Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number NIHR135449. The contractual start date was in November 2021. The final report began editorial review in May 2022 and was accepted for publication in October 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Blank et al. This work was produced by Blank et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Blank et al.

Results

Included reviews

The total number of hits from our searches was 566, of which 518 were excluded at the title and abstract stage, leaving 48 that were considered as full papers for inclusion in the review. In total, we identified 20 papers that met the inclusion criteria for the review and could contribute to answering one of the research questions. Although individual quality appraisal was not undertaken, the reviews all met minimum standards for conducting and reporting systematic reviews. Two had no identifiable disaggregated data for the UK studies they included (Mamataz et al., 2021, Supervia M, Medina-Inojosa JR, Yeung C, Lopez-Jimenez F, Squires RW, Perez-Terzic CM, et al. Cardiac rehabilitation for women: a systematic review of barriers and solutions. Mayo Clin Proc 2017;13:13). These two reviews (both of cardiac rehabilitation) have been included in the review-level analysis as they are relevant but they do not contribute any data at the primary study level). For the remaining 18 reviews, disaggregated data on at least one UK primary study were identified. There was a bias towards reviews considering cardiac rehabilitation, with these numbering 15; only 5 reviews considered pulmonary rehabilitation. Seventeen reviews included qualitative data from studies that reported on factors which facilitate or impede attendance at rehabilitation from patient (n = 9) or provider/system (n = 6) perspectives or considered both perspectives (n = 2). Three reviews reported on interventions to improve referral, uptake, adherence and/or completion of rehabilitation.

Population

In terms of defining the population under interest, most reviews that considered cardiac rehabilitation did not limit their included studies to any particular stage of, or setting for, the rehabilitation. Only three reviews included studies only from one specific stage of rehabilitation that included phase one cardiac rehabilitation patients (acute), phase 2 cardiac rehabilitation (subacute), and rehabilitation either at the intake appointment or at six weeks post hospital discharge.

Location

Eight reviews mentioned the location of rehabilitation, which specifically included outpatient clinics, patients post hospital discharge, in patients programmes, home- and centre-based programmes in hospital or outpatients, or after an acute care hospitalization (which included home or hospital-based rehabilitation). One review considered virtual education delivery of cardiac rehabilitation programmes via online platforms.

Primary studies

From the included reviews, a total of 60 UK primary studies were identifiable that were relevant to the review questions. Of the 60 identifiable primary studies that considered factors affecting attendance at rehabilitation, 42 considered cardiac rehabilitation, with the remaining 12 considering pulmonary rehabilitation. Over half of the papers reported on factors from the patient point of view (n = 23), with 17 considering the views of professionals involved in referral or treatment. It was more common for factors to be reported as impeding attendance at rehabilitation rather than facilitating it (despite the fact that most factors could be reported as their inverse). We grouped the reported factors as those from a patient perspective (including support, culture, demographics, practical, health, emotions, knowledge/beliefs, and service factors) and from a professional perspective (knowledge: staff and patient, staffing, adequacy of service provision, and referral from other services (including support and wait times).

Intervention reviews

In total, three reviews identified interventions; two that considered cardiac rehabilitation and one pulmonary rehabilitation. The two reviews of cardiac rehabilitation (Matata BM, Williamson SA. A review of interventions to improve enrolment and adherence to cardiac rehabilitation among patients aged 65 years or above. Curr Cardiol Rev 2017;13:252–62; Santiago de Arauja Pio C, Chaves G, Davies P, Taylor R, Grace S. Interventions to promote patient utilization of cardiac rehabilitation: Cochrane systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med 2019;8:189) included the same UK study (McPaul J. Home Visit Versus Telephone Follow‐up in Phase II Cardiac Rehabilitation Following Myocardial Infarction. MSc dissertation. Chester: University of Chester; 2007). However there were no statistics details for the UK study by Matata and Williamson (2017). Whereas in Santiago de Araujo Pio et al. (2019), the intervention was reported to study the effects of home visits versus telephone follow-up by an occupational therapist on attendance for cardiac rehabilitation.

The review by Early et al. (Early F, Wellwood I, Kuhn I, Deaton C, Fuld J. Interventions to increase referral and uptake to pulmonary rehabilitation in people with COPD: a systematic review. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 2018;13:3571–86) was the only review to address pulmonary rehabilitation. This review included six UK-based studies as a part of a narratively synthesised systematic review. The review aimed to establish the effectiveness of interventions to improve referral to and uptake of pulmonary rehabilitation in patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) when compared with standard care, alternative interventions or no intervention. Four studies reported statistically significant improvements in referral (range 3.5–36%) and two studies reported statistically significant increases in uptake (range 18–21.5%).

Balance of factors

In considering our typology of factors that improve or impede attendance at cardiac and/or pulmonary rehabilitation, it is interesting to note that most of the identified interventions were implemented to address barriers to access in terms of provider perspective. This was particularly true of the studies identified by Early et al. (2018), which considered access to pulmonary rehabilitation. A better understanding of the access challenges from the patient perspective may facilitate interventions to address the service provision challenges they experience more effectively. Only two interventions to improve attendance at cardiac rehabilitation were identified. However, these did better address some of the patient barriers to access, including improving support and motivation to exercise, and overcoming issues with travel to cardiac rehabilitation. Overall, however, the majority of access challenges identified by patients would not be addressed by the identified interventions. This reflects the very small number of patient access interventions identified.

Effectiveness

One small study on an intervention to improve attendance at cardiac rehabilitation suggested a positive effect (McPaul, 2007), although the change was not statistically significant. For pulmonary rehabilitation, two intervention studies reported an increase in referral rates (Roberts CM, Gungor G, Parker M, Craig J, Mountford J. Impact of a patient-specific co-designed COPD care scorecard on COPD care quality: a quasi-experimental study. NPJ Prim Care Respir Med 2015;25:15017; Hopkinson NS, Englebretsen C, Cooley N, Kennie K, Lim M, Woodcock T, et al. Designing and implementing a COPD discharge care bundle. Thorax 2012;67:90–2) but one-third were not effective (Graves J, Sandrey V, Graves T, Smith DL. Effectiveness of a group opt-in session on uptake and graduation rates for pulmonary rehabilitation. Chron Respir Dis 2010;7:159–64).

Unpublished interventions

Through additional website searching we identified 11 unpublished interventions not reported in the systematic review literature. Nine consisted of online delivery of cardiac rehabilitation (n = 7) or pulmonary rehabilitation (n = 2) during the COVID-19 pandemic. These interventions may have the potential to act on some of the patient barriers around access to services, including travel and inconvenient timing of services. One further intervention for cardiac rehabilitation trained staff in communication skills to encourage more patients to exercise, which may impact on patients’ knowledge and beliefs about rehabilitation. The final pulmonary rehabilitation intervention (developing a toolkit to increase inclusivity) may have the potential to impact on some of the demographic and cultural patient barriers identified in the factors literature.

Discussion

Implications for service delivery

Services should in particular, consider the barriers imposed for some patients by cultural and demographic factors which may require additional effort to:

-

make service alterations to improve engagement with specific patient groups (e.g. females, ethnic minorities)

-

consider the implications of group exercise on creating reluctance to attend for some individuals

-

provide patient educational interventions to alter perceptions of rehabilitation and ensure that patients have a good understanding of what it involves and how it is appropriate for their needs

-

provide staff training around engagement with specific patient groups, communication to encourage exercise and to better explain both the content and benefits of rehabilitation

-

consider the impact of location and timing of service provision on attendance, including whether the continued provision of online services may be appropriate in some instances.

As variations between the factors reported as impacting on cardiac or pulmonary rehabilitation are not due to fundamental differences in the patient reported factors (except those related to the specific condition (e.g. smokers reluctance for COPD rehabilitation), specialities can learn from each other in terms of potential interventions to improve attendance.

Implications for research

The existing review level literature on the factors which impact on attendance for rehabilitation of both pulmonary and cardiac conditions would benefit from a greater focus on what could be done to facilitate attendance as the evidence currently has a negative focus. Research into interventions to improve attendance at rehabilitation, both overall and for key patient groups, should be the focus moving forward. In developing interventions to improve access to an engagement with rehabilitation services the perspectives of both the patients and the services providers should be considered.

Conclusions

The factors affecting commencement, continuation or completion of cardiac or pulmonary rehabilitation consist of a web of complex and interlinked factors taking into consideration the perspectives of the patients and the service providers. Although most of the factors affecting participation were reported from a patient perspective, most of the identified interventions were implemented to address barriers to access in terms of the provider perspective. Thus, the majority of access challenges identified by patients would not be addressed by the identified interventions. Better understanding of these factors will allow future interventions to be more evidence based with clear objectives as to how to address the known barriers to improve access.

Funding

This report presents independent research funded by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR). The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the HSDR programme or the Department of Health.

Study registration

The study protocol is registered with PROSPERO [CRD42022309214].

Chapter 1 Introduction

Cardiac and pulmonary rehabilitation programmes vary, but usually consist of the key components of exercise, education, relaxation and emotional support. There is a considerable body of systematic review evidence considering the effectiveness of rehabilitation programmes on clinical outcomes,1,2 comparing one mode of delivery with another (e.g. community vs. centre-based rehabilitation)3 or considering the relative effectiveness of rehabilitation using new technologies. 4 However, much less is known about what is effective in terms of engaging patients in rehabilitation and sustaining that engagement over time. 5

Despite increasing awareness of the factors that influence engaging with and sustaining rehabilitation – including those related to environment, knowledge, attitudes and behaviours6 – a lack of understanding of these factors (particularly in relation to differential effects for different populations) continues to impact on implementation of rehabilitation programmes. 7 There is a need to map the evidence across both pulmonary and cardiac rehabilitation to understand the full range of potential intervention strategies; as existing reviews tend to be specific to a patient group and do not focus on understanding what might work for populations with lower uptake. 8

This review seeks to understand not only the factors that impede or facilitate engagement (also reported as participation) (commencement, continuation or completion) in rehabilitation, but also what interventions exist to address these specific factors and whether they have been shown to be effective in increasing access to, and continued engagement in rehabilitation, particularly for those patients at greater risk of not accessing services.

Objectives

The review addresses three related sub-questions:

-

What are the factors that impede or facilitate engagement (commencement, continuation or completion) in rehabilitation by patients with heart disease or chronic lung disease?

-

Which intervention components, evaluated or innovative, have been proposed to increase engagement in rehabilitation and which factors do they propose to address?

-

What evidence is there for the effectiveness of such interventions as documented at a review level?

An important subtext of these questions relates to health inequalities and differential uptake. Evidence suggests that inequalities that are already present are further exacerbated due to intrinsic features of rehabilitation programmes. 9–12

Chapter 2 Methods

Mapping review methodology

Following the methodology of James et al. (2016),13 we undertook a mapping review of systematic review-level evidence that considers the factors which facilitate or impede engagement (commencement, continuation or completion) with pulmonary and cardiac rehabilitation. According to Booth (2016),14 ‘a mapping review aims at categorizing, classifying, characterizing patterns, trends or themes in evidence production or publication’ (p. 14). Grant and Booth (2009)15 add that the point in conducting a mapping review is to ‘map out’ and thematically understand the pre-existing research on a particular topic, including assessing any gaps that could be addressed by future research. Mapping reviews are especially useful for topics where there is a lot of pre-existing literature, for investigating if there are gaps in the literature. 14

Eligibility criteria

We included systematic reviews that reported factors identified from a UK context, whether separately or within a wider systematic review. All included reviews are systematic reviews with a recognisable degree of systematicity. All included reviews have been published between 2017 and 2021 and include a minimum of one UK-based study. Reviews that did not include UK primary studies were excluded. Where possible, UK-specific data from primary studies conducted in the UK have been identified upon extraction and subsequent data presentation. Where UK specific data could not be disaggregated, systematic reviews were considered for inclusion on a case-by-case basis and in considering the number of UK focused reviews identified.

For inclusion a systematic review must have reported:

-

Cardiac or pulmonary rehabilitation.

-

Rehabilitation in any context. Rehabilitation is defined as ‘a set of interventions designed to optimize functioning and reduce disability in individuals with health conditions in interaction with their environment’. 7

-

Factors affecting commencement, continuation or completion of rehabilitation, including self-referral into rehabilitation, or an intervention that aims to increase the commencement, continuation or completion of rehabilitation.

We included systematic reviews published within the five years 2017–21 due to time constraints and to ensure that data were timely and did not reflect prior service provision. However, the period covered by the primary studies reported in the review is much greater (as outlined in Chapter 3, Results).

Systematic reviews that focused on the clinical effectiveness of rehabilitation or compared modes of rehabilitation (e.g. physical activity vs. other), or location of rehabilitation (e.g. community vs. hospital) were considered to be outside the scope of this mapping review.

Search strategy

We conducted a single search process to retrieve systematic reviews of both intervention effectiveness (i.e. quantitative) and of factors impacting upon engagement (i.e. qualitative). Sources searched include specific resources that focused on systematic reviews and other systematically conducted reviews (e.g. scoping and mapping reviews) and general resources where systematic reviews filters were run against search results (see Table 1). This project was conceived as a time-constrained mapping review and restriction of the databases searched was according to best evidence on database coverage. Using EMBASE as a supplement to PubMed covers 78% of publications and 88% of Cochrane-eligible effectiveness studies. 16 Similarly, a combination of PubMed and CINAHL (two commonly recommended databases for qualitative reviews) retrieves 82% of the publications. 16 Table 1 shows the databases searched in February 2022.

| Review-specific sources | General databases |

|---|---|

| Cochrane reviews (via Wiley) | EMBASE (via Ovid) |

| Epistemonikos (maintained by Epistemonikos Foundation) | MEDLINE (via Ovid) |

| CINAHL (via EBSCO) |

The search privileged the main subject headings for the two focal topics of interest: Cardiac Rehabilitation [MESH] and Lung Diseases/rehabilitation* OR Pulmonary Disease, Chronic Obstructive/rehabilitation. The rationale for this was that (1) systematic reviews are more likely to be indexed with main subject headings; and (2) the focus on qualitative aspects and overall effectiveness was less likely to match to granular subject headings. There are also no validated search filters for cardiac or pulmonary rehabilitation.

The main subject headings were combined with free-text terms and synonyms for engagement, uptake, completion, barriers and facilitators. The searches on MEDLINE, EMBASE and CINAHL used filters to retrieve references to review publications. The searches were limited to English language and peer-reviewed publications from 2017 to 2022. The search strategy for Ovid MEDLINE is included in Appendix 1. This search, once developed, was translated to the other databases. Records were managed in Endnote and a database of included studies with selection decisions is available.

The focus on UK developments also allowed for the inclusion of recent initiatives that are not reported in the peer reviewed literature at the systematic review level (due to being conducted too recently). These were identified through additional internet-based searches. Sources searched to find recent initiatives in April 2022 included the databases of the King’s Fund and the Health Services Management Centre, alongside brief internet-based searches.

Study selection

Study selection was undertaken independently by two reviewers. Following piloting of a test set each record was screened by two of the three reviewers. In cases of uncertainty each was cross-referred to the third reviewer.

A ‘light touch’ data extraction process was undertaken. This included review characteristics, number of included studies and proportion of UK studies. Where disaggregated data for UK primary studies were reported in the reviews, these were extracted individually on a study-by-study basis alongside the review-level data. Top-level themes were extracted for the qualitative syntheses and a summary of results and outcomes were extracted from the abstracts of included quantitative reviews where they included sufficient data. Where required for clarity, the full text of the papers were also scrutinised.

Interventions were characterised using a version of TiDIER-Lite,17 as pioneered by the team, using descriptive data from study characteristics. The TiDIER-Lite characteristics described the interventions in terms of the following questions:

-

What

-

By whom?

-

Where?

-

To what intensity?

-

How often?

Extraction were undertaken using purpose-designed forms. The factors identified were initially characterised (where it was possible to differentiate) as:

-

factors facilitating commencement

-

factors impeding commencement

-

factors facilitating completion

-

factors impeding completion.

Data relating to PROGRESS-plus variables18 were also extracted where reported. These included: place of residence, race, occupation, gender, religion, education, socioeconomic status, social capital, personal characteristics associated with discrimination (e.g. age, disability), features of relationships (e.g. smoking parents, excluded from school), time-dependent relationships (e.g. leaving the hospital, respite care, any temporary disadvantage).

Outcomes and prioritisation

Extracted data included both programme outcomes (e.g. completion of the programme, rates of withdrawal or dropout etc., satisfaction) and clinical outcomes. The results of primary outcomes of interest have been presented. However, other relevant outcomes have also been mapped as part of the analysis of reviews. Data on the characteristics of participants upon initiation (demographic and clinical characteristics) have been a particular focus of presentation.

Risk of bias in individual studies

Given that the purpose of the mapping exercise was to describe factors identified as important in connection with engagement, no quality assessment was required for the qualitative reviews. The quality of the quantitative reviews has been briefly summarised, based on the aggregative quality of the included studies. Quality assessment of the included reviews has not been undertaken except when reconciling conflicting evidence to facilitate interpretation.

Data synthesis

Data synthesised from quantitative studies was determined by the reporting characteristics of the included reviews. Interventions have been tabulated alongside the summary results of included reviews.

Formal subgroup analyses were not undertaken; however, studies were coded against ethnic minority composition and any other salient features from the PROGRESS-Plus classification. 18 Studies or study populations meeting these features have been separately analysed and reported in comparison to the characteristics and results for a non-specific population.

The time-constrained characteristics of this review prohibit formal analysis of meta-biases as they relate to aspects of reporting and publication bias. However, the review includes published and formally evaluated projects and programmes together with recent initiatives awaiting evaluation. In particular, the team has sought to prevent pro-innovation bias – the unconscious favouring of new initiatives that have not undergone formal evaluation. 19

There is no formal requirement to complete Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation (GRADE) or GRADE-CERQual assessments of the strength of evidence as recommendations are not made. The focus was on presenting a descriptive map of factors, intervention components and intervention effects.

Chapter 3 Results

Review-level data

Included reviews summary

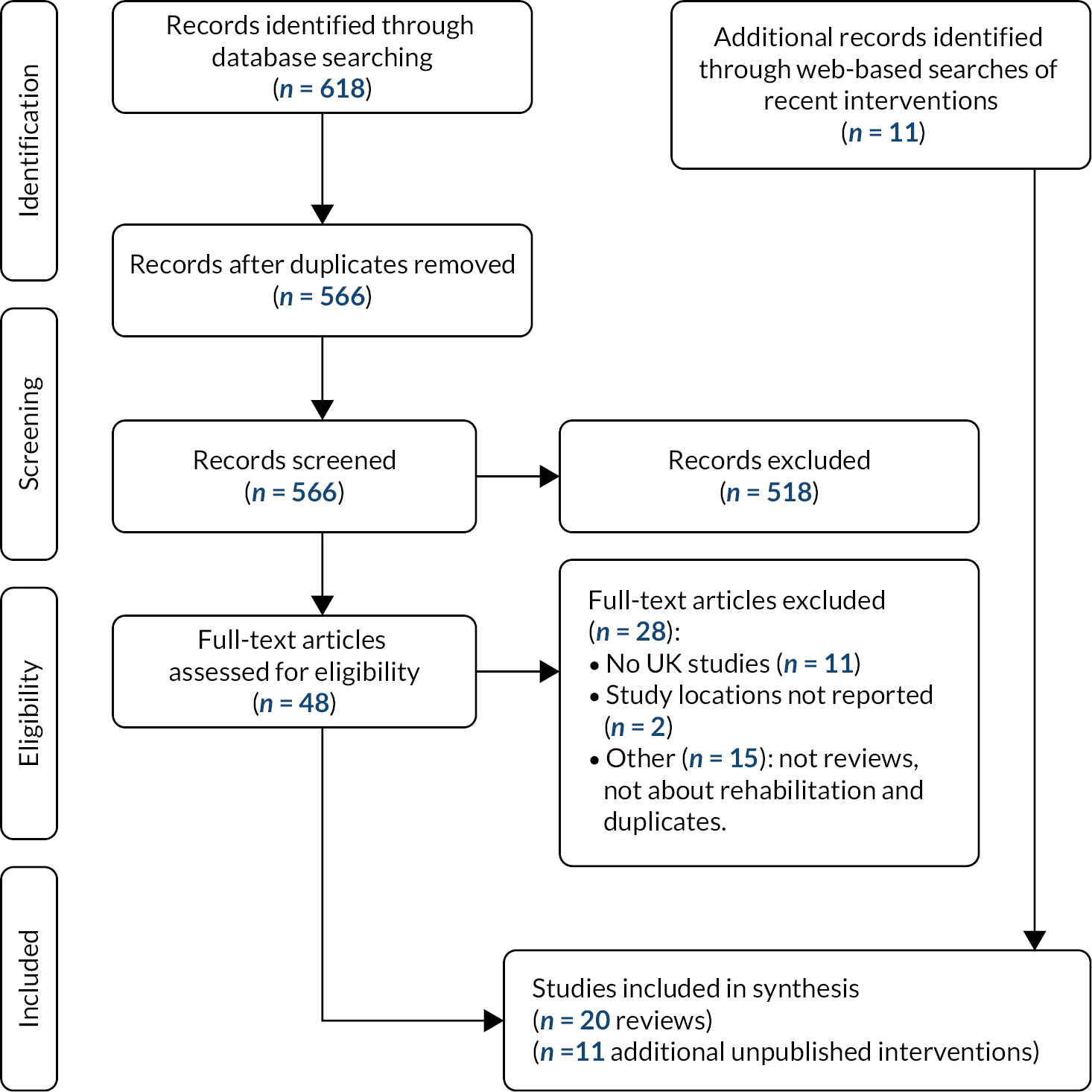

The total number of hits from our searches was 566, of which 518 were excluded at the title and abstract stage, leaving 48 which were considered as full papers for inclusion in the review (see Figure 1). In total, we identified 20 papers that met the inclusion criteria for the review and could contribute to answering one of the research questions (see Table 2). Full extraction data for each included review are available on request from the lead author. Of the 20 review papers, 2 had no identifiable disaggregated data for the UK studies they included. 10,20 These two reviews (both of cardiac rehabilitation) have been included in the review-level analysis as they meet the inclusion criteria for the review, but they do not contribute any data at the primary study level. For the remaining 18 reviews, disaggregated data on at least one UK primary study were identified. In addition, a further 28 reviews were excluded after consideration at the full paper stage (see Appendix 2). The reasons for exclusion include no UK primary studies (n = 11), primary study locations not reported (n = 2) and other (n = 15), which included papers that were not reviews or were not about rehabilitation, and duplicates.

FIGURE 1.

The process of study selection.

| Study, location | CR/PR | Approach | C+A (continuation or completion) | Search date range | Publication date range | Included UK studies | UK primary study results (factors or intervention data]) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Campkin et al. (2017),9 Canada | CR | Factors, patient views | C+A ‘initiation and continued participation’ | Database inception – May 2015 | 2000–14 | Sriskantharajah and Kai (2007)41 | Health fears, social support improve participation; negative cultural/religious views of exercise (seen as selfish) decreased participation |

| Farooqi et al. (2000)49 | Cultural factors (language barriers, mixed gender facilities) dissuaded participation | ||||||

| Galdas et al. (2012)64 | Concerns regarding personal safety and environment (weather conditions) reduced participation; attentive staff improved adherence | ||||||

| Shaw et al. (2012)48 | Negative emotion (unable to establish self-worth), social pressure, and inconvenient class times reduced adherence | ||||||

| Cole et al. (2013)68 | Fear (consequences of not attending) improved adherence | ||||||

| Dunn 201446 | Self-confidence (rehabilitation not intimidating) and peer support (sense of togetherness) improved adherence | ||||||

| Daw et al. (2021),28 UK | CR | Factors, professional views and system factors | Unclear: ‘delivery’ | Not reported | 2010–20 | Dalal et al. (2012)46 | Improves ‘delivery of services’: skill mix of staff; tailored guidelines; different modes of delivery; impedes ‘delivery of services’: poor evidence base; non-tailored guidelines; lack of resources; lack of commissioning; blurred roles; lack of patient pathways |

| Fowokan et al. (2020),24 Canada | CR | Factors, system factors | Commencement (‘referral and uptake’) | Database inception – December 2019 | 1997–2019 | Buttery et al. (2014)54 | Being younger improved attendance (uptake and maintenance) |

| Houghton and Cowley (1997)59 | Being female impeded attendance (uptake and maintenance) | ||||||

| Hall et al. (2017),21 Australia | CR | Factors, patient views | Commencement (‘implementation’) | January 2003 – December 2014 | 2004–12 | Kilonzo and O’Connell (2011)73 | Patients: individualised information provided, and given time to be understood improves commencement; professionals: ‘views differed’ |

| Proudfoot et al. (2007)71 | Lack of staff and funding impedes commencement | ||||||

| Smith and Liles (2007)41 | Younger age (less interested) impedes commencement | ||||||

| Jahandideh et al. (2018),5 Australia | CR | Factors, system factors | C+A (‘initiation and sustained engagement’) | Database inception – 13 January 2017 | 1998–2018 | Bennett et al. (1999)107 | Outcome expectancies (no definition: relates to whether expecting success) predicted intention to engage in a healthy diet and regular exercise |

| Sniehotta et al. (2010)108 | Action planning (precise plan about where and when patients planned CR) improved uptake | ||||||

| Jolly et al. (2007)37 | No relevant data included | ||||||

| Mamataz et al. (2021),10 Canadaa | CR | Factors, patient views (female) | A (‘adherence’) | Database inception – May 2020 | 2002–20 | Asbury et al. (2007)109 | No disaggregated data for UK studies |

| Madison (2010)110 | |||||||

| Matata and Williamson (2017),23 UK | CR | Interventions to improve uptake/adherence | C+A (‘enrolment or adherence’) | Database inception –May 2017 | 2003–12 | McPaul (2007)70 | Home visit interview with an occupational therapist instead of a phone call |

| McHale et al. (2020),29 UK | CR | Factors, patient views | C (‘engagement’) | January 1990 –December 2017 | 2004–17 | Clark et al. (2004)47 | Embarrassment about group/public exercise, misunderstood the role of exercise in rehab, cardiac misconceptions (perception of condition severity), perceptions of fitness and lack of post event communication and advice impedes attendance; faith in body, fitness, willing to support others, believed exercise important to recovery increased attendance |

| Cooper et al. (2005)42 | Beliefs about course content, perceptions of exercise, the benefits of CR and CR knowledge influenced attendance decisions; some viewed CR as important to recovery, others misunderstood the role of exercise; cardiac misconceptions were present and negatively influenced attendance | ||||||

| Herber et al. (2017)66 | Personal factors, programme factors and practical factors influenced participation; barriers: participants perceived themselves unsuitable and lack of knowledge and/or misconceptions about CR | ||||||

| Hird et al. (2004)63 | Impedes engagement: transport problems; family commitments; increases engagement: wanting to reach previous exercise levels | ||||||

| Jones et al. (2007)67 | Impedes engagement: participation in alternative exercise, other health problems, lack of motivation (especially for females), age appropriateness of rehabilitation considered low | ||||||

| Robertson et al. (2010)61 | Engagement affected by emotionality relating to body prior to cardiac event, male identity, self-confidence in physical ability | ||||||

| McCorry et al. (2009)69 | Impedes engagement: not recognising health benefits of exercise/rehabilitation; professionals viewing medication more important than rehabilitation | ||||||

| Shaw et al. (2012)48 | Increases participation: feeling positive about CR; impedes: believe active enough already, other health problems, feeling unsupported in class, competing demands, self confidence in physical ability, perceive CR as not appropriate | ||||||

| Resurreccion et al. (2017),11 Spain | CR | Factors, patient views (female) | C+A (‘non participation and dropping out’) | Database inception – September 16 2016 | 1992–2013 | Cooper et al. (2005)42 | Barriers to non-participation: lack of family and social support; barriers to non-participation: embarrassment (due to group format); barriers to non-participation and drop out: work conflicts, employment restrictions |

| MacInnes (2005)60 | Barriers to non-participation: self-reported health problems (in women), health beliefs (heart attacks cannot be prevented) | ||||||

| Sherwood and Povey (2011)50 | Barriers to non-participation: health beliefs (beliefs that women could manage or solve their heart problem by themselves), time constraints, feelings of embarrassment (due to group format), communication difficulties (language) | ||||||

| Chauhan et al. (2010)36 | Barriers (drop out): self-reported health problems, religious reasons; barriers (non-participation): transport (not having suitable transport), negative experiences with health system | ||||||

| Rowley et al. (2018),30 UKa | CR | Factors: adherence to rehabilitation (duration) | A (‘adherence/completion’) | Date range varied for different conditions not clearly reported. | 2002–16 | Duda 201433 | Longer length schemes (20+ weeks) had higher adherence to physical activity prescribed, than those of shorter length (8–12 weeks) |

| Edwards 201362 | Participants with risk of CVD more likely to adhere to the full programme than those with mental health conditions; those with high deprivation were more likely to complete the programme | ||||||

| Littlecott 201465 | Individuals with CVD risk in the control group participated in more PA per week than those in the intervention group with CHD risk factor | ||||||

| Murphy 201235 | – | ||||||

| Anokye 201234 | – | ||||||

| Hanson 201356 | Leisure site attended was a significant predictor of uptake and length of engagement; more successful for over 55s, and less successful for obese participants | ||||||

| Mills 201353 | Those with CVD, more likely to attend and adhere, compared with pulmonary disorders; link between age and attendance | ||||||

| Rouse 2011111 | – | ||||||

| Webb 2016112 | Community-based exercise increased adherence (vs. continuously monitored exercise programme) | ||||||

| Santiago de Araujo Pio et al. (2019),22 UK/Canada | CR | Interventions to improve uptake/adherence | C+A (‘enrolment, adherence, completion’) | 2013 – July 2018 | 1999–2016 | McPaul (2007)70 | Home visit interview with an occupational therapist instead of a phone call |

| Supervia et al. (2017),20 USA | CR | Factors, patient views (female) | C+A (‘referral, enrolment, completion’) | Database inception – October 20 2016 | 1998–2016 | Jolly et al. (1998)27 | No disaggregated data for UK studies |

| Jolly et al. (2007)37 | |||||||

| Vanzella et al. (2021a),26 Canada | CR | Factors, patient views | Commencement | Database inception – April 2021 | 2001–21 | Devi et al. (2014)57 | Virtual learning in CR programmes. Enablers: manage their time (learn according to their availability), patient empowerment (improves treatment adherence, reduced stress and anxiety). Barriers: format of the delivered materials, older age |

| Higgins et al. (2017)58 | Technology as a facilitator to virtual learning; format of the delivered materials, and sessions that were too long were barriers to participation; for older individuals the use of animation tools and websites that were easy and simple to navigate facilitated the learning process | ||||||

| Vanzella et al. (2021),12 Canada | CR | Factors, patient views (ethnicity) | C+A (‘referral, enrolment, completion’) | Database inception – 10 February 2020 | 1997–2019 | Astin et al. (2005)38 | Barriers to CR enrolment: lack of family support, language |

| Bhattacharyya et al. (2011)39 | Barriers to CR enrolment: lack of family support language, culture, age psychological status, knowledge/beliefs/interest, religion and socioeconomic status; provider level: CR knowledge | ||||||

| Chauhan et al. (2010)36 | Barriers to CR enrolment: language, culture, age psychological status, knowledge/beliefs/interest, religion and socioeconomic status; provider level: CR knowledge, system-level – practical/logistical barriers | ||||||

| Darr et al. (2008)51 | Barriers to adherence and completion: practical/logistical, language, religion, culture | ||||||

| Jolly et al. (2005)40 | Barriers to CR enrolment: lack of family support language, system-level – practical/logistical barriers; barriers to adherence and completion: practical/logistical, individual perceptions | ||||||

| Jones et al. (2007)67 | – | ||||||

| Jolly et al. (2009)113 | Barriers to adherence and completion: Practical/logistical, individual perceptions | ||||||

| Visram et al. (2007)43 | Barriers to adherence and completion: practical/logistical, individual perceptions, language, lack of knowledge about CR programmes, culture, socioeconomic status, psychological status and family support | ||||||

| Webster 199752 | Barriers to adherence and completion: individual perceptions, lack of knowledge about CR programmes, religion | ||||||

| Vanzella et al. (2021c),25 Canada | CR | Factors, professional views and system factors | Adherence | Database inception – 15 March 2021 | 1984–2018 | Astin 200844 | Barriers to adherence: habits, cultural aspects, time constraints, lack of knowledge, financial situation; facilitators: family support, individual financial situation |

| Leong et al. (2004)45 | Facilitators to adherence (healthy eating habits): family support, older age | ||||||

| Cox et al. (2017),6 Australiab | PR | Factors, patient views and professional views | C+A ‘uptake and completion’ | Database inception –July 2016 | 1999–2016 | Arnold 200674 | Completers of PR (n = 16) interviews categorised by: positive influence of referring practitioner, self-help, enjoying programme/seeing improvement, the effect of the group; non-completers (n = 4) identified: social support and motivation |

| Bulley 200980 | Three key themes identified: desired benefit of attending PR – most participants had positive and realistic expectations; evaluating threat of exercise – fear of exercise deterred some from participating while determination conveyed a more positive attitude; attributing value to PR – information (or lack of) provided at referral had an important influence on attendance | ||||||

| Foster et al. (2016)75 | Current smokers were more evident among those who declined referral; those who accepted a referral included a higher percentage of individuals on O2; of those who declined, a greater proportion lived alone, were divorced or separated; incentives to promote PR included in-house education sessions, changes to practice protocols, and ‘pop-ups’ and memory aids (mugs and coasters) | ||||||

| Garrod et al. (2006)76 | Quads strength (p = 0.03), smoking pack years (p = 0.04), SGRQ (health status) (p = 0.02) and depression (p < 0.001) independently discriminated between completers and dropouts; depression a risk factor for dropout | ||||||

| Graves 201088 | 59% undertook PR assessment, 52% proceeded to undertake PR, of whom 88% completed | ||||||

| Harris et al. (2008)81 | Losing control, gaining control | ||||||

| Harris et al. (2008)84 | Changing roles of members of healthcare team; communication: logistics of referral for PR; patients’ willingness to accept referral | ||||||

| Harrison et al. (2015)82 | Construction of the self (impact of acute exacerbation on personal identity); relinquishing control (struggle to maintain agency following acute event); engagement with others | ||||||

| Hayton et al. (2013)77 | Independent predictors of attendance: LTOT, OR 0.45 (0.22, 0.96) p = 0.038, cohabitation OR 1.82 (1.02, 3.24) p = 0.042; adherence: age (youngest and oldest quartiles least likely to complete PR); current smoking status (44.9% adherence vs. 79.9% ex-smoker adherence); LTOT use (59.3% adherence vs. 73.0% adherence in non-LTOT users) | ||||||

| Lewis et al. (2014)83 | Uncertainty related to lived experience temporally | ||||||

| Moore et al. (2012)78 | Difficulties with access due to geography or timing; difficulties in prioritising the treatment; contrary beliefs about the role and safety of exercise; fears about criticism exposure and inadequacy | ||||||

| Walker et al. (2011)79 | Significant difference in PR attendance by season (summer 74% vs. winter 64%, p < 0.05); weak positive correlation between attendance and maximum temperature (r = 0.51), minimum temperature (r = 0.44), daylight hours (r = 0.55); weak negative correlation between attendance and rainfall (r = –0.33) | ||||||

| Early et al. (2018),8 UK | PR | Interventions to improve uptake/adherence | Commencement (‘referral and uptake’) | Search start date not reported –end of January 2018 | 2007–16 | Angus et al. (2012)89 | Barriers for PR: PR referral; interventions: computer-guided review, based on NICE guidance, by practice nurses during routine COPD review |

| Hopkinson et al. (2012)85 | Barriers for PR: PR referral, staff education, staff monitoring/knowledge of PR (e.g. ward staff attended PR sessions), patient information; interventions: ward-based staff education; discharge care bundle with referral for PR assessment; patient offered phone call 48–72 hours post discharge to check if they were improving; plan–do–study–act cycles to refine the process; prize draw for staff completing checklist; ward staff attended hospital PR sessions; PR patient information leaflet | ||||||

| Hull et al. (2014)90 | Barriers for PR: PR referral, service identification/monitoring of patients (lack of patients on relevant registers, financial incentives for KPIs), completed care plans; 8 networks of GPs; financially incentivised key performance indicators; care package based on NICE guidance; information technology infrastructure; support from community respiratory team; network boards to review practice performance against targets; quarterly community COPD multidisciplinary team meeting; rapid email/phone advice from consultant | ||||||

| Roberts et al. (2015)87 | Barriers for PR: PR referral, patient information, completed care plans, pre referral assessment; interventions: patient-held scorecard containing 6 care quality indicators comparing patient’s care with the standard; sent to patient with letter advising patient to discuss scorecard at the next COPD review; telephone helpline for patients | ||||||

| Foster et al. (2016)75 | Barriers for PR: PR referral, staff education, secondary care discussions about PR; interventions: increasing referrals; briefing note based on questionnaire feedback and literature review with suggestions for standardising PR knowledge and increasing referral (in-house education, practice protocols, ‘pop-ups’ and memory aids to prompt discussion about PR) | ||||||

| Graves et al. (2010)88 | Barriers for PR: PR referral, patient information, self-management, pre referral assessment; interventions: group opt-in session (1.5 hours) prior to assessment for PR; run by physiotherapist and clinical psychologist; discussion of patient case study, self-management, PR information, alternatives to PR | ||||||

| Milner et al. (2018),32 Canadac,d | PR | Factors, professional views | C (‘referral’) | Database inception –28 July 2017 | 2007–16 | Harris et al. (2008)81 | Enablers to commencement: having a streamlined referral process in place, adequate local service provision, short waiting time for patients to get into PR, protected time for info giving (time to tell patients about PR); barriers: difficult to access service (availability, wait times), unable to refer/difficult referral process, lack of time |

| Gautam 2011114 | – | ||||||

| Jones 2012115 | – | ||||||

| Martin 2012116 | – | ||||||

| Gaduzo 2013117 | – | ||||||

| Jones 2013118 | – | ||||||

| Sewell 2013119 | – | ||||||

| Thompson 2013120 | – | ||||||

| Hull 201490 | – | ||||||

| Jones 2014121 | – | ||||||

| Roberts 201587 | – | ||||||

| Foster et al. (2016)75 | Enablers to commencement: PR training/experience in thoracic outpatient clinics or rehab/reading/mentoring/teaching; PR awareness events; prompt on review template/computerised pop-ups (making it part of workflow/ reminders); barriers: low knowledge of/don’t know what PR is; low knowledge of/don’t know what/don’t believe in PR benefits; don’t know enough about patient eligibility; don’t know about/low knowledge of referral process; lack of clear within-practice referral guidelines | ||||||

| Swift et al. (2020),31 UK | PR | Factors, professional views | Commencement (‘referral’) | 1998 – August 2019 | 2005–19 | Foster et al. (2016)75 | Poor knowledge of pulmonary rehabilitation, especially from GPs impeded referral; strategies to increase referrals: running sessions at the GP practice to increase awareness, memory aids, prompts on yearly review forms, and development of a pulmonary rehabilitation referral practice specific protocol |

| Harris et al. (2008)81 | Perceived barriers to referral: lack of clarity (whose role it was to refer), lack of knowledge about referral process, long wait times, communication issues when introducing PR and time associated with discussion | ||||||

| Summers et al. (2017)91 | Barriers: difficulty establishing realistic patient goals, difficult for patients to begin exercise, services issues (funding, less input from other disciplines, time constraints, cost effectiveness, need to justify) | ||||||

| Wilson et al. (2007)86 | Barriers: patients need better understanding of COPD to reduce exercise anxiety, educates patients and their relatives about exacerbations, psychological effects as important as physical; benefits: assists with depression, low self-esteem and smoking related remorse | ||||||

| Bohplian and Bronas (2021),122 USA | PR, CR | Factors, patient views | C+A (participation and adherence) | 2010–19 | 2010–18 | Russell 201092 | Support from health care professionals improves adherence |

The included reviews (published between 2017 and 2021) included a wide variety of search date ranges, the earliest search date being 1984 and the latest including publications up to 2021. There was a bias towards reviews considering cardiac rehabilitation, with these numbering 15; only 5 reviews considered pulmonary rehabilitation. Seventeen reviews included qualitative data from studies that reported on factors which facilitate or impede attendance at rehabilitation from patient (n = 9) or provider/system (n = 6) perspectives, or considered both perspectives (n = 2). Three reviews reported on interventions to improve referral, uptake, adherence and/or completion of rehabilitation.

Included reviews

Study populations

Cardiac rehabilitation

In terms of defining the population of interest, most reviews that considered cardiac rehabilitation did not limit their included studies to any particular stage (acute, subacute, intensive outpatient or ongoing) of, or setting for, the rehabilitation. Only three reviews included studies only from one specific stage of rehabilitation, which included phase 1 (acute) cardiac rehabilitation patients,21 phase 2 (subacute) cardiac rehabilitation22 and rehabilitation either at the intake appointment or at six weeks post hospital discharge. 23

Eight reviews mentioned the location of rehabilitation, which specifically included outpatient clinics,24 patients following hospital discharge,20,23 inpatient programmes,21 home- and centre-based programmes,5 in hospital or as an outpatient,25 or after an acute care hospitalisation (which included home- or hospital-based rehabilitation). 22 Vanzella et al. 12 considered virtual education delivery of cardiac rehabilitation programmes via online platforms.

Most review authors included rehabilitation for any cardiac event or condition,10,12,20,22,23,25,26 but seven were more specific. Those who limited their included studies by disease population defined them as follow:

-

patients with acute myocardial infarction and coronary artery disease, postoperative cardiac surgery, and post-coronary intervention27

-

post myocardial infarction (women and South Asian populations)9

-

heart failure28

-

patients in hospital with heart failure24

-

patients in hospital with coronary heart disease (CHD)21

-

rehabilitation to stabilise, slow, or reverse cardiovascular disease and facilitate prevention of further cardiac events5

-

acute coronary syndrome cardiovascular rehabilitation29

-

female patients with cardiovascular disease11

-

persons with cardiovascular, mental health, and musculoskeletal disorders, including participants with CHD or who were at increased CHD risk, cardiovascular disease or at increased risk of disease, and participants with hypertension. 30

Most reviews did not limit the studies they included by PROGRESS-Plus classification: place of residence, race, occupation, gender, religion, education, socioeconomic status, social capital, personal characteristics associated with discrimination (e.g. age, disability), features of relationships (e.g. smoking parents, excluded from school), time-dependent relationships (e.g. leaving the hospital, respite care, any temporary disadvantage), with the exception of four reviews that included studies of cardiac rehabilitation for women 9–11 and/or ethnic minority populations. 9,12

Pulmonary rehabilitation

The four reviews that considered pulmonary rehabilitation included all populations of patients receiving pulmonary rehabilitation31 or pulmonary rehabilitation for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD),6,8,32 but did not limit their study population further in terms of location or criteria for rehabilitation, and did not use any PROGRESS-Plus classification to define their inclusion criteria.

Primary papers: factors studies

Seventeen reviews included qualitative data from studies which considered factors affected commencement, continuation and completion of rehabilitation. In many cases the factors were reported individually (and for the identifiable UK primary studies are discussed further below). In addition, the authors of six reviews (of which only one considered pulmonary rehabilitation)31 attempted to create a typology of the types of factors affecting commencement, continuation and completion of rehabilitation. The reviews included a mixture of UK and non-UK studies and, as a result, the typologies should only be used to give a sense of the type of factors being reported. Overall, where typologies were reported, the factors were categorised by the review authors as follows:

-

Campkin et al. 9 described factors as external (pragmatic and social considerations such as safety, accessibility and social support networks), internal (physical, cognitive, and emotional domains, which include fear, motivation, and mood), and cultural factors influence exercise initiation and continued participation.

-

In Resurreccion et al.,11 ‘barriers’ to rehabilitation were grouped into five categories which included intrapersonal barriers, interpersonal barriers, logistical barriers, CR program barriers, and health system barriers.

-

Swift et al. 31 summarised the ‘barriers’ they identified as those which incorporated a lack of knowledge, a lack of resources, practical barriers, patient barriers, and healthcare professionals being unsure that it was their role to refer.

-

Vanzella et al. 12,26,27 described the factors as individual, provider and system/environmental levels.

Interventions

Three reviews reported on interventions, of which two reviews (of cardiac rehabilitation interventions) included a single UK-based study. 22,23 The review by Early et al. 8 contained the largest number of UK studies (6 of 14 included papers). This review considered interventions to improve participation in pulmonary rehabilitation.

Included UK primary studies

From the included reviews, a total of 76 UK primary studies were identifiable (see Appendix 3). Of these, 11 were included in more than one review. However, for 11 of the primary studies, no disaggregated data were presented in the review papers or supplementary material. Of the 65 primary studies with disaggregated data presented, 5 were not relevant to this review as they reported on general exercise referral schemes,33–36 or did not report factors relating to attendance. 37 Thus, 60 primary studies were included in the analysis.

Factors papers

UK primary studies

Of the 60 identifiable primary studies that considered factors which affected attendance at rehabilitation, 42 considered cardiac rehabilitation, with the remaining 18 considering pulmonary rehabilitation (see Figure 2). The majority of papers reported on factors from the patients’ point of view, with fewer considering the views of professionals involved in referral or treatment. It was more common for factors to be reported as impeding attendance at rehabilitation rather than facilitating it (despite the fact that most factors could be reported as their inverse).

FIGURE 2.

Factors identified in UK disaggregated study data

We grouped the reported factors as those that were from a patient perspective (including support, culture, demographics, practical, health, emotions, knowledge/beliefs, and service factors) and those from a professional perspective (knowledge: staff and patient, staffing, adequacy of service provision, and referral from other services (including support and wait times).

Cardiac rehabilitation

Forty-two UK primary studies on cardiac rehabilitation with disaggregated data presented were identified by the systematic reviews. Thirty-five reported from the patient perspective and a further five considered professional views. The remaining two studies reported factors from both viewpoints.

Patient perspective

Family/peer support

Feeling supported, either by friends, family or peers within a rehabilitation group setting, was reported to influence attendance (enrolment, adherence and/or completion) in 10 studies of cardiac rehabilitation. Lack of family support was reported as impeding enrolment in cardiac rehabilitation in three studies. 38–40 Two further studies reported a lack of social support41,42 and/or family support42 as impeding continued participation in cardiac rehabilitation. Visram et al. 43 also reported that lack of family support impeded both adherence to, and completion of, cardiac rehabilitation. Conversely, a positive association between family support and adherence to cardiac rehabilitation was reported in two studies,44,45 the latter of which focused solely on outcomes related to healthy eating habits. In addition, peer support (sense of togetherness) was reported to improve adherence to cardiac rehabilitation46 and a willingness to support others in their cardiac rehabilitation was also reported to increase attendance. 47 However, social pressure (feeling unsupported in class) reduced adherence. 48

Cultural factors

Cultural factors (either reported generally as ‘cultural factors’, or specially as language barriers) were reported to influence attendance (enrolment, adherence and/or completion) in 10 studies of cardiac rehabilitation.

Language

Having communication difficulties with the rehabilitation service due to a language barrier was reported as a factor that diminished enrolment36,38–40,49,50 and continued adherence51 to cardiac rehabilitation.

Culture

‘Cultural factors’ were listed as factors that impeded cardiac rehabilitation enrolment36,39 and adherence/completion. 38,43,51 ‘Religious factors’ were also reported as factors that impeded adherence and/or completion of cardiac rehabilitation,51,52 although no further detail was given. In addition, Farooqi et al. 49 reported that mixed gender facilities dissuaded participation in rehabilitation owing to different cultural acceptability, and Sriskantharajah and Kai41 noted that negative cultural and religious views of exercise (with exercise being seen as selfish) also decreased participation in cardiac rehabilitation.

Demographic factors

Demographic factors (age, gender, socioeconomic status, financial status) were reported to influence attendance (enrolment, adherence and/or completion) in 19 studies of cardiac rehabilitation.

Age:

Bhattacharyya et al.,39 Chauhan et al. 36 and Mills et al. 53 all reported age as a barrier to enrolment in cardiac rehabilitation, but the systematic review authors did not report the direction of the association. 12,30 Buttery et al. 54 found that being younger improved attendance (uptake and maintenance) at cardiac rehabilitation. Conversely, Smith and Liles55 found that those of younger age were ‘less interested’ in cardiac rehabilitation, which impeded commencement, and Hanson et al. 56 found that rehabilitation attendance was ‘more successful for over 55s’. Leong et al. 45 found that older age facilitated adherence to the healthy eating aspects of a cardiac rehabilitation programme.

Devi et al. 57 considered virtual learning in cardiac rehabilitation programmes and reported older age as a barrier to participation. Higgins et al. 58 also considered technology as a facilitator to virtual learning and found that, for older individuals, the use of animation tools and websites that were easy and simple to navigate facilitated the learning process.

Gender

Houghton and Crowley59 reported that being female impeded attendance (uptake and maintenance) to cardiac rehabilitation. Farooqi et al. 49 identified that mixed gender facilities also dissuaded participation in cardiac rehabilitation where this was a cultural concern for women. Smith and Liles55 considered factors that impede engagement with cardiac rehabilitation and noted that participation in ‘alternative exercise’ (not defined), having other health problems and lack of motivation were especially problematic for females. Two other studies were conducted with women only and reported factors that impede engagement with cardiac rehabilitation including self-reported health problems60 and health beliefs that women could manage or solve their heart problem by themselves. 50 Robertson et al. 61 reported that engagement with cardiac rehabilitation was ‘affected by male identity’, although this was not elaborated on.

Socioeconomic status/finance

Socioeconomic status was reported as a barrier to cardiac rehabilitation both in terms of enrolment36,39 and also adherence and completion,43 but the systematic review did not report the direction of the association. 12 Financial status (being more financially secure was also reported facilitate adherence to cardiac rehabilitation). 44 However, Edwards et al. 62 reported that patients of ‘high deprivation’ were more likely to complete the programme.

Practical factors

Practical factors, including time constraints, travel problems and poor weather, were reported as impeding engagement in cardiac rehabilitation in seven studies.

Time constraints

Generic ‘time constraints’ were reported to impede adherence to cardiac rehabilitation,44,50 as well as particular time constraints relating to family commitments. 63 Time constraints related to work conflicts and employment restrictions were reported to increase non-participation and drop out. 42 Shaw et al48 reported that inconvenient class times reduced adherence due to competing demands on participants’ time. With respect to virtual learning in cardiac rehabilitation programmes, Devi et al. 57 found that participants being able manage their time (learn according to their availability) was an enabler to participation.

Travel

Hird et al. 63 reported that experiencing transport problems impedes engagement with cardiac rehabilitation.

Weather:

Galdas et al. 64 found that concerns regarding personal safety and environment (weather conditions) reduced participation in cardiac rehabilitation.

Health

Health-related measures, including measure of physical and psychological health and perceived physical health status, were considered by 13 studies in relation to cardiac rehabilitation attendance.

Physical health:

Four studies reported on patients’ physical health. Participants with a diagnosis of cardiovascular disease (CVD) or at risk from developing CVD were more likely to adhere to attend and adhere the full programme than those with mental health or pulmonary conditions (Edwards et al. 2013,62 Littlecott et al. 2014,65 Mills et al. 201353). Engagement with cardiac rehabilitation was found to be less successful for obese participants. 56

Psychological health:

Three studies reported that poor psychological status impeded both enrolment in, or adherence and completion of, cardiac rehabilitation. 36,39,43

Perceived physical health:

Two studies found that a person having low perceptions of their own fitness impedes attendance at cardiac rehabilitation. 47, 66 Conversely, three studies found that having faith in their body and fitness increased attendance. 47,48,61 Participation in alternative exercise and believing that they were ‘active enough already’ impeded participation in cardiac rehabilitation, as participants perceived it was not appropriate for them. 48,67 However, a desire to reach previous exercise levels could increase engagement in cardiac rehabilitation. 63

Emotional factors

Ten studies reported on emotional factors that may affect engagement with cardiac rehabilitation, including motivation, self-confidence and empowerment, embarrassment and health fears.

Motivation:

Jones et al. 67 reported that lack of motivation for cardiac rehabilitation (especially for females) impeded engagement. Feeling positive about cardiac rehabilitation also improved participation. 48

Self-confidence/empowerment:

Three studies reported positive associations between self-confidence and attending cardiac rehabilitation. Dunn et al. 46 found that self-confidence (feeling that attending rehabilitation was not intimidating) improved adherence. Robertson et al. 61 found that engagement with rehabilitation services was improved by being confidence in their physical ability to complete the programme, as well as ‘emotionality relating to body prior to cardiac event’. Further, Devi et al.,57 in relation to virtual learning in cardiac rehabilitation programmes, found that patient empowerment improves treatment adherence and reduced stress and anxiety. Additionally, Shaw et al. 48 reported that experiencing negative emotion (being unable to establish self-worth) reduced adherence to cardiac rehabilitation as it impeded self-confidence in physical ability.

Embarrassment:

Three studies reported that embarrassment due to the group exercise format of cardiac rehabilitation impeded attendance. 42,47,50

Health fears:

Fears regarding the health consequences of not attending cardiac rehabilitation improved adherence in two. 41,68

Knowledge and beliefs relating to rehabilitation programmes

Fourteen papers reported that having a lack of knowledge, or particular (inaccurate) beliefs about rehabilitation could limit participation, along with having negative expectations of rehabilitation, and perceiving rehabilitation as not important.

Knowledge:

A lack of knowledge about cardiac rehabilitation was a barrier to enrolment in,36,39 adherence to,42–44,52,66 and completion of cardiac rehabilitation. 43,52 Misunderstanding the role of exercise in rehabilitation was also said to impede attendance. 47

Beliefs:

Cooper et al. 42 further reported that inaccurate beliefs about course content, perceptions of exercise, and the benefits of cardiac rehabilitation influenced attendance decisions; some viewed cardiac rehabilitation as important to recovery, others misunderstood the role of exercise. A further barrier to attendance was participants who perceived themselves unsuitable for cardiac rehabilitation. 66 Clark et al. 47 reported that where a participant believed exercise important to recovery, this increased attendance at cardiac rehabilitation; conversely, misunderstanding the role of exercise in rehabilitation impeded attendance. In addition, inaccurate health beliefs (that heart attacks cannot be prevented)60 and health misconceptions (inaccurate perception of condition severity)47 impeded attendance at cardiac rehabilitation.

Perceived importance of rehabilitation:

Believing that exercise is important to recovery increased attendance at cardiac rehabilitation. 47 Some viewed cardiac rehabilitation as important to recovery, while others misunderstood the role of exercise. 42 Perceiving cardiac rehabilitation as not appropriate,48 and not recognising health benefits of exercise or rehabilitation69 both impeded engagement and participation in rehabilitation. McPaul70 reported that support from interventionists to improve self-determined motivation and exercise behaviours was important in cardiac rehabilitation.

Expected outcomes:

Having had negative expectations of cardiac rehabilitation prior to attending impeded commencement of cardiac rehabilitation. Bennett at al. 42 reported that ‘outcome expectancies’ (not defined in the review17 but relates to whether participants were expecting success) predicted intention to engage in a healthy diet and regular exercise.

Service provision factors

Our searches identified seven studies on patient views of specific aspects of cardiac rehabilitation in terms of whether they impeded or improved service access. There were a further seven studies on professional views on aspects of cardiac rehabilitation that affected attendance.

Patient views on service provision:

Clark et al. 48 found that a lack of post event communication and advice impedes attendance at cardiac rehabilitation. However, having ‘attentive staff’ improved adherence. 29 Receiving individualised information and being given time to be understood improved commencement of cardiac rehabilitation. 39 Webb et al. 67 found that community-based exercise increased adherence (vs. continuously monitored exercise programme) and Hanson et al. 64 reported that leisure site attendance was a significant predictor of uptake and length of engagement. In terms of virtual learning in cardiac rehabilitation, barriers to participation could include the format of the delivered materials. 70,71 For older individuals, the use of animation tools and websites that were easy and simple to navigate facilitated the learning process. 71

Professional perspective

Professional views on service provision

In seven studies, the professional involved in cardiac rehabilitation identified a number of factors that impacted on the likelihood of participants attending cardiac rehabilitation.

Service factors:

A lack of service funding was said to impede commencement in cardiac rehabilitation,71 along with a lack of resources and a lack of service commissioning. 72 A lack of staff also impeded commencement of rehabilitation. 71 Dalal et al. 72 further reported that ‘delivery of services’ was improved by tailored guidelines, offering different modes of delivery, and impeded by a poor evidence base, non-tailored guidelines and a lack of clear patient pathways.

Staff factors:

Low referrer level knowledge of cardiac rehabilitation was a barrier to enrolment,36,39 as was professionals viewing medication as more important than rehabilitation. 69 A good skill mix improved ‘delivery of services’, but blurred professional roles impede delivery of services. 72 Kilonzo and O’Connell73 also considered the views of cardiac nurses on service provision, but the systematic review21 reported only that they ‘differed in their perception of what was most important but also in their perception of the value of their instruction with patients’.

Pulmonary rehabilitation

Eighteen UK primary studies on pulmonary rehabilitation with disaggregated data presented were identified by the four systematic reviews. Seven studies reported from the patient perspective and a further nine considered professional views on service provision. The remaining two studies reported factors from both viewpoints.

Patient perspective

Arnold et al. 74 reported that non-completers of pulmonary rehabilitation identified lack of social support as a barrier.

Demographic factors

Foster et al. 75 found that current smokers were more evident among those who declined referral for pulmonary rehabilitation. Garrod et al. 76 also found that more years of smoking reduced the likelihood of participation in pulmonary rehabilitation (p = 0.04). Hayton et al. 77 also found that a predictor of pulmonary rehabilitation non-attendance was current smoking status (44.9% current smoker adherence vs. 79.9% ex-smoker adherence).

Living arrangements also predicted attendance, with Foster et al. 75 reporting that of those who declined to participate in pulmonary rehabilitation, a greater proportion lived alone, were divorced or separated. Hayton et al. 77 found that cohabitation was a predictor of attendance compared with other living arrangements (OR 1.82 [1.02, 3.24]; p = 0.042).

Hayton et al. 77 also reported that age predicted adherence to pulmonary rehabilitation (with the youngest and oldest quartiles least likely to complete their rehabilitation).

Practical factors

Time constraints/travel:

Moore et al. 78 reported difficulties with accessing pulmonary rehabilitation due to geography (location) or timing, as well as difficulties in prioritising the treatment.

Weather:

Walker et al. 79 reported a significant difference in pulmonary rehabilitation attendance by season (summer 74% vs. winter 64%; p < 0.05) plus weak correlations with temperature and rainfall.

Health

Three studies reported different rates of attendance at pulmonary rehabilitation by health condition. Two studies found that those who accepted a referral to pulmonary rehabilitation included a higher percentage of individuals on oxygen therapy,75 and that an independent predictor of reduced attendance was long term oxygen therapy (OR 0.45 [0.22, 0.96]; p = 0.038; 59.3% adherence vs. 73.0% adherence in non-LTOT users). 77 Garrod et al. 76 reported that quads strength (p = 0.03), St. George's Respiratory Questionnaire (health status) (p = 0.02) and depression (p < 0.001) independently discriminated between completers and dropouts, with depression being a risk factor for dropout from rehabilitation.

Emotional factors

Fears about criticism exposure and inadequacy limited engagement with pulmonary rehabilitation. 78 On evaluating the ‘threat of exercise’, Bulley et al. 80 found that fear of exercise deterred some from participating while determination conveyed a more positive attitude. Arnold et al. 74 identified lack of motivation as a barrier to completion of pulmonary rehabilitation. Harris et al. 81 considered the ratio of losing control and gaining control on pulmonary rehabilitation attendance (with more control improving attendance) and Harrison et al. 82 reported that relinquishing control (struggle to maintain agency following acute event), limited attendance due to an ‘impact of acute exacerbation on personal identity’. Similarly, Lewis et al. 83 noted that uncertainty (related to the ‘lived experience temporally’) impeded engagement in rehabilitation.

Knowledge and beliefs relating to rehabilitation programmes

Moore et al. 78 found that having ‘contrary beliefs about the role and safety of exercise’ impeded participation in pulmonary rehabilitation.

Perceived importance of rehabilitation

Arnold et al. 74 found that ‘self-help’ defined as enjoying the programme and seeing improvement due to the effect of the group having a positive impact on participation in pulmonary rehabilitation. Further, Bulley et al. 80 found that attributing positive value to pulmonary rehabilitation through information provided at referral had an important influence on increasing attendance.

Expected outcomes

Bulley et al. 80 also described ‘desired benefit of attending pulmonary rehabilitation’, where most participants had positive and realistic expectations engagement with pulmonary rehabilitation increased as a result.

Service provision factors

Two studies reported the impact of service provision factors on pulmonary rehabilitation attendance. Arnold et al. 74 found that participants who reported a positive influence of referring practitioner were more likely to complete their pulmonary rehabilitation. Harris et al. 84 reported on changing roles of members of healthcare team, which could impact on communication and the logistics of referral for pulmonary rehabilitation, including patients’ willingness to accept referral, which was improved by good communication.

Staff perspective

Staff knowledge:

Barriers to patients accessing pulmonary rehabilitation included referring professionals (especially general practitioners) having low knowledge of, or not knowing what pulmonary rehabilitation is, or not believing in the benefits of pulmonary rehabilitation. 84 In addition, where professionals do not know enough about patient eligibility or have low knowledge of the referral process, referral is impeded. 75 An overall lack of staff education was also reported as a barrier to access, with staff monitoring and knowledge of pulmonary rehabilitation (e.g. ward staff attended rehabilitation sessions) improving engagement with rehabilitation services. 85

Patient knowledge:

There was a recognised need to provide patients with a better knowledge and understanding of COPD to reduce exercise anxiety, educate patients and their relatives about exacerbation, and to understand that psychological effects are as important as physical. 86 Patient knowledge could also act as a barrier to accessing rehabilitation, with a lack of patient information reported in three studies. 85,87,88

Referral process:

Lack of clear within-practice referral guidelines impeded referral to (and therefore commencement of) pulmonary rehabilitation. 75 Further perceived barriers to referral were lack of clarity (whose role it was to refer) and a lack of knowledge about the referral process. 81 Having a streamlined referral process in place encouraged referral. 81 Referral to pulmonary rehabilitation was also listed as a barrier to attending rehabilitation in five further studies in the review by Early et al. 8 but, unfortunately, no further clarity was provided by the authors in reference to this statement. 85,87–90 Early et al. 8 also listed the lack of a pre-referral assessment as a barrier to rehabilitation in two studies. 87,88

Adequate service provision:

Enablers to commencement of pulmonary rehabilitation included adequate local service provision and protected time for information giving (time to tell patients about pulmonary rehabilitation). 81

Barriers to commencement included lack of time, communication issues when introducing pulmonary rehabilitation and subsequent time associated with discussion,81 an overall lack of funding and time constraints. 91 A lack of service identification (due to patients not being on relevant registers) and poor monitoring of patients was also said to reduce engagement with rehabilitation. 90 Patients with completed care plans87,90 and those with high self-management88 were less likely to commence rehabilitation. There was also a view that less input from other disciplines limited access to rehabilitation, along with cost effectiveness and a need to justify the service. 91 Secondary care discussions about pulmonary rehabilitation were said to improve engagement with services. 75

Waiting time:

A short waiting time for patients to get into pulmonary rehabilitation facilitated commencement, whereas when there was difficultly accessing services (due to availability and long wait times) commencement was impeded. 81

Primary papers: interventions

Interventions identified in the UK disaggregated study data

The following section outlines the features of interventions to increase uptake and adherence described in the included reviews. In total, three reviews (see Table 3) identified interventions, two which considered cardiac rehabilitation and one pulmonary rehabilitation.

| UK study | Review | PR/CR | Attendance/adherence | Intervention type/facilitating action | Effective/considered successful or ineffective/unsuccessful/no significant effect1 | RCT design? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Angus et al.89 | Early et al.8 | PR | Attendance (referral) | Computer-guided review, based on NICE guidance by practice nurses during routine COPD review | N/A no comparative data | No |

| Hopkinson et al.85 | Early et al.8 | PR | Attendance (referral) | 1) Ward-based staff education 2) Discharge care bundle with referral for PR assessment 3) Patient offered phone call 48–72 hours post discharge 4) Plan–do–study–act cycles to refine the process 5) Prize draw for staff completing checklist 6) ward staff attended hospital PR sessions 7) PR patient information leaflet |

Effective (reported increases in referral) | No |

| Hull et al.90 | Early et al.8 | P | Attendance (referral) | 1) 8 networks of GPs 2) Financially incentivized key performance indicators 3) Care package based on NICE guidance 4) Information technology infrastructure 5) Support from community respiratory team 6) Network boards to review practice performance against targets 7) Quarterly community COPD multidisciplinary team meeting 8) Rapid email/phone advice from respiratory consultant |

Cannot establish effectiveness; increase in referral over time; no comparative data reported | No |

| Roberts et al.87 | Early et al.8 | PR | Attendance (referral) | Patient-held scorecard containing 6 care quality indicators comparing patient’s care with the standard. Sent to patient with letter advising patient to discuss scorecard at the next COPD review; telephone helpline for patients | Effective (reported increases in referral) | No |