Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number 17/42/42. The contractual start date was in February 2019. The draft manuscript began editorial review in March 2022 and was accepted for publication in May 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Adams et al. This work was produced by Adams et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Adams et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background: scientific background and explanation of rationale

Burden and impact of staff sickness absenteeism and presenteeism on the National Health Service and patients

The NHS in the UK is one of the top 10 employers in the world, with 1.3 million employees. 1 However, sickness absenteeism costs the NHS approximately £2.4 billion per year2 (£1 in every £40 of total NHS budget), with an annual average of just under 10 absence days per employee. 3 In 2016, this was 46% higher than other UK industries and 27% higher than the average in the public sector4,5 and is associated with worse patient outcomes, such as increased inpatient mortality, hospital acquired infections, longer bed stays, reduced completion of patient-care tasks and reduced patient satisfaction. 6–10 There is a well-established association between mental ill health among staff, reduced patient satisfaction and increased medication errors. 7–10 Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, rates of absenteeism have risen and reports of stress and mental ill health have increased. 1,11,12

A greater potential cost is that of presenteeism (attending work while unwell),13–15 with 44% of NHS staff in 2020 reporting pressure to attend work when feeling unwell,11 with associated reduction in ability to work effectively and negative impact on patients. 8

With greater than ever pressure within the NHS, interventions to tackle the main determinants of work productivity (absenteeism and presenteeism) are increasingly important for staff well-being, improving patient care and for the economy. Estimates suggest that reducing staff absence levels by a third could save 3.4 million working days a year. 16

The health of National Health Service staff

Among NHS hospital staff overall, 44% reported feeling unwell as a result of work-related stress and 29% experienced musculoskeletal problems (MSK) as a result of work activities in the last 12 months. 11 Local surveys indicate that nearly half of hospital staff are overweight or obese, staff generally have low levels of exercise and 10–12% smoke (unpublished local NHS data). 17,18 While the prevalence of cardiovascular disease (CVD) is up to five times greater amongst those over 50 years old, MSK and mental health problems are common across all age groups of NHS staff (unpublished local NHS data). 19

Determinants of absenteeism and presenteeism among National Health Service staff

The main cause of sickness absenteeism in the NHS is mental ill health at 25.4% of all recorded days lost in 2019, nearly double that of 201020 and peaking at 32.4% during the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic. 21 This is followed by MSK complaints affecting 16%. 22 Poor lifestyle (smoking, lack of physical activity) and overweight/obesity are also important independent determinants of absenteeism and presenteeism,23–27 with CVD being up to five times greater amongst staff over 50 years old (unpublished local NHS data). 19 Absenteeism varies by occupational group, being highest in the lowest-paid (healthcare assistants), professions allied to medicine and infrastructure support staff,28 those working unsocial hours,4,16 and among older workers (unpublished local NHS data). 29 Presenteeism rates follow similar patterns. 30

National Health Service health and well-being policy

In response to the high levels of staff ill health and sickness absenteeism, NHS England created a ‘Healthy Workforce Programme’, supported by the Royal College of Physicians,31 with a £450 million financial incentive for Trusts to improve staff health and well-being and thereby patient care. 32 Key actions included making the NHS CVD health check (for those aged 40–74 years without pre-existing diabetes or CVD)33 more accessible for staff in the workplace and improving access to physiotherapy, mental health, weight management and smoking cessation services. 34 In most hospitals, occupational health services, which are often outsourced, do not have a preventive or well-being role and therefore new initiatives are required. Since then, mainly in response to staff need during the pandemic, NHS hospitals have implemented a variety of health and well-being initiatives, although most are focused on mental well-being, are likely to be short term and have yet to be thoroughly evaluated. 35,36

Recommended interventions for identification and management of mental health, musculoskeletal health and cardiovascular disease in the general population

Mental health complaints

Screening for anxiety/depression improves outcomes when followed by clinical assessment and treatment for screen positives. 37 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends using validated screening tools for common mental disorders, for example, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items (PHQ-9),38 Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7)39 questionnaire to assess, stratify and guide effective evidence-based stepped care,40 according to three categories of severity.

Musculoskeletal complaints

National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends using risk tools for assessing MSK pain (e.g. STarT Back41) to guide treatment. 42–45 STarT Back is a simple prognostic questionnaire that helps clinicians identify modifiable risk factors (biomedical, psychological and social) for back pain disability. The resulting score stratifies patients into three risk categories which are matched to a treatment package [self-management, physiotherapy and physiotherapy with cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT)]. This approach has been shown to reduce disability and to be cost-effective. A similar tool has been developed for other MSK disorders (STarT MSK). 46 For NHS staff with MSK disorders, NHS England recommends rapid access to rehabilitation. 47

Cardiovascular risk

Public Health England recommends a national risk assessment and management programme for 40- to 74-year-olds without pre-existing diabetes or CVD (the NHS health check). 48 The NHS health check includes CVD risk stratification (e.g. using the QRISK2 tool), with behavioural change support and treatment (e.g. with statins or antihypertensives) of newly identified risk factors, with appropriate management based on relevant NICE guidance. Evaluations of the NHS health check suggests that the programme has benefits in identification and management of those at high risk of CVD, and in impacting on risk factors, such as reduction in body mass index (BMI). 49 However, uptake and proper implementation of health checks are relatively low, particularly among those of working age,33,50 and their long-term effectiveness is controversial. 51

Workplace interventions to address absenteeism and presenteeism

There are several systematic reviews and many individual studies which evaluate the effectiveness of workplace health promotion or return-to-work programmes,24,52–54 but few are conducted among healthcare staff, and they rarely consider impact on absenteeism or presenteeism, or include a control group. Most interventions for healthcare staff are aimed at promoting mental health and well-being. 55

Of most relevance, an evaluation of health screening specifically targeted to 635 low-paid government workers aged 40 and over using the NHS health check with referral to appropriate interventions56 showed improvement in most markers of cardiovascular health after 9 months, although attendance rates were relatively low (20%).

In another feasibility study, 253 hospital employees attended a workplace CVD health check in three NHS hospital sites, received tailored advice, signposting to health-related information, relevant free services and advice to visit their general practitioner (GP) where appropriate. 52 Forty-seven per cent were overweight/obese and many reported existing health problems. Participants perceived the clinic to be convenient, informative and useful for raising awareness of health issues. After 5 weeks, they reported dietary changes (41%); increase in physical activity (30%); smokers reported quitting/cutting down (44%) and those exceeding alcohol limits reported cutting consumption (48%). Fifty-three per cent of those advised to visit their GP complied.

No studies have, however, evaluated the cost effectiveness of interventions targeted at screening for and early management of the main causes of sickness absenteeism in healthcare settings – essential evidence before Trusts will invest limited healthcare resources. The evidence available reinforces the need to focus on high-risk groups, provide interventions of sufficient intensity and optimise attendance to maximise the chances of interventions being effective. 57,58 The most effective model is likely to be a combination of health screening and health/wellness programmes with targeted interventions. 59

Based on learning from a recent pilot staff health screening clinic (SHSC) set up at Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham (QEHB), we have developed a health screening service, including pathways for direct invitation, assessment for MSK, mental health and CVD problems (the three major causes of staff absenteeism) and onward referral, for hospital employees.

We present the results of a pilot randomised controlled trial (RCT) to assess the feasibility of conducting a full RCT to evaluate the effectiveness and cost effectiveness of this service in reducing absenteeism and presenteeism within NHS hospitals.

Chapter 2 Methods

Aims and objectives

The aim of this pilot trial was to assess the feasibility of a definitive RCT evaluating the clinical and cost effectiveness of a health screening clinic compared to usual care, in reducing sickness absenteeism and presenteeism amongst NHS staff.

The key objectives were to:

-

describe recruitment rates

-

describe participant characteristics and assess generalisability compared to the hospital workforce

-

describe intervention screening assessment results

-

describe recommended referrals and attendance at those referrals

-

assess the feasibility of measuring the outcomes relating to the definitive trial, and obtain an estimate of the standard deviation (SD) of the proposed primary outcomes for a full RCT

-

assess levels of contamination between intervention and usual care arms to inform RCT design (individual vs. cluster RCT)

-

describe and explain the fidelity to the intervention and evaluate the barriers and enablers to participation

-

describe the views, experiences and satisfaction of participants and those delivering the health checks

-

explore feasibility of the trial/service in other NHS and non-NHS settings

-

quantify the costs of undertaking the screening service and its consequences.

Trial design

A multicentre, two-arm, parallel group, open-label, 1 : 1 individually randomised pilot RCT of a complex intervention comparing a SHSC with usual care.

Participants

Setting

The trial was conducted in three large urban hospitals and one rural district general hospital within three NHS Hospital Trusts in the West Midlands (see Table 1), allowing the testing of practical aspects in a range of sites.

| Hospital | Staff | Setting |

|---|---|---|

| QEHB (University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust) | 9000 | The largest single-site hospital in the country. Regional centre for cancer, largest solid organ transplantation programme in Europe, a regional Neuroscience and Major Trauma Centre. Ethnically diverse staff recruited locally |

| Heartlands Hospital (University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust) | 11,000 | Includes four secondary care city-based hospital sites (Heartlands, Good Hope, Solihull and the Chest Clinic); one of the top five employers in the West Midlands |

| Birmingham Children’s Hospital (Birmingham Women’s and Children’s NHS Foundation Trust) | 6000 | Secondary and Tertiary care hospital serving 384,000 women and children annually |

| Hereford Hospital (Wye Valley NHS Trust) | 3000 | One of the smallest rural District General Hospitals in England, serving a population of 180,000 |

Eligibility criteria

All employees in the participating hospitals who were able to provide informed consent were eligible to participate except those who had previously attended a pilot health screening clinic at QEHB or who were currently taking part in another drug trial (with the exception of COVID-related drugs/vaccines) or health and well-being trial.

Recruitment

Recruitment occurred in several phases, aiming to reflect the workforce characteristics of each hospital. Anonymous human resources (HR) data providing sociodemographic and occupational characteristics were obtained to choose wards which reflected the characteristics of the whole hospital population. Posters advertising the trial were displayed in departments/wards for a minimum of 2 weeks (or more if local arrangements required) before invitations were sent out, during which time staff could request not to receive an invitation. In order to be accessible to the full workforce, participants were informed of the trial through staff meetings, noticeboards and ward champions, and invited through multiple approaches including e-mail and personal invitation. Reminder letters were sent to non-responders after 2 weeks, with up to two further reminders if necessary. Local staff were engaged to raise trial awareness and arrange cover to allow attendance at the health screening clinic.

Consent

Potential participants joined the trial via a weblink to a custom-designed electronic trial data collection platform hosted by the Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit (BCTU). Those with limited access to the internet could complete a paper-based expression of interest through the internal mail system, then attend the clinic to complete consent and other forms online. Consent was obtained through the trial platform, via participants’ own electronic devices or using tablets provided to the health screening clinic staff, and ongoing consent was confirmed at each follow-up point. The participant information sheet (was provided with the initial invitation and was also available on the trial platform). Participants could contact the research team by telephone or request contact from the research team via the trial platform to ask any questions.

Randomisation and blinding

On completion of the baseline questionnaire, clinic staff received an alert to check eligibility criteria and consent, and participants were then randomised to intervention or usual care using an integrated randomisation module on the trial platform. Randomisation was at the level of the individual in a 1 : 1 ratio, using a minimisation algorithm (with random element) to ensure balance on the following variables:

-

age (< 40, ≥ 40 years)

-

sex (male, female, prefer not to say)

-

job category (categories as self-reported)

-

nightshift work (yes/no)

-

hospital.

Given the nature of the intervention, blinding of participants and nurses conducting the screening clinic was not possible.

Interventions

Intervention arm

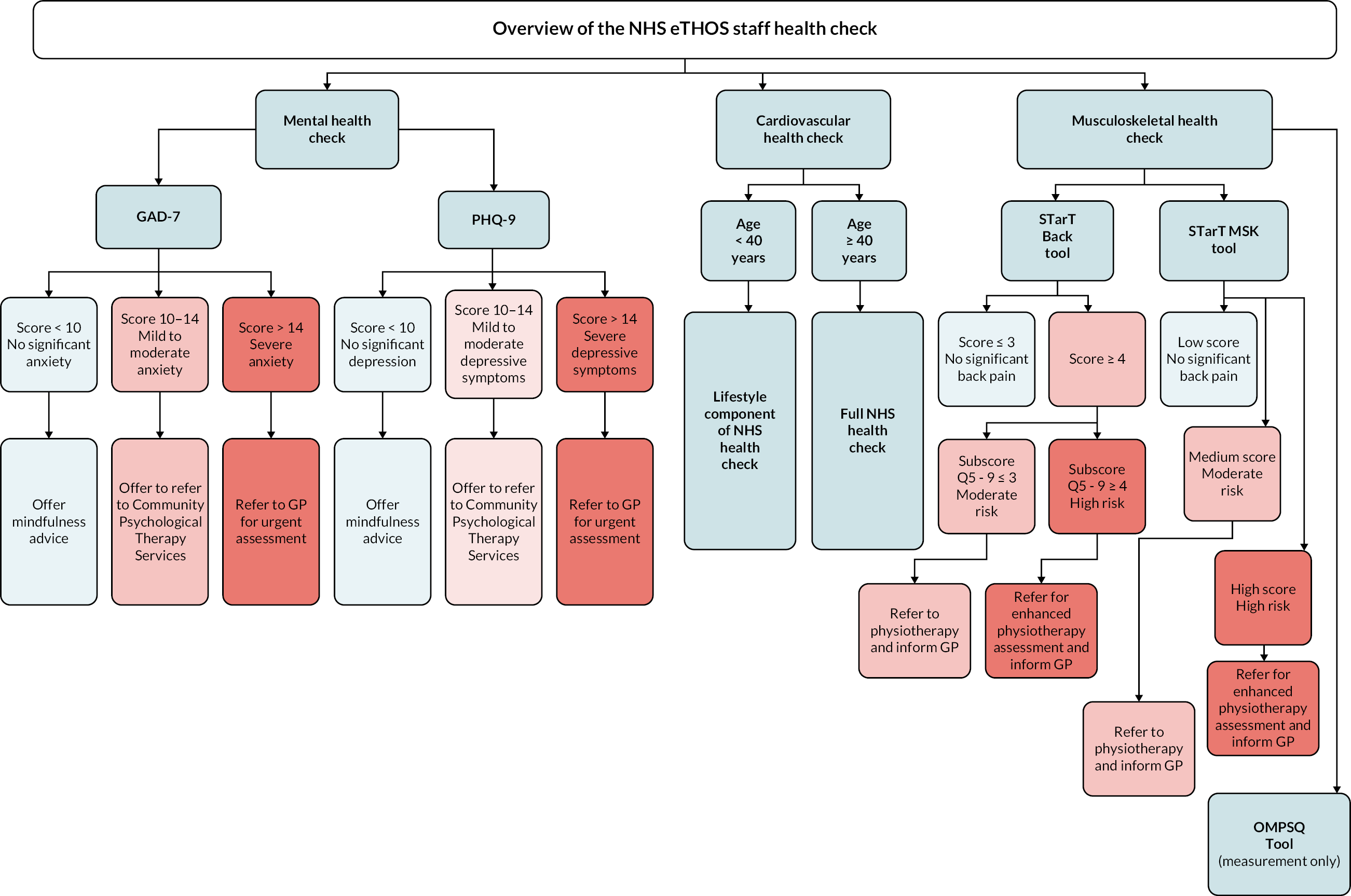

Participants received an invitation to a SHSC, available during or outside work time (generally 7 a.m.–5 p.m., Monday–Friday), administered by trained clinic nurses [hereafter known as enhancing the Health of NHS Staff (eTHOS) nurses]. A maximum of three attempts was made to contact participants to arrange an appointment. The screening appointment consisted of two stages: (1) screening assessment for three components: mental health, MSK health and finally cardiovascular health, followed by (2) advice and/or referral, according to level of risk, to appropriate services for management according to NHS/NICE recommendations (see Figure 2). The screening assessment was delivered by nurses, with consultant physician oversight at each centre, supported by a standardised protocol and prompts from the electronic data platform. All data from participants were entered directly onto the electronic platform in a paperless system.

FIGURE 1.

Overview of staff health screening intervention. From National Institute for Health and Care Excellence 2016. 60

The eTHOS nurses explained the screening scores to participants and, where applicable, any recommended actions. Local pathways were used; these included self-referral to the staff physiotherapy service, local mental health support (e.g. healthy minds, Frontline19), lifestyle changes as directed in appropriate leaflets and websites, advice to visit their GP, recommendations to the GP that a direct referral be made for the participant and/or a request that the GP arrange a follow-up appointment with the participant. Where there were concerns regarding safety, the eTHOS nurse would immediately inform the local site principal investigator (PI) who would then contact the GP.

Participants reporting relevant diagnosed conditions currently being treated did not receive the referral element of that component. A results letter detailing findings and recommendations was sent to participants and their GPs for appropriate action.

Mental health check

Participants self-completed the GAD-739,40 (anxiety) and PHQ-938,40 (depression) screening questionnaires to assess mental health and were categorised into three levels of risk (see Figure 1). Participants without significant anxiety/depressive symptoms were offered online mindfulness advice. 61 Those who were moderately affected were advised to seek support from local counselling services such as Birmingham Healthy Minds,62 and those severely affected were referred to their GP for immediate treatment.

Musculoskeletal health check

The Keele STarT Back Screening Tool41 was self-completed to categorise risk of future disability of low back pain into three levels (low, moderate and high risk). The STarT MSK tool (also three levels) was used for non-back complaints,46 and the Orebro musculoskeletal pain screening questionnaire (OMPSQ) score63 was also calculated to enable comparison with international studies. Based on a model of stratified care, those with moderate or high scores on the STarT Back or STarT MSK tools were referred to physiotherapy teams according to NICE guidance,42–45 either directly or via their GP. Those with high scores were recommended to receive enhanced physiotherapy including CBT to address associated psychological problems. In practice, in part, due to pressures of the COVID-19 pandemic, direct referrals and CBT were largely unavailable.

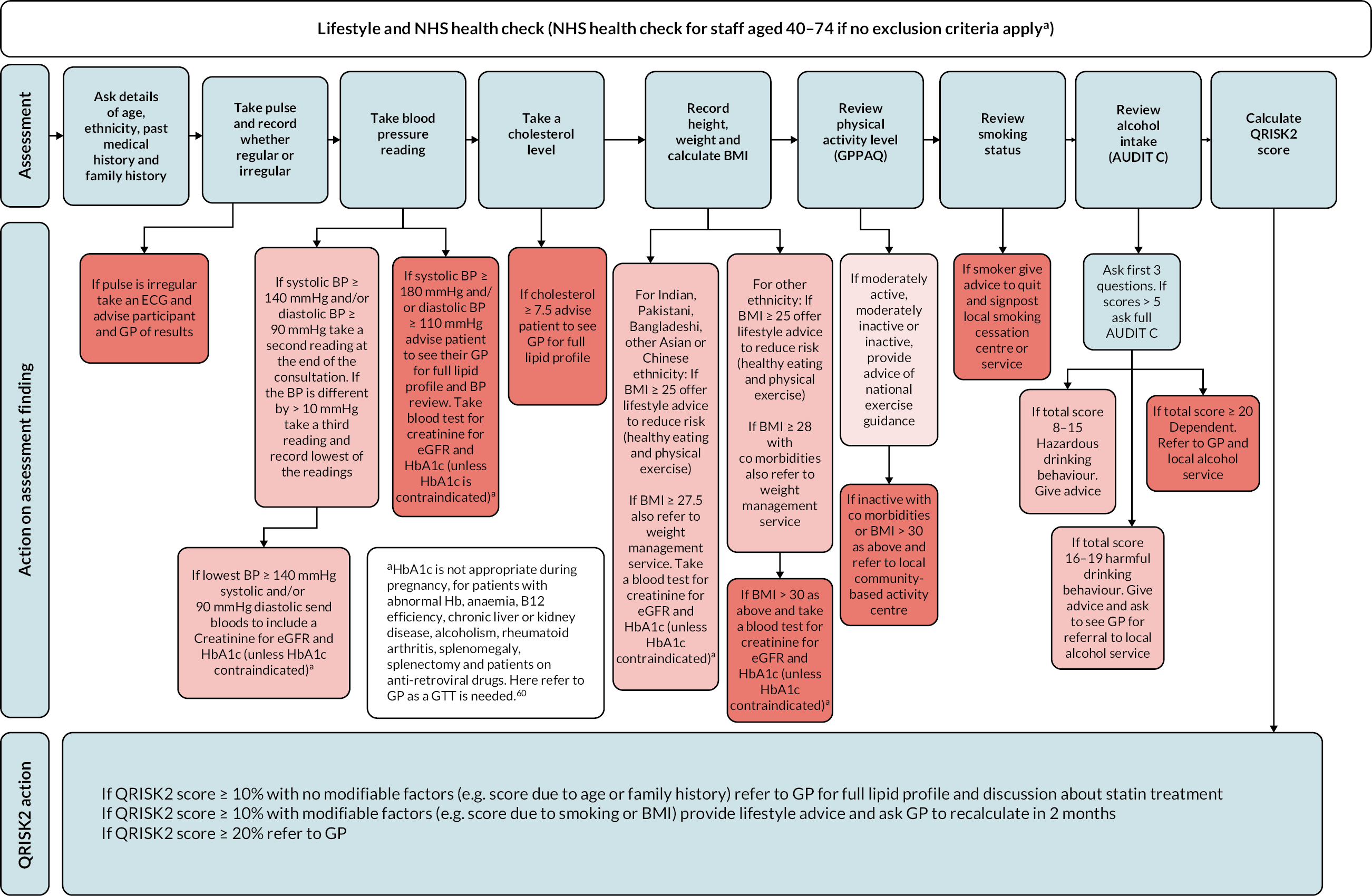

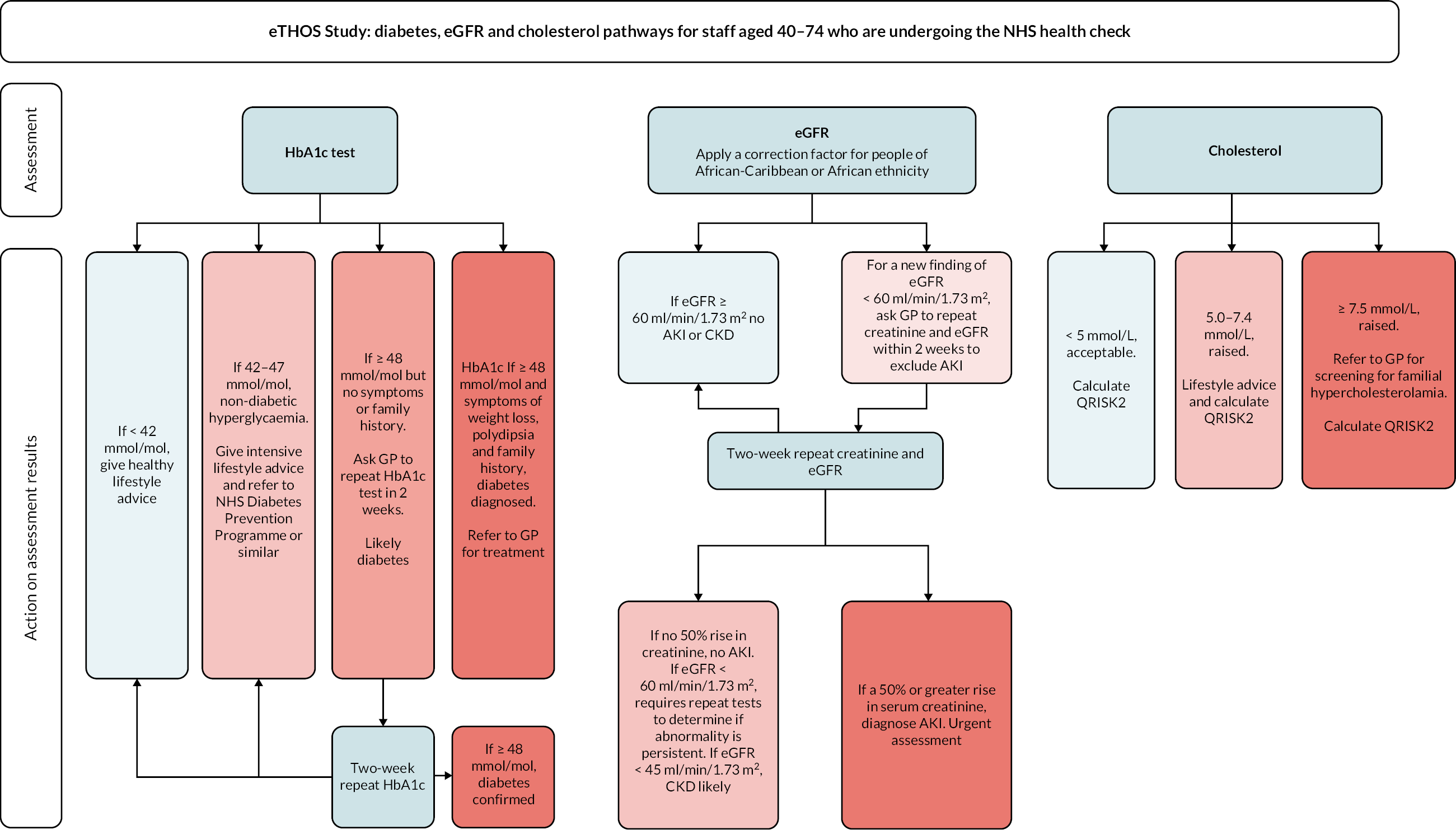

Cardiovascular health check

Participants aged 40 years and over received the NHS health check, delivered face to face by the eTHOS nurses. 48 This included lifestyle checks with self-completed questionnaires and clinical measures: BMI, exercise level [general practice physical activity questionnaire (GPPAQ) questionnaire],64 smoking status, alcohol intake (AUDIT C questionnaire);65 QRISK2 score66 and clinical measures [pulse, blood pressure, electrocardiogram (ECG), cholesterol, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c), estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) and creatinine tests if appropriate]. Actions included referral to GP, weight management, smoking cessation and alcohol reduction services, as well as brief advice on exercise and diet according to UK recommendations (see Figure 1). The dementia awareness component for those over 65 years was excluded as there were known to be few employees in this category. Participants aged under 40 years were assessed for lifestyle components of the NHS health check only: BMI, exercise level, smoking status and alcohol intake, with the same advice applied and referrals to appropriate services. Clinical measures and associated blood samples were not collected from participants aged under 40 years.

Occupational health

All participants with an identified health condition were also asked whether they perceived that their condition was affected by/or affected their ability to work and what adjustments at work might improve their workability. If affected, they were offered an additional optional referral to occupational health.

Usual care

Participants randomised to receive usual care did not attend the health screening clinic. Usual care consisted of standard access to medical services for management of any presenting condition (either through occupational health or their GP) and any health promotion/counselling initiatives provided for staff during the pandemic. They remained eligible for the NHS health check via their GP as usual if they were aged 40 years or older.

Outcomes

This pilot trial was originally planned to have a 52-week follow-up to fully test the processes for a definitive trial but was reduced to 26 weeks due to the pandemic-related delays.

Primary outcomes and stop/go criteria

Three coprimary outcomes were originally planned to inform criteria to progress to the definitive trial:

-

Recruitment (consented) as a proportion of those invited.

-

Referral to any recommended services as a result of the three screening components (usually GP, local physiotherapy/community psychological services) – intervention arm only.

-

Attendance at any recommended services at 26 weeks (self-report) – intervention arm only.

We defined ‘referral’ as anyone who was eligible for a referral, that is, they recorded a suitable risk value and were not already being treated for that condition.

Due to additional pandemic-related delays, following discussions with the funder, it was agreed not to extend the duration of the trial in order to complete follow-up of all participants to 6 months. This meant that only a small number of participants reached the 26-week follow-up assessment, leaving limited data available to reliably assess the third coprimary outcome on attendance. After discussion with the Trial Oversight Committee (TOC), it was agreed that acceptance of the referral (signifying intention) which was collected during the screening assessment, should be used as a proxy for attendance.

The decision to continue to a full trial was informed by progression criteria using a traffic light system as guidance (see Table 2), with flexibility built in to allow for uncertainty in cost effectiveness despite either low participation, referral or attendance rates. The three coprimary outcomes formed stop/go criteria when considered together. If any of these values fell into the ‘amber’ zone, then the trial would require modifications to proceed to full trial. If all were ‘red’, then the trial would be considered unfeasible.

| Criteria | Description | Progression criteria | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Green (go), % | Amber (pause), % | Red (stop), % | ||

| Recruitmenta | % of invited employees consenting to take part | > 25 | 15–25 | < 15 |

| Referred to a serviceb (defined as eligible for a referral) | % of participants randomised to intervention arm referred to specified services | > 30 | 10–30 | < 10 |

| Attendance at referralsc (defined as accepting a referral) | % of referrals which resulted in self-reported attendance at the service at least once. Measured at 26 weeksd | > 50 | 30–50 | < 30 |

| ACTION | If ALL criteria are GREEN, proceed to full trial with protocol unchanged | If ANY of these criteria are AMBER, adapt protocol appropriately using information from the process evaluation before proceeding to full trial | If ALL of these criteria are RED, consider whether current protocol is not feasible. If ONE OR TWO of these criteria are RED, consider whether adaptations are needed | |

Secondary outcomes were collected to inform the design of the definitive RCT and any modifications required:

Secondary outcomes

-

Comparison of baseline characteristics of included participants and hospital population for assessing generalisability.

-

Description of the results of the intervention screening assessments.

-

Number and type of referrals to recommended services (intervention arm only).

-

Attendance at each individual recommended service (acceptance of referral during screening assessment, self-report at 26 weeks; intervention arm only).

-

Lifestyle relevant to screening intervention advice and referrals (self-report at 26 weeks compared with baseline) including Physical Activity Index measuring exercise levels (GPPAQ),64 smoking status, weight (kg).

-

Acceptability of intervention to participants and health screening clinic staff (interviews within the Process Evaluation).

-

Feasibility of trial processes (completeness of relevant data items, interviews).

-

Indication of contamination (comparing pre/post data for health behaviours and health care/other service utilisation in control arm).

Outcomes related to the definitive trial

-

Sickness absenteeism at 26 weeks with reasons, measured by days and spells:

-

self-report absolute absenteeism, relative absenteeism and relative hours of work – for last 7 days and last 28 days [World Health Organization Health and Work Performance Questionnaire (WHO-HPQ)]69

-

self-report absenteeism using 6-month recall period

-

employee records of absenteeism, which will be the primary outcome of the definitive trial. Routinely collected data from the NHS Electronic Staff Record Programme, linked to employee ID.

-

-

Presenteeism at 26 weeks [self-report absolute presenteeism and relative presenteeism for last 28 days (WHO-HPQ)]. 69

-

Attendance at occupational health service at 26 weeks (self-report).

-

Healthcare utilisation at 26 weeks (self-report) including GP consultations and hospital admissions.

-

EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) index value measuring health-related quality of life (HRQoL) (EuroQol EQ-5D 5-level)70 at 26 weeks.

-

Resource use and costs collected by self-report questionnaire to participants on health service utilisation and information from the screening assessment regarding duration and resources used.

Data collection and management

Data were collected at several points during the trial: eligibility screening, baseline, during the screening clinic and at the 26-week follow-up (see Table 3). Study data were entered into a custom-designed REDCap (Research Electronic Data Capture) database hosted by the University of Birmingham, either directly by participants or by clinic staff. 71,72

| Visit | Eligibility screening, consent and randomisation | Baseline | Intervention screening visit | 26-week follow-up data collection (± 4 weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Trial registration | X | |||

| Consent to eligibility screening | X | |||

| Eligibility screening | X | |||

| Participant information and contact details | X | |||

| Valid informed consent | X | |||

| Staff payroll number | X | |||

| NHS number (optional) | X | |||

| Demographics (DOB, gender, education, marital status) | x | |||

| Smoking status | x | x | ||

| Exercise level (GPPAQ questionnaire) | x | x | x | |

| Ethnicity | x | |||

| Diagnosed medical conditions | x | |||

| Current medications | x | |||

| Health status (EQ-5D questionnaire) | x | x | ||

| Height | x | |||

| Weight | x | x | ||

| Health service utilisation | x | x | ||

| Current employment | x | X | ||

| Absenteeism and presenteeism (WHO-HPQ questionnaire) | x | x | ||

| Occupational Health Resource Utilisation | x | x | ||

| Randomisation | X | |||

| Health screening (intervention group only) | ||||

| MSK health (if applicable) | ||||

| STarT Back screening tool (participant completion) | x | |||

| STarT Back screening tool (review) | x | |||

| STarT MSK screening tool (participant completion) | x | |||

| STarT MSK screening tool (review) | x | |||

| OMPSQ tool (participant completion) | x | |||

| OMPSQ tool (review) | x | |||

| Impact on work questions: MSK health | x | |||

| Mental health (if applicable) | ||||

| GAD-7 questionnaire (participant completion) | x | |||

| GAD-7 questionnaire (review) | x | |||

| PHQ-9 questionnaire (participant completion) | x | |||

| Impact on work questions: Mental health | x | |||

| Cardiovascular health (if applicable) | ||||

| Personal details checked from baseline (age, ethnicity) | ||||

| BMI | x | |||

| Smoking status (review from baseline questionnaire) | x | |||

| Alcohol intake (review of AUDIT C questionnaire) | x | |||

| Exercise level (review of GPPAQ questionnaire) | x | |||

| Cardiovascular risk calculator (QRISK2 score) | x | |||

| Clinical measures (if age ≥ 40 years) | ||||

| ECG | x | |||

| Pulse | x | |||

| Blood pressure | Up to three readings | |||

| Blood tests (criteria for taking blood must be met) | x | |||

| Cholesterol | x | |||

| HbA1c (if indicated as per NHS health check) | x | |||

| eGFR (if indicated as per NHS health check) (calculated using creatinine or U&Es, according to Trust policy) | x | |||

| Recommendations from the health screening clinic (intervention group only) | x | |||

| Recently diagnosed health conditions | x | |||

| Trust staff characteristics | X | |||

| Trust absenteeism rates | X | |||

| Participant absenteeism data | X | x |

Self-reported data were collected on all participants prior to randomisation. All respondents were provided with the option to provide reasons for taking/not taking part in the study. For those who consented to take part, we collected contact details and NHS number, where available (this was optional), to assess the feasibility of future linkage to routine data such as hospital admissions, GP records, other healthcare utilisation and mortality data. In the baseline questionnaire, we collected information on demography, employment details, selected diagnosed medical conditions and current medications, absenteeism (WHO-HPQ),69 presenteeism (WHO-HPQ),69 HRQoL (EQ-5D-5L),70 smoking status, height, weight, exercise levels (GPPAQ),64 receipt of NHS health check and health service utilisation. Where the baseline remained incomplete, prompts were sent after 24 hours, 2 and 7 days, and then a final reminder giving participants the option to complete it at a later date.

At 26 weeks, participants were sent a follow-up questionnaire for online completion to report attendance at any recommended services (intervention arm only), and other outcomes as detailed above. Where follow-up questionnaires remained incomplete, one reminder was sent.

Consent was obtained from trial participants to collect the following additional linked data from HR records:

-

participant age, sex, ethnicity, staff group and staff grade

-

number of hours contracted to work

-

hours worked – full-time equivalent

-

sickness absenteeism and non-sickness absences relating to COVID-19 only, for the previous 24 months and from randomisation to 26 weeks follow-up (start/end dates, duration in days, recorded reason)

-

leaving date (should participant leave employment of the Trust during trial participation).

Additional anonymised data were collected at the time of site set-up from hospital HR records, at whole hospital level and for those invited, on age, sex, ethnicity, job role and number of days absent in order to assess the generalisability of the included participants.

Key data collection forms and questionnaires are available on the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Funding and Awards website https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/42/42.

Sample size

As the eTHOS trial was a pilot study, no formal sample size calculations were undertaken. The study was not designed or powered to detect a statistically significant difference in efficacy between the two trial arms. However, preliminary sample size calculations were computed for the definitive RCT. To detect a clinically important effect size for days of sickness absence of 0.1 of a SD would require 4200 participants for an individually randomised trial.

A relatively large number of participants were required for this pilot trial in order to achieve reliable estimates of the referral and attendance rates downstream along the screening pathway and to allow assessment of the intervention in different hospitals, better precision in determining the SD of the primary outcome and provision of health economic information required to persuade other hospitals to consider investing in participating in the definitive trial. We aimed to recruit 480 participants (20 per week) in 24 weeks. The target recruitment for each site differed depending on their total staff number and capacity to deliver the intervention: 170 each for QEHB and Heartlands Hospital, 93 for Birmingham Children’s Hospital and 47 for Hereford Hospital. With this sample size, the 95% confidence interval (CI) for the proportion of staff recruited could be estimated to be 4% either side of the estimate (e.g. for a 25% recruitment rate, the 95% CI would lie between 21% and 29%).

Statistical methods

The primary comparison groups were composed of those randomised to the health screening (intervention) arm and those randomised to the usual care (control) arm. All analyses used the intention-to-treat principle, that is, all participants were analysed in the treatment group to which they were randomised, irrespective of adherence or other protocol deviation. Analyses used available data only, although the number of missing data is reported in order to inform decisions regarding data collection for the definitive trial.

Primary outcomes

Recruitment rate was calculated in two ways:

-

percentage of invited employees that consented to take part in the trial with 95% CI

-

percentage of invited employees who were randomised into the trial with 95% CIs.

Referral to a service was calculated as the percentage (with 95% CI) of participants randomised to the intervention arm that were eligible for a referral to any of the specified services (GP, physiotherapy, community psychological services). Participants were eligible for a referral if they met the score requirement for any of the mental health, MSK or cardiovascular health check assessments and were not already being treated for the referring concern.

As there were few follow-up data on self-reported attendance at referrals (because of resources restrictions forcing early trial closure), attendance at any recommended service was estimated by self-reported ‘intention’ (as agreed with the TOC). During the intervention screening, participants were given the option to accept or reject a referral to any service. The estimate of attendance at any recommended service was then determined by the proportion of participants in the intervention arm eligible for a referral that accepted that referral and presented as a percentage with 95% CI. Data from the 26-week follow-up questionnaires are provided in Appendix 2.

Secondary outcomes

Analyses were mainly descriptive, summarising binary outcomes using number of responses with percentages, and continuous outcomes with means and SDs, or medians and interquartile ranges as appropriate. No statistical modelling was undertaken, and no p-values are reported. No subgroup analyses were planned for this feasibility study.

Process evaluation

A mixed-methods process evaluation explored programme reach, fidelity of screening delivery, attendance at referrals and participants’ views of the intervention to support any modifications required for the design of the definitive trial.

Quantitative data collection and analysis

Quantitative data to support the process evaluation were obtained from:

-

Recruitment and intervention data, for example, response rate; proportions of those invited consenting, being randomised and attending the screening.

-

Baseline questionnaire to assess characteristics, for example, age, ethnicity, marital status, Index of Multiple Deprivation, educational attainment and employment role of the employees recruited to study (programme reach). We also obtained hospital-level HR data to compare the characteristics of those invited and those consenting with the whole hospital populations.

-

Logs kept by the staff health screening programme recording attendance, trial database records of screening tests undertaken and duration of contacts (fidelity).

-

Healthcare issues identified at the employee screening, and referrals made to GP and other services (fidelity).

-

Self-report of attendance, and intention to attend at recommended services from intervention screening and 26-week follow-up questionnaire (uptake).

-

Brief questionnaire at eligibility stage to staff not taking up the offer of the study to ascertain reasons for not participating (reach).

Findings were presented with descriptive statistics.

Qualitative data collection and analysis

Aims

The overall aim of the qualitative process evaluation was to obtain the views of relevant stakeholders on the feasibility and acceptability of the staff health screening intervention and trial and inform any protocol adaptations needed for a full trial. This was done by interviewing: NHS staff who received the trial intervention (trial participants); the eTHOS nurses who were delivering the intervention; providers of follow-on services, for example, GPs and ‘Healthy minds’; and outside agencies who could potentially benefit from the intervention, for example, other NHS organisations who might be willing to run the trial such as ambulance services and GP groups, and non-healthcare organisations who might be interested in delivering and evaluating such a service for their setting.

Objectives

Specific objectives of the interviews were to obtain:

-

trial participants’ views and experiences:

-

views and experiences of the health screening – the concept of health screening and their experiences of it

-

views about being offered the screening and whether or not it has enabled them to access health screening that they may not otherwise have accessed

-

views and experiences of the trial processes

-

evidence of contamination amongst the usual care arm

-

acceptability of being randomised to usual care

-

barriers and facilitators to accessing/attending the screening intervention

-

views and experiences of booking the appointment

-

views and experiences of screening location

-

reasons for not attending

-

views on confidentiality in relation to the screening and the potential for findings to be used by an employer

-

views on the role of occupational health services

-

response to referral recommendations.

-

-

research staff views and experiences:

-

any contextual differences in delivery of the intervention

-

satisfaction in relation to the training received

-

acceptability of the intervention in theory/practice and experiences of delivering the intervention.

-

-

providers of follow-on services:

-

acceptability of health checks

-

experience of receiving referrals, the acceptability of the process and impact of referrals on capacity

-

availability of appropriate referral pathways.

-

-

outside agencies’ views of potential feasibility of service:

-

reflections on feasibility and acceptability of the intervention and trial and conducting it in other local contexts.

-

Participants and recruitment

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic-related delays and forced truncation of the trial, recruitment for the process evaluation took place over 4 months (July–October 2021), instead of the planned 14-month period. All trial participants were eligible for interviews if they had agreed to be approached for the qualitative study. Those eligible were invited using their preferred methods of contact and the study information sheet either e-mailed or posted to them. Where recruitment targets had not been reached, one reminder was sent to those who had not yet responded.

We contacted representatives from providers of follow-on services (e.g. GPs or physiotherapists) to whom trial participants had been referred either directly or using contacts known to the trial team.

We also contacted a range of relevant outside agencies where staff health screening might be of interest in the future. This included those providing services for the hospitals involved in the trial, non-hospital-based NHS organisations, organisations independent of the NHS concerned with health care and local large businesses completely unrelated to health care as suggested by the trial team. Study information sheets were e-mailed to potential interviewees once an appropriate person within the organisation had been identified.

Participants were given the option to complete their consent form online or on paper (and post it back to the substudy team). When completing their consent, trial participants could also agree to the qualitative team contacting their GP, declining did not exclude them from participating in the 1 : 1 interview. Participants were permitted to withdraw up to 2 weeks after the interview.

Sampling

We aimed, where possible, to recruit a purposive, maximum variation sample of trial participants with a broad representation of age, gender, ethnicity, occupation, site, shift pattern and department who had had different experiences of the trial (see Table 4). The other interview groups were chosen pragmatically. Table 4 also includes details of our target numbers for recruitment, and the time frame for recruiting from the different groups as originally planned, with reasons. Regarding site, we also aimed to match the distribution of the target recruitment numbers using the ratio outlined in Table 5.

| Participant group | Target numbers | Time frame post randomisation | Reason |

|---|---|---|---|

| Trial participants | Total = 48 | ||

| Intervention arm | |||

|

8 | After 3 months | Allow time to book appointment |

|

10 | Within 3 months | Get immediate feedback on trial experience |

|

25 | 3–4 months | Give participants chance to arrange referrals |

|

5 | 3 months | Allow time for contamination to occur |

| From start of recruitment | |||

| eTHOS nurses | 10 | 3 months | Allow time to get experience of intervention delivery |

| Providers of follow-on services | 12 | 3 months | Allow time to ascertain impact of trial on service provision |

| Outside agencies | 10 | No delay | Get immediate feedback on views relating to the trial |

| Ratio | |

|---|---|

| QEHB | 4 |

| Heartlands Hospital | 3 |

| Birmingham Children’s Hospital | 2 |

| Hereford Hospital | 1 |

However, due to COVID-19, this plan could not be adhered to and a pragmatic approach was taken instead. All eligible participants in the intervention arm were invited to participate, and invitations were sent to all controls until the target number of participants had been reached.

Data collection

Trial participants were invited to 1 : 1 focused qualitative interviews lasting approximately 30 minutes, with a choice of either zoom, telephone or face-to-face interviews if COVID-19 restrictions allowed. Other participants were offered the choice of 1 : 1 interview or a group interview with their colleagues if they preferred. Participants who did not attend screening (see Table 4) were also invited to respond to written questions via e-mail or post (see NIHR Funding and Awards website https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/42/42). Semistructured topic guides (see NIHR Funding and Awards website https://fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/17/42/42) guided interview conduct and were refined iteratively following initial interviews.

Data were recorded either on Zoom or an encrypted recorder and transferred via secure file transfer to an external company for transcription. Interviews were transcribed intelligent/clean verbatim and anonymised. All video files were destroyed as soon as transcription was complete.

Analysis

A thematic analysis of content was informed by the framework analytical approach. 73 Analysis and discussion included the experienced qualitative team: RR, a qualitative researcher; KJ, a GP and public health consultant with experience of mixed-methods research; KR, a nurse and epidemiologist with experience of mixed-methods research; RLA, a nurse and qualitative researcher in primary care and public health; CP, a non-clinical qualitative researcher in primary care; CH, a physiotherapist postgraduate with experience of mixed-methods research; RJ, an epidemiologist with experience of mixed-methods research; PA, a public health consultant with experience of mixed-methods research; with input from the patient and public involvement (PPI) and trial oversight and collaborator’s groups to provide multiple perspectives on the data. Data collection and analysis ran concurrently so that emergent analytical themes could inform further data collection.

As soon as two trial participants’ interviews had been completed from groups B–D (see Table 4), the data collection team (RLA, CH and CP) each independently coded the transcripts using NVivo 12 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). The team then met to discuss and compare codes and agree a combined, draft coding index. The revised draft was shared with the wider qualitative team (RR, KJ, KR, RJ, PA) and further refined. The data collection team then selected two new transcripts on which to independently test the revised index; the index was further refined and the rest of the transcripts coded.

Transcripts from the other participant groups were coded using the same index with minor modifications. RLA (a nurse) collected the data for and coded the eTHOS nurses’ transcripts. CH (a physiotherapist) collected the data for and coded the physiotherapist transcripts with support from RLA. PB (non-clinical) collected the data for and coded the transcripts from the outside agencies with support from RLA. RLA collected the data for and coded the single GP transcript.

The codes were then exported to a single framework file and the data were summarised by the participant group by RLA and CP. Emergent themes were discussed with the wider qualitative team throughout.

Health economic analysis

Data collection focused on estimating the NHS resources required for screening and resulting costs and measuring the baseline quality of life of all participants using EQ-5D-5L. A descriptive analysis was then undertaken presenting information on the average costs of screening per participant and quality-of-life outcomes.

Resource use

All participating centres were contacted to collect information on their estimated time taken for each screening clinic task, the grade of the member of staff responsible and the cost of the individual blood tests. Responses were collated and a typical duration for each task was agreed upon by the study team. The amount of staff time required for each screening task was then multiplied by the relevant unit costs obtained from standard sources74 (see Table 6). Unit costs are shown in Tables 6 and 7.

| Job title | Pay band or specialty training years | Cost per working hour (£) |

|---|---|---|

| Registrar | ST3 | 50.00 |

| Nurse specialist/team leader | Band 6 | 50.00 |

| Nurse | Band 5 | 40.00 |

| Healthcare assistant | Band 3 | 27.00 |

| Healthcare assistant | Band 2 | 25.00 |

| Blood tests | Unit cost (£) |

|---|---|

| Cholesterol | 1.35 |

| eGFR | 3.18 |

| HbA1c | 8.00 |

Costs

The cost of screening included the cost of staff time to undertake all tasks and the cost of blood tests. The total cost of blood tests per participant was weighted taking into account the proportion who received each type of blood test. Those tasks that were directly related to processing and reporting blood tests were only applied to the proportion who had at least one blood test. Costs were only applied to those who actually attended screening.

Certain tasks could be performed by healthcare professionals of different pay bands (e.g. a nurse, band 5; a nurse specialist, band 6; or a healthcare assistant, band 2 or 3). Analysis was undertaken so that the cost of screening per participant could be presented for all possible combinations, including the highest possible cost (where all tasks are carried out by the higher potential pay bands) and the lowest possible cost (for the lower pay bands).

Quality of life

The EQ-5D-5L questionnaire, containing five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain and discomfort, anxiety and depression), was given to participants to complete at baseline and responses were valued using the cross-walk algorithm. 75 Descriptive analysis was undertaken to calculate the mean, SD and range of the overall EQ-5D-5L score, and also the frequency of responses within each dimension.

Patient and public involvement

We recruited a participant advisory group (PAG) consisting of four to six clinical, administrative and retired NHS staff who could provide us with their insights on how the eTHOS trial might be received by NHS staff. They met on a regular basis throughout the project to provide advice. The group was led by Margaret O’Hara (PPI expert coinvestigator) who assisted in recruiting members to the PAG and facilitating communication with the eTHOS team. There was also a hospital staff member of the TOC.

The general contribution of the PAG included: version testing the eTHOS database to ensure it was user-friendly, discussions on how to keep participants engaged during delays due to the COVID-19 pandemic and reviewing study documents. They were specifically asked how the eTHOS team could encourage ethnic diversity; the PAG recommended staff networks to reach out to, including ethnic minorities, faith centres and chaplaincies. It was also suggested that managers be asked to actively encourage all staff to participate. If eTHOS proceeds to full trial, the PAG recommended that funding for dedicated community engagement should be included to encourage grass root communication.

We also recruited a stakeholder advisory group representing a wider body of professionals, for example, GPs relevant to the trial. They provided advice at regular intervals; one GP highlighted that referral for certain high-risk conditions, for example, severe depression would be most effective if by direct telephone call.

Overall, the PAG and the stakeholder group were very supportive of the trial and its potential impact on the health and well-being of the NHS staff.

Data storage and confidentiality

Participants’ personal data were held securely and treated as strictly confidential, in line with the General Data Protection Regulation 2018. Electronic records were held on a secure, password protected, web-enabled customised database hosted by BCTU or on secure, password-protected University of Birmingham servers (including audio recordings). Paper records were transferred from the participating study centres to the trial office at BCTU and kept in a locked cabinet in a locked room. Any data processed outside BCTU were anonymised. Data will be stored for at least 10 years according to the University of Birmingham policy.

Monitoring

Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit, a UK Clinical Research Collaboration (UKCRC) registered trials unit, was the co-ordinating centre and was involved in the development, design and conduct of the trial since conception. A Trial Management Group oversaw research methodology, clinical trial coordination, data management, statistical analysis, compliance with Good Clinical Practice and all regulatory requirements, in conjunction with the sponsor. A TOC (combining the function of trial steering and data management committees) with an independent chair and lay representative oversaw, advised on and monitored the trial.

Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on trial delivery and summary of changes

Although ethical approval for the trial was obtained in March 2020, it was not able to commence due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Two hospital sites granted permission to commence the trial in December 2020, but after a short period, in February 2021, recruitment was paused again due to a spike in COVID-19 cases. The trial recommenced in May 2021 in all four sites. A 6-month extension to the trial was awarded from the funder until October 2021. The original trial was planned to include a 52-week follow-up; however, due to the delays, a 26-week follow-up was then agreed instead, but only a few people reached this time point before trial closure. Changes therefore were:

-

shortened total recruitment period and reduced number of participants recruited

-

limited 26-week follow-up data (both self-report and hospital personnel data)

-

no 52-week follow-up data (including no information to inform likely effect size)

-

modification to definition of attendance at referrals

-

modification to data collection documents to include reference to COVID-19 illness and adjusted working arrangements

-

reduced number of qualitative interviews, with adjusted time frame and sampling

-

health economic analysis reduced in scope

-

modifications to trial delivery (inability to promote the trial during face-to-face staff meetings, part of the screening intervention carried out online in some cases, all qualitative interviews carried out online)

-

reduced scope for consulting PPI and stakeholder groups.

A list of protocol amendments is found in Appendix 1.

Chapter 3 Results of the trial

Recruitment, participant flow and impact of the COVID-19 pandemic

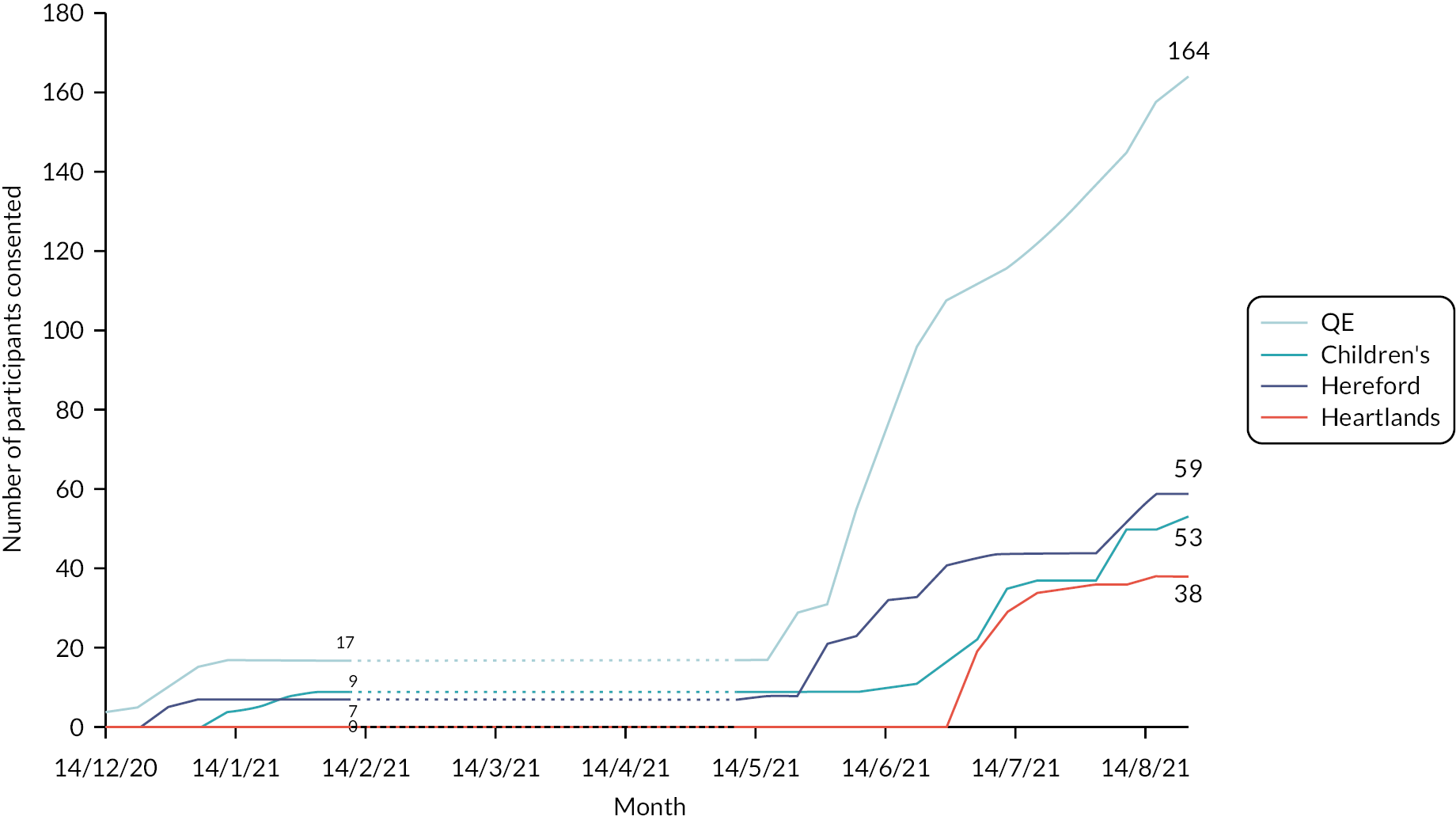

The eTHOS trial was initially due to commence recruitment in March 2020 but was delayed due to a pause in non-essential hospital research during the early phases of the COVID-19 pandemic. After a 2-week opt-out period, recruitment commenced in the first site on 16 December 2020, followed by a second and third site in early mid-January 2021. Shortly afterwards, the trial was paused to recruitment due to an increase in COVID-related hospital admissions and was then restarted on 21 May 2021 when a 6-month extension was granted. Recruitment continued until 27 August 2021 when the trial closed to recruitment to allow the data to be analysed before the end of the funding extension (see Figure 2). Therefore, recruitment and follow-up did not follow the original plans.

FIGURE 2.

Cumulative recruitment by site; dashed line indicates when the trial was paused.

Overall, 3788 from a total of 24,344 NHS staff across the four sites were invited to take part (see Figure 3). Of the 490 staff who provided a response, 422 (86.1%) expressed interest in taking part. Three hundred and nine (73.6%) stated that they were most prompted to take part because of receiving an e-mail about the study. Thirty-five (8.3%) had seen the posters about the trial, 25 (6.0%) were prompted by an invitation pack through the Trust postal system and 22 (5.2%) had heard about the trial from a colleague (see Table 8). Sixty-one staff gave reasons for not taking part in the trial. Reasons given included: not being interested in taking part in research (24.6%), too busy (21.3%), worried about confidentiality (13.1%) and felt they were unable to take time out of work (9.8%). Other reasons (44.3%) were also given, the majority of these being that they were leaving/retiring/going on maternity leave.

FIGURE 3.

Participant flow through the eTHOS pilot trial. AKI, acute kidney injury; CKD, chronic kidney disease; UHB, University Hospitals Birmingham. a26-week follow-up was only collected in those participants recruited prior to the study pausing to recruitment.

| Total (N = 490) (%) | |

|---|---|

| Are you interested in taking part in the eTHOS trial? | |

| Yes | 422 (87.4) |

| No | 61 (12.6) |

| Missing | 7 |

| If no, why are you not interested in taking part?a | |

| I’m not interested in taking part in research | 15 (24.6) |

| I’m too busy | 13 (21.3) |

| I’m worried about confidentiality | 8 (13.1) |

| I can’t take time out of work | 6 (9.8) |

| I have already had a health check | 5 (8.2) |

| I have concerns relating to the COVID-19 pandemic | 1 (1.6) |

| Other | 27 (44.3) |

| If yes, what most prompted you to take part in the eTHOS trial? | |

| I received an invitation pack through the Trust’s postal system | 25 (6.0) |

| I received an invitation by e-mail | 309 (73.6) |

| I heard about the trial from a colleague | 22 (5.2) |

| I heard about the trial at my team/department meeting | 11 (2.6) |

| My location of work has displayed posters/cards about the trial | 35 (8.3) |

| My location of work has been visited by ward champions/research team | 13 (3.1) |

| Other | 5 (1.2) |

| Missing | 2 |

Of the 353 eligible to take part, 314 consented (8.3% of those invited and 65.4% of our planned target of n = 480). Consent rates varied by site (see Table 9). In total, 236 were randomised into the study; n = 118 to the intervention screening arm and 118 to usual care. Seventy-eight participants were not randomised as they did not complete the baseline questionnaires or forms or were ineligible. Of the 118 randomised to the intervention, 101 (85.6%) attended and completed the screening clinic. Very few participants [26/236 (11.0%)] had reached the 26-week follow-up data collection time point by trial closure.

| Centre | Date opened | Trial pause date | Trial restart date | Trial end date | Weeks opena | Number invited | Number consented | Percentage consented of those invited (%) | Mean no. consented per week |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QEHB | 2 December 2020 | 13 January 2021 | 25 May 2021 | 27 August 2021 | 20 | 1811 | 164 | 9.1 | 8.2 |

| Heartlands Hospital | 16 June 2021 | – | – | 27 August 2021 | 11 | 654 | 38 | 5.8 | 3.5 |

| Birmingham Children’s Hospital | 18 December 2020 | 7 February 2021 | 7 June 2021 | 27 August 2021 | 19 | 844 | 53 | 6.3 | 2.8 |

| Hereford Hospital | 8 December 2020 | 11 January 2021 | 25 May 2021 | 27 August 2021 | 19 | 479 | 59 | 12.3 | 3.1 |

| Total | 2 December 2020 | 7 February 2021 | 25 May 2021 | 27 August 2021 | 27 | 3788 | 314 | 8.3 | 11.6 |

Baseline characteristics of participants

Table 10 provides baseline characteristics for each of the treatment groups and overall. The mean (SD) age of participants was 42.5 (10.4) years and included staff between the ages of 22 and 68 years. The majority were female [188/236 (79.7%)] and of white British ethnic origin [n = 192/236 (82.1%)], and 107 (45.7%) lived in areas within the poorest two quintiles of deprivation. Seventy-six (32.2%) were allied health professionals, scientists or technical staff and 63 (26.7%) were registered nurses or midwives. Half of participants (50.4%) were recruited from the QEHB hospital, with the remainder spread across the other three sites.

| SHSC (N = 118) (%) | Control (N = 118) (%) | Total (N = 236) (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimisation variables | |||

| Age (years) | |||

| < 40 | 45 (38.1) | 44 (37.3) | 89 (37.7) |

| ≥ 40 | 73 (61.9) | 74 (62.7) | 147 (62.3) |

| Mean (SD) | 42.4 (10.1) | 42.6 (10.7) | 42.5 (10.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 42.0 (34.0–51.0) | 43.5 (33.0–51.0) | 43.0 (34.0–51.0) |

| Range | 23.0–65.0 | 22.0–68.0 | 22.0–68.0 |

| Sex | |||

| Male | 24 (20.3) | 24 (20.3) | 48 (20.3) |

| Female | 94 (79.7) | 94 (79.7) | 188 (79.7) |

| Prefer not to say | 0 (–) | 0 (–) | 0 (–) |

| Job category | |||

| Allied health professionals/healthcare scientists/scientific and technical | 39 (33.1) | 37 (31.4) | 76 (32.2) |

| Medical and dental | 5 (4.2) | 8 (6.8) | 13 (5.5) |

| Registered nurses and midwives | 31 (26.3) | 32 (27.1) | 63 (26.7) |

| Nursing or healthcare assistants | 9 (7.6) | 11 (9.3) | 20 (8.5) |

| Wider healthcare team | 15 (12.7) | 12 (10.2) | 27 (11.4) |

| General management | 3 (2.5) | 4 (3.4) | 7 (3.0) |

| Other occupational group | 16 (13.6) | 14 (11.9) | 30 (12.7) |

| Nightshift worker | |||

| Yes | 5 (4.2) | 2 (1.7) | 7 (3.0) |

| No | 113 (95.8) | 116 (98.3) | 229 (97.0) |

| Hospital | |||

| QEHB | 61 (51.7) | 58 (49.2) | 119 (50.4) |

| Heartlands Hospital | 14 (11.9) | 17 (14.4) | 31 (13.1) |

| Birmingham Children’s Hospital | 18 (15.3) | 19 (16.1) | 37 (15.7) |

| Hereford Hospital | 25 (21.2) | 24 (20.3) | 49 (20.8) |

| Sociodemographic variables | |||

| Highest level of qualification | |||

| No formal qualifications | 1 (0.9) | 2 (1.7) | 3 (1.3) |

| GCSE, CSE, O level or equivalent | 12 (10.2) | 13 (11.0) | 25 (10.6) |

| A-level/AS level or equivalent | 18 (15.3) | 17 (14.4) | 35 (14.8) |

| Degree level or higher | 79 (67.0) | 78 (66.1) | 157 (66.5) |

| Other | 8 (6.8) | 8 (6.8) | 16 (6.8) |

| Marital status | |||

| Single, never married | 23 (19.5) | 25 (21.2) | 48 (20.3) |

| Married or domestic partnership | 78 (66.1) | 82 (69.5) | 160 (67.8) |

| Widowed | 2 (1.7) | 0 (–) | 2 (0.9) |

| Divorced | 11 (9.3) | 9 (7.6) | 20 (8.5) |

| Separated | 4 (3.4) | 2 (1.7) | 6 (2.5) |

| Live alone | |||

| Yes | 7 (5.9) | 11 (9.3) | 18 (7.6) |

| No | 111 (94.1) | 107 (90.7) | 218 (92.4) |

| Ethnic group | |||

| White/white British | 101 (86.3) | 91 (77.8) | 192 (82.1) |

| Mixed/multiple ethnic groups | 4 (3.4) | 5 (4.3) | 9 (3.9) |

| Asian/Asian British | 9 (7.7) | 11 (9.4) | 20 (8.6) |

| Black/African/Caribbean/Black British | 2 (1.7) | 3 (2.6) | 5 (2.1) |

| Other ethnic group | 1 (0.9) | 5 (4.3) | 6 (2.6) |

| Prefer not to say | 0 (–) | 2 (1.7) | 2 (0.9) |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Index of Multiple Deprivation (quintile)a | |||

| 1 (most deprived) | 27 (22.9) | 26 (22.4) | 53 (22.7) |

| 2 | 26 (22.0) | 28 (24.1) | 54 (23.1) |

| 3 | 29 (24.6) | 31 (26.7) | 60 (25.6) |

| 4 | 24 (20.3) | 16 (23.8) | 40 (17.1) |

| 5 (least deprived) | 12 (10.2) | 15 (12.9) | 27 (11.5) |

| Missing | 0 | 2 | 2 |

Seventeen (7.6%) reported being a current smoker, while 48 (21.5%) were ex-smokers (see Table 11). From self-reported weight, only 68 (30.6%) were classified as of healthy weight, whereas 38.7% were overweight and 30.2% obese. Seventy-two (30.9%) were either inactive or moderately inactive, and 155 (65.7%) reported being in good or very good health. Forty-three (18.5%) reported a previous clinical diagnosis of asthma, 71 (30.7%) anxiety, 67 (28.5%) depression, 25 (10.7%) hypertension, 24 (10.3%) hypercholesterolaemia and 12 (5.2%) diabetes.

| SHSC (N = 118) (%) | Control (N = 118) (%) | Total (N = 236) (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Demographic and baseline variables | |||

| Smoking status | |||

| Never smoked | 73 (66.4) | 85 (75.2) | 158 (70.9) |

| Ex-smoker | 26 (23.6) | 22 (19.5) | 48 (21.5) |

| Current smoker | 11 (10.0) | 6 (5.3) | 17 (7.6) |

| Missing | 8 | 5 | 13 |

| If current or ex-smoker, pack yearsa | n = 24 | n = 18 | n = 41 |

| Mean (SD) | 10.0 (8.1) | 13.7 (10.6) | 11.5 (9.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 11.0 (2.8–15.8) | 9.5 (6.0–18.0) | 9.5 (4.0–16.0) |

| Range | 0.3–27.8 | 3.0–39.0 | 0.3–39.0 |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| BMI (kg/m2)b | |||

| Underweight | 1 (0.9) | 0 (-) | 1 (0.5) |

| Healthy weight | 38 (33.9) | 30 (27.3) | 68 (30.6) |

| Overweight | 43 (38.4) | 43 (39.1) | 86 (38.7) |

| Obese | 30 (26.8) | 37 (33.6) | 67 (30.2) |

| Missing | 6 | 8 | 14 |

| GPPAQ | |||

| Inactive | 16 (13.8) | 14 (12.0) | 30 (12.9) |

| Moderately inactive | 22 (19.0) | 20 (17.1) | 42 (18.0) |

| Moderately active | 31 (26.7) | 38 (32.5) | 69 (29.6) |

| Active | 47 (40.5) | 45 (38.5) | 92 (39.5) |

| Missing | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| General health | |||

| Very good | 27 (22.9) | 23 (19.5) | 50 (21.2) |

| Good | 53 (44.9) | 52 (44.1) | 105 (44.5) |

| Fair | 36 (30.5) | 40 (33.9) | 76 (32.2) |

| Bad | 2 (1.7) | 3 (2.5) | 5 (2.1) |

| Very bad | 0 (-) | 0 (-) | 0 (-) |

| EQ-5D-5L c | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.799 (0.171) | 0.789 (0.165) | 0.793 (0.168) |

| Median (IQR) | 0.812 (0.740–0.879) | 0.768 (0.696–0.879) | 0.795 (0.711–0.879) |

| Range | 0.0140–1.000 | 0.255–1.000 | 0.0140–1.000 |

| Missing | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Diagnosed medical conditions (self-reported) | |||

| Asthma | 21/117 (18.0) | 22/116 (19.0) | 43/233 (18.5) |

| COPD/chronic bronchitis/emphysema | 0/115 (–) | 2/117 (1.7) | 2/232 (0.9) |

| Cancer | 1/117 (0.9) | 4/117 (3.4) | 5/234 (2.1) |

| Heart failure | 0/117 (–) | 2/115 (1.7) | 2/232 (0.9) |

| Hypercholesterolaemia (high cholesterol) | 14/117 (12.0) | 10/117 (8.6) | 24/234 (10.3) |

| Anxiety | 38/117 (32.5) | 33/114 (29.0) | 71/231 (30.7) |

| Depression | 35/118 (29.7) | 32/117 (27.4) | 67/235 (28.5) |

| Rheumatoid arthritis | 5/116 (4.3) | 1/116 (0.9) | 6/232 (2.6) |

| High blood pressure | 11/117 (9.4) | 14/117 (12.0) | 25/234 (10.7) |

| Stroke/TIA (mini stroke) | 1/116 (0.9) | 0/116 (–) | 1/232 (0.4) |

| Heart disease | 3/117 (2.6) | 0/116 (–) | 3/233 (1.3) |

| Atrial fibrillation | 2/115 (1.7) | 3/116 (2.6) | 5/231 (2.2) |

| Diabetes | 7/117 (6.0) | 5/116 (4.3) | 12/233 (5.2) |

| Chronic kidney disease | 0/116 (–) | 0/117 (–) | 0/233 (–) |

| Peripheral arterial disease | 0/117 (–) | 0/115 (–) | 0/232 (–) |

| Other medical condition(s) | 48/117 (41.0) | 47/117 (40.2) | 95/234 (40.6) |

Overall, 56 (24.1% of all respondents and 38.6% of 145 eligible participants over 40 years) reported ever having received an NHS health check to assess CVD risk (see Table 12). One hundred and nineteen (50.6%) had consulted a healthcare professional previously for a mental health problem and 150 (63.6%) for a MSK problem. Thirty-two (13.6%) had attended a weight management programme in the past and 13 (5.5%) a smoking cessation programme.

| SHSC (N = 118) (%) | Control (N = 118) (%) | Total (N = 236) (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Over 40s NHS health check | |||

| Ever received over 40s NHS health check? | |||

| Yes | 23 (19.7) | 33 (28.7) | 56 (24.1) |

| No | 94 (80.3) | 82 (71.3) | 176 (75.9) |

| Missing | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| If yes, when? | n = 23 | n = 33 | n = 56 |

| < 1 year ago | 2 (8.7) | 1 (3.0) | 3 (5.4) |

| 1–5 years ago | 15 (65.2) | 18 (54.6) | 33 (58.9) |

| > 5 years ago | 6 (26.1) | 14 (42.4) | 20 (35.7) |

| If no, why not? | n = 94 | n = 82 | n = 176 |

| I am under 40 years old | 43 (45.7) | 42 (51.9) | 85 (48.6) |

| I have been invited, but I’m not interested | 0 (–) | 0 (–) | 0 (–) |

| I have been invited, but didn’t have time to attend | 3 (3.2) | 3 (3.7) | 6 (3.4) |

| I have been invited, but I forgot to attend | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (1.1) |

| I have not been invited to receive the health check | 46 (48.9) | 34 (42.0) | 80 (45.7) |

| Other | 1 (1.1) | 1 (1.2) | 2 (1.1) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Number of times consulted a GP during past 14 days | |||

| 0 | 96 (82.1) | 102 (87.2) | 198 (84.6) |

| 1 | 18 (15.4) | 12 (10.3) | 30 (12.8) |

| 2 | 3 (2.6) | 3 (2.6) | 6 (2.6) |

| Missing | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Number of times consulted a practice nurse during past 14 days | |||

| 0 | 110 (93.2) | 116 (98.3) | 226 (95.8) |

| 1 | 7 (5.9) | 2 (1.7) | 9 (3.8) |

| 2 + | 1 (0.9) | 0 (-) | 1 (0.4) |

| Number of times consulted a pharmacist during past 14 days | |||

| 0 | 114 (96.6) | 113 (96.6) | 227 (96.6) |

| 1 | 4 (3.4) | 3 (2.6) | 7 (3.0) |

| 2 | 0 (–) | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.4) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Ever consulted a healthcare professional (or equivalent) for mental health problems? | |||

| Yes – in the last year | 33 (28.0) | 16 (13.7) | 49 (20.9) |

| Yes – more than 1 year ago | 30 (25.4) | 40 (34.2) | 70 (29.8) |

| No | 55 (46.6) | 61 (52.1) | 116 (49.4) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Ever consulted a healthcare professional (or equivalent) for MSK problems? | |||

| Yes – in the last year | 35 (29.7) | 39 (33.0) | 74 (31.4) |

| Yes – more than 1 year ago | 43 (36.4) | 33 (28.0) | 76 (32.2) |

| No | 40 (33.9) | 46 (39.0) | 86 (36.4) |

| Ever attended a smoking cessation programme? | |||

| Yes – in the last year | 0 (–) | 0 (–) | 0 (–) |

| Yes – more than 1 year ago | 7 (6.0) | 6 (5.1) | 13 (5.5) |

| No | 110 (94.0) | 112 (94.9) | 222 (94.5) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Ever attended a weight management programme? | |||

| Yes – in the last year | 5 (4.3) | 7 (5.9) | 12 (5.1) |

| Yes – more than 1 year ago | 8 (6.8) | 12 (10.2) | 20 (8.5) |

| No | 104 (88.9) | 99 (83.9) | 203 (86.4) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Admitted to hospital for any unplanned reason in last 12 months | |||

| Yes | 8 (6.8) | 4 (3.4) | 12 (5.1) |

| No | 110 (93.2) | 114 (96.6) | 224 (94.9) |

| If yes, number of times | n = 8 | n = 4 | n = 12 |

| 1 | 6 (75.0) | 4 (100.0) | 10 (83.3) |

| 2 | 2 (25.0) | 0 (-) | 2 (16.7) |

| If yes, total nights | |||

| 0 | 0 (-) | 1 (25.0) | 1 (8.3) |

| 1 | 3 (37.5) | 2 (50.0) | 5 (41.7) |

| 2 + | 5 (62.5) | 1 (25.0) | 6 (50.0) |

| Admitted to hospital for any planned reason in last 12 months | |||

| Yes | 5 (4.3) | 4 (3.5) | 9 (3.9) |

| No | 112 (95.7) | 111 (96.5) | 223 (96.1) |

| Missing | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| If yes, number of times | n = 5 | n = 4 | n = 9 |

| 1 | 3 (75.0) | 4 (100.0) | 7 (87.5) |

| 2 | 1 (25.0) | 0 (-) | 1 (12.5) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| If yes, total nights | |||

| 0 | 0 (-) | 0 (-) | 0 (-) |

| 1 | 1 (25.0) | 4 (100.0) | 5 (62.5) |

| 2 + | 3 (75.0) | 0 (-) | 3 (12.5) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 | 1 |

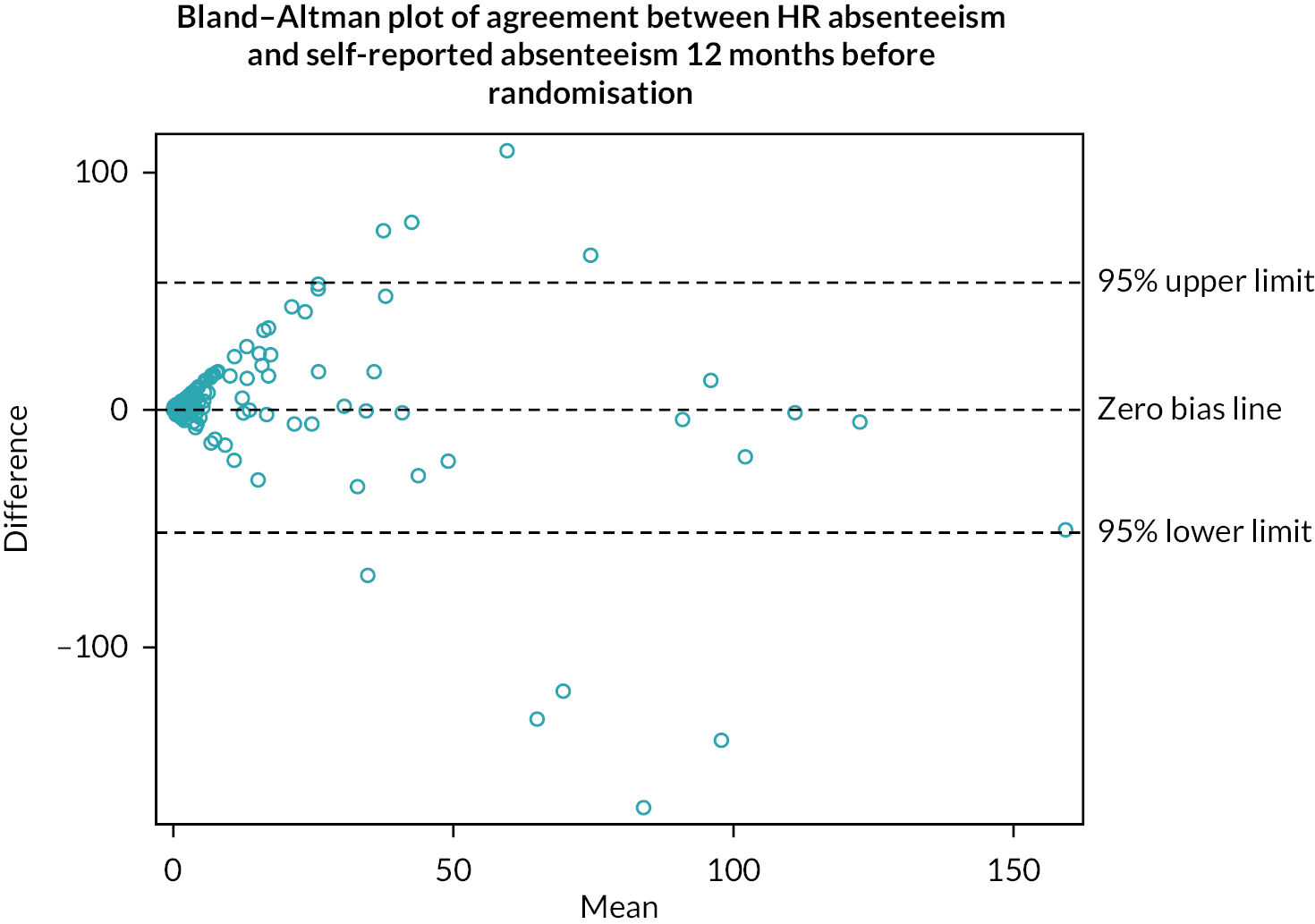

There was an even spread of duration of employment and most people (94.5%) had permanent contracts with a median working week of 4.0 days (see Table 13). Fifty-nine (25.0%) worked rotating shifts, while the majority (69.9%) worked daytime only. One hundred and forty-one (60.0%) reported being absent from work in the last year for reasons of ill health, where the mean (SD) number of days was 10.5 (29.9) and the maximum was 185 days. Conversely, data from HR records indicated a mean of 13.2 (27.3) days absent. There was no clear correlation (r = 0.52) or systematic error between self-reported absenteeism and HR absenteeism data (see Figure 4). As measured by the WHO-HPQ, participants report a mean (SD) of 77.2% (SD 18.5) absolute presenteeism which indicates that participants actual performance at work is 77.2% that of their best possible performance, over the previous 4 weeks. Reasons for sickness absesnteeism before randomisation are provided in Table 14. One hundred and thirty-four out of the 314 (42.7%) consenting participants provided an NHS number.

| SHSC (N = 118) (%) | Control (N = 118) (%) | Total (N = 236) (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Employment details | |||

| Years at current workplace | |||

| < 1 year | 10 (8.5) | 9 (7.6) | 19 (8.1) |

| 1–2 years | 14 (11.9) | 19 (16.1) | 33 (14.0) |

| 3–5 years | 22 (18.6) | 21 (17.8) | 43 (18.2) |

| 6–10 years | 16 (13.6) | 20 (17.0) | 36 (15.3) |

| 11–15 years | 19 (16.1) | 21 (17.8) | 40 (17.0) |

| > 15 years | 37 (31.4) | 28 (23.7) | 65 (27.5) |

| Contract type | |||

| Permanent | 114 (96.6) | 109 (92.4) | 223 (94.5) |

| Temporary – with no agreed end date | 1 (0.9) | 1 (0.9) | 2 (0.9) |

| Fixed period – with an agreed end date | 3 (2.5) | 8 (6.8) | 11 (4.7) |

| Shift pattern | |||

| Regular daytime | 87 (73.7) | 78 (66.1) | 165 (69.9) |

| Regular night | 5 (4.2) | 2 (1.7) | 7 (3.0) |

| Rotating | 24 (20.3) | 35 (29.7) | 59 (25.0) |

| Other | 2 (1.7) | 3 (2.5) | 5 (2.1) |

| Usual shift length (hours) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 9.0 (1.9) | 9.5 (2.0) | 9.3 (2.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 8.0 (7.5–10.0) | 8.8 (7.8–11.8) | 8.4 (7.5–11.5) |

| Range | 5.5–13.0 | 5.8–13.0 | 5.5–13.0 |

| Missing | 4 | 2 | 6 |

| Number of days worked a week, including overtime/extra hours | |||

| Mean (SD) | 4.3 (0.9) | 4.2 (1.0) | 4.2 (0.9) |

| Median (IQR) | 4.0 (4.0–5.0) | 4.0 (3.0–5.0) | 4.0 (3.5–5.0) |

| Range | 2.0–7.0 | 2.0–6.0 | 2.0–7.0 |

| Absenteeism/presenteeism | |||

| Absenteeism up to 12 months before randomisation (HR records) | |||

| Absenteeism (WTE days) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 13.6 (27.4) | 12.8 (27.3) | 13.2 (27.3) |

| Median (IQR) | 1.6 (0.0–10.0) | 2.0 (0.0–11.4) | 2.0 (0.0–10.7) |

| Range | 0.0–137.0 | 0.0–136.8 | 0.0–137.0 |

| 0 | 50 (42.7) | 46 (40.0) | 96 (41.4) |

| 1–2 | 18 (15.4) | 16 (13.9) | 34 (14.7) |

| 3–5 | 11 (9.4) | 12 (10.4) | 23 (9.9) |

| 6–9 | 6 (5.1) | 8 (7.0) | 14 (6.0) |

| 10–19 | 8 (6.8) | 13 (11.3) | 21 (9.1) |

| 20 + | 24 (20.5) | 20 (17.4) | 44 (19.0) |

| Missing | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Absenteeism (spellsa) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.2 (1.5) | 1.5 (1.9) | 1.3 (1.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) |

| Range | 0.0–7.0 | 0.0–10.0 | 0.0–10.0 |

| Missing | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Absenteeism 12–24 months before randomisation (HR records) | |||

| Absenteeism (WTE days) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 12.0 (25.1) | 16.5 (31.9) | 14.2 (28.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 1.8 (0.0–11.0) | 3.7 (0.0–16.0) | 2.7 (0.0–12.1) |

| Range | 0.0–164.7 | 0.0–186.0 | 0.0–186.0 |

| 0 | 48 (41.0) | 39 (33.9) | 87 (37.5) |

| 1–2 | 15 (12.8) | 12 (10.4) | 27 (11.6) |

| 3–5 | 12 (10.3) | 16 (13.9) | 28 (12.1) |

| 6–9 | 10 (8.6) | 10 (8.7) | 20 (8.6) |

| 10–19 | 14 (12.0) | 15 (13.0) | 29 (12.5) |

| 20 + | 18 (15.4) | 23 (20.0) | 41 (17.7) |

| Missing | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Absenteeism (spellsa) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.4 (1.7) | 1.5 (1.6) | 1.5 (1.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) | 1.0 (0.0–2.0) |

| Range | 0.0–10.0 | 0.0–8.0 | 0.0–10.0 |

| Missing | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Absenteeism (self-reported) | |||

| Taken time off work during the last 12 months due to ill health or otherwise? | |||

| Yes | 69 (58.5) | 72 (61.5) | 141 (60.0) |

| No | 49 (41.5) | 45 (38.5) | 94 (40.0) |

| Missing | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Number of days off work in the last 12 months (0 days for those who have not taken any time off) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 7.1 (19.0) | 13.7 (37.2) | 10.5 (29.9) |

| Median (IQR) | 0.0 (0.0–3.0) | 0.0 (0.0–4.0) | 0.0 (0.0–4.0) |

| Range | 0–130.0 | 0.0–185.0 | 0.0–185.0 |

| 0 | 58 (56.8) | 59 (54.6) | 117 (55.7) |

| 1–2 | 11 (10.8) | 12 (11.1) | 23 (11.0) |

| 3–5 | 15 (14.7) | 14 (13.0) | 29 (13.8) |

| 6–9 | 2 (2.0) | 5 (4.6) | 7 (3.3) |

| 10–19 | 6 (5.9) | 4 (3.7) | 10 (4.8) |

| 20 + | 10 (9.8) | 14 (13.0) | 24 (11.4) |

| Missing | 16 | 10 | 26 |

| Absenteeism (WHO-HPQ) | |||

| Absolute absenteeismb (using 7-day estimate) (hours lost per month) | |||

| Mean (SD) | −4.3 (38.2) | −11.7 (50.7) | −8.0 (45.0) |

| Median (IQR) | 0 (−19.0–0) | 0 (−30.0–0) | 0 (−22.0–0.0) |

| Range | −130.0–146.0 | −212.0–150.0 | −212.0–150.0 |

| Missing | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Absolute absenteeismb (using 28-day estimate) (hours lost per month) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 11.6 (43.6) | 5.5 (43.2) | 8.6 (43.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 0 (−10.0–20.0) | 0 (−10.0–15.0) | 0 (−10.0–17.0) |

| Range | −130.0–160.0 | −132.0–150.0 | −132.0–160.0 |

| Missing | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Relative absenteeismb (using 7-day estimate) | |||

| Mean (SD) | −0.06 (0.49) | −0.14 (0.63) | −0.10 (0.57) |

| Median (IQR) | 0.0 (−0.14–0.0) | 0.0 (−0.20 0.0) | 0.0 (−0.16–0.0) |

| Range | −4.3–1.0 | −4.4–1.0 | −4.4–1.0 |

| Missing | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Relative absenteeismc (using 28-day estimate) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.05 (0.51) | −0.02 (0.64) | 0.02 (0.58) |

| Median (IQR) | 0.0 (−0.07–0.17) | 0.0 (−0.07–0.11) | 0.0 (−0.07–0.13) |

| Range | −4.3–1.0 | −4.7–1.0 | −4.7–1.0 |

| Missing | 3 | 3 | 6 |

| Relative hours of workd (using 7-day estimate) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 1.1 (0.5) | 1.1 (0.6) | 1.1 (0.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 1.0 (1.0–1.1) | 1.0 (1.0–1.2) | 1.0 (1.0–1.2) |

| Range | 0.0–5.3 | 0–5.4 | 0–5.4 |

| Missing | 2 | 1 | 3 |