Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number NIHR127430. The contractual start date was in October 2019. The final report began editorial review in October 2021 and was accepted for publication in June 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Millar et al. This work was produced by Millar et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Millar et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Improving the collaboration and integration of services has become a mantra for health-care systems around the globe. The need to work across organisational boundaries is promoted as a solution for achieving the necessary innovation, coordination, efficiency and relationships to meet the financial, demographic, workforce and quality challenges currently being faced. 1 The COVID-19 pandemic has sharpened the policy focus on interorganisational collaborations (IOCs) and partnership working as a response to the pressures brought on by the pandemic. 2

Interorganisational collaboration includes the formation of alliances, groups, associations, networks and mergers. 3–7 Such arrangements have been closely linked to policy contexts where governments have mandated collaboration or have sought to create conditions for ‘co-opetition’ between providers to expand the market position of high-performing organisations. 1

A variety of factors have been attributed to achieving success within such initiatives, including the importance of organisational capacity, having a shared vision with realistic aims, building trust, the availability of robust governance structures and collaborative leadership. 8–13 However, realising the advantages of collaboration is far from straightforward. 14 Notable barriers to IOCs are include the geographical distance between partners, the influence of historical events, competitive behaviour, the regulatory environment, a lack of organisational resources and coordination, power imbalances, and incompatible organisational structures and cultures. 8,15–17

Historical developments

England, UK, has seen no shortage of attempts to promote IOC. The apparent need for improved partnership working can be traced back at least as far as the introduction of ‘national planning systems’ in the 1960s. Subsequent policy developments include the 1974 NHS reorganisation and the National Health Service and Community Care Act 1990. 300 Both policy developments encouraged improved collaboration between the NHS and local authorities. 18 The New Labour government, during its early years of government, espoused a shift away from competition to collaboration with a raft of policy initiatives, including joint commissioning arrangements, pooled budgets, health improvement programmes, health action zones and a duty of partnership for NHS bodies and local authorities. 8,19,20 Nevertheless, these initiatives struggled to achieve their desired goals and outcomes,19,21 with the ambiguity surrounding collaborative arrangements, such as joint commissioning, posing further practical and technical challenges to attributing any performance improvements being made. 22 The challenging policy logics of hierarchical control and market competition that characterised New Labour’s term of office are also noted as challenges for developing collaboration across NHS providers. 23,24

The Five Year Forward View

Although the Health and Social Care Act 2012301 promoted competition, the Five Year Forward View3 gave emphasis to developing and piloting new care models to encourage interorganisational and cross-sectoral partnership working. 25,26 In response to significant variations in quality across the NHS provider sector, the Care Quality Commission (CQC)27 also promoted a range of partnership options for ‘challenged’ organisations and organisations assessed as requiring ‘special measures’. 6 The options included options for mandated support, with the appointment of one or more partner (or ‘buddy’) organisations to provide support, with-longer term options including merger and acquisition. To improve coordination and standardisation of services across the provider sector, the 2014 Dalton review4 outlined a menu of collaborative approaches, including the voluntary pooling of resources by multiple organisations (e.g. joint ventures and federations) and consolidation arrangements (e.g. integrated care organisations and mergers), as well as buddying arrangements between lower- and better-performing organisations to facilitate the sharing of best practices.

A stream of research has sought to evaluate the collaborative approaches introduced by the Five Year Forward View. 10,12,25,28 Studies provide evidence of how new care models have helped to stimulate organisational innovation and promote system-wide collaboration. 25 Billings et al. 10 note a set of facilitative factors, including the development of relationships and alliances, effective local and national leadership, the availability of expert knowledge and skills, and additional tranches of funding. Challenges have also been highlighted with regard to overly ambitious policy expectations and the collection and use of performance information, as well as difficulties in developing ongoing relationships with regulators. Furthermore, questions remain about whether or not the agenda has had sufficient time and support to develop approaches responsive to population need. 26 In addition, questions remain about the limited effect of the vanguard programme on reducing hospital activity. 29

Mergers and acquisitions between under- and well-performing providers have received much attention, with concerns raised regarding the time, cost and complexity for stakeholders involved, and the variable financial and clinical quality improvements being achieved. 30 The impact of ‘buddy’ hospitals providing support to struggling organisations or those in special measures appears to have aided organisational improvement and turnaround, as measured by the CQC performance ratings. 6,31 Despite the Health and Social Care Act 2012301 promoting competition, Allen et al. 32 note how commissioners chose mainly to use collaborative strategies to affect major service reconfigurations, and this was also endorsed as a suitable approach by providers.

The NHS Long Term Plan and beyond

The policy focus on collaboration continued with the publication of the NHS Long Term Plan. 33,34 Building on Sustainability and Transformation Partnerships (STPs), integrated care systems (ICSs) have been introduced, which bring together mental health, social and acute care, specialist services, primary care and local government, with the aim of promoting greater regional coordination and more of a population health focus. 33,35 Primary care networks (PCNs) hold shared budgets, with the aim of developing new services to enhance integration, improve sustainability, secure additional funding and improve economies of scale. 36,37 NHS provider collaboratives also contribute towards the ICS agenda with the development of specialist mental health-care pathways. 38

Within the current context of the pandemic,39 new Health and Care Bill aims to accelerate the shift towards greater collaboration with the accompanying legislation to accomplish much of what was put forward in the NHS Long Term Plan. 40 Proposals include a duty for the NHS and local authorities to collaborate with ICSs, which are now statutory bodies, comprising ICS Health and Care Partnerships (bringing systems together to support integration) and an ICS NHS body (responsible for day-to-day running of the ICS), and include commissioning functions. The arrangements will allow NHS providers and Clinical Commissioning Groups (now ICS NHS bodies) to make joint decisions via joint committees and committees-in-common arrangements, as well as bring in other partners. Competition law [through the Competition and Markets Authority (London, UK)] and regulatory functions promoting competition are removed, along with the need for competitive tendering if not providing value. The introduction of provider collaboration reviews by the CQC to encourage learning about health and social care collaboration provides a further statement of intent with regard to how regulation can facilitate collaboration and partnership working in the delivery of services. 41

The formation of a mandated ICS agenda raises questions about the potential of ICSs to undermine existing collaborative relationships and their susceptibility to enacting hierarchy-based governance and behaviours, rather than ‘place-based collaboration’. 42 Emerging findings from ICS so far point to challenges ahead in developing the relationships, trust, accountability and authority for successful joint working. 43 A similar picture is painted with regard to PCNs, with limited progress being reported. 37 Concerns have also been raised about the regulatory implications of the policy proposals. For example, with the current inspection regime focused on individual organisations,44 it is not at all clear how ICSs will be scrutinised and performance rated. 45 Sanderson et al. 46 note that, although the intention of STPs was to create conditions for common pool resources at a ‘system’ level, local actors often struggle to agree local rules, citing conflicts with the continued regulatory focus on the financial sustainability of individual organisations.

Research rationale

Despite the burgeoning evidence base and increased policy emphasis on collaborative working, notable gaps in knowledge persist. 17,47,48 Criticisms have been lodged at the limited number of actionable insights generated from integrated care policies,49 and the failure to demonstrate successful outcomes for staff, users, financial sponsors or other stakeholders. 21 Collaboration often falls short of expectations, so much so that its continued appeal to policy-makers has been likened to ‘an expression of faith’, rather than driven by tangible evidence. 50

The ambiguities and uncertainties surrounding the nature and effect of collaboration mean that achieving ex ante objectives is unlikely, given that ‘the act of collaborating with others often results in the interactive adaptation of perceptions and performance goals’ over time. 51 The term collaboration is also deemed problematic in the way it potentially glosses over the diverse array of mechanisms that can be used to describe how organisations work together and the relative appropriateness of these mechanisms for different tasks and contexts. 52

As a result, our understanding of the mechanisms and processes for spreading and sustaining evidence about successful relationships is limited. Many questions remain about how interorganisational arrangements, such as mergers, alliances, joint ventures and buddying collaborations, work, for whom and in what circumstances. Indeed, appeals have been made to further identify the elements of successful collaboration, particularly the assessment of effectiveness for horizontal collaborations between health-care providers. 1 There is also a need for further empirical research to better understand the interplay of barriers and their context dependence, as well as their underlying causes and visible symptoms. 15

The literature in this area calls for more robust theoretical frameworks and more sustained empirical research to explore which types of partnership approaches work (or not) in particular circumstances, why and for whom. 13 Although general theories of how IOCs work have been proposed, establishing the causal links between issues such as culture, leadership and governance in strengthening or weakening collaborations requires further development. Auschra,15 for example, calls for greater understanding of the barriers to the integration of care in interorganisational settings, with the need for more attention devoted to using existing organisation and network theories that address such barriers. Auschra15 notes that ‘while reviewing existing literature, it became clear that the notion of “barriers” lacks theoretical underpinning’. 15

Given the complexities of collaborative arrangements, Guarneros-Meza et al. 53 advocate ‘theories of change’ approaches to assess how collaboration synergies and coordination are shaped by contexts, behaviours and structures, and this is achieved by asking ‘how’ and ‘why’ partnership practices are carried out in different contexts. Applications of realist methodology in relation to partnership working are also advocated as an approach well suited for studying multiple interventions implemented in diverse contexts with a range of stakeholders. 54 However, applications of realist approaches to understanding IOCs within health-care settings has hitherto remained an underdeveloped area.

Research aims and objectives

The aim of our research is to provide useful intelligence regarding how, why and in what circumstances different approaches to IOC are effective in improving the performance of NHS provider organisations. To do this, a realist synthesis of evidence was carried out with the following inter-related supporting objectives:

-

To explore the main strands of the literature about IOC and identify the main theoretical and conceptual frameworks that can be used to shed light on the conditions and antecedents for effective partnering across sectors and stakeholders.

-

To assess the empirical evidence with regard to how different interorganisational practices may (or may not) lead to improved performance and outcomes.

-

To understand and learn from NHS evidence users and other stakeholders about how and where IOC can best be used as a mechanism to support turnaround processes.

-

To develop a typology of IOC that considers different types and scales of collaborative ventures that are appropriate for particular NHS provider contexts.

-

To generate evidence-informed practical guidance for NHS providers, policy-makers and others with responsibility for implementing and assessing IOC arrangements in the NHS.

Our research provides practical guidance and learning to support NHS leaders with assessments of the different candidate partnering approaches available. Our research has important implications and learning, regarding the principles and methods that are required if collaborative approaches are to work successfully across boundaries and to engage the workforce and wider population within these collaborative efforts, for those engaged in leadership.

Chapter outline

This report is structured into eight chapters and arranged as follows. Chapter 2 provides the context for this work, with a review of typologies, drivers and dynamics associated with the life cycle of collaboration. Chapter 3 presents the methodology employed, providing an overview of the realist synthesis approach and our stakeholder analysis. Chapter 4 presents the results of the realist synthesis, drawing on 86 items of literature and analysing how, why and for whom do IOCs in health-care work in particular circumstances. Chapter 5 refines understanding of collaborative functioning with the presentation of findings based on primary data collected from a range of stakeholders, including policy-makers, practitioners and patient representatives. Chapter 6 presents findings from the stakeholder interviews and develops a novel theory of collaborative performance that aims to further explicate the mechanisms underlying collaboration that drive performance improvement. Chapter 7 assesses the implication of the findings, with an outline of the final version of our realist theory of how and why IOC works. Chapter 7 also presents options for the translation of our research into practice, with the development and piloting of tools designed to assess the readiness for collaboration. The report concludes (see Chapter 8) with a summary of how the project has fulfilled its objectives and with recommendations for developing future research, policy and practice in this important area of policy and practice.

Chapter 2 Background

The purpose of this chapter is to start the process of gaining a better understanding of IOCs. Given the large, multifaceted and complex nature of IOCs, the aim here is to provide an essential first step of theory-building in articulating ‘what the programme is’, ‘who is the supposed target’ and ‘what is the supposed outcome’. 55,56 To this end, we combine a review of grey literature (e.g. policy and organisational strategy documents within the NHS) and narrative and systematic reviews of evidence to capture key definitions, typologies, ingredients and outcomes associated with IOCs (see Appendix 1 for methods). Excerpts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Aunger et al. 61 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Definitions and terminology

A variety of terms have been used to describe joint working, including integration, collaboration, partnering and partnership working. Partnership working is a widely used to describe the joint development of organisational structures or working across boundaries by the sharing of resources, authority and accountability. The following definitions capture these arrangements:

. . . a mutually beneficial process by which stakeholders or organizations work together towards a common goal. 57

. . . a negotiation between people from different organisations with a commitment to working together over more than the short term to secure improvements which could not have been achieved by acting alone. 17

. . . a series of events in the history of a system, leading to the evolution of new structures of interaction and new shared meanings. 54

‘Partnering’ is another term that is commonly used in the literature. Miller and Millar13 suggest that partnering is useful term for understanding various joint working arrangements. Crowley and Karim58 define partnering as:

. . . a cooperative strategy [that an organization implements] by modifying and supplementing the traditional boundaries that separate organizations in a competitive climate. In this way, partnering can be used to create a cohesive atmosphere [in which] all project team members openly interact and perform. 58

Interorganisational collaboration is a similar term and has been defined as follows:

. . . interorganizational collaboration is the set of communicative processes in which individuals representing multiple organizations or stakeholders engage when working interdependently to address problems outside the spheres of individuals or organizations working in isolation. The outcomes of these processes have the potential to benefit or harm the parties to the collaboration, as well as others. 59

[Interorganizational collaboration] the belief that more valuable knowledge can be created than if each organization were to work alone as complementary resources and competencies from partners can create interorganizational synergies. 60

Although defined differently by different authors, common to many definitions of partnership working, partnering and collaborating is the notion of working together to achieve benefits that would otherwise not be attainable by working alone. The core notion of ‘working together’ is a commonality across these terms. We will primarily be using the term IOC in this report, but the terms partnership working and partnering may also be used in particular instances of joint working.

Types of partnering

A range of scales and types of partnership working can be identified, and these different types of partnering have been presented as existing along a continuum by various authors. 8,61,62 Glasby et al.,8 for example, distinguish between ‘depth and breadth’ of partnership arrangements. Similarly, Sullivan and Skelcher62 categorise several different collaborative relationships, ranging from networks (i.e. informal ad hoc relationships) through to formal partnerships, federations and mergers (see Table 1).

| Form of collaboration | Loose network | Merger into single organisation |

| Rules of governance | Self-government | Hierarchy and overarching constitution |

| Organisational and policy terminology | Network | Integration |

With a particular focus on NHS providers, Miller and Millar13 identify a variety of partnering practices linking NHS providers, ranging from structural partnering, such as organisational mergers and acquisitions, through to individual partnering arrangements, such as buddying between executives and clinicians across provider organisations to provide mentoring support and guidance. 13 Miller and Millar13 also suggest that partnering can sit along a continuum, from a voluntary intrinsic act to work together through to partnerships that are mandated by government regulators (see Figure 1).

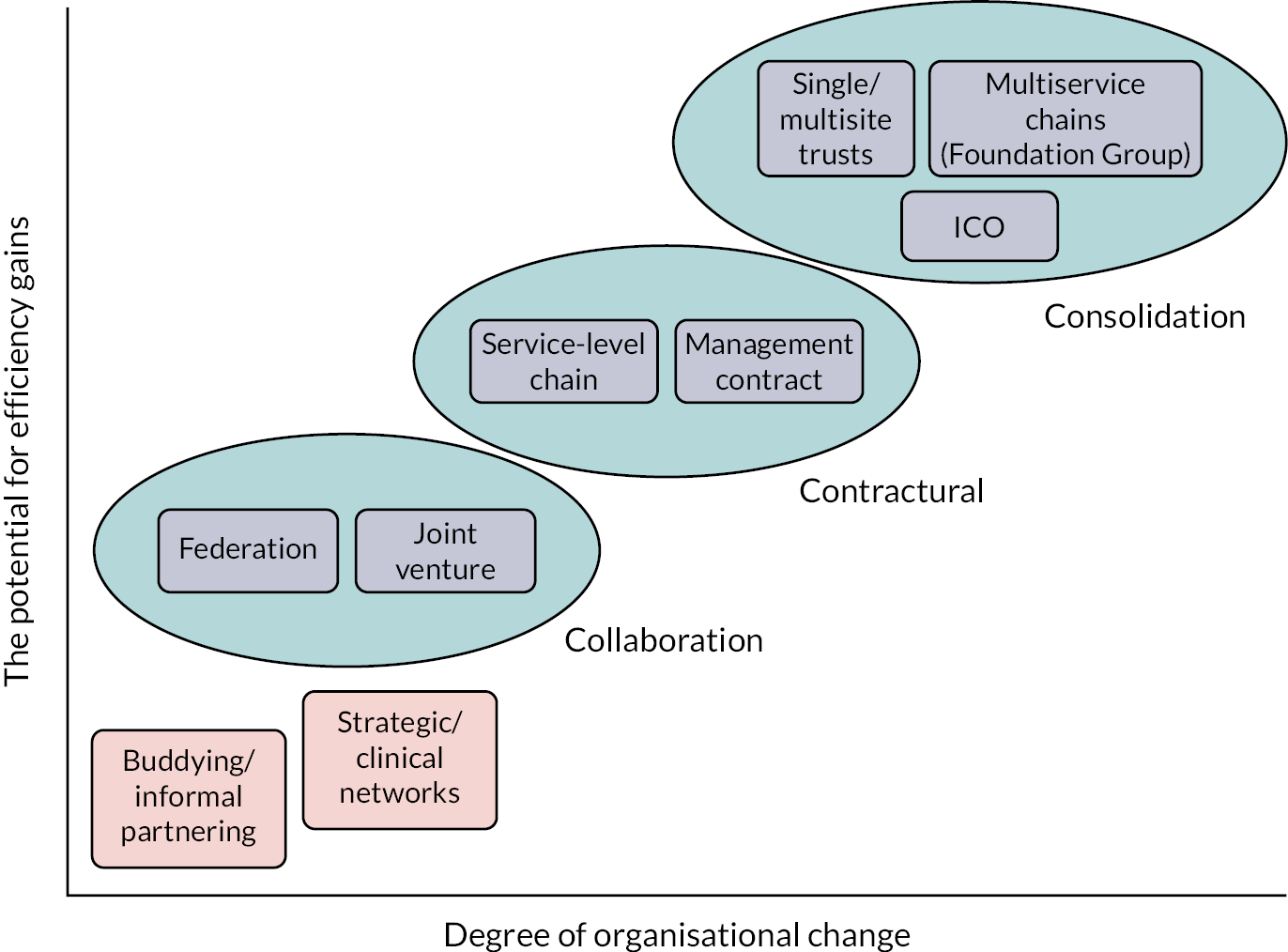

The 2014 Dalton review4 outlined a range of provider models of care. The Dalton review distinguished between different interorganisational forms, including collaborative arrangements (i.e. a voluntary pooling of resources, which involves two parties creating a third to provide a particular service to both initiators), contractual arrangements (i.e. more formalised agreements) and consolidatory arrangements (i.e. a change of ownership, encompassing mergers and acquisitions)4 (see Figure 2).

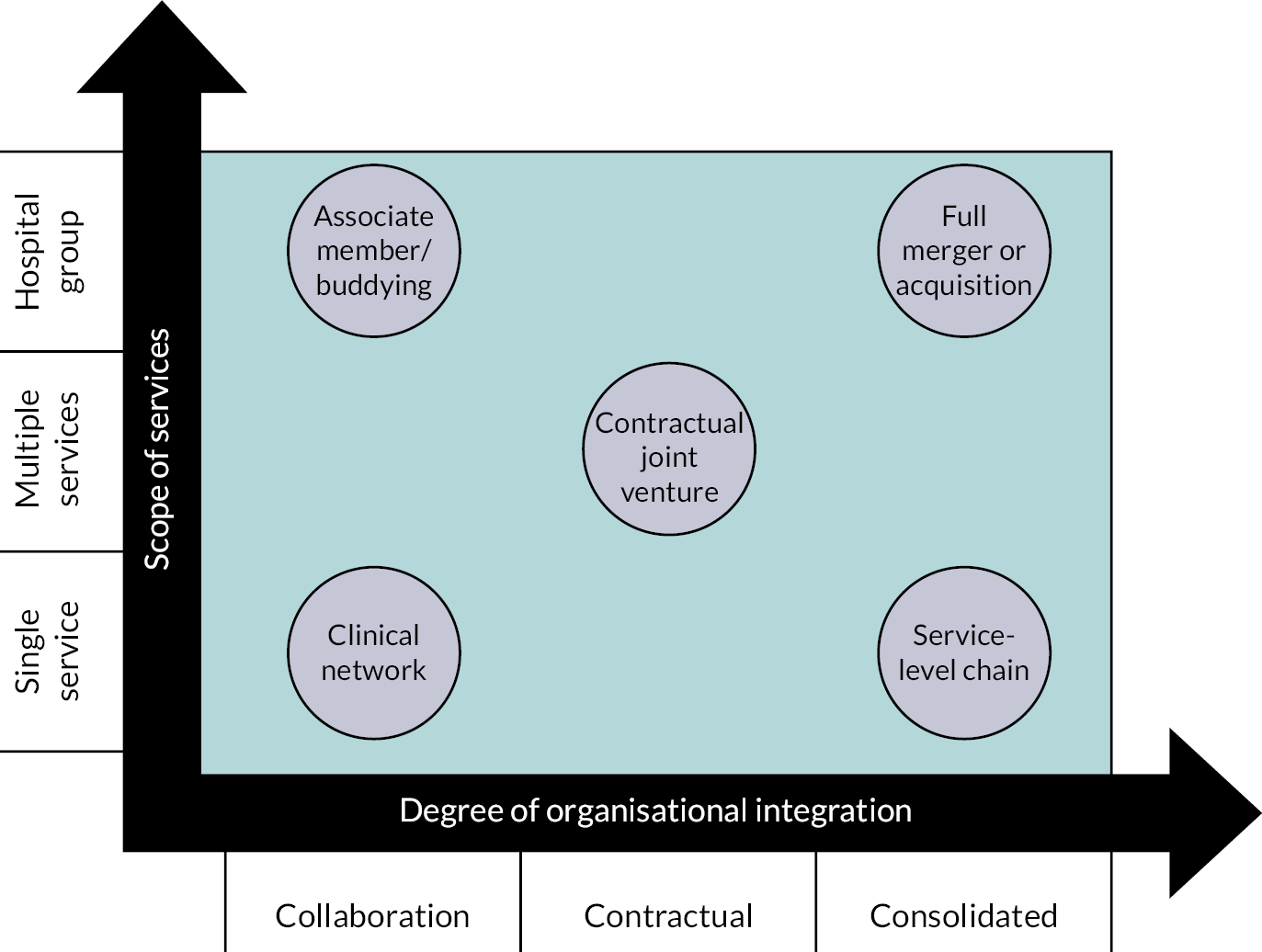

The NHS England publication ‘No Hospital is an Island’64 built on the Dalton review typology by developing a framework for acute care collaboration models. The NHS England publication64 depicted organisational forms by their degree of organisational integration, as well as by the scope of services they intend to deliver (see Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

A framework of acute care collaboration models, depicting organisational forms by their degree of organisational integration, as well as the scope of services they intend to deliver (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). 64

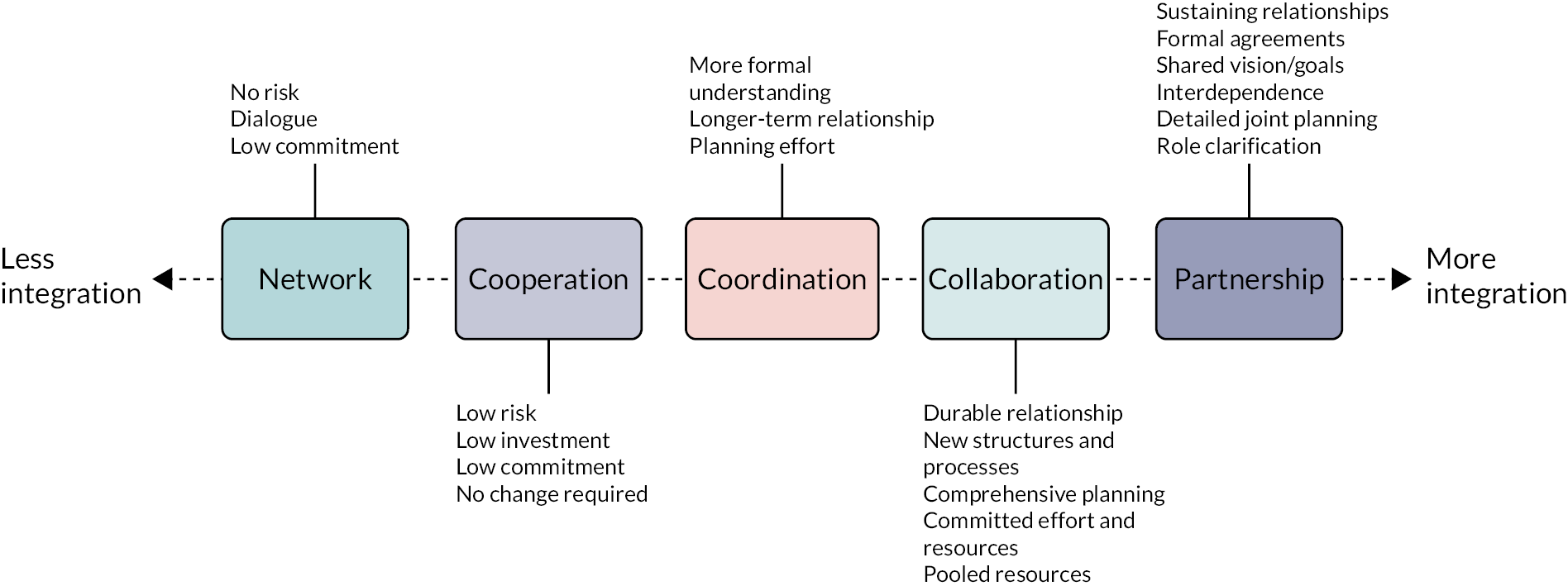

Another example comes from the Northern Ireland Audit Office (Belfast, UK). 65 The Northern Ireland Audit Office arranges different partnering arrangements by their degree of integration, from networks characterised by low commitment at the bottom of the spectrum, through cooperation, coordination and collaboration, to fully fledged partnerships, which require formal agreements and detailed joint planning (see Figure 4). 65

Across these various typologies, the key characteristics at play are the degrees of integration, whether a collaboration is mandated or voluntary, and whether the collaboration is cross-sector or within specific services. Although the terminologies used to describe such arrangements (i.e. alliances vs. hospital groups) can be fluid and are not universally agreed on,61 the typologies use a range of partnering types (see Table 2).

| Type | Definition |

|---|---|

| Informal partnering | Voluntary arrangements characterised by flexible small-scale collaborations focused on sharing organisational learning |

| Buddying | A form of mandated collaboration to encourage organisational turnaround. Buddying often involves organisations with more experience being asked to mentor, advise or train other organisations of lesser performance |

| Federation | A relatively informal agreement whereby several organisations collaborate on delivery of a service or administrative provision. Legal agreement is not required but a memorandum of understanding is required |

| Clinical network | A network that intends to reduce unwarranted variation in particular subtypes of care by fostering collaboration to optimise these particular care pathways |

| Joint venture | Creation of a new legal entity by multiple other entities that serves to deliver a service for, and on behalf of, the multiple originator entities |

| Provider collaborative | Partnerships of providers with new responsibilities for pathway and budget management for specialised services (e.g. mental health) |

| PCN | General practices and community, mental health, social care and pharmacy services collaborating to deliver primary care |

| Service-level chain | A provider that is contracted to provide services for another |

| Multiservice chain, group or alliance | A separate ‘group’ that sets governance, standards, protocols and procedures, often with procurement and back office functions. Each site has delegated decision-making within the parameters set by the designated board |

| Management contract | When control of a set of operations is handed to another organisation to manage for an agreed duration |

| ICS | Multiple organisations from primary, community, acute, mental and public health, and social care get brought together to manage patients across defined care pathways |

| Merger | The combination of two organisations to form a new organisation |

| Acquisition | The subsumption of one organisation by another |

What are collaborations intending to achieve?

Despite emphasis being placed on collaboration and integration across health-care systems, questions continue to be raised about the lack of robust evidence regarding whether or not such relationships lead to desired outcomes. 48 This has largely been explained by the ‘wicked problems’ collaboration is often looking to solve and the resulting challenges and dilemmas regarding how to measure collaborative effectiveness and success. 53,66 Guarneros-Meza et al. 53 review a range of measures and frameworks to demonstrate how collaborative performance can include several measures, comprising the quantity and quality of service outputs, consumer satisfaction, service objectives, expenditure data, equity in the allocation of resources and service outcomes. 67 The measures and frameworks can encompass common models of assessing performance, relating to goal attainment (outcomes), performance targets (outputs) and cultural efficacy-measuring factors, such as changes in rhetoric, emotions and symbols. 48 Silvia,51 drawing on Mandell and Keast,68 shows how effectiveness can be measured at three inter-related levels of network operations:

-

The operating level: the extent to which participants have developed a better understanding of each other, and whether or not they have developed a shared language and culture, new ways of communication and the ability to find common ground.

-

The organisational level: activating, framing, mobilising and synthesising activities, as measured by the creation of a shared vision, the establishment of member commitment to the network’s mission and the inclusion of all network members in the collaborative process.

-

The environmental level: the ability to successfully meet the needs of external stakeholders and constituencies (e.g. citizen awareness and the outcome proxies).

A review of partnering outcomes by Aunger et al. 61 found that evidence from NHS policy documents, such as the Dalton review4 and NHS Five Year Forward View,3 advocates different collaborative arrangements to provide a range of potential benefits to population health by improving care, quality and efficiency. A review of NHS provider mergers by NHS Improvement (2017b) claims that merged organisations have the potential to help the local health economy by standardising care and quality, increasing market share in clinical services, improving financial sustainability, avoiding market share erosion and improving reputation to aid in staff recruitment (see also Aldwych Partners30). Aunger’s et al.’s review of strategic plans from 26 NHS providers demonstrated how intended outcomes can be arranged into the four broad categories of ‘delivering consistent high quality care’, ‘developing our people’, ‘leveraging scarce resources’ and ‘embracing innovation’. 69 Within these larger categories, long-term and multiple medium-term objectives can also be identified. For example, within delivering consistent high-quality care, an objective is to ‘provide members (i.e. clinicians) with access to world-leading specialists from within the Healthcare Alliance’, by ‘enabling clinician-to-clinician relationships, facilitating knowledge share and access to specialist opinion’. 69

Drivers for interorganisational collaboration

Alongside outcomes, a range of perspectives and empirical research has been put forward to understand the stated and unstated drivers for IOCs. Table 3 summarises the results of the systematic search, which identified the following domains and organisation theories associated with the formation of IOCs in health care.

| Domain | Driver for IOCs | Underlying theories of organisation |

|---|---|---|

| Expansion | Seeking competitive advantage | Strategic choice: organisations pursue IOCs to increase competitiveness or market power Agency: individuals pursue IOCs to benefit primarily themselves rather than organisations |

| Consolidation | Efficiencies and economies of scale | Transaction cost economics: organisations should organise boundary-spanning activities to minimise production and transaction costs |

| Participation | Increasing responsiveness and alignment to needs | Stakeholder: organisations require greater alignment with stakeholder groups who can affect or are affected by the achievement of objectives |

| Learning | Enhancing position through superior knowledge | Absorptive capacity: IOCs are driven by value, assimilation and application of new knowledge Normative isomorphism: IOCs are driven by professions and interorganisational network pressures regarding best practice |

| Sustenance | Fulfil resource needs and manage scarce resources | Resource dependency: organisations must engage in exchanges with their environment to obtain resources to survive or prosper Common pool resource: IOCs are driven by self-management of limited resources in a way that benefits all |

| Mimicry | Obtain legitimacy or conformance to prevailing social norms | Mimetic isomorphism: IOCs are driven by intentionally and unintentionally copying to prove legitimacy |

| Coercion | Mandated pressures to conform | Coercive isomorphism: IOCs pursue activities in agreement with prevailing government rules, requirements and norms |

These dynamics can be summarised as follows.

Expansion

Drivers for IOC draw attention to the organisational expansion within market environments where collaboration is sought for competitive advantage and strategic position. 70 Forming an IOC for market expansion can be linked with strategic choice theory, which proposes that an organisation will enter into a collaboration if the benefits exceed the costs and if the collaboration will increase the ability of the firm to deliver superior products, improve service efficiency or increase market power. 71

The perspective of expansion is captured by Postma and Roos,78 who draw attention to how the formation of health-care mergers can represent a strategic attempt by organisations to gain market power by merging with a competitor. 72–75 Angeli and Maarse76 investigate the evolution of mergers and acquisitions across Western European health-care providers. Angeli and Maarse76 chart the rise of financial service organisations acting as acquirers in mergers and acquisitions, which have been driven by the introduction of market elements in health-care financing and provision, the broadening of private practice and for-profit medicine, the retrenchment of public financing arrangements and the closure of public hospitals or the conversion of public hospitals into more private-like entities. Expansion of market power can also be attributed to the self-interests and personal ambition of managers as a potential motive for collaboration. 77,78 Such a perspective resonates with agency theory, which suggests that managers act as utility maximisers,79 where the architects of IOCs may seek to have their organisations partner with others to increase their reputation in the marketplace or to increase their benefits by managing a larger organisation. 78

Consolidation

The formation of IOCs is driven by the need to consolidate services within a market environment. Connections are made here with transaction cost economics and theories of interfirm collaboration,80,81 which focus on how organisations organise their boundary-spanning activities to minimise production and transaction costs.

Various collaborative efforts37,70 highlight the economic drivers for overall and unit cost savings through improved economies of scale. Much of the coverage related to transaction cost economics underpins the rationale for mergers. 76,82,83 A literature review and secondary data analysis by Gaynor et al. 84 traced the hospital ‘merger mania’ in England between 1997 and 2006. The review84 highlights how the drivers for these mergers included facilitating hospital or service closures to release capacity in the short term, secure financial viability of smaller organisations and enlarge the hospital to provide better services for the buyers of services. Fulop et al. 85,86 outline similar economic drivers for trust mergers as an opportunity to take advantage of economies of scale and scope (especially regarding management costs) to rationalise the provision of services by reducing excess capacity to treat patients. Resulting efficiencies can lead to improved clinical quality, as usage of specialised unit increases, quality of medical training increases, and staff recruitment and staff retention become more effective.

Participation

Drivers for IOC draw attention to how such forms can increase participation of stakeholders to reduce environmental uncertainty. Such assumptions connect with a stakeholder theory of organisations at the centre of an independent web of stakeholders with a responsibility to consider their needs with making decisions/transactions. 87,88 In a health-care context, these stakeholders are typically patients, members of the public, staff, board members and government. 78,89,90

Increased participation is aligned to multi-hospital arrangements that are better able to improve quality by ensuring community needs are identified, assessed and assigned priority for service, with comprehensive services reaching those most in need. 70 Greater alignment with patients and public interests is connected to the ethos of integrated care in ‘meeting the needs of people with chronic diseases’91 and the drivers for joint commissioning as a way to overcome fragmentation by achieving ‘a seamless service’ where ‘assessment of need is unhindered by organisational boundaries’. 302 Reflecting on partnership working in mental health, Glasby and Lester92 and others have identified the importance of a service with a single point of contact as beneficial for service users and their carers who can often experience fragmented services, a lack of continuity and conflicting information in situations where local agencies fail to collaborate effectively. 92,93 Smith et al. 37 document how improvements to patient care and service provision featured as reasons to form collaborations in primary care. Collaborating between practices can help fill gaps in service provision where single practices are not able to provide all services, where patients need better coordinated care and where improved planning and provision of services at a population level is needed. Hunter and Perkins’ study94,95 of local strategic partnerships and local area agreements found that providing a coordinated approach to tackling public health issues was a prerequisite of effectively resolving such issues.

Learning

Drivers for IOCs often arise from a desire for greater organisational learning and to improve the ability of organisations to absorb knowledge from partners. 96,97 Absorptive capacity is central to such an approach, with a firm’s ability to recognise the value of new knowledge, assimilate it and apply it in a business setting. 98 A rationale for IOC formation is that firms form partnerships to capitalise on opportunities to learn or enhance their competitive position through superior knowledge. 99

Within IOCs, such conditions for learning have the potential to increase capability and innovation through education and skills development. 70 Studies of mergers of health-care providers identified organisational learning and shared practice as stated drivers for merging. 86 Sharing of knowledge fosters coordination of care, as best practices become shared between organisations,90 including learning from different perspectives. 92,94,95,100 Van Raak et al.,90 in their study of integrated care in the Netherlands, finds motivations to collaborate based on opportunities for learning about other providers whom they had never encountered before, and generating new concepts for care delivery to improve performance. Westra et al. 101 examine how health-care organisations balance competition and cooperation in a situation of ‘coopetition’, where knowledge-sharing and interorganisational learning are considered the primary motives to cooperate with competitors. Leach et al. 102 present a case study of a buddying agreement to help teams undertake change and develop a medical pathway where ‘improved learning’ underpins the aim to promote close working partnerships, compassionate leadership and improve quality and safety.

Sustenance

Drivers for IOC resonate with the desire for sustainability and the need to fill a perceived resource need or to exert power or control over organisations that possess scarce resources. The sustainability of IOCs draws attention to systems and how organisations must engage in exchanges with their environment to obtain resources. Resource dependence theory posits that organisations require resources from their environment and, therefore, cooperative interorganisational relationships will be formed as a managerial response to the need for critical resources controlled by others in the environment. 90,103,104

In their review of multi-hospital systems in the USA, Provan103 documents drivers to establish such forms as the need to access critical resources, with Markham and Thomas noting the development of ‘lateral’ or ‘service alliances’, in which similar types of organisations with similar needs and dependences come together to achieve benefits, such as economies of scale, enhanced access to scarce resources and increased collectives. 78 Van Raak et al. 90 also capture how access to resources was an important reason for becoming involved, where participants benefited from cooperation to exert power over organisations that possessed desired means. Smith et al. 37 note how issues of sustainability, both in terms of finances and the primary care workforce, emerged as significant across their evaluation of PCNs, and were identified as key reasons to enter into collaborations in primary care.

Mimicry

Drivers for IOCs in health care draw attention to the institutional environments shaping how organisations collaborate to obtain legitimacy or to succumb to isomorphic pressures by mimicking or copying others. Such a viewpoint aligns with institutional theory, which posits that environments impose pressures on organisations to appear legitimate and to conform to prevailing social norms. 71,105 Legitimacy can gain access to critical resources and expertise, as well as enhance reputation and gain visibility.

Dickinson and Glasby17 note that, through interorganisational partnerships, smaller organisations can gain legitimacy by increasing their recognisability, image and standing. Collaborations can also be perceived as socially desirable because of the positive outlook that partnership working inspires. Field and Peck77 outline how ‘the modus operandi of the perceived market leaders is likely to be copied by other organisations in the belief that this is the most effective way of operating’, with merger motives connected to examples of ‘mimicking’ (i.e. uncritically copying business practices from the private sector). 78 In their study of joint commissioning, Dickinson and Glasby22 document how joint commissioning can be understood as producing efficiencies, empowerment and productivity, but also with other potential meanings as inherently a ‘good thing’. Connections to institutional theory can also be found in Dickinson and Glasby’s17 analysis of a mental health partnership. Dickinson and Glasby17 found that a large number of staff members found it hard to identify what their partnership had been set up to achieve. Although some previous internal policy documents set out process-based aspirations (e.g. a single point of access for service users), these process-based aspirations were often very unspecific and often focused on processes and outputs, rather than on outcomes.

Coercion

Contributions draw attention to the interlinkages between mimetic pressures to conform and wider institutional and systemic pressures mandating collaboration. 78,86,90 What Works Scotland198 notes that many partnerships that claim to operate through collective governance are, in reality, also shaped by mandates from central government. The presence of such hierarchical mechanisms leads to less powerful partners feeling disenfranchised and lost within the partnership106 and, in turn, less likely to engage. 107

Fulop et al. 86 note that the unstated drivers for mergers include facilitating hospital or service closures and securing financial viability of smaller organisations. 108 In the research by Fulop et al.,86 common to all mergers was the need to maintain quality and level of service in the context of external policy drivers, with reconfigurations informed by pressures for improvements to services and closer cooperation with local government and partnership agencies. Dickinson and Glasby17 also find that, although staff often claim that mental health partnerships provide better services for users, the majority of the potential benefits cited by staff are to do with responding to national and local politics to make more efficient use of scarce organisational resources. Central government produced coercive isomorphism by both explicit techniques (e.g. a legal duty for health and social care agencies to work together) and more subtle techniques (e.g. making partnership a necessary feature for some sources of funding).

Although the stated goals of PCNs in the United Kingdom (UK) are to improve population health, share staff and improve personalisation of care,109 Smith et al. 37 also found that the reasons to enter PCNs appear to be more tightly focused on policy and financial incentives, with practices obligated to form PCNs and accept the financial incentives associated with networks for fear that they would be ‘left behind’. 37 In their study of STPs, Sanderson et al. 46 argue that, although the intention of STPs was to create conditions at a ‘system’ level for purchasers and providers to act as a self-governed common pool, local actors were not able to agree local rules, citing the conflict with the continued regulatory focus on the financial sustainability of individual organisations.

These various drivers draw attention to the often paradoxical and multifaceted nature of a collaborative endeavour (see Figure 5). The drivers also show how individual theories and perspectives are in themselves insufficient for capturing the complexities, norms and traditions involved in relationship formation. 63,71

FIGURE 5.

Depicting the drivers for IOC.

Initial ‘ingredients’ for success

A range of ingredients for success have been outlined to determine the key shaping factors affecting collaboration. In an exploratory empirical study of mergers, buddying and contracting across NHS providers, Miller and Millar13 identified the ‘ingredients’ for successful partnering, which included effective senior and clinical leadership, the importance of trust between partners, acquiring meaningful data, and regulatory approaches that combine both quality improvement and assurance approaches. In addition, Hudson and Hardy110 depict how the determinants of a successful partnership include having an existing local history of partnership working, effective monitoring and reviewing of organisational learning, having a shared vision, and development and maintenance of trust through behaviours and attitudes, such as ‘fairness’, openness and honesty, sacrifice and accountability.

Likewise, a recent systematic review of reviews12 sought to determine ‘shaping factors’ of how cross-sector health-care collaborations work, and identified resources and capabilities (e.g. organisational capacity), motivation and purpose (e.g. shared vision, unrealistic aims, competing aims, national policies, commitment), relationships and cultures (e.g. trust, historic relationships, communication), governance and leadership (e.g. decision-making, accountability, leadership support) and external factors (e.g. geography, social/economic context) as key ‘shaping factors’.

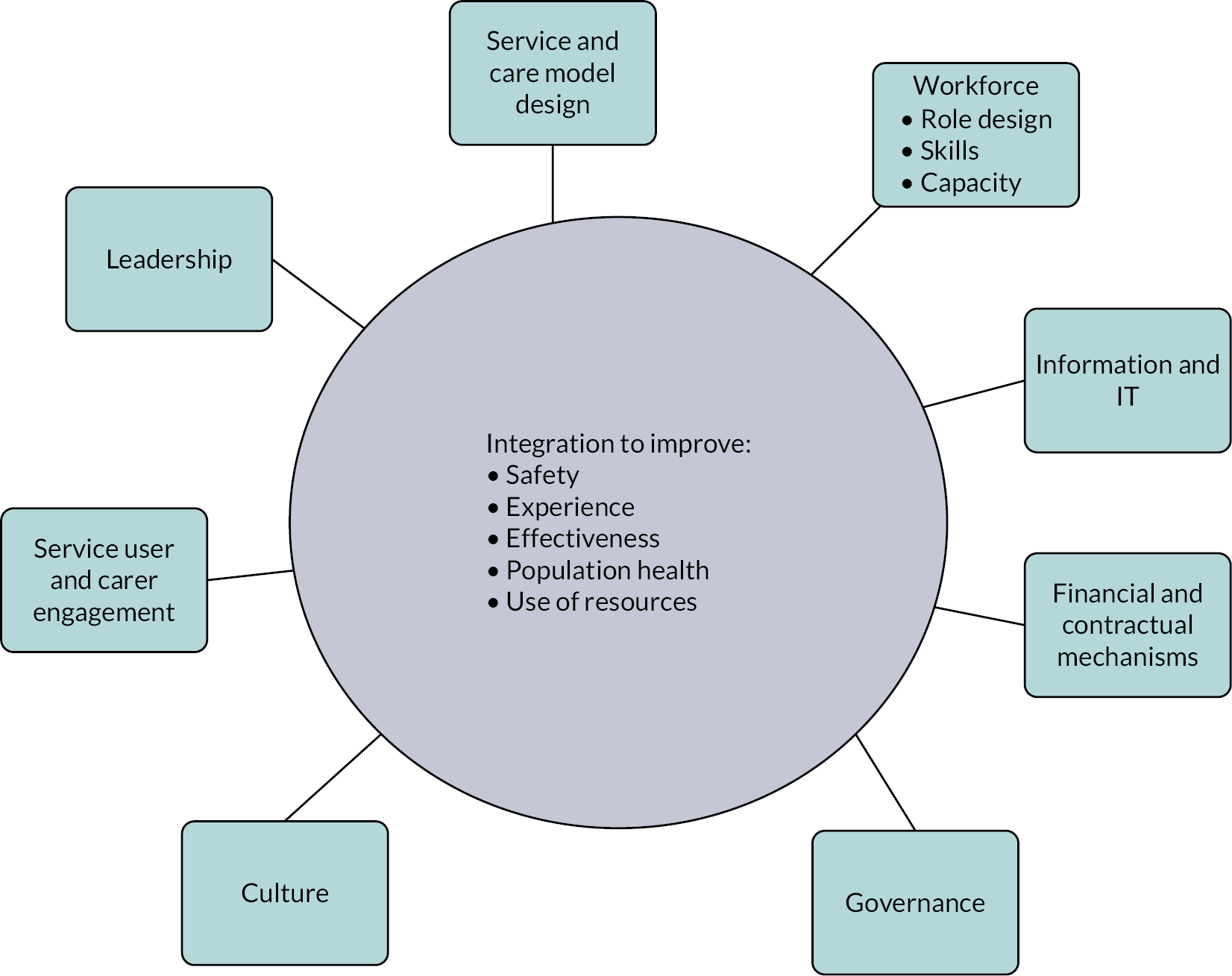

In addition, Aunger et al. 61 developed a typology of shaping factors for successful collaboration that incorporated a typology by the Advancing Quality Alliance111 (see Figure 6) and was supplemented with other emerging evidence from the review. 17,65,112–114

Aunger et al. 61 argue that the examination of organisational perspectives and theories surrounding the integration of these elements leads to the understanding that different partnering types are likely to interact with some elements more than others (see Table 4). For example, a partnership synergy theory suggests that certain characteristics are intrinsic to partnerships, namely leadership, administration and management, governance and efficiency. 115 As such, one could argue that partnering interventions largely exert their forces of change through changes to service and care model design, leadership, governance, and financial and contractual mechanisms, and that subsequent changes to information technology (IT) systems, culture and workforce occur as knock-on effects.

| Domain | Definition | Emerging evidence regarding factors affecting partnering success |

|---|---|---|

| Culture | The values and common behaviours of the workforce | Organisations have cultures that provide staff with a sense of autonomy Mutual agreement to work together A proper cultural integration plan is put into place in cases where high integration is required |

| Leadership | The senior management at the organisation(s) | Leadership style, which involves all levels of workforce in partnership arrangements Building networks and shared vision Leaders with charismatic and inspirational leadership styles Approaching the partnership with a strong belief in partnership Performance of due diligence (i.e. robust cultural integration plans, team-building across sites, role modelling, realistic expectations and plans, and utilising employee input) |

| Governance | The systems and processes concerned with ensuring the direction, effectiveness, supervision and accountability of the organisation(s) | Ability to align internal and external resources, activities and demands The ability to share power between partners Proper establishment of shared accountability between partners |

| IT systems | The IT infrastructure in place to support the organisation(s) | Enablement of information-sharing across partners The degree to which resources are dedicated to this aspect of integration Understanding of data requirements across partners |

| Workforce | The collective staff that work at each organisation | How well workforce practices and procedures are aligned Coordination to reduce variation in quality of care Having performed appropriate due diligence in the lead up to any workforce changes Engagement of staff at all levels of the organisation in the partnership process Understanding of workforce capability and capacity Group accountability and shared values |

| Service user engagement | Involving stakeholders in the partnership process | Engagement and involvement of a range of perspectives with those affected by changes to services Feedback mechanisms throughout partnering process Patients and users have ability and power to influence the partnership process in a manner that improves outcomes for them |

| Service and care model design | The way in which health care is delivered | Mutual agreement between partners on the new care model, arising from partnership Agreement between partners on desired outcomes of partnership |

| Financial and contractual mechanisms | How organisation(s) are supported by finances and a legal framework | Performance of appropriate due diligence and cost–benefit analyses to determine ideal partnership type for organisations involved (e.g. in strategic outline cases) Agreement on shared outcomes and joint performance measures |

Stages of the collaboration life cycle

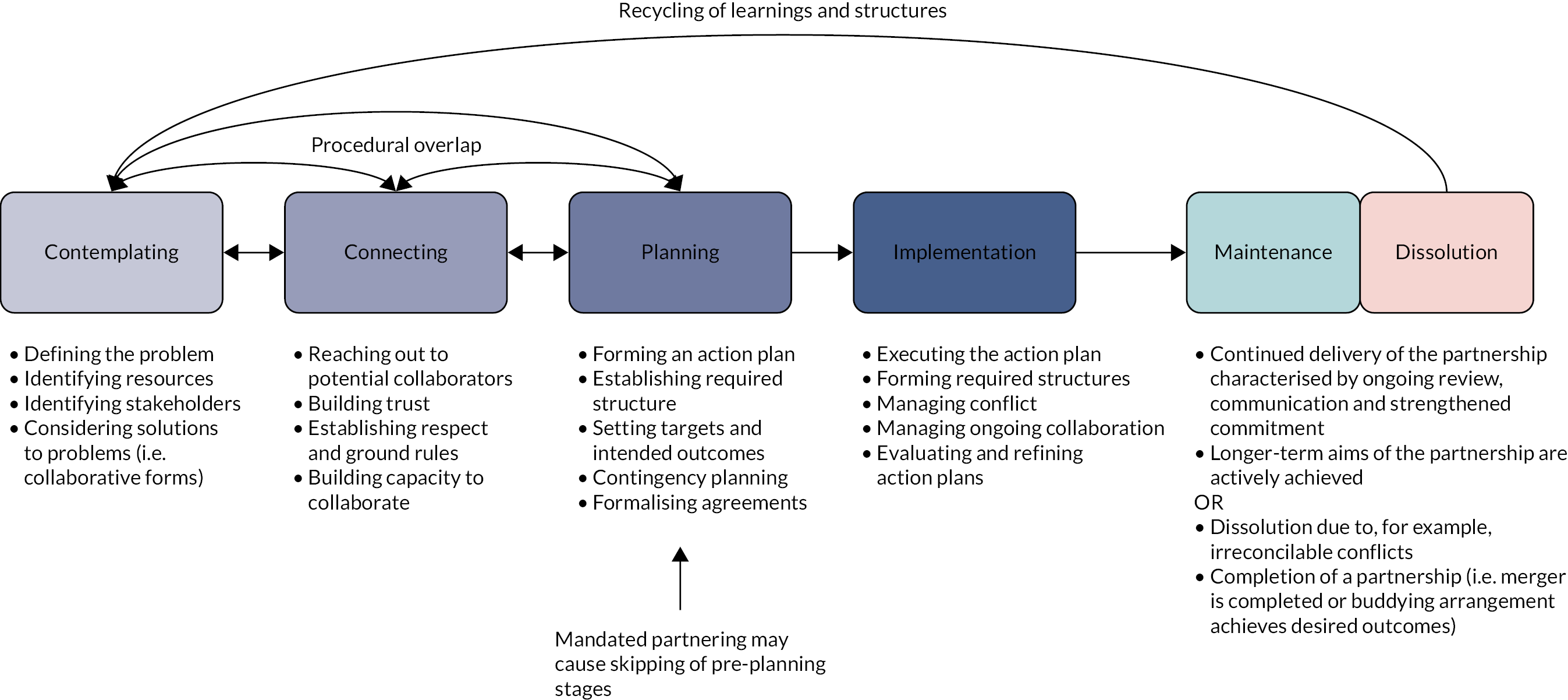

A variety of contributions have sought to capture how organisations may go through multiple collaborative arrangements throughout their lifetime. We conducted a systematic review and ‘best-fit’ framework synthesis116 to identify key literature regarding the life cycle of collaborations in a health-care setting, and this resulted in the formation of several key stages, including contemplating, connecting, planning, implementation and maintenance or dissolution (see Figure 7). The full methodology can be seen in Appendix 2.

FIGURE 7.

A life cycle model of IOC conclusion.

The contemplation aspect of collaborating incorporates behaviours analogous to ‘thinking about’ collaborating before it actually begins. 117,118 For example, the paper by Hudson et al. 119 puts forward behaviours such as ‘recognizing the need to collaborate’ and ‘identification of a legitimate basis for collaboration’. These behaviours and others have been integrated into the model as ‘defining the problem’, ‘identifying resources’, ‘identifying stakeholders’ and ‘considering solutions to problems, i.e. collaborative forms’. 119

The connecting phase revolves around behaviours that establish the initial processes of relationship-building between actors. For example, Lowndes and Skelcher89 put forward ‘informality, trust and cooperation, willingness to work together’ as key features of connecting. Likewise, ourpartnership.org.uk121 establish that, in this stage, ‘partners get to know each other and plan future activities’ and undergo ‘realistic self-appraisal and appraisal of partners’. 89,120,121

The planning phase includes behaviours such as ‘setting targets, establishing management teams’,122 ‘fostering partnership working values and engagement’123 and ‘developing basic agreement’. 120

The implementation phase includes behaviours such as ‘managing inevitable conflict between partners’,121 ‘experience of difficulties in new relationship’120 and ‘evaluating and refining action plan’,122 and is characterised by the beginning and middle phases of putting the collaboration into action, undergoing problem-solving as conflicts arise.

The maintenance phase refers to ‘building mechanisms to overcome barriers’120 and ‘sustaining trust between members’. 124,125 In this phase, the ultimate outcomes of partnerships are most likely to be achieved, as the focus moves from the functioning of the partnership to the achievement of goals.

Dissolution-type behaviours, such as ‘letting partnership die, or keeping certain aspects but not others’89 and ‘ending one or more partners’ involvements’121 can also feature at this phase due to either irreconcilable conflicts or the aims of the collaboration being achieved.

Figure 7 depicts the full life cycle model, which includes the behaviours and processes identified that are intrinsic to various stages of a collaborative life cycle.

The aim of this chapter has been to provide insights into the principles, characteristics and outcomes associated with health-care IOCs. Given the complex and multifaceted nature of IOCs, the next stage is to develop these findings with a methodological approach able to grasp these underlying contexts, dynamics and outcomes over time. In the next chapter, we outline how a realist synthesis approach is employed to better understand how IOCs work, why and for whom do they benefit.

Chapter 3 Methodology

This chapter will present the design and methods for the realist review and evaluation aspects of the project. Excerpts of the chapter have been reproduced from Aunger et al. 137,138 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Taking a realist perspective

A variety of theoretical contributions have sought to improve understanding of IOCs in health care. 14,48,110,126,127 These authors have generated valuable insights as to ‘what’ leads to successful partnering, but less so to how and why particular features enable collaborations to be successful. In this sense, IOCs can be seen as interventions that frequently fall into the trap of what Dixon-Woods and Martin128 term ‘magical thinking’, that is, the assumption that ‘doing X’ will lead to outcome Y without any articulation of how and why this change will occur, and this means that, often, the assumptions underlying how collaboration is intended to work are left implicit.

Any collaborative effort is likely to have a long and complex process of implementation, from initial discussions between stakeholders to the realisation of the intended benefits and/or failure. However, until now, few have used a realist lens to shed light on this phenomenon. Using a realist methodology to identify when, how and in what circumstances the causal links during implementation break or hold, as well as why collaboration may lead to better performance. A realist methodology also enables synthesis of all literature types in acknowledging the complexity of the interventions that constitute an area such as IOC.

Realist methods are built on the epistemological approach of critical realism, which is based on the concept of generative causation, where mechanisms generate outcomes that are context sensitive. 129,130 In realist terms, contexts refer to the situations into which interventions are introduced that affect the operation of the intervention mechanisms. 129 An intervention may work through one mechanism in one set of contextual features, but work through a different mechanism, producing a different outcome, in another. As a result, context and mechanism are keenly interlinked and cannot be separated. 129 Mechanisms, in realist terms, are the interactions between programme resources and the changes in reasoning by programme actors that occur as a result. 131 Mostly, these mechanisms are not directly observable but, nonetheless, can be explanations of why particular outcomes come to be. 129

Those who have used a realist perspective to understand IOCs have focused on particular subtypes and contexts of collaboration. 127,132,133 However, to the best of our knowledge, none have yet attempted to address the wider topic of IOCs between health-care providers. In this project, we have drawn on realist methodology in both synthesis and evaluation types to test and refine a robust theory of how IOCs in health-care work, to what extent, why and in what circumstances.

A starting point of realist evaluation is identifying the ideas and assumptions underlying how programmes or interventions work, known as programme theories. Realists also work with the premise that programmes are never universally successful, rather how they work (i.e. their mechanisms) to produce outcomes is shaped by contextual features. The goal of realist evaluation is to explain how contextual features shape the mechanisms through which a programme works, and this is achieved through testing and refining programme theories, expressed as context–mechanism–outcome configurations (CMOCs). Initially, CMOCs are tentative ideas, and as the project progresses these ideas are brought into conversation with evidence (i.e. tested in relation to the evidence) and are then refined to produce a more detailed explanation of how context shapes mechanisms. 129,130 A refined theory can support the process of adapting the intervention to local circumstances. The aim of this project is to produce a fully refined and actionable theory for practitioners and those implementing such arrangements.

Methods: realist synthesis

Details of search strategies

Theory gleaning

Searching processes in realist reviews tend to be evolutionary in nature, and that was the case here. 134 Initially, systematic searches were conducted to gather evidence about how IOC works and the contextual factors that shape across a range of entities, such as alliances, buddying, mergers, acquisitions and hospital groups. Searches were run between 20 February 2020 and 4 March 2020 on databases including the Healthcare Management Information Consortium (HMIC), MEDLINE, Social Policy and Practice and PsycINFO (see Appendix 3 for search strategies). The HMIC commentary search (see Appendix 3) was run on 12 January 2021. The searches were limited to 1990 onwards to provide the most up-to-date literature. In addition, a Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) search was conducted on 11 March 2020 to identify any grey literature or papers missed. The Google Scholar search used the terms ‘theory organisational collaboration’ to identify theoretical papers and ‘interorganisational collaboration healthcare’. Reference-scanning and citation-tracking was also employed to ensure as many papers were identified as possible (see Appendix 3 for the full systematic search strategy).

After data synthesis, we realised that we lacked elucidation on some of the mechanisms underlying how leadership, among other elements, may be key to understanding the process of collaboration. Therefore, a non-systematic purposive search was used to identify middle-range theories (MRTs), which would allow us to gain further insight into mechanisms uncovered through our analysis of papers identified in our initial searches. MRTs were identified using terms and combinations of terms such as ‘inter-organisational conflict’, ‘inter-organisational communication’, ‘inter-organizational trust’, ‘organisational capacity’, ‘collaborative leadership’, ‘organizational flexibility and effectiveness’, ‘collaborative accountability and governance’ and ‘collaborative regulatory environment’. The searches were conducted in Google Scholar in May 2020. Finally, we conducted an additional Google Scholar search in December 2020 using the terms ‘confidence’ and ‘trust’, ‘formalisation’, ‘contract’ and ‘contractualization’, combined with ‘inter-organisational collaboration’ or ‘partnership’ or ‘network’, for further MRT papers.

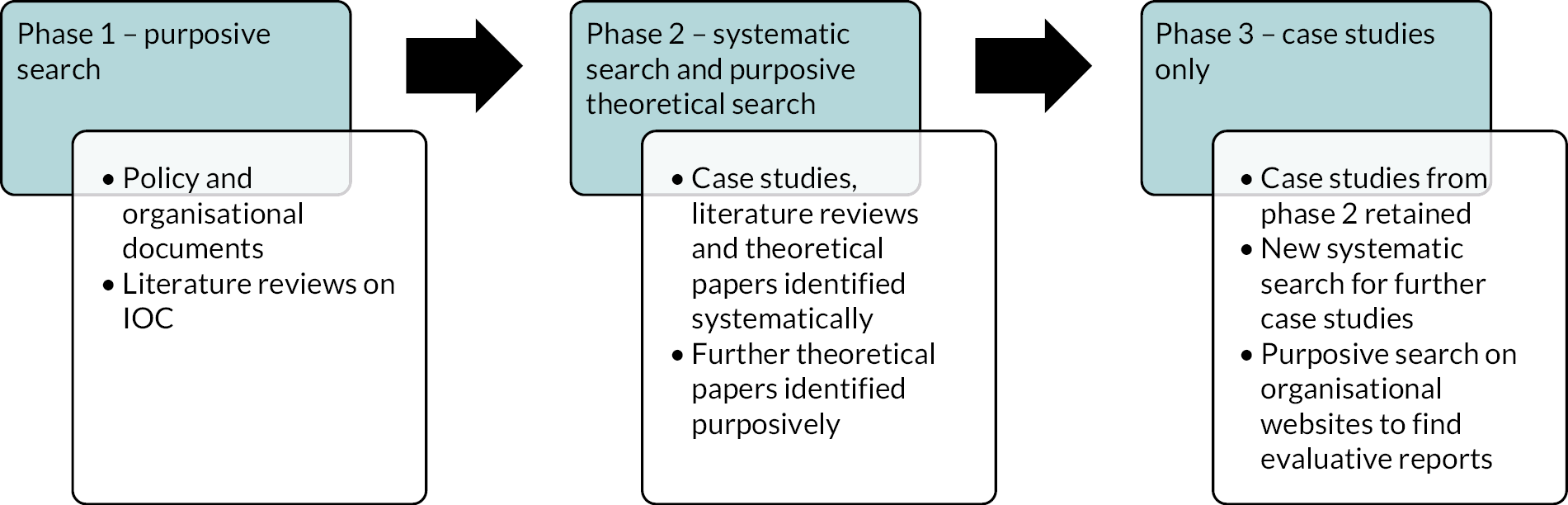

Theory refinement

Literature for this refinement stage of our realist synthesis was identified through a combination of existing literature from prior stages (systematically searched), novel (to this stage) systematic searches intended to locate case study literature explicitly and grey literature sources (for identifying organisational reports and evaluations), as is typical of a realist synthesis. 134 Case studies from the existing search were included here, with these case studies being brought over into this refinement stage of the synthesis. In addition, a novel systematic search was conducted on 10 June 2020 on the Social Policy and Practice database to identify additional case studies. Further searches for grey literature were conducted on 7 October 2020 and 8 October 2020 on UK-specific websites for evaluations of collaboration types, including The King’s Fund (London, UK), the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) (London, UK), the Nuffield Trust (London, UK), The Health Foundation (London, UK) and NHS Employers (London, UK). The searches were on the publication sections of each website, with a focus on identifying evaluative reports. The searches used the terms ‘collaboration’, ‘partnership’ and ‘integration’ and were limited to 2012 onwards to maximise relevance to contemporary developments in collaborative arrangements. Figure 8 depicts the full methodology of this realist project.

FIGURE 8.

Depiction of phases in developing realist theory. Adapted with permission from Aunger et al. 135 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Inclusion criteria

Theory gleaning

Selection of documents was performed on the basis of relevance to the realist synthesis, as is typical of a realist review. 130 The systematic review used the following inclusion criteria for the title and abstract stage: ‘the paper clearly relates to collaborations between one or more public sector organisations on either a structural or individual level’ and ‘the paper is a case study, evaluation, opinion, or review’. In the full-text screening, as well as that for relevance, the paper had to include ‘propositions about the success or failure of collaboration in the public sector, mechanisms underlying how collaboration works, or include information about “entry points” (i.e. drivers of collaboration)’. Exclusion criteria for all stages included papers that ‘relate to collaborations or partnerships between staff and patients rather than between organisations’. Titles and abstracts were screened by Justin Avery Aunger, with a subset of 10% screened by Ross Millar in accordance with other systematic reviews. 12 Agreement was reached for all selected papers.

Theory refinement

For the refinement stage, we included only papers that (1) were case studies or evaluations (defined as reporting results of arrangements using descriptive methods), (2) report on an IOC between health care-providing organisations and (3) were in English (because of resource limitations of the study). Some papers had both literature review and case study portions, and these papers were also included, but data extraction was performed on the case study parts only. Selected studies were then subject to rigour and relevance checks in line with realist synthesis methodology.

Rigour and relevance screening

In line with guidance from Wong,136 the screening for rigour was ongoing during the analysis process and aimed primarily to increase the trustworthiness of the findings. This process involved including a CMOC only when supported by (1) clear data in included studies and (2) multiple sources. 136 For theoretical sources of evidence, only theories that had seen significant use in the literature since publication were used in the building of our MRTs and CMOCs. If documents were excluded on the basis of trustworthiness, then the reasons for doing so were to be recorded; however, no studies or extracts were excluded on this basis.

Data extraction

Data extraction was carried out by one reviewer (JAA), which involved combing the included papers for information relating to mechanisms underlying collaboration, programme theories and contextual factors (often termed ‘success factors’ or barriers). As is typical of a realist review,134 identified passages in the documents were highlighted for relevance, before being extracted into separate documents according to realist logic and how they aided in understanding the intervention. This was performed using custom data extraction forms (available on request).

For the refinement stage, another custom data extraction form was created, which recorded the study, collaboration type, primary driver (as best deduced from the study), CMOCs that fit into prior theory and novel CMOCs (which could be novel in context, mechanism or outcome) that did not fit wholesale into the prior theory. This type of custom form is typical in a realist synthesis and is available in Report Supplementary Material 1. In addition, we attempted to extract information on whether studies were reporting on externally mandated forms of partnering or voluntary forms, but it was not always possible to determine this information, unfortunately, because of inconsistent reporting by authors.

Realist synthesis methods

Theory gleaning

The highlighted passages from the included documents were coded according to whether the passage sheds light on entry points into collaboration, contextual factors, mechanisms or other elements relating to collaborations that helped elucidate the underlying ideas and assumptions regarding how collaboration was intended to work and the sorts of contextual features that might shape the different mechanisms underpinning these. Most successful factors and barriers were typically identified to be the inverse of one another, and so these factors/barriers were amalgamated into becoming contextual factors at a later stage of the synthesis. As more papers were extracted, categories that were found to be thematically similar were merged to result in the final categories seen in this review. Contextual factors, mechanisms, outcomes and entry points into collaboration were coded separately, but contextual factors had their posited underlying mechanisms recorded alongside them, as well as any potential outcomes. The sources that supported the existence of these contextual factors were also recorded. Synthesis results were regularly discussed by Justin Avery Aunger and Ross Millar to maintain validity and consistency.

In some cases, mechanisms were explicit in papers identified in the systematic review and in other cases the evidence was missing. Therefore, in cases where analysis was completed and mechanisms were missing, a purposive search was used to locate MRTs that could elucidate mechanisms that were triggered by these contextual features inherent to collaborations. Contextual factors were then clustered according to their underlying mechanisms and the case study and review literature, and MRT evidence synthesised. The theoretical clarity of mechanisms and the evidence underpinning them were discussed by two authors (JAA and RM), and CMOCs were then formed. Included documents then underwent a second pass, using specific search terms relating to mechanisms, and identified contextual factors to ensure all sources of relevant information were included.

Theory refinement

Using the existing realist programme theories from step 2 of this realist synthesis process as a base, we aimed to test our existing CMOCs against case studies and improve our understanding of how CMOCs are situated temporally and causally to improve our theory of collaboration in health care, and this constituted phase 3 of our overall analysis (see Figure 9). Literature was identified through systematic searches of databases and searches of organisational websites. The literature was then categorised by collaboration type, as well as whether the collaboration was a mandated or voluntary arrangement (as could best be identified), and the literature was then rigorously searched to identify CMOCs. Testing of existing CMOCs then occurred against the newly identified literature from this stage’s searches, and this comprised identifying whether CMOCs were identical to the existing CMOCs from the theory gleaning phase, or could be considered novel in terms of context, mechanism or outcome content or novel in terms of the relationship of one CMOC to another. Although we did not intend for the focus here to be on theory gleaning, novel CMOCs were still included when identified with sufficient evidence to support them. Both CMOCs from the existing theory that had support as well as novel CMOCs not present in the existing theory were recorded. Any conflicting information about the configuration of existing CMOCs was also recorded.

FIGURE 9.

Evolution of literature synthesis by phase of review. 61,138 Adapted with permission from Aunger et al. 135 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

The process resulted in significantly more overall CMOCs than were present in our prior realist phase, and this allowed us to gain a greater understanding of how the outcomes of certain CMOCs can become a context for another further down the chain. To identify these relationships, these CMOCs were deductively coded in NVivo 12 into categories according to their mechanism to better investigate the literature for presence of demiregularities, which, in realist terms, are patterns of how outcomes generally come to occur. 137 The data were then used to refine the MRT and programme theories to provide a better understanding of the links between these elements. This chapter was written according to the RAMESES (Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards) II reporting standards. 134 All data requests can be submitted to the corresponding author for consideration.

Methods: realist evaluation

Objectives

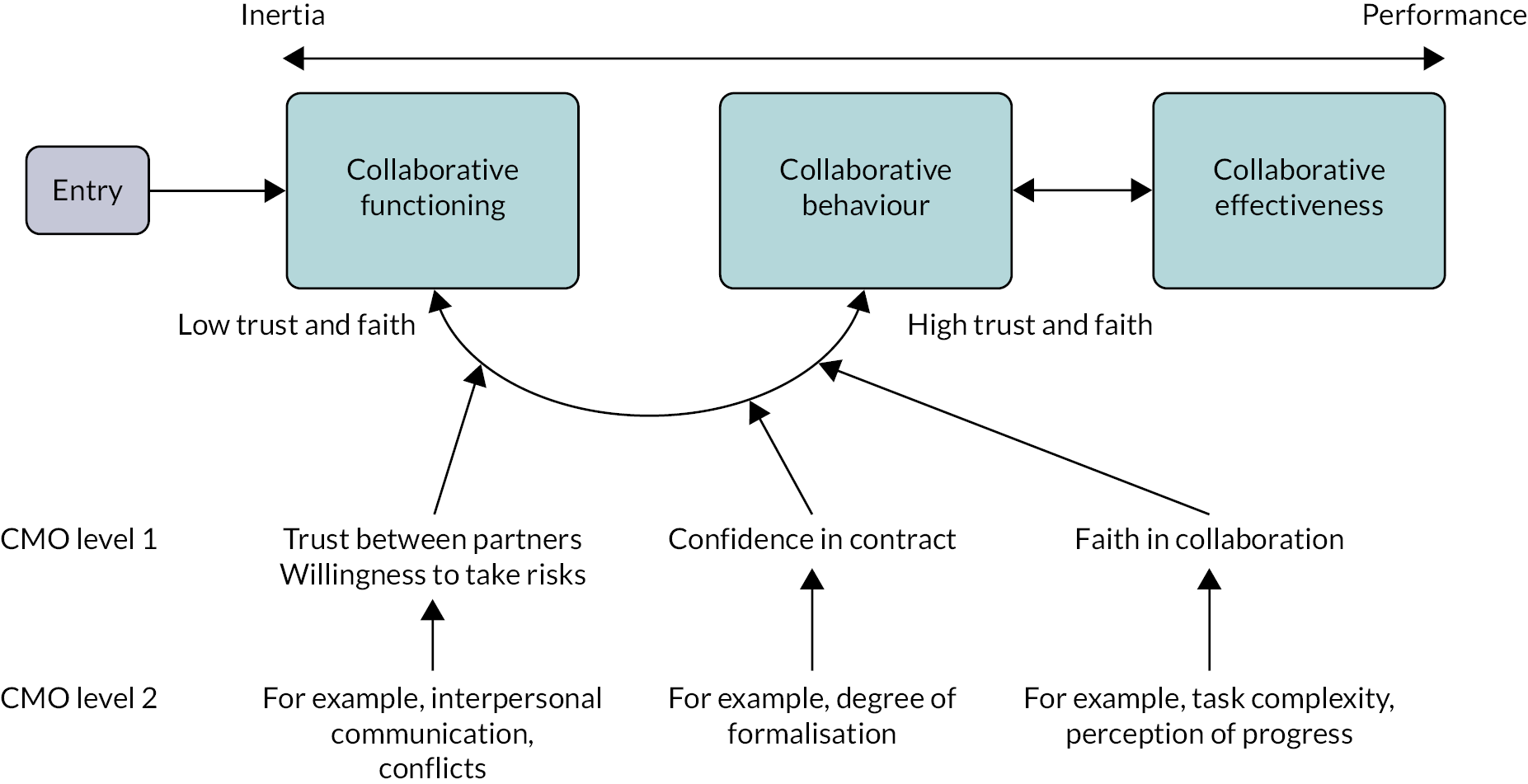

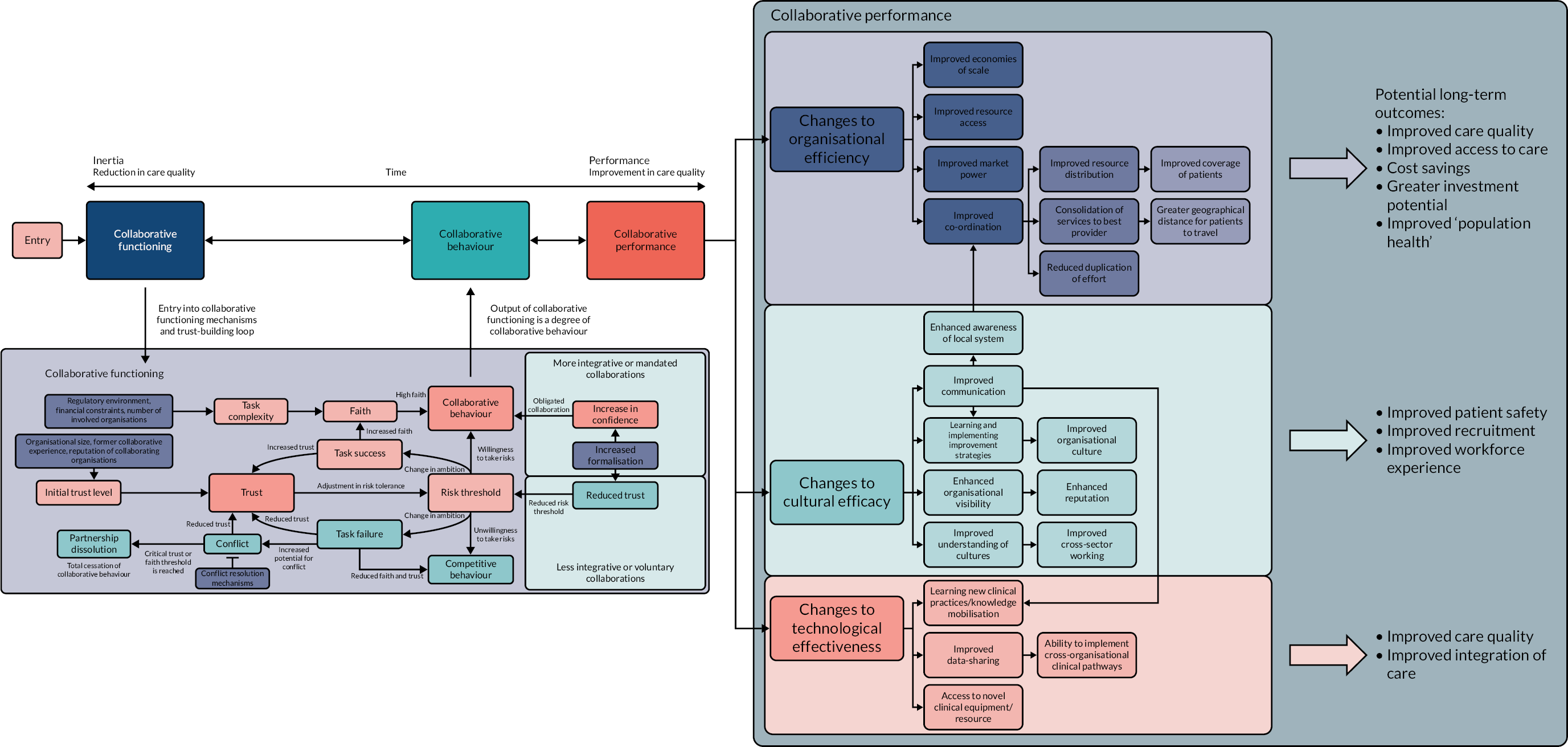

We conducted a realist evaluation to further test our refined programme theory by exploring the experiences of a range of stakeholders across several examples of IOCs in England. Our primary objective was to test the mechanisms of collaborative functioning and CMOC derived from literature against the stakeholders’ views to explore whether previously identified mechanisms and CMOCs, and causal links between them, were affirmed, refuted or revised, and to refine our understanding of how IOCs work, in which circumstances and why. In addition, we sought to elucidate the part of the causal chain that links collaborative behaviour to collaborative performance to identify how and why performance benefits may arise from the process of collaborating. We intended to produce a refined realist programme theory rooted in both literature and practice, with a view towards practical use in the future.

In the realist evaluation, for collaborative functioning, our prior programme theory135 was adopted as a MRT, against which interview data were ‘tested’, based on the realist synthesis, and this means that we explored if and how interview findings affirmed prior CMOCs, proposed refinements to existing CMOCs or, and to what degree, identified CMOCs that were novel. This theory, which we adopted as the MRT, will be outlined in the following realist synthesis chapter.

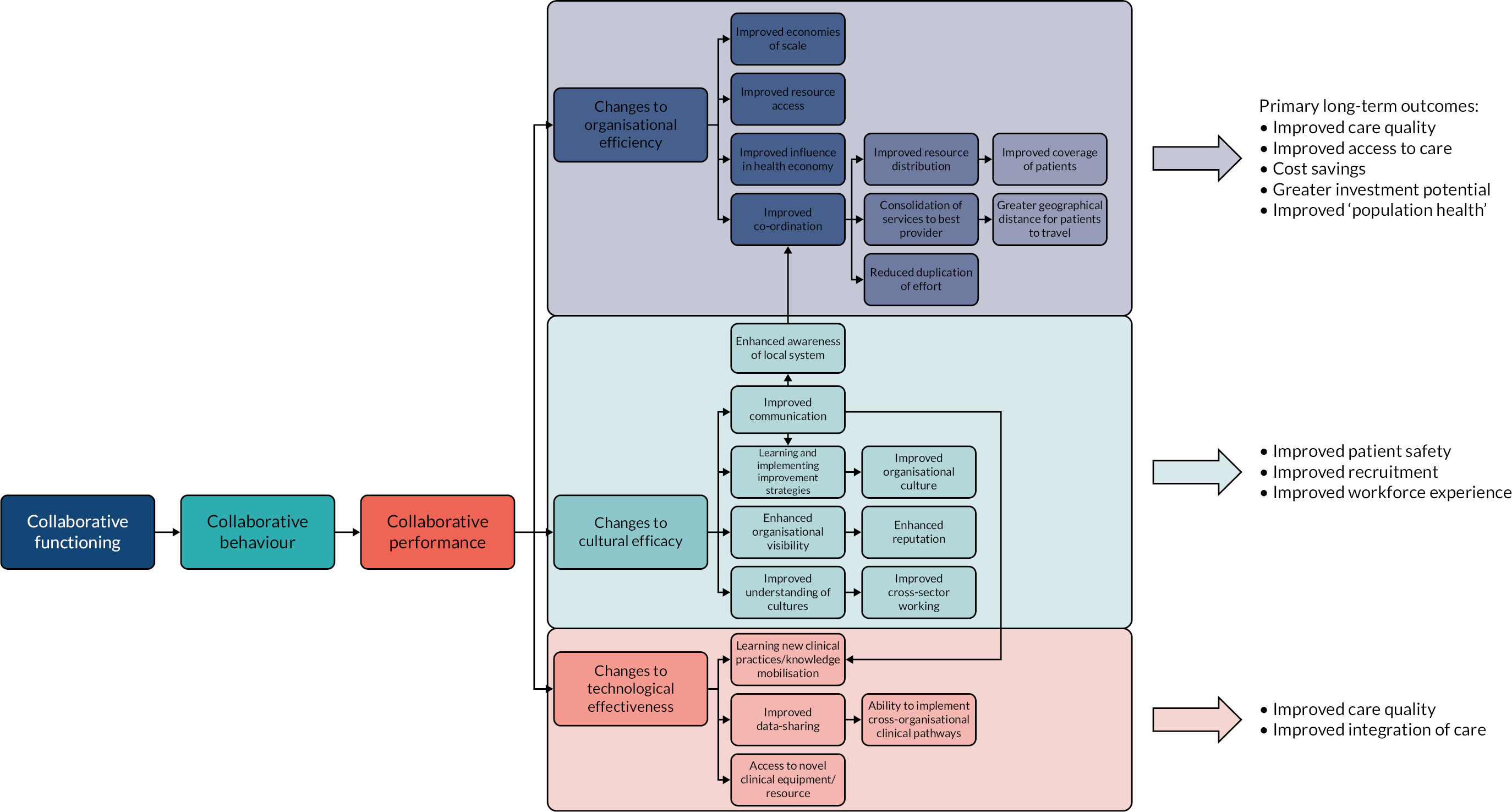

For understanding collaborative performance, Dickinson and Sullivan’s48 framework (adapted from McKenzie216) was adopted as a MRT to inform our analysis. Dickinson and Sullivan’s48 framework was selected as a MRT for three main reasons: (1) the framework focuses on performance rather than the functioning aspect of the causal chain; (2) the framework provides three criteria against which realist mechanisms can be categorised and (3) the framework captures cultural efficacy, which neatly complements the concept of programme mechanisms as changes in participant reasoning within realist theory. Thereby, we assume that frameworks relying purely on the ‘techno-bureaucratic’ aspects of performance would likely neglect key social components of the causal chain. Enabling a greater understanding of collaborative performance forms an essential part of the overall programme theory.

Therefore, the final aim of our realist evaluation was to produce a refined MRT, seeking to answer ‘what works in IOCs, for whom, under what circumstances, why and how?’, as well as ‘how do performance improvements in IOCs in health care arise, why, and what underpins them?’. This chapter was written in accordance with the RAMESES II reporting standards for realist evaluations. 139

Details on programmes evaluated

The ‘programmes’ evaluated comprised a range of IOCs, as outlined in our initial realist theory paper. 61 The programmes included arrangements of relatively low integration (i.e. buddying) through to highly integrative types, such as mergers. Our interviewees had direct experience of four different types of IOC and comprised five examples of hospital groups, two alliances, three ICSs and two mergers. The IOCs reflect a range of drivers and contextual differences. Although mergers result in formation of a singular organisation, we consider mergers to be collaborative entities during the merger process until the fully merged organisation begins operating38 (see Table 2 for full details on the types of IOCs and regulatory organisations included in this evaluation).

Data collection methods

The realist evaluation drew on interviews conducted with an ‘issue network’140 of stakeholders, comprising the leaders or architects of collaborative programmes, regulators, policy-makers, professional bodies, front-line staff and patient representatives. We defined these stakeholders as ‘a broad collection of individuals possessing knowledge about the issue in question with some influence on policy outcomes’.

Recruitment process and sampling strategy

Participants were identified through contacts via our Study Advisory Group and from direct contact with potential individual and organisations identified through scoping work. Phase 1 interviews were conducted, which had a particular focus on ‘theory gleaning’ and explored current programme theories being used to develop partnering approaches across NHS providers. Recruitment to phase 1 used a purposive sampling approach, with further snowball sampling employed to identify relevant stakeholders within this ‘issue network’. Phase 2 participants were also recruited, drawing on a selection of key informants from NHS provider organisations currently engaged in a range of partnering activities. Here, particular attention was paid to testing and refining programme theories identified in from the literature and the theory gleaning interviews to produce refined theory.

Participants were chosen based on their likelihood of being able to provide rich information about various aspects of the programme theory, from being engaged in implementing such arrangements themselves to delivering the policy and regulatory agendas.

Participants were approached to participate via e-mail. Patient representatives were recruited from patient representative bodies and were intended to be greater experts on outcomes rather than ‘mechanisms’. 141

Sample

The final sample comprised 37 interviews with 34 participants and one focus group with 8 patient representatives. The interviews and focus group were conducted across England between January 2020 and May 2021. Table 5 outlines the characteristics of the participants.

| Case studies of IOC programmes | Role (interview code) |

|---|---|

| Hospital group 1 (South) | Director (2) × 2 |

| Hospital group 2 (South) | Director (3) × 2 |

| Hospital group 3 (South) | CEO (18) |

| Hospital group 4 (South) | Lead (29) Director of improvement (35) |

| Alliance 1 (North) | Executive nurse (10) Former CEO (12) Director (20) CEO (22) Medical director (23) Workforce director (26) |

| Alliance 2 (North) | CEO (17) Director (19) |

| ICS 1 (North) | CEO (13) |

| ICS 2 (South) | Lead (14) |

| ICS 3 (South) | Lead (25) |

| Integrated care provider (North) | Manager (16) |

| Merger (South) | Director (21) |

| Wider stakeholder perspectives | Academic and non-executive (1) |

| Provider policy lead (4) | |

| Provider policy inspectorate lead (5) | |

| NHS provider association [6 (× 2) and 11] | |

| Professional regulator (7) | |

| Regional inspectorate lead (8) | |

| Policy transformation lead (9) | |

| Patient representative lead (15) | |

| Third sector representative (24) | |

| Local government representative (28) | |

| Private sector representative (27) | |

| Patient representatives (30–34; focus group) |

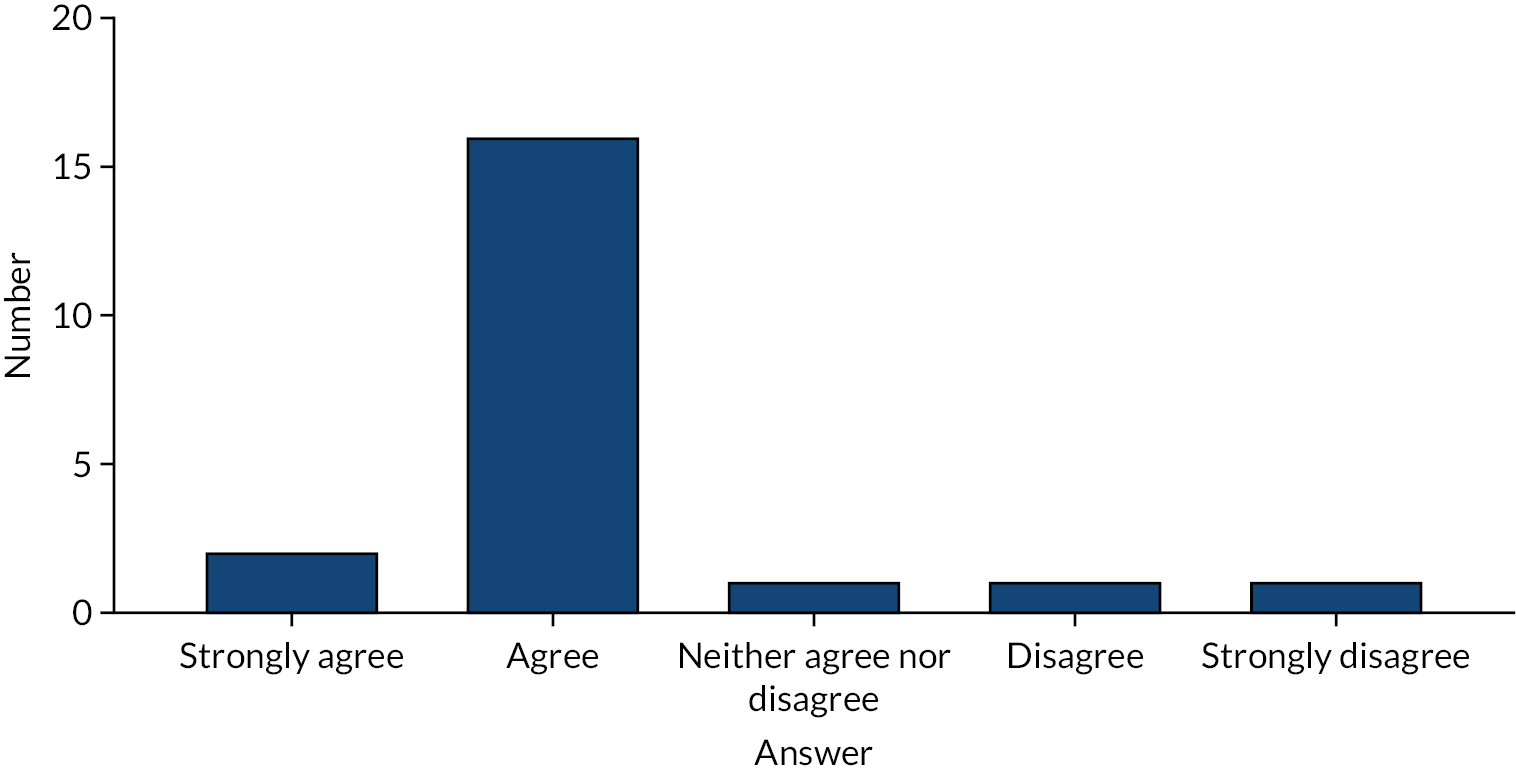

Interviews and setting