Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number NIHR128068. The contractual start date was in September 2019. The final report began editorial review in December 2021 and was accepted for publication in October 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final manuscript document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this manuscript.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Webb et al. This work was produced by Webb et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Webb et al.

Chapter 1 Background

Background research

Perinatal mental health (PMH) difficulties can occur during pregnancy or after birth. They affect up to one in five women and the cost to the UK is estimated to be £8.1 billion for every annual cohort of women, with 72% of this cost attributable to the long-term impact on the child. 1 PMH difficulties commonly consist of anxiety disorders, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and stress-related conditions such as adjustment disorder. Many disorders are comorbid2,3 and severe postnatal mental illness is one of the leading causes of maternal death. 2

Perinatal mental health difficulties are particularly important because of the potential negative impact on women, their partners, children and families. This impact varies according to the type of mental illness, severity and timing (e.g. whether pre- or postnatal; acute or chronic; pre-existing or new onset) but, overall, the evidence shows a severe and enduring impact. For example, perinatal mental illness (PMI) is associated with a range of adverse outcomes for women, such as an increased risk of stillbirth4–6 as well as an increased risk of maternal suicide. 2,7–9 PMH difficulties are also associated with a decline in relationship satisfaction and an increased risk of relationship breakdown. 10–12 In terms of infant and childhood outcomes, PMH difficulties are associated with an increased risk of pre-term birth,13,14 and longer-term impacts on children’s cognitive15–18 and behavioural development,17,19,20 as well as being associated with an increased risk of children developing mental health difficulties themselves. 21–23

It is therefore important to identify and assess PMH difficulties quickly so that women who need treatment are able to access it. However, a survey of 200 women living in the UK found that 23% had not sought professional help for their symptoms. 24 It is also estimated that only 30–50% of women with PMH difficulties are identified and less than 10% are referred to specialist care. 25,26 This is likely due to a range of factors at individual, health professional (HP), interpersonal, organisational political and societal levels. For example, HPs not asking about mental health, lack of effective assessment, barriers to women seeking help or attending treatment, clinician barriers to diagnosis and treatment, lack of services to refer on to or limited understanding of effective treatments.

Recognising the barriers and facilitators to identification, assessment, referral and treatment for PMH difficulties is therefore important for health and social care services working with perinatal women. The need for this is evident in calls for research,27 UK strategy and policy,28,29 and clinical guidelines. 30,31 For example, in 2014, the National Health Service (NHS) set out plans for £365 million to be spent on PMH services from 2016–2128 as part of the Five Year Forward View. These services were to ensure 30,000 more women each year would access evidence-based specialist mental health care during the perinatal period. Similarly, the Scottish Mental Health Strategy aimed to improve the recognition and treatment of PMH difficulties. 31 The full implementation of these plans would mean women being asked about their mental health and well-being during antenatal booking visits, being screened for mental health difficulties, assessment within two weeks of referral and being provided with evidence-based psychological interventions within one month of initial assessment. 30–32 Furthermore, in 2019 NHS England set out a Long Term Plan for PMH, pledging an additional £2.3 billion a year and stating that by 2023/24, 66,000 women with moderate to severe mental health difficulties should have access to specialist care from pre-conception to 24 months postnatal. 33 Identifying barriers to women accessing treatment, as well as barriers to implementing PMH assessment and treatment in NHS services, is therefore important to inform these initiatives.

This evidence synthesis therefore aims to identify potential barriers and facilitators to identification, assessment, referral and treatment of PMH difficulties across the care pathway, both in terms of women accessing care or treatment, as well as in terms of NHS services implementing new assessment and treatment initiatives. This will be used to inform a conceptual framework of barriers and facilitators to PMH care that will inform health care services and practice, care pathways, and highlight where further research is needed.

Evidence explaining why this research is needed now

Perinatal mental health is a priority for UK strategy and policy,28,29 clinical guidelines,30,31 HP organisations26,34,35 and third-sector organisations. 36,37 While there have been large improvements in PMH service provision since the publication of the Five Year Forward View,28 in a progress review carried out in 2017 by the All-Party Parliamentary Group on Mental Health, The Royal College of Psychiatrists stated that teenage pregnancies, care beyond the baby’s first year and comorbid substance abuse remained areas lacking in focus and investment. The King’s Fund also reported that in some local areas, recommendations for expanding PMH services were being achieved by retraining existing staff without employing more, an approach that is not sustainable in the long term. 38 Furthermore, in 2020 the Maternal Mental Health Alliance identified that 20% of clinical commissioning groups (CCGs) in England still did not have specialist PMH services. These gaps in specialist PMH service provision are even higher in Wales (71.4%) and Scotland (85.7%). 39 These treatment gaps may mean women are not accessing the care that they need. 26 Given the recent provision of £2.3 billion a year to PMH services,33 this is a crucial time to understand what barriers exist and how they can be overcome.

Reasons why women are not identified and treated for PMH difficulties are complex and multifaceted and likely due to two broad factors: (1) lack of availability of services, which in the current context is possibly due to difficulties implementing services; and (2) difficulties accessing services from women’s perspectives. These difficulties are likely to occur at multiple levels (e.g. individual level factors, HP factors, organisational and wider political-social factors40) and across the care pathway. 41 The care pathway has been defined by Goldberg and Huxley (1992)41 who provided a framework for understanding how a person reaches mental health services. Their Pathways to Care Model shows how, as a person moves through the care pathway, certain factors act as filters that prevent people from accessing mental health care. The first filter is ‘illness behaviour’, where a person needs to pay attention to their symptoms and then make the decision to seek help. If this is not done, this is the first ‘filter’ out of the care pathway. The second filter is the HP’s ability to recognise mental illness, the third is referral on to mental health services and the last filter is admission to hospital beds.

Difficulties in implementing services and accessing services from women’s perspectives are also likely to be impacted by an environment where health care services are highly heterogenous, with variation both within and between services. In some cases, care pathways and treatments are based on organisational factors or assumptions that are not evidence-based. For example, prior to 2016 some CCGs had never commissioned a PMH service and women in these areas were referred to mainstream adult psychiatry services. 42

Guidelines for implementing PMH services have been developed by both NHS England in 201643 and the National Collaborating Centre for Mental Health in 2018. 44 These state the need for multi-agency working across all levels of care and services, expansion of workforce capacity, working with providers and those with a lived experience, and evidence-based service plans. Despite this guidance, large treatment gaps are still reported. 45 The lack of consistent implementation and the development of future implementation plans suggests it is both timely and important to understand what factors may affect implementation of PMH care and at present there are no reviews on barriers and facilitators to implementing PMH care in the NHS or other health care services.

Several systematic reviews of qualitative literature have identified potential barriers to women seeking help for PMH difficulties. Barriers include a reluctance to acknowledge symptoms and lack of support from partners and family members; a lack of ability for women to talk about their feelings openly due to perceived social pressures and stigma; fear of losing custody of their child; and a lack of knowledge of PMH difficulties among mothers. 46–48 Women also cite practical factors influencing their decision to seek help, such as the cost of treatment, finding childcare, lack of health insurance and transport issues. 49

Other factors that may influence whether women access care or treatment include HP factors. For example, in a survey of general practitioners (GPs) and midwives, just under a third reported having had no training in PMH. 34,50 This lack of training may be particularly critical given the importance of interpersonal factors in whether women seek help and access treatment. For example, qualitative studies of women’s experiences of PMH care suggest having a trusting relationship with a HP and being helped to discuss feelings in an unrushed, conversational manner are associated with increased acceptability and disclosure. 51–53

In terms of organisational factors, research suggests that lack of referral pathways, lack of specialised services and inadequate assessment influence whether women receive treatment or not. 46,49

Social and cultural factors are also important. Different cultural norms and health care systems will influence women and HPs understanding of PMH as well as the availability of assessment and treatment. Attitudes towards mental health, such as stigma, may affect women’s willingness to disclose their symptoms and seek help. 46–48

Over 20 published systematic reviews have explored women’s barriers and facilitators to accessing PMH care. However, each systematic review varies slightly in relation to its aim, inclusion criteria and analysis and no evidence synthesis has been carried out to combine the results into a single body of evidence. This would make it easier for health care providers and policy makers to access the information and use it to inform their decisions. 54,55

Conceptual framework

The above evidence highlights that many factors may influence whether or not women are identified, assessed, referred, and receive treatment for PMH difficulties. These are likely to operate at different levels, and across the care pathway. They may be due to barriers in implementing services, or barriers from women’s perspectives in accessing services.

Critically, there are no reviews on barriers and facilitators to implementing PMH care in NHS or other health care services. In addition, no evidence synthesis has been carried out to combine the evidence of multiple reviews about barriers from women’s perspectives in accessing services into a single body of evidence. Lastly, no reviews have combined information from both implementation literature and barriers and facilitators to accessing PMH care from women’s perspectives. Synthesising this literature coherently would make it easier for health care providers and policy makers to access the information and use it to inform their decisions about PMH services and care. One way to do this is through the use of a conceptual framework. A conceptual framework can be defined as a ‘network, or a plane, of interlinked concepts that together provide a comprehensive understanding of a phenomenon or a phenomena’. 56 The development of a conceptual framework can highlight areas for improvement and provide an empirical basis for recommendations for future practice and research.

Definitions and scope

The literature on PMH, identification, assessment and treatment is complex so it is important to define the key terms and scope of this synthesis.

Perinatal mental health difficulties include common affective disorders experienced during pregnancy or the first year after birth, such as depression and anxiety (e.g. generalised anxiety disorder, phobias, panic, obsessive compulsive disorder), stress-related disorders (e.g. acute stress disorder, PTSD), adjustment disorders, and other psychiatric disorders (e.g. psychosis, personality disorders). Symptoms can be mild, moderate or severe. All PMH difficulties were included. We excluded substance misuse disorders because they raise unique challenges in terms of assessment and treatment that may not be generalisable to other disorders.

We define PMH care as identification, assessment, referral and treatment for PMH difficulties.

How assessment of PMH is conceptualised is important. In particular, the distinction between assessment and case identification is important because they have different implications in terms of barriers and facilitators to accessing treatment. PMH assessment refers to identifying women who may be at risk for PMH difficulties, or who have PMH difficulties. Case identification uses psychiatric definitions of disorders, such as the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual57 to identify women who fulfil diagnostic criteria for a disorder. Women who meet criteria (i.e. cases) are more likely to reach the threshold for onward referral and treatment. In this project we include both assessment and case identification to examine their implications in terms of barriers and facilitators to accessing care or treatment.

Perinatal mental health treatment refers to any treatment or prevention strategy to reduce PMH symptoms. Services offering treatment vary widely. In primary care or maternity care GPs, midwives and health visitors may offer supportive care for women with mild or moderate PMH difficulties. Evidence suggests primary care is the main provider, with 90% of common mental disorders being managed in primary care. 41 Specialist mental health services vary. For example, the NHS England specialist PMH services target the top 5% of women, that is, those with the most severe difficulties. These are likely to be women with severe postpartum depression, psychosis or other complex disorders, many of whom may require inpatient psychiatric treatment. In contrast, NHS Talking Therapies (formerly known as Improving Access to Psychological Therapies, IAPT) is a community-based outpatient service that predominantly treats moderate affective disorders such as anxiety, depression, PTSD and adjustment disorders. Increasing numbers of NHS Talking Therapies services now have a PMH specialist. In addition, there are increasing community services provided by third-sector organisations, such as peer support services for women with moderate PMH difficulties. These different settings (primary care, maternity care, psychiatric and specialist PMH services) will have different barriers in terms of implementing services and women accessing treatment. In this project we aimed to consider different health and social care settings throughout.

Some services provide interventions focused on outcomes associated with poor PMH. These include parent-infant, couple or family interventions. In this project we focus on interventions for maternal mental health and exclude literature that focuses on mother-infant, couple or family interventions because these are aimed at associated outcomes rather than PMH per se and raise different issues in terms of accessing services.

The scope of this project is also on PMH of women and those who identify as women, rather than partners or those who identify as men. Partner’s and men’s PMH is important but is an area that requires research and evidence synthesis in its own right. Current research into partner’s and men’s PMH is sparse compared to research on women, and there are likely to be differences in barriers and facilitators to PMH care for men compared to women.

Chapter 2 Research questions and overview

Based on the literature summarised above, our research question was: what are the barriers and facilitators to PMH assessment, care and treatment at individual, interpersonal, organisational, political and societal levels? How can these be used to inform and improve PMH care in different health and social care settings?

Primary research objective

Our primary research objective was to develop a conceptual framework of barriers and facilitators to PMH care (defined as identification, assessment, care and treatment) to inform PMH services, and highlight where further research is needed.

Secondary objectives

Our secondary research objectives were to:

-

determine the barriers and facilitators to implementing PMH assessment, care and treatment in health and social care services;

-

identify differences in barriers and facilitators across different health and social care settings;

-

evaluate the quality of this evidence;

-

extract recommendations for implementation, practice and research based on the barriers and facilitators identified;

-

determine the barriers and facilitators to women accessing PMH care or treatment;

-

evaluate the quality of these reviews;

-

map the geographical distribution of the evidence to establish generalisability and gaps in the evidence;

-

map the findings on to a conceptual framework;

-

conduct a consultation of the conceptual framework and recommendations with a panel of expert stakeholders (e.g. women, GPs, commissioners, third-sector organisations, etc.);

-

make recommendations for practice and future research for PMH assessment, care and treatment.

Research overview

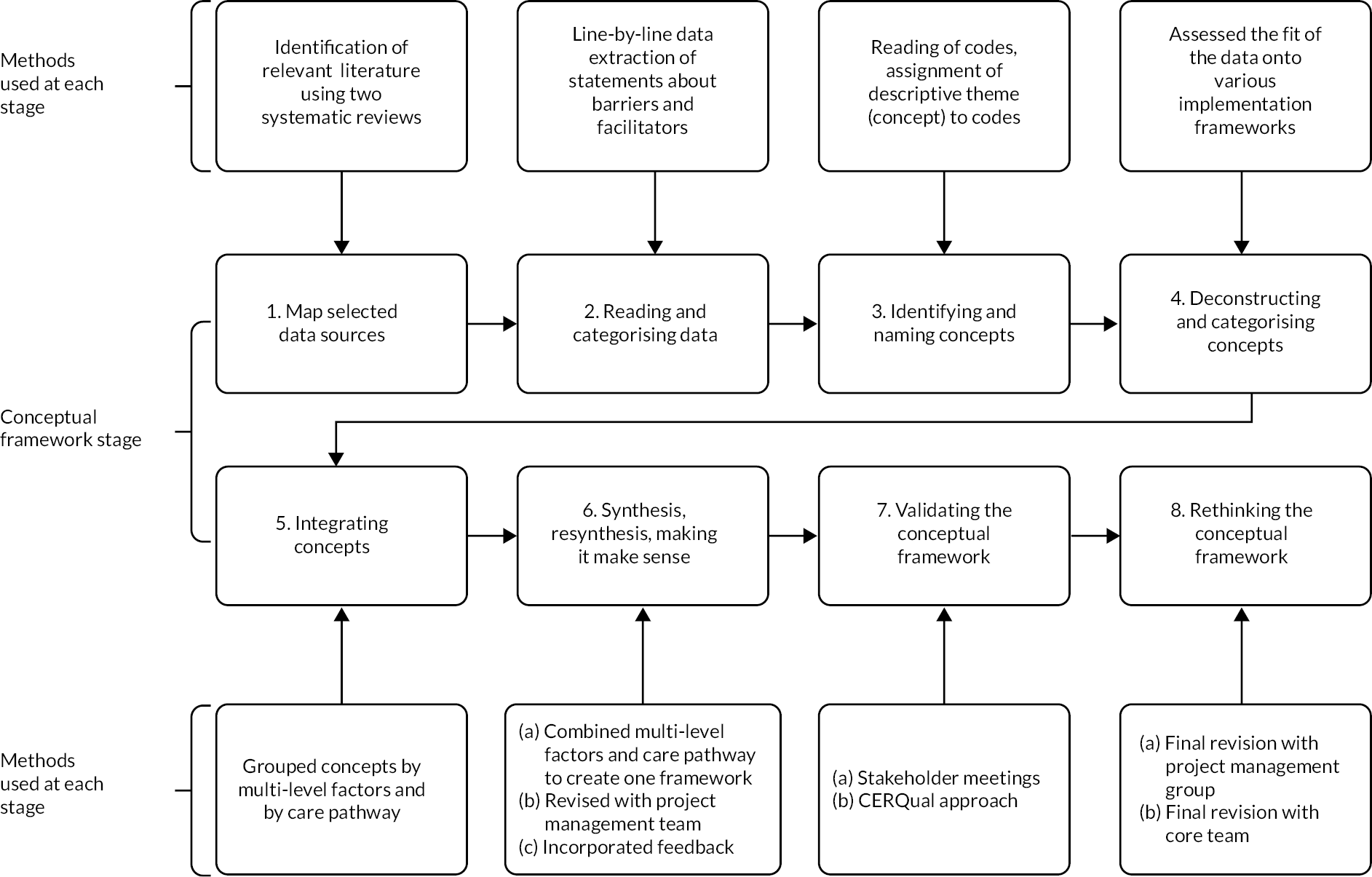

This research used a focused systematic review [Review 1 (R1)], a meta-review of reviews [Review 2 (R2)], conceptual framework and expert stakeholder panel to answer the research questions. It was carried out in three phases: Phase 1 was a focused systematic review of research into implementing PMH care into health and social care services (R1). Phase 2 was a meta-review of reviews into the range of barriers and facilitators to women accessing PMH care (R2). Phase 3 mapped the findings from phases 1 and 2 on to a conceptual framework and refined it through consultations with three expert panels of stakeholders (see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

MATRIx study overview.

Patient public involvement

This project was developed with patient public involvement (PPI) representatives from the National Childbirth Trust (NCT) in England (Jennifer Holly and Sarah McMullen) and the Maternal Mental Health Change Agents (MMHCA), a group of women with lived experience of PMH difficulties in Scotland (collaborators). These organisations ensured that we had PPI input from perinatal women generally as well as those affected by PMH problems. Representatives from the NCT and MMHCA co-ordinated PPI input throughout the research and were involved in the dissemination of the project.

Chapter 3 Review methods

This chapter outlines the methods for the two systematic reviews: R1 barriers to implementing assessment, care and treatment for PMH difficulties into health and social care settings, at individual, HP, organisational and wider levels; and R2 barriers and facilitators to women deciding to seek help, accessing help and engaging in PMH care using a systematic review of reviews.

Protocol and registration

Both reviews were registered on PROSPERO: R1 PROSPERO (CRD42019142854); R2 PROSPERO (CRD42020193107).

Ethical review

Ethical permission is not required for systematic reviews of available literature.

Search strategy

Literature searches and study selection are reported according to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. 58

Search terms were identified through hand searches of PMH literature, scoping searches and in consultation with a specialised librarian at the University of Oxford Bodleian Health Care Libraries, Nia Roberts.

To identify papers for R1 we used a mixture of the PICO (Population, Intervention, Comparison, Outcome)59 and SPIDER (Sample, Phenomenon of Interest, Design, Evaluation, Research type)60 research question format to identify four clusters of search terms (see Table 1) relating to:

-

Population: NHS and other health or social care services for women in the perinatal period treating women with mental health difficulties.

-

Phenomenon of interest: implementing assessment, supportive care or treatment interventions, programmes or protocols for PMH into health or social care services.

-

Outcome: qualitative implementation outcomes (e.g. acceptability, feasibility).

-

Evaluation: barriers/facilitators.

| Search terms for R1 (barriers and facilitators to implementation) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Population | Screening/intervention | Implementation | Barriers/facilitators | |

| Perinatal period | Mental health difficulties | |||

| Search terms for R2 (barriers and facilitators from women’s perspective) | ||||

| Population | Screening/intervention | Barriers/facilitators | Study design | |

| Perinatal period | Mental health difficulties | |||

| Prenatal care/; perinatal care/; postnatal care/; pregnancy/; pregnant women/ pregnancy; pregnant; pre-nat*; prenat*; prepart*; prepart*; ante-nat*; antenat*; ante-part*; antepart*; peri-nat*; perinat*; peri-part*; peripart*; puerper*; post-nat*; postnat*; post-part*; postpart*; parent?; mother*; maternal; father*; paternal; infan*; newb;n?; neonat*; baby; babies |

mental disorders/; exp anxiety disorders/; exp mood disorders/; exp ‘trauma and stressor related disorders’/; Adaptation/; Psychological/ mental*; psych*; anxiety; anxious; depress*; mood?; affect*; distress*; stress; trauma*; posttrauma*; post-trauma*; adjustment disorder*; phobia*; phobic; obsessive compulsive; wellbeing; well-being |

Mass screening/; diagnosis/; early diagnosis/; psychotherapy/; behavior therapy/; exp cognitive behavioral therapy/; counseling/exp directive counseling/; antidepressive agents/exp anti-anxiety agents/ screen*; detect*; diagnos*; assess*; identifi*; prevent*; prophyla*; intervention?; counsel*; therap*; healing; listen*; supp;t*; care; healthcare; service; medication*; drug?; antidepress*; anti-depress*; antianxiety; anti-anxiety; improving access to psychological therap*; iapt |

Implementation Science/; Health Plan Implementation/; Program Evaluation/; Implement*; impact*; feasibl*; acceptab*; process; project*; system*; evaluat* |

barrier?; challenge?; obstacle?; facilitat*; enabl*; opportunit* |

| Prenatal care/; perinatal care/; postnatal care/; pregnancy/; pregnant women/ prenancy; pregnant; pre-nat*; prenat*; prepart*; prepart*; ante-nat*; antenat*; ante-part*; antepart*; peri-nat*; perinat*; peri-part*; peripart*; puerper*; post-nat*; postnat*; post-part*; postpart*; parent?; mother*; maternal; father*; paternal; infan*; newb;n?; neonat*; baby; babies |

mental disorders/; exp anxiety disorders/; exp mood disorders/; exp ‘trauma and stressor related disorders’/; Adaptation/; Psychological/ mental*; psych*; anxiety; anxious; depress*; mood?; affect*; distress*; stress; trauma*; posttrauma*; post-trauma*; adjustment disorder*; phobia*; phobic; obsessive compulsive; wellbeing; well-being |

Mass screening/; diagnosis/; early diagnosis/; psychotherapy/; behavior therapy/; exp cognitive behavioral therapy/; counseling/exp directive counseling/; antidepressive agents/exp anti-anxiety agents/ screen*; detect*; diagnos*; assess*; identifi*; prevent*; prophyla*; intervention?; counsel*; therap*; healing; listen*; supp;t*; care; healthcare; service; medication*; drug?; antidepress*; anti-depress*; antianxiety; anti-anxiety; improving access to psychological therap*; iapt |

barrier?; challenge?; obstacle?; hurdle?; obstruct*; drawback?; issue?; difficult?; promot*; supp;t; encourag*; fact;?; facilitat*; enabl*; opp;tunit*; engage*; assist* | Systematic review; meta-analysis; evidence synthesis; realist synthesis; realist review; qualitative synthesis; meta-synthesis*; meta synthesis*; metasynthesis; meta-ethnograph*; metaethnograph*; meta ethnograph*; meta-study; metastudy; meta study |

Pre-planned searches were carried out by a specialist librarian, Nia Roberts, on MEDLINE (1946–present), EMBASE (1974–present), PsychInfo (1806–present) and CINAHL (1982–present). Full search syntax and databases searched can be found in the supporting information of the published review61 and Supplementary material S1.

To identify papers for R2 we used the SPIDER research question60 to identify four clusters of search terms relating to:

-

Sample: women in the perinatal period (conception to one year postpartum).

-

Phenomenon of interest: assessment, care or treatment for PMH.

-

Design: systematic review papers.

-

Evaluation: women’s barriers and facilitators.

Pre-planned searches were carried out by a specialist librarian, Nia Roberts, on MEDLINE (1946–present); EMBASE (1974–present); PsychInfo (1806–present); CINAHL (1982–present), Scopus; and Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (Issue 8 of 12, August 2021). Full search syntax and databases searched can be found in Supplementary material S2.

Search process

Medical subject heading (MeSH) terms and search terms described above were used to query the databases for literature published from inception to 11 December 2019 for R1 and to 4 August 2021 for R2. Forward and backward searches of included studies were carried out by Rebecca Webb and were completed by 31 March 2020 for R1 and 8 September 2021 for R2.

Eligibility criteria

For R1, the following parameters were used for inclusion in the review:

-

Population: NHS and other international health or social care services for women in the perinatal period.

-

Intervention: implementing assessment, care, referral pathways or treatment interventions, programmes or protocols for PMH into health or social care services.

-

Outcome: implementation outcomes (i.e. barriers, facilitators).

Studies were included if they made statements about factors that either facilitated or impeded implementation of PMH assessment, care, referral or treatment. These statements could be from qualitative interviews with HPs or women; or from studies describing the implementation of PMH care.

For R2, studies with the following characteristics were eligible for inclusion in the review:

-

Population: women in the perinatal period (conception to 12 months after birth) experiencing mental health difficulties, who may or may not have decided to seek help, accessed help or engaged in PMH care (defined as assessment, referrals and/or treatment/intervention programmes) from health or social care services.

-

Outcome: barriers and facilitators (defined as any individual, HP, interpersonal, organisational, political or societal factors that women believed impeded (barriers) or aided (facilitators) them to seeking, accessing or engaging in help for PMH difficulties).

-

Design: systematic reviews that used a PRISMA search strategy.

Studies were included if they made descriptive statements about barriers and facilitators to women deciding to seek help, accessing help and engaging in PMH care. These descriptions had to be drawn from perinatal women’s experiences. Only systematic reviews were included. Reviews that did not use a clearly reported PRISMA58 search strategy were excluded. Reviews were also excluded if they were not conducted on the target population (e.g. focused on men/partners, HPs); focused on substance misuse (which has unique challenges in terms of assessment and treatment); did not focus on the mental health of perinatal women; did not examine any barriers/facilitators regarding seeking help, accessing help and engaging in PMH care; and were non-English publications.

Study selection

For both reviews, search results were initially imported into Endnote and duplicates were removed by a specialist librarian, Nia Roberts.

For R1 animal studies, case reports and book reviews were also removed. Remaining studies were imported into Eppi-Reviewer 4, where results were screened by title and abstract by Nazihah Uddin, the research assistant on the project. A proportion (10%) of the results were double screened by Rebecca Webb, the research fellow on the project. Decisions to include or exclude were concordant between reviewers in 88.11% of cases. Following abstract and title screening, full text screening was carried out by Rebecca Webb. A proportion of full texts (10%) were double screened by Nazihah Uddin and decisions to include or exclude were concordant between reviewers in 90.90% of cases. Disagreements for both title and abstract and full text screening were discussed and resolved by both researchers.

For R2, once duplicates were removed, the specialist librarian also removed papers relating to fetal distress, oxidative distress and those not published in English. Remaining studies were imported into Eppi-Reviewer 4, where results were double screened by title and abstract by Rebecca Webb and Georgina Constantinou, a research assistant in maternal and child health research. An additional proportion (n = 166, approximately 7%) of titles and abstracts were triple screened by Nazihah Uddin. Decisions to include or exclude were concordant between Rebecca Webb and Georgina Constantinou in 94.2% of cases and between Rebecca Webb and Nazihah Uddin in 99.4% of cases. Disagreements were discussed and resolved by all reviewers by applying the relevant inclusion criteria. Once title and abstract screening was complete, full text screening was carried out by Rebecca Webb and Georgina Constantinou. An additional proportion (n = 9, approximately 10%) were triple screened by Nazihah Uddin. Decisions to include or exclude were concordant between Rebecca Webb and Georgina Constantinou in 91.4% of cases and between Rebecca Webb and Nazihah Uddin in 100% of cases.

Data extraction

For R1, data extraction was carried out by Rebecca Webb using Eppi-Reviewer 4 which allows for line-by-line coding. A new ‘codeset’ labelled ‘data extraction’ was created and contained every item to be extracted from the data (e.g. year of publication, country of study). Each paper was read in full, and relevant parts of the text highlighted (e.g. the country of the study) and applied to the relevant code.

For R2, data extraction was carried out using Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) by Rebecca Webb. Each paper was read in full, and relevant parts of the text inputted into the relevant part of the spreadsheet. Methodology of included reviews was copied on to one sheet, and results on to another to aid analysis. Double coding of extracted data was carried out for a proportion of included reviews (n = 3, 10%) by Georgina Constantinou. Data extraction matched in 85% of cases.

The data that were extracted was guided by the Cochrane Systematic Review for Intervention Data Collection form62 for both reviews, and the AMSTAR 263 critical appraisal tool for R2 (see Table 2 for extracted data).

| R1 | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Study characteristics | Sample | Assessment/care/treatment characteristics | Implementation outcomes |

| R2 | |||

| Review characteristics | Characteristics of included studies | Characteristics of included participants | Outcomes |

| Year | Size | Type (intervention, assessment, support) | Barriers |

| Country | Age | Name | Facilitators |

| Setting | Ethnicity | Year started | |

| Design | Employment | Year ended | |

| Aim | Education | Description | |

| Children | Who care is aimed at | ||

| Socio-economic status | Theoretical model of care | ||

| Mental health difficulties | Medium of care (e.g. face to face) | ||

| Measurement of mental health difficulties | Person providing care | ||

| Obstetric details | Training of people providing care | ||

| Gender/sex | |||

| Other demographic details | |||

| Recruitment | |||

| Year | Number of studies included | Mental health difficulty examined | Barriers |

| Aim | Year of each study’s publication | Number of participants | Facilitators |

| Design | Country of each of the studies | Age of participants | |

| Search strategy | Perinatal period | ||

| Inclusion/exclusion criteria | Ethnicity of participants | ||

| Screening/study selection | Socio-economic status of participants | ||

| Data extraction | Other demographic details of participants | ||

| Quality assessment | |||

| Data analysis | |||

Assessing the robustness of results

For R1, the methodology sections of included studies were assessed for quality with the Joanna Briggs Critical Appraisal Tools for qualitative research,64 cross-sectional studies65 and text and opinion. 66 Each point on the checklists can be coded as either yes, no, unclear or not applicable. Each tool was separated into domains that reflected the question of interest (see Box 1). Where most questions within a domain were answered with yes, this domain was rated as having high quality; where the majority were answered with no, this domain was rated as having low quality. Medium quality was when there was a mixture of yes and no answers.

-

Is there congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology?

-

Is there congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives?

-

Is there congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data?

-

Is there congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data?

-

Is there congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of results?

-

Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically?

-

Is the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice versa, addressed?

-

Are participants, and their voices, adequately represented?

-

Is the research ethical according to current criteria or, for recent studies, is there evidence of ethical approval by an appropriate body?

-

Do the conclusions drawn in the research report flow from the analysis, or interpretation, of the data?

-

Is the source of the opinion clearly identified?

-

Does the source of opinion have standing in the field of expertise?

-

Are the interests of the relevant population the central focus of the opinion?

-

Is the stated position the result of an analytical process, and is there logic in the opinion expressed?

-

Is there reference to the extant literature?

-

Is any incongruence with the literature/sources logically defended?

-

Were the criteria for inclusion in the sample clearly defined?

-

Were the study subjects and the setting described in detail?

-

Was the exposure measured in a valid and reliable way?

-

Were objective, standard criteria used for measurement of the condition?

-

Were confounding factors identified?

-

Were strategies to deal with confounding factors stated?

-

Were the outcomes measured in a valid and reliable way?

-

Was appropriate statistical analysis used?

Adapted with permission from the Joanna Briggs Institute (JBI), the JBI Critical Appraisal tools for use in JBI Systematic Reviews 2017. 64–66 Permission granted 28 November 2021.

Rebecca Webb completed the methodological quality assessments for the included papers, and dual critical appraisal of 16 (35%) papers was done by Nazihah Uddin. Nazihah Uddin initially screened nine papers, which were discussed, and conflicts were resolved. Following this screening, the final seven papers were screened by Nazihah Uddin. Coders assigned the same score to 13 (81%) of the 16 papers. All disagreements were discussed and resolved by both researchers, and the final appraisal for these 16 papers is based on agreed answers.

For R2, methodology sections of included reviews were appraised using the AMSTAR 263 criteria (see Box 2). Critical domains in the appraisal of systematic reviews according to AMSTAR 2 include protocol registration, adequacy of literature search, justification of study exclusion, risk of bias, appropriateness of meta-analytic methods, consideration of risk of bias when interpreting results and assessment of publication bias. If more than one critical domain is not met (critical flaw), a systematic review should be evaluated as having critically low confidence in the results of the review. One critical flaw means reviews should be evaluated as low confidence. More than one non-critical flaw means reviews should be evaluated as moderate confidence and no or one non-critical flaw means reviews should be evaluated as high confidence. 63

-

Did the research questions and inclusion criteria for the review include the components of PICO?

-

Did the report of the review contain an explicit statement that the review methods were established prior to the conduct of the review and did the report justify any significant deviations from the protocol?a

-

Did the review authors explain their selection of the study designs for inclusion in the review?

-

Did the review authors use a comprehensive literature search strategy?a

-

Did the review authors perform study selection in duplicate?

-

Did the review authors perform data extraction in duplicate?

-

Did the review authors provide a list of excluded studies and justify the exclusions?a

-

Did the review authors describe the included studies in adequate detail?

-

Did the review authors use a satisfactory technique for assessing the risk of bias (RoB) in individual studies that were included in the review?

-

Did the review authors report on the sources of funding for the studies included in the review?

-

If meta-analysis was performed, did the review authors use appropriate methods for statistical combination of results? (Not applicable.)

-

If meta-analysis was performed, did the review authors assess the potential impact of RoB in individual studies on the results of the meta-analysis or other evidence synthesis? (Not applicable.)

-

Did the review authors account for RoB in primary studies when interpreting/discussing the results of the review?

-

Did the review authors provide a satisfactory explanation for, and discussion of, any heterogeneity observed in the results of the review?

-

If they performed quantitative synthesis did the review authors carry out an adequate investigation of publication bias (small study bias) and discuss its likely impact on the results of the review? (Not applicable.)

-

Did the review authors report any potential sources of conflict of interest, including any funding they received for conducting the review?*

a Critical domain for this review.

Shea BJ, Reeves BC, Wells GA, Thuku M, Hamel C, Moran J, et al. 63 AMSTAR 2: a critical appraisal tool for systematic reviews that include randomised or non-randomised studies of healthcare interventions, or both. BMJ 2017;21:358.

Given that all studies in this review were qualitative, the AMSTAR 263 items related to meta-analysis were not relevant and were removed. Further, given the debate in the literature regarding the appropriateness of conducting risk of bias assessments on qualitative research, we downgraded the items relating to risk of bias from being a critical flaw, to just a flaw. Quality appraisal of all studies was carried out by Nazihah Uddin and Rebecca Webb. Ratings were concordant in 90% of cases.

A large proportion of the reviews were rated as having low and critically low confidence in the evidence (see Chapter 4). A decision was made to include reviews where confidence in results was evaluated as low and critically low because some of these reviews focused more on marginalised women, such as refugees, migrant women, women with a low income and women living in lower middle income countries (LMIC). Including these reviews ensured that the experiences of these seldom heard women were captured. To improve validity of results, a qualitative sensitivity analysis was carried out to assess whether themes remained consistent across all reviews, regardless of their quality rating. The methods proposed by Harden (2007)67 and Carroll et al. (2012)68 were followed, so sensitivity analysis was carried out in two ways: (1) synthesis contribution; and (2) evidence of adequate description of themes.

To examine whether higher quality reviews contributed more to the themes, a measure of ‘synthesis contribution’ was calculated for each review (as outlined by Harden, 200767). This involved dividing the number of barriers and facilitators identified by the specific review in question (see ‘Number of themes’ column in Table 3) by the total number of barriers and facilitators identified in R2 (n = 62 themes). For example, the findings from Bina (2020)69 contributed to 31 out of 62 themes, giving this review a synthesis contribution score of 50% (see Table 3).

| Study | Number of themes | Overall synthesis contribution % (all themes) |

|---|---|---|

| Bina, 202069 | 31 | 50.00 |

| Brealey et al., 201074 | 13 | 20.97 |

| Button et al., 201746 | 26 | 41.94 |

| Dennis and Chung-Lee, 200647 | 28 | 45.16 |

| Evans et al., 202075 | 8 | 12.90 |

| Giscombe et al., 202076 | 6 | 9.68 |

| Hadfield and Wittkowski, 201772 | 25 | 40.32 |

| Hansotte et al., 201770 | 19 | 30.65 |

| Hewitt et al., 200977 | 13 | 20.97 |

| Holopainen and Hakulinen, 201978 | 6 | 9.68 |

| Jones et al., 201479 | 10 | 16.13 |

| Jones, 201980 | 19 | 30.65 |

| Kassam, 201981 | 8 | 12.90 |

| Lucas et al., 201982 | 9 | 14.52 |

| Megnin-Viggars et al., 201548 | 26 | 41.93 |

| Mollard et al., 201683 | 5 | 8.06 |

| Morrell et al., 201684 | 16 | 25.81 |

| Newman et al., 201985 | 13 | 20.97 |

| Nilaweera et al., 201486 | 6 | 9.68 |

| Praetorius et al., 202087 | 3 | 4.84 |

| Randall and Briscoe, 201888 | 2 | 3.23 |

| Sambrook Smith et al., 201989 | 19 | 30.65 |

| Schmied et al., 201790 | 27 | 43.55 |

| Scope et al., 201791 | 13 | 20.97 |

| Slade et al., 202092 | 15 | 24.19 |

| Sorsa et al., 202193 | 19 | 30.65 |

| Staneva et al., 201594 | 11 | 17.74 |

| Tobin et al., 201895 | 19 | 30.65 |

| Viveiros and Darling, 201849 | 16 | 25.81 |

| Watson et al., 201996 | 28 | 45.16 |

| Wittkowski et al., 201497 | 2 | 3.23 |

Each study’s synthesis contribution scores were plotted against the number of quality criteria the study met (see Figure 4). Statistical analysis (Pearson’s correlation) was used to help interpret the plots. To examine whether removing lower quality reviews influenced the number of themes, themes that were only supported by lower quality reviews were identified.

To examine whether removing lower quality reviews influenced the description of themes, data were assessed for ‘thickness’ or ‘thinness’ (as done by Carroll et al., 201268). A ‘thin’ description refers to a set of statements, such as this quote about HPs dismissing women’s symptoms:

[The study authors] found that women also felt that providers were downplaying the symptoms they were experiencing. 70 (p12)

A ‘thick’ description provides the context of experience and circumstances71 such as this description of HPs minimising symptoms:

Having symptoms dismissed or attributed to factors other than [postpartum depression] PPD by HPs led to women ‘remaining silent’. Some women perceived that their difficulties would only be taken seriously when there were concerns about risk of harm to themselves or the infant. One woman said, ‘I kept going to this doctor and he used to give me a pep talk and send me home …’. 72(p738)

It is argued that the extent to which a text provides a thick description shows evidence of the authenticity of the results. 73

Data analysis

Review 1 results were analysed by Rebecca Webb using thematic synthesis;98 line-by-line data extraction of statements referring to facilitators or barriers to implementing PMH assessment, care and treatment was carried out in Eppi-Reviewer. Next, codes were re-read and assigned a descriptive theme based on their meaning and content. Themes were developed and revised as each study was re-read. Once all codes had been assigned into themes, these themes were mapped on to a systems level model adapted from Ferlie and Shortell’s (2001) Levels of Change framework40 (e.g. individual level factors, HP factors, organisational factors and larger system factors) and then grouped to reflect different stages of the care pathway adapted from Goldberg and Huxley’s (1992) Pathways to Care model41 (e.g. deciding to disclose, assessment of PMH and access to care and treatment). Mapping of descriptive themes was developed deductively from the initial theoretical framework and then inductively revised as new themes emerged. The mapping of descriptive themes aided the development of the analytical themes. Here, inferred barriers and facilitators were generated. Following this, recommendations for implementing PMH care were drawn from a dictionary of implementation strategy terms and definitions. 99,100

Review 2 results were also analysed by Rebecca Webb using a thematic synthesis98 in NVivo (QSR International, Warrington, UK) and Microsoft Excel. First, line-by-line data coding of statements referring to facilitators or barriers to accessing PMH care from the results section of each paper was carried out. Next, codes were revisited and assigned a descriptive theme based on their meaning and content. Themes were developed and revised as each review was re-read. Once all codes had been assigned into themes, these themes were mapped on to a multi-level framework adapted from Ferlie and Shortell’s (2001) Levels of Change framework40 and the findings from R1. 61 Mapping of descriptive themes was developed deductively from the initial theoretical framework and then inductively revised as new themes emerged. The mapping of descriptive themes was discussed by the project research team before being finalised.

Chapter 4 Studies included in the reviews

Study selection

Both reviews were reported in accordance with PRISMA guidelines. 58 Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the Synthesis of Qualitative (ENTREQ) research guidelines101 were also followed.

Results of searches are shown in Figures 2 and 3. For R1, database searching identified a total of 21,535 citations. After screening by title and abstract, 10,130 records were excluded, leaving 931 papers to be screened by full text. Screening of full texts left 43 studies to be included in the review. Forward and backward searches identified a further three papers. Therefore, 46 qualitative studies were included in the qualitative synthesis (see Figure 2). Excluded texts are given in Supplementary material S3.

FIGURE 2.

PRISMA flow diagram for R1.

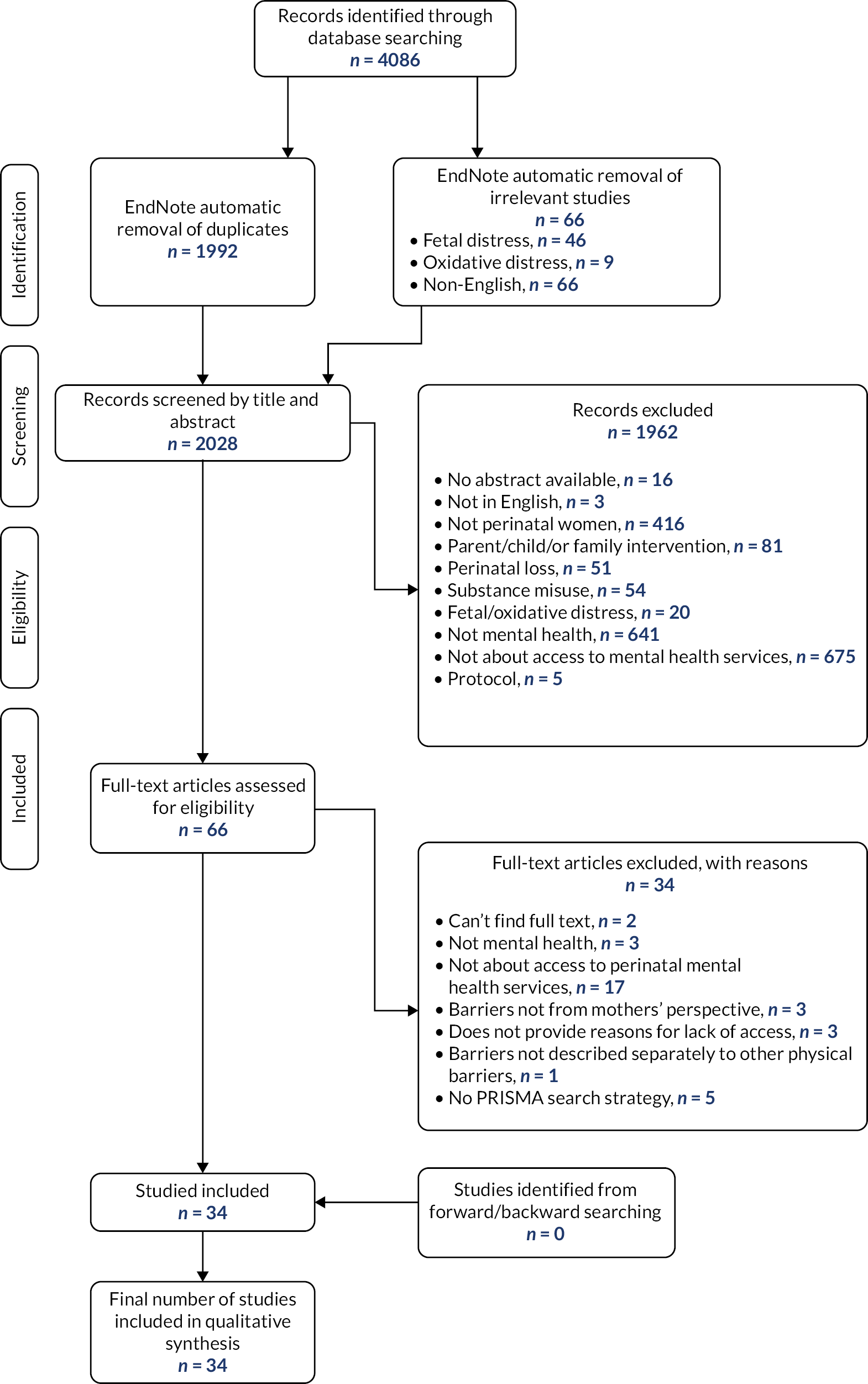

FIGURE 3.

PRISMA flow diagram for R2.

For R2, database searching identified a total of 4086 citations. After duplicates, and studies not meeting inclusion criteria were removed, 2028 articles were left to be screened. Screening by title and abstract led to 1962 records being excluded, leaving 66 papers to be screened by full text. Screening of full texts identified 32 reviews, all of which were qualitative, to be included in the meta-review (see Figure 3). Excluded texts are given in Supplementary material S4.

Characteristics of included studies

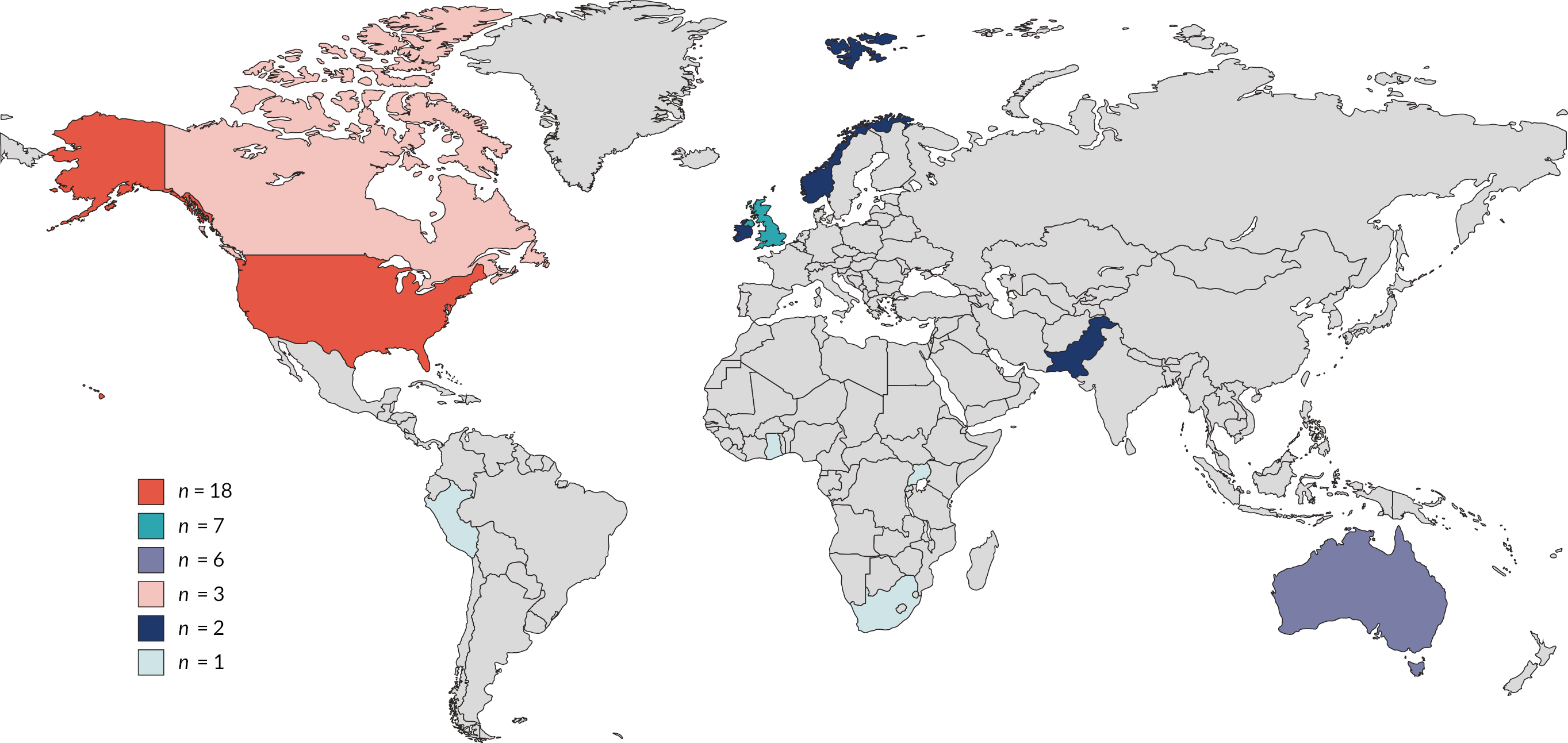

For R1, studies were mainly (n = 39) carried out in higher income countries (HICs)102 with well-established highly ranked health care systems. 103 The majority were carried out in the USA (n = 16). Implementation occurred in a wide range of settings including hospitals (n = 14); primary care (n = 12); community-based care, such as community clinics or home visiting (n = 12); online or remote (n = 3); maternity care (n = 3) and specialist PMH care (n = 2). No studies examined implementation in social care settings. Most of the studies (n = 22) looked at the implementation of care services (including screening, referral and treatment); 18 studies were about the implementation of interventions and 6 were about screening only. For the intervention studies most were implementing cognitive behavioural therapy (n = 7) or another type of talking therapy (n = 8). For the screening studies, most were implementing the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS)104 (n = 5).

Ten of the studies were descriptive papers, describing the implementation of PMH care. The remaining were qualitative papers, interviewing key stakeholders about their views and experiences on the implementation of the care. Twenty studies interviewed only HPs, nine interviewed only perinatal women and seven interviewed both. Sample sizes ranged from 6 to 809 with a mean of 46.81; median = 24; interquartile range (IQR) = 16.25–33.35 (see Appendix 1 for more details).

For R2, reviews were published between 2006 and 2021 (M = 2017, Mdn = 2018; IQR = 2016–2019). The number of studies included in each review varied from 4 to 40 (M = 16, Mdn = 13, IQR = 9–19) with a total of 344 papers included across all systematic reviews. The number of women included in each review varied from 95–85,190 (M = 5080; Mdn = 463; IQR = 226–1715). The reviews included studies carried out in 24 different countries, the majority of which were HICs, mostly the USA and UK. One review included studies that were carried out only in sub-Saharan Africa. 97 Most reviews (n = 23) focused on perinatal depression, followed by a mixture of perinatal mood disorders (e.g. depression, anxiety, distress; n = 5). Only one study focused on postnatal psychosis105 and one on birth trauma. 92 Included studies were carried out across the perinatal period. Twenty-four of the reviews included studies that reported recruiting ethnic minority women. Six reviews included studies on the experiences of migrant women and/or ethnic minority women (see Appendix 2 for more details).

Analysis of the robustness of the results (sensitivity analyses)

For R1, most studies (n = 44) had a quality rating above 70% suggesting that studies were well-conducted with a low risk of bias. Seven studies were assigned a 100% quality rating (see Appendix 3).

For R2, the majority of reviews were evaluated as having low (n = 14) or critically low (n = 5) confidence with their results. The remainder had moderate (n = 8) or high (n = 5) confidence (see Appendix 4).

As described above, a sensitivity analysis was carried out for R2. In terms of synthesis contribution, there was no correlation between synthesis contribution and the number of criteria each review met (r = 0.142, p = 0.437) (see Figure 4). Furthermore, only four themes (cultural/spiritual causes of mental illness, age, previous diagnoses and appropriateness of care) were only identified by lower quality studies showing that the majority of themes (58 out of 62; 93.55%) were supported by both higher quality and lower quality papers.

FIGURE 4.

Synthesis contribution vs. quality appraisal criteria met for papers in R2.

In terms of richness of data, removing lower quality papers meant that the identified theme Language barriers lost some of its richness. For example, it led to the removal of quotes expressing frustration from women whose first language was not English:

… you don’t know where to go, what to do, who to trust, especially when you are coming by yourself … you believe that you speak English, but when you get here you realize that you don’t … 90(p18)

Sometimes when you have a baby, a woman comes from the hospital. Bengali girls don’t come with the midwife, we don’t understand what they say, we just sit there staring at their faces. 46(p695)

The removal of lower quality papers from the sub-theme Fear of being seen as a bad mum also led to the loss of richness of data, such as the removal of quotes from women who had migrated from their country of birth:

Back home, if someone has this problem, everyone gossips, you get this feeling that people are not dealing with you normally or as if you are abnormal almost …90(p12)

Lastly, the removal of lower quality studies meant important information was removed from the Characteristics of service sub-theme, such as women feeling services prioritised physical needs (n = 2), lack information about screening guidelines (n = 2) and the logistics of care (e.g. location, time of appointments) (n = 3).

Overall, the qualitative sensitivity analysis found that the majority of themes were supported by both the higher quality and lower quality reviews. Including all reviews meant there was more richness in the data and greater inclusion of marginalised women, such as refugees, migrants and women living in sub-Saharan Africa. This sensitivity analysis suggests that the results from R2 can be interpreted with reasonable confidence.

Chapter 5 Results of the reviews

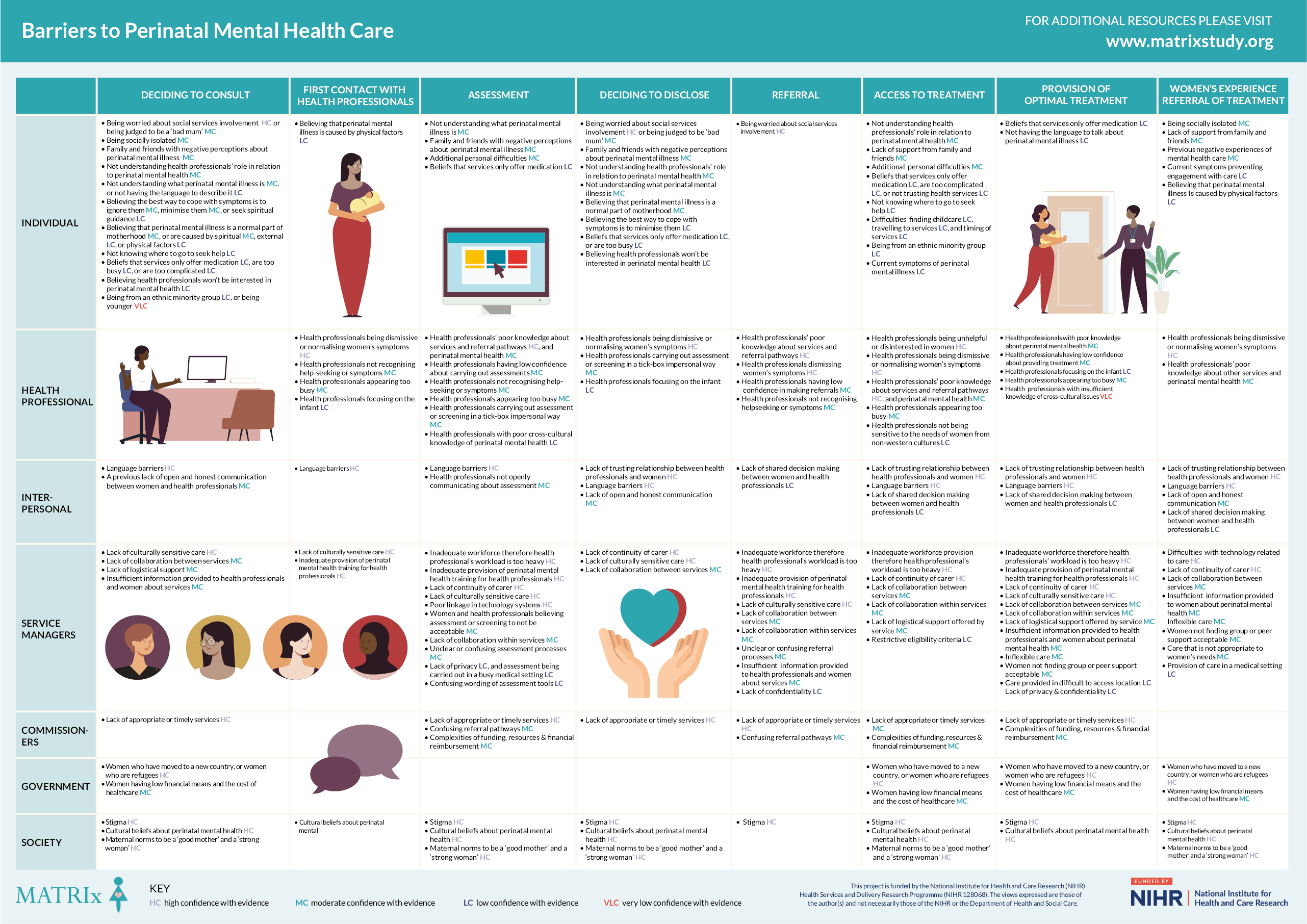

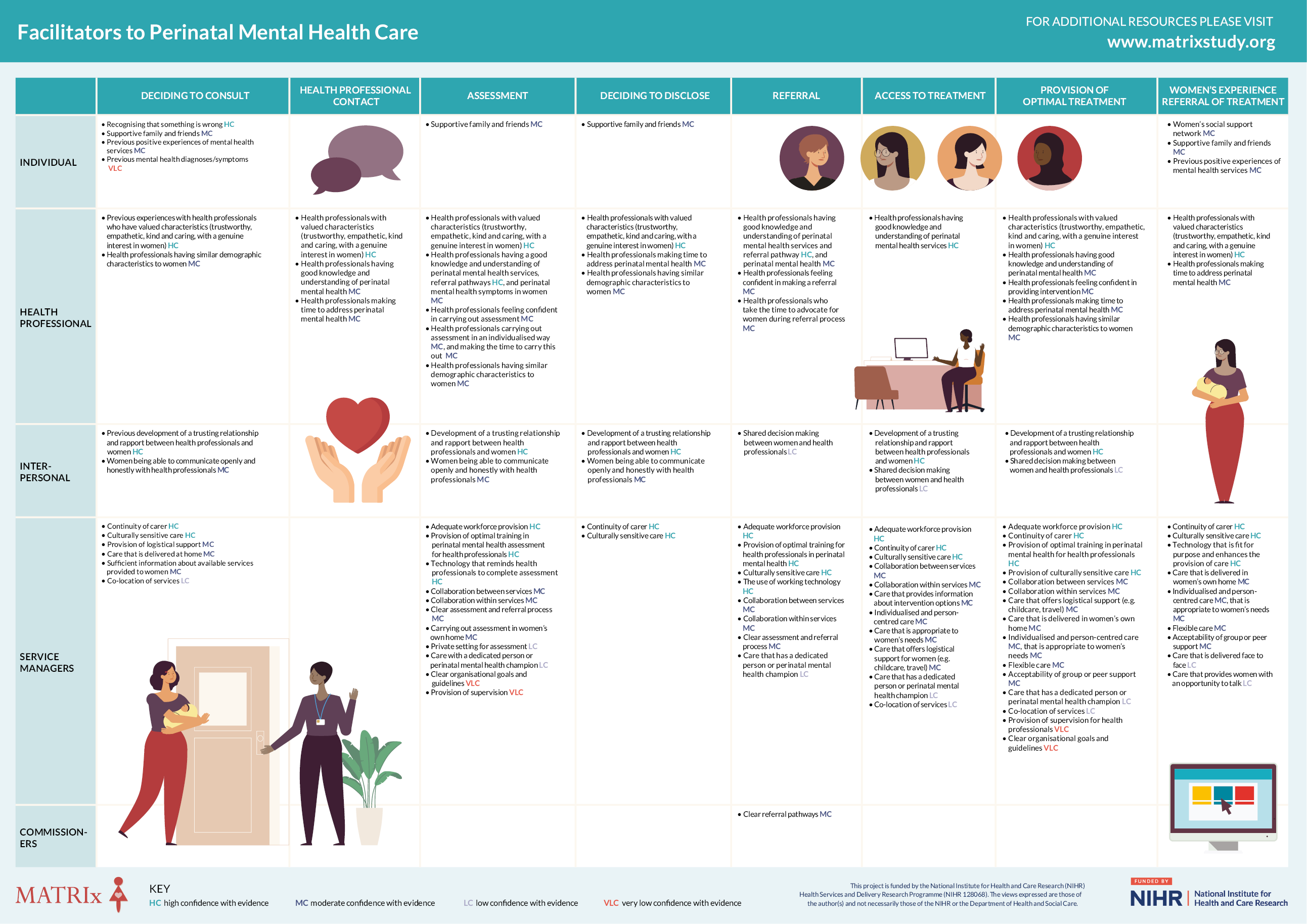

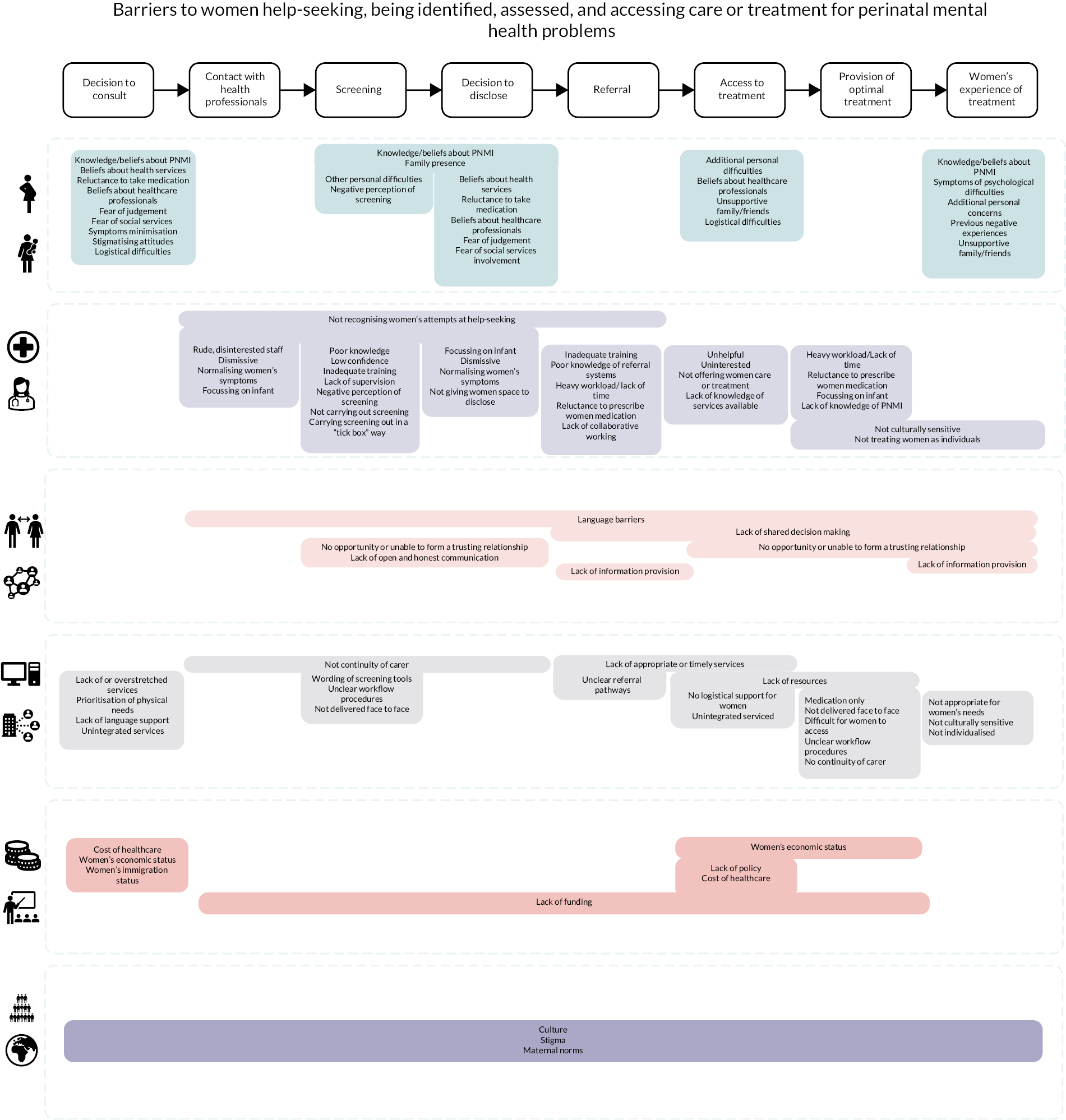

This chapter outlines the theoretically informed care pathway structure and multi-level framework used to summarise areas in which barriers to PMH care may arise. The most commonly cited barriers and facilitators are then described at each stage of the care pathway, and for each level of the multi-level framework. This section includes results from both reviews combined.

Frameworks for presenting the results

Care pathway

We used a care pathway based on Goldberg and Huxley’s (1992)41 Pathways to Care model to understand how a woman may access mental health services. In Goldberg and Huxley’s model, as a person moves through the care pathway, there are certain factors that act as filters, which prevent people from accessing mental health care. The first filter is illness behaviour, where a person needs to pay attention to their symptoms and then make the decision to seek help. If this is not done, this is the first filter out of the care pathway. The second is the HP’s ability to recognise mental illness; the third is referral on to mental health services and the last filter is admission to hospital beds.

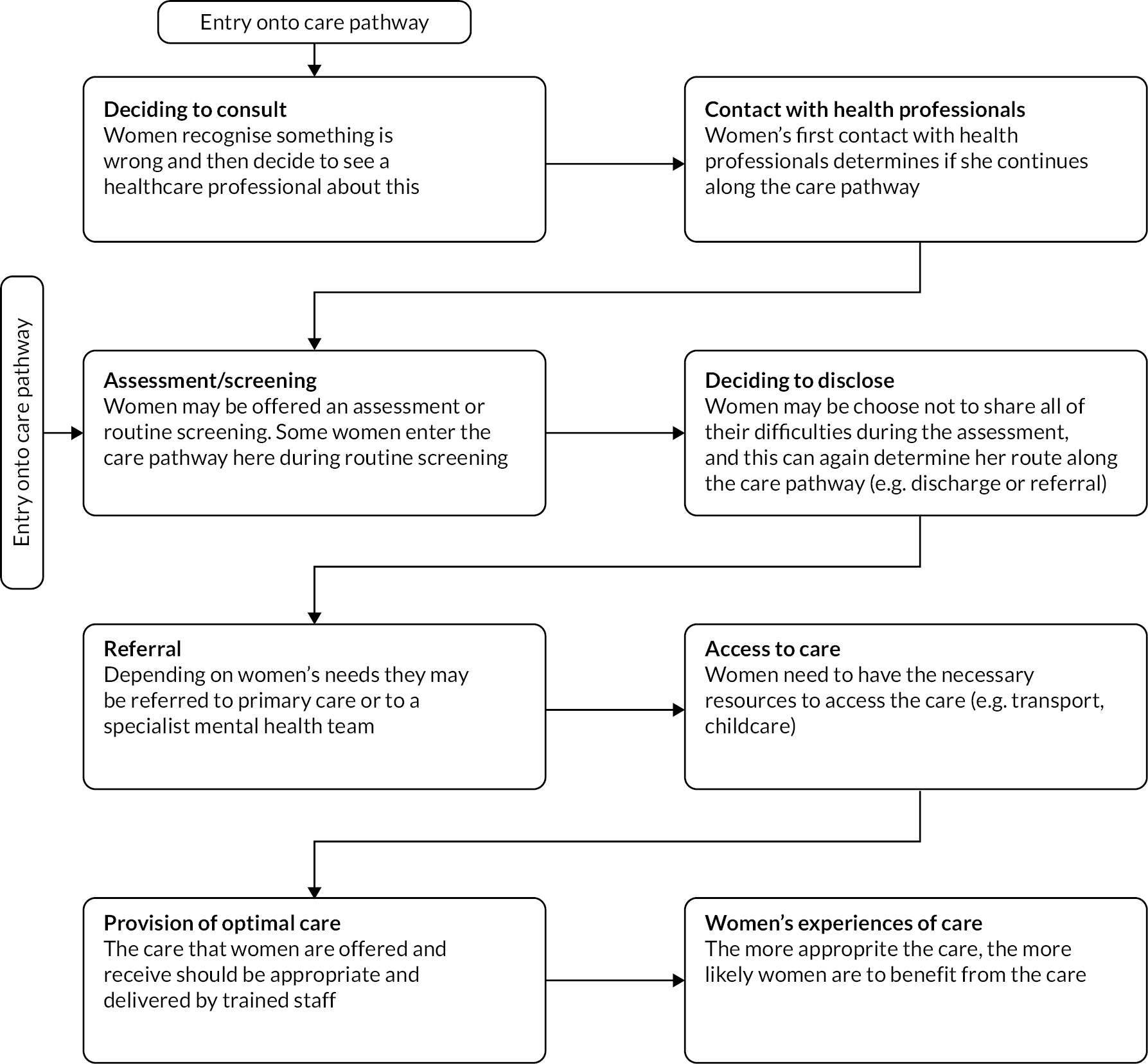

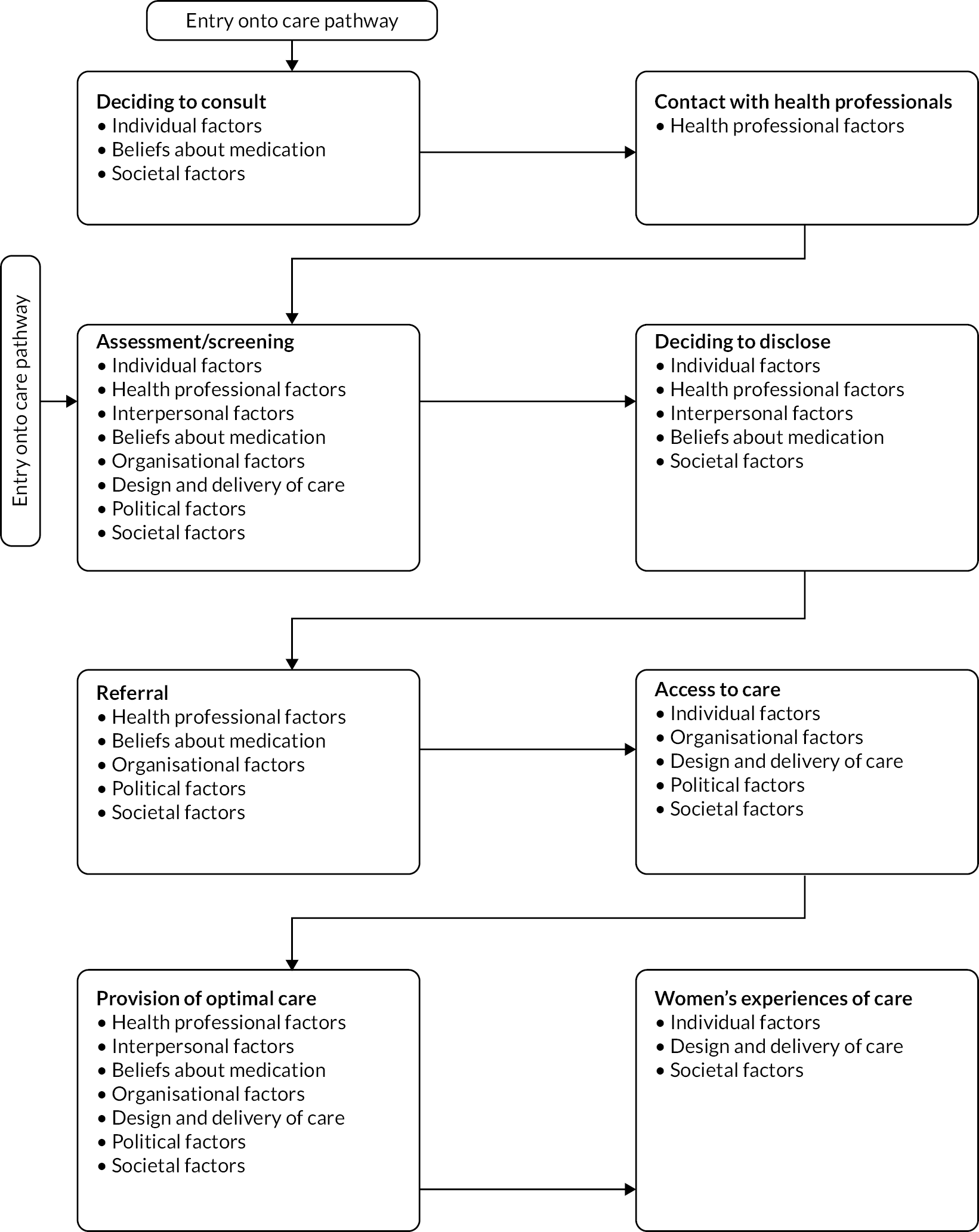

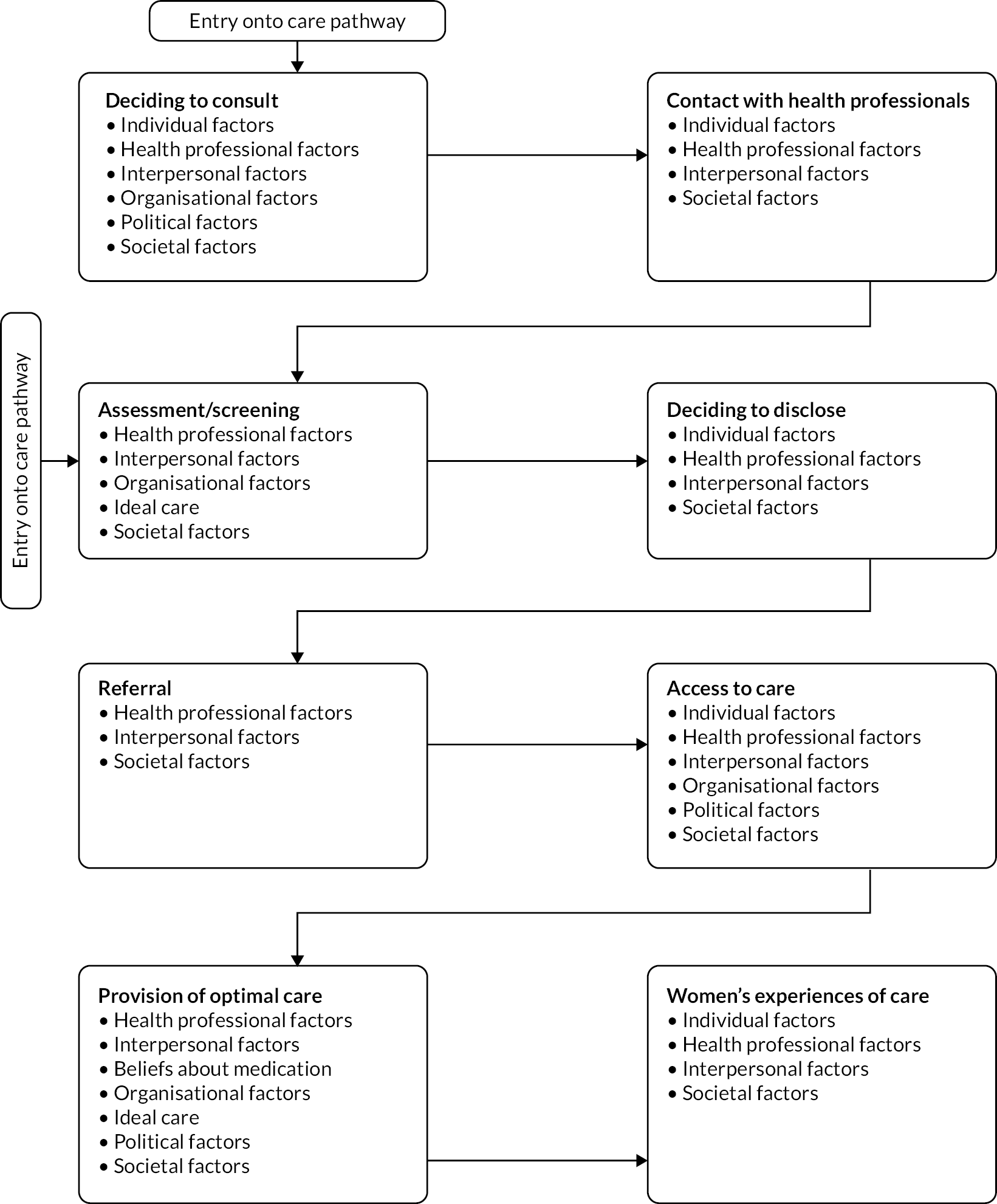

Our care pathway is more detailed and includes the following eight stages: (1) deciding to consult for PMH difficulties; (2) first contact with HPs; (3) assessment/screening for PMH; (4) deciding to disclose PMH difficulties; (5) referral on to appropriate services; (6) access to treatment; (7) provision of optimal care and treatment; and (8) a woman’s experience of treatment (see Figure 5). It is possible that at each stage in the care pathway, a woman may fall through the gaps and ultimately not receive the care that she needs. The decision to disclose has been included after assessment because women have a choice about whether they complete an assessment honestly and thus disclose their symptoms. However, women may also decide whether to disclose their symptoms on first contact with a HP, especially if they are seeking help from their GP. Therefore, it is important to note that a woman may enter the care pathway either stages 1 or 3, and that some parts of the pathway are redundant in health care systems where the woman can contact mental health services directly (e.g. via NHS Talking Therapies services in the UK). Further, the process is not always linear, and some women might jump over certain stages or repeat certain stages.

FIGURE 5.

The MATRIx care pathway.

Multi-level framework

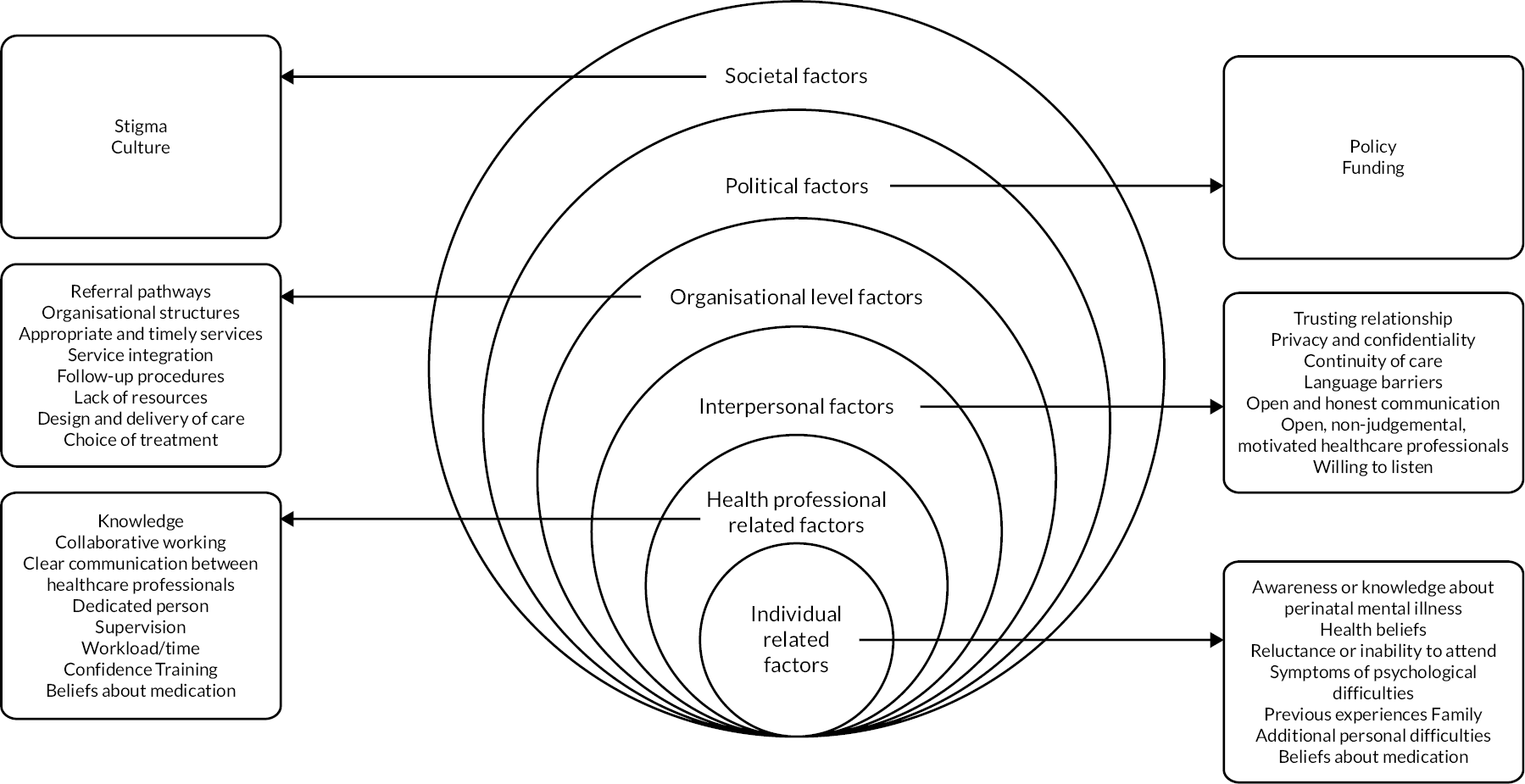

Ferlie and Shortell’s Levels of Change framework40 was adapted to describe the seven different levels at which barriers and facilitators to PMH care may occur: (1) individual level factors (e.g. beliefs about mental illness, inability to attend care); (2) HP level factors (e.g. knowledge about PMI, confidence in addressing PMI); (3) interpersonal factors (e.g. the relationship between women and HPs); (4) organisational level factors (e.g. service integration, continuity of carer, choice of assessment tools); (5) commissioner level factors (e.g. referral pathways); (6) political factors (e.g. women’s immigration status); and (7) societal factors (e.g. stigma).

Determining the barriers and facilitators to perinatal mental health care

System level barriers and facilitators will be described at each step of the care pathway and include results from both reviews (R1 and R2). Please note that in the process of merging results from both reviews a new multi-level factor was added (commissioner level) therefore the levels and themes described may differ slightly to the published papers.

The most commonly cited barriers and facilitators will now be described at each stage of the care pathway, and for each level of the multi-level framework. The stage of the care pathway will be blue, bold and italicised; the level of the multi-level framework being described will be in italic font. For information on all of the multi-level factors at each stage of the care pathway (see Appendix 5).

Deciding to consult

At the individual level some women believed there was no point in seeing a HP because they would only be offered medication:46,48,69,80,83,84,86,90

I knew she would just write a prescription and send me away … that wasn’t what I wanted. 46(p695)

Other factors that acted as barriers to women’s decision to consult were not understanding HPs roles,46,48,83,84,86,90 or not understanding what PMI is:46,47,69,70,72,80,82,84,85,89–91,95,96

I don’t really know what their job is. Nobody gave me, like, the parameters of this role of the health visitor and, so, I think if that happened then you’d … be able to use them better. 46(p695)

Nobody has ever told me what it is really [postpartum depression]…I just sit here sometimes and I am crying for no reason, but I could have detected it earlier if someone had explained to me what your first symptoms were, but nobody told me. 82(p11)

Linked to this, if women believed their symptoms were caused by spiritual factors,46,90,97,106–108 external causes such as life stressors,46,47,69,82,90,94–96 physical causes such as hormones46,69,79,85,89,90,94,96,105 or were a normal part of motherhood,47,49,76,79,89,90,92,93 deciding to consult could be hindered by women seeking out spiritual guidance before seeking professional help,70,81,90,96 or ignoring symptoms:69,72,80,85,90,92

They say that she (mother) is being possessed, so instead of medicines they go for talisman (spiritual treatment). 106(p6)

I thought it was just lack of sleep and this heavy cold. I thought that after a good night’s sleep it would get better, and I would be able to manage. 46(p696)

Not knowing where to go to seek help,47,48,69,70,90,93,95,109 fear of social services involvement47,80,96,105,110 and a lack of support from friends and family46,47,69,78,80,82,86,89,90,93,105 were also barriers to women consulting.

The largest individual level facilitators to women deciding to seek help were recognising that something was wrong:46,49,69,72,92,93,94,105

That’s when I thought, you know: ‘Something is really wrong here, I need to go to the doctors if I’m thinking about killing myself’. 46(p694)

At the organisational, commissioner and political levels, a lack of culturally sensitive care,47,69,80,90,96 no appropriate or timely services48,49,80,85 and a woman’s economic status69,70,80,82,95 prevented help-seeking:

That is probably why a lot of Black women don’t bother going to the system … the majority have had nightmares. So you’re thinking, ‘What’s the point in going back?’96(p9)

… if she has no money, how is she going to find help [with PPD]?70(p12)

At the societal level, stigma,46,47,49,69,70,72,80,81,83,86,93,95,96,108 culture46,47,76,80,81,87,89,90,94–97,106–108 and maternal norms of being a strong woman and a good mother46,69,70,72,78,81–83,86,90,93,94,111 all prevented women from deciding to consult:

There’s a huge stigma about feeling depressed, particularly postnatal. 46(p696)

The pressure to cope alone was also part of the social imperative to be ‘a strong Black woman’.

(author quote)95(p97)

Contact with health professionals

Women’s first contact with HPs was important and mostly impacted by factors at the HP level. The most frequent reasons for women dropping out of the care pathway at first contact with HPs was due to them being dismissive about mental illness, or normalising women’s symptoms,46,47,70,72,85,93,96,105 not recognising women’s attempts at help-seeking48,49,95,96 or appearing too busy and not making enough time to address PMH concerns:77,96,112

I did ask for support, but I didn’t really get any. And the health visitor’s response – ‘Well you seem like you’re doing all right’ – which kind of closes it off, doesn’t it. 46(p696)

I kept going to this doctor and he used to give me a pep talk and send me home […] those years were horrible because virtually he said to me … that I would just have to put up and shut up!72(p732)

Assessment/screening

Multiple factors affected assessment of PMI. At the individual level, the most cited barrier was the presence in the consultation of family and friends with negative beliefs about mental illness:113–119

I think they were actually stifled in being able to speak and talk and get it out because their partner was always sitting beside her. 116(p5)

At the HP level, a lack of knowledge about PMI47–49,69,92,107,115,120 and assessment-specific behaviours such as carrying it out in a tick box way49,74,89,90,92,96,114,118,119,121–123 were barriers to assessment. On the other hand, carrying out an assessment in an individualised way, taking women’s individual differences into account was a facilitator:

I try and tie it in with pain. We have certain protocols that we ask for pain levels and things like that. So, you know, when I ask them, ‘How’s your pain? Have you had a chance to take care of your postpartum depression screening? No, okay that’s fine. I’ll just stop back later’. I incorporate it into other things, so it doesn’t seem to be such a nagging thing. 123(p451)

At the interpersonal level, women and HPs being able to speak open and honestly about assessment was the most cited facilitator:74,77,114,124,125

And I was so grateful, and then I just talked to her, and it was so nice to be able to talk freely with her [about the EPDS] at the time. 124(p617)

At the organisational level, facilitators were having enough staff in order for assessment to take place,49,107–109,115,116,118,122,125,128 HPs who had received training in assessment,69,74,107,109,113,116,119,122,125,127–131 and a clear assessment and referral process within the organisation. 109,119,122,123,128 Where this was not the case, these factors acted as barriers to assessment:

How much extra time do you need to allocate when you get a high positive? You need to have the capacity within your system to manage it if you’ve got someone who’s suicidal. 122(p6)

I’ve never received any formal training in this area. I do not feel adequately trained to detect postpartum depression. 128(p170)

Other organisational level factors impacting assessment were the wording of the assessment tools,46,74,77,114,119,123 for example whether the questions made sense, and the acceptability of assessment or screening for both HPs and women:48,49,74,75,77,83,89,109,113,114,118,122–125,127,128

I have some moms [who] ask questions about it, like, ‘What does it mean where things are getting on top of me? What do you mean?’ You know, so they, they don’t always understand the questions114(p532)

No. I didn’t mind doing that. I mean it was quick, and simple and … it was nice. 124(p616)

Deciding to disclose

Women deciding to disclose their PMH symptoms was also affected by multiple factors. At the individual level, fear of being judged as a bad mother46,49,74,79,82,92,93 and fear of social services involvement69,74,75,85,124,127 were the most cited barriers:

I even went in at 3 months and I talked to a health nurse, and I just lied through my teeth because I thought, what are they going to do if they find out I can’t be a good mom?72(p732)

Because of the fear of postnatal depression and the taboo of social services and having your children taking [sic] away from you, I wasn’t going to admit anything to anyone …46(p696)

At the HP level, appearing too busy was the most cited barrier to disclosure:46–48,92,127

The health visitor said something like: ‘You know, in this community we have to look after a thousand and something babies’. And that instilled in me the feeling, like: ‘Oh, they are very busy these people, and I don’t have to be bothering them all the time’. 46(p696)

The most cited facilitator was HPs appearing genuinely interested in women’s well-being:46,85,92,96,119,127

Women were more likely to discuss their concerns with professionals who appeared caring and genuinely interested in their well-being: ‘She asked how I was. As soon as she said it, you know, “How are you feeling?”, I just cried’. 46(p696)

At the interpersonal level, a lack of a trusting relationship between women and HPs74,77,95,109,116,119,124,125,127,130 was the most cited barrier to disclosure:

I didn’t trust them I suppose so I didn’t tell the health visitors how I was feeling. 124(p618)

I: What are your views about the midwife asking these type of screening questions about mental health at the booking visit? P: If I didn’t know the midwives and they hadn’t known my history I think I probably wouldn’t have been honest with them. 119(p44)

At the organisational level, a lack of continuity of carer48,72,74,89,96,122,125,132 was the most cited barrier:

All CRs [community representatives] and some HPs [health professionals] regarded continuity of carers as critical to build trust, improve symptom monitoring and encourage disclosure: ‘everyday my doctor was changed I couldn’t make a relationship with … my doctor’. 122(p7)

At the societal level, stigma,46,48,76–78,84,93,96,116,119,122,124,127,130,134 culture47,48,74,76–78,87,89,90,95,96,116,127 and maternal norms46,47,72,74,77,79,89,92,119,124 were all barriers preventing the disclosure of PMH symptoms:

Oh well, I think there’s plenty, I mean I think there’s a huge stigma about feeling depressed particularly postnatal depression and people want to be, not to be thought of as a, you know, not being good mothers. 124(p618)

… in a context where suicide is still seen as a sign of weakness, a character flaw, it is difficult for individuals to ‘confess’ suicidal states and suicidal feelings. 87(p440)

I didn’t just … open up totally … to them. I wouldn’t want to … You know, it’s like an African community, and I felt, you know … If one person knows about it, 2 people know about … 3 people know about it … so I just cut off, um … I know it’s just the stigma … It’s just, you know, oh … look at the girl … I think it’s just, it’s just that I don’t want the stigma to just keep following me around. 78(p1742)

Referral

The most commonly cited factors affecting referral were HP and organisational level barriers. At the HP level, their knowledge about services and referral pathways49,70,109,120 was the most cited barrier. At the organisational level, lack of collaborative working across services69,112,113,116,120,127,129 and confusing organisational referral procedures116,120,122,127,129,130,134 were barriers.

The HPs interviewed in both Trusts were not always aware of the services available in other areas of the health service and recommended the provision and circulation of named links to support more joined up working.

Links with mental health are not the best, it is difficult to refer women unless they need to be admitted. (author quote)120(p103) If they are stable the mental health team are not so interested. Sometimes there is a lack of information from the key worker and information being shared. 120(p103)

At the commissioner level, confusing referral pathways was a barrier. 113,116,120,122,125,126 Participants spoke about the complexity of negotiating referrals:

We have to send the form; the patient has to ring to say did you get the form and I am now confirming that I am going to go and then they get an appointment, for someone who is very distressed and you are asking them to jump through hoops. 116(p5)

Access to treatment

Multiple factors influenced access to treatment. At the individual level, the most cited barriers to accessing care were logistical issues such as not having childcare,46,47,69,70,84,85,89,91,95,96,113,114,134,135 the location of the care and difficulties travelling there69,70,83–85,95,96,108,114,134–137 and the timing of appointments. 47,69,85,91,96,133,135 In some cases, these barriers could be exacerbated by a lack of support from family and friends:86,96,108–110,122,133,137

… they cannot take their child with them to their session … (and) a lot of times they cannot afford day care. 113(p4)

Yes, there was the issue of travelling. I cannot drive and my husband was admitted to the hospital …137(p4)

I can’t share my issues with my family. They don’t care about me, they don’t help me with the activities or remind me to do them or are willing to accompany me to the hospital. 133(p9)

Additional personal difficulties such as a lack of employment70,106,120,130,138 or women’s symptoms of their mental illness49,93,110,135 were also individual barriers to care:

My husband’s business is not doing well, financially we are struggling, we have children to look after, we have the responsibility to marry them off and give them dowry etc., all these worries are pulling me down. Talking to [the peer volunteer] can’t help me. 106(p6)

When I was experiencing mental health issues, it was harder for me to get out, sort of on a schedule and be punctual. 93(p15)

At the interpersonal level, language barriers were the biggest barrier to women accessing care48,70,89,96 and, related to this, a lack of culturally sensitive care was the most cited organisational level barrier to access:46,49,70,76,89,90,96

Hispanic women reported feeling ‘shuttled from service to service’ because no one knew how to take care of their culture. (author quote)90(p18)

Similarly, women reported that services did not recognise their cultural needs:

You need someone who’s on the same wavelength as you, who shares the same cultural experiences as you, which sometimes isn’t available. 46(p695)

Where logistical support was provided this was a facilitator to access, but when it was not provided it was a barrier:46,72,83,85,91,96,108,109,122,137,139

And we were offered a crèche facility; I used to take him there; otherwise it would have been really difficult for me. 137(p4)

At the commissioner level, the most cited barrier to access was a lack of appropriate or timely services for women:46,48,49,69,85,89,95,109,112,113,130

You shouldn’t have to press that danger button of ‘I’m gonna self-harm’ or ‘I’m gonna hurt my children’ for someone to help you. 48(p756)

At the political level, refugee or immigrant women fearing deportation70,81,90,95,109,134 and a lack of financial resources to pay for health care49,69,70,81,82,95,106,108,109,113,114,134,139,140 were barriers to access. These were often interlinked and exacerbated by each other:

… as Hispanics we do not have insurance and money is what really counts. 70(p12)

Because when you’re legal you can take the child to the day care and look for a job … if you don’t work, it’s like you’re dead, being alive. We want our papers so we can progress; not so we can leave or be a load to anyone, but just to work – to buy a home and give our kids a good life … I get depressed because I can’t live like normal people because I’m always thinking if I leave or if I stay …90(p13)

At the societal level, stigma,47,70,72,91,95,96,110,134 culture49,70,76,89,106 and maternal norms49,96 were also barriers for women choosing to access care:

It was difficult for me to accept that [I should see a psychiatrist] because, in our country, those who go to a psychiatrist are crazy. And I thought, ‘I’m not crazy. I don’t need it.’ And [the social worker] told me, ‘Not only crazy people need a psychiatrist, necessarily. In your case, you need it’. 110(p938)

Provision of optimal care

HP, interpersonal and organisational level factors were most likely to impact provision of optimal care. At the HP level, a lack of knowledge about PMH and treatment options,48,109,116,129,141–143 and low confidence in addressing PMH133,138,139,143,144 were barriers to the provision of optimal care:

[Women report] ‘Oh I was seeing so and so but when they found out I was pregnant they discontinued my medication’. That … happens frequently. Very frequently … their provider won’t [prescribe] because of their pregnancy. 142(p171)

Look, I feel insecure at the moment, as I have not yet had the chance to try IPT [interpersonal therapy], and I have to practice, and along with that get ready to try this method with a client and feel comfortable with it. 144(p79)

On the other hand, HPs possessing valued characteristics,94,105,106,114,130,138,145,146 such as being trustworthy and caring, were facilitators to the provision of optimal care:

… She was always there if I have a question or something and she always gets back to me no matter what. 114(p530)

At the interpersonal level, a lack of trusting relationship was a barrier to optimal care provision:69,72,91,146,147

Sometimes, I don’t feel very connected to the person that I call … so, sometimes, it gets awkward during the phone conversation. 146(p8)

At the organisational level, facilitators were collaborative working between106,109,116,120,122,129,131,142 and within organisations:122,126,129,130,134,136,138,139,148

[A patient] was discontinued off her lithium … [when she] found out she was pregnant … she wanted to hang herself … the OB [obstetrician] attending was saying, ‘She’s this far along in her pregnancy; the lithium isn’t going to hurt … and what’s worse for this woman? To expose her baby to lithium or to hang herself?’ … we were able to facilitate a conversation between the OB doctor and the patient’s psychiatrist and she did a great job … (and) put the woman back on lithium …142(p172)

A lack of training related to PMI and interventions was the most cited organisational level barrier74,106,109,114,120,126,132,138,141,143,146–149 to the provision of optimal care:

Midwives are not well equipped with mental health knowledge and skills. If midwives were trained on mental health they could do a better job …108(p6)

Organisational level facilitators to the provision of optimal care included providing culturally sensitive care47,81,95,96,109,116,146 that is individualised,48,49,114,116,123,132,137,145,146,148,150 appropriate to the women’s needs,116,132,133,138,139,143–149 flexible,93,109,129,133,138,144,146 delivered at home72,126,138,141,147 and provides information about PMI:47,48,72,80,84

… the online course, it was tailored to my needs at the time and I think that’s how it helped so much. 151(p26)

Flexibility in length of appointments was identified as a facilitator of effective assessment and support of immigrant women.

(author quote)109(p194)

Finally, another commonly valued aspect of support was receiving information from the HP. While the women found it helpful to learn about mental health and PPD [postpartum depression], they also valued the inclusion of information or feedback about parenting.

(author quote)72(p731)

At the commissioner level, a lack of appropriate and timely services79,108,113,116,120,138,147 and complexities around funding services were the most cited barriers to providing optimal care:109,120,128,134,135,139,140

Someone with PMH issues really does not belong in the general psychiatric outpatient clinic. 116(p6)

We are unable to serve every woman in need of ongoing care. We are therefore working on additional funds, both internally and externally, to secure long-term physical and behavioral health care for our patients. 140(p7)

At the political level, immigration status, such as being dependent on one’s partner,76,81,90,95,96 was a barrier to care:

Because we make argument, sometimes he hit me. I was alone and nobody to help me. Sometimes I was very nervous. I felt I’m his slave not his wife. He wanted everything to his hand and make control for everything in my life. I don’t think this is life. 90(p14)