Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number NIHR129488. The contractual start date was in July 2020. The final report began editorial review in January 2022 and was accepted for publication in September 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final manuscript document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this manuscript.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Randell et al. This work was produced by Randell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Randell et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Overview

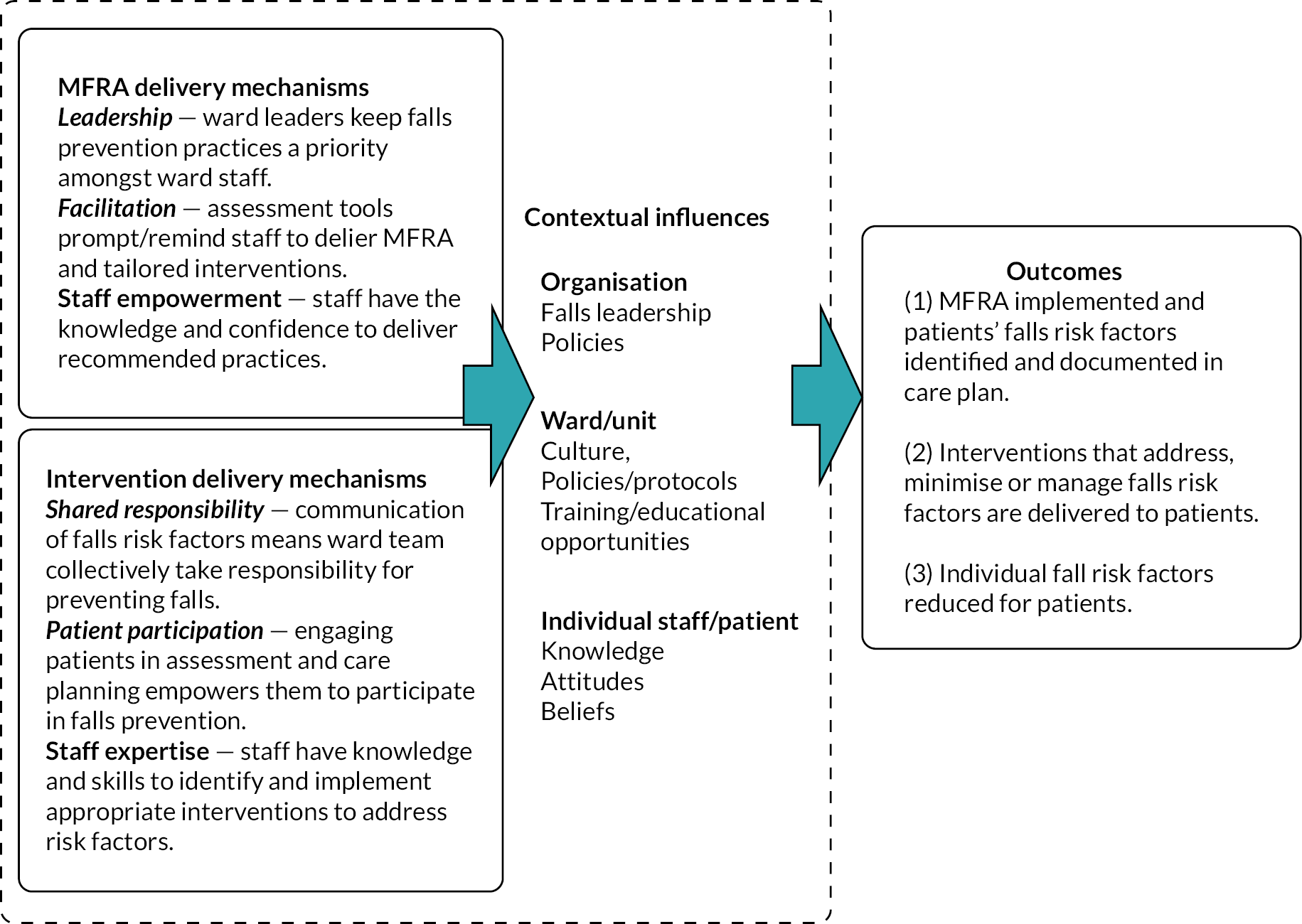

This study sought to understand what supports and constrains delivery of multifactorial falls risk assessment (MFRA) and tailored multifactorial falls prevention interventions in acute NHS Trusts in England. This was achieved through a realist review, a review of Trust falls prevention policies, and a multisite case study. The following chapter provides the background for the study, introducing the issue of inpatient falls and approaches to falls risk assessment and prevention, presents the study aims and objectives, and outlines the structure of the remainder of the report. Some text in this chapter has been reproduced from Randell et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Background

Inpatient falls

Falls are generally defined as ‘an unexpected event in which the participant comes to rest on the ground, floor, or lower level’. 2 They are the most common type of safety incident reported by acute hospitals. 3 More than 240,000 falls are reported in acute hospitals and mental health trusts in England and Wales each year,4 although under-reporting may mean the true incidence of falls is higher. 5,6 Falls are most common in patients aged 65 years or older, representing 77% of inpatient falls. 3 The majority of falls result from multiple interacting causes, most commonly age-related physiological changes, medical causes, medications and environmental hazards. 7

Overall, 28% of inpatient falls result in some level of harm and patients aged 65 years or older are more likely to be harmed. 3 The proportion of falls resulting in any fracture ranges from 1% to 3%, with reports of hip fracture ranging from 1.1% to 2.0%. 6 In 2015–6, inpatient falls in England resulted in 2500 hip fractures. 8 Outcomes for patients who acquire hip fractures in hospital are far worse than for those in the community who acquire hip fractures, with significant differences in mortality [relative risk (RR) = 3.00; 95% confidence intervals (CIs) 1.05 to 8.57], discharge to long-term high-level nursing care facilities (RR = 2.80; 95% CIs 1.10 to 7.09), and return to preadmission activity of daily living status (RR = 0.17; 95% CIs 0.06 to 0.44). 9

Even where no physical harm occurs, falls can lead to fear of falling and associated loss of confidence. 5,8 They can result in slower recovery,8 even when physical harm is minimal, and can have longer-term consequences for the patient’s health, as fear of falling may lead to restriction of activity and associated loss of muscle and balance function, increasing risk of falling. 5 Falls can also be a cause of significant distress for families and staff. 6,8 Falls in hospital are a common cause of complaints10 and can be a source of litigation. 11 They are also associated with increased length of stay and greater amounts of health resource use. 6 NHS Improvement (now part of NHS England) estimated inpatient falls cost the NHS and social care an estimated £630 million annually. 3 It is therefore a priority to reduce the number of patients who fall, and their risk of injury, in acute hospital settings.

Falls risk assessment

The traditional approach to managing falls in acute hospitals is to complete a falls risk prediction tool, sometimes referred to as falls risk screening tools or falls risk scores (such as STRATIFY12). Such tools typically provide a list of falls risk factors, assign a numerical value to the presence or absence of the risk factor, and then sum the numerical values together to represent the individual’s risk of falling (high, medium, low). 13 Interventions are then used to target individuals at high risk. 14 There are issues with the predictive validity of such tools; a systematic review of falls risk prediction tools found only moderate accuracy, comparable to the accuracy of nursing staff clinical judgement. 13 Consequently, such tools may either provide false reassurance about patients identified as low risk or result in most patients on a ward being identified as high risk. 14 Such tools are often completed only once, typically on admission, while a patient’s risk of falling can vary over time. There is also concern that their use gives false reassurance something is being done, even if no action to address falls risks has been taken. Additionally, with a tool of this kind, actions tend to be linked to the score and can lead to a ‘one size fits all’ approach even though the issues and needs of individual high-risk patients can be very different. 14 A stepped-wedge cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT) showed removing the risk score component from falls risk prediction tools does not negatively impact falls outcomes and can reduce time spent completing paperwork. 15

In light of the limitations of falls risk prediction tools, the NICE guideline on falls in older people states they should not be used and instead a MFRA should be undertaken. 16 The recently published World Falls Guidelines, for falls prevention and management for older adults, also recommend patients in hospital should receive a MFRA and advise against using falls risk prediction tools. 17 A multifactorial approach to falls risk assessment identifies individual risk factors for each patient, which may make them at risk of falling and that can be treated, improved, or managed during their stay (what tend to be referred to in the falls research literature as ‘modifiable’ risk factors). MFRAs, unlike risk prediction tools, do not include unmodifiable risk factors (i.e. cannot be treated, improved, or managed) such as age and sex. The NICE guideline includes the following modifiable risk factors: cognitive impairment; continence problems; falls history, including causes and consequences (e.g. injury and fear of falling); unsuitable or missing footwear; health problems that may increase a patient’s risk of falling; medications that increase the risk of falls; postural instability, mobility problems and/or balance problems; syncope syndrome; and visual impairment. The NICE guideline states that a MFRA should be undertaken for all inpatients 65 years or older and inpatients aged 50–64 years judged to be at higher risk of falling due to an underlying condition. Based on this assessment, a multifactorial intervention should be provided for the patient, tailored to their individual risk factors. For example, if visual impairment is identified, it might be decided that an optician visit should be arranged if the patient has lost their glasses or, if there is no known reason for poor eyesight, an ophthalmology referral is made. 18 In this way different patients, who have different risk profiles, will receive different interventions to reduce their risk of falls.

Preventing inpatient falls completely would only be possible with unacceptable restrictions to patients’ independence, dignity and privacy, such that some falls may be considered an inevitable consequence of promoting rehabilitation and autonomy. 6,10 Thus, there is a need to balance the risk of harm from falls and the risk of deconditioning. Nonetheless, it is estimated introduction of MFRA and tailored interventions, as recommended by the NICE guideline, could reduce the incidence of inpatient falls by 25–30% and the annual cost of falls by up to 25%. 3 Despite the NICE guideline being updated to include these recommendations in 2013, the 2022 National Audit of Inpatient Falls (NAIF) report noted that 34% of Trusts are still using falls risk prediction tools and, while there has been improvement in the proportion of patients receiving documented assessment for components of the MFRA included in the NICE guideline, there has been a reduction in the proportion of patients assessed for delirium. 19 Documented vision assessment (52%) and lying and standing blood pressure (LSBP, 39%) remain concerningly low. In interventions, a mobility care plan was in place for 90% of patients who required one, a continence care plan for 78% of patients who required one, and a delirium care plan for 61% of patients who required one. This suggests variation in the extent to which the NICE guideline is being followed and opportunities are being missed to reduce the likelihood of inpatient falls.

Given these findings, it is necessary to understand the contextual factors that support and constrain use of MFRA and tailored falls prevention interventions in acute hospitals, to improve practice.

Aims and objectives

The study aim was to determine how and in what contexts MFRA and tailored falls prevention interventions are used as intended on a routine basis in acute hospitals in the NHS in England. The objectives were as follows:

-

Use secondary data to develop a programme theory that explains what supports and constrains routine use of MFRA and tailored falls prevention interventions.

-

Refine the programme theory through mixed method data collection across three acute hospital Trusts.

-

Translate the programme theory into guidance to support MFRA and prevention and, in turn, adherence to the NICE guideline.

In addition, the study aimed to include the perspectives of patients and members of the public through involvement of lay people as members of the research team at all stages and through their regular evaluations of progress.

Structure of the remainder of the report

Chapter 2 describes the study design and research methods, including the methods used for public and patient involvement (PPI).

Chapter 3 presents findings of the theory construction phase of the realist review.

Chapter 4 presents the results of, and outputs of the steps we went through during, the prioritisation of theories for testing in later phases of the study.

Chapters 5 to 8 present findings of the theory testing phase of the realist review, a review of NHS Trust falls prevention policies, and the multisite case study, organised according to the four theories that were prioritised for testing. These four theories relate to leadership for falls prevention, shared responsibility for falls prevention among the multidisciplinary team, tools to facilitate falls risk assessment and care planning, and patient participation in falls prevention.

Chapter 9 concludes the report by reflecting on the implications of the study findings and outlining future research priorities.

Chapter 2 Design and methods

Public and patient involvement

Throughout the study, we were supported by DW, the lay member of the project management group, and a group of lay researchers recruited to the project (service users and carers who had either fallen themselves or cared for someone who fell in hospital); while we describe their involvement in the conduct of the research throughout the chapter, we conclude the chapter by providing a fuller account of our approach to PPI.

Overview

Realist evaluation provided an overall framework for this study. We conducted a realist review to develop programme theories, which were further refined through a multisite case study across three acute NHS Trusts. The study culminated with presentations to case sites to work with participants to determine implications of the study findings for practice. Below, we begin by describing realist evaluation before describing the three study phases. Some text in this chapter has been reproduced from Randell et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Realist evaluation

Falls risk assessment and prevention can be characterised as a complex intervention, aimed at producing change in the delivery and organisation of healthcare services and comprising several separate components that may act both independently and interdependently. 20 The study of complex interventions requires a strong theoretical foundation, to make explicit often implicit assumptions regarding how and why the intervention will provide the desired impact21 and how this is influenced by context. 22 Realist evaluation23 offers a framework for understanding for whom and in what circumstances complex interventions work. It involves building, testing, and refining the underlying assumptions or theories of how such interventions are supposed to work. It has been used for studying the implementation of a number of complex interventions in health care,24–26 including clinical guidelines. 27

From a realist perspective, interventions in and of themselves do not lead to outcomes. Rather, it is how recipients of the intervention choose to make use of, or not, the resources an intervention provides that determine outcomes, and such choices are highly dependent on context. For example, whether the introduction of a form for MFRA leads to the use of tailored falls prevention interventions and a subsequent reduction in falls depends on if, and how, nurses use that form. This choice may vary according to contextual factors, such as workload, confidence in their ability to undertake the assessment, and belief in the value of the assessment and associated interventions. Therefore, a realist approach is suitable when studying interventions where uptake and subsequent impacts have been found to be variable. Realist approaches are concerned with constructing programme theory that details how intervention components trigger responses in recipients (intervention mechanisms) within particular contexts to generate outcomes, described as context mechanism outcome configurations (CMOcs).

Realist review

Realist review represents a divergence from traditional systematic review methodology. 28 It starts by identifying programme theories and then uses empirical evidence from published studies to systematically evaluate these, allowing us to compare how an intervention is intended to work with how it actually works. Realist reviews are useful when considering the literature on interventions where there is limited primary research because, in contrast to systematic reviews, diverse sources of data can be considered as evidence, enabling reviews to make use of, for example, reports of local evaluations and quality improvement (QI) initiatives that have not been subject to peer review. 29

Realist approaches can be thought of as consisting of three phases: theory construction, theory testing and theory refinement, and we use this structure to describe the process of the realist review undertaken in this study.

Phase 1: theory construction

Search strategy

In July 2020, three sets of searches were undertaken by an information specialist with expertise in realist reviews (JW). Subject headings and free-text words were identified for use in the search concepts for all searches by the information specialist and project team members. The searches were also peer reviewed by another information specialist. The searches included words and synonyms for falls, risk assessment/accident prevention, and acute hospital settings (see Appendix 1 for full search strategies).

Practitioner theory search. Because stakeholders are likely to express how they think interventions work in informal contexts such as editorials, comments, letters and news articles,29 we searched the following databases for commentary-type articles and studies mentioning theories/conceptual models for falls risk assessment in acute hospital settings:

-

CINAHL (EBSCOhost)

-

HMIC Health Management Information Consortium (Ovid)

-

Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-process and Other Non-indexed Citations and Daily 1946 to 21 July 2020.

‘Key journal’ search of falls risk assessment articles. The project team identified the following key professional/trade journals and magazines: Nursing Times, Nursing Standard, Health Service Journal and Pharmaceutical Journal. These were searched using the following databases:

-

CINAHL (EBSCOhost)

-

EMBASE Classic + EMBASE (Ovid)

-

HMIC Health Management Information Consortium (Ovid)

-

Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-process and Other Non-indexed Citations and Daily 1946 to 21 July 2020.

Academic theory search. The discussion sections of systematic reviews often include authors’ theories about why interventions did or did not achieve the desired effect. 30 Therefore, we searched the following databases for systematic reviews of falls risk assessment:

-

CINAHL (EBSCOhost)

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (Wiley) Issue 7 of 12, July 2020

-

Epistemonikos www.epistemonikos.org/

-

HMIC Health Management Information Consortium (Ovid)

-

International HTA Database (INAHTA)

-

Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-process and Other Non-indexed Citations and Daily 1946 to 21 July 2020

-

PROSPERO www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/.

The results of these three sets of searches were stored and de-duplicated in an EndNote library. In addition, an advanced Google search was carried out, using the terms ‘falls prevention’ and ‘hospitals’.

Review strategy

Titles and abstracts were screened for relevance by three reviewers, NA, LM and HZ, guided by the following questions:

-

Is this about falls risk assessment and/or falls prevention interventions in the acute hospital setting?

-

Does it potentially contain ideas about how falls risk assessment and prevention work, for whom, and in what circumstances?

More specifically, the inclusion/exclusion criteria listed in Table 1 were applied.

| Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|

|

|

Initially a liberal accelerated approach was to be used, where all abstracts and full texts are reviewed once and then those excluded are reviewed again by a different reviewer. 31 This approach is less time- and resource-intensive than having all records screened twice, while maximising inclusion, increasing the number retained in comparison to each record being reviewed once. 32 However, a large number of potentially relevant titles of papers were identified in the initial round of title/abstract screening. Given that the liberal accelerated approach would lead to inclusion of more citations for full-text retrieval from the second screen of excluded references, this number was considered unfeasible for the researchers to manage within the time frame allocated for theory construction. Ten randomly selected full texts from the included citations were found to be of limited relevance for theory construction. Therefore, the following inclusion criteria were added: (1) focus on risk assessment, rather than risk prediction and (2) use of multifactorial rather than single assessment tools. Longer-term settings were also excluded, explicitly. The refined criteria were used to rescreen the included citations, thus increasing the relevance of included literature for theory construction, while reducing numbers to a more manageable size. Use of the literature in theory construction allows flexibility as the aim is to capture ideas and assumptions, rather than perform an exhaustive search of the topic, and therefore this was considered a reasonable revision to our approach.

Full texts of potentially relevant texts were then retrieved and reviewed using the above criteria, but with emphasis on whether they contained ideas about how and why falls risk assessment and prevention strategies were implemented; the contextual factors that supported and constrained implementation; and/or the consequences or outcomes of these processes.

Data extraction and analysis

Initially, we had intended to analyse the data by importing papers into NVivo (QSR International, Warrington, UK) and coding them as contexts, mechanisms and outcomes, thereby drawing together coded data from multiple studies to configure a series of CMOcs. However, on trialling NVivo for this purpose, we found this approach resulted in coding large sections of text, which did not facilitate analysis. Therefore, data extraction forms were created in Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) with sections that enabled relevant discussions and data about the CMO concepts to be summarised. The form was also used to note any substantive theories referred to in the paper. To check consistency in use of data extraction forms, two researchers (NA, LM) used the forms to extract data from a systematic review and a practitioner theory paper and then met to discuss their experience and come to a shared understanding of the type of data to extract using the forms.

To summarise findings, data matrices (one line per citation, with columns capturing data on contexts, mechanisms and outcomes, drawn from summaries in the data extraction forms) were created. From these matrices, CMOcs were constructed, presented in tables with the first column providing details of the citation(s) that informed the CMOc. We did not assess the quality of papers in this phase, because the focus was to identify and catalogue ideas about how and why interventions work, rather than to assess the validity of those ideas. 33

Use of substantive theory

Drawing on substantive theory is recommended within realist methods. 23 In addition to noting substantive theories referred to in the included papers, we used Google Scholar to search for implementation theories. We first sought to identify mechanisms from the literature reviewed, with the intention of returning to the substantive theories, if necessary, to help address gaps in our CMOcs. Substantive theory supported organisation of the findings from Phase 1 of the review.

Prioritisation of theories for testing

Prioritising which CMOcs should be tested in later phases of the study was undertaken in collaboration with the Lay Research Group and Study Steering Committee (SSC). To facilitate this, the CMOcs were refined into a series of If–Then statements. CMOcs that were not feasible to test and/or did not have the potential to inform practice were removed. To prioritise this subset of CMOcs, the Lay Research Group and SSC were asked to rank the If–Then statements using an online form. Both groups were asked to give top rankings to the statements they believed were most likely to work in practice, and the Lay Research Group was asked, in addition, to give a high rank to statements likely to have most impact for patients and carers. Both groups then met, separately, in December 2020 to discuss their rankings. Members were offered an opportunity to rerank the statements following those meetings, if they had changed their minds. The SSC gave the Lay Research Group’s ideas precedence in determining the project’s next steps, in recognition of the importance of falls prevention for patients and carers.

Phase 2: theory testing

The CMOcs prioritised for testing encompassed similar mechanisms. To facilitate searches, we grouped mechanisms where appropriate, identifying six key concepts. The searches were conducted in two stages, based on the six concepts.

Stage 1: original EMBASE search

The first search took place in March 2021 using EMBASE (the most comprehensive health database) to gauge the size of the relevant literature in each concept and refine the search terms, before using them to search other databases.

Six searches were conducted to capture evidence for each concept. Subject headings and free-text words were identified for use in each search block (see Table 2 for concepts and search blocks; see Appendix 2 for full details of each search). For example, the ‘hospitals’ search block included the search words and headings: hospital, hospitalisation, nursing staff, medical staff, inpatient, acute patient, hospital patient, ward, hospital department, rehabilitation unit. No language or publication date limits were applied to the searches. Each concept was searched separately and downloaded into an EndNote library. Records were coded to record which concept search they derived from, and then the searches were combined in a single EndNote file, with separate groups for each of the six concepts. Duplicates were removed. There was a high degree of overlap between the records found by different searches. We tagged each EndNote record with the search or searches from which it had been generated so, even after duplicate removal, we could identify all the records retrieved for a particular concept.

| Concepts | Leadership | Staff empowerment | Facilitation | Patient-centred care | Shared responsibility | Expertise |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Search blocks | Leadership, champions Implementation Falls risk assessment or prevention Hospitals | Staff training, empowerment Implementation Falls risk assessment or prevention Hospitals | Assessment tools or health information technology Implementation Falls risk assessment or prevention Hospitals | Patient-centred care Hospitals Falls reduction | Teams, shared responsibility Hospitals Falls reduction | Expertise Hospitals Falls reduction |

Two researchers (NA, LM) screened all citations and abstracts for relevance for theory testing using the following questions:

-

Is the study concerned with the context (acute hospitals) and the intervention (MFRA and/or falls prevention interventions) of interest in this study?

-

Does the study report the findings of an empirical investigation?

-

Does it include evidence to test the CMOcs?

While a clear theoretical divide can be made between traditional risk stratification and MFRA tools, hybrid approaches with the use of a risk stratification tool plus some tailoring may be seen in the literature and in practice and were included in the review. This approach enabled us to include studies such as those relating to the Fall Tailoring Interventions for Patient Safety (TIPS) study in the USA, which used the Morse Fall Scale to stratify patients according to risk, while leveraging health information technology (HIT) to select interventions tailored to identified risks. 34–38

The two researchers screened just over 10% of the citations to check consistency in decision-making. Conflicts were resolved between them. The number of relevant citations returned suggested the search strategy was identifying useful literature. To better understand their potential for theory testing, full texts were retrieved and reviewed for over 10% of included citations for the four concepts ranked highly by both the Lay Research Group and SSC: leadership, facilitation, patient participation and shared responsibility. Additionally, these concepts were prioritised because they included two that focused on implementation – leadership and facilitation – and two that focused on how implementation of practices might reduce patients’ falls risks – patient participation and shared responsibility. Based on full text review, and with consideration of the weight and volume of evidence and researcher time available, the decision was made to focus on these four CMOcs going forward and not test the CMOcs for staff empowerment and expertise.

Stage 2: additional database searches

Searches for the four CMOcs were designed following analysis of the original EMBASE search terms and scope of the CMOcs, using the following four search questions:

-

Leadership: search included terms for hospitals, falls prevention/assessment, implementation/adherence to guidelines and strategies, leadership and multifactorial risk assessment.

-

Facilitation: search included terms for hospitals, falls prevention/assessment, engagement/implementation, assessment tools/HIT and workflows.

-

Patient participation: search included terms for hospitals, falls prevention/assessment, multifactorial risk assessment, person-centred care and empowerment compassion.

-

Shared responsibility: search included terms for hospitals, falls prevention/assessment, multifactorial risk assessment, teamwork and shared responsibility.

Table 3 lists the information resources used in the initial search in May 2021. Within the project time frame, we were able to complete the synthesis for facilitation and patient participation. Searches for these two theory areas were rerun in August 2022 on all databases except NICE Evidence, which ceased in April 2022.

| Information resource | |

|---|---|

| Published literature | CINAHL (EBSCOhost) Ovid MEDLINE(R) ALL 1946 to 5 May 2021 Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Web of Science) 1975+ Science Citation Index-Expanded (Web of Science) 1900+ Social Sciences Citation Index (Web of Science) 1900+ Emerging Sources Citation Index (Web of Science) 2015+ |

| Grey literature | NICE Evidence Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science (Web of Science) 1990+ Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Social Science and Humanities (Web of Science) 1990+ |

Subject headings and free-text words were identified for use in the search concepts for all searches by the Information Specialist and project team members (see Appendix 2 for full search strategies). The searches were peer reviewed by a second Information Specialist.

The results of the database searches were stored separately from the original EMBASE searches in an EndNote Library. Duplicate records were removed and titles and abstracts from the additional searches were screened using the same criteria as the original EMBASE search. Full texts of potentially relevant papers were reviewed using the same questions used in screening, with an emphasis on whether papers were considered useful for theory testing.

Phase 3: theory refinement

For theory refinement, NVivo was used to categorise sections of the manuscripts to support theory testing. For example, for facilitation, an overarching theme ‘Type of facilitation’ in NVivo had subthemes relating to alerts and reminders, and decision support. A sample of manuscripts was reviewed to identify additional themes, for example, in relation to study details (including intervention descriptions and study rationales) and influences on staff practices, with the development of subthemes, such as individual staff beliefs and attitudes. The themes were added to NVivo and tested for usability using a sample of manuscripts (n = 5) that varied in aims and methods and included qualitative and quantitative data. Researchers coded the manuscripts and met to discuss their experiences, suggest refinements, and develop a shared understanding of how to apply the themes to the texts. After refining the coding framework, manuscripts from the four concept searches were imported into NVivo and coded using the framework by NA and LM.

All manuscripts were coded using an overarching framework. Researchers began analysis of two CMOcs: one focused on implementation – facilitation – and one focused on falls risk reduction – patient participation. Details about the studies reported in these texts, including methods used, settings, samples, intervention description and comparator (if appropriate) were extracted into Excel.

Data from the concept-specific searches were collated. Analysis began by examining the interventions described by study authors, to understand the extent to which they reflected the resource component of the initial CMOc. The type and range of interventions were then described in narratives, prepared by the researchers. Following intervention description, manuscripts were reviewed to understand what the data suggested about the outcome of interest in the CMOcs. For example, for facilitation, the primary outcome of interest was whether recommended practices (e.g. MFRA) were implemented as intended, and for patient participation, the primary outcome of interest was the extent to which falls rates were reduced. Outcome data were recorded in tables to understand variation in intervention impact across studies.

After tabulating outcomes, researchers examined coded data and the original manuscripts to collate evidence to help explain variations in outcomes, and to assess the extent to which the mechanisms and context expressed in the original CMOc were evidenced by the literature. In doing so, they looked for data that supported and diverged from the CMOc logic. Narrative summaries were then written and were used to refine the initial CMOcs.

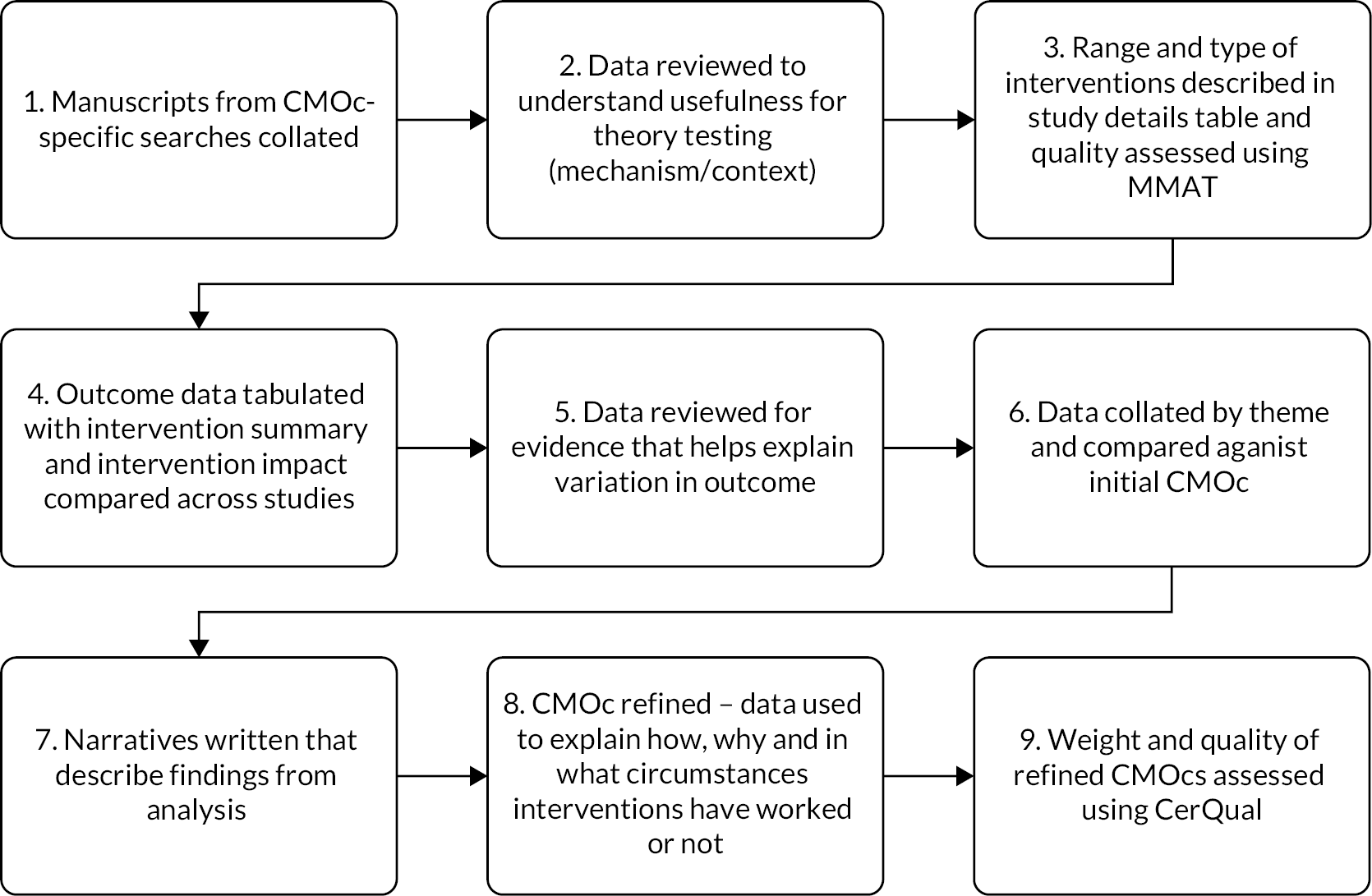

Following the steps of analysis depicted in Figure 1, the aim was to refine the first two CMOcs and then continue with the remaining two if time allowed. Although coded, time limitations meant we were not able to undertake theory refinement for leadership and shared responsibility, so the decision was made that data for testing the leadership CMOc would consist of the review of falls prevention policies (see Review of acute NHS Trust falls prevention policies) and data collected in the multisite case study, while data for testing the shared responsibility CMOc would consist of data gathered in the multisite case study only.

FIGURE 1.

Realist review analysis flowchart.

Quality assessment

The included texts for facilitation and patient participation were appraised using the mixed methods appraisal tool (MMAT),39 recorded in Excel, with the exception that such appraisals could not be undertaken for QI papers that did not contain sufficient information about methods.

To assess the strength of the body of evidence for the refined CMOcs, we used Grades of Recommendation, Assessment, Development and Evaluation-Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research (GRADE-CERQual). 40 GRADE-CERQual has been used in previous realist reviews41,42 and fits well with the realist approach, involving consideration of the theoretical contributions of studies and encouraging reviewers to be sensitive to the importance of context. 43 It involves assessing each individual review finding based on the four components of methodological limitations, coherence, adequacy of data, and relevance. 40 Refinements to the facilitation and patient participation CMOcs were expressed as claims and linked to the specific studies that evidenced the claims. The evidence supporting each claim, and consequently the CMOc, was assessed for quality using GRADE-CERQual by NA, LM and RR. They undertook assessments separately and then came together to reach consensus, rating confidence in each claim as either high, moderate, low or very low.

Review of acute NHS Trust falls prevention policies

As a source of evidence for testing the leadership CMOc, we reviewed the policies of acute Trusts regarding falls risk assessment and prevention. The motivation was that this would provide insight into whether organisational-level policies support or constrain effective falls risk assessment and prevention. We aimed to collect and analyse falls policies from a random sample of around 10% of English Trusts (approximately 22 policies) but, if variation was found, we would increase the sample to around 15% (approximately 33 policies) to get a better sense of the variation. Policies were identified using the following sources:

-

a Google search using the following terms: ‘falls policy’ restricted to domain ‘nhs.uk’, ‘acute hospital falls policies’, ‘falls policy uk’, ‘inpatient falls hospitals uk’ (January 2021)

-

Freedom of Information sections of the websites of those Trusts for which we had a possibly outdated policy (February 2021)

-

the Falls and Fragility Fracture Audit Programme, who sent a request to a sample of Trusts that participate in the National Hip Facture Database (March 2021), including nine Trusts for which we already had policies but were unsure if they were up-to-date and to another 14 Trusts randomly selected from a list of English acute Trusts on the NHS website (www.england.nhs.uk/publication/nhs-provider-directory/) and

-

local collaborators in the three case study sites (see Multisite case study), who provided the most up-to-date falls policies for their Trusts.

Policies dated before 2013, when NICE multifactorial guidance was introduced, were excluded.

When reviewing these policies, we sought to assess adherence to the NICE guideline on falls in older people by checking whether a falls risk prediction tool was recommended; whether an approach was recommended that was tailored to the patient’s individual risk factors; and by looking for specific elements of the assessments undertaken (such as whether continence and cognitive impairment were assessed), as specified by NICE and captured also in the NAIF.

Multisite case study

Having completed the realist review, we continued refining our prioritised theories via a multisite case study with embedded units of analysis. 44 In line with a realist approach, we used a combination of qualitative and quantitative methods to gather data on the processes and contexts of falls risk assessment and prevention as well as the impacts. 29

Sampling of case sites

Data were collected across three NHS acute Trusts in England. This number was chosen to provide a balance between breadth and depth of investigation,45 enabling identification of organisational-level factors that impact on falls risk assessment and prevention while providing confidence in the generalisability of findings that are consistent across sites. Trusts were selected to ensure variation in key NAIF indicators at the time of writing the proposal,8 the HIT in place, and to include both teaching and district general hospitals (Table 4).

| Site | Per cent of eligible patients who received assessment/care plan | EHR | Hospital type | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Delirium | Continence CP | BP | Medication | Vision | Call-bell | Mobility aid | |||

| 1 | 10 | 82 | 39 | 43 | 56 | 80 | 69 | Locally developed | Teaching |

| 2 | 8 | 100 | 31 | 50 | 25 | 75 | 100 | Locally developed/AllScripts | Teaching |

| 3 | 67 | 67 | 8 | 7 | 13 | 50 | 17 | Cerner Millennium | District general |

We chose to sample across clinical areas in each site to enable us to be able to distinguish differences due to clinical area and Trust/unit-level factors. We decided that, in each Trust, we would undertake data collection in one older person/complex care ward and one orthopaedic ward. These areas were selected because they would provide different patient populations with different lengths of stay and different staff experience, with longer length of stay and staff having experience in managing older people at risk of falling on older person/complex care wards. Specific wards were identified through discussion with local collaborators at each site. An introduction to each ward is provided in Table 5. The two wards for Site 1 were located in different hospitals within the Trust; for Sites 2 and 3, the two wards were located within the same hospital.

| Site | Ward | Beds | Number of bays/side rooms | Nursing team organisation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Complex | 27 | Patients located either in single-bed side-rooms, including rooms in a separate side-ward (isolation unit), or on one of four, four-bed bays. | Nurses and HCAs were organised in three teams, each responsible for a number of beds: red group, blue group, and green group (in the isolation side ward). The ward board showed that ideally there should be four registered nurses (RNs) on each shift and five HCAs on the early and late shifts and three RNs and five HCAs on the night shift. |

| Orth | 23 | Patients located either in single-bed side-rooms or in one of five, four-bed bays. | Nurses and HCAs were organised in teams: sometimes three teams – blue, green, red and sometimes two teams only, blue and red. The ward board showed that ideally there should be three RNs on each shift and six HCAs on the early and late shifts and two RNs and six HCAs on the night shift. | |

| 2 | C | 28 | Patients located either in single-bed side-rooms of in one of five, four-bed bays. | Staff worked in three teams, responsible for groups of beds: the red team, blue team, and green team. The ward board showed that ideally there should be four RNs, four HCAs and one nursing associate on early and late shifts, and three RNs and three HCAs on the night shift. |

| O | 28 | Patients located either in single-bed side-rooms or in one of five, four-bed bays. | Staff worked in four teams, responsible for groups of beds: dark blue, pale blue, red, and yellow. The ward board showed that ideally there should be four (and sometimes five) RNs, six HCAs and one nursing associate on early and late shifts, and three RNs (sometimes four) and four HCAs on the night shift. | |

| 3 | C | 30 | Patients located on one of two sides to the ward. On each side, there was one large bay divided by a half-wall with 12 beds and other beds were in single side-rooms. | Staff worked on either the side of the ward that cared for up to 15 male patients, or the side that cared for up to 15 female patients. The ward board showed there should be five RNs and four HCAs on the early shift, four RNs and five HCAs on the late shift, and four RNs and four HCAs on the night shift. |

| O | 22 | Patients located either in single-bed side-rooms or in one of two–two-bed or two–three bed bays. | The ward was organised into three ‘pods’. Ideally there should be one RN and one healthcare worker per pod (referred to as a 3 : 3 ratio), amounting to four RNs and four HCAs on the early shift, four RNs and three HCAs on the late shift, and three RNs and three HCAs on the nightshift. |

Sampling within case sites

The intention had been to conduct two 4-hour periods of observation in each ward per month over 5 months. However, ward closures due to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) meant we needed to take a more flexible approach to data collection, undertaking data collection in those wards we could access, and spreading data collection over a longer period of time. Data collection was undertaken between November 2021 and June 2022. Observations were scheduled to ensure they took place at different times of day, including night shifts, and different days of the week, including weekends. In total, 251.25 hours of observations were undertaken. Table 6 provides a summary of the data collected.

| Site | Ward | Record review | Observations | Interviews | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patient/carer | Ward staff | Organisation | ||||

| 1 | Complex | 10 | 48.5 | 5 | 10 | 4 |

| Orth | 10 | 40.5 | 5 | 5 | ||

| 2 | C | 10 | 41 | 5 | 5 | 4 |

| O | 10 | 41.25 | 5 | 8 | ||

| 3 | C | 10 | 40 | 6 | 8 | 2 |

| O | 10 | 40 | 5 | 4 | ||

| Total | 60 | 251.25 | 31 | 40 | 10 | |

Sampling of interviews

Interviews were undertaken with a purposive sample of ward-level staff who had been observed, representing a range of professional groups, including doctors (three consultant geriatricians, one ortho-geriatrician and one trainee), nurses, healthcare assistants (HCAs) and physiotherapists (Table 7). Organisational staff with a remit for falls prevention beyond specific wards were identified and approached by the local collaborator in each site. Roles included Senior Nurse for Professional Practice Standards and Safety Team (Site 1), Deputy Chief Nurse (Site 2), Falls Specialist Nurses (Site 2) and Dementia Lead (Site 3). A total of 50 staff interviews were undertaken. Recruiting ward-level staff was challenging due to the pressures on the NHS at the time of undertaking data collection. Formal interviews were complemented by informal interviews, carried out while undertaking observations.

| Site | Ward | Ward manager/matron | Nurse-in-charge/senior nurse | Nurse | Doctor | Nurse associate/student nurse | HCA | Physiotherapist | OT | Pharmacist | Other |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Complex | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Orth | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 2 | C | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| O | 2 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | |

| 3 | C | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| O | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | |

| Total | 7 | 5 | 7 | 5 | 2 | 5 | 4 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

Interviews were undertaken with a purposive sample of patients/carers where the patient was either aged 65 or older or between 50 and 65 and judged to be at higher risk of falling and their care had been observed. Sampling sought to ensure variety in patients’ falls risk (based on staff advice) and to include both patients that staff deemed to be without cognitive impairment and carers of patients that staff deemed to have dementia. Twenty-eight patients were interviewed. The ability to recruit carers (to interview and provide consultee agreement for patients with cognitive impairment) was limited, owing to restrictions on visiting during much of the observation period; three family members and carers were interviewed. Therefore, in total 31 patients and carers were interviewed.

Sampling of patients for record review

On each ward, we reviewed the falls risk assessment and falls care plan for 10 patients (total = 60). This number was chosen on the basis it was a feasible amount of data to collect within the time frame of the study and would provide enough data for quantitative analysis to be undertaken.

Data collection

Ethnographic observations

Ethnographic methods, such as non-participant observation, have been used in previous realist evaluations as part of the process of theory testing and refinement,25,27 providing insight into the processes and contexts of care. The importance of observation for determining how and if guidelines are used in practice has been demonstrated. 27

In each case site, three researchers (NA, LM, RR) conducted observations independently in the same ward and at similar times. An observation protocol was developed, based on the CMOcs being tested and with input from the Lay Research Group and SSC, which defined what the researchers should pay attention to (see Appendix 3). Researchers recorded observations in fieldnotes. Following in the ethnographic tradition, in the early stage of study researchers kept the scope of the notes wide, on the basis that what previously seemed insignificant may come to take on new meaning in light of subsequent events. 45 In addition, the researchers recorded incidents of observer effects (e.g. participants asking ‘What are you writing?’) to allow analysis of whether participants’ awareness of the researchers’ presence changed over time. 46 The researchers regularly compared their notes to ensure they were capturing the necessary information at an appropriate level of detail and to reflect on what they were observing and identify necessary additions to the observation protocol. Fieldnotes were written up in detail as soon after data collection as possible, using a fieldnote template based on the observation protocol.

For the first two observation periods in each ward, the researchers undertook general observations, to become familiar with staff and the work of the ward. We sought to understand ward routines, including handovers, safety huddles, and multidisciplinary team meetings, and to capture wards’ physical layout. Attention was also paid to other artefacts that support falls prevention, such as electronic (or manual) whiteboards that indicate which patients are at risk of falling. Following this, the researcher selected a bay to observe where there was at least one patient aged 65 years or older or aged 50–64 years and judged to be at higher risk of falling due to an underlying condition. Ethnographic notes focused on patient care (for patients who had consented to be observed) or general staff activities, with attention to activities contributing to falls prevention. For example, whether walking aids were in reach of patients, whether and how call-bells were used. Visiting restrictions limited our ability to observe the contribution of carers to falls prevention, although these were eased towards the end of the observation period.

In each site, it was agreed the researcher would report inappropriate practice to the ward manager. The researcher would only intervene immediately if they witnessed dangerous or abusive behaviour.

Staff interviews

Semistructured interviews were conducted with staff to discuss our CMOcs. For this purpose, the interviews were conducted using the ‘teacher learner cycle’. 47 Here, the interviewer describes the theories to the interviewee, through their interview questions, and the interviewee is then invited to comment, expand on and discuss the theories, based on their experience. Through this process, the interviewer channels the interviewee’s responses to the task of developing and refining the theories. Staff interviews ranged between 10 and 90 minutes in duration, taking place at staff convenience on the ward or via Microsoft Teams. Interview topic guides were established for ward-level staff and organisational-level staff, based on the CMOcs. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Interviews with patients and carers

Semistructured interviews were conducted with patients and/or their carers. Interview topic guides were established for patients and carers, based on the CMOcs and with input from the Lay Research Group. Interviews ranged between 5 and 50 minutes in duration. All interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Record review

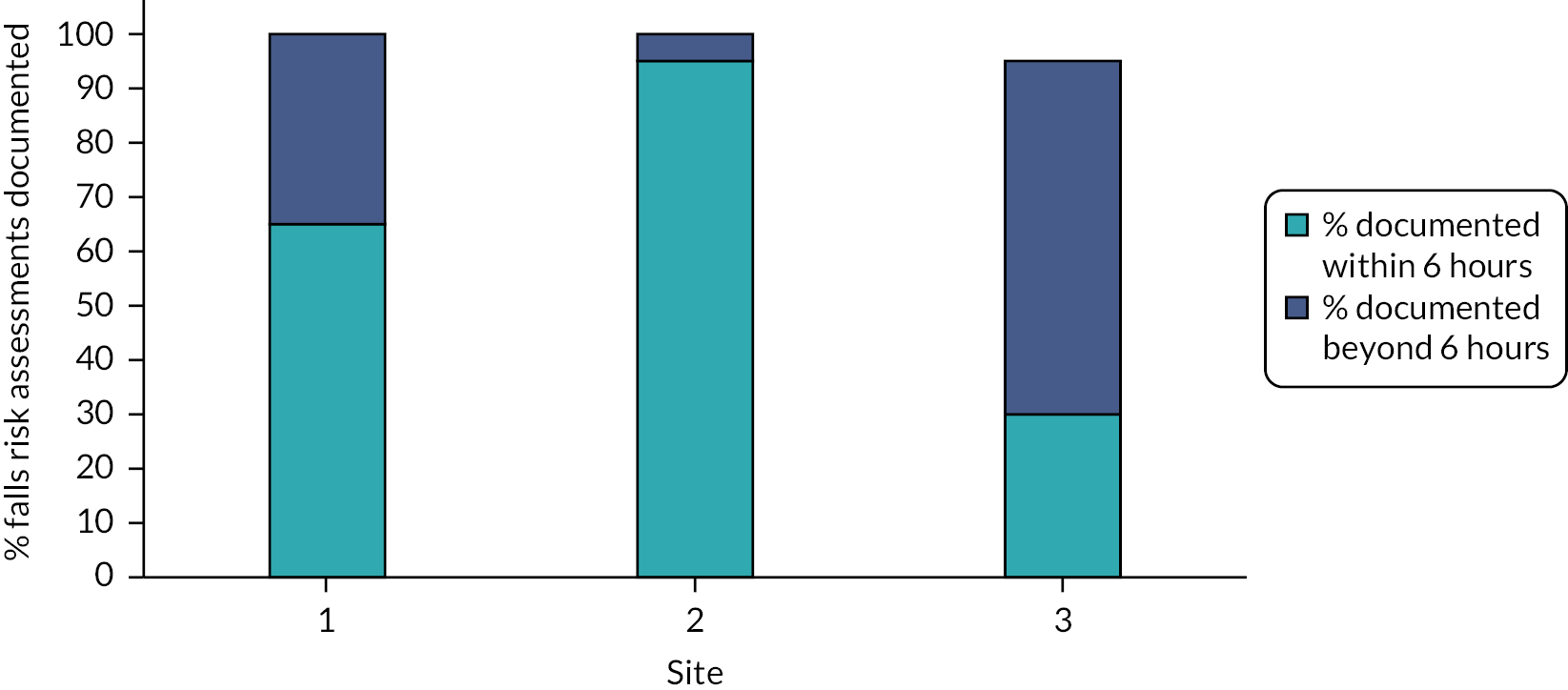

An Excel spreadsheet was developed for recording information from the patient record. The falls risk assessment and care planning documentation was situated within the electronic health record (EHR) in all sites. Data were extracted to assess whether (1) a falls risk assessment was completed for the patient on admission and within 6 hours (a policy at Site 1 and Site 2); (2) a care plan was documented for the patient and if this was completed on a day or night shift; and (3) the care plan was updated and if updates were completed on a day or night shift. In extraction, an assessment or care plan was documented as complete if all items included in the tool had a response documented. While we had hoped to undertake the record review prior to observing a patient’s care, so observations could be used to determine if the care plans were enacted, we were not granted EHR access at the sites in time for this to be possible.

Routinely collected data

Routinely collected data on reported number of falls and reported falls-related harms per ward per month was received from each Trust.

Analysis

Qualitative data analysis followed the steps of framework analysis. 48 The researchers began by familiarising themselves with the data by reading a selection of the observation and interview transcripts – a process facilitated by ongoing reading of transcripts throughout data collection. Researchers then met to discuss construction of a thematic framework to facilitate CMOc testing. Based on previous experience of indexing data for CMOcs, the decision was made to minimise the number of themes by keeping themes abstract to encompass explanation of mechanisms and contextual influences for example, for facilitation, ‘use of physical artefacts’ encompassed description of tools used, how they were used by staff and factors that appeared to support or constrain tool use. The thematic framework was then used to index the data. A series of matrix displays, based on the case dynamics matrices described by Miles and Huberman,49 were used as a next stage in analysis to facilitate cross-case analysis and obtain an overview of the data. One matrix display was produced for each site and for each CMOc being tested (12 in total). The matrix column headings summarised the content of the starting CMOc – clarifying the hypothesised contextual influences, resources offered, participant responses and impacts. In each matrix row, data were summarised, with reference to the indexed data, by Trust and ward, with rows representing organisational site interviews, orthopaedic ward staff interviews, orthopaedic ward observations, older person/complex care ward staff interviews, older person/complex care ward observations. The frameworks informed the site presentations, where findings were presented and discussed with participants, and then formed the basis of narrative summaries that described how the data supported or suggested a refinement or addition to the CMOc.

In addition, the Lay Research Group undertook an analysis of the qualitative data. After defining the task and what qualitative data analysis involved, the Lay Research Group members had about a month before the data analysis session to consider individually two sets of observation notes (one from an orthopaedic ward and one from an older person/complex care ward) and two interview transcripts (one from a patient and one from a carer). Following a general discussion about the materials and the effect of reading them on members, the Lay Research Group shared their thoughts on the individual observation notes and interviews. A number of patterns or themes were identified in the text, including themes about acknowledging patients as people and the impact staff attitudes had on falls prevention. Their analysis resulted in the recommendation of some approaches in falls care planning, such as using imagery (e.g. picture cards) in interactions with patients with communication difficulties such as people with dementia, or speak different languages. Their analysis was reported to the project management group and fed into the wider data analysis process described above. Because of this, their analysis is not reported separately in the following results chapters, but is, rather, incorporated within them (e.g. the importance of knowing patients as people is reflected in the analysis of case study data relating to patient participation in Chapter 8). Reflections on the results or outcomes of PPI itself on the study are reported in Chapter 9.

Analysis of quantitative data

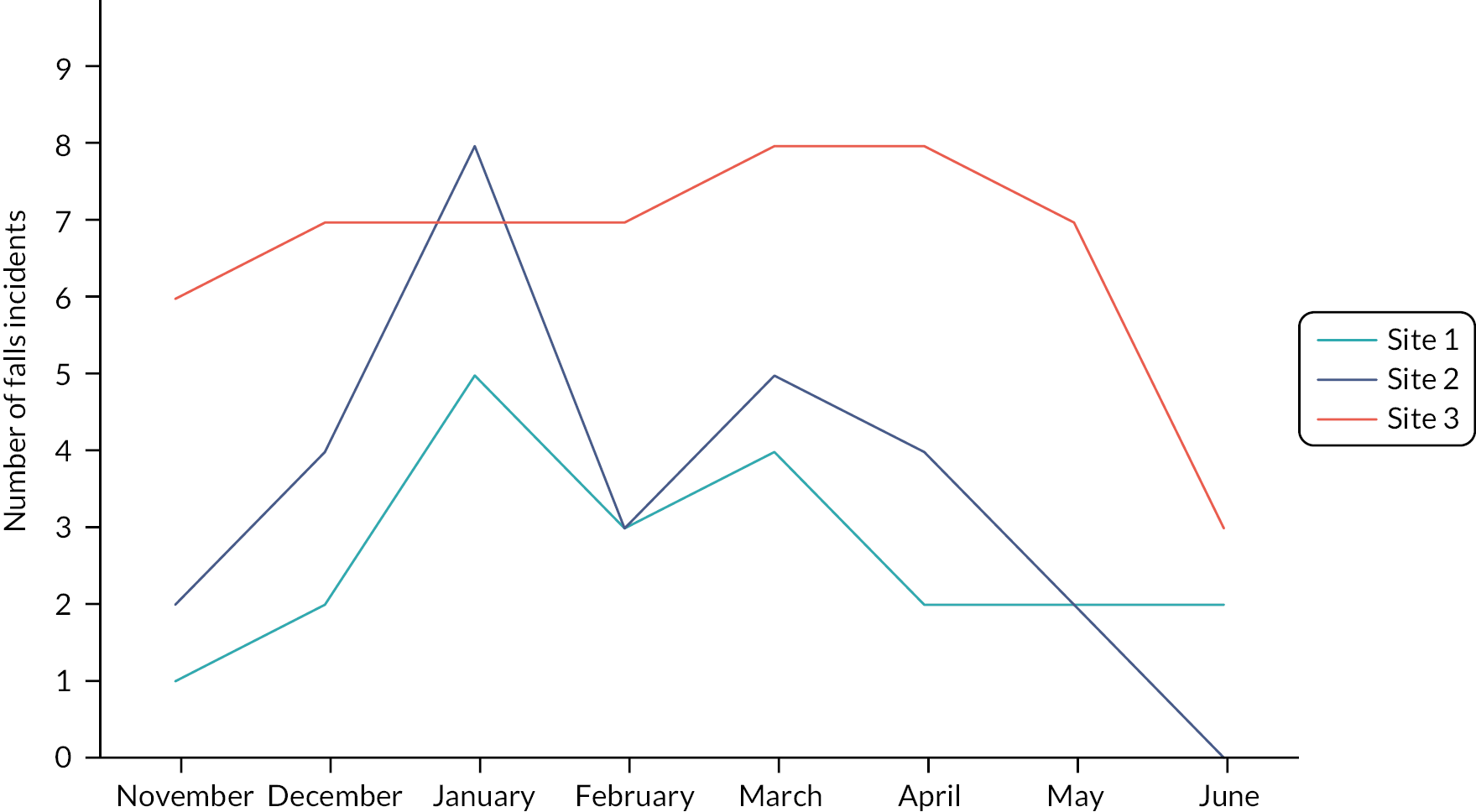

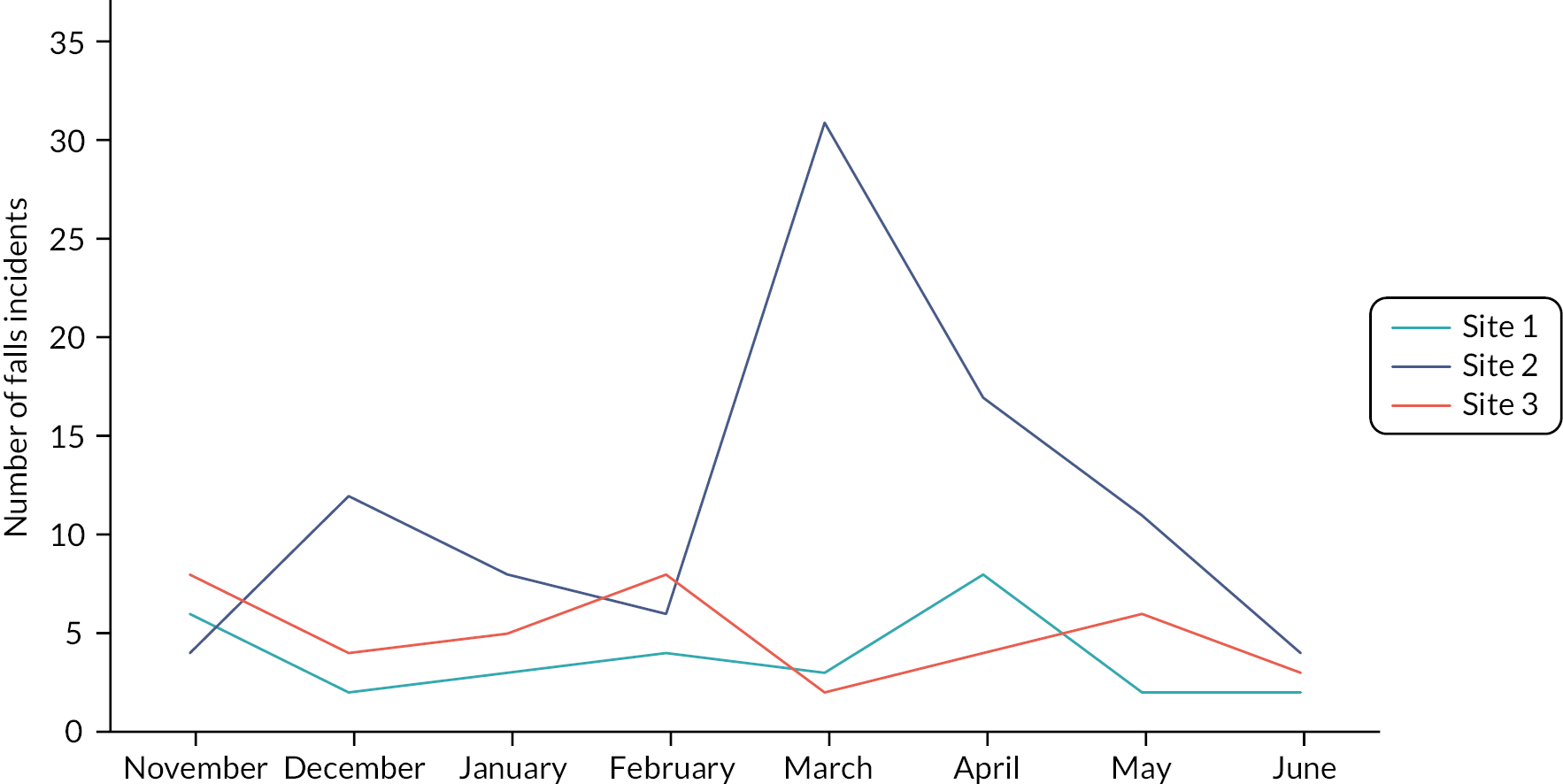

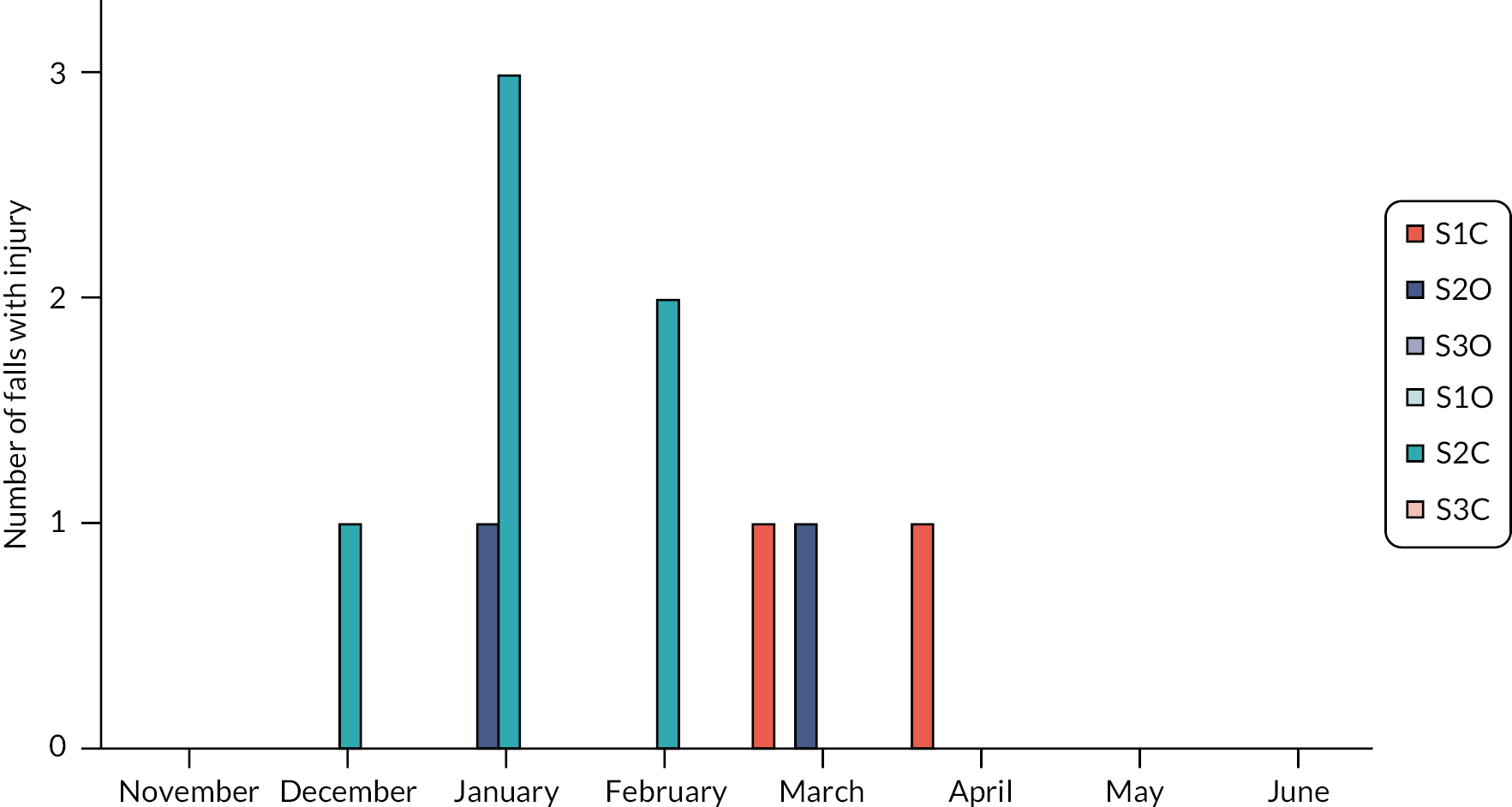

Quantitative data consisted of, for each ward, the record review as described above. Descriptive statistics were produced in Excel, broken down by ward. While we also gathered routinely collected data on number of falls and falls-related harms, we did not undertake quantitative analysis of these data, because there may be differences in falls rates between wards that are unrelated to the effectiveness of their falls prevention practices; we present the data as line graphs purely as contextual information (see Appendix 4, Figures 9–11).

Development of guidance

In September 2022, we held online presentations at each case site, reporting our findings. These acted as a form of respondent validation, providing an opportunity for those we observed to say whether they recognised what we described. We also used these meetings to gather participants’ perspectives on the implications of the research for practice and how guidance should be disseminated, which we discuss in Chapter 9.

Study management

The study was undertaken by a multidisciplinary project management group, providing expertise in falls risk assessment and prevention, clinical decision-making, HIT and realist methods. Members brought different clinical expertise (nursing: DD, FH, AL; pharmacy: VL, HZ), while DW provided a patient perspective. Two researchers were employed on the project (NA, LM), both of whom had previously worked on projects using realist methods. In addition, both had received training in realist methods; NA has a PhD in realist evaluation, supervised by Ray Pawson, and LM had attended training at the Centre for Advancement in Realist Evaluation and Synthesis, University of Liverpool. A SSC was convened, which met with members of the project management group at three points over the course of the project.

The Lay Research Group

Rebecca Randell, the study Principal Investigator, and DW, the lay member of the project management group, met at an event organised by NIHR INVOLVE (a national advisory group that promotes public involvement in health and social care research). On preparing the outline application for this study, RR invited DW to join the project team. Following an initial meeting of RR, DW and NA to discuss the approach to PPI, DW drafted the PPI section of the submission. It was agreed we would recruit a team of ‘lay researchers’, rather than a more conventional lay advisory group; the term was chosen to reflect the active role we hoped to encourage in the project. Alongside this, NA met with DW to provide background information about realist methods. When the project was funded, RR and DW worked together to prepare an information sheet to send to lay people interested in joining. Four lay researchers were recruited from Leeds Older People’s Forum and from service user and carer contacts at Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust and, headed by DW, the Lay Research Group was formed. The Lay Research Group members were from diverse backgrounds (e.g. different ages, ethnicities and sex) who had either fallen themselves or who had cared for someone who had fallen in hospital. LM supported the group by setting up meetings, circulating papers, and taking notes, as well as offering advice and support throughout the project. LM and DW worked together to provide any necessary training for the Lay Research Group. Due to restrictions imposed by the COVID-19 pandemic, all Lay Research Group meetings took place online. An early activity, encouraged by DW, was for both Lay Research Group and project management group members to produce ‘mini-CVs’: short, informal, one-page documents describing background relevant to the project, relevant PPI or professional roles, and other interests; these provided a way for the project management group and Lay Research Group to get to know each other, while also emphasising everyone had something valuable to bring to the project. As described above, the lay researchers contributed to the prioritisation of theories for testing at the end of Stage 1 of the realist review, development of data collection tools for the multisite case study, and analysis of qualitative data collected within the multisite case study. DW regularly attended the project management group meetings, minutes of project management group meetings were shared with the Lay Research Group, and a joint Lay Research Group/project management group meeting was held as an opportunity for lay, clinical and academic colleagues to meet and consider the outputs of the study and its dissemination, and together agree on further work. Lay Research Group members also contributed to project dissemination, writing posts for the project blog (www.bradford.ac.uk/health/research/frames/blog/), presenting to a Commissioning Support Unit about the approach to PPI within the project, and participating in the site presentations. Further details of our approach to PPI are reported elsewhere, in a paper written jointly by lay and academic researchers. 50

In addition to meetings held for the activities described above, the Lay Research Group met three times over the course of the study to evaluate the PPI approach taken (discussed in Chapter 9). The evaluation method drew on the Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public (GRIPP2) short form reporting checklist,51 the UK standards for public involvement for better health- and social-care research. 52,53 and a scoring system developed by the NIHR Yorkshire and Humber Patient Safety Translational Research Centre on a scale of one to six, with a score of one reflecting poor adherence to the UK standards and a score of six reflecting excellent adherence. An evaluation sheet was developed to capture discussions. In the first evaluation in summer 2021, the Lay Research Group met to evaluate progress and allocate scores, then RR, NA and LM met separately to carry out their own review. Both groups decided on topics for discussion independently. Finally, they met together to review progress overall and a joint summary of progress against each standard was produced. For the second and third evaluations in February and October 2022, respectively, a ‘lighter touch’ was used, in which the Lay Research Group met to discuss whether anything had changed since the previous evaluation. In addition, the final evaluation also considered reflective statements written by lay and academic researchers as part of the process of co-authoring the PPI paper mentioned above,50 which focused on how it had felt to work together as partners on the project; what impact this had had on each person and/or the project; and what they felt had supported this.

Chapter 3 Theory construction

Introduction

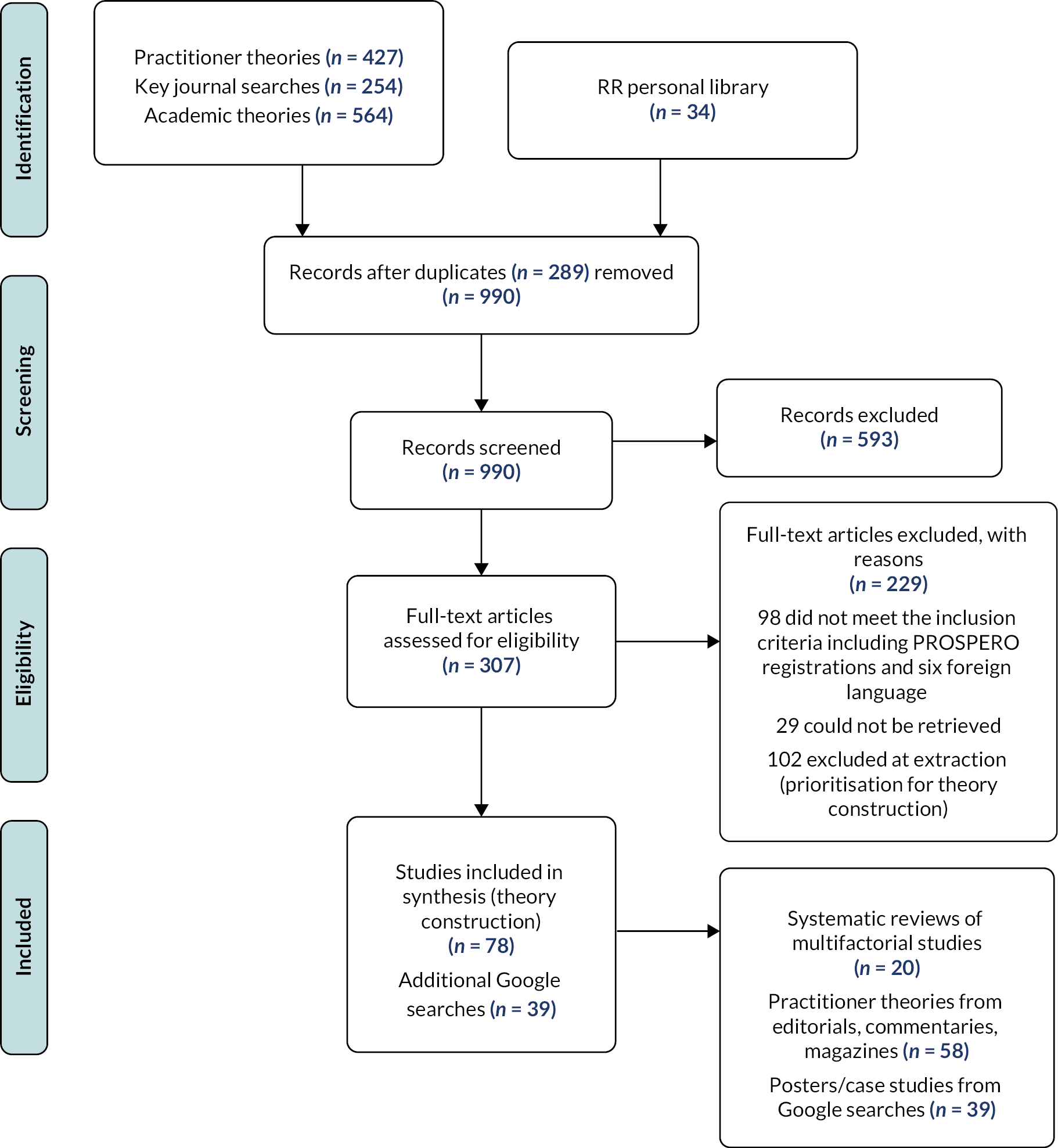

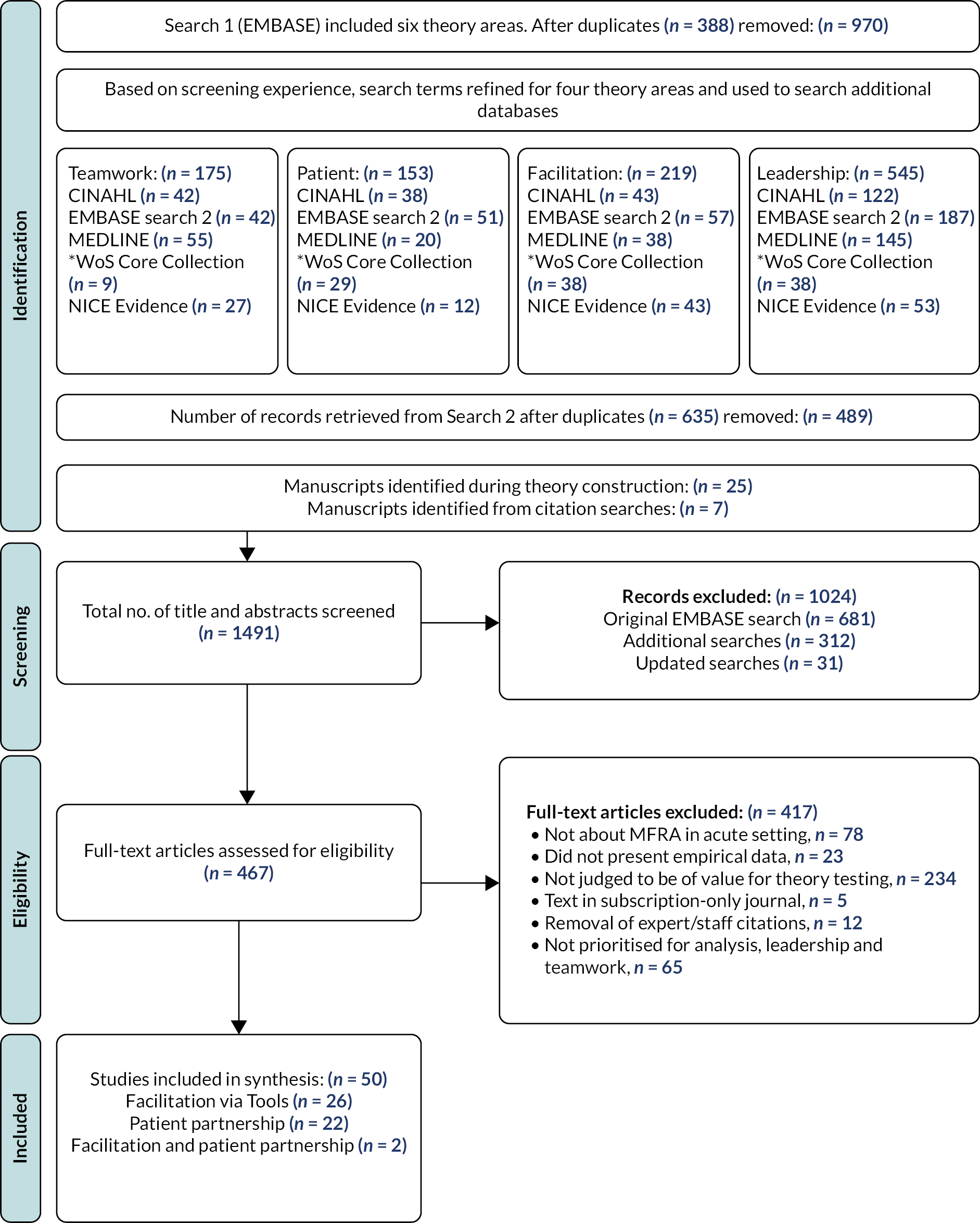

This chapter presents the findings of the theory construction phase of the realist review. The searches identified 1029 unique references to be screened, of which 117 were included in the synthesis [see the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram in Figure 2]. We first provide a summary of the included papers, including the interventions for preventing falls they describe, and the context of inpatient falls. We then use the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR)54 to organise the findings from the practitioner papers because it provides a comprehensive framework to categorise mechanisms, supports and constraints across multilevel contexts that is, at the micro (individual), meso (service/organisation) and macro levels (national).

FIGURE 2.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses diagram for theory construction searches.

Summary of included papers

The papers included in the analysis related to multifactorial risk assessment and prevention strategies specifically and falls prevention strategies more generally. While some papers talked about falls risk assessment and prevention being multidisciplinary, a limitation of the literature is that the majority focused specifically on it as an aspect of nursing practice.

Studies included in the reviews we identified took place in a range of countries with a similar healthcare system, including the USA, UK, Australia, Singapore, Sweden, France, Switzerland, the Netherlands and Germany. 55,56 Each covered multifactorial assessments and interventions in acute settings (sometimes compared with other settings and/or with single-factor interventions).

The term ‘multifactorial’ was interpreted in different ways, some authors emphasising interprofessional working,57 while others described the process of assessing risks and providing tailored combinations of interventions. 55,57 Assessment tools also varied, including comprehensive geriatric assessments58 and self-developed tools to assess patients’ multiple falls risks. 55,59 Some reviews included studies in which falls risk prediction tools were used, such as the Morse falls scale,55,60,61 TNH-STRATIFY,55 and the Hendrich II falls risk model. 55 While such tools are explicitly excluded from multifactorial approaches by NICE,62 we found the distinction between those tools and a multifactorial approach was often unclear: for example, a falls prevention toolkit in one study63 in the Avanecean et al. 55 review used HIT to generate interventions tailored closely to patient-specific areas of risk, identified via the Morse falls scale, including recent history of falling, gait characteristics and impaired mental status, all of which are recommended by NICE. Therefore, we included papers which incorporated the tailoring of interventions to individual risk factors, even where they were associated with the use of risk prediction tools.

The context of inpatient falls and falls prevention

Choi et al. 64 and others55,58 group risk factors as extrinsic (environmental) or intrinsic (patient-related) in nature, with each risk group comprising many different elements. Ward layout and medications given to patients were characterised as extrinsic factors, for example, while intrinsic factors include patient age, history of falls, and physical and cognitive health. The presence of both extrinsic and intrinsic risk factors can, in fact, make hospitals dangerous places for frail, older people, increasing their risk of falling. 64 A report from The National Patient Safety Agency on Slips, Trips and Falls in Hospital, discussed by Hairon,65 showed the most common time for falls is mid-morning, when patients are most likely to be moving around, and most falls are unwitnessed, sometimes owing to extrinsic factors associated with ward layout, which mean that a nurse caring for one patient behind closed doors or curtains cannot observe other at-risk patients at the same time.

Extrinsic and intrinsic risk factors require different interventions, tailored to manage the risks of individual patients. For example, it was noted above that many falls are unwitnessed and take place when patients are attempting to mobilise on their own, often to visit the toilet. Interventions that attempt to address these risks may include proactive nursing assistance with toileting, hydration and moving, such as hourly or intentional rounding; regular observation or moving beds closer to nursing stations; and use of special equipment, including height-adjustable beds and chairs, bed alarms and call-bells. 55,66,67 As well as these targeted interventions, Christy68 drew attention to basic, universal safety measures that should always be in place to address some extrinsic risk factors, such as ensuring patient rooms and hallways are free from trip hazards and flooring is dry.

Choi et al. 69 categorised these different types of interventions as environmental-related; care process and culture-related; and technology-related, with the latter two types being more frequently implemented than the first. According to this model, MFRA is an intervention categorised under ‘care process and culture’ that could trigger use of several other interventions to address individual risk factors for assessed patients and may be used alongside other universal interventions, for example, ward layout. However, this model did not explain what multifactorial practices involved, for example, which tools were used, how they were integrated into work routines, supports or constraints or links with reductions in falls risk. Therefore, we drew on practitioner ideas to develop our CMOcs.

Practitioner theories of implementation and impact

Intervention characteristics

Intervention characteristics in the CFIR cover how intervention features, such as complexity, strength of evidence, and adaptability, influence implementation. The included papers discussed implementation of national guidelines for falls prevention and the development of specific tools to assess and document falls risks and prevention strategies. They also considered interventions designed to support or improve implementation of guidelines and associated tools, such as the use of champions and falls education and training. In this section we focus on characteristics of national guidelines and the assessment tools themselves and discuss other types of intervention within the remaining domains.

Barker70 compared the 2004 and 2013 versions of NICE guideline on falls in older people, pointing out that a lack of integration between the two guidelines (the first focused on community care while the second was updated to incorporate inpatient falls) made the 2013 version difficult for clinicians to interpret, owing to visible differences in writing style and layout of the two elements. These differences were said to affect the quality of the guideline and make interpretation more difficult for clinicians, especially those who worked across care settings. Additionally, they noted that, to support clinicians, NICE had developed a falls in older people pathway, designed to be used interactively on the NICE website, although this might not be feasible for clinicians during their working day. There is a paper alternative, but it was 12 pages long, difficult to follow and not considered user friendly. This suggests ease of access to recommendations and their presentation may influence their use in practice. Furthermore, Glasper71 referenced a number of guidelines and resources, developed by NICE, the Royal College of Physicians, and the Care Quality Commission, available to support falls prevention in hospital but noted that ‘no matter how much advice bodies such as NICE produce it is often nurses who have to reconcile the reality of care delivery and the quest to reduce falls’ (p. 807), pointing to the practical day-to-day challenges of delivering recommendations, which are likely to vary between organisations depending on resources available.

Multifactorial falls risk assessment tools

A key component of the NICE guidelines is delivery of MFRA. A number of falls risk prediction tools were discussed in the literature, but Matarese and Ivziku72 noted that no single tool could identify all patients at risk of falls or accurately exclude all those who were not at risk of falling, a fact which underpins the NICE62 guidance. It was not clear in the literature reviewed (which included international studies and perspectives) if any standardised tools were used specifically for MFRA. Kelly and Dowling73 pointed out that there was no single, universally adopted assessment tool; institutions tended to develop their own. However, they described the most important characteristics of any tool were that it is easy to use, quick to complete, and reliably identifies at-risk patients. An assessment tool with a care plan was provided as an example of best practice, highlighting the importance of linking identified risks with actions to improve, manage or address risks. However, they also noted that the efficacy of the assessment depended on the skills of the healthcare professional undertaking it, indicating the influence of individual knowledge and experience on accurate risk identification. Christy supported this idea, commenting that nurses should not rely on assessment tools alone and that they should apply their clinical judgement to prevent falls. Characteristics of individuals that influence implementation and risk reduction are discussed further in Staff characteristics.

The idea that falls prevention practices should be easy to implement was echoed by Miake-Lye et al. 56 who noted that engagement of clinicians in design and development can help ensure an intervention will ‘mesh’ with existing clinical procedures, suggesting that to support implementation, falls prevention practices and tools should connect with and complement existing systems. Promoting this idea, Avanecean et al. 55 suggested that adherence to intervention protocols was supported where components were easily incorporated into existing practices and where it supported ongoing evaluation of falls prevention programmes. To this end, Sutton et al. 74 reflected on the use of a multifaceted care bundle to minimise patients’ falls risk and suggested that a rolling programme of auditing the care bundle elements could be incorporated into routine processes to support implementation by informing adaptations for example, by streamlining the documentation process. Analysing falls documentation and practice in this way has been argued to be an important part of falls prevention. 75

Health information technology

Health information technology can be used to capture and present data about falls to evaluate the causes of incidents and adherence to intervention components. 56 Hempel et al.,60 for example, note that integrating falls risk assessment into EHRs could support falls audit and feedback processes by providing ready access to data. A different function of HIT was discussed by Mashta,76 who described the use of an electronic alerting system, in which alerts generated by the hospital information system notified staff as soon as a new patient was admitted with a history of falls, while Barrett et al. 77 discussed use of HIT in their hospital’s falls prevention programme. Nurses used the EHR to record admission details and it acted as a prompt for the initial nursing assessments. A falls risk score was added as a mandatory screen in the EHR and nurses were required to enter a falls risk score directly into the patient’s electronic record on admission and to update it weekly until discharge. In their review of falls prevention strategies in the USA, Spoelstra et al. 75 reported on the use of an IT system to generate tailored falls prevention posters for individual patients and patient-specific alerts, in a study by Dykes et al. 63 Finally, Grant and McEnerney,78 in their article about one-to-one nursing, commented that nursing staff are often busy with routine clerical duties, which may constrain intervention delivery. They argued that EHRs make these clerical duties quicker to complete, giving nurses more time to spend with patients, and thereby reducing the likelihood of serious falls occurring.

Staff characteristics

The CFIR domain ‘characteristics of individuals’ refers to people’s knowledge and beliefs about the intervention. These factors may support the implementation of falls risk assessment and prevention practices, or they may constrain it, even if the intervention has features deemed supportive. For example, Miake-Lye et al. 56 discussed nurses’ ‘buy-in’ or commitment to falls prevention as an implementation support, but also noted the need to change the attitude that ‘nothing can be done’. Changing individual and group attitudes or motivation towards falls prevention programmes was discussed in many of the manuscripts reviewed,56,75,79 often with reference to the use of educational and training interventions to increase knowledge of falls risks and, consequently, attitude towards intervention delivery. For example, Glogovsky80 discussed how, when nurses understand falls prevention interventions, they are more engaged in preventing falls. A nurse supported this assertion; Johnson81 reported that reading a continuing professional development (CPD) article improved their knowledge of falls risk assessment tools, including the importance of completing an assessment for older inpatients both on admission and regularly during their hospital stay. They explained that this knowledge increased their confidence in undertaking the assessments and that they were more aware of the importance of taking a holistic approach, incorporating risk factors that they had not considered previously, such as oxygen tubing, which can present a trip hazard. The CPD article outlined the physical and psychological factors nurses should consider when undertaking assessments, and the effects that older people may experience because of a fall. The importance of engaging practitioners undertaking the assessment in this way was highlighted by Lindus,82 who described a nurse’s realisation of ‘going through the motions’ when undertaking a falls risk assessment. The nurse reflected that they were shown how to complete the falls prevention paperwork but had not made the association between the risk and the specific patient assessed.

Falls champions

The availability of staff dedicated to falls prevention was identified as a potential implementation support. Several authors described studies of staff – often nurses – who were dedicated to falls prevention activities, for example, in the role of falls ‘champions’. The amount of time and other resources available and the precise nature of the role varied. In one study included in the Avanecean et al. 55 review, for instance, two research nurses were made responsible for delivering a care planning intervention and received intensive training on delivery, implementation, and care plan development. While the intensive training may have generated the necessary ‘buy-in’ and engagement in risk identification, an additional support on delivery of the falls prevention strategy was that champions had ‘as much time as needed’ (p. 3022) to fulfil their responsibilities.