Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number NIHR127920. The contractual start date was in February 2020. The draft manuscript began editorial review in January 2023 and was accepted for publication in November 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Siriwardena et al. This work was produced by Siriwardena et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Siriwardena et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction and objectives

Overview

In this chapter, we set out the background, context, gaps in evidence and aims of the Community First Responder (CFR) role in the current and future rural health and care workforce. We describe the rationale for and development of CFR schemes in the UK in response to the need to provide timely emergency care to rural communities, discuss what we know about CFR schemes and CFRs, and set out the gaps in evidence, before describing the composition and expertise of the study team, the aims and objectives of the research and the structure of the report.

Background

Development of Community First Responder schemes

Community First Responder schemes have supported ambulance services to provide emergency care to rural communities since the 1990s, when the UK government encouraged the use of volunteers to get help more quickly to people with emergencies in rural areas. 1,2 CFR schemes organise volunteers to support Emergency Medical Services (EMS) working with ambulance services who dispatch them to provide urgent care to patients in both rural and urban areas. 3 CFRs are members of the public or off-duty medical, nursing or allied health professionals who volunteer to reach a potential life-threatening emergency, primarily in their local community, in the first vital minutes and who provide appropriate care until more highly skilled ambulance staff arrive. 3

Volunteering has been defined as ‘any activity in which time is given freely to benefit person, group, or organization’. 4 Theories about why people volunteer have been extensively explored, and these are based on individuals’ characteristics and their relationships with others, and the community context in which they live or work. 4 From an individual motivational perspective, functionalist theory describes the importance of values (acting on values such as humanitarianism), understanding (seeking to exercise or learn skills), enhancement (the potential to grow and develop psychologically), career (access to current or future career-related experience), social (strengthening social relationships and networks) and protective functions (reducing negative feelings, e.g. guilt, or addressing personal problems) served through volunteering. 5 The first three are considered more common reasons for and more important motivators of volunteering than the last three. 5

Community First Responders need to be distinguished from First Responders, a term used widely in the USA primarily to refer to EMS staff, including paramedics and emergency medical technicians (EMTs) and also other emergency services staff such as fire service and police staff, who are trained and equipped to respond to emergencies to complement EMS in rural areas, but this term has been loosely expanded more recently to include lay people, including sports centre staff, teachers, lifeguards or workplace first aiders, who respond to an emergency. 6,7 CFRs have operated in a number of countries other than the UK, including the USA (for over four decades),8 Ireland,9 Sweden,10 Norway,11 Japan,12 Thailand,13 India,14 Uganda,15 Iraq16 and South Africa,17 but evidence for their role and activity has been obtained largely using case study, qualitative or survey methods. 3,18 Their role in different countries has varied from dealing primarily with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest (OHCA),9–13 road traffic accidents and traumatic injury14–16 to more general first aid for a wider variety of incidents. 8,17

The number of CFR schemes has grown to the current number of around 2431, using over 12,000 volunteers, in the UK. 19 A decade ago CFRs responded to around 2% of calls,1 but the literature suggests that this figure may have increased,20 particularly in the context of pressure on healthcare budgets, centralisation of health resources and workforce shortages. 21 CFRs are considered an increasingly important part of the pre-EMS care workforce both in the UK and elsewhere, especially in rural areas where it is more difficult to provide or access emergency care within a reasonable time. 1,21 Although they do not replace ambulance clinicians, CFRs are thought to add capacity and capability to an ambulance service’s response. 1

Community First Responders have been considered important particularly for providing emergency care, and particularly in rural areas,12,22 where health services are less accessible and outcomes from OHCA and trauma are worse. This is due to various factors affecting rural areas, including an older population, difficulties recruiting skilled health personnel, the centralisation of healthcare services towards larger urban communities, and longer intervention or transport times. 23,24

Another driver of CFRs in rural areas has been poorer access to EMS and the worse health outcomes that result from this. A systematic review of 31 studies from the USA, Australia, Europe and Asia found that EMS in urban areas were more likely to have shorter response, on-scene and transport times than EMS operating in rural areas and that patients in urban areas attended by EMS had greater rates of survival from OHCA or trauma. 24 In this review, rurality was defined differently in different countries because ‘the distinction between the urban and the rural population is not yet amenable to a single definition that would be applicable to all countries or, for the most part, even to the countries within a region’. 25

A number of CFR schemes in England operate as independent charities (funded by public donations) working with ambulance services or as volunteer groups overseen by ambulance services. These include specific charities such as Lincolnshire Integrated Voluntary Emergency Service (LIVES) in Lincolnshire and Hatzola (https://hatzola.org/) in London and Manchester (and metropolitan areas in other countries),26 and CFR schemes involving medical students, linked to medical schools in England. 27 CFRs are often but not always trained, equipped and managed by ambulance services, but they sometimes use marked response vehicles and may be dispatched to a variety of emergencies. 3,27,28

Community First Responders complement the work of ambulance services,22 improving a patient’s condition by arriving quickly, recording vital signs (e.g. pulse, blood pressure or temperature) and performing basic clinical techniques, such as cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR)9 of people whose heart has stopped (cardiac arrest), before handing care over to ambulance staff. 1,19

Organisation of Community First Responder schemes

Community First Responders are usually organised and dispatched based on their geographical location and level of training and experience, ranging, for example, from level 1 (basic) to level 4 (enhanced) depending on work experience (e.g. qualified paramedic, nurse or doctor) and training, but the number of and criteria for different levels may vary from one service to another. The training of CFRs generally consists of first-person on-scene first aid administered prior to the arrival of an ambulance,22 and covers medical topics such as emergency first aid, basic life support, airway management, CPR, oxygen therapy, defibrillator use, recognition and initial management of cardiac conditions, choking, strokes, significant bleeds and breathing difficulties. Although CFRs were developed primarily to respond quickly to life-threatening emergencies such as OHCA, their role has expanded so that they respond to different types of emergencies such as falls or patients with chronic conditions. 1,18

In participating ambulance trusts, there is a dedicated procedure whereby all incoming 999 calls are assessed for signs of critical illness or injury before the decision is made to dispatch a CFR or an ambulance clinician. The decision to dispatch a CFR is generally based on a combination of fixed dispatch criteria, clinical decision-making of the dispatcher and availability of a CFR. CFRs vary in the types of emergencies they respond to, what they are trained to do and the equipment they carry; they are classified by ambulance services according to these skills [e.g. in East Midlands Ambulance Service (EMAS) CFRs are classed from level 1 to level 6]. 1

Community First Responders can be dispatched during the day or night to a broad range of patients depending on availability and skill levels. They are not usually sent to children, pregnant women, those in labour or with acute abdominal pain or to incidents deemed unsafe because they involve violence or firearms. Ambulance clinicians are usually dispatched when a CFR is sent unless they are not available, in which case the CFR is required to seek advice from a clinician or refer the patient to other services (D Skarratts, personal communication, 22 March 2022; J Costerd, personal communication, 13 April 2022).

Effectiveness of Community First Responders

When considering the effectiveness of CFRs, attention has been focused largely on OHCA. OHCA affects around 60,000 people each year in England alone, for whom resuscitation is commenced or continued by ambulance staff. Early recognition by relatives or bystanders, accessing EMS and providing rapid CPR and defibrillation using an automated external defibrillator (AED) significantly increase the chance of resuscitation, survival and a good neurological recovery but only 55% of cases not witnessed by EMS receive CPR and only around 2% defibrillation with 25.8% being admitted to hospital alive and 7.9% surviving to hospital discharge. 29

Community-level initiatives to increase lay responders and CFRs, for example in the Heart Safe programme in Minnesota, USA, have led to greater use of CPR and AEDs by bystanders and first responders before the ambulance arrives,30 but the effect on OHCA outcomes is less clear. Another community initiative in Piacenza, Italy, ‘Progetto Vita’, has led to survival to hospital discharge of 41.4% (39 of 95) patients treated under the scheme compared with 5.9% (193 of 3271) of EMS patients.

A systematic review of observational studies of public access defibrillation (PAD) showed a high median overall survival of 40% for patients with OHCA treated with PAD, but this compared non-dispatched lay first responders with dispatched professional (fire or police officer) first responders and found higher survival to hospital discharge with the former (53.0%, range 26.0–72.0%) than with the latter (28.6%, range 9.0–76.0%). 31

In a Cochrane review of randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and quasi-randomised control studies investigating the effect of CFRs dispatched to OHCA in adults and children (older than 4 weeks of age), comparing a combination of CFRs and EMS with EMS alone for outcomes of survival and neurological function, two completed studies met the inclusion criteria, and although one noted higher rates of CPR and the other greater AED use before the ambulance arrived, neither found improvements in survival beyond admission to hospital, which was recorded in only one of the studies. 32

An evaluation of a rural CFR scheme, LIVES in England in 2003, found that around 10% of ambulance calls were attended by CFRs, and when CFRs attended they arrived first in 60% of incidents, with benefits in speed of response and high rates of patient satisfaction, but no clear advantage in return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) from OHCA. 33

Gaps in the evidence base for Community First Responders

Evidence for CFRs’ role and activity is largely derived from qualitative or survey studies,3,18 but, despite this limitation, CFRs are broadly perceived as positive by ambulance services and communities. 1,18,22 This has led to general support for their incorporation in EMS in the UK. A Delphi study of UK ambulance service chief executives, operational leads and medical directors on future EMS design found high agreement that CFRs, including lay and health professional members of local communities, should be trained and fully integrated into the EMS. 34

A systematic review of the international literature on CFRs found that volunteers were motivated to become CFRs for altruistic reasons, wanted more feedback on their contribution to patient care and were often confused in the public mind with ambulance staff. 3 A previous interview study of CFRs’ experiences with patients and ambulance staff broadly supported these findings. 18 Whereas this latter study explored experiences and insights of CFRs themselves, the views of other key stakeholders, including service users (patients and others involved in contacting the ambulance service) and ambulance staff, were lacking from this and previous studies.

Despite considerable investment in schemes from the volunteers themselves, donations and contributions from health services, a recent scoping review identified key unanswered questions: how effective are CFR schemes, how do they achieve anticipated benefits, what do they cost, how are they perceived by service users and healthcare providers, and how might they develop and be improved in future for rural and other communities?3

The evidence for effectiveness of CFRs is unclear, even for OHCA,32 the condition for which CFRs were first introduced in rural areas. There have been few, if any, studies looking into the costs or other outcomes of care of CFR schemes. 3

Innovations and developments currently fall into two main categories: first, innovation from expanding the CFR workforce (e.g. fire and rescue services providing CFR capability), and, second, innovation in the types of emergencies CFRs attend; for example, in some regions CFRs attend older people who fall but are at low risk of injury.

As a result, further evidence is needed on how CFRs contribute to rural services in terms where they operate (i.e. rural or urban areas) and the type of calls and the demographics of the people they attend, as well as what they do, how this is perceived by various interested stakeholders, the cost of provision, what effect this has on service users and outcomes and how this could be improved or expanded. 3

This study sought to provide evidence on the contribution and costs of CFR schemes to rural health as well as how these services can be optimised or developed further to benefit rural communities.

Study team

We brought together an interdisciplinary team, including patient representatives (AB, PM), members of the healthier ageing patient and public involvement (HAPPI) group and a patient panel (see below), research clinicians from relevant clinical backgrounds (AS, IT, RØ), and those with expertise in health services research and mixed methods (AS), statistics (ZA, VB), economics and econometrics (MS, CR, MH), sociology [(general practice (GP)], qualitative methods (AS, GP, VP, JP, IT, RØ) and trauma psychology (RØ). Several members of the team had worked together on a systematic scoping review,3 an exploratory qualitative study18 and an evaluation of a CFR falls service (the falls response partnership) in Lincolnshire,35 which laid the groundwork for the study. This core team was augmented by scientific, clinical and lay experts who contributed to the study steering and oversight committees.

Study aim

We aimed to investigate the current activities, costs of provision and outcomes of CFR schemes, and explore views of patients, public, CFRs, CFR leads and primary care commissioners on CFRs, working with our stakeholders to develop recommendations for future innovations in rural CFR provision.

Our research questions were:

-

How are CFRs contributing to rural health care?

-

Do they provide value for money?

-

How are they perceived by patients and other providers?

-

How can CFR schemes develop to support future rural health and care services?

Study objectives

Our objectives were to:

-

1. Describe the contribution of CFRs to rural healthcare provision in terms of the numbers and timing of calls attended, together with the types of conditions and the characteristics of people attended.

-

2. Evaluate the costs, funding sources and consequences of CFR schemes.

-

3a. Explore ambulance policies, guidelines and protocols for CFRs.

-

3b. Explore stakeholder (patients, relatives, ambulance staff, primary care, commissioners, CFRs and CFR scheme organisers) experiences and perceptions of CFRs’ current role and potential for future developments and innovations. We also aimed to ask CFRs and CFR scheme organisers about the challenges in and solutions to recruiting, training and retaining CFRs in rural areas and how to ensure governance and accountability for safe, high-quality care.

-

4. Assimilate and integrate data derived from objectives 1–3, synthesising these to develop a list of recommendations for future innovations.

-

5. Prioritise recommendations for future developments/innovations in rural CFR provision through a consensus stakeholder workshop.

Report structure

The study objectives related closely to the work packages and the mixed methods used. We used a cross-sectional design to investigate CFR activity, a questionnaire to collect data on workforce and costs, econometric methods to estimate outcomes, a documentary content analysis of policies, protocols and guidelines and a qualitative interview study to explore CFR, patient–public, ambulance service and wider stakeholder experiences and perceptions of CFRs’ current role and potential for future development. We integrated the data from these earlier work packages to inform a stakeholder consensus workshop at which a modified nominal group technique (mNGT) was used to agree recommendations for potential future innovations for the CFR workforce.

The methods and methodology are described in Chapter 2, including the design, setting, theoretical basis, ethics and details of the component studies. The results are presented in Chapter 3 for each of the component studies addressing the different objectives above, including the integration of results and details of patient and public and stakeholder involvement. The study fundings are discussed in Chapter 4 and the conclusions are presented in Chapter 5.

Chapter 2 Methods

Overview

This chapter sets out our research methods, including the overall design of the study, our theoretical approach, ethics and governance approvals and details of the methods of the component studies, including cross-sectional studies describing calls attended by CFRs, the resource survey summarising cost information, and the studies detailing the outcomes of CFR attendance, including the effect of CFR presence on time of attendance, on the outcomes of OHCA, and on a CFR service responding to calls for people who had fallen at home. We also describe the qualitative methods used in the documentary analysis of CFR policies, guidelines and protocols and an interview study of stakeholders involved in CFR schemes including patients, their relatives, CFRs themselves and CFR leads as well as ambulance staff and ambulance commissioners. Finally, we describe the methods used to integrate the quantitative and qualitative findings and how these informed the consensus study that sought to prioritise potential innovations for CFRs, particularly those working in rural communities.

Overall study design and setting

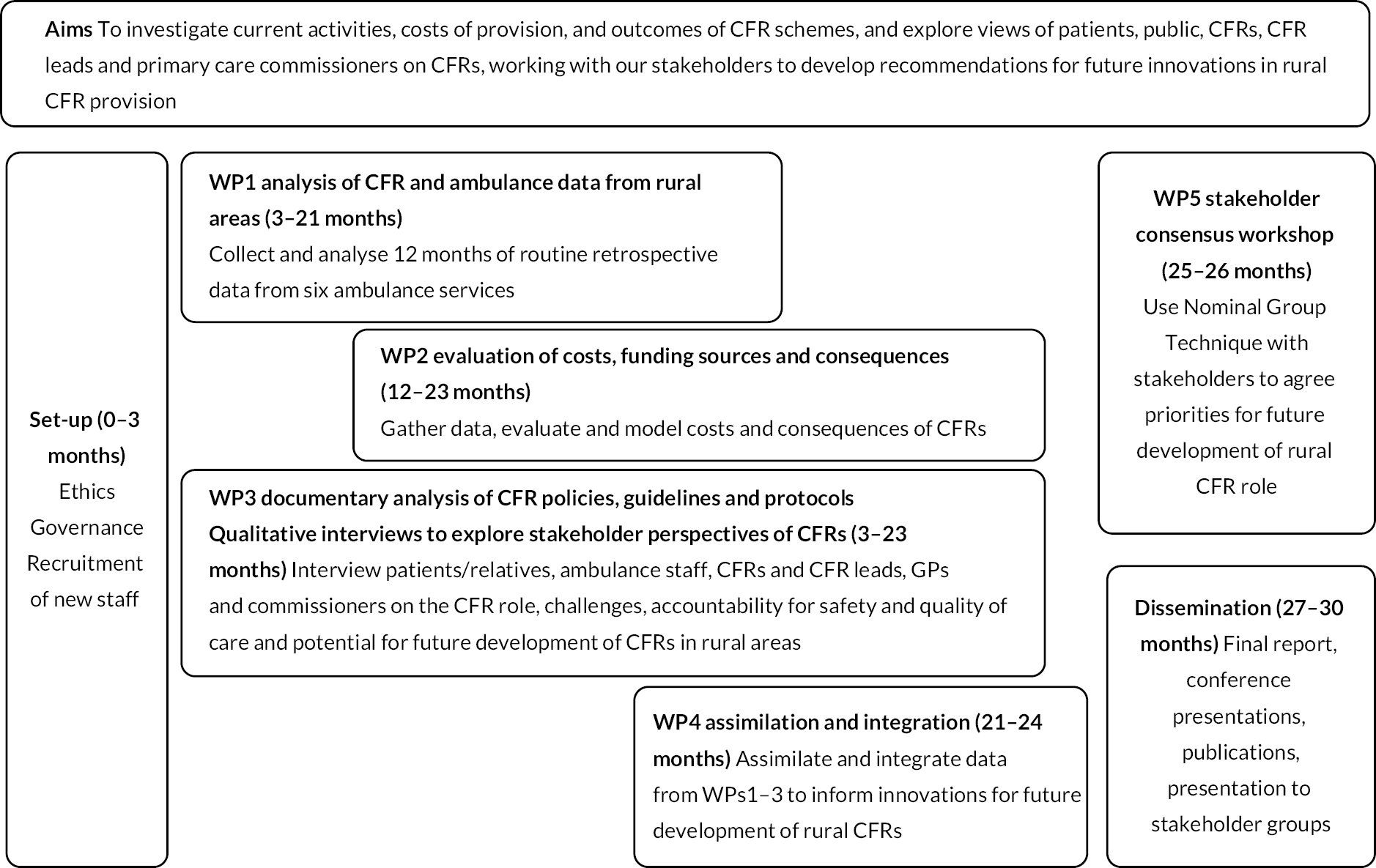

We used a complex, convergent, mixed-methods design36 to guide our approach, working with expert and lay stakeholders throughout the research to increase the validity of our findings, add weight to the recommendations and increase the chance of their future adoption. The flow chart of study activities is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Community First Responders’ role in the current and future rural health and care workforce: study flow chart.

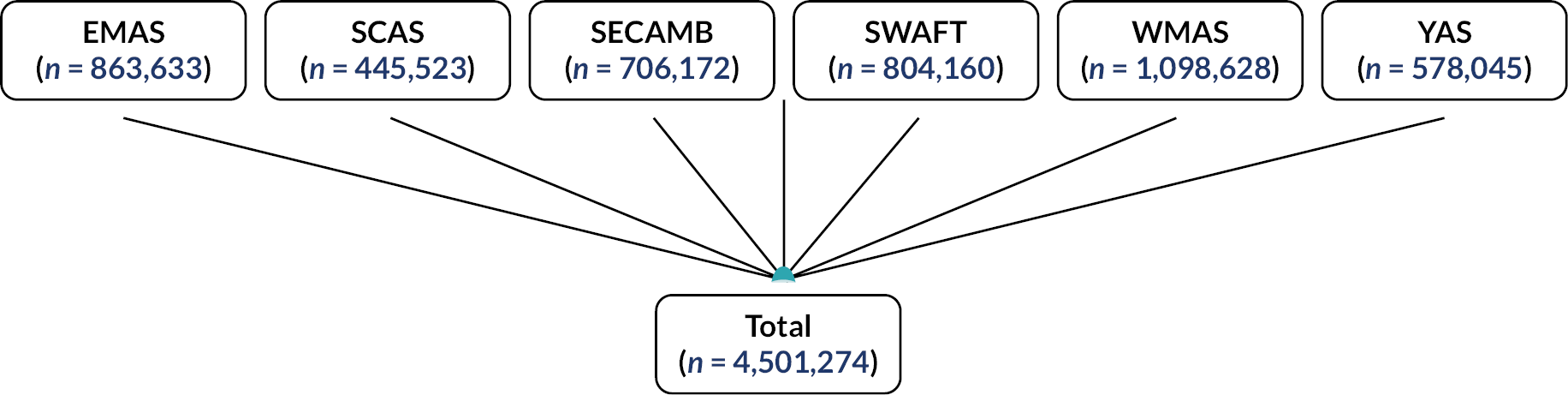

We analysed quantitative data (ambulance and CFR data and costs) and qualitative data (ambulance CFR policies, guidelines and protocols together with interviews exploring stakeholder experiences and perceptions) from six regional ambulance services providing care to a large part of rural England. The services were EMAS, South East Coast Ambulance (SECAmb), South Central Ambulance Service (SCAS), West Midlands Ambulance Service (WMAS), Yorkshire Ambulance Service (YAS) and South Western Ambulance Service Foundation Trust (SWASFT) NHS Trusts.

We assimilated and integrated the findings and presented these to a stakeholder consensus event involving all these trusts and including members of our patient and public involvement (PPI) panel and a wider stakeholder group, using a mNGT to prioritise areas for future development and innovation in CFR schemes.

Theory

We used a lens of pragmatism,37 which enabled us to combine qualitative and quantitative methods focusing on outcomes. Our aim, to develop recommendations for future developments and innovations in rural CFR provision, required a broad theoretical approach that acknowledged three key aspects: multiple ‘actors’ in a complex system, ‘behaviour change’ and ‘causal pathways’. The ‘actor’, ‘behaviour change’ and ‘causal pathway’ (ABC) framework38 incorporates these to increase the likelihood that recommendations for change are implemented.

Community First Responders work in a complex system of multiple ‘actors’ (health and social care providers and staff) and environments (health and social care organisations and contexts) that interact with and adapt to each other at macro (interorganisational), meso (intraorganisational) and micro (healthcare worker–patient) levels. We integrated quantitative and qualitative findings using the method of triangulation described as ‘following a thread’, developed by Moran-Ellis et al.,39 and described by O’Cathain et al.,40 to explore hypotheses generated using one method with another, to gain a fuller understanding of the different phenomena identified. This allowed us to describe an ‘actor-based system map’, defining the problems to be addressed, depicting the main actors currently involved in solving these and examining the relationships between them. This also helped us to articulate the structural and behavioural changes needed to address the problems identified in a sustainable way. Through the integration of data we sought to develop possible causal impact pathways, theories of action (pathways and interventions promoting actor-level change) and a theory of change (i.e. the ways in which actor-level changes could lead to systems changes and impacts). 38 The approach to integration was to some extent dependent on findings from the different components of the study and is described in Chapter 3, Integration. 40

This approach also took heed of the theory of co-production, with problems and solutions focused on the main outcome of producing recommendations for future CFR scheme development in rural areas, explored in collaboration with both lay public and professional stakeholders. 41

Ethics and governance

Ethics approval was obtained from the NHS Research Ethics Committee (IRAS project ID 277205, registration reference NCT04279262). The necessary research permissions were approved by the NHS Health Research Authority, and the study was conducted in accordance with the principles of the Research Governance Framework for Health and Social Care. Research governance permissions were granted by the participating ambulance NHS trusts. The general monitoring of the study was performed by a combination of ethics and NHS governance review and monitoring by quality assurance staff from the University of Lincoln as the sponsor.

Cross-sectional study describing calls attended by Community First Responders

Design

We used a retrospective observational study design. Routine data were collected for analysis from electronic clinical records accessed from 6 of 10 ambulance services in England between 1 January 2019 and 31 December 2019. 42

Data collection and processing

Routine anonymised individual patient data sets, assigned a unique (non-personally identifiable) number from the six ambulance services, were collected and analysed. These included resource type, call category, clinical condition (chief complaint and impression group), date and time, geographical location (incident postcode), demographic information (age, sex, ethnicity) and whether they were conveyed by ambulance to hospital. The data sets were standardised and cleaned to derive the same variables for all of them. Rurality was defined according to the following categories under current UK government definitions: major conurbation (A1), minor conurbation (B1), city and town (C1), city and town in sparse setting (C2), town and fringe (D1), town and fringe in sparse setting (D2), village (E1), village in sparse setting (E2), hamlets and isolated dwellings (F1), hamlets and isolated dwellings in a sparse setting (F2). 43 Rural areas were identified based on the incident postcode and a new standardised binary variable representing rurality was created with 1 assigned to rural categories (D1, D2, E1, E2, F1, F2) and 0 to the urban categories (A1, B1, C1, C2). According to the Office for National Statistics (ONS), all rural settlements have a population of under 10,000 people. Postcode records allowed linkage with Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD) decile, ranging from 1, highest deprivation level, to 10, lowest deprivation level, which was included as another variable.

The data set obtained from the six ambulance services consisted of routinely collected clinical dispatch records from two triage systems, the Advanced Medical Priority Dispatch System (AMPDS)44 or NHS pathways. 45 The AMPDS was used by EMAS, SWASFT and YAS and the NHS pathways were used by WMAS, SECAmb and SCAS. Due to the heterogeneity and the multitude of dispatch records, the chief complaints were divided by a clinician (NS) into the following main categories: injury/trauma, cardiorespiratory, gastrointestinal/urinary, obstetric/gynaecological, neurological/endocrine, infections/allergies and psychosocial/palliative. The conditions without a specific label (e.g. other medical condition) were grouped in a category labelled as ‘other’. Examples of the most common chief complaints in each category can be seen in Appendix 1, Table 22. Thus, the dispatch data were standardised for all ambulance services. There were five call categories from category 1, the most urgent category representing an immediate response to a life-threatening condition, to category 5, a non-urgent category representing stable cases that require hospital transport. Patient age was separated into five categories: ≤ 19 years, 20–39 years, 40–59 years, 60–79 years and ≥ 80 years. Time taken to arrive, computed as the difference between arrival and dispatch time, was divided into nine categories: < 3 minutes, 3 to < 5 minutes, 5 to < 7 minutes, 7 to < 10 minutes, 10 to < 15 minutes, 15 to < 20 minutes, 20 to < 30 minutes, 30 to < 60 minutes and ≥ 60 minutes.

Statistical analysis

Descriptive statistical analyses presented numbers and percentages of call categories, condition categories, conveyance and patient demographics attended first in rural or urban areas by CFRs or other ambulance staff. Proportion tests were used to directly compare the differences between CFR and ambulance attendances in both rural and urban areas. Univariable logistic regression models were used to identify independent predictors of CFRs’ first presence on scene. To account for possible confounding effects, a multivariable logistic regression model was computed to establish which factors predicted the presence of a CFR first on scene. Due to the limited previous evidence on the role of CFRs, the multivariable logistic model used was exploratory and thus the selection of the predictor variables was not based on variables defined a priori. The only hypothesis formulated based on previous evidence was that CFRs would attend more cases in rural areas and more urgent cases given that their initial role was to attend OHCA, and this was confirmed by our descriptive analysis and multivariable logistic model.

The variables rurality, call category, condition category, age, gender, ethnicity, deprivation index, conveyance and arrival time were used as predictors and the assumptions of multicollinearity, and no outliers were checked. The assumptions of independence of observations and no multicollinearity] [Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) < 1.5] were met, and the maximum likelihood estimation method was used. The assumption of the linear relationship between continuous predictors and the logit transformation of the outcome was not checked as all predictors were binary or categorical. The predictor variables chosen were based on the descriptive statistics reported in this paper and their suitability was confirmed using DAGitty software,46 which facilitates the construction of causal diagrams and confirmed that no further adjustments were needed to estimate the effects of the predictors on the outcome.

The mathematical model representing the logistic regression given the selected predictors was:

The analysis of the multivariable logistic model was run in Stata version 16 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) using the following line of code:

Survey of Community First Responder costs and resource use

Background

There has been a lack of attention to the cost of providing CFRs. Although CFRs are volunteers, there will be inevitable costs of workforce management as well as of providing training and equipment, and possibly other expenses.

Design

We used a self-administered cross-sectional survey design to assess workforce and resources used for CFRs in the ambulance services. A bespoke questionnaire was designed for issue to ambulance trusts, asking for information on the trust workforce of volunteer CFRs, the budget allocated to CFRs and the actual expenditure incurred in managing their CFRs; data were sought for the financial years 2017–8, 2018–9 and 2019–20. The questionnaire was sent by e-mail to trust directors of research and heads of research.

The first version of the questionnaire (v1.0) was piloted with EMAS. After minor amendments arising from responses received to the pilot, a second version of the questionnaire (v2.0) was drafted and issued (see Report Supplementary Material 1) to the other ambulance trusts. The second version was not reissued to EMAS.

The questionnaire was separated into three parts: (1) human resources, (2) financial resources and (3) detailed financial breakdown. In total there were 17 questions, all but one of which asked for entry of a data value.

Counterfactual analysis of effect of Community First Responders attendance on response time

Background

An important aspect of the EMS response is the time taken to respond and attend, with a short wait for help contributing to patients’ experiences of care and their sense of feeling reassured that services had attended to help. 47 Response time has been used for many years to measure service quality in terms of timeliness and this is supported by extensive studies, involving a wide range of stakeholders including patients and the public as well as service providers and commissioners, into important measures of the quality and impact of ambulance service care. 48

Ambulance services are required to attend patients within a target timeframe that depends on the triaged category of the emergency. 49 The attendance targets are among the list of key performance indicators set by NHS England that ambulance services are required to meet. The attendance targets, six in total, are expressed as minimum time thresholds, applying to the following measures: the average of the time taken to attend patients by emergency severity categories 1 and 2; and the (90th) percentile in the distribution of those attendance times, again varying by emergency severity, categories 1–4. The target thresholds are listed in Table 1 (most severe = category 1 to least severe = category 4).

| Call severity category | Mean target (minutes) | 90th percentile target (minutes) |

|---|---|---|

| 1: life-threatening/very serious injuries | 7 | 15 |

| 2: emergency calls | 18 | 40 |

| 3: urgent calls | – | 120 |

| 4 and 5: moderately urgent or less urgent calls | – | 180 |

Design

We used a counterfactual analysis based on a geography local to the scene of the incident to estimate the timing benefit that may be attributable to CFRs’ presence compared with their absence. The counterfactual episodes are assumed to represent what the ambulance response would be without the presence of CFRs. We compared, by severity category and urban–rural classification, the travel time distributions of the CFR episodes to counterfactual episodes as well as the attendance times of both to the target thresholds.

The important reference time points for attendance targets are the time when the emergency (999) call is received by the ambulance emergency operations centre (EOC) and the time when an emergency vehicle (EV) first attends the patient. Evidence has shown that ambulance services have increasingly struggled to meet attendance targets since these were introduced in 2017. 49

Dispatching a CFR to an emergency stops the target clock if the CFR is first to arrive at the scene and attend the patient. Accordingly, first-on-scene attendance is one aspect where a workforce of volunteer CFRs may contribute value.

A second comparison focuses on travel time, from when the EV first departs to the incident until its arrival at scene. The calculation of travel time modifies the attendance time by removing from its calculation the period prior to dispatch that is due to the EOC organising the response to the emergency. The shorter the travel time, the sooner the CFR or ambulance clinician reaches the patient.

Data collection and processing

Episode data for the calendar year 2019 were supplied by EMAS in two tranches: (1) episodes of dispatch for EVs that arrived at scene, and (2) episodes involving EVs stood down pre arrival. To avoid underestimation of attendance time, it was necessary to include data from the second tranche for the circumstance in which a dispatched EV was stood down prior to arrival at scene but was later re-engaged by the EOC to the original call and did eventually attend at scene. EV attendance time calculations were constructed by including the sum of repeated durations of periods of dispatch to stood down, to which was added the time of final dispatch up to attendance at scene, which was obtained using the first tranche of data.

Key time points and data variables in the progression from the beginning of the emergency until emergency services attended at scene are displayed in Figure 2. The blue labels are variable names either taken directly from the episode data or constructed.

FIGURE 2.

Engagement of emergency services units up to attendance.

A single call number was generated for each incident and either one or many EV resources identified by call sign were allocated to each call number. Concatenating the call sign to the call number ensured that each EV involved was represented by a single unique identifier. Whether or not the assigned EV arrived was indicated using resource stood down and time resource arrived at scene. The latter was also utilised to establish order of arrival when multiple EV resources attended the same incident.

Resource type was used to designate CFR involvement, indicated in particular by ‘Community First Responder’, ‘First Responder Intermediate’, ‘Lives Responder Scheme’, ‘Medical First Responder’, ‘Mountain Rescue’, ‘RAF CAR’ and ‘Volunteer Aid Society Vehicle’. For purposes of assigning episode comparators, the following EVs were included: ‘dual-crewed ambulance’, ‘solo responder (car)’, ‘private ambulance service’ and ‘urgent vehicle’.

Urban–rural indicators were assigned to each episode according to its postcode location linked to ONS-NSPL (National Statistics Postcode Lookup) data, where the rural–urban classification is dated to the 2011 census.

Counterfactual episodes over a localised geography

The counterfactuals to CFR episodes were constructed using those episodes that did not involve CFRs occurring either at or in the neighbourhood of the same postcode as the location of the incident, ensuring a like-for-like comparison. We define this neighbourhood – the localised geography – as the next highest geography beyond postcode level in the ONS hierarchy, the ‘lower super output area’ (LSOA11). The ONS-NSPL data contain linked pairings of postcode-level and LSOA11 geographies.

Descriptive statistics were used to compare the distributions of attendance times for CFR episodes with counterfactual episodes as well as both with the target thresholds. The key assumption underlying the following comparisons was that the counterfactual episodes represented what the ambulance response would be without dispatch of CFRs.

Comparison of achievement of target thresholds

The first comparison concerned success at achieving NHS target thresholds. We computed two statistics – mean and 90th percentile – on data constructed as time resource arrived at scene less time call taken when, for CFR dispatches, the CFR was the first to attend on-scene, and for counterfactual dispatches not involving CFRs when we used the first ambulance to attend on-scene to locations within the localised geography.

Comparison of travel time to attend

The second comparison used data constructed as time resource arrived at scene less time resource mobile. This was formed across all CFR dispatches provided they attended at scene. Each CFR dispatch was matched with a counterfactual set of ambulance-only dispatches to its localised geography. From the mean of travel times of the latter, we subtracted the travel time of the CFR dispatch and term this quantity Δ where, should Δ > 0, the CFR takes less time to travel to the emergency than the ambulance. Descriptive statistics are used to describe Δ.

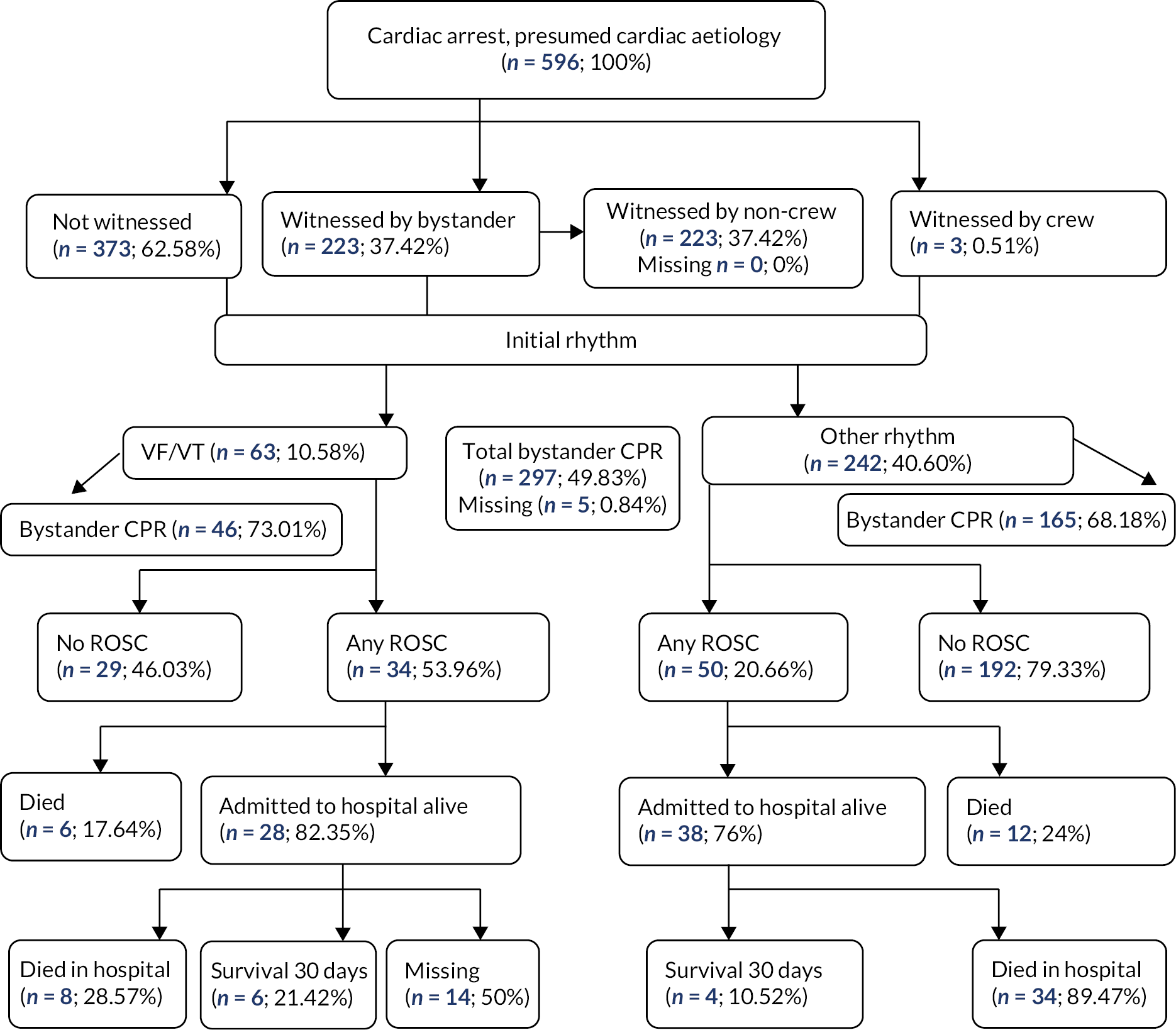

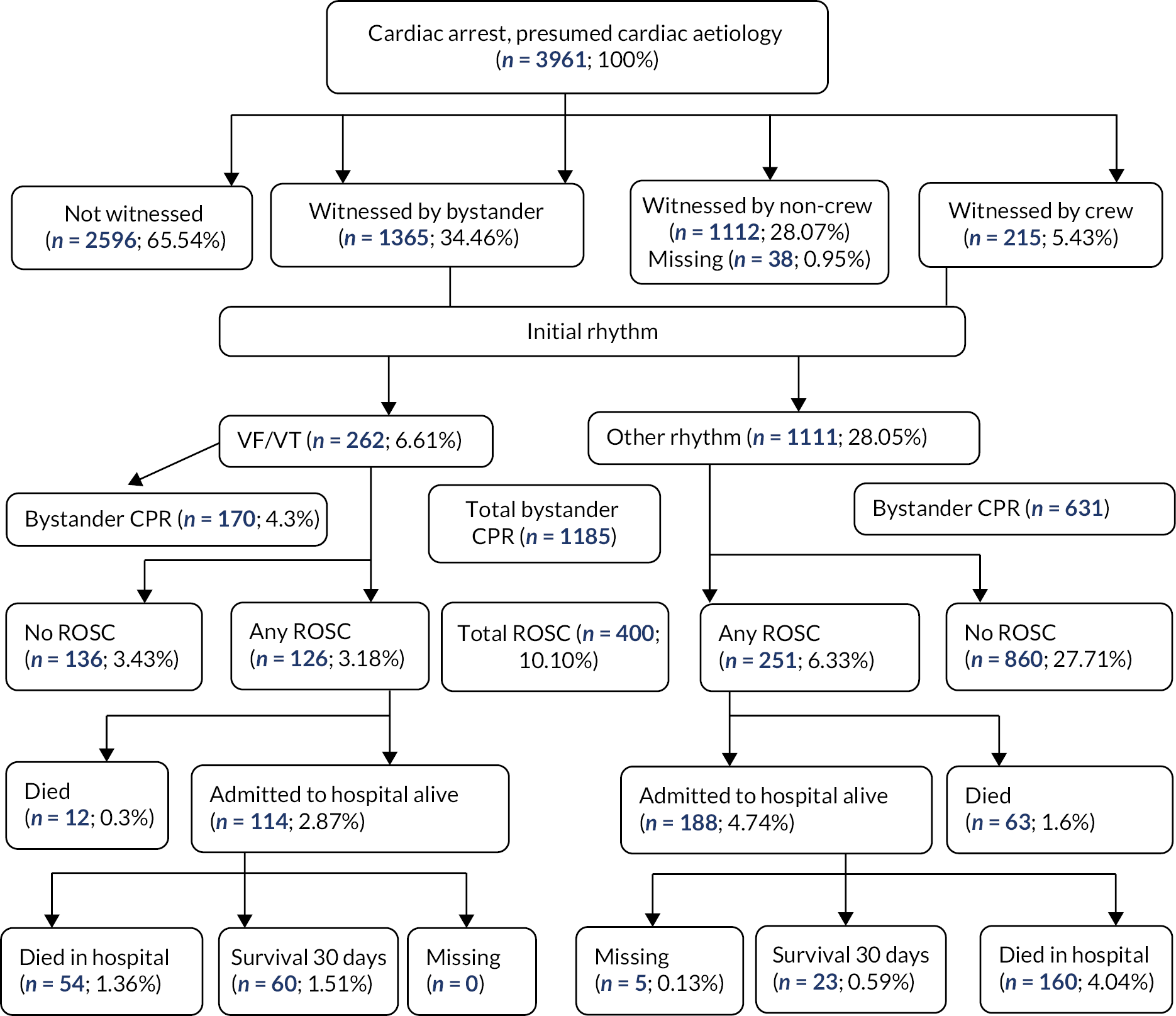

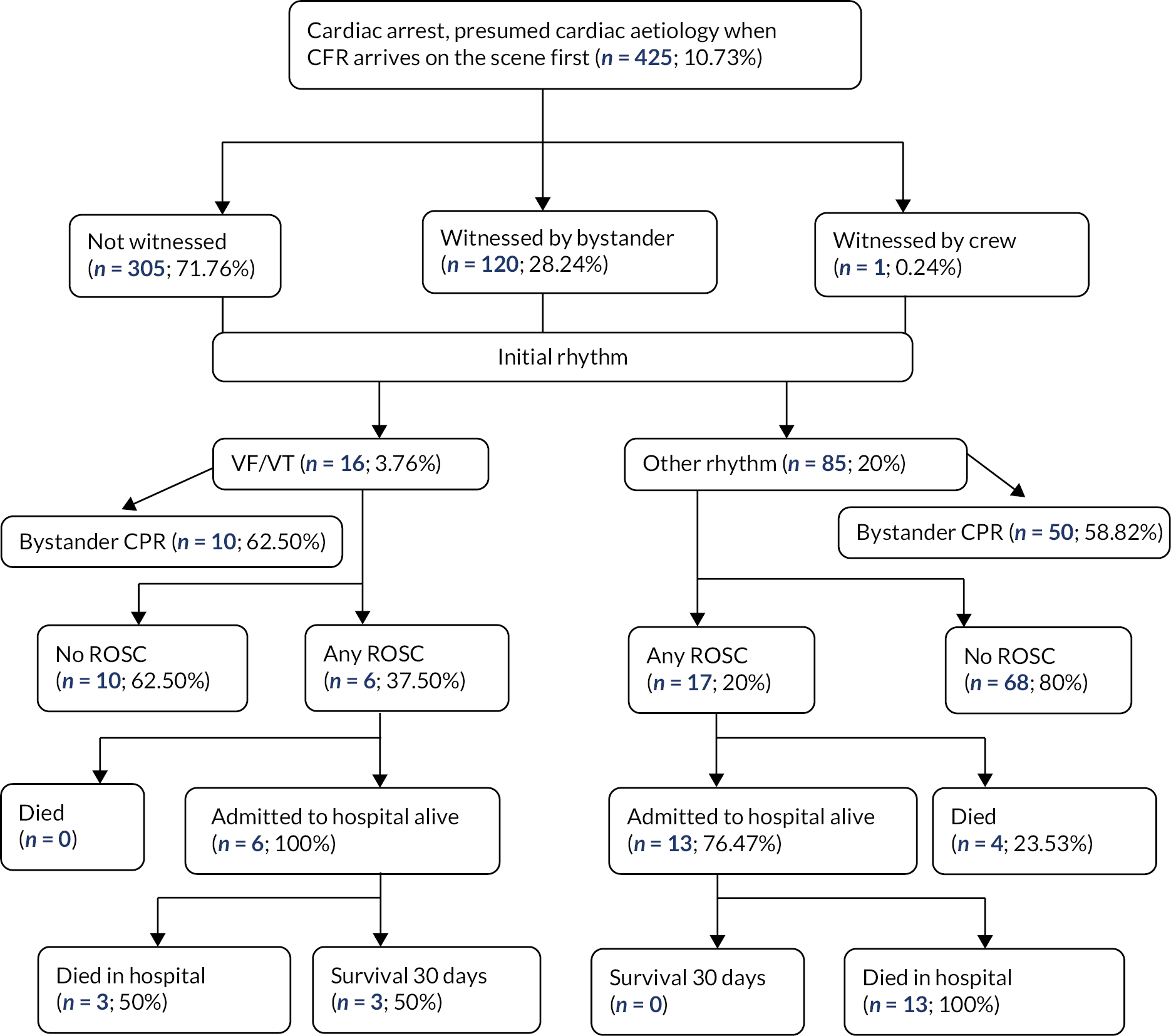

Cross-sectional study of Community First Responder response to out-of-hospital cardiac arrest outcomes

Design

We used a cross-sectional design linking data from EMAS and LIVES on OHCA to investigate the effect of CFRs attending on outcomes.

Data collection and processing

We were provided with routinely collected data from EMAS and LIVES for OHCA between the 999 calls to hospital transportation from electronic patient report forms (ePRFs) and data related to survival status at hospital discharge. EMAS screened their electronic clinical database of patient records for OHCA case records, dispatch codes and related clinical or treatment terms. Incidents of OHCA cases were entered into a cardiac arrest database, cleaned and verified by trained members of the EMAS clinical audit team. Outcome data on admission to hospital and survival at hospital discharge were gathered from regional hospitals for those patients conveyed to hospital under data-sharing protocols.

Data submitted included the following information:

Inputs and outcomes – whether occurrence witnessed, initial cardiac rhythm, ROSC at any time, ROSC at hospital handover, survival to hospital discharge.

Demographic information – patient age and sex, date/time of event, event location, aetiology, receiving hospital.

Interventions – bystander CPR, PAD use, other interventions, airway management.

Timing – call time, time to arrive, on-scene time, time to convey to hospital.

By examining timings provided by EMAS and LIVES, we were able to differentiate between episodes where a CFR arrived before or after EMS.

Analysis

We derived Utstein-style50 templates for OHCA incidents presenting to EMAS attended by both CFRs (LIVES) and ambulance staff. We compared outcomes for ROSC and 30-day survival using multivariable regressions models comparing CFR arrival before EMS with EMS alone for both.

Evaluation of a Community First Responder response to adults who had fallen

Background

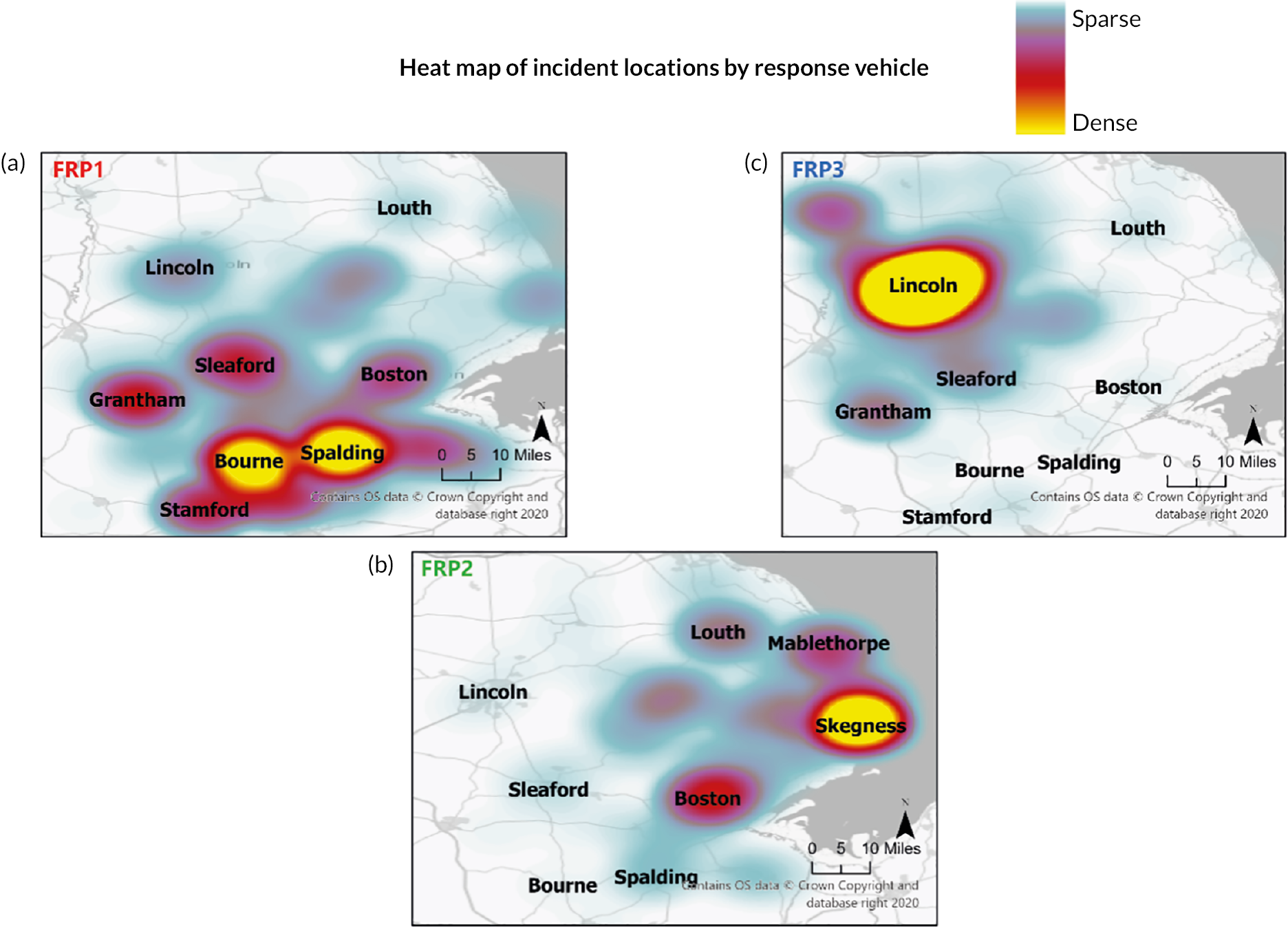

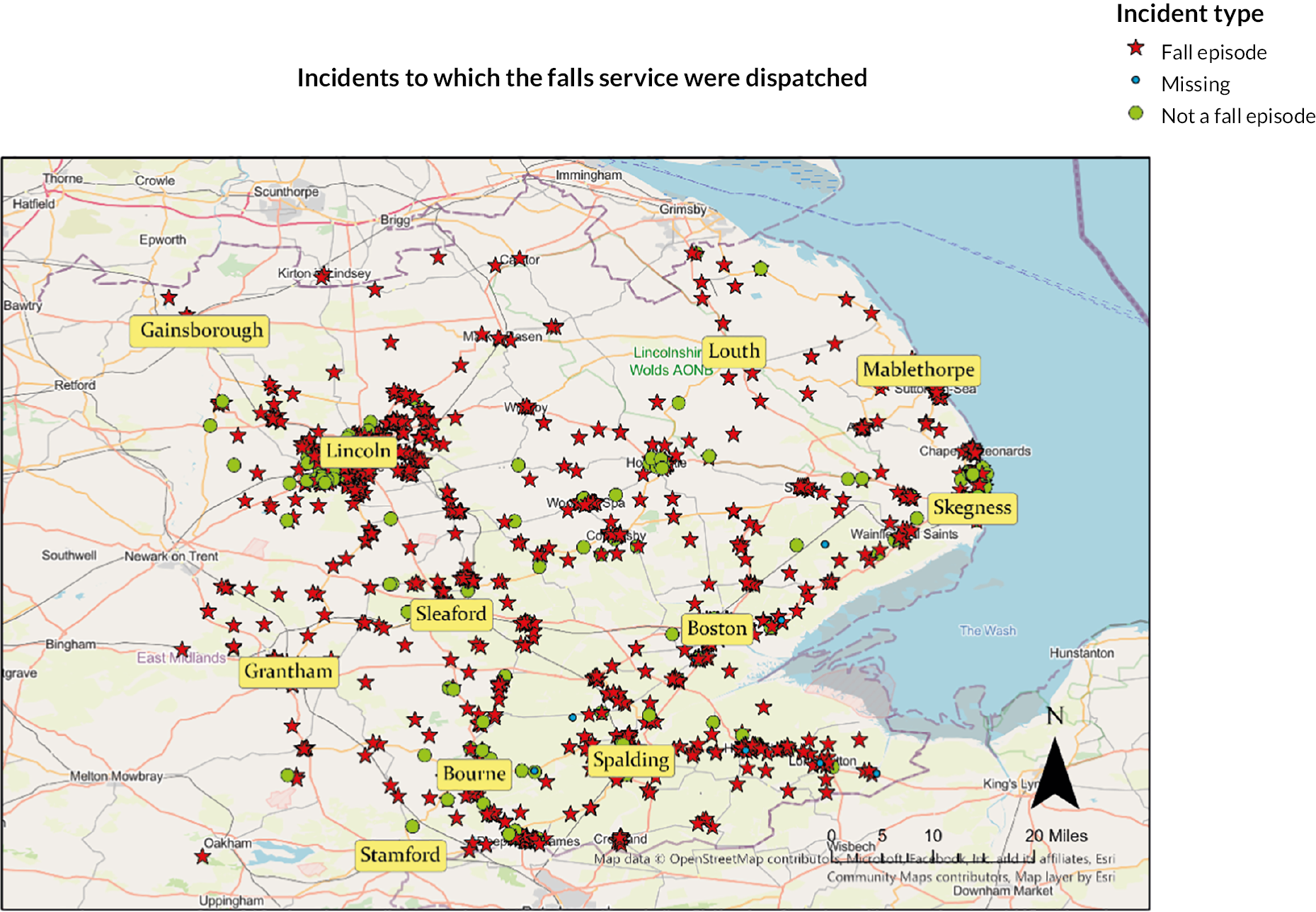

The falls response partnership combines the EMAS NHS Trust and LIVES Lincolnshire First Responders to form an innovative approach ensuring a safe health and social care response to people in Lincolnshire who fall. Its aims were foremost to recover the patient from their fall and then conduct a follow-up in which patient needs could be identified and appropriate service referrals made so that future falls could be prevented. In addition, the design aimed to reduce pressures on the ambulance service and emergency departments and to help retain staff at LIVES.

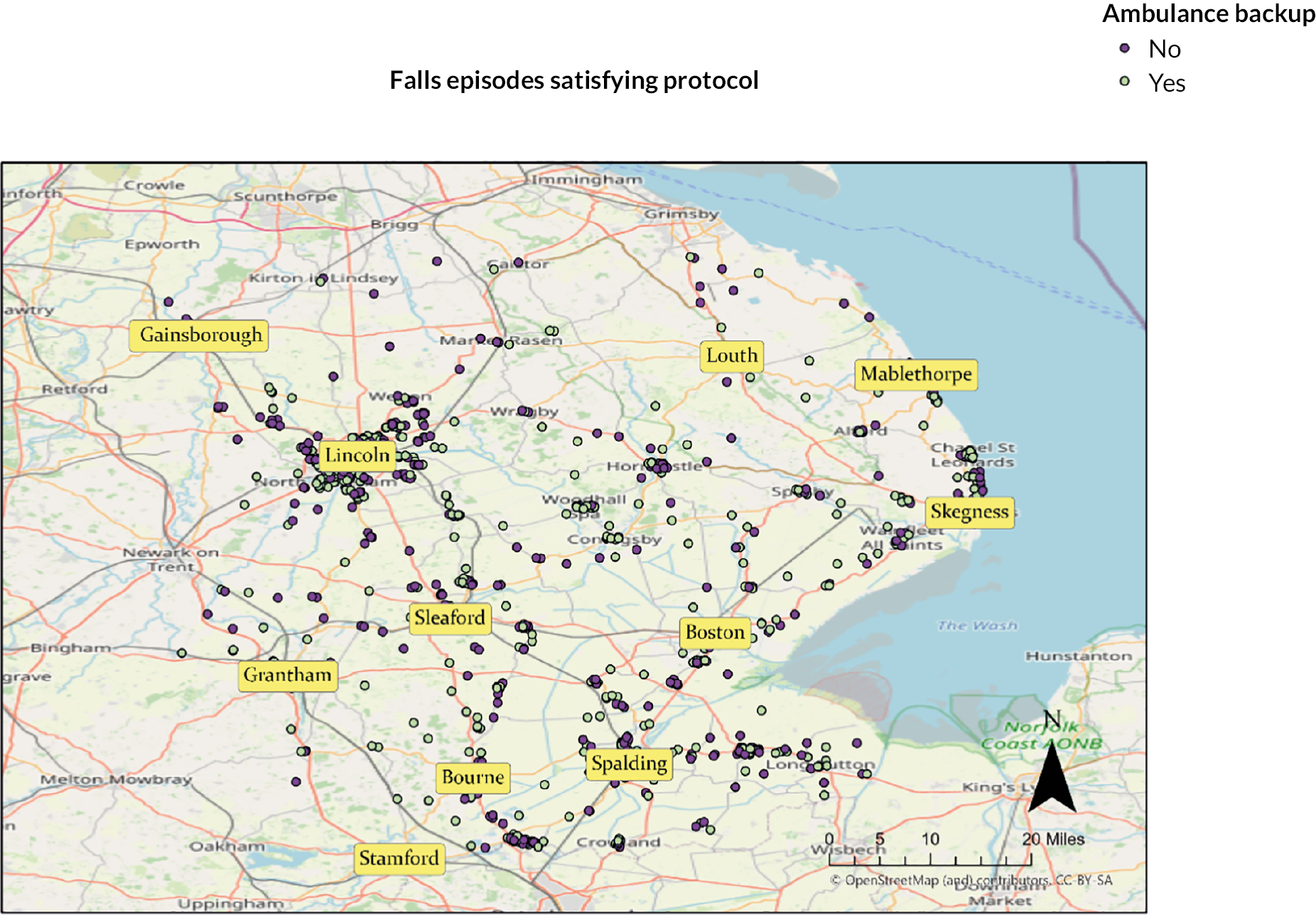

Lincolnshire Integrated Voluntary Emergency Service CFRs are trained and supported with two-staffed, lifting-equipped vehicles [bariatric service vehicles (BSVs)] that, when on-call, may be despatched by EMAS to attend adults who fall. Remote management of the incident from the EMAS EOC is provided by the EMAS clinical assessment team (CAT) in real time. Following treatment, the patient may either be discharged at-scene or ambulance backup may be despatched for further at-scene paramedic support and treatment with the further possibility of conveying the patient to hospital. While the service was initially designed for patients assessed by computer-aided dispatch (CAD) to have had a (least severe) category 4 fall, after approximately 2 months of operations this was upgraded to include falls assessed to be category 3 and category 2 (Box 1).

Category 1: life-threatening/very serious injuries.

Category 2: emergency calls.

Category 3: urgent calls.

Category 4: less urgent calls.

The FRP commissioned LIVES to provide an immediate patient assessment on arrival, treating the individual in their own home with basic first aid if required, assisting them back to their feet and, if the patient was then discharged, ensuring that they were in a comfortable and safe environment, with a follow-up assessment conducted within 24 hours to ensure an appropriate referral to prevent further falls. The follow-up assessment (including a standardised falls risk assessment tool) was done by LIVES and an onward referral for additional support made where appropriate. The options for further action included referral to the Lincolnshire Wellbeing Service for further assessment, support or equipment; a GP referral for assessment of frailty, dizziness, hyper-/hypotension, other medical problems or medication review; services providing strength and balance training; or to an occupational therapist working in the community falls team based at Lincolnshire Community Health Services NHS Trust for more complex needs.

The FRP was initiated in December 2018 with operating hours of 8 a.m. to 8 p.m. It began with just one EMAS-owned BSV loaned to LIVES (call sign BSV5), and a second BSV was soon added (call sign BSV4). By the end of June 2019, a total of 445 episodes of care involving FRP had been recorded. By vehicle, BSV5 responded to falls in West and South Lincolnshire and operated within the City of Lincoln, North Kesteven, West Lindsey, South Kesteven and South Holland; BSV4 responded to falls in East Lincolnshire and Boston and operated within the borough of Boston and East Lindsey.

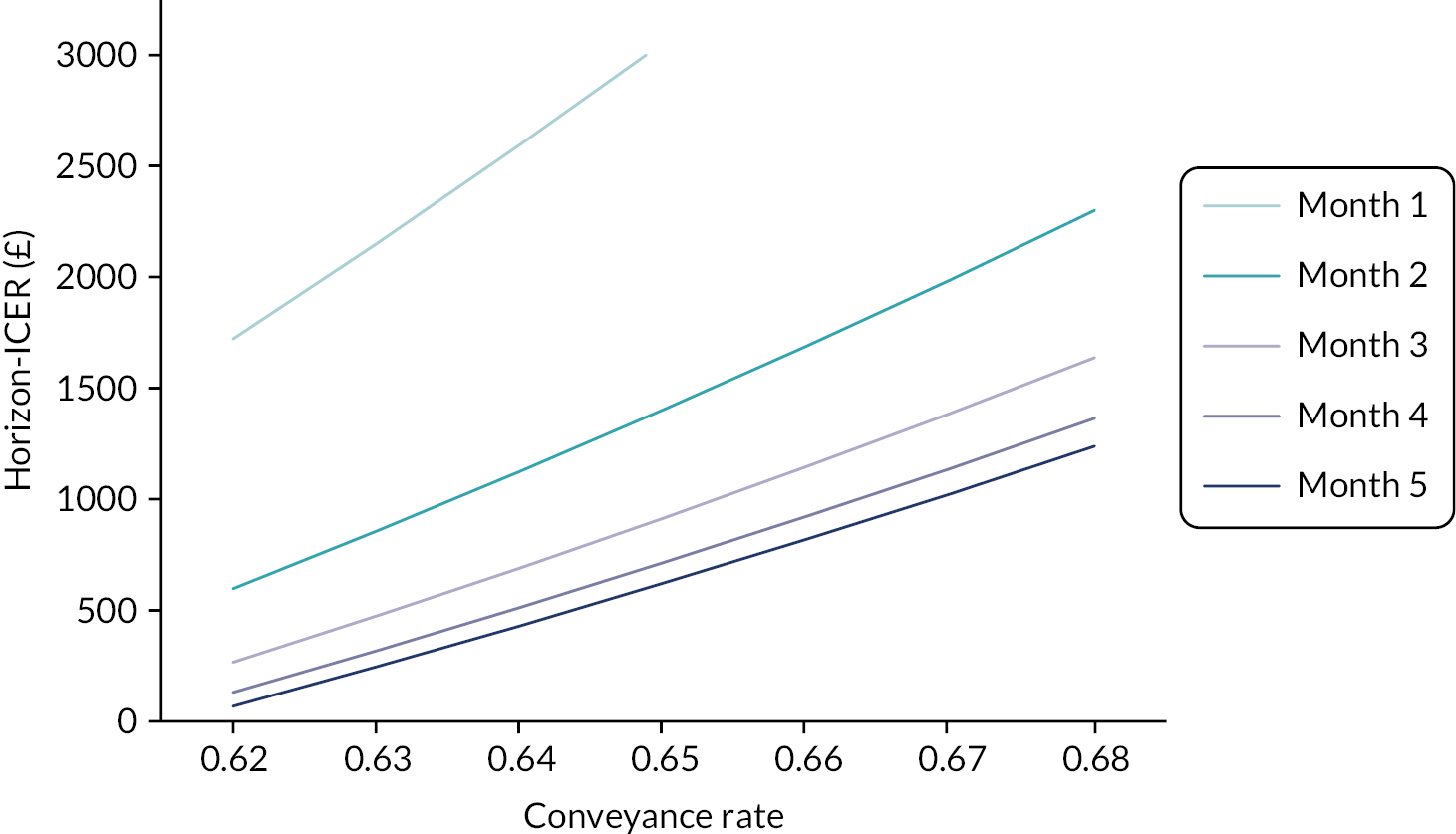

Pilot economic evaluation

Smith et al. 35 reported on a model-based economic evaluation of the FRP during the pilot period December 2018 to June 2019 (see Report Supplementary Material 3). Their main finding was that improvement in effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of FRP compared with standard care was inversely related to ambulance backup and conveyance rates following FRP attendance, for as those rates increase so do costs and FRP patient referral rates decrease. Patient benefit, that is mitigation of the risk of recurrent falls, depended on attendance to referred clinicians, whether that be to the patient’s GP or to a community falls services or to occupational therapists at Lincolnshire Community Health Services NHS Trust. Their baseline modelling, for a hypothetical cohort of size 1000 falls patients, is given in Table 2, where the incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) by at-risk time horizon, hereafter ‘horizon-ICER’, can be selected from 1 month up to 5 months beyond the initial fall. The perspective of the analysis was the NHS, and all prices were expressed in 2019–20 values.

| Month | Per-patient cost (£) | Cost increment (£) (1) | Total cohort falls | Benefit increment (2) | aICER:(1)/(2)/1000 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FRP | Standard care | FRP | Standard care | ||||

| 1 | 1316.14 | 1113.49 | 202.66 | 1398 | 1448 | −50 | £4544.17 |

| 2 | 1839.67 | 1612.15 | 227.52 | 1556 | 1648 | −92 | £2298.97 |

| 3 | 2047.92 | 1835.48 | 212.44 | 1619 | 1738 | −119 | £1636.86 |

| 4 | 2130.76 | 1935.49 | 195.26 | 1644 | 1778 | −134 | £1363.92 |

| 5 | 2163.71 | 1980.28 | 183.42 | 1654 | 1796 | −143 | £1238.05 |

These results can be explained as follows. For the FRP, the model begins with 1000 falls costing the NHS in the first month £1316 per fall. Under standard care the corresponding figure is £1113; thus the incremental per-patient cost of the FRP compared with standard care is £203. During the first month, 1398 falls were predicted under the FRP, implying 398 patients with repeat falls by the end of the first month. The corresponding figures under standard care were 1448 and 448. During the first month, the baseline model predicted 50 fewer repeat falls under the FRP than with standard care for a cohort size of 1000, yielding a 1-month at-risk horizon-ICER of £4544; that is, the additional cost to the NHS of using the FRP rather than standard care to prevent one fall was £4544 for an at-risk period of 1 month beyond the initial fall. However, on extending the at-risk horizon to 5 months, the horizon-ICER reduced to £1238 per fall avoided.

A key driver of the baseline case is the differential between the rates of conveyance to hospital for falls patients; for the FRP, the observed rate over the pilot period was 68%, while for standard care the observed rate was 62.7%, a difference of 5.3% compared with the FRP. Under the FRP, a substantial cost is added when patient circumstances dictate that ambulance backup is required; in particular, estimates of the average intervention cost are £195 without backup but £440 when backup is required. 35

A scenario analysis that examined variation in FRP backup rates (set between 62% and 68%) resulted in Figure 3, which displays the horizon-ICERs against a continuum of conveyance rates. Improvement occurs as conveyance rates fall (i.e. moving from right to left on the graph) and is uniform at any selected at-risk time horizon.

FIGURE 3.

Horizon-ICER by FRP conveyance rate.

For example, matching the FRP backup rate to that observed in standard care (62.7%), with all other factors held constant, the value of the 5-month horizon-ICER dropped to £192 per fall avoided. Indeed, further extrapolation beyond that depicted in the graph to the FRP backup rate of 56.3% finds FRP dominating standard care at every time at-risk horizon, and FRP becomes cost saving at this point.

The LIVES-EMAS FRP was recommissioned by Lincolnshire County Council in February 2020. In this study we revisit the FRP and examine its operation using descriptive statistics over the period April 2020 to December 2021 using a cross-sectional design that linked FRP episode data from EMAS and LIVES.

Documentary analysis of Community First Responder policies, guidelines and protocols

Background

The documentary analysis addressed the research objective of understanding CFR structures (e.g. guidelines, protocols, personnel, equipment, training) in participating ambulance services.

NHS England’s Five Year Forward View51 emphasises community engagement in decision-making as a means of strengthening future health and care services. The CFR schemes have been in line with the community engagement initiative, and over 2500 CFR schemes have been operationalised in the UK. Keeping the diverse range of CFR schemes in mind, we aimed to conduct an inquiry into policies, protocols and guidelines developed for the regulation of CFRs.

Design

We conducted an analysis of ambulance/CFR policy, guideline and protocol documents in participating ambulance services using content and discourse analysis to understand current structures for CFR involvement. 52

Collection of documents

We requested CFR leads and managers in the ambulance trusts to provide documents developed as policies, guidelines and protocols for CFR roles. We analysed the documents using a comparative method by employing an institutionalist approach to policy analysis. 53 In establishing and developing public policy, the institutionalist perspective outlines the roles of the state or a government body in developing procedures and relationships between policy-makers and those that are subject to policy and how the latter are affected. Our analysis used two prominent document-analysis methods, namely content analysis and discourse analysis. 53,54

Content and discourse analysis

Content analysis was used to quantify the occurrence of certain key words, phrases, topics and concepts in the policies, guidelines and protocols retrieved. The discourse analysis developed themes that were identified from the content analysis and focused on how the CFRs were discussed in the policy documents, including how CFR roles were structured, the governance mechanism, support services, training and equipment.

Qualitative study of Community First Responder roles, governance of Community First Responder schemes, innovations and future developments

Background

The aim of the qualitative study was to explore the experiences and perceptions of CFR stakeholders on the current roles of CFRs, governance of CFR schemes, challenges, solutions and future opportunities. The objectives of this aspect were:

-

to explore patients’ and relatives’ experiences and perceptions of care provided by CFRs

-

to explore the experiences and/or perceptions of ambulance staff, CFRs, CFR scheme organisers, primary care staff and commissioners on the CFR role, the governance of CFR schemes, and the potential for further development of and innovation in the CFR role

-

to explore the views of CFRs and CFR scheme organisers about challenges and solutions to recruiting, training and retaining CFRs in rural areas.

This section addresses the study objectives by analysing primary qualitative data from a range of stakeholders involved in the operation of CFR schemes, that is CFRs, CFR leads and managers, ambulance staff, commissioners, and patients and relatives of the patients.

Design

Qualitative methods seek to elaborate the views and beliefs of participants to understand complex social phenomena,55 and it was appropriate to address the research questions, which required an exploration of the operation of CFR schemes, particularly the experiences, perceptions and actions of stakeholders involved in the CFR processes. Therefore, we adopted an interpretivist paradigm of research and conducted this qualitative study in six rural ambulance services and regions in England, UK. The six research sites were rural ambulance services, which enabled us to explore and understand the functions of CFR schemes in rural health care, where CFR services are crucial.

Recruitment

The selection of participants was informed by the concept of purposive sampling56 to include a diverse range of stakeholders and their perceptions, experiences, practices and innovations until data saturation was achieved. 57,58

We purposively sampled patients, relatives and ambulance staff identified from records of patients who had been attended by a CFR in a rural location in the previous 6 months using the quantitative data from ambulance services in the cross-sectional study above. For each ambulance service, from the data set provided, a random sample was generated of 100 incidents where a CFR had attended a rural emergency in the latter half of 2019. The data set included details of patient age group, sex and ethnicity, together with chief complaint, clinical impression, incident rurality, IMD, call category, AMPDS code and outcome (see and treat at scene or see and convey to hospital). To recruit participants, the ambulance services were asked to contact the patient, CFR and ambulance staff members for tranches of 10–20 incidents, ideally with all three involved in the same incident.

Although we sought to interview patients, relatives, CFRs and ambulance staff attending the same event, this was only achieved for one set of interviews. Ambulance staff were also recruited through ambulance service research leads. CFRs were also recruited through ambulance CFR leads and we sought to recruit CFRs, patients and relatives through social media (X, San Francisco, CA, USA). Primary care commissioners were recruited through the National Ambulance Commissioner’s Forum.

We sought to recruit a maximum variation sample of patients (according to age, sex, condition and ethnicity), ambulance staff (sex, experience, ethnicity and role), CFR (sex, ethnicity, length of experience, skill level) and CFR scheme leads (independent charity and ambulance trust oversight schemes). We also advertised the study and recruited via internal advertisements, e-mails and social media at the ambulance services involved in the study and their associated CFR schemes.

Data collection

Three researchers (VHP, JP and IT) conducted the interviews using separate interview schedules for each participant category (see Report Supplementary Material 2). These were developed based on the participants’ roles and responsibilities to discuss and explore a wide range of experiences and practices in the CFR functions. The interviews took place between April 2020 and December 2021, which was in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic and frequent nationwide lockdowns and led us to conduct the in-depth interviews online. 59 The interviews were audio-recorded with the participants’ written consent and subsequently transcribed. The length of the interviews ranged from 30 to 60 minutes.

Data analysis

We familiarised ourselves with the interviews and the emergent data through reading the transcripts. A thematic analysis approach guided the data analysis. 60 The thematic analysis consisted of several steps in which we (GP, VHP, JP and NS) organised and synthesised data by constructing short-codes, grouping the short-codes and synthesising meaning based on more broadly identified themes. Three researchers (GP, VHP and JP) used NVivo12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) to inductively code the transcripts, periodically compiled to produce a comprehensive list of codes as they were identified from the data. The codebooks were combined to create a coding framework, and the framework was then amended following a series of discussions within the research team (GP, VHP, JP, IT and NS). NVivo12 supported the production of data outputs for each code. GP and VHP extracted the data outputs and documented the variations in practices, governance and experiences of CFR operations within each ambulance service. They further collapsed the similar themes and organised them under higher-level themes. The data outputs were read, reviewed and re-read to identify overarching themes.

Data debriefing with PPI and information validation for improved methodological rigour are discussed later in this chapter.

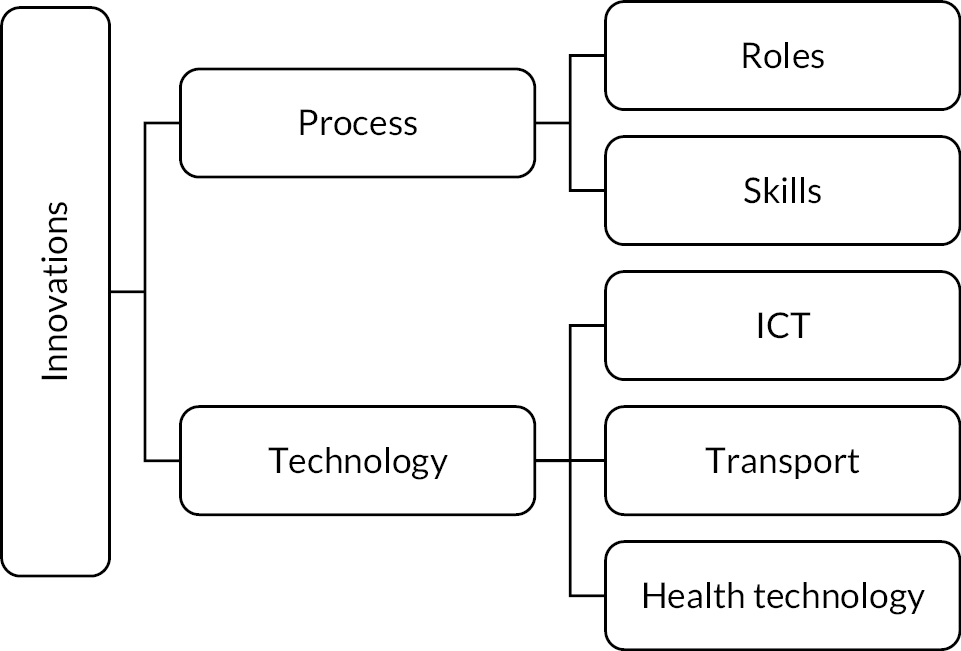

Stakeholder consensus workshop prioritising Community First Responder innovations

Background

A consensus workshop of stakeholders was convened to present and discuss recommendations developed from the earlier studies and to prioritise recommendations for development and innovation in CFR schemes. We applied nominal group technique (NGT) methods to innovations relevant to the current and future roles of CFRs.

Design

We used a mNGT as a consensus method to introduce, generate, discuss and prioritise actual and potential innovations for CFRs and CFR schemes, particularly focusing on those in rural areas. The mNGT, also termed expert panel method, is a structured, facilitated, face-to-face meeting of key informants designed to generate ideas, agree a list of those most relevant through discussion and rank them through two or more rounds of voting to reach a consensus, if possible, on the priorities for innovation. 61,62 The modifications of the original NGT introduced in this study included use of a hybrid meeting format, allowing in-person and online participation, together with introduction of learning from previous quantitative and qualitative components of the wider study. Important to NGT is a combination of qualitative (discussion) and quantitative (voting or ranking) methods to understand why certain innovations are prioritised more than others.

Recruitment

We invited stakeholders and representatives from seven rural regional ambulance services in England to the consensus meeting. We ensured that experts from different disciplines were invited, including patient representatives, CFRs, ambulance clinicians and leads. Although the consensus meeting took place in 2022 after the majority of the adult population had been vaccinated against the SARS-Cov-2 virus, cases of COVID-19 were still high in England, travel was affected and some individuals were still at risk and therefore avoiding meetings, so we organised this as a hybrid face-to-face and online meeting. We checked participants’ availability and preference for mode of participation, either face to face at the University of Lincoln campus or online via Microsoft Teams (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). A list of participants was finalised based on their consent to participate.

Structure

The consensus meeting was structured in four stages or sessions: (1) presentation of information to all participants; (2) silent generation of ideas, and discussion in small groups; followed by (3) voting on ideas, feedback and discussion by all; and (4) a final vote, discussion and summary by all participants. Each session was facilitated by the chief investigator, with members of the research team facilitating small-group discussions to ensure that all participants’ opinions and ideas were included and discussed throughout the consensus process. Participants were allocated in advance to small groups to ensure that each group represented a diverse range of stakeholders, ambulance services and regions.

Session 1

The presentation session comprised a series of three presentations by members of the research team to provide insight into the empirical study’s key findings. The purpose of these presentations was to expand participants’ knowledge and understanding of the CFR schemes and research findings in order to foster meaningful engagement from all stakeholders, irrespective of their experience with the CFR schemes or research.

The quantitative section analyses data from ambulance services that identified how many people CFRs attended, the proportion of ambulance calls attended, the characteristics of people (age, sex, condition) attended, how quickly CFRs attended and what happened to patients when the ambulance arrived.

The econometrics section discussed the costs of CFR scheme provision and the funding sources and provided information on their value to ambulance services.

The qualitative section presented an overview of perceptions, experiences, challenges and governance of CFRs, CFR organisers, ambulance staff and commissioners.

Each presentation included a brief question-and-answer session, and a discussion among participants to elicit reflections on the study findings.

Session 2

The second session built on the discussion from session 1 to supplement ideas for innovations and change. Participants were organised into three groups, one face to face and two online via Microsoft Teams. Each group was assigned facilitators to help guide the generation of ideas, as well as (in a non-participatory way) observing and documenting the discussion in their groups. At the end of this session, the ideas were collated and summarised in advance of an initial process of voting to rank innovations.

Session 3

Participants reconvened in the main group. A member of the research group presented the synthesised version of the innovations, and these were discussed again in the main group. Participants (excluding research team members) voted on all the innovations presented. This was followed by feedback on the ranking and a discussion of the votes. The content of the discussion was informed by the minutes or observation notes from session 2, as well as the results of the vote.

Session 4

The concluding session consisted of a further vote to rank and a final discussion among the participants.

Data analysis

The ranking or prioritisation of innovations was achieved using a joint information systems committee (JISC) online survey (www.jisc.ac.uk/online-surveys) circulated to participants so that they could vote anonymously during the consensus meeting. All the innovations presented, suggested through the generation of ideas, and discussed were collated and entered into the JISC survey. These were rated individually by participants (excluding research team members) using a Likert scale of 1 to 5, with 1 representing ‘not a priority’ and 5 representing an ‘essential priority’. The first survey was administered during session 3, followed by a discussion and a further survey during session 4. The results at the end of each round were exported to Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and these were ranked using median scores and interquartile ranges.

The discussion (qualitative component) during the consensus meeting was important for understanding why certain innovations were ranked (quantitative component) above or below others. The consensus meeting was audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim for later analysis. We used inductive and deductive thematic analysis60 to explore the varying viewpoints on the innovations presented and discussed. This involved reading and re-reading transcripts and inductive coding using NVivo 12. Later, a deductive analysis was performed, based on the attributes of innovations framework. 63

Patient, public and wider stakeholder involvement

Background

The importance of PPI in health and social care research has been widely accepted in the UK and supported by funding bodies such as the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) and patient organisations such as Involve (https://involve.org.uk/). In the last decade, public engagement in research has shifted from the passive provision of data as research participants to a much more active role working alongside researchers to design, develop, conduct and disseminate research. 64 In this study, we included two public contributors as co-applicants and research team members, both members of the HAPPI group, a wider PPI panel recruited for this study and a public member of the oversight committee. In the following section we describe how the partnership between researchers and PPI members informed and facilitated the research activities.

The patient and public involvement panel

On the advice of the oversight group, we expanded our public contributors on the study. A group of seven patient and public representatives were selected from a pool of expressions of interest received from open recruitment through the NIHR Applied Research Collaboration East Midlands to other Applied Research Collaborations and related organisations. We selected members to ensure a wide geographical representation to include the regions of participating ambulance services and to ensure wider representation of people of different sex, ethnic minority status and disabilities. 65

Professional advisory groups as stakeholders

We engaged with a number of key professional stakeholder groups during the study. The National Ambulance Research Steering Group (NARSG), which was composed of research leads from ambulance services in the UK, was involved in the initial design of the study and recruitment of participating sites. This group reports to the National Ambulance Services Medical Directors’ group, which itself reports to the Association of Ambulance Chief Executives. We also engaged with the College of Paramedics Research and Audit Committee through its chairperson, also a member of NARSG, and with the National Ambulance Service First Responder Managers’ Forum. We invited members of these groups, and they attended the consensus workshop.

Summary

The PPI panel members in this study were recruited to increase geographical and demographic representation. The public contributors and professional advisory groups contributed throughout the various aspects of the study, providing input on study design, advising on recruitment, reviewing findings, and contributing to the study steering and oversight groups and the consensus workshop.

Chapter 3 Results

Text in this section is reproduced from Botan V, Asghar Z, Rowan E, et al. What Is the Contribution of Community First Responders to Rural Emergency Medical Service Provision in the UK? Paper presented at: Society for Academic Primary Care Annual Scientific Meeting: Recovery and Innovation; 4–6 July 2022; University of Central Lancashire, Preston, England, which is an open access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons CC BY-NC licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, for non-commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

Overview

This chapter sets out our findings from each of the work packages and substudies that relate to the objectives. This includes a detailed description of CFR activities in the cross-sectional study. We presented data on resource use, workforce and costs from the survey designed to investigate this. The outcomes of CFR attendance are described in terms of timeliness of response, response to falls and outcomes for OHCA. The documentary analysis of CFR policies, guidelines and protocols explores the structures in ambulance services supporting CFRs’ roles and responsibilities. The qualitative interviews describe CFR recruitment training and retention, their role, governance and innovations, and their activities providing care for patients. The findings from each of these are integrated to develop an actor-based system map. Finally, the results of the consensus meeting summarise the priorities given to different innovations that had or could be introduced into rural CFR schemes.

Cross-sectional study findings

Rural versus urban

We found 4,501,274 separate ambulance attendances to individual patients in the sample from the six participating ambulance services (see Appendix 1, Figure 16). Missing data varied for the variables used, from no missing data for deprivation or rurality to high rates for ethnicity (see Appendix 1, Table 20).

Of these ambulance attendances, 3,671,512 (82.8%) were in urban areas and 763,553 (17.2%) were in rural areas. CFRs were present overall in 136,438 (3.0%) and arrived first in 86,880 (1.9%) of these calls.

Community First Responders were present on scene first for 3.9% of all rural attendances and for 1.5% of urban attendances (Table 3). Proportion tests indicated that CFRs attended first on scene for a statistically significant higher proportion of the calls in rural than in urban areas.

| CFR | Rural, n (%) | Urban, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Present first* | 29,741 (3.9) | 54,207 (1.5) |

| Present after ambulance* | 17,645 (2.3) | 34,845 (1.0) |

| Not present** | 716,167 (93.8) | 3,582,460 (97.5) |

| Total | 763,553 (100.0) | 3,671,512 (100.0) |

Call urgency

Community First Responders attended more than 9% of the total number of category 1 calls and almost 5% of category 2 calls, with a statistically significant higher proportion of more urgent call categories 1 and 2 in both rural and urban settings. While 14.4% of CFR first attendances in rural areas were for category 1 calls, only 5.8% of ambulance staff attendances in rural areas were for category 1 calls. Similarly, 14.2% of CFR first attendances and only 7.4% of ambulance staff attendances in urban areas were for category 1 calls. When looking at category 2 calls, these represented 67.3% of CFR first attendances in rural areas and only 56.4% of ambulance staff first attendances. The results were similar for urban areas, with 70.8% of CFR first attendances for category 2 calls and only 55.8% of ambulance attendances for category 2 calls. Compared with ambulance staff, CFRs also attended a statistically significantly lower proportion of category 3 calls in both rural and urban settings and of category 4 calls only in rural settings. Detailed results can be seen in Table 4.

| Call category | Rural: CFR on scene | Urban: CFR on scene | Overall: CFR on scene | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, n (%) | Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | Yes, n (%) | |

| 1** | 42,714 (5.8) | 4274 (14.4) | 267,066 (7.4) | 7706 (14.2) | 313,035 (7.4) | 12,434 (14.3) |

| 2** | 413,924 (56.4) | 20,013 (67.3) | 2,017,328 (55.8) | 38,375 (70.8) | 2,467,140 (58.2) | 60,174 (69.4) |

| 3** | 209,436 (28.5) | 4631 (15.6) | 1,027,743 (28.4) | 6937 (12.8) | 1,249,389 (29.5) | 12,120 (14.0) |

| 4* (only rural) | 36,639 (3.4) | 430 (1.5) | 98,762 (2.7) | 637 (1.2) | 127,536 (3.0) | 1118 (1.3) |

| 5 | 12,247 (1.7) | 337 (1.1) | 68,814 (1.9) | 499 (0.9) | 82,345 (1.9) | 922 (1.1) |

Clinical conditions

Community First Responders attended a statistically significant higher proportion of people with cardiorespiratory and neurological/endocrine conditions. The most common cardiorespiratory conditions were breathing difficulties, chest pain and stroke, whereas the commonest neuroendocrine conditions were loss of consciousness or fainting, convulsions and hypo- or hyperglycaemia (see Appendix 1, Table 22).

In the overall sample, 30.2% of CFR attendances were for cardiorespiratory conditions while only 19.2% of ambulance staff attendances were for this condition category, and 13.4% of CFR attendances were for neurological/endocrine conditions compared with 8.8% of ambulance staff attendances. Detailed results with differences between rural and urban areas can be seen in Table 3 (and differences by ambulance service are shown in Appendix 1, Table 21). An important proportion of CFR attendances was for injury/trauma conditions (20.1%), but this was lower than for ambulance staff attendances (23.2%). CFRs also attended a lower proportion of gastrointestinal/urinary and psychosocial/palliative conditions than ambulance staff, as seen in Table 5.

| Chief complaint category | Rural: CFR on scene | Urban: CFR on scene | Overall: CFR on scene | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, n (%) | Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | Yes, n (%) | |

| Cardiorespiratory** | 142,330 (20.3) | 8912 (31.1) | 654,448 (18.9) | 15,318 (29.5) | 807,533 (19.2) | 25,229 (30.2) |

| Gastrointestinal/urinary* | 42,491 (6.1) | 1279 (4.5) | 211,081 (96.1) | 2443 (4.7) | 256,904 (6.1) | 3925 (4.7) |

| Infections/allergy/ENT/ophthalmology | 10,593 (1.5) | 563 (2.0) | 54,778 (1.6) | 1022 (2.0) | 65,914 (1.6) | 1639 (2.0) |

| Injury/trauma** | 164,227 (23.4) | 5925 (20.7) | 800,349 (23.1) | 10,347 (19.9) | 975,405 (23.2) | 16,798 (20.1) |

| Neurological/endocrine** | 56,504 (8.1) | 3925 (13.7) | 310,450 (9.0) | 6975 (13.4) | 370,430 (8.8) | 11,210 (13.4) |

| Obstetric/gynaecological | 3337 (0.5) | 40 (0.1) | 21,606 (0.6) | 79 (0.2) | 25,241 (0.6) | 125 (0.2) |

| Psychosocial/palliative* | 29,137 (4.2) | 567 (2.0) | 220,408 (6.4) | 1579 (3.0) | 252,927 (6.0) | 2224 (2.7) |

| Other** | 251,891 (36.0) | 7475 (26.1) | 1,186,880 (34.3) | 14,175 (27.3) | 1,450,916 (34.5) | 22,272 (26.7) |

Comparison across ambulance services

Community First Responders first attendances compared with ambulance staff first attendances across all ambulance services presented a series of common characteristics, including the higher percentage of attendances in rural areas (see Appendix 1, Table 21), a higher percentage of attendances for the most urgent call categories 1 and 2 (see Appendix 1, Table 23) and for cardiorespiratory and neurological/endocrine conditions (see Appendix 1, Table 24).

Conveyance to hospital

On average, the percentage of patients conveyed to hospital by ambulance services when CFRs were on scene was slightly lower in both rural and urban settings. The difference was small (about 2%) but statistically significant (Table 6). The demographic characteristics of patients are represented in Table 7.

| Outcome | Rural: CFR on scene | Urban: CFR on scene | Overall: CFR on scene | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, n (%) | Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | Yes, n (%) | |

| Conveyed** | 451,058 (68.4) | 18,841 (65.9) | 2,138,626 (67.8) | 34,522 (65.8) | 2,616,985 (67.9) | 55,098 (65.6) |

| See and treat** | 208,858 (31.7) | 9771 (34.2) | 1,016,235 (32.2) | 17,966 (34.2) | 1,240,296 (32.2) | 28,882 (34.4) |

| Variable | Rural: CFR on scene | Urban: CFR on scene | Overall: CFR on scene | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No, n (%) | Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) | Yes, n (%) | |

| Age group (years) | ||||||

| < 19 | 56,929 (8.7) | 2558 (9.4) | 335,455 (10.4) | 4811 (9.9) | 396,904 (10.1) | 7685 (9.8) |

| 20–39 | 77,172 (11.8) | 2760 (10.2) | 586,212 (18.2) | 6894 (14.1) | 670,131 (17.1) | 9972 (12.7) |

| 40–59 | 96,814 (14.8) | 4082 (15.1) | 580,166 (18.0) | 8484 (17.4) | 684,484 (17.4) | 13,017 (16.5) |

| 60–79 | 191,112 (29.3) | 8473 (31.3) | 817,666 (25.3) | 13,583 (27.9) | 1,021,359 (26.0)* | 22,974 (29.2) |

| ≥ 80 | 230,320 (35.3) | 9233 (34.1) | 909,794 (28.2) | 15,001 (30.8) | 1,153,170 (19.4)** | 25,069 (31.9) |

| Sex | ||||||

| Female | 351,996 (52.8) | 14,634 (52.4) | 1,781,189 (53.2) | 27,101 (53.3) | 2,156,036 (53.1) | 43,158 (52.9) |

| Male | 315,110 (47.2) | 13,285 (47.6) | 1,565,606 (46.8) | 23,739 (46.7) | 1,902,169 (46.9) | 38,501 (47.5) |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Ethnic minority | 3632 (1.1) | 132 (1.0) | 88,395 (5.9) | 1012 (4.1) | 92,361 (5.0)* | 1150 (2.9)* |

| Mixed ethnicity | 1331 (0.4) | 60 (0.4) | 12,552 (0.8) | 187 (0.8) | 13,973 (0.8) | 251 (0.6) |

| White | 320,850 (98.5) | 13,523 (98.6) | 1,398,953 (93.3) | 23,725 (95.2) | 1,739,903 (94.2)** | 38,346 (96.5)** |

| Deprivation | ||||||

| Low income (IMD ≤ 5)** | 213,812 (29.1)* | 9310 (31.3)* | 2,244,710 (62.0) | 27,195 (50.2) | 2,485,155 (56.4) | 38,743 (44.6) |

| High income (IMD > 5)** | 520,000 (70.9)* | 20,431 (68.7)* | 1,372,595 (38.0) | 27,012 (49.8) | 1,923,105 (43.6) | 48,137 (55.4) |

Predictors of Community First Responder attendance

Univariable and multivariable logistic regression models determined the factors predicting CFRs presence on scene (Table 8). For the multivariable model, the assumption of no multicollinearity (Spearman’s rho < 0.7, the highest value being 0.28) was met, and the model showed a good fit to the data [χ²(25) = 12,887.51, p < 0.001]. The main predictors of CFR presence were rurality [odds ratio (OR) 2.05, 95% confidence interval (CI) 1.99 to 2.11; p < 0.001], conditions including cardiorespiratory (OR 9.20, 95% CI 5.08 to 16.64; p < 0.001) and neurological/endocrine (OR 9.26, 95% CI 5.12 to 16.77; p < 0.001) and call categories 1 (OR 5.19, 95% CI 3.86 to 6.99; p < 0.001) and 2 (OR 4.44, 95% CI 3.31 to 5.96; p < 0.001), with the narrow CIs indicating that their estimates were extremely precise. CFRs were also less likely to attend patients from minority ethnic backgrounds, those from more deprived areas and those aged < 39 years.

| Predictor of CFR presence on scene | Univariable model, OR (95% CI) | Multivariable model, OR (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|

| Rurality (urban) | 1 (–) | 1 (–) |

| Rural | 2.70 (2.67 to 2.74) | 2.05 (1.99 to 2.11) |

| Chief complaint category (obstetric/gynaecological) | 1 (–) | 1 (–) |

| Cardiorespiratory | 6.31 (5.29 to 7.52) | 9.20 (5.08 to 16.64) |

| Gastrointestinal/urinary | 3.09 (2.58 to 3.69) | 5.13 (2.83 to 9.33) |

| Infections/allergies/ENT | 5.02 (4.18 to 6.03) | 6.10 (3.34 to 11.13) |

| Injury/trauma | 3.48 (2.92 to 4.15) | 5.36 (2.96 to 9.71) |

| Neurological/endocrine | 6.11 (5.12 to 7.29) | 9.26 (5.12 to 16.77) |

| Psychosocial | 1.78 (1.48 to 2.13) | 4.20 (2.31 to 7.64) |

| Other impressions | 3.10 (2.60 to 3.70) | 6.20 (3.43 to 11.22) |

| Call category (5) | 1 (–) | 1 (–) |

| 1 | 3.55 (3.32 to 3.79) | 5.19 (3.86 to 6.99) |

| 2 | 2.18 (2.04 to 2.33) | 4.44 (3.31 to 5.96) |

| 3 | 0.87 (0.81 to 0.93) | 1.12 (0.83 to 1.50) |

| 4 | 0.78 (0.72 to 0.85) | 0.77 (0.54 to 1.11) |

| Arrival time categories in minutes (15–20 minutes) | 1 (–) | 1 (–) |

| < 3 | 1.11 (1.06 to 1.16) | 1.14 (1.06 to 1.23) |

| 3 to < 5 | 1.23 (1.19 to 1.28) | 1.27 (1.20 to 1.34) |

| 5 to < 7 | 1.33 (1.29 to 1.38) | 1.35 (1.28 to 1.42) |