Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 16/01/17. The contractual start date was in September 2017. The final report began editorial review in February 2021 and was accepted for publication in June 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2021 Fisher et al. This work was produced by Fisher et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Fisher et al.

Chapter 1 Background and introduction

Parts of this chapter have been adapted with permission from Fisher et al. 1,2 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

The NHS landscape

Stroke has a devastating and lasting impact on people’s lives and on the nation’s health and economy. Stroke is one of the top four causes of death and one of the largest causes of adult disability. 3 Recovery can continue for many years after an individual has a stroke; therefore, it is important that consideration is given to how to provide stroke rehabilitation services. The NHS Long Term Plan4 recommends increased investment in community health-care services. The provision of rehabilitation for stroke survivors following hospital discharge has also been highlighted as a national priority.

In England, the National Clinical Guidelines from the Royal College of Physicians5 and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence6 recommend the provision of early supported discharge (ESD) as part of an evidence-based stroke care pathway. ESD is a multidisciplinary team (MDT) intervention that facilitates discharge from hospital and the delivery of stroke-specialist rehabilitation at home and at an intensity equivalent to that provided in an acute stroke unit. There is currently widespread implementation of stroke ESD services in the UK. However, despite research and policy drivers, national audit reports showed that the type of ESD services that stroke patients receive is variable and, in some regions, ESD is still not offered at all. 7 Alternative models of operation have been adopted, but it is not known how close they are to the evidence-based models that have demonstrated effectiveness in clinical trial settings. It remains unclear whether or not health and cost benefits of the ESD intervention are achieved when services are implemented in practice.

This report presents findings from a multimethod study investigating what, why and how ESD services are implemented and operate in real-world settings. The study responds to the second translation gap between clinical trials and clinical practice, with the view to facilitate further implementation of ESD nationally and internationally. We drew on realist evaluation (RE) principles to unpick the interplay between ESD services and the context within which they operate, and to determine whether or not and how they are effective and in what conditions. 8

Existing evidence

There is strong research evidence to show that the provision of stroke-specialist rehabilitation enhances recovery. 9,10 Service delivery models that offer home-based stroke rehabilitation have gained increasing interest, particularly as health-care services face the challenges of cost reduction and integrated care provision. 4,11 Cumulative evidence from clinical trials has shown that ESD can reduce the length of hospital stay and the risk of dependency of stroke survivors. 10

Our research to date, together with national clinical guidelines, has defined core evidence-based components of ESD,12,13 essential characteristics that theory suggests need to be implemented for the intervention to remain effective in practice. These include that ESD should be delivered by a stroke-specialist MDT, and consist of co-ordinated discharge from hospital and rehabilitation provided to eligible patients in their own home. 5,6,12–14 Findings so far have informed the successful implementation of a number of evidence-based ESD services in areas across the East Midlands. 12 What remains to be investigated is the impact of ESD in other geographical areas, given that these areas may differ in the ways that may influence how ESD operates.

In most other high-income countries, ESD has not been well developed in practice, resulting in some locally established services but a lack of large-scale implementation. 15 In many countries it is unclear what provision of rehabilitation there is for stroke survivors beyond the hospital setting, with the majority of national audits or registries focusing on acute stroke care. 16 There are also unanswered questions relating to the implementation of ESD in rural settings, with the original clinical trials mainly conducted in urban sites. 10,13 It has been reported that the role of ESD services in more dispersed rural communities has not really been adequately addressed. 17

In England, with outcome-based commissioning being a priority in the NHS, it is important to investigate whether or not ESD services are still effective in real-life clinical settings. Distinguishing between effective and ineffective implementation is crucial to addressing inequities in service provision and plan service improvements. 18 It is also vital with regard to informing the implementation of sustainable evidence-based service models.

Study aims

-

To investigate the effectiveness of ESD services when implemented at scale, in practice.

-

To understand how the context within which they operate influences the implementation and effectiveness of ESD schemes.

-

To identify transferable lessons to drive effective implementation of stroke ESD in clinical practice.

Research questions

-

What adopted models of ESD exist and how do these relate to evidence-based recommendations?

-

Can realised benefits of implementing ESD be quantified by defined measures of effectiveness: reduction in length of hospital stay, responsiveness of the service, amount of rehabilitation delivered and changes in patient dependency?

-

What site, model and patient-level characteristics influence the effectiveness of ESD services?

-

What are the cost consequences of adopted ESD models?

-

What contextual elements influence whether or not ESD is implemented in the first place and how do they shape the model of the service adopted?

-

What are the perceived outcomes of implementing ESD from the perspective of service users, clinicians, managers and commissioners, and how are these achieved in practice?

-

What are the conditions that contribute to the successful implementation and sustainability of ESD in practice?

Theoretical implications

Large-scale implementation of ESD needs to be considered in the light of the complexity inherent in the delivery of this type of intervention. ESD is a multidisciplinary and multicomponent health-care intervention that involves a critical mass of stakeholders working across different organisation settings along the stroke care pathway. It is acknowledged that successful community-based care requires not only a shift in budget investment from acute to community services but also dissolving traditional occupation and organisational boundaries. 4,19

Early supported discharge services do not operate in the controlled environments of experimental settings but in a complex and multilevel system, such as the NHS. They are, therefore, exposed to a range of contextual influences at different levels of the health-care system that act synergistically or antagonistically to evidence-based implementation. Decoding the observed variability requires distinguishing between receptive and non-receptive contexts, as well as understanding the interplay between these environments and the programme’s ‘active ingredients’. 14 This process of inquiry permits a better understanding of why the programme works in certain settings and not in others, what mechanisms underlie the programme’s success and what steps we need to make to achieve the desired outcomes. Findings can then inform future implementation, reconfiguration and improvement of ESD services to facilitate provision of evidence-based stroke care.

Implications for the NHS

This research was designed to benefit patients affected by stroke by investigating the effectiveness of services that they experience and to identify ways to improve the provision of care. The research focuses on provision of care at a particularly distressing time: when stroke survivors leave the hospital and face the consequences of stroke back at home. By investigating models of community service in practice and identifying the consequences of adopting different ESD models in variable contexts, we hope to provide clear guidance to commissioners with regard to the outcomes and impact of their decision-making, and, hence, to influence the commissioning of stroke services and address inequity in service provision.

Patient and public involvement

The Nottingham Stroke Partnership group is a group of stroke survivors and caregivers who meet bimonthly to provide a patient and public perspective to stroke research at the University of Nottingham (Nottingham, UK). This group is co-chaired by stroke survivors and Dr Rebecca J Fisher. This group have provided guidance and support throughout this study. Their concerns about inequitable access to stroke care in the community, particularly in rural areas, informed the study protocol. Trevor Gard and Frances Cameron have been members of our steering group, offering guidance on interpretation of findings, approaches to patient interviews and lay summaries of our results. They advised us on our approach to sending a feedback package to our patient participants, in which we summarised our findings and offered our thanks.

Chapter 2 Study design and methods

Overview of the study

Work package 1: how effective is early supported discharge when implemented at scale in practice?

This work package (WP) addresses research questions 1–3 (see Chapter 1, Research questions).

Work package 2: how do contextual factors influence the implementation and effectiveness of early supported discharge in practice?

This WP addresses research questions 4–7 (see Chapter 1, Research questions).

Methodology

Conceptual framework

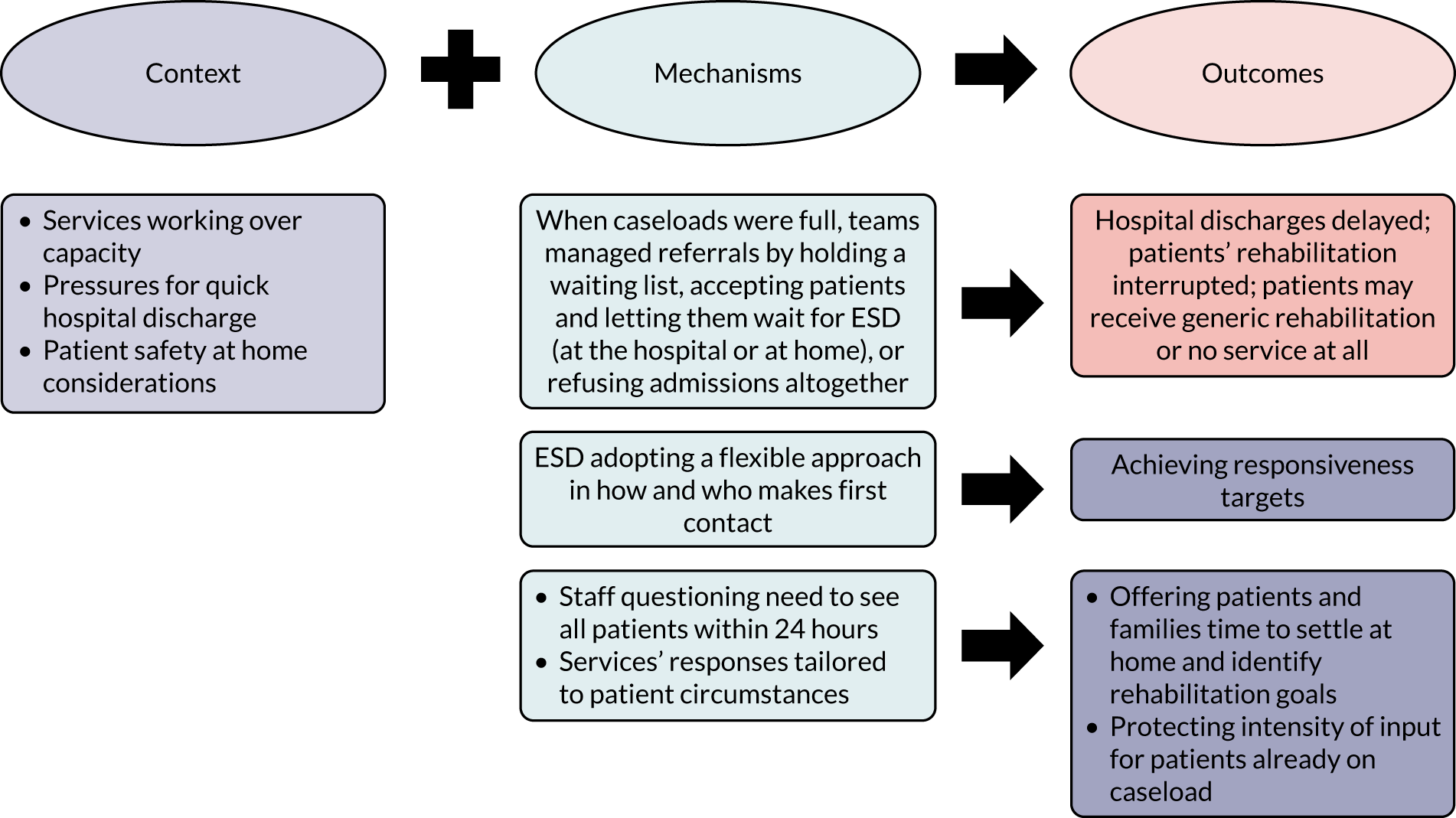

To address our research questions, we drew on a RE approach. 8 RE is a theory-driven research evaluation that attempts to unpack the black box between complex health-care programmes and the generated outcomes (i.e. it attempts to explain the processes through which complex health-care programmes generate outcomes). Health-care programmes are perceived to be the manifestation of explicit or implicit theories that embody the developers’ and implementers’ assumptions about how the programme works. 8,20

The evaluation starts by eliciting these key theories and mapping them into context–mechanisms–outcome (CMO) configurations. CMO configurations are essentially hypotheses that explain what works, for whom, under what circumstances and how. In the process of data collection, realist hypotheses are put to the test, revised and refined, leading to a better understanding of how programmes achieve their outcomes and in what settings. 21 We started our inquiry, as advocated by the evidence base and RAMESES standards, by surfacing the core ‘formal programme theory’ about how ESD schemes work. 8,20–22 Our previous research and national clinical guidelines have shed light on the ‘active ingredients’ that make an ESD service effective by defining evidence-based core components; these are the proposed essential characteristics that theory suggests need to be implemented for the programme to work in clinical practice. 12,13

Formulated as a CMO proposition, this evidence suggests that in urban settings (context), the provision of timely hospital discharge and intensive home rehabilitation (mechanism) by co-ordinated, stroke specialist multidisciplinary ESD teams (mechanism), reduces length of in-hospital stay and improves long-term functional outcomes (outcomes).

Articulated in RE terms, it becomes apparent that the formal theory only partially explains how and in what contexts the programme works. In addition to patient-level factors (i.e. stroke severity), previous research suggests that contextual elements operating at the levels of the team and the organisation, as well as features of location, need to be considered as part of an investigation of ESD services. 12,13,23 This fits well with current implementation research frameworks that highlight the importance of considering the characteristics of context at the meso- and macro-levels. 14,24

Given that ESD is delivered to patients in their own home, thus necessitating the delivery of rehabilitation over potentially large geographical areas, the influence of the geographical location within which the service operates also needs to be understood. The question of how ESD schemes might operate in rural settings has been raised, given that most of the original trials were conducted in urban settings. What needs to be stressed, however, is that the mere description of context does not explain why a different context generates different outcomes. 25 Examining the interaction between contexts and programme mechanisms is also required to understand how the conditions within which the programme works to activate and shape these mechanisms.

Regarding the underlying mechanisms, formal theory implies a causal relationship between the core components of the intervention and its outcomes. 14 We tested this with quantitative analyses in WP1. However, according to the realist understanding of causation, interventions cannot directly cause outcomes, but they provide (or take away) resources. 21 Programme mechanisms are understood to be an interaction between the opportunities offered by the interventions and the stakeholders’ reasoning and responses to these resources. Realists’ definition of mechanisms highlights the importance of human reasoning and interpretation as vital to understanding how an intervention works. 20 Evidence suggests that the behaviour of individual ESD team members, particularly across organisational boundaries, might influence the adoption and delivery of ESD services. 23 This also resonates with current implementation theory, which acknowledges the importance of actors involved in implementation, as well as the context in which they are operating. 24 To fulfil the study’s aim, the formal theory needs to be refined and preliminary realist hypotheses developed, codified into CMO conjectures, and tested through data collection.

We drew on the work of Dalkin et al. ,26 who suggested that explicitly disaggregating mechanisms into resources and responses highlights the difference between the intervention and the generative mechanisms, and facilitates the formulation of CMO configurations. We conceptualised the evidence-based core components of ESD services as the programme resources and we sought to surface the perspectives and behaviours of actors and stakeholders (staff and patients) who are making ESD happen on the ground. As intended outcomes, we used the process and patient outcomes examined by clinical trials and the national stroke audit, but we also allowed for exploration of unintended outcomes, mainly through the qualitative component of the study.

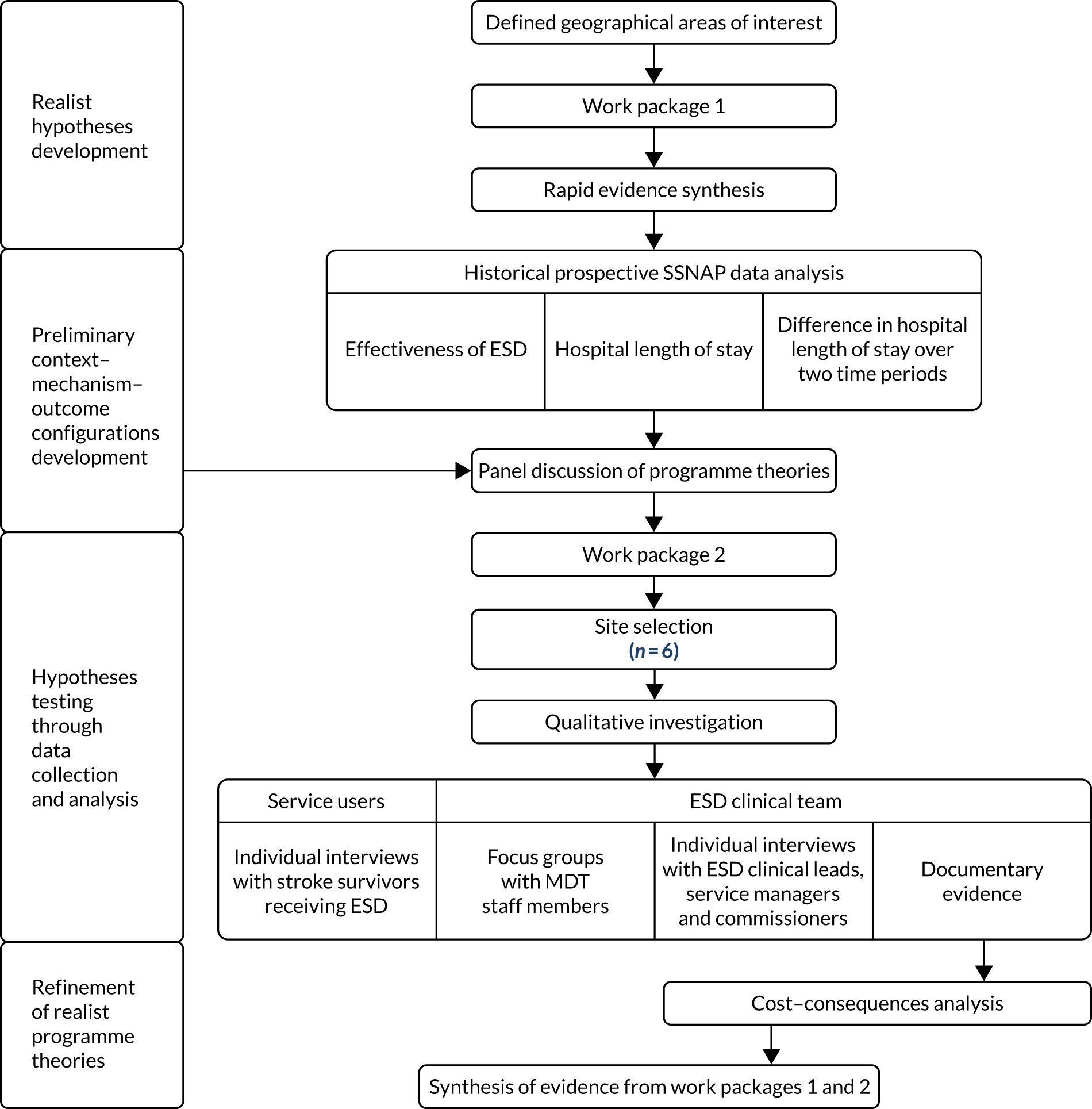

Study design

We adopted a mixed-methods design to draw information from multiple complementary sources. Our previous research and quantitative data analysis informed mainly the ‘Context’, ‘Mechanisms-resources’ and ‘Intended Outcomes’ and qualitative data used to elicit ‘Mechanisms-responses’ and ‘Unintended outcomes’. 12,13,23 The study was conducted in stages corresponding to two interlinking WPs undertaken sequentially (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart of the study, including WPs 1 and 2.

Work package 1 began with a literature review that aimed to identify key contextual determinants to the implementation of ESD services and elicit potential mechanisms. Quantitative analyses of historical prospective Sentinel Stroke National Audit Programme (SSNAP) data were then performed. The nature of the statistical modelling approaches used meant that context was explored in terms of defined and measurable variables, some of which were treated as ‘confounding’ (or ‘controlled for’) factors. We recognise that this is somewhat at odds with the philosophy of RE. However, the decision was made to use this quantitative analysis primarily to test the causal relationship between the core components of the intervention and the outcomes and, hence, findings were written up in line with recognised statistical convention.

These analyses did enable an investigation of the predictor variables of interest (as mechanisms-resources) in terms of our measure of adoption of evidence-based core components. By investigating the relationships between context, mechanisms-resources and outcomes as measurable ‘factors’, we were able to test our preliminary programme theories from a quantitative perspective. Findings informed the development of CMO hypotheses, which were tested through WP2.

Work package 2 generated insights from the perspectives of actors and stakeholders who make ESD happen in the real world, enabling mechanism-responses to be explored. An exploratory, multiple-case study design allowed ESD sites featured in WP1 to be investigated qualitatively, drawing information from individual interviews, focus groups and documentary evidence. A cost–consequences analysis (CCA) was performed to investigate the costs associated with ESD implementation, drawing information from interviews and documentary evidence. Finally, data from each WP were synthesised in relation to programme theories (with underpinning CMOs) that address the study’s questions.

Work package 1: how effective is early supported discharge when implemented at scale in practice?

Rapid evidence synthesis (see Chapter 3)

Given that context is a ‘slippery’ notion, identifying the salient contextual conditions relevant to the operation of ESD services was an important step with regard to developing and testing realist hypotheses. A rapid evidence synthesis (RES) was conducted to identify contextual features that have the potential to facilitate or impede the implementation of services providing home-based stroke rehabilitation. 27 RES is gaining popularity because it provides a robust and pragmatic approach to conducting a literature review to address specific questions. Key contextual determinants to the implementation of ESD services identified by the RES informed the development of CMO configurations to be tested through data collection and analysis.

Site selection

This study was designed to investigate the impact of different models of ESD operating over defined geographical regions of the East Midlands, West Midlands, East of England and North of England (clinical network boundaries). This allowed an investigation of the consequences of a Midlands and East initiative to implement ESD, which began in 2012,28 compared with a region (North of England) that has been slower to implement ESD based on SSNAP post-acute organisational audit data. 7 Sites in each of the four regions were defined according to Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) and local authority boundaries. All individual ESD teams in each site that participate in the SSNAP clinical audit were included.

Data collection and analysis

Work package 1 involved the analysis of historical prospectively collected SSNAP data from hospital and community providers across the East Midlands, West Midlands, East of England and North of England Strategic Clinical Networks. In line with our programme theories, a key aim of WP1 was to investigate whether or not the degree to which an ESD service had adopted an evidence-based model (mechanism-resources) was related to better outcomes. The influence of rurality of the ESD service location, as a key contextual factor of interest, was also investigated.

The effectiveness of ESD was measured with evidence-based metrics, as defined by national clinical guidelines for stroke and that reflect outcome measures used in the original ESD trials. 10 Outcomes of interest were process measures (ESD responsiveness and rehabilitation delivered) and patient dependency (modified Rankin Scale)29 and effects of ESD on length of hospital stay.

To conduct these analyses, we employed multilevel modelling. This is an appropriate technique for analysing outcome variables that are generated from a clustered/nested structure, whereby the outcome under consideration is produced by patients in different ESD team/hospital settings. Measuring the effects that ESD teams have on their patients was a necessary first step to learning how ESD practices combine to generate differences between teams. Combining SSNAP clinical audit data at the patient level with post-acute organisational audit data at the ESD team level, we measured the ‘true’ effects that ESD teams have on their patients. This was carried out by fitting two-level patients nested within teams multilevel models to patient and process outcomes, in which covariate adjustments were made for a range of patient and ESD team characteristics.

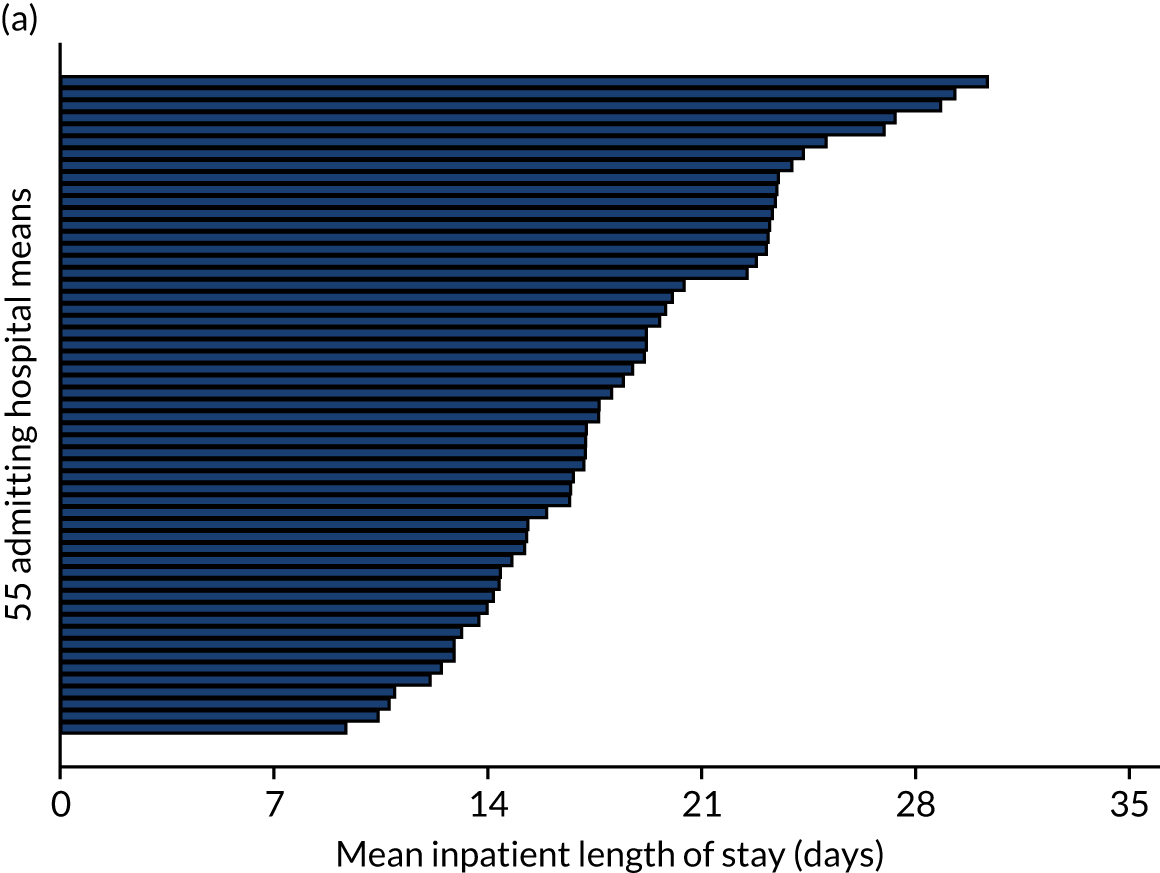

Evaluating the effectiveness of early supported discharge service provision (see Chapter 4)

To investigate our study hypotheses, information about each ESD service, collected by SSNAP in the 2015 post-acute organisational audit, was collated by the research team. ESD team models were then analysed by comparing ESD service information with ESD consensus statements and national clinical guideline recommendations. 5,6,13 An ESD consensus score was then applied to each ESD team. Multilevel modelling enabled us to appreciate the variation in outcomes as a mixture of patient variability nested within ESD service provision variability. This approach is displayed graphically in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Schematic representation of the WISE (What is the Impact of Stroke Early supported discharge?) study multilevel modelling approach. The triangle represents the fact that many patients are nested within fewer ESD/hospital units in a multilevel structure.

Additional ‘contextual’ variables at the patient level in the model, obtained from the 2016 SSNAP clinical data, included age at admission, sex, pre-stroke independence, comorbidities, National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS) score on admission, type of stroke and modified Rankin Scale score at discharge from hospital. 29,30 These reflect previously validated stroke case-mix models. 31,32 A key factor of interest at the ESD team level (in addition to the ESD consensus score) was the level of rurality. 33 Effectiveness of ESD service provision was measured with the following outcome variables: responsiveness (time from hospital discharge to first contact), rehabilitation intensity (total number of treatment days/total days with ESD) and stroke survivor outcome (modified Rankin Scale score after ESD delivered).

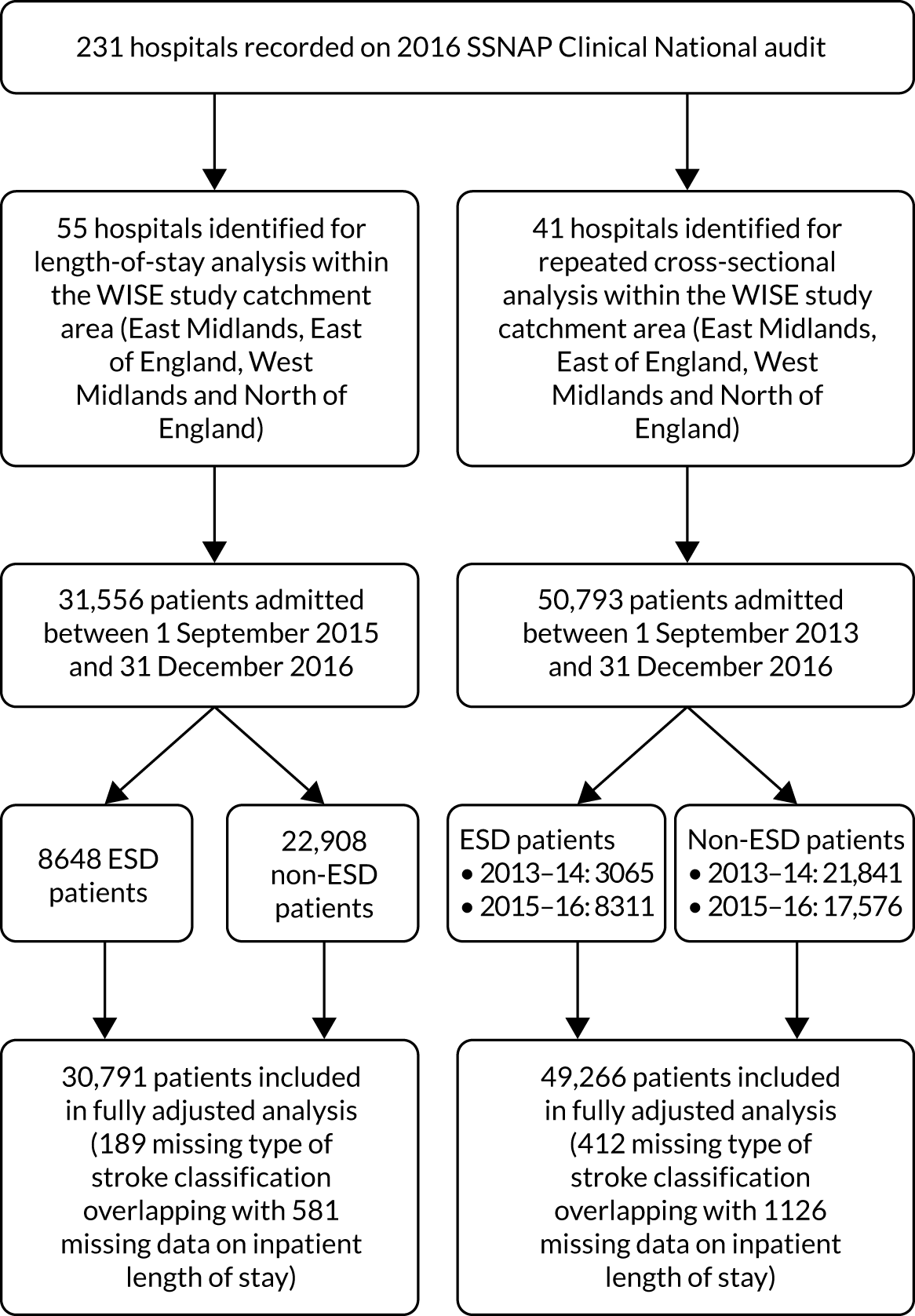

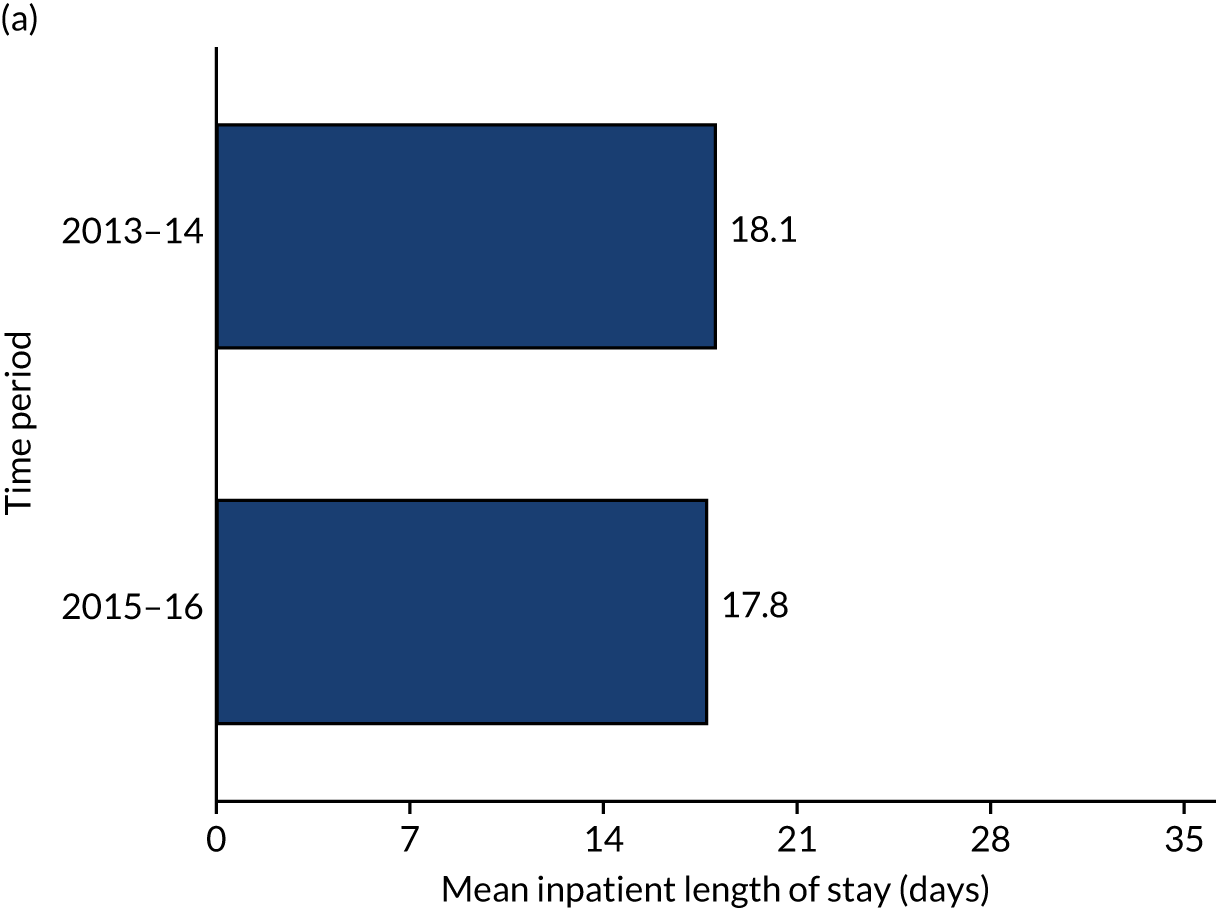

Early supported discharge impact on patient length of hospital stay (see Chapter 5)

A key benefit of ESD that was identified in the original randomised controlled trials was a reduction in the length of hospital stay. 10 Using our multilevel modelling framework and controlling for our covariates, this analysis examined how patient length of hospital stay was influenced by the presence or absence of an ESD service on their care pathway.

Independent of the ESD team data, 2015–16 hospital SSNAP data were analysed to determine if patients from admitting hospitals who had ESD available as part of their care pathway differ in their total length of inpatient stay from patients from admitting hospitals who do not have ESD available, while controlling for confounding variables (e.g. patient-level characteristics highlighted above). For this analysis, patients were nested within admitting hospitals rather than ESD teams and, hence, different data sets were used. The outcome variable for these analyses was hospital length of stay at the patient level. A repeated cross-sectional analysis using two sets of SSNAP data (2013–14 and 2015–16) was also used to establish whether or not the length of hospital stay changed over time and whether or not any change was attributable to ESD. The implementation of ESD was measured in terms of ESD being offered as part of the patients’ care pathway from their admitting hospital and across the two time periods.

Work package 2: how do contextual factors influence the implementation and effectiveness of early supported discharge in practice?

Site selection

Using a purposive sampling approach, case study sites from WP1 were selected based on the level to which evidence-based ESD had been implemented (contrasting ESD models) and the influence of rurality on ESD effectiveness (urban vs. rural sites). Table 1 displays the site characteristics that we focused on to select our six study sites.

| Site | ESD consensus score in 2015 | Staff in 2015 (n) | Total WTE staff in 2015 | New referrals in 2015 (n) | Rural population in 2011 (%) | Stroke patients from December 2017 to March 2018 (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aa | 7 | 20 | 5.1 | 214 | 0.08 | 27 |

| Ba | 14 | 14 | 6.7 | 125 | 4.53 | 42 |

| C | 11 | 26 | 22.1 | 558 | 33.88 | 92 |

| D | 12 | 14 | 12.4 | 209 | 49.95 | 71 |

| E | 12 | 27 | 23.9 | 424 | 66.16 | 95 |

| F | 10 | 42 | 41.4 | 639 | 70.90 | 194 |

Service descriptions (see Chapter 6)

To investigate the contextual factors that stakeholders may not readily articulate and to understand the operation costs of each service, we also gathered documentary evidence. This comprised service specifications, monthly and annual reports, meeting notes and paperwork used by the teams as part of their day-to-day operational activities. Costs were explored using forms that were developed to be completed by service managers. Other information to inform service descriptions was obtained from staff interviews (see Appendix 2).

Cost–consequences analysis (see Chapter 7)

Cost implications are likely to be an important consideration with regard to successful adoption and implementation of interventions, such as ESD. Economic evaluation methods for complex interventions, such as ESD, should ideally consider the wider costs and benefits associated with the intervention. It has been argued that generic outcomes, such as quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs), may not be suitable to capture these wider effects. 34 In addition, standard cost-effectiveness measures have poor recognition of the importance of context, lacking interest in links between causal mechanisms and relevant contexts that are thought to produce expected outcomes. Resources associated with the delivery of a complex intervention are likely to equate to different costs in different places. 35

Given these issues, a CCA was deployed. This form of analysis has been recommended for complex interventions that have multiple effects because it offers a more flexible approach to presenting costs and benefits alongside each other rather than combining these into a single measure. 34 This approach also fits with the realist approach of the study, in that costs associated with ESD-related mechanisms were considered in the light of the context in which they are operating and the outcomes or benefits that are achieved.

To obtain the cost data necessary for an analysis of this kind, contrasting ESD model types represented by the six teams selected for inclusion in WP2 were used. SSNAP post-acute organisational audit data were supplemented by more detailed information gathered from the teams directly (e.g. service specifications). The MDT composition and workload [whole-time equivalent (WTE)] information was used to calculate the associated NHS costs. Staff training budgets were considered (given the importance of stroke-specific expertise). Travel costs associated with the delivery of rehabilitation were estimated by defining the geographical area over which the ESD service operates, determining the average distances travelled and the number of patient visits made. Using patient caseload information, direct costs per patient were also calculated. Consequences were expressed as the total ESD consensus score obtained (out of 17). This measure (developed in WP1) was used as a consequence to indicate the level by which each service had adopted an evidence-based service model.

Staff and patient interviews (see Chapters 8 and 9)

Staff interviews

Semistructured, one-to-one interviews were conducted at each ESD site with up to eight NHS staff informants at the senior management, service lead and commissioning levels. Stakeholders (e.g. commissioners and ESD team leads) were identified through collaboration with the national audit team and stroke clinical leads operating in each region.

Semistructured interviews allowed us to explore the individual stakeholder perceptions on a one-to-one basis, using a topic guide and prompts informed by our programme theories. These ‘realist’ interviews were designed to expose individual stakeholder perspectives on the mechanisms involved in the implementation, delivery and effectiveness of ESD, and how these relate to contextual factors and desired outcomes.

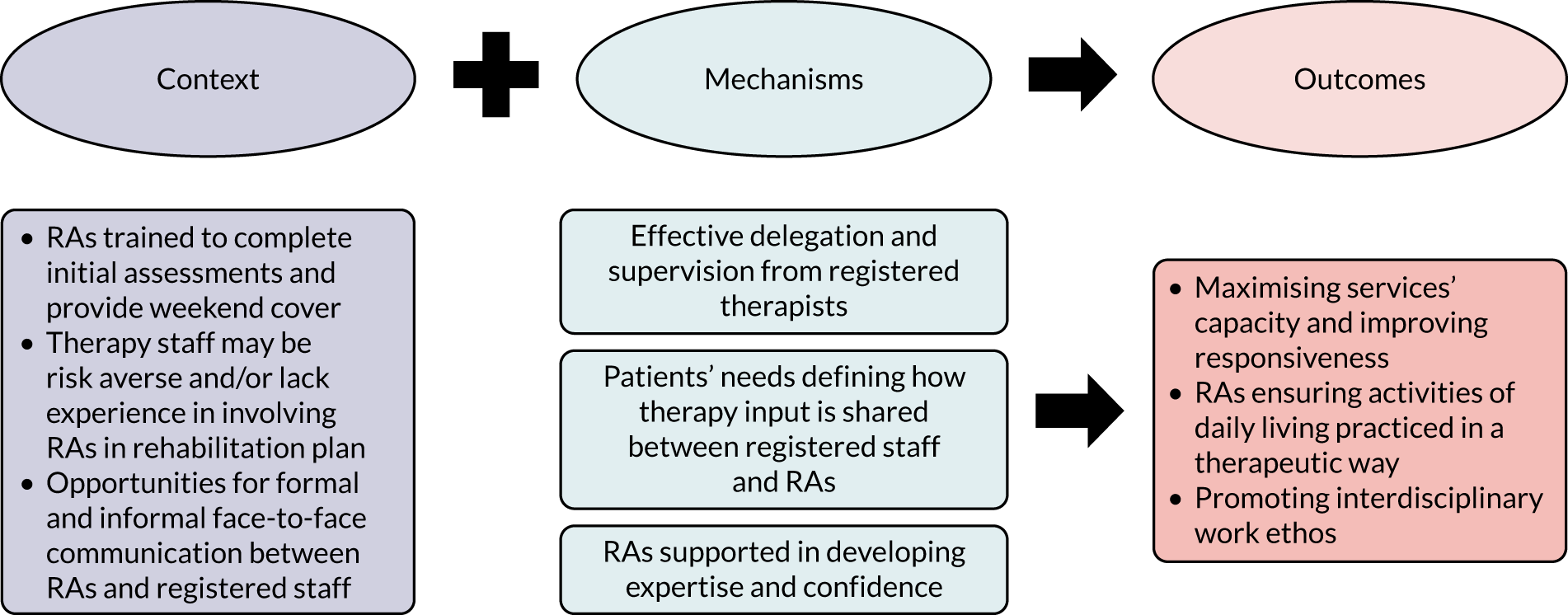

Early supported discharge team interviews

We also conducted two group interview sessions at each site. Two sessions ensured a representative sample of the ESD team [e.g. physician, nurses, therapists and rehabilitation assistants (RAs)]. The aim was to facilitate group discussion to uncover shared group perspectives on how and why the ESD service operated as a whole and how this related to performance and sustainability. Teams were given the opportunity to reflect on contextual conditions and processes that they perceived contributed to service effectiveness and to consider how this related to their environment and team make up. These were then discussed in relation to their perspectives on effectiveness and the outcomes that the service achieves.

Stroke survivor interviews

Interviews were also conducted with purposively selected ESD patients from each ESD site. Patients were recruited by the ESD teams in consultation with the research team, selecting patients currently on their caseload. Purposive sampling ensured that the sample included patients with a variety of experiences. Semistructured interviews focused on areas such as experience of rehabilitation at home, staff interaction and what aspects of ESD mattered most to patients. Interviews also explored what stroke survivors believed the purpose of ESD to be and how services could be improved and why. A realist interviewing approach did not prove feasible because patient interviews required a more informal conversational style.

Qualitative analysis

Staff interview data were analysed iteratively, following a retroductive approach. 21 Predefined programme theories and related CMO configurations were used as a framework to guide the analysis (deductive approach). However, as data collection and analysis progressed the framework was revised and refined to reflect the cumulation of new insights (inductive approach) (see Chapter 8 for further information on the analysis of staff interviews). Given that realist standards were not enforced, patient interview data were analysed using a thematic analysis approach. 36

Synthesis of findings from work packages 1 and 2 (see Chapter 10)

A synthesis of findings from WP1 and WP2 was conducted when data sets had been analysed separately. This allowed consideration of CMO configurations relating to outcomes perceived to be important by stakeholders on the ground and how this related to the implementation and effectiveness of ESD, as measured by the national audit. Findings were also considered in relation to existing implementation frameworks. 14,24

Ethics approval

Ethics approval for WP1 was obtained from the University of Nottingham (28 July 2017; ethics reference number 86-1707) because it involved the analysis of national stroke audit data. Governance approvals for data access were obtained by application to Healthcare Quality Improvement Partnership (HQIP) and a data-sharing agreement was signed between HQIP (data controller), the Royal College of Physicians (data provider) and the University of Nottingham (October 2017; application number HQIP 189). The study protocol, including the statistical analysis plan, is available online. 37 Ethics approval for WP2 was granted by the Nottingham 1 Research Ethics Committee (IRAS ID 243066; 18/EM/0160) and the Health Research Authority on 23 July 2018.

Chapter 3 Work package 1: programme theories and rapid evidence synthesis

This chapter presents the initial programme theories and how these were informed through conducting a RES before data collection and analysis. The three overarching programme theories were defined a priori from the proposal stage of this project informed by our previous research and national clinical and policy guidelines on ESD operation. 12–14,23,38 This chapter begins with a description of the content and origins of each programme theory.

Description of overarching programme theories

Programme theory 1

Our first programme theory hypothesised that the adoption of evidence-based ‘core components’ of ESD is important for the intervention to be effective in practice. 13 Our previous research12,13,23,38,39 and national clinical guidelines5,6 have shed light on the ‘active ingredients’ that make an ESD service effective by defining evidence-based core components; these are the proposed essential characteristics that theory suggests need to be implemented for the programme to work in clinical practice. 14 The core components include that ESD is delivered by stroke-specialist staff operating as a co-ordinated MDT [e.g. physician, physiotherapist, occupational therapist (OT), and speech and language therapist (SLT)]; that the ESD team has weekly MDT meetings and regular meetings with stroke unit hospital staff; and that an effective ESD intervention consists of co-ordinated, facilitated discharge from hospital and the provision of timely rehabilitation for eligible (mild to moderate) stroke patients at home. 13 We have previously shown that the adoption of these identified core components of ESD, by two services in urban areas of Nottinghamshire, led to a reduction in the length of hospital stay and accelerated patient recovery. 12

Framed in realist teams, the formal theory implied by the evidence base would suggest that in urban settings (context), the provision of timely hospital discharge and intensive home rehabilitation (mechanism) by co-ordinated, stroke specialist multidisciplinary ESD teams (mechanism), reduces length of in-hospital stay and improves long-term functional outcomes (outcomes). What this theory fails to consider, however, is how these components operate in contexts other than urban environments and how they are influenced by known and unknown contextual determinants. As with every complex intervention, a causal relationship between the intervention characteristics and the intervention outcomes cannot be assumed, but there is a need to understand the effect of human agency, the perspectives and behaviour of actors involved with the implementation of the intervention. Under a RE approach, we conceptualised the evidence-based core components of ESD services as the programme resources, and the stakeholders’ (staff and patients) reasoning and responses to these resources as the underlying mechanisms that interact with the context to produce intended and unintended outcomes. As intended outcomes, we used the process and patient outcomes examined by clinical trials and the national stroke audit (WP1) and we allowed for exploration of unintended outcomes, mainly through the qualitative component of the study (WP2).

Programme theory 2

Given that ESD is delivered to patients in their own home, thus necessitating the delivery of rehabilitation over potentially large geographical areas, the influence of the geographical location within which the service operates also needs to be understood. The second programme theory suggested that core components of ESD will operate differently in urban and rural settings. The question of how ESD might operate in rural settings has been raised given that the majority of randomised controlled trials were conducted in urban settings. 10 ESD services will typically deal with fewer patients dispersed over greater distances, which can have implications for how these services are resourced. 13 However, the delivery of ESD services in dispersed, rural communities has not yet been adequately assessed. 13

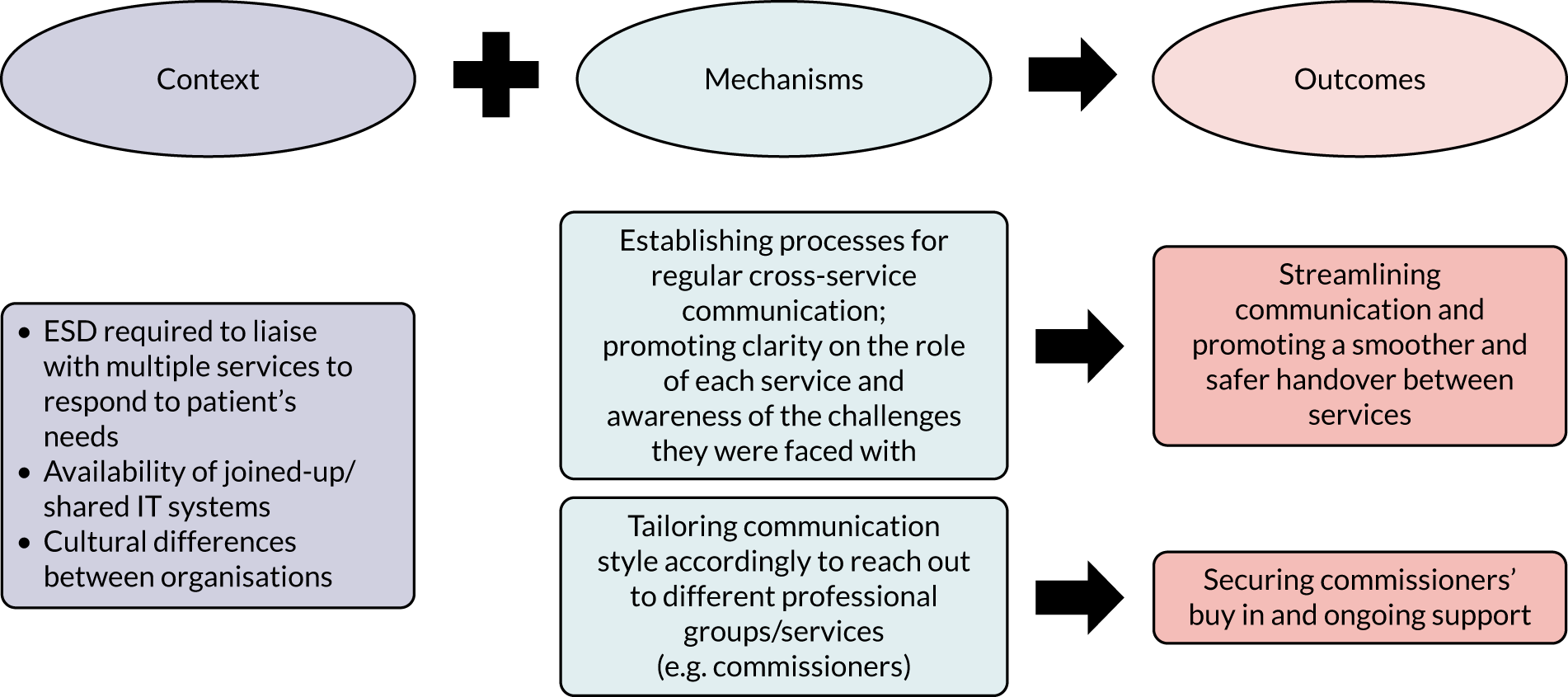

Programme theory 3

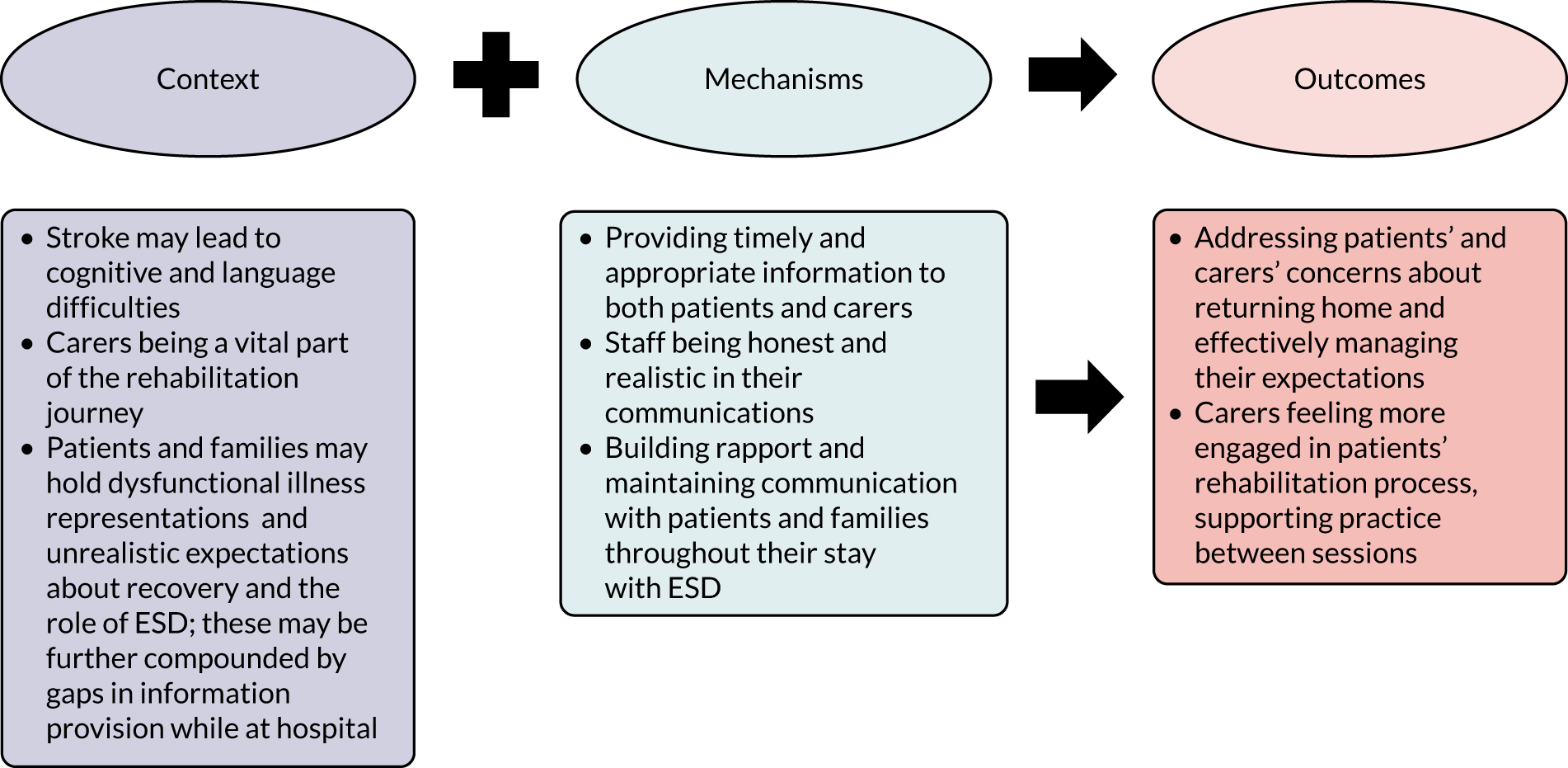

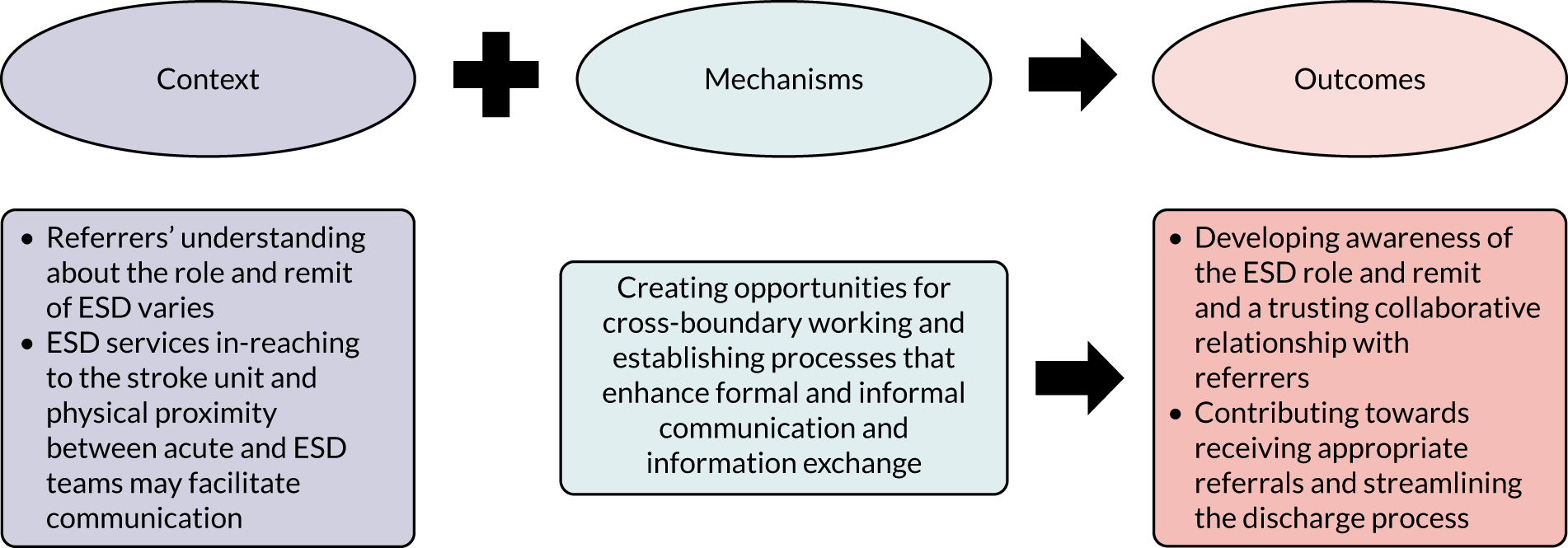

Our third programme theory suggested that the quality of the communication processes between key stakeholders and services in the pathway will influence the implementation of an evidence-based service. Evidence suggests that the behaviour of individual ESD team members, particularly across organisational boundaries, might influence the adoption and delivery of ESD services. 40 Our previous research12,13,23,38,39 has highlighted the need to consider the broader organisation and the value of strong links with other health-care and social care providers on the stroke care pathway. The importance of effective communication and liaison between inpatient services, ESD teams, community services and commissioners was identified as a key factor to successful outcomes for ESD. 13,23 Preliminary evidence suggests that effective cross-service communication might be promoted through processes such as staff rotations, boundary-spanning roles and data-sharing practices. 23 The role of ongoing communication and the provision of information to patients and carers has also been identified as important for providing a patient-centred rehabilitation, responsive to service users’ needs. 38

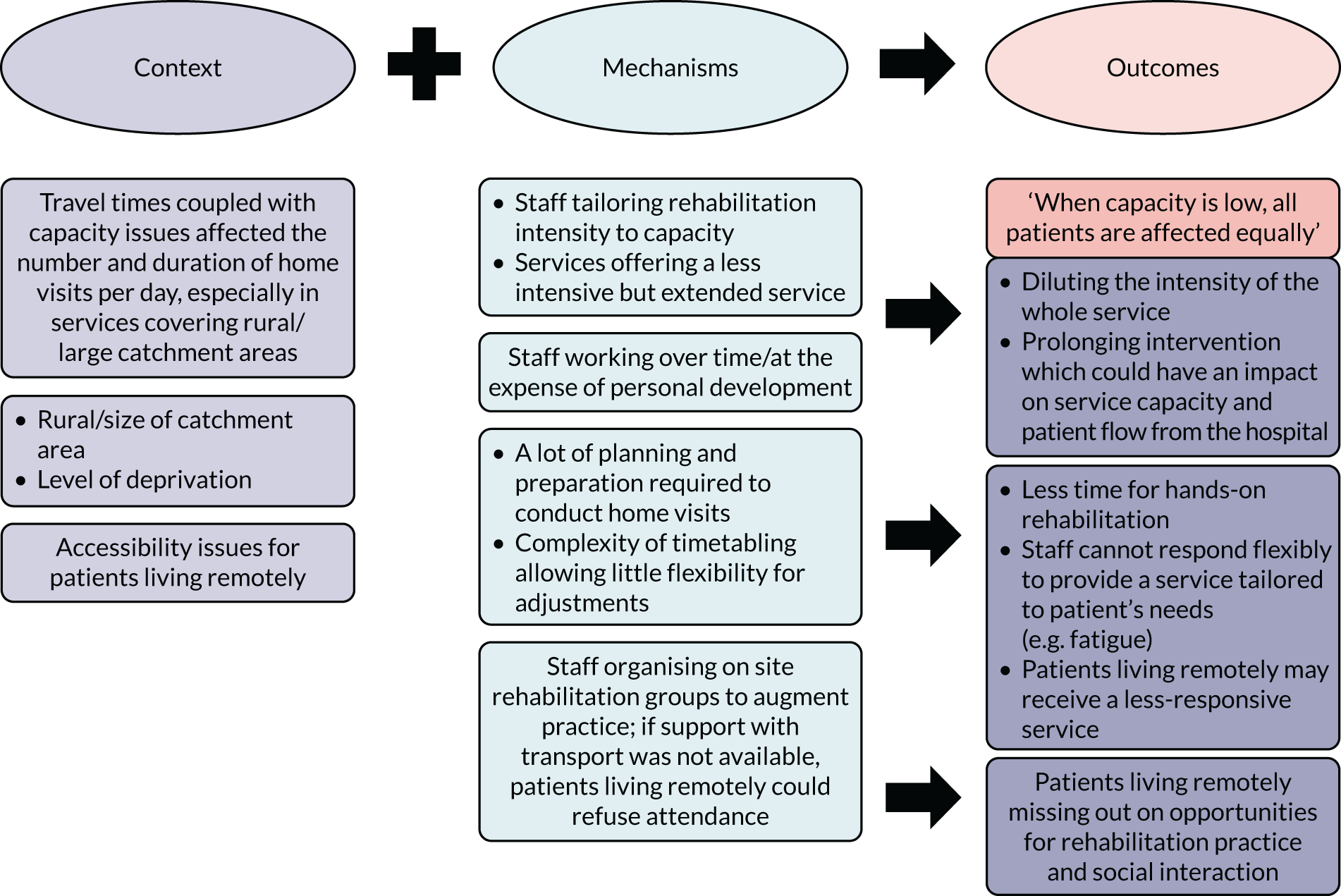

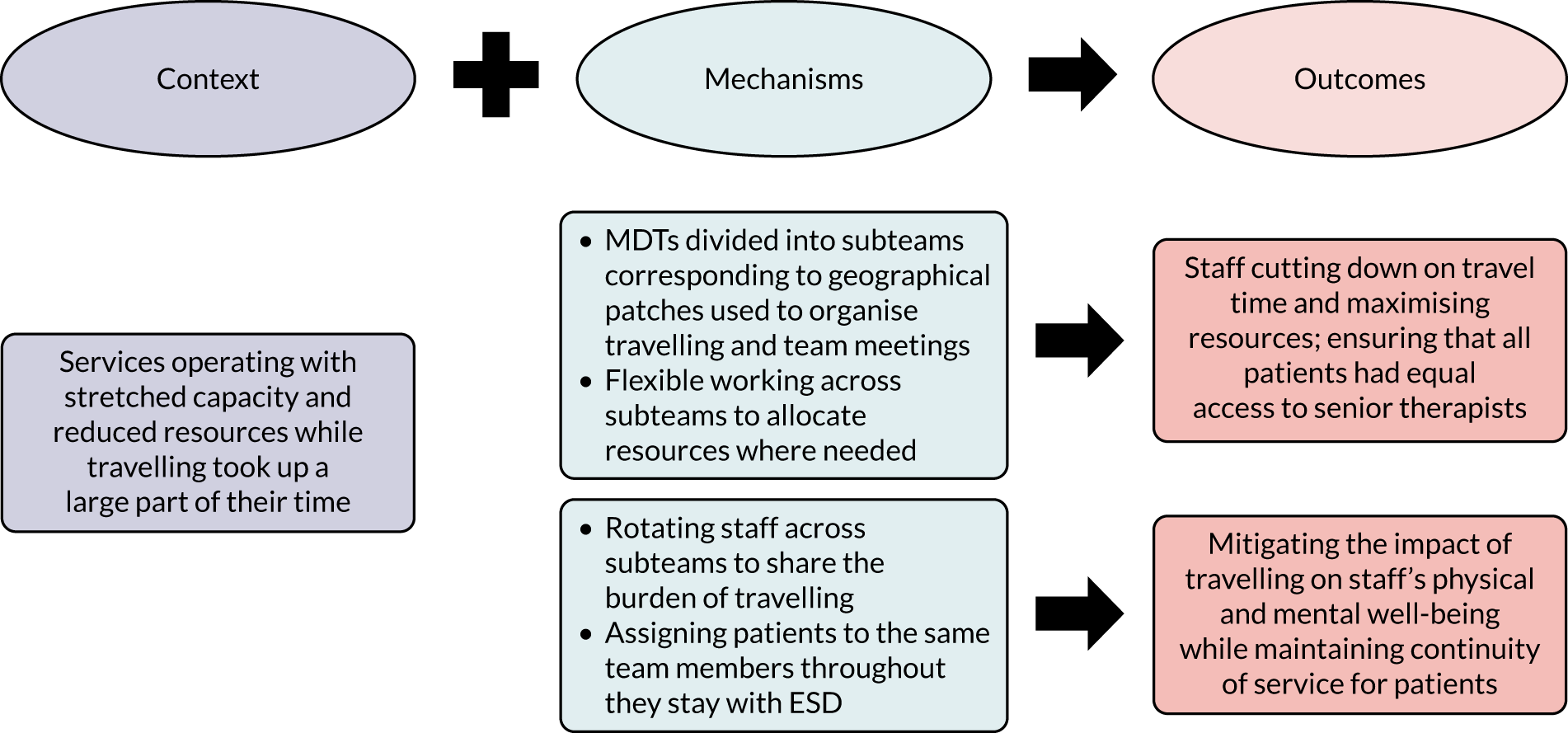

Table 2 depicts our conceptualisation of the interaction between contextual influences, evidence-based intervention components and staff and service users’ reasoning and responses, and how this interaction leads to intended and unintended outcomes. This framework underpins our three programme theories and it was used to guide the development of specific hypotheses in the form of CMO configurations to be tested through data collection and analysis. The table also presents an example of CMO development concerning the influence of rurality. More specifically, the CMO explores how the rurality of the location of the ESD service may lead to a facilitatory or countervailing interaction with mechanisms to generate intended or unintended outcomes.

| Context | Mechanisms | Outcomes | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resources | Responses | ||

| Capacity | Eligibility criteria | Accelerated transfer of care from hospital to home | |

| Geography | Team composition | ||

| Commissioning and financial arrangements | WTE | Staff perspectives/behaviour | Rehabilitation delivery: responsiveness |

| ESD provider organisation | Staff-to-patient ratio | Patient perspectives/behaviour | Rehabilitation delivery: intensity of rehabilitation |

| Stroke specialism and staff training | |||

| Referring services characteristics and locations | MDT co-ordination (e.g. meetings) | Patient outcomes: recovery | |

In conceptualising ‘context’, it became apparent that we needed to focus our exploration of contextual features linked to the delivery of ESD. Identifying the salient contextual conditions relevant to the operation of ESD services was a necessary first step towards the development of realist hypotheses. We conducted a RES41 to identify contextual determinants with the potential to facilitate or impede the implementation and routine delivery of services providing home-based stroke rehabilitation.

Rapid evidence synthesis

Aims and objectives

The synthesis aimed to identify evidence on barriers to and facilitators of influencing the delivery of home-based stroke rehabilitation. We were also interested in factors influencing the discharge process and the transition from hospital to home. We intended to use our findings to clarify key determinants that we needed to consider in our exploration of context and to inform the development of specific CMO hypotheses to be tested through data collection and analysis.

Methods

Although there are no established standards for conducting and reporting RES, there is agreement that the process involves summarising and synthesising evidence from quantitative and/or qualitative studies to address specific research questions. 27 We adopted an integrated mixed-research synthesis approach,42 where both qualitative and quantitative studies were considered for inclusion by their relevance to the research aims and were grouped based on their findings rather than their methods.

The RES was conducted between May and September 2018. Database searches were carried out in the MEDLINE (via Ovid), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and EMBASE™ (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands) databases for articles published between January 2000 and June 2018. Search terms included ‘stroke/cerebrovascular accident’, ‘community based/home rehabilitation’, ‘early supported discharge/ESD’, ‘early/earlier/prompt/accelerated/supported discharge’, ‘early/earlier/prompt/accelerated/supported return home’, ‘reduce duration or length of hospital stay’, ‘organised/multidisciplinary discharge team’, ‘intermediate care/community care’, ‘barriers/facilitators/enablers’, ‘health services/implementation research’ and ‘community healthcare and service delivery/organisation’. The search strategy and inclusion and exclusion criteria are presented in Appendix 1.

Abstracts were independently assessed by two authors (NC and AB) who read all titles and abstracts. Differences in opinion were discussed between reviewers until consensus was reached.

We used the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme43 as a structured approach to understand the quality of available evidence; this checklist is a frequently used instrument that is recommended by the Cochrane Collaboration. 44 However, studies were not excluded on the basis of quality appraisal, but inclusion was decided based on the study’s ability to address the research aims. As suggested by Pawson,45 even methodologically weak studies may contain potentially valuable ‘nuggets’ of information relevant to the review. A data extraction form was created that included studies’ aims, methods and key findings. Identified studies were also coded in relation to the type/level of contextual determinants that they described. This categorisation process was informed by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) model of contextual determinants influencing implementation. 14 Following the initial coding, and where adequate information was available, data were synthesised into emerging CMO patterns that informed data collection and testing (Table 3; see Appendix 2 for the accompanying interview schedules).

| Type/level of contextual influences | Context | Mechanisms | Outcomes | Interview schedule group of questions | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive influences | Negative influences | Resources | Reasoning | Intended | Unintended | ||

| Characteristic of the intervention (adaptability) | Flexibility of the ESD service’s model of operation | Lack of appropriate follow-up on services; disjointed transition between ESD and future services | Staff members adopting a flexible approach around the length of the intervention | To account for local context/patients’ individual needs | Patients receiving patient-centred care/rehabilitation services tailored to their needs | Failure to meet targets and demonstrate effectiveness | Staff interview schedule: factors influencing model of operation (see Appendix 2, section 3) |

| Intervention (team composition) | Access to social worker | Disjointed transfers between services on the stroke care pathway | Improved communication and co-ordination between health-care and social care services | Successful discharge planning and timely care transition | Improved ESD responsiveness |

Assessed through WP1 and WP2 Staff interview schedule: factors influencing model of operation (see Appendix 2, section 3) Team-level factors (see Appendix 2, section 5.2) |

|

| Characteristics of individuals (patients’ and carers’ expectations) | Home is perceived as a comforting place in which patients can reclaim autonomy supported by family members | Patients having unrealistic expectations of recovery | Ongoing communication and collaborative working between ESD, patients and carers | Patients and carers feeling safe at home | Effective management of expectations and successful adjustment to life after stroke |

Staff interview schedule: patient-level factors (see Appendix 2, section 4) Patient interview schedule: patients’ experience of ESD (see Appendix 2, section 2) Outcomes of the service (see Appendix 2, section 3) |

|

| Networks and communications (stakeholder engagement in implementation) | Developing formal implementation plan; initial consultation with other services, commissioners | Services implemented against background of cultural and organisational divides | Active involvement of multiple stakeholders in the development of the service | Promoting a shared sense of ownership | Ensuring that services fit with the pathway | Service responsive to local needs | Team leads and managers’ interview schedule: factors influencing the adoption and model of ESD (see Appendix 2, section 2) |

Results

A total of 33 papers that met the inclusion criteria were identified for full-text review and 20 publications were included in the final evidence synthesis based on whether or not they could address the research aims. The papers were published between 2000 and 2017, with two studies conducted in Australia,46,47 six in Sweden48–53 and the rest in the UK. 13,19,23,38,39,54–60 Ten studies focused on stroke ESD services,13,19,23,38,46,47,49,50,54,58 four investigated community stroke rehabilitation services39,57,59,60 and six examined stroke patients’ transition from hospital to home. 48,51–53,55,56 Data collection methods mainly involved qualitative interviews; two studies conducted surveys,46,56 two undertook observations,19,59 two used consensus methods and one provided insights from a service development project. 60 Eleven studies examined health-care professionals’ perspectives13,19,23,39,46–48,56,57,59,60 and six studies captured carers’ opinions. 19,38,49,54,55,57

The following section provides a summary of key findings, organised thematically based on the level and type of determinant that they described. The categorisation and definition of concepts were informed by the CFIR model. 14

The intervention

Relative advantage

This theme refers to stakeholders’ perception of the advantage of implementing ESD. 14 Studies reported differing views among health-care professionals regarding the relative advantage of ESD. In the studies by Chouliara et al. 23 and McGinnes et al. ,60 the provision of specialist rehabilitation in the patient’s home was positively regarded by staff members. Kraut et al. 46,47 investigated referrers’ beliefs and attitudes towards ESD and captured their concerns about the capability of ESD to provide an intensive stroke-specialist service. Staff reported more disadvantages and fewer benefits than patient participants, although the authors did not find any evidence suggesting that staff’s beliefs had a negative impact on patient views of ESD. 47 They also noted that concerns were mainly voiced by less experienced staff, which, according to the authors, highlighted the need for ongoing education of referrers and communication of evidence-based ESD outcomes.

The idea of home-based rehabilitation was highly valued by stroke survivors and was a consistent finding across the qualitative studies investigating patients’ beliefs of ESD. 38,47,49–51 Benefits included being in a familiar environment and supported by family members;38 becoming autonomous and having control over daily routines;50 and developing a more equal relationship with health-care professionals than in a hospital setting. 49

Adaptability

This theme concerns the degree to which ‘periphery components’ of the intervention can be adapted and tailored to meet local needs. 14 In addition to defining core components, two consensus documents13,39 commented on the need to adjust certain elements of the intervention, such as its time limitation, in response to the local context and clinical needs. In the study by Fisher et al. ,13 ESD triallists agreed that the length of ESD interventions should be adapted to patient need and the existence and type of other community-based stroke services in the area. It was also suggested that clinical judgement should be exercised in relation to how patients were admitted to ESD, an opinion shared by staff members interviewed by Chouliara et al. 23 The study by Cowles et al. 54 further reiterated the need to tailor ESD to patients’ needs and preferences.

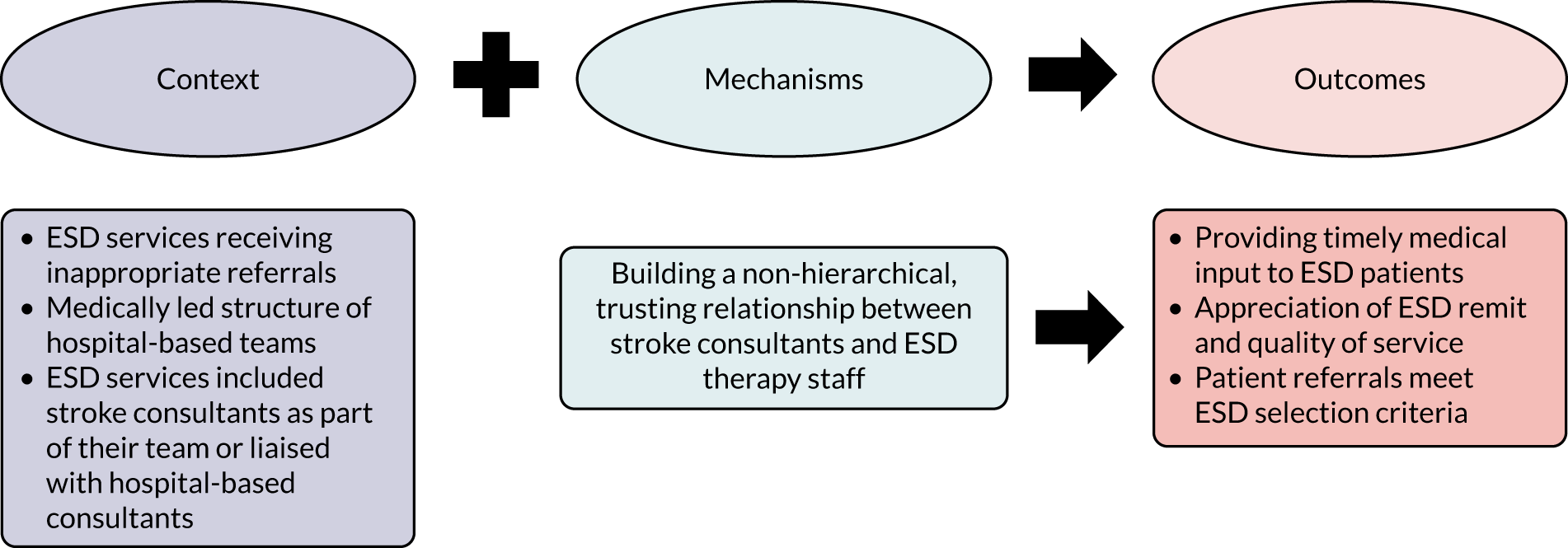

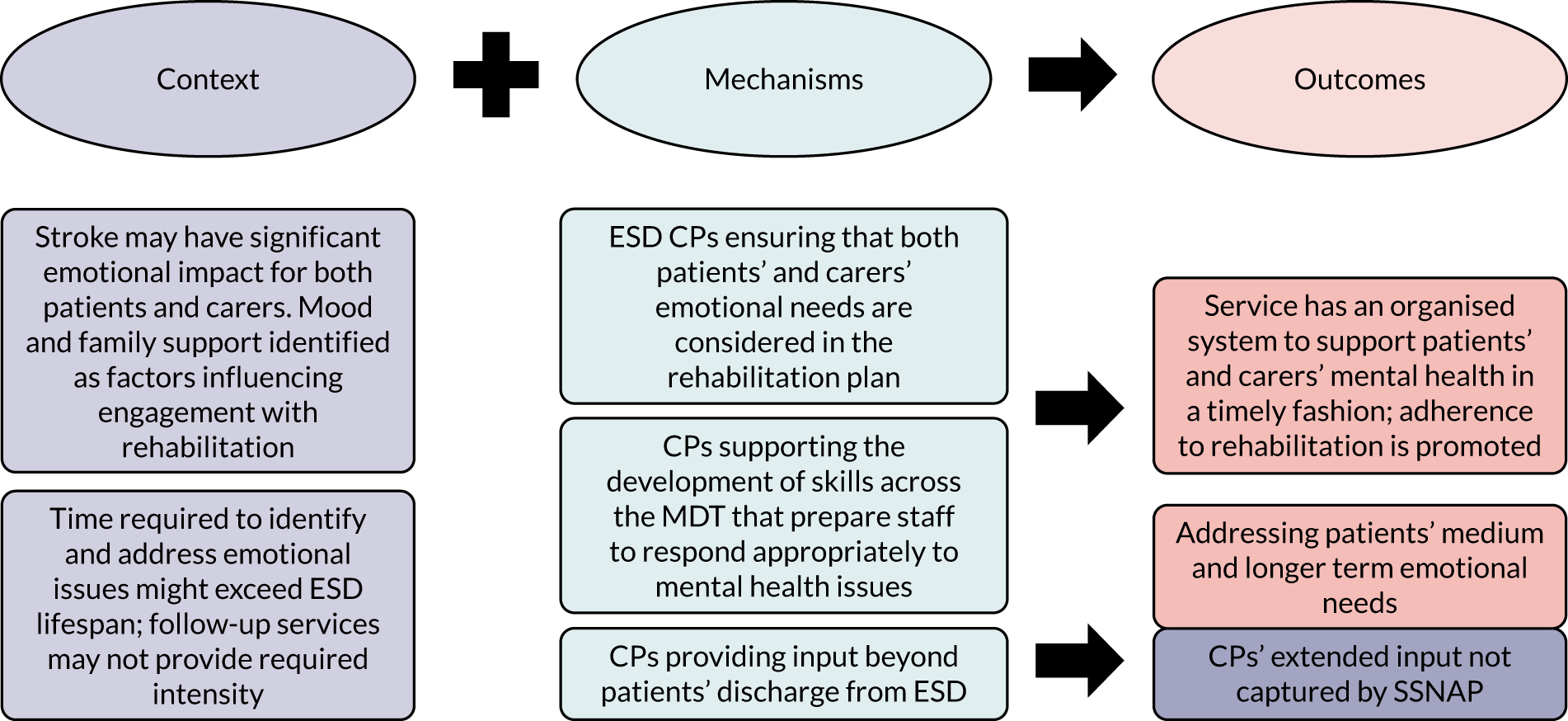

Composition of the multidisciplinary team

The role of certain professions in shifting barriers to the operation of ESD was discussed in some of the included studies. Geddes and Chamberlain59 suggested that ESD teams need medical support from a consultant, who would have a ‘product champion’ and a boundary-spanning role between acute services, general practitioners (GPs) and service managers. The need for access to a stroke physician, although not necessarily as part of the team, was further stressed by Fisher et al. 13 Their findings also supported the need to liaise with a social worker and SLT, and provided some evidence on the benefits of including RAs as part of the team. The contribution of RAs in promoting the sustainability of the service was further discussed by Chouliara et al. 23 Cowles et al. 54 noted that having psychology input overseen by a clinical neuropsychologist promoted psychological thinking in the team and contributed to the effective management of mood issues for service users.

Characteristics of individuals

Patients’ and carers’ knowledge and beliefs about the intervention

Patients’ experiences of care through their hospital stay and transfer home appeared to influence their expectations of ESD. Lou et al. 49 noted that patients’ and carers’ feelings of security about going home related to their confidence in the judgement of hospital staff. Ellis-Hill et al. 55 commented on how a positive relationship between staff members and patients during their hospital stay set the tone for their perception of a trusting relationship with health-care professionals in the community. By contrast, when patients felt abandoned and unsupported during discharge, they felt that their return home was accelerated owing to pragmatic reasons, for example the hospital needing beds, rather than clinical reasons. In the study by Wottrich et al. ,48 MDT professionals thought that introducing home visits during the hospital stay helped alleviate both staff and patient concerns and anxiety about returning home. Having a positive experience of ESD staff streamlining their transfers into and out of the service contributed to patients feeling that they were safe and supported. 54

Patients’ and carers’ expectations of recovery

Patients’ and carers’ perceptions of ESD were also influenced by their own expectations of recovery,52 which were shaped by life experiences as well as previous interactions with health-care professionals. 55 For example, Lou et al. 49 discussed differences in expectations between retired stroke survivors and younger patients of working age. In the study by Kraut et al. ,47 patient opinion regarding the level of mobility required for discharge with ESD was influenced by their expectations of recovery along with the level of support available at home. Patients and carers may have unrealistic beliefs, anticipating fast recovery or even complete dependency on their relatives; it was suggested that effective management of these expectations by the ESD team promoted engagement with the rehabilitation process. 50,52

Networks and communications

Communication and co-ordination with other services

The importance of good communication and co-ordination between services on the stroke care pathway was a prevalent theme in the reviewed literature. In their qualitative investigation of a stroke community rehabilitation team (CRT), Ryan-Woolley et al. 57 found that lack of clarity about the service’s remit and inadequacies in communication with other services were factors undermining the successful implementation of the service. The need for ongoing education and improved communication and information exchange were shown to be important for the timely transfer of appropriate patients to ESD services. 23,46,53 Close working relationships with the acute service were particularly emphasised, as was ongoing communication with commissioners. 13,23,39 Co-ordination with social workers during discharge was described as problematic, leading to unnecessary delays and disjointed transfers. 23,56 Cross-service communication was deemed particularly important during the early stages of the service development. 23,57,59 Studies highlighted the need to invest time in consultation with local health and social services to clarify service remit and local relevance in the pathway and alleviate concerns. Strategic leadership and the development of a network with service representation from across health, social and voluntary sectors were identified as key for achieving partnership working and integration along the local pathway. 39,59 It was noted that the availability and use of information communication technologies had a role to play in facilitating communication and discharge planning,19 as well as promoting service integration. 23

Communication with patients and carers

The need to establish processes that promote communication and information provision with patients and carers was a consistent finding in the literature. Interviews with patients and carers highlighted the importance of having access to stroke-specialist information in appropriate formats. 38,49,55,58 Managing endings through timely and constant communication was identified as one of the factors contributing to a positive patient experience in a study by Cowles et al. 54

Conclusion

The RES was a first step in assessing our initial programme theories and informing the development of CMO hypotheses to be tested through data collection and analysis. In line with our third programme theory, findings further supported the need to consider the services’ wider networks and communication processes. They also identified certain patient-level factors that deserve further exploration, including patients’ beliefs and expectations of their own recovery and how ESD could contribute to their recovery process. One of the included studies suggested that certain features of physical geography (i.e. hilly terrain) were a common patient-reported barrier to outdoor physical activity. 53 We did not identify any other studies investigating the impact of rurality on ESD, highlighting a paucity of research in relation to the influence of geographical factors.

We are aware that this synthesis was pragmatically tailored to resources and time constraints and, therefore, very focused. As a result, it did not consider findings from a wider body of evidence (e.g. different population groups, grey literature) that could have further enriched insights from this review. Although our intention was to include quantitative studies, very few studies contained any description of contextual factors relevant to the purpose of this study. The decision to include studies based on their relevance to our research question, rather than their scientific quality, was a pragmatic one, considering the small sample size of relevant studies. Although this decision could have introduced bias, we need to note that in the context of the wider project this synthesis was a starting point to further data collection and hypotheses testing. Although we attempted to configure findings across studies into CMO hypotheses, this study was not a realist synthesis and, therefore, we did not engage in the process of distinguishing between contextual features and underlying mechanisms. None of the included studies had attempted to make these links, reiterating the need to better understand the interaction between contextual influences and the evidence-based active ingredients of the intervention.

Chapter 4 Work package 1: evaluating the effectiveness of early supported discharge service provision

Parts of this chapter are adapted with permission from Fisher et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Introduction

The SSNAP is the national stroke register of England, Wales and Northern Ireland in which all acute admitting hospitals and post-acute stroke teams are mandated to participate. 61 SSNAP has played a key role in monitoring the performance and improving the provision of acute stroke care. The collection of SSNAP data from community stroke services now offers a unique opportunity to investigate the large-scale impact of ESD.

Clinical guidelines recommend that ESD services should provide responsive and intensive rehabilitation (with treatment at home beginning within 24 hours of hospital discharge), with the aim to promote stroke survivor recovery. 5,6,62–65 By investigating if and how these aspects of an effective ESD service can be realised in practice, this study aims to inform the provision of evidence-based care for stroke survivors.

Our previous research has hypothesised that the active ingredients of ESD can be defined with evidence-based core components,13 and that these core components are essential characteristics that need to be implemented for the ESD intervention to be effective in practice. 12 The aim of this study was to determine if such core components had been adopted by ESD teams in real-world settings in England and whether or not these related to realised benefits of ESD.

Methods

Study design

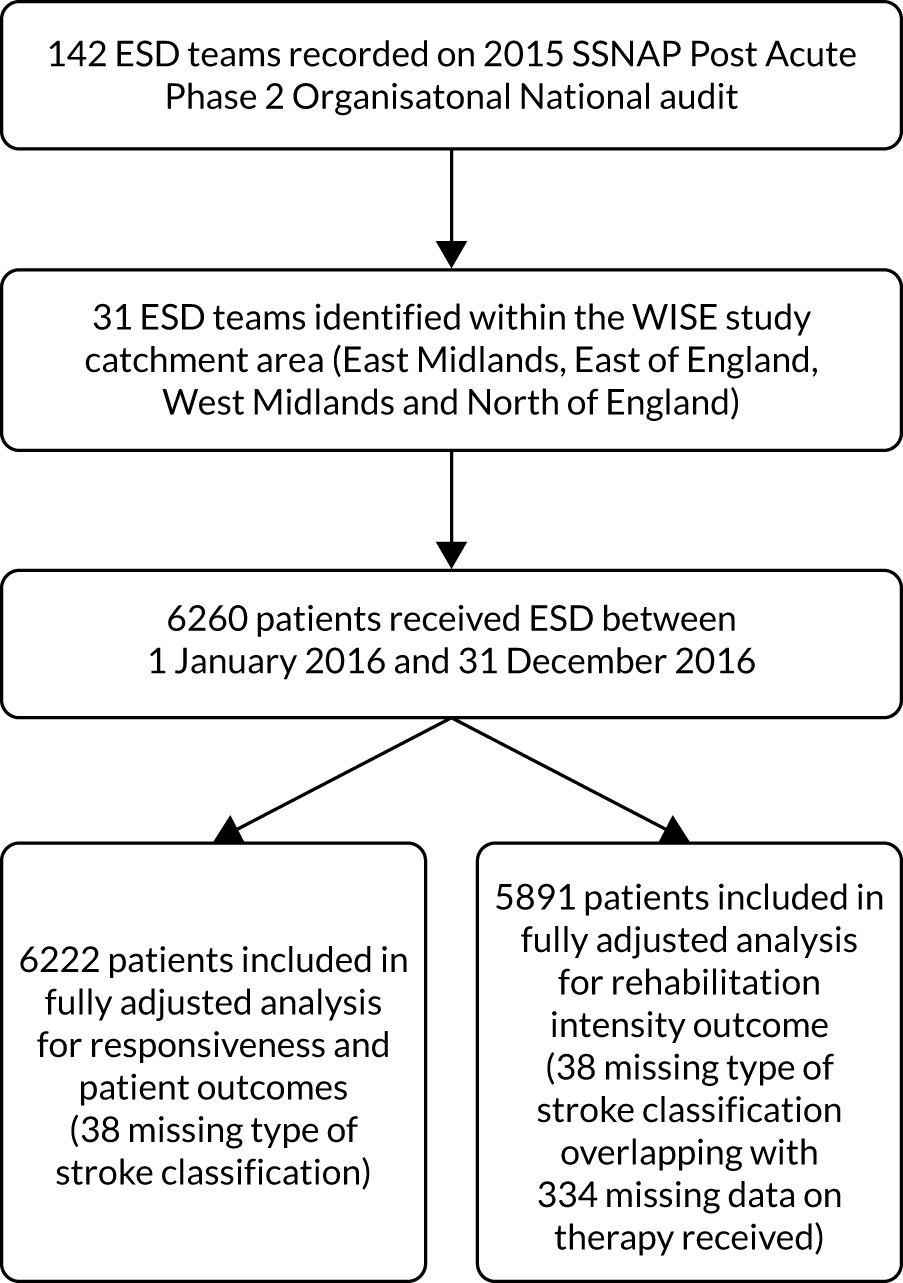

We present results from this observational cohort study (Figure 3), which was conducted as part of the larger mixed-methods study. 37 We determined a priori a sample size of 4750 patients for a study power of 80% to detect standardised effect sizes of 0.25 for each outcome.

FIGURE 3.

The ESD study design flow chart. WISE, What is the Impact of Stroke Early supported discharge?

Setting

Early supported discharge services were sampled across a large geographical area of England. The sampling strategy was devised in accordance with the overall mixed-methods study design and included all ESD services in specific regions of England. 37 Here we report the findings from the quantitative investigation of ESD effectiveness across the West and East Midlands and East of England (across which a specific initiative to promote ESD was initiated in 2010), and the North of England, a region with a defined lack of ESD. 7,28

Data sources and participants

The aim of this study was to examine the association between ESD service models and process and patient outcome measures of ESD effectiveness. Information about ESD service models included in the study was obtained from SSNAP post-acute organisational audit data, which were published freely in the public domain in 2015. 7 ESD teams had participated in the 2015 post-acute organisational audit by completing questionnaires that investigated the organisational characteristics of their service in relation to evidence-based standards, which were distributed and collated by SSNAP. 7

Patient-level SSNAP data are entered by clinical teams onto a secure webtool with real-time data validations to ensure data quality. 61 Historical, prospective, clinical (patient-level) SSNAP data from all SSNAP-participating ESD teams in the geographical area of interest (n = 31) were obtained with permission from HQIP.

Key predictor: early supported discharge consensus score

We hypothesised that the adoption of evidence-based core components of ESD was important for the ESD intervention to be effective in practice. An ESD consensus score was developed using defined evidence-based core components of ESD, as outlined in an international consensus document and evidence-based post-acute organisational audit criteria utilised by SSNAP in the post-acute audit (Table 4). 7,13 Statements defining core components of ESD from the consensus document (derived using an international panel and modified Delphi process) were compared with items from the post-acute organisational audit questionnaire that was used previously by SSNAP. Using this process, a 17-item ESD consensus score was designed by the study team to measure the adoption of core components of an ESD service model, for example team composition (core team and others), staff training, team meetings and service specificity (Table 5). This 17-item ESD consensus scoring system was then applied to organisational audit questionnaire data (categorical data previously collected by SSNAP) for each of the 31 ESD teams involved in the study. The adoption of evidence-based core components was measured by calculating an ESD consensus score for each of the 31 teams.

| ESD consensus score component | Yes | No |

|---|---|---|

| Core team members meeting or exceeding recommended WTE level per 100 stroke patientsa | ||

| Doctors: ≥ 0.1 | 1 | 0 |

| Nurses: ≥ 0.4 | 1 | 0 |

| Occupational therapists: ≥ 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Physiotherapists: ≥ 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Speech and language therapists: ≥ 0.3 | 1 | 0 |

| Access to other team members | ||

| Clinical psychologists | 1 | 0 |

| Social workers | 1 | 0 |

| Rehabilitation assistants | 1 | 0 |

| Training opportunities | ||

| Nurses | 1 | 0 |

| Therapists | 1 | 0 |

| Rehabilitation assistants | 1 | 0 |

| MDT meetings | ||

| Weekly meetings | 1 | 0 |

| Core team attend | 1 | 0 |

| ESD member attends acute meeting | 1 | 0 |

| Service | ||

| Stroke specific | 1 | 0 |

| Median waiting time between referral and ESD of ≤ 1 day | 1 | 0 |

| Weekly service of > 5 days | 1 | 0 |

| ESD consensus score component | ESD teams, n (%) |

|---|---|

| Core team members meeting or exceeding recommended WTE level per 100 stroke patientsa | |

| Doctors: ≥ 0.1 | 3 (9.7) |

| Nurses: ≥ 0.4 | 15 (48.4) |

| Occupational therapists: ≥ 1 | 15 (48.4) |

| Physiotherapists: ≥ 1 | 15 (48.4) |

| Speech and language therapists: ≥ 0.3 | 22 (71.0) |

| Access to other team members | |

| Clinical psychologists | 15 (48.4) |

| Social workers | 4 (12.9) |

| Rehabilitation assistants | 31 (100) |

| Training opportunities | |

| Nurses | 21 (67.7) |

| Therapists | 30 (96.8) |

| Rehabilitation assistants | 30 (96.8) |

| MDT meetings | |

| Weekly meetings | 30 (96.8) |

| Core team attend | 7 (22.6) |

| ESD member attends acute meeting | 22 (71.0) |

| Other service characteristics | |

| Stroke specific | 31 (100) |

| Median waiting time between referral and ESD of ≤ 1 day | 20 (64.5) |

| Weekly service of > 5 days | 14 (45.2) |

To evaluate the level of service provided by the ESD teams, we proposed a scoring system, as set out in Table 4, that relates ESD organisational audit data directly to evidence-based core components. Based on our proposed scoring system, an ESD team can score a maximum of 17 points: a maximum of 5 points for core team members meeting or exceeding the recommended WTE level per 100 stroke patients, and a maximum of 3 points each for access to other team members, training opportunities, MDT meetings and level of service provided.

Process and patient outcome measures

The measures of the effectiveness of ESD were based on clinical guidelines and ESD systematic review recommendations, and were dependent on what patient-level SSNAP data variables were collected routinely. 5,10 Using historical prospective SSNAP clinical data (1 January 2016 to 31 December 2016), measures of ESD effectiveness were ‘days to ESD’ (number of days from hospital discharge to first face-to-face contact; number of patients, n = 6222), ‘rehabilitation intensity’ (total number of treatment days/total days with ESD; n = 5891) and stroke survivor outcome (modified Rankin Scale score at discharge from ESD; n = 6222). The measure of rehabilitation intensity was based on established approaches used by SSNAP. 66 The modified Rankin Scale score, routinely collected at discharge from the ESD service, was used as the stroke survivor outcome and in analysis was controlled for by modified Rankin Scale score at discharge from hospital.

‘Days to ESD’ was a binary variable (0 = ESD team sees the patient within 1 day; 1 = ESD team sees patient after ≥ 1 day) and ‘rehabilitation intensity’ was a natural log-transformed continuous measure (the results presented in the text have been back transformed to give the per cent change per unit). The stroke survivor outcome measure of modified Rankin Scale (at ESD discharge) was treated as an ordinal categorical variable with the following categories of increasing dependency: 0, 1, 2, 3 and 4–5 (combined owing to small patient numbers).

Other variables

To investigate the effect of ESD consensus score on the process and patient outcomes, we controlled for a number of covariates, which were measured at the ESD team level (level 2 in our multivariate model described in Statistical analyses) or the patient level (level 1).

We identified a need to control for the effect of preceding hospital care and geographical context of delivery of rehabilitation. At the site (or ESD team) level, we included two confounding variables: a rurality score and a hospital SSNAP rating score. The rurality score was based on the rural–urban classification reported for the geographical area associated with the NHS CCG who had procured each ESD team. 67 Each CCG in England has a geographical area over which it operates to procure NHS services. Where an ESD team included in this study was managed by multiple commissioning groups, the weighted average level of rurality was calculated based on the prevalence of stroke and transient ischaemic attack in that commissioning area (figures obtained from NHS Quality and Outcomes Framework68).

The hospital rating scores used in this study were an overall quality rating for each hospital obtained from SSNAP (total key indicator score derived across 10 domains of stroke care, with adjustments made for case ascertainment levels and the quality of data submitted to SSNAP). The score for each referring hospital (associated with each ESD team of interest) was used as an indication of the overall standard of inpatient care prior to ESD referral. 69 For ESD teams with multiple discharging hospitals, a weighted average SSNAP rating score was calculated based on the number of patients being discharged to those ESD teams.

To account for differing patient characteristics between ESD teams, we also included variables at the patient level. These were stroke patient characteristics, reflecting validated stroke case-mix models and collected as part of the SSNAP data set, and included age, sex, pre-stroke independence, comorbidities, NIHSS score on admission, type of stroke and modified Rankin Scale score at discharge from hospital. 31,32

Statistical analyses

Multilevel modelling was used to investigate the relationships between ESD model and process and patient outcomes in an approach consistent with previous observational studies of this type. 31,32,70,71 By combining SSNAP post-acute organisational audit data at the site (ESD team) level with SSNAP clinical audit data at the patient level, we fitted generalised linear mixed models on two levels, ESD team (level 2) and patient nested within an ESD team (level 1), to process and patient outcome variables. Covariate adjustments were made for site (ESD team) (level 2) and patient (level 1) variables. Models were fitted for ‘days to ESD’, ‘rehabilitation intensity’ and modified Rankin Scale score at ESD discharge using multilevel logistic, linear logistic and ordinal logistic models, respectively.

The ESD consensus score was used in three different ways: total score, disaggregated by component and, where appropriate, as an individual item. We began by assessing the significance of the total score in relation to our outcomes of interest (both unadjusted and adjusted). If a significant association was found, further analyses by components and then by individual items were conducted to uncover the key driver(s) behind the significant association(s). Any statistically significant components were tested for linearity (using likelihood ratio tests) to assist with substantive inference. Where possible, variables were interpreted in a continuous fashion, otherwise they were treated as categorical if any variable could not be interpreted in a linear way.

We chose multilevel modelling to evaluate the effectiveness of ESD service provision because it can accommodate and appreciate the variation that may exist within and between different ESD teams. Furthermore, the intraclass correlation coefficient was calculated as a measure of the proportion of the total variance in outcomes that is attributable to variance within ESD services as opposed to between services.

The adequacy of different statistical models was compared using the log-likelihood, Akaike information criterion and Bayesian information criterion values from single-level and multilevel regression models for each outcome variable, with multilevel preferable on each occasion. Multicollinearity was investigated by examining variance inflation factor scores of all predictor variable sets and was found not to be an issue. Covariate linearity was examined by checking the consistency of a linear trend in relation to each outcome variable. To explore the impact of missing data, we conducted a sensitivity analysis excluding any teams that had missing outcome data; no substantial differences were found. A two-tailed significance level of 0.05 was used in all hypothesis tests. We carried out all analyses using Stata/SE® 15.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

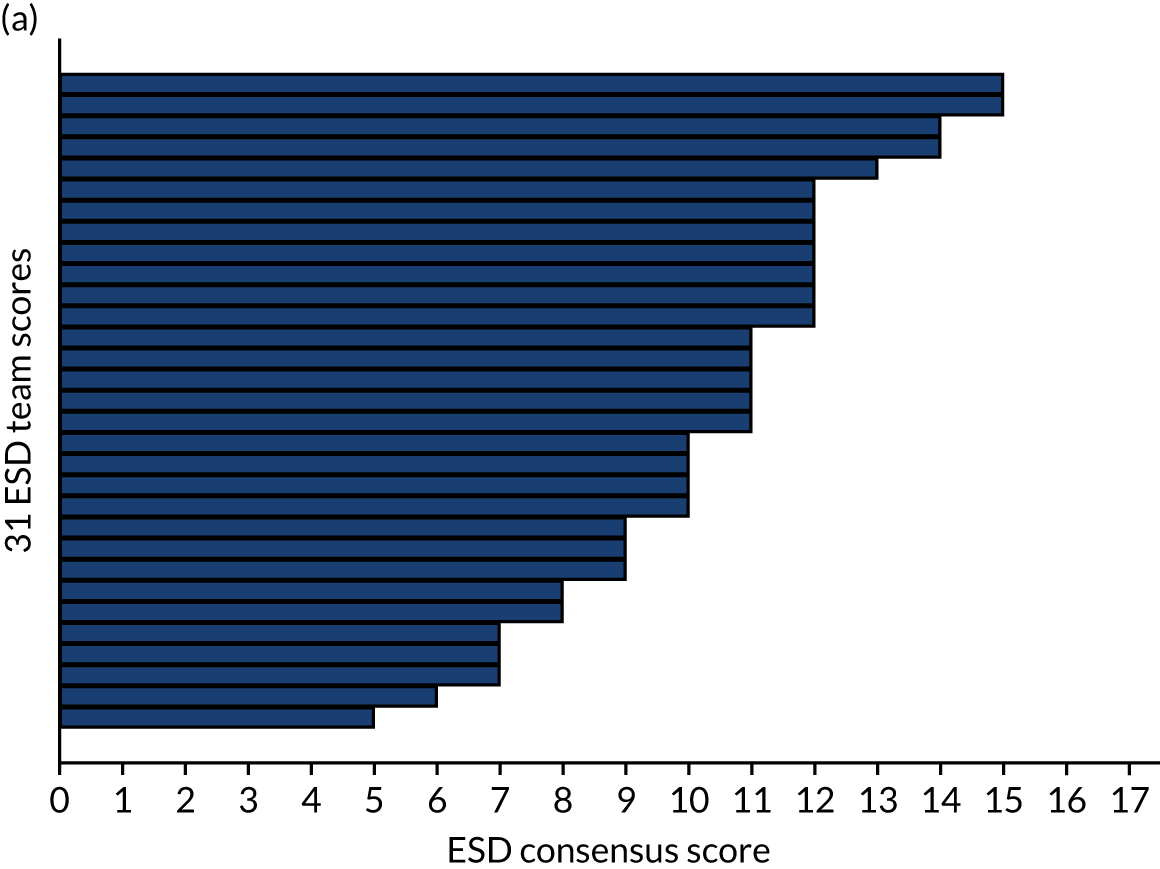

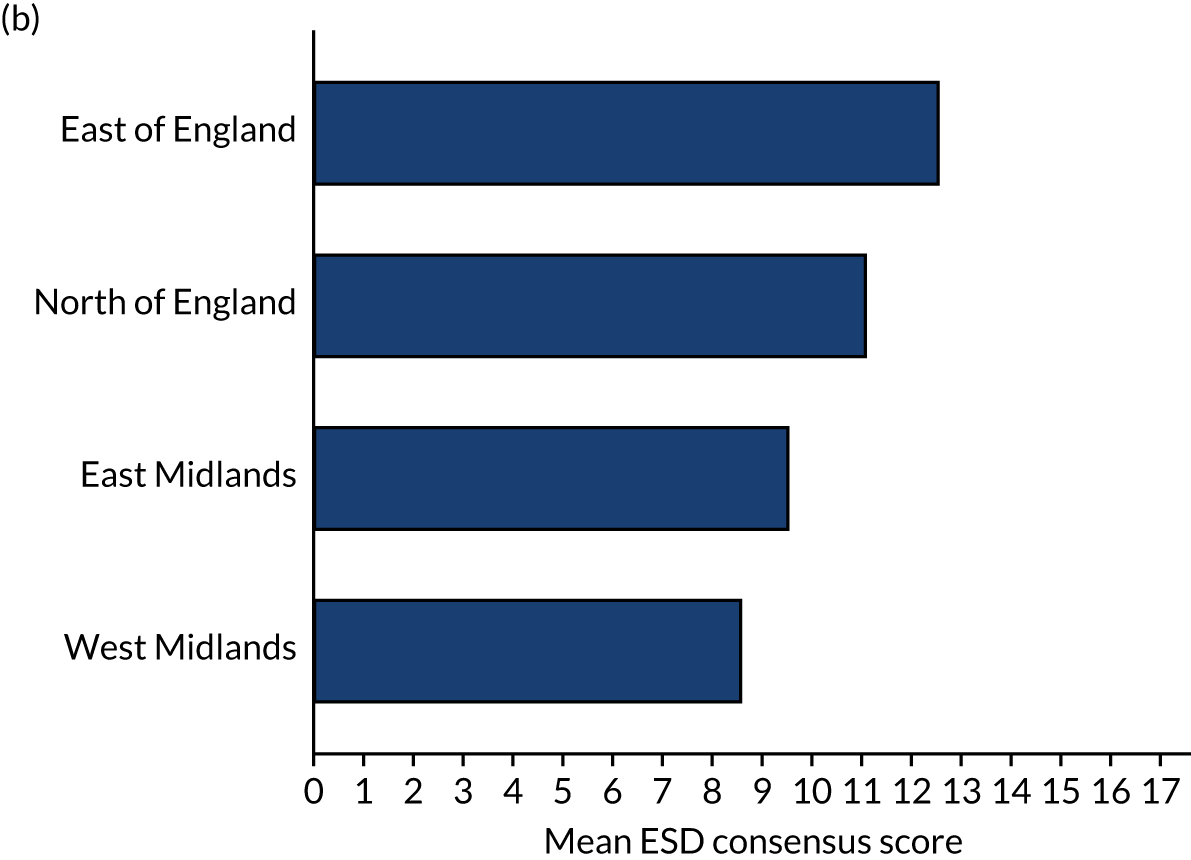

Results

Figure 4 shows the variation of ESD consensus scores across the 31 ESD teams and four English regions. The total ESD consensus scores across the 31 teams varied between 5 and 15 {mean 10.6 [standard deviation (SD) 2.4]}, with no team achieving 100% adherence, reflecting that a range of ESD models had been adopted. In terms of the English regions, adherence to the core components of ESD service delivery was greatest in the East of England.

FIGURE 4.

Distribution of ESD consensus score by (a) study team; and (b) region.

All 31 ESD teams included in this study reported that they provided a stroke-specific service (see Table 5). Only three teams reported having at least the recommended level of input from doctors and only four teams said that they had access to social workers. For the range of ESD models, there was a mixture of urban and rural settings [mean level of rurality 35.6 (SD 21.8)], as well as varying performance of associated referring hospitals [mean SSNAP hospital rating score 72.2 (SD 12.1)].

Data from 6260 patients with a completed NIHSS score were included in the primary analysis, and their characteristics are shown in Table 6. The majority of patients (91.9%) had a mild or moderate stroke (NIHSS score of < 15). The most common age group was 70–79 years (30.8%) and 4151 (66.3%) patients were functionally independent prior to their stroke (modified Rankin Scale score of 0).

| Patient characteristic | Number of patients (N = 6260) (%) |

|---|---|

| Age (years) | |

| < 60 | 1058 (16.9) |

| 60–69 | 1181 (18.9) |

| 70–79 | 1926 (30.8) |

| 80–89 | 1708 (27.3) |

| > 89 | 387 (6.2) |

| Sex: male | 3530 (56.4) |

| Already inpatient at time of stroke: yes | 197 (3.2) |

| Congestive heart failure prior to admission: yes | 241 (3.9) |

| Hypertension prior to admission: yes | 3410 (54.5) |

| Atrial fibrillation prior to admission: yes | 970 (15.5) |

| Diabetes prior to admission: yes | 1281 (20.5) |

| Stroke/transient ischaemic attack prior to admission: yes | 1487 (23.8) |

| Modified Rankin Scale score before stroke | |

| 0 | 4151 (66.3) |

| ≥ 1 | 2109 (33.7) |

| NIHSS score on arrival | |

| 0 | 746 (11.9) |

| 1–5 | 3407 (54.4) |

| 6–14 | 1597 (25.5) |

| 15–24 | 452 (7.2) |

| > 24 | 58 (0.9) |

| Type of stroke | |

| Ischaemic | 5648 (90.8) |

| Intracerebral haemorrhage | 574 (9.2) |

| Modified Rankin Scale score at inpatient discharge | |

| 0 | 790 (12.6) |

| 1 | 1703 (27.2) |

| 2 | 1376 (22.0) |

| 3 | 1570 (25.1) |

| 4–5 | 821 (13.1) |

In terms of the outcomes, 69% of the sampled patients were seen after ≥ 1 day, with 31% of patients seen within 1 day for the ‘days to ESD’ variable. The median rehabilitation intensity value of the sampled patients was 0.38 treatment days for every day with the ESD team, with the 25th percentile being 0.19 and the 75th percentile being 0.59. For the stroke survivor outcome measure, 9% of sampled patients were classified as moderate to severe at ESD discharge (modified Rankin Scale score of 4–5), with the percentages of patients with a modified Rankin Scale score of 0, 1, 2 and 3 being 9%, 31%, 31% and 20%, respectively.

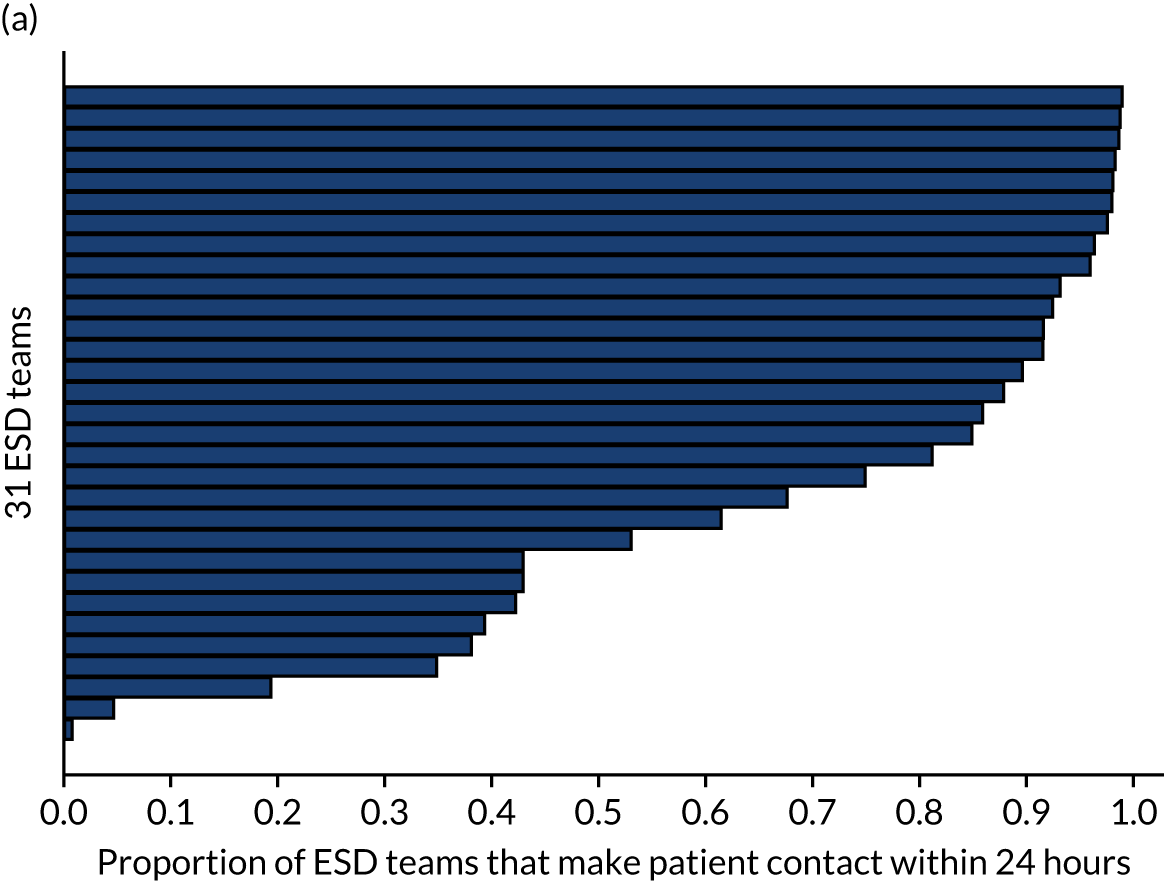

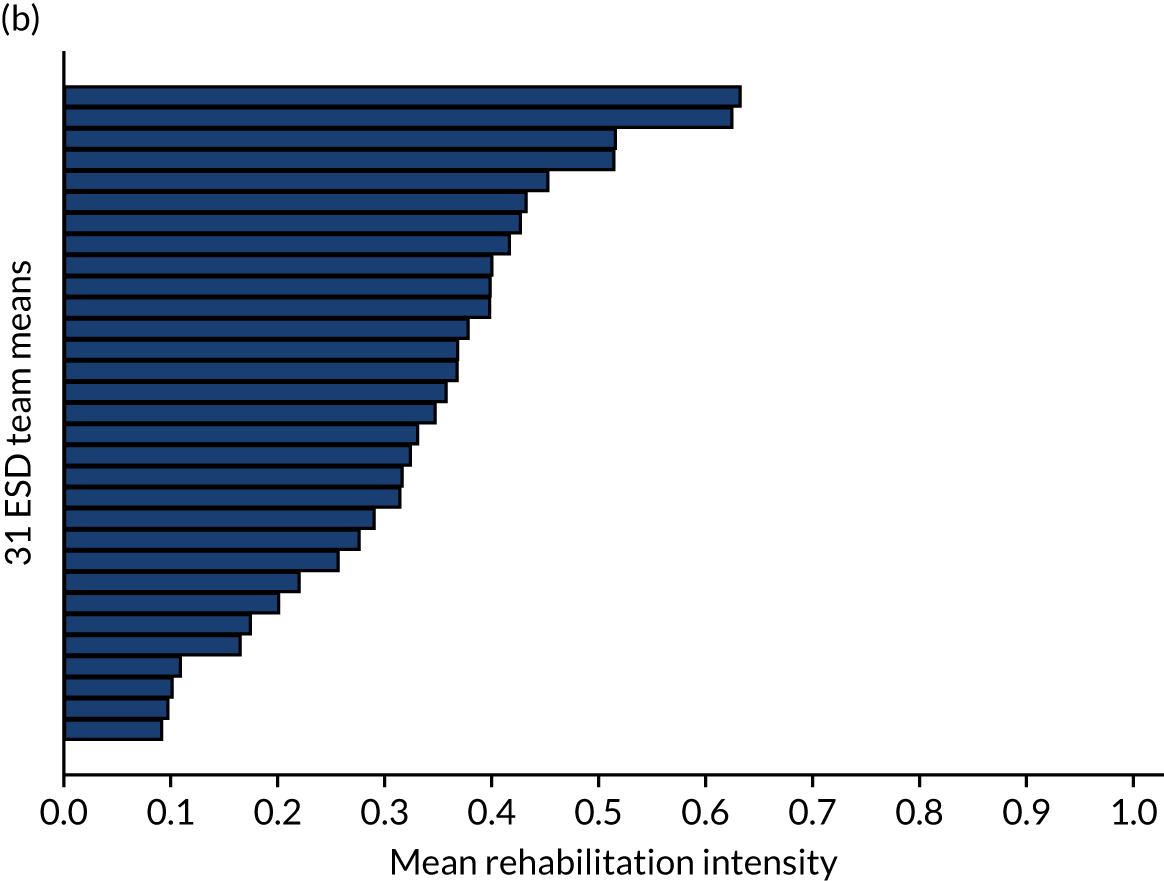

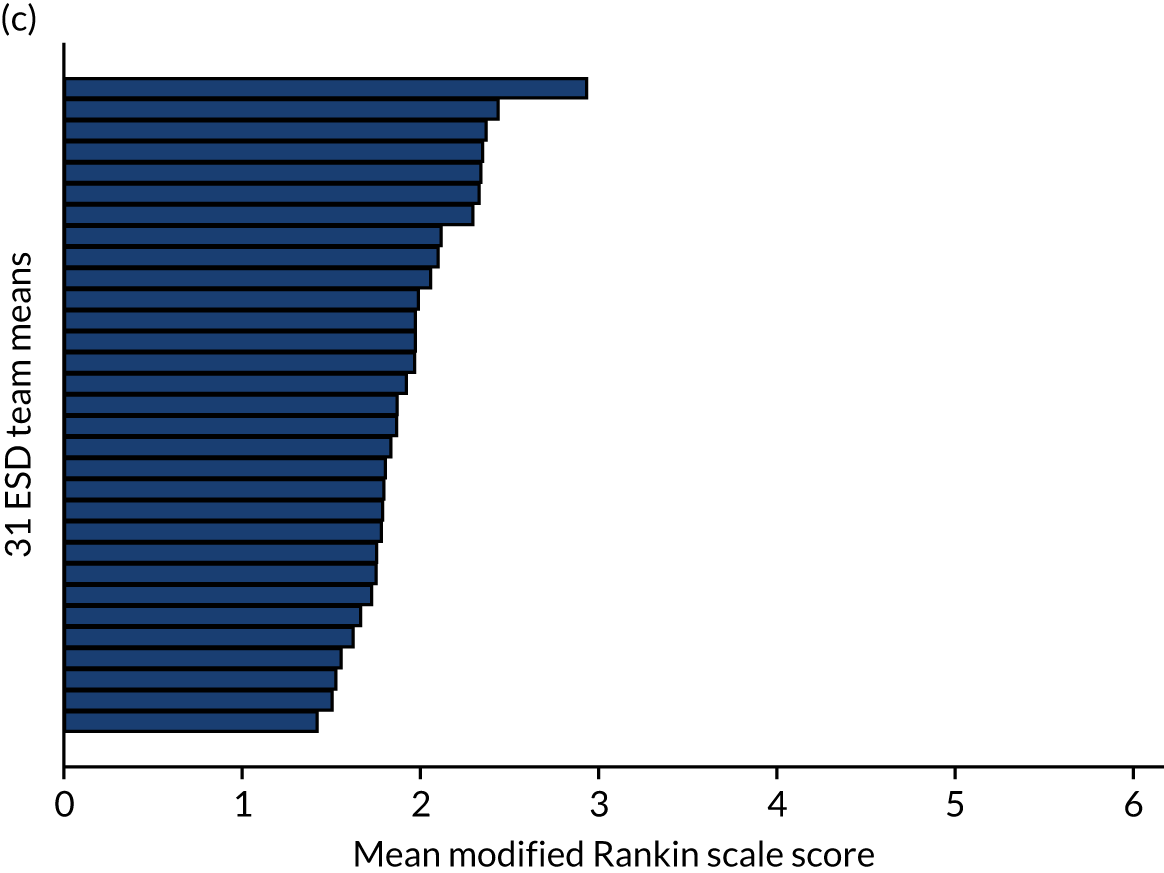

Results of the multilevel modelling are presented below. The degree of clustering was greater for the process measures ‘days to ESD’ and ‘rehabilitation intensity’ than that for the patient outcome measure of modified Rankin Scale score (adjusted intraclass correlation coefficients: 0.56, 0.26 and 0.08, respectively). Figure 5 shows the amount of variation among the 31 ESD teams in relation to the outcomes of this study.

FIGURE 5.

Distribution of study outcome variables across study teams. (a) Proportion of EDS teams that make patient contact within 24 hours; (b) mean rehabilitation intensity; and (c) mean modified Rankin Scale score.

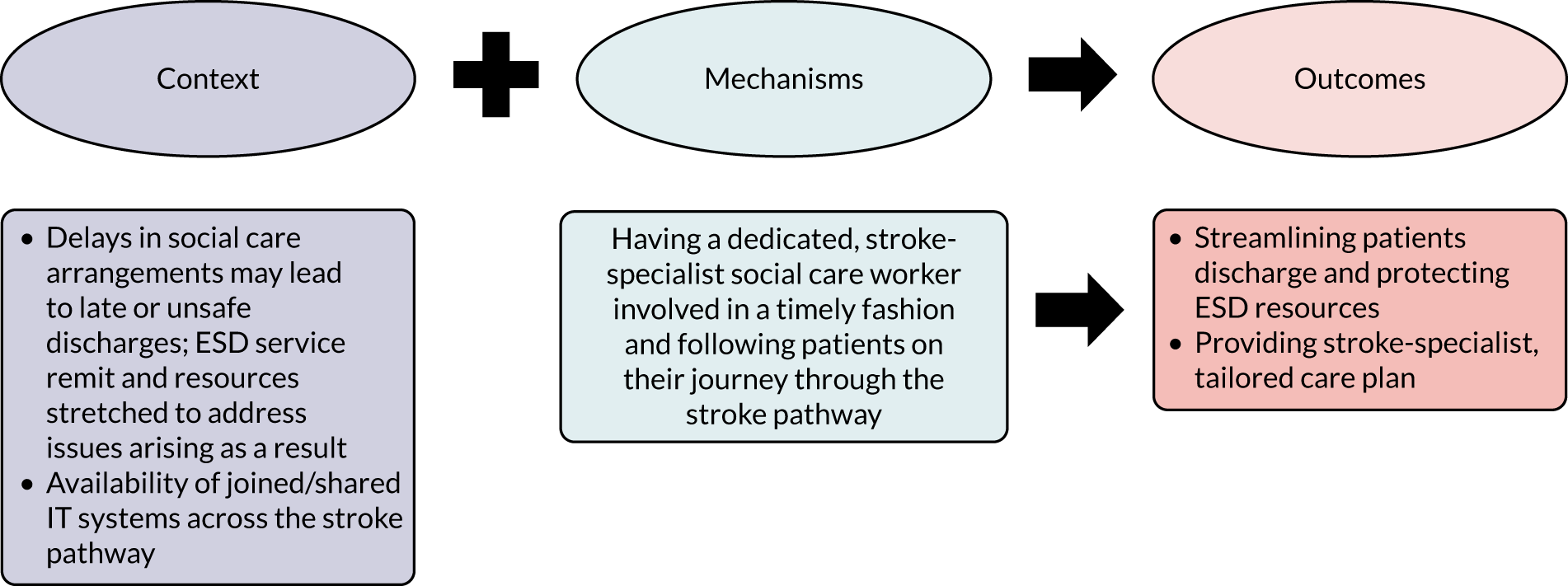

Results for the association between the total ESD consensus score and the ‘days to ESD’ variable are shown in Table 7, which are unadjusted and adjusted for all patient characteristics, the level of rurality and weighted average SSNAP hospital score. Odds ratios are also presented in Table 7, with percentage odds reported here. From the adjusted results, a 1-unit increase in the ESD score was associated with an odds ratio of 0.71 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.51 to 0.99] or, in other words, with a reduced odds (by 29%) of the ESD team seeing the patient after ≥ 1 day following hospital discharge. Hence, an increase in ESD consensus score was associated with a more responsive ESD service. Exploring the effect of components, this association appeared to be driven by having more core team members meeting or exceeding the recommended WTE level per 100 stroke patients [a 1-unit increase was significantly associated with a 47% reduction in the odds of the ESD team seeing the patient after ≥ 1 day (95% CI 14% to 67%)]. There was some evidence at borderline significance of an effect of access to other team members (reduced odds of 70%, 95% CI –8% to 92%). Further investigation at an individual item level showed that having access to a social worker was associated with more responsive ESD service, with a 97% reduced odds of the ESD team seeing the patient after ≥ 1 day (95% CI 61% to 99%).

| Unadjusted | Adjusteda | |

|---|---|---|

| ESD models | ||

| Patients | 6260 | 6222 |

| ESD teams | 31 | 31 |

| Patients per ESD team | ||

| Minimum | 32 | 32 |

| Mean | 201.9 | 200.7 |

| Maximum | 481 | 479 |

| Intraclass correlation coefficient | 0.56 | 0.56 |

| ESD core components, odds ratio (95% CI); p-value | ||

| ESD consensus score | 0.69 (0.52 to 0.92); 0.011 | 0.71 (0.51 to 0.99); 0.041 |

| Core staff (WTE per 100 patients) | 0.52 (0.32 to 0.83); 0.006 | 0.53 (0.33 to 0.86); 0.010 |

| Access to other team members | 0.31 (0.11 to 0.86); 0.025 | 0.30 (0.08 to 1.08); 0.066 |

| Training opportunities | 0.51 (0.13 to 2.01); 0.335 | 0.54 (0.14 to 2.15); 0.386 |

| MDT meetings | 1.48 (0.48 to 4.52); 0.491 | 2.94 (0.85 to 10.16); 0.089 |

| Other service characteristics | 0.71 (0.28 to 1.80); 0.467 | 0.84 (0.31 to 2.30); 0.739 |