Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number NIHR133641. The contractual start date was in November 2020. The final report began editorial review in June 2022 and was accepted for publication in October 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Appleby et al. This work was produced by Appleby et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Appleby et al.

Chapter 1 Context

Background

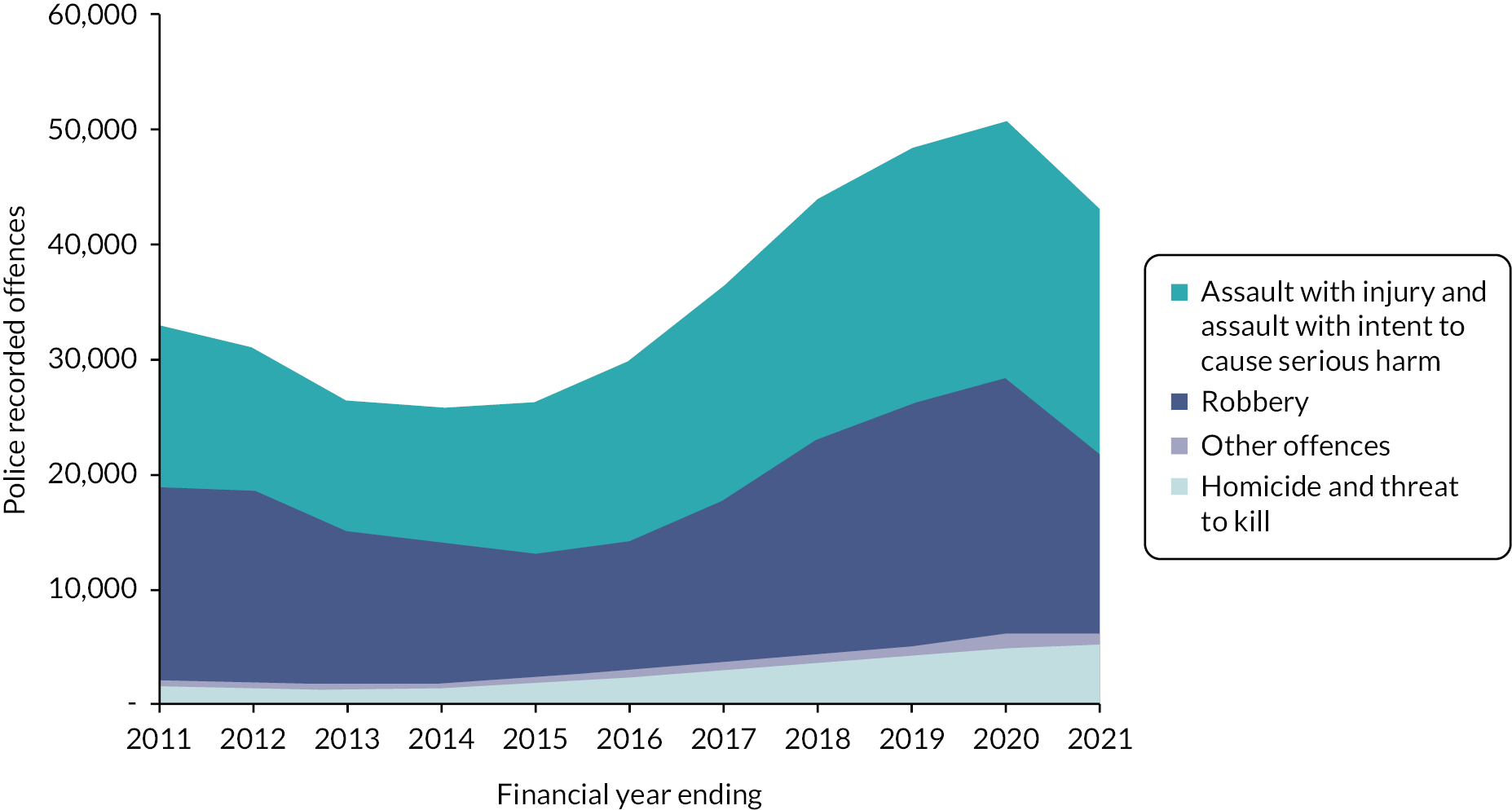

There are rising levels of knife crime and other serious injuries among young people in London and elsewhere in the UK. The Office for National Statistics1 showed that, excluding homicides and threats to kill, figures for violence-related crime offences involving a knife or sharp object rose by 46% to 45,863 offences between 2010 and 2020 in England and Wales (Figure 1). The drop in offences between April 2020 and March 2021 is almost certainly related to COVID-19 and, in particular, measures introduced to combat the pandemic such as lockdowns and school closures.

FIGURE 1.

Number of police recorded offences involving a knife or sharp instrument, year ending March 2011 to year ending March 2020: England and Wales.

Assault with injury and assault with intent to cause serious harm rose by 58% between 2010 and 2021. Meanwhile, the number of hospital episodes with a classification of assault by a sharp object (including, but not limited to, knives) has fluctuated over the past 10 years, falling between 2010/11 and 2014/15, then rising to 2018/19 and dipping in 2019/20 and 2020/21 (Figure 2). 2 As with violent offences, the dip in 2020/21 is almost certainly associated with COVID-19 and measures taken to deal with the pandemic.

FIGURE 2.

Finished consultant episodes for assault by sharp instrument (clinical code X99 in ICD-10): England 2010/11 to 2020/21.

In addition, assault-injured young people are at significant risk of repeat injury. 3 The rate of repeat visits to the emergency department (ED) for violence-related injuries may be as high as 44%, and the risk of recurrent injury may be 80 times that of ‘unexposed’ individuals. 4,5

When assessed in the ED, the majority of injured young people and their parents believe that their injuries were preventable, and over one-third also believe that a similar violence-related injury is likely to occur in the future. 3 Moreover, youth assault injuries are often related to repeated disagreements and retaliatory behaviour that fuels repeated violence. 6 Interrupting this cycle of reactive decision-making has the potential to significantly reduce the burden of injury to young people in the UK.

The causes of these recent trends in violent assaults are multiple and varied and include factors related to deprivation and childhood poverty,7,8 and suggest multi-agency approaches to tackle the problem. Scotland, for example, has pioneered a public health approach to violence as advocated by the World Health Organization,8 including knife crime. 9 This has included educational programmes, multi-agency working and interventions such as the Navigator programme based in EDs and designed to support people who have suffered injury from violence. 10

As we discuss in Chapter 3, there is a literature base going back to the late 1990s and early 2000s describing violence prevention strategies that target vulnerable younger people and aim to reduce physical and emotional harm from peer violence. 6,11,12 ED youth violence prevention programmes have been studied more extensively in the United States than in the UK, including using randomised controlled trial (RCT) and comparative study designs. These programmes vary in their implementation and approach, and may be supported by specialist youth workers, social workers, community mentors and wider interdisciplinary teams of experts. There is also a literature about ‘brief interventions’,13 which are also delivered in emergency care settings and involve screening young people for safety risks and providing structured, short-term support. Common to all these interventions is engaging with a young person in an urgent care hospital setting and trying to reduce that patient’s exposure to harm in the community by encouraging positive behaviour change following discharge.

Research suggests that injuries serious enough to require medical intervention may make young people and their parents uniquely susceptible to behavioural intervention. 3 As Wortley and Hagell (p. 6)14 observe, ‘The incident bringing the young person to the ED may provide a hook for change’. Consequently, ED-based interventions that provide a ‘teachable moment’ offer a unique opportunity to identify and reach young victims of violence, inform individuals of the benefits of lifestyle changes and link them with supportive treatment programmes and agencies that can function in their daily life beyond the hospital, such as in education. However, as we discuss in this report, the evidence base about the implementation and impact of these programmes in the UK health system is still small (albeit growing) because these programmes are relatively new to the NHS.

Youth violence intervention programmes in the UK

Youth violence intervention programmes (YVIPs) and, in particular, those based in EDs, are part of a broader strategy and policies to tackle violence in general at national and local levels and involving many agencies, including local authorities, the police, the NHS and third-sector organisations. For example, in London, the Mayor’s Office set up the Violence Reduction Unit15 in 2019 with a 10-point plan16 that includes reducing the prevalence and impact of violence through a variety of interventions; notably, a public health approach, and involving NHS organisations and others such as specialist youth worker groups. As part of this approach, the NHS in London established a violence reduction clinical network in 2019,17 part of whose aim is to define best practice standards for in-hospital violence reduction services currently embedded in EDs.

Out of a total of 38 such services across England, Wales and Scotland, currently across London, 15 trusts have ED-embedded YVIPs involving a number of organisations providing such services in partnership with the NHS18 (Table 1).

| Trust | Service provider |

|---|---|

| King’s College Hospital | Redthread |

| St George’s Hospital | |

| St Mary’s Hospital | |

| Homerton University Hospital | |

| Croydon University Hospital | |

| University Hospital Lewisham | |

| Queen Elizabeth Hospital, Woolwich | |

| University College London Hospital | |

| Royal London Hospital | St Giles |

| Newham Hospital | |

| Northwick Park Hospital | |

| Whittington Hospital | |

| Whipps Cross Hospital | |

| North Middlesex University Hospital | Oasis |

| St Thomas’ Hospital |

Redthread

One provider – Redthread – currently operates in eight hospitals in London and five hospitals in the Midlands. Redthread is a charity set up in 1995 with the aim of involving young people in community activities. It developed interventions to improve young people’s access to health care, originally in general practices and, more recently, in hospitals. Its YVIP was designed to support young victims of violence. 19 The programmes embed trauma-informed, crisis intervention specialist youth workers into existing health systems, capitalising on ‘teachable moments’ to engage young people and encourage positive change (Box 1).

As the Behavioural Insights Team noted in their 2020 report20 for the London Violence Reduction Unit, there are currently hundreds of violence prevention interventions and approaches (not just those based in the NHS) being delivered across London, of which the vast majority are not being rigorously evaluated. This is reflected in the relative paucity of studies and economic evaluations of YVIPs and limited knowledge about their implementation processes and mechanisms, leading to repeated recommendations for further research and evaluation. Prior attempts to demonstrate the efficacy of ED-based programmes have also been underpowered and, although promising, results have been largely equivocal. 5

With the opening of the Redthread service at University College London Hospital (UCLH) and in consultation with Redthread and UCLH clinical colleagues, an evaluation of the service as part of the work of the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Rapid Service Evaluation Team (RSET) was originally planned and scoped in 2019/20 with a start date in April 2020. However, the impact of COVID-19 on services required a delay in some aspects of the evaluation (although some desk-based work was possible), and a final protocol was published in May 2021 with the evaluation planned for one year. 21

A team of Redthread’s specialist crisis intervention youth workers is embedded in the ED at the participating hospital.

-

The team aims to meet every young person aged between 11 and 24 years who attends the ED as a victim of violence, assault or exploitation, or where there are concerns around undisclosed vulnerabilities.

-

The team uses the ‘teachable moment’ of arriving at hospital as a foundation from which to build a beneficial, trusting relationship with young people.

-

The team completes safety planning and risk assessments – identifying risk indicators and mapping personal and professional support networks for each young person.

-

The team creates a bespoke package of support for each young person according to their needs and goals, prioritising the building and scaffolding of robust professional networks. They:

-

Support (re-)engagement with professional agencies for young people who are known to statutory services and already engage.

-

Advocate on behalf of young people and co-ordinate networks of professionals across disciplines and locations.

-

Support other agencies and scaffold key professional relationships.

-

Make ‘relational referrals’ to new key worker, inviting professionals into the hospital or accompanying young people to initial meetings – for young people who do not have any current input from statutory agencies.

-

Complete intensive casework with young people, including goal setting for the future or discussions around self-esteem, safety or healthy relationships.

-

-

Supports and trains medical staff and other professionals to increase their confidence in working with young people and identifying those who may be at risk.

Study aims and research questions

Using quantitative and qualitative research methods, the overall aim of the study for both phases of the evaluation was to evaluate the implementation and local impact of the Redthread intervention at UCLH, including a cost-effectiveness analysis (CEA) of the intervention, and identify wider lessons and insights for similar initiatives drawing on published literature and the analysis of secondary data. The main objectives were as follows:

-

To conduct a scoping review of peer-reviewed evidence and grey literature about hospital-based violent crime interventions that focus on young people and behaviour change, identifying lessons for researchers, health professionals and policy makers.

-

To review and summarise existing and current evaluation(s) of Redthread interventions/services, in particular evaluation methods and main findings to identify lessons for Redthread, evaluators and NHS trusts.

-

To evaluate processes of local implementation and capture perceptions of UCLH staff and relevant local stakeholders concerning the intervention and its impact.

-

To assess the feasibility of using routine secondary care data such as national Hospital Episode Statistics (HES), local UCLH records to evaluate the impact of Redthread intervention through the comparison of appropriate control and intervention groups.

-

To conduct a CEA of the Redthread intervention at UCLH from the perspective of the NHS and personal social services.

-

To draw conclusions about the types of evaluation approaches and methodological designs that appear well suited and feasible for evaluations of the Redthread service and similar youth-based interventions in the NHS.

Key research questions were as follows:

-

What measurable impacts on the use of NHS services and wider benefits does implementation of the Redthread YVIP have at UCLH for both staff and patients?

-

What evidence exists in the published research and grey literature about the effectiveness, benefits and impact of interventions in urgent care and hospital settings that focus on violent crime and young people? What lessons can be learned from UK and international studies to help NHS trusts implementing such interventions?

-

How can a combination of routine secondary care and Redthread data inform an evaluation of the impact of the Redthread service on the use of NHS hospital services?

-

What are the views of UCLH NHS staff (e.g. paediatric consultants, ED nurses, service managers) of the Redthread intervention, its feasibility, service-level impacts and overall effectiveness?

-

What organisational factors, processes, resources and staff training are necessary for the successful implementation and delivery of the Redthread service?

-

How cost-effective is the implementation of the Redthread service at UCLH?

-

What evaluation approaches and methodological designs appear particularly well suited and feasible for evaluations of the Redthread service and similar services in the NHS?

Structure of the report

The rest of this report covers the methods used to evaluate the Redthread service (see Chapter 2, further elaborated in following chapters where appropriate); the review of the international published evidence on interventions similar to Redthread (see Chapter 3); findings from the qualitative research examining the programme theory and implementation of Redthread at UCLH (see Chapter 4); a description and review of data used to manage Redthread’s services at UCLH (see Chapter 5); an analysis of the costs and consequences of Redthread (see Chapter 6), a feasibility assessment of options to evaluate the impact of Redthread (see Chapter 7); and finally, a discussion of the evaluation and some conclusions.

Chapter 2 Methods

Design

The evaluation was designed as a mixed-methods multiphased study, including an in-depth process evaluation case study and quantitative and economic analyses. The project was undertaken in different stages over two years, starting with desk-based research and an exploratory phase suitable for remote working while COVID-19 was affecting NHS services. During the second stage we gathered more in-depth insights about the effectiveness of the intervention, including processes of implementation, staff perceptions and economic evaluation. We also conducted quantitative analyses to ascertain suitable measures of impact to inform stakeholders and future evaluations.

Phase 1

Phase 1 was the feasibility and scoping stage of the study, including a literature review of published evidence. Our activities in this phase were:

-

An evidence review of the literature including a review of other Redthread evaluations.

-

Documentary analysis alongside qualitative scoping interviews (conducted remotely) with the Redthread team and youth workers to confirm the interpretation of Redthread’s programme theory and the intervention at UCLH. This included any recent adaptations due to COVID-19.

-

An investigation into the feasibility of a quantitative evaluation of the service by studying local data flows and processes and analysing routine hospital data.

-

A desk-based review of available Redthread and UCLH documents to inform the economic analysis.

-

Setting up an advisory group for the project.

Evidence review

The evidence review was conducted in two parts and focused on youth interventions delivered in hospital settings to reduce or prevent violent crime and harm to young people (e.g. from criminal and gang exploitation) and involving professionals such as social workers, trauma experts and youth specialists who work alongside clinicians. We followed recommendations on conducting systematic scoping reviews22 (e.g. predefined eligibility criteria and research questions) to map out the topic and to identify recent evidence available on this topic and any theories or conceptual frameworks that have been applied. We used a two-phased search process – one exploratory, one targeted – focusing on the medical literature to understand what was currently known about youth-orientated violence reduction services delivered in hospital settings, specifically their impact and outcomes monitored, and to determine whether there are gaps in knowledge such as, for example, cost-effectiveness. We also looked for evidence of factors that either support or hinder the implementation of such services and identified any conceptual or theoretical lenses applied in this area, such as behavioural concepts applied to evaluate ‘teachable moments’ and drawn from social science subdisciplines, such as cognitive psychology. Our searches looked for evidence about these interventions from both within the UK and internationally.

Further details on the methods used in the review including the search methodology are described in Chapter 3.

Qualitative scoping interviews and documentary analysis

Qualitative data collection was conducted in two phases, and involved semistructured interviews, observations of staff meetings and review of Redthread documents and materials. Phase 1 was an exploratory stage which aimed to understand the Redthread programme theory and the background to the introduction of the charity at UCLH. Phase 2 (described below) consisted of a single-site, process case study to understand implementation of the Redthread intervention at UCLH as well as staff perceptions of Redthread’s impact and progress.

All interviews were conducted from April 2021 once Redthread youth workers were back on site at UCLH. Recruitment used a mixture of purposive and snowball sampling to capture the views of a range of respondents, both those close to the Redthread intervention (e.g. youth workers), subject experts and those who might be less familiar with Redthread (e.g. junior doctors/nurses working in emergency care). The main criteria for UCLH staff respondents to take part was being directly involved in the care of young people at risk of harm and in a position to refer young people to the Redthread service. Staff were identified with the support of UCLH clinical collaborators and all respondents were emailed an information sheet prior to taking part and given the opportunity to ask questions about the evaluation and interview process.

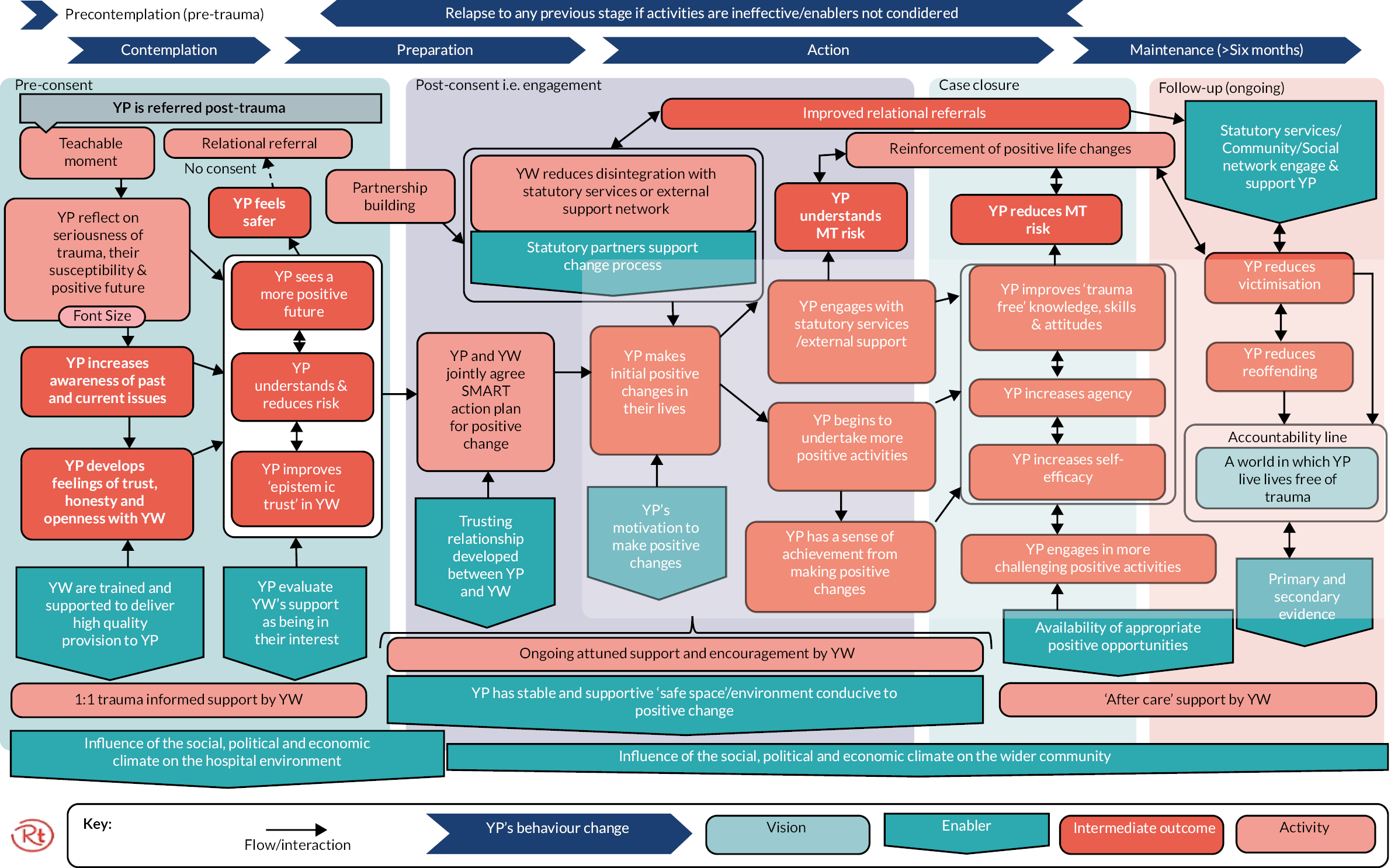

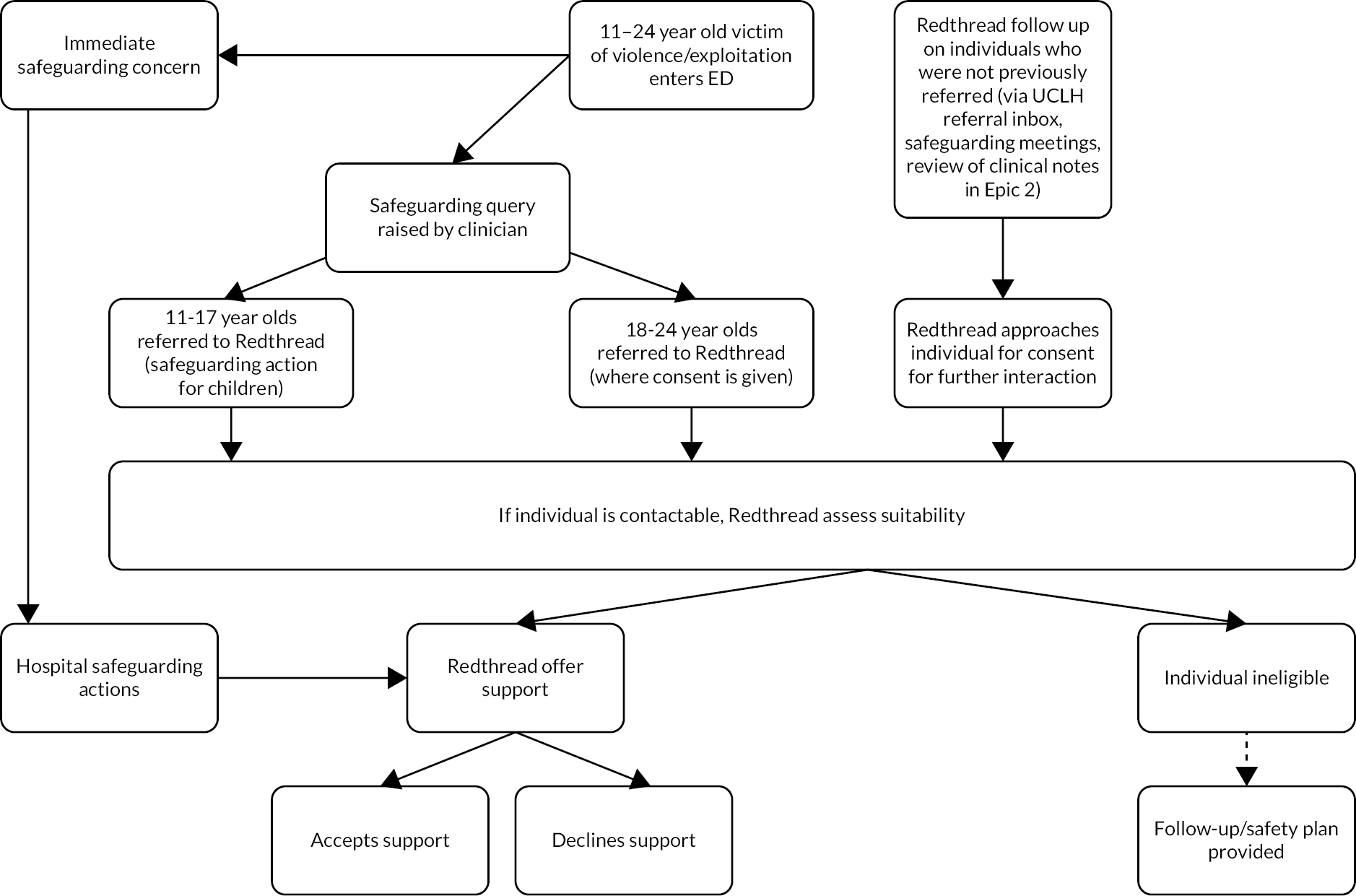

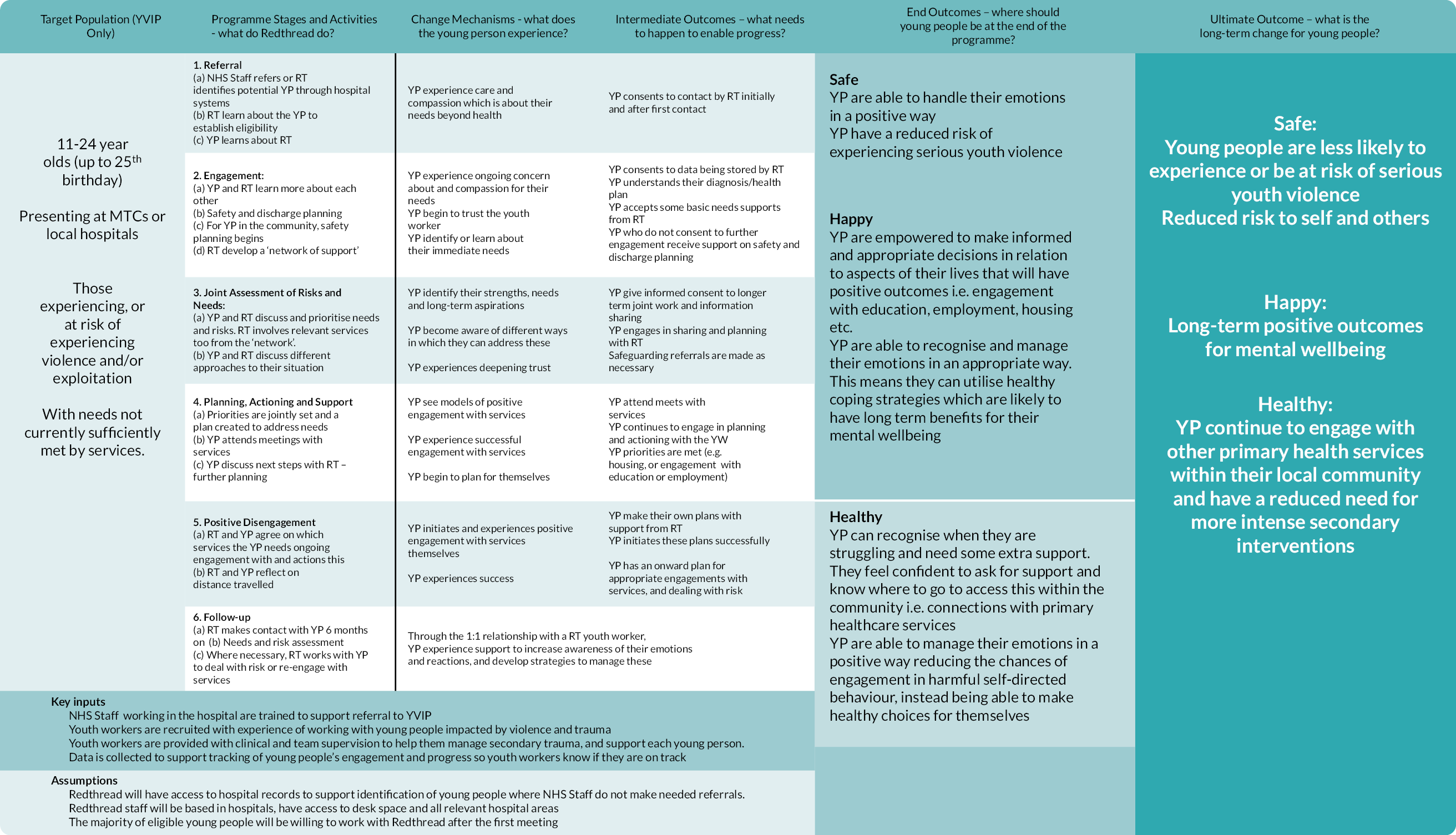

During phase 1, available Redthread documents were supplied to the evaluation team to map out referral pathways into the service and analyse the programme theory; that is, what the intervention aimed to do and how, and its main component parts. Programme theory can be defined as describing ‘how an intervention is expected to lead to its effects and under what conditions’. 23 We sought to understand Redthread’s programme theory (what they call their ‘theory of change’) to explore how the service was being implemented and was understood by staff at UCLH and to identify any contextual adaptations. We did not attempt to further develop or revise the Redthread logic model but were aware that the charity regularly reviews and updates its own materials.

This work was supplemented by exploratory discussions with key stakeholders at UCLH and members of the evaluation advisory group. We also examined the findings of previous Redthread evaluations undertaken at other trusts to see how they interpreted the Redthread programme.

During phase 1, we conducted nine scoping qualitative interviews with key stakeholders. Respondents were: two hospital consultants working in children and young people’s services at UCLH, six Redthread youth workers and other staff (e.g. managers, programme co-ordinators) and one senior NHS director involved with youth violence reduction interventions with knowledge of similar programmes at other NHS trusts. The aim of these interviews, which were semistructured, was to capture insights about the early introduction of the Redthread service at UCLH and the wider context. In particular, the early interviews aimed to understand what meaningful success looked like to those involved in delivering the intervention at UCLH (e.g. reduction in admissions, onward referrals to other services, positive case work with an individual) and to explore any skills and training required to deliver the intervention. Finally, we noted any novel service components that were new to the UCLH setting or arising because of COVID-19 (e.g. virtual delivery). Further details of our methods are described in Chapter 4.

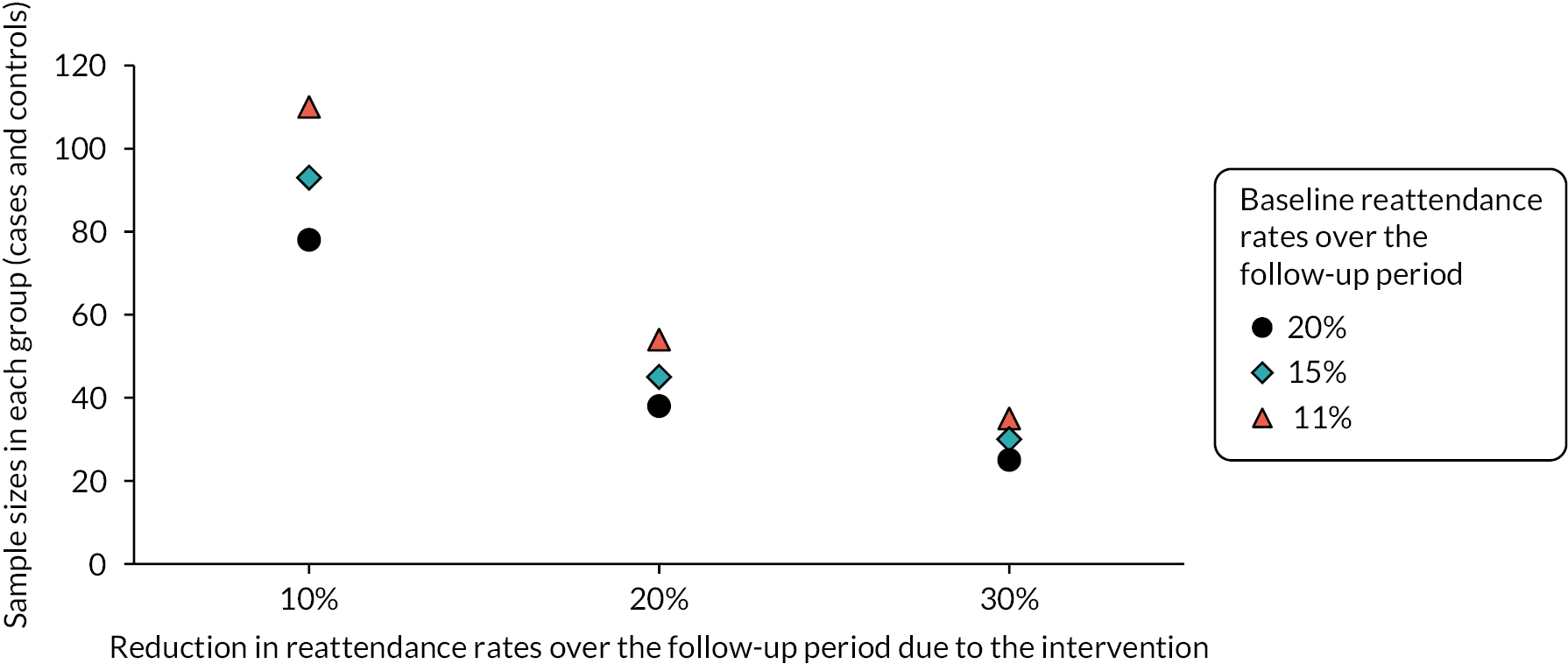

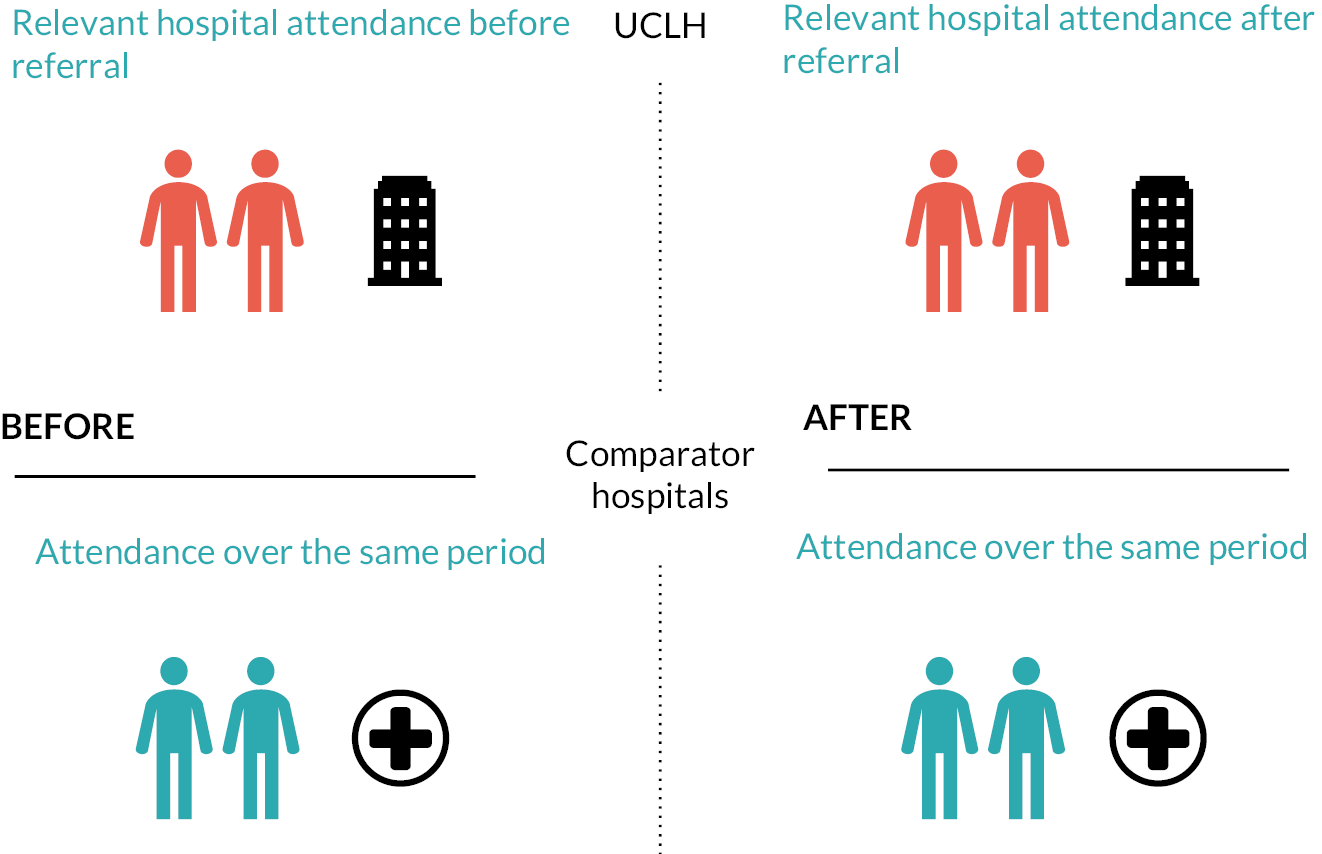

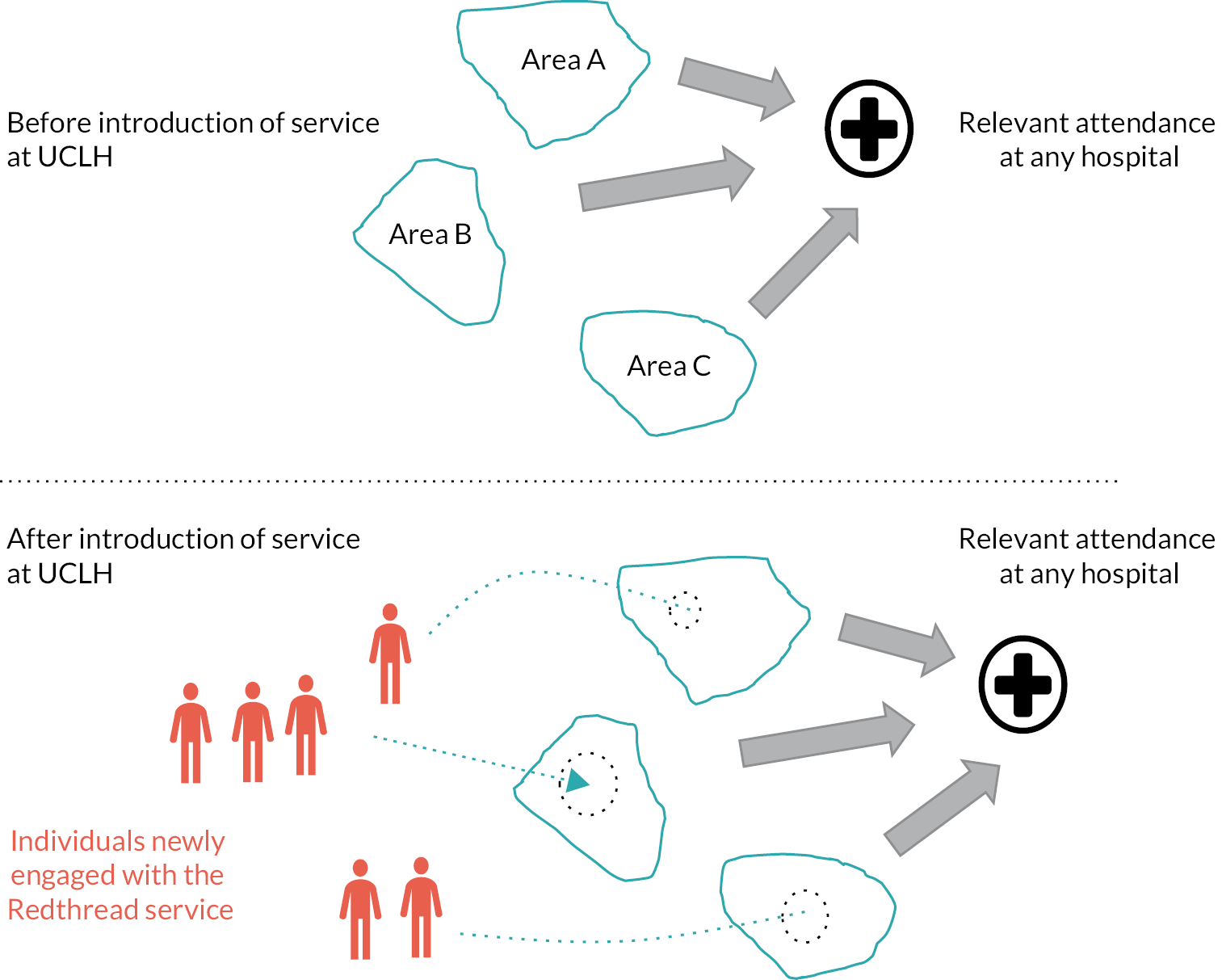

Feasibility study of a quantitative evaluation

The aim of the quantitative component of phase 1 was to explore the feasibility of evaluating the impact of the Redthread service given the available data. The results of this investigation would then inform the nature of any quantitative analysis that would be undertaken in phase 2.

For a measure of impact, we focused on the use of hospital services, specifically, future hospital attendance either at ED or as an inpatient relating to assault, mental health, substance abuse as well as those who were perceived to be at risk of harm. We developed a set of options for evaluating impact that covered different perspectives:

-

the perspective of someone using the service

-

the perspective of the acute trust where the service is based (UCLH)

-

the perspective of the local communities where people using Redthread’s service live.

These perspectives were assessed by investigating the data requirements of each option, including any access to individual person-level data, the linking of their records, the identification of comparators and necessary sample sizes. We also identified possible barriers to accessing the necessary data such as patient consent, information governance approvals and time to obtain these approvals in relation to the duration of the project. Our analysis was informed by an investigation of HES admitted patient care and ED datasets and the Emergency Care Dataset (ECDS) alongside discussions with Redthread, UCLH, NHS Digital and our expert advisory group. Further details on the methods used in this feasibility analysis are described in Chapter 6 and Appendices 3–5.

Preliminary economic assessment

During phase 1 we conducted a documentary analysis of the Redthread evaluations that had already taken place since 2021. We collected information on the evaluation aims, their main components and their results, to identify the existing gaps in the evidence. This informed the assumption and parameters we adopted in our economic analysis.

Set-up of an evaluation advisory group

During phase 1 we also set up an evaluation advisory group to meet up to three times during the course of the evaluation (virtually or in person) and involving representatives from the NHS, health-care and relevant public agencies. Terms of reference were drafted with the aim of each meeting to provide helpful challenge and advice to the evaluation team from stakeholders more external to the programme.

Phase 2

Phase 2 involved a more in-depth study of the service at UCLH and included:

-

A qualitative process evaluation with interviews with staff at Redthread and UCLH, to understand the perceived impact and effectiveness of the service as well as identifying factors that enable the successful delivery of YVIPs.

-

Analysis of data collected by Redthread over the course of the project to understand more about the delivery of the service and what it tells us about who engages with it.

-

A cost–consequence analysis (CCA) using local data on the costs of the Redthread service and relevant hospital interventions.

We had intended to include a quantitative evaluation of the service as part of phase 2, but our phase 1 work established that this would not be feasible.

Process evaluation – qualitative case study

For phase 2 of the qualitative data collection, we completed a process evaluation, where the unit of analysis was emergency and specialist children’s and adolescent services at UCLH. A process evaluation was considered suitable because the Redthread service is a complex intervention and randomisation was not feasible in this study. What was required were insights about delivery and overall impact to inform future implementation. 24 Process evaluations aim to understand how a programme or intervention is implemented, including any important decisions that influence how it operates in practice, any important adaptations, and the contextual factors that influence the intervention and its implementation. 25 We were therefore particularly interested in understanding:

-

the different processes and mechanisms at work locally, such as different referral pathways to access the Redthread service

-

any adaptations made to the service over time (e.g. due to COVID-19)

-

the reach of the service (e.g. the extent to which it had spread across different hospital departments)

-

critical implementation factors (e.g. what was reported to help youth workers to deliver the programme, or hospital staff to refer young people to it).

This part of the study involved additional qualitative data collection (13 further semistructured interviews and three observations of staff meetings) and focused on the mechanisms and emergent themes identified in phase 1, including any linkages between them, and any features of the hospital setting and its environment that were shaping delivery of the Redthread programme. Examples of the factors that we explored in this phase included:

-

Internal context: departmental leadership and cross-departmental working; professional buy-in (especially by emergency, trauma and paediatric staff); hospital data sharing and governance policies; senior/executive team support for the intervention; staff training; perceptions of need; communication of information about the intervention.

-

External context: demands on hospital services (e.g. young people presenting at UCLH and their needs); any trust collaboration with external public agencies; lines of accountability within the area (e.g. responsibility for youth crime prevention and safeguarding for children and young adults).

The additional semistructured interviews were with clinical and non-clinical UCLH employees and Redthread staff. They included hospital social workers, Redthread youth workers and managers, a paediatric nurse, consultants (children and young people’s services, child and adolescent psychiatry) and a junior doctor. Of the interview respondents, a small number of individuals were interviewed twice (in phases 1 and 2) because of their close involvement with implementing the Redthread service. All interviews and observations were conducted remotely via Microsoft Teams® (due to COVID-19) following consent to participate. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim. Three observations of staff meetings were completed [e.g. an adolescent ward psychosocial multidisciplinary team (MDT) meeting] alongside review of essential Redthread documents. Anonymised field notes taken during staff meetings.

To support analysis and interpretation of the qualitative findings, the qualitative researcher and wider evaluation team held discussions with the evaluation advisory group, and held meetings with other researchers involved in Redthread evaluations at different NHS trusts, plus meetings with Redthread staff and UCLH clinical collaborators. For the final analysis, all interview transcripts (n = 22) and observational field notes were read by the lead researcher for data familiarisation, alongside key materials such as the Redthread planning and implementation guidance, and other relevant documents (e.g. the Redthread youth worker manual). Findings were analysed thematically with a specific focus on answering the evaluation questions (see Chapter 4 for further details of the themes).

Unfortunately, it was not possible to conduct interviews with young people who had experienced the Redthread service at UCLH or at other NHS trusts for ethical and practical reasons (e.g. identifying young people would have data sharing and confidentiality implications), although this possibility was explored with Redthread. Further details on the methods employed are described in Chapter 4.

Analysis of local Redthread data

Over the course of the project, we obtained data from Redthread that included the characteristics and reasons for hospital presentation of individuals who engaged with the service and of those who declined to take part. Using univariate analyses, we compared these characteristics to identify any differences between those who chose to engage and those who did not. All the data were provided at an aggregated level for each characteristic separately, which precluded more complex multivariate approaches. Further details of the methods employed are described in Chapter 5.

Economic evaluation

Based on the outcomes of phase 1 of the evaluation and documentary analysis, we conducted a CCA of the Redthread service at UCLH. Consequences were derived from Redthread’s risk assessment tool, which measures changes in perceived risks faced by young people before and after intervention. Costs of delivering the service were obtained from Redthread, and these were compared with the costs of hospital ED attendances and admissions for reasons that might suggest eligibility for Redthread, over the three-year period 2018–2021. Hospital costs were obtained from UCLH. Further details of the methods are described in Chapter 6.

Patient and public involvement

We involved patients and the public in this evaluation in a number of ways. During the RSET patient and public involvement panel meeting in November 2021, we asked our patient representatives for suggestions on how to effectively disseminate study findings to various stakeholders. While writing up this report, we worked with our patient representatives (Raj Mehta, Fola Tayo, Jenny Negus and Nathan Davies) to ensure that the plain English summary was clear and accessible. In line with the RSET patient and public involvement strategy, our patient representatives were paid for their support in the development and write-up of this evaluation. We will also involve our patient representatives in producing accessible output to share the study findings.

We wanted to involve young people who had received support from Redthread or who had similar lived experience in the planning and delivery of the evaluation. However, as the study progressed, a number of barriers to engaging with young people became evident (as described in Chapter 4) and it was decided that this approach would not be pursued.

Ethical and local research and development permissions

On the basis of the NHS Health Research Authority’s online decision tools, the study was classified as a service evaluation. We undertook local data collection after obtaining permission from clinical leads at UCLH (e.g. consultant paediatricians) and a formal letter of support from the clinical director of emergency services.

Chapter 3 Evidence reviews

What was already known?

-

Hospital-based violence intervention programmes (HVIPs) have been adopted since the late 1990s and early 2000s in the United States following high rates of gun crime and mortality rates among young people across American cities. A number of these HVIPs have been studied using RCTs and experimental designs to estimate efficacy, although often with relatively small follow-up time period (e.g. 12 months).

What this chapter adds

-

An up-to-date review of evidence about hospital-based (ED/trauma centre) youth interventions and programmes that aim to bring about behaviour change in young people and reduce their overall level of risk to harm found:

-

a limited evidence base in the UK; specifically, a lack of empirical studies

-

a lack of studies that focused on ways to increase referrals or reasons for low uptake by young people

-

studies reporting a variety of outcomes for both case management and brief interventions instigated in EDs: depressive and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms; decreased feelings of aggression and involvement in peer violence; varying effects on victimisation; outcomes related to service uptake and use; mortality and morbidity outcomes; recidivism

-

two literature review studies confirming our findings that there are few studies following long-term outcomes, which limits conclusions about impact, as do the small sample sizes in studies

-

studies from the United States which suggest that there may be positive benefits with respect to recidivism and patient reported involvement in violence from interventions in ED settings

-

a small, recent and emerging grey literature consisting of evaluations evidencing the impact of programmes in the UK, such as Oasis and Redthread

-

-

Suggestions for future research and evaluation (e.g. multisite, longitudinal comparative studies, and more qualitative research with staff and young people, especially to understand reasons why some engage and some choose not to engage).

Background

Offences classified as assault with injury and assault with intent to cause serious harm have risen by 46% between 2011 and 2020 in England and Wales. 1 The number of repeat violent offenders is also rising. The majority of cases are concentrated within metropolitan areas, and most offenders, as well as victims, are male (55–74%). Also of note, in 2018, 37% of homicides in London were gang related, and just 14% of all violent incidents in England were linked to alcohol use. 1,26 Risk factors for involvement in violent crime are complicated and multi-factorial. Offenders and victims often have a history of childhood maltreatment, and strong evidence links future violence with having suffered violent experiences or abuse as a child. 27 There is some limited evidence to suggest that school exclusion and undiagnosed mental health issues are also contributors to youth violence. 28,29 Other well-accepted risk factors are linked to environmental exposures and include living in areas of socioeconomic deprivation and where damaged community relations with law enforcement exist. 30,31

Research evidence indicates that assault-injured youths are at significant risk of repeat injury. 3 While estimates vary, the risk of recurrent injury may be 80 times that of an ‘unexposed’ individual. 4,5 When assessed in the ED, the majority of injured youths believe their injuries are preventable, although over one-third also believe that a similar violence-related injury will occur in the future. Patients face significant obstacles after discharge (such as access to follow-up care, safe housing, return to work/school, or managing post-traumatic stress). Such hurdles often lead to continued engagement in high-risk behaviours that lead to repeat injury. Moreover, youth assault injuries are often related to repeated disagreements, and retaliatory feelings fuel repeated violence. 6 Over time, the victims and perpetrators become interchangeable. The goal of ED-based interventions is to interrupt the cycle of reactive decision-making.

Prior studies further suggest that trauma serious enough to require medical intervention may make youths uniquely susceptible to behavioural intervention and change. Consequently, ED-based interventions may provide a ‘teachable moment’ and a special opportunity to identify and reach youth victims of violence, as well as inform them of the benefits of intervention and link them with supportive treatment programmes that can function beyond the hospital.

Aims and methods

The evidence review aimed to answer the following overarching questions:

-

What evidence exists in the published research and grey literature about the effectiveness, benefits and impact of interventions in urgent care and hospital settings that focus on violent crime and young people?

-

What lessons can be learned from UK and international studies to help NHS trusts implementing such interventions?

In addition, the review aimed to:

-

identify existing gaps in the knowledge base, such as the cost-effectiveness and any economic evaluation of youth-orientated services based in hospital settings

-

identify factors that support or hinder the implementation and impact of youth-focused behavioural and preventative interventions delivered in hospital settings, particularly those that involve collaboration between secondary care professionals and youth workers/specialists

-

identify any conceptual or theoretical lenses applied in this area, such as behavioural concepts applied to evaluate ‘teachable moments’ with young people.

The review was organised into two phases, one conducted early into the evaluation project to inform data collection and provide a clearer understanding of the topic, and a scoping review conducted later into the project to ensure any recent, peer-reviewed evidence was captured.

Phase 1: exploratory search

Phase 1 consisted of an initial scoping review focused on youth-focused interventions delivered in emergency and hospital settings to reduce violent crime and address safeguarding risks (e.g. from knife crime, assault). It was led by one researcher (JF) with input from another researcher (JL). The review was intended to be broad in scope, with the aim of better understanding the topic and confirming the types of key terms that could be employed in a more targeted search to be conducted later. It was conducted in the earliest stages of the project, prior to empirical data collection.

A population, intervention, control/comparison, outcome framework was used to define the search terms:

-

population: youth patients 10–24 years of age, victims of interpersonal violence (excluding victims of self-harm, sexual violence, and child abuse)

-

intervention: youth or social worker hospital-based interventions

-

comparison: standard of care, no treatment, or differential treatment of a control group

-

outcome: recidivism, readmission, social services use, feasibility or patient self-reported outcomes.

The exploratory search was conducted in January 2020 and limited to English text sources but with no date restriction as the review was intended to be exploratory, as part of an initial search for available papers. The databases searched were PubMed, MEDLINE, the Cochrane Library and Embase databases. The a priori decision was made to limit screening to the first 200 hits (as sorted by best match) to provide a manageable number of initial sources of evidence; thereafter, further inclusions were determined based on reviewing cited literature for its relevance. Conference abstracts, editorials and commentaries were excluded. Fourteen studies were identified for inclusion due to their relevance to the evaluation, namely, studies that could help the researchers to understand the wider context of youth violence hospital interventions and programmes, and the types of prevention strategies commonly found in health care settings. These findings are presented in this chapter.

Phase 2: structured scoping review

A rapid scoping review was deemed appropriate due to the complexity of the topic, the emerging nature of the knowledge in this field, a need to understand the nature of the evidence base quickly and any knowledge gaps. In short, we needed a quick overview of the latest evidence related to hospital-based, youth-focused emergency care interventions such as Redthread. The findings of the phase 1 exploratory search informed drafting a review plan (not published) to guide a more systematic search of the medical and health care literature databases, which received team input (e.g. listing key words). The phase 2 scoping search also took into account early empirical findings from the qualitative interviews to understand the Redthread programme at UCLH (see Chapter 4).

This review was open to capturing a range of potential benefits of youth violence prevention services and youth worker programmes in hospital settings and followed a modified version of the PICO structure used in phase 1. As per guidelines for scoping reviews, we were chiefly focused on the population, concept (e.g. ‘teachable moment’, youth intervention following admission for trauma) and context (e.g. EDs) due to the wide range of possible outcomes of YVIPs. In terms of types of evidence, we were interested in identifying peer-reviewed published studies using a variety of study designs and any other evidence reviews (e.g. systematic and scoping).

The guiding questions and aims of the review remained the same, as outlined above, and the review inclusion criteria was as follows:

-

Population: young people, adolescents and children (aged up to age 30 years, to capture a wider literature), specifically groups at risk from gang-related exploitation, physical assault and injury (e.g. from knife attacks, shootings), sexual exploitation, human trafficking and other forms of violence (e.g. from peers and fighting).

-

Intervention: youth or social worker (or equivalent roles) hospital-based interventions aimed at risk management and prevention, and initiated within EDs/major trauma centres (MTCs).

-

Context: hospital-based interventions.

Inclusion parameters:

-

Study type: any [e.g. feasibility study/pilot, RCT, qualitative, evaluation, mixed-methods, cost–benefit analysis (CBA)] and literature reviews (narrative, scoping, systematic).

-

English language.

-

Peer-reviewed (i.e. no conference proceedings or abstracts).

-

Publication period: 2012–2022.

Searches were carried out on two medical databases (Medline and Embase) in February 2022 to focus on the health literature using key words and medical subject headings terms (see Appendix 1).

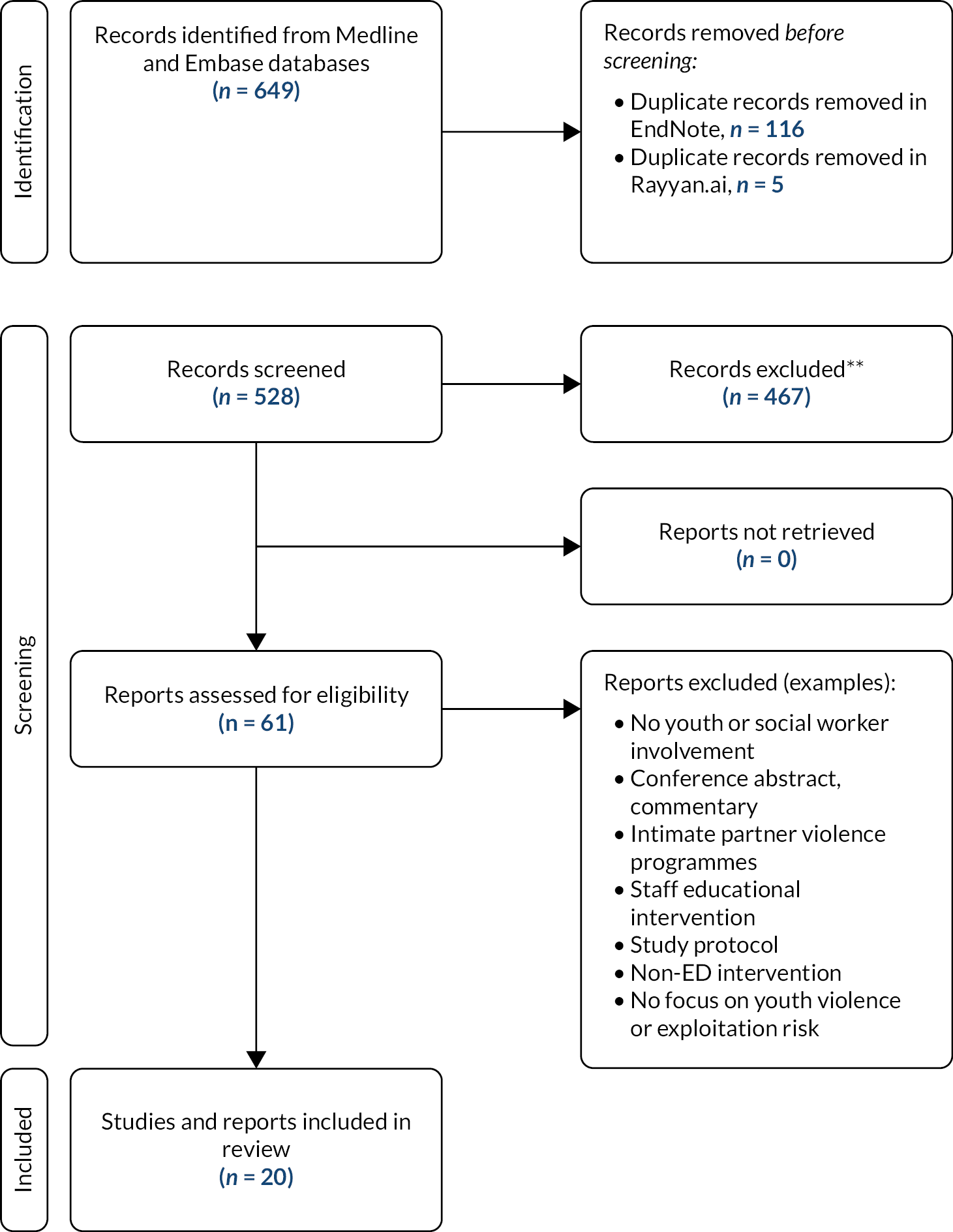

Results from Medline and Embase were imported into EndNote for deduplication and then exported to Rayyan.ai software for screening. Two researchers (JL and JF) independently assessed the retrieved sources using the inclusion criteria and considering relevance for answering the aims of the review. Papers were discussed and selected against the inclusion criteria and in light of their quality (e.g. an explication of the study design, nature of the intervention, intervention context and any limitations). Excluded papers included crisis interventions that did not feature a hospital-based youth or social worker’s input or equivalent role (e.g. sexual health crisis teams), conference and meeting abstracts and clinical case reports. A large number of studies were found to focus on community-based youth interventions, where young people are recruited to external programmes via EDs and seen by community youth workers or mentors, and this required further discussion and accessing full papers. It was decided that these studies should also be excluded. However, the boundary between hospital and community interventions was sometimes difficult to discern. Finally, mental health crisis interventions and any programmes designed to educate health professionals about youth violence (e.g. e-learning modules) were also excluded. The results for phase 2 are provided in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis diagram below (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Phase 2 search results.

As we were following guidance for scoping reviews and conducting the search under resource and time restrictions, the focus was on mapping the evidence base in the literature rapidly, with the aim of describing the types of studies available according to our predefined eligibility criteria and analysing any knowledge or research gaps in light of this rapid evaluation. The evidence search was not intended to be a systematic review, and no meta-analysis of the results was performed. Results were limited to two databases and we summarised the findings in a table detailing the study type and main findings. Extracted data focused on study location, intervention characteristics/components, population; setting/context, outcomes and key findings.

In the final phase, we performed Google search for grey literature using key terms (e.g. ‘youth hospital violence programme’, ‘Redthread evaluation’, ‘violence prevention and hospital’) to see if there was any additional evidence arising from the UK. We also engaged with the Redthread charity about past or current service evaluations with which they were involved. In this way, we identified some evidence scans and evaluation reports that had not been picked up in our search of health-care databases, as well as published evaluations of youth violence prevention programmes. We discuss these at the end of this chapter. All sources were assessed for their relevance to the evaluation, namely, a focus on youth violence prevention and hospital-based interventions (i.e. programmes such as Redthread or similar).

Principal findings

Phase 1: exploratory review

Approaches to the prevention of violence in children and young people

Early intervention programmes aim to improve parenting skills and early child–parent relationships. They are often home-based and targeted at vulnerable parents whose children are at risk of poor outcomes. There is a solid base of literature supporting their efficacy and long-term cost savings. 33,34 More specifically, such programmes are designed to improve parenting practices and reduce child maltreatment, leading to less down-the-line behavioural problems and mental health issues that would otherwise increase the likelihood of a youth being involved with violence. The Nurse Family Partnership (United States and UK), Early Start (New Zealand) and Triple P (Australia) are well-known examples of such programmes. An economic evaluation of the Nurse Family Partnership found that the programme generated a saving of US$2.88 for every $1.00 invested; and by 15 years of age, youths whose parents participated in the programme ran away from home less, had fewer arrests or criminal convictions and fewer behavioural problems or substance abuse issues. An evaluation of Triple P suggested that the programme could reduce conduct disorder by 25–48%. 34,35 Furthermore, assessment of a similar intervention in the UK for parents of five-year-old children with conduct disorder estimated that a saving of £9288 per child could be generated over a 25-year period, when accounting for future potential NHS, social service and criminal justice system costs. 36

Prevention strategies for older (e.g. aged between 18 and 24 years) at-risk youths, in the form of substance-use deterrence, after-school enrichment programmes or social media campaigns have been less effective at reducing violence than early-life prevention programmes. Although promising, such interventions, including those to deter alcohol use (shown to strongly correlate with violence in some environments), have proved especially difficult to evaluate. 37–39 After-school enrichment programmes offer academic support and recreational activities to at-risk youths. Evaluation of such programmes in the United States and UK have demonstrated mixed and even negative effects on violence deterrence, especially when interventions single out high-risk youths. 34,40,41 Little evidence also exists to support the effectiveness of challenging social norms through mass media campaigns. Such programmes have demonstrated effects on changing social perceptions, but not on changing actual behaviour or violent outcomes, although social campaigns do serve to drive social debate and support other prevention work. 42,43 For example, the ‘#KnifeFree’ campaign in the UK uses real-life stories of youths involved in violence to encourage more positive alternative choices. 44

Other interventions, most of which come from outside the UK, consist of ‘therapy’ based and behavioural programmes to break the cycle of repeated youth violence. 45 Comprehensive meta-analytical studies have found that ‘skill’ building-based interventions are strongly correlated with recidivism reduction, measured as repeat contact, probation violation or incarceration, and self-reported ‘delinquency’. 46 The most successful ‘skill’ building programmes for young people are designed around cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT) techniques and aim to develop adaptive behaviour and social skills. Effective programmes, beyond providing counselling or mentoring, also include multiple co-ordinated community services and are restorative in nature, involving the participation of family members. This combination of efforts is collectively referred to as ‘multisystemic therapy’. 47,48

Criminal justice system-based interventions, such as increased use of ‘stop and search’ techniques or installing weapon detection systems in schools, are rarely effective in isolation, although they may have merit as part of larger, multisystemic interventions when thoughtfully implemented. There are data to suggest that such strategies may work as effective short-term deterrents, make some youths feel more secure in their environment and increase school attendance. 49,50 However, this type of policing also has the potential to stigmatise, induce anxiety and cause resentment among those who might be searched or caught, as well as damage police–community relationships when used more often against members of ethnic minority groups. 39,50 The Offensive Weapons Bill, which was passed by Parliament in May 2019, further limits youths’ ability to purchase bladed weapons, firearms and corrosive substances. Little is known, however, regarding the effectiveness of such policies and prior similar legislative efforts, such as knife amnesty or longer prison sentences for possession, have had no lasting effect on youth violent crime deterrence. 34,51 Finally, ‘zero tolerance’ or fear-based police enforcement of laws has been shown to either have no effect on or exacerbate violence. 52

Hospital-based youth violence prevention programmes

There have been a number of studies going back to the late 1990s and early 2000s describing HVIPs, some of which compare these interventions to outcomes arising from standard to care.

One RCT was conducted in Baltimore, MD, by Cheng et al. from 2000 to 2001 at a large urban level-1 trauma centre. 53 Eighty-eight youth victims of violence were enrolled who were aged 12–17 years. Patients were identified by records review and enrolled within two weeks over the phone. A 14-point standardised assessment was performed during the initial interview to assess needs and then prioritise services. The treatment group were assigned master’s-trained youth workers who oversaw their case. The case workers offered intense weekly services by telephone and in person for a period of four months, as well as facilitating the use of community resources and programmes by the patient and the family as deemed appropriate. The control group received referrals to further services as appropriate at time of enrolment alone. Follow-up interviews were assessed at six months. There was no significant difference between the study groups on social service use; there was also no difference in reported fighting, fight injury or weapon carrying. Limiting factors were a low overall follow-up rate (57%) and an average time from ED visit to enrolment of 19.5 days, more than two weeks after the violent event and potentially missing the ‘teachable moment’.

A larger follow-up RCT was performed by the same group (Cheng et al.) in the Washington DC–Baltimore metropolitan area from 2001 to 2004 at two large level-1 trauma centres, where 166 youth victims of violence aged 10–15 years were included. 11 Patients were enrolled either in hospital or by phone just after admission, and the initial needs assessment was conducted at the home residence of the patient through a standardised process. The treatment group received an assigned youth worker ‘mentor,’ recruited from the community, who met with them at least six times over a six-month period. Mentors spent time with the participants in an activity at either their home or in the community, while also completing a standardised violence prevention curriculum based on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Best Practices in Youth Violence Prevention. The curriculum was based on social cognitive theory and included constructive skill-ascertainment focused sessions on conflict management, problem-solving and decision-making. Parents of participants also received three home visits by licensed health educators who went over topics covered in the youth curriculum and conducted sessions on parental monitoring and involvement. The control group received case management in the hospital setting and two follow-up telephone calls, and tailored referrals were made for patients to appropriate community services and programmes. Follow-up assessments were conducted at six months. More than 90% of treatment group participants were satisfied with their experience, 71% completed follow-up interviews, and 54% completed the entire programme. A trend toward significance was found for self-reported ‘misdemeanour activity’, aggression scores and general ‘self-efficacy’ (increased conflict avoidance). No differences were found among youths regarding self-reported or parental-reported aggression, attitudes about retaliation or weapon carrying. Low study power, despite a higher number of participants, remained a limiting factor in detecting differences between study groups.

In a retrospective study, Marcelle and Melzer-Lange conducted chart analysis of youth victims of violence were who treated in an urban ED in Milwaukee, WI, in 1998. 54 Patients were aged 10–18 years; 218 of 394 received the intervention and were included in the analysis. Those in the treatment group were assigned an experienced youth worker during the initial ED visit who then arranged further programme services, such as home visitation counselling, mental health services and youth activities. Referral to additional community services was also provided on an ongoing basis. Only three youths returned to the ED with a new injury within 12 months of study enrolment. This was the only outcome measure reported. Outcomes of control youths and attendance to other EDs in the area were not tracked, and no comparison was made between study groups.

‘Caught in the Crossfire’ is another example of a hospital-based YVIP, based in Oakland, CA. Youth victims of violence were tended to in the hospital by experienced youth workers, called ‘intervention specialists’, who were themselves prior victims of violence. These interventionalists provided case management and mentorship, and connected both the patient and family to further community services for up to 12 months following the violent event. Two separate retrospective reviews of the programme have been performed. The first analysis was conducted by Becker et al. in 2004. 55 They evaluated 138 patients admitted to a large urban hospital who received the intervention aged 12–20 years between 1999 and 2000. Matched controls were over-selected from violently injured youths admitted in 1998 to the same hospital who had not received the intervention. Follow-up was assessed at six months, and 43 of 69 patients (62%) in the intervention group completed the treatment and were included in the analysis. There was no significant difference in subsequent arrests or any criminal involvement between treatment or control groups.

A larger retrospective evaluation of Caught in the Crossfire was carried out by Shibru et al. in 2007. 56 They evaluated 158 victims of youth violence aged 12–20 years who received the intervention and were admitted to the same hospital between 1998 and 2003. Follow-up was assessed at 18 months in this study and criminal justice data were also obtained by the Oakland Police Department for review. Those eligible for inclusion in the treatment group were required to have had a minimum of five interactions with programme services outside of the hospital. Matched controls were selected, similar to the first evaluation. There was no difference between study groups regarding reinjury or rehospitalisation. The treatment group did demonstrate a statistically significant lower risk of subsequent criminal justice involvement at 18 months (relative risk reduction of 0.67). The authors estimated US$750,000 to $1.5 million in annual societal savings based on county juvenile detention system costs and number-needed-to-treat analysis. It was not clear, however, given the requirements for treatment group inclusion, whether some of the controls started in the treatment group. Moreover, the choice at the onset to limit ‘non-users’ of programme services from inclusion in the treatment group affects the broader validity of the findings. Small cohort sizes also limited statistical power.

Summary: phase 1

Our exploratory review found evidence regarding different types of interventions to reduce youth violence recidivism, dating from the early 1990s onwards. This suggests that: (1) successful programmes are generally long term, restorative in nature, and based on CBT techniques designed to help victims identify cognitive distortions and develop adaptive social skills, (2) successful interventions often include active participation of family members and coordinated community services, and (3) hospital-based youth worker programmes may increase social services use, decrease self-reported peer violence, and lower hospital recidivism rates. However, most of the available literature is limited by reporting outcomes over a period of less than one year, and the long-term durability of self-reported effects and recidivism rates is unknown. Moreover, recidivism rates are often described at single institutions, potentially limiting their validity as an outcome measure. Long-term, multicentre longitudinal studies are necessary to better understand the effect of hospital-based youth violence interventions.

Phase 2

The phase 2 structured search identified 20 academic articles and more recent studies. The search focused on papers published post-2012 to bring the first review up-to-date. The findings below are organised thematically around our evaluation questions and lines of enquiry. Table 2 outlines the 20 studies, 15 of which involved young people directly. Studies were predominately from the USA, plus one study from Canada and one from the UK. Programmes covered a wide age range (6–30 year olds), included males and females and different ethnic groups (Black, White, Asian, Turkish, Mixed, Hispanic).

| No. | Study type | Reference | Location | Intervention characteristics/components | Target population | Setting | Outcome(s) monitored | Key findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Case series (no control group) | Bell et al. 201857 | Indianapolis, IN | HVIP: Prescription for Hope | 328 patients (aged 15–30 years) | Hospital trauma centre (urban, public hospital) | Violent-injury recidivism in state-level data (ED visits for new injuries) in 328 patients enrolled in the programme between 2009 and 2016 | Only 15 patients (4.4%) were found to have recidivated due to physical assault, firearm or stabbing injuries. Of the cohort experiencing new injuries, more than half were treated at different hospitals (access to multiple hospital datasets is key for evaluation). Range of medical problems associated with violent injury – for example, pain and chronic pain (patients re-present in ED for issues from the original injury) |

| 2 | Cross-sectional study | Bernardin, Moen and Schnadower (2021)58 | Missouri, USA | HVIP: social workers assess all ED paediatric presentations for violence and firearm injury and offer enrolment in the programme | 407 patients (aged 6–19 years) | Hospital ED | Service uptake/enrolment | 104 (25.6%) of those offered the HVIP were enrolled. Average age of enrolled young people was 14 years. Those least likely to enrol in the programme were older adolescents, on probation or had illicit substance misuse. No significant difference in enrolment between injury type, physical assault or firearm |

| 3 | Descriptive Single-Site Case Study | Bernstein et al. (2017)13 | Boston, MD | HPA screen young people for risky behaviours using a survey (e.g. substance misuse, violence, safety concerns). Structured conversation (brief intervention) resulting in a plan to address behaviours, and referral to community/other relevant services if needed. Gun and knife crime victims are referred to the hospital-based trauma programme | 2149 eligible patients (aged 14–21 years) | Paediatric ED department | Engagement and implementation | HPA programme went beyond drug and alcohol issues to assessing young people’s level of risk. HPA role required integration into clinical teams so that staff would use the service and to ensure staff bought into the preventative approach. HPA role had to be distinguished from other professional roles, for example, hospital social workers. Administrative and budgetary issues a challenge for the service. 636/785 screened at risk for drug or alcohol use and received the brief intervention. Numbers on those receiving support for violence not reported |

| 4 | Retrospective review (firearm injuries) | Borthwell et al. (2021)59 | Los Angeles, CA | BAs for individuals with firearm injuries; history taking around social, medical, behavioural, educational factors, and violence and gang exposure. Hospital introduced a HVIP | 115 young people (aged under 18 years) | Hospital trauma centre | Use of inpatient BAs (specialist trauma consultations, post-discharge services (e.g. financial advice) and HVIP service | 57% of young people were ‘bystanders’ injured by crossfire. 21% were reported to be gang-related assaults. 43% completed BAs. 17 patients enrolled in the HVIP service (implemented for last two years of the study). HVIP integration with trauma approach and BAs. Need to link inpatient and outpatient care for patients at risk |

| 5 | Quasi-experimental study | Carter et al. (2016)60 | Michigan, USA | One aspect of a violence prevention programme: a 30-minute behavioural intervention based on motivation interviewing techniques. Standardised, computer-assisted counselling delivered by a therapist to a young person about their involvement in violence | 618 eligible patients (aged 14–20 years) | Hospital ED | Physical aggression, victimisation, and self-efficacy for avoiding fighting (intervention group and comparator) | Only 17.9% of young people refused the intervention. Self-reported data at 2 months suggested a significant decrease in violent aggression and self-efficacy for avoiding fighting. There were no significant changes for victimisation. 86% of participating young people rated the intervention as ‘very’ or ‘extremely helpful’ |

| 6 | RCT | Cunningham et al. (2012)61 | Michigan, USA | SafERteens intervention: BI delivered by TBI or CBI, plus control group. Intervention aimed at adolescents who screened positive for violence and alcohol use | 4296 eligible patients (aged 14–18 years) | Hospital ED | Alcohol and aggression: self-reported survey data at 12 months | 829 individuals met the study criteria and 726 completed the baseline survey, with 607 completing the 12-month follow-up survey. Mean number of participants was 16.8. The main reason for ED presentation was injury (26.8%) or a medical condition (65.7%). Participants receiving TBI were less likely to report severe peer aggression and peer victimisation at 12 months compared to the control arm. Effects were better for TBI than CBI. Empathy from a therapist may be a factor in explaining the findings |

| 7 | Retrospective study | Cunningham et al. (2013)62 | Michigan, USA | SafERteens: secondary data analysis focused on dating violence subgroup of the study above (Cunningham et al. 2012). Intervention content tailored to dating violence prevention strategies (e.g. a role play). Delivered as a stand-alone CBI or T+CBI | 397 individuals who endorsed dating violence when surveyed (aged 14–18 years), a subgroup of 726 in the programme | Hospital ED | Dating victimisation and aggression self-reporting at 3, 6 and 12 months | Effects seen for dating victimisation with CBI at 6 months. CBI+T was effective at 12 months for those with a more severe history of dating violence. CBI is effective at reducing dating violence within ED settings |

| 8 | RCT | Ehrlich et al. (2016)63 | Michigan, USA | ‘U-Connect’ study: BI delivered by a computer or therapist for young people screening positive for risky drinking, and admitted for any reason | 4389 eligible patients screened (14–20 years), 836 of whom were enrolled in the intervention – one-third of whom had presented with injury (intentional or unintentional) | Hospital ED | Alcohol consumption and consequences follow-up at three months | Those with injury more likely to be male; injured patients more likely to have higher alcohol consumption at 3-month follow-up than other medical patients. CBI or TBI can reduce alcohol consequences and consumption among young people, and a computer BI was found to be effective for those presenting with an injury |

| 9 | Single-site service evaluation | Jacob et al. (2020)64 | England, UK | Hospital-based youth worker prevention service aimed at young people suspected of involvement (victim, perpetrator or neither) in gang-related violence. 12 sessions working with a youth worker was the minimum for completing the programme. Based around concept of ‘teachable moment’ | 496 young people (aged under 25 years) referred to the service | Hospital ED | Self-reported risk screening tools: Strengths and Difficulties Questionnaire; Asset: What Do You Think questionnaire; feedback from young people | The mean age of referrals in the study was 14. 9 years (range 7–26). Most were seen on the weekends having been caught up in violence, and nearly 25% had involved a weapon; 17% engaged with youth workers and 18% completed the programme; 31% declined the service, 29% could not be contacted and 22% were ineligible (e.g. out of area). Of those that completed, 93% showed reduced or no change in their criminality and emotional disturbance scores. Young people interviewed welcomed the programme |

| 11 | Prospective, randomised pilot study and retrospective data analysis | Lumba-Brown et al. (2020)65 | St. Louis, MI | EYIPP, 2012–2015: social workers are based in emergency services for timely engagement with young people. Patients enrolled in EYIPP received mentoring and advocacy support by specially trained social workers who deliver individual and group therapy, and family training. These mentors are described as being both therapists and advocates and help with a range of activities (e.g. court appearances, education) | Young people aged <19 years who presented for interpersonal violence in the ED (family or any type of assault) | Paediatric ED | Morbidity (ED visits with injury) and mortality (secondary to interpersonal violence), recidivism (self-reported or police reported) | Following pilot, programme was rolled out as standard care. 160 were approached in ED to take part. 16 were ineligible and 78/135 eligible young people declined the intervention. 57 received the intervention, with a median age of 14.5 years. Most were black males. Participants spent 25–40 hours over 1 year receiving mentorship. Morbidity and recidivism rate 3.5%. There were no mortalities. Co-location of social workers deemed critical for feasibility of the intervention due to some eligible victims of violence not being admitted as patients. High numbers of eligible young people decline to take part (e.g. nearly 60% in the standard programme) |

| 12 | Integrative systematic review | Mikhail et al. (2016)12 | N/A | Youth violence interventions based in trauma centres | N/A | N/A | N/A | 10 studies included, published between 1970 and 2013, and limited to interventions in the USA. Authors applied a social ecological model to their analysis. Outcome measures were variable across all included studies (e.g. self-reported, referrals, ‘needs met’, re-arrest, conviction, reinjury and trauma recidivism). Case management that leverages community resources more likely to be associated with violence reduction than BIs |

| 13 | CBA simulation | Purtle et al. (2015)66 | N/A | HVIPs using data from 2012, with calculations for different effect sizes | Hypothetical patient population of 180 individuals violently injured – half of whom are allocated to the HVIP, and half who are not | N/A | Health-care costs, intervention costs, criminal justice costs, and ‘lost productivity’ costs, calculated over 5 years | Savings US$82,765–4,055. HYIPs can produce cost-savings for hospital and society (e.g. criminal justice costs), although their estimates are more conservative than those identified in other studies |

| 14 | Feasibility study and pilot RCT | Ranney et al. (2018)67 | USA | iDOVE: a BI instigated in the ED (in person, computer assisted), followed by an eight-week programme of automated text messaging based around CBT. Participants are screened by research assistants. Those included were deemed at risk for violence (victimisation or perpetration) and depression | 1190 patients presenting in ED, aged 13–17 years | Paediatric ED | Changes in peer violence and depressive symptoms at eight and 16 weeks (self-reported) from screening, baseline and follow-up, retention rates and enrolment. Ratings by service users | 1063 patients were screened, 142 were eligible and 116 eligible patients consented to take part in the trial. The mean for the ED intervention was 22 minutes. All participants rated the programme as ‘excellent’ or ‘good’. High participation rates (86%) and retention (91% at 16-week follow-up). Study unable to prove efficacy of the intervention to reduce peer violence and depression symptoms |

| 15 | Cost-Effectiveness Study (based on a prior RCT) | Sharp et al. (2014)68 | USA | SafERteens study: BI for adolescents presenting in ED and screened positive for aggression and alcohol consumption in past 12 months. Intervention is social worker-delivered, computer assisted, and based around motivation interviewing techniques | N/A | ED | Peer aggression, peer victimisation, and violence consequences as cost estimates; intervention costs | Implementation costs of the intervention were estimated to be US$70,000. Intervention estimated to avoid 4208 violent events per year among adolescents at $17 per episode. Downstream benefits of violence reduction were not calculated (e.g. additional use of mental health and criminal justice services) |

| 16 | Feasibility and pilot RCT | Snider et al. (2020)69 | Winnipeg, MB | EDVIP based on the ‘Circle of Courage’ framework. Support workers who have direct experience of violence contacts the young person in hospital, and then conducts assessments with a social worker to set goals for a programme of support lasting up to 1 year, and engaging with community resources | 130 eligible young people aged 14–24 year presenting with a violence-related injury | ED | Recruitment, fidelity, adherence, safety, hospital visits for repeat injury, mental health and substance use | 452 screened patients were deemed eligible. Uptake was low: 36% of eligible youth consented to take part in the cohort study. 68 participants were randomised to the EDVIP and 65 to a control arm. 74% of participants were still engaged in the intervention at six months and 57% at 1 year. Non-significant decrease in violence-related injuries among the intervention group (10.4%) and injury from a weapon. Participants were also more likely to present earlier to ED for repeat violence-related injury |

| 17 | Quality improvement project | Watkins et al. (2021)70 | Wisconsin, USA | Project Ukima – a HVIP: young people receive case management support and crisis intervention, with links to community support | 7–18-year-olds presenting with injuries related to violence assault | ED/TC | Referrals | Staff sought to increase referrals to the HVIP from 32.5% to 70% within 1 year. They did this through educating staff regarding eligibility requirements and other staff-based interventions. Referrals increased from 32.5% to 61.1%, but the improvement was not maintained |

| 18 | Scoping review | Wortley and Hagell (2021)14 | N/A | Youth violence interventions involving youth workers and ‘teachable moments’ | N/A | N/A | N/A | 13 papers identified, published between 2004 and 2018. No evidence that these interventions cause harm. Study sample sizes tend to be small. Results about overall impact are inconclusive, although there are positive indications of success (e.g. feedback from young people) |

| 19 | RCT | Zatzick et al. (2014)71 | Washington, USA | Stepped collaborative care intervention focused on risk behaviours and symptoms: young people received screening and an intervention based around motivational interviewing techniques, delivered by a social workers and nurse practitioner | Patients aged 12–18 years admitted with intentional or unintentional physical injury and admitted for 24 hours or more | ED | Risk scores for violence, alcohol and drug use, and symptom scores for PTSD and depression – all at 2, 5 and 12 months | Of 598 admitted patients, 493 were eligible for participation and 120 were randomised to the intervention or standard care. One-third of engaged young people that participated had scored for carrying a weapon; significant reductions found in weapon carrying at 12 months after hospitalisation found among the intervention group |

| 20 | Qualitative | James et al. (2014)72 | Boston, USA | Violence Intervention Advocacy Program: advocacy, case, needs assessment, management and onward referral to other relevant services | Victims of penetrating trauma aged over 15 and under 30 years | ED | Client experiences and perceptions | 10 interviews with English-speaking ED patients aged 18 years or over and enrolled in the programme. Key themes among patients were fear and safety; trust (or rather, lack of trust); isolation; bitterness; PTSD symptoms and mental health aspects of violent injury. The intervention can provide positive life-changing experiences through mentorship and support, helping to build trust in clients |

What is the evidence of effectiveness, benefits and impact of youth violence interventions in hospital settings?

The majority of studies of ED youth violence prevention programmes originate from the USA due to the high number of gun-related deaths and injuries affecting young people, a large proportion of which may simply be ‘bystanders’ harmed by gun crossfire. 59

Some hospitals have introduced hospital-based YVIPs aimed at lowering a young person’s risk of harm with a focus on physical injury and gun-related hospital attendances, supported by youth and social workers. There are also ‘brief interventions’ delivered in EDs which involve screening and assessing young people’s safety risks, such as harm resulting from substance misuse, fights and aggression, and involving shorter, structured interventions focused on motivating young people to make changes. Common to these interventions is approaching a young person in an ED and using a young person’s clinical presentation as an opportunity to conduct a risk assessment, reduce the individual’s exposure to risk in the community, engage the young person in positive behaviour change, and to refer the engaged young person to other types of support following discharge, such as charities or services based in the community.

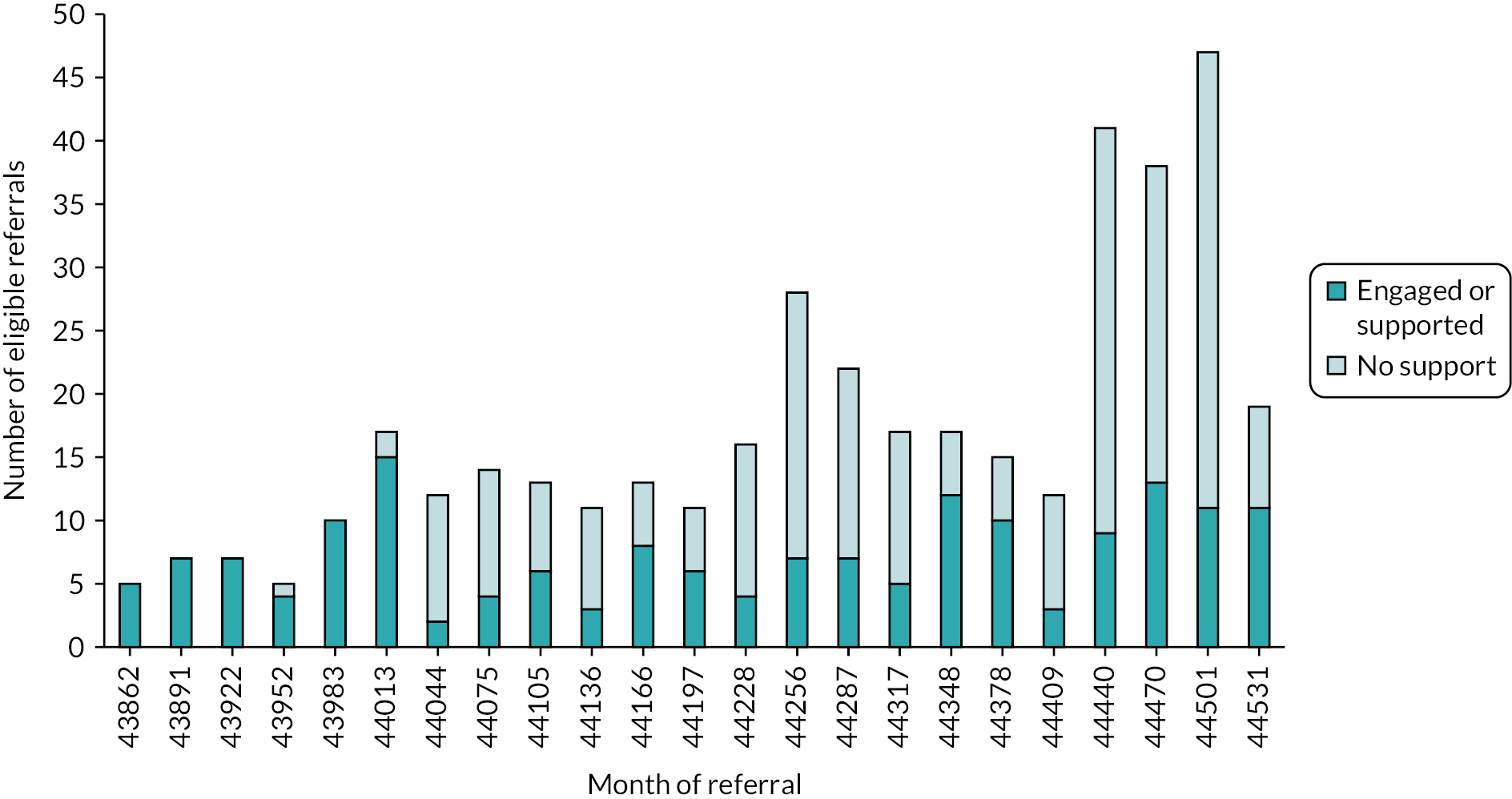

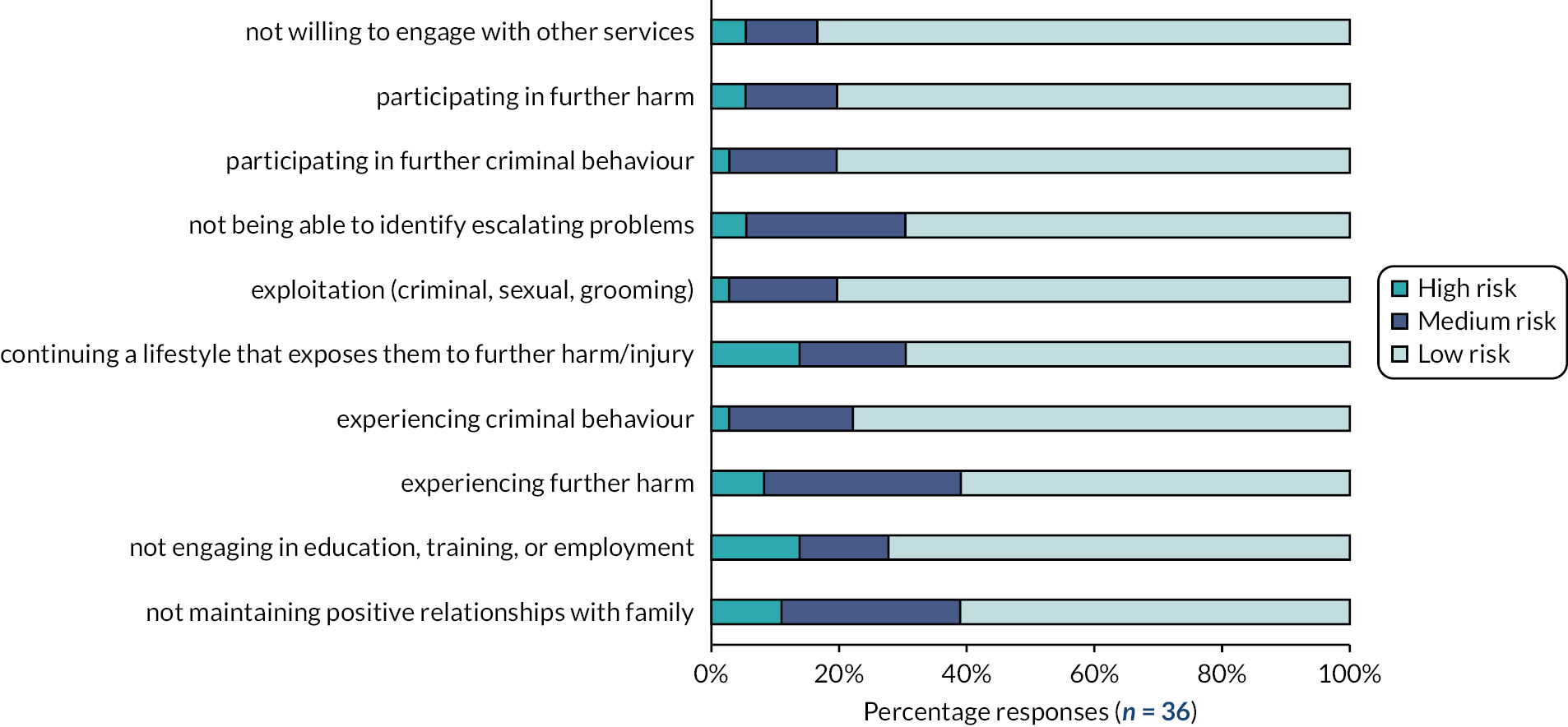

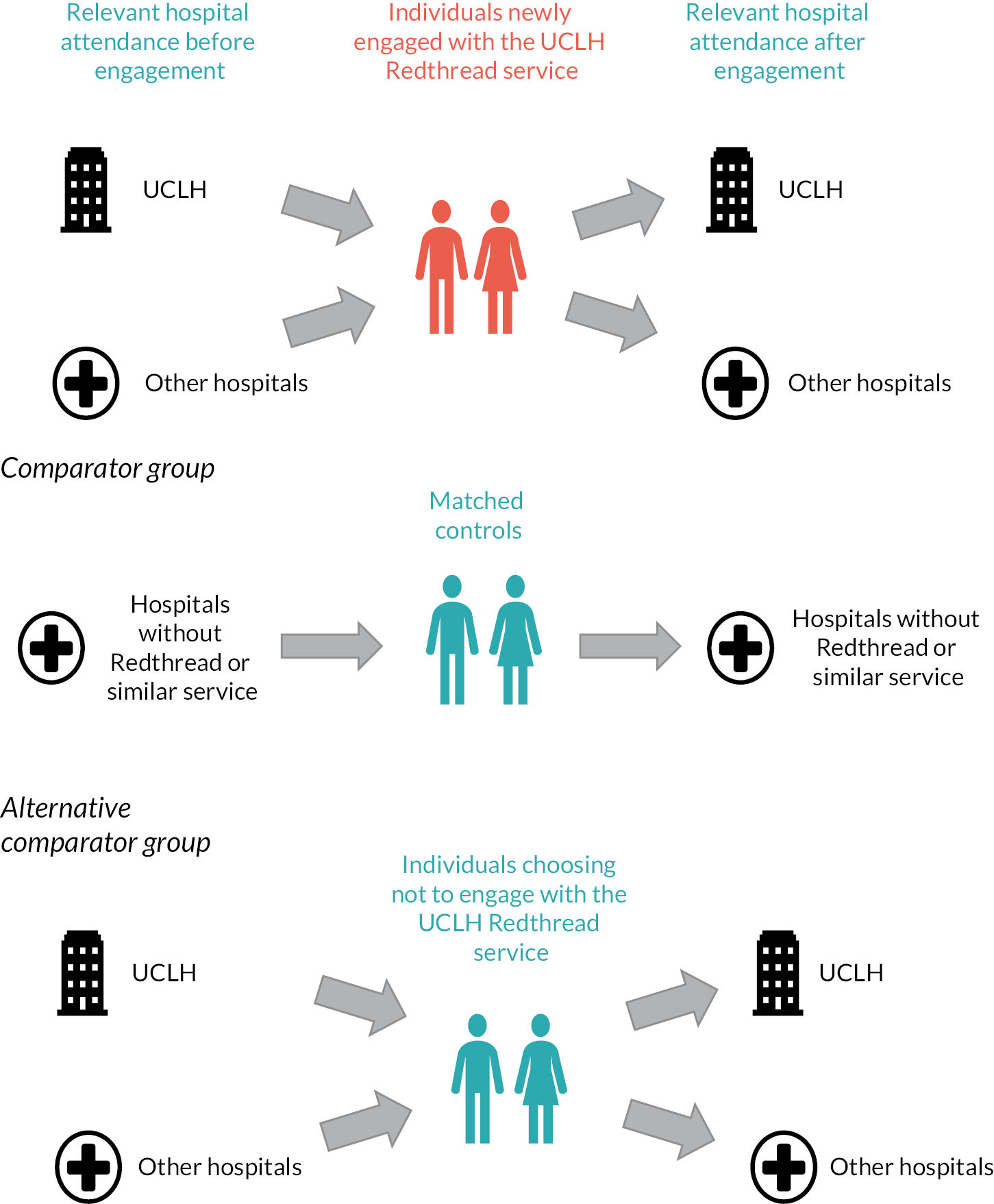

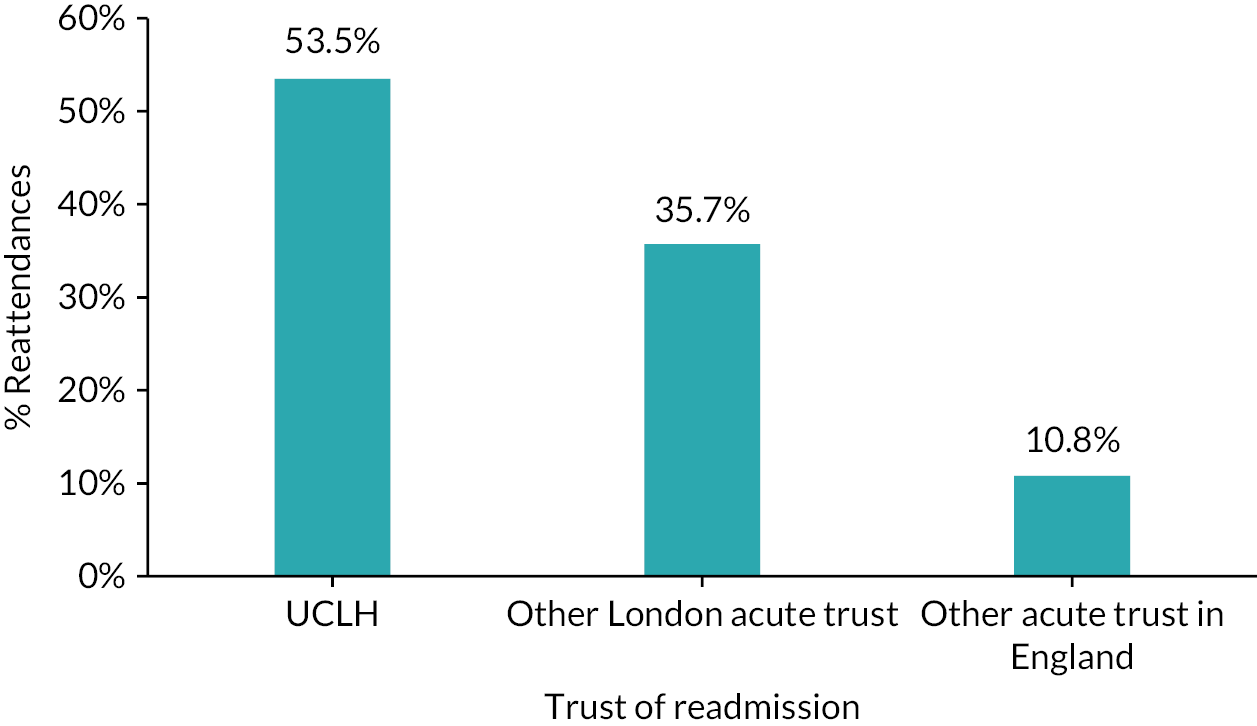

As found in the initial exploratory review, hospital-based youth violence interventions involve specialist social and youth workers working alongside health professionals to support young people. A primary outcome of these interventions is a reduction in re-admissions to EDs for injury. For example, Bell et al. 2018 describe the ‘Prescription for Hope’ HVIP in Indiana, USA. 57 The programme was set up in 2009 and treats young people aged 15 to 30 presenting in EDs and ‘admitted to the trauma centre for treatment of injuries that were inflicted by another person and resulted from assault, a firearm, or stabbing’. The intervention provides multidisciplinary and holistic support to young people via social workers, youth violence specialists and advocates. Through enrolment in the programme, young people obtain assistance with securing a health insurance plan, primary care access, full-time employment/a return to education and help with meeting other needs (e.g. legal, housing).