Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 17/05/03. The contractual start date was in September 2016. The final report began editorial review in September 2021 and was accepted for publication in May 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final manuscript document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this manuscript.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Briggs et al. This work was produced by Briggs et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Briggs et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction and context

Background

‘Vital signs’ is the term for a group of important physiological characteristics that indicate the status of the body’s vital (i.e. life-sustaining) functions. They include such measures as blood pressure (BP), heart (pulse) rate, oxygen saturation and breathing (respiration) rate.

The frequency at which patients should have their vital signs measured on general medical and surgical wards is currently unknown. Monitoring protocols in use at present are based on expert opinion,1–3 but supported by little empirical evidence. 4 The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that all patients in acute hospitals are observed at least every 12 hours and more frequently if abnormal physiology is detected. 2 Early warning score (EWS) systems, such as the National Early Warning Score (NEWS),1 provide the means to quantify that abnormality by combining observations into a single score. However, while there is some evidence to support the use of EWSs to identify patients most at risk of adverse outcomes [e.g. death, cardiac arrest, unanticipated intensive care unit (ICU) admission],5–7 the associated monitoring protocols are currently based solely on expert consensus. 1,4 The absence of data to inform clinical practice is a major patient-safety issue, as treatment will be delayed if deterioration is missed due to under-observation. 8–10 Likewise, over-observation redirects nursing time away from other essential aspects of patient care. Indeed, several studies have shown that adherence to current monitoring protocols is often poor,11–14 with many observations missed, particularly at night. This is in part due to available nursing resources. 15–17 One solution would be to continuously monitor all patients, as is the case on high-dependency wards. However, at present this is costly4 and a 2016 systematic review of clinical trials concluded that current evidence is ‘insufficient to recommend continuous vital signs monitoring in general wards as routine practice’. 18

Rationale

What is the problem being addressed?

In 2007, NICE recommended that all patients in acute hospitals should have their vital signs measured and recorded at least every 12 hours and more frequently if abnormal vital signs are observed. 2 In addition, they advised the use of a ‘system’ to identify patients at risk of deterioration. In response to this, UK hospitals have tended to use EWS as the ‘system’.

In 2012, the Royal College of Physicians London (RCP) introduced the NEWS1 to encourage a consistent approach across the NHS. EWS systems, NEWS included, permit a set of vital signs observations to be converted into a single integer score, quantifying a patient’s overall level of physiological disturbance. As part of the NEWS system, the NEWS score is also used to guide how frequently the patient should be monitored. 1 While there is an evidence base to support the use of NEWS to predict which patients are more likely to experience adverse outcomes (in-hospital mortality, cardiac arrest, unanticipated ICU admission),5–7,19 the measurement frequency of vital signs in general hospital wards has been described as ‘an evidence-free zone’. 4 A later revision of the protocol (NEWS220) made no significant changes to these monitoring schedules. With no data to support clinical practice, monitoring protocols still vary widely across NHS trusts and may well waste limited staff resources.

This study aims to recommend observation frequency based on the risk of missing significant deterioration in the intervening period. Prospective observations of nursing staff will allow us to quantify the cost of different monitoring protocols, based on varying thresholds of risk.

Why is it important?

Implications for patient safety

There is now substantial evidence that inadequate monitoring is a major patient-safety issue, contributing to avoidable deaths and other significant adverse outcomes. 3,8,13 The Keogh review into 14 hospital trusts with high mortality rates noted that ‘a consistent theme throughout almost all of the organisations reviewed was the management of complex deteriorating patients and the monitoring of Early Warning Scores’. 9 The Keogh report is not unique in identifying mismanagement of physiological deterioration of patients in hospital. Numerous reports on patient safety and avoidable deaths have identified the failure to observe or respond to patient deterioration as a significant contributory factor. 1,8,9,21 This is often referred to as ‘failure to rescue’ and is thought to be sensitive to the quality of care provided, including levels of nurse staffing. 15–17,22,23 While progress in statistical modelling techniques and development of electronic medical records will likely lead to more sophisticated and accurate risk-prediction algorithms to detect deterioration from vital signs and other clinical data,24–26 they will not directly provide evidence on how frequently these measurements should be obtained.

Implications for staff resources

Whereas under-observation can delay the opportunity to detect patient deterioration and initiate remedial treatment,8,9 over-observation uses valuable nursing resources that could be better deployed to other essential aspects of patient care. Indeed, compliance with current monitoring protocols is often poor, with many observations missed or delayed. 11–14 This is particularly evident at night,12,27,28 when staffing is at its lowest. Results from our HS&DR ‘Missed Care’ study (ISRCTN: 17930973) show that compliance with vital signs observations is significantly (p < 0.05) associated with the level of available nursing staff. 29,30 Estimates of the time required to take observations are scarce, but a survey of 2917 registered nurses (RNs) across 46 acute hospitals in England showed that one-third had felt unable to undertake all necessary patient surveillance due to lack of time on their last shift. 15 However, even when staffing is sufficient, there are valid clinical reasons why nursing staff will deviate from protocols. Therefore, it is essential to have a monitoring protocol that is achievable on the ward and does not compromise other aspects of care.

With this in mind, and by adapting techniques from our previous work,15,31,32 part of this study is a prospective observation of recording vital signs across a range of wards. This will allow us to understand better the impact on staff workload and factors that might affect compliance with patient surveillance.

Evidence explaining why this research is needed now

Current UK professional guidance1,2,13,33,34 suggests that the frequency of monitoring should be determined by some measure of physiological disturbance. One such measure is the NEWS,1 which provides a simple integer score based on the degree to which a patient’s vital signs are outside the normal range. There is now some evidence to support its ability to predict a patient’s risk of adverse outcomes,5,7,35–37 albeit with high false-positive rates. However, we were unable to identify any large studies to support the vital sign monitoring intervals suggested by the original guidelines from the Royal College of Physicians. 1 For example, the NEWS Development and Integration Group (NEWSDIG) recommended at least hourly observations for any patient with acuity of NEWS 5 or more. To put this recommendation into context, the surveillance protocol for patients with NEWS 5 at Portsmouth Hospitals was 4 hourly in the period to 2018, and there was only 50–70% compliance with protocol at this frequency, for a number of potentially legitimate reasons. Without an evidence base, compliance is seen mainly as a superficial mechanistic proxy for quality of care.

As discussed above, under-observing patients run the risk of missing early signs of deterioration, but taking repeated measurements in patients is also a drain on valuable staff resources. Obtaining vital sign measurements is one part of the ‘chain of prevention’,38 necessary to effectively recognise and manage the deteriorating patient. For example, a national enquiry into patients who underwent cardiopulmonary resuscitation in hospital8 showed 20–40% did not have a clear monitoring plan in the 48 hours prior to the event, despite over 70% having significant physiological abnormalities. It is therefore crucial for safety that patients’ observations are correctly targeted and escalated appropriately. However, this must be balanced with other negative consequences. For example, obtaining observations can be disturbing for patients39 and might be associated with negative health outcomes if they contribute to sleep disruption. 28,40 Monitoring protocols that demand observations when staff deem it futile in certain situations, in particular if these may have adverse effects, risk delegitimising the EWS protocol.

One solution would be to implement continuous monitoring for all patients. However, systems for continuous monitoring are at present costly4 and there is little evidence that they improve patient outcomes. 18,41,42 There are also legitimate concerns that continuous monitoring might introduce other risks, such as loss of nurse interaction with patients to pick up soft signs, alarm fatigue and technology failures (e.g. detached monitoring devices). A recent systematic review and meta-analysis18 of randomised trials of continuous and intermittent observation concluded there was ‘insufficient evidence to recommend continuous vital signs monitoring in general wards as routine practice’. Despite a number of trials of wearable devices to measure vital signs outside intensive care,43,44 no device is capable of measuring all vital signs required to generate the NEWS (e.g. BP is rarely possible). In the UK, we found one recent randomised controlled trial (ISRCTN: 60999823) of a continuous monitoring device. 45 A prospective cohort study (SNAP40-ED) trialled the use of a wearable device to detect deterioration in patients in the emergency department. 46

Aim and objectives

This study aimed to investigate observation frequencies based on the risk of missing significant deterioration in the intervening period.

The objectives included to:

-

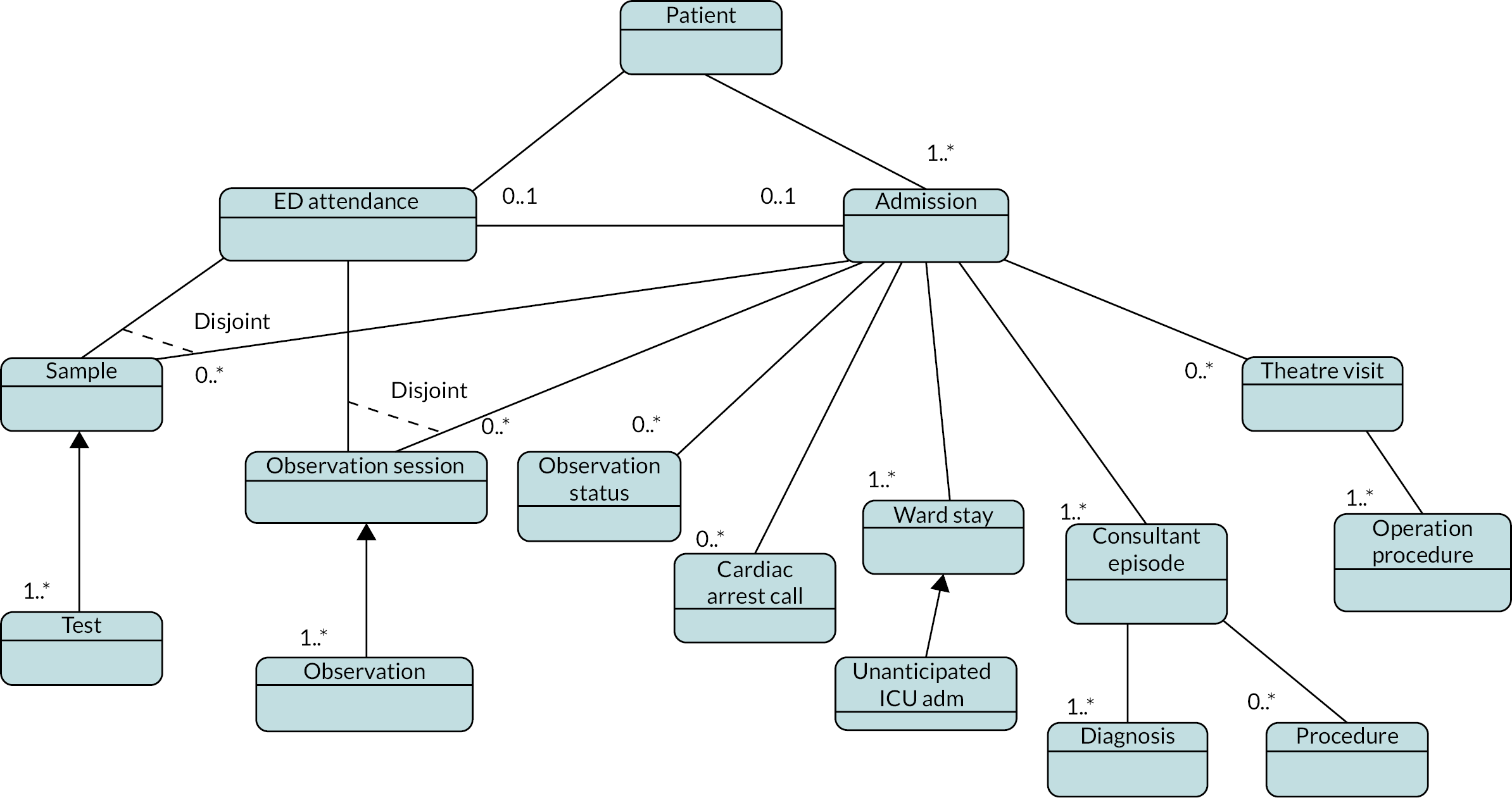

Develop a data warehouse of linked admission records with information on patient demographics, vital signs observations and adverse events (cardiac arrests, unanticipated ICU admissions, in-hospital mortality).

-

Estimate the rate of clinically significant changes in vital signs over the course of patients’ admission.

-

Explore the relationship between vital signs and adverse outcomes over time.

-

Determine the extent to which relationships between the time to deterioration and risk of adverse outcomes vary across different patient groups.

-

Organise stakeholder (nurse, doctor, patient) events to identify additional factors relevant for selecting an optimal monitoring protocol.

-

Undertake prospective observations of nursing care to estimate the time taken to obtain and respond to vital signs observations, using techniques adapted from previous work.

-

Derive a set of simple monitoring protocols by identifying any threshold effects between the risks over time predicted by our models.

-

Use estimates from our observational work to model the marginal costs and consequences for all protocols with better or equal performance compared to the current protocols for detecting deterioration.

Structure of the team, the project and this report

This project was a collaborative effort involving a large team of people from four organisations:

-

University of Portsmouth (lead organisation)

-

University of Oxford

-

University of Southampton

-

Portsmouth Hospitals University NHS Trust (PHU).

The project was organised into six work packages (denoted WP0–5) reflecting the major aspects of the work. While work packages 0 (administration) and 5 (dissemination) were purely functional, it is useful to understand how the others contributed to the totality of the work. The major tasks were:

-

the retrospective study of historic data on patient admissions to explore the relationships between vital signs and outcome (WP1 to create the warehouse of data extracted from the participating hospitals; WP2 to carry out the analysis of that data);

-

the observational study of nursing staff to ascertain the time taken to perform vital sign observations (WP3).

These were both supplemented by WP4, which addressed stakeholder engagement and experiences with patient observation and monitoring in hospital. It also allowed us to validate our results with stakeholders. WP5 coordinated the production of this report and a number of papers (specified later).

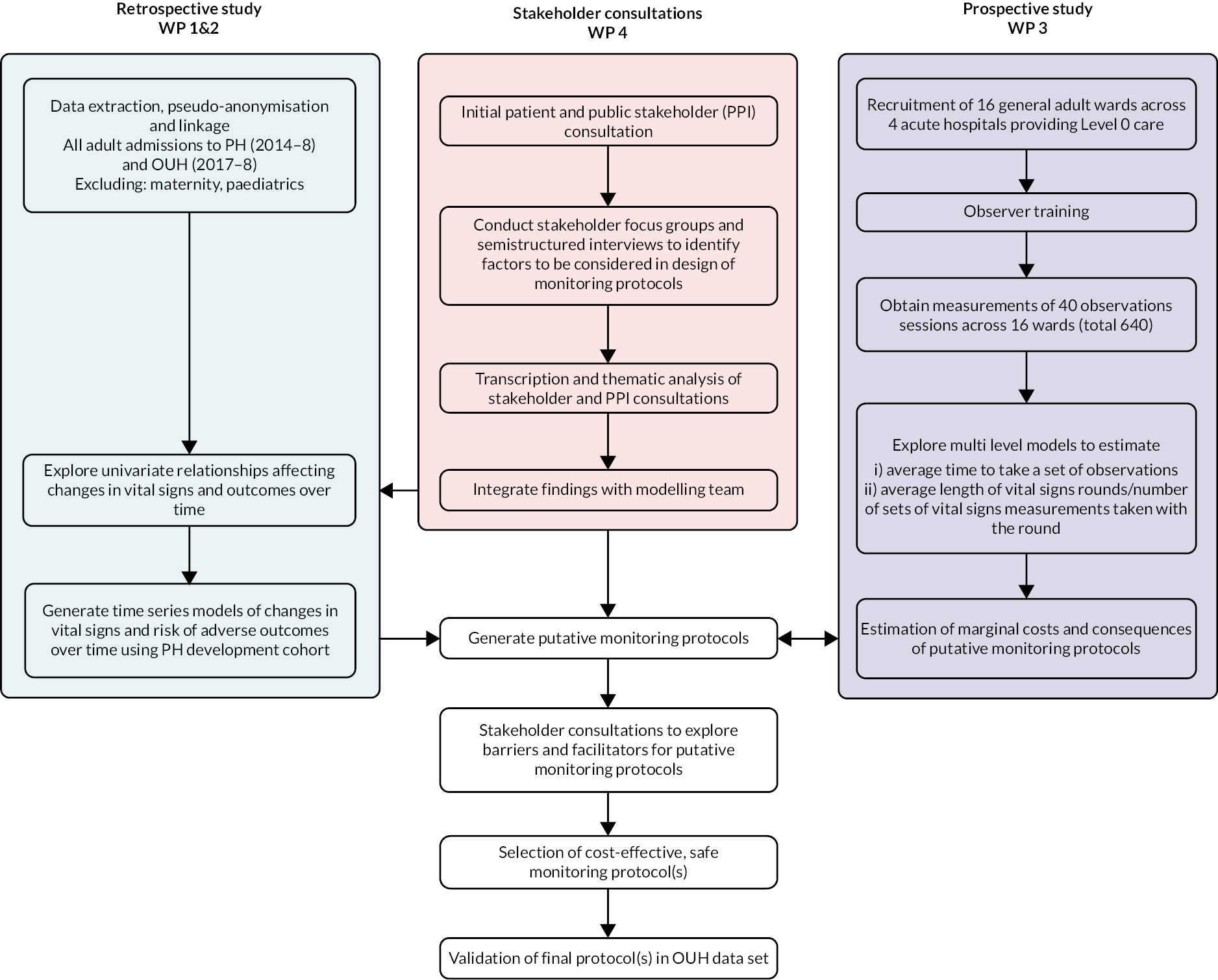

The relationship between the main work packages is shown in Figure 1. In particular, WP4 was designed to inform the later stages of the retrospective study in identifying factors to be considered in monitoring protocols.

FIGURE 1.

Study flow chart.

In this report, we first of all describe the results of our literature reviews. We completed two reviews, one related to each major task. These were: a scoping study (described in Evidence for best vital-sign monitoring practice: a scoping review) to determine what evidence already existed on the optimum frequency for monitoring vital signs; and a systematic review (described in What is the nursing time and workload involved in taking and recording patients’ vital signs? A systematic review) of evidence regarding the time nurses take to monitor and record vital signs observations.

We then describe our observational study. This followed nursing staff as they conducted vital signs observations to measure how long they took and what factors influenced the time taken. This was a prerequisite to informing estimates of the costs and effects of changes to practice. Chapter 3 describes the methods adopted and Chapter 4 describes the results.

Following that, we describe our retrospective study. This analysed data from two hospital trusts to assess the relationships that the time between vital sign observations has with the patient’s outcome. Chapter 5 describes the methods adopted and Chapter 6 describes the results.

Chapter 7 describes how our stakeholder engagement work was integrated into protocol recommendations.

The project conclusions are discussed in Chapter 8.

Chapter 2 Literature review

Evidence for best vital sign monitoring practice: a scoping review

The objective of this scoping review is to map existing evidence and identify gaps in our current knowledge on the optimum frequency for monitoring vital signs of patients admitted to hospital to inform future research into vital sign monitoring and the development of new monitoring protocols.

Methods

Scoping reviews are ideally suited to map the scope and size of existing research in a field of interest and to identify knowledge gaps in the literature. 47 Compared to systematic reviews, scoping reviews have a less structured approach to data extraction. They permit inclusion of different study designs, do not necessarily assess the quality of included studies and typically use a qualitative synthesis of the evidence. 48–50

We followed the scoping review methodology by Arksey and O’Malley,51 including the following stages: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) study selection; (4) charting the data; and (5) collecting, summarising and reporting the results. The methodology summarises existing literature on a topic in terms of volume, nature and characteristics of the primary research and identifies gaps in existing literature.

Research question

The review aims to address the question: ‘How often should vital signs be measured as part of routine monitoring of patients in hospital?’ Our search strategy for identifying and selection of studies is outlined below. The studies were divided into the following categories based on similarities in their design, main objectives and themes: primary research, review articles.

Identifying relevant studies

The initial literature search was conducted in November 2019 only including articles in English in the following databases: MEDLINE and EMBASE. The database search was expanded to remove language restrictions in April 2020. We checked for newly published relevant studies in April and October 2021 by screening papers citing studies already included in this review.

The search strategy was developed together with an academic librarian at Bodleian Health Care Libraries at the University of Oxford through a series of preliminary searches. Our search strategy included two key elements: (1) terms describing timing, frequency and intervals; and (2) terms related to routine monitoring of patients using EWSs or medical emergency team (MET) systems, as well additional search terms to exclude studies on non-adult patient populations as well as conference abstracts. We included primary research and relevant review articles in this scoping review because the latter further highlighted the existing evidence gap. The full list of resulting search terms is provided in Appendix 1.

Study selection

The initial screening for inclusion was based on the title and abstract of studies to eliminate studies that did not meet the minimum inclusion criteria. Two of the project team members (CK and IK) reviewed titles and abstracts generated by the original search against agreed inclusion and exclusion criteria. Any disagreements regarding inclusions were resolved through discussion, or, in the case of continued disagreement, by a third team member (OR). A full-text copy of each study was assessed against eligibility criteria by CK and IK to decide on final inclusion. Reference sections of selected studies were checked manually to identify additional relevant studies that were potentially missed in the database search. Relevant references as well as studies identified through other sources then underwent the same two-stage screening process to be included in this review.

Inclusion criteria: This review focuses on the monitoring of adult patients admitted to hospital wards. This review included publications in any language that reported on the speed of patient deterioration or the impact of patient monitoring on outcomes. Review articles addressing either of these questions were also included.

Exclusion criteria: Case studies, studies limited to outpatient care or care provision in community or rehab centres as well as studies on paediatric, pregnant or post-partum patients and patients directly admitted to ICU (without any monitoring on general wards) were excluded. Primary research studies were excluded if the article did not specify which frequency or protocol was used to monitor patients. Studies focusing on the escalation of care once deterioration was detected were also excluded, as were studies assessing compliance with an existing monitoring protocol. For primary studies that did not compare different monitoring regimes, studies were excluded if they did not present longitudinal vital sign data and hence did not provide information on the speed of deterioration which could potentially be used to guide the development of future monitoring protocols.

Charting data

Data from each article meeting the eligibility criteria were extracted separately by the two reviewers using a standardised data-extraction sheet. Collection included the following items: authors, year of publication, journal, type of study, study design and setting, patient population, vital signs and EWS monitored, monitoring protocols in intervention and control group (if applicable), methods and interventions, outcome measures, summary of results, key conclusions, recommendations, source. Identified studies were grouped into key themes based on similarities in their study design.

Results

Search results

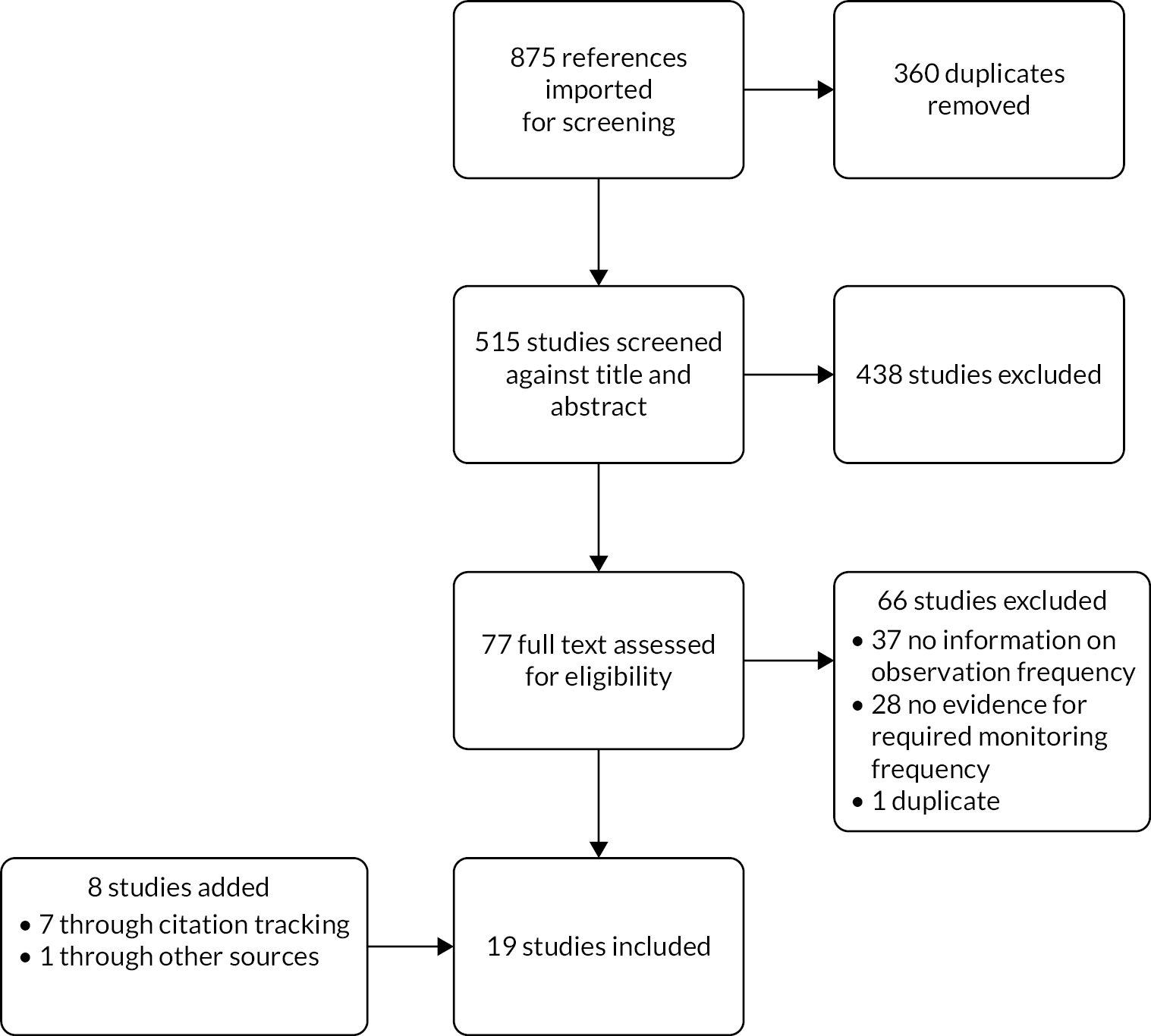

Initial searches yielded 515 studies (after removal of duplicates), of which 77 were selected for full-text review. Eleven papers met eligibility criteria and an additional eight were added through citation tracking and other sources before undergoing data extraction [see Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram, Figure 2]. The selected papers ranged from 2006 to 2020. The methodological quality of the studies was not formally assessed in line with the framework of scoping reviews. Meta-analysis was not feasible due to heterogeneity of study design, study populations and outcome measures.

FIGURE 2.

PRISMA flow diagram for the scoping review.

Of the 66 articles excluded during full-text assessment, 28 did not provide sufficient detail on the monitoring frequency used to collect data and a further 37 neither compared different monitoring protocols nor presented longitudinal vital sign or EWS data with high temporal resolution. We also excluded one study by Petersen et al. 52 that merely summarised, and hence duplicated, the results from an already included study53 as part of a published PhD thesis.

General characteristics of included studies

The majority of identified articles (68.4%) were published in 2016 or later. We identified two groups of articles:

-

twelve primary research studies (see Appendix 2),41,45,53–62 of which one was a survey of hospital policies on the management of the deteriorating patient;55

-

seven review articles (see Appendix 3)3,4,18,63–66 including one editorial4 and one opinion piece. 64

Key characteristics of primary research studies and review articles are detailed separately below.

Primary research

Of the 12 primary research studies identified (see Appendix 2):

-

three were randomised controlled trials (RCTs),45,53,67 of which two were cluster/ward randomised;45,53

-

seven were observational before-and-after studies or parallel group studies comparing different monitoring practice;56–62

-

one was a retrospective observational study, assessing trends in EWS observations;54

-

one was a qualitative review of hospital policies and guidelines on managing patient deterioration which is summarised separately below. 55

Articles reporting primary research originated from a variety of countries: three each from the USA, UK and Denmark, and one each from the Netherlands, Greece and Australia.

The majority of studies were carried out at a single institution: only one study involved two hospitals (one public and one private56). Study duration ranged from 8 weeks to 24 months, with six studies lasting between 3 and 7 months and four studies lasting 16 months or more.

The 11 quantitative studies involved a wide range of different study populations. One study focused on patients with acute exacerbated chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. 57 Five studies involved both medical and surgical patients41,53,57,61,62 and five involved different groups of surgical patients at different stages of their treatment journey. 45,56,58–60 The latter included one study of postoperative patients,56 one study of patients in a surgical trauma step-down unit,58 one with neurosurgical patients,59 one study of general elective patients45 and one study of elderly patients (≥ 65 years) with elective major abdominal cancer surgery. 60

Ten out of the 12 primary research studies examined interventions created by implementing or trialling new monitoring practice involving a change in monitoring frequency. Most commonly, studies compared intermittent and continuous monitoring practice (seven studies),41,45,57–61 followed by comparisons of different intermittent monitoring protocols (three studies). 53,56,62

Most studies involving continuous monitoring showed that continuous monitoring was able to identify more periods of deranged physiology;57–60 however, only one study investigated whether this had an impact on clinical outcomes. 60

Five studies investigated the effect of changes to monitoring regimes on adverse events or clinical outcomes such as length of stay (LOS), mortality, time to intervention of rapid response team (RRT) activation and ICU admission. 41,45,53,59,61 Evidence for the benefit of changing to continuous monitoring was varied. While some studies observed reduction in LOS either in hospital45 or in ICU61 and reduction of event rates including cardiac arrest, sepsis, mortality, ICU admission45,61 or RRT activation,59 others did not find significant differences in outcome rates such as mortality, cardiac arrest or transfer to high care. 41,59 One study (focused on the impact of different intermittent monitoring protocols in low-risk patients) found no benefit in increasing monitoring frequency to more than twice daily in this patient group. 53

Some studies highlighted technical problems and patient compliance with wearing continuous-monitoring devices as real issues. 41,45

One study showed that protocolised monitoring (three times daily) improved compliance over a clinical judgement model. 62

Two studies presented deterioration rates or patterns, providing indirect evidence for optimal monitoring frequency. 54,58 One study showed that 4-hourly monitoring of an EWS can provide an indication of a patient’s ICU LOS and mortality. 54

The paper by Freathy et al. 55 was a qualitative review of policies on the response to deterioration from 55 hospitals; 65% of hospitals used NEWS and all hospitals collected vital sign observations at a minimum frequency of two times a day, although observation protocols varied widely even when the same EWS was used. The study also revealed that policies often lacked specifics such as out-of-hour guidelines (missing in 40% of policies), and rarely specified the maximum permitted response time once deterioration was identified. It suggested that clear dissemination of service information to clinical staff is required and that hospitals need to review their policies and operating procedures, including guidance for whole 24-hour periods.

Included reviews

Seven of the articles we included were reviews, of which three were systematic18,65,66 and four were narrative reviews,3,4,63,64 reports from consensus conferences or opinion pieces (see Appendix 3). All but two3,65 were published in 2016 or later. Systematic reviews covered from 14 to 22 studies, while narrative reviews covered between 7 and 149 references.

One article pointed out that current monitoring practice is often based on tradition or clinical judgement. 64

Five articles discussed both continuous and intermittent monitoring,18 while one review focused on intermittent monitoring only63 and another considered vital signs measurements on ‘a routine basis’. 65

Four review articles concluded that there is some evidence that monitoring frequency has clinical relevance. 4,18,65,66 However, reviews presented varying evidence regarding the impact of continuous monitoring on clinical outcomes when compared to existing intermittent-monitoring practice. Cardona-Morell et al. 18 found no significant evidence for reduction in mortality with continuous versus intermittent monitoring but significant impact between different intermittent-monitoring practices. Sun et al. 66 concluded that the clinical evidence showed that continuous monitoring can reduce mortality, LOS, ICU admission and RRT activation, and Smith et al. 4 suggested that changes in monitoring practice can affect outcomes. Four review articles concluded that there is some evidence that monitoring frequency has clinical relevance. 4,18,65,66 However, reviews presented varying evidence regarding the impact of continuous monitoring on clinical outcomes when compared to existing intermittent-monitoring practice. Cardona-Morell et al. 18 found no significant evidence for reduction in mortality with continuous versus intermittent monitoring but significant impact between different intermittent-monitoring practices. Sun et al. 66 concluded that the clinical evidence showed that continuous monitoring can reduce mortality, LOS, ICU admission and RRT activation, and Smith et al. 4 found that changes in monitoring practice generally affect outcomes.

All selected review articles highlighted the lack of clinical evidence regarding optimum monitoring practice. They called for more research, particularly large clinical trials, into the clinical benefit of different monitoring frequencies, including the benefit of continuous monitoring.

One review pointed out that compliance with protocolised, intermittent-monitoring frequency is poor. There was no consensus on whether the introduction of protocolised monitoring (intermittent or continuous) improves adherence to monitoring schedules, with one article supporting this hypothesis18 and one suggesting evidence was inconclusive. 4

Recommendations regarding monitoring frequency

Overall, the studies we identified presented little robust evidence and few recommendations to support the development of evidence-based monitoring protocols. Almost all studies called for further research into the clinical effectiveness of different monitoring frequencies, with studies highlighting a lack of evidence supporting either currently implemented intermittent-monitoring regimes or the benefit of continuous monitoring.

The most specific recommendations identified through this scoping review are listed below:

-

Monitoring should be protocolised rather than based on tradition or clinical judgement, as this results in better compliance and more reliable RRT activation. 62 At the moment, however, intermittent monitoring of patients is predominantly tradition-based56,64 with large variations across NHS trusts. 55

-

Some evidence suggests that there is no benefit in monitoring low-risk patients more frequently than twice daily, that is 12 hourly. 53

-

Clinical consensus is that the minimum observation frequency is 12 hourly. However, this recommendation is not evidence-based.

-

Clinical consensus also suggests that patients should be monitored with individual intermittent-monitoring schedules based on their risk. 3,64

-

There is large variation in vital sign monitoring and scheduling across different hospitals, and guidelines often lack specifics. 55

-

There are very few studies comparing two different intermittent-monitoring protocols and most focus on compliance rather than outcomes or clinical effectiveness.

-

Most comparisons of different monitoring frequencies compare intermittent with continuous monitoring, often focusing on staff workload and alarm fatigue.

-

Where studies investigate the clinical benefit or effectiveness of continuous monitoring compared to intermittent monitoring, the evidence is inconclusive or controversial. 41,45,58,59

Discussion

The review revealed a general shift from studies describing the development, implementation and validation of EWSs68–71 to studies assessing the effectiveness of their associated escalation and monitoring protocols. 12,72–75

Lack of evidence on monitoring frequencies identified

The first paper to address the question of monitoring frequency was published by DeVita et al. 3 in 2010. The report from a consensus conference set out recommendations for identification and treatment of deteriorating patients. They highlighted that there was no evidence for the optimum monitoring frequency of patients in hospital but agreed that the assessment of vital signs should be made every 12 hours as a minimum. This review largely confirmed the lack of evidence regarding vital signs monitoring practices and timing of observations. A 2017 editorial by Smith et al. 4 stressed the need for research into best vital sign monitoring practice and required compliance with protocol. Storm-Versloot et al. 65 assessed the clinical relevance of routine vital signs observations and also indicated a lack of evidence. Other studies have also described the lack of consensus regarding necessary observation frequency but highlighted the importance of considering the nurse workload generated by monitoring demands. 74 This is also reflected in large variations in hospital policies guiding the observation of vital signs. 55

Protocolisation improves monitoring frequency

In an observational study of 804 surgical patients, Ludikhuize et al. 76 showed better detection of deteriorating patients with a regime for three sets of observations daily rather than nurse discretion. Their findings agree with several other studies showing that protocolised monitoring increased the number of observations taken and resulted in reduced adverse outcomes compared to monitoring based on clinical expertise or tradition. McGregor et al. 77 found standardised monitoring improved its reliability and was a step towards a patient-centred approach, while van Galen et al. 72 found the introduction of a protocolised EWS assessment was a good screen for major adverse events in the hospital population. In 2013, Hands et al. 12 found there was only partial adherence to the observation protocol with definite morning/evening observation peaks indicating observation rounds, although time to next observation (TTNO) decreased with increasing VitalPAC Early Warning Score (ViEWS), but not necessarily in line with the protocol. While these studies support the shift from monitoring guided by clinical expertise to protocolised monitoring, they were largely outside the scope of this review because they either did not provide enough information on the monitoring protocol used or did not investigate the impact of different intermittent monitoring schedules.

The evidence regarding the clinical benefit of an intermittent protocol is extremely scarce. This review identified only one observational study and one ward-level randomised non-blinded control trial53,62 that compared different monitoring regimes and investigated outcomes. Petersen et al. 53 showed that for low-risk patients observations made twice daily were as effective as three times per day in identifying clinical deterioration. However, they did not address the question of varying observation frequency based on patient risk. We did not find any patient-level RCTs investigating vital sign monitoring schedules.

Continuous versus intermittent monitoring

A number of recent studies have investigated devices to automate the observation of patient vital signs in an effort to gather evidence that supports widespread continuous monitoring of patients. Studies largely focus on the accuracy of these devices compared to manual observations by nursing staff,78 but some also investigated the comfort of wearable devices. 59,79–81 However, not all patients found the device acceptable and nearly a quarter of those in the study did not wear the monitoring device for the required time. 45 One study by Mestrom et al. 82 showed that automated systems can result in better compliance with protocols but results did not show an impact on outcomes in high-risk surgical patients.

The majority of studies identified in this review compared intermittent and continuous monitoring,41,57–61 exploring the potential benefits and drawbacks associated with continuous monitoring outside the ICU, and concluded that overall more research was deemed necessary. Watkinson et al. 41 found mandated electronic vital signs monitoring had no effect on adverse events or mortality in high-risk medical and surgical patients. A recent study by Areia et al. 79 identified benefits of continuous monitoring but suggested its use should be carefully considered given limitations such as excess noise, comfort, potential impact on patient mobility and direct nurse–patient contact should not be replaced.

Another potential issue associated with automated and/or continuous monitoring is the fact that, while evidence suggests that it improves vital sign documentation,82 it might reduce recognition and escalation as technology cannot replace clinical knowledge and acumen. 83 Introduction of continuous monitoring bears the risk of a reduction/limitation of nurse–patient interaction. Recognising the importance of nurse–patient interaction, which is often driven by vital sign observation, Klepstad et al. 179 recommended a maximum interval of 12 hours between observations, in line with DeVita et al. 3 and a suggestion by our stakeholders (see Chapter 7).

Our review showed that while continuous monitoring has the potential to play a major role at some point in the future, current evidence supporting the effectiveness of continuous monitoring is scarce41,45,59,66 and existing studies have identified issues with patient compliance45,59,61 and high alarm rates. 45,58,59,84,85

Compliance with existing protocols

While outside the scope of this review, we would like to highlight that any future evidence-based monitoring protocol will have to take into account that compliance with observation schedules will be limited. Hands et al. 12 found the vital signs monitoring protocol was only partially followed, although sicker patients were more likely to have overnight observations. Pimental et al. 86 reported that most deviations from protocol were attributable to various factors such as clinical judgement, the wish to avoid disturbing the patient at night and escalation might be more sensitive to nurse staffing levels than monitoring, which all need to be considered when developing new monitoring protocols. Similarly, Toth et al. 87 suggested avoiding waking low-risk patients at night might improve outcome (and patient satisfaction) as well as boost the efficiency of healthcare provision.

In summary, no evidence was found describing the best regime for intermittent monitoring, although for low-risk patients there was no support for assessing vital signs more than twice per day. There are trends towards the use of continuous monitoring and automation but benefits to support this outside of ICU are limited, while drawbacks include staff alarm fatigue and loss of nurse–patient contact. Therefore, further research into how different regimes for evidence-based intermittent vital signs monitoring is required.

What is the nursing time and workload involved in taking and recording patients’ vital signs? A systematic review

Before conducting our observational study to establish how long it takes nursing staff to perform and record vital signs, we carried out a systematic review of the literature on that topic.

The results of that review were published as:

-

Dall’ora C, Griffiths P, Hope J, Barker H, Smith G. What is the nursing time and workload involved in taking and recording patients’ vital signs? A systematic review. J Clin Nurs 2020;29(13–14);2053–68. https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.1520288

The following summarises the contents of that paper (reproduced with permission).

Introduction

Patients’ vital signs and associated trends are accurate predictors of clinical deterioration,89–91 and a failure to monitor them is associated with adverse patient outcomes, including death. 13,92 Often the measured vital signs values are used within aggregate early warning scoring systems to provide a single numerical assessment of the patient’s risk of deterioration – an EWS (e.g. the NEWS). 20 Measuring and recording vital signs and calculating an EWS are fundamental aspects of nursing work in acute care hospitals. 93,94 However, these activities are often incomplete10,74,95 or sometimes omitted completely,96–99 with inadequate nurse staffing29,95,100 or long nursing shifts101 cited as possible underlying reasons.

This raises the question of what the workload associated with taking vital signs observations is, and it highlights the importance of understanding the costs and benefits of changes in vital signs observation frequency. A recent systematic review found that implementing continuous monitoring in acute wards outside of ICU is feasible and may improve patient safety; however, the cost-effectiveness of such an approach is still unknown. 102 Current guidance on the recommended frequency of vital signs collection is supported by minimal empirical evidence,4 and has largely been based on expert opinion. 2,3,103 While the evidence broadly points towards benefits from more frequent observations, the absence of precise guidance combined with uncertainty about the resources required makes comparison between alternative strategies difficult.

The precise contribution that measuring and recording vital signs makes to overall nurse and nursing assistant workloads is unknown. However, it will depend upon (1) the time taken to collect and document the vital signs; (2) the number of patients in a given clinical area needing to have vital signs measured at any one time; and (3) the chosen frequency of measurements for individual patients, which is dictated by clinical opinion and/or national policy. 2,4 This is summarised in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Process of taking vital signs observations. aRepeated measurements sometimes required in order to check accuracy of the measured value. bThis calculation might be automatic following the entry of vital sign data.

Methods

Search strategy

We undertook a literature search up to 17 December 2019 to identify quantitative studies reporting the time spent by members of the nursing workforce (i.e. registered and licensed nurses, nursing assistants and equivalent roles – henceforth referred to as ‘nursing staff’) in undertaking vital signs observations, the length of time to take a set of observations or factors that influenced the time taken. The study methods were compliant with the PRISMA checklist. We searched CINAHL, MEDLINE, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library using the following search terms: vital signs; monitoring; surveillance; observation; recording; EWS; workload; time; and nursing (see Appendix 4). The search strategy was agreed by all authors and one author conducted the search.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included studies that provided an evaluation of the time spent by members of the nursing workforce in gathering and recording any of the following vital signs (which are those included in NEWS). 20 These are heart (or pulse) rate; respiration rate (RR); body temperature; BP; level of consciousness; peripheral oxygen saturation (SpO2), and the inspired gas (air or oxygen) at the time of SpO2 measurement. 20 Because we anticipated that we would find limited evidence, we decided not to exclude studies that were not explicit in reporting which vital signs were being measured, provided that the focus appeared to be on these ‘standard’ observations. We focused on adult secondary and tertiary care ward settings, excluding studies exclusively in paediatric or maternity settings, as the necessary vital signs measurements are often different for these populations. We excluded qualitative-only studies, as our review question was quantitative in nature (i.e. time involved in vital signs activities). We retained studies that included other observations (e.g. patient weight, urine output) within the total times offered, as long as any or all of the components of NEWS were measured.

Data selection

One reviewer conducted the first screening of titles and abstracts for relevance. Two reviewers independently assessed the list of potentially relevant studies and identified studies for inclusion; any disagreements were resolved by discussion.

For quality appraisal, we focused on describing key aspects of the study likely to affect the validity of the results, including design, the methods of observation and recording, the vital signs observed and the setting and sample sizes, using a framework based on the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal checklist for descriptive/case series. 104 Items that were not applicable to the main study question (such as confounding) were omitted from the checklist. The checklist comprises some items relating to risk of bias, and some concerning adequate reporting and statistical analysis, and poses questions to which possible answers are ‘no’, ‘yes’ and ‘unclear’. A response of ‘no’ or ‘unclear’ to any of the questions implies lower quality or else insufficient detail to judge the quality of a study. The checklist was completed by two reviewers, and one further reviewer resolved any disagreements. We did not exclude any studies based on their quality.

Data extraction

We extracted the following data from included studies: country; study design; sample size and setting; methods of vital signs measuring and recording; data collection; results; vital signs definition; mean (minutes); standard deviation (minutes).

Data analysis

Where authors reported only mean and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), we calculated the standard deviation as: (√n*(upper limit – lower limit)/t-value*2), where n is the sample size, upper limit and lower limit are those from confidence intervals. If the sample size is > 100, the 95% confidence interval is 3.92 standard errors wide. We initially considered conducting a meta-analysis, but the high heterogeneity between studies, in terms of sample sizes, settings and vital signs timing measurements, rendered this unfeasible.

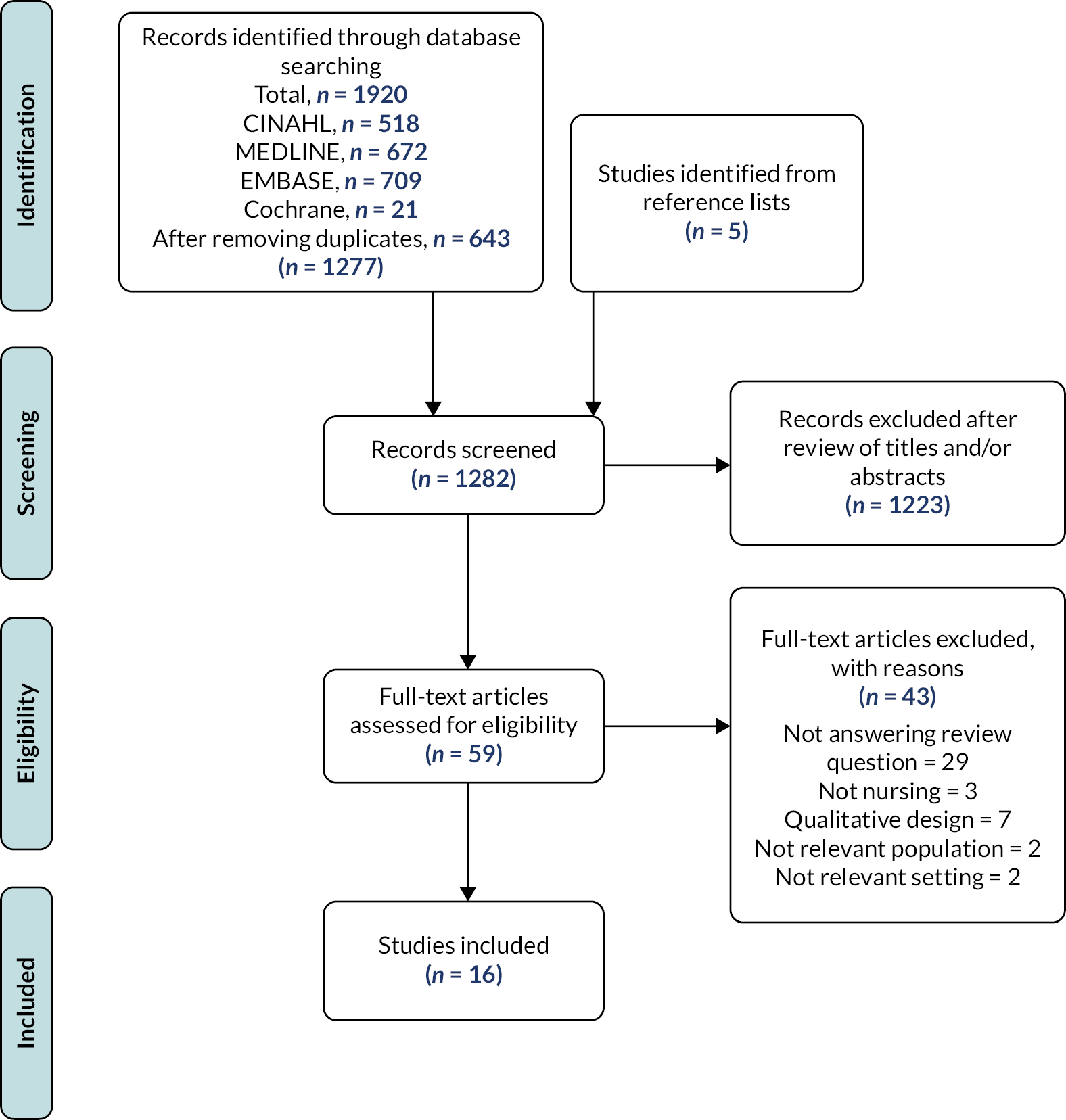

Results

The database search retrieved 1277 papers, of which 11 studies met the inclusion criteria. An additional five studies were identified from the reference lists of papers accessed in full text (n = 59). The article screening and selection process is reported in Figure 4. The results of all 16 included studies are summarised in Appendix 5.

FIGURE 4.

Article screening and selection process.

Overall, the quality of the reports was low, with unclear reporting and significant limitations across many items in most studies (Table 1). No study reported any reliability assessment of their measure of time, and no study scored a positive response to all remaining items on the checklist.

| Study | Random or representative sample from defined population? | Clear inclusion/exclusion criteria? | Clear description of methods of assessment (time)? | Clear description of what was included/excluded in vital signs? | Was the assessment reliable? | Was information given to determine the precision of the estimate? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bellomo et al. 2012 | U | N | N | Y | U | Y |

| Clarke 2006 | N | ?N | Y | Y | U | Y |

| Ito et al. 1997 | N | N | Y | N | U | N |

| Kimura et al. 2016 | N | N | N | Y | U | Y |

| McGrath et al. 2019 | N | N | Y | Y | U | N |

| Travers 1999 | Y | Y | Y | Y | U | N |

| Wager et al. 2010 | U | N | N | Y | U | Y |

| Wong et al. 2017 | U | N | Y | Y | U | Y |

| Zeitz 2005 | U | N | N | Y | U | Y |

| Zeitz et al. 2006 | U | N | N | Y | U | Y |

| Adomat and Hicks 2003 | N | N | Y | N | U | N |

| Erb and Coble 1989 | N | N | N | Y | U | N |

| Fuller et al. 2018 | N | N | N | Y | U | N |

| Hendrich et al. 2008 | Y | Y | Y | N | U | N |

| Hoi et al. 2010 | Y | Y | Y | N | U | N |

| Yeung et al. 2012 | U | Y | Y | Y | U | Y |

Design of studies

Five publications were described as before-and-after studies,32,105–108 mostly evaluating the impact of introducing automatic electronic vital signs systems or continuous vital signs monitoring. Ten studies were classified as descriptive observational,56,109–116 and one study was a pilot study of a bedside clinical-information system. 117

Most (n = 11) used time-and-motion methodologies. 32,56,106,108,109,111,112,114–116,118 In eight studies, researchers collected data by directly observing nursing staff. 32,56,108,112,114–116,118 One study used data from a video recording of 48 continuous shifts. 109 Another plotted the number of steps that nurses took from the bedside to the computer when documenting vital signs in addition to measuring the time taken to complete and record vital signs observations using time-and-motion methodology. 106 In three studies, nurses were asked to estimate the time they had taken to complete vital signs observations. 107,110,111 In one of these studies, nurses noted the time taken to complete vital signs for each patient and calculated the total time spent on this activity. 107 In one time-sampling study, nurses were asked to report the activity they were engaged in when a personal digital assistant they were carrying vibrated at random times during the shift. 111 As indicated in Table 1, seven studies did not provide a clear description of how time to complete a set of vital signs was assessed; among these, three studies did not give any meaningful detail about how the time to complete a set of vital sign observations had been collected. 105,113,117 Among these, one study was available as abstract only. 113

Setting of studies

Coverage of settings ranged from 1 to 36 hospital wards of various types, namely: acute surgical/medical general wards, ICU, an emergency department, a cardiovascular unit, a trauma ward and a radiology unit. One study did not specify the type of hospital or which wards were included. 113

Methods of vital signs measurement

The 16 studies generally described taking vital signs observations as the time to measure/collect vital signs and the time to record/document vital signs. However, the specific set of vital signs chosen for measurement differed by study, which inevitably affected the overall time taken. Some included seven different physiological signs in a complete vital-sign set,32 while others included only four. 113 All studies reporting physiological signs measured temperature, heart rate (HR), RR and BP. 32,56,105,106,108,114–118 Some studies offered no specific description of the vital signs collected. 107,109,111,112 Also, studies did not always specify whether only complete sets of vital signs had been included for analysis. A number of studies included additional observational and assessment activities in the time taken to complete vital signs, such as completing fluid balance charts, checking an infusion pump and weighing the patient. 105,117 The measurement tools did not vary substantially across the years.

Methods of time recording

In general, the time involved in vital signs recording and documenting was reported in two different ways. A number of studies reported a mean time for taking a vital-sign set, mean time to record vital signs on charts or both. 32,56,105,107,108,110,113,114,116,118 Other studies reported the amount of time that nursing staff spent taking vital signs and/or recording them over a shift, per hour, per patient or over an amount of time (e.g. over 44.5 hours). 106,109,111,112,115,117 None attempted to disentangle the time taken to collect or document each vital sign (i.e. BP or oxygen saturations or RR) or EWS value separately.

Studies reporting mean times

Ten studies provided a total of 12 samples to estimate mean times for taking and/or recording vital signs (Table 2).

| Study | Mean (minutes) | Standard deviation | Vital signs included | Vital signs activities assessed |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Studies involving taking and documenting vital signs | ||||

| Bellomo et al. 2012 | 4.10 | 1.3 | Temperature, HR, RR, BP, oxygen saturations, consciousness, urine output | Measure vital signs and document them with paper |

| Bellomo et al. 2012 | 2.50 | 0.5 | Temperature, HR, RR, BP, oxygen saturations, consciousness, urine output | Measure vital signs and document them electronically at bedside |

| Clarke 2006 | 5.80 | 3.72 | Cardiovascular, respiratory, body temperature data | Measure vital signs and document them with paper |

| McGrath et al. 2019 | 2.15 | Not reported | Temperature, HR, RR, BP, oxygen saturations | Continuous monitoring (multiple monitors) and document vital signs electronically at bedside |

| McGrath et al. 2019 | 2.98 | Not reported | Temperature, HR, RR, BP, oxygen saturations | Continuous monitoring (single monitor) and document vital signs electronically outside bed space |

| Travers 1999 | 4 | Not reported | BP, pulse, RR, tympanic temperature | Measure vital signs observations |

| Wong et al. 2017 | 3.58 | 8.9a | Temperature, HR, RR, BP, oxygen saturations, oxygen therapy, consciousness | Measure vital signs and document them with paper |

| Wong et al. 2017 | 2.50 | 0.74a | Temperature, HR, RR, BP, oxygen saturations, oxygen therapy, consciousness | Measure vital signs and document them electronically at bedside |

| Zeitz 2005 | 5.80 | 2.56 | Temperature, HR, RR, BP | Measure vital signs and document them with paper |

| Zeitz et al. 2006 | 5.80 | 2.56 | Temperature, HR, RR, BP | Measure vital signs and document them with paper |

| Studies reporting documentation only | ||||

| Ito et al. 1997 | 0.90 | Not reported | Not specified | Document vital signs electronically at bedside using RFID from continuous monitor |

| Ito et al. 1997 | 2.02 | Not reported | Not specified | Document vital signs electronically outside bed space |

| Kimura et al. 2016 | 1.27 | 0.55 | Body temperature, oxygen saturations, HR, BP | Document vital signs electronically at bedside with hand-held device |

| Kimura et al. 2016 | 1.47 | 0.62 | Body temperature, oxygen saturations, HR, BP | Document vital signs electronically outside bed space |

| Wager et al. 2010 | 1.24 | 2.17 | BP, temperature, HR, SpO2, RR | Mean time difference between the time vital signs were taken and when the data were recorded on paper in the patient’s record (paper to paper) |

| Wager et al. 2010 | 9.15 | 7.25 | BP, temperature, HR, SpO2, RR | Mean time difference between the time vital signs were taken on paper and when the data were recorded on a computer on wheels |

| Wager et al. 2010 | 0.59 | 1.42 | BP, temperature, HR, SpO2, RR | Mean time difference between the time vital signs were taken on a vital-sign monitor and when the data were recorded on PC tablet |

When studies investigated the time involved in measuring and documenting vital signs using pen-and-paper methods, mean times ranged from 3.58 minutes32 to 5.80 minutes. 56,116 When documentation was performed using electronic systems, mean times for measurement and documentation were lower, at 2.50 minutes in both studies. 32,105 We did not find any differences in mean times involved in vital signs measuring and documenting that could be attributed to different clinical settings, nor to different nursing personnel (i.e. RNs vs. nurse assistants). Differences in mean times appeared to be related to the combination of vital signs included within the recorded data set; the method(s) of vital signs measurement; the timing of entry into the patient record; the method of recording; the calculation of EWS values. In addition to mean times being variable between studies, it was clear that there was considerable variation in the time taken within some studies, as standard deviations were high.

All studies where reported times focused only on vital signs documentation involved continuous patient monitoring and focused on electronic systems of data transfer to the patient record. Electronic systems where vital signs were entered at the bedside seemed to be associated with reduced time. The mean times to document vital signs observations electronically at the bedside ranged from 0.90107 to 1.27 minutes,113 and the mean time for documenting vital signs outside the bed space was between 1.47 minutes113 and 2.02 minutes. 107 One study focused on the mean time difference between the time vital signs were taken and when the data were recorded in the patient’s record, and found that when staff were recording data on a vital signs monitor at the bedside and transferring them to a PC tablet the mean difference was 0.59 minutes; when vital signs observations were transcribed from handwritten notes to patient notes the mean difference was 1.24 minutes; and for handwritten observations to be transferred to a computer on wheels outside the bed space, the latency time was 9.15 minutes. 114

Studies which do not provide mean time estimates

Four studies reported the time involved in collecting and recording vital signs by hour or by nursing shift. 109,111,112,115 Hoi et al. found it took 144 minutes of total nursing time per day for a patient in the most highly acute and dependent category, where assistance with all care needs and multiple treatments were often required. 112 Adomat and Hicks showed that charting observations and record-keeping in two units ranged from a mean average of 5.44 to 10.78 minutes per hour in an HDU and from 10.66 to 17.43 min/hour in ICU. 109 Hendrich et al. showed that vital signs took up 7.2% of nursing time or 30.9 minutes in a 10-hour shift. 111 According to Yeung et al., the total time spent by each nurse performing vital signs observations was on average 12 minutes, albeit the unit of observation was not reported (i.e. per hour, per shift or per patient). 115

Erb and Coble reported vital signs documentation on a new automated system, where nurses record all vital signs at the bedside using a monitor that measures BP, pulse rate and temperature. 117 Vital signs data are stored on a computer at the nurse station unit, and the bedside unit and nurse station unit are connected directly. The authors compared this system to an older manual system, and found that it offered an overall mean time saving per nurse per shift of 11.86 minutes. 117 Fuller et al. reported that the time taken to document vital signs in a computer was 7 minutes per 10 patients,106 suggesting a mean time below that of any study reporting a per patient time.

Discussion

This is the first systematic review of evidence to identify the amount of nursing time required to take vital signs observations. We found 16 studies that evaluated the time taken by nursing staff to perform and/or record vital signs observations. Studies varied considerably in their time estimates, although most estimates demonstrate the potential for this activity to occupy a considerable amount of nursing time, especially if undertaken with high frequency. However, this variation and uncertainty in the evidence means that we were unable to give a reliable estimate of time taken. A variety of factors influence the times taken to complete vital signs observations and, while the studies illustrate these factors, they are inconsistently and incompletely recorded in the literature, making direct comparisons of their influence on total times difficult or impossible.

We identified a number of key variables related to overall times recorded in the studies:

-

the combination of vital signs included within the recorded data set;

-

the method(s) of vital signs measurement;

-

the timing of entry into the patient record;

-

the method of recording;

-

the calculation of EWS values.

Across studies, there was variation in the data set of vital signs measured each time, as these are often determined by local guidance. There was also variation in the methods of measurement of vital signs observations. Some vital signs (e.g. HR and respiratory rate) can be measured manually (i.e. without the use of equipment) or automatically using devices/monitors. Some parameters (e.g. consciousness level) can only be measured on general wards using manual techniques, while others (e.g. SpO2) can only be measured using an electronic monitor. Studies considered in this review either involved a mixture of manual and automatic methods of measuring vital signs or did not clearly report them. 107,109,111,112

A further source of variation seen in the papers described in this review was the timing of entry of measured vital signs data into charting systems. Nursing staff entered data either in real time at the patient’s bedside105–108,117 or after leaving the bedside (i.e. delayed). 32,114,115 In some studies, vital signs data were entered in real time at the bedside on paper charts, and in others they were manually entered on electronic or paper medical records after collection. However, in the papers reviewed here, when data were recorded at the bedside, it was mostly done using hand-held electronic devices, where data were either uploaded automatically or required the nurse to physically transfer data to a central database using a wired system. Results from studies where real-time electronic systems had been introduced showed a reduction in the time involved in vital signs monitoring and recording compared to traditional paper-based methods, especially if the latter required further transcribing at the end of the observation sessions.

In the papers we studied, there was little indication of the approach to the calculation of EWS values even though determination of risk based on vital signs is now seen as an important function of taking the observations. 4 It would be possible for these to be calculated manually (i.e. without using a device), using a device such as a calculator, within a free-standing, mobile app, or automatically using a hand-held device or as part of the data measurement/entry system. In this review, two studies reported that the electronic systems being piloted were designed to calculate EWS values automatically after the entry of vital signs data. 32,105 In both studies, the EWS values were displayed on the electronic systems alongside clinical advice (e.g. escalation to a doctor or RRT) based on the automatically calculated EWS value. Previous studies reported that calculation of EWS with hand-held devices improves accuracy of EWS values119 and saves nursing time, with one study reporting that using a programmed digital assistant (i.e. VitalPAC™) was on average 1.6 times faster than using the traditional pen and paper method. 120

The workload involved in vital signs activities for nursing staff is potentially significant56,110,116 with important clinical consequences. However, we have shown that there is a very limited body of research that might inform workload planning. The studies surveyed here also highlight that there is currently no standardised way of measuring vital signs workload or interpreting it. Several publications affirm that failure to engage with vital signs activity leads to adverse patient outcomes, including mortality. 90,121,122 Nursing staff have previously reported that workload is an important factor in the timeliness and ability to observe patients regularly,74,123 so that the absence of reliable evidence to determine the workload involved with vital signs observations is surprising. This is of particular importance, especially as vital signs monitoring and recording is regarded as a fundamental component of nursing care. Clinical guidelines recommending the frequency of vital signs observations do not take into account the time required to complete them. 2,20

If nursing staff perceive the vital signs workload as excessive, they may choose to prioritise other activities and follow their clinical judgement rather than an observation schedule dictated by a protocol124 At present, there is no evidence to determine whether the nursing workforce is sufficient to accommodate existing demand – or potentially an increase in demand – arising from increasing compliance with current observation protocols, or from changing such protocols because the demand is not clearly quantified. Based on the current literature we cannot yet tell whether observations for all patients in a 30-bed unit might require an hour of work (2 minutes per patient) or two and a half hours (5 minutes per patient) or indeed considerably more or less if these estimates are inaccurate, or suboptimal systems are in place.

The investigation of time and workload involved in taking vital signs observations activities has focused mainly on reporting average times. However, mean times varied substantially due to different physiological parameters being measured across studies and, where reported, different methods of measurement and vital signs documenting. Future research that can determine the workload associated with nurses’ activities around vital signs observations is warranted. Future studies should be more explicit in describing contexts and systems in use. In particular, for new electronic systems, it would be worthwhile establishing how accessible it is for nursing staff to observe vital signs observation trends of their patients and how accessible these systems are for temporary staff.

Limitations

In appraising studies, we applied a checklist based on the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal checklist for descriptive/case series,104 and all studies were of low quality. We highlighted key omissions of important details, for example which vital signs were included and how they were measured and recorded, or how nurses and/or patients were sampled. The results of the review illustrate the variety of factors that may influence the time estimates derived from the studies and demonstrate where information is missing. While we used a reproducible search strategy searching MEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE and the Cochrane Library, it is possible that we did not identify studies indexed elsewhere and not cited by the included studies. It seems unlikely that these exist in sufficient quantity to substantively change our conclusions.

Conclusions

There is currently insufficient robust evidence around the time nurses require to perform vital signs activities. To increase consistency and impact, we propose a framework for future studies to adopt measuring the time and workload involved in vital signs observations that includes (1) the methods of measurements, (2) the timing of entry of measured data into the charting system and (3) the approach to calculation of EWS values. This categorisation would be suitable for vital signs measured on an individual patient basis, or on the basis of vital signs ‘rounds’, where the mean time for each patient on the round could be calculated.

Recommendations for vital signs observations need to consider the workload involved and include consideration of the potential opportunity costs if observations are given higher priority at the expense of other aspects of nursing work. Vital signs observations are considered to be a fundamental aspect of nursing work and key to ensure early detection of patient deterioration. The lack of robust evidence means that those making clinical and managerial decisions about resource allocations, including workload planning around vital signs observations, must make these in the face of considerable uncertainty. Uncertainty means that the workload associated with changes to the frequency of observations associated with EWSs is unknown. At a system level, the costs from changes in policy such as the shift from NEWS to NEWS2, which increased the frequency of observations for some patient groups, are unquantifiable. On a ward level, the feasibility of implementing such changes and integrating them into existing work is uncertain. On another hand, workload reductions associated with the introduction of technology that facilitates continuous monitoring, which might reduce requirement for nurses to take vital signs observations, are equally uncertain. Measuring patients’ vital signs at times that are appropriate is key to avoiding patient deterioration and adverse outcomes. In the interest of patient safety, further research that uses vital signs and patient objective data aiming to define the optimal frequency of vital signs observations should be conducted.

Chapter 3 Methods: prospective observational study

Adapted with permission from Dall’ora C, Griffiths P, Hope J, Briggs J, Jones J, Gerry S, Redfern OC. How long do nursing staff take to measure and record patients’ vital signs observations in hospital? A time-and-motion study. Int J Nurs Stud 2021;118:103921. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103921125

Study setting

The observational ‘time and motion’ study aimed to provide reliable estimates of the nursing work involved in measuring vital signs and to identify factors influencing the time involved with measuring and recording vital signs. It was undertaken in 16 adult general wards at 4 acute general NHS hospitals in four trusts. The sample of hospitals was largely one of convenience informed by geographical location in the Southeast/South Central Region, but we sought variation in the approach to recording vital signs observations when we approached potential participants beyond the two sites participating in the rest of the study.

Sample and recruitment

All hospitals used NEWS2 to guide the frequency at which patients are observed. Three hospitals used electronic systems to record vital signs. These electronic systems differed in each hospital, but they shared the embedded algorithm to calculate NEWS2 scores. In one hospital, vital signs were recorded on paper charts at the patient’s bedside and the NEWS2 was calculated manually.

Eligible wards were those classified as adult general (medical/surgical) wards. As there is no generally accepted precise definition of this, we asked participating trusts to identify wards against the following criteria:

-

Adult (18+) patients. Wards that occasionally admit adolescents of younger age would remain eligible provided this was not a common occurrence.

-

Open at weekends with most patients experiencing overnight stays of 1 day or more.

-

Ward provides Levels of Care 0, or 0 and 1.

[Note: Level 0 care: patients whose needs can be met through normal ward care in an acute hospital and patients at risk of their condition deteriorating. Level 1 care: patients recently relocated from higher levels of care, whose needs can be met on an acute ward with additional advice and support from the critical care team. Levels of care above 1 (levels 2 and 3) are delivered for the most part in specified critical care areas. The majority of patients receiving care above level 1 will require support for one or more major organ systems. 126]

Exclusions:

-

wards which routinely cater for large numbers of younger people (< 18);

-

wards in which a significant proportion of patients require protective isolation;

-

wards that are intended to exclusively provide Level 1+ care;

-

wards where the risk of acute deterioration is low or where the primary reason for continued hospital stay is not medical/surgical treatment/recovery (e.g. rehabilitation units, other post-acute wards);

-

wards where full vital signs measurements are not routinely taken;

-

small wards.

We then randomly selected four wards in each hospital. If a ward manager did not agree to participate, we randomly selected another ward. In each ward, the ward manager provided consent for the research on behalf of the ward staff, and we sought to recruit all nursing staff [i.e. RNs, healthcare assistants (HCAs), nursing associates, student nurses] working on the ward at the time of each observation session. Staff were given the chance to opt out of the research when the observation session began and when approached during the session. Their consent to participate was implicit – we chose not to record it in writing because that would have imposed additional workload on the staff concerned. Patients and relatives were informed about the study through posters displayed on the ward and through explanation given by the researchers and/or nursing staff when patients were having their vital signs monitored. We explained to patients that they were not the focus of our studies and that we were observing nursing staff only, and gave them the option to opt out in case they did not want to have researchers near their bed space, which only occurred twice. These procedures were reviewed and approved by the relevant ethics committees (NHS REC and University of Southampton).

There were few existing data to help calculate the required sample size and estimation was further complicated by clustering of observations in nurses and units. As a guide, we used the confidence intervals reported by Wong and colleagues,32 a study with a similar clustering structure to our planned study, to provide an estimate. Based on their 95% confidence intervals, we inferred a standard error of 10.96 [standard error = 95% CI/(2*1.96)]. Based on their standard error, in a sample of 280 observations from wards with electronic recording of vital signs, we calculated that a sample of 640 sets of observations would give an estimated mean with a precision of ± < 10% if each set of observations took 3 minutes. For each ward, we planned to observe for a total of 8 hours, spread across four sessions, aiming to observe a minimum of 10 sets of vital signs measurements per session.

Data collection

Data were collected by trained non-participating observers using the Quality of Interactions (QI) tool, bespoke software on an Android tablet that enables users to enter data in real time. The QI tool also enabled us to collect contextual data, including the total number of patients on the ward, and numbers of RNs, nursing assistants and student nurses on shift during the observation session as well as qualitative observations on factors influencing the measurement and recording of vital signs, including reasons for, and the nature of, interruptions. In order to achieve the required sample size sessions were scheduled at times ward staff reported that we could expect to see a lot of vital signs activity. At the end of each 2-hour session, researchers also asked staff whether they had modified their practice as a result of being observed. The general approach to observation and the tool have been used previously. 127 We adapted the approach to focus specifically on activities related to taking vital signs and associated interruptions.

The vital signs-related activities recorded during observations are reported in Appendix 6. Observers recorded start and finish times for vital signs rounds, individual vital signs measurements and interruptions. We were interested in the preparation time occurring at the beginning of the observations round, as this is work associated with vital signs, and we wanted to take interruptions into account if they contained any vital signs-related activity. A vital signs round was deemed to start every time nursing staff sourced vital signs equipment or vital signs documentation, and to finish when one or more sets of vital signs observations were taken and the vital signs equipment and/or documentation were replaced. A vital signs observation set was deemed to start when a nurse entered the bed space and measured one or more of the six physiological parameters of the NEWS2 scoring system, and to end when the nurse left the bed space and the measuring of vital signs as defined by NEWS2 had finished.

Observers were trained using an observation guide. The guide was found to be easy to use and led to a high level of inter-rater agreement, with a mean difference between raters of only 3 seconds per set of vital signs observation (mean observation estimate 3 minutes 47 seconds) and limits of agreement from + 19 to −13 seconds. The cumulative difference over 4 hours of observation during the training sessions was less than 2% of the total time observed. See Dall’ora et al. 128 for more detail on the development of the standardised approach, observer training and reliability testing.

Data management

After each observation session, data were uploaded onto the QI tool server. This server and the associated databases were located at, and managed by the IT team of, the raters’ institution. We did not store any personal data. Before data analysis, one member of the team checked all data extracts for any errors: for example, if an observer had indicated that the timing of an interaction was incorrect (e.g. where there had been an inadvertent delay in recording the end of the observation). These instances were rare (n = 37) and were corrected, and all interruptions were coded as vital-sign-related or not vital signs related.

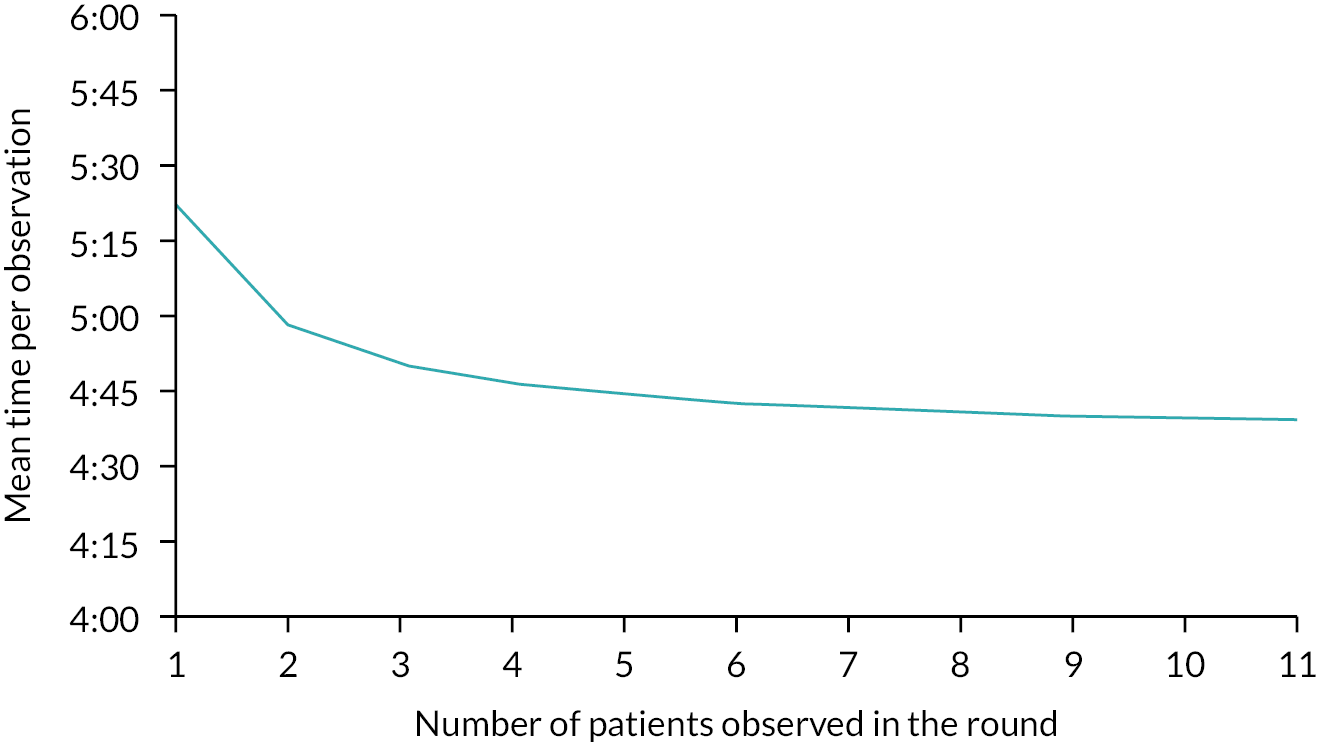

Statistical analysis

Our data comprised sets of vital sign observations within observation rounds. As well as the time taken to measure and record vital signs, each round included preparation time and interruptions. For this reason, we estimated the time taken to perform a set of vital sign observations in three ways:

-

Our first estimate (E1) was calculated by dividing the length of the round by the number of vital signs observation sets.

-

Our second estimate (E2) was the time taken at the patient’s bedside, between when the nurse entered and left the bed space.

-

Variants of the E1 and E2 estimates were calculated by removing time associated with some or all interruptions (e.g. non-vital signs related such as discussions with relatives).