Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number NIHR128268. The contractual start date was in June 2020. The draft manuscript began editorial review in February 2023 and was accepted for publication in July 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Abel et al. This work was produced by Abel et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Abel et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and rationale

The move to online primary health care services

The National Health Service (NHS) is under pressure due to the increasing demands of a growing and ageing population, technological progress and changing expectations among the public. Successive governments have viewed technology as part of a solution in addressing the pressures facing primary care, and policy for delivery of general practice has reflected this thinking. 1

Recent years have seen a push towards the adoption of online services in primary care, ranging from booking appointments and ordering repeat prescriptions through to the use of alternatives to face-to-face consultation with a patient (e.g. e-mail, video). By 2022, the reach of such services had extended to 22 million users. 2 Current NHS policy in England emphasises use of digital services in primary health care, and to date 28 million people have downloaded the NHS app, and 40 million people have acquired an NHS login. 2 Drivers behind the move to online primary care provision include the assumption that online services lead to improved choice, convenience, and ease of access for users, improved triage systems and streamlining of service delivery. 3

Context of this research: the COVID pandemic

In March 2020, the UK recognised the global health emergency of a pandemic associated with rapidly spreading COVID virus. In the UK, COVID led to widespread changes in society and within the healthcare system. From the perspective of this research, some relevant policy initiatives4 are summarised in Box 1. Overall, the pandemic was associated with increasing and substantial pressure for many staff in primary care, and for primary care within the healthcare system. The British Medical Association has estimated that numbers of full-time equivalent general practitioners (GPs) fell by nearly 6% between 2015 and 2021. 5 Moreover, the telephone first consultation, which was available pre-pandemic and widely adopted during the COVID pandemic, initially generated a 33% increase in the mean number of GP contacts per patient per 28 days,6 and during the pandemic increased telephone consultations from 39% to 51%. 7

-

Introduction of COVID alert status.

-

Travel restrictions and various public health measures (e.g. social distancing, advice on personal hygiene) 25 February 2020.

-

Introduction of national lockdown on 23 March 2020.

-

Initial restrictions to online booking of appointments 23 March 2020, and associated with a rapid reduction in the number of GP face-to-face appointments from 15.9 million per month (March 2020) to 7.5 million (April 2020). 8

-

Rapid introduction and procurement of telephone, web-based and video technologies and consulting platforms in primary care. Detailed guidance and updates were produced for primary care clinicians and practices, for example, in respect of the implementation of total triage systems aimed at managing and reducing total footfall in primary care facilities. 9 Around three-fifths of UK adults who used the NHS during the early phase of the pandemic said that in doing so they used technology either in a new way or more than before. 10

-

Widespread use of apps and devices to facilitate home-working by NHS staff. 10

-

Escalation in remote linkages between practices and pharmacy suppliers.

-

Widespread promotion of the NHS app.

-

Introduction of large-scale vaccination programme (8 December 2020) utilising many health resources, including GP facilities and personnel, and primary care resources.

General practice settings moved to using remote methods of consultation to enable safe delivery of care. The shift was dramatic, with a rapid change to 90% remote GP consulting (46% for nurses) by April 2020. 11 The researchers in that study noted a universal consensus that remote consulting was necessary. Telephone consulting was sufficient for many patient problems, video consulting was used more rarely, and appeared less essential as lockdown eased. Short message service (SMS)-messaging increased more than threefold. 11,12

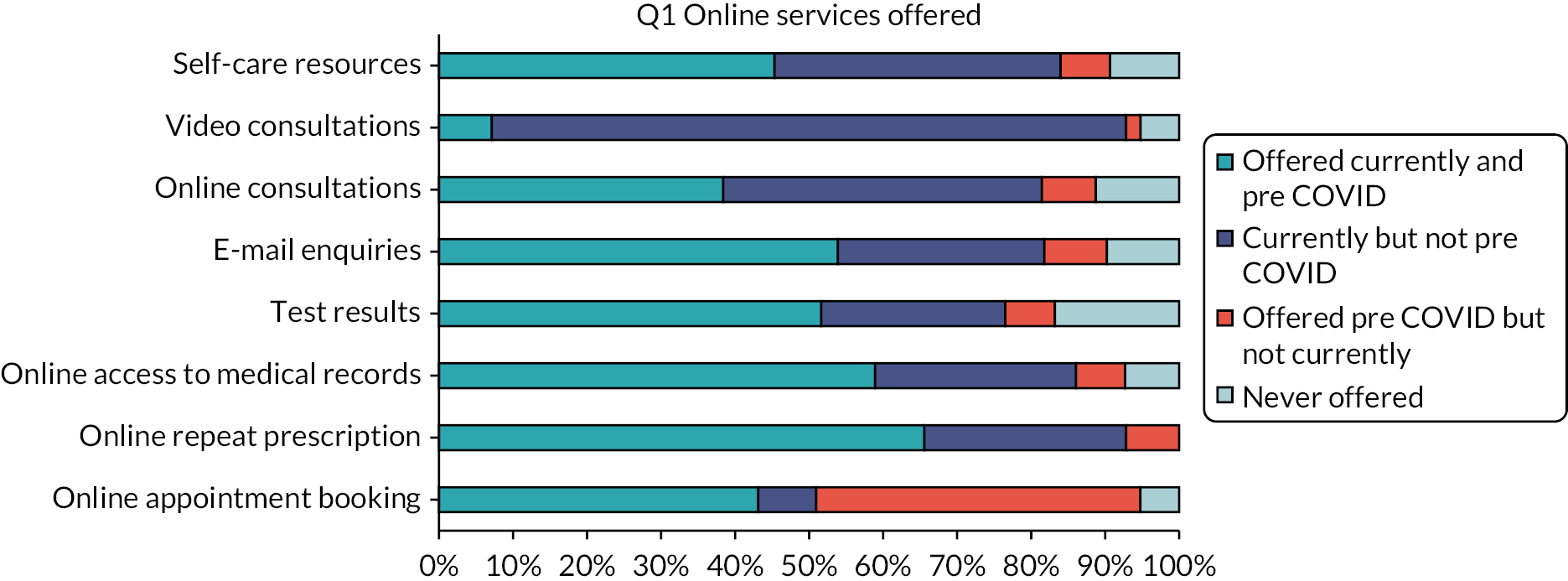

Figures from 2022 for use of technology and online primary care services show an increasing use of NHS online services13 (increased from 44% of respondents reporting that they had ‘recently used’ such services, to 55% in the year to July 2022) – covering areas such as ordering repeat prescriptions online (26–31%), having an online consultation or appointment (18–22%), booking appointments online (19–21%) or accessing personal health records (7–17%). Geographical variation across England is evident in the application of online general practice services (GP services) by integrated care systems (ICS), with usage ranging from 46% of patients using an online GP service in the past 12 months to a maximum of 70% across 42 systems. Increases were evident in the proportion of patients reporting use of their GP practice’s website (from 36% in 2018 to 60% in 2022) with around 66% of respondents reporting the practice’s website being ‘easy to use’ in 2022.

Prior to the pandemic, research studies had established that for patients a face-to-face consultation is seen as the ‘gold standard’ and was the most used type of consultation. 13 The rapid change occurring in general practice means that digital services are now more widely available to all patients, and they may be expected to use them, regardless of digital confidence, proficiency and ease of access to the required technology and connectivity. For some patients, this change in patterns of access has been beneficial, for others it has been more challenging. 14

Moving to online provision – impacts and sequelae

The introduction of digital services and the move to a digital-first health service envisaged at the time this research was commissioned, raises important questions about digital access in the population. The research reported here has taken place in a changing policy environment – from the early days of a ‘digital-first’ vision for access to primary care services, through the ‘total triage’ model encouraged by NHS England during the COVID-19 pandemic to reduce footfall in general practices and to protect staff and patients, and, more recently, to a refined and nuanced vision of GP access, encompassing a range of modes of access, responding to the needs and ambitions of the NHS and of local patients and populations. In order for GP practices and patients to gain the potential benefits that technological innovation can bring to primary care,15 patients must be able to, and wish to, access and use online services. Digital inequalities tend to adversely affect certain groups of people. In this context, individuals from older age groups, non-white ethnicities, those in lower socioeconomic groups, those in poorer health and individuals in rural settings are recognised as vulnerable groups who may struggle to access digital services. 16–19 As online delivery of primary care is a key priority for policy-makers,2,20–23 it is important to understand how barriers to uptake might be overcome and inequality avoided. In attempting to mitigate the potential for digital inequalities, the research literature suggests that meaningfully involving users, tailoring services and interventions to target groups’ contexts, delivering credible messages and having a clear understanding of how services using technology improve health are key elements in developing relevant interventions. 24 One way to combat these potential inequalities is via digital facilitation (DF) – actively supporting patients and carers in using practice-based online services.

Value of online services

Financial investment in online health services is enormous. In the USA, for example, digital health doubled between 2019 and 2020, being seen as a ‘quarter trillion dollar opportunity’, and investment in online and digital health being described as ‘skyrocketing’ in recent years. 25 The number of health apps available globally is rapidly increasing, and was estimated at around 318,000 by 2017. 26 Such substantial investment and development activity highlights the need to estimate the value of such services to the population being served – does the investment yield significant returns in terms of health and well-being or patient experience of care, and is it cost-effective?

These are reasonable questions to ask, but challenging questions to answer. UK investment in online healthcare provision is comparable to that from other advanced economies, all of whom have moved to increasing online provision of health services; in 2021 it was estimated that around US$40 billion was invested in digital health globally with around US$5 billion being invested in Europe/Switzerland, and a further US$4 billion being invested in the UK alone. 27 Capital investments within this sector support a variety of facilities and provision. These range from providing core infrastructure through to developing support for accessing services, and the development and delivery of necessary software to support online delivery of care to whole populations, or to those with specific health needs28,29 – such as the development of applications to provide support and care to people living with mental health conditions. 29

At a national level the NHS in England has described a range of sequelae associated with increasing digital health provision – seen as important for the NHS in its ability to achieve strategic health and social care priorities, and with potential benefits for patients and carers, and the wider healthcare system (Box 2). 30 Specifically, the introduction of a major NHS-funded programme aimed at widening digital healthcare participation amongst individuals with low digital health literacy was associated with substantial increases (59%) in confidence regarding use of online health information, substantial reductions (52%) in a sense of loneliness or isolation, a 21% reduction in visits to the GP for minor ailments, increased use (by around 20%) in booking GP appointments online and in ordering prescriptions online, and an apparent substantial saving in time through carrying out health transactions online. 31 A recent evaluation of that programme estimated a return on investment of £6.40 for every £1.00 spent by the NHS on digital inclusion support. 30 Earlier research32 calculated the social return on investment of digital inclusion for individuals and for workers. For individuals, getting online for general purposes was estimated to be worth £1064 a year due to increased confidence, less social isolation, financial savings and opportunities in employment and leisure. For workers, getting online was estimated to be worth £3568 a year due to opportunities for remote working and increased earnings opportunities. In England, digital transformation of health and social care services is seen as a top priority for the Department of Health and Social Care and National Health Service England (NHSE) with estimates of many billion GBP investment – for example, the anticipation of £2 billion of funding (against a commissioning budget of £153 billion)33 to support electronic patient records to be in all NHS trusts, and additional help for over 500,000 people to use digital tools to manage their long-term health conditions in their own homes. 2 A fully integrated, digitally based health and social care system covering primary and secondary care sectors is seen as the goal to be achieved. The stakes are high to ensure implementation of a nationally co-ordinated plan ensuring that all individuals, including those most vulnerable in society, are given opportunity to benefit from these dramatic and costly changes.

Proposed benefits to patients and carers:

-

improved self-care for minor ailments

-

improved self-management of long-term conditions

-

improved take-up of digital health tools and services

-

time saved through accessing services digitally

-

cost saved through accessing services digitally

-

reduced loneliness and isolation.

Proposed benefits for the health and care system:

-

lower cost of delivering services digitally

-

more appropriate use of services, including primary care and urgent care

-

better patient adherence to medicines and treatments.

a Reused in line with the Open Government Licence for public sector information. 34

Patients: inequality

Although there is a clear drive towards the development, promotion and use of online GP services, the impact for patients and for GP practices remains unclear. There is potential for NHS patients and primary care staff to benefit through reduced administrative burden for staff, better communication between patients and practices, expanded health knowledge for patients and improved access to care services. 35 But there is also the danger that such initiatives create or exacerbate inequalities in access to healthcare information and services. 36

Medically underserved and vulnerable populations are less likely, than other patient groups, to engage with online services. 37 For example, indices of deprivation were one of the strongest determinants of non-use of patient portals among patients with chronic kidney disease attending renal clinics in the UK, with patients from postcode areas with the lowest levels of deprivation being 2.4 times more likely to register for portals than patients from postcodes with the highest level of deprivation in England and Wales, and 3.2 times more likely in Scotland. 38 Underserved and vulnerable population groups span those captured by the PROGRESS Plus39 and NHSE40 criteria and include groups classified as vulnerable due to issues of race, ethnicity, culture or language; occupation; gender/sex; religion; education; socioeconomic status; social capital; age; disability; homelessness or migration status.

Engaging ‘harder to reach’ patients and reluctant users of online services may offer potential to reduce inequality of access, but also to improve patient health and potentially reduce GP and/or other NHS costs. Other sectors of health, commerce and business have developed initiatives to support clients in using online services, for example, Barclays ‘Digital Eagles’, where selected individuals acted as champions to encourage confidence and improve skills in use of digital services. 41

Patients: digital literacy

The concept of digital literacy, first proposed in 1997,42 is highly relevant where the health of individuals and populations and the uptake of online health services are at stake. Rowlands has proposed a definition of digital health literacy as ‘the ability to seek, and understand, and appraise health information from electronic sources and apply the knowledge gained to preventing, addressing or solving a health problem’. 43 Encompassing both technical skills and sociocultural domains, digital health literacy is recognised to vary widely across the population, to be measurable using standard instruments,44 and to be a key driver of the digital divide – the health inequality experienced by ‘populations able to benefit from access to and use of health information and services online and populations unable to take up such opportunities’. 45 Low digital health literacy is associated with low health literacy, and with poorer health outcomes, an effect seen, especially amongst poorer, more vulnerable sections of the population. 44 In planning their scoping review of digital health focused interventions, Hamilton and colleagues helpfully identify the need to address the digital health divide by targeting both the acquisition of necessary skills, especially in vulnerable individuals, and also to target health systems and healthcare practitioners and their need to be responsive to the digital health needs of the individuals and populations they serve. 45 Finally, Kim and Xie44 note that interventions aimed at addressing poor health literacy should not just offer online health services tailored to individual’s health literacy levels, but ‘should include education about how to access online resources for health information and disease management, how to search for information effectively, and how to evaluate the quality of online health information’.

Challenges to staff engagement with online services

The digital competence of healthcare professionals and their acceptance of online service provision are also important for successful implementation of online patient services. Konttila et al. 46 argue that healthcare professionals are more accepting of digital technologies when they perceive the technology as helpful for patients and supportive of the practice’s workflow, but that factors such as a lack of comfort or perceived issues of competence with using the technology can decrease acceptance and uptake. Healthcare professionals were found to be less accepting of digital technologies when they misunderstood the purpose of the technology, or found it difficult or uncomfortable to use, or when it was not seen as part of their principal work. Others47 have identified the potential loss of ‘valuable non-verbal communication’ in remote consultations as a specific concern. Israeli qualitative research48 identified the potential for better quality care resulting from integration of medical expertise – recognising the phenomenon of the patient, empowered with e-knowledge and challenging traditional boundaries of medical care. Konttila and colleagues’46 systematic review also found that healthcare professionals often experienced IT education for themselves as pointless, under-resourced, time-consuming and with poorly understood benefits. However, supportive organisations and managers were found to facilitate support for staff education and acceptance of digital technologies. It thus appears that support for practice staff in using and supporting patients in using digital health technologies is crucial, and must be carried out in a sensitive and constructive manner.

System: inverted investment

Concern has been expressed at the limited investment by healthcare planners and governments in addressing gaps identified around the uptake and use of services and innovations underpinning effective medical care. In system terms, NHS online services may be judged as potentially ‘effective’ and therefore potentially subject to implementation delays and delays in uptake. 49 In addition, the decision to introduce digital care on a widespread scale came before consideration of how that rollout might be achieved. This inverted approach to supporting implementation is exemplified by the introduction of toolkits to support practices delivering online consultations sometime after, and not alongside or before, the relevant policy and funding statements. 50

Challenges to patient engagement with online services

The reasons for the lower engagement of some sections of the population with digital and online health services are complex and include factors that limit access to technologies as well as factors affecting motivations to use the technologies. Specific barriers to engagement with online services for these groups include a lack of experience with using the internet,37,51 lower health literacy37,52 and a lack of trust towards the information being provided through online interfaces. 37,53 Issues relating to ‘usability’ can also impede older users from accessing information through patient portals. For example, when older users lost required access codes after registering on patient portals, they became discouraged in their use of the service. 37 Research in Scotland has identified technical and practical considerations (poor connection, ‘frozen’ images, poor sound quality, slow broadband) in adopting IT innovations,54,55 including amongst rural populations, who may have limited access to good quality broadband services. In research undertaken in homeless populations,56 qualitative research findings have highlighted the importance of addressing practical and technological barriers as well as supporting communication and choice for mode of consultation. In their reviews of the literature, Irizarry et al. 52 and others23 have concluded that the ability of patients to access online health services is strongly influenced by combinations of personal factors such as health literacy, health status, age, ethnicity, education level and whether individuals have caring responsibilities. 57 Likewise, in a systematic review of qualitative studies examining the factors affecting patient recruitment to digital health interventions, O’Connor et al. 58 concluded that greater investment is required to improve computer literacy to ensure that technologies are accessible and affordable. Cognisant of these issues, we have been involved in research examining the unintended consequences of providing some online services in primary care,59,60 and investigating patient use and experience of online booking in general practice.

Supporting the move to online services

For the purposes of this research, our focus is on services accessed via a primary care practice website (e.g. booking appointments, access to records) and via online platforms provided by general practices. From 1 November 2022, patients were due to have online access to new entries in their personal medical records,61 although this initiative has been delayed in implementation at the time of writing.

Digital facilitation

In this research, we address ‘digital facilitation’, a unique term defined as ‘that range of processes, procedures and personnel which seeks to support NHS patients in their uptake and use of online services’. The specific focus of this study relates to those processes, procedures and personnel provided by or on behalf of GP practices to support access by their registered patients, and carers of those patients, to NHS online primary care services. Support in accessing and using services is required at all stages, from supporting registration with practices, downloading and using the NHS app, and supporting patients in navigating NHS online provision and accessing the wide range of health resources and information of relevance to NHS patients.

At the inception of this project we were connected to Lea Valley Health Federation (9 GP practices, 86,000 patients), who took early steps to support patients to use digital services by employing a local digital facilitator officer to support patients’ and staff engagement with their online services. 62 In Lea Valley, implementation was driven by a ‘Primary Care Demand and Capacity Audit’. 63 The appointment of a digital facilitator was undertaken with the ambition of engaging patients and staff who might otherwise not engage, for personal or economic reasons or because they might lack the digital skills, with online GP services. Appointment of such an individual represents one approach to supporting and facilitating patient and user access. There is, however, no existing evidence as to the nature and scope, effectiveness, or cost impact of appointing such an individual. Other routes to achieve those aims, such as using volunteers to provide support or referring patients to community programme, may be of potential value, but the nature and extent of innovative approaches offered by practices are currently unknown.

Although research on the use of DF is relatively limited to date, there is evidence to support its use and its ability to reduce inequalities in access to digital resources amongst ‘harder to reach’ and vulnerable groups. One approach to facilitation identified by O’Connor et al. involved the use of ‘direct engagement’, including ‘consultations with health professionals, employers, personal recommendations from family or friends or being spoken to by research or management staff’. 58 Personal recommendations from family or peers, or the endorsement of digital resources by practice staff were found to increase enrolment in digital health technologies. This is further supported by evidence from systematic reviews which find that patients more generally, including comparatively less well-served populations, are more likely to engage with digital health resources when they have the encouragement of friends or family members. 51,64,65 Evidence also suggests that people with lower education levels and older people require more support than other patient groups in order to use digital health applications. We have not identified any evaluations of such engagement approaches in practice, although we have identified that poor understanding of service provision may be a barrier to service uptake,66 and that staff have expressed concerns regarding adverse workload implications which might ensue. There is also evidence showing that introducing the NHS App was associated with improved digital access during its pilot testing phase with 64% (out of 3192) of users of the App reporting that they had previously not used online services to access GP services. 67 Feedback from practice staff during the pilot testing of the NHS App identified that some practice staff wanted additional training and support in order to effectively communicate with patients about the app.

Other interventions designed to target direct engagement with digital technologies have been identified, for example, the use of staff ‘champions’ for GP online services,68 as well as specific interventions to improve people’s online health literacy. 69 Cowie et al. evaluated the implementation of an online tool providing advice to support self-management and the opportunity to digitally consult with a GP, concluding that the presence of a champion within the practice was a significant factor in ensuring successful integration of the tool. 68 Amongst some patients, who had no previous computer experience, training on computer and internet use, development of effective search skills and interpretation of online information was associated with greater health information seeking and interpretation skills, and with increased self-management.

It is thus important to understand the extent to which digital facilitators or other approaches to DF are being used, how they are being used, what impact they are having on uptake of online services, and how such uptake may be impacting patient health and access to healthcare information and services, GP practices and the wider NHS.

Aims, objectives and study structure

The overarching aims for the research study were to:

-

Identify, characterise and explore the potential benefits and challenges associated with different models of DF currently in use in general practice which are aimed at improving patient access to online services in general practice in England.

-

Use the resulting intelligence to design a framework for future evaluations of the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of such interventions.

-

Explore how patients with mental health conditions experience DF and to gauge their need for this support.

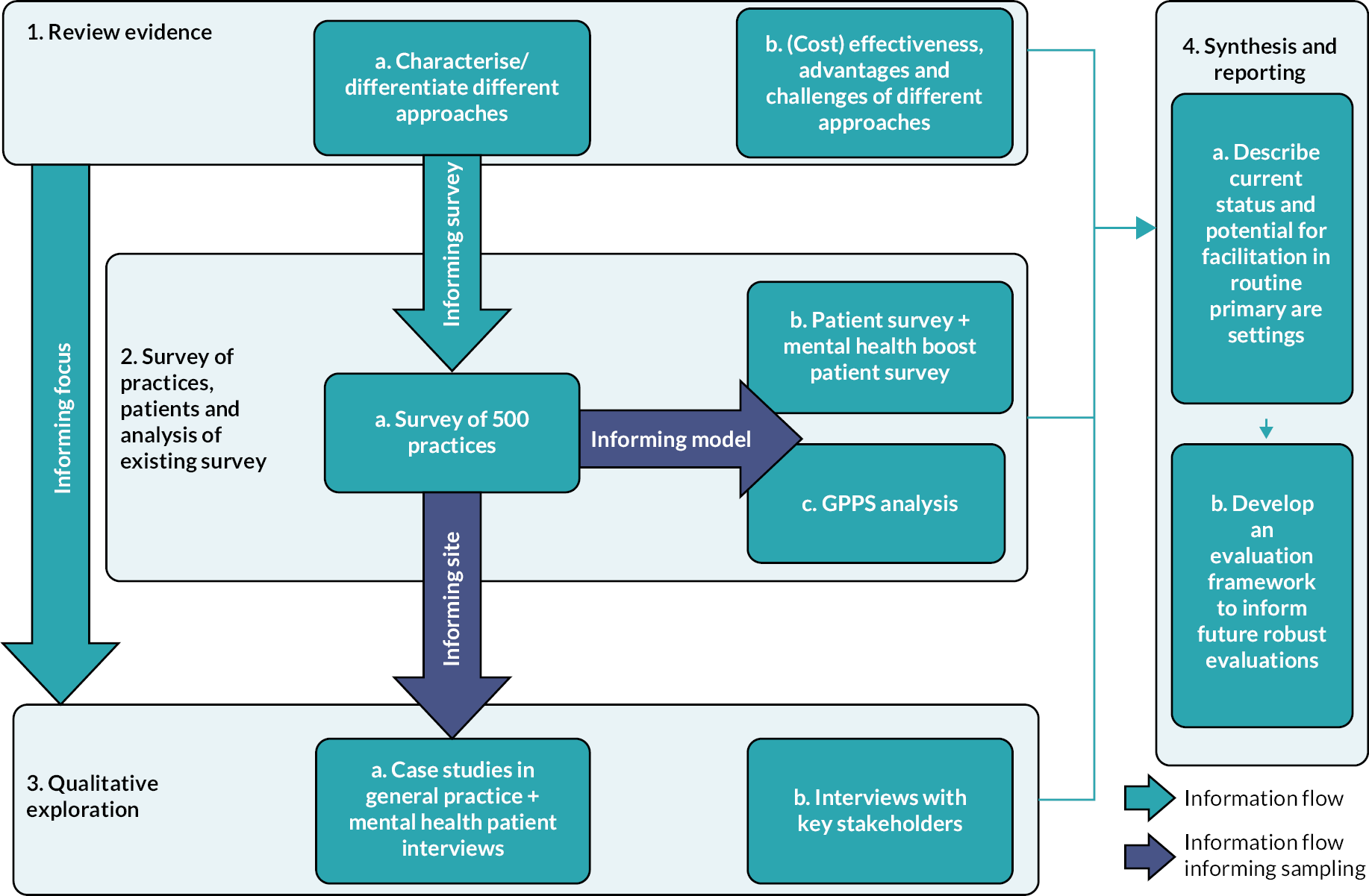

To address these aims, we have conducted a series of interlinked research work packages (WPs) (Figure 1). The objectives of the WPs were to:

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of study showing work stage flow.

-

review published literature to understand and characterise the range, effectiveness and cost effectiveness of models of DF for improving access to online services within health and other sectors, and to develop a typology of DF (WP1)

-

undertake a practice staff survey to investigate the range of DF services currently offered in a sample of English primary care practices and relating this to patient experience of care in those practices as measured by the national General Practice Patient Survey (GPPS) (WP2A)

-

undertake a patient survey to investigate patient views of DF in a sample of English primary care practices and relating this to different modes of DF identified in the practice survey and to explore how patient factors predict awareness and uptake of DF (WP2B)

-

conduct a qualitative exploration seeking to understand in-depth and from the perspective of practice staff, patients and other stakeholders the potential benefits and challenges associated with different models of DF (WP3).

Synthesise learning from these elements and develop a framework for future evaluations of effectiveness and cost effectiveness of models of DF (WP4).

During the course of the project, we successfully responded to a NIHR commissioning brief to apply for further project funding to extend the scope of the project to perform additional work focusing on patients living with mental health conditions. In doing so, a further objective was added to the project:

-

Explore the experiences of patients living with mental health conditions by (1) augmenting our existing patient survey with a boost sample of patients with mental health conditions (added to WP2B) and (2) conducting additional qualitative interviews with patients with mental health conditions (added to WP3). In both cases, findings will be integrated with those from the original patient survey and patient interviews.

Outcome

The ultimate outcome of the project is a summary of the current status of DF as presently implemented within primary care. This includes what is known about the likely effectiveness, cost and equity of access implications of the approaches identified, and an indication of the prevalence of various approaches in four regions of England (East of England and North London; South-West; West Midlands;). We have provided recommendations for future development and implementation of promising approaches to DF, and a framework for future evaluations to assess the effectiveness, cost effectiveness and impact on inequalities of access to the online services, of relevant facilitation approaches within primary care settings.

Theoretical framework

We have used Weiss’s theory-based evaluation as our theoretical framework to understand how, and in what ways, different models of DF bring benefits and challenges to general practice. 70 Weiss distinguishes between ‘programme theory’, which specifies the mechanism of change, and ‘implementation theory’, which describes how the intervention is carried out.

We have done this by drawing on the findings of the evidence synthesis, surveys and case studies to develop the ‘programme theory’ and ‘the implementation theory’.

To develop the ‘programme theory’ we used a realist approach to describe provision of DF. A realist approach asks ‘What works for whom, in what circumstances, in what respects, and how?’71

We explored this in terms of:

-

context (e.g. characteristics of the general practice, the target patient population, the policy framework, and the IT infrastructure)

-

the theory and assumptions underlying the intervention (how and why DF might lead to benefits)

-

the flow of activities that comprise the intervention (the key processes that occur when patients make use of DF)

-

intended benefits/outcomes (those deemed important to patients and practitioners).

The ‘implementation theory’ explored moderating factors which influence the extent to which the process and outcomes were achieved, such as factors acting as barriers and facilitators to practices offering DF or to different groups of patients using them.

Patient and public involvement and engagement

This research is underpinned by recognition that patient and public involvement and engagement (PPIE) is an integral part of research practice. Patients’ voices should be reflected and addressed in the design and delivery of health research in order to ensure that research outputs are meaningful and relevant to them. As a research team we have followed the UK standards framework for public involvement in research including: inclusive opportunities, working together, support and learning, governance, communications and impact. 72

From the outset we have worked with patients to shape the scope and objectives of this research and continued to work collaboratively with patients throughout the research. Patients and carers have been active partners and included at all stages of the research process, including in setting the research agenda and analysing data. 73 The approach to involvement, the impact on the research and reflections on how it worked are included throughout the report.

Chapter 2 Literature review (work package 1)

Sections of this chapter have been reproduced from Leach et al. 74 under licence CC-BY-4.0. 75

Aims of literature review

The aims of this scoping review, conducted in autumn 2020, were to: identify, characterise and differentiate between different approaches to DF in primary care; and establish what is known about their effectiveness and cost effectiveness, perceived advantages and challenges, and how they affect inequalities of access to online services. We also sought early indications of the extent to which the COVID pandemic may be associated with changing approaches to DF. Our particular focus is on DF within general practice in England, but we also consider DF in other geographical areas and sectors where there is clear relevance to primary care.

In the following sections, we describe our review methods and document and discuss our results, including outlining a typology of DF, providing evidence on the efficacy of DF and reporting factors that enable successful DF. We highlight implications of our findings for medically underserved and vulnerable populations, and the potential role of DF in reducing inequalities in access to and use of online services for health purposes.

Methods

We conducted a systematic scoping review of the literature, as the basis for the remainder of the research. We sought to understand the current landscape of DF in primary care. Scoping reviews are appropriate for clarifying conceptual boundaries on topics, such as DF, where a concept is new and poorly defined. 76 By including multiple searches, the scoping review method allows the search strategy to evolve as conceptual boundaries are clarified through screening activities. Our protocol was based on guidelines from the PROSPERO international register of systematic reviews77 and was prospectively registered with that website. 78

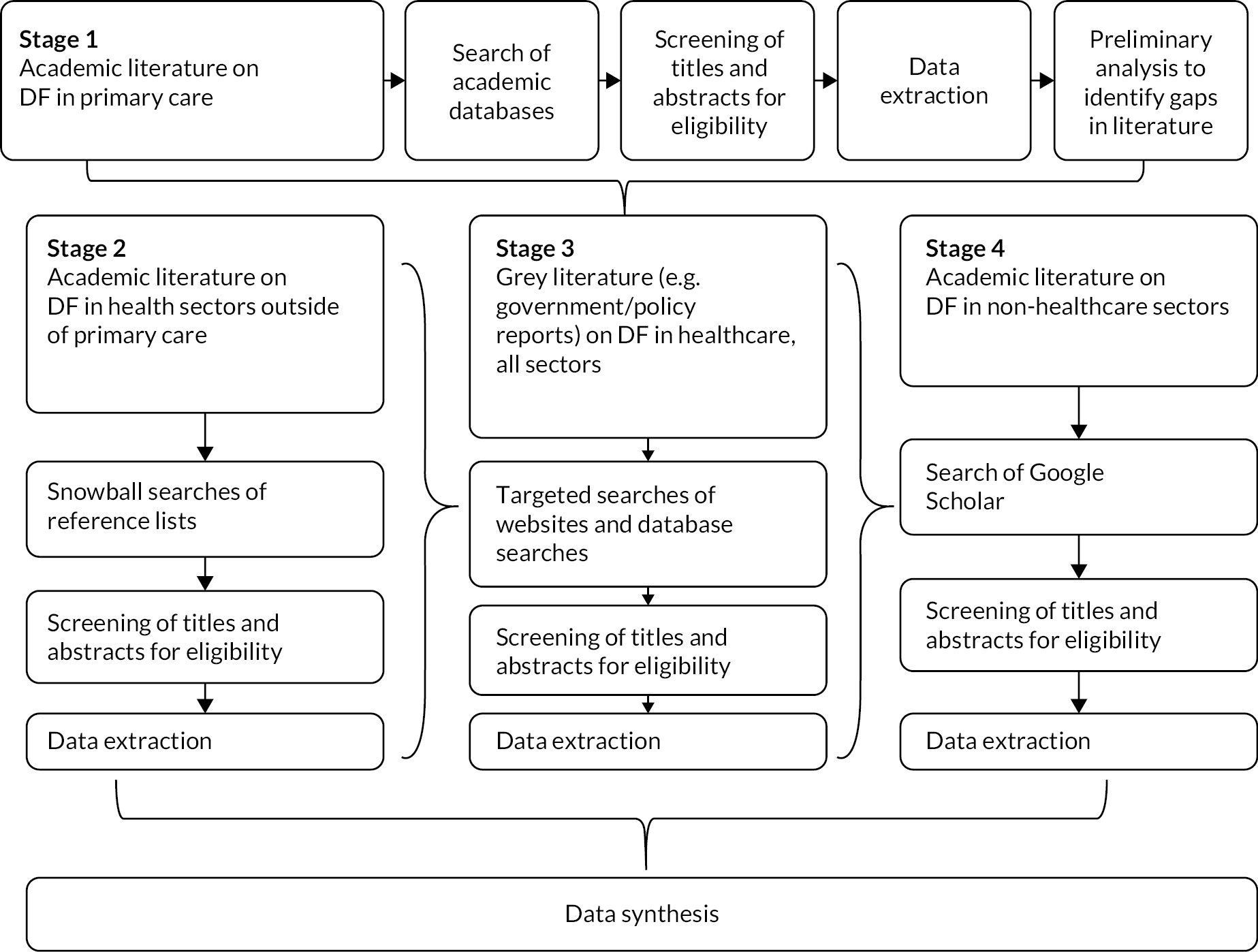

The scoping review was conducted in stages as shown in Figure 2 to allow learning from earlier stages to feed into later stages. 78 All searches were restricted to English-language publications. Details of all stages’ search strings and numbers of results by database are available in Appendix 1, Tables 20–27.

FIGURE 2.

Overview of literature review process. This figure74 was originally published in the Journal of Medical Internet Research (www.jmir.org), 14 July 2022 and licensed under CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). For further details, see Publications.

Searches

Stage 1: academic literature on digital facilitation in primary care

We searched the databases: PubMed, EMBASE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Web of Science and the Cochrane Library (we did not search the Global Health database as specified in our PROSPERO protocol78 because we did not have access to the database except at additional cost). The search strategy focused on three concepts: (1) online services; (2) DF and (3) primary care settings. Members of the Patient Advisory Group (PAG) contributed to the development of the search strategy and operationalisation of key terms, including ‘digital facilitation’. We restricted the searches to European economic area (EEA) and Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) countries as likely to be most relevant to primary care practice in England. We restricted the time period for the Stage 1 search to literature published in 2015 or later (up to June 2020, when the Stage 1 searches were conducted).

Stage 2: snowball searches to identify literature on digital facilitation in health sectors outside of primary care but relevant to primary care

Stage 2 consisted of snowball-type searches whereby we screened the reference lists of articles identified during Stage 1 for non-primary care health sector studies on DF that might nevertheless have relevance for DF in primary care (see Table 1 for eligibility criteria). We first screened the reference lists of studies included for full-text extraction from Stage 1. Next, we screened the reference lists of articles that we identified during Stage 1 as not fitting the inclusion criteria due to article type restrictions (e.g. protocols or editorials) but which were otherwise relevant. We searched for snowballed literature from 2010 onwards, on the grounds that although predating 2015 it was still evidently considered of some significance in 2015 or later. We did not search for snowballed literature earlier than 2010 due to the rapid change in the extent of online services since then.

| Stage of process | Criteria | Include | Exclude |

|---|---|---|---|

| All stages | Scale and spread of intervention | All scales and geographic levels from individual site to national coverage | None |

| Country | EEA or OECD countries | Countries not in the EEA or OECD | |

| Language | English | Languages other than English | |

| Availability | Full-text availability | Title and/or abstract only Conference proceedings with no full text article |

|

| Stages 1, 3 and 4 | Year of publication | 2015–January 2020 | 2014 or earlier |

| Stage 2 | Year of publication | 2010–January 2020 | 2009 or earlier |

| Stage 1 only Screening of academic literature on DF in primary care |

Topic relevance | Digital facilitation of online services in primary health care settings where DF was implemented in some form:

|

Where there is no reference to facilitation being implemented by or on behalf of primary care practices. Thus, solely theoretical papers are excluded |

| Article type | Original research |

|

|

| Stage 2 only Screening of literature on DF in health sectors outside of primary care |

Topic relevance | Digital facilitation of online services in non-primary care health sectors where DF was implemented in some form:

|

Where no reference to facilitation being implemented by or on behalf of healthcare providers. Thus, solely theoretical papers are excluded Articles that address aspects of DF already covered included articles identified in Stage 1 |

Articles that address aspects of DF found not to be covered by articles identified in Stage 1. Key gaps include:

|

|||

| Article type | Original research |

|

|

| Stage 3 only Screening of grey literature on DF in health care, all sectors |

Topic relevance | Digital facilitation of online services in health care, all sectors | Where there is no reference to facilitation being implemented by or on behalf of healthcare providers. Thus, solely theoretical papers are excluded Articles that address aspects of DF already covered by included articles identified in Stage 1 |

Articles that address aspects of DF found not to be covered by articles identified in Stage 1. Key gaps include:

|

|||

| Article type | Grey literature (i.e. literature produced in electronic and print formats outside of commercial publishing). To include, but not limited to:

|

Trial registrations (i.e. articles registered on ClinicalTrials.gov or the WHO ICTRP registry) | |

| Article type | Original research |

|

Stage 3: grey literature on digital facilitation in health care

In Stage 3 we searched grey literature from January 2015 to June 2020 to identify policy reports on DF in health care. The search had two main components: targeted searches of four health policy and professional association websites [The Health Foundation, The King’s Fund, The Nuffield Trust and The Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP)}; and a general search of the Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) database. The targeted searches of websites used combinations of terms such as ‘online services’, ‘digital’, ‘access’ and ‘patients’, using Boolean operators where website search functions allowed. The HMIC database allowed more complex searches, so we adopted a search strategy capturing concepts related to online (e.g. online, digital, virtual, technology) and facilitation (e.g. uptake, encourage, increased use). Full details of the grey literature search strategy are given in Appendix 1 (see Table 25).

Stage 4: academic literature on digital facilitation in non-healthcare sectors

We also looked, in Stage 4, for relevant academic literature from January 2015 to June 2020 on DF in non-healthcare sectors on Google Scholar. The searches were aimed at two sectors that the study team identified as potentially relevant based on their business models, which incorporate both online and offline customer services, namely: the tourism and travel sector, and the retail banking sector. Full details of the search strategy for these non-healthcare sectors are in Appendix 1 (see Table 27).

Screening

Publications for Stages 1, 3 and 4 were restricted to English-language articles published since 2015. We initially included articles from 2010 to January 2020; however, the resulting number of included publications from Stage 1 (n = 154) exceeded the scope of the project. We therefore then restricted to publications published since 2015, with the understanding that DF and widespread use of online services in primary care are relatively recent phenomena and therefore the most relevant literature was still likely to be captured by our revised inclusion criteria. For Stage 2, where publications were identified through snowball-type searches of reference lists, we expanded the eligibility to 2010–20 so as not to omit references still evidently deemed important post 2015.

A key inclusion criterion for all publications was that they addressed facilitation of online services. We operationalised this criterion as detailed in Table 2. Further eligibility criteria were tailored to the stage of the screening process (e.g. primary care literature, non-healthcare sector literature). The detailed inclusion and exclusion criteria for each stage of the screening process are presented in Table 1.

| Concept | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Digital facilitation | Papers including reference to what is done to help patients to access and use online services, including (but not limited to):

|

Papers without information on what was done to help patients to access and use online services |

| Online services | Online services accessed through a website or app, such as

|

|

Prior to full screening, we undertook a pilot exercise examining 2% of the 11,853 publications from Stage 1 (n = 237), during which publications were jointly screened by two reviewers (EG and SP). The reviewers compared and discussed their results, and amended the inclusion and exclusion criteria, raising any points of concern with the members of an internal advisory group convened to advise on the scoping review. This group comprised members of the research team who were not directly involved in the literature search and screening process, but who have expertise in literature reviews (see Acknowledgements).

Data extraction and preliminary analysis

Data from eligible studies were extracted independently by two reviewers (EG and SP) using a data-charting form developed for this study. The form was piloted to ensure data extraction was consistent across reviewers. We extracted data relevant to DF (digital technology type, facilitation purpose, method, mode of delivery, target population, setting) and study details (study type, outcomes, size, setting), aiming to capture health outcomes; staff and patient/carer experience; impact on service use, cost and equity of access to healthcare services and information; and the nature and extent of other reported outcomes. Studies were not formally assessed for quality as this was a scoping review and furthermore, the breadth of study and article types included makes the use of formal quality tools impractical. However, reviewers noted the quality of the evidence source, clarity of aims, quality and comprehensiveness of the work, and any conflicts of interest from the authors (see Appendix 1, Table 28 for details) to assist with judging the quality of the overall evidence base for DF. A list of all data fields captured in the form is available in Appendix 1 (see Table 28).

During data extraction the team met frequently to discuss emerging findings, resolve uncertainties regarding the boundaries of DF activities and clarify eligibility criteria.

Before conducting further searches (see Figure 2), we undertook preliminary analysis of the extracted Stage 1 data, including in a study team workshop (attended by EG, BL, SP and JS) to identify themes emerging and gaps in the literature that might indicate a need to expand or alter the scope of our search during later stages.

We then discussed the identified themes and gaps at a second workshop with seven members of the PAG. The PAG members suggested that a barrier to DF could be the use of locums. This was an important gap in our preliminary analysis and one that was under-represented in the Stage 1 literature. The use of locums, and high staff turnover more generally, is an important potential barrier to DF because these staff might not have the proper training or buy-in for DF programmes. The PAG members at the workshop also confirmed the legitimacy of some themes we identified in the literature, including that awareness of online services by GP practices and training for staff members may be important enablers of DF, and that data privacy or security concerns by GPs or patients might hamper DF efforts. The PAG participants highlighted that although it can be challenging for members of some vulnerable patient groups to access or use online services, for others, such as those with limited mobility, online services might improve access to health care. These discussions aided in the identification of themes in the literature and later data synthesis.

Data synthesis

Data analysis followed the principles of narrative descriptive synthesis. 79 We began by identifying key themes captured during charting, which were then refined and expanded upon during preliminary synthesis. We did this through a process of study team discussions, analysis and writing. Preliminary synthesis was followed by further refinement of themes through a workshop including members of the wider study team, including a PPIE representative. The narrative synthesis further aimed to characterise and differentiate between different types of facilitation and to synthesise evidence relating to effectiveness or cost effectiveness, inequalities of access to online services, or potential advantages and challenges of different approaches.

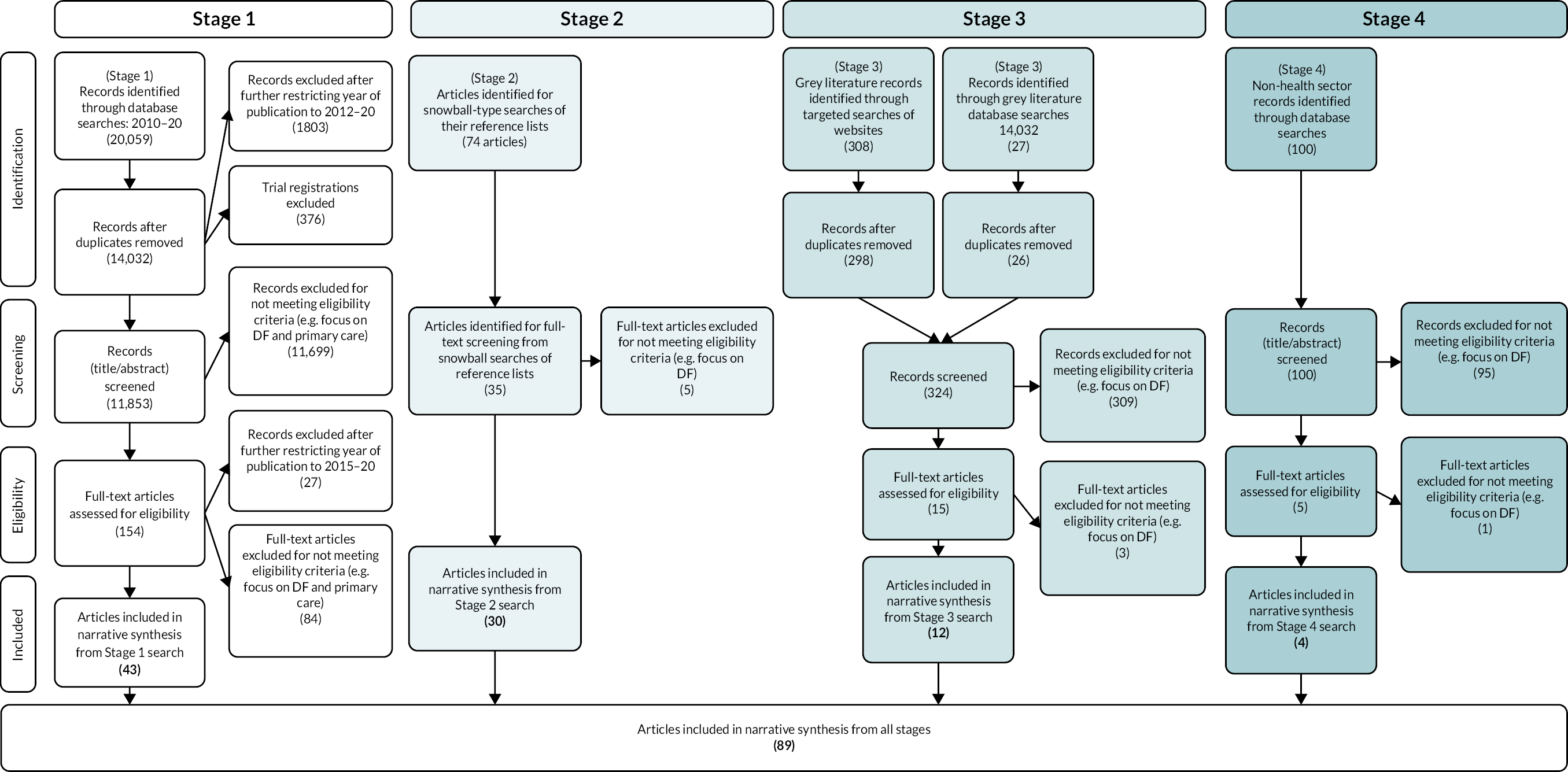

Results

Figure 3 shows the process of the literature search through a Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram. In Stage 1, we screened 11,853 records of which 43 met the criteria for inclusion. Later stages identified an additional 46 publications eligible for inclusion, for a total of 89 full-text publications included in the review. These are listed in Appendix 1 (see Table 29), along with information about the types of interventions and study designs.

FIGURE 3.

PRISMA flow diagram of search and screening process for scoping review, by stages. This figure74,78 was originally published in the Journal of Medical Internet Research (www.jmir.org), 14 July 2022 and licensed under CC BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/). For further details, see Publications.

Typology of digital facilitation

There are a wide variety of DF efforts discussed in the literature. Table 3 illustrates the typology we developed based on our findings. Although DF efforts are usually directed at patients, some are aimed at primary care staff to enable them to better support patients in using digital services. The DF efforts discussed in the literature review include those that are part of routine service delivery, and those that were introduced as part of an experimental study where facilitation was implemented for research purposes.

| Typology of DF | Definition | Examples of facilitation approaches | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Digital facilitation aimed at patients | Promotion | Broad category that captures ways of raising awareness of and knowledge about digital services, endorsements of specific digital services to patients, and methods of encouraging patients to use them. | Recommendation and prescription of digital services and other communication-centred interventions; e-mails and written reminders; video introductions to digital services. |

| Training and education | Education or training to help patients acquire technical skills to use digital services or to help patients understand what features of a digital service can be helpful to them. | Initial assistance with use of digital services. | |

| Guidance and support | Ongoing help provided by clinicians or other primary care staff to patients to use digital services. | Coaching and ongoing guidance from clinicians and other staff. | |

| Digital facilitation aimed at primary care staff | Interventions to increase staff’s knowledge of digital services so that they can better support patients in their use of the services, or to increase their trust in services. | Certified list of apps and websites (for staff to recommend to patients); practice champions (to increase buy-in); training to generate awareness of online services and how to use them. | |

Digital facilitation aimed at patients

Most efforts to facilitate uptake and continued use of online services are aimed directly at patients. Within the literature we reviewed, DF was usually delivered by primary care staff such as GPs and nurses, although other staff such as receptionists were also sometimes involved. It is important to note that the literature likely under-represents unplanned or ad hoc DF activities such as promotion of online services by receptionists. The types of facilitation aimed at patients that we identified can be grouped into three categories: (1) promotion, (2) training and (3) guidance and support.

Promotion

Promotion refers to ways of raising awareness of, and knowledge about, digital services; staff endorsing specific digital services to patients; and encouraging patients to use them. A lack of knowledge by patients of available online services is a barrier that primary care staff can help overcome. 80 Promotion can be via a range of media, including online, in-person during appointments, and in less personalised forms such as placing posters or promotional material in waiting rooms. Promotion efforts for digital services also vary in terms of how active providers and other primary care staff need to be. Some DF efforts require that providers actively raise the topic of digital services during consultations or that receptionists send e-mails to patients,81 while others do not require much action by staff, for example, posters or brochures in waiting rooms. 82

Examples of online promotion include practices: featuring links on their website to promote an e-consultation and self-help web service,83 sending reminders or links to online services via e-mail or SMS and using online promotional videos. Engaging patients by providing a tablet for use in the practice waiting room, rather than simply relying on verbal recommendations, has also been explored in a feasibility study as a way of motivating patients to keep using an online self-regulation programme once they return home. 84

There have been various types of offline promotion within UK primary care practices, such as leaflets, posters and television screens with information about online services. 83 Verbal recommendation by staff is one of the most widespread routinely used methods of DF. General practitioners were willing to recommend online services if they knew they could trust the service, or if they had been involved in its design.

Training and education

Training and education may also promote uptake and use of digital services, both by helping patients to acquire technical skills to use online services and by helping patients to understand what features of an online service can be most helpful. 85 In the literature we reviewed, training was delivered online through videos,86 or offline through presentations or seminars,87 and was delivered either in one session86 or over several. 87

Guidance and support

Guidance and support refers to ongoing help provided by clinicians or other primary care staff, through in-person meetings or phone calls. It can be focused on technical aspects of using digital services, similar to training, but appears to most often focus on interventions that help patients set goals, keep track of progress, improve adherence and other less technical aspects of digital services.

Practice champions88 have been used in primary care to increase the use of online services. As experts in a particular online service, they provide assistance and ongoing support to patients, with the potential to increase both initial uptake and continued use thereafter. An evaluation of 11 primary care practices in the UK concluded that practice champions could promote appropriate use by patients of a web-based consultation system, as well as encourage engagement of staff. 68

Clinician support was discussed in the literature as a way to provide ongoing guidance and support to patients, for example, a US study of an app to help military veterans manage symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) concluded that adding clinician support improved access and utilisation of the app. 89 A study of an internet platform for cardiovascular self-management in the Netherlands, where patients had the option of contacting health coaches (e.g. practice nurses), concluded that human support was crucial to initial and sustained engagement with the platform. 90 Another evaluation found that patients overwhelmingly wanted online or face-to-face technical support, such as a helpdesk. 91

Digital facilitation aimed at primary care staff

For primary care staff to be able to help patients use online services, they must first be aware of what services are available, how they work, why they are useful and trustworthy, and how they can benefit specific patient groups. 68 Healthcare professionals also need to be clear about their role in endorsing and facilitating online services. 92 There is evidence of some GPs being opposed to the use of online services by patients. 93 Efforts have been made to train primary care staff and increase their knowledge, understanding and confidence in online services.

In the UK, researchers held practice-level discussions with GPs with the aim of tackling the strong views held by some GPs against prescribing online information, albeit with limited effect. 93 In Spain, an experimental study examined the effects of doctors prescribing apps that had been certified by public health authorities, on patient uptake and use of digital services. Since staff buy-in is an important enabler to DF, having a list of trusted apps can be valuable. 94

Other studies show that healthcare practitioners may benefit from training to acquire the technical skills to use online services;95 or to improve their communication strategy and relationship building skills, so that patients or their families are more likely to follow advice to use digital services. 96,97 Such training may be delivered through online meetings, face-to-face sessions, presentations or by sending explanatory videos to staff. 98

Is digital facilitation associated with increased uptake and use of digital services?

The evidence relating to whether different DF approaches increase uptake and use of digital services is summarised in Table 4 and described below.

| Typology | Digital facilitation effort | Evidence on increasing uptake and use |

|---|---|---|

| Promotion | Recommendation or prescription of digital service to patient | Staff recommendation/endorsement of a digital service was shown to be one of the most effective ways to increase patient uptake and use in two literature reviews on the topic.52,99 Qualitative evidence from primary studies also supports staff recommendation/endorsement as an effective way to boost use of digital services.100–102 |

| Strong evidence from RCTs that prescription and referral pads for digital services are effective in increasing patient uptake,98,103 along with evidence from a review on the topic.104 | ||

| Some evidence that a list of certified apps and websites (approved by a regulating body) may help providers to prescribe apps and websites to patients.94 But a study in the UK NHS found a similar approach ineffective in encouraging the use of high-quality online services.105 | ||

| Multiple mixed-methods studies suggest that recommendation/endorsement may be more effective when staff focus on specific aspects of a digital service that will be useful to particular patients, and gradually introduce patients to digital services based on their individual needs at that time.105–109 | ||

| Communication-centred interventions | Qualitative evidence and a RCT suggest that recommendation/endorsement of digital services may be more effective when staff are trained in how to best engage patients using specific communication strategies and shared messaging around the service.83,90,96,97,107,110 | |

| Strong evidence from three RCTs that interventions that help patients form specific ‘if–then’ plans are effective in increasing continued use of digital services.111 | ||

| E-mail and written reminders | Several mixed-methods and qualitative studies have shown that written materials such as brochures, leaflets and advertisements may increase patient use of digital services, and they require little effort from providers.83,106,112 | |

| Reminders (e.g. SMS messages and push notifications) have been implemented in some areas,110,113 and feedback from patients and service users suggests they may help to increase uptake and use.90,114 | ||

| Video introductions to digital services | Mixed evidence from RCTs on whether video introductions are effective in increasing uptake of digital services. No evidence that they are effective in increasing sustained use of digital services.86,115–117 | |

| Public information campaigns | In the UK, a public information campaign and personalised invitations to patients to use an electronic health record system were found to be ineffective in encouraging enrolment.82 | |

| Training | Initial assistance with use of digital services | Mixed evidence from RCTs and quantitative studies on whether initial assistance in registering and logging into digital services is effective in increasing uptake and use.38,87,118,119 Qualitative evidence suggests patients and providers feel this type of assistance would be useful,120,121 but the weight of the evidence suggests that it is likely ineffective, and that additional continued support is needed to encourage continued use of digital services. |

| Qualitative evidence suggests that allowing patients to log into and use digital services in primary care practices (e.g. in the waiting room on tablets) may encourage patients to continue using a service outside the practice.84,122 This intervention has been implemented within studies with some success.110 | ||

| Technical training support | There is a body of literature (including strong evidence from a systematic review and a RCT) emphasising the importance of technical support to patients using digital services and wider support around digital literacy and digital health literacy in encouraging patient use of digital services,81,107,114,115,123,124 particularly for older patients, patients from ethnic and racial minority groups and patients in low-income settings. At least one RCT found that simply providing information on using the internet was not effective in increasing use of digital health services.93 | |

| Guidance and support | Coaching and ongoing guidance for patients | Mixed evidence from RCTs and non-randomised trials on whether ongoing coaching and support increases uptake and sustained use of digital services.89,125–128 The weight of evidence suggests that certain forms of ongoing support are likely effective (see below). |

| Strong evidence from three RCTs and qualitative studies suggesting that ongoing guidance focused on adherence, content of digital services and goal setting is likely more effective than ongoing guidance on technical aspects alone in increasing use of digital services.111,120 | ||

| Qualitative evidence suggests that both face-to-face and telephone support are likely important in encouraging patients to continue to use digital services.90,91,94,129,130 |

Promotion

Recommendation and prescription of digital services and other communication-centred interventions

Studies suggest that promotion may increase the initial uptake and subsequent use of digital services. We explore factors that make DF efforts successful in What makes digital facilitation successful?.

A literature review of ways to promote engagement with patient portals suggested that endorsement by healthcare staff is one of the most influential factors for patient uptake and use. 52 Interviews with staff, patients and families indicate that staff recommending digital services to patients may be effective at increasing uptake of those services,100–102 especially when staff focus on specific features of a digital service that will be useful to individual patients,106,107,131 where staff are trained in how to best engage patients97 and where staff have a shared understanding of the messaging around digital services. 83,110

Other promotion-based DF strategies that appear to increase patient uptake of digital services include the use of written prescription or referral pads,98,104 and having a list of certified apps and websites that have been approved by a regulating body and to which practice staff can refer patients or issue prescriptions. 94,103 However, an NHS accreditation scheme in 2009 to certify online information so as to increase use of high-quality sources by patients was not very effective. 105

Certain communication strategies may be particularly effective. In a randomised controlled trial (RCT) examining the use of an online depression prevention programme for adolescents, intervention sites that were assessed as more completely implementing communication and relationship building techniques to help develop and maintain trust, authenticity and sincerity with adolescent patients were more effective in encouraging enrolment. 96 The literature also points to the effectiveness of gradually introducing patients to digital services and to new features rather than explaining all functions at one time. 108,109 Interviewing and conversational techniques such as motivational interviewing,90 and discussing patients’ ideas, concerns and expectations to help address patients’ misconceptions,107 have been shown to increase uptake of digital services. Helping patients form specific plans around the use of digital services was shown to be one of the strongest predictors of adherence in a RCT of an internet-based intervention for depression. 111

E-mails and written reminders

Written material that healthcare staff can give to patients about digital services may also be useful in encouraging uptake, with minimal staff time and effort. 106,112 In a study in the UK where an e-consultation and self-help web service were promoted through posters, leaflets and advertisements on television screens in waiting rooms and on practice websites, 79% of those who used the web service reported that they found out about the service through these promotion efforts. 83 Reminders for participants can also be helpful,90,114 for example, through SMS messages sent by receptionists with links to online tools,110 or sent to patients at key times, such as when healthcare staff upload new notes to patient portals, which in one quasi-experimental study resulted in over 85% of patients viewing at least one note on the patient portal. 113 However, a RCT of an internet-based therapy programme for depressive symptoms among high school students found that neither tailored nor standardised e-mails increased adherence. 132

Training and education

Initial assistance with and education on use of digital services

The evidence is mixed about whether initial assistance with, and education on, the use of digital services are effective in increasing uptake and continued use, and the weight of evidence from quantitative studies suggests that more support to patients is likely to be needed after initial introduction sessions to promote long-term use of digital services.

For example, a quantitative study of uptake and use of patient portals for patients with chronic kidney disease found that patients of renal clinics who were helped with initial login and registration to the portal were 20% more likely to be continued users of the portal after 3 years than in other clinics. 38 But there is contradicting evidence from a study on use of patient portals indicating that initial training/introductory educational sessions have little impact on actual use after initial sign-up. 119

A RCT of an initial 10-minute standardised personal information session on internet-based depression interventions found that these sessions were ineffective in increasing adherence in an inpatient and outpatient rehabilitation setting for diabetes care. 118 Similarly, a RCT from the Netherlands showed that initial group education sessions for patients with type 2 diabetes to help them use online platforms did not increase use of the service. 87

An interview-based study suggests that letting patients use tablet devices or computers in practice waiting rooms may encourage later use at home. 84 Both healthcare staff and patients expressed enthusiasm about the potential to access health information122 and complete digital screening tests110 on tablets while waiting for appointments. Other studies of initial educational sessions for patients where staff help patients sign up, install apps, provide pamphlets and answer questions on how to use online services have found that these may increase uptake and use of patient portals. 38,120,121

Video introductions to digital services

Four RCTs evaluated the effectiveness of video introductions on patient uptake and use of digital services. Two studies found that online video-based trainings increased patient uptake compared with people who received no form of training or introduction,115 although sustained use after 6 months was still very low in one of the studies. 116 The two remaining RCTs found contradictory results. One RCT found that a 3-minute video did not increase uptake or use of an online intervention for chronic pain,117 but another RCT found that a 7-minute video was effective in increasing acceptance of internet-based interventions for depression, although actual use was not measured. 86

Guidance and support

Coaching and ongoing guidance from clinicians and other staff

There is some evidence that ongoing support from clinicians and other staff is effective in increasing the use of digital services. Although some quantitative studies found that these interventions were ineffective, the weight of the evidence suggests that certain forms of ongoing support are effective.

Several RCTs evaluated the effectiveness of having clinicians or other staff guide patients in the use of digital services as compared to self-directed services. One study found that patients using online therapy for chronic pain who were guided by a psychologist completed more modules than unguided groups and had lower attrition rates. 125 But two other RCTs showed either mixed126 or no evidence127 for the effectiveness of guides and coaches to increase patient uptake and use of digital services. A series of RCTs in Germany133 found that both content-focused (personalised written feedback, reminders) and adherence-focused guidance (reminders, and ability to request feedback) were equally effective in increasing adherence as compared to administrative guidance (technical support). 133

Several quantitative studies with non-randomised control groups also tested the effectiveness of coaching sessions to help patients engage with app content. Interventions such as sessions with health coaches,89 hands-on and telephone assistance from nurses, and an intensive course for patients,128 may increase uptake and use of digital services.

Qualitative evidence also suggests that face-to-face support for patients along with ongoing web support may facilitate the uptake and use of digital services. 91,94,129,130 For example, incorporating digital services into regular care and providing patients with a way to message providers for support may encourage sustained engagement. 90 In addition, ongoing training in the use of particular digital services or more generally to increase digital literacy skills may encourage uptake and use. 91,107,114 However, a quasi-randomised control trial in the UK found that providing patients with general information about using the internet for health purposes did not increase patients’ readiness to use electronic health services. 93

Evidence relating to inequality between different population groups

A few studies identified strategies that may be effective at increasing uptake and use of digital services in specific patient populations. A systematic review found that technical training and assistance programmes have the best evidence for increasing portal use for vulnerable populations (elderly people; racial minorities; individuals with low socioeconomic status, low health literacy, chronic illness or disabilities), and that other interventions lack sufficient evidence. 81 A US study found qualitative evidence that ongoing training, both in the use of a particular service and more generally to increase digital and health literacy skills, can help address barriers to receiving care faced by African American and Latino patients134 and patients in low-income areas. 124

Ongoing training and support may also be helpful in encouraging uptake and use of digital services amongst older people. 114 Despite concerns about older groups being less able or willing to use technology,92,101 evidence suggests they are often willing to use tablets,122 patient portals,52 remote video consultations108 and health-related apps. 135 Some studies showed that older patients were more likely to use digital services after facilitation efforts115 or point to the importance for older patients of ongoing human support90 and training on both technical aspects of digital services and on general digital literacy skills. 114 Several studies include subgroup analyses, which revealed that patients with lower health literacy136 or with disabilities are less likely than others to use digital services even after facilitation efforts. 87,99,115

Cost effectiveness

No studies in the literature we found assessed the costs of DF efforts.

Evidence of disadvantages and risks from digital facilitation efforts

The literature identifies some disadvantages and risks associated with DF efforts. For example, communication-based facilitation efforts that require high levels of emotional engagement may contribute to distress and fatigue among staff. 96 Approved app lists may risk being biased in the sample of apps considered when the onus is on app developers to apply to be included on approved lists. 135 Reference is also made to some patients worrying whether the ongoing engagement to get involved with digital services meant they would replace valued in-person contact. 90 E-mail reminders can irritate some patients to the extent that they avoid certain online services. 130 Lastly, facilitation efforts that involved providing patients with tablets or computers to use digital services in waiting rooms may compromise patient confidentiality. 110

Evidence also suggests that healthcare staff’s perceptions of harms from digital services, such as negative impacts on the patient–provider relationship, increased workload and patients misinterpreting online health information, may negatively affect their willingness to recommend digital services to patients. 106

There is some evidence that providers may be more willing and able to engage in DF efforts with patients who are already confident users of digital services, including the ‘worried well’, potentially exacerbating inequalities in access to digital health resources. 105,137 A review found that providers are more likely to recommend digital services to patients they perceive as more technologically knowledgeable, and these perceptions may be based on age, socioeconomic status, education level and ethnic group. 106,116,138

Non-health literature in the area of banking focuses on digital exclusion, with concerns that financial institutions will market digital services more among high-income groups that are already more likely to use online banking. This literature points to the role of regulators in protecting vulnerable populations which may otherwise be digitally excluded. For example, regulators may enact inclusion objectives and they may address security concerns that deter people from participating in digital finance. 139

What makes digital facilitation successful?

The success of DF is influenced by the following factors.

Perceptions of usefulness of the digital service

One of the most important factors in the success of DF efforts is the perception, both from the patients and the healthcare staff, that the digital service will be useful. 85,92,94,95,109,140 Qualitative evidence suggests that healthcare staff’s likelihood of recommending a digital service to patients may be influenced by the alignment of information within apps and websites with the health information and recommendations that doctors commonly provide to patients,85 and by the existence of rigorous evaluations of digital services that demonstrate patient benefit. 80,107 Patients are more likely to use services that have been recommended by healthcare staff if they see the information and functionality as novel,82 if they are able to customise the service to their own needs and preferences,52,130 and if the service is specific enough to fit their needs. 141

Time and capacity in primary care

Challenges in terms of staff having enough time to implement DF efforts were commonly identified in the literature. 80,84,94,96,100,108,110,129,131,142,143 However, the literature also indicated ways to help address this issue. E-mail templates, protocols and scripts can help staff to automate some aspects of patient engagement. 104 Passive facilitation efforts such as posters and brochures can also help to mitigate time pressures in primary care. 112 In some studies, it was found helpful to have non-GPs engage with patients in DF efforts, due to time constraints for physicians,110,112,120,131 or to use the time that patients spend in waiting rooms as an opportunity to facilitate access to online services. 84,110,122 One study suggested that facilitation efforts may be more feasible during certain kinds of appointments where patients may have less pressing concerns (e.g. vaccination, contraception, nutritional and physical activity-focused appointments). 84

Staff buy-in

Staff buy-in and motivation were important enablers of successful facilitation efforts in many of the studies we found,38,96,135,144–146 and negative staff attitudes or a lack of motivation towards an intervention were often barriers to facilitation efforts. 93,94,97,143 In several studies, buy-in was encouraged through: early engagement of staff when developing an intervention, initial education or training sessions in practices to introduce staff to new online services or interventions, ongoing communication with staff and incorporation of digital services into discussions at staff meetings. 68,80,97,100,120 Early engagement of GPs and other primary care staff may also help by addressing anticipated barriers early in the implementation process. 68,80,84,147 Ongoing education and training for healthcare staff in how to use digital services has also been indicated as important in helping them to engage in DF. 104,106,107,148 Practice champions, that is, designated staff responsible for promoting digital interventions among other staff and patients, could also help. 68,112,120,143

Re-shaping roles may also be important in securing staff buy-in. 99,108,149 This not only applies to GPs and nurses, but also to wider primary care support teams. Seeing DF as part of their role rather than something added onto their existing job was important in increasing buy-in among practice receptionists. 110

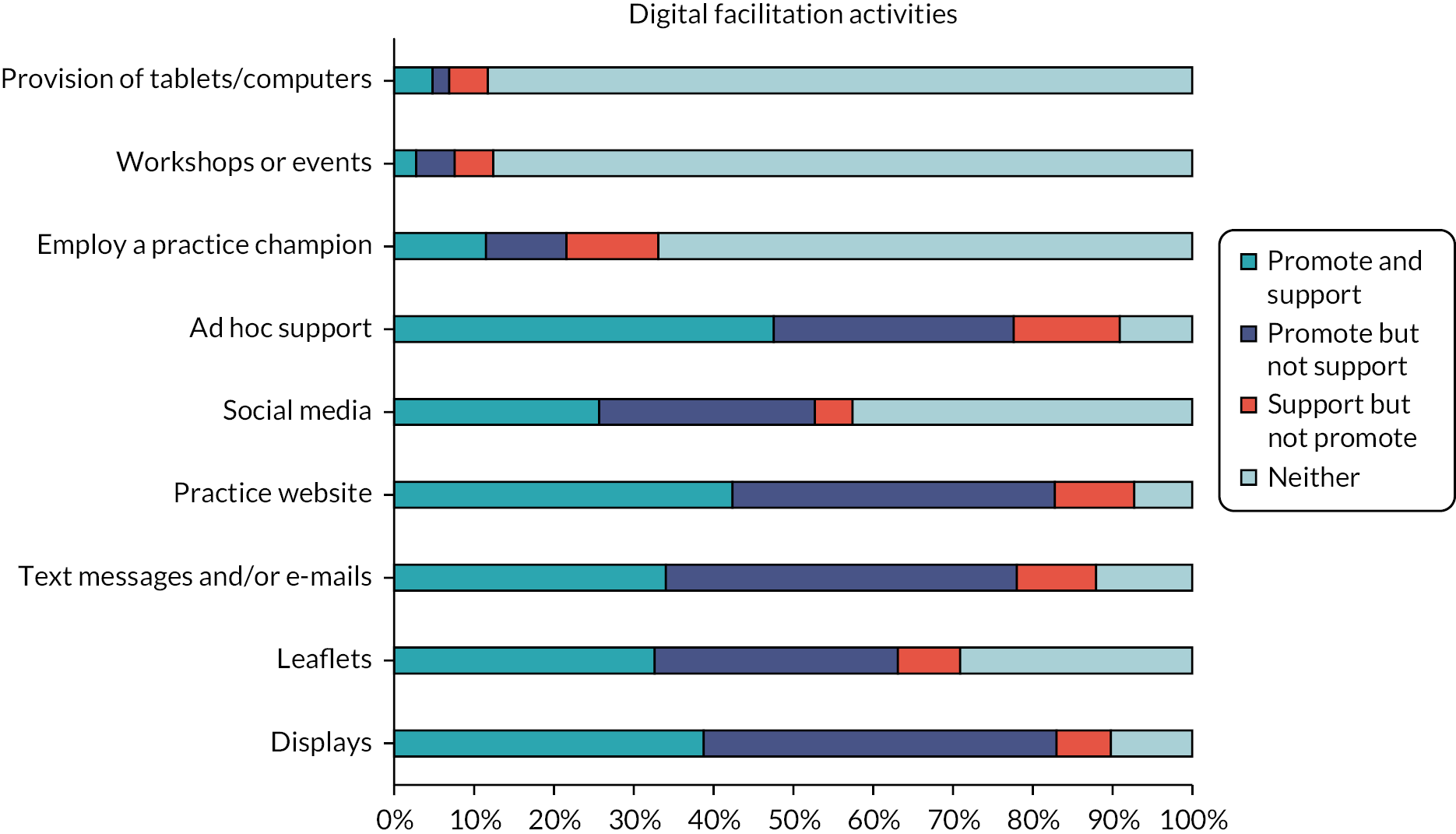

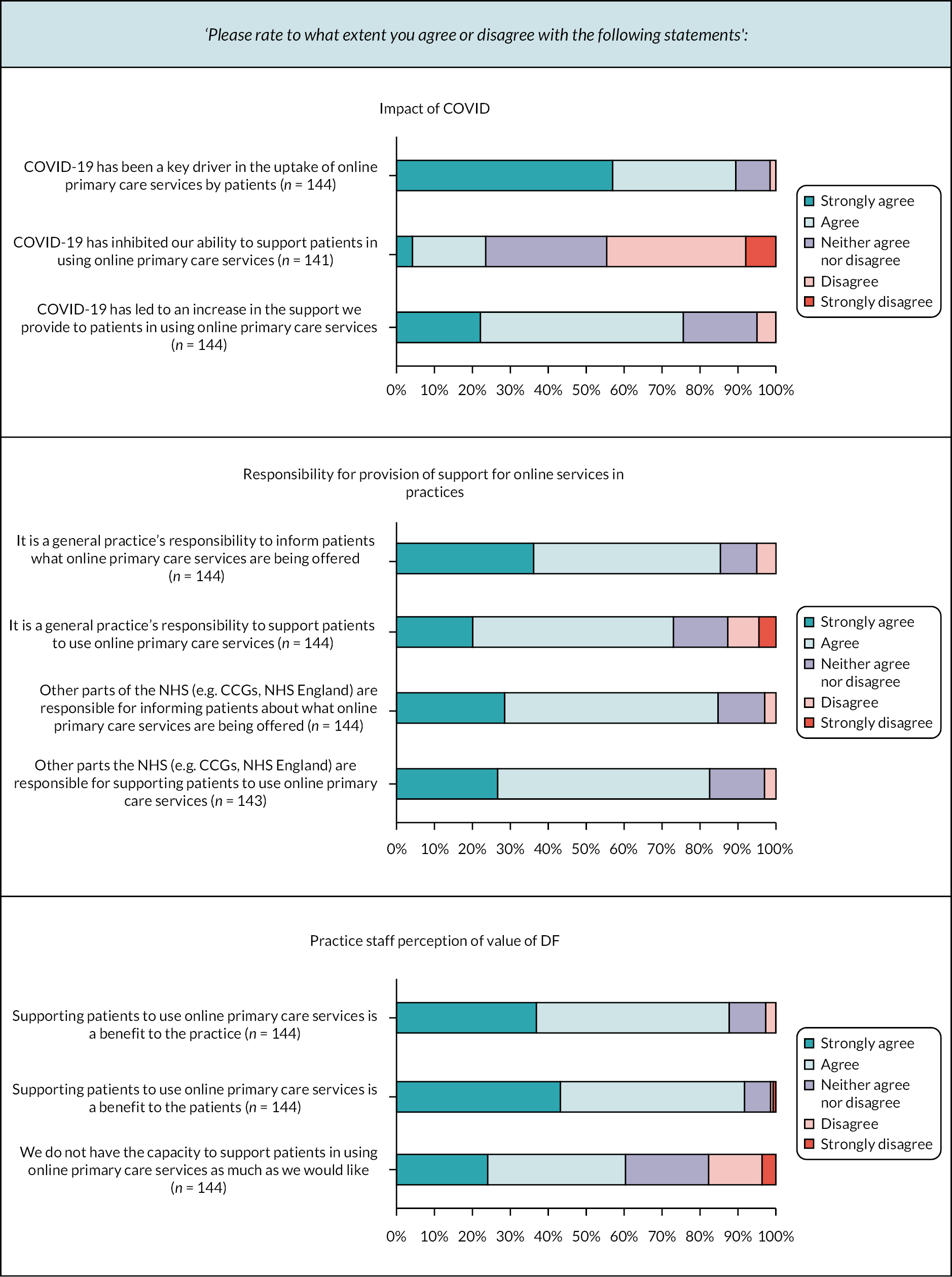

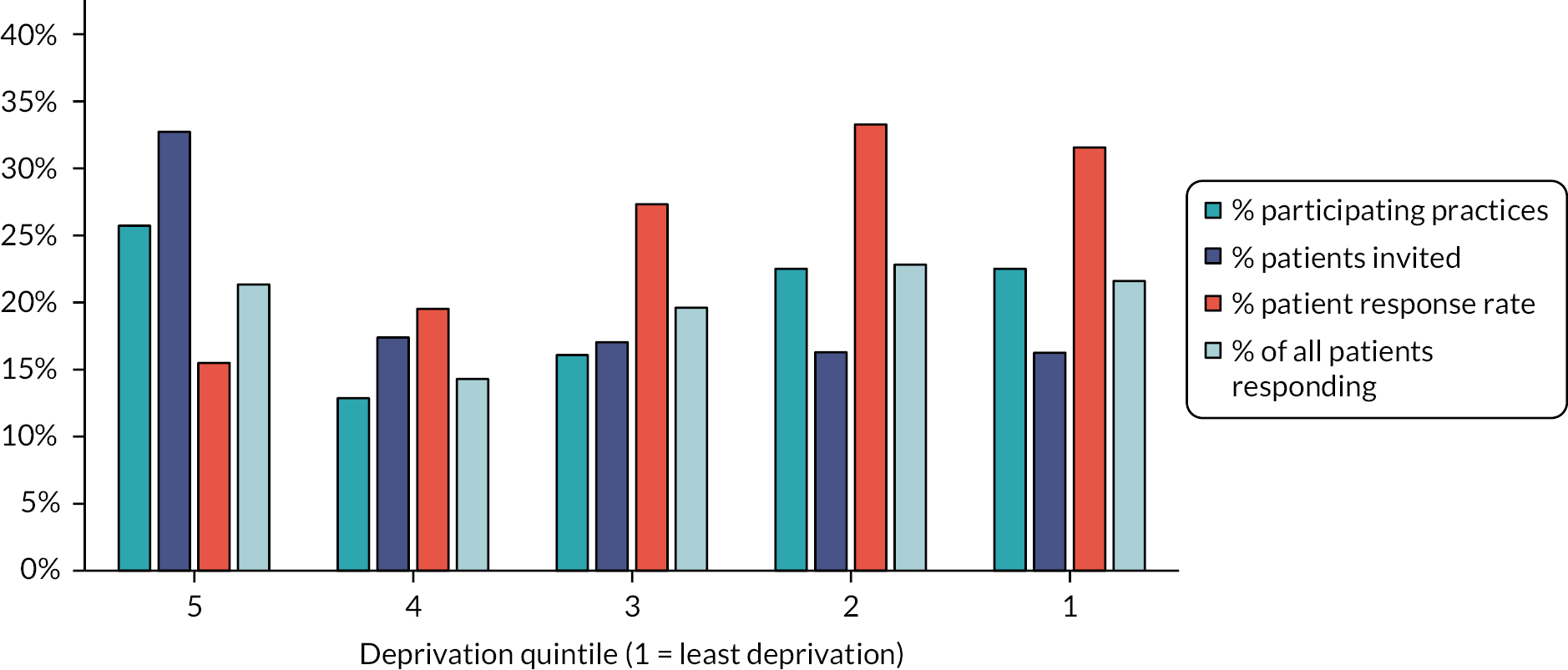

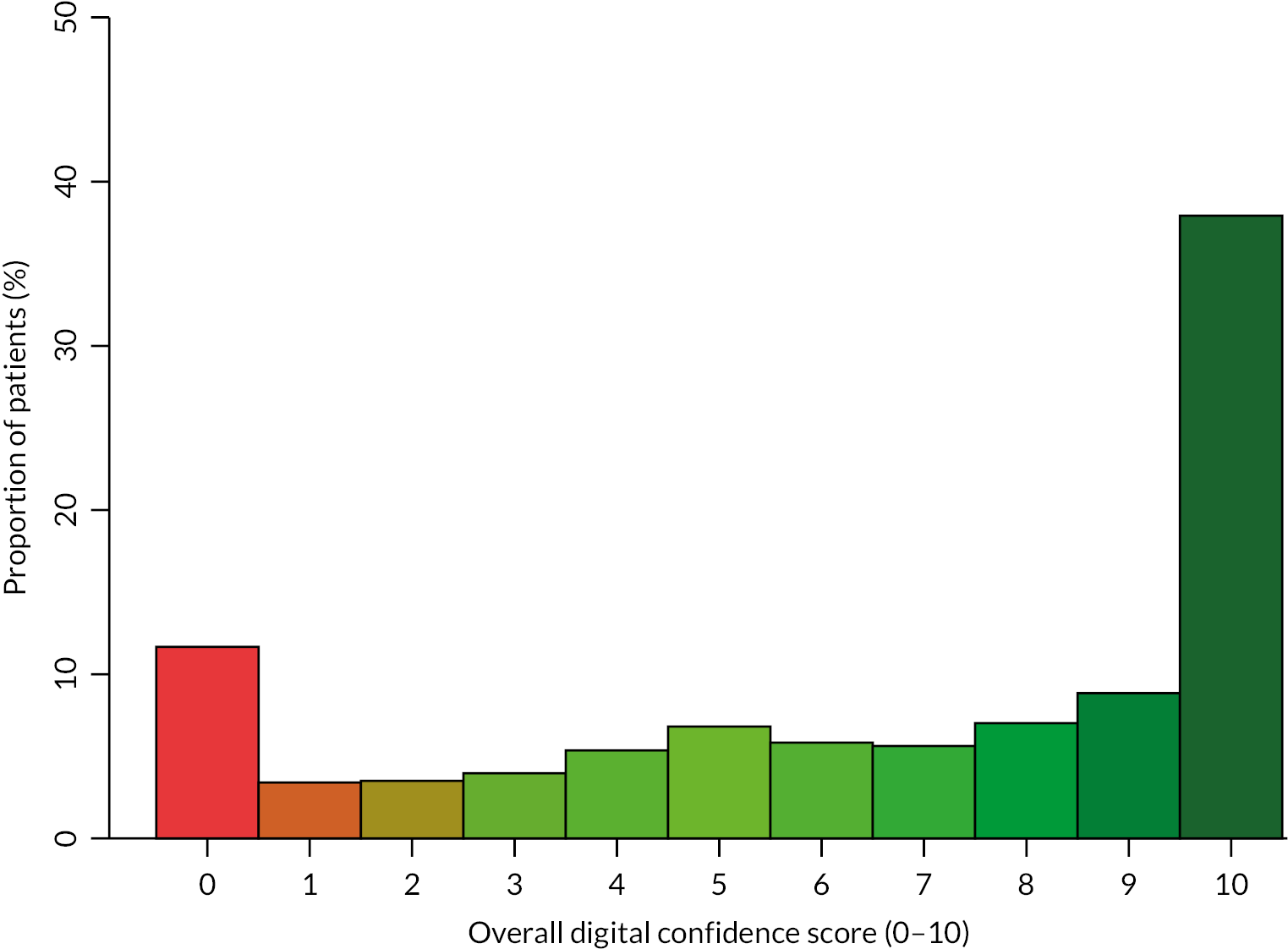

Trust in, and knowledge of, digital services