Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/21/21. The contractual start date was in February 2016. The final report began editorial review in December 2021 and was accepted for publication in March 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Knapp et al. This work was produced by Knapp et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Knapp et al.

Chapter 1 Background

There is insufficient evidence on how we should treat children and young people (CYP) across a range of health conditions. Unfortunately, adult research findings are not transferrable to CYP. Safety, dosage and effectiveness data are lacking for paediatric populations, meaning that most medical treatments for CYP are used off-label. 1

The effectiveness and safety of healthcare interventions are best determined by evidence from randomised controlled trials (RCTs); when they are well-designed and conducted, trials have greater validity than other study designs through reduced bias. High-quality trials involving CYP are essential to ensure that medication and treatments used in CYP are effective and safe. 2–4 However, it has been reported that in the UK only 6% of registered trials involve children. 5 While the publication rate of trials in adults almost doubled between 1990 and 2010, the rate increase over the same period was just 20% in paediatric trials. 6 In 2013, the UK Chief Medical Officer7 stressed the need to increase the size and rigour of the evidence base for treating CYP, as well as to actively involve CYP in that process: ‘The National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Clinical Research Network … should work with CYP to input to the design of clinical studies … to facilitate (their) increased participation in trials’. There is now international recognition of the importance of paediatric clinical trials to inform healthcare decisions for CYP. 2–4,8

In the past, the scarcity of paediatric trials was mainly thought to be due to a concern for the vulnerability of CYP, leading to a reluctance of clinicians to undertake trials. 5,9 However, it is apparent that there are many reasons for a lack of CYP trial evidence, including low recruitment, such that a third of trials have delayed completion and about a fifth are discontinued due to inadequate recruitments,10,11 and high levels of participant attrition. 12,13 In any patient population, poor recruitment and retention of trial participants are costly14 and contribute to research waste. 15,16

Challenges in recruitment and retention in paediatric trials arise partly from difficulties with informed consent or assent, which, in legal terms, is more complex than with adults. In the UK, parental consent is needed when a child aged under 16 is immature (‘not competent’), or when a mature (‘competent’) child is being enrolled into a Clinical Trial of a Medicinal Product (CTIMP). In non-CTIMP trials consent may be given by the mature child or through a parent or guardian, although legal uncertainty means that dual consent may be preferable. 17,18 However, anecdotal reports are that parents are often preferentially approached, even when a child’s consent would be equally valid. The child may often be in a better position than their parent to envisage, and prepare for, what participation will mean19,20 and so excluding the child from decision-making may increase the chance of misunderstanding and subsequent withdrawal. Furthermore, when parents are consenting for a child, the perceived threshold for consent is higher than for parents themselves;21 that is, parents and clinicians tend to be risk-averse and will opt for standard care rather than a trial for a child, more often than would be the case for an adult. 22

The information provided to potential participants plays a crucial role in decision-making about trial recruitment in all age groups, and may facilitate participation. 23 In the UK, as in many countries, written information to inform a research consent decision is legally required, and its content and format must be approved by a Research Ethics Committee (REC). In most cases the mandated written information is provided to patients in printed form, although this form of information has received prolonged criticism for being too long and technical, unappealing and hard to navigate. 24–27 Patients with lower levels of literacy are most likely to be affected by these deficiencies. 28 The UK Health Research Authority (HRA) has responded to these criticisms by encouraging researchers to provide shorter participant information sheets for low-risk research, as part of its proportionate review initiatives, and recommending exploration of the use of non-print media. 29 However, the provision of shorter or condensed participant information sheet (PIS) has been shown to have no impact on trial recruitment rates in adults. 30

It is uncertain if length of recruitment information is the only feature determining its utility. For example, in a series of studies in adults, printed trial participant information sheets were revised through information design, plain English and user testing, although the amount of written content was not reduced. The utility of the sheets was significantly improved, with participants preferring the revised versions and finding them easier to navigate and understand. 31–33 This finding illustrates the importance of theory and evidence in the development of patient information, as well as the crucial role played by performance testing with potential end-users. 34 Unfortunately, revising sheets in this way has subsequently been found to have no effect on trial recruitment rates in adult patients35 although the studies did not assess the ease of understanding, people’s preferences or the quality of decision-making, and none were undertaken with CYP.

An alternative to printed information is to provide information digitally via PC, laptop, tablet computer or smartphone. Digital provision could enable the use of multimedia information in research recruitment, that is, through a combination of animations, talking-head videos, diagrams and photos, as well as written text. 28,36,37 The user can receive the information aurally and visually. Furthermore, users can select the order in which they access the information, according to personal preference, to use the resource most effectively. People’s increasing familiarity with websites and with obtaining mandated and health information online, means that digital multimedia information may now be used intuitively by most people.

In a range of health settings, multimedia information resources (MMIs) have been found in most cases to be more effective in informing people than printed information. 38–41 Informational MMIs about medical procedures can improve patient knowledge,42–48 but their effect on patient understanding is variable. 49 However, few studies have included children or young people. One trial of CYP undergoing endoscopy reported that presenting the information digitally resulted in more certain decisions by CYP about consent to the procedure, compared to printed information. 50

A number of studies involving CYP, some of them using controlled designs, have tested the effect of video animations as informational tools. Video animation is multimedia, featuring sound and visual content, although animations themselves may be just one component of a larger MMI. A systematic review of video animations showed them to have consistently positive effects on patient knowledge, and some evidence of positive effects on patient cognitions and health-related behaviours51 in a range of health conditions when compared to spoken information from a clinician, printed information or static images. The review included several studies involving CYP. For example, in CYP with epilepsy, the addition of an animated video to usual clinician interaction increased medication adherence and patient knowledge,52 and two trials in respiratory conditions reported that video animations increased the length of young children’s ‘co-operative time’ with a spacer device53 and the proportion of children able to use an intranasal device. 54

There is limited evidence on the effects of multimedia patient information on research recruitment rates,36,37 although several recent studies have examined the use of MMIs in trials involving adults. For example, in a study involving adults with cancer, multimedia information about a trial resulted in more positive attitudes to the research and a greater stated willingness to be involved, than printed information. 55 Another study reported that multimedia produced greater comprehension of the trial, compared to printed information, and that this knowledge was more likely to be retained. 56 A small study of adults with osteoporosis compared multimedia information on tablet computer with traditional printed information, and reported no effect on comprehension. 57 However, those recruiting the participants preferred the multimedia information, despite it taking longer to administer. In Hispanic adults with cancer in the USA, multimedia about a trial was positively evaluated by participants, although the study revealed mixed success with cultural adaptation of the information. 58 Finally, in the UK, one study reported that multimedia and PISs resulted in similar trial recruitment rates. 33,59

For CYP one study has reported greater understanding of trials from multimedia information when compared with traditional paper-based information,28 but otherwise there is a lack of evidence in this population. Several studies have used video for informed consent, as a limited form of multimedia. 60 However, the video presentation used has been restrictive for end-users, requiring them to view the video from start to finish, and offering less user flexibility than in other MMIs.

MMIs have the potential to inform and engage potential trial participants in ways that printed information can struggle to do. MMIs have several potential advantages:

-

information presentation is non-linear, enabling people to choose what they view and in what order

-

increased choice of content effectively allows users to personalise content

-

concurrent delivery in sound and vision, which, according to dual channel theory make multimedia more effective at holding attention and increasing understanding30

-

concurrent delivery may make more efficient demands on cognitive load61

-

possible benefits through ‘signalling’ (the provision of cues within MMIs)62

-

possible benefits through a lack of ‘information redundancy’, ensuring that content is not duplicated. 62

However, multimedia also has potential disadvantages. Producing an MMI for a trial may be more time-consuming and expensive than producing participant information sheets, and there may be connectivity problems when using online resources in some hospitals. Furthermore, among potential users easy internet access is commonplace but not universal. Consequently, health inequalities may be widened if information is exclusively provided on MMIs, or if MMIs and printed information are provided as alternatives, but the MMI content is of higher quality. MMIs may also have negative connotations in some users: video and animations have potential to appeal and engage, although it is vital this is not achieved through superficiality or imbalance. Finally, a recent scoping review identified that CYP with long-term health conditions may associate digital health technologies with concerns about privacy, trust and confidentiality. 63

There is a research evidence gap for the use of multimedia participant information for trials involving CYP. In particular, there is a lack of knowledge about the preferred format and content of MMIs, and their effectiveness and acceptability for informing consent decisions in young patients and their parents. More generally, in CYP there is scant evidence into the science of recruitment, which contrasts with a recent acceleration in the number of such studies in adults. The most recent update of the Cochrane systematic review into recruitment interventions includes 68 trials and 72 intervention comparisons. However, only one of the included studies involved CYP, which is noted as a key research gap. 64 Similarly, the Cochrane systematic review on interventions aimed at increasing trial retention also features a dearth of evidence in CYP among its 70 included studies. 65

The science of trial recruitment and retention is being developed through the Study Within A Trial (SWAT) method; these are ‘self-contained studies that have been embedded within a host trial with the aim of evaluating or exploring alternative ways of delivering or organising a particular trial process’. 64,66,67 SWATs provide evidence on improving different aspects of trial processes and outcomes, including the recruitment and retention of patients, maximising questionnaire returns and the effective reporting of trial results. The quality of SWATs is being enhanced through a repository, currently containing almost 200 studies, to encourage pre-SWAT protocol registration and the sharing of findings. 68 Furthermore, the volume of SWATs in the UK is increasing as a result of dedicated funding, which encourages researchers to incorporate a SWAT within a funded host trial. 67 However, the majority of SWATs are still being undertaken in RCTs involving adult patients and there remains a lack of SWATs and a consequent lack of evidence for trial recruitment and retention strategies in the CYP population.

Study aims and objectives

The immediate aims of the TRials Engagement in Children and Adolescents (TRECA) study were to evaluate the potential for MMIs to improve rates of recruitment to trials involving CYP, the quality of decision-making about participation in trials and the impact on trial retention.

The long-term aims of the project are to increase the available research evidence base for the treatment of CYP, including those with long-term health conditions.

The objectives were as follows:

-

to develop template MMIs through participatory design, for use when recruiting CYP to clinical trials

-

to obtain and analyse qualitative data from interviews and focus groups with members of key stakeholder groups (i.e. young patients; parents or guardians; and clinicians) to ensure that the content, format and delivery of the MMIs reflect their preferences

-

to user-test the MMIs with CYP (and their parents or guardians), to test the ability of the MMIs to inform potential users

-

to establish a Patient and Parent Advisory Group (PPAG) and actively liaise with them in the development and evaluation of the MMIs

-

to evaluate the developed MMIs in a series of trials nested within trials (aka SWATs), to test their effects on recruitment and retention rates, and patient decision-making, by comparing the provision of MMIs instead of standard printed participant information (as the primary research question), and the provision of MMIs in addition to standard printed participant information (as the secondary research question).

The projected effects of the MMIs on recruitment, retention and decision-making were anticipated to happen through positive effects on use of the information, leading to benefits to knowledge, attitudes to trials and decisional-confidence (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Logic model for potential benefits of MMI provision.

The TRECA objectives were met through a two-phase study:

-

Phase 1 of TRECA involved the development of template MMIs through two empirical studies (a qualitative study with stakeholders; a user testing study with potential MMI users) and by drawing on a range of relevant expertise (in published research; in plain English writing and readability metrics; and through an active PPAG).

-

Phase 2 of TRECA comprised a series of six SWATs within host clinical trials involving CYP, assessing the effects of information format on recruitment rates, retention rates and participant decision-making, followed by a pre-planned meta-analysis of these data from the SWATs.

Chapter 2 Methods

In order to achieve the objectives of the TRECA study, a two-phase study design was used:

-

Phase 1, in which two templates for the MMIs were developed.

-

Phase 2, in which the developed MMIs were evaluated for effectiveness within a series of SWATs, to assess their effects on trial recruitment and retention, and decision-making among CYP and parents being asked to participate in a trial.

Phase 1 studies

The overarching objective of Phase 1 was development of the MMIs, and we decided to create two MMI templates, for use in the recruitment of the following: (1) young children (aged 6–11) and (2) older children (12–18) and parents/guardians. When we undertook the Phase 1 study, we had yet to recruit the six host trials for Phase 2, and so did not know the target ages of the host trials, nor how many different age-group versions of the PIS there would be. Therefore, although two templates were developed, there was an understanding of the possible need for their adaptation according to the sample age ranges of the host trials.

Templates for the MMIs were developed for three reasons:

-

to ensure the MMIs being evaluated in Phase 2 had sufficient similarity to enable comparisons between them, and a valid statistical meta-analysis

-

to increase the efficiency of Phase 2, so that MMIs for individual host trials could be developed quickly

-

to allow the templates to be used in trials involving CYP beyond the TRECA study, if using the MMIs was shown to be feasible, effective and acceptable.

Phase 1 was driven by participatory design (aka co-design), that is, the involvement of end-users of the MMIs, including CYP, parents and clinicians and researchers involved in trial recruitment. This decision was taken to ensure that the MMIs met the needs and preferences of end-users, particularly CYP, and to ensure they functioned as effective information resources, in being understandable, easily navigable and appealing.

Participatory design (aka co-design) has a variety of forms,69 varying in the degree of control that potential end-users have over the process and the resultant product. In TRECA the participatory design process was researcher-led and end-user-informed, largely because there were some constraints on the design and content of the MMIs we were developing. That is, they would be the digital equivalents of the printed participant information sheets and so would need to be acceptable both to trial researchers and RECs. Furthermore, their development was being undertaken within a commercial contract with a production company, which placed some limits on what was possible.

Phase 1 was a multicomponent study, comprising four main sources of data:

-

a qualitative study

-

a user testing study

-

rewriting of the written content, including readability testing

-

enhanced patient and parent involvement.

More details of the individual Phase 1 components are provided in Chapters 3, 4 and 5 but are summarised briefly below.

The qualitative study with potential end-users of the MMIs involved two stages, followed by iterative, thematic analysis: (1) to ascertain people’s priorities for information about trials to inform consent decisions, and their preferences for MMI appearance and design features; (2) to receive their feedback on two age-group versions of a prototype MMI (about a recently completed trial), so we could adapt it accordingly.

The user testing study involved a form of performance-based testing, in which small samples of potential end-users were observed using a prototype MMI in order to answer a series of factual questions based on its content. User testing gives an indication of two essential features of an information resource: whether specific content can be found and once found, whether it can be understood. User testing used the same prototype MMI that was used in the qualitative study.

The written content of the MMIs would need to be the equivalent of the printed participant information sheets, to meet ethical and governance requirements. The MMIs for older children and parents would contain all the content of the PIS; the MMIs for younger children (6–11) would contain less content, but be sufficient to inform assent decisions. Rewriting of the content was guided by the principles of plain English (e.g. use of short sentences, short words and explanations for technical terms) and age-appropriateness, and the use of a range of readability metrics (through ReadabilityFormulas.com). Finally, the written content was structured to enhance navigation, including the use of a small number of information subsections, which has previously been shown to enhance patient understanding of information about trials. 33 This process of rewriting and restructuring was applied to written text included in the prototype MMIs; it was also applied to the actual MMIs that were evaluated in Phase 2 of the TRECA study.

We formed a PPAG at the start of the TRECA study, which met regularly and provided feedback on written documents and animation images, to ensure the aims and objectives of the study were being met with due consideration of the needs and preferences of patients and parents. The PPAG was active throughout Phase 1 of the study and continued to meet and provide feedback during the development of the six MMIs that were tested in the Phase 2 SWATs.

Phase 2 studies

The aim of Phase 2 was to evaluate the developed MMIs when used within six trials involving CYP.

The primary outcome was trial recruitment rates, evaluating the effect of MMIs as an alternative to participant information sheets (i.e. MMI-only vs. PIS-only).

Secondary outcomes were as follows:

-

Trial recruitment rates, evaluating the effect of MMIs in addition to participant information sheets, compared to participant information sheets alone (i.e. combined MMI and PIS vs. PIS-only).

-

Participant decision-making scores, evaluating the effect of MMIs as an alternative to participant information sheets (i.e. MMI-only vs. PIS-only).

-

Participant decision-making scores, evaluating the effect of MMIs in addition to participant information sheets, compared to participant information sheets alone (i.e. combined MMI and PIS vs. PIS-only).

-

Trial retention rates, evaluating the effect of MMIs as an alternative to participant information sheets (i.e. MMI-only vs. PIS-only).

-

Trial retention rates, evaluating the effect of MMIs in addition to participant information sheets, compared to participant information sheets alone (i.e. combined MMI and PIS vs. PIS-only).

The MMIs were evaluated within a series of SWATs, aka embedded or nested trials. SWATs involve a second randomisation process in addition to the random allocation of participants within the host trial. In TRECA, the SWATs were used to evaluate the effects of information format on participant behaviours (recruitment and retention) and decision-making (at the point of recruitment).

Host trials involved in the six SWATs were able to choose between a two-arm and a three-arm SWAT. The primary question for TRECA was whether MMIs could be used effectively as an alternative to (or replacement for) the PIS; in the development of the study outline and its methods, this question was the primary interest of staff from the clinical trial units that were engaged in discussion. However, the combined MMI and PIS information arm was included for two reasons. First, to permit evaluation of the effectiveness of the MMI in addition to the PIS; given that providing printed information has become the conventional approach over past decades, it was thought useful to evaluate the effects of adding another format. Secondly, because it would give an option in case either the host trial personnel or the REC were unwilling to accept potential trial participants not being provided with participant information sheets; in that case, a two-arm SWAT would be possible, comparing combined MMI and PIS versus PIS-only.

The results of the six SWATs were combined and analysed within preplanned meta-analyses, which were undertaken in the assessment of the primary outcome and all secondary outcomes. Preplanned meta-analyses make the same statistical and methodological assumptions as retrospective meta-analyses following systematic review. The advantages of a preplanned meta-analysis are that it can ensure that individual included studies are sufficiently similar to permit meta-analysis, and it ensures that the meta-analysis has sufficient statistical power to avoid type II statistical error.

Statistical analysis plan

Design

Host trials

Host trials used individual or cluster randomisation as deemed practical and appropriate.

Trial objectives

The immediate aims of TRECA were to evaluate the potential for MMIs to improve the quality of decision-making about participation in healthcare trials involving CYP, and to assess the impact on trial recruitment and retention.

The long-term aim of the project is to increase the available clinical evidence base for the treatment of children and adolescents, including those with long-term health conditions.

The aim of Phase 2 of TRECA was to evaluate the MMIs in a series of SWATs, and test their effects on recruitment and retention rates, and decision-making, by comparing the effects of providing standard written participant information with provision of the MMIs either alone or in addition to the standard written participant information.

Hence, the two pairwise comparisons of the three TRECA arms of interest are whether the MMI provision could replace (MMI-only vs. PIS-only) or supplement (MMI and PIS vs. PIS-only) the standard written participant information. The results of the individual trials were combined statistically in a meta-analysis.

Sample size

Overall

The sample size for each SWAT was ultimately determined, and constrained, by the number of people approached to take part in the host trial.

An example sample size calculation based on the expected baseline recruitment rate of the host trials (i.e. their recruitment rate without the intervention) is provided. Baseline recruitment rates in trials vary greatly, often ranging from 20% to 80%. A baseline rate of 80% was assumed.

We estimated the sample size based on the relative effect of MMI-only (when compared to PIS-only). Further, we assumed 80% power at standard 5% type I error (α rate) to detect the specified effect and we characterised the effect size as the relative increase in recruitment rate (i.e. a relative risk increase).

Assuming the baseline recruitment rate (in the PIS-only arm) was 80%, to detect an increase to 88% in the MMI arm in a single RCT (with 1 : 1 randomisation between MMI and PIS arms), a sample size of 329 per group was needed. This figure was multiplied × 3 to account for the three-arm randomisation in the SWATs (n = 987).

Results from each SWAT were ultimately combined in a meta-analysis. Given that the Phase 2 host trials had variation in the age and health condition of participants, the baseline recruitment rates and the evaluated interventions, it was thought plausible that MMI effectiveness would vary; that is, there would be heterogeneity in the observed effect across trials. Adjusting for this was approximate (particularly as the heterogeneity was unknown before the host trials were undertaken). However, a rule of thumb for the I2 statistic of 50% in the meta-analysis was applied, having the effect of doubling the sample size, deriving an overall sample of 1974 across the six SWATs.

Therefore, the six SWATs in TRECA should (on average) each be approaching 329 people, assuming a baseline trial recruitment rate of 80% of those approached.

This calculation has been updated from that included in the initial published protocol, due to reproducibility issues. However, this does not impact on the validity of the results as the sample size of the overall project was driven by the individual SWATs that were undertaken and could not be pre-determined.

Bone Anchored Maxillary Protraction trial hypothetical setting substudy

The primary outcome of this hypothetical setting substudy was the mean Decision-Making Questionnaire (DMQ) total score. We estimated that a sample size of 109 would give 90% power (alpha 0.05) to detect a statistically significant difference between the groups. A sample of 109 participants (54 and 55 in the two trial arms), allowed for 10% of those randomised not being able to complete the questionnaires. We assumed that a mean between-groups difference of 4.5 on the total DMQ score would be meaningful and estimated that the standard deviation (SD) of the pooled scores would be 6.75 (assuming that 95% scores would fall between 4.5 and 31.5). 70

Randomisation

Allocation to groups in the SWATs was achieved either by random number generator or by another randomisation method that suited the practicalities of the host trial.

Masking of the allocation at outcome measurement was not possible but was also irrelevant: the patient could not be masked to the information format they received but, as they were unaware of the SWAT (the information trial), a lack of masking did not affect their responses on the self-completion measures or have any biasing effect on their decisions on trial participation or continuation.

Outcomes

Primary outcome

Recruitment – MMI-only versus PIS-only

The primary outcome was recruitment to each host trial between the MMI-only arm and the PIS-only arm. For recruitment we calculated the proportion of patients who agreed to participate from the total approached, for each arm of the SWAT. We assumed that patient eligibility for host trial participation would have been assessed before an approach was made.

Data on recruitment to the host trial were recorded automatically within the host trial data set.

Secondary outcomes

Recruitment – MMI and PIS versus PIS-only

The secondary recruitment outcome was recruitment to each host trial between the combined MMI and PIS arm and the PIS-only arm.

Retention

For the retention outcome, we obtained data on the number and timing of dropouts from each host trial. A single time point was specified for use in the analyses. Data on trial retention were recorded automatically within the host trial data set.

Quality of decision-making

We also measured the quality of decision-making by potential host trial participants. Children and adolescents were asked to complete a brief decisional scale, adapted from one used within the REFORM trial71 and drawing conceptually on the SURE72,73 and DelibeRATE scales. 74 When a parent/guardian was involved in the participation decision, we also asked them to complete the scale. The scale was adapted to facilitate completion by young children (see Web Documents 1 and 2). We aimed to obtain decision quality scores both from individuals who decided to participate in the host trial and those who declined. In patients who decided to take part, the CYP and/or parent/guardian were asked to complete the decisional scale once the host trial participation documentation had been completed. In patients who declined participation, they were asked to complete the measure in the clinic or have them posted at home or e-mailed, as appropriate.

The older child and parent/family versions of the questionnaire contained the same number of questions, with slight changes in the phrasing of questions. The decisional scale contained nine Likert questions (with five possible answer options) and there were a further three free text questions, which gave participants the opportunity to give further opinions. The younger patient version of the questionnaire was of a similar format. The decisional scale contained three Likert questions (each with five possible answer options) and the further three ‘free text’ questions (see Web Document 1).

The decision-making scales were scored for both the three- and nine-question versions. Answers to each Likert question were allocated a value of 0–4. The values for each question were summed to create an overall score, out of 12 and 36, for the two scale versions. Up to three missing responses were allowed on the nine-question scale. One missing value was allowed on the three-question version of the scale. A total score was calculated by replacing missing values with the mean score from the completed responses given by the participant. Any questionnaires with more than three (older child/parent/family version) or more than one (younger patient version) missing values, were not scored.

Other important information

To assess any potential moderating influences of other variables on the effectiveness of the MMIs, we aimed to obtain data within each host trial of CYP age, gender and deprivation score, according to allocation in the embedded trial and to host trial participation decision.

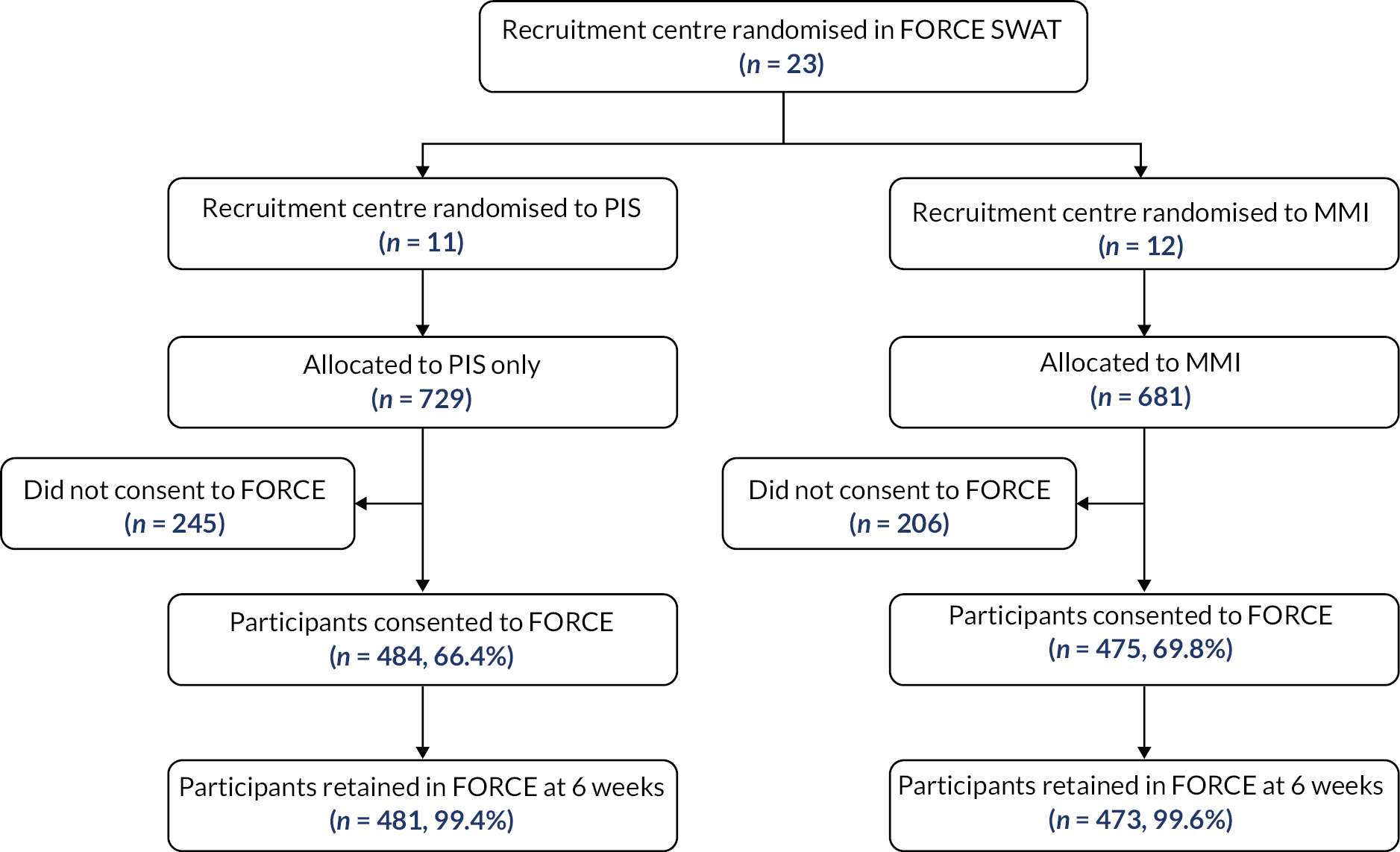

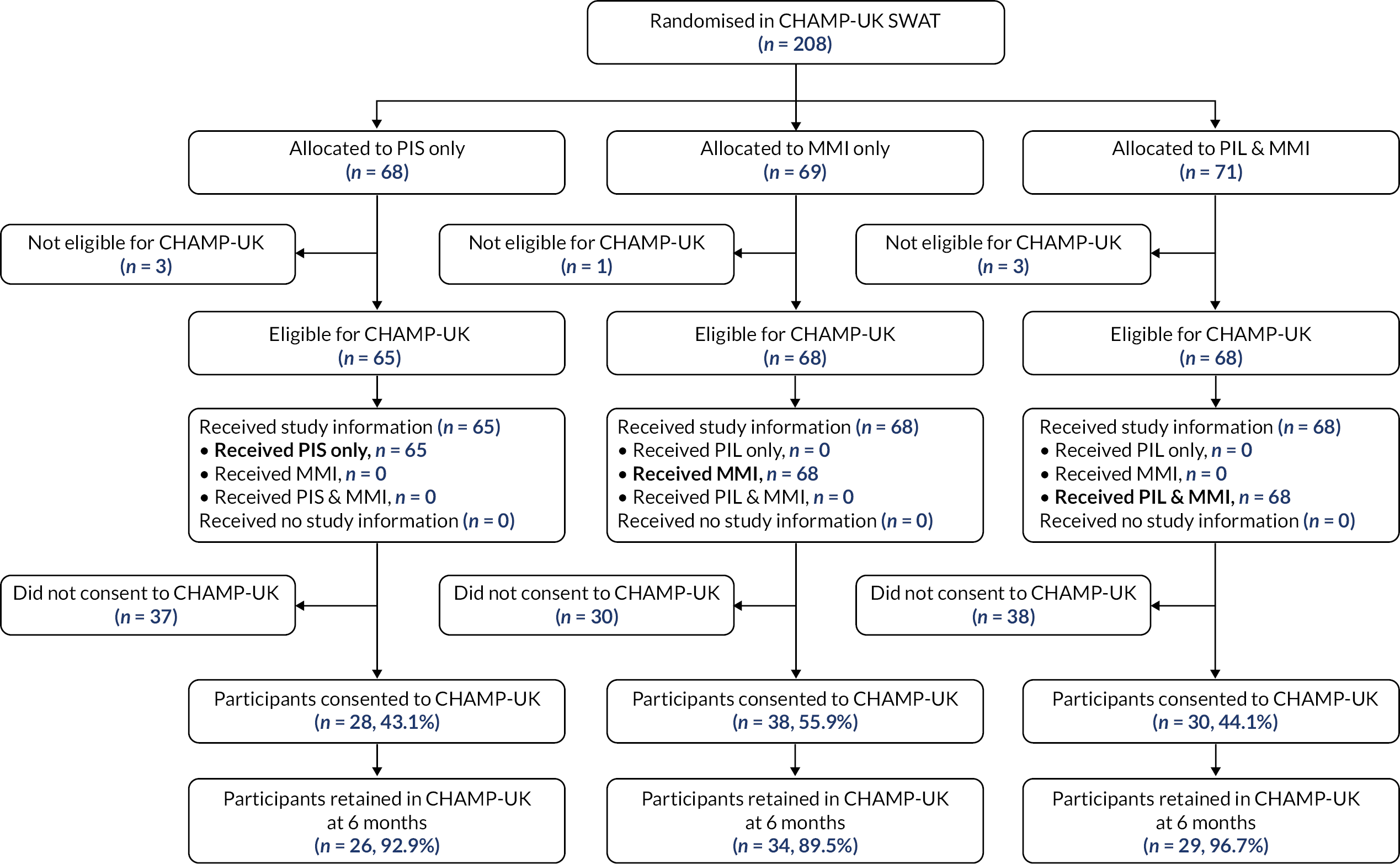

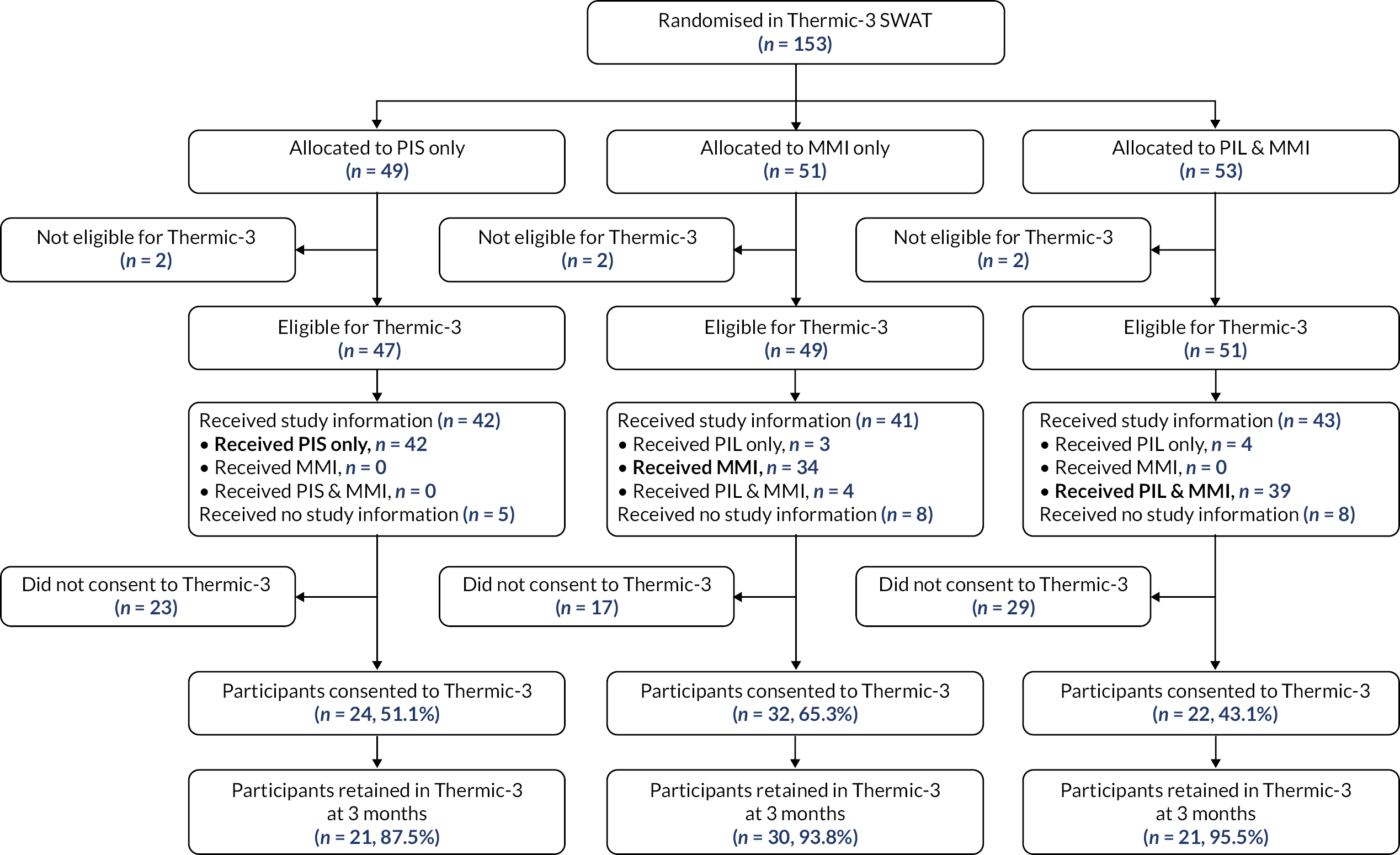

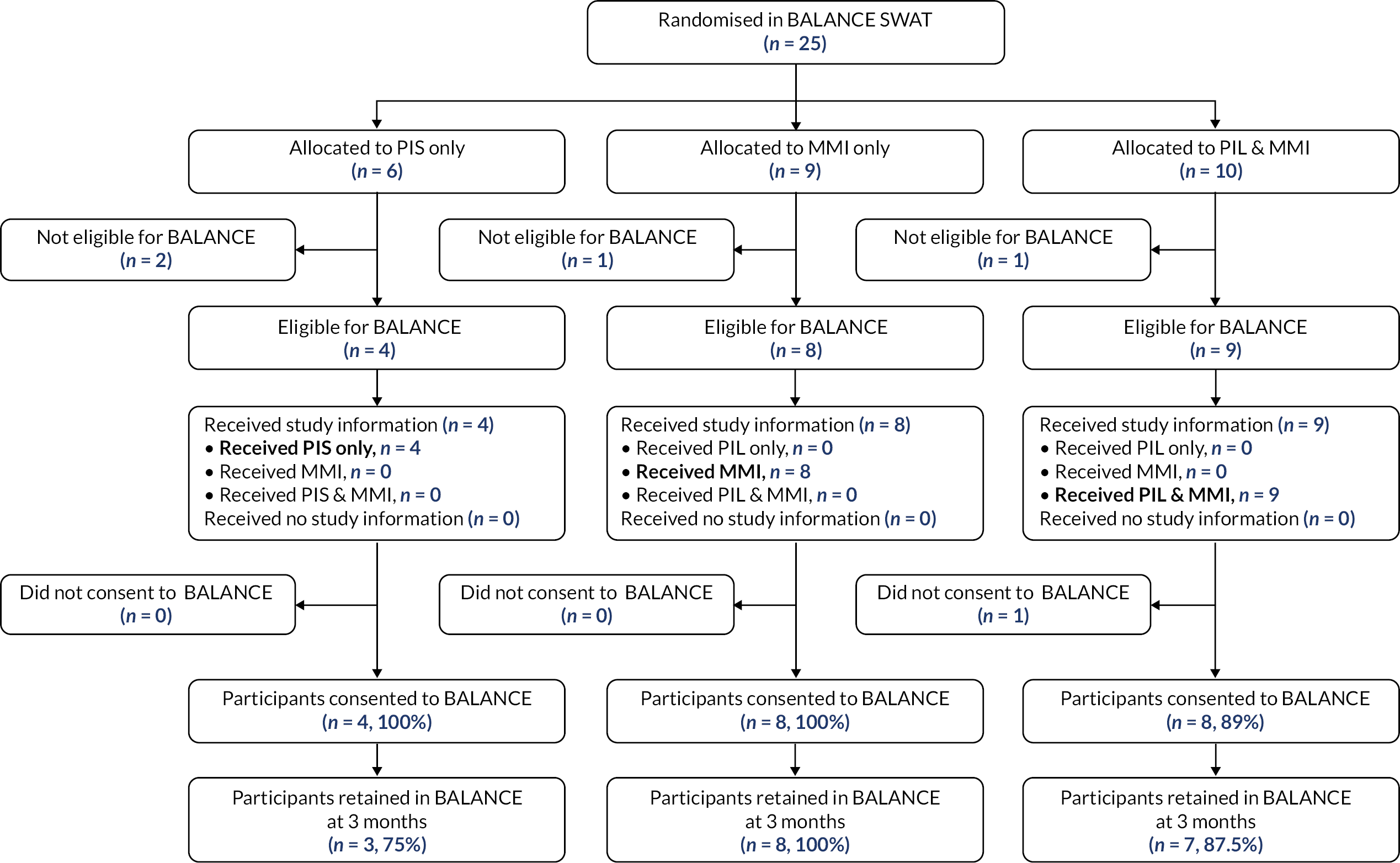

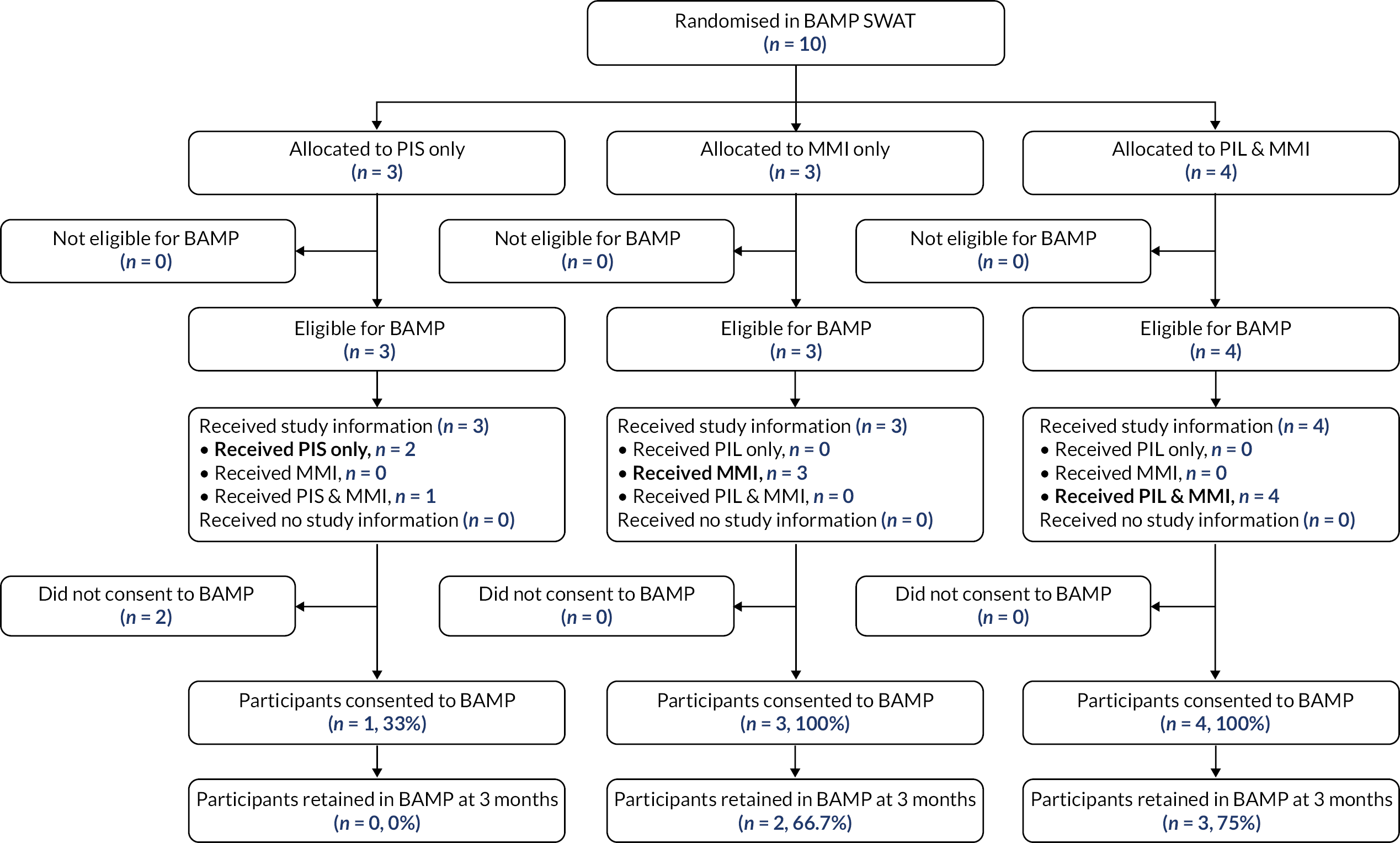

Analysis

A Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) diagram displaying the flow of participants through each SWAT has been reported.

All analyses were conducted in STATA® v16 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, USA),75 following the principles of intention-to-treat (ITT) with participants’ outcomes analysed according to their original, randomised group. The analysis, outcomes and significance levels were pre-specified in a statistical analysis plan (SAP) before the analysis was conducted.

Analysis of the primary outcome was checked independently by a second statistician after the analyses had been conducted. The data relating to the main Bone Anchored Maxillary Protraction (BAMP) trial and the BAMP substudy were analysed separately. Appropriate model diagnostics were assessed when models were fitted, including checking normality (for continuous outcomes), checking normality of random effects and checking the homoscedasticity of residuals.

As all the analyses include the PIS-only arm, it was important to consider the effect on the type 1 error rate. However, we did not adjust for multiplicity as we only had a single primary outcome comparison.

Statistical analysis has firstly used a modified ITT approach, with participants analysed according to their randomly allocated arm but after the removal of any participants who were subsequently found to be ineligible for the host trial. We have also undertaken a per-protocol analysis, in which participants have been analysed only if they received the information in the format as randomly allocated.

Baseline data

All participant baseline data have been summarised descriptively by TRECA trial arm. No formal statistical comparisons were undertaken. Continuous measures have been reported as means and standard deviations (normality was checked and if non-normal, medians and interquartile ranges were reported) and categorical data were reported as counts and percentages. Baseline data for the host trials varied due to different trial data collection; all data that were collected have been reported. Baseline data were only available for participants who were randomised into each host trial.

Primary analysis

Recruitment – MMI-only versus PIS-only

The proportion of eligible patients entering the trial, which was defined as the number randomised over the number of eligible participants approached have been reported by the SWAT trial arm. Recruitment rates were compared using logistic regression, with TRECA allocation included as a covariate. Clustering was accounted for in the analysis of FORCE, by including the cluster variable as a random effect. The primary comparison was between the MMI-only arm and the PIS-only arm, hence this pairwise comparison was extracted from the model. The results from the regression have been presented as odds ratios, with associated 95% confidence intervals and p-values.

Secondary analyses

Recruitment – MMI and PIS versus PIS-only

The secondary outcome is looking at the effect of the addition of MMI to PIS. This pairwise comparison was extracted from the same model as for the primary analysis. This outcome was not applicable for FORCE as that trial only used the MMI-only and PIS-only arms.

Retention

The time point for assessing retention in each trial is given in Table 8. The proportion of participants who were retained at the specified time point have been reported. This is defined as the number of participants who reached that time point, over the number of participants randomised in the host trial.

The retention rate was compared using logistic regression for each host trial, with host trial allocation (except for the Thermic-3 trial, in which it was not available) and TRECA allocation included as covariates. Where a host trial used stratification variables (Table 1) in the randomisation, these were included as covariates. Clustering was accounted for in the analysis of FORCE, by including the cluster variable as a random effect. Similar to the recruitment analyses, two pairwise comparisons were used: MMI-only versus PIS-only, and MMI and PIS versus PIS-only. The results have been presented as odds ratios, with associated 95% confidence intervals and p-values.

| Trial | Stratification factors |

|---|---|

| BALANCE | Type of amblyopia and centre by stratification |

| BAMP | Gender by stratification |

| CHAMP-UK | Centre, ethnicity, severity of myopia. The unit of randomisation will be the participant (not the eye) using a minimisation algorithm |

| FORCE | Age and centre by stratification |

| THERMIC-3 | Risk adjustment for congenital heart surgery (RACH scores) by stratification |

| UKALL-2011 | Cytogenetic risk and minimal residual disease (MRD) level, National Cancer Institute (NCI) risk, early morphologic response by stratification |

Quality of decision-making

The responses to each question (including the number of missing responses) and the calculated total scores of the decisional questionnaire were summarised descriptively overall and broken down by host trial, TRECA allocation and type of questionnaire (younger patient, adolescent or parent/family).

As a patient and their parent/carer may have both completed a questionnaire, all the data from all three questionnaires were not combined, due to lack of independence. Hence, scores for patients (younger or older) and parents/family questionnaires were analysed separately using a linear regression, with TRECA allocation and host trial status (whether the participant entered the trial) included as covariates. Clustering was accounted for by using the cluster variable as a random effect. Mean difference has been presented with 95% confidence intervals.

If both the younger and older patient questionnaires were used in a host trial, the questionnaire data from the younger and older patient questionnaires were combined. The scores for these were standardised within the trial by subtracting the sample mean score from the observed score and dividing the result by the sample standard deviation, where the ‘sample’ refers to the subset of participants that used that questionnaire. Then the standard scores for all participants were analysed as described above.

The results were compared using a regression model, adjusted for SWAT allocation, and whether the patient consented to participate in the trial. To assess the robustness of the method used to replace the missing values, a sensitivity analysis was conducted, where the analysis was repeated using only the questionnaires in which all nine questions were answered.

The analysis including missing values was repeated but for only those participants who went on to consent to the host trial.

Meta-analyses

Results from each SWAT were combined in meta-analyses. A two-stage random-effects meta-analysis was used in each case, where the results from each model were combined using an inverse-variance approach. No further adjustments were made to these results. The BAMP substudy was not included due to its hypothetical trial setting.

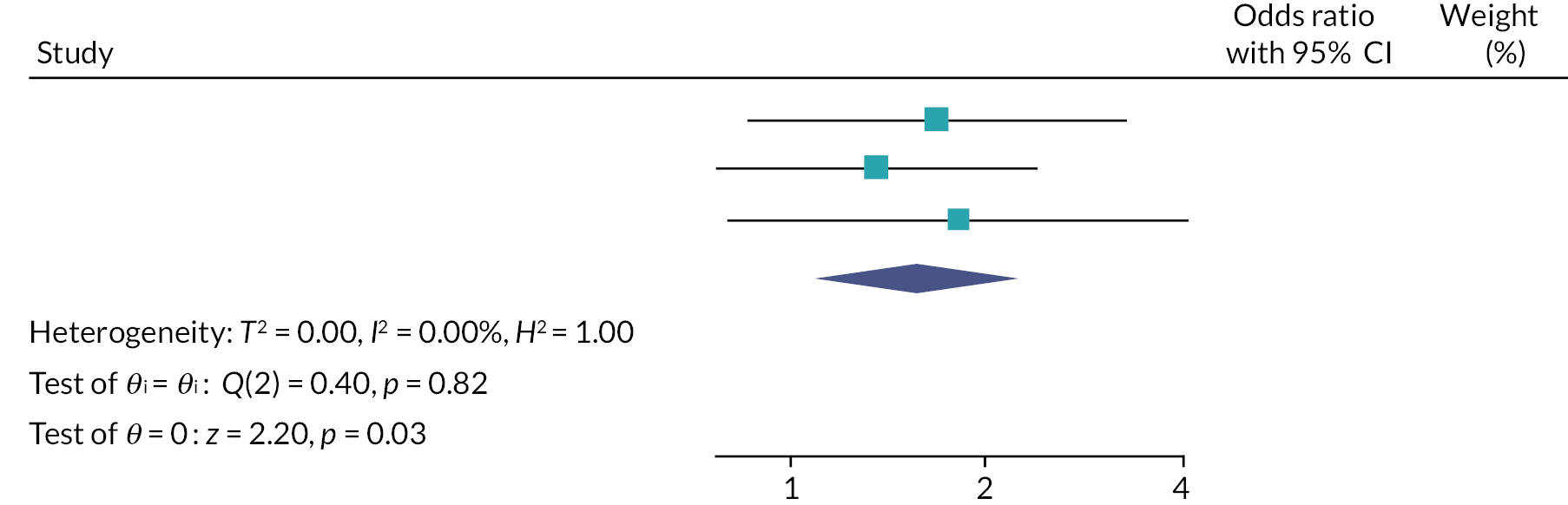

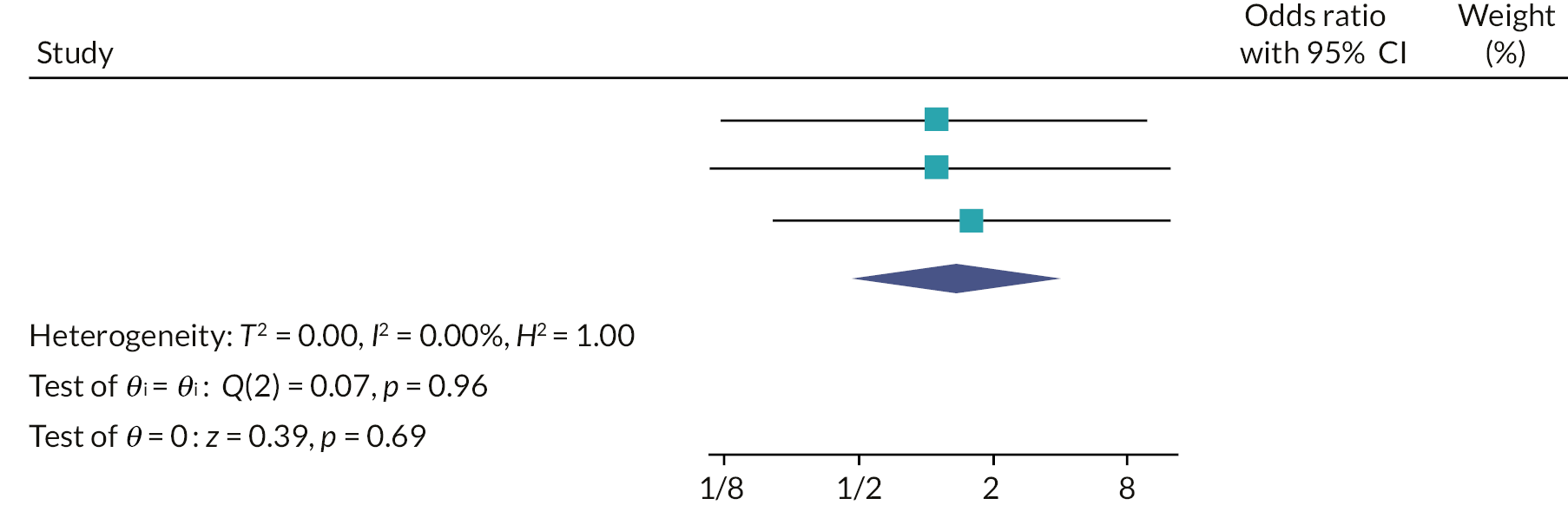

Recruitment

Two random-effects meta-analyses were conducted using the odds ratio for each of the host trials which were calculated in the recruitment primary analysis (PIS-only vs. MMI-only) and the recruitment secondary analysis (MMI and PIS vs. PIS-only). FORCE could not be included in the second meta-analysis as only two arms were used in the trial. The I2 statistic was used to assess the heterogeneity between the trials.

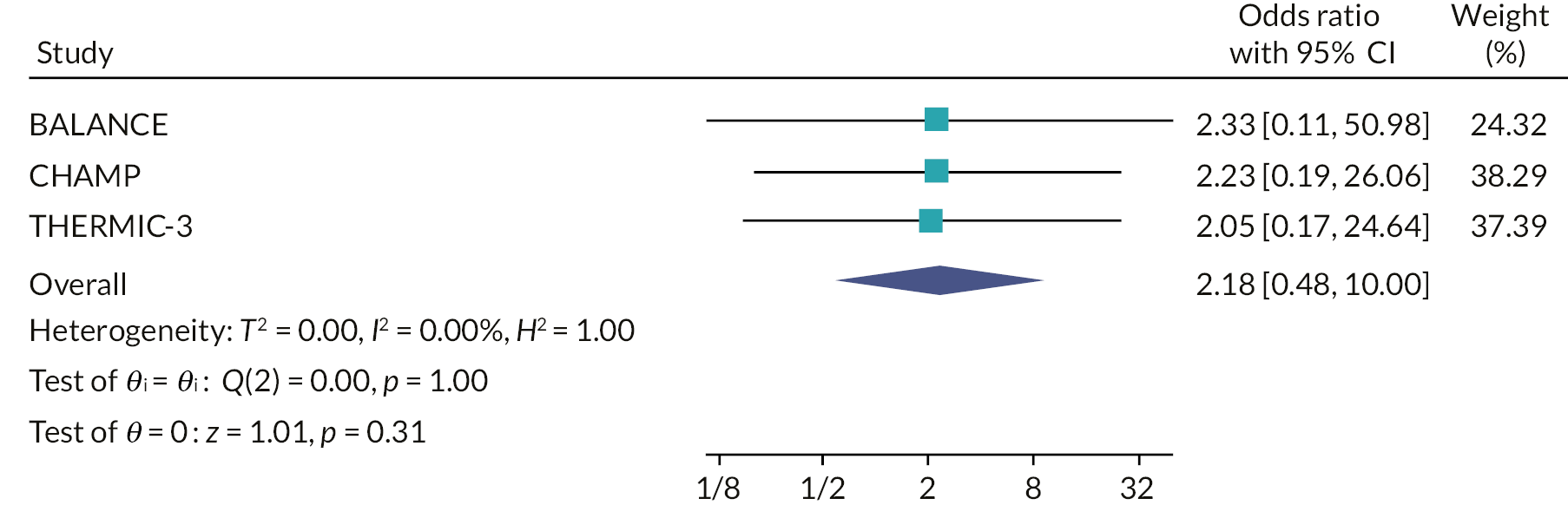

Retention

Two random-effects meta-analyses were conducted using the odds ratio for each of the host trials, which were calculated in the retention secondary analyses. The I2 statistic was used to assess the heterogeneity between the trials.

Quality of decision-making

The decision-making data from all six SWATs (and not the BAMP substudy) were also combined in four meta-analyses. Mean difference scores from each of the trials were combined in a random-effects meta-analysis.

Research ethics and registration

The TRECA study received approval from the NHS Yorkshire & the Humber – Bradford Leeds Research Ethics Committee (17/YH/0082) and the HRA (IRAS ID 212761) on 14 July 2017.

Trial and SWAT registration: TRECA ISRCTN73136092 and Northern Ireland Hub for Trials Methodology Research SWAT Repository (SWAT 97). The SWATs were undertaken through amendments to REC approvals obtained by the host trial research teams.

Chapter 3 Phase 1 – qualitative study

Sections of this chapter have been reproduced from Martin-Kerry et al. 76 and Martin-Kerry et al. 77 These articles are distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

This chapter reports the qualitative interview and focus group study with children, young people, parents and professionals, which helped inform the development of the MMIs. The qualitative study drew on the principles of participatory design (aka co-design) to ensure that the newly developed MMIs would meet the preferences and needs of CYP being approached about trial participation, while also being acceptable to professionals and parents. The role of professionals and parents as gatekeepers to children’s access to information about trials or treatments means that their acceptance of a MMI template for information content and format was crucial. 78 Here we describe the qualitative study, including the use of a novel interactive ranking exercise, and how we used the findings to inform the development of the MMIs.

Methods

The qualitative study involved two rounds of interviews (individual, joint or focus group discussions). The focus of the first round was on the identification of participants’ preferences and needs for information about trials, while the second round sought participants’ views on prototype versions of the MMIs that had been developed based on the first round of data collection. We aimed to include the same participants in both data collection rounds, to maximise the iterative development of the resources, but with replacement of participants for the second round, as required.

Participant sampling and recruitment

We used two routes to recruit children, young people and parents: a paediatric hospital in north-west England, and a Generation R Young Persons’ Advisory Group (YPAG) based in the English Midlands, whose members are CYP and which advises on various aspects of research involving CYP in the NHS, including research priorities, design and materials. Recruitment via the hospital route involved nurses contacting families of children receiving specialist care for long-term conditions; the YPAG route involved the co-ordinator contacting members and parents or guardians by text message or phone. The interviewer then telephoned those who agreed to contact, to explain the study and arrange a suitable interview time.

Sampling of children, young people and parents was intended to achieve diversity in a number of characteristics, including gender, age, ethnicity, long-term condition and trial experience. Professionals were initially contacted by e-mail by an academic paediatrician working in the study hospital. Those expressing an interest were contacted by the interviewer by e-mail to arrange the interview date. Sampling of professionals was intended to achieve diversity in paediatric specialities and roles within trials.

We provided participants with printed study information sheets with different versions for children, young people, parents and professionals. Participants aged under 16 years gave assent and their parents provided consent for participation. Participants aged 16 years and over provided consent. After the interview each participant received a gift voucher (£10).

Data collection

Topic-guided, semistructured interviews were undertaken with CYP with long-term health conditions, their parents and professionals. The same interviewer (Martin-Kerry) conducted the interviews over the two rounds (held July–October 2016 and November 2016–January 2017). At the start of the interviews, it was explained that all comments were welcome and that the primary aim of the interviews was to inform the development of MMIs (described as ‘websites about trials’) that would be suitable for potential users. Interviews and focus groups were audio-recorded and fully transcribed. Transcripts were then checked for accuracy and pseudo-anonymised before analysis.

First round of interviews

The interviews began with participants being asked about their experiences of health research. Following discussion, all participants were shown 20 cards, each naming a topic that adults had previously identified as being important when deciding to take part in a trial. 79 Participants were asked to rank the topics (Box 1) into three categories: ‘important’, ‘somewhat important’ or ‘not important’,80,81 using an interactive ‘target game’ ranking exercise. 77 While they were undertaking the ranking, participants were asked to comment on the decisions and also suggest any other information not included on the 20 cards that they thought would be important for someone deciding whether or not to take part in a trial.

-

Why is the study happening?

-

Why have I been invited?

-

Do I have to take part?

-

What will happen if I don’t want to carry on with the study?

-

What will happen to me if I take part?

-

Will it cost me any money to take part?

-

Will I be paid for taking part?

-

What is being tested in the study (e.g. what drug or device)?

-

What are the different treatments or types of health care being provided in the study?

-

What are the risks of taking part?

-

What are the possible benefits of taking part?

-

What happens when the study ends?

-

What would happen if a problem happens in the study/could I make a complaint?

-

Will my taking part be kept confidential (private)?

-

Will my general practitioner (GP)/family doctor be told about my taking part?

-

What will happen to any blood tests or other samples that I have as part of the study?

-

What will happen to the results of the study?

-

Who is running the research?

-

Who is paying for the research?

-

Who has reviewed the study?

We had previously reviewed ranking methods and identified the diamond exercise82,83 as promising. However, this needed adaptation for our purpose as it had a maximum number of topics (usually 9), whereas we needed to include 20 topics. Therefore, we used a ranking exercise that involved an A0 size mock target and laminated brightly coloured cards, which named each topic. The activity combined the ‘ranking’ and ‘sorting’ features recommended by Colucci,84 with participants being asked to place each card on an area of the target according to its importance: ‘important’ (yellow; centre circle of target); ‘somewhat important’ (red; intermediate circle of target); or ‘not important’ (blue; outer circle of target). Research can be quite an abstract and challenging topic particularly for younger participants, and this exercise helped to facilitate discussion and support participants in identifying what was important to them. 85

Participants were then asked to discuss their preferences for different designs of multimedia websites. The interviewer showed participants examples of several existing websites, animations and a video (Hi-Light Trial video, see Table 2 for details), as well as examples of character designs for animations, which had been developed by the website creation company; participants were asked to comment on these. The website and character examples represented a range of presentation and design styles.

| Resource | Example of | Link |

|---|---|---|

| HeadSpace | Website | https://www.headspace.com/ |

| Toca | Website | https://tocaboca.com/ |

| Health Research: making the right decision for me (Nuffield Council on Bioethics) | Animation | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6yaKwLG_vlE |

| What is a randomised trial? (Cancer Research UK) | Animation | https://www.cancerresearchuk.org/about-cancer/find-a-clinical-trial/what-clinical-trials-are/randomised-trials |

| Can we tell which children with febrile neutropenia have a bad bug or infection? (Dr Bob Phillips) | Animation (Lego) | https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z1AXzJqatds |

| Hi-Light Trial video | Video of child and parent talking about participating in the trial | Video not publicly available. Hi-Light protocol is available87 |

Finally, participants were asked to discuss how the multimedia websites should function and look by asking them to rank six cards, each of which included a criterion for assessing websites. 86 These cards covered content, structure and navigation, visual design, interactivity, functionality and credibility. An initial analysis of the first round of interviews informed the design of the prototype MMIs.

Second round of interviews

The second round of interviews explored participants’ views of the prototype multimedia websites. The second round topic guides were developed with contributions from a qualitative methodologist (BY) with extensive relevant experience, and an expert in children’s education (SH). The prototype MMIs concerned a trial involving children with type 1 diabetes,88 with one MMI version aimed at 6–11-year-olds and parents/guardians, and the other intended for young people aged 12 years upwards and parents/guardians. [A summary of the subcutaneous insulin: pumps or injections (SCIPI) MMIs can be accessed at: https://www.york.ac.uk/healthsciences/research/health-policy/research/scipi.] The text was checked and edited for readability for the different age groups. The multimedia websites included two age-generic animations: one that functioned as a trial-specific ‘explainer’ animation, summarising the trial; and a trial-generic animation ‘why do we do trials’, which outlined the rationale for conducting trials. We showed participants the animations and the multimedia website that was suited to their age (and the other website version if they wanted) and asked them for their views (Box 2). We also invited their suggestions for improving the animations and MMIs.

Can we talk about what your first impressions of the MMI are?

Now I would like us to discuss different aspects of the MMI:

Visual design-

What do you think about how the MMI looks?

-

What parts of the MMI appearance do you like? Which do you not like?

-

How did you find moving through the different parts of the MMI?

-

How was it to find and understand information?

-

What do you think about the mix of video, text, pictures and animation? Should anything be added or changed?

-

How did the MMI pages load?

-

Were there any problems accessing the different parts of the MMI?

-

What do you think about the information content of the MMI?

-

Do you feel it gives you enough information about what is involved in participating in a clinical trial?

-

Can you tell me about anything that you think is missing from the MMI?

Is there anything else that you like about the MMI that we haven’t covered?

Is there anything you particularly liked about the MMI?

Is there anything that you didn’t like about the MMI?

What should we focus on, if anything, to improve the MMI?

Can you tell me how you think you would use the MMI?

Data collection with the youngest study participants (aged 6–8 years) and their parents was not undertaken until the second round, as we thought that the content of the first interview round would be too abstract to engage young children. More concrete information materials (the prototypes) were available for the second round of interviews.

Data analysis to inform the development of the multimedia websites

The initial data analysis was largely deductive descriptive, drawing on rapid ethnographic methods89 in order to provide feedback to the web development company on the MMIs. This analysis focused on the design aspects and content of the MMIs. Subsequent analyses were iterative and thematic, including both inductive and deductive aspects. 90,91 This process involved repeated reading of transcripts to aid familiarisation, followed by line-by-line coding to identify recurrent ideas, which were then organised into themes and subthemes. Interviews were also compared across participant groups in order to identify differences and similarities. Analysis was undertaken by one researcher (Martin-Kerry) with regular guidance and advice provided by two experienced qualitative researchers. Findings were also discussed with the TRECA PPAG, in order to incorporate their views on the development of the multimedia websites. Data coding and indexing was assisted by Microsoft Excel 2010 software.

Results

Participants

A total of 87 people were invited to take part across the two rounds, of whom 62 were interviewed. Among the 87 people invited:

-

35 were professionals of whom 17 were interviewed; those who declined either were unavailable for interview or did not respond

-

28 were parents of whom 24 were interviewed

-

24 were young people of whom 21 were interviewed (see Appendix 8, Table 48).

Those parents or young people who declined did so either due to other commitments or because they did not want to participate.

Among the 62 participants, 15 participated only in round 1 (6 CYP, 6 parents, 3 professionals), 22 only in round 2 (10 CYP, 10 parents, 2 professionals) and 25 participated in both rounds (5 CYP, 8 parents, 12 professionals).

Table 3 provides a summary of participant characteristics and Appendix 8, Table 48 shows detailed participant characteristics.

| Participant group | n | Age, years, mean (range) | Gender | Experience of being approached about a children’s trial | Had taken part in a trial |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CYP | 21 | 12 (6–19) | 8 males 13 females |

10 | 8 |

| Parents | 24 | – | 8 males 16 females | 13 | 12 |

| Health professionals | 17 | – | 4 males 13 females | n/a | n/a |

Among the 21 CYP interviewees, 16 preferred to be interviewed with a parent(s). The five young people who were members of the YPAG preferred to take part in focus group interviews, as did all of the professionals except three. Focus groups contained four to nine participants. One parent participant was interviewed individually via Skype; the remaining interviews were held face-to-face in a room at the hospital or at a YPAG meeting. The child and young person participants had a range of long-term health conditions including asthma, cancer, arthritis and neurological and muscular conditions.

Findings

The findings of the two rounds of interviews are reported together, including participants’ views on important aspects when considering trial participation, plus their preferences for the design, wording and tone of the MMIs, and how these views informed the MMI development.

One notable overarching finding is that most participants spoke about the need for the preferences and views of CYP to be central to the design of the MMIs. One parent commented:

It’s more important to get across to the teenagers because it’s the teenagers who are going through it, you know, the parents are just a by product of what is happening (Parent/33, male, no experience of being approached about a paediatric trial).

While the aspiration to prioritise the views of CYP may have shaped people’s accounts, there were also areas in which the participant groups (children, young people, parents, healthcare professionals) differed in their views. Taking account of such differences is important, particularly given the role that parents and professionals have in guiding and sometimes limiting children’s and young people’s access to the internet and to health information more generally.

Content of the multimedia websites

The following sections outline the aspects of information content and provision that participants prioritised when discussing the developing MMIs.

That you can leave a trial

This piece of information was particularly important to CYP. CYP with trial participation experience emphasised the importance of knowing that leaving the trial was ‘okay’. For example, knowing that they would be free to leave if the treatment caused significant side effects, helped them to say ‘yes’ to a trial. One young person said this information was her only priority. Professionals also ranked this as an important aspect for families; they reported emphasising it during initial discussions with families about trials.

Knowing that you can stop at any time is also good because say you just didn’t want it anymore and you were getting bad side effects and you didn’t like it, then they could stop it just then and there.

(CYP/16, male, 10 years old, experience of being approached about a trial)

If I don’t feel comfortable in the trial anymore or if I didn’t want to take part because I didn’t think it was working for me, could I just stop it – and they were really good at explaining that you could just stop at any time that you wanted and you just have to let them know … so that was one of the only questions that I had really.

(CYP/23, female, 16 years, experience of being approached about a trial)

Therefore, information that participants could leave the trial at any time and without a reason was given prominence within the MMIs.

What is involved if I participate?

Children, young people and parents wanted to understand what trial participation involved. Several with prior experience of being approached about a trial commented that they would have liked to have known more about what was going to be required. In particular, young people wanted detailed information about the frequency of hospital or clinic visits, whether they would need to take time off school, and what the treatments involved, including what they might experience during treatment and beyond. One parent said that participant information sheets never gave details on how participation would affect the day-to-day life of their child.

Some CYP had a pronounced fear of needles and wanted to avoid pictorial or animated portrayals of injections in the MMIs that could be ‘aggressive’ or ‘scary’. This fear was not only expressed by younger participants. CYP also wanted information about the taste of oral medicines, although professionals noted it can be difficult to provide this information in advance for new drug treatments. Parents often spoke of the need to know how participation would affect their child emotionally and whether it would cause ‘burden’ or ‘undue stress’. Some young people and parents talked about the importance of stress, and that it was not often covered in written trial information. Professionals echoed this, agreeing that most families wanted to know about the potential impact of trial participation.

For young people what’s often overlooked is missing out on things like school and social, that’s often not mentioned.

(CYP/18, female, 18 years, experience of being approached about a trial)

How much time is this going to take? That’s by far the biggest anxiety that our families have that they’re going to have to make extra visits to the hospital or extra tests to do, extra diaries to fill in at home. The burden to them is really important and then safety.

(Professional/15, male)

Detailed information about what trial participation would involve was included in the MMIs. The potential for MMIs to include diagrams, photos and animations also make it much easier to convey this detail.

What is the trial testing?

Children and young people with trial experience often described the science behind their condition and treatment and indicated an interest in knowing how the treatment being tested was thought to work. Parents did not always prioritise such information but some wanted to know whether treatments had been tested previously. Professionals talked about the need to explain the science in simple terms, in order to convey the trial rationale. They stressed the need to be clear that professionals not knowing the best treatment for a condition is the rationale for a trial. Therefore, we ensured that this content was prominent in the MMIs.

Risks associated with the trial – and how to inform about them

Most participants talked about the importance of having risks explained in a ‘balanced’ way. Parents specifically wanted to know about possible side effects of treatments. However, they also thought there was sometimes ‘too much information’ about risks, and that some risks were ‘tiny’ but the explanation of them could be ‘scary’ for young people. Young people and some children wanted to know what they were consenting to in terms of risks and side effects but preferred the focus to be on ‘likely’ risks. A list of every ‘potential’ risk could result in being ‘overwhelmed’. Professionals noted that families often wanted to understand risks and safety issues associated with a trial.

Well risks is mostly for, I’d say mostly for the person taking part because it’s going to happen to you if there is any possible risks. Like I know that my drug doesn’t always work because I’ll have a very, very bad flare up and that’s kind of a risk. It can’t always work but I think it’s really important to know that what could happen to you, what you’re getting yourself into. That just makes you feel, I don’t want to do this or I’m willing to do this. I think that’s really important.

(CYP/23, female, 16 years, experience of being approached about a trial)

The risk factor thing is a huge thing, you know, to me some of the information sheets I’ve read I wouldn’t do it because I mean potentially some of those side-effects are tiny but yet the way it’s put across is so scary that you just wouldn’t do it. I know they have to do it, but is there a better way of doing that?

(Parent/24, female, experience about being approached about a paediatric trial)

Therefore, information about the risks were provided within the key section ‘taking part in the trial’.

Possible benefits of trial participation

Parents and young people wanted to know how trial participation might benefit others, as well as any possible personal benefit for themselves or their child. One parent stressed that clinicians should convey this information, because it is ‘important’ to future patients.

But one thing I do like about trials is that I like to know that the trial is going to benefit somebody in the future.

(Parent/36, female, no experience about being approached about a paediatric trial)

That it’s just going to help other people if they’ve got problems.

(CYP/16, male, 10 years, experience of being approached about a trial)

Sometimes families thought that their child may get better treatment in a trial, which led to a concern for some that non-participation, or quitting the trial, could lead to reduced quality of care. This indicated the importance of emphasising that children will receive good care regardless of their decision on trial participation. The issue of possible differences in care quality between trial participants and non-participants, was difficult to address in the MMI template, given the trial specificity of the issue. However, the MMI section on potential benefits of the trial was made prominent, including its potential to inform future treatments to the benefit of other patients.

Confidentiality

Confidentiality was interpreted differently by different participants. Some parents expected that their child’s data would be shared amongst care providers and NHS organisations, including the General Medical Practitioner, to enable continuity of care. However, others thought it was not important for the general practitioner (GP) to be informed of their child’s trial participation. One parent said GPs are ‘copied into everything’, implying an automatic and sometimes unnecessary sharing of information. Young people and parents said that confidentiality was important but they ‘assumed’ it would be observed; therefore, there was not a need to emphasise this information on the MMIs. Professionals did not see information about confidentiality as a priority for families, particularly for CYP, when considering trial participation.

Well you kind of assume your information is confidential anyway so it’s not an issue that you would encounter getting normal health care so you’d assumed the rules wouldn’t be different in a research study (CYP/18) … But it’s nice to be reassured about it.

(CYP/20, male, 20 years, no experience of being approached about a trial)

In the light of these differing interpretations, we decided to include information on confidentiality in the MMIs, but as a topic within the ‘Questions and Answers’ section, rather than giving it prominence.

Who has reviewed or funded the trial

Most children, young people and parents similarly assumed that quality control of trials was undertaken as a matter of course, and that they trusted the organisations running studies to provide scrutiny. However, some young people and parents talked about preferring hospital-led over commerciallyfunded trials, implying that funding sources was of interest to them. Indeed, some professionals thought that families were more willing to join studies being led by doctors they knew. Therefore, there were mixed views on its prominence within the MMIs. Parents also thought that the inclusion of a relevant logo on the MMIs was important:

If I saw that NHS logo, for me, it gives it more credibility I think.

(Parent/60, male, no experience of being approached about a paediatric trial)

Parents further emphasised the need to know that a website their child was accessing was credible, and that a credible, reputable logo would reassure them. Young people were generally less concerned about website credibility but liked the inclusion of a logo. Therefore, given the range of views, we included information on trial scrutiny and funding but did not make this prominent, and we included logos within the MMIs.

Information about payments

Children and young people did not think that information about incentive payments would influence the decision to take part in a trial. However, they worried that such payments could lead others to overlook the risks, and that payment to trial participants could be ‘dodgy’. Professionals noted that incentive payments to participants in UK paediatric trials were rare. In contrast, professionals and young people agreed that for studies involving healthy volunteers undertaking multiple blood tests with no personal benefit, information about payments would be necessary to achieve recruitment. Most participants did not think that providing information about payments for patient participation was advisable. As a compromise, information on payment was included but in the less prominent ‘Questions and Answers’ section.

Design and tone of the multimedia websites

Colour

Young people thought that colour in multimedia websites was important for engagement but noted a need for balance to ensure a ‘professional’ appearance. Young children (aged 6–11 years) and their parents preferred brighter colours whereas young people preferred more muted colours. Some parents and professionals advised avoiding a particular shade of green, due to associations with illness. Participants liked that the animation characters in the prototype websites represented a range of ethnicities, but there was concern among some parents to ensure that skin tones were realistic. In response to these comments, we changed the skin tone for several of the characters after the second interviews. The colours of the MMIs were also selected to vary according to target age, using bright colours (predominantly orange) for children and more muted colours (predominantly teal) for young people.

Layout

The need for the MMIs to be well-structured and easily navigable was stressed by young people, with main points ‘staring right in your face’ and ‘simple’ headings. They gave examples of websites that they liked, which were clearly laid out and easy to use, despite having a lot of content. They liked the relative ‘formality’ and ‘professionalism’ of the prototype MMIs and wanted the inclusion of characters and other images to balance out the text; this would make them more interesting. We ensured these aspects were included in the MMIs.

Font, characters, quirkiness and details

Young people had preferences for the font to be easy to read. Indeed, they had little tolerance for decorative fonts that were difficult to read and said this could stop them from using a website. Large font size was particularly important for young children; following their comments we further increased the font size after the second round of interviews.

Something else that is really important is the type and size of font because it’s obvious that people don’t think about. If you can’t read the font then there is no point to making a website.

(CYP/18, female, 18 years, experience of being approached about a trial)

In the first round of interviews participants stated that they wanted the drawn characters to resemble people rather than more abstract ‘blobs’. Both CYP preferred characters that they could ‘relate to’ and easily recognise the role a character was representing:

Maybe you need a nurse that suits a teenager because they [nurse characters in prototype website] seem like they’re a children’s one with the bear. You need one that you can relate to.

(CYP/35, female, 16 years, no experience of being approached about a trial)

Some of the characters in the websites were revised to ensure that portrayed roles were easily identifiable.

Overall, CYP were drawn to characters with brighter clothing and details (e.g. red dress with white spots) and we incorporated these details into the final character set. Quirky or slightly unexpected details often received favourable responses. For example, the initial ‘why do we do trials’ animation often prompted families of young children to begin talking together about the animation:

It was funny wasn’t it the guy with the pan on his head, it’s quite funny.

(Parent/41, female, experience of being approached about a paediatric trial)

Funny. That was funny with the pan on his head [laugh].

(CYP/43, male, 9 years, experience of being approached about a trial)

Consequently, we included characters in the MMIs with interesting details and quirky elements within the animations, to increase engagement.

Animations

Participants stressed the need for animations to be concise, with most saying they would watch animations for up to 90 seconds, implying that longer animations would not sustain their attention. Young people were particularly critical of repetition and some parents also found this distracting. Several animations were shown to participants in the first round of data collection. One animation about a health condition, depicted using Lego characters and narrated by a child, was popular particularly with children (9–11 years) and their parents. Hearing the child’s voice engaged children. However, young people often said that this animation style and narration was too ‘young’ for them. Another animation, ‘Making the right decision for me’, was narrated by a young person and used sounds to accompany actions and was popular with most children, young people and parents.

It was so intriguing just like the video and what she was saying all went together really nicely. You could put yourself physically in it and just imagine it (CYP/20, male, 18 years, no experience of being approached about a trial).

However, one group of professionals responded very negatively to this particular animation commenting that it was ‘absolutely horrendous’ (Professional/3). The animation depicted a young person arguing with her parents when deciding whether to participate in research. These professionals felt the tone was negative and the content condescending as it implied that assent was less important than consent.

Despite differing views on this animation, all participants agreed that animations were a suitable means of providing information, regardless of patients’ age. Parents often talked about the benefits of seeing and hearing an animation to convey complex information. Consequently, we developed four trial-generic animations and a fifth trial-specific ‘explainer’ animation, which would succinctly summarise the key features of a particular trial.

I was thinking just then of watching it as an adult that even though it was an animation, you think animations are for children but actually when you look at it, sometimes when you just read something on a page or you’ve just got somebody speaking at you, it doesn’t necessarily go in easily and I would say it doesn’t matter that it’s an animation like that for an adult watching it even, because you tend to think of it as just for children don’t you? But they’ve made it [Nuffield animation] nice and simple (Parent/32, female, no experience of being approached about a paediatric trial).

Narration

Young people were sensitive to the tone and sound of the narrator’s voice. As previously noted, children and parents liked the example animation narrated by a child:

I really like it because of the Lego and the child’s voice. That catches your attention doesn’t it? (Parent/27, male, experience of being approached about a paediatric trial).

However, young people and parents thought that a child’s voiceover would make relating to the animation harder, and several found imperfect pronunciation distracting. Therefore, we decided to use an adult’s voice to narrate the prototype animations. However, when the prototype was shown, most young people reacted negatively to it, commenting that they found it ‘boring’, ‘monotonous’ or ‘robotic’ and that this could stop them from focusing on the animation. Parents did not generally comment on the voiceovers. In order to address young people’s concerns, we asked the narrator to rerecord the narrations with greater tonal variation.

Hearing from other families about their experience of trials

We showed participants a short example video in the round one data collection of a parent and young child talking about their trial participation. 87 Most parents, young people and children responded favourably, saying that they found it ‘reassuring’ to hear from those actually involved in the trial or treatment. Professionals echoed this, saying that children would want to hear from and see other children in trials, rather than parents or other adults.

It needs to be people who are actually in trials so then it will put people of my age and younger under reassurance that other people have had a trial before (CYP/51, female, 15 years, experience of being approached about a trial).

Therefore, we created and included short video clips of trial participants and parents talking about being in a trial for the MMIs.

Interactivity

Participants differed in the value they placed on interactivity in MMIs, and they varied in how they defined interactivity (which could explain the differences in opinion). For some, interactivity meant including games, while others felt it referred to being able to ask questions and receive a response, and others thought it could mean following a pathway through the website. One young patient interpreted websites with multimedia to be interactive because you can ‘hear and see things’ rather than just read them.