Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/70/146. The contractual start date was in December 2016. The final report began editorial review in April 2021 and was accepted for publication in December 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Kingsbury et al. This work was produced by Kingsbury et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Kingsbury et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this chapter have been adapted from Czoski Murray et al. 1 This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Background

Hip and knee arthroplasty has revolutionised the management of degenerative joint disease. There is a good evidence showing that hip and knee arthroplasty is both highly clinically effective, reducing symptoms of pain and functional limitations for the vast majority of patients,2,3 and highly cost-effective, resulting in cost savings for health-care systems and increasing benefits for patients compared with alternatives, such as no surgical interventions and conservative management. 4–6 In the UK, the lifetime risk of having a knee replacement is estimated to be 10.8% for women and 8.1% for men, and the lifetime risk of having a hip replacement is estimated to be 11.6% for women and 7.1% for men. 7 In 2018–19, a total of 95,677 primary total hip replacements (THRs), 106,617 total knee replacements (TKRs), 12,261 unicompartmental knee replacements (UKRs), 1790 revision hip procedures and 6708 revision knee procedures were carried out in the UK,8 an increase of 25% in only 4 years and of 300% over the past 20 years.

Age-related osteoarthritis is the primary indication for THR, TKR and UKR (collectively referred to as primary replacements throughout this report) and 65% of patients are aged ≥ 65 years at surgery. The proportion of the UK population that is aged ≥ 65 years is rapidly increasing, growing from 15% to 17% over the last 25 years, and is predicted to reach 23% by 2035. 9 Owing to medical advances, the elderly are more medically fit than previous generations and this, together with improved anaesthetic techniques, means that a greater proportion of the population is now eligible for surgery. Furthermore, improvements in implant technology and associated survival rates have reduced the average age of arthroplasty patients, although recent National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines on hip fracture management require that all patients who are independently mobile before fracture, not cognitively impaired and medically fit for anaesthesia to be offered joint replacement. 10

Ultimately, these factors have contributed to a rapid increase in the number of primary arthroplasties conducted in the UK annually and a consequent increase in revision procedures. Future projections of THR and TKR numbers based on 2010 figures, accounting for projected population changes in age, sex and body mass index (BMI), estimated 95,877 THRs and 118,666 TKRs to be performed in the UK in 2035;11 however, these numbers were already exceeded in 2018–19. 8

Joint replacements are associated with reduced pain, enhanced function and improved quality of life for patients. 12,13 However, there is a risk of adverse events following surgery, including perioperative complications, mortality and revision surgery, in which implant components are removed, added or replaced. 14 Adverse events are cost-intensive, with revision in particular being associated with increased length of stay (LOS) at the hospital and substantial health-care costs. 14,15 Nevertheless, the risk of revision is low, ranging from 4.6% to 6.8% for knee replacements and from 4.7% to 6.4% for hip replacements at 10 years after primary surgery,14 and approximately 75% of those revisions are expected to occur after 5 years following the primary joint replacement. 16

Follow-up after joint arthroplasty represents an effective way to detect the need for revision,17 as well as an important source of information for physicians to improve both arthroplasty performance and patients’ health outcomes, given the potential increased risk of failure of the implanted prosthesis over time. 18 Failure of the prosthesis may be caused by a number of factors, including the material used to make prosthetic implants (in addition to their design, size and positioning), infection, dislocation and trauma, as well as unexplained pain or aseptic loosening with or without osteolysis. 18,19 Early (defined as < 5 years) complications are often symptomatic and include infection and technical errors. 20 Arthroplasty failure in the longer term (defined as > 5 years), constituting 50% of revision surgery, is usually caused by bearing surface wear and associated consequences of periprosthetic osteolysis or aseptic loosening, and may be asymptomatic until clinical and radiographic failure have occurred. 20,21 Complex revision surgery is considerably more costly in terms of both surgical and subsequent rehabilitation costs, is more traumatic to the patient and carries higher complication risks. However, with modern on-the-shelf revision implants and surgical techniques of allografting and impaction grafting, there is often less urgency to proceed to revision surgery for asymptomatic radiographic changes than there was 10 years ago. Cases are commonly kept under observation, with development of symptoms often the trigger to proceed to surgery.

Currently, approximately 500,000 to 1,000,000 outpatient follow-up visits are offered to hip and knee replacement patients per year in the UK. 1 Orthopaedic services are already one of the poorest performers across the NHS in terms of failure to meet waiting list targets, with an estimated 8000 orthopaedic NHS breaches each month. 9 With a rapidly ageing population and medical advances that mean less stringent criteria for surgery eligibility,10 there is no sign that demand will recede in coming years, and orthopaedic services will soon be stretched to breaking point. With pressure to meet waiting list targets and maintain budgets, there is significant pressure on orthopaedic centres to reduce the amount of follow-up care.

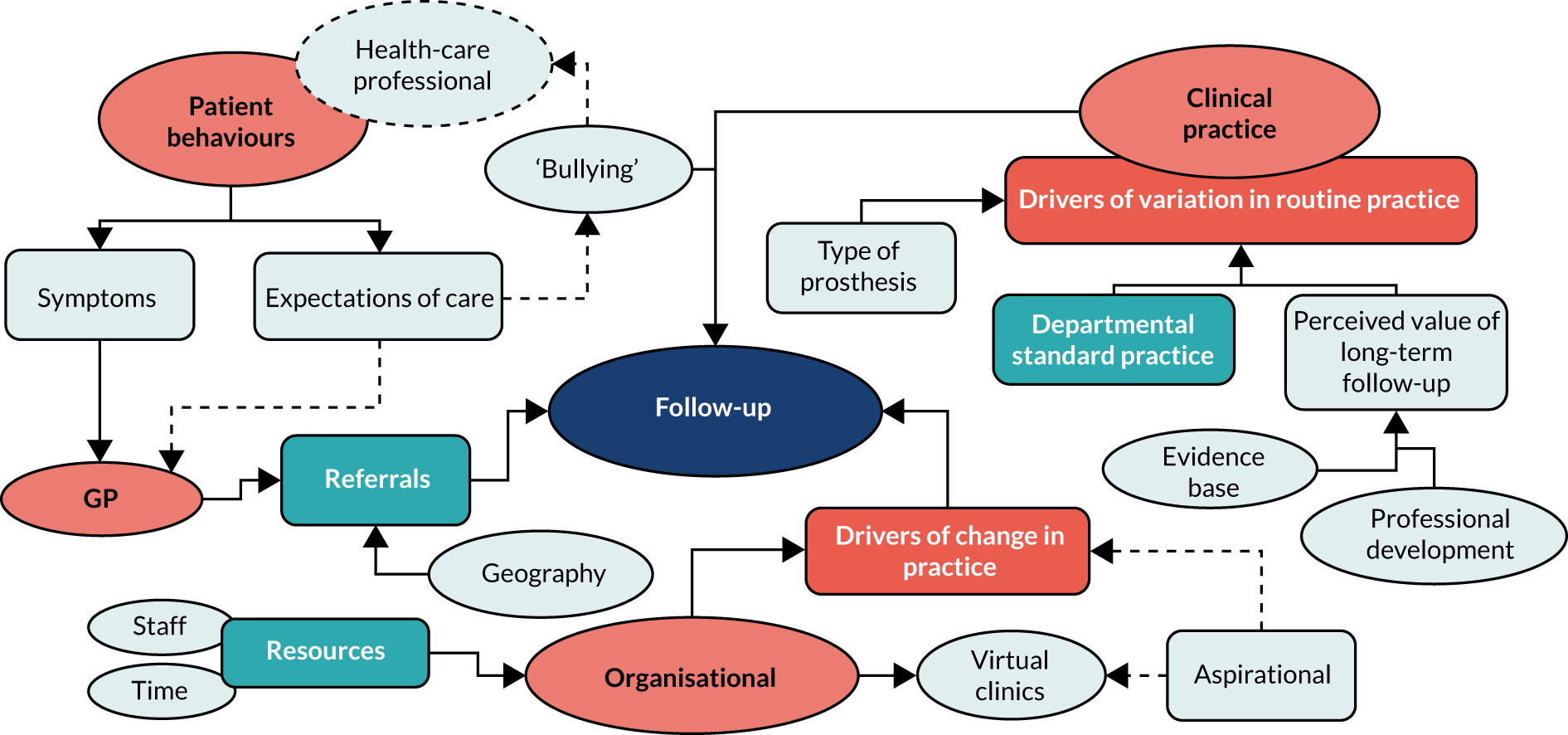

Our recent work identified considerable diversity across the UK with respect to arthroplasty follow-up pathways, in terms of timing, how follow-up is conducted and which health professionals are involved. This is despite British Hip Society [(BHS) London, UK] and British Orthopaedic Association [(BOA) London, UK] guidelines22,23 that recommend outpatient follow-up at 1 and 7 years and every 3 years thereafter for Orthopaedic Data Evaluation Panel 10A (ODEP-10A) implants, with more frequent follow-up for novel implants. Many centres do not have an established policy for follow-up. In some centres, follow-up services after an early postoperative check have been curtailed or stopped entirely, and this trend appears to be increasing, to cope with the demand on orthopaedic outpatient services. 24 However, there is no evidence base to support that such disinvestment is safe for patients. In contrast, other centres follow up all patients beyond 10 years. Importantly, many centres do not distinguish between hip and knee joints, using identical follow-up plans for both joints despite increasing debate regarding the considerable differences between rates of symptomatic and asymptomatic failure in these joints. Similarly, with the exception of metal-on-metal implants, follow-up plans do not take implant or patient-related factors into account. This wide variation causes problems in both directions. In centres where a full follow-up plan is followed for all patients, this potentially leads to unnecessary patient visits, unnecessary NHS expenditure and use of specialist time that may be better employed in other areas of the orthopaedic pathways. Moreover, follow-up may not be targeted at the postoperative period when failure is most likely to occur and may, therefore, not improve ability for early detection of joint failure. In centres where no follow-up is conducted, there is the potential risk of lack of sensitivity for detecting serious problems, resulting in subsequent unnecessary patient suffering and delayed care/treatment needs.

With pressure to reduce costs across the NHS, arthroplasty follow-up is under threat and disinvestment is likely to increase. Therefore, urgent work is required to determine the most cost-effective follow-up pathway to minimise potential harm to patients. This timely project aimed to examine the consequences, if any, of disinvestment in arthroplasty follow-up.

Evidence explaining why this research is needed now

Hip and knee replacement is one of the great success stories of medicine in the twentieth century. Sir John Charnley pioneered this work over 50 years ago. In the early days of this surgery, all patients were followed for life with annual radiographies. As the techniques became mainstream, the need for universal follow-up passed. The ‘optimal’ follow-up of these patients has never been established. Gradually, the orthopaedic community has drifted away from long-term follow-up, for no particular scientific reason, but driven by a variety of factors. However, sporadic cases of catastrophic failure of implants, for example the 3M™ Capital™ Hip System (3M Health Care Ltd, Loughborough, UK) and the metal-on-metal hip replacements, have awakened interest in follow-up. Appropriately, some of this has been driven by patients themselves, with a culture of patients knowing that there can be failure that is not associated with symptoms.

Current recommendations22,23 require updating, as they do not provide a consensus on follow-up times post surgery. A range of recommendations for post-arthroplasty follow-up has been published by different expert bodies, with varying evidence bases. Although the BHS provided updated guidelines in 2012, these guidelines were formulated by consensus, with limited evidence to support their advice. 22 For knee surgery, there is greater disparity, with different recommendations advising follow-up at varying times post surgery. 23 Our scoping searches revealed some effectiveness evidence25,26 for the range of clinical pathways and follow-up methods, and there is opportunity to include this in guidance. In addition to the limited evidence base for current recommendations, there are a number of further limitations to these guidelines. 22,23 Current recommendations are based on replacement technologies that have changed and, for the hip, do not reflect the shift in UK practice from cemented to uncemented femoral stems, with a twofold increase in cementless procedures since 2005. 9 With the exception of metal-on-metal procedures, which are covered by a mandatory Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA)-specified follow-up pathway, there is no recognition that specific technologies and implants may require different follow-up pathways. 22 For example, more frequent follow-up may be required for non-ODEP-10A implants. 22 Despite efforts to increase the use of ODEP-10A implants (the current gold standard), as recommended by NICE,27 there has been no significant change in the use of stems achieving the 10-year benchmark over the last 3 years. Current National Joint Registry (NJR) data suggest that 30–50% of stems/cups used across the UK have not been submitted for Orthopaedic Data Evaluation Panel (ODEP) evaluation and, therefore, follow-up pathways that account for an ODEP rating are pertinent. Current recommendations for follow-up also do not account for increasing surgical fitness of the ageing population or improvements in bone stock restoration at modern revision surgery.

In the current economic climate, and with increasing demand on NHS services due to an ageing multimorbid population and increasing consumer expectations, there is huge pressure for health authorities to consider priorities around investment and disinvestment and for implementation of rational evidence-based changes to practice. Given that current routine practice for post-hip and knee arthroplasty follow-up costs the NHS in the region of £100M per year, disinvestment in this service may be perceived as an easy cost-saving measure, enabling resources to be focused elsewhere. In addition to budgetary issues, there are many other factors that may affect decision-making around service planning in the NHS and that result in large variation across the UK as to how arthroplasty follow-up is conducted. These factors include staffing pressures, particularly as a result of the European Working Time Directive, which has reduced junior doctor support; the use of non-ODEP implants, testing and development of new implants, and involvement in beyond-compliance studies, which may result in more intensive follow-up regimes being implemented at individual centres; and presence (or indeed absence) of patient participant groups and their ability to engage with commissioners and have involvement in decision-making processes. We explored these factors within this programme, with particularly interest in the last factor and understanding how patients should be involved in care planning for orthopaedic follow-up.

The fact that research on follow-up is currently piecemeal further complicates the decision-making process and, importantly, means that current decisions to decommission, restrict, retract or substitute orthopaedic follow-up services lack an evidence base, and the impact of such changes to practice on long-term patient outcomes is unclear. Similarly, the benefits of more expensive regular follow-up of patients may be limited. Although we are aware that research is currently ongoing to evaluate new technologies for monitoring patients both at a distance and virtually to reduce the costs of hospital attendance, such monitoring technologies are themselves expensive, and before such technologies are employed into routine clinical practice an evidence base for arthroplasty follow-up must first be established. Proposals have also been put forward at government level to move orthopaedic follow-up away from secondary care and into the hands of general practitioners (GPs) and specialist nurses in the community. However, a recent study found that 77% of patients, 95% of GPs and 100% of orthopaedic trainees believed this to be inappropriate, indicating that such a move could cause potential harm to patients and would remove an important training opportunity for orthopaedic trainees to ensure that they acquire the appropriate skills to treat their patients safely. 28

It is imperative that follow-up takes into account a variety of factors, including implant type, the joint involved and patient factors, and that a decision to alter follow-up pathways considers the long-term impact on patients, health professionals and the NHS as a whole. Robust and collaborative research is required to definitively address the question of how hip and knee arthroplasty follow-up should be conducted. Key to this is ensuring that any decision to disinvest does not result in patient harm.

The need for this programme of research was further supported by a number of recent reports:

-

The 2012 Briggs9 report on improving the quality of orthopaedic care within the NHS in England states that all patients should receive appropriate follow-up to detect complications and disease recurrence early.

-

The Academy of Medical Royal Colleges29 recently highlighted the increasing pressure on the NHS to preserve standards of care in an environment of growing demand and increasingly constrained budgets. The report29 by the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges challenges the NHS to consider waste in terms of unnecessary use of clinical resources and low-value services. The report highlights the widespread overuse of tests and interventions that bring little benefit to patients, and, in some cases, may even do more harm than good (e.g. tests involving ionising radiation) and prevent NHS resources from being used to bring the best health outcomes to patients. Disinvestment in unnecessary procedures is a key step in focusing NHS spending, optimising health outcomes and improving patient care. However, the Academy of Medical Royal Colleges advises that such disinvestment must be based on robust evidence to ensure that the interest of the patient remains at the centre of NHS care. 29

-

Monitor30 recently highlighted an urgent need to identify mechanisms to close the NHS funding gap while ensuring that the interests of patients remain protected and that the standard of service provision is not compromised. Key areas for investigation within the Monitor30 report, and which this project is designed to address, include improving productivity within existing services, ensuring that the right care is delivered in the right settings, developing new and innovative ways of delivering health care and allocating spending more rationally. These areas directly align with the remit of the Health and Social Care Delivery Research programme.

-

In March 2014, the James Lind Alliance and National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) Priority Setting Partnership for Hip and Knee Replacement for Osteoarthritis listed defining the ideal postoperative follow-up period and the best long-term care model for people with osteoarthritis who have had hip/knee replacement among its top 10 research priorities,31 highlighting the importance of appropriate follow-up to ensuring the health of patients.

-

Since the commencement of the UK SAFE study, NHS England commissioned NICE to develop a clinical guideline on joint replacements. This guideline,32 which was published in June 2020, drew particular attention to the importance of rehabilitation, as well as long-term follow-up and monitoring after hip, knee and shoulder joint arthroplasty, but also highlighted the need for further evidence on follow-up.

During the development of this project, we discussed the issue of arthroplasty follow-up with key stakeholders, including orthopaedic surgeons, NHS managers, Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) managers, GPs and patients, as well as with all of the key orthopaedic societies. There was strong support from all stakeholders for the need for this programme of research. Orthopaedic surgeons expressed frustration that they no longer had the resources to appropriately follow up all of their patients and believed that decisions to change practice were often based on financial pressures rather than robust evidence. From a primary care perspective, GPs were keen to understand whether or not follow-up for knee/hip replacement was a cost-effective use of resources and what the potential impacts would be on patients. The CCG managers were keen to understand if savings could be made and whether or not these savings could be utilised to greater benefit in another area of the health economy. CCG managers were also keen to apply the learning from this study to local pathways. In addition, there was support for examining novel methods of follow-up, for example exploring the use of telephone-/questionnaire-based methods or, indeed, video consultations, if applicable, acknowledging that the traditional model of face-to-face follow-up may not always be cost-effective for the NHS or the patient (factoring in hospital-related expenses and travel and time costs). GPs and orthopaedic surgeons were also strongly supportive of engaging patients in the study. Of note, ensuring the perception of care for patients was felt to be a key factor and there was strong belief that disinvestment in arthroplasty follow-up services must not be supported without robust evidence that this would not have the potential to cause harm to patients.

Aims and objectives

Research question

-

Is it safe to disinvest in mid- to late-term follow-up of hip and knee replacement?

Objectives

-

To identify which patients need follow-up and when this should occur for primary total hip surgery and total and unicompartmental knee arthroplasty surgery by making use of routine data.

-

To understand the patient journey (in primary and secondary care) to revision surgery by recruiting patients admitted for elective and emergency hip and knee revision surgery.

-

To establish how and when patients are identified for revision surgery and to understand why some patients are missed from regular follow-up and present acutely with fracture around the implant [i.e. periprosthetic fracture (PPF)], by using prospective and retrospective data.

-

To identify the most appropriate and cost-effective follow-up pathway to minimise potential harm to patients by undertaking cost-effectiveness modelling.

-

To provide evidence- and consensus-based recommendations on how the follow-up of primary hip and knee joint replacement should be conducted.

Chapter 2 Cost-effectiveness of recovery pathways following primary hip and knee arthroplasty: a systematic review

Background

Despite the annual increment in hip and knee replacement procedures currently performed in the UK, largely due to an increasing elderly population, as well as the growing obesity epidemic,11 a number of NHS hospital trusts have reportedly disinvested in primary joint arthroplasty follow-up services as a means of dealing with the increasing pressure on their orthopaedic and other health-care services. 24 Against the continuing background of austerity in the UK and its impact on NHS-funded patient care, there is a clear need to evaluate and ascertain the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of follow-up clinical pathways in hip and knee arthroplasty. 33,34 It is within this context that the present systematic review aimed to assess the published evidence on follow-up care pathways for hip and knee joint replacement, including any evidence on cost-effectiveness.

Research questions

The overall aim of this review was to evaluate the existing evidence in relation to the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of follow-up care pathways for hip and knee joint replacement. Specific research questions were:

-

What is the clinical evidence base for current and emerging follow-up care pathways for hip and knee joint replacement and the consequences for patients?

-

What are the main follow-up care pathways for primary hip and knee replacement?

-

What is the cost-effective evidence for models of delivering follow-up to these patients?

-

What are the barriers to and facilitators of follow-up after hip and knee arthroplasty?

Methodology

Parts of this section have been adapted from Czoski Murray et al. 1 This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

This systematic review was conducted in accordance with the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) criteria. 35 The protocol for the present study was registered on PROSPERO (reference CRD42017053017) and has been published elsewhere. 1

Identification of studies

Between May and June 2017, and updated in June 2019 and April 2020, we conducted a world literature search, focusing on hip and knee arthroplasty follow-up care pathways studies. Searches were developed for hip or knee arthroplasty and follow-up care pathways or risks of complications, such as arthroplasty failures or revision surgery. We searched the following databases: Bioscience Information Service (BIOSIS) Previews® (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA; 1969 to week 26 2017), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature [CINAHL; via EBSCOhost (EBSCO Information Services, Ipswich, MA, USA); 1981–present], ClinicalTrials.gov (US National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD, USA), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (issue 5 of 12; May 2017), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (issue 6 of 12; June 2017), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effect (issue 2 of 4; April 2015), EMBASE Classic and EMBASE™ (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands; 1947 to 25 May 2017), Health Technology Assessment Database (issue 4 of 4; October 2016), Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) (1983–present), IDEAS (research papers in economics), Ovid® (Wolters Kluwer, Alphen aan den Rijn, the Netherlands) MEDLINE® Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, Ovid MEDLINE Daily and Ovid MEDLINE (1946–present), NHS Economic Evaluation Database (issue 2 of 4; April 2015), ProQuest® (ProQuest LLC, Ann Arbor, MI, USA) Dissertations & Theses Abstracts & Indexes (A&I) database (1743–present), ProQuest Dissertations & Theses database UK & Ireland, PsycInfo® (American Psychological Association, Washington, DC, USA; 1806 to week 4 May 2017), PubMed® (National Library of Medicine, Bethesda, MD, USA) (1946–present), Arts and Humanities Citation Index (Clarivate Analytics; via the Web of Science™) (1975–present), Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science (Clarivate Analytics; via the Web of Science) (1990–present), Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Social Science & Humanities (Clarivate Analytics; via the Web of Science) (1990–present), Sciences Citation Index (Clarivate Analytics; via the Web of Science) (1900–present), Social Sciences Citation Index (Clarivate Analytics; via the Web of Science) (1900–present) and Web of Science Core Collection: Citation Indexes (Clarivate Analytics) (1900–present) (see Appendix 1, Tables 20–35).

Subject headings and free-text words were identified for use in the search concepts by text analysis tools, including PubReMiner and medical subject heading (MeSH). Further terms were identified and tested from known relevant papers.

In addition, the reference lists of included studies were reviewed for potentially relevant papers. A sample search strategy and the databases searched are detailed in Appendix 1, Tables 20–35.

Selection of studies

Studies were included based on if they described follow-up care pathways after primary total or unicompartmental knee or total hip arthroplasty and if they (1) reported the benefits to patient and/or cost-effectiveness of arthroplasty or (2) involved planned elective revision or emergency revision and provided follow-up data after primary arthroplasty. All models of follow-up care were included. Any form of operating technique and prosthesis were included. No restrictions on language or study design were applied.

Studies were excluded if no total hip or total or unicompartmental knee arthroplasty was performed. We also excluded studies in which patient-reported outcomes [e.g. Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC®),36 Oxford Hip Score (OHS),37 Oxford Knee Score (OKS),37 Knee Society Clinical Rating System (KSS)38 and Harris Hip Score (HHS)]39 or clinical outcomes (e.g. joint range of motion and walking distance) were not reported. If a study did not explicitly report data (e.g. expert opinions, comments and editorials) or lacked follow-up information, then it was excluded. Similarly, we excluded studies that included fractures resulting from falls or trauma, rather than catastrophic failure of a previous hip or knee arthroplasty. Studies that included metal-on-metal arthroplasty were reviewed but excluded if there was no mention of non-metal-on-metal arthroplasty having been part of the study design. We also excluded ongoing studies, duplicate studies and studies with a follow-up of < 5 years, as the purpose of this study was to examine longer-term follow-up. Finally, studies that included patients aged < 18 years of age were also excluded.

Titles and abstracts of all identified studies were screened for eligibility, and full-text versions of papers not excluded at this stage were obtained for detailed review. 40 All abstracts were reviewed by one researcher (JM), with a random selection (20%) independently screened by a second reviewer (CJCM or KH). Potentially relevant studies were then independently assessed by three reviewers (JM, CJCM and KH) to determine whether or not they met the inclusion criteria. Differences of opinion were discussed until a consensus was reached, with clinical input from Lindsay K Smith. For the updated searches, the same process was undertaken by Carolyn J Czoski Murray and Byron KY Bitanihirwe.

Data extraction

Data extraction was carried out by one reviewer (JM) using a standardised pro forma and double-checked by another reviewer (BKYB). Extracted data included citation details, study design, location, patient characteristics, disease characteristics (e.g. osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis), type of arthroplasty (i.e. total or unicompartmental knee or total hip arthroplasty), joint details (i.e. fixation type and joint material), joint material (e.g. cemented, titanium, polyethylene), outcome measures, follow-up details and key findings. Assessment of bias was carried out as part of this process.

Assessment of bias

Quality assessment was carried out by one reviewer (JM) and double-checked by another reviewer (BKYB). When possible, studies were assessed using previously developed scoring systems. The Newcastle–Ottawa Scale was utilised for cohort and case–control studies. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) was used to evaluate the quality of mixed-methods studies. The ROBIS (Risk of Bias in Systematic Review) and AMSTAR (A MeaSurement Tool to Assess systematic Reviews) tools were used to assess risk of bias and quality of systematic reviews, respectively.

Studies at risk of bias were not excluded, but an appraisal of the strength of existing evidence is reported. Findings were interpreted in the light of this.

Data synthesis

Study characteristics and findings relating to clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness and study quality were summarised in narrative and tabular form. Data pooling for meta-analysis was not feasible because of study heterogeneity.

Overview

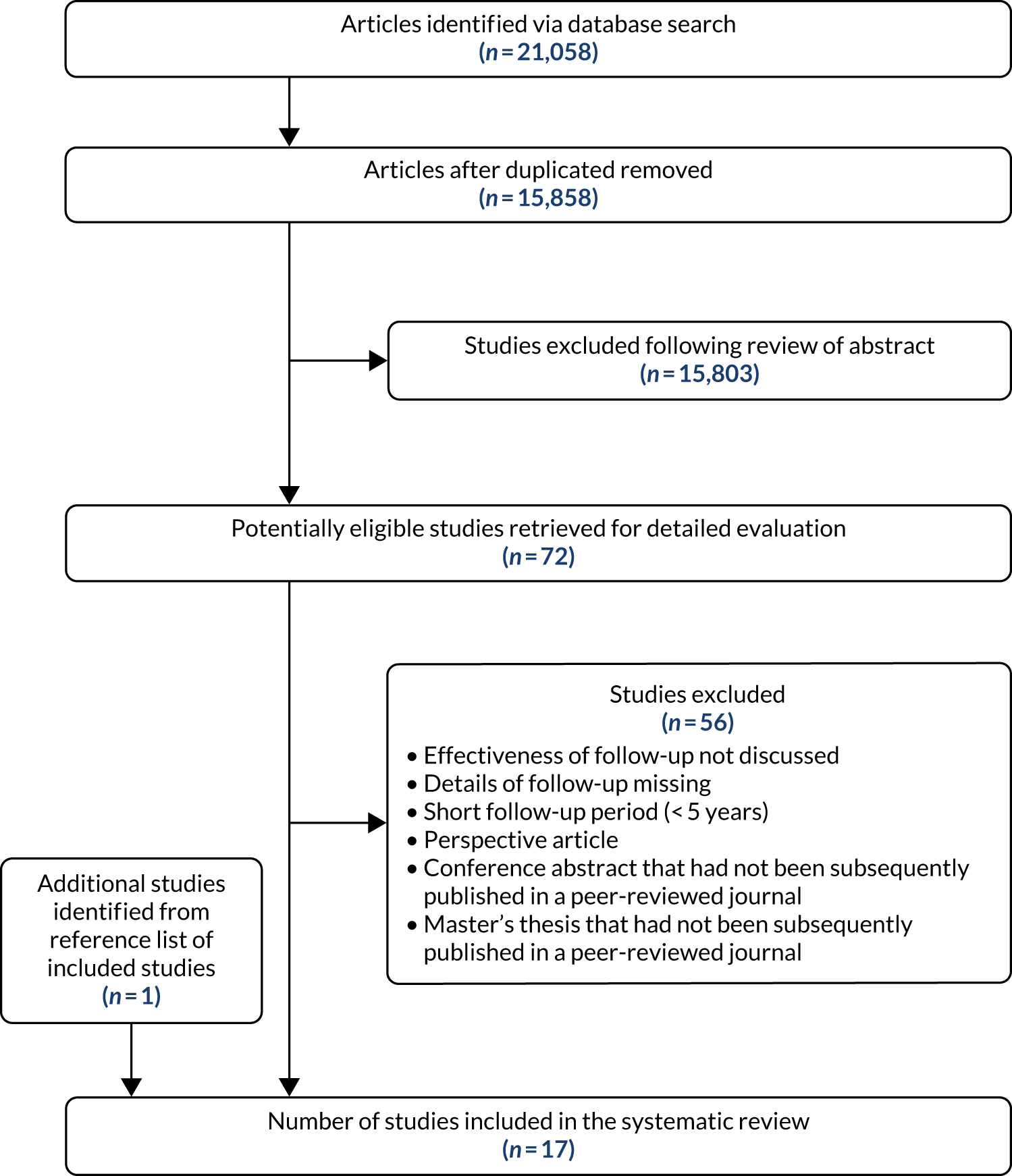

The search strategy identified 21,058 articles. There were 15,858 articles after duplicate articles were removed, of which 72 articles met the inclusion criteria and were subject to detailed review (Figure 1). We retrieved the full text of an additional paper that was identified from the reference list (i.e. snowballing) of the articles that met the inclusion criteria and included this study. In the end, 17 papers41–57 were included in the final analysis.

FIGURE 1.

A PRISMA flow chart.

Populations

Around a half of the studies were carried out in North America (n = 9),42,45,48–50,53–55,57 with the remaining studies emanating from Europe (n = 7)43,44,46,47,51,52,56 and Oceania (n = 1). 41 Just over two-fifths of the European studies were conducted in the UK (n = 4). 43,44,47,52 One study involved separate centres from two countries (i.e. Germany and Greece),56 whereas another was a systematic review of the world literature44 (Table 1). The sample size varied greatly between studies, ranging from tens of patients (range 12–82 patients; n = 3) to hundreds of patients (range 104–844 patients; n = 12). It was not possible to determine participant numbers in one study and another study (systematic review) comprised 17 separate studies (range 10–700 patients). The follow-up period in the study ranged from 5 to 14 years. Most papers were published in the last 10 years (n = 11).

| Continent/country | Number |

|---|---|

| North America | 9 |

| USA | 9 |

| Europe | 8 |

| Denmark | 1 |

| Greece | 1 |

| Germany | 1 |

| Sweden | 1 |

| UK | 4 |

| Oceania | 1 |

| Australia | 1 |

Outcomes and follow-up studied

Of the various areas evaluated in this review, 13 studies42,44–46,48–55,57 focused on the types of follow-up investigated and included the length of time of follow-up. Only one study56 specifically focused on determining cost-effectiveness.

Quality assessment

None of the included studies employed a controlled trial methodology, with 11 studies41,42,47–55 being case–control or cohort studies (Table 2). Eight studies41,47–49,52–55 involved retrospective data collection. Two studies41,42 involved review of medical records and/or analysis of data from prospective registry databases. A single study43 collected data using a questionnaire followed by semistructured interviews (i.e. sequential mixed-methods evaluation). Secondary analysis of data was conducted in an individual systematic review. 44 Patient satisfaction surveys, by questionnaire, direct mail, fax or telephone completion were also well represented in this study.

| Study design | Number |

|---|---|

| Descriptive survey (before and after) | 1 |

| Case–control | 2 |

| Cost–benefit analysis/cost estimation | 1 |

| Cohort | 9 |

| Cross-sectional | 2 |

| Systematic review | 1 |

| Sequential mixed methods | 1 |

One study56 involved multiple locations (in Germany and Greece) and has been included under each included country.

Risk of bias within studies

Twelve41,42,45–54 of the 1341,42,45–55 observational studies assessed were reported to have a low risk of bias, and one study55 was reported to have a moderate risk of bias. In a single study,56 the level of potential bias was unclear, as the premise of this study was a cost-effective analysis. In the only systematic review44 that was included in this study, there was a low risk of bias (according to the ROBIS tool58) and the study quality was deemed moderate (according to AMSTAR criteria59). One study,43 which applied a sequential mixed-methods approach evaluation, was rated as being of ‘considerable’ quality according to the MMAT (with a MMAT score of 75%). Both of the case–control studies,50,51 which were retrospective, were rated as being low for potential bias (both scored 7/9). Similarly, nine cohort studies41,42,47–49,52–55 (eight retrospective) were rated as having low potential for bias (median 8; range 7–9).

None of the studies received funding from commercial device companies.

Results

Clinical effectiveness of follow-up care pathways

The main treatment goals of joint arthroplasty are to reduce pain, improve function and increase quality of life. 18 The primary outcomes of interest can be measured by a range of established tools, including WOMAC,36 OHS,37 OKS,37 KSS38 and HHS. 39 Thirteen41–43,45–50,52,53,55,56 of the 17 studies identified here as evaluating the clinical effectiveness of follow-up of hip and knee replacement surgery applied such a tool. Three studies41,46,53 did not specify which tool was used, although the authors stated that the tool had previously been validated in patients who had undergone hip or knee replacement. Two studies45,47 used a combination of tools, whereas four studies44,51,54,57 did not apply any tools. Seven studies43,45,47–50,56 evaluated patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), such as EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L), Short Form questionnaire-6 Dimensions (SF-6D), WOMAC, KSS, OKS and OHS, in relation to hip or knee replacement, whereas three studies42,44,54 utilised clinician-based outcome measures, including HHS scores to assess joint functionality (see Appendix 1, Table 36).

Synthesis of these findings reveals that both pain and functional ability at follow-up in individuals who have undergone primary hip or knee arthroplasty serve as important indicators for detecting emerging signs of implant failure. Indeed, in a cohort study conducted by Singh et al. 42 it was reported that both absolute HHS postoperative scores and HHS score change at up to 5 years post surgery are predictive of revision risk after primary THR. This does not, however, extend to longer-term post 5-year revisions. In another study50 that utilised patient records in conjunction with internet search techniques – so as to locate patients who had not returned for follow-up after total knee arthroplasty – it was found that there was no difference between patients who had and those who had not attended follow-up appointments at a minimum of 5 years post operation. Specifically, assessments of pain and function according to the KSS tool were found to be similar between these groups, and no patient who had not attended follow-up appointments had required revision surgery. 50 Interestingly, one study47 observed that radiographic changes of the hip prosthesis at mid-term review (i.e. 6–9 years of follow-up) could not be predicted by changes in the OHS. This evidence refutes the suggestions that adequate surveillance can be achieved with the use of PROMs alone and emphasises the importance of including radiographic review in the follow-up of hip arthroplasty. 52

In two studies48,49 that considered quality of life in the context of follow-up joint replacement surgery, postoperative SF-6D60 scores at follow-up were significantly higher than the original preoperative scores, although no relevance was drawn to the use of this health index for identifying individuals requiring revision replacement surgery. In another study that examined radiographic changes in the hip prosthesis at follow-up in conjunction with the EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D)61 (i.e. a standardised instrument for use as a measure of health outcome and currently recommended by NICE62), no significant differences were reported in the participants’ perception of quality of life,47 suggesting that use of this instrument alone may not be useful in identifying individuals requiring revision hip or knee replacement surgery.

In the only systematic review44 included in this study, which focused on identifying surrogate markers of long-term outcomes in primary hip arthroplasty as a means for monitoring the status of prosthetic implants, it was found that radiostereometric analysis (RSA) and Einzel-Bild-Röntgen-Analyse are effective for measuring implant migration and wear. 44 Attention was brought to the fact that, although both of these techniques can detect migration and wear of the implant, which can be used to predict early prosthesis failure due to aseptic loosening, unfortunately they cannot effectively detect other modes of implant failure.

Care pathways for primary knee and hip replacement

A total of five studies41,43,45,51,54 was identified that described a care pathway through which patients were brought in for hip and knee replacement surgery. In two of these studies,45,51 only individuals undergoing elective revision knee or hip replacement surgery were included. In contrast, a third study41 included patients who had decided to undergo elective follow-up of primary hip arthroplasty in addition to patients who had presented to the emergency room. The main indications for revision hip replacement surgery comprised aseptic loosening, dislocation, PPF, osteolysis and infection, with only a small fraction of individuals presenting for asymptomatic revisions. 41 Loosening and instability of the knee prosthesis represented the principal indications for revision knee replacement surgery. 54 In the last study, Parkes et al. 43 developed a virtual clinic model that allows for long-term monitoring and screening of symptomatic patients by clinicians, using web-based outcome scores (i.e. PROMs) and radiographs as a care pathway through which individuals can be directed to hip and knee replacement. Although the virtual clinic process appeared to be well accepted by patients and to provide cost savings (by freeing up face-to-face clinic capacity), a key concern was the difficulties encountered in using the system and the need for clear pathways to address this concern.

Cost-effectiveness of follow-up

A single study56 considered cost-effectiveness in terms of long-term follow-up care after total joint arthroplasty. This study56 applied a cost–benefit analysis to compare a virtual mobile-based health-care system [i.e. providing follow-up for primary arthroplasty patients through questions about symptoms in the replaced joint via tools, including WOMAC36 and Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36),60 and through a radiological examination of knee or hip joint], with the traditional way of supporting follow-up in terms of health-care and travel costs per patient (per annum). The results of this study indicated significant cost savings (i.e. a reduction of 63.67% in relation to a re-admission rate of 5%) in the standard health-care total cost of all hip and knee replacements when the mobile-based health-care system is applied. 56 Other relevant research by Kingsbury et al. ,52 which focused on the value of an outpatient clinic, using radiograph review in conjunction with a questionnaire as a potential cost-effective total hip and knee ‘virtual clinic’ follow-up mechanism, found a substantial agreement between a questionnaire and radiograph reviewed remotely by an orthopaedic surgeon and an arthroplasty care practitioner-led outpatient follow-up in terms of clinical decision-making. In a separate study conducted by Stilling et al.,51 which applied a cost-analysis approach comparing assessment techniques for measuring the level of polyethylene that is worn away following hip arthroplasty, it was shown that follow-up with PolyWare software (Draftware Developers Inc., North Webster, IN, USA) has a clinical precision similar to that of RSA, but is less expensive. In the context of the present study, although PolyWare software is not commonly used in the UK, RSA, in contrast, can be used for follow-up assessment of orthopaedic implants, although this is not practical in routine follow-up. 63

Barriers to and facilitators of referral pathways

Although consensus recommendations for knee and hip arthroplasty follow-up in the USA has favoured annual or biennial visits following surgery,57 this is not commonly the case in a global setting. Indeed, it is appreciated that factors such as age, education and geographical locality, as well as socioeconomic circumstances, represent significant barriers to patient follow-up. 45,50,55 However, advances in novel and emerging cost-effective methods (e.g. virtual clinics or virtual consultations) have been suggested to facilitate the early identification of patients who may benefit from revision hip or knee arthroplasties. 43,52,56

Discussion

This systematic review provided an insightful perspective into the existing evidence dealing with follow-up of individuals who have undergone primary hip or knee arthroplasty and how these individuals are identified and referred for revision of a prosthesis before it causes significant impact on their health and quality of life. Our findings, although limited by the existing evidence, suggest that patient-specific outcome scores, such as SF-36 and EQ-5D-3L, following joint arthroplasty can help in identifying individuals for whom the prosthesis is starting to fail at follow-up,42 and that the use of such approaches during routine follow-up may prove to be cost-effective. 56 However, conclusive evidence as to the clinical benefit and cost-effectiveness of this process remains scarce.

Although the benefits of hip and knee replacement surgery are widely accepted,18 there are still considerable gaps in our knowledge regarding follow-up after joint replacement surgery, and the limitations of the current state of research needs to be highlighted. In this regard, of the 17 studies identified herein, few involved a clear focus on, or description of, the care pathway (i.e. elective vs. emergency surgery) or comparison in terms of the way in which individuals were identified for revision surgery. 41,45,54 In a similar context, only one study56 drew specific attention to the cost-effectiveness of routine follow-up after primary joint arthroplasty surgery. Few studies considered quality of life (e.g. SF-6D and EQ-5D-3L) in the context of helping to identify individuals for whom the prosthesis was starting to fail. 47–49 Unfortunately, more quality-of-life studies have tended to focus on the preoperative and postoperative benefits to patients. However, one study47 assessed radiographic changes in the hip prosthesis at follow-up in conjunction with the EQ-5D-3L health questionnaire and reported no significant differences in the patients’ quality-of-life scores.

Given that the majority of the work identified here stemmed from observational studies, it was possible to grade the quality and robustness of this evidence. Notably, 1241,42,45–54 of the 1341,42,45–55 observational studies assessed were reported to have a low risk of bias, with one study55 reported as having a moderate risk of bias. Similarly, for the only systematic review44 that was included in this study, there was a low risk of bias (according to the ROBIS tool58) and the study quality was deemed to be moderate (according to AMSTAR criteria59). Taken together, this information would suggest that the studies included in the present systematic review are methodologically sound.

The number of revision joint arthroplasties carried out in the UK is projected to rise over the next few decades because of an increased incidence of primary hip and knee arthroplasties, as well as an expansion of the indications for joint arthroplasty, such as obese patients, younger and more active patients, and limitations of implant longevity. 11 Therefore, it is important to establish whether or not follow-up is cost-effective if a particular model of care is preferred. Unfortunately, the lack of information and research on how people are identified and referred for revision of a prosthesis before it causes significant impact on their health and quality of life makes it difficult for clinicians and policy-makers to draw a solid conclusion on this matter. In this context, follow-up services after joint arthroplasty have the potential to deliver significant costs savings and to improve patient satisfaction for the NHS. Gathering this information is key and must be reported in future studies to identify best practice and to support decision-making.

Follow-up appointments after primary joint arthroplasty are commonly recommended by orthopaedic surgeons, even if the patient should be asymptomatic. 57 The key purpose of routine assessment of asymptomatic patients is to detect early signs of implant failure so as to guide recommendations for early intervention. 18,57 Some of the factors known to feed into this decision-making process include aspects such as the implant design, surgical technique, patient age, activity level, BMI, revision arthroplasty, bone quality, a history of joint sepsis and other underlying disease processes. 64,65 Because early signs of failed total joint arthroplasty have been suggested to include an increase in pain or a decrease in joint function,64,66 patients who present with these symptoms may require revision joint arthroplasty. 64,66 With this in mind, being able to identify preoperatively which patients may wish to undergo routine postoperative visits, as opposed to those who would prefer less frequent follow-up intervals, may allow for a strategic implementation in which health-care costs can be reduced while simultaneously improving patient satisfaction.

Conclusion

With the significant rise of primary hip and knee replacement surgeries in the UK, an understanding of implant survival patterns and reliable clinical outcomes for detecting emerging failure are necessary to facilitate the timely identification of need for revision. 11 Against this background, the main emphasis of the present systematic review was to investigate the follow-up of individuals who have undergone primary hip or knee arthroplasty and to establish how they are identified and referred for revision of a prosthesis. Similarly, a key focus was placed on establishing the cost-effectiveness of follow-up visits after primary total joint arthroplasty. It should be noted that the development novel cost-effective methods for hip or knee arthroplasty follow-up (e.g. virtual clinics) will potentially assist in facilitating the identification of patients who may benefit from revision surgery. 67

Similarly, beyond structural changes to the care pathway and incentives to support surgeons in providing preoperative education to patients and promoting follow-up, additional research will be required to accurately determine the cost-effectiveness of follow-up visits and how many patients must be seen routinely as a means of obviating total joint failure.

Limitations

Despite the important observations made in this systematic review, some notable limitations must be acknowledged. First, heterogeneity among the included studies prevented a meta-analysis from being performed. Second, only 443,44,47,52 of the 1741–57 studies included in this review stemmed from the UK. Unfortunately, the UK referral data do not provide all information in terms of the case mix of patients and, as such, it is difficult to ascertain which individual factors have an impact on patient referrals. In the broader literature, several patient factors were identified as being predictive of follow-up after primary joint arthroplasty, including age, education, geographical locality and socioeconomic circumstances. 45,50,55 Third, despite an extensive search yielding more than 10,000 unique records, we cannot guarantee that our search was completely exhaustive of the relevant literature. However, having searched a multitude of sources, including those containing grey literature, as well as reference lists of all included articles, we are fairly confident to have included all available relevant studies. Last, more research is needed in relation to prospective multicentre randomised studies to determine the cost-efficacy of clinical pathways to patients who need to undergo hip and knee replacement.

Recommendations

Additional research is needed that focuses on recovery pathways following primary hip and knee arthroplasty to accurately determine the cost-effectiveness of follow-up visits and how many patients must be seen routinely to minimise complicated joint failure.

There is a paucity of literature correlating quality of life with follow-up after arthroplasty of the hip and knee. Conducting further research with regard to predicting long-term risk of prosthetic failure in the context of quality of life is, therefore, recommended;68 for instance, further assessment of the EQ-5D-3L in relation to primary hip and knee arthroplasty, given that this instrument is widely used by health economists and it is the preferred measure of health-related quality of life (HRQoL) by NICE. 69 However, it should be emphasised that EQ-5D-3L responses do not necessarily reflect the entirety of individual patient impact from a joint replacement. 68

Carrying out more research on morbidity and mortality following revision surgery, in addition to conducting case studies to determine what key aspects and factors individuals who have undergone primary hip or knee arthroplasty feel are important to them with regard to the follow-up process, is recommended. Routinely collected NHS data together with registry data may contribute to greater understanding.

Chapter 3 Analysis of routine NHS data 1: CPRD–HES and NJR–HES–PROMs

Parts of this chapter have been adapted from Smith et al. 70 This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Parts of this chapter have been adapted from Smith et al. 71 This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

What does analysis of routine NHS data tell us about mid- to late-term revision risk after hip and knee replacement?

Aims

The aim of this chapter is to identify which patient groups require follow-up based on their mid- to late-term revision risk (i.e. ≥ 5 years post primary surgery). We used national linked data from primary care [i.e. Clinical Practice Research Datalink (CPRD)] and secondary care [i.e. NJR and Hospital Episode Statistics (HES)] to identify predictors of mid- to late-term revision.

Methods

Parts of this section have been adapted from Czoski Murray et al. 1 This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to copy, redistribute, remix, transform and build upon this work for any purpose, provided the original work is properly cited, a link to the licence is given, and indication of whether changes were made. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Study design

This was nationwide retrospective cohort study.

Setting and source of data

CPRD–HES

The CPRD comprises the entire computerised medical records of a sample of patients attending general practices in the UK. 72 The CPRD contains information on more than 11 million unique patients (i.e. around 7% of the UK population) registered at over 600 general practices in the UK. With 4.4 million active (i.e. alive and currently registered) patients meeting quality criteria, approximately 6.9% of the UK population are included, and patients are broadly representative of the UK general population in terms of age, sex and ethnicity. 73,74 GPs in the UK play a key role in the delivery of health care by providing primary care and referral to specialist hospital services. Patients are registered with one practice that stores medical information from primary care and hospital attendances. The CPRD is administered by the MHRA. The CPRD records contain all clinical and referral events in both primary and secondary care, in addition to comprehensive demographic information, prescription data and hospital admissions data. Data are stored using Read and Oxford Medical Information Systems codes for diseases that are cross-referenced to the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10). Read codes are used as the standard clinical terminology system within UK primary care. Only practices that pass quality control are used as part of the CPRD database. Deleting or encoding personal and clinic identifiers ensures the confidentiality of information in the CPRD.

The CPRD GOLD data were linked to the HES database. CPRD already provide access to the HES data that are held under the CPRD Data Linkage Scheme. CPRD and HES-linked data are available for around 50% of patients in the CPRD database. Previous research by the CPRD team has shown that linked practices/patients are representative of the CPRD GOLD population as a whole. 73

NJR–HES–PROMs

Starting in 2003, the NJR has collected information on all hip and knee replacements performed each year in both public and private hospitals in England, Wales, Northern Ireland and the Isle of Man. Data are entered into the NJR using forms completed by surgeons at the time of surgery and revision operations are linked using unique patient identifiers. Data recorded in the NJR includes prosthesis and operative information (e.g. prosthesis type, approach and thromboprophylaxis use), patient information [e.g. age, sex, BMI and American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) grade] and surgical and unit information (e.g. surgeon and unit caseload and public/private status).

The HES database holds information on all patients admitted to NHS hospitals in England, including diagnostic ICD-10 codes providing information about a patient’s illness or condition and OPCS Classification of Interventions and Procedures version 4 (OPCS4) procedural codes for surgery. HES include episodes of care delivered in treatment centres (including those in the independent sector) funded by the NHS, episodes of care in England when patients are resident outside England and privately funded patients treated within NHS England hospitals. HES cover a smaller geographical area than the NJR (excluding patients operated on in Wales and Northern Ireland) and do not include privately funded operations. However, HES provide additional information for every patient (including detailed comorbidity information and deprivation indices) and about every procedure (including LOS and need for blood transfusion or critical care). Additional records contain details of readmissions, reoperations and revisions not recorded in the NJR database. Data for all-cause mortality are provided by the Office for National Statistics (ONS) and are linked to the HES database.

Since April 2009, PROMs data have been collected on hip and knee replacements performed in public hospitals in England. Preoperative and 6-month postoperative quality-of-life questionnaires (i.e. the EQ-5D75) and joint-specific PROMs (i.e. the OHS76 and OKS77) are collected along with patient-reported measures of preoperative disability and postoperative satisfaction. For this analysis, we used NJR records linked to data from the HES and PROMs databases on all hip and knee replacement operations.

Participants

Anonymised records were extracted for all patients aged ≥ 18 years receiving primary hip or knee replacement surgery. For CPRD–HES data, the time span covers the years 1995–2016. For NJR–HES–PROMs data, the time span covers the years 2008–16. Patients were included if they had primary THR or TKR, primary hip resurfacing (metal-on-metal hip resurfacing) or UKR. We excluded patients who had revision surgery and total joint replacement (TJR) of unspecified fixation. The following exclusions were made to remove potential case mix issues: diagnostic codes indicating fracture or cancer of the hip bones, other injuries due to trauma (e.g. transport accidents and falls), non-elective admissions and a diagnosis other than primary hip/knee osteoarthritis. There was overlap between patients in the two data sources (e.g. around 7% of patients receiving knee replacement between 2009 and 2016); however, these anonymised data sets were analysed independently of each other.

Primary outcome

Early (defined as < 5 years after surgery) complications are often symptomatic and include infection and technical errors. 20 Arthroplasty failure in the longer term (defined as after 5 years), constituting 50% of revision surgeries, is usually caused by bearing surface wear and associated consequences of periprosthetic osteolysis or aseptic loosening, and may be asymptomatic until clinical and radiographic failure have occurred. 20,21 The primary outcome was defined as mid- to late-term revision (defined as > 5 years post primary surgery). Revision is defined as the removal, exchange or addition of any of the components of arthroplasty.

In the NJR–HES–PROMs-linked data sets, operative details are completed using the NJR data set, rather than the OPCS4 coding used by the HES data set. The NJR collects operative data using two forms, one for primary operations and the other for revision operations [and both are available via URL: www.njrcentre.org.uk (accessed 10 February 2022)]. In both cases, all component labels from the surgery are attached to the form and it is from these that the component details were collected. Revision operations were linked to primaries using unique patient identifiers and so two operations on the same knee/hip would be linked using this system. The combination of the separate coding at source and the secondary linkage to revision procedures gave confidence that primary and revision operations were correctly identified. In the CPRD data set, patients with a revision surgery procedure were identified using the Read/Oxford Medical Information Systems codes and OPCS4 codes could be used for those with HES-linked data.

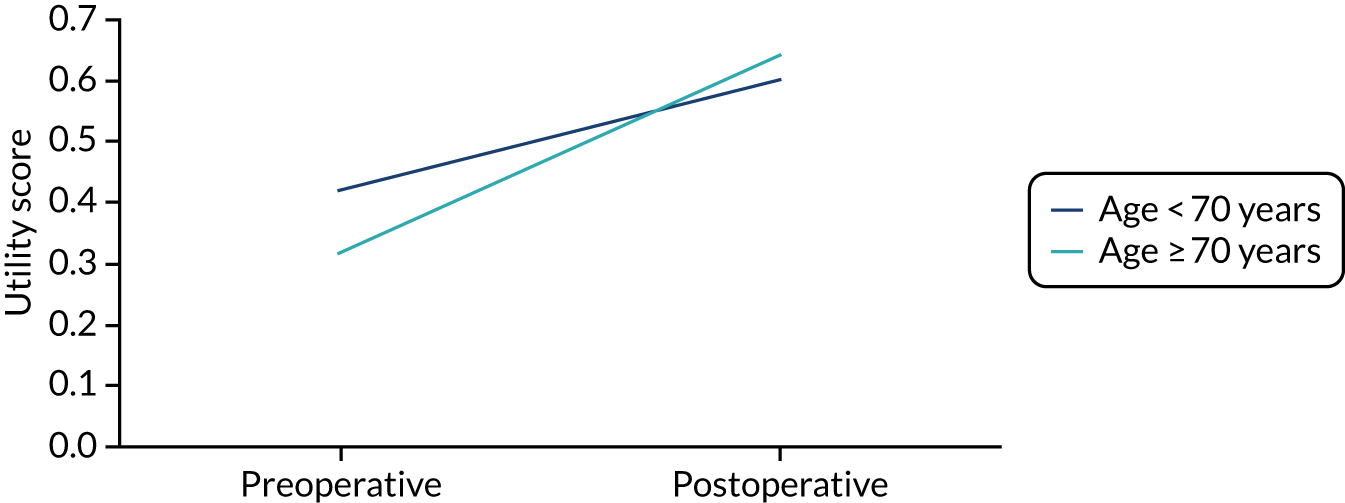

Exposures

Secondary care predictors

Patient-level characteristics available in NJR and HES include age, sex, BMI, area deprivation, rurality, ethnicity, Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI)78 (calculated from HES using ICD-10 codes at the time of admission for surgery) and ASA grade. Data from the NJR provided additional information on surgical and operative factors, including whether or not a minimally invasive technique was used, annual surgeon volume/caseload, operative time, grade of operating surgeon, surgical approach, patient position, implant fixation, type of mechanical or chemical thromboprophylaxis and unit type (e.g. public, private, independent sector treatment centre). Data from the PROMs database provided additional information on symptoms of pain, function and HRQoL preoperatively and at 6 months post surgery. Pain and function were measured using the OHS and OKS. The EQ-5D consists of five questions (assessing mobility, self-care, ability to conduct usual activities, degree of pain/discomfort and degree of anxiety/depression), ranging from 1 (no problem) to 3 (severe problems). The EQ-5D can be expressed as a preference-based overall index (graded from –0.594 to 1) or as ordinal responses for each category. Preoperatively, patients rate their general health on a five-point Likert scale, from very poor to excellent, and are asked to report if they considered themselves to suffer from a disability (yes or no).

Primary care predictors

The CPRD database includes information on age, sex, BMI, joint replaced (hip/knee), year of joint replacement operation, recorded diagnosis of osteoarthritis (yes/no), fracture pre surgery (yes/no), calcium and vitamin D supplements, use of bisphosphonates, use of selective oestrogen receptor modulators, oral glucocorticosteroid therapy, smoking status and alcohol intake recorded closest to the date of the primary surgery, Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD), region of UK, comorbid conditions (i.e. asthma, malabsorptive syndromes, inflammatory bowel disease, hypertension, hyperlipidaemia, ischaemic heart disease, stroke, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, chronic kidney failure, neoplasms and diabetes) registered by the physician and use of drugs that can affect fracture risk (e.g. proton pump inhibitors, antiarrhythmics, anticonvulsants, antidepressants, anti-Parkinson drugs, statins, thiazide diuretics and anxiolytics).

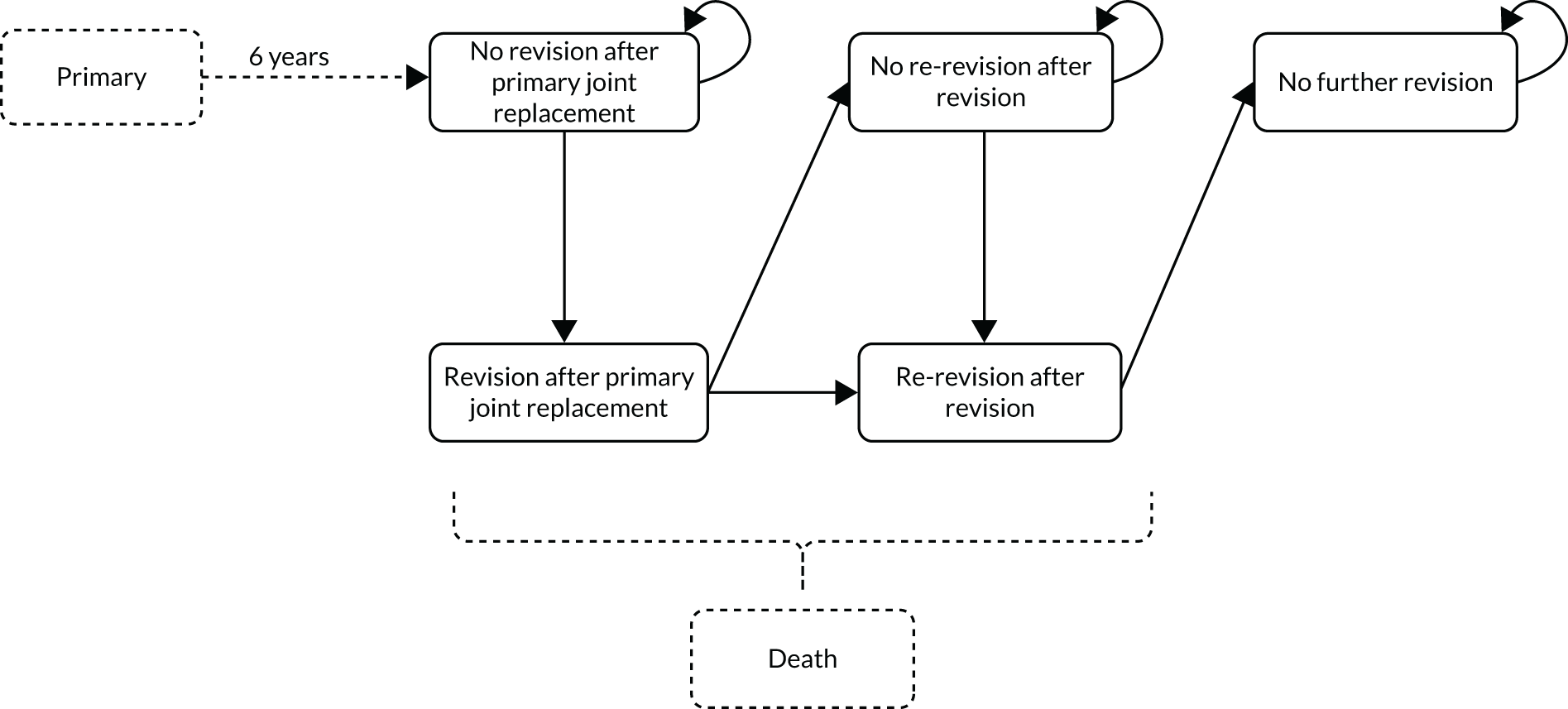

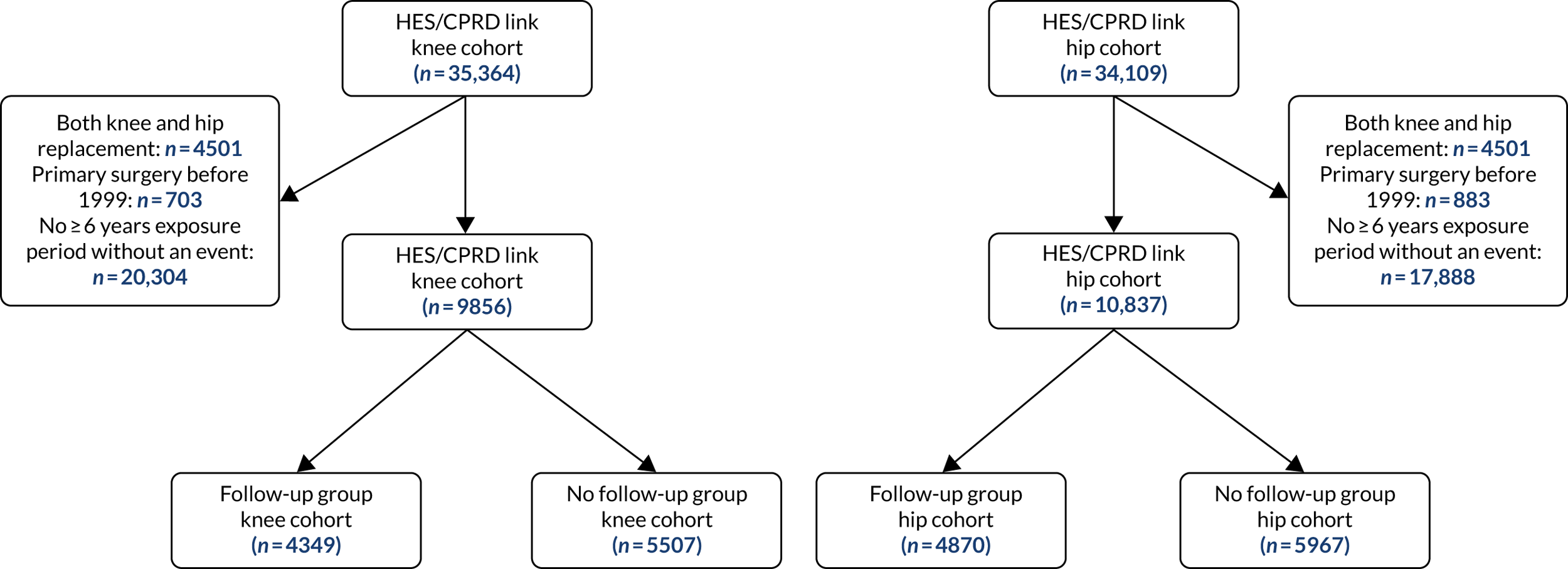

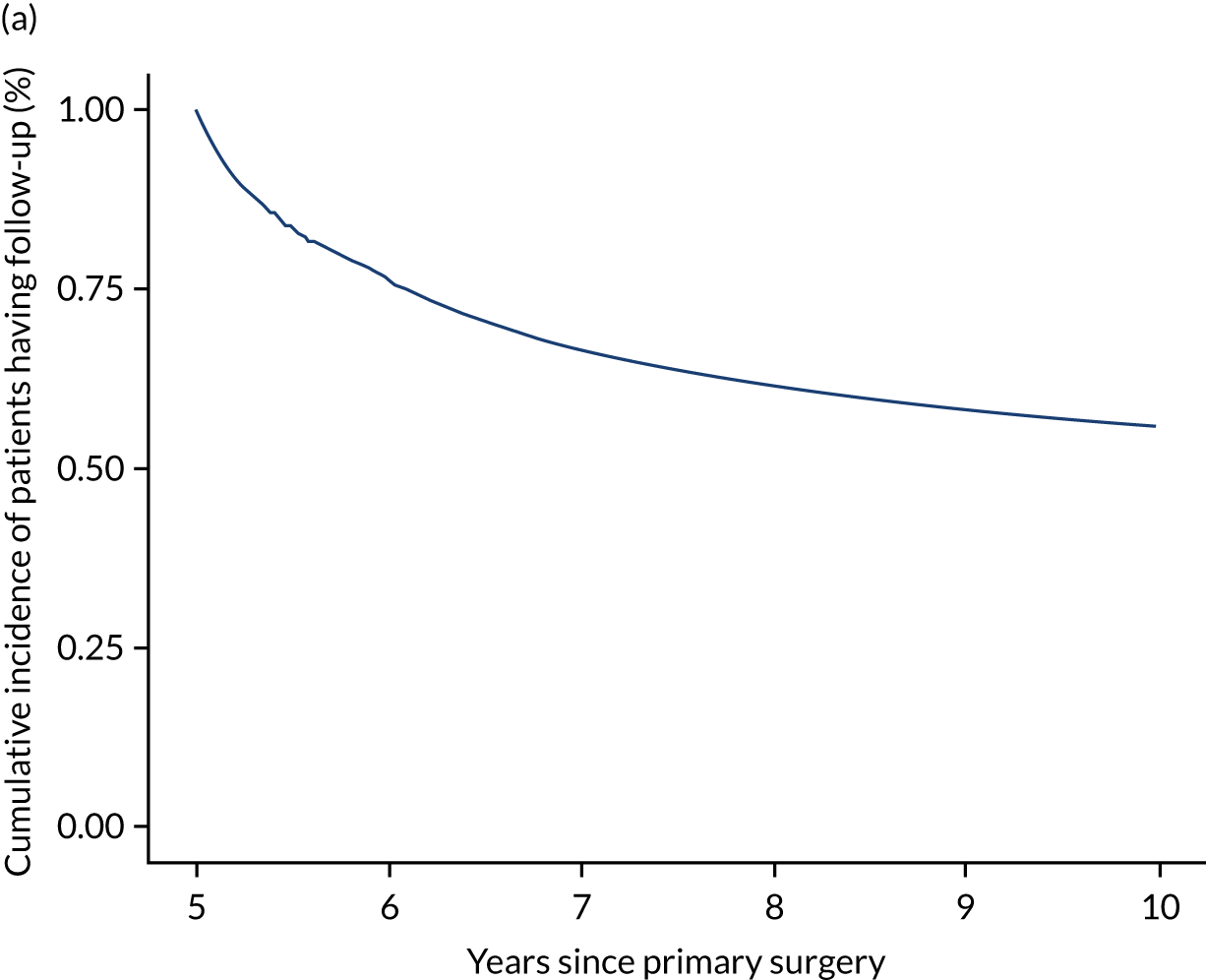

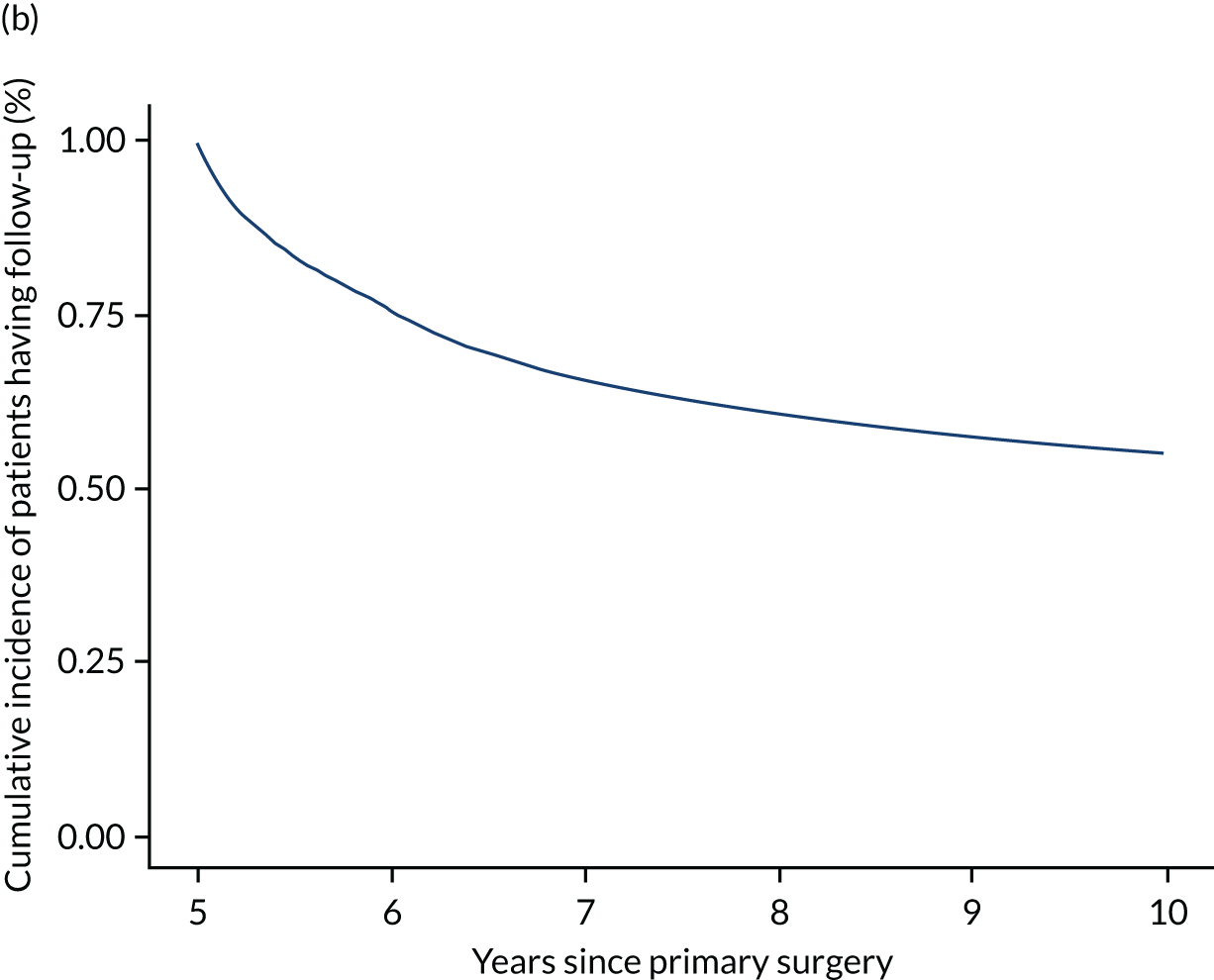

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included only patients receiving planned elective primary surgery for hip and knee osteoarthritis (Figures 2 and 3). For the NJR–HES–PROMs data, this covered the years 2008–16 (as our requested linked HES data were from 2008 onwards and earlier years of data were not available to us). For the CPRD–HES data, this time frame spanned the years 1995–2016. For both data sets, we excluded patients receiving a primary joint replacement after 2011 to ensure that all patients had at least 5 years of follow-up, as we were interested in revisions occurring 5 years after the primary replacement surgery.

FIGURE 2.

Flow diagram showing selection of patients for inclusion in this study.

FIGURE 3.

Flow diagram showing selection of patients for inclusion in this study (hospital data).

Statistical methods

Survival analysis was used to model time to revision. To identify patients most likely to require revision, proportional hazards regression modelling was used to identify pre, peri and postoperative predictors of mid- to late-term revision. The date of a patient’s first hip or knee replacement was used as the start time. The event of interest in all time-to-event models was the first recorded revision operation.

Linearity of continuous predictors was assessed using fractional polynomial regression modelling. Proportionality assumptions were checked using Shoenfeld residuals. Missing data were handled by using multiple imputation methods using the imputation by chained equations procedure. 79 Standard errors were calculated using Rubin’s rules. We included all predictor variables in the multiple imputation process, together with the outcome variable (i.e. Nelson–Aalen estimate of survival time and whether or not the patient had the outcome), as this carried information about missing values of the predictors. Analyses were conducted separately for hip and knee arthroplasty.

For the CPRD–HES primary care data set, 10 imputed data sets were generated for THR and knee replacement, respectively. Data were imputed for the variables BMI, deprivation index, smoking status and drinking risk factors. For the NJR–HES–PROMs secondary care data set, a single imputed data set was generated for THR and knee replacement, respectively. Imputed variables were BMI, deprivation index, rurality, ethnicity, OHS/OKS baseline scores and EQ-5D item for anxiety and depression. Data were imputed for type of primary cup fixation, type of primary stem fixation and bearing surfaces for the THR model. Univariate Cox regression models were run. Risk factors with a p-value of < 0.20 were selected for multivariable models. Backward selection of variables was used to identify variables to keep in the final model, in which risk factors were included with at least one category with a p-value of < 0.05. For the CPRD–HES primary care data set, we present two final models, one with medication use as yes/no variables and the other model with defined daily doses (DDDs) calculated from the 1 year prior to the primary surgery and divided in tertiles. In addition, we conducted sensitivity analyses using a Fine–Gray competing risk model to account for the competing risk of death.

Data applications

NJR–HES–PROMs-linked data

In the NJR, before personal data and sensitive personal data are recorded, express written patient consent is provided. The NJR records patient consent as either ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘not recorded’. With support under Section 251 of the National Health Service Act 2006,80 the Health Research Authority (HRA) Confidentiality Advisory Group (CAG) allows the NJR to collect patient data when consent is indicated as ‘not recorded’. Approval for NJR data was received on 3 October 2016 (NJR internal reference ‘Is it safe to completely disinvest in TJR follow-up or will this expose people to harm?’). CAG Section 251 approval was received on 24 February 2017 (CAG reference 17/CAG/0030). A Data Access Request Service (DARS) application was made to NHS Digital (formally known as the Health and Social Care Information Centre) for HES and PROMs data to be linked to data from the NJR. This was approved, with the data-sharing agreement signed by NHS Digital on 4 July 2018 and by Oxford University Research Services on 31 July 2018.

CPRD–HES linked data

The CPRD has ethical approval from the National Research Ethics Service (NRES) for all anonymised, observational research. The study was approved by the Independent Scientific Advisory Committee (ISAC) for Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) database research (protocol number 11_050AMnA2RA2).

Data summary

A team of clinicians has supported us in defining code lists for variables based on ICD-10 diagnosis codes, including OPCS4 operation codes, Read codes for GP consultations and product/British National Formulary codes for medications. The team has worked closely with the data manager in resolving queries and checking codes. All data sets were made ready as ‘flat’ files for statistical analysis.

Results

Descriptive statistics

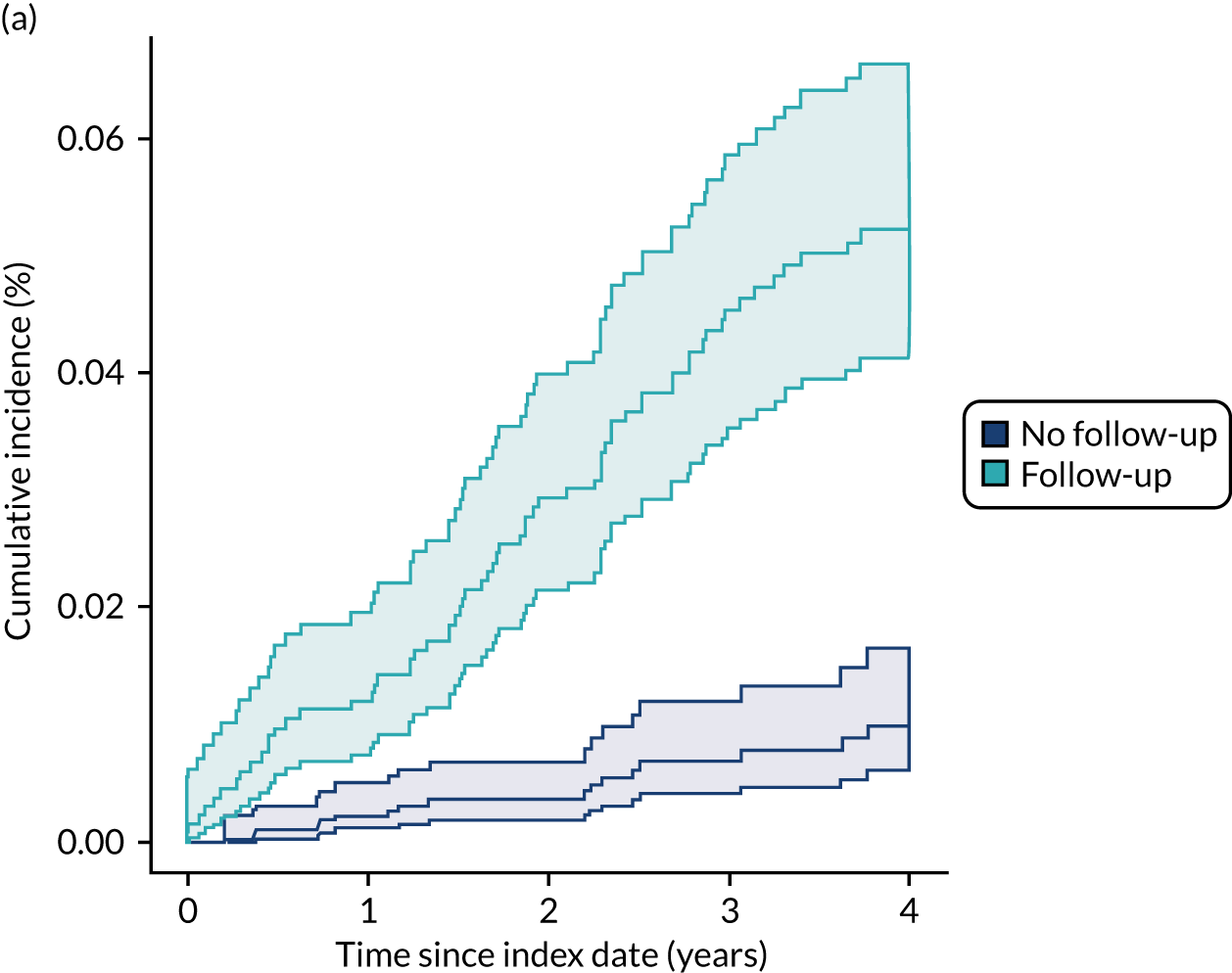

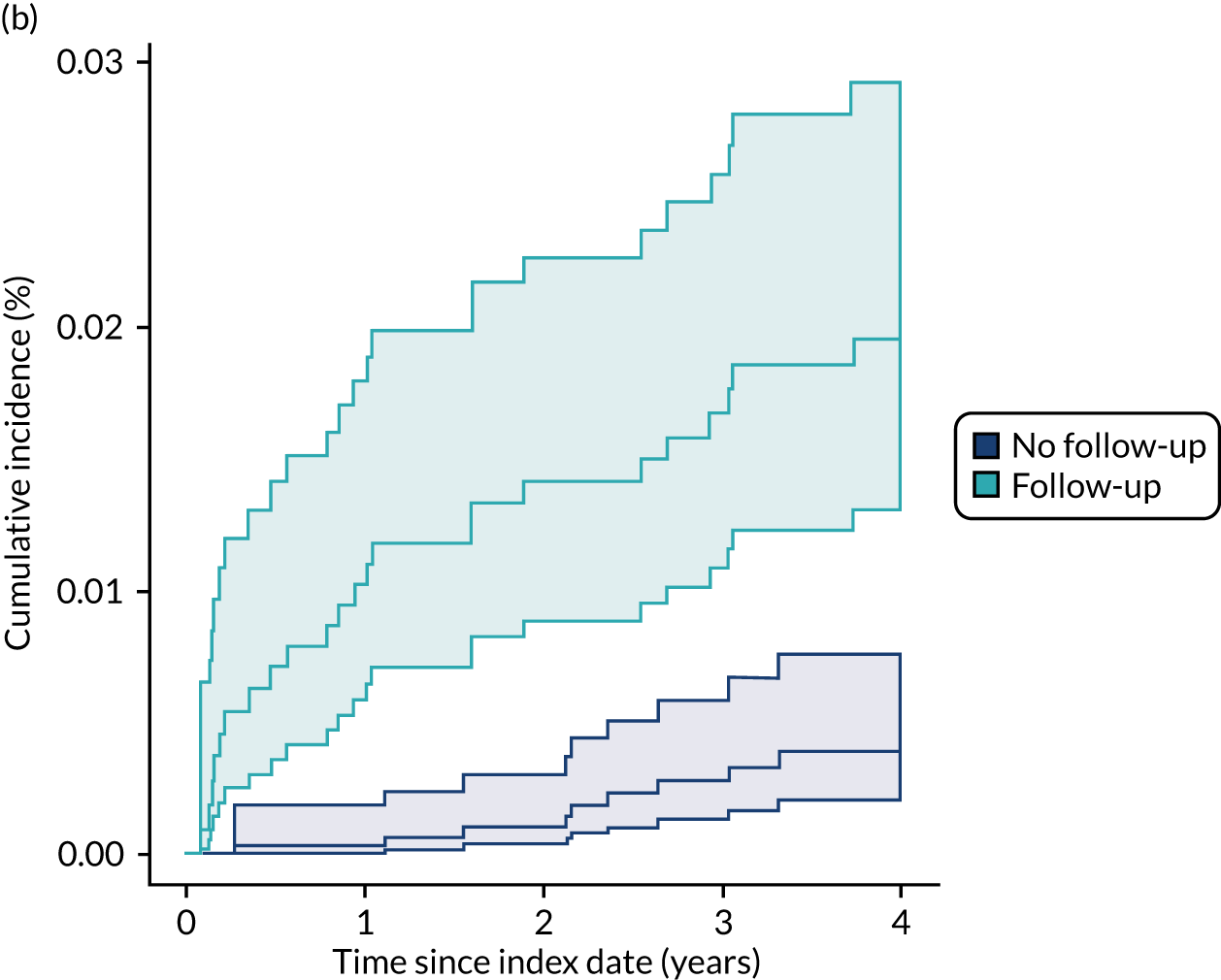

Summary statistics for patients in the CPRD–HES- and the NJR–HES–PROMs-linked data sets are provided in Appendix 2, Tables 37 and 38. In the NJR–HES–PROMs data set, data were available from 2008 to 2011 on 142,275 THRs and 188,509 knee replacements (see Figure 2). The CPRD–HES-linked data covered a longer time period: between 1995 and 2011 on 22,312 THRs and 17,378 KRs (see Figure 3). The age and sex distribution of patients was similar across both data sets, with a mean age of 70 years for both hip and knee replacement and the proportion of women being 62% for hip replacement and 57% for knee replacement. An extensive range of patient case mix, surgical, operative factors and primary care prescribing data was available for analysis (see Appendix 2, Tables 37 and 38).

In the NJR–HES–PROMs data, for THRs there were 3582 (2.5%) revision procedures over a median of 1.9 years of follow-up (range 0.01–8.7 years), of which 598 (0.4%) were mid- to late-term revisions. For KRs, there were 8607 (4.6%) revisions, with a median follow-up of 1.8 years (range 0–8.8 years), of which 1055 (0.6%) were mid- to late-term revisions.

The CPRD–HES data set had a longer follow-up. For THRs, there were 982 (5.8%) revisions over a median follow-up period of 5.3 years (range 0–20 years), with 520 (3.1%) mid- to late-term revisions. For KRs, there were 877 (5.1%) revisions over a median follow-up of 4.2 years (range 0.02–18.3 years), with 352 (2.0%) mid- to late-term revisions.

Predictors of mid- to late-term revision

Patient demographics

Older age at the time of primary operation was associated with a lower risk of mid- to late-term revision (Tables 3–6). The effect of age was linear and the association was stronger for knee replacement. For knee replacement, a 1-year increase in age at surgery reduced the risk of outcome by 5%. For THR, a 1-year increase in age at surgery reduced the risk of outcome by 3%. These findings were consistent across the CPRD–HES and NJR–HES–PROMs data sets. There was no effect associated with sex for patients receiving THR. However, for knee replacement, males had a greater risk of mid- to late-term revision than females. This was observed in only the CPRD–HES data, in which males had a 32% increased risk of outcome, but the effect size was weaker and non-significant in the NJR–HES–PROMs data set.

| Risk factors (reference category) | Crude analysis, HR (95% CI); p-value | Patients undergoing THR (n = 22,312), HR (95% CI); p-value | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Drug yes/no | Drug DDD | ||||

| Adjusted analysis | Adjusted competing risk analysis | Adjusted analysis | Adjusted competing risk analysis | ||

| Year of primary THR (2010–11) | |||||

| 1995–9 | 4.34 (1.88 to 9.98); p < 0.01 | 4.98 (2.14 to 11.59); p < 0.01 | 7.31 (3.18 to 16.79); p < 0.01 | 5.02 (2.14 to 11.76); p < 0.01 | 7.22 (3.12 to 16.68); p < 0.01 |

| 2000–4 | 2.78 (1.22 to 6.32); p = 0.02 | 3.16 (1.38 to 7.23); p = 0.007 | 4.33 (1.91 to 9.80); p < 0.01 | 3.22 (1.40 to 7.42); p = 0.006 | 4.32 (1.90 to 9.83); p < 0.01 |

| 2005–9 | 2.59 (1.13 to 5.91); p = 0.02 | 2.74 (1.20 to 6.28); p = 0.017 | 3.46 (1.53 to 7.85); p = 0.003 | 2.73 (1.19 to 6.25); p = 0.018 | 3.40 (1.50 to 7.71); p = 0.003 |

| Age at primary THR (continuous variable) | 0.97 (0.96 to 0.98); p < 0.01 | 0.97 (0.96 to 0.98); p < 0.01 | 0.96 (0.95 to 0.96); p < 0.01 | 0.97 (0.96 to 0.98); p < 0.01 | 0.96 (0.95 to 0.96); p < 0.01 |

| Smoking status (non-smoker) | |||||

| Ex-smoker | 1.31 (0.77 to 2.22); p = 0.49 | 0.91 (0.72 to 1.17); p = 0.47 | 0.88 (0.69 to 1.13); p = 0.31 | 0.91 (0.71 to 1.16); p = 0.44 | 0.88 (0.68 to 1.12); p = 0.29 |

| Current | 1.31 (0.77 to 2.22); p = 0.58 | 0.73 (0.54 to 0.99); p = 0.041 | 0.67 (0.50 to 0.91); p = 0.01 | 0.73 (0.54 to 0.98); p = 0.037 | 0.67 (0.50 to 0.91); p = 0.009 |

| Fracture in pelvis, proximal/humerus, wrist/forearm, spine or rib | 1.51 (0.96 to 2.40); p = 0.08 | 1.68 (1.06 to 2.67); p = 0.027 | 1.64 (1.04 to 2.61); p = 0.035 | 1.76 (1.10 to 2.82); p = 0.018 | 1.75 (1.09 to 2.79); p = 0.02 |

| Comorbidities | |||||

| Malabsorption | 4.17 (1.24 to 14.01); p = 0.02 | 3.97 (1.13 to 13.94); p = 0.032 | 3.69 (1.05 to 12.95); p = 0.042 | ||

| Hypertension | 0.72 (0.58 to 0.89); p < 0.01 | 0.77 (0.61 to 0.96); p = 0.02 | 0.77 (0.62 to 0.97); p = 0.025 | 0.76 (0.60 to 0.95); p = 0.014 | 0.77 (0.61 to 0.96): p = 0.021 |

| Antidepressants | 1.40 (1.17 to 1.68); p < 0.01 | 1.37 (1.14 to 1.65); p = 0.001 | 1.32 (1.09 to 1.59); p = 0.004 | ||

| Statins | 1.07 (0.86 to 1.34); P = 0.54 | 1.43 (1.12 to 1.81); p = 0.004 | 1.37 (1.08 to 1.75); p = 0.01 | ||

| Glucocorticoid steroid injections (intra-articular) | 1.32 (1.06 to 1.65); p = 0.01 | 1.32 (1.06 to 1.66); p = 0.015 | 1.33 (1.06 to 1.67); p = 0.014 | ||

| DDDs 1-year prior surgery | |||||

| Bisphosphonates DDD (no dose) | |||||

| < 140 | 1.02 (0.48 to 2.16); p = 0.96 | 1.16 (0.54 to 2.48); p = 0.70 | 0.99 (0.46 to 2.11); p = 0.98 | ||

| ≥ 140–340 | 0.42 (0.16 to 1.12); p = 0.08 | 0.43 (0.16 to 1.17); p = 0.10 | 0.40 (0.15 to 1.09); p = 0.072 | ||

| > 340 | 1.70 (0.84 to 3.45); p = 0.14 | 2.03 (0.99 to 4.18); p = 0.054 | 1.77 (0.85 to 3.68); p = 0.13 | ||

| Dose missing | 0.42 (0.11 to 1.70); p = 0.23 | 0.52 (0.13 to 2.09); p = 0.35 | 0.43 (0.11 to 1.75); p = 0.24 | ||

| Antidepressants DDD (no dose) | |||||

| < 85 | 1.42 (0.97 to 2.06); p = 0.07 | 1.35 (0.92 to 1.98); p = 0.12 | 1.31 (0.90 to 1.92); p = 0.16 | ||

| ≥ 85–365 | 1.67 (1.24 to 2.25); p < 0.01 | 1.65 (1.22 to 2.24); p = 0.001 | 1.57 (1.16 to 2.13); p = 0.003 | ||

| >365 | 1.57 (0.96 to 2.59); p = 0.07 | 1.56 (0.93 to 2.61); p = 0.089 | 1.46 (0.87 to 2.43); p = 0.15 | ||

| Dose missing | 1.24 (0.96 to 1.59); p = 0.09 | 1.21 (0.93 to 1.56); p = 0.15 | 1.17 (0.90 to 1.51); p = 0.23 | ||

| Statins DDD (no dose) | |||||

| < 280 | 1.26 (0.88 to 1.81); p = 0.20 | 1.61 (1.12 to 2.33); p = 0.01 | 1.55 (1.07 to 2.23); p = 0.02 | ||

| ≥ 280–370 | 1.16 (0.85 to 1.60); p = 0.35 | 1.59 (1.14 to 2.23); p = 0.007 | 1.51 (1.08 to 2.12); p = 0.016 | ||

| > 370 | 1.01 (0.64 to 1.59); p = 0.97 | 1.34 (0.84 to 2.15); p = 0.22 | 1.32 (0.82 to 2.11); p = 0.25 | ||

| Dose missing | 0.33 (0.10 to 1.01); p = 0.05 | 0.44 (0.14 to 1.36); p = 0.15 | 0.42 (0.13 to 1.31); p = 0.13 | ||

| NSAID cox DDD (no treatment) | |||||

| < 60 | 0.96 (0.53 to 1.74); p = 0.89 | 0.97 (0.53 to 1.78); p = 0.93 | 1.00 (0.55 to 1.83); p = 0.99 | ||

| ≥ 60–280 | 0.51 (0.27 to 0.96); p = 0.04 | 0.53 (0.28 to 1.01); p = 0.053 | 0.55 (0.29 to 1.04); p = 0.064 | ||

| > 280 | 1.10 (0.56 to 2.13); p = 0.79 | 1.09 (0.56 to 2.12); p = 0.80 | 1.15 (0.59 to 2.25); p = 0.67 | ||

| Dose missing | 1.18 (0.80 to 1.74); p = 0.42 | 1.26 (0.84 to 1.88); p = 0.26 | 1.25 (0.84 to 1.87); p = 0.27 | ||

| Intra-articular steroids DDD (no treatment) | |||||

| < 55 | 1.18 (0.71 to 1.97); p = 0.53 | 1.14 (0.68 to 1.93); p = 0.62 | 1.14 (0.67 to 1.92); p = 0.63 | ||

| ≥ 55 | 2.22 (1.15 to 4.31); p = 0.02 | 2.28 (1.14 to 4.54); p = 0.019 | 2.13 (1.07 to 4.25); p = 0.031 | ||

| Dose missing | 1.29 (1.01 to 1.66); p = 0.04 | 1.30 (1.01 to 1.67); p = 0.043 | 1.31 (1.02 to 1.69); p = 0.037 | ||

| Risk factors (reference category) | Patients undergoing THR (n = 142,275), HR (95% CI); p-value | Adjusted analysis (competing risk), HR (95% CI); p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Crude analysis | Adjusted analysis | ||

| Age at primary THR (continuous variable) | 0.98 (1.0 to 1.0); p < 0.01 | 0.97 (0.97 to 0.98); p < 0.01 | 0.97 (0.96 to 0.97); p < 0.01 |

| Sex (woman) | |||

| Man | 1.17 (1.0-1.4); p = 0.08 | 1.22 (1.02 to 1.45); p = 0.029 | 1.17 (0.98 to 1.39); p = 0.088 |

| ASA grade (P1 – fit and healthy) | |||

| P2 – Mild disease, not incapacitating | 0.93 (0.7-1.2); p = 0.52 | 0.97 (0.76 to 1.22); p = 0.77 | 0.95 (0.75 to 1.21); p = 0.70 |

| P3–5 | 0.70 (0.5-1.0); p = 0.04 | 0.67 (0.47 to 0.94); p = 0.022 | 0.58 (0.41 to 0.82); p = 0.002 |

| Bearing surface (MoP) | |||

| CoC | 1.08 (0.9-1.3); p = 0.44 | 0.73 (0.56 to 0.94); p = 0.015 | p = 0.02 |

| CoP | 0.93 (0.7-1.2); p = 0.57 | 0.75 (0.57 to 0.99); p = 0.039 | 0.76 (0.58 to 1.00); p = 0.052 |

| CoM-MoC | 2.28 (1.3-4.1); p = 0.01 | 1.62 (0.87 to 2.99); p = 0.13 | 1.65 (0.89 to 3.05); p = 0.11 |

| Head size (≤ 28 mm) | |||

| 32 mm | 1.28 (1.0-1.6); p = 0.02 | 1.33 (1.07 to 1.65); p = 0.012 | 1.28 (1.03 to 1.60); p = 0.026 |

| 36–42 mm | 1.24 (1.0-1.5); p = 0.05 | 1.21 (0.94 to 1.56); p = 0.15 | 1.17 (0.91 to 1.51); p = 0.23 |

| ≥ 44 mm | 3.12 (1.4-7.0); p = 0.01 | 2.63 (1.12 to 6.19); p = 0.027 | 2.56 (1.09 to 6.02); p = 0.031 |

| OHS: 6-month score (points) (0–9 points) | |||

| 10–14 | 0.75 (0.60 to 0.95); p = 0.02 | 0.73 (0.58 to 0.91); p = 0.006 | 0.73 (0.58 to 0.92); p = 0.007 |

| 15–18 | 0.66 (0.52 to 0.83); p < 0.01 | 0.61 (0.49 to 0.78); p < 0.01 | 0.62 (0.49 to 0.79); p < 0.01 |

| 19–23 | 0.39 (0.29 to 0.53); p < 0.01 | 0.36 (0.26 to 0.49); p < 0.01 | 0.36 (0.27 to 0.50); p < 0.01 |

| 24–48 | 0.39 (0.30 to 0.51); p < 0.01 | 0.34 (0.26 to 0.45); p < 0.01 | 0.35 (0.27 to 0.46); p < 0.01 |

| Risk factors (reference category) | Crude analysis | Patients undergoing TKR and UKR (n = 17,378), HR (95% CI); p-value | Patients undergoing TKR and UKR with missing dose for bisphosphonates and opioids excluded (n = 14,470), HR (95% CI); p-value | ||