Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 17/100/13. The contractual start date was in October 2018. The final report began editorial review in January 2020 and was accepted for publication in September 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Gangannagaripalli et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Up to 30% of hospital admissions of older people are associated with drug-related problems resulting from adverse drug reactions (ADRs). 1–3 The concurrent use of multiple medications (polypharmacy) is associated with both ADRs and prescribing errors. 4,5 Patients taking seven or more concurrent medications simultaneously have an 82% risk of an ADR. 6 Evidence suggests that between 30% and 55% of admissions due to ADRs could be prevented by more appropriate prescribing,7–9 by appraising age-related changes in pharmacodynamics and pharmacokinetics, balancing risks and benefits (including cost-efficiency and life expectancy) and listening to patients’ and carers’ concerns. 10–12 The task is further complicated because older patients with multiple morbidities are often excluded from clinical trials. 13

Potentially inappropriate medication in older adults

The prescription of potentially inappropriate medications to older people is highly prevalent, ranging from 12% in community-dwelling elderly people to 40% in nursing home residents in Europe and the USA. 14 Older people are particularly vulnerable to inappropriate prescribing because of their multiple drug regimens, comorbid conditions and age-associated physiological processes. 15 Drug-related problems and potentially inappropriate prescribing are highly prevalent among older adults and can exert a significant disease burden. In addition, they have been associated with adverse drug events (ADEs) (which includes ADRs and medication errors), leading to hospitalisation and death, and increased health resource utilisation. 16–18 A 2007 national population study in Ireland by Cahir et al. 19 estimated a cost of potentially inappropriate prescribing of > €38M.

Medicines in older people are considered appropriate when they have a clear evidence-based indication, are cost-effective and are well tolerated in the majority of the population. Although potentially inappropriate prescribing and ADRs are generally associated with overprescription, potentially inappropriate prescribing may also occur when a patient is not prescribed appropriate medication for the treatment and prevention of a disease or condition. 20 This might occur for many reasons, such as ageism, fear of adverse events, economic concerns and lack of prescribing knowledge. 21–23

Screening tools for medication optimisation in older adults

Detecting potentially inappropriate prescribing early may prevent ADEs and cost-effectiveness of medicines, which gives an opportunity for improving quality of care in older adults. 10,24 In addition, the quality of life of older people can be improved by discontinuing inappropriate medications. 25 Currently, prescribing and reviewing medications are largely based on clinicians’ clinical judgement for older patients. However, guidelines and systematically developed evidence-based tools have emerged in recent years to facilitate a comprehensive clinical approach to medication review. These typically consist of lists of appropriate medications for older people to predominantly avoid harmful prescriptions in the older population.

Adverse drug events and cost inefficiencies can be reduced by identifying potentially inappropriate prescribing. 10 Screening tools for supporting medicines optimisation of older adults have been developed in an attempt to address this. The most widely used are the Beers criteria for potentially inappropriate medication use in older adults and the combination of the Screening Tool of Older People’s Prescriptions (STOPP) and Screening Tool to Alert to the Right Treatment (START). Almost half of the drugs in the Beers criteria are unavailable for prescribers in Europe,26,27 several of the drugs are not contraindicated in older people, as per the British National Formulary,10 whereas other contraindicated drugs are omitted. 26 Given these shortcomings, the STOPP/START tools have recently received increased interest in European countries. 28

Development of STOPP/START tools

Two versions of STOPP/START were developed by a team of researchers at the University of Cork, Ireland. The first iteration. STOPP/START (version 1), was developed in 2008. 28 They are valid, reliable and comprehensive screening tools that enable the prescribing physician to appraise an older patient’s prescription drugs in the context of his/her concurrent diagnoses. To establish their content validity, a two-round Delphi survey was conducted with an 18-member expert panel in geriatric pharmacotherapy from academic centres in Ireland and the UK. Sixty-five of the 68 original STOPP criteria and all 22 of the original START criteria received consensus from the expert panel. Inter-rater reliability of the STOPP/START tools was also assessed by determining the kappa statistic and high levels were established between physicians and pharmacists.

Owing to the changing evidence base behind the initial version of STOPP/START tools, the licensing of important new drugs since 2008 and a long list of potentially inappropriate medications included in the first version, an updated version of the tools was deemed necessary. In addition, a number of STOPP/START criteria were no longer considered completely accurate or relevant, a small number (12 in total) of criteria were lacking in clinical importance or prevalence and there were some important criteria that were absent from STOPP/START version 1. The updated version (i.e. version 2) was developed based on an up-to-date literature review and consensus validation among a European panel of experts to reflect Europe-wide prescribing practices in the general population of older people (see Appendix 1).

Impact of STOPP/START tools

An updated recent Cochrane systematic review of the evidence base for interventions to improve the appropriate use of polypharmacy for older people concluded that it was unclear whether or not they could improve appropriate polypharmacy. 29 Although previous versions of the review highlighted STOPP/START as the basis for promising interventions,30 no specific examination was conducted of STOPP/START-based interventions.

A systematic review based on 13 randomised and non-randomised studies that was conducted up to 2012 using STOPP/START tools in community-dwelling, acute care and long-term care older patients found that its use reduced falls, hospital length of stay, care visits and medication cost. 31 A more recent systematic review of randomised clinical trials was conducted on the effectiveness of the STOPP/START tools. 12 This review identified four randomised controlled trials (RCTs). Two studies were judged as having a low risk of bias and two studies were judged as having a moderate to high risk of bias. Meta-analysis of the four RCTs found that the STOPP tool reduced potentially inappropriate medications rates, but study heterogeneity prevented the calculation of a meaningful statistical summary. There was evidence that using STOPP/START tools was associated with a reduction in falls, delirium episodes, hospital length of stay, care visits (primary and emergency) and medication costs, but there was no evidence of improvements in quality of life or mortality. The authors concluded that their use may be effective in improving prescribing quality, and in improving clinical, humanistic and economic outcomes. 12

Current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance on medicines optimisation includes the recommendation to consider using a screening tool for adults such as the STOPP/START to identify potential medicines related patient safety incidents in some groups of people, especially in relation to adults taking multiple medicines (polypharmacy), adults with chronic or long-term conditions and older people. 32 However, the evidence for this recommendation is limited. One of the research recommendations in the guideline is for research on the impact of using clinical decision support systems. The focus of the recommendation is specific for computerised systems. Even this particular application of the decision tools would benefit from knowledge on the mechanisms by which such interventions work more generally to optimise their implementation and to maximise their benefits.

Rationale for realist methodology

To date, and to the best of our knowledge, no attempt has been made to appraise evidence to explain how, when and why intervention based on the STOPP/START tools might improve medicines management in older people.

Systematic reviews can sometimes provide a picture of ‘outcome patterns’ and give indications of where the intervention was successful and where it was not. In systematic reviews, this variation is ignored and what matters is the mean effect across trials. The current evidence base for the STOPP/START tool, as reviewed by conventional methods, is limited for all types of population (especially frail older and community-living patients receiving primary care). Both a Cochrane review29 and a systematic review by Greenhalgh et al. 33 demonstrates the importance of eliciting with sufficient detail the mechanisms that lead to success of interventions and the context in which those interventions are conducted to appraise and eventually maximise their transferability. 33,34 Rather than simply assessing whether interventions based on STOPP/START tools are effective or cost-effective in a binary sense, review methods seek to explain how and why these tools are more or less effective in different circumstances or for different patient groups, thereby facilitating the development of optimal implementation strategies. This is particularly relevant at a time when improving care for older people with complex care needs, who frequently require complex medication regimens, is a priority for the NHS.

We can start to investigate the patterns in realist synthesis. Were there any contextual features that were common to the positive trials? How might we explain this? Does this give any hints as to possible mechanisms? This review is complementary to the two previous reviews,29,33 which did not have a realist approach. The review provides greater understanding and insight into how, when and why interventions work in practice, and the differences between settings, clinician types, patient groups, patient ages and shared decision-making, all of which are very important in terms of optimising implementation of the STOPP/START tools. We have also broadened our search to include studies from 2014 to 2019 and searched for evidence from non-RCTs and qualitative studies, unlike the other two reviews. In addition, we extracted the information from the relevant reports from the NHS.

In contrast to a conventional systematic review of cost-effectiveness, in which it is typically presumed that empirical evidence about the costs and cost-effectiveness of an intervention solely exists in economic evaluations or comparative cost analyses, a realist review with a cost-effectiveness review question should take an integrated approach:

-

Evidence about the supposed (i.e. programme theory) and actual costs and cost-effectiveness of interventions and comparators should be sought and captured in a wider range of study types, including economic evaluations, costing studies, effectiveness studies and other study types about the interventions or programmes of interest.

-

It should be acknowledged that ‘effectiveness outcomes’ and ‘economic outcomes’ are not mutually exclusive categories. Most effectiveness outcomes, whether clinical or patient reported, are also resource committing and therefore cost affecting in some way (e.g. the treatment of ADEs and the reduction in medications taken).

-

The underlying mechanisms of an intervention are the consequences of providing a particular combination of resources.

Both Pawson’s original conception of programme theory35 and more recent clarifications of the realist notion of mechanism36 clearly acknowledge that intervention mechanisms are fundamentally how people, providers and clients respond to particular (usually new) resources. As well as identifying the resource consumption required for intervention mechanisms to exist, realist review must also then identify the resource changes or commitments implicit in outcomes, and any resource implications of salient contexts.

Chapter 2 Aims and objectives

Aim

The overall aim of this synthesis was to understand how, when and why the use of the STOPP/START tools improves medicines management in older people.

Objectives

The objectives were as follows:

-

to identify the ideas and assumptions (programme theories) underlying how interventions based on STOPP/START tools are intended to work, for whom, in what circumstances and why, and to test and to refine these programme theories to explain how contextual factors shape the mechanisms through which the STOPP/START tools produce better outcomes for patients

-

to identify and describe the resource use, cost requirements or impacts of the different context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configurations.

Chapter 3 Methods

A realist synthesis was conducted following Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES II) guidelines for realist synthesis. 37 The approach was chosen to inform the implementation of initiatives using STOPP/START tools, as it recognises that interventions are not universally successful and that outcomes are context dependent. 35 Realist synthesis is a theory-based approach that seeks to explain how context shapes the mechanisms through which programmes produce intended and unintended outcomes. 35 This is accomplished through the identification and refinement of underlying programme theories. These seek to explain how the generative mechanisms triggered by the resources offered by the intervention or programme are shaped by conditions or contexts, and the pattern of outcomes produced. In this case, context refers to the ways in which the intervention is designed and the circumstances in which the intervention is implemented, which may either support or constrain how participants respond to the intervention, whereas outcome refers to both the intended and unintended effects of the intervention on participants.

The study was registered in the International prospective register of systematic reviews PROSPERO 2018 CRD42018110795: Jaheeda Gangannagaripalli, Joanne Greenhalgh, Rob Anderson, Ian Porter, Simon Briscoe, Emma Cockcroft, Carmel Hughes, Rupert Payne, Jim Harris, Ignacio Ricci-Cabello, Jose M Valderas. How, when and why do STOPP/START tools-based interventions improve medicines management for older people: a realist synthesis. URL: www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?ID=CRD42018110795.

Phase 1: identification of programme theories

In this phase we identified programme theories or ideas and assumptions about how the STOPP/START tools are intended to work, for whom, in what contexts, why (e.g. ideas about what drug groups and/or conditions these tools applied to, and why they do not work and in what patient population) and whether or not (and how) patients are being involved in shared decision-making in stopping or starting medicines. STOPP/START-based interventions are clearly primarily intended to improve health and avoid harms. Therefore, in phase 1 of the review, we did not actively seek theoretical mechanisms that exclusively explain the cost or cost-effectiveness of STOPP/START-based interventions, but rather sought to identify and make explicit which underlying CMOs are resource-consuming or cost-generating, in what ways and to what extent. The aim of this first phase of realist synthesis was to capture in detail the reasoning that underlies the intended outcomes of an intervention.

In summary, we produced a longlist of programme theories with CMO configurations (from peer-reviewed and grey literature, interviews with experts and PPI consultations) that were refined to a single logic model structured around three key mechanisms (embedded within specific sets of CMO configurations) through which STOPP/START tools were expected to work (i.e. personalisation, systematisation and evidence implementation).

Search strategy

We carried out searches of relevant bibliographic databases to identify theories and assumptions about how the STOPP/START tools are intended to work. The search aimed to identify position pieces, commentaries, letters, editorials and critical pieces on the STOPP/START tools wherein theories and assumptions about the tool would be discussed, but not necessarily tested. The search strategy was developed using MEDLINE (via Ovid) by an information specialist (SB) in consultation with the review team. A combination of indexing terms (e.g. medical subject headings in MEDLINE) and free-text terms (i.e. title and abstract terms in the bibliographic records) were used. We included search terms that described the STOPP/START tools combined with a published publication-type search filter that included search terms such as ‘comment’, ‘letter’, ‘opinion’, ‘views’ and ‘news or newspaper article’. 38 A publication date limit of 2008 to the date of the search was applied. No English-language filter was applied.

The search strategy was finalised in MEDLINE and translated for use in a selection of relevant bibliographic databases, including:

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (via EBSCOhost)

-

EMBASE (via Ovid)

-

Health Management information Consortium (HMIC) database (via Ovid).

The search strategies for all databases and the number of hits retrieved per database are reported in Appendix 2, Tables 8–11. Searches of all databases were carried out on 29 October 2018. The results were exported to EndNote X8 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and de-duplicated using the automated de-duplication feature and manual checking.

Screening

Documents were selected based on relevance (i.e. whether or not data could contribute to theory building). A random sample of 10% of articles were selected, read, assessed and discussed by three reviewers (JBG, JG and JMV) using a preliminary set of inclusion/exclusion criteria (Box 1).

-

The paper describes how STOPP/START tools and/or STOPP/START tools-based interventions work, which may or may not include a formal theoretical framework.

-

The paper reviews ideas and/or provides a critique about how STOPP/START tools and/or STOPP/START tools-based interventions are intended to work.

-

The paper provides opinions of how STOPP/START tools and/or STOPP/START tools-based interventions do/do not work.

-

The paper outlines, discusses or reviews problems with the implementation of STOPP/START tools and/or STOPP/START tools-based interventions.

-

The paper outlines, discusses or reviews potential unintended consequences of STOPP/START tools and/or STOPP/START tools-based interventions.

-

Studies including children and adults aged < 65 years.

The remaining 90% of articles were completed by the same reviewers independently. However, a number of these necessitated discussion between the reviewers, as they were pivotal papers or difficult to understand/integrate. (In realist reviews, the study itself is rarely used as the unit of analysis. Instead, realist reviews may consider small sections of the primary study, e.g. the introduction or discussion sections, to test a very specific hypothesis about the relationships between CMOs.)39 We therefore refined our studies based on the knowledge we acquired about the theory development of the impact of the STOPP/START tools. At the end of this process, we retained the papers that provided the clearest examples of the ideas underpinning STOPP/START-based interventions.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for searches in phase 1

Data extraction

The realist review method obtained information by note-taking and annotation rather than standardised data extraction (using a specific software or data extraction form), as used in a traditional systematic review. Documents were examined for data that contributed to theories on how an intervention was supposed to work, which were then highlighted, noted and given an appropriate label. Three researchers (JBG, JG and JMV) initially extracted information from a small set of documents to ensure consistency and then each of them extracted information separately for a subset of papers. The information was subsequently organised by one researcher (JBG). Quality appraisal is integrated into the synthesis narrative, rather than reported separately. Formal quality assessment was not undertaken as part of phase 1.

Synthesis and strategy for prioritisation and finalisation of the candidate programme theories

The final candidate theories were summarised through narrative synthesis, using text, summary tables and a single logic model to summarise individual papers/reports and draw insights across papers/reports.

The initial set of theories on how STOPP/START-based interventions are intended to work were informed by the following steps:

-

searching and identifying programme theories from the literature

-

qualitative interviews with experts in the field

-

ongoing engagement with PPI, including two workshops to ground the study in real-life experience.

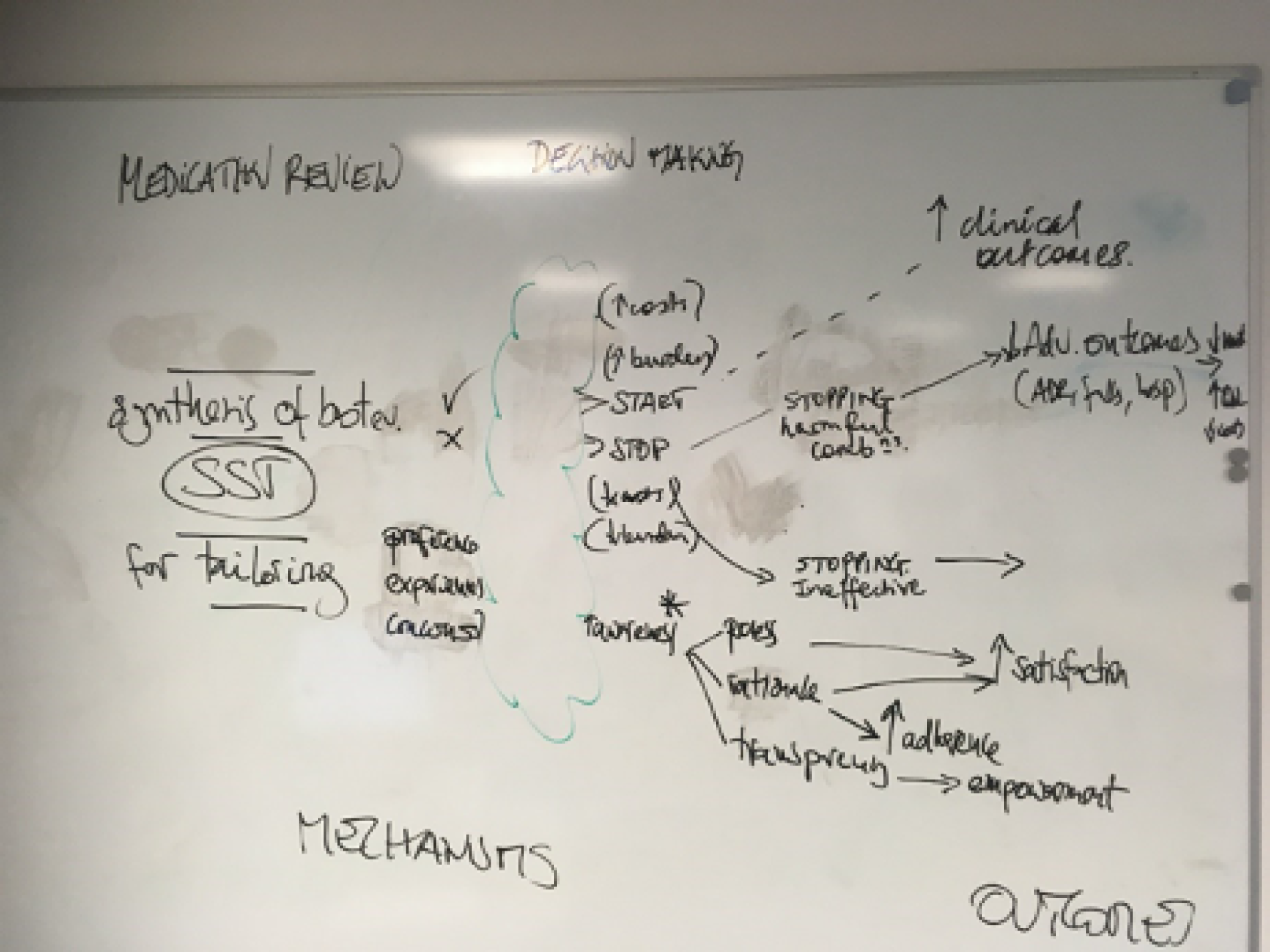

The initial list of draft theories from the literature, findings from the interviews and refined list of draft theories from an initial meeting with the Patient Advisory Group were presented to the project team in February 2019. Following productive discussions among the team members, a narrative of each draft theory was developed during the meeting. The group was asked to reflect on the triangulation of findings, to validate theories and to prioritise those appropriate for realist review. From working with the group, we were able to discuss and produce a flow chart with emerging examples of the causal links between CMOs. After working and reworking on the flow chart, we were able to develop the first draft of the single logic model (see Appendix 3, Figure 16). The draft model was circulated to the project team, and with the subsequent feedback we produced the candidate programme theories.

Interviews with experts

To prioritise the most important or explanatory programme theories, we consulted topic experts, NHS stakeholders and a patient group. Expert consultations were achieved through ongoing conversations with experts in the field on why the STOPP/START tools work, who they work for, in what circumstances and why. This involved semistructured interviews with experts to triangulate the emerging theories resulting from the literature review. Given the scope and the realist nature of these interviews (i.e. realist hypotheses are confirmed or abandoned not through saturation but rather through relevance and rigour), we expected that approximately 10 interviews would meet our needs, although the final number was confirmed by how interviews uncovered how emerging mechanistic and contextual factors might contribute to the outcome patterns emerging from the empirical literature. 35,40

We aimed to include and recruited clinicians with a special interest in medicines optimisation, drug safety and pharmacotherapy, experts involved in medicines optimisation at NHS RightCare (Leeds, UK), providers of care in primary and secondary care [e.g. geriatricians, general practitioners (GPs) and other clinicians], care home managers, and academics and those involved in developing education and guidance for older people. In addition, researchers involved in the development of the STOPP/START tools were recruited through Academic Health Science Networks, Clinical Research Networks, the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) and through co-applicant networks. Following the advice from the board, we considered inviting British Geriatrics Society (BGS) experts. We also considered inviting contributors to the NHS England Toolkit for General Practice in Supporting Older People Living with Frailty41 and the NICE Multimorbidity Guideline Committee. 42 Ethics approval for the interviews was granted by the University of Exeter Medical School Research Ethics Committee on 19 November 2018 (reference RG/CB/18/09/181).

Interviews were based on a pre-established stakeholder topic guide (see Appendix 4) that was developed collaboratively by three of the researchers (JBG, JG and JMV) and based on the emerging findings of the literature review. Interviews were planned to last up to 30 minutes and were conducted either face to face or by telephone at the participant’s convenience. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and analysed thematically by two researchers (JG and IP)43 to expand and refine our programme theories. The purpose of the expert interviews was threefold: (1) to gain input on our list of candidate CMO configurations, (2) to identify additional CMO configurations and (3) to identify additional literature and/or relevant concepts that we may have missed. This was supported by further literature searches in this phase. Interviews were conducted after the patient advisory meeting and before completing candidate theory development.

Phase 2: testing the theory

Phase 2 tested the programme theories obtained from phase 1 (through exploratory search and expert consultation) by synthesising using published and unpublished empirical quantitative and qualitative evidence.

Search strategy

The search to identify studies to test the programme theory included searches of bibliographic databases, checking the reference lists of included studies, forwards citation searching of included studies and searching the websites of relevant organisations. The bibliographic database search was developed using MEDLINE (via Ovid) by an information specialist (SB) in consultation with the review team. We developed a highly sensitive search that identified all studies that mentioned the STOPP/START tools in the title or abstract fields of the databases searched. No publication-type filter or any other search terms were used. This approach was taken because the number of hits retrieved by searching for STOPP/START tools terminology was feasible to screen in full by two reviewers within the available time and resources. Therefore, the strategies were not designed to target the evidence for prioritised theories, but were very broad and aimed at identifying all empirical studies of interventions based on the use of STOPP/START tools. No indexing (e.g. medical subject headings in MEDLINE) was used, as we did not identify any indexing terms for the STOPP/START tools that were not also used for other prescribing tools. A publication date limit of 2008 to the date of the search was applied. No English-language filter was applied.

The final search strategy was finalised in MEDLINE and translated for use in a selection of relevant bibliographic databases. The full set of bibliographic databases searched included:

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (via Cochrane Library)

-

CINAHL (via EBSCOhost)

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR) (via Cochrane Library)

-

EMBASE (via Ovid)

-

HMIC (via Ovid)

-

MEDLINE (via Ovid)

-

NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) (via the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination website)

-

Social Policy & Practice (via Ovid).

The search strategies for all databases and the number of hits retrieved per database are reported in Appendix 5, Tables 12–19. Searches of all databases were carried out on 11 June 2019. The results were exported to EndNote X8 and de-duplicated using the automated de-duplication feature and manual checking.

The reference lists of included studies identified by the bibliographic database searches were manually inspected. Forward citation searching of included studies was carried out on 11 October 2019 using, primarily, Web of Science. If a study was not indexed in Web of Science, we used Scopus or Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) instead, depending on where the study was indexed. The results of forward citation searching were exported to EndNote X8 and de-duplicated before screening.

We searched the repository for grey literature (i.e. OpenGrey). The searches and number of hits are reported in Appendix 6, Table 20. URLs that linked to the search results were sent to the review team by e-mail for screening.

We additionally searched the websites of the following organisations on 11 October 2019 (see Appendix 6):

-

Age UK (URL: www.bgs.org.uk/search/node)

-

BGS (URL: www.bgs.org.uk).

Screening

In realist reviews, the study itself is rarely used as the unit of analysis. Instead, realist reviews may consider small sections of the primary study (e.g. the introduction or discussion sections, to test a very specific hypothesis about the relationships between CMOs). 39 We therefore assessed studies based on the knowledge we acquired about the theory development of the impact of the STOPP/START tools. Title and abstract screening were carried out by three reviewers (AD, IP and IRC) in Rayyan (Rayyan Software/Qatar Computing Research Institute, Doha, Qatar), with JMV resolving discrepancies (Box 2).

-

The paper describes the evaluation of an intervention (medication reviews or equivalent) using STOPP/START tools or the paper presents an economic evaluation and/or cost analysis of STOPP/START-based interventions.

-

The patient population of the study is adults aged ≥ 65 years.

-

The study reported in the paper has any of the following designs: comparative effectiveness study (e.g. a RCT), process evaluation, review of primary research (if method is stated), qualitative research, surveys, history, descriptions of models of care, uncontrolled before and after, cohort and reanalysis of routine data, systematic reviews and narrative reviews.

-

Studies including children and adults aged < 65 years.

-

Intervention: not a medication review or where review takes place but does not explicitly use STOPP/START tools (although if any doubt include at this stage).

-

Study design/publication type: editorials, opinion pieces and advertorials.

-

Abstract only (no full text exists).

-

Protocols of ongoing reviews.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria for documents for phase 2

Data extraction

The realist review method obtains information by note-taking and annotation rather than standardised data extraction, as used in a traditional systematic review. Documents are examined for data that contribute to theories on how an intervention is supposed to work, which are then highlighted, noted and given an approximate label. The reviewer may make use of forms to assist the sifting, sorting and annotation of primary source materials, but do not take the form of a single standard list of questions, as used in a traditional systematic review. As such, we created a reference framework to guide extraction, which was intended to be a guide through the process, rather than to be applied in a routine one-size-fits-all manner. The extraction framework had three sections:

-

Standard information collected on all studies (e.g. year, author, title, study type, aims, outcomes, etc.).

-

Evidence of CMOs in studies to support the candidate programme theories.

-

Evidence in studies to refute/refine CMOs in the candidate programme theories.

The data extraction form was piloted by four reviewers (JMV, IP, JBG and AD) and approved by other project team members. The form was then used to extract the above information from all included studies by four reviewers (IP, JBG, AD and IRC). IP was responsible for co-ordinating and merging the data extracts from all the reviewers.

Quality appraisal

Quality assessment used the concept of rigour (i.e. whether or not the methods used to generate the relevant data are credible and trustworthy). Sources were classified as conceptually rich (thick) or weak (thin). This strategy has been found to be practical and useful in theory-driven synthesis, as it allows the reviewer to focus on the stronger sources of programme theories without excluding weaker sources that may make an important contribution. Quality appraisal from this perspective is integrated into the synthesis narrative, rather than reported separately.

Appraisal tools may also be used to determine rigour if appropriate. 44 We used the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme45 to further determine the rigour of the included studies. The importance of transparency in a realist review is similar to that of systematic reviews to ensure the validity, reliability and verifiability of findings and conclusions. 39,44 With the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme, study quality was considered low if half or less than half of the criteria were met, medium if more than half but less than three-quarters of the criteria were met, and high if most were met. 46 The scores were produced, summed and ranked high and medium quality for both randomised and non-randomised studies.

Data synthesis

Synthesis of the diverse sources of evidence was conducted through a structured process that included the following approaches:

-

Juxtaposition of sources of evidence (e.g. where evidence about the STOPP/START tools from one source enables insights into evidence about outcomes from another source).

-

Reconciling of sources of evidence (i.e. where results differ in apparently similar circumstances, further investigation is appropriate to find explanations of why these different results occurred).

-

Adjudication of sources of evidence (on the basis of methodological strengths or weaknesses). 47

-

Consolidation of sources of evidence (i.e. where outcomes differ in particular contexts, an explanation can be constructed of how and why these outcomes occur differently).

Based on the standardised information extracted for each study, each intervention was assigned to one or more mechanisms by consensus from two of the reviewers (IP and JMV).

For each causal link leading in the logic models, we summarised the number and quality of studies supporting, refuting or qualifying it. We first categorised the link’s evidential support in each study as providing:

-

no evidence (where the study did not provide any empirical evidence on the link)

-

positive evidence (where there were studies providing empirical evidence supporting the link in the direction predicted by the logic model)

-

negative evidence (where there were studies providing empirical evidence on the link but not in the direction predicted by the logic model or the associations did not reach statistical significance).

We further categorised the strength of each causal link’s evidential support across all studies as:

-

positive evidence [i.e. having a substantial majority of positive evidence studies (> 70%)]

-

mixed evidence (i.e. having both positive and negative evidence studies and both categories exceeding 30% of studies)

-

negative evidence [i.e. having a substantial majority of negative evidence studies (> 70%)]

-

no evidence (i.e. all studies classified as providing ‘no evidence’).

Patient and public involvement

The PPI lead used her extensive contacts to establish and manage a patient group that worked with us throughout the review. A group of five older people with experience of taking multiple medicines assisted in theory development, shaping the focus of the review after screening and synthesis stages in the review process, interpretation and dissemination of findings. The group consisted of five patients (two men and three women) who were all aged ≥ 50 years, with multiple health conditions and taking multiple medications. The role on the advisory group for this project was advertised to a larger Patient Advisory Group (i.e. Peninsula Public Involvement Group), which is part of the National Institute for Health Research Applied Research Collaboration South West Peninsula. The group provided regular feedback on documents and met regularly to support and provide direction to the research.

We worked with the Patient Advisory Group at all phases of the project to ensure that the research questions and outcomes of interest remained important and aligned to the needs of patients, and the group members was particularly critical in supporting key stages of the project. Specific Patient Advisory Group meetings were organised to address key issues that arose during the implementation of the review:

-

Further review of the application in the light of the feedback received and finalising the protocol, once funding is in place. This meeting was replaced with the development of an initial list of draft theories.

-

Discussion with reviewers in relation to the screening criteria. This was not considered important, as the screening criteria were very short and succinct and we did not think that holding a meeting was an efficient use of resources. Instead, we worked further with the Patient Advisory Group to refine the programme theories.

-

Interpretations of findings from the review.

-

Dissemination of the findings, including the preparation of the final report.

EC provided support and training for patient representatives, which included an introduction to realist synthesis. The patient co-applicant (JH) attended all research project team meetings. This ensured that all discussions throughout the project were informed by patient experience.

Chapter 4 Results: identification of the programme theories

Phase 1 literature search results

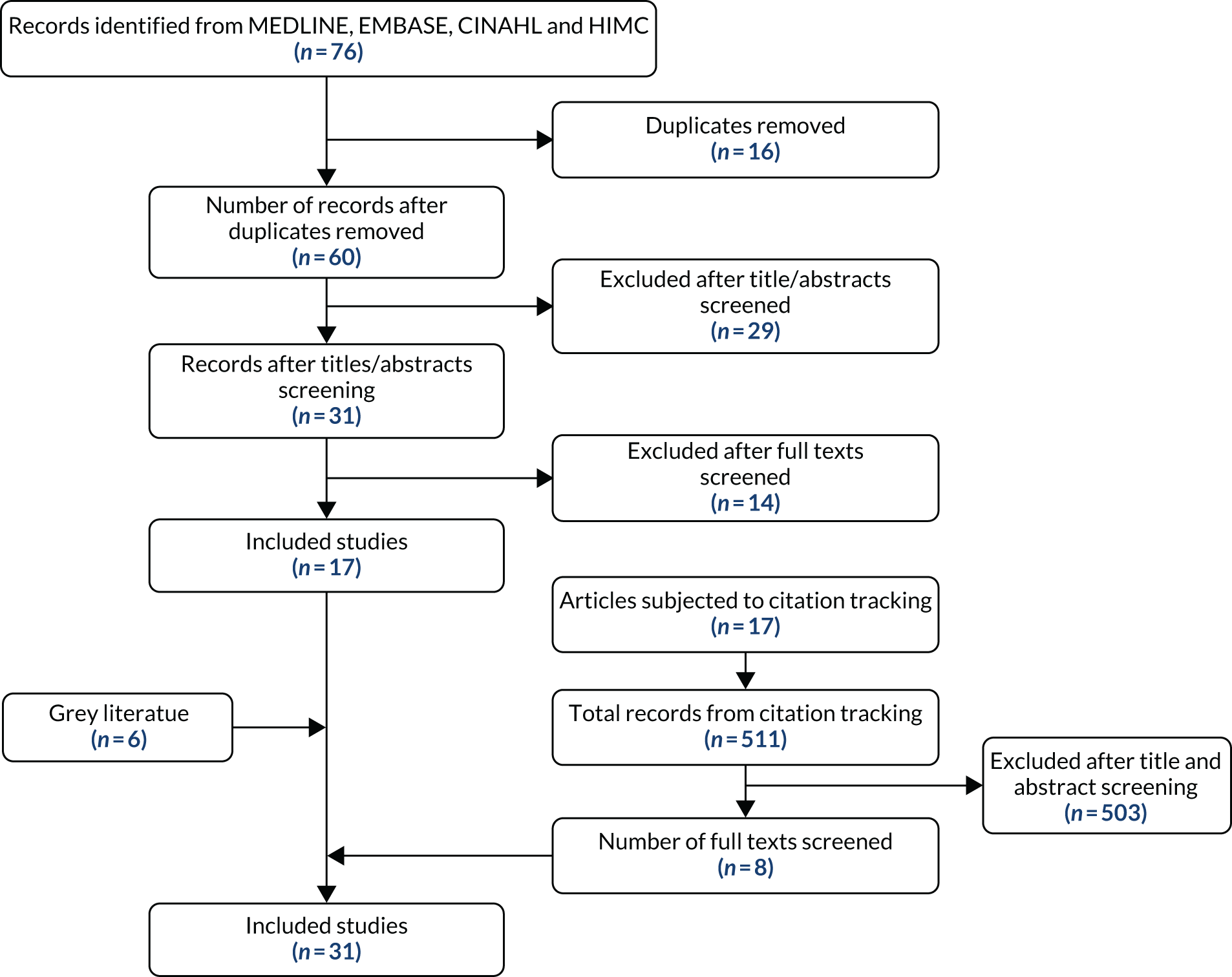

Sixty studies were identified after de-duplication in the initial search (Table 1). Thirty-one abstracts were selected after sifting. At full-text screening, 17 papers were selected for inclusion, as they provided the clearest examples of the ideas underpinning STOPP/START-based interventions. Forwards and backwards citation tracking of the 17 key articles, and additional iterative searches in Google as key subtheories emerged (Google search first 10 pages) identified a further 14 papers. The full texts of these papers were then read and notes were taken about the key ideas and assumptions regarding how the STOPP/START-based interventions were intended to work. Of the 31 papers identified, eight were purposively selected as ‘best exemplars’ of the ideas reflected in the papers as a whole. Regular discussion of these ideas among the project group and circulation and feedback of draft working papers outlining the theories ensured that the full range of different theories was represented. Figure 1 summarises the flow of studies from identification through to inclusion in the final document.

| Database | Number of documents |

|---|---|

| MEDLINE and MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations | 29 |

| EMBASE | 37 |

| HMIC | 5 |

| CINAHL | 5 |

| Total results | 76 |

| Unique results | 60 |

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram for identification of relevant documents for theory development.

Initial programme theories from the literature

How is the underlying problem conceptualised?

Chronic diseases and multiple medical conditions prevail in older people; therefore, there is a high prevalence of polypharmacy, which has been associated with negative health outcomes. 5 Lack of awareness of pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics changes in older people can contribute to inappropriate medicine use, resulting in adverse drug effects. Some of these reactions may be confused with progression of the given pathology or with some typical age-related syndromes. 48

The risks of potentially inappropriate medications outweigh their benefits, especially when a safer or more effective alternative therapy is available. The use of potentially inappropriate medications is considered a major problem among older people, and may contribute to increased risk of adverse drug effects and to developing drug–drug and drug–disease interactions. 19

Patients are often treated by different clinicians following either an outpatient visit or an acute admission, and the consultant may not be aware of the existing medication that a patient may be on. Most often, these health conditions are treated in general practice, which results in the attribution to GPs of the responsibility of whether or not prescribing has taken into account the patient’s clinical history.

Role of the professionals in prescribing: who does what?

Professional boundaries play a key role in prescribing practices. There is an implicit assumption that clinicians with expertise in older people (e.g. geriatric pharmacotherapists) will be more aware of medications that are inappropriate for older people. There are different perspectives on the onus being on GPs or consultants to ensure that they prescribe drugs that do not lead to drug–drug interactions or ADEs, compared with pharmacists picking these issues up during a review of medications. Furthermore, if GPs identify these problems, it remains to be determined if and how GPs can change/challenge the prescribing of consultants, or reflect on their own prescribing practice or that of their colleagues. Finally, if and when pharmacists pick these up, it is unclear if (and, if so, how) pharmacists can challenge or modify prescribing by GPs or consultants.

These challenges operate within existing sets of expertise, relationships, professional boundaries and remits between GPs, consultants, pharmacists and nurse prescribers. These play out on a ‘macro/meso level’ in terms of national/professional norms that exist about the remit of different practitioners and the expertise of specialists compared with generalists, but is also subject to local variations in the ways in which these different clinicians work together. They are also likely to be influenced by the existing relationship and knowledge a GP or a consultant has with a patient (and therefore their knowledge about their history, etc.). These sets of relationships form an important background against which the STOPP/START tools are used.

Context of a STOPP/START medication review

To address these problems, current NICE guidance on medicines optimisation includes as a recommendation to consider using a screening tool for adults such as the STOPP/START to identify potential medicines related patient safety incidents in some groups of people, especially in relation to adults taking multiple medicines (polypharmacy) and adults with chronic or long-term conditions and older people. 32 Medication reviews can take several forms and vary in terms of their comprehensiveness, purpose and whether or not the patient is present during the review. Medication reviews could be carried out by the prescribers themselves or by an independent reviewer (usually a pharmacist). However, in the immediate context of the medication review, the process of the review might position them differently, either as someone reflecting on their own prescribing and making changes to their own practice, or as someone who is reviewing another clinician’s practice or decisions and therefore attempting to change their practice. Most of these patients are seen by a number of different physicians/prescribers, each of them with a partial knowledge of the patient, the patient’s problems and the medications. This makes it unlikely that anybody could use it for reviewing their own prescribing. The only exception (certainly at a stretch) would be the GP. This has a number of implications for thinking about the context in which the STOPP/START tools are used, how we conceptualise any programme theories and the kinds of higher-level theories we might draw on to think about it:

-

It changes the nature of the intervention and the underlying assumptions about how it is intended to work (i.e. it changes the programme theories).

-

It has implications for the broader theories that might come into play to think about the relevant contextual factors that might shape the intervention. For example, if it is about reviewing and making changes to someone else’s prescribing decisions or behaviour, theories about interprofessional boundaries come into play, and if it is about reviewing own practice then audit and feedback theories might come into play.

Some types of review are carried out in the absence of the patient (e.g. prescription reviews), whereas others are carried out with the patient present (e.g. a ‘clinical medication review’). Therefore, the type and nature of the medication review will also form an important context that might shape how STOPP/START tools work, especially in relation to some of the programme theories around patient-centred care. Several pieces of guidance advocate the use of the STOPP/START or other tools to assist in these processes. Exactly how they are intended to assist and, therefore, the underlying programme theories about their use vary.

What resources do STOPP/START tools offer?

The STOPP/START tools provide a comprehensive list of medications that clinicians should consider stopping in older people generally or, for some medications, in older people with certain conditions. In addition, they provide a list of medications that clinicians should consider starting if certain conditions are met.

Positive programme theories about how they are expected to work are as follows:

-

The STOPP/START tools provide a systematic and structured way of carrying out the medication review process (resource). The assumption is that clinicians will use the tools to structure the way in which the review is carried out [i.e. the tools could either replace the usual way in which the task is carried out or the tools might somehow integrate the structure provided by the tool with usual practice (mechanism)]. The use of a more structured approach is expected to enable the clinician to identify a larger number of potentially inappropriate medications, ADRs or unmet need than if clinical judgement had been used alone (outcome).

-

As the STOPP/START tools are evidence based, comprehensive and structured, the assumption is that they can be used with little need for clinical judgement (mechanism) and, therefore, can be used by a range of clinicians who may not be specialists (context) in older people to identify potentially inappropriate medication. This in turn increases the capacity for medication reviews to take place, rather than just to rely on clinicians who are specialists in older people.

-

The identification of potentially inappropriate medications using the STOPP/START tools will prompt the clinician to start or guide discussion with the patient about whether they wish to stop or start particular medications and what their priorities are (mechanism), which is expected to result in care that is more patient centred (outcome). However, this is likely to depend on whether or not the patient is actually present at the review (context).

These theories envisage STOPP/START tools as screening tools and a means of identifying problems. However, to work this way, this assumes a number of contextual features being present or that certain mechanisms will trigger these features. These include the following:

-

The clinician undertaking the review either knows about, or is able to access information about, the patient’s existing conditions and existing medication.

-

The clinician undertaking the review agrees with the criteria set out in the tool (i.e. they do not clash with clinical judgement).

-

The clinician undertaking the review has the time to go through the entire tool systematically.

-

Clinicians will know how to act when potentially inappropriate medications have been identified and that the clinician will discuss this with the patient.

We identified a number of opposing theories about STOPP/START tools that are expected to work:

-

The STOPP/START tools offer resources that enable clinicians to identify potential medication problems, it does not provide resources about the context of the individual patient in terms of how these criteria apply to specific patients. Therefore, the clinician needs to integrate their clinical judgement, information gathered from a discussion with the patient and the alerts from the STOPP/START tools (mechanism) to make a decision about whether to stop or start any medicines (outcome). This challenges the idea that the tool can be used without the need for clinical judgement and raises questions about the degree of specialist knowledge that is needed.

-

Some authors have argued that one of the reasons why a clinician’s use of the tool may not enable them to identify as many potentially inappropriate medicines (outcome) is because clinicians do not use it ‘rigorously’, implying that clinicians ignore some of the alerts identified through the tool and therefore do not follow through on stopping medication when the tool guidance identifies it as potentially inappropriate (mechanism). This theory implies that the tool is intended to act not just as a means of identifying problems, but as a decision support tool whereby the tool acts as an instruction to decisions (i.e. the guidance should be followed, not just considered). This implies that clinical judgement is not required.

These two different positions highlight the contested nature of the tools and their role and purpose vis-à-vis clinical judgement and patient input. One set of theories position the tools as something that provides advice or alerts to clinicians, whereas the other set of theories position the tools as decision support tools:

-

Paper versions of the tools (resource/context) are time-consuming to use and require familiarity with the content of the tools (context). As many clinicians do not have time or are not familiar with their content (context), they do not use the tools or skim over them (mechanism) and this means that potentially inappropriate medications are missed (outcome).

-

Clinicians may not have all the information to hand (context) and so they are unable to use the tools to carry out the review with the full information (mechanism).

Potential solutions to these two problems are as follows:

-

STOPP/START tools should be used electronically (context) and the clinician using the tool can draw on information in a patient’s electronic health record to carry out the review.

-

It may be possible to design an algorithm based on the tools that carries out the review automatically (context) and simply presents the clinician with an alert about potentially inappropriate medications (resource). The clinician is then expected to accept and trust this alert and follow through on the advice accordingly (mechanism).

We might also consider a further set of theories a bit further down the implementation chain about how, when and why clinicians do actually make prescribing changes based on the use of the tool. This might depend on who uses the tool (e.g. a pharmacist), their remit to instigate changes and who actually makes the prescribing changes (e.g. GP, consultant) and the roles, remits and relationships between these different social actors. For example, if a pharmacist uses the tool to conduct a review, they may only be able to advise what changes might need to be made to either the GP or the consultant, who may choose to follow this advice or may choose to ignore it.

We further discussed the initial theories that arose from the literature and developed the succinct list of theories (Table 2).

| Question | Theory |

|---|---|

| Why these tools? |

|

| To what aim should they be used? |

|

| How to use them? |

|

| How should they be implemented? |

|

Expert interviews

Eleven semistructured interviews were conducted with experts in the field (i.e. GPs, geriatricians, pharmacists and academics) either face to face (n = 1) or by telephone (n = 10) at participants’ convenience (Table 3) (see Appendix 4 for interview topic guide). The one participant who attended a face-to-face interview was not reimbursed for travel, as she was an academic based in the University of Exeter. Eight participants were from the UK, one was from the Netherlands, one was from Canada and one was from Ireland.

| Characteristic | Number/range |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Female | 7 |

| Male | 4 |

| Age range (years) | 30–60 |

| Expertise | |

| STOPP/START developers | 1 |

| Academics | 4 |

| GPs | 6 |

| Geriatricians | 1 |

| Pharmacists | 4 |

A total of nine themes emerged from the analysis, which are discussed below.

Familiarity with STOPP/START tools

Some participants were very familiar with the STOPP/START tools and others had become familiar with it only recently. Participants reflected on how familiar different professional groups were with the STOPP/START tools. Some professionals (particularly GPs) seemed not to be familiar with the STOPP/START tools at all.

What are STOPP/START tools and what is their purpose?

Participants expressed mixed views about the role of STOPP/START tools in the decision-making process, such as whether patients should be involved in shared decision-making or if decisions should be solely the decision of the health-care professional. Some participants considered the STOPP/START tools as prompts and others considered the tools as checklists. In addition to supporting decision-making, some participants said that they can be used for improving prescribing appropriateness and some others said that they can be used as an education tool. Participants also discussed the need for using clinical knowledge and clinical judgement when applying the STOPP/START tools.

What are STOPP/START tools?

Some participants considered STOPP/START tools as prompts, some considered them as a good starting point and others perceived them as tools that can provide guidance. Others described the tools as a checklist and some participants considered them to be a structured approach for conducting medication reviews.

What is the purpose of STOPP/START tools?

Participants described the purpose of STOPP/START tools in different ways. Participants said that STOPP/START tools could be used as an educational tool and for improving quality of prescribing, changing culture, personalising care, shared decision-making and supporting evidence-based practice.

Some participants felt that STOPP/START tools are supposed to get prescribers to think about the appropriateness of the drug and others thought that they should be introduced as a part of a routine medication review process. Some participants proposed undertaking quality improvement activities around STOPP/START tools:

And I know certainly here we have HIQA [Health Information and Quality Authority], which is our health information and quality authority. I don’t know what the equivalent with you would be in the UK. I don’t know, but certainly here anyway, anyone who’s over the age of 75 and who has more than four medications, they’re obliged to have a 6-monthly structured medication review. And we recommend that you use a tool such as STOPP/START in doing that . . .

Interviewee 6, geriatrician

Some participants considered it an effort to enhance pharmacy expertise to bring about a change in culture in general practice:

I know that it depends on where exactly you work, but I think there is some funding from NHS England for pharmacy support. So, that’s one way of doing it. Seeing it as pharmacy thing and bringing that pharmacy expertise into practice and changing the culture.

Interviewee 5, GP

Participants considered STOPP/START tools to be individualised tools:

You start with the criteria but then you really have to apply them in a patient-oriented manner, think about the patient, what does the patient really want? For example, we have done some work in which we used goal attendance scaling of patients where we first asked the patients what do they really want and then, when the patient says, OK I don’t like drugs, I have too many drugs and you then start applying STOPP/START criteria . . .

Interviewee 3, pharmacist

Most of the participants felt that patients or carers should be involved in a shared decision-making process, but others did not think that patient enablement was part of their scope.

Participants mentioned that STOPP/START tools are aligned with NICE guidelines and provide the best evidence.

Participants described STOPP/START tools as educational tools for both professionals and patients, and particularly for professionals who may be unfamiliar with geriatric pharmacotherapy.

Target patients

Participants described which patients should be targeted, and proposed that those with multimorbidity and multiple medications might benefit most from the use of STOPP/START tools:

. . . but often, because of the cognitive problems with many older patients, they themselves may not be able to engage positively or negatively because of their cognitive problems. But that’s why we need to have a look at their medications to see if those medications are potentially causing cognitive problems or worsening the cognition, or if they’re going to survive long enough to derive any benefit from these drugs.

Interviewee 6, geriatrician

Appropriate setting

Participants expressed different views on the specific settings that STOPP/START tools would be applicable to, and considered primary care, hospitals, care homes and nursing homes as potential settings where they could be of value:

I very much feel STOPP/START feels like a hospital tool. It feels like the sort of tool you can use if you’ve got a fair bit of time with the patient, you are specifically seeing them for the review, and you’re going through the body system.

Interviewee 5, GP

In care homes, in – yeah in the elderly and the [inaudible 17.55] morbidity really because those are the ones that are most of risk of interactions and unnecessary drug side effects.

Interviewee 8, GP

One showing that in a nursing home environment that you can reduce the risk of falls the risk of hospitalisation over a 6-month period by intervening with STOPP and START criteria through multidisciplinary discussion and review of medications.

Interviewee 6, geriatrician

Professionals

Participants had mixed views about their role in the use of STOPP/START tools. Some participants said that they can be used by doctors (e.g. geriatricians or GPs), nurses [e.g. clinical nurse specialists, nurse consultants in geriatric medicine or practice nurses (diabetics/respiratory clinics)] or pharmacists (e.g. general practice pharmacists, hospital pharmacists or pharmacy technicians). Most of the participants proposed that a pharmacist as part of a multidisciplinary team and with access to the patient’s clinical history is the ideal professional to use STOPP/START tools.

It appears that the purpose of the tools is perceived by some as core to the scope of the practice of geriatricians. Some participants also believed that less experienced professionals could benefit more from using them than more experienced professionals, who may not benefit from using them at all. This may particularly be the case for geriatricians:

I think it can have a big impact. I mean the first example here is what we do so you know independent medication reviews – we use the patient notes and we have the patient there in a face-to-face encounter and we can make recommendations and follow them up so you know the STOPP/START interventions can have a huge impact on that as sort of guidance and I think, useful for people who are less experienced in medication review.

Interviewee 9, pharmacist

I think hospitals and geriatricians and, say, clinical nurse specialists, or nurse consultants in geriatric medicine, I think they have a role to play here as well. I think often GPs are very overburdened and they’re not geriatricians. GPs have to know about paediatrics, obstetrics, psychiatry, everything. I actually think that this kind of complex problem, perhaps geriatricians should have much more of a role and there should be much more of a demand for them.

Interviewee 6, geriatrician

I think the context of where you use it, I think contributes to the success of the tool because medication patient records are not available for example, at say the community pharmacy or in an emergency department or anything like that. I think there are issues around how the best places it’s got to be used or it can be used successfully.

Interviewee 10, pharmacist

Resources

Participants discussed various resources that would be needed for ensuring that STOPP/START tools would have the expected impact, including training, time, staff availability and costs.

Training and education

Some participants said that they would need training in using STOPP/START tools, whereas others were using it as a training tool. Some participants mentioned ongoing education as the most effective intervention.

Time

Participants expressed concerns about the time required to do medication reviews using STOPP/START tools. Some participants felt that they were very time-consuming processes and would not be ideal tools to squeeze into shorter consultations in primary care. Other participants agreed that using STOPP/START tools is time-consuming, but considered this to be within the scope of geriatric medicine.

Staff

Participants expressed concerns about lack of staff and staff availability, as medication reviews using STOPP/START tools need additional staff to carry out the review.

Costs

Participants said that implementing and performing medication reviews using STOPP/START tools would involve additional costs, if they are to be widely accessible.

Impact of the STOPP/START tools

Several participants expressed views about the degree of potential impact of using STOPP/START tools. Some participants were positive about their potential, whereas others reflected on several negative impacts.

Uncertainty about degree of potential impact and how to capture it

Participants were unsure about the degree of potential impact and expressed their views on how to capture it:

It’s difficult to say isn’t it, because I don’t think it seems to quantify the impact of the effects that you had necessarily, it’s not easy to say well definitely stopping that Zopiclone, will stop that fall, it’s hard to say . . .

Interviewee 4, pharmacist

Positive impact on quality of life and patient satisfaction

Participants perceived that STOPP/START tools could reduce hospital admissions, morbidity and mortality, and improve quality of life and patient satisfaction:

I have seen different things with patients around quality of life, so slowly reducing antipsychotics and sedating drugs to actually people then are no longer bed bound, sit in a chair or lounge, so you can see lots of really good impact when you actually start to take away reducing these medicines. I think it’s hard to quantify.

Interviewee 4, pharmacist

Challenges, barriers and facilitators for using the tools

Several challenges, barriers and facilitators were identified, including effective patient engagement, the user-friendly nature of the tools (or lack thereof), availability of electronic formats, accessibility and integration of the tools into existing systems.

Challenges

Participants recognised the difficulties in ensuring effective patient engagement and considered approaches for overcoming them:

I think it’s hard because it depends how it’s presented and I think it depends on the patient because there are some patients, you know of the people that I can think, there are some patients who absolutely want to be involved, they want to see, you know they want to know why, they want to know the evidence, they’d quite like to see a STOPP/START and this is why and be given the rationale for why you’re making suggestions and then equally there are other patients who don’t want to know.

Interviewee 9, pharmacist

Facilitators

Some participants described the STOPP/START tools as user-friendly. Some participants also believed that availability of electronic formats was crucial for uptake. Participants believed that one of the requirements for the tools to be used in daily practice is to make them widely accessible. Participants proposed that the tools be embedded in everyday practice for conducting medication reviews and integrated into existing systems. Leadership and incentivisation through inclusion and as part of quality improvement initiatives were also mentioned as relevant facilitators:

I suppose it would mean maybe somebody being a bit of a champion for it. I don’t know whether that would be just one lead GP who could disseminate the information and give a bit of training at a clinical meeting or something like that. That’s what I would probably do but whoever the lead GP is, they’d need a bit of sort of training on it.

Interviewee 2, GP

Barriers

Some other participants found the original version of the STOPP/START tools to be non-user-friendly, hefty and cumbersome. Lack of electronic versions was also considered a barrier to wider uptake.

Suggestions for implementation

Most of the participants were very keen to have automated, computerised STOPP/START tools, but they also raised concerns about the problems with implementation. Some participants felt that there needs to be a more sophisticated system to prioritise actions resulting from using the tools:

I think there is always a risk of information or alert overload, so I think perhaps prioritising intervention, to say OK which are the most dangerous or top 10 most risky, instances of potentially inappropriate prescribing and in fact that’s what we are doing with this study that we are just in the process of completing, we have identified the top 10 most common, well not just top 10, we have ranked the STOPP/START criteria in order of prevalence in our population . . .

Interviewee 7, GP

Patient and public involvement in theory development

The Patient Advisory Group provided support throughout the process of theory development, including helping to revise drafts and providing feedback. In addition, two meetings were convened with the Patient Advisory Group to discuss specific issues, provide feedback on the initial set of theories (see Appendix 7) and provide feedback on a subsequent subset of specific and key theories. There was also a discussion on other concepts and ideas considered as potential theories by the advisory team.

The first meeting took place before conducting the expert interviews. The aims of the project and the concept of a realist synthesis were presented. Instead of using the term ‘theory’ (which is complex), we instead used the term ‘idea’. In total, we had 29 ‘ideas statements’ that were focused on why, what, how and implementation. These simplified statements were derived from initial literature searches. Patients initially worked in two groups, each facilitated by one of the researchers. The groups worked through and discussed each statement. The groups were then asked to rank the ideas based on how important they thought it was to pursue that idea. Notes were made to capture discussions around this decision. In the final section of the workshop, a whole-group discussion was held to discuss the most important ideas (see Appendix 8).

In a subsequent meeting, 13 specific theories were shared with the advisory members who discussed if the statements were relevant or not important to pursue. Notes from discussions were captured by the PPI facilitator. The meetings finished with agreement among the group on which three theories should be taken forward.

Integration of the ideas and discussion from the Patient Advisory Group meetings into the wider project was ensured by (1) having researchers present at meetings to hear discussions first hand and (2) sharing notes around the wider research team and discussing these in project group meetings where decisions were finalised.

Key theories that emerged during the meetings are listed below:

-

Using STOPP/START tools enables patient preferences, concerns and experience to be taken into account, resulting in increased adherence, satisfaction and empowerment.

-

STOPP/START tools provide a structured approach that allows a greater reduction in unnecessary or harmful medication combinations, burden, adverse outcomes and resource use, which is more effective than relying on clinical judgement alone.

-

For STOPP/START tools to be effective, the clinician undertaking the review must have time to go through the entire tool systematically. Guidance should be followed, not just considered.

During the second meeting, there was also discussion around specific concepts or ideas that the group considered to be important as potential programme theories. The discussion focused on reluctance of pharmacists to take on the role and concerns about pharmacist limitations in knowledge authority and access to patient notes. Carers’ presence during the medication review was also highlighted and communication was suggested as a potential theory. One of the important issues considered in the meeting was the reason triggering the review. The advisory members provided the following examples of potential triggers:

-

the patient having problems

-

part of Quality and Outcomes Framework (‘tick-boxing’)

-

financial incentives.

Candidate theories

A refined list of theories produced from the literature and results from the interviews were discussed during project team meetings, which resulted in a comprehensive single logic model of how STOPP/START-based interventions operate (see Appendix 3). For convenience, this single model is presented in relation to three different mechanisms.

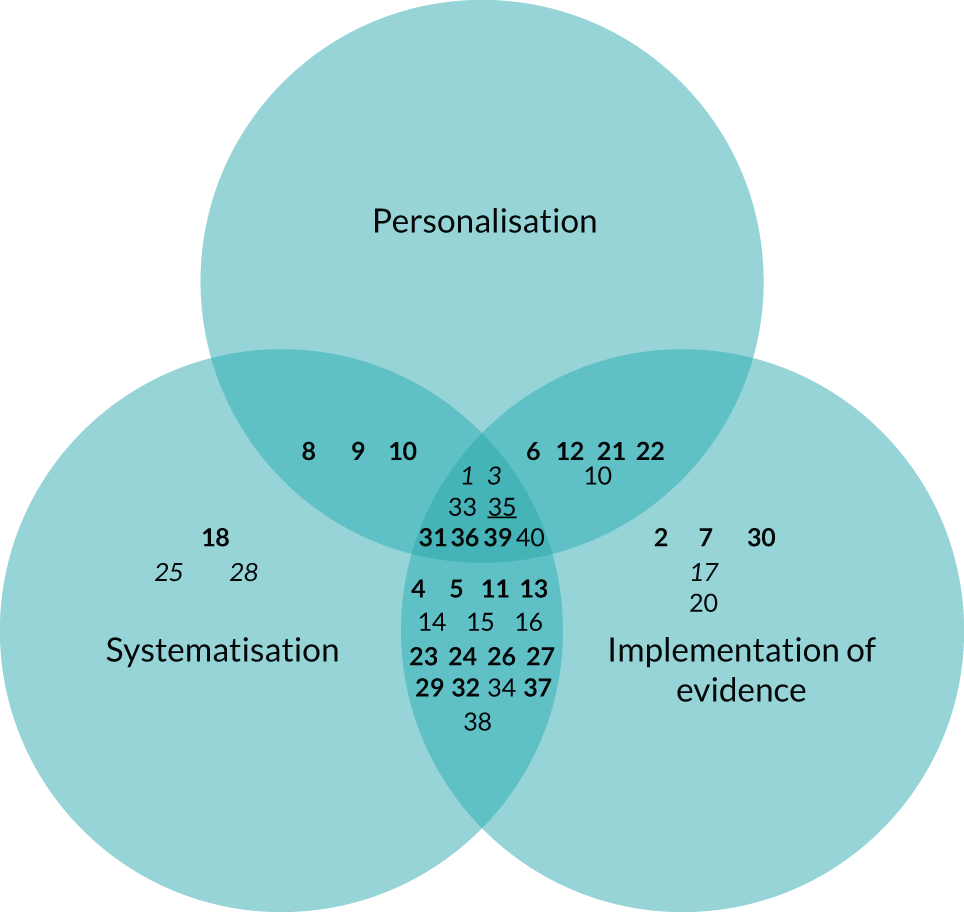

Three main mechanisms were identified: (1) personalisation of the medication review, (2) systematisation of medication review processes and (3) implementation of evidence. These mechanisms are used as the organising principle of programme theories. It was hypothesised that each of these mechanisms has a strong association with particular contexts and outcomes, which we outline below. That is not to say that these are unique or the only possible combinations; however, these are the mechanisms that we consider at this stage to be the strongest. They are not mutually exclusive, but rather are expected to work synergistically. However, the focus was on testing each of the programme theories separately, which, depending on the evidence, would be rejected or refined.

A refined list of theories produced from the literature and from the interviews was developed by the project team. The list was extensively discussed during a project face-to-face team meeting and follow-up consultation, which resulted in a comprehensive single logic model of how STOPP/START interventions operate.

We presented the initial list of theories to the PPI advisory team. Following productive discussions, the PPI advisory group rated the theories based on their perceived importance (see Appendix 8) and provided additional feedback. This information was used to prioritise theories for the subsequent (testing) phase.

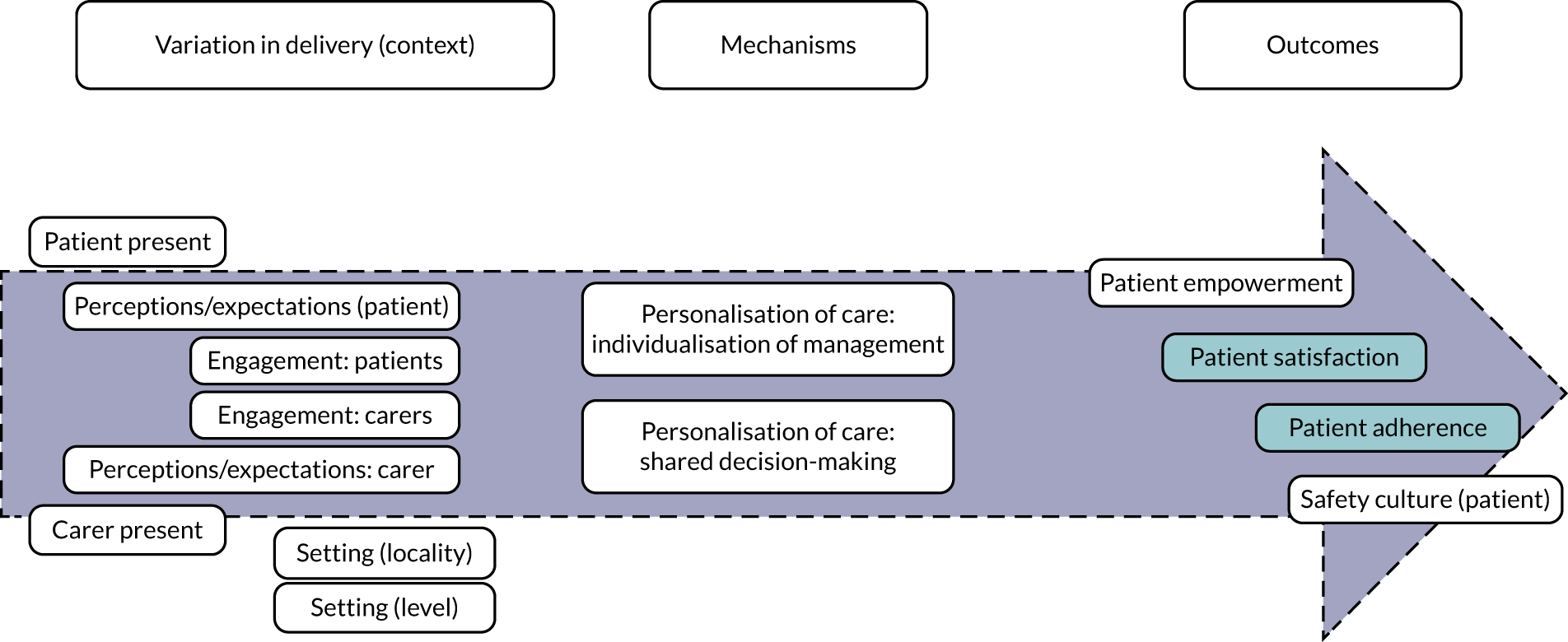

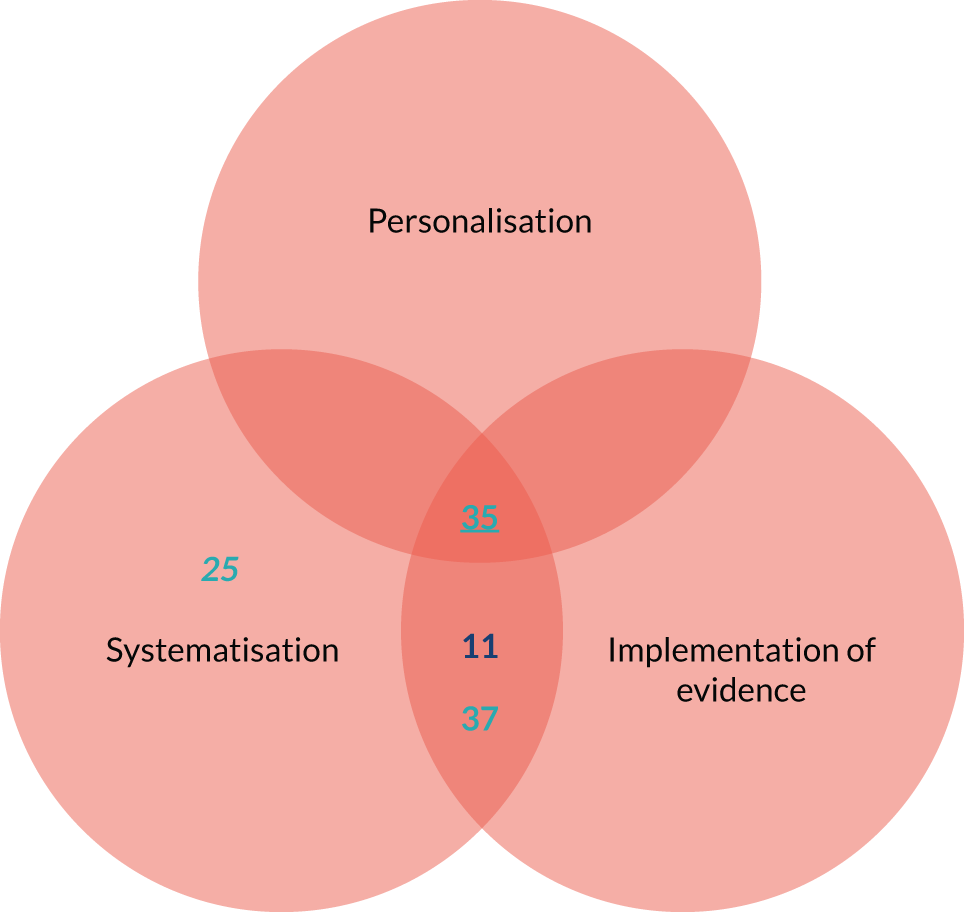

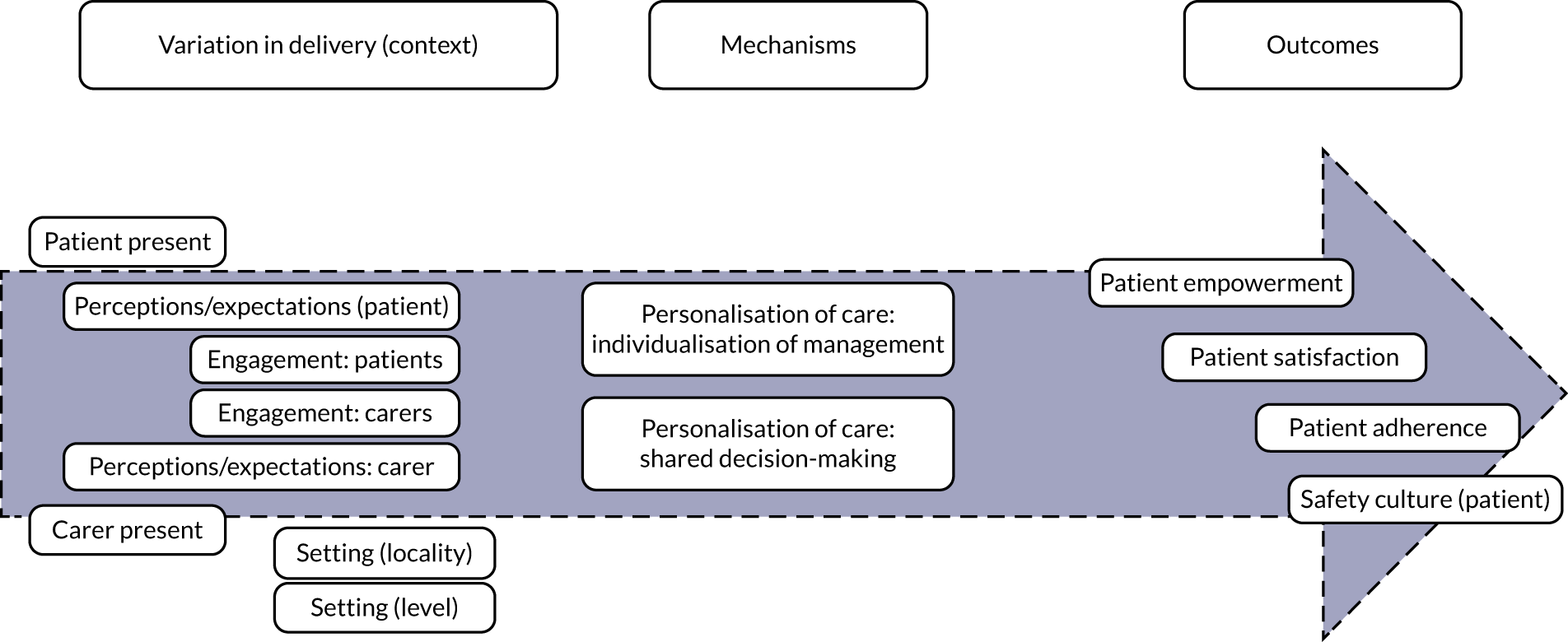

Personalisation of the medication review

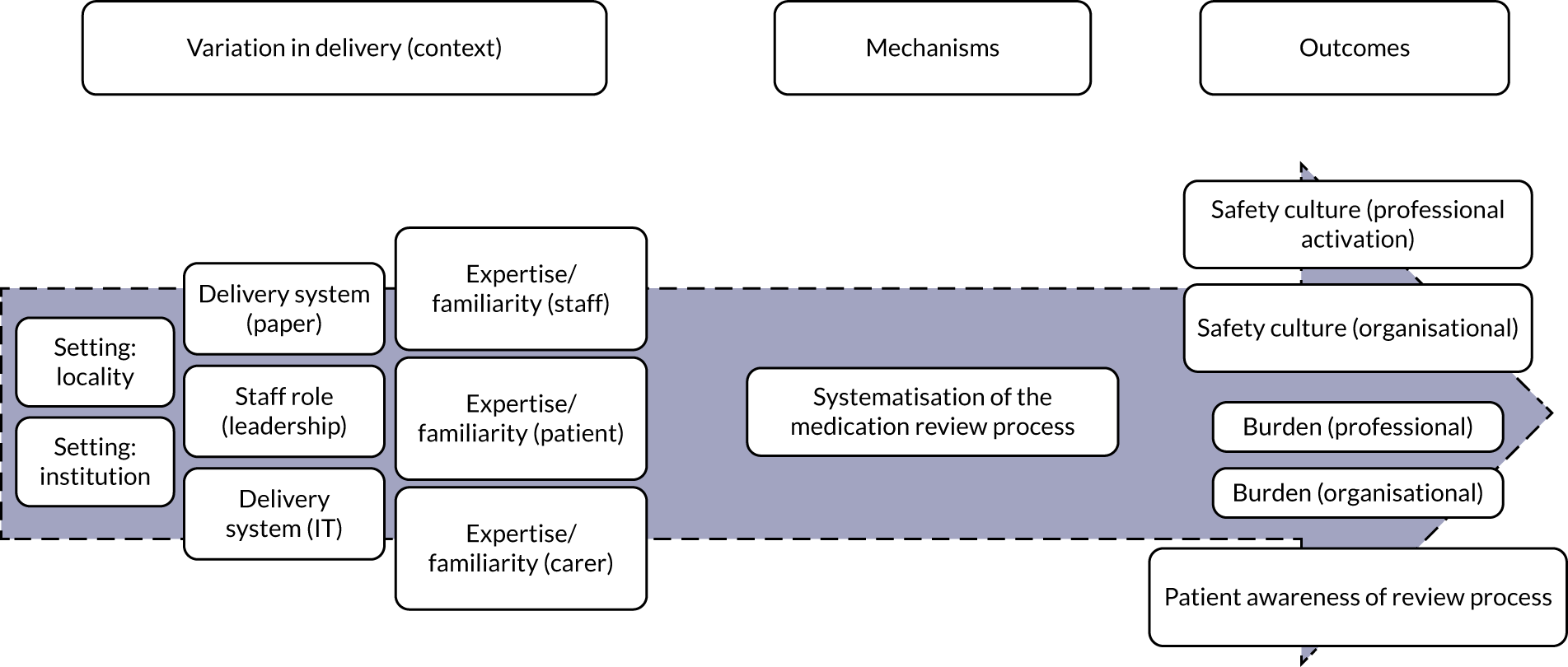

Personalisation of the medication review (Figure 2) refers to the degree to which the medication review processes and outcomes are tailored to each individual patient. STOPP/START tools are being promoted to support shared decision-making (taking into account patient preferences, experiences and expectations) (mechanism). For STOPP/START-based interventions to achieve the hypothesised improvement in patient awareness of the medication review process, adherence to the therapeutic plan, satisfaction with care, patient empowerment and quality of life, and to decrease patient burden and support a patient safety culture (outcomes), patients and/or carers need to be present and engaged in the process, and there should be sufficient time to carry out the review [i.e. variation in intervention delivery (context)].

FIGURE 2.

Logic model for personalisation.

The full set of related key variables (context and outcomes) was included in a logic model (see Figure 2). Note that, in Figures 2–4, the distance along the horizontal axis between any variable and the corresponding mechanism represents the expected degree of the association along the proximal–distal continuum. For example, individualisation of management is expected to trigger a cascade of effects that may result in improved patient empowerment, which can trigger an improvement in patient satisfaction, which can result in increased adherence and eventually modify the safety culture of patients. The link between individualisation of management and the latter outcome is expected to be more tenuous than between individualisation of management and patient empowerment.

Based on discussions and feedback from the PPI advisory group, we prioritised the following theories for phase 2:

-

STOPP/START tools lead to greater adherence to pharmacological treatment when patients are present at their medication review.

-

STOPP/START tools increase patient empowerment when patient perceptions and expectations are taken into account (elicited and acted on).

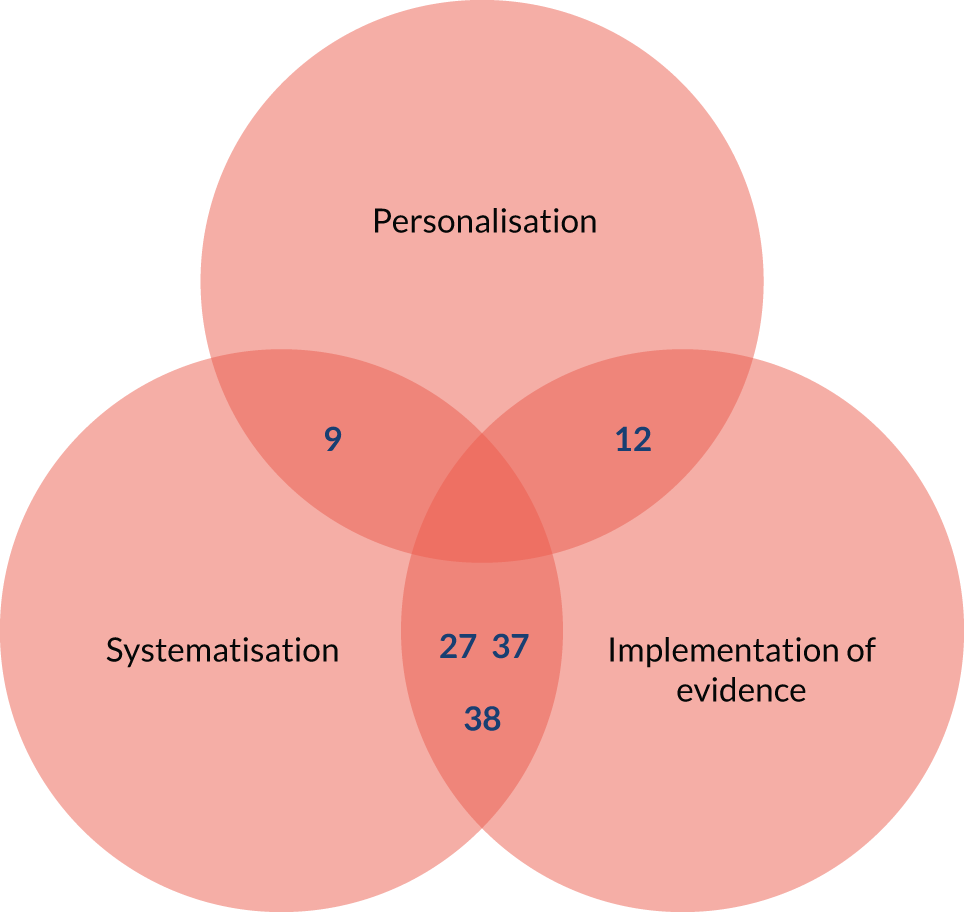

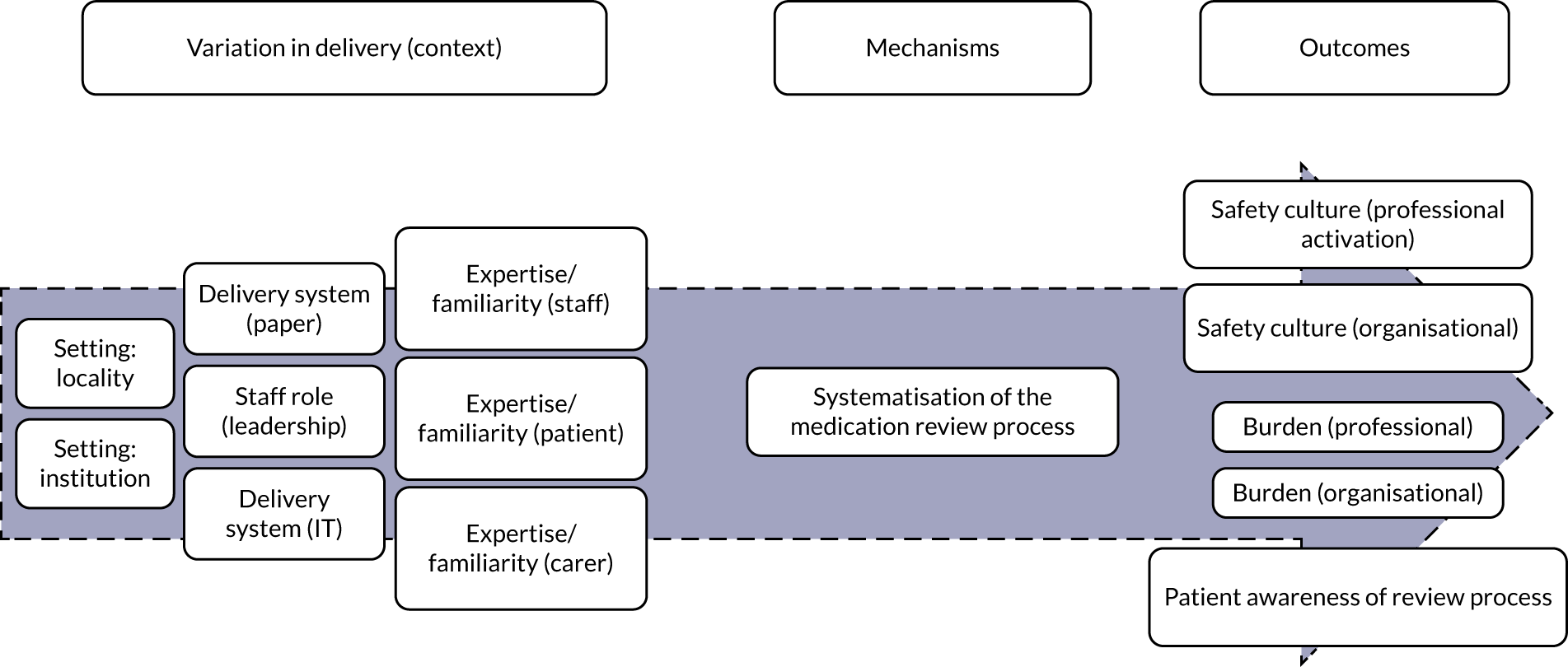

Systematisation (of medication review processes)

Systematisation (of medication review processes) (Figure 3) refers to the degree to which the medication review is formalised and systematically implemented. STOPP/START tools support a standardised/systematic approach for medication reviews (mechanism). For STOPP/START tools to change professional and organisational culture, burden and costs, and for patients to be aware that a review has taken place (outcomes), there needs to be a delivery system (paper or computer based) that is linked to a patient’s medical records and information from previous reviews using STOPP/START tools. Information must also be shared between relevant professionals, teams and organisations [i.e. variation in intervention delivery (context)].

FIGURE 3.

Logic model for systematisation. IT, information technology.

Based on discussions and feedback from the PPI advisory group, we prioritised the following theories for phase 2:

-

STOPP/START tools change professional and organisational cultures when there are computerised systems linked to medical records, access to previous STOPP/START tools data, and data-sharing takes place (with relevant professionals, teams and organisations).

-

STOPP/START tools reduce professional and organisational burden in medication management when there is sufficient familiarity with the tool.

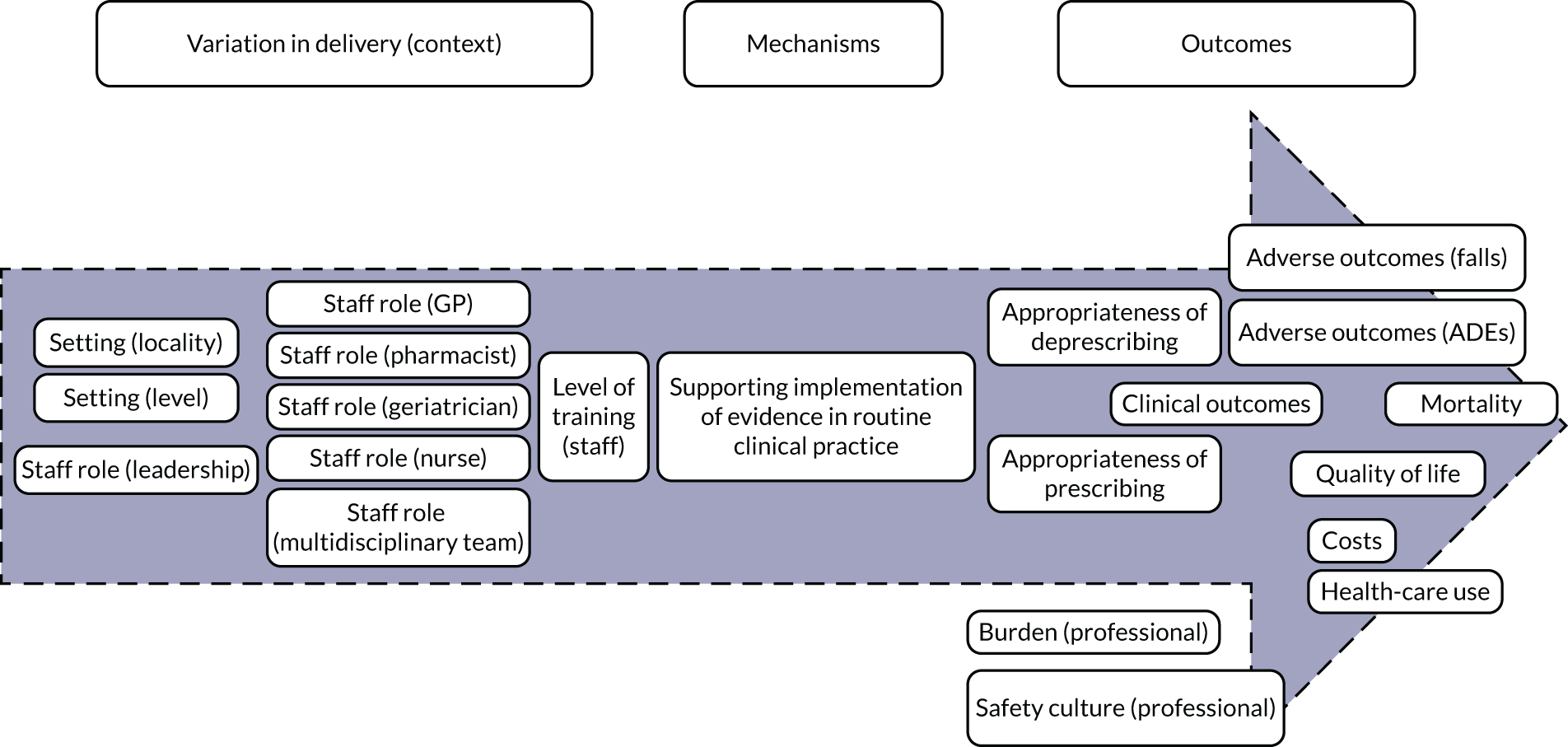

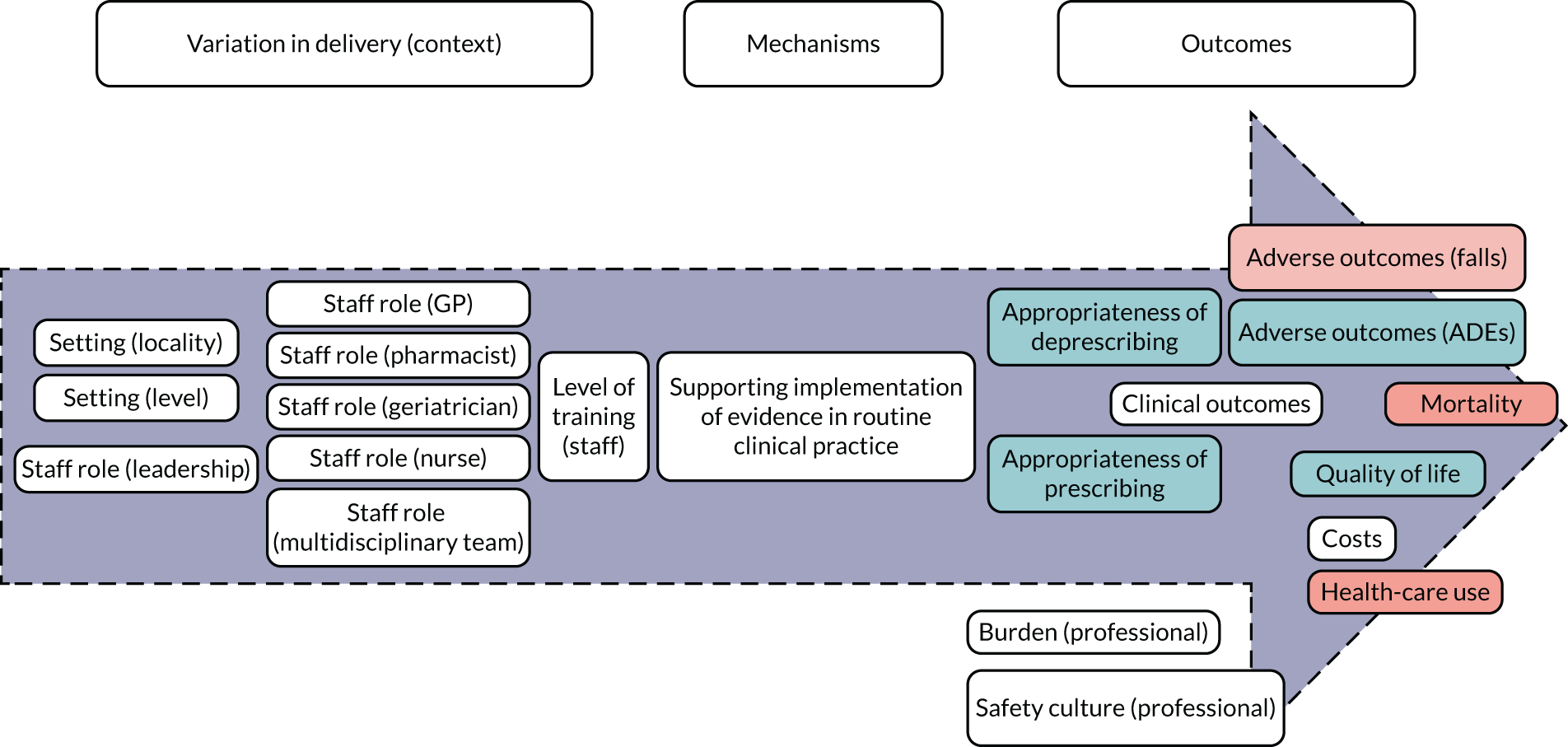

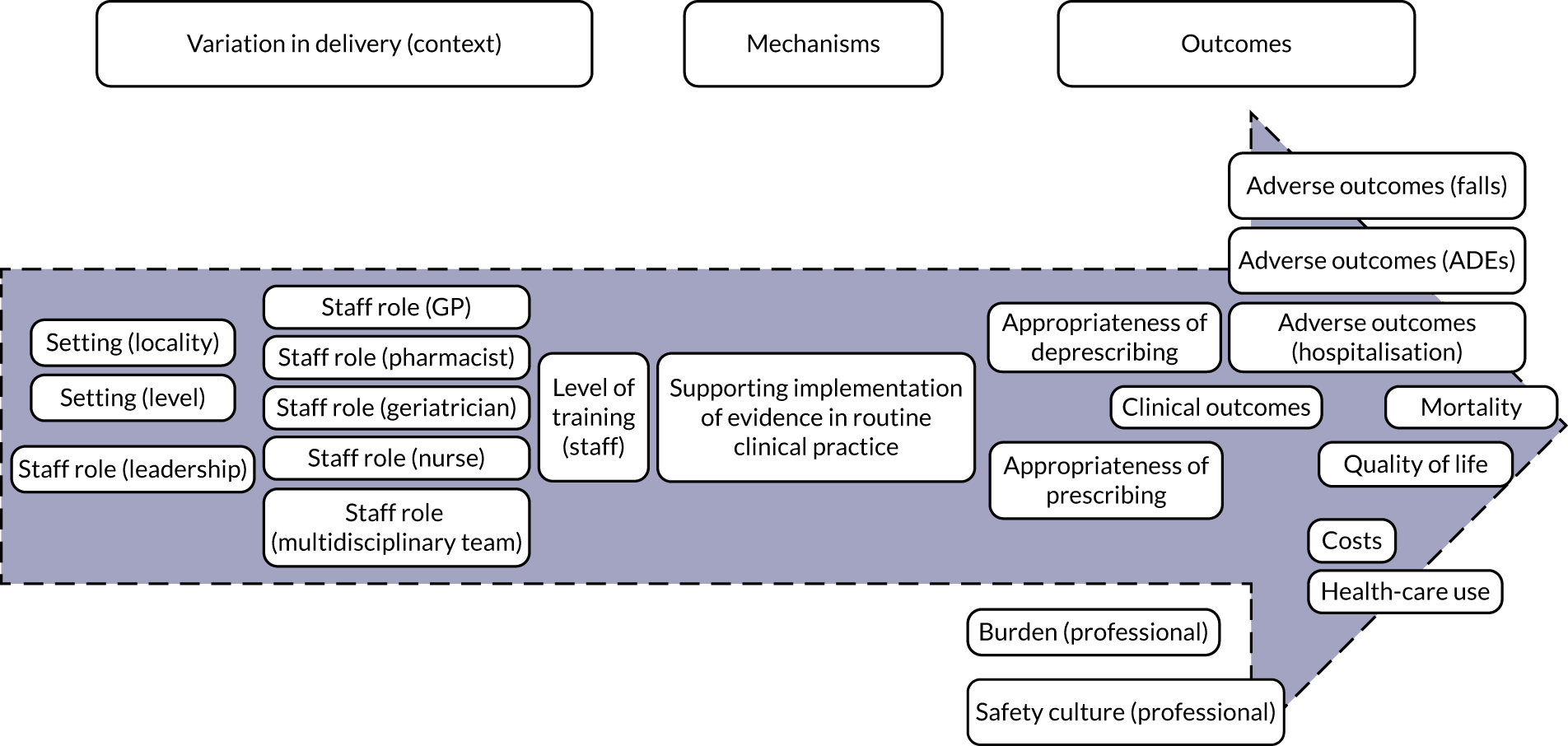

Implementation of evidence

Implementation of evidence (Figure 4) captures the degree to which an intervention oriented to support the medication review focuses on promoting the dissemination and use of the best-available evidence. Delivery of STOPP/START-based interventions is based on implementation of evidence (mechanism). For STOPP/START-based interventions to result in greater appropriateness of prescribing/deprescribing, reduction in adverse outcomes and hospitalisations, improvements in clinical outcomes, mortality and quality of life, along with having an impact on costs, health-care use, professional burden and organisational culture (outcomes), the supporting evidence base needs to be actively promoted by people in leadership roles and requires training of relevant clinicians (e.g. GPs, pharmacists, geriatricians or nurses) [i.e. variation in delivery of the intervention (context)].

FIGURE 4.

Logic model for the implementation of evidence.

Based on discussions and feedback from the PPI advisory group, we prioritised the following theories for phase 2:

-

STOPP/START-based interventions are associated with increased appropriateness of prescribing/deprescribing when there are lower levels of familiarity with the evidence base (i.e. non-geriatricians, non-pharmacists and more junior professionals).

-

STOPP/START-based interventions reduce adverse outcomes through appropriate prescribing/deprescribing.

-

STOPP/START-based interventions can change professional culture in settings less familiar with the supporting evidence base.

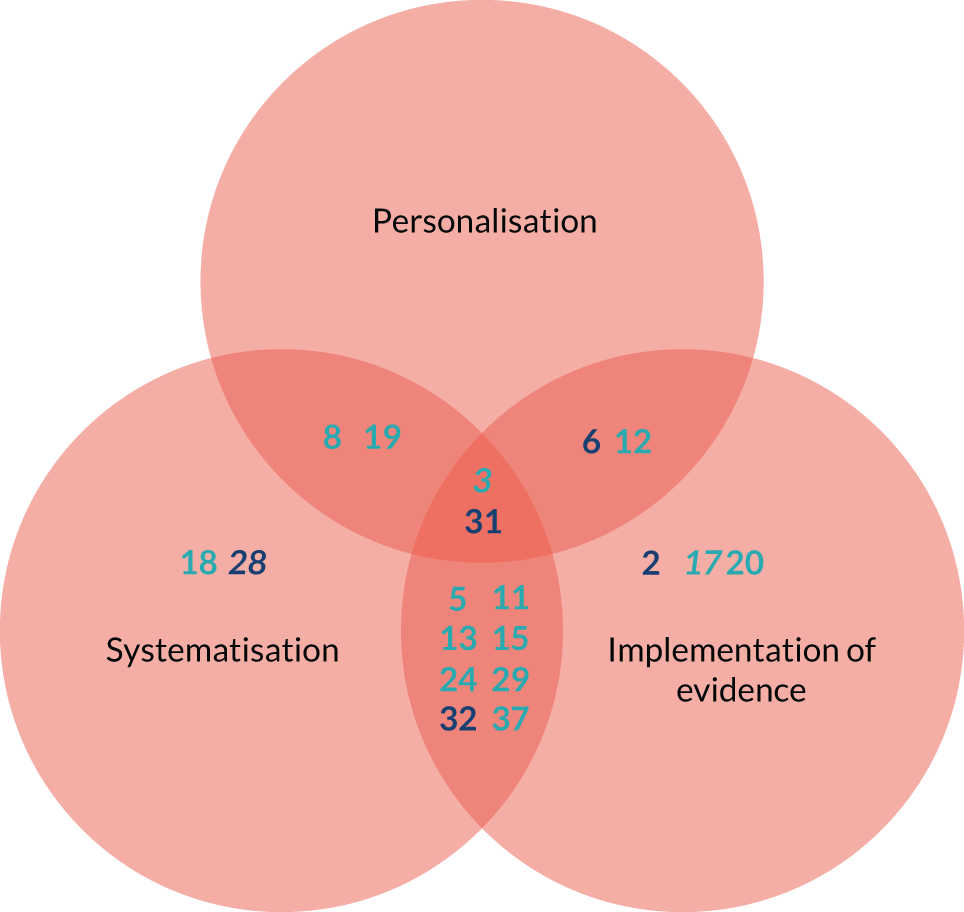

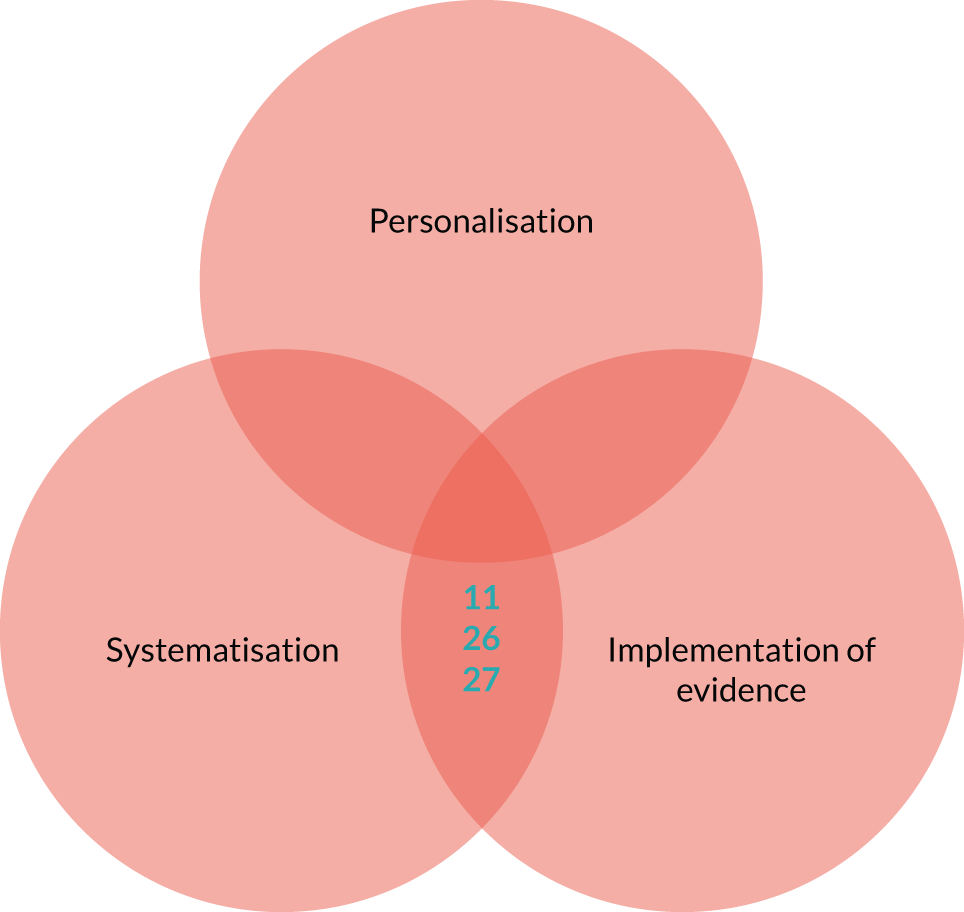

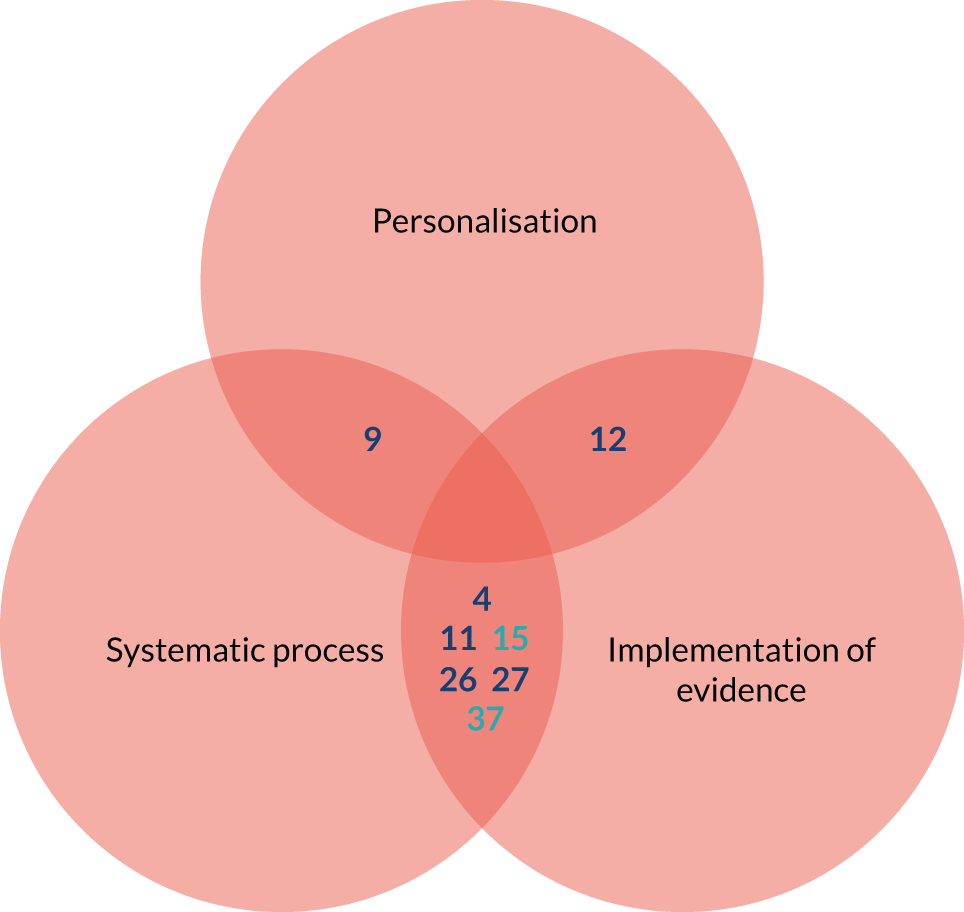

Summary of findings