Notes

Article history

The research reported here is the product of an HS&DR Evidence Synthesis Centre, contracted to provide rapid evidence syntheses on issues of relevance to the health service, and to inform future HS&DR calls for new research around identified gaps in evidence. Other reviews by the Evidence Synthesis Centres are also available in the HS&DR journal.

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number NIHR127257. The contractual start date was in June 2019. The final report began editorial review in January 2021 and was accepted for publication in July 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Chadborn et al. This work was produced by Chadborn et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Chadborn et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Parts of this chapter are reproduced with permission from Gordon et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Care home context

Around 420,000 people, most of whom are aged > 85 years, live in UK care homes. Care homes are primarily a social care setting and yet many residents have long-term health conditions, frailty and dementia. 2 These complex conditions can generate a diversity of care needs that, in turn, require input from number of different professionals and carers. 3 Most care homes rely on general practitioners (GPs) to co-ordinate and deliver medical care and to access specialty community and hospital services for their residents. How GPs work with care homes is variable and is determined by local custom and practice, as well as the availability of other health-care services to augment or replace some aspects of the GP role. Previous research and evaluation has suggested that differences in provision result in undesirable variation in care delivery and health outcomes, and are likely to contribute to increased unscheduled use of NHS resources. 4,5 As care homes are just one of many responsibilities for GPs, they must compete for attention and resource with other commitments. Parts of the British Medical Association (London, UK) have suggested that it is not sustainable for GPs to continue to support the complex needs of care home residents in addition to their other work. 6 Some improvement initiatives have sought to remove part of the responsibility for routine health-care provision to care homes from GPs, whereas others have sought to encourage GPs to become more engaged with care homes via specific commissioning arrangements and incentive payments. 7,8

The Optimal study9–11 found that health-care services for care homes achieved better outcomes when NHS staff were given time and space to develop relationships with care home staff and residents, and their work with care homes was legitimised through role specification and valued by their employer. Specific expertise in care of older people, particularly in the management of dementia, supported these relationships with care home staff. A further enabling feature was where multiple services were commissioned to work together and link with care home staff. This provided ‘wrap-around’ support for care homes that was less reliant on single practitioners, such as the GP, as the main clinician. Interactions with GPs were, however, identified as being integral to how residents interpreted the quality of their health care, particularly around medication management and the role that the GP played in this. The Optimal study9–11 reported that the way services were organised around, and with, GPs influenced the willingness of GPs to engage and be proactive with care homes and their residents.

Quality improvement and other types of advancing practice

The ProactivE heAlthcare for older people living in Care Homes (PEACH) study12 looked at how a quality improvement (QI) collaborative could be used to improve health care for older people living in care homes. It found that GPs could play a role in broader improvement initiatives that extended beyond their specific duty of care as doctors because they were powerful and well connected within local health and social care economies. However, when GPs sought to play a central role, their limited capacity (owing to conflicting commitments) could limit progress. 12

In many countries, developing and improving care in long-term care institutions is not the responsibility of generalist medical practitioners. In the USA, medical directors have specific obligations to support the quality of health-care delivery in nursing homes. These medical directors undergo training in leadership and management competencies to support their role in service development and QI. 13,14 In the Netherlands, the specialty of elderly care medicine is separate from geriatric medicine and is a primary care specialty based in nursing homes. Doctors are expected to play an explicit role in institutional leadership, with a focus on quality assurance and improvement, in addition to their specialist clinical input. 15

The NHS England framework for Enhanced Health in Care Homes (EHCH), published in 2016, was proposed as the basis for a national improvement programme around health care in care homes. 16 EHCH laid out an approach to health care in care homes that favoured enhanced primary care support, access to multidisciplinary services, access to rehabilitation, high-quality end-of-life and dementia care, workforce development, collaborative approaches to commissioning health and social care, and effective use of data. NHS England has stated the ambition to have every area in England develop a plan to implement the EHCH model by 2024. 17 Early evaluations of pilot sites using this approach have demonstrated better resident outcomes than sites without this approach. 5,18 Modifications to EHCH, announced during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020, led to the allocation of NHS-employed professionals as ‘clinical leads’ for care homes. 19 These roles lacked detailed specification, but were intended to enable engagement between health-care and care home staff, with a focus around the organisation and delivery of health care. Although there are similarities between the ‘clinical lead’ role and the role of medical directors in the USA, the lines of responsibility and accountability for ‘clinical leads’ remain unclear. Clinical leads are not required to be doctors and they do not take over the role of primary health-care practitioner from a resident’s GP. 20 There is a danger that these recently implemented changes could compound longstanding problems with accountability and responsibility, which have confounded previous attempts to improve care delivery in the sector. 21 Given the lack of clarity about the role of the GP in these recent changes, constraints on the capacity of GPs, and the continued centrality of the GP to primary care delivery more generally, we need to know when and where GP engagement or support is an important requirement for improvement work around health care in care homes. This is particularly important if the improvements envisaged as part of EHCH are to be delivered consistently, at scale and pace.

What we mean by ‘quality’ and ‘quality improvement’

The Institute of Medicine defined quality health care as being safe, effective, patient centred, timely, efficient and equitable. 22

Health care is, of course, only one part of what care homes are supposed to offer. Much of the literature focused on quality in long-term care has stressed the importance of a broader, more holistic, approach to health and well-being, with emphasis on capturing what is important to residents and their families, adhering to principles of person- and relationship-centred care. 23–25 The Care Quality Commission (i.e. the regulator for all care providers in England) has attempted to capture these principles for care homes by specifications within a regulatory framework organised under the same headings it uses for health-care providers. 26

An iteration of these principles was developed to define quality in social care through the ‘Quality Matters’ programme27 led by the UK Department of Health and Social Care, with input from 24 organisations, including representatives of patient groups, social and health-care providers and commissioners, the care home sector, the nursing and social work professions, and regulators. This programme defined quality as having three service user-centred domains and two service provider domains. User domains of quality comprised a positive and safe experience, as well as an effective service, whereas provider domains comprised services that are committed to improvement and learning, and services that are sustainable and equitable. 27

The Quality Matters board suggested four action areas that could help to drive up quality in social care. Actions included effective use of data, enabling improvement and use of feedback. 27

Quality improvement is defined as any activity that might drive up quality in one or more of the domains described. The Institute of Healthcare Improvement (Boston, MA, USA) describes this as being delivered by iterative activities defined by planning, implementation, measurement and reflection. 28 Although QI infrastructure in long-term care is relatively underdeveloped,29 these processes have been shown to deliver improvement in care homes30 where the complexity of care delivery demands that improvement is delivered by teams comprising professionals from multiple disciplines and sectors. GPs have, in numerous recent initiatives, been expected to become involved in such approaches where they apply to health-care delivery for care home residents. 30

The General Practitioners’ Role in Advancing Practice in Care Homes study

Aim

-

To understand the roles that GPs have played in the development and improvement of health care in care homes.

-

To inform ongoing and future improvement work within the sector.

Objectives

-

To develop a programme theory describing contexts in which GPs can improve care in UK care homes and in international settings similar to UK care homes.

-

To describe the causative mechanisms whereby GP involvement with care homes results in outcomes of service development, implementation of evidence and improved quality of care.

A realist review was chosen by the project team as a suitable method with which to address the complex nature of QI that occurs at the interface between medical and social care sectors. Key to developing this understanding, as described earlier, is the ability to take account of varying care home and primary care contexts around the country and how these are likely to have an impact on the role required of, and played by, GPs. Localism has previously been identified as a long-standing, persistent and legitimate approach to care delivery in care homes. This subtends the agendas of multiple and diverse care home provider organisations and other issues, such as availability of NHS staff to support care homes, to mean that variation is, and will continue to be, the rule so far as the care home sector is concerned. 4 A context-sensitive approach was required to describe and make sense of this situation and this was the rationale for using realist review.

Chapter 2 Methods

Realist review is a theory-driven approach to evidence review often used to address complex issues of health service delivery. Realist approaches recognise that context always influences a social programme’s outcomes. By testing different plausible explanations of how particular contexts trigger responses or mechanisms to achieve (or not) certain outcomes, it provides an evidence-based narrative of what is most likely to work, how and when. 31,32 Realist theories are often expressed as a statement of (1) context (i.e. social and environmental factors), (2) mechanism (i.e. the causal powers that lead to patterns of behaviour or choices) and (3) outcome (i.e. the change in process, relationships or empirical measure). 33 Several contexts–mechanisms–outcomes (CMOs) may be linked together into a programme theory that describes the key attributes and or activities of an intervention necessary for it to achieve the desired outcomes. The realist review method is iterative and revisits, reinterprets and tests the evidence against the programme theory as it evolves. These core concepts are further described in Box 1.

Context can be broadly understood as any condition that triggers and/or modifies the behaviour of a mechanism, that is, the ‘backdrop’ conditions (which may change over time). For example, education and qualifications of care home staff and residents’ functional abilities.

Mechanism (M)A mechanism is the generative force that leads to outcomes. Often denotes the reasoning (cognitive or emotional) of the various ‘actors’, that is, care home staff, residents, relatives and visiting HCPs. Identifying the mechanisms goes beyond describing ‘what happened’ to theorising ‘why it happened, for whom and under what circumstances’.

Outcomes (O)Outcomes are the result of mechanisms and may be processes or empirical observations. These may be the expected outcomes and address the aim of the programme, or there may be unexpected outcomes. If the context does not sufficiently support the mechanism, there may be a lack of outcome. For health systems, outcomes could include quality of life of residents, a reduction in episodes of unplanned hospital admissions and improvement in medication management or staff confidence.

Programme theoryProgramme theory specifies what mechanisms are associated with which outcomes and what features of the context will affect whether or not those mechanisms operate. The programme theory encapsulates ideas about what needs to be changed or improved in how NHS services work with care home staff, and what needs to be in place to achieve an improvement in residents’ health and organisations’ use of resources.

HCP, health-care professional.

Reproduced from Goodman et al. 9 Contains information licensed under the Non-Commercial Government Licence v2.0.

Here, the social programme that we are describing relates to the role played by GPs, or primary care doctors, in service development, implementation of evidence and improvement in care homes. The scope of the project was purposefully broad to explore how GPs engage with a range of improvement approaches and topic areas. Although we include QI, we acknowledge that this term is used differently and, therefore, have not constrained our search to this term. The diversity of QI initiatives, together with diversity of GPs and care homes, prompted the project team to select realist review because the method is capable of synthesising complex systems. Furthermore, our review proceeded with a primary search followed by secondary iterative searches to enable flexibility and refinement of scope and to enable greater focus on emergent themes.

Protocol, registration and ethics approval

A protocol for the General Practitioners’ Role in Advancing Practice in Care Homes (GRAPE) study has been published1 and the work has been registered with PROSPERO (CRD42019137090). 34 Following scoping searches and discussion with the project team, the decision was made to amend the protocol by focusing on studies based within UK. This was because the context of general practice is distinct within the UK’s NHS and, therefore, international literature will be based within different contexts that may elicit different mechanisms.

This review conforms to the RAMESES (Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards) quality standards for realist reviews35,36 and follows the outline of necessary processes as set out by Pawson31 (see Appendix 6 for details).

Ethics approval was given by University of Nottingham Research Ethics Committee (reference 354-1907). Subsequent discussion with the project team indicated that a modification of the recruitment of participants would require a minor amendment to the ethics approval. Approval of the minor amendment was granted on 20 October 2019.

Co-applicant Group: the project team

The authors are the project team. All authors were co-applicants on the initial grant proposal except for Neil H Chadborn. We have a patient and public involvement (PPI) representative (KS) as both a co-applicant and a team member. Our PPI member attended all project meetings, contributed extensively to theory generation and is a co-author of this report. Kathleen Sartain referred back to a PPI group based in the Division of Rehabilitation and Ageing at the University of Nottingham, which meets four times per year. We will share findings, including the final version of this report, with this group and will seek their advice about dissemination plans and future research proposals.

Stakeholder Group: Context Expert Group

The Context Expert Group was recruited through professional networks and comprised GPs, a care home manager, a pharmacist and a care home nurse. Participants of the interviews were also invited to join the group. The group met twice (once during step 3 to discuss programme theory 1 of the realist review and again during step 3 to discuss programme theory 2) for half a day each time. These meetings were conducted using videoconferencing technology because of COVID-19 lockdown restrictions during the period that the research was conducted. A presentation was given about the background and progress of the review, including putative programme theories, and members were asked to reflect on these (see Report Supplementary Material 1 and 2). Members were asked if CMO configurations resonated with their experience or if their views differed from our interpretation and if they could add or amend to improve our interpretation. Members were asked to highlight any further documents that may have been missed from our searches. Individual members of the group were also consulted before, between and after meetings to consult on emerging programme theories. Notes were taken during meetings, but the discussion was a stakeholder consultation and was not treated as research data.

Steps of the realist review

The review followed a four-step approach:

-

locating existing theories and developing putative programme theories (i.e. if/then statements)

-

searching for evidence

-

extracting and organising data

-

synthesising the evidence and drawing conclusions.

Although described as discrete, these steps were an iterative approach that moved between the literature, stakeholder interviews and our Context Expert Group to develop a robust and evidenced programme theory that addressed the aims and objectives. This is summarised in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram summarising iterative review process.

Step 1: locating existing theories

This initial step explored what has worked well when GPs work with care homes, how the different elements of GP working are thought to have made this happen and what is needed to be in place for it to occur. The scope included service development, delivery and improvement in care homes. Our starting point was the theories developed within two realist studies: the Optimal study9,10 and the PEACH study. 12,37 These studies had identified key principles of working across health and social care, with the former focusing on design, provision and delivery of statutory services and the latter focusing on bottom-up QI initiatives driven by practitioners in response to the needs of residents. Both studies9,10,12,37 identified the issues of how GPs work with care homes to be a particular issue for further study. Examples from the Optimal study9,10 included how incentive payments to GPs could have both anticipated and unanticipated effects on practice, depending on how GPs integrated specified activities into existing models of working. The PEACH study,12,37 meanwhile, identified GPs as prominent leaders within primary and community health care who could influence the success or failure of an initiative by virtue of their level of engagement and the ‘permission’ they gave, either implicitly or explicitly, for improvement to proceed. The reference lists from these studies, alongside initial scoping reviews of the literature, using broad search terms around care homes and general practice, enabled us to structure a series of theory-gleaning interviews with GP leaders and practitioners. We describe the ways in which these findings led to the stakeholder interviews in Chapter 3 and we provide a schedule for these interviews in Appendix 1 as a way of making transparent how previous research informed and shaped interviews. Interviews, in turn, informed further scoping reviews (see Figure 1). This work enabled us to iterate towards a definitive search strategy for step 2.

For the interviews, we recruited a purposive sample of GPs through professional networks from different parts of England. Participants had experience of QI work in care homes or had senior leadership roles. Participants were given participant information sheets and asked to give written consent. Interviews were semistructured and took place by telephone or videoconference. Themes for the interview schedule were developed from the scoping literature and discussions within the project team (see Appendix 1). Themes included the range of approaches used by GPs working with care homes to achieve health-care improvement. In addition, interviewees were asked about the extent to which the achievement of improvement objectives were influenced by the support and involvement of GPs, and the ways in which this operated through engagement with other professional groups. We asked how the GP contribution was affected by the presence or absence of other care professionals. Furthermore, we explored aspects of context identified in the literature as important for QI and improved resident outcomes. Interviews were transcribed and coded in qualitative data analysis software (NVivo 12; QSR International, Warrington, UK). From analyses of GP interviews, and scoping literature, as well as the expert knowledge of the project team, we built an initial programme theory that shaped our literature searches during step 2.

Step 2: searching for evidence

We used our initial programme theories (from the literature scoping and theory-gleaning interviews with GPs) to structure the evidence search terms and review parameters. There were specific topics that had been the focus of improvement interventions in care homes and were particularly relevant to the role of the GPs, namely medication optimisation through medication review and end-of-life care. Our stakeholder interviews and Context Expert Group suggested that the ways in which GPs worked with and for QI in these areas could provide case studies to inform more general programme theories about the how GPs participate in improvement in care homes. Discussions with the project team about the context raised the concern that international literature may not be informative because of the distinct context of the GP within the NHS in UK. Therefore, searches were limited to UK literature.

Three searches, in addition to citation searches, were conducted across five academic databases [MEDLINE, EMBASE™ (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Web of Science™ (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and PsycInfo® (American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, USA)] and also the Cochrane Library. In consultation with information specialists, we decided to use Web of Science rather than the Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), as had been proposed in the protocol,1 because initial searches indicated that the social science focus of ASSIA would result in relatively low yield. In summary, the searches were as follows:

-

primary search – GP and care homes, limited to UK, 2000 to April 2020 (see Appendix 2)

-

secondary search – medication review or pharmacy optimisation and care homes (but not specifying GP), limited to UK, 2010 to April 2020

-

secondary search – end-of-life care or palliative care and care homes (but not specifying GP), limited to UK, 2010 to April 2020

-

citation searches of key authors and key articles.

We chose different date ranges for these searches based on criteria of relevance and rigour. 36 Relevance relates to whether or not data within a document can contribute to theory building and/or testing, and rigour describes the extent to which the methods used to generate the relevant data are credible and trustworthy. We found that, when focusing on GPs and care homes, much of the literature before 2000 did not describe QI and was less relevant to current models of clinical practice because of changes in how primary care has been configured in relation to care homes over the intervening period. Arrangements such as GPs charging retainer fees to care homes and a focus on care delivery at the individual resident level were prevalent in papers from the early 2000s. 38–40 These arrangements were less of a focus from 2010 onwards, when articles shifted to focus on structured interaction between GPs and care homes at an organisational level, and on contractual arrangements. In topic-specific searches, we did not specify ‘GP’ and searches were intentionally broader; however, screening to investigate GP involvement in each article was more time-consuming and, therefore, we focused on more recent literature (from 2010 to April 2020) that would be more reflective of current contexts.

As improvement and other types of development work undertaken in care homes are frequently discussed outside academic literature, we searched for grey literature using web searches (Google; Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) to look for outputs from royal colleges, specialist societies and other professional bodies, such as the British Medical Association (including local medical councils), the National Association of Primary Care (London, UK) and the Social Care Institute of Excellence (London, UK). Websites of charities, such as the Nuffield Foundation (London, UK) and the Health Foundation (London, UK), were also searched. We made enquiries via the Health Foundation ‘Q Community’, which is a national network of practitioners, leaders, managers and academics that is focused on health-care improvement, and through the community geriatrics and general practice special interest groups of the British Geriatrics Society (London, UK) to further source relevant grey literature.

Step 3: extracting and organising data

The initial programme theories informed the design of a bespoke data extraction tool that included details about the study type, the intervention, the improvement approach and the number of care homes, staff, residents and GPs (see Appendix 4).

Evidence reviewed included a description of the involvement of GPs in the implementation of a new service or service model, or evidence that described an intervention to improve the quality of existing health care. Articles were excluded if they described routine health-care provision outside the context of service development, implementation or improvement, if they described social care in isolation from health care or if the role of GPs was not explicitly considered. Screening at all stages of the inclusion/exclusion steps was conducted by one reviewer (NHC). Relevant data from studies were extracted onto a bespoke data extraction form by two reviewers (NHC and RD). The list of included/excluded articles, the text of included articles and how these articles were used to populate the data extraction form, were reviewed and discussed by all team members at regular project meetings.

Qualitative synthesis was undertaken in qualitative analysis software (NVivo 12). All interview transcripts, selected articles and selected grey literature were imported into the software. Nodes were created based on the putative programme theories described in step 2.

Step 4: synthesising the evidence and drawing conclusions

In step 4, analysis focused on how the evidence built on, refuted or provided alternative explanations for key aspects of GP work in care homes, where outcomes may be at the level of the organisation or the resident.

We looked for outcomes in articles that mapped to our outcomes in our emergent CMO patterns. These outcomes largely related to improved partnership working or improved co-ordination of care processes. For each CMO, we visited our collated literature, first to look for evidence that supported our theory and then for evidence that contradicted or required us to adjust it. We focused on CMOs in which there was evidence from more than one paper that there was some replication of the way in which contexts triggered mechanisms to achieve outcomes (i.e. demi-regularities).

Chapter 3 Findings

Step 1: locating existing theories – theory-gleaning interviews and a scoping literature review

In step 1 of the review, we explored three sources to develop our putative programme theories that would be the basis of the literature search strategy. These comprised (1) the views and expertise of the project team (i.e. the authors), (2) theory-gleaning interviews with senior GPs and (3) scoping of literature and grey literature.

Views from project team

The project team met regularly throughout the review and discussed key findings from previous research projects, QI initiatives and clinical experiences. The following is a summary of the topics raised.

The Optimal study9,10

-

Improvement initiatives could not leave GPs out of health-care delivery, even if systems aimed to substitute for GP tasks.

-

Initiatives did not always recognise the work of GPs.

-

Referrals of residents with multiple health problems to multiple services could be problematic. There was co-ordination and triage of referrals that could introduce bottlenecks and direct access that was quick but could lead to duplication. These tensions featured in discussions about the role of GPs.

The PEACH study12

-

Improvement initiatives struggled to ‘get off the ground’ without GP input.

-

In some instances, teams started initiating plans on the basis of what could be achieved in the absence of GPs because, in these instances, the engagement of GP colleagues was unpredictable or uncertain.

-

When GPs did engage, they were found to play an essential role in brokering relationships and legitimising improvement initiatives across the broader health and social care community.

Views of patient and public involvement based on experience of several research projects

-

There had been limited focus on what resources GPs need to support care home initiatives.

-

GPs do not consistently have topic expertise in the care of older people, which our PPI member argued was essential to care delivery in care homes.

-

The role of the GP as gatekeeper for referrals in the NHS was important to their role in improvement initiatives.

-

GPs are busy and have an area of specific expertise and, therefore, should not be expected to do ‘non-GP’ tasks.

Clinical experience from general practitioner and geriatrician team members

-

The GP–care home relationship is often overlooked.

-

This should be considered at the level of local systems, as well as at the patient level.

-

We should consider how QI initiatives influences GP–care home relationships.

-

General practitioner stakeholder interviews

Seven participants took part in telephone interviews that lasted between 28 and 50 minutes. Backgrounds and experience of participants are summarised in Table 1.

| ID | Category | Area of England |

|---|---|---|

| #02 | Clinical academic | Midlands |

| #06 | Clinical academic | Midlands |

| #10 | Practising | Midlands |

| #11 | Clinical academic (retired) | London |

| #16 | Commissioner | South West |

| #19 | Practising | London |

| #21 | Practising | London |

Emergent themes are summarised in Box 2 and are discussed in greater detail below.

-

Diversity of ways of working among GPs.

-

Recognising relationships with care homes.

-

Capacity and skill in QI.

-

Specialist expertise in medicine for older people.

-

Medication review.

-

End-of-life care.

Diversity of ways of working

The diversity of ways of working ranged from a single general practice working exclusively with a single care home to GPs as ‘care home specialists or leaders’ and making improvements at a system level across multiple care homes. It was noted, although this is not typical, that some care homes are GP owned.

The usual contractual relationship between a GP and care home residents is the same as for patients living in their own home and is outlined in the General Medical Services contract. Additional or alternative contractual arrangements have made available additional financial resource for general practice staff to attend care homes, including Personal Medical Services and Local Enhanced Service contracts. 41,42

There was a concern that national policy discourses and local commissioning may not fully acknowledge GPs’ concerns about the day-to-day practice of delivering care within care homes, and a sense that GPs had latitude in how they prioritised their care home work. Several respondents indicated that they were part of a minority of GPs who had an interest in care homes and highlighted that the majority were not similarly inclined. The implication is that the majority of GPs tend to regard residents on an individual basis and do not always consider the contribution to care delivery from care home staff.

The Royal College of General Practitioners’ (London, UK) curriculum learning outcomes on older adults, identified through our scoping review, highlights five complex roles required of GPs. 43 One of these roles is to co-ordinate with other organisations and professionals, including care homes, and that the GP should be an advocate for residents. 43 Care homes are framed as locations and not as partners in care delivery. Care homes are identified as one of several organisations with which GPs must liaise. This supports the views expressed in the stakeholder interviews that the organisational importance of care homes in the delivery of relationship-centred care is not widely recognised in general practice. Within these roles, medication review and end-of-life care planning are included and described as areas of particular focus, highlighting that these could be a lens through which to better understand GP involvement with care homes. 43

Recognising relationships with care home

The Optimal study9 and the PEACH study,12 our starting points for this work, had highlighted the importance of relational working to achieve effective partnership between GPs and care homes. This was endorsed by participants who cited a key context as GPs not recognising care homes as partners in care delivery. Attempts to change GP alignment with care homes as part of EHCH was an example of an attempt to change the patterns of working, creating continuity and fostering closer working relationships between one general practice and a care home. 16 Therefore, implementation of alignment through additional contract arrangements triggered a closer alignment and relationship between GPs and care homes. Some respondents felt this meant that GPs, simply because of increased frequency of contact and familiarity, were given the opportunity to acquire a greater awareness of care home organisations:

Because they were in care homes so often and could see how things weren’t working . . .

Participant #16

The recent reconfiguration of general practices into primary care networks also had the potential for constructive working with care homes because it organised GPs at a regional, rather than practice, level. This was seen as offering more consistent and co-ordinated approaches to GPs working with care homes:

. . . so we might see a shift in commitment and involvement and responsibility for care home residents maybe.

Participant #11

There was a recognition, as well, that the onus was not exclusively on GPs when it came to building meaningful relationships for QI. One participant described how the heterogeneity of care home types affected what was carried out and who engaged. The care homes that belonged to large corporate provider chains would carry out their own QI projects led by the organisations’ directors of quality, but GPs were often not engaged in these corporate initiatives. In contrast, small independent care homes struggled to find resource or capacity for co-ordinated QI activity.

The impact of the regulator on how care homes worked with GPs was also seen as important. Inspections require evidence of access to health care and appropriate procedures, but one interview participant did not think that the Care Quality Commission inspections asked for evidence or recognised the importance of ongoing QI work or partnering with local NHS providers:

. . . this is a real problem with CQC [Care Quality Commission], they are not very proactive about understanding about QI methodology.

Participant #16

Capacity and skill in quality improvement

One participant reflected on QI projects and the expertise that they had seen in other parts of the NHS, and suggested that there was a relative paucity of experience and training in QI among GPs. This participant described a recent improvement workshop that they had led:

. . . realise how little training is done in primary care around QI methodology . . . we had maybe 60 GPs and ANPs [advanced nurse practitioners] in the room and we asked them, for example do you know what a PDSA [Plan Do Study Act] cycle is, and they didn’t, maybe two hands went up.

Participant #16

This was seen as a fundamental reason that could explain why GPs would struggle to engage with improvement in care homes:

I don’t think you’ll ever have GP-led QI programme in care homes because they don’t know enough, don’t understand enough . . .

Participant #06

This was at odds with earlier statements about GPs being well placed to build relationships with care homes and to identify foci for improvement, suggesting a tension between QI competencies (which were regarded to be lacking) and clinical competencies and the ability to carry out day-to-day care (which were more evident).

Many of the improvement projects that participants had seen undertaken around care homes had been led by non-GP health-care professionals. This was attributed to work pressures, how clinical work was prioritised and the limited capacity of GPs to take on these kind of roles. Some respondents felt, however, that this left GPs exposed to risks associated with improvement projects and without any control over their content or progress. This respondent described an experience of working with pharmacist-led improvement, and felt that GPs had been left to ‘pick up the pieces’:

Unless the pharmacist is working at the highest level of their competency, then either they are unsafe, or the workload falls back on primary care anyway.

Participant #16

This lack of time and training in QI, coupled with worries about responsibility or accountability, were seen as significant barriers to GPs engaging in QI more generally and in care homes in particular.

Tension between developing specialism and maintaining generalism

Multiple respondents described how health care in care homes was complex and challenging and required subspecialist skills or knowledge. Some respondents felt exposed by the lack of expert multidisciplinary support in the community:

. . . somebody’s diabetes had gone really off and it just didn’t feel like we’d got the resources in the care home to manage this and that he needed to go in the hospital.

Participant #02

One respondent went as far as to suggest that specialists in acute medicine or care of older people, rather than GPs, should be attending to older people in care homes, with support from a multidisciplinary team (MDT):

Care home residents are some of the most medically complex patients . . . a group of people that need that expertise of the internist with a multidisciplinary team.

Participant #06

This group of hospital-based specialists, however, have limited or no experience of community working. One respondent described the development of a special interest group for GPs as part of the British Geriatrics Society. The group wanted to develop a GP with special interest model, in which some GPs would step away from their other responsibilities to focus on care of older people, including in care homes. The group expressed frustration that training and accreditation mechanisms did not currently enable them to fully pursue this approach in their working:

. . . we’ve had challenges about whether or not, in order to remain accredited, we have to do what is seen as standard general practice or Geri-GP [GP with extended role in geriatrics] work, and there is inconsistency across the country. So some appraisers are saying that GPs have to do sessions in normal primary care and other assessors are saying we don’t.

Participant #16

General practitioners’ relationship with pharmacists

General practitioner participants described the value of pharmacists conducting medication reviews of care home residents, particularly for residents with complex medication regimes that may have been adjusted following hospital admission:

. . . in 6 weeks’ time when I have got the notes, have I got the time then to do the medication review properly? So, they are all potential areas of error.

Participant #21

There were concerns about limited capacity for pharmacists to conduct follow-up consultations. Another participant questioned whether or not pharmacists would have the broader knowledge of care of older people, such as mental capacity legislation. Therefore, GPs considered that risks arising from pharmacists changing medication could increase the workload of the GP. When there was an established and trusting relationship between GP and pharmacist, however, the GP could see the advantages provided by the pharmacist’s skills and expertise:

. . . if you’ve got a very good pharmacist, I think GPs are only too happy for them to do some of the work . . .

Participant #16

General practitioners supporting end-of-life care

General practitioner participants discussed advance care plans (ACPs) and end-of-life care. Two participants had been involved in implementing a data-sharing system (electronic palliative care system) to improve continuity of care for people with end-of-life care plans:

. . . if you can get into a good system of making advance care planning routine on admission [to the care home] . . . the conversation is had, wishes and preferences are gathered. That information is then stored but then is shared, so obviously we are lucky that we are able to do that with [electronic palliative care system].

Participant #21

One participant mentioned that there could be a problem if care home staff did not approve of implementing advance directives, possibly because of a lack of confidence or resources:

Problem of staff member who doesn’t approve of providing high level of care and refuses to deliver an ACP.

Participant #11

Therefore, GP participants recognised the importance of palliative care and advance care planning in care homes. They also described how good end-of-life care is dependent on good communication, not only between the GP and the care home, but also with the resident, family members and other health practitioners (e.g. paramedics).

Scoping the literature

The interviews described variability in practice driven by variable GP interest in, and engagement with, the care home sector, lack of training in specialist care of older people, lack of training and experience in QI, and nervousness about working with other disciplines around improvement projects for fear that it may generate additional work. The improvement work involving GPs that had taken place had focused on integrated working between GPs and care homes, medication management and end-of-life care. The scoping review focused on evidence to support these findings and inform the programme theory development.

Patterns of general practitioner working with care homes

To gain understanding of multiple and varied contexts, scoping searches aimed to identify the challenges or problems of GPs delivering care within care home settings that had been described in observational studies (i.e. surveys, cohort studies, descriptive studies or qualitative studies). A qualitative study of English GPs in 200344 explored views on continuity of care and the challenges of maintaining people’s GP as they move into a care home (as opposed to changing to a GP assigned to the care home). The study44 concluded that if one practice cared for all residents within a care home, then interactions could be more efficient because the GP could establish working relationships with the care home staff, which, in turn, could lead to improvements in resident care. The benefits and additional workload of regular clinics at the care home were acknowledged but not resolved. Reviewing contractual arrangements for GPs was described as one possible one way of addressing increased workload.

In two consecutive studies45,46 surveying GPs in Ireland, experiences, training needs and workload issues around care home practice were explored. The studies found that GPs with small numbers of care home residents on their lists had low confidence in care home practice, particularly around ethically complex issues, such as decision-making around end-of-life care. A proportion of GPs felt that their training in geriatric medicine could be improved. The majority of respondents felt uncertain about how to handle safeguarding issues in partnership with care home staff. 45 Approximately three-quarters of respondents indicated that they conducted medication reviews at least annually, with the authors suggesting that a national quality standard (i.e. Health Information and Quality Authority standard number 15) was a major driver behind this high level of compliance. 46

Two recent reviews47,48 give a broad perspective on the topic of improving health care in care homes. In the first review, Barker et al. 47 conducted a systematic review of primary care in care homes. The selection criteria for this review included a comparator group (e.g. controlled trials) and reporting quantitative outcomes. Only 9 out of 24 studies in this review included GPs (family physician) as playing a role within the intervention. In five of these studies, a geriatrician contributed medical expertise, whereas in another three studies the intervention was led by a specialist nurse. One small study,49 based in Australia, described a multidisciplinary intervention led by the GP.

The second review was a scoping review of QI in care homes48 with broad inclusion criteria selected 65 international studies. A striking finding was the absence of evidence or discussion about how GPs were involved, although a few studies referenced the involvement of specialists in gerontology/geriatric medicine. However, only one article,50 based in Canada, included a family physician as part of the intervention.

Foci of improvement programmes

We searched for current or recent programmes in grey literature. The ‘Primary Care Home’ project in England is a GP improvement project, running across 248 sites in England, and is supported by the National Association of Primary Care. 51,52 Only 15 projects mention care homes and, of these, only 11 had commenced. Four projects describe MDTs providing care in place of regular GP visits. Three projects involve medication review and proactive care planning. One project, Health 1000, is a GP partnership that specialises in care of older people and includes four nursing homes. 53

The Scottish General Medical Services contract54 described the following: pharmacist-led medication reviews in care homes, with this replacing work previously undertaken by GPs, and advanced clinical practitioners assessing and treating care home residents to release GP time to focus on complex cases in care homes.

The findings of the scoping review identified recurring topics of interest as the focus of improvement projects that involved GPs (Box 3).

-

End-of-life care.

-

Polypharmacy/pharmacist/medication review.

-

Urgent care and out-of-hours care (i.e. information transfer).

-

Training GPs.

-

GPs facilitating learning.

-

MDT case conference or virtual conference.

-

Voice of patient and/or family.

-

Dementia diagnosis/behaviour psychotropic de-prescribing.

The most commonly described interventions are highlighted in bold.

Conclusions and development of putative programme theories

At the end of this step (i.e. locating existing theories) we had evidence of the following:

-

Variability in practice between GPs.

-

Variability in how GPs prioritise and relate to care homes, and the extent to which they recognise care homes as partner organisations.

-

Conflict between traditional training and remuneration structures, which supported variability in practice, and more recent innovations (e.g. EHCH and primary care networks), which were seen as providing opportunities for more standardisation of approach.

-

Limited capacity, training and experience that would enable GPs to lead QI.

-

Limited engagement with the complex care of older people in care homes by GPs and uncertainty in how to work with care homes as social care organisations.

-

Many improvement projects with care homes were led by specialists other than GPs, and a recognition that limited GP involvement could have unintended consequences for GP workload and sustaining improvements.

-

Improvement projects had focused predominantly around end-of-life care, de-prescribing (including psychotropic de-prescribing) and integration of health care around care homes.

We developed a series of ‘if/then’ statements based on initial interviews and the scoping of the literature. These are summarised below and related to:

-

polypharmacy and review of medications

-

developing ACPs

-

the extended role of GPs and expertise in care of older people.

Polypharmacy and review of medications

Inappropriate polypharmacy is associated with adverse outcomes in people with multimorbidity and frailty. 55 Medication review can address these concerns, with a balancing of risk and benefit of multiple drugs. This can potentially be achieved through multiprofessional working, involving a pharmacist, doctor and the care home staff to explore where drugs may no longer be necessary, especially where side effects can be problematic, where drug interactions could be avoided or where non-pharmacological interventions could be substituted56 (Box 4).

If the GP reviews prescriptions together with a pharmacist, then they may find opportunities to alter prescription or regimens to reduce the ‘burden’ of medication and adverse outcomes, improving the quality of care.

Developing advance care plans

Developing an ACP has been shown to improve outcomes for older people living in care homes as they approach the end of life, and doctors have been reported to have a key role within this process, which is, nevertheless, multidisciplinary. 57,58 The role of the GP in this process is to provide diagnostic and care planning expertise, and to support and clarify the documentation process of residents’ preferred priorities of care for professionals and care staff. 59 It is an area of QI that can support future continuity of care and confidence that resident wishes, and those of their representatives, will be observed60,61 (Box 5).

If GPs are involved in documenting and implementing ACPs, then it will ensure that all those involved in providing and receiving care will be able to review medical diagnoses in a way that reflects residents’ priorities and inform care provision and ongoing decision-making.

The extended role of general practitioners and expertise in care of older people

The interviews had identified different views about whether or not GPs were qualified or sufficiently supported to be the clinician responsible for care home residents. Specialism could lead to specific GPs having confidence, skills and expertise to participate or lead QI projects, but not all GPs were thought to have time or motivation. GP specialism would, therefore, be an important context of other programme theories.

The interviews with GPs suggested that to ensure effective medication review there was the need for a trusting relationship and recognition of GP and pharmacist skills. When the GP is confident in their own pharmacy knowledge and had the capacity, then there was commitment to medication review.

Another interview discussed the additional skill level required to effectively deliver acute care in care homes, which may be required for ‘hospital at home’ or step-up care (hospital avoidance), supported discharge from hospital and end-of-life care.

General practitioners may be motivated to develop special interests or extended roles for a number of reasons (over and above financial reward), such as career development, the opportunity to focus on a topic of interest and to lead or develop a service area. 62–64 Owing to the increased engagement, this may be a route by which GPs would engage in QI (Box 6).

If support, training or professional networks are available, then GP may develop special interests and expertise in care homes, leading to fuller engagement with QI and resident outcomes.

Step 2: search strategy, PRISMA flow diagram and included articles

We developed an iterative search strategy based on the putative programme theories developed in step 1 to capture the GP role in improvements under these headings to provide case studies that would inform programme theory development. We have summarised this search strategy in Chapter 2 and in Appendix 2.

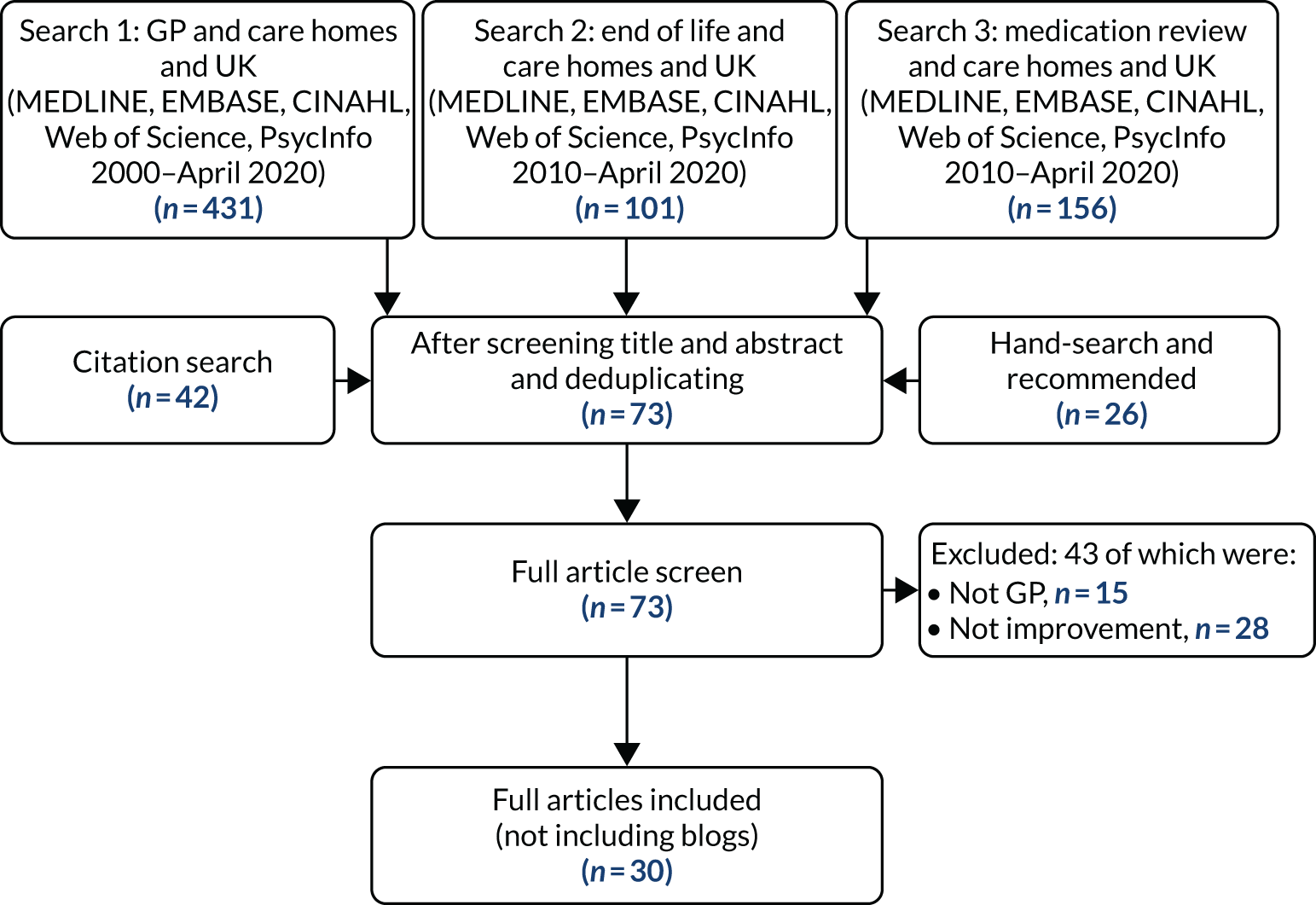

A PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) flow diagram is shown in Figure 2. The primary search for UK articles including care homes and GPs (with a publication date range of 2000 to April 2020) retrieved 431 articles (see Appendix 3, Table 8). Secondary iterative searches were performed for end-of-life care and medication review (both with care homes, but GP was not specified in search terms), with the aim of identifying articles that may have been missed by the primary search. These searches (with a publication date range of 2010 to April 2020) retrieved 101 and 156 articles, respectively (see Appendix 3, Tables 9 and 10). Citation searches were conducted, as well as hand-searches of selected journals and follow-up of recommendations from the project team and interview participants. After removing duplicates and screening, 73 articles were included in a full-text screen. Twenty-eight articles were excluded following the screen of the full text because the studies were observational (e.g. qualitative, cross-sectional survey or database analyses), rather than studying an intervention, QI or other type of change management process. Fifteen articles were excluded because they were found to not describe GP involvement (e.g. GP records may have been used to identify participants or extract data as an outcome, but the GP was not specifically involved in the intervention). Thirty articles were finally selected for data extraction and synthesis, as listed in Table 2.

FIGURE 2.

A PRISMA flow diagram.

| Programme theory | Study keyword | Date | First author surname | Title | Journal | Study type | Key findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | New care models | 2018 | Elvey | Implementing new care models: learning from the Greater Manchester demonstrator pilot experience | BMC Family Practice | Qualitative observation of pilot projects | Challenges identified were trust to enable collaboration, especially relating to data-sharing | 65 |

| 1 | Palliative care | 2016 | Iliffe | Improving palliative care in selected settings in England using quality indicators: a realist evaluation | BMC Palliative Care | Realist evaluation | GPs could not be recruited. Care homes could not be retained. The quality indicators set were not motivating for GPs or care homes (they may have been too specialist) | 66 |

| 1 | EVIDEM-EoL | 2016 | Amador | Evaluation of an organisational intervention to promote integrated working between health services and care homes in the delivery of end-of-life care for people with dementia: understanding the change process using a social identity approach | International Journal of Integrated Care | Qualitative appreciative inquiry |

The intervention supported integrated working due to shared goals and recognition of different expertise Bottom-up process of implementing context-specific practice innovations and tools The approach accommodates diversity |

67 |

| 1 | End-of-life care | 2011 | Evans | Factors influencing emergency hospital admissions from nursing and residential homes: positive results from a practice-based audit | Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice | QI: audit | Initial audit showed that 55% of deaths occurred in the care home, whereas this had increased to 75.5% in the second audit. GP visits to nursing home patients increased by 10.3%, but visits to residential home patients decreased by 5.4%. There was a 43% reduction in emergency admissions with a 45% decrease in deaths in hospital | 68 |

| 1 | Vanguard | 2018 | Stocker | Care home services at the vanguard: a qualitative study exploring stakeholder views on the development and evaluation of novel, integrated approaches to enhancing healthcare in care homes | BMJ Open | Qualitative study of planned implementation | There was a moral imperative for proposed change to services. However, integrated working was not clearly understood. There was a perception of the programme being ‘top-down’ and imposed by the health service. Trust within the system was valued | 69 |

| 1 | Antipsychotic de-prescribing | 2016 | Szczepura | Antipsychotic prescribing in care homes before and after launch of a national dementia strategy: an observational study in English institutions over a 4-year period | BMJ Open | Quantitative retrospective analysis | Prescribing rates did not change following implementation of the policy, nor was there a shift to second-generation antipsychotics. Duration of prescribing was excessive in 69.7% of cases. There was an association between high prescribing and deprivation of the area of the care home. There was an association between low prescribing and single general practice | 70 |

| 1 | Medication review | 2011 | Patterson | A cluster randomized controlled trial of an adapted U.S. model of pharmaceutical care for nursing home residents in Northern Ireland (Fleetwood Northern Ireland study): a cost-effectiveness analysis | Journal of the American Geriatrics Society | Cluster randomised controlled trial | Psychoactive drugs were taken by fewer residents after 12 months of the intervention (19.5%) compared with control (50%). No differences in falls rates were observed | 71 |

| 1 | Medication review | 2003 | Hughes | Information is care: the need for data to assess the quality of care in UK nursing and residential homes | Expert opinion on drug safety | Expert opinion | There is a lack of data on prescribing | 72 |

| 1 | Neuroleptic de-prescribing | 2002 | Ballard | Can psychiatric liaison reduce neuroleptic use and reduce health service utilization for dementia patients residing in care facilities | International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry | Non-randomised controlled trial | Liaison service was associated with a reduction in use of neuroleptics and a decrease in deterioration of expressive language skills, but no change in well-being. There were fewer GP contacts | 73 |

| 1 | Medication review | 2000 | Khunti | Effect of systematic review of medication by general practitioner on drug consumption among nursing-home residents | Age & Ageing | Evaluation | A total of 51% of patients had a medication stopped and 26% of patients changed to a cheaper alternative or reduced dosage | 74 |

| 1 | WHELD | 2016 | Ballard | Impact of WHELD intervention on neuropsychiatric symptoms, antipsychotic use and quality of life in people with dementia living in nursing homes: a cluster randomized trial | American Journal of Psychiatry | Factorial cluster randomised controlled trial | There was a reduction of antipsychotic prescription by 50% with a reduced mortality. Social interaction and exercise mitigated the detrimental impact of de-prescribing antipsychotics on neuropsychiatric symptoms | 75 |

| 1 | WHELD | 2018 | Ballard | Impact of person-centred care training and person-centred activities on quality of life, agitation, and antipsychotic use in people with dementia living in nursing homes: a cluster-randomised controlled trial | PLOS Medicine | Cluster randomised controlled trial | Improvement in quality of life, agitation and neuropsychiatric symptoms. Rates of prescribing of antipsychotic were low and did not change | 76 |

| 1 | WHELD | 2020 | Ballard | Improving mental health and reducing antipsychotic use in people with dementia in care homes: the WHELD research programme including two RCTs | Programme Grants for Applied Research | Programme report | A systematic review found four training manuals with randomised controlled trial evidence. Meta-synthesis identified four key elements, including antipsychotic review by GPs. A factorial randomised controlled trial showed a reduction in drug use, and exercise and social interaction were needed to mitigate detriment of drug withdrawal. Focus groups indicated need for a whole-home approach, including sustained relationships. A 9-month randomised controlled trial showed improvement in quality of life, agitation and neuropsychiatric symptoms. Health and social care costs were reduced. Delivering the intervention required a flexible approach. An e-learning module was developed for GPs | 77 |

| 1 | Shine | ND | Baqir | Blogs | Health Foundation | QI | Various aspects of a QI initiative are described, including responding to diversity of GP working practices | 78–80 |

| 1 | Shine | 2014 | Northumbria Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust | Shine 2012 final report. A clinico-ethical framework for multidisciplinary review of medication in nursing homes | Health Foundation | QI | Similar to Baqir 2013 | 81 |

| 1 | Shine | 2014 | Baqir | A clinico-ethical framework for multidisciplinary review of medication in nursing homes | BMJ Open Quality | QI | Similar to Baqir 2013 (see below) | 82 |

| 1 | Shine | 2013 | Baqir | A clinico-ethical framework for multidisciplinary review of medication in nursing homes: a Health Foundation Shine project | International Journal of Pharmacy Practice | QI | A total of 422 residents were reviewed and 17.4% of medicines were stopped (6% were stopped because of safety concerns). A total of 2.1% of residents had potential adverse events, but these were reversed. One-hour nursing time was released per day because of fewer medications. Care home nurses and GPs were supportive and allowed access to records | 83 |

| 1 | Shine | 2017 | Baqir | Impact of medication review, within a shared decision-making framework, on de-prescribing in people living in care homes | European Journal of Hospital Pharmacy | QI | A total of 70.6% of patients had at least one medicine stopped. No significant difference in medicines stopped between pharmacists alone or pharmacist plus GP | 84 |

| 1 | Medication review | 2006 | Zermansky | Clinical medication review by a pharmacist of elderly people living in care homes – randomised controlled trial | Age & Ageing | Randomised controlled trial | Pharmacist recommended to GP 3.1 drug changes whereas GP alone made 2.4 changes per patient. There was a lower rate of falls in pharmacist-attended residents (0.8 vs. 1.3 falls per patient for the GP group). A total of 75.6% of pharmacist recommendations were accepted and, of these, 76.6% were implemented | 85 |

| 1 | Independent prescribers | 2016 | Bond | GP views on the potential role for pharmacist independent prescribers within care homes: Care Homes Independent Pharmacist Prescribing Study (CHIPPS): ‘there has to be something in it for me’ | International Journal of Pharmacy Practice | Qualitative interview study | GPs welcomed the pharmacist service. Some concerns about pharmacist initiating medicines. Issues raised: trust, governance and knowledge of older people’s medicine | 86 |

| 1 | Independent prescribers | 2019 | Inch | The Care Home Independent Prescribing Pharmacist Study (CHIPPS) – a non-randomised feasibility study of independent pharmacist prescribing in care homes | Pilot and Feasibility Studies | Non-randomised feasibility study | A total of 44 general practices and 16 pharmacists were recruited and were retained. Forty residents were recruited and were retained. Outcomes selected were number of falls, Drug Burden Index score, hospitalisations, mortality, activities of daily living and quality of life. The service was well received by care homes and GPs | 87 |

| 2 | Difficult Conversations | 2018 | Brighton | ‘Difficult Conversations’: evaluation of multiprofessional training | BMJ Supportive & Palliative Care | Evaluation | A total of 655 participants, including GPs, nurses, social care staff, allied health professionals and care home staff. All groups showed increased self-confidence, knowledge and skills. They appreciated interprofessional learning | 60 |

| 2 | GSF-CH | 2009 | Badger | An evaluation of the implementation of a programme to improve end-of-life care in nursing homes | Palliative Medicine | Evaluation | Significant improvements in end-of-life care, increase in proportion of residents who had an ACP and increase in proportion of residents who died in the care home. Crisis admissions to hospital were reduced | 88 |

| 2 | GSF-CH | 2011 | Hall | Implementing a quality improvement programme in palliative care in care homes: a qualitative study | BMC Geriatrics | Qualitative study of QI |

Benefits included improved symptom control, team communication, external support (including GP), staff confidence, residents’ choice, reputation of home Barriers included increased paperwork, lack of knowledge, costs, problems with lack of co-operation of GPs |

89 |

| 2 | GSF-CH | 2012 | Badger | An evaluation of the impact of the Gold Standards Framework on collaboration in end-of-life care in nursing homes. A qualitative and quantitative evaluation | International Journal of Nursing Studies | Qualitative and quantitative evaluation | Challenges to collaboration: working with many GPs and poor access to out-of-hours and specialist services. Improved collaboration was identified by 33% of managers. Staff reported increased knowledge and confidence, and discussing care with GP and palliative specialists | 61 |

| 2 | GSF-CH | 2014 | Kinley | The provision of care for residents dying in U.K. nursing care homes | Age & Ageing | Review of deceased care records | Dependency of residents increased, with 56% dying within 1 year of admission. Within the last 6 months of life, support from health-care specialists was variable | 90 |

| 1 | CMHT | 2018 | Stewart | Provision and perceived quality of mental health services for older care home residents in England: a national survey | International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry | Survey | Only 18% of CMHTs for older people allocated staff for care homes and services varied. Forty per cent of teams provided training to care homes staff. Service manager was likely to report their service as good if the service had a systematic process for reviewing mental health and antipsychotic prescriptions, including contact with a GP | 91 |

| NA | Nutrition review | 2014 | Madigan | A cluster randomised controlled trial of a nutrition education intervention in the community | Journal of Human Nutrition & Dietetics | Cluster randomised controlled trial | GPs and nurses who attended an educational intervention about supporting patients following discharge from hospital showed greater knowledge than the control, although this was not sustained at 6 months | 92 |

| NA | Stroke | 2017 | Sadler | Shaping innovations in long-term care for stroke survivors with multimorbidity through stakeholder engagement | PLOS ONE | Qualitative study | Thirty-seven participants, including GPs, selected the following purposes as priorities for data improvement: continuity of care, mental health, access to health and social care, and multiple risk factors. From this consultation, a decision support tool was co-designed | 93 |

| NA | Quality and Outcomes Framework | 2011 | Shah | Quality of chronic disease care for older people in care homes and the community in a primary care pay for performance system: retrospective study | British Medical Journal | Quantitative retrospective | Quality indicators of chronic disease care were lower for residents of care homes than for the community over 14 out of 16 indicators (after adjustment). Residents of care homes were more likely to be excluded by GPs from targets within the Quality and Outcomes Framework | 94 |

| NA | Fracture prevention | 2008 | Cox | Educating nursing home staff on fracture prevention: a cluster randomised trial | Age & Ageing | Cluster randomised trial | There were no differences between the intervention and control in primary outcomes, incidence of total fractures or total hip fractures. No differences were found for falls or hip protector use. An increase in prescription of bisphosphonate, calcium and vitamin D was observed in the intervention group | 95 |

These articles and grey literature are arranged according to the programme theory for which they provide evidence. Four articles did not provide in-depth description of the role of the GP and were not consistent with either programme theories 1 or 2 and are, therefore, noted as not assigned.

Steps 3 and 4: extracting and organising data, synthesising evidence and drawing conclusions

Owing to the iterative and cyclical nature of steps 3 and 4, as outlined in Figure 1, we have presented these steps together. Across the 30 articles found and included in the review, there was often only superficial or passing mention of GP involvement in improvement. From these 30 articles, we were able to piece together two main programme theories: one relating to negotiated working with GPs around local improvement initiatives and one outlining the role of GPs in a national improvement programme. Table 3 lists the main articles used to develop the programme theories. In addition, Table 3 lists articles that did not contribute to theory development and provides the reason for exclusion.

| Programme theory | CMO | Main study used | Articles limited in relevance or rigour | Rationale for exclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Programme theory 1: negotiated working with GPs on local improvement initiatives | CMO 1: pharmacist-led medication review | CMR,83 CHIPPS85,87 | Data for quality72 | Rigour: commentary without empirical evidence |

| RCT: pharmaceutical care71 | Relevance: limited involvement of GP | |||

| Shine84 | Pharmacist independent prescribers86 | Richness: limited description of change | ||

| Evaluation of Vanguard69 | Relevance: described future improvements | |||

| CMO 2: de-prescribing, working with care home staff | WHELD77 | Evaluation of national policy70 | Relevance: no description of change | |

| Medication review by GP74 | Richness: limited description of change | |||

| CMO 3: collaborating for end-of-life care | EVIDEM-EoL67 | Quality indicators for end-of-life care66 | Relevance: could not engage GPs in improvement | |

| Implementing new care model 65 | Relevance: unable to attribute change to care home | |||

| Programme theory 2: role of GPs in supporting national improvement programmes | CMO 4: GP-led end-of-life care | GSF-CH61,89,96 | Critique of GSF-CH study97 | Rigour: opinion piece |

| Response to critique98 | Rigour: opinion piece | |||

| Difficult Conversations60 |

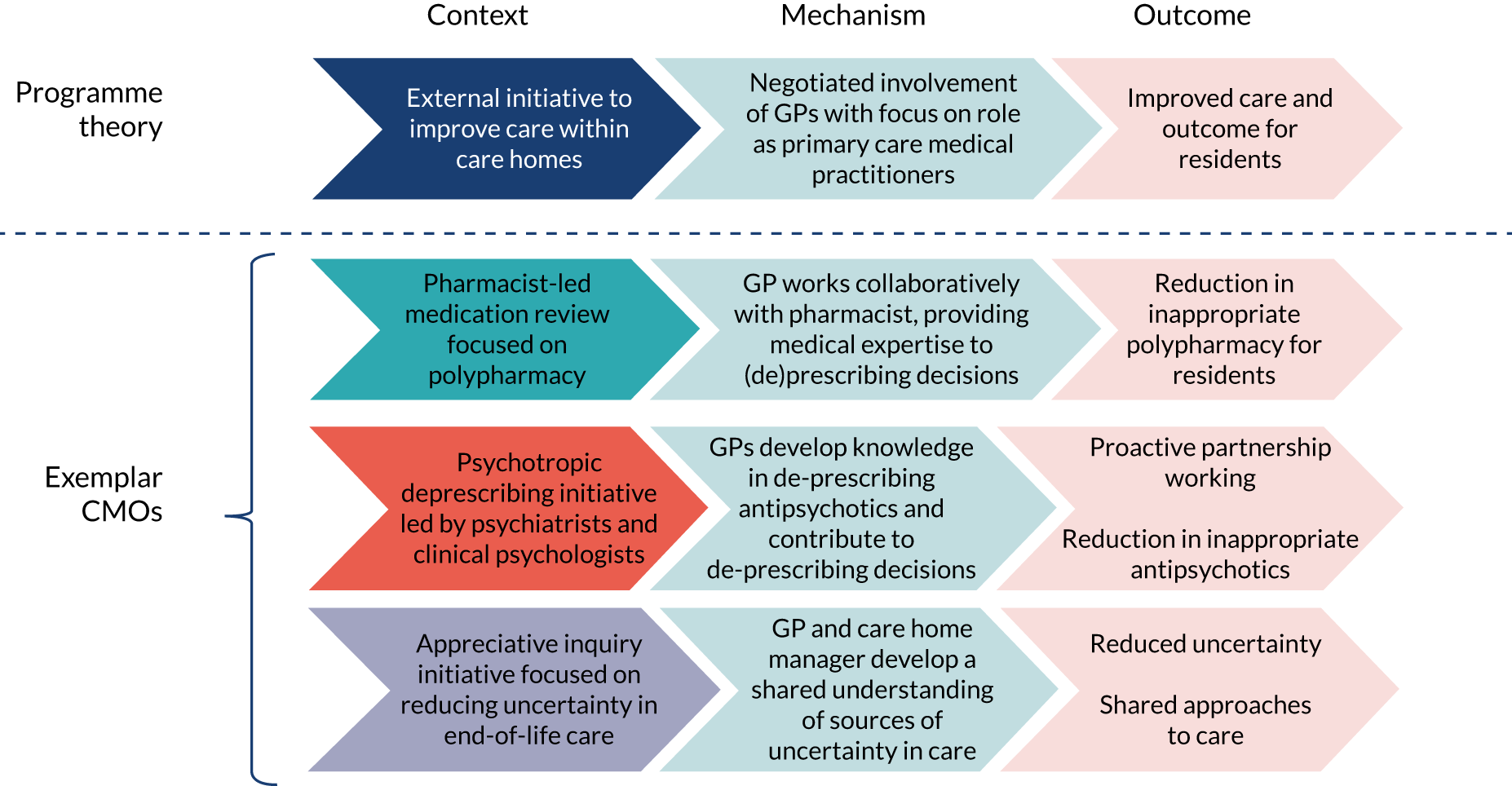

Programme theory 1: negotiated working with general practitioners around local improvement initiatives

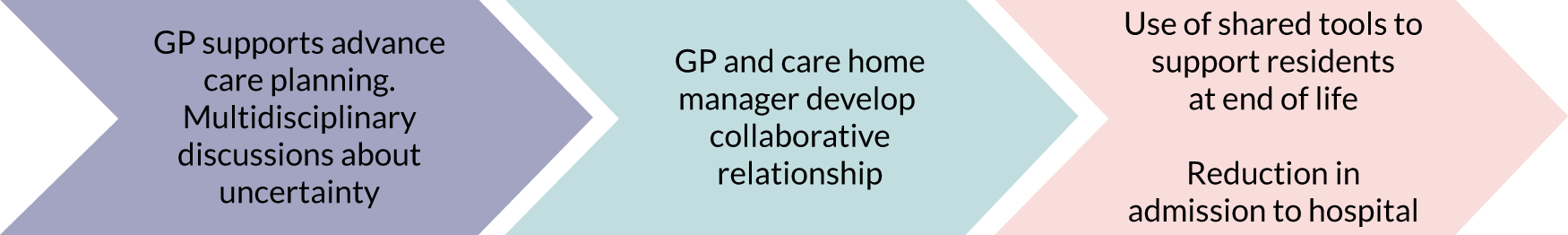

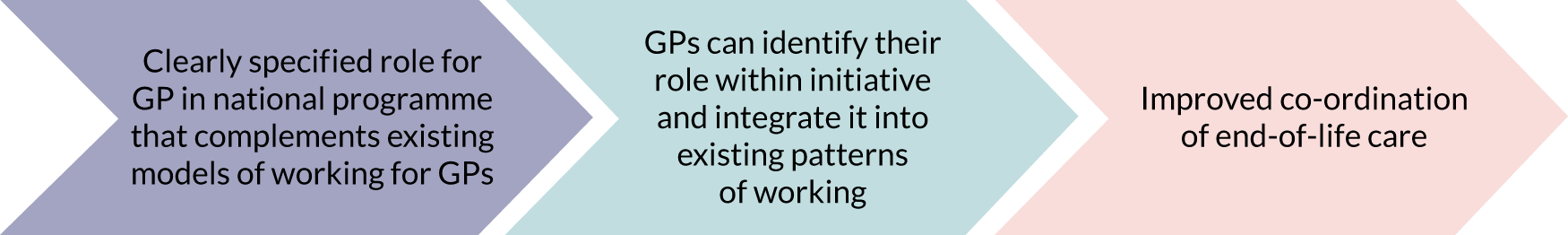

We found only a small number of articles about local or regional improvement initiatives that were primarily led by GPs. We found no articles describing how GPs became involved in initiatives, what role they played, what resources were involved or how projects could be sustained or replicated. We did, however, find evidence of initiatives that were led by other professionals where GPs formed part of the mechanism by which outcomes were realised. These are summarised in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Programme theory 1: negotiated involvement of GPs in local improvement initiatives.

In each of the examples found, an initiative that commenced outside general practice was deliverable only through the direct involvement of GPs. To each initiative, GPs brought technical medical expertise, their understanding and an overview of how health-care delivery in the community operates. In addition, GPs also provided a legitimising function by virtue of their role as the doctor, with overall responsibility for co-ordinating patient care in the community. Their role within the improvement initiative had to be negotiated and worked out. The professionals, or external practitioners, had neither the expertise nor authority to specify the role that GPs should play within the improvement programme and this had to be worked out in conjunction with GPs, alongside their competing responsibilities outside the care home setting.

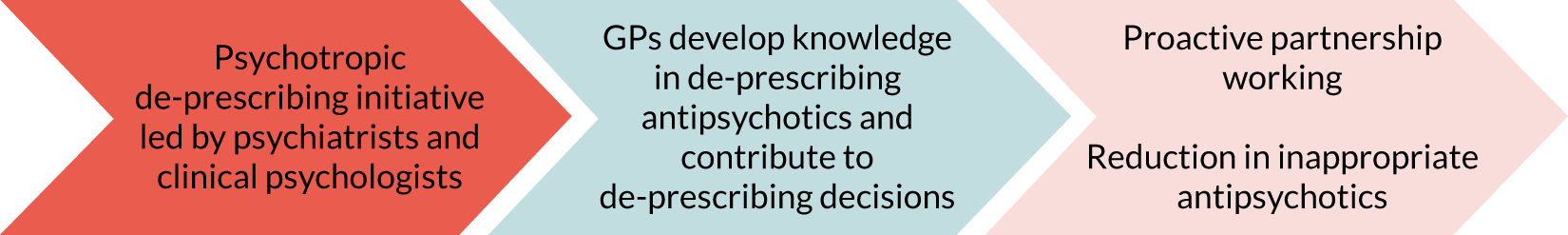

We present here three exemplar CMOs where similar principles played out. These relate to:

-

pharmacist-led medication review (CMO 1)

-

psychotropic de-prescribing led by psychiatrists and clinical psychologists (CMO 2)

-

teamwork focused on reducing uncertainty in end-of-life care (CMO 3).

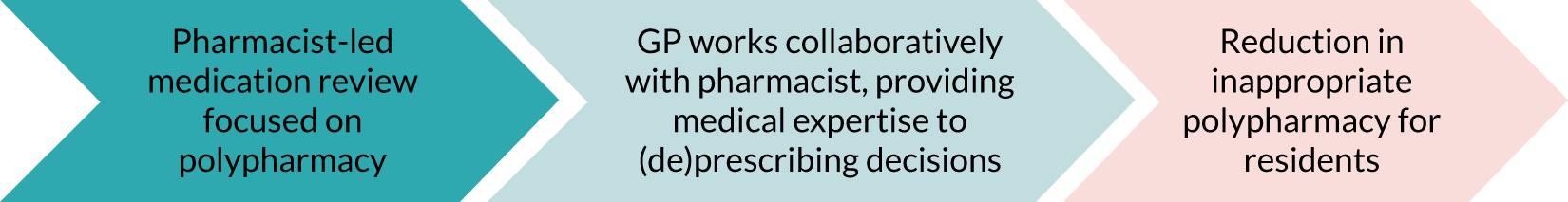

Exemplar CMO 1: pharmacist-led medication reviews

The schematic outlining this CMO is provided in Figure 4 and details of supporting evidence for each component is provided in Table 4.

FIGURE 4.

Schematic of exemplar CMO 1: pharmacist-led medication review.

| Context | Mechanism | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Medication review is challenging and complex (interview #16)84 | Trusted relationship between GP and pharmacist develops within framework of consultations (interview #19)84,85,87 | Reduction in inappropriate polypharmacy, reduced costs, reduced falls and reduced hospitalisation84,85 |

| Multidisciplinary meetings with a focus, including prescribing9,84 | Negotiated adaptation of implementation to take account of diverse ways of working, enabling GP to engage in a way that is consistent with their working practice81,84 |

Where GP attended a MDT there were greater numbers of prescription changes per resident84 Resident input into meetings78 |

| GP fear of adverse events and responsibility for these81 | GP authorises the process, but does not contribute to individual resident reviews81,85 | Fewer medication changes may be implemented |

Table 4 identifies key references or quotations from interview transcripts and greater detail of analysis is given in Appendix 5. Qualitative analysis software (NVivo 12) was used to create codes that detailed aspects of context across all sources of evidence for pharmacist-led medication review. This coding is summarised in Table 4, column 1. In a similar way, mechanisms were coded and summarised in Table 4 to match the context described in those sources. Finally, where outcomes were measured or observed, these were also extracted (see Appendix 5), summarised and aligned with the contexts and mechanisms (see Table 4). Some sources indicated a lack of outcome (see Table 4, bottom row) and for these problems or deficiencies in the context were identified that explain the lack of firing of mechanisms (see Appendix 5). Our interpretation of a synthesis of CMO across multiple evidence sources is represented in the schematic (see Figure 4).

The medication review projects, which have been described in several programmes82,87 in England, introduce an intervention that modifies the context. The intervention involves new personnel to supplement the GP input (e.g. a pharmacist-independent prescriber) and the additional process of collecting information about the individual. 85 The latter includes extracting information from the GP records, as well as care home records (e.g. to identify any falls). This provisional step requires GP approval. 86