Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number NIHR135589. The contractual start date was in April 2022. The draft manuscript began editorial review in April 2023 and was accepted for publication in November 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Daniel et al. This work was produced by Daniel et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Daniel et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Box 1 provides a summary of Chapter 1 of this report.

-

Historically, women’s health has been confined to a focus on reproductive health. However, there has been a call for broader conceptualisations.

-

Women’s sexual and reproductive health needs are complex and vary across the life course from menarche to post menopause. A range of organisations, venues and professionals are involved in service provision for women’s health. Services in England are often not well integrated across organisations and there are challenges in access, workforce and resources and fragmented commissioning.

-

Local teams across the UK established Women’s Health Hubs (WHHs) in response to these challenges to improve provision, experiences and outcomes. These emerging models have been highlighted as best practice and wider adoption has been recommended.

-

The government identified the opportunity to integrate women’s health services more effectively, with a more woman-centred, life-course approach, reflected in the Women’s Health Strategy for England. The strategy, published in July 2022, encouraged the expansion of WHHs across the country, with additional funding to support implementation announced in March 2023.

-

There was no agreed definition of a WHH. Hubs were not necessarily a ‘place’, but a ‘concept’, and the term had been applied differently across health and care services.

-

In response to WHHs being identified as an important policy topic, the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) asked the BRACE Rapid Evaluation Centre to undertake a rapid evaluation of current hub evidence and practice. This evaluation aimed to provide information on hub models, how they were being implemented and how successfully.

-

The evaluation was supported by Stakeholder and Women’s Advisory Groups.

What is women’s health?

Conceptualisations of women’s health

Women’s health has historically been confined to a focus on sexual and reproductive health, including childbearing and menstruation. However, there has been a call for broader conceptualisations:1,2

Women’s health involves women’s emotional, social, cultural, spiritual and physical wellbeing and is determined by the social, political and economic context of women’s lives as well as by biology. 2 (p. 118)

The focus on sexual and reproductive health may be linked to the role that contraception and abortion access has played in transforming women’s autonomy, to make choices about having a family. 3 Organisations such as the Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare conceptualise women’s health as existing on a continuum, with experiences and needs throughout the life course. 2–4 This acknowledges that needs change alongside life events and with age and draws attention to both stages and points of transition (e.g. the start of menstruation through to menopause). 3,4 This enables a preventive, rather than just reactive, approach to women’s health and extends beyond a medical model to improve health and well-being across generations. 4

Service provision

Women’s health needs can be understood and grouped in a number of ways and include pregnancy-related (e.g. pregnancy planning, fertility), sexual health-related (e.g. sexual pleasure) and non-pregnancy-related (e.g. incontinence). 5,109 These are met by a range of providers, professionals and venues, which also varies locally, as described in Box 2.

Organisations:

-

As part of their core service, primary care practices provide advice and treatment, for example contraception [excluding fitting of long-acting reversible contraception (LARCs)], sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing, cervical screening, menopause management and treatment. They refer women as required, for example specialist Sexual and Reproductive Health or gynaecology clinics. They may fit LARCs as part of a Locally Enhanced Service contract.

-

Sexual and reproductive health services – are sometimes called sexual health, family planning or genitourinary medicine (GUM) clinics. They offer a full range of contraception and STI testing and advice. They may also offer sexual-assault support, hepatitis and human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccination, post-exposure prophylaxis for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and cervical screening.

-

Pharmacies – provide access to contraception, emergency contraception, advice and STI screening.

-

LARC hubs – in some areas, hubs have been established to improve access to and uptake of LARC for contraceptive and/or gynaecological reasons, for example at a designated GP practice.

-

Community gynaecology services – can provide enhanced-level gynaecological care beyond what is offered in primary care, for example ultrasound, hysteroscopy, biopsy, management of complex menopause and heavy menstrual bleeding. Some may offer complex contraception. This may be provided in community settings to avoid the need for hospital gynaecology referrals.

-

Hospital gynaecology services – provide a range of outpatient assessment, testing and treatment for more specialised or complex gynaecological conditions, including suspected cancer, in secondary care settings. Provide inpatient care including gynaecological surgery.

-

Maternity services – provide inpatient, outpatient and community care during pregnancy, antenatal, intrapartum, postnatal and neonatal care.

-

Abortion services – provide access to support and perform termination of pregnancies, for example in a hospital or clinic. Often provided by private-sector organisations.

-

Private clinics – provide access to any and all of the above on a fee basis, for example screening, menopause, sexual health and contraception provision and support.

-

Outreach and specialised services for particular communities – often provided by outreach teams, for example local sexual health services, and offer support such as access to contraception for homeless women.

Professionals:

-

GPs and GPs with special interest in women’s health or sexual health.

-

Practice nurses.

-

Advanced nurse practitioners.

-

Pharmacists.

-

Consultant gynaecologists – medical and surgical care for conditions that affect the female reproductive system, including cancer.

-

Consultants in community sexual and reproductive health care – trained to deliver specialist care with a focus on population health management, for example for contraception, medical gynaecology, menopause and pregnancy and unplanned pregnancies.

-

Genitourinary medicine consultants – diagnose and manage STIs, genital infections and conditions.

-

Specialty doctors and specialty trainee doctors in the specialties listed above, physician associates, nurses and healthcare assistants in the specialties listed above.

In England, these services are provided in a range of primary and secondary care settings, with a variety of funding and commissioning arrangements. The complexity of the landscape often means that provision is not well integrated, and artificial divisions between contraception and reproductive health have led to challenges in access to contraception in England. 6 Following the 2012 Health and Social Care Act, responsibility for the provision of contraception, sexual and reproductive health provision was split between different commissioning bodies, for example local authorities, NHS England, and Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs), which have now been replaced by Integrated Care Systems (ICSs). 6,7 Services have been described as ’shaped by the source, availability and amount of funding available, rather than by women’s needs’ (p. 12). 6 Local authorities have largely had responsibility for preventive and public health services, including sexual health and contraception services, whereas the NHS has responsibility for the assessment and treatment of disease in primary care (including prescribing) or via referral for specialist health services. This fragmented model of commissioning can result in services that are disjointed, which may not reflect local population needs, and may lead to unwarranted variation in spending by local organisations, and difficulties in comparing investment between localities. 7 A particular consideration is that long-acting reversible contraception (LARCs), specifically intrauterine devices/systems (coils), may be required for either contraceptive purposes or gynaecological reasons. Separate sexual health and gynaecology commissioning arrangements mean that services are often not funded to provide coils for both reasons in one setting. A case has been made for collaborative commissioning, with a clear mandate and resources, supported by strong public health leadership. 8

Several factors seem to be interacting to increase perceived pressure on women’s health services: NHS budgets are under pressure, and local government has experienced cuts to funding; there are workforce and training gaps, for example insufficient staff with the right skills and experience. The COVID-19 pandemic and waiting-list backlogs have impacted on access. 4,6,9 Suggested improvements have included more strategic leadership accountability, models of care that incorporate sexual and reproductive health needs, sustainable workforce models that provide care for those with complex needs and provision for all. 4

Women’s experiences

The challenges described above can result in negative experiences for women seeking care. Women may be moved between services due to gaps in care pathways, have difficulty accessing appointments (including long waiting), experience variation in interest and expertise at the first point of contact, and may be required to attend multiple appointments with different providers, wasting time and resources. 6 Women are ‘being left without clear direction of where to access the support and services they need’,10,11 as care is not structured around their needs. 10,11

The Better for Women report by the Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists emphasised the need to focus on and adopt a life-course approach to women’s health. 9 As part of the report, a UK-wide survey of women was commissioned, which highlighted poor access to basic women’s health services, barriers to care and a need for improvements to services. 9 To inform the first Women’s Health Strategy for England,12 the government collected evidence from women. Five topics were identified for prioritisation: gynaecological conditions; fertility, pregnancy loss and postnatal support; the menopause; menstrual health and mental health. 13

Areas in need of improvement included women not feeling heard and difficulties with service access. 14 Women reported that their symptoms were often dismissed and that obtaining a diagnosis was challenging. Most respondents relied on family or friends for information and identified a particular lack of information on menstrual well-being, menopause and gynaecological conditions. Being taken seriously and offered appropriate treatments for menopause were further areas where shortcomings were reported. The majority of women suggested that service access was not convenient regarding location or time. 14 Women suggested changes at system level, including hubs and drop-in centres, as well as greater diversity in provision. 14 The evidence collected supported the need for a more joined-up approach to women’s health care and the implementation of WHHs, including one-stop shops (discussed further later).

Geographical variation and inequalities

Across the country, there is also variation in the quality and availability of sexual and reproductive health services, with a lack of ownership and accountability in the system for women’s healthcare needs. 4,9,15–17 This has been shown to particularly affect women seeking support for fertility treatment and menopause4 and cervical screening. 18 It has been suggested that political prioritisation of women’s health services is required to drive improvements, particularly for women from disadvantaged backgrounds, who experience the worst outcomes. 18 There are significant inequalities in sexual and reproductive health, with young people and ethnic minority groups among those disproportionately impacted. 15,19 For example, unmet need in contraception access is suggested by higher abortion rates among people from socially disadvantaged and/or ethnic minority backgrounds, and under 25s. 4 Additionally, women with disabilities can face barriers in accessing cervical screening or contraception. 4 It is also important to consider lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, questioning and other sexual and gender identities (LGBTQ + ) service users. There is a paucity of high-quality research in this area, and routine data are not often collected in a way that enables appropriate examination of health inequalities. 20 Long-standing inequalities in service access and provision for women from disadvantaged and minority groups have likely widened because of COVID-19. 18

Development of Women’s Health Hubs

In recognition of these issues, there have been increasing calls for a more collaborative, holistic and integrated approach to delivering women’s health care, designed around women’s needs. 6,9,15 Local teams across the UK responded to the challenges in delivering services by establishing WHHs to improve access, experience and outcomes for their population, to address inequalities, and reduce costs. Some known models were already well established, while others were set up and/or starting to function around the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Hubs function to meet the integrated needs of women’s reproductive health care by providing access to a practitioner with appropriate skills, in a community setting (usually primary care, although not necessarily at their own practice or provided by their own practice team). Although still emerging, these early models were highlighted as best practice,11,21 with wider roll-out recommended. 9 There appeared to be an increasing expectation among women in the population that healthcare provision needed to change. For example, in the UK-wide Royal College of Obstetrics and Gynaecology women’s survey, almost half of participants supported the idea that one-stop women’s health clinics and/or drop-in facilities would improve access. 9

The Primary Care Women’s Health Forum has actively promoted and supported the development of new ‘hub’ models. It has drawn together the expertise of hub leaders across England, and launched a WHH toolkit, to support others to implement these models. 11,93 Their work is evidence of the significant learning available within the professional community from the early experience of hub development, but it also illustrates the ongoing diversity of models and local variation in provision.

Policy context in England

The opportunity to integrate women’s health services more effectively, with a more woman-centred, life-course approach, was reflected in the first Women’s Health Strategy for England (the Strategy), published in July 2022. To support implementation and raise the profile of women’s health, a Women’s Health Ambassador was also appointed. 12 The Strategy aimed to improve the health and well-being of women and girls in England, by taking a life-course approach and ‘embedding hybrid and wrap around services as best practice’ (p. 8). 12 The Strategy set out several immediate steps being taken to improve women’s experiences and outcomes, including ‘encouraging the expansion of women’s health hubs around the country and other models of one-stop clinics, bringing essential women’s services together to support women to maintain good health and create efficiencies for the NHS’ (p. 8). 12 It described how WHH models ‘provide integrated women’s health services at primary and community care level, where services are centred on women’s needs and reflect the life-course approach, rather than being organised by individual condition or issue’ (p. 8). 12 Reducing the LARC backlog for both gynaecological and contraceptive reasons was an impetus for the development and roll-out of WHHs, as stated in the Strategy: ‘A key aim of hub models is to improve women’s access to the full range of contraceptive methods, and in particular LARC’ (p. 8). 12

Local commissioners and providers were strongly encouraged to consider adopting these models of care. 12 In mid-March 2023, a £25 million investment to ‘accelerate the development of new women’s health hubs to benefit women’ was announced with the aim to see at least one hub in every ICS. 22 The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) was also working collaboratively with multidisciplinary stakeholders to develop resources to support the creation of WHHs, including a best-practice guide. 22

While WHHs are emerging, there are many examples of models of integrated care which provide more joined-up care closer to home. Integrated care first appeared in targets and legislation in 1972, with further developments in later years. For example, in 2006, the Department of Health launched ‘Care Closer to Home’ demonstration sites to define appropriate new models of care. The sites were in six specialties, one of which was gynaecology; all sites attempted to reduce repeated visits, improve access and address the need for integrated and/or one-stop services. 23 In 2008, Integrated Care Pilots were launched to explore different ways of integrating care, with an aim of providing care closer to service users. 24 Later developments were driven by major policy reforms: for example, commitments to integrated care in the 2014 Five Year Forward View,25 and the introduction of the New Care Model Vanguard sites, which aimed to pilot new models of care for the health and care system that could be rolled out more widely. 26 Specific ‘hub’ models are also increasingly mentioned in NHS policy and are outlined in Chapter 2.

Moves towards greater integration in commissioning and delivery of sexual and reproductive health services mirror a wider direction of travel in English policy with the government’s commitment to integration of care across a population footprint. 27–29 This was reflected in the development of primary care networks (PCNs), place-based partnerships and ICSs to integrate care across organisations and settings and improve population health. In addition, GP federations have been established in some areas. These are groups of primary care providers which form a single entity with shared systems and records. They work together to deliver services for women across multiple PCNs, and to bridge the gap between ICSs and PCNs. 30 Federations, PCNs and ICSs provide opportunities for supporting the development and implementation of WHHs across England. 6,9

What is a Women’s Health Hub?

When this evaluation commenced in 2022, WHHs were understood differently by stakeholders, and we did not identify a single agreed definition of a WHH. Hubs were referred to as not necessarily a ‘place’, but a ‘concept’, and the term was used differently across health and social care services.

The Primary Care Women’s Health Forum, described WHHs as follows:

At the core of any Women’s Health Hub framework is convenient access to a range of services for all women. Women’s Health Hubs bring existing healthcare services together to provide holistic, integrated care. This care is accessible, delivered by trained healthcare professionals, supported by specialists. This results in better outcomes for patients. A Women’s Health Hub is not a building, there is no need to invest in new physical space. It is not a major financial investment, it’s about efficiencies of scale. 31

In the Women’s Health Strategy, a vision for WHHs was described: ‘hub models can provide management of contraception and heavy bleeding in one visit, integrate cervical screening with other aspects of women’s health care, or manage menopause at the same time as contraception provision for women over 40’ (p. 26). 12

There was, however, an emerging consensus that WHHs were characterised by some core features which provided the basis for a working definition for the evaluation.

A working definition for the evaluation

Through work with experts and service users, it was evident that a detailed definition for the evaluation was needed to draw boundaries around what a WHH is, distinct from other specialist services, for example a community gynaecology service or LARC hub. We have sought to build on the definitions from the Primary Care Women’s Health Forum and in the Women’s Health Strategy. 12 The working definition which underpinned this evaluation was a set of common features which were widely recognised by the community of practitioners as typifying a hub approach, as follows:

-

Women’s Health Hubs are based in the community and work at the interface between primary and secondary care and/or the voluntary sector and wider.

-

Women’s Health Hubs offer more than a single service (and include the provision of both gynaecological services and contraception) or demonstrate plans to do so.

-

Women’s Health Hubs have more than one organisation involved in the process of service delivery, including in design, commissioning and/or provision of care, beyond simply referring in.

Our interim evaluation report included an additional criterion:

WHHs are co-commissioned or joint-commissioned, meaning two or more organisations are responsible for tasks such as awarding or reallocating contracts to providers32 (or moving towards this) and/or have evidence of integrated governance and leadership models. 33 (p. 12)

However, during the course of the evaluation we observed that a number of hubs were currently able to provide both contraception and gynaecology services without a formal joint-commissioning arrangement. While some were working towards more integrated commissioning, this was not always the case. Similarly, there were not consistent integrated formal governance and leadership approaches across WHH models. Rather than exclude these models from our definition and evaluation, we revised our definition to be more inclusive in the final evaluation report. We discuss the challenges and opportunities for integration further in the results and discussion sections.

Although there may be future lessons from private models of WHHs, in this evaluation we focus on WHHs funded and operating within the NHS only.

The evaluation

Women’s Health Hub models are largely new and emerging, with examples of hubs in planning or set-up, and wider roll-out of hubs recommended. However, there was a paucity of research on these models. Through our scoping work for the evaluation, we identified significant diversity in the existing landscape, and a need to define, map and understand the current approaches and produce learning, to inform future development and investment.

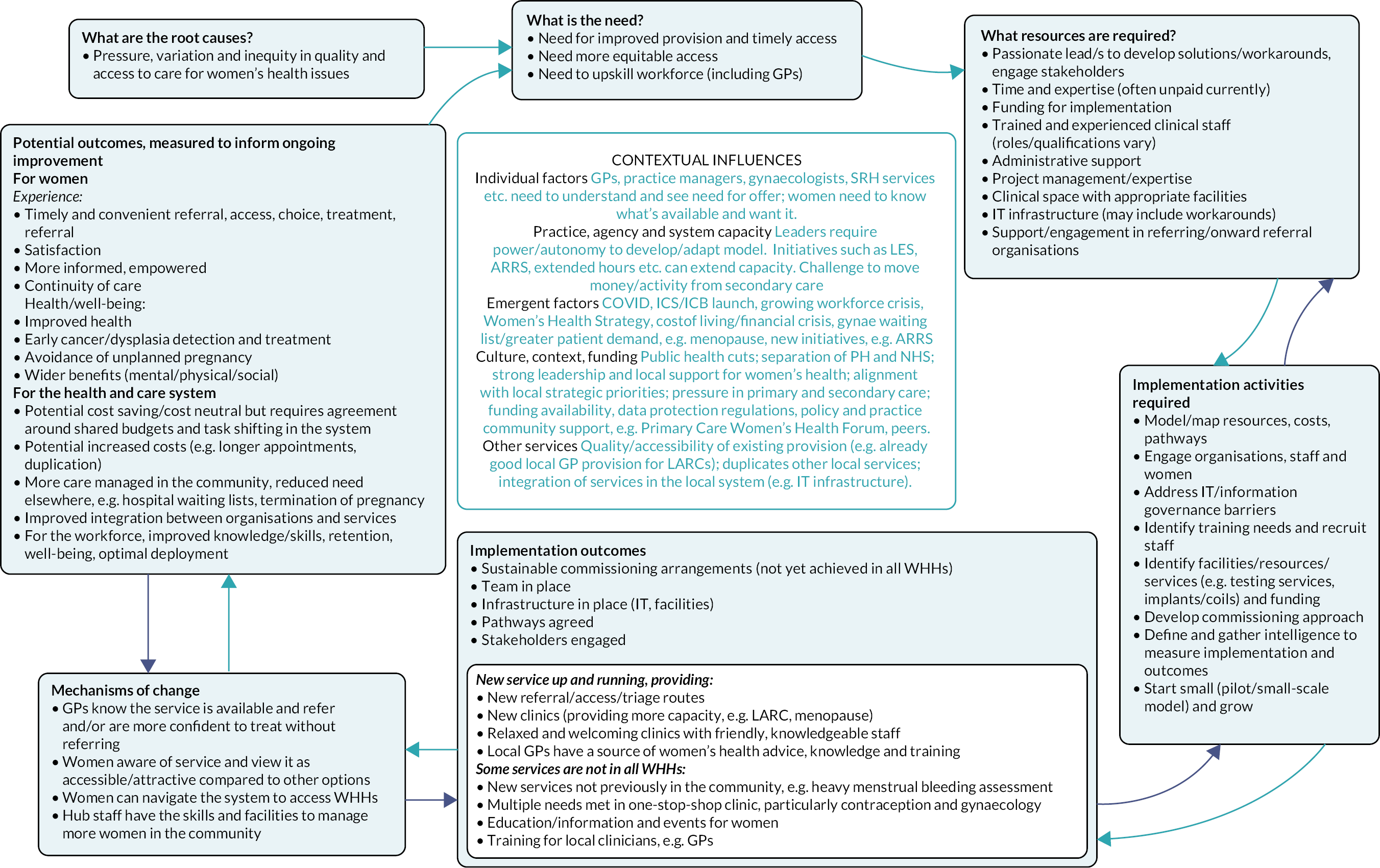

Evaluation aim

The overall aim of the evaluation was to explore the ‘current state of the art’, mapping the landscape, studying experiences of delivering and using hub services and defining key features and early markers of success to inform policy and practice. Specifically, the study evaluated why, where and how hubs have been implemented; why different approaches have been taken; how inequalities have been considered and experiences of implementation, delivery and receiving services. The evaluation explored the successes and challenges of hubs and potential improvements, including different stakeholder group perspectives of what hubs are intended to achieve, and whether hubs were making progress towards this. It also explored what is known about performance, outcomes and costs and how they are measured.

Evaluation questions

The study sought to answer the following evaluation questions:

-

What are WHHs, and is there variation in how stakeholders name and define them?

-

How many WHHs have been established or are in development across the UK, where are they, and what are their characteristics, including models of structure, commissioning and delivery?

-

Why have WHHs been implemented, and how are they intended to address health inequalities?

-

What have WHHs achieved to date? How do WHHs achieve this?

-

What are the experiences and perspectives of staff regarding WHH set-up, commissioning, funding, implementation and delivery?

-

What are the experiences and perspectives of women who have used hub services?

-

How are WHHs’ performance, outcomes and costs measured, and how might they be measured in future?

Development of the evaluation design

The protocol was developed after a detailed scoping phase in early 2022 which included:

-

Interviews with 10 key stakeholders to gather insights and experiences of WHHs and to define the evaluation scope (this included WHH leaders, national policy and practice leaders and representatives of key organisations including the Primary Care Women’s Health Forum, Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare and Royal College of Obstetricians and Gynaecologists).

-

Identification and review of relevant published and grey literature to locate existing WHHs to understand the context and inform evaluation design and questions.

-

Establishment of a Stakeholder Advisory Group to support the evaluation.

-

A stakeholder workshop to refine the evaluation focus and questions.

-

A meeting with three women with lived experience of NHS women’s health services to discuss their views about what the evaluation should explore.

Wider input

Stakeholder Advisory Group

A multidisciplinary Stakeholder Advisory Group provided expertise and advice to support the study, meeting three times. The group discussed a range of topics related to women’s health, the Strategy and the evaluation. We also sought advice and guidance from the group on an ad hoc basis throughout. Details on the group’s specific input can be found in Chapter 3.

Women’s Advisory Group

The evaluation involved women with lived experience of NHS care for women’s health issues from the outset. Three women took part in the scoping work, and subsequently joined our Women’s Advisory Group. The Women’s Advisory Group provided input throughout the evaluation and used lived experiences to shape the project. This comprised a diverse group of seven women with varying experiences of NHS care for women’s health issues, including smear tests, endometriosis and menopause. The Group was chaired by a woman with experience of public involvement in research and evaluation. The team also met separately with an eighth member who was unable to join the main group meetings, who provided additional input including on terminology, the hub concept and delivery and inequalities. Our public contributors were drawn from across England and included different demographic backgrounds including age, ethnicity and sexual orientation.

Four virtual meetings were held with the group at key points in the evaluation. Meeting dates were agreed with the Group in advance, and any relevant documentation, for example topic guides, was shared before each meeting, along with meeting slides and an agenda. Where members were unable to attend, they could meet researchers separately later, or provide feedback via e-mail.

The Group helped to shape the study, provided advice and feedback, and contributed to framing and prioritisation of findings. Their input included:

-

Highlighting the need to include a more diverse group of women who may not access WHHs. As a result, we changed the methods to include focus groups with women in communities to hear about awareness and understanding of hubs, and any potential barriers to access.

-

Advising on appropriate ways to recruit women to participate, suggesting routes for data collection with patients using hub services and stressing the importance of flexibility and appropriateness, being mindful of women’s differing needs and preferences.

-

Providing guidance and perspectives regarding important criteria for selecting the hubs to be involved in in-depth evaluation.

-

Suggesting that we explore patient pathways in/out and back into WHHs, and how this is understood by and communicated to women.

-

Providing input into the design of evaluation tools, reviewing tools and providing feedback.

-

Reviewing the plain language summary for the protocol and report.

-

Reflecting and commenting on emerging findings and their relevance to women.

-

Providing advice about framing and disseminating the findings, particularly for the public.

-

Reflecting on the concept of WHHs as emerging models of care.

Working with policy-makers

We liaised closely with the Women’s Health Ambassador and Women’s Health Policy team at the DHSC in several ways, including:

-

discussing the interim report findings, and areas of evaluation focus

-

discussing priorities and work plans to ensure complementary approaches and avoid duplication

-

sharing copies of evaluation tools for example interview guides

-

sharing our working theory of change to inform policy discussions

-

sharing a working list of identified WHHs, which could be shared with ministers

-

meeting to discuss costs and benefits of women’s health models and potential considerations for economic analysis

-

connecting our stakeholders with the policy team to aid their work around understanding costs and benefits of models

-

reviewing a DHSC survey tool designed to collect information on hub costs

-

presenting at the policy team’s WHHs Expert Forum, held to initiate collaboration with stakeholders and support local areas to implement WHH models

-

meeting to discuss key conditions for funding of WHHs.

Structure of the report

In October 2022, an interim report was published, which focused on early findings from an online survey to map the current UK WHH landscape. 33 This report builds on the earlier output. Chapter 2 summarises relevant literature. Chapter 3 provides an overview of the methods utilised in the evaluation, and the findings are presented in Chapter 4. Chapter 5 presents insights from the Women’s Advisory Group and Chapter 6 summarises and discusses the study findings, exploring implications for research, policy and practice.

Chapter 2 Mapping of relevant literature

To locate this study within existing research and evidence on integrated care, specifically hub models, we undertook an initial pragmatic and rapid review of relevant academic and grey literature, revisiting our searches throughout the course of the evaluation. This included exploration of evidence for integrated care models outside the context of women’s health. A summary of the topics we reviewed can be found in Table 1. This section first explores what is known about WHHs, to demonstrate gaps in knowledge addressed in this evaluation. We then describe the literature on hub models, followed by relevant evidence and theory from the broader integrated care literature.

| Topic area | Relevance to the evaluation |

|---|---|

| WHHs | The grey literature describing WHHs provides a wide range of practice-based evidence to support hub implementation, though there is a lack of formal academic research on this topic. A review of what is known about WHHs provides a foundation on which the evaluation builds. |

| Hub models | Literature that describes hub models for women’s health is limited. We draw on the wider evidence exploring hub models in other health contexts to inform the evaluation. |

| Integrated care literature | The integrated care evidence base offers insights into the implementation, impact and dimensions of integrated care which can be applied to WHHs. Integrated care theory acts as a ’sensitising’ concept for the evaluation, supporting the interpretation of findings. |

What do we know about Women’s Health Hubs?

Although WHHs are a relatively new concept and we did not identify any published academic literature describing or evaluating their effectiveness, the grey literature offers important insights into these models and how they are intended to improve health services for women. The Primary Care Women’s Health Forum WHH webpages describe what a WHH is at a high level,11 and share early learning through case studies34 and a toolkit to support services with planning and implementation. 35–37 Key messages from the Primary Care Women’s Health Forum case studies are summarised in Table 2.

| Overarching aims | |

| Drivers | |

| Challenges | |

| Enablers | |

| Early benefits |

A number of models and ways of organising and providing women’s health services are described in the Primary Care Women’s Health Forum case studies and wider literature on WHHs. These include hub-and-spoke models,34 one-stop-shop models,39,43 PCN-based models,34 inter-practice referral models44 and community gynaecology models. 34 However, definitions of these terms are unclear. In our findings, we explore and, where possible, define models.

The case studies and resources provide valuable evidence to support hub implementation. Case studies were developed collaboratively with leaders and early implementers in WHHs. However, there has not been any comprehensive mapping of WHHs to date, and descriptions of models in the grey literature vary in detail and focus, with no in-depth exploration of the experiences of WHH staff and women using services. Our evaluation builds on and addresses the gaps in current evidence.

What is known about ‘hub’ models in health care?

Hub models are increasingly mentioned in NHS policy across a variety of contexts and are being implemented for different purposes across England. For example, NHS England recently set out plans to create health and well-being hubs, known as ‘Cavell Centres’, aiming to bring health and social care services together in one building. 45 Hub models in the literature focus on a number of different health conditions and services, such as child and family hubs, which include voluntary and community organisations pooling resources. 46 However, the evidence for hub models has not been synthesised, and there is no agreed definition of a hub, and terms are used inconsistently in policy and academic literature. Hubs and similar models can be adapted to a range of contexts, and a key message from the evidence is that one size does not fit all. 47–50

Hub-and-spoke models are described as providing complex services in a central ‘hub’ (typically a hospital), linked to a network of more local ’spokes’ (less specialised hospitals/community venues). 51 A model may have a single hub or multiple hubs; similarly, any number of spokes may feature in a hub model. 52 The activities within hubs and spokes may vary, along with the way they are managed. For example, different spokes may provide different services and there may be variation in the way women access them. 52 In hub-and-spoke models of maternity services, a hub may be a consultant-led ward in a hospital, surrounded by midwifery-led units. 53

Hub models can provide care as a one-stop shop, meaning a broad number of services are available under one roof,54 ideally in a single visit, reducing the need for numerous appointments. 55 There are a range of examples of one-stop shops, bringing together professionals and service providers to improve and integrate care. 56–58 These models have been described as user-focused, providing opportunities for staff development, and were recommended by the Royal College of Gynaecologists and Obstetricians during COVID-19 to reduce risk of exposure for staff and women. 59 One-stop-shop models in primary care have been associated with improved patient satisfaction, particularly with continuity of care and accessibility. 54 In an evaluation of a GP hub-and-spoke model of sexual and reproductive health services, a sexual health centre acted as a hub, with GP practices as spokes. The model was led by nurses, and hub staff provided training and education to upskill nurses in sexual and reproductive health care, so that the GPs and nurses could provide human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/sexually transmitted infection (STI) testing and treatment, with more complex cases referred to the hub. 60 The model was found to be acceptable and feasible by women and by clinicians, integrating with usual practice well. 60 However, there are concerns that providing all services under one roof may have a negative impact on the sustainability of standalone services, and data on the cost-effectiveness of these models are inconclusive. 61

Bostock and colleagues describe a number of limitations in evaluations of hub-and-spoke models in health care, including a lack of clarity in the definition, the absence of service user voice in evaluations, and limited evaluation of the role of context. 52 Predictors of a ’successful spoke’ are also uncertain, specifically in the context of SRH services. 60 This evaluation adds to a limited body of literature on hub models in women’s health care.

Integrated health care

In this evaluation, integrated care is used as a ’sensitising concept’ to support our exploration of how WHHs are set up, structured, staffed and measured. Sensitising concepts act as a starting point for analysis and are ‘background ideas that inform the overall research problem’ (p. 2). 62 Integration is a key concept in descriptions of hub models, and a core aim of WHHs is to integrate services and care for women, but integration has many dimensions. Here, we provide an overview of integrated care definitions, theory and evidence and highlight key challenges to evaluating integrated care. The literature offers insights into the implementation, impact, and dimensions of integrated care which can be applied to WHHs. 47,63,64 It also provides a framework for understanding the examples of hub models identified in this evaluation, supports our interpretation of findings and shows the ways in which WHHs may function. Evaluations of integrated care for women’s health are sparse in the literature, and there is a lack of evidence for decision-makers to assess which care models work best for women’s health, are most effective and likely to be used by those with greatest need. 60 In the discussion of this report, we reflect on the extent to which our evaluation adds clarity for decision-makers.

Definitions

There is no widely accepted definition of integrated care, which has been described in the literature as ‘diverse’, ’synergistic’, ‘ambiguous’ and ‘dynamic’, evolving to meet the changing needs of a population. 65–67 Integrated care can be:

… best understood as an emergent set of practices intrinsically shaped by contextual factors, and not as a single intervention to achieve predetermined outcomes … [it] is a broad concept, used to describe a connected set of clinical, organizational, and policy changes aimed at improving service efficiency, patient experience, and outcomes. 67 (p. 446)

Integrated care is generally understood to be co-ordinated, be that through combining physical resources (e.g. rooms and buildings), by workforce, through bringing together professionals from different services, and by systems, for instance integrating patient record systems across sectors of care. 65 Integrated care involves the removal of boundaries within the health sector (such as those between primary and secondary care), between health and associated services (e.g. health and social care) or both (e.g. in bringing specialised teams together to address both mental and physical health aspects of a condition). 25 Integration can be vertical, with integration between organisations involved at different stages of the patient pathway (e.g. hospitals running GP practices) or horizontal, between organisations at similar stages of a patient pathway, such as GPs working within PCNs. 68

Aims of integrated care

Integrated care intends to achieve the NHS quadruple aim of improving patient experience, population health, the efficiency of healthcare systems (i.e. value for money) and workforce well-being. 69 Integrated care initiatives also often aim to address health inequalities,70 and evidence suggests that benefits of integration may be greater in deprived areas, by improving access to care for underserved populations. 70

Models often tend to be implemented by high-performing early adopters. 70 They are often run by passionate volunteers, by organisations with a strong history of integrated working, and where funding and guidance are provided from national bodies. 71,72

Aims of integrated care vary by stakeholder groups and are often contradictory, meaning positive outcomes for one stakeholder group may lead to negative outcomes for others. 73 Integrated care can require investments in space, specialist resources and staff, and time for patients to be heard, and this does not always align with organisational objectives to reduce costs. 67 A common feature of integrated care is patient-centredness,65,71,73–75 designing services around the needs, preferences and values of patients and families and the type of care they feel is required. 65,71 Our evaluation explores a range of stakeholder perspectives, including those of women using WHHs and others in the community who may find it more difficult to access services. A summary of aims of integrated care can be found in Box 3.

Theory and evaluations of integrated care programmes suggest that these models aim to:

-

Change the way in which health and social care services are delivered71

-

Improve the efficiency25 and cost-effectiveness of healthcare systems71

-

Manage demand82 in light of increasing chronic care expenditure83

-

Reduce hospital admissions71,83 and improve population health25

-

Improve patient experience,25 for instance, by ensuring patients feel heard71

-

Reduce the need for repeat appointments23

-

Produce better patient outcomes,25 including health65 and clinical effectiveness,71 particularly those with the most complex needs,73 such as those with multiple long-term conditions71

-

Provide person-centred care71 with patient and carer involvement in the services they receive74,75

-

Ensure professional adherence to disease-specific protocols and guidelines67,83

-

Share financial responsibility with other stakeholders, and in the long term83

Benefits of integrated care

Stated advantages and outcomes of models of integrated care are numerous and relate to healthcare resources and health system function (e.g. efficiencies in the workforce), improved quality of patient care (e.g. improvements in mortality and morbidity, a reduction in unnecessary harm) and outcomes for staff (e.g. staff work satisfaction). 47,65,73,76–79 For example, the NHS has advocated models of care which bring ‘care closer to home’ for many years. 47,76,77,80,81 Outcomes for integrated care models are often context-specific, meaning they may be unique to the demographics and needs of a local population and geography (e.g. due to variations in transport and proximity to a patient’s home of services). 66,71,72

The advantages of integrated care models may vary according to clinical severity and complexity. It has been suggested that integrated care has the potential to improve outcomes among patients with the most complex needs, particularly given the risk of increased costs of care in these groups. 73

Evidence

The relationship between greater care integration and outcomes is complex, and evidence of effectiveness of integrated care is mixed. 65,73 This is, in part, due to the methodological difficulty of evaluating integrated care initiatives. Programmes are heterogeneous in terms of interventions and outcomes,70 and existing evidence has been reported to be of variable quality and reliability, largely observational and small scale. 67,70 Nevertheless, there is evidence in the literature of improvements in patient experience, health outcomes, staff experience and cost savings following the implementation of integrated care models. 70–72 For example, stakeholders involved in an early evaluation of vertical integration describe the overall impact on health system costs as beneficial, with improvements in managing patient demand. 82 In children and young people’s services, a range of benefits have been described. These include better communication between clinicians and patients, care received closer to home and improvements to quality of life, staff experience and a reduction in unnecessary tests. 70

The evidence of cost-effectiveness of integrated care remains limited and mixed, with some studies identifying potential savings, but others reporting increases in costs. 67,70,71,73,84–87 This is somewhat paradoxical, in light of consistent strong support for integrated care among decision-makers. 67,73 Conclusions from evaluations and reviews of the evidence show a need for better understanding of which integration approaches work best, in which contexts, and what influences success. 71 Concerns have also been expressed about safety, affordability, balancing efficiency with choice, expectations about impact not being met and failure to integrate rather than simply co-locate services. 47,81,88

Integrated care theory

A variety of frameworks is available to describe and explore integrated care, and they can be used to inform evaluations of these models. 89,90 In this evaluation, we drew on integrated care frameworks to explore the different dimensions of integration in WHHs. 90

Available frameworks have been developed using systematic literature reviews and stakeholder and expert consultations. They explore how care is integrated (i.e. the specific integration activity or intervention implemented), and the level at which the integration takes place (e.g. meso/mico/macro levels). 65,91 There was no single framework of integrated care that was best suited for this evaluation. However, Table 3 summarises five key dimensions of integration we explored, underpinned by a framework from van der Klauw. 92 This was selected due to its comprehensiveness, clear presentation of integrated care and utility for the evaluation. This was supported by theory from two other frameworks: Singer et al. 65 and Hughes et al. 67

| Type of integration | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Functional/administrative | ‘Back office’ and support functions and the extent to which they are integrated and co-ordinated across organisations and/or sectors. This may include formal documentation and protocols that support decision-making and accountability. | Technologies to facilitate communication and information-sharing (e.g. shared electronic health records). |

| Structural/organisational | Formal connections (or physical, financial and operational ties) and relationships between organisations that can be used to ensure continuity in transitions between organisations and/or professionals. | Alliances, contractual arrangements, organisational change (e.g. mergers), MDTs/integrated care teams, and joint commissioning. |

| Interpersonal | Collaboration and teamwork between professionals within and between organisations. | Working together to overcome barriers to implementation. |

| Clinical | The co-ordination, streamlining and integration of care/services with the aim to maximise the value for patients. | Integrated care pathways, single point of entry for multiple services, service integration (e.g. gynaecology and contraception, inter-practice referrals, training clinics). |

| Systems and whole systems | Focuses on the whole healthcare system, and the systems within it, and may involve consideration of the extent to which these are supportive of integration, including from a regional and national perspective. | PCNs, place-based partnerships, ICSs/boards. A whole-system approach to integration seeks to implement multiple, often interrelated, changes or interventions. |

We used this table to assist in the exploration of forms of integration in the hub models in our evaluation, which is described in the relevant sections of the results and discussion. There is a need for further empirical research to assess the validity of integrated care frameworks.

Chapter 3 Methods

Box 4 provides a summary of Chapter 3 of this report.

-

The evaluation adopted a rapid mixed-methods design, combining quantitative and qualitative data collection at local, regional and national levels.

-

The evaluation comprised three work packages (WPs):

-

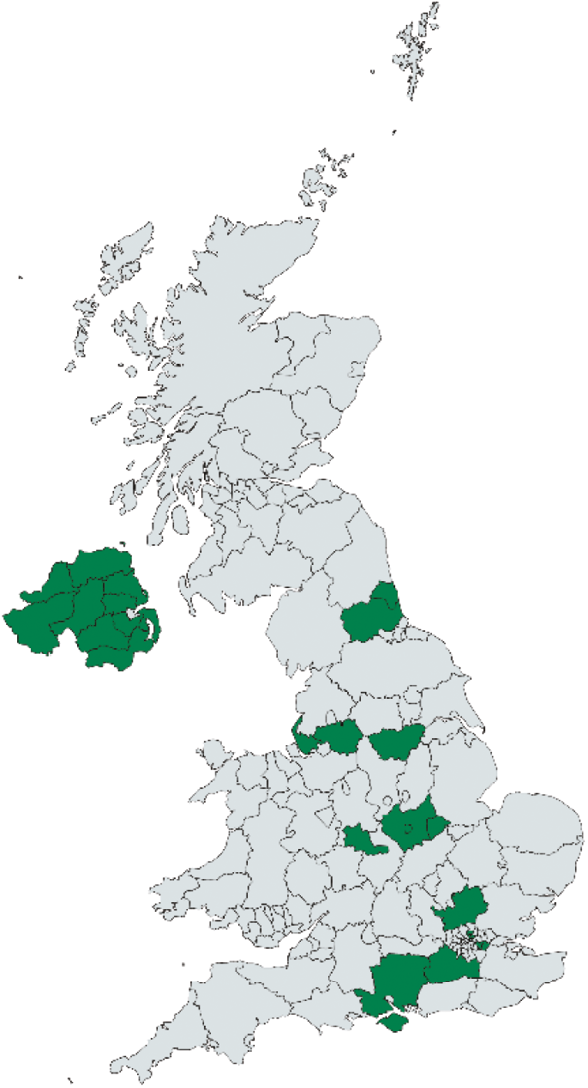

Work package 1: Mapping the current landscape and context for WHHs. This included analysis of pre-evaluation scoping interviews, desk research an online survey of leads from hubs across the UK, development of a database of UK WHHs and interviews with regional stakeholders in England.

-

Work package 2: Detailed research in four purposively selected exemplar hub sites in England, including interviews with staff and service users, focus groups in local communities and documentary analysis.

-

Work package 3: Interviews with national stakeholders, and consolidation of findings from all WPs to generate evidence on WHH models.

-

-

Participants included: 85 interviews (40 WHH and wider staff, 7 regional stakeholders, 6 national stakeholders and 32 patients); 4 focus groups with 48 women and 10 evaluation scoping interviews undertaken prior to commencing the study were included in analysis.

-

Analysis: qualitative data from interviews, focus groups and documents were analysed using a team-based rapid analysis approach; quantitative survey data were analysed descriptively. Different data sources were analysed separately, and collaboratively reviewed, refined and combined by the team, to develop findings and implications.

Study design

The evaluation aimed to be rapid and responsive, exploring a policy-relevant issue during its implementation, producing findings that are relevant and beneficial for policy and practice in real time employing rapid evaluation approaches. We set out to locate hubs and capture useful insights regarding how they were working and early learning that could improve understanding of these models. The exploratory evaluation was conducted with predominantly qualitative methods. Formal quantitative evaluation of impact was beyond scope, with many hubs at an early stage of implementation, and with limited availability of relevant quantitative data. Impact evaluations require adequate time for services to be implemented and embedded within a system, for individuals to use the service, for data owners to collect and curate data, and for researchers to obtain these data. 94

A mixed-methods approach was taken in order to explore the ‘current state of the art’ of WHHs, mapping the landscape, studying experiences of delivering and using hub services and defining key features and early markers of success to inform policy and practice (the aim and research questions are presented in detail in Chapter 1). The evaluation combines national mapping, in-depth work in purposively selected sites and interviews with regional and national leaders to generate evidence which balances breadth with depth to inform scale-up and spread of WHHs.

The evaluation comprised three WPs, summarised in Table 4.

| Work package | Methods overview | Description | Evaluation questions |

|---|---|---|---|

| WP1 |

|

Mapping of the current landscape and context for WHHs, providing a description of different hub characteristics and models in place | RQs 1–3, 7 |

| WP2 | In-depth work in four exemplar hub sites

|

In-depth work with four exemplar hub sites to understand more about why and how hubs have been funded, commissioned and implemented, experiences of hub delivery (including patient experiences), measurement of performance and outcomes and successes and challenges | RQs 1–7 |

| WP3 |

|

Bringing together and consolidating findings from WPs 1 and 2 to generate evidence on WHH models and provide implications for policy, practice and research | RQs 1, 7 |

Mixed methods were employed as follows:

-

Pre-evaluation scoping interviews (qualitative) informed the design of the hub database and mapping survey (quantitative), and the topic guides for all interviews and focus groups (qualitative).

-

The pre-evaluation scoping interviews (qualitative) and mapping survey findings (quantitative) informed the sampling of the exemplar hub sites (qualitative).

-

At the analysis and interpretation stage, we drew on quantitative and qualitative findings to answer the research questions and identify implications for policy, practice and research, integrating different data sources relevant to the questions explored. The role of quantitative and qualitative findings varied according to the questions and topics addressed. The triangulation of different data sources is described in further detail in Data analysis and triangulation across all work packages.

At scoping, in collaboration with policy and practice leaders, a decision was made to focus the in-depth evaluation in England to build contextual knowledge and enable a comparative approach that would not be possible if models from the devolved nations were included, as they differ in terms of health policy, structure and commissioning.

All data collection was undertaken between April 2022 and March 2023, before the recent announcement of funding to support WHH development. 22

The qualitative analysis framework can be found in Appendix 1. Design of the evaluation tools, including the survey and topic guides, and data analysis was undertaken by the evaluation team. This was underpinned by the study aims and evaluation questions, and informed by the scoping work (see Chapter 1), relevant literature (see Chapter 2), emerging findings from the mapping survey, and with input from our Stakeholder and Women’s Advisory Groups.

Protocol approval

The study topic was prioritised for rapid evaluation by NIHR after receiving a request from the DHSC in 2021, in respect of evaluating WHHs. An initial scoping note was prepared in October 2021, followed by the preparation of a full protocol in 2022. The protocol drew on scoping findings to better understand the context and landscape of WHHs. More details on the scoping methods are in Chapter 1. The protocol was revised in July and November 2022 to reflect feedback from the project’s Women’s Advisory Group and to make minor amendments, for example to the timelines for regional interviews following delays to the publication of the Women’s Health Strategy. 12 This was published on the NIHR HSDR webpage.

Ethical approval

The study was approved by the Research Ethics Committee at the University of Birmingham (ERN_22-0669). The project team completed the HRA Decision Tool and liaised with the Head of Research Ethics and Governance at the University of Birmingham, who confirmed that the study met the criteria for service evaluation. Approval by the Health Research Authority or an NHS Research Ethics Committee was therefore not required.

Participants, sampling and data collection

Work package 1 participants, sampling and data collection: mapping the current landscape and context

National scoping interview data (pre-evaluation work, January–February 2022)

The scoping work which informed the evaluation design included interviews with 10 key informants, which were conducted between January and February 2022. Participants included experts leading WHH policy and practice, with roles in commissioning, clinical care, leadership, policy-making, education and training. Stakeholders were from organisations including the DHSC, Primary Care Women’s Health Forum, Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare, local authorities, NHS primary and community care and hospital trusts. Interviews followed a topic guide developed by the study team informed by discussions with policy stakeholders, which explored definitions, hub aims and contexts, existing locations and models, evidence, indicators of success and plans for scaling up.

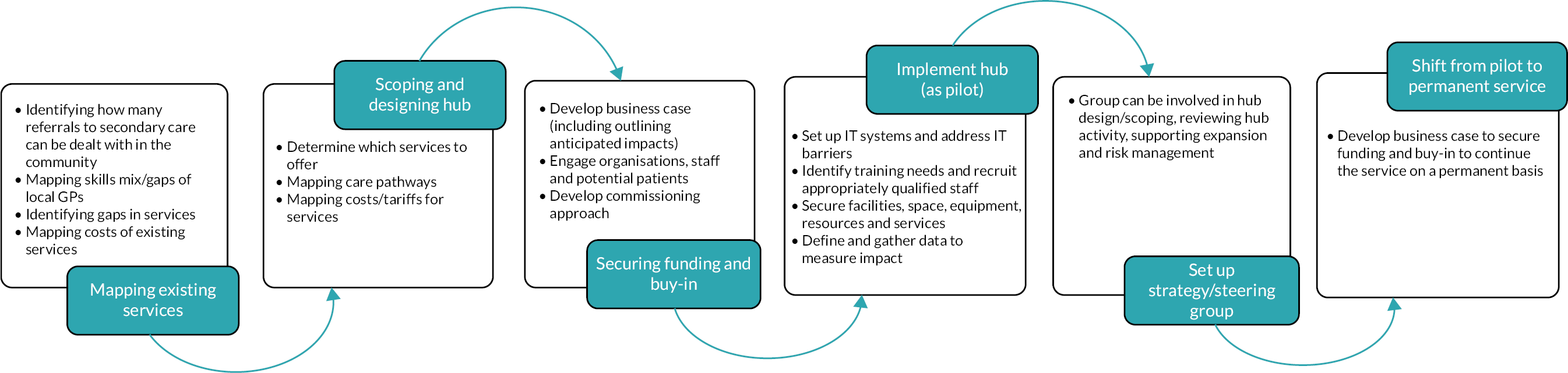

Desk research to inform the database of Women’s Health Hubs (pre-evaluation work, updated throughout the study)

Scoping work included the interviews described above, and a review of relevant published and grey literature to locate existing WHHs and understand the context was undertaken. Scoping findings were used to develop a database of UK WHHs, which was refined throughout the evaluation. To identify models in addition to those located during the scoping work, the team conducted desk research. Requests for information about current and planned WHHs were disseminated via the Primary Care Women’s Health Forum, Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare and the Stakeholder Advisory Group.

We built on the database throughout the evaluation, adding and refining information through methods including desk research, insights from the Stakeholder Advisory Group and the survey. Desk research identified documentary/video evidence which was reviewed to inform mapping and understanding of models, including service websites and materials produced for the Primary Care Women’s Health Forum as part of their WHH toolkit. For example, case studies, videos, webinars and guidance created to support the development of new WHHs. The focus of this work was on identifying models which met our working definition of a WHH, and LARC-only or community gynaecology models were not included in the database.

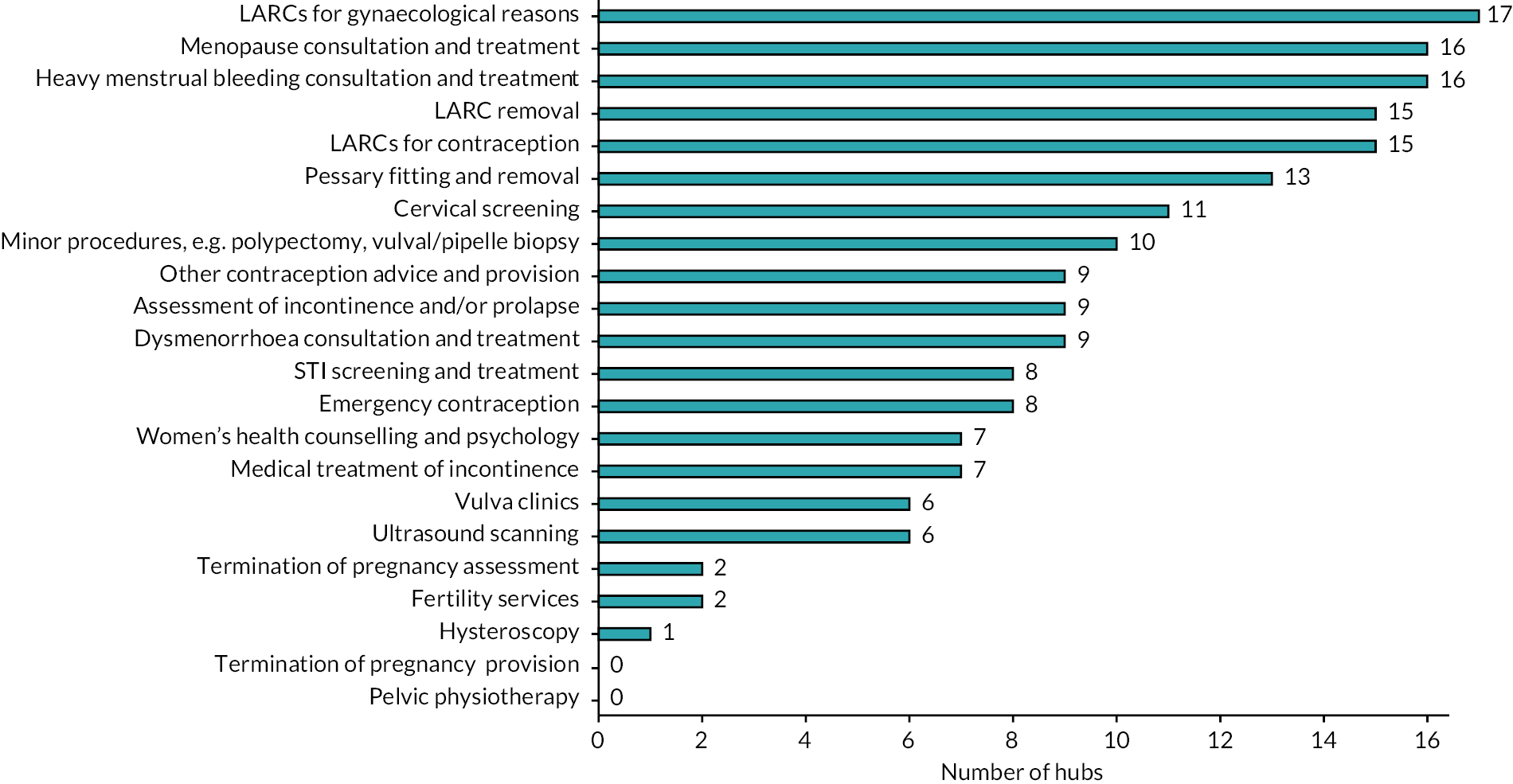

Survey of Women’s Health Hubs leads (May–December 2022)

An online survey of leaders of all known hubs across the UK was undertaken to gather descriptive information and map the current landscape (see Box 5 for topics covered). The survey participants were service leaders (e.g. lead commissioners, hub providers). In the survey, in recognition of the complex women’s health landscape and varied terminology in use services were referred to as ‘integrated community WHHs or services’. The questionnaire was informed by the evaluation questions and pre-evaluation scoping work, with additional input from a consultant in sexual and reproductive health and a health economist with expertise in sexual health and women’s reproductive health. The survey was piloted and refined with a consultant in sexual and reproductive health to ensure that the questions were appropriate, and to check for ease of comprehension and completion.

-

Respondent information.

-

Hub background (e.g. stage of development, year launched, populations served, organisations involved in design/delivery, rationale and aims).

-

Commissioning and funding (e.g. commissioning arrangements, contractual arrangements, additional funding, leadership/governance).

-

The service and pathways (e.g. delivery model, services provided, venues, out-of-hours provision, referral/triage processes).

-

Workforce (e.g. different roles involved, existing local sexual/reproductive health services, training, competency assessment).

-

Data/metrics used to measure hub activity or quality.

-

Additional information (e.g. how hub is reducing inequalities, patient/public involvement in design or delivery of hub).

-

Facilitators and barriers to hub implementation.

The survey was open from May until December 2022 to enable information on new and developing WHHs to be gathered and was administered using the online platform SmartSurvey.

The survey was distributed in several ways: by e-mail to a lead stakeholder in each known hub in the database; the Stakeholder Advisory Group who shared the survey link within their networks and throughout the course of the project provided iterative support to identify new hubs for inclusion; the survey was advertised via the Primary Care Women’s Health Forum, Faculty of Sexual and Reproductive Healthcare and social media. Known contacts were sent multiple reminders to complete the survey. Four hub leads participated in a call or provided e-mail correspondence to complete the survey with a member of the evaluation team. Seventeen survey responses are included in the analysis for this report (Table 5), from a range of respondents (Table 6). Due to the open recruitment approach, and unknown denominator (the number of hubs in the UK was not known), it was not possible to determine a response rate.

| Total | 39 |

|---|---|

| Included in analysis (see Chapter 4) | 17 |

| Excluded as the services did not meet our definition of a WHH (e.g. focused on providing gynaecological services only, with no plans to expand into contraception) | 9 |

| Excluded as respondents reported that there was no WHH in their area | 13 |

| Role | Respondents |

|---|---|

| GP with special interest in women’s health (England)/GP with enhanced skills in gynaecology (Northern Ireland) | 5 |

| GP | 5 |

| Consultant in community gynaecology and reproductive health care | 3 |

| Consultant in sexual and reproductive health | 1 |

| Other | 3 |

Interviews with regional stakeholders (October–November 2022)

To further understand the landscape in which WHHs are situated, following the publication of the Strategy12 we interviewed seven regional stakeholders across six NHS England and NHS Improvement regions. One interviewee provided both regional and national perspectives. We aimed to interview leaders with a regional perspective in each of the NHS England regions, but it was not possible to locate an appropriate contact in one region.

A purposive sampling approach was taken, identifying key informants using desk research with input from known contacts, including members of the Stakeholder Advisory Group. Potential interviewees were approached by e-mail, which included an information sheet and consent form. Reflecting the heterogeneity in women’s health services across England, we identified a variety of regional stakeholders for interview, for example a senior commissioning manager and a sexual and reproductive health consultant who offered regional insights.

Interviews were semistructured and followed a tailored topic guide developed by the study team, informed by the evaluation questions, scoping work (national interviews, review of relevant published and grey literature and scoping workshops) and other emerging findings. This included current context for development and early progress of WHHs, challenges in provision of women’s SRH and how hubs relate (or not) to other developments, such as ICSs.

Work package 2 participants, sampling and data (exemplar hub evaluation)

Sampling and recruitment of exemplar hub sites (July–October 2022)

The identification of WHH exemplar sites involved a series of steps to understand existing hubs, explore and define criteria for selection, and then finalise the case-study hubs. To select the WHH exemplar hub sites for in-depth evaluation, findings from the 11 WHH survey respondents received at the time of hub sampling (July 2022) were analysed, along with public health profiles from Public Health England’s Fingertips portal95 and rurality information from the Office for National Statistics. 96 A summary was produced of site characteristics, similarities and differences for all known WHHs. This included hub status, launch year, leadership, commissioning arrangements and information about deprivation, ethnicity and rurality. We then held an internal workshop to identify potential characteristics and factors to guide the selection process.

The early evaluation work helped to guide this process, for example:

-

Findings from the survey, in particular the heterogeneity of models, highlighted the need to maximise diversity in selection.

-

A review of integrated care literature showed the importance of contextual factors, such as whether hubs were located in urban or rural areas.

A list of over 10 dimensions of hub model/context variation was developed, including size/catchment area, workforce mix and local deprivation. To select the sites, we presented survey findings, alongside potential hub characteristics and dimensions, to our Stakeholder and Women’s groups to further develop and prioritise the list. Five priority criteria were used for the final site selection, the process for which took place over several team meetings. The criteria are presented below:

-

Stage of development of hub site: most sites were still in development as hubs were a relatively new initiative often characterised by incremental improvements and growth. Only WHHs actively offering services to women were selected for in-depth evaluation.

-

Location/geography: this was considered to encompass urban, rural and regional variation.

-

Clinical leadership (e.g. GP-led or consultant-led): early evaluation work suggested this may be an important dimension to explore.

-

Commissioner (e.g. commissioned by NHS or local authority commissioners, or joint-commissioned) and role of commissioning: as above, early work suggested this may be a key area of variation.

-

Type of hub model (e.g. hub and spoke, one-stop shop): an aim of the evaluation was to capture a variety of hub structures.

Other criteria from our ‘long list’ were also considered to ensure relevance of findings generated, for example deprivation. We selected the four sites to maximise diversity of the priority characteristics, though due to the number of sites and characteristics identified, and heterogeneity of hubs, it was not possible for the sample to include all of them. Sites in Northern Ireland were excluded from selection due to the evaluation’s focus on the English context.

A researcher was allocated to each site to act as their point of contact and to conduct data collection, which supported consistency and enabled relationship-building. All researchers had substantial experience of undertaking and analysing qualitative interviews. A lead stakeholder was also identified at each site, using our prior knowledge and information from the survey. Contact was made with each of the four lead stakeholders via e-mail, inviting them to participate and including an information sheet detailing the purpose of the in-depth evaluation and what was involved. The lead researcher for each site subsequently arranged a virtual meeting with lead stakeholders to discuss the evaluation process, obtain an overview of local context, hub plans and implementation and to identify key local stakeholders. All four sites approached agreed to participate in the evaluation.

Exemplar hub site interview and focus-group sampling, recruitment and data collection (October 2022 to March 2023)

Interviews with 72 participants were conducted in the sites (Table 7), and 4 focus groups were held with 48 people. Professional backgrounds of clinical staff participants included general practice (15), nursing (4), gynaecology (2) and sexual and reproductive health (5). Non-clinical participants were in management and administration (10) and commissioning (4) roles.

| Site | Directly involved in the hub services, for example sexual and reproductive consultants, administrators, nurses, GPs | Other stakeholders, for example referring GPs, hospital consultant | Women | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Site 1 | 6 | 4 | 8 | 18 |

| Site 2 | 8 | 3 | 7 | 18 |

| Site 3 | 8 | 1 | 8 | 17 |

| Site 4 | 7 | 3 | 9 | 19 |

| Total | 29 | 11 | 32 | 72 |

Staff interviews

In each site, researchers interviewed staff involved in the hub, and staff in the wider health system, based on their roles in relation to WHHs. Individuals were identified through discussions with the local hub leads to identify key roles, and by snowballing via other interview participants. Between September 2022 and January 2023, 40 staff were interviewed (Table 7). Lead hub stakeholders facilitated contact. Sampling focused on identifying a range of key informants in different roles and contexts. Participants included GPs, nurses, sexual and reproductive health consultants, commissioners, administrators and referring GPs. Potential interviewees were approached by e-mail, which included a consent form and information sheet. Interviews were conducted face to face, online or by telephone, with most conducted online. In two sites, researchers interviewed staff at the hub site. Written or verbal consent was obtained from all participants. Participants either returned a signed consent form (hard copy or electronically by e-mail), or, in instances where verbal consent was provided, interviewers read out consent statements at the beginning of interviews and asked participants to confirm their consent. This process was audio-recorded. Semistructured interviews followed two separate topic guides, developed by the study team and informed by the evaluation questions and emerging findings from other WPs. Topic guides were tailored for (1) WHH staff and (2) staff in the wider health system. Topics included hub aims, experiences of implementing a hub and delivering services, what worked well and less well, early impacts and links with local systems. The majority of interviews were 45 minutes to 1 hour in duration.

Interviews with service users

Interviews were conducted with 32 women who had used their local WHH in each of the 4 sites to explore their experiences (Table 7). The Women’s Advisory Group recommended a flexible approach to recruiting service users to participate, tailored to consider the context in each site. A convenience sampling approach working through clinical gatekeepers was taken, with two different approaches adopted in different sites, described below:

-

In three sites, hub professionals shared information about the evaluation with women during appointments. A ‘consent to contact’ approach was adopted, whereby those interested were asked to consent for their details to be shared with researchers who would contact them to arrange an interview. Interviews were undertaken either by telephone or by videoconferencing [Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, CA, USA) or MS Teams], depending on interviewee’s preference.

-

In one site, six of the seven women who took part were interviewed face to face, by a researcher visiting two different hub clinic locations on that day in order to recruit women from different geographical areas and hub settings (a seventh woman also took part online). The health professional running the clinic shared information about the evaluation with all women attending the clinic, and those who were willing to be interviewed met with the researcher in a separate area following their appointment.

Information about the study, including background details and study purpose, was provided to participants via information sheets and verbally, with participants able to speak with researchers should they have had any questions. Verbal or written consent was obtained as described earlier. Women interviewed face to face provided written consent in person. Interviewees received a £10 shopping voucher as compensation for their time. The topic guide was informed by the evaluation questions, emerging findings from other evaluation work, and insights from the Women’s Advisory Group. It was also reviewed and refined by the study Women’s Group. It included questions exploring awareness of women’s health services, experiences of services including accessibility and satisfaction, and what could be improved. Women were also asked to complete a demographics form, though it was not possible to collect this from all participants (Table 8). Of those for whom it was possible to collect this information, most of the sample were White British, all described their sex as female and over two-thirds left education at or before 18.

| Demographic variable | Category | Service user interview participants | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | % all (n = 32) | % providing data (n = 23) | ||

| Age | 18–19 | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| 20–29 | 3 | 9 | 13 | |

| 30–39 | 4 | 13 | 17 | |

| 40–49 | 5 | 16 | 22 | |

| 50–59 | 9 | 28 | 39 | |

| 60–69 | 1 | 3 | 4 | |

| 70–79 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Missing data | 9 | 28 | – | |

| Sex | Female | 23 | 72 | 100 |

| Missing data | 9 | 28 | – | |

| Gender identity | Yes (same as at birth) | 21 | 66 | 91 |

| No, non-binary | 1 | 3 | 4 | |

| Missing data | 10 | 31 | – | |

| Sexual orientation | Heterosexual | 18 | 56 | 78 |

| Bisexual | 2 | 6 | 9 | |

| Gay or lesbian | 1 | 3 | 4 | |

| Other | 1 | 3 | 4 | |

| Prefer not to say | 1 | 3 | 4 | |

| Missing data | 9 | 28 | – | |

| Age when completed full-time education | 16 years | 3 | 9 | 13 |

| 18 years | 7 | 22 | 30 | |

| 19 years | 2 | 6 | 9 | |

| 21 years | 1 | 3 | 4 | |

| 22 years | 5 | 16 | 22 | |

| Other | 5 | 16 | 22 | |

| Missing data | 10 | 31 | – | |

| Ethnic group | White: English, Welsh, Scottish, Northern Irish or British | 18 | 56 | 78 |

| White: Irish | 1 | 3 | 4 | |

| White: any other white background | 1 | 3 | 4 | |

| Mixed or multiple ethnic groups | 2 | 6 | 9 | |

| Black, Black British, Caribbean or African | 1 | 3 | 4 | |

| Missing data | 9 | 28 | – | |

| Long-term health conditions | Yes | 7 | 22 | 30 |

| No | 16 | 50 | 70 | |

| Missing data | 9 | 28 | – | |

Focus groups with women in local communities

Following input from the Women’s Advisory Group (see Chapter 5), the evaluation plan was extended, to add focus groups with women in communities perceived by hub leaders/stakeholders to be less likely to access a hub. The aim was to capture the experiences of women who may find it harder to access WHH services.

One focus group was undertaken in each site (Table 9), two were face to face in local community venues and two were online (to suit availability and preferences of the women taking part). Demographic information is presented in Table 10. A purposive sampling approach was used to identify community groups to host focus groups, in populations where WHH site leads/stakeholders reported barriers to access to women’s health services or those who were less likely to engage with services. In three sites, a community group was identified to host a focus group via the lead hub stakeholder, who helped the team broker access and facilitated recruitment. In the fourth site, where the hub lead did not have an existing link, the team identified and contacted a suitable community group through one of the other interview participants. Overall, a convenience sampling approach was taken for participants, where a researcher attended existing group events, and group members were invited to join a group discussion during/after their usual session. However, for one of the virtual focus groups, a separate meeting was arranged at the request of the participants.

| Focus group | Group information (type of group and participants) | Participants |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Women’s group with women from African backgrounds | 10 |

| 2 | Women’s exercise group serving a deprived community | 16 |

| 3 | Women’s health group serving those who live in a more rural community | 5 |

| 4 | Women’s group based in an ethnically diverse community | 17 |

| Demographic variable | Category | Women’s focus-group participants | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Frequency | % all (n = 48) | % providing data (n = 17) | ||

| Age | 18–19 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| 20–29 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| 30–39 | 1 | 2 | 6 | |

| 40–49 | 4 | 8 | 24 | |

| 50–59 | 1 | 2 | 6 | |

| 60–69 | 5 | 10 | 29 | |

| 70–79 | 6 | 13 | 35 | |

| Missing data | 31 | 65 | – | |

| Sex | Female | 17 | 35 | 100 |

| Missing data | 31 | 65 | – | |

| Gender identity | Yes (same as at birth) | 15 | 31 | 88 |

| No, non-binary | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Missing data | 33 | 69 | – | |

| Sexual orientation | Heterosexual | 17 | 35 | 100 |

| Bisexual | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Gay or lesbian | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Other | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Prefer not to say | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Missing data | 31 | 65 | – | |

| Age when completed full-time education | 16 years | 8 | 17 | 47 |

| 18 years | 3 | 6 | 18 | |

| 19 years | 3 | 6 | 18 | |

| 21 years | 1 | 2 | 6 | |

| 22 years | 1 | 2 | 6 | |

| Other | 1 | 2 | 6 | |

| Missing data | 31 | 65 | – | |

| Ethnic group | White: English, Welsh, Scottish, Northern Irish or British | 17 | 35 | 100 |

| White: Irish | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| White: any other white background | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Mixed or multiple ethnic groups | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Black, Black British, Caribbean or African | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Missing data | 31 | 65 | – | |

| Long-term health conditions | Yes | 5 | 10 | 29 |

| No | 12 | 25 | 71 | |