Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 17/05/30. The contractual start date was in November 2018. The final report began editorial review in December 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Islam et al. This work was produced by Islam et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Islam et al.

Chapter 1 Context and introduction

This report presents the findings of a 35-month study funded by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Health and Social Care Delivery Research programme. The study explored how terminally ill patients with advanced illness from ethnically diverse backgrounds and their family caregivers (FCGs) thought ahead about preferences related to anticipated deterioration and dying, and whether or not, and how, they engaged with health-care professionals (HCPs) in end-of-life care planning (EOLCP). In this study we have used the term ‘ethnically diverse’ to describe individuals who are diverse in terms of language, culture and ethnic background. It should be noted that when using the term ‘ethnically diverse’, we are referring to all ethnic minority groups except the white British group. Throughout this report, the term ‘ethnically diverse’ also refers to white ethnic minorities, such as European, Gypsy, Roma and Irish Traveller groups. 1

When someone has an illness that is very advanced, progressive and terminal, a shift in the approach of care may be considered in the last months of their life that integrates a focus on symptom management, quality of life and preparation for dying. For some people this approach may be integrated alongside treatments aimed at prolonging life; for others this palliative approach may be the main focus of care to help people to live as comfortably as possible. Advance care planning (ACP) provides an opportunity for people to express their wishes about many things, including care and treatment in the future, should they subsequently lose capacity to do so: these principles are embedded in the Mental Capacity Act 2005 and national UK end-of-life care (EOLC) policy. 2,3 Offering the opportunity to patients with advanced disease to have discussions about their illness and future care planning is identified as good practice by the General Medical Council, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) and the NHS. 4–7 Throughout this report, we use ‘EOLCP’ as an umbrella term for the processes of discussion and documentation (including ACP) that aim to achieve the best outcomes for people with advanced disease who are at risk of deterioration and dying in the coming months.

End-of-life care planning enables the supportive and palliative care needs of both the patient and family to be identified and met during the last phase of life and into bereavement. It includes consideration of physical care; management of pain and other symptoms; provision of social care; and psychological, spiritual and practical support. 3 It is regarded as key to improving experiences and outcomes for patients and families, and to aligning care and treatment to a patient’s wishes. Furthermore, it optimises the use of health-care resources, including acute hospital care; emergency services; and drug, surgical and other treatments. 5–11

Evidence regarding the effectiveness of EOLCP is limited, but suggests that patients who have engaged in EOLCP are more likely to die at home; receive less invasive treatment in the period preceding death; and report a better experience of care, along with their relatives. 12,13 There is limited evidence that EOLCP alters outcomes such as number of hospital admissions and use of health-care resources, but there is some evidence of increased patient satisfaction; higher-quality EOLC; and reduced stress, anxiety and depression among surviving relatives. 12–19 There is low-level evidence that EOLCP is also potentially associated with lower health-care costs. 20

It is apparent that EOLCP remains uncommon in most areas of professional practice, and patients and professionals tend to avoid discussions they find difficult. 7–13,20–22 Patient and family responses to EOLCP outcomes remain poorly understood. Very significantly, much of the research about the approach to and benefits of EOLCP excludes patients from ethnically diverse groups, most especially those who cannot speak English. 19,22 There is a small body of work that suggests that ethnically diverse patients value what palliative and end-of-life care (PEOLC) would offer them, and our local research and preliminary patient and public involvement (PPI) work and clinical experience echoed this.

Evidence, mainly from outside the UK, highlights disparities and inequality of access to PEOLC by ethnically diverse patients. 23 They are less likely to access palliative services and are more likely to die in hospital and to receive more intensive treatments at the end of life. 24,25 Little is known about the nature of ethnically diverse patients’ preferences for EOLC or how current UK EOLCP policy and practice ‘fit’ with diverse cultural values and beliefs. There is the possibility that development of more culturally sensitive EOLC, based on evidence, may prompt a revision of the current model and norms of the EOLCP approach.

This study contributes to the currently limited knowledge regarding how ethnically diverse patients and their families live with advanced illness and consider the prospect of deterioration and dying. Using qualitative methodology, this study also makes a substantial contribution to understanding the barriers to and facilitators of EOLCP with ethnically diverse patients.

End-of-life care planning and policy

Every year, approximately 40 million people are in need of palliative care services worldwide, and only 14% of these people gain access to these services. 26 In England and Wales in 2008, the Department of Health and Social Care published an EOLC strategy to ‘bring about a step change in access to high quality care for all people approaching the end of life . . . irrespective of age, gender, ethnicity, religious belief, disability, sexual orientation, diagnosis or socioeconomic status’3 in all care settings. EOLCP is a major feature of this strategy. The first step of the care pathway set out in the End of Life Care Strategy is ‘discussions as the end of life approaches’ involving ‘open, honest communication’ and ‘identifying triggers for discussion’. 3

End-of-life care planning is in line with the provisions of the Mental Capacity Act 2005,2 which provides a legal framework to promote and safeguard decision-making by an individual. It empowers and enables people to plan ahead and communicate their wishes for a time when they might lose capacity and protects their place in the decision-making process. EOLCP may benefit patients by increasing their autonomy in deciding about their future care and choice of place of death. EOLCP is intended to align care to patient preferences before their health and decision-making ability deteriorate as a result of progression of illness and to reduce uncertainty about care decisions; thus, EOLCP may help ease the grieving process for families and result in more effective use of health-care resources. 27–29 A patient may refuse treatments, but cannot insist on treatments that are not clinically appropriate.

End-of-life care planning should be an ongoing process whereby patients, their families and health-care providers discuss the patient’s goals and values and how these should inform their current and future medical care. 30 These discussions help promote a shared understanding of what might happen, help make decisions about life-sustaining treatments and provide an opportunity to discuss potential preferences for care with patients and their families. 31,32

End-of-life care planning conversations aim to inform and empower patients to have a say about their current and future treatment in consultation with HCPs, family members and other important people in their lives. 3,33 From the patient’s perspective, there is evidence that the purpose of EOLCP is not only preparing for potential incapacity, but also preparing for dying. 34 For patients, the focus of EOLCP appears to be less on completing written advance directive forms or advance statements of wishes and more on the social processes that are enabled by discussions about dying. As a result, EOLCP is not based solely on autonomy and the exercise of control, but also on personal relationships and consideration of the impact of advanced disease and relieving burdens placed on others. With this perspective, EOLCP does not occur solely within the context of the physician/HCP–patient relationship, but also within relationships with close loved ones. 35

We have very little insight on a population-wide basis in how current EOLCP policy and practice ‘fits’ with the cultural values and beliefs of ethnically diverse patients and their end-of-life experiences. National satisfaction surveys such as the Views of Informal Carers – Evaluation of Services (VOICES)36 post bereavement and Quality Health37 have a low representation of patients from ethnically diverse communities (2.9% and 5%, respectively). However, ethnically diverse patients appear to use specialist palliative care services later and less often than white British patients. 3,38,39 There is a limited evidence base for the possible reasons for this, as discussed in the following sections: Resuscitation decisions, Communication and knowing the patient and family, Health literacy and inequalities, Cultural mores and religious beliefs and Embracing diversity in end-of life care planning.

Resuscitation decisions

Do not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation (DNACPR) is a recording of an advance medical decision to not attempt cardiopulmonary resuscitation when someone’s heart stops. Without a recorded decision, however, the default policy for health and care professionals is to initiate resuscitation, which may be distressing to all and may not be aligned with the preferences of the patient. The heart stopping is the last part of the dying process and is a certainty for all dying patients. In this situation, resuscitation will not work. For a few patients, who are not thought to be dying imminently, their heart may stop in a sudden and unexpected context.

Discussions of DNACPR are complex. From the perspective of the health professional, resuscitation is a key aspect of EOLCP discussions because the default position is to resuscitate and because it will not work as a treatment when someone has died from their illness, and may increase and prolong suffering for people with advanced illness. In England and Wales, the legal basis for DNACPR decisions are provided by the Human Rights Act 199840 and the Mental Capacity Act 20052 and interpreted in case law. There are nationally agreed professional guidelines that interpret this law and provide standards of practice for professionals when a decision about offering resuscitation is, first, a clinical decision about whether or not it can be offered. 7,28

In addition, a documented DNACPR decision may help a patient who is dying to avoid an emergency admission to hospital, enabling them to spend the last hours of their life in their preferred place of care. 7 These facts and the context of the need for such discussions are seldom known or understood by the public, or by patients, and little has been explored about the perspective of the public. 7

Our previous work explored, with HCPs, the nuances of discussing resuscitation and, more specifically, DNACPR discussions with ethnically diverse patients and relatives in the UK. 41 This work highlighted that HCPs recognised that these conversations were sensitive, and occurred at a challenging time for the patient and their families. They were also aware that both patients and their relatives had beliefs, expectations and emotions that influenced resuscitation discussions. These expectations related to both resuscitation specifically and to death and dying more broadly. Participants also understood that their own beliefs and expectations, alongside their understanding of laws and policies regarding DNACPR orders and the clinical circumstances of the patient, influenced these conversations. However, in general, there was a lack of understanding by HCPs of how forms of intersectionality, such as class, ethnicity, sexual orientation, age, religion, disability, gender, education and life experiences, are interwoven and affect patients’ and their families’ perceptions of EOLCP discussions and related resuscitation decisions. 42

Like other studies, our earlier work has found that challenges in communication between HCPs and ethnically diverse patients and their families are key barriers to resuscitation discussions. 24,41,43 Overcoming communication issues was regarded as a key enabler of DNACPR discussions, helping build rapport, particularly when patients and their families appeared to have limited understanding of their prognosis. At a practical level, certain words may not be translatable, and more exploration of the understanding of the procedures of cardiopulmonary resuscitation, the possible harms and the evidence of success rates, was required in such discussions.

Although the themes of language, family and religious beliefs are well documented within discussions of transcultural clinical practice, our findings identified how these cause uncertainty and considerable heart-searching for professionals when patients are so sick that they might die and the discussion of DNACPR might falsely appear to be a discussion about choosing whether to live or to die. Like Kai et al.,43 findings from our previous work41 show how this uncertainty within a highly emotive context can lead to disempowerment and a search for more ‘knowledge’ to become skilled and empowered.

Health-care professionals in our previous work felt more confident in having DNACPR discussions when they had existing knowledge about patients’ religious, spiritual and cultural values, and their confidence in initiating these conversations was developed through experience. However, our findings highlighted the need and desire of HCPs for further training to develop ‘cultural intelligence’ to navigate the cultural and individual beliefs about death and to deliver culturally sensitive EOLC, including discussing deterioration and decisions about resuscitation. 24,41

Communication and knowing the patient and family

The principles of good palliative care (patient centred, holistic, founded on listening to the patient’s needs and guided by their wishes) can be undermined when communication is difficult. 42 Clinicians are encouraged to actively seek to explore a patient’s cultural preferences and choices on a case-by-case basis to understand how best to approach different contexts of EOLC, such as family choices in decision-making and sharing information about their diagnosis and prognosis. 44 Knowing the patient and their family is an essential ingredient to good EOLC, yet attaining this can be challenging, especially for HCPs working with patients from culturally and linguistically diverse communities. HCPs have, for example, reported that, when trying to manage pain, they may encounter confusing messages from patients who believe in the importance of stoicism when experiencing physical pain. 45–47 Such patients downplay the extent of their pain, making it more difficult for clinicians to understand the patient experience and effectively manage pain. 48 On the other hand, patients who cannot articulate their needs to clinicians about their pain may find the experience distressing and isolating, may feel disempowered and may feel discriminated against because of their inability to competently communicate in English. 48–50 In addition, ethnically diverse patients may not want to initiate discussions even when they experience intolerable pain in late stages of life, but may later communicate a desire to engage in EOLCP discussions with HCPs once they have accomplished all their wishes with their family. 50–53

In their small UK-based study, Owens and Randhawa54 point out that staff seemed concerned that they frequently did not have the linguistic skills or sufficient understanding of a patient’s cultural background to ‘make them comfortable’. 54 Doctors in Karim et al.’s55 study highlight these issues as being major obstacles and key to the under-referral of ethnic minority patients to palliative care. The majority of the 27 doctors interviewed in this small UK study felt that palliative care services need to be sensitive to religion and culture and that this could not be achieved unless staff from black and Asian communities, fluent in the language spoken by the patient, were present in the workforce. 55

Effective communication between health-care providers and patients is complex. Patients describe having a positive care experience when knowing their needs were listened to and understood. 56 Interpreters can assist in mutual understanding between HCPs and patients and their families; however, this is not without challenges. As in other studies, HCPs in our previous work acknowledged their lack of understanding of the training and quality assurance of professional interpreters and the absence of training for HCPs on working effectively and safely with these essential team members. 41 Using professional interpreters becomes difficult when family members are not in support of this, sometimes because of concerns of confidentiality. When interpreting services are not available or not used, this can result in reduced access to services and not receiving information. There are often concerns about the accuracy and quality of information exchanged with patients, particularly those involving a family member as interpreter,55–58 with HCPs often left questioning if the information iterated to and from the patient has been verbatim. 41

Health literacy and inequalities

Patients’ and their families’ lack of understanding of the concepts used in health care, such as the palliative care approach, can affect care preferences. As an Australian study highlights,48 ethnically diverse communities confused a patient returning home as indicative of the onset of the dying process, in contrast to remaining in hospital, thought to indicate hope for recovery regardless of the illness progression. In addition, having no equivalent term for ‘palliative care’ in many languages has caused challenges in understanding and explaining this concept. 48,59 Equally, the concept of EOLCP can be foreign to some ethnically diverse groups, as one Canadian study exploring the perspectives of the South Asian community highlights:60 EOLCP was often associated with other end-of-life issues, such as organ donation and estate planning. 60

Many migrant communities have experience of health-care systems that are limited and require payments. Understanding of the NHS, hospice services and care homes may be limited and has considerable potential for misperceptions. 23,61 For example, both UK and international studies highlight that, among the Chinese community, lack of knowledge of and exposure to palliative services from their ‘home’ country is attributed to struggles in understanding the concept of palliative care services in their ‘host’ country. 49–51 For some, palliative care services never existed in their country of origin (at least by the time they migrated), and this influences their uptake for this kind of service in their new place of residence. 49 In addition, many are not clear about what palliative care services offer regarding pain control, and misunderstanding and misconceptions of the effects of drugs to manage pain results in fear of developing opioid addiction. 51 It seems that immigrants who are able to speak English have a better understanding of palliative care and palliative care services than others, but, even so, may still be reluctant to use these services, highlighting the role of other factors such as cultural, religious or personal beliefs, which are further explored in the following section. 41

In the UK, navigating the health-care system for patients and families from ethnically diverse communities is associated with level of health illiteracy, characterised by lack of accessible information about illnesses and possible prognoses and available services. 62,63 Evidence, mainly from the USA, documents a disproportionate gap in knowledge about palliative care among minority older adults.

Cultural mores and religious beliefs

Research, predominantly from outside the UK, provides some insights into some of the issues that relate to the nuances of how minoritised culture and religious beliefs may affect discussions, care and outcomes at the end of life. For example, among some African Americans, spiritual and religious beliefs may conflict with the goals of palliative care, and they may mistrust the health-care system because of past injustices in research. 64,65 Cultural mores that may present a barrier to the use of palliative care include an apparent attitude of non-disclosure of terminal illness among some Asian and Hispanic patients in the USA. 66 Cultural norms can significantly influence the perspectives of some South Asians of EOLCP, with some expressing the belief that planning ahead is not necessary because of close family ties, predefined roles within the family and trust in shared decision-making within the family. 60

Other challenges among ethnically diverse communities to a palliative care approach and anticipatory discussions about deterioration include cultural ‘taboos’ and fears of harm; believing that death is more likely to happen, or possibly be hastened, if openly acknowledged, verbalised or discussed; and strongly held ways of living whereby only their god knows the timing of death. 60,67–69 In such cultural and religious contexts, there is a strong desire to remain hopeful and, consequently, avoid discussing subjects such as cancer and end of life. People may avoid talking about the prospect of dying as it is viewed as not only demoralising but also inappropriate, upsetting and harmful. 48,60

Although striving to remain hopeful is not exclusive to families from minoritised ethnic communities, there is undeniably a complex interplay between culture, religion and care in the everyday experience of HCPs in the transition from active treatment to a palliative approach when dealing with patients and families from ethnically diverse communities. 48,70 Faith and religion can play a prominent role in many people’s lives and may become even more important when coping with illness and the end of life. However, the practice of faith and religion, linked perhaps to the philosophy and mores discussed previously, has sometimes been found to be in tension and conflict with medical treatment plans when patients ignore their doctor’s advice in the belief that the moment of death is divinely determined, and this negates discussion about the benefits or harms of treatments. 48

Yet there is also tension within religious philosophy. A report commissioned by the charity Compassion in Dying highlights the hesitancy among Muslims around the extent to which they can or should engage in an EOLCP. A hesitancy that is rooted in notions of divine will or god’s purpose that yields a mindset of ‘what is to happen, will happen’ is in tension with other instructions found in faith that endorse planning ahead, and, in fact, strongly encourage committing to such plans. Recommendations from this report stress that there is considerable support for the notion of EOLCP in theological terms, but little is known about this among health-care services specialising in EOLCP.

The inability to accurately translate terms used and equating the meaning of palliative care with being close to dying prompted some families to request clinicians to consciously refrain from using this term when talking to their ailing loved one in one Australian study48 exploring patient and caregiver perspectives across cultures and linguistic groups, and provider perspectives. Some families reported needing to do some kind of homework to aid their understanding of the subject of palliative care; others preferred to avoid discussions regarding terminal prognoses and planning for end of life altogether; and others recalled an explanation by a clinician, but not in a way they could understand. 48

There is great diversity within ethnically diverse groups, as well as between them. Ethnically diverse patients are indeed diverse, with the existence of ‘micro-cultures’. 71 In a small study (four participants) regarding the views of ethnically diverse patients attending a day-care centre in the UK,71 the participants involved showed a distinct lack of culturally specific needs. Instead, the authors found that ‘acculturation emerged as a strong theme’, and, moreover, that ‘regardless of a particular participant’s cultural group, their needs can be highly individual’. 71 This highlights both the significance of providing person-centred, holistic care and the need to embrace diversity and complexity and work competently in the context of uncertainty.

Our previous work, alongside a wider body of work, has identified that HCPs feel disempowered by the uncertainty that arises because of sociocultural and religious complexity and that staff training needs to respond to this. 41,72 Some cultural groups predominantly share familial responsibility for decision-making, in tension with the emphasis on autonomy and individual choice within UK policy. 23,41,72–76 Some groups predominantly prefer non-disclosure of diagnosis and prognosis, and discussing deterioration and planning for preferences related to dying is, potentially, unacceptable. Our work in cancer highlighted that professionals were concerned about offending or expressing culturally insensitive practices. 43,58,77,78 As a consequence of this uncertainty, professional disempowerment and reticence resulted in inequalities and lower-quality care, with poorer outcomes for patients and families. Patient ethnicity can influence the behaviour of HCPs, resulting in disparities in care. 24,58,79

Considering ethnic diversity in policy

In the UK, contemporary policy is directed at trying to increase the proportions of death that occur at home (or usual place of residence), both because this is seen by the majority of patients and the public as their ‘ideal’ environment in which to die and because cost savings are anticipated once a shift occurs from hospital to community care. 80 There is some evidence that this ‘ideal’ is not met for people from minority ethnic groups, who die at home less often than the ethnic majority in the USA and in Canada. 3,23,81–86 In the UK, it has been found that those of Caribbean origin were less likely to say that caregivers or patients were given sufficient choice about the location of death. 87 There also appears to be little support for Gypsies and Travellers to die at home (which also appears to be their wish). 23,84 It is, however, difficult to compare this evidence of place of death with the preferences for place of death because evidence of such preferences for ethnically diverse groups is not available. 23

Seymour et al. 88 suggest that this policy is largely based on ‘ethnocentric assumptions about the preferences of dying people and their informal caregivers for place of care and also for being somewhat blind to the problems (and household costs) with which older people and their informal carers may be confronted in accessing help and support during a final illness’. 88 In their research comparing findings from two linked studies of white (n = 77) and Chinese (n = 92) older adults living in the UK, in which they sought views about EOLC, they focused on experiences and expectations in relation to the provision of EOLC at home and in hospices. Concerns about dying at home were shared by both groups, and related to the demands on family that may arise from having to manage pain, suffering and the dying body within the domestic space. Among the white elders, these concerns appeared to be based on largely practical considerations, but were expressed by Chinese elders in terms of explanatory cultural beliefs about ‘contamination’ of the domestic home (and, by implication, of the family) by the dying and dead body. 88

In addition, they found that white elders perceived hospices in idealised terms, which resonate with a ‘revivalist’ discourse of the ‘good death’, and would choose this if home were not possible. In marked comparison, for those Chinese elders who had heard of them, hospices were regarded as repositories of ‘inauspicious’ care in which opportunities for achieving an appropriate or good death were limited. 89–91 They instead expressed preferences for the medicalised environment of the hospital and actively rejected death at home, because of the contamination and inauspiciousness this entailed.

Although having family present during death is perceived as a measure of the good quality of end of life, some patients may not want to die at home to avoid imposing on the family and burdening them with caring responsibilities and with having to witness the deterioration and death of a loved one. 49,57,92 Even when there is an expectation to receive care from family members out of familial bonding and personal sense of duty, this may sometimes be complicated by factors such as cultural beliefs that, if a patient is allowed to die at home, they ruin the chances of selling the house in future. 50,93,94 Evidence also suggests that some ethnically diverse patients and their families may require more support with symptom management, decision-making and communication, as they may interpret palliative care specialists’ support as an effort to stop curative treatment and focus on end of life, and hence continue to underuse hospice services. 81,95,96

Some people prefer to care for their loved ones at home, especially if they doubt the competence of the doctor and their ability to make decisions and judgements that fully consider the best interests of the patient, and also to avoid draining family resources in paying for nursing home charges. 72,97 Other studies have found that certain ethnically diverse groups express a strong ‘preference’ for death at home. 98,99 This preference is often unmet for all patients, but even more so for ethnically diverse patients. Koffman and Higginson’s87 survey of the family and friends of deceased first-generation black Caribbean and UK-born white patients with advanced disease found that the greatest single preference for location of death was at home and that twice as many Caribbean as white patients sought this location.

Only one-fifth of all these patients had died in their own home, with 61% dying in hospital, 12% in a hospice and 6% in a residential/nursing home. Although similar proportions of patients in both ethnic groups who wanted to die at home did so, the family members and friends of deceased black Caribbean patients felt that more could have been done to involve both the patient and themselves in decision-making about location of death. This points to a need to improve training in discussing care and treatment choices, including location of death, and a deeper qualitative understanding of the cultural and other factors that may facilitate or prevent home deaths, including the intersectionality of socioeconomic and cultural factors. 87

In Frearson et al.’s99 study exploring preferences for place of care and death among the British Hindu community, participants expressed an overwhelming wish to die at home. One reason for the preference for home was the central role of family members in providing care and sense of filial responsibility ‘with the wish to care being accompanied by a need to be seen to do so’. 99 This view also influences decision-making by professionals; for instance, the doctors in the study by Karim et al. 55 believed that black/minority ethnic families prefer to provide palliative care for ill members themselves. Despite having no empirical basis, doctors believed that sending elders to die in an unknown place and in the hands of unknown people ‘would be indicative of failure on the family’s part and a decision worthy of shame from within the particular ethnic community’. 55 Doctors in this study also believed that the extended family of patients from ethnic minority communities had the ‘resources to cope with this kind of demand’ more adequately than the ‘White community for whom the extended family is close to becoming a thing of the past’. 55

However, although home death was indicated as the ‘ideal’ in the Frearson et al. 99 study, it was also recognised by participants as not feasible for all and that care should ‘only be at home if the family was able to cope’. This study went on to consider the practicalities and the true reality of caring for a relative at home. 99 Similarly, Somerville’s57 study exploring Bangladeshi bereaved carers’ experiences highlights the numerous challenges faced by carers, including the demands and stresses of caring, which can leave carers isolated. These practical concerns are similar to those expressed by white elders in Seymour et al.’s88 study discussed previously, all of which highlight the shift between the ‘ideal’ place of death and the pragmatic choices that determine the actual place of death.

Embracing diversity in end-of-life care planning

The research considered throughout this chapter has highlighted the complexity of undertaking EOLCP in general and the additional complexity of navigating such discussions with ethnically diverse patients and their families when HCPs have limited understanding of the impact cultural mores and religious beliefs have on thinking ahead, deterioration and dying. 24,43,69 Evidence presented in the sections above can be summarised as follows:

Professionals should be sensitive to individual variations in perspectives and avoid stereotyping patients and their families, for example, by assuming a patient would or would not want to be told bad news, or have particular styles of coping or use of denial.[100,101] They should seek, as far as possible, to explore each patient and family’s wishes and attitudes to sharing of information and decision-making as a generic principle.

Reproduced from Kai et al. 58 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 3.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/

The need for consideration of individual needs, to provide ‘person-centred’ holistic care and to avoid cultural assumptions, coupled with the anxieties about cultural competence among HCPs and the consequences of such anxieties, are of great significance in providing EOLC to patients and families from ethnically diverse communities.

An appreciation of general cultural influences, as well as of the diversity of individual preferences, is essential for sensitive and effective EOLCP and to enable patients and families to understand and appraise the options open to them. 102,103 The importance of such an understanding is articulated in formally derived international consensus recommendations from the European Association for Palliative Care. 9 Most participants in this consensus recognised (at least within the context of ethnically ‘other’) that a diversity of preferences exist for how decisions are made and who makes them, but understanding was very limited as to how to work with this when the dominant ethic and duty of care is that of patient autonomy.

Models of decision-making and how this is shared between the patient and the clinician and with a wider stakeholder group are beginning to be more widely explored in the literature. Acculturation to Western Christian medical–ethical frameworks appears to be a dominant factor in the development of autonomous decision-making104 This should, however, be integrated in practice with consideration of a patient’s desire for varying family involvement and their own desired level of self-involvement in decisions, which has been shown to vary within ethnicities, including that of white British. 105 Findings from our previous work suggest that supporting clinicians in how to assess these factors and develop skills in wider ‘stakeholder’ decision-making would be valuable. 41,72,97 In this work, doctors and nurses discussed the interventions that they perceive have improved their confidence, knowledge and skills in these situations. It was clear that training was limited and failed to address the impact of such nuances between and within different communities. This is reiterated in Calanzani et al.’s23 seminal report in which they appraise the evidence from 45 literature reviews to describe the current state of PEOLC provision for ethnically diverse populations living in the UK and in other English-speaking countries.

Envisaged ‘solutions’ for working in such uncertainty and in such emotionally challenging scenarios are often to increase confidence through the provision and assimilation of more factual ‘knowledge’. However, HCP participants in our previous study (which focused on the experiences of HCPs in one aspect of EOLCP: decision-making about resuscitation with ethnically diverse patients and families) sought to access reflective support, sharing of practices with colleagues and learning through simulated scenarios. 41 In addition, our work using Q methodology (a structured way of eliciting and prioritising preferences) to explore the views of ethnically diverse public participants about resuscitation discussions in advanced, terminal illness indicates both a receptiveness (in terms of both desire and acceptability) to engage in the topic of end of life and the value to participants of receiving such information. The actions participants indicated that they would take as a result of the information and the decisions that they would make were diverse and reflective of the intersectionality of their beliefs, culture, experiences, circumstances and other factors. 41,97

The evidence from our own work and from Calanzani et al.’s23 report highlighted the need for further research with ethnically diverse patients and families, exploring how these factors influence end-of-life decision-making to inform evidence-based training. This could, in turn, support HCPs in developing ‘cultural intelligence’ when discussing the value of medical interventions with patients who are at risk of deterioration and dying.

Study justification

The evidence discussed previously, along with that presented in the work of Calanzani et al.,23 points to considerable gaps in knowledge, specifically in the existence of microcultures and in the experiences of, preferences for and goals of care of ethnically diverse patients with advanced illness, and those of their families. 23,71 We also know that ethnically diverse patients are disadvantaged in terms of access to palliative care services, especially those who cannot speak English confidently. 106

Despite UK policy prioritisation of EOLCP, 2015 work by Pollock and Wilson72 (funded by the Health and Social Care Delivery Research programme) found that EOLCP remains generally uncommon and problematic. Although this work added much to the body of knowledge about the real-world practice of EOLCP, it did not include patients or carers from ethnically diverse backgrounds. Nonetheless, Pollock and Wilson’s72 work alluded to the additional complexity perceived by HCPs in EOLCP with ethnically diverse patients and their families.

This evidence, along with emergent findings from our previous work, indicated considerable challenges in this area of practice and the desire from HCPs for evidence-based training. 41 The paucity of evidence about how culture affects the experience and anticipation of death and dying highlights the urgent need for this study. This study contributes to the currently limited knowledge regarding how patients from ethnically diverse backgrounds and their families live with an advanced illness and consider the prospect of deterioration and dying. Using qualitative methodology, this study also makes a substantial contribution to understanding the barriers to and facilitators of EOLCP with ethnically diverse patients. The design employed three approaches to exploring people’s experiences:

-

workstream (WS) 1: longitudinal cases studies with patients, FCGs and HCPs

-

WS2: individual interviews with bereaved family caregivers (BFCGs) who have experienced the loss of someone due to an advanced illness

-

WS3: findings from WSs 1 and 2 discussed with members of the public and professionals via virtual workshops and workbooks.

Aims and research question

The study aims to improve the quality and experience of EOLC for ethnically diverse patients and their families by addressing the research question: what are the barriers to and enablers of ethnically diverse patients, FCGs and HCPs engaging in EOLCP?

Objectives

-

To explore how terminally ill patients from ethnically diverse backgrounds, their FCGs and the HCPs who support them think ahead about deterioration and dying, to explore whether or not and how they engage in EOLCP, and to identify barriers to and enablers of this engagement.

-

To explore the experiences and reflections of BFCGs on EOLC, and the role and value of thinking ahead and of engagement with HCPs in EOLCP.

-

To identify information and training needs to support best practices in EOLCP and to produce an e-learning module with guidance notes available free to NHS staff and hospice providers.

Structure of the report

This chapter has provided a background to the study and considers the policy context in which it is set, alongside evidence available from previous studies. The next chapter outlines the design and methods of the study before subsequent chapters present a summary of PPI, followed by participant demographics. Findings are then presented and discussed for WSs 1 and 2. The response to these findings as introduced in WS3 are then deliberated. The conclusion provides a summary of the findings and their significance, and considers their implications for the development of policy and practice. This also includes implications of, and recommendations arising from, the study. The final chapter discusses outputs from the project, early dissemination and impact.

Chapter 2 Methodology

Study design

This was an exploratory study, which was carried out within a constructivist qualitative tradition of research. Qualitative research is concerned with eliciting how participants understand and experience the world through the cultural filters internalised through developmental processes of socialisation and through interaction with others in real-world situations and contexts. 107 Constructivism seeks to ‘see what happens’ in real-world settings and to illuminate the relevance of social context and processes for resilience, self-reliance, and the opportunities and constraints that govern access to resources for individuals and connected groups. This research approach aims to elicit and understand how research participants construct, negotiate and share meanings around the phenomenon of interest. In this study the phenomenon is deterioration, dying and medical treatments at the end of life.

The study was designed to undertake an in-depth exploration of the diversity and complexity of experience within a limited number of cases. There were three WSs:

-

WS1: longitudinal patient-centred case studies comprising an ethnically diverse patient with advanced illness, one or two of their FCGs and a HCP nominated by the patient

-

WS2: single interviews with bereaved FCGs who have experienced the loss of an ethnically diverse family member due to advanced illness

-

WS3: public and professional stakeholder virtual workshops to discuss fictionalised, EOLCP scenarios, derived from real-life experiences reported by participants.

Qualitative methods of data collection and analysis are particularly suitable for use when little is known about the issue and in the study of sensitive and complex topics. Semistructured interviews enable the exploration of key topics, while concurrently allowing the flexibility to follow up on new issues of interest and importance. 107–109 Recruiting severely ill patients to take part in research projects presents challenges, which required flexibility and sensitivity in engaging FCGs and patients in a way and at a level that they could comfortably accommodate. We adopted the case study approach because the issues are socially and culturally complex. Case studies aim to explore complexity through an intensive, holistic focus on the components of each case, rather than obtain limited data from a larger number of single types of unconnected respondents. 110–112 Case studies are suited to the investigation of complex real-world situations in which a diversity of perspectives are at play. 113,114 Engaging different participants within each case across longitudinal follow-up enables the comparison of different perspectives and the exploration of processes and experiences emerging over time, rather than the cross-sectional snapshot provided by one-off interviews. Interview data were supplemented when possible by additional data from a focused review of medical records. Each case was followed up, when possible, for a period of approximately 6 months.

Setting/context

The geographical setting for the study was the East Midlands across Leicester, Leicestershire, Nottingham and Nottinghamshire. Throughout the report, we shall refer to the settings as ‘Leicester’ and ‘Nottingham’. Patient participants were under the care of services in these areas and health professionals for WS1 and WS2 worked in these areas. FCGs for WS1 and WS2 did not have to be resident in these areas. Participants for WS3 were largely from these areas, but some key stakeholders worked elsewhere in the midlands or UK.

All research activity took place in this geographical area, and Leicestershire and Rutland Organisation for the Relief of Suffering (LOROS) Hospice was the single recruiting research site. For WS1 and WS2, interviews with FCGs who were not resident in these areas took place in a venue within a reasonable distance of LOROS Hospice or, after a protocol amendment in relation to COVID-19, virtually, as highlighted in the following section.

Ethics and governance approval

NHS Research Ethics Committee approval was obtained in December 2018 (reference number 18/WM/0310), and then two substantial amendments followed. Substantial amendment 1 (1 May 2019): we did not give copies of audio-recorded consent to the participants. This related to potential difficulties with participants having access to appropriate technology to listen to it. When interpreters were used, we informed participants that consent would be audio-recorded. The recording was then retained as source data. Paper copies of the consent forms were filed and a copy given to the participant. For practical and resource reasons, copies of audio-recordings were not distributed to participants. To enable greater flexibility for patient participation, we increased the time of maximum involvement from 4 months to 6 months, to enable our engagement with them to be at a slower pace should patients need this.

In the light of government and NIHR guidance on COVID-19, substantial amendment 2 (9 March 2020) was made to the study protocol to ensure the safe delivery of the remainder of the study. The first priority was the safety of participants, many of whom were very vulnerable to the virus. The second consideration was to minimise the burden on health services and professionals. In WS1, we completed the remaining interviews for existing participants by telephone, and also amended the timeline for these in the protocol from 6 months to 6–9 months. We recognised that, in these challenging times, it was not possible for us to review all medical records as originally planned, so we amended the relevant text in the protocol to capture this. In WS2, we obtained consent by telephone for the remaining participants and completed the single interview for these participants by telephone. In WS3, we amended the protocol to allow the workshops to be conducted face to face, via webinar or by individually completing a workbook via e-mail.

Although COVID-19 did not unduly affect the scientific quality of the project, it affected the progress of analysis and development of WS3. The chief investigator (CI) was redeployed clinically for 5 months from April to the end of August 2020. This had a knock-on effect on the timeline for study outputs. Hence, a case was put forward, and subsequently granted, for a 5-month costed extension.

As a research team, we believe that not offering vulnerable people the choice to take part in research because of assumptions made about their experiences and preferences is inequitable and exclusionary. 111–114 We also recognise that any research engaging with severely ill patients and bereaved FCGs presents challenges and needs to be broached with sensitivity and flexibility throughout the research process.

Prior to the decision to take part, participants were asked to contemplate how they would feel about deliberating their experience of illness and dying. They were assured that participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study at any time. To further mitigate the potential risks for participants and researchers, an information sheet with contacts for further information or support was provided, and a follow-up telephone call with the study CI, if desired, was also offered. We developed a ‘pyramid of support needs’ to manage distress within the study, which comprised assessment by the interviewer, resulting in (1) no support required, (2) signposting to a general practitioner (GP), (3) written information provided about local third-sector organisations or (4) formal referral initiated for counselling (via study CI). Patients’ GPs were also informed that the patients were participants in this study to enable the GP to document this in their medical records as evidence of participation.

Eligibility

Workstream 1: longitudinal patient case studies

Patients were aged ≥ 18 years and from diverse ethnic backgrounds. This included patients from ethnic minority groups (i.e. not white British) and white minorities, such as European, Gypsy, Roma and Irish Traveller groups, who were identified by their treating health professional as being at risk of deteriorating and dying in the next year (note that the participant information leaflet addressed the question of why a patient has been identified using the phrase ‘because you are living with a serious illness that may get worse over the next year’). 1 Patients needed to agree to the use of an interpreter to translate on their behalf, if required.

Family caregivers were aged ≥ 18 years, had capacity to consent to take part and were nominated by the patient participant. If a patient lacked capacity to consent, the FCG who was closely involved in the care of the patient was nominated by the consultee. See Recruitment, Workstream 1: longitudinal patient case studies, for further details.

A HCP was nominated by each patient participant as currently significant to their care. They may have been drawn from a wide range of staff (including doctors, nurses and health-care assistants) in services within the community and in secondary care. For patients who lacked capacity, the consultee was asked to nominate the HCP.

Workstream 2: experiences of bereaved relatives

Bereaved FCGs were aged ≥ 18 years and had cared for a close adult family member from a diverse ethnic background. This included people from ethnic minority groups (except the white British) and white minorities, such as European, Gypsy, Roma and Irish Traveller groups, who had died within the preceding 3–12 months from a progressive illness.

Workstream 3: public and professional virtual workshops

The potential participants included the following:

-

public stakeholders, including faith and community figureheads, across Leicester and Nottingham

-

commissioners of health, social care and health education across the East Midlands

-

health-care educators in nursing and medical schools across acute and community trusts and hospices

-

health and social care professionals

-

academics focusing on end-of life issues.

Sample size and structure

There are no hard and fast criteria for establishing the sample size required in qualitative research. 115 Rather, this is determined by the circumstances and context of each study. Morse116 and Malterud et al. 110 propose that the number of participants required depends on the range and depth of information collected about each participant or case (information power): the greater this is, the fewer participants required. A qualitative sample size of between 20 and 40 participants is likely to include the majority of views and experiences to be found within the target population and is in line with previous longitudinal studies in EOLC adopting a similar design and method. 72,106,115,117

Purposive sampling, which involves participant selection being guided by strategic choices regarding the individuals who or groups that can yield the most valuable and relevant information for the study, is a strategy that can optimise the depth and breadth of data in a sample and reduce the sample size required to achieve thematic saturation (i.e. when no additional themes about the research topic are emerging from the participant interviews). Stake113 cautions against increasing the number of cases much beyond 15 because the number of qualitative data generated by a larger number of cases will become unmanageable. However, a guiding principle of qualitative research is that the nature and adequacy of the final sample must be kept continuously under review, and adjustments made if necessary, to enable the study to achieve its aims. 110 Above all, it is the relevance of the participants and the quality of the data that are important, rather than the number of participants per se.

In WS1 and WS2, we purposively sampled participants across three elements of diversity:

-

religious/faith group

-

ethnic backgrounds (ethnically diverse groups)

-

disease/illness group.

Findings from our previous work suggested that cultural–religious customs and mores are one of the key factors that increases the complexity of navigating EOLC and achieving patient preferences. 41,97 It was our intention that we achieve the greatest heterogeneity of religion/faith and ethnicity in the samples of WS1 and WS2.

This concern with cultural–religious diversity was complemented by selection criteria for recruitment across illness contexts and we also purposively sampled to achieve heterogeneity across a number of disease groups (including cancer, frailty in old age, and heart and renal disease).

In addition, demographic data were recorded, including gender, age and migration generation, and we aimed to include a diversity of these characteristics in the sample.

A sampling frame was utilised to target recruitment to achieve these purposive sampling aims and to construct a matrix that may be important for attribution of themes/subthemes and in our search for examples of variance within the data. The nationally agreed guidelines to characterise self-reported ethnicity into a set of 16 codes were used. 118

Recruitment

Taking on board best practice in recruitment for research involving ethnically diverse participants, an extensive programme of awareness-raising about the project took place within community groups and organisations. 119,120 This work was informed by the networks and experiences of our PPI lead (IM) and PPI consultees [named public, carers and bereaved relatives (PCBR) research consultees] and of the co-applicants and advisors to the project. The work involved communicating the project objectives and the opportunity to be involved in research through social and traditional media; the placement of flyers in organisations and services including, but not limited to, general practices, hospice services, patient and carer support groups, community and faith groups, and libraries; and attendance at meetings and events of patient and carer support groups and community and faith groups by members of the project team.

Workstream 1: longitudinal patient case studies

The Clinical Research Network East Midlands (in which co-applicant Simon Royal and the CI have clinical leadership roles); Clinical Commissioning Group research networks and the well-established clinical and research links of the CI and co-applicants Simon Royal, Simon Conroy and Alison Pilsworth; and collaborators including specialist nurses and research nurses within participant identification centre site services were engaged to promote awareness among HCPs of the study, to promote understanding of the criteria of case eligibility and to seek identification of patients within the participant identification centre sites, which were as follows:

-

five general practices with a substantial population of ethnically diverse patients and the linked community nursing services

-

community and primary health-care services that support a population with particularly harder-to-reach ethnically diverse communities (e.g. Somali)

-

palliative care services in community, hospice and hospital sectors

-

community and secondary care services for heart failure, elderly and psychogeriatric care, renal medicine and oncology.

In total we engaged with 110 community groups in Leicester and 67 community groups in Nottingham and attended 15 community events. Our engagement with a variety of community groups provided a platform to discuss the study and how it aimed to explore experiences and improve EOLC, thus achieving a high level of community engagement in the study. In small part this was about widening recruitment; in large part it was about underpinning dissemination of findings in the future and maximising the potential for impact on patient and family care, and outcomes.

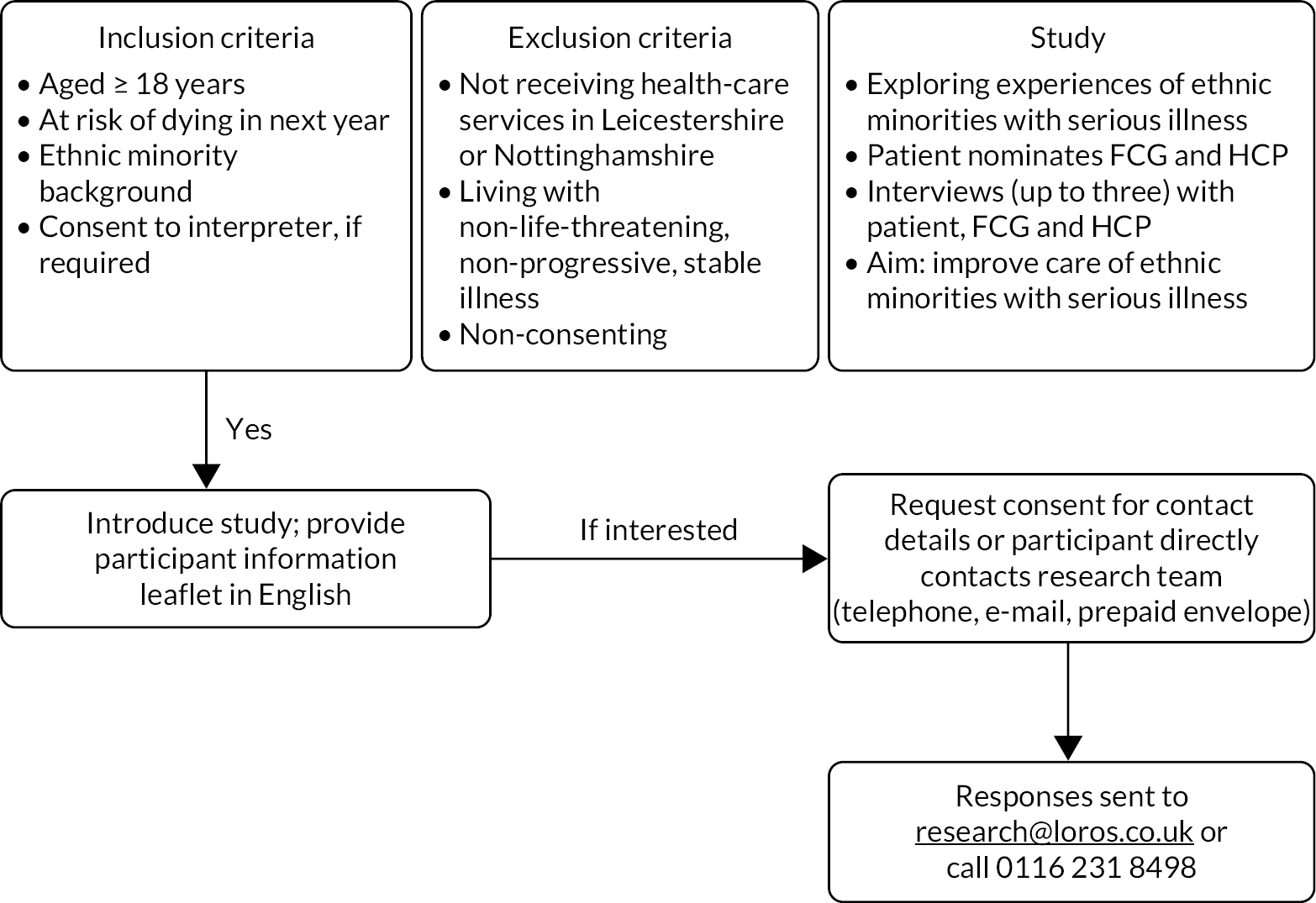

We liaised and worked with research and EOLC leads, practice managers, nurses and other workers and primary care patient participation groups to promote understanding of the study. Presentations were delivered by the CI, the principal investigator (PI), a research fellow and a research associate at a number of meetings, including those of cardiology and renal teams, general practices and local hospices within the area, and at a number of community events in which the recruitment process was discussed (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Workstream 1: patient recruitment flow chart.

Health-care professionals were asked to identify eligible patients through a variety of means, depending on their role and the systems in place within their service. HCPs were provided with the Supportive and Palliative Care Indicators Tool (SPICT™, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh, UK)121 as a means of identifying patients at risk of deteriorating and dying with one or more advanced, progressive and life-threatening conditions and the Gold Standards Framework ‘surprise’ question: ‘would you be surprised if this patient were to die in the next 12 months?’. 80,122

A HCP known to the patient was the first to approach a patient and provide them with the participant information leaflets for patients and FCGs. Patients, or someone acting on their behalf, then contacted the research team directly about their interest in the study by telephone, e-mail or returning a reply slip in a freepost envelope given to them by the HCP. Alternatively, if they preferred, they could give permission to the HCP who first approached them to pass their contact details to the research team, requesting that the team contact them.

If a patient did not speak English, the HCP would direct the patient (or FCG, if they were interpreting on their behalf) to the appropriate information video on the LOROS project website and/or ask if a researcher with shared language skills may contact them.

If potential patient participants lacked the capacity to give any or full consent owing to the nature of their illness (e.g. dementia), the study was introduced to them and to their FCG by a known HCP. If the FCG considered that the patient would want to consider involvement, then information about the study was shared with both parties in the ways described previously. For such patients, their involvement could be limited to permission to review their medical records and to approach a FCG and a HCP to seek their involvement. However, patients were not excluded from contributing to the study through interviews if the consultee considered that this would be appropriate and acceptable.

The research team contacted patients, or their consultees, who indicated that they were interested in the study and provided them with full participant information, including in audio/video format in their first language if needed. This was available in Gujarati and Hindi translations via the LOROS website link to the study. Audio-/video-recorded methods of facilitating informed consent are regarded as acceptable alternatives to written consent for study populations in which literacy skills are variable. 123

Workstream 2: interviews with bereaved family caregivers

Bereaved FCGs of ethnically diverse patients deceased from an advanced illness in the preceding 3–12 months were identified by HCPs in the services described in WS1. The HCPs identified and then contacted the BFCGs if they met the inclusion criteria in the first instance in the same way as described in WS1. BFCGs were also identified through the community networks of our PPI lead; through networks developed in our previous work, which included community groups and organisations; and through the awareness-raising work described previously. We also allowed participants to come forward themselves to engage in the research, provided they met the recruitment criteria. In such instances, potential participants could directly contact the research team via contact information provided in the study flyer. A member of the research team would then contact them and provide them with the study information sheet. Participants were purposely sampled in a way similar to that described in WS1. The recruitment and consenting of participants who did not speak English was facilitated in the same way as described in WS1.

Workstreams 1 and 2: consent

The process for obtaining participant-informed consent at the outset was undertaken with Research Ethics Committee guidance, and in accordance with good clinical practice and General Data Protection Regulation (2018)124 regulatory requirements.

The participants in WS1 and WS2 were given a copy of the original signed and dated consent form. The original signed and dated consent form was retained in the trial master file.

For patients who lacked capacity, a consultee was asked to complete the consultee declaration form in accordance with the process of the Mental Capacity Act 20052 and the Health Research Authority guidance.

The decision regarding participation in the study was entirely voluntary. The researcher emphasised to all participants that consent regarding study participation could be withdrawn at any time without penalty, without affecting the quality or quantity of their future medical care, and without loss of benefits to which the participant was otherwise entitled.

-

Written consent was taken.

-

If the participant’s first language was a language other than English, consent was taken verbally via a digital recorder, as well as the participant completing a written consent form in English. The interpreter was also asked to sign the written consent form under ‘witness signature’.

-

Informed consent took place at least 24 hours after the participant had been given the full participant information, or as long as they required to decide.

Consent from patients and FCGs (WS1) and BFCGS (WS2) was undertaken face to face, and via a professional interpreter accompanying the researcher when needed. Patients were seen in the LOROS Hospice, in their own home or at a suitable location of their choice. For those individuals thought not to have capacity to give fully informed consent, we used the provisions of the Mental Capacity Act 20052 and the consultee provided information regarding the patient’s wishes about participation in research.

For HCPs, consent was taken immediately before the interview. For telephone interviews, consent was taken verbally via a digital recorder and consent forms were sent to the HCP and they signed and sent the original back to the researcher by post, fax or e-mail. Further details of the consent process are detailed in Ethics and governance approval.

Data collection

Case studies: workstream 1

Longitudinal case studies comprised sequential interviews over a period of up to 9 months with a patient, FCGs and a HCP nominated by the patient. Participants took part in a semistructured, audio-recorded interview arranged at their convenience. Interviews with the patient and FCG participants were mostly face to face, but, post COVID-19, some were via telephone. If a patient died during the follow-up period, a bereavement interview was requested with each FCG at a minimum of 8 weeks after the death. When possible a review of each patient’s medical records was also undertaken.

We intended to be as inclusive as possible and each case study was explored on its own terms. It is not necessary for case studies to conform to a ‘standard’ composition and patients were given flexibility and options in how they wanted to be part of the study. Consequently, the data set includes the following:

-

patients who lacked FCGs or who were unwilling/unable to nominate specific FCGs or a HCP

-

patients who nominated more than one FCG to take part in their case study.

In some case studies, the greater part of the interview data were drawn from interviews with FCGs and HCPs. This occurred in the following situations:

-

Patients did not wish to participate in some or all interviews, but were willing for their nominated FCG(s) and HCP to do so and to have their notes reviewed.

-

Patients lacked capacity to give full consent from the start (e.g. patients with dementia or a brain tumour).

The number of interviews conducted with each participant was determined by the circumstances of each case study. A minimum of two interviews was needed for each case study. A maximum of two follow-up interviews over 6–9 months were undertaken with each patient and FCG. Interviews were with patients and FCGs separately, jointly or a combination, according to participant preferences and convenience.

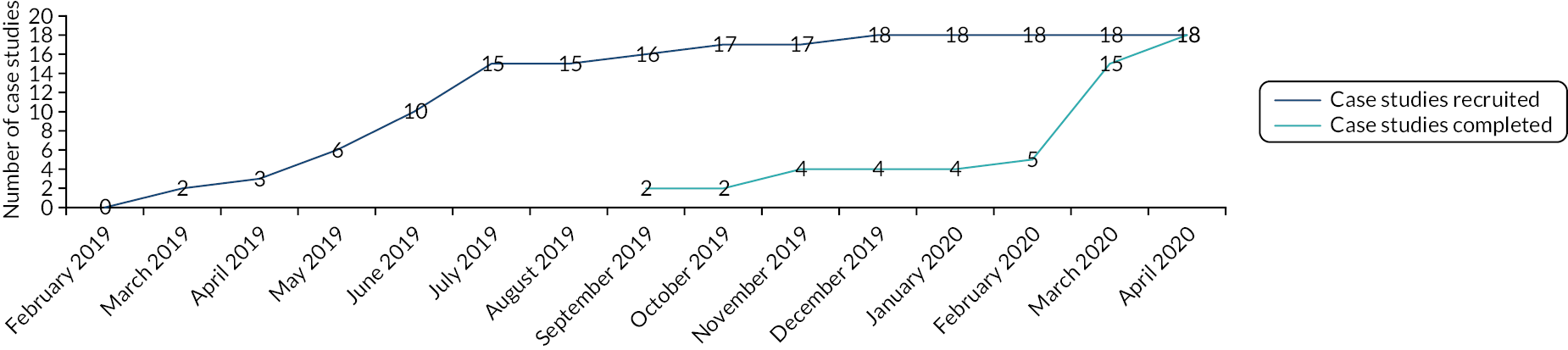

A nominated HCP was invited to take part in at least one interview, and, at most, two interviews, to discuss their involvement in the case (see Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Patient case study composition.

Experienced researchers conducted all interviews. The same researcher conducted all the interviews with each participant in the patient’s case study.

The content discussed in each interview developed over time, but, in general, interviews with patients and FCGs included exploration of the following themes:

-

experience of living with serious illness

-

understanding of the illness and the prognosis

-

goals and values with regard to their future care

-

anticipation of and thinking about the future, about decision-making and treatment preferences, and the significant factors influencing these

-

preferences in how such decisions are made

-

expectations and experiences of professional support and communication about deterioration, EOLC and EOLCP.

We were mindful that the experience of taking part in the interviews may have had an influence on the individuals. 125 Participation in research has the potential to change the nature of the patient and their family’s way of living and coping with their illness and their future, and this was to be incorporated as a topic in the interviews. The potential impact would be beneficial in that the patient/carer may communicate more effectively with care providers. The listening skills of the researcher and the facilitation of reflection and discussion may potentially change things for the participant.

In subsequent interviews, we asked the following questions:

-

How are things?

-

What’s changed in the illness?

-

Have they been thinking about the future?

-

Have they had any conversations with family/HCPs about their illness/wishes and future death (if the patient brings this into the conversation)?

-

Do they think that they have done anything differently as a result of having these conversations/being part of the study?

Such actions were explored as an outcome of the research; importantly, such observations may provide information about potential facilitators of EOLCP, as discussed in the findings and discussion in Chapter 5.

The interview with HCPs also included the following themes:

-

their experience of providing care and support for the patient and family

-

barriers to and enablers of their care of the patient and family in:

-

understanding the illness and prognosis

-

thinking about the future

-

decision-making

-

EOLCP.

-

Health-care professionals were also asked for their assessment of whether or not they felt that being part of this study (either they themselves or the patient or FCG) had an impact on their relationship with the patient/carer or any other research-related outcomes. This will be further discussed in Chapter 5.

Medical record review

Patients were asked to give permission for access to relevant parts of their medical records and related documents recording future care preferences.

At the end of patient involvement in the study (after 6–9 months or at death), when possible, the medical records, including nursing and allied health professional records, were sourced. These included palliative care services, primary care, community services and hospital services. The records were scrutinised for data concerning the following:

-

discussions and information-sharing about prognosis, deterioration, dying, EOLC and EOLCP

-

records relevant to recording patient views and wishes, and EOLCP, including advance care plan and DNACPR documentation

-

preferences regarding place of death.

Data from electronic and paper case notes were extracted verbatim and entered into the electronic case report form for subsequent analysis. The date, place of discussion and role of the HCP were noted for each data extracted. The researcher also added an explanation of the circumstances of the discussion to provide context for the narrative.

Completed case report forms were incorporated within the project database and form part of the data set relating to each case. This is discussed further in Chapter 5.

Workstream 2: data collection

Interviews with recently bereaved FCGs of ethnically diverse patients who died following a period of advanced disease and deterioration were conducted, either face to face or by telephone, by experienced researchers in a participant’s primary language (using translation strategies described in WS1). The interviews explored participants’ perspectives of the following:

-

living with serious illness and EOLC

-

thinking ahead about deterioration and dying

-

information-sharing, communication and decision-making in illness deterioration with the patient, family members and HCPs involved in providing care

-

the role and value of EOLCP

-

the role of the HCP in helping patients and families prepare for deterioration and dying.

Interpreters and transcription of interviews

Our research team have considerable language skills to conduct interviews in the language preferred by a participant, and one of the BFCG interviews was conducted by the bilingual PI (ZI) in Punjabi. Zoebia Islam translated the audio-recorded interview into an English-recorded version before a professional transcriber transcribed the interview. This method has previously been employed by Zoebia Islam. 126 Professional interpreters were used for patient participants in four of the case studies.

There is limited guidance available for how to appropriately brief and debrief interpreters before/after each interview. Therefore, the research team developed its own to ensure that the interpreters felt suitably prepared for the types of questions that would be posed and the sensitive nature of these. Zoebia Islam also checked that each interpreter was able to pose the questions and obtain responses in debrief meetings, especially when there may not have been any literal translations for certain words. The debrief meeting also added further explanation and understanding to the data collected. This was particularly pertinent in one case for which the interpreter was able to explain the reasoning behind certain cultural beliefs as they held the same beliefs as the participant.

All interviews were audio-recorded. Interviews in English were transcribed verbatim. Interviews in other languages recorded Zoebia Islam asking the question in English and the interpreter then repeating this in the participant’s first language. After the participant responded in their first language, the interpreter would then repeat the response in English. The English parts of the audio-recording were transcribed verbatim. Again, this method has previously been employed by Zoebia Islam. 126

All transcripts were checked for accuracy against the audio file and anonymised. Turns of phrase, idioms and metaphors were sometimes complex to translate and a note was made on the transcript of literal translation, as well as the meaning constructed by the translation during the interviews conducted by Zoebia Islam. These notes were an important aspect of quality assurance and data accuracy.

Workstream 3: public and professional virtual workshops

Workstream 3 involved conducting virtual stakeholder workshops, with participants joining a virtual workshop or participants completing a workbook. Based on the findings from WS1 and WS2, we developed topic guides for workshops and workbooks. These had commonalities, but also included materials that were specific to each of the different participant groups; they iteratively evolved during the course of the workshops. Stakeholders were categorised as members of the public from diverse ethnic backgrounds (lay), community and faith leaders, academics, educators or HCPs.

Workstream 3: sampling and recruitment

For WS3, we purposively recruited and sampled across the range of stakeholders. The recruitment of stakeholder participants was via a process of snowballing. The study team and all collaborators, including members of the PCBR group, identified potential participants via local small-world networks. Study flyers and e-mails were circulated. Through this process, > 140 potential participants were contacted. Potential participants were contacted by e-mail, were sent a participant information leaflet and reply slip, and were offered the opportunity to attend a workshop or compete a workbook in their own time.

Workstream 3: data collection

Based on the findings from WS1 and WS2, eight fictionalised stories were developed for use in the workshops. Each of the stories highlighted key themes identified in WS1 and WS2. A topic guide for workshops and workbooks for those unable to attend workshops was drafted for each of the different stakeholder groups. These draft stories, topic guides and accompanying workbooks were piloted with the PPI lead (IM) and members of the PCBR group, and were refined based on their comments and after further discussion within the core research team. The HCP topic guide and accompanying stories were also piloted with professionals, with subsequent refinement.

The workbooks and topic guides had some commonalities; for instance, all participants were asked to identify challenges within each story and best practice for HCPs in supporting patients in EOLC discussions and planning, and to comment on the implication of these best practices for training and for service delivery. Key questions were as follows: what are the ‘generic’ issues? Are there any specific ethnically diverse issues? How do ethnically diverse backgrounds overlay/increase complexity of the generic issues? How do professionals make ‘best-interests’ decisions in the cross-cultural context?

Each stakeholder workshop also included material that was tailored to each of the different groups and that iteratively evolved during the course of the workshops. The stories and the key themes highlighted in each will be further discussed in Chapter 6 and are presented in Appendix 1.