Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/209/66. The contractual start date was in July 2014. The final report began editorial review in February 2020 and was accepted for publication in October 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Shepperd et al. This work was produced by Shepperd et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Shepperd et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Older people are being admitted to hospital as an emergency in increasing numbers. From a system perspective, this trend is not sustainable, and from a patient perspective there are many reasons to question whether or not a hospital is the best place of care for older adults with frailty. There is some evidence that hospital care can be potentially harmful because of a lack of patient mobility and a risk of hospital-acquired infection. There is also concern about the suitability of the hospital for older people with complex health-care problems who are often in need of some form of rehabilitation, and for whom the process of recovery is likely to be multidimensional and recursive. 1 The high cost of hospital-based care is also a major driver of innovation.

Evidence

In recent decades, the focus of health care for older people has been on comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA), defined as a multidisciplinary process to determine the older person’s medical, functional, psychological and social needs that leads to a co-ordinated plan for the delivery of health care. Organising acute hospital care for older people along these lines increases the likelihood that patients will be living in their own homes after 3 and 12 months’ follow-up, and CGA is now viewed as the gold standard for hospital-based health care delivered to older people. 2

It is possible that implementing CGA in an older person’s home, instead of in an acute hospital setting, will lead to a greater improvement in health outcomes at a lower cost. Despite service innovations seeking to expand the application of CGA as hospitals deal with the rise in emergency admissions, it is not known how CGA works in community settings that seek to provide an alternative to admission to hospital [e.g. admission avoidance hospital at home (HAH)]. Furthermore, the evidence on cost is uncertain, and older people’s and family caregivers’ participation and their contribution to the processes of CGA for their longer-term health-care needs have not been explored. Prior to this randomised trial, the main source of evidence regarding the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of admission avoidance HAH was a meta-analysis published in a Cochrane review. 3 However, because of the small number of small trials included in this meta-analysis, the evidence of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness was uncertain. 3 Key questions to be answered include ‘Is it clinically effective and cost-effective to deliver CGA in an admission avoidance HAH setting (as opposed to delivering CGA in an inpatient setting)? and ‘Does this have an impact on older people and their caregivers?’.

Hypothesis

Consistent with the concept of healthy ageing, we hypothesised that older people who received geriatrician-led admission avoidance HAH with CGA might experience less of a decline in functional and cognitive capacity and maintain a level of independence that is difficult to achieve in a more restricted hospital environment.

Our aim was to conduct a robust evaluation, in the form of a multisite pragmatic randomised trial and process evaluation, of admission avoidance HAH services with CGA compared with admission to hospital, delivered mostly in specialised elderly care services, for which there is considerable evidence of effectiveness. 2 We report the clinical and health economic outcomes. In addition, we report the findings of a process evaluation that assessed the experiences of patient and caregivers of receiving health care in each setting, and the components and practices of organising HAH compared with those of bed-based hospital care.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Shepperd S, Butler C, Cradduck-Bamford A, Ellis G, Gray A, Hemsley A, et al. Is comprehensive geriatric assessment admission avoidance hospital at home an alternative to hospital admission for older people? A randomised trial [published online ahead of print April 20 2021]. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2021. 6 https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-5688. © American College of Physicians.

The study protocols for the randomised trial4 and the process evaluation5 have been peer reviewed and published. Amendments to the protocol are listed in Appendix 1.

Setting

Participants were recruited mainly from primary care referrals to admission avoidance HAH with CGA at the Aneurin Bevan University Health Board or a hospital-based acute assessment unit in Bradford Royal Infirmary, Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, the Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trust, University Hospital Monklands, St John’s Hospital, Livingston, Victoria Hospital, Kirkcaldy, Southern Health and Social Care Trust or Belfast Health and Social Care Trust. Five of the sites were based in mainly urban areas and two in a semirural area, one site covered an urban and rural area and one a mainly rural area.

Eligibility criteria

We recruited older people with frailty who required an urgent hospital admission because of an acute change in their health, such as a sudden functional deterioration, delirium or a fall, against a background of complex comorbidity.

We recruited patients who were (1) aged ≥ 65 years; (2) willing and able to give informed consent to participate in the study, or who had a relative, a friend or an independent mental capacity advocate who was involved in making a decision in the best interests of the individual if that person did not have capacity to give consent; and (3) referred to the geriatrician-led admission avoidance HAH with CGA and would otherwise require hospital admission for an acute medical event. The presence of a carer depended on the patient’s individual circumstances and was at the discretion of the clinician responsible for the patient, in accordance with current clinical practice at each site. Participants were excluded if they (1) had an acute coronary syndrome (this included myocardial infarction and unstable angina, characterised by cardiac chest pain and associated with electrocardiographic changes), (2) required an acute surgical assessment, (3) had a suspected stroke, (4) were receiving end-of-life care as part of a palliative care pathway, (5) refused HAH or were considered by clinical staff to be too high risk for home-based care (e.g. those who were physiologically unstable or at risk to themselves, or if the carer reported that home-based health care was not acceptable) or (6) were living in a residential or nursing care home setting.

Interventions

The intervention was geriatrician-led multidisciplinary admission avoidance HAH with CGA (otherwise known as hospital in the home) as an alternative to admission to hospital (also known as hospital in the home).

At the outset, during the design of the randomised trial, we established four core elements of HAH that had to be present for a site to be eligible to recruit participants:

-

geriatrician-led admission avoidance HAH

-

a multidisciplinary team (MDT)

-

health-care provision guided by the principles of CGA, which include multidisciplinary meetings and virtual ward rounds

-

direct access to elements of acute hospital-based health care, such as diagnostics and transfer to a hospital if required.

These components were considered essential to the delivery of the core function of a service that provides an alternative to inpatient hospital health care for older people, and differentiate admission avoidance HAH from the range of other services that operate across primary and secondary care. 7 The attending geriatrician had clinical responsibility in all but one site (where a primary care physician and senior nurse had clinical responsibility) and was responsible for discharging patients from the service. The MDT included nurse practitioners, who were responsible for clinical assessments, arranging investigations, documentation, discharge summaries and prescribing, physiotherapists and occupational therapists. Access was also provided to social care and mental health nurses and old-age psychiatrists. Virtual rounds were held at least daily. An existing primary care out-of-hours service provided out-of-hours health care. Between HAH visits, patients could communicate with the HAH team by telephone.

The MDT implemented treatment and management recommendations and, if required, referred patients to other services (e.g. older people’s mental health services, diagnostic services, social work, dietetics, speech and language therapy, pharmacy support and outpatient follow-up). Patients had access as usual to hospital inpatient care, general practitioners (GPs) and the primary health-care team. Intravenous drug administration and oxygen therapy were available in five sites, three sites provided intravenous administration but not oxygen therapy and one site did not provide either. Health care was provided 7 days per week, from 09.00 to early evening, admissions were restricted to Monday to Friday in all but one site, and emergency medical cover was available via the usual emergency services 24 hours per day.

At the outset, and following consultation with site principal investigators, it was anticipated that approximately 80% of those allocated to the control group (i.e. hospital) would receive their care from a geriatrician-led elderly care medicine service with CGA either in a dedicated ward or by means of input to a care plan on another type of hospital ward.

Outcome measures

Primary outcome

The main outcome was ‘living at home’, defined as the inverse of death or living in a residential care setting, measured at 6 months after randomisation.

The secondary outcomes were as follows:

-

each component of the primary outcome, including mortality and new long-term residential care, measured at 6 and 12 months

-

incident and persistent delirium, measured at 3 days, 5 days and 1 month using the confusion assessment method (CAM) (a brief questionnaire that has been used extensively for screening and case ascertainment)8

-

cognitive impairment, measured with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) (normal range 26–30)9

-

activities of daily living, measured with the Barthel Index10

-

readmission or transfer to hospital

-

health status, measured with the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L), instrument to produce a single index value for use in the cost-effectiveness analysis11

-

length of stay in HAH and hospital

-

resource use

-

satisfaction, measured with the patient-reported experience questionnaire at 1 month, developed by Picker Institute Europe (Oxford, UK) and used in the National Audit of Intermediate Care. 12

We also collected data on ‘living at home’ (i.e. the inverse of death or living in a residential care setting) at 12-month follow-up.

Serious adverse event and adverse event reporting

We identified the following potential risks to participants: a fall (in either setting), hospital- or community-acquired infection, hospital admission (for those randomised to HAH), post-discharge hospitalisation in either group and death. We categorised an adverse event as serious if it resulted in death, was life-threatening, necessitated hospitalisation or the prolongation of existing hospitalisation, resulted in persistent or significant disability or incapacity, or was an otherwise important medical event. These categories corresponded with the expected events among this population, which include falls, pressure sores, hospital- or community-acquired infection and transfer to hospital. All serious adverse events that were related to the administration of any of the research procedures, were unexpected and were observed by the recruiting clinician or reported by the participant were recorded on the case report form (CRF) and were forwarded by the site to the trial manager after the site clinician had assessed the severity. As a minimum, the following details were recorded: description, date of onset, end date, assessment of relatedness to the intervention, other attributions/co-interventions, and action taken. The chief investigator reported serious adverse events that, in the opinion of one of the clinical leads, were ‘related’ and ‘unexpected’ in relation to the study to the Research Ethics Committee (REC) within 15 working days of becoming aware of the event.

Recruitment

We implemented a recruitment pathway that mapped to existing arrangements for referral to HAH. Eligible participants were identified from those patients who were referred by their GP to a single point of access, or who were transferred from the emergency department to an acute assessment unit and were assessed as suitable for HAH. At referral to the trial, each participant was provided with a participant information leaflet that described the research, and they were also given an opportunity to ask any questions and discuss any concerns about the research with a research nurse. Each participant had the right to withdraw from the study at any time, and reasons for withdrawal were recorded in the CRF.

Randomisation procedure and concealment of allocation

The unit of randomisation was the individual participant. We used a 2 : 1 randomisation ratio (i.e. HAH to hospital inpatient admission). We opted for this ratio to address the concern expressed by clinical leads that a 1 : 1 randomisation ratio would place unmanageable pressure on inpatient services. Randomisation was conducted by a local member of the research team using Sortition, the Oxford University’s Primary Care Clinical Trials Unit’s validated in-house online randomisation system. Telephone randomisation was used if sites did not have online access. A computer-generated randomisation sequence was used and randomisation was stratified by site, gender and known cognitive decline [measured using the Informant Questionnaire on Cognitive Decline in the Elderly (IQCODE)]. 13

Data collection

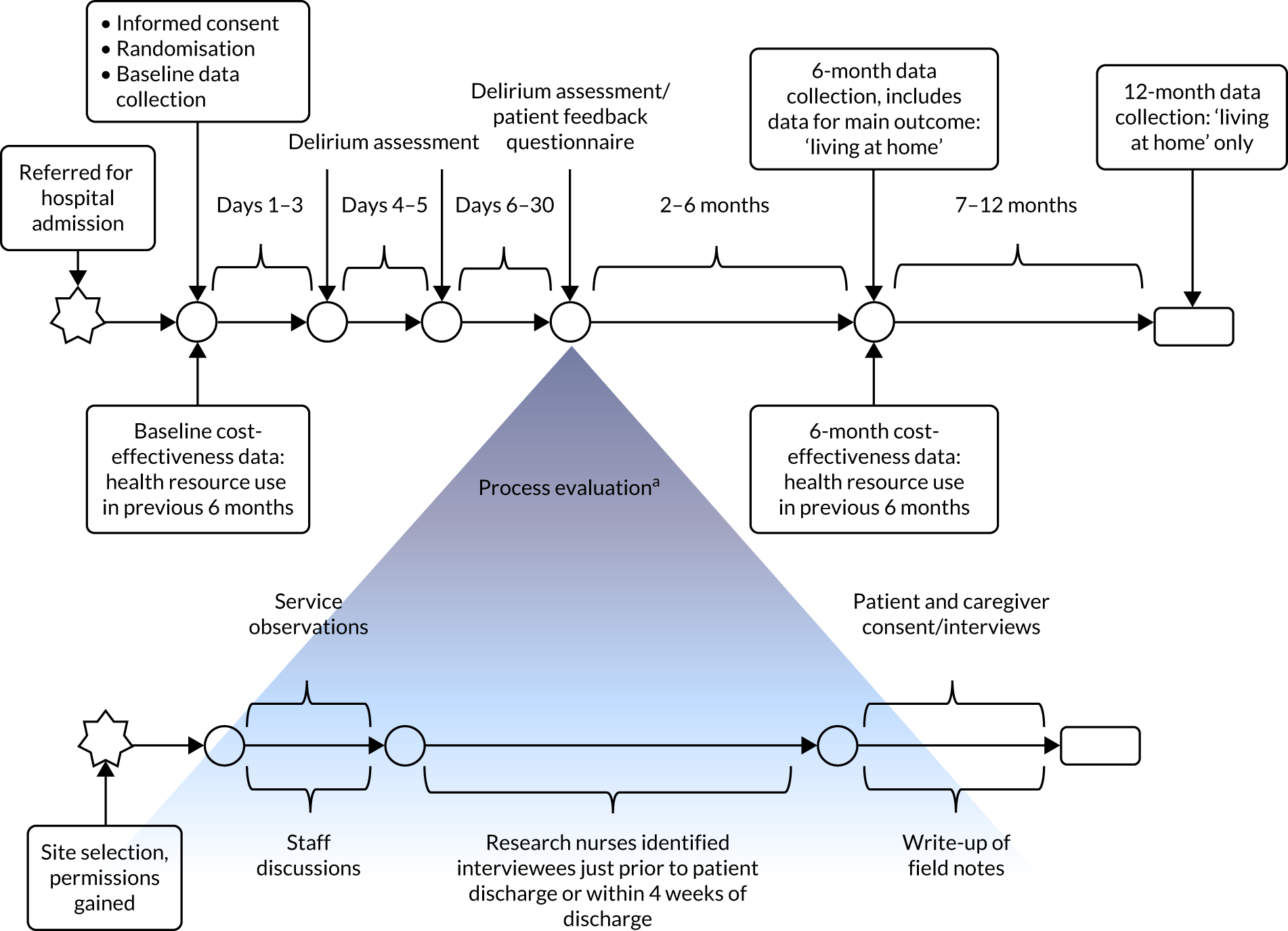

Research nurses at each site collected data on the primary outcomes from participants (and from their caregiver, if the caregiver was the designated consultee) at baseline and at 6 and 12 months, with the exception of an assessment of delirium, which was carried out 3 days, 5 days and 1 month after recruitment (Figure 1). At each site a form was completed to record whether or not death had occurred, as well as the date these data were collected from the medical records. Place of residence was recorded by the research nurses at each follow-up visit. Data were collected using a paper form or were directly entered on an electronic pro forma on OpenClinica Enterprise V.3.5 Data Management System (Waltham, MA, USA).

FIGURE 1.

Data collection during the study. a, Exact timelines varied depending on the availability of staff and interviewees.

At baseline we collected data from the patient’s clinical notes and from the clinical lead on the presenting problem that required admission to hospital, as well as demographic information (including age and education). We also collected data on the patient’s background cognitive status (using the 16-item informant-based IQCODE questionnaire),13 incident and persistent delirium (measured using the CAM8), comorbidity (measured with the Charlson Comorbidity Index14), activities of daily living (measured with the Barthel Index10), current cognitive impairment (measured with the MoCA9), health status (measured with the EQ-5D-5L11) and major health service use (see Economic analysis) during the 6 months prior to the patient’s current illness. If a participant appeared to be burdened, we collected data in two stages. We collected core data (i.e. IQCODE13 and CAM8 scores) after obtaining consent and prior to randomisation, and administered the remaining measures [i.e. the Barthel Index,10 Charlson Comorbidity Index,14 MoCA,9 EQ-5D-5L11 and the Health Resource Use Questionnaire (HRU)] soon after randomisation.

At the 6-month follow-up point, we collected data from all patients on mortality, new long-term residential care, cognitive impairment, activities of daily living, quality of life, length of stay, readmission or transfer to hospital, admission to hospital or HAH, health resource use, residential care and informal care (see Economic analysis). Twelve-month follow-up data on living at home were collected from the medical records and/or place of assessment.

Data management

We stored all paper and electronic data in a secure environment and referred to participants only by their trial number. Participants’ names appeared only on the signed consent forms, which were stored securely at each site. We followed the standard operating procedures of the University of Oxford Primary Care Clinical Trials Unit (Oxford, UK), which are compliant with the Data Protection Act15 and good clinical practice. No one outside the study team had access to either the CRFs or the database. Members of site research teams accessed identifiable data so that they could collect follow-up data. Direct access was granted to authorised representatives from the sponsor and host institution for monitoring and/or audit of the study to ensure compliance with regulations. Staff at each site entered data directly into OpenClinica or on paper versions of the CRF and questionnaires. Data from paper forms were double entered by Primary Care Clinical Trials Unit staff. Researchers from each site were asked to check the data for completeness before returning the forms to the trial team. In the case of those sites entering data directly into the database, internal validation checks were run for each data field. Any inconsistencies or missing data were highlighted as queries to be resolved by the site. The same checks were applied to paper CRFs by the data manager after data entry. Data queries were returned to sites for resolution on a regular basis.

Study oversight

The overall supervision of the trial progress was carried out by the Trial Steering Committee. An independent Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) met every 6 months to review trial progress and unblinded data, including all serious adverse events reports. The sponsor was the University of Oxford.

Statistical analysis

Data from previous trials3 and a before-and-after study of older people who received health care in an acute care of elderly unit in Scotland,16 with a length of follow-up that ranged from 6 to 12 months, informed our sample size calculation. Our proposed study effect estimate was based on a hospital event rate of 50%, with a 10 percentage point reduction in a residential setting, to 40% in the HAH group, equal to a relative risk (RR) of 0.80, which is towards the top end of the 95% confidence interval (CI) for a pooled estimate for mortality. Initially, we calculated that the sample size required to provide 90% power and based on 15% attrition for the primary outcome at 12 months would be 1552 patients. At the fifth meeting of the DMC the decision was made to amend the follow-up time for the primary outcome to 6 months, as it was agreed that it was more likely that any effect would be detected prior to 12 months in the population recruited. When we observed a lower attrition of 6%, we revised the sample size to 1055 patients, reduced the power to 83% and reduced the significance level (two-sided) for the primary outcome to 0.05 to reflect a reduced rate of recruitment towards the end of the trial. This was agreed by the Trial Steering Committee and the DMC, which had oversight of the study, and was approved by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). It was also agreed to reduce data collection at 12 months for the primary outcome because of concern about the burden of data completion on the study population, who were old, and because changes in the secondary outcomes were also more likely to occur at 6 months.

The original plan was to analyse data collected at both 6 and 12 months in the same model. However, it was later decided to perform separate analyses for 6- and 12-month data, based on the view that 6-month outcome data could be reported before the completion of 12 months’ follow-up. However, the 6-month analysis was delayed because of the data cleaning process. For this reason, we carried out the analysis in accordance with the statistical analysis plan, and the full model, which incorporated both time points, was analysed in a sensitivity analysis.

The primary analysis population was defined as all participants for whom data were available, and according to the group to which participants were randomly allocated regardless of deviation from protocol. For the primary outcome of living at home at 6 months, and other binary outcomes (i.e. long-term residential care, mortality, readmission or transfer to hospital, cognitive impairment and delirium), we used a generalised linear mixed-effects model (robust Poisson model with log-link function) with unstructured covariance matrix. A linear mixed-effects model was used for activities of daily living, measured by the Barthel Index. The models adjusted for intervention arm, gender and IQCODE score as fixed effects, and site as a random effect. The models for cognitive impairment, delirium and activities of daily living were also adjusted for the corresponding baseline score as a fixed effect. 17 Individual logistic regressions were performed for each baseline covariate to obtain the p-value for the association of missingness with the primary outcome. Missing IQCODE scores at baseline (n = 10) were imputed using the mean IQCODE at baseline. A fully inclusive multiple imputation was conducted with gender, age, education, place of baseline assessment, whether or not consent was signed by ‘consultee’ and other factors expected to be related to the main outcome as covariates, and the primary outcome reanalysed. Analysis was carried out using Stata SE® version 16.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

We planned one subgroup analysis of the effect of setting (home vs. hospital) on the incidence of delirium18 in people who were cognitively impaired (defined as having a MoCA score of < 26). 19 Owing to the small number of participants with delirium, assessed by the CAM,18 six individual log-Poisson generalised linear mixed models with robust standard errors were fitted to the data, one at each of the three time points for one subgroup with a MoCA score of < 26 and another subgroup with a MoCA score of ≥ 26. The models included site as a random effect.

Sensitivity analyses

Four pre-planned sensitivity analyses were conducted with respect to living at home to explore the sensitivity of the results to different assumptions: (1) missing data for long-term residential care and/or death status were replaced with either living at home and/or alive, or not living at home and/or dead; (2) missing data were imputed using multiple imputation; (3) the model was adjusted for factors that predicted that data were missing (e.g. education level, place of assessment, presenting problem) for the outcome of living at home; and (4) both the 6- and 12-month outcomes of living at home were analysed in the same model. The model included an additional fixed effect for the interaction between intervention arm and time point so that possible differences in treatment effect could be assessed at each time point.

Economic analysis

Parts of this section have been reproduced from Singh et al. 20 © The Author(s) 2021. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the British Geriatrics Society. All rights reserved. For permissions, please email: journals.permissions@oup.com. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. For commercial re-use, please contact journals.permissions@oup.com.

We estimated the resource use, costs and health outcomes in each trial arm up to the 6-month follow-up point on an intention-to-treat basis. Costs were estimated taking the NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) perspective, as well as the wider societal perspective, which also included the cost of informal care. Following the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence’s (NICE’s) recent recommendation, we converted EQ-5D-5L responses at baseline and 6 months to utilities using a crosswalk algorithm developed by EuroQol. 21 Quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) were then calculated by using the exact days between the two EQ-5D-5L measurement points to estimate the area under the curve per patient. As the follow-up period was 6 months, the maximum within-trial QALY gain per patient was 0.5. We also measured health outcomes in terms of life-years living at home (LYLAHs), a proxy measure of independence and well-being in an older population, which we had used previously in an incremental cost-effectiveness analysis of individual patient data from the randomised trials that contributed to a Cochrane systematic review of the effectiveness of CGA. 2 LYLAHs were calculated by subtracting the sum of the total nights in hospital and/or in residential care over 6 months from the follow-up time (183 days or 6 months) if a participant was alive, or from randomisation to death if the patient died during follow-up.

Type and source of resource use

We collected information on health and social service resources used, and on the number of hours of informal care (i.e. unpaid help) that participants received from family and friends as a result of their health problems (Table 1). Site research nurses completed the HRU and CRF by obtaining details from participants’ medical records, and from participants and their caregivers. We also checked adverse event trial records for data on hospital and residential care admissions. Most resource use data were derived from the HRU, with the exception of data on length of stay in residential care, hospital and HAH length of stay, and readmissions or transfers to hospital, which were obtained from the medical records and entered on the CRFs or a data query form. Extreme values of all data were checked against data sources. We replaced missing values for resource use with zero if individuals had filled out any question in the HRU, assuming that the missing response meant zero use. If a patient did not have a single response on the HRU, the missing responses were treated as such.

| Cost | Source |

|---|---|

| NHS and PSS costs | |

| Primary care | HRU |

| Hospital care | HRU, CRF and data query form, supplemented by adverse event data for transfer to hospital |

| Outpatient care | HRU |

| PSS | HRU |

| Hospital transportation | HRU |

| Care home | HRU, CRF and data query form |

| HAH | HRU, CRF and site budgets |

| Societal costs | |

| Unpaid help | HRU |

Intervention costs in the analysis included the initial length of stay in hospital or HAH after randomisation, plus the length of stay associated with the initial assessment if the participant had been recruited from a hospital assessment unit. When resource use was collected daily or weekly over a period of 6 months, we multiplied by 183 or 26, respectively.

Valuation of resource use

Unit costs were obtained from secondary sources for each health and social care service. 18,22–25 Appendix 2 provides a list of the unit costs and their sources. Unit costs were inflated to 2017/18 prices, where necessary, using the hospital care and health services inflation index. The unit costs of hospital inpatient care were calculated by using the weighted average of all elective and non-elective hospital admissions relevant to the trial population (e.g. admissions to neonatal units were excluded), obtained from NHS Reference Costs 2017–2018. 24 Non-elective admissions were divided in to short and long stays using the length of stay per participant available in the trial data. Respite at home was not costed, as 99.5% of patients reported zero use of this service at baseline and 6 months, and we could not identify a reliable unit cost for this type of service. Volunteer work and NHS 24 (in Scotland) unit costs were not costed. Sitting service costs were set at a notional £5, as these services either are free or have a small charge. There is no defined unit cost for luncheon clubs, but a number of community centres have stated costs ranging from £2 to £6 and so we allocated an average cost of £4 per attendance. 17,26,27 The amount of health or social service used by each patient was then multiplied by the relevant unit cost.

The cost per bed-day of admission to HAH was calculated by dividing each site’s annual total spent budget in 2017/18 for HAH by the total number of bed-days (i.e. number of patients multiplied by the average length of stay per patient) in the same year.

Cost perspective

Following NICE guidelines for health technology appraisal, we estimated the costs per participant from an NHS and PSS perspective, which included costs of HAH, primary and community care, outpatient visits, hospitalisation, ambulance transportation and PSS (e.g. home care and meals on wheels). 28 Results from a societal perspective, in which the productivity cost of unpaid caregivers was added to all other costs, were reported separately.

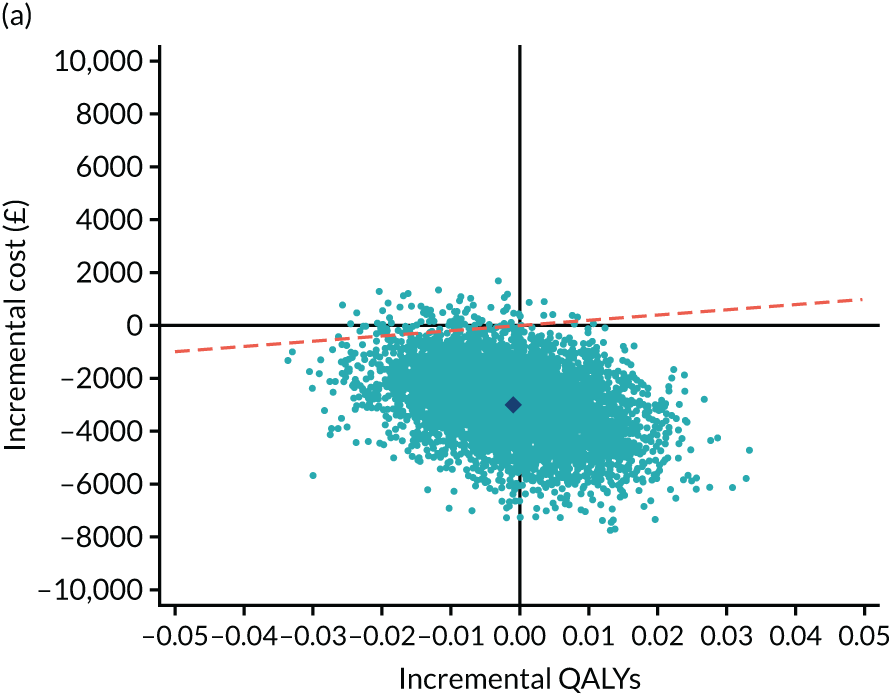

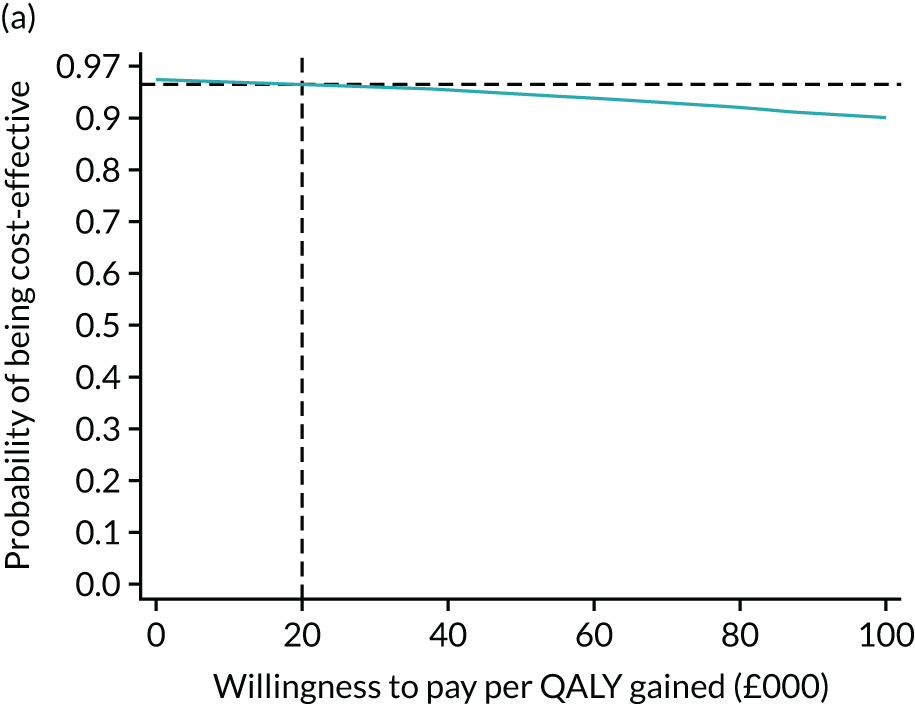

Cost-effectiveness analysis

As the time horizon for the cost-effectiveness analysis was from baseline to 6 months, discounting of costs and outcomes was not applied. We performed an incremental analysis to assess the differences in mean costs, mean QALYs and mean LYLAHs between the two treatment groups, and estimated the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) in terms of cost per QALY and cost per LYLAH using:

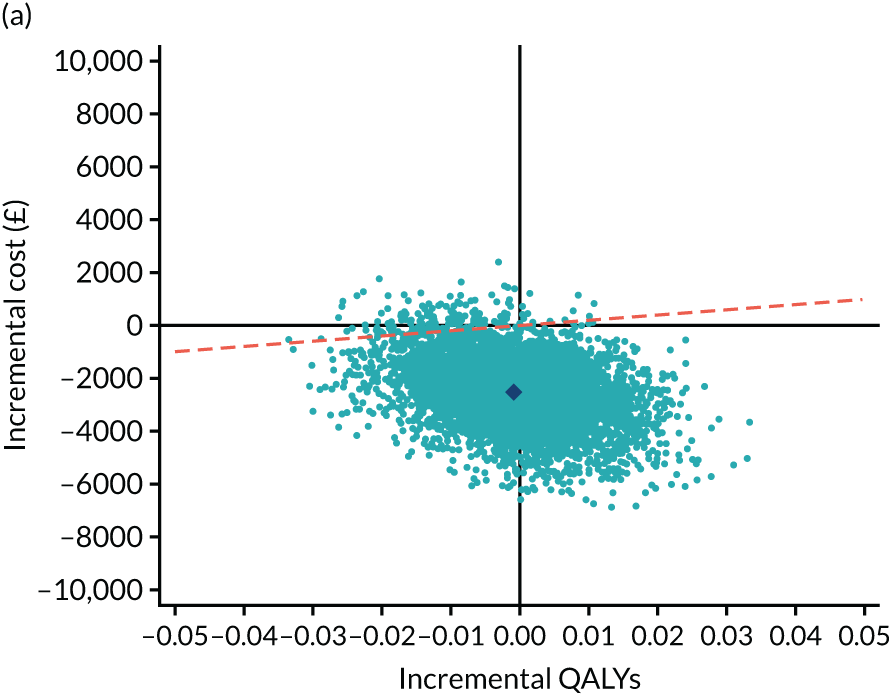

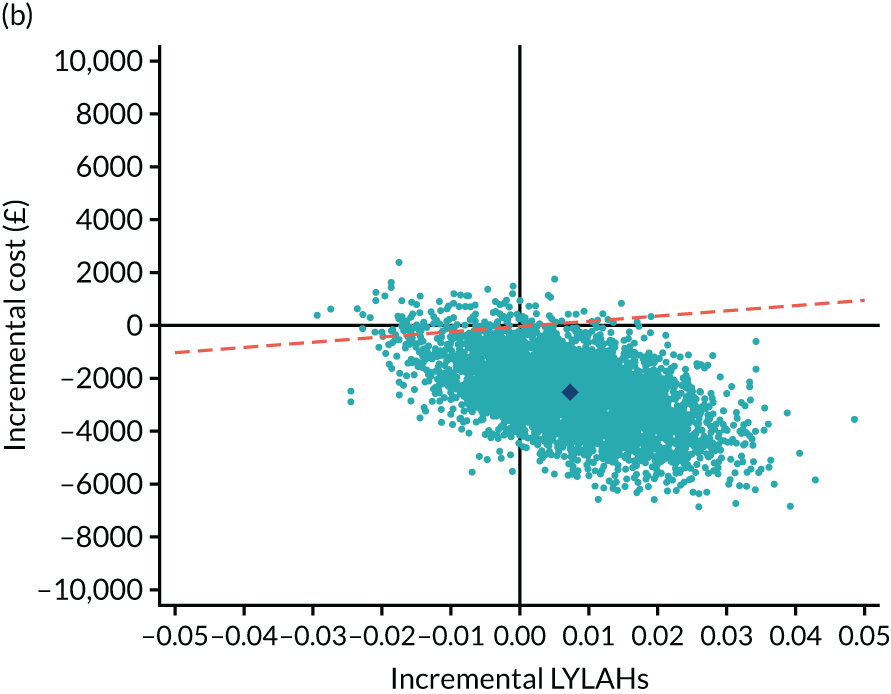

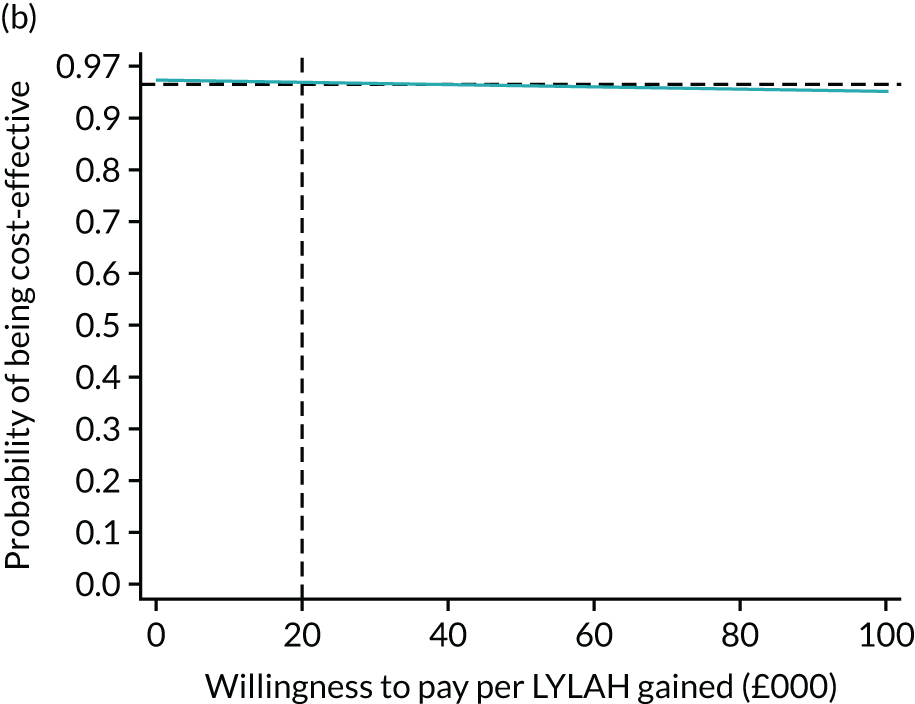

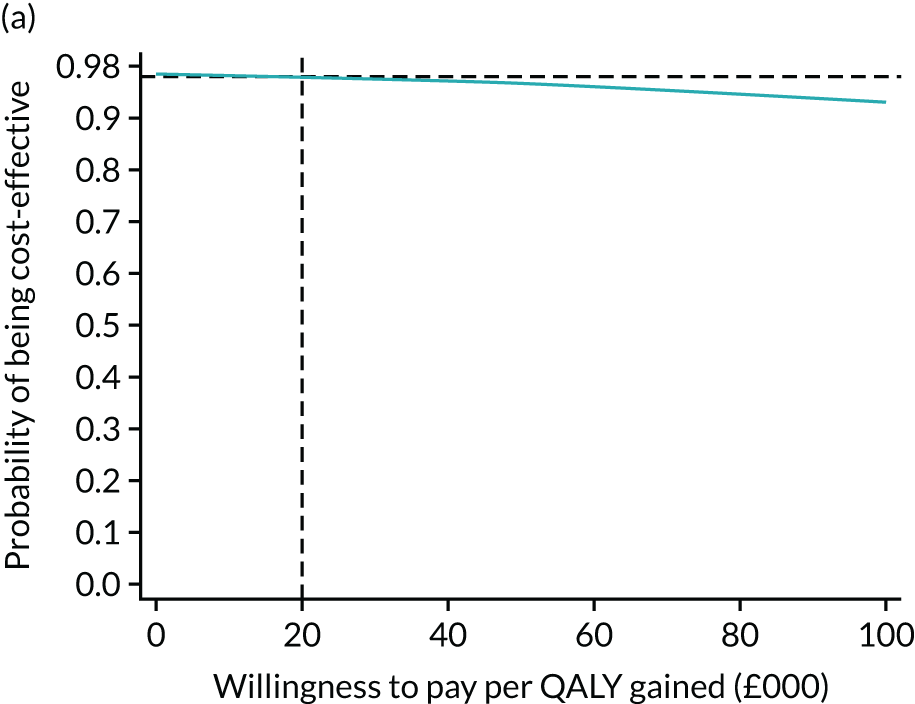

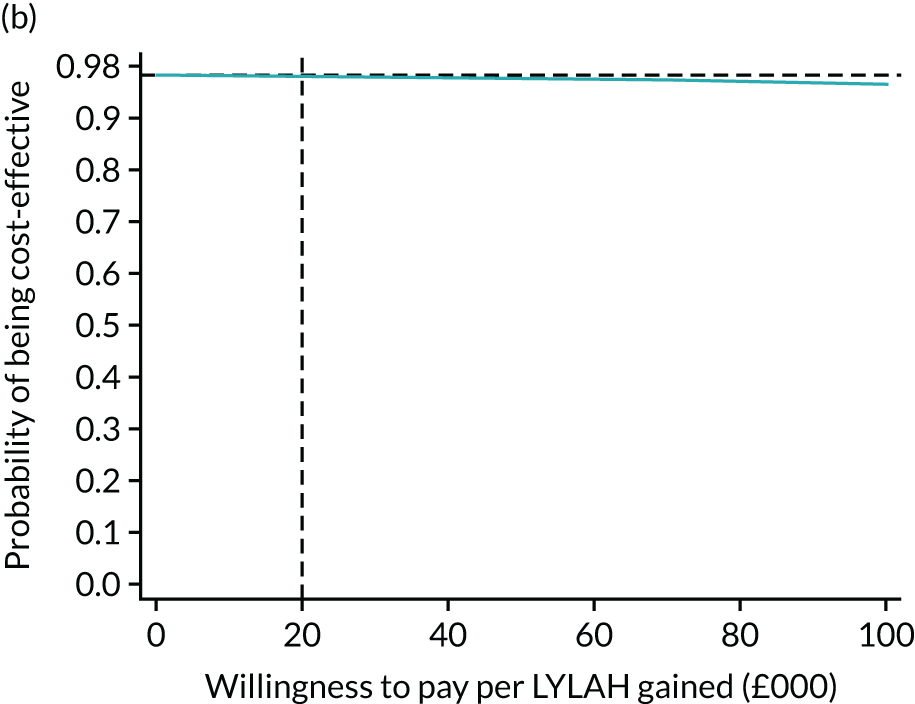

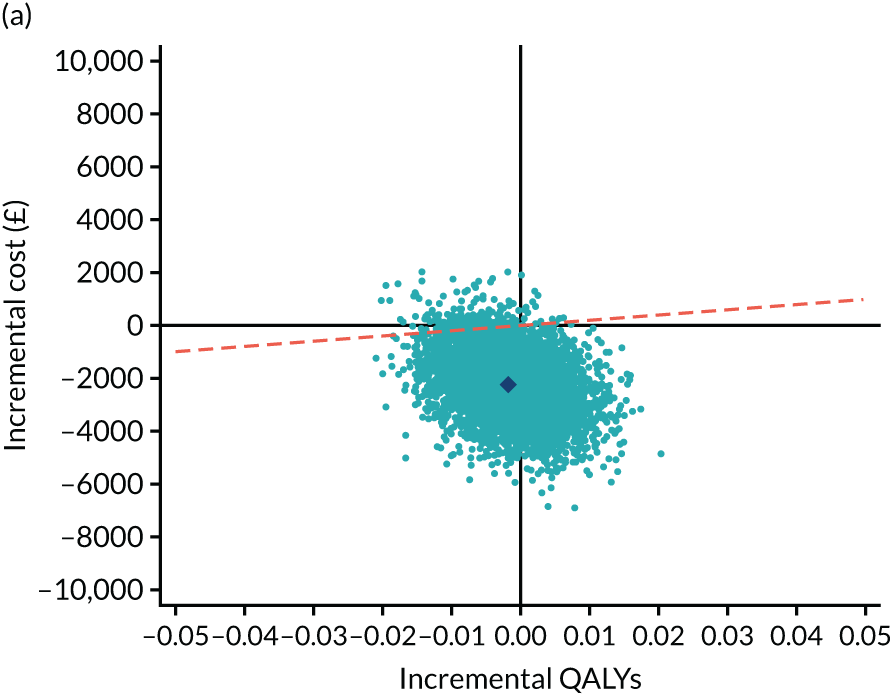

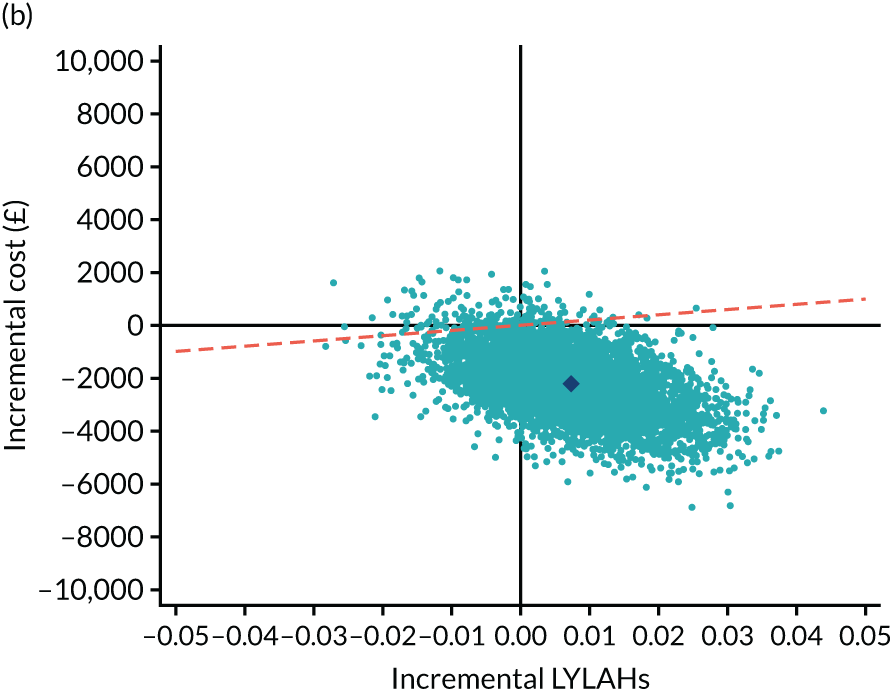

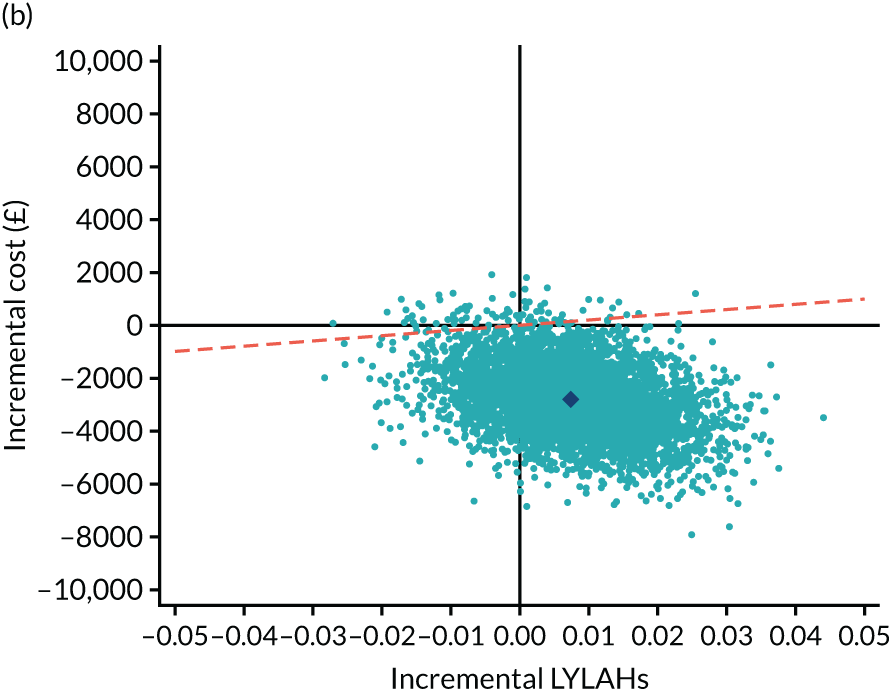

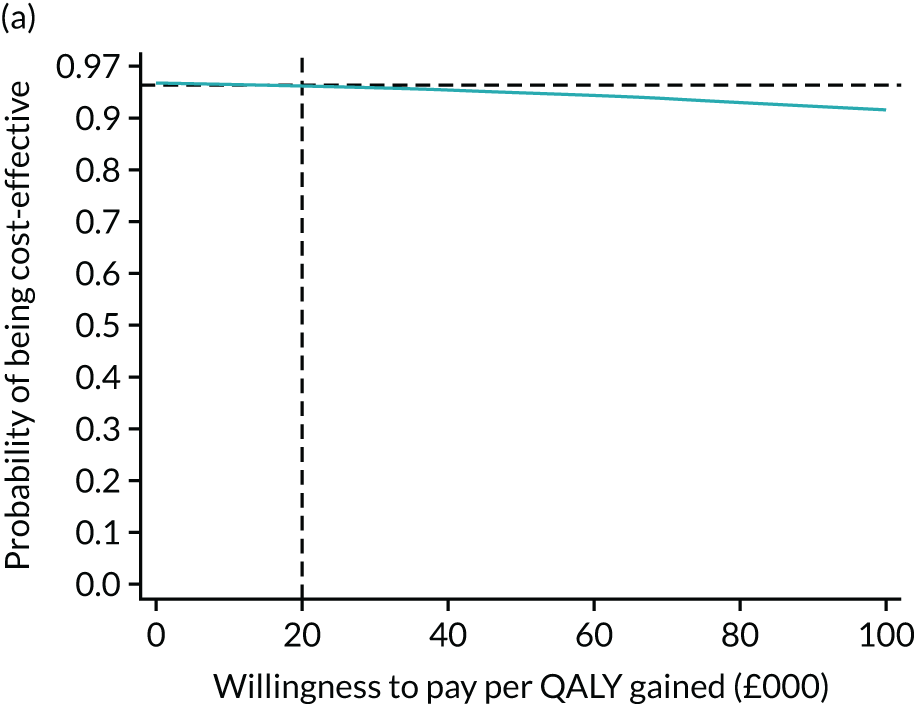

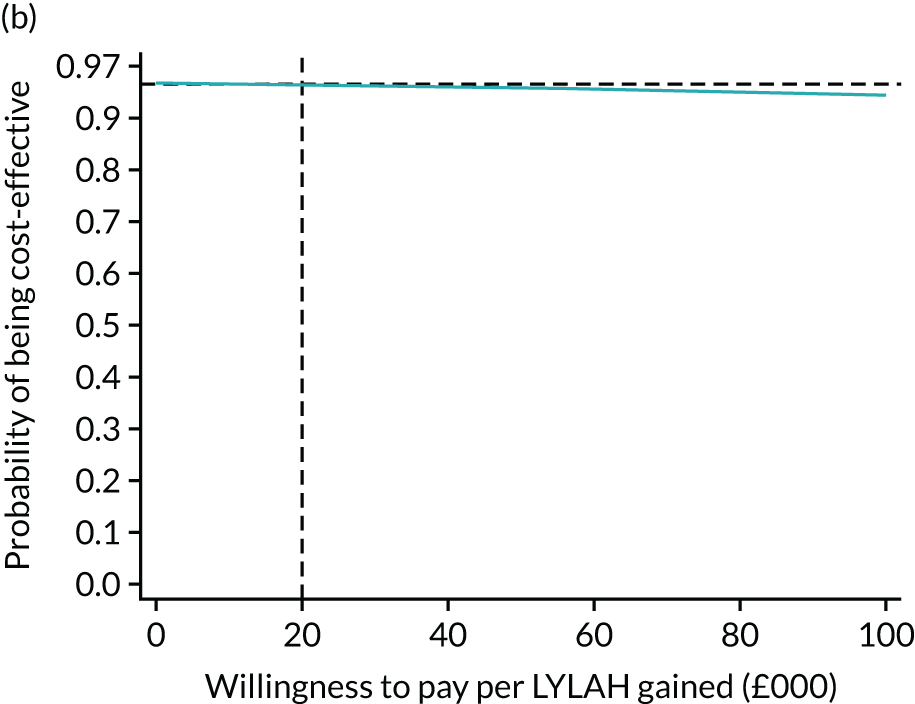

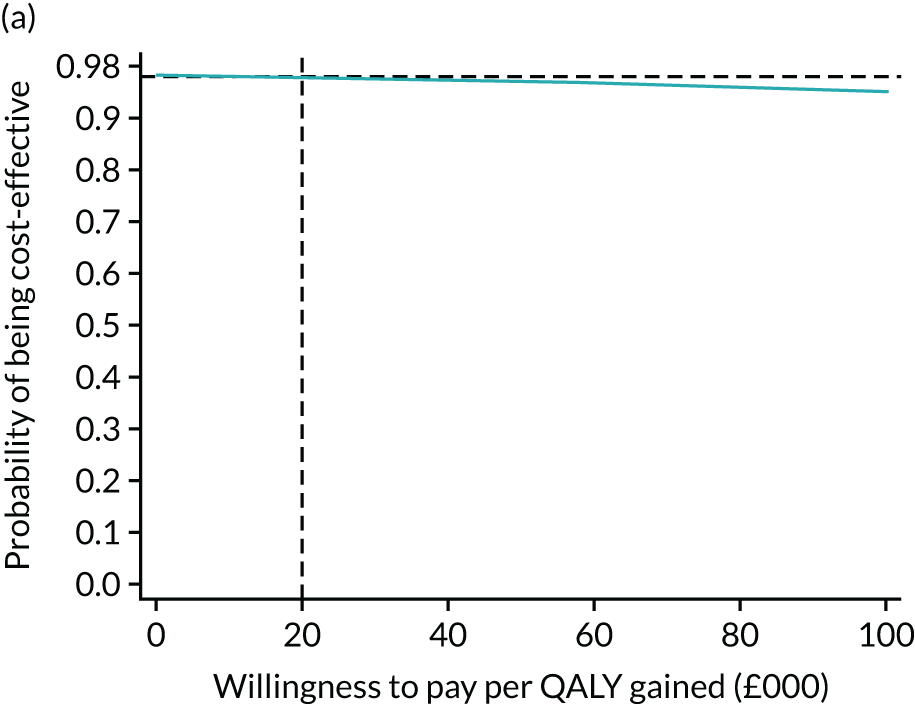

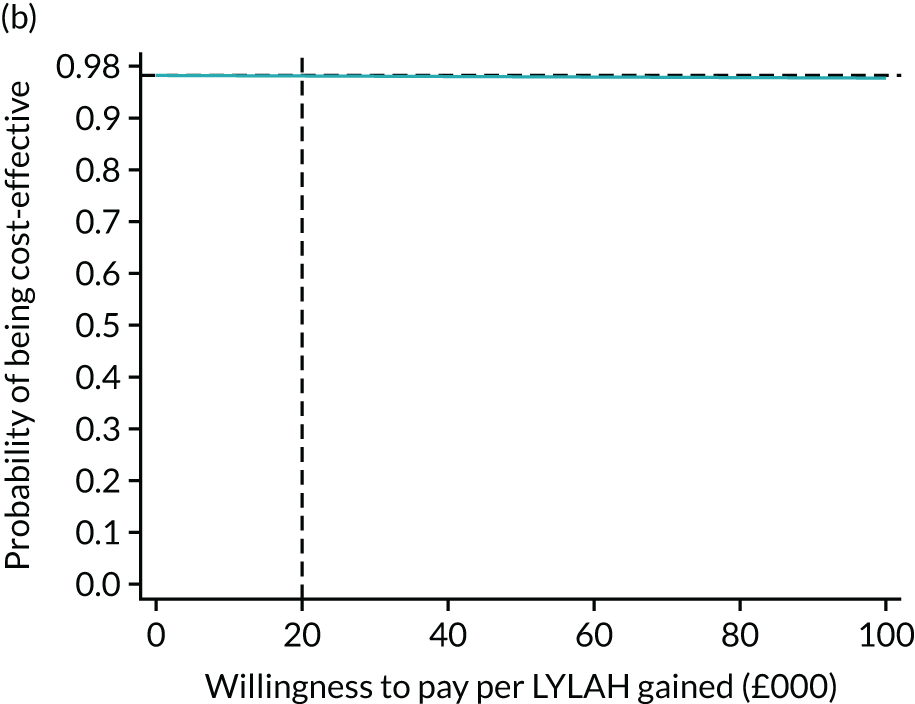

For the main analysis, we used the observed data to estimate differences in means and conducted t-tests to test for statistically significant differences. The main economic analysis is based on complete cases. The ICERs were reported from an NHS and PSS perspective, and separately from a societal perspective. Uncertainty associated with the ICER was assessed using non-parametric bootstrapping with replacement. For each of the 5000 bootstrapped samples, we estimated the means and mean between-group differences (with 95% CIs using the percentile method) in costs, QALYs and LYLAHs, and plotted ICERs on cost-effectiveness planes. Cost-effectiveness acceptability curves were displayed to show the probability that HAH was cost-effective at different levels of willingness to pay for a QALY and LYLAH gained.

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted two sensitivity analyses. First, we used linear mixed-effects regression models fitted on complete cases to estimate the differences in mean costs, QALYs and LYLAHs between the two treatment groups, after adjusting for baseline gender, known cognitive decline, baseline utilities and pre-randomisation costs as fixed effects, and site as a random effect. Pre-randomisation costs were included in the regression to estimate the differences in mean costs, and baseline utilities were included in the regression to estimate differences in mean QALYs. 29 Bootstrapped ICERs were then produced using the same method as in the main analysis. Second, we performed multiple imputation to address the impact of missing data for costs, EQ-5D-5L utilities and LYLAHs on the estimated ICERs. We first imputed missing utilities and costs at baseline using an unconditional mean estimate, as performing multiple imputation by treatment group can increase the covariate imbalance between control and treatment groups at baseline. 30,31 We also used imputed hospital length of stay at baseline using an unconditional mean estimate for the purpose of imputing LYLAHs. We then performed multiple imputation using chained equations to impute missing observations in utilities, costs at 6 months and LYLAHs based on utilities, costs and hospital length of stay at baseline, respectively, as well as gender and age. The multiple imputation process was partitioned by treatment group and 20 imputed data sets were generated, following standard practice, which suggests generating a number of imputed data sets equal to the percentage of missingness. 32 The imputed data sets were then used in the bootstrapping process similar to the main analysis.

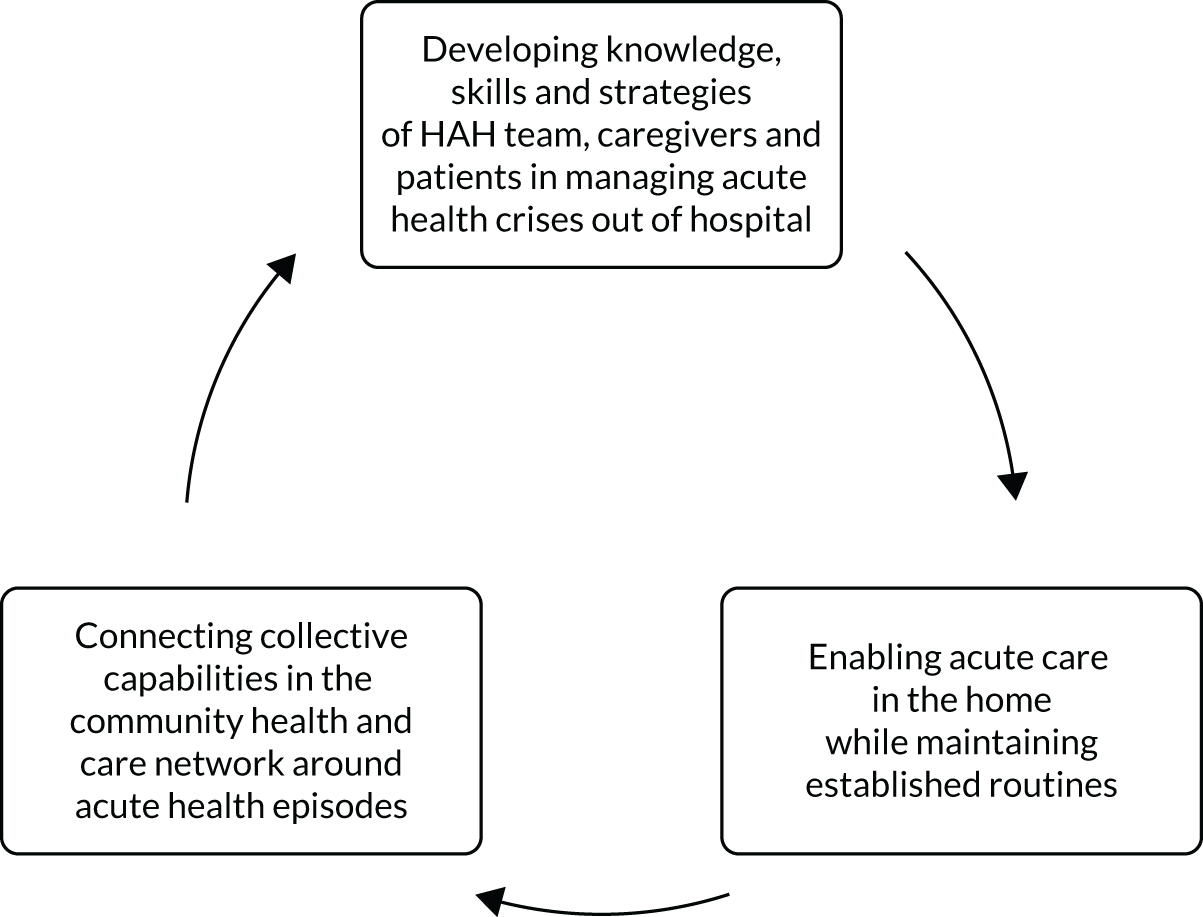

Process evaluation

We followed Medical Research Council guidance in designing the process evaluation. 33,34 Our intention was to undertake the process evaluation with sufficient flexibility to allow us to identify and address additional questions that arose during the study, recognising that local and broader aspects of these domains were likely to become more salient as the research developed. 35,36 We aimed to identify the factors that facilitated the implementation of HAH, how the risk of functional and cognitive decline was managed in a home setting, how ongoing coping and social support was maintained, and how these factors compared with acute health care delivered in hospital.

The objectives of the process evaluation were to:

-

explore the components, practices and experiences of HAH and hospital inpatient settings

-

assess the contextual factors in terms of the organisational features and local policy across the sites and how these might affect implementation of the intervention and the randomised trial

-

identify unanticipated consequences and aspects of the trial that were not necessarily captured quantitatively.

Methodology

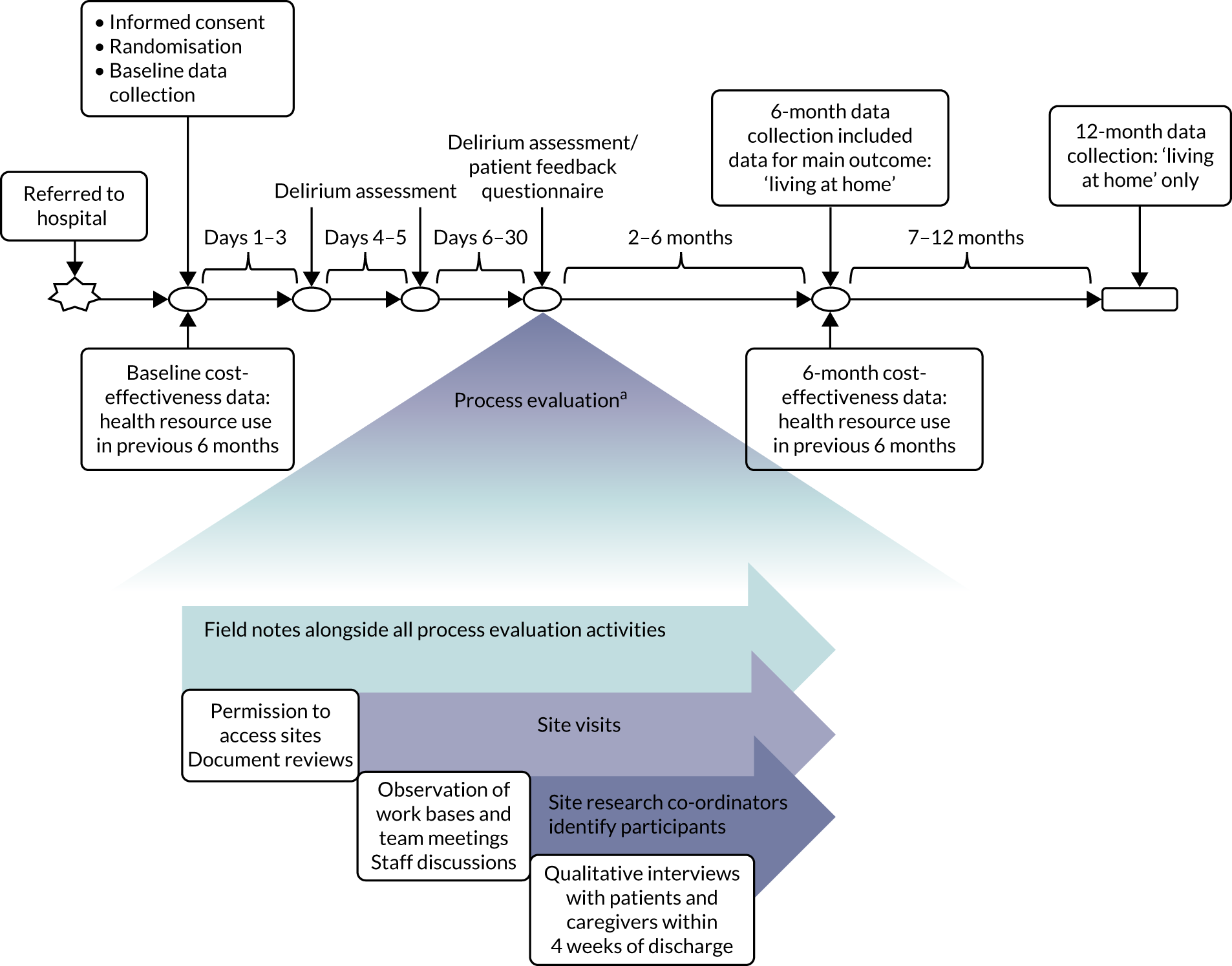

Our qualitative research methodology was driven by the aim of understanding participants’ perspectives and the meanings they attached to their experiences. We combined periods of fieldwork at sites with phenomenological inquiry through interviews, using open-ended questions to yield narrative data and capture the complexity of views. Figure 2 illustrates how the process evaluation was conducted alongside the randomised trial.

FIGURE 2.

The timeline for the process evaluation conducted alongside the randomised trial. a, Exact timelines varied according to the availability of staff and interviewees.

Methods

Parts of this section have been reproduced from Mäkalä et al. 50 © The Author(s) 2020. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the British Geriatrics Society. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/), which permits non-commercial re-use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. For commercial re-use, please contact journals.permissions@oup.com.

We followed the Medical Research Council guidance for process evaluations. 34 We collected data on key process variables from all nine sites throughout the trial by site visits, telephone calls with the site principal investigators, conference calls with the research nurse or co-ordinator from all sites [which were organised by the trial manager (ACB)] and e-mail correspondence to obtain a detailed understanding of how the services operated in each site.

The process evaluation was located in three sites that recruited participants to the randomised trial, two NHS trusts in England and one NHS trust in Scotland. We were limited to conducting the qualitative study at three sites because funding for the process evaluation was limited to 18 months. The three selected sites (Lanarkshire, Bradford and London) represented different geographical areas, service compositions, populations and organisational arrangements that might influence the delivery and effectiveness of the intervention.

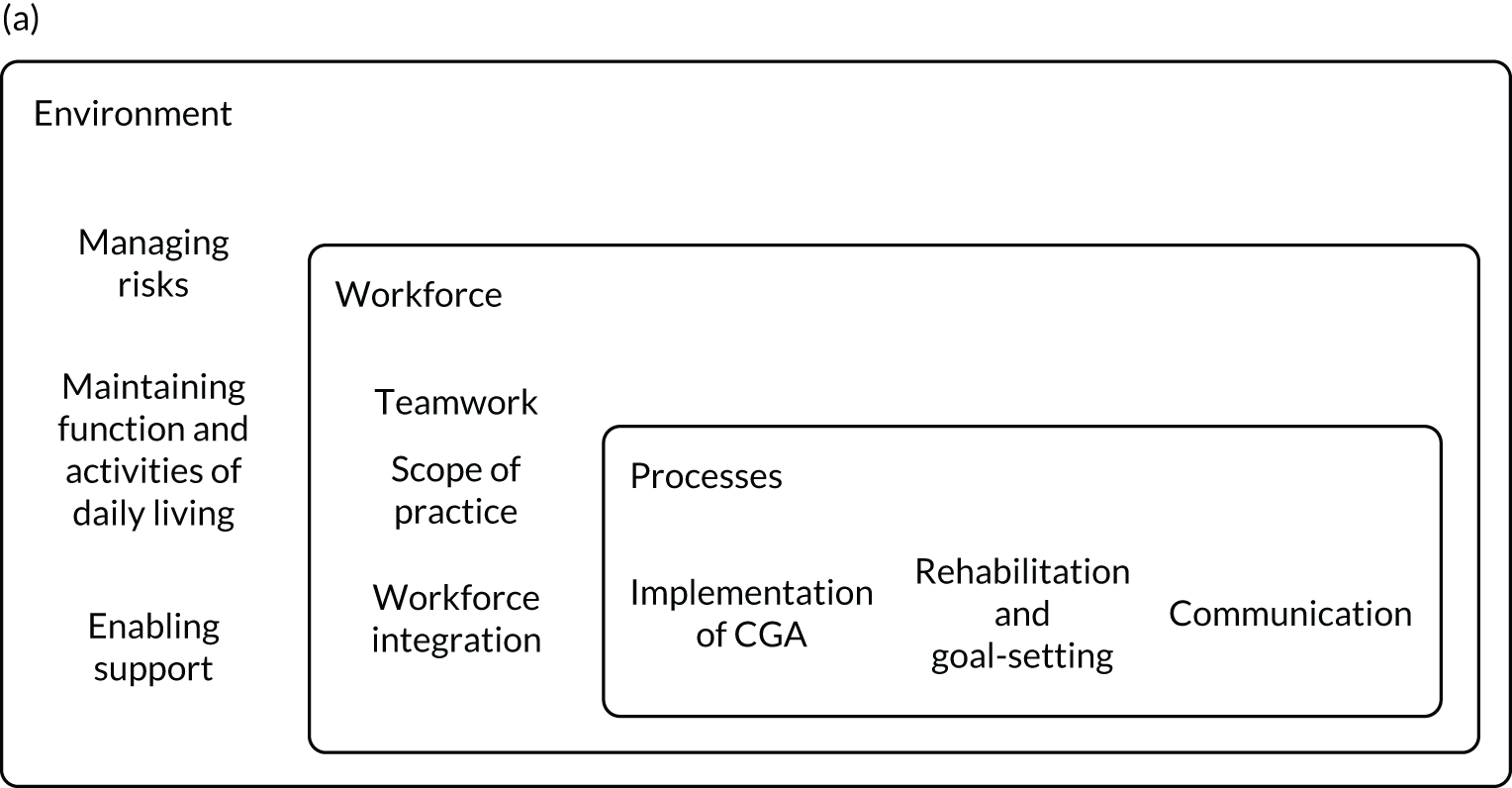

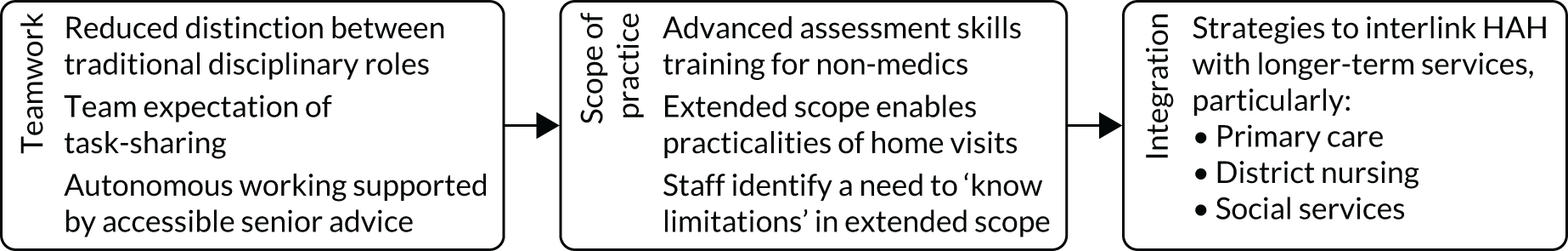

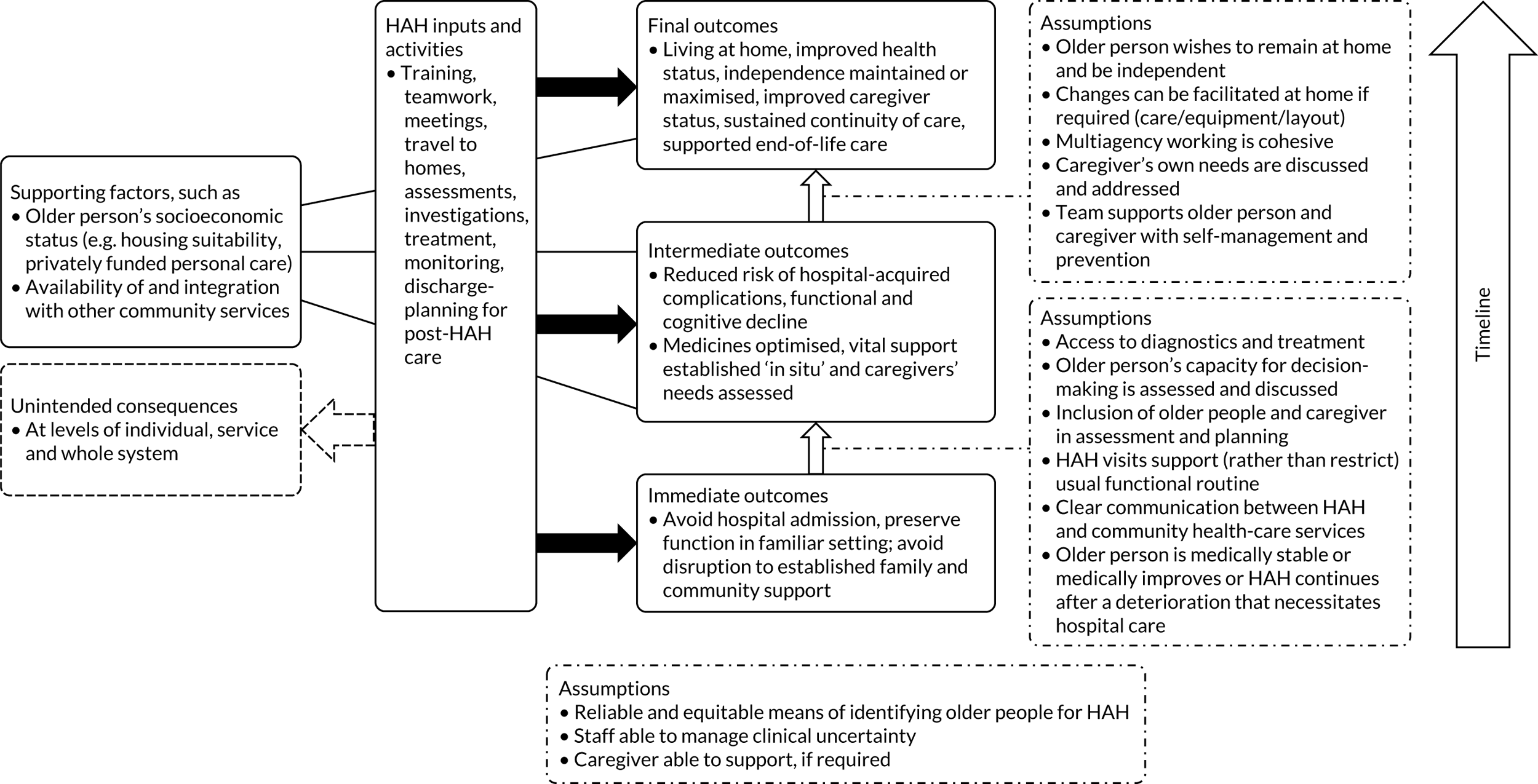

We used the five domains of the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research:37,38 (1) outer setting (i.e. factors external to the organisation), (2) inner setting (i.e. characteristics of the organisation), (3) intervention characteristics, (4) characteristics of the individuals involved in the intervention and (5) processes of implementation (Table 2). In addition, we used a logic model of CGA delivered in hospital (Figure 3) as an initial guide to setting out the relationship between resources, activities and intended results. We used normalisation process theory (NPT) to guide our analysis and interpretation of the data from interviews with older people and carers. 39,40

| Domain | Focus |

|---|---|

| Context |

|

| Implementation |

|

| Recruitment |

|

FIGURE 3.

Adapted logic model of CGA. ADL, activities of daily living.

Data generation

Components of the process evaluation included document reviews of websites, operational plans, patient information leaflets, service evaluations, audit reports and presentations by the services, non-participant observations of the HAH and hospital services (including MDT meetings, discussions with staff who delivered the services and the research team) and patient and carer interviews. Field notes were taken during the observations, discussions and interviews and were de-identified. These activities were undertaken by the qualitative researcher (PM) at each of the three process evaluation sites.

Interviews with older people and their caregivers

We conducted semistructured interviews with a purposive sample of older people and their caregivers who were recruited to the randomised trial. These were conducted between June 2017 and July 2018 so that relationships with each site could be established. We invited people with and people without family caregivers or formal carers and, when available, we invited family caregivers to participate in joint interviews if patients agreed to this.

Sampling

We purposively invited participants with cognitive impairment, if they had the appropriate support and were able to consent to take part, and those who were physically frail and who had experienced varied types of health crisis (e.g. sudden onset of illness, deterioration in the context of multiple health problems and acute exacerbation of a chronic condition) that might have an impact on recovery. We aimed to achieve variation at the whole-sample level across the three process evaluation sites.

In view of the practical difficulties of arranging and conducting interviews in participants’ homes across geographically dispersed sites, and in identifying participants who were randomised to each arm of the randomised controlled trial (RCT) (with a 2 : 1 randomisation ratio, intervention to control), convenience sampling was also necessary. 41 The planned sample size was six participants (with a family member, caregiver or significant other) from each arm of the RCT at each of the three sites (i.e. 36 interviews in total). We were willing to increasing the number of interviews if required to explore potentially promising lines of inquiry that we had not anticipated. We continuously reviewed the recruitment strategy to ensure adequate sampling and to address any practical issues that might have affected timely access to participants.

Recruitment

The qualitative researcher approached participants after initial contact was made by the trial research nurse or co-ordinator at the site. During this initial contact, nurse or co-ordinator confirmed that participants were medically stable and were not receiving end-of-life care and that there were no other reasons why it might be inappropriate to invite them to participate in the interviews. The nurse or co-ordinator provided participants with written information about the qualitative interview and confirmed that the participants agreed to further contact. The qualitative researcher then discussed the qualitative interview with the participant or consultee, answered questions and arranged a convenient time for the interview, which was around the time of discharge, or soon after discharge, from HAH or hospital. The availability of eligible participants determined the timing of the interviews and this resulted in interviews being conducted at different points in time across the three sites. The researcher conducted interviews in participants’ homes or hospital wards and recorded field notes to document contextual information on settings and interactions.

Consent processes

Patients who were recruited to the randomised trial could have reduced, fluctuating or no capacity to consent to trial participation. As capacity to consent refers to a time- and decision-specific ability,42 capacity was assessed for inclusion in the qualitative interview study as an additional consideration to consent for overall RCT participation. The qualitative researcher (PM) obtained informed consent for the interview study, and the consent process took into account implications of the Mental Capacity Act (2005) in England43 and the Adults with Incapacity Act (2000) in Scotland. 44 If the assessment indicated that a participant lacked capacity to consent, the researcher discussed the qualitative interview study with a personal consultee who was ‘engaged in caring for the person or was interested in their welfare’ and was involved in making decisions that reflected the participant’s views and values. 45 The researcher also invited the personal consultee to the qualitative interview, following their informed consent, to share their own experiences and perspectives and to support the older person. We emphasised that participants and caregivers were not under any obligation to participate in the qualitative interview and that, if they agreed to take part, they were free to withdraw at any time without having to provide an explanation and without any effect on their usual care. We explained that all personal information was de-identified and that the researchers were not involved in participants’ clinical care.

Interview processes

The researcher recorded the participant and caregiver interviews using an encrypted digital audio-recording device, subject to permission by participants. Interviews lasted between 30 and 60 minutes. We used topic guides as prompts for the semistructured interviews, with versions adapted for experiences of HAH or hospital inpatient care. We developed the topic guides from earlier iterations, informed by focus group discussions with older people and family caregivers who had experience of HAH or admission to hospital in an earlier study. 46 Questions were formulated to avoid jargon and to reflect experience, for example ‘Can you describe ways the health-care team supported you?’. Areas covered by the interviews included:

-

participants’ accounts of their presenting event and means of accessing HAH

-

perceptions of interactions with health-care professionals and other staff throughout the trajectory of service input for their presenting episode, from assessment to discharge, and any follow-up received

-

whether or not patients and caregivers were provided with any documentation and, if so, how this was perceived and used (e.g. service information leaflets, goal sheets, medication information, discharge letters)

-

how patients understood the intervention or other measures to have contributed to their recovery from the presenting event and their ability to continue to manage after discharge

-

caregivers’ perceptions of positive and negative aspects of the health-care experience and how effectively they perceived the patient’s and their own needs to have been addressed

-

how and where patients received input from health-care services, and how health-care professionals communicated transitions to or discussed transitions with patients.

Field visits

We visited the sites to hold discussions with a range of multidisciplinary staff, managers, commissioners and representatives of primary care and social services to find out how the services were organised, the scope of HAH, the organisation of inpatient hospital care and the interaction with related services that delivered health and social care. We reviewed policy and guidance documents referred to by staff, service assessment documents, discharge templates, protocols or other documentation considered important to the services. In addition, we observed MDT meetings and virtual ward round meetings at each process evaluation site. We used a framework to record our field notes to ensure that we collected information on the local environment, ways of working, roles, interactions, relationships, activities, documents, methods of communication and other aspects that facilitated teamwork, clinical processes and older person and caregiver interactions.

Health-care professionals

We held discussions with a range of health-care professionals to ensure that there was diversity of roles and experience, and we aimed to obtain ‘information-rich’ discussions. These discussions were approved by relevant service managers and were not recorded. The qualitative researcher explained the purpose of the discussions and gained verbal consent from each professional before commencing. We also used snowball sampling: managers or clinical leads identified clinicians and support staff who had suitable experience of the service and for whom a brief ‘release’ from workload activities had been agreed so that they could participate in a discussion with the qualitative researcher. Discussions were undertaken individually or in small groups, depending on staff time constraints and availability. We continued discussions with staff throughout the study or until we had obtained credible explanations that helped to address the research questions. 47 These discussions built on those that we had during the development of the research proposal.

Multidisciplinary staff invited to discussion at each of the three sites included managers and clinical leads for services participating in the randomised trial, allied health professionals across a range of seniorities, staff nurses, ward sisters and matrons, health-care assistants, rehabilitation support workers, consultant geriatricians, junior doctors, physician assistants, primary care representatives (e.g. GPs, district nurses, community matrons), pharmacists, social workers, administrative staff, and health-care commissioners in England and representatives of Health and Social Care Partnerships in Scotland. We took account of variation in staffing between teams, including, where appropriate, pharmacists or social workers. We anticipated that team composition would be dynamic throughout the study.

Data management and analysis

Audio data were fully transcribed by a professional agency and were checked by the researcher for accuracy. We allocated pseudonyms to all participants and de-identified the transcripts. All personally identifiable data were stored in password-protected files in a secure environment. Signed consent forms for the qualitative interviews were securely stored at each site. Field notes from the site visits and observations from interviews in hospital and home settings were also de-identified. We used a spreadsheet to log all ‘raw’ data generated to detail progress and to highlight potential gaps in the evaluation. Data were managed in NVivo 11 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) to aid organising the large number and different types of data, and to facilitate analysis.

Analysis of contextual data

We produced a narrative, descriptive account of the organisation of services at each site studied, using data collected from observations and field notes that were recorded during site visits, a review of formal documents that related to the organisation and delivery of health care, and notes from discussions with a range of health-care professionals. We focused on factors guided by the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research domains: intervention characteristics, outer setting (i.e. external to the organisation), inner setting (i.e. within the organisation), individuals involved and the processes of implementation. The evaluation of trial implementation explored the sustainability of activities and strategies used at the interface between service delivery (in varied clinical settings) and the randomised trial protocol requirements.

Analysis of qualitative interviews with patients and caregivers

We followed emergent design principles of qualitative research, which involved revisions as the research progressed. Our initial plan was to follow a grounded theory approach; however, this was adapted when we recognised that a more deductive approach was required to sensitise us to the dynamic health-care processes and the key areas that were relevant to the process evaluation. 40 We used a framework analysis to facilitate a comparative analysis of content to organise data into themes and guide the synthesis. 48 Specifically, the initial framework comprised elements from the logic model for CGA that described the inputs and activities intended to bring about the desired outcome of living at home to identify the essential features of health care in each setting of hospital or home. 2 We coded the data using NVivo, expanded through an inductive exploration of data that was not accommodated by the framework. 12

To understand the broader context of the implementation of health care in the two settings, and to assess how people individually and collectively work towards maintaining health, we used four interlinked concepts from NPT as a sensitising device to examine patients’ and caregivers’ participation in their health care. 39,49 The four concepts were (1) sense-making work (i.e. understanding what is happening), (2) relational work (i.e. interpersonal aspects of determining and meeting needs), (3) enacting work (i.e. undertaking and co-ordinating collective tasks) and (4) appraising work (i.e. reflecting on change and ongoing processes of adjustment). We developed an analytic framework, starting with the four NPT concepts, to identify the work required of patients and caregivers in relation to CGA-guided HAH and in hospital. In the second stage, we expanded the analysis by identifying factors that influenced patients’ and families’ capacity to undertake this work. We summarised findings narratively and included extracts of qualitative data to illustrate our interpretations and selected extracts across all three sites to ensure a balance. The qualitative researcher (PM) led the analysis, with SS reviewing the transcripts and GE, RS and DJS assisting with interpretation of the qualitative data.

Chapter 3 Main trial results

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Shepperd S, Butler C, Cradduck-Bamford A, Ellis G, Gray A, Hemsley A, et al. Is comprehensive geriatric assessment admission avoidance hospital at home an alternative to hospital admission for older people? A randomised trial [published online ahead of print April 20 2021]. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2021. 6 https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-5688. © American College of Physicians.

Screening and recruitment

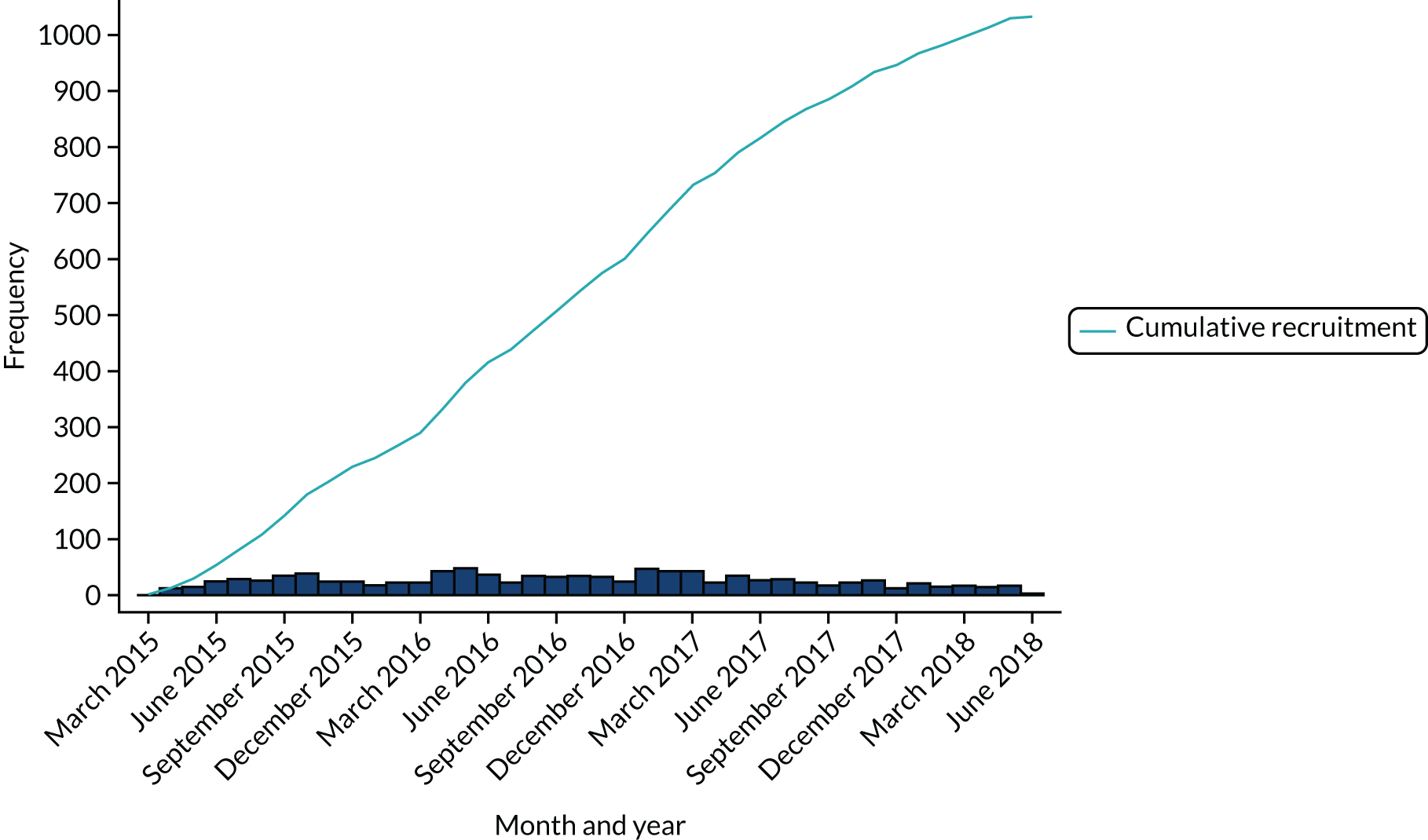

Sites maintained screening logs throughout the recruitment phase of the trial (i.e. between 9 February 2015 and 18 June 2018). A total of 4805 participants were screened for eligibility: 2169 (45%) were not eligible, 1581 (33%) were eligible but declined to participate and 1055 (22%) were recruited to the trial using a 2 : 1 allocation ratio [HAH, n = 700 (66.4%); inpatient hospital, n = 355 (33.7%)] (Table 3). The first participant was recruited on 14 March 2015 and the final participant was recruited on 18 June 2018 (Figure 4).

| Site | HAH (N = 700), n (%) recruited | Hospital (N = 355), n (%) recruited | Total randomised (N = 1055), n (%) recruited | Length of time site recruited (months) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Belfast Health & Social Care Trusta | 5 (0.7) | 4 (1.1) | 9 (0.9) | 13 |

| Bradford Royal Infirmary, Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 219 (31.3) | 109 (30.7) | 328 (31.1) | 35 |

| Victoria Hospitala | 15 (2.1) | 9 (2.5) | 24 (2.3) | 11 |

| Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust | 57 (8.1) | 30 (8.5) | 87 (8.3) | 23 |

| University Hospital Monklands | 148 (21.1) | 74 (20.8) | 222 (21.0) | 36 |

| St John’s Hospital | 74 (10.6) | 36 (10.1) | 110 (10.4) | 23 |

| Aneurin Bevan University Health Boardb | 158 (22.6) | 77 (21.7) | 235 (22.3) | 34 |

| Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trusta,c | 17 (2.4) | 11 (3.1) | 28 (2.7) | 31 |

| Southern Health and Social Care Trusta | 7 (1.0) | 5 (1.4) | 12 (1.1) | 21 |

FIGURE 4.

Monthly and cumulative recruitment.

Factors affecting recruitment

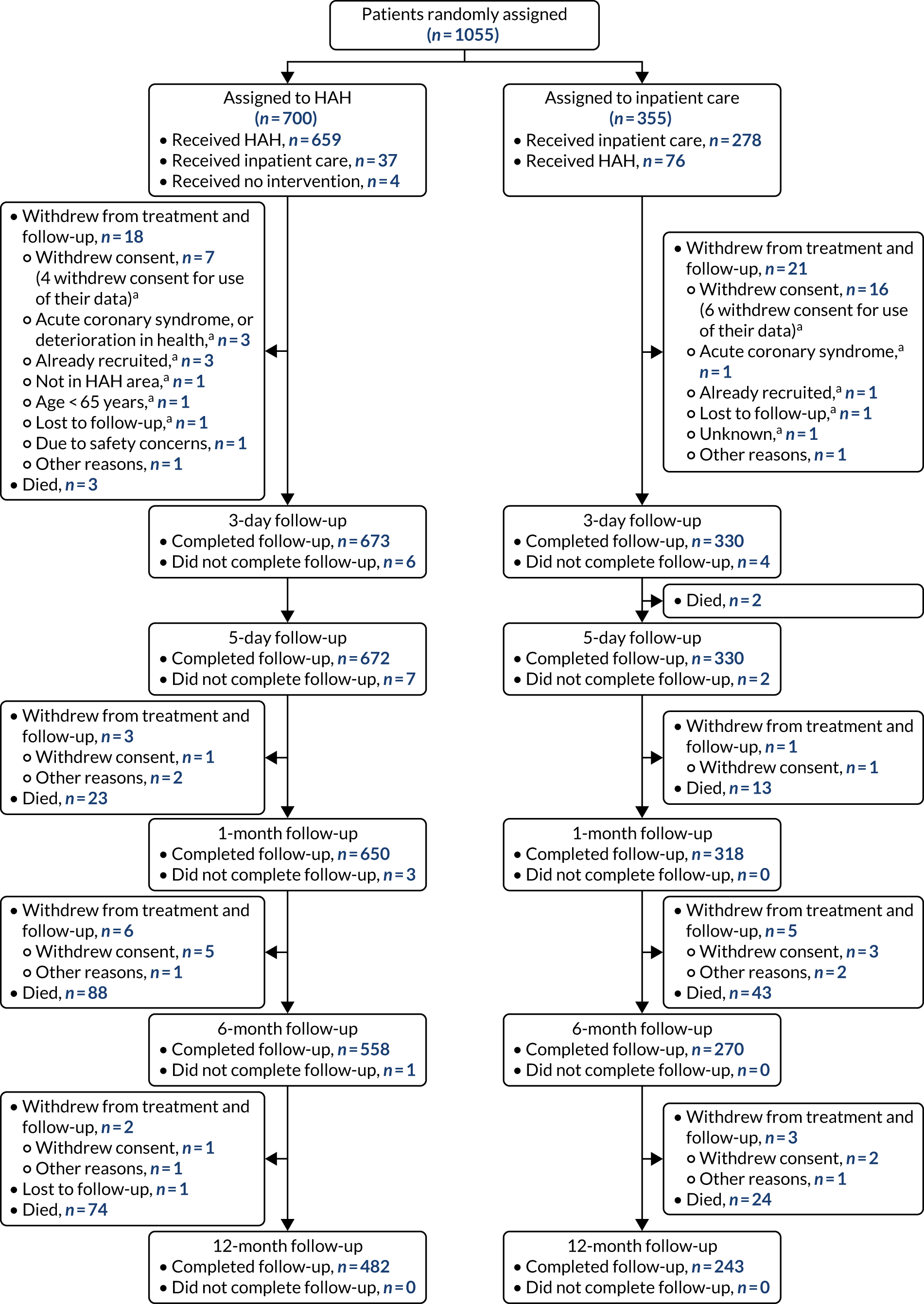

Discussions with the research nurses and site principal investigators identified a range of factors that contributed to successful recruitment and referral to HAH. These included a strong link between hospital-based consultant geriatricians and those leading the delivery of the HAH services and hospital doctors’ experience of HAH. Three of the sites that had a robust referral system to HAH had established an in-reach function, usually by a matron or an acute care of the elderly nurse who would review all acute medical admissions. One site received referrals from a dedicated hospital ward that had established a system of rapid clinical assessment and ‘discharge to assess’ with onward referral to HAH. Older people who had been assessed in an acute health-care setting for > 24 hours were not eligible for recruitment, and this was a problem if there were delays (such as transport difficulties), if sites had a lengthy assessment process or if additional hospital-based investigations had been arranged. The main reason for older people declining to participate in the study was a strong preference by them or their families for HAH or, less often, a preference for hospital care. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram is shown in Figure 5.

FIGURE 5.

A CONSORT flow diagram of trial participants. a, Data not available to include in the analysis. Reproduced with permission from Shepperd S, Butler C, Cradduck-Bamford A, Ellis G, Gray A, Hemsley A, et al. Is comprehensive geriatric assessment admission avoidance hospital at home an alternative to hospital admission for older people? A randomised trial [published online ahead of print April 20 2021]. Annals of Internal Medicine. 2021. 6 https://doi.org/10.7326/M20-5688. © American College of Physicians.

Completion of follow-up, withdrawals and switching group (crossovers)

The completion of follow-up for all the outcomes is described in Table 4. For the primary outcome (i.e. ‘living at home’), follow-up at 6 months was completed for HAH by 97.8% (672/687) and for hospital by 95.1% (328/345). At 12 months, follow-up was completed for HAH by 97.5% (670/687) and for hospital by 94.2% (325/345).

| Assessment | HAH (N = 687), n (%) | Hospital (N = 345), n (%) | Total randomised (N = 1032), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Living at home | |||

| 6-month follow-up | 672 (97.8) | 328 (95.1) | 1000 (96.9) |

| 12-month follow-up | 670 (97.5) | 325 (94.2) | 995 (96.4) |

| Presence of delirium (CAM) | |||

| Baseline | 685 (99.7) | 343 (99.4) | 1028 (99.6) |

| 3-day follow-up | 644 (93.7) | 311 (90.1) | 955 (92.5) |

| 5-day follow-up | 635 (92.4) | 307 (89.0) | 942 (91.3) |

| 1-month follow-up | 602 (87.6) | 295 (85.5) | 897 (86.9) |

| Mortality | |||

| 6-month follow-up | 673 (98.0) | 328 (95.1) | 1001 (97.0) |

| 12-month follow-up | 670 (97.5) | 325 (94.2) | 995 (96.4) |

| New long-term residential care | |||

| 6-month follow-up | 646 (94.0) | 311 (90.1) | 957 (92.7) |

| 12-month follow-up | 646 (94.0) | 311 (90.1) | 957 (92.7) |

| Cognitive impairment (MoCA) | |||

| Baseline | 524 (76.3) | 266 (77.1) | 790 (76.6) |

| 6-month follow-up | 407 (59.2) | 183 (53.0) | 590 (57.2) |

| Activities of daily living (Barthel Index) | |||

| Baseline | 684 (99.6) | 338 (98.0) | 1022 (99.0) |

| 6-month follow-up | 521 (75.8) | 256 (74.2) | 777 (75.3) |

| Readmission or transfer to hospital | |||

| 1-month follow-up | 672 (98.3) | 330 (96.0) | 807 (78.2) |

| 6-month follow-up | 621 (92.0) | 302 (88.0) | 920 (89.1) |

| Comorbidity (Charlson Comorbidity Index) | |||

| Baseline | 576 (83.8) | 271 (78.6) | 847 (82.1) |

| 6-month follow-up | 475 (69.1) | 227 (65.8) | 702 (68.0) |

| Quality of life (EQ-5D-5L) | |||

| Baseline | 659 (95.9) | 327 (94.8) | 986 (95.5) |

| 6-month follow-up | 480 (69.9) | 236 (68.4) | 716 (69.4) |

Between randomisation and 12-month follow-up a total of 59 (5.6%) participants withdrew from the study. Of those randomised to hospital, 19% (64/345) received health care on a general ward, 40% (138/345) on a geriatric ward and 12% (42/345) on a general ward with geriatric input. The type of hospital care was not recorded for the remaining participants. A total of 118 (11.4%) participants received the alternative form of care (i.e. switched group immediately after randomisation) (Table 5). Of these participants, 76 (21%) who were randomised to hospital received HAH and 37 (22%) who were randomised to HAH received hospital care for the episode of health care immediately after randomisation. There was variation among the sites, with a larger number of crossovers from HAH to hospital in one site because of participant preference and in two sites because of high bed occupancy during the winter months.

| Site | Allocated to HAH, received hospital | Allocated to hospital, received HAH | Crossover of participants recruited from each site, n/N (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aneurin Bevan University Health Board | 4 | 34 | 38/224 (16.9) |

| Bradford Royal Infirmary, Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 12 | 20 | 32/323 (9.9) |

| Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust | 2 | 10 | 12/86 (14.0) |

| University Hospital Monklands | 11 | 2 | 13/219 (6.0) |

| St John’s Hospital | 6 | 3 | 9/110 (8.0) |

| Victoria Hospital | 2 | 4 | 6/23 (26.1) |

| Royal Devon and Exeter NHS Foundation Trust | 0 | 0 | 0/27 (0) |

| Belfast Health & Social Care Trust | 0 | 0 | 0/8 (0) |

| Southern Health and Social Care Trust | 0 | 3 | 3/12 (25.0) |

| Total | 37 | 76 | 113 |

The baseline characteristics of participants were well balanced (Table 6). No tests of statistical significance for differences between randomised groups on baseline variables were performed. The results are reported for HAH compared with hospital.

| Characteristic | HAH (N = 687) | Hospital (N = 345) | Total randomised (N = 1032) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 83.3 (7.0) | 83.3 (6.9) | 83.3 (7.0) |

| Range | 65.0–102.5 | 65.1–102.9 | 65.0–102.9 |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Gender, n (%) | |||

| Male | 269 (39.2) | 138 (40.0) | 407 (39.4) |

| Female | 418 (60.8) | 207 (60.0) | 625 (60.6) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Education level, n (%) | |||

| Left school < 16 years old | 577 (85.2) | 287 (85.9) | 864 (85.5) |

| Upper secondary | 58 (8.6) | 26 (7.8) | 84 (8.3) |

| Higher education | 42 (6.2) | 21 (6.3) | 63 (6.2) |

| Missing | 10 | 11 | 21 |

| Place of assessment, n (%) | |||

| Hospital-based assessment centre that included a frailty unit | 524 (76.3) | 277 (80.3) | 801 (77.6) |

| Patient’s home | 160 (23.3) | 68 (19.7) | 228 (22.1) |

| Other | 3 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.3) |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Consent signed by consultee, n (%) | |||

| Yes | 107 (30.9) | 58 (33.3) | 165 (31.7) |

| No | 239 (69.1) | 116 (66.7) | 355 (68.3) |

| Missing | 341 | 171 | 512 |

| Presenting problem, n (%) | |||

| Acute functional deterioration | 254 (36.97) | 128 (37.10) | 382 (35.4) |

| Fall | 145 (21.1) | 74 (21.5) | 219 (21.2) |

| Confusion, dementia, delirium | 48 (7.0) | 19 (5.5) | 67 (6.5) |

| Respiratory tract infections | 23 (8.5) | 6 (4.4) | 29 (7.1) |

| Shortness of breath | 79 (29.0) | 42 (30.4) | 121 (29.5) |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 23 (8.46) | 17 (12.3) | 40 (9.8) |

| Urological disorders | 11 (4.0) | 11 (8.0) | 22 (5.4) |

| Congestive cardiac failure | 16 (5.9) | 6 (4.4) | 22 (5.4) |

| Musculoskeletal disorders | 15 (5.5) | 9 (6.5) | 24 (5.9) |

| Othera | 71 (10.33) | 33 (9.6) | 104 (10.0) |

| Missing | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| Heart failure | 51 (7.6) | 21 (6.4) | 72 (7.2) |

| Infection | 301 (44.7) | 142 (43.4) | 443 (44.3) |

| Delirium | 19 (2.8) | 14 (4.3) | 33 (3.3) |

| Othera | 303 (45.0) | 150 (45.9) | 453 (45.3) |

| Missing | 13 | 18 | 31 |

| Presence of delirium (CAM), n (%) | |||

| Present | 46 (6.7) | 24 (7.0) | 70 (6.6) |

| Missing | 1 | 2 | 3 |

| Cognitive impairment (MoCA), n (%) | |||

| Abnormal (score of < 26) | 375 (71.6) | 196 (73.7) | 571 (72.3) |

| Normal (score of ≥ 26) | 149 (28.4) | 70 (26.3) | 219 (27.7) |

| Missing | 163 | 79 | 242 |

| Activities of daily living (Barthel Index), n (%) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 15.3 (4.1) | 14.8 (4.7) | 15.2 (4.3) |

| Range | 0.0–20.0 | 0.0–20.0 | 0.0–20.0 |

| Missing | 3 | 7 | 10 |

| Known cognitive decline (IQCODE) (a higher score indicates greater cognitive decline) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 3.5 (0.6) | 3.5 (0.6) | 3.5 (0.6) |

| Range | 2.0–5.0 | 1.0–5.0 | 1.0–5.0 |

| < 3.5, n (%) | 425 (62.6) | 217 (63.3) | 642 (62.8) |

| ≥ 3.5, n (%) | 254 (37.4) | 126 (36.7) | 380 (37.2) |

| Missing | 8 | 2 | 10 |

| Comorbidity (Charlson Comorbidity Index) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 6.0 (1.9) | 5.9 (1.8) | 6.0 (1.8) |

| Range | 1.0–15.0 | 1.0–12.0 | 1.0–15.0 |

| Missing | 111 | 74 | 185 |

| EQ-5D-5L mobility, n (%) | |||

| No problems | 86 (12.7) | 55 (16.6) | 141 (14.0) |

| Slight problems | 164 (24.3) | 64 (19.3) | 228 (22.6) |

| Moderate problems | 233 (34.5) | 117 (35.2) | 350 (34.7) |

| Severe problems | 162 (24.0) | 71 (21.4) | 233 (23.1) |

| Unable to walk | 31 (4.6) | 25 (7.5) | 56 (5.6) |

| Missing/ambiguous | 11 | 13 | 24 |

| EQ-5D-5L self-care, n (%) | |||

| No problems | 248 (36.8) | 129 (38.9) | 377 (37.5) |

| Slight problems | 154 (22.8) | 76 (22.9) | 230 (22.9) |

| Moderate problems | 160 (23.7) | 73 (22.0) | 233 (23.2) |

| Severe problems | 64 (9.5) | 30 (9.0) | 94 (9.3) |

| Unable to wash or dress | 48 (7.1) | 24 (7.2) | 72 (7.2) |

| Missing/ambiguous | 13 | 13 | 26 |

| EQ-5D-5L usual activities, n (%) | |||

| No problems | 170 (25.2) | 92 (27.5) | 262 (26.0) |

| Slight problems | 165 (24.5) | 74 (22.2) | 239 (23.7) |

| Moderate problems | 166 (24.6) | 78 (23.4) | 244 (24.2) |

| Severe problems | 103 (15.3) | 45 (13.5) | 148 (14.7) |

| Unable to do usual activities | 70 (10.4) | 45 (13.5) | 115 (11.4) |

| Missing/ambiguous | 13 | 11 | 24 |

| EQ-5D-5L pain/discomfort, n (%) | |||

| No pain or discomfort | 261 (38.7) | 129 (38.6) | 390 (38.7) |

| Slight pain or discomfort | 143 (21.2) | 79 (23.7) | 222 (22.0) |

| Moderate pain or discomfort | 147 (21.8) | 69 (20.7) | 216 (21.4) |

| Severe pain or discomfort | 106 (15.7) | 48 (14.4) | 154 (15.3) |

| Extreme pain or discomfort | 17 (2.5) | 9 (2.7) | 26 (2.6) |

| Missing/ambiguous | 13 | 11 | 24 |

| EQ-5D-5L anxiety/depression, n (%) | |||

| Not anxious or depressed | 337 (50.2) | 171 (51.2) | 508 (50.5) |

| Slightly anxious or depressed | 162 (24.1) | 87 (26.0) | 249 (24.8) |

| Moderately anxious or depressed | 133 (19.8) | 55 (16.5) | 188 (18.7) |

| Severely anxious or depressed | 31 (4.6) | 15 (4.5) | 46 (4.6) |

| Extremely anxious or depressed | 8 (1.2) | 6 (1.8) | 14 (1.4) |

| Missing/ambiguous | 16 | 11 | 27 |

| EQ-5D visual analogue scale | |||

| Mean (SD) | 56.8 (21.4) | 55.6 (22.9) | 56.4 (21.9) |

| Range | 0.0–100.0 | 0.0–100.0 | 0.0–100.0 |

| Missing | 13 | 14 | 27 |

‘Living at home’ at 6 months

There was no evidence of a difference in ‘living at home’ (i.e. not being dead and living at home, or the inverse of death or new long-term residential care) at 6 months. The adjusted RR for HAH compared with hospital was 1.05 (95% CI 0.95 to 1.15; p = 0.36). The number and percentage of participants living at home at 6 months are presented in Table 7. The results of the analysis for each of the outcomes that contributed to ‘living at home’ (i.e. mortality and new long-term residential care) are reported in Tables 9 and 10.

| HAH (N = 687) | Hospital (N = 345) | |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Living at home’ at 6 months, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 528 (78.6) | 247 (75.3) |

| No | 144 (21.4) | 81 (24.7) |

| Missing | 15 | 17 |

| Adjusted RR (95% CI): HAH vs. hospital | 1.05 (0.95 to 1.15) | |

| p-value | 0.36 | |

| Unadjusted RR (95% CI): HAH vs. hospital | 1.04 (0.94 to 1.16) | |

| p-value | 0.44 | |

‘Living at home’ at 12 months

The adjusted RR for HAH compared with hospital for ‘living at home’ at 12-month follow-up was 0.99 (95% CI 0.89 to 1.10; p = 0.80). The frequency and percentage of participants living at home at 12 months, by randomised arm, are presented in Table 8.

| HAH (N = 687) | Hospital (N = 345) | |

|---|---|---|

| ‘Living at home’ at 12 months, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 443 (66.1) | 219 (67.4) |

| No | 227 (33.9) | 106 (32.6) |

| Missing | 17 | 20 |

| Adjusted RR (95% CI): HAH vs. hospital | 0.99 (0.89 to 1.10) | |

| p-value | 0.80 | |

| Unadjusted RR (95% CI): HAH vs. hospital | 0.98 (0.88 to 1.10) | |

| p-value | 0.72 | |

Mortality at 6 and 12 months

There was no evidence of a difference between the HAH and hospital groups in the risk of mortality at 6 months (adjusted RR 0.98, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.47; p = 0.92) or at 12 months (adjusted RR 1.14, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.62; p = 0.47). The frequency and percentage of participants alive and dead at 3-day, 5-day, 1-month, 6-month and 12-month follow-up, and the adjusted RRs with 95% CIs, are presented in Table 9.

| Mortality | HAH (N = 687) | Hospital (N = 345) |

|---|---|---|

| Mortality at 3 days, n (%) | ||

| Dead | 3 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) |

| Alive | 679 (99.6) | 334 (100.0) |

| Missing | 5 | 11 |

| Mortality at 5 days, n (%) | ||

| Dead | 3 (0.4) | 2 (0.6) |

| Alive | 679 (99.6) | 332 (99.4) |

| Missing | 5 | 11 |

| Mortality at 1 month, n (%) | ||

| Dead | 26 (3.8) | 15 (4.5) |

| Alive | 652 (96.2) | 318 (95.5) |

| Missing | 9 | 12 |

| Mortality at 6 months, n (%) | ||

| Dead | 114 (16.9) | 58 (17.7) |

| Alive | 559 (83.1) | 270 (82.3) |

| Missing | 14 | 17 |

| Adjusted RR (95% CI): HAH vs. hospital | 0.98 (0.65 to 1.47) | |

| p-value | 0.92 | |

| Unadjusted RR (95% CI): HAH vs. hospital | 0.98 (0.65 to 1.49) | |

| p-value | 0.94 | |

| Mortality at 12 months, n (%) | ||

| Dead | 188 (28.1) | 82 (25.2) |

| Alive | 482 (71.9) | 243 (74.8) |

| Missing | 17 | 20 |

| Adjusted RR (95% CI): HAH vs. hospital | 1.14 (0.80 to 1.62) | |

| p-value | 0.47 | |

| Unadjusted RR (95% CI): HAH vs. hospital | 1.14 (0.80 to 1.63) | |

| p-value | 0.47 | |

New long-term residential care at 6 and 12 months

There was a significant difference between the HAH and hospital groups in the risk of new long-term residential care at 6 months. The adjusted RR at 6 months was 0.58 (95% CI 0.45 to 0.76; p < 0.001) and at 12 months was 0.61 (95% CI 0.46 to 0.82; p < 0.001). The frequency and percentage of participants requiring new long-term residential care at the 6- and 12-month follow-ups, and the adjusted RRs with 95% CIs, are presented in Table 10.

| New long-term residential care | HAH (N = 687) | Hospital (N = 345) |

|---|---|---|

| New long-term residential care at 6 months, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 37 (5.7) | 27 (8.7) |

| No | 609 (94.3) | 284 (91.3) |

| Missing | 41 | 34 |

| Adjusted RR (95% CI): HAH vs. hospital | 0.58 (0.45 to 0.76) | |

| p-value | < 0.001 | |

| Unadjusted RR (95% CI): HAH vs. hospital | 0.54 (0.43 to 0.69) | |

| p-value | < 0.001 | |

| New long-term residential care at 12 months, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 39 (6.0) | 27 (8.7) |

| No | 607 (94.0) | 284 (91.3) |

| Missing | 41 | 34 |

| Adjusted RR (95% CI): HAH vs. hospital | 0.61 (0.46 to 0.82) | |

| p-value | < 0.001 | |

| Unadjusted RR (95% CI): HAH vs. hospital | 0.57 (0.45 to 0.73) | |

| p-value | < 0.001 | |

Any residential care at 1-, 6- and 12-month follow-up and the adjusted relative risks (post hoc analysis)

There was no evidence of a difference in the risk of short- or long-term residential care at 1 month (adjusted RR 0.67, 95% CI 0.34 to 1.31; p = 0.24). At the 6- and 12-month follow-ups there was a significant reduction for those allocated to HAH (adjusted RR 0.64, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.76, p < 0.001; and adjusted RR 0.63, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.76; p < 0.001, respectively). The frequency and percentage of participants admitted to any residential care at 1, 6 and 12 months, and the adjusted RRs are presented in Table 11.

| Any residential care | HAH (N = 687) | Hospital (N = 345) |

|---|---|---|

| Any residential care at 1 month, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 15 (2.2) | 10 (3.0) |

| Short term | 15 (2.2) | 10 (3.0) |

| Long term | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| No | 656 (97.8) | 320 (98.0) |

| Missing | 16 | 15 |

| Adjusted RR (95% CI): HAH vs. hospital | 0.67 (0.34 to 1.31) | |

| p-value | 0.24 | |

| Any residential care at 6 months, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 51 (7.9) | 34 (11.0) |

| Short-term | 14 (2.2) | 7 (2.3) |

| Long-term | 37 (5.7) | 27 (8.7) |

| No | 595 (92.1) | 277 (89.1) |

| Missing | 41 | 34 |

| Adjusted RR (95% CI): HAH vs. hospital | 0.64 (0.54 to 0.76) | |

| p-value | < 0.001 | |

| Any residential care at 12 months, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 59 (9.1) | 40 (12.9) |

| Short term | 20 (3.1) | 13 (4.2) |

| Long term | 39 (6.0) | 27 (8.7) |

| No | 587 (90.9) | 271 (87.1) |

| Missing | 41 | 34 |

| Adjusted RR (95% CI): HAH vs. hospital | 0.63 (0.53 to 0.76) | |

| p-value | < 0.001 | |

Delirium

The adjusted RR for HAH compared with hospital for the presence of delirium at 3 days was 1.21 (95% CI 0.54 to 2.29; p = 0.76), at 5 days was 0.93 (95% CI 0.34 to 2.47; p = 0.87) and at 1 month was 0.38 (95% CI 0.19 to 0.76; p = 0.006). The number and percentage of participants with delirium at baseline, 3 days, 5 days and 1 month, by randomised arm, and the adjusted RRs with 95% CIs are presented in Table 12. The proportion of participants with a clinical diagnosis of delirium at baseline was smaller in the HAH group [HAH 19/687 (2.8%); hospital 14/345 (4.3%)].

| Presence of delirium | HAH (N = 687) | Hospital (N = 345) | Relative riska (95% CI) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Presence of delirium (CAM) at baseline, n (%) | 46 (6.7) | 24 (7.0) | ||

| Missing | 1 | 2 | ||

| Presence of delirium (CAM) at 3 days, n (%) | 25 (3.9) | 11 (3.5) | 1.12 (0.54 to 2.29) | 0.76 |

| Missing | 42 | 33 | ||

| Presence of delirium (CAM) at 5 days, n (%) | 17 (2.7) | 9 (3.0) | 0.93 (0.34 to 2.47) | 0.87 |

| Missing | 49 | 37 | ||

| Presence of delirium (CAM) at 1 month, n (%) | 10 (1.7) | 13 (4.4) | 0.38 (0.19 to 0.76) | 0.006 |

| Missing | 85 | 48 |

The mean [standard deviation (SD)] MoCA score in the group with delirium, measured with the CAM, at each follow-up time is reported in Table 13. On average, this group had a lower mean MoCA score than the study population at baseline [mean 20.5 (SD 6.7), range 0–31; n = 790].

| MoCA score | HAH (N = 687) | Hospital (N = 345) |

|---|---|---|

| Baseline MoCA score among those CAM positive at baseline | ||

| n (%) | 37 (5.4) | 20 (5.8) |

| Mean (SD) | 10.7 (5.4) | 13.6 (7.7) |

| Range | 3–21 | 5–28 |

| Missing | 22 | 12 |

| Baseline MoCA score among those CAM positive at 3 days | ||

| n (%) | 20 (2.9) | 9 (2.6) |

| Mean (SD) | 14.2 (8.6) | 12 (9.8) |

| Range | 3–26 | 3–21 |

| Missing | 11 | 5 |

| Baseline MoCA score among those CAM positive at 5 days | ||

| n (%) | 15 (2.2) | 5 (1.4) |

| Mean (SD) | 13.0 (5.4) | 7.3 (5.1) |

| Range | 3–19 | 3–13 |

| Missing | 6 | 2 |

| Baseline MoCA score among those CAM positive at 1 month | ||

| n (%) | 9 (1.3) | 12 (3.5) |

| Mean (SD) | 19.8 (4.4) | 16.6 (9.4) |

| Range | 13–24 | 1–27 |

| Missing | 4 | 5 |

Cognitive impairment measured with the Montreal Cognitive Assessment at 6 months

There was no evidence of a difference in the risk of cognitive impairment (defined using the MoCA) at 6 months (adjusted RR 1.06, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.21; p = 0.36). The frequency and percentage of participants who were cognitively impaired at baseline and at 6-month follow-up, and the adjusted RR with 95% CI, are presented in Table 14.

| Cognitive impairment | HAH (N = 687) | Hospital (N = 345) |

|---|---|---|

| Cognitive impairment (MoCA) at baseline, n (%) | ||

| Abnormal (score of < 26) | 375 (71.6) | 196 (73.7) |

| Normal (score of ≥ 26) | 149 (28.4) | 70 (26.3) |

| Missing | 163 | 79 |

| Cognitive impairment (MoCA) at 6 months, n (%) | ||

| Abnormal (score of < 26) | 273 (67.1) | 115 (62.8) |

| Normal (score of ≥ 26) | 134 (32.9) | 68 (37.2) |

| Missing | 280 | 162 |

| Adjusted RR (95% CI) group A vs. group B | 1.06 (0.93 to 1.21) | |

| p-value | 0.36 | |

Activities of daily living (Barthel Index) at 6 months

The adjusted mean difference for activities of daily living (Barthel Index) at 6 months was 0.24 (95% CI –0.33 to 0.80; p = 0.411). The mean scores at baseline and at 6 months and the adjusted mean difference are presented in Table 15.

| Activities of daily living | HAH (n = 687) | Hospital (n = 345) |

|---|---|---|

| Activities of daily living (Barthel Index) at baseline | ||

| Mean (SD) | 15.3 (4.10) | 14.8 (4.7) |

| Range | 0.0–20.0 | 0.0–20.0 |

| Missing | 3 | 7 |

| Activities of daily living (Barthel Index) at 6 months | ||

| Mean (SD) | 15.8 (4.4) | 15.6 (4.9) |

| Range | 0.0–20.0 | 0.0–20.0 |

| Missing | 166 | 89 |

| Adjusted mean difference (95% CI): HAH vs. hospital | 0.24 (–0.33 to 0.80) | |

| p-value | 0.41 | |

The adjusted mean difference at 6 months was 0.0002 (95% CI –0.1452 to 0.1455; p = 0.998) (Table 16).

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score | HAH (n = 687) | Hospital (n = 345) |

|---|---|---|

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score at baseline | ||

| Mean (SD) | 6.01 (1.85) | 5.93 (1.77) |

| Median (IQR) | 6 (5–7) | 6 (5–7) |

| Range | 1–15 | 1–12 |

| Missing | 111 | 74 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score at 6 months | ||

| Mean (SD) | 6.17 (1.94) | 6.00 (1.93) |

| Median (IQR) | 6 (5–7) | 6.0 (5–7) |

| Range | 1.0–13.0 | 1–15 |

| Missing | 212 | 118 |

| Adjusted mean difference (95% CI): HAH vs. hospital | 0.0002 (–0.1452 to 0.1455) | |

| p-value | 0.998 | |

| Charlson probability at baseline | ||

| Mean (SD) | 0.16 (0.24) | 0.17 (0.23) |

| Median (IQR) | 0.02 (0.00–0.21) | 0.02 (0.00–0.21) |

| Range | 0–0.96 | 0–0.96 |

| Missing | 111 | 74 |

| Charlson probability at 6 months | ||

| Mean (SD) | 0.15 (0.23) | 0.17 (0.24) |

| Median (IQR) | 0.02 (0.00–0.21) | 0.02 (0.00–0.21) |

| Range | 0–0.96 | 0–0.96 |

| Missing | 212 | 118 |

| Adjusted mean difference (95% CI) | ||

| Group A vs. group B | –0.0004 (–0.0138 to 0.0131) | |

| Group B vs. group A | 0.0004 (–0.0131 to 0.0138) | |

| p-value | 0.956 | |

Readmission or transfer to hospital at 1 month and 6 months

There was a significant difference in the risk of readmission or transfer to hospital at 1-month follow-up (adjusted RR 1.32, 95% CI 1.06 to 1.64; p = 0.012). There was no evidence of a difference at 6-month follow-up (adjusted RR 0.95, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.06; p = 0.40). The frequency and percentage of participants requiring readmission or transfer to hospital at each time point, and the adjusted RRs, are presented in Table 17.

| Re-admission or transfer | HAH (N = 687) | Hospital (N = 345) |

|---|---|---|

| Readmission or transfer to hospital at 1 month, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 173 (25.7) | 64 (19.4) |

| No | 499 (74.3) | 266 (80.6) |

| Missing | 15 | 15 |

| Adjusted RR (95% CI): HAH vs. hospital | 1.32 (1.06 to 1.64) | |

| p-value | 0.012 | |

| Readmission or transfer to hospital at 6 months, n (%) | ||

| Yes | 343 (54.4) | 171 (56.6) |

| No | 288 (45.6) | 131 (43.4) |

| Missing | 56 | 43 |

| Adjusted RR (95% CI): HAH vs. hospital | 0.95 (0.86 to 1.06) | |

| p-value | 0.40 | |