend caregivers were identified through general practices and palliative care registers, hospices, the caseloads of community and SPC professionals and through local community organisations. BFCGs were approached between 8 weeks and 6 months after the death of their relative by a HCP known to them. They were posted or given an information pack, which included a covering letter, the information sheet and a reply slip with return envelope, along with contact details for the research team. Individuals then made contact directly with the researchers if they were interested in taking part in the study.

Workstream 2: case studies

Family-centred case studies were established around the care of a patient who was likely to be in the last 6 months of life and who was in receipt of a complex medication regimen or experiencing issues with medicines management. Such complexity was associated, for example, with the number of medicines required, but could also be related to the need for different routes of administration or the use of technologies to support medicines’ use. Key HCPs were also invited to take part after being nominated by the key participant. In case studies where the patient was not recruited as a participant, a FCG was identified as the core participant.

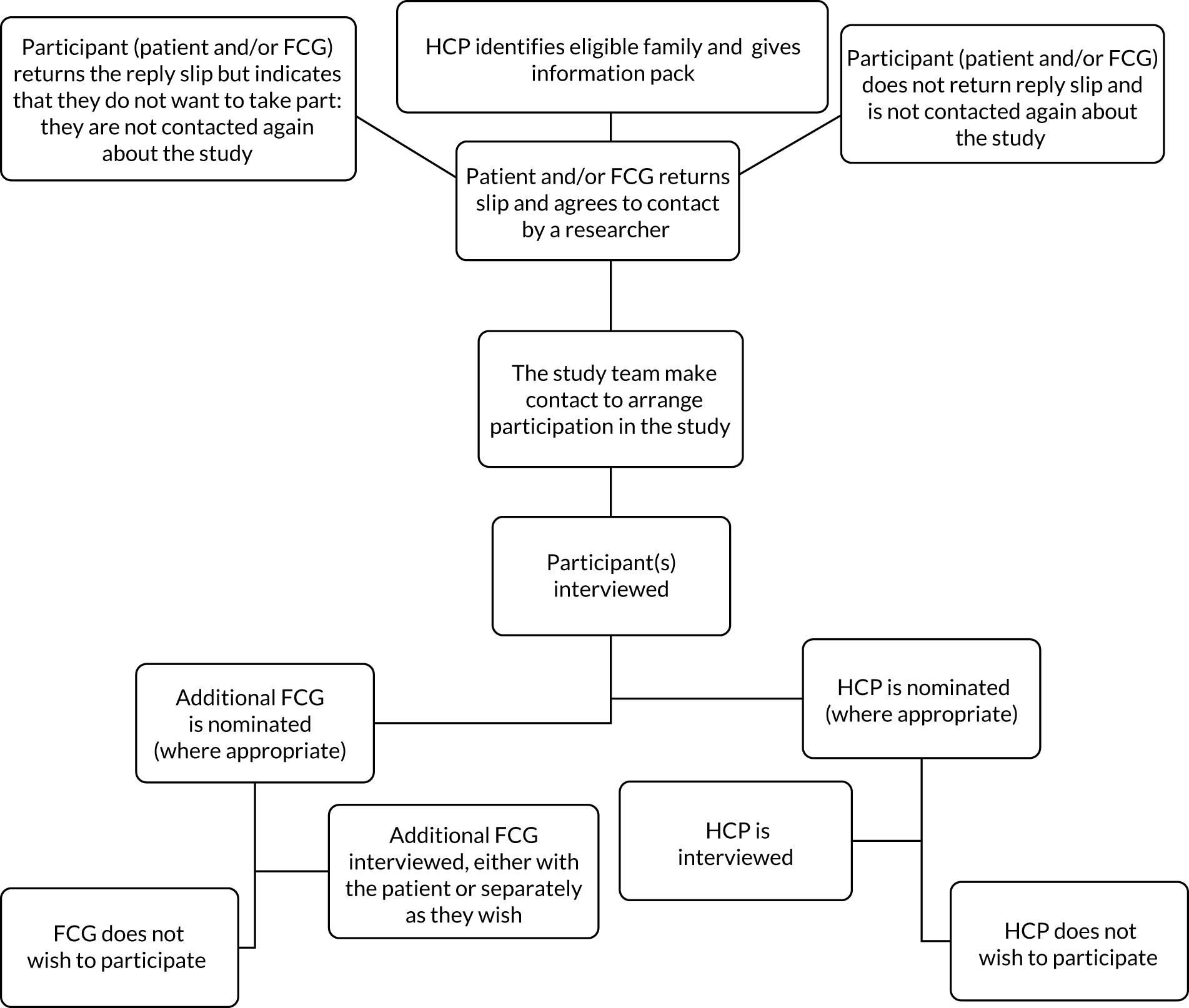

A purposive sampling strategy was employed to promote recruitment of a culturally and socially diverse sample of patients and FCGs. This included individuals from communities underserved by palliative care services, such as those from ethnic minority groups, those with learning disabilities and those with experience of conditions other than cancer [e.g. chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder (COPD) and renal failure]. In addition, we aimed to recruit approximately equal numbers of participants from SPC services and generalist community services; Figure 1 shows the recruitment flow chart.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of participant recruitment to the study.

Workstream 3: stakeholder workshops

Members of stakeholder groups who had experience and/or expertise of medicines management for patients being cared for at home at the end of life were invited to take part in one of two workshops, which were held in Nottingham and Leicester in June 2019. Invitations were sent to all of the HCPs who had participated in the study, all key professional links to the study and our professional networks, the University of Nottingham Dementia, Frail Older and Palliative Care Patient and Public Involvement Advisory Group (Nottingham, UK) and the Marie Curie Research Voices PPI Group (London, UK). We also asked all invitees to disseminate to their own networks and promoted these events on Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; URL: www.twitter.com) and ResearchGate (ResearchGate, Berlin, Germany; URL: www.researchgate.net). The workshops took place in Nottingham and Leicester to make them as accessible as possible to the local teams who had engaged with the study throughout.

Data collection

Workstream 1: health-care practitioner and bereaved family caregiver interviews

A single semistructured interview was carried out with BFCGs to explore their experiences and perspectives of looking after their deceased relative and the management of their medicines. HCPs were also interviewed once about their experience of supporting patients towards the end of life with medicines management.

Workstream 2: case studies

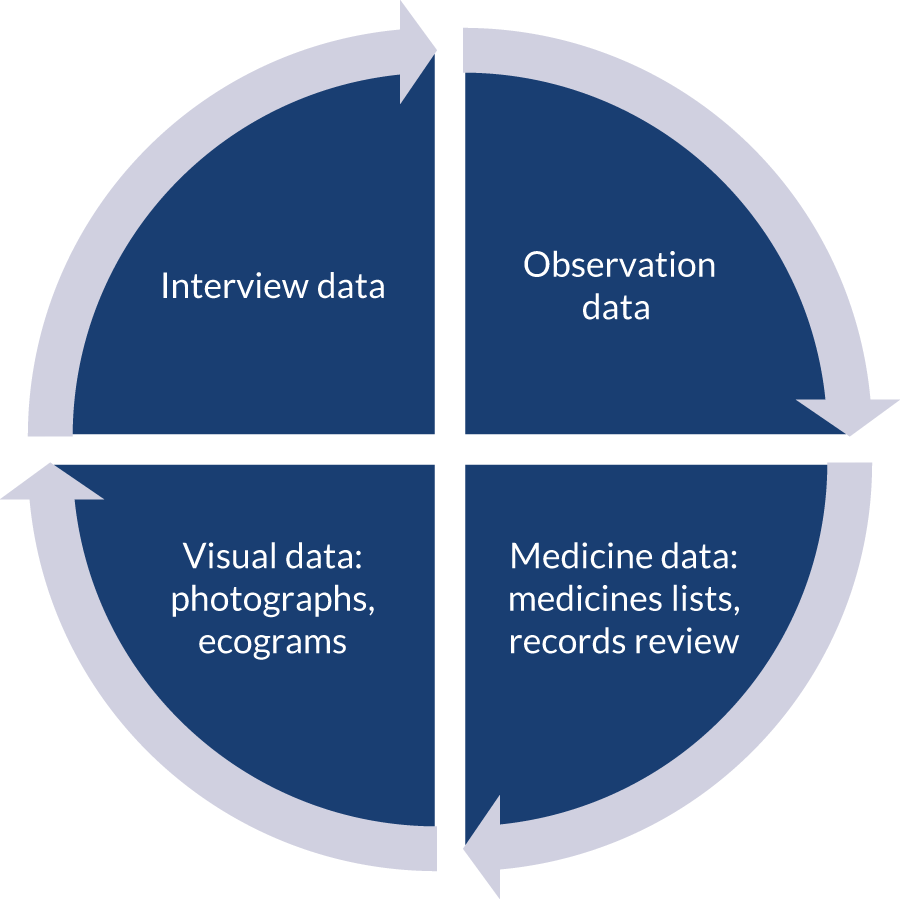

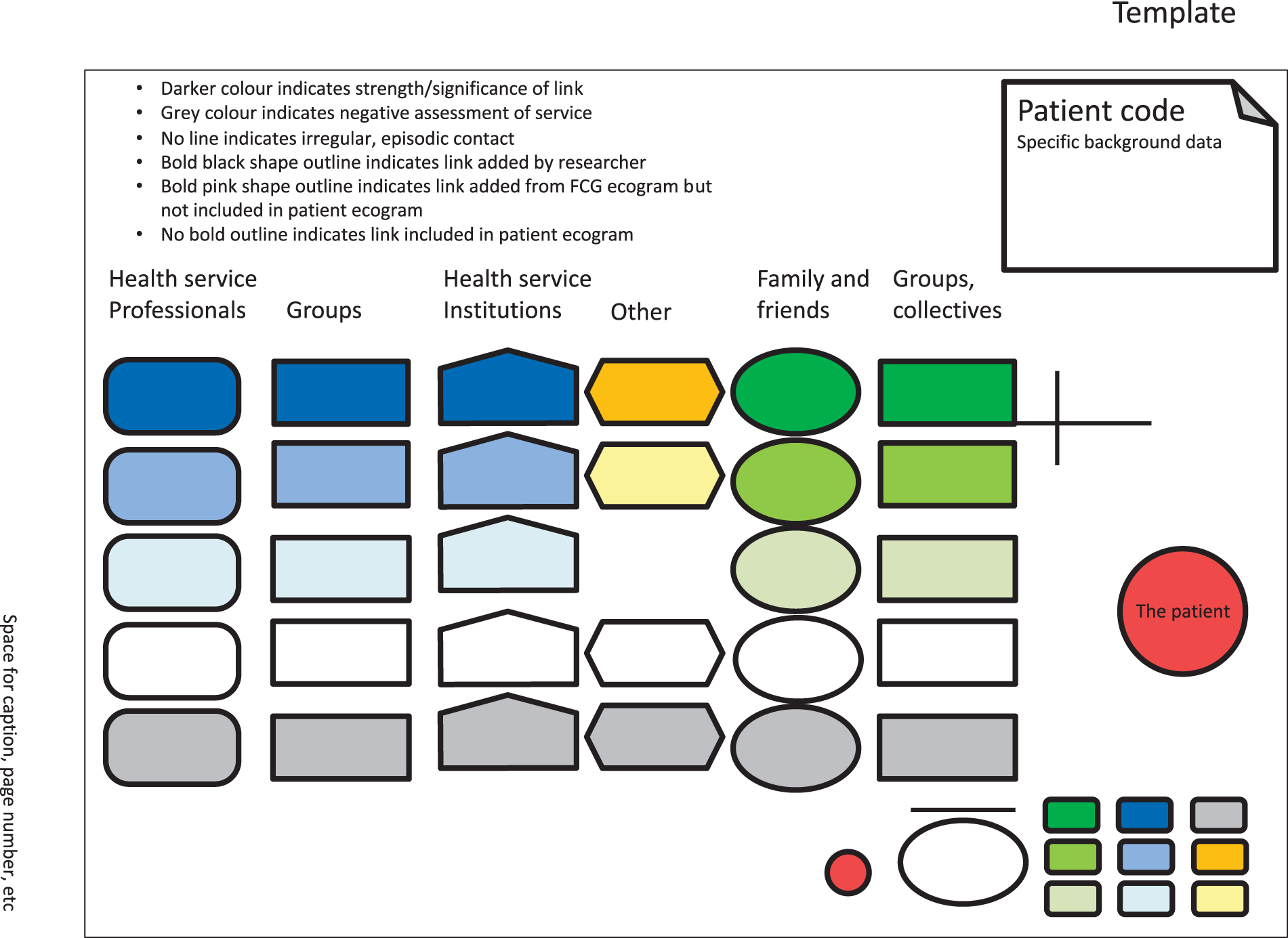

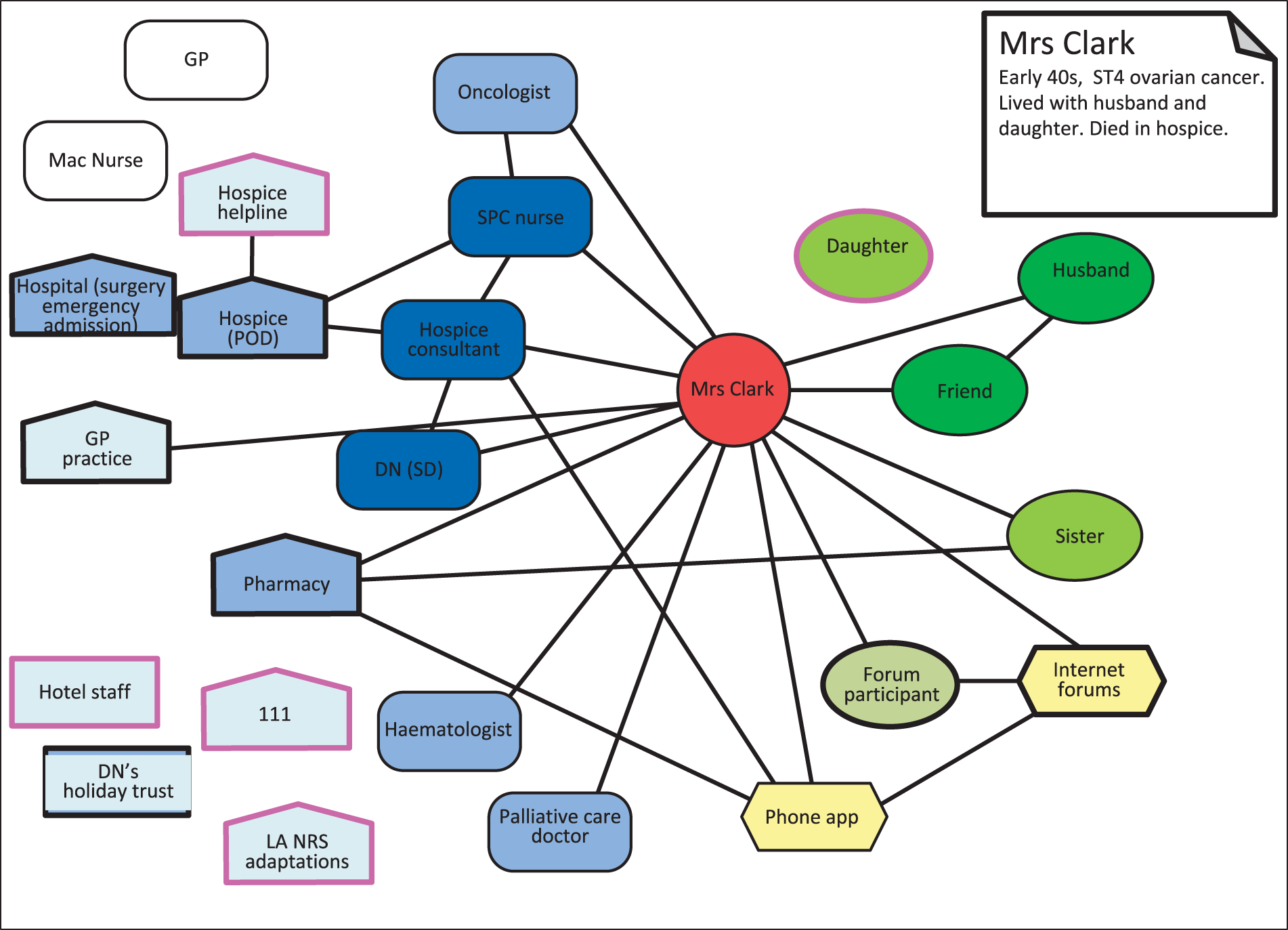

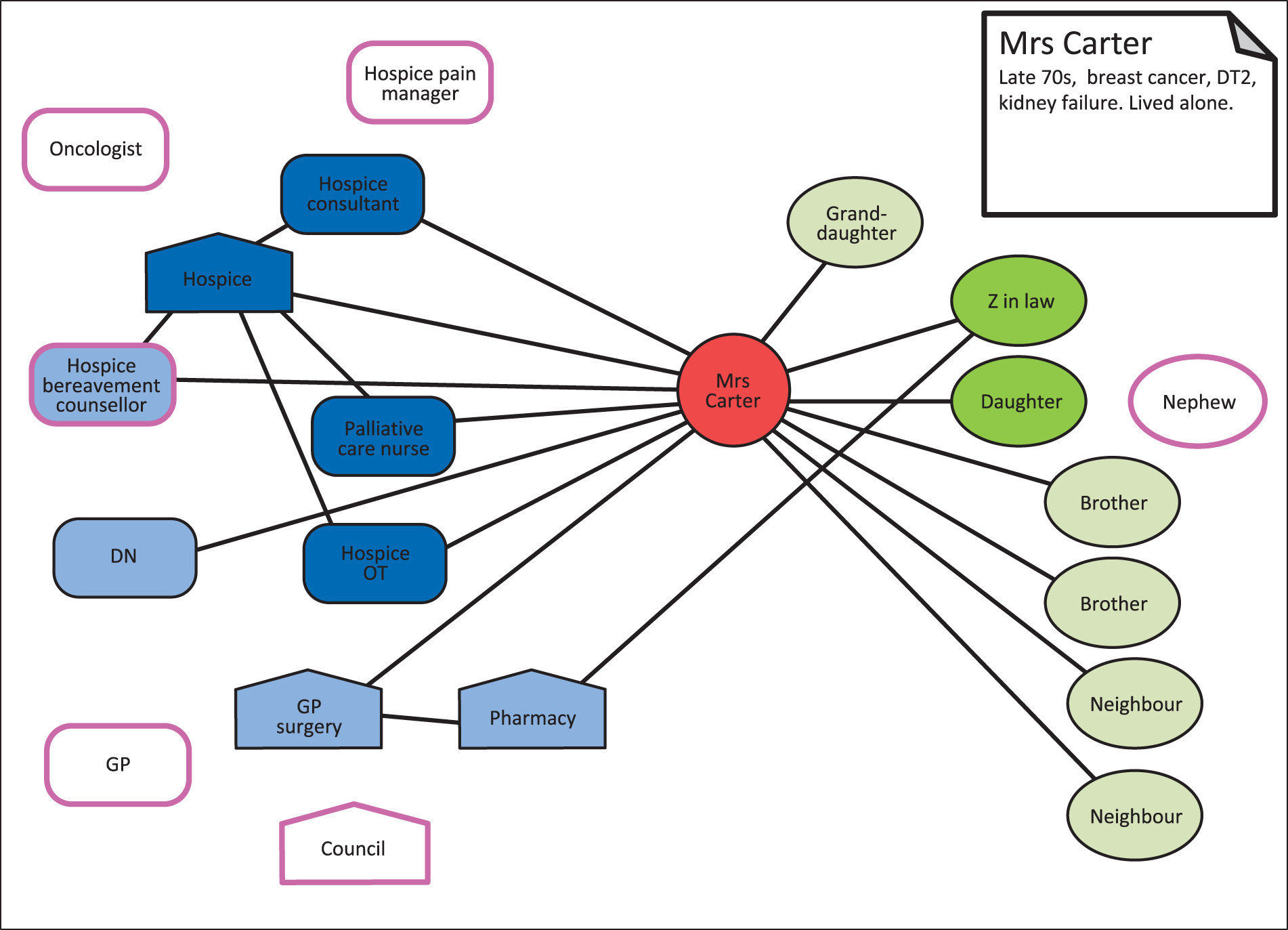

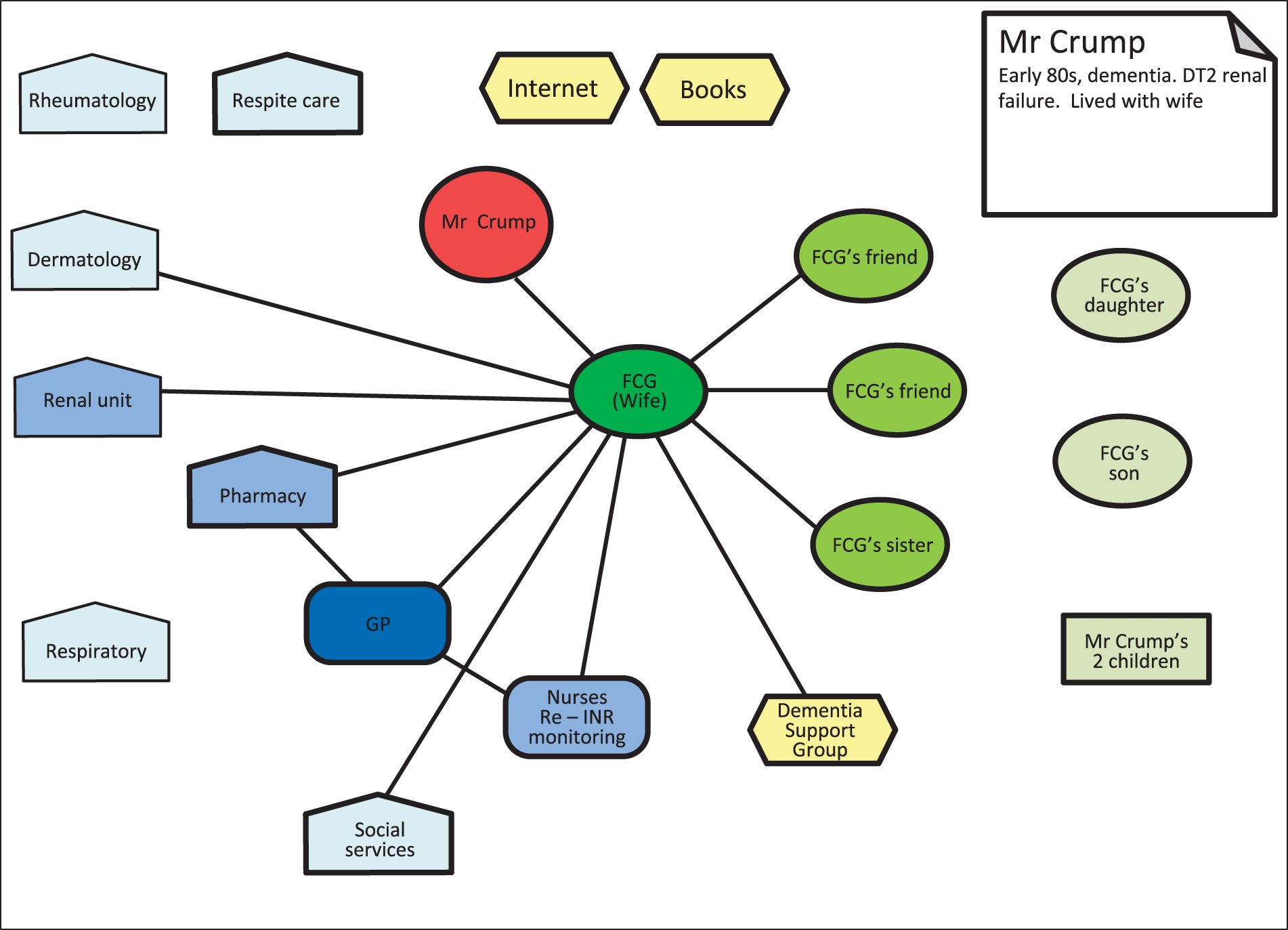

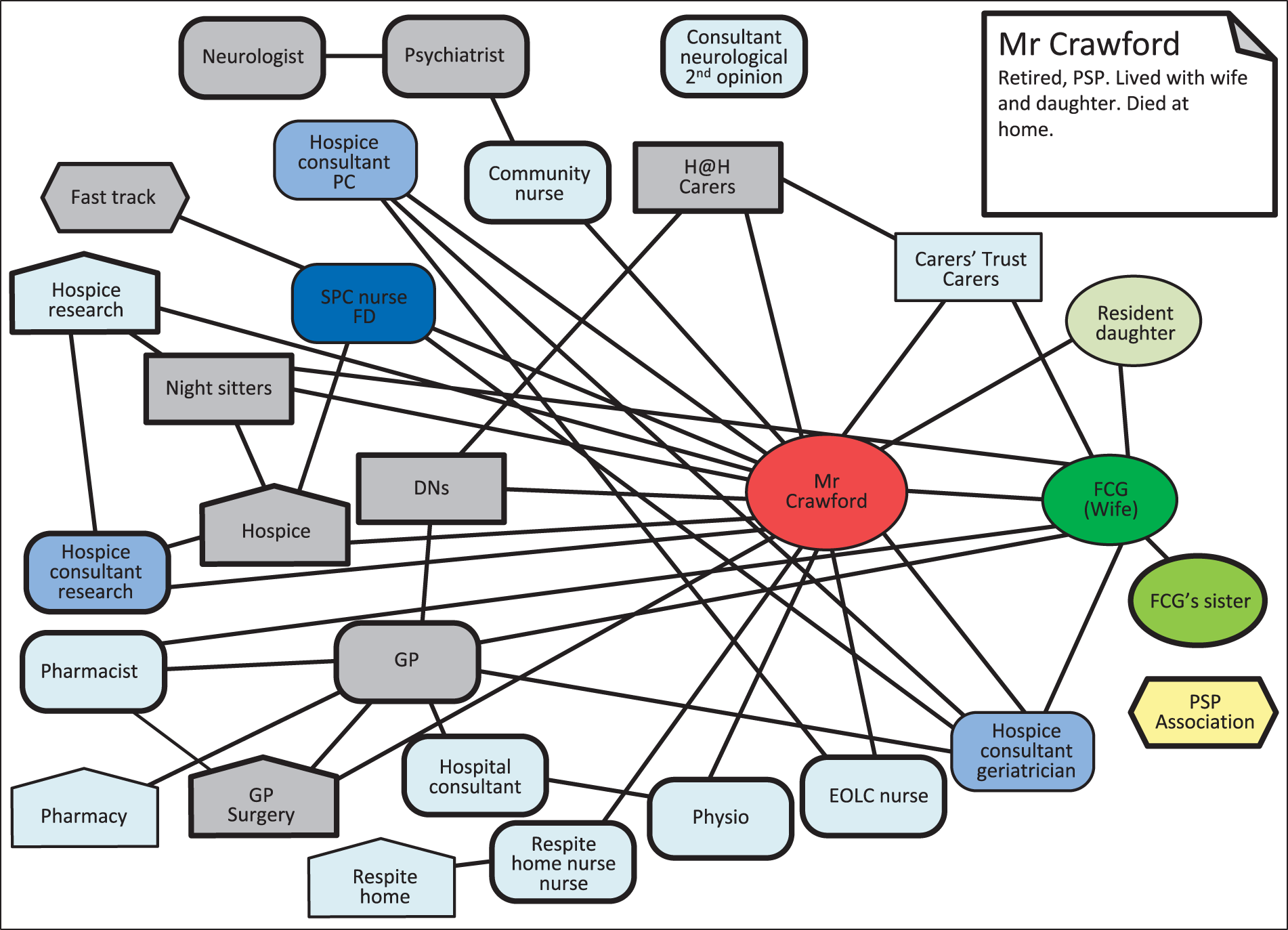

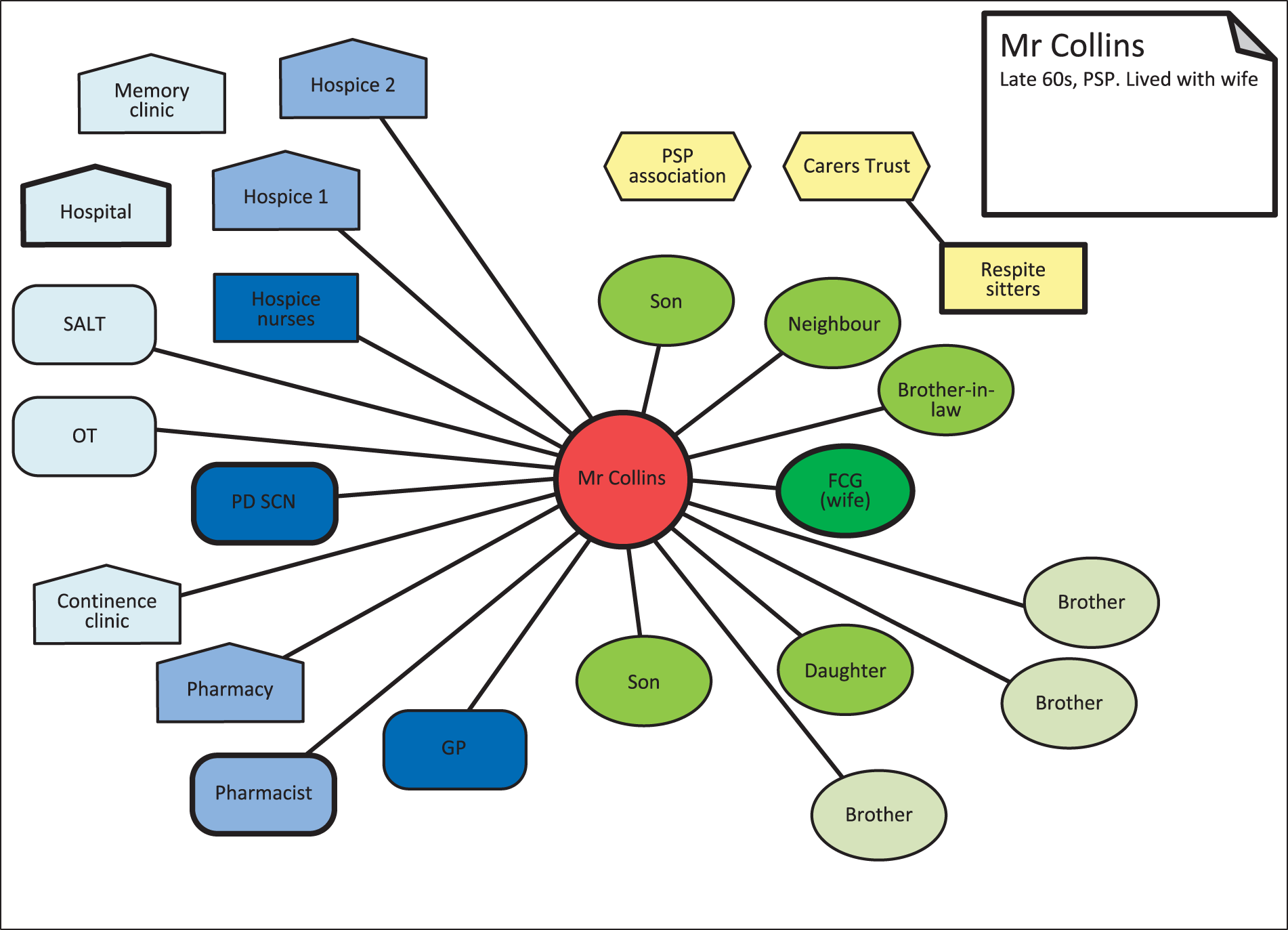

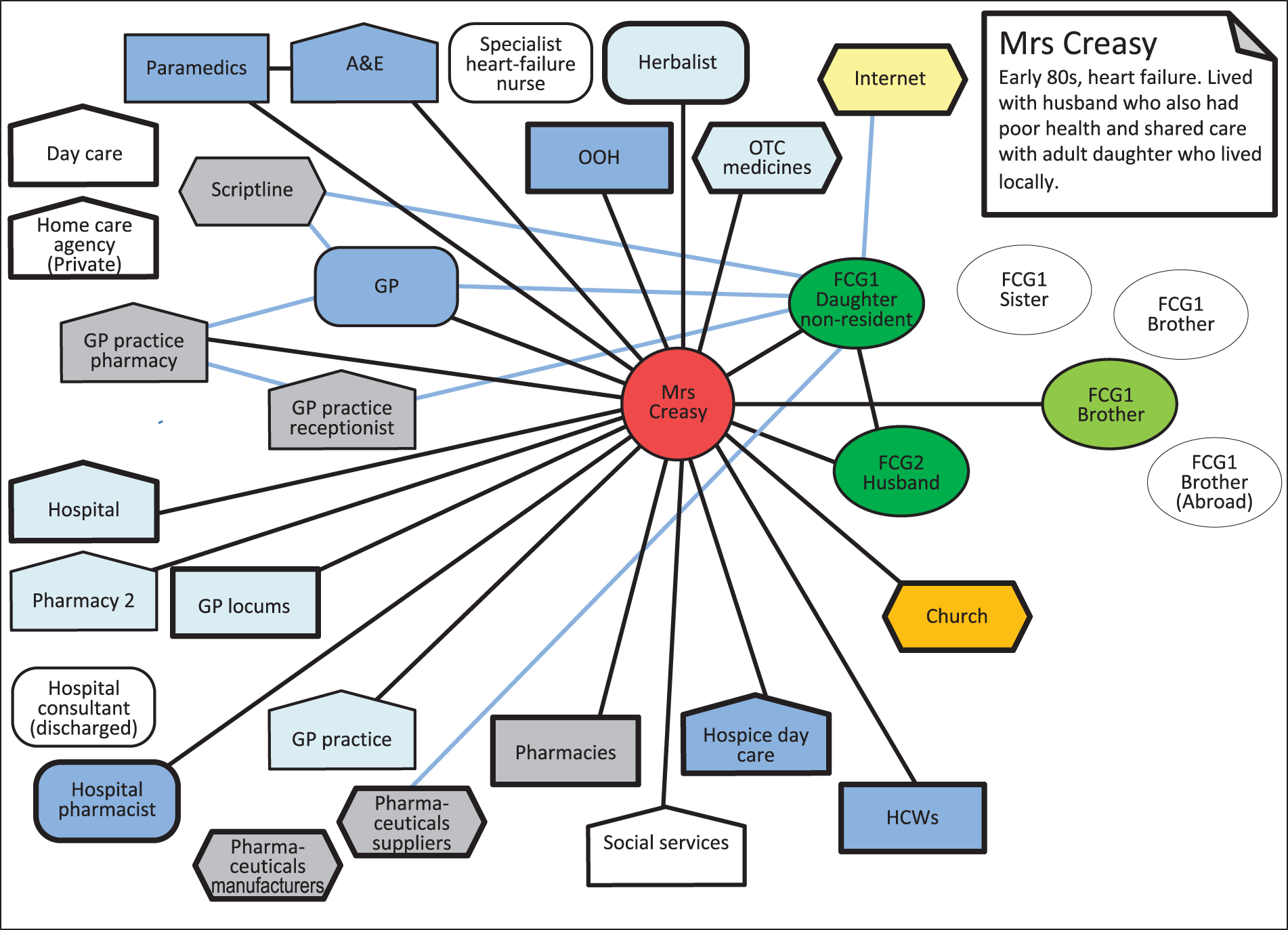

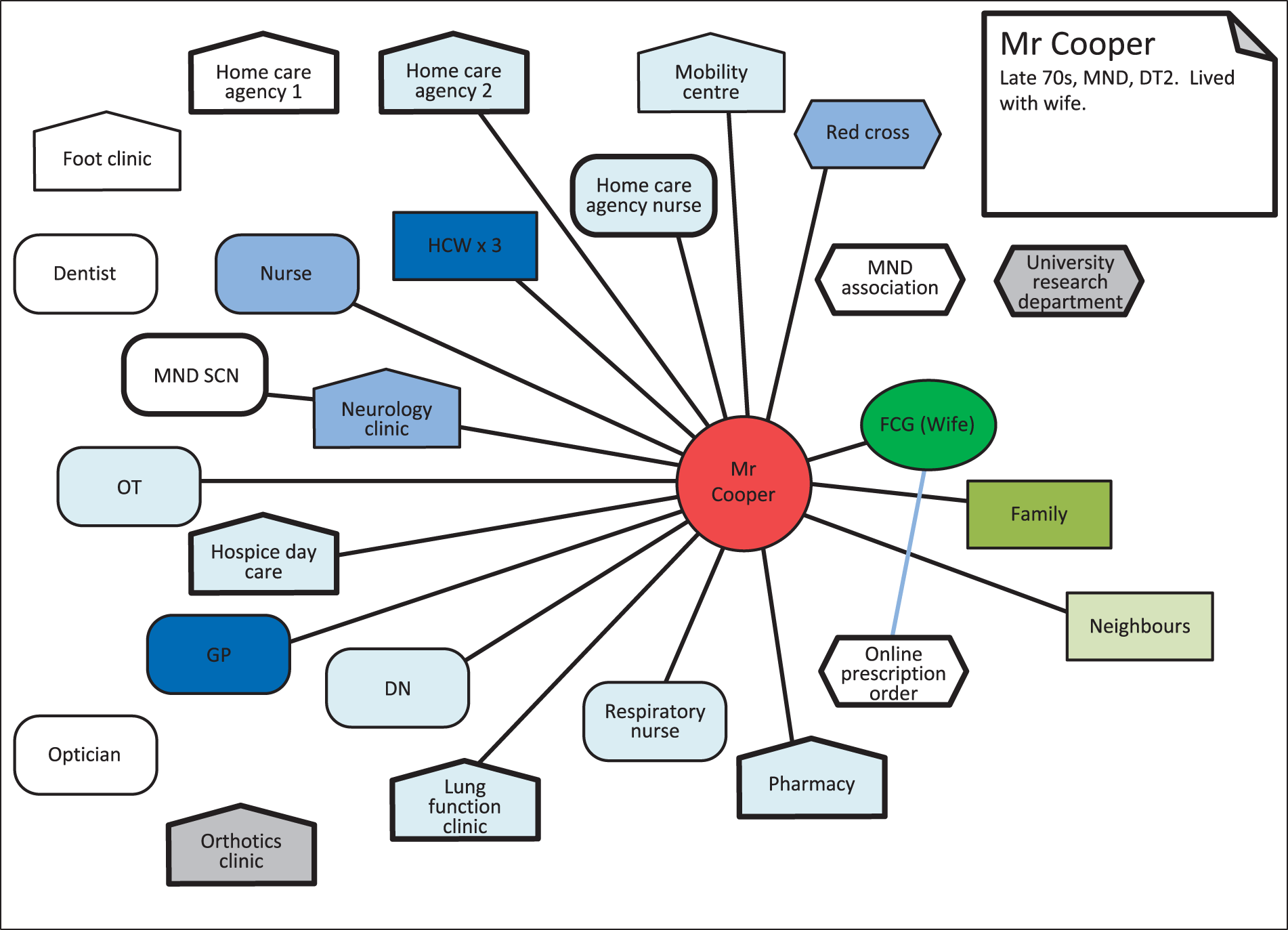

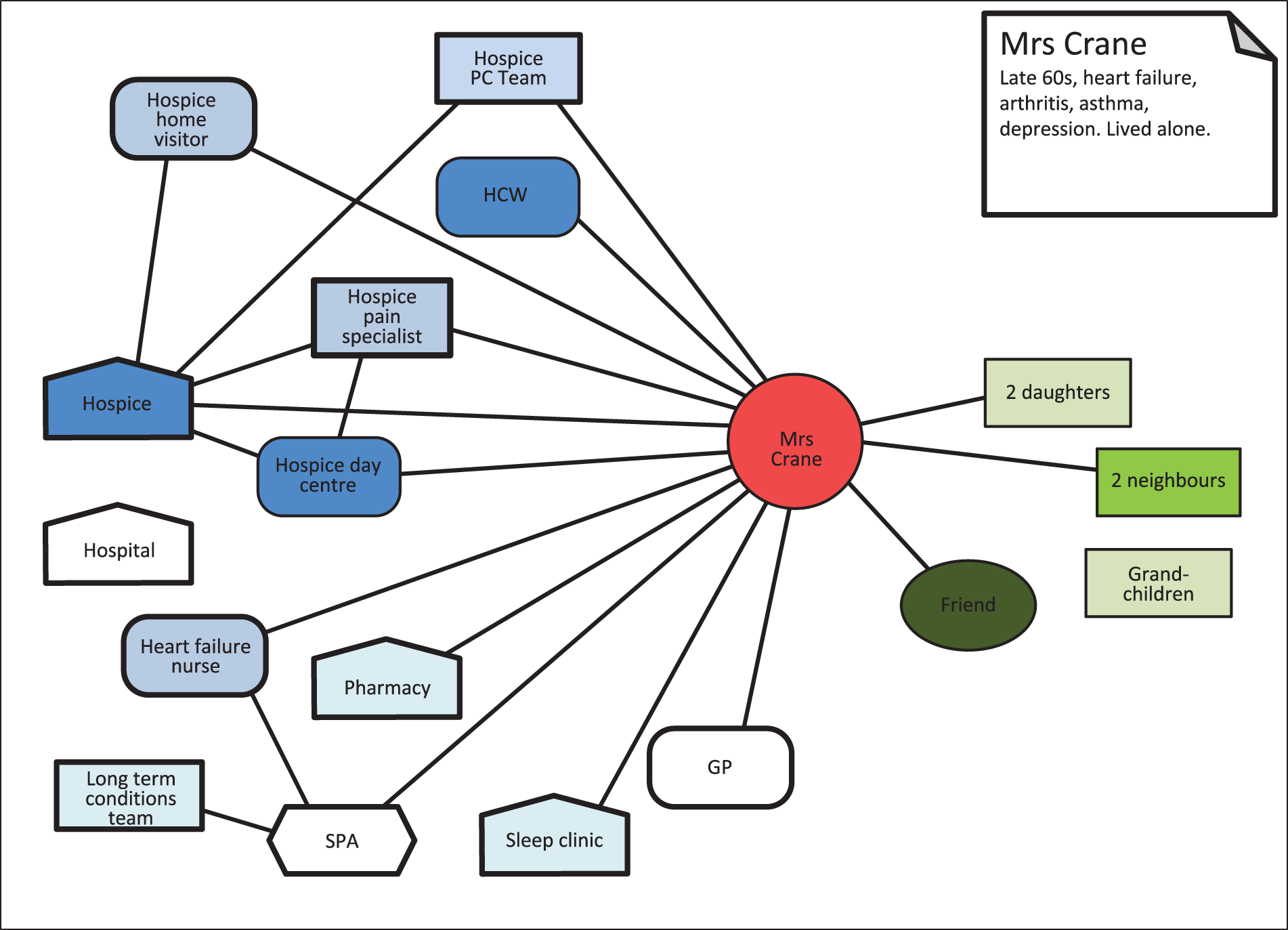

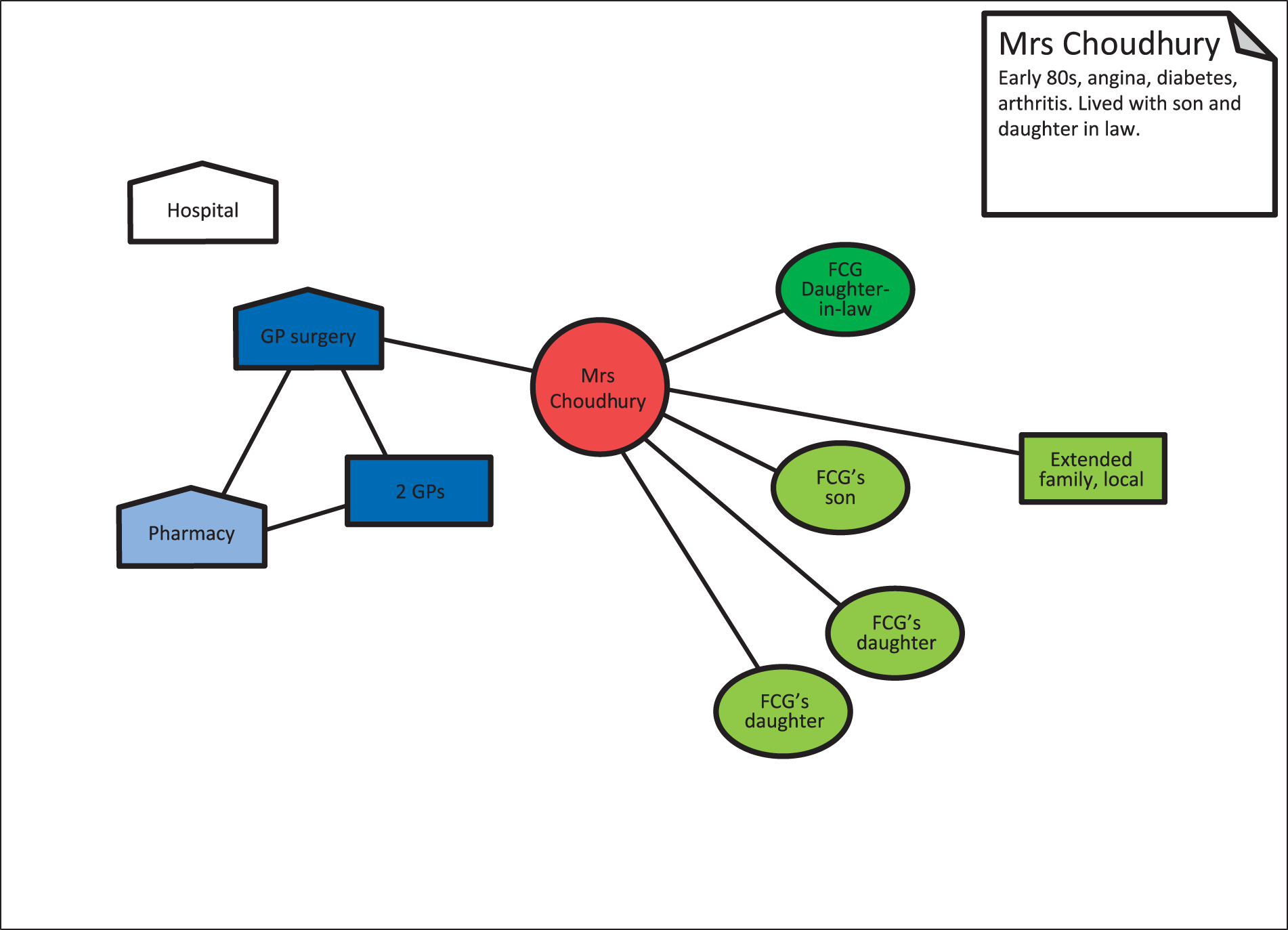

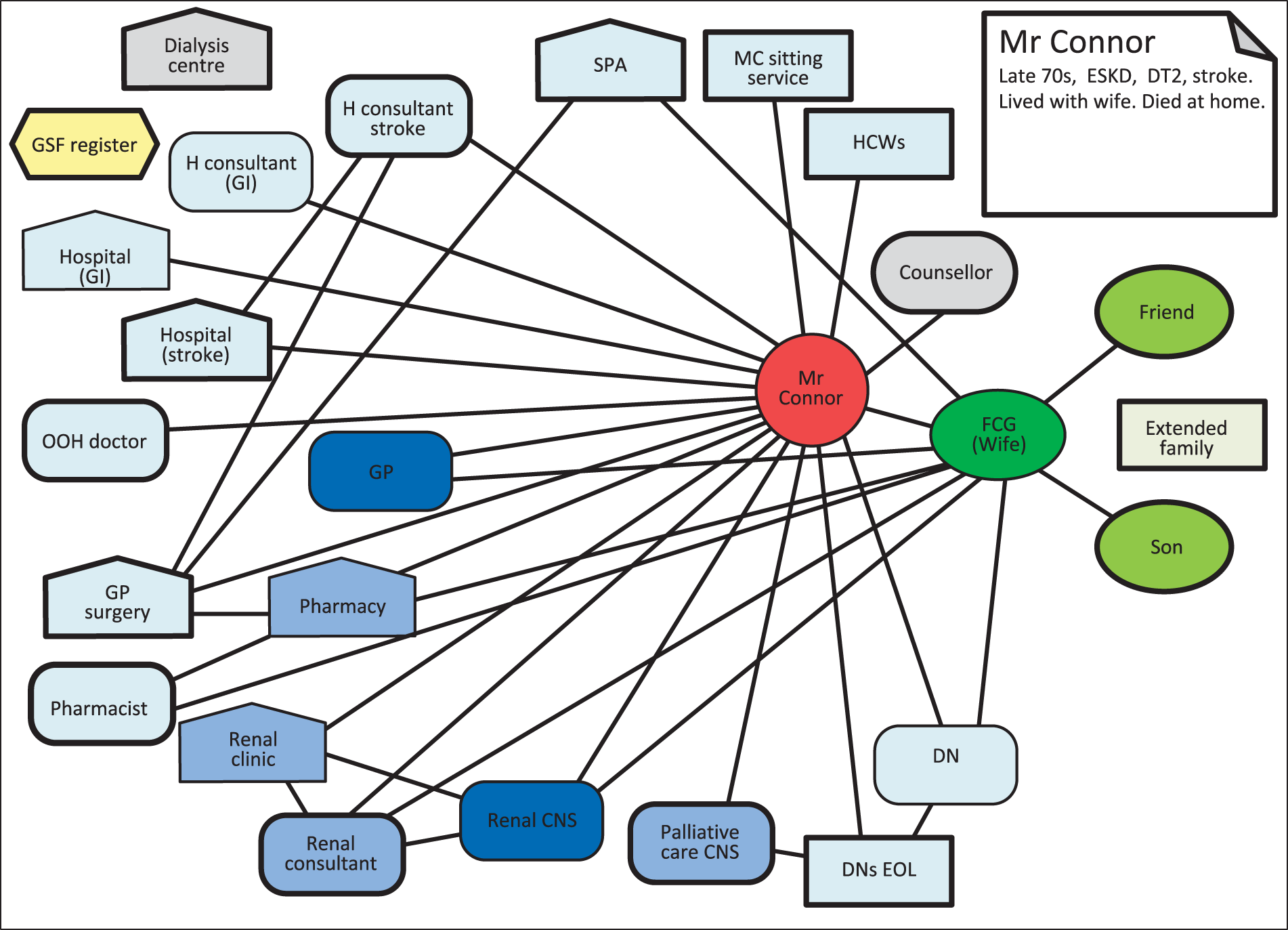

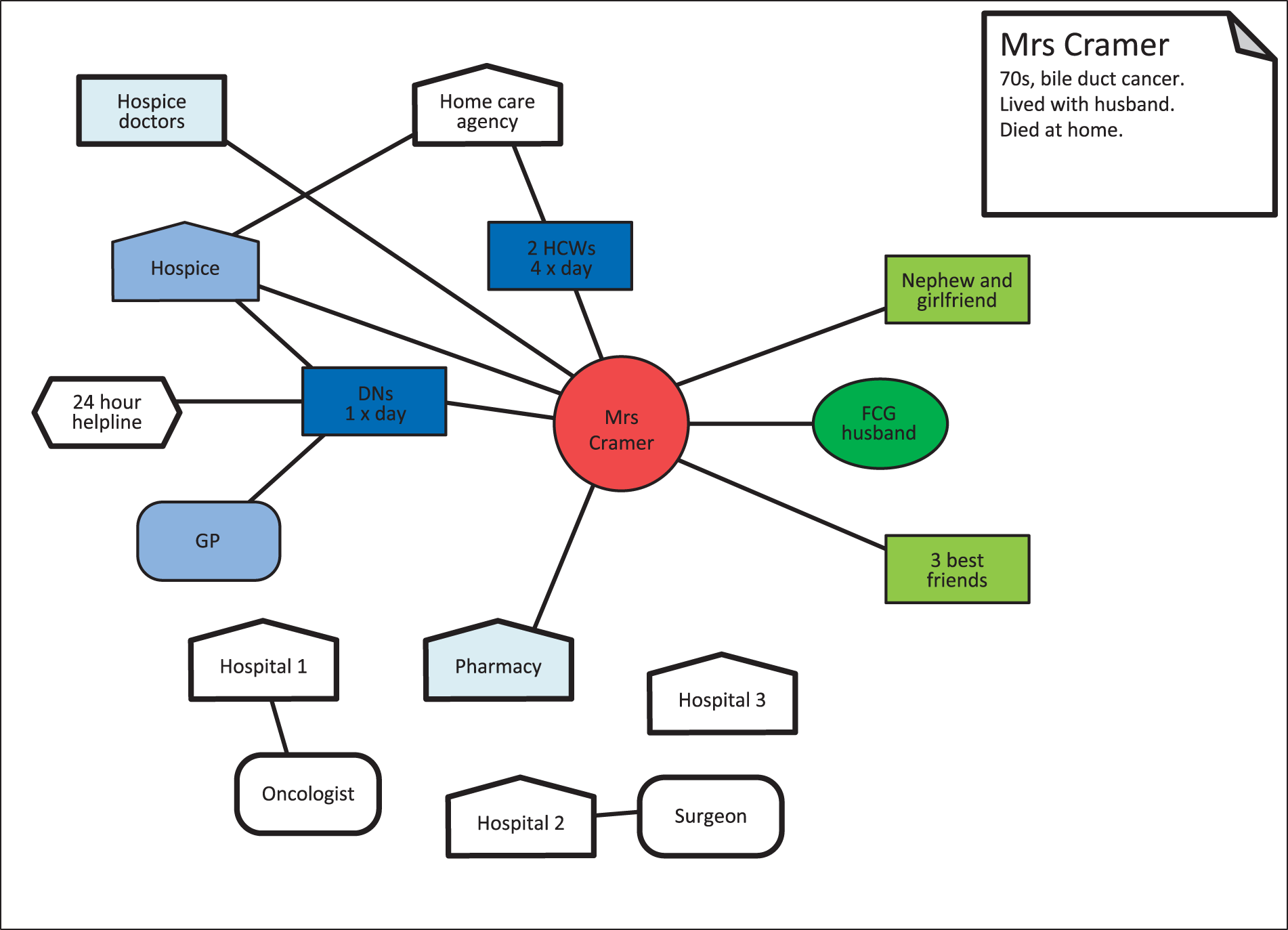

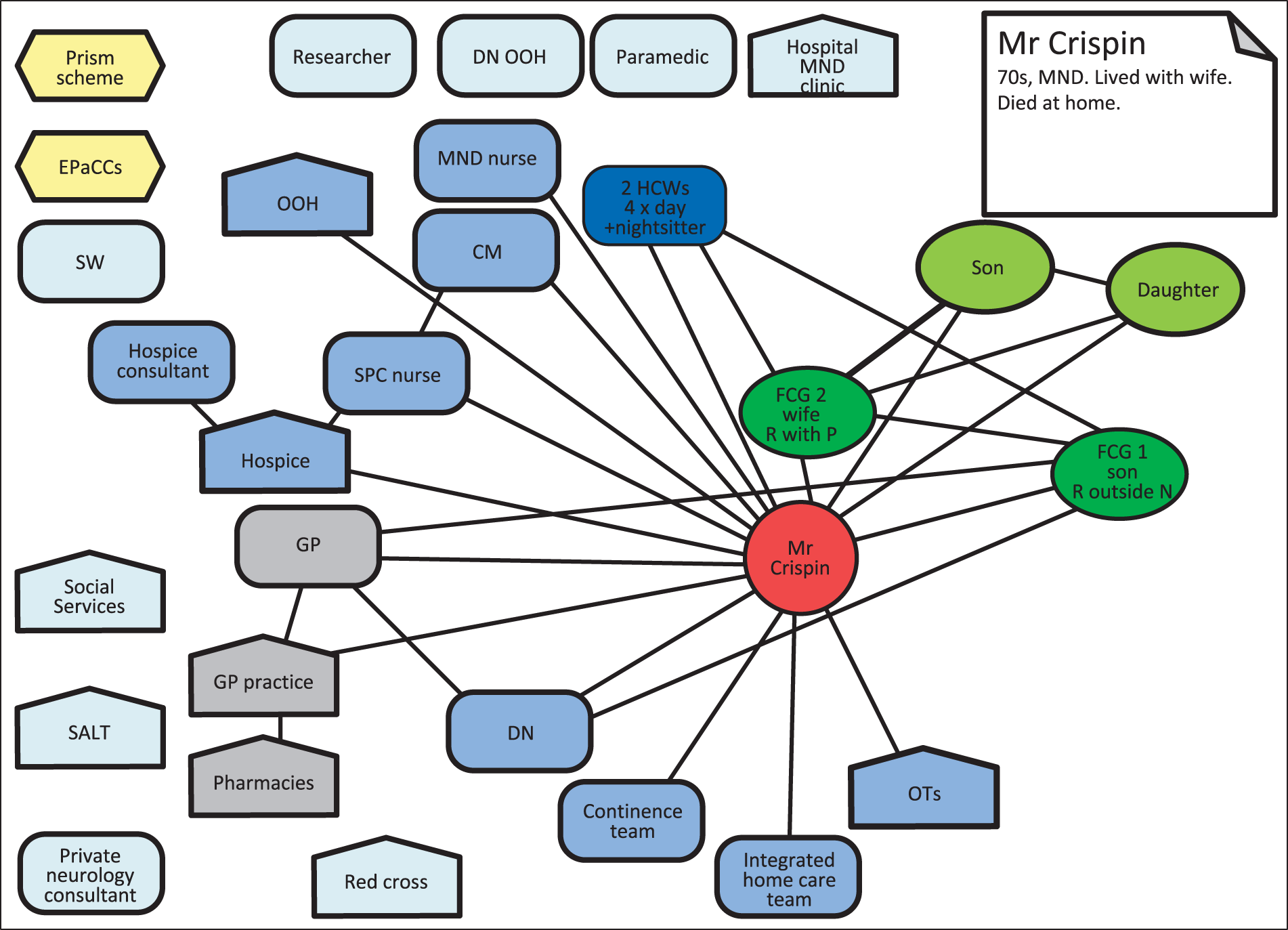

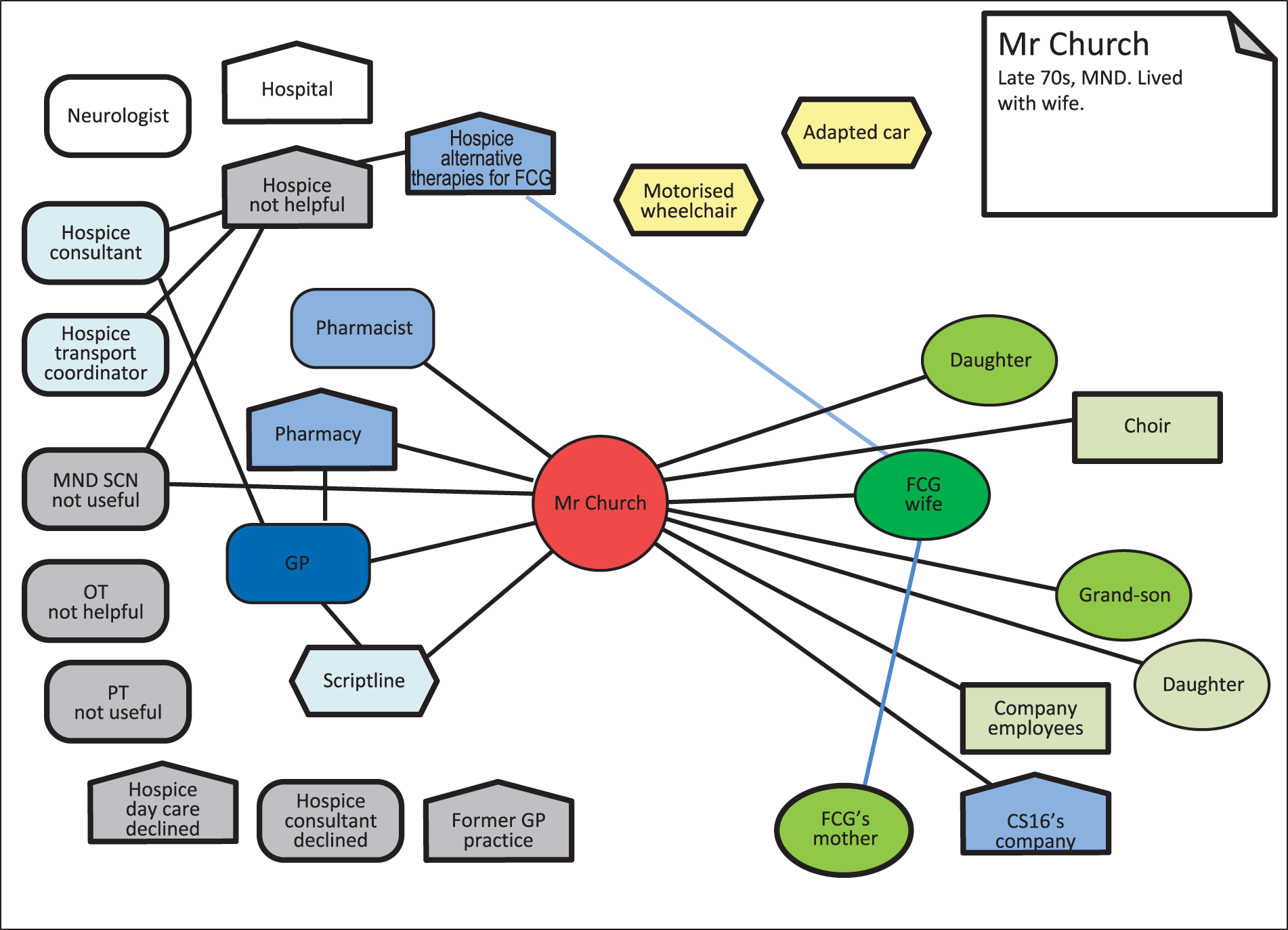

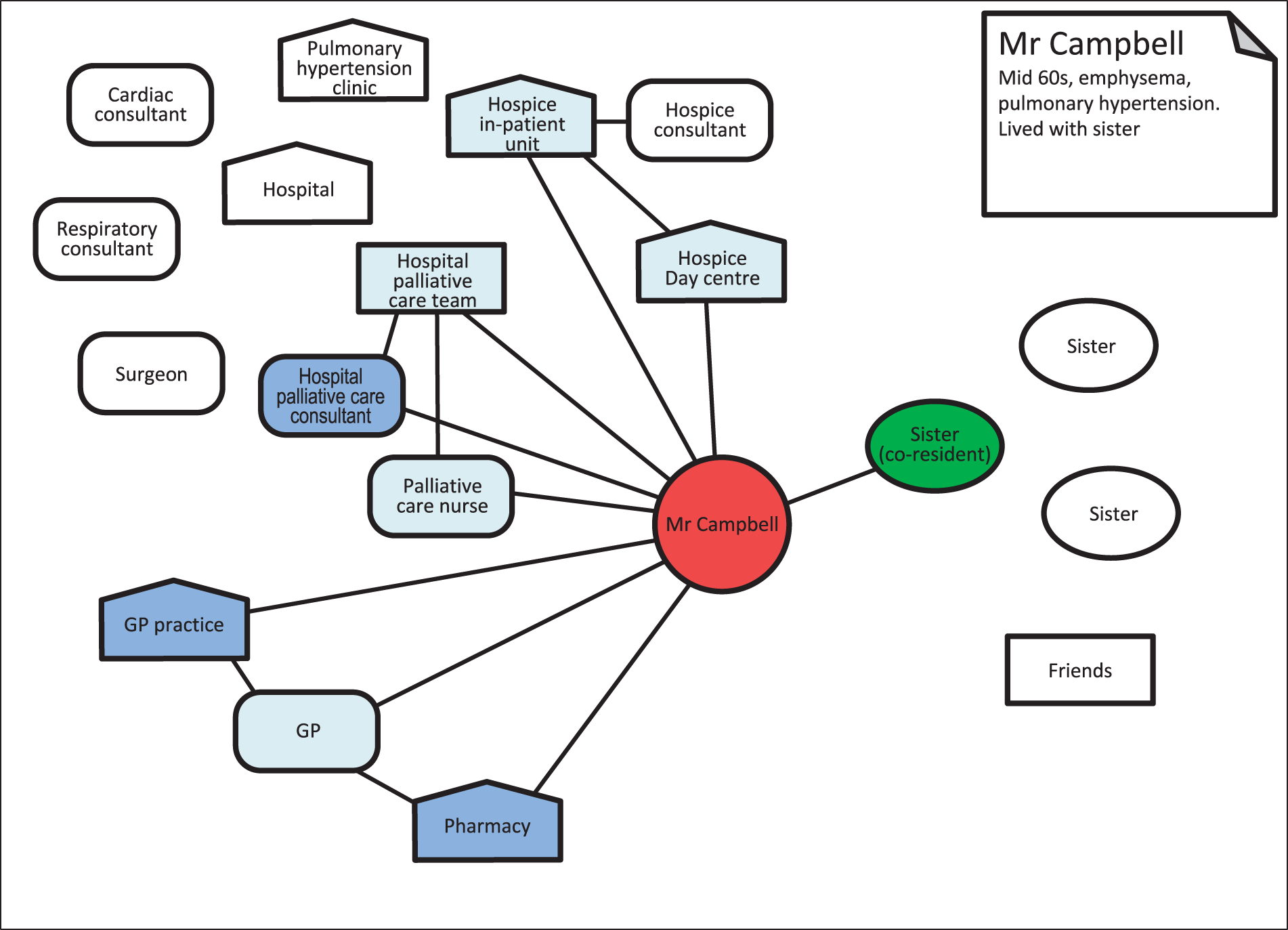

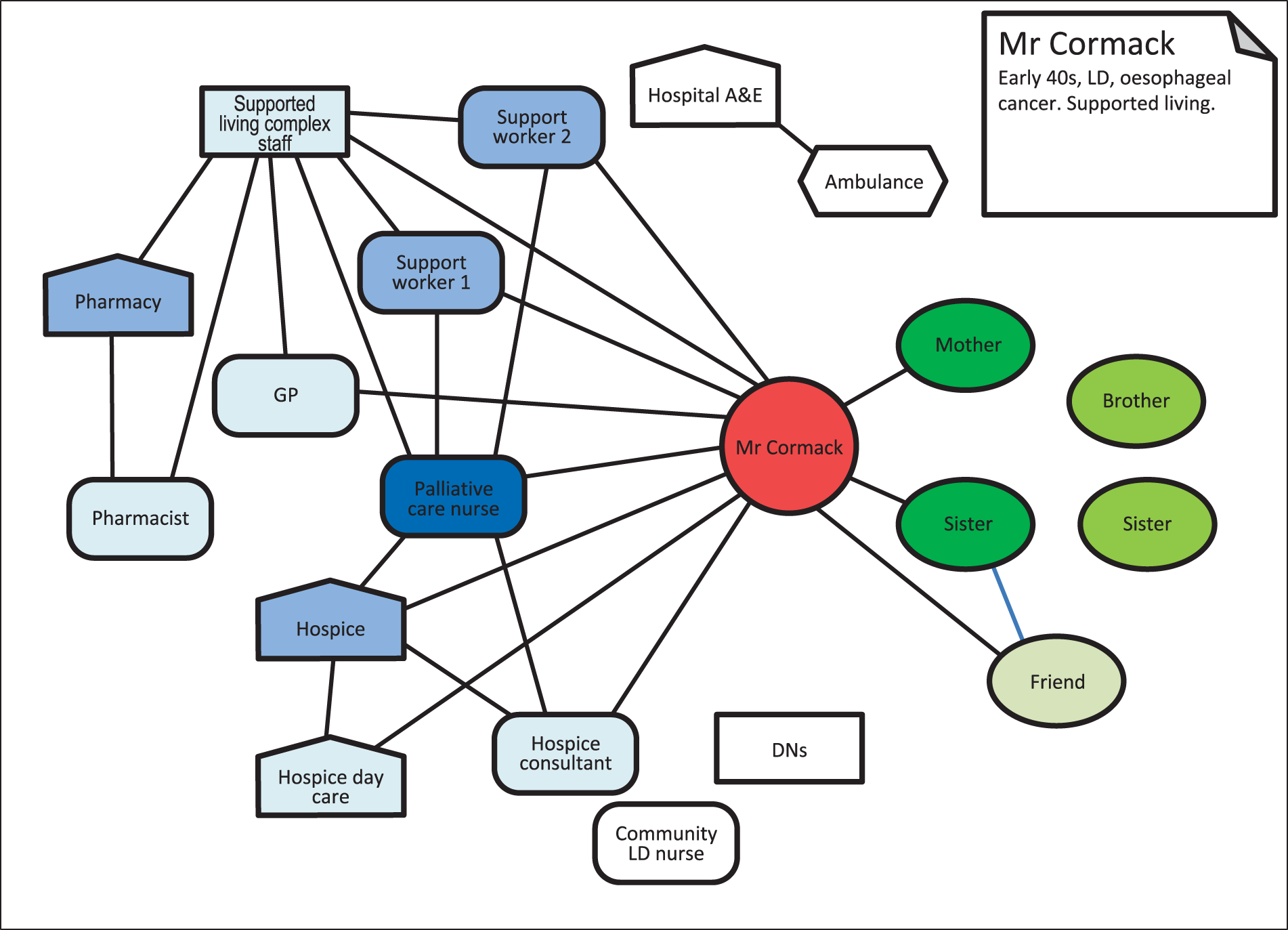

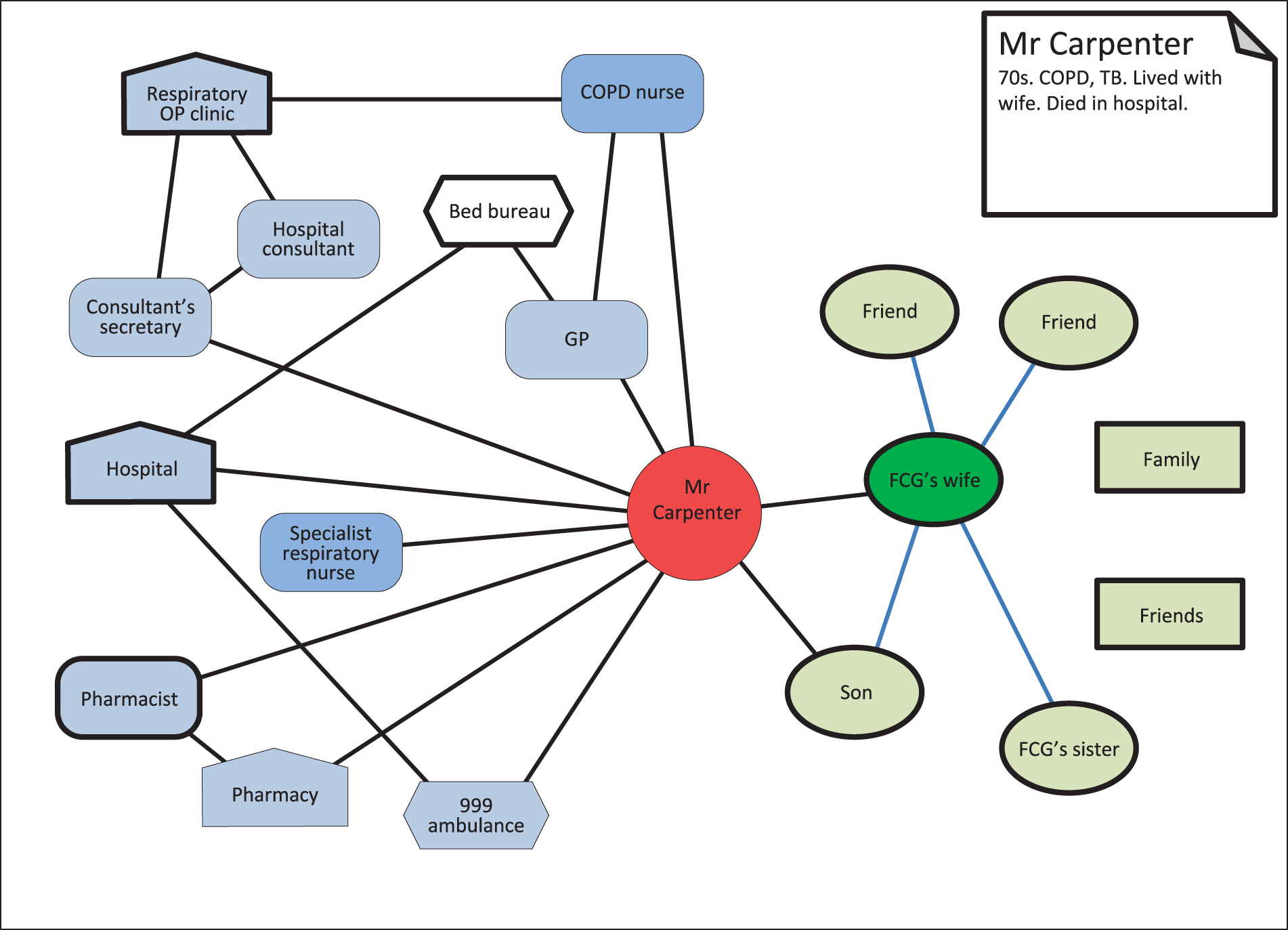

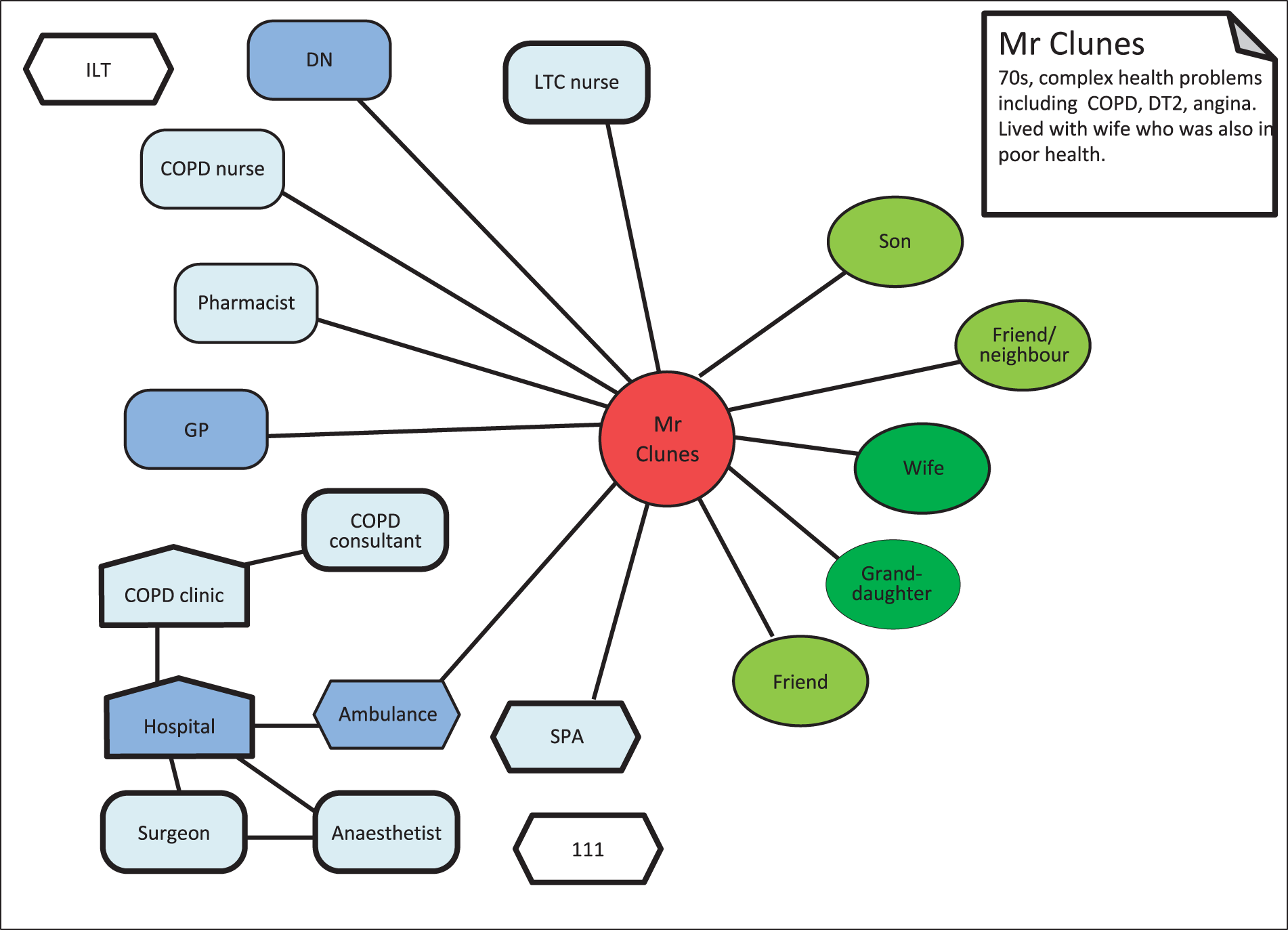

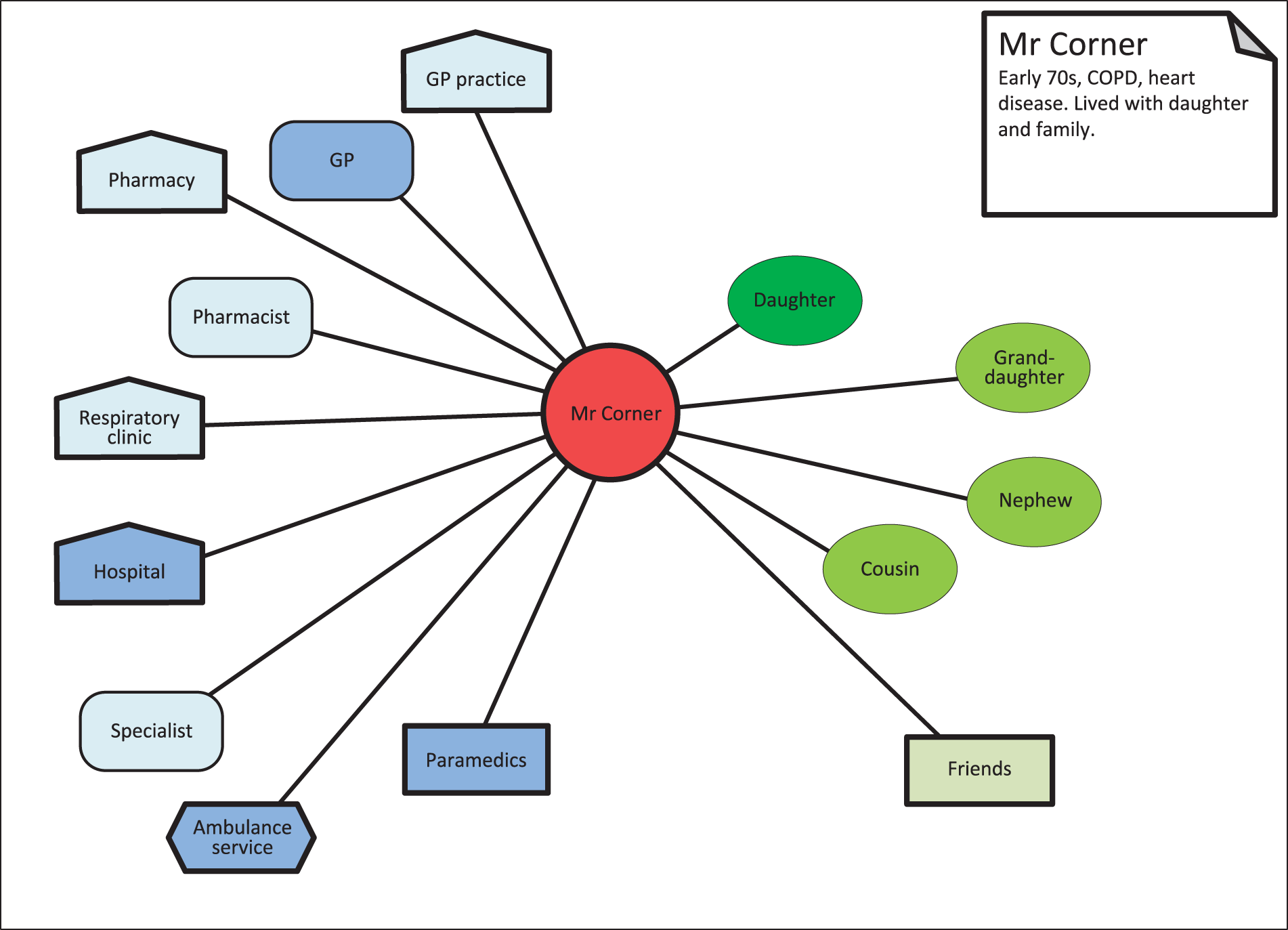

The key participant in each case study was interviewed at least once and, in most cases, also on at least one further occasion over a period of 3–4 months. This could be the patient or the FCG and, in some cases, both, where interviews were undertaken jointly. Where appropriate, participants (i.e. the patients and/or FCGs) were invited to nominate a HCP who they considered to play a significant part in patient care to take part in an interview. Each case was singular and established in its own terms and could be composed of patients, FCGs and key HCPs. In addition to semistructured interviews, participants were invited to construct simple ecograms to represent their support networks. Where participants had given written consent to consider photographs being taken of medicine storage and equipment used in the home, verbal consent was confirmed prior to these being recorded. Care was taken not to include identifying information or images of people. With the permission of all of those involved, observations were carried out of some consultations with professionals and medicine-taking. The patient consent form also included an option to allow permission to review medical notes. In cases where the patient was not a participant, their medical notes were not reviewed. These data were collected via general practices and one of the participating hospices. Figure 2 shows the potential types of data generated as part of a ‘case’. A narrative summary and composite ecogram for each case is given in Appendix 1.

FIGURE 2.

Types of data generated from each type of participant within the cases.

All interviews were recorded with permission. We experienced one failed recording in the BFCG data set and one participant requested not to be recorded. Comprehensive field notes were made after each interview.

Workstream 3: stakeholder workshops

The purpose of the workshops was twofold. First, they were dissemination events for representatives from a wide range of stakeholder groups, including HCPs, managers, commissioners, educators and PPI representatives. Workshop participants were, in turn, encouraged to disseminate awareness of the study findings and its implications for practice through their wider networks. Second, they were a forum to identify priorities for implementation and to initiate collaboration with members of the research team to develop further research proposals, training and information resources, and strategies to implement the findings in education and practice at regional and national levels and for lay and professional audiences.

During the first part of the session, data were presented on three key topic areas. For the second element, participants were allocated to a table for a small group discussion based on one of the three topics. Each table was provided with a topic sheet, which included three questions central to that issue to be used as guidance for the discussions. With permission, each discussion was audio-recorded and used as a form of group interview data. Each group was led and guided by a researcher, who also asked participants to make a note of what they considered to be three key points or issues raised as part of their discussion group. The workshops were half-day events held in Nottingham and Leicester. The findings and recommendations arising from the workshops are presented in Chapter 8.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement was a key element of this study from the outset. The Dementia, Frail Older and Palliative Care Patient and Public Involvement Advisory Group gave feedback on the developing proposal, were involved in two engagement sessions to discuss the issues raised by one of the cases, and co-designed a patient poster to encourage greater consultation with CPs about medication issues. Several members of the group, including Alan Caswell, have reviewed and commented on sections of this report. Alan Caswell was a co-applicant on the grant application and has been very actively involved from the outset as a key member of the project team. He has been involved in a wide range of activities, including study design, ethics review, data analysis and dissemination. PPI involvement is discussed further in Chapter 3, including Alan Caswell’s reflections on his role throughout the study.

Analysis

Workstream 1: health-care practitioner and bereaved family caregiver interviews

The qualitative software program NVivo 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) was used to facilitate a thematic analysis of the data set based on the principle of constant comparison. 139 The analysis was carried out through an initial process of open coding, when segments of interview transcripts were allocated to one or more broad ‘nodes’ within NVivo to capture all text relating to an idea or topic. The coding frame was then developed through an iterative process of reading coding and discussion of the data to identify, compare and link ‘themes’ occurring within and across the two data sets involved in workstream 1. After open coding was complete, a more refined and selective process of coding of individual nodes was undertaken to explore, differentiate, reorganise and relate the themes identified as of greatest relevance to the study objectives. These were grouped hierarchically within broad categories that represented key themes identified in each data set. Further exploration was undertaken by comparing themes between each series of interviews to enable an understanding of the key issues relating to medicines management for BFCGs and HCPs, and the degree of difference, overlap and mutual understanding that exists between them.

Workstream 2: case studies

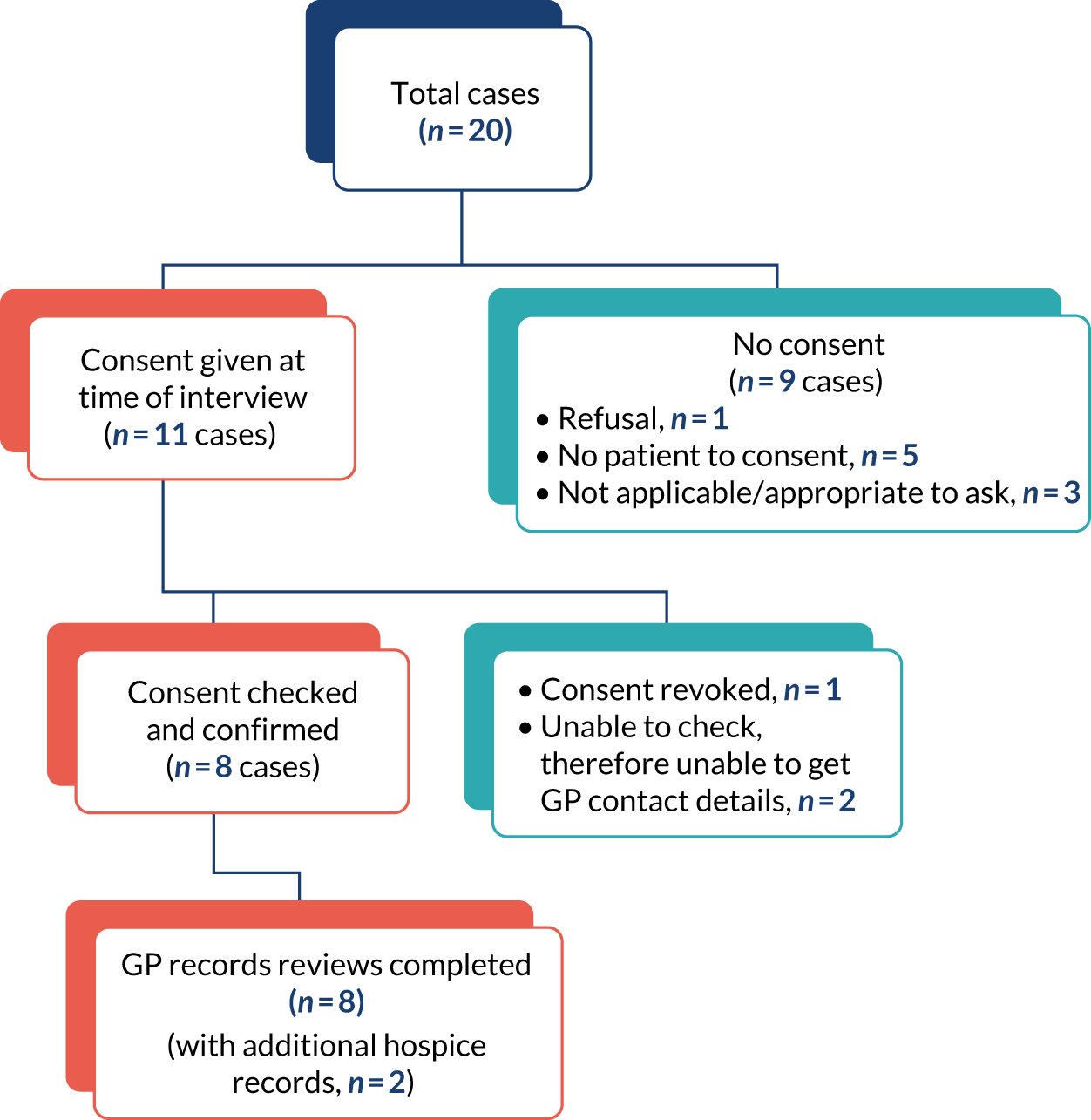

Case study analysis combined different data sources, including baseline and follow-up interviews with patients, FCGs and HCPs, observations, medicines lists, photographs, reviews of clinical records and analysis of ecograms (Figure 3). 142 Individual case narratives (see Appendix 1) synthesised the entire body of data for each case to provide a clearer view of the key elements in participants’ living situation, care input, support, medications and changes over time. These were the basis for within- and between-case comparison, using matrix charting. Follow-up interview data went beyond cross-sectional and static accounts of specific participants and groups of stakeholders to enable an understanding of how medicines at the end of life are managed over time within a complex network of care. 142 In addition, each parallel data set within the case studies (i.e. patients, FCGs and HCPs) was subject to a separate and comparative thematic analysis. 139

FIGURE 3.

Sources of data within each case.

The ecograms were used to generate context and perspective on how the work of medicines management is undertaken within the patient’s home and through professional communication and inter-relations within the wider network of services and family involved in each case. 17,44,148–150 When obtained from the patient or FCG, medicines lists were compared with data generated from record reviews. These provided greater detail around prescribing choices, information about the prescriber and the most up-to-date list of current medications. Photographic data could also be compared across the cases to identify similarities and be specific examples to use as visual illustrations. Such cross- and within-case analytical formats allow for complexity of themes to be explored without losing the context of each case.

Analysis of social networks

The ecograms constructed during interviews with case study participants were intended to provide a diagrammatic representation to support the researchers’ understanding of the network of people and organisations involved in supporting the patient’s care, particularly in relation to medicines management. The process of completing the ecograms provided a prompt for participants to think through and reflect on the nature and significance of the different kinds and sources of support that they received, including those that were negative or absent. We wanted to identify key contacts within the network and get some idea of the extent to which these were linked or independent. However, participants reacted very differently to the task of drawing an ecogram, with variable levels of detail and criteria for inclusion. In most cases, it became clear that these omitted many sources of support and information mentioned throughout the interviews and other sources of data. In addition, ecograms drawn by different participants showed some variation in the links identified and how these were assessed. As we wished to gain an idea of the range of individual networks and the resources to which participants had access, we opted to draw on all relevant information available throughout the case, rather than confine analysis to the more limited content of ecograms drawn by individual participants. Moreover, participant ecograms were generated at different points in the illness trajectory. For example, some included information relating to a late stage in the patient’s illness, including after death, and may, therefore, be considered more comprehensive than others. The diagrams included in each case summary (see Appendix 1) indicate which links were included in the initial ecograms drawn by participants and which were subsequently added by the researchers. The ecograms include, in addition to informal and professional caregivers, a range of services and institutions (e.g. hospice, hospital and pharmacy) where these were referred to generically, as well as other links identified by participants as important resources. We have been careful not to overinterpret the comprehensiveness or significance of an interpretive exercise in reconstruction. However, taken together with the wider data we have about each case, we have found the ecograms valuable as a means of visualising the network of care, including informal and professional links, and the range and nature of contacts as a way of aiding analysis of each case. They also provide a simple way of exploring the range and distribution of informal and formal contacts and their significance within each case (see Appendix 1).

Workstream 3: stakeholder workshops

The researcher facilitating each group made detailed notes of the discussion. Further notes were made from listening to the audio-recordings from each of the workshop table discussions and key passages were transcribed verbatim. The recorded discussions echoed and reinforced many of the themes identified in the study data. These notes were amalgamated with the written notes provided by the participants. Already grouped into the three broad topics presented on the day, these notes were then further examined using a thematic approach to identify additional themes within and across the three topics, with a particular focus on potential areas of implementation and learning for practice (see Chapter 8).

Reflexivity

The researcher carrying out social research inevitably has an impact on, and is impacted by, the research. During this project, three researchers carried out recruitment, data collection and analysis and here we reflect briefly on our positionality and its impact. We are white female social scientists from non-clinical backgrounds. Our experience in terms of research into medicines and their use varies: the principal investigator has a substantial track record in the field, but we are all experienced qualitative end-of-life researchers. We utilised several techniques to enhance the quality of the data we generated and the analysis that we carried out. First, for each instance of data collection we wrote field notes, enabling reflection on the content, process and outcome of each interview and observation. Second, we consulted regularly with our PPI team member, the project team and the project oversight group to share findings and our developing analysis of them. In this way, we were able to access input from a range of relevant professions, including pharmacists, nurses and doctors. Third, we worked together on the analysis, with regular discussions of the ongoing process, ensuring that each transcript was coded by at least two researchers. We believe that, as non-clinicians, we are well placed to explore processes of medicines management for people approaching the end of life, but that our analysis is enhanced by input from our clinical colleagues.

Chapter 3 Patient and public involvement

Introduction

The Managing Medicines project team has been fortunate to work with the established University of Nottingham Dementia, Frail Older and Palliative Care, Patient and Public Involvement Advisory Group (Nottingham, UK). The group supports a wide range of research projects undertaken in the Schools of Health Sciences and Medicine. Members advise on every stage of the research process, including early discussion of topic, design, ethics issues, content of information sheets and interview schedules. They also contribute to data collection, data analysis and publications, including review of the final project reports. The Managing Medicines study has benefited from the inclusion of group member Alan Caswell as co-applicant on the grant. This has enabled greater integration and continuity of PPI involvement from the outset and has enabled Alan Caswell to develop a deep understanding of the study and its challenges. As researchers, we have benefited from Alan Caswell’s involvement in many ways. His perspective as a public advocate has allowed us to see the study from a different perspective, and this has improved the way in which the study was planned and delivered. He has embraced working with clinicians, researchers and academics and has been considered by the team to bring considerable expertise, as well as collegial support. From the outset, we agreed with Alan Caswell that he should take on elements of study engagement only to the extent that he felt comfortable in doing so. However, his involvement has been considerable and has extended throughout all stages of the research. Alan Caswell has taken on active roles in data analysis, dissemination and public engagement. We have welcomed Alan Caswell’s support as a very level-headed ‘critical friend’, as well as his encouragement and ongoing support through all stages of the study. Alan Caswell’s account of his involvement in the study is given below (see Box 1).

At the outset, members of the PPI group endorsed the value of the research and its resonance with their personal experience, as well as the research priorities identified by the James Lind Alliance (Southampton, UK). The group has commented on participant materials, including information sheets and consent forms. Group members have discussed and commented on the study design, ethics issues and findings. They have contributed to the co-produced patient poster workshop and to the two end-of-project stakeholder workshops. Members expressed concern about the sensitive nature of the topic, the need for skilled interviewing and the risk of the interviews causing distress to participants at a very challenging and vulnerable period of their lives. It was also suggested that FCG participants might, in reflecting on their experience, become aware of shortcomings in the care received by their relatives. The researchers have been mindful of these concerns throughout the process of data collection for the project. Illustrative extracts from the PPI member reviews of the final report are given below.

Case study: Mr Conner

The case study in its depth and quality of narration was brought to life for us. It brought back our memories of our different experiences of managing medicines but also our lived pain of coping as carers in end-of-life situations.

The detail was its strength, its authenticity. It read as though the researcher was walking alongside Mr and Mrs Connor and knew their path. The journey showed the professional strengths and unspoken underlying compassion of health-care staff. It also realistically showed the gaps in end-of-life care provision which pointed to how hard joined-up care can be when so many are involved.

Demographics

I found this section difficult to read. Could more of the figures be presented in diagrammatic or tabulated form, as is done later in this section? I appreciate from a research point of view for future reference it is valuable to know the uptake achieved from each source but is it necessary for this project?

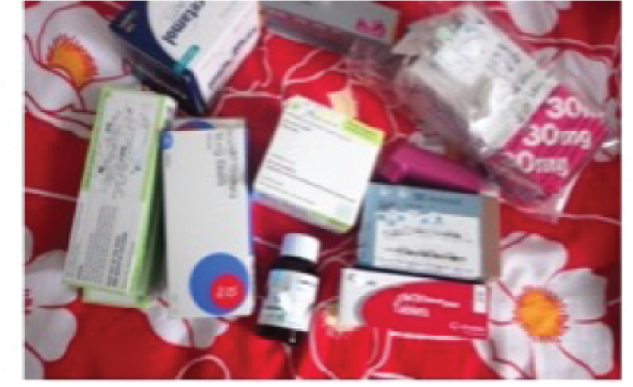

Findings

Initially I had reservations about the photographs, however I now consider they graphically show the intrusion and medicalisation of the family home and are integral to understanding how the participant and carer had to make space and adjust to the burden of storing and administering medicines and aids placed on them. It shows a home changed to a medical storeroom. It highlights the narrative, showing the distress of illness, the responsibility of managing so many medicines and acknowledges the inevitability of the outcome of the following months.

Conclusions: consequences of managing medicines at home

Experience of a loved one dying at home can be a nightmare and one which lives with the FCG for ever. Sitting with a dying loved one unsure/unable to administer medication, without support of a HCP and not knowing what to expect; death is not always peaceful. Accessibility of HCP 24/7 [24 hours per day, 7 days per week] needs to be alongside managing medicines at home. FCGs are not only managing medicines at home but managing daily life – cooking, cleaning, changing beds, sometimes dealing with highly charged stressful situations. It cannot be assumed that FCGs have a good relationship with the terminally ill patient.

Overarching comment

This research has exposed the complexity of how we live and how we die. How do the many disciplines of health care, pharmacists, consultants, GPs, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, community nurses of all types, social care workers, social workers interact with each other and with their patients and their families and friends when people become ill?

Patient and public involvement group members have identified with the problems reported by study participants in relation to decisions about when to use medicines, getting the dose right, problems of access and supply, and, especially, effectively managing pain. Their own experience of problems resulting from poor communication between members of the MDT, particularly GPs and nurses, were shared and also the value of carers having 24-hour access to advice and information. They anticipated that provision of such a service would result in saving NHS costs by reducing unscheduled hospital admissions and achieving more rational and effective prescribing. PPI group members highlighted the importance of considering diversity and the problems of minority and disadvantaged groups in medicines management at the end of life, and of maintaining focus on the lived experience of families caring for a dying relative at home. All of these issues feature in the report of the study findings, which are detailed in the following chapters.

In addition to Alan Caswell, we thank four members of the PPI group, Kate Sartain, Maureen Godfrey, Margaret Kerr and Marianne Dunlop, for their reviews and detailed feedback on the draft final report. They provided reassurance about the depth of detail included in reporting the study findings, particularly in the extended case study presented in Chapter 5, and identified priority areas for further research. Reviewers also pointed out parts of the draft chapters that were unclear or difficult to read, overly detailed and unnecessarily complex. These comments have been extremely helpful in revising and improving the text of the final report.

The PPI reviewers highlighted the importance of further research into the following areas:

-

the prescribing and use of AMs, in particular the emotional and psychological as well as practical issues that these entailed for patients and FCGs

-

the great variation in patient and FCGs’ experience of treatment and input from different HCPs and services, particularly the lack of co-ordination, structural barriers and bureaucracy that they encounter

-

the lack of communication between HCPs involved in patient care and the apparent unwillingness of individual HCPs to take on a ‘liaison’ role in helping patients and HCPs navigate the health-care system

-

the role of domiciliary home health-care workers (HCWs) in supporting families and the much greater recognition that should be awarded to training and development of staff in this role in future

-

the variability in FCG capacity and willingness to engage with managing medicines at home

-

the role of GPs and their expectations of their role in supporting patients at the end of life

-

the consequences of COVID-19 for changing norms in patient and public attitudes and discussion of death and dying, and how recently configured primary care networks will impact on social care and its integration with health-care services.

Box 1 gives an account by Alan Caswell, our PPI co-applicant, of his involvement in the Managing Medicines study and collaborative working with the research team. This is followed by a summary of the extension work undertaken for the project, which resulted in a learning article and positional paper about extending pharmacist involvement in supporting medicines management for seriously ill patients and a co-produced patient-facing poster for display in pharmacies, general practices and other community settings. The extension work was led by Asam Latif.

In 2015, at the University of Nottingham, at a meeting of the Dementia, Frail Older and Palliative Care, Patient and Public Involvement Advisory Group, Professor Kristian Pollock spoke to the group about a proposed research project titled ‘Managing medicines at the end-of-life: supporting patients, carers, and professionals in community care settings’. During this discussion she suggested that if a member of the Patient and Public Involvement Group (PPI) felt that they wanted to be involved with this research as a PPI representative, they should contact her.

A couple of days later after giving this proposed research project some thought I contacted Professor Pollock and said that I would like the opportunity to discuss this further with her. The following week we met and during a couple of hours’ discussion, we explored both personal and work experience in this area. I agreed to be involved and most importantly, from my point of view, Professor Pollock felt that I would have something to offer to the research working group.

Before making the application for funding to the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) there was a lot of work to do to prepare the proposal and all the necessary documentation. During this time the research title changed to ‘Managing medicines for patients with serious illness being cared for at home’ (MM@H). I became a study co-applicant, contributed to, and approved, the ‘Plain English summary’ section of the application and undertook to review and comment on the protocol and associated documents.

During this period, it was agreed that my PPI involvement would be in the following areas:

Once NHIR approved funding, I was next involved with the preparation of documents so that we could apply for ethical approval through National Health Service National Research Committee (NRES). I contributed to, and reviewed, all patient-facing materials, such as patient information sheets, consent forms and letters. I also went with Professor Pollock to the NRES committee meeting at which our application was reviewed, and even answered a question. We received a favourable opinion, so enabling MM@H to start.

My ongoing involvement in the project has been in the following areas:

At all the project team meetings I was an active participant and was, on occasion, directly asked what my thoughts were on any given subject. I always felt that my views were listened to and given due consideration by all the other members of the team. The discussions covered many aspects of the study and we often had to consider ethics dilemmas. On one occasion we even went back to the NRES committee on a particularly vexing issue, and we were given ethics approval to go ahead with it.

At the end of the study, MM@H was given a no-cost extension of 6 months, during this time work was ongoing around the area of pharmacy data, and a 1-day workshop was arranged to look at the possibility of producing a poster for use at pharmacies to explain their role in advising about medication. As a PPI member I was involved with that workshop, again greeting people, giving out information packs, ensuring the participants received vouchers for attending. I also participated in the workshop and we produced a poster at the end of the day.

I was approached by Katie Porter, Assistant Research Manager NIHR, and asked if I would be willing to speak at a workshop about my experiences as a PPI co-applicant in MM@H. On 6 February 2020 I attended a PPI workshop at NIHR Southampton and along with Doreen Tembo, Patient and Public Involvement and External Review, Senor Research Manager NIHR, gave a joint presentation which lasted 2 hours. My involvement was:

It is hoped that a paper I am writing with Dr Eleanor Wilson on PPI involvement with MM@H will eventually be published.

From being involved with this project I have become more informed on how patients, relatives and friends view the support they are given at a very difficult point in their lives; the experiences varied from good to pretty poor. Likewise, I gained a better understanding about how differing staff views on risk could lead to disagreements. For example, in one case professionals differed in their views as to the acceptability of just in case pain relief medication being given by relatives or friends, which could lead to an accidental overdose. This is a serious area and one where both relatives and professionals need support.

I also developed a better understanding of how the researchers approached the subject and at times had to develop strategies to achieve the goals of the research.

Overall, I am pleased I took the opportunity to be involved with this research project, and I would encourage other PPI members to become involved with research projects that they would have an interest in.

Co-produced pharmacist learning article, positional paper and co-produced patient-facing poster: Asam Latif

The findings of this study151 revealed considerable scope for better co-ordination and streamlining of the processes of medicines prescribing, supply and access, and greater involvement of CPs in providing support for patients and FCGs, as well as to other HCPs. The findings particularly exposed opportunities for HCPs to better engage patients and carers. An educational learning article aimed at front-line CPs was written to illustrate the practical ways that pharmacists could help patients manage their medicines at the end of life. The learning article covers the following areas:

-

What is palliative and end-of-life care?

-

A holistic approach to palliative care.

-

The case for greater involvement of CPs in palliative care.

-

Opportunities for pharmaceutical care.

-

Medicine optimisation.

-

Understanding the work that patients do to manage their medications.

-

Diversity and disadvantage.

-

Appreciating the system and the complexity from the lay perspective.

-

New palliative care models.

-

Pharmaceutical care after the death.

A positional paper aimed at pharmacy professional bodies, commissioners and policy-makers is currently under review. This aims to provide clarity and vision for future medicines management for palliative and end-of-life patients. Through this, we intend to spark a debate and illustrate the need for pharmacists to take on new roles, as well as provide guidance for educators on how best to support them.

Poster workshop

One significant finding was that patients/FCGs were often unaware of the support available from the CP. It was decided that a co-produced patient-facing poster displayed in CPs and general practices could be a simple way to raise patient and carer awareness of ways to access much needed help with medicines from their CP.

Twelve participants were recruited to a 3-hour mixed patient and professional workshop to discuss the findings and co-produce a poster. There was a range of participants, all of whom had personal experience as a FCG or an interest in palliative care. They included three patients/PPI representatives, two FCGs, three pharmacy support staff (two pharmacy dispensers and one accredited checking technician), three pharmacists and one GP. A £25 goodwill voucher was given to each participant as a token of appreciation.

Prior to the workshop, a draft patient poster was developed by the study team based on the findings of the study (Figure 4). It was intended that this would not be revealed to workshop participants until after they had co-produced their poster. The workshop began with an overview presentation of the study findings. Participants were then divided into two groups, each comprising a mix of patients and professionals. Each group formed ideas for the poster, which were then produced onto an A4 flip chart. Finally, the study team draft poster (see Figure 4) was then compared with the workshop participant poster and a composite version was produced. The new poster was subsequently circulated after the workshop to participants via e-mail for further editing, minor revision and refinement for producing a final version (Figure 5).

FIGURE 4.

Poster 1: pre-workshop poster designed by the study team.

FIGURE 5.

Poster 2: post-workshop co-produced poster.

Conclusion

Patient and public involvement has played a very significant part in the Managing Medicines study, and we are grateful to group members for their continuing support throughout the project. We have been encouraged by members’ endorsement of the topic and its importance, and their response to the study findings, which resonated with their own experience. At the outset, members expressed concern that the study should be conducted in such a way as to minimise the risk of distress or burden to participants. Throughout, they have stressed the importance of incorporating diversity in recruitment and representation of diversity within the findings, as well as staying close to the lived experience of participants in managing medicines at home. Although we have not managed to incorporate every point raised by the PPI reviewers, the comments and concerns they have expressed throughout the study have made a significant contribution to its focus and reporting of the findings.

Chapter 4 Findings: participant demographics

This chapter presents demographic information about participants in workstreams 1 and 2. Details of participants in workstream 3 are given in Chapter 8.

Recruitment

Workstream 1

Twenty-one BFCGs were recruited over a 15-month period between August 2017 and November 2018. Although we do not know how many information packs were subsequently given or sent to BFCGs, we have recorded that at least 94 information packs were given to 16 different HCP teams to distribute. Over half (12/21) of the participating BFCGs were referred via two hospices engaged with the study. Five were recruited through hospital teams across three hospitals. Two more were recruited via community nursing teams and the final two via community organisations.

Forty HCPs were recruited through a variety of routes over a 16-month period between June 2017 and October 2018. Information about the study was sent directly to key professional contacts, primarily via e-mail, and they were asked to distribute this to their networks. We also employed a snowball sampling technique by asking those interviewed to suggest other suitable HCPs or pass on information packs to colleagues. The Clinical Research Network representative supported engagement with general practices and several were visited to explain the study and leave information packs for both workstreams. We particularly targeted SPC teams, GPs, pharmacists and community nursing teams to obtain a range of perspectives from different professional roles.

Workstream 2

Over 136 patient information packs and 103 FCG information packs were provided to 16 different HCP sources. We do not know how many of these were given out. Twenty-two patient cases were recruited over a 15-month period between August 2017 and November 2018. Two patients were subsequently withdrawn: one died before sufficient data could be collected and it emerged, during interview, that the other did not meet the eligibility criteria for the study. Twenty patient case studies were completed. Nine further patients or FCGs expressed an interest in the study, but subsequently died or became too ill to take part. In addition, we are aware of 26 potential patients identified by HCPs and discussed with the research team for eligibility who did not go on to engage with the study. In some instances, the HCP subsequently decided that it was not appropriate to discuss the study, often because of a deterioration in the patient’s condition or family circumstances. In other instances, the patients or FCGs who received information packs decided against taking part and did not contact the researchers.

The 20 completed case study participants were recruited through one of three hospices (9/20), a hospital team such as respiratory (5/20), their GP (3/20), a CN (2/20) or a community organisation (1/20). The central participant in the case could be a patient or FCG, who could then go on to nominate other key people. Nominated individuals were then given information about the study and were asked to take part. We utilised a range of key contacts to recruit patients with conditions other than cancer and, where possible, from diverse or disadvantaged groups.

Study participation

Workstream 1: bereaved family caregiver interviews